Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was commissioned and funded by the HTA programme on behalf of NICE as project number 08/96/01. The protocol was agreed in July 2009. The assessment report began editorial review in February 2010 and was accepted for publication in July 2010. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HTA editors and publisher have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the referees for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2011. This work was produced by Picot et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This journal is a member of and subscribes to the principles of the Committee on Publication Ethics (COPE) (http://www.publicationethics.org/). This journal may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NETSCC, Health Technology Assessment, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2011 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Description of underlying health problem

Multiple myeloma (MM) is a type of cancer. The cancer (myeloma) tends to be located at more than one site where there is bone marrow, such as the pelvis, spine and ribs, which is why it is known as MM. 1 MM occurs when a plasma cell begins to proliferate in an unregulated way. Plasma cells are a specialised component of the bone marrow and immune system and they normally produce specific antibodies to fight infection. In MM the myeloma cells produce large quantities of one type of abnormal antibody – monoclonal immunoglobulin protein (M-protein). 2 As the abnormal myeloma cells build in number, the normal functions of bone marrow become impaired to varying degrees of severity because the abnormal myeloma cells may disrupt the function of normal cells, and because the space available for normal bone marrow may be reduced.

In the early stages of MM there may not be any symptoms or a range of symptoms may be present, which are not specific to MM, such as fatigue, weight loss and increased infections. A common presenting symptom of MM is bone pain, and/or bone fracture due to lytic bone lesions. Lytic bone lesions are a typical feature of MM and are caused because the malignant plasma cells impair normal bone repair functions. MM cells both produce and influence chemokines and cytokines, which causes bone resorption to become uncoupled from bone formation such that resorption predominates. 3

The most common finding on clinical investigation is anaemia. 4 This occurs because the presence of proliferating myeloma cells in the bone marrow negatively impacts on the ability of the bone marrow to produce red blood cells, leading to a reduction in red blood cells in the circulation, which contributes to the symptom of fatigue. Likewise, circulating numbers of other cells produced in the bone marrow are also reduced. The reduction in normal white blood cells and the antibodies these produce (hypogammaglobulinaemia) leads to an increased risk of infection, while the reduction in platelets contributes to easy bruising and other bleeding.

Other common findings on clinical investigation are M-protein, which is secreted by the myeloma cells, and an excess of calcium in the blood (hypercalcaemia), which occurs as a result of bone destruction. 5 The presence of M-protein in serum may increase blood viscosity, which is associated with an increased risk of thrombosis. A high level of serum protein (hyperproteinaemia), M-protein and light chains may also contribute to renal failure. The aetiology of this is generally multifactorial, and hypercalcaemia is another common contributing factor.

Multiple myeloma is one of a number of lymphoproliferative diseases classified by the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases 10th edition (ICD-10) as malignant neoplasms of lymphoid, haematopoietic and related tissue. 6 The exact aetiology of MM is unknown but it is clear that the malignant cells arise from a single plasma cell. Therefore, research has focused on gaining an understanding of the chain of events that occurs between haematopoietic stem cells giving rise to B lymphocytes in the bone marrow, and these B cells subsequently differentiating to form plasma cells. 7,8

Normally, plasma cells would contain a pair of each of the 22 autosomal (non-sex) chromosomes. Myeloma cells, however, display a variety of genetic abnormalities. Common abnormalities of MM cells include aneuploidy (an abnormal number of chromosomes) and translocations (exchange of material between two different chromosomes). When aneuploidy is present, monosomies (one copy of a chromosome) are more common than trisomies (three copies of a chromosome). One of the most common monosomies is the loss of one copy of chromosome 13, which is associated with a shorter survival and lower response rate to treatment. 9,10 Of the translocations t(11;14)(q13;q32) and t(4;14)(p16.3;q32) are the most common; the former is associated with improved survival, whereas the latter is an indication of an unfavourable prognosis. 9,10 The genetic abnormalities underlying cases of MM can be identified by cytogenetic techniques, such as conventional karyotype analysis and fluorescence in situ hybridisation.

Prognosis

Myeloma is not curable, but can be treated with a combination of supportive measures and chemotherapy to improve survival and quality of life (QoL). A range of factors affects prognosis. These include factors related to burden of disease [e.g. beta2-microglobulin (β2-microglobulin)], characteristics of the myeloma cells’ biology (e.g. the type of cytogenetic abnormality present), the microenvironment surrounding the myeloma cells (e.g. bone marrow microvessel density), patient-related factors (e.g. age and performance status) and treatment response factors [e.g. whether complete response (CR) is achieved with initial therapy]. 5 Because of the number of factors that affect prognosis, survival of patients from the point of diagnosis varies from months to over a decade. 4 In the UK and Ireland, median survival increased from around 2 years in the 1980s and early 1990s to around 4 years in the late 1990s. 11 There is evidence from some cohorts of patients that novel therapies can extend median survival time to 8 years. 12

Epidemiology

Multiple myeloma is the second most common haematological cancer after lymphoma in the UK. In 2007 there were 3357 new diagnoses of MM in England,13 with the highest incidence among those aged 75–79 years (Table 1). In Wales, in the 3 years from 2004 to 2006, an average of 252 new MM diagnoses were recorded. 14 MM is rare before the age of 40 years. The average incidence rates were higher in men than in women, and higher for both sexes in Wales compared with England (Table 2). There are ethnic differences in incidence rates that have been observed in data from the USA; in black people (African American and other black people, but not Hispanic people) the incidence of MM is about twice that of white people, whereas in Asian people the incidence is lower than that of white people. 15 The statistical information team at Cancer Research UK has used incidence and mortality data for 2001–5 to estimate the lifetime risk of developing MM, which is 1 in 148 for men and 1 in 186 for women in the UK. 16 There are currently approximately 10,000–15,000 people living with MM in the UK. 17

| Age group (years) | Nos.a | Ratesb | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Males | Females | Males | Females | |

| 20–24 | 2 | 1 | 0.1 | 0.1 |

| 25–29 | 3 | 4 | 0.2 | 0.2 |

| 30–34 | 9 | 4 | 0.5 | 0.2 |

| 35–39 | 11 | 7 | 0.6 | 0.4 |

| 40–44 | 26 | 17 | 1.3 | 0.9 |

| 45–49 | 47 | 31 | 2.7 | 1.7 |

| 50–54 | 96 | 51 | 6.3 | 3.3 |

| 55–59 | 158 | 91 | 10.3 | 5.7 |

| 60–64 | 214 | 174 | 15.1 | 11.7 |

| 65–69 | 239 | 176 | 22.2 | 15.2 |

| 70–74 | 300 | 217 | 32.7 | 20.9 |

| 75–79 | 324 | 248 | 44.8 | 26.8 |

| 80–84 | 256 | 238 | 53.2 | 32.3 |

| 85+ | 173 | 240 | 50.2 | 31.7 |

| Men | Women | |

|---|---|---|

| England | 6.0 | 3.9 |

| Wales | 6.8 | 4.9 |

The risk factors for developing MM are not well defined but there is evidence for involvement of genetic factors because the first-degree relatives of people with MM are at greater risk of developing MM and related conditions than the first-degree relatives of people without MM. 8,18 Epidemiological studies have looked for evidence of a causal link between a range of potential environmental risk factors and MM but, in general, these have not produced consistent results. 4,8

Diagnosis and staging

Multiple myeloma is typically diagnosed in secondary care using a combination of tests such as urine tests, blood tests, bone marrow examination, imaging, plain radiograph and/or magnetic resonance imaging. If necessary, further tests can be conducted to find out the stage of disease. 1 There are two systems for staging MM. The Durie–Salmon19 (DS) staging system, which has been in use since 1975, is one of the systems but this is gradually being replaced by an updated system, the International Staging System (ISS). 20 This new system is based on measurement of two serum proteins, β2-microglobulin and albumin (Table 3). A patient with stage I disease will not necessarily proceed linearly through disease stages. Stage III disease can be reached without a requirement to pass through stage II first. It is also noteworthy that staging does not have a significant influence on treatment. If MM is symptomatic, treatment is required irrespective of disease stage.

| Stage | Criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| DS19 | ISS20 | |

| I | All of the following:

|

|

| II | Fitting neither stage I nor stage III | Not stage I or III:

|

| III | One or more of the following:

|

|

| Subgroup for each stage |

A – If relatively normal renal function (serum creatinine value < 2.0 mg/100 ml) B – If abnormal renal function (serum creatinine value ≥ 2.0 mg/100 ml) |

|

Current service provision

The aim of treatment for MM is to extend the duration and quality of survival by alleviating symptoms and achieving disease control while minimising the adverse effects of the treatment. 21 First-line treatment aims to achieve a period of stable disease (plateau phase) for as long as possible, prolonging survival and maximising QoL. In England and Wales the choice of first-line treatment depends on a combination of factors, including age, comorbidity, social factors and performance status of the patient. High-dose chemotherapy (HDT) with autologous stem-cell transplantation (SCT) will be offered if appropriate for the patient. However, the British Society for Haematology (BSH) guidelines on the diagnosis and management of MM (2005)22 state that (p. 428) ‘Although high-dose is recommended where possible, the majority of patients will not be able to receive such therapy because of age, specific problems or poor performance status’. For those patients who are not able to withstand such an intensive type of treatment, single-agent or combination chemotherapy (which is less intensive) may be offered as a first-line treatment. Patients eligible for HDT will get initial chemotherapy to reduce disease burden before transplant.

Typically, combination therapies include chemotherapy with an alkylating agent (such as melphalan or cyclophosphamide) and a corticosteroid (such as prednisolone or dexamethasone). The treatment recommended by the 2005 guidelines for patients who are unable to receive intensive treatment was either melphalan or cyclophosphamide, given either with or without prednisolone. 22 More recent treatment options may also include drugs such as thalidomide23–25 (Thalidomide Celgene®, Celgene, Uxbridge, UK) and bortezomib26 (Velcade®, Janssen–Cilag, High Wycombe, UK). Such drugs are being investigated in ongoing clinical trials, such as the Medical Research Council (MRC)-funded Myeloma IX study,27 which has compared thalidomide in combination with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone (CTDa) against the standard drug combination of melphalan with prednisolone (MP).

The BSH guideline on the diagnosis and management of MM is being revised and updated. The draft of these revised guidelines28 contains a recommendation that, for older and/or less fit patients in whom high-dose therapy is not planned, the initial therapy should consist of either a thalidomide-containing regimen in combination with an alkylating agent and steroid [such as thalidomide in combination with MP (MPT) or CTDa] or bortezomib in combination with melphalan and prednisolone (VMP). The draft revised guideline indicates that the choice of first-line therapy should take into account patient preference, comorbidities and the toxicity profile of the treatments. 28

After first-line treatment most patients will show a response. Response is usually assessed based on changes in serum levels of M-protein and/or urinary light chain excretion, and ranges from partial to complete remission, but almost all patients will eventually relapse. A minority of patients will have disease that proves resistant to primary treatment.

In addition to chemotherapy, patients also require concomitant supportive therapy to control the symptoms of the disease, including bisphosphonates to treat bone disease, erythropoietin to treat anaemia, antibiotics to treat infections and various types of pain medication. Prophylaxis against thrombosis is recommended in the thalidomide summary of product characteristics (SPC) for the first 5 months that patients receive thalidomide. 29 In the UK this recommendation for prophylaxis against thrombosis is followed, but there is less agreement about whether to continue with prophylaxis for the entire duration of thalidomide therapy. Therefore, clinical practice is likely to vary. Side effects of treatment may result in discontinuation or change of chemotherapy treatment.

UK clinical experts have indicated that the most common combination therapy used as a first-line treatment for patients who are not able to withstand high-dose therapy is CTDa. The second most common therapy is MPT, with the ratio of patients on CTDa to those on MPT being approximately 2 : 1, although in some areas the ratio may be nearer 3 : 1. Intolerance to thalidomide limits its use in some patients, and occurrence of peripheral neuropathy limits the duration of treatment in some patients (clinical opinion expert advisor). VMP is not widely used as a first-line treatment, but may be used in the subgroup of patients who have renal impairment or failure at presentation. Use of MP is declining, but this is still used in patients who cannot tolerate thalidomide or where the use of thalidomide is contraindicated (clinical opinion expert advisor).

As noted above (see Description of underlying health problem) there is some evidence that myeloma that is characterised by a high-risk cytogenetic abnormality can demonstrate a poor response to conventional treatment. However, although there is interest in the use of cytogenetic data as a prognostic indicator, the incorporation of cytogenetic data into decisions about treatment choice is not currently supported in the UK. 22,28

When patients relapse after first-line treatment most will receive a second-line treatment. The choice of second-line treatment is individualised to the patient and, in theory, a patient could receive the same therapy that they received as a first-line treatment, particularly if this had been effective and the remission had lasted a long time. However, in current UK practice many patients will receive bortezomib monotherapy as a second-line treatment because, as noted below, this has been recommended by the National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence (NICE). Similarly when patients relapse after second-line treatment the treatment recommended by NICE for this patient group is lenalidomide.

In addition to the BSH guidelines on the diagnosis and management of MM,22 two NICE technology appraisals have been completed for MM. NICE (TA12930) has previously recommended bortezomib monotherapy for relapsed MM as a possible treatment for progressive MM for people:

-

whose MM has relapsed for the first time after having one treatment, and

-

who have had a SCT, or who are unsuitable to receive one.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has also recommended lenalidomide (a structural derivative of thalidomide) when used in combination with dexamethasone as a possible treatment for MM when people have already received at least two other treatments (TA17131). Neither of these NICE appraisals considered first-line therapy for MM.

One technology appraisal is in development – denosumab for the treatment of bone metastases from solid tumours and MM – but the scope of this appraisal was not available at the time of writing (January 2010). A draft scope for consultation was issued in March 2010.

The National Institute for Health and Clinical Excellence has also published Guidance on Cancer Services – Improving Outcomes in Haematological Cancers – The Manual. 32 This document covers all haematological cancers, including MM, and makes recommendations for service delivery and organisation. Some information about current service costs are included but these relate to the haematological cancer service as a whole.

Description of technology under assessment

Two interventions are being considered in this assessment:21 bortezomib in combination therapy with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid, and thalidomide in combination therapy with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid. The scope of this review allows for the inclusion of bortezomib or thalidomide when used in combination with any alkylating agent and any corticosteroid. This may therefore include drug combinations that are not covered by the licences for bortezomib and thalidomide, for example CTDa.

Place of the interventions in the treatment pathway

In this assessment bortezomib and thalidomide are being considered for use in combination therapy with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid as a first-line treatment for MM in patients who are not eligible for HDT with autologous SCT.

Bortezomib

Bortezomib (Velcade®, manufacturer Janssen–Cilag, High Wycombe, UK) is a proteasome inhibitor that is specific for the 26S proteasome of mammalian cells and it has been designed to inhibit the chymotrypsin-like activity of this proteasome. Inhibition of the proteasome by bortezomib affects cancer cells in a number of ways, resulting in cell cycle arrest and apoptosis, which causes a reduction in tumour growth. 33

Bortezomib is administered by injection. It was initially granted a marketing authorisation in the European Union in 2004 as a therapy for patients with MM who had received at least two prior lines of treatment. Subsequently, in 2005, the indication was extended to enable treatment, earlier in the course of the disease, for relapsed MM in patients who have progressed after receiving at least one previous line of treatment. 34

In 2008 the marketing authorisation for bortezomib was extended further for the following indication: ‘Velcade in combination with melphalan and prednisone is indicated for the treatment of patients with previously untreated MM who are not eligible for high-dose chemotherapy with bone marrow transplant’ (p. 2). 34

The SPC for bortezomib33 recommends nine 6-week treatment cycles for combined therapy with VMP. During these treatment cycles bortezomib is administered as a 3- to 5-second bolus intravenous injection through a peripheral or central intravenous catheter at a dose of 1.3 mg/m2 of body surface area, followed by a flush with sodium chloride 9 mg/ml (0.9%) solution for injection. In the first four cycles of treatment, bortezomib is administered twice weekly. For cycles 5–9, bortezomib is administered once weekly. Melphalan (9 mg/m2) and prednisone (60 mg/m2) are both administered orally on days 1, 2, 3 and 4 of the first week of each cycle. The dose and total number of cycles may change depending on the patient’s response to treatment and on the occurrence of certain side effects. Because the licence for bortezomib does not cover its use in combination with agents other than melphalan and prednisone the SPC does not provide dosage information for any other alkylating agents or corticosteroids.

The net price for a 3.5-mg vial of bortezomib is £762.38. 35 Full details of the estimated drug costs associated with the use of bortezomib as a first-line treatment for MM are described within our independent economic evaluation (see Chapter 5, SHTAC data sources, Estimation of costs).

Thalidomide

Thalidomide is an immunosuppressive agent with antiangiogenic and other activities that are not fully characterised. It is also a non-barbiturate centrally active hypnotic sedative. Although the precise mechanism of action is unknown and under investigation, the effects of thalidomide are immunomodulatory, anti-inflammatory and antineoplastic. 29

Thalidomide (formerly known as Thalidomide Pharmion) is taken orally. It was granted a marketing authorisation in 2008 for use in combination with melphalan and prednisone as first-line treatment for patients with untreated MM, aged ≤ 65 years or who were ineligible for HDT. Because thalidomide is a known human teratogen it must be prescribed and dispensed according to the Thalidomide Pharmion Pregnancy Prevention Programme.

The SPC for thalidomide29 recommends an oral dose of 200 mg per day, taken as a single dose at bedtime to reduce the impact of somnolence. However, the advisory group for this review has indicated that treatment usually starts with a lower dose, which is gradually increased if the patient can tolerate this. In the UK, most patients who are ineligible for HDT and SCT are likely to receive a 100-mg dose. A maximum number of 12 cycles of 6 weeks is recommended. Thromboprophylaxis should also be administered for at least the first 5 months of treatment, especially in patients with additional thrombotic risk factors. The dose and total number of cycles may change depending on the patient’s response to treatment and on the occurrence of certain side effects.

The SPC does not recommend particular doses or dosing schedule for melphalan and prednisone when administered in combination with thalidomide (licensed indication). Because the licence for thalidomide does not cover its use in combination with agents other than melphalan and prednisone the SPC does not provide dosage information for any other alkylating agents or corticosteroids.

The net price of a 50-mg × 28-capsule pack of thalidomide is £298.48. 35 Full details of the estimated drug costs associated with the use of thalidomide as a first-line treatment for MM are described within our independent economic evaluation (see Chapter 5, SHTAC data sources, Estimation of costs).

Chapter 2 Definition of the decision problem

This section states the key factors that will be addressed by this assessment, and defines the scope of the assessment in terms of these key factors in line with the definitions provided in the NICE scope. 21

Decision problem

Two interventions are included within the scope of this assessment. These are (1) bortezomib in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid and (2) thalidomide in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid. In both cases the focus of this assessment is the use of these combination chemotherapies for the first-line treatment of MM.

The population that is being considered by this assessment is people with previously untreated MM, for whom HDT with SCT is not appropriate. If sufficient evidence is available consideration will be given to specific patient subgroups, for example patients with different prognostic factors such as β2-microglobulin, performance status and stage, patients whose MM has different cytogenetic features, and patients who have a comorbidity such as renal impairment. Additionally, if the evidence allows, consideration will be given to the number of treatment cycles and continuation rules for treatment.

The interventions will be assessed when compared with melphalan or cyclophosphamide in combination with prednisolone or dexamethasone. The NICE scope also allows for the interventions to be compared with one another. In this assessment we will include interventions using prednisone as well as prednisolone. Prednisone, which is not used in the UK, is converted into the biologically active steroid prednisolone by the liver. 36 Prednisone and prednisolone are equally effective, they are used in the same manner, and doses are largely equivalent.

The clinical outcomes of interest include overall survival (OS), progression-free survival (PFS), time to progression (TTP), response rates, health-related quality of life (HRQoL), and adverse effects (AEs) of treatment. Other outcomes of interest, such as duration of treatment, or second-line treatments received may also be reported. Outcomes for the cost-effectiveness assessment will include direct costs based on estimates of health-care resources associated with the interventions as well as consequences of the interventions, such as treatment of AEs.

Overall aims and objectives of assessment

The aim of this health technology assessment (HTA) is to systematically assess the evidence on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of bortezomib or thalidomide in combination regimens with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid for the first-line treatment of MM. 21

Chapter 3 Methods

The a priori methods for systematically reviewing the evidence of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness are described in the research protocol (Appendix 1), which was sent to our expert advisory group for comment. None of the comments we received identified specific problems with the methods of the review. The methods outlined in the protocol are briefly summarised below.

Search strategy

The search strategies were developed and tested by an experienced information specialist. The strategies were designed to identify studies reporting clinical effectiveness, cost-effectiveness, HRQoL, resource use and costs, epidemiology and natural history.

The following databases were searched for published studies and ongoing research from 1999 (earliest use of thalidomide for MM37 and earliest description of bortezomib as a potential cancer therapy38) to December 2009: MEDLINE, MEDLINE In-Process, EMBASE, Web Of Science, BIOSIS, Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE), HTA, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL). Bibliographies of articles and grey literature sources were also searched. Reference lists within drug manufacturers’ submissions (MSs) to NICE were searched for any additional studies that met the inclusion criteria. Our expert advisory group was asked to identify additional published and unpublished references. Searches were restricted to English language. Further details, including an example search strategy, can be found in Appendix 2.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Study design

-

For the systematic review of clinical effectiveness, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion. In addition, evidence from good-quality observational studies was also eligible for consideration if the data from available RCTs were incomplete (e.g. absence of data on outcomes of interest).

-

For the systematic review of cost-effectiveness economic evaluations (such as cost-effectiveness studies, cost–utility studies, cost–benefit studies) were eligible for inclusion.

-

Abstracts or conference presentations of studies were eligible for inclusion only if sufficient details were presented to allow an appraisal of the methodology and the assessment of results to be undertaken.

-

Case series, case studies, narrative reviews, editorials and opinions were excluded, as were non-English-language studies. Systematic reviews and clinical guidelines were used only as a source of references.

Intervention(s)

-

Bortezomib in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid for first-line treatment of MM.

-

Thalidomide in combination with an alkylating agent and a corticosteroid for first-line treatment of MM.

-

Studies of treatment with either bortezomib or thalidomide as a single agent were excluded.

Comparator(s)

-

Interventions described above compared with each other.

-

Melphalan or cyclophosphamide in combination with prednisolone/prednisone or dexamethasone.

-

Other chemotherapy regimens or SCT were excluded.

Population

-

People with previously untreated MM who are not candidates for HDT with SCT.

-

Studies of MM patients who had received previous treatment(s) were excluded.

Outcomes

Studies were included if they reported on one or more of the following outcomes:

-

overall survival

-

progression-free survival (deaths counted as events)

-

time to progression (deaths are excluded from the calculation of this outcome)

-

response rates

-

health-related quality of life

-

cost-effectiveness [such as incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gained]

-

adverse events of treatment were reported when available within the trials that met the inclusion criteria.

Response definitions

-

Response to treatment is usually assessed based on changes in serum levels of M-protein and/or urinary light chain excretion. Two different systems for categorising response are included in this report, the European Group for Blood and Marrow Transplantation (EBMT) criteria39 and the Intergroupe Francophone du Myélome (IFM) criteria. 23 Where there are differences in the two systems, in general the EBMT criteria require a slightly greater improvement. For example, in the definition of partial response (PR) one of the IFM requirements is more than a 75% reduction in 24-hour urinary light chain excretion, whereas one of the EBMT criteria for PR is a 90% decrease in urinary light chain excretion. The EBMT and IFM criteria for judging response are provided in Appendix 3.

Adverse event definitions

-

Two slightly different National Cancer Institute (NCI) criteria have been used to grade AEs, the NCI Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE) version 4, and the NCI Common Toxicity Criteria (CTC) version 2. The NCI CTCAE version 4 grades AEs on a five-point scale (1–5) and the NCI CTC version 2 grades AEs on a six-point scale, as 0 is included (0 = no AE or within normal limits). Events of a higher grade are more serious than those at a lower grade, with a grade 1 event described as ‘mild’, grade 2 ‘moderate’, a grade 3 event would be considered ‘severe’, while a grade 4 event could be ‘life threatening’. Grade 5 is reserved for deaths related to an AE.

Inclusion and data extraction process

Studies were selected for inclusion in the systematic reviews of clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness through a two-stage process. Literature search results (titles and abstracts) were screened independently by two reviewers to identify all of the citations that might meet the inclusion criteria. Full manuscripts of selected citations were then retrieved and assessed by one reviewer against the inclusion/exclusion criteria and checked independently by a second reviewer. Discrepancies were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Data from included studies were extracted by one reviewer using a standardised data extraction form and each data extraction was checked for accuracy by a second reviewer. Again discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved by discussion, with involvement of a third reviewer when necessary.

Critical appraisal strategy

The quality of included clinical effectiveness studies was assessed using the CRD criteria. 40 Quality criteria were applied by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer with any disagreements resolved by consensus and involvement of a third reviewer where necessary.

Methods of data synthesis

Clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness studies were synthesised through a narrative review with tabulation of results of included studies. Results of included RCTs were meta-analysed if appropriate (more than one trial with populations, interventions and outcomes believed to be sufficiently similar) and possible (adequate data reported). For time-to-event analyses (OS and PFS) the log-hazard ratio (HR) and its standard error (SE) for each outcome were used to calculate a summary HR and 95% confidence interval (CI) using the Cochrane Collaboration Review Manager 5.0.23 software. However, as the SEs of the log-HRs were not reported by the RCTs, these had to be estimated using the methods and Microsoft Excel spreadsheet of Tierney and colleagues. 41

This report contains reference to confidential information provided as part of the NICE appraisal process. This information has been removed from the report and the results, discussions and conclusions of the report do not include the confidential information. These sections are clearly marked in the report.

Chapter 4 Clinical effectiveness

Results of the systematic review of clinical effectiveness

Quantity and quality of research available

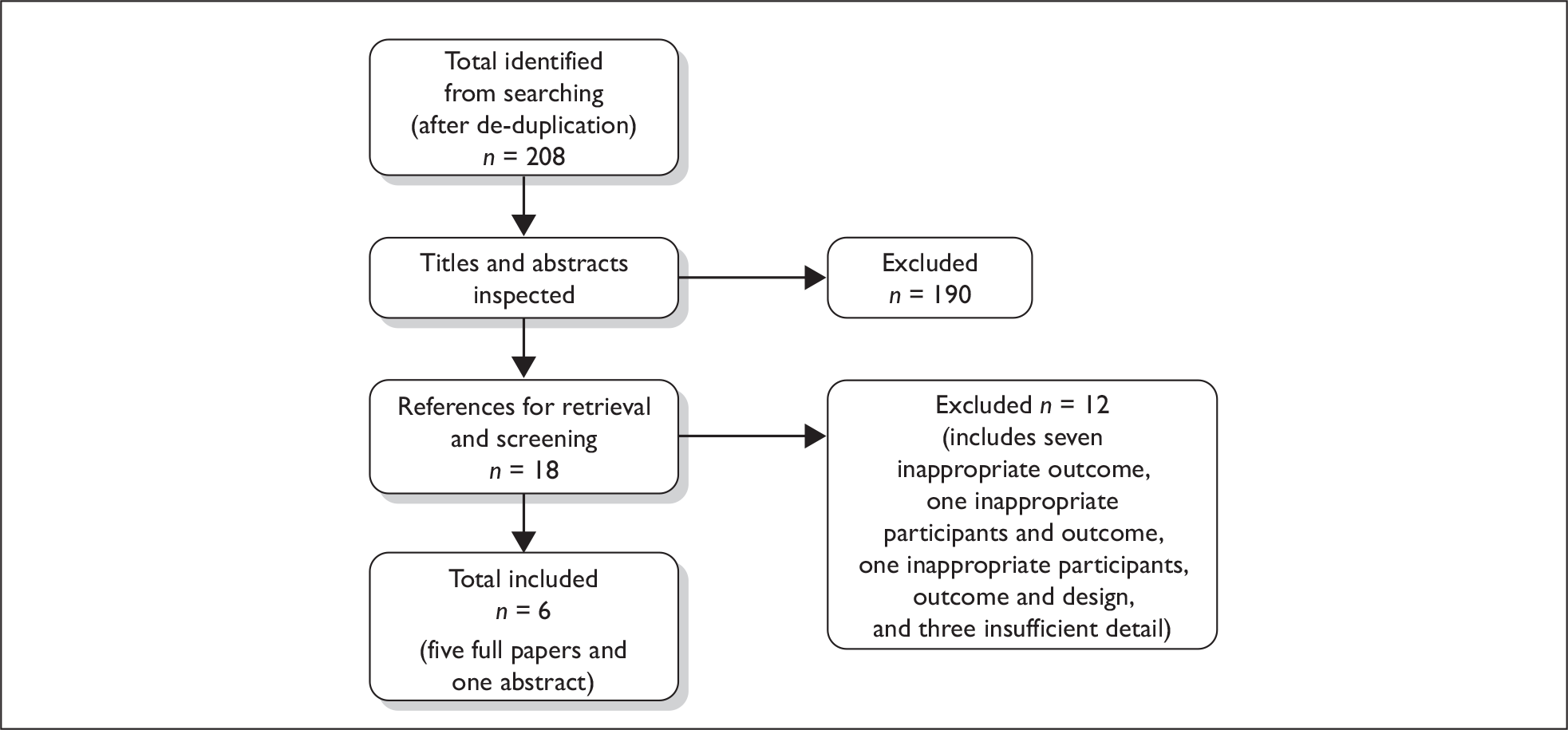

Titles and, where available, abstracts of a total of 1436 records were screened and full copies of 40 references were retrieved. Of these, six were excluded after inspection of the full article (see Appendix 4). Two of these articles were excluded because they were not clinical trial reports, two were abstracts that were excluded because they described maintenance therapy with thalidomide, another abstract was excluded because it did not report on any of the outcomes of interest, and a sixth abstract described a systematic review with meta-analysis. Five full papers described four RCTs that met the inclusion criteria of the review (Figure 1 and Table 4). Each RCT was described by at least one full paper, with linked abstracts also being available. As the full papers provided the most complete data these were the primary source of information for the review.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of reference screening processes. a, Additional information was received from the trialists providing details for one RCT only described in conference abstracts. The additional details allowed us to appraise the study methodology and make judgements about study quality. Results from this RCT could therefore be considered for inclusion in the systematic review of clinical effectiveness. b, Outcomes from these studies could not be included because of insufficient details about study methodology and insufficient details about study quality. These studies, which are all ongoing, are briefly summarised below (see Ongoing studies).

| Study detailsa |

VISTA trial Multicentre RCT at 151 centres in 22 countries in Europe, North and South America, Asia 682 enrolled |

Facon et al. 23 IFM 99/06 trial Multicentre RCT at 73 centres in France, Belgium, and Switzerland 447 enrolled to all three groups |

Hulin et al. 59 IFM 01/01 trial Multicentre RCT at 44 centres in France and Belgium 232 enrolled |

Palumbo et al. 24 GIMEMA network Multicentre RCT at 54 centres in Italy 331 enrolled (255 followed up) |

MMIX Trial: non-intensive pathway49,52 Multicentre RCT (AiC/CiC information has been removed) in the UK (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| Median follow-up |

Abstract 25.9 months60 Abstract 36.7 months61 |

51.5 monthsb | 47.5 monthsb |

38.4 months MPTc 37.7 months MP |

(AiC/CiC information has been removed)d (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| Intervention |

VMP: n = 344 9 × 6-week cycles of bortezomib (1.3 mg/m2) on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29 and 32 during cycles 1–4 and on days 1, 8, 22 and 29 during cycles 5–9 + MP melphalan (9 mg/m2) plus prednisone (60 mg/m2) on days 1–4 of each cycle |

MPT: n = 125 Thalidomide < 400 mg daily for 12 MP cycles (i.e. 72 weeks) + MP 12 × 6 week cycles of melphalan 0.25 mg/kg and prednisone 2 mg/kg on 4 days per cycle |

MPT: n = 115 Thalidomide 100 mg daily for 72 weeks + MP 12 × 6 week cycles of melphalan 0.2 mg/kg and prednisone 2 mg/kg on days 1–4 of each cycle |

MPT: n = 167 (129 followed up) Thalidomide 100 mg daily for six MPT cycles (i.e. for 24 weeks) + MP 6 × 4 week cycles of melphalan 4 mg/m2 and prednisone 40 mg/m2 on days 1–7 of each cycle |

CTDa: (AiC/CiC information has been removed) Thalidomide: 50 mg daily for 4 weeks, increasing every 4 weeks by 50-mg increments to 200 mg daily + Cyclophosphamide: 500 mg once a week, on days 1, 8, 15 and 22 of each cycle Dexamethasone: 20 mg daily on days 1–4 and 15–18 of each cycle Cycle length 4 weeks, to maximal response, but with a minimum–maximum number of cycles of 6–9 |

| Comparator |

MP: n = 338 MP: 9 × 6-week cycles of melphalan (9 mg/m2) plus prednisone (60 mg/m2) on days 1–4 of each cycle |

MP: n = 196 MP: 12 × 6 week cycles of melphalan 0.25 mg/kg and prednisone 2 mg/kg on 4 days per cycle Third arm did not meet inclusion criteria |

MP + placebo: n = 117 Placebo daily for 72 weeks + MP 12 × 6 week cycles of melphalan 0.2 mg/kg and prednisone 2 mg/kg on days 1–4 of each cycle |

MP: n = 164 enrolled (126 followed up) MP: 6 × 4 week cycles of melphalan 4 mg/m2 and prednisone 40 mg/m2 on days 1–7 of each cycle |

MP: (AiC/CiC information has been removed) MP: Six to nine cycles of melphalan 7 mg/m2 and prednisolone dose 40 mg on days 1–4 of a 4-week cycle |

| Key attributes of participants |

Not candidates for HDT with SCT because of age 65 years or over, or co-existing conditions Newly diagnosed and previously untreated Measurable disease |

Aged between 65 and 75 years Previously untreated MM at DS stage II or III Patients younger than 65 years were included if they were ineligible for high-dose treatment Patients with DS stage I MM who met criteria of high-risk stage I disease |

Aged at least 75 years Newly diagnosed MM at DS stage II or III Patients with DS stage I MM who met criteria of high-risk stage I disease Patients with non-secretory or oligosecretory MM allowed |

Older than 65 years of age Younger participants included if unable to undergo transplantation Previously untreated DS stage II or III MM Measurable disease |

Aged at least 18 years Newly diagnosed symptomatic MM or non-secretory MM |

| Selected baseline characteristics |

Median age (years, range): VMP 71 (57–90) MP 71 (48–91) |

Age ≥ 70 years: MPT 50/125 (40%) MP 84/196 (43%) |

Age ≥ 80 years: MPT 43/113 (38%) MP + placebo 40/116 (34%) |

Median age (years): MPT 72 MP 72 |

(AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| Gender (M : F) |

VMP 175 : 169 (51% : 49%) MP 166 : 172 (49% : 51%) |

MPT 63 : 62 (50% : 50%) MP 109/87 (56% : 44%) |

MPT 43 : 70 (38% : 62%) MP + placebo 61 : 55 (53% : 47%) |

NR | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| Disease stage (DS or ISS criteria) |

ISS stage: Stage I VMP 19%, MP 19% Stage II VMP 47%, MP 47% Stage III VMP 35%, MP 34% |

DS stage II or III MPT 112/125 (90%) MP 177/196 (91%) |

DS stage II or III MPT 100/113 (89%) MP + placebo 107/116 (93%) |

DS stage II or III MPT 129/129 (100%) MP 126/126 (100%) Calculated by reviewer |

(AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| Performance statuse |

Karnofsky performance status ≤ 70: VMP 122 (35%) MP 111 (33%) |

WHO performance index 3–4: MPT 10/125 (8%) MP 13/196 (7%) |

WHO performance index 3–4: MPT 9/113 (8%) MP 7/116 (6%) |

WHO performance index 3–4: MPT 9/129 (7%) MP 6/126 (4%) |

WHO performance index 3: (AiC/CiC information has been removed) WHO performance WHO performance index 4: (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| Bone lesions present |

VMP 224/343 (65%) MP 222/336 (66%) |

MPT 90/125 (76%) MP 154/196 (79%) |

MPT 87/113 (78%) MP + placebo 93/116 (82%) |

NR | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| Primary outcome(s) | Time to disease progression | OS | OS | Response rates, PFS | OS, PFS, response |

| Secondary outcomes | Rate of CR, duration of response, time to subsequent myeloma therapy, OS, PFS | Response, PFS, survival after progression, toxicity | Safety, response rates, PFS | OS, time to first evidence of response, prognostic factors, frequency of any grade 3 or higher AEs | QoL, skeletal-related events, height loss, toxicity, proportion receiving bortezomib–dexamethasone as ‘early rescue’ on induction chemotherapy, or at relapse |

One ongoing RCT, the Myeloma IX (MMIX) Trial, which is a UK-based MRC collaborative RCT with two treatment pathways, appeared to meet the inclusion criteria of the review and was described in conference abstracts. The search for studies of clinical effectiveness identified four abstracts for this RCT,42–45 with a further three abstracts identified in the MSs. 46–48 Four of the abstracts,42–44,47 were excluded because they described the intensive pathway or thalidomide maintenance treatment that did not meet the inclusion criteria for this review. Three abstracts45,46,48 described the non-intensive pathway that met the inclusion criteria. The final results from the 3-year median follow-up have not yet been published. However, because of this RCT’s potential relevance to our inclusion criteria, the Clinical Trials Research Unit (CTRU) at the University of Leeds, who are coordinating the RCT, provided the trial protocol,49 additional background information50,51 and trial baseline data,52 and have also made the results from the non-intensive treatment pathway53–58 available to NICE and the authors of this report in academic confidence. As the trial protocol and results provided directly by the CTRU provided the most complete and up-to-date data these were used as the primary source of information for the review.

Four additional ongoing RCTs were described in conference abstracts but it was unclear whether these met the inclusion criteria for this review. These ‘unclear’ studies are briefly described later in this chapter (see Ongoing studies). The total number of records assessed at each stage of the systematic review screening process is shown in the flow chart in Figure 1.

One of the included RCTs evaluated VMP (VISTA trial),26 while three RCTs evaluated MPT [IFM 01/01 trial,59 IFM 99/06 trial,23 and the Gruppo Italiano Malattie Ematologiche dell’Adulto (GIMEMA – Italian Group for Adult Hematologic Diseases) trial24]. The fifth RCT, the MMIX Trial (non-intensive pathway), evaluated CTDa. The comparator in all five of the included RCTs was MP.

Bortezomib in combination with melphalan and prednisone (VISTA trial)

The RCT investigating VMP was a randomised (1 : 1), open-label, Phase III trial conducted in 151 centres in 22 countries in Europe, North and South America, and Asia. The RCT enrolled 682 participants and was funded by two industry sponsors (see Table 4).

Patients received nine 6-week cycles of melphalan (at a dose of 9 mg/m2 of body surface area) and prednisone (at a dose of 60 mg/m2) on days 1–4, alone or in combination with bortezomib (at a dose of 1.3 mg/m2), by intravenous bolus on days 1, 4, 8, 11, 22, 25, 29 and 32 during cycles 1–4 and on days 1, 8, 22 and 29 during cycles 5–9. The dose of bortezomib or melphalan was reduced if there was any prespecified haematological toxic effect or grade 3 or 4 non-haematological effect. Patients with myeloma-associated bone disease received bisphosphonates unless such therapy was contraindicated.

Patients were eligible if they had newly diagnosed, untreated, symptomatic, measurable myeloma and were not candidates for HDT plus SCT because of age (≥ 65 years) or co-existing conditions. Measurable disease was defined as the presence of quantifiable M-protein in serum or urine, or measurable soft-tissue or organ plasmacytomas. Over 80% of patients had ISS stage II or III disease, about one-third had a Karnofsky performance score of ≤ 70%, and over 60% had lytic bone lesions. Most participants were white. No exclusion criteria for study entry were stated.

During the 54-week treatment period, blood and urine samples were collected every 3 weeks. After completion of treatment, samples were collected every 8 weeks until disease progression. Patients were followed after disease progression at least every 12 weeks for survival and subsequent myeloma therapy.

The primary outcome measure was time to disease progression. The study was powered at 80% for the primary outcome but no power calculations were reported for patient subgroups. Secondary outcomes were rate of CR, duration of response time, time to subsequent myeloma therapy, OS and PFS. Disease progression was defined by EBMT criteria and assessed by investigators. The sponsors also determined progression with the use of a computer algorithm that applied EBMT criteria. Data are presented in the published paper from the assessment by investigators and from the algorithmic analysis. TTP, time to subsequent myeloma therapy and OS were analysed from randomisation to the event of interest.

Thalidomide in combination with melphalan and prednisone (IFM and GIMEMA trials)

All three of the included RCTs investigating MPT were multicentre trials. The number of centres ranged from 44 to 73 and all were located in one or more European countries (France, Belgium, Switzerland, Italy). The IFM RCT by Facon and colleagues23 was the largest, recruiting 447 patients; however, only 321 participants are reported on here because this trial had a third arm (reduced-intensity SCT), which is not relevant to this review as the intervention does not meet the inclusion criteria. The GIMEMA group RCT by Palumbo and colleagues24 enrolled 331 participants, and the remaining IFM RCT, Hulin and colleagues,59 enrolled 232 participants (see Table 4). All of the RCTs received free thalidomide for the study from the drug manufacturers but other funding costs were met by grants from other sources (see Appendix 5).

The dosing schedules of the RCTs varied in terms of overall length and the drug doses used. Hulin and colleagues59 and Facon and colleagues,23 the two IFM RCTs, had 72-week treatment periods consisting of 12 six-week treatment cycles. The treatment period in the GIMEMA group RCT by Palumbo and colleagues24 was shorter, lasting for 24 weeks and consisting of six 4-week treatment cycles. The intervention in each RCT was MPT. Thalidomide was prescribed as a set 100-mg daily dose in the RCTs by Hulin and colleagues59 and Palumbo and colleagues,24 whereas a 400-mg daily dose was the goal of Facon and colleagues (if this could be tolerated). 23 In the two IFM RCTs,23,59 doses were described according to body weight. The dosing schedule of MP (on days 1–4 of each 6-week treatment cycle) and prednisone dose (2 mg/kg prednisone) were the same in both RCTs, while the melphalan doses differed slightly (Hulin and colleagues,59 0.2 mg/kg of melphalan; Facon and colleagues,23 0.25 mg/kg of melphalan). Palumbo and colleagues24 described drug doses according to body surface area. Melphalan (4 mg/m2) and prednisone (40 mg/m2) were taken on days 1–7 of each 4-week treatment cycle. All RCTs allowed thalidomide dose adjustments. In each RCT the comparator was MP alone (no thalidomide prescribed), provided in the same manner as in the MPT arms as described (also see Table 4). Only one RCT, Hulin and colleagues,59 included a placebo in place of thalidomide in the comparator arm.

As mentioned earlier, to be included in this systematic review, RCTs had to report on treatment of participants with MM who were not eligible for HDT with SCT and who had not been previously treated. All participants in each RCT met these criteria. The two IFM RCTs differed in the target age range of participants: Hulin and colleagues59 focused on people aged at least 75 years, whereas Facon and colleagues23 focused on people aged between 65 and 75 years, with younger patients being eligible for inclusion providing they were not eligible for HDT. Palumbo and colleagues24 focused on people who were older than 65 years of age without specifying any upper age limit, and, like Facon and colleagues,23 did include participants who were younger than 65 years, providing that they were unable to undergo SCT. All RCTs included people whose MM was at DS stage II or III, and the two IFM RCTs23,59 also included patients with DS stage I MM if they met the criteria for high-risk stage I disease. The percentage of participants in the IFM23,59 and GIMEMA24 RCTs with a WHO performance status score of 3 or 4 ranged from 4% to 8%. Over three-quarters of the participants in the IFM RCTs had bone lesions but this information was not reported by Palumbo and colleagues24 (see Table 4). None of the RCTs reported on the ethnicity of the participants.

All three RCTs specified their exclusion criteria. In the two IFM RCTs23,59 these were almost identical, the only difference being that Hulin and colleagues59 excluded anyone with a history of venous thrombosis during the previous 6 months in addition to the other exclusions [anyone with previous neoplasms (except basocellular cutaneous or cervical epithelioma); primary or associated amyloidosis; a WHO performance index of 3 or higher, if unrelated to MM; substantial renal insufficiency with creatinine serum concentration of 50 mg/l or more; cardiac or hepatic dysfunction; peripheral neuropathy; HIV infection, or hepatitis B or C infections]. Palumbo and colleagues24 listed fewer exclusion criteria. Two were similar to those of the IFM RCTs (exclusion of people with another cancer or any grade 2 peripheral neuropathy) and one was novel to this RCT (exclusion of people with psychiatric disease). Palumbo and colleagues24 also stated that abnormal cardiac function, chronic respiratory disease, and abnormal liver or renal functions were not criteria for exclusion.

The timing of clinic visits during the RCTs varied. Palumbo and colleagues24 monitored response to treatment every 4 weeks, whereas visits were scheduled every 6 weeks for the RCT by Hulin and colleagues59 until treatment completion or study withdrawal. Facon and colleagues23 saw participants after inclusion at 3 months, 6 months and then every 6 months thereafter until withdrawal from the RCT. When scheduled clinic visits ended (after withdrawal or end of treatment), Palumbo and colleagues24 continued to assess participants every 2 months, and the two IFM RCTs23,59 continued to assess participants every 6 months.

Overall survival was the primary outcome measure for the two IFM RCTs. 23,59 Both RCTs were powered at 80% for the primary outcome but recruitment was stopped early in both RCTs because interim analyses had demonstrated a clear survival advantage. The secondary outcomes of these RCTs were response rates,23,59 PFS,23,59 survival after progression,23 toxicity23 and safety. 59 Facon and colleagues23 report some of their outcomes for more than one follow-up period. OS, PFS and survival after progression analyses were reported for a data point of 8 January 2007; these outcomes were also reported along with all other outcomes for the earlier date point of 8 October 2005. In contrast, the primary outcomes of the RCT by Palumbo and colleagues24 were stated as response rates and PFS. A power calculation was reported for the response outcome. The secondary outcomes of this RCT were OS, time to first evidence of response, prognostic factors, and frequency of any grade 3 or higher AEs.

Thalidomide in combination with cyclophosphamide and attenuated dexamethasone (MMIX Trial)

The MMIX RCT non-intensive pathway evaluated CTDa in comparison with MP. Participants were randomised in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either CTDa or MP. Within each treatment arm, participants were also randomised to bisphosphonate treatment with either sodium clondronate or zoledronic acid. This multicentre RCT was conducted [academic-in-confidence (AiC) and/or commercial-in-confidence (CiC) information has been removed] in the UK (AiC/CiC information has been removed) (see Table 4). The RCT was funded by a core grant from the MRC, with some other funding provided by five industry sponsors and one charitable sector sponsor (see Appendix 5).

The treatment period with CTDa in the intervention arm was designed to be between 24 and 36 weeks, equivalent to a minimum of six, or a maximum of nine, 4-week treatment cycles. Thalidomide was prescribed as a daily starting dose of 50 mg with the aim that this would be increased every 4 weeks by 50 mg to a maximum of 200 mg. During each 4-week treatment cycle 500 mg of cyclophosphamide was taken once a week on days 1, 8, 15 and 22, and dexamethasone 20 mg was taken daily on days 1–4 and days 15–18 of each cycle. Participants in the comparator arm received MP (melphalan 7 mg/m2 and prednisolone 40 mg) on days 1–4 of each 4-week cycle. Dose adjustments were permitted in both RCT arms.

In common with the other included RCTs, patients were eligible if they were newly diagnosed with symptomatic MM or non-secretory MM and had not received previous treatment for myeloma (other than local radiotherapy). The MMIX non-intensive pathway was designed for older (generally ≥ 70 years of age) or less fit patients (who could be younger than 70 years) but strict age restrictions were not in place to ensure that fit older patients were not excluded from the intensive therapy arm. (AiC and CiC information has been removed.) Exclusion criteria included asymptomatic MM, solitary plasmacytoma of bone and extramedullary plasmacytoma (without evidence of myeloma). People with acute renal failure were excluded but those with a history of ischaemic heart disease or psychiatric disorder could be considered for inclusion at the discretion of the clinician. Further details of exclusion criteria can be found in Appendix 5.

Overall survival, PFS, and response were the co-primary outcomes and power calculations were provided for both survival and response. Secondary outcomes were QoL, skeletal-related events, height loss, toxicity (thromboembolic events, renal toxicity, haematological toxicity, graft-versus-host disease) and proportion receiving bortezomib–dexamethasone as ‘early rescue’ on induction chemotherapy, or at relapse.

Quality assessment of included studies

The outcome of the quality assessment of included RCTs is summarised in Table 5.

| Study | Randomisation sequence | Allocation concealment | Balanced baseline characteristics | Blinding | Dropout imbalance | More outcomes than reported | ITT analysis | Missing data accounted for |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Miguel et al.26,60 | NR | NR | Yes | No | ? | No | Yes | ?a |

| Facon et al.23 | NR | NR | ? | NR | ? | No | Yes | ? |

| Hulin et al.59 | NR | Yes | Yes | ? | ? | No | Yes | ? |

| Palumbo et al.24 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | ? | No | Yes | ? |

| MMIX49,50,52 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | NR | No | Yes | ? |

Bortezomib in combination with melphalan and prednisone

The VISTA study of VMP versus MP was an RCT, with randomisation stratified according to baseline levels of β2-microglobulin, serum albumin and region. However, no details are given on the methods used to generate random numbers or conceal allocation to treatment group, and therefore it is not possible to know whether the RCT is at risk of selection bias due to unbalanced confounding factors and failure to adequately conceal allocation. Baseline demographics and disease characteristics are reported to be well balanced between the two groups. The RCT is described as open label, which suggests that researchers and/or participants were not blinded. As bortezomib is administered intravenously the researchers may have felt blinding was not possible. However, for objective outcomes, such as OS, risk of bias is low regardless of lack of blinding. There is no evidence that more outcomes were measured than reported by study authors. The authors did not report whether there were any unexpected imbalances in dropouts between the groups. TTP, time to subsequent myeloma therapy, and OS from randomisation were analysed in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population (all randomised patients). For TTP analyses, data from patients for whom there was no disease progression were censored at the last assessment, or at the start of subsequent therapy. Although not explicitly stated it is assumed that deaths without disease progression were not included in the outcome of TTP. Details of censoring in terms of number of patients with censored data and reasons for censoring in each group are not given. The response analysis was not ITT as seven patients in each group could not be evaluated for a response: five did not receive the study drug; three patients in the VMP arm and six patients in the MP arm had no measurable disease at baseline on the basis of assessment by a central laboratory (although the patients met the eligibility criteria of measurable disease according to evaluation by a local laboratory).

Thalidomide in combination with melphalan and prednisone

All of the included studies were RCTs of MPT versus MP. However, one of the three RCTs, Facon and colleagues,23 did not report on the methods used to generate random allocations or how the allocations were concealed. Without this information we cannot be certain that the randomisation method balanced out confounding factors or that allocation bias has been avoided in this RCT. Hulin and colleagues59 did not report on the method used to generate the randomisation sequence but the central allocation of patients should have provided adequate allocation concealment. Palumbo and colleagues24 were the only authors to report sufficient information about randomisation and allocation concealment, allowing this RCT to be judged at low risk from unbalanced confounding factors and low risk of allocation bias.

All three MPT RCTs reported on the baseline characteristics of participants according to treatment group. Hulin and colleagues59 provided an indication that statistical testing had been used to test the similarity of the groups at baseline, and reported that the only statistically significant difference was for sex (more female participants in MPT group, p = 0.03). However, Facon and colleagues23 did not report on whether the groups had been judged to be similar at baseline. Palumbo and colleagues24 stated that baseline demographics and other characteristics of the two groups were balanced.

One of the three MPT RCTs, Palumbo and colleagues,24 was not blinded, and this was clearly stated by the authors. One of the RCTs, Hulin and colleagues,59 involved the use of a placebo in the comparator arm, which suggests blinding may have been in place although this was not explicitly stated. The third MPT RCT did not report whether blinding was in place or not. In each RCT some of the outcomes were objective (e.g. survival) and therefore the risk of bias for these would be low, regardless of whether blinding was in place or not.

There was no evidence in any of the MPT RCTs that more outcomes were measured than were reported. But for each of the three MPT RCTs it was unclear whether there were any unexpected imbalances in dropouts between groups because none of the RCT authors commented on this. 23,24,59

All of the MPT RCTs stated that an ITT analysis had been conducted but the details of these analyses and methods used to account for missing data were unclear due to poor reporting. Hulin and colleagues59 stated that an ITT analysis was conducted, but in this case the ITT analysis appears to have excluded three randomised participants who discontinued before study treatment (two in the MPT group and one in the MP group). Facon and colleagues23 stated that an ITT analysis was conducted and, from the numbers provided in the results for OS and PFS, but not response, their ITT analysis appears to have included all patients randomised, including those who were not treated as assigned. Palumbo and colleagues24 stated an ITT analysis had been conducted at 6 months (the only outcome point eligible for inclusion in this review) but at the time of analysis not all randomised participants had been enrolled for 6 months. Therefore, 76 out of the 331 randomised participants (38 in each arm) were not included in the analysis of 6-month data. As these RCTs reported time-to-event data, such as OS and PFS, it was expected that some data would be censored. However, only one RCT, Hulin and colleagues,59 stated when data on patients who were alive were censored in the survival analysis and when data on patients without disease progression were censored for the analysis of PFS. One of the MPT RCTs, Facon and colleagues,23 marked the position of censored data on the survival plots but none of the RCTs reported details of how many participants’ data were censored, and for what reason (e.g. censored due to withdrawal, censored due to death from an unrelated cause such as a car accident or censored as event of interest not experienced). It is not possible to determine whether the amount and pattern of censoring was comparable between the groups and whether this had any effect on outcomes.

Thalidomide in combination with cyclophosphamide and attenuated dexamethasone

The MMIX study of CTDa versus MP was an RCT (with randomisation) that used a minimisation algorithm, stratified by centre, haemoglobin, corrected serum calcium, serum creatinine and platelets. 49,52 No details are reported on the methods used to generate random numbers; however, allocation to treatment groups was adequately concealed by the use of an automated 24-hour telephone system. The RCT is therefore at a low risk of selection bias. (AiC/CiC information has been removed.) The RCT was not a blinded RCT, but, as already noted for the other included RCTs, the risk of bias is low for the objective outcomes. There is no evidence that more outcomes have been measured during the RCT than are reported. The authors did not report whether there were any unexpected imbalances in dropouts between the groups. All summaries and analyses were by ITT unless stated otherwise and ITT was defined as all patients randomised, with the exception of those misdiagnosed. For the QoL data the analysis includes all patients who agreed to take part in the QoL study. Patients with missing follow-up data or who had not experienced progression were censored on the last date they were known to be alive and progression free. OS was calculated from initial randomisation to death. Patients with missing follow-up data, or not known to have died at time of analysis, were censored on the last date they were known to be alive. It was not reported whether the amount and pattern of censoring was comparable between the groups. PFS was calculated from random assignment to progression or death. There was no other censoring of data.

Assessment of effectiveness

Overall survival

Overall survival was a secondary outcome in the VISTA RCT of VMP versus MP (Table 6) and was calculated from randomisation. A statistically significant survival benefit for VMP compared with MP is reported in an abstract60 after a median follow-up of 25.9 months (HR = 0.64, p = 0.0032). Three-year survival rates in a more recent abstract61 after a median follow-up of 36.7 months were 68.5% versus 54%, respectively. At the earlier median follow-up of 16.3 months, reported in the published paper,26 median OS had not been reached. However, San Miguel and colleagues26,60 stated that a survival benefit was associated with bortezomib because 45 patients (13%) in the VMP group had died in comparison with 76 patients (22%) in the MP group (HR 0.61, p = 0.008) (despite 43%60 of MP patients receiving subsequent bortezomib therapy after disease progression – see Table 21). The most recent abstract reports that median OS is 43.1 months in the MP group but not estimable in the VMP group. 61

| Study | Median follow-up (months) | Treatment arms | HR and p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| San Miguel et al.26 VISTA | ||||

| VMP (n = 344) | MP (n = 338) | |||

| OS (abstract61) | 36.7 | Not estimable | 43.1 months | 0.653; 0.0008 |

| OS (abstract60) | 25.9 | NR | NR | 0.64; 0.0032 |

| OS26 | 16.3 | Median survival not reached | Median survival not reached | 0.61; 0.008 |

| Deaths26 | 45/344 (13%) | 76/338 (22%) | ||

| Three-year survival rate (abstract61): % | 68.5 | 54.0 | NR | |

| Three-year survival rate (abstract60): % | 72 | 59 | NR | |

| Facon et al.23 IFM 99/06 | ||||

| MPT (n = 125) | MP (n = 196) | |||

| OS:a median (SE, IQR) |

51.5 (IQR 34.4–63.2) |

51.6 (4.5, 26.6 to ‘not reached’) months | 33.2 (3.2, 13.8 to 54.8) months | 0.59 (95% CI 0.46 to 0.81); 0.0006 |

| Deaths | 62/125 (50%) | 128/196 (65%) | ||

| Hulin et al.59 IFM 01/01 | ||||

| MPT (n = 113) | MP + placebo (n = 116) | |||

| OS: median (95% CI) | 47.5 | 44.0 (33.4 to 58.7) months | 29.1 (26.4 to 34.9) months | 0.68 (95% CI not reported); 0.028 |

| Deathsb | 58/113 (51%) | 76/116 (65.5%) | 0.03 | |

Two23,59 of the three RCTs investigating MPT versus MP alone reported OS as their primary outcome. Both RCTs calculated OS from randomisation but only one of them, Hulin and colleagues,59 explained that data on patients who were alive at the time of analysis were censored in the survival analysis on the last date they were known to be alive. For the third RCT,24 OS was a secondary outcome and was not eligible for inclusion in this systematic review because participants received maintenance therapy with thalidomide after the six 4-week cycles of MPT were completed.

A statistically significant difference in OS in favour of the MPT group was found by both RCTs (see Table 6). Facon and colleagues23 reported their results after a median follow-up of 51.5 months. In the MPT group there were 62 events (deaths) and median survival was 51.6 months [interquartile range (IQR) 26.6 to ‘not reached’], whereas in the MP group, where there were 128 events, median survival was 33.2 months (IQR 13.8–54.8). The difference in OS was statistically significant, with an estimated HR for median OS in favour of MPT of 0.59 (95% CI 0.46 to 0.81, p = 0.0006). When adjusting for prognostic factors (e.g. WHO performance index; β2-microglobulin, albumin, etc.) the results showed that MPT remained the superior treatment in terms of the specified outcome OS (HR 0.49, 95% CI 0.33 to 0.73, p = 0.0002) (see Appendix 5). Similarly Hulin and colleagues,59 reporting after a slightly shorter median follow-up of 47.5 months, found that the median survival of 44 months (95% CI 33.4 to 58.7) in the MPT group was statistically significantly longer than in the MP + placebo group where median survival was 29.1 months (95% CI 26.4 to 34.9). In this RCT the reported HR for median OS in favour of MPT was 0.68 (95% CI for the HR not reported, p = 0.028).

As noted above, neither RCT reported on the amount of censored data, or the reasons for this. It is therefore not possible to determine whether censored data had any impact on the outcome of OS.

The MMIX RCT49 OS outcome was not eligible for inclusion in this systematic review because participants were entered into a second randomisation to receive either maintenance therapy with thalidomide or no maintenance therapy after they had completed first-line treatment with either CTDa or MP.

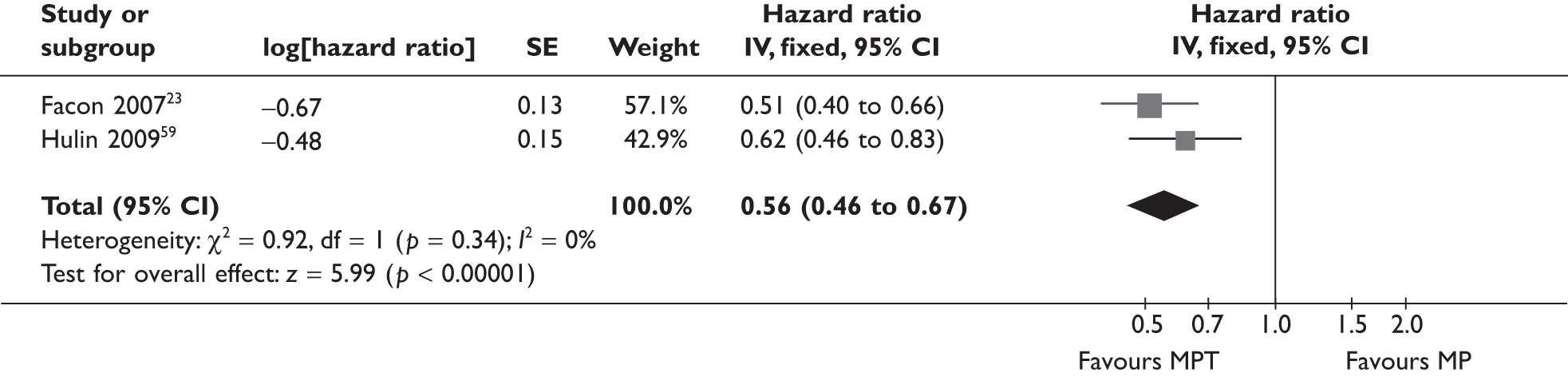

Two MPT versus MP RCTs23,59 reported OS outcome data that met the inclusion criteria of the review. A fixed-effects meta-analysis was conducted and, as can be seen in Figure 2, the I2-test suggests there is little or no heterogeneity between the two RCTs for this outcome. The summary OS HR was 0.62 (95% CI 0.50 to 0.77) in favour of MPT.

FIGURE 2.

Melphalan, prednisolone/prednisone plus thalidomide vs MP OS.

The Facon study23 CIs shown in Figure 2 obtained from Review Manager are slightly different to those reported by the published paper and shown in Table 6. The difference arises from the estimating method41 used to obtain the SEs for the log-HRs needed to undertake the meta-analysis.

Deaths during treatment

In the VISTA RCT26 of VMP versus MP, death rates during treatment were similar for the VMP group and the MP group (5% and 4%, respectively) (Table 7). San Miguel and colleagues26 also report that treatment-related deaths were similar in the two groups, but the time at which these deaths occurred is not reported (treatment-related deaths VMP 1% and MP group 2%).

| Study | Treatment arms | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| San Miguel et al.26 VISTA | |||

| VMP (n = 344) | MP (n = 338) | ||

| Deaths during treatment (%) | 5 | 4 | NR |

| Treatment-related deaths (%) | 1 | 2 | NR |

| Facon et al.23 IFM 99/06 | |||

| MPT (n = 124) | MP (n = 193) | ||

| Toxic death | n = 0 | n = 4 (2%), all due to infection | NR |

| Early death – in first 3 months of treatment (n, %) | 3/124 (2) | 13/193 (7) | NR |

| aHulin et al.59 IFM 01/01 | |||

| MPT (n = 113) | MP + placebo (n = 116) | ||

| Toxic death (intestinal perforation) | n = 1 | n = 1 | NR |

| Early death – after 1 month of treatment | n = 3 | n = 3 | NR |

| Early death – after 3 months of treatment | n = 5 | n = 6 | NR |

| MMIX49,53,54 | |||

| CTDa (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | MP (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | ||

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

The two RCTs of MPT that report OS23,59 also provide some information about the deaths that occurred. Facon and colleagues23 provided very limited information, commenting on only toxic deaths (no definition is provided but the term toxic death usually refers to a treatment-related death) and deaths within the first 3 months of treatment (see Table 7). In the MPT group there were no toxic deaths and only three deaths in the first 3 months of treatment. In the MP group there were both more toxic deaths (four deaths all due to infection) and more early deaths (13 deaths) but, as no statistical comparison between the arms is reported, it is not known whether these differences were statistically significant.

Hulin and colleagues59 reported only one toxic death in the MPT group and one in the MP + placebo group. Both of these toxic deaths were caused by intestinal perforation. The number of early deaths was also very similar between the groups. In the MPT group three deaths were reported after 1 month of treatment, and five deaths after 3 months of treatment. In the MP + placebo group, three deaths were reported after 1 month of treatment and six after 3 months of treatment. For both study arms it is not clear whether the number of deaths reported after 3 months is a cumulative value, i.e. including the deaths reported after 1 month of treatment, or whether these are additional deaths that have occurred in months 2 and 3.

(AiC/CiC information has been removed.)

Response to treatment

Various response to treatment rates are reported as secondary outcomes in the VISTA RCT of VMP (Table 8),26 although the analysis is not ITT as previously explained. The time at which response was assessed is not reported. Rates of PR or better (according to EBMT criteria, Appendix 3) were 71% in the VMP group and 35% in the MP group (p < 0.001), and the CR rates were 30% and 4%, respectively (p < 0.001). The rate of PR was 40% in the VMP group and 31% in the MP group and minimal response (MR) rates were 9% and 22%, respectively. Stable disease rates were 18% in the VMP group and 40% in the MP group, and progressive disease rates were 1% and 2%, respectively.

| Study | Treatment arms | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| San Miguel et al.26 VISTA | |||

| VMP (n = 344): n/N (%) | MP (n = 338): n/N (%) | ||

| Rate of PR or better | 238/337 (71) | 115/331 (35) | < 0.001 |

| Rate of CR | 102/337 (30) | 12/331 (4) | < 0.001 |

| Rate of PR | 136/337 (40) | 103/331 (31) | NR |

| MR | 32/337 (9) | 72/331 (22) | NR |

| Stable disease | 60/337 (18) | 113/331 (40) | NR |

| Progressive disease | 3/337 (1) | 7/331 (2) | NR |

| Facon et al.23 IFM 99/06 | |||

| MPT (n = 125): n/N (%) | MP (n = 196): n/N (%) | ||

| CR at 12 months | 10/75 (13) | 4/165 (2) | 0.0008 |

| At least PR at 12 months | 57/75 (76) | 57/165 (35) | < 0.0001 |

| At least very good PR at 12 months | 35/75 (47) | 11/165 (7) | < 0.0001 |

| Hulin et al.59 IFM 01/01 | |||

| MPT (n = 115): n/N (%) | MP + placebo (n = 117): n/N (%) | ||

| CR at 12 months | 7/107 (7) | 1/112 (1) | < 0.001 |

| At least PR at 12 months | 66/107 (62) | 35/112 (31) | < 0.001 |

| At least very good PR at 12 months | 23/107 (21) | 8/112 (7) | < 0.001 |

| Palumbo et al.24 GIMEMA | |||

| MPT (n = 167, 129 analysed): n/N (%) | MP (n = 164, 126 analysed): n/N (%) | Absolute difference MPT–MP: % (95% CI) | |

| CR at 6 months | 20/129 (15.5) | 3/126 (2.4) | 13.1 (6.3 to 20.5) |

| Complete or PR at 6 months | 98/129 (76.0) | 60/126 (47.6) | 28.3 (16.5 to 39.1) |

| PR | 78/129 (60.4) | 57/126 (45.2) | 15.2 (3.0 to 26.9) |

| Near CR | 16/129 (12.4) | 6/126 (4.8) | NR |

| 90–99% M-protein reduction | 11/129 (8.5) | 6/126 (4.8) | NR |

| 50–89% M-protein reduction | 51/129 (39.5) | 45/126 (35.7) | NR |

| MR at 6 months | 7/129 (5.4) | 21/126 (16.7) | –11.2 (–19.2 to –3.6) |

| No response at 6 months | 7/129 (5.4) | 19/126 (15.1) | –9.7 (–17.4 to –2.2) |

| Progressive disease at 6 months | 10/129 (7.8) | 21/126 (16.7) | –8.9 (–17.2 to –0.8) |

| Not available | 7/129 (5.4) | 5/126 (4.0) | NR |

| MMIX49,53,54 | |||

| CTDa (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | MP (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | p-value | |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

| (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) | (AiC/CiC information has been removed) |

All three RCTs investigating MPT reported on response to treatment (see Table 8). 23,24,59 The two IFM RCTs23,59 reported the response at 12 months as a secondary outcome, and response was judged according to their own criteria. These criteria are very similar, but not identical, to the EBMT criteria that were used in the RCT by Palumbo and colleagues24 to assess response at 6 months, which was the primary outcome of this RCT (see Appendix 5). Facon and colleagues23 stated that all analyses were undertaken on an ITT basis; it is therefore unclear why response to treatment outcomes are reported for only 60% of the MPT group (75 of the 125 participants enrolled to this group) and 84% of the MP group (165 of 196 enrolled). Hulin and colleagues59 did not indicate that all analyses were ITT (only survival analyses were clearly stated to be ITT) but response to treatment is reported for 93% of the MPT group and 96% of the MP + placebo group. Palumbo and colleagues24 reported on all of those who contributed to the 6-month follow-up results. However, as noted earlier, not all of the randomised participants contributed data to this outcome because some participants had not achieved 6 months of follow-up when these data were analysed.

At 12 months, statistically significant differences in CR in favour of the MPT group were observed in both the IFM RCTs. 23,59 Facon and colleagues23 reported 13% of 75 participants in the MPT group had achieved CR at 12 months in comparison with just 2% of 165 participants in the MP group (p = 0.008). Caution must be applied in interpreting these results, however, which appear to be based on a small proportion of the participants. The difference between the groups reported by Hulin and colleagues59 was less marked but still statistically significant (MPT 7% of 107 participants CR versus 1% of 112 participants in MP + placebo group, p < 0.001). Palumbo and colleagues24 reported an absolute difference in CR MPT–MP at 6 months of 13% (95% CI 6.3 to 20.5).