Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by PGfAR as project number RP-PG-0407-10184. The contractual start date was in August 2007. The final report began editorial review in November 2012 and was accepted for publication in August 2013. As the funder, the PGfAR programme agreed the research questions and study designs in advance with the investigators. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The PGfAR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

For objective 1, one subanalysis was a collaboration with Manchester University (funded by the Colt Foundation). For objective 5, collaborations with Healthcare for London and the National Audit Office (NAO) were developed.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Wolfe et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction to report

This report brings together the outputs from a 3-year programme of health services research in stroke. The report provides a Scientific summary with the key findings from the programme. Chapter 2 provides the background to the programme submitted as part of the original National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) programme grant submission. Chapter 3 provides detailed methodology of the South London Stroke Register (SLSR), the main data set used for modelling and evaluating cost-effective services to reduce the impact of stroke. Chapters 4–9 address each scientific objective and Chapter 10 addresses the conclusions from the work, the implications for policy, practice and further research. Appendices 1–4 contain the original application, information on the Stroke Research Patients and Family Group (SRPFG), capacity building and the scientific outputs from the programme.

The SLSR commenced in 1995 and has been funded by a variety of government and charity grants over its 17 years. This programme utilises data taken since 1995 to address the objectives. For each objective, there are deliverables with a timeline for completion during the programme, which are specified in each chapter.

Each chapter begins with an abstract describing the aims, methods and results, followed by the deliverables, for the objective. For each deliverable, only a brief background is provided as the full rationale for the analyses is given in the original bid. The chapters differ in length as some entail more analyses and deliverables than others. The results are presented as succinctly as possible and, if the data were already in the public domain, we provide only abstracts of the findings and reference the original source that contains the detailed methodologies and results. There is a discussion of the results for each deliverable and, at the end of each chapter, conclusions and implications for further research are reported. Chapter 10 brings the conclusions for all objectives together and describes the legacy of the programme, the main findings and the implications for policy, practice and research.

The programme built on our existing stroke research group at King’s College London and the objectives and deliverables were managed by the authors, managing groups of researchers to address each one within the timeline. The group met fortnightly to oversee the progress of analysis and fieldwork, and there was an annual meeting of the collaborators of the programme to monitor the progress.

Chapter 2 Background to the programme from original programme submission as rationale for the objectives and deliverables in the report

It is estimated that each year 5.3 million people worldwide die as a result of stroke and there are over 9 million survivors. 1 There are significant variations in incidence worldwide. 2,3 In the UK, the incidence is 1–2 per 1000 population,4,5 with significantly higher risk in ethnic minorities and lower socioeconomic groups. 4,6

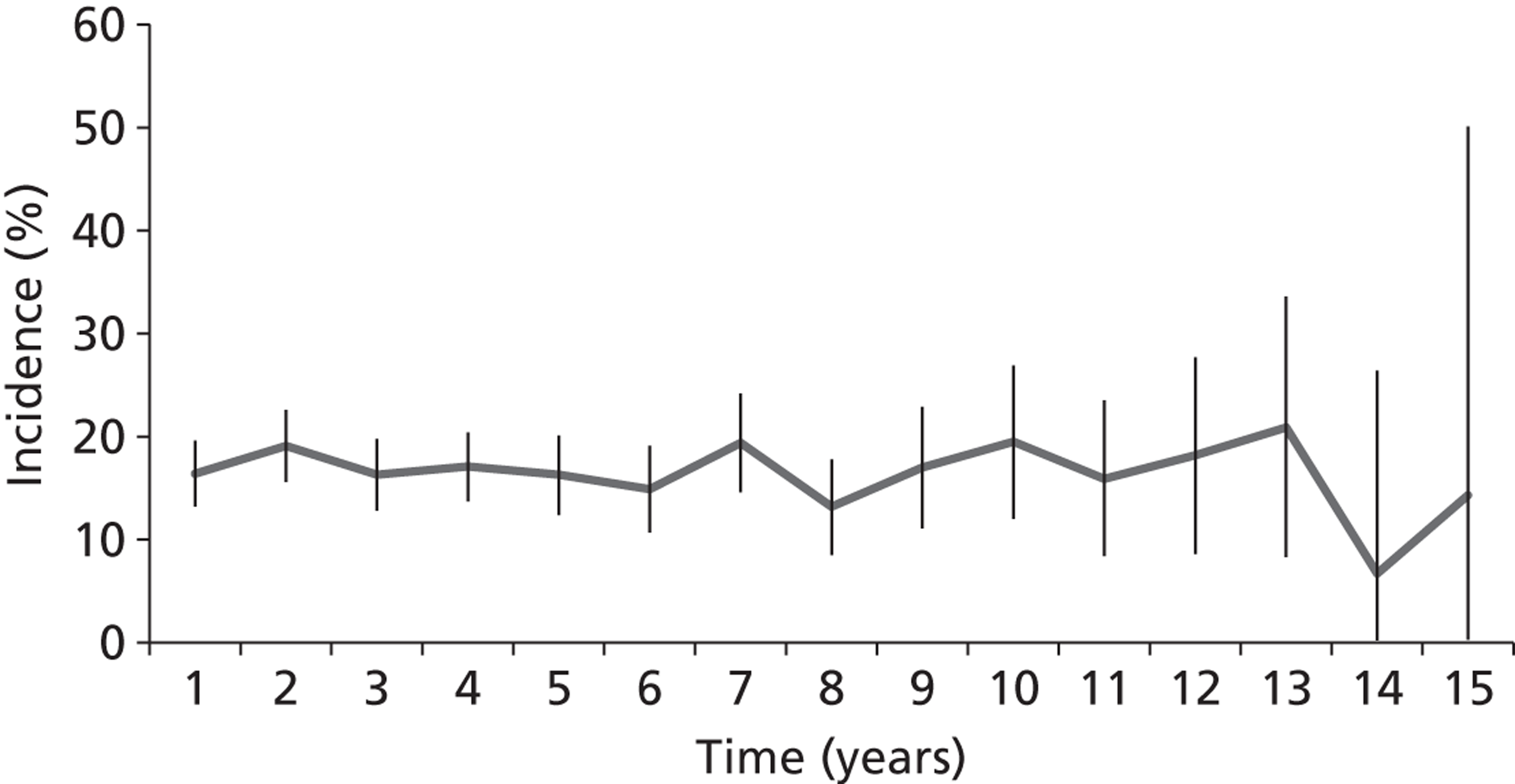

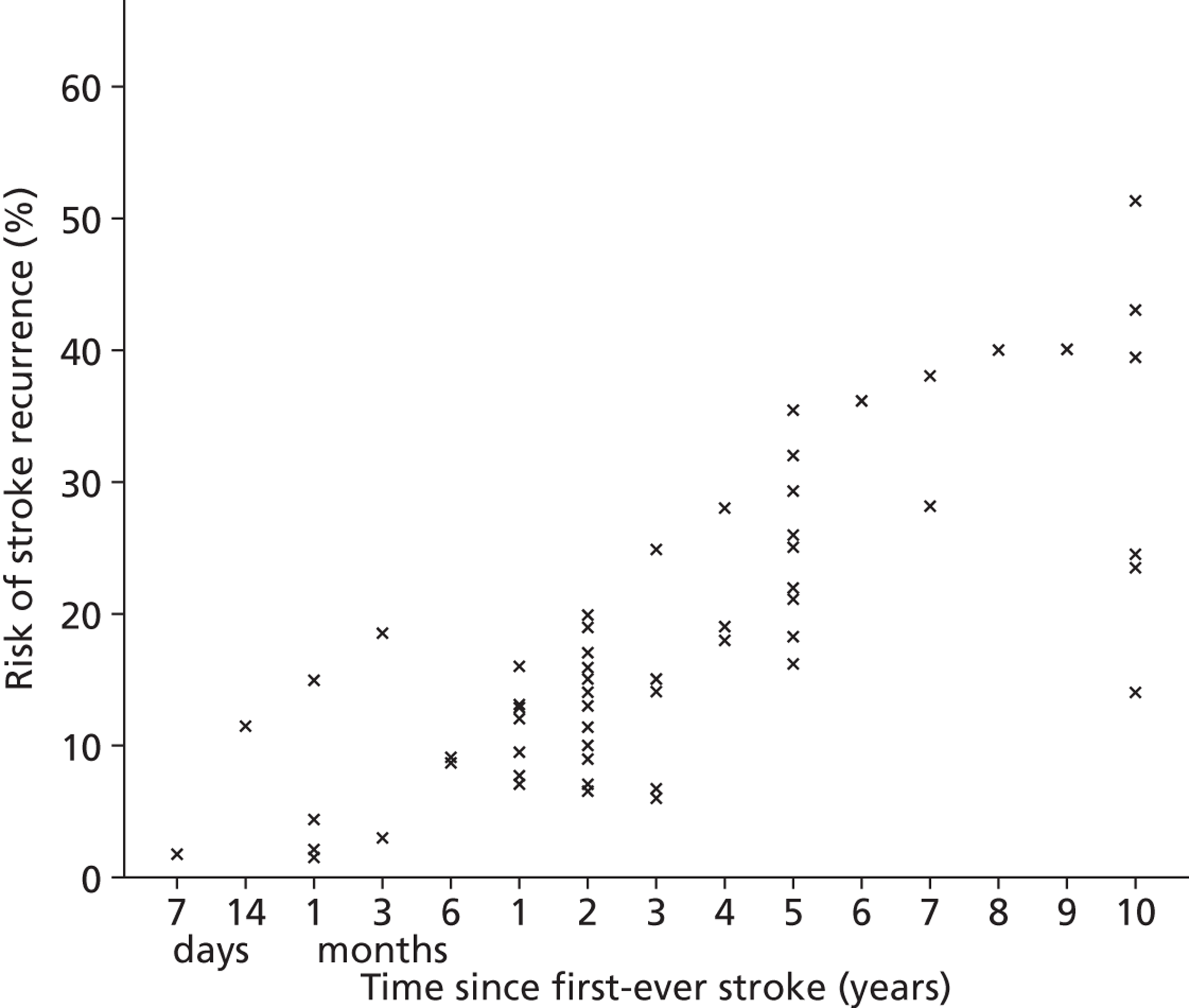

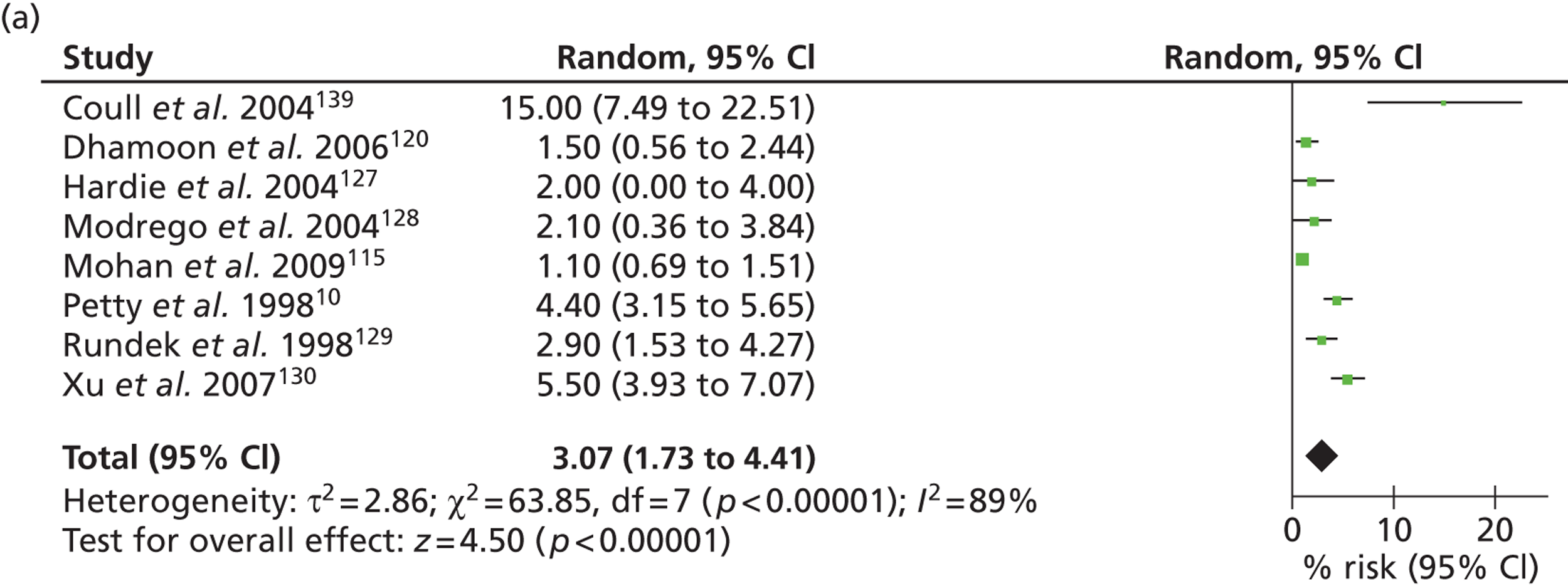

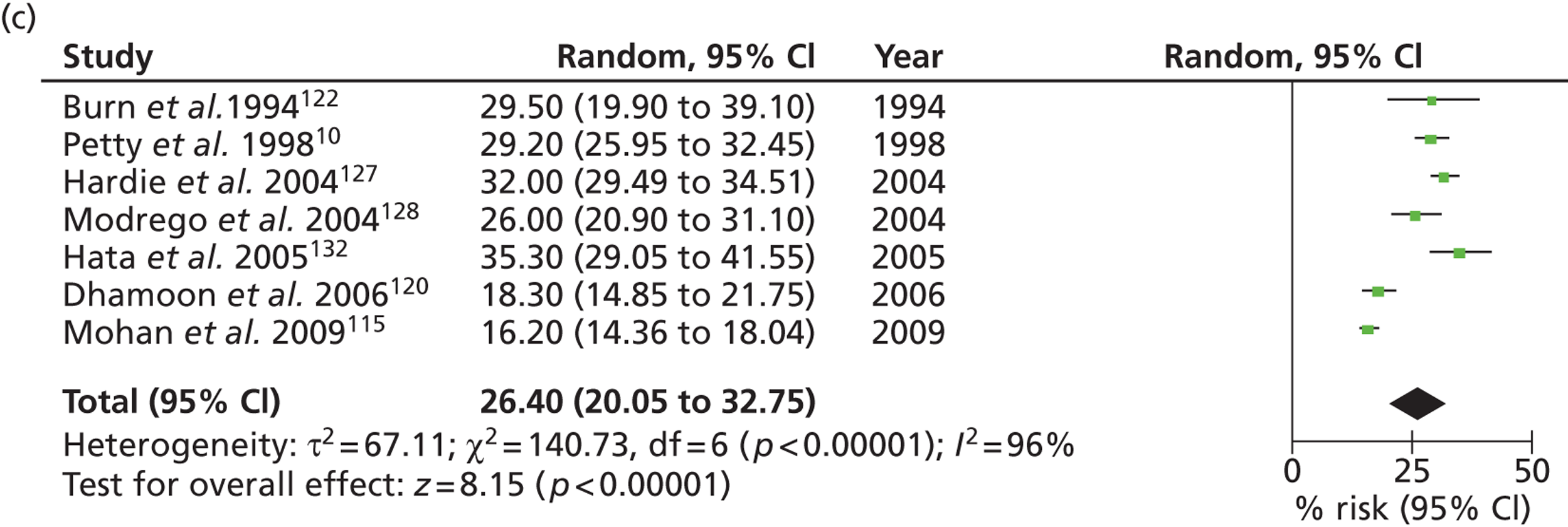

It has been estimated that by 2023 the absolute number of patients experiencing a first-ever stroke will be approximately 30% higher than in 1983, although no robust estimates have been made recently that take into account trends in incidence and differences in risk in ethnic groups. 7 One year after a stroke, 45% of survivors are functionally dependent, and it has been reported that stroke is the major cause of adult disability. 8 The risk of a recurrent stroke over 5 years varies between 17% and 30%9,10 and estimates of the prevalence of stroke survivors suggest that there may be as many as 11.8 per 1000 population. 11 Epidemiological data suggest that the decline in stroke incidence and mortality seen since the 1970s has plateaued since the mid-1990s. 3

There is considerable evidence that mortality, morbidity, limitation of activity and participation, poor quality of life and resource use can be reduced significantly by co-ordinated strategies of prevention, acute care and rehabilitation. 12 There are significant variations in survival2 and outcome13 between countries and there is evidence that the UK is one of the poorer performers in stroke care in Europe. 2,13 There are significant variations in outcome between ethnic and socioeconomic groups in the UK. 4,6

The NHS is committed to reducing the impact of stroke, as reflected in the National Service Framework for Older People, the quality and outcomes framework targets of primary care and guidance on stroke services to primary care trusts. 14,15 This programme will provide robust evidence to underpin the recommendations of the Department of Health’s stroke strategy, which is currently being consulted on, and ‘A Framework For Action’, the review of services in London. 16,17 The evidence base on which many services are based is nearly 20 years old and an adequate response to these priorities requires an accurate estimation of the current and future prevention, rehabilitation and long-term health-care needs of stroke patients living in the community, the range of service available and the expected changes in these needs and services with time.

It is estimated that up to 80% of stroke survivors are discharged home after initial hospital admission, over half of whom have hemiparesis, 22% cannot walk, 25% have communication problems and 53% are dependent on informal caregivers. 18 Caregivers’ physical and psychosocial well-being is affected, with up to 48% of caregivers reporting health problems and two-thirds a decline in social life, and there are also high self-reported levels of strain. 18 In England and Wales, strokes cost over £7B, £2.4B of which is informal care costs in the community. 19 Department of Health initiatives such as Our Healthier Nation, the National Service Framework for Older People and the stroke strategy have called for surveillance of stroke and effective provision of stroke services. 14,16

The National Sentinel Audit reported improved in-hospital survival and stroke care, but also highlighted large gaps in community stroke provision. 20 There was increased pressure from the Payment-By-Results Tariffs to reduce lengths of hospital stay, which requires in-depth understanding of the post-discharge needs of stroke survivors and development of appropriate community-based services. 21 Despite the anticipated beneficial effects of the new Quality and Outcomes Framework targets for stroke prevention, little was known about what determines whether or not general practices meet targets and whether or not this translates into reduced risk. There was evidence of inequality of provision of adequate preventative care to groups such as older people (≥ 65 years), women and socially deprived groups. 22,23 Primary care-based strategies did not adequately address the specific preventative needs of ethnic minority populations, who had a twofold higher incidence rate of stroke. 2 The first National Audit Office (NAO) report on stroke care in England and Wales reported that progress in the efficiency and effectiveness of the stroke treatment provided varies considerably, with scope for savings and improved outcomes. 19

The Department of Health’s Stroke Strategy group (of which two subgroups were chaired by the applicants) aimed to develop a national strategy to improve stroke prevention and care. The outputs from this programme will inform the strategy regarding the recommendations for ‘awareness’, ‘emergency care’ and ‘life after stroke’. 16

There is a need for robust, up-to-date information about the size of the problem, deficiencies in current care, how we can best predict those at risk of stroke recurrence and poor outcomes, and what models of service are potentially cost-effective and can deliver the proposed strategies. Such data will underpin health-care policy and locality-based commissioning. We proposed to analyse data from the population-based SLSR, an internationally unique data set but with national and international relevance, and annual follow-up data of all surviving stroke patients in a defined population. These analyses would allow professionals, planners and users to obtain estimates in areas not covered by routine data such as the current Department of Health ASSETT tool (action on stroke services: an evaluation toolkit), e.g. incidence by ethnic group, stroke subtypes, aetiology of stroke subtypes and their underlying risk factors, case severity, outcomes, patterns of care and appropriateness compared with national guidance for up to 15 years after stroke. Epidemiological data need to be contextualised and user perspectives of the impact of a disease need to be taken into account; therefore, we planned to undertake qualitative studies of the longer-term impact of stroke. The evidence base for post-acute stroke care is small and the interventions complex. 12 We planned to use the SLSR data to model alternative cost-effective service configuration solutions using both definitive trial data available in the literature and preliminary findings from pilots and ongoing studies, both locally and nationally. This would build on our initial NAO analyses of the likely benefits of thrombolysis and stroke unit care. 19 The programme would synthesise a wealth of information on needs utilising register data and patient, carer and professional perspectives and on effective interventions available from different sources to proposed innovative service strategies that can be implemented within the NHS. Finally, we planned to develop proposals to underpin the Department of Health’s Stroke Strategy and ‘A Framework For Action’ review of services in London, to develop recommendations based on these findings and to address this aspect of the programme in collaboration with the Royal College of Physicians Clinical Effectiveness Unit that has been evaluating stroke care nationally for > 10 years. 24

UK stroke incidence rates are comparable to international rates. 2,3 Apart from data from Oxford on trends in incidence in the last 20 years,5 there is little information regarding the changing nature of risk in different population groups. Further data are required on the risk of subtypes of stroke, including different aetiological subtypes and different sociodemographic and ethnic groups, if preventative stroke services are to be more appropriately targeted. Recovery in some aspects continues up to 5 years after stroke for a subsample of younger stroke patients (< 65 years of age). 25 Recovery after stroke plateaus after about 1 year but varies between groups;26 however, these studies are limited in terms of the outcomes assessed and the time points for analysis. In this programme, we aimed to overcome these limitations with the SLSR cohort available over the life course of the programme. There is evidence that, prior to stroke, risk factors are not well managed,5,22,23 and there is also evidence of inequalities in access to stroke care. 27

The evidence base for prevention and early management of stroke is considerable, much of which is randomised controlled evidence in areas such as early prevention of recurrence, stroke unit care, early supported discharge (ESD), carer education and early rehabilitation. 12 Research on organised stroke unit care has resulted in considerable reductions in mortality and institutionalisation of hospitalised stroke patients. 28 Up to 80% of patients are discharged home, many with limited abilities, restricted participation in wider activities of daily living, poor quality of life and increased dependence on family members. 29

This programme will provide long-term estimates of risk and prediction of outcome that will be used to model cost-effective configurations using epidemiological and health economic techniques that will contribute new scientific knowledge and provide highly relevant data for commissioners and clinicians in developing and running stroke services.

Chapter 3 South London Stroke Register methodology

The SLSR is the cornerstone of the application and is described in detail in the references throughout this chapter; additional specific details about data items and statistical methodologies are provided in Chapter 2 . The SLSR is a community-based register of incident stroke patients registered continuously since 1995 with a projected 4200 patients for study at the outset based on annual accrual. The methodology of the register has been covered in detail in key papers on incidence30,31 and longer-term outcomes,32 two of which are directly related to programme funding and analyses. 31,32

The programme employed a junior statistician and a data analyst to maintain, update and produce bespoke data sets for the analyses. This entailed working with the fieldworkers to ensure that data collection was as complete as possible and that data were valid and entered in a timely fashion. The data set was regularly ‘cleaned’ and, hence, was in a state fit for analysis. All procedures are documented and updated in a manual with standing operating procedures for each aspect of fieldwork and data handling. In addition to undertaking these tasks, the statistician has enrolled for a PhD analysing the SLSR data with regard to missing data and developing models of imputation. The data analyst has co-authored several papers and led an analysis of quality of life after stroke. Supervision of these staff was by Dr Heuschmann and Professor Grieve in the first half of the programme before they left King’s College London and subsequently by three lecturers in statistics and Professor Prevost oversaw all statistical analyses for the programme. Their specific work is detailed in subsequent analyses for the programme objectives. This team trained and supervised the fieldworkers employed on the register by the programme funding who were undertaking analyses (see Appendix 3 ).

Ethics statement

This programme was approved by the St Thomas’ Hospital Research Ethics Committee, The King’s College Hospital Research Ethics Committee, The Wandsworth Local Research Ethics Committee, The Riverside Research Ethics Committee and the National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery and the Institute of Neurology Joint Research Committee. Continued ethics review has been by the National Research Ethics Committee with regular reporting of findings through their reporting systems.

Population coverage

The SLSR is a prospective population-based stroke register set up in January 1995 as part of a Department of Health Cardiovascular Research programme managed by Northern and Yorkshire Regional Health Authority Research and Development, recording all first-ever strokes in patients of all ages for an inner area of south London based on 22 electoral wards in Lambeth and Southwark. The register uses ‘hot pursuit methods’ to ensure maximal registration of incident stroke patients resident in the electoral wards of the study area and as such is considered to be less biased than most research registers that use either only hospital cases or do not employ multiple sources of ascertainment to reduce bias in the registration process. Data that were collected between 1995 and 2012 have been used for the various objectives, depending on the focus of the analysis and the year of the programme in which the data were analysed, and we have tried to maximise the power of the analyses at all times by utilising an up-to-date set of data whenever possible. At a maximum, there are 15 years of incidence data and follow-up, but most analyses have utilised data available at the time of analysis during the programme.

The total source population of the SLSR area was 271,817, 63% of whom were white, 28% were black [9% black Caribbean (BC), 15% black African (BA) and 4% black other] and 9% were of other ethnic group at the 2001 census. Between the most recent censuses of 1991 and 2001, the proportion of ethnic groups other than white population increased from 28% to 37%; in 1991 the largest ethnic minority group was BC (11%) , but by 2001 BAs made up the largest ethnic minority group (15%). Mid-year estimates from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) were used to adjust the population size. For estimation of incidence rates, ONS mid-year estimates or regression modelling was used to determine the denominator population. Urban populations are more mobile with poorer registration, particularly in younger age groups (< 65 years). This may affect total risk rates but has less effect on age specific rates, which are more relevant to this programme.

Case ascertainment

Standardised criteria were applied to ensure completeness of cases ascertainment, including multiple overlapping sources of notification. Stroke was defined according to the World Health Organization (WHO) criteria and all subarachnoid haemorrhages (SAHs), International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10 code I60.-), intracerebral haemorrhages (ICD-10 code I61.-), cerebral infarctions (CEIs) (ICD-10 code I63.-) and unspecified strokes (ICD-10 code I64) were included. 30–32 Patients admitted to hospitals serving the study area (two teaching hospitals within and three hospitals outside the study area) were identified by regular reviews of acute wards admitting stroke patients, weekly checks of brain imaging referrals and monthly reviews of bereavement officers and of bed manager records. This changed over the study period with the radical changes to stroke care in the Healthcare for London Initiative, but essentially the same hospitals were visited by the SLSR fieldworkers but the frequency had to alter to those designated as ‘hyperacute’ stroke units receiving stroke patients for the first 2–3 days of their care. Additionally, national data on patients admitted to any hospital in England and Wales with a diagnosis of stroke were also screened for additional patients using Hospital Episode Statistics information. To identify patients not admitted to hospital, all general practitioners (GPs) within and on the borders of the study area were contacted regularly (by newsletter and letters notifying them of a registered patient) and asked to notify the Register of stroke patients, particularly those not admitted to hospital. Regular communication with GPs was achieved by telephone contact and quarterly newsletters. Over the time period of the programme, register fieldworkers and investigators scheduled visits to practices to update GPs and although these were well received, they were logistically difficult to arrange and appeared not to identify further incident cases. Referral of non-hospitalised stroke patients to a neurovascular outpatient clinic (from 2003) or domiciliary visit to patients by the study team was also available to GPs which, along with outpatient brain scanning, improved out of hospital registrations. Community therapists in Lambeth and Southwark were contacted every 3 months. Death certificates were checked regularly at the Coroner’s Office until the late 2000s when the coroner decided it was not possible for us to review death certificates under the Data Protection Act. However, we ‘flagged’ all registered patients with the ONS, which provided us with regular data on deaths of SLSR patients. Completeness of case ascertainment, using these multiple sources, has been estimated at 88% by a multinomial-logit capture–recapture model using the methods described in detail by the programme team in its initial analysis for objective 1. 31 We believe the SLSR has provided an exemplary model of ‘hot pursuit’ case ascertainment in a complex urban environment but this requires a highly trained fieldwork team with rigorous systems in place to ensure that backlogs of potential cases do not develop.

Data collection

Specially trained study doctors, nurses and other fieldworkers collected all data prospectively whenever feasible. The programme funded a clinician and a research nurse and additional fieldwork was undertaken by researchers employed by charity grants for other projects, as is necessary for the ‘hot pursuit’ methods. A study doctor verified the diagnosis of stroke with input from Professor Rudd and Dr Bhalla on difficult cases and interpretation of scans and deciding on the stroke subtype. Patients were examined within 48 hours of referral to SLSR when possible and over the study period, this became more feasible with all hospitalised patients being referred to hyperacute stroke units and others referred to neurovascular clinics.

The following sociodemographic characteristics were collected at initial assessment: sex, age and self-definition of ethnic origin (census question) as stratified into white, black (BC, BA and black other) and other ethnic group. Socioeconomic status was categorised as non-manual (I, II and III non-manual), manual (III manual, IV and V) and economically inactive (retired and no information on previous employment) according to the patient’s current or most recent employment using the Registrar General’s occupational codes. The SLSR did not collect data on educational status, which is an additional variable that would be useful in certain analyses. Classification of pathological stroke subtype [ischaemic stroke, primary intracerebral haemorrhage (PICH) and SAH] was based on results from at least one of the following: brain imaging performed within 30 days of stroke onset (computerised tomography or magnetic resonance imaging), cerebrospinal fluid analysis (in all living cases of SAH in which brain imaging was not diagnostic) or necropsy examination (rarely used in programme years). Cases without pathological confirmation of stroke subtype were classified as undetermined (UND). For the data details collected for aetiological subtyping and for stroke risk factors and their management, see Chapter 4 , Objective 1.

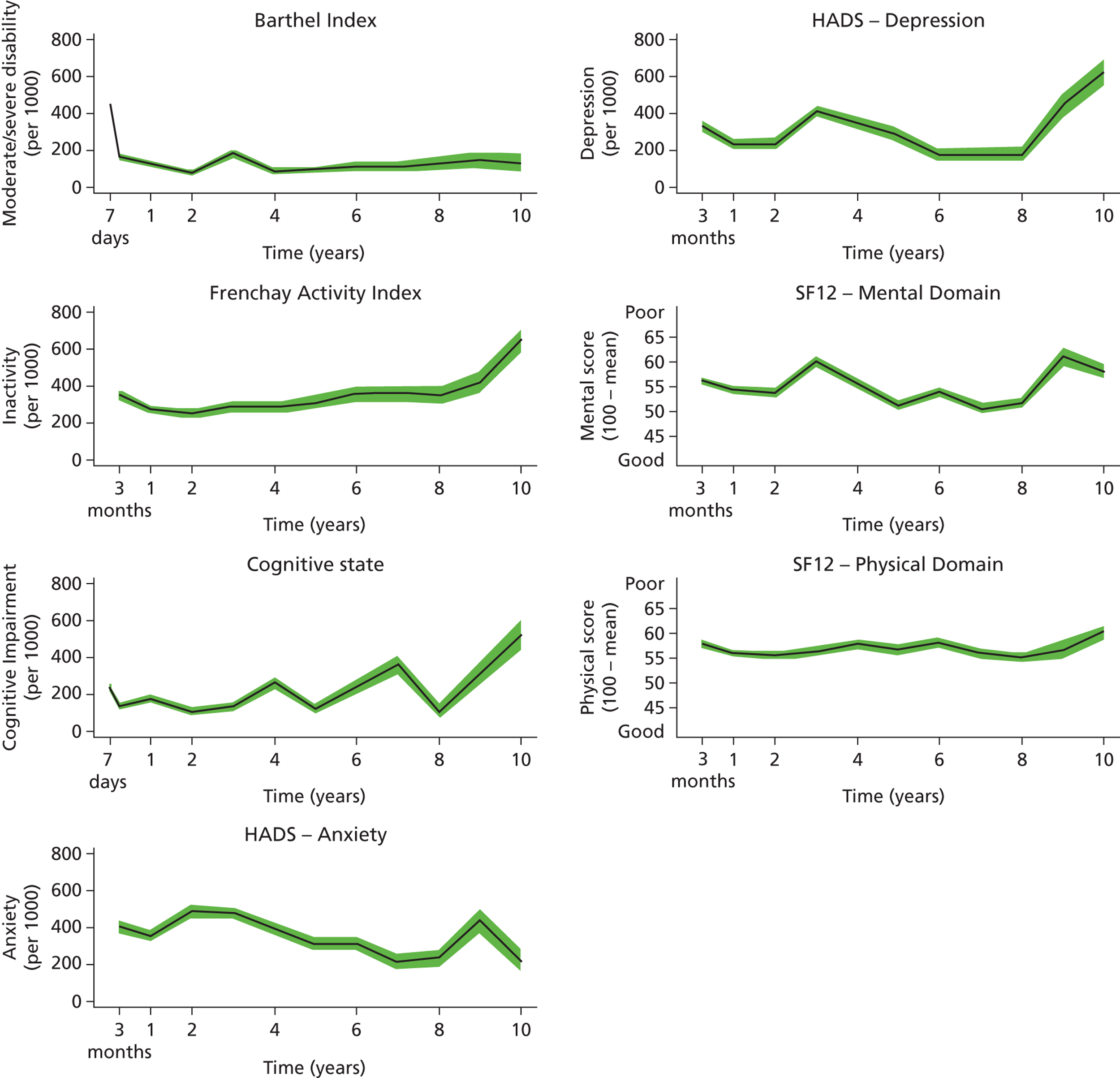

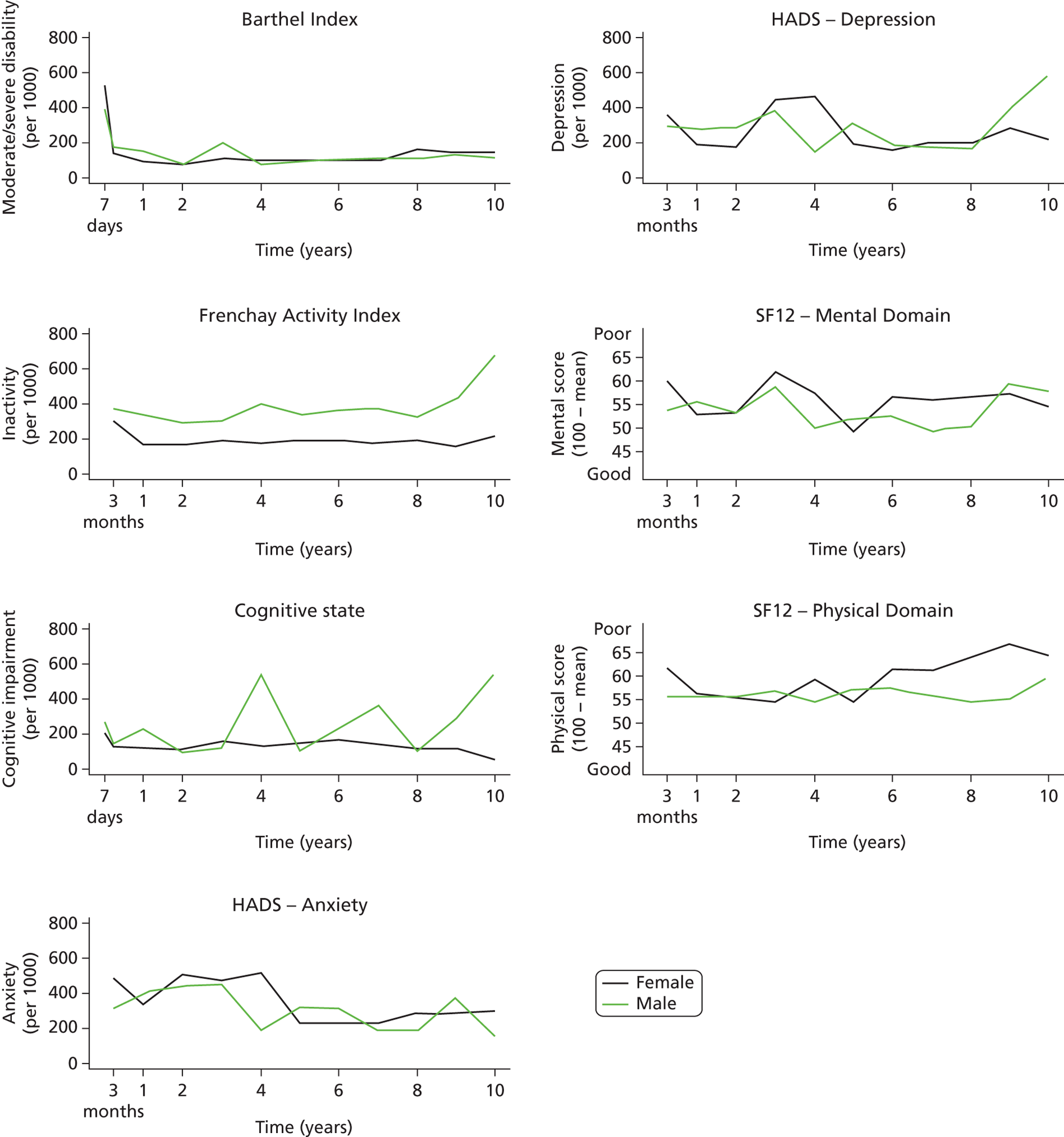

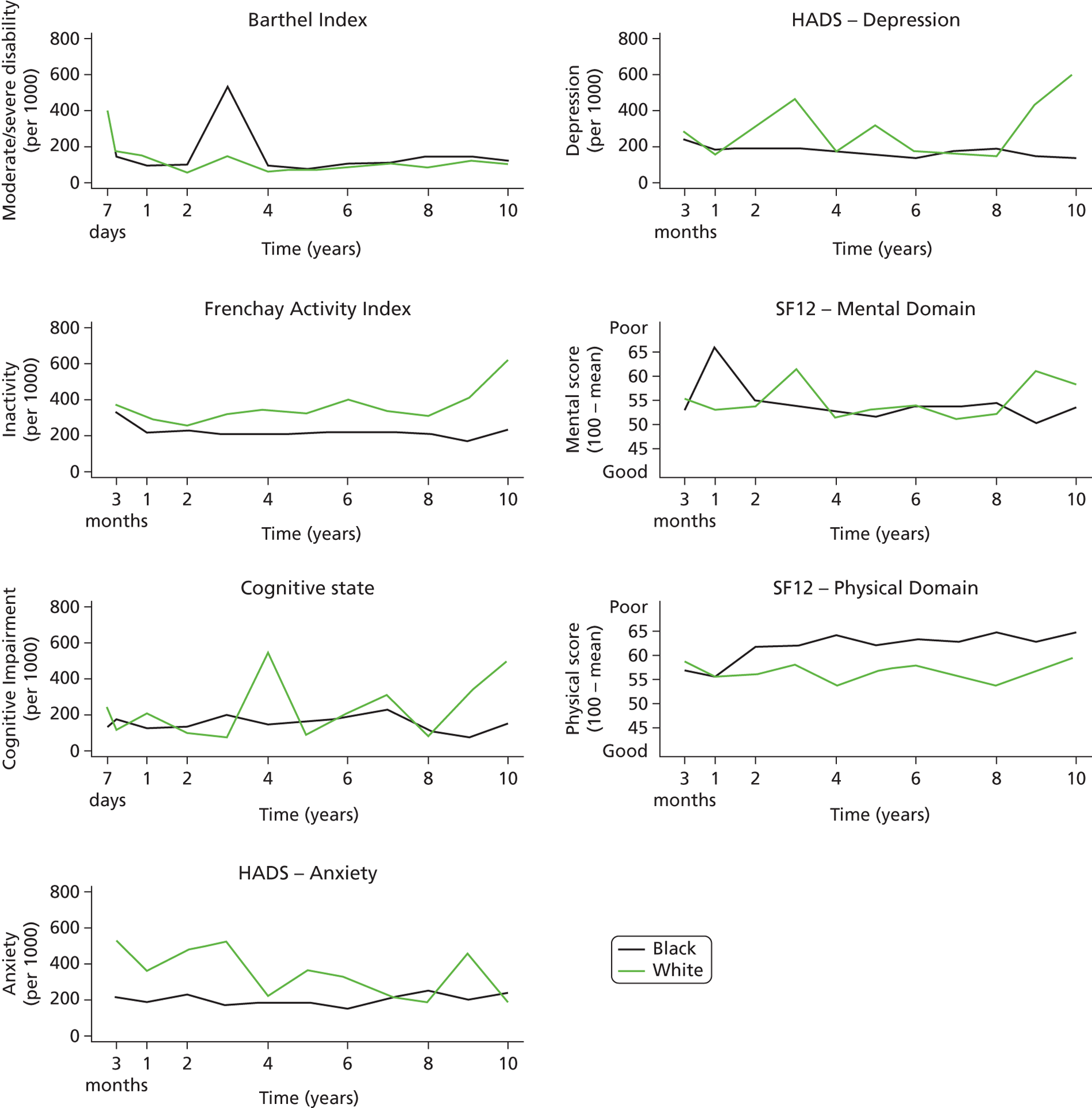

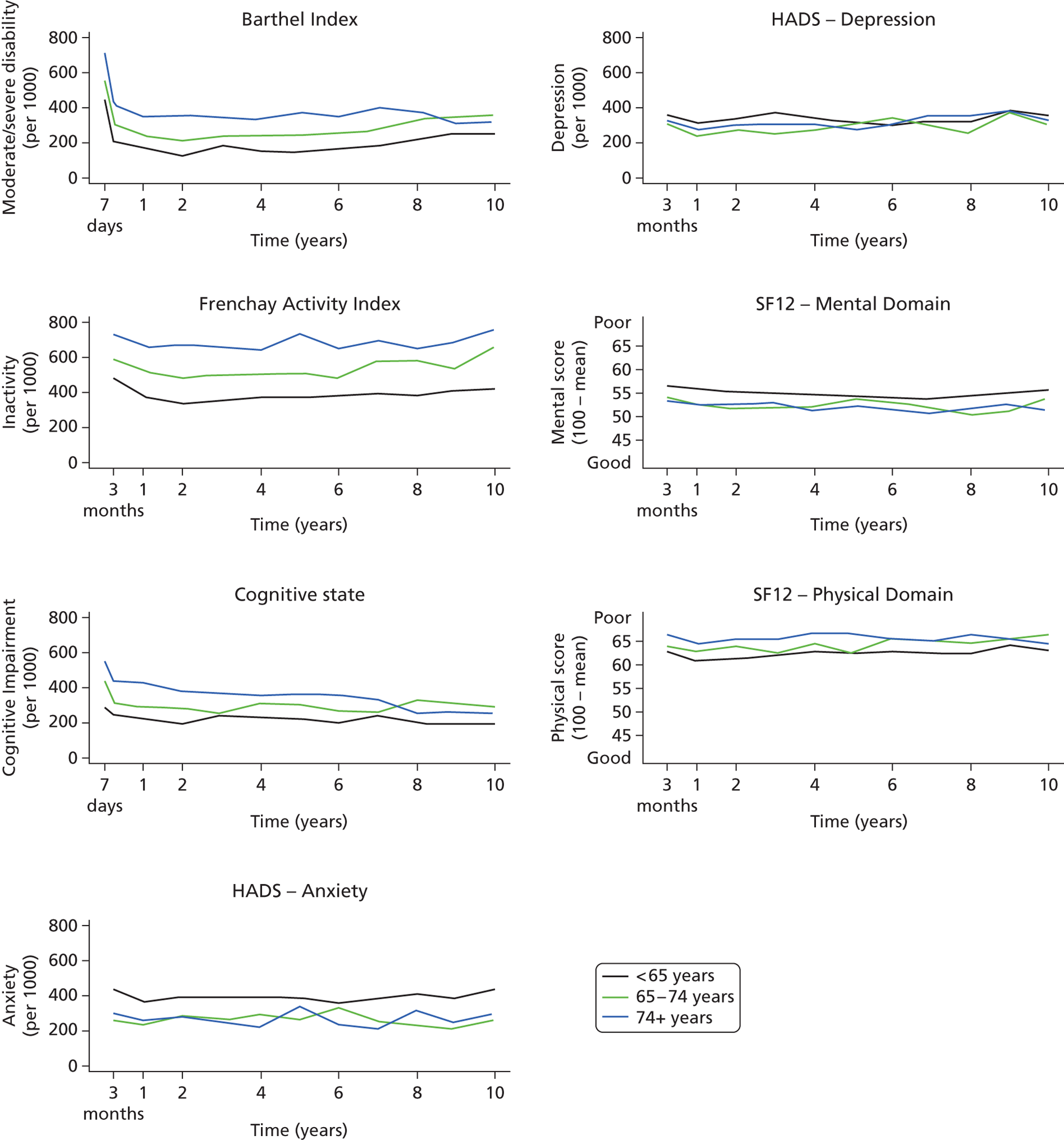

Follow-up data were collected by validated postal or face-to-face instruments with patients and/or their carers and the interview lasted < 1 hour. If a patient had left the SLSR study area, they were followed up if at all possible using the methods described using face-to-face, telephone or postal questionnaires. Patients were assessed at 3 months and annually after a stroke. Outcome measures include activity of daily living using the Barthel Index (BI),33 extended activities of daily living (EADL) (social activities) using the Frenchay Activity Index (FAI),34 health-related quality of life (HRQoL) using the UK version of the Short Form questionnaire-12 items (SF-12) and Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36),35,36 cognitive impairment using the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE)37 or Abbreviated Mental Test (AMT)38 and anxiety and depression using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS). 39 All interviewers underwent regular standardised training in the use of the different scales. These outcomes are described in Chapter 5 , objective 2. These measures were chosen as they were validated scales used in stroke research and trials and are relatively easy to administer. More detailed scales with diagnostic properties (e.g. depression and cognitive function) would be useful as well; however, such a register needs to balance capturing the breadth of impact with more detail in certain areas of interest.

Cut-off points for determining poor outcomes were defined a priori. 32 The BI was assessed in the acute phase (7–10 days post stroke) and at all follow-up interviews. A score on the BI of < 15 was used to identify patients with moderate (BI 10–14) to severe (BI ≤ 9) disability. 40 The FAI was administered at all follow-up points and participants with a score < 15 were categorised as ‘inactive’. 41

The SF-36 was used to measure HRQoL in follow-up interviews conducted before 1 March 1999, after which the shortened version, the SF-12, was introduced. The 12 items of the SF-12 have been adopted from the SF-36 verbatim and summary scores are replicable and reproducible. 36,42 Therefore, the specific items from the SF-36 questionnaires in earlier follow-ups were used to derive SF-12 summary scores across all time points. The SF-12 was selected to measure HRQoL because of its strong psychometric properties, wide use, reliability, validity and responsiveness. 41,43 It assesses eight domains of health status – Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, General Health, Vitality, Social Functioning, Role-Emotional and Mental Health – and each domain is scored between 0 and 100. Absence of any problems is indicated by scores of 100 for Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain, Social Functioning and Role-Emotional, and scores of 50 in General Health, Vitality and Mental Health. These domains were then computed to produce two summary scores representing physical and mental health. 36 Domains for physical health summary score include Physical Functioning, Role-Physical, Bodily Pain and General Health. Mental health summary score includes Vitality, Social Functioning, Role-Emotional and Mental Health. The summary scores range from 0 to 100 and are based on norms with a mean of 50 and a standard deviation of 10. Summary scores in this study are presented as 100 minus the original score, with higher values signifying poorer outcome.

Cognitive state was assessed in the acute phase as well as at follow-up. Prior to 1 January 2000, all assessments were conducted using the MMSE, after which the AMT was administered. Subjects were defined as cognitively impaired according to predefined cut-off points (MMSE score < 24 or AMT score < 8). 43,44

The HADS consists of two subscales and was originally developed as a screening tool for anxiety and depression in hospital patients but has also been validated for use in stroke patients45 and in the general population. 46 Each subscale is scored from 0 to 21 and used to identify possible cases of anxiety and depression (score > 7). 46

Chapter 4 Objective 1: estimate the risk of stroke, including its underlying causes and trends over time in black and white populations (improved targeting of prevention strategies and acute care)

Abstract

Aim

To estimate the risk of stroke, including its underlying causes and trends over time in black and white populations.

Methods

Incidence rates were calculated, and age adjusted to the European population for comparative purposes. Time trends were estimated using incidence rate ratios (IRRs) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). To investigate the effect of air pollution, a small area-level ecological study in 948 census output areas of SLSR area was undertaken. Particulate matter 10 (PM10) and nitrogen dioxide (NO2) concentrations were modelled as measures of exposure. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess the significance of time trends in risk factors and to examine factors associated with risk factor diagnosis and management.

Results

Stroke incidence has decreased significantly since 1995, the greatest decline being in the white group but with a higher stroke risk in black groups. There are significant variations in risk factors and aetiological subtypes of stroke between ethnic groups and a large number of strokes occurred in people with untreated risk factors with no improvement in detection of risk factors observed over time. The study highlighted substantial ethnic differences in risk factors not explained by socioeconomic deprivation. There was little change in the use of primary prevention medication in stroke patients during the study period. Analysis of the effect of air pollution identified that there was no significant association between outdoor air pollutants and stroke incidence but a 10 μg/m3 increase in NO2 was associated with a 28% increase in risk of death. A 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 was associated with a 52% increase in risk of death.

Introduction and dissemination for objective

The programme specifically wished to estimate the risk of stroke by sociodemographic group and by pathological and aetiological subtype of stroke, along with trends over time and analysis of underlying risk factors contributing to stroke risk and their trends over time. There were six deliverables:

-

deliverable 1: overall incidence rates by sociodemographic group and pathological subtype of stroke – year 1

-

deliverable 2: trends in underlying risk factors for stroke – year 1

-

deliverable 3: trends in incidence – year 1

-

deliverable 4: incidence by aetiological subtypes – year 2

-

deliverable 5: trends in incidence by ethnicity – year 3

-

deliverable 6: trends in incidence by aetiology – year 4.

In addition, work using the national General Practice Research Database (GPRD) and air pollution data were considered highly relevant to this objective and are described here.

Dissemination

The programme has published one main paper relating to deliverables 1–331 and another relating to deliverable 4. 47 Further analyses updating the trends in incidence rates by ethnicity and aetiology (deliverables 5 and 6) are in abstract form. 48 Analyses of risk factor management over time have also been undertaken and are described in this chapter. In addition, we have undertaken additional work using the GPRD, led by Dr Gulliford of the programme team, as it is clear that routine data may be an important source of incidence data and risk factor prevalence and management in a national sample. We considered it important to explore the utility and validity of routine primary care data in estimating risk factor management. A summary of these analyses is presented as we consider these to be important as the NHS moves towards the Clinical Practice Research Datalink programme, sampling over half the general practices in England and linking with other national data sources. 49–53 Two papers addressing air pollution and stroke risk and survival using the SLSR data and the skills of programme staff have been published with colleagues from Manchester University, showing that, by linking routine air pollution monitoring data with research databases such as SLSR, this can address public health concerns around air pollution and health. 54,55 A list of all publications using the SLSR data is in Appendix 4 .

As these analyses have mainly been published and are in the public domain, we will summarise the methods and results here with full details in the references cited.

Background and rationale for objective

Deliverable 1: overall incidence rates by sociodemographic group and pathological subtype of stroke – year 1 and deliverable 3: trends in incidence – year 1.

UK stroke incidence rates are comparable to international rates. 2,3 Apart from data from Oxford on trends in incidence in the last 20 years,5 there is little information about the changing nature of risk in different population groups internationally. Further data are required on the risk of subtypes of stroke, including different aetiological subtypes and in different sociodemographic and ethnic groups, if preventative and stroke services are to be more appropriately targeted. There is also evidence that, prior to stroke, risk factors are not well managed, potentially increasing the stroke risk. 5,22,23

Methods

South London Stroke Register data collection methods are described in Chapter 3 . The analyses for deliverables 1–3 were at the start of the programme restricted to incident cases for the full years 1995–2004, inclusive, as these were the complete data available in 2008 for analysis and described fully in the paper by Heuschmann et al. 31 The source population of the SLSR for 2004, taking the extension of the study area into account, was calculated by extrapolating from the extended area population in 2001 UK Census and assuming a similar increase of study population as in the original SLSR area. Crude incidence rates were calculated and age adjusted to the European population for comparative purposes. CIs for incidence rates were calculated using the Poisson distribution. A multinomial-logit capture–recapture method was used to address issues of changing ascertainment rates over time. As there were a number of subgroups in these analyses, we reported data in 2-year time intervals. Time trends were estimated using IRRs with 95% CIs using the delta method. Statistical analyses were performed using Statistical Analysis System (SAS) software version 9.1 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results (summary of reference 31)

A total of 2874 patients in all age groups experiencing theor first-ever stroke between 1995 and 2004 were included. Total stroke incidence decreased over the 10-year study period in both men (IRR 1995 to 1996 vs. 2003 to 2004 0.82, 95% CI 0.69 to 0.97) and women (IRR 0.76, 95% CI 0.64 to 0.90). A similar decline in total stroke incidence could be observed in both white men and women (IRR 0.76, 95% CI 0.62 to 0.93 vs. IRR 0.73, 95% CI 0.59 to 0.89 respectively); in the black population, total stroke incidence was reducing only in women (IRR 0.48, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.75).

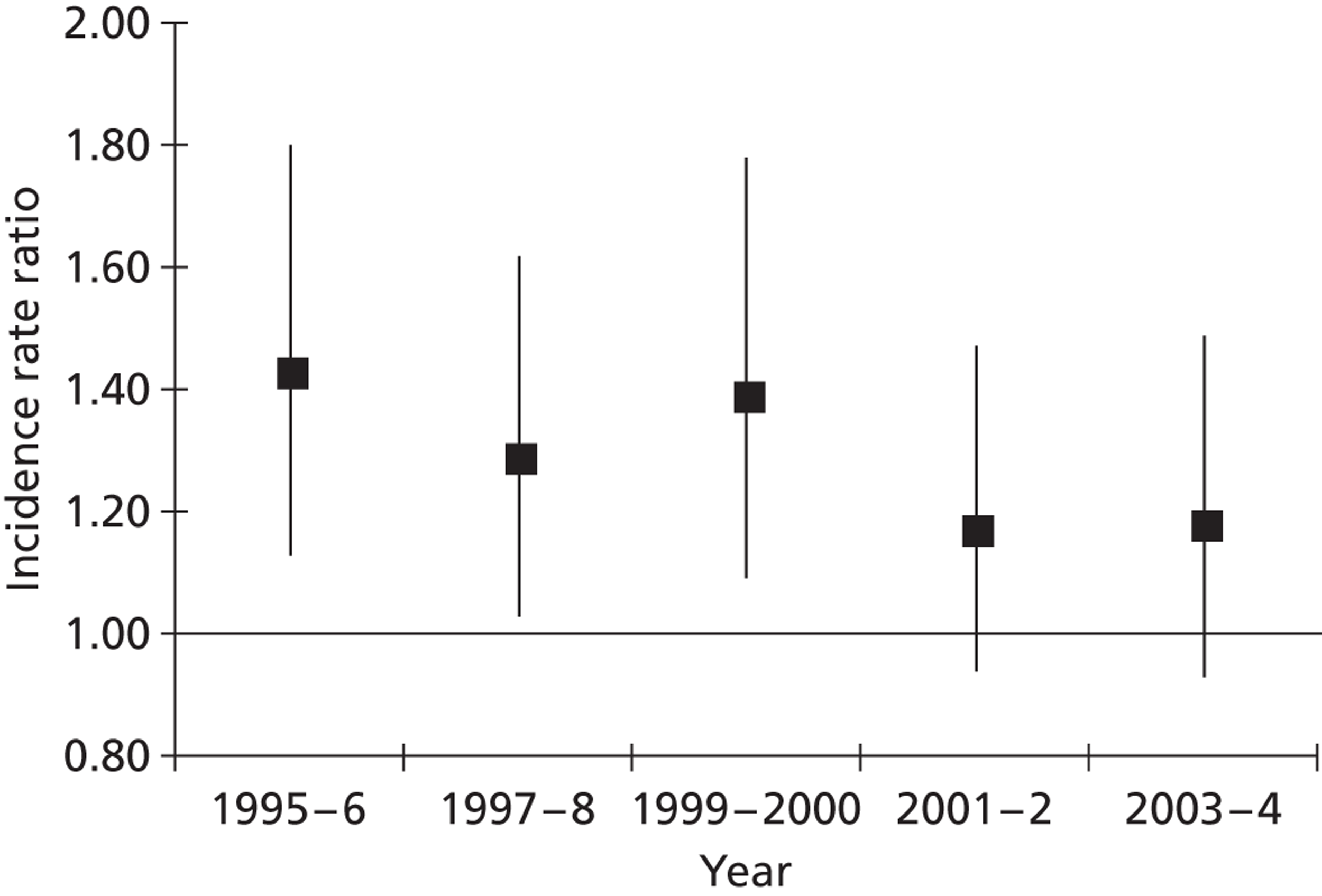

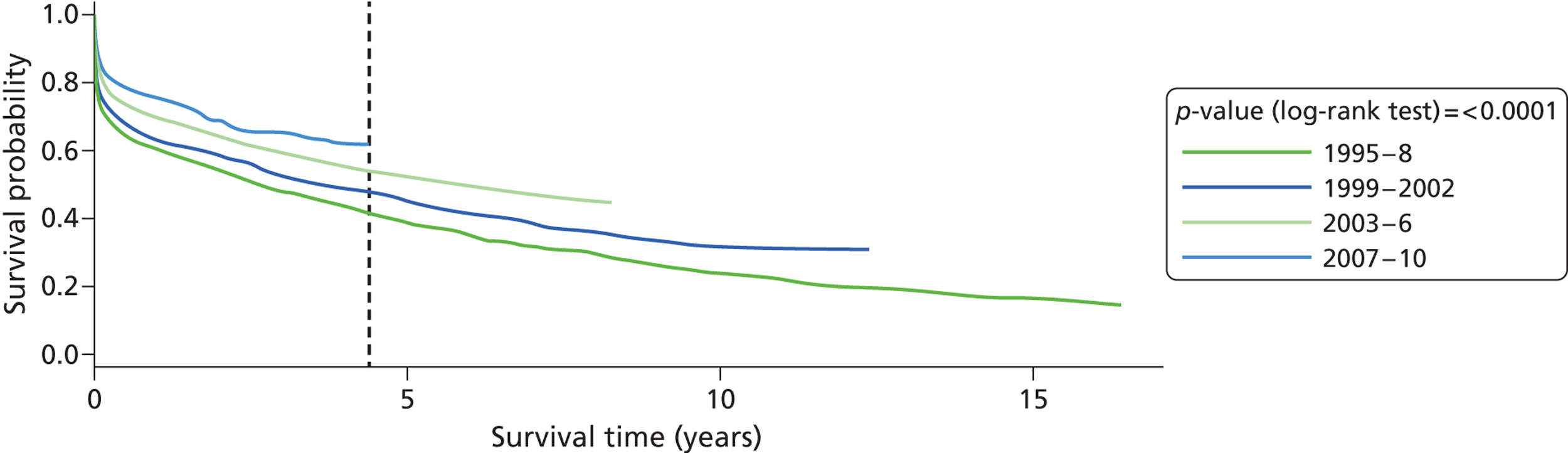

Total annual stroke incidence per 100,000 inhabitants age-standardised to the European population was 136.7 (95% CI 114.8 to 161.7) for the white male population compared with 96.5 (95% CI 78.2 to 117.8) in women; among the black population, it was 173.0 (95% CI 148.2 to 200.8) in men compared with 124.5 (95% CI 103.6 to 148.4) in women. The overall black-to-white age-adjusted IRR was 1.27 (95% CI 1.10 to 1.46) for men and 1.29 (95% CI 1.11 to 1.50) for women; black-to-white IRR was higher in PICH (IRR 1.87, 95% CI 1.36 to 2.56 for men and IRR 1.40, 95% CI 0.93 to 2.12 for women) than in ischaemic stroke (IRR 1.21, 95% CI 1.02 to 1.44 for men and IRR 1.37, 95% CI 1.15 to 1.63 for women) and SAH (IRR 1.14, 95% CI 0.65 to 2.00 for men and IRR 1.00, 95% CI 0.56 to 1.80 for women). Over the 10-year time period, the IRR between the black and white populations decreased from 1.43 (95% CI 1.13 to 1.82) to 1.18 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.49) ( Figure 1 ).

FIGURE 1.

Ten-year time trends in IRR and corresponding 95% CI of total stroke incidence among black and white stroke patients (white patients served as reference group). Reproduced with permission from Heuschmann PU, Grieve AP, Toschke AM, Rudd AG, Wolfe CD. Ethnic group disparities in 10-year trends in stroke incidence and vascular risk factors: the South London Stroke Register (SLSR). Stroke 2008;39:2204–10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1161/STROKEAHA.107.507285. 31

Completeness of case ascertainment was estimated using indirect methods, revealing a potential under-detection rate ranging from 16% to 25%. We used a capture–recapture model with a prespecified set of covariates rather than our previous model using a stepwise choice of covariates as stepwise choices can lead to models of differing complexity depending on the number of sources of notification that are used. The estimated completeness for 1995 to 1996 was similar in both models (84% with prespecified covariates and 88% with stepwise set of covariates).

In the white population, the prevalence of prior-to-stroke hypertension, atrial fibrilation (AF) and smoking decreased, and the prevalence diabetes mellitus showed a borderline statistically significant increase (p for trend was 0.0686). In the black population, a borderline statistically significant decrease in prevalence of prior-to-stroke hypertension was observed (p for trend was 0.0586), which was more pronounced for females (p for trend was 0.0386) than for males (p for trend was 0.4826); no other statistically significant trends or sex differences were detected.

Total stroke incidence was higher in the black population than in the white population (IRR 1.27, 95% CI 1.10 to 1.46 in men; IRR 1.29, 95% CI 1.11 to 1.50 in women), but the black–white gap reduced during the 10-year time period (from IRR 1.43, 95% CI 1.13 to 1.82, in 1995 to 1996 to 1.18, 95% CI 0.93 to 1.49, in 2003 to 2004). Independent capture–recapture models were fitted at 2-year time intervals and completeness was estimated to be 84% in 1995 to 1996, 83% in 1997 to 1998, 76% in 1999 to 2000, 75% in 2000 to 2001 and 81% in 2003 to 2004. Overall, the prevalence of hypertension, AF and smoking decreased over the 10-year time period whereas prior-to-stroke diabetes mellitus increased slightly, although the increase did not reach statistical significance.

Discussion

These analyses illustrate the advantages of such a register being funded long term to enable such unique trend data in risk to be estimated.

Stroke incidence decreased over the initial 10-year time period of 1995 to 2004. The greatest decline in incidence was observed in black women, but ethnic group disparities still exist, with stroke risk significantly higher in the black population than in the white population. Advances in risk factor reduction observed in the white population were not seen in the black population.

Total stroke incidence decreased by 18% in men and by 24% in women over the 10-year study period between 1995 and 2004. Reduction of stroke incidence was similar among white men and women and, in the black population only, a statistically significant decrease of total stroke incidence in black women was observed. This was mainly attributed to, approximately, an 80% decline in PICH rate. Ethnic group disparities in stroke incidence still exist, indicating higher attack rates in the black population; however, the black–white gap in stroke risk was slightly reducing at the end of the 10-year time period. The observed decline in stroke attack rates might be attributed to changes in prior-to-stroke risk factors. Among white patients, a decrease in hypertension, smoking and AF was observed as well as a statistically non-significant increase in the prevalence of diabetes mellitus. No changes in the prevalence of the main prior-to-stroke risk factors could be detected in the black group over the study period, except a trend toward lower prevalence of hypertension, especially in women.

The decreasing stroke incidence over a 10-year time period in whites can be linked with a decrease in most of the main risk factors in the population; however, SLSR analyses are unable to assess this as the control population or whole population data would be required. However, the observed increase in diabetes mellitus in the white population, although only borderline statistically significant, might outweigh some achievements and needs further attention. Overall, higher attack rates were found in black groups, although the black–white gap in stroke incidence was reducing slightly over time. More research is needed for a better understanding of reasons for black–white disparities, especially for the failing of transferring advances in risk factor reduction in the white to the black population.

A subsequent analysis in the final year of the programme reanalysed the trends in incidence over 15-year period (deliverables 5 and 6). Further analyses updating the trends in incidence rates by ethnicity and aetiology (deliverables 5 and 6) are presented briefly as abstracts. 48

Methods

The same methodologies were employed as for the analyses by Heuschmann et al. 31 extending the analysis to the end of 2010, which enabled analysis by BC and BA groups separately.

Results

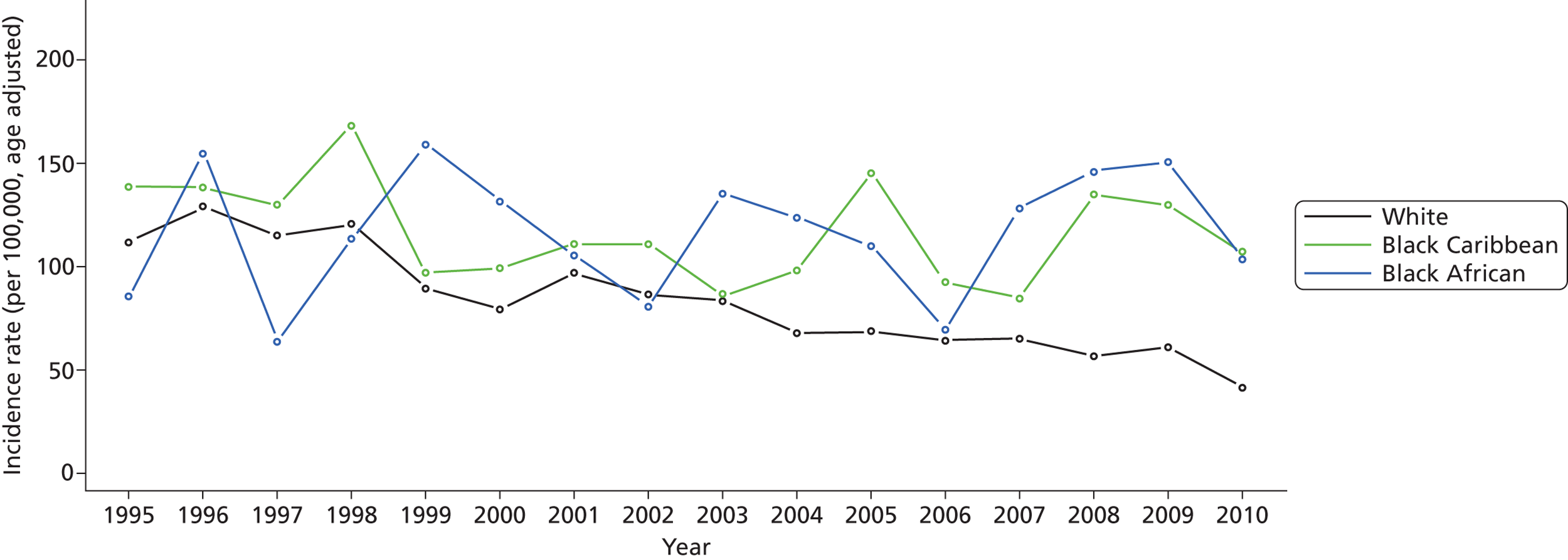

Between 1995 and 2010, 4212 patients with first-ever stroke of all age groups were included in the study and total stroke incidence decreased over the 16-year study period. Among the white population, the incidence rate decreased substantially from 111.78 per 100,000 in 1995 to 41.58 per 100,000 in 2010 (all incidence rates were adjusted for age to the south London population) ( Figure 2 ). Among the BC population, the incidence rate decreased moderately from 138.42 per 100,000 in 1995 to 107 per 100,000 in 2010. However, among the BA population, the incidence rate increased slightly, from 85.34 per 100,000 in 1995 to 103.6 per 100,000 in 2010. Although, in general, the incidence of stroke decreased in women, this was not observed in the BC group and incidence remained constant in BC women, 126.58 per 100,000 in 1995 and 124.04 per 100,000 in 2010. Among the white population, the prevalence of prior-to-stroke hypertension (p < 0.0001), myocardial infarction (MI) (p = 0.0047), AF (p = 0.0002), previous transient ischaemic attack (TIA) (p = 0.0001) and smoking (p < 0.0001) decreased, whereas no statistically significant changes in prior-to-stroke risk factors were observed in the BC or BA groups ( Table 1 ). Total stroke incidence was similar in black compared with white groups, but the black–white gap seems widened over this 16-year time period.

FIGURE 2.

Annual stroke incidence rate by ethnicity: SLSR 1995–2010.

| Characteristic | 1995–8 | 1999–2002 | 2003–6 | 2007–10 | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 71.6 (14.1) | 69.7 (14.8) | 69.3 (15.1) | 69. 5 (15.9) | 0.0003 |

| Age group: > 65 years | 961 (73.6%) | 710 (66.1%) | 660 (66.4%) | 551 (65.7%) | < 0.0001 |

| Sex: male | 638 (48.9%) | 535 (49.8%) | 537 (54%) | 410 (48.9%) | 0.0818 |

| Ethnic group | |||||

| White | 1028 (78.8%) | 753 (70.1%) | 671 (67.5%) | 553 (65.9%) | < 0.0001 |

| BC | 163 (12.5%) | 115 (10.7%) | 135 (13.6%) | 123 (14.7%) | |

| BA | 50 (3.8%) | 87 (8.1%) | 77 (7.7%) | 82 (9.8%) | |

| Others/unknown | 64 (4.9%) | 119 (11.1%) | 111 (11.2%) | 81 (9.7%) | |

| Socioeconomic status | |||||

| Non-manual | 320 (24.5%) | 286 (26.6%) | 264 (26.6%) | 257 (30.6%) | < 0.0001 |

| Manual | 775 (59.4%) | 555 (51.7%) | 548 (55.1%) | 338 (40.3%) | |

| Others/unknown | 210 (16.1%) | 233 (21.7%) | 182 (18.3%) | 244 (29.1%) | |

| Stroke subtype | |||||

| Infarct | 916 (70.2%) | 786 (73.2%) | 776 (78.1%) | 631 (75.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| PICH | 177 (13.6%) | 163 (15.2%) | 124 (12.5%) | 76 (9.1%) | |

| SAH | 71 (5.4%) | 71 (6.6%) | 51 (5.1%) | 19 (2.3%) | |

| Unclassified/unknown | 141 (10.8%) | 54 (5%) | 43 (4.3%) | 113 (13.5%) | |

| Prior risk factors | |||||

| Hypertension | 846 (64.8%) | 555 (51.7%) | 630 (63.4%) | 522 (62.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| MI | 170 (13%) | 94 (8.8%) | 96 (9.7%) | 74 (8.8%) | 0.0006 |

| AF | 253 (19.4%) | 138 (12.8%) | 147 (14.8%) | 119 (14.2%) | < 0.0001 |

| Previous TIA | 196 (15%) | 105 (9.8%) | 111 (11.2%) | 71 (8.5%) | < 0.0001 |

| Diabetes | 209 (16%) | 178 (16.6%) | 194 (19.5%) | 172 (20.5%) | 0.0846 |

| Current smoker | 464 (35.6%) | 338 (31.5%) | 288 (29%) | 227 (27.1%) | < 0.0001 |

Discussion

Stroke incidence continued to decrease over the 16-year period. The greatest decline in incidence was observed in the white population, but ethnic group disparities still exist, indicating a higher stroke risk in black groups. The estimates in the BA and BC groups are based on smaller numbers and hence the fluctuations in the rates. However, they do show that, although moderated reductions in the risk of stroke have been seen in the Caribbean group, there is a suggestion of an increasing risk in the African group. The prior-to-stroke risk factors are helpful in understanding in the stroke population only what the prevalence of the risk factors are and whether or not they have been managed. It appears from this analysis that in all groups there remain inequalities in risk factor detection and management. The next section of this objective’s chapter looks in more detail at the risk factor management prior to stroke in this group. From these observations on stroke incidence, it is clear that, in terms of a prevention strategy, inequalities in risk factor detection and management remain an issue. There are particular issues relating to the differences in risk in the different ethnic groups and how prevention strategies can address these in culturally sensitive ways, as well potentially different medication regimens.

Trends in risk factor prevalence and management prior to stroke: data from the South London Stroke Register 1995–2011 (deliverable 2)

Background

Despite efforts to improve the primary prevention of stroke through the implementation of international guidelines and government policies, vascular risk factors are often poorly controlled. Knowledge of how risk factors and their treatment have changed over time, and factors associated with medication use, could help target future strategies for stroke primary prevention.

We sought to examine trends over time in risk factors and their management prior to stroke, using data from the SLSR from 1995 to 2011. We aimed to examine how risk factors varied among age, sex, ethnic group, socioeconomic groupings and by stroke subtype, and to investigate factors associated with the prescription of primary prevention medication.

Methods

Data on prior hypercholesterolaemia (from 2001), hypertension, AF, MI, heart failure, TIA and diabetes, and data on primary prevention prescription prior to stroke (antiplatelets, anticoagulants, antihypertensive drugs, and cholesterol-lowering drugs) were collected from the patient and routinely verified from hospital records or contacting the patient’s usual GP. Deprivation was estimated using Carstairs scores. The index was derived from 2001 census data for each lower-layer superoutput area (SOA) covered by the register. Lower-layer SOAs cover an average population of 1500 residents and were the smallest area for which information was available. Carstairs scores for each patient were obtained by matching postcodes covered by the SOAs to those in which the patients lived at the time of stroke.

The prevalence of prior-to-stroke risk factors (hypertension, hypercholesterolaemia, AF, diabetes, prior MI and prior TIA) was assessed in 2-year groups to increase numbers per group. The chi-squared test for trends was used to assess the significance of changes in age, sex, ethnicity and stroke subtype over time. Multivariate logistic regression models were used to assess the significance of time trends in risk factors and examine factors associated with risk factor diagnosis and primary prevention use. The model used for time trends was adjusted for sex, age, ethnicity, stroke subtype and deprivation. The use of hypoglycaemic drugs was not evaluated, as they are not indicated for every diabetic patient. The models used in assessing risk factor diagnosis and primary prevention use were adjusted for sex, age, ethnicity, stroke subtype, deprivation and year of stroke. Possible interactions between dependent variables were assessed. Analyses omitted patients with missing data.

Results

Between January 1995 and 2011, 4416 patients with a first stroke were registered. The median age was 72.4 [interquartile range (IQR) 61.2–81.1]. Ethnicity of patients was white (70.5%), black (21.2%; 13% BC, 7.6% BA and 0.6% black other) and other (5.7%). Stroke pathological subtypes were ischaemic (73.8%), PICH (12.7%), SAH (5%) and undefined (8.4%). White and black patients had significantly lower deprivation scores than patients in other ethnic groups [mean Carstairs score: white ethnicity 9.421, black ethnicity 9.662, other ethnic groups 10.21; p analysis of variance (ANOVA) = 0.006]. There were high levels of data completeness for prior-to-stroke risk factors and primary prevention use (95–97% for risk factors; 96–97% for primary prevention).

The prevalence of known hypercholesterolaemia increased over time (2001–02 13.6% vs. 2009–10 35.9%, p < 0.001) whereas prior-to-stroke MI significantly reduced (1995–96 9.7% vs. 2009–10 3.4%, p < 0.001). There was no significant change in hypertension, diabetes or AF. Black patients had significantly higher odds of hypertension [odds ratio (OR) 2.01, 95% CI 1.69 to 2.40] and diabetes (OR 2.93, 95% CI 2.43 to 3.54) than white patients and lower odds of AF (OR 0.42, 95% CI 0.31 to 0.56) and prior MI (OR 0.55, 95% CI 0.40 to 0.75). Overall proportions prescribed primary prevention medication were hypertension 62%, hypercholesterolaemia 75%, MI on antiplatelets 32%, AF on anticoagulants 16% and AF on antiplatelets 25%. Prescription of cholesterol-lowering drugs increased significantly over the study period and, among those with AF, there was a small reduction in antiplatelet prescription together with a small increase in anticoagulant prescription. Older patients had significantly lower odds of anticoagulant prescription (age > 85 years vs. < 65 years: OR 0.16, 95% CI 0.07 to 0.35); but there was no difference between ethnic groups. Black patients with hypertension were more likely to be treated than white patients (OR 1.63, 95% CI 1.33 to 2.01) and there were no significant differences in prescription of primary prevention between ethnic groups for other risk factors. There was no significant association of any risk factor prevalence or primary prevention prescription with deprivation.

Discussion

This analysis provides evidence that levels of diagnosed risk factors have remained largely stable over the 16-year period, with the exception of a substantial increase in diagnosed hypercholesterolaemia. The study highlights substantial ethnic differences in stroke risk factors that were not explained by socioeconomic deprivation, with hypertension and diabetes significantly more common in black patients, but AF and prior-to-stroke MI significantly more common in white patients. There was little change in the use of primary prevention in this stroke cohort during the 15-year study period. Although a majority of patients with known hypertension and hypercholesterolaemia were treated (62% and 75% respectively), only a minority of stroke patients with AF or prior MI were on appropriate treatment.

Ethnicity, socioeconomic deprivation and risk factors

This study has confirmed the findings of previous research,56–58 that there are large differences in diagnosed risk factors prior to stroke among people of different ethnic groups. Previous studies have found that black and ethnic minority populations have poorer access to health services. 59 We found no difference in primary prevention prescription between ethnic groups, with the exception of hypertension, for which black patients were significantly more likely to be prescribed treatment than white patients. Furthermore, we did not assess the adequacy of risk factor control, but merely whether or not treatment was prescribed, which is a potential weakness. Several UK observational studies, including one with over 49,000 participants, have found significant differences in hypertension control: not only is the prevalence of hypertension significantly higher among black people than white people, but blacks are less likely than whites to show good control. 60–62 The lack of impact of deprivation on risk factors contrasts with previous research in the USA, which found that income differences explained much of the difference in risk factor prevalence between white and African-American patients. 57 In this UK study, we found no significant difference in risk factor prevalence or prescription of primary prevention drugs and large differences in risk factors among ethnic groups remain after adjustment for Carstairs scores. This discrepancy could reflect differences in health-care provision for deprived populations between the UK and USA; research from the USA has found poorer treatment and control of cardiovascular risk factors among people without health insurance. 63 This contrasts with a UK-wide study of hypertension using Quality and Outcome Framework data from 2005 to 2007 general practice records, which found that deprivation had no significant effect on control. 64

Anticoagulation in atrial fibrillation

Anticoagulants have been proven to be highly effective for the primary prevention of stroke in people with AF and substantially more effective than aspirin. 65 Consequently, a recent UK consensus statement has recommended that aspirin is no longer used for stroke prevention in AF. 66 Despite this evidence, the proportion of those with AF prescribed an anticoagulant remained extremely low over the study period and the majority of patients were on no treatment at all. Of the 16% of the SLSR population diagnosed with AF prior to stroke, 63% were not prescribed either an antiplatelet or anticoagulant prior to stroke and older patients were significantly less likely to be treated with anticoagulants. Research in the UK general population has found significantly lower rates of risk factor treatment among older people, despite advancing age being the most important risk factor for cardiovascular disease. 67 It is unclear from these data whether or not those not taking anticoagulants had other contraindications to taking anticoagulants and observational data from the USA have found low warfarin use in those with no contraindications. 68 One trial found that warfarin in elderly people was superior to aspirin for stroke prevention and was associated with no significant difference in haemorrhagic complications. 69 The data from the SLSR suggest that there is much room for improvement in the use of primary prevention in AF.

Ethnicity and atrial fibrillation

This study has confirmed the results of previous studies58,70 that black stroke patients are substantially less likely to be diagnosed with AF prior to stroke than white stroke patients. This difference is not likely to be confounded by under-diagnosis as a similar discrepancy was found in rates of AF detected by electrocardiography (ECG) after admission to hospital. It is unclear whether this is solely due to lower AF prevalence in black people in the general population71 or whether the aetiological role of AF in stroke varies depending on ethnicity. 72

Evidence on the effectiveness of anticoagulation comes overwhelmingly from white populations,73 with only 6% of the population of anticoagulation trials being non-white. 72 Similarly, the commonly used tools for identifying those with AF who are at high stroke risk do not incorporate ethnicity and have not been validated in black populations. 73–76 A large retrospective US hospital-based study found that the risk of warfarin-related intracranial haemorrhage was higher in black than in white patients. 72,77 These data may raise the question of whether or not the balance of benefit and harm with anticoagulation varies among different ethnic groups. 72

This study has the strength of being population based, rather than hospital based, with a wide recruitment base. Risk factors diagnoses were checked with the patient’s usual GP and did not rely solely on patient recall. However, the results represent not the prevalence of risk factors, but rather rates of diagnoses. In particular, the prevalence rates may appear artificially low owing to poor uptake or provision of cardiovascular risk screening and treatment in primary care. The substantial increase in hypercholesterolaemia seems likely to be explained by better detection.

Although statin use has significantly increased, there have been no important improvements in the treatment of AF, MI or hypertension over the 16-year study period. Prior-to-stroke risk factor profiles vary significantly among ethnic groups, with black stroke patients having a higher prevalence of hypertension and diabetes but a lower prevalence of AF and prior-to-stroke MI than white patients. Ethnic differences in risk factors were not explained by socioeconomic deprivation.

Risk of stroke by aetiological subtype in the South London Stroke Register population47

Deliverable 4: incidence by aetiological subtypes – year 2

Background

The risk of stroke varies significantly internationally and, although estimating overall stroke risk is relevant to planning stroke care, more detailed assessment of the underlying risk factor profile in stroke populations is relevant to understanding the aetiology and how preventative strategies may need to be tailored in different sociodemographic groups. 3 Population-based studies following key methodological criteria are able to deliver this information, but registers that have investigated aetiological stroke subtypes using a mechanism-based classification system,78 such as the Trial of ORG 10172 in Acute Stroke Treatment (TOAST) classification system,79 are few. They include studies in Germany,80 the USA,81–84 New Zealand85 and Chile86 but none estimates risk in European multiethnic populations or in different groups in the black population.

The aim of this deliverable was to estimate the incidence by aetiology of first-ever ischaemic stroke in different ethnic groups within the SLSR population to determine whether or not patterns of population risk vary with ethnicity, which is relevant information for targeting of prevention services.

Methods

Data collection on aetiological subtype commenced in 1999. Ischaemic strokes were investigated according to an investigation algorithm and categorised by a study clinician into aetiological subtypes according to the TOAST classification with local modifications to improve investigation rates in different ethnic groups. 31 This modified classification has excellent inter- and intraoperator agreement and has been adapted to enable conditions such as sickle-cell disease to be classified specifically in ‘other’. Ischaemic stroke subtypes included large artery atherosclerosis (LAA) (including extracranial LAA and intracranial LAA), cardioembolism (CE), small vessel occlusion (SVO), other aetiology (OTH) [including other vascular aetiology, other haemoglobinopathy aetiology, other hypercoaguable aetiology, migrainous stroke, OTH not previously mentioned), aetiology undetermined (UND) and multiple or concurrent aetiologies (CONC)].

Crude incidence rates of ischaemic stroke were calculated for age group, sex, ethnic groups and stroke aetiology, and specific incidence rates for sex, ethnic group and aetiological subtype were age adjusted to the standard European population. 87 Ninety-five per cent CIs for the age-specific rates and age-adjusted rates were calculated using the Poisson distribution. IRRs were calculated for each aetiological subtype to compare stroke incidence between different ethnic groups, with the white group being the reference group, and 95% CI for the direct standardised IRRs were calculated using the delta method. 88 Differences in proportions of prior-to-stroke risk factors among aetiological stroke subtypes were explored by running separate logistic regression models for each risk factor, adjusted for age, sex, ethnicity and socioeconomic status (SES), as appropriate. Two-tailed probability values are reported and a p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant in all analyses. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS software version 9.1.

Results

Between September 1999 and August 2006, 1181 patients with first-ever ischaemic stroke were included in the study, this being the latest complete data available for analysis in year 1 of the programme. In 12 of these patients, TOAST classification was not possible, mainly because of missing or incomplete diagnostic information. Among the remaining 1169 patients included in subsequent analyses, mean age was 71.4 years, 50.6% were female, 71.3% were of white origin, 20% of black origin (12.8% BC, 6.7% BA and 0.5% black other), 5.7% were of other origin and 3.1% of unknown ethnic origin. A total of 86.6% of the patients underwent ECG, 59.5% underwent a transthoracic or transoesophageal echocardiography and 66.9% underwent vascular imaging (carotid Doppler and/or transcranial colour duplex). The distribution of the aetiological subtypes was as follows: LAA, 109 (9.3%); CE, 325 (27.8%); SVO, 316 (27.0%); OTH, 40 (3.4%); UND, 283 (24.2%); CONC, 96 (8.2%). The annual age-adjusted incidence rate per 100,000 for total ischaemic stroke was 101.2 (95% CI 82.4 to 122.9) in men and 75.1 (95% CI 59.1 to 94.1) in women. The annual age-adjusted incidence rate per 100,000 for LAA was 10.4 (95% CI 5.1 to 18.9) in men and 6.8 (95% CI 2.7 to 14.2) in women. For CE it was 23.0 (95% CI 14.6 to 34.5) in men and 21.5 (95% CI 13.4 to 32.8) in women and for SVO it was 30.3 (95% CI 20.5 to 43.2) in men and 20.3 (95% CI12.5 to 31.3) in women.

The overall IRR for black patients was 1.25 (95% CI 1.07 to 1.46); it was 1.31 (95% CI 1.09 to 1.58) for BC patients, 1.22 (95% CI 0.93 to 1.61) for BA patients and 1.24 (95% CI 0.96 to 1.61) for other ethnic groups. Compared with the white ethnic group, IRRs for SVO were significantly higher in blacks as well as for the subgroups of BA and BC patients of both sexes. IRRs for OTH were significantly higher in all black women and in BA patients of both sexes than in the white ethnic group. Relative to whites, IRRs for other ethnic groups were higher for SVO in females and for UND in males.

Discussion

This study represents the first European data on the incidence of aetiological stroke subtypes in different ethnic groups, including white, black and other ethnic groups, using a modified TOAST classification. It has demonstrated stark differences between the white, black and other ethnic groups, such as age at stroke onset and patterns of prior-to-stroke risk factors and aetiological subtypes in different ethnic groups. In this study, the risk of SVO was increased in BA, BC and other ethnic groups in both sexes, and for OTH the risk was increased in black females and in BA compared with the white ethnic groups.

Differences in risk of stroke between different ethnic groups might be caused by differences in underlying risk factors. Age at onset of stroke is significantly lower in all ethnic groups than in whites in the SLSR population and in other previously reported literature. 4,89 We have previously identified that there are significant variations in underlying risk factor patterns in the SLSR: the BC/BA group have higher rates of prior-to-stroke hypertension and diabetes but reduced rates of smoking, history of TIA and obesity,90 and these findings mirror the results from another, non-population-based, south London study assessing differences in stroke subtypes between ethnic groups to which SLSR data contributed. 91 By comparing results with international studies that contrast ethnic groups, similar differences have been observed in the USA with regard to increased hypertension and diabetes in black Americans and Hispanics in northern Manhattan and in blacks in Greater Cincinnati. 81,92 The increased rates of hypertension are linked to SVO, but in a parallel study in London, using the population of SLSR, even after adjustment for hypertension, there was an excess of SVO in the black group. 92 This study reported a relative excess of small vessel disease and intracranial atherosclerosis in black patients compared with an excess of extracranial atherosclerosis and cardioembolic stroke in white patients, independent of conventional risk factors and social class. 62, In contrast to the study by Markus et al. 91 and population-based studies in the USA, LAA IRRs did not differ between ethnic groups. 81,91,92

We also observed that IRRs for SVO were higher in females and for UND aetiology were higher in males in other ethnic groups than in the white group. Thus, the increased risk of stroke in different ethnic groups compared with the white group might represent a non-ethnic group-specific migration effect. This effect might be caused by variations in socioeconomic status, differences in access to health-care services or different attitudes towards preventative measures between native and migrant populations.

Important differences in patterns of risk of subtypes of ischaemic stroke have been demonstrated between different ethnic groups, which strengthen the case for assessing stroke risk strategies separately in these populations. Furthermore, the pattern of aetiological subtypes seen in these ethnic groups demonstrates the importance of studying individual subtypes in multiethnic populations. The reasons for the significantly increased risk SVO in black and other ethnic groups and of ‘other’ aetiologies in BAs have to be explored in more detail. Further characteristics of populations, with regard to genetic risk and other environmental and life course factors, is required to develop tailor-made prevention programmes adapted to the needs of specific ethnic groups.

Additional analyses undertaken by programme team for objective 1 utilising programme employed staff and/or South London Stroke Register data collected during the programme

The advantage of the long-standing register is that we are asked to collaborate with groups that wish to answer relevant questions for this NIHR programme but the resources for which are not available solely from the programme. In addition, we have been approached to undertake reviews and write editorials, some of which contribute to the programme’s aims.

Socioeconomic status and stroke: an updated review93

The team was asked to undertake a review for stroke. The article reviews the relationship between socioeconomic status and risk of stroke, quality of care and outcome. The review is pertinent to the findings of the register in relation to inequalities in risk, care and outcome identified throughout the programme’s analyses. A summary is presented here with full details in Addo et al. 93

Background

Rates of stroke incidence and mortality vary across populations with important differences reported between socioeconomic groups worldwide. Knowledge of existing disparities in stroke risk is important for effective stroke prevention and management strategies. This review updates the evidence for associations between socioeconomic status and stroke.

Methods

Studies were identified with electronic searches of MEDLINE and EMBASE databases (January 2006 to July 2011) and reference lists from identified studies were searched manually. Articles reporting the association between any measure of socioeconomic status and stroke were included.

Results

The impact of stroke as measured by disability-adjusted life-years lost and mortality rates is over threefold higher in low-income than in high- and middle-income countries. The number of stroke deaths is projected to increase by > 30% in the next 20 years, with the majority occurring in low-income countries. A higher incidence of stroke, stroke risk factors and rates of stroke mortality is generally observed in low socioeconomic groups, both within and between populations worldwide. There is less available evidence of an association between socioeconomic status and stroke recurrence or temporal trends in inequalities. Those with a lower socioeconomic status have more severe deficits and are less likely to receive evidence-based stroke services, although the results are inconsistent.

Discussion

Poorer people within a population and poorer countries globally are most affected in terms of incidence and poor outcomes of stroke. Innovative prevention strategies targeting people in low socioeconomic groups are required, along with effective measures to promote access to effective stroke interventions worldwide.

Analysis of the General Practice Research Database

Our programme of work has identified inequalities in the risk of stroke by sociodemographic group and varying trends in risk over time in south London, but there are no comparable national data available using the classic disease register methodologies and hot pursuit techniques. Analysis of electronic health records from GPRD is potentially complementary to the epidemiological research of the SLSR. The GPRD provides nationally representative data for large populations in primary care, albeit with clinical data rather than protocol-driven epidemiological data collected by SLSR. We wanted to assess whether or not GPRD is a potential source on incident and recurrent stroke patients with detailed follow-up information on new diagnoses and treatments. The details of these analyses are in references 49–53. Our research has

-

developed case definitions for stroke in electronic patient records

-

documented the utility of GPRD records of blood pressure, cholesterol and antiplatelet therapy for prospective studies of stroke management

-

demonstrated improving trends in risk factor management post stroke

-

associated these with declining case fatality following stroke.

Novel risk factors for stroke risk and survival

The programme addresses the role of traditional cardiovascular and stroke risk factors and their management on stroke risk in objective 1 in an inner-city setting. The opportunity arose to collaborate with a group at Manchester University to look at the effects of air pollution, monitored continuously in London, on stroke risk and outcome. This uses the time of the programme’s SLSR data manager and statistician to extract data. More importantly, these analyses were felt important to begin to understand the differences in risk in different groups of the population. Air pollution and policy around low emission zones made it pertinent to utilise SLSR data with minimal resource and two papers have been published in Stroke as a result of the project. 54,55

Outdoor air pollution and incidence of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke: a small area level ecological study54

Background

Evidence linking outdoor air pollution and incidence of stroke is limited. We examined the effects of outdoor air pollution on the incidence of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke at the population level. In this paper we have reported the results of a small-area-level ecological study we carried out to examine the effects of outdoor air pollution on stroke incidence at the population level using data from the SLSR and examining the effects on ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke separately. We also examined the effects in middle-aged and older people separately as previous studies suggest that older people are more susceptible to the adverse effects of air pollution and examined the effects on fatal and non-fatal stroke as there is a suggestion that the effect is stronger for fatal stroke.

Methods

We used a small-area-level ecological study design and SLSR data on incident cases of first-ever stroke occurring in a defined geographical area in south London (948 census output areas) where road traffic contributes to spatial variation in air pollution. We used modelled PM10 and NO2 concentrations as measures of exposure to outdoor air pollution. Previous research has shown that, when PM10 or NO2 are controlled for, the effects of other pollutants such as carbon monoxide, sulphur dioxide and ozone become mostly non-significant. Population-weighted averages were calculated for output areas using outdoor NO2 and PM10 concentrations modelled at a 20-metre resolution. The model took into account a range of pollution sources and emissions including major and minor road networks modelled with detailed information on vehicle stock, traffic flows and speed on a link-by-link basis, pollution sources in the London Atmospheric Emissions Inventory including large and small regulated industrial processes, boiler plants, domestic and commercial combustion sources, agriculture, rail, ships, airports and pollution carried into the area by prevailing winds. We used the Income Domain of the Index of Multiple Deprivation as a measure of socioeconomic deprivation at the small-area level.

Results

There were 1832 ischaemic and 348 haemorrhagic strokes in 1995–2004, occurring amongst a resident population of 267,839. Mean [standard deviation (SD)] concentration was 25.1 (1.2) μg/m3 (range 23.3–36.4 μg/m3) for PM10 and 41.4 (3.0) μg/m3 (range 35.4–68.0 μg/m3) for NO2.

For ischaemic stroke, adjusted rate ratios per 10 μg/m3 increase, for all ages, and for 40–64 years and 65–79 years, were 1.22 μg/m3 (range 0.77–1.93 μg/m3), 1.12 μg/m3 (range 0.55–2.28 μg/m3) and 1.86 μg/m3 (range 1.10–3.13 μg/m3) for PM10 and 1.11 μg/m3 (range 0.93–1.32 μg/m3), 1.13 μg/m3 (range 0.86–1.50 μg/m3) and 1.23 μg/m3 (range 0.99–1.53 μg/m3) for NO2.

For haemorrhagic stroke, the corresponding rate ratios per 10 μg/m3 for all ages, and for 40–64 years and 65–79 years, were 0.52 (range 0.20–1.37), 0.78 (range 0.17–3.51) and 0.51 (range 0.12–2.22) for PM10 and 0.86 (range 0.60–1.24), 1.12 (range 0.66–1.90) and 0.78 (range 0.44–1.39) for NO2.

Discussion

While there was no significant association between outdoor air pollutants and ischaemic stroke incidence for all ages combined, there was a suggestion of increased risk amongst people aged 65–79 years. There was no evidence of increased incidence in haemorrhagic stroke and we found no evidence that air pollution was more likely to be associated with fatal rather than non-fatal stroke. Adjustment for socioeconomic deprivation at the small-area level made little difference to the associations observed.

A number of potential limitations to our study need to be considered. The association between air pollutants and ischaemic stroke was seen in only a subgroup of the population and needs to be interpreted with caution. As this was an ecological study, the possibility of ecological bias (the situation in which the association seen at the area level is different from that which exists at the individual level) cannot be ruled out. However, we used very small geographical units that might be expected to reduce ecological bias. Exposure misclassification is possible as we took only residential exposure into consideration. We could adjust for a only limited number of potential confounders and the possibility that the association might be explained by other unmeasured confounders cannot be ruled out. The SLSR was specifically established to examine stroke incidence at a population level and the study team confirmed all cases; however, subtype could not be established for a proportion of cases. Case capture was possibly incomplete, potentially introducing further error, the population denominator counts were a further source of error and census under-enumeration is known to have been greater amongst younger people and, to a lesser extent, amongst very old people. 94 The ONS had adjusted population estimates to take into account estimated undercounts. While these estimates are likely to be reliable at a large-area level, such as the whole SLSR study area, it would be difficult to adjust accurately for spatial variation in undercounts at a very small-area level, such as the output area level we used in this analysis. However, examining age groups limited to the 40–79 years age category would have minimised the impact of under-enumeration. In addition, the limitations may be expected to have affected rates of ischaemic and haemorrhagic stroke to similar extents and the strength of our study is the comparative analysis of these stroke subtypes.

In summary, while we found no significant association between outdoor air pollutants and ischaemic stroke incidence in our population-based study for all ages combined, there was a suggestion of increased risk amongst people aged 65–79 years. Further studies are needed to examine if ischaemic stroke risk associated with outdoor air pollution is more pronounced amongst older people.

Impact of outdoor air pollution on survival after stroke: population-based cohort study55

Background

The impact of air pollution on survival after stroke is unknown. We examined the impact of outdoor air pollution on stroke survival by studying a population-based cohort.

Methods

All patients who experienced their first-ever stroke between 1995 and 2005 in the SLSR study area, where road traffic contributes to spatial variation in air pollution, were followed up to the end of June 2006. Outdoor concentrations of NO2 and PM10 modelled at a 20 m grid-point resolution for 2002 were linked to residential postal codes. Hazard ratios (HRs) were adjusted for age, sex, social class, ethnicity, smoking, alcohol consumption, prestroke functional ability, pre-existing medical conditions, stroke subtype and severity, hospital admission and neighbourhood socioeconomic deprivation.

Results

There were 1856 deaths among 3320 patients and median survival was 3.7 years (IQR 0.1–10.8 years). Mean exposure levels were 41 μg/m3 (SD 3.3 μg/m3, range 32.2–103.2 μg/m3) for NO2 and 25 μg/m3 (SD 1.3 μg/m3, range 22.7–52.0 μg/m3) for PM10. A 10 μg/m3 increase in NO2 was associated with a 28% (95% CI 11% to 48%) increase in risk of death. A 10 μg/m3 increase in PM10 was associated with a 52% (95% CI 6% to 118%) increase in risk of death. Reduced survival was apparent throughout the follow-up period, ruling out short-term mortality displacement.

Discussion

Survival after stroke was lower among patients living in areas with higher levels of outdoor air pollution. If causal, a 10 μg/m3 reduction in NO2 exposure might be associated with a reduction in mortality comparable to that for stroke units. Improvements in outdoor air quality might contribute to better survival after stroke.

Objective 1: conclusions and implications for further research