Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 08/99/18. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The final report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew Clark and Pamela Ewan are inventors on a patent application covering the peanut protein dose range.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Anagnostou et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Peanut allergy is a common and important medical condition, affecting 1% of children in developed countries. 1–3 Unlike other common childhood food allergies (e.g. to hen’s eggs), resolution is uncommon. 4 Peanut allergy is the most common cause of severe and fatal food allergic reactions and it is not possible to identify those at highest risk. 5 The quality of life (QoL) of affected families is reduced because of constant fear over food choices and the likelihood of anaphylaxis. 6,7 Despite the current best management, families of peanut-allergic children have poor knowledge of how to avoid and also treat food allergy emergencies. 8 Accidental reactions are common (annual incidence rates for accidental reactions of 3%, 14% and 50% have been reported). 9

Peanut allergy puts patients at risk of severe reactions and death, and has a profound effect on their QoL. There is no disease-modifying treatment and spontaneous resolution is rare; therefore, the case is made for development of disease-modifying therapies. Oral immunotherapy (OIT) seems to be the most promising short- to medium-term solution to this problem, given its apparent efficacy in other allergies.

Grass pollen immunotherapy given by subcutaneous injection has been used for over a century to treat allergic rhinitis and has proven efficacy and safety. 10 An early study of subcutaneous immunotherapy for peanut allergy showed a trend to benefit, but was terminated after severe adverse reactions. 11 The oral route may be associated with increased safety and has been studied in cases of egg and milk allergy. 12–15

The recent House of Lords Science and Technology Committee report on allergy stressed that allergy research directly related to health care is an area of unmet need that requires greater priority. 16 According to the report, ‘immunotherapy is a valuable resource in the prophylactic treatment of patients with life threatening allergies . . . so its wider use could potentially result in significant long-term savings for the NHS’,16 © Parliamentary copyright 2007, Contains Parliamentary information licensed under the Open Parliament Licence v1.0, URL: www.parliament.uk/site-information/copyright/open-parliament-licence/.

There are few data on desensitisation to foods; however, this is an established treatment for inhalant allergies (e.g. pollen-induced rhinitis) and insect venom anaphylaxis. Subcutaneous injection immunotherapy for pollen-induced rhinitis is effective and disease modifying in that it results in persistent tolerance after stopping therapy. Efficacy is confirmed by a recent Cochrane meta-analysis showing a clear benefit in symptom score and medication use against placebo. 17 Similarly, success is seen in subcutaneous injection immunotherapy for insect venom allergy, for which it is possible to safely desensitise patients with life-threatening reactions. 18

Sublingual immunotherapy (SLIT), administering doses under the tongue, is a relatively recent development that has high efficacy and tolerability for pollen desensitisation (for severe hay fever). A Cochrane review confirmed the efficacy of SLIT compared with placebo in terms of a reduction in symptom scores and antiallergic medication requirements. Of particular note is the apparent safety of SLIT, which has encouraged us to pursue the oral route in the current proposal. 19

Subcutaneous peanut immunotherapy was first attempted in a small study in 1992; three subjects exhibited a 67–100% reduction in symptoms induced by peanut challenge, suggesting that this is an effective therapy. No subject suffered anaphylaxis during immunotherapy. 11 SLIT for hazelnut allergy has been the subject of a more recent randomised controlled trial (RCT), which showed significant increases in tolerance to hazelnut [assessed by double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge (DBPCFC)] and systemic reactions were observed in only 0.2%. 20 We chose to use the oral route as we expect this to induce fewer side effects than injection immunotherapy, while still being efficacious, as demonstrated for pollen immunotherapy. There are also preliminary studies on desensitisation to other food allergens such as milk and egg. 12–15

We have pilot data on children aged 5–18 years using a study design identical to that of the active arm in the proposed trial. All had peanut allergy confirmed by blinded challenge before progressing to OIT according to the current proposal. To date, 19 out of 22 children have reached the final dose of 800 mg of peanut protein and are taking this, the equivalent of five peanuts, at home with no reaction. OIT doses taken at home and on the research ward are well tolerated and no subject has had a severe or generalised reaction during up-dosing. 21,22

A recent systematic review of studies of peanut OIT identified a single small randomised controlled study in 28 children. 23 It suggested a positive effect of peanut OIT, but was too small to estimate efficacy. 23 There is a need for systematic study of peanut OIT. We performed a phase 1 study that showed good tolerability and an indication of good efficacy. 21,22 The current study is a phase 2 randomised controlled study of the efficacy of peanut OIT in achieving desensitisation in a well-characterised population.

Chapter 2 Method

Setting

We undertook this single-centre RCT at the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus between January 2010 and March 2013. The study was conducted according to the principles of Good Medical Practice for clinical trials.

Patient and public involvement

Patient representatives were involved from the outset. We surveyed the pilot study participants to gather feedback that informed the design of the current trial. The national patient support group, the Anaphylaxis Campaign, has reviewed the current protocol and they have ratified the design and confirmed the study end points are important and relevant to their membership. Furthermore, a representative of the Anaphylaxis Campaign joined as a member of the Trial Steering Committee.

The result will be disseminated by an article in the Anaphylaxis Campaign’s newsletter and website.

Aims

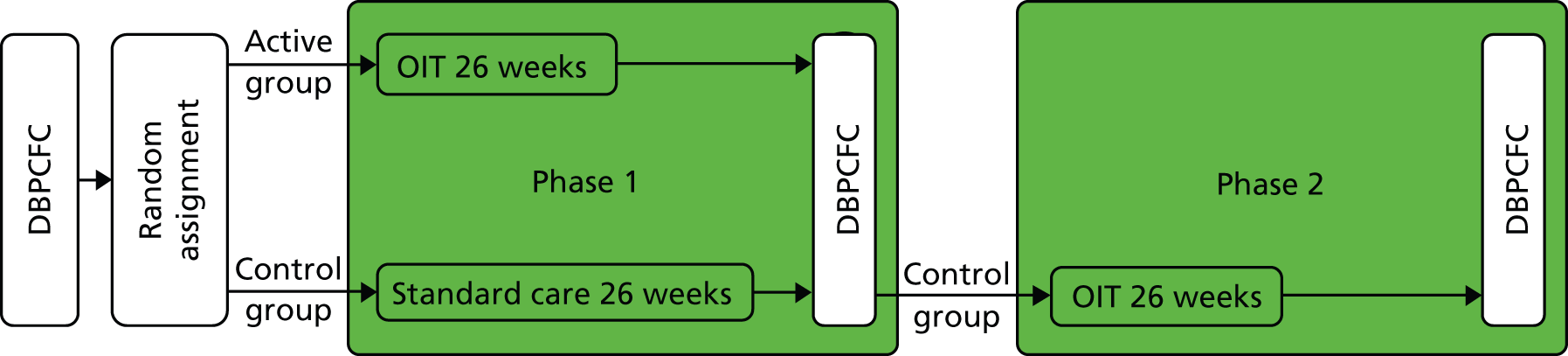

The overarching objective was to determine efficacy of OIT in desensitising children with peanut allergy. We aimed to determine whether or not the treatment was successful in the intervention group compared with the control (phase 1) and whether or not it is successful when offered to the control group (phase 2) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The Study of induction of Tolerance to Oral Peanut (STOP II) study design.

Participants

Participants were recruited both locally (allergy clinic) and nationally (through the national patient support group Anaphylaxis Campaign). Eligible participants were 7–16 years of age with an immediate-type hypersensitivity reaction after peanut ingestion, positive skin prick test (SPT) to peanut (extract from ALK-Abelló, Hørsholm, Denmark) defined by a weal of ≥ 3 mm in diameter in the presence of a negative saline and positive histamine control, and positive DBPCFC. 19 We excluded participants if they had a significant chronic illness (except for eczema, rhinitis and asthma) because this is an immunomodulatory therapy, if a care provider or current household member had suspected or diagnosed allergy to peanut, or if there was unwillingness or inability to comply with study procedures. We did not exclude participants who had a previous life-threatening reaction, tree nut allergy or a history of severe asthma.

The Cambridge Central Ethics Committee approved the study (09/H0308/154) and the guardian of each participant gave his or her informed consent. Children of an appropriate age (≥ 12 years) were encouraged to provide their own assent.

Randomisation

Subjects were randomised (1 : 1) via an audited online system (Randomizer, Medical University of Graz, Graz, Austria) to the active or control group (see Figure 1). Minimisation was used to reduce imbalance of baseline covariates, with a random element using a weighting probability of 0.8. Factors were sex, age, challenge threshold, peanut-specific serum immunoglobulin E (IgE), severity from history and presence of asthma or other food allergy. Group allocation was unblinded.

During phase 1, the active group underwent 6 months of active OIT and the control group underwent 6 months of standard care (peanut avoidance). Minimisation was used to avoid imbalance of baseline covariates, with a random element using a weighting probability of 0.8. At the end of phase 1 (6 months) all participants were assessed for peanut allergy by DBPCFC. During phase 2, participants in the control group still allergic to peanut after 6 months of standard care were given active OIT, followed by a DBPCFC after 6 further months (see Figure 1). There were no important changes to method after commencement.

Participants underwent an initial DBPCFC followed by 1 : 1 randomisation. During phase 1, participants in the active group underwent OIT for 26 weeks. Participants randomised to the control group were asked to continue normal peanut avoidance for the first 26 weeks of the study (standard care). Both groups then underwent a second DBPCFC. In phase 2, control group participants underwent active OIT for 26 weeks followed by a third DBPCFC at 52 weeks (end of phase 2).

Patients were not blinded to allocation groups; however, the primary outcome was assessed using an objective blinded measure, i.e. ‘no reaction’ during a DBPCFC. Challenge assessors were blinded to the challenge placebo/active arm, but not to the treatment allocation. Study personnel were the chief investigator, a clinical fellow, a study nurse and a scientist. All study personnel were masked to the randomised active/placebo assignment in the challenge except the scientist who prepared the challenge material but had no interaction with the participant or study team. Allocation was saved in a locked database accessible only to the unblinded scientist.

Procedures

The primary end point was the proportion of desensitised subjects at the end of phase 1. Desensitisation was defined as ‘no reaction’ during peanut DBPCFCs, with a cumulative dose of 1400 mg of peanut protein.

Oral challenges

All peanut challenges were undertaken as DBPCFCs according to best practice,19 using separate active and placebo phases and masked using the validated EuroPrevall dessert food carrier recipe (range of doses: 5 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 300 mg and 1000 mg of peanut protein). 20 We chose a cumulative challenge dose equivalent to approximately 10 peanuts to demonstrate desensitisation to an amount of peanut that we considered unlikely to be encountered accidentally following OIT. Random number lists determined the order of DBPCFC placebo and active arms. All study personnel were masked to the challenge assignment except the unblinded scientist, who prepared the challenge material but had no interaction with the participant or study team.

Secondary end points were the proportion who responded to treatment after receiving OIT (a response to treatment was defined as ingesting 800 mg of peanut protein regularly for up to 6 months); the proportion of the control group who were desensitised or responded to treatment during phase 2; the fold and absolute increase in threshold [maximum tolerated peanut protein (mg)] after OIT; change in QoL [measured by food allergy quality of life – parent form (FAQLQ-PF) 0–12 years] scores from baseline to the end of phase 1 and phase 2; number and type of adverse events; and change in immunological outcomes [basophil area under curve (AUC) of percentage of CD63 and mean fluorescence intensity (MFI), peanut IgE, total IgE, and SPT diameter]. There were no changes to outcomes after commencement.

Oral immunotherapy

The active intervention (OIT) was administered in daily doses throughout and was given in two phases. First, there was a gradual up-dosing phase with 2-weekly increments to 800 mg/day, followed by a maintenance phase during which the highest tolerated dose (with a target of 800 mg/day) was taken continuously to complete a total of 6 months’ immunotherapy. The same characterised peanut flour used in the challenges was also used for up-dosing (light roast flour; Golden Peanut Company, Alpharetta, GA, USA). The up-dosing phase increments were 2 mg, 5 mg, 12.5 mg, 25 mg, 50 mg, 100 mg, 200 mg, 400 mg and 800 mg of peanut protein (patent applied for dosing regime). All dose increases took place in the Wellcome Trust Clinical Research Facility and subjects were observed for 2 hours. The same dose was administered at home daily for 2–3 weeks. At the final two up-doses, subjects ingested the equivalent dose as whole-roasted peanuts.

Patients were provided with a symptom diary that they were asked to complete each day and hand back to the study team at each visit. Patients were asked to take their dose with food and instructed not to exercise for 1–2 hours after taking a dose. Families had 24-hour contact access to the study team. Patients were free to take antihistamines as they wished throughout the study.

Flow cytometric analysis (fluorescence-activated cell sorting) of patient samples was undertaken on whole-blood specimens by study staff to quantify the percentage and MFI CD63+ basophils. SPTs were undertaken using a standardised peanut extract from ALK-Abelló and a single-point lancet. Peanut-specific serum IgE was measured using the ImmunoCAP system (Thermo Scientific, Hørsholm, Denmark).

Basophil activation tests

Peripheral blood was collected into heparin and processed within 2 hours. Laboratory workers performing basophil activation tests were not blinded to treatment allocation. Briefly, 100 µl of heparinised whole blood aliquoted into 12 × 75 mm flow cytometry tubes (Becton Dickinson) was stimulated with interleukin 3 (3 ng/ml final concentration; R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN, USA) in a 37 °C water bath for 10 minutes. The blood samples were then activated for 20 minutes at 37 °C, with the same volume of varying concentrations of endotoxin-free crude peanut extract (0.001–100 µg/ml) in Ca2+- and Mg2+-free phosphate-buffered saline (PBS) (Sigma, Santa Fe, MN, USA). Positive controls included N-formylmethionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (2 µM; Sigma, Santa Fe, MN, USA) and polyclonal anti-IgE (1/10,000; AbD Serotec, Kidlington, UK) and PBS and endotoxin-free ovalbumin (1 µg/ml; Sigma, Santa Fe, NM, USA) as negative and food allergen-negative controls, respectively. Degranulation was stopped by incubating on ice for 5 minutes. Cells were stained with a saturating antibody cocktail of CD63-fluorescein isothiocyanate (clone H5C6; Becton Dickinson), CD123-phycoerythrin (clone 9F5; Becton Dickinson) and HLA-DR-PerCP (human leucocyte antigen peridinin-chlorophyll protein; clone L243; Becton Dickinson) in the dark, on ice, for 20 minutes. The whole-blood samples were lysed and fixed with Becton Dickinson FACS™ (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) lysing solution for 15 minutes, at room temperature. After two washes (0.26% weight per volume bovine serum albumin; 2 mM ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid in PBS), the cell pellet was resuspended in 1% paraformaldehyde and acquired on a FACSCalibur™ (Franklin Lakes, NJ, USA) flow cytometer (Becton Dickinson Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA). At least 200,000 events were acquired for each sample. Activated basophils were identified as CD63+/CD123+/HLA-DR– and changes in the frequency (%CD63+) and expression (net CD63 MFI) was measured.

Statistical analysis

The full analysis population was all subjects who were randomised and participated in at least one post-baseline assessment. The criteria for per-protocol analysis of the outcome of peanut challenge at the end of immunotherapy consisted of desensitisation and continuation of immunotherapy up to the maintenance dose of 800 mg of protein.

Fisher’s exact test was used to compare the proportion of those with desensitisation to peanut after 6 months in the active group with the control group at the end of phase 1. Multiple logistic regression was used to adjust the odds of desensitisation for baseline characteristics. Secondary analyses tested for treatment differences with Fisher’s exact test (proportion response to treatment in active group and control group at end of phase 2), paired and independent sample t-tests (absolute and fold change in threshold), and Mann–Whitney U-tests (change in QoL scores, basophil AUC of percentage of CD63 and MFI, peanut-specific serum IgE and SPT weal diameter). All statistical tests described in this section use a two-sided 5% significance level. We assessed analysis on the intention-to-treat population that included all those who were randomised and participated in at least one post-baseline assessment.

Sample size was based on Fisher’s exact test with 90% power and 5% significance (two-sided). A sample size of 49 in each group is sufficient to detect proportions of participants, with desensitisation to peanut of 0.64 and 0.30 in the active and control groups, respectively, at the end of phase 1. Allowing for a 5% dropout increased the required sample size to 52 participants in each group and 104 subjects overall. Based on the above, we would expect 35 waiting list group patients to proceed to the active intervention in phase 2. Non-parametric tests may be used instead of parametric tests if the assumptions are not appropriate.

A statistical analysis plan, which embodies all the calculations performed, was agreed and signed off before any analysis was undertaken on the database (see Appendix 1).

Results

We enrolled 104 children, aged 7–16 years (median 12.4 years), to the study. Five children did not react during their baseline peanut challenge, thus not meeting the inclusion criteria, and were excluded from further participation in the study. Therefore, 99 children were randomised: 49 out of 99 to the active group and 50 out of 99 to the control group (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT diagram of patient flow through the study.

One child was discontinued and five withdrew from the active group during phase 1. In the control group, four children withdrew and one was discontinued during phase 1. Two further children withdrew from the control group when they underwent the intervention in phase 2.

There were no significant differences in baseline characteristics between allocation groups (Table 1).

| Characteristic | Control group (N = 50) | Active group (N = 49) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | ||

| n | 50 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 11.9 (2.67) | 12.4 (2.42) |

| Median (range) | 12.3 (7.2–16) | 12.3 (8.1–16.3) |

| Sex (male), n (%) | 36 (72) | 34 (69.4) |

| Weight (kg) | ||

| n | 47 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 44.3 (16.4) | 45.7 (15.5) |

| Median (range) | 39 (21–82) | 43 (23–81) |

| Asthma, n (%) | 29 (58) | 29 (59.2) |

| Eczema, n (%) | 27 (54) | 24 (49) |

| Rhinitis, n (%) | 27 (54) | 29 (59.2) |

| Family history of peanut allergy, n (%) | 35 (70) | 31 (63.3) |

| Severity of worst clinical reaction WAO score23 | ||

| Grade 1, n (%) | 25 (51) | 20 (40.8) |

| Grade 2, n (%) | 13 (26) | 25 (51) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 9 (18.4) | 3 (6.1) |

| Grade 4, n (%) | 2 (4.1) | 1 (2) |

| Other food allergy, n (%) | 13 (26) | 10 (20.4) |

| FAQLQ-PF QoL score | ||

| n | 20 | 19 |

| Mean (SD) | 2.69 (1.60) | 3.26 (1.26) |

| Median (range) | 2.28 (0.3–5.54) | 3.61 (0.47–5.44) |

| Peanut SPT weal diameter (mm) | ||

| n | 50 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 8.54 (3.08) | 8.92 (3.02) |

| Median (range) | 9 (3–14) | 9 (0–16) |

| Other nut SPT weal diameter | ||

| < 3 mm, n (%) | 34 (68) | 38 (77.6) |

| ≥ 3 mm, n (%) | 16 (32) | 11 (22.4) |

| Total IgE (kU/l) | ||

| n | 50 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 539 (467) | 597 (844) |

| Geometric mean | 385.9 | 312.9 |

| Median (range) | 355.5 (44–1942) | 295 (20–3971) |

| Peanut-specific IgE (kU/l) | ||

| n | 50 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 79.5 (117) | 202.9 (539) |

| Geometric mean | 24.0 | 29.9 |

| Median (range) | 41.6 (0.39–463) | 37.9 (0.35–3649) |

| Tryptase (ng/ml) | ||

| n | 26 | 33 |

| Mean (SD) | 4.55 (1.85) | 5.10 (2.94) |

| Median (range) | 4.5 (1.7–8.9) | 4.9 (0–15.6) |

| DBPCFC WAO severity score23 | ||

| Grade 1, n (%) | 11 (22) | 13 (26.5) |

| Grade 2, n (%) | 37 (74) | 33 (67.3) |

| Grade 3, n (%) | 2 (4) | 3 (6.1) |

| Grade 4, n (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| DBPCFC: total peanut protein consumed (mg) | ||

| n | 50 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 151.9 (274.0) | 99.8 (76.8) |

| Geometric mean | 66.2 | 63.9 |

| Median (range) | 55 (5–1400) | 60 (5–400) |

| DBPCFC: LOAEL (mg) | ||

| n | 50 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 147.9 (274.6) | 94.6 (77.4) |

| Geometric mean | 63.5 | 58.1 |

| Median (range) | 55 (5–1400) | 55 (5–400) |

| DBPCFC: NOAEL (mg) | ||

| n | 50 | 49 |

| Mean (SD) | 41.5 (80.1) | 28.4 (36.8) |

| Geometric mean | 14.3 | 0 |

| Median (range) | 5 (5–400) | 5 (0–155) |

| Basophil AUC of CD63 MFI against peanut protein concentration | ||

| n | 22 | 13 |

| Mean (SD) | 34,039 (27,513) | 40,198 (33,488) |

| Geometric mean | 205,556 | 29,271 |

| Median (range) | 31,438 (1219–109,006) | 34,955 (4930–118,532) |

| Basophil AUC of percentage of CD63-positive cells against peanut concentration | ||

| n | 22 | 13 |

| Mean (SD) | 6505 (2774) | 7322 (1609) |

| Geometric mean | 5205 | 7133 |

| Median (range) | 6958 (179–9553) | 7107 (3828–9284) |

Clinical end points

Primary objective

There was a significant difference between the numbers of patients who tolerated 1400 mg of peanut protein during DBPCFC at the end of phase 1 in the active (24/39) and the control groups (who underwent peanut avoidance for 24 weeks) (0/41) (p < 0.001) (Table 2). The proportion desensitised during phase 1 after 24 weeks was 0.62 (range 0.45–0.78) and 0 (range 0–0.091) in the active and control groups, respectively.

| End points | Control | Active | Control vs. active p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Clinical end points | |||

| n = 46 | n = 39 | ||

| Phase 1 | |||

| Number and proportion desensitised and able to tolerate daily ingestion after phase 1 | |||

| Desensitised | 0 | 24 | < 0.001b |

| Not desensitised | 46 | 15 | |

| Proportion desensitised (95% CI) | 0 (0 to 0.091) | 0.62 (0.45 to 0.78) | – |

| Proportion able to tolerate daily ingestion (95% CI) | 0 | 0.84 (0.70 to 0.93) | – |

| Within-patient changes in NOAEL (mg), absolute and fold change | |||

| Median (range) absolute change in NOAEL (mg) | 0 (–95 to 45) | 1345 (45–1400) | 0.002, < 0.001c |

| Median (range) fold change in NOAEL (mg) | 0.81 (0.05–1.82) | 25.5 (1.82–280) | 0.003, < 0.001c |

| NOAEL (mg) after phase 1 | |||

| NOAEL (mg) median (range) | 5 (5–400) | 1400 (100–1400) | < 0.001d |

| Median difference in NOAEL (mg) between groups | |||

| Median (95% CI) | 1395 (395 to 1395) | < 0.001d | |

| Phase 2 | |||

| Proportion desensitised and able to tolerate daily ingestion after phase 2 (treatment) | |||

| Proportion desensitised (95% CI) | 0.54 (0.35 to 0.72) | – | – |

| Proportion able to tolerate daily ingestion (95% CI) | 0.91 (0.79 to 0.98) | – | – |

| QoL end points | |||

| n = 20 | n = 19 | ||

| Median (range) change in score from baseline to post-treatment | –1.41 (–4.83 to 1.38) | –1.61 (–4.87 to 0.24) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

Secondary objectives

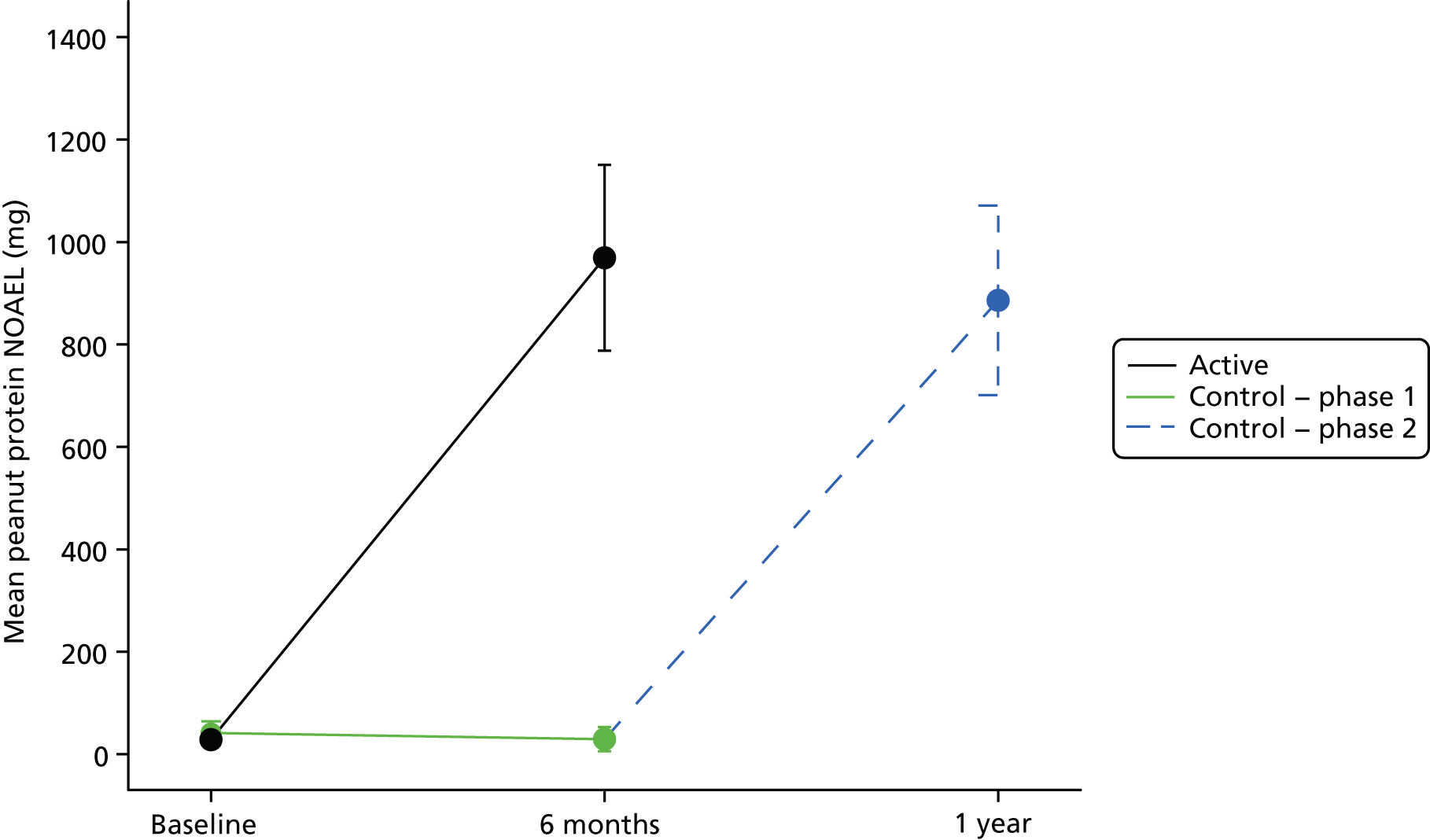

Response to treatment, defined by the ability to tolerate daily doses of 800 mg of peanut protein after 24 weeks of immunotherapy, occurred in 0.84 [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70 to 0.93] of the active group at the end of phase 1 and 0.91 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.98) of the control group at the end of phase 2 (post immunotherapy). There was a significant increase in peanut no observed adverse effect level (NOAEL) in the active group after phase 1, with a median change in threshold of 25.5-fold (p < 0.001) (Figure 3) compared with a small positive change in peanut threshold (NOAEL) in the control group during phase 1 (0.81, range 0.05–1.82).

FIGURE 3.

Mean and 95% CI peanut protein NOAEL (mg) by treatment group. NOAEL, highest dose of peanut protein tolerated in mg of protein during challenge or OIT (active treatment); difference at 6 months, p < 0.001. p-value from the Mann–Whitney U-test.

The proportions of patients who achieved desensitisation (0.54, 95% CI 0.35 to 0.72) or response to treatment (0.91, 95% CI 0.79 to 0.98) in the control group after 24 weeks of OIT (end of phase 2) were similar to that in the active group.

Quality-of-life end points

Quality-of-life scores assessed by the FAQLQ-PF measure were similar between active and control groups at baseline. FAQLQ-PF (aged 5–12 years) was available from 19 children in the active group and 20 in the control group, before and after treatment. After treatment in both groups there was a similar and clinically meaningful improvement (decrease) in QoL scores (see Table 2).

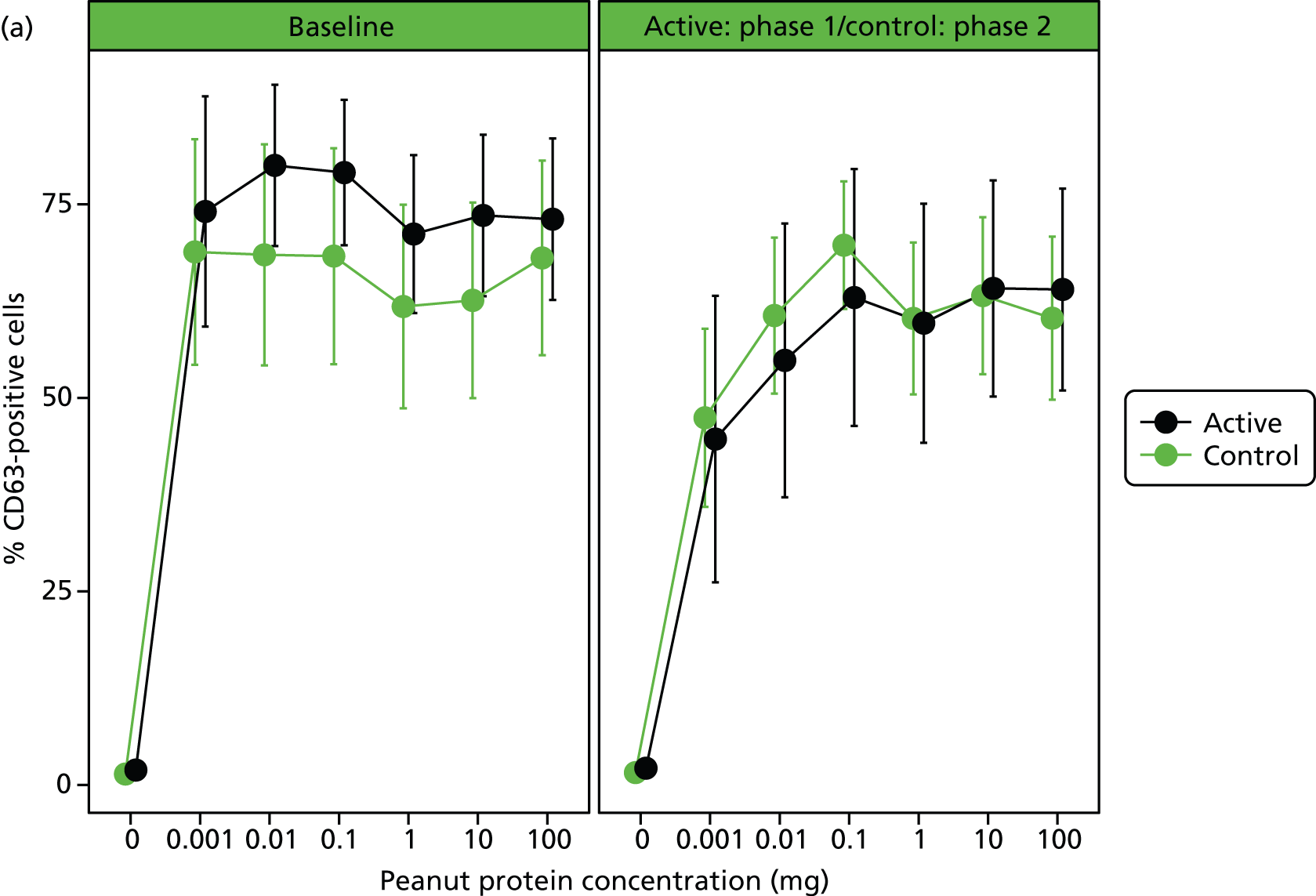

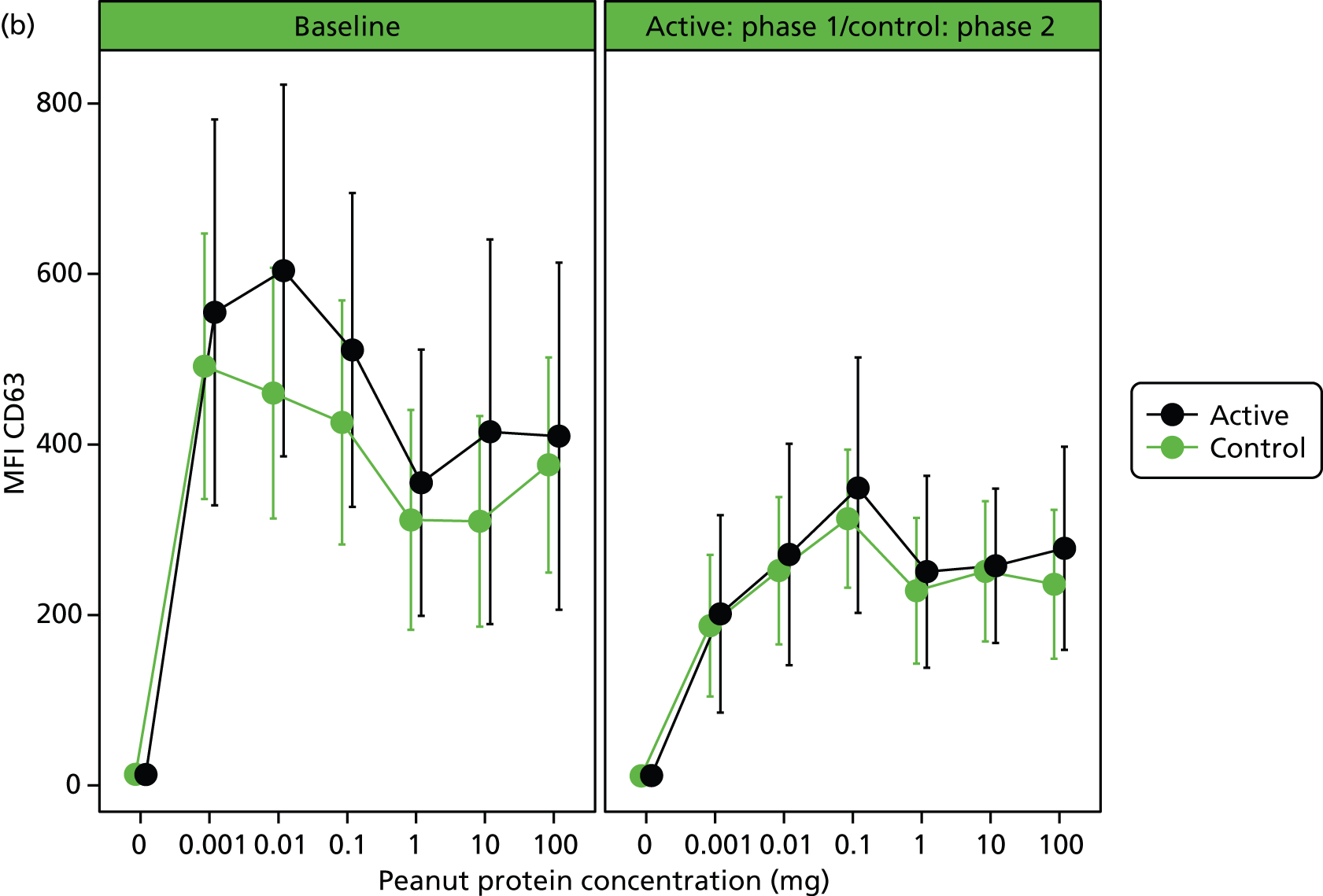

Immunological end points

Immunological assessments revealed a significant small reduction in median SPT weal diameter (–1 mm, range –8 to 4 mm; p = 0.0015) and an increase in peanut-specific serum IgE [12.7 kilounit (kU)/l, range –18.6 to 1359 kU/l; p < 0.001] after 24 weeks’ OIT in the active group. Basophil stimulation data were expressed as the AUC of plots of MFI and percentage of CD63-positive cells against concentration of peanut protein. No significant within-patient differences were found after treatment for AUC of MFI or percentage of CD63, although there was a reduction in MFI and percentage of CD63 at the lower peanut doses (Table 3 and Figure 4).

| Immunological end points | Control (n = 46) | Active (n = 39) | p-valuea |

|---|---|---|---|

| Within-participant changes in SPT weal diameter (mm) | |||

| Median (range) change from baseline to post treatment | –1.5 (–8 to 9) | –1 (–8 to 4) | 0.0693, 0.0015 |

| Within-participant changes in total IgE (kU/l) by group | |||

| Median (range) change from baseline to post treatment | 24 (–303 to 1582) | 99 (–164 to 1411) | 0.0109, < 0.001 |

| Within-participant changes in peanut-specific serum IgE (kU/l) | |||

| Median (range) change from baseline to post treatment | 74.5 (–55 to 637) | 12.7 (–18.6 to 1359) | < 0.001, < 0.001 |

FIGURE 4.

(a) In vitro basophil activation by peanut before and after desensitisation as percentage of CD63-positive cells. Heparinised whole blood was stimulated with a range of peanut protein concentrations (0.001–100 µg/ml) and flow cytometry was used to assess CD63 expression (%) within the basophil population. Differences in AUCs were not significant. (b) In vitro basophil activation by peanut before and after desensitisation as CD63 MFI (MFI of CD63 marker). Heparinised whole blood was stimulated with a range of peanut protein concentrations (0.001–100 µg/ml) and flow cytometry was used to assess CD63 expression (MFI) within the basophil population. Differences in AUCs were not significant.

Logistic regression

Logistic regression revealed several baseline covariates had an influence on the final NOAEL (the highest amount of peanut tolerated after OIT) (Table 4). Treatment, log-baseline NOAEL, age, family history and log-transformed peanut-specific IgE have a statistically significant effect on log-transformed NOAEL at 6 months. On average, patients in the OIT group have a log-NOAEL at 6 months 4.12-fold higher than those in the waiting list group. For every unit increase in log-transformed baseline NOAEL, the log-transformed NOAEL at 6 months, on average, increases 0.33-fold. For every year increase in age at baseline the log-transformed NOAEL at 6 months decreases, on average, by 0.17. Patients with a family history of peanut allergy have, on average, 0.64 lower log-transformed NOAEL at 6 months than patients who do not have a family history of peanut allergy.

| Covariates | Estimate | 95% CI | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| OIT | 105.5 | 67.73 to 164.40 | < 0.001 |

| Log (baseline NOAEL + 1) | 1.40 | 1.15 to 1.69 | < 0.001 |

| Age | 0.76 | 0.65 to 0.89 | < 0.001 |

| Female | 1.42 | 0.87 to 2.31 | 0.16 |

| Weight | 1.04 | 1.01 to 1.06 | 0.004 |

| QoL | 1.12 | 0.89 to 1.42 | 0.32 |

| Asthma | 1.09 | 0.65 to 1.74 | 0.79 |

| Eczema | 0.82 | 0.53 to 1.26 | 0.36 |

| Rhinitis | 0.69 | 0.46 to 1.05 | 0.09 |

| Other food allergy | 0.84 | 0.52 to 1.36 | 0.48 |

| Family history of peanut allergy | 0.41 | 0.24 to 0.71 | 0.001 |

| WAO grade 2 | 2.88 | 1.65 to 5.01 | < 0.001 |

| WAO grade 3 | 0.86 | 0.44 to 1.68 | 0.66 |

| WAO grade 4 | 0.62 | 0.21 to 1.82 | 0.40 |

| Peanut SPT weal diameter | 1.02 | 0.94 to 1.11 | 0.60 |

| Other nut SPT weal diameter > 3 mm | 1.37 | 0.81 to 2.31 | 0.23 |

| Tryptase | 1.06 | 0.95 to 1.19 | 0.32 |

| Log (peanut-specific IgE + 1) | 0.60 | 0.51 to 0.71 | < 0.001 |

| Log (total IgE + 1) | 1.74 | 1.35 to 2.23 | < 0.001 |

| Log (basophil activation CD63 MFI AUC) | 0.98 | 0.73 to 1.32 | 0.91 |

For every unit increase in log-transformed baseline peanut-specific IgE, the log-transformed NOAEL at 6 months decreases, on average, by 0.31.

For every unit increase in log-transformed baseline total IgE, the log-transformed NOAEL at 6 months increases, on average, by 0.36.

A Tobit regression model was used to fit the data, showing OIT treatment and log-baseline NOAEL was associated with a statistically significant increase in log-transformed NOAEL after 24 weeks of OIT (see Table 4). On average, patients in the OIT group had a log-NOAEL at 6 months 4.66-fold higher than those in the control group after phase 1.

A Tobit model allows for censoring in positive dependent variables, i.e. in this study the NOAEL (peanut threshold) was censored at 1400 mg, and the maximum cumulative dose of peanut protein administered to patients was 1400 mg and patients who did not react at 1400 mg may not react at even higher cumulative doses of peanut protein. A total of 24 out of the 85 patients included in this analysis achieved a NOAEL of 1400 mg at 6 months.

Adverse events

The number of adverse events was similar in both groups after treatment (Table 5). The majority of events were gastrointestinal, with oral itching being the most common (occurring after 6.3% of all doses). Cutaneous events were uncommon, appearing after only 0.16% of doses. Wheezing occurred after 0.41% of doses and was treated with inhaled beta-2 agonists or oral antihistamines in all cases, except for one participant who also received intramuscular epinephrine on two occasions, with rapid resolution of his symptoms. There were no serious adverse reactions and no cardiovascular events.

| Events | n (%) of participants who experienced an adverse event | n (%) of adverse events per dose of OIT |

|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | ||

| Mouth itch | 76 (81) | 1121 (6.30) |

| Abdominal pain | 54 (57) | 460 (2.59) |

| Nausea | 31 (33) | 393 (2.21) |

| Vomiting | 31 (33) | 134 (0.75) |

| Diarrhoea | 1 (1) | 5 (0.03) |

| Urticaria | 12 (13) | 29 (0.16) |

| Angiooedema | 18 (19) | 71 (0.40) |

| Erythema | 20 (21) | 41 (0.23) |

| Rhinitis | 23 (24) | 65 (0.37) |

| Wheezing | 21 (22) | 73 (0.41) |

| Laryngeal oedema | 1 (1) | 1 (0.01) |

| Cardiovascular collapse or fainting | 0 (0) | 0 (0.00) |

| Outcome | ||

| Admission to ITU/SAR/SUSAR | 0 (0) | 0 (0.00) |

| Use of inhaled beta-2 agonist | 18 (19) | 63 (0.35) |

| Use of IM epinephrine | 1 (1) | 2 (0.01) |

Discussion

Daily doses of peanut OIT up to a maximum dose of 800 mg of protein had a clinically meaningful effect on the disease, demonstrated by a high incidence of desensitisation, large absolute and fold increases in NOAEL threshold and a significant improvement in QoL score.

These results provide the first well-controlled and accurate estimate of the efficacy, benefits and risks of desensitisation using peanut OIT. Previous studies were either uncontrolled or too underpowered to estimate the effect size of the intervention. 20,21

Peanut allergy is a common long-lived disease with onset in childhood. Fear of severe reactions and the effect this has on social behaviour reduces QoL, which can often be lower than it is for children with other chronic diseases such as type 1 diabetes or rheumatological conditions. 6,7 Parental perception of disruption in daily activities is mainly due to the perceived risk of their children’s death,6 leading to anxiety related to making food choices inside and outside the home. 7 Secondary effects of anxiety lead to socially disadvantageous behaviour in some, for example avoiding eating outside the home. 7

This study confirms the improvement in QoL shown by an earlier uncontrolled study of peanut OIT. 24 Following OIT, our patients reported that they no longer avoid eating foods with precautionary labelling and they now eat out at restaurants without checking ingredients.

Most peanut-allergic patients are able to avoid accidentally eating large amounts of peanut; however, if untreated, they are at constant risk of reacting to peanut hidden in foods. Without OIT, the attitude of both patients and families to selecting potentially contaminated foods varies widely and is determined mostly by subjective judgements and previous experience. 25 Consequently, accidental reactions are not uncommon, occurring in 14–55% per year. 9 A recent study combined published data on peanut thresholds, peanut contamination of chocolate and patterns of population food consumption using probabilistic modelling to estimate the absolute risk of reacting to precautionary-labelled foods. 26 The risk of a peanut-allergic child reacting after eating a chocolate with precautionary labelling was 0.61% (95% CI 0.47% to 0.81%). The authors showed that 36% (95% CI 31% to 42%) of chocolate bars for which peanut was not listed in the ingredients, sourced from France and the USA, contained detectable peanut protein, with a median of 8.25 mg/kg protein (95% CI 6.54 mg/kg to 10.54 mg/kg). 26 A study of 62 catering establishments in Northern Ireland found that 21% served a peanut-contaminated meal, despite a request for a peanut-free meal. 27 The highest level of contamination was found in a chicken curry containing 4.795 mg of peanut protein. 27 Our data show that peanut OIT can raise the reactive threshold by 25.5-fold so that 83–91% of patients can eat 800 mg of peanut protein regularly without reacting (approximately equal to four to six whole peanuts). In addition, 54–64% of children could tolerate a challenge with 1400 mg of protein without reacting, providing protection to approximately 10 peanuts. Raising the reactive threshold for patients is a key part of this treatment, protecting patients from greater amounts than they are likely to encounter on a day-to-day basis in contaminated snacks or meals.

Our primary end point was the proportion of patients desensitised after 6 months of OIT. Peanut allergy may resolve in up to 20% of children over several years,4 but there are no data over a short period such as 6 months. There is currently no disease-modifying treatment for peanut allergy; therefore, the control group underwent the current best treatment for peanut allergy – peanut avoidance – to identify the proportion whose allergy resolved spontaneously over the 6-month period of phase 1, to reduce type 1 error.

We did not use a placebo during the control period because the risk of including it outweighed any potential benefit. During the pilot study, participants receiving peanut OIT reported that they significantly relaxed their peanut avoidance behaviour during the first 6 months of treatment, despite advice to the contrary. Therefore, we could not exclude the likelihood that a significant proportion of placebo-treated patients in this phase 2 study would relax their avoidance practice, guessing they were taking active treatment and, therefore, risking a severe reaction. Placebos in general are included to reduce the risk of type 1 error (i.e. false-positive results) in studies for which the primary end point can be influenced by knowing one is receiving a treatment, attention from health-care professionals, and the expectations of a treatment’s effectiveness by those running the research study. However, the risk of a type 1 error in the context of this trial was acceptably low because the primary end point was measured using a blinded objective measure (i.e. ‘no reaction’ to a large amount of peanut during DBPCFC) that could not be influenced by these factors. A limitation of this study is that secondary outcomes such as QoL scores may have been influenced by knowledge of treatment allocation.

There was a small risk of bias as participants who knew they were receiving active treatment may have under-reported minor symptoms at the higher challenge doses, although these symptoms would have been infrequent and subjective. Additionally, during phase 1, 10 subjects did not undergo a post OIT challenge because they had withdrawn or not reached the target maintenance OIT dose at 6 months. It is probable that in phase 1 the true response rate is lower than estimated; however, in phase 2, for which there were few dropouts, we still observed a large effect. A very conservative sensitivity analysis was performed in which all the unobserved subjects in the active group were imputed as not desensitised and all the unobserved subjects in the control group were imputed as desensitised. The analysis gave a risk difference of 0.41 (exact 95% CI 0.21 to 0.58), which supports the conclusions of the main analysis.

It is probable that long-term peanut protein ingestion will be required to provide continued protection from accidental exposure and that long-term desensitisation rather than clinical tolerance is a realistic end point for treatment. During OIT, there is evidence of basophil and mast cell desensitisation (i.e. reduced SPT weal size), accompanied by a gradual change in peanut-specific T-cell surface markers from Th2 to Th1 phenotype (Dr Katherine Anagnostou, University of Cambridge, 2010, personal communication). Recent data from our group show that elevated peanut-specific serum IgE levels persist for several years after starting OIT, despite apparent clinical desensitisation (Dr Katherine Anagnostou, personal communication).

However, preliminary work suggests that extending the dose interval to 800 mg once weekly after 2–3 years of daily treatment is well tolerated, resulting in ongoing protective desensitisation (Dr Katherine Anagnostou, personal communication).

We chose a single maintenance treatment dose of 800 mg, pragmatically, as the largest amount of peanut that would be feasible/acceptable to take on a daily basis. From the limited data available in published studies, it is apparent that the rapidity of the up-dosing schedule has a greater effect on safety and efficacy than the magnitude of the maintenance dose, with semi-rush regimes showing poor efficacy and more frequent reactions. The starting dose of 2 mg of protein was developed from dose-ranging work in our pilot studies. 21,22

Prognostic factors were explored using logistic regression revealing baseline covariates related to a change in log-transformed NOAEL threshold post OIT. Treatment with OIT was not surprisingly the most influential factor. Age, family history and peanut-specific serum IgE were associated with a significant decrease in log-transformed NOAEL after 24 weeks of OIT, implying that these might predict a less favourable outcome.

Not surprisingly, there were many more allergic events during active treatment than during periods of peanut avoidance. The safety data in this trial show that most adverse events were mild and due to gastrointestinal symptoms (e.g. oral itching), as expected from the route of administration. Skin reactions were uncommon (urticaria after 0.16% of doses). Reactions involving wheezing occurred after 0.41% of doses or approximately one-fifth of participants. Although wheezing could be taken as a sign of a more severe reaction, in all but one participant it was mild and responded to standard doses of inhaled bronchodilator drugs. A single subject self-administered epinephrine at home with good results on two occasions for wheezing after his peanut OIT doses; thus, he was withdrawn from the study. No one experienced hypotension.

There is no disease-modifying treatment for peanut allergy, meaning that families have to rely on avoidance practice and reduced QoL, leading to accidental reactions and carrying emergency medication. Peanut OIT is a promising novel treatment that shows good efficacy and an acceptable side effect profile. As this is the first study of its type, the findings are relevant to the population studied, but safety and efficacy will require confirmation using other patient subgroups and phase 3 trials. Because of the significant risks involved, OIT should be restricted to specialist centres.

Conclusions

We performed the first study with a design and size appropriate to derive an accurate estimate of the effect size of the treatment. We have demonstrated good efficacy and safety for peanut OIT, with a large effect size. Importantly, we studied a representative population of peanut allergic children, without excluding children with a history of severe reactions. The implication is that this treatment will be suitable for children with any severity of peanut allergy.

Peanut allergy is a highly homogeneous disease, with well-validated diagnostic tests and minimal variation in phenotypic characteristics. Future phase 2 and 3 confirmatory trials are desirable, including other doses but, given the highly homogeneous nature of the illness and the strong effect size observed in this study, such trials are unlikely to require large numbers of patients. This cohort of patients, followed to 6 months, requires longer-term follow-up to determine the long-term adverse event profile and frequency of administration required to continue a state of desensitisation. Indicators of tolerance to peanut should be studied.

Research recommendations

-

Confirmatory phase 3 trials for peanut OIT using this regime.

-

Studies of long-term tolerance beyond 6 months’ treatment.

-

Application of this method to other allergens such as tree nuts and other foods.

Acknowledgements

The National Institute for Health Research/Wellcome Trust Cambridge Clinical Research Facility on the Cambridge Biomedical Campus supported the research. We are also grateful to Gareth Jones, Head of The Perse Prep School in Cambridge, and the Perse Prep Parents for fundraising to buy equipment used during this work. We would like to thank Clare Mills at the Institute for Food research, Norwich, UK for manufacturing the challenge meals. We thank our Data Monitoring Committee [Dr Nicola Brathwaite (chairperson), Dr Ken Ong and Dr Carlo Acerini] and members of our Trial Steering Committee [Dr Robert Boyle (chairperson), Dr Chris Palmer and Mrs Hazel Gowland]. We are extremely grateful to the Anaphylaxis Campaign who reviewed the study protocol, funding application and patient information sheets, and provided a patient representative (Hazel Gowland) as a member of the Trial Steering Committee. Finally, we thank our participants.

Contributions of authors

Katherine Anagnostou performed immunotherapy challenges and interpretation, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Sabita Islam performed blinding of challenges and all laboratory work; prepared immunotherapy doses, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Yvonne King performed recruitment, immunotherapy challenges and interpretation, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Loraine Foley prepared immunotherapy doses, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Laura Pasea designed and performed statistical analysis, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Chris Palmer determined trial design, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Simon Bond was responsible for oversight and design of statistical analysis; and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Pamela Ewan contributed to study design, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Andrew Clark conceived the study, defined the primary objective, performed immunotherapy challenges, and drafted, appraised and approved the submitted version.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, MRC, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health.

References

- Venter C, Arshad H, Grundy J, Pereira B, Clayton B, Voigt K, et al. Time trends in the prevalence of peanut allergy: three cohorts of children from the same geographical location in the UK. Allergy 2010;65:103-8. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.02176.x.

- Sicherer SH, Munoz-Furlong A, Sampson HA. Prevalence of peanut and tree nut allergy in the United States determined by means of a random digit dial telephone survey: a 5-year follow-up study. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2003;112:1203-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0091-6749(03)02026-8.

- Kanny G, Moneret-Vautrin DA, Flabbee J, Beaudouin E, Morisset M, Thevenin F. Population study of food allergy in France. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2001;108:133-40. http://dx.doi.org/10.1067/mai.2001.116427.

- Ho MH, Wong WH, Heine RG, Hosking CS, Hill DJ, Allen KJ. Early clinical predictors of remission of peanut allergy in children. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:731-6. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.11.024.

- Pumphrey RS, Gowland MH. Further fatal allergic reactions to food in the United Kingdom, 1999–2006. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:1018-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.01.021.

- Primeau MN, Kagan R, Joseph L, Lim H, Dufresne C, Duffy C, et al. The psychological burden of peanut allergy as perceived by adults with peanut allergy and the parents of peanut-allergic children. Clin Exp Allergy 2000;30:1135-43. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2222.2000.00889.x.

- Avery NJ, King RM, Knight S, Hourihane JO. Assessment of quality of life in children with peanut allergy. Ped Allergy Immunol 2003;14:378-82. http://dx.doi.org/10.1034/j.1399-3038.2003.00072.x.

- Kapoor S, Roberts G, Bynoe Y, Gaughan M, Habibi P, Lack G. Influence of a multidisciplinary paediatric allergy clinic on parental knowledge and rate of subsequent allergic reactions. Allergy 2004;59:185-91. http://dx.doi.org/10.1046/j.1398-9995.2003.00365.x.

- Clark AT, Ewan PW. Good prognosis, clinical features and circumstances of peanut and tree nut reactions in children treated by a specialist allergy centre. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;122:286-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2008.05.015.

- Durham SR, Walker SM, Varga EM, Jacobson MR, O’Brien F, Noble W, et al. Long-term clinical efficacy of grass-pollen immunotherapy. N Engl J Med 1999;12:468-75. http://dx.doi.org/10.1056/NEJM199908123410702.

- Nelson HS, Lahr J, Rule R, Bock A, Leung D. Treatment of anaphylactic sensitivity to peanuts by immunotherapy with injections of aqueous peanut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol 1997;99:744-51. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S0091-6749(97)80006-1.

- Meglio P, Bartone E, Plantamura F, Arabito E, Giampietro P. Allergy 2004;59:980-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00542.x.

- Buchanan A, Green T, Jones S, Scurlock A, Christie L, Althage K, et al. Egg oral immunotherapy in non-anaphylactic children with egg allergy. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2007;119:199-205. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2006.09.016.

- Staden U, Rolinck-Werninghaus C, Brewe F, Wahn U, Niggemann B, Beyer K. Allergy 2007;62:1261-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01501.x.

- Longo G, Barbi E, Berti I, Meneghetti R, Pittalis A, Ronfani L, et al. Specific oral tolerance induction in children with very severe cow’s milk–induced reactions. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2008;121:343-7. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2007.10.029.

- House of Lords Science and Technology Committee 6th Report of Session 2007.

- Calderon MA, Alves B, Jacobson M, Hurwitz B, Sheikh A, Durham S. Allergen injection immunotherapy for seasonal allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2007;24.

- Boyle RJ, Elremeli M, Hockenhull J, Cherry MG, Bulsara MK, Daniels M, et al. Venom immunotherapy for preventing allergic reactions to insect stings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;10. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD008838.pub2.

- Wilson DR, Torres LI, Durham SR. Sublingual immunotherapy for allergic rhinitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2003;2.

- Enrique E, Pineda F, Malek T, Bartra J, Basagaña M, Tella R, et al. Sublingual immunotherapy for hazelnut food allergy: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study with a standardized hazelnut extract. J Allergy Clin Immunol 2005;116:1073-9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.jaci.2005.08.027.

- Clark AT, Islam S, King Y, Deighton J, Anagnostou K, Ewan P. Successful oral tolerance induction in severe peanut allergy. Allergy 2009;64:1218-20. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2009.01982.x.

- Anagnostou K, Clark A, King Y, Islam S, Deighton J, Ewan P. Efficacy and safety of high-dose peanut oral immunotherapy with factors predicting outcome. Clin Exp Allergy 2011;41:1273-81. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2222.2011.03699.x.

- Nurmatov U, Venderbosch I, Devereux G, Simons FE, Sheikh A. Allergen-specific oral immunotherapy for peanut allergy. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2012;9. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/14651858.CD009014.pub2.

- Factor JM, Mendelson L, Lee J, Nouman G, Lester MR. Effect of oral immunotherapy to peanut on food-specific quality of life. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol 2012;109:348-52. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.anai.2012.08.015.

- Rimbaud L, Heraud F, La Vieille S, Leblanc J, Crepet A. Quantitative risk assessment relating to adventitious presence of allergens in food: a probabilistic model applied to peanut in chocolate. Risk Anal 2010;30:7-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1539-6924.2009.01322.x.

- Barnett J, Leftwich K, Muncer K, Grimshaw R, Shepherd M, Raats MM, et al. How do peanut and nut-allergic consumers use information on the packaging to avoid allergens?. Allergy 2011;66:969-78. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1398-9995.2011.02563.x.

- Leitch S, Walker MJ, Davey R. Food allergy: gambling your life on a take-away meal. Int J Environ Health Res 2005;15:79-87. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09603120500062052.

Appendix 1 Statistical analysis plan

Appendix 2 Food allergy quality-of-life questionnaire – parent form (0–12 years)

List of abbreviations

- AUC

- area under curve

- CI

- confidence interval

- DBPCFC

- double-blind placebo-controlled food challenge

- FAQLQ-PF

- food allergy quality-of-life questionnaire – parent form

- IgE

- immunoglobulin E

- MFI

- mean fluorescent intensity

- MRC

- Medical Research Council

- NIHR

- National Institute for Health Research

- NOAEL

- no observed adverse effect level

- OIT

- oral immunotherapy

- PBS

- phosphate-buffered saline

- QoL

- quality of life

- RCT

- randomised controlled trial

- SLIT

- sublingual immunotherapy

- SPT

- skin prick test