Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 10/90/03. The contractual start date was in October 2012. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Denise Howel was a member of Health Services and Delivery Research Commissioning Board until 30 November 2015.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Khanna et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Scientific background and rationale

Primary biliary cirrhosis (PBC) is a chronic liver disease affecting approximately 20,000 patients in the UK (prevalence 35/100,000). 1 In 2015, the name of the disease was changed to primary biliary cholangitis at the request of international patient groups. 2 The revised name better reflects the disease process present in the majority of patients. The disease is characterised pathologically by inflammation within the portal tracts in the liver and progressive loss of small intrahepatic bile ducts. 3 A relatively small proportion of patients progress, if untreated, to cirrhosis and end-stage liver disease requiring liver transplantation. 4 Bile acid therapy in the form of the first-line agent ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA) is effective at slowing or stopping progression to the end stage in the majority of patients, probably through a reduction of secondary liver injury as a result of retention of cytotoxic hydrophobic bile acids occurring in the context of bile duct loss. 5–9 Up to 40% of PBC patients are under-responsive to UDCA and are at increased risk of progression of the disease to cirrhosis. 10–12 Second-line bile acid therapy in the form of obeticholic acid (a modified bile acid that has enhanced farnesoid X receptor agonist properties that lead to reduced endogenous bile acid synthesis) has recently been approved in the USA and Europe for use in patients showing an inadequate response to UDCA and was approved by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence in early 2016. 13,14

The high levels of autoantibodies seen in PBC patients, strong associations with other autoimmune diseases and pattern of immunogenetic susceptibility (which points to a key role for immune dysregulation in the disease) all point to PBC being an autoimmune disease. 15–18 It is increasingly clear, however, that the disease is multistage in nature, with initial immune injury to the target epithelial cells lining the small intrahepatic bile duct being followed by secondary cholestatic injury in which toxic hydrophobic bile acids retained in the liver as a consequence of early bile duct injury cause further bile duct injury. This cycle has the potential to be self-perpetuating. 19

Fatigue: the commonest symptom in primary biliary cirrhosis

Historically, the main focus in terms of clinical impact and its treatment in PBC has been progression of the disease to cirrhosis and, ultimately, death. In recent years, with the advent of large-scale representative patient cohorts and validated patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), it has become widely accepted that there is another important aspect to patient impact: that is quality-of-life impairment related to systemic symptoms. 12,17,20–24 Although quality-of-life impairment can be significant in patients with decompensated cirrhotic disease, this state is very uncommon in the condition, meaning that the conventional complications of end-stage liver disease contribute relatively little to overall quality-of-life burden. 25,26 In contrast, the disutility associated with the non-stage-specific symptoms is substantial. 24 Data from the very large UK-PBC cohort have also demonstrated that the burden of impaired quality of life is age related, with younger patients experiencing the worst symptoms and the greatest quality-of-life burden. 27

The symptom reported most frequently by PBC patients is chronic fatigue, which is present in > 50% and which has an often striking impact on patients. 28–30 There are currently no effective treatments for fatigue in PBC, with international treatment guidelines recommending only supportive treatment. 31 Unsurprisingly, given its prevalence, impact and the lack of effective treatments, fatigue is frequently identified by PBC patients as the principal priority area for new therapy development. There has been a significant recent increase in the understanding of the potential mechanisms that might contribute to fatigue in PBC, and significant advances in the development of clinical tools that are able to quantify the impact of that fatigue and that represent key tools for the study of fatigue pathogenesis and, critically, treatment. The key advance in this regard has been the development of the PBC-40, a patient-derived, disease-specific, quality-of-life measure that has become the standard measure used in all clinical trials. 14,21,32

Fatigue severity in PBC is not associated with the stage of the disease and is frequently seen in its most severe form in patients with early disease and a seemingly very good prognosis from the point of view of risk of death from their liver disease. 12,28,33 This can result in a discrepancy between the physician’s and patient’s perception of how well the patient is doing, with the former seeing a level of liver injury suggesting a good prognosis and the latter focusing on their severe fatigue. 30 Furthermore, there is no evidence to suggest that either current first- (UDCA) or second-line therapy has any impact on fatigue severity. 12,14 As prognostic management gets better in PBC, so the contrast between length of life and quality-of-life improvement will become increasingly marked.

The issue of the role played by depression in the expression of fatigue in PBC is a controversial one, with many patients being clinically labelled as having depression simply because they are fatigued, making the association self-fulfilling. Although depressive problems can clearly occur in fatigued PBC patients (frequently as a consequence of the considerable limitation to lifestyle that they experience), and positive coping strategies are an important part of managing fatigue, overt depressive illness is actually a rare cause of fatigue in PBC. 34,35 In fact, in most fatigued PBC patients it is peripheral, activity-limiting fatigue that predominates. 36 Fatigue in PBC can be associated with significant fatigue disturbance (in particular daytime somnolence) and autonomic dysfunction (particularly in the form of baroreflex sensitivity loss). The extent to which these associations reflect causes or consequences of chronic fatigue is unclear at present. 1

The scale of the problem of fatigue in primary biliary cirrhosis

Population-based studies undertaken using the PBC-40, which contains a fully validated fatigue domain, have suggested that > 50% of PBC patients across the UK experience moderate or severe fatigue, with > 20% experiencing sustained severe fatigue (≈4000 patients nationally), with a profound impact on life quality. 12,24,27 Fewer than 20% of severely fatigued patients are able to work, with the majority of this group dependent on state benefits for income. Severe fatigue also causes social isolation in people who lack the energy to leave their house and interact with others, a particular issue among younger patients. 24 Severely fatigued PBC patients also frequently have problems with their ability to care for others (90% of PBC patients are female and they often have young children and/or dependent elder relatives themselves), with cases of Meals on Wheels being provided for the children of socially isolated, severely fatigued PBC patients being far from uncommon. The management of severe fatigue in PBC, which is currently largely supportive, is a major draw on NHS budgets (the trial investigators are currently following up > 150 severely fatigued patients with, typically, monthly clinic follow-up). 26,31 Severe fatigue is also a frequent driver for patients seeking liver transplantation, although the evidence to suggest that there is any benefit from transplantation for PBC fatigue is limited. 25,37 Treatment able to reduce the impact of severe fatigue in PBC would transform the lives of patients and their families, substantially reduce the costs of NHS treatment (the costs of follow-up and supportive management of fatigued patients and the costs of transplantation where the indication is advanced liver disease but the patient driver is fatigue) and, importantly, the costs to society of this socially isolated, economically unproductive and dependent group of people. 38

Bioenergetic abnormality is frequent in primary biliary cirrhosis and is associated with fatigue

Primary biliary cirrhosis patients’ descriptions of fatigue emphasise an inability to sustain physical activity and concepts related to ‘energy’ or ‘power’ depletion (a further group describe ‘brain fog’, which is associated with significant cognitive symptoms). Furthermore, on repeat testing, handgrip strength reduces rapidly in fatigued PBC patients and is associated with perceived fatigue severity. 36 More recently, using magnetic resonance (MR) spectroscopy approaches, we demonstrated (and replicated in a second cohort) the presence of significant peripheral muscle bioenergetic abnormality in PBC patients. 39,40 Abnormality is also present in cardiac muscle, suggesting the presence of a broadly based bioenergetic abnormality. 41 These studies have suggested the presence of abnormality in mitochondrial function (in particular, recovery response to the energetic burden of repeat exercise) and a tendency for excessive intramuscular acidosis during, and in the recovery from, exercise. Intramuscular acidosis in a well-recognised contributing factor to muscle fatigue in the general population. 42

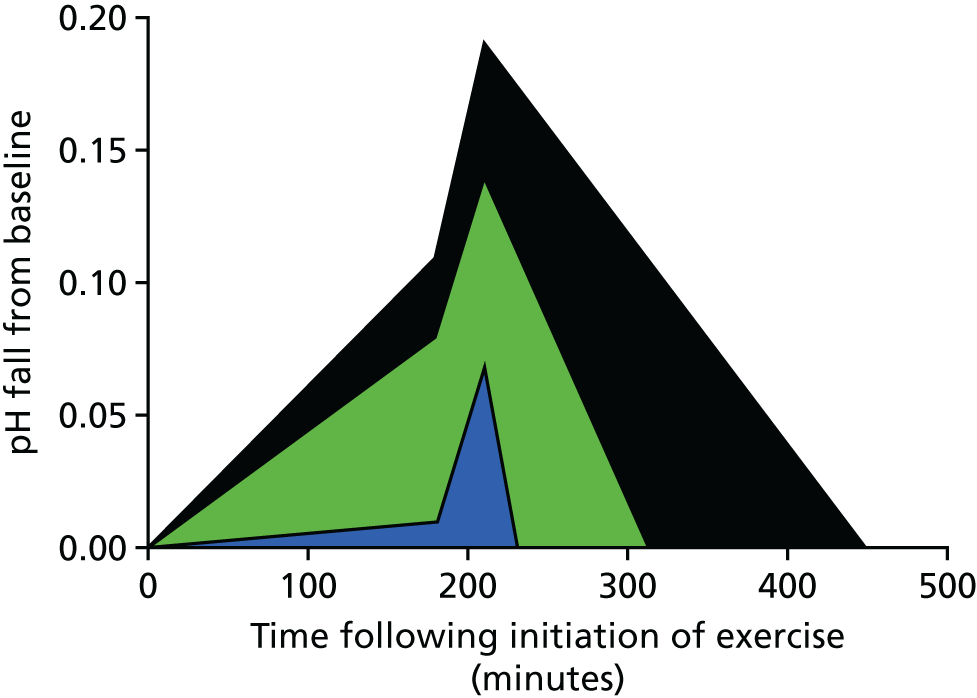

In PBC, the length of time that significant acidosis is present in muscle and the rate of recovery from that acidosis are strongly associated with the severity of fatigue that patients experience. 43–45 The cumulative effect of a pro-acidotic effect and delays in recovery is well demonstrated using an integrative approach exploring the ‘area under the curve’ (AUC) for pH during exercise and in the recovery from exercise, which gives a measure of the scale of excess proton exposure in PBC and its association with fatigue (Figure 1). Recent studies using metabolomics approaches have shown lactate accumulation within tissues in PBC. 46 Our own unpublished study of anaerobic threshold in PBC patients (compared with age- and sex-matched patients with primary sclerosing cholangitis and sedentary control subjects), assessed using an incremental exercise approach, shows significantly lower anaerobic threshold values in PBC that cannot be accounted for by either deconditioning or by the presence of cholestatic liver disease per se. 47 These observations further support the presence of bioenergetic abnormality in PBC and critically do so using complementary experimental approaches. Taken together, these studies all point to excessive utilisation of anaerobic metabolism pathways in muscle in PBC [metabolism of pyruvate to lactate via the actions of lactate dehydrogenase rather than to acetyl coenzyme A via the actions of pyruvate dehydrogenase (PDH)]. This leads, we hypothesised, to excessive and inappropriate lactic acid accumulation in muscle in PBC and, in the absence of an effective adaptive response to it, fatigue. In this model, capacity to adapt to acid load is a physiological variant that is naturally protective from fatigue in some people and that can be induced by exercise therapy. The critical question is ‘why do PBC patients seemingly overutilise anaerobic metabolism pathways and how can we use that knowledge to treat their fatigue?’.

FIGURE 1.

Area under receiver operating characteristic (AUROC) changes in pH vs. recovery time following exercise. Blue is normal, green is non-fatigued PBC patients and black is fatigued PBC patients.

Primary biliary cirrhosis is characterised by autoimmune responses directed at bioenergetic enzymes

The obvious link between PBC as an autoimmune disease and PBC as a disease characterised by overutilisation of anaerobic pathways and associated fatigue is the characteristic autoantibody response in PBC, which is directed at PDH, the enzyme that controls entry into aerobic metabolism pathways. High-titre anti-PDH antibodies are present in > 95% of PBC patients and are able to fully block PDH function during in vitro assays. 48,49 The basis of this inhibitory function (which is so consistent that one of the assays for anti-PDH in PBC utilises inhibitory capacity as a readout) is the specific reactivity of anti-PDH antibodies with a lipoic acid cofactor present on the E2 and E3 binding protein components of PDH, to which the principal autoepitopes have been localised, which is essential for enzymatic function and which is blocked by antibody binding. 50

Targeting autoreactive responses in primary biliary cirrhosis as a potential therapy for fatigue

Three strands of evidence support a potential direct role for anti-PDH antibody responses in bioenergetic abnormality and fatigue in PBC.

-

The mitochondrial bioenergetic abnormality in PBC is directly associated with the level of serum anti-PDH antibody, with median anti-PDH titre being > 200-fold higher in patients with mitochondrial bioenergetic abnormality than in those without (9.9 × 105 vs. 4.1 × 103; p < 0.05). 39 At least part of the anti-PDH autoantibody response in PBC is directed at the lipoate component of PDH and is reactive with free lipoic acid in the circulation. 50 Given that free lipoic acid plays an important role in regulating PDH function (it activates PDH through inhibition of PDH-kinase), its consumption by autoantibody in PBC represents one potential mechanism for the bioenergetic effect of that antibody. 51

-

Patients who are anti-PDH antibody positive but who have normal liver function (‘pre-PBC’ patients) experience fatigue of the same severity as ‘classic’ PBC patients, suggesting that fatigue is a feature of the presence of anti-PDH rather than PBC per se. 52

-

Fatigue is typically not improved following liver transplantation in PBC. 38,53 Anti-PDH universally remains present at unchanged levels following liver transplantation in PBC.

A direct role for anti-PDH antibody in bioenergetic abnormality and fatigue was the justification for exploration of therapies able to deplete the B-cell compartment, exemplified by the anti-CD20 antibody rituximab (MabThera®, Roche Products Ltd) as a treatment for fatigue in PBC.

Rituximab in primary biliary cirrhosis

A pilot study performed in Canada exploring the use of rituximab in PBC (in 13 patients) provided proof of concept, showing that the agent is safe and well tolerated in patients and is associated with a clinically significant reduction in fatigue. 54 Fatigue severity was assessed using the Fatigue Severity Scale (potential range 9–63 points), with a fall being seen from pre treatment (median 36 points, range 11–59 points) to post treatment (median 29 points, range 12–55 points). Taking into account the floor value for the Fatigue Severity Scale, this represents a median fall in fatigue severity over 6 months of 26%. This compares with our own case–control study of fatigue in PBC, which suggests that fatigue severity in age- and sex-matched normal controls is 30% lower than in PBC patients, suggesting the potential for rituximab therapy to return PBC patients to close to normal with regard to their perceived fatigue. 28 However, this pilot study did not attempt to explore the mechanism of the effect and, as it did not use severe fatigue as an inclusion criterion, the extent of possible improvement for such patients is unclear. Moreover, the study was not optimised for the study of fatigue (fatigue was a secondary outcome and only some of the patients who participated had fatigue, potentially underestimating the clinical effect). Other evaluations of rituximab in PBC have focused exclusively on disease severity as an end point. 55 Both studies showed a sustained reduction in anti-PDH antibody levels of all isotypes, supporting the concept that rituximab has a beneficial effect on fatigue through depletion of PDH-reactive antibody. In all studies in PBC to date, rituximab has been found to be well tolerated.

Study objectives

The importance of severe fatigue in PBC and the current lack of treatments, the strong theoretical basis for the approach and the supportive pilot trial proof-of-concept data all, we believe, justified a formal clinical trial of rituximab targeting fatigue in PBC. Secondary outcome measures included an extended panel of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs), [including the other domains of the PBC-40 markers (cognitive, itch, social, emotional and other symptoms), and tools for depressions, anxiety, sleep disturbance and autonomic dysfunction], assessment of bioenergetics function [including anaerobic threshold assessed using conventional cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET) and post-exercise muscle pH assessed using MR] and physical activity monitoring. 17,56,57

The primary objective of the study was to undertake a placebo-controlled trial to assess the efficacy of rituximab as a treatment for moderate to severe fatigue in PBC.

The secondary objectives of the study were to explore:

-

the mechanism of any observed improvement in fatigue severity in relation to the identified associated mechanisms of fatigue related to bioenergetics abnormality in the cardiovascular system and peripheral muscle function in PBC

-

the mechanisms underpinning physiological abnormality in PBC and their relationship to fatigue through the study of the baseline data for the study cohort

-

any effects of rituximab therapy on biochemical parameters of disease severity in PBC.

Chapter 2 Methods

The text in this section is reproduced from the trial protocol we published in Jopson et al. 38 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Study conduct

This single-centre randomised controlled trial was conducted in the clinical research facility of the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals Foundation Trust, commencing 1 October 2012. 38 The final study visit was on 12 September 2016. The study was conducted in accordance with the principles of Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and received a favourable ethics opinion from the National Research Ethics Service Committee North East – Newcastle & North Tyneside 1 (12/NE/0095) on 16 May 2012 and a clinical trial authorisation from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) on 15 August 2012. The trial was managed through the Newcastle Clinical Trials Unit (NCTU) with a Trial Management Group, together with an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC). Monitoring was performed by NCTU and the trial was audited by the sponsor, the Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

The clinical trial protocol has been published (https://njl-admin.nihr.ac.uk/document/download/2005806; accessed September 2017) and the statistical analysis plan (see Report Supplementary Material 1) was finalised prior to the final analyses. All participants provided written informed consent prior to screening.

Patient and public involvement

Fatigue was identified by our patient group as a major research priority area. LIVErNORTH and the PBC Foundation were involved in the development of the trial concept and protocol. The final protocol was seen and approved by the patient groups. A patient representative (from LIVErNORTH) was a member of the TSC. The patient groups were updated throughout the course of the trial and played an important role in increasing awareness of the trial and thus in recruitment.

Trial design

This was a Phase II, single-centre, randomised controlled, double-blinded trial comparing rituximab with placebo in fatigued primary biliary cholangitis (cirrhosis) patients over 12 months. 38 Randomisation was in a 1 : 1 ratio.

Participants

Participants were all patients with a clinical diagnosis of definite or probable primary biliary cholangitis (cirrhosis); this was established using recognised epidemiological criteria:

-

cholestatic liver biochemistry at disease outset [defined as elevation in the serum alkaline phosphatase (ALP) level or gamma-glutamyl transpeptidase (GGT)]

-

associated autoantibody [anti-mitochondrial antibody (AMA) or PBC-associated anti-nuclear antibody by immunofluorescence or anti-PDH, anti-Gp210 or anti-Sp100] at a titre of ≥ 1 : 40

-

diagnostic or compatible liver biopsy.

Patients exhibiting all three criteria are defined as having definite PBC. Patients with two of the three criteria probably have PBC. Clinical practice has moved away from using liver biopsy to confirm diagnosis (because of the diagnostic accuracy of the combination of the other two parameters, which exceeds 95%), so the majority of patients in any clinical cohort fall into the probable disease category. Patients in whom ALP and GGT levels return to normal with therapy retain their diagnostic status, as current therapy approaches are disease suppressive not curative and biochemical deterioration is inevitable with universal discontinuation of therapy.

Inclusion criteria

-

Patient had capacity to consent and provided written informed consent for participation in the study prior to any study-specific procedures.

-

Moderate or severe fatigue as assessed using previously designated cut-off points of the PBC-40 fatigue domain (i.e. fatigue domain score of > 33).

-

Presence of AMA (anti-PDH antibody) at a titre of > 1 : 40.

-

Adequate haematological function (haemoglobin level of > 9 g/l), absolute neutrophil count of > 1.5 × 109/l and platelet count of > 50 × 109/l.

-

Bilirubin level of ≤ 50 µmol.

-

International normalised ratio ≤ 1.5.

-

Child–Pugh score of < 7.

-

Eastern Cooperative Oncology Group performance status of < 2.

-

Adequate renal function: Cockcroft–Gault estimation of > 40 ml/minute.

-

Women of childbearing potential had a negative pregnancy test prior to study entry and were using an adequate contraception method, which was continued for 3 months after completion of treatment. Acceptable forms of effective contraception included established use of oral, injected or implanted hormonal methods of contraception:

-

placement of an intrauterine device or intrauterine system

-

barrier methods of contraception – condom or occlusive cap (diaphragm or cervical/vault caps) with spermicidal foam/gel/film/cream/suppository

-

male sterilisation (with the appropriate post-vasectomy documentation of the absence of sperm in the ejaculate)

-

true abstinence – when this was in line with the preferred and usual lifestyle of the subject

-

aged ≥ 18 years.

-

Exclusion criteria

-

Advanced or decompensated disease (variceal bleed, hepatic encephalopathy or ascites).

-

History or presence of other concomitant liver diseases (including hepatitis due to hepatitis B virus or hepatitis C virus or evidence of chronic viraemia on baseline screening), primary sclerosing cholangitis or biopsy-proven non-alcoholic steatohepatitis).

-

Average alcohol ingestion of > 21 units per week (for males) or > 14 units per week (for females).

-

Chronic sepsis or intercurrent condition likely to predispose the patient to chronic sepsis during the study.

-

Previous treatment with B-cell-depleting therapy.

-

Previous history of aberrant response or intolerance to immunological agents.

-

Presence of significant untreated intercurrent medical condition itself associated with fatigue.

-

Presence of significant risk of depressive illness [Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) score indicating cosiness].

-

Current statin therapy or statin use within 3 months of enrolment.

-

Ongoing participation in other clinical trials or exposure to any investigational agent 4 weeks prior to baseline or within five or fewer half-lives of the investigational drug.

-

Major surgery within 4 weeks of study entry.

-

Vaccination within 4 weeks of study entry; patients requiring seasonal flu or travel vaccines will be required to wait a minimum of 4 weeks post vaccination to enrol in the study.

-

Pregnant or lactating women.

-

Psychiatric or other disorder likely to have an impact on informed consent.

-

Patient was unable and/or unwilling to comply with treatment and study instructions.

-

Any other medical condition that, in the opinion of the investigator, would interfere with safe completion of the study.

-

Hypersensitivity to the active substance (rituximab) or to any of the excipients [sodium citrate, polysorbate 80, sodium chloride, sodium hydroxide, hydrochloric acid and water (for infusion)] or to murine proteins.

-

Active, severe infections (e.g. tuberculosis, sepsis or opportunistic infections).

-

Known human immunodeficiency virus infection.

-

Clinical history of latent tuberculosis infection unless the patient had completed adequate antibiotic prophylaxis.

-

Aspartate transaminase (AST)/alanine transaminase (ALT) levels four times above the upper limit of normal.

-

Severe immunocompromised state.

-

Severe heart failure (New York Heart Association class IV) or severe uncontrolled cardiac disease.

-

Malignancy (other than basal cell carcinoma) within the last 10 years.

-

Demyelinating disease.

-

Previous participation in this study.

-

Any contraindication to rituximab therapy not covered by other exclusions.

Withdrawal criteria

The study protocol required that the study drug be discontinued if:

-

the participant developed elevated serum ALT/AST levels four times above normal limits for each local laboratory

-

the participant decided they no longer wished to continue

-

cessation of study drug was recommended by the investigator.

Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time for any reason and without giving a reason. The investigator also had the right to withdraw patients from the study drug in the event of intercurrent illness, adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs), protocol violations, cure, administrative reasons or other reasons. If a patient decided to withdraw from the study, all efforts were made to report the reason for withdrawal as thoroughly as possible. If a patient withdrew from the study drug only, efforts were made to continue to obtain follow-up data (with the permission of the patient).

Participants who wished to withdraw from study medication were asked to confirm whether or not they were still willing to provide:

-

study-specific data at follow-up visits 5–19 [https://njl-admin.nihr.ac.uk/document/download/2005806 (p. 33); accessed September 2017]

-

end-of-study data as per visit 19, at the point of withdrawal

-

questionnaire data collected as per routine clinical practice at annual follow-up visits.

If participants agreed to any of the above, they were asked to complete a confirmation of withdrawal form to document their decision.

Participants withdrawing from the study after receiving the second infusion were not replaced. In practice, all seven withdrawals from the study were replaced prior to study drug administration.

Setting

All screening, consent, treatment and follow-up assessments requiring patient attendance took place at the clinical research facility at the Royal Victoria Infirmary in Newcastle. Data recording took place in the same setting.

Screening and recruitment processes

-

Information about the study was widely disseminated via all relevant patient groups as part of our patient and public involvement activity and through the Newcastle Clinical Service.

-

Potential participants were initially identified through routine clinic outpatient appointments by their treating physician in the hosting NHS trust [the principal investigator (PI) or other member of the research team with documented, delegated responsibility]. Once the trial was under way, participant identification centres (PICs) were established across the region, allowing local-level identification of possible participants. During the course of the trial, the UK-PBC Stratified Medicine Programme (www.UK-PBC.com; accessed September 2015) was established; this developed a national database of PBC patients with phenotyping data and, if given, consent to be approached about follow-on studies (including trials), which were relevant given the patient phenotype. This approach identified potential participants, both in the host NHS trust and in PICs, aiding recruitment and opening up access to patients from across the UK. For patients who were identified through either PICs or the UK-PBC platform, all screening, recruitment and trial-related activity still took place at the single trial centre.

-

In all cases, eligible participants were invited to participate by their consultant and the study was explained to them. A study patient information sheet was provided and the participants had a minimum of 48 hours to consider the information before giving written informed consent.

-

The chief investigator or member of the research team with documented, delegated responsibility witnessed, signed and dated the written informed consent form.

-

Patients were then invited to participate in the formal screening process.

-

An eligibility screening form was completed by the investigator to document fulfilment of the entry criteria for all patients considered for the study and subsequently included or excluded. The log also ensured that potential participants were approached only once.

-

The original signed consent form was retained in the investigator site file, with a copy in the clinical notes and a copy provided to the participant. The participant specifically consented for their general practitioner to be informed of their participation in the study.

-

The right to refuse to participate without giving reasons was respected.

-

Arrangements were in place for translation for potential participants who were non-English speaking. In practice, this option was not required.

-

The screening assessments had to occur within the 4-week period prior to the baseline visit. If there was a delay beyond 4 weeks for any reason, patients underwent rescreening.

Intervention

The study intervention consisted of two treatments administered on study days 1 and 15, with patient conditioning immediately prior to each treatment. The protocol required a minimum interval of 2 weeks between the two treatments. A 2-day visit window was allowed for each dispensing visit. Study medication was prescribed by a study clinician in accordance with the protocol and administered to the patient by clinical staff according to local pharmacy policy. All interventions were administered in the presence of a clinician. All participants had been encouraged to have adequate oral hydration in the 24 hours prior to attendance. Resuscitation equipment was immediately available during the infusion period. Blood pressure, heart rate and temperature were monitored during the infusions. Participants remained under observation in the clinical research facility for at least 2 hours after the infusion.

All unused study medication was stored in pharmacy until the end of the study, or until the trial manager had completed appropriate reconciliation. Documentation of prescribing, dispensing and return of study medication was maintained for study records.

Experimental intervention: rituximab therapy

The investigational medicinal product (IMP) used in the clinical trial was 1000 mg of intravenous (i.v.) rituximab (MabThera). This product was approved by the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products (marketing authorisation number EU/1/98/067/002). The licence holder of MabThera is Roche Products Ltd. The product was supplied as vials containing 500 mg of rituximab at a concentration of 10 mg/ml. Supplies of rituximab were stored in a refrigerator at between 2 °C and 8 °C in a secure location in their original packaging in order to protect them from light. Supplies of rituximab were labelled as IMP in accordance with regulatory requirements. Storage and supply of the rituximab was delegated to the local pharmacy at the trial centre. Rituximab was released for use in the study once all the appropriate regulatory and governance approvals were in place. Patients randomised to receive rituximab therapy were given treatment at the infusion rates recommended for rheumatoid arthritis (RA) patients (i.e. for the first infusion at an initial rate of 50 mg/hour; after the first 30 minutes the rate could be increased in increments of 50 mg/hour every 30 minutes to a maximum rate of 400 mg/hour). Second doses were infused at an initial rate of 100 mg/hour and increased by 100 mg/hour at 30-minute intervals to a maximum of 400 mg/hour. Rituximab has a shelf life of 30 months. The prepared infusion solution of rituximab (MabThera) was physically and chemically stable for 24 hours at temperatures between 2 °C and 8 °C and subsequently for 12 hours at room temperature. Further details can be found in the MabThera Summary of Product Characteristics [https://njl-admin.nihr.ac.uk/document/download/2005806 (p. 56)].

Control intervention: placebo infusion

Patients randomised to receive placebo received conditioning in addition to the control saline infusion. The control infusion was delivered in a double-blind manner to participants using the same placebo that was used in our RA studies, under the supervision of a clinician (as per the clinical research facility protocol).

Conditioning

In line with recommendations for the administration of rituximab in other conditions, patients received a conditioning regimen prior to the infusions of study medication on days 1 and 15. Given that this was a double-blinded trial, both arms received the conditioning regimen. This conditioning regimen was administered 30 minutes prior to infusion of study medication and to all patients, to maintain the double blind. The conditioning regimen comprised 1 g of paracetamol orally, 10 mg of i.v. chlorpheniramine and 100 mg of i.v. methylprednisolone. The paracetamol, chlorpheniramine and methylprednisolone were sourced locally.

Adverse reactions during treatment administration

During the infusion, patients were clinically monitored for the onset of clinical features of infusion-related reactions (IRRs), the most common AEs in rituximab usage.

The protocol stated that patients who developed evidence of severe IRRs, especially severe dyspnoea, bronchospasm or hypoxia, would have the infusion interrupted immediately, with restart of the infusion (at not more than half the rate at which the reaction took place) not taking place until complete resolution of all symptoms and normalisation of laboratory values and chest radiographic findings. If the same severe adverse reactions (ARs) occurred for a second time, the treatment would be stopped. Such reactions were not observed in the study and this protocol was therefore not invoked.

Mild or moderate IRRs were addressed by halving the rate of infusion. The infusion rate was increased again on improvement of symptoms. Paracetamol and/or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs were allowed for the symptomatic management of IRRs.

Concomitant medication

Concomitant therapies were managed as per the MabThera Summary of Product Characteristics. A complete listing of all concomitant medication received during the treatment phase was recorded in the case report form (CRF).

For patients who were receiving UDCA therapy, the dose of UDCA could not be changed during the patients’ 12-month participation in the study. No other disease-modifying agents could be introduced during the trial. Therapy aimed at reducing pruritus and its impact could be introduced if unavoidable at the discretion of the investigators; however, this proved unnecessary.

Live vaccines could not be administered during the study (see Exclusion criteria).

Outcomes

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome variable was fatigue severity in PBC patients, assessed at 3 months using the fatigue domain of the PBC-40: a fully validated, psychometrically robust, disease-specific quality-of-life measure. 21

Secondary outcome measures

The following secondary outcome measures were prespecified:

-

The PBC-40 domain scores covering itch, cognitive, emotional, social and other symptom domains at 3, 6, 9 and 12 months.

-

Physical activity assessed using 7-day physical activity monitoring.

-

Perceived fatigue severity assessed using a self-completion fatigue diary.

-

Daytime somnolence [as assessed using the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)57], vasomotor autonomic symptoms [assessed using the Orthostatic Grading Scale (OGS)58] and functional status [assessed using Patient-Reported Outcomes Measurement Information System Health Assessment Questionnaire (PROMIS HAQ), incorporating the Cognitive Failure Questionnaire (COGFAIL)29]. Reduction in depressive and anxiety-related symptoms was assessed using the HADS. 59

-

Serum anti-pyruvate dehydrogenase complex (PDC) antibody levels assessed using enzyme-linked immunosorbent assays (to confirm whether or not any clinical effect is directly related to antibody modulation). 60,61

-

Peripheral muscle bioenergetic function on exercise (to confirm whether or not any clinical effect was directly related to effects on muscle bioenergetic function). Approaches used included MR spectroscopy assessment of muscle pH change during a fixed exercise protocol, time taken for recovery of pH to baseline following exercise, AUC for pH (a measure of total muscle pH exposure with exercise) and anaerobic threshold assessed using cardiopulmonary exercise testing (CPET). 39,40,47

Exploratory end points

-

Biochemical parameters associated with severity of the liver disease in PBC (ALP), ALT, bilirubin and albumin.

-

Serum immunoglobulins (Igs) [total Ig, immunoglobulin G (IgG) and immunoglobulin M (IgM)].

During the course of the study, a continuous variable model for the prediction of outcomes in PBC was described and validated. This used routinely collected clinical data and could be incorporated into the protocol as exploratory end points. 62 Concern had also developed around second-line therapeutics in PBC and cardiovascular risk related to lipids. In the light of these changes, the following exploratory end point was added during the study:

-

blood lipid levels.

-

Experimental assessments

Quality-of-life and symptom assessment tools

Fatigue severity for the primary end point was assessed using the PBC-40 fatigue domain. This is a validated, disease-specific and patient-derived quality-of-life measure. The fatigue domain score ranges from 11 to 55 (11 items scored 1–5), with higher values denoting worse fatigue.

Other symptom severity was assessed by the relevant domain of the PBC-40 (itch, cognitive, social, emotional and other symptoms). Functional status was assessed using the PROMIS HAQ to assess function. The PROMIS HAQ measures the functional and physical ability of the participants (covering, dressing, arising, eating, walking, hygiene, reach, grip and activity). The score is on a 0–100 scale with higher scores indicating worse functional ability. Anxiety and depression were assessed by HADS score (range 0–42). Daytime somnolence was assessed using the ESS (range 0–24), vasomotor autonomic symptoms using the OGS (range 0–20) and cognitive functionality using COGFAIL (range 0–100), where higher scores indicate worse outcome for all cases.

Fatigue diaries

Participant-held diaries were used to gather qualitative information on symptoms and functional ability. The diaries measured fatigue using a scale of 1–6 (1 = no fatigue and 6 = extreme fatigue). Participants were asked to complete the diaries six times during the study. They completed the diaries for a period of 1 week during the first week of each month at baseline and 1, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. Participants returned the diaries at their final visit.

Magnetic resonance spectroscopy

Magnetic resonance data relating to muscle energetics and pH were acquired at baseline and at 12 weeks using a 3-T Intera Achieva scanner (Philips, Best and NL; Philips Medical System, Andover, MA, USA). The steps used for acquisition and analysis have been described, in detail, in published protocols. 39,40 In summary, this involved controlled plantarflexion using a purpose-built exercise apparatus developed for operation within the MR imaging scanner. Participants performed two 180-second bouts of plantarflexion contractions at 25% and then at 35% of maximal voluntary contraction, with each bout preceded by 60 seconds of rest and followed by 390 seconds of recovery. Phosphorous spectra were collected at 10-second intervals. The minimum pH seen in the exercise and recovery period, the time required post exercise for pH to return to within 0.01 units of baseline levels (calculated as the sum for each individual for the three bouts to form a total pH recovery time) and the mean AUC for pH for the three exercise episodes, which reflected total acid exposure, were calculated.

Anaerobic threshold

Anaerobic threshold was assessed using conventional CPET. Participants cycled on a stationary ergometer (Lode BV, Groningen, the Netherlands) at between 60 and 70 revolutions per minute. The test was terminated either voluntarily by the participant or when they were unable to maintain a pedal frequency of 60 revolutions per minute. Expired air was collected at rest and during exercise using a breathing mask and analysed online using a gas analysis system (MetaLyzer II, CORTEX Biophysiks GmbH, Walter-Kohn, Germany). Anaerobic threshold was determined using the computerised v-slope method at baseline and at the 12-week follow-up.

Physical activity levels

Participants completed physical activity monitoring using wrist-worn tri-axial GENEActiv accelerometers (Activinsights Ltd, Cambridgeshire, UK). The accelerometer was worn continuously on the right wrist for a period of 7 days in free-living conditions. Raw accelerometer data were processed in R studio (www.cran.r-project.org; accessed February 2017) using R-package GGIR version 1.2.8 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). Patients were included in the analysis if they had worn the monitor for a minimum period of 5 days (with at least one of these days at the weekend). Only days with at least 22 hours of valid data were retained for further analysis. The first and last days of the raw accelerometer measurement were excluded as they were influenced by the monitor distribution and collection procedure.

Following data processing and the exclusion of patients who did not meet the wear-time criteria, the average magnitude of wrist acceleration was calculated via metric Euclidean Norm Minus One (ENMO) as previously described. 63 The output from metric ENMO is in mg (1 mg = 0.001 g = 0.001 × 9.8 m/s2 = 0.001 × gravity). In addition, the average acceleration (mg) during the most active 5-hour period of each day was assessed pre versus post intervention.

Immunology

Quantification and phenotyping of total B-cell populations and B-cell subsets was undertaken using a standard fluorescence-activated cell analysis-based approach. Total B-cell levels in peripheral blood were evaluated using a direct immunofluorescence reagent (Fast Immune™ CD19/CD69/CD45, BD Biosciences, San Jose, CA, USA).

Anti-PDH antibody total and individual isotype levels were studied on day 0 and at the primary end point (12 weeks after therapy), using a well-established enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay developed within our research group. 61

Biochemistry and haematology

Biochemical (liver biochemistry, electrolytes and lipids) and haematological (platelet count) assessments were undertaken using the routine clinical laboratories at the research centre. These are quality-assured clinical parameters. The UK-PBC risk score was calculated using the published formula. 62 The values generated are percentage risks of death from liver-related causes or need for liver transplant at 10 years.

Randomisation

Randomisation was conducted by the NCTU web-based system in a 1 : 1 ratio using random-permuted blocks with random block length. The randomisation system generated a treatment number for each participant, which linked to the corresponding allocated study drug. The treatment number was then documented by the investigator on the trial prescription to ensure that the study pharmacist dispensed the correct study medication.

Patients in the study were randomised to receive either:

-

rituximab therapy on days 1 and 15 (study drug) or

-

placebo (normal saline) on days 1 and 15 (control).

Patients could be randomised into the study only by an authorised member of staff at the study research site, as detailed on the study delegation log. Patients could be randomised into the study once only.

Blinding

Assignment to either the rituximab or placebo arm was blinded to both the participant and investigators/assessor.

A code-break list was kept in the pharmacy and could be accessed only in an emergency (preferably with authorisation from the chief investigator). If the code was broken, details including the participant number, who broke the code, why and when were recorded and maintained in the site file. Code breaks were not routinely opened for participants who completed study treatment. One patient in the placebo arm was unblinded during the course of the study for emergency medical reasons (a SAE). The patient remained blinded.

Data management and monitoring

Study data were entered into a paper CRF and then uploaded by the data manager into the MACRO database system (Elsevier Ltd).

The study was managed through the NCTU. The Trial Management Group included the chief investigator/PI, senior trial manager, trial manager, trial statistician, database manager, clinical research fellow and other members of the trial team when applicable. NCTU provided day-to-day support for the site and provided training through the site initiation visit and routine monitoring visits. The PI was responsible for the day-to-day study conduct at the site.

Quality control was maintained through adherence to sponsor standard operating procedures, NCTU standard operating procedures, Newcastle Magnetic Resonance Centre standard operating procedures, the study protocol, the principles of GCP, the Research Governance Framework and clinical trial regulations.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

An independent DMEC was appointed, the terms of reference of which were governed by a signed DMEC charter. It consisted of an independent chairperson, an independent expert clinician and an independent statistician and was convened to undertake independent review. The purpose of this committee was to monitor efficacy and safety end points. Only the independent DMEC members and the unblinded statistician had access to unblinded study data. The committee met eight times during the study.

Trial Steering Committee

A TSC was established to provide overall supervision of the study, the terms of reference of which were governed by a signed TSC charter. The TSC consisted of an independent chairperson, an independent clinician, an independent consumer representative, the chief investigator/PI, senior trial manager, trial manager and trial statistician. Representatives of the sponsor were invited to all TSC meetings. The committee met eight times during the study.

Study monitoring

Monitoring of study conduct and data collected was performed by a combination of central review and site monitoring visits to ensure that the study was conducted in accordance with GCP, the protocol and clinical trial regulations. Study site monitoring was undertaken by the trial manager. The main areas of focus included consent, SAEs, essential documents in the investigator site file and drug accountability and management.

Site monitoring included the following:

-

All original consent forms were reviewed as part of the study file (the presence of a copy in the patient hospital notes was confirmed for 20% of participants).

-

All original consent forms were compared against the study participant identification list.

-

All reported SAEs were verified against treatment notes/medical records (source data verification).

-

Essential documents were accessible in the investigator site file.

-

Source data verification of primary end point data and eligibility data was undertaken for 20% of participants entered in the study.

-

Drug accountability and management was checked; an unblinded monitor conducted pharmacy monitoring visits.

Central monitoring included the following:

-

All applications for study authorisations and submissions of progress/safety reports were reviewed for accuracy and completeness, prior to submission.

-

All documentation essential for study initiation was reviewed prior to site authorisation.

Statistical methods

Sample size

The study was planned to detect a mean change in PBC-40 fatigue domain score of 5 units at 3 months’ follow-up (equating to an average of a 0.5-point change per question, a difference in PBC-40 score demonstrated in our population-based studies to be associated with significantly higher levels of social function). 24 Previous studies had shown a standard deviation (SD) of 8 units and a correlation of 0.6 between baseline and follow-up, so, using a power of 90% and a 5% significance level, this required outcome data from 35 participants per arm. A total of 78 participants (39 per arm) was planned to be recruited and randomised, assuming 10% attrition at 3-month follow-up. 21

However, as recruitment was slower than expected, even after expanding recruitment beyond the north-east region of England, a revised sample size calculation was undertaken. Consequently, trial recruitment was extended by 6 months and the power of the trial was reduced to 80%, with a revised target sample size (with other estimates of parameters unchanged) of 58 participants (29 per arm). These changes to the design of the trial were agreed by the funder and submitted as a substantial amendment, which was accepted by both the Research Ethics Committee (REC) and MHRA during October 2015.

Statistical analysis

A complete statistical analysis plan was finalised and signed before datalock and unblinding (see Report Supplementary Material 1). It provides full details of statistical analyses, variables and outcomes.

All analyses were performed on the intention-to-treat (ITT) population. A pragmatic ITT approach was used in which patient outcomes were reported at their visit nearest the scheduled appointment date. Baseline characteristics of the study population were summarised separately within each randomised group.

The primary analysis was the PBC-40 fatigue domain. Descriptive statistics were reported at each time point (baseline and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months) in both arms. PBC-40 fatigue domain scores at 3 months were compared in the intervention and placebo groups using multiple linear regression with adjustment for baseline PBC-40 fatigue score, age in years, UK-PBC risk model score at 10 years and patient location (managed by the Newcastle Clinics for Research and Service in Themed Assessment centre for at least 1 year or not) at baseline. The results were reported as an adjusted difference in means with a 95% confidence interval (CI). Bootstrap estimation was used throughout. The time course of the comparison between intervention and control groups over the 12-month follow-up period using the time points above was assessed for PBC-40 fatigue domain using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA).

The above analyses for PBC-40 fatigue score were repeated for secondary outcomes, namely:

-

other PBC-40 domain scores (itch, cognitive, social, emotional and other symptoms)

-

clinical symptom and functional capability scales (ESS, OGS, PROMIS HAQ, COGFAIL, HADS and fatigue diary)

-

metric ENMO activity monitoring (daily average and best 5 hours)

-

bioenergetics outcomes (minimum pH post exercise, pH recovery half-time, pH fall with exercise, AUC for pH and anaerobic threshold)

-

biological outcomes [serum immunoglobin level (IgG and IgM)].

Euclidian Norm Minus One, bioenergetics and biological outcomes were collected only at baseline and 3 months, so no repeated measures analyses were performed.

Descriptive analyses were reported for other secondary outcomes listed below [additional repeated measures (ANOVA up to 12 months) were carried out for bilirubin and serum ALP outcomes]:

-

full blood count (haemoglobin concentration, white blood cell count and platelet count)

-

liver function test [prothrombin time, bilirubin level, ALP level, ALT level, AST level, albumin level, GGT level, activated partial thromboplastin time and C-reactive protein (CRP) concentration]

-

lipid profile [low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL), high-density lipoprotein cholesterol (HDL) and triglyceride]

-

urea and electrolytes (U&E) (urea, creatinine, sodium and potassium concentrations)

-

anti-mitochondrial antibody titre (expressed as number and percentage) and anti-PDC antibody level

-

CD19 B-cell depletion.

Change in serum ALP level (at 3 and 12 months from baseline) was also measured and we classified a drop in level of > 15% or normalisation (within normal range) as being clinically significant. The number (%) of clinically significant results in each arm was reported.

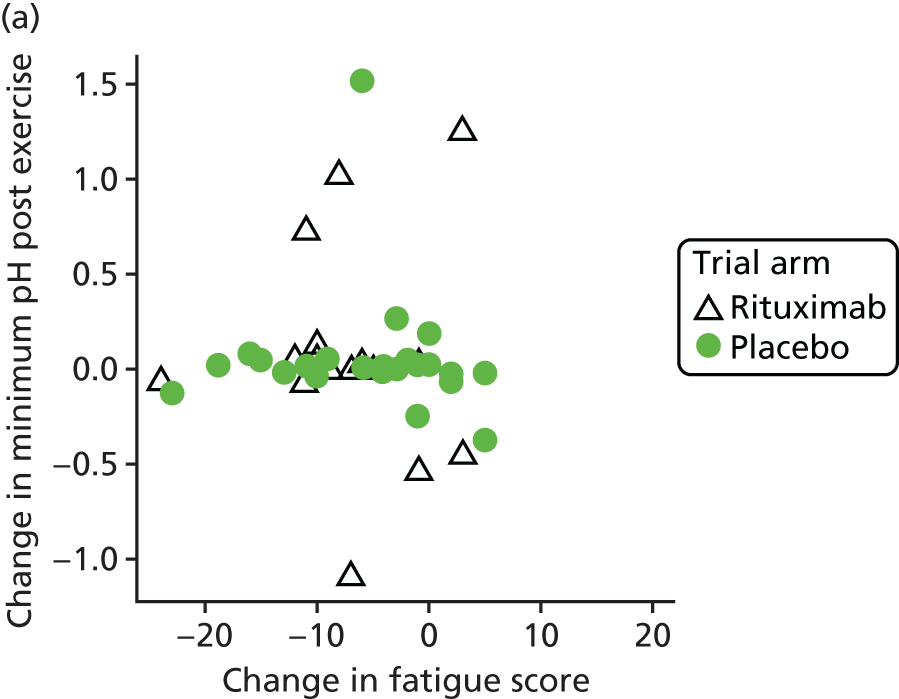

Mechanistic analyses

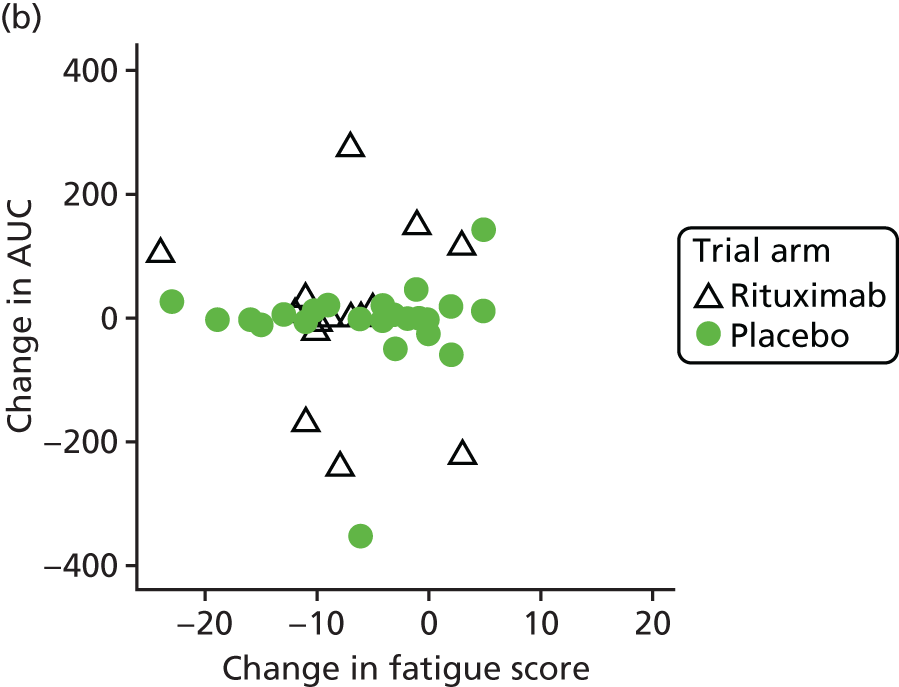

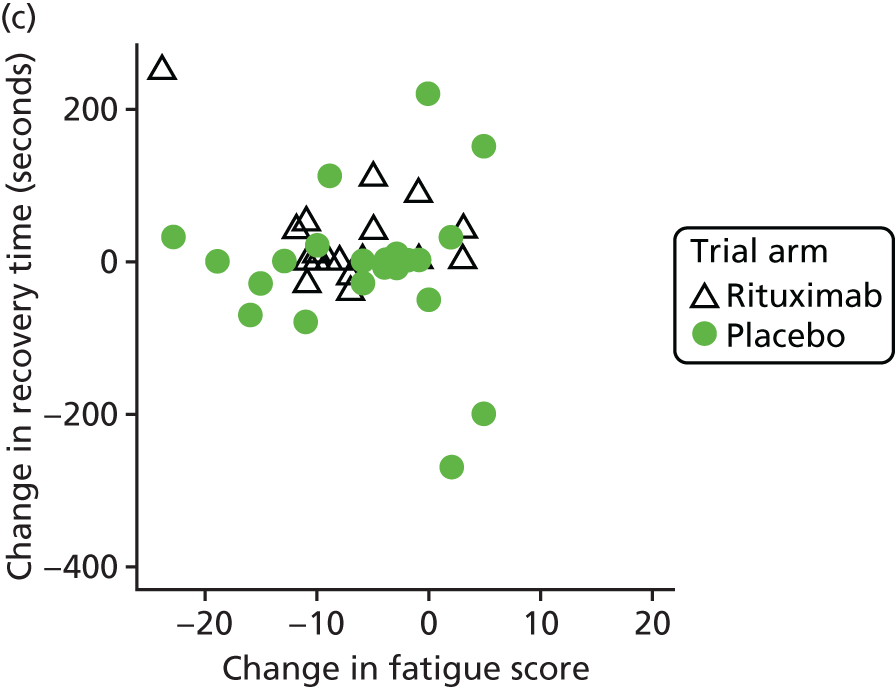

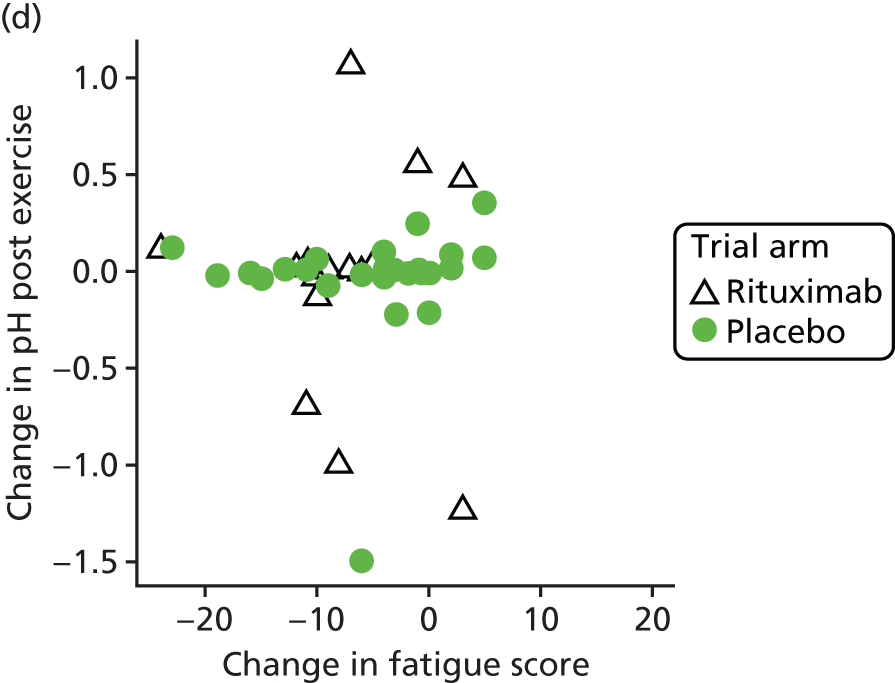

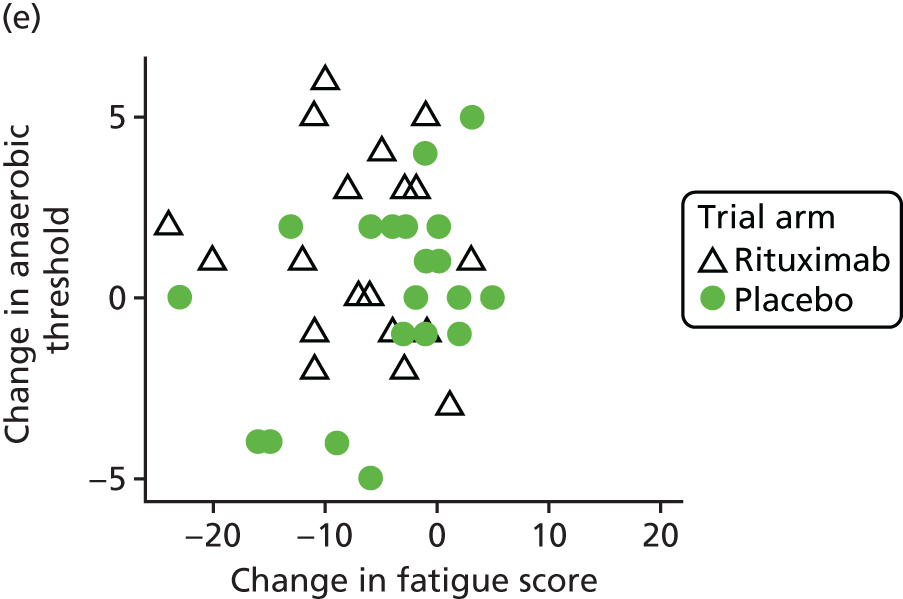

Scatterplots and correlations between the change in PBC-40 fatigue domain score over 3 months and change in five bioenergetics outcomes were produced (see Figure 4).

All statistical analyses were performed using the statistical software package Stata® (version 14.1; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Safety

Monitoring for safety was undertaken in accordance with GCP. Full details and definitions of AEs, SAEs, ARs, serious adverse reactions (SARs), unexpected adverse reactions, suspected serious adverse reactions and SUSARs, as well as severity of AEs and expected ARs, are given in the trial protocol in section 19.1 (https://njl-admin.nihr.ac.uk/document/download/2005806). The local investigator responsible for the care of the participant was asked to assign causality, in accordance with the study protocol. Causality was defined as described in section 19.1 (https://njl-admin.nihr.ac.uk/document/download/2005806; accessed September 2017).

Protocol specifications

For purposes of the specific study protocol:

-

All non-SARs were recorded at visits 2–19.

-

Any SAEs were recorded throughout the duration of the trial until 12 months after trial therapy was stopped

-

The SAEs excluded any pre-planned hospitalisations (e.g. elective surgery) that were not associated with clinical deterioration.

-

The SAEs excluded routine treatment or monitoring of the studied indication that was not associated with any deterioration in condition.

-

The SAEs excluded fatigue (primary outcome measure, already documented and monitored within study).

Adverse reactions during treatment administration

During the infusion, patients were monitored clinically for the onset of clinical features of IRRs (the most common AEs in rituximab usage). Patients who developed evidence of severe IRRs, especially severe dyspnoea, bronchospasm or hypoxia, would have had the reaction managed as outlined in Adverse reactions during treatment administration. In practice, this did not occur.

Recording and reporting of serious adverse events or reactions

All AEs were reported. Depending on the nature of the event, the reporting procedures below were followed (or would have been followed if relevant).

Adverse events (including adverse reactions)

All non-SAEs/SARs during drug treatment were reported on the study CRF and sent to the NCTU management team within 2 weeks to be entered into the MACRO database. Severity of AEs will be graded on a five-point scale (mild, moderate, severe, life-threatening, causing death). Any relationship between the AE and the treatment was assessed by the investigator at the site. The investigator at the site was responsible for managing all AEs/ARs according to the local protocol.

Serious adverse events and reactions (including suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions)

All SAEs, SARs and SUSARs during drug treatment were reported to the chief investigator within 24 hours of the site being notified of its occurrence. The initial report was made by via the secure fax to e-mail reporting system (Soho66, Sunderland UK), which generates a copy for the chief investigator, trial manager, senior trial manager and sponsor. In the case of incomplete information at the time of initial reporting, all appropriate information was provided as follow-up as soon as this became available. The relationship between the SAE and the treatment was assessed by the investigator at the site, as was the expected or unexpected nature of any SARs.

The MHRA and main REC were to be notified by the chief investigator or NCTU (on behalf of the sponsor) of all SUSARs occurring during the study in accordance with the following time lines: fatal and life-threatening within 7 days of notification, and non-life-threatening within 15 days. No SUSARs, however, occurred.

Chapter 3 Results

Participant flow

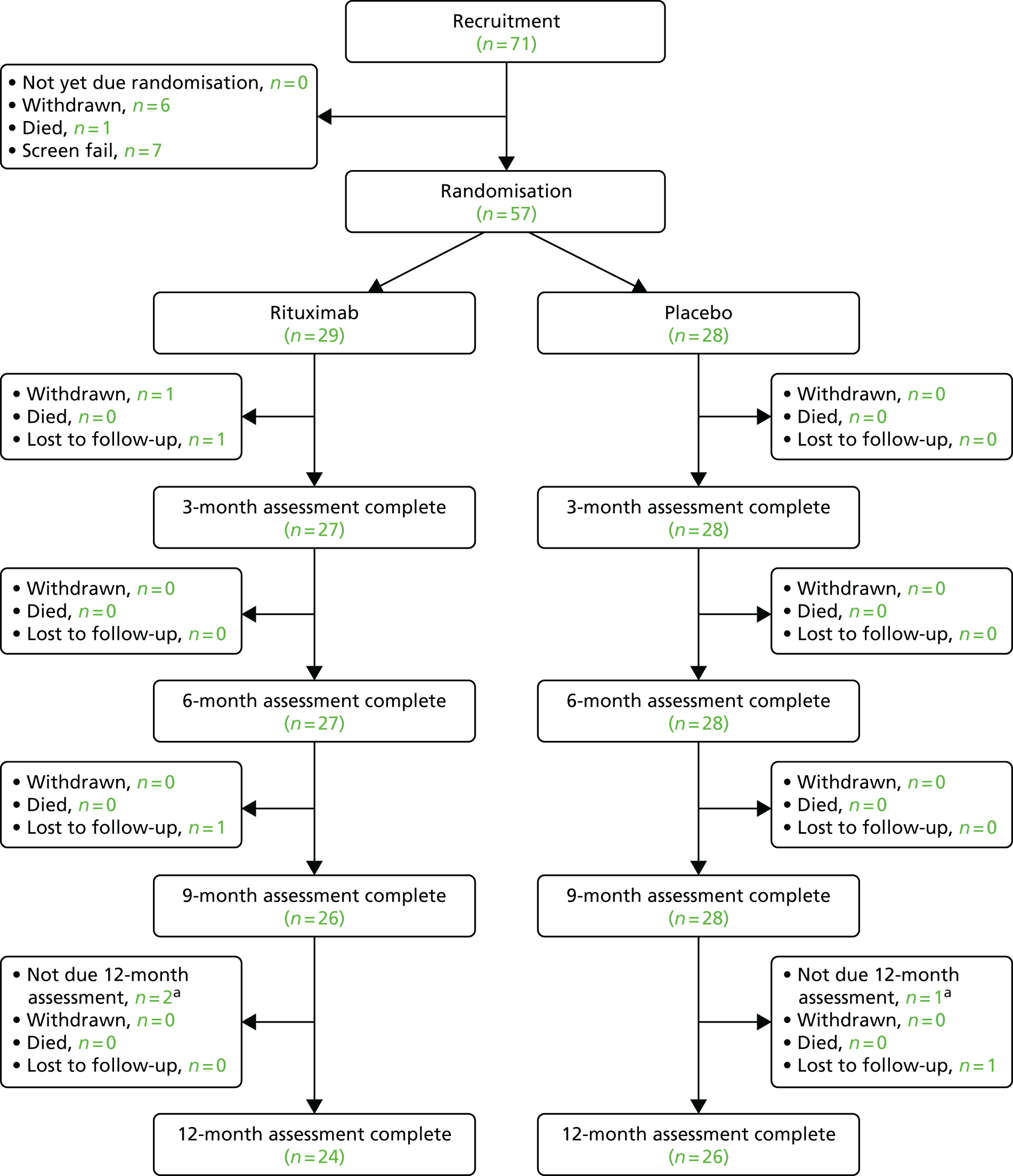

Figure 2 shows the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram giving details of recruitment, randomisation and retention in the trial.

FIGURE 2.

Recruitment flow chart. a, Trial was terminated early on 12 September 2016, so these patients forwent their 12-month follow-up visits that were due after this date.

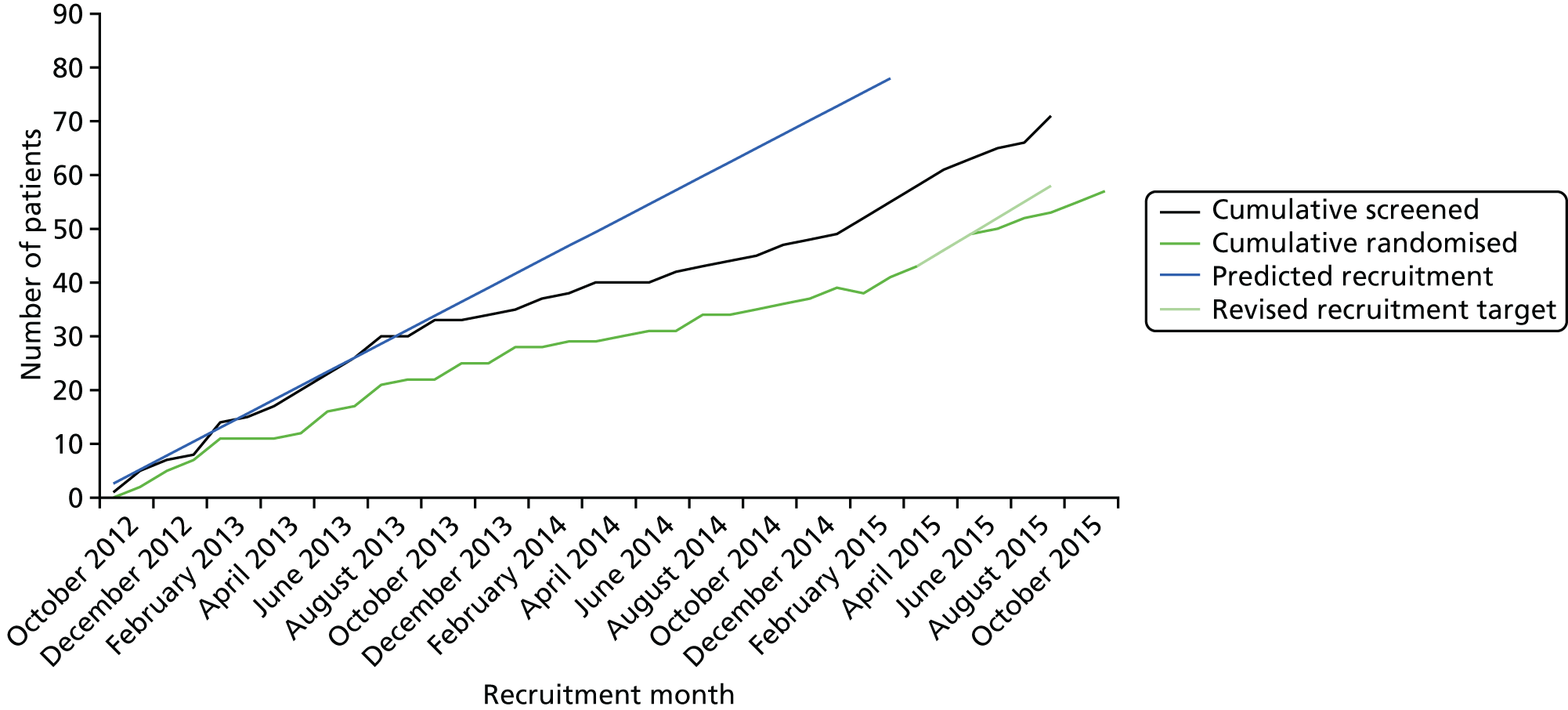

Recruitment

The trial opened to recruitment on 1 October 2012, but due to slower than expected recruitment a no cost extension was obtained, resulting in the trial closing to recruitment on 1 October 2015 (Figure 3). The original target recruitment number was 78 participants, but this was later revised to 58 when recruitment was slower than expected. Seventy-one participants were recruited into the trial, but only 57 were randomised due to seven screen failures, six withdrawals and one death; the last patient was randomised on 18 November 2015. Rates of attrition were low, with 50 participants staying in the trial for the full 12 months’ follow-up: 55 provided outcome data at 3 and 6 months and 54 provided outcome data at 9 months, with two participants being lost to follow-up and one withdrew. The trial was terminated early on 12 September 2016 following consultation with the MHRA and REC and with the endorsement of the DMEC and TSC. This early termination enabled the final analysis to start once all the 9-month follow-up data were complete, to meet the final draft report submission deadline. The early termination of the trial had no effect on the primary end point of the trial, which was measured at 3 months. It might have had an impact on the secondary objective of the trial, which was to look for any sustained effect of rituximab; however, the chief investigator did not foresee any impact as being significant, as it was anticipated that any sustained effects of rituximab would have worn off after 6 months, as seen in other indications (i.e. RA). 38 For this reason, three participants forwent their final 12-month follow-up visit and finished the study early after their 9-month follow-up visit.

FIGURE 3.

B-cell-depleting therapy (RITuximab) as a treatment for fatigue in Primary Biliary Cirrhosis trial recruitment tracker.

Numbers analysed

Primary outcome analysis was performed on 29 patients in the rituximab group and 28 patients in the placebo group, with all participants remaining in their original randomisation groups. Some of the secondary outcome and additional analyses (in particular physical activity and fatigue diary, and muscle bioenergetics, respectively), were performed on smaller numbers because of issues with usability of the data (MR-based bioenergetics and physical activity monitoring) and patient compliance of a sufficient level to meet assessment duration requirements (fatigue diaries and physical activity monitoring).

Data were analysed using a pragmatic ITT approach throughout. A sensitivity analysis for a compliant ITT (± 1 week at visit 16 at 3 months) for the primary outcome was additionally specified. No participants completed their PBC-40 questionnaire, which included the primary fatigue domain outcome, within 83–97 days from the date of randomisation. When the more appropriate time between first infusion at visit 2 to completion of the PBC-40 questionnaire at 3 months was used, only 17 out of 55 participants had completed primary outcome questionnaire data within a week of the primary outcome collection target date. However, departures from this were generally quite small, with an overall median of 9 days in the combined arms [interquartile range (IQR) 7–15 days, range 0–29 days] from the due date, and similar between arms. The compliant ITT subgroup analysis was not performed because of the small numbers of those who were compliant (17/55 participants), even using the less stringent infusion time point rather than randomisation date.

Outcomes and estimation

Baseline data

The baseline clinical data are outlined in Tables 1 and 2. The study population was predominantly female, in keeping with the established demographic profile of PBC. 12 The distribution of UK-PBC risk score data at baseline suggested a low overall risk, in keeping with the established observation that fatigue severity in PBC is unrelated to the severity of underlying disease. Participants were predominantly of white ethnicity and most were not current smokers. More than two-thirds of participants had been managed at Newcastle Clinics for Research and Service in Themed Assessment centre for at least 1 year. The median age was ≈54 years and typical body mass index scores were relatively high, indicating that there were some potentially overweight participants in each arm. Alcohol consumption was modest in both arms and well below the recommended weekly intake. The distributions were well balanced between the intervention and control arms, with the exception of the proportion of UDCA responders and UK-PBC risk score at 10 years prediction.

| Categorical variable | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rituximab (N = 29) | Placebo (N = 28) | |

| Sex: female | 28 (96.5) | 27 (96.5) |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 28 (96.5) | 28 (100) |

| Non-white | 1 (3.5) | 0 (0) |

| Smoking status | ||

| Never | 16 (55) | 12 (43) |

| Past | 7 (24) | 8 (28.5) |

| Current | 6 (21) | 8 (28.5) |

| Managed by the Newcastle Clinics for Research and Service in Themed Assessment centre for at least 1 year | ||

| Yes | 20 (74) | 19 (68) |

| UDCA use: yes | 24 (89) | 27 (96.5) |

| If yes: responder | 19 (79) | 16 (59) |

| Continuous variable | Trial arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab (N = 29) | Placebo (N = 28) | |||||

| n | Median (IQR) | Range | n | Median (IQR) | Range | |

| Age (years) | 28 | 55.9 (48.8–60.0) | 34.0–66.7 | 27 | 53.3 (49.9–58.8) | 39.2–72.1 |

| Alcohol consumption (units per week: drinkers) | 17 | 4 (2–8) | 1–12 | 9 | 4 (2–12) | 1–14 |

| Alcohol consumption (units per week: all) | 29 | 1 (0–4) | 0–12 | 28 | 0 (0–1.5) | 0–14 |

| Body mass index (kg/m2) | 29 | 28.7 (24.5–30.5) | 19.8–40.5 | 28 | 26.7 (22.9–30.7) | 18.7–43.5 |

| UK-PBC risk score at 10 years | 25 | 1.26 (0.94–1.74) | 0.21–3.55 | 27 | 1.75 (1.12–3.04) | 0.20–12.90 |

Primary outcome

Data for the primary outcome, fatigue severity assessed at 3 months using the PBC-40 fatigue domain, are summarised in Table 3. The primary comparison was at 3 months, in which the mean PBC-40 fatigue scores were 36.2 in the rituximab arm and 38.1 in the placebo arm. This represents a decrease in score from baseline of around 5 units in each arm. The unadjusted mean PBC-40 fatigue score was 1.9 units lower in the rituximab arm at 3 months, but when the distribution of covariates was taken into account, the adjusted mean difference was –0.9 (95% CI –4.6 to 3.1). Although the 95% CIs are wide, they do not extend beyond the clinically important difference of 5.

There was little difference in mean fatigue scores between trial arms at any of the time points. The time course of the comparison between the intervention and control arms over the 12-month follow-up period was assessed for the primary outcome (PBC-40 fatigue domain) using repeated measures ANOVA at the time points of baseline and 3, 6, 9 and 12 months. There was no significant difference between the two trial arms (F = 1.81; p = 0.18) or in the interaction between arms over time (F = 0.41; p = 0.80).

| Time point | Trial arm | Difference in PBC-40 (scale range 11–55) fatigue domain score at 3 months [adjusted difference in meansb (rituximab – placebo) (95% CI)] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | Placebo | ||||||

| n | Mean PBC-40 (scale range 11–55) fatigue domain scorea (SD) | Range in PBC-40 (scale range 11–55) fatigue domain score | n | Mean PBC-40 (scale range 11–55) fatigue domain scorea (SD) | Range in PBC-40 (scale range 11–55) fatigue domain score | ||

| Baseline | 29 | 41.2 (5.5) | 32–54 | 28 | 43.0 (5.9) | 31–54 | –0.9 (–4.6 to 3.1) |

| 3 months | 27 | 36.2 (8.4) | 14–52 | 28 | 38.1 (8.7) | 17–51 | |

| 6 months | 27 | 36.6 (7.6) | 19–51 | 28 | 39.9 (7.5) | 18–54 | |

| 9 months | 25 | 38.1 (8.3) | 20–53 | 28 | 39.6 (8.6) | 17–55 | |

| 12 months | 23 | 39.5 (8.2) | 26–54 | 26 | 39.5 (6.5) | 30–53 | |

| Repeated measures ANOVA up to 12 months between: | |||||||

| Trial arms: F-test (p-value) | 1.81 (0.18) | ||||||

| Arms × time points: F-test (p-value) | 0.41 (0.80) | ||||||

Secondary outcomes

The prespecified secondary outcome data are presented in the following sections by category.

Immunological

Immunological analyses suggested that rituximab was effective in mediating depletion of B-cells, its primary proposed mode of action. Virtually complete B-cell depletion was seen in all rituximab-treated patients by the 3-month assessment point (Table 4). Assessment was through CD19, a surface marker distinct from the molecular target for the drug (CD20), excluding treatment-related surface marker change following drug action as an explanation. No depletion was seen in the placebo arm. Complete depletion was maintained at 6 months, with gradual repopulation to 50% of the baseline level by 12 months. These kinetics for cell numbers are in keeping with previous reports of rituximab therapy. 54,55 The kinetics of fatigue reduction in the rituximab group mirrored the kinetics of B-cell depletion and recovery. However, in the placebo group the improvement in fatigue score was not mirrored with similar changes in kinetics of B-cell depletion and recovery.

| Trial arm | Time point | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | |||||||||||

| n | Median (IQR) in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | Range in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | n | Median (IQR) in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | Range in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | n | Median (IQR) in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | Range in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | n | Median (IQR) in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | Range in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | n | Median (IQR) in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | Range in CD19 B-cell depletion (%)a | |

| Rituximab | 27 | 11.9 (8.4–14.8) | 3.75–27.9 | 26 | 0.1 (0.02–0.07) | 0–0.49 | 25 | 0.1 (0.05–2.9) | 0.02–3.95 | 24 | 2.3 (0.6–4.9) | 0.2–12.2 | 24 | 5.3 (1.9–8.4) | 1.2–16.3 |

| Placebo | 28 | 9.9 (6.7–13.9) | 3.1–29.0 | 28 | 10.9 (6.88–14.1) | 3.09–25.3 | 28 | 10.4 (7.3–13.8) | 3.2–27.3 | 28 | 10.5 (8.2–14.6) | 3.5–27.5 | 26 | 9.3 (7.7–14.7) | 2.6–29.4 |

Distribution of AMA titre outcome is given in Table 5. Reduction in the levels of anti-PDC antibody (the characteristic autoantibody of PBC) was also seen in the rituximab (but not the placebo) arm (Tables 5 and 6). Although reduction was seen at 3 months, peak reduction was seen at 6 months and sustained at 9 months. This correlates with the known mechanistic effects of rituximab.

| Time point, AMA titre category | Trial arm, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | Placebo | |

| Baseline | ||

| 40 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| 80 | 1 (5) | 1 (5) |

| 160 | 2 (9) | 1 (5) |

| 320 | 3 (14) | 7 (33) |

| > 640 | 15 (68) | 11 (52) |

| 3 months | ||

| 40 | 2 (11) | 1 (6) |

| 80 | 0 (0) | 2 (12) |

| 160 | 4 (21) | 0 (0) |

| 320 | 5 (27) | 4 (24) |

| > 640 | 8 (42) | 10 (59) |

| Time point | Trial arm | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | Placebo | |||||

| n | Mean % from baseline (SD) | Range in % from baseline | n | Mean % from baseline (SD) | Range in % from baseline | |

| 3 months | 27 | 70.4 (18.0) | 29.5–101.5 | 28 | 92.6 (12.5) | 60.9–110.3 |

| 6 months | 26 | 54.4 (21.6) | 12.9–93.2 | 28 | 96.7 (15.2) | 45.5–124.8 |

| 9 months | 25 | 59.9 (24.1) | 14.9–121.4 | 28 | 99.5 (15.3) | 61.8–140.9 |

| 12 months | 24 | 78.5 (29.0) | 22.2–144.4 | 26 | 102.2 (21.6) | 77.6–186.3 |

A reduction in IgM fraction was seen at 3 months in the rituximab arm (Table 7). There was a small reduction in total Ig and IgG levels in the rituximab-treated group and to a lesser extent in the placebo arm. The incomplete nature of antibody depletion in contrast to the complete depletion of B-cells is in keeping with previous reports54,55 of rituximab therapy. The known cellular targeting (CD20) expression is seen at a much lower level in plasma cells than in earlier lineage B-cells, leading to more effective depletion of the latter.

| Ig fraction | Trial arm | Difference in mean serum Ig levels at 3 months [adjusted difference in means (rituximab – placebo) (95% CI)b] | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | Placebo | ||||||||

| n | Mean serum Ig levelsa (SD) | Median serum Ig levelsa (IQR) | Range in serum Ig levelsa | n | Mean serum Ig levelsa (SD) | Median serum Ig levelsa (IQR) | Range in serum Ig levelsa | ||

| Total IgG | |||||||||

| Baseline | 22 | 12.5 (3.4) | 11.6 (10.3–13.8) | 7.5–22.2 | 22 | 11.8 (2.55) | 11.7 (10.4–12.8) | 7.6–17.9 | |

| 3 months | 20 | 11.0 (2.8) | 10.8 (9.4–12.1) | 6.1–18.6 | 19 | 11.2 (2.4) | 10.9 (9.4–12) | 7.7–17.1 | 0.98 (0.50 to 1.50) |

| Total IgM | |||||||||

| Baseline | 22 | 3.7 (2.1) | 3.2 (2.3–5) | 0.9–8.7 | 22 | 3.2 (2.1) | 3.0 (1.8–4.3) | 0.5–10.3 | |

| 3 months | 20 | 2.0 (1.0) | 1.7 (1.3–2.7) | 0.5–3.8 | 19 | 3.0 (2.2) | 2.8 (1.5–3.8) | 0.5–9.9 | 1.24 (0.76 to 1.88) |

| Total Ig level | |||||||||

| Baseline | 22 | 18.6 (5.0) | 17.4 (15.4–19.7) | 11.4–32 | 22 | 17.1 (4.4) | 17 (14.4–19.1) | 9.8–28.3 | |

| 3 months | 20 | 15.16 (3.6) | 14.2 (13.8–15.7) | 8.6–26.3 | 19 | 16.2 (4.1) | 15.3 (13.8–17.9) | 10.2–27.3 | |

Additional patient-reported outcome measures

Additional PROMs were used to assess other aspects of the patient experience (the five non-fatigue domains of the PBC-40 addressing cognitive, emotional, social and mixed symptoms along with itch), the ESS (daytime somnolence), OGS (autonomic dysfunction), COGFAIL (cognitive symptoms), HADS (depression and anxiety) and fatigue diary scores (Table 8). The unadjusted questionnaire score means showed little difference between trial arms at 3 months and, when the distribution of covariates was taken into account, there was still little or no difference between mean questionnaire scores. The 95% CIs were generally wide but there was no suggestion that the results were consistent with any clinically important differences.

| Questionnaire domain | Time point or period | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | 3 months | 6 months | 9 months | 12 months | Up to 12 months; repeated measures ANOVA between: | ||||||||||||

| n | Mean score (SD) | Range in score | n | Mean scorea (SD) | Range in score | Adjusted difference in meansb (rituximab – placebo) (95% CI) | n | Mean score (SD) | n | Mean score (SD) | n | Mean score (SD) | Trial arms | Arms × time points | |||

| F-test | p-value | F-test | p-value | ||||||||||||||

| PBC-40 domain | |||||||||||||||||

| Itch (0–15) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 29 | 4.7 (2.7) | 0–9 | 27 | 4.5 (2.8) | 0–10 | –0.8 (–0.3 to 1.8) | 27 | 4.3 (2.7) | 25 | 4.4 (3.1) | 23 | 4.7 (3.8) | 5.45 | 0.023 | 1.13 | 0.343 |

| Placebo | 28 | 6.5 (3.4) | 0–15 | 28 | 5.5 (3.5) | 0–15 | 28 | 6.4 (3.6) | 28 | 6.4 (3.4) | 26 | 6.2 (3.0) | |||||

| Cognitive (6–30) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 28 | 20.0 (4.2) | 12–30 | 27 | 19.3 (4.0) | 9–27 | 0.8 (–1.5 to 3.3) | 27 | 19.4 (3.2) | 25 | 19.2 (4.5) | 22 | 19.6 (3.0) | 0.16 | 0.690 | 0.22 | 0.928 |

| Placebo | 27 | 19.8 (5.3) | 7–28 | 28 | 18.3 (5.7) | 6–30 | 28 | 19.3 (5.8) | 28 | 19.0 (4.8) | 26 | 20.0 (4.7) | |||||

| Social (8–50) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 28 | 33.0 (7.6) | 21–50 | 27 | 32.6 (7.1) | 16–47 | 1.5 (–1.6 to 5.0) | 27 | 31.9 (8.3) | 25 | 32.2 (7.6) | 28 | 32.5 (7.6) | 0.00 | 0.945 | 1.07 | 0.374 |

| Placebo | 27 | 33.3 (6.4) | 23–43 | 28 | 30.8 (7.4) | 15–45 | 28 | 32.9 (8.1) | 28 | 31.3 (8.1) | 26 | 30.3 (7.5) | |||||

| Emotional (3–15) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 28 | 9.4 (3.3) | 4–15 | 27 | 9.3 (3.3) | 4–15 | 0.6 (–0.9 to 2.0) | 27 | 9.3 (3.5) | 25 | 9.1 (3.5) | 22 | 9.0 (2.9) | 0.26 | 0.609 | 0.67 | 0.617 |

| Placebo | 26 | 9.8 (2.9) | 3–15 | 28 | 9.0 (3.2) | 3–15 | 28 | 9.6 (3.6) | 28 | 9.6 (3.4) | 25 | 9.1 (3.4) | |||||

| Other symptoms (6–35) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 29 | 17.6 (4.4) | 7–27 | 27 | 16.9 (3.7) | 8–23 | 0.2 (–1.2 to 1.5) | 27 | 18.2 (4.9) | 25 | 17.8 (5.1) | 23 | 18.5 (4.7) | 0.01 | 0.908 | 0.59 | 0.671 |

| Placebo | 28 | 18.5 (3.4) | 10–26 | 28 | 17.6 (3.3) | 10–23 | 28 | 18.2 (3.5) | 28 | 18.1 (4.0) | 26 | 18.9 (4.7) | |||||

| ESS (0–24) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 28 | 12.3 (5.5) | 0–24 | 26 | 10.9 (6.1) | 1–24 | –0.7 (–3.0 to 1.6) | 27 | 11.4 (5.4) | 25 | 10.8 (5.9) | 24 | 11.2 (5.8) | 1.51 | 0.224 | 0.80 | 0.523 |

| Placebo | 27 | 13.3 (5.0) | 4–24 | 28 | 11.9 (5.1) | 3–24 | 27 | 12.6 (5.9) | 28 | 13.3 (5.2) | 26 | 11.8 (4.5) | |||||

| OGS (0–20) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 28 | 4.1 (3.1) | 0–13 | 26 | 4.7 (4.0) | 0–15 | 0.4 (–1.0 to 1.9) | 25 | 5.5 (4.1) | 24 | 5.7 (4.0) | 23 | 4.7 (4.1) | 0.28 | 0.601 | 0.91 | 0.459 |

| Placebo | 26 | 4.9 (3.3) | 0–12 | 28 | 4.8 (4.1) | 0–15 | 26 | 5.7 (4.3) | 28 | 5.4 (3.8) | 25 | 5.8 (4.1) | |||||

| PROMIS HAQ (0–100) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 29 | 9.4 (8.7) | 0–40 | 26 | 13.7 (14.0) | 0–56.3 | 1.4 (–3.3 to 7.3) | 27 | 11.2 (11.2) | 25 | 12.4 (10.6) | 24 | 12.6 (11.1) | 1.65 | 0.205 | 1.25 | 0.290 |

| Placebo | 28 | 12.0 (11.2) | 0–50 | 28 | 14.0 (13.1) | 0–50 | 27 | 16.5 (14.5) | 28 | 17.0 (17.1) | 26 | 16.5 (15.2) | |||||

| COGFAIL (0–100) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 27 | 57.3 (13.6) | 31–81 | 25 | 59.7 (14.7) | 32–82 | 1.7 (–5.7 to 8.6) | 27 | 57.6 (15.7) | 24 | 57.1 (16.2) | 22 | 57.8 (14.7) | 0.96 | 0.331 | 0.50 | 0.739 |

| Placebo | 26 | 52.2 (16.2) | 17–77 | 28 | 52.9 (17.2) | 22–93 | 26 | 54.2 (19.2) | 28 | 54.4 (20.1) | 26 | 55.7 (17.3) | |||||

| HADS (0–42) | |||||||||||||||||

| Rituximab | 28 | 13.5 (6.7) | 5–29 | 22 | 12.4 (6.5) | 3–25 | –1.1 (–3.8 to 1.2) | 25 | 13.8 (7.9) | 24 | 13.7 (8.6) | 24 | 13.0 (6.6) | 0.03 | 0.872 | 0.52 | 0.723 |

| Placebo | 27 | 12.1 (7.4) | 4–30 | 28 | 12.3 (6.7) | 2–31 | 25 | 14.0 (7.9) | 26 | 14.2 (7.5) | 25 | 13.0 (7.6) | |||||

| Fatigue diary (1–6) | |||||||||||||||||