Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 09/150/12. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in October 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Thomas R Lynch reports grants from the University of Southampton during the conduct of the study and personal fees from New Harbinger Publications and R.O.B.T Ltd outside the submitted work. Roelie J Hempel is co-owner and director of Radically Open Ltd. No money was exchanged between Roelie J Hempel and the company before, during or immediately after the study. David Kingdon reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme during the conduct of the study. Heather O’Mahen reports personal fees from the Charlie Waller Institute and personal fees from Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies outside the submitted work and reports being a member of the Guidelines Development Group National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) 2014 Antenatal and Postnatal Mental Health, an executive member of the British Psychological Society Perinatal Faculty, a NICE expert advisor for the Centre for Clinical Practice and a member of the Clinical Reference Group for Perinatal Mental Health. Maggie Stanton reports personal fees from British Isles DBT Training, personal fees from Stanton Psychological Services Ltd and personal fees from the Routledge, Taylor and Francis Group outside the submitted work. Michaela Swales reports personal fees from British Isles DBT Training and personal fees from Guilford Press, Taylor and Francis and Oxford University Press outside the submitted work. Ian T Russell reports grants from Health and Care Research Wales during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

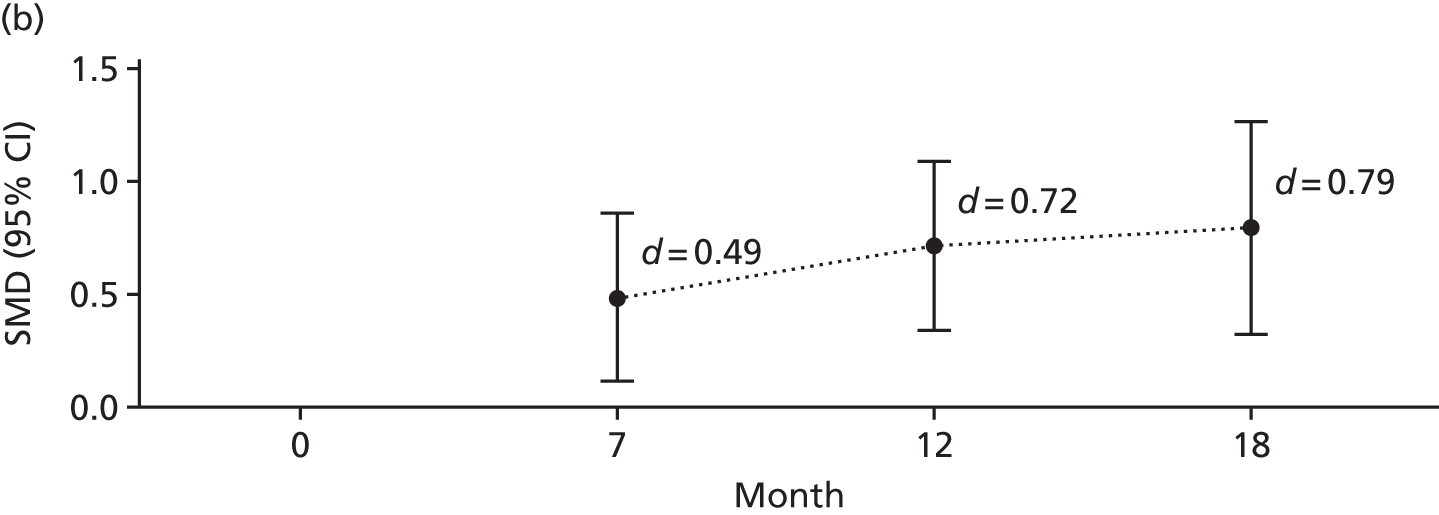

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Lynch et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Treatment resistance

Major depressive disorder is a disabling condition that causes substantial impairment in psychosocial functioning and quality of life, especially in the workplace, at home and with friends. 1 By 2030, depression will be the leading cause of disability in developed countries and the second leading cause of disability worldwide. 2

Only 30–40% of individuals treated with antidepressant medication (ADM) achieve full remission and only half of individuals respond to psychological treatment. 3 About one-third of patients do not respond to ADM4 and, of those non-responding patients, fewer than one-third benefit from adding, or switching to, cognitive therapy. 5,6 Approximately 50% of patients who are diagnosed with major depressive disorder experience recurrent or chronic illness needing long-term treatment. 7 Those with chronic depression are least likely to respond to currently available treatments. 8,9 Thus, treatment resistance is a common outcome for individuals with major depression and reported prevalence rates range from 15% to 60%, depending on how treatment-resistant depression (TRD) is defined. 7,10–12

Defining refractory depression

Definitions of TRD and refractory depression vary across studies; for example, Berlim and Turecki3 found > 10 different definitions of TRD. In practice, chronic depression and TRD often overlap, with many patients meeting both definitions. In the present study, we define ‘refractory depression’ as comprising both TRD, that is, depression that does not respond to adequate intervention, and chronic depression, that is, depression lasting > 2 years.

In a recent systematic review of TRD, Negt et al. 9 found that, compared with acute or episodic depression, chronic depression is associated with earlier age at onset, higher rates of adverse childhood experiences, more comorbid disorders and poorer social adjustment.

The costs of refractory depression

The economic burden of depression is substantial, especially for refractory depression. The total cost of adult depression across England in 2007 was > £7.5B, including £1.6B for patient care (treatment and social care) and £5.8B for loss of earnings. 13 Many of these costs are a result of refractory depression; for example, Crown et al. 7 found that depression-related costs for treatment-resistant inpatients were 19 times greater than those for patients not meeting criteria for treatment resistance and the costs for treatment-resistant outpatients were 2.5 times greater than for those not meeting the criteria. Similarly, in a US-based study, Ivanova et al. 14 reported that, after adjusting for differences in baseline comorbidities, risk-adjusted costs for employees with TRD were US$11,600 more than for depressed control employees who did not have TRD.

Psychological intervention research for refractory depression

Most studies investigating psychological interventions for depression have focused on acute or episodic depression rather than refractory depression.

For acute or episodic depression, cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT), behavioural activation, interpersonal psychotherapy (IPT) and short-term psychodynamic psychotherapy have the strongest empirical support. 9 Meta-analyses of psychotherapies for non-chronic depression typically find effects (Cohen’s d) relative to waiting list and minimal treatment control groups ranging from a d of 0.70 to a d of 0.90, whereas placebo control groups result in smaller effect sizes, averaging a d of 0.36. 15 A recent systematic review found weak evidence that behavioural therapies and other psychological therapies for acute depression are equally effective. 16

The evidence for these treatments for chronic depression is much more limited. 9 Cuijpers et al. 15 conducted a meta-analysis of studies investigating psychological treatments for chronic depression or dysthymia. It included 16 studies published between 1966 and 2009, of which only four studied chronic major depression; the remainder studied dysthymia, double depression (both major depressive disorder and dysthymia), or other categories of chronic depression or dysthymia. Of the psychological treatments investigated, seven were CBT and six were IPT, in addition to eight other treatments, including the Cognitive Behavioural Analysis System of Psychotherapy (CBASP), problem-solving therapy, cognitive-interpersonal group psychotherapy for chronic depression and supportive therapy. The authors reported a small but significant effect size (Cohen’s d) with a d of 0.23 for psychotherapy on depression symptom scores when compared with control groups. McPherson et al. 17 identified 12 studies investigating psychotherapeutic treatment for TRD, but only four were controlled trials and none recruited > 25 participants;17 the effect sizes ranged from a d of 1.23 to a d of 3.10.

One of the reasons that there are fewer trials that investigate psychotherapy for refractory depression is because most established treatments have been developed for less severe forms of depression. However, recently, treatments and studies have been developed specifically for refractory depression. The most investigated treatment to date is CBASP, a behavioural analytic therapy focusing on behaviour and its consequences. 18 McCullough18 hypothesises that chronically depressed individuals have deficits in social problem-solving and interpersonal communication, arising from early adverse events (AEs). Although the treatment was originally developed for individual therapy, CBASP has been modified for group formats. 19,20 A recent meta-analysis of six randomised trials,19,21–25 studying 1510 patients, found a small effect size for CBASP, with a d of 0.34. 9 Remission rates ranged from 19% to 57% in the CBASP groups (median 35%), compared with 6–50% in the control groups (median 25%).

Another recently developed treatment for chronic depression is the Relief of Chronic Or Resistant Depression (Re-ChORD) programme, an intensive, time-limited outpatient programme lasting 4 months. The major components of the Re-ChORD programme are medication management, group-based IPT and group occupational therapy. 26 The Re-ChORD study was a parallel-group, open randomised trial comparing the Re-ChORD programme with treatment as usual (TAU). This study was somewhat underpowered because (1) the authors chose a binary primary outcome [clinical remission, defined as a Hamilton Rating Scale for Depression (HRSD) score of ≤ 7 points after 4 months] and (2) they recruited only 64 patients. As a result, the difference in the proportion of patients remitting after 4 months (36% in the Re-ChORD programme group vs. 13% in the TAU group) was only on the borderline of statistical significance.

The Tavistock Adult Depression Study27 was a small pragmatic randomised trial evaluating long-term psychoanalytic psychotherapy (LTPP) as an adjunct to TAU for 129 patients with long-standing major depression who had failed to respond to at least two different treatments. Patients received either TAU alone or LTPP plus TAU and were assessed at 6-monthly intervals until 42 months, including the 18 months of treatment. Complete remission (i.e. a HRSD score of ≤ 8 points) was infrequent and never significantly different between groups. Partial remission (i.e. a HRSD score of ≤ 12 points) was significantly more likely in the LTPP plus TAU group than in the TAU-alone group (at 24 months, 39% vs. 19%; at 30 months, 35% vs. 12%; and at 42 months, 30% vs. 44%). Similarly, the difference between the group means became significant only at 24 months, when the LTPP plus TAU group started to show significantly larger decreases in HRSD scores than those shown in the TAU-alone group, with moderate effect sizes.

The CoBalT (Cognitive Behavioural Therapy as an adjunct to pharmacotherapy for primary care patients with treatment-resistant depression: a randomised controlled trial)28 recruited 213 primary care patients with TRD to evaluate the clinical effectiveness of CBT as an adjunct to TAU, compared with TAU alone. The trial found that 28% of patients in the CBT group and 15% of those in the TAU group achieved remission [i.e. a Beck Depression Inventory®-II (BDI®-II) score of < 10 points]. The difference between groups in improving BDI-II scores had an effect size with a d of 0.53. A recently published follow-up study29 reported that this effect size still had a d of 0.45 at around 40 months after the end of treatment (BDI-II scores at 6 months: CBT, 18.9 points and TAU, 24.5 points; BDI-II scores at 40 months: CBT, 19.2 points and TAU, 23.4 points). The CoBalT team concluded that CBT as an adjunct to usual care that includes ADM is clinically effective and cost-effective over the long term for individuals whose depression has not responded to pharmacotherapy.

In summary, immediately after treatment, CBASP had a small beneficial effect on depression,9 whereas CBT and the Re-ChORD programme had moderate beneficial effects on depression. 26,28 Moreover, emerging evidence suggests that longer and more complex treatments may be needed for treatment-resistant and chronic forms of depression than for more acute forms of depression. 30

Major paradigm shift: refractory depression reconceptualised as personality dysfunction

A major premise of the Refractory depression: Mechanisms and Efficacy of RO DBT (RefraMED) trial is that when psychopathology is long-standing and does not respond to efficacious first-line treatments, then broad-based personality dimensions and overlearned perceptual and regulatory biases are preventing change. Biotemperamental deficits, combined with damaging family environmental influences, are hypothesised to severely handicap openness and flexible responding, resulting in habitual overcontrol or undercontrol of socioemotional behaviour. This distinction shares features with the well-established division between internalising and externalising disorders. 31 Major depressive disorder exemplifies this perspective of limited openness and flexible responding, resulting in an overcontrolled coping style. This is further supported by studies reporting that 40–60% of unipolar depressed patients meet the criteria for comorbid personality disorder (PD),32–34 the most common being paranoid, avoidant and obsessive–compulsive PDs, all of which are overcontrolled PDs that do not respond well to treatment. 8,32,35 However, most trials exclude the most severely unwell individuals, for example those with PDs who are known to respond less favourably to existing treatments for acute depression, notably CBT. 8

Previous studies have reported that adults with chronic depression are characterised by overcontrolled traits, including rigid internalised expectations, excessive control of spontaneous emotion, greater self-criticism, inordinate fears of making mistakes and impaired autonomy. 34 Excessive self-control has been linked to social isolation, aloof interpersonal functioning, maladaptive perfectionism, disingenuous emotional expression and mental health problems such as anorexia nervosa, obsessive–compulsive PD and chronic depression. 36–40 However, current treatments neglect the potential mediating role of personality and maladaptive emotional overcontrol in refractory depression.

Radically open dialectical behaviour therapy

A novel transdiagnostic psychotherapy,41,42 RO DBT was designed specifically to address maladaptive emotional overcontrol and associated loneliness. The neurobiosocial theory underlying RO DBT proposes that individuals presenting with problems of overcontrol are biotemperamentally predisposed to exhibit heightened threat sensitivity, diminished reward sensitivity and heightened capacities for self-control and detailed-focused processing. 41,42 These biotemperamental biases can be strengthened by family, cultural and environmental histories that value performance and self-control and by avoiding risk and masking emotions. A person with heightened threat sensitivity is more likely to scan new or unfamiliar circumstances for potential harm rather than reward: their sympathetic nervous system – responsible for defensive-arousal and flight–fight responses – is activated while the ventral vagal complex of their parasympathetic nervous system withdraws. 43 Unfortunately, as a result of withdrawal of the parasympathetic nervous system ventral vagal complex, facial expressions become frozen and the ability to express oneself flexibly is lost; in other words, prosocial co-operative social signalling becomes impaired. 44 People who are inexpressive or who show expressions that do not match their inner experiences are often perceived as inauthentic or untrustworthy by others, which may lead to social ostracism and emotional loneliness. 41,45,46 Consequently, RO DBT emphasises the importance of targeting social-signalling deficits and uniquely links the communicative and facilitative functions of emotional expressions to the formation of close social bonds and uses micromimicry as a means to understand and increase emphatic behaviours. 41,42,47 The skills that are taught in RO DBT focus on relaxing rigid inhibitory self-control, activating the social safety system, expressing context-appropriate emotions and vulnerable self-disclosure, practising self-enquiry to learn from new experiences and critical feedback, and reducing maladaptive social comparisons related to envy and bitterness.

Earlier versions of RO DBT (RO DBT-E) have shown promise in two small randomised trials48,49 for patients with refractory depression and comorbid PD. The first study49 explored the feasibility of a group intervention for TRD in chronically depressed older adults aged > 60 years. The treatment comprised 28 weeks attending a skills training group and weekly 30-minute telephone contact with an individual therapist, followed by 3 months in which telephone contact was made every 2 weeks and 3 months in which it was made every 3 weeks. The 17 participants who received RO DBT-E showed significantly greater improvements than the 17 control participants in self-rated and interviewer-rated depression (d = 0.71). Post-treatment interviewer ratings showed that 71% of RO DBT-E recipients met criteria for remission [i.e. a Beck Depression Inventory® (BDI) score of ≤ 9 points or a HRSD score of ≤ 7 points], but only 47% of control participants did so. After 6 months, the corresponding percentages were 75% and 31%, respectively. In addition, RO DBT-E recipients improved significantly in adaptive coping and dependency, whereas control participants did not.

The second trial48 compared 24 weeks of both individual and group RO DBT-E plus ADM in 21 adults aged > 55 years who had PD and depression with ADM alone in 14 similar adults. To be included, participants had to demonstrate TRD prospectively by having a poor response to an 8-week course of researcher-controlled ADM. The RO DBT-E recipients showed significantly greater decreases in interpersonal sensitivity and aggression than control participants. At the end of the skills group, 71% of RO DBT-E recipients were in remission (i.e. had a HRSD score of < 10 points), compared with only 50% of control participants. Both groups of participants showed significant reductions in clinician-rated depression, with a between-group d of 0.85.

Objectives

The RefraMED trial aimed to conduct an appropriately powered randomised trial to evaluate the efficacy and investigate the mechanisms of RO DBT in patients with TRD who were, thus, difficult to treat. The study had five main objectives, as detailed in the following sections.

Efficacy

The primary objective was to estimate the efficacy of RO DBT for refractory depression in addition to TAU, compared with TAU alone, over the course of 18 months. This objective can be achieved in two ways: first, as the effect of being randomly allocated to RO DBT plus TAU, rather than TAU alone; and, second, as the effect of exposure to specific ‘doses’ of RO DBT, in which exposure was measured by adherence to RO DBT treatment protocols and zero exposure corresponded to TAU. For both methods, the primary outcome was depressive symptoms measured using HRSD score at 12 months (i.e. 5 months after the end of treatment). To interpret this outcome, the resulting rates of remission and measures of other symptoms were used, including suicidal ideation or behaviour and global functioning.

Conventional analysis ‘by treatment allocated’ was used to fulfil the first of these approaches. Although this analysis provided an unbiased pragmatic estimate of the effectiveness of RO DBT in clinical practice, this is not identical to ‘efficacy’ under ideal conditions because participants varied in their adherence to the recommended course of treatment, and, therefore, there was heterogeneity in exposure to RO DBT. To account for this, estimations of the causal effect of exposure to RO DBT were sought. In doing so, this allowed for the fact that attendance at therapy sessions occurred after randomisation and, thus, could be subject to confounding.

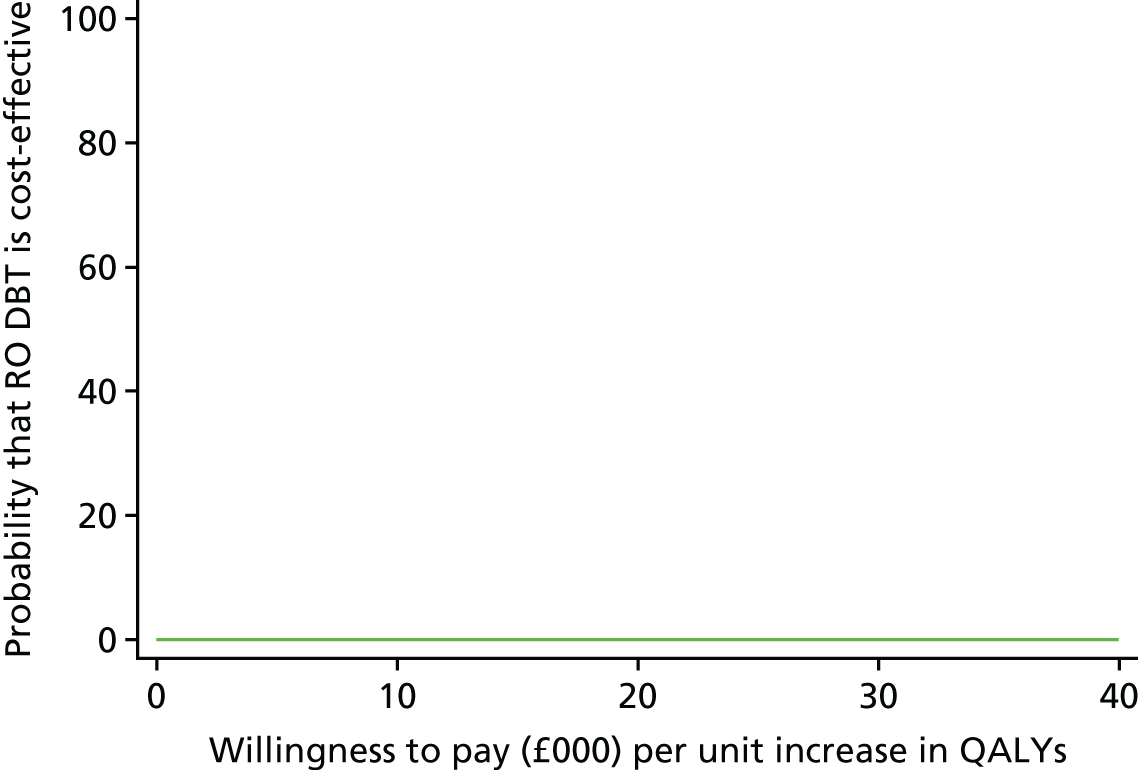

Cost-effectiveness

Analysis ‘by treatment allocated’ was used to estimate the relative cost–utility of RO DBT plus TAU in comparison with TAU alone over 12 months. We calculated cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) using the EuroQoL Questionnaire-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L). 50 We also explored cost-effectiveness using HRSD score. The economic perspective was that of the NHS and personal social services, as preferred by the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 51 The addition of productivity losses was explored, resulting from time off work because of illness, in the sensitivity analysis.

Mechanisms

We extended the efficacy analysis, which addressed questions relating to the effect of allocation and exposure to treatment, to ask questions about how RO DBT might have been efficacious. The approach included both RO DBT-specific and transtheoretical concepts, and recognised that important elements of psychotherapy might be common to many treatments.

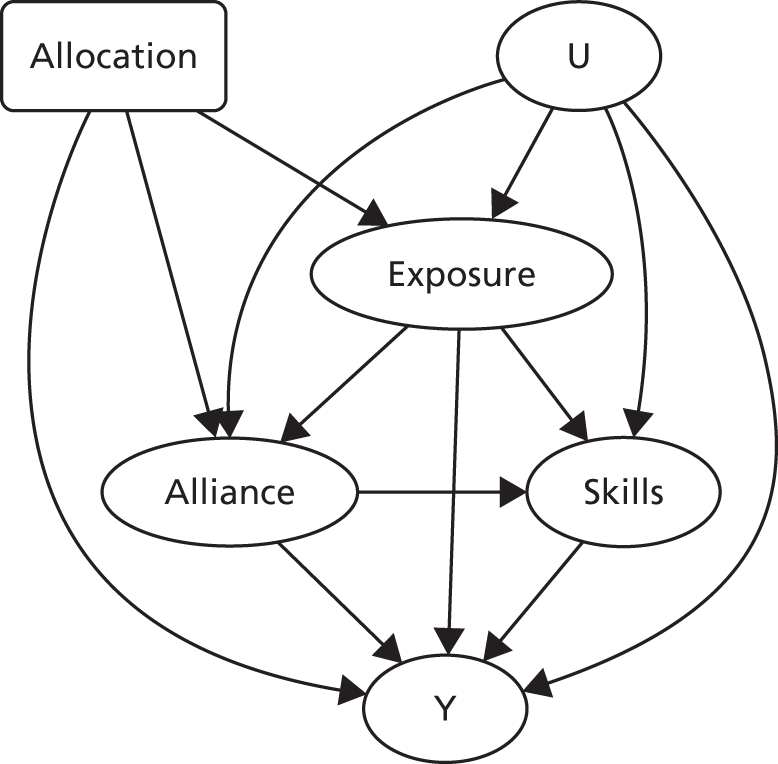

The primary aim was to estimate the causal effects of the pathways through which RO DBT is hypothesised to reduce depressive symptoms (as measured via the HRSD score) for patients in the trial. The chief challenge in doing this was the potential presence of unobserved confounding. Bias from unobserved confounding potentially arises because, unlike the treatment itself, patients are not randomly allocated to the number of sessions that they attend, the strength of the therapeutic alliances that they develop with their therapists or the degree to which they acquire new skills through engaging with the treatment. Patients make decisions to engage with treatment in a non-random manner that may be related to their underlying mental health. For example, suppose that patients with certain characteristics choose to attend as many sessions as possible, form strong alliances with their therapists and develop the skills needed for RO DBT; if these same characteristics are also associated with a milder form of refractory depression, then the statistical estimates of these pathways obtained using standard pathway models52 will overstate the causal effect of each pathway because of uncontrolled confounding bias.

There are two main objectives of this analysis:

-

to specify a series of pathway models to decompose the overall effect of RO DBT into that resulting from the pathways through which the treatment is hypothesised to work

-

to estimate the decomposition of this treatment effect using:

-

standard adjustments for confounding variables

-

instrumental variables (IVs) to adjust for possible unobserved confounding.

-

The analyses focused on four specific pathways between allocation and outcome: treatment exposure, therapeutic alliance, skill acquisition and expectancy. To estimate the causal effect of mediators, the trial manipulated selected mediators in a random fashion. We also measured variables that represented sources of variation in mediators that were unlikely to be contaminated by selection effects. In other words, IVs were identified, both experimental and observational, to facilitate causal analyses.

In addition to these primary pathways, several potential modifiers of treatment outcomes were measured. Based on this study and other research showing links between refractory depression and PD,32 temperamental risk aversion and reward insensitivity53–55 and childhood adversity,56 we assessed potential moderators of treatment response by measuring the following at baseline:

-

PD diagnosis

-

invalidating childhood experiences

-

reward sensitivity or risk aversion.

These variables will be used to conduct a complementary analysis of repeated measurements of outcomes and mediators using longitudinal models. This analysis will address theoretically driven questions about the ordering of changes in key variables.

Temporal patterns and precedents of change

In conjunction with the causal analyses of the therapeutic alliance, the study wanted to examine patterns of change and cross-lagged effects among depressive symptoms, alliance ratings and skills learned in RO DBT. In addition, whether or not there are differential rates of change in positive versus negative affect and whether or not different patterns of temporal ordering exist for positive affect and negative affect will be investigated. Previous research has highlighted the distinct and important role of positive affect in adaptive coping. 57 Positive affect is thought to broaden an individual’s attentional focus and behavioural repertoire and, as a consequence, build social, intellectual and physical resources. 58 A change in positive affect is expected to be more rapid and more closely associated with factors common to psychosocial interventions (e.g. expectancy and alliance) than for change in negative affect and to precede improvements in coping strategy. Furthermore, ecological momentary assessment will enable questions to be answered in relation to the variability of affect in treated versus untreated patients. Daily variability in affect is expected to rise early in treatment for RO DBT participants (as a consequence of the difficult work clients undertake with therapists), but to decline relative to the TAU group patients by 7 months. Although these longitudinal analyses estimate temporal ordering or so-called ‘Granger causality’ rather than true causality, they complement the primary mediation analyses by providing a richer picture of patterns of change in response to treatment.

Chapter 2 Methods

Please note that for the sake of consistency, several paragraphs from the methods section of the published protocol paper in BMJ Open59 have been reproduced. Published by the BMJ Publishing Group Limited. For permission to use (where not already granted under a licence) please go to http://group.bmj.com/group/rights-licensing/permissions. This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

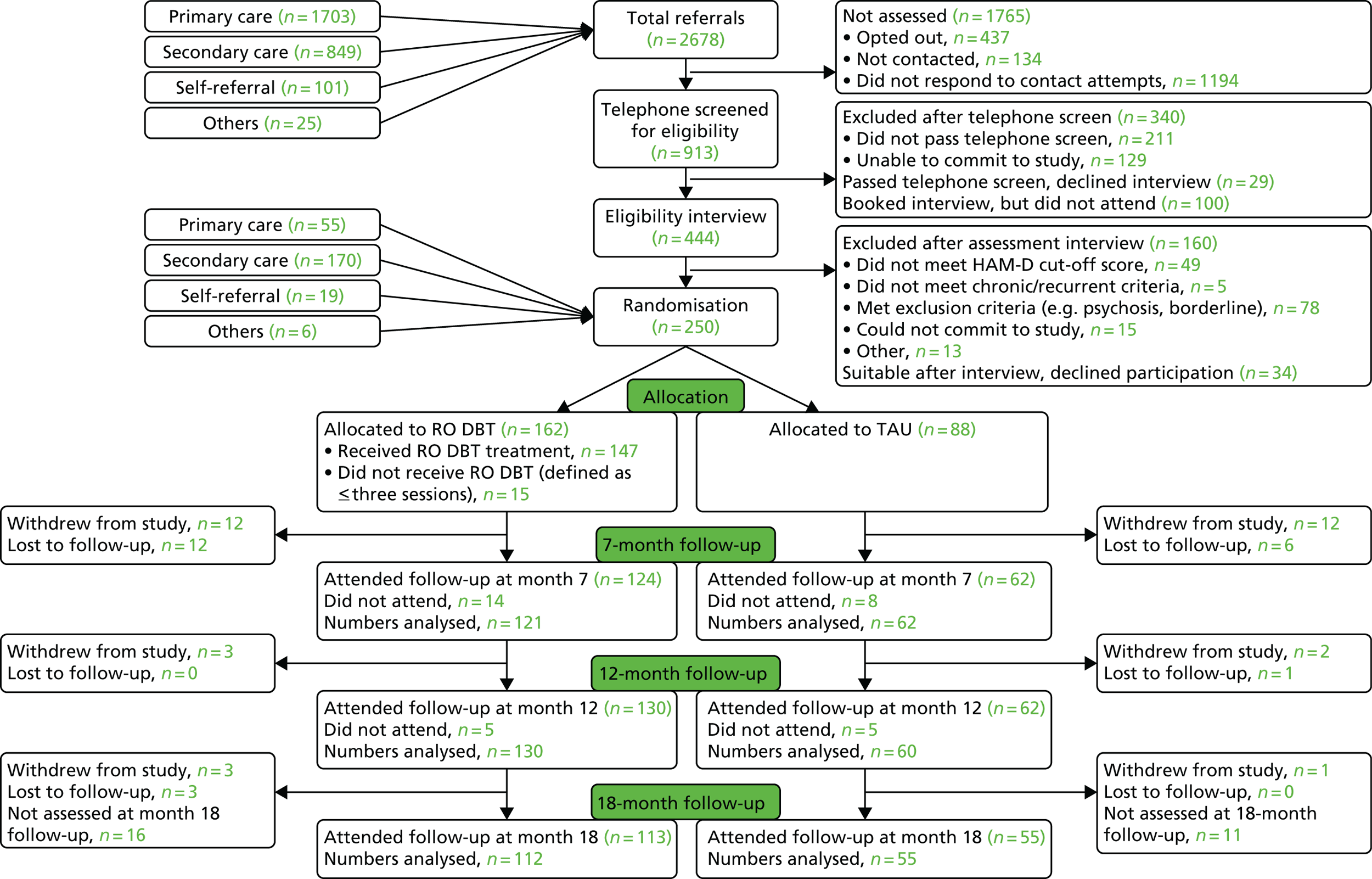

Trial design

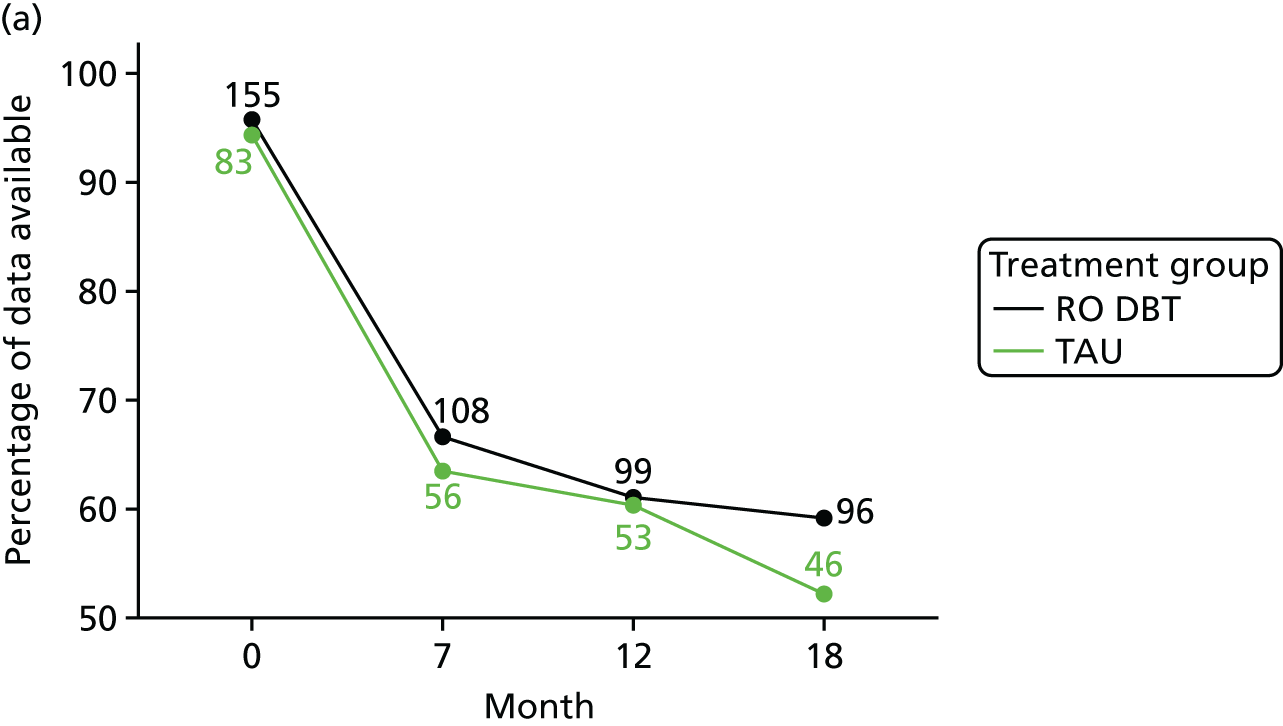

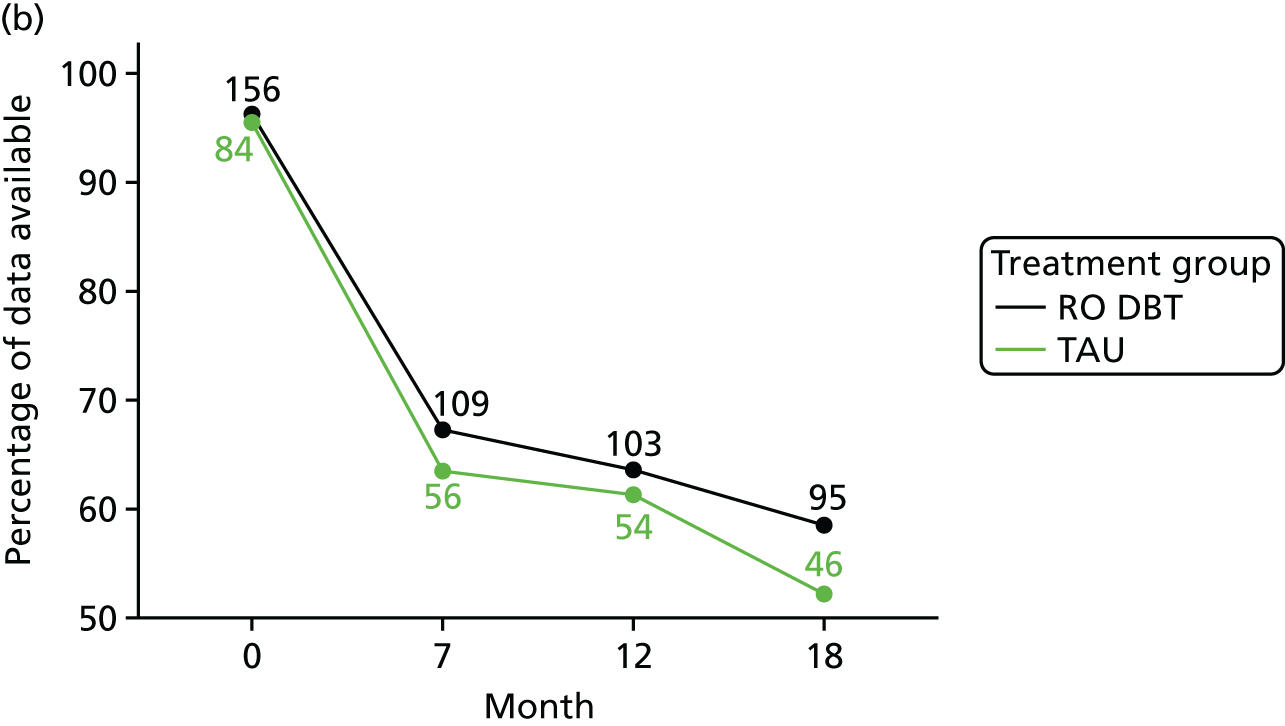

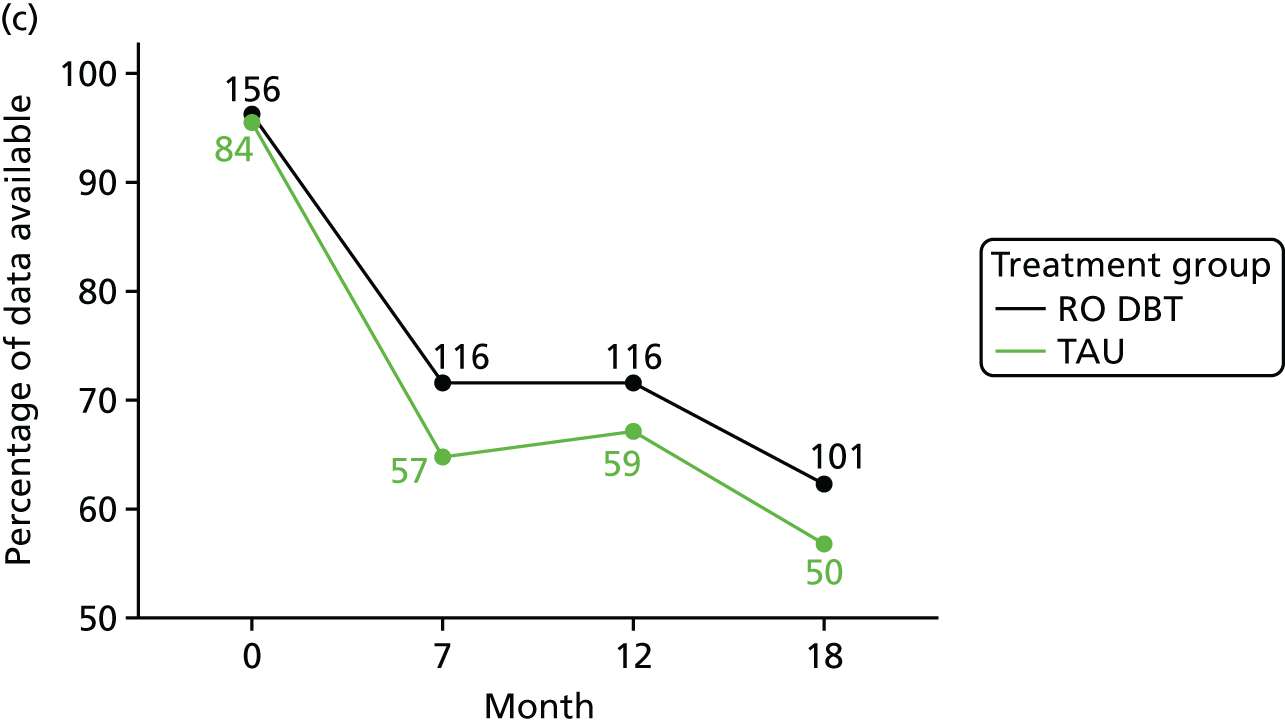

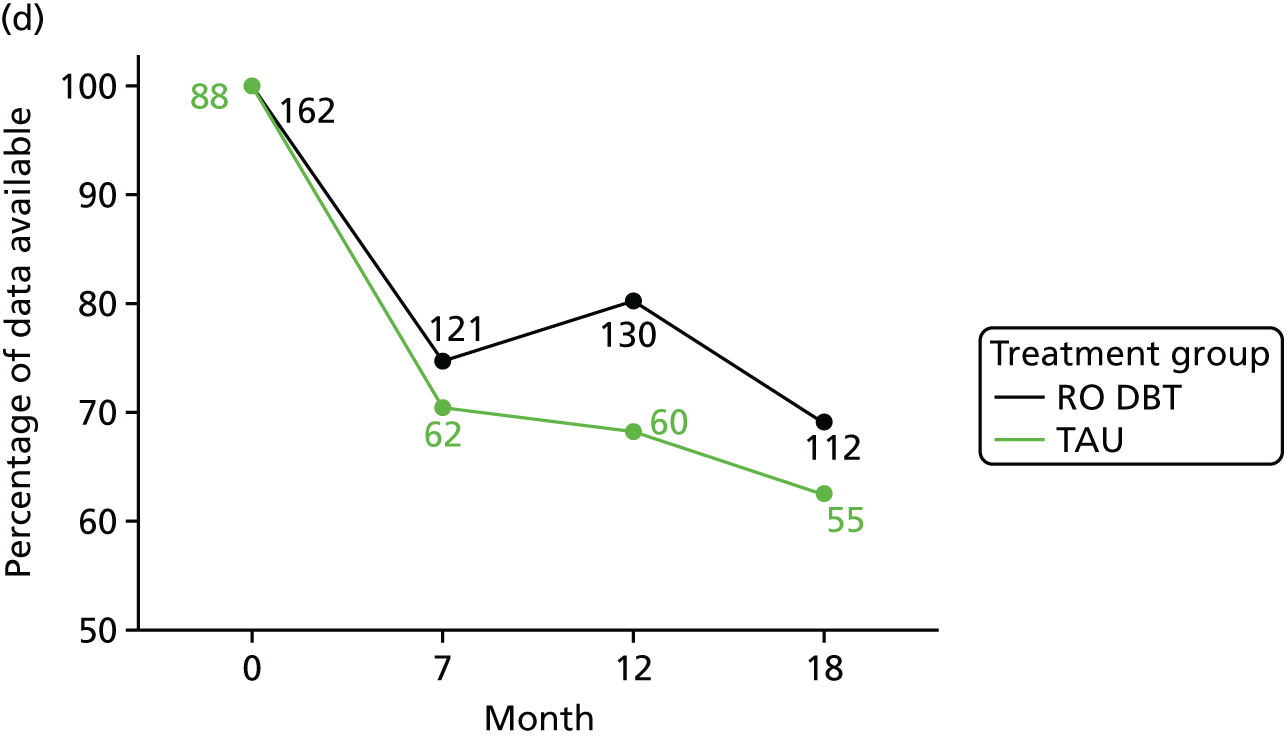

The RefraMED trial is a multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) conducted at three NHS sites in the UK: Dorset, Hampshire and North Wales. All trial participants received TAU, but those allocated, at random, to the experimental arm also received approximately 29 weeks of RO DBT. Participants were further allocated, at random, between non-therapeutic alternatives designed to facilitate mediational analyses. Clinical outcomes were assessed at four time points (baseline and at 7, 12 and 18 months after randomisation) using assessors blind to participants’ allocated treatment.

Sample size estimation

Two pilot studies of RO DBT-E for refractory depression report effect size for group differences in change on the HDRS score (from baseline to the end of treatment) with a d of 0.7149 and with a d of 0.85. 48 In addition, one trial of standard DBT for TRD61 reports an effect size with a d of 1.45 (see Table 19 in Appendix 1 for more details). Therefore, it was judged feasible, and desirable, to recruit enough analysable participants to yield an 80% power to detect, at a statistically significant level of 5%, a standardised difference of 0.4 between groups (RO DBT and TAU). This equates to a between-group difference on the HRSD of > 2 points. Furthermore, it was judged that NICE would consider this difference clinically important.

Simulations of the random-effects models described in the following sections suggest that, if there were no intraclass correlation, a sample of 200 analysable participants would detect a mean difference of 2 points on the HRSD (equivalent to a standardised difference of 0.4). We expected to collect analysable data from at least 83% of participants and, therefore, increased the target to 240. To increase the power of the analysis of the mechanisms of RO DBT, it was planned to randomise in the ratio of 3 : 2, seeking to allocate 144 ‘unclustered’ patients to RO DBT and 96 to TAU.

However, although participants in the RO DBT arm were clustered by therapist, the 96 control participants were not. To allow for an intracluster correlation coefficient of 0.025 between the HRSD scores and an average cluster size of 11 participants for each of the expected 16 therapists, we increased the RO DBT sample size to 180, yielding the same statistical power as 144 unclustered participants. Thus, initially, it was aimed to randomise 276 patients, namely 180 to RO DBT and 96 to TAU, giving an allocation ratio of 15 : 8.

Adjusted sample size targets

Recruitment rates in all centres were limited by available assessor time. The consequent difficulty in meeting target recruitment rates and a reduced therapist capacity in one centre forced there to be a re-evaluation of the target sample size. In consultation with the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC), we agreed to recalculate the sample size using less conservative assumptions and, consequently, reduced the target number of patients randomised to 240.

Randomisation

Primary randomisation and allocation ratio

Participants were allocated between treatments through an adaptive randomisation algorithm administered by the Swansea Trials Unit. This system of randomisation maintained the balance across groups of the three stratifying variables stochastically, rather than deterministically, chosen as potential outcome moderators to minimise the risk of subversion:60

-

early onset of depression (before or after 21 years of age)

-

depression severity at baseline (a HRSD score of < or ≥ 25 points)

-

PD [meets the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis II (SCID-II) criteria for cluster A or cluster C or not].

Participants were allocated to RO DBT or TAU using a final allocation ratio of 15 : 8 in favour of RO DBT.

Secondary randomisation

Within the RO DBT group, participants were further randomly allocated to their therapist and the three IVs listed below. An adaptive randomisation method was used to allocate patients between therapists so as to use as many as feasible of the treatment slots at each centre. We also randomly allocated all RO DBT participants to one of eight combinations of contextual non-therapeutic features (i.e. IVs) within a 2 × 2 × 2 factorial design:

-

the participants received individual RO DBT in either a standard therapy room or an enhanced therapy room that potentially improves both the strength of the alliance with the therapist and attendance at treatment sessions

-

after every session the participants either did or did not have the opportunity to provide written feedback to their therapist, which potentially improves the strength of the alliance with the therapist61

-

the participants received compensation for questionnaire completion either personally (via their therapists) or impersonally (via mail), potentially increasing attendance at treatment sessions.

The allocation sequence was determined dynamically using a database independently administered at the Swansea Trials Unit. The database incorporated a study-specific version of a published dynamic randomisation allocation method62 and the resulting allocations were then sent by e-mail to the trial manager for further dissemination to participants and study therapists.

Participants

Inclusion criteria

Participants were considered eligible if they were aged ≥ 18 years, had a HRSD63 score of at least 15 points (note that a HRSD score of 14 points is regularly used as the upper limit for partial remission), had a current diagnosis of major depressive disorder [as assessed with the Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders (SCID-I)64] and had refractory depression, which was defined as two or more previous episodes of depression or having experienced their current episode for ≥ 2 years. Finally, participants had to have taken an adequate dose of ADM for at least 6 weeks without symptom relief during their current episode.

Exclusion criteria

We excluded those participants who met criteria for dramatic–erratic PD (cluster B), bipolar depression, psychosis or a primary diagnosis of substance dependence or substance abuse disorder. Patients had to have an intelligence quotient of > 70 and speak English well enough to participate in the treatment and the study. Finally, patients who were receiving standard DBT at the time of recruitment were not eligible to take part in the current study because standard DBT aims to treat borderline PD, which was one of the exclusion criteria.

Discontinuations

Participants were allowed to withdraw from the treatment or the study at any time without their regular care being affected. Treatment withdrawal was defined as participants being unable or unwilling to attend RO DBT sessions; on such occasions, we encouraged participants to provide follow-up data. Study withdrawals were defined as participants being unable or unwilling to attend follow-up sessions; on such occasions, we permitted participants to continue with RO DBT if they had been allocated to that treatment arm. However, if participants withdrew consent to participate in the study, we did not seek additional data.

Procedures

Recruitment and eligibility screening

Participants were recruited through mental health professionals, such as psychologists, psychiatrists and mental health nurses, through general practitioners (GPs) and via advertisements in secondary and primary care clinics (e.g. waiting rooms or GP surgeries) and in the community (e.g. libraries). We carried out database searches for potential participants in the primary and secondary care services, although GPs and secondary care clinicians could also refer patients directly to the study. In addition, patients could self-refer after seeing posters, leaflets or the website.

In the primary care settings, database searches were conducted by the GP practice staff; medical records were checked for eligibility using the inclusion and exclusion criteria and the resulting lists were screened by GPs. The GPs and practice staff then signed pre-prepared letters describing the study and inviting patients to contact their local RefraMED clinical studies officer if they were considering participating in the trial. Patients who called to express an interest provided oral consent to be screened for eligibility.

In secondary care, database searches were carried out by the local RefraMED clinical studies officers. The resulting lists were screened by the responsible clinicians before letters were sent out. Patients received letters describing the study and inviting them to opt out or consider participating in the trial. Unless patients opted out, the clinical studies officer tried to contact them by telephone to discuss the study and, with their oral consent, screened them for eligibility.

Recruitment started at the Dorset site in March 2012 and at the other two sites in September 2012, and ended at all sites in March 2015. The last follow-up interviews were completed in May 2016.

Eligibility interview

In-person appointments were made with trained assessors for the potential participants who were eligible at the telephone screening stage and willing to attend the study assessment. The participants signed a formal consent form on arrival. The team of trained assessors screened them for eligibility and conducted baseline assessments of the outcome measures set out in Table 1 for those who were found to be eligible for study inclusion. After the interview, participants received further questionnaires for home completion.

| Outcome | Time point (months) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Treatment | Follow-up | ||||||||||||

| 0 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | 18 | |

| Primary | ||||||||||||||

| Depression (assessed via the HRSD and LIFE-RIFT) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Health-related quality of life (assessed via the EQ-5D-3L) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Health services use/costs (assessed via the AD-SUS) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Secondary | ||||||||||||||

| Suicide (assessed via the MSSI and SBQ) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||

| Depression and affect (assessed via the PHQ-9 and PANAS) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Mechanisms and mediators | ||||||||||||||

| Psychosocial function (assessed via the AAQ-II, WBSI, the 3-item SSQ, IIP-PD-25 and DBT-WCCL) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||

| Emotional approach and expectancy (assessed via the EAC and CEQ) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Alliance and delivery of treatment (assessed via the CALPAS, CSQ-8 and number of sessions attended) | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||

| Moderators of RO DBT effectiveness | ||||||||||||||

| Personality and PDS (assessed via the CID-I and II, NEO FFI-C, applied conscientiousness task and SVS) | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Temperament and emotional control (assessed via the UPPS, PNS, Ego-Undercontrol, Ego-Resiliency, BIDR-16 and FMPS) | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Childhood experience and invalidation (assessed via the ICES and MOPS) | ✓ | |||||||||||||

Assessment training and inter-rater reliability

Assessors were trained to competence on the Structured Clinical Interviews for DSM-IV (SCID) and HRSD by a clinical psychologist who was experienced in administering the SCID and HRSD in clinical trials. Ongoing queries regarding the SCID and HRSD were discussed at weekly consensus meetings and inter-rates reliability on the HRSD was re-assessed at regular (9-month) intervals to ensure ongoing adherence with the HRSD.

Following the recommended training sequence of SCID, all assessors read through the SCID and HRSD and watched the SCID training digital versatile discs (DVDs). Assessors watched key sections of the SCID training tapes of interest for this study (i.e. mood episodes, anxiety disorders and DSM-IV Axis II) together with the trainer, in order to ensure depth of diagnostic and assessment learning. In-group learning included role-plays of both the SCID and HRSD with assessors and with the trainer, followed by questions and discussion. Assessors subsequently conducted role-plays of the SCID and HRSD with a colleague and compared their ratings with the expert ratings from the training DVDs. Assessors then either audiotaped an assessment and had this assessment reviewed by the trainer or shadowed an experienced assessor and completed an initial joint assessment.

We included an embedded ‘reliability study’ in which all assessors coded audiotaped interviews that had been taped and coded by another member of the team. Krippendorff’s alpha65 was used, as it can assess reliability between multiple raters and it handles nominal data and missing data.

Blinding

The assessors were blind to participant allocation. All participants were informed of allocation by the trial manager or administrator. Follow-up assessments were carried out at different locations from treatment locations to ensure that the research assistants carrying out the follow-ups remained blind to treatment allocations. Precautionary strategies included consideration of locations for follow-up assessments, participants being reminded by the assessors not to talk about allocation before the assessment and, after the initial assessment, assessors not looking at clinical notes. If an allocation was revealed, then reblinding occurred by using another rater for the subsequent follow-up. If the blinding was broken during an assessment session, then these ratings were used. Unblinded ratings were used for 17 7-month follow-ups, 12 12-month follow-ups and zero 18-month follow-ups.

Reimbursement

Participants in both groups were reimbursed by cheque for their time spent completing research questionnaires and attending the follow-up interviews. The total amount of reimbursement ranged from £0 to £150, depending on whether or not the participants were still in the study and the number of follow-up assessments they attended. Participants received £30 after they had been in the study for 3 months, £40 for attending the first follow-up interview after 7 months, another £50 for attending the follow-up interview after 12 months and a final £30 for attending the follow-up interview after 18 months.

Settings and locations of data collection

Participants were recruited, assessed and treated at three different NHS trusts across the UK: Dorset HealthCare University NHS Foundation Trust, with locations in Bournemouth and Poole (Dorset); Southern Health NHS Foundation Trust, with locations mainly in Winchester, Eastleigh and Southampton (Hampshire); and Betsi Cadwaladr University Health Board, with locations in Bangor and Rhyl (North Wales). All three sites routinely offer outpatient psychological treatment.

To ensure accuracy, completeness and reliability, trained assessors collected outcome data during interviews in person or by telephone following standard operating procedures for data collection and transferred the data to the trial office in Southampton. In addition, monthly paper questionnaires were posted directly to participants with a postage paid envelope, and text or e-mail reminders were sent after 10 days if the questionnaires had not been received by the trial office.

Electronic data capture system

All paper-based data were entered twice onto Signalbox (version 2.3.7; B Whalley, Plymouth, UK),66 a validated electronic data capture system. All duplicate replies were then checked by an experienced data manager and, in the case of discrepancies between the two replies, the correct reply was selected for further processing. This system also collected data from automated telephone calls used to collect certain measures (described in Measures) and prompted therapists to enter their online treatment notes through weekly electronic reminders.

Changes to methods and procedures after trial commencement

After the trial commenced, we added the following exclusion criteria: patients were excluded if they were on a standard DBT waiting list or were attending standard DBT at the time of assessment.

The original trial protocol states that outcome measures would be assessed at baseline and at 6, 12 and 18 months after randomisation. However, the 6-month assessment was pushed back to 7 months once it became apparent that those participants in the RO DBT group would still be receiving active treatment 6 months after randomisation, whereas we aimed to assess participants immediately after treatment, which was, on average, 7 months after randomisation. This change was made before any patient was due their 6-month follow-up and did not differentially affect follow-up times in the two groups.

In addition, as a result of decreased therapist availability and limited research assessor time, recruitment did not progress at the expected rate. Three changes were made to ensure that the trial finished within the allocated time and budget:

-

we extended the recruitment period by 9 months

-

the target sample size was reduced from 276 to 240 participants

-

participants who were recruited after 1 September 2014 were followed up for 12 months instead of 18.

These changes affected a total of 27 participants who were still in the study after 12 months.

Ethics considerations

We asked trial participants to give consent on three occasions:

-

oral consent before answering questions via the telephone screening interview

-

signed consent before the baseline assessment, in which they confirmed that they had read and understood the information sheet and gave permission for the interview to be audio-recorded

-

signed consent to participate in the trial for eligible participants, stating that they had understood all information provided to them and were willing to participate in the trial.

Personal information was kept in a password-protected database, which was accessible only to members of staff of each site who needed these details for making assessment appointments and sending out letters. These were the only files in which both personal information and the participant identification numbers were stored.

We conducted the RefraMED trial in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. 67 Prior to the start of the study, we received approval from the Hampshire Research Ethics Committee (National Research Ethics Service reference number 11/SC/0146) and the ethics and research governance department of the sponsor of this study, the University of Southampton.

Study monitoring

Two committees, which were independent from the funder and the sponsor, monitored the trial to ensure that it complied with the rigorous standards defined in the National Institute for Health Research Clinical Research Network’s guidelines for good clinical practice:68 the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and DMEC. The TSC met, via a conference call, twice a year during the study and the DMEC met twice in the first year and annually after that.

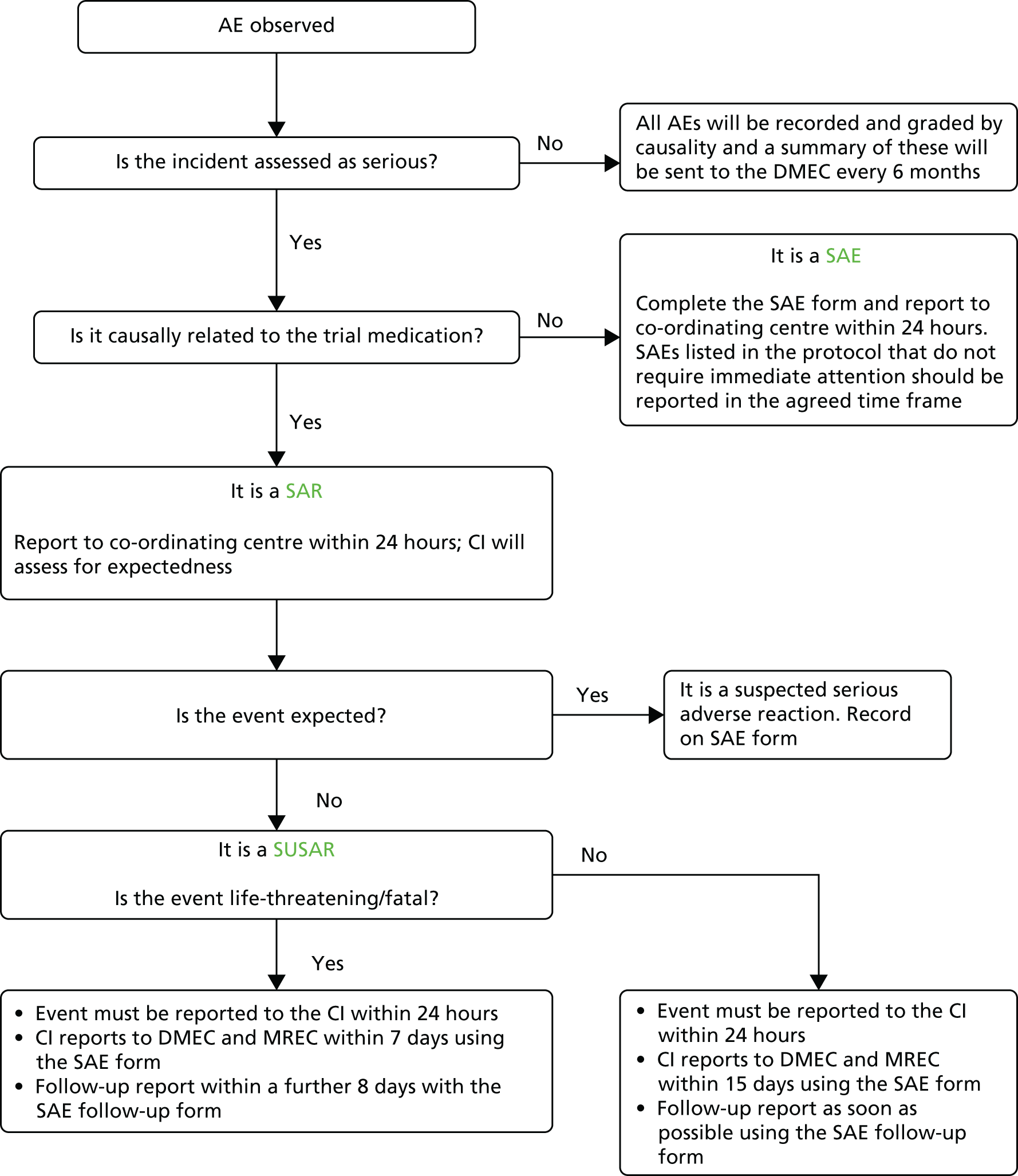

Reporting of adverse events and study termination

Site principal investigators were responsible for monitoring and reporting serious adverse events (SAEs). These were immediately reported to the chief investigator. The trial office reported these events annually to the DMEC or immediately in the case of a suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR). The trial procedure for evaluating and reporting AEs and SAEs can be found in Appendix 2.

Patient and public involvement

Service users were actively involved with the development of patient information leaflets, the management of the study and the dissemination of the study information and results. The Mental Health Research Network (London, UK) and INVOLVE (Southampton, UK) helped with recruitment of service users. Four mental health service users were recruited: two for the TSC and two for the Trial Management Group (TMG).

Interventions

Treatment as usual

All participants received TAU, consisting (primarily) of prescribed ADM or psychotherapy (with the exception of standard DBT). At each follow-up assessment, participants were asked to report the type of ADM, their adherence to it and the type and amount of psychotherapy that they had accessed in the months since their previous assessment (or in the 6 months preceding their baseline assessment). In addition, we did not restrict access to appropriate mental health care during follow-up. ‘Service contact’ may have served different functions, namely for the purpose of (1) assessment, (2) psychological treatment or (3) routine clinical monitoring of needs and risk. TAU differed across sites.

In Dorset, the practice of many services was to assess patients (with services typically offering three assessments) to formulate their difficulties and determine their needs, before putting their name on a waiting list for appropriate treatment. During the waiting period, the patient may have received input from a Community Mental Health Team (CMHT) to review their needs, risk and medication. Patients who had been referred to CMHTs received variable treatment, which may have included CBT, schema-focused cognitive therapy, standard DBT-based skills groups or cognitive–analytic therapy (CAT), all of which delivered was by psychologists, occupational therapists or nurses. Alternatively, the patients were case managed by CMHT staff, which did not include a therapeutic model as such. In many services the wait to receive treatment was long, typically up to 1 year. Some patients were seen only by their GP and TAU consisted of ADM and whatever support their GP offered in the administration and monitoring of ADM.

In North Wales, patients referred to mental health services were assessed via a single-point-of-access system that occurred within hours for urgent cases and within 28 days for routine cases. Typically, all of these patients were already in receipt of ADM. Patients who were assessed as having mild depression were seen in primary care mental health services, in which the interventions offered included basic behavioural activation, support and monitoring of ADM and occasionally CBT. Others may also have been referred to third-sector counselling services and, in some areas, access to mindfulness-based cognitive therapy groups was available. Patients with moderate to severe problems were seen in secondary care by the CMHTs and would typically have a generic case manager and may also have been seen by the psychiatrist or a clinical psychologist. In most areas, the clinical psychologist would offer a formulation-based psychological intervention; the models offered would include CBT, dialectical behavior therapy (DBT)-informed, schema-focused cognitive therapy, acceptance and commitment therapy and CAT. Depending on their geographical area, patients may also have received CBT from a CBT therapist. Waiting lists for therapy were long, ranging from 3 months to 2 years, depending on the area, and the approximate average wait was 12 months.

In Hampshire, some GP practices and all universities provide a counselling service. There is also an active voluntary sector, which provides support, information, counselling and group work. Patients could self-refer or be referred to Increasing Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services. IAPT offers a stepped approach to treatment for anxiety and depression with telephone sessions, group sessions, couple work or up to 20 individual sessions of CBT or IPT. Patients with more severe and enduring difficulties were referred to their CMHT by their GP. The patients were typically seen within a few weeks for an assessment of their needs. They may also have received regular monitoring and case-management by CMHT staff, including problem-solving, reviewing of risk and medication advice or being offered a range of treatment options, for example, group work, such as mindfulness or standard DBT-based skills groups. If the patient required more intensive input, then a home treatment team or admission to an inpatient acute unit was available. In addition to these options, patients could have been referred for specific psychological therapy. The waiting time would typically be up to 4 months from referral, and therapy options included group and individual work using CBT, DBT-informed, schema-focused cognitive therapy, CAT or acceptance and commitment therapy.

Radically open dialectical behaviour therapy

Radically open dialectical behaviour therapy is a transdiagnostic treatment designed to address a spectrum of difficult-to-treat disorders, including chronic depression. RO DBT significantly differs from other treatment approaches, most notably by linking the communicative functions of emotional expression to the formation of close social bonds and by skills targeting social signalling and changing neurophysiological arousal.

The experimental intervention was fully manualised and comprised 29 weekly individual therapy sessions lasting 50–60 minutes and 27 weekly skills training classes lasting 2.5 hours, including 15-minute breaks. 41,42,69 In addition, RO DBT therapists met weekly in person for a consultation team meeting that lasted 1.5–2.5 hours and by telephone when needed. The RO DBT treatment commenced as soon as possible after the participant had been notified of their treatment allocation. Although RO DBT participants received ADM as prescribed, we strongly discouraged them from seeking additional psychotherapy during RO DBT. The RO DBT treatment developer and study chief investigator (Thomas R Lynch) did not contribute to treatment delivery.

The RO DBT lesson plan used in this trial is presented in Appendix 3. The research manual comprised a combination of newly developed RO DBT lessons, which are now part of a fully comprehensive RO DBT skills manual,69 and standard DBT. 70

Radically open dialectical behaviour therapy therapist training, supervision and adherence

Twenty-three therapists (male, n = 2, female, n = 21; age range from 32 to 61 years), who were trained in RO DBT, delivered the treatment across the three sites (Dorset, n = 8 therapists; Hampshire, n = 10 therapists; and North Wales, n = 5 therapists). All therapists received a minimum of 10 days of specific training in RO DBT from the treatment developer and chief investigator of the study (Thomas R Lynch).

Therapist selection

In order to be recruited onto the trial, therapists were required to have three treatment tapes rated as adherent on the standard DBT Adherence Rating Scale (Marsha M Linehan and Kathryn Korslund, University of Washington, Seattle, WA, 2003, personal communication): a score of ≥ 4.0 points on the 5-point scale denoted adherence. This scale is the gold standard measure of adherence in standard DBT and is commonly used in research trials. 71,72

Training, supervision and adherence

The RO DBT training and supervision were conducted by the treatment developer (TRL) and covered the biosocial theory of the development of overcontrolled behavioural patterns; the novel RO DBT mechanism of change, linking open expression of emotion to increased trust and social connectedness, which are new overcontrolled treatment targets; modifications to the relationship strategies; the importance of social signalling and mindfulness practices, including loving kindness, self-enquiry and the new radical openness (RO) skills. Some therapists elected to attend the training offered for the treatment on more than one occasion.

On commencing the trial, all therapists attended weekly 2.5-hour RO DBT consultation team meetings. The RO DBT consultation team meeting served several important functions; the meetings not only provided a platform for therapist practice of RO, they also helped to reduce therapist burnout and enhance empathy and adherence to the treatment. During consultation team meetings, therapists presented problems that they were experiencing within the treatment and sought consultation from each other. This involved showing video clips of therapy sessions and feedback about how best to apply the treatment to resolve clients’ difficulties or address challenges.

Each team was led by a practitioner who had many years’ experience of delivering standard DBT to individuals with borderline personality disorder (BPD) in NHS settings. Three of the four clinical team leads (the clinical lead for the Dorset trust changed part way through the trial) were experienced trainers in standard DBT and were well versed in developing and shaping a team towards adherent treatment delivery. To support the team leads in this vital role, the chief investigator supervised each team lead on a selection of their cases. Supervision involved a detailed microanalysis of therapy tapes in order to increase skill and expertise in the delivery of RO DBT and also to shape skills in how to supervise others in learning RO DBT. On average, team leaders were supervised once every 8 weeks in the early part of the study. The frequency of supervision reduced as competency developed. Therapists also received supervision from the chief investigator via site visits and individual supervision as required.

Finally, a random selection of RO DBT session tapes were coded for adherence using the standard DBT Adherence Rating Scale (Linehan and Korslund, personal communication). Feedback was provided to the site team lead and the individual therapist on the score obtained, with brief guidance on how to improve adherence if necessary. The four coders were trained to reliability with the scale developer and rerated for reliability at the mid-point of the trial.

Measures

Table 1 presents an overview of all included measures.

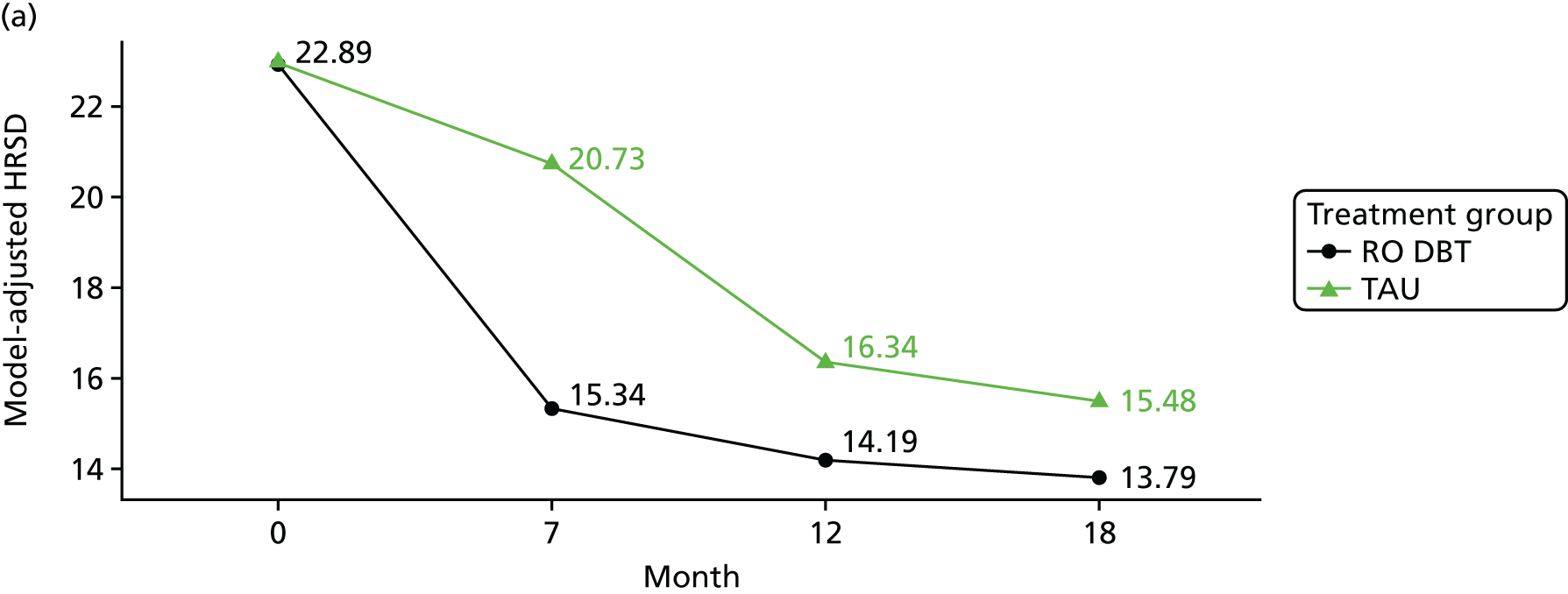

Primary outcomes: depression symptoms

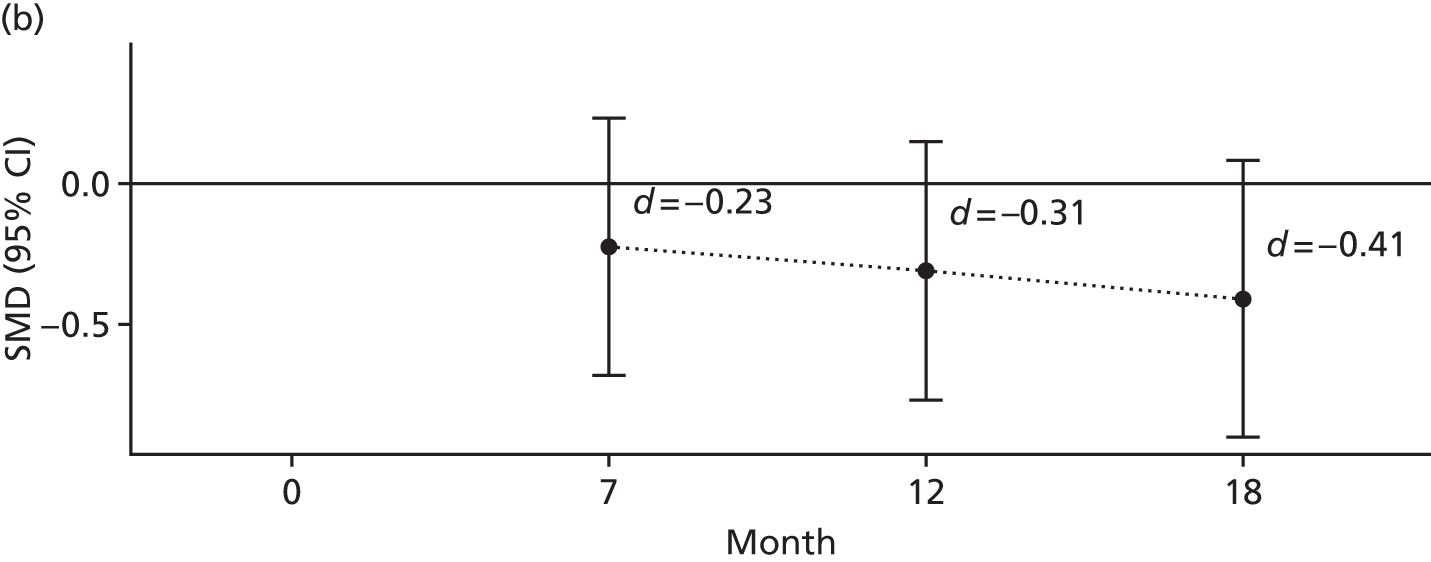

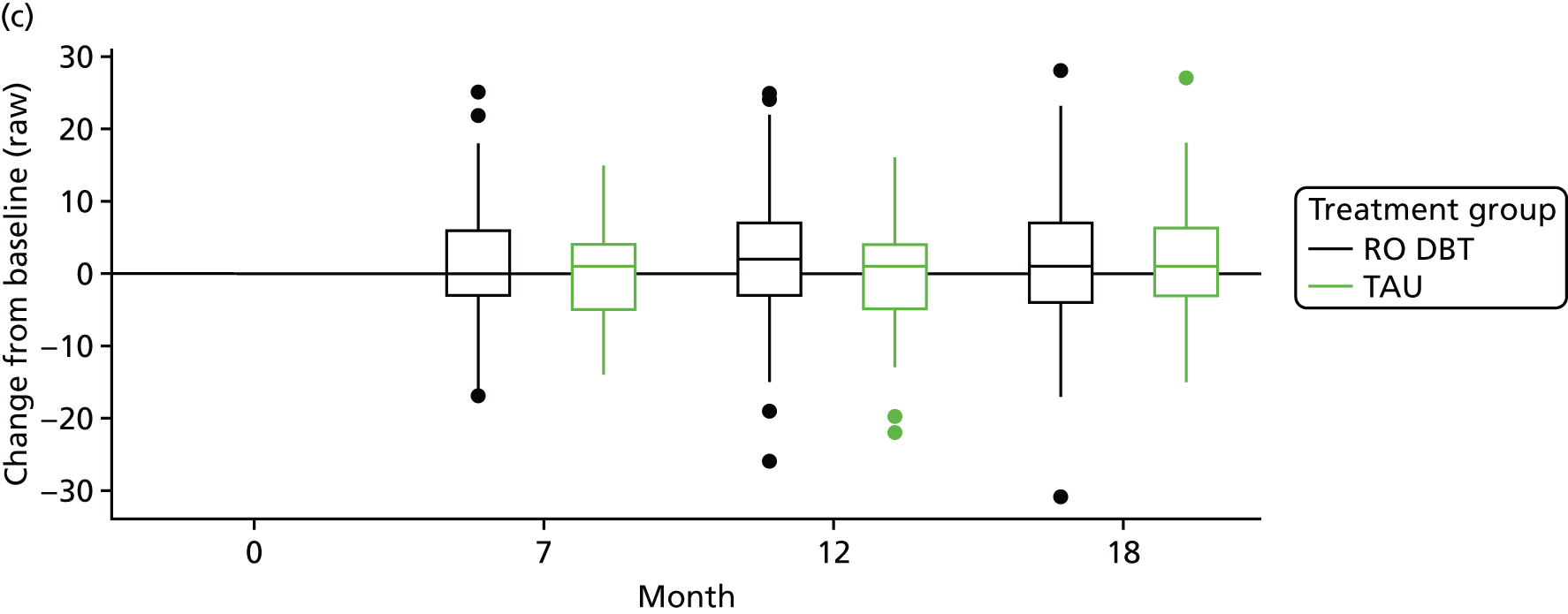

The primary outcome was the difference in depressive symptoms at 12 months between patients receiving RO DBT and TAU, as measured using the 17-item HRSD. 63 The HRSD was assessed at four time points (baseline and at 7, 12 and 18 months after randomisation) by trained assessors.

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes at the same four time points included remission status and suicidal ideation and behaviour. We also examined clinically significant change post hoc using reliable change indices. 73

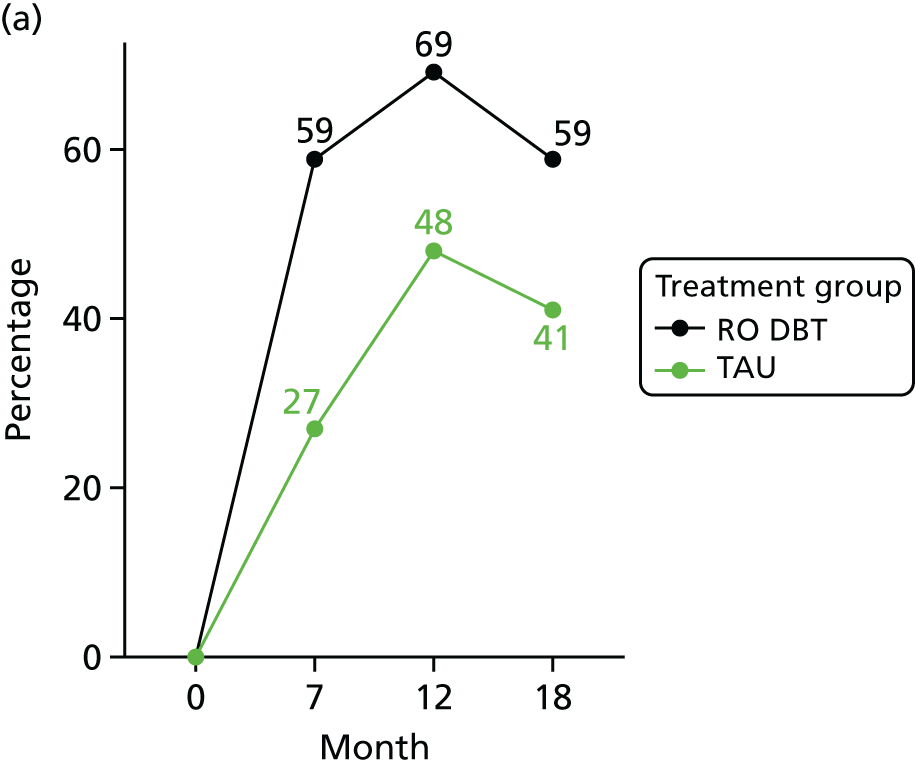

Remission status

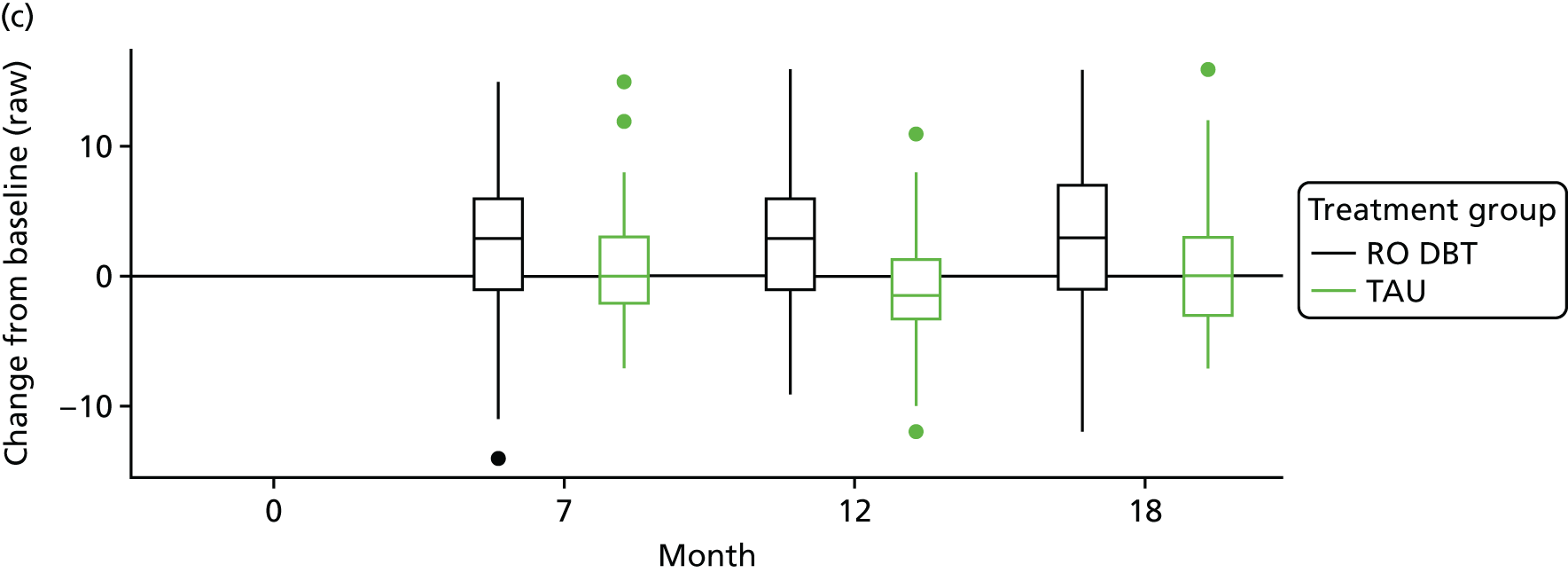

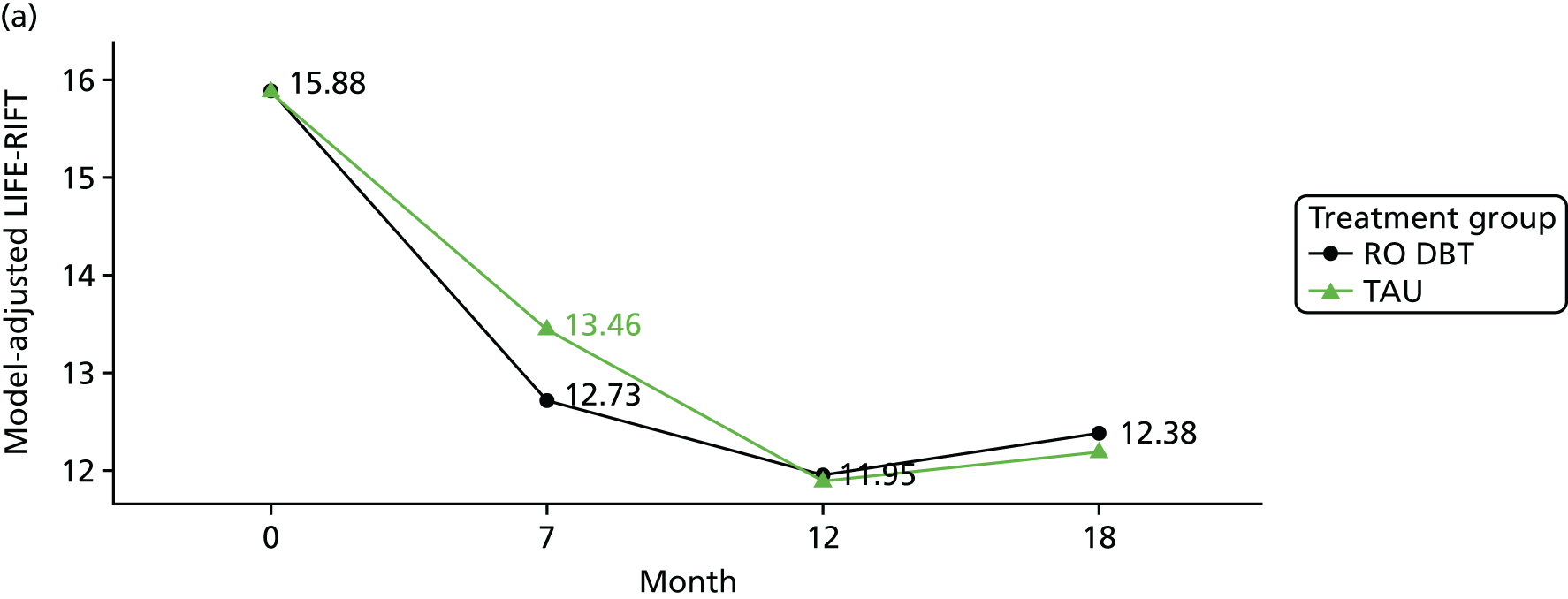

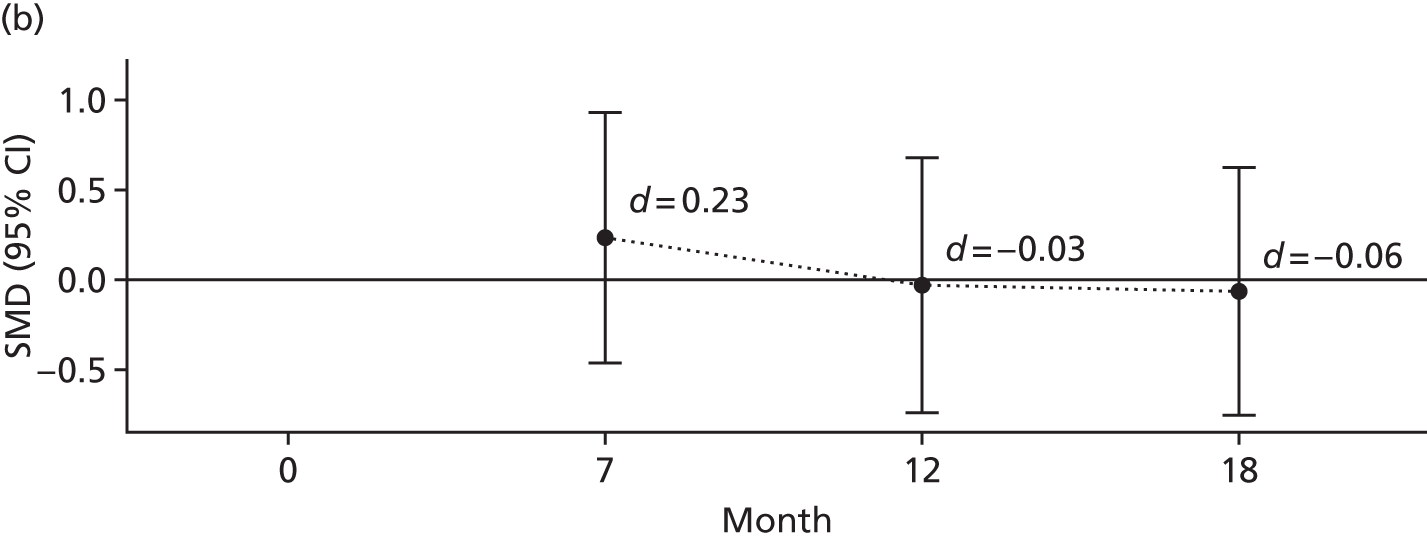

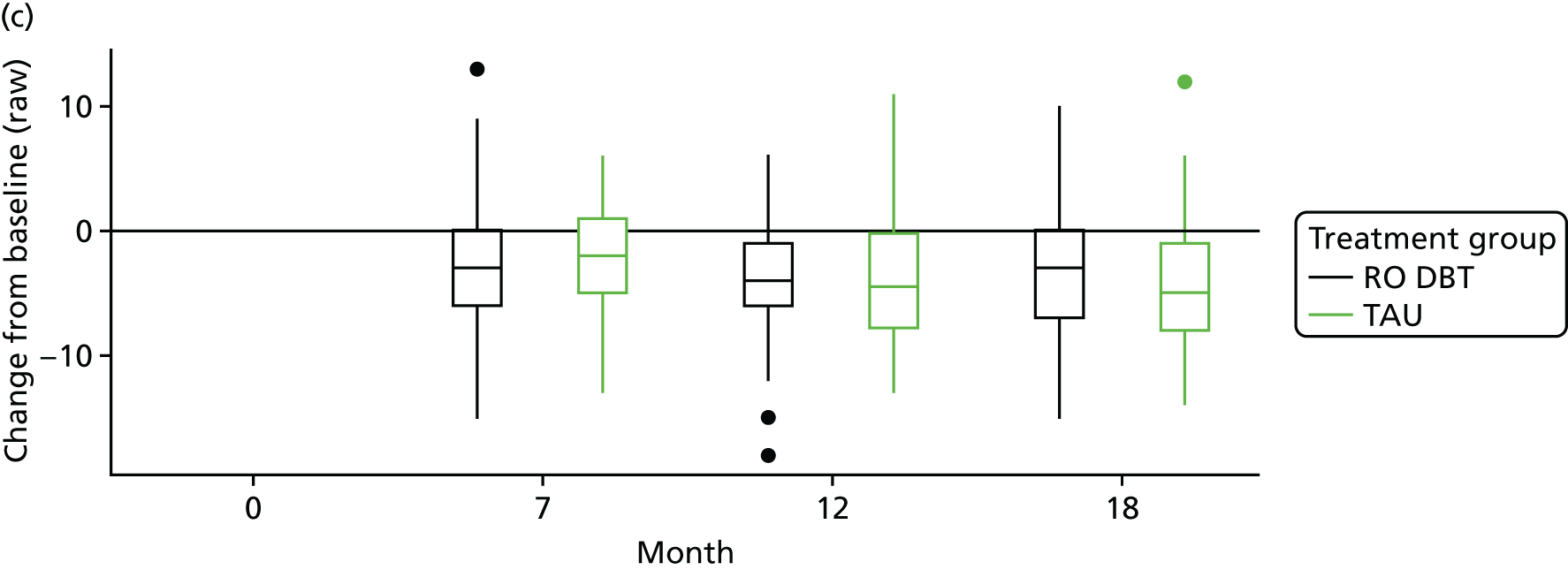

In line with recommendations from Greer et al. ,1 remission status was based on the level of depression symptoms (as measured using the HRSD) and psychosocial functioning level [as measured with The Longitudinal Interval Follow-up Evaluation – Range of Impaired Functioning Tool (LIFE-RIFT)]. 74

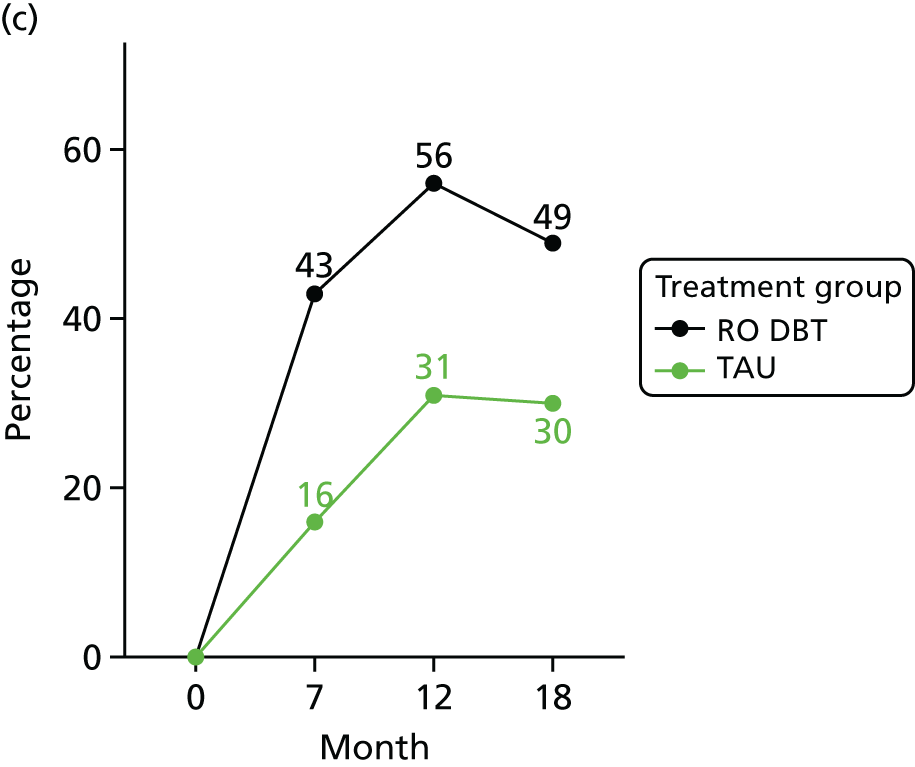

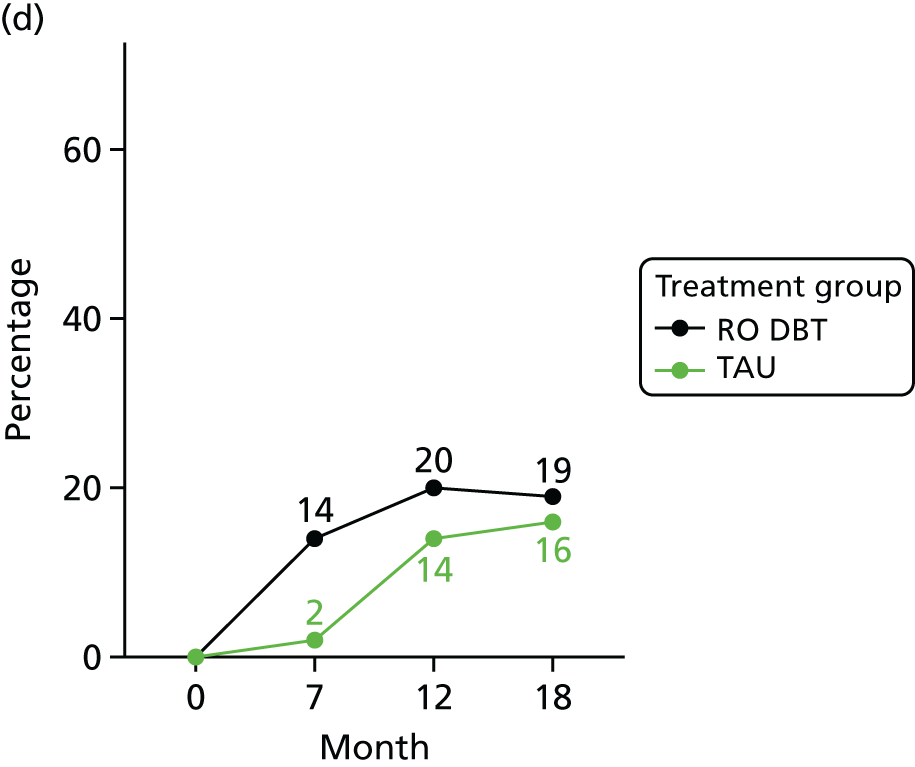

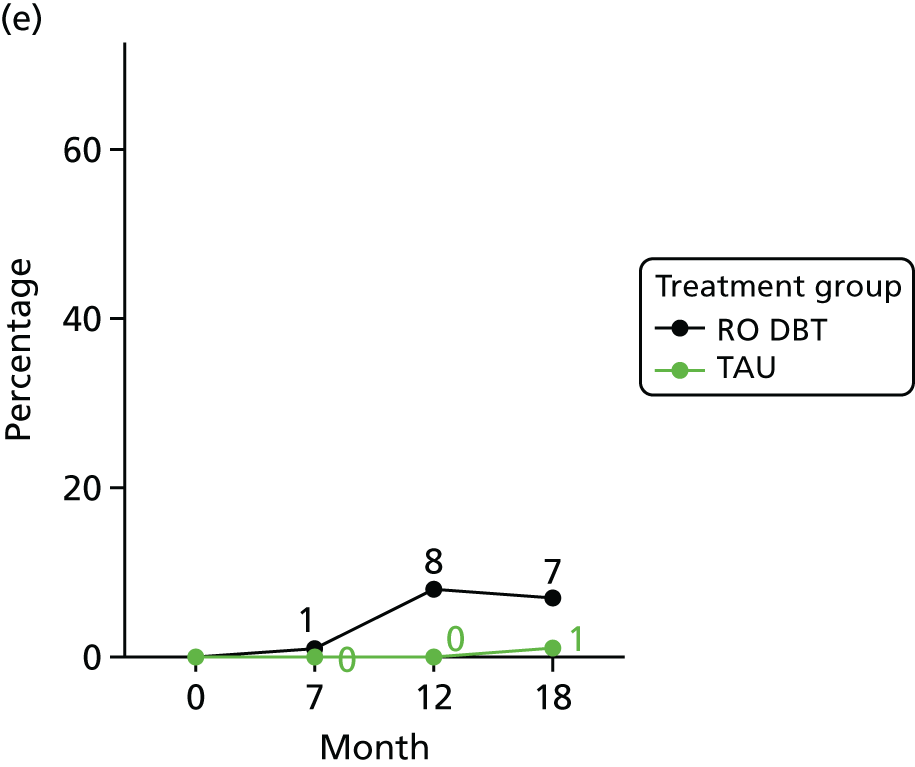

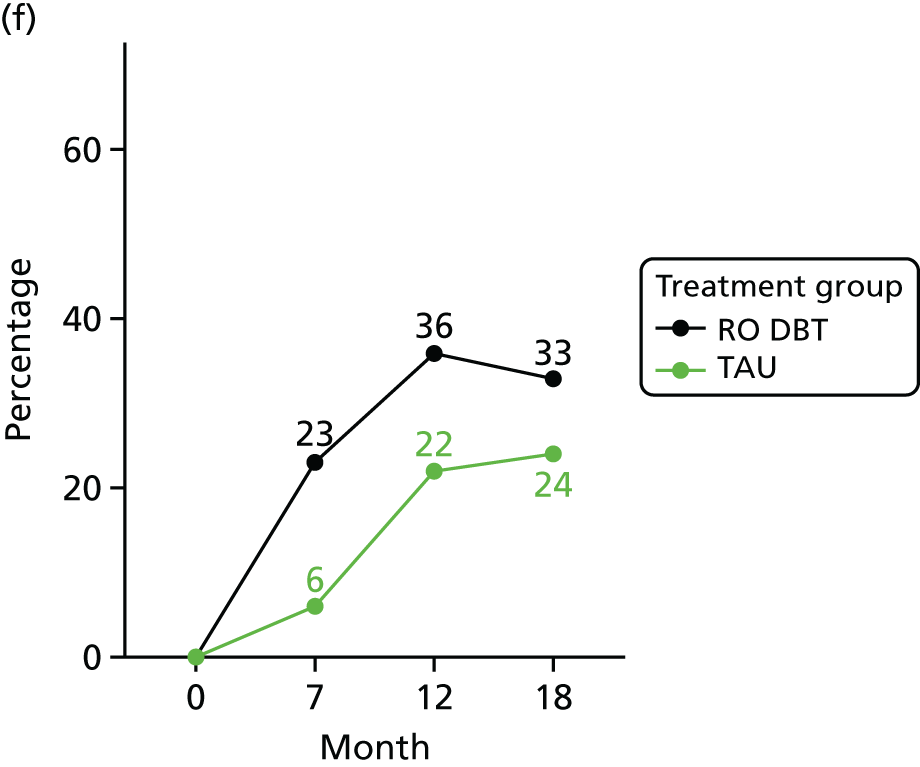

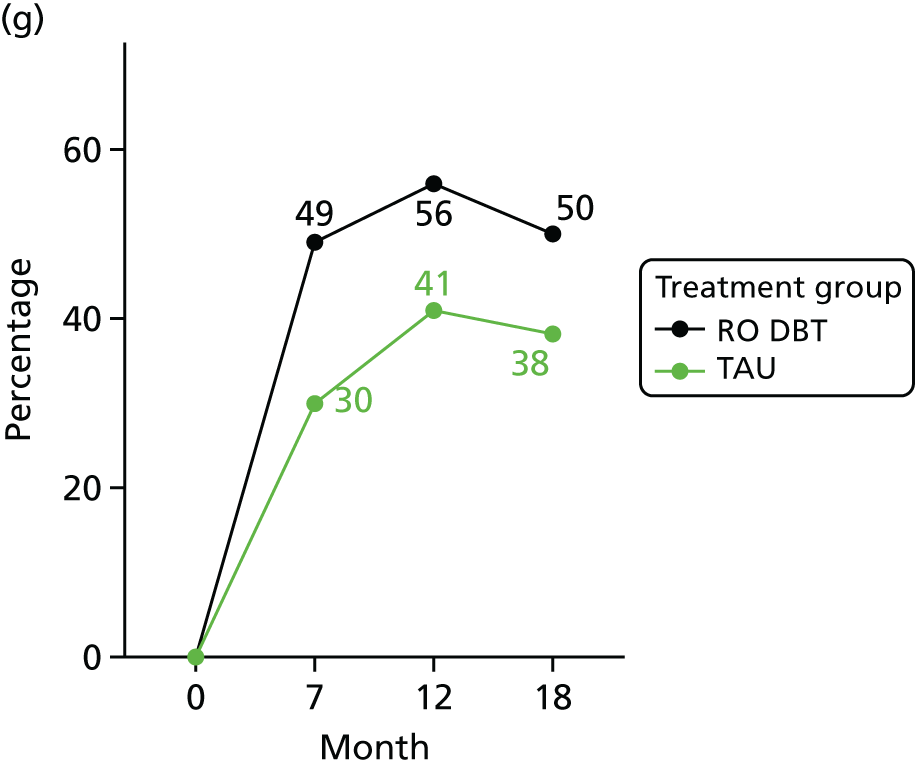

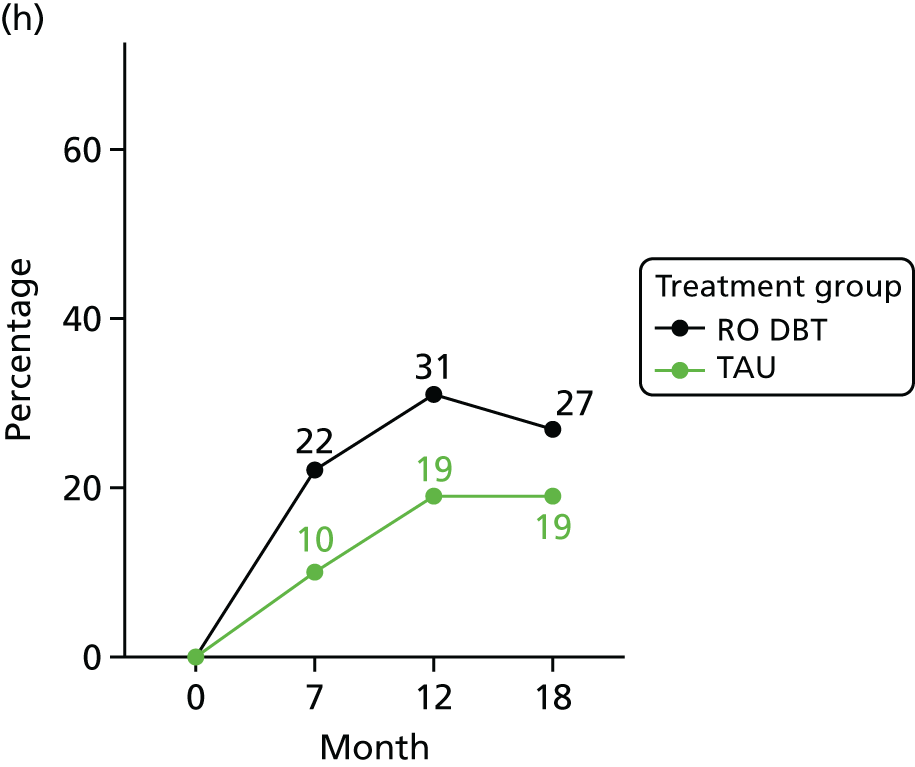

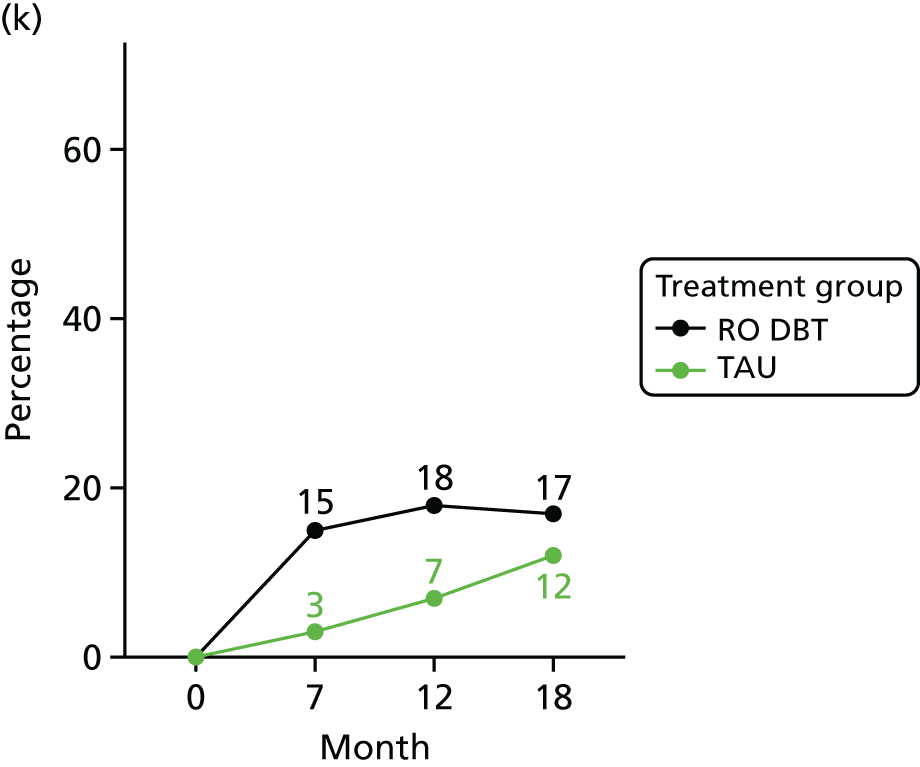

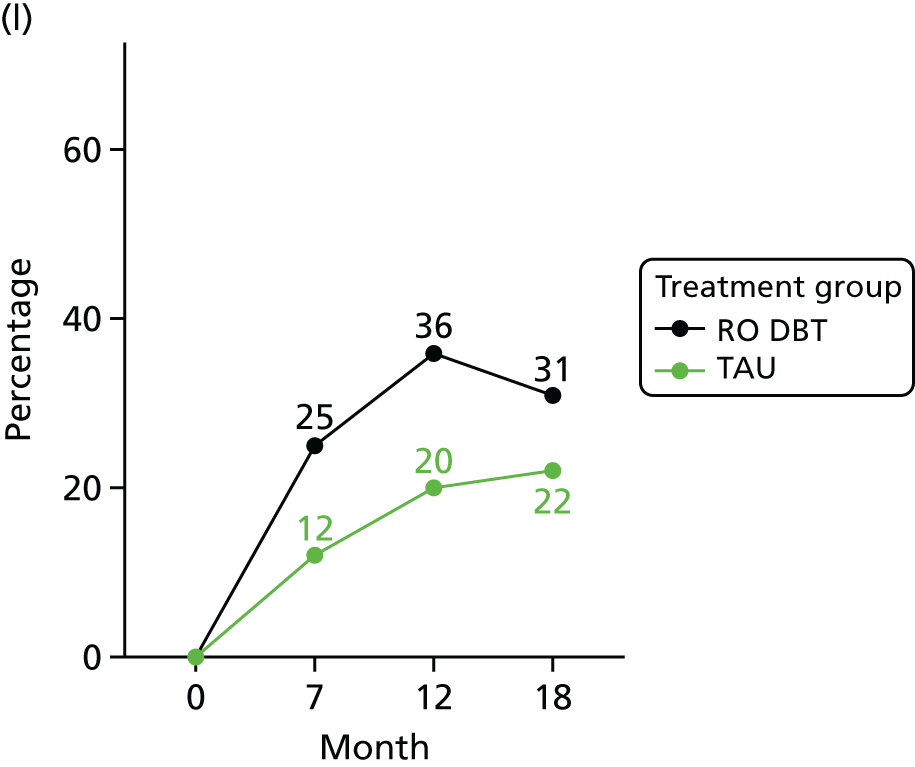

For the primary definition of remission the HRSD and LIFE-RIFT were recoded in the following way: Patients with a HRSD score of < 15 points and a LIFE-RIFT score of < 13 points were defined as experiencing partial remission. Patients with a HRSD score of < 8 points and a LIFE-RIFT score of < 13 points were identified as in full remission. Other patients were defined as experiencing ‘no remission’ or, when data were missing, as having ‘unknown’ remission status. Because patient numbers differed in the two arms, we present the percentage of patients in each category, using the number (n) allocated to treatment as the denominator.

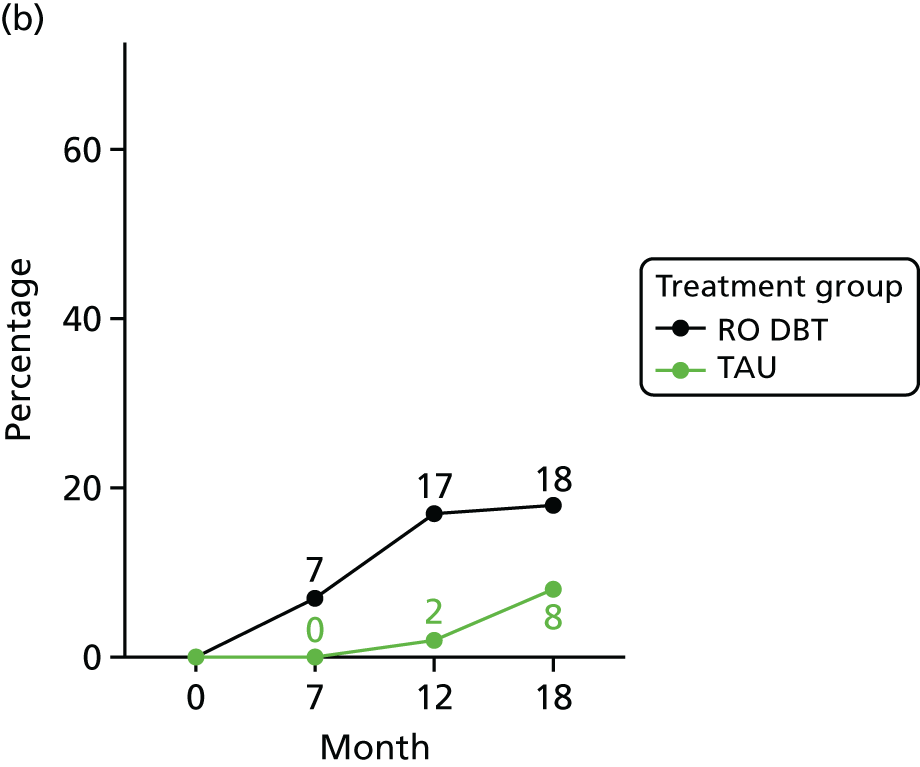

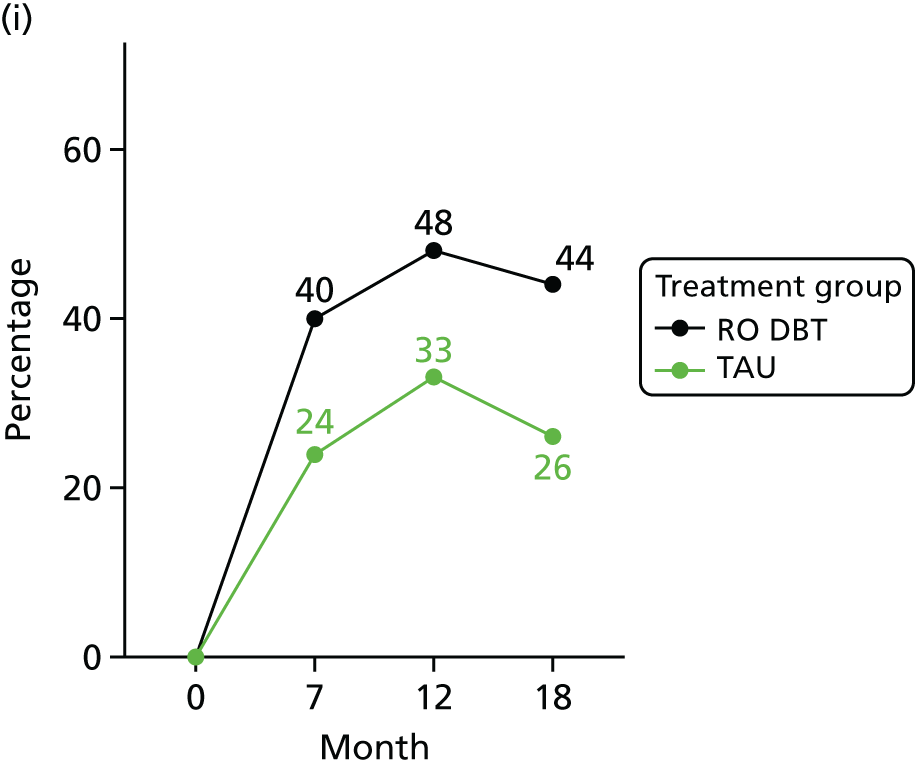

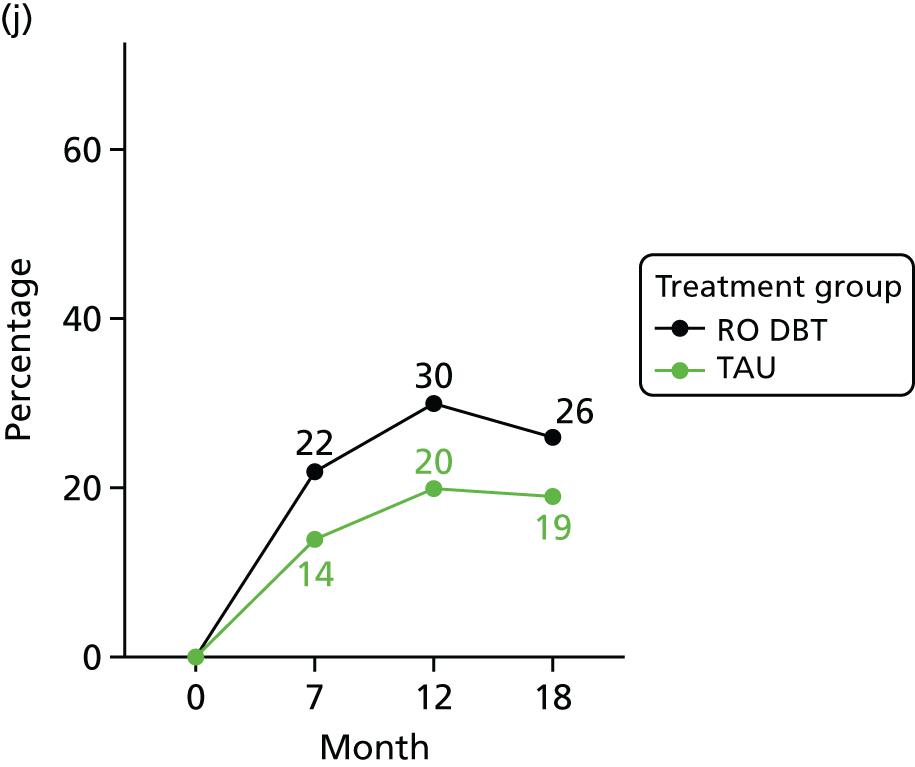

In addition, because remission rates are defined in a number of ways in the literature, and because the selection of any single criterion is somewhat arbitrary,75 we also computed a number of other thresholded scores based on the HRSD. These other thresholded scores included:

-

Patients whose HRSD score dropped to < 8 points, and thus meet NICE’s 2009 definition of ‘not depressed’.

-

Patients experiencing > 17.5% or > 50% change in symptoms from baseline. Externally anchored criteria, or those defined by distributions of ‘sick’ and ‘well’ patients,73 may fail to capture patients’ own views of their improvement. Recent work has mapped patients’ ‘global rating of change’ to psychometric scale scores and found that a 17.5% change in symptoms corresponded to the minimal clinically important difference from the patient perspective. 76 This previous work has used the BDI, but because correlations between BDI and HRSD are high (in the region of r = 0.777) we adopted the same approach using the HRSD.

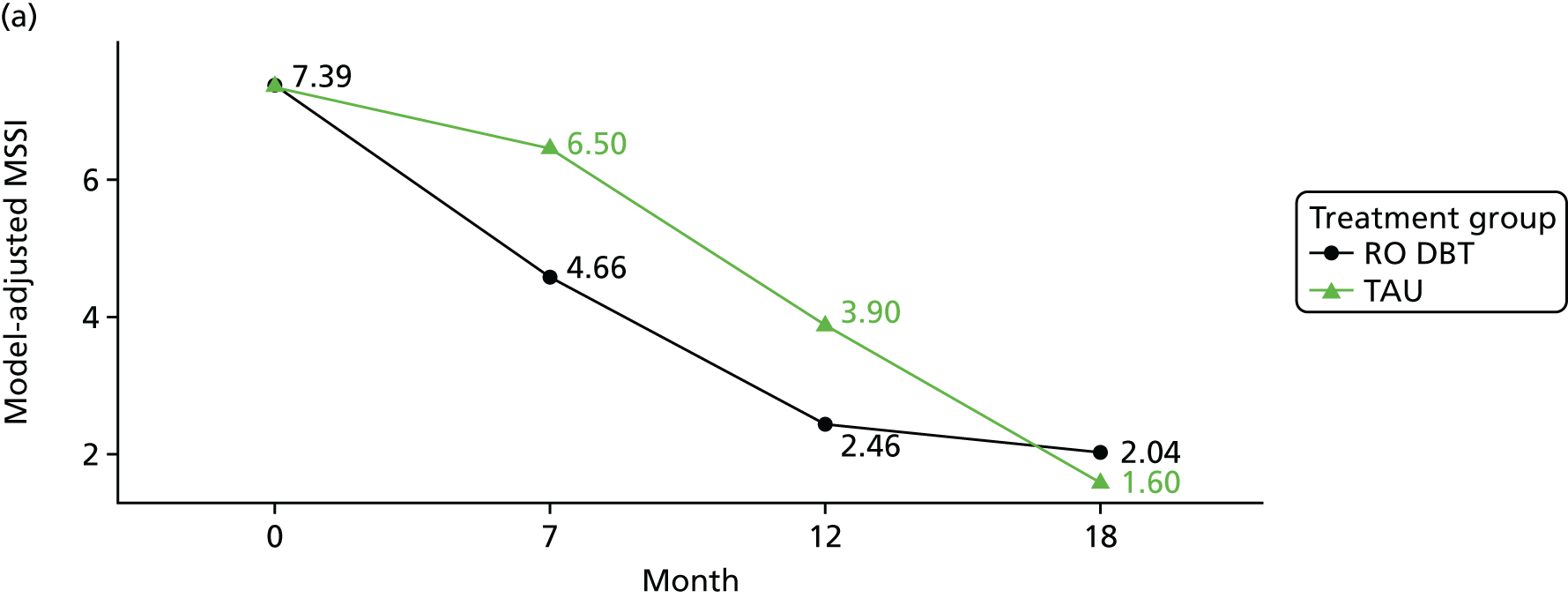

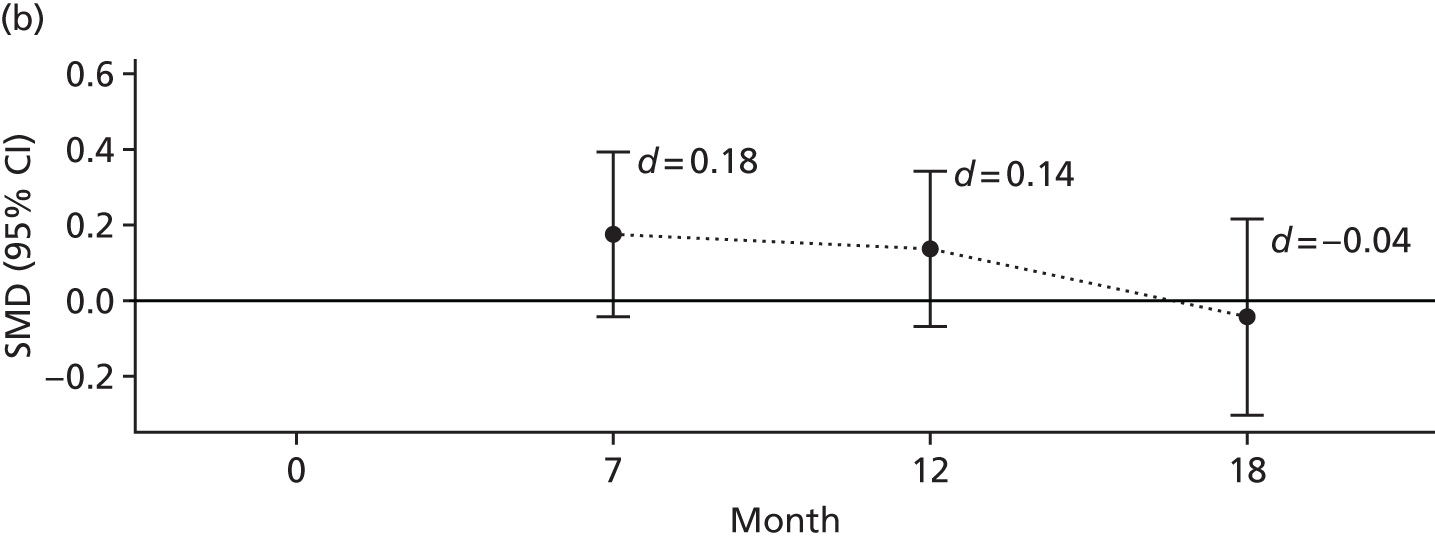

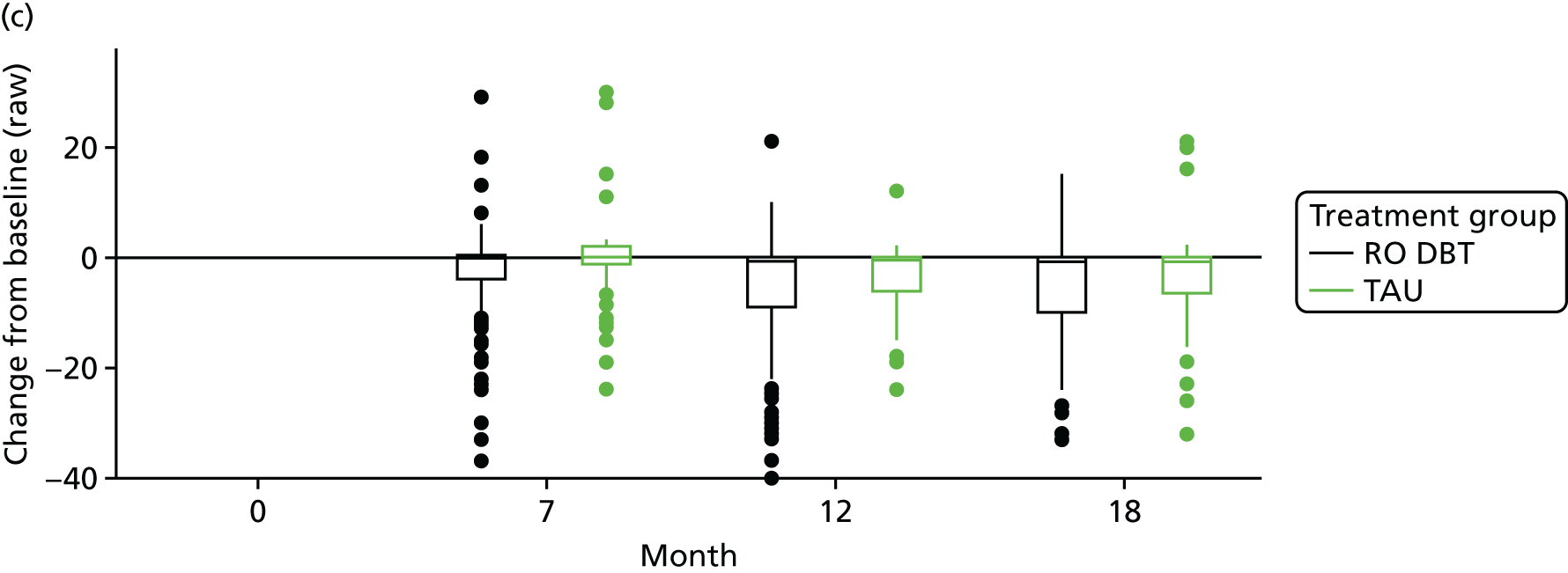

Suicidal ideation and behaviour

In addition, we evaluated changes in suicidal thoughts and behaviours. Suicidal ideation was measured using the assessor-rated Modified Scale for Suicidal Ideation (MSSI). 78 All participants were asked to answer the first four questions of this scale. As per the instructions of the scale, only those who scored ≥ 2 points on questions 1 and 2 and ≥ 1 points on questions 3 and 4 were asked to answer questions 5–18. The questions are scored from 0 to 3 points, with higher scores indicating increased suicidal ideation. Scores of ≤ 8 points indicate low suicidal ideation, 9–20 points indicate mild to moderate suicidal ideation and 21 points or higher indicate severe suicidal ideation.

To measure suicidal and self-harm behaviour, we used an adapted version of the self-reported Suicidal Behaviors Questionnaire. 79 Suicide behaviour and intent was calculated using the sum score of the first 10 questions (we omitted questions 4 and 9 of the original scale to avoid repetitiveness). Self-harm behaviour was calculated summing the scores of all behaviours listed in questions 12a–k of the original scale.

Economic measures

We collected resource-use data using a version of the Adult Service Use Schedule (AD-SUS), which is designed for depression populations. The AD-SUS collects service use and associated data and has been successful in a range of adult mental health population trials. 80 Completed in interview with participants, the questionnaire records use of hospital- and community-based health and personal social care services for all causes. For medications, we asked participants to report prescribed antidepressants, antipsychotics, sleeping tablets and painkillers. To avoid unblinding researchers, participants reported their use of all talking therapies on a separate self-report questionnaire. We collected information about time off work as a result of illness alongside the AD-SUS, using the productivity questions from the World Health Organization (WHO) Health and Work Performance Questionnaire. 81 We asked participants to complete the AD-SUS and WHO’s Health and Work Performance Questionnaire at baseline to cover the previous 6 months and at the 7-, 12- and 18-month interviews to cover the time since the previous interview, thus covering the full period from baseline to final follow-up. We extracted information on RO DBT-related service use, including the number of individual sessions and group sessions attended by each participant, from therapy records.

We estimated QALYs from EQ-5D-3L scores at baseline and at 7, 12 and 18 months. The EQ-5D-3L is a non-disease-specific measure for describing and valuing health-related quality of life. 50 The measure includes a rating of health in five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression) and a rating of own health using a visual analogue scale (a thermometer scaled from 0 to 100). The health states described in the EQ-5D-3L were assigned a utility weight or score using responses from a representative sample of adults in the UK. 82 These weights were applied to the time between interviews and QALYs calculated using the area under the curve approach. 83 The EQ-5D-3L has been validated in economic evaluations for common mental health disorders. 84

Moderating variables

At baseline we collected the following data on potential moderating variables (see Table 1):

-

Basic demographics, including age, sex and marital status.

-

Balanced Inventory of Desirable Responding-Short Form85 – this is a 16-item questionnaire that is answered using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = totally disagree to 7 = totally agree; the scale assesses two dimensions: (1) self-deceptive enhancement and (2) impression management.

-

Ego-Undercontrol and Ego-Resiliency Scales86 – the Ego-Undercontrol Scale has 37 questions and the Ego-Resiliency Scale has 14 questions; both questionnaires are answered using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = disagree very strongly to 4 = agree very strongly.

-

Invalidating Childhood Experiences Scale87 – this scale asks 14 questions about negative childhood experiences (≤ 18 years) in relation to each parent. Each item is rated on a Likert-type scale (1 = never; 5 = all the time). The levels of perceived invalidation by mothers and fathers are given by the mean score for the 14 items for each parent. Higher scores reflect a greater perception of invalidation by that parent. Four additional questions include descriptions of three types of invalidating environment (perfect, chaotic or typical) and one description of a validating environment. The items were rated on a five-point scale (‘not like my family’ to ‘like my family all of the time’). Higher mean scores indicate greater levels of either the validating environment or the three types of invalidating environment.

-

Personal Need for Structure Scale88 – this 11-item scale comprises two subscales: desire for structure and response to lack of structure. Questions are answered using a six-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 6 = strongly agree.

-

Urgency Premeditation Perseverance Sensation Seeking Scale89 – this is a 45-item questionnaire consisting of four subscales: (negative) urgency, (lack of) premeditation, (lack of) perseverance and sensation-seeking. Questions are answered using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = agree strongly to 4 = disagree strongly.

-

SCID-I and SCID-II64,90 – these are semistructured diagnostic interviews for identifying DSM-IV Axes I and II mental health and PDs, respectively.

Both participants and therapists completed the following:

-

Cambridge Prospective Memory Test91– this is a laboratory measure of prospective memory that comprises a total of six prospective memory tasks, three cued by time and three cued by events. Participants were asked to work on some distractor tasks, such as word-finder puzzles or a general knowledge quiz, for a 20-minute period while they also had to remember to perform the prospective memory tasks. For each task, between 0 and 6 points are awarded depending on whether or not the tasks were completed and to what degree they required prompting from the assessor, with higher scores reflecting better prospective memory performance.

-

Conscientiousness Subscale [of the NEO (neuroticism, extraversion and openness) Five-Factor Inventory]92 – this subscale comprises 12 items scored using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

-

The Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale93 – 35 questions are answered using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. We computed separate scores for adaptive and maladaptive perfectionism. 94–96

-

Schwartz Values Scale97 – 57 statements are rated on a nine-point Likert scale indicating the degree to which each statement is ‘a guiding principle’ in the participant’s life. The items reflect 10 universal value types: security, power, achievement, hedonism, stimulation, self-direction, universalism, benevolence, conformity and tradition.

In addition, therapists completed:

-

Measure of Parenting Style Scale98 – this scale measures perceived parenting style across three domains: indifference, abuse and overcontrol. Fifteen items ask about the behaviour of the participant’s parents towards them during the first 16 years of their life for each parent separately. The items are rated from 0 = not true at all to 3 = extremely true.

Mediating variables

Data on potential mediators were collected at 0, 3, 7, 12 and 18 months using the following questionnaires (see Table 1):

-

Acceptance and Action Questionnaire-II (AAQ-II)99 – this questionnaire is a 7-item scale measuring psychological inflexibility. Questions are answered using a seven-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never true to 7 = always true.

-

Ambivalence over Emotional expression Questionnaire100 – this is a 28-item questionnaire measuring conflict over emotional expression. It is answered using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = never to 5 = very often.

-

The Dialectical Behaviour Therapy Ways of Coping Checklist (DBT-WCCL)101 – this checklist is based on the earlier Revised Ways of Coping Checklist and is an inventory of emotional coping skills taught in standard DBT. It comprises 59 items rated on a three-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = never used to 3 = regularly used. The scale has three subscales: DBT skills use, general dysfunctional coping and blaming others.

-

Inventory of Interpersonal Problems–Personality Disorders102 – this 25-item dimensional PD measure is answered using a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 4 = extremely. Five subscales can be calculated: interpersonal sensitivity, interpersonal ambivalence, aggression, need for social approval and lack of sociability.

-

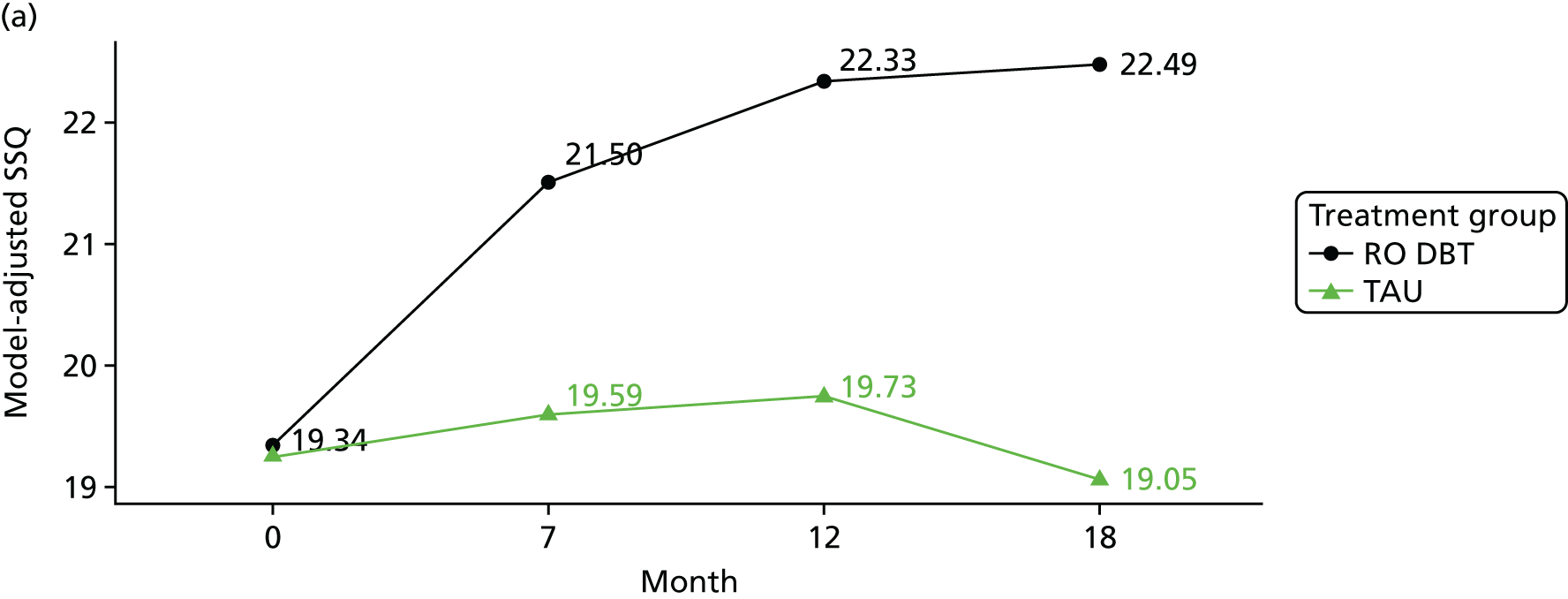

The 3-item Social Support Questionnaire (SSQ)103 – this questionnaire asks participants to list the initials of people who provide support to them in three different manners and participants are asked to rate their degree of satisfaction for each manner of support received using a Likert scale ranging from 1 = very dissatisfied to 6 = very satisfied.

-

White Bear Suppression Inventory104 – this 15-item questionnaire measures suppression and avoidance of unwanted thoughts using a five-point Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree.

Temporal sequencing measures

Participants were asked to complete the following measures at baseline, then once a month for the first 12 months and again at 18 months:

-

The Patient Health Questionnaire-9105 – this is a 9-item psychometrically valid assessment of depressive symptoms using a three-point Likert scale ranging from 0 = not at all to 3 = nearly every day.

-

The Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS)106 – the 20-item PANAS provides independent estimates of positive and negative affect and is rated from 1 = very slightly/not at all to 5 = extremely.

-

The Emotional Approach Coping scale (EAC)107 – this scale comprises eight items and has two subscales: emotional processing and emotional expression. Items are rated from 1 = I usually don’t do this at all to 4 = I usually do this a lot.

-

The Credibility/Expectancy Questionnaire108 – this questionnaire indexes positive expectancies for treatment and comprises six items with various scales. The first four items aim to measure credibility and the last two items aim to measure expectancy.

In addition to the listed questionnaires, we also used an automated telephone system to measure mood using the 10-item PANAS Short-Form109 and coping skills using the six items from the DBT-WCCL101 once a week over the first 6 months that participants were in the trial (ecological momentary assessments).

Therapeutic alliance

To measure therapeutic alliance, patients allocated to RO DBT were asked to complete the patient version of the California Psychotherapy Alliance Scales110 during the first 4 weeks of treatment and then once a month until the end of treatment. Therapists were asked to complete the therapist version at the same time points.

Therapist characteristics

To investigate whether or not therapist characteristics, and their relationship with patient characteristics, influence outcome, we asked them to complete measures of conscientiousness (the conscientiousness scale from the NEO Five-Factor Inventory),92 perfectionism (Frost Multidimensional Perfectionism Scale),93 personal values (Schwartz Values Scale)97 and attachment experiences (Measure of Parenting Style Scale). 98 More detailed descriptions of the scales are available in Moderating variables.

We also measured therapists’ capacity to generate strong alliances before the trial by asking several patients from the caseload of each therapist to complete the California Therapeutic Alliance Scale. 110 This measure was used as an IV for strength of therapeutic alliance.

Client Satisfaction Questionnaire

To assess the acceptability of the treatment and the study as a whole, we asked the first 50 participants to complete the Client Satisfaction Questionnaire-8. 111

Statistical methods

Data processing and reduction

We stored study data in several databases, which were subsequently linked for analysis using the five-digit participant code (in which the first digit indicates study site) provided with each randomisation request. In parallel to the randomisation database, the main study database stored questionnaire responses and notes, and further databases stored additional information on therapists and therapist sessions.

Data validation included confirmation of the consistency of information in various databases, and thorough checks on the fidelity of double-entry data, with inconsistencies checked against original paper forms. Following such checks and the resolution of all identified inconsistencies, documented audits of questionnaire responses across a range of questionnaires and time points were undertaken, in each case using a random selection of participants representing all study sites and both study arms.

Study data were exported from the main study database and subsequently processed by a series of scripts (primarily written in Stata®, version 14; StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA) that renamed variables, created labels for variables and variable values, created codes for reasons for missing data, identified canonical responses for double-entry data, resolved time points to specific months, defined pairings of participant and therapist and scored questionnaires, using agreed rules on the treatment of missing data. Each script generated an interim file for any further checking required. The final stage dropped all intermediate variables and individual responses before merging the reduced data set with randomisation and therapist information to create a final data set for use in the analyses.

Statistical analysis

Primary and secondary outcome analyses: continuous variables

The primary outcome, HRSD score, and all continuous secondary outcomes were analysed by treatment allocated, modelling differences between groups at baseline and then at 7, 12 and 18 months after randomisation. Covariates in the primary analyses included treatment site (Dorset, Hampshire, North Wales), baseline HRSD score, baseline PD status (presence or absence) and early-onset depression (yes or no). A three-level mixed-effects model was used to account for clustering of data by patient and therapist. Notably, this model does not assume that all therapists are equally effective. 112 These mixed models are efficient and unbiased in the case that data are missing at random, that is, missing at random conditional on the covariates included in the model. As suitable auxiliary data were not available, missing scale responses were not imputed (e.g. via multiple imputation). However, missing questionnaire items were imputed for rows when fewer than 10% of items were missing in a given scale. This item imputation was performed by linear regression using the other scale items as covariates.

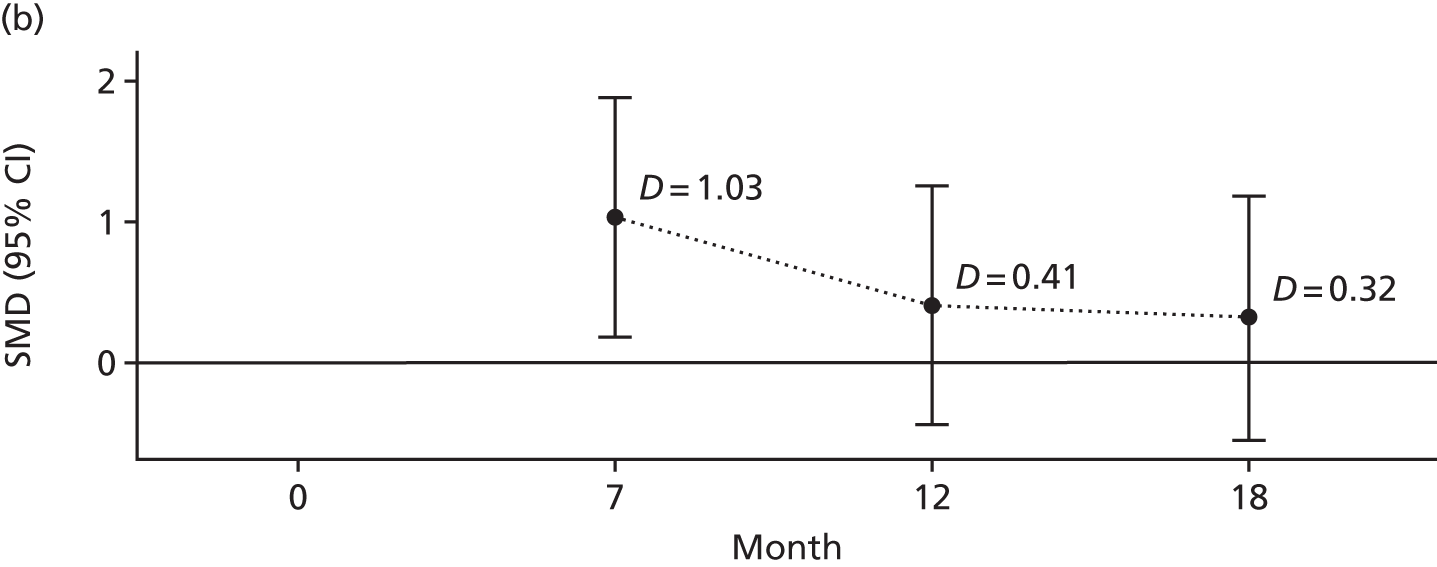

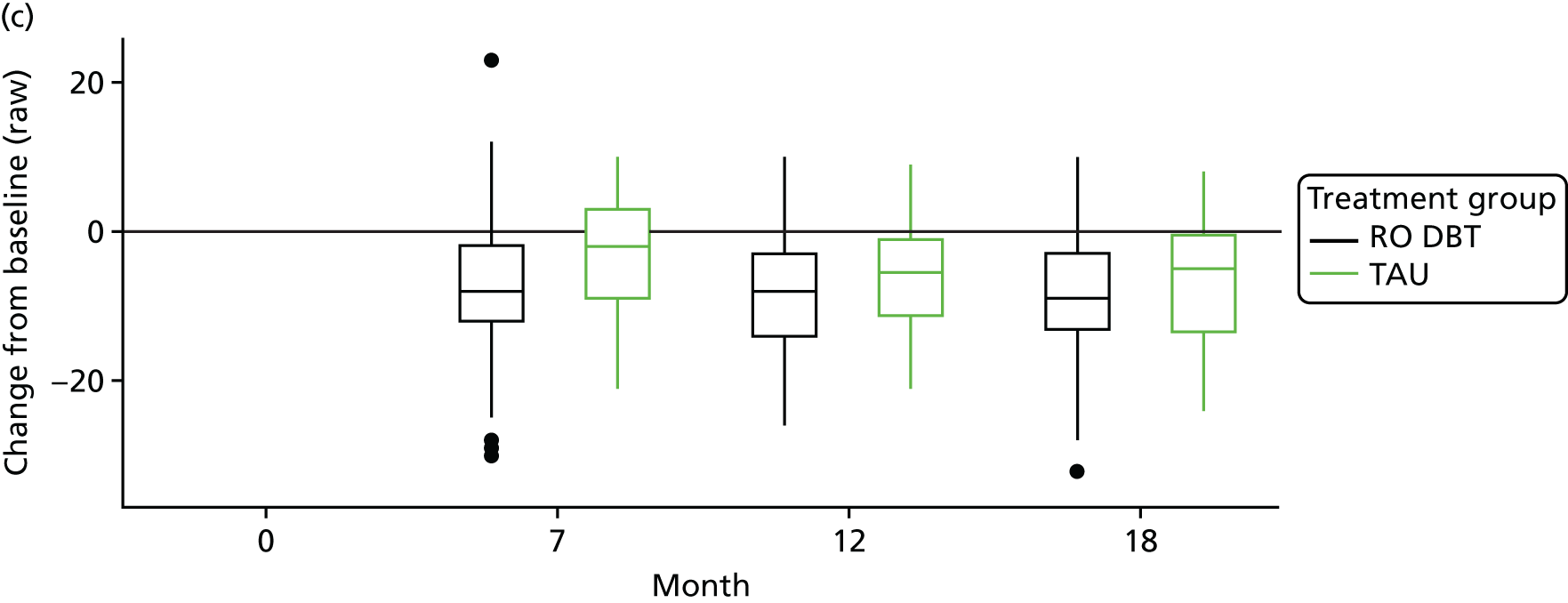

For each outcome, the main effects of time and treatment allocation and the interaction of time and treatment were tested for. Planned contrasts were then made for each outcome at 12 months. Secondary analyses computed differences between treatment groups at months 7 and 18. Details of the analyses are available in Box 1.

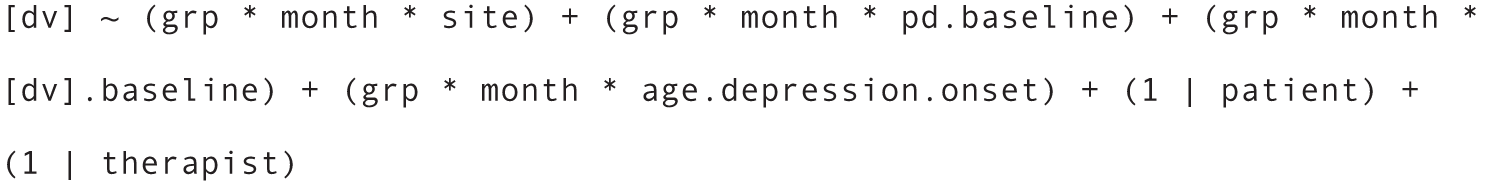

Both primary and secondary outcomes were modelled using mixed-effects models using the Lmer package in R (version 3.3.3; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). 113 Models for primary and secondary outcomes were specified in the form:

In these models [dv].baseline indicates baseline score for the dependent variable, and pd.baseline denotes a binary predictor for the presence of any PD at baseline. The month, patient and therapist variables are factors. Type III tests of fixed effects were computed using Satterthwaite correction114 for degrees of freedom, and between-group contrasts at each time point were computed using the contrast function within the emmeans package. As the sample of therapists was small, null-hypothesis tests on the random effects in the models were not performed, but the proportion of variance attributable to therapists (see Chapter 3, Variations in therapist performance) was reported.

Outcome analyses: binary or categorical outcomes

Remission status and thresholds for clinically reliable/significant change

As remission rates require the application of binary thresholds to an underlying continuous score, the primary and secondary outcome models (as described in Primary and secondary outcome analyses: continuous variables) were used to compute predictions for each patient and calculate remission or change rates based on these predictions, which are, thus, adjusted for baseline covariates. As remission rates are based on an underlying continuous score, more powerful models of these continuous variables were used for statistical inference and significance tests for the difference in rates between groups are not presented.

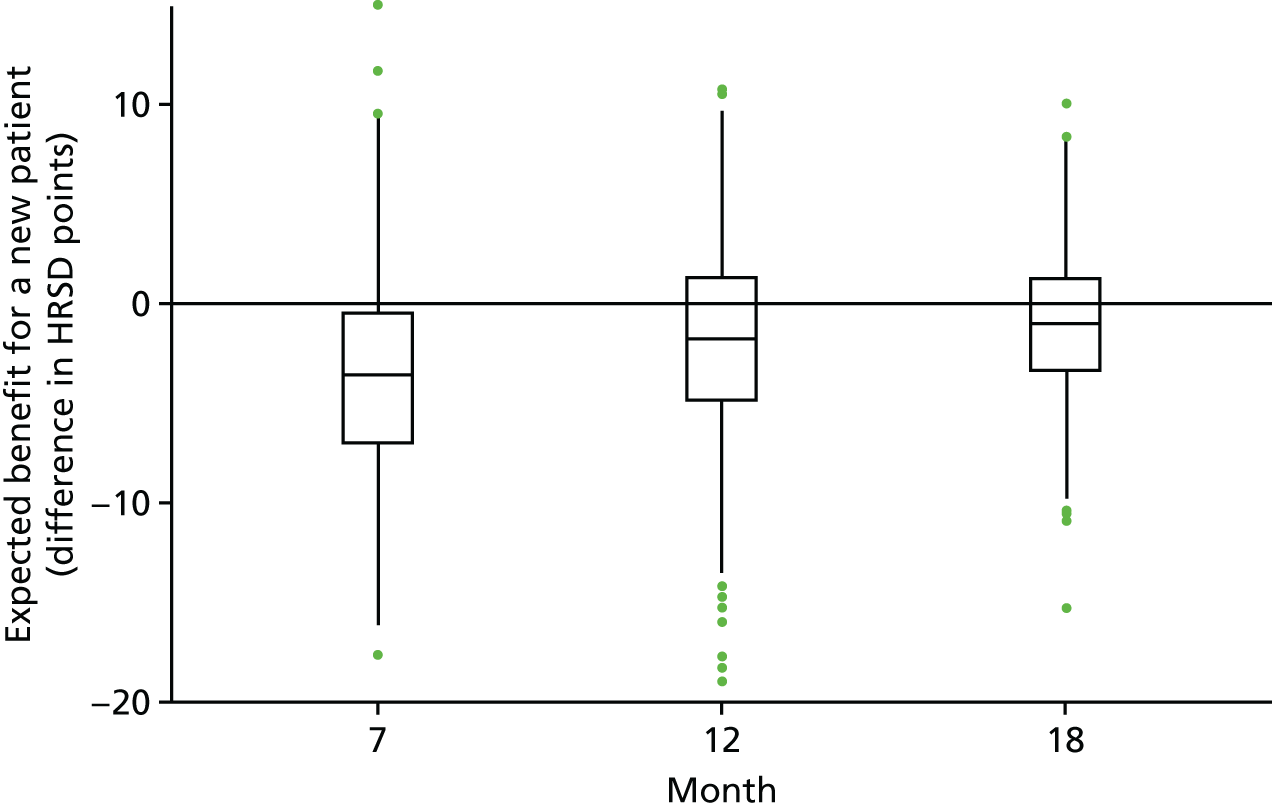

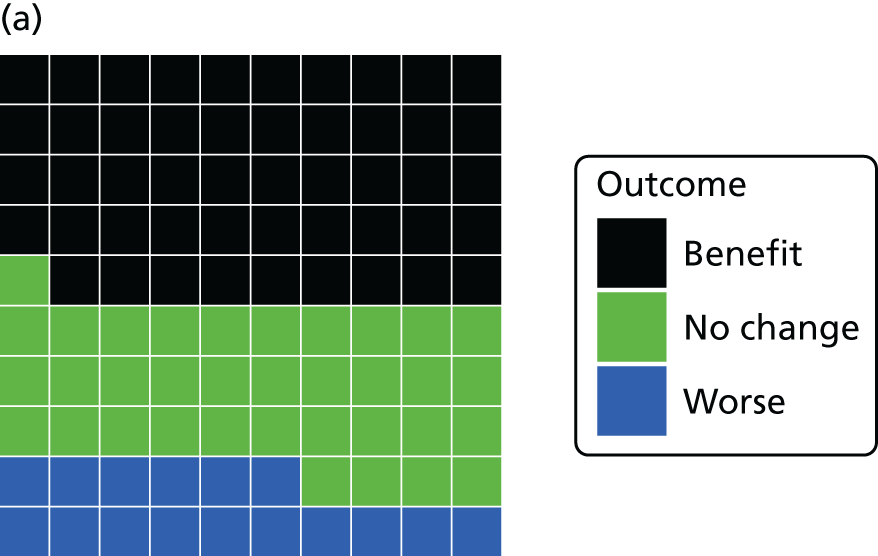

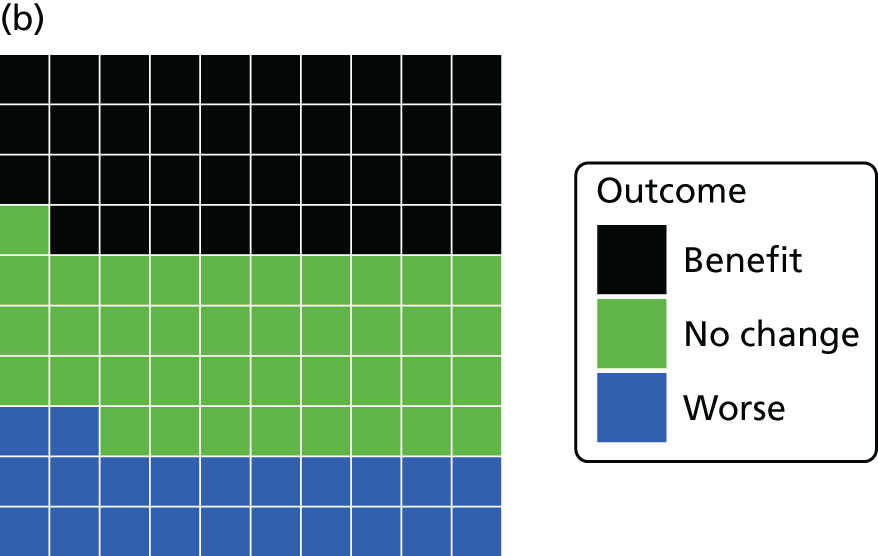

Clinical predictions for new patients

Understandably, most reports of clinical trials focus on mean differences between treatment groups and the precision of this difference. However, clinicians and patients may be less concerned with the average population effect of a treatment (and the associated p-value for this contrast) than with the likely range of clinical outcomes given different treatment choices. For example, patients might wish to know what benefit they may obtain if the treatment is successful, or is less successful than hoped, compared with continuing in TAU. To provide this information the primary outcome model was reran for HRSD using the popular Bayesian modelling package, Stan® (see http://mc-stan.org/). This model was identical to the primary model in all respects, except that (1) the model was fit using Stan’s Hamiltonian Monte Carlo sampling routines, (2) uninformative priors were placed on all model parameters and (3) for simplicity and to aid convergence, the non-significant interaction between PD status at baseline and treatment group was removed. Prior distributions were normal (0,10) for regression parameters and Cauchy (0,2) for variance parameters.

Once the model converged satisfactorily (judged by visual inspection of Markov Chain Monte Carlo traces), observations were simulated, representing new patients who did or did not accept RO DBT, by drawing from the posterior distribution. 115 Descriptive statistics based on these simulations are presented in Chapter 3, Clinical predictions for new patients.

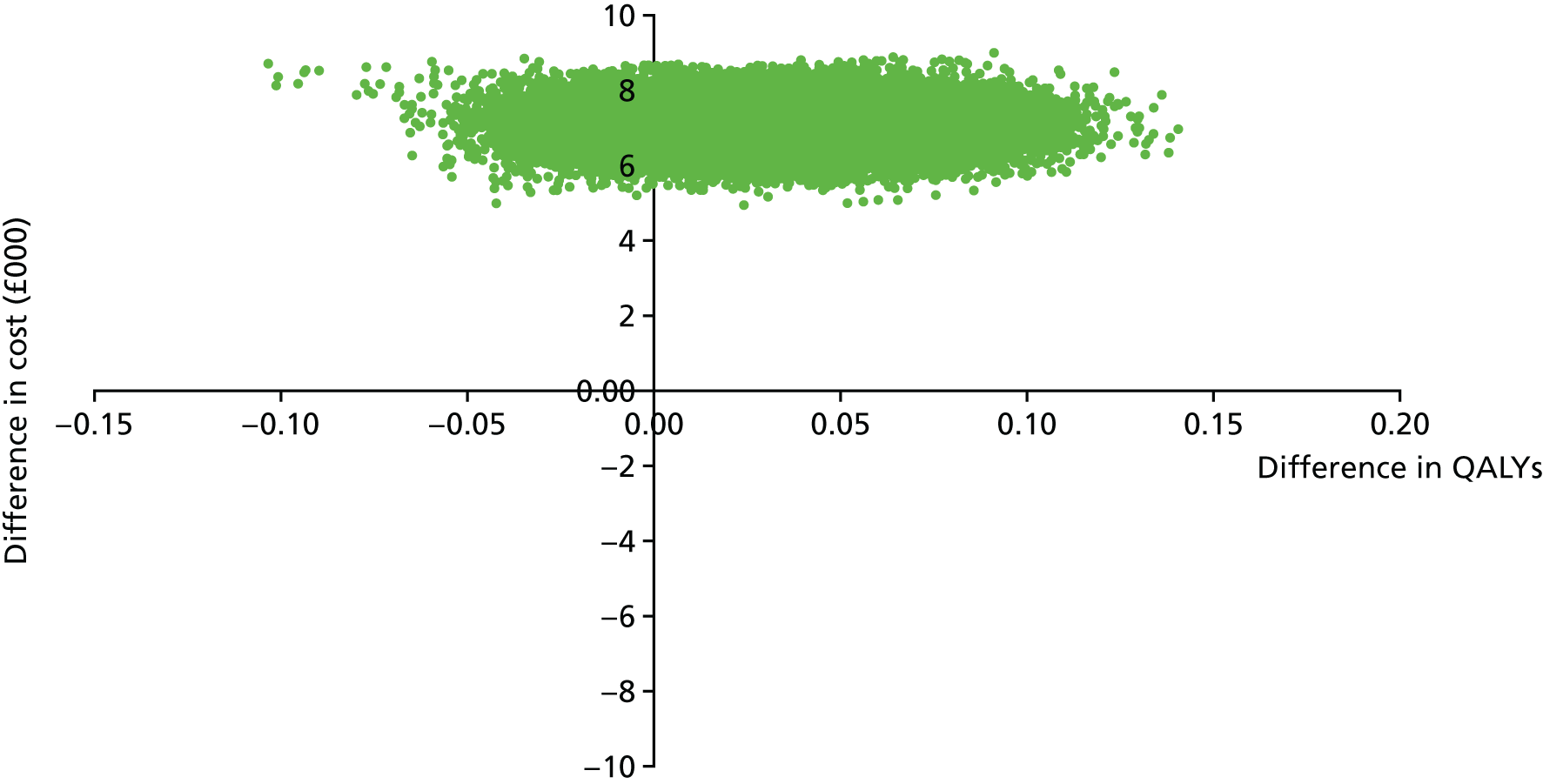

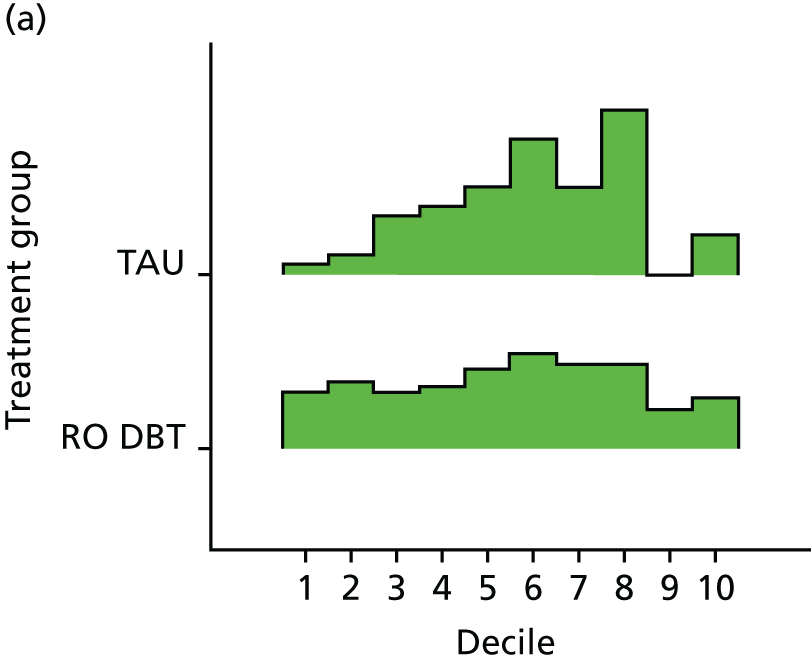

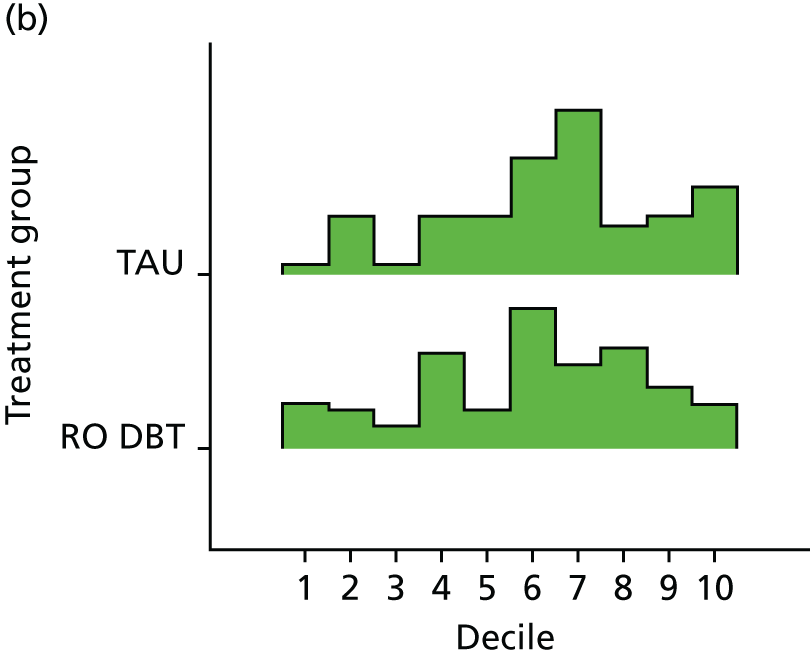

Economic evaluation

Perspective

The economic evaluation took the perspective of NHS and personal social services preferred by NICE51 and explored the impact that productivity losses attributable to time off work as a result of illness had in the sensitivity analysis.

Unit costs

With the exception of RO DBT, mean costs of health and social services were estimated for each group by multiplying patients’ reported use by unit costs from national sources. 116–118 All unit costs, summarised in Table 2, were for the financial year 2014–15 and uprated, when necessary, using the Hospital and Community Health Services Index. 116 Medication costs were based on the median dose of the most common category of drug (e.g. ADM or antipsychotic medication) reported by participants. Assuming full compliance, participant-reported start and finish dates were used to estimate the duration of their time using that drug. Costs associated with depression-related absenteeism and presenteeism for patients in paid employment were estimated using the human capital approach based on the national gross average wage. 122,123

| Item | Source | Unit cost |

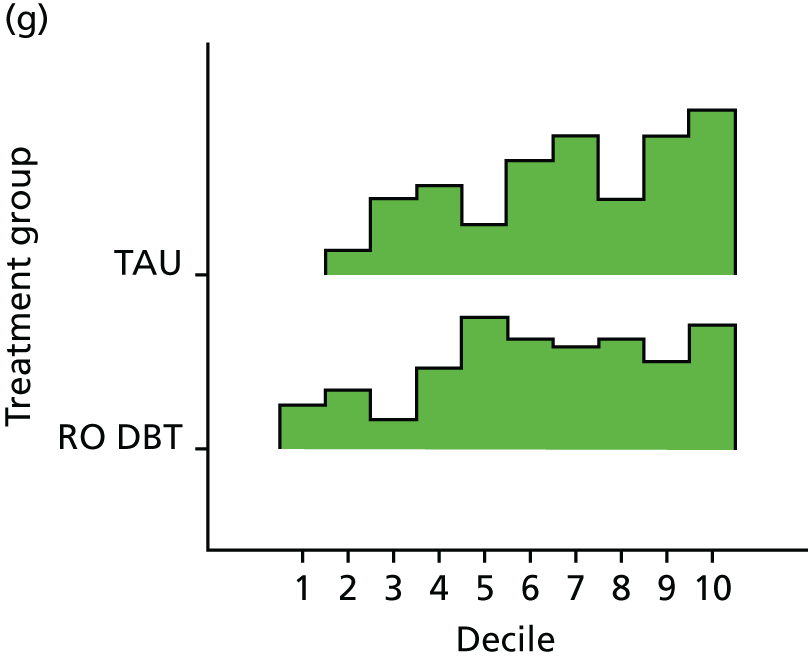

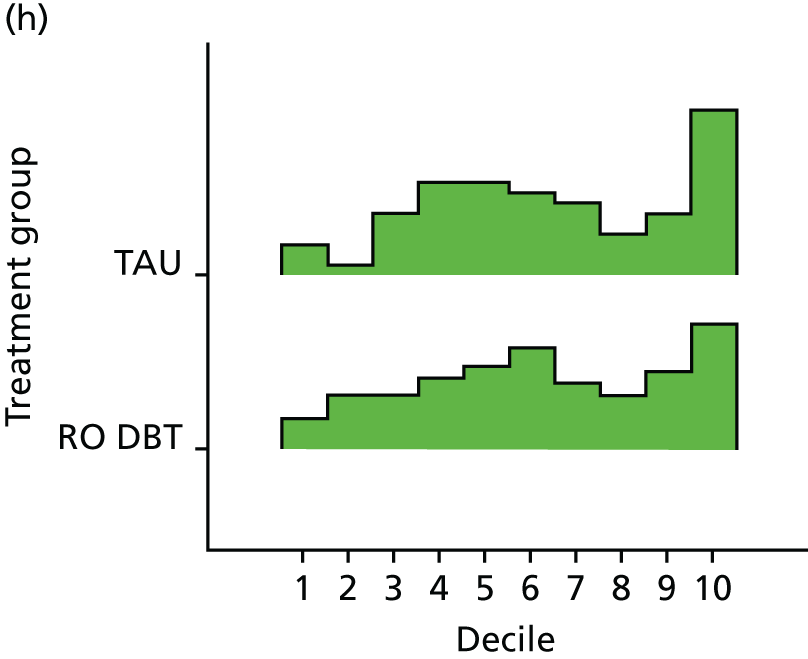

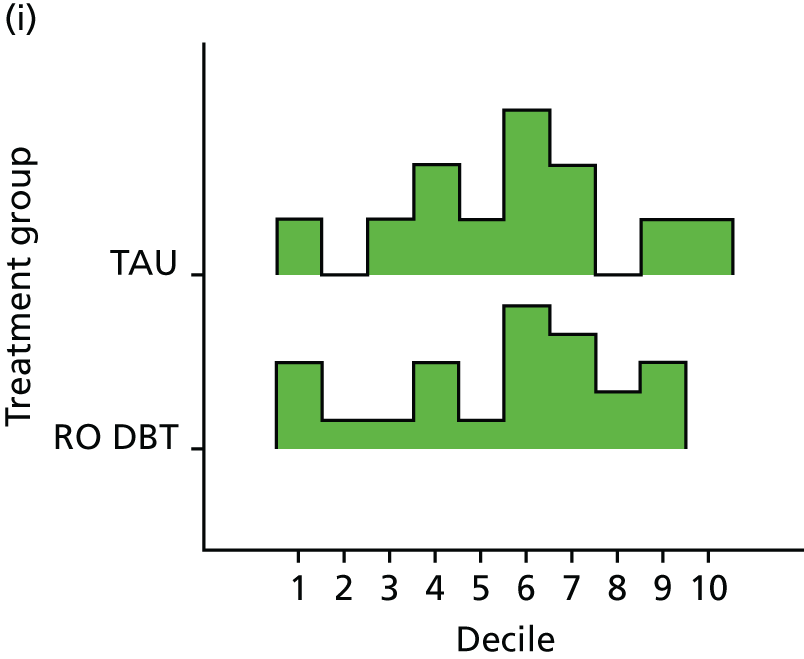

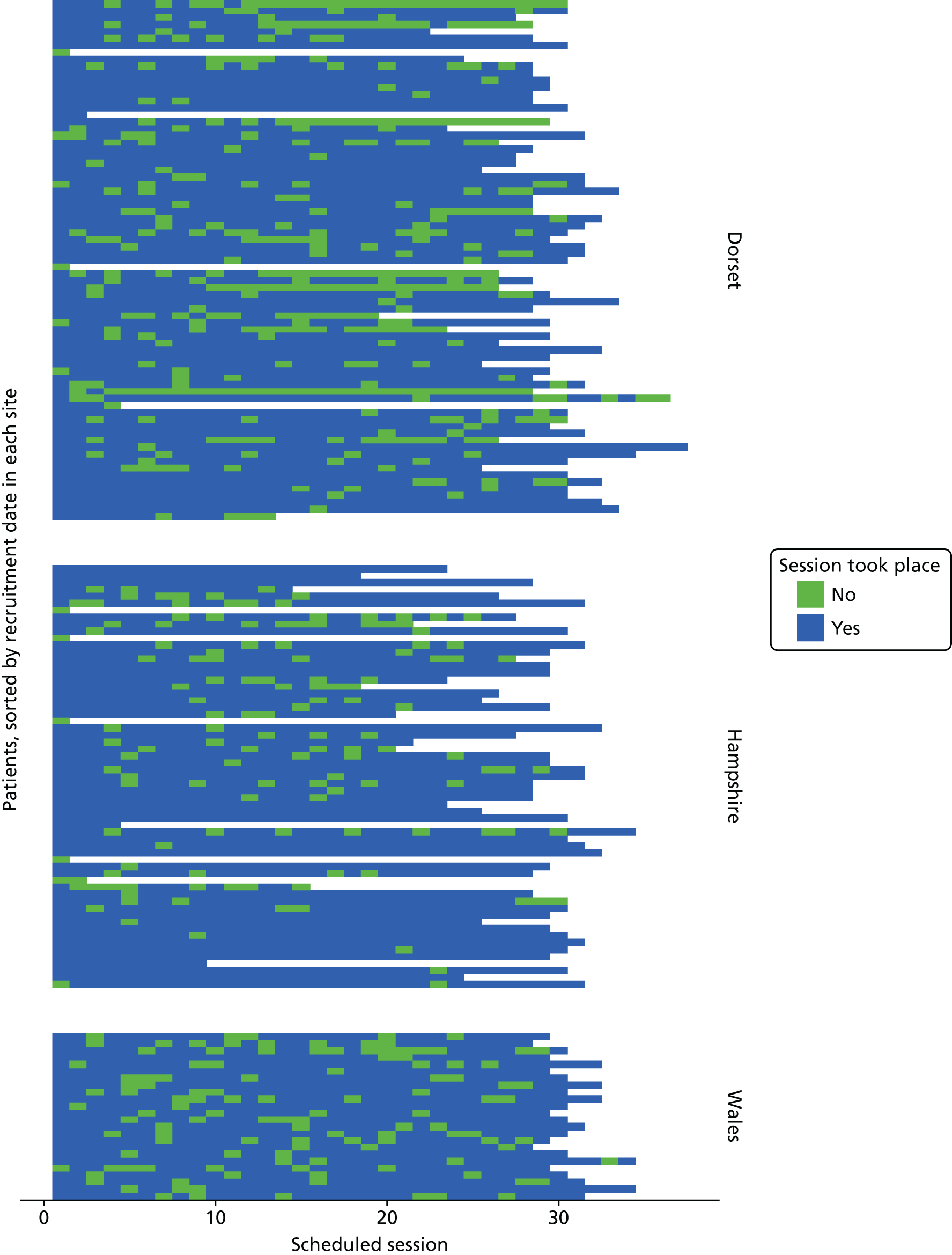

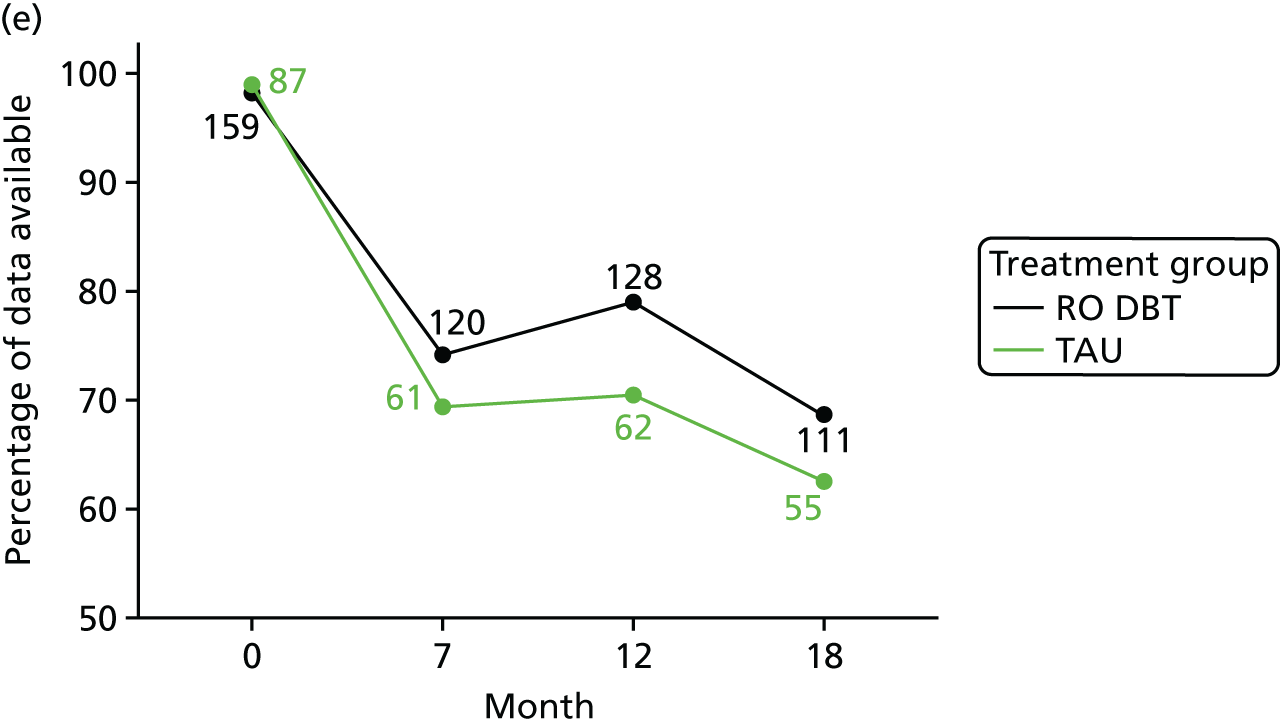

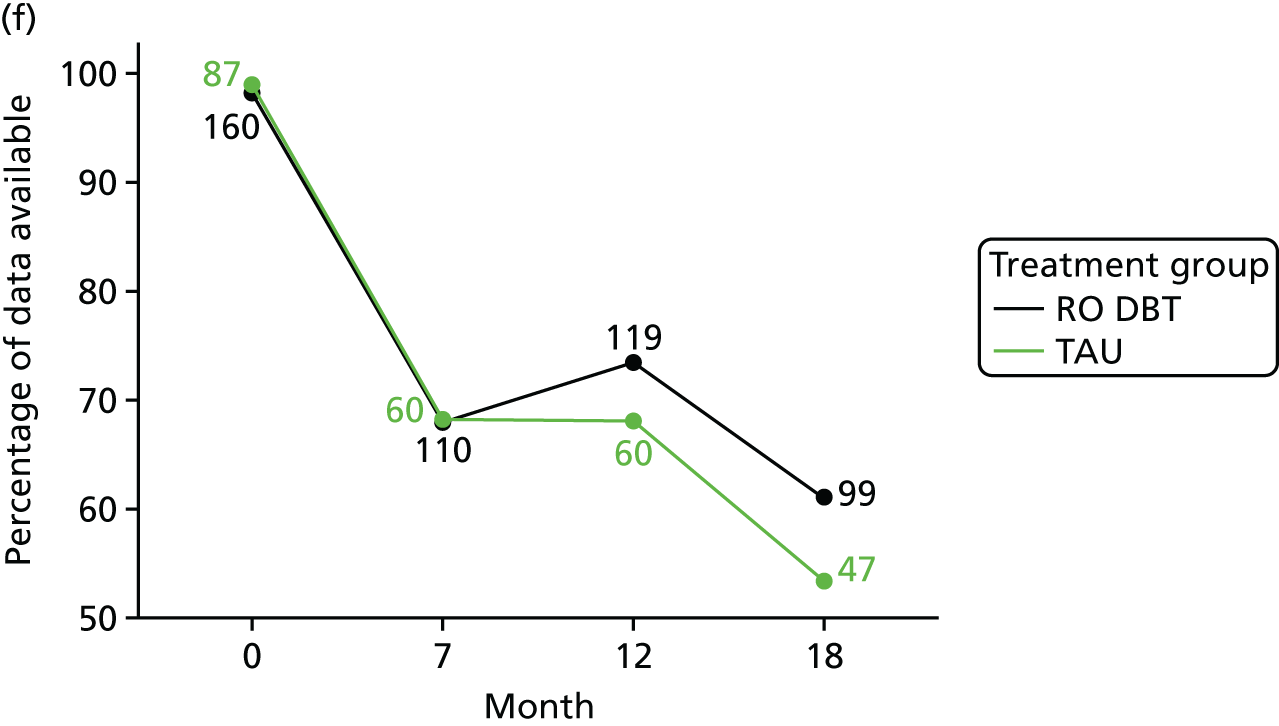

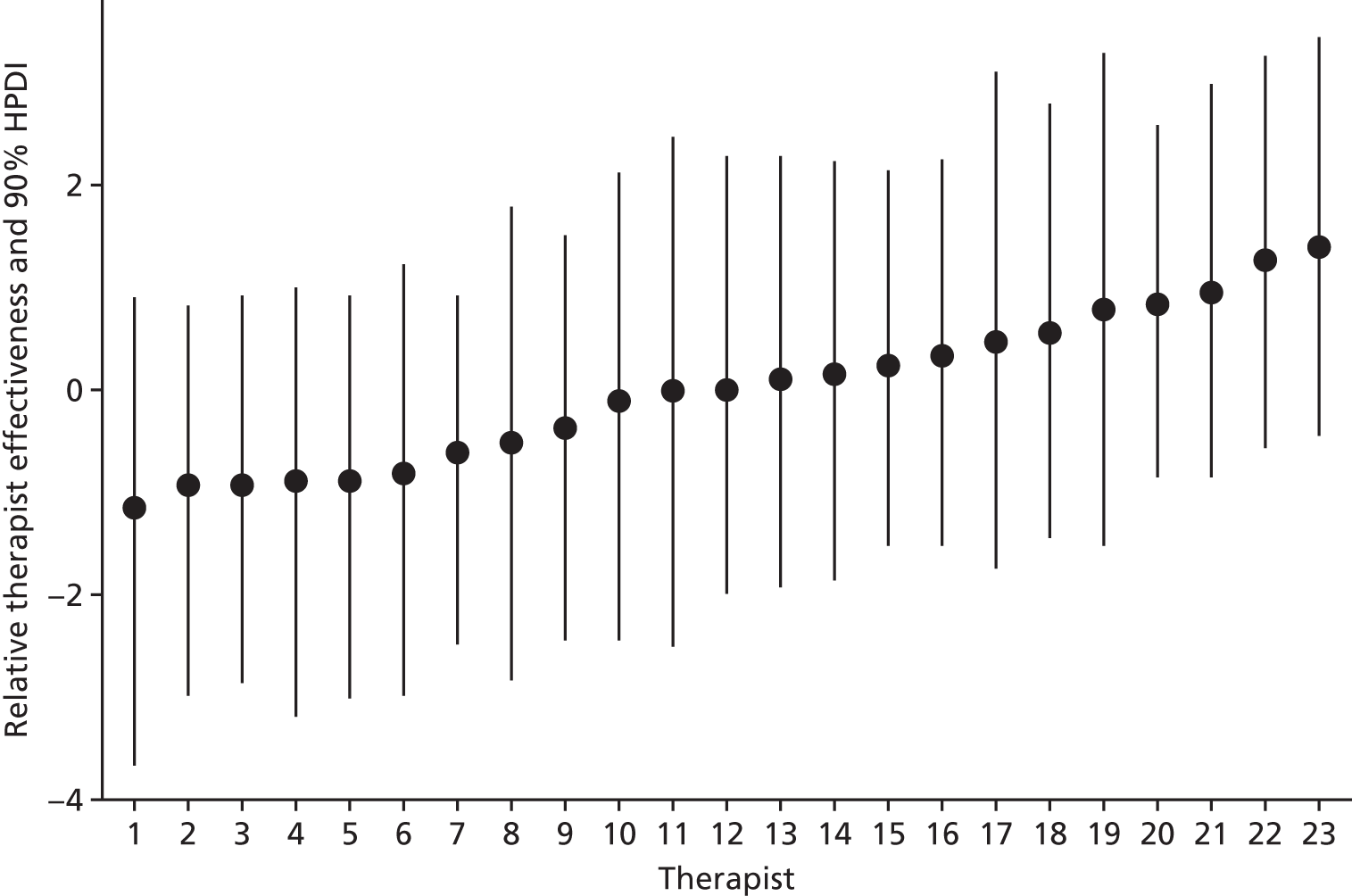

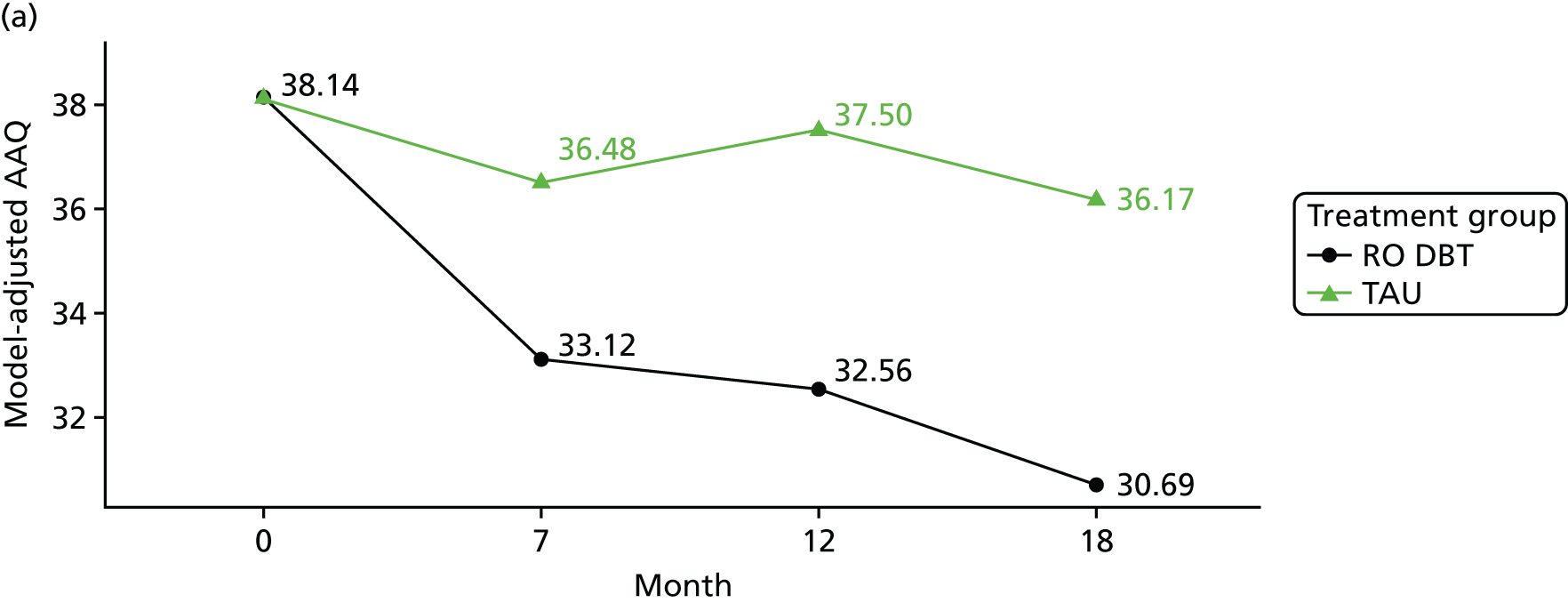

|---|---|---|