Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 14/202/03. The contractual start date was in January 2016. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts from group session recordings obtained in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Borek et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Optimising the effectiveness of health-related behaviour change interventions is contingent on understanding the mechanisms by which such interventions can bring about change and developing techniques to alter processes underpinning this change. Recent work on behaviour change has led to the identification, classification and integration of > 80 behaviour change theories1,2 and > 90 categories of behaviour change techniques. 3,4 Some techniques are frequently employed in behaviour change interventions and can be reliably identified from descriptions of interventions. 5 Evidence indicating which theorised mechanisms and which types of techniques might improve intervention effectiveness when targeting particular behaviours is accumulating. 6–8 For example, self-regulatory behaviour change techniques, such as goal-setting and self-monitoring, have been found to be associated with increased effectiveness in interventions targeting diet and physical activity. 6,8 However, the majority of the theorised mechanisms and technique types studied to date focus on individual-level, intrapersonal change, with little or no consideration of social, interpersonal or group-based processes and factors that shape health-related behaviour patterns. Furthermore, these mechanisms and techniques are often assumed to work similarly in interventions regardless of their delivery mode or setting (e.g. when self-delivered, delivered one to one, through group sessions, online or over the telephone).

For decades, small groups have been used to facilitate personal change in health-care, community, commercial and work settings. Theories explaining, and research into, how such groups work have developed over many years and across multiple disciplines. Research has demonstrated that groups are not just an intervention delivery mode (that allow delivery of an intervention simultaneously to many people) but, additionally, provide ‘active ingredients’ in facilitating personal change. For example, as early as 1905, Joseph Pratt highlighted the importance of group identification (or group ‘spirit’), social support and shared hope in psychotherapy groups for tuberculosis patients. 9 In addition to psychotherapy,10 groups have also been used to promote personal change in human relations training (also called sensitivity training or ‘T’ groups)11,12 and self-help and support programmes. 13 More recently, many health promotion and health-related behaviour change programmes have been delivered in groups. For example, interventions supporting self-management of chronic conditions,14–16 including type 2 diabetes mellitus17 and cancer,18 are commonly delivered in groups. Groups have also been used in preventative contexts to promote breastfeeding,19 walking and physical activity,20,21 smoking cessation22 and weight loss. 23,24

There is increasing evidence from systematic reviews that group-based interventions are effective for supporting change in a number of behavioural targets. 17,22,23 Indeed, particularly for weight loss, group interventions appear to be more effective than similar interventions delivered individually. 24 Group-based interventions therefore provide a time-effective and potentially cost-effective way to address important health challenges, including those related to growing rates of overweight and obesity that are contributing to the increasing burden of chronic conditions.

Group-based interventions show wide variation in their design and delivery. Perhaps because of this, there is still limited understanding of, and evidence on, which mechanisms lead to personal change in group interventions, how short- and long-term behaviour change is best facilitated in groups and what design features, change processes or delivery methods optimise the effectiveness of group interventions. Identifying important design features, change processes occurring in groups and techniques that can be used to facilitate changes is, therefore, a first step towards improving the effectiveness of group-based interventions. Group-based delivery provides an ideal opportunity for use of change techniques involving interpersonal interaction, such as ‘providing opportunities for social comparison’ or ‘prompting identification as a role model’. 3 Furthermore, some types of change techniques are unique to group settings, such as ‘engage group support’ or ‘communicate group member identities’. 25 It is unclear, however, how pre-categorised change techniques and processes operate in groups and how they are influenced by group characteristics, context and facilitation, and which currently undefined, group-specific techniques and processes may support personal change in groups. Therefore, the lack of clarity about what works and how is even more acute in group-based than individual behaviour change interventions.

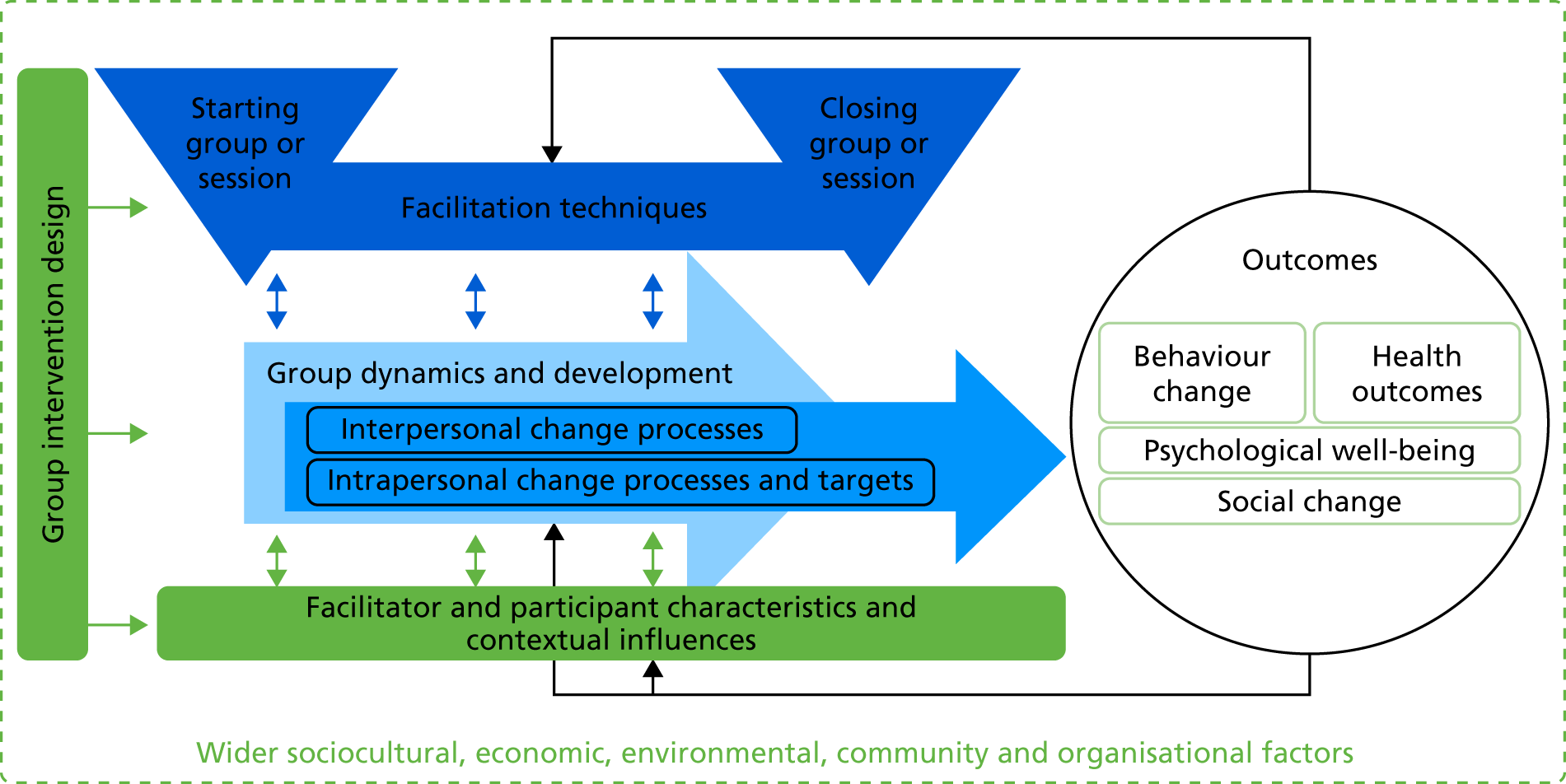

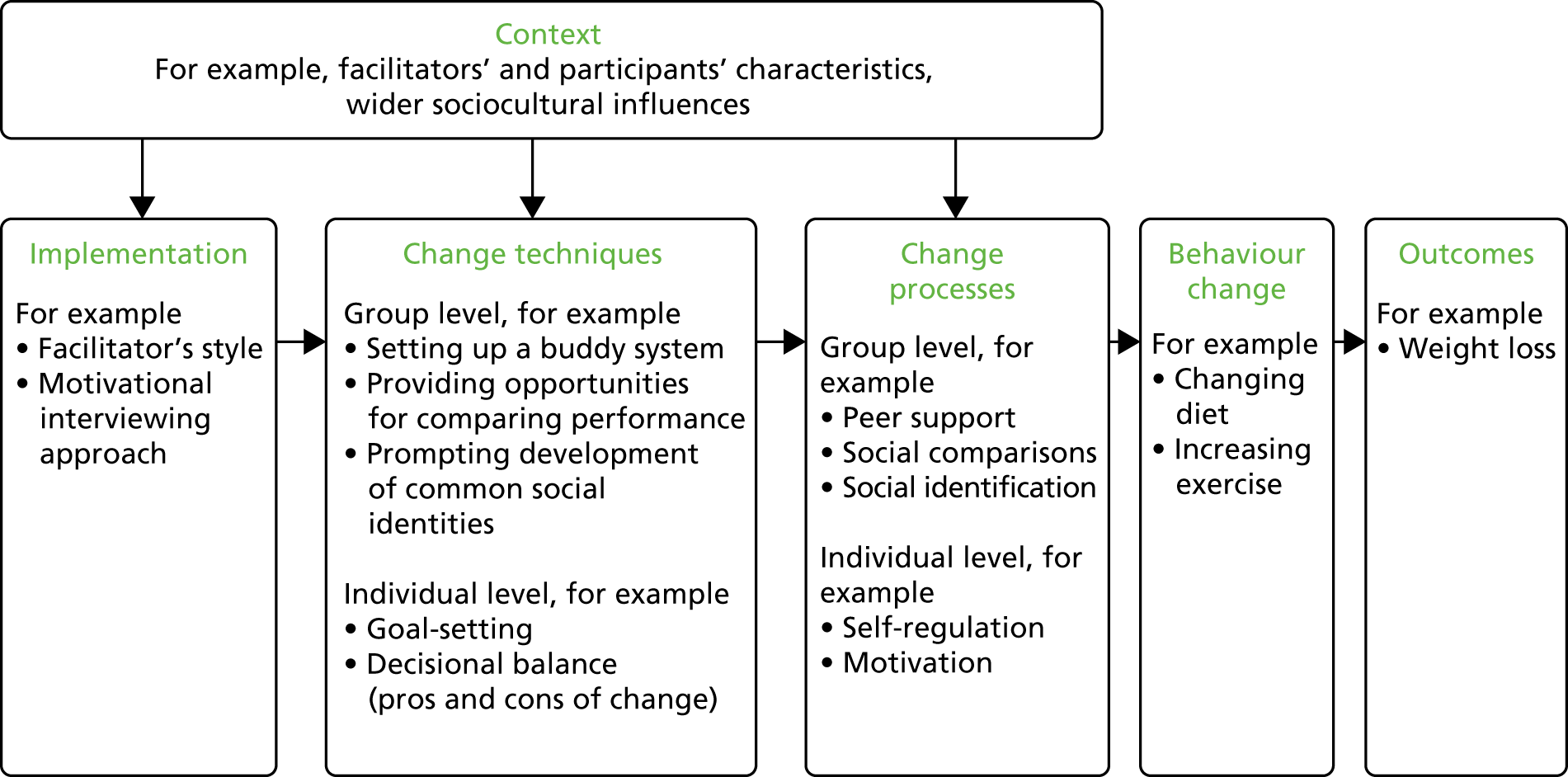

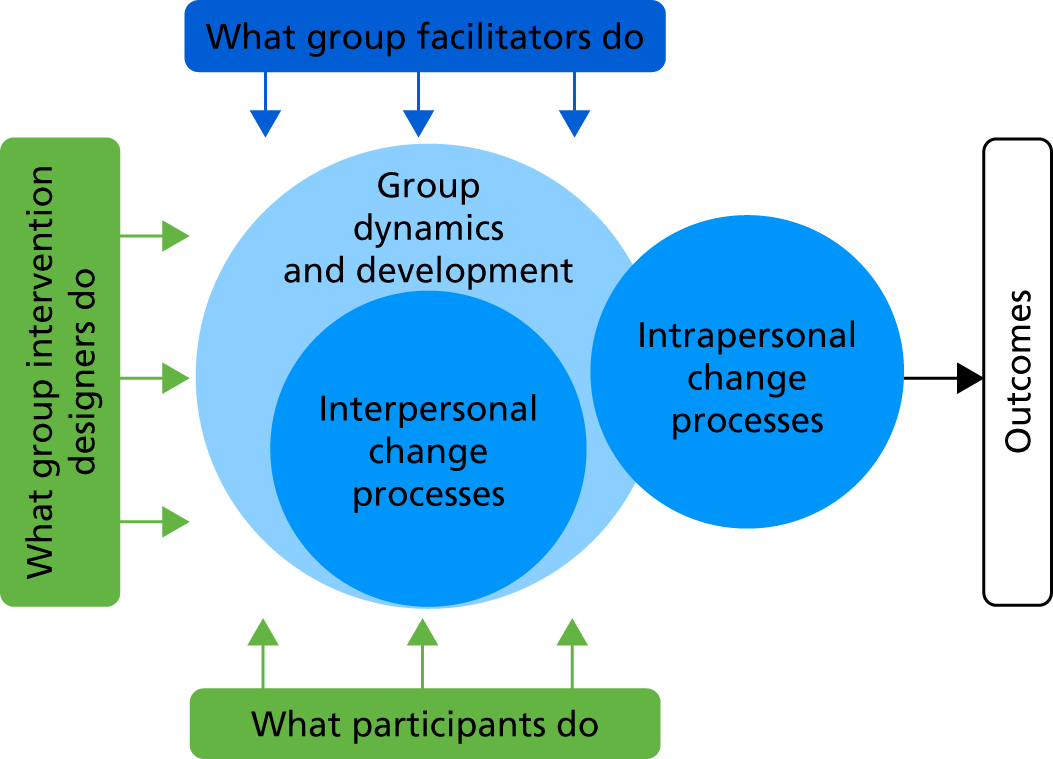

Understanding change processes in groups is crucial to the design and evaluation of group-based health interventions. Medical Research Council (MRC) guidance26,27 on developing complex health interventions highlights key questions that intervention designers need to ask, including about what the intervention aims to achieve and change, and how. Considering groups only as a delivery mode limits their potential to contribute to the theoretical underpinnings, often represented in a logic model explaining the mechanisms by which the intervention works. MRC process evaluation guidance28,29 further emphasises that, in order to understand how complex interventions work, it is important to describe and assess (1) how they are delivered and implemented (fidelity and quality of implementation), (2) their mechanisms of action (causal processes generating change) and (3) whether or not, and how, they may work differently across settings and contexts (contextual influences). As shown in Figure 1, all three of these domains have implications for delivering health interventions in groups.

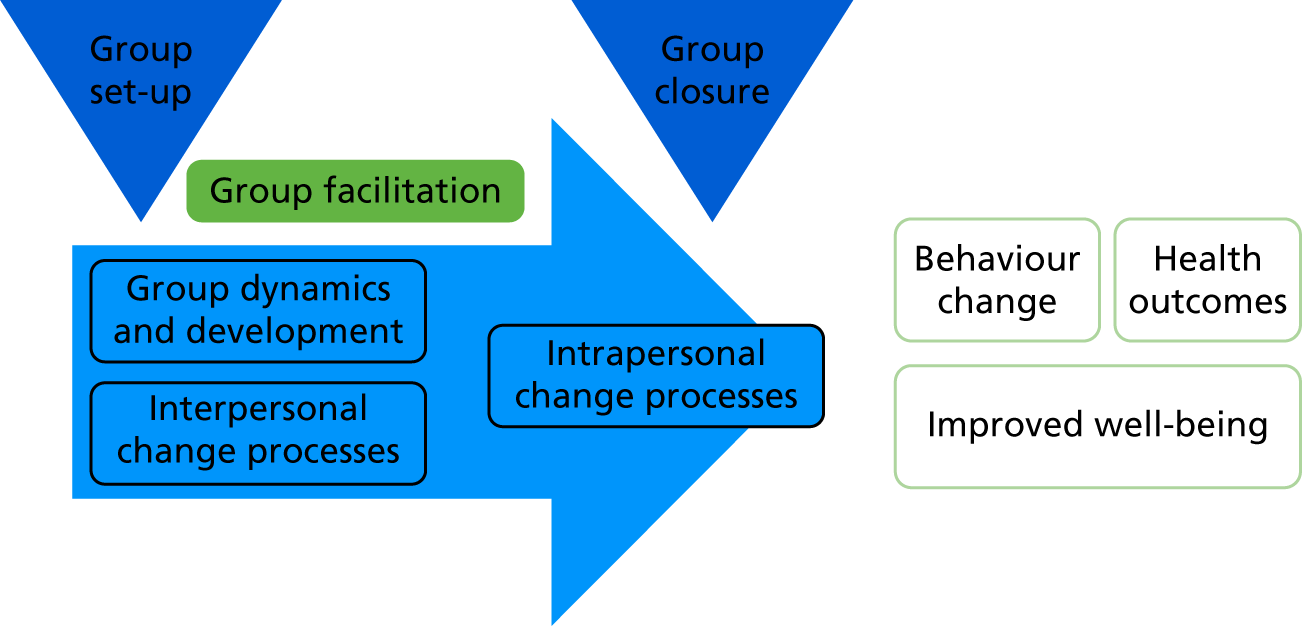

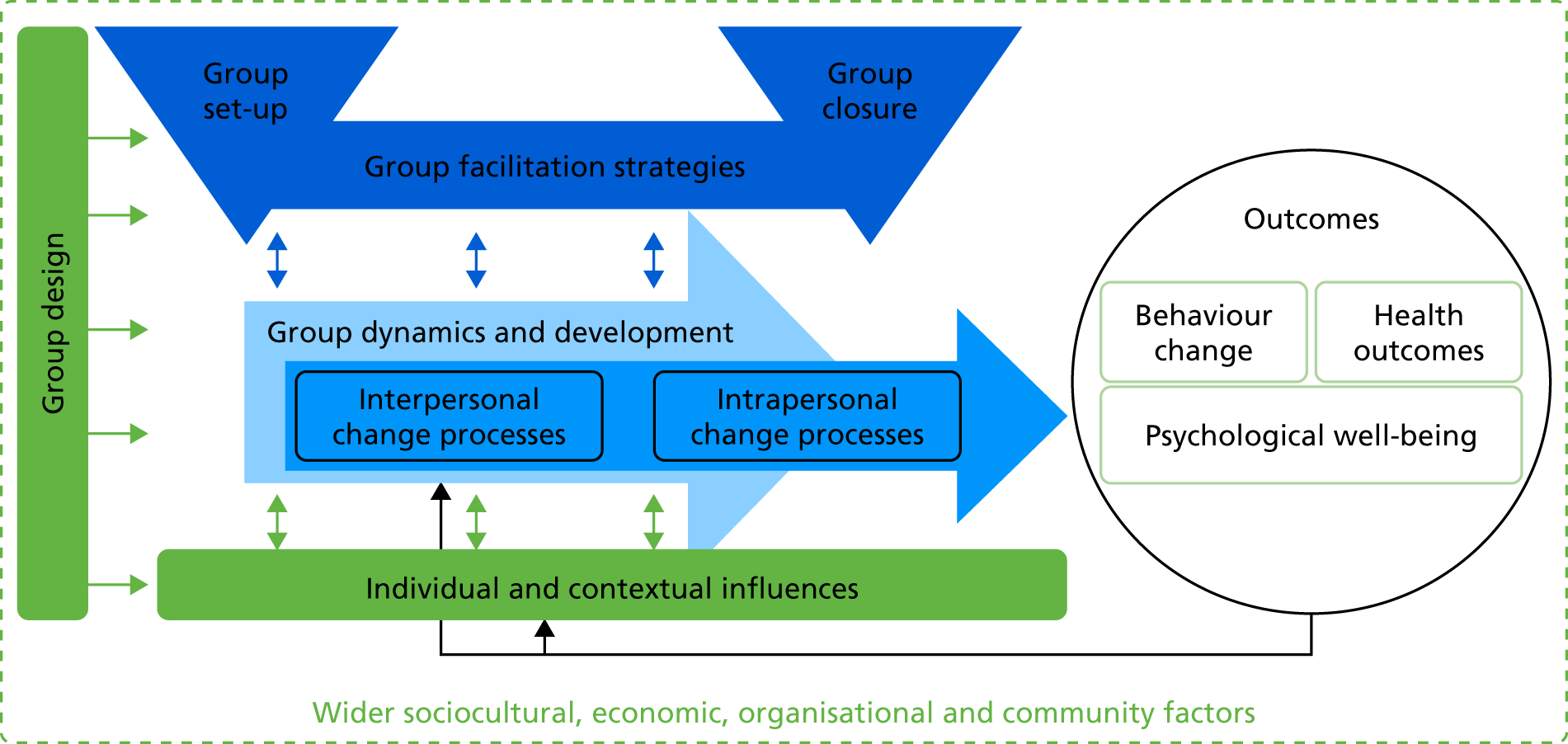

FIGURE 1.

Logic model of components influencing behaviour change and outcomes in group interventions. Note: the figure draws on logic model framework presented in MRC process evaluation guidance28,29 showing generic processes that may occur in group-based interventions that are broadly organised into the key commonly included process evaluation elements of context, implementation, mechanisms of action (i.e. how interventions produce change in participants) and outcomes. 28,29

First, it is important to document and investigate how interventions are implemented in groups, including the amount (‘dose’) and pattern of group contact, training of facilitators, resources used, fidelity of delivery and if, or what, adaptations in delivery are made when the same group-based intervention is replicated in different contexts. It may also be important to explore differences between groups in relation to facilitator delivery style and participant engagement and interaction. Second, investigating change processes in groups is important in understanding mechanisms by which they have an impact on psychological and behaviour change, including potentially unexpected or adverse processes and consequences. Third, group interventions may be affected by contextual factors, including the wider sociocultural environment (e.g. social norms and values), organisational context (e.g. climate, setting or type of organisation) or individual characteristics and circumstances that participants and facilitators bring to groups (e.g. gender, available external support and social networks). These group-related moderators of intervention effects are often omitted in studies that focus on mechanisms or mediators of intervention effects in isolation, such as studies in which change techniques are considered separately from aspects of implementation and context. 30

The lack of understanding about how behaviour change interventions work, particularly when delivered in groups, is further compounded by reliance on systematic reviews and meta-analyses to explore quantitative relationships between intervention features and outcomes across previous studies. 6,8,31 Despite the importance of synthesising data across multiple studies, this type of research assumes that descriptions of interventions, which are often brief in journal articles or design protocols, are complete and accurate reflections of what was delivered in practice. A critical limitation of this approach is that it cannot account for differences in fidelity (i.e. the extent to which the intervention was delivered in line with the protocol) or style of delivery. This review of group-based weight loss interventions has shown that details of fidelity assessment in group session delivery, the methods used to facilitate groups, group processes observed and change techniques employed are rarely reported. 23 A review of group studies in nursing journals showed that information on the conduct of groups and attempts to account for group-level effects in analyses were largely absent. 32 This makes it impossible to identify the ‘active ingredients’ and change mechanisms in group interventions from study reports included in systematic reviews. It also makes it difficult to accurately replicate effective group-based interventions.

In addition, meta-analytic data are only as good as the categories used to group and differentiate between the included interventions. Consequently, if the categories are too inclusive (i.e. they count interventions as having similar features when they are, in reality, different), then the results can be misleading. This has been referred to as the ‘apples and oranges’ problem. Abraham33 illustrated how this problem may affect interpretation of meta-analytic studies in which the authors sought to identify techniques designed to alter psychological processes in behaviour change interventions. Consider, for example, a category of change techniques such as ‘encouraging social support’. This refers to a variety of facilitation techniques designed to prompt change in interpersonal relationships between the target person and some other person(s). Yet we know that there are many different types of social support that can be provided by many different people and evidence shows that these have quite different psychological effects on the receiver. 34 Similarly, meta-analytic studies may generate misleading findings if they do not include categories of techniques that are critical to real-world change. For example, a review of 72 evaluations of interventions designed to alter eating behaviour identified 19 categories of techniques employed to modify or manage impulsive processes associated with unhealthy eating behaviour, many of which had not been used in previous meta-analyses of healthy eating interventions. 35 There is, therefore, a need for research to enrich understanding and enhance specificity of how similarities and differences between behaviour change interventions are conceptualised.

This need is especially evident in relation to group-based health-related behaviour change interventions, for which research is needed to identify what processes underpin personal change in such groups and which techniques, or groups of techniques, can be employed to modify those processes. Such research can draw on an extensive literature from social psychology, education and organisational studies on how groups in general work and how they influence individuals. Unfortunately, however, this literature has been largely ignored in designing and evaluating group-based health interventions. 36 In particular, social psychological literature on group dynamics from which more specialist fields evolved (e.g. work-related teams and educational groups) describes how both intrapersonal and interpersonal processes operate in groups. 37–39 A review of this literature40 has identified a number of theories describing change processes in groups, such as social comparisons,41 social learning,42 social identity43 and social facilitation44 theories, that could be used to enhance our understanding of how groups influence individuals and how group context and facilitation can enhance or inhibit change in health interventions. Moreover, the ‘social cure’ approach to health applies social identity theory to conceptualise links between group membership and improved health. 45,46 Qualitative studies with group participants and facilitators also highlight the importance of the group context in influencing engagement with health interventions and behaviour change. For example, interviews conducted with participants in three different group-based health interventions showed that making social comparisons, developing a shared social identity and creating a supportive and friendly group context were important factors that facilitated participants’ engagement with the interventions and lifestyle changes. 47–49 Effective facilitation of groups to promote these group-level processes can be challenging, particularly for lay leaders,50 and it requires specific competencies. For example, 23 facilitator competencies, such as ‘encourage group discussions’ or ‘encourage mutual support’, have been identified as being required to deliver group-based smoking cessation interventions. 51 However, there is little evidence on which (and how) skills and competencies are employed in practice, which might lead to inadequate training of group facilitators.

The importance of employing systematic approaches to designing and evaluating group-based health interventions has been stressed previously. 36 This provided an important first step by identifying some of the key factors in group interventions related to group leaders, participants, community and environment. However, it does not show how these factors are related to change techniques and mechanisms of change. Borek and Abraham40 present a conceptual model linking our understanding of group processes and personal change to change mechanisms in group interventions. The work reported in this study extends that model and seeks to identify change techniques that may optimise the effectiveness of group interventions.

In contrast to many of the recent approaches to behaviour change, we began with an assumption – based on wider research on groups – that change processes can be influenced by, or even unique to, group delivery. Therefore, the promotion of individual change in groups may be critically different from that in individual behaviour change interventions because the former activate distinct interpersonal change processes. More generally, different delivery modes (e.g. internet based vs. face to face) may prompt different change processes and so affect effectiveness even when intervention content appears similar.

Groups provide opportunities for enhancing individual change processes and instigating social change processes, but may also impede some change processes or have adverse or unintended negative consequences. For example, groups may enhance individual problem-solving by providing opportunities to share and draw from others’ ideas, access peer support and identify with people in a similar situation. However, lack of time and/or tailoring to individual needs in a group might impede individual goal-setting and review, negative group dynamics might impede engagement and/or attendance, and poorer performance compared with other group members might lead to decreases in self-efficacy. Moreover, group facilitators’ characteristics and skills may improve effectiveness for one group but decrease effectiveness for another, depending on relationships between the facilitators and group members. 52 Techniques to alter normative beliefs may promote behaviour change among young people but reduce intervention effectiveness for older recipients. 53 Group climate and group cohesion may increase attendance and self-efficacy (in exercise classes). 54 The use of humour may help engage middle-aged men in a weight loss intervention55 but have an opposite effect among young women in a sexual health intervention. 56 Furthermore, many health-related behaviour patterns are influenced by sociocultural contexts (e.g. social norms) and are social practices enacted in social contexts (e.g. eating with others, eating out) with attached meanings, norms and values. Groups can, therefore, help change behaviour patterns that are both individual and social. For example, they can help change individual perceptions of social norms, identify solutions to common barriers encountered in social contexts, change meanings and values attached to social practices, or provide opportunities to practise relevant social skills, such as communication skills. Consequently, sophisticated models of group operation including specification of change mechanisms, group composition, facilitator characteristics and techniques employed by facilitators to promote personal change, as well as other influences of group implementation and context, are needed to optimise group-based interventions.

In summary, although group interventions are effective and commonly used in health-care and public health contexts, their mechanisms of action, representing how and why they work, have not been systematically explored. It is therefore not clear how groups operate and group processes function to engender or impede personal change, and what factors related to implementation and context influence mechanisms of change and intervention outcomes. Most current thinking about mechanisms that underpin behaviour change is based on individual-level theories. Moreover, meta-analyses of intervention components associated with effectiveness are mainly based on descriptions of interventions, which, particularly for group interventions, are limited by a lack of comprehensive reporting and inadequate categorisation of the real-world differences between interventions. Distinctions between group implementation, facilitation, change processes, change techniques and contextual factors are rarely clarified in a way consistent with the MRC framework for process evaluation,28,29 and there is little evidence on how these components are manifested in practice. The most modifiable elements of group-based interventions are the change techniques that facilitators use and their style of delivery. We do not, however, have a conceptual framework for systematically investigating what processes and techniques operate, and are effective, in group interventions, or for identifying facilitators’ delivery techniques and styles, and their influences on these processes. This is problematic for the construction of logic models in intervention development, the design of process evaluations and the training of facilitators in intervention delivery. Only with a better understanding of the change mechanisms in group interventions, and guidance on how important processes can be activated and facilitated, will we be able to guide development and delivery of interventions to optimise effectiveness. Starting with the MRC process evaluation guidance28,29 and existing literature on groups, this study is a step towards addressing these gaps in the research.

Study aims and objectives

This Mechanisms of Action in Group-based Interventions (MAGI) study aimed to develop a better understanding of mechanisms of action in group-based health-related behaviour change interventions by identifying, describing and synthesising possible processes of change in groups. It also aimed to develop and illustrate methods for exploring the influence of change processes in group-based behaviour change interventions (GB-BCIs). We focused on the example of group-based weight loss interventions targeting diet and physical activity. Our hypothesis was that behaviour change interventions delivered in groups involve change techniques and change processes that are specific to the group setting, and that may be influenced by implementation and contextual factors. The successful initiation and facilitation of these change techniques and processes would lead to increased engagement with the intervention and more effectively promote behaviour change (e.g. diet and physical activity), thereby improving intervention outcomes (e.g. weight loss). Overall, the project aimed to increase understanding in order to guide the future design, delivery and evaluation of GB-BCIs.

In order to achieve this aim, the study had three more specific objectives. These were to:

-

develop a generalisable framework of mechanisms of action in GB-BCIs by identifying, defining and categorising potentially important group design features, group processes, facilitation techniques and contextual factors in groups

-

test and refine the framework, using a coding schema derived from it, as a tool for identifying these group features, processes and facilitation techniques in the recordings of sessions from three GB-BCIs (focused on diet, physical activity and weight loss), and to provide examples to illustrate framework elements

-

develop mixed-methods approaches based on the framework to explore why some groups may be more or less successful than others, and to illustrate their use with available qualitative and quantitative data from a GB-BCI.

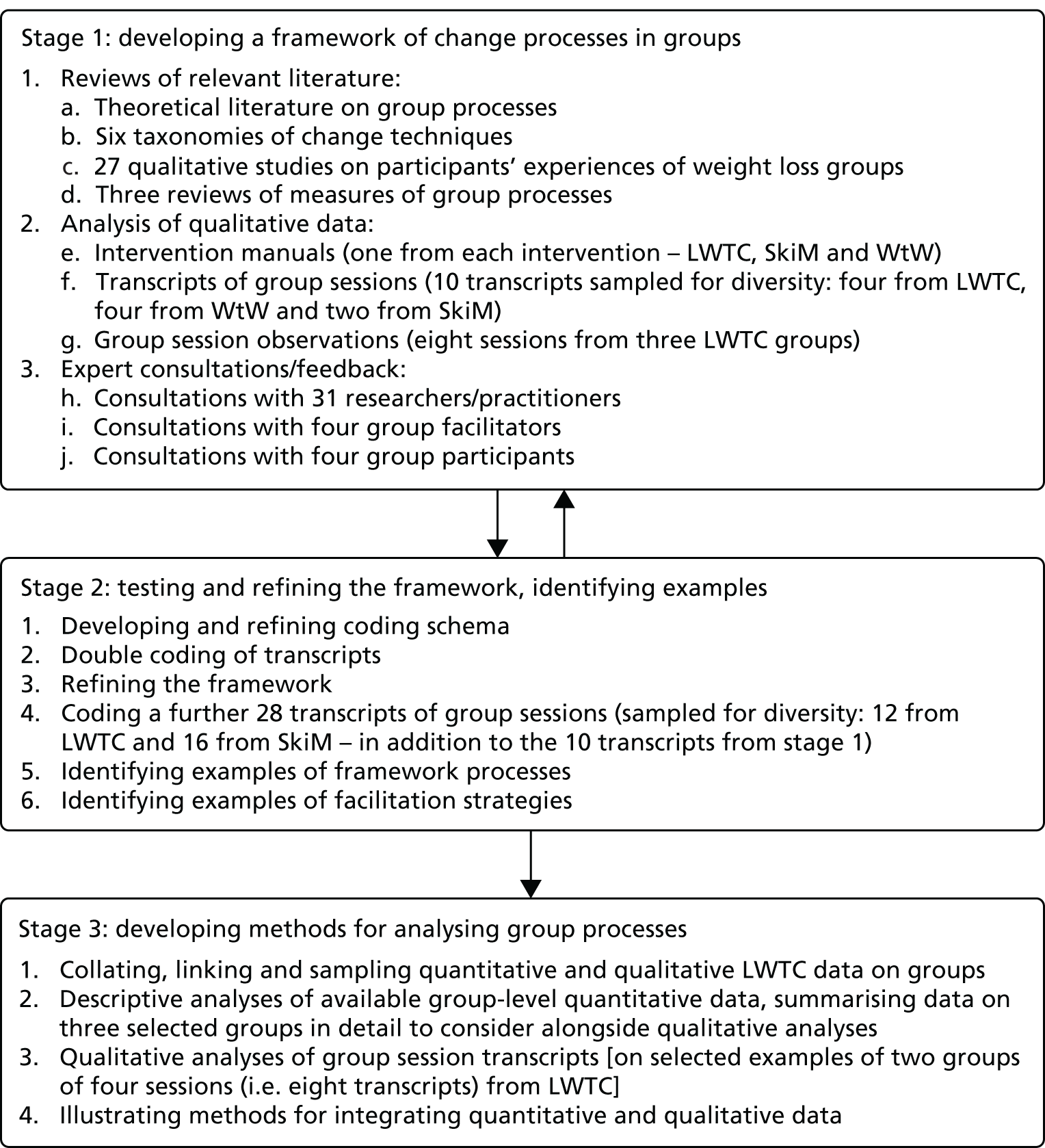

Study outline

These three objectives were addressed in three stages, which are reported in the subsequent chapters: Chapter 2 provides a description of the framework and its development (objective 1), Chapter 3 reports on the development and use of a coding scheme derived from the framework for analysing group sessions and provides examples of the concepts, processes and techniques included in the framework (objective 2), and Chapter 4 reports on the development of methods for applying the framework to analyse how groups work in a weight loss intervention and how such methods might be employed to explore potential links with outcomes (objective 3). Figure 2 outlines the tasks completed in the three stages over 20 months between January 2016 and August 2017.

FIGURE 2.

Outline of the key stages of the MAGI study. LWTC, Living Well Taking Control; SkiM, Skills for weight loss Maintenance; WtW, Waste the Waist.

Sources of data: three group-based interventions

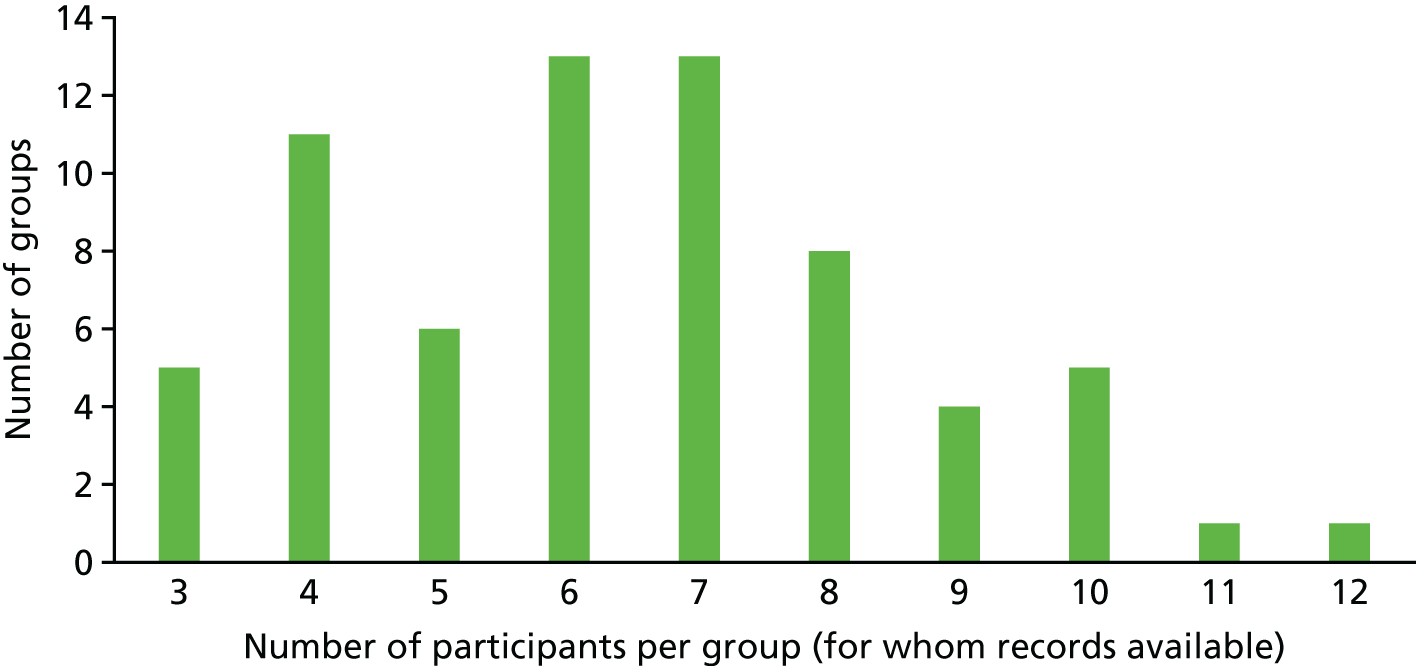

The MAGI study builds on three studies of GB-BCIs: the ongoing (at the time of conducting this study) Community-based Prevention of Diabetes (ComPoD) trial (Jane Rebecca Smith, University of Exeter Medical School, September 2017, personal communication) that evaluated the Living Well Taking Control (LWTC) programme and the Skills for weight loss Maintenance (SkiM) study (Colin Greaves, University of Exeter Medical School, September 2017, personal communication), and the completed Waste the Waist (WtW) study. 57–59 All three were primarily delivered in South West England and targeted adults who were overweight [average body mass index (BMI) in the obese range]. The ComPoD and WtW studies targeted other risk factors for chronic disease, and recruited samples that were older but otherwise broadly representative of local populations in terms of their gender mix and low numbers of participants from non-white British backgrounds. The interventions all targeted lifestyle changes, such as improving diet and increasing physical activity, in order to achieve or maintain a healthy weight and prevent obesity-related diseases (i.e. type 2 diabetes, cardiovascular diseases). The interventions were delivered in small groups (up to 12 participants) by facilitators with backgrounds in health promotion, and in accordance with intervention delivery manuals. In this study, we used secondary data that were already available or able to be collected as part of the ongoing studies, including intervention delivery manuals, audio-recordings of group sessions and outcome data. In particular, we used audio-recordings made as part of the process evaluations and quality assurance in the three studies (ComPoD: ≈80 sessions, SkiM: ≈88 sessions, and WtW: ≈36 sessions). The three studies had received research ethics committee approvals (ComPoD: 14/NW/1113, SkiM: 5/SW/0126, WtW: 10/H0206/74) with participants giving consent for audio-recording the sessions for use in research. In the following sections, we describe each study, and Table 1 summarises the key details of the interventions and data used from each study.

| Study details | Intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| LWTC/ComPoD | SkiM | WtW | |

| Intervention details | |||

| Aim | Improve diet, increase physical activity and improve well-being to promote weight loss and prevention/management of type 2 diabetes in those at risk/newly diagnosed | Address weight loss maintenance issues in obese adults accessing weight management services | Promote healthy eating, physical activity and weight loss for people with high cardiovascular risk in primary care |

| Setting, venue | Community venues in and around Exeter and Birmingham | Community venues in Devon | Community venues in Bath and North East Somerset |

| Provider | Westbank Community Health and Care, westbank.org.uk (Exeter); Health Exchange, healthexchange.org.uk (Birmingham) | Westbank Community Health and Care, and the Healthy Lifestyles service of Torbay and South Devon NHS Foundation Trust | Local, community-based facilitators recruited for the research study |

| Contact time | Four weekly 1- to 2-hour group sessions plus five follow-up support contacts at 2, 3, 6, 9 and 12 months (varying in delivery format across time points/sites) and access to ≥ 5 hours of classes/activities (e.g. exercise classes, walking groups, cooking classes) | 14 fortnightly 1.5-hour sessions | Four weekly 2-hour sessions plus five 1.5-hour follow-up sessions, up to 1 year |

| Main content | Information and addressing common misconceptions around type 2 diabetes, clinical risk factors (e.g. HbA1c levels) and lifestyle changes | Address weight loss maintenance issues based on principles including the personal assessment and management of sources of ‘tension’ caused by making lifestyle changes and managing internal and external influences on this tension | Promotion of healthy eating, physical activity and weight loss, plus motivation, social support, self-regulation and understanding of the behaviour change process |

| Participants’ materials | Participant handbook, self-monitoring diaries | Participant handbook, self-monitoring diaries, automated telephone text reminder service | Participant handbook, self-monitoring diaries |

| Group composition and allocation of participants | Up to 12 participants (partners could attend), allocated to groups based on location/time | Up to 15 participants | 8–12 participants (partners could attend), allocated to groups based on location |

| Number and professional background of facilitators | One facilitator per group with nutrition or physical activity background | One facilitator with weight loss management background and | Two co-facilitators per group, with nutrition, physical activity, fitness or health promotion background |

| One assistant per group with visiting experts (dietitian, fitness trainer) in some sessions | |||

| Facilitator training and materials | 1-day training in intervention delivery; facilitator manual | 2-day training in intervention delivery, person-centred counselling style and group facilitation; feedback meetings every 2 months to discuss progress and to problem-solve any barriers to delivery; facilitator manual | 2.5-day training in intervention delivery and person-centred counselling style; feedback meetings every 2 months to problem-solve any barriers to delivery; facilitator manual and slides |

| Data used in the MAGI study | |||

| Delivery manuals | LWTC – Pre-diabetes Training Manual (v4, August 2013, 52 pages); authors: Westbank and Health Exchange, with advice from Colin Greaves, University of Exeter Medical School, (unpublished, available from authors on request) | SkiM weight management programme – Programme Manual (v1, March 2016, 185 pages); authors: Colin Greaves, University of Exeter Medical School, and Leon Poltawski (unpublished, available from authors on request) | WtW – Lifestyle Coaches Manual (2011, 73 pages); authors: Colin Greaves, University of Exeter Medical School, Afroditi Stathi and Fiona Gillison (unpublished, available from authors on request) |

| Session recordings (see Appendix 1) | 24 in total | 18 in total | 4 in total |

| Stage 1 | Four transcripts: two from two groups, delivered by two facilitators | Two transcripts from one group, delivered by one facilitator | Four transcripts: two from two groups, co-delivered by two of five facilitators |

| Stage 2 | 12 transcripts from eight groups, delivered by four facilitators | 16 transcripts: four from four groups, delivered by two facilitators | |

| Stage 3 | Eight transcripts from two groups, delivered by two facilitators | ||

| Session observations | In stage 1: eight sessions from three groups | None | None |

| Quantitative data | In stage 3: participant characteristics, attendance and outcomes collected by providers as part of programme | None used | None used |

Living Well Taking Control programme in the Community-based Prevention of Diabetes trial (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN7022167060,61)

The LWTC programme was an existing community-based diabetes prevention and management programme delivered by voluntary sector organisations from late 2013. The structure, content and delivery of LWTC were intended to be compliant with all 11 recommendations of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance for diabetes prevention interventions. 62 A before-and-after service evaluation of the LWTC programme led by the University of the West of England was completed in September 2016. 60 The clinical outcomes and cost-effectiveness of the diabetes prevention component were evaluated in the ComPoD trial, which was a randomised waiting list controlled trial completed in March 2017. In the ComPoD trial, 314 adults at a high risk of developing type 2 diabetes were recruited via general practices and randomised to receive the LWTC programme either immediately (intervention group) or after 6 months (waiting list control group). The study primary outcome was objective weight loss, and secondary outcomes included changes in physical activity (assessed via accelerometers), blood glucose levels [indicated by levels of glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c)] and self-reported diet and well-being at 6 months, with observational follow-up at 12 months of the intervention group only.

Skills for weight loss Maintenance study (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN45134679)

The SkiM study is a feasibility study using an action research design and observational (pre–post) evaluation of weight outcomes, which was ongoing at the time of writing. The aim is to develop intervention materials that specifically address weight loss maintenance and integrate them into existing weight management services. The study aims to inform development of a future trial that will be used to evaluate the resulting intervention programme. A total of 45 adults with a BMI of > 30 kg/m2 were recruited in the first round of intervention delivery. They had agreed to take part in one of two existing tier 2 community-based weight loss programmes delivered by local participating voluntary sector and NHS-based service providers. As well as feasibility measures for a future trial (e.g. recruitment, attendance, retention rates), the study outcomes include change in weight at 6, 12 and 18 months, physical activity (assessed via accelerometers), BMI, waist circumference and self-reported health status. A process evaluation assesses engagement, processes of change, intervention fidelity and ways in which the intervention could be improved using participant and provider interviews, questionnaires, session recordings and observations. Data gathered during a first presentation of the intervention was used to refine the intervention, then evaluated in a second iteration.

Waste the Waist study (www.isrctn.com/ISRCTN1070789957–59)

The WtW study, completed in 2013, was a pilot randomised controlled trial of a theory-based group intervention. A total of 108 adults at a high risk of type 2 diabetes or heart disease were randomised to the group-based intervention plus usual care or to usual care alone. The primary outcome was change in objective measures of weight at 12 months. Secondary outcomes included changes in diet, physical activity (assessed via accelerometers), markers of cardiovascular risk (e.g. blood pressure, blood glucose) and quality of life at 4 and 12 months.

Key terms

Throughout this report, we use a number of key terms, some of which are defined in Table 2. Other terms, in particular those derived from the literature reviews, are defined in Table 3.

| Key terms | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Mechanisms of action | Components of interventions in health behaviour change interventions, including change techniques and change processes, through which an intervention has its effect, in our examples leading to changes in participants’ behaviour and health outcomes |

| Change processes | Processes that are theorised to lead to individual behaviour or other psychological change, and thus, other intervention outcomes; they may instigate and facilitate change, or impede it. For example, motivational, learning processes |

| Interpersonal change processes | Change processes that are instigated through interaction with, or presence of, one or more other people |

| Intrapersonal change processes | Psychological processes that occur within individuals to bring about personal change |

| Change techniques | Techniques that facilitators can use, or prompt participants to use, to instigate or support change processes. Although these are commonly referred to as ‘behaviour change techniques’, we refer to them as ‘change techniques’ because they initially instigate psychological change that may or may not lead directly to behaviour change. For example, use of ‘if–then’ plans is initially an intrapersonal change that may/may not lead to change in behaviour patterns. Note too that when we refer to change techniques, we really mean a set of categories or types of technique because, for example, if–then plans take many different forms |

| Facilitation techniques | Techniques that facilitators use to facilitate groups, group interaction and change processes. They may include change techniques or more generic techniques to facilitate interaction. For example, facilitating group discussion, prompting individual introductions in groups |

| Interventions | Interventions, programmes or treatments that aim to facilitate individual health-related change processes, and thus improve health or prevent illness |

| Modes of delivery | Overall approach to how an intervention is delivered, such as through one-to-one consultations, groups, self-delivery (e.g. manuals, apps or websites), in person or online |

| Group | At least three people who interact with each other |

| Group-based interventions | Interventions partly or fully delivered in groups, that is, including at least three participants (or group members) and usually at least one facilitator (or leader) |

| Behaviour change interventions | Interventions, or programmes, that aim to bring about changes in individual behaviours |

| Group-specific change techniques/processes | Processes or techniques that are delivered through interaction between two or more people, and, thus, may be unique, or particularly suitable, to group-based delivery. For example, buddying up, peer support |

| Group-sensitive change techniques/processes | Processes or techniques that can be self-delivered on one’s own, one on one or in a group setting, but when delivered in groups, they may be affected by the group interactions. For example, problem-solving or goal-setting – conducted individually vs. discussed in a group (e.g. involving sharing ideas, suggestions, modelling) |

Chapter 2 Development of the Mechanisms of Action in Group-based Interventions framework (stage 1)

Background and rationale

As noted in Chapter 1, there is a wealth of research on group processes and how groups affect individuals,37,38,64,65 and a long tradition of using small groups to support personal change, promote health and deliver education (e.g. in group psychotherapy and counselling,10,12,66 self-help and support groups,13 chronic disease self-management programmes,14,17 health-promoting interventions20–22 and team-based learning initiatives67). Delivery of health interventions in groups allows people to support and learn from each other and takes better account of the fact that many health-related behaviours are performed with, or in the presence of, other people and are subject to social influences. With the increased prevalence and social and economic burden of preventable, lifestyle-related diseases, groups therefore offer a suitable and potentially cost-effective way to deliver health-related behaviour change interventions.

To date, theories specifying processes capable of regulating and changing behaviour patterns and techniques that may be used to modify those processes have focused on intrapersonal change, occurring within individuals. However, change processes are often initiated and facilitated through social interaction, and are affected by social context, including group settings. Thus, social, interpersonal processes may direct and alter intrapersonal processes. Yet our understanding of how interpersonal interaction in groups initiates and shapes intrapersonal change is limited. This might be because research into group-promoted personal change and research into intrapersonal change processes that explain changes in individual behaviour have developed in parallel with little cross-fertilisation of ideas. Further research is needed to ascertain how health behaviour change interventions work in group settings, how intrapersonal change processes might be shaped by group context and which interpersonal change processes are critical to group effectiveness. Such research would be greatly facilitated by a synthesis of the current knowledge of group processes and change mechanisms in groups. Therefore, in the first stage of this study, we aimed to identify important elements related to the design, implementation, context and change processes operating in GB-BCIs. Drawing on existing research, we aimed to develop a framework to bring together and categorise potentially important intervention components, and change processes and techniques that explain the mechanisms of action in GB-BCIs.

Methods

We developed a framework of change processes in group-based interventions by bringing together findings from three approaches. We focused in particular on face-to-face, adult groups that target health-related behaviour and other psychological change. First, we built on reviews of relevant literature, including theoretical literature on group dynamics and group change processes, taxonomies of categories of change techniques, qualitative studies of participants’ experiences of group-based weight loss interventions, and measures of group processes. Second, we qualitatively coded the content of delivery manuals and recordings of group sessions from three recent GB-BCIs targeting weight loss. Third, we consulted experts, including group participants, facilitators and researchers. The findings from each approach helped to develop, refine and revise the framework in an iterative fashion. For an outline of this stage of the research, and how it fits in with other stages of the study, see Chapter 1. The three approaches used and how findings from them were brought together are described in detail in the following sections.

Reviews of relevant literature

Foundational previous research

The initial concepts used in the framework were based on an earlier programme of work on GB-BCIs,68 in particular a checklist for reporting of GB-BCIs69 and a conceptual review and model of change processes in groups. 40 In this work, we identified and reviewed relevant theoretical literature on how groups work and how group processes can enhance or impede individual change.

A systematic review of theoretical literature on change processes in groups was not feasible because of the extensiveness of this literature, which spanned a number of decades and disciplines. A search for ‘group dynamics’ in MEDLINE in early 2016 resulted in over 33,000 references, and searching and screening of The British Library catalogue identified > 160 potentially relevant books. 40 Consequently, we employed a pragmatic approach to identify and integrate relevant concepts, processes and theories. We began with a previously developed model of change processes in groups (see Appendix 2)40 and key books summarising research on groups. 10,12,37,64,70 We conducted further selective searches of electronic databases (e.g. MEDLINE, PsycINFO) for this study using key search terms relevant to specific processes included in the previous model (e.g. ‘social support’) and types of groups (e.g. ‘support groups’). We also hand-searched for relevant, useful articles in recent issues of the following journals: Psychological Review, Psychological Bulletin, Social Science & Medicine, Sociological Review, Educational Review, Journal for Specialists in Group Work and Group Dynamics: Theory, Research and Practice. Concepts or processes identified in these sources were compared with, and added to, the earlier concepts, resulting in the development of an initial framework. We also used the key books and articles on groups37,38,71 to extract definitions of key concepts, which were then discussed and agreed on with the study team members.

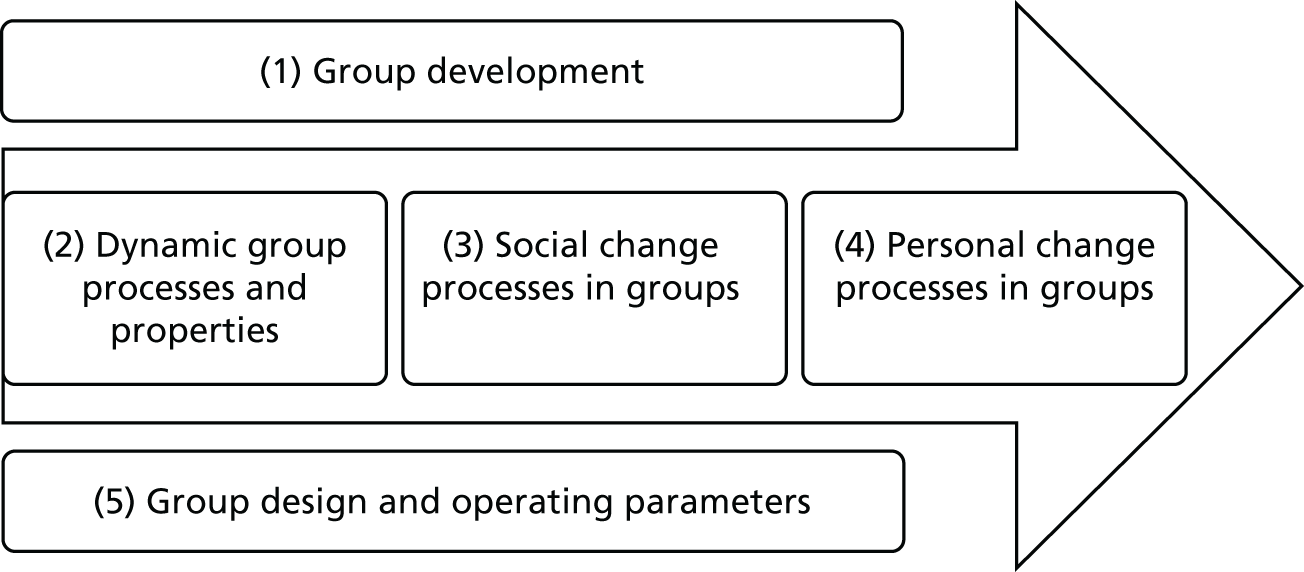

The earlier research40 resulted in a conceptual model identifying five categories of interacting processes: (1) group development processes, (2) dynamic group processes and properties, (3) social change processes, (4) personal change processes and (5) group design and operating parameters. Each of these categories encompasses a variety of theorised mechanisms explaining individual change in small groups. Key change processes included in each of these categories are shown in Appendix 2. This work provided a conceptual foundation for stage 1 of the MAGI study.

Taxonomies of change techniques

A series of taxonomies have defined categories of change techniques3,4,35,53,72 and some have linked these to change mechanisms specified by empirically tested theories. 3,53,72 These categories refer to sets of techniques that may differ in implementation across interventions. For example, ‘encouraging social support’, ‘inducing cognitive dissonance’ or ‘facilitating formation of if–then plans’ can be implemented in quite distinct ways and so refer to different practices in different interventions. 33 Nonetheless, we will use the term ‘technique’ as shorthand for a defined category of potentially effective actions or practices assumed to influence a specified change mechanism that, consequently, may/may not be effective in prompting behaviour change in particular contexts. 23,33

Taxonomies of change techniques were used as a source of potentially important change processes and techniques in group settings. One researcher (AJB) initially used the taxonomies to select techniques that were likely to be specific to group-based delivery (i.e. group specific) or that could be affected by group delivery (i.e. group sensitive) and incorporated them into the developing framework. Then, after the framework was further developed, two researchers (AJB and CA) reviewed each taxonomy again and compared each technique category included in these taxonomies for correspondence with the draft framework. Any additional techniques were considered for relevance to GB-BCIs (being either specific or sensitive to group setting) and, when relevant, added to the framework.

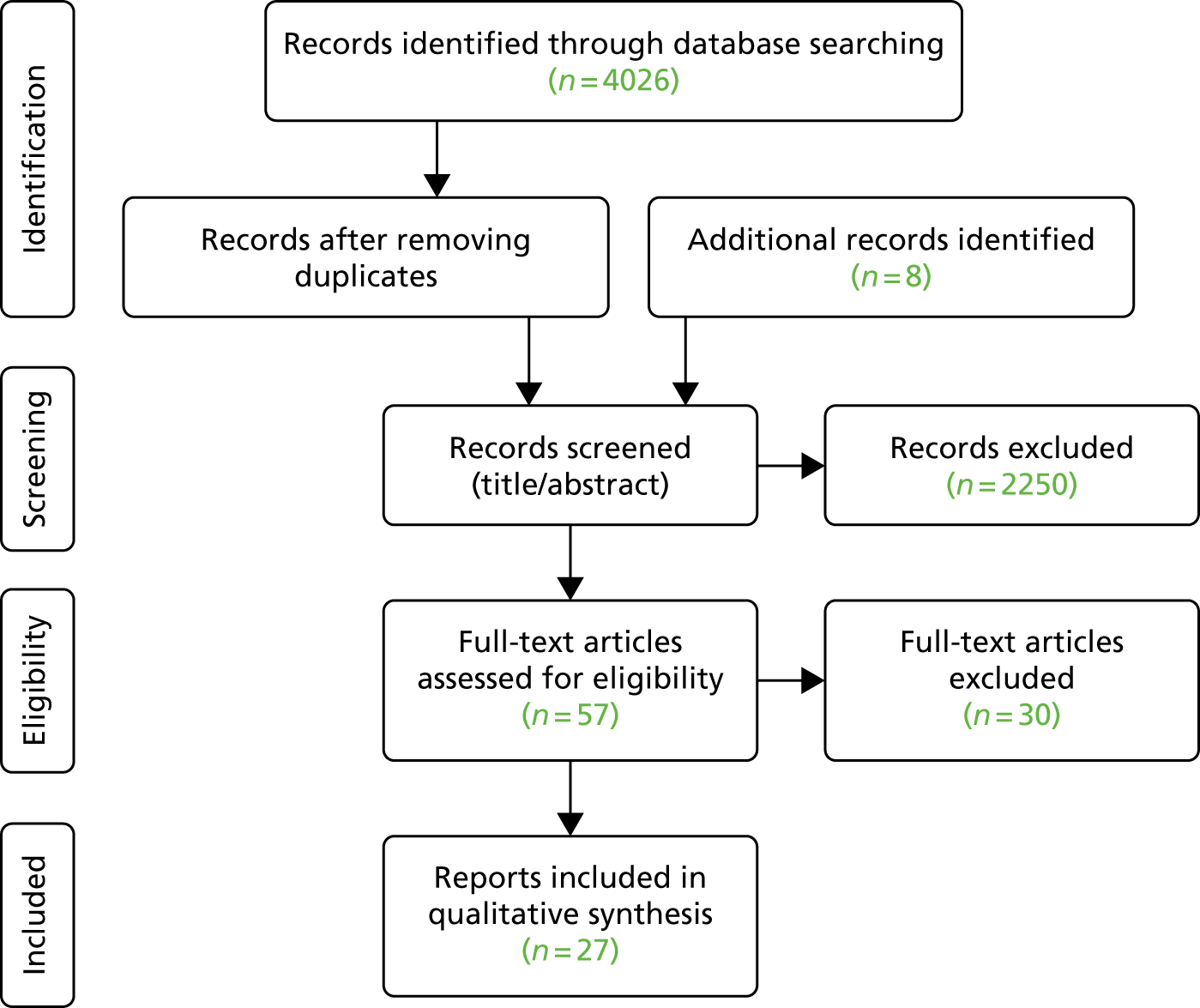

Qualitative studies

One researcher (AJB) searched electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycINFO, PsycARTICLES, EMBASE, Social Policy and Practice accessed via Ovid platform) between January 2000 and June 2016 using a detailed search strategy [based on the PICOS (participants, interventions, comparisons, outcomes, study design) model,73 see Appendix 3] to identify qualitative studies of participants’ experiences or perceptions of group-based weight loss programmes. We included qualitative studies of lifestyle-based weight loss interventions for overweight or obese adults that reported findings related to group-based delivery (e.g. participants’ perceptions of groups, how the group setting might have influenced their experience of the intervention, behaviour change or weight loss). The included reports were uploaded to NVivo software, versions 10 and 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), in which the findings were coded for themes common across studies. The identified themes were compared with and, when relevant, added to the developing framework. After the framework was further refined (following stage 2, see Chapter 3), the themes developed from the qualitative studies were revised to correspond with the structure of the framework and, when appropriate, individual codes were renamed to match the framework categories. For further details of the review of qualitative studies, see Appendix 3.

Measures of group processes

We initially intended to search electronic databases for individual measures of group processes. However, our scoping searches identified existing reviews of such measures. Consequently, we used these reviews to extract details of, and references to, measures of group processes and change in groups. We then compared the concepts operationalised in these measures with the developing framework, and any new concepts or processes were considered for inclusion in the framework. Following this, we decided not to conduct further specific database searches for individual measures.

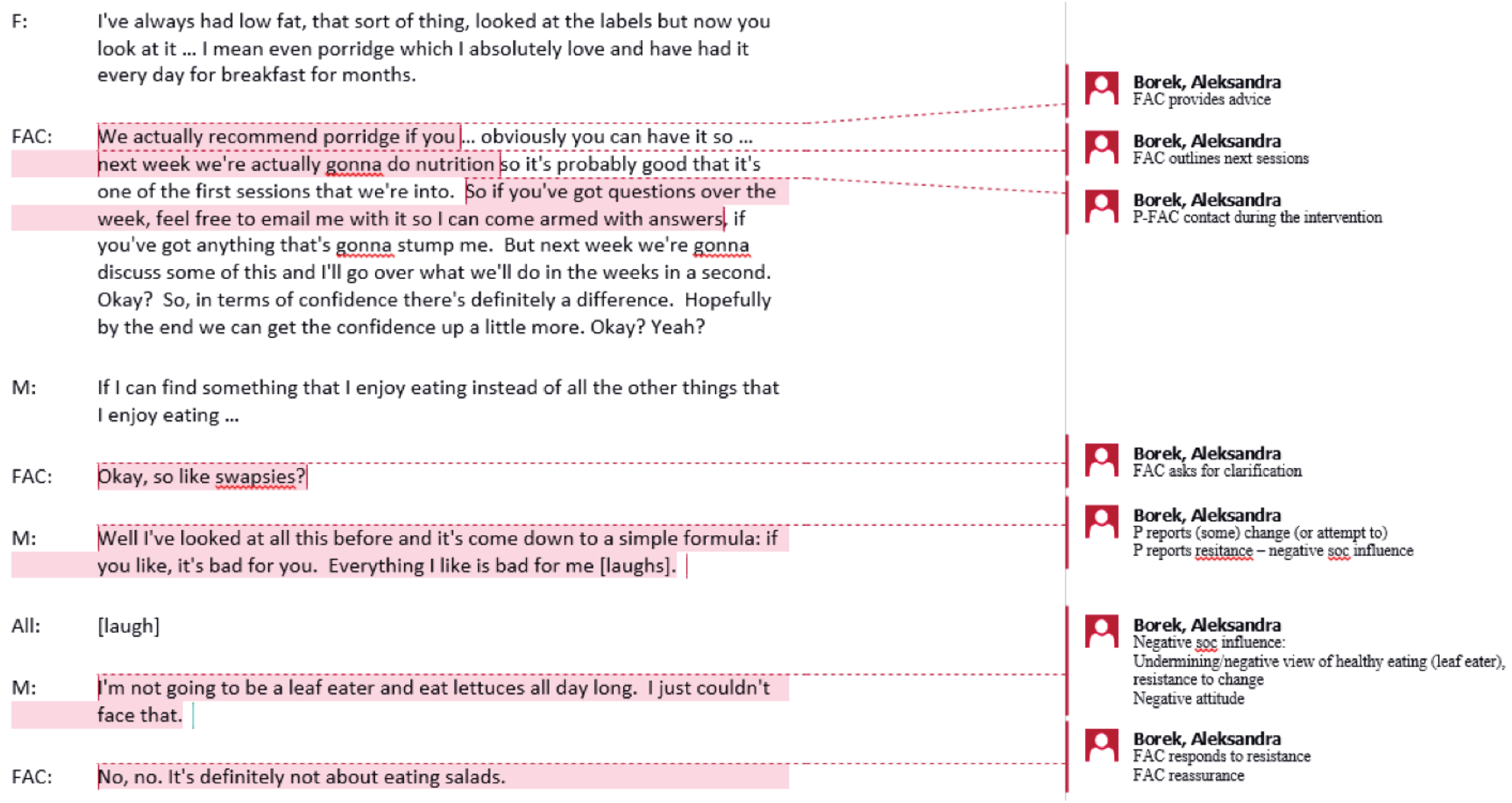

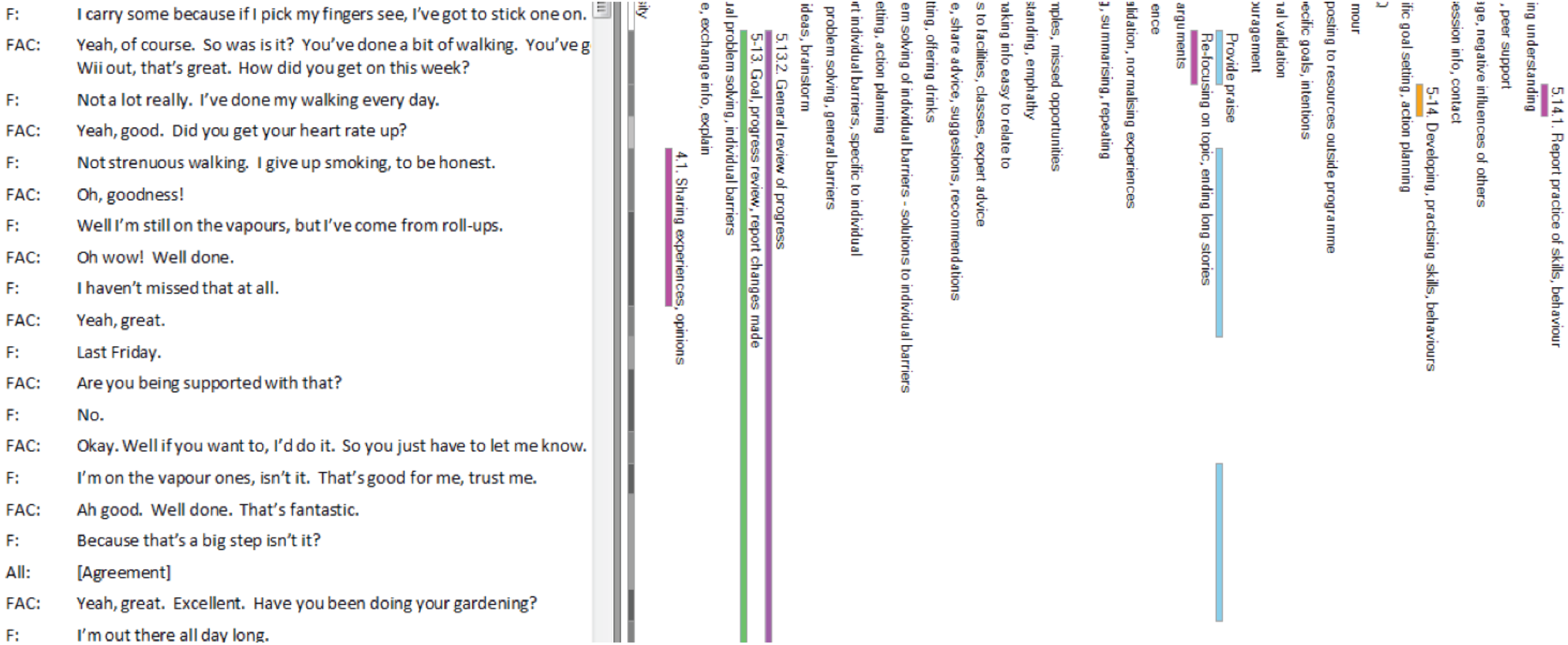

Analysis of qualitative data

In order to include in the framework categories that would apply to ‘real-life’ GB-BCIs and to help clarify and refine the definitions of the framework categories, we conducted qualitative coding of the content of intervention manuals and group sessions sampled from three recent GB-BCIs: LWTC, SkiM and WtW (see Table 1). The secondary data from these interventions were uploaded to, and coded in, NVivo software (v10/11).

Intervention manuals

We selected one primary intervention manual from each study. The manuals provided information to be used by the group facilitators as the basis for delivering the intervention. The content of the manuals was coded thematically, and the emerging coding schema was compared with the developing framework. Any additional concepts or processes relevant to group-based delivery that were not captured by the framework were considered for adding to the framework. After the framework was developed, the coding of the manuals was revised to make it consistent with the framework’s headings and structure.

Recordings of group sessions

We sampled 10 audio-recordings of group sessions for diversity, representing all three interventions, different stages of the group programmes (beginning, middle and end sessions) and different facilitators (for details of all transcripts used, see Appendix 1). Recordings were transcribed verbatim by a transcription company, and one researcher (AJB) checked the transcripts against the original recordings for accuracy and as part of data familiarisation, paying attention to elements that were not transcribed (e.g. tone of voice indicating engagement, laughter, speaking over each other, etc.). One researcher (AJB) then coded the transcripts inductively (i.e. bottom up, without using the a priori framework) to capture what happened in the group sessions. The codes were then compared with the developing framework and matched with the framework categories, prompting revisions to the framework and to the coding schema. Further revisions to the framework were conducted following stage 2 of the research that involved coding additional transcripts of group sessions (see Chapter 3). In brief, stage 2 involved deductive coding (using a coding schema derived from the draft framework) of 28 additional transcripts of sessions from the LWTC and SkiM interventions, also sampled for diversity. The two stages were iterative but the framework presented in Results is the final version revised in stage 2.

Observations of group sessions

Our analyses of the intervention manuals and group session recordings were supplemented with observations of ongoing group sessions in the LWTC programme. One researcher (AJB) observed eight sessions from three different groups, taking notes about what happened in the sessions and how participants interacted with each other and the facilitator. These observations provided additional insight into processes that could not be ascertained from, or identified in, the intervention manuals, audio-recordings or transcripts of group sessions, for example seating arrangements, what happened when the audio-recorder was turned off (i.e. at the beginning and end of sessions) and non-verbal behaviour of participants and facilitators. These observations were not conducted in a structured manner and were not formally coded or analysed; instead, they provided supplementary insights that facilitated interpretation of the more formal data analyses.

Consultations with experts

Throughout the study, we discussed the developing framework with experts, including researchers working with group-based interventions, group facilitators and group participants. The aims of these consultations were to (1) identify important elements that should be included in the framework, (2) collect examples and insights helpful for defining the framework categories and hypothesising about links between techniques, processes and outcomes, and (3) seek feedback on the developing framework. For a full list and details of the conducted consultations see Appendix 4. In summary, in the early stages of the study we conducted two meetings with participants who had attended the LWTC groups, and we met with two group facilitators (from the LWTC and SkiM interventions). Throughout the study, we sought feedback from researchers and practitioners at relevant conferences, and we sought feedback at an internal seminar and an external workshop, which we organised. In the final stage of the study, we met with four group facilitators (from the LWTC and SkiM interventions) and sought written feedback from researchers and practitioners on the near-final version of the framework. We discussed with each group of experts their understanding of how groups might facilitate or impede behaviour changes and other outcomes (e.g. weight loss), and what the important processes in groups might be (including different facilitation techniques, and benefits and challenges of the group setting). We also sought feedback on the emerging framework and suggestions for any new components, or potential links between the framework categories.

Developing and revising the framework

We followed a process drawing on the ‘best fit’ approach to framework synthesis. 74 We used a conceptual model developed in our previous work40 as an a priori framework. We then used the other sources (i.e. literature reviews, data analyses and consultations) and the expertise of the study team to identify (through coding concepts and processes described in these sources) and list all potentially important processes, concepts and design elements. Each identified relevant ‘candidate’ element was compared with the a priori (and then revised) framework, and added to the framework, combined or separated, and sorted into a category. We then defined categories, described the hypothesised relationships between them and developed diagrams to summarise the framework. Further refinements to the framework were made following its application to code additional transcripts of session recordings in stage 2 (see Chapter 3), so this was an iterative process that extended throughout the study. The process of developing and refining the framework, including decisions about the framework categories and their definitions, involved extensive discussions with the study team members, all of whom have relevant experience and expertise (for details of study team meetings, see Appendix 4).

Results

Findings from relevant literature

Theoretical literature

Before developing the framework, we identified and defined the key concepts used in this study, as relevant to the intended framework. In doing so, we drew on the expertise of our study team members and on selected summaries of theoretical literature. 37,38 We discussed and agreed on the key concepts and their ‘working definitions’ in meetings with, and through written feedback from, team members. The terms related to theoretical conceptualisations of groups are reported in Table 3; other relevant terms were defined in Chapter 1.

| Terms | Definitions/descriptions |

|---|---|

| Group | An entity that is more than a collection of individuals: ‘a collection of individuals who have relations to one another that make them interdependent to some significant degree’ (p. 46)37 |

The following characteristics are commonly cited as distinguishing a group from a collection of individuals:37,75

|

|

| Types of groups | Groups can be classified in different ways; for example, they can be based on:

|

| Based on the above classification, a goals-and-process matrix for groups classifies groups based on goal (i.e. a purpose that guides the direction of a group) and process (i.e. the type of interaction characteristic of the working stage of the group)76,77 | |

|

|

|

|

| Group dynamics and group processes | ‘Group dynamics’ is often used in different ways, referring to:

|

| We use ‘group dynamics’ to refer to group properties and within-group processes that help explain how groups work and change | |

For clarity, we distinguish between ‘group dynamics’ and:

|

These definitions of key concepts provided a basis for the framework and helped establish its scope and focus. For example, based on the experience and expertise of the study team, we agreed that GB-BCIs are most likely to be small, psychoeducational or counselling groups with shared personal goals and led by professional or peer facilitators. Therefore, in developing the framework we focused on the literature, processes and concepts most relevant to these types of groups, rather than, for example, work groups, sports teams or large groups that have different characteristics and types of group processes operating. Moreover, we included some of the defining characteristics of groups (e.g. group identification, goals, cohesion) that were relevant to GB-BCIs in the framework.

We began developing the framework of change processes in groups by listing potential change processes identified in our previous work40,69 and in selected other helpful summaries of theoretical literature on group processes and personal change in group interventions. 9,10,12,36,38,64,71,75,78,79 We kept a record of helpful references (available on request) including > 160 books on groups, and > 335 articles and book chapters, which were classified and filed for reference depending on the topic (e.g. concept, process or theory). These were also used as a source of framework elements. The theoretical literature on groups can be divided into three categories related to how groups function (we refer to this type of theory/process as ‘group dynamics’), how groups generate individual psychological or behavioural change (we refer to this as ‘change processes in groups’) and how factors external to a group may affect a group and its members (we refer to this as ‘contextual factors’). These categories broadly map onto the MRC’s process evaluation model,28,29 which refers to ‘implementation’ (mapping onto group delivery and group dynamics), ‘mechanisms of impact’ (covering change processes in groups) and ‘context’ (covering ‘contextual factors’). This provided initial ‘scaffolding’ for the MAGI framework and all processes and concepts that were identified in the theoretical literature and, through other sources, were used to populate these overarching categories.

Taxonomies of change techniques

We selected and reviewed six taxonomies of change techniques listing categories of techniques designed to bring about psychological change, which we considered to be the most established, widely used and relevant to our study. These included the initial taxonomy developed by Abraham and Michie,3 the CALO-RE (Coventry, Aberdeen & London – Refined) taxonomy for diet and physical activity interventions,80 the Behaviour Change Technique Taxonomy v1 (BCTTv1)4, the Intervention Mapping taxonomy,72 the Oxford Food and Activity Behaviours (OxFAB) taxonomy of techniques used by participants for weight loss81 and a taxonomy of group-specific techniques used in smoking cessation programmes. 25 In these taxonomies, we identified very few group-specific categories of change techniques (i.e. techniques that are unique to groups or particularly suitable to be delivered in group settings, and that facilitate interpersonal change processes), but a larger number of techniques that could be sensitive to group delivery (i.e. techniques that can be delivered in other ways than groups, but may be adapted to, or affected by, group delivery in how they facilitate personal change). Selected examples are presented in Table 4.

| Group-specific change techniques | Group-sensitive change techniques and their possible adaptations to engage group processes | |

|---|---|---|

|

|

Delivered in groups through group discussion and sharing of information and ideas |

|

Delivered in groups through group participants sharing experiences, information and ideas, and modelling behaviours of other group participants | |

|

Delivered in groups through group activities, group demonstrations/modelling and group discussions | |

Qualitative studies

The searches for qualitative studies of participants’ experiences of group-based weight loss groups resulted in the identification of > 4000 potentially relevant references (see Appendix 3, Figure 19). After screening 57 full texts, 27 articles49,82–152 were included. Common themes related to participants’ perceptions of, and experiences in, weight loss groups were identified (see Appendix 3). These included factors affecting participants’ experiences of groups and behaviour change and weight loss [i.e. factors related to individuals (e.g. previous experiences of weight loss), group design (e.g. contact time, venue), facilitators (e.g. personal and professional qualities), group context (e.g. group climate), change processes (e.g. accountability to the group, peer pressure), and practical delivery techniques and content (e.g. group activities and topics)]. These lower-level categories were added to the developing framework or were used to refine framework categories. The content of the coded themes and subthemes from the reviewed qualitative studies provided additional insights that contributed to the framework, defining the framework categories and hypotheses around the potential importance of, and relationships between, the framework concepts and processes (see Appendix 3 for more details of this review).

Measures of group processes

We identified and used three reviews of measures of group processes. 108–110 and looked up other potentially relevant measures. 54,111–119 The identified measures could be divided into four types: (1) screening tools used with participants to assess their suitability for, or fit with, the group, (2) measures to assess group facilitators’ skills and behaviours, (3) measures to assess group interaction (used by researchers, observers or coders) and (4) questionnaires to assess participants’ perceptions of groups and group processes. In addition, qualitative approaches, such as interviews with participants, were identified as a way of assessing participants’ experiences and perceptions of the groups. The measures identified in these reviews were listed, and the concepts and processes that these measures focused on were mapped onto the developing framework (see Appendix 5 for details and examples of measures.).

Findings from analysis of qualitative data

One researcher (AJB) coded three facilitator manuals (two of which were co-authored by one of the study team members: CJG) and 10 transcripts of group session recordings, including four sessions from the LWTC programme (with two different facilitators), two sessions from SkiM (with one facilitator) and four sessions from WtW (with five different facilitators, cofacilitating the sessions) as shown in Table 1, with further details on the transcripts provided in Appendix 1. The coding resulted in identification of categories from the transcripts, which were compared with, and helped to refine, the a priori framework. The coding was supplemented with notes from observations of eight group sessions (e.g. checking whether or not any other potentially important elements were missing). The inductively developed codes are reported in Appendix 6. In an iterative manner, the evolving framework underpinned the further coding of group sessions presented in Chapter 3 but findings from this also informed the later versions of the framework.

Findings from consultations with experts

Feedback received in the expert consultations was incorporated into the framework by adding new elements, or contributed to defining framework categories and relationships between them. The details of the consultations and main changes in the framework resulting from these are reported in Appendix 4 and can be matched with the evolving versions of the framework presented in Appendix 2.

Mechanisms of Action in Group-based Interventions framework

The literature reviews, qualitative analyses and consultations were used as sources for developing the MAGI framework. Appendix 7 includes a summary of the framework categories matched with the sources that they were identified from. Appendix 2 provides the evolving framework diagrams and tables, illustrating the process of refinement. The full version of the framework, which is intended to be a stand-alone document, is presented in Report Supplementary Material 1.

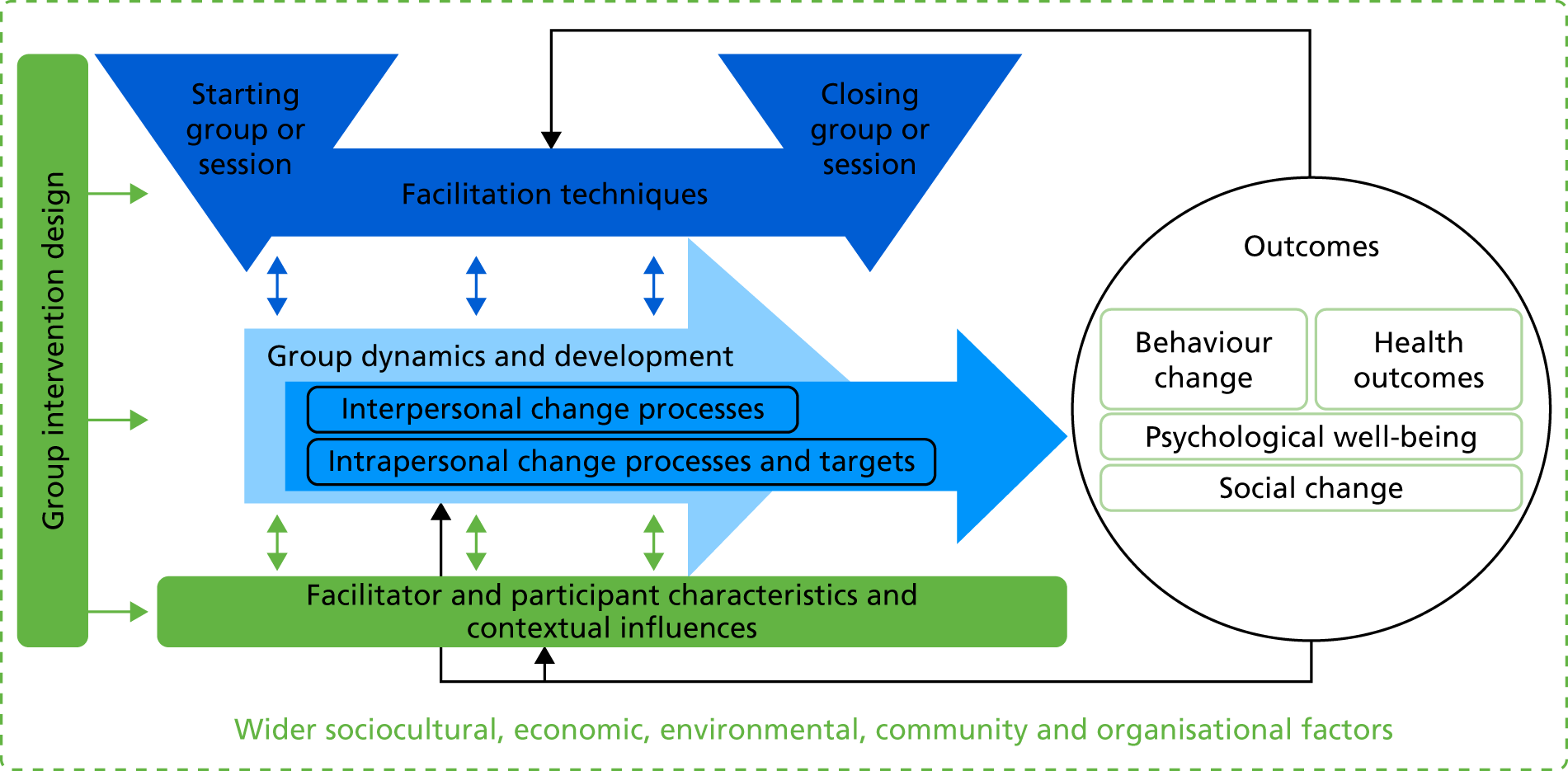

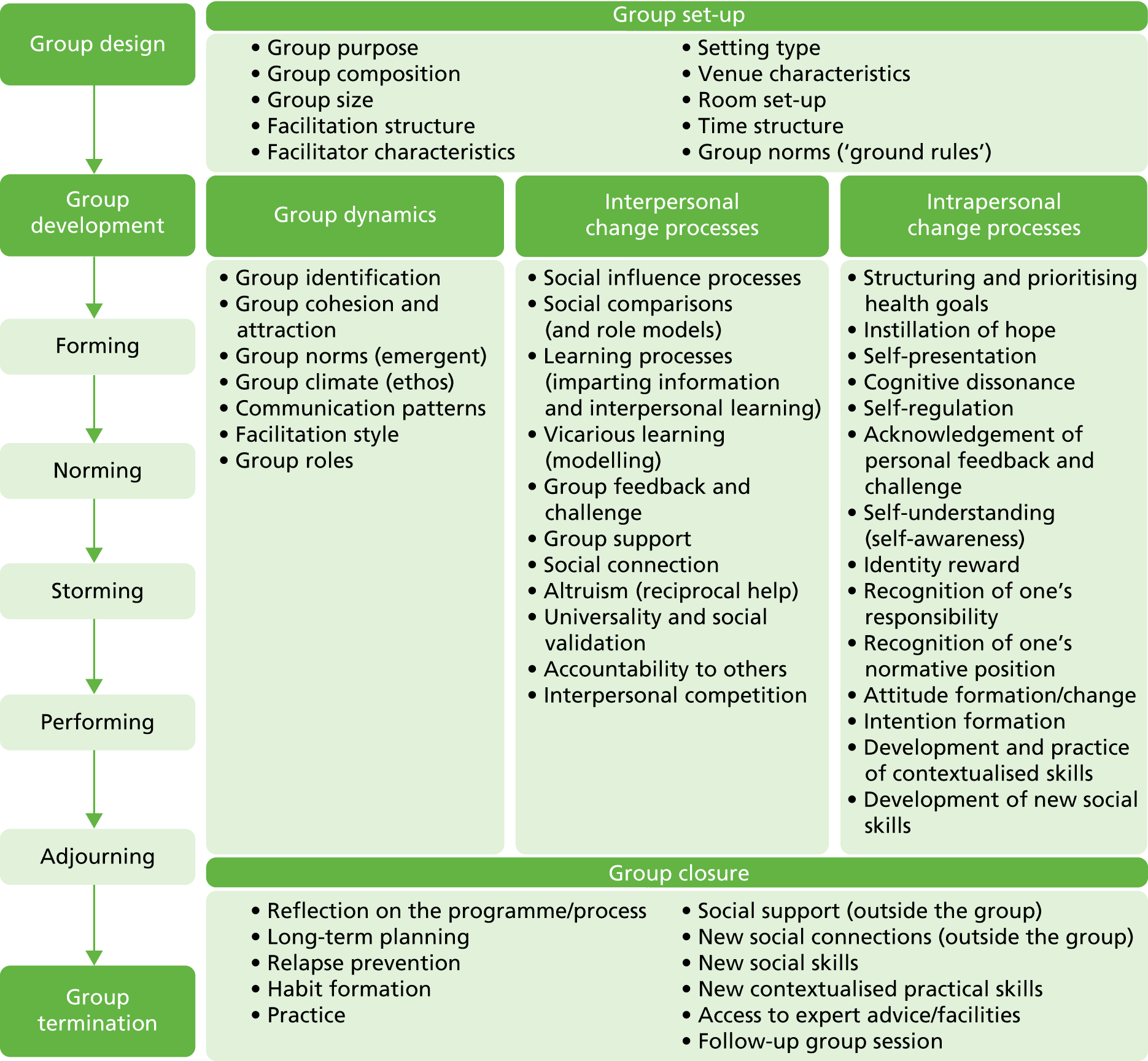

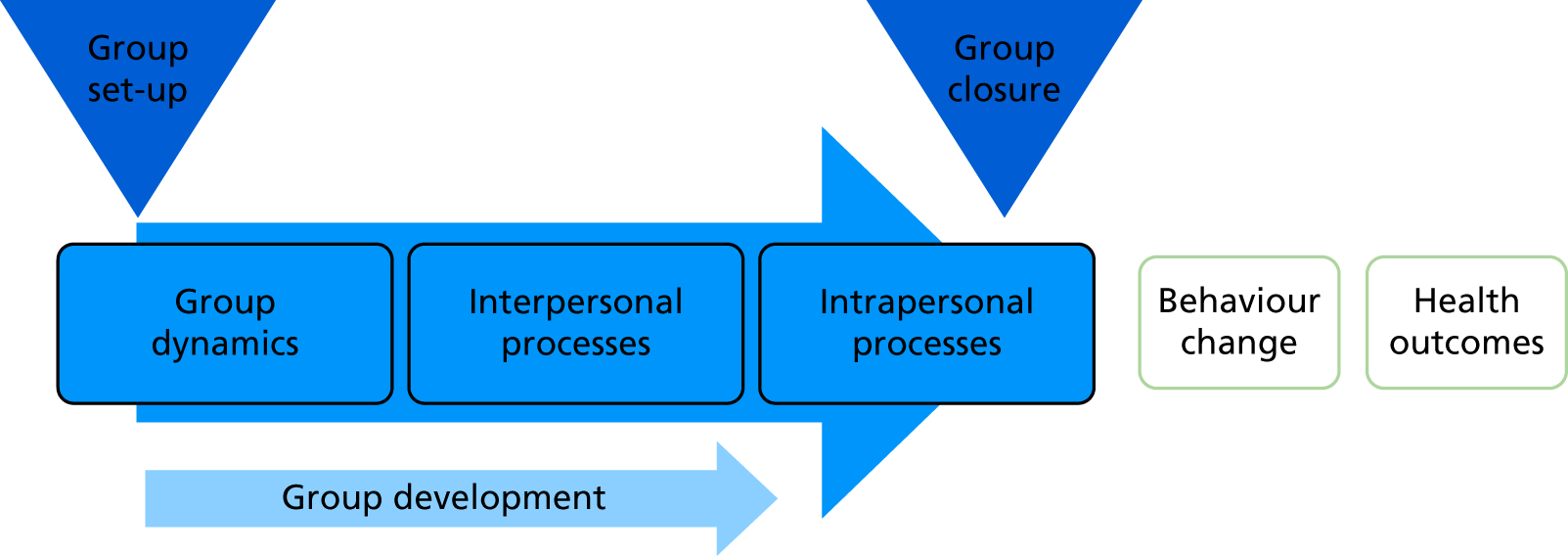

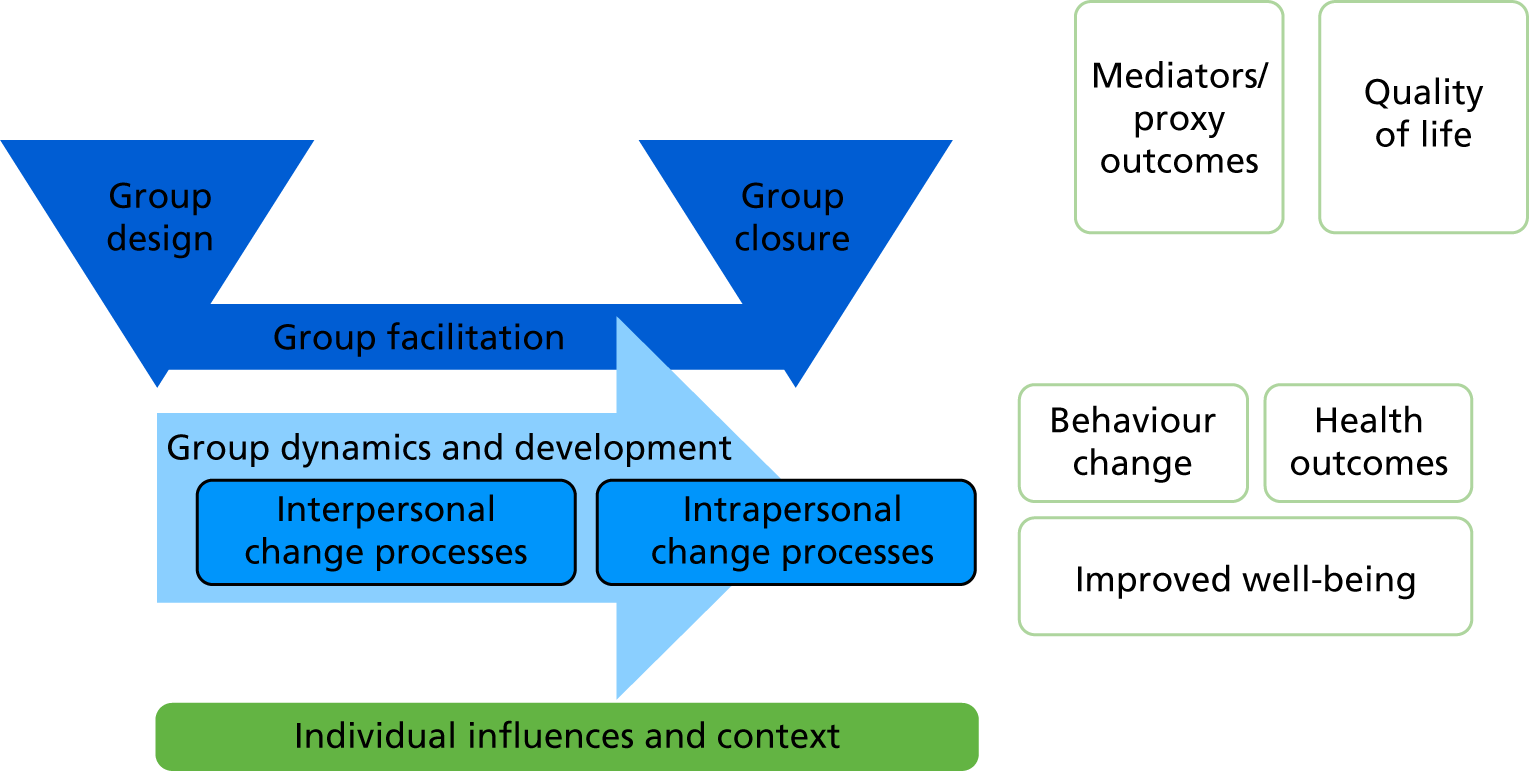

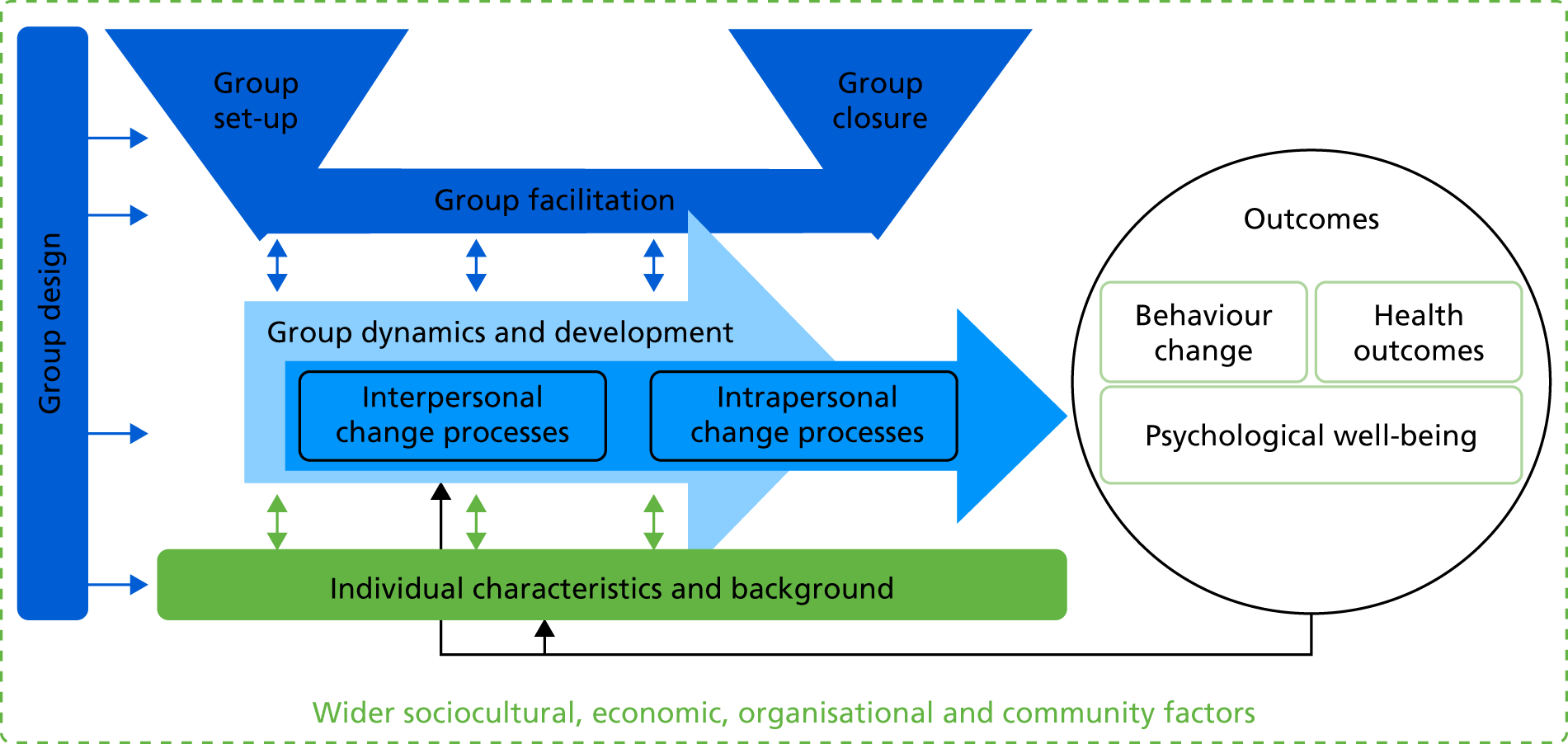

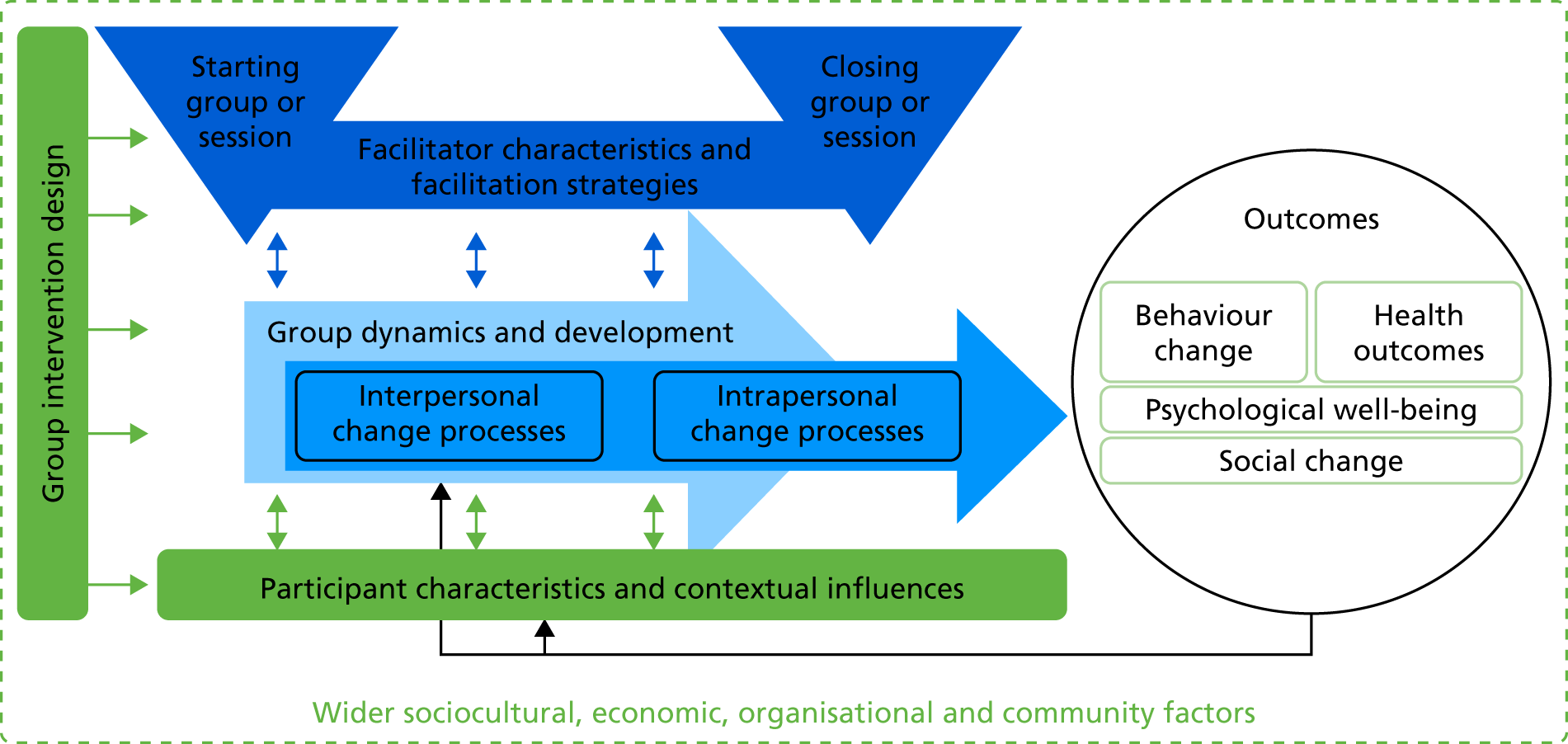

The identified processes, techniques and concepts helpful in explaining the mechanisms were grouped into six overarching categories: (1) group intervention design, (2) facilitation techniques, (3) group dynamics and development, (4) interpersonal change processes, (5) intrapersonal change processes and targets and (6) facilitator characteristics, participant characteristics and other contextual influences. On the basis of the reviewed literature and expert consultations, we hypothesise that the group features, processes, change targets, and techniques included in these categories are critical to the operation of groups and the mechanisms by which groups generate individual and collective psychological and behavioural change. The structure of the framework is illustrated in Figure 3 and described in the following sections.

FIGURE 3.

Main MAGI framework categories and relationships between them. Note: the green boxes (corresponding with categories 1 and 6 described below) and the green line around the diagram represent external influences on the group (e.g. design prior to group sessions, influences from outside the group sessions); the blue triangles and box between them (referring to category 2) represent the techniques that facilitators use to facilitate the group and instigate or support group processes; the blue arrows (categories 3, 4 and 5) represent within-group processes leading to change, that is, what happens during a group-based intervention to bring about behaviour change and other outcomes. Reproduced from Borek et al. 63 © 2019 The Author(s). Published by Informa UK Limited, trading as Taylor & Francis Group. This is an Open Access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Category 1: group intervention design elements

These are features of the design of group-based interventions that are important for the functioning of the group and facilitation of change processes. These features should be considered during the intervention design stage (i.e. before the groups are set up) and decided on in alignment with the intervention logic model and intended change processes. When a group intervention is delivered, these features are likely to affect other elements of the intervention implementation (group facilitation, group dynamics and development) and change processes in the group.

Category 2: facilitation techniques

These refer to techniques that facilitators can use to facilitate the group and particular change-inducing interactions within the group. In Figure 3, we highlight the techniques, or tasks, that are important when establishing groups and starting group sessions, and when closing groups or sessions (these specific time points are emphasised by the blue triangles). The techniques for starting the groups or sessions are particularly important for establishing an interpersonal context conducive to engaging participants and inducing change processes, whereas techniques for closing the groups or sessions might help reinforce participants’ commitment to return to the next session, change processes and maintenance of behaviour change. Other techniques can also be used and their deployment determines how a group works (i.e. group dynamics and development) and which inter- and intra-personal change processes are initiated and sustained within the group. Facilitation techniques might change over time; for example, the facilitators might adapt which techniques they use, and how, depending on the needs and characteristics of the group, emerging group dynamics and change processes, or participants’ characteristics and their progress in achieving goals and intervention outcomes (this is represented in Figure 3 by the dark-blue two-way arrows).

Category 3: group dynamic and development processes

These refer to generic group properties and processes used to describe how groups work and change over time (i.e. this time change is represented by the light-blue arrow). These processes are group specific (i.e. unique to a group setting) and are relevant to any type of group, regardless of whether or not they target personal change. Positive group dynamics, and a successful progression into a cohesive group that works collaboratively to achieve group goals (the so-called performing stage of group development), optimises the social environment conducive to the operation of change processes. Conversely, negative group dynamics or impeded development may inhibit change processes and negatively affect participants’ experiences of the group (potentially also leading to low attendance or drop-out). Therefore, group dynamics and development are conceptualised as underpinning change processes in groups (in Figure 3 this is represented by the darker blue arrow being on top of the ‘group dynamics’ arrow). Group dynamics can be affected by facilitation techniques, including how groups are set up, by facilitator and participant characteristics (including the relationship and interaction between facilitators and participants) and by other contextual influences (e.g. social norms). These influences could include both planned changes (e.g. in facilitation techniques) and unplanned influences on group dynamics that the group responds to (e.g. progress of group members or attendance rates).

Categories 4 and 5: interpersonal and intrapersonal change processes

Interpersonal change processes are instigated in social or group contexts and through social or group interactions, whereas intrapersonal change processes and targets operate within an individual and may extend beyond the duration of a group session or a group (i.e. time is represented by the dark-blue arrow, which extends beyond the duration of the group and the associated ‘group dynamics’ arrow). Indeed, that this lasting change extends beyond the group is the aim of GB-BCIs. Interpersonal change processes might prompt or influence intrapersonal change processes or they may happen simultaneously. For example, when people are talking with others in the group, they engage both inter- and intrapersonal processes, as any conversation does. Both of these types of change processes may be affected by, and affect, the group dynamics and development when facilitated in groups (as opposed to other modes of delivery). As the arrows represent, they may also be instigated or facilitated by facilitator techniques, and may be influenced by facilitator and participant characteristics and the wider sociocultural context within which the groups operate.

Category 6: facilitator and participant characteristics, and other contextual influences

These refer to factors external to the group that may influence, and be influenced by, what happens in the groups. They include characteristics of group facilitators and group participants, which they ‘bring’ to the group, for example individual cognitive (e.g. beliefs) and emotional factors (e.g. anxieties), previous experiences (e.g. of groups, weight loss) and health conditions. These may influence participants’ interactions and the development of relationships in the groups. In particular, participants’ experience of, and engagement with, the intervention and behaviour change might be influenced by the relationship with, degree of rapport with, and perceptions of the facilitator. Other contextual factors, such as available support networks or social norms, may also influence the groups, and change processes. These factors and participants’ and facilitators’ characteristics may change over time as a result of participating in, or facilitating, the groups (e.g. increased assertiveness, confidence, skills; see Outcomes), which is represented by the arrows in Figure 3.

Outcomes

The outcomes of group-based health interventions include a range of intended and unintended consequences, for example changes in psychological processes (e.g. cognitions) underpinning behaviours, behaviours (e.g. diet), health-related outcomes (e.g. outcomes), well-being or quality of life (e.g. resulting from social connection), or social change across a collection of individuals (e.g. social norms or practices). Outcomes of group-based interventions may be affected, directly or indirectly, through change processes, and the underlying group context and dynamics. Moreover, observing or receiving feedback on outcomes, or progress towards them, can create a feedback loop, affecting the group dynamics, change processes, the use of facilitation techniques, and individual characteristics and contextual factors (this is represented by the black arrows going from outcomes back to the group, facilitation techniques, and facilitator and participant characteristics). Because the (targeted or unintended) outcomes are specific to each intervention, we do not further describe or discuss the different outcomes. Methods that can be used to explore potential links between group processes and outcomes are described in Chapter 4.

Wider influencing factors

Finally, wider influencing factors, such as sociocultural, economic, environmental, community and organisational factors, may influence all aspects of GB-BCIs, including their design, implementation, processes, facilitators and participants, and outcomes. For example, economic factors may affect participants (e.g. costs of accessing the group or buying health food) or intervention design and implementation (e.g. prespecified requirements set, or resources provided, by programme commissioners). Although we acknowledge that these wider determinants are very important, and recognise their impact on group functioning, these are beyond the focus of our study (and hence are not further discussed).

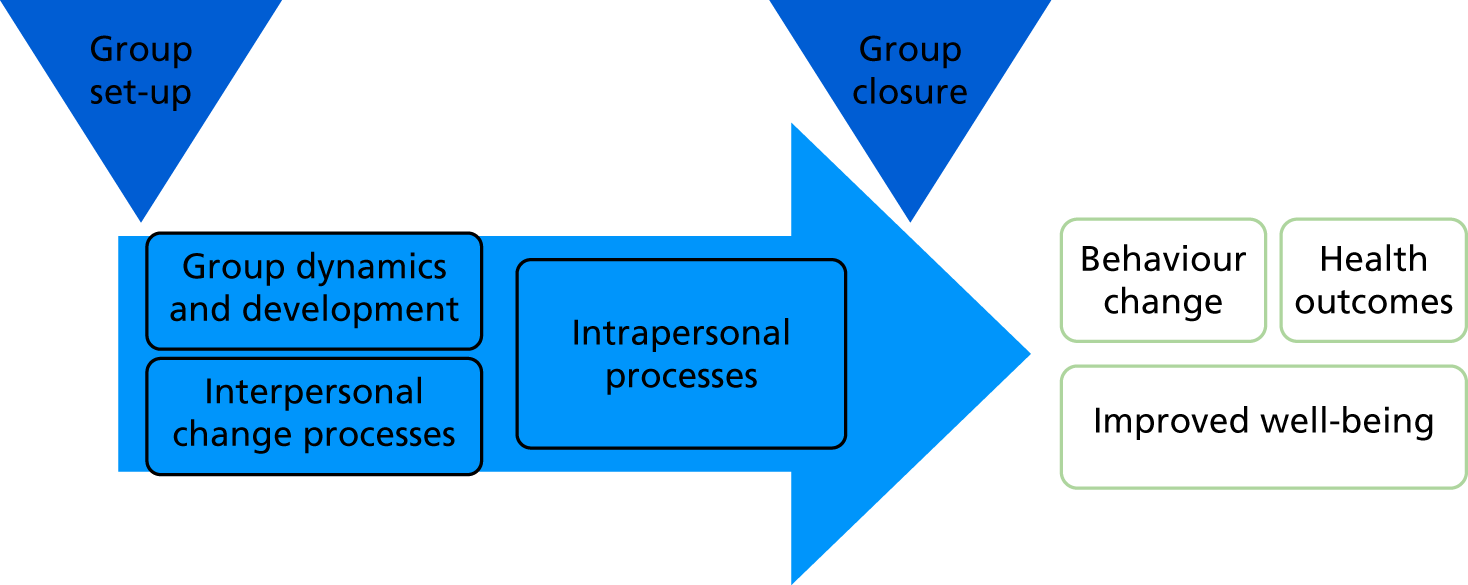

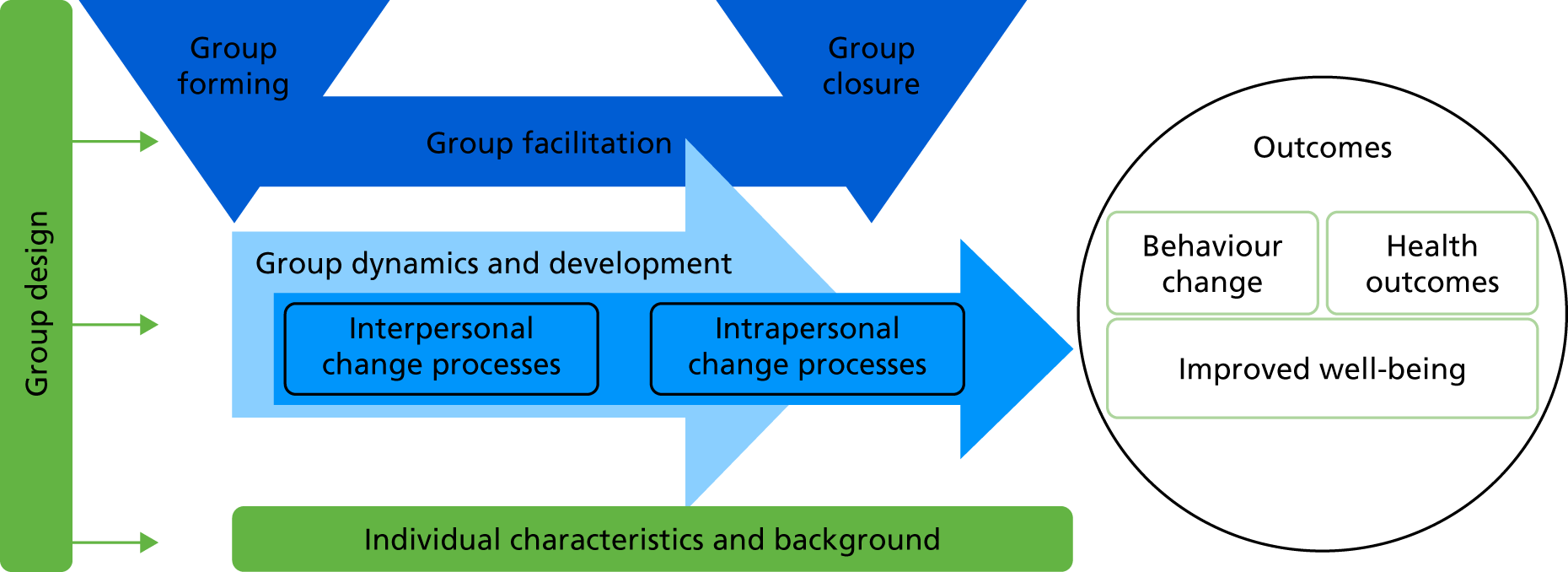

The MAGI framework provides conceptual guidance on questions of how key change agents shape group processes and change processes in GB-BCIs. This is illustrated in Figure 4, which highlights who these agents are, what they do and what they bring to group-based intervention design and operation. For example, group intervention designers have control over, and responsibility for, decisions about intervention design, which affect group dynamics, development and change processes. Group facilitators bring to the group their own characteristics (e.g. beliefs, experiences), professional and interpersonal skills, and facilitation techniques. Group participants also bring their own characteristics, social contexts and change-related factors (e.g. motivation, readiness to change). All of these influence, and contribute to, what happens in the group sessions, including group dynamics and change processes (represented by the blue circles in Figure 4) that lead to outcomes.

FIGURE 4.

Agency and processes in group-based interventions. Note: green boxes represent external influences on the group (e.g. design prior to group sessions, participants’ influences from outside the group sessions); the blue box represents the techniques that facilitators use to facilitate the group and instigate or support group processes; and the light and dark blue circles represent within-group processes leading to change (i.e. what happens during a group to bring about the outcomes).

Table 5 summarises group features, processes, targets and techniques included in the framework categories described above. Detailed definitions, with descriptions of their importance and hypothesised links between them (based on the literature and expert consultations), are fully reported in Report Supplementary Material 1 and are summarised below.

| 1. Group intervention design | 2. Facilitation techniques | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 2.1. Techniques to start the group/session | 2.2. Generic facilitation techniques | 2.3. Techniques to facilitate group dynamics | 2.4. Techniques to facilitate interpersonal change processes | 2.5. Techniques to facilitate intrapersonal change processes | 2.6. Techniques to end the group/session | |

|

3. Group dynamic and development processes | |||||

|

|

|

||||

| 4. Interpersonal change processes | 5. Example intrapersonal change processes and targets | |||||

|

|

|

||||

| 6. Facilitator and participant characteristics and contextual influences | ||||||

| 6.1. Facilitator characteristics | 6.2. Participant characteristics | 6.3. Other contextual influences | ||||

1. Group intervention design