Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 12/164/16. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2019 and was accepted for publication in March 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2020. This work was produced by Chappell et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2020 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Randomised controlled trial of ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy

Parts of this chapter has been reproduced with permission from Chappell et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP), also called obstetric cholestasis (OC), is the most common liver disorder that is specific to pregnancy. The disease is characterised by maternal pruritus and raised serum bile acid concentrations, with maternal symptoms and abnormal biochemical tests typically resolving post partum. A systematic review and individual patient data meta-analysis have recently shown that ICP is associated with increased rates of spontaneous and iatrogenic preterm birth, meconium-stained amniotic fluid and neonatal unit admission. 2 The risk of stillbirth is increased, but only in women with peak serum bile acid concentrations ≥ 100 µmol/l,2 in contrast with the previously held belief that this risk existed for all women with ICP. 3

Ursodeoxycholic acid (UDCA), used outside pregnancy to treat primary biliary cholangitis and other hepatobiliary disorders, has also been used as treatment in ICP. 4 UDCA is a naturally occurring bile acid, present in small amounts in humans; it has several actions that result in improvement of cholestasis, including increasing biliary bile acid excretion through upregulation of hepatic metabolising enzymes and bile acid transporters, stabilisation of the plasma membrane and protection of cholangiocytes of the biliary epithelium against cytotoxicity of bile acids, and hepatocyte protection against bile acid-induced apoptosis. 5,6 UDCA is recommended in six national guidelines for management of ICP,7 principally for improvement of maternal symptoms and biochemical tests, and surveys of practice have reported wide usage (97%) by obstetricians for treating this disorder. 8

Despite these widespread recommendations for the use of UDCA in the treatment of ICP, the evidence base is scant. Two meta-analyses had been undertaken shortly before trial inception. One concluded that UDCA was effective in reducing pruritus, improving liver test results in women with ICP and might benefit fetal outcomes; however, the largest randomised controlled trial included had 84 participants. 9 A subsequent Cochrane systematic review assessing the effectiveness of UDCA for this indication concluded that, although it might ameliorate pruritus by a small amount, definitive evidence for improvement in perinatal outcomes was lacking and that ‘large trials of UDCA to determine fetal benefits or risks are needed’. 10 That review judged many of the trials to be at moderate to high risk of bias, and the largest trial included only 111 women. 11

We undertook a randomised, placebo-controlled trial to evaluate whether or not UDCA reduces adverse perinatal outcomes in women with ICP, and to investigate the effect of UDCA on other short-term maternal and infant outcomes, and on health-care resource use.

Methods

Trial design

We carried out a parallel-group, masked, multicentre, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with individual randomisation to UDCA or placebo using a 1 : 1 allocation ratio. There were no substantial changes to the study design or methods after commencement of the trial.

Participants

Women were eligible if the attending clinician considered that they had a diagnosis of ICP (defined as maternal pruritus with a raised, randomly timed, serum bile acid concentration above the upper limit of normal as measured in the local laboratory),12 were between 20+0 and 40+6 weeks of pregnancy on day of randomisation, with a singleton or twin pregnancy, had no known lethal fetal anomaly, were aged ≥ 18 years, and were able to give written informed consent. A woman was not included in the trial if a decision had already been made for delivery within the next 48 hours, she had any known allergy to any component of the UDCA or placebo tablets, or if she had a triplet or higher-order multiple pregnancy. We undertook the trial in 33 maternity units in England and Wales. Seventeen units used a threshold of 14 µmol/l as the upper limit of normal, whereas the remaining units used thresholds between 9 and 13 µmol/l, in accordance with local laboratory reference ranges. The trial was approved by the East of England – Essex Research Ethics Committee (number 15/EE/0010).

Interventions

We allocated women to the group taking either UDCA tablets or matched placebo tablets, which were manufactured and supplied by Dr Falk Pharma GmbH (Freiburg im Breisgau, Germany). Each film-coated UDCA tablet contained the active ingredient, 500 mg of UDCA, and the inactive ingredients magnesium stearate, polysorbate 80, povidone K25, microcrystalline cellulose, colloidal anhydrous silica, crospovidone and talc. The matched placebo tablet was identical in colour and shape to the UDCA tablet and contained the same inactive ingredients. The tablets were packaged for oral administration and did not require any special storage conditions.

We recommended that women were started on a dose of two oral tablets per day (equivalent to 500 mg of UDCA twice per day), which was increased by a health-care professional in increments of one tablet per day every 3–14 days if there was no biochemical or symptomatic improvement, to a maximum of four tablets per day. The dose could be reduced to one tablet per day at a clinician’s discretion (e.g. if a woman’s weight was < 50 kg or if gastrointestinal side effects occurred). We advised that doses should be spread evenly throughout the day, but that no specific instructions to take with or without food needed to be given. In addition, we recommended that treatment should be continued from enrolment until the infant’s birth.

Outcomes

Outcomes were recorded on the web-based trial database through case note review by trained researchers after discharge from hospital of the woman and baby.

The primary perinatal outcome was prespecified as a composite of perinatal death (defined as in utero fetal death after randomisation or known neonatal death up to 7 days) or preterm delivery (< 37 weeks’ gestation) or neonatal unit admission for at least 4 hours (from infant delivery until hospital discharge). Each infant was counted once within this composite.

Secondary maternal outcomes (measured on clinical visits between randomisation and delivery) were maternal serum concentration of bile acids, alanine transaminase (or aspartate transaminase), total bilirubin and gamma-glutamyltransferase and maternal itch score (marked by the woman as the worst episode of itch over the past 24 hours in millimetres on a 100-mm visual analogue scale, where 100 mm is the worst possible itch). Additional secondary maternal outcomes (assessed on case note review after maternal hospital discharge) were gestational diabetes mellitus, mode of onset of labour and estimated blood loss after delivery.

Secondary perinatal outcomes (assessed on case note review after infant hospital discharge) included the components of the primary outcome, mode of delivery, birthweight, birthweight centile, gestational age at delivery, presence of meconium, Apgar score at 5 minutes, umbilical arterial pH at birth and total number of nights in the neonatal unit. All other secondary outcomes were descriptive only.

Health resource use post enrolment (i.e. collected at case note review after maternal and infant discharge from hospital) was the total number of nights in hospital (antenatal, intrapartum and postnatal) together with the level of care including adult intensive care unit, mode of delivery and UDCA cost (in the intervention group) for the woman, and total number of nights for the infant in the neonatal unit, together with the level of care (e.g. intensive care) for the infant.

There were no changes to primary or secondary outcomes after the trial started.

Sample size

The sample size was informed by the Cochrane meta-analysis,10 from which the event rate for the primary outcome for infants of untreated women was estimated as 40%. We determined that 550 infants of women with ICP (275 per group) were required to have a 90% chance of detecting (as significant at the two-sided 5% level) a reduction in the primary outcome measure from 40% in the control group to 27% in the treated group, corresponding to an absolute risk reduction of 13% and a risk ratio (RR) of 0.675. This was conservative compared with the effect sizes seen in the Cochrane meta-analysis10 for the three individual end points (RR 0.31, 0.46 and 0.48 for perinatal death, preterm delivery and neonatal unit admission, respectively). We planned to recruit 580 women in total, to allow for the possibility of 5% of infants being lost to follow-up. During the recruitment phase, we amended the protocol to permit continued recruitment of additional participants to allow for women who discontinued the intervention or withdrew from the trial. Interim analyses were undertaken for presentation only to the Data Monitoring Committee, to be reviewed when they met at least annually.

Randomisation

Randomisation was performed using a probabilistic minimisation algorithm13 to ensure approximate balance within the following groups: study centre, gestational age at randomisation (< 34, 34 to < 37, ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation), single versus twin pregnancy, and highest serum bile acid concentration prior to randomisation (< 40 µmol/l, ≥ 40 µmol/l). Randomisation was managed via a secure web-based randomisation program (MedSciNet, Stockholm, Sweden).

Allocation concealment

Packs containing UDCA or placebo were produced by the central manufacturing unit at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London, UK, prior to shipping to site pharmacies. Packs were labelled with unique pack identifiers according to a randomly generated sequence known only to the manufacturing unit and the trial programmers. Participants were allocated a pack identifier at randomisation and, if more packs were required, the randomisation program was used to allocate further packs containing the same allocation.

Implementation

The minimisation algorithm was implemented by a MedSciNet database programmer, with balance and predictability checked by an independent National Perinatal Epidemiology Unit Clinical Trials Unit statistician during the trial. Research teams at sites approached women to confirm eligibility and provided verbal and written information. A trained clinician obtained written informed consent. A research team member entered baseline data on a web-based database at study enrolment and then allocated a pack number using the web-based randomisation, which corresponded to a pack for dispensing by that site’s pharmacy.

Clinical teams reviewed participants at routine care clinic visits until delivery. Antenatal care, in particular the timing and mode of delivery, was left to the discretion of the responsible clinician. Research teams undertook standard assessments of safety, with reporting of adverse events and serious adverse events following usual governance procedures.

Masking

Trial participants, clinical care providers, outcome assessors and data analysts were all masked to allocation. The UDCA and placebo tablets appeared identical in size, shape and colour.

Statistical methods

Analysis

The analysis and presentation of results follows the recommendations of the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) group. Full details of the Statistical Analysis Plan were prespecified. 14 Analysis was performed in Stata® version 15 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Unmasked data were made available for analysis only after full database lock (after all data entry had been completed and queries resolved) or on request by the Data Monitoring Committee. All analyses followed the intention-to-treat principle, that is, all randomised women (and infants) were analysed according to the group they were allocated to, irrespective of the treatment they received, if any.

Demographic and clinical data were summarised with counts and percentages for categorical variables, means with standard deviations (SDs) for normally distributed continuous variables, and medians with interquartile or simple ranges for other continuous variables. All comparative analyses were performed adjusting for minimisation factors at randomisation,15 with centre as a random effect and the other variables fitted as fixed effects. In addition, for perinatal outcomes where the denominator was the number of infants, the correlation between twins was accounted for by nesting the mother’s identification number as a random effect within centre. Both unadjusted and adjusted effect estimates are presented, adjusted for centre, gestational age at randomisation (< 34, 34 to < 37, ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation), single versus multifetal pregnancy and serum bile acid concentration prior to randomisation (< 40 µmol/l, ≥ 40 µmol/l), but the primary inference is based on the adjusted estimates.

Binary outcomes were analysed using mixed-effect Poisson regression models with robust variance estimation and results presented as adjusted risk ratios (aRRs) with confidence intervals (CIs). 16 Continuous outcomes were analysed using mixed-effect linear regression models and presented as adjusted mean differences with CIs. Skewed continuous variables were analysed using quantile regression with minimisation factors (excluding centre) fitted as fixed effects, and results presented as median differences with CIs. Analysis of outcomes that were measured repeatedly over time (severity of itch and biochemistry measures) used repeated measures models, with means or geometric means of the post-randomisation observations reported,17 and the trial arms were compared using a mean difference (MD) or geometric mean ratio (GMR), adjusted for the baseline measures (such that the summary statistics are adjusted for chance imbalances at baseline) and minimisation factors.

As only two infants were excluded from the analysis of the primary outcome, multiple imputation for missing data was not undertaken. Any missingness for data for baseline characteristics and outcomes is reported in the results tables.

Prespecified subgroup analysis

Prespecified subgroup analyses were performed for the primary outcome and its components, the serum bile acid concentrations and itch outcomes, using the statistical test of interaction. Binary outcomes are presented as RRs with CIs on a forest plot. Prespecified subgroups were based on the criteria selected for minimisation: serum bile acid concentration at baseline (10–39 µmol/l, ≥ 40 µmol/l); gestational age (participants recruited before 34 weeks’ gestation, 34 to 36+6 weeks’ gestation, ≥ 37 weeks’ gestation); singleton, twins.

Post hoc analyses

Following discussion of the results of the prespecified analysis, and in the light of recent evidence,2 the Trial Steering Committee and Data Monitoring Committee requested two additional post hoc analyses: first, the number and percentage of women with peak serum bile acid concentrations of < 100/≥ 100 µmol/l prior to randomisation, with the primary outcome and its components stratified by this; and, second, the number and percentage of infants with a spontaneous preterm birth, or with an iatrogenic preterm birth, with a subgroup analysis of these by the minimisation factors specified for the other subgroup analyses. A Kaplan–Meier survival curve of time from randomisation to delivery estimate has been included at the request of a reviewer (see Figure 2).

Prespecified sensitivity analyses

Sensitivity analyses were conducted for the primary outcome, itch score and serum bile acid concentration between randomisation and delivery, excluding women or infants of mothers who did not adhere to the intervention (< 90% medication adherence consistently self-reported).

Level of statistical significance

The 95% CIs were reported for all primary and secondary outcome comparisons, including subgroup analyses.

Economic analysis

Data on health-care resources were collected by review of maternity case notes detailing outpatient visits and inpatient admissions. Data on mother and infant inpatient care and mode of delivery were costed using the National Schedule of Reference costs18 (Table 1). The cost of UDCA (derived from British National Formulary19 as £45 per 60-tablet pack) was included for women randomised to receive the intervention. Descriptive statistics are reported including mean cost per participant and 95% CIs constructed using bootstrapping (7000 iterations) to account for the skewed nature of the data. Comparative difference in costs was calculated using linear regressions, and adjusting for gestational age at randomisation, serum bile acid concentration, multifetal pregnancy and centre as a random effect.

The full protocol is published. 14

| Resource use item | Cost per bed-day (£) |

|---|---|

| Antenatal admission | 846 |

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery | 1189 |

| Induced laboura | 1137 |

| Caesarean delivery | 1418 |

| PROM and stimulation of labourb | 823 |

| High-dependency unit maternal stay | 1096 |

| Infant inpatientc | 427 |

Additional trial information

Provision of trial medication

The UDCA and placebo tablets were provided at cost by Dr Falk Pharma GmBH. Dr Falk Pharma GmBH has had no input into study design, collection, management, analysis and interpretation of data, writing of the report, or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Results

Participant flow, recruitment and numbers analysed

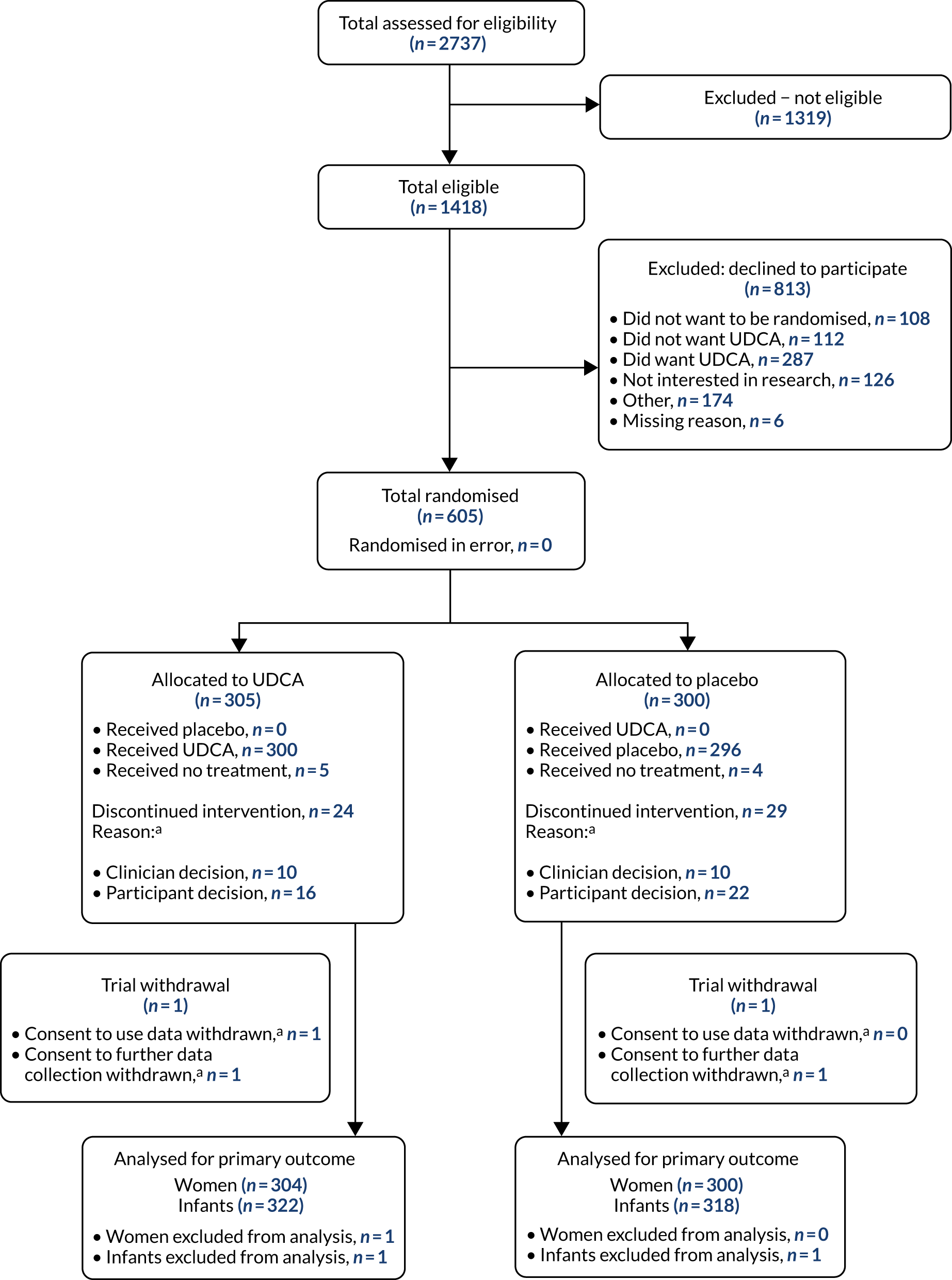

Between 23 December 2015 and 7 August 2018, 605 women (43%) were recruited out of 1418 women who were found to be eligible, including 37 women with a twin pregnancy (Figure 1), across 33 maternity units (Table 2).

FIGURE 1.

The CONSORT flow diagram. a, Not mutually exclusive.

| Hospital | Number of participants enrolled |

|---|---|

| Birmingham Women’s Hospital | 15 |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary | 26 |

| Burnley General Hospital | 14 |

| Darlington Memorial Hospital | 8 |

| Frimley Park Hospital | 4 |

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital | 2 |

| Ipswich Hospital | 30 |

| James Paget University Hospital | 13 |

| Leighton Hospital | 12 |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital | 48 |

| Nottingham City Hospital | 20 |

| Nottingham – Queen’s Medical Centre | 16 |

| Peterborough City Hospital | 18 |

| Princess of Wales Hospital, Bridgend | 11 |

| Queen Alexandra Hospital, Portsmouth | 11 |

| Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital | 13 |

| Queen’s Hospital, Burton | 21 |

| Royal Blackburn Hospital | 15 |

| Royal Preston Hospital | 26 |

| Royal Stoke University Hospital | 15 |

| Royal Sussex County Hospital | 6 |

| Royal Victoria Infirmary | 2 |

| Singleton Hospital | 18 |

| St George’s Hospital | 22 |

| St Richard’s Hospital | 23 |

| St Thomas’ Hospital | 56 |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | 42 |

| The James Cook University Hospital | 16 |

| University Hospital of North Durham | 5 |

| Warrington Hospital | 22 |

| West Middlesex University Hospital | 33 |

| Worthing Hospital | 11 |

| York Hospital | 11 |

A total of 305 women were allocated to the UDCA group, with data from 304 women (one woman withdrew, with consent to use all data withdrawn) and 322 infants included in the primary outcome analysis. A total of 300 women were allocated to the placebo group, with all 300 women analysed (one woman withdrew, with consent to use baseline data but not to collect outcome data) and 318 infants included in the primary outcome analysis. Follow-up to maternal and infant discharge from hospital continued until December 2018. As we recruited ahead of schedule, we continued recruitment up to the number of women who discontinued the intervention or withdrew from the trial (with approval of the funder, sponsor and ethics committee), such that our total number of women recruited (n = 605) included the target sample size (n = 550 women), the number who discontinued the intervention (n = 53) and those who withdrew (n = 2). Recruitment ended after 605 women had been enrolled.

Baseline data

Baseline characteristics were similar between the two groups (Table 3). At trial enrolment, the groups were well balanced on minimisation factors (see Table 3).

| UDCA (N = 304) | Placebo (N = 300) | |

|---|---|---|

| Woman’s age (years), mean (SD) | 30.5 (5.6) | 30.8 (5.3) |

| Woman’s ethnic group, n (%) | ||

| White | 247 (81.3) | 246 (82.0) |

| Black | 10 (3.3) | 7 (2.3) |

| Asian | 34 (11.2) | 40 (13.3) |

| Other | 11 (3.6) | 7 (2.3) |

| Not known | 2 (0.7) | 0 |

| Body mass index at booking (kg/m2), mean (SD) | 27.4 (6.4) | 26.9 (6.1) |

| Smoked at booking, n (%) | 33 (11.4) | 44 (15.1) |

| Deprivation level (quintiles of Index of Multiple Deprivation)a | ||

| 5 (most deprived) | 76 (26.3) | 81 (28.3) |

| Previous pregnancy ≥ 24 weeks, n (%) | 178 (58.6) | 193 (64.3) |

| Previous stillbirths, n (%) | 2 (0.7) | 2 (0.7) |

| History of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy, n (%) | 92 (52.6) | 90 (47.4) |

| Pre-pregnancy liver disease, n (%) | 3 (1.0) | 6 (2.0) |

| Liver ultrasound at randomisation, n (%) | 79 (27.0) | 78 (26.7) |

| Normal | 65 (84.4) | 57 (74.0) |

| Abnormal – gallstones | 9 (11.7) | 12 (15.6) |

| Abnormal – other | 3 (3.9) | 8 (10.4) |

| Missing result | 2 (2.5) | 1 (1.3) |

| Previous operation for gallstones, n (%) | 20 (6.7) | 17 (5.8) |

| Pre-pregnancy diabetes, n (%) | 4 (1.3) | 4 (1.3) |

| Gestational age (weeksb), median (IQR) | 34.4 (32.1–35.9) | 34.4 (31.5–36.0) |

| < 34 weeks | 133 (43.8) | 131 (43.7) |

| 34 to < 37 weeks | 141 (46.4) | 141 (47.0) |

| ≥ 37 weeks | 30 (9.9) | 28 (9.3) |

| Twin pregnancy,b n (%) | 18 (5.9) | 19 (6.3) |

| Gestational diabetes, n (%) | 32 (10.6) | 25 (8.4) |

| Itch scorec (mm), mean (SD) | 57.1 (25.1) | 59.5 (25.1) |

| Medication for pruritus,d n (%) | 146 (49.0) | 137 (46.1) |

| Antihistamine | 121 (40.6) | 119 (40.1) |

| Topical emollient | 102 (34.2) | 101 (34.0) |

| UDCA | 15 (5.0) | 13 (4.4) |

| Highest baseline maternal serum concentrations prior to randomisation | ||

| Bile acidb (µmol/l) [geometric mean (95% CI)] | 28.1 (26.0 to 30.3) | 26.9 (24.9 to 29.0) |

| < 40 µmol/l, n (%) | 232 (76.3) | 228 (76.0) |

| ≥ 40 µmol/l, n (%) | 72 (23.7) | 72 (24.0) |

| Alanine transaminase (U/l) | n = 286 | n = 286 |

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 70.0 (61.5 to 79.6) | 59.5 (52.0 to 68.1) |

| Aspartate transaminase (U/l) | n = 47 | n = 48 |

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 49.0 (38.4 to 62.5) | 61.6 (46.8 to 81.0) |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferase (U/l) | n = 135 | n = 138 |

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 23.3 (20.6 to 26.4) | 21.0 (19.0 to 23.2) |

| Bilirubin (µmol/l) | n = 289 | n = 275 |

| Geometric mean (95% CI) | 8.5 (7.9 to 9.1) | 8.0 (7.4 to 8.6) |

Outcomes and estimation

There was no evidence of a significant difference between the groups in the incidence of the primary outcome (perinatal death, preterm delivery or neonatal unit admission for at least 4 hours): 74 (23.0%) infants in the UDCA group compared with 85 (26.7%) infants in the placebo group experienced the primary outcome (aRR 0.85, 95% CI 0.62 to 1.15; p = 0.279) (Table 4). Similarly, there was no evidence of a significant difference between the groups in the incidence of the individual components of the primary outcome components (see Table 4). There were three in utero fetal deaths after randomisation, one in the UDCA group and two in the placebo group, with two occurring at 35 weeks’ gestation and one at 37 weeks’ gestation.

| UDCA (N = 322) | Placebo (N = 318) | Adjusted effect estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary outcome, n (%) | ||||

| Perinatal death, preterm delivery or neonatal unit admission | 74 (23.0) | 85 (26.7) | Risk ratio 0.85 (0.62 to 1.15) | 0.279 |

| Secondary perinatal outcomes, n (%) | ||||

| In utero fetal death | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) | Risk ratio 0.51 (0.04 to 6.25) | 0.598 |

| Pre-term delivery (< 37 weeks’ gestation) | 54 (16.8) | 65 (20.4) | Risk ratio 0.79 (0.57 to 1.10) | 0.171 |

| Known neonatal death up to 7 days (prior to hospital discharge) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | – | – |

| Neonatal unit admission for at least 4 hours | 45 (14.0) | 54 (17.0) | Risk ratio 0.81 (0.58 to 1.13) | 0.212 |

| Live birth, n (%) | 321 (99.7) | 316 (99.4) | ||

| Gestational age at delivery (weeks), median (IQR) | 37.6 (37.1–38.1) | 37.4 (37.0–38.1) | Median difference 0.1 (0.0 to 0.3) | 0.065 |

| Birthweight (g), median (IQR) | 3105 (2775–3390) | 3040 (2660–3320) | Median difference 94.0 (18.7 to 169.3) | 0.014 |

| Birthweight centile,a mean (SD) | 59.3 (28.4) | 56.3 (27.8) | ||

| < 10th customised centile | 16 (5.0) | 18 (5.7) | Risk ratio 0.89 (0.47 to 1.69) | 0.725 |

| < 3rd customised centile | 7 (2.2) | 7 (2.2) | Risk ratio 1.09 (0.38 to 3.12) | 0.877 |

| Mode of delivery, n (%) | ||||

| Spontaneous vaginal (cephalic) | 193 (59.9) | 182 (57.2) | Risk ratio 1.04 (0.91 to 1.20) | 0.562 |

| Vaginal (breech) | 1 (0.3) | 3 (0.9) | ||

| Assisted vaginal (cephalic) | 21 (6.5) | 35 (11.0) | ||

| Pre-labour caesarean section | 71 (22.0) | 62 (19.5) | ||

| Caesarean section | 36 (11.2) | 36 (11.3) | Risk ratio 1.00 (0.68 to 1.46) | 0.995 |

| Presence of meconium-stained amniotic fluid, n (%) | 34 (10.6) | 52 (16.5) | Risk ratio 0.65 (0.43 to 0.98) | 0.040 |

| Apgar score at 5 minutes post birth (in live births only), median (IQR) | 9.0 (9.0–10.0) | 9.0 (9.0–10.0) | Median difference 0.0 (–0.4 to 0.4) | 1.000 |

| Apgar score of < 7 at 5 minutes | 8 (2.5) | 7 (2.2) | ||

| Umbilical cord blood sampling (n) | 114 | 112 | ||

| Arterial pH, mean (SD) | 7.2 (0.1) | 7.2 (0.1) | MD –0.02 (–0.04 to 0.01) | 0.182 |

| Total number of neonatal unit nights (infants with at least one night), median (IQR) | 5.5 (3.0–13.0) | 6.0 (2.0–16.0) | Median difference 0.0 (–3.2 to 3.2) | 1.000 |

| Main diagnosis for first neonatal unit admission, n (%) | n = 45 | n = 54 | ||

| Prematurity | 14 (31.1) | 17 (31.5) | ||

| Respiratory disease | 16 (35.6) | 15 (27.8) | ||

| Infection suspected/confirmed | 5 (11.1) | 7 (13.0) | ||

| Otherb | 10 (22.2) | 15 (27.8) | ||

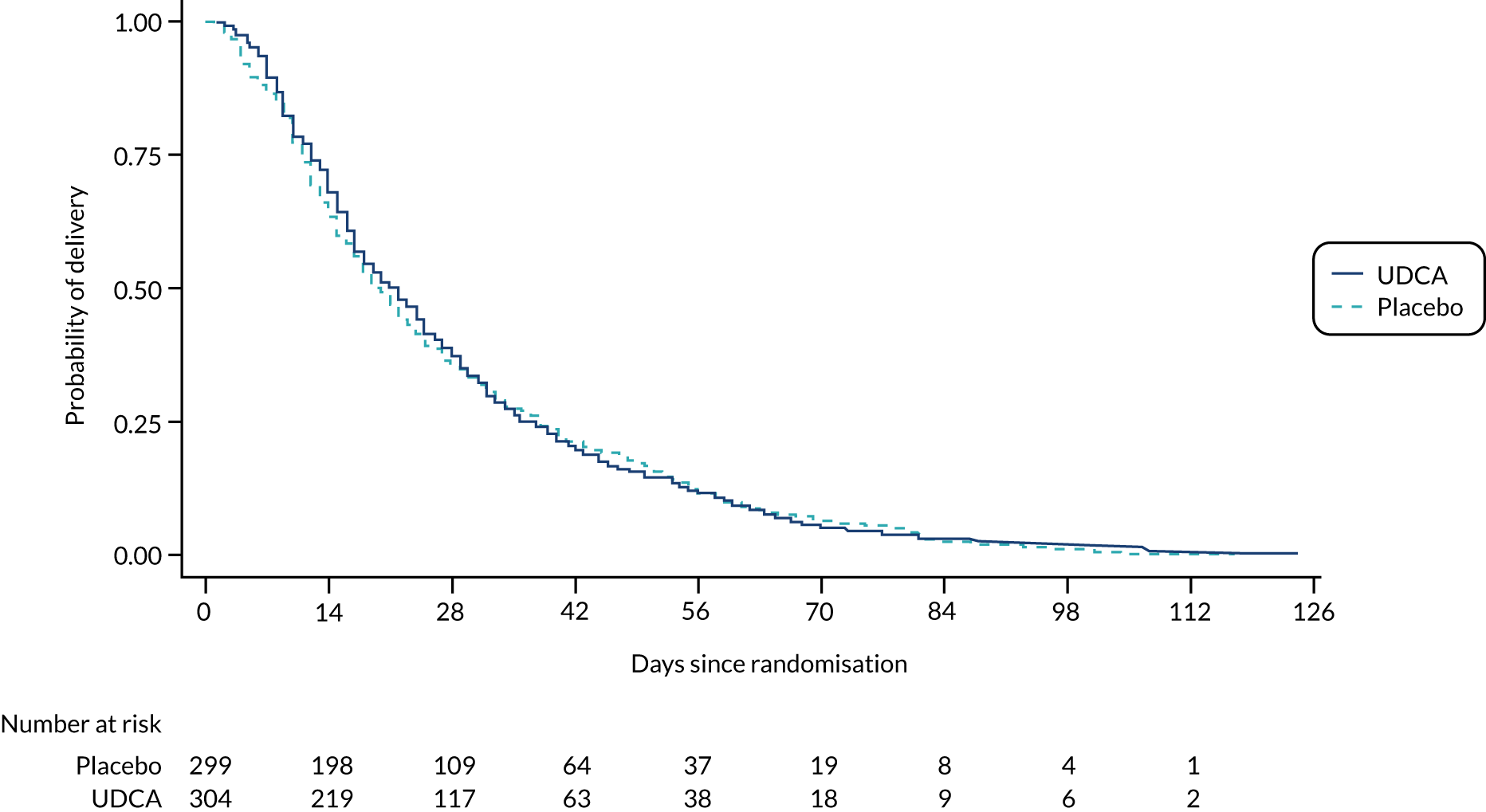

There was no evidence of a significant difference in median gestational age at delivery (Table 4); time to delivery is shown in Figure 2. The proportion of women having spontaneous vaginal births or caesarean sections was similar in both groups (Table 4). No evidence of significant differences was seen between the groups in the total number of nights in the neonatal unit or in the main diagnosis for neonatal unit admission (the latter was not formally tested). A full listing of perinatal secondary outcomes is shown in Tables 4 and 5.

FIGURE 2.

Kaplan–Meier survival curve of time from randomisation to delivery estimate.

| UDCA (N = 322) | Placebo (N = 318) | |

|---|---|---|

| Indication for assisted vaginal delivery,a n (%) | n = 21 | n = 35 |

| Maternal comorbidity/complication | 0 (0.0) | 1 (2.9) |

| Failure to progress in second stage | 9 (42.9) | 20 (57.1) |

| Suspected fetal distress | 12 (57.1) | 21 (60.0) |

| Other | 0 (0.0) | 2 (5.7) |

| Indication for in-labour caesarean delivery,a n (%) | n = 36 | n = 36 |

| Previous caesarean delivery/uterine surgery | 0 (0.0) | 3 (8.3) |

| Failure to progress in first stage | 12 (33.3) | 14 (38.9) |

| Failure to progress in second stage | 6 (16.7) | 2 (5.6) |

| Suspected fetal distress | 14 (38.9) | 15 (41.7) |

| Failed instrumental delivery | 1 (2.8) | 4 (11.1) |

| Non-cephalic fetal position | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) |

| Twins | 0 (0.0) | 4 (11.1) |

| Other | 2 (5.6) | 2 (5.6) |

| Baby sex, n (%) | ||

| Male | 162 (50.3) | 174 (54.7) |

| Female | 160 (49.7) | 144 (45.3) |

| Neonatal unit admission | ||

| Infants in intensive care, n | 10 | 16 |

| Nights in intensive care, median (IQR) | 3.0 (2.0–3.0) | 2.0 (1.0–2.5) |

| Infants in high-dependency care, n | 20 | 17 |

| Nights in high-dependency care, median (IQR) | 2.0 (1.0–5.5) | 3.0 (1.0–5.0) |

| Infants in special care, n | 40 | 45 |

| Nights in special care, median (IQR) | 5.0 (3.0–12.5) | 5.0 (2.0–16.0) |

| Main diagnosis for first neonatal unit admission of at least 4 hours, n (%) | n = 45 | n = 54 |

| Congenital anomaly suspected/confirmed | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Continuing care | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Convulsions suspected/confirmed | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hypoxic–ischaemic encephalopathy suspected/confirmed | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Hypoglycaemia | 3 (6.7) | 5 (9.3) |

| Infection suspected/confirmed | 5 (11.1) | 7 (13.0) |

| Intrauterine growth restriction/small for gestational age | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Jaundice | 0 (0.0) | 1 (1.9) |

| Monitoring | 0 (0.0) | 5 (9.3) |

| Neonatal abstinence syndrome suspected/confirmed | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Poor condition at birth | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.9) |

| Poor feeding or weight loss | 1 (2.2) | 1 (1.9) |

| Prematurity | 14 (31.1) | 17 (31.5) |

| Respiratory disease | 16 (35.6) | 15 (27.8) |

| Surgery | 1 (2.2) | 0 (0.0) |

| Neonatal morbidity in survivors to discharge from hospital | ||

| Need for supplementary oxygen prior to hospital discharge, n (%) | 16 (5.0) | 20 (6.3) |

| Number of days when supplemental oxygen required, median (IQR) | 2.5 (1.5–4.5) | 2.0 (1.0–2.5) |

| Need for ventilation support,2 n (%) | 15 (4.7) | 18 (5.7) |

| Endotracheal ventilation | 5 (1.6) | 6 (1.9) |

| Continuous positive airway pressure ventilation | 9 (2.8) | 12 (3.8) |

| High-flow oxygen | 7 (2.2) | 9 (2.9) |

| Cerebral ultrasound scan performed, n (%) | 12 (3.7) | 11 (3.5) |

| Abnormalities found, n (%) | 3 (0.9) | 3 (0.9) |

| Intraventricular haemorrhage – grade 1 | 1 (0.3) | 1 (0.3) |

| Ventricular dilatation | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Confirmed sepsis (positive blood cultures), n (%) | 1 (0.3) | 2 (0.6) |

| Necrotising enterocolitis (Bell’s stage 2 or 3), n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Seizures confirmed by EEG or requiring anticonvulsant therapy, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Encephalopathy, n (%) | 2 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) |

| Treated with hypothermia | 1 (0.3) | 0 (0.0) |

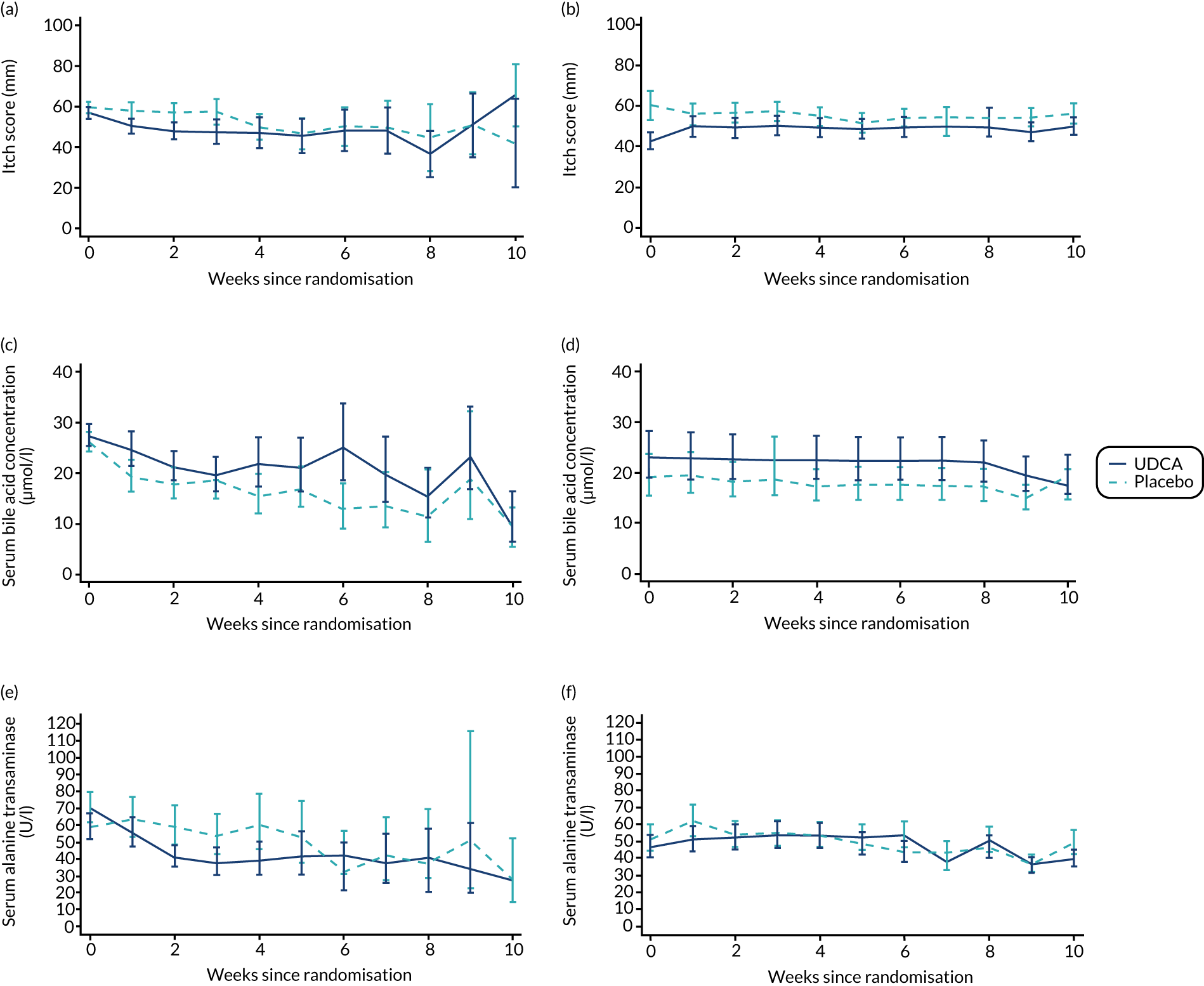

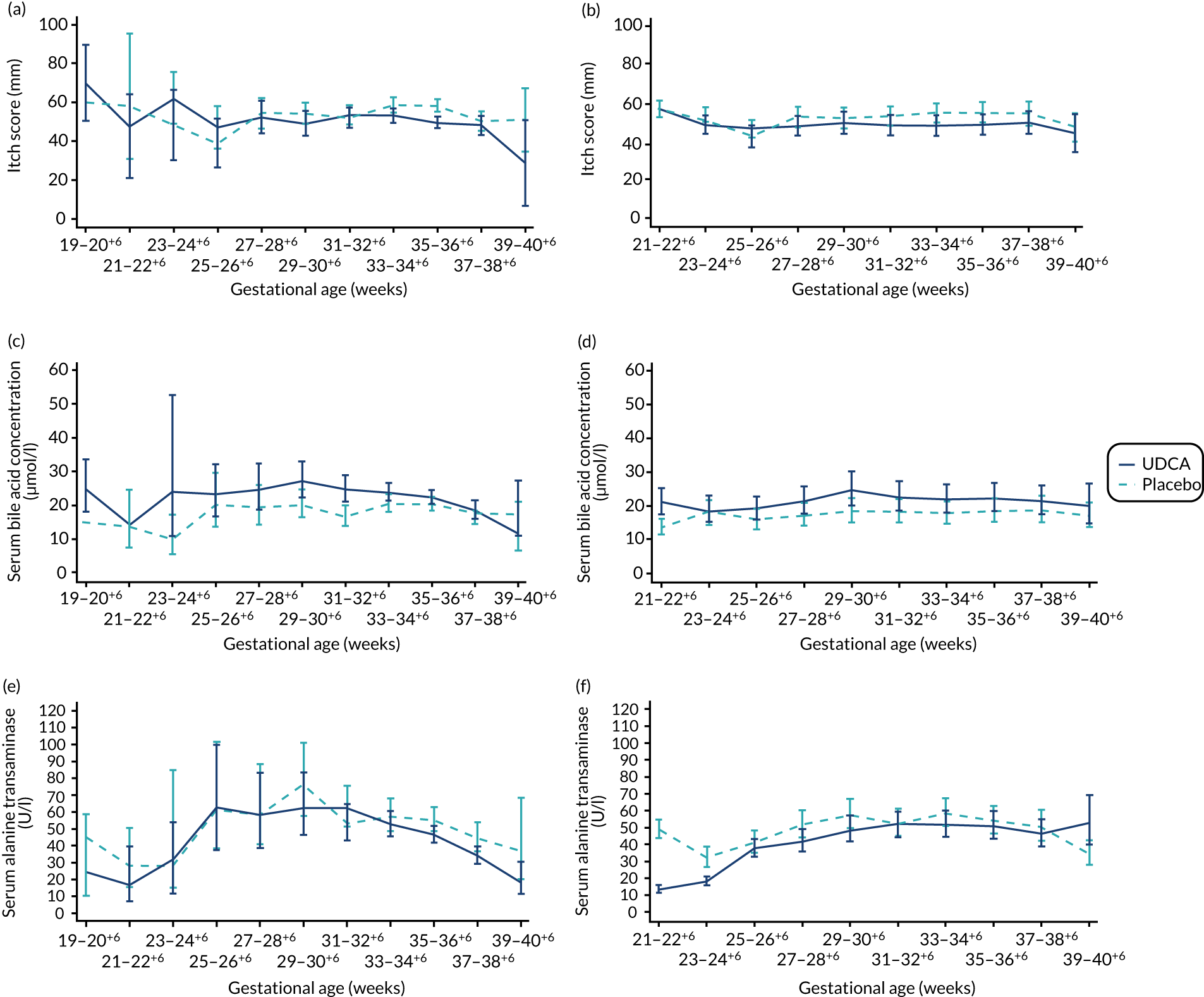

There was evidence of a significant difference between the groups on post-randomisation maternal itch score, which was lower in the UDCA group than in the placebo group (MD –5.7 mm, 95% CI –9.7 to –1.7 mm; p = 0.005) (Table 6). The actual and estimated mean trajectories are adjusted for the baseline measures and minimisation factors in Figures 3 and 4. Figure 3 shows the mean or geometric mean trajectory for maternal itch score, serum bile acid concentrations and serum alanine transaminase concentrations (with 95% CIs) up to 10 weeks post randomisation; Figures 3a, c and e show the observed trajectories and Figures 3b, d and f show the trajectories adjusted for the baseline value and minimisation factors. For example, Figure 3b shows that, at 1 week after randomisation, the mean itch score is estimated to be 56 mm (95% CI 51 to 61 mm) in the placebo group and 50 mm (95% CI 45 to 55 mm) in the UDCA group, after adjusting for the itch score at randomisation and minimisation factors. Figure 4 shows the same trajectories (actual and estimated) plotted against week of gestation throughout the trial from randomisation onwards. For example, Figure 4c shows that the observed geometric mean of serum bile acid concentration (µmol/l) when women were between 29+0 and 30+6 weeks’ gestation was 20 µmol/l (95% CI 17 to 25 µmol/l) in the placebo group and 27 µmol/l (95% CI 22 to 33 µmol/l) in the UDCA group. Serum bile acid concentrations reduced in both groups over time after study enrolment; however, there was evidence of less reduction in serum bile acid concentrations post randomisation in the UDCA group than in the placebo group [adjusted GMR 1.18 µmol/l (95% CI 1.02 to 1.36 µmol/l; p = 0.030)]. In contrast, there was evidence of a reduction in serum alanine transaminase concentrations post randomisation in the UDCA group compared with the placebo group (adjusted GMR 0.74 U/l, 95% CI 0.66 to 0.83 U/l; p < 0.001) (see Table 6, and the actual and estimated trajectories in Figures 3 and 4). Other maternal secondary outcomes are shown in Tables 6 and 7.

| UDCA (N = 304) | Placebo (N = 300) | Adjusted effect estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Itch score measureda (mm) | n = 241 | n = 227 | ||

| Mean (SD)b | 49.5 (12.9) | 56.9 (13.3) | MD –5.7 (–9.7 to –1.7) | 0.005 |

| Maternal serum bile acid concentrationa (µmol/l) | n = 256 | n = 247 | ||

| Geometric meanb (95% CI) | 22.4 (21.4 to 23.5) | 18.5 (17.7 to 19.4) | GMR 1.18 (1.02 to 1.36) | 0.030 |

| Maternal serum alanine transaminasea (U/l) | n = 242 | n = 240 | ||

| Geometric meanb (95% CI) | 49.5 (43.8 to 55.8) | 58.0 (51.0 to 65.9) | GMR 0.74 (0.66 to 0.83) | < 0.001 |

| Gestational diabetes mellitus, n (%) | 3 (1.0) | 9 (3.0) | Risk ratio 0.33 (0.10 to 1.10) | 0.071 |

| Additional therapy for cholestasis,b n (%) | 134 (51.3) | 125 (51.0) | ||

| Antihistamine | 102 (79.7) | 105 (89.0) | ||

| Topical emollient | 101 (78.9) | 93 (78.8) | ||

| Rifampicin | 1 (0.8) | 2 (1.7) | ||

| Open-label UDCA (tablets stopped) | 17 (12.6) | 21 (16.8) | ||

| Delivered before first follow-up visit | 33 | 42 | ||

| Maximum dose of trial medication, n (%) | ||||

| One tablet once per day | 4 (1.3) | 5 (1.7) | ||

| One tablet twice per day | 203 (66.8) | 198 (66.0) | ||

| One tablet three times per day | 62 (20.4) | 65 (21.7) | ||

| Two tablets twice per day | 35 (11.5) | 32 (10.7) | ||

| Mode of onset of labour, n (%) | ||||

| Spontaneous | 33 (10.9) | 55 (18.4) | Risk ratio 0.59 (0.42 to 0.83) | 0.003 |

| Induced or PROM and stimulation | 215 (70.7) | 200 (66.9) | Risk ratio 1.06 (0.95 to 1.17) | 0.302 |

| Pre-labour caesarean section | 56 (18.4) | 44 (14.7) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (< 0.1) | ||

| Indication for initiation of delivery,c n (%) | n = 271 | n = 244 | ||

| Severe maternal symptoms | 17 (6.3) | 28 (11.5) | ||

| Maternal serum bile acids | 53 (19.6) | 32 (13.1) | ||

| Fetal compromise | 24 (8.9) | 24 (9.8) | ||

| Reaching certain gestation | 161 (59.4) | 150 (61.5) | ||

| Maternal request | 32 (11.8) | 29 (11.9) | ||

| Otherd | 37 (14.3) | 33 (14.2) | ||

| Estimated blood loss at delivery (ml), median (IQR) | 350 (250–600) | 400 (250–600) | Median difference –50 (–95 to –5) | 0.029 |

| < 500, n (%) | 195 (64.1) | 185 (61.9) | ||

| ≥ 500 and ≤ 999, n (%) | 79 (26.0) | 80 (26.8) | ||

| ≥ 1000, n (%) | 30 (9.9) | 34 (11.4) |

FIGURE 3.

Changes in maternal itch score and serum concentrations of bile acid and alanine transaminase between randomisation and delivery over 10 weeks since randomisation with 95% CIs, by allocation. (a) Actual mean trajectory of changes in maternal itch score (mm); (b) estimated mean trajectory of changes in maternal itch score (mm); (c) actual geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum bile acid concentration (µmol/l); (d) estimated geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum bile acid concentration (µmol/l); (e) actual geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum alanine transaminase concentration (U/l); and (f) estimated geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum alanine transaminase concentration (U/l). The estimated geometric mean trajectories (b, d and f) are adjusted for baseline measures and minimisation factors.

FIGURE 4.

Changes in maternal itch score and serum concentrations of bile acid and alanine transaminase between randomisation and delivery by gestational age with 95% CIs, by allocation. (a) Actual mean trajectory of changes in maternal itch score (mm); (b) estimated mean trajectory of changes in maternal itch score (mm); (c) actual geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum bile acid concentration (µmol/l); (d) estimated geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum bile acid concentration (µmol/l); (e) actual geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum alanine transaminase concentration (U/l); and (f) estimated geometric mean trajectory of changes in serum alanine transaminase concentration (U/l). The estimated mean trajectories (b, d and f) are adjusted for baseline measures and minimisation factors.

| UDCA (N = 304) | Placebo (N = 300) | |

|---|---|---|

| Maternal serum concentrations | ||

| Aspartate transaminasea (U/l) | n = 44 | n = 39 |

| Geometric meanb (95% CI) | 44.1 (35.7 to 54.5) | 64.3 (51.1 to 81.0) |

| Bilirubin (µmol/l) | n = 246 | n = 226 |

| Geometric meanb (95% CI) | 7.0 (6.6 to 7.5) | 8.6 (8.0 to 9.3) |

| Gamma-glutamyltransferasea (U/l) | n = 96 | n = 100 |

| Geometric meanb (95% CI) | 18.3 (16.0 to 21.0) | 21.0 (18.8 to 23.4) |

| Number of fetuses with completed estimated fetal weight post randomisationa | n = 176 | n = 150 |

| Estimated fetal weight on ultrasound > 90th centile, n (%) | 17 (9.7) | 15 (10.0) |

| Myometrial contractions on cardiotocography approximately 1 week (3–14 days) post randomisation, n (%) | 165 (63.2) | 153 (61.4) |

| Average number of contractions in 10 minutes, n (95% CI) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) | 0.0 (0.0 to 0.0) |

| Delivered before first follow-up visit | n = 33 | n = 43 |

| Maternal administration of steroids during pregnancy, n (%) | 60 (19.7) | 55 (18.3) |

| 1 dose | 2 (3.3) | 5 (9.1) |

| 2 doses | 57 (95.0) | 48 (87.3) |

| 3 or more doses | 1 (1.7) | 2 (3.6) |

| Method(s) of induction if induced,c n (%) | n = 215 | n = 200 |

| Prostaglandin | 178 (82.8) | 156 (78.0) |

| Artificial rupture of membranes | 111 (51.6) | 95 (47.5) |

| Syntocinond | 74 (34.4) | 60 (30.0) |

| Other | 8 (3.7) | 9 (4.5) |

| Maternal death, n (%) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Highest serum bile acid concentration at randomisation,e n (%) | ||

| < 100 µmol/l | 299 (92.9) | 301 (94.7) |

| ≥ 100 µmol/l | 23 (7.1) | 17 (5.3) |

| Primary perinatal outcome,e n/N (%) | ||

| < 100 µmol/l | 65/299 (21.7) | 78/301 (25.9) |

| ≥ 100 µmol/l | 9/23 (39.1) | 7/17 (41.2) |

| In utero fetal death after randomisation,e n/N (%) | ||

| < 100 µmol/l | 0/299 (0.0) | 2/301 (0.7) |

| ≥ 100 µmol/l | 1/23 (4.3) | 0/17 (0.0) |

| Preterm delivery (< 37 weeks’ gestation),e n/N (%) | ||

| < 100 µmol/l | 47/299 (15.7) | 58/301 (19.3) |

| ≥ 100 µmol/l | 7/23 (30.4) | 7/17 (41.2) |

| Neonatal unit admission for at least 4 hours,e n/N (%) | ||

| < 100 µmol/l | 41/299 (13.7) | 52/301 (17.3) |

| ≥ 100 µmol/l | 4/23 (17.4) | 2/17 (11.8) |

Around two-thirds of women took a maximum of one tablet twice per day (equivalent to 1000 mg in the UDCA group). Similar numbers of women in both groups discontinued the intervention [24 (7.9%) in the UDCA group compared with 29 (9.7%) in the placebo group], with similar numbers of discontinuations across the groups instigated by clinicians and participants (Table 8).

| UDCA (N = 304) | Placebo (N = 300) | |

|---|---|---|

| Serious adverse events, n | 2 | 6 |

| Causality: unrelated | 2 | 6 |

| System organ class, n | ||

| Congenital, familial and genetic disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Infections and infestations | 1 | 1 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 1 | 1 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Adverse events (number of events), n | 31 | 41 |

| Related to study drug | ||

| Not related | 15 | 31 |

| Possibly | 8 | 9 |

| Probably | 1 | 0 |

| Missing | 7 | 1 |

| System Organ Class, n | ||

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 4 | 4 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 10 | 10 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 7 | 18 |

| Other | 10 | 9 |

| Discontinued intervention, n (%)a | 24 (7.9) | 29 (9.7) |

| Clinician decision | 10 (41.7) | 10 (34.5) |

| Consultant wants participant to receive UDCA | 3 (30.0) | 2 (20.0) |

| Increased serum bile acid/alanine transaminase concentration and/or itch | 6 (60.0) | 8 (80.0) |

| Nausea/vomiting/upset stomach | 1 (10.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Participant decision | 16 (66.7) | 22 (75.9) |

| Itch improved/manageable without medication | 1 (7.7) | 1 (5.3) |

| Decided did not want medication/did not collect | 5 (38.5) | 4 (21.1) |

| Increased serum bile acid/alanine transaminase concentration and/or itch | 6 (46.2) | 8 (42.1) |

| Nausea/vomiting/upset stomach | 1 (7.7) | 2 (10.5) |

| Stopped trial drug for one week | 0 (0.0) | 1 (5.3) |

| Decided wanted UDCA | 0 (0.0) | 3 (15.8) |

| Not known | 3 | 3 |

| Action following discontinuation, n (%) | ||

| Prescribed UDCA | 17 (73.9) | 21 (77.8) |

| Not prescribed UDCA | 6 (26.1) | 6 (22.2) |

| Not known | 1 | 2 |

In a prespecified planned sensitivity analysis excluding infants whose mothers took < 90% of the trial medication, a similar proportion of infants experienced the primary outcome of perinatal death, preterm delivery or neonatal unit admission for at least 4 hours: 49 out of 217 (22.6%) infants in the UDCA group compared with 44 out of 190 (23.2%) in the placebo group (aRR 0.91, 95% CI 0.63 to 1.32; p = 0.627) (Table 9).

| UDCA | Placebo | Adjusted effect estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Infants included | N = 217 | N = 190 | ||

| Primary outcome: perinatal death, preterm delivery or neonatal unit admission, n (%) | 49 (22.6) | 44 (23.2) | Risk ratio 0.91 (0.63 to 1.32) | 0.627 |

| Women included | N = 188 | N = 166 | ||

| Itch score between randomisation and delivery (mm), mean (SD) | 49.7 (12.9) | 56.8 (12.9) | MD –5.7 (–0.4 to –1.1) | 0.016 |

| Women included | N = 192 | N = 173 | ||

| Serum bile acid concentration (μmol/l) between randomisation and delivery, geometric mean (95% CI) | 22.2 (21.0 to 23.4) | 18.2 (17.3 to 19.2) | GMR 1.21 (1.03 to 1.43) | 0.022 |

Ancillary analyses

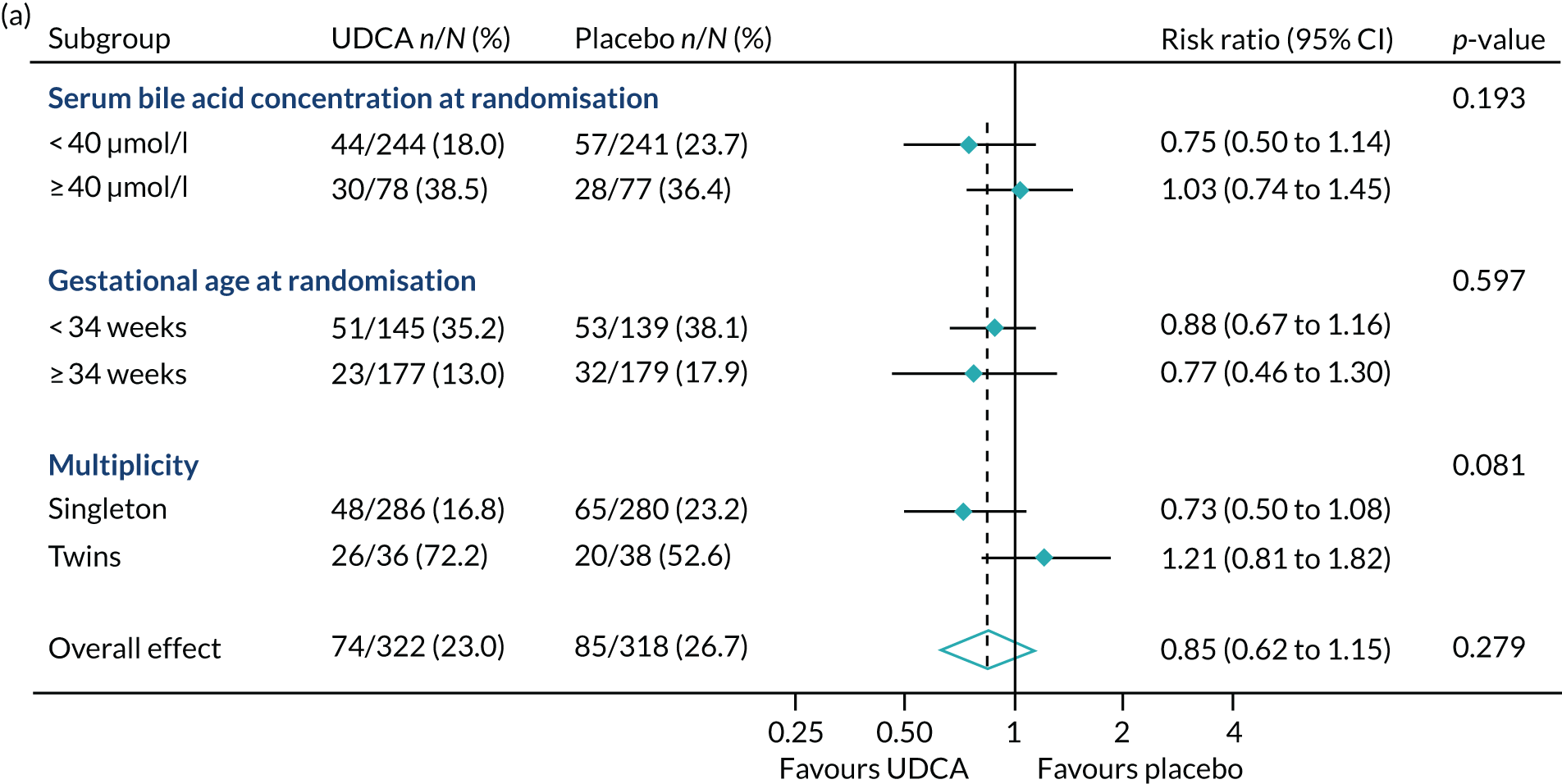

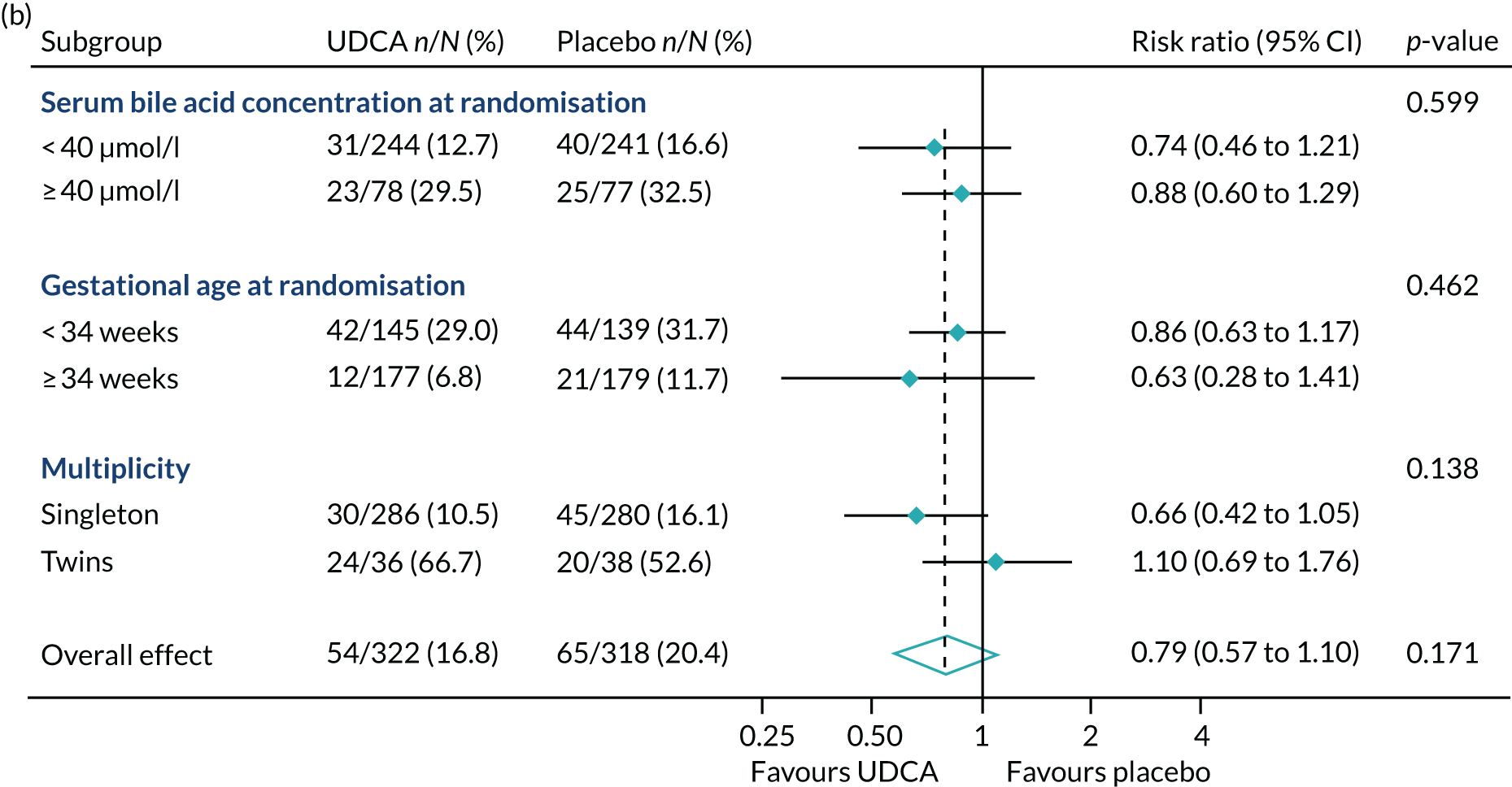

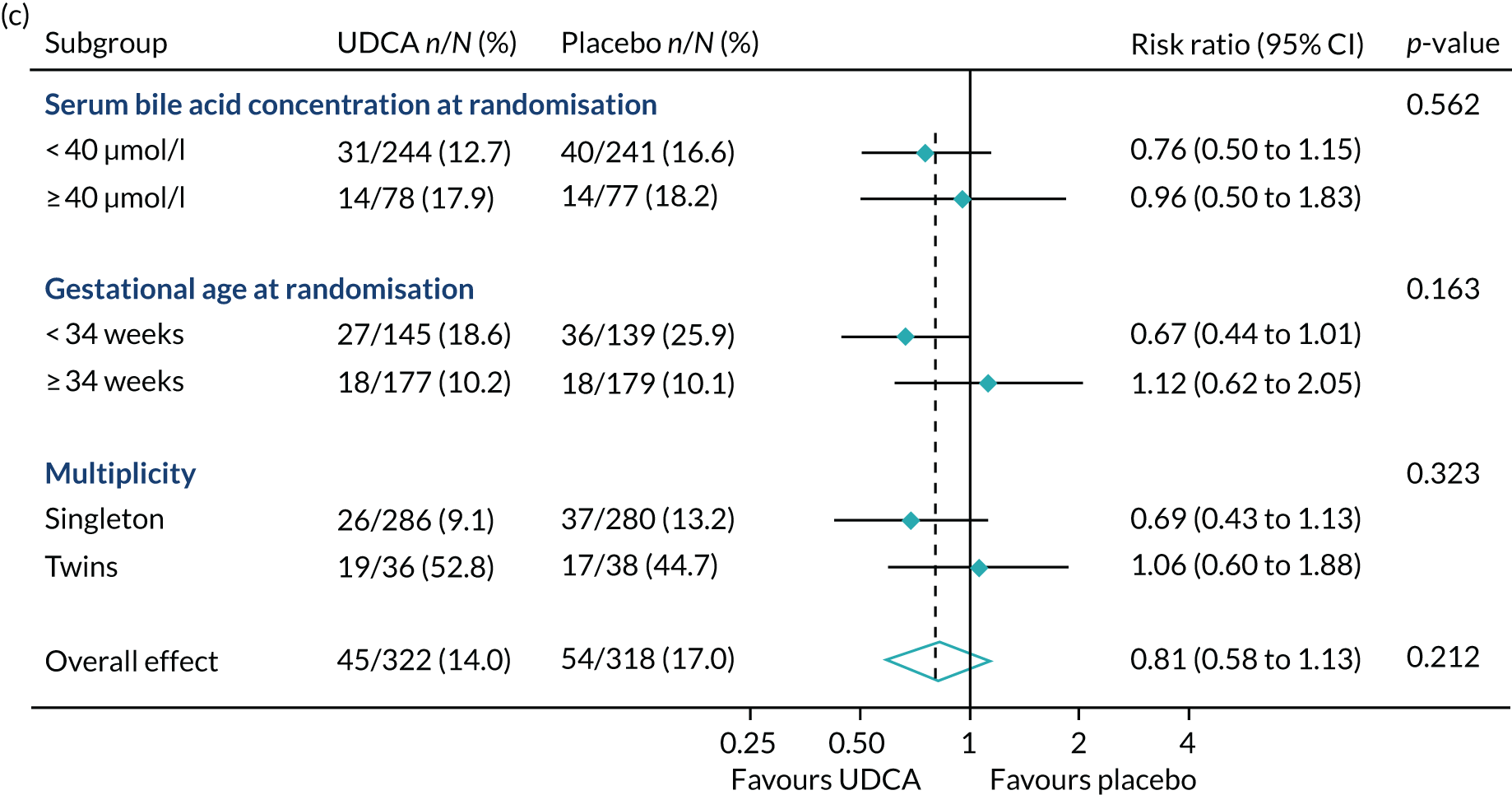

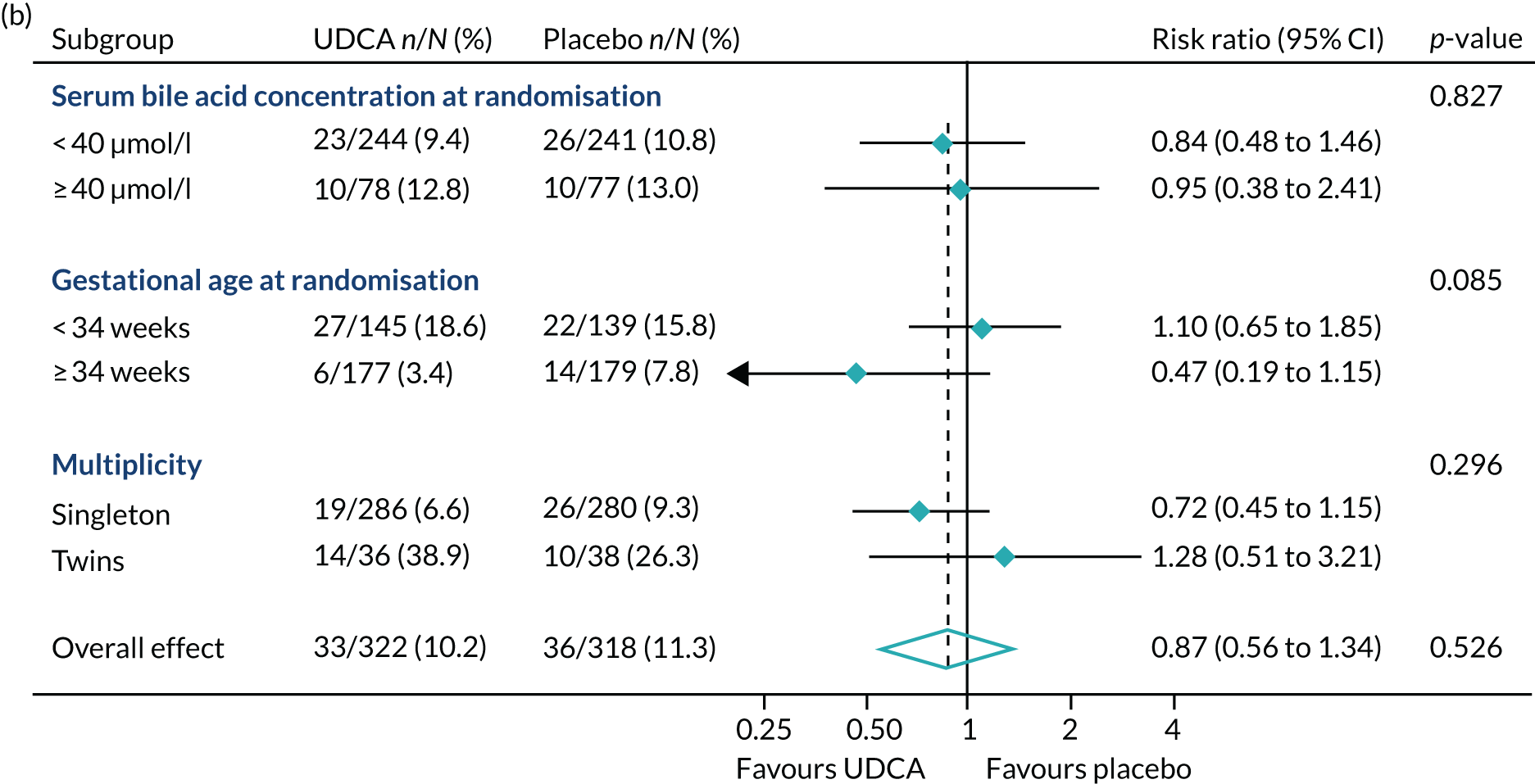

In prespecified planned subgroup analyses, we found that there was no evidence of a significant interaction of highest serum bile acid concentration prior to randomisation (stratified as < 40 µmol/l and ≥ 40 µmol/l), gestational age at randomisation (< 34 weeks’ gestation, ≥ 34 weeks’ gestation), or multiplicity (singleton or twin pregnancy) and the incidence of the primary outcome, nor its components, nor important maternal secondary outcomes (itch score and serum bile acid concentration post randomisation) (Figure 5 and Table 10).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plots showing subgroup analysis for the primary outcome and its main components. (a) Primary outcome; (b) preterm delivery; and (c) neonatal unit admission.

| UDCA | Placebo | Adjusted effect estimate (95% CI) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Serum bile acid concentration between randomisation and delivery | ||||

| Serum bile acid concentration at randomisation, median (IQR) | 0.455 | |||

| < 40 µmol/l | N = 196 | N = 191 | ||

| 18.6 (18.2–19.1) | 15.7 (15.4–16.1) | GMR 1.21 (1.03 to 1.43) | ||

| ≥ 40 µmol/l | N = 60 | N = 56 | ||

| 40.9 (38.1–43.8) | 32.3 (29.8–35.0) | GMR 1.06 (0.78 to 1.44) | ||

| Gestational age at randomisation, median (IQR) | 0.373 | |||

| < 34 weeks | N = 127 | N = 123 | ||

| 23.2 (21.6–25.0) | 18.4 (17.2–19.7) | GMR 1.25 (1.02 to 1.53) | ||

| ≥ 34 weeks | N = 129 | N = 124 | ||

| 21.7 (20.3–23.1) | 18.6 (17.5–19.8) | GMR 1.09 (0.88 to 1.36) | ||

| Multiplicity, n (%) | 0.565 | |||

| Singleton | N = 239 | N = 233 | ||

| 22.3 (21.2–23.5) | 18.4 (17.6–19.3) | GMR 1.16 (1.00 to 1.35) | ||

| Twins | N = 17 | N = 14 | ||

| 23.6 (19.1–29.2) | 20.8 (16.1–26.7) | GMR 1.40 (0.75 to 2.61) | ||

| Itch score (mm) between randomisation and delivery, n (%) | ||||

| Serum bile acid concentration at randomisation | 0.637 | |||

| < 40 µmol/l | N = 187 | N = 178 | ||

| 48.8 (13.1) | 55.5 (13.5) | MD –5.18 (–9.70 to –0.65) | ||

| ≥ 40 µmol/l | N = 54 | N = 49 | ||

| 52.1 (12.0) | 62.3 (10.9) | MD –7.50 (–16.04 to 1.03) | ||

| Gestational age at randomisation | 0.377 | |||

| < 34 weeks | N = 117 | N = 115 | ||

| 48.8 (12.6) | 55.9 (13.5) | MD –3.94 (–9.45 to 1.57) | ||

| ≥ 34 weeks | N = 124 | N = 112 | ||

| 50.2 (13.2) | 58.0 (13.1) | MD –7.55 (–13.37 to –1.74) | ||

| Multiplicity, n (%) | 0.469 | |||

| Singleton | N = 224 | N = 215 | ||

| 49.3 (13.0) | 57.0 (13.2) | MD –6.04 (–10.16 to –1.93) | ||

| Twins | N = 17 | N = 12 | ||

| 52.8 (11.2) | 56.4 (14.7) | MD 0.44 (–16.63 to 17.52) | ||

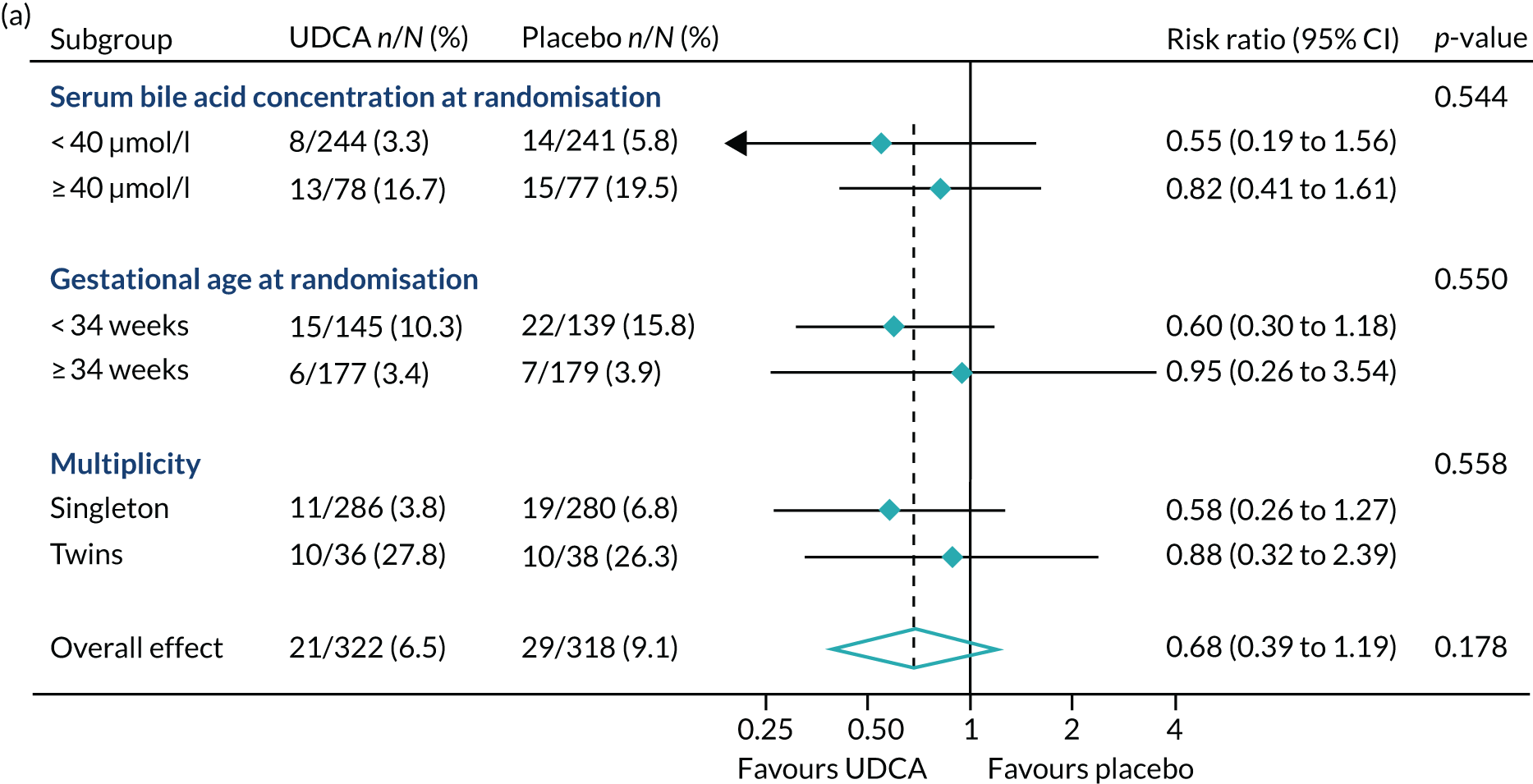

In requested post hoc exploratory analyses, the proportion of infants with the primary outcome in mothers with the highest serum bile acid concentrations of ≥ 100 µmol/l at randomisation were similar: 9 out of 23 infants (39.1%) in the UDCA group compared with 7 out of 17 (41.2%) in the placebo group (see Table 7). There was also no evidence of a difference in the proportion of women with spontaneous or iatrogenic preterm birth between the groups (Figure 6).

FIGURE 6.

Forest plots showing post hoc subgroup analysis for (a) spontaneous preterm delivery; and (b) iatrogenic preterm delivery.

Harms

Eight serious adverse events were reported, all of which were considered to be unrelated to the trial intervention. Two occurred in the UDCA group and six occurred in the placebo group, relating to a range of organ systems (Table 11). Seventy-three adverse events were reported: 31 in the UDCA group and 42 in the placebo group. Of note, the same number in each group (n = 10) reported adverse events related to gastrointestinal disturbances.

| UDCA (N = 304) | Placebo (N = 300) | |

|---|---|---|

| Serious adverse events (n) | 2 | 6 |

| Causality: unrelated | 2 | 6 |

| Severity | ||

| Mild | 1 | 1 |

| Moderate | 1 | 4 |

| Severe | 0 | 1 |

| Action taken | ||

| None | 2 | 4 |

| Discontinued temporarily | 0 | 1 |

| Discontinued | 0 | 1 |

| Outcome | ||

| Resolved | 2 | 1 |

| Not resolved | 0 | 2 |

| Fatal | 0 | 1 |

| Unknown | 0 | 2 |

| System Organ Class | ||

| Congenital, familial and genetic disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Hepatobiliary disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Infections and infestations | 1 | 1 |

| Metabolism and nutrition disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 1 | 1 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Adverse events (n) | 31 | 41 |

| Number of women with at least one adverse event | 22 | 34 |

| Intensity | ||

| Mild | 28 | 33 |

| Moderate | 3 | 7 |

| Severe | 0 | 1 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

| Related to study drug | ||

| Not related | 15 | 31 |

| Possibly | 8 | 9 |

| Probably | 1 | 0 |

| Missing | 7 | 1 |

| Outcome | ||

| Resolved | 31 | 38 |

| Resolved with sequelae | 0 | 1 |

| Missing | 0 | 2 |

| System Organ Class | ||

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 4 | 4 |

| Cardiac disorders | 2 | 0 |

| Endocrine disorders | 1 | 0 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 10 | 10 |

| Infections and infestations | 2 | 3 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 2 | 1 |

| Nervous system disorders | 2 | 1 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 7 | 18 |

| Psychiatric disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Vascular disorders | 1 | 2 |

| Missing | 0 | 1 |

Economic analysis

There was no evidence of a significant difference in total costs (maternal, infant and cost of UDCA) between the two trial groups: mean £5420 [standard error (SE) £284] in the UDCA group compared with mean £5892 (SE £353) in the placebo group [adjusted difference –£429, 95% CI –£1235 to £377: adjusted p-value 0.297 (Table 12)].

| Cost component | UDCA | Placebo | Unadjusted (95% CI) | Adjusted bootstrapped (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Maternal | N = 304 | N = 299 | ||

| Antenatal inpatient, % (n) with an admission | 51% (154) | 53% (157) | ||

| Antenatal inpatient, mean cost (SE) | 854 (76) | 939 (95) | ||

| Labour and postnatal | ||||

| Spontaneous vaginal delivery, mean cost (SE) | 3459 (572) | 3632 (448) | ||

| Induced labour, mean cost (SE) | 2829 (133) | 2967 (140) | ||

| Caesarean delivery, mean cost (SE) | 3697 (366) | 4028 (412) | ||

| PROM and stimulation, mean cost (SE) | 3760 (858) | 4070 (552) | ||

| All deliveries, mean cost (SE) | 3082 (132) | 3268 (139) | ||

| Maternal high-dependency unit, % (n) with an admission | 3% (8) | 4% (11) | ||

| Maternal high-dependency unit, mean cost (SE) | 47 (18) | 70 (23) | ||

| Total maternal, mean cost (SE) | 3983 (173) | 4276 (182) | ||

| Infant | n = 322 | n = 318 | ||

| Infant inpatient, % (n) with an admission | 89% (271) | 85% (254) | ||

| Infant inpatient, mean cost (SE) | 1378 (148) | 1610 (202) | ||

| Total | ||||

| Maternal and infant, mean cost (SE) | 5361 (284) | 5892 (333) | ||

| Cost analysis (including cost of treatment) | ||||

| Total cost (maternal, infant and UDCA) | 5420 (284) | 5892 (353) | –472 (–1330 to 386) | –429 (–1235 to 377) |

| Unadjusted p-value: p = 0.281 | Adjusted p-value: p = 0.297 | |||

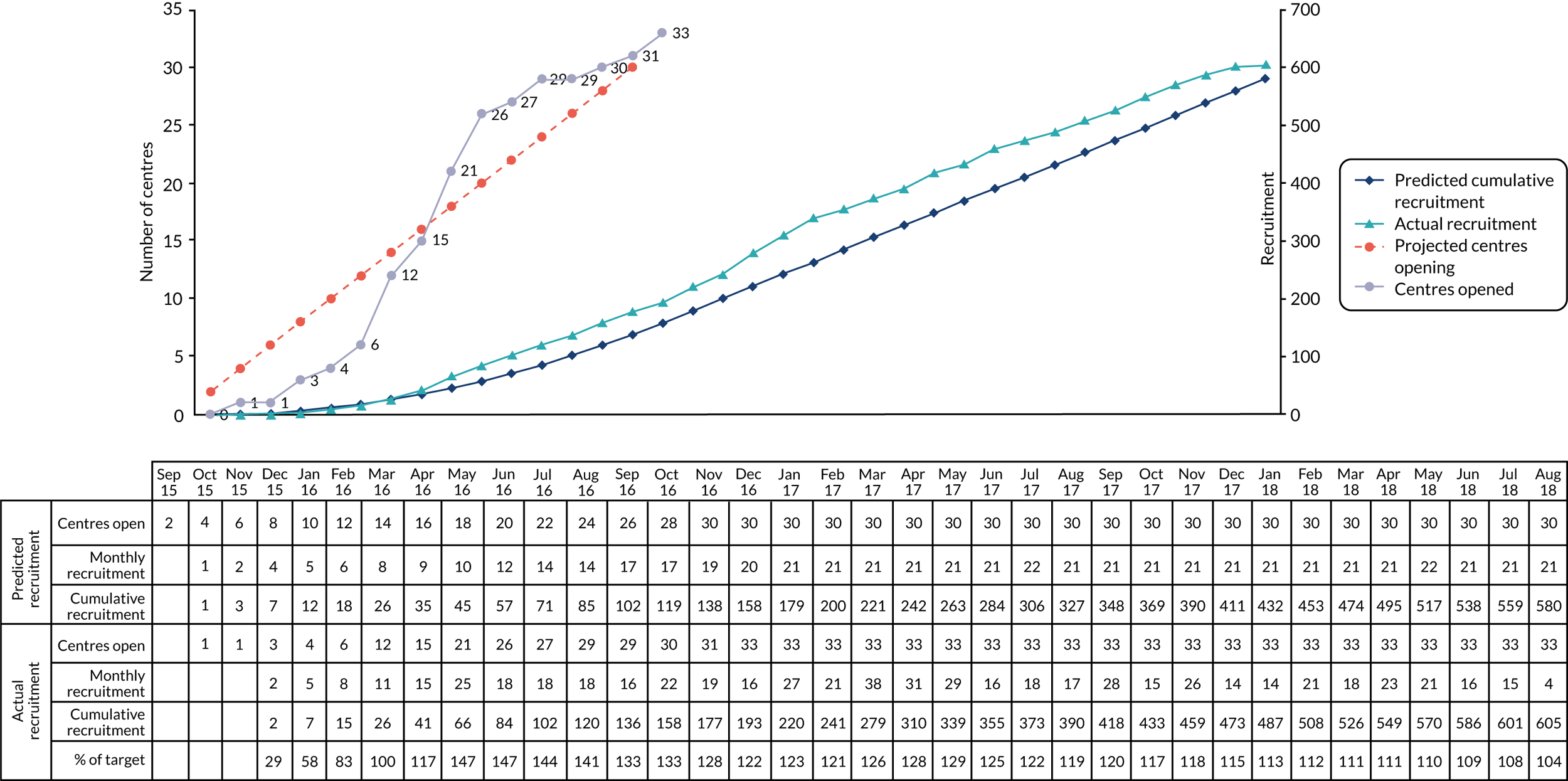

Additional information

Cumulative recruitment to the PITCHES trial is shown in Appendix 1, Figure 7. The list of collaborators is shown in Appendix 2, Table 15.

Discussion

In this trial of UDCA in women with ICP, there is no evidence that UDCA is effective in reducing a composite of adverse perinatal outcomes. Although we have shown that it appears to be safe, it has no clinically meaningful effect on maternal itch symptoms. UDCA does not reduce maternal serum bile acid concentrations, and the reduction in serum alanine transaminase concentration is of uncertain clinical significance, given the lack of correlation of alanine transaminase concentration with the risk of stillbirth or preterm labour. 2 The analysis in women who reported adherence to the intervention reduced the effect size for the primary outcome, and subgroup analyses did not identify any group likely to show a greater response to UDCA. Recent work has identified that the risk of stillbirth increases in women with ICP with peak serum bile acid concentrations ≥ 100 µmol/l, and that the risk of preterm birth increases with peak serum bile acid concentrations ≥ 40 µmol/l. 2 In subgroups of women identified by higher peak serum bile acid concentration at study enrolment, there was no discernible effect of UDCA on the primary perinatal outcome or its components, or on important maternal outcomes. It is unlikely that a biologically plausible and clinically important reduction has been missed. We have previously reported that clinicians and women considered a 30-mm (95% CI 15 to 50-mm) improvement in the itch score (from a baseline score of 60 mm) would be a clinically important difference;11 the 5-mm reduction in itch score reported in this trial is unlikely to be seen as clinically useful by many. Although some secondary outcomes appear to be significantly different (at 95% CIs), the effects do not support a unified action related to UDCA.

There was no significant difference in costs. Although there is the potential that the cost of UDCA would be covered by cost-savings elsewhere in the health-care system, in the absence of clinical effectiveness to recommend the use of UCDA, any cost-savings may not be clinically relevant.

To trial real-world effectiveness of the intervention, the trial included pregnant women presenting with pruritus and abnormal maternal serum bile acid concentrations, commonly used to identify women with ICP to whom clinicians would offer UDCA in the absence of other diagnoses. The population studied had a similar range of raised serum bile acid concentrations to other multicentre cohorts,22 with around three-quarters of women having serum bile acid concentrations of < 40 µmol/l.

The strengths of this study include its size, as it is considerably larger than any previous trial identified in the literature. The trial was rigorously conducted to a prespecified protocol without changes.

Generalisability

The study was undertaken in 33 maternity units across England and Wales, and included women representative of the wider pregnancy population in terms of demographics and spectrum of disease. Recruitment occurred within time and target, indicating equipoise and willingness to participate from clinicians and pregnant women.

Limitations

Limitations include a primary outcome event rate in the control group that was lower than that estimated for the sample size calculation. At the time of trial inception, we used the best available data (from the PITCH pilot study,11 which had a similar population of women with ICP, and the Cochrane systematic review in this area10) to estimate the event rate for perinatal death, preterm birth and neonatal unit admission. Our subsequent individual patient data analysis2 reported that 13.4% (412/3080) of women with ICP had spontaneous preterm birth, much lower than that reported in the Cochrane systematic review (43.8%; 39/89),10 highlighting the limitations of imprecise numbers to estimate our primary event rate. The trial primary outcome event rate was reviewed by the Data Monitoring Committee, but in the light of the lack of difference between the two groups noted, extending the trial was not considered by them to be necessary. Although it is possible that the trial has insufficient power to show a difference, the lack of effect in both the analysis for women who adhered to the intervention and in subgroup analyses in women at greatest risk of the adverse perinatal outcomes (serum bile acid concentrations ≥ 40 µmol/l at enrolment) suggest that this is unlikely. The difference shown in the study was much smaller (3.7%) than anticipated. It is possible and even likely that this difference may be too small to justify the use of UDCA in pregnancy, unless there was clear evidence that it reduces a robust and important endpoint (such as perinatal death).

In contrast to previous meta-analyses,9,10 we did not find that UDCA reduced maternal serum bile acid concentrations. Enzymic assays used to quantify total serum bile acids detect synthetic UDCA as well as cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid, the pathologically elevated bile acids in ICP that are implicated in the pathogenesis of fetal complications. 23 Treatment with UDCA reduces the proportion of cholic acid and chenodeoxycholic acid,23 but may be associated with some degree of increase in total serum bile acid concentration, due to elevated serum concentrations of the drug, making interpretation in clinical practice and in this trial more complex.

Sources of bias

We considered sources of possible bias for the trial. Selection bias is unlikely owing to the randomisation process including robust allocation sequence concealment. Performance bias was reduced by effective masking of the intervention to clinicians, women and data collectors, such that identification of the active treatment was minimal, with the two groups receiving the same antenatal and intrapartum care pathways. Assessment of outcome was also masked, minimising detection bias. Differences in attrition between the groups were minimal, with similar numbers discontinuing the intervention. We have aimed to avoid reporting bias, presenting all prespecified secondary outcomes, including the secondary analyses where effect size measures were calculated, and interpreting secondary outcomes with caution to avoid overinterpretation.

Interpretation

This trial suggests that there is no strong evidence base for routine use of UDCA in women with ICP for clinically useful amelioration of maternal symptoms or for reduction of adverse perinatal outcomes. The results support those from the pilot study,11 which reported only a small reduction in maternal itch symptoms, less than that judged by women and health-care professionals to be clinically useful. In the absence of any discernible significant effect in women with enrolment peak serum bile acid concentrations > 40 µmol/l, or in those presenting prior to 34 weeks’ gestation (on iatrogenic preterm birth) or on outcomes that are not related to clinician behaviour (i.e. iatrogenic preterm birth), a strong biological effect appears unlikely. It is possible that there are selected subgroups not currently identified that may benefit from treatment with UDCA.

As UDCA has been the only treatment consistently proposed in guidelines as a disease-modifying drug, there are no other treatments in current widespread use for prevention of the adverse perinatal outcomes associated with the disease, although a further study is planned evaluating rifampicin. 24 Our recent individual patient data analysis suggests that in women with peak serum bile acid concentrations < 100 µmol/l the risk of stillbirth is similar to that of the general pregnant population, whereas it is significantly higher in women with peak serum bile acid concentrations ≥ 100 µmol/l at any time in the pregnancy. The presence of coexisting pregnancy complications, such as pre-eclampsia or gestational diabetes, may add to the risk of stillbirth. 25 The only intervention that may have an impact on adverse perinatal outcomes is likely to be appropriately planned delivery.

Placing the research into wider context

Evidence before this study

The Cochrane systematic review on this topic, updated on 20 February 2013,10 concluded that ‘fewer instances of fetal distress/asphyxial events were seen in the UDCA groups when compared with placebo but the difference was not statistically significant’ and larger trials were needed.

Added value of this study

The trial reported here is five times larger than the largest previous trial and nearly three times larger than all previous trials combined. Women were managed in a high-income health-care setting with free access to care and regular surveillance (including repeated serum bile acid measurements), such that the trial is likely to represent contemporaneous management of this condition.

Implications of all the available evidence

The updated systematic review and meta-analysis26 including this trial, with the search conducted by the Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group, found that UDCA does not reduce the incidence of stillbirth [one stillbirth occurred in the UDCA group vs. six in the placebo group; RR 0.33 (95% CI 0.08 to 1.37); six trials, 955 participants]. However, UDCA may reduce total preterm birth (spontaneous and iatrogenic) [RR 0.60 (95% CI 0.37 to 0.97); three trials, 819 participants (I2 55%, indicating high heterogeneity)]. UDCA does not reduce neonatal unit admission [RR 0.77 (95% CI 0.55 to 1.08); two trials, 764 participants]. There appears to be no substantial clinical benefit of UDCA when used routinely for treatment of women with ICP.

Unanswered questions and future research

It remains uncertain whether or not there are as yet unidentified groups of women who may respond to UDCA treatment (such as those with or without comorbidities), for reduction of either maternal symptoms or adverse perinatal outcomes. Abnormally high serum bile acid concentrations are associated with stillbirth in ICP,2 and in vitro studies had shown that UDCA may be protective against bile acid-induced cardiac arrhythmias,27 potentially mediated through reduction of specific bile acid species. 23 However, further understanding of the pathophysiology underpinning stillbirth (and, therefore, the target for intervention) is needed. Additional work is also needed to confirm the likely pruritogen in ICP, with progesterone sulfates28 and lysophosphatidic acid29 proposed as candidates, to identify a target for therapeutic treatments to reduce troublesome symptoms of itch. Trials of other unlicensed treatments used for ICP, such as rifampicin, S-adenosylmethionine, dexamethasone, activated charcoal, guar gum and colestyramine, should be considered.

Chapter 2 PITCHES mechanistic studies (led by Professor Catherine Williamson and Dr Peter H Dixon)

Introduction

The initial PITCHES award included partial funding for technical support at three sites (St Thomas’, Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea, and Nottingham City Hospitals) to collect serum, urine and placental samples from trial participants. This was to facilitate the stated secondary objective of the study, namely to establish a biobank of samples to enable mechanistic studies to be undertaken to elucidate the mechanism of action of UDCA. Subsequently, through a variation to contract (VTC), some additional funding (£35,151) was provided to facilitate the collection of fetal heart rate data (using the Monica AN24 device; Monica Healthcare Ltd, Nottingham, UK) from trial participants.

Major milestones

PITCHES-M: sample collection for the mechanistic studies –

-

St Thomas’ and Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospitals have been open for these studies since the PITCHES trial began, with ethics approval under an existing research protocol (‘Obstetric Cholestasis (OC) Research Study’).

-

Nottingham City Hospital started recruiting in January 2018.

The set-up for the bile acid effects on fetal arrhythmia study (BEATS) is shown below in Table 13.

| Hospital | Ethics approval | R&D approval | SIV | Green light | First participant | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St Thomas’ Hospital | Pre September 2017 | Pre September 2017 | Pre September 2017 | 7 February 2018 | September 2017 | |

| Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea Hospital | Pre September 2017 | Pre September 2017 | Pre September 2017 | 7 February 2018 | September 2017 | |

| Nottingham City Hospital | 21 November 2017 | 28 February 2018 | 17 January 2018 | 28 February 2018 | May 2018 | |

| Nottingham – Queen’s Medical Centre | 21 November 2017 | 28 February 2018 | 17 January 2018 | 28 February 2018 | NA | Never recruited |

| Western Sussex Hospitals NHS Trust | 21 November 2017 | 20 March 2018 | 7 November 2017 | 20 March 2018 | Post PITCHES | |

| Warrington Hospital | 21 November 2017 | 20 April 2018 | 7 November 2017 | 20 April 2018 | NA | Staff member on extended leave – unable to recruit |

| Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital | 21 November 2017 | – | 7 November 2017 | – | NA | Reduced capacity at site – unable to recruit |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | 21 November 2017 | – | 7 November 2017 | – | NA | R&D did not have capacity to work on study |

| St George’s Hospital | 21 November 2017 | – | 7 November 2017 | – | NA | R&D never confirmed capacity and capability |

Recruitment report

The numbers of participants and samples is shown in Table 14.

| Hospital | Total | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| St Thomas’ | Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea | Nottingham City | ||

| PITCHES-M participants, n | 43 | 9 | 6 | 58 |

| PITCHES-M samples, n | 98 | 36 | 14 | 148 |

| Maternal blood | 31 | 10 | 4 | 45 |

| Maternal urine | 27 | 8 | 4 | 39 |

| Maternal faeces | 3 | 3 | 0 | 6 |

| Placenta | 12 | 7 | 3 | 22 |

| Umbilical cord blood | 12 | 7 | 0 | 19 |

| Meconium | 13 | 1 | 3 | 17 |

| Total number (number post VTC) of PITCHES–BEATS fetal ECG traces | 17 (7) | 3 (2) | 1 (1) | 21 (10) |

As Professor Williamson also has approval to collect samples from a Wellcome Trust grant and for BEATS from a Tommy’s Charity grant, 407 additional non-PITCHES ICP participants have been recruited to the OC Research Study at St Thomas’ (205 women), Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea (155 women), and Nottingham City (47 women) Hospitals. Since the VTC for BEATS was approved, 24 non-PITCHES ICP participants have been recruited to the fetal electrocardiogram (ECG) studies (14 at St Thomas’, six at Queen Charlotte’s and Chelsea, and three at Nottingham City Hospitals).

Safety reporting

There were no serious adverse events in either the PITCHES-M study or BEATS.

Discontinuations/withdrawals

There have been no discontinuations or withdrawals from the mechanistic studies.

Ongoing studies

As we were funded to collect only a biobank and fetal ECG traces, it will be necessary to apply for additional funds to generate research data from any of the samples. A request for use of the grant underspend was made, but declined as the work was hypothesis-generating rather than hypothesis-testing.

Chapter 3 Public and patient involvement (led by Ms Jenny Chambers, ICP Support)

Aim

We have had public and patient involvement from before the inception, dating back to the original feasibility study11 for this trial. Jenny Chambers (co-investigator) founded the patient support group, having had lived experience of ICP, including two stillbirths. The aim of the trial was to address the unmet need in finding an effective intervention that reduced the complications of ICP, particularly around adverse consequences for the baby.

Methods

Patient and public involvement has included valued contributions to the design, drafting and revision of the grant application, the protocol, participant information and written material, consideration of means of optimising recruitment while avoiding any sense of coercion at a potentially vulnerable time for women, raising awareness of the trial through publicity on the ICP Support website, review of progress at regular co-investigator meetings, interpretation of the results from a woman’s experience, and much more. We have also had a valued lay member of the Trial Steering Committee (also with lived experience) who contributed actively to discussion and oversight.

In addition, ICP Support produced a short video about the importance of research into ICP, giving the views of women who have had ICP about the need for more research into the condition. 30 We have shown this (to great impact) at collaborator meetings.

Professor Williamson runs a biennial course on ICP, unusual in that it is open to women (and their partners) who have experienced ICP, as well as to clinicians and researchers. The talks and discussions are thus held, and women with lived experience contribute to the discussions. We provided two places to every PITCHES site research team to the last conference, mid-way through the trial, enabling us to ensure that patient involvement was front of mind for the researchers and site teams.

Results

Patient and public involvement has been an integral part of all of our pregnancy research for many years, and shapes all aspects from ensuring that we are researching a question that is relevant to women and their families, to considering how pregnant women view participation in research, particularly for a drug trial in pregnancy, when the stakes are high. We used feedback in our newsletters to keep sites aware of the impact of such participation.

Discussion and conclusions

We have little doubt that the trial has recruited to time and target because of the:

-

continued importance of the research question to women (as well as clinicians)

-

involvement of women with lived experience as core members of the co-investigator and oversight groups

-

inclusion of relevant PPI material in newsletters and collaborator meetings

-

strong relationships between research teams (e.g. midwives) and women (using methods as described above).

Reflections/critical perspective

The longstanding and deep-seated patient and public involvement in our research programmes has continued to be a theme of this project and is an integral part of its success. There have been many positive aspects to it and we have not encountered any negative sides to this involvement.

Acknowledgements

We thank the independent Trial Steering Committee (David Williams, Judith Hibbert, Julia Sanders, Deborah Stocken, Julian Walters and Win Tin) and the independent Data Monitoring Committee {John Norrie [chairperson of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation (EME) programme and a member of the NIHR Health Technology Assessment (HTA) and EME Editorial Board], William McGuire (a member of the NIHR HTA and EME Editorial Board) and Jenny Myers}. We thank the site investigators, the research teams and the women who participated.

Contributions of authors

Lucy C Chappell (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6219-3379) (NIHR Research Professor of Obstetrics) conceived the study, was involved in securing study funding, was chief investigator for the trial and wrote the report.

Jennifer L Bell (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9571-0715) (Statistician) undertook the statistical analyses, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Anne Smith (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2985-9367) (Trial Manager) managed the day-to-day running of the trial, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Catherine Rounding (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1376-7572) (Assistant Trial Manager) assisted with day-to-day running of the trial, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Ursula Bowler (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0100-0155) (Senior Trials Manager) had oversight of the trial management, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Louise Linsell (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3205-6511) (Senior Statistician) had oversight of the statistical analyses, reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Edmund Juszczak (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5500-2247) (Clinical Trials Unit Director) had oversight of the trial conduct, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Sue Tohill (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2344-4347) (Research Midwife) supported site research midwives and related activities, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Amanda Redford (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5176-4789) (Research Midwife) supported site research midwives and related activities, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Peter H Dixon (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0197-2632) (Senior Research Scientist) was involved in securing study funding, contributed to sample collection management, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Jenny Chambers (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6022-1719) (Chief Executive Officer of ICP Support) was Public and Patient Involvement lead, was involved in securing study funding, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Rachael Hunter (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7447-8934) (Associate Professor of Health Economics) undertook the health economic analyses, was involved in securing study funding, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Jon Dorling (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-1691-3221) (Professor of Neonatology) had oversight of neonatology aspects of the trial, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Catherine Williamson (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6226-7611) (Professor of Obstetric Medicine) conceived the study, was involved in securing study funding, led sample collection management, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Jim G Thornton (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9764-6876) (Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology) conceived the study, was involved in securing study funding, contributed to trial conduct, and reviewed, contributed to and approved the final version of the report.

Publications

Chappell LC, Chambers J, Dixon PH, Dorling J, Hunter R, Bell JL, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in treatment of women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (ICP) to improve perinatal outcomes: protocol for a randomised controlled trial (PITCHES). Trials 2018;19:657.

Chappell LC, Chambers J, Thornton JG, Williamson C. Does ursodeoxycholic acid improve perinatal outcomes in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy? BMJ 2018;360:k104.

Chappell LC, Bell JL, Smith A, Linsell L, Juszczak E, Dixon PH, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (PITCHES): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;394:849–60.

Fleminger J, Seed PT, Smith A, Juszczak E, Dixon PH, Chambers J, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy: a secondary analysis of the PITCHES trial [published online ahead of print 16 October 2020]. BJOG 2020.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Requests must include a study protocol and analysis plan. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Patient data

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. There is huge potential to make better use of information from people’s patient records, to understand more about disease, develop new treatments, monitor safety, and plan NHS services. Patient data should be kept safe and secure, to protect everyone’s privacy, and it’s important that there are safeguards to make sure that it is stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data are used. #datasaveslives You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the MRC, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, NETSCC, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

- Chappell LC, Bell JL, Smith A, Linsell L, Juszczak E, Dixon PH, et al. Ursodeoxycholic acid versus placebo in women with intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy (PITCHES): a randomised controlled trial. Lancet 2019;394:849-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(19)31270-X.

- Ovadia C, Seed PT, Sklavounos A, Geenes V, Di Ilio C, Chambers J, et al. Association of adverse perinatal outcomes of intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy with biochemical markers: results of aggregate and individual patient data meta-analyses. Lancet 2019;393:899-90. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31877-4.

- Puljic A, Kim E, Page J, Esakoff T, Shaffer B, LaCoursiere DY, et al. The risk of infant and fetal death by each additional week of expectant management in intrahepatic cholestasis of pregnancy by gestational age. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2015;212:667-5. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2015.02.012.

- Carey EJ, Lindor KD. Current pharmacotherapy for cholestatic liver disease. Expert Opin Pharmacother 2012;13:2473-84. https://doi.org/10.1517/14656566.2012.736491.

- Roma MG, Toledo FD, Boaglio AC, Basiglio CL, Crocenzi FA, Sánchez Pozzi EJ. Ursodeoxycholic acid in cholestasis: linking action mechanisms to therapeutic applications. Clin Sci 2011;121:523-44. https://doi.org/10.1042/CS20110184.

- Beuers U. Drug insight: Mechanisms and sites of action of ursodeoxycholic acid in cholestasis. Nat Clin Pract Gastroenterol Hepatol 2006;3:318-28. https://doi.org/10.1038/ncpgasthep0521.