Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 11/100/29. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The final report began editorial review in September 2018 and was accepted for publication in May 2019. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2021. This work was produced by Awasthi et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2021 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Project introduction

Over 30,000 patients in the UK are affected by chronic ulcerative colitis (UC), which is an inflammatory condition associated with a pro-neoplastic drive. The longer and more extensive the inflammation, the higher the risk of colorectal cancer for individuals with UC. 1 The risk of cancer is greatest in those who have been diagnosed young and in those with extensive colonic inflammation,2 reaching 18% after 30 years. This results in > 1000 colectomies being performed each year in the UK for colorectal cancer or for cancer prevention in those for whom (precancerous) dysplastic lesions have been identified. Nevertheless, despite intensive colonoscopic surveillance with random sampling (> 10 biopsies) taken throughout the length of the affected bowel, most early tumours are missed. As many as 50% of cases progress to invasive cancer before neoplasia is detected. 3,4 The presence of advanced malignancy can prevent safe restoration of bowel continuity, require adjuvant chemotherapy and result in incurable disease and death which occurs in more than 40% of patients with colitis-associated large bowel cancer. 5

Currently, patients with colitis are stratified into three categories:

-

low risk – quiescent or left-sided inflammation

-

intermediate risk – mild inflammation or with a family member who developed colorectal cancer aged ≥ 50 years

-

high risk – extensive moderate or severe active inflammation, primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC), a history of dysplasia/colonic stricture, or with a first-degree relative who developed colorectal cancer aged < 50 years.

Surveillance in these groups is performed by colonoscopy at 5-, 3- or 1-yearly intervals respectively, enabling identification and biopsy of suspected neoplasia. 6 Standard colonoscopic surveillance involves 24-hour bowel preparation preceded by 36 hours of liquid diet, and is performed under intravenous sedation or nitrous oxide. The colonoscope is advanced to the small bowel junction and then withdrawn slowly. Biopsy protocols vary: most endoscopists perform a series of random biopsies that are formalin-fixed for histological analysis. The 2002 British Society of Gastroenterology guidelines7 suggest that two to four biopsies be taken every 10 cm. More recently,8 it has been recommended that the colonic mucosa should be dye-sprayed with targeted biopsy of any abnormalities and such enhanced ‘chromoendoscopy’ is now recommended in some guidelines6 as standard practice for colonic cancer surveillance in UC. However, a recent study suggests that benefits from techniques such as ‘dye spray’, may, at best, provide limited benefit. 9 There is considerable evidence of endoscopic practice varying across the UK10 and elsewhere. There is also likely to be variation in biopsy practice. Well-circumscribed dysplastic adenomas may be amenable to local endoscopic resection, but in the event of there being dysplastic change in flat mucosa or adenomatous change in a background of abnormal mucosa, the patient is generally offered prophylactic total colectomy. 9

Nevertheless, there is a pressing need to enhance the effectiveness of surveillance and early selection for prophylactic resection in order to increase clinician and patient confidence in the surveillance process. This was highlighted in the 2011 National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines,6 which recommend the identification of epigenetic and genetic biomarkers to aid more accurate patient identification. An ideal test would complement colonoscopy and biopsy by providing enhanced detection of pre-cancerous lesions (dysplasia), thereby delivering better patient selection for prophylactic resection.

Tumour development requires loss of tumour suppressor gene function and/or gain of oncogenic drivers. Historically, the role of chromosomal loss and genetic mutation of tumour suppressor genes has been well documented, but more recent data demonstrate the importance of epigenetic silencing, particularly in early tumourigenesis. Gene expression is modulated by ‘key’ methylation sites usually in the promoter region of the gene. Increased methylation, particularly in these promoter regions, will prevent the binding of transcription factors, which prevents transcription of ribonucleic acid and, thus, causes (epigenetic) silencing of the gene. Deoxyribonucleic acid (DNA) hypermethylation in gene promoter regions leads to this epigenetic silencing (of tumour suppressor genes). This phenomenon represents an attractive and identifiable diagnostic target (of early tumour development) as it reflects functional change, is stable in the DNA obtained from biological samples and can be detected reliably in DNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded (FFPE) biopsies.

A number of retrospective cohort studies over the past decade have shown frequent epigenetic silencing of tumour suppressor genes associated with promoter hypermethylation in the development of colitis-associated neoplasia. 11–16 Colitis-associated neoplasia is an especially suitable target for epigenetic change as, unlike sporadic colon cancer, the chronic inflammation creates a field change effect, resulting in multifocal disease. A molecular marker such as methylation change may, therefore, increase sensitivity of colonoscopy by detecting changes in methylation in mucosa where neoplastic change is not visible, or masked by chronic inflammation.

Studies of sporadic and genetic colorectal cancer have shown that hypermethylation and epigenetic silencing of secreted Wnt antagonists such as secreted frizzled-related protein (SFRP) 1 occurs early in tumour development17–19 and suggest that this methylation and silencing could be a ‘gatekeeper’ event, essential for large bowel neoplastic change. Wnt antagonist silencing, therefore, has the potential to provide a marker for detecting the development of neoplasia at the earliest stages. Moreover, the potential to identify changes that are present away from the site of neoplasia could significantly increase the sensitivity of the test.

Dhir et al. 20 carried out an analysis of methylation of Wnt signalling pathway genes [adenomatous polyposis coli (APC)1A, APC2, SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, SFRP5, Dickkopf-related (DKK) 1 gene, DKK3, WNT inhibitory factor 1 (WIF1) and liver kinase B1 (LKB1)] in the development of UC-associated neoplasia, finding that methylation of SFRP1/2 and APC1A/2 were associated with the progression to invasive disease. Guo et al. 21 demonstrated that SOX7, an independent checkpoint for beta-catenin function, can be hypermethylated in colorectal cancer and may play a role in UC-associated neoplasia.

Genetic variation in RUNX3 has been demonstrated as a risk factor for the development of UC22 and Garritty-Park et al. 23 demonstrated that hypermethylation of RUNX3 and MINT1 could be detected in the non-neoplastic mucosa from patients with colitis-associated neoplasia. Pilot data on UC mucosal biopsies indicated this in promoter region methylation of Wnt antagonists and, more recently, in an analysis utilising the Illumina Methylation450 platform (Illumina Incorporated; San Diego, CA, USA), in promoter hypomethylation of TUBB6 in non-neoplastic colonic mucosa from patients with UC-associated neoplasia. 24,25

Taken together, these data indicate that it should be possible to perform molecular identification of neoplastic change by analysis of background bowel mucosa, even if the neoplastic lesion(s) was missed at colonoscopy. This should complement surveillance colonoscopy by improved early tumour identification, enabling early treatment for these patients.

This developing information concerning the effect of chronic colonic inflammation on DNA methylation potentially modifying epithelial neoplastic pathways opens the possibility of developing a diagnostic test to identify inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) patients at a high risk for the development of colon cancer based on the methylation of an array of relevant genes, which was the aim of the ENDCaP-C (Enhanced Neoplasia Detection and Cancer Prevention in Chronic Colitis) study. The development of the test starts with the extraction of DNA from FFPE biopsies lodged in histology archives of samples taken during colonoscopic surveillance programmes. Pyrosequencing to detect differential promoter methylation of dysplastic tissue compared with non-dysplastic control tissues then allows a panel of biomarkers to be developed, which is prospectively tested in a real-life setting.

In recent years, with the advent of high-throughput genetic sequencing technology coupled with the capability of bioinformatics computing, the importance of the gut microbiome in both the pathogenesis of IBD and the development of colon cancer has been proposed. There has been sparse investigation of the effect of microbiome dysbiosis on epigenetic changes in colonic epithelium. A prospective study such as the ENDCaP-C study also provides an opportunity to collect a series of stool samples for such future studies.

The aims of the ENDCaP-C programme are therefore to:

-

establish and optimise a multimarker methylation panel for the detection of colitis-associated neoplasia

-

measure the accuracy of this panel in a prospective multicentre cohort of patients with colitis.

Ancillary exploratory objectives were to evaluate the utility of next-generation sequencing (NGS) as an alternative to pyrosequencing and to assess the feasibility of detecting markers of dysplasia-associated epigenetic methylation in serum and faecal samples collected from patients undergoing colonic surveillance as part of this programme. Hence, faecal samples were collected to characterise the faecal microbiome in this cohort of patients at a higher risk of colonic neoplasia, although the analysis of these samples does not form part of this report.

The overarching ambition of this multicentre project was to enhance future colon cancer surveillance for patients with chronic UC using novel biomarkers to stratify risk, improve early detection of cancer and rationalise colonoscopic programmes.

Chapter 2 Module 1: development of a multimarker methylation panel for the detection of colitis-associated neoplasia

Module 1: introduction

Chronic inflammation caused by UC causes a pro-neoplastic drive in the inflamed colon, leading to a markedly greater risk of invasive malignancy than that of the general population. 1 Although rates of UC-associated neoplasia seem to be decreasing,26 due in part to improved medical control of inflammation, there remains an elevated risk of developing colorectal cancer over the background risk in the unaffected population. The risk is particularly pronounced in patients with extensive colitis and an IBD diagnosis before 30 years of age. 2

Despite national and international colonoscopic surveillance protocols,27 50% of cases are reported to have developed invasive cancer before neoplasia is detected. The disease is frequently multifocal, which is presumed to be caused by the diffuse sensitisation of the large bowel mucosa by the chronic inflammatory process. Mutational events, such as KRAS and TP53 mutation,28 have been observed as part of this field cancerisation effect in UC, but no consistent pattern has been demonstrated.

Endoscopic therapy can provide local control of early dysplastic lesions, but enhanced detection strategies are required to aid early detection and ensure that progressive dysplasia is not missed during surveillance. 29–31

Chronic inflammation has been demonstrated to promote aberrant DNA methylation in conditions such as UC. 13 This may be as a result of a direct chemical effect causing cytosine methylation in the inflamed colon, shutting down genetic activity to protect the bowel wall. Use of abnormal DNA methylation as a biomarker for UC-associated neoplasia has considerable theoretical advantages: first, methylation tends to be gene-centric,32 centred around CpG islands and, second, it is usually homogenously distributed within the CpG island, having a functional effect on transcription factor binding and, thus, gene expression. This homogeneity facilitates simpler detection of abnormal methylation patterns. Another advantageous property of assaying methylation is that it tends to occur as part of a ‘field cancerisation’ effect whereby associated changes in methylation extend out past the dysplastic lesion in the colon and can therefore be detected in apparently normal mucosa some distance from the lesion. 33–35

The ENDCaP-C study sets out to establish whether or not an optimised methylation marker panel of suitable specificity could improve detection of early neoplastic lesions at colonoscopic surveillance diagnostic accuracy. The initial phase (module 1) aims to measure the accuracy of an optimised panel of markers on a multicentre, retrospective cohort of patients with UC before assessing their utility in a prospective multicentre test accuracy study (module 3).

Module 1: aims

-

Establish and optimise a multimarker methylation panel for the detection of colitis-associated neoplasia.

-

Measure the accuracy of this panel in a retrospective multicentre cohort of patients with colitis-associated neoplasia.

Module 1: methods

Patient recruitment

Patients were identified from archived histology biopsy samples in six hospitals across the West Midlands area. Patients were identified through tracing endoscopy records and correlation with histology reports. Searches were restricted to endoscopies after January 1996 because of changes to formalin fixation at that time, and to before January 2014 to minimise missed neoplasia through identification during the follow-up period. Mucosal biopsies were classified as one of:

-

neoplasia – defined as any of adenocarcinoma, high-grade or low-grade dysplasia

-

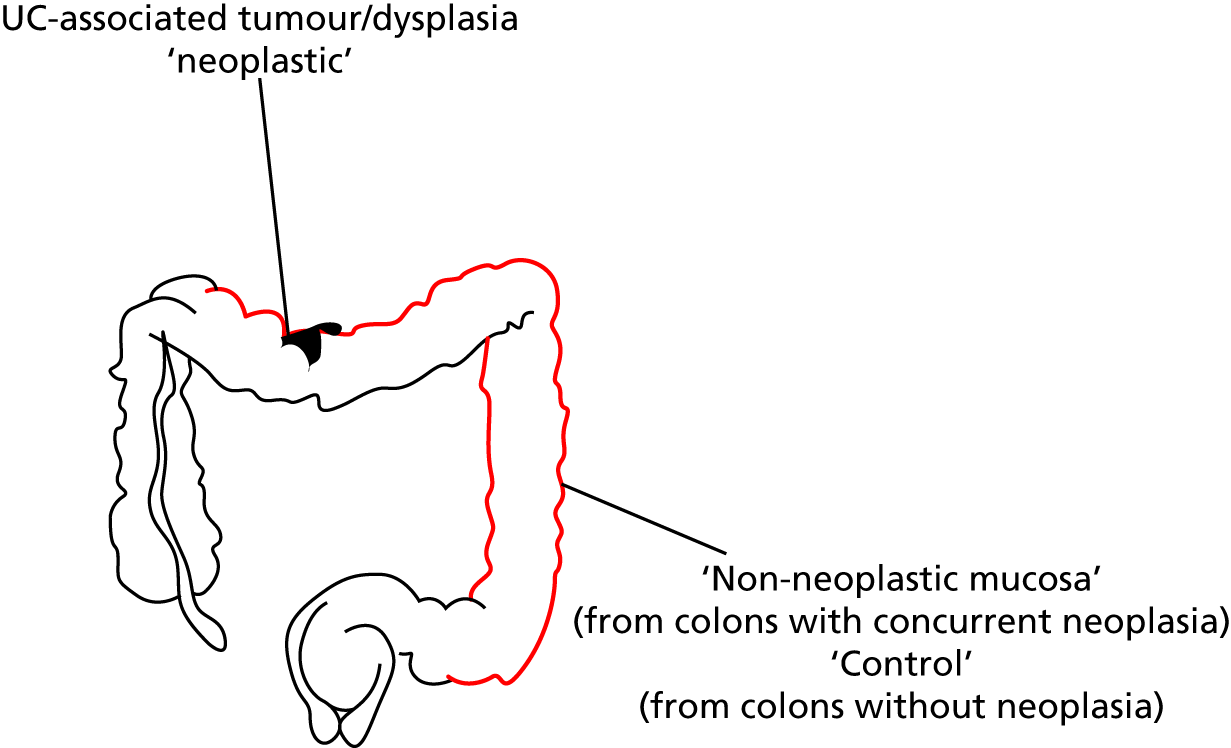

matched non-neoplastic – defined as non-neoplastic chronically inflamed colonic mucosal biopsies taken distant from areas of neoplasia (Figure 1)

-

control – defined as colonic mucosa, sampled from patients with chronic UC of duration of > 8 years and extending at least to the splenic flexure or patients with a diagnosis of both UC and PSC who had been screened for neoplasia without it being found.

FIGURE 1.

Diagram of colonoscopic sampling from patients for the ENDCaP-C study.

Ethics approval was from South Birmingham Research Ethics Committee (reference 08/H1207/104).

Sample processing

Biopsy samples from identified patients were retrieved from the histopathology archives at the six collaborating hospitals. For those patients with neoplasia in the large bowel, separate biopsies from different colonic segments were selected alongside the neoplastic biopsy. All blocks were reviewed centrally by the lead ENDCaP-C histopathologist, with representative sections undergoing DNA extraction. Histological diagnosis of dysplasia (the gold standard) was defined as an altered nuclear/cytoplasmic ratio, increased cell size and/or an increase in mitotic figures. DNA extraction of neoplasia was performed by needle macrodissection to enrich for tumour material; macrodissected material was extracted using the FFPE protocol of the Qiagen DNEasy FFPE kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Extracted DNA was quantified by both NanoDrop spectrophotometry (Nanodrop ND 8000 spectrophotometer; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA) and Qubit fluorimetry (Qubit 2.0 Fluorometer; Invitrogen, Life technologies, Carlsbad, CA, USA).

Neoplasia, matched non-neoplastic and control samples were included in mixed batches to ensure that test performance could be analysed at sequential analyses across the study duration. Each sample was labelled with only a study sample identification number and assays undertaken blinded to neoplasia status.

Deoxyribonucleic acid methylation analysis

A total of 500 ng of extracted DNA was bisulphite converted using a Zymo EZ-DNA methylation bisulphite conversion kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Two microliters of eluted bisulphite converted DNA was utilised in a pyrosequencing polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using the Qiagen PyroMark PCR kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany) according to the manufacturer’s protocol in a 25-µl reaction volume. PCR products were run on a 2% agarose gel with a DNA size ladder and successful amplification was defined as the presence of a band at the appropriate size for the marker run. PCR products were cleaned using streptavidin beads, washed and mixed with the requisite pyrosequencing primers. These were then sequenced on a Qiagen PyroMark Q96 instrument (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). All reactions were run with 100% methylated and unmethylated DNA positive and negative controls, as well as a water reaction. Methylated DNA was generated by incubating 1 µg of blood-derived control DNA with CpG methyltransferase (M.SssI) (New England Biolabs, Ipswich, MA, USA). Unmethylated DNA was generated by whole-genome amplification of 10 ng of blood-derived control DNA using the Qiagen Repli-G Mini kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany).

The marker panel chosen for this experiment was based on previous reported findings and consisted of the following markers: SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, SFRP5, WIF1, TUBB6, SOX7, APC1A, APC2, MINT1 and RUNX3. Primer sequences, chromosomal positions and reaction conditions are shown in Appendix 1, Table 17. After each run, sample data were examined using Qiagen PyroMark Q96 software (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). Samples that had failed Qiagen quality metrics were marked as failed on the sample sheet.

Sample size

The original planned sample size of 160 neoplastic and 320 control samples was determined to provide adequate events to develop a robust model (with > 10 events per marker) and provide estimates of sensitivity and specificity with adequate precision [with 95% confidence interval (CI) width < 16% for sensitivity and < 12% for specificity]. The 2 : 1 sampling ratio is determined based on access to sample banks.

Statistical analysis

Where a biomarker was examined at multiple CpG sites, the mean CpG value across sites was computed and used in all analyses. This was undertaken for consistency and was considered appropriate, as methylation within small regions tends to be distributed homogenously. 32 Statistical analysis was then undertaken in three stages.

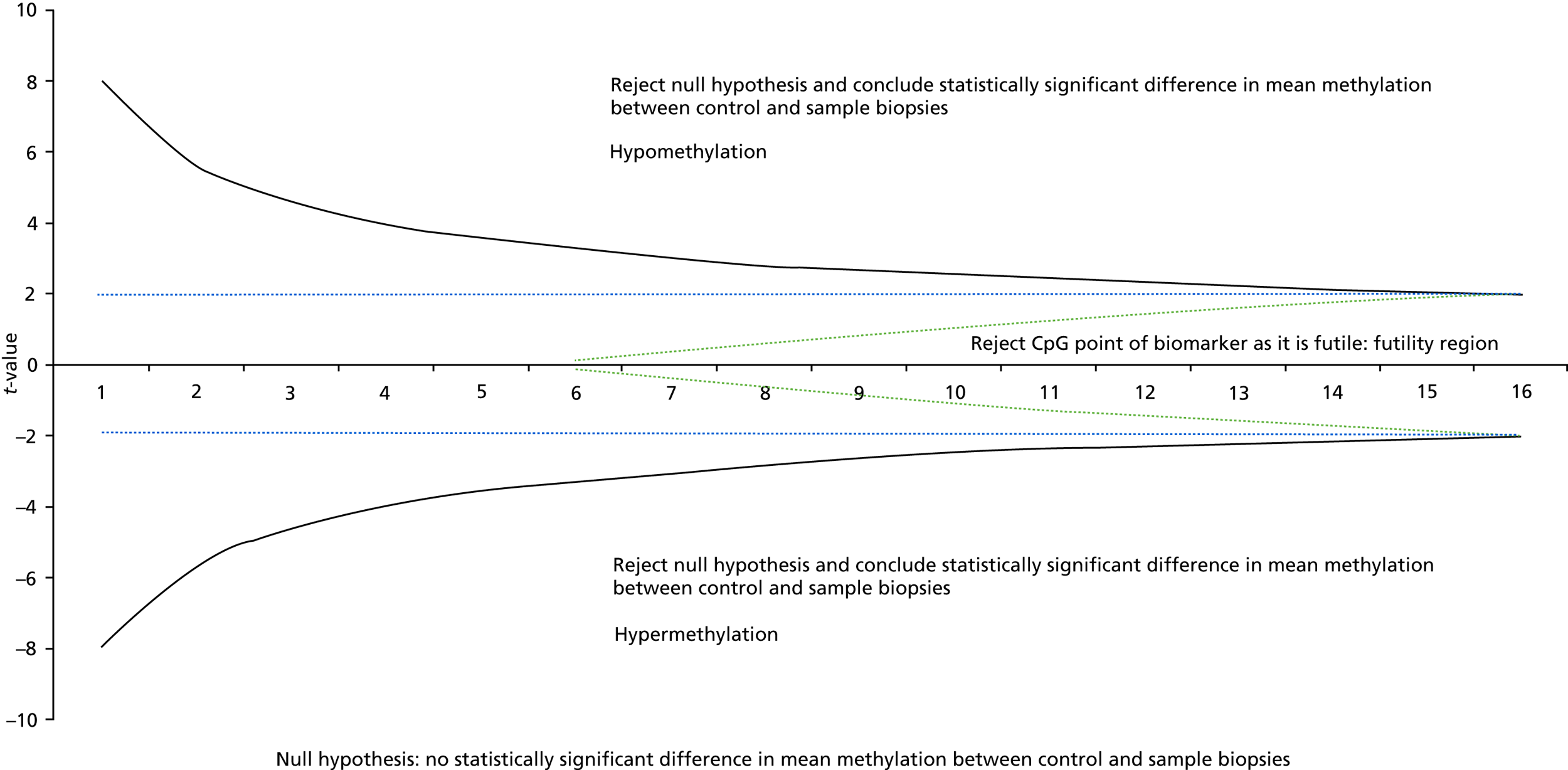

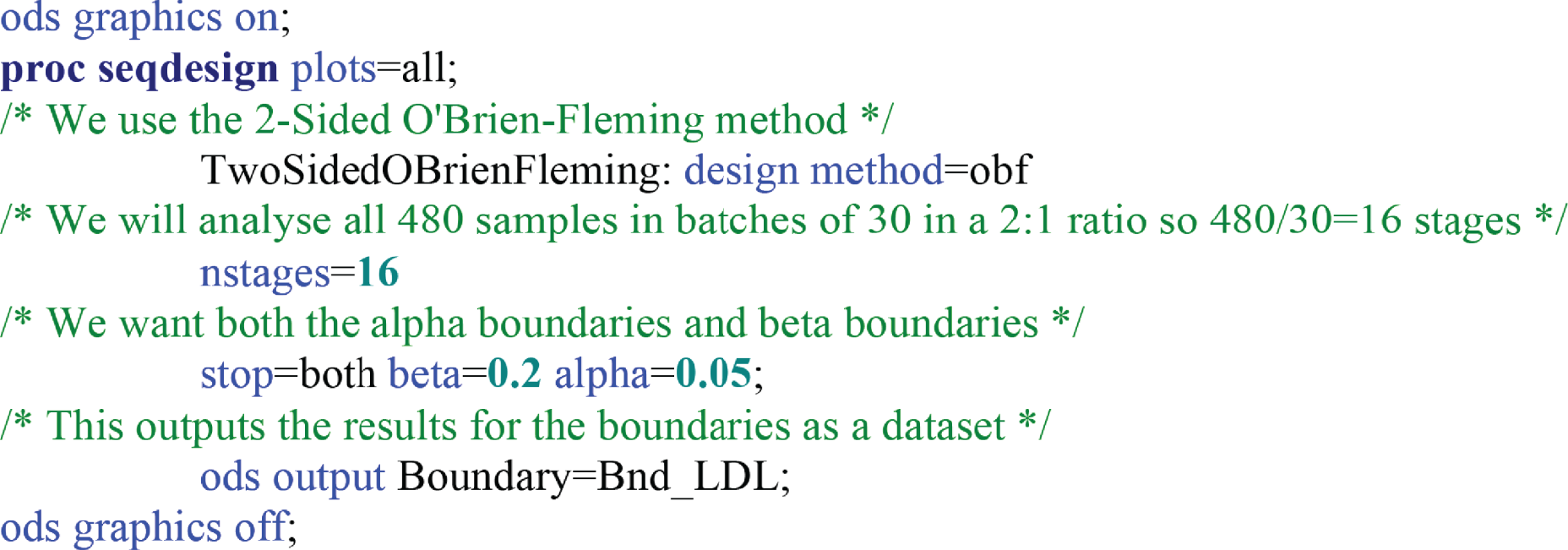

In stage 1, biomarkers that were futile with respect to their ability to discriminate between neoplastic samples and control samples were identified and testing was terminated early. The sample size required 320 control samples and 160 neoplastic samples (480 in total). To evaluate the performance of each biomarker as the samples were being processed in batches of 30 (20 control samples and 10 neoplastic samples), we planned to undertake 16 interim analyses for each biomarker (420 total samples divided by 30 batches of samples). To account for multiple testing, the results for each batch of samples for each biomarker were evaluated in a group sequential analysis following the O’Brien and Fleming method36 to assess whether further testing of each biomarker was justified or considered futile. Sequential boundaries were constructed according to the O’Brien and Fleming method,36 the t-statistic from the t-test computed for each biomarker at each analysis step, and the comparison made to the predefined boundary values to test for statistical significance or futility (see Appendix 1, Figure 18). The boundary values were computed using the SAS® statistics software (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA) and the SAS code is given under Appendix 1, Figure 18. (SAS and all other SAS Institute Inc. product or service names are registered trademarks or trademarks of SAS Institute Inc. in the USA and other countries. ® indicates USA registration.)

In this first stage, the distributions of the biomarker values were unknown and data were analysed without transformation. Once all data were accumulated, visual inspection of histograms demonstrated a positive skew (see Appendix 1, Figure 19) and the mean biomarker values for each sample were log-transformed prior to further analysis.

In stage 2, markers with responses suitable for inclusion in the predictive models were selected. Biomarkers that showed significant (p < 0.05) discrimination and attained amplification rates of > 85% were selected for inclusion. The ability of each marker to discriminate was described by computing the ratio of geometric means (with 95% CI) and statistical significance was assessed by two-sample t-tests undertaken on the log-transformed scale. Comparisons were made between (1) neoplasia samples and control samples and (2) matched non-neoplastic samples and control samples.

In stage 3, predictive models were fitted using logistic regression with outcome (1 = sample or 0 = control) and the mean log-CpG value for each patient for the biomarkers selected from stage 2. Only samples that had complete data for the selected biomarkers were initially included in these analyses. Three separate models were constructed: (1) differentiating neoplasia samples from control samples, (2) differentiating dysplasia samples from control samples and (3) differentiating matched non-neoplastic samples from control samples. Model 2 used the same patients and biomarker selection as model 1, but excluded any samples that were classed as adenocarcinomas.

Estimation of the adjustments for shrinkage and optimism in the model fit were computed using standard bootstrap internal validation techniques as recommended by Steyerberg. 37 The final models were produced including all samples, using multiple imputation using chained equations to impute missing biomarker data. Multiple imputation models used 50 iterations with pathology categorisation, sample type and measurements of all other biomarkers as predictors. The model coefficients were corrected for optimism by application of the shrinkage factor. To facilitate application of the model when individual or pairs of biomarkers are unavailable, reduced models were computed omitting each biomarker and possible pair of biomarkers from the multiple imputation model. Discriminatory performance for each model was measured by the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC).

One biomarker (TUBB6) was not selected for inclusion in models 1 and 2 in the stage 1 O’Brien and Fleming method36 analysis on untransformed data, but did show significant differences in stage 2 once log-transformations had been applied. Models 1 and 2 were fitted with and without this biomarker.

The clinical team considered that a positive test result should have a positive predictive value of at least 20% to be of clinical value. Given an assumed background incidence of 4% this corresponds to the point on the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve with a positive likelihood ratio [sensitivity/(1 – specificity)] of 6. The threshold at this point was identified from the ROC tabulation of each predictive equation, and estimates of sensitivity and specificity were obtained. We also identified thresholds for each model that corresponds with 90% of cases being detected.

Module 1: results

In total, 838 blocks from 575 patients were collected from six participating hospitals. Of these, 269 blocks were not used in the study because they were duplicates from the same patient, or deemed not useable after histological review. This left 569 blocks from 456 patients undergoing surveillance, consisting of 113 neoplastic, 113 matched non-neoplastic and 343 control blocks (Table 1). Of the neoplastic biopsy samples, 35 out of 113 contained adenocarcinoma and the remaining 78 out of 113 harboured dysplasia only. Baseline data for participants providing these blocks are shown in Table 2. These show that the control population was comparable with the test population in terms of risk factors associated with colitis-associated neoplasia and was a high-risk population.

| Histopathological type | Patients with neoplasia (N = 113) | Patients without neoplasia (control) (N = 343), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoplastic samples, n (%) | Matched non-neoplastic samples, n (%) | |||

| Neoplasia | ||||

| Cancer | Adenocarcinoma | 35 (31) | – | – |

| Dysplasia | High-grade dysplasia | 4 (4) | – | – |

| Low-grade dysplasia | 74 (65) | – | – | |

| Non-neoplasia | Normal mucosa | – | 113 (100) | – |

| Control (without neoplasia) | Normal mucosa | – | – | 343 (100) |

| Baseline characteristics | Patients with neoplasia (N = 113), n (%) | Patients without neoplasia (control) (N = 343), n (%) | Total (N = 456), n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Montreal classification | |||

| Distal (recto-sigmoid) | 23 (20) | 56 (16) | 79 (17) |

| Left sided (to splenic flexure) | 17 (15) | 61 (18) | 78 (17) |

| Extensive (beyond splenic flexure) | 67 (59) | 203 (59) | 270 (59) |

| Unknown/missing | 6 (5) | 23 (7) | 29 (6) |

| Smoker | |||

| No | 75 (66) | 197 (57) | 272 (60) |

| Yes | 7 (6) | 9 (2) | 16 (4) |

| Unknown/missing | 22 (19) | 125 (36) | 147 (32) |

| Ex-smoker | 9 (8) | 12 (3) | 21 (5) |

| PSC | |||

| No | 100 (88) | 293 (85) | 393 (86) |

| Yes | 8 (7) | 46 (13) | 54 (12) |

| Unknown/missing | 5 (4) | 4 (1) | 9 (2) |

| Family history of IBD | |||

| No | 85 (75) | 249 (73) | 334 (73) |

| Yes | 4 (4) | 20 (6) | 24 (5) |

| Unknown/missing | 24 (21) | 74 (22) | 98 (21) |

| Family history of colorectal cancer | |||

| No | 83 (73) | 257 (75) | 340 (75) |

| Yes | 6 (5) | 6 (2) | 12 (3) |

| Unknown/missing | 24 (21) | 80 (24) | 104 (23) |

Selection of biomarkers

Eight out of the 11 methylation markers had an amplification success rate of > 85% (Table 3 and see Appendix 1, Table 18). The three remaining primer sets were within the promoter regions of SFRP1, MINT1 and RUNX3. Because of the reduced reliability, these three primer sets were not taken forward for further analysis.

| Biomarker | Geometric mean (95% CI) | Ratio of geometric means (95% CI); p-valuea | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoplastic (n = 113) | Matched non-neoplastic (n = 113) | Control (n = 343) | Neoplastic vs. control | Non-neoplastic vs. control | |

| SFRP2 | 22.1 (19.7 to 24.9) | 14.0 (12.8 to 15.4) | 14.1 (13.4 to 14.9) | 1.57 (1.40 to 1.76) | 0.99 (0.89 to 1.11) |

| (n = 105) | (n = 106) | (n = 303) | p < 0.0001 | p = 0.92 | |

| SFRP4 | 44.7 (42.1 to 47.5) | 34.4 (31.8 to 37.2) | 32.0 (31.0 to 33.1) | 1.40 (1.31 to 1.49) | 1.07 (1.00 to 1.15) |

| (n = 108) | (n = 109) | (n = 312) | p < 0.0001 | p = 0.057 | |

| WIF1 | 21.6 (18.6 to 25.2) | 12.8 (11.1 to 14.8) | 13.9 (12.8 to 15.0) | 1.56 (1.33 to 1.83) | 0.93 (0.79 to 1.08) |

| (n = 104) | (n = 105) | (n = 292) | p < 0.0001 | p = 0.33 | |

| APC1A | 2.92 (2.37 to 3.60) | 2.54 (2.16 to 3.00) | 1.99 (1.83 to 2.17) | 1.47 (1.22 to 1.77) | 1.28 (1.07 to 1.52) |

| (n = 102) | (n = 102) | (n = 297) | p = 0.0001 | p = 0.006 | |

| APC2 | 35.4 (32.1 to 39.0) | 22.3 (20.4 to 24.4) | 20.2 (18.9 to 21.5) | 1.76 (1.55 to 1.99) | 1.11 (0.98 to 1.26) |

| (n = 111) | (n = 106) | (n = 322) | p < 0.0001 | p = 0.12 | |

| SFRP1 | 35.7 (30.5 to 41.9) | 24.1 (21.7 to 26.7) | 25.1 (23.2 to 27.1) | 1.42 (1.21 to 1.67) | 0.96 (0.82 to 1.13) |

| (n = 39) | (n = 29) | (n = 118) | p < 0.0001 | p = 0.62 | |

| SFRP5 | 7.14 (5.75 to 8.87) | 4.90 (4.08 to 5.90) | 6.40 (5.64 to 7.27) | 1.12 (0.87 to 1.43) | 0.77 (0.60 to 0.98) |

| (n = 102) | (n = 95) | (n = 275) | p = 0.38 | p = 0.03 | |

| MINT1 | 4.14 (3.32 to 5.16) | 3.40 (2.87 to 4.04) | 3.13 (2.82 to 3.48) | 1.32 (1.06 to 1.64) | 1.09 (0.89 to 1.33) |

| (n = 73) | (n = 70) | (n = 200) | p = 0.012 | p = 0.42 | |

| RUNX3 | 8.73 (7.15 to 10.7) | 7.58 (6.37 to 9.02) | 7.44 (6.68 to 8.29) | 1.17 (0.94 to 1.46) | 1.02 (0.83 to 1.25) |

| (n = 87) | (n = 97) | (n = 248) | p = 0.15 | p = 0.86 | |

| SOX7 | 5.70 (4.60 to 7.06) | 3.92 (3.41 to 4.51) | 5.41 (4.88 to 5.99) | 1.05 (0.85 to 1.30) | 0.73 (0.60 to 0.87) |

| (n = 100) | (n = 106) | (n = 280) | p = 0.63 | p = 0.001 | |

| TUBB6 | 12.2 (10.5 to 14.2) | 8.04 (6.93 to 9.34) | 9.34 (8.52 to 10.23) | 1.31 (1.10 to 1.56) | 0.86 (0.72 to 1.03) |

| (n = 108) | (n = 95) | (n = 292) | p = 0.003 | p = 0.11 | |

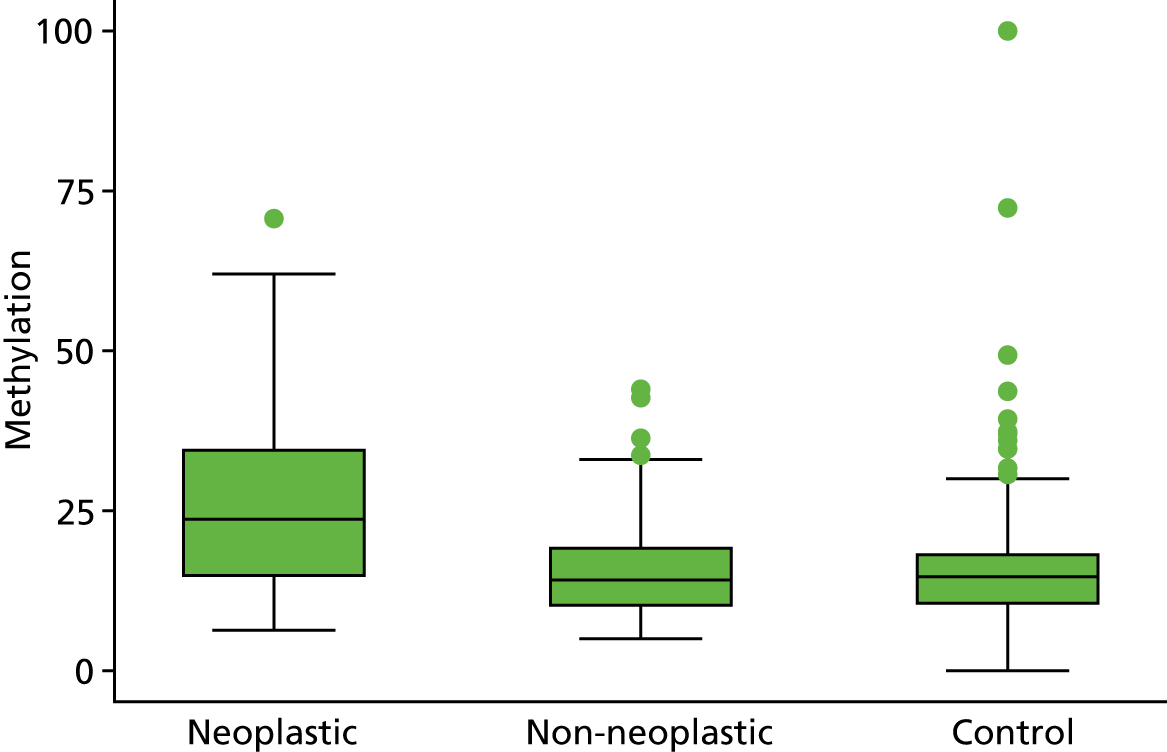

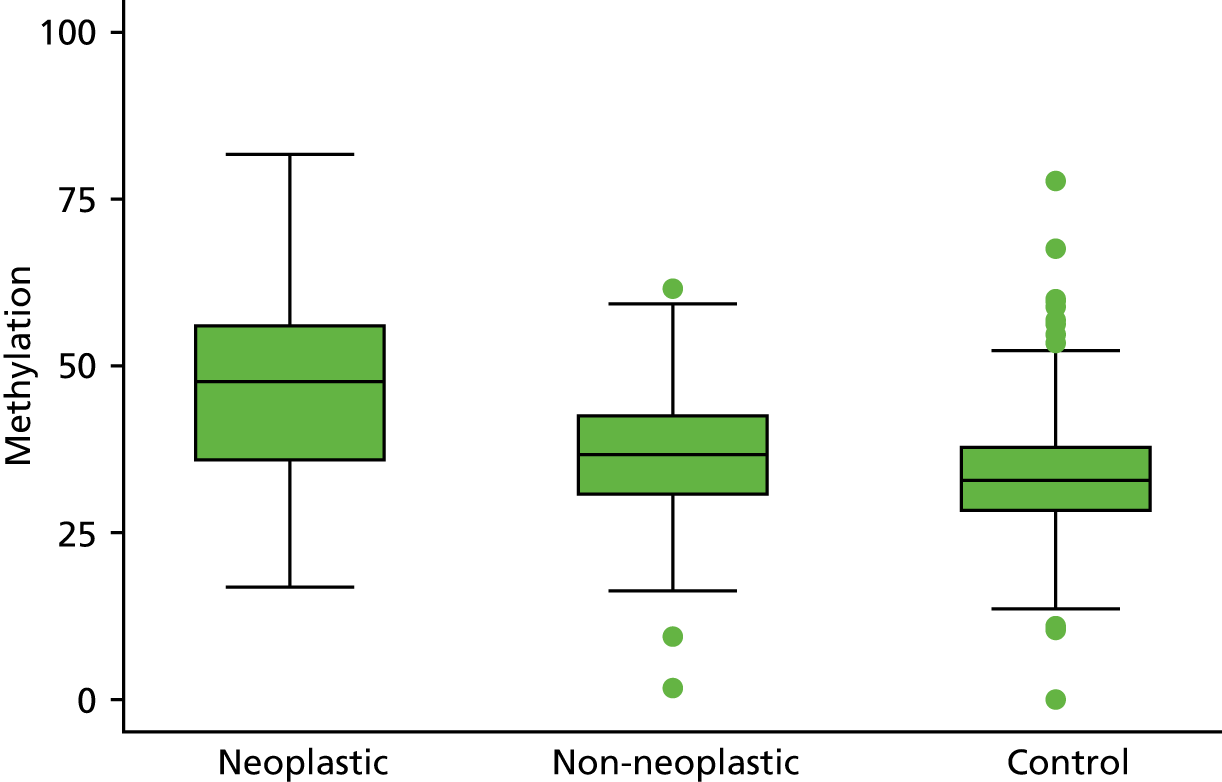

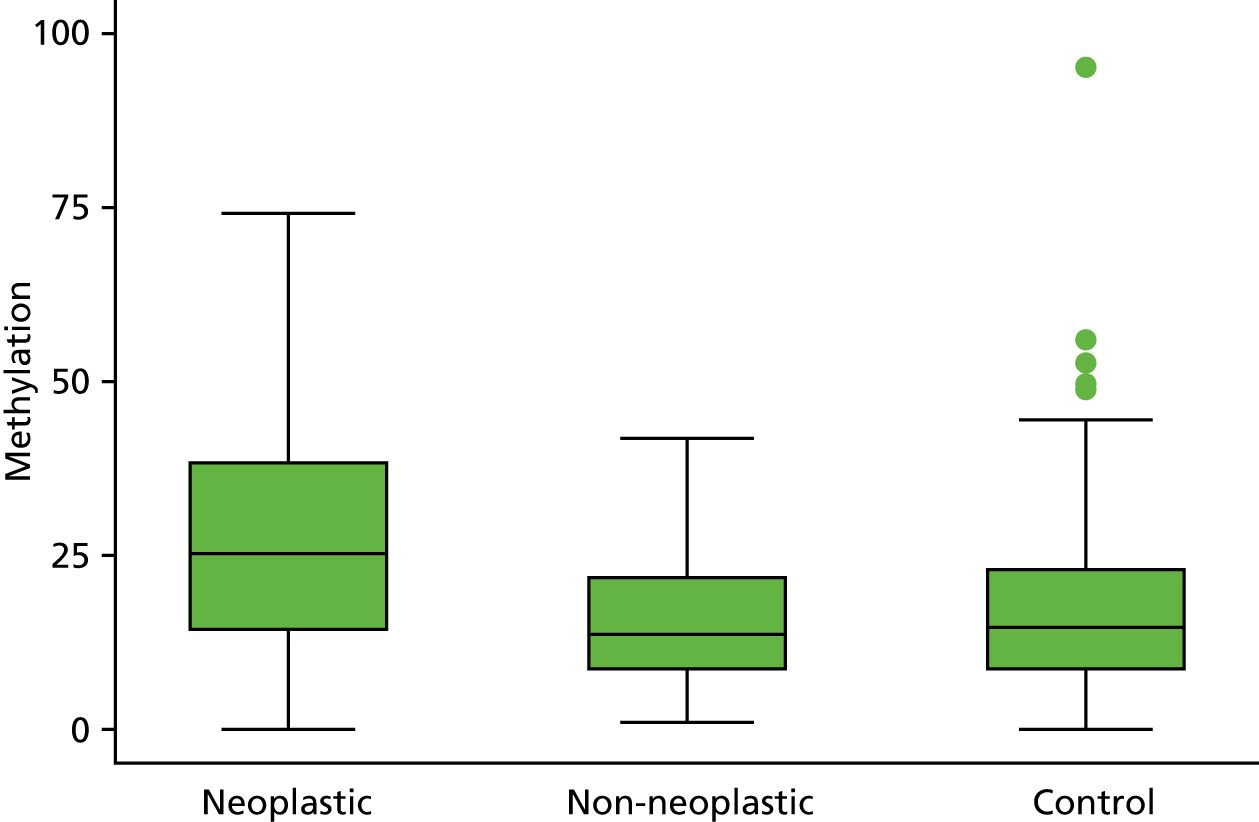

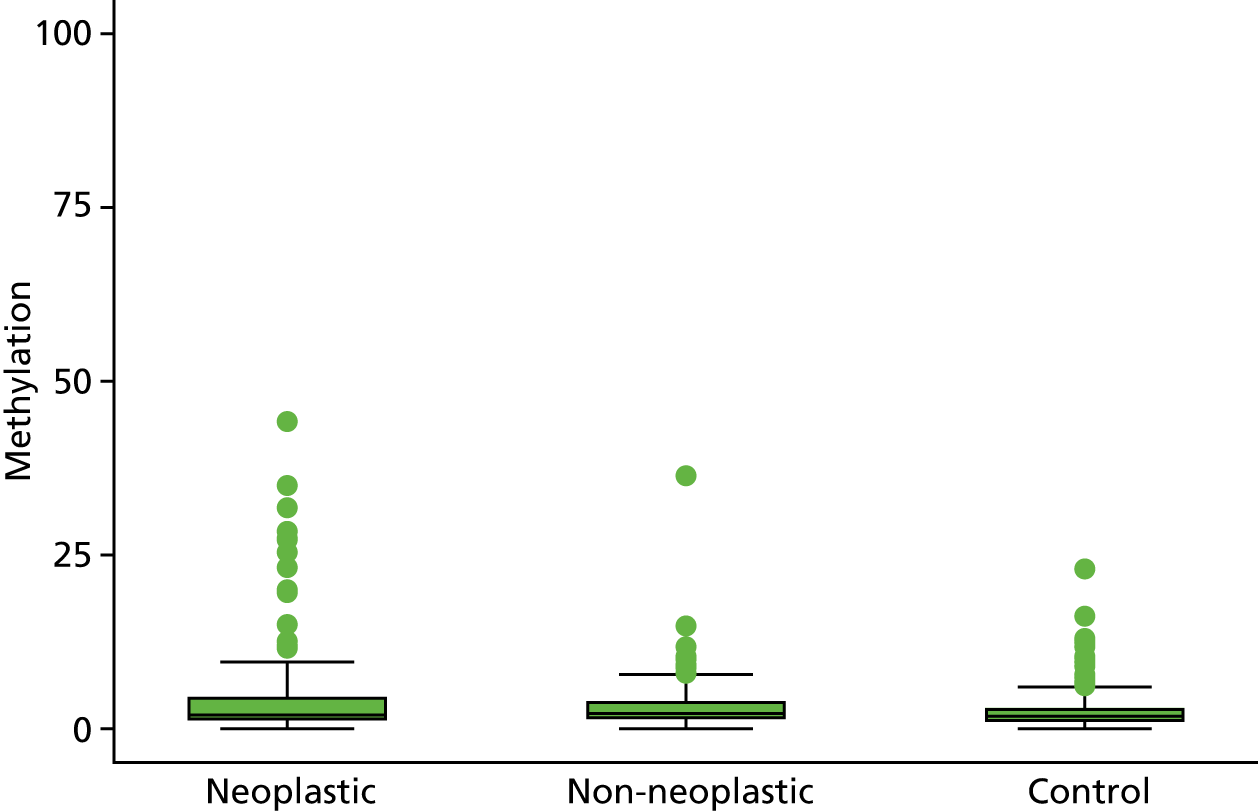

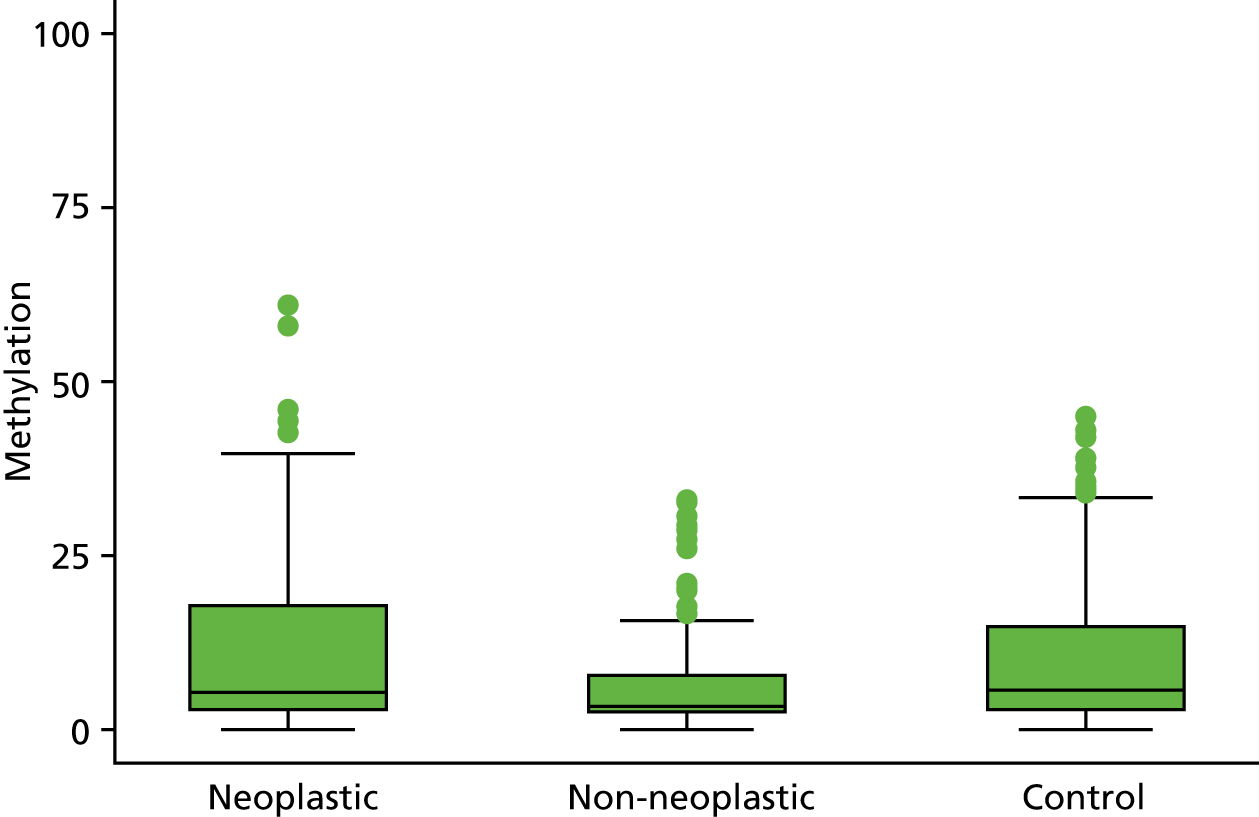

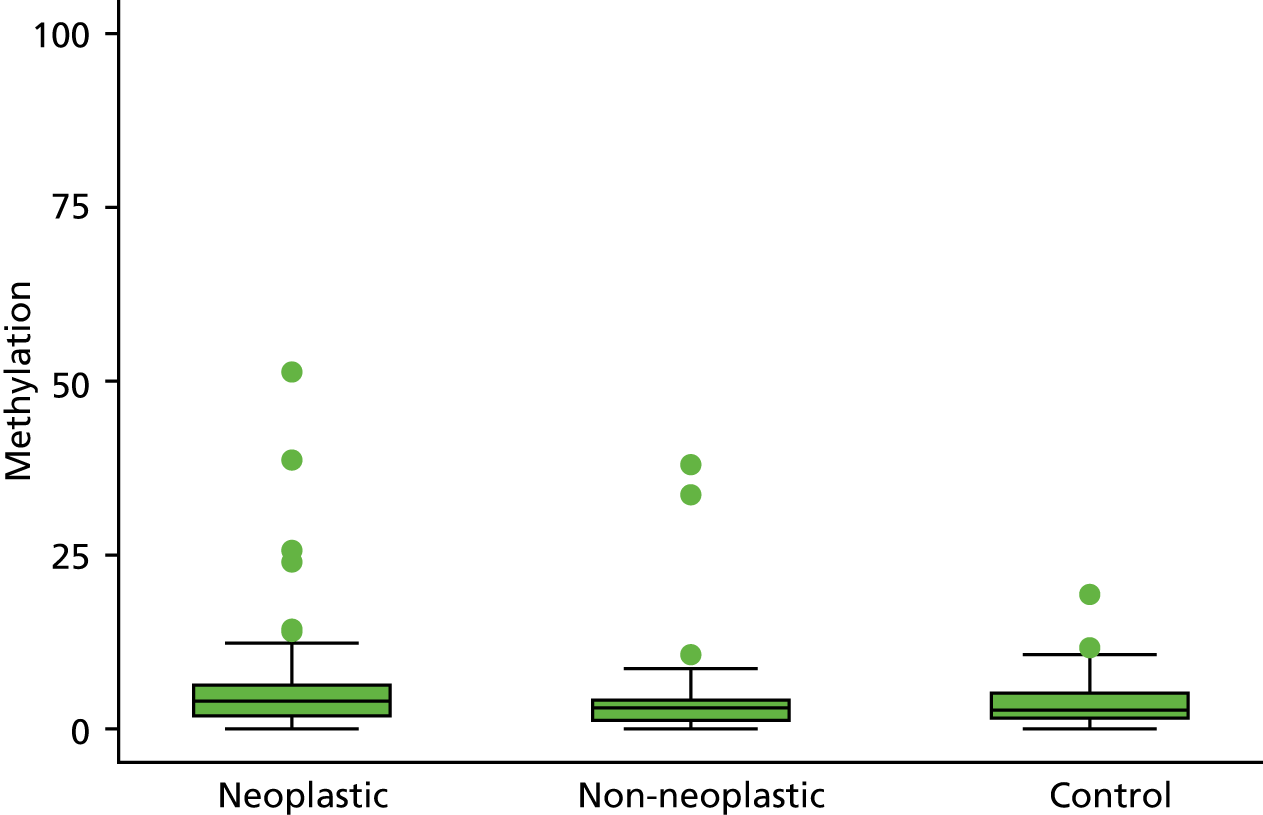

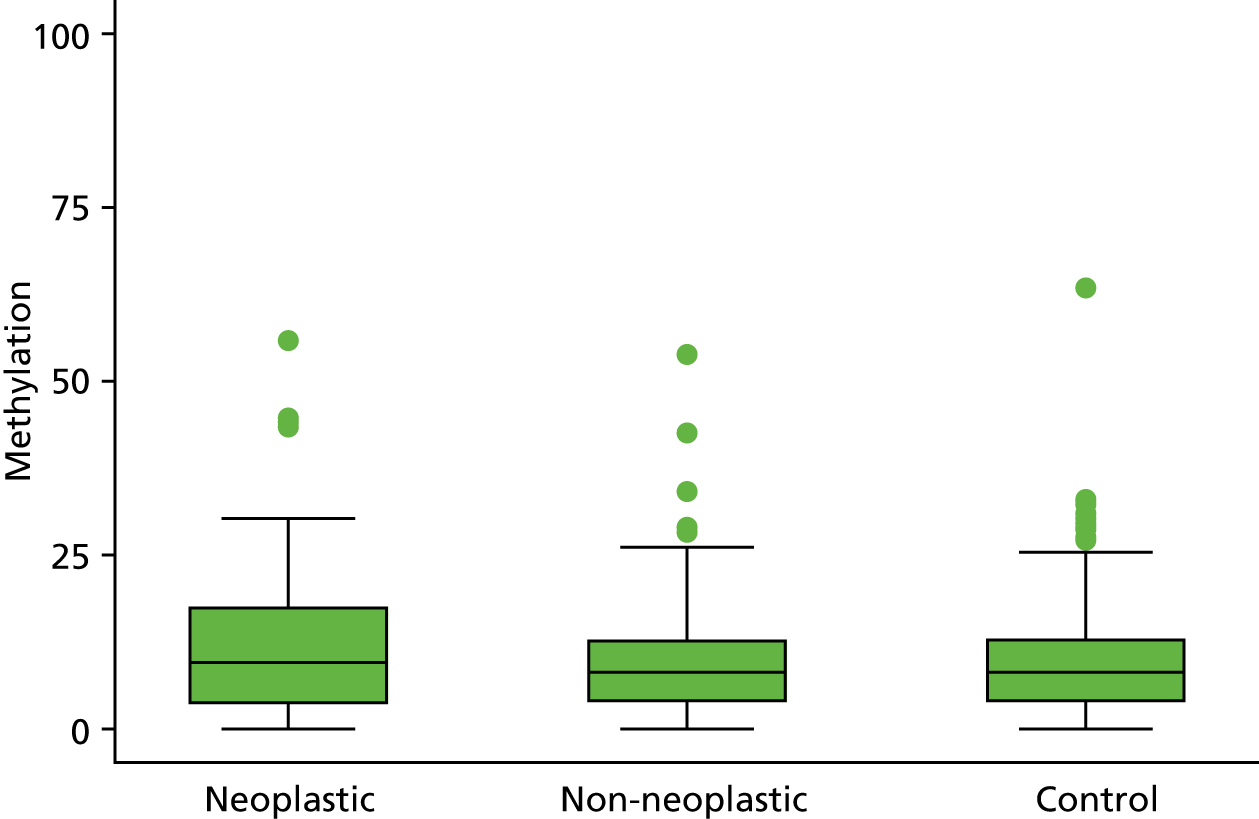

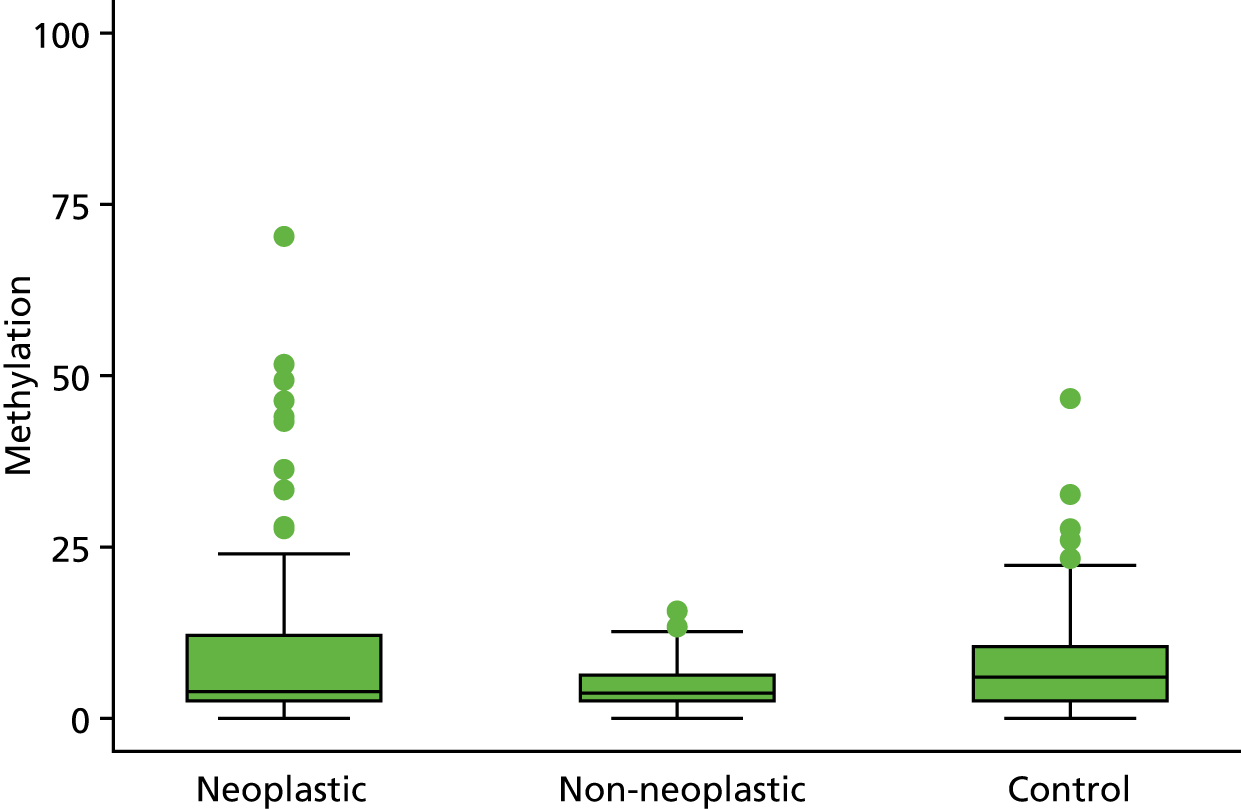

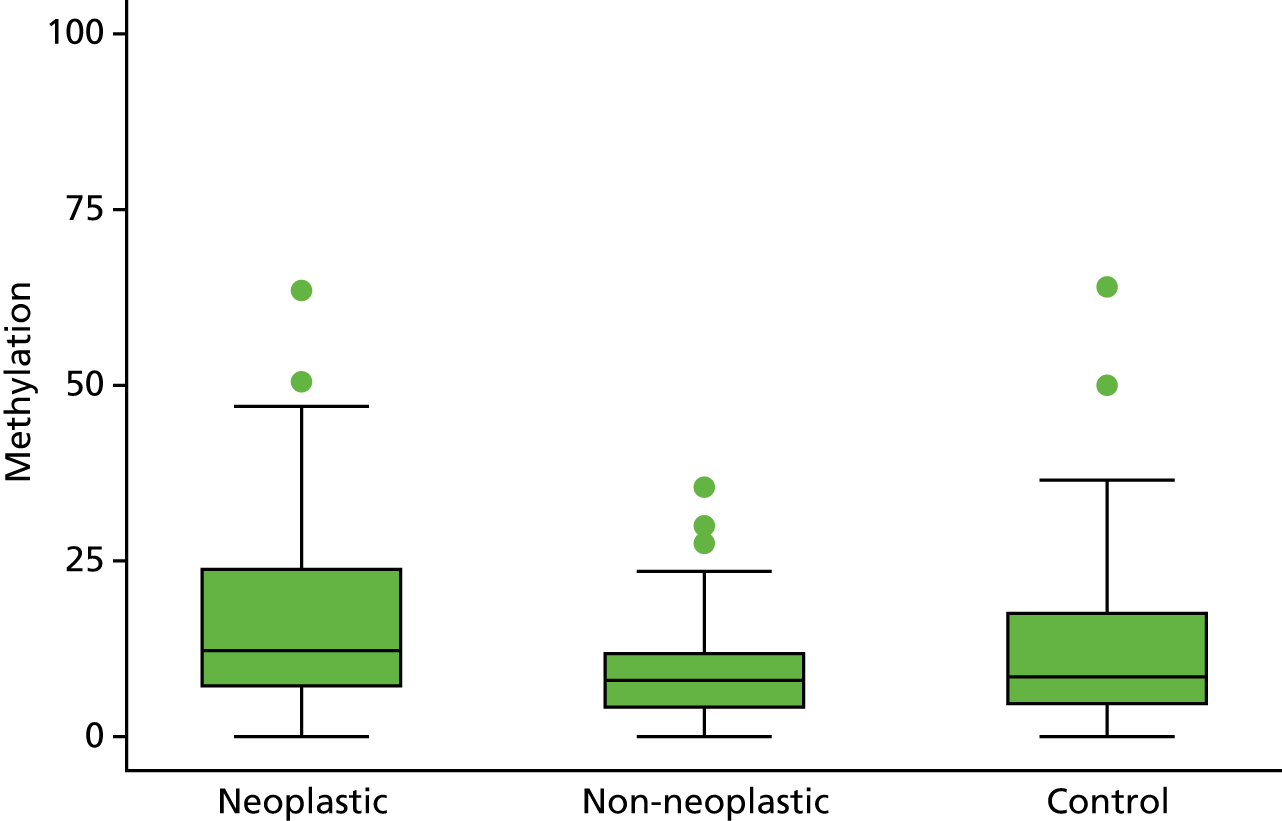

In the stage 2 analysis, five markers accurately discriminated between neoplasia and control samples with a p-value of < 0.0001: SFRP2, SFRP4, WIF1, APC1A and APC2 (see Table 3) (with between 40% and 76% increases in geometric mean values). TUBB6 showed a smaller (31%) increase, but this was also strongly significant (p = 0.003).

Comparing methylation in the samples of background mucosa (from patients with colitis-associated neoplasia) with control patients (with chronic UC only) showed some discrimination in four out of the eight promoter regions: SFRP4, APC1A, SFRP5 and SOX7 (see Table 3). Two of these markers (i.e. SFRP4 and APC1A) showed increases of in geometric mean values of 7% and 28%, respectively; the other two (i.e. SFRP5 and SOX7) showed decreases of 23% and 27%, respectively.

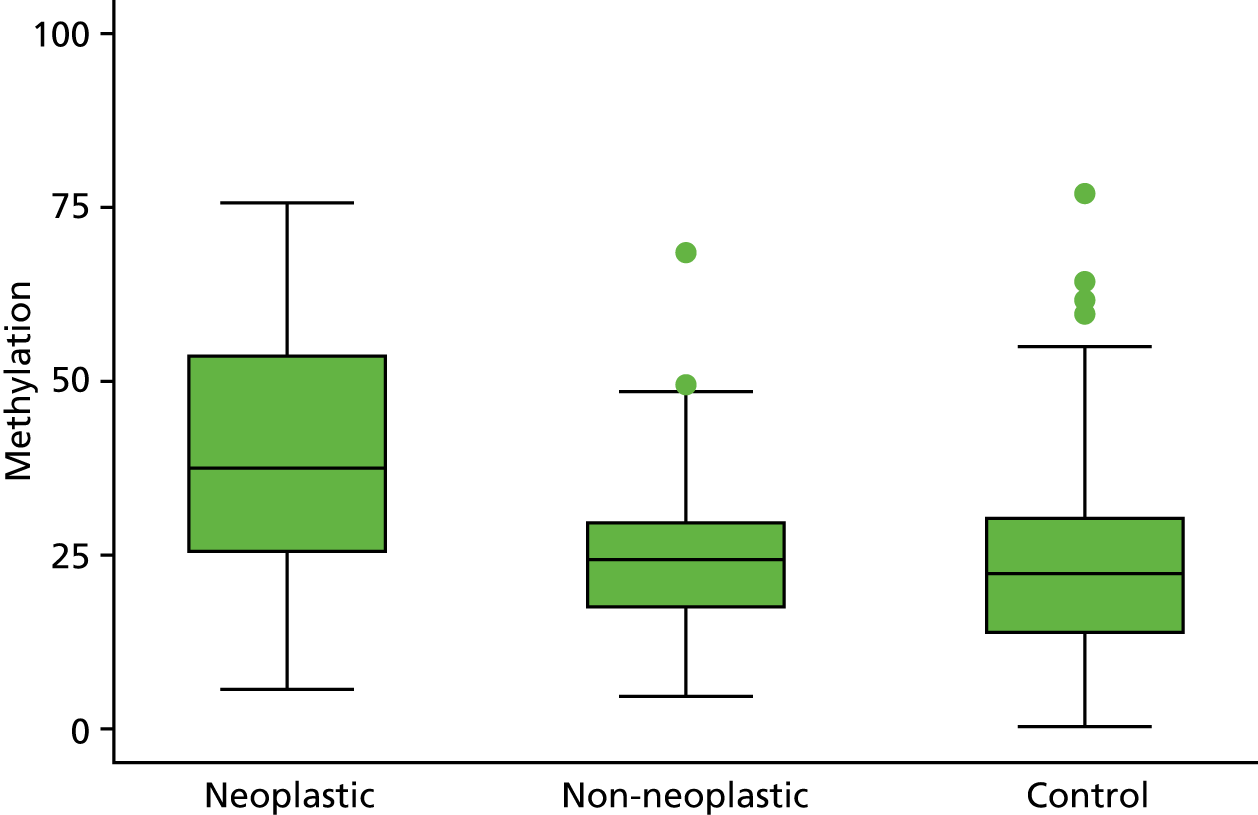

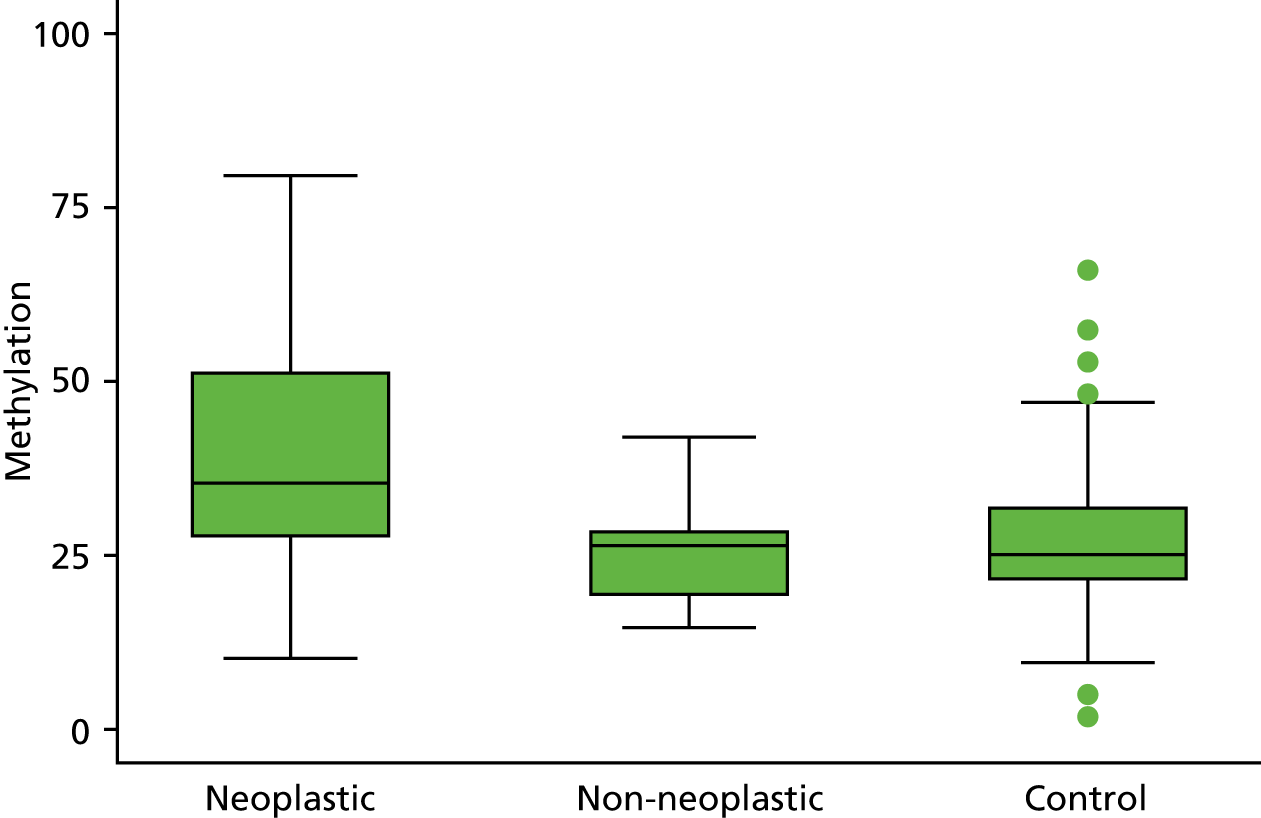

Performance of predictive models

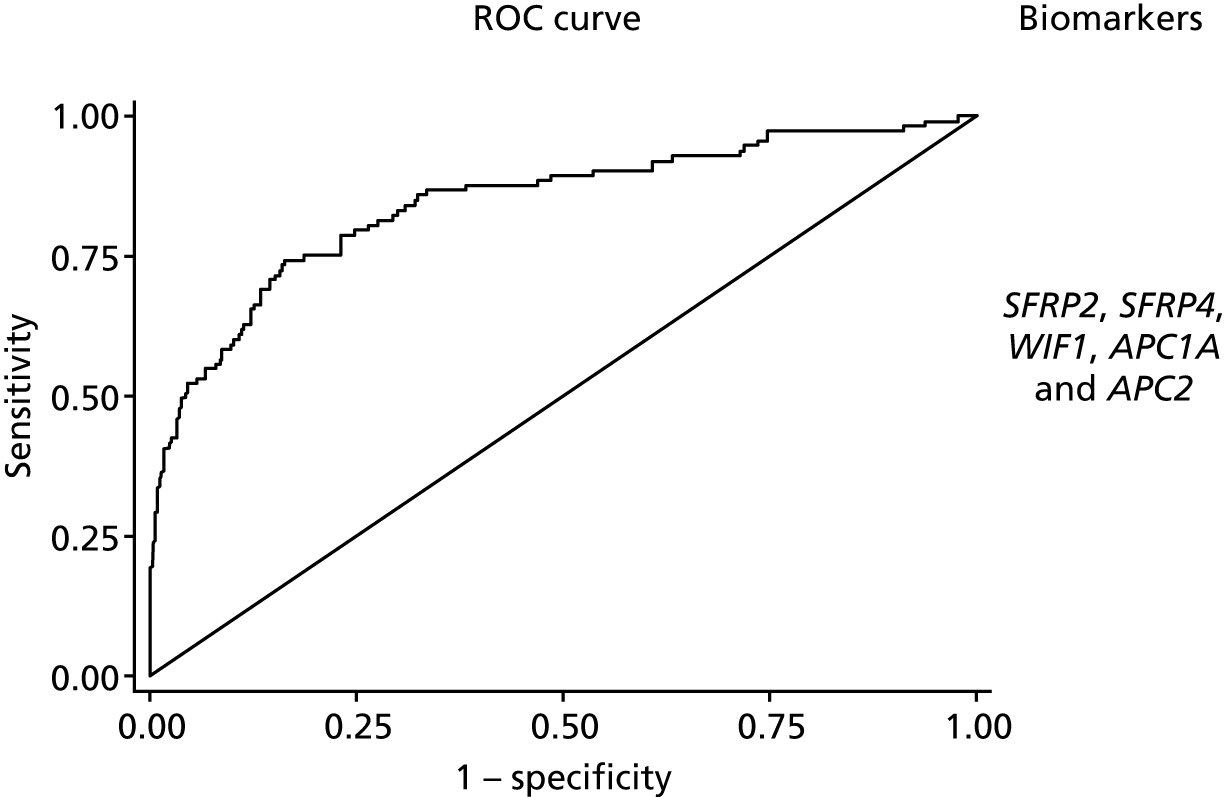

Predictive models to discriminate neoplasia samples from controls had good discrimination (Table 4). The optimism-adjusted AUC for model 1 detecting all neoplasia was 0.86 (95% CI 0.81 to 0.91) for the complete-case analysis (with a shrinkage factor of 0.93) but lower at 0.83 (95% CI 0.79 to 0.88) for the model using multiple imputation (see Table 4 and Figure 2). The addition of TUBB6 increased the AUC by only 0.001. When considered together in the panel, all markers other than WIF1 showed significant independent predictive value.

| Modela | Optimismb | Shrinkageb | Complete case AUC (95% CI) | Complete-case adjusted for optimism AUC (95% CI) | Multiple imputation AUC (95% CI) | Multiple imputation adjusted for optimism AUC (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1 | 0.012 | 0.93 | 0.871 (0.822 to 0.919) | 0.859 (0.810 to 0.907) | 0.845 (0.799 to 0.891) | 0.833 (0.787 to 0.879) |

| With TUBB6 | 0.015 | 0.91 | 0.875 (0.826 to 0.923) | 0.860 (0.811 to 0.908) | 0.848 (0.802 to 0.894) | 0.833 (0.787 to 0.879) |

| Model 2 | 0.012 | 0.91 | 0.930 (0.892 to 0.967) | 0.918 (0.880 to 0.955) | 0.892 (0.849 to 0.934) | 0.880 (0.837 to 0.922) |

| With TUBB6 | 0.015 | 0.88 | 0.932 (0.894 to 0.970) | 0.917 (0.879 to 0.955) | 0.894 (0.852 to 0.937) | 0.879 (0.837 to 0.922) |

| Model 3 | 0.021 | 0.90 | 0.682 (0.614 to 0.750) | 0.661 (0.593 to 0.729) | 0.696 (0.640 to 0.751) | 0.675 (0.619 to 0.730) |

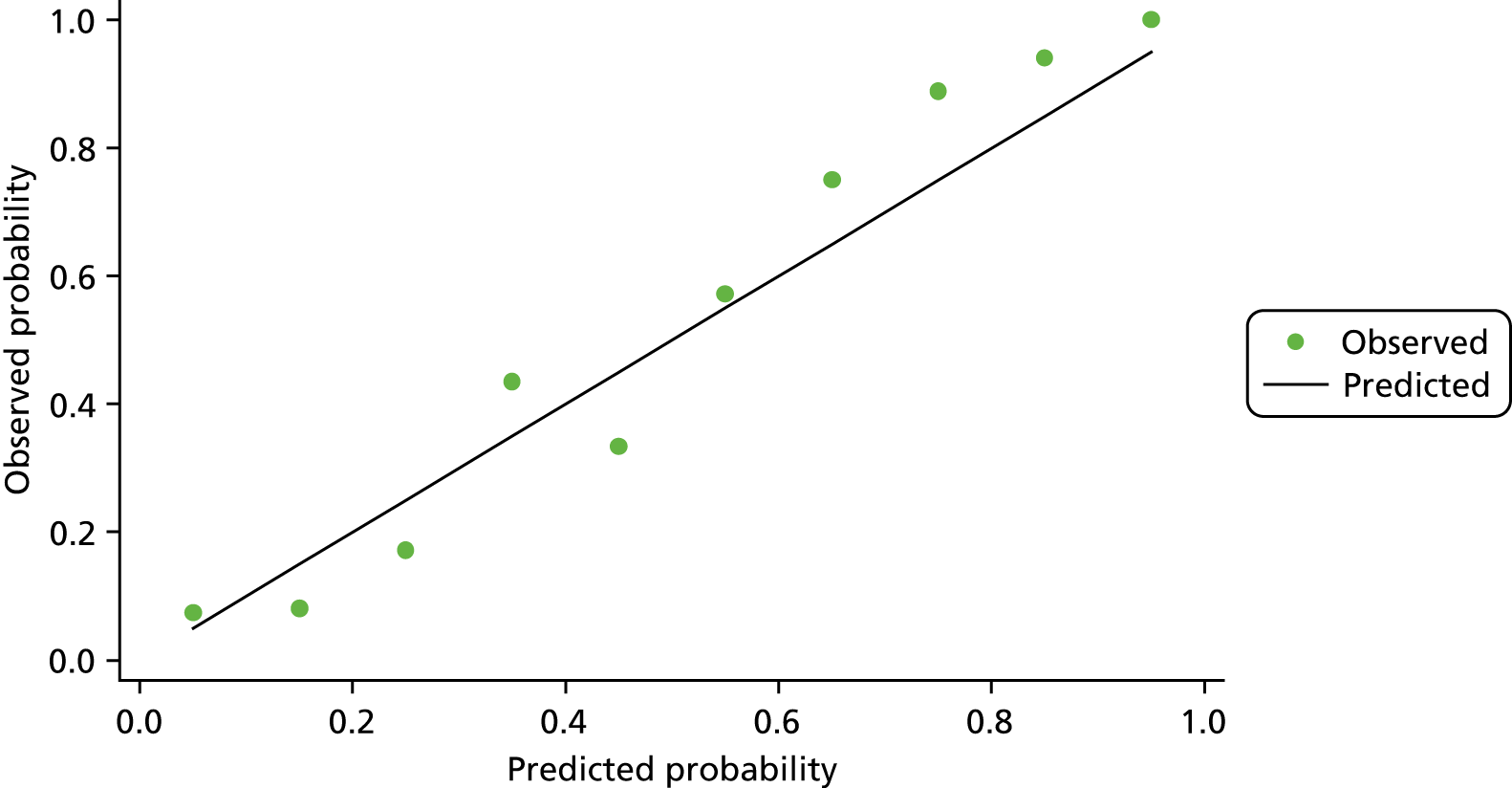

FIGURE 2.

The ROC curves for final fitted predictive models (after multiple imputation) for model 1 neoplasia vs. control, with the biomarkers used within this model.

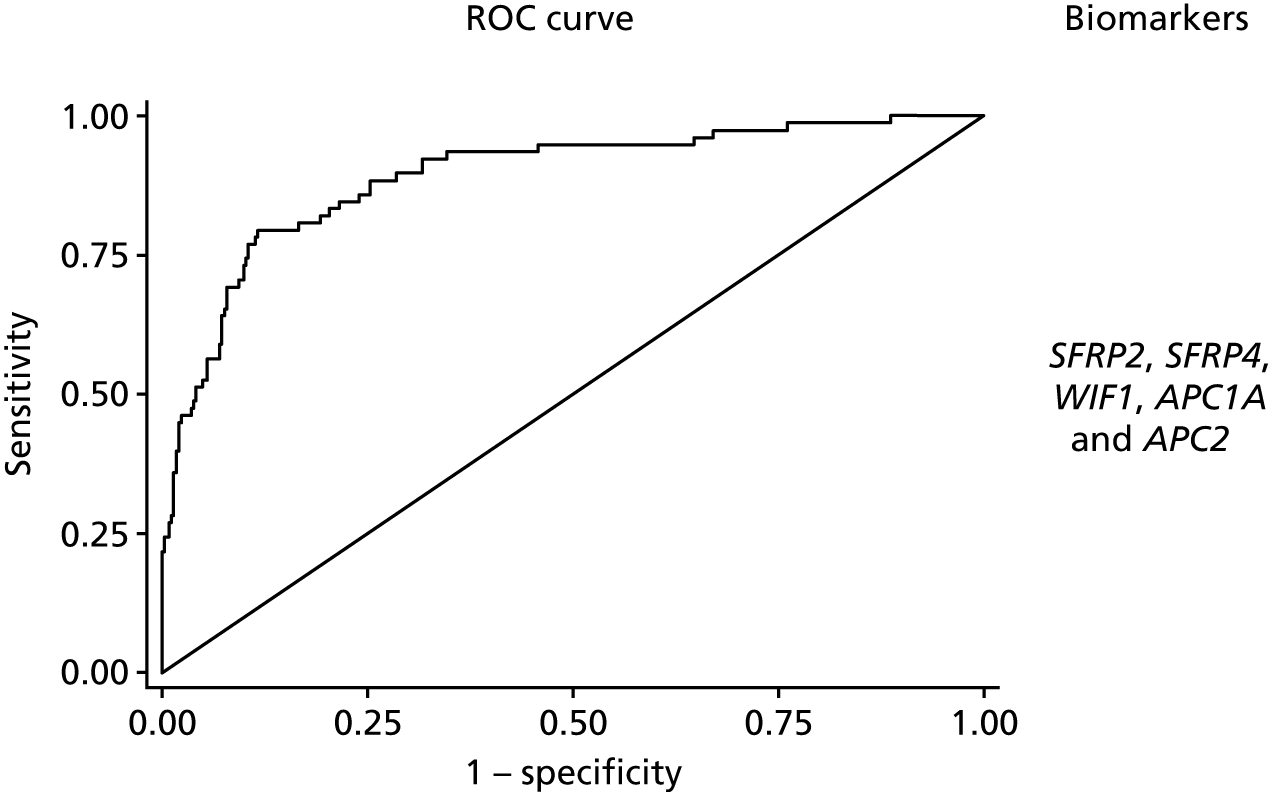

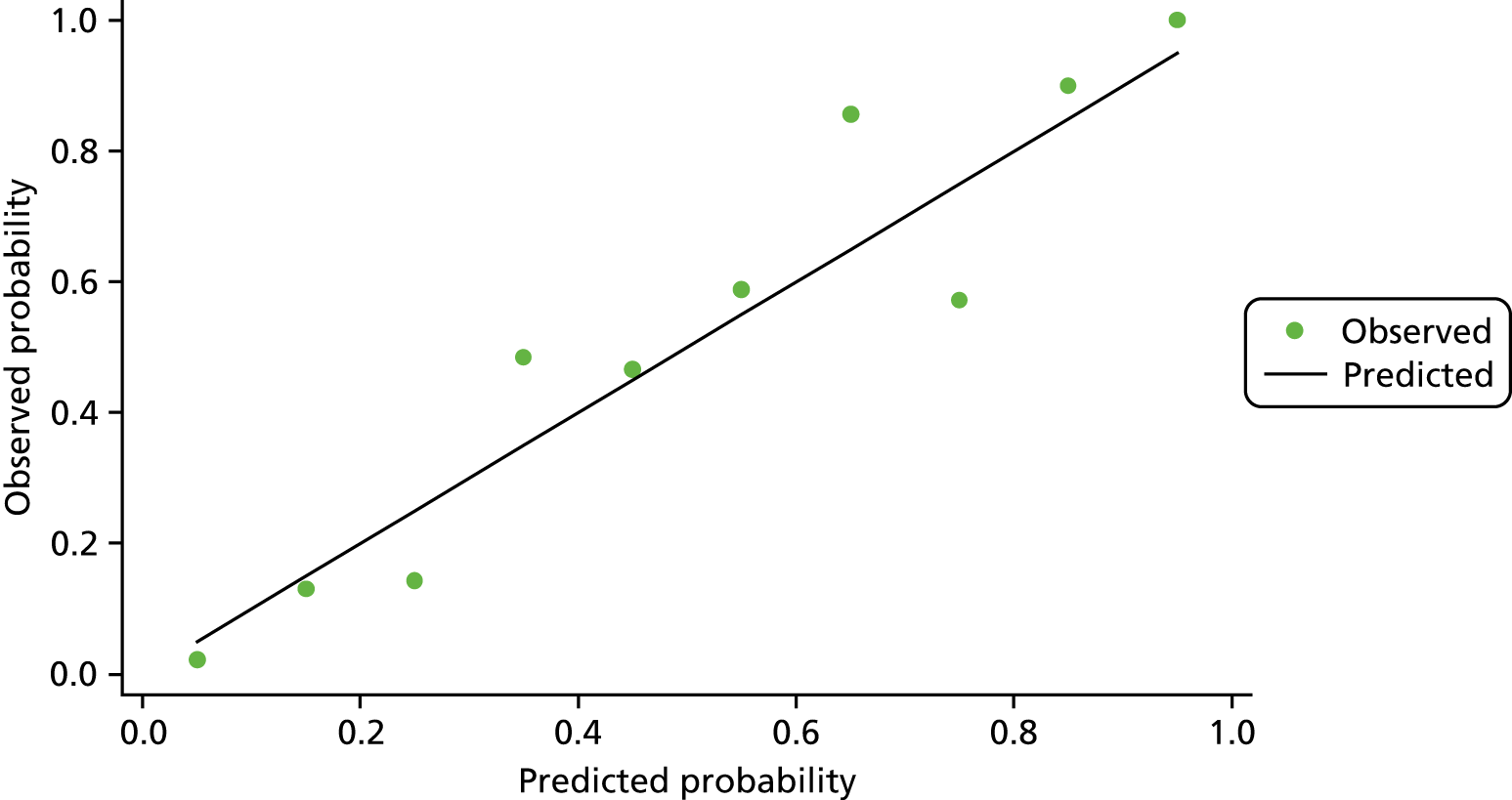

The discrimination of model 2, predicting only dysplasia (excluding adenocarcinoma cases), was higher with an optimism corrected AUC of 0.92 (95% CI 0.88 to 0.96) for the analysis of complete cases (with a shrinkage factor of 0.91) and 0.88 (95% CI 0.84 to 0.92) for the model using multiple imputation (see Table 4 and Figure 3). Again, adding TUBB6 made little difference, decreasing the AUC by 0.001. The coefficients for model 1 based on the multiple imputation data set are reported in Appendix 1, Table 19, and for model 2 in Appendix 1, Table 20. When considered together in the panel, all markers other than WIF1 showed significant independent predictive value.

FIGURE 3.

The ROC curves for final fitted predictive models (after multiple imputation) for model 2 dysplasia vs. control, with the biomarkers used within this model.

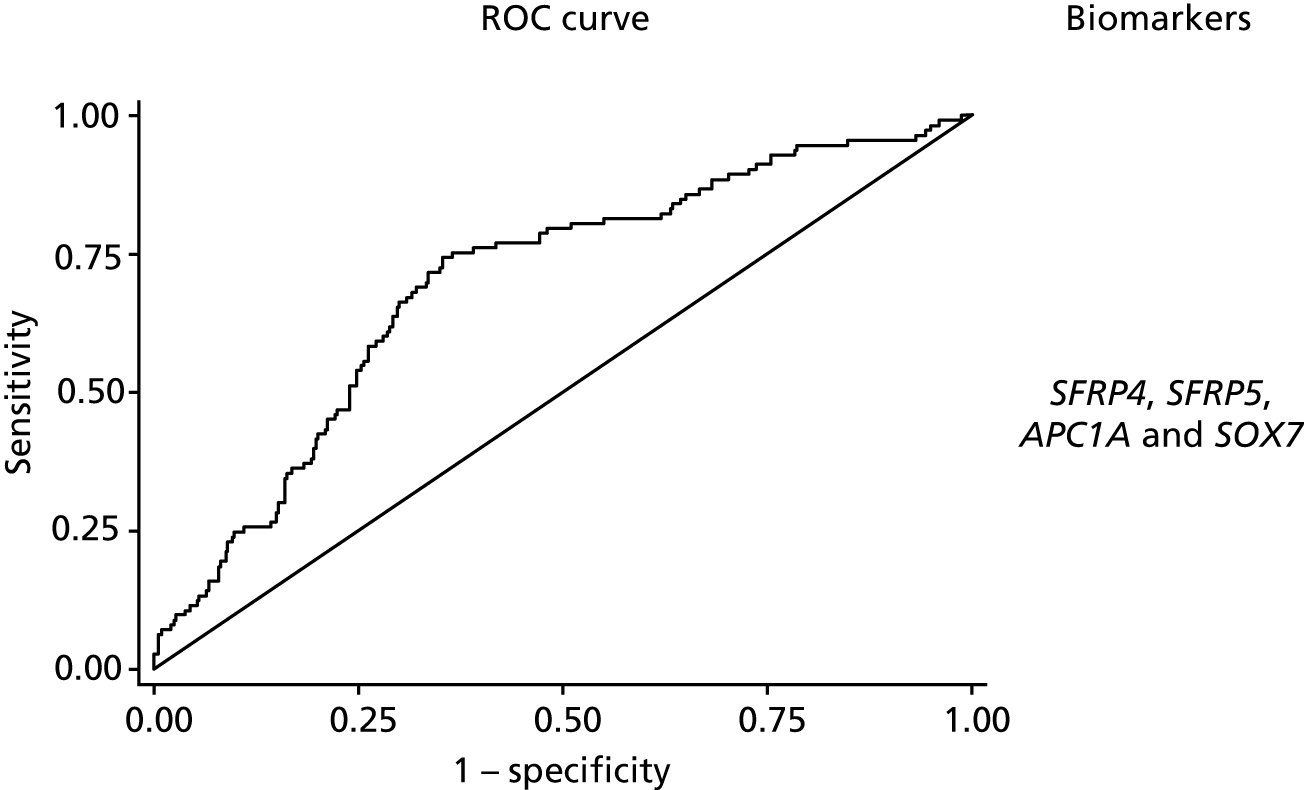

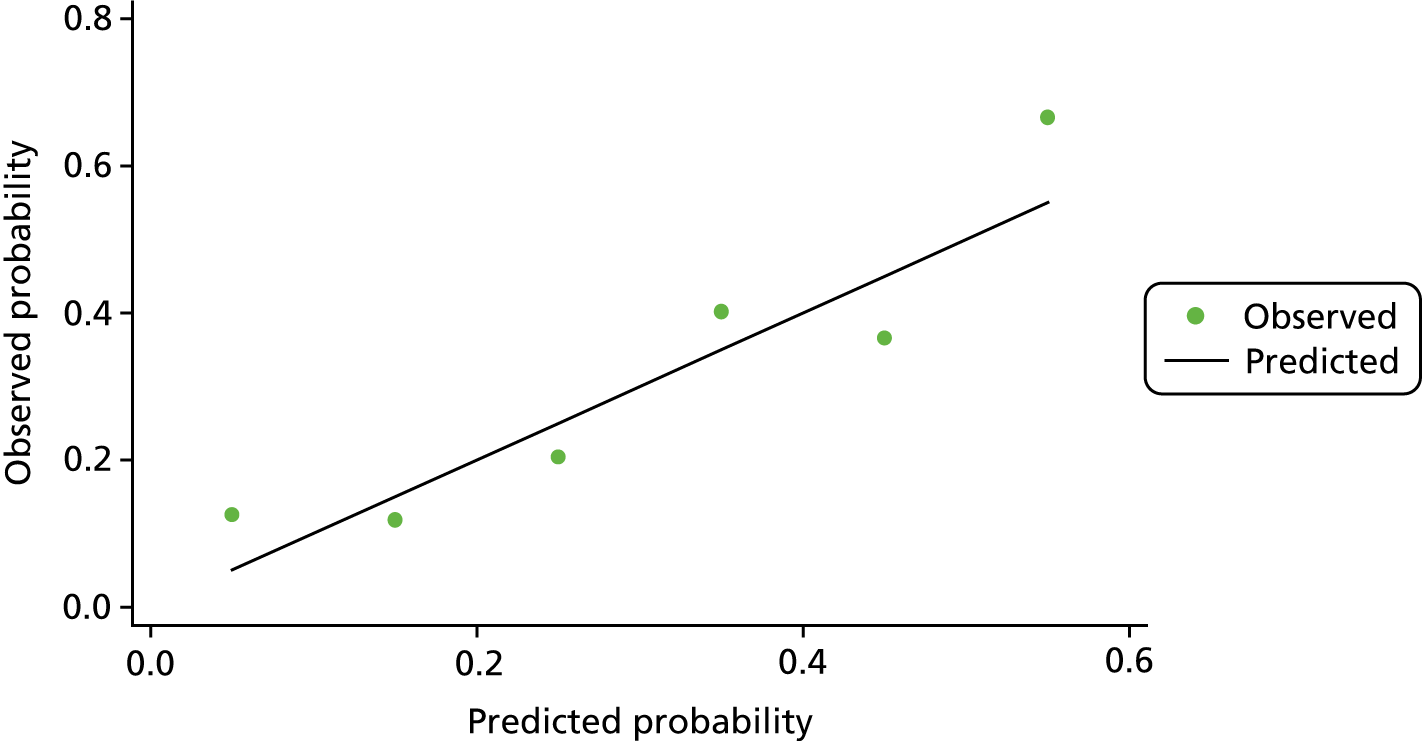

The predictive model to discriminate samples where there is methylation in the background mucosa (the matched non-neoplastic samples, model 3) from controls had poorer discrimination, with an optimism-adjusted AUC of 0.66 (95% CI 0.59 to 0.73) for the complete-case model (shrinkage factor 0.91) and 0.68 (95% CI 0.62 to 0.73) for the model using multiple imputation (Figure 4). We report coefficients for model 3 based on the multiple imputation data set in Appendix 1, Table 21. For SFRP5 and SOX7, lower levels of methylation were associated with neoplastic change in background mucosa. When considered together, only AP1CA and SOX7 showed significant independent predictive value.

FIGURE 4.

The ROC curves for final fitted predictive models (after multiple imputation) for model 3 matched non-neoplastic vs. control, with the biomarkers used within this model.

The calibration plot for model 1 after multiple imputation suggested that our final model for neoplasia detection after multiple imputation was reasonably well calibrated, with slight overestimation of probability at lower risk and overestimation at higher risk (see Appendix 1, Figures 19 and 32).

Identification of a diagnostic threshold

We identified the value of the predictive model corresponding to a likelihood ratio of at least 6, to identify thresholds that would have a positive predictive value of at least 20% when incidence of neoplastic disease was 4%. This corresponded to a threshold of 0.40 for model 1, 0.28 for model 2 and 0.50 for model 3. Sensitivity and specificity (with 95% CIs) at this threshold were 58.4% (48.8% to 67.6%) and 90.38% (86.8% to 93.3%) for model 1, 79.5% (71.0% to 86.6%) and 86.9% (82.8% to 90.3%) for model 2, and 7.1% (3.1% to 13.5%) and 98.8% (97.0% to 99.7%) for model 3.

To achieve a sensitivity of at least 90%, model 1 would use a threshold of 0.11 with a specificity of 46.4% (95% CI 41.1% to 51.8%), positive predictive value of 6.6% (95% CI 5.9% to 7.3%) and diagnostic odds ratio of 8.0 (95% CI 4.1 to 17.1); model 2 would use a threshold of 0.11 with a specificity of 68.2% (95% CI 63.0% to 73.1%), positive predictive value of 10.7% (95% CI 9.11% to 12.3%) and diagnostic odds ratio of 18.8 (95% CI 8.6 to 46.5); and model 3 would use a threshold of 0.19 with a specificity of 27.1% (95% CIs 22.5% to 32.1%), positive predictive value of 4.9% (95% CI 4.5% to 5.3%) and diagnostic odds ratio of 3.4 (95% CI 1.7 to 7.4).

Models for missing data

For model 1, to provide models for scenarios where data on fewer than five of the chosen biomarkers amplify, separate models accounting for all possible scenarios, where at least three out of the five biomarkers amplified, were created through re-analysis of the multiple imputation model with reduced sets of predictor variables. This created an additional 15 models (see Appendix 1, Table 22).

Module 1: discussion

In this study we have demonstrated that a five-marker methylation marker panel accurately predicts UC-associated dysplasia and invasive neoplasia from formalin-fixed mucosal biopsies taken at endoscopy. Recruitment of a diverse population (diagnosed in different hospitals and from different genetic pools) increases the likely generalisability of these findings. The study has also identified a second marker panel found in the background mucosa that is (more weakly) associated with neoplastic change. Our panels utilise epigenetic biomarkers, which are emerging as a reproducible method of quantifying disease risk in a population,38 and suggest that these markers may add value to endoscopic detection of colitis-associated neoplasia.

Specific patterns of methylation change have been observed in colorectal cancer39 as well as specific changes observed in the transition from dysplastic colorectal adenoma to malignant adenocarcinoma24 suggesting that methylation has good sensitivity as a biomarker of disease. To our knowledge, this is the first multiplex methylation biomarker panel in colorectal cancer.

Other cancer types have demonstrated potential utility of methylation analysis in screening for invasive disease. The UroMark study38 investigated the utility of multiplex bisulphite PCR amplicon NGS in the detection of muscle invasive bladder cancer in voided urine. Using a 150-marker panel based on differentially methylated CpG loci in a discovery study, they tested their marker panel in a cohort of 274 patients with muscle invasive bladder cancer, reporting an overall AUC of 0.97. Although the analysis may have been overfitted, a significant advantage was the ability to develop a marker panel based on an epigenome-wide association study, an approach that might be appropriate in UC-associated dysplasia, which has a heterogeneous genetic profile.

Generally it is accepted that an AUC of > 0.80 represents a ‘good’ biomarker panel for the detection of disease and multiple marker panels using several different technologies have been developed across multiple disease types that have reached this target. 40–42 The AUC for detection of colitis-associated neoplasia suggests this is an accurate test for neoplasia. However, we are seeking to enhance detection, not replace colonoscopy for which it is necessary for the test to also identify neoplasia missed on colonoscopy. Ultimately it is the early detection of occult disease that will determine the clinical value of this assay, and that requires prospective evaluation, which is undertaken in module 3 of the ENDCaP-C study.

It is likely with more extensive epigenetic analysis of this retrospective cohort we could enhance discrimination. The study has established that a reliable and robust assay can be developed for these patients. Although we under-recruited tumour blocks (113 rather than the planned 160), this still provided > 20 events per variable for generating our five-marker models but will have increased the maximum 95% CI width for sensitivity by 3%. The study was carried out on a genetically and geographically diverse population, supporting the generalisability of our findings.

This study has also developed a novel marker set for predicting the presence of co-existing neoplasia from analysis of the background mucosa. Unsurprisingly, the AUC value for this is significantly lower and the test is, therefore, less discriminating. But the true impact of these markers can be determined only in a prospective longitudinal analysis. These methylation changes are present in a subset of the UC population, without associated neoplasia. Follow-up of these patients will be required to determine whether or not this represents a high-risk population for whom therapeutic cancer prevention strategies can be developed.

Three biomarkers (i.e. SFRP1, MINT1 and RUNX3) were not taken forward because of poor amplification rates during PCR, which we hypothesised was because of the high GC (guanosine triphosphate cytidine triphosphate) content of these regions making primer design difficult for FFPE-derived DNA. In addition, WIF1 methylation was found not to contribute to the disease model, presumably because its methylation levels were similar to other genes that were analysed within this study that are all modulators of the Wnt signalling pathway. It was also noticed that the direction of methylation (towards hypomethylation) differed for the markers in model 3. It was hypothesised that this was because of the previously demonstrated ‘wave’ of hypomethylation43 that occurs as a precursor to invasive malignancy and, therefore, should occur in the disease-associated non-dysplastic mucosa that we sampled here.

In conclusion, we have successfully developed a multiplex methylation marker panel for the detection of UC-associated dysplasia and neoplasia that was validated in a retrospective cohort. Module 3 describes the validation of these markers in a prospective clinical study.

Chapter 3 Module 2: evaluation of next generation sequencing as an alternative to pyrosequencing

Module 2: introduction

The aim of the ENDCaP-C study module 2 was to evaluate the utility of NGS as an alternative to pyrosequencing – the technology routinely used to determine the methylation status of specific targets in FFPE extracted DNA. It was considered that pyrosequencing was not an appropriate platform to deliver a high-throughput strategy for introduction into routine clinical practice. Although pyrosequencing is already widely used in the clinical diagnostic setting, it does not offer the high-throughput level required for widespread use in UC patients. Moreover, both laboratory work and results analysis offer little space for automation, which has an impact on the turnaround time and standardisation.

A number of potential technical approaches were considered, but it was decided to evaluate an amplicon-based target enrichment strategy using the Fluidigm 48.48 Access Array (Fluidigm Corporation; San Francisco, CA, USA) system with subsequent sequencing analysis performed on the Illumina MiSeq platform (Illumina Incorporated; San Diego, CA, USA). The advantages of this system included speed, single nucleotide resolution, high coverage of each locus, low cost of simultaneously assaying multiple CpG loci and high-throughput capability. This approach has been proved successful in a number of studies. 44–46

Module 2: methods

Bisulphite DNA conversion

Bisulphite DNA conversions were performed using the EZ-96 DNA Methylation Gold MagPrep Kit (Zymo Research; Irvine, CA, USA) according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The amount of input DNA was variable, dependent on the sample source, ranging between 1 ng and 30 ng.

Target enrichment using the Fluidigm Access Array system

Multiplex PCR amplification was carried out on a 48.48 Fluidigm Access Array (Fluidigm Corporation, South San Francisco, CA, USA) following the methods of Lange et al. 44 using a Roche High Fidelity Fast Start Kit (Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland). The target specific primer sequences are given in Table 5.

| CS1 and CS2 Fluidigm tag (5′–3′) | Target sequence (5′–3′) | Primer name |

|---|---|---|

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GGGTGTTTTTGTTTAATAAGAATTGT | CS1-SFRP1-14-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GTTGTGGTTGTATATTTTTATGAGGG | CS1-SFRP4-15-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GTTTTAGTAGGTTGGGT | CS1-SFRP5-16-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GGGGTTAGGGTTAGGTAGG | CS1-APC1A-17-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | AGTTTGTAGTGGGAGAGT | CS1-APC2-18-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GTTTTTATGGTTTGGGTTAAGG | CS1-SOX7-19-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | AGGAGTAGGTTGTATAGAT | CS1-TUBB6-20-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | AATAGTTTTGGTTGAGGGAGTTGTA | CS1-WIF1-10-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GTGTTGAGAGAGTTTGAAAGAAATATTAT | CS1-MINT1-3-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GAGGAGGTTTTAGTGTTATAGTTTAGGG | CS1-RUNX3-4-for |

| ACACTGACGACATGGTTCTACA | GTTGTTGGGGTATAGTTAGAGTTTTT | CS1-SFRP2-6-for |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | ACTTAAACATCTCCAACCAATAAAAACC | CS2-SFRP1-14-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | CCCATTTACACCCTAAAATTCCTA | CS2-SFRP4-15-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | CAATACCTTAACATCCCTAC | CS2-SFRP5-16-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | TCCAACCAATTACACAACTACTTCTCTCT | CS2-APC1A-17-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | CTACCTACCTCCAACTCAAATAACAAC | CS2-APC2-18-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | ACCCAACATCTTACTAAACTC | CS2-SOX7-19-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | TCTCCCAAAATACAAAAACCATTCCTCT | CS2-TUBB6-20-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | CCCAAAAAATTTTTACTAAATAAAAAC | CS2-MINT1-3-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | AAATTACAAAAATCACAAACCC | CS2-RUNX3-4-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | CAACCAAAATTCCCTTCCAA | CS2-SFRP2-6-rev |

| TACGGTAGCAGAGACTTGGTCT | ACCAACAAACACAAAAAAATACTCC | CS2-WIF1-10-rev |

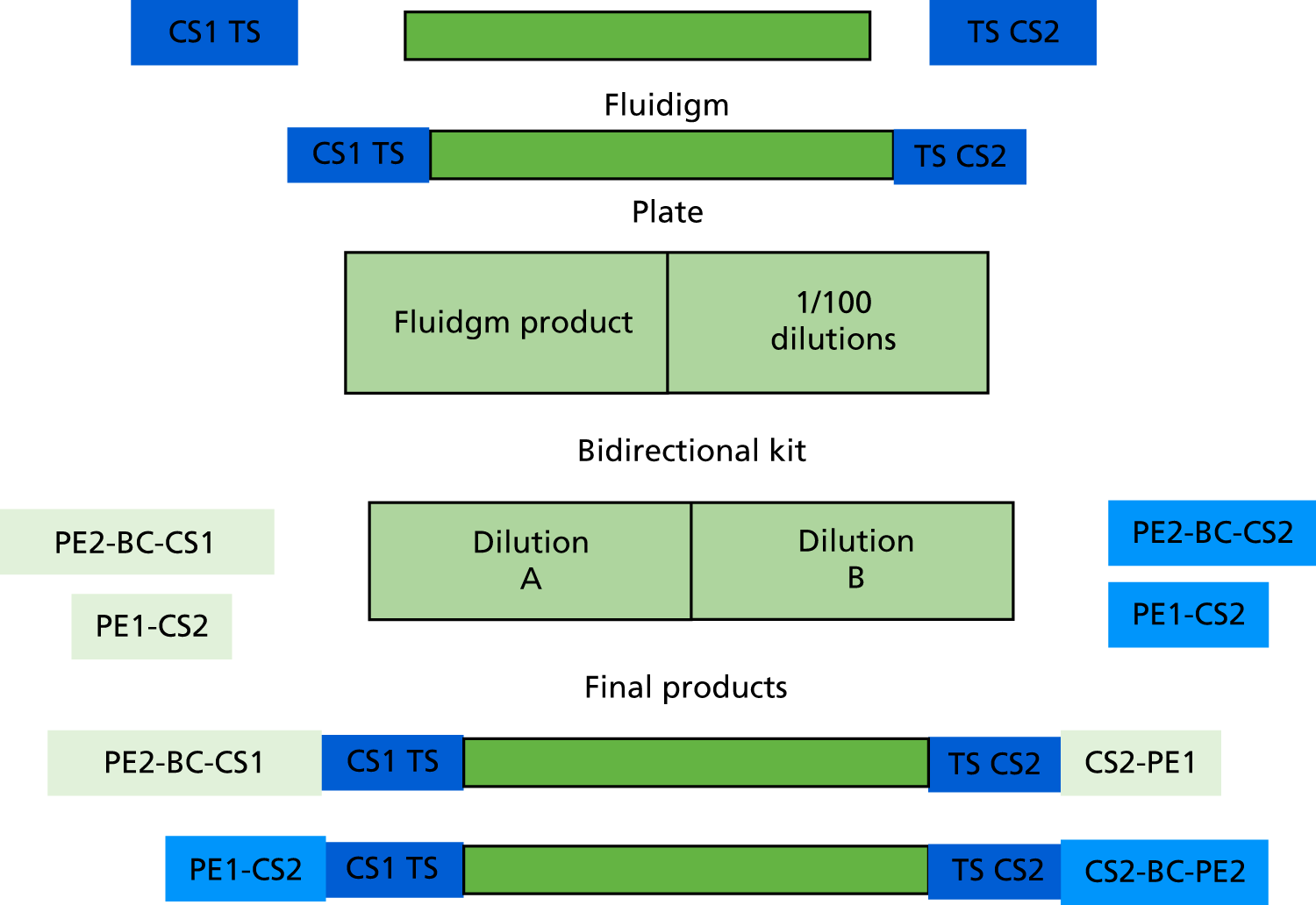

Sequencing adaptor and barcode primer incorporation

A bidirectional sequencing protocol was adopted as provided by Fluidigm (Access Array™ Barcode Bidirectional Library for Illumina Sequencers – 100–3771; Fluidigm Corporation, San Francisco, CA, USA) to facilitate simultaneous sequencing of the forward and reverse directions, which is important to provide sufficient base diversity content during subsequent MiSeq Illumina sequencing (Figure 5).

FIGURE 5.

Schematic representation of the bidirectional sequencing strategy adopted to overcome the low diversity issues.

For each sample, 1 µl of the 50-fold diluted PCR products was added to each of two PCR plates containing 15 µl of pre-sample mastermix containing 0.05 U/µl of FastStart™ High Fidelity Enzyme blend (Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland), 1 × FastStart High Fidelity Enzyme Buffer (Roche Holding AG, Basel, Switzerland), 200 µM each of dNTPs, 4.5 mM MgCl2 and 5% dimethyl sulphoxide. In the first plate, 4 µl of one pair of primers containing an individual 10-base barcode (BC) sequence, and sequence tags for reading in one direction (PE2-BC-CS1+PE1-CS) were added to each well. In the second plate, 4 μl of primers containing PE2-BC-CS2/PEI-CS2 were added to each well. Reaction products in plates were amplified for 15 cycles: 95 °C for 10 minutes, 15 cycles of 95 °C for 15 seconds, 60 °C for 30 seconds and 72 °C for 4 minutes, 1 cycle of 95 °C for 3 minutes.

Quantification and clean-up of deoxyribonucleic acid sequencing library

The barcoded products were pooled together and purified using AMPure XP beads (Beckman Coulter Life Sciences, Brea, CA, USA) using a bead to amplicon ratio of 1 : 1. The library was analysed and quantified using microfluidic electrophoresis on Agilent 2200 TapeStation (D1000 DNA screen tape) (Agilent Technologies Incorporated, Santa Clara, CA, USA) to ensure that the expected size was obtained (a main peak of 330 bp). A 2-nM library dilution was prepared, checked on the Agilent 2200 TapeStation (high-sensitivity tape) and sequenced on MiSeq sequencing platform according to the Illumina standard protocol.

Bioinformatic pipeline

An in-house bioinformatics pipeline was used to automate the cytosine methylation state detection ‘Bismark’ software (Babraham Bioinformatics; Cambridge, UK). 47 Briefly, CS (consensus sequences) were removed using cutadapt (v1.4.1) and target-specific sequences were analysed using Bismark package (version v0.10.0). Bismark utilised bowtie (v1.1.1) to align the trimmed reads allowing only one mismatch per 50 (high quality, Q > 28) bases. Methylation data were extracted using the bismark_methylation_extracter tool to generate a table of methylation counts. Methylation count data were mapped and converted to genomic locations using a custom Python script.

Raw data obtained from the MiSeq was quality assessed and filtered against a minimum Phred score of 30, using a sliding four-base window across each read. Reads were trimmed to remove the primer sequences using the cutadapt v1.4.1 tool.

Reads were processed using Bismark v0.10.1, which simultaneously aligned against in silico converted DNA and unmodified DNA reference sequences (the 11 amplicon sequences as defined by the target specific primers, hg19 genome assembly).

After alignment the ‘bismark_methylation_extractor’ script computed the number of counts corresponding to methylated and unmethylated bases to give the percentage of methylated reads. The ‘local’ alignment co-ordinates were then converted into genomic co-ordinates using a custom Python script to create a bed file for viewing methylation data on the Integrative Genomics Viewer 2.3 (The Eli and Edythe L Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard; Cambridge, MA, USA).

Module 2: results

Primer design and validation

Primers used in module 1 for the 11 chosen targets (i.e. SFRP1, SFRP2, SFRP4, SFRP5, WIF1, RUNX3, MINT1, SOX7, APC1A, APC2 and TUBB6) were single nucleotide polymorphisms checked to exclude common population variants with a frequency of > 1%. Primers included CS tags, which were required for the Fluidigm protocol.

Amplification performance of the primers was tested on anonymised normal control genomic DNA samples (using the Fluidigm 48.48 Access Array system) as described in the above methods. Products of the expected size were seen for all targets.

Alternative primers were designed for three poorly performing targets (RUNX3, MINT1 and SOX7). Sequence complexity prohibited the redesign of alternative primers for the APC2 locus. Primers were designed using the MethPrimer online tool (UroGene S.A., Genopole, France). 48 The new primers were tested in triplicate using normal FFPE tissue and resulted in a marked improvement in test performance.

Amplification metrics

A total of 729 samples were processed through the ENDCaP-C NGS workflow in duplicate. Samples for which there was insufficient DNA remaining for duplicate analysis were excluded. Targets for which < 100 reads were obtained have been excluded from the analysis (a marker of poor quality).

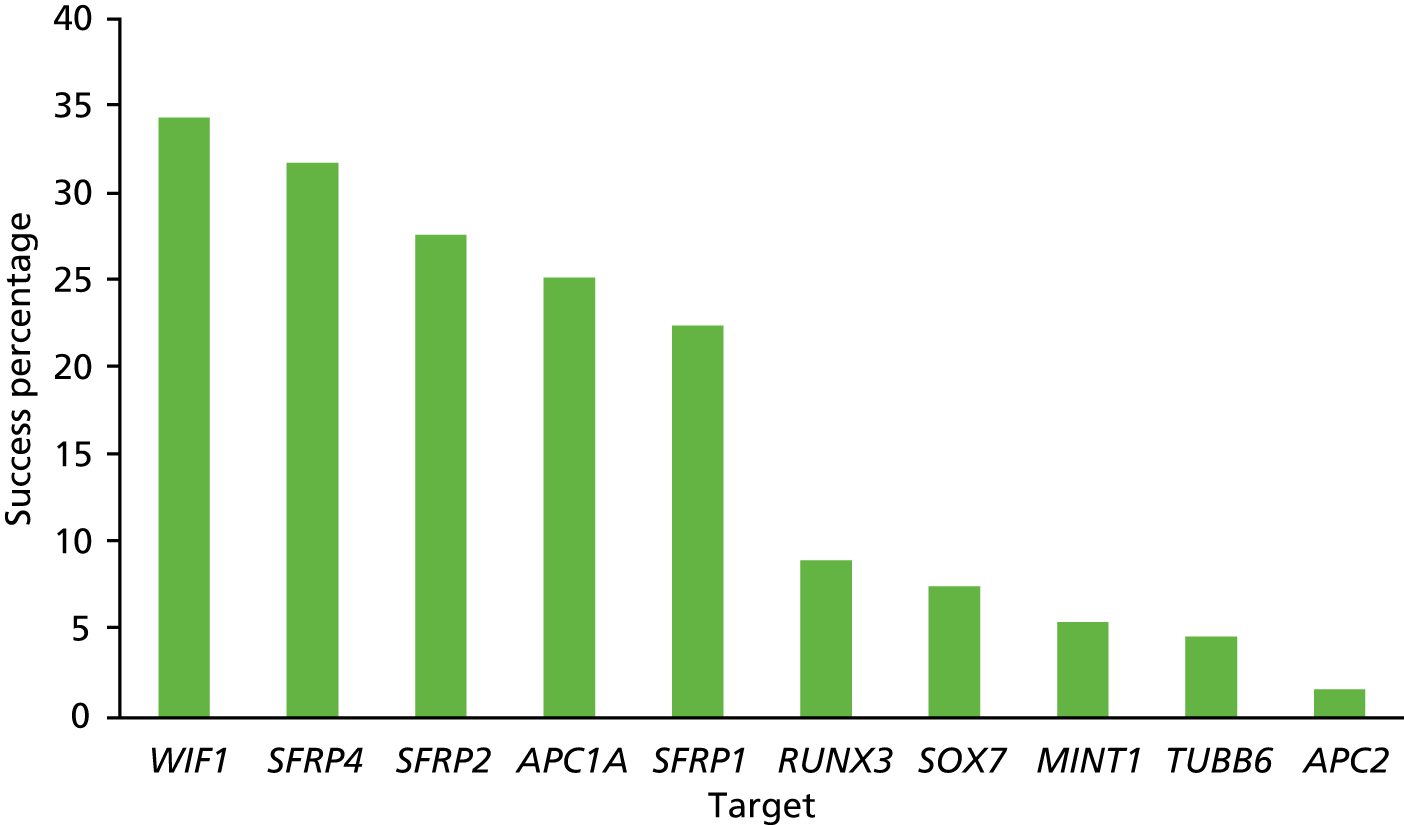

The average methylation percentage at each CpG site between replicates was calculated and this output was forwarded to the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit (BCTU) for statistical analysis.

The DNA amplification performance (a necessary first step for successful NGS) for each of the 11 targets is illustrated in Figure 6. On average, the success rate fell below 35% for each target. This low amplification rate is anticipated as small formalin-fixed biopsy samples will yield only small amounts of DNA strands of sufficient length for the amplification process. The variation between the different targets (from 34% to < 5%) reflects the variation in length of the amplicons and also the reduced sequence complexity (i.e. enrichment for adenine-thymine base pairs) during DNA bisulphite conversion, which affects the binding of the primers.

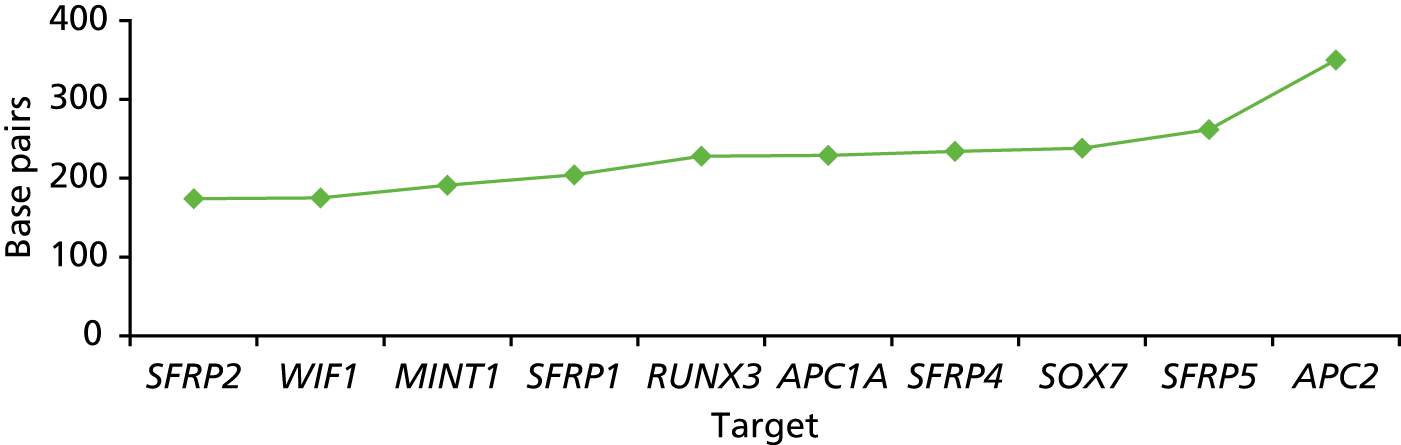

FIGURE 6.

Amplification success at each of the 11 targets for the 729 samples processed (in duplicate).

The reasons for poor amplification performance are multifactorial, including low DNA integrity, low concentration (below the minimum threshold required for the Fluidigm Access Array workflow) and the amplicon length. The relationship between DNA quality and performance of the NGS test is shown by comparing Figures 7 and 8. The relationship between amplicon length performance of the NGS test is shown by comparing Figures 9–11.

FIGURE 7.

Q-ratio of the ENDCaP-C input samples.

FIGURE 8.

The ENDCaP-C input samples performance of the NGS test. Green shading means pass, blue shading means fail and pale green shading means a result from only one duplicate.

| Sample 3 | Sample 2 | Sample 1 | Sample 6 | Sample 7 | Sample 5 | Sample 4 | Sample 8 | Sample 9 | Sample 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SFRP2 | WIF1 | WIF1 | RUNX3 | RUNX3 | SFRP1 | WIF1 | RUNX3 | WIF1 | SFRP4 |

| WIF1 | RUNX3 | SOX7 | SFRP5 | WIF1 | SFRP4 | SFRP2 | WIF1 | RUNX3 | SFRP2 |

| SFRP5 | SFRP2 | SFRP1 | WIF1 | APC1A | RUNX3 | SFRP4 | APC1A | SFRP1 | WIF1 |

| APC1A | SFRP4 | RUNX3 | APC1A | MINT1 | SFRP2 | RUNX3 | MINT1 | SOX7 | RUNX3 |

| RUNX3 | APC1A | SFRP4 | MINT1 | SFRP4 | WIF1 | SFRP1 | SFRP2 | APC1A | APC1A |

| SFRP4 | SFRP1 | SFRP2 | SFRP2 | SFRP1 | APC1A | SOX7 | SFRP4 | APC2 | MINT1 |

| SOX7 | SOX7 | APC1A | SFRP4 | SOX7 | MINT1 | APC1A | SFRP1 | SFRP2 | SFRP1 |

| SFRP1 | TUBB6 | MINT1 | SFRP1 | TUBB6 | SOX7 | APC2 | SOX7 | SFRP4 | SOX7 |

| TUBB6 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 | TUBB6 | SFRP2 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 |

| MINT1 | MINT1 | APC2 | APC2 | SFRP5 | TUBB6 | TUBB6 | TUBB6 | TUBB6 | TUBB6 |

| APC2 | APC2 | TUBB6 | SOX7 | APC2 | APC2 | MINT1 | APC2 | MINT1 | APC2 |

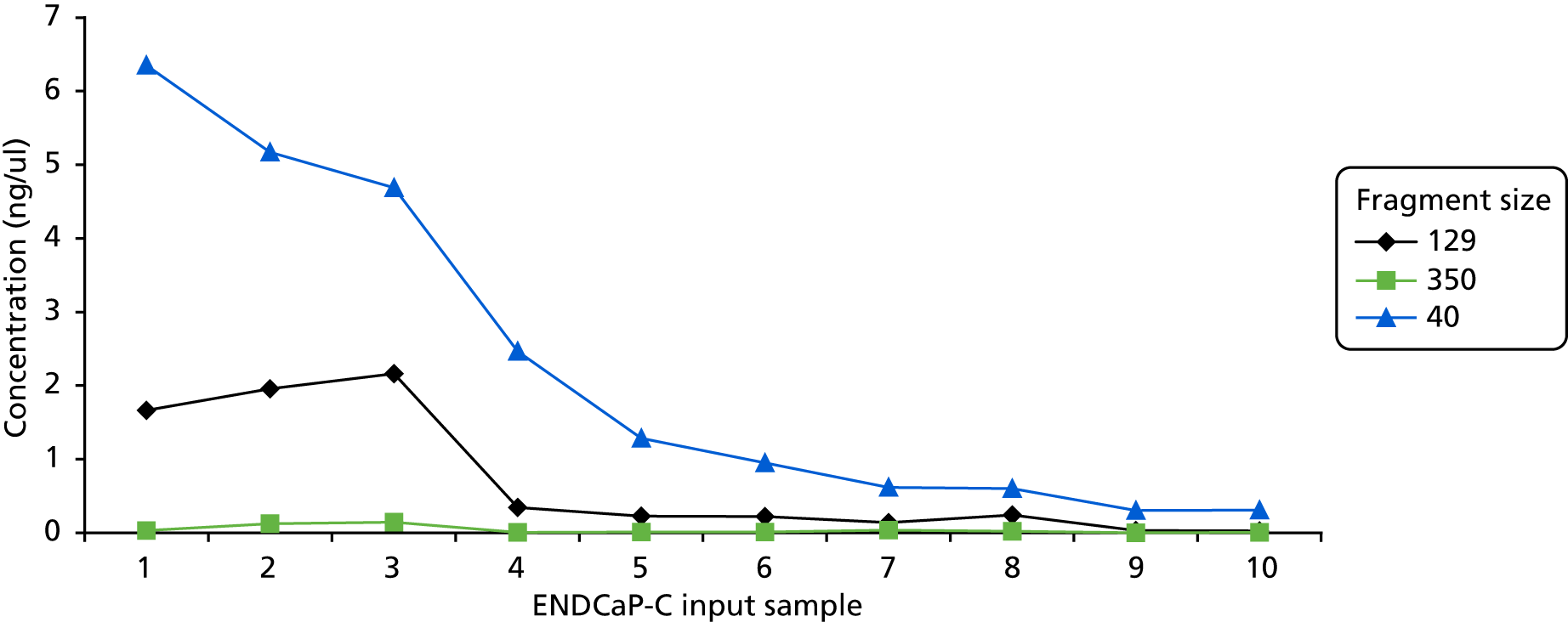

FIGURE 9.

Concentration (ng/µl) of the different fragment sizes (40, 129 and 350 bp) within the ENDCaP-C input samples as measured by qPCR using the KAPA hgDNA Quantification and QC Kit.

FIGURE 10.

The ENDCaP-C input samples performance of the NGS test. Green shading means pass, blue shading means fail and pale green shading means result from only one duplicate.

| Sample 1 | Sample 2 | Sample 3 | Sample 4 | Sample 5 | Sample 6 | Sample 7 | Sample 8 | Sample 9 | Sample 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WIF1 | WIF1 | SFRP2 | WIF1 | SFRP1 | RUNX3 | RUNX3 | RUNX3 | WIF1 | SFRP4 |

| SOX7 | RUNX3 | WIF1 | SFRP2 | SFRP4 | SFRP1 | WIF1 | WIF1 | RUNX3 | SFRP2 |

| SFRP1 | SFRP2 | SFRP5 | SFRP4 | RUNX3 | WIF1 | APC1A | APC1A | SFRP1 | WIF1 |

| RUNX3 | SFRP4 | APC1A | RUNX3 | SFRP2 | APC1A | MINT1 | MINT1 | SOX7 | RUNX3 |

| SFRP4 | APC1A | RUNX3 | SFRP1 | WIF1 | MINT1 | SFRP4 | SFRP2 | APC1A | APC1A |

| SFRP2 | SFRP1 | SFRP4 | SOX7 | APC1A | SFRP2 | SFRP1 | SFRP4 | APC2 | MINT1 |

| APC1A | SOX7 | SOX7 | APC1A | MINT1 | SFRP4 | SOX7 | SFRP1 | SFRP2 | SFRP1 |

| MINT1 | TUBB6 | SFRP1 | APC2 | SOX7 | SFRP1 | TUBB6 | SOX7 | SFRP4 | SOX7 |

| SFRP5 | SFRP5 | TUBB6 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 | TUBB6 | SFRP2 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 | SFRP5 |

| APC2 | MINT1 | MINT1 | TUBB6 | TUBB6 | APC2 | SFRP5 | TUBB6 | TUBB6 | TUBB6 |

| TUBB6 | APC2 | APC2 | MINT1 | APC2 | SOX7 | APC2 | APC2 | MINT1 | APC2 |

FIGURE 11.

Amplicon length of the targets.

Assessment of deoxyribonucleic acid quantity and quality

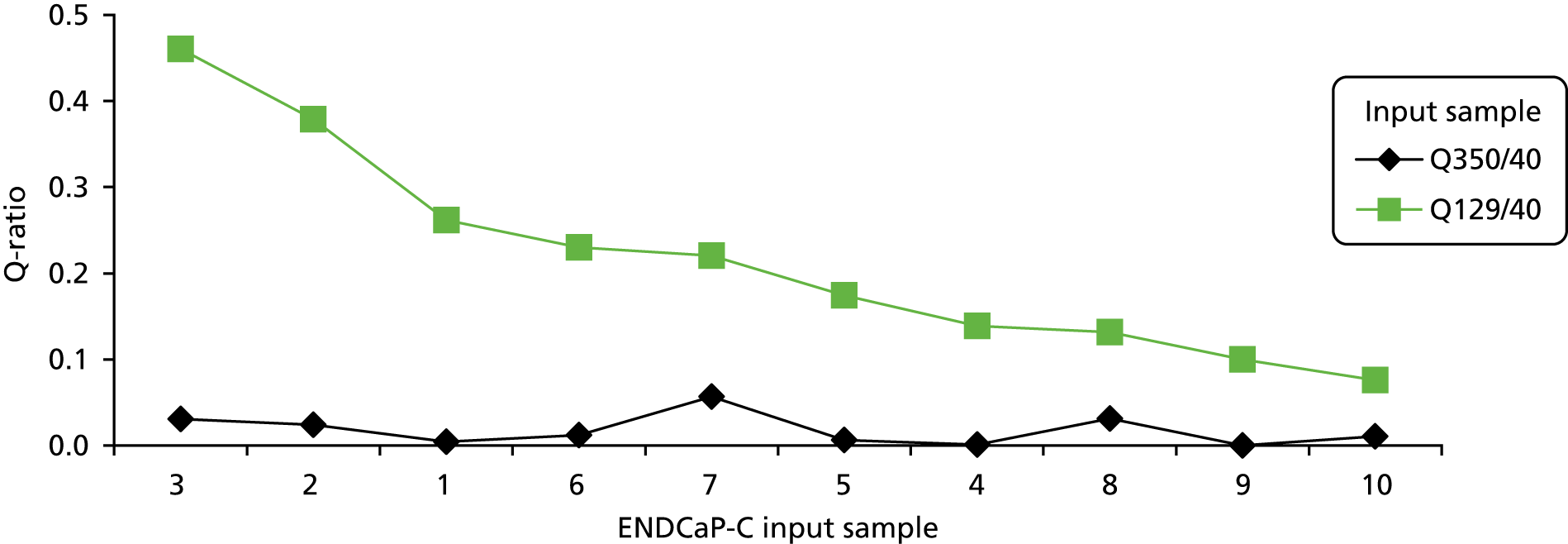

To better understand the reasons behind the high failure rate in the NGS platform, an analysis of the input DNA was carried out on a small number of representative samples, with a wide range of different DNA concentrations.

The concentration and quality of 10 DNA samples was assessed by:

-

quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) analysis to quantify the percentage of amplifiable DNA in the samples, performed using the KAPA hgDNA Quantification and QC Kit (Roche Holding AG)

-

NanoDrop (spectrophotometric analysis to assess purity; Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA)

-

fluorometric quantitation (Qubit platform; Thermo Fisher Scientific).

The qPCR assay determines the relative copies of three amplicons of different lengths (i.e. 350 bp, 129 bp and 40 bp) to assess DNA integrity and assign a Q-ratio. High-quality DNA has a 350 : 40 ratio and a 129 : 40 ratio close to 1 (Q-ratio), whereas for damaged DNA the ratio would be much lower.

Table 6 gives a summary of the three methods used to assess quantity and quality of DNA.

| Sample | NanoDrop | Qubit | qPCR (40 bp) | qPCR (129 bp) | qPCR (350 bp) | Q-ratio (129 : 40) | Q-ratio (350 : 40) | Success rate (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 48 | 14.50 | 6.349485 | 1.660897 | 0.027171 | 0.261580 | 0.004279 | 63.0 |

| 2 | 47 | 15.00 | 5.169203 | 1.958042 | 0.123428 | 0.378790 | 0.023878 | 58.5 |

| 3 | 15 | 3.10 | 4.688881 | 2.158972 | 0.144207 | 0.460445 | 0.030755 | 67.5 |

| 4 | 27 | 6.48 | 2.463435 | 0.342568 | 0.002739 | 0.139061 | 0.001112 | 13.5 |

| 5 | 45 | 13.00 | 1.283114 | 0.223549 | 0.008016 | 0.174224 | 0.006247 | 22.5 |

| 6 | 76 | 28.40 | 0.950962 | 0.218799 | 0.011400 | 0.230082 | 0.011988 | 49.5 |

| 7 | 24 | 4.37 | 0.616272 | 0.135763 | 0.034894 | 0.220297 | 0.056621 | 54.0 |

| 8 | 13 | 1.75 | 0.599380 | 0.240766 | 0.018792 | 0.131692 | 0.031352 | 22.5 |

| 9 | 3 | 0.30 | 0.299616 | 0.029897 | 0.000000 | 0.099783 | 0.000000 | 4.5 |

| 10 | 15 | 0.72 | 0.306560 | 0.023222 | 0.003233 | 0.075751 | 0.010546 | 13.5 |

Qubit quantification showed that for the majority of samples the amount of input DNA fell below that recommended for both the bisulphite conversion stage (> 200 ng) and the Fluidigm amplification (> 50 ng).

The Q-ratio scores for both the 129-bp and the 350-bp fragments are below 1 in all 10 samples assessed, indicating significant sample degradation. The Q-ratio scores have been compared directly with the NGS analysis performance (see Figure 5). This comparison shows a clear correlation between the Q-score and NGS success. For example, sample 3 has the highest 129-bp Q-score and also the best NGS performance (6 out of 11 fragments passed), whereas sample 10 has the lowest 129-bp Q-score and a very poor NGS performance (no fragments passed). It is important to note that the Q-score for the 350-bp fragment is at least 10-fold less than that of the 129-bp Q-score for each test sample, indicating low amplification potential for fragments of this size. This is significant because the NGS assay includes fragments up to 350 bp in size.

The concentration of input DNA was also shown to correlate closely with NGS performance, as illustrated in Figure 6 comparing the concentration of each fragment (40 bp, 129 bp and 350 bp) within the 10 representative input samples. For example, sample 1 gave the highest concentration of the 40-bp and 129-bp fragments (see Figure 9) as well as the best NGS performance (see Figure 10). As described above, the length of each NGS target fragment correlated well with overall performance (see Figure 11).

Assessment of predictive value of next-generation sequencing

Data produced from the module 2 NGS assay were analysed using the methods established in module 1 (see Chapter 2, Statistical analysis) to compare amplification performance with predictive ability.

Data analysis included an assessment of amplification performance for each target, comparing directly the NGS and pyrosequencing technologies. The statistical model derived from module 1 was then applied to the model 2 data set to assess whether or not the data obtained where amplification was successful maintained the same predictive ability as data from pyrosequencing used in module 1.

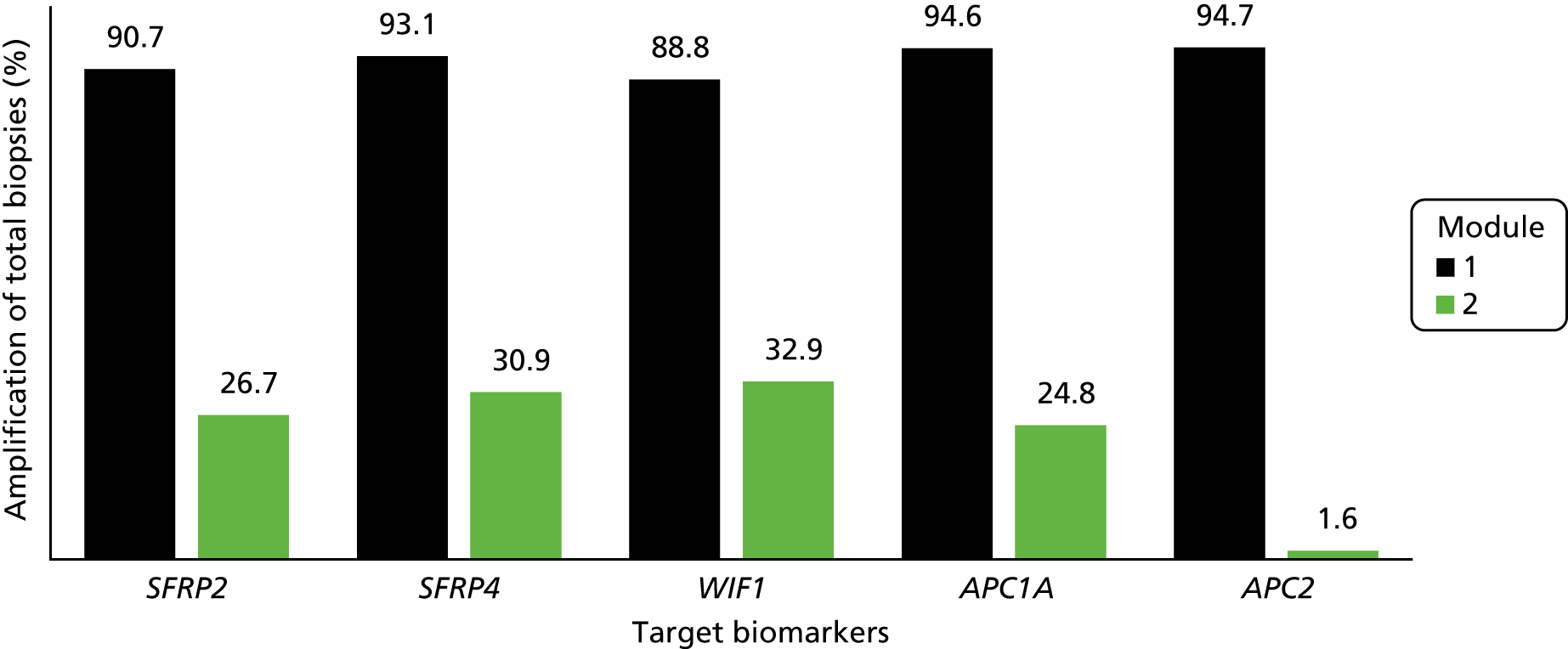

Overall, the NGS assay showed a significantly lower amplification success than the pyrosequencing method used in module 1 (Figure 12 and Table 7).

FIGURE 12.

Percentage amplification of target biomarkers (total biopsies) using pyrosequencing (module 1) and NGS (module 2).

| Biomarker | Amplification status | Sample biopsies, n (%) | Total (N = 569), n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neoplastic (N = 113) | Non-neoplastic (N = 113) | All controls (N = 343) | |||

| SFRP2 | Not amplified | 63 (55.8) | 81 (71.7) | 254 (74.1) | 398 (69.9) |

| Amplified | 49 (43.4) | 30 (26.5) | 73 (21.3) | 152 (26.7) | |

| Not done | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) | 16 (4.7) | 19 (3.3) | |

| SFRP4 | Not amplified | 58 (51.3) | 78 (69) | 238 (69.4) | 374 (65.7) |

| Amplified | 54 (47.8) | 33 (29.2) | 89 (25.9) | 176 (30.9) | |

| Not done | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) | 16 (4.7) | 19 (3.3) | |

| WIF1 | Not amplified | 59 (52.2) | 75 (66.4) | 229 (66.8) | 363 (63.8) |

| Amplified | 53 (46.9) | 36 (31.9) | 98 (28.6) | 187 (32.9) | |

| Not done | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) | 16 (4.7) | 19 (3.3) | |

| APC1A | Not amplified | 69 (61.1) | 79 (69.9) | 261 (76.1) | 409 (71.9) |

| Amplified | 43 (38.1) | 32 (28.3) | 66 (19.2) | 141 (24.8) | |

| Not done | 1 (0.9) | 2 (1.8) | 16 (4.7) | 19 (3.3) | |

| APC2 | Not amplified | 54 (47.8) | 60 (53.1) | 182 (53.1) | 296 (52) |

| Amplified | 4 (3.5) | 4 (3.5) | 1 (0.3) | 9 (1.6) | |

| Not done | 55 (48.7) | 49 (43.4) | 160 (46.6) | 264 (46.4) | |

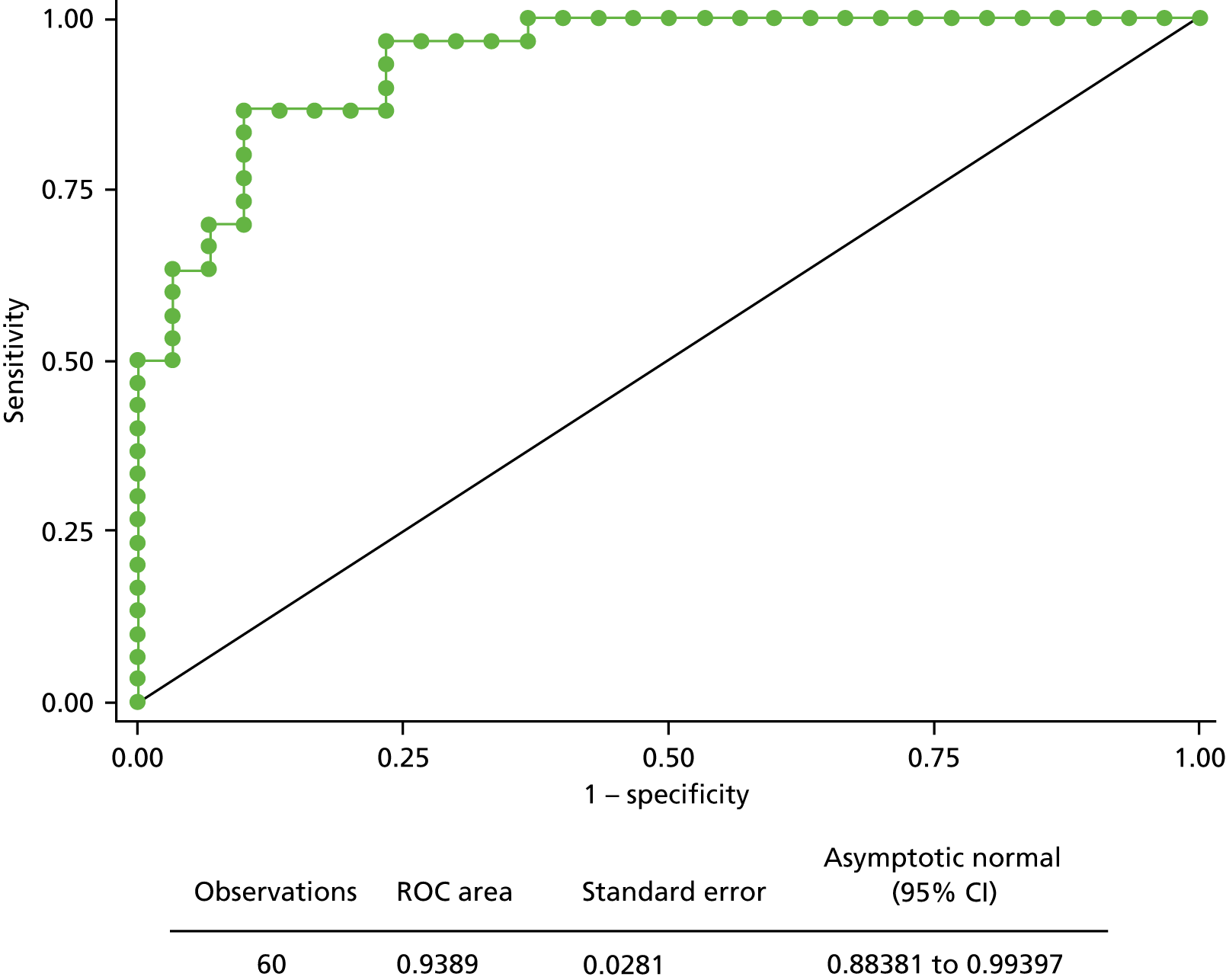

We fitted the model on data from the 60 participants for whom biomarker data were available for SFRP2, SFRP4, WIF1 and APC1A. Owing to very low levels of amplification for biomarker APC2 in module 2, this marker was not included in the model. The results are shown in Table 8 and Figure 13.

| Outcome (sample/control) | Coefficienta | p-value | 95% CI |

|---|---|---|---|

| Log – SFRP2 mean CpG | 0.829 | 0.004 | 0.27 to 1.39 |

| Log – SFRP4 mean CpG | 1.294 | 0.006 | 0.38 to 2.21 |

| Log – WIF1 mean CpG | 0.660 | 0.034 | 0.05 to 1.27 |

| Log – APC1A mean CpG | –0.273 | 0.503 | –1.07 to 0.53 |

| Constant term | –6.728 | 0.001 | –10.88 to 2.58 |

FIGURE 13.

The ROC curve of the fitted final logistic regression model for module 2.

This fitted model suggests that, despite the poor amplification success obtained in module 2, the data from the NGS platform have predictive ability as in module 1 (pyrosequencing), although the values of estimated coefficients differ (see Appendix 3, Tables 23–25).

Model 2: discussion

The aim of the ENDCaP-C study module 2 was to evaluate the utility of NGS as an alternative to pyrosequencing, which is the technology routinely used to determine the methylation status of specific targets in FFPE extracted DNA.

Results have shown that the Fluidigm approach is less robust than pyrosequencing, producing a relatively poor amplification performance, with the low DNA concentrations and DNA degradation leading to higher failure rates. In addition, the intrinsic lack of sequence complexity as a consequence of bisulphite-treated DNA creates several challenges to the sequencing platform, from library generation to data interpretation.

At present, there is not a gold standard NGS method for bisulphite-treated DNA. 49 Indeed, further work is needed to optimise the NGS workflow for its use on FFPE-derived DNA. A multiplex PCR strategy could be used to overcome the restrictions resulting from using a Fluidigm platform,50 but was not used in this study.

The DNA quality from FFPE tissue is a major challenge for any NGS platform. The treatment of tissue with formalin inevitably leads to damage of the nucleic acids but its use is at the base of several clinical diagnostic services as it preserves tissue morphology and represents a convenient and affordable way to store specimens.

One solution to DNA fragmentation from FFPE samples could be shortening the target regions needed for the NGS test used in module 2. Although modifying the amplicon length can be done when dealing with unmodified DNA, this proves quite unsuccessful when the DNA has been bisulphite converted. This procedure is key to identify methylated dinucleotides but inevitably determinates a reduction in base diversity content, therefore increasing the similarity of DNA sequences. As a result, when designing PCR primers for the test, finding unique stretches of bases becomes difficult and it is therefore often not possible to reduce the length of the amplicons.

A more suitable material for NGS testing is fresh-frozen tissue, which would be a better material as it provides high-quality nucleic acids; however, its collection requires changes in the clinical pathway that would require time to be implemented. 51

The Fluidigm system, although offering high-throughput and low-cost capabilities, has been shown to be less useful for the analysis of methylated FFPE DNA and is therefore not recommended to be used in to module 3.

Chapter 4 Module 3: prospective validation of a multimarker methylation panel

Module 3: introduction

Rationale for study

The clinical effectiveness of colonoscopy surveillance for colitis-associated neoplasia has been under scrutiny for some time. 6 Unlike colonoscopic examination for sporadic neoplasia, the inflamed or distorted background mucosa associated with chronic UC can compromise the detection of neoplastic change. The recognised ‘miss rate’ for neoplasia has reduced patient and clinician confidence in the procedure. Although some recent advances in optical technology hold promise of improvement, there is a need for an adjunctive test that can primarily increase the sensitivity of colonoscopy to detect neoplasia and secondarily to provide some stratification of future risk to enable colonoscopy to be better targeted at the highest risk population. In module 3, we prospectively assess whether or not the methylation marker panels generated in module 1 can detect neoplasia in this setting.

Selection of patients

The purpose of the study was to assess if there might be added value from methylation testing above that of colonoscopy. Study subjects were therefore selected from patients within surveillance programmes. One concern was that there would be insufficient cases of neoplasia (not recognised and missed at the index examination) to address the question. No similar study had been carried out on which to base the assessment. We therefore set out to select a high-risk population (see Chapter 4, Inclusion criteria). We also recognised that the surveillance population is heterogeneous and, therefore, to overcome centre bias we would seek to recruit from multiple hospitals across the country.

Introduction into routine practice

To demonstrate clinical value, we set up the DNA testing within a recognised NHS laboratory, rather than a research institute. This would help demonstrate the clinical applicability of the test as well as its generalisability.

Module 3: methods

Study-related information including the protocol and case report forms (CRFs) are available at: www.birmingham.ac.uk/ENDCaP-C (accessed 18 June 2018).

Objectives

The primary objective in module 3 was to prospectively evaluate the ability of the methylation assay to detect pre-cancerous lesions (dysplasia) missed by histology within a surveillance programme for colitis-associated neoplasia.

A secondary objective was to estimate the incremental accuracy of methylation testing in addition to colonoscopy and histology assessment within the existing colitis-associated neoplasia surveillance programme, and thereby gain experience of its applicability in the clinical setting.

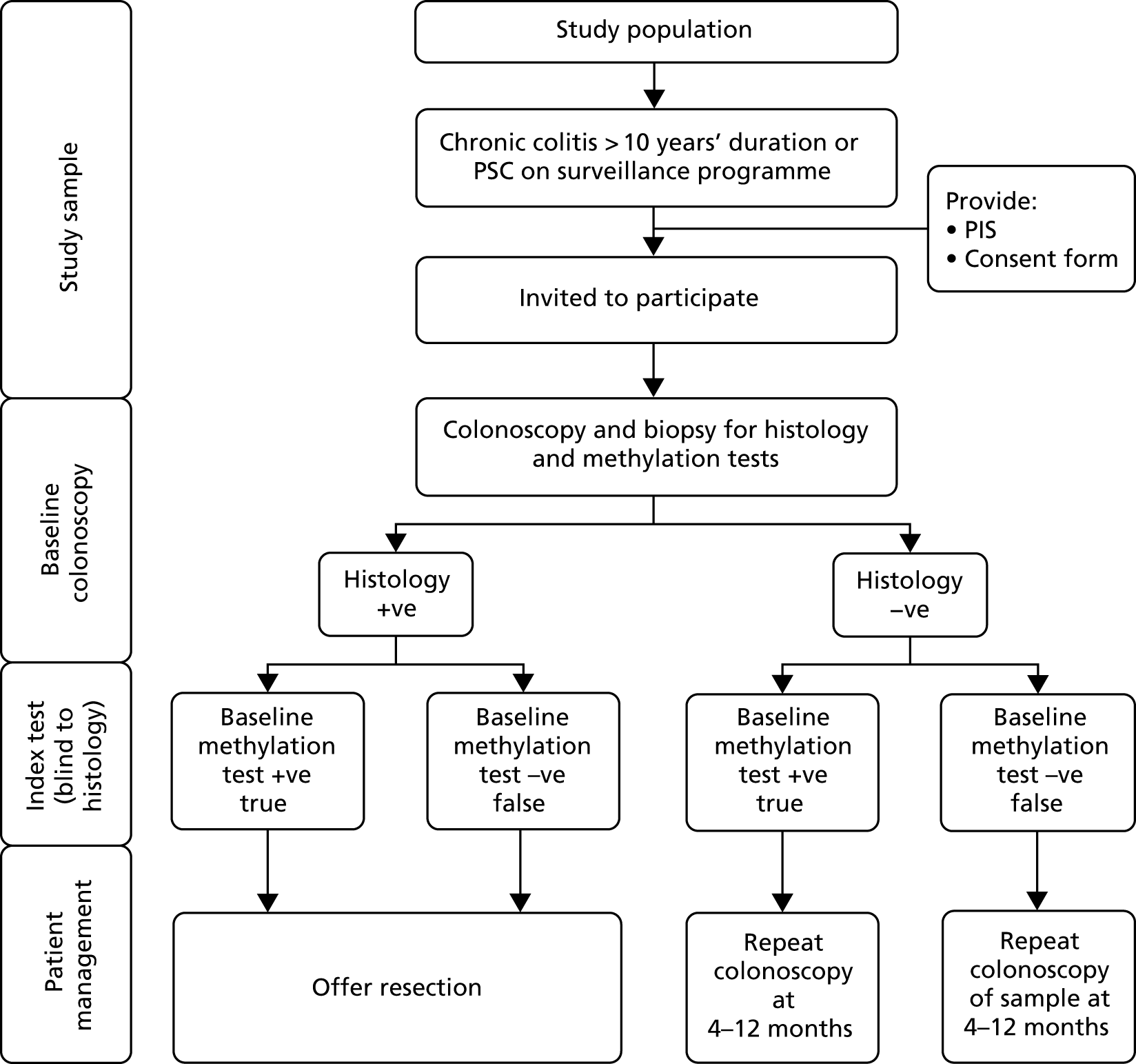

Trial design

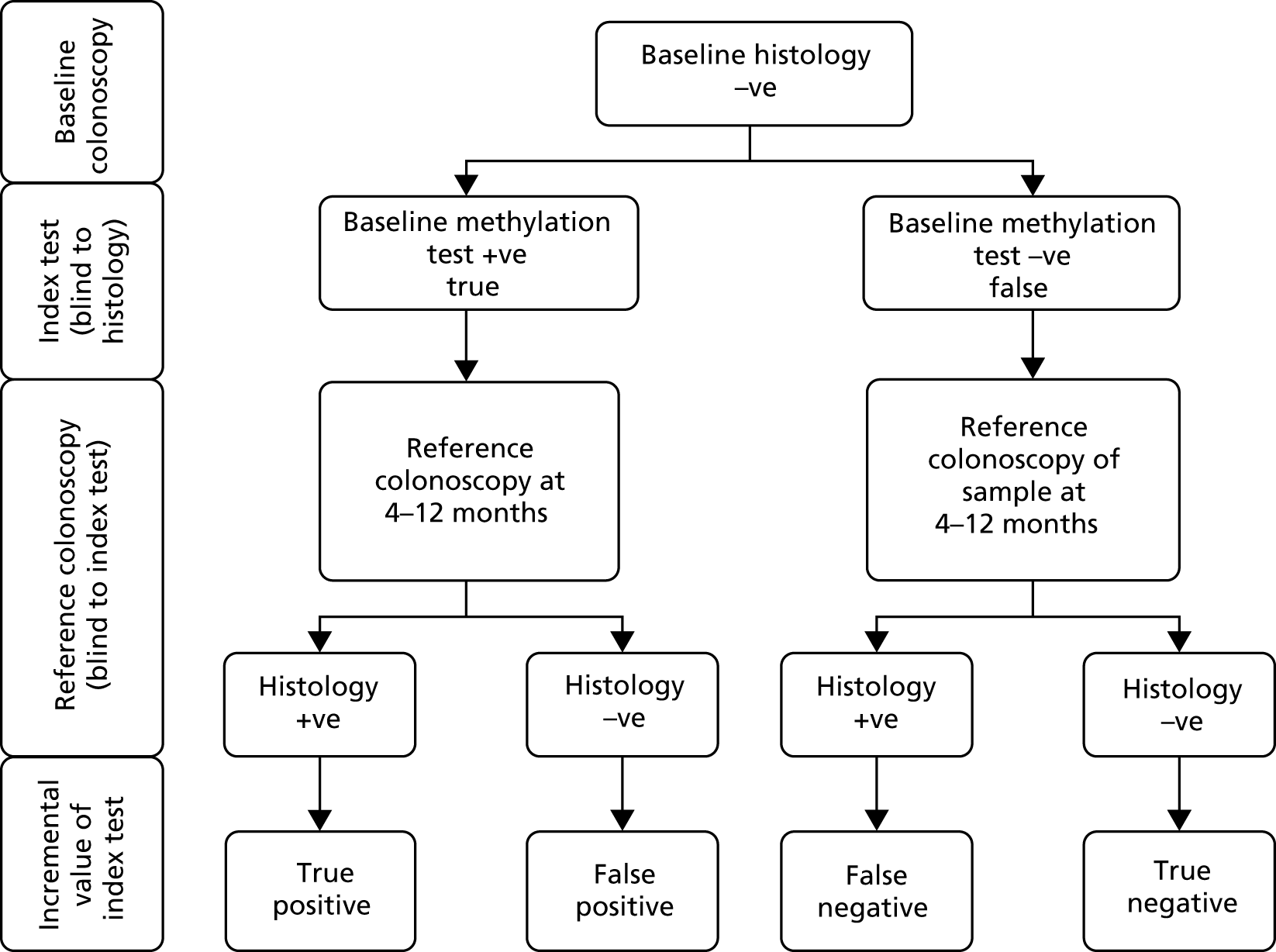

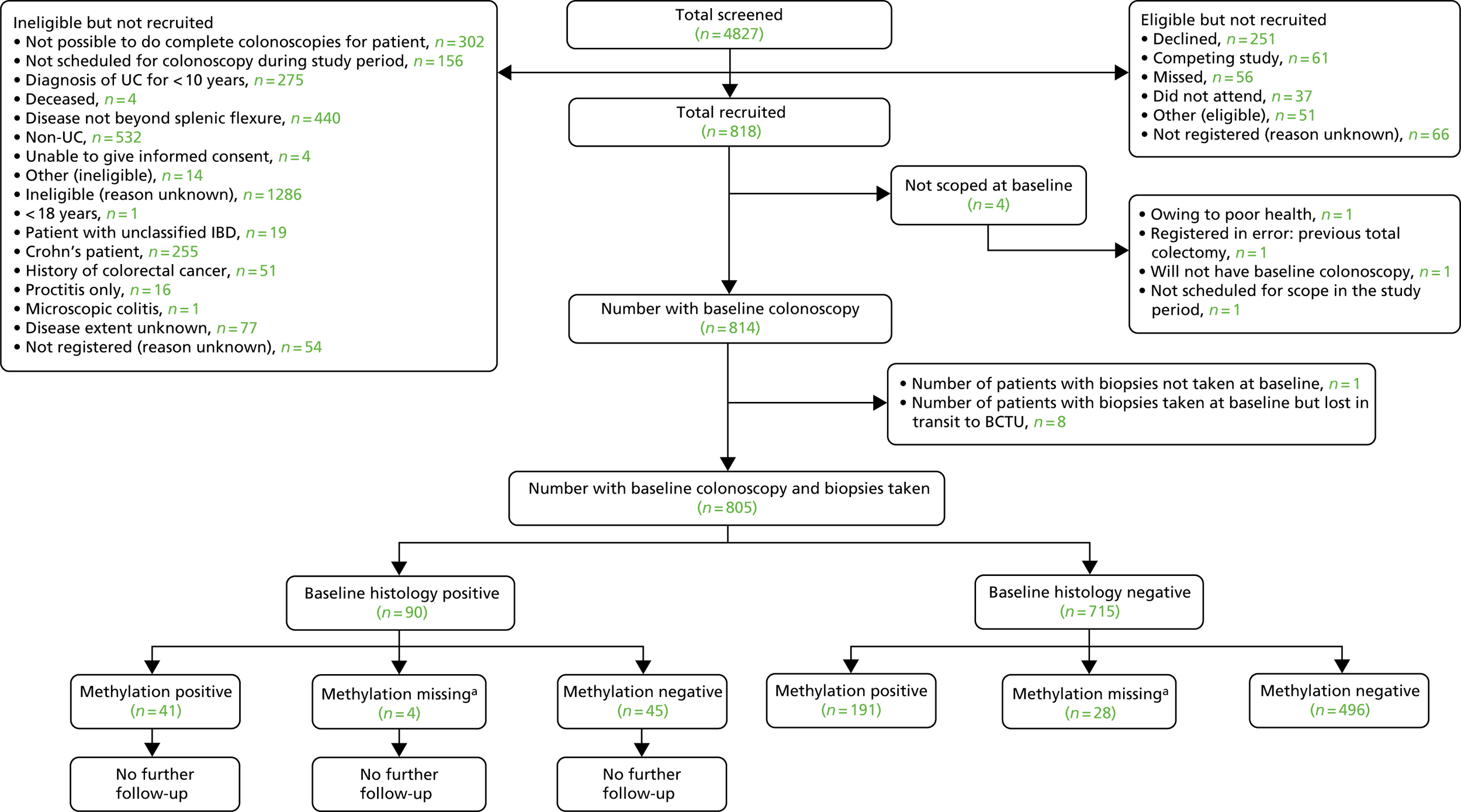

Module 3 of the ENDCaP-C study was a multicentre cohort test accuracy study for enhanced neoplasia detection and cancer prevention in patients with chronic colitis. In the first stage of the study (Figure 14) all participants underwent baseline colonoscopy, which assessed baseline histology and baseline methylation status. Baseline histology results were made available to patients and clinicians and were used to inform their immediate health care. Methylation test results were not released. This baseline methylation test is the index test under evaluation in the study. Those found to be histology negative at baseline were considered to be at risk of having dysplasia missed by colonoscopy and formed the key group of interest in the study to assess whether or not the methylation test can identify cases missed by colonoscopy. To assess this, this subgroup of participants progressed to the second stage (Figure 15).

FIGURE 14.

Study schema: baseline colonoscopies. PIS, patient information sheet. −ve, negative; +ve, positive.

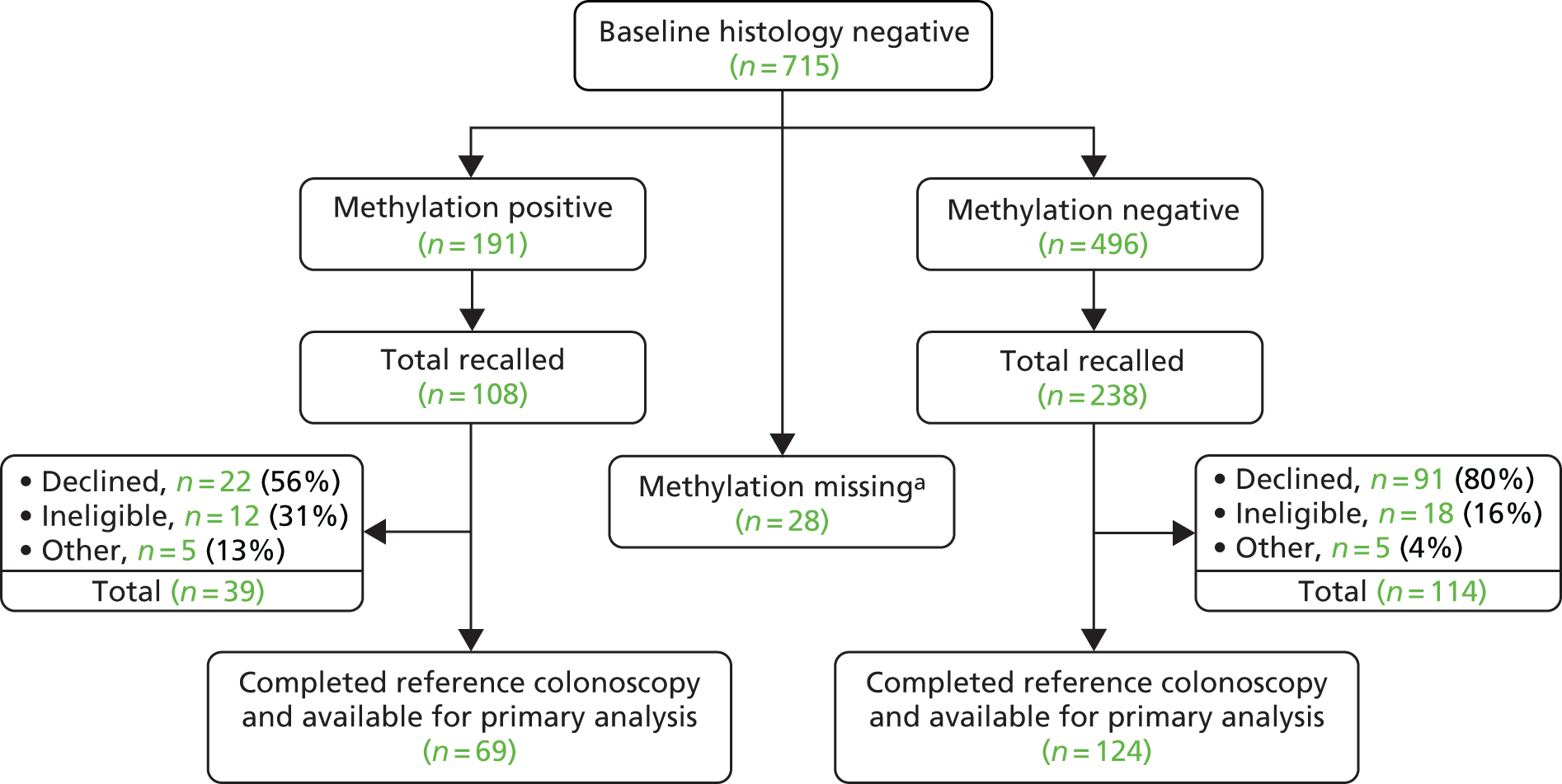

FIGURE 15.

Study schema: repeat colonoscopies. −ve, negative; +ve, positive.

In the second stage, a reference colonoscopy was undertaken 4–12 months after the baseline colonoscopy to identify dysplasia missed at baseline. The histological assessments made from the biopsy samples taken at the second colonoscopy form the reference standard in the study, with which the baseline methylation results were compared. The methylation tests were also repeated in these patients. Participants were selected for invitation to the second stage according to their baseline methylation results – all patients with positive baseline methylation status were invited as well as a random sample of methylation-negative patients (see Sample size for the justification for this design). The second stage reference colonoscopies, histology and methylation tests were undertaken blinded to information from the baseline methylation tests (it was known that the baseline histology was negative in all these cases).

Three additional comparisons were made within the study and are reported:

-

Accuracy of the methylation index test at baseline compared with baseline histology. This comparison assesses the accuracy of methylation testing compared with a reference standard obtained from the histological assessments made at the contemporaneous baseline colonoscopy, and provides a ‘proof of principle’ assessment as to whether or not methylation tests identify clinically evident neoplasia.

-

Agreement of methylation testing at the baseline and reference assessments to assess the stability of methylation assessments.

-

Accuracy of a combined baseline plus follow-up methylation assessment compared with a reference colonoscopy. This comparison redefines the index test according the combination of repeated assessments across two time points.

Participants

Module 3 of the ENDCaP-C study aimed to recruit 1000 patients with chronic colitis. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were as follows.

Inclusion criteria

-

Diagnosis of either:

-

Chronic UC with symptoms for > 10 years’ duration, or

-

PSC.

-

The above criteria ensured that a subset of patients at a higher risk of neoplasia were entered into the study:

-

were on the surveillance programme and undergoing a routine colonoscopy during the study period

-

were willing to accept the possibility of an additional colonoscopy between 4 and 12 months after registration

-

had no history of colorectal cancer

-

were aged ≥ 18 years

-

were able and willing to provide written informed consent for the study.

Exclusion criteria

-

Patients with bowel obstruction.

-

Patients in whom it was not possible to undertake complete colonoscopies.

-

Patients with proctitis only.

-

Patients unable to give written informed consent.

-

Patients aged < 18 years.

-

For UC only patients, excluded patients with –

-

Fulminant colitis.

-

Crohn’s colitis.

-

Unclassified IBD.

-

Microscopic colitis.

-

Consent and registration

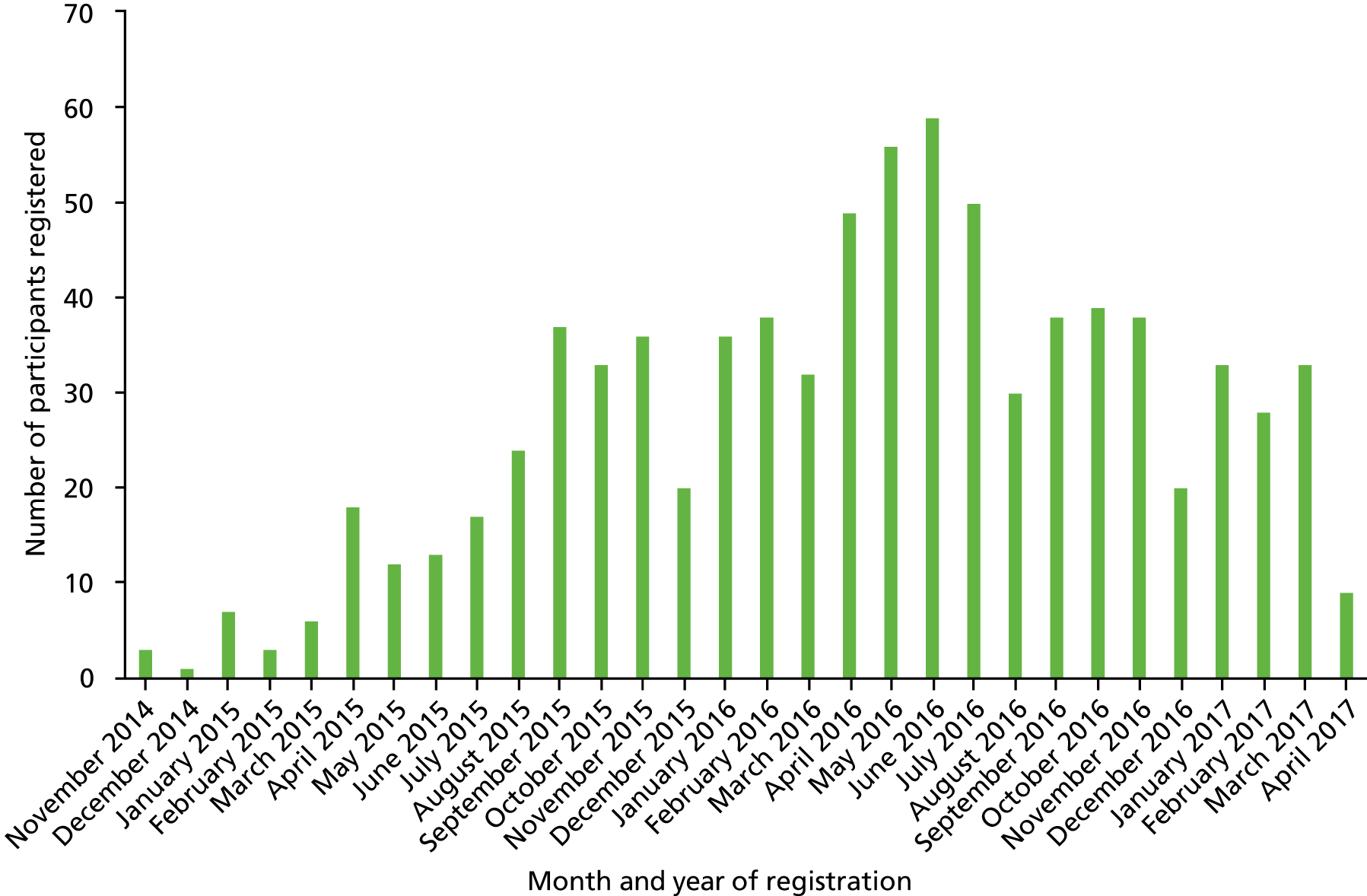

Recruitment

There were 32 UK hospital trusts open to recruitment into the ENDCaP-C study, all undertaking protocol driven surveillance based on national guidelines. Training on participant identification, selection and enrolment was provided via site initiation meetings that were conducted in person or by teleconference. Regular investigator and research nurse teleconferences were held to provide additional guidance on support in recruiting participants.

Eligible participants were identified by review of local IBD databases, in clinic or from endoscopy lists (varied from hospital to hospital). Those meeting the eligibility criteria were provided with study information, usually with their endoscopy appointment letter and an invitation to participate, in the form of the patient information sheet (PIS). At the pre-assessment or colonoscopy appointment, the patients met with a consultant gastroenterologist or surgeon to discuss the study. A participant’s eligibility was confirmed by a medically qualified doctor with access to and a full understanding of the potential participant’s medical history prior to registration.

Informed consent

Written informed consent to participate in the study was obtained before registration and after a full explanation of the study was given, with adequate opportunity for the participant to ask questions. Written informed consent could be obtained by a trained member of the research team (with clinical training, good clinical practice training, knowledge of the study protocol and delegated authority from the local principal investigator). Within the ENDCaP-C study, consent was usually obtained by a research nurse, gastroenterologist or surgeon at the site. Owing to the nature of the study, there was no minimum time between the patient being approached and being given the PIS before consent could be obtained.

Once written informed consent was obtained, the original copy was to be kept in the ENDCaP-C investigator site file and copies were to be given to the patient, kept in the patient’s notes and sent to the ENDCaP-C study office. Patients gave their explicit consent for the movement of their consent form, giving permission for the ENDCaP-C study office to be sent a copy. This was used to perform in-house monitoring of the consent process.

Informed consent was required before any study-related procedures were undertaken.

Registration

Once eligibility was confirmed and after written informed consent had been obtained, patients were registered into the study by a telephone call to the BCTU. Registration could take place before or (shortly) after the completion of the colonoscopy.

Tests and procedures

Baseline colonoscopy

All patients underwent baseline colonoscopy by a named colonoscopist as per usual NHS care. In the majority of cases this was part of the surveillance for colon cancer prevention but some were for other indications where the patient was in the surveillance programme.

During this procedure, routine biopsy samples were taken as per usual practice. The minimum study requirements were two biopsies from the left side of the colon, two from the right side of the colon and one from the rectum. If preferred by a site, the biopsies for use in the ENDCaP-C study were taken in addition to those for routine use. Each biopsy was to consist of two ‘bites’ from the mucosa using spiked endoscopy forceps, as is current standard practice. Endoscopists were permitted to take random biopsies or targeted biopsies, as per their routine practice. Only biopsies that had shown no dysplasia on histology were put forward for methylation testing.

Baseline histological assessment

Biopsy samples were fixed in formalin, embedded in paraffin and processed, and the sections were assessed as per local practice. The only study instruction was to embed biopsies from different sites (left, right and rectum) into separate blocks, one per site, to facilitate tracking. If this was not possible, guidance on how to identify the appropriate biopsies was required. Analysis of FFPE sections from biopsy material was co-ordinated by a named lead pathologist at each site. The histological assessments were provided on the histology CRF by the lead or the other delegated pathologist or, in a small number of instances, the principal investigator.

If dysplasia was detected in any of the biopsies, patients were offered endoscopic or surgical resection as decided by their multidisciplinary team. Details of the type (endoscopy, laparotomy and laparoscopy) and extent of resection was recorded on the surgery CRF along with updated pathological findings.

Methylation index test

The index test was the DNA methylation panel of markers; the combination of genes and loci that result in a classification of hypermethylation as defined in module 1. This was tested on the biopsies taken at the baseline colonoscopy.

After local histological analysis, FFPE blocks were sent to the ENDCaP-C study office before transfer to the pathology department at the Queen Elizabeth Hospital Birmingham. All blocks underwent central review by a specialist histopathologist (Dr Phillipe Taniere) before proceeding to DNA extraction. Samples were screened to ensure that no samples with (histological) neoplasia were sent for DNA analysis.

The DNA was extracted and transferred to the West Midlands Regional Genomics Laboratory at Birmingham Women’s Hospital for methylation analysis (bisulphite treatment and pyrosequencing). The data generated were sent to the BCTU, where the methylation positive/negative status was obtained by the study statistician by utilising model 1 from module 1. To ensure that the reference standard colonoscopy was undertaken blinded to the methylation status, only the study statistician was aware of the positive/negative methylation status. Methylation status was not released to patients in the trial, clinicians or any other members of the ENDCaP-C study team during the study period.

Reference colonoscopy

The reference standard was the histological analysis of biopsies obtained from a repeat colonoscopy (4–12 months post trial entry). Patients who were histologically negative at baseline with positive methylation status at the standard surveillance colonoscopy (test positives) were identified and invited to undergo this repeat colonoscopy. A proportion of histologically negative patients who had negative methylation status were also selected randomly (test negatives) by the ENDCaP-C study office and were invited to undergo repeat colonoscopy. Initially, the selection was completely at random but it became necessary to adapt the strategy to balance requests for repeat colonoscopies across centres and to ensure that the distribution of times between baseline and repeat colonoscopies was similar in test positives and test negatives. Matching by date reduced the chance of an important difference in the time between the initial and repeat colonoscopies for the test negatives compared with the test positives, which could introduce bias. When a test positive was found, we identified all test negatives who had a similar baseline test date (± 1 month), and then randomly chose matching patients weighting to achieve equal chance of recall across the centres. Lists of patients containing both test positives and test negatives (but without any indication of this status) were generated by the study statistician and provided to the ENDCaP-C study team to initiate patient recall.

This reference assessment was standardised using dye spray and targeted biopsy to maximise dysplasia detection and performed by nominated, experienced colonoscopists at each site. During this procedure, biopsy samples were taken. The minimum study requirements for number and location, histological assessment and methylation analysis were the same as for the baseline colonoscopy.

Blood and stool samples