Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 15/48/21. The contractual start date was in February 2017. The final report began editorial review in June 2020 and was accepted for publication in November 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© 2021 Garety et al. This work was produced by Garety et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2021 Garety et al.

Chapter 1 The SlowMo blended digital therapy randomised controlled trial

Introduction

Paranoia, or fear of deliberate harm from others, is one of the most common symptoms of schizophrenia-spectrum disorders, and is associated with significant distress and disruption to the person’s life. 1 This results in increased service use, including inpatient admissions, and high costs to mental health-care providers. Developing effective interventions for paranoia is, thus, a clinical priority. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence recommends cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for psychosis, including paranoia. 2 Meta-analytical studies of first-generation CBT for psychosis have found small to medium sized beneficial effects for delusions (e.g. Turner et al. 3) and positive symptoms more broadly. 4 However, there remain significant challenges to access, engagement, adherence and effectiveness. 1,5

We approached developing the SlowMo therapy in two main ways: first, by adopting an interventionist causal approach6 to increase CBT for psychosis effectiveness and, second, by incorporating inclusive, human-centred design methods to improve the user experience of therapy and to enhance engagement and adherence. 7 The interventionist causal approach involves identifying mechanisms playing a causal role in paranoia (e.g. reasoning, worry and sleep dysfunction) and then developing tailored interventions. 8 SlowMo therapy focuses on reasoning processes that are robustly associated with paranoia: the highly replicated jumping to conclusions (JTC) bias (forming rapid judgements based on a small amount of information) and belief inflexibility bias (the metacognitive capacity for reflecting on one’s beliefs, changing them in the light of reflection and evidence, and generating and considering alternatives). 8,9 Meta-analyses have established that JTC is associated with psychosis, with some specificity for delusions. It also increases the risk of psychosis and predicts outcome in response to treatment. 10–12 Meta-analytic evidence supports an association between belief flexibility and delusions. 13 These thinking patterns are common: in 1800 patients with psychosis in NHS services, difficulties in slow, analytic thinking were present in 60.3% of patients with severe paranoia. 14 In summary, there is converging evidence for a causal role of JTC and belief flexibility in delusion development and maintenance, thereby providing a target for both prevention and treatment strategies. 15

Systematic attempts to ameliorate reasoning in people with psychosis to reduce positive symptoms have included group-based metacognitive training (MCT),16 with a focus on JTC as a causal reasoning bias. One meta-analysis of nine studies of MCT yielded small, non-significant, effects on reasoning, positive symptoms and delusions. 17 The most comprehensive meta-analysis included 15 studies and reported positive effects for delusion change. However, when restricted to studies at low risk of bias, the meta-analysis found small effect sizes for positive symptoms [g = −0.28, 95% confidence interval (CI) −0.50 to −0.06] and non-significant effects for delusions (g = −0.18, 95% CI −0.43 to 0.06). 18

Given the strong theoretical rationale and the mixed empirical findings, we built on this MCT research and on CBT for psychosis approaches for paranoia19 to develop a new cognitive–behavioural intervention. This intervention aims to enhance the impact on paranoia and reasoning, specifically by helping people to build awareness of their tendency to jump to conclusions and by intensively targeting belief flexibility. We have also used inclusive, human-centred design to address the needs of those for whom the content and process of standard therapy present barriers to engagement. The therapy redesign focused on improving its ease of use, enjoyment and perceived usefulness (known as the user experience) to support engagement and adherence for the widest possible range of people. 20,21 The SlowMo intervention is the first blended digital psychological therapy for paranoia [i.e. a face-to-face therapy supported by digital technology, for both in-session content and a tailored mobile telephone application (hereafter referred to as ‘mobile app’)]; it is the end point of a decade of development. 7,22–25 In proof-of-concept and feasibility studies, we found changes in reasoning and improvements in paranoia severity. 22–24 In an experimental study of 100 people with delusions, we compared a brief reasoning-focused digital intervention with an active control condition and found preliminary evidence that changes in belief flexibility mediated improvements in paranoia. 25 Further work validated the user experience of the digital interface for a diverse user population. 7 Over time, as we developed the intervention, we focused more on enhancing belief flexibility than on reducing JTC. We also adopted the term ‘fast and slow thinking’ to communicate the underlying reasoning concepts. 7,15,26 SlowMo therapy aims to assist people with paranoia by supporting them to identify their upsetting concerns and fast-thinking habits, then providing them with strategies to slow down for a moment to focus on new alternative information and develop ways of feeling safer. It aims to improve the appeal, ease of use and clinical effectiveness of CBT for paranoia. 7,27

The current study tested the SlowMo therapy in a fully powered, methodically rigorous, multisite randomised controlled trial (RCT). We aimed to test its clinical efficacy in reducing paranoia, to examine its acceptability, to determine the mechanisms through which it works and to identify participant characteristics that might moderate its effectiveness. We selected treatment as usual (TAU) as the comparator condition. This was because there is a low penetration of evidence-based psychological treatment in the NHS and, thus, the key efficacy question to address at this stage is whether or not SlowMo therapy confers benefits over and above standard care. We have previously established the superiority of an earlier brief version of the intervention against an active control intervention. We predicted that SlowMo therapy would improve paranoia and reasoning and might improve a number of other outcomes, such as self-concept, worry, quality of life and well-being.

An important secondary goal was to evaluate mechanisms of action; the trial hypotheses concern reasoning and are best tested where the control condition is inactive with respect to the targeted psychological processes. We hypothesised that SlowMo therapy would improve reasoning and that the primary mechanism for its treatment effects on paranoia would be mediated through reasoning, specifically belief flexibility and JTC. We also examined worry as a potential mediator, as it has previously been shown to mediate change in paranoia. 28 However, given that worry was not directly targeted by the treatment, we hypothesised that worry would not mediate the treatment effects of SlowMo on paranoia. The treatment effects of a previous version of our intervention were moderated adversely by negative symptoms and working memory. 25 We included hypotheses concerning these potential moderators to examine whether this study replicated these effects or if the redesign worked as intended and rendered the intervention equally accessible and effective across a wide range of users with different cognitive capacities and symptom profiles.

The research questions examined were as follows:

-

Is SlowMo efficacious in reducing paranoia severity over 24 weeks when added to TAU, compared with TAU alone?

-

Does SlowMo lead to changes in the following outcomes: reasoning, well-being, quality of life, self-schemas and others schemas, service use and worry?

-

Does SlowMo reduce paranoia severity by improving fast thinking (reducing belief inflexibility and JTC)?

-

Do participant characteristics (i.e. their cognitive capacities, specifically working memory and thinking habits; and their symptoms, specifically negative symptoms) moderate the effects of the intervention?

-

Does outcome differ by adherence to the intervention?

-

Is SlowMo therapy acceptable, as assessed by therapy uptake and adherence?

Primary hypotheses

-

The intervention will reduce paranoia severity over 24 weeks.

-

Fast thinking (belief inflexibility and JTC) will improve in response to the intervention.

-

Reductions in fast thinking will mediate positive change in paranoia severity.

Secondary hypotheses

-

Poorer working memory and more severe negative symptoms will negatively moderate treatment effects.

-

Therapy adherence will moderate the effects of treatment on outcome.

-

Worry will not mediate reductions in paranoia severity.

Methods

Study design

We conducted a parallel-arm RCT, with 1 : 1 allocation and blinded assessors, to test the efficacy of the SlowMo intervention in reducing paranoia severity when added to TAU, compared with TAU alone. Participants were recruited from mental health services with the same procedures across three main trial sites in England: South London and Maudsley NHS Foundation Trust, Sussex Partnership NHS Foundation Trust and Oxford Health NHS Foundation Trust. Additional patient identification centres, comprising NHS trusts near each of the three main recruitment NHS sites, were also employed. Participants were patients of secondary care community mental health services.

The trial received a favourable ethics opinion from Camberwell St. Giles Research Ethics Committee (REC) (REC reference 16/LO/1862; Integrated Research Administration System 206680). The trial protocol,29 including all study hypotheses, was published.

Participants

We sought referrals of patients with psychosis and distressing persecutory beliefs from community clinical teams in our NHS settings. The inclusion criteria were patients aged ≥ 18 years; with persistent (≥ 3 months) distressing paranoia [as assessed using the Schedules for Clinical Assessment in Neuropsychiatry30) and scoring > 29 on the Green Paranoid Thoughts Scales (GPTS), part B, persecutory subscale31]; with a diagnosis of schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis (F20–29, International Statistical Classification of Diseases and Related Health Problems, Tenth Revision32); with the capacity to provide informed consent; and with sufficient grasp of the English language to participate in trial processes. Exclusion criteria were profound visual and/or hearing impairment; the inability to engage in the assessment procedure; being currently in receipt of other psychological therapy for paranoia; and a primary diagnosis of substance abuse disorder, personality disorder, organic syndrome or learning disability. All participants gave written informed consent.

Randomisation and masking

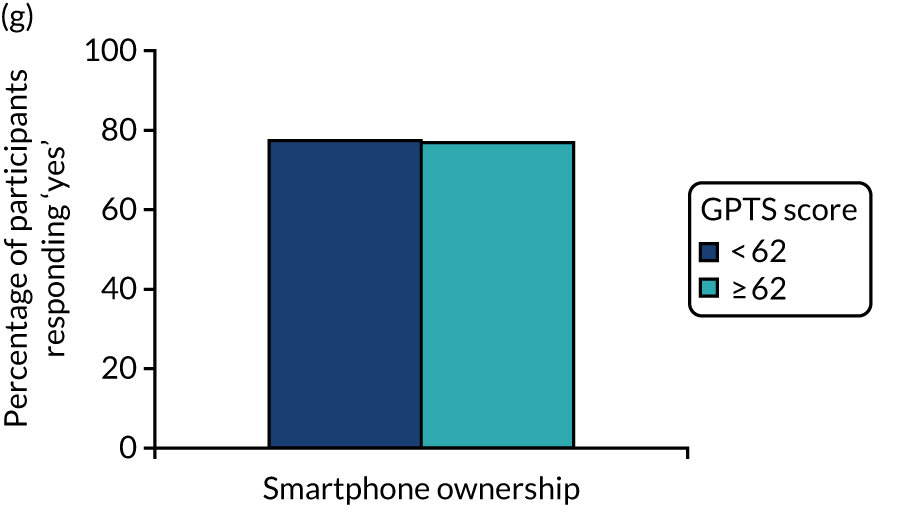

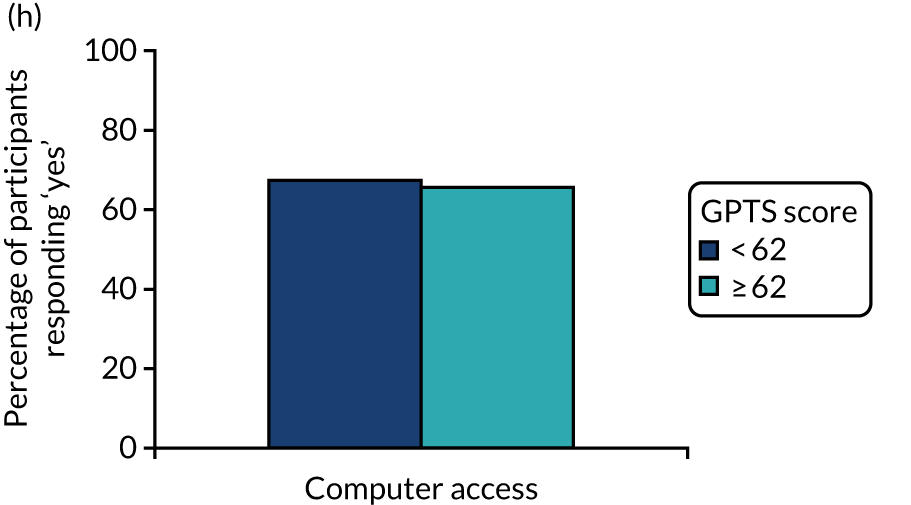

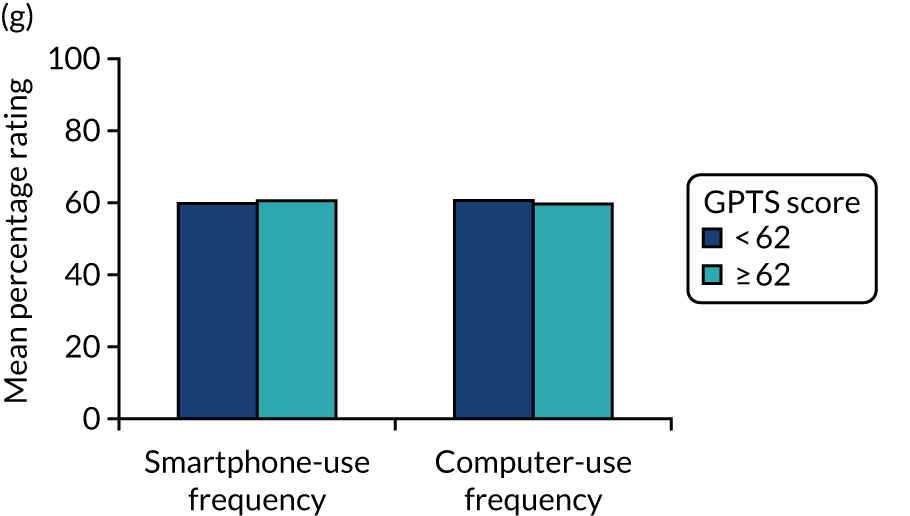

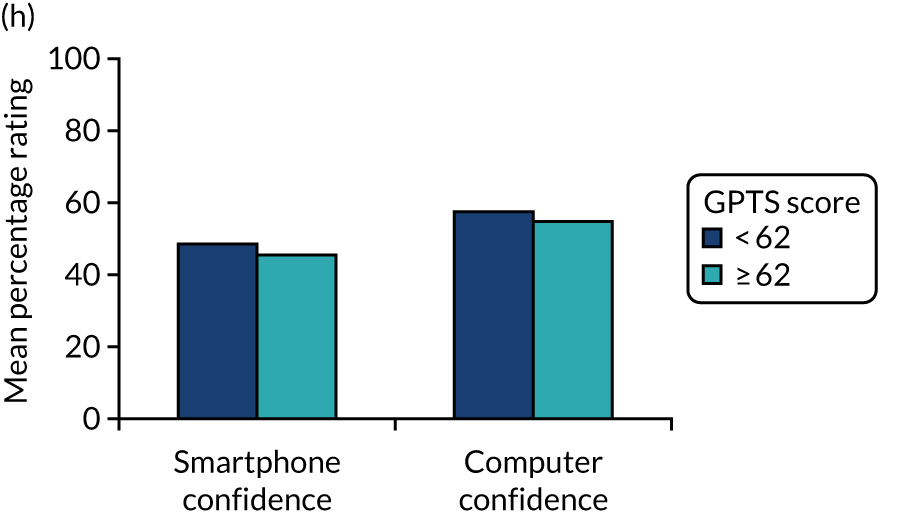

After a baseline assessment, we randomly assigned (1 : 1) eligible patients to either eight sessions of the SlowMo intervention delivered within 12 weeks plus TAU (SlowMo group), or TAU alone (control group). Randomisation took place using a password-protected independent web-based service hosted at the King’s Clinical Trial Unit. The randomisation list was generated using randomly varying permuted blocks, stratified by site and baseline paranoia severity [median split of ≥ 62 (GPTS31 part B)].

Research assessors (all graduate psychologists) were masked to therapy allocation. Masking was supported by the site co-ordinators having responsibility for randomising and informing participants. If an allocation was revealed to the assessor, then re-masking occurred as far as was operationally feasible by the use of another rater. Where an allocation was revealed during an assessment session and re-allocation was not operationally feasible, these ratings were used. All breaks in masking were recorded.

Procedures

The SlowMo intervention

SlowMo therapy consisted of eight individual face-to-face sessions, with each module addressing a specific topic. Sessions typically lasted 60–90 minutes and were delivered within a 12-week time frame. The therapy delivery was assisted by a web-based application (hereafter referred to as ‘web app’) delivered using a touchscreen laptop (the ‘SlowMo web app’), with interactive features including information, animated vignettes, games and personalised content, which was synchronised with a native mobile app installed on a standard Android (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) smartphone that was provided to participants to assist therapy generalisation. Before therapy began, the clinician met the patient for an initial introduction and orientation to the approach. Delivery of SlowMo was flexible, with sessions added where helpful, for example the splitting of web app modules across separate meetings (tailored to individual preference and engagement), and ‘out of clinic’ behavioural work to promote mobile app use and therapy generalisation to the real world.

The intervention followed a clinical trial manual that was consistent during the trial. The only modifications to the therapy during the trial involved improvements to the digital interface of the web app and mobile app to further support the user experience.

Therapy sessions were delivered locally to the participant at convenient locations of their choosing, including team bases, patient’s homes, general practices or other local centres (e.g. community centres). Behavioural work was carried out in the participant’s local area and was guided by the participant’s goals. It typically involved testing out the SlowMo strategies and the mobile app in locations such as town centres, local cafes, pubs and markets.

Initial sessions involve building the metacognitive skill of noticing thoughts and thinking habits (visualised as bubbles spinning slow or fast). People learn the normalising message that fast thinking is part of human nature and can be useful at times. However, fast thinking can fuel worries and thinking slowly can be helpful in dealing with difficult situations and fears about other people. This key principle frames the sessions in which participants are supported to try out ways to slow down for a moment, for example by considering the impact of mood and past experiences on concerns, and by looking for safer alternative explanations. The web app structure is delivered consistently, but content is tailored throughout as participants interact with personalised worry bubbles, safer/positive alternative thought bubbles, key learning and messages for the week ahead (recorded by the person at the end of each session in text or audio form and then synchronised with the mobile app for day-to-day, out-of-session personal support). The SlowMo mobile app allows people to notice their fears and thinking habits as they occur in daily life, and supports them to slow down for a moment by accessing SlowMo strategies or personalised safer alternative bubbles, thereby finding other ways of managing distressing experiences (see Hardy et al. 7 and Garety et al. 29 for further detail).

The therapy was delivered by trained clinical or counselling psychologists who were experienced in CBT for psychosis. A total of 11 psychologists (10 doctoral-level clinical and one counselling) delivered therapy across the three sites. This comprised six main trial therapists delivering the majority of therapy and a further five local therapists. Weekly group supervision, including the use of therapy audio-recordings, was provided by the trial therapy lead (TW) to the main trial therapists (with regular consultation provided by PG and EK); supervisory arrangements for local trial therapists were provided by site therapy leads.

Uptake of the therapy delivery was assessed by the number and duration of sessions attended. Adherence to the treatment manual was assessed by the SlowMo therapy fidelity checklist that was completed by therapists at the end of each session; adherence to the manual was defined as no more than one web app component missed for any attended therapy session. Adherence to the mobile app was operationalised as at least one out-of-session interaction for a minimum of three of the therapy sessions.

Treatment-as-usual (standard care) was delivered in accordance with national and local service protocols and best practice guidelines. This usually consisted of prescription antipsychotic drugs, contact with a community mental health worker and regular outpatient appointments with a psychiatrist. Participation did not alter usual treatment decisions about medication or additional psychosocial interventions. The delivery of additional psychosocial treatments in both groups was recorded with the modified Client Service Receipt Inventory. 33

Follow-up intervals and assessments at each visit

The assessments of outcome measures were completed at 0 weeks (baseline), 12 weeks (end of therapy) and 24 weeks (follow-up). Research assessors did the enrolment and assessments in clinic settings or at the participant’s home. Participants were rewarded for their time and effort by a sum of £20 at each research visit. The primary outcome was self-rated.

Outcomes and other measures

The prespecified primary outcome was self-reported paranoia severity measured by the GPTS31 over 24 weeks. The GPTS31 comprises two scales that assess thinking relevant to paranoia and which are rated over the preceding month: ideas of social reference and persecution. Two 16-item subscales assess ideas of social reference (part A) and persecution (part B). We also assessed paranoia on two observer-rated scales: the Psychotic Symptom Rating Scales (PSYRATS) delusions scale,34 for which scores are expressed as a total and as two factors (conviction and distress35); and the persecutory delusions and ideas of reference items from the Scale for the Assessment of Positive Symptoms (SAPS36). In addition, we report outcomes on the Revised-Green Paranoid Thoughts Scale (R-GPTS) over 24 weeks using both total scores and subscale scores. The R-GPTS,37 which was published after publication of the trial protocol using data independent of the current study, reported improved psychometric properties for a revised scale constructed from a subset of the GPTS items. Inclusion of the R-GPTS as a secondary outcome measure was added to a revision of the statistical analysis plan (version 1.2) before statistical analysis commenced. It comprises two scales that assess thinking relevant to paranoia based on items from the original scale that are rated over the preceding month on a slightly modified scale: ideas of social reference (eight items) and persecution (10 items).

We collected other secondary outcomes using published and established measures of well-being [the Warwick–Edinburgh Mental Wellbeing Scale38 (WEMWBS)], quality of life [Manchester Short Assessment of Quality of Life (MANSA39)], self-schemas and other schemas [the Brief Core Schema Scales40 (BCSS)], service use (the Client Service Receipt Inventory33), and worry [Penn State Worry Questionnaire41 (PSWQ)].

Reasoning was assessed as both an outcome and a potential mediator by belief flexibility assessed by the possibility of being mistaken [self-rated and observer-rated per cent taken from the Maudsley Assessment of Delusions Schedule42 (MADS)], alternative explanations (from the Explanations of Experiences interview43) (both are commonly used published methods of assessing lack of belief flexibility relating to delusional beliefs) and by the JTC Beads Data-gathering Task9 versions 85 : 15 and 60 : 40. In addition, we have developed a self-reported measure, the Fast and Slow Thinking Questionnaire44 [previously named the Thinking About Paranoia Scale29 (TAPS)]. The Fast and Slow Thinking Questionnaire comprises 10 statements that are rated on a 5-point scale (1 = not at all, 5 = totally). There are two scales: one assessing fast (intuitive) thinking, reflecting a lack of information gathering, consideration of the possibility of being mistaken and generation of alternative explanations, and one measuring slow (analytical) thinking. We included the Fast and Slow Thinking Questionnaire as a reasoning outcome, but it was not prespecified in our hypotheses as a mediator.

We also used the following established measures of clinical and cognitive characteristics, which were assessed at baseline only, as potential moderators of treatment effects: Scales for Assessment of Positive Symptoms, a semistructured interview assessing positive symptoms of psychosis;36 Brief Negative Symptom Scale (BNSS), a semistructured interview designed to assess negative symptoms of psychosis;45 Beliefs about Problems Questionnaire (BAPQ), a self-reported questionnaire designed to assess illness perceptions, including secondary appraisals of the nature, cause, duration, consequences and management of illness/problems;46 Letter–Number Sequencing Test, a cognitive task that assesses working memory;47 Trail Making Test,48 a neuropsychological instrument assessing visual attention, psychomotor speed and shifting cognitive set; and Perception of Carer Criticism, which is a single self-reported item adapted from Hooley and Teasdale49 and used in other published studies,50 which assesses the person’s perception of criticism from a carer (where one is identified) over the previous month.

Data quality

Data quality was ensured by close monitoring and routine auditing for accuracy throughout the data collection period. To ensure the accuracy of the data entered into the database, the main outcome measure entry was checked for every participant’s baseline assessment by comparing the paper record with that on the database. An error rate of no more than 5% was deemed acceptable a priori (see trial protocol29). The data quality was confirmed to be acceptable, with error rates of 0.03%.

Inter-rater reliability

The inter-rater reliability analysis was conducted on the main observer-rated measure of paranoia, the PSYRATS, and both observer-rated belief flexibility items (possibility of being mistaken and alternative explanations) for 45 of the baseline assessments selected randomly (15 per site) from assessments conducted after an initial training and consensus period. The intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) for the PSYRATS34 (absolute-agreement, two-way mixed-effects model, single measures) was 0.98 (95% CI 0.96 to 0.99), indicating excellent agreement. For alternative explanations, Cohen’s kappa was 0.96 (95% CI 0.87 to 1.00), in the ‘almost perfect’ range, and for possibility of being mistaken, Cohen’s kappa was 0.65 (95% CI –0.45 to 0.86), between the moderate and the substantial agreement ranges, according to Landis and Koch. 51 Table 1 lists all outcomes and other measures together with the schedule of assessments.

| Trial procedures | Time point | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolment: completed within 4 weeks | Allocation: within 2 weeks of baseline (0 weeks) | Post allocation | Follow-up: 24 weeks | ||

| 0–12 weeks | 12 weeks | ||||

| Enrolment: routine eligibility screen | ✗ | ||||

| Informed consent | ✗ | ||||

| Allocation | ✗ | ||||

| Interventions | |||||

| SlowMo and TAU | ✗ | ||||

| TAU | ✗ | ||||

| Assessments: primary outcome | |||||

| Paranoia severity (GPTS total, scales A and B) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Other paranoia outcomes | |||||

| PSYRATS delusions | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Delusions of persecution and reference items (SAPS) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Hypothesised mediators | |||||

| Possibility of being mistaken (MADS) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Alternative explanations (Explanations for Experiences) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Jumping to conclusions reasoning | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Other problems and processes | |||||

| SAPS | ✗ | ||||

| BNSS | ✗ | ||||

| BAPQ | ✗ | ||||

| Letter–Number Sequencing Test | ✗ | ||||

| Trail Making Test | ✗ | ||||

| Fast and Slow Thinking Questionnaire (formally TAPS) | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| PSWQ | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| BCSS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Perception of Carer Criticism | ✗ | ||||

| WEMWBS | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| MANSA | ✗ | ✗ | ✗ | ||

| Client Service Receipt Inventory | ✗ | ✗ | |||

Adverse events

Information about possible adverse events was actively monitored, up to week 24 of follow-up. Possible adverse events included hospital admissions (owing to physical or mental health deterioration), crisis team involvement, self-harming behaviour and suicide attempts, and violent incidents necessitating police involvement. A standard method of reporting was employed, categorising events by severity (five grades: A–E). Any relatedness to trial participation was also recorded. All adverse events were reviewed by the chairperson of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) for ratings of relatedness to trial participation and seriousness, and were subsequently reviewed by the DMEC.

Statistical analysis

We powered the study to detect a clinically meaningful 10-point reduction in the GPTS total score with a standard deviation (SD) of 25 (effect size = 0.4). We accounted for the partial nested design because of clustering in the SlowMo group, assuming an ICC of 0.01 with 10 therapists, and for no clustering in the TAU group using the clsampsi command in Stata® version 16 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). 52 With the 1 : 1 treatment allocation and the 0.05 significance level, a simple two-tailed t-test with 150 people per group had 90% power to detect an effect size of 0.4 and 80% power to detect an effect size of 0.35. To allow for a conservatively high 20% attrition, we aimed to recruit 360 patients at baseline split equally across three sites (120 per site, 60 per group per site).

We report data in line with the Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) 2018 Statement for Social and Psychological Interventions,53 showing attrition rates and loss to follow-up. All analyses are performed using the intention-to-treat population, incorporating data from all participants, including those who do not complete therapy. The statistical analysis plan was agreed with an independent DMEC before any inspection of post-randomisation data by the research team. Statisticians became unblinded following all data collection only, and the statistical analysis was performed unblinded owing to the need to account for therapist effects in the SlowMo group. No interim analysis was performed. All analysis was conducted in Stata version 16.0.

Descriptive statistics by randomised group are presented for baseline values, with no tests of statistical significance or CIs for differences between groups.

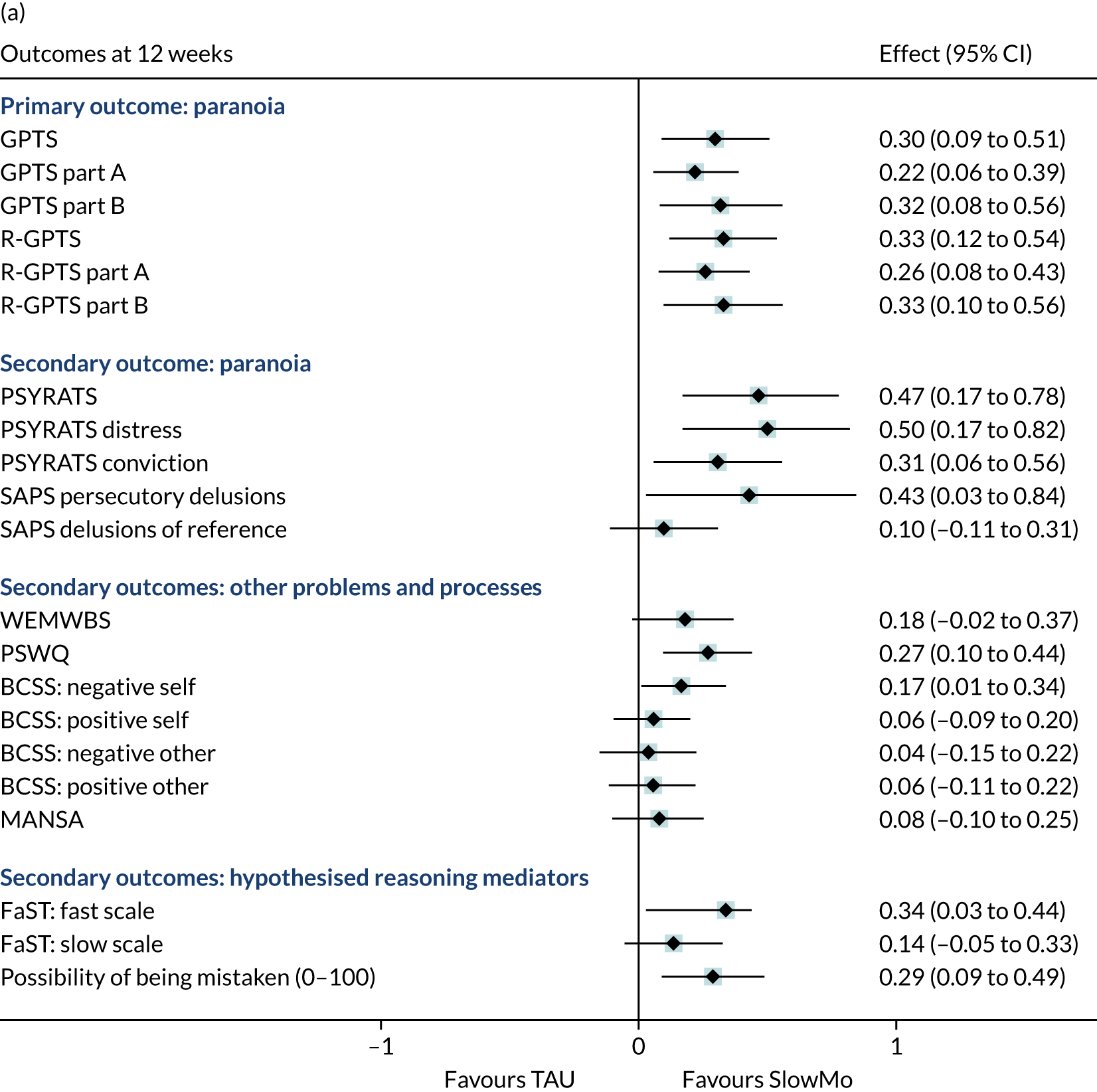

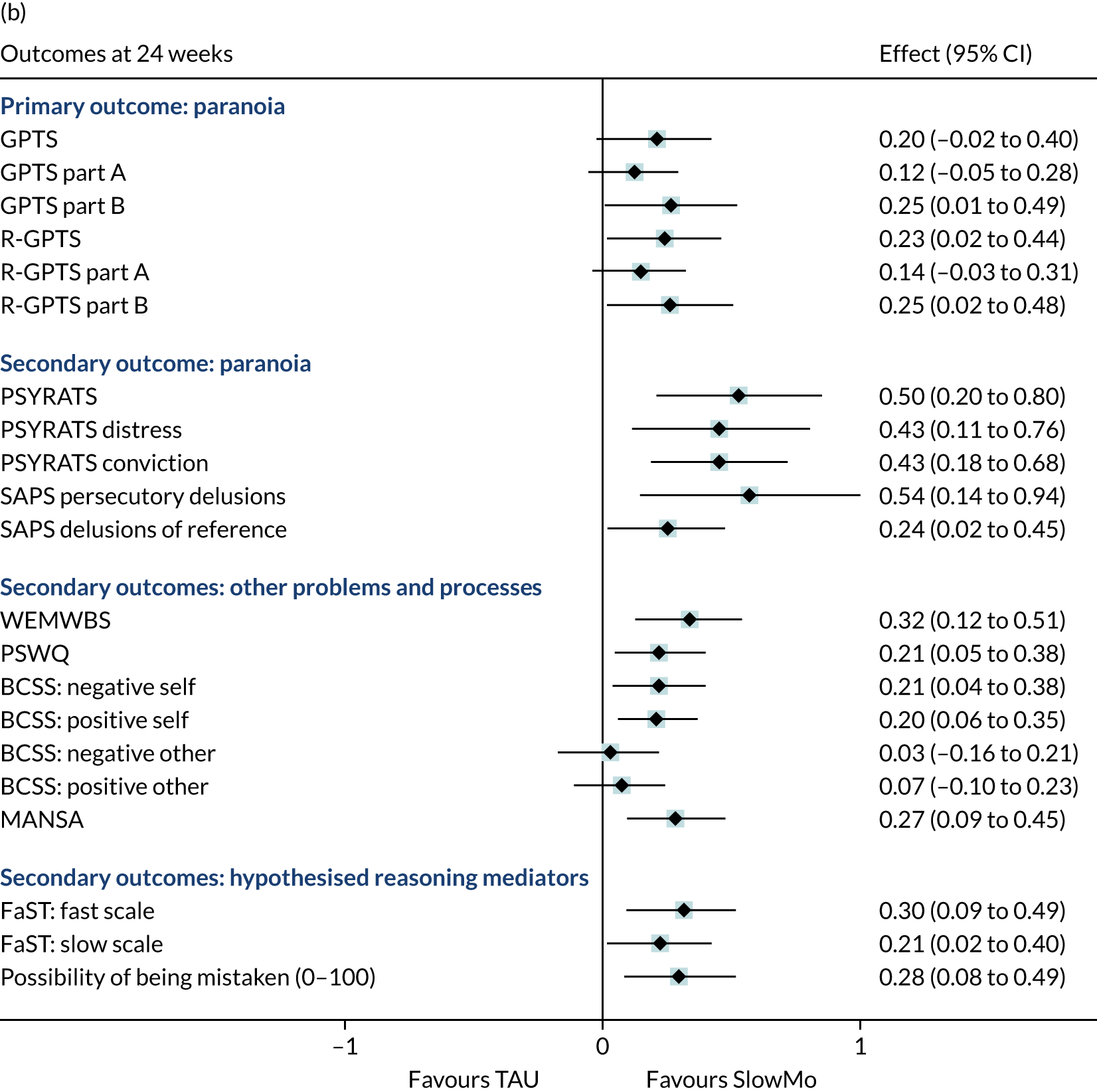

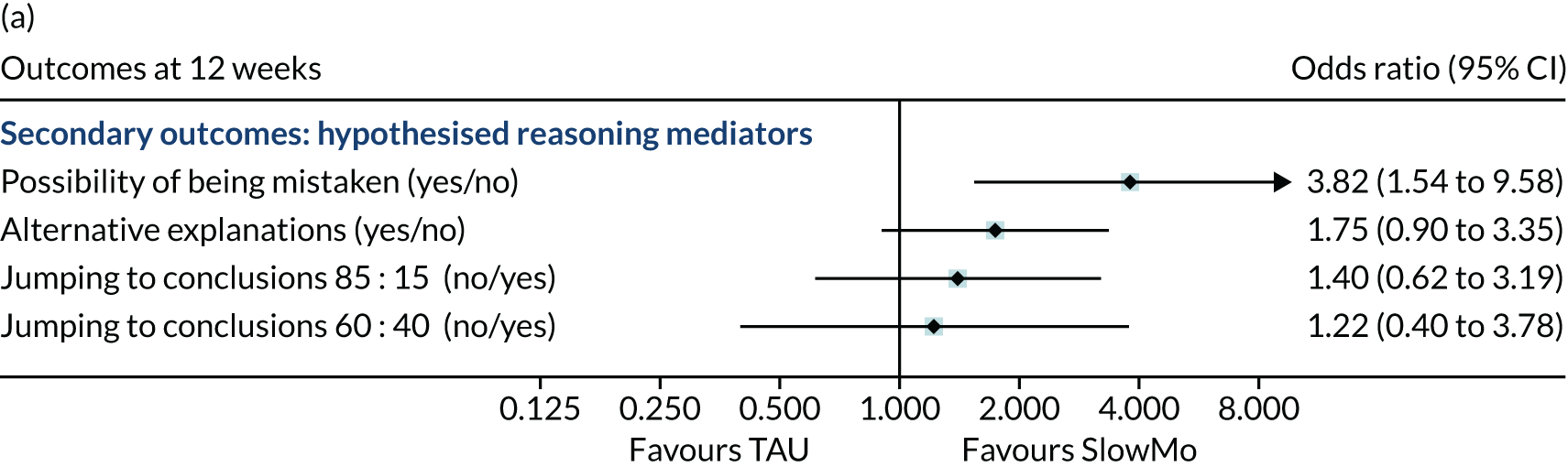

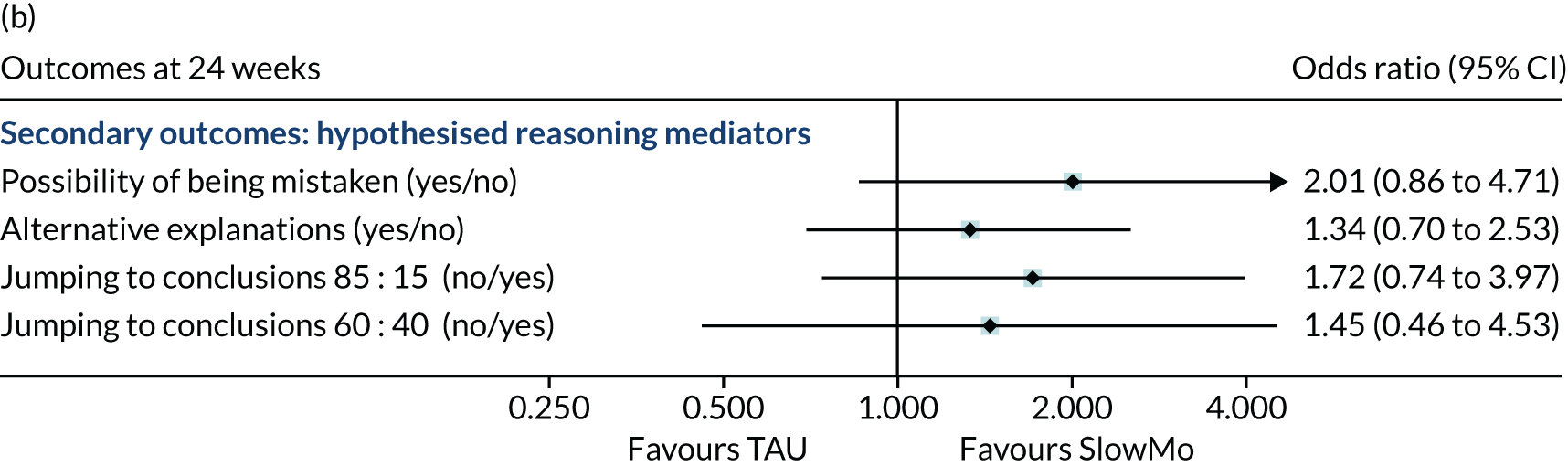

To test the primary hypothesis that the intervention would reduce paranoia severity over 12–24 weeks, we fitted a linear mixed model that allowed for clustering by both participants and therapists to the repeated measures of GPTS. 31 The model included the following as fixed effects: randomised group, time (coded as categorical), time by randomised group interaction, treatment site, baseline paranoia severity and the corresponding baseline assessment for the outcome under investigation. The treatment effect (adjusted between-group mean difference) was estimated from the model for each time point separately. All secondary outcome measures were analysed using the same modelling approach: linear mixed models for continuous outcomes and logistic mixed models for binary outcomes and reporting conditional odds ratios. Cohen’s d effect sizes at 12 and 24 weeks were calculated as the adjusted mean difference of the outcome divided by the sample SD of the outcome at baseline. These are displayed in a forest plot for all continuous outcomes and as odds ratios for binary outcomes (see Figures 2 and 3).

The moderation analyses investigated whether or not the effect of the SlowMo intervention on GPTS,31 R-GPTS37 and PSYRATS34 was moderated by the following:

-

the baseline measure of the outcomes

-

reasoning – belief flexibility (possibility of being mistaken42 and alternative explanations43) and JTC (beads task9 85 : 15: more than two beads drawn, yes/no)

-

negative symptoms (BNSS45)

-

BAPQ46

-

working memory (Letter–Number sequencing test47)

-

set-shifting [trail-making task48 (B–A)]

-

presence of a carer (yes/no)

-

perceived criticism of carer,49 if present.

For a continuous moderator, the difference in treatment effect between unit levels of the moderator can be interpreted as the difference in the estimated treatment effect between a participant with a moderator value at baseline of α + 1 and a participant with a moderator value at baseline of α. For a binary moderator (e.g. presence of a carer), the difference in treatment effect can be interpreted as the difference in the estimated treatment effect between participants with a carer and participants without a carer.

The mediation analyses examined the potential mechanisms underlying the effect of SlowMo plus TAU compared with TAU on clinical paranoia outcomes, GPTS,31 R-GPTS37 and PSYRATS. 34 Jumping to conclusions,9 belief flexibility (possibility of being mistaken42 and alternative explanations43) and worry41 at 12 weeks were individually considered as mediators of the effect on the outcomes at 12 weeks and 24 weeks separately. The analysis used causal mediation analysis based on parametric regression models. 54 This involved estimating a linear model for each mediator with random assignment, baseline outcome, baseline mediator, site and paranoia cut-off point at baseline as covariates, and separately estimating a linear model for each outcome with the mediator, group assignment, baseline outcome, baseline mediator, site and paranoid cut-off point as covariates. The effect of group assignment on the mediator is multiplied by the effect of the mediator on outcome to estimate the indirect effect, and the effect of SlowMo on outcome in the model including mediator is an estimate of the direct effect. The indirect and direct effects sum to the total effect, and bootstrapping with 500 replications was used to obtain valid standard errors (SEs) for the causal effects; 95% CIs are based on the percentile of the bootstrap distribution. The proportion mediated is the indirect effect divided by the total effect.

To account for departures from random allocation in the SlowMo group who received therapy, we performed two compliance-adjusted analyses for a binary compliance measure (attending at least one session of SlowMo therapy) and a continuous measure of the number of sessions received. Both analyses used a two-stage instrumental variables approach. The first stage involved regressing the treatment receipt measure on randomisation, baseline GPTS,31 site and paranoia, and saving the predicted value of the treatment receipt measure. In the second stage, this predicted value was included in the analysis models in place of the randomisation variable. Both models were estimated in a single bootstrap procedure to produce valid SEs for the effect of treatment received, with resampling at the participant level.

The first measure of compliance indicates anyone who receives at least one session of therapy. The treatment effect is interpreted as the complier-average causal effect, where complier is defined as those participants randomised to the SlowMo group who received at least one session of therapy and those participants randomised to the TAU group who would have received at least one session of therapy had they been randomised to the SlowMo group (a counterfactual, based on predictions from a model). The treatment effect is the adjusted mean difference between randomised groups within this subgroup of compliers.

The second measure of compliance is the number of sessions of therapy attended. This is observed for all participants in the SlowMo group (ranging from no sessions to eight sessions) and is fixed by design at zero in the TAU group. The treatment effect is the effect of one additional session of therapy on the outcome, assuming a linear effect, for example going from s sessions to s + 1 sessions for any s between 0 and 8. Details of the statistical approach for mediation analysis and departures from random allocation are outlined in Dunn et al. 55

Missing data on individual measures were prorated if > 90% of the items were completed; otherwise the measure was considered missing. We checked for differential predictors of missing outcomes by comparing responders to non-responders on key baseline variables. Maximum likelihood estimation in the mixed models accounts for missing outcome data under a missing-at-random assumption, conditional on the covariates included in the model.

The numbers of serious adverse events (SAEs) and adverse events are presented as the number of events and number of individuals with events for each randomised group.

Results

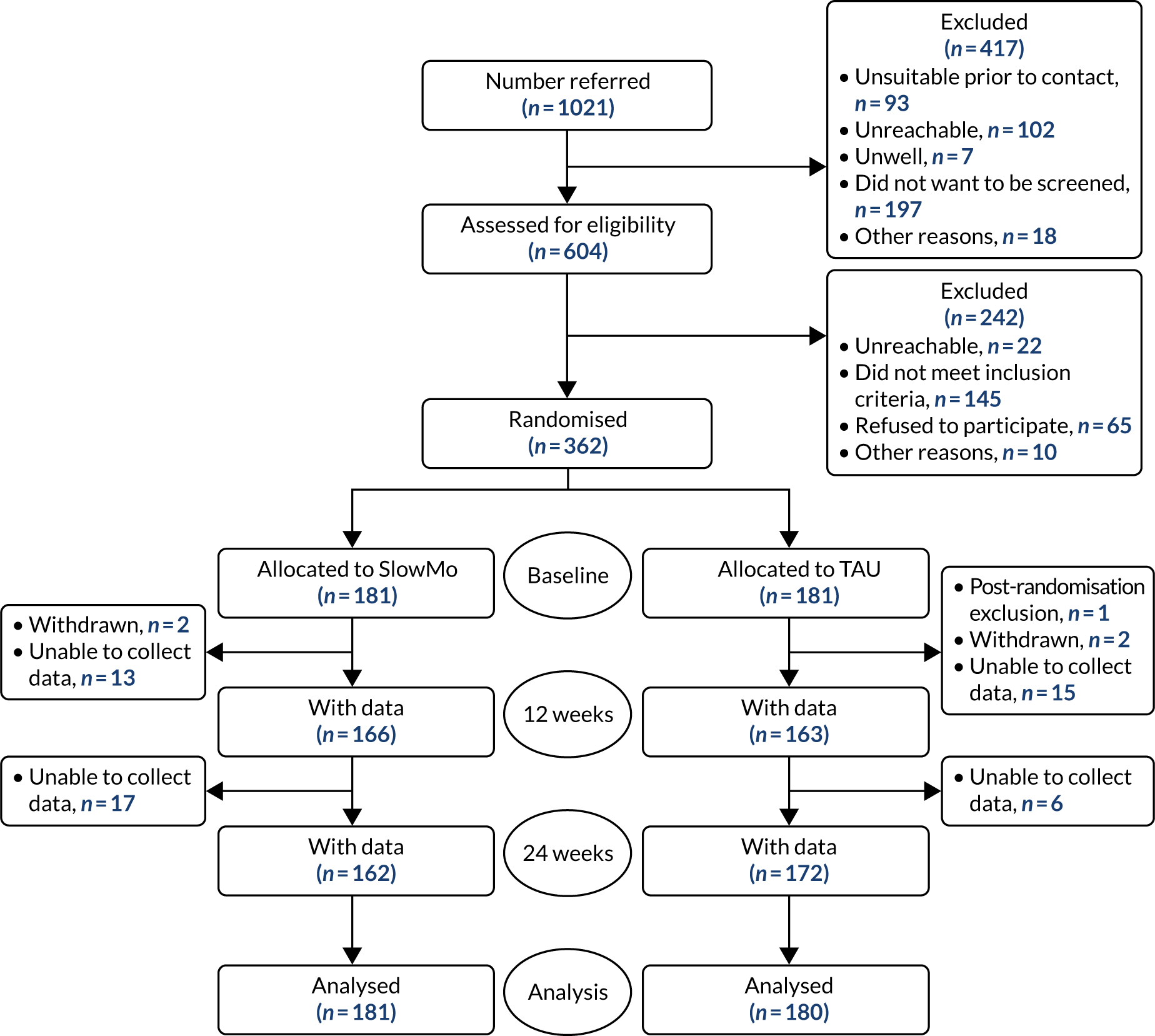

From 1 May 2017 to 14 May 2019, we assessed 604 people for eligibility and, of these, recruited 362 participants. In total, 181 participants were allocated to the SlowMo group and 181 participants were allocated to the treatment as usual group (Figure 1). There was one post-randomisation withdrawal: a participant in the control group who withdrew fully from the trial and requested that no data were included. The final sample was, therefore, 361 participants (Table 2 and see Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Trial profile and participant flow diagram (CONSORT).

| Site | Total referrals (n) | Excluded pre screening or awaiting screening (n) | Assessed for eligibility (n) | Screened: ineligible (n) | Screened: refused/unreachable/other (n) | Consented (n) | Randomised (n) | 12-week follow-up, n (%) | 24-week follow-up, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | 339 | 128 | 211 | 33 | 47 | 131 | 131 | 114 (87) | 117 (90) |

| Oxford | 373 | 192 | 181 | 60 | 22 | 99 | 99 | 96 (97) | 94 (95) |

| Sussex | 309 | 97 | 212 | 52 | 28 | 132 | 132 | 118 (89) | 122 (92) |

| Total | 1021 | 417 | 604 | 145 | 97 | 362 | 362 | 328 (91) | 333 (92) |

Data were available for over 90% of the sample at each follow-up point (12 weeks: n = 328, 91%; 24 weeks: n = 333, 92%) (see Table 2). The 12-week assessments were conducted at a mean of 13.5 weeks (range 8.6–19.6 weeks) and the 24-week assessments were conducted at a mean of 25.2 weeks (range 12.9–38.3 weeks). Unmasking without replacement of an assessor occurred in 22 participants (6.7%) at 12 weeks and 19 participants (5.7%) at 24 weeks; however, in some instances unblinding occurred after a number of measures, including the primary outcome measure, had been collected: at 12 weeks, only 12 (3.6%) and, at 24 weeks, only 11 (3.3%) of the primary outcome GPTS data were collected unmasked (Table 3).

| Site | Participants for whom unblinding occurred, n (%) | 12-week follow-up, n (%) | 24-week follow-up, n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Some data collected unblinded | GPTS collected unblinded | Some data collected unblinded | GPTS collected unblinded | ||

| London | 15 | 9 | 5 | 9 | 4 |

| Sussex | 18 | 8 | 4 | 3 | 2 |

| Oxford | 15 | 5 | 3 | 7 | 5 |

| Total | 48 (13.3) | 22 (6.7) | 12 (3.6) | 19 (5.7) | 11 (3.3) |

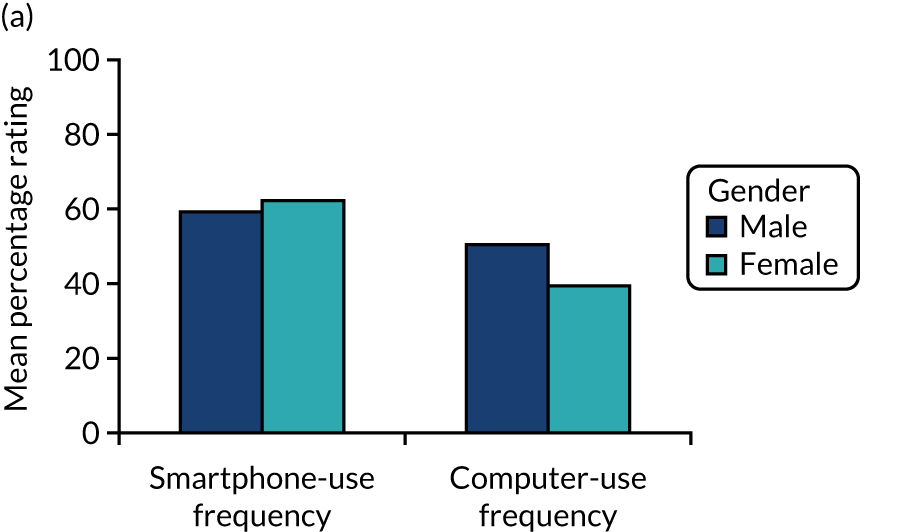

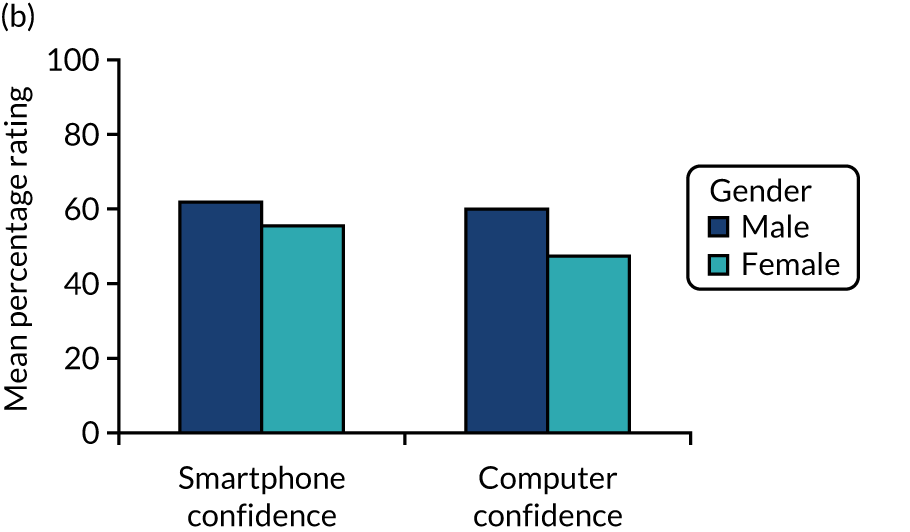

The baseline characteristics of the participants are shown in Table 4. As is typical of samples of people with persisting psychosis, there was a preponderance of male participants (70%) and there was an average age of 42.6 years. Other clinical characteristics (diagnosis, years in contact with services and medication equivalent dosages) were also typical. Eighty per cent of participants had clinical diagnoses of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder. Approximately 70% of the total participant sample were of white ethnicity, 58% lived alone and about 80% were unemployed. There were no marked demographic, diagnostic or clinical differences between the groups. Their paranoia was severe: 94.4% and 93.9% of the TAU and the SlowMo groups, respectively, met the criteria37 for likely presence of persecutory delusions on the GPTS31 (see Appendix 1, Table 17). Table 4 also shows the stratification factors (paranoia severity and site) and Table 5 shows the baseline values of negative symptoms, cognitive measures and carer characteristics examined as putative moderators.

| Characteristic | Treatment group | Overall (N = 361) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SlowMo (N = 181) | TAU (N = 180) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 43.1 (11.7) | 42.2 (11.6) | 42.6 (11.6) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 132 (72.9) | 120 (66.7) | 252 (69.8) |

| Female | 49 (27.1) | 60 (33.3) | 109 (30.2) |

| Marital status, n (%) | |||

| Single | 145 (80.1) | 137 (76.1) | 282 (78.1) |

| Cohabiting | 6 (3.3) | 6 (3.3) | 12 (3.3) |

| Married or civil partnership | 22 (12.2) | 24 (13.3) | 46 (12.7) |

| Divorced | 7 (3.9) | 10 (5.6) | 17 (4.7) |

| Widowed | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (1.1) |

| Self-defined ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 120 (66.3) | 129 (71.7) | 249 (69.0) |

| Black Caribbean | 9 (5.0) | 9 (5.0) | 18 (5.0) |

| Black African | 12 (6.6) | 10 (5.6) | 22 (6.1) |

| Black other | 16 (8.8) | 12 (6.7) | 28 (7.8) |

| Indian | 0 (0.0) | 3 (1.7) | 3 (0.8) |

| Pakistani | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.2) | 8 (2.2) |

| Chinese | 1 (0.6) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.3) |

| Other | 19 (10.5) | 12 (6.7) | 31 (8.6) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) |

| Highest level of schooling, n (%) | |||

| Primary school | 4 (2.2) | 3 (1.7) | 7 (1.9) |

| Secondary, no exams or qualifications | 30 (16.6) | 34 (18.9) | 64 (17.7) |

| Secondary O Level/CSE equivalent | 50 (27.6) | 51 (28.3) | 101 (28.0) |

| Secondary A Level equivalent | 23 (12.7) | 16 (8.9) | 39 (10.8) |

| Vocational education/college | 43 (23.8) | 44 (24.4) | 87 (24.1) |

| University degree/professional qualification | 31 (17.1) | 30 (16.7) | 61 (16.9) |

| Missing | 0 (0.0) | 2 (1.1) | 2 (0.6) |

| Current working status, n (%) | |||

| Unemployed | 141 (77.9) | 150 (83.3) | 291 (80.6) |

| Employed full time | 8 (4.4) | 8 (4.4) | 16 (4.4) |

| Employed part time | 15 (8.3) | 14 (7.8) | 29 (8.0) |

| Self-employed | 4 (2.2) | 2 (1.1) | 6 (1.7) |

| Retired | 10 (5.5) | 2 (1.1) | 12 (3.3) |

| Student | 1 (0.6) | 3 (1.7) | 4 (1.1) |

| Housewife/husband | 2 (1.1) | 1 (0.6) | 3 (0.8) |

| Normal living situation, n (%) | |||

| Living alone | 108 (59.7) | 103 (57.2) | 211 (58.4) |

| Living with partner | 19 (10.5) | 28 (15.6) | 47 (13.0) |

| Living with parents | 25 (13.8) | 30 (16.7) | 55 (15.2) |

| Living with other relatives | 4 (2.2) | 4 (2.2) | 8 (2.2) |

| Living with others | 25 (13.8) | 15 (8.3) | 40 (11.1) |

| Site, n (%) | |||

| London | 66 (36.5) | 64 (35.6) | 130 (36.0) |

| Oxford | 49 (27.1) | 50 (27.8) | 99 (27.4) |

| Sussex | 66 (36.5) | 66 (36.7) | 132 (36.6) |

| GPTS part B (stratification factor), n (%) | |||

| < 62 | 110 (60.8) | 109 (60.6) | 219 (60.7) |

| ≥ 62 | 71 (39.2) | 71 (39.4) | 142 (39.3) |

| Diagnosis, n (%) | |||

| Schizophrenia | 116 (64.1) | 109 (60.6) | 225 (62.3) |

| Schizoaffective | 30 (16.6) | 34 (18.9) | 64 (17.7) |

| Delusional disorder | 3 (1.7) | 3 (1.7) | 6 (1.7) |

| Psychosis (other) | 32 (17.7) | 34 (18.9) | 66 (18.3) |

| Time in contact with services (years), n (%) | |||

| < 1 | 7 (3.9) | 6 (3.3) | 13 (3.6) |

| 1–5 | 22 (12.2) | 33 (18.3) | 55 (15.2) |

| 6–10 | 40 (22.1) | 44 (24.4) | 84 (23.3) |

| 11–20 | 70 (38.7) | 70 (38.9) | 140 (38.8) |

| > 20 | 42 (23.2) | 27 (15.0) | 69 (19.1) |

| Chlorpromazine-equivalent dose of antipsychotic drug (mg/day), mean (SD) | 452.96 (399.45) | 519.97 (419.80) | 486.37 (410.53) |

| Moderator | Treatment group | Overall (N = 361) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| SlowMo (N = 181) | TAU (N = 180) | ||

| BNSS total, mean score (SD); n | 7.0 (8.4); 179 | 5.8 (8.1); 179 | 6.4 (8.2); 358 |

| BAPQ total, mean score (SD); n | 47.4 (6.4); 179 | 48.0 (5.5); 177 | 47.7 (6.0); 356 |

| Letter–Number Sequencing raw score, mean (SD); n | 7.6 (2.9); 176 | 8.2 (3.0); 171 | 7.9 (3.0); 347 |

| Trail-making task (B–A), mean score (SD); n | 69.7 (47.4); 157 | 63.3 (44.8); 160 | 66.5 (46.1); 317 |

| Trail-making part A, mean score (SD); n | 40.9 (16.9); 165 | 41.7 (20.2); 163 | 41.3 (18.6); 328 |

| Trail-making part B, mean score (SD); n | 110.6 (54.5); 165 | 105.0 (52.6); 163 | 107.8 (53.5); 328 |

| Carer, n (%) | |||

| No | 75 (41.9) | 72 (40.2) | 147 (41.1) |

| Yes | 104 (58.1) | 107 (59.8) | 211 (58.9) |

| How critical is your carer, n (%) | |||

| 0 (not at all) | 37 (35.6) | 30 (28.8) | 67 (32.2) |

| 1 | 11 (10.6) | 12 (11.5) | 23 (11.1) |

| 2 | 18 (17.3) | 17 (16.3) | 35 (16.8) |

| 3 | 19 (18.3) | 20 (19.2) | 39 (18.8) |

| 4 | 10 (9.6) | 18 (17.3) | 28 (13.5) |

| 5 (extremely) | 9 (8.7) | 7 (6.7) | 16 (7.7) |

In terms of treatment uptake, the average number of SlowMo sessions attended was 6.8 sessions (SD 2.6 sessions), rising to 7.3 sessions (SD 1.9 sessions) for those who attended at least one session. In total, 145 (80%) of those participants randomised to SlowMo (n = 181) completed all eight therapy sessions, 13 (7%) did not attend any sessions and a further 23 (14%) discontinued between session 1 and session 7. The mean session duration was 75 minutes (SD 29 minutes), including web app delivery and out-of-clinic work. Adherence to the delivery of the web app content was high, with each of the eight sessions reaching adherence ratings of at least 90%. Adherence to the mobile app was also high: of those who attended at least one therapy session and, therefore, were given a mobile telephone with the app installed, 71.4% met criteria for adherent use.

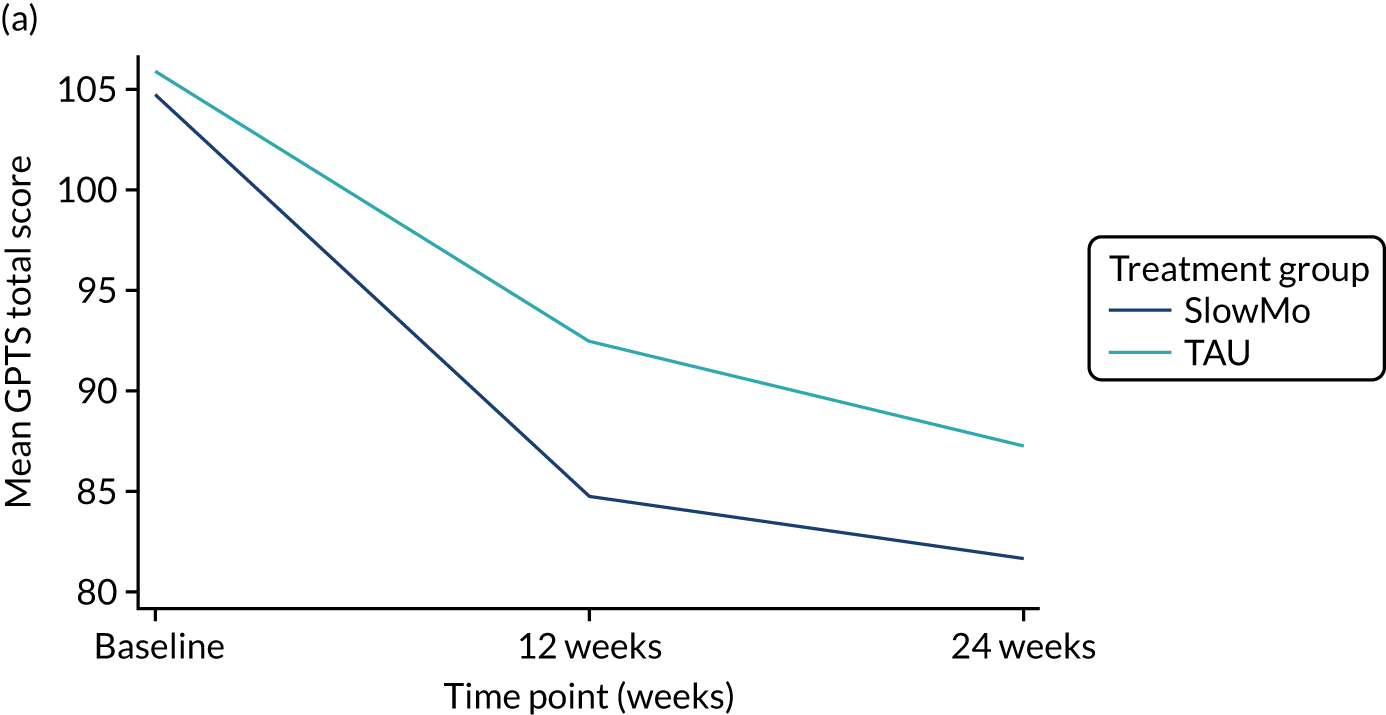

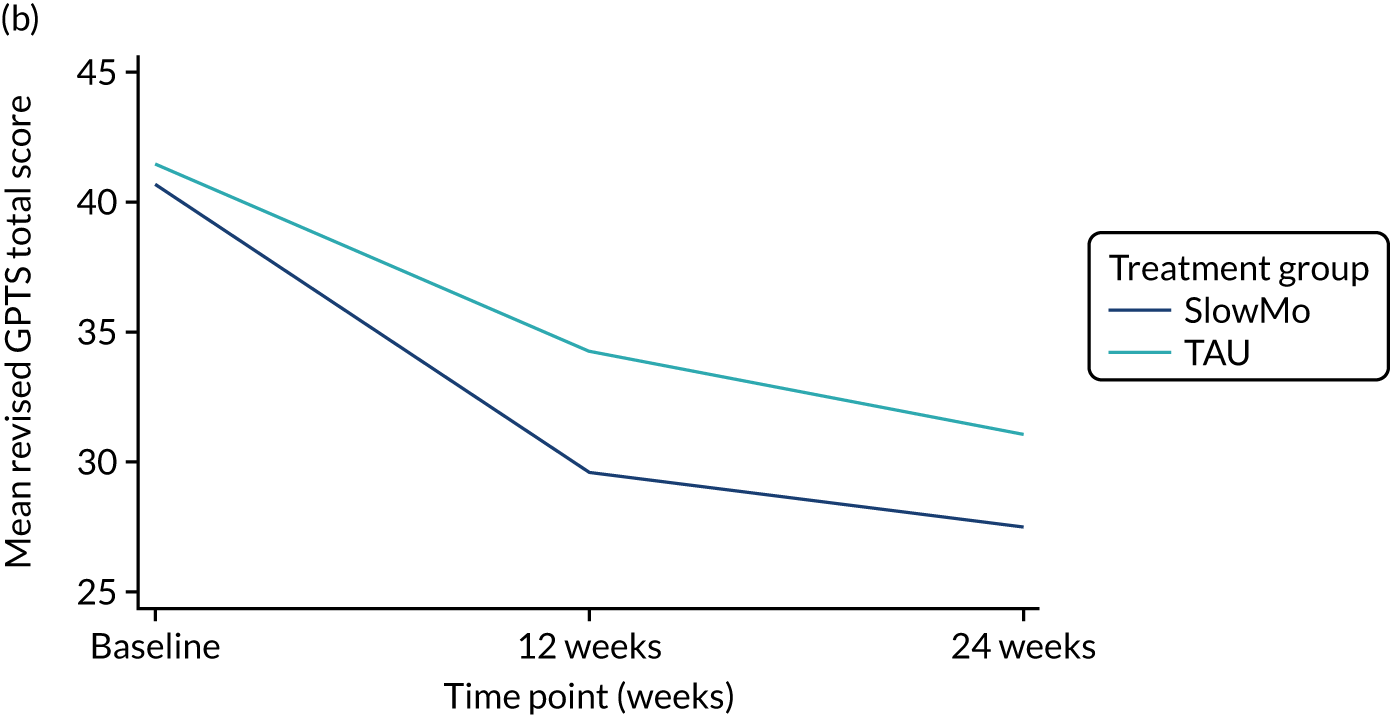

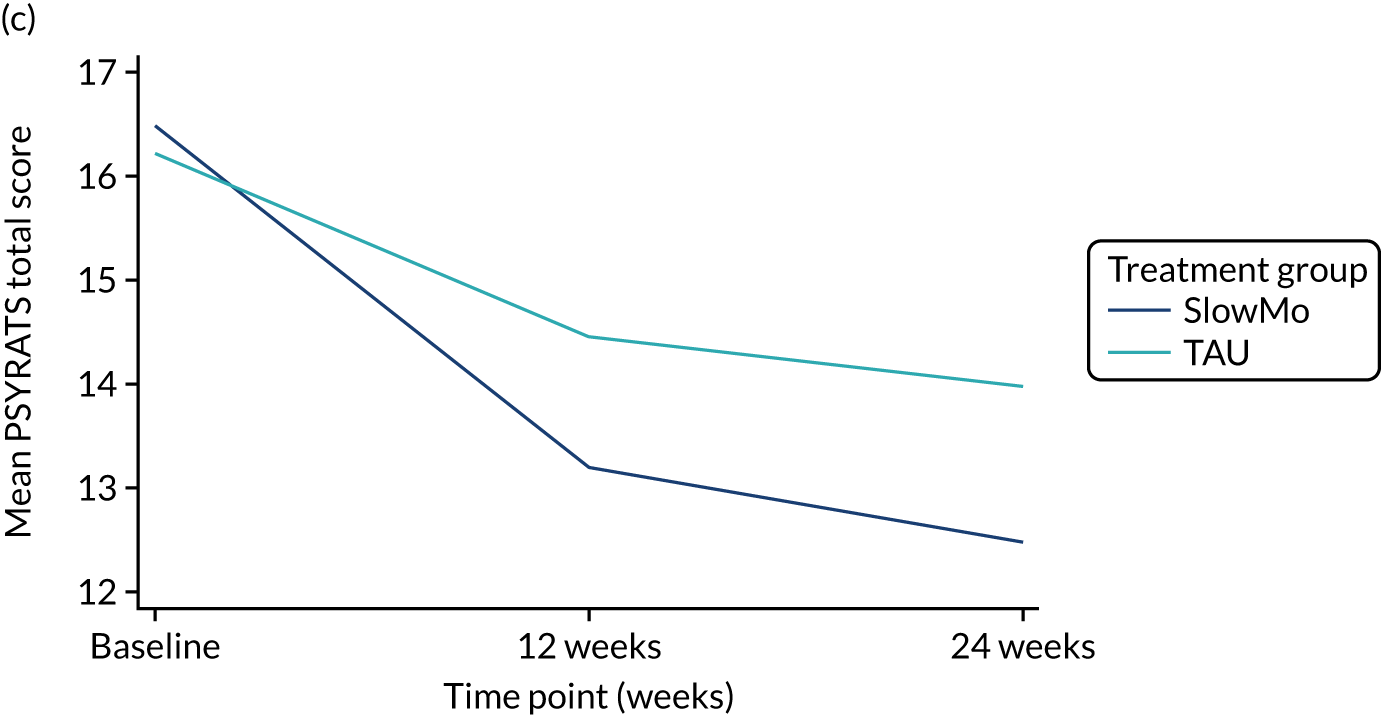

Both the descriptive statistics for all of the primary and secondary outcomes (Tables 6 and 7), and the effect estimates (Figures 2 and 3) show that SlowMo led to greater reductions in paranoia than TAU, as assessed by the total score of our primary outcome measure (GPTS31) post treatment [–8.06 (SE 2.85), 95% CI –13.64 to –2.48; p = 0.005] and at 24 weeks [–5.27 (SE 2.84, 95% CI –10.83 to 0.29; p = 0.063]. The reduction in paranoia on GPTS31 part B (persecutory) was significant at both time points, as was the R-GPTS37 total, PSYRATS34 delusions and SAPS36 persecutory delusion (see Figures 2 and 3). However, effects were less consistent for ideas of reference (as measured by GPTS31 part A, R-GPTS37 social reference and SAPS36 ideas/delusions of reference), with significant effects found either post treatment or at follow-up, but not at both time points (see Figure 2). See Appendix 1, Figure 9, for outcomes by group at three time points for the GPTS, R-GPTS and PSYRATS. Effect sizes were small (approximately Cohen’s d = 0.3) on the GPTS31 total, and moderate (Cohen’s d = 0.5) for PSYRATS34 total and SAPS36 persecutory delusions.

Treatment effects were found for some but not all of our reasoning measures: of the measures of belief flexibility, the possibility of being mistaken,42 both as a continuous rating and as a dichotomous rating, improved significantly, but alternative explanations43 did not improve. Jumping to conclusions9 showed little evidence of improvement (with only one significant finding: beads drawn at 12 weeks). The fast scale of the Fast and Slow Thinking Questionnaire44 showed improvements at both time points and the slow scale showed improvements at 24 weeks. Significant improvements, with a small effect size of approximately Cohen’s d = 0.3, were found for SlowMo in the following secondary outcome measures at either or both time points, and most consistently at 24-week follow-up: well-being (WEMWBS38), quality of life (MANSA39), worry (PSWQ41) and self-concept but not other-concept as measured on the BCSS40 (see Table 7 and Figure 2).

| Outcome | Treatment group, mean score (SD); n | Adjusted mean difference (SE) | 95% CI; p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlowMo | TAU | |||

| GPTS total | ||||

| Baseline | 104.7 (27.6); 180 | 105.9 (26.0); 179 | ||

| 12 weeks | 84.8 (30.8); 165 | 92.5 (33.1); 163 | –8.06 (2.85) | –13.64 to –2.48; 0.005 |

| 24 weeks | 81.7 (31.6); 161 | 86.3 (33.2); 171 | –5.27 (2.84) | –10.83 to 0.29; 0.063 |

| GPTS part A | ||||

| Baseline | 48.6 (15.9); 181 | 50.3 (15.1); 179 | ||

| 12 weeks | 40.2 (14.9); 165 | 44.2 (15.8); 163 | –3.49 (1.34) | –6.12 to –0.86; 0.009 |

| 24 weeks | 39.2 (15.0); 161 | 42.0 (15.8); 172 | –1.79 (1.34) | –4.41 to –0.83; 0.180 |

| GPTS part B | ||||

| Baseline | 56.2 (14.4); 180 | 55.9 (13.8); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 44.6 (18.1); 166 | 48.2 (18.7); 163 | –4.51 (1.71) | –7.87 to –1.15; 0.009 |

| 24 weeks | 42.2 (18.2); 161 | 45.1 (18.9); 171 | –3.53 (1.71) | –6.89 to –0.18; 0.039 |

| R-GPTS total | ||||

| Baseline | 40.7 (15.4); 179 | 41.5 (14.8); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 29.6 (17.2); 166 | 34.3 (18.6); 163 | –5.00 (1.61) | –8.16 to –1.86; 0.002 |

| 24 weeks | 27.5 (17.6); 160 | 31.1 (18.6); 169 | –3.42 (1.61) | –6.57 to –0.27; 0.034 |

| R-GPTS social reference | ||||

| Baseline | 16.0 (7.8); 180 | 17.1 (8.2); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 11.9 (7.6); 166 | 14.2 (8.1); 163 | –2.05 (0.70) | –3.42 to –0.68; 0.003 |

| 24 weeks | 11.3 (7.6); 160 | 13.1 (8.0); 172 | –1.15 (0.70) | –2.51 to 0.22; 0.099 |

| R-GPTS persecution | ||||

| Baseline | 24.7 (9.3); 180 | 24.4 (8.7); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 17.7 (11.1); 166 | 20.1 (11.7); 163 | –2.97 (1.07) | –5.07 to –0.88; 0.005 |

| 24 weeks | 16.3 (11.2); 161 | 18.0 (11.6); 169 | –2.25 (1.07) | –4.34 to –0.16; 0.035 |

| PSYRATS | ||||

| Baseline | 16.5 (3.3); 180 | 16.2 (3.1); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 13.2 (4.9); 166 | 14.5 (5.0); 162 | –1.53 (0.50) | –2.50 to –0.56; 0.002 |

| 24 weeks | 12.5 (5.2); 161 | 14.0 (5.5); 171 | –1.62 (0.49) | –2.59 to –0.65; 0.001 |

| PSYRATS distress | ||||

| Baseline | 8.1 (1.8); 181 | 7.9 (1.7); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 6.3 (2.8); 166 | 7.0 (2.8); 162 | –0.87 (0.29) | –1.44 to –0.30; 0.003 |

| 24 weeks | 6.0 (3.0); 161 | 6.8 (3.0); 171 | –0.76 (0.29) | –1.32 to –0.19; 0.009 |

| PSYRATS conviction | ||||

| Baseline | 8.4 (2.0); 180 | 8.3 (1.9); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 6.9 (2.5); 166 | 7.4 (2.6); 163 | –0.62 (0.25) | –1.11 to –0.13; 0.014 |

| 24 weeks | 6.4 (2.5); 161 | 7.2 (2.8); 172 | –0.84 (0.25) | –1.33 to –0.35; 0.001 |

| SAPS persecutory delusions | ||||

| Baseline | 3.5 (0.8); 181 | 3.4 (0.9); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 2.8 (1.3); 164 | 3.0 (1.3); 161 | –0.37 (0.18) | –0.71 to –0.03; 0.035 |

| 24 weeks | 2.5 (1.5); 161 | 2.8 (1.4); 171 | –0.46 (0.18) | –0.80 to –0.12; 0.009 |

| SAPS ideas and delusions of reference | ||||

| Baseline | 2.5 (1.8); 181 | 2.7 (1.7); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 2.2 (1.9); 165 | 2.4 (1.8); 161 | –0.18 (0.19) | –0.55 to 0.19; 0.350 |

| 24 weeks | 1.9 (1.9); 160 | 2.4 (1.9); 171 | –0.41 (0.19) | –0.79 to –0.04; 0.028 |

| Outcome | Treatment group | Effecta | 95% CI; p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SlowMo | TAU | |||

| WEMWBS,b mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 39.3 (9.1); 179 | 40.5 (8.7); 175 | ||

| 12 weeks | 42.2 (9.4); 164 | 41.6 (9.1); 157 | 1.56 (0.89) | –0.18 to 3.30; 0.079 |

| 24 weeks | 43.3 (11.0); 157 | 41.2 (9.6); 165 | 2.82 (0.89) | 1.08 to 4.56; 0.001 |

| PSWQ, mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 56.9 (10.8); 179 | 56.6 (10.1); 175 | ||

| 12 weeks | 53.2 (11.6); 158 | 55.4 (11.5); 157 | –2.81 (0.90) | –4.57 to –1.04; 0.002 |

| 24 weeks | 52.2 (11.6); 154 | 54.5 (11.5); 163 | –2.24 (0.90) | –4.00 to –0.48; 0.013 |

| BCSS: negative self, mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 9.9 (5.8); 181 | 10.3 (5.5); 178 | ||

| 12 weeks | 9.0 (6.0); 162 | 10.0 (6.0); 159 | –0.98 (0.48) | –1.92 to –0.04; 0.04 |

| 24 weeks | 8.4 (5.9); 160 | 9.7 (5.8); 167 | –1.19 (0.48) | –2.12 to –0.25; 0.013 |

| BCSS: positive self,b mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 10.7 (5.6); 181 | 10.8 (5.4); 178 | ||

| 12 weeks | 11.5 (5.6); 164 | 11.5 (5.6); 159 | 0.33 (0.41) | –0.48 to 1.13; 0.427 |

| 24 weeks | 12.5 (5.5); 159 | 11.6 (5.8); 168 | 1.11 (0.41) | 0.31 to 1.92; 0.006 |

| BCSS: negative other, mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 13.3 (6.1); 181 | 13.3 (5.8); 178 | ||

| 12 weeks | 12.9 (6.1); 163 | 13.0 (6.0); 159 | –0.21 (0.55) | –1.30 to 0.88; 0.703 |

| 24 weeks | 12.6 (6.2); 159 | 12.7 (6.3); 168 | –0.16 (0.55) | –1.25 to 0.92; 0.767 |

| BCSS: positive other,b mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 11.6 (5.2); 180 | 11.1 (4.9); 177 | ||

| 12 weeks | 12.2 (5.1); 164 | 11.8 (4.8); 159 | 0.28 (0.42) | –0.55 to 1.12; 0.504 |

| 24 weeks | 12.4 (4.8); 158 | 12.1 (4.8); 168 | 0.34 (0.42) | –0.49 to 1.17; 0.420 |

| MANSA,b mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 46.8 (9.9); 161 | 48.1 (10.2); 164 | ||

| 12 weeks | 48.1 (10.7); 145 | 48.9 (10.6); 146 | 0.76 (0.91) | –1.02 to 2.55; 0.401 |

| 24 weeks | 50.5 (11.7); 135 | 49.1 (9.5); 148 | 2.75 (0.92) | 0.94 to 4.55; 0.003 |

| Possibility of being mistaken (0–100),b mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 34.6 (30.9); 181 | 35.1 (31.0); 180 | ||

| 12 weeks | 48.9 (32.2); 165 | 39.9 (33.2); 161 | 9.02 (3.16) | 2.83 to 15.21; 0.004 |

| 24 weeks | 45.3 (31.8); 161 | 37.7 (31.1); 172 | 8.88 (3.16) | 2.70 to 15.07; 0.005 |

| Possibility of being mistaken, yes/no (% yes/% no)b | ||||

| Baseline | 105/76 (58/42) | 106/74 (59/41) | ||

| 12 weeks | 124/41 (75/25) | 100/61 (62/38) | OR 3.83 | 1.53 to 9.59; 0.004 |

| 24 weeks | 105/56 (65/35) | 100/72 (58/42) | OR 2.01 | 0.86 to 4.70; 0.108 |

| Alternative explanations, yes/no (% yes/% no)b | ||||

| Baseline | 79/102 (44/56) | 85/94 (48/52) | ||

| 12 weeks | 90/74 (55/45) | 78/83 (48/52) | OR 1.74 | 0.90 to 3.36; 0.097 |

| 24 weeks | 87/73 (54/46) | 87/82 (52/48) | OR 1.33 | 0.70 to 2.55; 0.387 |

| JTC 85 : 15, yes/no (% yes/% no) | ||||

| Baseline | 103/77 (57/43) | 83/96 (46/54) | ||

| 12 weeks | 70/95 (42/58) | 68/91 (42/58) | OR 0.71 | 0.31 to 1.62; 0.422 |

| 24 weeks | 55/105 (34/66) | 62/107 (37/63) | OR 0.58 | 0.25 to 1.34; 0.204 |

| JTC 85 : 15 (number of beads drawn), mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 3.8 (4.4) | 3.9 (4.0) | ||

| 12 weeks | 4.3 (4.3) | 4.1 (3.9) | 0.39 (0.43) | –0.45 to 1.22; 0.365 |

| 24 weeks | 5.2 (4.8) | 4.1 (3.3) | 0.99 (0.42) | 0.16 to 1.83; 0.019 |

| JTC 60 : 40, yes/no (% yes/% no) | ||||

| Baseline | 72/108 (40/60) | 59/120 (33/67) | ||

| 12 weeks | 47/118 (29/71) | 42/117 (26/74) | OR 0.82 | 0.26 to 2.51; 0.722 |

| 24 weeks | 43/117 (27/73) | 44/125 (26/74) | OR 0.69 | 0.22 to 2.18; 0.531 |

| JTC 60 : 40 (number of beads drawn), mean (SD) | ||||

| Baseline | 5.7 (5.4) | 5.7 (5.1) | ||

| 12 weeks | 7.0 (5.7) | 6.8 (5.4) | 0.28 (0.49) | –0.68 to 1.25; 0.563 |

| 24 weeks | 7.0 (5.2) | 6.5 (4.9) | 0.49 (0.49) | –0.47 to 1.45; 0.321 |

| FaST: fast scale, mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 16.9 (4.7); 174 | 16.7 (4.3); 169 | ||

| 12 weeks | 15.3 (4.9); 165 | 16.2 (5.0); 160 | –1.07 (0.47) | –1.98 to –0.16; 0.022 |

| 24 weeks | 15.0 (4.4); 160 | 16.2 (5.1); 168 | –1.33 (0.46) | –2.23 to –0.42; 0.004 |

| FaST: slow scale,b mean score (SD); n | ||||

| Baseline | 19.9 (4.7); 174 | 19.7 (4.8); 169 | ||

| 12 weeks | 20.3 (4.8); 165 | 19.3 (4.8); 160 | 0.66 (0.45) | –0.22 to 1.55; 0.140 |

| 24 weeks | 20.3 (4.4); 160 | 19.3 (4.8); 168 | 1.00 (0.45) | 0.12 to 1.88; 0.027 |

FIGURE 2.

Forest plot of all continuous outcomes at (a) 12 weeks and (b) 24 weeks.

FIGURE 3.

Forest plot of binary outcomes at (a) 12 weeks and (b) 24 weeks.

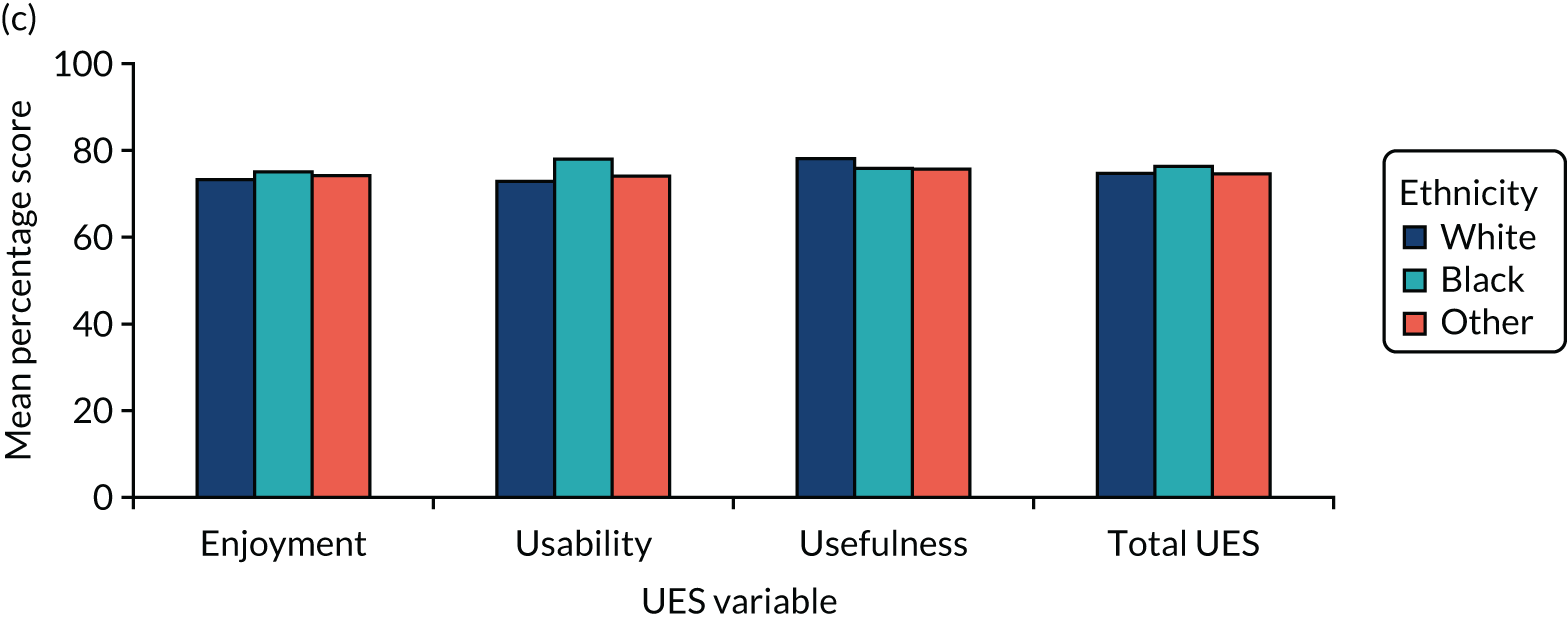

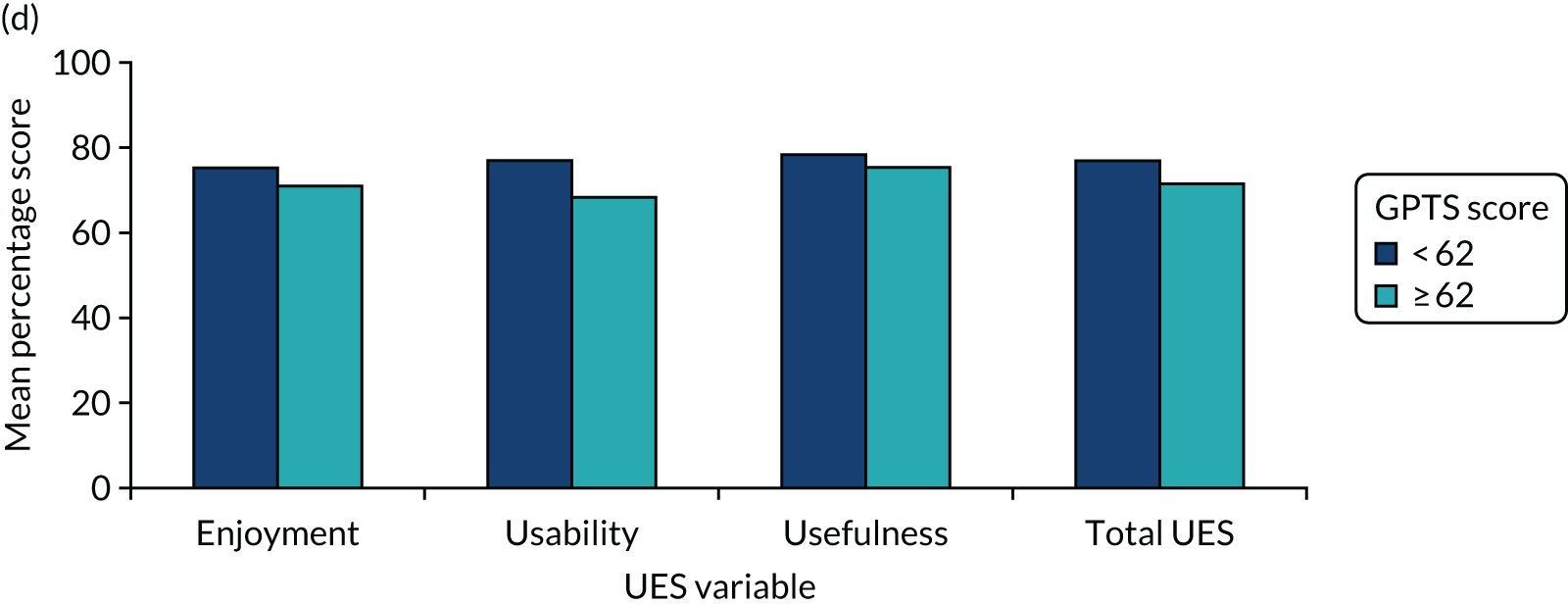

The moderation analysis (Table 8) found no differential effects on the paranoia outcome as measured by the GPTS31 or the R-GPTS. 37 There was only one moderation effect, on the PSYRATS,34 with p < 0.05. However, given the number of tests conducted, this finding may have occurred by chance. These results show that the treatment is effective against paranoia at all levels of the moderators.

| Moderator | Outcome, difference in treatment effect (95% CI); p-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GPTS | R-GPTS | PSYRATS | |

| Baseline outcome | |||

| 12 weeks | –0.08 (–0.28 to 0.13); 0.469 | –0.06 (–0.27 to 0.15); 0.568 | –0.31 (–0.62. to –0.01); 0.045 |

| 24 weeks | –0.12 (–0.32 to 0.09); 0.263 | –0.12 (–0.33 to 0.09); 0.271 | –0.24 (–0.54 to 0.07); 0.129 |

| BNSS | |||

| 12 weeks | 0.27 (–0.41 to 0.95); 0.439 | 0.02 (–0.37 to 0.42); 0.910 | –0.01 (–0.13 to 0.11); 0.922 |

| 24 weeks | –0.10 (–0.78 to 0.58); 0.777 | –0.07 (–0.47 to 0.32); 0.708 | 0.06 (–0.06 to 0.18); 0.317 |

| BAPQ | |||

| 12 weeks | 0.06 (–0.89 to 1.02); 0.896 | 0.08 (–0.46 to 0.62); 0.775 | 0.07 (–0.09 to 0.24); 0.383 |

| 24 weeks | 0.10 (–0.85 to 1.06); 0.833 | 0.02 (–0.52 to 0.56); 0.934 | 0.06 (–0.10 to 0.23); 0.452 |

| Letter–Number Sequencing raw score | |||

| 12 weeks | –0.44 (–2.31 to 1.42); 0.641 | –0.21 (–1.26 to 0.85); 0.697 | –0.21 (–0.54 to 0.12); 0.210 |

| 24 weeks | –0.21 (–2.06 to 1.63); 0.822 | –0.09 (–1.14 to 0.96); 0.867 | –0.30 (–0.62 to 0.03); 0.075 |

| Trail making task (B–A) | |||

| 12 weeks | 0.05 (–0.08 to 0.18); 0.436 | 0.03 (–0.04 to 0.10); 0.448 | 0.00 (–0.02 to 0.02); 0.889 |

| 24 weeks | 0.04 (–0.09 to 0.16); 0.574 | 0.01 (–0.06 to 0.09); 0.701 | 0.02 (0.00 to 0.04); 0.069 |

| Presence of a carer (yes/no) | |||

| 12 weeks | 7.71 (–3.56 to 18.98); 0.180 | 3.70 (–2.67 to 10.07); 0.255 | 1.12 (–0.85 to 3.08); 0.265 |

| 24 weeks | 1.23 (–10.01 to 12.46); 0.831 | 0.84 (–5.54 to 7.22); 0.796 | 0.48 (–1.47 to 2.44); 0.628 |

| Criticism of carer (only if carer present, n = 208) | |||

| 12 weeks | –0.28 (–4.73 to 4.17); 0.903 | –0.14 (–2.65 to 2.38); 0.915 | –0.62 (–1.41 to 0.17); 0.122 |

| 24 weeks | 2.48 (–1.93 to 6.88); 0.270 | 1.32 (–1.16 to 3.81); 0.297 | 0.14 (–0.64 to 0.92); 0.716 |

| Alternative explanations (yes/no) | |||

| 12 weeks | 2.62 (–8.50 to 13.75); 0.644 | 1.99 (–4.29 to 8.27); 0.534 | 1.15 (–0.79 to 3.09); 0.245 |

| 24 weeks | 4.39 (–6.69 to 15.46); 0.438 | 2.29 (–3.98 to 8.57); 0.474 | –0.12 (–2.05 to 1.81); 0.905 |

| Possibility of being mistaken (yes/no) | |||

| 12 weeks | 3.88 (–7.49 to 15.24); 0.504 | 3.07 (–3.36 to 9.51); 0.349 | 0.79 (–1.17 to 2.76); 0.429 |

| 24 weeks | 2.71 (–8.60 to 14.02); 0.639 | 1.67 (–4.76 to 8.10); 0.610 | 0.16 (–1.79 to 2.12); 0.871 |

| Jumping to conclusions (yes/no) | |||

| 12 weeks | –0.72 (–11.97 to 10.52); 0.90 | –0.75 (–7.10 to 5.60); 0.817 | –0.33 (–2.29 to 1.63); 0.744 |

| 24 weeks | 7.63 (–3.59 to 18.85); 0.183 | 5.76 (–0.60 to 12.11); 0.076 | 1.12 (–0.84 to 3.07); 0.264 |

The results of the mediation analysis on the GPTS31 at 12 and 24 weeks are shown in Table 9. The results for the R-GPTS37 and the PSYRATS34 are presented in Appendix 1 (see Tables 18 and 19). Only the possibility of being mistaken42 (whether measured as a binary variable or as a continuous measure) and worry41 mediated the effects of the treatment on all paranoia outcomes at 12 and 24 weeks. Approximately 40% of the total effect was mediated through each mediator at 12 weeks and 56% was mediated at 24 weeks.

| Mediator | Effect, causal mediation effect (bootstrap SE); 95% CI | Proportion mediated | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | Direct | Indirect | ||

| Alternative explanations | ||||

| 12 weeks | –7.44 (2.98); –13.32 to –1.14 | –7.01 (2.94); –12.81 to –0.67 | –0.43 (0.44); –1.46 to 0.15 | 5.8 |

| 24 weeks | –4.86 (2.90); –10.74 to 0.92 | –4.55 (2.84); –10.12 to 1.03 | –0.31 (0.38); –1.33 to 0.26 | 6.4 |

| JTC 85 : 15 task | ||||

| 12 weeks | –7.24 (3.09); –13.03 to –0.64 | –6.89 (3.04); –12.80 to –0.83 | –0.34 (0.49); –1.27 to 0.58 | 4.7 |

| 24 weeks | –4.02 (2.94); –9.69 to 1.87 | –3.76 (2.92); –9.31 to 2.06 | –0.26 (0.41); –1.14 to 0.63 | 6.5 |

| JTC 60 : 40 task | ||||

| 12 weeks | –7.63 (3.05); –13.61 to –0.98 | –7.55 (3.04); –13.70 to –1.00 | –0.09 (0.44); –0.99 to 0.80 | 1.1 |

| 24 weeks | –4.60 (2.91); –10.14 to 1.29 | –4.57 (2.90); –10.12 to 1.42 | –0.03 (0.22); –0.48 to 0.44 | 0.7 |

| Possibility of being mistaken (yes/no) | ||||

| 12 weeks | –8.35 (2.99); –14.13 to –2.07 | –6.00 (2.93); –11.86 to 0.05 | –2.35 (1.08); –4.71 to –0.59 | 28.1 |

| 24 weeks | –5.26 (2.92); –11.14 to 0.53 | –3.55 (2.78); –8.67 to 1.96 | –1.71 (0.92); –3.93 to –0.39 | 32.5 |

| Possibility of being mistaken (1–100) | ||||

| 12 weeks | –7.58 (2.98); –13.44 to –1.01 | –4.86 (2.83); –10.21 to 0.97 | –2.72 (1.07); –5.04 to –0.91 | 35.9 |

| 24 weeks | –4.89 (2.89); –10.30 to 1.12 | –2.13 (2.69); –7.51 to 3.39 | –2.76 (1.02); –4.75 to –0.75 | 56.4 |

| Worry | ||||

| 12 weeks | –7.78 (3.00); –13.63 to –1.17 | –4.74 (2.96); –10.44 to 1.74 | –3.04 (1.10); –5.52 to –1.09 | 39.1 |

| 24 weeks | –4.46 (2.90); –10.42 to 1.12 | –1.95 (2.91); –7.48 to 4.02 | –2.51 (1.11); –5.13 to –0.97 | 56.3 |

The results of the compliance-adjusted analysis on the GPTS,31 R-GPTS37 and PSYRATS34 are shown in Table 10. Given that there is no access to SlowMo therapy for the TAU group, the complier-average causal effect is an adjustment to the intention-to-treat effect for each outcome divided by the predicted proportion of those in the SlowMo group who were observed to attend at least one session of therapy. The results show significant treatment effects of SlowMo therapy compared with TAU in the compliers at all time points. The dose–response effect shows that the treatment effect increases as the number of SlowMo sessions increases.

| Outcome | Compliance measure, treatment effect (bootstrap SE), 95% CI; p-value | |

|---|---|---|

| Any sessions (≥ 1) | Number of sessions | |

| GPTS | ||

| 12 weeks | –8.73 (2.52), –13.68 to –3.79; 0.001 | –1.19 (0.32), –1.83 to –0.56; < 0.001 |

| 24 weeks | –5.64 (2.47), –10.47 to –0.81; 0.022 | –0.77 (0.34), –1.44 to –0.10; 0.024 |

| R-GPTS | ||

| 12 weeks | –5.57 (1.40), –8.32 to –2.83; < 0.001 | –0.76 (0.19), –1.14 to –0.38; < 0.001 |

| 24 weeks | –3.79 (1.41), –6.56 to –1.02; 0.007 | –0.52 (0.20), –0.91 to –0.12; 0.010 |

| PSYRATS | ||

| 12 weeks | –1.64 (0.39), –2.41 to –0.87; < 0.001 | –0.22 (0.05), –0.33 to –0.12; < 0.001 |

| 24 weeks | –1.79 (0.42), –2.61 to –0.96; < 0.001 | –0.24 (0.06), –0.37 to –0.12; < 0.001 |

Fifty-four adverse events were reported over the course of the trial, of which 51 were serious events, occurring in 19 people in the SlowMo group and 21 in the TAU group (Table 11). There were no deaths recorded. More than half of the SAEs were mental health hospital admission or crisis referrals (SlowMo, n = 13; TAU, n = 16) or physical health crises (SlowMo, n = 8; TAU, n = 2), none of which was rated as being related to participation in the trial. One SAE in the TAU group was rated as ‘definitely related’ to trial involvement: it involved a complaint made when the research team shared information with the clinical team under a duty of care (confirmed as such by an independent ethics review). (The participant subsequently requested that their data be withdrawn and is, therefore, a ‘post-randomisation exclusion’ in the data analysis.)

| Adverse event | Treatment group, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| SlowMo | TAU | |

| Serious events (people) | ||

| Yes | 25 (19) | 26a (21) |

| No | 3 (3) | 0 (0) |

| Type of adverse events (people) | ||

| Physical | 8 (8) | 2 (2) |

| Self-harm | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Serious violent incidents (victim) | 0 (0) | 1 (1) |

| Serious violent incidents (accused) | 1 (1) | 2 (2) |

| Referrals to crisis care | 5 (5) | 2 (2) |

| Admission to psychiatric hospital during follow-up | 8 (8) | 14 (10) |

| Deaths | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Other | 5 (5) | 5 (4) |

| Intensity of events | ||

| Mild | 2 (7.1) | 0 (0.0) |

| Moderate | 11 (39.3) | 10 (38.5) |

| Severe | 15 (53.6) | 16 (61.5) |

| Relationship to trial participation (serious events) | ||

| Definitely related | 0 (0.0) | 1 (3.8) |

| Probably related | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Possibly related | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Unlikely related | 1 (4.0) | 0 (0.0) |

| Not related | 23 (92.0) | 25 (96.2) |

Concomitant treatments (psychosocial, psychological therapy and medications) and services (days in crisis care and in admission to hospital) that were provided to both groups as usual treatment were monitored from case note review and using a modified version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory33 (see Appendix 1, Tables 20 and 21).

Discussion

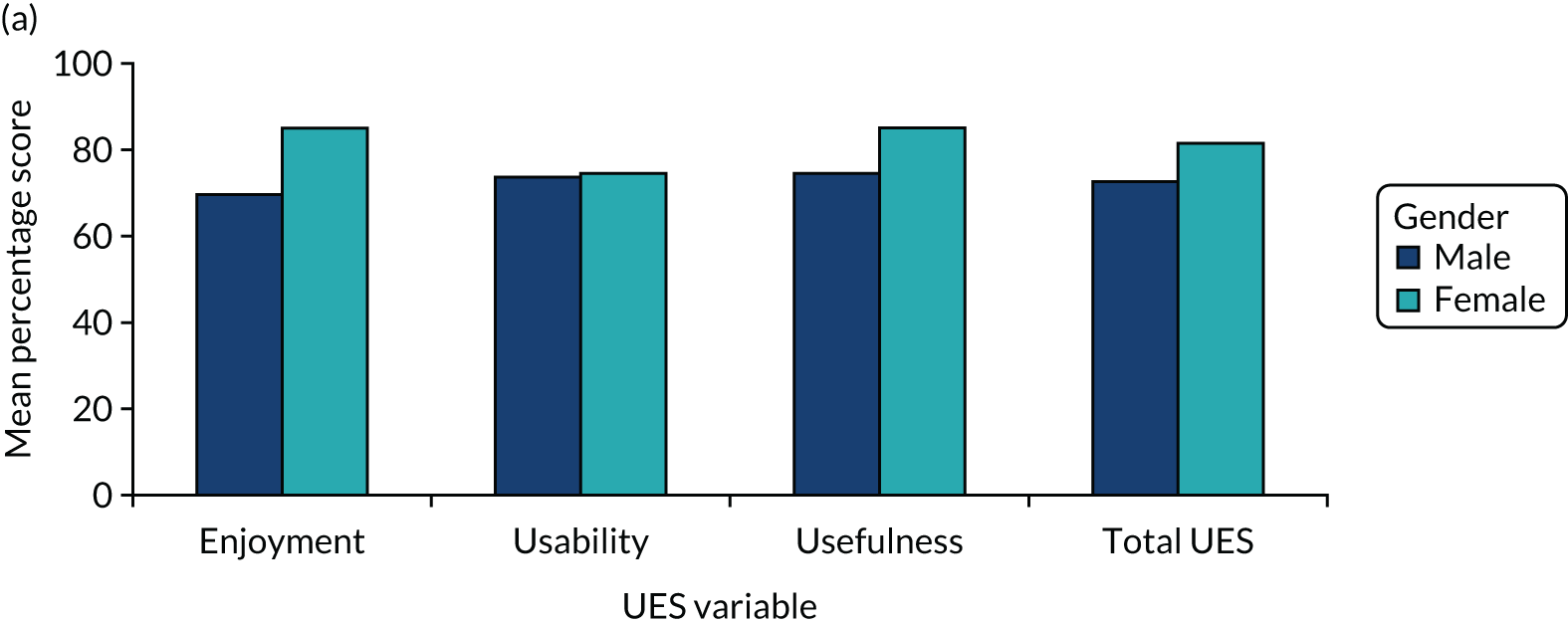

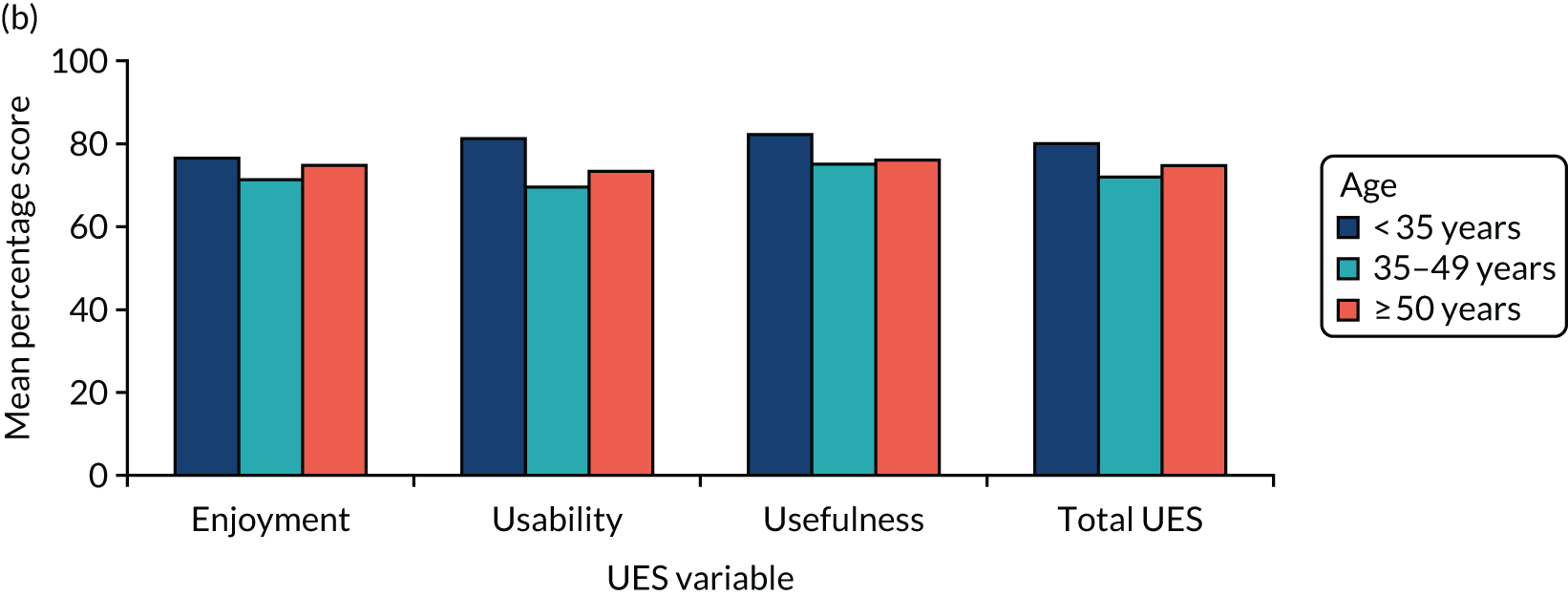

To the best of our knowledge, the SlowMo trial is the largest trial to date of a psychological therapy focused on fear of harm from others (paranoia) undertaken in a clinical population. We recruited the target of 362 participants, with over 90% followed up at each time point. We addressed two main goals: to improve effectiveness and to overcome user experience barriers to engagement and adherence. The study results suggest that SlowMo therapy is clinically effective and supports the intended user experience.

We found consistent significant effects of SlowMo therapy on paranoia when added to routine treatment, compared with routine treatment alone, over and above the generally improving trajectory of both groups. Improvements were demonstrated on all paranoia and persecutory delusions outcomes across the 6 months (ranging from small to medium effect sizes). The effects were less consistent for ideas of reference, with significant effects at either post treatment or follow-up, but not both time points. There were also improvements in the reasoning targets of belief flexibility (possibility of being mistaken,42 but not alternative explanations43) and self-reported reasoning on the Fast and Slow Thinking Questionnaire44 (the fast subscale at both time points, and the slow subscale at 24 weeks). There was, however, little evidence of improvement in JTC9 (a single significant effect of the eight measured). There were treatment effects with small effect sizes on improving well-being, quality of life, self-concept and worry, with these important gains seen most consistently at the longer-term (6-month) follow-up. These represent sustained improvements in well-being and quality of life, and are highly valued by service users. 56

The therapy uptake and adherence were all in the upper range, suggesting that SlowMo therapy is highly acceptable. Furthermore, the effects were not moderated by hypothesised characteristics, indicating that it is beneficial regardless of cognitive capacity, baseline symptoms, the presence of a carer, or carer criticism. The treatment targeted reasoning to improve paranoia; we found that this outcome was, as hypothesised, mediated by improvement in a fundamental aspect of reasoning, belief flexibility (possibility of being mistaken42) and also, but not as hypothesised, reducing worry.

We found no evidence of the intervention being harmful. Both groups generally improved across the course of the trial and there were similar numbers of SAEs across the two groups. The most common SAEs of hospital crisis and inpatient admission were smaller in number of days at follow-up in both groups (see Appendix 1, Table 21). No SAE was considered definitely related to trial participation in the SlowMo group by the independent DMEC; the only SAE definitely related to trial involvement in the TAU group involved a complaint that information was shared under duty of care (see above). The relatedness of adverse events to the digital hardware and software supporting SlowMo therapy is reported in Chapter 3.

We used a range of measures of paranoia and a limitation of the study is that our primary outcome measure, the self-reported GPTS,31 was revised during the course of the trial. 37 Therefore, we report outcomes using both versions. These have similar results, but the newer, more psychometrically robust, revision37 yields slightly larger treatment effects and results in the follow-up effect for the total score moving into the range for conventional significance. SlowMo, although brief, at eight sessions, had a clinically worthwhile effect on delusions: using the new cut-off points provided by Freeman et al. 37 for the GPTS persecution, 38.5% of the SlowMo group (compared with 31.6% of the TAU group) no longer met the criteria for presence of a persecutory delusion at follow-up (increasing from 10% and 11%, respectively, at baseline) (see Appendix 1, Table 17). Furthermore, on observer-rated measures of paranoia (PSYRATS34 and SAPS36), the effect sizes were, in general, moderate and, for this reason, were greater than the rates reported in meta-analyses of longer courses of CBT for psychosis for delusions using these measures. 3,57 The clinically important target of distress associated with the delusion was reduced by the end of treatment with SlowMo compared with TAU, and sustained at follow-up.

SlowMo targets reasoning to improve paranoia. As intended, improvements were observed in belief flexibility and the possibility of being mistaken. 42 By contrast, JTC9 showed little evidence of change. On the tests of reasoning as a mechanism, the possibility of being mistaken mediated change in paranoia, explaining about 56% of the variance at follow-up. This is consistent with our earlier proof-of-concept study, which also found that the possibility of being mistaken mediated paranoia, but JTC did not mediate paranoia. 25 In the light of this and other meta-analytic evidence,10 we suggest that JTC (as assessed through the classic beads task9) may be best considered as trait like and relatively unresponsive to change over time, conferring vulnerability to persecutory beliefs, but with less evidence of a dynamic relationship with paranoia severity. This evolving understanding of reasoning biases and paranoia has resulted in our foregrounding of the promotion of ‘slow thinking’ and greater flexibility, with the aim of generating compensatory strategies for real-world fast thinking by encouraging the deliberative act of slowing down in the moment (see Ward and Garety15). Self-reported reductions in fast and slow thinking, as assessed by the Fast and Slow Thinking Questionnaire,44 suggest that the therapy may have changed awareness of and preferences for both unhelpful fast styles of thinking and useful slow styles of thinking, in keeping with the explicit and consistent SlowMo focus on building meta-cognitive awareness of thinking ‘habits’.

As Freeman58 has noted, persecutory delusions arise from a combination of causes, with each causal factor increasing the probability of such fears occurring. Another factor is worry. The Worry Intervention Trial28 demonstrated comparable changes in paranoia on PSYRATS delusions (Cohen’s d = 0.49) using a brief, six-session, cognitive–behavioural worry intervention and provided evidence that these changes were mediated through worry. 28 SlowMo showed a similar change in paranoia on the PSYRATS (Cohen’s d = 0.5) and, although not explicitly targeted in SlowMo, the observed changes in worry were also found to act as a mechanism of change in paranoia; paranoia improved as a consequence of reducing worry, with a similar proportion of the variance to that found for belief flexibility. This was not hypothesised. However, given that worry is a mechanism that clearly drives paranoia, which is described by participants as part of an emotional reaction to fast thinking, and SlowMo altered worry, we can conclude that worry reduction constitutes part of the treatment route for SlowMo.

We note that SlowMo shares features with worry reduction techniques. Both involve noticing one’s thoughts, consider approaches for decentring worrying thoughts and help with strategies to shift attention elsewhere, for example, in SlowMo, shifting from fast thoughts to alternative and safer (i.e. less worrying) thoughts. However, worry improved less in SlowMo than when it was directly targeted in the Worry Intervention Trial,28 as might be expected. Furthermore, we cannot tell from the current study how far worry and belief flexibility are independent routes to change, nor whether or not there might be other mechanisms for treatment effects, such as the parallel improvements in self-concepts and well-being that occurred.

Our original hypotheses, specified in our trial protocol, derived from a theory of change in which the primary process underpinning SlowMo was through reasoning. However, the evidence from this study suggests that there is the potential for other processes to also be involved in treatment effects. Indeed, our long-standing cognitive model of paranoia has proposed multifactorial causality, particularly highlighting both reasoning and emotional processes,59 and these findings are consistent with a multifactorial theory of change; future research should investigate the mechanisms to elucidate both the treatment effects of SlowMo and the causal mechanisms of paranoia. We intend to pursue these questions in future studies.

A limitation of the study is that the design did not control for the effects of time with a therapist. The choice of a TAU control was made because we wanted to test whether or not SlowMo confers benefits over and above standard care. In addition, we aimed to examine the mechanism of change and wished, therefore, to have a control condition which was, as far as possible, inert with respect to reasoning. Adjunctive treatments in TAU were closely monitored and were found to be similar across the groups: a few participants were given individual psychological therapy (albeit, as would be expected, slightly more in the TAU group). The types, dosage and frequency of antipsychotic and other medication were similar in each group.

Another limitation of the study is that when recruiting participants we focused on persecutory beliefs in the context of a clinical diagnosis of schizophrenia-spectrum psychosis and did not make an independent research diagnosis. The resulting clinical and demographic profile of participants appears to have been typical of a community sample of people with psychosis and long-standing delusions. The relatively high consent rate and low attrition rates indicate that our findings should be generalisable to this population; however, a fuller diagnostic and symptomatic assessment might have been more informative in terms of the generalisability of the findings to diagnostically selected participants.

Finally, we found that the effects of SlowMo are more consistent on persecutory delusions than ideas of reference. This was unanticipated. It may be that the persecutory beliefs, in improving, shifted down the hierarchy of paranoia60 to milder ideas of reference, but that therapy prevented such ideas and their experiential components from being actively elaborated into paranoid fears of intentional harm. Whether or not this was the case, we infer, however, that SlowMo should be developed to enhance work on referential ideas.

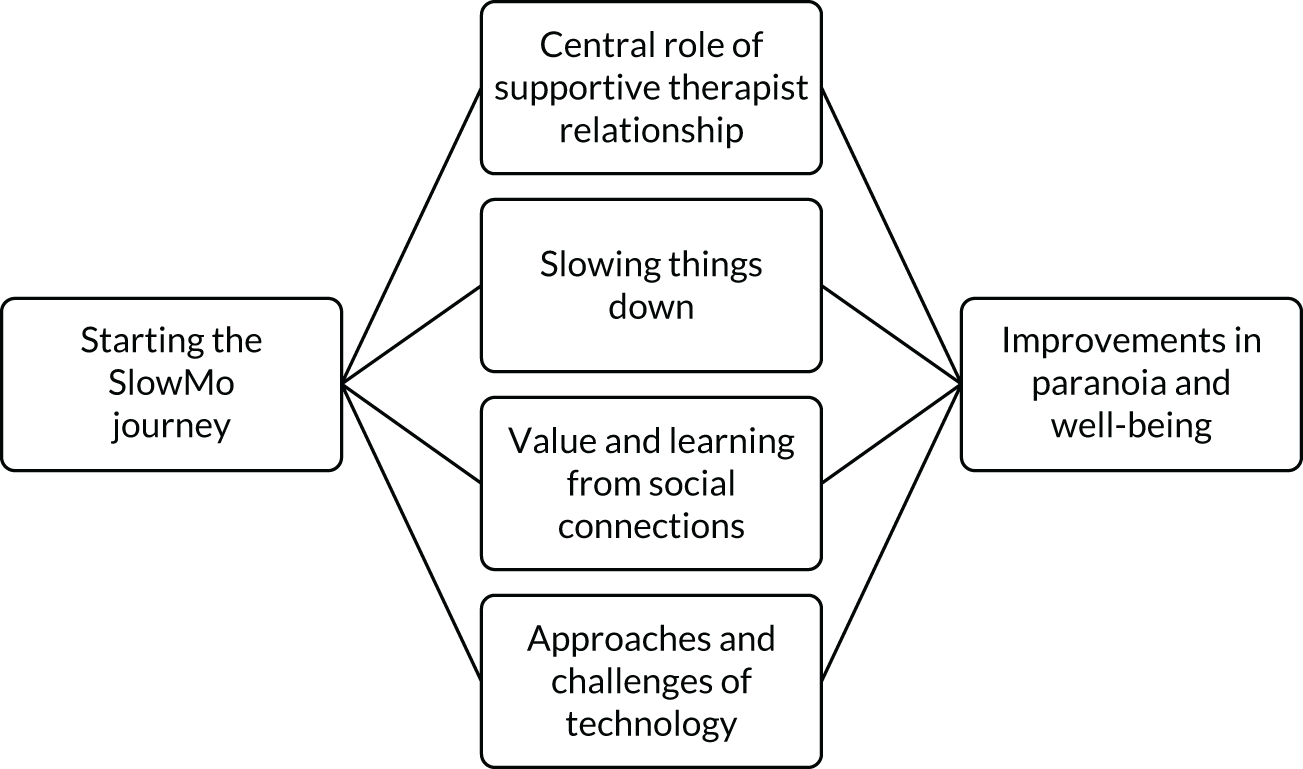

A central focus of developing SlowMo was to enhance the user experience of therapy to address implementation barriers. We used inclusive, human-centred design to create, to the best of our knowledge, the first blended digital therapy for paranoia, which sought to accommodate a diversity of needs. The impact of this on the service user’s experience is explored further in Chapter 3. We also worked with user research interviewers in a coproduction research model; this enabled us to evaluate the experience of participation in the trial and of therapy qualitatively, as reported in Chapter 4. We found that treatment effects were not moderated by baseline clinical or cognitive characteristics, or the presence of a carer. Thus, the SlowMo therapy design appears to be effective irrespective of these variations, something of crucial significance in relation to real-world implementation. Consistent with these findings, there was excellent uptake of face-to-face sessions and the mobile app. This suggests that the design achieved its aims of being trustworthy, enjoyable, memorable and easy to use. 7

A flexible approach to formulation aimed to ensure that the understanding of targeted processes (fast and slow thinking) was individualised and accessible. Out-of-clinic behavioural work modelled app use and promoted therapy generalisation. The mobile app enabled further personalisation of the therapy, using bubbles as visual metaphors to support learning, with step-by-step support to slow down in the moment, and immediate access to safer thoughts (that might otherwise be hindered by memory difficulties and threat-related arousal). The findings suggest that targeted CBT for psychosis, incorporating design and technology to improve people’s therapy experience and uptake, can facilitate a focus on the processes most likely to result in real-world change.

Conclusions

The SlowMo trial has demonstrated clinically worthwhile results, with consistent, sustained positive effects across a range of outcomes. These effects match or exceed those typically observed for standard CBT for psychosis, but were achieved in fewer sessions, which were accompanied by excellent engagement and retention, validating the therapy redesign. The results indicate that the treatment worked, in part, to help people to slow down their thinking, to be more flexible about their beliefs and to worry less, and was not moderated by baseline clinical severity, cognitive problems or the carer relationship. Further understanding of the mechanisms that mediate these improvements would be valuable. The trial results also argue for further implementation studies testing SlowMo’s real-world delivery within clinical pathways for persecutory delusions in a range of clinical settings.

Chapter 2 The impact of patient and public involvement in the SlowMo trial: reflections on peer innovation

Background

Definitions of patient and public involvement in research

The National Institute for Health Research INVOLVE guidance61 on patient and public involvement (PPI) defines PPI as ‘research being carried out “with” or “by” members of the public rather than “to”, “about” or “for” them’ (reproduced with permission from INVOLVE. 61 Copyright INVOLVE February 2012). Consultation is defined as one-off or regular advice that may or may not be acted on, whereas collaboration involves service users and researchers working in partnership with clearly agreed roles.

Theoretical rationale and influences

The theoretical rationale behind PPI in the SlowMo trial is the expectation of epistemic improvements in the rigour, relevance and reach (the three ‘Rs’) of the research. 62 Indeed, there is growing evidence of the impact of PPI on the processes and outcomes of mental health research through the increased reach of recruitment,63 the relevance of dissemination that involves service users,64,65 and the enhanced rigour, openness and honesty of responses when service user participants are interviewed by their peers. 66–68 The roles for PPI in the SlowMo trial were, thus, focused on support for recruitment, qualitative interview data collection and dissemination strategies. The identification of clear roles also served to minimise the risk of tokenism in the PPI contribution, wherein the absence of specific aims for PPI aims leads to a self-fulfilling prophecy of failure to demonstrate value and impact. 69

Consistent with the epistemic framework for PPI, the study incorporated a consideration of these three Rs on the impact of PPI; the PPI outcomes are reported in this paper with reference to the Guidance for Reporting Involvement of Patients and the Public 2 (GRIPP-2) reporting checklist for PPI in research. 70 This approach was influenced by the previous experiences of the PPI lead (KG) in collaborating with experts by experience, peer researchers and consultants,71,72 and by the research team’s interaction with service users in the development of the intervention and subsequent grant application (as outlined in Chapter 3 and elsewhere7).

Conceptual models and influences