Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 11/100/76. The contractual start date was in December 2012. The final report began editorial review in September 2019 and was accepted for publication in May 2020. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2022. This work was produced by Humby et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health and Care Research, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2022 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parts of this report are reproduced or adapted with permission from Rivellese et al. 1 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic autoimmune disease characterised by synovitis and joint damage that results in considerable morbidity and an increased mortality. 2 Although biological therapies have transformed the outlook for RA patients, the lack of any meaningful response to treatment in approximately 40% of patients, the potential side effects and the high cost of these drugs means that there is a need to define predictive markers of response and stratify patients according to therapeutic outcome. 3

B cells are pivotal to RA pathogenesis, driving synovial inflammation through the production of local disease-specific autoantibodies,4 the secretion of pro-inflammatory and osteoclastogenic cytokines,5 and acting as antigen-presenting cells. The pivotal role of B cells is also confirmed by the efficacy of the B-cell-depleting agent, rituximab (MabThera, F. Hoffman La-Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). 6 Rituximab is licensed for use in RA following failure of conventional synthetic disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs (csDMARDs) and tumour necrosis factor inhibitor (TNFi) therapy. However, in this more therapy-resistant patient cohort, clinical response to rituximab is heterogeneous, with only 30% of patients achieving a 50% improvement in the American College of Rheumatology (ACR) response criteria at 6 months. 7

Given the mechanism of action of rituximab, it could be hypothesised that the analysis of pre- or post-treatment circulating B-cell numbers could be used to predict treatment response. However, post hoc analyses of several randomised controlled trials (RCTs) have shown that the numbers of pretreatment peripheral B cells or the depth of their depletion, as measured by conventional flow cytometry, are not associated with clinical outcome. 6–14 In contrast to the complete depletion of peripheral blood B cells, variable depletion of B cells and other immune cells in synovia following treatment with rituximab has been described. 15–23 In particular, the number of pretreatment synovial CD79a+ B cells,15,19 the pretreatment synovial molecular signatures22 and a reduction in synovial plasma cells17 have been identified as factors associated with response to rituximab. However, the small number of patients analysed and the use of different time points make it difficult to draw conclusions about the association of synovial B-cell signatures with treatment response to rituximab.

We have recently demonstrated synovial heterogeneity in patients with early RA,24 with ≥ 50% of patients showing low/absent synovial B-cell infiltration and defined synovial cellular and molecular markers predictive of prognosis and therapeutic response to csDMARDs. Given that these patients presented with high levels of disease activity, it can be plausibly reasoned that synovial inflammation in their joints is driven by alternative cell types. This prompted us to test the hypothesis that, in patients lacking significant synovial B-cell infiltration, an alternative biological agent to rituximab that targets different biological pathways [e.g. interleukin 6 (IL-6)], inhibited by a specific biological agent [tocilizumab (RoActemra, F. Hoffman La-Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland)], may be more effective. We report results from the first pathobiology-driven, multicentre randomised controlled trial (RCT) in RA [R4-RA (A Randomised, open-labelled study in anti-TNFalpha inadequate responders to investigate the mechanisms for Response, Resistance to Rituximab versus Tocilizumab in Rheumatoid Arthritis patients)] that evaluated whether or not patient stratification according to synovial B-cell-rich/poor status enriches for response/non-response to rituximab.

Chapter 2 Methods

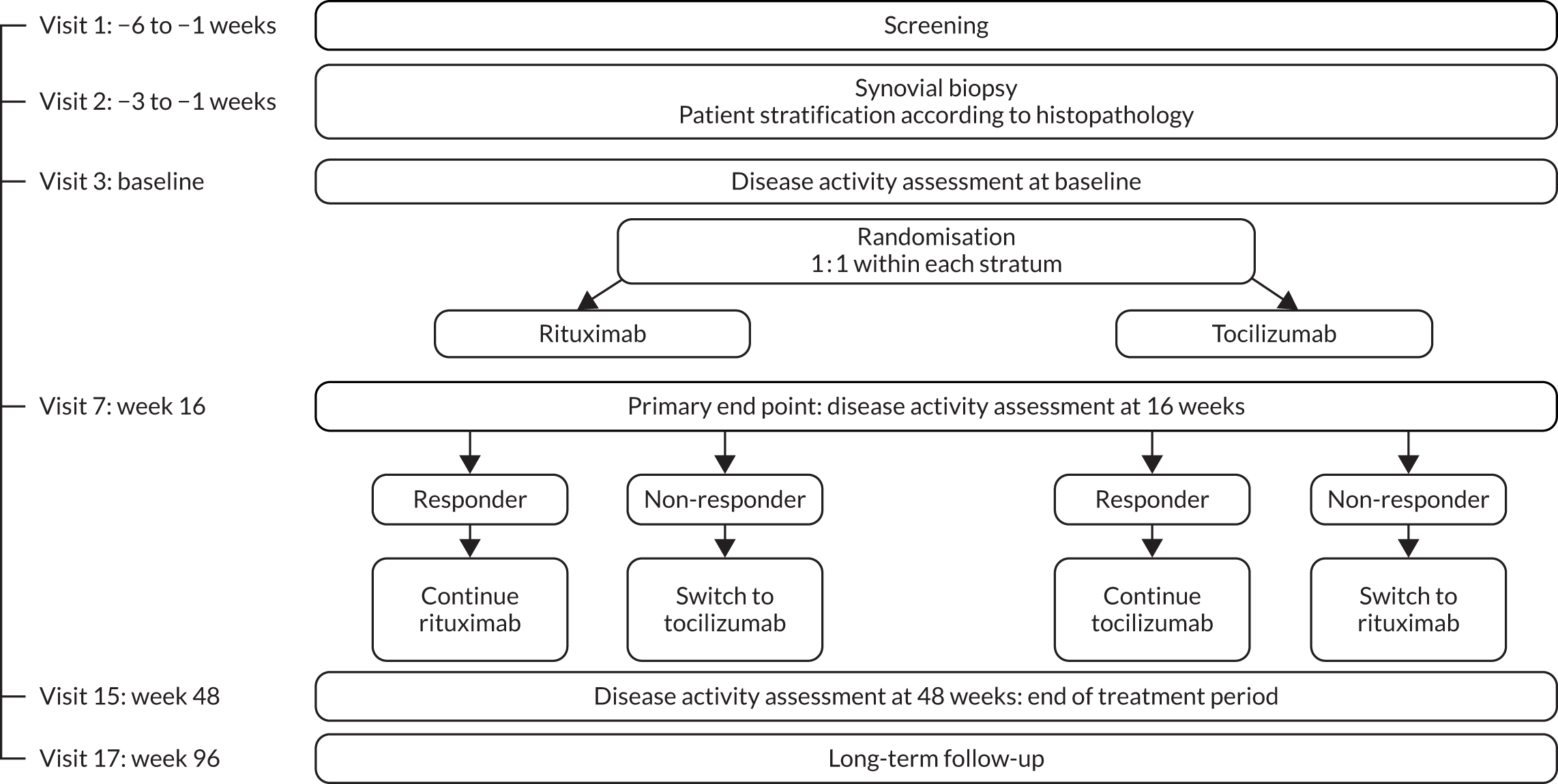

Trial design

We conducted a Phase IV, open-label RCT in 19 European centres. Given that ultrasound-guided biopsy is not part of routine care and that patients are not familiar with the biopsy procedure, multiple centres were required because of the relatively small number of RA patients presenting with TNFi-resistant RA25 at each centre. The study was conducted in compliance with the Declaration of Helsinki,26 International Conference on Harmonisation Guidelines for Good Clinical Practice,27 and local country regulations. The final protocol, amendments and documentation of consent were approved by the institutional review board of each study centre and relevant independent ethics committees. The trial was supported by an unrestricted grant from the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR). The study protocol is available at www.r4ra-nihr.whri.qmul.ac.uk (accessed 12 October 2020).

Participants

Patients aged ≥ 18 years fulfilling the 2010 ACR/European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) classification criteria for RA28 who were eligible for treatment with rituximab therapy in accordance with UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidelines [i.e. failing or intolerant to csDMARD therapy and at least one biological therapy, excluding trial investigational medicinal products (IMPs)]29 were eligible for recruitment to the study and identified through rheumatology outpatient clinics at each study site. A complete list of the inclusion and exclusion criteria is provided in Appendix 1, Table 5. All patients provided written informed consent.

Several updates to the eligibility criteria were made during the trial. This was to provide further clarification to investigators rather than to amend the patient population to be included in the trial. Substantial amendment no. 3 involved the addition of the exclusion criterion ‘Prior exposure to rituximab or tocilizumab for the treatment of RA and oral prednisolone more than 10 mg per day or equivalent ≤ 4 weeks prior to biopsy visit’ (previously specified elsewhere in the protocol, but not in the exclusion criteria), and minor amendments to several other exclusion criteria already listed. Substantial amendment no. 6 specified that a hepatitis B screening test must be performed at or in the 3 months preceding the screening visit. Substantial amendment no. 9 specified that participants must be ≥ 18 years of age (previously stated ‘over 18 years of age’). The exclusion criteria were also updated to provide further clarification (changes shown in italics): ‘History of or current primary inflammatory joint disease, or primary rheumatological autoimmune disease other than RA (if secondary to RA, then the patient is still eligible)’; ‘Known HIV [human immunodeficiency virus] or active hepatitis B/C infection. Hepatitis B screening test must be performed at or in the preceding 3 months of screening visit’; ‘Patients unable to tolerate synovial biopsy or in whom this is contraindicated including patients on anti-coagulants (oral anti-platelet agents are permitted)’.

Interventions

Synovial biopsy, histological and molecular classification/analyses

Patients underwent a synovial biopsy of a clinically active joint at entry to the trial, which was performed according to the expertise of the local centre either as an ultrasound-guided or as an arthroscopic procedure, as previously described. 30

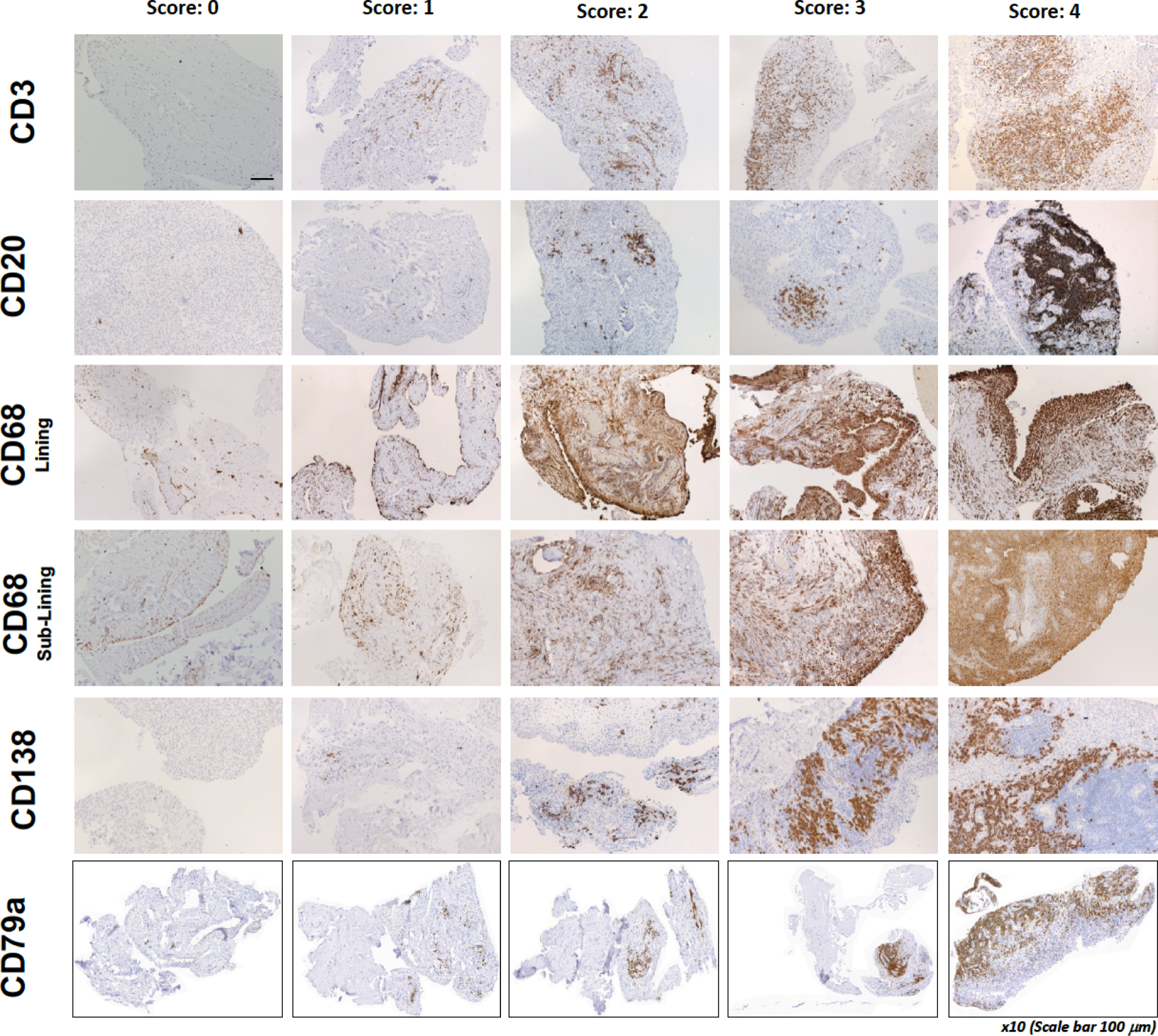

Histological classification/analysis

For the histological analysis, a minimum of six synovial biopsies were paraffin-embedded en masse by the Core Pathology Department at Queen Mary University of London (QMUL) . Tissue sections that were 3–5 µm thick were stained with haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) for immunohistochemical markers CD20 (B cells), CD3 (T cells), CD138 (plasma cells), CD21 [follicular dendritic cells (FDCs)] and CD68 (macrophages) in an automated Ventana Autostainer machine (F. Hoffman La-Roche Ltd, Basel, Switzerland). CD79a (B cells) and CD3 (T cell) staining was performed on deparaffinised tissue after antigen retrieval (30 minutes at 95°C) followed by peroxidase and protein blocking steps. The primary antibodies CD79a clone JCB117 (Dako, Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) or CD3 clone (F7.238, Dako) were used at a dilution factor of 1 : 50 or 1 : 80 for 60 minutes at room temperature. Visualisation of antibody binding was achieved by a 30-minute incubation with Dako EnVision™+ before completion by the addition of 3,3′-diaminobenzidine (DAB+) for 10 seconds. Slides were counterstained with haematoxylin.

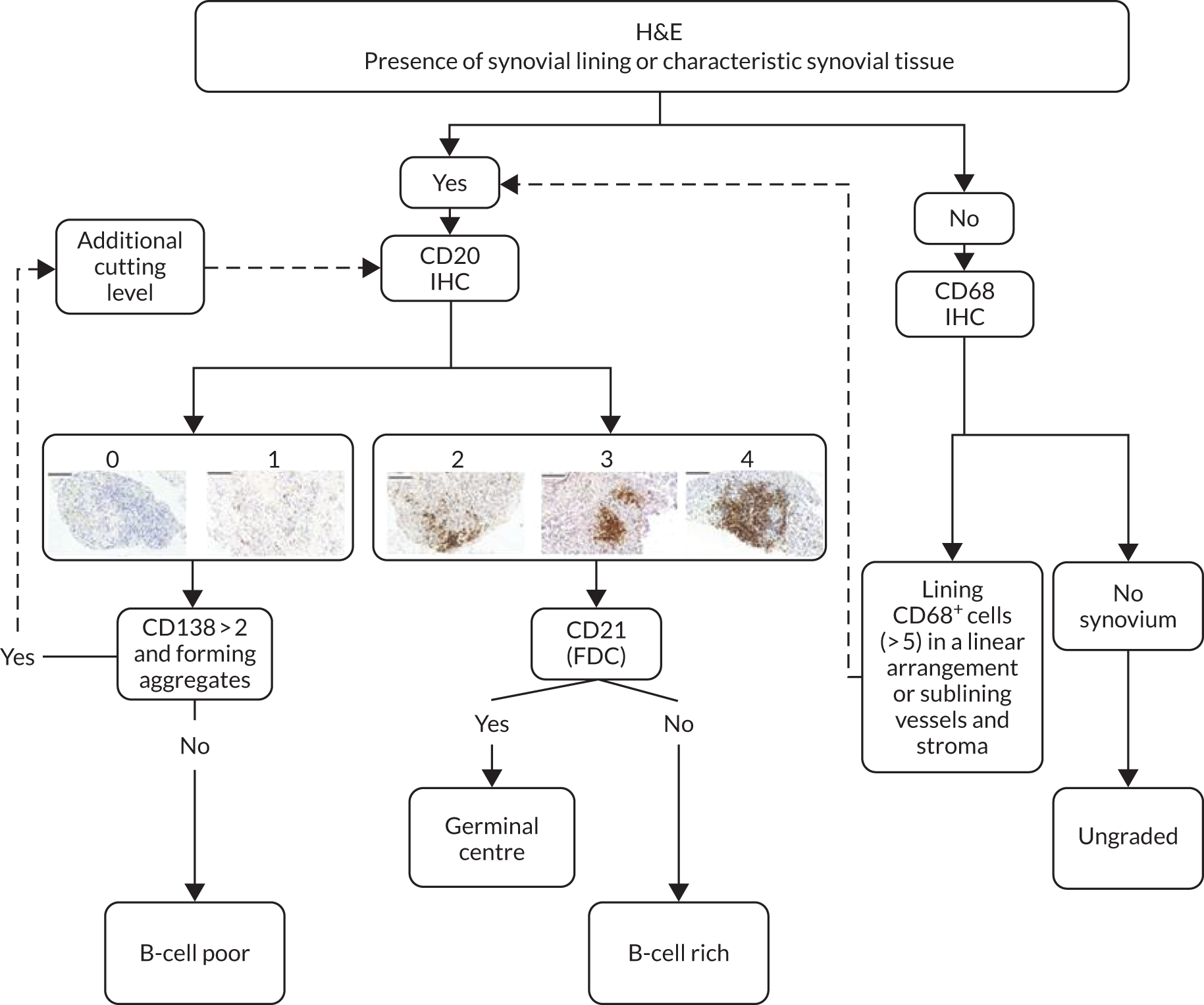

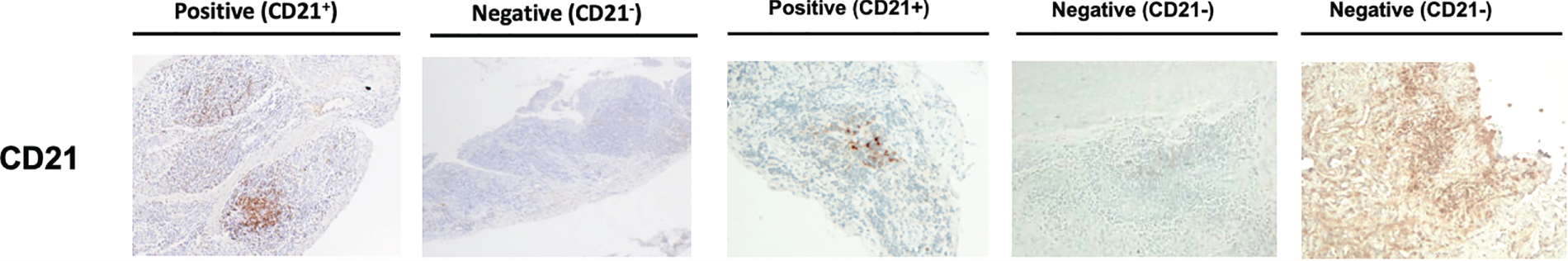

Following immunohistochemical staining, sections underwent semiquantitative scoring (0–4) to determine the levels of CD20+ and CD79a+ B cells, CD3+ T cells, CD138+ plasma cells and CD68+ lining (L) and sublining (SL) macrophages (see Appendix 1, Figure 6) adapted from a previously described score. 15,31–33 The CD20+ B-cell score was validated against digital image analysis (DIA) and the transcript levels were determined using the gene set derived from the Functional ANnoTation Of the Mammalian genome (FANTOM5) project. 34,35 Haematoxylin- and eosin-stained slides also underwent evaluation to determine the level of synovitis. 36 If CD20+ cells were identified, staining for CD21 was also performed. 4 Patients were then classified as B-cell rich or B-cell poor if definite synovial tissue could be identified (see Appendix 1, Figure 7) in the NHS pathology laboratory of Barts Health NHS Trust by a consultant pathologist (HR). In addition, synovial tissue underwent independent histological classification in the research laboratories of QMUL by a second expert in synovial pathology (GT), and any discrepancies in classification were resolved through mutual agreement. The B-cell status of patients in whom definite synovial tissue could not be identified was classified as ‘unknown’. Patients were classified as B-cell rich or B-cell poor according to a semiquantitative score: patients with a CD20 score of ≥ 2 and with CD20+ B-cell aggregates were classified as B-cell rich whereas those with a CD20 score of < 2 were classified as B-cell poor. 19 The score was validated against DIA and the transcript levels were determined using the gene set derived from FANTOM5. 34,35 B-cell-rich samples were further classified as germinal centre (GC) positive if CD21+ FDC networks were subsequently identified (see Appendix1, Figure 8). Only patients classified as B-cell rich or B-cell poor were included in the primary analysis of the trial presented here, that is GC-positive patients or patients unclassifiable histologically were excluded from analysis, as predefined in the statistical analysis plan.

Molecular classification/analysis

A minimum of six synovial samples per patient were immediately immersed in RNAlater (Invitrogen, Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, Massachusetts, USA) and ribonucleic acid (RNA) was extracted from synovial tissue using one of two protocols: either using phenol–chloroform isolation or via a Zymo Direct-zol™ RNA MicroPrep – total RNA/miRNA extraction kit (Zymo Research, Irvine, CA, USA). In both methods, tissue was lysed in Trizol solution (Thermo Fisher Scientific) using a LabGen125 homogeniser (Cole Parmer Instrument Co. Ltd, Saint Neots, UK). Briefly, for the phenol–chloroform extraction method, 1–10 mg of tissue was lysed and sheared using a 21-gauge needle. The tissue lysate was then mixed vigorously with chloroform before centrifugation. The aqueous phase was removed and mixed with ice-cold isopropanol for 30 minutes. After further centrifugation, the RNA pellet was washed in 70% ethanol before air drying and resuspending in ribonuclease (RNase)-free water. Extraction of samples using Zymo Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep – total RNA/miRNA extraction kits was carried out in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. Briefly, 1–10 mg of tissue lysate was run through the Zymo-Spin™ ion chromatography column. Columns were then washed using the appropriate kit wash buffers before RNA was eluted and resuspended in RNase-free water. Quality control was carried out by quantifying samples by spectrophotometer readings on a NanoDrop ND2000C (Thermo Fisher). RNA integrity was measured using Pico chip (Agilent, Santa Clara, CA, USA) technology on a 2100 Bioanalyzer (Agilent) to determine a RNA integrity number (RIN). All RNA samples were sent to Genewiz UK Ltd (Takeley, UK) for RNA sequencing (RNA-seq).

RNA sequence data processing

A total of 184 paired-end RNA-seq samples of 150 base pairs were trimmed to remove the Illumina (San Diego, CA, USA) adaptors using BBDuk from the BBMap package version 37.93 (https://jgi.doe.gov/data-and-tools/bbtools/bb-tools-user-guide/bbmap-guide/; accessed 12 October 2020) using the default parameters. Transcripts were then quantified using Salmon version 0.13.137 (https://combine-lab.github.io/salmon; accessed 12 October 2020) and an index generated from the GENCODE release 29 transcriptome following the standard operating procedure. Tximport version 1.13.10 (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/tximport.html; accessed 12 October 2020) was used to aggregate the transcript-level expression data to genes, and counts were then subject to variance-stabilising transformation (VST) using the DESeq2 version 1.25.9 package (https://bioconductor.org/packages/release/bioc/html/DESeq2.html; accessed 12 October 2020). 38 One sample was removed as an outlier with the assistance of principal component analysis.

Bioinformatic analysis

Starting with the ‘length scaled tpm counts’ from tximport, the limma voom method39 was followed to normalise the data and calculate the weights for linear modelling. For the linear mixed modelling, limma was used, using the ‘duplicate Correlation’ function method, in which patient ID is fitted as a random effect to take into account added correlation between the repeated measurements on an individual patient. For gene-set-level analysis using the B-cell module or IL-6 pathway, we used the limma ‘fry’ function.

Synovial tissue from 162 patients was available for RNA extraction and was subsequently sent for RNA-seq analysis. Patients classified histologically as GC+ (n = 9) were excluded from subsequent analyses. Of the remaining 153 patients, one patient was withdrawn before the IMP was administered and 28 were excluded following RNA-seq quality control or because of poor mapping. Therefore, 124 patients had RNA-seq data available for subsequent analysis.

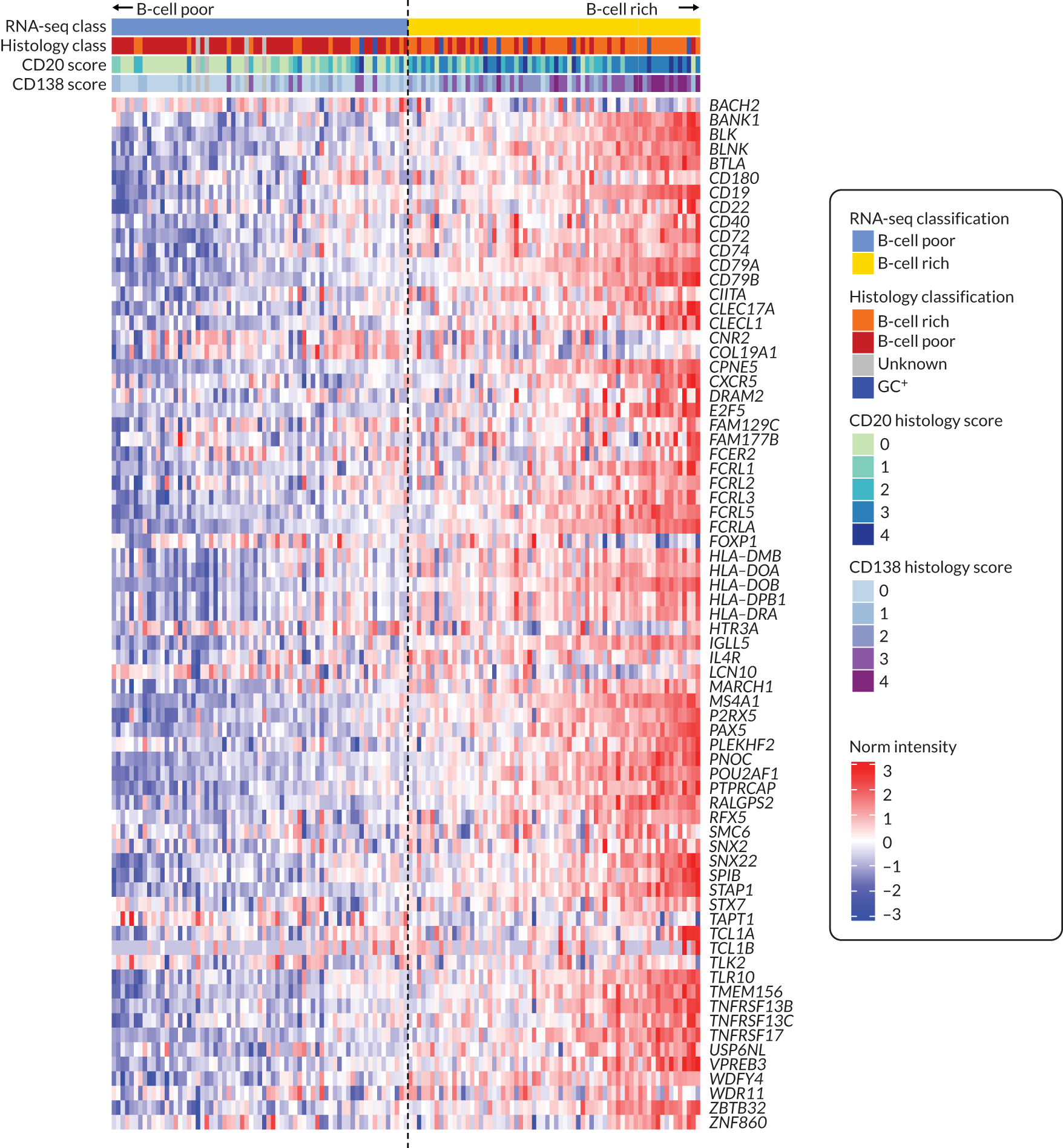

Patients were classified as B-cell poor/rich according to a previously developed B-cell-specific gene module derived from the analysis of FANTOM5 gene expression data,34 which was validated using RNA-seq of drug-naive early RA synovial biopsies. 40 In addition, this method was used to validate the histopathology score (see Histological classification/analysis),35 applied to a RNA-seq data set derived from the synovial biopsies. Given that no predetermined cut-off points for B-cell transcript classification were found in the literature, and to avoid potential bias, patients were classified as B-cell poor/rich according to the median transcript module value (see Appendix 1, Figure 9).

Randomisation and masking

Patients were randomised to receive rituximab or tocilizumab and were stratified into four blocks according to histological classification of their baseline synovial biopsy (i.e. B-cell poor, B-cell rich, GC+ or unknown) and by site (QMUL vs. all other sites). Patients were randomised within blocks (1 : 1), with random block size of six and four. The randomisation list was prepared by the trial statistician and securely embedded with the application code so that it was not accessible to end users. The randomisation result was sent electronically by the R4–RA trial office to all of the clinical trial staff at each site, except the named joint assessor (research nurse/assistant) who remained blinded to study drug allocation. Thus, determination of the primary outcome [improvement in the Clinical Disease Activity Index (CDAI) of ≥ 50% from baseline] and secondary outcomes, including joint counts, was performed by a joint assessor blinded to study drug allocation. Clinical trial staff remained blinded to histological subtypes throughout the study.

Trial procedures

Following synovial biopsy and subsequent randomisation, either rituximab as two 1000-mg infusions at an interval of 2 weeks or tocilizumab infused at a dose of 8 mg/kg at 4-weekly intervals was administered at baseline. Throughout the 48-week trial treatment period, patients were followed up every 4 weeks, at which point RA disease activity measurements and safety data were collected (see Appendix 1, Figure 10). An optional repeat synovial biopsy of the same joint that was sampled at baseline was carried out at 16 weeks, with the histological analyses described above repeated.

Outcomes

The study was powered to test the superiority of tocilizumab over rituximab at 16 weeks in the B-cell-poor population. The primary end point was defined as an improvement in the CDAI score41 of ≥ 50% from baseline.

Secondary outcomes included the B-cell-rich assessment of CDAI response (as defined for primary outcome analysis) at 16 weeks, where the efficacy of rituximab compared to tocilizumab was evaluated.

Patients deemed to be responders at 16 weeks continued with their allocated treatment, and rituximab infusions were repeated at 24 weeks. Non-responders were defined, as per the primary end point, as not reaching an improvement in the CDAI score of ≥ 50% from baseline. In addition, as prespecified in the protocol, patients were considered to be non-responders if they did not achieve an improvement in the CDAI score of ≥ 50% and a CDAI score of < 10.1, which is defined from now on for simplicity as CDAI-major treatment response (CDAI-MTR). Non-responders were switched to the alternative biological therapy (switch patients) and treatment response to the switched therapy was determined at 16 weeks post switch.

The primary efficacy analysis evaluated the number of patients achieving the primary end point (improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%). Supplementary efficacy analysis included evaluating the number of B-cell-rich and B-cell-poor patients (classified according to the molecular methodology; see Histological and molecular classification/analyses and Synovial biopsy) achieving CDAI score of ≥ 50% improvement and CDAI-MTR). Additional secondary efficacy analyses of the following parameters were performed at week 16 in the B-cell-rich and B-cell-poor populations separately, with and without week 16 switch patients: mean improvement in Disease Activity Score in 28 joints (DAS28); C-reactive protein (CRP) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR); number of patients in remission (DAS28 of < 2.6) and with low disease activity (DAS28 of < 3.2); and percentage of patients with low disease activity (CDAI score of < 10.1). Other key secondary end points, such as rate of DAS28 CRP ESR, low disease activity and remission (at time points other than week 16), and patient-reported outcomes, such as fatigue, are defined in Appendix 1, Table 6. Additional exploratory analyses included evaluation of B-cell molecular signatures of response to rituximab and tocilizumab.

The incidence and severity of all adverse events were recorded. The incidence and severity of treatment and procedure emergent adverse events were monitored throughout the study; adverse event coding was carried out in accordance with Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 22 (www.meddra.org; accessed 12 October 2020).

Sample size

A sample size of 82 B-cell-poor patients was planned to provide 90% power to detect a 35% difference in the proportion of patients who had a response (assuming 55% response in the tocilizumab group and 20% response in the rituximab group). The assumed proportions of B-cell-poor, B-cell-rich and GC+ recruited patients were 60%, 35% and 5%, respectively. After accounting for 10% ungradable biopsy samples and a 5% dropout rate, we estimated that a total of 160 patients were required to achieve 90% power for the study. No power calculation was conducted on the B-cell-rich population.

Statistical analyses

The primary end point and other binary end points were analysed using a two-sided chi-squared test or, where appropriate, a Fisher’s exact test with an alpha of 0.05. For each continuous secondary outcome, an analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) was performed on the score change from baseline, with treatment as factor and baseline score as covariate, to analyse the difference between treatment groups. If the residuals of the model were not normally distributed (normality was tested using the Shapiro–Wilk test), the data were log-transformed before the analysis and the estimates were back transformed or analysed through non-parametric ANCOVA. Changes from baseline in the groups were analysed by a paired Wilcoxon signed-rank test. As an additional secondary measure, the area under the curve (AUC) of mean change in DAS28 (ESR/CRP) was calculated for each individual as a function of time. A generalised linear mixed model (GLMM) with treatment as a fixed effect and baseline DAS28 as a covariate was run to test the treatment effect. Although we did not power the study on the B-cell-rich group, we tested non-inferiority of rituximab to tocilizumab in such patients with a 0.2 margin on the relative risk of response as a supplementary analysis.

The analysis of the interaction between treatments and pathotypes (B-cell poor and B-cell rich, excluding GC) was conducted using the likelihood ratio test between two nested logistic regression models: one with pathotype and treatment as covariates and the other with pathotype, treatment and their interaction as covariates. For all of the binary and continuous outcomes, separate analyses were computed for B-cell-poor and B-cell-rich subpopulations.

All efficacy analyses were carried out in the intention-to-treat (ITT) population and then on the per-protocol (PP) population to assess the robustness of the results. The PP population included all subjects from the ITT population who did not have any major protocol violations. The list of deviations that exclude a subject from the PP population was reviewed at a classification meeting prior to data lock and is documented in the trial master file. Safety analyses were carried out on the safety analysis set (by ITT, including only participants who received at least one dose of the trial medication), in which patients were analysed according to their actual treatment in case this differed from the scheduled treatment (i.e. randomised or switched). A separate analysis was conducted on patients who switched treatment at week 7 or 8 (either from rituximab to tocilizumab or from tocilizumab to rituximab) to test the treatment effect through a chi-squared/Fisher’s exact test. All statistical analyses were carried using R, version 3.5.1 (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The trial was registered on the International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number (ISRCTN) database (as ISRCTN97443826). An independent Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee met on a 6-monthly basis during the trial to review the accruing trial data and assess whether or not there were any safety issues, and to make recommendations to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC).

Handling of missing data

Missing values for the primary outcome were considered separately from other variables. The CDAI response at visit 8 was used as the primary outcome for five patients who did not attend visit 7, and the CDAI response at visit 6 was used as the primary outcome for one patient who withdrew from the study at visit 6. Primary end-point data that were missing under other circumstances (for three patients) were imputed assuming that data were missing at random (MAR). The same assumption was used for missing data on the components for all secondary end points: ESR, CRP, swollen joint count, tender joint count, visual analogue scale (VAS) score, patient global assessment and physician global assessment. When applicable, the estimates were log-transformed or transformed to the squared root for the imputation and for use in secondary measures and then back-transformed for reporting. Missing values assumed to be MAR were imputed using multiple imputation by chained equations (MICE) and implemented using R package ‘Amelia’ 1.7.5. The imputation model included treatment, histological pathotype, delta CDAI, CDAI at visit 7, sex, ethnicity, age, body mass index (BMI) and blood pressure. Such imputation was run five times and the pooled results were used for the analysis. The performance of the imputation was examined through the convergence and marginal distributions, and no substantial issue was detected.

Chapter 3 Results

Patients and demographics

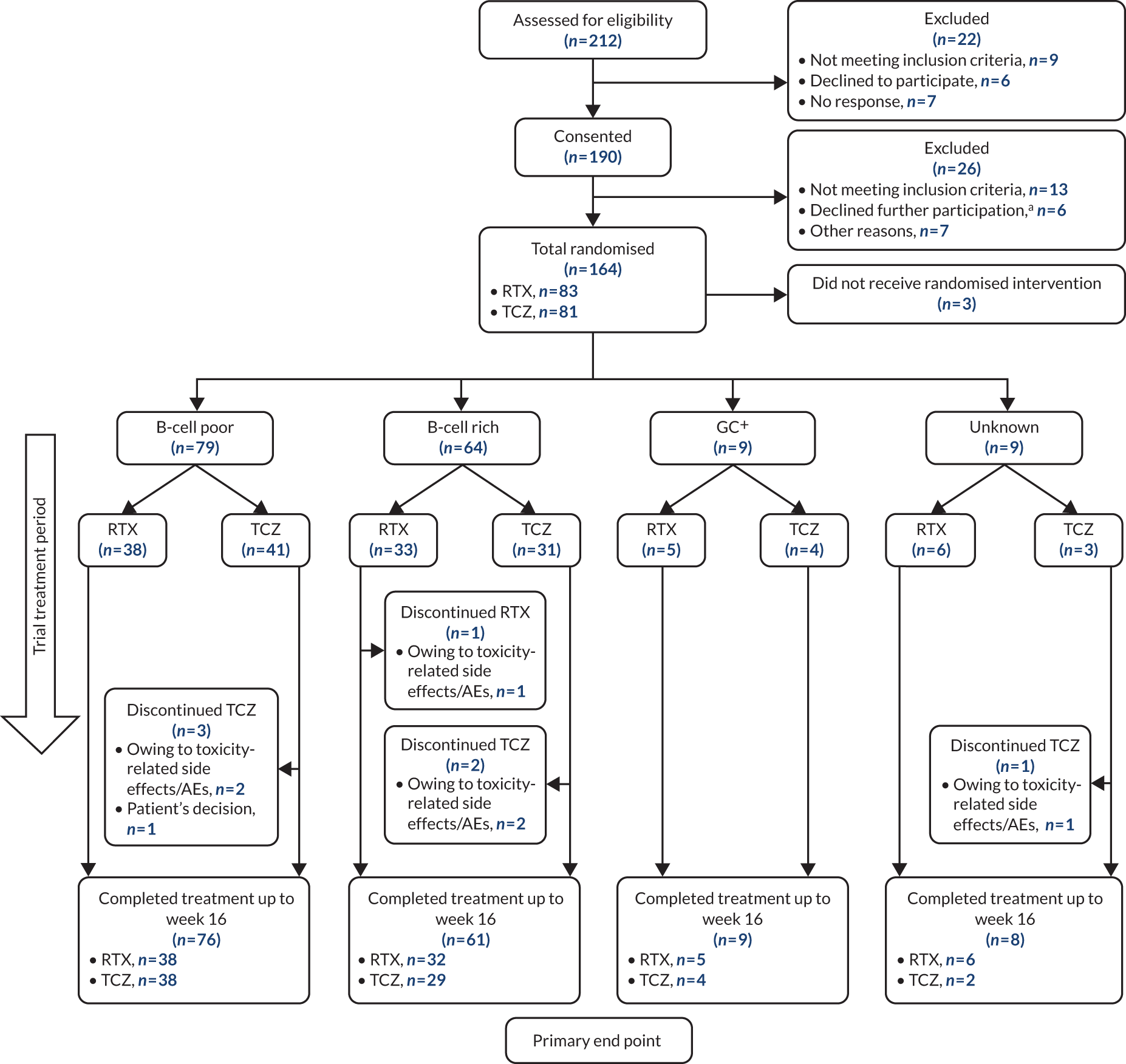

Patient disposition in a Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) format is shown in Figure 1: 212 patients were screened, 190 provided consent and 164 were randomised. The first patient visit was on 28 February 2013 and the last patient visit was on 17 January 2019. The trial ended because recruitment targets were reached. A total of 83 patients were randomised to receive treatment with rituximab and 81 with tocilizumab. In total, 161 patients received the IMP (rituximab, n = 82; tocilizumab, n = 79), of whom 99% (81/82) and 92% (73/79) of patients, respectively, completed treatment to the primary end point at week 16 (see Figure 1). The largest proportion of patients (38%, 62/164) was recruited at Barts Health NHS Trust (see Appendix 1, Table 7). Patient disposition from week 16 to week 48 is summarised in Appendix 1, Figure 11 (B-cell-poor group), and Appendix 1, Figure 12 (B-cell-rich group).

FIGURE 1.

Patient disposition to week 16 (primary end point). a, Owing to biopsy. AE, adverse event; RTX, rituximab; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Baseline characteristics, disease activity and histological groups were balanced across the treatment groups (Table 1 and see Appendix 1, Table 8). Most patients were female (80%) and the majority were seropositive for rheumatoid factor (RF) (74%) or anti-citrullinated peptide antibodies (ACPAs) (80%). The median disease duration was 9 years [interquartile range (IQR) 4–19 years]. Disease activity was high, with a mean DAS28(ESR) of 5.8 [standard deviation (SD) 1.2]. Almost half of the patients (49%, 79/161) were classified as B-cell poor, 40% (64/161) as B-cell rich, 6% (9/161) as GC+ and 6% (9/161) as unknown status.

| Patient characteristic | Total (N = 161) | Treatment group | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab (N = 82) | Tocilizumab (N = 79) | ||

| Pathotype, n (%) | |||

| B-cell poor | 79 (49) | 38 (46) | 41 (52) |

| B-cell rich | 64 (40) | 33 (40) | 31 (39) |

| GC+ | 9 (6) | 5 (6) | 4 (5) |

| Unknown | 9 (6) | 6 (7) | 3 (4) |

| Sex (female), n (%) | 128 (80) | 62 (76) | 66 (84) |

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 55.5 (47.4–65.3) | 55.7 (47.7–65.5) | 55.5 (47.3–65.1) |

| Disease duration (years), median (IQR) | 9 (4.0–19.0) | 10 (4.0–20.7) | 9 (4.0–18.0) |

| CDAI score, median (IQR) | 29.8 (21.7–40.6) | 30.6 (22.8–40.6) | 29.4 (21.5–40.3) |

| ESR (mm/hour), median (IQR) | 31.0 (17.0–48.0) | 34.5 (17.0–48.0) | 28.0 (18.5–46.5) |

| CRP (mg/l), median (IQR) | 11.0 (5.0–27.0) | 10.0 (5.0–23.0) | 15.0 (5.0–32.0) |

| RF/ACPA positive, n (%) | 140 (87) | 73 (89) | 67 (85) |

| RF positive, n (%) | 119 (74) | 64 (78) | 55 (70) |

| ACPA positive, n (%) | 128 (80) | 67 (82) | 61 (77) |

| Haemoglobin (g/l), median (IQR) | 123.0 (110.5–131.5) | 121.0 (109.0–131.0) | 123.0 (111.5–131.7) |

| Tender joint count (28), median (IQR) | 11.0 (6.0–18.0) | 10.5 (6.2–18.7) | 11.0 (6.0–16.0) |

| Swollen joint count (28), median (IQR) | 6.0 (3.0–10.0) | 6.00 (4.0–9.0) | 6.0 (3.0–10.5) |

| DAS28(ESR), mean (SD) | 5.81 (1.25) | 5.84 (1.19) | 5.78 (1.31) |

| DAS28(CRP), mean (SD) | 5.31 (1.20) | 5.30 (1.15) | 5.33 (1.26) |

| Ultrasound 12maxa score (PD), median (IQR) | 4.0 (1.0–9.0) | 4.0 (0.2–8.0) | 6.0 (1.5–10.0) |

| Ultrasound 12maxa score (ST), median (IQR) | 15.0 (11.5–22.0) | 16.0 (13.0–22.0) | 15.0 (10.0–20.2) |

| SHSS: total score, mean (IQR) | 8.50 (2.50–39.62) | 8.50 (2.50–39.62) | 9.25 (2.50–36.88) |

| SHSS: JSN score, mean (IQR) | 6.75 (1.12–29.62) | 6.25 (1.25–29.62) | 7.00 (1.38–29.00) |

| SHSS: ER score, median (IQR) | 1.50 (0.00–8.88) | 3.25 (0.12–8.88) | 0.75 (0.00–8.38) |

| SHSS: ER progressive (score of ≥ 1), n (%) | 45 (55) | 24 (63) | 21 (48) |

| Methotrexate, n (%) | 161 (100) | 82 (100) | 79 (100) |

| Prednisolone, n (%) | 90 (56) | 44 (54) | 46 (58) |

| Previous biologicals, n (%) [anti-TNF/other]b | |||

| 1 | 116 (72) [116/0] | 62 (76) [62/0] | 54 (68) [54/0] |

| 2 | 36 (22) [32/4] | 14 (17) [11/3] | 22 (28) [21/1] |

| 3+ | 9 (6) [5/4] | 6 (7) [3/3] | 3 (4) [2/1] |

Treatment response in the B-cell-poor population: 16 week outcomes

Histological classification

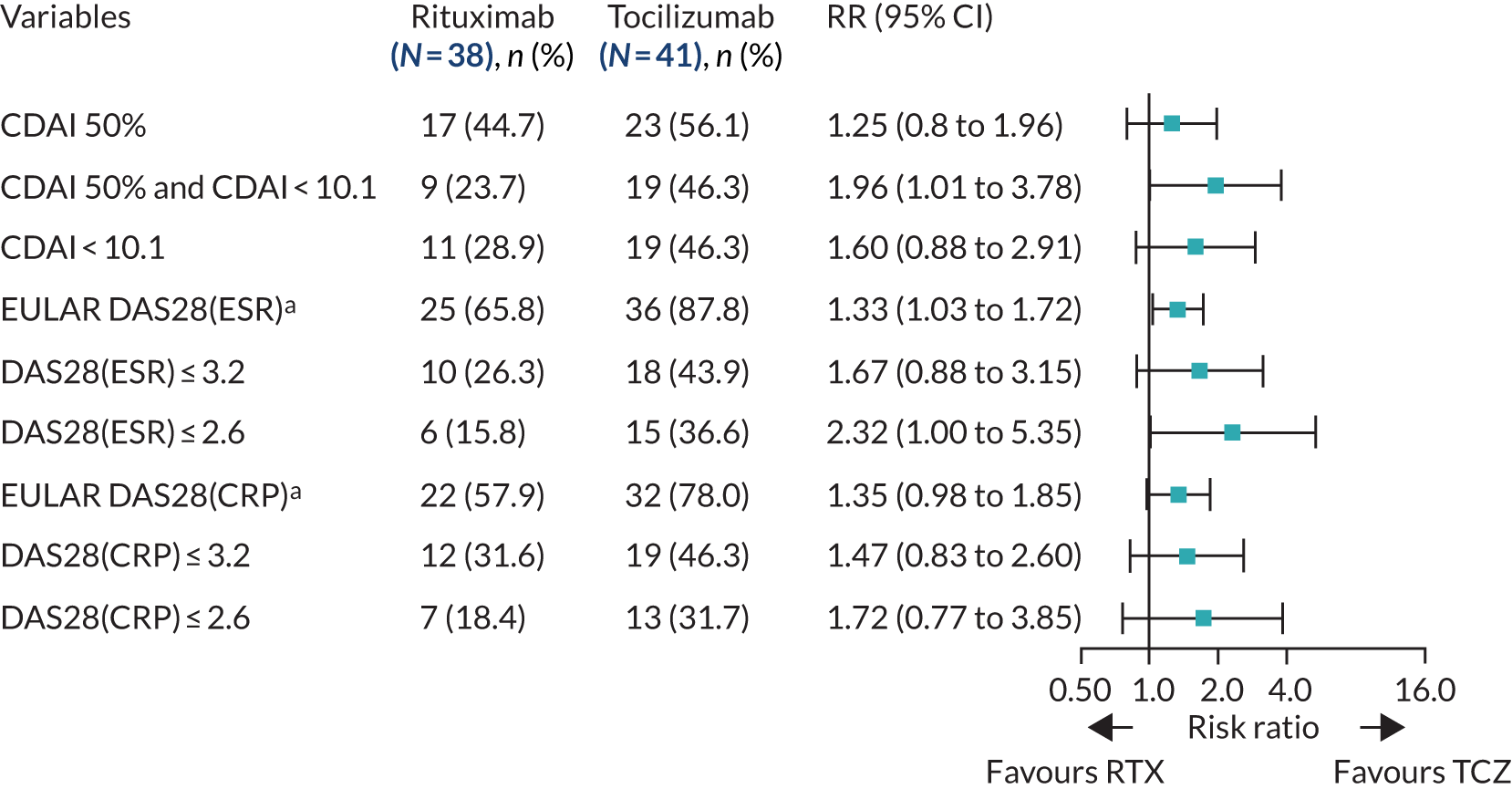

Almost half (49%, 79/161) of the patients who received the IMP were classified as B-cell poor histologically. Of these patients, 48% (38/79) were randomised to the rituximab group and 52% (41/79) were randomised to the tocilizumab group (see Figure 1). At 16 weeks, no significant difference between groups was observed in the primary outcome, the proportion of patients achieving an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% [risk ratio (RR) 1.25, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.8 to 1.96]. A supplementary analysis of CDAI-MTR, however, did reach statistical significance (RR 1.96, 95% CI 1.01 to 3.78). In addition, response rates were higher in the tocilizumab-treated patients on a number of secondary end points, including disease remission (CDAI score of < 10.1) (RR 1.6, 95% CI 0.88 to 2.91), DAS28(ESR) moderate/good EULAR response (RR 1.33, 95% CI 1.03 to 1.72), DAS28(ESR) low disease activity (RR 1.67, 95% CI 0.88 to 3.15), DAS28(ESR) remission (RR 2.32, 95% CI 1 to 5.35), DAS28(CRP) moderate/good EULAR response (RR 1.35, 95% CI 0.98 to 1.85), DAS28(CRP) low disease activity (RR 1.47, 95% CI 0.83 to 2.6) and DAS28(CRP) remission (RR 1.72, 95% CI 0.77 to 3.85) (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Primary and secondary efficacy end-point analyses: B-cell-poor population (histological classification). a, Moderate/good EULAR response. RTX, rituximab; TCZ, tocilizumab.

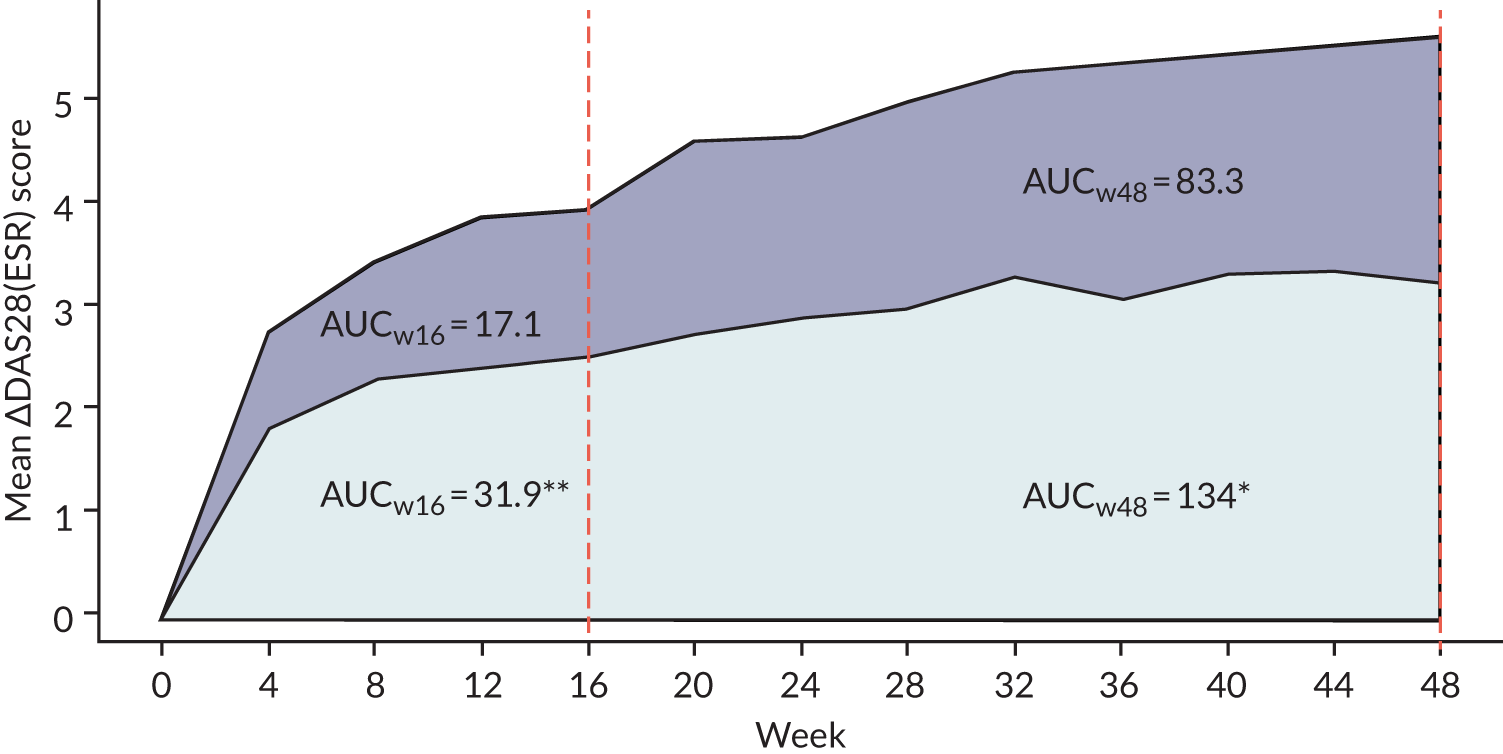

Other week 16 secondary end points also favoured tocilizumab, including greater decreases in DAS28(ESR/CRP) and CDAI score (see Appendix 1, Table 9). Quality-of-life (QoL) outcome measures [Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) and the Short Form questionnaire-36 items (SF-36) scores] also had higher levels of improvement between baseline and 16 weeks in tocilizumab-treated patients (see Appendix 1, Table 9). We observed little difference in ultrasound synovial thickness (ST) or power Doppler (PD) or Health Assessment Questionnaire (HAQ) scores between the IMP groups (see Appendix 1, Table 9). In addition, the AUC of mean change in DAS28(ESR/CRP) between baseline and 16 weeks was significantly greater in patients treated with tocilizumab than in those treated with rituximab (see Appendix 1, Figure 13).

Molecular classification

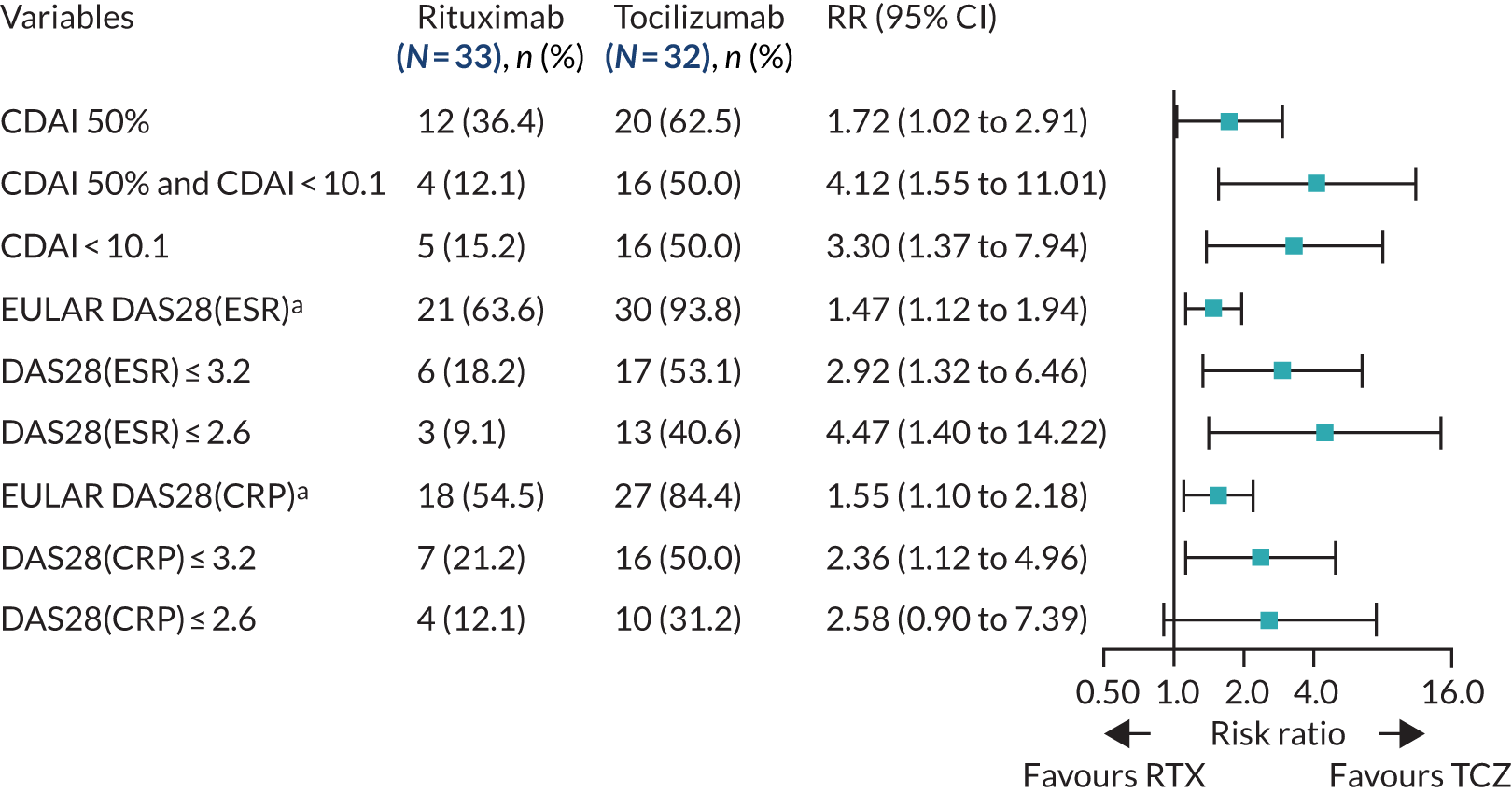

Using the median B-cell module value, 65 out of 124 patients were classified as B-cell poor. When clinical outcomes were compared between treatment groups in the group of patients categorised as B-cell poor according to RNA-seq, we observed a significantly higher response rate in the tocilizumab group than in the rituximab group, as determined by the number of patients achieving an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%, the primary outcome measure (RR 1.72, 95% CI 1.02 to 2.91), and CDAI-MTR (RR 4.12, 95% CI 1.55 to 11.01). A number of secondary outcomes, including EULAR DAS28(ESR/CRP) good/moderate response, DAS28(ESR/CRP) low disease activity (DSA28 ≤ 3.2) and DAS28(ESR) remission (DSAR ≤ 2.6) (Figure 3), also favoured tocilizumab. In addition, the decrease in CDAI and DAS28(ESR/CRP) between baseline and 16 weeks was greater in the tocilizumab group than in the rituximab group (see Appendix 1, Table 10), and there was a trend towards greater improvements in QoL measures [FACIT and SF-36 Mental Component Summary (MCS) and Physical Component Summary (PCS)] in tocilizumab-treated patients (see Appendix 1, Table 10).

FIGURE 3.

Primary and secondary efficacy end-point analyses: B-cell-poor population (molecular classification). a, Moderate/good EULAR response. RTX, rituximab; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Using the molecular classification, 28 patients were excluded following RNA-seq quality control, as explained in Chapter 2, Histological classification/analysis, Bioinformatic analysis. To understand whether the molecular classification identifies a subset of the histological B-cell-poor population or a different group, we also compared the two classification methods.

Of the 124 patients for whom RNA-seq data were available, four were ungraded by histology. Of the remaining 120 patients, the majority (96 patients, 80%) were classified in the same category by both histology and RNA-seq, whereas only 24 patients (20%) were mismatched. Out of these 24 mismatched patients, 14 histological B-cell-poor patients, those with a semiquantitative B-cell score of 0 or 1, were classified as B-cell rich by molecular analyses. On the other hand, 10 histological B-cell-rich patients, all with a semiquantitative B-cell score of 2, were classified as B-cell poor by molecular analyses. Importantly, all patients with a histological semiquantitative B-cell score of 3 or 4 were confirmed to be B-cell rich by molecular analysis, which clearly indicates the presence of a grey area in the histological classification, particularly around the cut-off point.

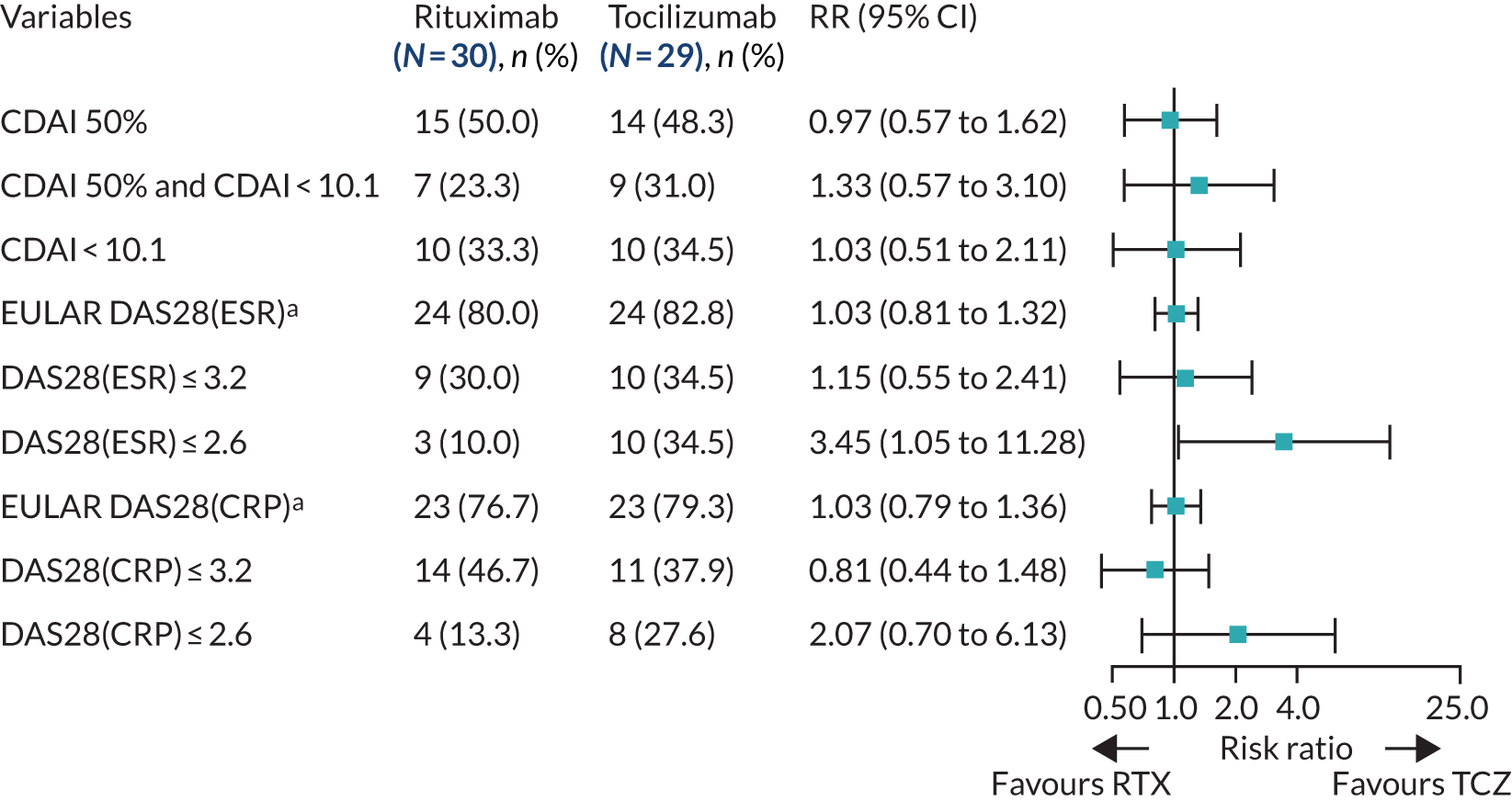

Treatment response in the B-cell-rich population: 16-week outcomes

Histological classification

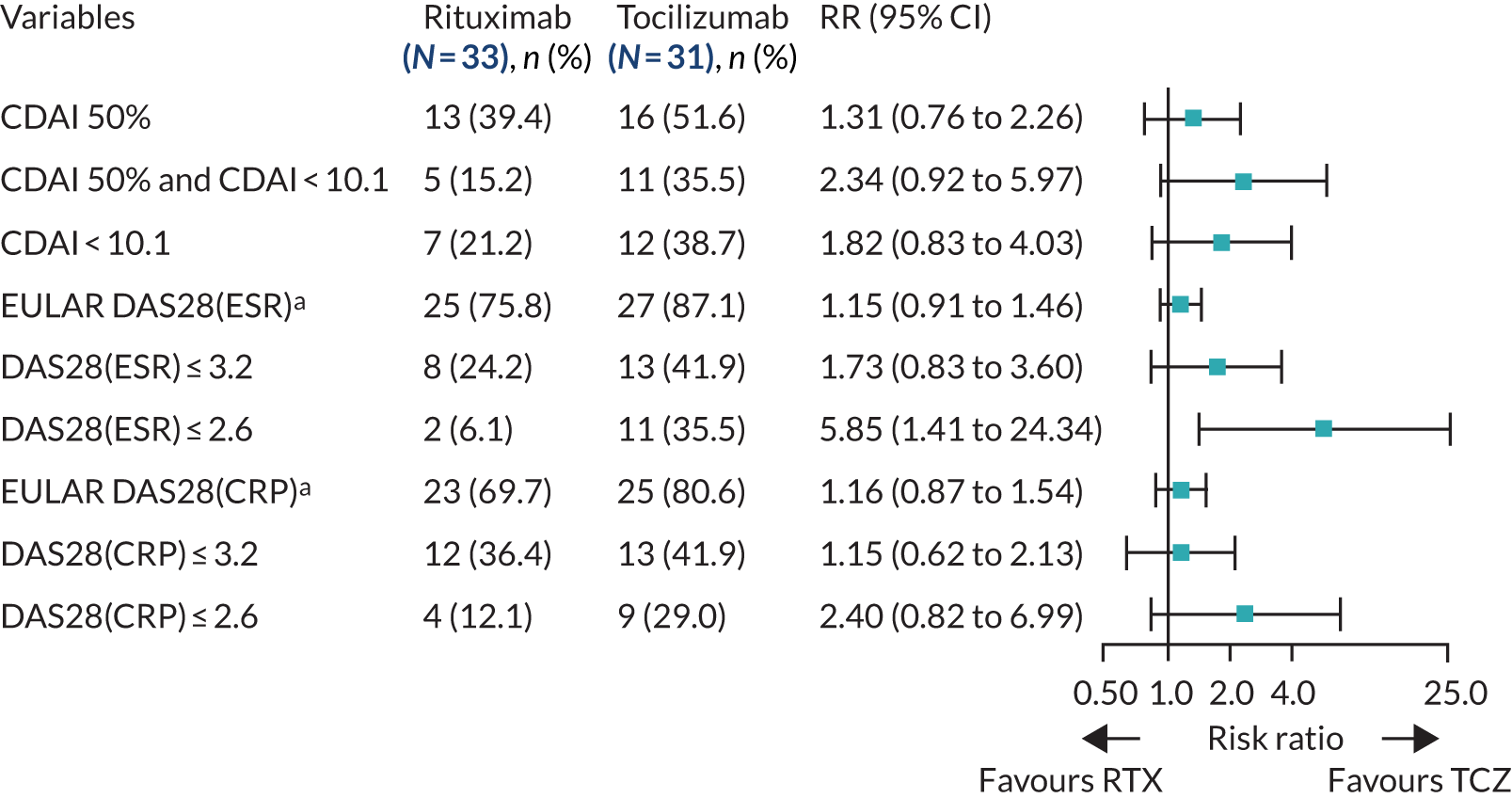

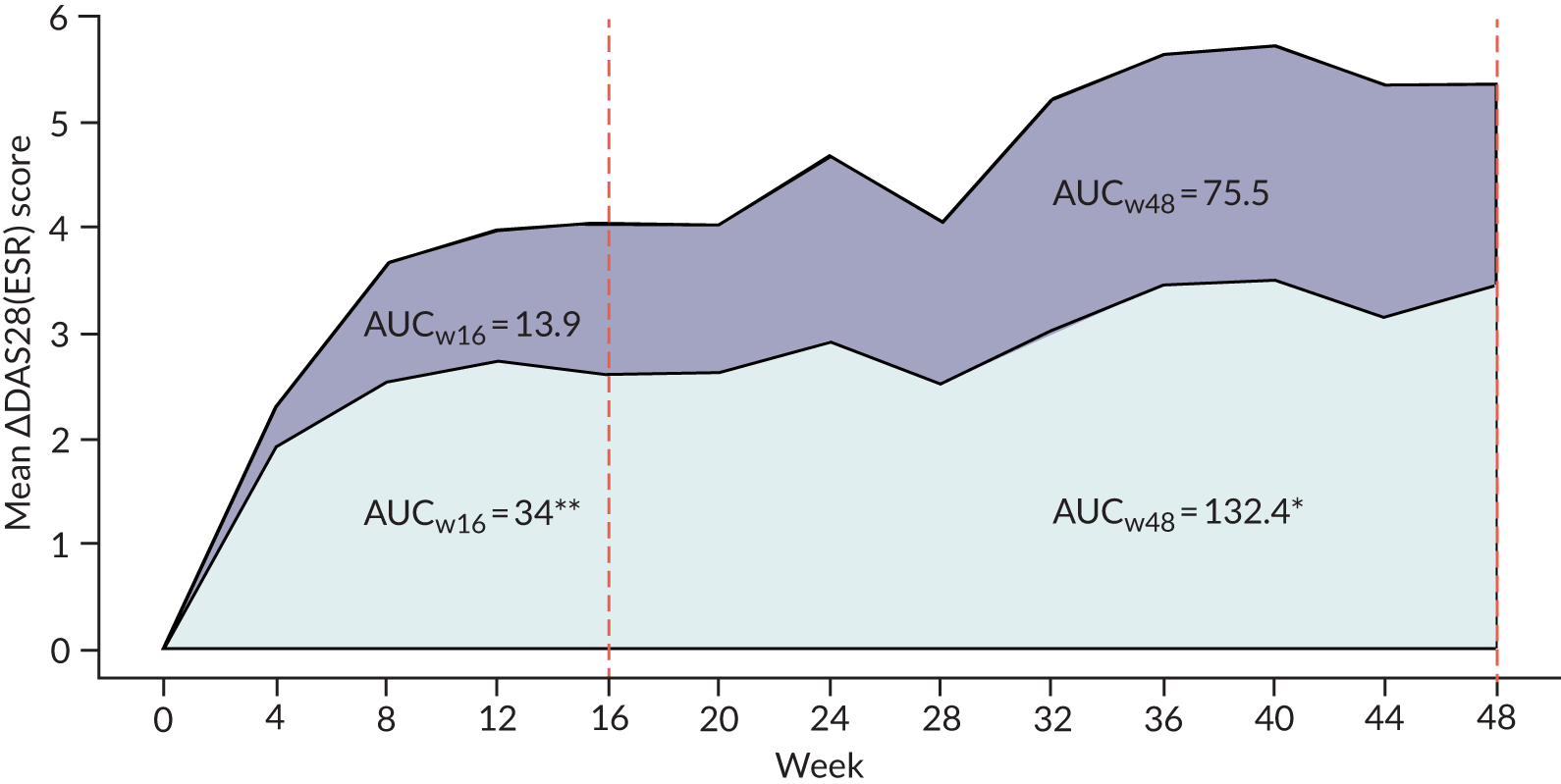

In total, 40% (64/161) of the patients who received an IMP were classified as B-cell rich, 52% (33/64) of whom were randomised to the rituximab group and 48% (31/64) to the tocilizumab group (see Figure 1). Although the study was not powered for the analysis of the B-cell-rich group week 16 response rates, we observed similar response rates for the majority of end points analysed, including the proportion of patients achieving an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% (RR 1.31, 95% CI 0.76 to 2.26) and CDAI-MTR (RR 2.34, 95% CI 0.92 to 5.97) (Figure 4). A number of additional secondary end points showed similar results, including larger decreases in DAS28(ESR/CRP) between baseline and 16 weeks in tocilizumab-treated patients than in rituximab-treated patients (see Appendix 1, Table 11). In comparison with the analysis in the B-cell-poor group, we saw minimal differences in QoL measures (FACIT and SF-36) between the rituximab- and tocilizumab-treated groups (see Appendix 1, Table 11). We also observed larger decreases in ultrasound ST and PD scores between baseline and 16 weeks in the tocilizumab-treated patients. As observed in the B-cell-poor subgroup, the AUC of mean change in DAS28(ESR/CRP) between baseline and 16 weeks was significantly greater in B-cell-rich patients treated with tocilizumab than in those treated with rituximab (see Appendix 1, Figure 14).

FIGURE 4.

Primary and secondary efficacy end-point analyses: B-cell-rich population (histological classification). a, Moderate/good EULAR response. RTX, rituximab; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Molecular classification

The 16-week outcomes were then evaluated between treatment groups in patients classified as B-cell rich according to RNA-seq classification criteria (n = 59). No significant difference between rituximab- and tocilizumab-treated patients was observed in the primary end point (improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%), and outcomes for the majority of the primary and secondary efficacy end points that were evaluated were generally similar in the rituximab- and tocilizumab-treated groups (Figure 5; see also Appendix 1, Table 12).

FIGURE 5.

Primary and secondary efficacy end-point analyses: B-cell-rich population (molecular classification). a, Moderate/good EULAR response. RTX, rituximab; TCZ, tocilizumab.

Interaction between treatment response and B-cell status

The likelihood ratio test was performed through logistic regression. No evidence of an interaction between the IMP and the histologically defined B-cell subgroups was observed for the primary end point (p = 0.95) or CDAI-MTR (p = 0.82). When testing the interaction between RNA-seq-defined B-cell subgroup and IMP, no significant interaction was observed for the primary end point (p = 0.096) but a significant interaction was observed for CDAI-MTR (p = 0.049). The study was not powered for this analysis, as it would require a larger number of patients.

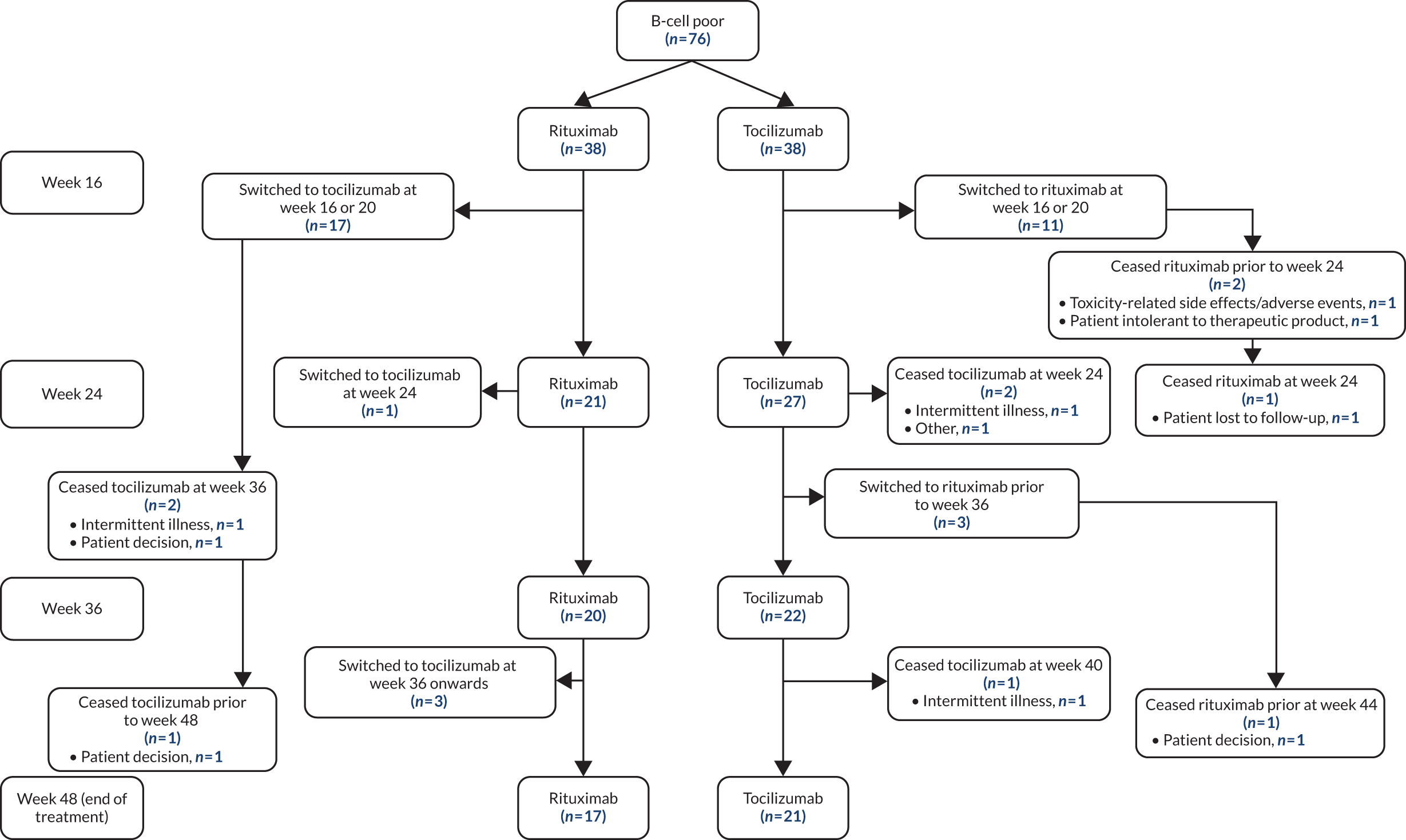

Treatment responses beyond 16 weeks: B-cell-poor population

Patients not reaching predetermined CDAI targets at 16 weeks and/or developing side effects to treatment at 16 weeks and beyond were switched to the alternative IMP (from rituximab to tocilizumab or from tocilizumab to rituximab) (see Appendix 1, Figure 10), as PP. Therefore, the number of patients continuing on the initial IMP decreased beyond 16 weeks (see Appendix 1, Figure 10): not because of patients dropping out but because of the PP treatment switch. At 24 weeks, 55% (21/38) of the B-cell-poor patients continued with rituximab and 65% (27/41) continued with tocilizumab. At 36 weeks, 53% (20/38) of patients continued with rituximab and 54% (22/41) continued with tocilizumab. At 48 weeks, 45% (17/38) of patients continued with rituximab and 51% (21/41) continued with tocilizumab (see Appendix 1, Figure 11 and Table 13). The analysis of secondary end points at 24, 36 and 48 weeks in the B-cell-poor population was consistent with the 16-week analysis, with response rates favouring tocilizumab for the majority of outcome measures, including an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% and CDAI-MTR responses and changes in CDAI score and DAS28(ESR/CRP) between baseline and 16 weeks (see Appendix 1, Table 13).

We performed further analyses comparing patients who responded to the first-line IMP (n = 38) with those who switched to the alternative IMP after failing to achieve primary end point at 16 weeks (switch patients, n = 18). We evaluated treatment responses at 16, 24 and 32 weeks following treatment initiation. The results again demonstrated higher response rates in the tocilizumab-treated groups than in the rituximab-treated groups for the majority of outcome measures evaluated (see Appendix 1, Table 14). Per-protocol analyses showed results consistent with the ITT analysis (see Appendix 1, Table 15).

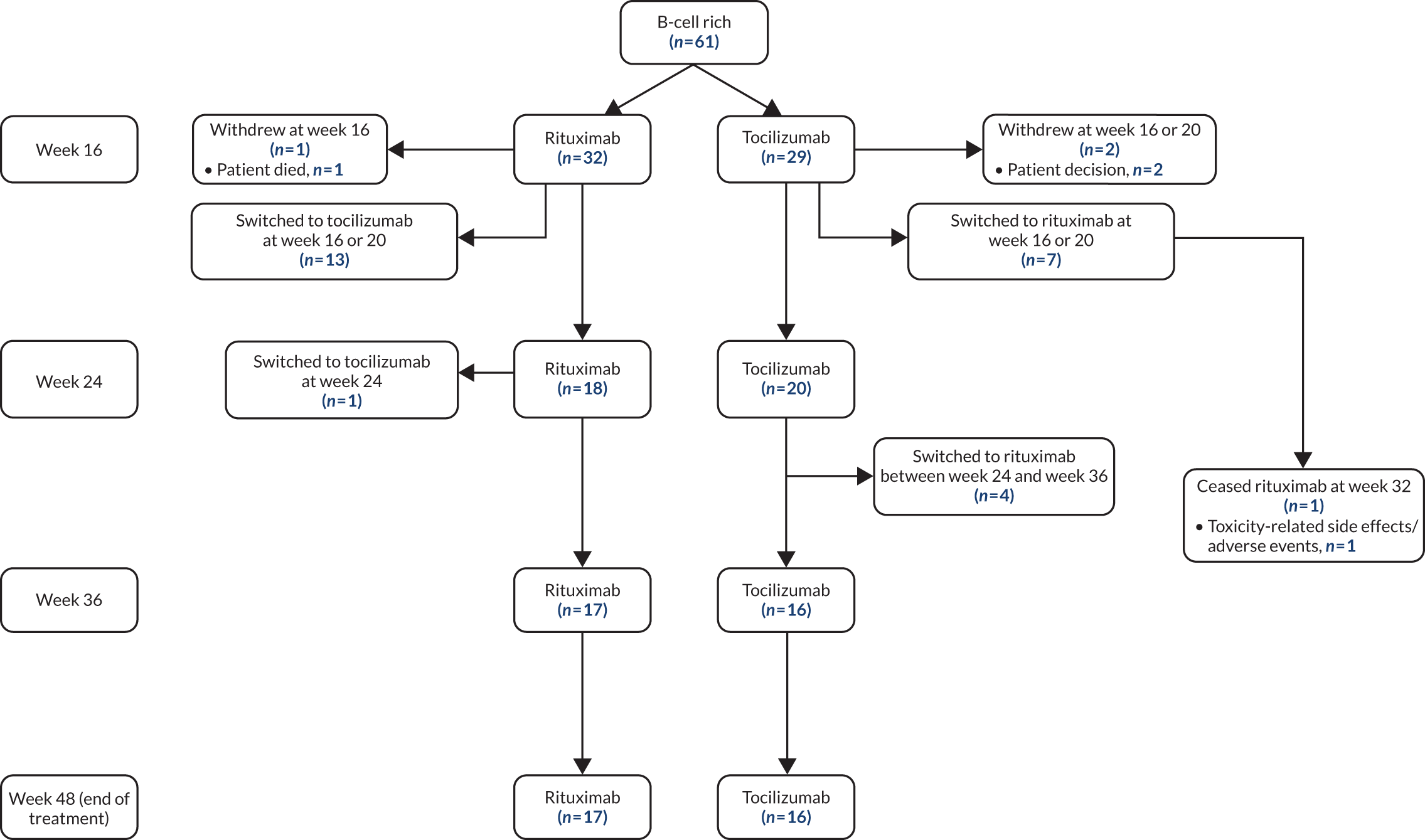

Treatment responses beyond 16 weeks: B-cell-rich population

At the 24-week follow-up in the group of patients classified as B-cell rich, 18 out of 33 patients continued treatment with rituximab and 20 out of 31 patients continued treatment with tocilizumab (see Appendix 1, Figure 12 and Table 16). At 36 weeks, 17 out of 33 patients continued with rituximab and 16 out of 31 patients continued with tocilizumab. At 48 weeks, 17 out of 33 patients continued with rituximab and 16 out of 31 patients continued with tocilizumab. Overall, the results at 24, 36 and 48 weeks were consistent with the primary analysis at week 16, with similar response rates in the tocilizumab- and rituximab-treated groups (see Appendix 1, Table 16). Analyses including patients who switched to the alternative IMP at week 16 (following treatment failure to the primary drug) (see Appendix 1, Table 17) and the PP analysis (see Appendix 1, Table 18) were consistent with the primary analyses.

Treatment responses in the total trial population independent of pathotype stratification

To establish whether or not tocilizumab was more effective than rituximab, regardless of the B-cell-poor/-rich classification, clinical outcomes were analysed in the total patient population at 16 weeks. Although we observed a trend for higher response rates in the group treated with tocilizumab than in the group treated with rituximab, there was no significant difference in response rate between the treatment groups for the primary outcome (improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%: RR 1.23, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.68); however, a significant difference was observed for CDAI-MTR (improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% and CDAI score of < 10.1: RR 2.14, 95% CI 1.31 to 3.49) (see Appendix 1, Table 19). We continued to observe larger improvements in patient QoL measures (FACIT and SF-36) in the tocilizumab-treated groups (see Appendix 1, Table 19).

Treatment response to rituximab

We next evaluated differences in response rates to rituximab treatment, defined as an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%, between patients classified histologically as B-cell rich or B-cell poor and found no significant differences in outcome (Fisher’s exact test p = 0.81).

Modulation of synovial histopathobiology following treatment

Immunohistochemical parameters

No differences were found between the rituximab- and tocilizumab-treated groups in the baseline histological parameters evaluated, which included histological synovitis, CD20+ and CD79+ B cells, CD138+ plasma cells, CD3+ T cells, and CD68+ L and SL layer macrophages (Table 2). A paired week 16 synovial biopsy was available for 41 patients treated with rituximab and 24 patients treated with tocilizumab. In the rituximab group, we saw a significant decrease in CD20+ and CD79a+ B cells, synovitis score (p < 0.001), CD138+ plasma cells and CD68+ SL macrophages (p < 0.05) at 16 weeks (see Table 2). The decreases in CD20+ and CD79a B cells were also significantly greater in the rituximab group than in the tocilizumab group (–81% vs. –20% and –49% vs. –5%, respectively; p < 0.05).

| Variable | Unpaired analysis (all patients) | Paired analysis | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline biopsya | Rituximab group (n = 41) | Tocilizumab group (n = 24) | Treatment effect | ||||||

| Rituximab (n = 82), mean (SD) | Tocilizumab (n = 79), mean (SD) | Baseline, mean (SD) | Week 16, mean (SD) | Absolute change (percentage change) | Baseline, mean (SD) | Week 16, mean (SD) | Absolute change (percentage change) | Least squares mean difference (95% CI) | |

| CD20+ | 1.62 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.88 (1.4) | 0.35 (0.8) | –1.53b (–81) | 1.67 (1.3) | 1.33 (1.3) | –0.34 (–20) | 1.02 (0.52 to 1.52)d |

| CD79a+ | 1.54 (1.3) | 1.6 (1.4) | 1.77 (1.4) | 0.9 (1.1) | –0.87b (–49) | 1.54 (1.3) | 1.47 (1.2) | –0.07 (–5) | 0.55 (0.04 to 1.06)d |

| CD138+ | 1.43 (1.3) | 1.42 (1.4) | 1.68 (1.3) | 0.92 (1.1) | –0.76c (–45) | 1.58 (1.4) | 1.25 (1.1) | –0.33 (–21) | 0.36 (–0.16 to 0.88) |

| CD3+ | 1.43 (1.1) | 1.47 (1.2) | 1.63 (1.1) | 1.52 (1.2) | –0.11 (–7) | 1.58 (1.1) | 1.42 (1.2) | –0.16 (–10) | –0.08 (–0.64 to 0.49) |

| CD68+ L | 1.11 (1) | 1.2 (1.1) | 1.2 (1) | 1.07 (0.9) | –0.13 (–11) | 1.46 (1.1) | 1.38 (1.1) | –0.08 (–5) | 0.2 (–0.27 to 0.66) |

| CD68+ SL | 1.67 (1) | 1.75 (1.1) | 1.88 (0.8) | 1.3 (0.6) | –0.58c (–31) | 1.92 (1) | 0.88 (0.7) | –1.04c (–54) | –0.43 (–0.78 to –0.08)d |

| Synovial score | 3.99 (2.6) | 3.88 (2.9) | 4.63 (2.5) | 3.23 (2) | –1.4b (–30) | 4.38 (2.8) | 3.46 (2.4) | –0.92 (–21) | 0.32 (–0.69 to 1.32) |

When patients in the rituximab-treated group were stratified into week 16 responders (n = 15) and non-responders (n = 26) (response being defined as an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%), significant decreases in CD20+ and CD79a+ B cells were observed between baseline and 16 weeks in both groups, although the percentage decrease was larger in the responder group (CD20+ –96% vs. –72%; CD79a –56% vs. –43%; p < 0.001) (Table 3). Similar effects were seen for the synovitis score (–34% vs. –28%). Changes in CD68+ SL macrophages were identical between responder and non-responder groups (–31%); however, this finding was significant in the non-responder group only (p < 0.05), probably because of the different numbers of patients in each group. CD138+ plasma cells was the only histological parameter that decreased significantly only in those who responded to rituximab treatment (–1.07 vs. –0.58; p < 0.05) (see Table 3). In patients treated with tocilizumab for whom a paired biopsy was available (n = 24), the only significant change at week 16 was a decrease in CD68+ SL macrophages (absolute change –1.04, percentage change –54%; p < 0.05), and this decrease was also significantly greater than that observed in rituximab-treated patients (–54% vs. –31%; p < 0.05), with decreases in CD20+ or CD79a+ B cells, CD138+ plasma cells and CD3+ T cells being minimal or only modest (see Table 2). When tocilizumab-treated patients were stratified into responder (n = 10) and non-responder (n = 14) groups as above, the changes in histological parameters were less notable than in the rituximab-treated group on the B-cell lineage, with only CD68+ SL macrophages showing a significant change from baseline and a significant difference in change between responders and non-responders (absolute change –1.7, percentage change 77% vs. absolute change –0.57, percentage change –33%; p < 0.05). Notably, when all patients (n = 161) were stratified into those undergoing a 16-week repeat biopsy (n = 65) or not (n = 96), although there were no significant differences in baseline clinical parameters between the groups, the number of patients who failed to achieve an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% or CDAI-MTR was significantly larger in the repeat biopsy group than in the no biopsy group (see Appendix 1, Table 20). These results indicated that the repeat biopsy group was skewed by the inclusion of more patients failing to respond to first-line IMP. This is in line with expectations because patients responding well to treatment would be less keen to have a second biopsy.

| Variable | Treatment group | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | Tocilizumab | |||||||||||||

| Non-responders (n = 26) | Responders (n = 15) | Treatment effect | Non-responders (n = 14) | Responders (n = 10) | Treatment effect | |||||||||

| Baseline, mean (SD) | Week 16, mean (SD) | Absolute change (percentage change) | Baseline, mean (SD) | Week 16, mean (SD) | Absolute change (percentage change) | Least squares mean difference (95% CI) | Baseline, mean (SD) | Week 16, mean (SD) | Absolute change (percentage change) | Baseline, mean (SD) | Week 16, mean (SD) | Absolute change (percentage change) | Least squares mean difference (95% CI) | |

| CD20+ | 1.88 (1.3) | 0.52 (1) | –1.36 (–72)a | 1.87 (1.5) | 0.07 (0.3) | –1.8 (–96)a | –0.46 (–0.97 to 0.06) | 1.71 (1.3) | 1.21 (1.3) | –0.5 (–29) | 1.6 (1.3) | 1.5 (1.3) | –0.1 (–6) | 0.34 (–0.64 to 1.33) |

| CD79a+ | 1.54 (1.4) | 0.88 (1.1) | –0.66 (–43)a | 2.13 (1.4) | 0.93 (1.1) | –1.2 (–56)a | –0.25 (–0.88 to 0.38) | 1.64 (1.4) | 1.31 (1.2) | –0.33 (–20) | 1.4 (1.3) | 1.83 (1.2) | 0.43 (31) | 0.4 (–0.57 to 1.36) |

| CD138+ | 1.58 (1.4) | 1.0 (1.3) | –0.58 (–37) | 1.87 (1.2) | 0.8 (0.9) | –1.07 (–57)a | –0.31 (–1.01 to 0.38) | 1.5 (1.4) | 1.21 (1.1) | –0.29 (–19) | 1.7 (1.4) | 1.3 (1.2) | –0.4 (–24) | 0.01 (–0.84 to 0.86) |

| CD3+ | 1.58 (1.1) | 1.4 (1.2) | –0.18 (–11) | 1.73 (1.1) | 1.73 (1.3) | 0 (0) | 0.27 (–0.45 to 0.98) | 1.57 (1.2) | 1.57 (1.1) | 0 (0) | 1.6 (1.1) | 1.2 (1.4) | –0.4 (–25) | –0.38 (–1.38 to 0.61) |

| CD68+ L | 1.08 (0.9) | 1.08 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1.4 (1.2) | 1.07 (1) | –0.33 (–24) | –0.11 (–0.69 to 0.48) | 1.5 (1.3) | 1.71 (1.2) | 0.21 (14) | 1.4 (0.8) | 0.9 (0.9) | –0.5 (–36) | –0.76 (–1.51 to 0) |

| CD68+ SL | 1.85 (0.8) | 1.28 (0.6) | –0.57 (–31)a | 1.93 (1) | 1.33 (0.7) | –0.6 (–31) | 0.04 (–0.39 to 0.47) | 1.71 (1.1) | 1.14 (0.8) | –0.57 (–33) | 2.2 (0.9) | 0.5 (0.5) | –1.7 (–77)a | –0.7 (–1.31 to –0.09)b |

| Synovitis score | 4.46 (2.2) | 3.2 (2.1) | –1.26 (–28)a | 4.93 (3) | 3.27 (1.8) | –1.66 (–34)a | –0.16 (–1.29 to 0.98) | 4.43 (3) | 4.0 (2.5) | –0.43 (–10) | 4.3 (2.6) | 2.7 (2.3) | –1.6 (–37) | –1.26 (–3.26 to 0.74) |

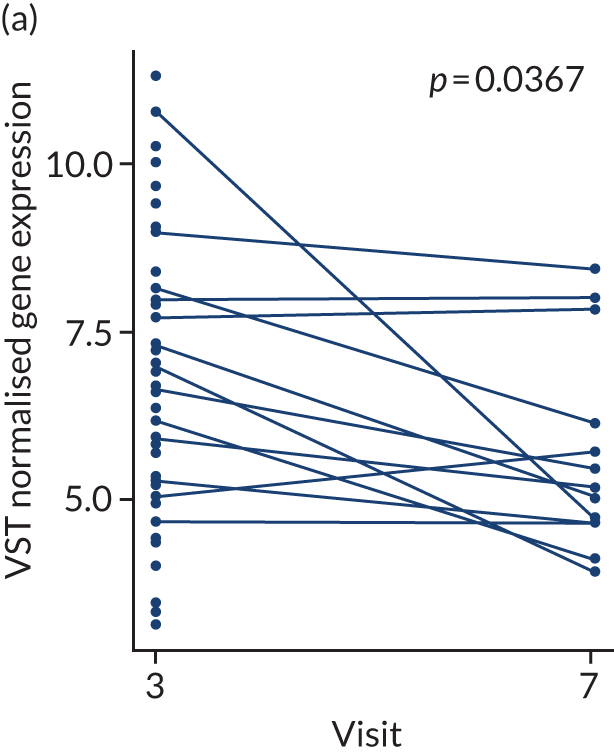

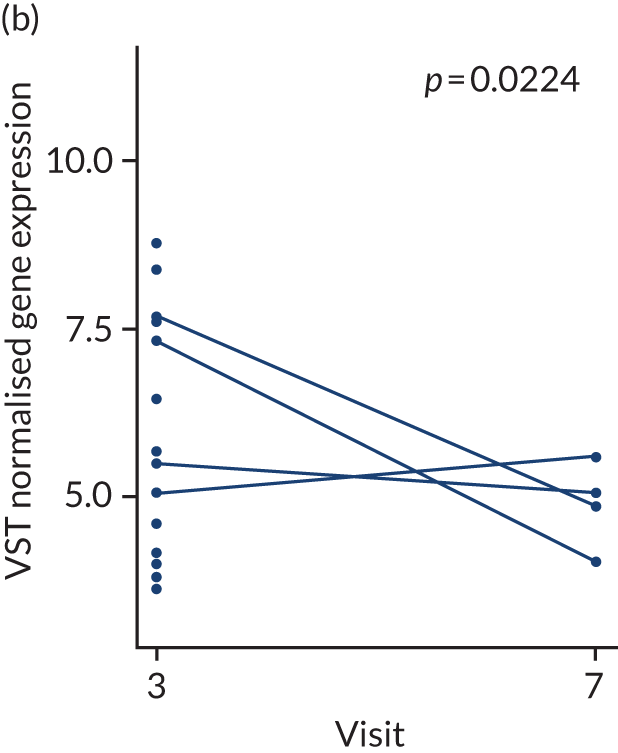

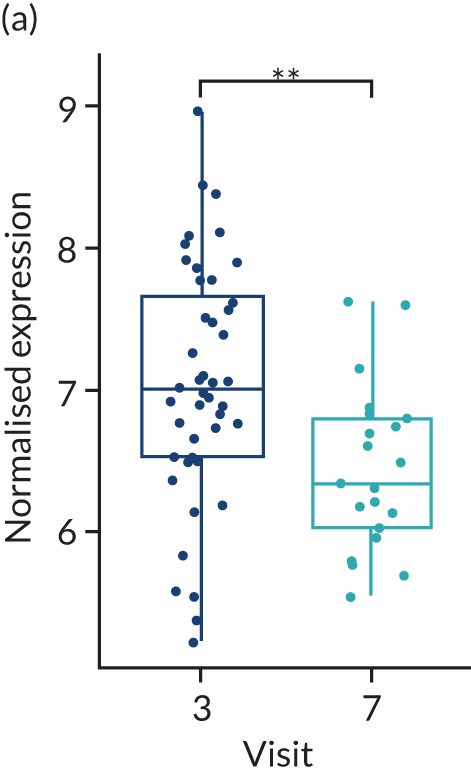

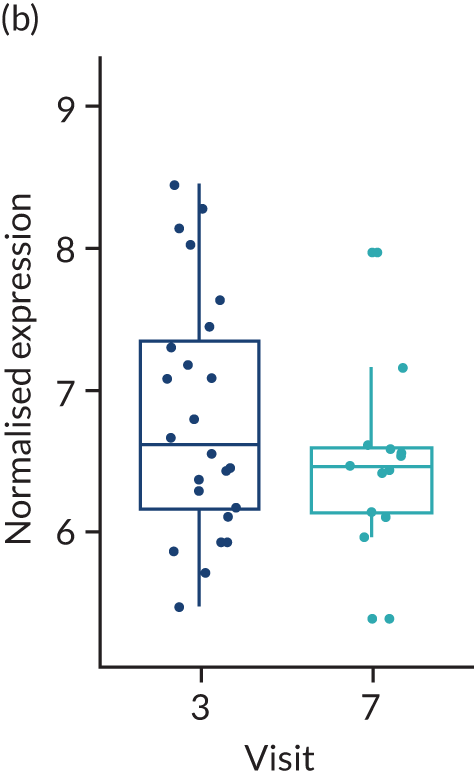

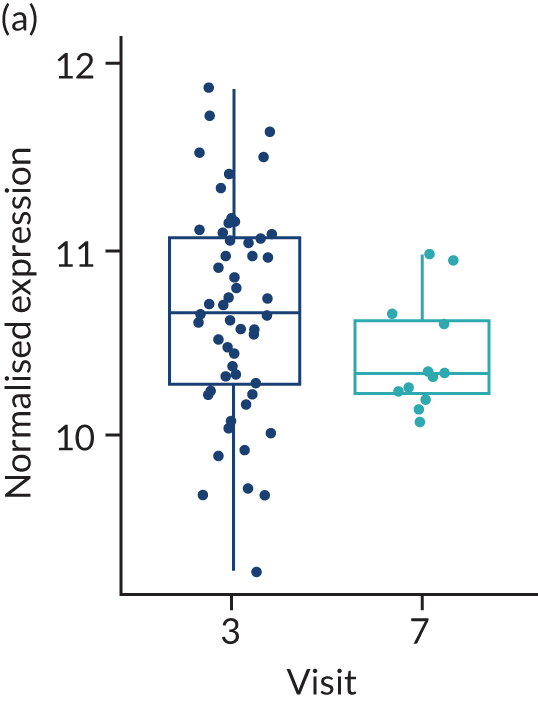

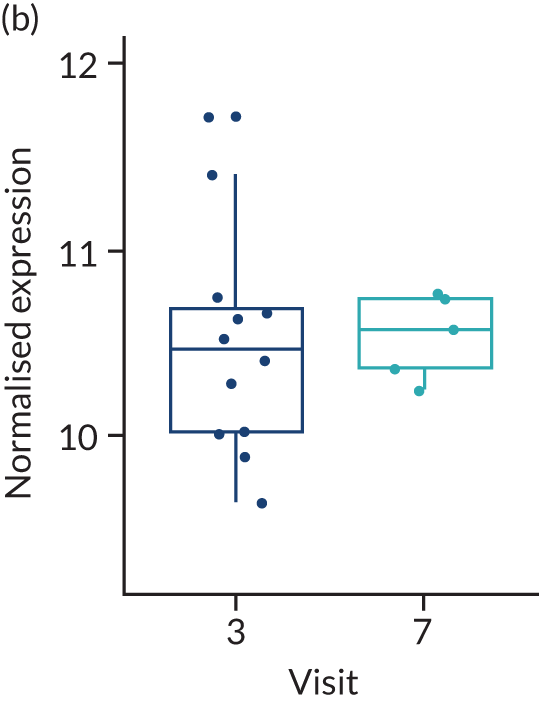

Change in gene expression levels between baseline and 16 weeks

The rituximab (baseline, n = 68; week 16, n = 33) and tocilizumab (baseline, n = 65; week 16, n = 17) patient samples were analysed separately to assess the differences in the change in gene expression (from baseline to week 16) between responders and non-responders without the confoundment of different biological therapy. Linear mixed models were used because the data had quite a few unmatched samples between visits.

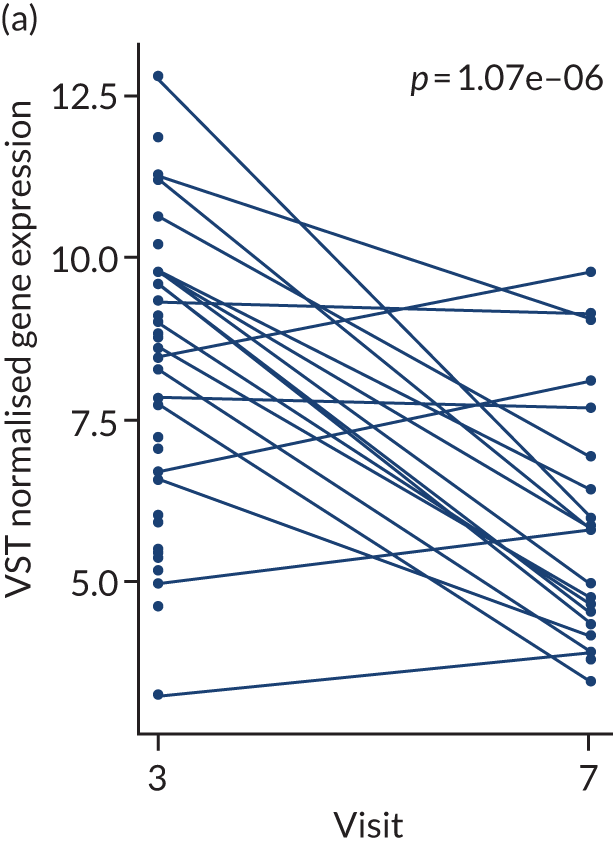

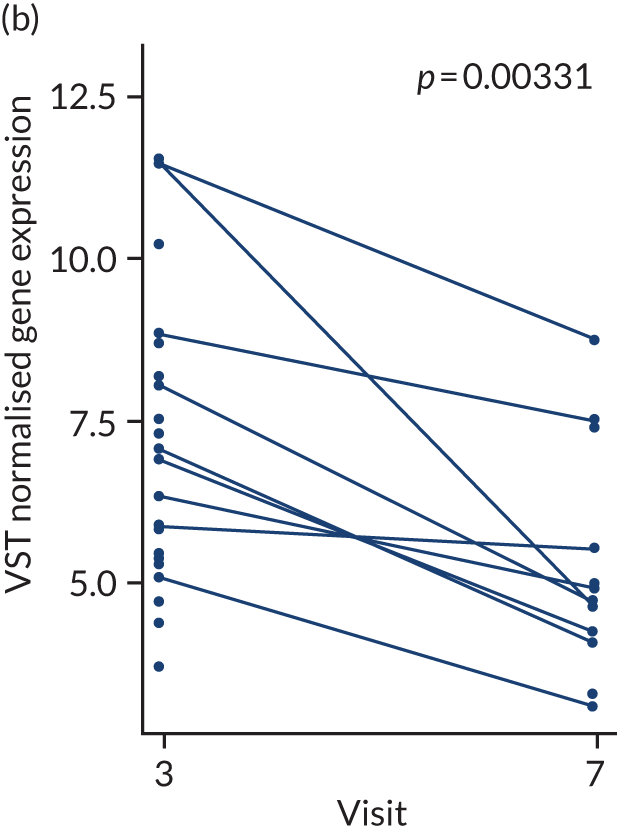

In the gene-level analysis, we examined the change in MS4A1 in the rituximab-treated group in the responders and non-responders separately, and the response interaction (see Appendix 1, Figure 15). The decrease in MS4A1 expression was greater in responders [log2 fold change (FC) = –0.51] than in non-responders (log2FC = –0.45). The p-value was smaller in responders (p = 1.07 × 10–7) than in non-responders (p = 0.0031), which may suggest that individuals responded better because of a more profound B-cell depletion in synovial tissue. However, the responders group was larger (n = 65) than the non-responders group (n = 37), and the interaction p-value was not significant. Next, we examined the change in IL-6 gene expression in the tocilizumab-treated group for responders and non-responders, and performed a statistical test for interaction (see Appendix 1, Figure 16). In responders, there was a significant reduction in IL-6 gene expression over time (p = 0.038; n = 65), but there was no significant difference in non-responders (n = 17). The interaction p-value was not significant.

Next, we examined the change in module or pathway expression using the same statistical comparisons that were made at the gene level for the B-cell module (see Appendix 1, Figure 17) and IL-6 module genes (see Appendix 1, Figure 18). Over time, the B-cell module decreased significantly in responders in the rituximab-treated group (log2FC = –0.13; p = 0.0013), but not in rituximab non-responders (log2FC = –0.07), with a significant p-value for interaction (p < 0.05). There were no significant changes in IL-6 module expression in the tocilizumab-treated group in this preliminary analysis.

Safety and adverse events

The safety and adverse events data are summarised in Table 4 and Appendix 1, Table 21. It can be seen that more adverse events (327 vs. 284) and serious adverse events (18 vs. 8; p < 0.05) were observed in patients treated with tocilizumab than in those treated with rituximab. One patient in the rituximab-treated group who reported a serious unexpected serious adverse reaction (corneal melt) and three patients in the tocilizumab group who reported serious adverse events (pleural effusion, chest pain and cytokine release syndrome) discontinued the IMP because of these events. The serious adverse events comprised three infections in each group, four ischaemic cardiac events in the tocilizumab group and one ischaemic cardiac event in the rituximab group (see Appendix 1, Table 21). One death because of suicide was reported in the rituximab group. No malignancies were reported during the 48-week trial period. Three patients underwent randomisation but did not receive a study drug and no serious adverse events were reported in these patients. Importantly, no serious adverse events related to synovial biopsy were reported.

| Variable | Treatment group, n (%) | Total,a n | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rituximab | Tocilizumab | ||

| Patients exposed to IMP | 108 | 116 | 224 |

| Patients with adverse events | 60 (55.6) | 70 (60.3) | 135 |

| Patients with serious adverse events | 8 (7.4) | 12 (10.3) | 20 |

| Patients with serious infections | 3 (2.8) | 3 (2.6) | 6 |

| Patients who discontinued the study drug because of serious adverse event | 2 (1.9) | 2 (1.7) | 4 |

| Patients with confirmed cancerb | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 |

| Deaths | 1 (0.9) | 0 (0) | 1 |

| Total events | |||

| Adverse events | 280 | 331 | 659 |

| Serious adverse events | 8 | 18c | 26 |

| Infections | 3 | 3 | 6 |

Chapter 4 Discussion

Rituximab remains a pivotal therapeutic option for RA patients; however, response to therapy remains heterogeneous, with only 20% of patients achieving clinically meaningful American College of Rheumatology 70% (ACR70) response rates6 when rituximab is used as first-line biological therapy. On the other hand, rituximab therapy can be very effective, transforming the life of many patients. Thus, understanding the mechanism of response/non-response is critical to avoid the unnecessary use of an expensive and potentially toxic drug. Although B cells are considered key players in RA pathogenesis, particularly in the development of systemic autoimmunity in RF/ACPA-positive patients, which may precede clinical manifestations by years, their contribution in seronegative RA is less clear. 42 In addition, at the disease tissue level (synovium), synovial B-cell infiltration is highly heterogeneous, being low or absent in a significant proportion of patients (approximately 50%) despite high disease activity. 24 This suggests that in these patients synovial inflammation is sustained by alternative cell types and that, if CD20+ B cells are absent from the disease tissue or present at only a very low level, the therapeutic response to rituximab may be poor and an alternative therapy with a mode of action not dependent on B-cell depletion may be more effective. The R4–RA study was designed and supported by the NIHR Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation programme and aimed to determine whether or not specific cellular (CD20+ B cells) and molecular (B-cell-associated) signatures in the synovial biopsy can mechanistically explain specific disease outcomes. To our knowledge, this is the first biopsy-based randomised controlled trial in RA and, although the histological classification of patients as B-cell poor did not appear to stratify patients for clinical response to rituximab or tocilizumab when response was defined as an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%, we observed no significant difference in the primary end point (improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% from baseline) between the IMP groups. However, a supplementary analysis evaluating a prespecified definition of non-response as failure to achieve an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% and a CDAI score of < 10.1 (defined as CDAI-MTR) did reach statistical significance. Moreover, when patients were classified as B-cell poor/rich according to the FANTOM5-derived34 B-cell molecular module (73 genes), which became available at the end of the trial, based on RNA sequencing of the synovial biopsy, both primary end points (improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50%) and CDAI-MTR (improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% and CDAI score of < 10.1) reached statistical significance. Furthermore, although logistic regression analysis showed no evidence of an interaction between the IMP and the histologically defined B-cell subgroups for the primary end point, a statistically significant interaction between RNA-seq-defined B-cell subgroup and IMP was observed when using CDAI-MTR (p = 0.049), providing evidence that the treatment effect was different between RNA-seq-defined B-cell-rich and B-cell-poor groups.

The reasons for these differences are likely to relate to the sensitivity of the classification technique. CD20+ staining was evaluated at three cutting levels using a semiquantitative score on a minimum of six biopsies, as recommended for use in clinical trials and reported to be representative of the whole joint tissue. 43 However, although the semiquantitative score used for balanced stratification of patients prior to randomisation had been validated against both DIA and the transcript levels determined using the FANTOM5-derived gene set,34,35 the cut-off point was set arbitrarily as 0–1 for B-cell-poor patients and 2–4 for B-cell-rich patients. Given that a binary classification has never been attempted before and no published ‘gold standard’ is available, it is possible that the histological cut-off point may not have been set at an optimal level.

Turning to the molecular B-cell-poor/-rich classification, this was determined by applying the same FANTOM5-derived module used to validate the semiquantitative score and included 73 genes associated with B cells34,35 scored against the RNA-seq of six pooled homogenised biopsy samples. This provides richer granularity of the pathobiological processes (expression of 30,000 genes) of the entire active joint and, arguably, a more precise estimate of the number not only of mature CD20+ B cells but also of B cells at different stages of differentiation, with the gradual loss of CD20 gene expression that in itself is likely to influence the response to rituximab, which specifically targets CD20. Thus, the application of the molecular classification, an objective method using the transcript-level median value of a B-cell module gene set derived from FANTOM5, enables a number of limitations of histological classification to be overcome, including the relatively subjective assessment of synovial B-cell infiltration by histopathology.

We recognise that a proportion of patients (28 out of 152, 18.4%) could not be classified by molecular analysis, as their samples failed RNA-seq quality control. The most likely reason for this is the decision to use deep genotyping (150-bp-long reads, 50 million reads per sample), which allows, for instance, the analysis of split variants, but requires larger amounts of RNA. Despite this limitation, the use of RNA-seq has allowed the identification of specific signatures, such as the FANTOM5-derived B-cell module that we used to classify patients into B-cell-rich and B-cell-poor groups. In the future, it will be possible to overcome such limitation by analysing these modules with alternative molecular techniques, such as NanoString (NanoString Technologies, Seattle, WA, USA), which is based on a selection of specific gene probes, thus requiring less material and most likely resulting in a smaller number of unclassified patients.

Importantly, we also evaluated clinical outcomes in the overall study population (irrespective of pathotype). Although we observed a trend for higher response rates in the tocilizumab-treated patients, there was no significant difference in the numbers achieving the primary outcome (CDAI score improvement ≥ 50%) at 16 weeks, and so, in this first head-to-head trial of rituximab versus tocilizumab, the data do not justify modification of current biological prescribing algorithms to favour the use of tocilizumab over rituximab in patients failing to respond to TNFi therapy.

Data from the longitudinal analysis of the synovial tissue following treatment with rituximab are in line with previously published data from observational cohorts, which report significant decreases in synovial B cells post treatment with rituximab, but no significant associations between the degree of synovial B-cell depletion and the clinical response. 15,17,18 However, our molecular analysis demonstrated a greater decrease in both MS4A1 and B-cell module gene expression in patients who responded to rituximab treatment than in non-responders, suggesting an increased sensitivity of molecular versus histological techniques to detect change. To confirm that the number of CD20+ B cells was not underestimated owing to internalisation of the CD20 molecule, we also evaluated the expression of CD79a, with the results being consistent for both markers. 44 Importantly, our data identified CD138+ plasma cell depletion as a significant marker of response to rituximab, in line with a previous study that found that poor depletion of CD138+ plasma cells was associated with non-response to rituximab treatment. 17 The concept that synovial plasma cells are an important therapeutic target is supported by data from an independent cohort, in which decreases in synovial immunoglobulin synthesis were associated with response to rituximab. 18 The effects of tocilizumab on synovial immune cell infiltrate were less pronounced, with only CD68+ SL macrophage numbers decreasing significantly in both the total and the responder cohorts. The molecular findings were in line with the histological results, with insignificant decreases in IL6 and IL6 pathway gene expression in either responder or non-responder groups in the tocilizumab-treated patients. Although others have also reported a decrease in CD68+ macrophage numbers post tocilizumab treatment,45 it was associated with decreases in other immune cell types, something that we did not observe. However, when interpreting data from our analysis, the significantly larger numbers of non-responders to the IMP in the population of patients undergoing a second biopsy may be attributed to patients who responded well to treatment being less keen to have a second biopsy and/or having no suitable joints to biopsy. This resulted in a skewed population that is likely to underestimate the immunomodulatory effects of IMP on synovial immune cell infiltrate and may also explain the lack of consistent significant decreases in CD68+ SL macrophage numbers in responder groups that may have been predicted in the light of previous studies identifying this marker as a validated outcome measure. 46,47 However, notably, other studies evaluating synovial response to rituximab have not identified significant decreases in CD68 SL in responders to therapy. 17,18

Although we report a larger number of serious adverse events and adverse events in patients treated with tocilizumab than in those treated with rituximab, these were largely unrelated to the study drug; nevertheless, this finding in this first head-to-head trial of rituximab and tocilizumab may suggest that tocilizumab is less well tolerated. Importantly, there were no serious adverse events related to synovial biopsy, supporting previously published data relating to the safety of minimally invasive synovial biopsy techniques performed by rheumatologists. 30,48

Study limitations

To our knowledge, this is the first randomised controlled biopsy-based trial in RA and, inevitably, the study had limitations:

-

The important issue of the binary B-cell-poor/-rich classification discussed will require further analysis of the trial to determine a more accurate cut-off point or may lead in the future to a different quantification method using, for example, continuous variable data (e.g. transcript levels) as a sensitive tool to predict clinical response as reported for other therapeutic targets, for example programmed cell death-1 (PD1). 49

-

The choice of tocilizumab as an active comparator to rituximab might not have been optimal because tocilizumab itself modulates B-cell function and survival. 50 Thus, if a biological lacking direct B-cell modulatory effects had been selected (e.g. an alternative TNFi or abatacept), a more pronounced effect on treatment differences within pathotype groups may have been observed.

-

Of critical relevance, tocilizumab is known to act faster than rituximab and the study design might have favoured the fast-acting drug, despite the deliberate choice of a relatively late primary time point (16 weeks). In the same vein, the lack of double blinding for the IMP may have amplified the clinical response to tocilizumab, which is given as a monthly infusion rather than, as with rituximab, at 24 weeks. Although the clinical staff remained blind at all times to the pathotype status of patients, the frequency of the infusions may have created an unconscious bias, potentially in both patients and clinical staff. The selection of tocilizumab was a pragmatic choice based largely on the accessibility of NHS trusts participating in the trial to this biological treatment beyond second-line therapy, and it was considered unethical to inconvenience those patients randomised to the rituximab group with a monthly placebo infusion.

-

It is conceivable that, despite a washout period for previous biological therapies, as well as standardisation of steroid and csDMARD therapy prior to trial entry, these therapies and/or other concomitant therapies may have modulated baseline synovial pathobiology. Future studies evaluating synovial pathobiological markers and clinical response to biological treatment in patients naive to therapy are certainly warranted to address this issue.

-

Finally, the choice of an improvement in CDAI score of ≥ 50% as a primary binary outcome rather than, for example, EULAR/DAS28(ESR) response rates, illustrates the lack of precision of current assessment methods, as the choice of the latter would have led to a positive trial based on the results of even by the histopathological classification. Thus, to achieve precision, future rheumatology studies should aim to refine both the current assessment tools (originally designed mainly for regulatory purposes) and the pathobiological classification so that a truly integrated clinical and molecular pathology algorithm can be developed for the optimal management of RA.

Conclusion

We report the results from what is, to our knowledge, the first pathobiology-driven, multicentre, randomised controlled trial in RA. Although we were unable in our primary analysis to demonstrate that tocilizumab is more effective than rituximab in patients with a B-cell-poor pathotype, superiority was suggested in some supplementary and secondary analyses. These analyses overcame possible unavoidable weaknesses in our original study plan, in which the histological method of determining B-cell status may have misclassified some participants and our chosen primary outcome was insufficiently sensitive. In particular, using the molecular classification, the results suggest that in B-cell-poor RA patients tocilizumab is significantly more likely than rituximab to induce a clinical response, whereas in patients presenting with a B-cell-rich synovium rituximab is as effective as tocilizumab. However, owing to the limitations of the study discussed above, these finding are insufficiently robust to justify change in clinical practice. Future research will focus on the refinement of the molecular pathology classification and replication of the R4–RA findings in independent studies to determine whether or not stratification of patients according to cellular and molecular signatures may have clinical utility for treatment allocation of specific targeted biological therapies depending on the level of expression of their cognate target in the disease tissue.

The ability to target biological therapies to the right patients, rather than continue the current practice of trial and error, may enrich for clinical response with the potential to have a significant impact on the health economics of RA with reduced exposure of patients to expensive and potentially toxic drugs. This would also align clinical practice in rheumatology with specialties such as oncology in which stratification of patients according to the tissue expression of drug targets has been adopted in routine clinical practice. 51

Acknowledgements

The funder of the study had no role in study design, data collection, data analysis, data interpretation or writing of the report. The corresponding author had full access to all the data in the study and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication.

Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology staff

Please see the R4-RA website for all contributors to the R4-RA trial at the Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology: www.r4ra-nihr.whri.qmul.ac.uk/docs/contributors_r4ra-for_website.pdf (accessed 26 October 2020).

Rheumatology Research Unit staff, Barts Health NHS Trust

Ms Mary Githinji (Research Nurse).

Ms Celia Breston (Research Nurse).

Ms Emily Harvey (Clinical Trial Practitioner).

Ms Fatima Bibi (Clinical Trial Practitioner).

Dr Alessandra Nerviani (Academic Clinical Lecturer and Specialist Registrar in Rheumatology).

Dr Felice Rivellese (NIHR Clinical Research Fellow).

Dr Gloria Lliso-Ribera (Versus Arthritis Clinical Research Fellow).

Dr Stephen Kelly (Consultant Rheumatologist).

Dr Arti Mahto (Clinical Fellow).

Principal investigators and sites

Special thanks to all research staff at participating centres who recruited and cared for patients during the trial.

Dr Fran Humby, Mile End Hospital (Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK) and Whipps Cross (Barts Health NHS Trust, London, UK); Professor Patrick Durez, Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium; Professor João Eurico Fonseca, Intituto de Medicina Molecolar & Santa Maria Hospital, Lisbon, Portugal; Dr Pier Paolo Sainaghi, Universita’ del Piemonte Orientale, Novara, Italy; Professor Ernest Choy, University Hospital of Wales, Cardiff, UK; Professor John Isaacs, Royal Victoria Infirmary, Newcastle, UK; Professor Christopher Edwards, Southampton General Hospital, Southampton, UK; Dr Nagui Gendi, Basildon University Hospital, Basildon, UK; Dr Juan D Cañete, Hospital Clínic de Barcelona, Barcelona, Spain; Professor Bhaskar Dasgupta, Southend University Hospital, Southend-on-Sea, UK; Professor Maya Buch, Chapel Allerton Hospital, Leeds, UK; Professor Alberto Cauli, University of Cagliari, Cagliari, Italy; Dr Piero Reynolds, Homerton University Hospital, London, UK; Professor Peter Taylor, Nuffield Orthopaedic Hospital, Oxford, UK; Professor Robert Moots, Aintree University Hospital, Liverpool, UK; Dr Pauline Ho, Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester, UK; Dr Nora Ng, Guy’s Hospital, London, UK; Professor Carlomaurizio Montecucco, University of Pavia, Pavia, Italy; and Professor Patrick Verschueren, University of Leuven, Leuven, Belgium.

Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

Professor Max Parmar (Independent Chairperson), Professor of Medical Statistics and Epidemiology, University College London.

Professor John Gribben (Independent Member), Professor and Consultant Medical Oncologist, Queen Mary University of London.

Dr Chris Deighton (Independent Member), Consultant Rheumatologist and Honorary Associate Professor, University Hospitals of Derby and Burton NHS Foundation Trust.

Trial Steering Committee

Professor Patrick Kiely (Independent Chair), Consultant Physician in Rheumatology and General Medicine and Honorary Senior Lecturer, St George’s University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust.

Dr David O’Reilly (Independent Member), Consultant Rheumatologist, West Suffolk NHS Foundation Trust.

Professor Maya Buch (Non-Independent Member), Professor of Rheumatology and Honorary Consultant Rheumatologist, University of Leeds.

Ms Di Skingle (Independent Member), Patient Representative.

Dr James Galloway (Non-Independent Member), Lecturer and Honorary Consultant Rheumatologist, King’s College London.

Professor Adam Young (Independent Member), Professor of Rheumatology and Honorary Consultant in Rheumatology, University of Hertfordshire.

Trial participants

The study team are indebted to all the patients who volunteered to participate in the trial.

Patient and public involvement

In the original application we indicated that there were no plans for active involvement of patients or public for this research project. However, this was continually reviewed as the project advanced to ensure that patients were at the centre of the research. First, we approached the rheumatology patient group based at Barts Health NHS Trust to identify independent representatives to advise on the ongoing running of the trial. Second, we contacted the Queen Mary Trials Advisory Group, which offers independent advice on all Barts Clinical Trials Unit trials by providing feedback on trial design and research proposals, reading and critiquing the patient-facing documentation, reviewing consent procedures, representing the wider community in meetings and discussion groups, and providing advice on approaching specific communities, and the need for trial-specific consumer groups.

As part of our biopsy-driven research programme on stratified medicine for the treatment of RA, we worked closely with the Medical Research Council-funded Maximising Therapeutic Utility for Rheumatoid Arthritis (MATURA) Consortium, which has a dedicated patient and public involvement (PPI) stream. The MATURA Patient Advisory Group (MPAG) forged links with local patient support groups to raise the profile of research studies and identify barriers to recruitment. The group also assisted with activities such as advising on participant information materials, with a focus on the acceptability of the biopsy and understanding of our stratified medicine concept. The group met regularly to receive updates on our research portfolio and this included R4–RA.

Support from PPI groups for R4-RA included:

-

Reading and critiquing the patient documentation (e.g. patient information leaflet, consent forms and end of trial letter).

-

Representing the wider patient community by participating in meetings.

-

Organising educational events for RA patients on the potential of stratified medicines, particularly at hospitals recruiting patients to trials coordinated by the Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology.

-

A patient who had undergone synovial biopsy discussed their experience of the biopsy procedure in a video. This was provided for patients who were considering taking part in the Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology biopsy-driven studies. This video was approved by the Ethics Committee on 30 August 2017 for use in the R4–RA trial.

-

A recruitment poster was created for R4–RA, which was reviewed by a PPI group prior to being submitted to the Ethics Committee.

The MPAG members were invited to the MATURA symposium (RCP CPD 127665) on 30 September 2019, where the results of R4–RA were presented; they will have another opportunity to discuss the results at the next MPAG meeting, where we will also consult on the dissemination of the results.

A patient representative (Di Skingle, National Rheumatoid Arthritis Society Trustee) joined the R4-RA TSC in 2016, and attended the TSC meetings thereafter to provide oversight of the conduct of the trial from a patient’s perspective.

Contributions of authors

Frances Humby (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1280-9133) (Co-Investigator, Consultant Rheumatologist) contributed to the design of the study, data collection, data analysis and interpretation, and was the lead in drafting the report.

Patrick Durez (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7156-2356) (Principal Investigator, Professor of Rheumatology), Maya H Buch (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8962-5642) (Principal Investigator, Professor of Rheumatology), Michele Bombardieri (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3878-5216) (Professor of Rheumatology), Hasan Rizvi (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9013-0324) (Consultant Histopathologist), Liliane Fossati-Jimack (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3757-3999) (Senior Scientific Officer), Rebecca E Hands (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9969-6452) (Centre for Experimental Medicine and Rheumatology Laboratory Manager), Felice Rivellese (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6759-7521) (Clinical Research Fellow, Rheumatology), Juan D Cañete (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-2606-0573) (Principal Investigator, Consultant Rheumatologist), Peter C Taylor (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-7766-6167) (Principal Investigator, Professor of Musculoskeletal Sciences), João E Fonseca (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1432-3671) (Principal Investigator, Professor of Rheumatology) and Ernest Choy (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4459-8609) (Principal Investigator, Professor of Rheumatology) contributed to data collection, the analyses and interpretation of the results, and critical revision of the article.

Myles J Lewis (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-9365-5345) (Consultant Rheumatologist and Senior Lecturer) was responsible for the gene expression analyses and interpretation of the results, and conducted critical revision of the article.

Christopher John (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4453-9484) (Biostatistician) conducted the gene expression analyses and interpretation of the results, and conducted critical revision of the article.

Louise Warren (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3381-6175) (Trial Manager) coordinated the running of the trial and the collection, cleaning and provision of the trial data, and drafting the report.

Joanna Peel (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8160-3131) (Trial Manager) oversaw and co-ordinated the running of the trial, site set-up, trial monitoring, amendments to the protocol, and conducted critical revision of the article.

Giovanni Giorli (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-8248-2298) (Trial Statistician) conducted the statistical analysis and interpretation of the results, and contributed to the drafting the report.

Peter Sasieni (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1509-8744) (Principal Statistician) had overall responsibility for the statistics, he authored the statistical analysis plan and conducted critical revision of the article.