Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 11/100/34. The contractual start date was in April 2013. The final report began editorial review in September 2022 and was accepted for publication in December 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Stringer et al. This work was produced by Stringer et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Stringer et al.

Introduction

Scientific background

Kidney transplants do not last for the natural lifespan of most recipients, 30–40% of patients have their transplant for < 10 years1 and around 3% of prevalent kidney transplants fail annually. 2 This places a large burden on healthcare services. The single biggest cause of transplant failure is immune-mediated injury, the target of which are mismatched donor human leucocyte antigens (HLA).

A validated prognostic biomarker of kidney transplant failure is the appearance of circulating antibodies (Ab) against HLA. 3–8 Patients with HLA Ab have a three-fold greater risk of graft failure compared to those without7,8 and if these are specific for the kidney donor HLA [donor-specific antibodies (DSA)] there is an even higher risk of graft loss compared to those Ab that are not donor-specific (non-DSA). Inappropriately low levels of immunosuppression, either physician-led or due to patient non-adherence, is an important factor allowing the immune-mediated damage to begin and promoting the appearance of the HLA Ab. 9

Rationale for the study

The mechanisms driving graft dysfunction leading to graft failure are most likely complex and although the HLA Ab themselves might be damaging,10 other components including T- and B-lymphocytes may also play a role. 11 Various novel therapies have been tested in small scale, often uncontrolled human studies with some promising results. 12,13 Two randomised controlled trials concluded that B cell depletion with Rituximab was ineffective at preventing graft dysfunction in patients with biopsy-proven chronic antibody-mediated rejection (CAMR)14,15 as did a smaller trial of the anti-IL-6 receptor Ab tocilizumab. 16 However, two small RCTs of the anti-IL-6 monoclonal Ab Clazakizumab have shown benefit17,18 A larger RCT of clazakizumab, with a planned recruitment of 350 patients is underway (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03744910). Several other studies have suggested that optimised oral treatment with tacrolimus (Tac) and mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) can stabilise graft function in small numbers of patients with existing graft dysfunction. 15,19–26 However, to date there have been no large-scale trials testing this strategy by intervening in patients who develop HLA Ab prior to developing graft dysfunction, and none that have assessed if graft failure can be prevented.

Methods

Sections of this report have been reproduced from Dorling et al. 27 under licence CC-BY-2.0.

Sections of this report have been reproduced from Stringer et al. 28 under licence CC-BY-4.0.

Design

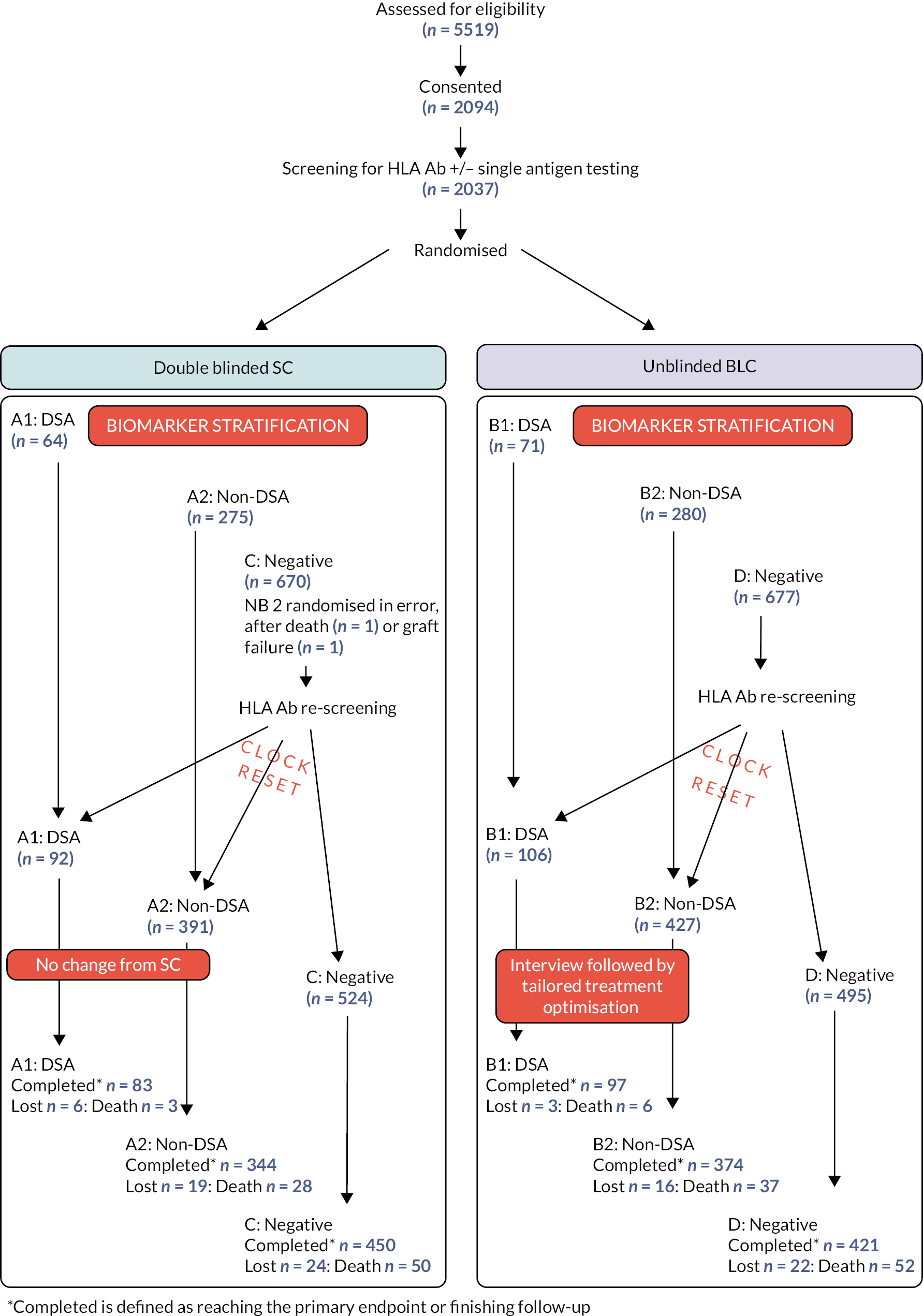

OuTSMART was a prospective, open labelled, randomised marker-based strategy (hybrid) trial design, with two arms stratified by biomarker (HLA Ab) status. Recruits were followed up with regular structured visits for at least 32 months (maximum 64 months) and primary endpoint assessed by remote evaluation after approximately 43 months post-randomisation (or post ‘clock reset’ – see below) was achieved by all. The trial design is represented in Figure 1. All eligible patients were screened for HLA Ab before being randomised 1 : 1 into either double-blinded standard care (SC) or unblinded biomarker-led care (BLC). Biomarker stratification generated three groups of recruits in each arm (DSA+, non-DSA+ and HLA Ab-neg). Patients in the blinded SC arm (groups A1, A2 and C in Figure 1) were blind to their biomarker status and remained on baseline immunotherapy throughout, whereas patients in the unblinded (groups B1, B2 and D in Figure 1) knew their HLA Ab status; in this arm, those with HLA Ab were offered ‘intervention’, whereas HLA Ab-negative patients remained on their existing immunotherapy.

FIGURE 1.

Trial design/flow of patients. Legend to figure 1: Randomisation took part in the HLA laboratory, after the first HLA Ab screening round to allow biomarker stratification within the respective arms. All participants assigned to the HLA Ab negative groups in each arm underwent rescreening for HLA Ab every 8 months till month 32. In both arms, recruits changing from HLA Ab negative to positive, at any time after enrolment were asked to complete a further 32 months follow-up (=‘clock reset’), so that the maximum time under structured follow-up for any recruit was 64 months. To maintain blinding, the randomisation system was programmed at each screening round to choose a small random group of HLA Ab-negative recruits from the SC group to complete a further 32 months follow-up. Therefore, a subset of HLA Ab-negative patients had ‘clock reset’ in the blinded SC arm, whereas only HLA Ab+ participants in unblinded BLC had ‘clock reset’.

Both groups of HLA Ab-negative recruits had regular Ab status monitoring for the first 32 months. Those patients who became positive during subsequent screening rounds were moved to the appropriate HLA Ab positive groups (DSA+ or non-DSA+) for final data analysis. All patients in groups C and D found to be positive on second or subsequent rounds were intensively followed up for an additional 32 months from the time they become positive (=‘clock reset’): those in the BLC arm were also offered the same ‘intervention’ as those patients who were positive in the first screening round. To maintain blinding in the SC arm, the randomisation system was programmed at each screening round to choose a small random group of HLA Ab-negative recruits from this arm to complete a further 32 months follow-up. Thus the maximum amount of time any single patient remained in intensive follow-up was 64 months. At the end of intensive follow-up, most data collection related to secondary endpoints ceased, but data related to graft failure or death were recorded for all participants up and until the end of the trial (see below), irrespective of the length of follow-up.

Primary objective

Determine the time to graft failure in unblinded BLC HLA Ab+ recruits identified at baseline or within 32 months of randomisation, compared to the control group of blinded SC HLA Ab+ recruits who remain on their established immunotherapy and whose clinicians are not aware of their Ab status. The primary endpoint was to be assessed remotely when approximately 43 months post-randomisation or post-‘clock reset’ had been achieved by all. Graft failure was defined as restarting dialysis or requiring a new transplant. In 2020, because of the impact of the first COVID-19 pandemic, the primary endpoint was redefined as that obtained at the last follow-up prior to 16 March 2020.

Secondary objectives

-

determine the time to graft failure in patients randomised to ‘unblinded’ HLA Ab screening, compared to a control group randomised to ‘blinded’ HLA Ab screening;

-

determine whether ‘treatment’ influences patient survival;

-

determine whether ‘treatment’ influences the development of graft dysfunction as assessed by presence of proteinuria (protein:creatinine ratio > 50 or albumin:creatinine ratio > 35) and change in estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR);

-

determine whether ‘treatment’ influences the rates of acute rejection in these groups;

-

determine the adverse effect profiles of ‘treatment’ in this group, in particular whether they are associated with increased risk of infection, malignancy or diabetes mellitus (DM);

-

determine the cost-effectiveness of routine screening for HLA Ab and prolonging transplant survival using this screening/treatment protocol;

-

determine the impact of biomarker screening and ‘treatment’ on the patients’ adherence to drug therapy and their perceptions of risk to the health of the transplant.

For all except (1) and (2), the secondary outcomes were assessed at the end of the intensive follow-up period, which for most was at month 32 but for some was up to 64 months post-enrolment.

Interventions

All Unblinded HLA Ab+ recruits were interviewed by the site principal investigator (PI) and the importance of drug adherence was re-enforced. Changes in drug treatment were tailored to the individual patient, according to compliance, tolerance and achievement of target levels (for Tac). Failure to tolerate one or more of the components of the drug protocol (or refusal to take any of the agents) was not used as a reason for withdrawal from the study.

The ‘optimised treatment’ protocol in the two groups (B1, B2, Figure 1) with HLA Ab was:

-

MMF bd, tds or qds, or enteric-coated mycophenolic acid (MPA) bd, with daily dose determined according to local unit guidelines. The patient was stabilised on the maximum tolerated dose.

-

Tac once daily (od) or bd, according to local unit preference, with dose titrated to achieve 12-hour post-dose levels of 4 μg/L to 8 μg/L (4–8 ng/ml). The patient was stabilised on the maximum tolerated dose that achieves these levels.

-

Prednisolone od starting at 20 mg for two weeks, then reducing by 5 mg od every two weeks down to their previous maintenance dose or 5 mg od, if not previously taking.

After consultation with the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency, all these medicines (but no others) were classed as investigational medical products (IMPs) MMF/MPA was used outside of its Marketing Authorisation (which states that it should be used with ciclosporin). However, because it is used so widely in combination of Tac in most units in the United Kingdom (UK), the two were regarded as ‘SC’. Thus, none of the three drugs required labelling in line with annex 13 and all IMPs were managed in the same way as normal that is GP or hospital prescription (as appropriate) and did not require special labelling/accountability/storage, etc.

Setting

Thirteen UK Kidney transplant outpatient clinics.

Participants

Renal transplant recipients > 1 year post-transplantation.

Identification and recruitment

The local transplant clinic database of their prevalent population was used to identify patients meeting the baseline inclusion/exclusion criteria. At the start of the trial, the entire population of transplant clinic attendees who met the eligibility criteria were potentially eligible for recruitment. On subsequent screening rounds, patients who reached 12 months post-transplantation after the start of the trial became eligible. Potentially eligible patients were approached at a routine clinic appointment by the PI or research nurses and given printed and verbal information about the trial. They had the opportunity to return for a second consultation within a few days to give informed consent for recruitment into the study or to do this on their next routine appointment. Alternatively, some eligible patients were sent information about the study through the post, for discussion and consent at their next routine appointment. Following consent, full eligibility criteria were reviewed. This included testing for chronic viral disease (if no such test within last 5 years) or pregnancy (if history suggests possibility of pregnancy).

Randomisation procedure

Prior to randomisation but after consent, site staff registered all recruits online and each assigned a MACRO PIN. Samples from all recruits were sent to the relevant HLA laboratory, along with this PIN and a sample request form containing the other information required for randomisation. HLA laboratory staff performed a screen for HLA Ab and performed single antigen bead testing on positive screening samples to check for the presence of DSA. Once this information was known, the laboratory staff accessed the randomisation system and randomised the patient, using the HLA Ab results and information on the sample form to stratify.

Allocation to SC (blinded) or BLC (unblinded) arms was assigned (1 : 1) by stratified block randomisation with randomly varying block sizes, using a web-based randomisation service provided by the King’s Clinical Trials Unit. Randomisation was stratified by (1) HLA Ab status, to generate three groups within each arm (DSA+, non-DSA+ or HLA Ab-negative), (2) current immunosuppression (to ensure balanced numbers already on Tac or MMF) and (3) site (N = 13). The randomisation allocation was initiated by staff within the five HLA (tissue-typing) laboratories involved in the trial.

Blinding

There was no blinding of arm allocation. In all sites, immediately after randomisation, the PIs and nurses were automatically emailed with information about whether the patient was in the blinded or unblinded groups. If in the unblinded group, the email to the PI contained information about the HLA Ab status. The system told trial staff to enter HLA Ab-negative patients into the subsequent 8 monthly screening rounds.

In blinded patients, HLA Ab status was not fed back to the PIs or trial staff in the emails. All blinded patients had samples taken 8 monthly for HLA Ab screening, though upon sample receipt, HLA laboratory staff used their knowledge of the HLA status to determine those from HLA Ab-negative patients which underwent screening and samples from HLA Ab-positive patients were discarded.

On the second and subsequent HLA Ab screening rounds, the laboratory staff updated the randomisation system within 52 days from the date the rescreen sample was taken. Only the results from patients in the unblinded groups were forwarded to the PI and lab staff, via email. This indicated whether status had changed and triggered the initiation of the treatment protocol in those that had changed from HLA Ab negative to positive. It also indicated that patients who had become HLA Ab+ needed ‘clock reset’ to extend the period of intensive follow-up for a further 32 months.

In the blinded arm, PIs were emailed with a list of patients who required ‘clock reset’ so they got follow-up for a further 32 months. This list contained all the recruits who had become HLA Ab+ on rescreening, but also an equivalent number of recruits who had stayed HLA Ab-; these recruits were randomly chosen by the randomisation system as a mechanism to maintain physician and patient blinding to HLA Ab status within this arm.

There were no blinded study medications in the trial so no emergency code break was required. There were no requests for recruits’ HLA Ab status to be unblinded.

Inclusion criteria

-

sufficient grasp of English to enable written and witnessed informed consent to participate;

-

aged 18–75 years;

-

estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR by four variable MDRD) of ≥ 30 ml/min (within the previous 6 months of signing consent or taken at screening if not done in the previous 6 months).

Exclusion criteria29

-

recipient requiring HLA desensitisation to remove Ab for a positive cross match (XM) transplant;

-

recipient known already to have HLA Ab who has received specific intervention for that Ab or for CAMR/chronic rejection;

-

recipient of additional solid organ transplants (e.g. pancreas, heart, etc.);

-

history of malignancy in previous 5 years (excluding non-melanomatous tumours limited to skin);

-

HBsAg+, HepC immunoglobulin G (IgG+) or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV+) recipient (on test performed within previous 5 years);

-

history of acute rejection requiring escalation of immunosuppression in the 6 months prior to screening;

-

patient enrolled in any other studies involving administration of another IMP at time of recruitment;

-

known hypersensitivity to any of the IMPs;

-

known hereditary disorders of carbohydrate metabolism;

-

pregnancy or breastfeeding females (based on verbal history of recipient);

-

pre-menopausal females who refuse to consent to using suitable methods of contraception throughout the trial.

Participant withdrawal

Individual recruits were free to withdraw at any time and the PIs also had the right to withdraw patients from the study drug in the event of inter-current illness, adverse events (AEs), serious adverse events (SAEs), suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions, protocol violations, cure, administrative or other reasons. After every withdrawal from ‘treatment’, efforts were made to obtain permission to continue to collect study-specific data before patients were completely withdrawn from the study. Failure to tolerate one or more components of the ‘treatment’ was not seen as a reason to withdraw an individual participant from the trial.

Significant amendments to study protocol

The complete list of changes over the course of the trial is included in Appendix 1. The following are those judged to have altered the conduct of the trial. All changes were discussed and approved by the Trial Steering Committee or Chairman and, where appropriate, by the Data Monitoring Committee.

In Version 4 (13/5/2013), we clarified that the eGFR measurement on which eligibility was be assessed had to be within 1 month of signing consent, and also clarified the definition of a positive HLA Ab test, which was confusing in the previous protocol versions.

In Version 5 (9/7/2013), the definition of diabetes mellitus was updated to incorporate the WHO definition (use of HbA1c) and the reporting of AEs in this type A trial to the sponsor was clarified.

In Version 7 (7/4/2014), we removed the exclusion criteria ‘history of ongoing or previous infection that would prevent optimisation’ which was being interpreted differently within and across sites. In addition, the gap for the testing of eGFR from within 1 month of signing consent was increased to within the previous 6 months of signing the consent. Finally, the timing of the optimisation process was changed from within 3 months of HLA Ab positivity to ideally within 3 months after positive screening for HLA Ab and allocation to the unblinded treatment arm or as soon as possible thereafter BUT within 8 months of positive screening. This coincided with the realisation that some patients were proving difficult to contact to arrange optimisation and the change was felt to enhance the optimisation process without affecting the outcome of the trial.

In Version 8 (1/7/2014), the time that tissue typing laboratories had to perform the randomisation of patients, was increased from 28 to 56 days post-consent. This was to enhance batching of patient serum for testing, reducing the number of experimental controls and HLA screening beads needed, and therefore the cost of screening.

In Version 10 (11/08/2015), the upper limit for eligibility into the study was increased from 70 to 75 years.

In Version 11 (26/11/2015), the primary objective and endpoint were changed from 3-year graft failure rates in HLA Ab+ patients in the SC versus BLC arms27 to ‘time to graft failure with variable follow-up (with a minimum of 43 months post-randomisation)’. The new primary endpoint was to be assessed remotely from patient notes once 43 months post-randomisation had been achieved by all. This change was required because, after 16 months recruitment, an audit of HLA Ab screening results revealed that the expected 9% prevalence and 3% incidence rates of DSA were actually 5.8% and 1.6%, respectively. 28 All patients already recruited were reconsented to allow this change. This change allowed for a reduction in the number of DSA patients to be recruited, and a significant shortening in the expected study duration while maintaining the power of the study.

Because there was no additional funding for these changes, existing workload was reduced by changing the timing of follow-up visits from 4-monthly to 8-monthly, the end visit for each participant changed from 36 to 32 months, along with the timing of the secondary endpoint assessments. Finally, there was a major reduction in the requirement for SAE reporting to the sponsor.

In Version 12 (1/12/16), we stopped collection of research blood samples and removed the secondary experimental/exploratory ‘scientific’ endpoints. This was required by the funder, who requested that the salary costs associated with the exploratory aspects of the trial be reallocated towards supporting the primary endpoint data collection.

Finally, in Version 14 (08/07/2020), we changed the timing of the collection of the primary endpoint, as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, in addition to the proposal to included additional sensitivity analyses for the primary endpoint and extension of the study end date.

Statistics methodology

Sample size and power calculations

The primary purpose of the trial was to demonstrate superior outcomes using the defined treatment strategy in BLC recruits, and at the same time demonstrate non-inferior outcomes when the screening strategy is applied to the entire patient population. Time to graft failure was chosen as a clinically relevant primary outcome. As a reference for power calculations, we used the observed failure rates reported by Lachmann et al. 7 for HLA Ab+ and HLA Ab-neg patients. Since Lachman showed that failure rates differed between DSA+ and non-DSA+ patients, sample size calculations were carried out separately for these groups. The estimates of the differences in primary outcome between groups were based on two things; first, the results of preliminary data from patients with CR treated with a similar regime as used here; second, our assessment that large differences in primary outcome would be needed to make the screening programme cost-effective. Our sample size calculations were updated with the change to the protocol in version 11 (see above) and the revised calculations28 are reported here.

Statistical hypotheses

-

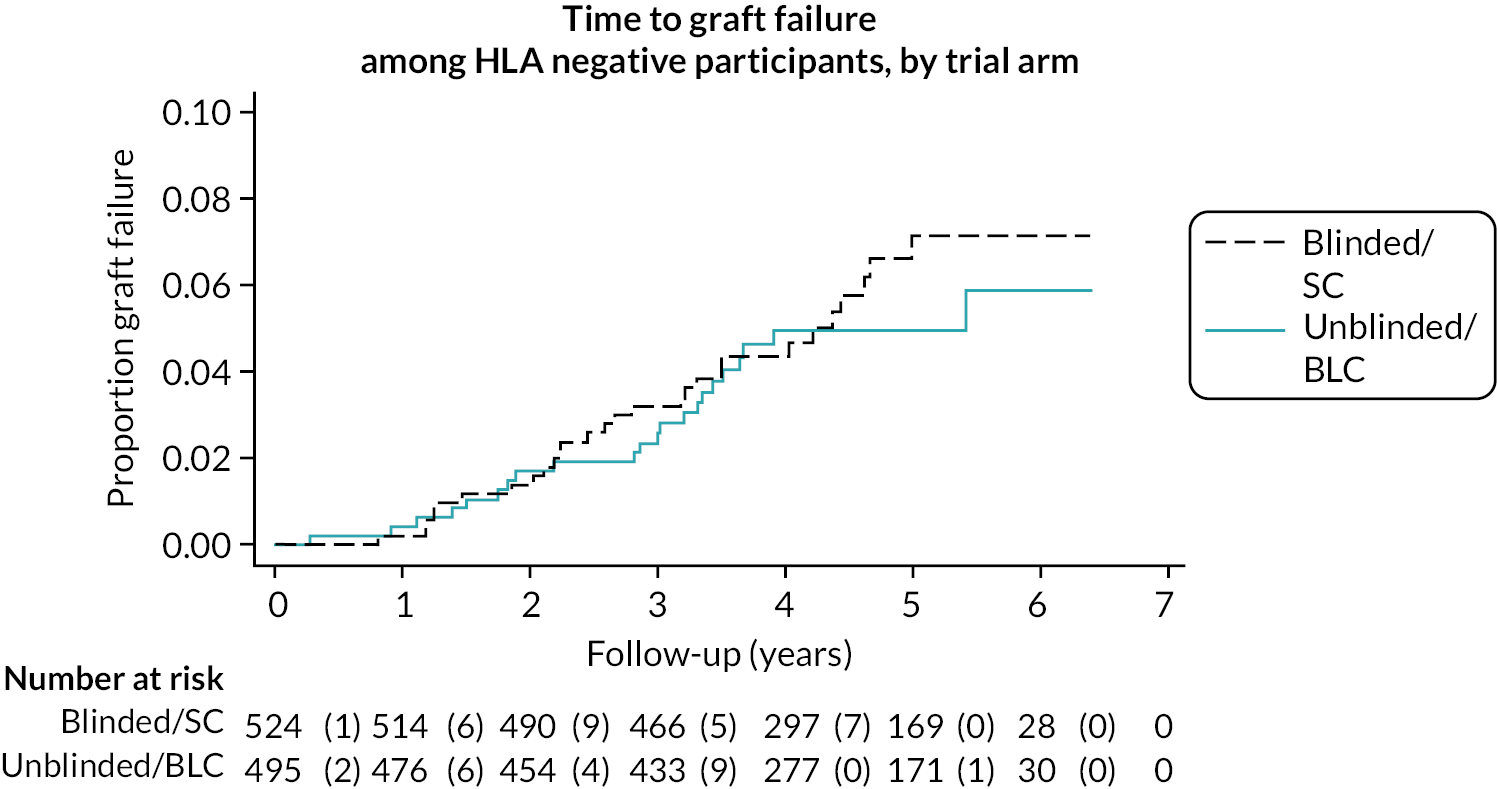

Superiority on Biomarker Positive Patients: refer to Figure 1 for groups

-

1.1) Group A1 > group B1: HLA Ab+ patients with DSA, randomised to SC (A1) were hypothesised to show higher graft failure rates than patients randomised to BLC (B1). We then hypothesised that the experimental treatment would bring the failure rate in group B1 down to that of non-DSA patients in SC (A2). Assuming 30% in group A1 should have experienced graft failure by 3 years follow-up (as in7), we expected treatment in group B1 to reduce the rate down to 16%, corresponding to a hazard ratio (HR) of 0.489. The expectation was for 11% and 21% failure among recruits with DSA in group A1 at 1 and 2 years follow-up, respectively, and extrapolating using a HR of 0.489, we expected BLC to reduce these to 5.5% and 10.9%. Using a variable follow-up design assuming an average accrual monthly rate of 3.6 patients per month, and a minimum follow-up of 43 months, recruiting 165 patients with DSA would allow us to observe 23/83 (28%) graft failures under BLC (group B1) and 39/82 (47%) in the SC group (A1). This would provide 80% power and 5% type 1 error for a 2-sided log-rank test.

-

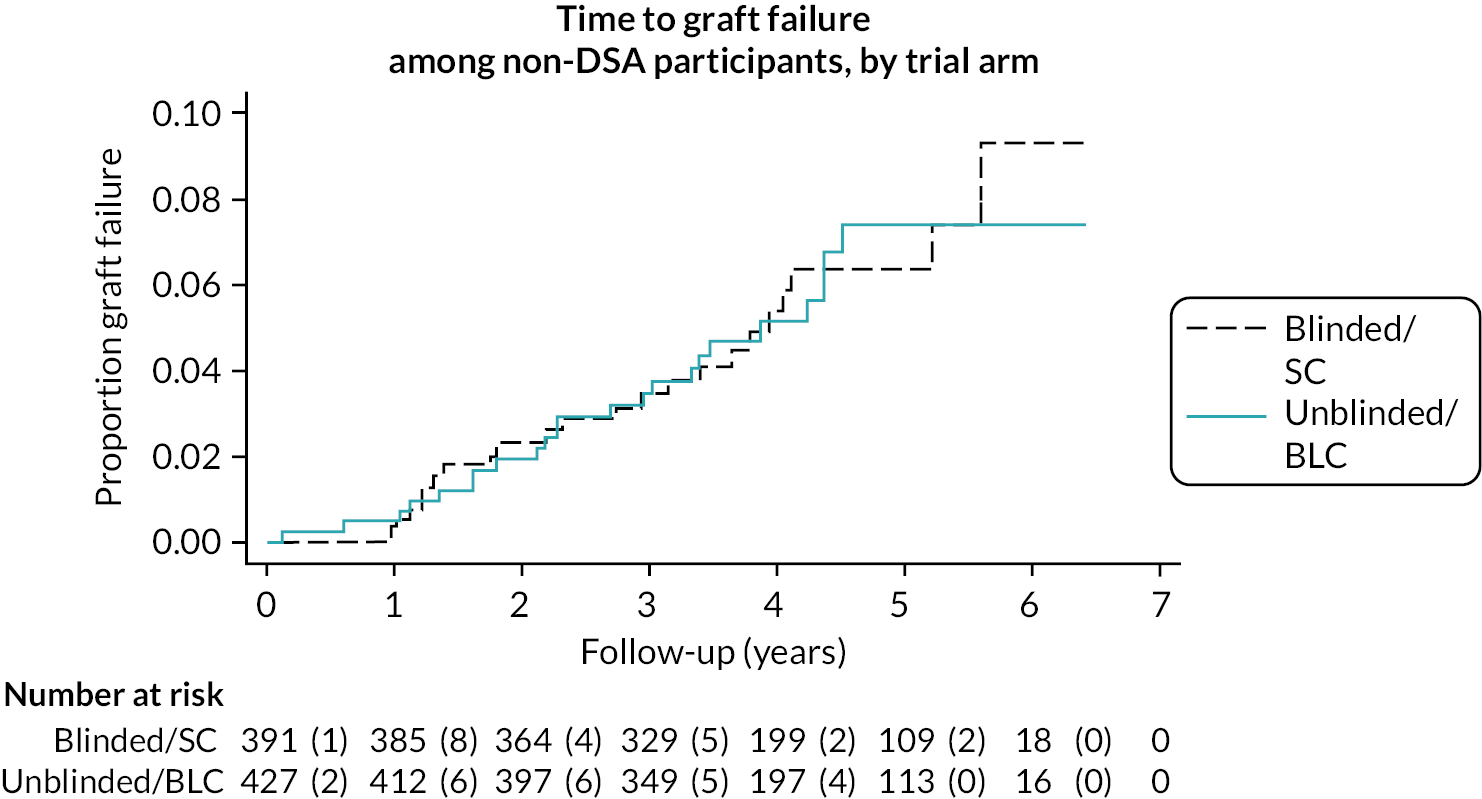

1.2) Group A2 > group B2: HLA Ab+ patients, with non-DSA, randomised to SC (A2) were hypothesised to show higher graft failure rate than patients randomised to BLC (B2). We then hypothesised that the experimental treatment would bring the failure rate in group B2 down to that of HLA Ab-negative patients in SC (C). Assuming 16% with non-DSA in group A2 should have experienced graft failure by 3 years follow-up (as in7), we expected treatment in group B2 to reduce the rate down to 6%, corresponding to a HR of 0.351. The expectation was for 3% and 11% failure among recruits with non-DSA in group A1 at 1 and 2 years follow-up, respectively, and extrapolating using a HR of 0.351, we expected BLC to reduce these to 1.1% and 4.1%. Using a variable follow-up design assuming an average accrual monthly rate of 15.5 patients per month, and a minimum follow-up of 22.4 months, recruiting 296 patients with non-DSA would allow us to observe 8/149 (5.3%) graft failures under BLC (group B2) and 21/147 (14%) in the SC group (A2). This would provide 80% power and 5% type 1 error for a two-sided log-rank test.

-

-

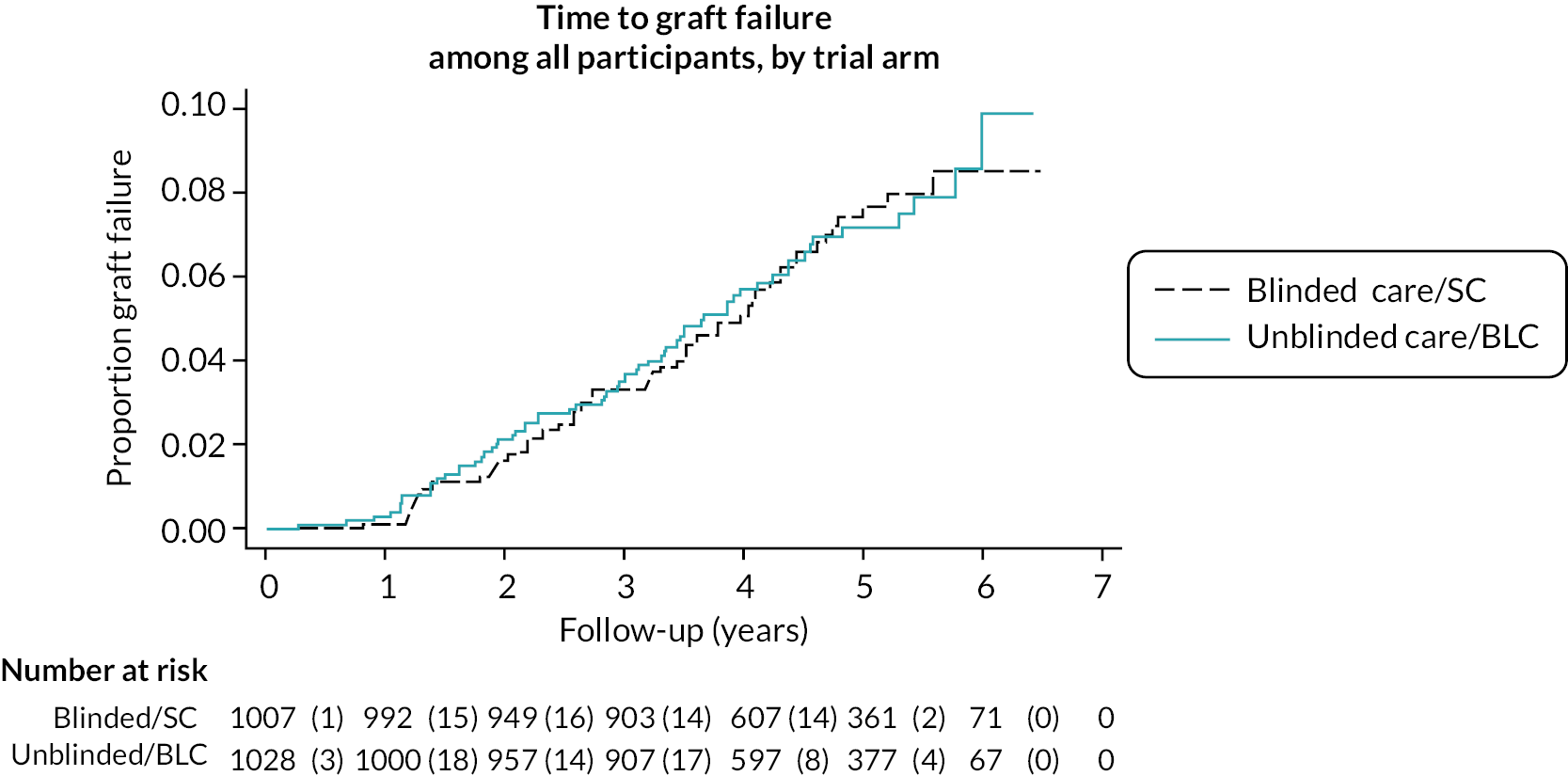

Non-inferiority of all unblinded patients compared to all blinded patients:

-

2.1) Groups A1 + A2 + C ≥ Groups B1 + B2 + D: All patients randomised to unblinded screening were hypothesised to show equal or lower graft failure rates than all patients randomised to blinded screening, irrespective of biomarker status. At the end of the trial, we expected 58% of patients to be in the HLA Ab negative groups, 7% in DSA+ groups and 35% non-DSA+ groups (after dropouts). At the time of planning the trial, based on all the assumptions above, we therefore calculated that the graft failure rate in the whole SC arm would be 13.9%.

-

We established a non-inferiority limit of 5% absolute difference in graft failure rate at 3 years, so that the BLC group would be considered inferior to SC group if they had a graft failure rate of ≥ 18.9%. This corresponded to a HR of 1.4 under the null hypothesis and an HR of 0.63 under the alternative. Therefore, we estimated that recruiting 672 patients to groups C&D (336 per group) with a minimum follow-up of 18.21 months would allow us to observe 22/337 (6.5%) graft failures in the SC group and 32/335 (9.5%) in the BLC group. This would provide 90% power to demonstrate non-inferiority with a one-sided 95% confidence interval (CI) of the HR estimated using a Cox regression model.

Following these calculations, we estimated the number to be screened, based on expected dropout rates, expected screening results and eligibility criteria. We assumed that 6% of initially Ab-neg patients would become Ab+ in each screening round (1/3rd with DSA) and that DSA recruits would comprise 7% of all recruits at the end of the trial. We therefore estimated that we needed to recruit 2357 patients overall to ensure we achieved 165 with DSA. The result of this was that the number of recruits to the other groups was higher than the minimum required as discussed above.

Following 16 months of recruitment, we performed an audit of our assumptions: the observed % of DSA patients (including those from rescreening rounds) was 6.6%. Although the percentage of Ab+ patients at baseline was 35.1%, considerably higher than expected (25–30%), only 5.8% of all patients had DSA at baseline (expected 9%). 300 Ab-neg patients had been rescreened as part of the month-8 screening round, of whom 23 had developed de-novo Ab (7.6% – expected 6%). Five out of the twenty-three had DSA (1.6% of all – expected 2%). Thus, as described above, we redefined the primary endpoint to ‘time to graft failure’ to allow the trial to recruit reduced numbers of DSA+ patients while maintaining power.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was on an intention-to-treat basis. All outcomes were analysed separately within the subgroups of DSA+ and non-DSA+ recruits. Recruits initially HLA Ab-negative who become positive during subsequent screening rounds were moved to the appropriate HLA Ab+ groups (DSA+ or non-DSA+) for analysis. These recruits, who were all followed up for an extra 32 months after the Ab was first discovered, were analysed from the time they became HLA Ab+ in the primary endpoint analyses. In the secondary analysis of time to graft failure in SC versus BLC participant using all recruits, they were analysed from time of randomisation (see below). The statistical analysis plan (SAP) contained detailed descriptions of how we would describe recruit characteristics, broken down by HLA Ab status.

Outcome assumptions and data collection periods

The following treatment effect contrasts for the primary and secondary outcomes were estimated:

-

1a. DSA+ BLC versus DSA+ SC participants (both at randomisation and rescreening);

-

1b. non-DSA+ BLC versus non-DSA+ SC participants (both at randomisation and rescreening);

-

2. all randomised BLC versus SC participants.

For the primary outcome, contrasts 1a and 1b were tested for superiority and contrast 2 was tested for non-inferiority, with non-inferiority concluded if the upper bound of the 95% CI for the HR was less than 1.4. For all secondary outcomes, all contrasts were tested for superiority.

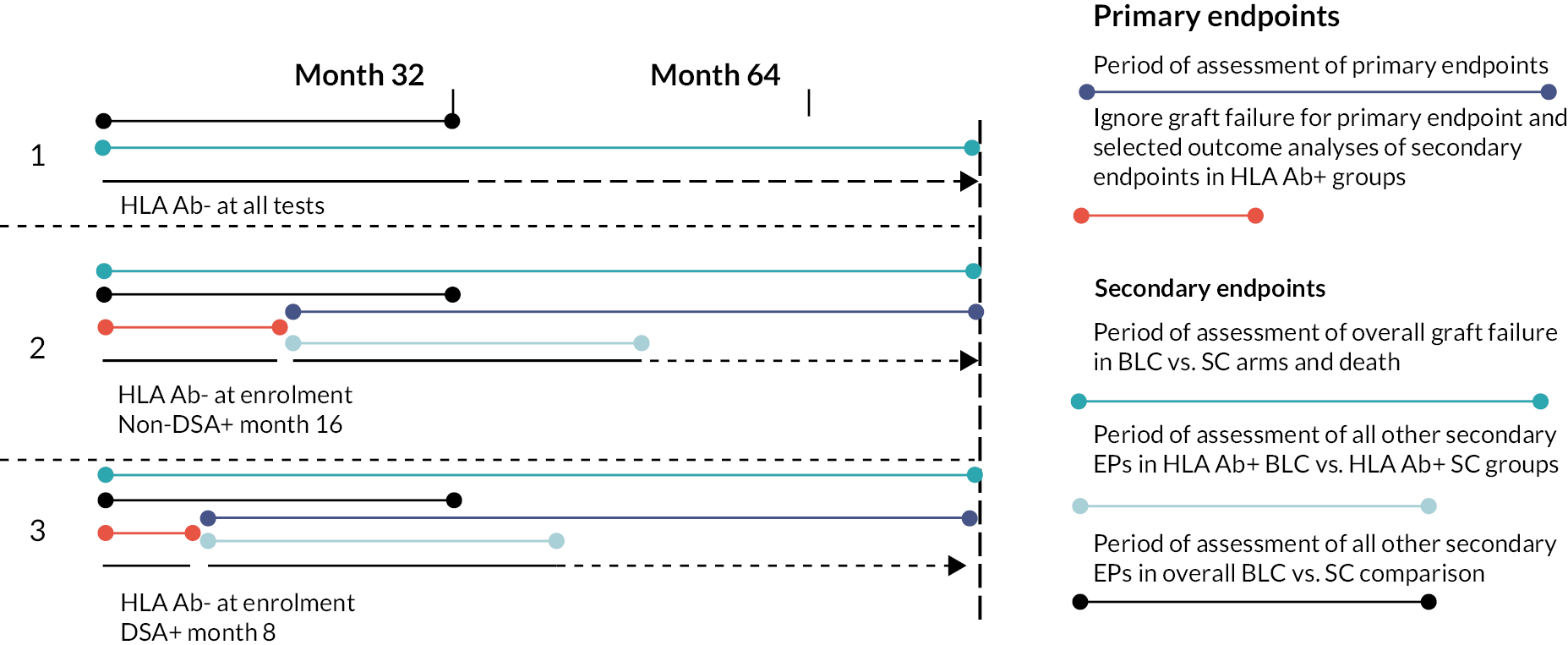

Different comparisons/outcomes used different observation periods. This is outlined in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Diagram to help explain how endpoints were assessed. Figure depicts three recruitment scenarios and explains how different outcomes were assessed, either in relation to recruitment/randomisation or, in the case of recruits turning from HLA Ab-negative to +, in relation to rescreening.

The purpose of these different observation periods for the different comparisons, is that the within DSA+ and within non-DSA+ comparisons aim to estimate the treatment effect of unblinding + optimisation in HLA+ve participants and so include participants at risk from the time they were found to be HLA+ve. The overall unblinded (BLC) versus blinded (SC) comparison aims to estimate the overall effect of the blinding strategy, and so participants time at risk is the time of blinding/unblinding to the HLA result (which is randomisation for all participants).

For the DSA+ and within non-DSA+ comparisons, time at risk started at randomisation for those HLA positive at randomisation and at time of rescreening for those HLA-negative participants who became HLA positive later at rescreening rounds. For the primary outcome, patients’ follow-up time was used up until the pre-COVID-19 collection period. For the overall comparison (statistical hypothesis 2), time at risk started at randomisation for all participants up until the pre-COVID-19 collection period. This was also true for the secondary outcome of death.

For the other secondary outcomes, these were only collected in the intensive data collection period which was from randomisation to 32 months post-randomisation, or in the case of participants who became HLA positive at rescreening rounds, 32 months post-rescreening. Therefore for these secondary outcomes, for the within DSA+ and within non-DSA+ comparisons, time at risk starts at randomisation for those HLA positive at randomisation and at time of rescreening for those HLA-negative participants who became HLA positive later and ends 32 months later. However, for the overall unblinded (BLC) versus blinded (SC) comparison for these other secondary outcomes, time at risk starts at randomisation for all participants and ends 32 months post-randomisation (ignoring any additional follow-up for rescreening HLA-positive participants).

For the primary outcome, the proportional hazards assumption was checked by testing for an interaction between treatment and time or more precisely, testing for a non-zero slope in a generalised linear regression of the scaled Schoenfeld residuals on functions of time (which is equivalent to testing the interaction).

Data analysis plan

The primary analysis used data collected up until 16 March 2020 and analyses were conducted for each of the hypotheses as outlined below. Several sensitivity analyses were also carried out for the primary outcome. These used the same covariates/modelling strategy as the primary analysis unless stated:

-

Excluding site as a covariate: There were a large number of sites, and this was a stratification factor adjusted for the model. However, there were low numbers of participants recruited for some sites such that some estimates for the site covariate were not estimated in the model. An analysis excluding site was carried out to ensure this was not causing instability in treatment effect estimates.

-

A competing risks analysis using competing risk regression, according to the method of Fine and Gray30 (1999), was carried out to examine sensitivity of the results to the competing risk of death. The subhazard ratio for graft failure was estimated.

-

For COVID-19 data: An analysis was carried out using additional follow-up data up until 30 November 2020, which we called the post-COVID-19 time point as these participants’ outcomes may have been affected by the COVID-19 pandemic. The analysis was otherwise exactly the same.

-

Using the primary model for the HLA Ab non-DSA group but restricting it to those participants who were assessed as definite non-DSA (as opposed to non-DSA in the absence of any conclusive evidence of DSA).

-

A sensitivity/per-protocol analysis restricting those in the HLA Ab+ DSA and HLA Ab+ non-DSA groups to those who received the full optimisation protocol (taking MMF, Tac and prednisolone at the visit following the optimisation interview).

Superiority

NB here, hA1(t), hB1(t), etc. represent the graft failure hazard rates in each of the groups.

In order to test superiority for the primary outcome in the BLC (HLA Ab) positive groups (Hypothesis 1.1 and 1.2), we used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the graft failure HR between the BLC and SC groups and test at the 5% level of significance. Results are given as estimates and 95% CIs. Within the model, we adjusted for previous immunosuppression regimen and research site (as these are the randomisation stratification factors) for increased statistical efficiency. We checked the proportional hazards assumption by examining Kaplan–Meier plots and by testing for an interaction between group (BLC or SC) and time to graft failure within the model.

Non-inferiority

In order to test for non-inferiority of the unblinded groups compared to the blinded groups (hypothesis 2.1), we used Cox proportional hazards regression models to estimate the graft failure HR. We adjusted for stratification factors in the model as outlined above and checked the proportional hazards assumption by examining Kaplan–Meier plots and by testing for an interaction between unblended and blinded group and time to graft failure. We concluded non-inferiority if H0 was rejected at 5% significance, and the corresponding upper bound of the 95% CI for the HR excluded the limit δ (HR of 1.4).

All secondary outcomes were analysed comparing BLC versus SC groups within the HLA Ab+ DSA participants and within HLA Ab+ non-DSA participants as well as between unblinded and blinded groups overall, as per the primary outcome analysis. We used similar procedure using Cox proportional hazards regression for the analysis of secondary time-to-event (survival) outcomes. For the secondary outcome of death an additional sensitivity analysis restricting the follow-up time to the first 32 months was carried out (as the original protocol implied that all secondary outcomes will be carried out on the 32 months intensive follow-up period only).

Where numbers allowed, secondary binary outcomes were analysed using logistic regression with adjustment for stratification factors. Where numbers were too small for this, the Z-test or Fisher’s exact was used. For continuous secondary outcomes, linear regression was used (or linear mixed models where accounting for repeated measures), adjusting for baseline values of the outcome and stratification factors. Transformations were considered where data was skewed. Results are given as estimates (odds ratios or differences in proportions) and 95% CIs.

The secondary outcomes of biopsy-proven rejection, infection, malignancy, and diabetes de novo were all analysed using logistic regression, with the outcome as to whether the participant experienced the event (at least once) over the intensive 32-month follow-up period (from randomisation or from rescreening as appropriate). Site was not included as a covariate in these models as small numbers recruited in some sites would lead to perfect prediction and observations being dropped. Baseline immunosuppression was included as a covariate as per the primary outcome model. All participants were included if they had at least one observation post-randomisation (or post-rescreening).

The outcome of proteinuria at month 32 was analysed using a logistic (longitudinal) mixed model, with all observations included between randomisation (or rescreening as appropriate) and month 32 at 4 monthly intervals, although most participants only had data at 8 monthly intervals as frequency of follow up was changed to 8 monthly in Protocol V10 (11 August 2015). Trial arm, time point, an interaction between time point and trial arm and stratification factors were included as covariates. A random intercept was included for participant. Treatment effects at month 32 were estimated using post-estimation commands. All participants were included if they had at least one observation post-randomisation (or post-rescreening).

The outcome of eGFR was analysed using a linear (longitudinal) mixed model, with time points as per the proteinuria model. Trial arm, time point, an interaction between time point and trial arm, baseline eGFR and the stratification factors were included as covariates. A random intercept was included for participant. Treatment effects at month 32 were estimated using post-estimation commands. All participants were included if they had at least one observation post-randomisation or post-rescreening (and so estimates are unbiased under a missing at random assumption as the model uses maximum likelihood).

Statistical considerations

Pre-specified instructions for dealing with missing data (baseline and outcome) are detailed in the SAP (see Supplementary Material). We made no formal adjustment of p-values for multiple testing. An exploratory per-protocol analysis was carried out comparing time to graft failure in only those participants who were optimised to the full treatment protocol in the unblinded arm against all blinded participants, within both the HLA Ab+ DSA and HLA Ab+ non-DSA groups. The proportional hazards assumption was checked for the primary outcome model by testing for an interaction with time. For secondary outcomes, where normally distributed outcomes were assumed, this was checked and transformations considered where departures from normality occurred. Residuals were plotted to check for normality and inspected for outliers.

Changes to the analysis from the SAP following discussion of the results and peer review comments

The following changes were made to the analysis following discussion/review of the results and peer review comments and are not covered in the final SAP (V2.4 09/02/2021):

-

a post-hoc exploratory sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome was carried out (for each of the three comparisons) using only BLC participants taking all three IMPs and with Tac trough levels of between six and eight compared to SC participants;

-

a post-hoc exploratory sensitivity analysis for the primary outcome was carried out (for each of the three comparisons), further adjusting for time of transplant and sex as covariates given chance imbalances between arms for these variables;

-

McNemar tests were carried out comparing whether numbers on immunosuppression medications for BLC HLA+ participants (both DSA and non-DSA) changed from pre-optimisation to the last visit. This was to try to demonstrate that the optimisation intervention did change these participants immunosuppression medications as intended;

-

a post-hoc analysis of the interaction between persisting DSA and time to graft failure in the main analysis was added to test whether those with persisting DSA and those without had different treatment effects;

-

the definition of what was classified as a biopsy-proven rejection was not strictly defined in the SAP or the protocol. This was erroneously taken to be only those participants who showed rejection on the primary pathology for renal biopsies originally. Biopsy-proven rejection is a secondary outcome. This became clear when responding to peer review and the chief investigator (CI) clarified that rejection on secondary pathology should also have been defined as biopsy-proven rejection. This analysis was therefore amended to include these few additional events and the results changed slightly.

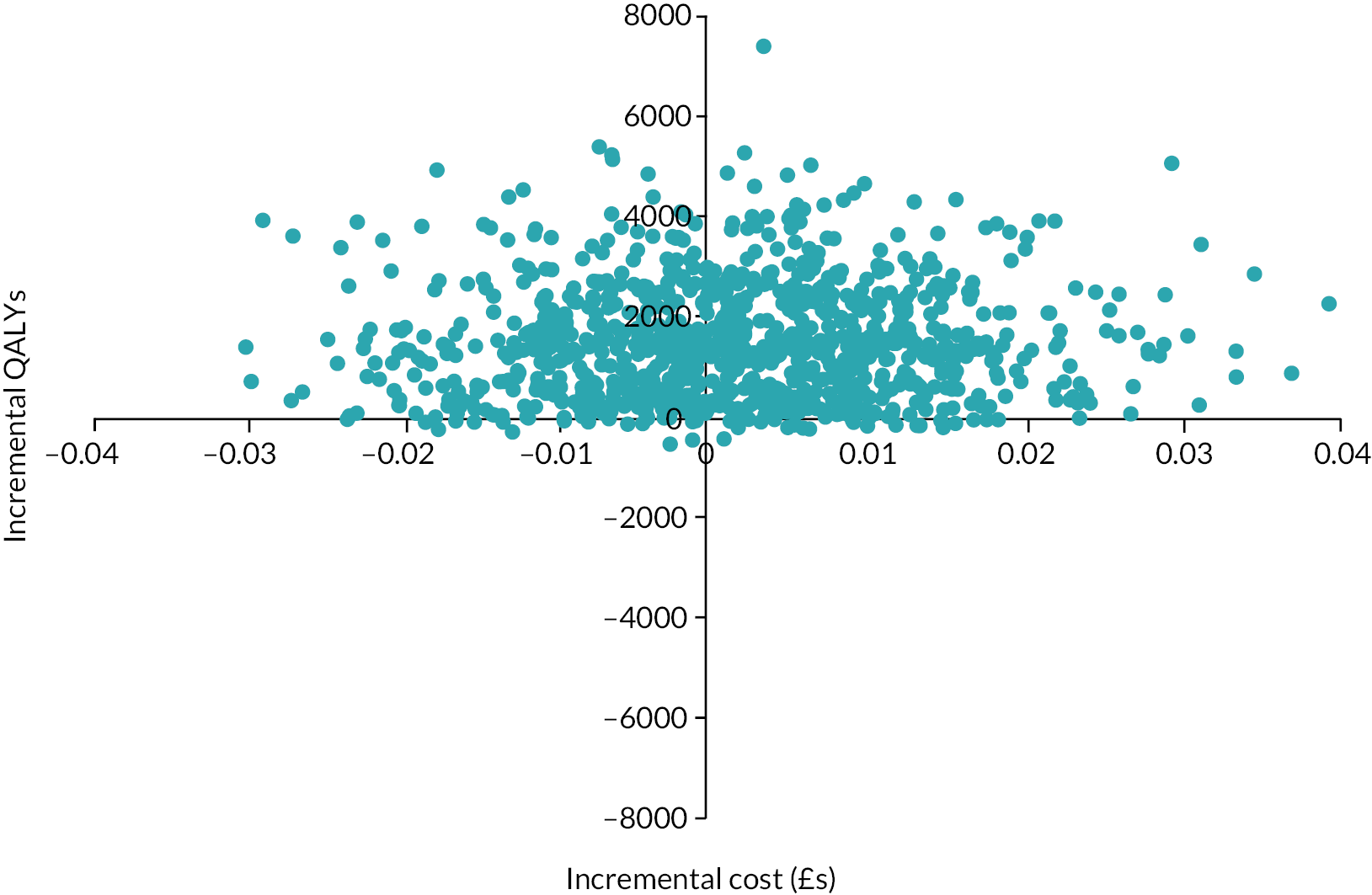

Economic evaluation

Aims and methods

The aims of the economic evaluation were to (1) compare health and social care use between both trial arms for HLA Ab + cases, (2) compare health and social care costs between arms and (3) assess the cost-effectiveness of unblinded care compared to blinded care in terms of quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) accrued. We adopted a health and social care perspective in line with National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommendations. A within-trial analysis was conducted and we focussed on HLA-positive cases with comparisons made between those receiving unblinded care and those with double-blinded care. Two time points provided data for these analyses: the one-year period prior to baseline assessment and the 12-month period prior to 16-month follow-up.

Service use was measured with an adapted version of the Client Service Receipt Inventory. 31 This asked respondents about use of health (primary care and secondary care) and social care service use in the previous 12 months. The number of contacts was recorded or in the case of inpatient care and residential care we asked for the number of days.

Service use was combined with appropriate unit cost information for the year 2019/20 in order to estimate service costs. Unit costs were obtained from the University of Kent’s annual compendium32 and the Department of Health and Social Care (https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/2019-20-national-cost-collection-data-publication/). For inpatient care, we had data on length of stay and assumed a cost of £500 per day rather than applying a cost for each admission. A list of unit costs used is shown in Table 1. One key cost excluded is the cost of screening itself. It is unknown what this will be in routine practice, and this is addressed in the discussion of the findings.

| Service | Unit | Cost (£s) |

|---|---|---|

| Residential care | Day | 102 |

| Renal inpatient | Day | 500 |

| Intensive care | Day | 1349 |

| Other inpatient | Day | 500 |

| Renal outpatient | Appointment | 135 |

| Other outpatient | Appointment | 135 |

| Day hospital | Visit | 100 |

| A&E | Visit | 182 |

| GP | Appointment | 34 |

| Physiotherapist | Contact | 64 |

| OT | Contact | 85 |

| Speech therapist | Contact | 109 |

| Dietitian | Contact | 92 |

| Nutritionist | Contact | 92 |

| Social worker | Contact | 51 |

| Homecare worker | Contact | 28 |

| Psychologist | Contact | 88 |

| Complementary healthcare | Contact | 58 |

| District nurse | Contact | 43 |

| Psychiatrist | Contact | 135 |

| Counsellor | Contact | 58 |

Quality-adjusted life-years are the outcome measure used in most economic evaluations in the UK. They combine quantity and quality of life, although here we had a time horizon that was restricted to 16 months. The EQ-5D-5L33 was used to derive QALYs and consists of five domains (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression). Each domain is scored with an integer from 1 (no problems) to 5 (extreme problems). The health states are then converted into a utility score anchored by 1 (full health) and 0 (death), with negative values indicating health states considered worse than death. The UK crosswalk method was used to derive these values. QALYs were then calculated using the area under the curve method base on a linear change from baseline to 16-month follow-up.

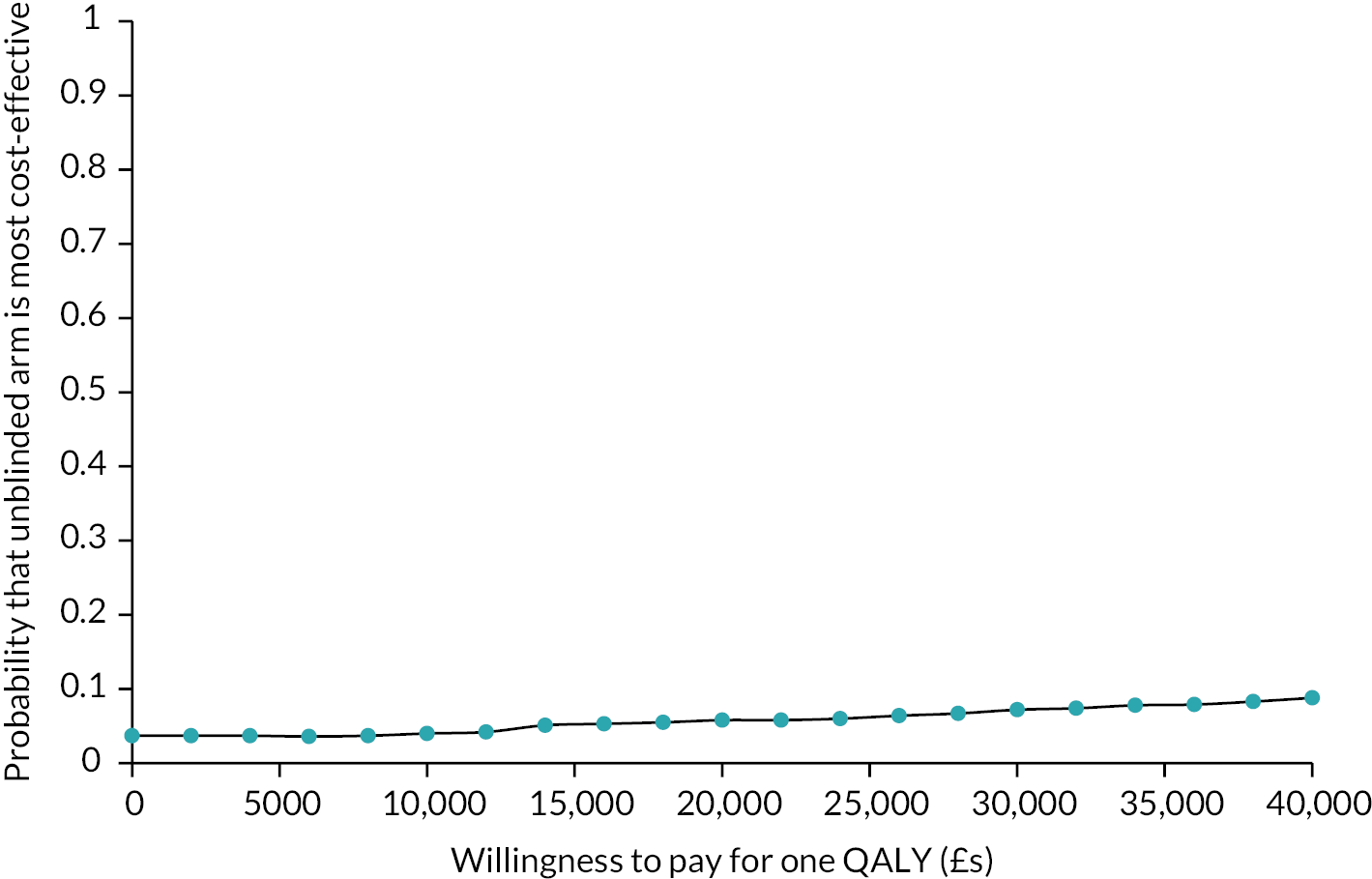

Use of services was compared descriptively between the arms. Total costs and QALYs were compared between arms using a seemingly unrelated regression model to take account of the possibility of correlated errors. In the estimation of cost differences adjustment was made for the baseline costs while for QALYs we adjusted for baseline utility. The model was bootstrapped with 1000 resamples due to the likely skewed cost distribution. The cost difference between arms was divided by the difference in QALYs to produce an incremental cost-effectiveness ratio (ICER). The saved bootstrapped cost and QALY differences were plotted against each other to produce a cost-effectiveness plane and used to derive incremental net benefit values to plot a cost-effectiveness acceptability curve. Discounting was not applied as the time horizon was only 16 months.

Adherence to drug therapy and perceptions of risk to the health of the transplant

Health surveys, consisting of validated psychological measures adapted for this specific health context, were performed at baseline and 12 and 24 months post screening for HLA Ab+, and included the medication adherence report scale (MARS) questionnaire, which consisted of measuring six items on a five-point Likert scale with higher scores representing greater adherence. Most items assessed intentional medication non-adherence; one item measured unintentional non-adherence. MARS was completed for each medication patients received. MARS correlates well with relatively objective measures of adherence in a range of illness contexts, including electronic measures of inhaled corticosteroids for asthma and blood pressure control for hypertension. 34,35 It has also been shown to have good levels of internal consistency, test-retest reliability and construct validity. 35 For Tac, 12-hour trough levels were also compared against the target trough levels (4–8 ng/ml) and a composite adherence scale based on combining MARS scores with trough levels was developed. Concern about the risk of transplant failure was measured using the Brief Illness Perceptions Questionnaire. 36

Analysis of questionnaires was performed separately to the main trial data by the team at University College London. Analyses were based on imputed data: where values were missing for a given survey item, the mean score for that item across all participants was used, providing that a given case had at least 80% complete data for other items on that scale. Mann–Whitney U or chi-squared tests were used to compare scores or proportions across patients in the BLC DSA+ compared to SC DSA+ groups, and BLC non-DSA compared to SC non-DSA groups.

Anti-HLA Ab determination

Serum prepared from 10 mL of blood was used in the commercially available LABScreen tests (One Lambda, Canoga Park, CA through VH Bio, Gateshead, UK), analysed on Luminex equipment (Luminex Corp, Austin, Texas) in the five original sites (Guy’s, Birmingham, Manchester, Leeds and Royal London). All worked to the same standard operating procedure, agreed pre-trial (see Appendix 2). Serum was first analysed using mixed HLA Class I and Class II Ab screening beads, with a positive or negative result assigned based on batch-specific cut-offs designated using validated protocols at the Guys laboratory site. In those patients with positive results, serum was further analysed using single antigen-coated Class I or Class II beads. A positive result was defined as giving a mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of binding ≥ 2000. Laboratory staff then compared assigned DSA/non-DSA status depending on whether HLA Ab were directed against a mismatched donor HLA antigen. HLA Ab in which it was difficult to label as DSA+ or non-DSA+ (because of insufficient data on donor mismatches, for instance), were categorised as being non-DSA+. Samples with a positive reaction on screening but lacking reactivity with the single antigen beads were considered negative. Screening of all HLA Ab– patients was undertaken every 8 months.

Trial oversight

Trial management group

A trial management group (TMG) was chaired by Professor Anthony Dorling (CI of the study) and consisted of co-applicants of the trial grant, the trial manager, Caroline Murphy (King’s CTU) and Olivia Shaw (Viapath, GSTT Tissue Typing Lab) and members of the research team. The TMG was responsible for decisions on the day-to-day running of the trial. The TMG met quarterly initially, but less frequently as the trial progressed.

Trial Steering Committee

A Trial Steering Committee (TSC) chaired by Professor Christopher Watson (Professor of Transplantation, Cambridge University) was convened in the post-award period. The members were Dr Craig Taylor (HLA Scientist, Addenbrookes Hospital), Professor Sunil Bhandari (Consultant Nephrologist, Hull & York Medical School) and Mr Paul Newton (Representative from the GSTT Kidney Patients Association), Professor Anthony Dorling (CI), the trial manager, Mr Dominic Stringer (Trial Statistician) and two co-applicants of the trial grant. The TSC met every 6 months initially, then annually, according to Terms of Reference drafted prior to recruitment.

Data Monitoring Committee

The Data Monitoring Committee (DMC) was chaired by Dr Nicholas Torpey (Consultant Nephrologist, Addenbrookes Hospital). The DMC remit was to safeguard the interests of trial participants, potential participants, their families, their carers, investigators, and the sponsor; to assess the safety and efficacy of the intervention during the trial and to monitor the trial’s overall conduct and protect its validity and credibility. A DMC charter was drafted prior to recruitment. The members of the DMC were Dr Issy Reading (Independent statistician, University of Southampton), Dr Alan Wong (Trials Pharmacist, Royal Free Hospital) and Dr Vaughan Carter (HLA Scientist, NHS Blood and Transfusion Service). Mr Dominic Stringer (Trial statistician) presented a closed report at each meeting. The DMC met every 6 months initially, then annually, approximately 2 weeks before the TSC.

Patient and public involvement

Kidney transplant patients were involved in the grant application process, first, via their involvement in the local review of projects at GSTT via the TRU Project Board Steering Committee, and second, through a specific meeting with members of the GSTT Kidney Patients Association during the grant application process. At this stage patient involvement led to three significant changes in trial design, including dropping the inclusion of protocol kidney transplant biopsies, reducing the maximum dose of prednisolone used, and because of concerns about the communication of risk associated with the biomarker, recruitment of Professor Rob Horne into the team. The KPA helped Prof Horne with the design of the patient information sheets for the trial and also provided a representative to sit on the TSC. Throughout the conduct of the trial, the KPA were kept updated about how the trial was progressing via their representative on the TSC and through regular updates via the MRC Centre for Transplantation newsletter, annual Clinical Trials Day literature and CI contributions to their quarterly newsletter.

Results

Participants, recruitment and flow

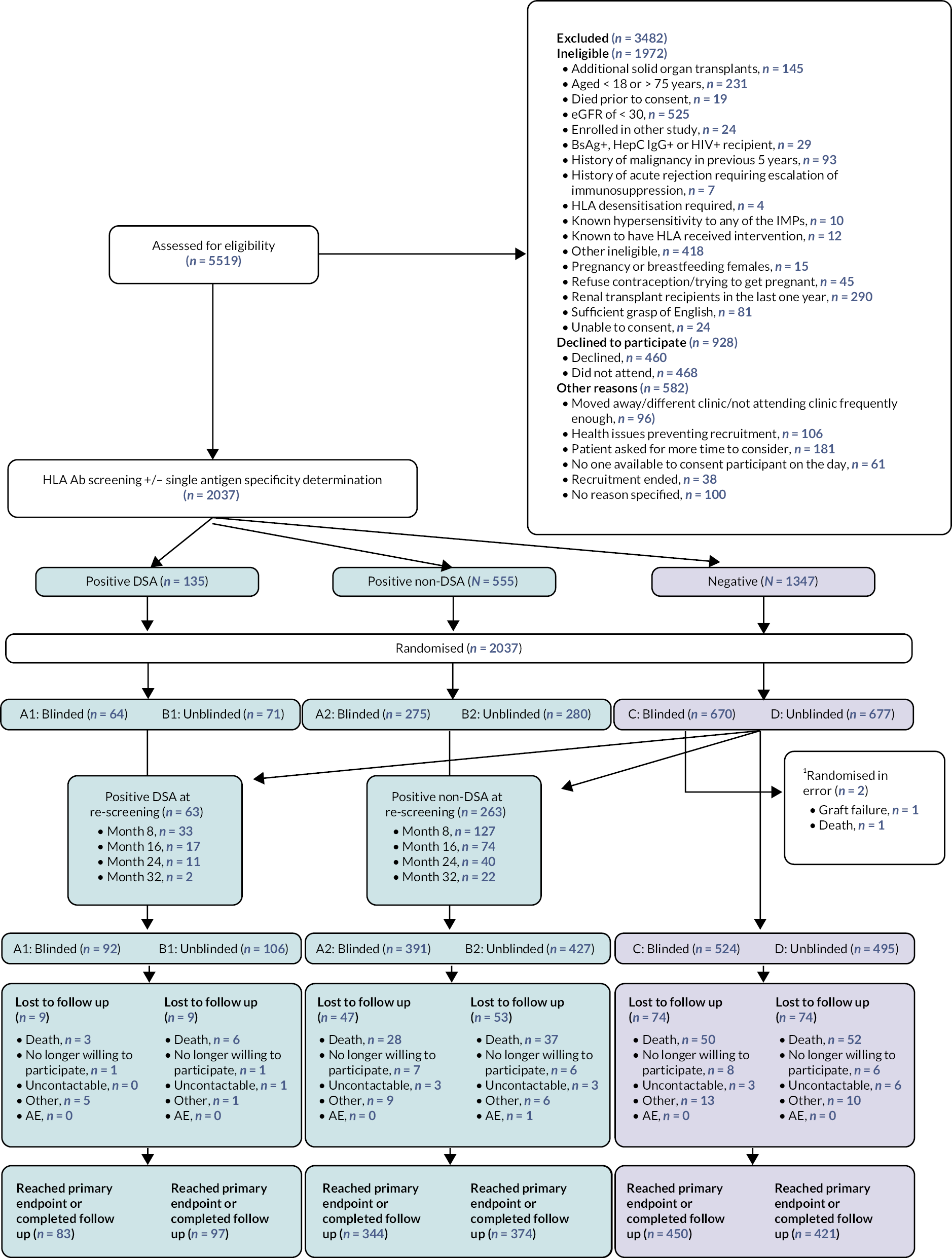

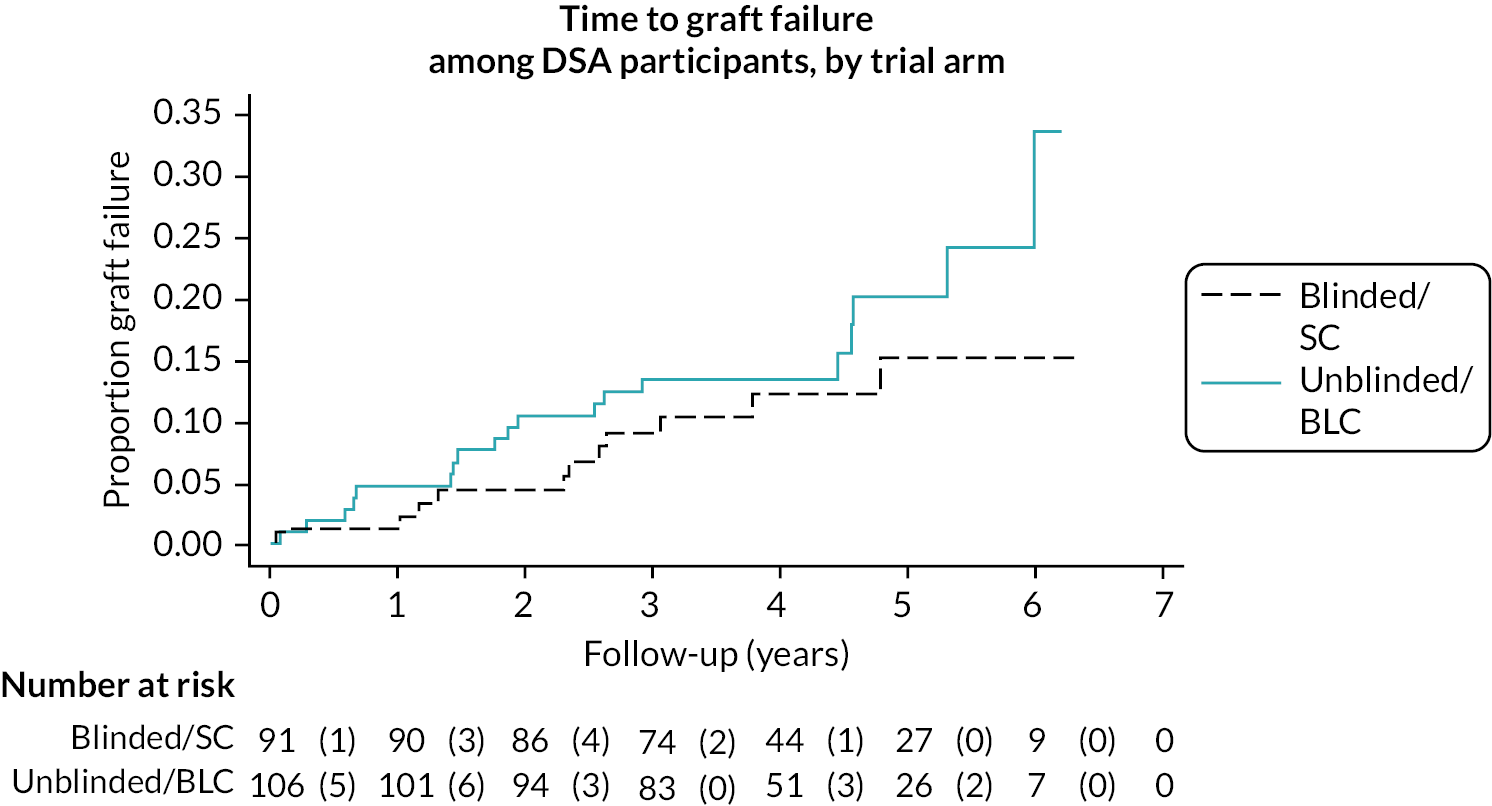

Recruitment was from 13 UK transplant centres and took place between 11 September 2013 and 27 October 2016. During that time, 5519 renal transplant recipients (see Figures 1 and 3) were assessed for eligibility of which 2094 were enrolled after consent. Fifty-seven patients were found to be ineligible after post-consent checks. 2037 were randomised after HLA Ab screening into two arms, each containing three groups based on the HLA Ab screening results; blinded SC (A1, A2 or C), and unblinded BLC (B1, B2 and D). Randomisation broken down by site and year is shown in Table 2. Screening of the HLA Ab-negative groups for HLA Ab finished in June 2017, at which time a further 63 with DSA (28 blinded, 35 unblinded) and 263 non-DSA (116 vs. 147) were identified, leaving 1019 remaining HLA Ab-negative through the course of screening (524 vs. 495). The end of the intensive follow-up period (last person, last visit) occurred 32 months later in March 2020, with the remote primary endpoint collection at a minimum of 43 months post-randomisation, originally scheduled for June 2020 moved to March 2020 because of the pandemic (as described above).

FIGURE 3.

Consort diagram for OuTSMART. 1 Two patients were randomised in error to blinded HLA Ab-negative SC group. These were included from the intention-to-treat analysis. Refer to Supplementary Material for further information.

| Site | 2013 (%) | 2014 (%) | 2015 (%) | 2016 (%) | Total (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| St James’s University Hospital, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Trust | 17 (15) | 128 (17) | 92 (18) | 54 (8.5) | 291 (14) |

| The Royal London Hospital, Bart’s Health NHS Trust | 0 (0.0) | 18 (2.3) | 63 (12) | 49 (7.7) | 130 (6.4) |

| Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust, London | 100 (86) | 291 (38) | 90 (18) | 48 (7.5) | 529 (26) |

| Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust | 0 (0.0) | 147 (19) | 98 (19) | 67 (10.5) | 312 (15) |

| Queen Elizabeth Hospital, University Hospitals Birmingham NHS Foundation Trust | 0 (0.0) | 145 (19) | 72 (14) | 0 (0.0) | 217 (11) |

| King’s College Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London | 0 (0.0) | 38 (4.9) | 32 (6.3) | 73 (11) | 143 (7.0) |

| The York Hospital, York and Scarborough Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 29 (5.7) | 24 (3.8) | 53 (2.6) |

| University Hospitals Coventry and Warwickshire NHS Trust | 0 (0.0) | 3 (0.4) | 35 (6.8) | 15 (2.3) | 53 (2.6) |

| Royal Preston Hospital, Lancashire Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 65 (10) | 65 (3.2) |

| Salford Royal Hospital, Northern Care Alliance NHS Foundation Trust | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 52 (8.1) | 52 (2.6) |

| Bradford Royal Infirmary, Bradford Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 48 (7.5) | 48 (2.4) |

| Royal Free Hospital NHS Foundation Trust, London | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 125 (20) | 125 (6.1) |

| Epsom and St Helier University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 19 (3.0) | 19 (0.9) |

Of the 90 patients ‘lost’ during the trial, 29 withdrew consent (group A1 n = 1: A2 n = 7: B1 n = 1: B2 n = 6: C n = 8: D n = 6), 16 became uncontactable (group A1 n = 0: A2 n = 3: B1 n = 1: B2 n = 3: C n = 3: D n = 6), 1 was withdrawn for an AE (group B2) and the remaining 44 were withdrawn for reasons listed as ‘other’, but 43 of these were because patients had transferred care to another, non-trial transplant unit and were therefore out of touch (group A1 n = 5: A2 n = 9: B1 n = 1: B2 n = 6: C n = 13: D n = 10).

Protocol violations/randomisation errors

There were two randomisation errors, both participants were randomised to the blinded (SC) arm and were HLA Ab-negative at baseline. One participant had graft failure prior to randomisation and one participant was randomised but was found to have died shortly before randomisation. Randomisation was carried out by lab staff following HLA screening and in error, it was not communicated to the lab staff that these events had occurred prior to randomisation. These participants are excluded from all analyses.

Further, for the primary analysis, one rescreened randomised participant is not included in the DSA group as they were found to have graft failure prior to being rescreened and becoming HLA Ab+ DSA and so were not at risk for the purpose of this analysis. This participant is included in any group/sensitivity analyses where time at risk starts at randomisation for all.

There were several other errors in recording of HLA status in the randomisation system. As per the intention-to-treat principle, these were analysed in the original groups as recorded in the randomisation data and not in the corrected group (as the HLA status as per randomisation data was communicated to the PI if in the unblinded arm, and treatment strategy would have been based on this data). These errors were the following:

-

One participant randomised to the BLC arm and entered as HLA Ab+ DSA at baseline in randomisation system was actually HLA Ab+ definite non-DSA at baseline according to the lab data.

-

One participant randomised to the SC arm and entered as HLA Ab+ DSA at baseline was actually HLA Ab+ definite non-DSA at baseline according to the lab data.

-

One participant in the BLC arm was moved from the HLA Ab-negative to the HLA Ab+ DSA group at rescreening (month 16). However, according to their lab data, their Ab at that time indicated ‘unknown whether DSA’ and should have been allocated to the non-DSA group as per the protocol.

-

One participant randomised to the BLC arm and entered as DSA at baseline actually had Ab at that time indicating ‘unknown whether DSA’ and should have been randomised to the non-DSA group.

-

Two participants randomised to the SC arm who were HLA Ab-negative at baseline were rescreened according to lab data at month 16 and became HLA Ab+ with unknown DSA. However, this was erroneously not entered into the randomisation system (and are considered HLA Ab-negative for the purpose of ITT analysis).

Baseline data

Demographics

There was generally good balance in baseline demographic characteristics between Ab+ and Ab- groups at point of randomisation (see Table 3). The DSA+ unblinded group had a higher proportion of males, longer time from transplant and higher proportion with previous transplants. There was no obvious imbalance in baseline variables after rescreening had finished (see Table 4).

| Characteristic | DSA+ | Non-DSA+ | HLA Ab negative | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blinded (SC) | Unblinded (BLC) | Blinded (SC) | Unblinded (BLC) | Blinded (SC) C | Unblinded (BLC) | |

| Group | A1a (N = 64) | B1 (N = 71) | A2 (N = 275) | B2 (N = 280) | (N = 670) | D (N = 677) |

| Age (years) Mean (SD) | 49.5 (12.0) | 47.0 (14.6) | 50.0 (11.9) | 50.6 (12.6) | 50.3 (13.30) | 50.5 (13.2) |

| Male (%) | 66% | 80% | 56% | 59% | 73% | 72% |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 9.4% | 14% | 13% | 13% | 11% | 13% |

| Black | 19% | 14% | 7.6% | 11% | 11% | 9.7% |

| White | 69% | 70% | 76% | 72% | 75% | 75% |

| Mixed | 1.1% | 0% | 1.5% | 1.4% | 0.6% | 0.1% |

| Other | 1.6% | 1.4% | 2.5% | 1.8% | 2.4% | 2.5% |

| Site [N (%)]b | ||||||

| Leeds | 8 (2.7%) | 8 (2.7%) | 41 (14%) | 40 (14%) | 96 (33%) | 98 (34%) |

| Royal London | 6 (4.6%) | 5 (3.8%) | 11 (8.5%) | 12 (9.2%) | 48 (37%) | 48 (37%) |

| Guy’s | 21 (4.0%) | 24 (4.5%) | 69 (13%) | 72 (14%) | 170 (32%) | 173 (33%) |

| Manchester | 8 (2.6%) | 8 (2.6%) | 44 (14%) | 47 (15%) | 103 (33%) | 102 (33%) |

| Birmingham | 3 (1.4%) | 2 (0.9%) | 31 (14%) | 27 (12%) | 77 (36%) | 77 (36%) |

| King’s College Hospital | 6 (4.2%) | 4 (2.8%) | 21 (15%) | 21 (15%) | 44 (31%) | 47 (33%) |

| York | 2 (3.8%) | 2 (3.8%) | 6 (11%) | 7 (13%) | 18 (34%) | 18 (34%) |

| Coventry | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (1.9%) | 6 (11%) | 7 (13%) | 18 (34%) | 21 (40%) |

| Preston | 1 (1.5%) | 4 (6.2%) | 11 (17%) | 8 (12%) | 21 (32%) | 20 (31%) |

| Salford | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.9%) | 6 (12%) | 8 (15%) | 19 (37%) | 17 (33%) |

| Bradford | 3 (6.2%) | 5 (10%) | 8 (17%) | 9 (19%) | 12 (25%) | 11 (23%) |

| Royal Free | 5 (4.0%) | 6 (4.8%) | 18 (14%) | 19 (15%) | 38 (30%) | 39 (31%) |

| St Helier | 0 (0.0%) | 1 (5.3%) | 3 (16%) | 3 (16%) | 6 (32%) | 6 (32%) |

| Cause of renal failure [N (%)] | ||||||

| DM | 4 (6.9%) | 2 (3.4%) | 7 (2.9%) | 13 (5.4%) | 38 (6.7%) | 40 (6.8%) |

| GN | 22 (38%) | 19 (33%) | 93 (39%) | 94 (39%) | 216 (38%) | 224 (38%) |

| PKD | 7 (12%) | 9 (16%) | 32 (13%) | 34 (14%) | 105 (19%) | 100 (17%) |

| Hypertension | 6 (10%) | 6 (10%) | 20 (8.3%) | 22 (9.2%) | 43 (7.6%) | 47 (8.0%) |

| Congenital | 7 (12%) | 7 (12%) | 31 (13%) | 22 (9.2%) | 66 (12%) | 47 (8.0%) |

| Obstructive | 8 (14%) | 10 (17%) | 38 (16%) | 34 (14%) | 54 (9.5%) | 80 (14%) |

| Other | 4 (6.9%) | 5 (8.5%) | 19 (7.8%) | 20 (8.3%) | 45 (8.1%) | 46 (7.9%) |

| Previous transplants [N (%)] | ||||||

| 0 | 48 (76%) | 52 (73%) | 193 (71%) | 198 (71%) | 613 (92%) | 633 (94%) |

| 1 | 12 (19%) | 18 (25%) | 71 (26%) | 65 (23%) | 55 (8.2%) | 35 (5.2%) |

| 2 | 3 (4.8%) | 1 (1.4%) | 8 (2.9%) | 13 (4.7%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (0.7%) |

| 3 | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 1 (0.4%) | 3 (1.1%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Time (years) since Tx Median (IQR) | 6.6 (3.0–12.0) | 9.7 (3.9–14.3) | 5.7 (2.2–10.9) | 4.9 (2.3–11.2) | 5.4 (2.4–9.2) | 5.1 (2.4–9.7) |

| Immunosuppression | ||||||

| CsA [N (%)] | 17 (27%) | 18 (25%) | 49 (18%) | 49 (18%) | 121 (18%) | 120 (18%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 170.3 (49.8) | 199.4 (68.5) | 168.6 (65.0) | 168.7 (60.4) | 180.7 (67.9) | 168.7 (63.0) |

| Mean trough level [μg/L (SD)] | 72.3 (34.8) | 80.9 (55.3) | 102.8 (84.8) | 88.6 (56.1) | 100 (71.4) | 109.6 (88.5) |

| Tac [N (%)] | 39 (61%) | 41 (58%) | 205 (75%) | 205 (73%) | 499 (74%) | 501 (74%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 6.14 (6.72) | 4.01 (2.24) | 5.08 (3.51) | 5.60 (4.60) | 5.50 (4.12) | 4.89 (3.65) |

| Mean trough level [μg/L (SD)] | 6.49 (2.64) | 5.65 (2.06) | 6.95 (2.93) | 6.86 (2.29) | 6.91 (2.31) | 6.71 (2.47) |

| MMF [N (%)] | 40 (63%) | 41 (58%) | 177 (64%) | 176 (63%) | 460 (69%) | 471 (70%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 1156 (476) | 1098 (422) | 1131 (450) | 1117(483) | 1155 (490) | 1136 (466) |

| Aza [N (%)] | 15 (23%) | 19 (27%) | 52 (19%) | 39 (14%) | 90 (13%) | 94 (14%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 88.3 (45.2) | 69.7 (33.9) | 76.7 (43.3) | 86.5 (39.3) | 85.3 (34.7) | 85.1 (35.1) |

| Sirolimus [N (%)]c | 2 (3.1%) | 5 (7.0%) | 10 (3.6%) | 4 (1.4%) | 17 (2.5%) | 25 (3.7%) |

| Median dose [mg (SD)] | 2.5 (0.71) | 1.6 (0.55) | 2 (0.82) | 2 (0.82) | 1.65 (0.70) | 2 (0.91) |

| Prednisolone [N (%)] | 37 (58%) | 38 (54%) | 153 (56%) | 154 (55%) | 369 (55%) | 372 (55%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 4.97 (1.72) | 4.97 (2.13) | 4.99 (1.45) | 4.99 (1.62) | 5.08 (1.67) | 5.2 (1.62) |

| Taking Tac/MMF/Pred [N (%)] | 13 (20%) | 13 (18%) | 82 (30%) | 70 (25%) | 192 (29%) | 189 (28%) |

| Renal function | ||||||

| Creatinine (μmol/l) [Mean (SD)] | 128.97 (40.32) | 124.96 (37.29) | 123.23 (35.42) | 122.61 (35.81) | 126.17 (38.78) | 126.73 (36.76) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) [Mean (SD)] | 52.31 (15.36) | 56.27 (17.70) | 52.12 (16.54) | 52.89 (16.32) | 53.77 (15.90) | 53.76 (17.26) |

| PCRd (mg/mmol) [Median (IQR)] | 26.50 (15.50–48.25) | 16.50 (10.75–39.25) | 18.00 (8.00-37.25) | 20.00 (9.00–42.50) | 17.00 (9.00–41.25) | 21.00 (10.00–41.00) |

| ACR (mg/mmol) [Median (IQR)] | 1.90 (1.40-1.95) | 5.30 (2.75-7.85) | 2.80 (1.30–6.30) | 7.05 (3.13–15.10) | 3.20 (1.20–9.22) | 3.30 (0.95–10.20) |

| Past medical history [N (%) experienced in that system] | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 41 (64%) | 43 (61%) | 157 (57%) | 166 (59%) | 406 (61%) | 418 (62%) |

| Respiratory | 9 (14%) | 5 (7%) | 46 (17%) | 51 (18%) | 72 (11%) | 84 (12%) |

| Hepatic | 3 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 3 (1%) | 13 (5%) | 13 (2%) | 32 (5%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 14 (22%) | 9 (13%) | 63 (23%) | 59 (21%) | 123 (18%) | 134 (20%) |

| Genitourinary | 30 (47%) | 33 (46%) | 119 (43%) | 131 (47%) | 269 (40%) | 286 (42%) |

| Endocrine | 24 (38%) | 16 (23%) | 78 (28%) | 91 (33%) | 218 (33%) | 218 (32%) |

| Haematological | 6 (9%) | 3 (4%) | 26 (9%) | 40 (14%) | 80 (12%) | 62 (9%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 23 (36%) | 13 (18%) | 69 (25%) | 83 (30%) | 156 (23%) | 162 (24%) |

| Neoplasia | 4 (6%) | 5 (7%) | 19 (7%) | 31 (11%) | 46 (7%) | 37 (5%) |

| Neurological | 12 (19%) | 6 (8%) | 23 (8%) | 37 (13%) | 66 (10%) | 75 (11%) |

| Psychiatric | 2 (3%) | 3 (4%) | 10 (4%) | 12 (4%) | 20 (3%) | 24 (4%) |

| Immunological | 5 (8%) | 1 (1%) | 17 (6%) | 27 (10%) | 19 (3%) | 31 (5%) |

| Dermatological | 11 (17%) | 11 (15%) | 44 (16%) | 44 (16%) | 85 (13%) | 91 (13%) |

| Allergies | 5 (8%) | 4 (6%) | 33 (12%) | 34 (12%) | 60 (9%) | 76 (11%) |

| Ophthalmological | 6 (9%) | 4 (6%) | 11 (4%) | 23 (8%) | 59 (9%) | 43 (6%) |

| Ear, nose, throat | 6 (9%) | 3 (4%) | 17 (6%) | 20 (7%) | 38 (6%) | 27 (4%) |

| Other | 12 (19%) | 13 (18%) | 56 (20%) | 75 (27%) | 153 (23%) | 132 (20%) |

| Characteristic | DSA+ | Non-DSA+ | No HLA Ab | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blinded (SC) | Unblinded (BLC) | Blinded (SC) | Unblinded (BLC) | Blinded (SC) | Unblinded (BLC) | |

| Group | A1b (N = 92) | B1 (N = 106) | A2 (N = 391) | B2 (N = 427) | C (N = 526) | D (N = 495) |

| Age (years) Mean (SD) | 48.1 (13.7) | 46.8 (14.0) | 49.4 (12.7) | 50.3 (12.6) | 51.1 (12.7) | 51.0 (13.3) |

| Male (%) | 72% | 81% | 61% | 59% | 72% | 75% |

| Ethnicity (%) | ||||||

| Asian | 9.9% | 12% | 12% | 14% | 11% | 13% |

| Black | 16% | 12% | 10% | 12% | 9.5% | 8.7% |

| White | 72% | 74% | 74% | 71% | 76% | 76% |

| Mixed | 1.1% | 0% | 1.5% | 0.9% | 0.4% | 0.2% |

| Other | 1.1% | 1.9% | 2.0% | 1.9% | 2.9% | 2.6% |

| Site [N (%)]c | ||||||

| Leeds | 11 (3.8%) | 12 (4.1%) | 70 (24%) | 76 (26%) | 64 (22%) | 58 (20%) |

| Royal London | 8 (6.2%) | 8 (6.2%) | 17 (13%) | 18 (14%) | 40 (31%) | 39 (30%) |

| Guy’s | 32 (6.0%) | 34 (6.4%) | 105 (20%) | 121 (23%) | 123 (23%) | 114 (22%) |

| Manchester | 12 (3.8%) | 9 (2.9%) | 50 (16%) | 54 (17%) | 93 (30%) | 94 (30%) |

| Birmingham | 5 (2.3%) | 12 (5.5%) | 47 (22%) | 42 (19%) | 59 (27%) | 52 (24%) |

| King’s College Hospital | 8 (5.6%) | 5 (3.5%) | 29 (20%) | 28 (20%) | 34 (24%) | 39 (27%) |

| York | 4 (7.5%) | 4 (7.5%) | 9 (17%) | 16 (30%) | 13 (25%) | 7 (13%) |

| Coventry | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (3.8%) | 8 (15%) | 12 (23%) | 16 (30%) | 15 (28%) |

| Preston | 2 (3.1%) | 5 (7.7%) | 13 (20%) | 12 (19%) | 18 (28%) | 15 (23%) |

| Salford | 1 (1.9%) | 1 (1.9%) | 8 (15%) | 8 (15%) | 17 (33%) | 17 (33%) |

| Bradford | 3 (6.2%) | 7 (15%) | 8 (17%) | 12 (25%) | 12 (25%) | 6 (13%) |

| Royal Free | 5 (4.0%) | 6 (4.8%) | 24 (19%) | 22 (18%) | 32 (26%) | 36 (24%) |

| St Helier | 1 (5.3%) | 1 (5.3%) | 3 (16%) | 6 (32%) | 5 (26%) | 3 (16%) |

| Cause of renal failure [N (%)] | ||||||

| DM | 5 (6.0%) | 7 (8.0%) | 17 (5.1%) | 22 (5.9%) | 27 (6.0%) | 26 (6.1%) |

| GN | 28 (34%) | 30 (34%) | 128 (38%) | 147 (40%) | 175 (39%) | 160 (38%) |

| PKD | 10 (12%) | 12 (14%) | 45 (14%) | 54 (15%) | 89 (20%) | 77 (18%) |

| Hypertension | 7 (8.4%) | 7 (8.0%) | 28 (8.4%) | 34 (9.2%) | 34 (7.6%) | 34 (8.0%) |

| Congenital | 13 (16%) | 10 (11%) | 41 (12%) | 34 (9.2%) | 50 (11%) | 32 (7.6%) |

| Obstructive | 12 (15%) | 16 (18%) | 50 (15%) | 48 (13%) | 38 (8.5%) | 60 (14%) |

| Other | 8 (9.6%) | 6 (6.7%) | 25 (7.5%) | 31 (8.4%) | 35 (7.7%) | 34 (7.9%) |

| Previous transplants [N (%)] | ||||||

| 0 | 71 (78%) | 85 (80%) | 301 (77%) | 337 (79%) | 482 (92%) | 461 (94%) |

| 1 | 17 (19%) | 20 (19%) | 79 (20.%) | 73 (17%) | 42 (8%) | 25 (5.1%) |

| 2 | 3 (3.3%) | 1 (0.9%) | 8 (2.1%) | 13 (3.1%) | 0 (0%) | 5 (1.0%) |

| 3 | 0 (0%) | 9 (0%) | 1 (0.3%) | 3 (0.7%) | 0 (0%) | 0 (0%) |

| Time (years) since Tx | ||||||

| Median (IQR) | 5.9 (3.0–11.9) | 6.7 (3.0–12.4) | 5.4 (2.2–9.8) | 5.1 (2.4–10.8) | 5.4 (2.4–9.6) | 5.1 (2.4–9.8) |

| Immunosuppression | ||||||

| CsA [N (%)] | 26 (28%) | 22 (21%) | 69 (18%) | 74 (17%) | 90 (17%) | 89 (18%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 187.3 (62.8) | 199.6 (63.6) | 174.4 (62.5) | 160.6 (58.9) | 176.3 (67.8) | 174.7 (62.9) |

| Mean trough level [μg/L (SD)] | 89.3 (56.2) | 80.7 (51.5) | 101.2 (79.8) | 87.3 (52) | 91.9 (52.3) | 116.4 (97.2) |

| Tac [N (%)] | 56 (64%) | 67 (64%) | 296 (76%) | 313 (73%) | 392 (75%) | 366 (74%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 6.18 (5.97) | 4.62 (3.33) | 5.14 (3.66) | 5.41 (3.73) | 5.44 (4.13) | 4.70 (3.15) |

| Mean trough level [μg/L (SD)] | 6.56 (2.86) | 5.83 (2.18) | 6.88 (2.74) | 6.68 (2.21) | 6.93 (2.26) | 6.72 (2.52) |

| MMF [N (%)] | 59 (64%) | 62 (59%) | 254 (65%) | 271 (63%) | 361 (69%) | 351 (71%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 1165 (482) | 1145 (399) | 1134 (457) | 1112 (472) | 1147 (495) | 1136 (473) |

| Aza [N (%)] | 19 (2.0%) | 26 (25%) | 66 (17%) | 61 (14%) | 71 (13%) | 69 (14%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 90.8 (43.5) | 76.9 (32.3) | 78.2 (40.8) | 88.5 (39.4) | 85.2 (33.4) | 83.6 (35.9) |

| Sirolimus [N (%)]d | 2 (2.2%) | 6 (5.7%) | 10 (2.6%) | 6 (1.4%) | 16 (3.0%) | 18 (3.6%) |

| Median dose [mg (SD)] | 2.5 (0.71) | 1.5 (0.55) | 2 (0.82) | 2 (0.89) | 1.62 (0.72) | 2.06 (0.8) |

| Prednisolone [N (%)] | 53 (58%) | 62 (59%) | 210 (54%) | 227 (53%) | 295 (56%) | 274 (55%) |

| Mean dose [mg (SD)] | 5.16 (1.81) | 5.1 (1.87) | 5.01(1.39) | 5.13 (1.53) | 5.11 (1.75) | 5.11 (1.43) |

| Taking Tac/MMF/Pred [N (%)] | 19 (21%) | 24 (23%) | 114 (29%) | 106 (25%) | 152 (29%) | 139 (28%) |

| Renal function | ||||||

| Creatinine (μmol/L) [Mean (SD)] | 129.09 (39.30) | 126.06 (38.25) | 124.08 (35.23) | 121.17 (35.25) | 126.02 (39.71) | 129.07 (36.96) |

| eGFR (ml/min/1.73 m2) [Mean (SD)] | 52.93 (15.23) | 56.16 (18.01) | 52.80 (16.39) | 54.12 (17.30) | 53.59 (15.95) | 52.82 (16.57) |

| PCRe (mg/mmol) [Median (IQR)] | 26.50 (13.75–49.75) | 23.50 (13.00–49.50) | 18.00 (8.00–38.00) | 19.00 (9.00–37.25) | 17.00 (9.00–39.00) | 21.00 (10.00–43.00) |

| ACR (mg/mmol) [Median (IQR)] | 2.00 (1.90–45.60) | 2.30 (0.80–8.00) | 2.80 (1.20–7.70) | 6.40 (2.82–20.10) | 3.20 (1.35–9.22) | 2.55 (0.90–8.75) |

| Past medical history [n (%) experienced in that system] | ||||||

| Cardiovascular | 60 (65%) | 70 (66%) | 221 (57%) | 254 (59%) | 323 (62%) | 303 (61%) |

| Respiratory | 11 (12%) | 9 (8%) | 56 (14%) | 69 (16%) | 60 (11%) | 62 (13%) |

| Hepatic | 3 (3%) | 2 (2%) | 5 (1%) | 17 (4%) | 11 (2%) | 27 (5%) |

| Gastrointestinal | 17 (18%) | 11 (10%) | 81 (21%) | 85 (20%) | 102 (19%) | 106 (21%) |

| Genitourinary | 46 (50%) | 42 (42%) | 169 (43%) | 198 (46%) | 203 (39%) | 207 (42%) |

| Endocrine | 32 (35%) | 34 (32%) | 118 (30%) | 144 (34%) | 170 (32%) | 147 (30%) |

| Haematological | 8 (9%) | 4 (4%) | 36 (9%) | 59 (14%) | 68 (13%) | 42 (8%) |

| Musculoskeletal | 27 (29%) | 25 (24%) | 90 (23%) | 119 (28%) | 131 (25%) | 114 (23%) |

| Neoplasia | 5 (5%) | 6 (6%) | 26 (7%) | 40 (9%) | 38 (7%) | 27 (5%) |

| Neurological | 16 (17%) | 7 (7%) | 33 (8%) | 54 (13%) | 52 (10%) | 57 (12%) |

| Psychiatric | 3 (3%) | 5 (5%) | 11 (3%) | 15 (4%) | 18 (3%) | 19 (4%) |

| Immunological | 5 (5%) | 1 (1%) | 21 (5%) | 37 (9%) | 15 (3%) | 21 (4%) |

| Dermatological | 13 (14%) | 13 (12%) | 55 (14%) | 59 (14%) | 72 (14%) | 74 (15%) |

| Allergies | 8 (9%) | 10 (9%) | 42 (11%) | 51 (12%) | 48 (9%) | 53 (11%) |

| Ophthalmological | 8 (9%) | 7 (7%) | 19 (5%) | 29 (7%) | 49 (9%) | 34 (7%) |

| Ear, nose, throat | 11 (12%) | 3 (3%) | 23 (6%) | 22 (5%) | 27 (5%) | 25 (5%) |

| Other | 20 (22%) | 17 (16%) | 79 (20%) | 98 (23%) | 122 (23%) | 105 (21%) |

HLA Ab status

The HLA Ab status at time of transplant was known for 91% of patients. Of the DSA+, fewer than 25% in either group had HLA Ab at the time of transplantation, indicating that > 75% had developed de novo DSA, whereas 35–40% of the groups with non-DSA HLA Ab, and 7% of the HLA Ab-negative group had HLA Ab at the time of transplantation (see Table 5). Approximately 45% of recruits in each of the DSA+ groups had DSA directed against HLA DQB antigens with a median MFI of 6200–7000, and 15–26% had DSA against HLA A antigens with a median MFI of 3600–4000 (see Table 6). Site investigators were not prevented from asking for routine HLA Ab tests via the normal clinic pathway. 374 patients had their HLA Ab status checked during the trial, including 191 in the blinded care arm. The split by group is illustrated in Table 6. Interestingly, 75–80% of the patients identified at recruitment or on rescreening as having a DSA, and who had DSA status reassessed at the last visit (month 32 post-Ab-detection), had become DSA-negative (see Table 5), with no obvious differences between SC and BLC groups.

| DSA+ | Non-DSA+ | No HLA Ab | ||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blinded (SC) A1 | Unblinded (BLC) B1 | Blinded (SC) A2 | Unblinded (BLC) B2 | Blinded (SC) C | Unblinded (BLC) D | |||||||||||||

| Time of Tx | Post-screening | End | Time of Tx | Post-screening | End | Time of Tx | Post-screening | End | Time of Tx | Post-screening | End | Time of Tx | Post-screening | End | Time of Tx | Post-screening | End | |

| Number of Ab+ (%) | 21 (22.8) | 92 (100) | 34 (37*) | 23 (21.7) | 106 (100) | 38 (35.0) | 158 (40.4) | 389 (99.5) | 106 (27.1) | 153 (35.8) | 425 (99.5) | 99 (23.1) | 37 (7) | 2 (0.4) | 9 (1.7) | 33 (6.7) | 0 (0) | 8 (1.6) |

| Definite DSA | - | 91 (98.9) | 18 (19.6) | - | 103 (97.2) | 25 (23.6) | - | 0 (0) | 13 (3.3) | - | 0 (0) | 3 (0.7) | - | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) | - | 0 (0) | 1 (0.2) |

| Definite non-DSA | - | 1a (1.1) | 13 (14.1) | - | 1a (0.9) | 10 (9.4) | - | 346 (88.5) | 86 (22) | - | 383 (89.7) | 92 (21.5) | - | 0 (0) | 7 (1.3) | - | 0 (0) | 5 (1) |

| Unknown whether DSA | - | 0 (0) | 3 (3.3) | - | 2a (1.8) | 3 (2.8) | - | 43 (11) | 7 (1.8) | - | 42 (9.8) | 4 (0.9) | - | 2b (0.6) | 0 (0) | - | 0 (0) | 2 (0.4) |

| Number of Ab– (%) | 64 (69.6) | 0 (0) | 35 (38) | 72 (67.9) | 0 (0) | 40 (37.7) | 192 (49.1) | 0 (0) | 191 (48.8) | 230 (53.9) | 1c (0.2) | 210 (49.2) | 449 (88.5) | 521 (99) | 437 (83.1) | 431 (87.1) | 489 (98.8) | 402 (81.2) |

| Missing data | 7 (10.5) | 0 (0) | 23 (25) | 11 (10.4) | 0 (0) | 28 (26.4) | 41 (10.5) | 2 (0.5) | 94 (24) | 44 (10.3) | 1 (0.2) | 118 (27.6) | 40 (7.6) | 3 (0.6) | 80 (15.2) | 31 (6.3) | 6 (1.2) | 85 (17.2) |

| Total | 92 (100) | 92 (100) | 92 (100) | 106 (100) | 106 (100) | 106 (100) | 391 (100) | 391 (100) | 391 (100) | 427 (100) | 427 (100) | 427 (100) | 526 (100) | 526 (100) | 526 (100) | 495 (100) | 495 (100) | 495 (100) |

| DSA+ | Non-DSA+ | No HLA Ab- | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Blinded (SC) A1 (N = 92) | Unblinded (BLC) B1 (N = 106) | Blinded (SC) A2 (N = 391) | Unblinded (BLC) B2 (N = 427) | Blinded (SC) C (N = 526) | Unblinded (BLC) D (N = 495) | |||||||

| HLA | Donor MM N (%): *assumed | DSA % [median MFI] | Donor MM N (%) *assumed | DSA % [median MFI] | Donor MM N (%) *assumed |

DSA % [median MFI] | Donor MM N (%) *assumed |

DSA % [median MFI] | Donor MM N (%) *assumed |

DSA % [median MFI] | Donor MM N (%) *assumed |

DSA % [median MFI] |

| A | 78 (85%) *0 | 26% [3998] | 87 (82%) *1 | 15% [3630] | 273 (70%) *0 | 0 | 285 (67%) *0 | 0 | 402 (76%) *0 | 0 | 352 (71%) *0 | 0 |

| B | 84 (91%) *0 | 9.8% [2424] | 93 (88%) *0 | 13% [5990] | 287 (73%) *0 | 0 | 300 (70%) *0 | 0 | 435 (83%) *0 | 0 | 385 (78%) *1 | 0 |

| C | 73 (79%) *1 | 16% [3733] | 80 (76%) *2 | 10% [3401] | 246 (63%) *1 | 0 | 258 (60%) *1 | 0 | 364 (69%) *3 | 0 | 322 (65%) *1 | 0 |

| DRB1 | 65 (71%) *1 | 6.5% [2645] | 89 (84%) *7 | 18% [3155] | 200 (51%) *2 | 0 | 220 (52%) *2 | 0 | 307 (58%) *1 | 0 | 284 (57%) *2 | 0 |

| DRB3 | 16 (17%) *3 | 4.3% [3148] | 17 (16%) *2 | 3.8% [4290] | 38 (9.7%) *0 | 0 | 35 (8.2%) *0 | 0 | 58 (11%) *0 | 0 | 65 (13%) *2 | 0 |

| DRB4 | 17 (19%) *0 | 2.2% [13850] | 25 (24%) *1 | 7.5% [6373] | 42 (11%) *1 | 0 | 49 (12%) *2 | 0 | 58 (11%) *0 | 0 | 82 (17%) *0 | 0 |

| DRB5 | 7 (7.6%) *0 | 1.1% [5326a] | 8 (7.5%) *0 | 0.94% [5568a] | 28 (7.2%) *0 | 0 | 28 (6.6%) *0 | 0 | 50 (9.5%) *0 | 0 | 49 (9.9%) *1 | 0 |

| DQA | 8 (8.7%) *2 | 4.3% [12005] | 9 (8.5%) *6 | 4.7% [12845] | 9 (2.3%) *5 | 0 | 14 (3.3%) *2 | 0 | 10 (1.9%) *2 | 0 | 8 (1.6%) *1 | 0 |

| DQB | 66 (72%) *5 | 44% [6947] | 78 (74%) *5 | 46% [6279] | 161 (41%) *5 | 0 | 189 (44%) *6 | 0 | 281 (53%) *0 | 0 | 265 (54%) *4 | 0 |

| DPB | 11 (12%) *5 | 3.3% [5623] | 9 (8.5%) *4 | 0.94% [5177a] | 31 (7.9%) *15 | 0 | 34 (8%) *15 | 0 | 35 (6.7%) *6 | 0 | 33 (6.7%) *18 | 0 |

| Recruits (%) having HLA Ab test outside trialb | ||||||||||||

| 28 (30%) | 27 (26%) | 75 (19%) | 89 (21%) | 88 (17%) | 67 (14%) | |||||||

Baseline and change in IS during the study

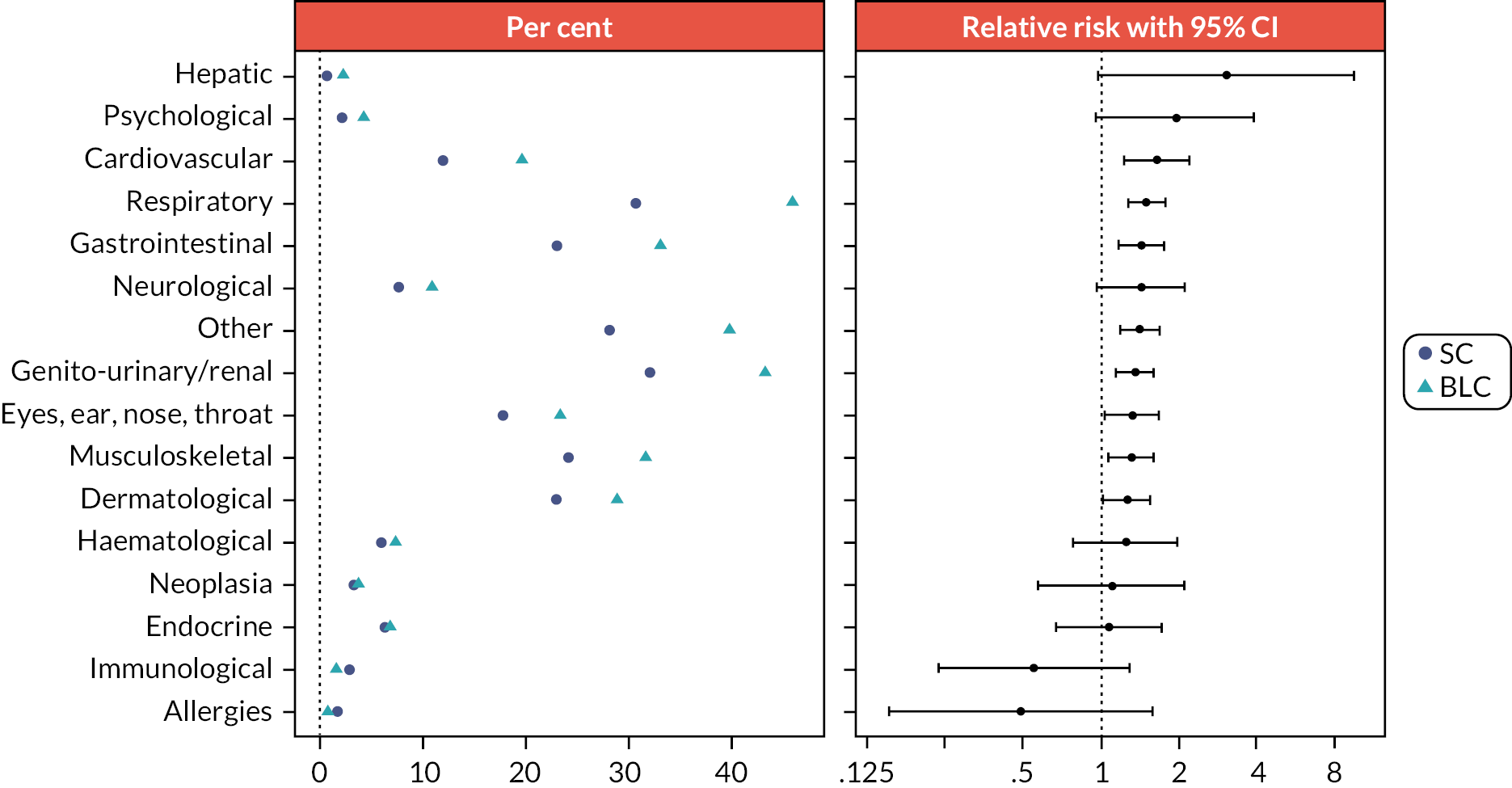

Eighteen per cent of all participants were taking ciclosporin at randomisation, and 15% taking azathioprine. Interestingly, the proportions on ciclosporin or azathioprine were highest in those with DSA compared to those with non-DSA and those who were HLA Ab-negative (see Table 3). The majority of patients were taking Tac (73%) or MMF (67%) at randomisation, though fewer were taking maintenance prednisolone (55%). The proportions on Tac or MMF were lowest in those with DSA, compared to those with non-DSA and those who were HLA Ab-negative (see Table 3). Finally, 27% overall were taking all three drugs. The proportion taking all three drugs was lowest in those with DSA compared to those with non-DSA and those who were HLA Ab-negative (see Table 3). These differences were maintained when considering patients who developed new HLA Ab during the rescreening process. Therefore, the proportions on ciclosporin or azathioprine were still highest in those with DSA after rescreening compared to those with non-DSA and those who were HLA Ab-negative (see Table 4). The proportions on Tac or MMF were still lowest in those with DSA after rescreening, compared to those with non-DSA and those who were HLA Ab-negative (see Table 4). Finally, the proportion taking all three drugs was still lowest in those with DSA after rescreen, compared to those with non-DSA and those who were HLA Ab-negative (see Table 4).