Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 13/50/17. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Cro et al. This work was produced by Cro et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Cro et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Material throughout the report has been adapted from the trial protocol by Cornelius et al. 1 © The Author(s). 2018 Open Access This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits unrestricted use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons license, and indicate if changes were made. The Creative Commons Public Domain Dedication waiver (https://creativecommons.org/publicdomain/zero/1.0/) applies to the data made available in this article, unless otherwise stated.

Parts of this report are also based on Cro et al. 2 © 2021 British Association of Dermatologists.

Scientific background

Psoriasis is a common condition (estimated prevalence of 2% in the UK) that is known to have an impact on quality of life at a level comparable to other major diseases, including chronic heart disease and cancer. 3,4 Pustular forms of psoriasis are characterised by painful, intensely inflamed red skin studded with sheets of monomorphic, sterile, neutrophilic pustules. These pustules may be chronic. Pustular psoriasis is typically localised and involves the hands and feet [known as acral pustular psoriasis (APP)], although it can also occur more rarely as generalised, episodic and potentially life-threatening [generalised pustular psoriasis (GPP)]. 5,6 Some individuals may experience both forms throughout their life.

Although pustular psoriasis constitutes < 10% of all cases of psoriasis, it often ranks the highest of all psoriasis phenotypic variants in terms of symptoms (itch, pain and functional impairment, causing limited mobility and interference with daily living tasks and work). 7–9 Ultimately, the consequential impact is immense and equivalent to that of psychiatric illness and other major medical diseases. 10,11

Over the past decade, significant investment in novel therapies and the advent of biological therapies have revolutionised the treatment and management of plaque-type psoriasis. This has been primarily driven by scientific investigations of underlying genetic and immunological disease pathways. 12 By contrast, the treatment options for pustular psoriasis are currently profoundly limited. Super-potent (topical) corticosteroids, phototherapy, oral treatments [e.g. acitretin (Neotigason®, Teva UK Ltd, Harlow, UK), methotrexate (Hospira UK Ltd, Maidenhead, UK) and ciclosporin (Capimune®, Mylan, Canonsburg, PA, USA)] and targeted biologic therapies (notably tumour necrosis factor antagonists) are all used, although the evidence for their benefit is poor. 13 There is, therefore, a very significant unmet need in this patient group.

Rationale for the study

Recent evidence indicates that the molecular pathways underlying pustular psoriasis are distinct (from that observed with plaque-type disease) and involve the interleukin (IL) 36/IL-1 axis. Research has identified functionally relevant IL36RN mutations in both GPP and APP. 14–16 IL36RN encodes the IL-36 receptor antagonist IL-36Ra (this is an IL-1 family member that antagonises the pro-inflammatory activity of IL-36 cytokines). Disease mutations disrupt the inhibitory function of IL-36Ra, causing enhanced production of downstream inflammatory cytokines (including IL-1). 15,16 Indeed, in individuals with IL36RN mutations, IL-1 production has been shown to be significantly upregulated in response to IL-36 stimulation. 15 Furthermore, IL-1 is a cytokine that is known to sustain the inflammatory responses initiated by skin keratinocytes. 17

Interleukin 1 antagonists have previously shown therapeutic benefits in the treatment of IL-1-mediated diseases (many of which feature neutrophilic infiltration of the skin). 18 Furthermore, there has been research that suggests a key pathogenic role for IL-1 in pustular forms of psoriasis. 19,20

The model IL-1 antagonist proposed for the study was anakinra [Sobi (Swedish Orphan Biovitrum AB), Stockholm, Sweden]. Anakinra is an IL-1 receptor antagonist that is licensed for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis and, during the timeline of this trial, periodic fever syndromes and Still’s disease. Anakinra was selected in preference of other licensed IL-1 antagonists for several reasons. It uniquely blocks the activity of both IL-1a and IL-1b. 18 Financially, it has the lowest drug acquisition cost (and this is of relevance to the NHS should anakinra show efficacy) and we had access to fully funded trial drugs through the manufacturer Sobi. Anakinra also possesses a rapid onset of action and an established safety profile (with > 70,000 patient-years’ exposure). Furthermore, there is early evidence of therapeutic benefit in participants with pustular psoriasis. 21

Hypothesis

We hypothesised that an IL-1 blockade would deliver therapeutic benefits in pustular forms of psoriasis. Therefore, this project aimed to investigate the clinical efficacy of an IL-1 blockade in palmoplantar pustulosis (PPP) (the most common form of pustular psoriasis) using the model IL-1 antagonist, anakinra, in a randomised, placebo-controlled trial with a two-staged adaptive design, followed by an open-label extension (OLE).

Study objectives

Primary objective

The primary objective of the study was to determine the efficacy of anakinra (compared with placebo) in the treatment of adults with PPP. The primary end point was change in disease activity at 8 weeks, adjusted for baseline, measured using the Palmoplantar Pustulosis Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PP-PASI).

Secondary objectives

-

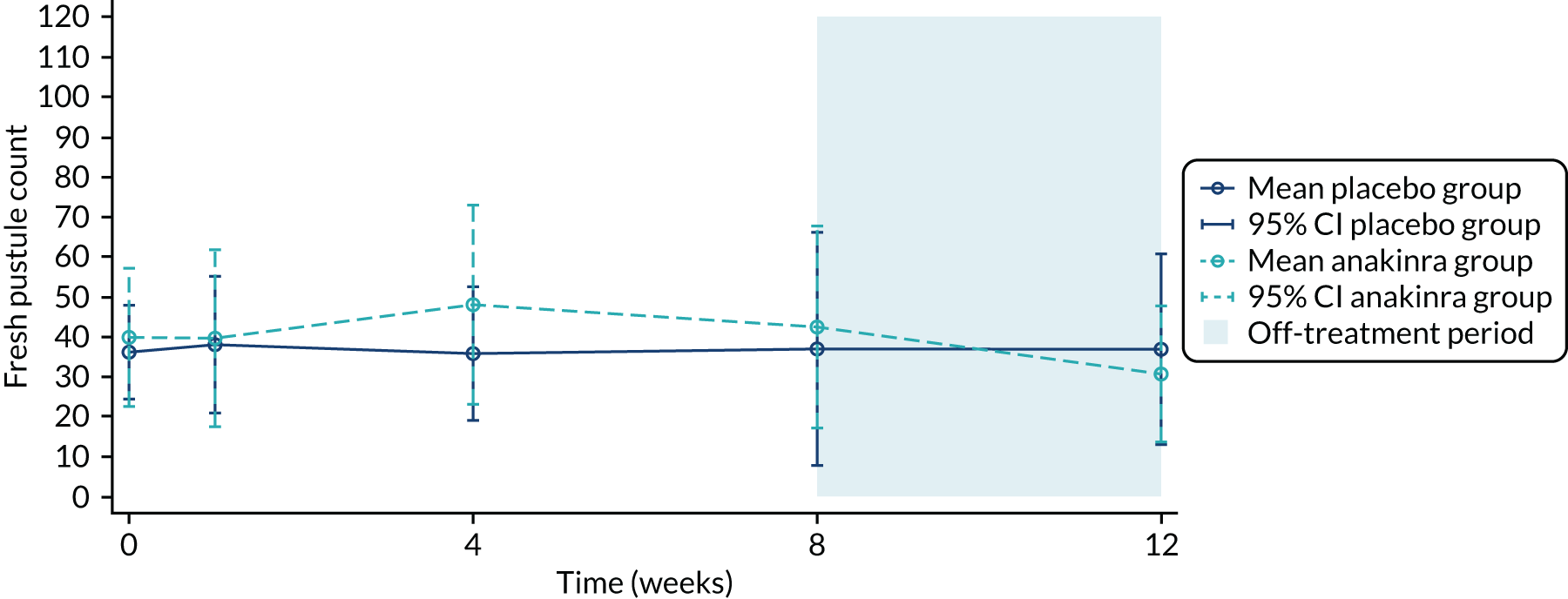

Determine the treatment group difference in fresh pustule count, adjusted for baseline.

-

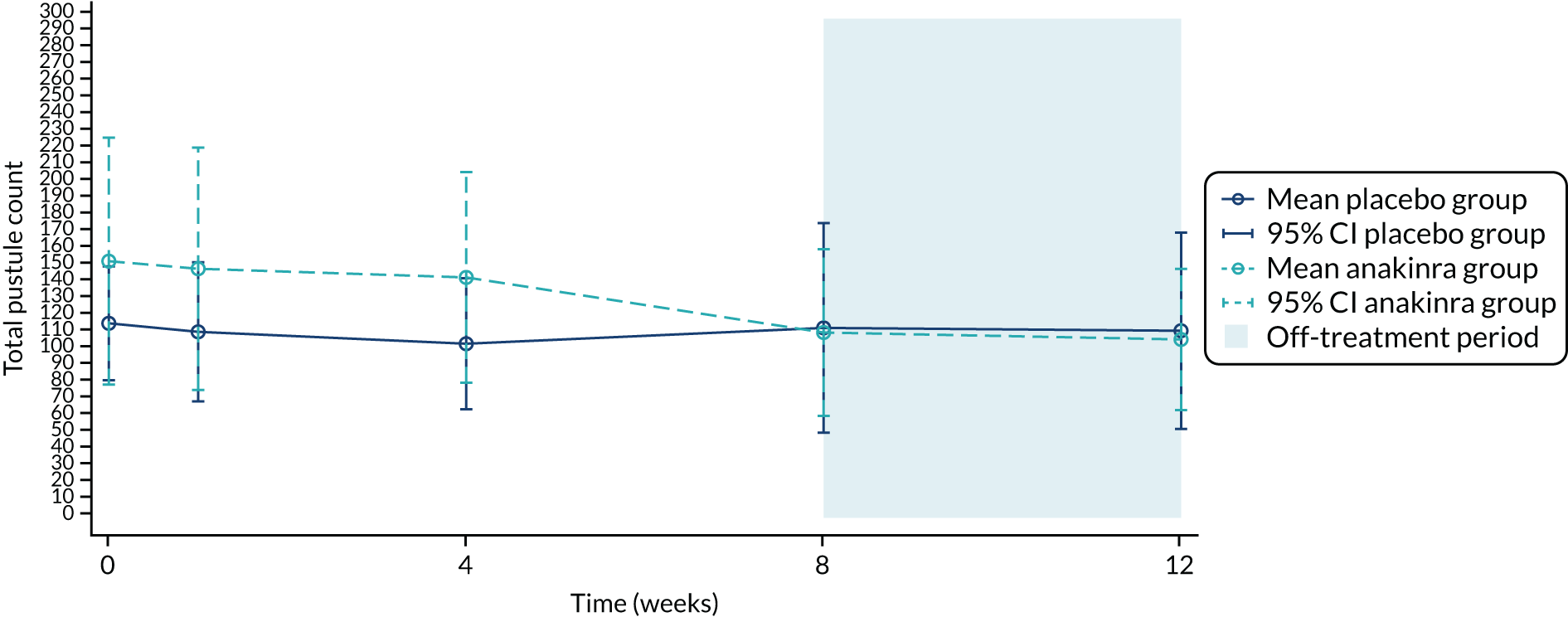

Determine the treatment group difference in total pustule count, adjusted for baseline.

-

Determine the time to response of PPP (defined as a 75% reduction in fresh pustule count compared with baseline) and relapse rate (defined as return to baseline fresh pustule count) with anakinra compared with placebo.

-

Determine the proportion of randomised participants who achieved clearance of PPP with anakinra compared with placebo by 8 weeks.

-

Determine the treatment effect on the development of a disease flare (> 50% deterioration in PP-PASI score compared with baseline) at 8 weeks.

-

Determine any treatment effect of anakinra in pustular psoriasis at non-acral sites as measured by change in percentage area of involvement at 8 weeks compared with baseline.

-

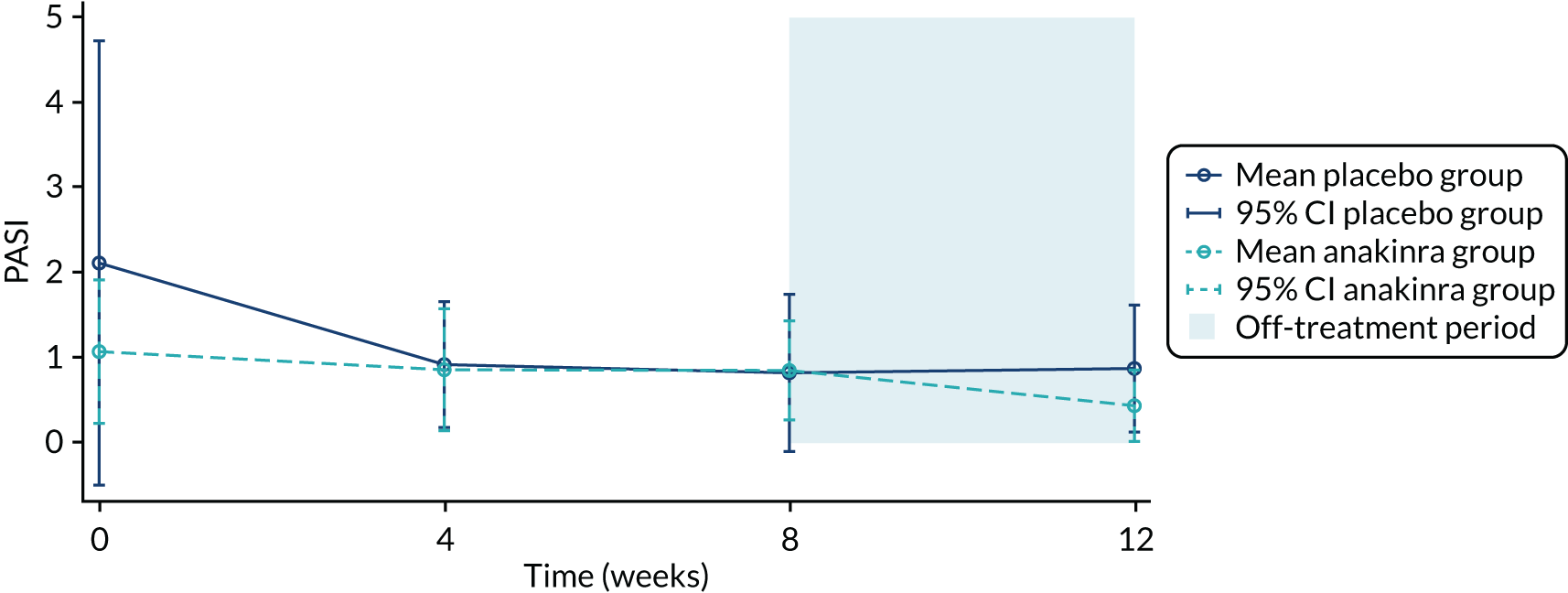

Determine any treatment effect of anakinra in plaque-type psoriasis (if present) measured using the Psoriasis Area Severity Index (PASI) at 8 weeks compared with baseline.

-

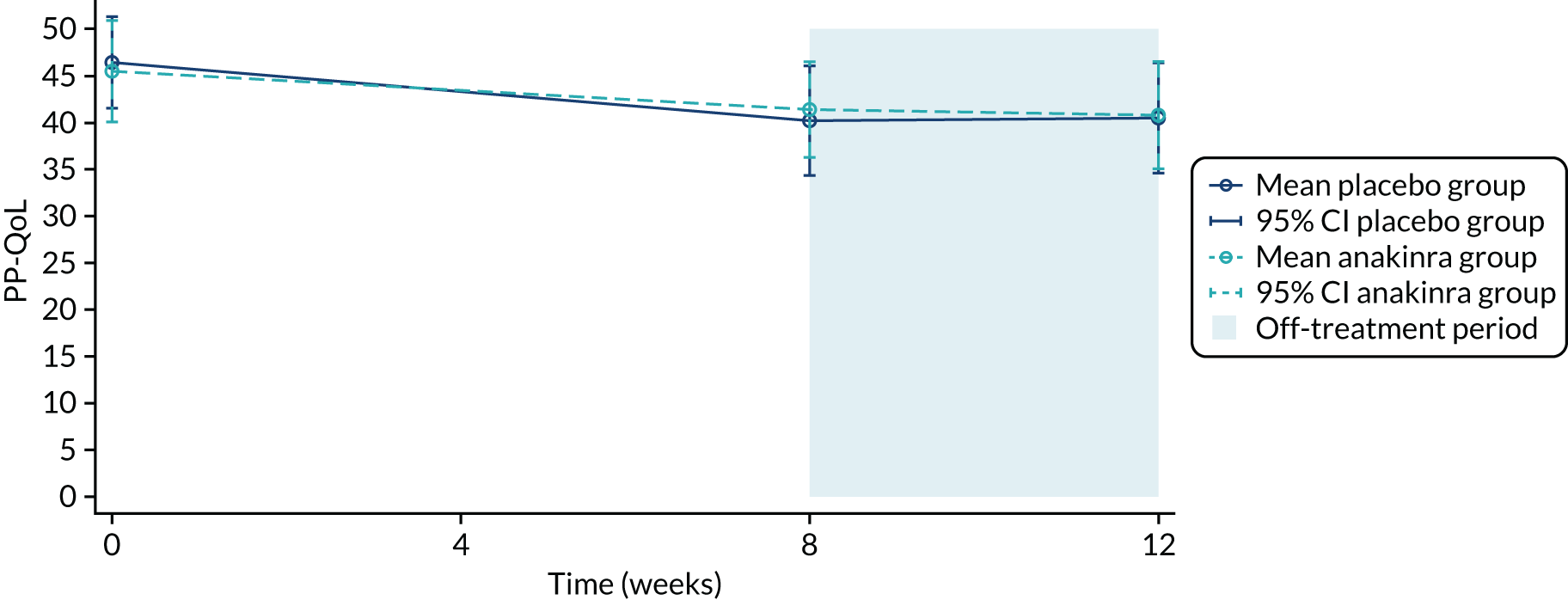

Determine the impact of anakinra on participants’ symptoms and quality of life compared with placebo at 8 weeks, adjusted for baseline, as assessed using the Palmoplantar Quality of Life (PP-QoL) instrument, Dermatology Life Quality Index (DLQI), Participants Global Assessment (PGA) and EuroQol-5 Dimensions, three-level version (EQ-5D-3L).

-

Determine the proportion of randomised participants who found the treatment acceptable or ‘worthwhile’.

-

Determine the proportion of randomised participants who adhered to treatment.

-

Determine whether or not there are any treatment group differences in episodes of serious infections, as defined by any infection leading to death or hospital admission or requiring intravenous antibiotics.

-

Determine whether or not there are any treatment group differences in neutropenia (neutrophil count of ≤ 1.0 × 109/l on at least one occasion).

-

Collect data on the adverse event (AE) profile and adverse reactions induced by anakinra compared with placebo to evaluate the safety and tolerability of anakinra in the treatment of PPP.

Exploratory objectives (mechanistic studies)

-

To validate the hypothesis that abnormal IL-1 signalling is a key driver in the pathogenesis of pustular psoriasis.

-

To determine the genetic status of individuals who responded to treatment as a preliminary step for future pharmacogenetic studies by comparing the genotypes of responders with those of non-responders.

-

To characterise the immune phenotype of all subjects entering the trial to establish whether or not the disease was associated with alterations in the number or activation status of IL-1-producing cells.

-

To collect mechanistic sample data sets on participants with pustular psoriasis for studies investigating disease pathogenesis [pustular psoriasis – elucidating underlying mechanisms (PLUM)].

Open-label extension objectives

The primary objective of the OLE was to boost recruitment; it was introduced part-way through the trial when funding for the required additional anakinra IMP was secured. In addition, we also obtained the following:

-

observational data on disease activity on anakinra [measured using the PP-PASI, fresh pustule count, total pustule count, Palmoplantar Pustulosis – Investigators’ Global Assessment (PPP-IGA) and PASI] over an initial 8-week treatment period for individuals originally prescribed placebo who chose to continue into the open-label component

-

observational data on disease activity on anakinra (measured using the PP-PASI, fresh pustule count, total pustule count, PPP-IGA scores and PASI scores) over a second 8-week treatment period for individuals originally prescribed anakinra who chose to continue into the open-label component

-

additional safety data following 8 weeks of anakinra treatment and also at 90 days post last dose of anakinra for individuals originally prescribed placebo

-

longer-term safety data on anakinra for individuals originally prescribed anakinra in the double-blind study period.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

This was a Phase IV, two-stage (stages 1 and 2), double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial with an adaptive element followed by an OLE. 1 Participant data from both stages were included in the main stage 2 analysis.

Stage 1 compared treatment groups to ensure that there was sufficient efficacy and safety to progress to stage 2. The pre-planned interim analysis for stage 1 occurred after 24 participants had been randomised and followed up for 8 weeks. A decision to embark on stage 2 was made using stop/go efficacy criteria. Fresh pustule counts and PP-PASI scores at week 8 were compared between treatment groups to assess efficacy. If, at the end of stage 1, the placebo group did as well as, or better than, the anakinra group on both of the two outcomes, then the study would be stopped. However, because the anakinra group did better than the placebo group for at least one outcome, the study proceeded (to stage 2).

Furthermore, the primary outcome for stage 2 was chosen at the end of stage 1. The two candidate primary outcomes assessed were the fresh pustule count (across palms and soles) and the PP-PASI score. These were recorded at baseline and at weeks 1, 4, 8 and 12. To determine the efficacy of anakinra for PPP compared with placebo, the primary end point for stage 2 was prespecified to be the change in disease activity at 8 weeks (adjusted for baseline) measured using fresh pustule count (the default primary outcome) unless the PP-PASI score was judged to be more reliable and discriminating.

Stage 2 commenced with the PP-PASI score designated as the primary outcome (see Chapter 3, Stage 1). Stage 2 included the randomisation of a further 40 participants (64 in total). 1,22

Interventions

Participants were randomised (1 : 1) to receive (100 mg per day) either anakinra or placebo for 8 weeks, which was self-administered daily as a subcutaneous injection.

Participants who opted to take part in the OLE received a further 8 weeks of anakinra (100 mg per day) treatment, which was self-administered daily as a subcutaneous injection. The OLE was optional, and was offered to all participants who completed the 8-week treatment period and the 12-week follow-up visit.

Setting

The trial was set in 16 hospitals across England, Scotland and Wales.

Participants

Given that GPP is rare, episodic and potentially life-threatening, including GPP participants in a trial setting would have been difficult and potentially unethical (with the placebo group). Thus, the population designated for the study was participants with PPP. This chronic, localised form of pustular psoriasis involves the hands and/or feet, and is associated with significant disability. It is the most common form of pustular psoriasis, making recruitment feasible, and typically features chronic development of pustules so that we would expect to capture any treatment effect within the 8-week treatment period.

All participants were adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of PPP that had been made by a trained dermatologist, with a disease duration of > 6 months and disease of sufficient impact and severity to require systemic therapy. To be randomised into the study, at the baseline visit participants had to exhibit at least moderate disease on the PPP-IGA, with evidence of active pustulation on palms and/or soles.

Women who were pregnant, breastfeeding or of child-bearing age and not on adequate contraception and men planning conception were excluded from taking part in the trial.

The specific inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria for the double-blind, placebo-controlled trial and the OLE are detailed below.

Identification and recruitment

Potentially eligible participants were identified by the following four methods:

-

In clinic at participating sites. Potentially eligible participants were identified in clinics and were approached directly by a member of the trial team and/or clinical care team, who explained the study to the patient and provided them with the patient information leaflet. Participants were then given as much time as they required (and at least 24 hours) to read the information leaflet and come to a decision about their participation.

-

Searching existing local health-care/medical databases at participating sites. Once sites were opened, local study teams identified potentially eligible participants through searching local clinic and pharmacy lists, electronic patient records, referral lists and letters, research databases and other lists (as appropriate). Potential participants were then contacted by their consultant and the research team (by letter, e-mail or telephone call), were invited to participate the study and were provided with the patient information leaflet.

-

Self-referral. Potential study participants identified themselves after becoming aware of the study. The study website (http://apricot-trial.com/; accessed 28 February 2020) included a specific page (which was taken down following the end of recruitment) on which participants could register through an interactive web-based patient recruitment questionnaire (see Appendix 1, Figure 19) for more information. These results were automatically sent to the trial manager and were used as the first line of eligibility screening. The trial manager/research nurse contacted potentially eligible patients by telephone and e-mail and invited them to participate (and provided them with the patient information leaflet if this had not already been downloaded by the patient from the trial website). If the patient remained interested in participating, then, with their consent, their contact details were provided to the trial team geographically closest to them to arrange a formal research consultation.

-

Participant identification centres (PICs). Potential study participants were identified at PICs following clinic visits or review of local clinic and pharmacy lists, electronic patient records, referral lists and letters, research databases and other lists. They were then contacted by their direct clinical care team (usually by letter, e-mail, telephone call or in person) and then invited to self-refer on the trial website (as detailed above) or (with their agreement) referred directly to the team at their chosen trial site for further information regarding participation.

Randomisation procedure

The randomisation service for the study was provided by the King’s Clinical Trials Unit (CTU). Following written consent at the screening visit, each participant was registered on the MACRO electronic case report form system version 4 (InferMed Macro) that generated a unique patient identification number (PIN). This unique PIN was then recorded on all source data worksheets and was used to identify the participants throughout the study.

At the baseline visit, randomisation occurred via a bespoke web-based randomisation system hosted by the King’s CTU (https://cturandomisation.iop.kcl.ac.uk/APRICOT/Login.aspx?ReturnUrl%20=%20%2fAPRICOT; accessed 1 September 2020). Authorised site staff were allocated a username and password for the randomisation system by the trial manager. An authorised staff member (typically the principal investigator or research nurse) logged into the randomisation system and entered in the patient’s details, including the unique study PIN.

Once a participant was randomised, the system automatically generated e-mails to key study staff. For example, an e-mail was sent to the local site pharmacy to alert the staff to a participant’s treatment group (treatment 1 or 2). Additional blinded and unblinded e-mails were generated from the randomisation system to notify key trial site staff (e.g. the chief investigator and trial manager) depending on their role in the study.

The randomisation sequence was generated using blocked randomisation, stratified by centre.

Blinding

Investigational medical product

Participants, investigators, co-investigators, research nurses, clinical trial co-ordinators and clinical trial practitioners were blind to the IMP allocation for the duration of the trial.

Each randomised participant was provided with a card giving the code-break telephone numbers and emergency contact details.

Emergency code-break services were provided by ESMS Global (London, UK): a 24-hour cover service. To support patient safety, emergency unblinding could be performed according to strict criteria.

In the event of an emergency code break, ESMS Global was to notify the King’s Health Partners Clinical Trials Office of any emergency code break requests received, irrespective of outcome. The King’s Health Partners Clinical Trials Office clinical research associate would then inform the chief investigator and relevant principal investigator of the instance of unblinding. This would then be recorded so that the study statistician could be informed at the analysis stage of the trial.

Skin assessments

The active trial medication is known to cause injection site reactions in the majority of participants. If such reactions were apparent during study skin assessments, this could have led to inadvertent unblinding. 23 To avoid this, primary outcome assessments of fresh pustule count and PP-PASI score were carried out by an independent assessor blind to study treatment (a member of the study team trained in the assessment protocol but independent of the rest of the trial). At study visits, the independent blinded assessor was introduced as such to the participant by the clinical research team and had sight of the participant’s hands and feet only (injection site reactions occur at the site of administration, which is generally the abdomen/thighs). The independent blinded assessors were also instructed not to speak to the participant to maintain blinding.

Once the relevant outcome measures were assessed, the independent blinded assessor was instructed to leave the consulting room and the treating physician or research nurse then conducted the rest of the study visit (and the protocol-mandated procedures).

A second assessment of the PP-PASI score and PPP-IGA was also conducted by the treating physician or research nurse at each study visit.

Site staff were instructed that, whenever possible, the independent blinded assessor for a particular participant should be the same throughout the study.

During stage 1, fresh pustule counts were also assessed by a central blinded assessor using photography (prespecified views of palms and soles at baseline and weeks 1 and 8 of treatment; see Appendix 8, Figures 21 and 22).

Inclusion criteria for the double-blind treatment stage, placebo-controlled study

-

Adults (aged ≥ 18 years) with a diagnosis of PPP made by a trained dermatologist, with disease of sufficient impact and severity to require systemic therapy.

-

Disease of duration of > 6 months and not responding to an adequate trial of topical therapy, including very potent corticosteroids.

-

Evidence of active pustulation on palms and/or soles to ensure sufficient baseline disease activity to detect efficacy.

-

At least moderate disease on the PPP-IGA.

-

In the case of women of child-bearing potential, being on adequate contraception (see Appendix 2, Contraception guidelines, for guidance) and not pregnant or breastfeeding.

-

Written informed consent to participate.

Exclusion criteria for the double-blind treatment stage, placebo-controlled study

-

Previous treatment with anakinra or other IL-1 antagonists.

-

A history of recurrent bacterial, fungal or viral infections that, in the opinion of the principal investigator, presented a risk to the patient.

-

Evidence of active infection or latent tuberculosis (TB), human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) positivity or hepatitis B or C seropositivity.

-

A history of malignancy of any organ system (other than treated, localised non-melanoma skin cancer), treated or untreated, within the past 5 years.

-

Use of therapies with potential or known efficacy in psoriasis during or within the following specified time frame before treatment initiation (week 0, visit 1):

-

very potent topical corticosteroids within 2 weeks

-

topical treatment that is likely to impact signs and symptoms of psoriasis (e.g. corticosteroids, vitamin D analogues, calcineurin inhibitors, retinoids, keratolytics, coal tar, urea) within 2 weeks

-

methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin and alitretinoin (Toctino®, Stiefel, Brentford, UK) within 4 weeks

-

phototherapy or psoralen and ultraviolet A radiation (PUVA) within 4 weeks

-

etanercept (Enbrel®, Pfizer, New York, NY, USA) or adalimumab (Humira®; AbbVie Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) within 4 weeks

-

infliximab (Remicade®, Janssen Biotech Inc., Horsham, PA, USA) or ustekinumab (Stelara®, Janssen Biotech Inc.) or secukinumab (Cosentyx®, Novartis Pharmaceuticals UK Ltd, London, UK) within 3 months

-

other tumour necrosis factor (TNF) antagonists within 3 months

-

other immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy within 30 days or five half-lives prior to treatment initiation, whichever was longer

-

any other investigational drugs within 30 days (or 3 months for investigational monoclonal antibodies) or five half-lives prior to treatment initiation, whichever was longer.

-

-

Moderate renal impairment (defined as creatinine clearance of < 50 ml/minute).

-

Neutropenia (defined as neutrophil count of < 1.5 × 109/l).

-

Thrombocytopenia (defined as platelet count of < 150 × 109/l).

-

Known moderate hepatic disease and/or raised hepatic transaminases [alanine aminotransferase (ALT) or aspartate aminotransferase (AST)], more than two times the upper limit of normal (ULN), at baseline. Participants who failed this screening criterion could still be considered following review by a hepatologist and confirmed expert opinion that study entry was clinically appropriate.

-

Live vaccinations within 3 months prior to the start of study medication, during the trial and up to 3 months following the last dose.

-

In the case of women, pregnancy, breastfeeding or being of child-bearing age and not on adequate contraception and, in the case of men, planning conception.

-

Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, asthma and concomitant therapy that may interact with anakinra (e.g. phenytoin or warfarin) or any condition in which, in the opinion of the investigator, anakinra would a present risk to the patient.

-

Unable to give written informed consent.

-

Unable to comply with the study visit schedule.

-

Diagnosis (or historic diagnosis) of either childhood- or adult-onset Still’s disease.

Inclusion criteria for the open-label extension

-

Participation in the double-blind placebo-controlled study.

-

Completion past visit 4 (week 8) of the double-blind placebo-controlled study.

-

In the case of women of child-bearing potential, being on adequate contraception (see Appendix 2, Contraception guidelines for guidance) and not pregnant or breastfeeding.

-

Written informed consent to participate.

Exclusion criteria for the open-label extension

-

A history of recurrent bacterial, fungal or viral infections that, in the opinion of the principal investigator, presented a risk to the patient.

-

Evidence of active infection or latent TB or of HIV positivity or hepatitis B or C seropositivity (required only for participants who were beyond visit 5, the double-blind treatment stage, of the placebo-controlled study).

-

A history of malignancy of any organ system (other than treated, localised non-melanoma skin cancer), treated or untreated, within the past 5 years.

-

Use of therapies with potential or known efficacy in psoriasis during or within the following specified time frame before treatment initiation (visit OLE 1):

-

methotrexate, ciclosporin, acitretin or alitretinoin within 4 weeks

-

phototherapy or PUVA within 4 weeks

-

etanercept or adalimumab within 4 weeks

-

infliximab, ustekinumab or secukinumab within 3 months

-

other TNF antagonists within 3 months

-

other immunosuppressive or immunomodulatory therapy within 30 days or 5 half-lives prior to treatment initiation, whichever was longer

-

any other investigational drugs within 30 days (or 3 months for investigational monoclonal antibodies) or 5 half-lives prior to treatment initiation, whichever was longer.

-

-

Moderate renal impairment (defined as creatinine clearance of < 50 ml/minute).

-

Neutropenia (defined as neutrophil count of < 1.5 × 109/l).

-

Thrombocytopenia (defined as platelet count of < 150 × 109/l).

-

Known moderate hepatic disease and/or raised hepatic transaminases (ALT/AST), more than two times the ULN, at baseline. Participants who failed this screening criterion could still be considered following review by a hepatologist and confirmed expert opinion that study entry was clinically appropriate.

-

Live vaccinations within 3 months prior to the start of study medication, during the trial and up to 3 months following the last dose.

-

In the case of women, pregnancy, breastfeeding or being of child-bearing age and not on adequate contraception or, in the case of men, planning conception.

-

Poorly controlled diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease and asthma, and concomitant therapy that may interact with anakinra (e.g. phenytoin or warfarin) or any condition in which, in the opinion of the investigator, anakinra would present a risk to the patient.

-

Inability to give written informed consent.

-

Inability to comply with the study visit schedule.

-

Having been previously invited to have the OLE therapy and declined.

-

Diagnosis (or historic diagnosis) of either childhood-onset or adult-onset Still’s disease.

Concomitant medication, prohibited medication and rescue therapy information

The list of concomitant medication, prohibited medication and rescue therapy for the double-blind RCT is presented in Appendix 3, Table 36. The list of prohibited medication for the OLE is presented in Appendix 3, Table 37.

Participant pathway (trial procedures)

The participant pathway consisted of four periods: a screening period, a treatment period, a follow-up period and an optional OLE.

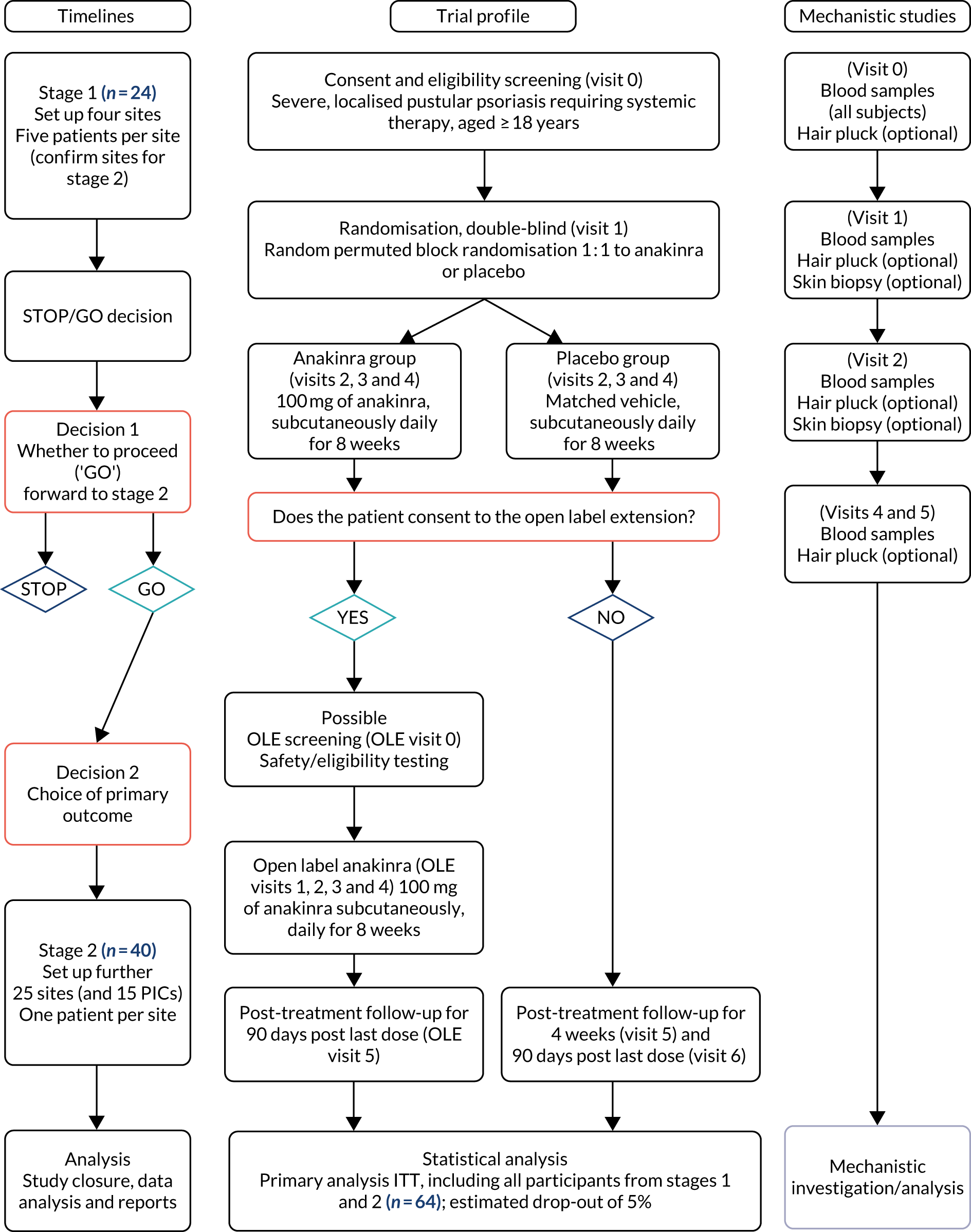

The overall study flow is detailed in Figure 1 and the detailed visit schedule is listed in Appendix 2, Tables 33–35.

FIGURE 1.

Trial flow chart. ITT, intention to treat.

The screening period, that is the period between the screening visit (visit 0) and baseline (visit 1), was a minimum of 5 days and a maximum of 3 months, and was used to assess eligibility and to taper off prohibited medicines (as part of the washout period for the study). Participants who failed the screening period (did not satisfy one or more eligibility criteria) had the option to be re-screened if clinically appropriate.

The treatment period (visits 1–4) was 8 weeks. At the start of the treatment period, eligible participants were randomised to receive the intervention (as described above).

The follow-ups (visits 5 and 6) at week 12 and 90 days post last treatment date were used to assess disease relapse off study treatment, to follow up any AEs that had been previously reported and to plan for post-treatment management of the participants’ condition.

If a participant decided to take part in the optional 8-week OLE, there were two possible pathways:

-

Participants who decided to take part in the OLE before or at the week 12 follow-up visit (visit 5) were to begin their 8-week OLE period directly after the week 12 follow-up (i.e. their OLE baseline visit could be on the same day as the week 12 follow-up visit). Their final follow-up visit would take place 90 days after their last dose of anakinra.

-

Participants who were beyond the week 20 follow-up visit (visit 6) may have been receiving another treatment for their PPP when they decided to take part in the OLE. These participants were required to have an OLE screening visit, a possible washout period (as per the study protocol) and an OLE baseline visit arranged once the required washout period was completed. A final follow-up visit was then conducted 90 days after the last dose of anakinra.

To achieve the exploratory objectives (mechanistic studies), all participants were invited to provide biological samples for use in exploratory laboratory tests. These were blood samples taken at visit 0, and longitudinal blood samples were taken at visits 1, 2, 4 and 5.

In addition, participants were invited to provide microbiopsy samples from the skin on the lateral edge of the base of their feet or palms prior to treatment initiation at baseline (visit 1) and then at visit 2 (approximately 1 week later). These samples were used to understand the underlying pathogenesis of pustular psoriasis and the mechanism by which anakinra may work, and to identify potential biomarkers of response.

Participant withdrawal

Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time and for any reason. The principal investigator also had the right to withdraw participants from the study drug in the event of intercurrent illness, AEs, serious adverse events (SAEs), suspected unexpected serious adverse reactions (SUSARs) or protocol violation, or for administrative reasons or other pertinent reasons.

Participants had to discontinue the investigational product (and non-investigational product at the discretion of the investigator) in the event of any of the following:

-

withdrawal of informed consent (if the participant decided to withdraw for any reason)

-

the occurrence of any clinical AE, laboratory abnormality or intercurrent illness that, in the opinion of the investigator, indicated that continued participation in the study was not in the best interest of the participant

-

the need, in the principal investigator’s opinion, to administer concomitant medication not permitted by the trial protocol

-

pregnancy (in which case the chief investigator was notified immediately).

If a participant decided to withdraw from the trial, all efforts were made to report the reason for withdrawal as thoroughly as possible and participants were encouraged to provide follow-up data for the remaining trial visits, but at a minimum were asked for outcome data and safety data (AE records) at week 8 and at 90 days post last dose follow-up. They were also asked if they were willing to provide trial-specific clinical data (i.e. outcome measures) and/or samples for mechanistic study, as per the remaining trial schedule. All data and samples collected up to the date of withdrawal were retained.

Safety bloods should have been taken as per the trial schedule for all participants and/or as considered appropriate by the principal investigator.

Significant amendments to the study protocol

For a summary of amendments, see Appendix 4, Table 38.

Removal of visits from the study schedule

In April 2017 (as part of substantial amendment 4), the week 2 and week 6 visits were removed from the study protocol (originally visits 3 and 5, respectively). The study visits were renumbered accordingly (as required) throughout the protocol to accommodate this change.

The visit schedule was amended to decrease visits (while still maintaining the necessary safety assessments) to make the study more enticing to potential participants (by making it less burdensome to them). These changes were made in response to recruiting clinician feedback and informal participant feedback from the initial recruits.

The week 1 visit (visit 2) stayed in place to ensure that an early set of outcome measures were still collected, with some of the procedures that were previously undertaken at the week 2 visit being undertaken at the week 1 visit (visit 2).

At the time of this change, only 11 participants had been recruited. The analysis model was flexible enough to accommodate the change and the data from participants who had already provided the week 2 outcomes could be included in all analyses, substituted for week 1.

These protocol changes had no impact on the mechanistic work.

Open-label extension introduction

An OLE was added to the study in July 2019 (as part of substantial amendment 11). The primary purpose of the OLE was to enhance recruitment to the randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, so that all participants had the potential opportunity to access anakinra. The OLE was added when agreement and funding for the required additional anakinra IMP were secured from the trial drug manufacturer, Sobi.

To retain the integrity of the primary randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled study, only participants who had completed the 8-week treatment period schedule, as well as the week 12 follow-up visit, could take part in an optional 8-week period of anakinra treatment as an OLE to the trial.

To ensure equality of access, all participants who had already participated in APRICOT (Anakinra for Pustular Psoriasis: Response in a Controlled Trial), were currently taking part in APRICOT or were considering taking part in APRICOT were made aware of the 8-week OLE therapy and the criteria for enrolment. The only exceptions were the seven participants from the Manchester site, who were not offered the OLE because of a lack of research capacity, and one participant from the Guy’s Hospital site who wished to defer entry because of concerns about risk associated with travel to the study site during the COVID-19 pandemic [this participant has since been offered study anakinra IMP outside the context of the OLE for 8 weeks, with permission from the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA)].

Inclusion/exclusion criteria amendments

Thrombocytopenia

New safety information in the summary of product characteristics (SmPC) led to the decision to add exclusion criterion viii [with thrombocytopenia (defined as platelet count of < 150 × 109/l)] and this formed part of substantial amendment 4 to the protocol in April 2017.

The requirements for reporting and temporary treatment discontinuation were also amended following consultation with the study collaborator expert, who recommended that a platelet count of < 75 × 109/l should be reported as an important medical event and trigger a temporary halt in IMP treatment.

Latex allergy

During stage 1 of the study, latex was removed from the IMP containers and packaging and, thus, all trial stock was confirmed as being latex free. Therefore, the original exclusion criterion xii [latex allergy (inner needle cover of pre-filled syringe contains natural rubber)] was removed as part of substantial amendment 4 to the protocol in April 2017.

Still’s disease

Following an update to the information in the SmPC, it was found that there were reports of cases of macrophage activation syndrome (MAS) in Kineret-treated participants with Still’s disease. It must be noted that a causal relationship between Kineret® (Sobi Inc., Stockholm, Sweden) and MAS has not (yet) been established.

Following discussion within the Data Monitoring Committee (DMC), the study team opted to treat this finding with extreme caution and explicitly excluded participants with Still’s disease from the trial (submitted as substantial amendment 12 in September 2019 to update the protocol accordingly). Thus, exclusion criterion xv [diagnosis (or historic diagnosis) of either childhood-onset or adult-onset Still’s disease] for the double-blind, placebo-controlled study and the OLE were added as part of this amendment. This is a rare condition, and no participants with this condition entered into the trial.

Statistics methodology

Sample size

The overall sample size for APRICOT was calculated prior to the completion of stage 1 of the study, at which time the primary outcome of the main trial analysis was unknown. 24

The sample size was calculated using a standardised effect size. A large effect size of 0.9 standard deviations (SDs) was selected to be the minimum important difference to detect because of the cost of the drug and high patient burden arising from the requirement for participants to adhere to daily self-administered subcutaneous injection treatment. In addition, larger effect sizes have been reported with oral retinoids (historically etretinate and now acitretin), a recommended systemic intervention for pustular psoriasis. 25–27

To achieve 90% power with a 5% significance level for the detection of a difference of 0.9 SDs, a sample size of 27 participants per group was required. To allow for a (conservative) approximate 15% withdrawal rate, 32 participants per group (n = 64 in total) were required for the study. In APRICOT, the observed SD for the baseline PP-PASI score (n = 64) was 10.5; therefore, 0.9 SDs was approximately equivalent to a change of 9.5 in the PP-PASI score.

The sample size for stage 1 was based on the correct ordering of group means. A high probability of continuing (‘go’) was needed if there was a true (conservative) difference in means between the groups of 0.5 SDs in favour of the treatment group. With 20 participants (n = 10 per group), assuming a real difference of 0.5 SDs, the probability that the mean for the treatment group would be correctly ordered (i.e. the treatment mean is greater than the placebo mean) was 0.85. If two outcomes were assessed, each with an expected difference of 0.5 SDs, then the overall probability of failing to ‘go’ was (1 – 0.85)3 = 0.0225, that is less than 3 in 100. There was, therefore, a minimal chance of failing to continue if the treatment really was beneficial. If there was no treatment benefit, the probability of not progressing to the next stage was 0.25 based solely on these rules. Stage 1 did not involve statistical tests. To ensure that 10 participants contributed to each group, it was planned that the interim stage 1 analysis would be carried out after 24 participants had been randomised and followed up.

Statistical analysis

General statistical principles

The analysis was conducted subgroup blind (i.e. as group A vs. group B) in accordance with the APRICOT statistical analysis plans,22,24 which were finalised prior to database lock. The main analysis was based on the intention-to-treat (ITT) principle, that is all participants with at least one follow-up were analysed in the group to which they were randomised regardless of subsequent treatment received. The use of a longitudinal model for the primary analysis meant that a minimal number of participants would be excluded. Every effort was made to obtain all follow-up data for all participants, including those who stopped treatment.

The safety set population consisted of all participants who received at least one dose of the assigned IMP intervention and was used in the analysis to describe AEs.

All regression analyses included adjustment for centre because this was a stratification factor in the randomisation. The inclusion of this adjustment was necessary in the analysis to maintain the correct type I error rate. 28,29

Estimates are presented with 95% confidence intervals and p-values. A p-value of < 0.05 was interpreted as statistically significant for the primary outcome. All analyses were conducted using Stata® version 15.1 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Stage 1 analysis22

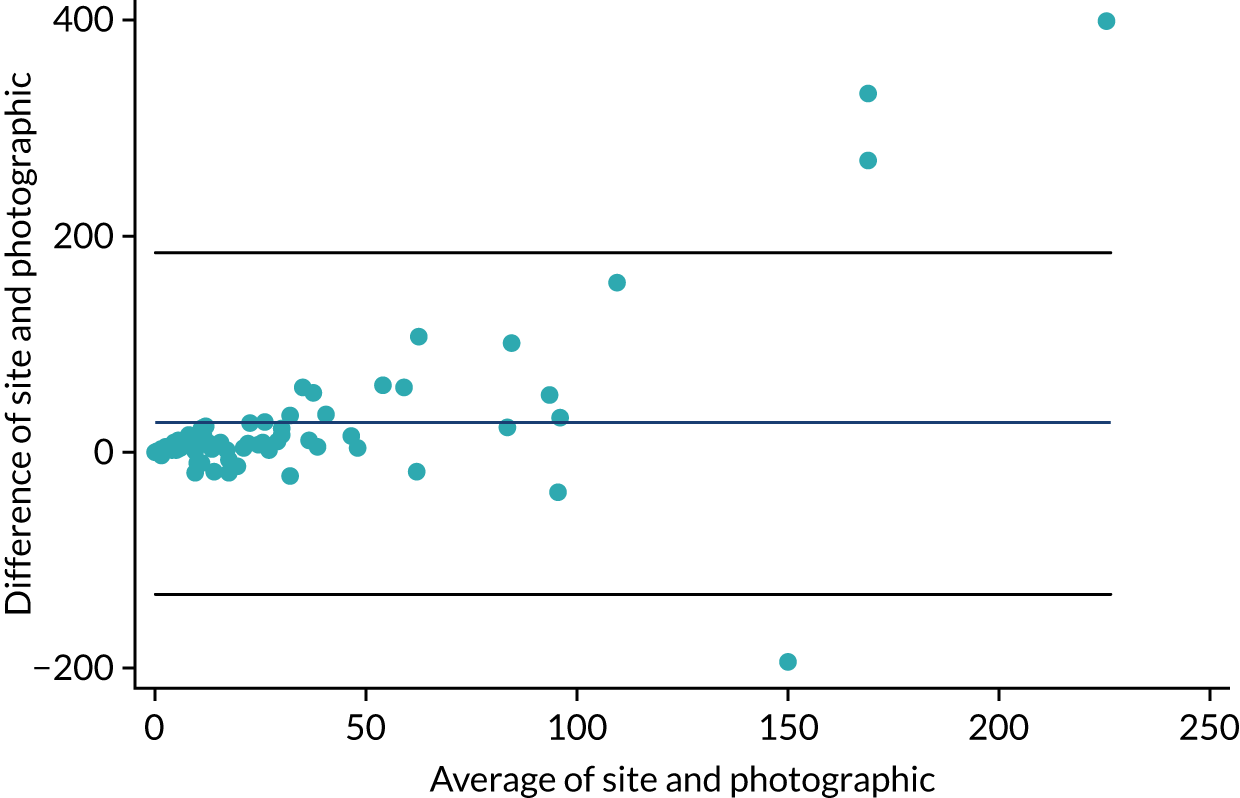

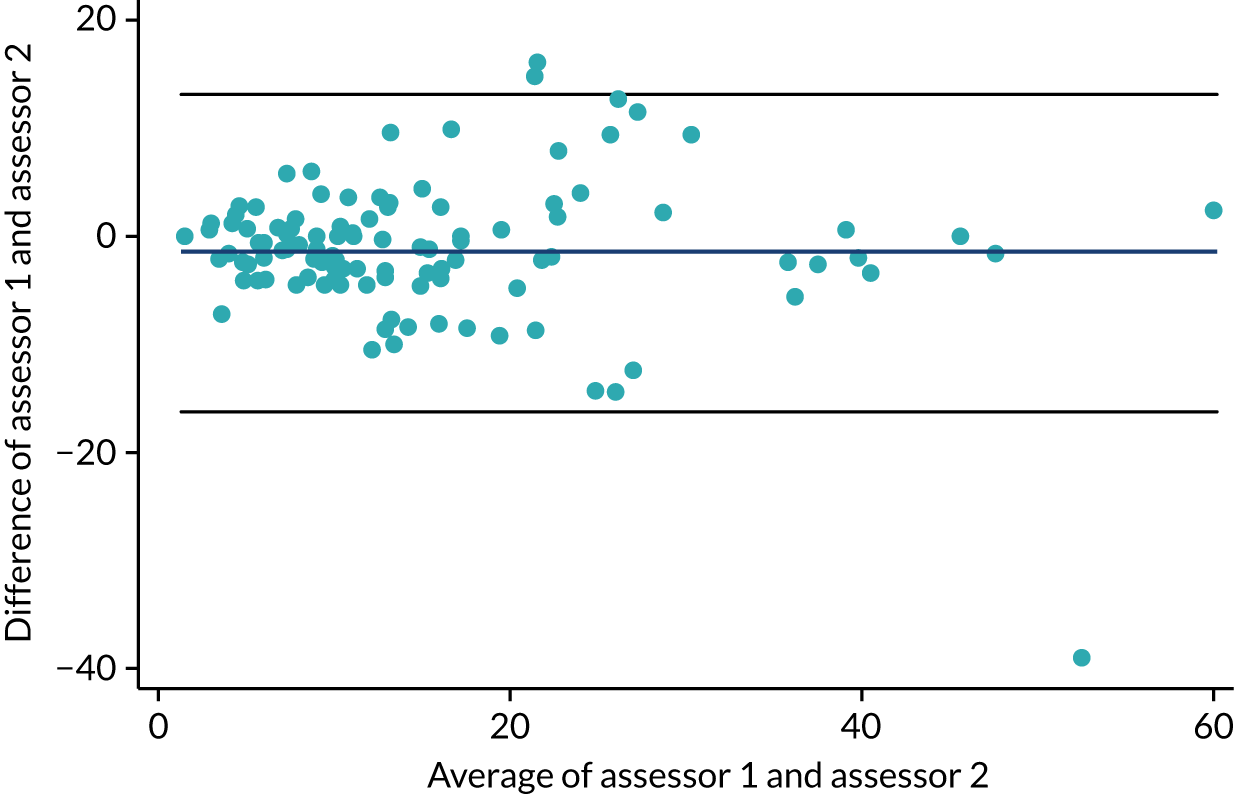

At the end of stage 1, the baseline-adjusted mean treatment group differences in the fresh pustule count and PP-PASI score, averaged across follow-up visits, were calculated using a linear regression model. These results informed the decision to progress to stage 2. The trial continued to stage 2 if the treatment group did, on average, better than the placebo group on at least one measure. The primary outcome for stage 2 was selected based on an assessment of reliability and distributional properties for two candidate outcomes: the fresh pustule count and the PP-PASI score. The reliability of the fresh pustule count was assessed by examining the agreement between the assessments made at the site and those assessed centrally based on photographs. Agreement was formally assessed using the Bland–Altman method and the intraclass correlation coefficient (ICC) was calculated using a mixed-effects analysis of variance (ANOVA) with a random intercept for patient and rater. 30,31 The closer the ICC value was to 1, the better the level of consistency. The reliability of the PP-PASI was assessed by examining the agreement between assessments made at the site by two independent assessors using the same methods outlined above. Distribution properties for each candidate outcome were assessed using standardised mean differences and histograms by treatment group.

Stage 2 analysis24

A Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow chart32 was constructed to summarise the participant flow through the study. Baseline characteristics were summarised by treatment group to examine the balance between the groups at baseline. Treatment adherence, reasons for withdrawal and use of rescue medication, prohibited therapy and other topical treatments were summarised by treatment group. All primary and secondary outcomes were also summarised by time point and treatment group. Continuous variables were summarised using the mean (SD) where approximately normally distributed and the median [interquartile range (IQR)] where skewed. Categorical variables were summarised by frequency and percentage.

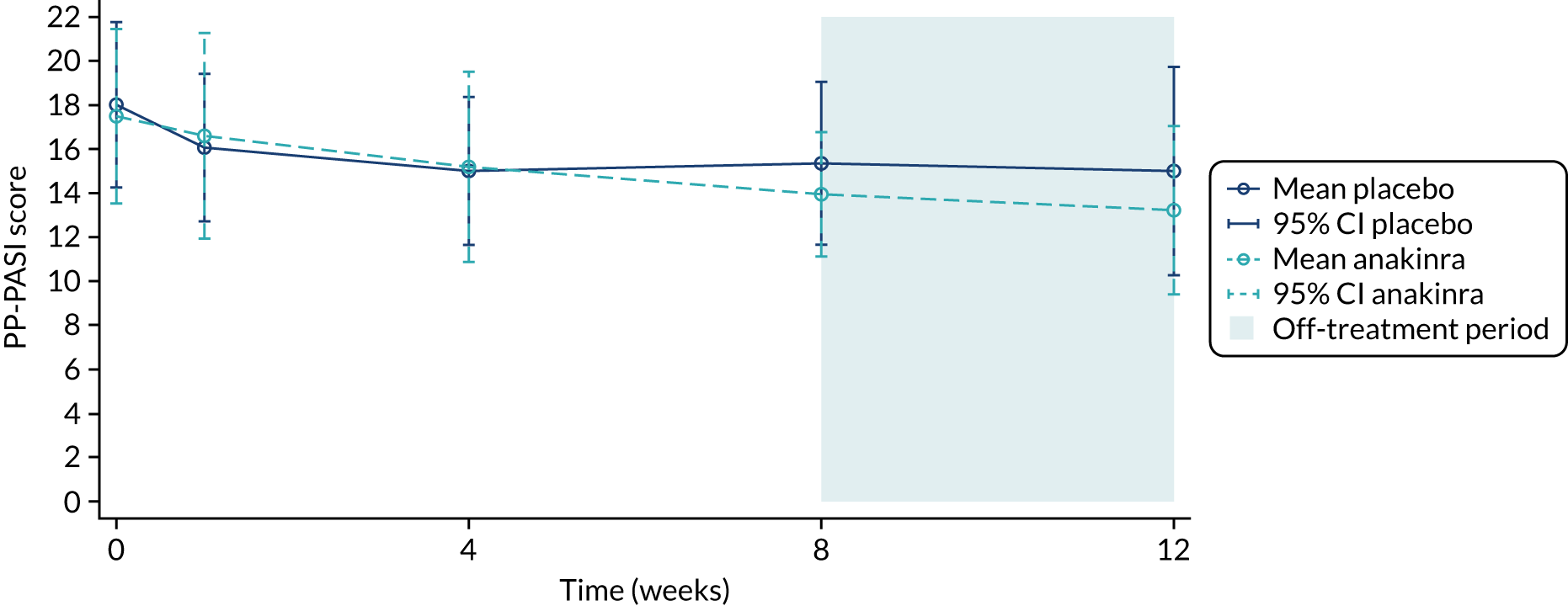

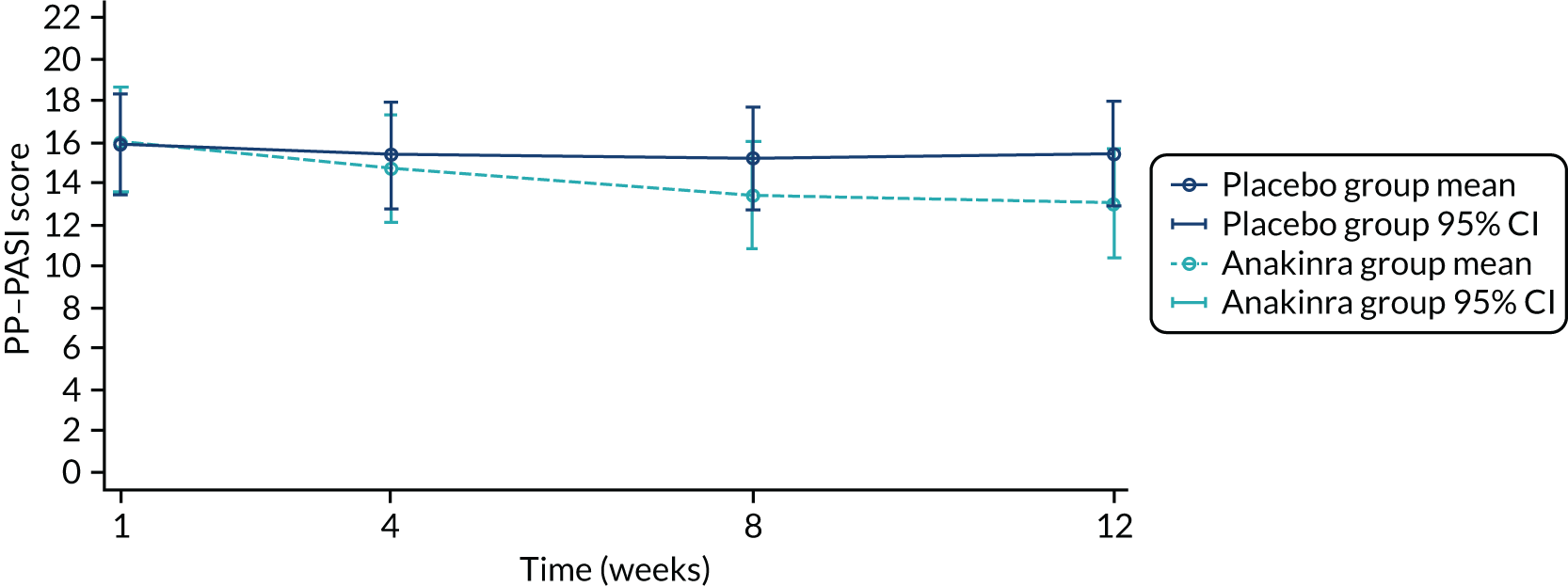

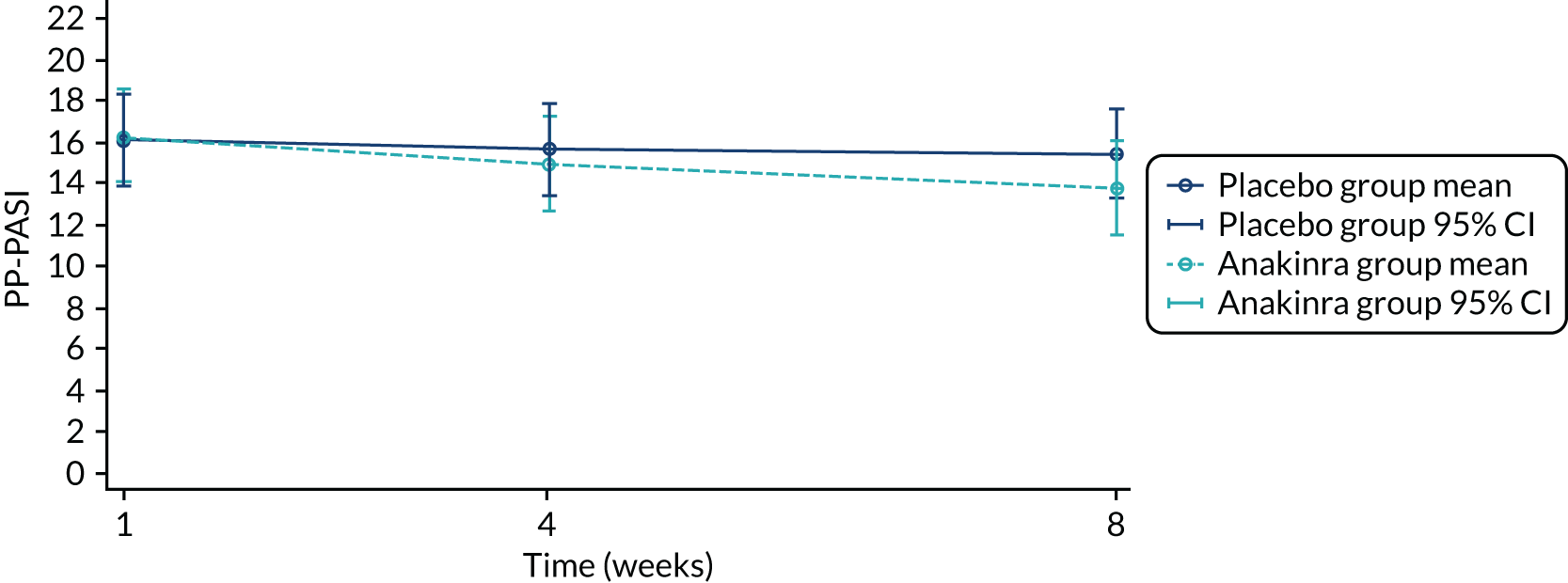

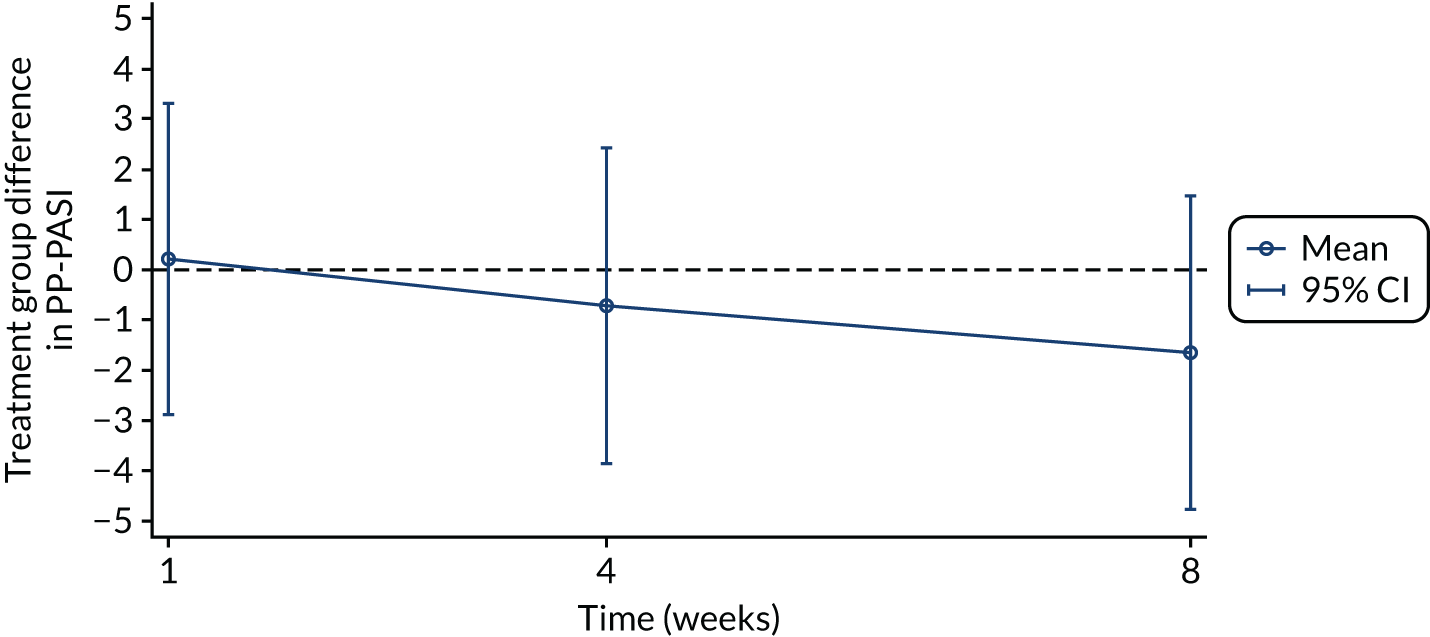

The primary analysis was based on the ITT principle and estimated the effect of the treatment policy. 33 A linear (Gaussian) mixed-effects model including PP-PASI data from weeks 1, 4 and 8 was utilised to obtain an estimate of the mean treatment group difference in PP-PASI scores at week 8. The model included random intercepts for participant and centre and fixed effects for study visit, treatment group, study visit by treatment group interaction and baseline PP-PASI scores. An unstructured covariance matrix was used to model the covariance structure, as it allows for all variances and covariances to be distinct, and the model was fitted with restricted maximum likelihood. The mean difference in the week 8 PP-PASI scores, adjusted for baseline, between the two treatment groups formed the focal point of the primary outcome analysis. The main conclusion of the trial was, therefore, based on this (week 8) analysis time point. However, treatment effects at weeks 1 and 4 were also calculated and reported.

In accordance with the ITT principle, all participants who provided data from at least one follow-up visit (at weeks 1, 4 or 8) were included in the primary analysis model as randomised. All missing response values were assumed to be missing at random (MAR) (i.e. the probability that the response is missing does not depend on the value of the response after allowing for the observed variables).

A pre-planned sensitivity analysis was performed to explore the impact of departures from the main MAR analysis assumption and potential missing not at random (MNAR) mechanisms on the trial results using multiple imputation (MI) and a pattern mixture approach. 34,35

Four pre-planned supplementary analyses targeted alternative treatment estimands for the trial’s primary outcome:

-

Supplementary analysis that estimated the treatment effect if rescue therapy was not available. Data post initiation of rescue therapy were set as missing and MI was used to explore the impact of a worse outcome post initiation on rescue therapy on trial results. The primary analysis model was retained for use in the analysis, following MI.

-

Supplementary analysis that estimated the treatment effect if rescue therapy and prohibited therapy were not available. Data post initiation of rescue therapy and prohibited medication were set as missing, and MI was used to explore the impact of a worse outcome post initiation on rescue therapy on the trial results. The primary analysis model was retained for use in the analysis, following MI.

-

Supplementary analysis that estimated the treatment effect if all topical therapy was not available. Data during the use of topical therapy were set as missing and MI was used to explore the impact of observing on-treatment behaviour (MAR) in the absence on topical therapy on the trial results. The primary analysis model was retained for use in the analysis, following MI.

-

Supplementary analysis to estimate the complier-average causal effect (CACE). The CACE preserves the benefits of randomisation and compares the average outcome of the compliers in the treatment group with the average outcome of the comparable group of ‘would-be compliers’ in the placebo group. To identify the CACE it is assumed that (1) members of the placebo group have the same probability of non-compliance as members of the intervention group and (2) being offered the treatment, that is randomisation itself, has no effect on outcome. We estimated the CACE using a two-stage least squares instrumental variable regression for the primary end point. Here, we initially defined a ‘complier’ as anyone who had received > 50% of the total number of planned injections (at any time point). Randomisation was used as an instrumental variable for treatment received, with adjustment for baseline PP-PASI scores (excluding centre from the analysis). We also calculated the CACE by defining a complier as, alternatively, anyone receiving 60–90% of the total number of planned injections.

Secondary outcome statistical analysis

Continuous secondary outcomes were analysed using the same modelling approach as specified above for the primary outcome. Binary outcomes were analysed using mixed logistic regression models and ordered categorical outcomes using mixed ordered logistic models. Similar to the primary analysis model, the models for secondary outcomes included participant and centre as a random intercept and fixed effects for time, time by treatment group interaction and baseline value of the outcome.

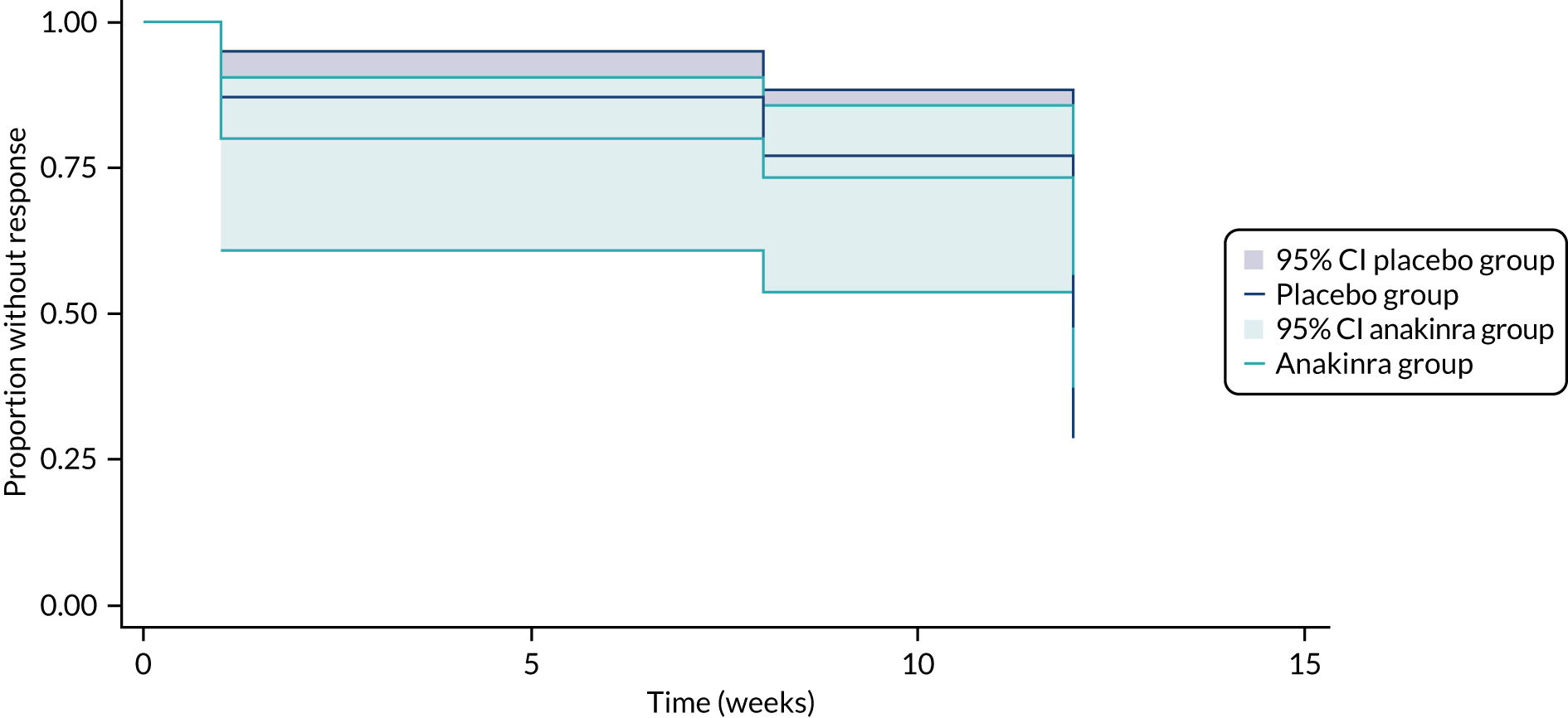

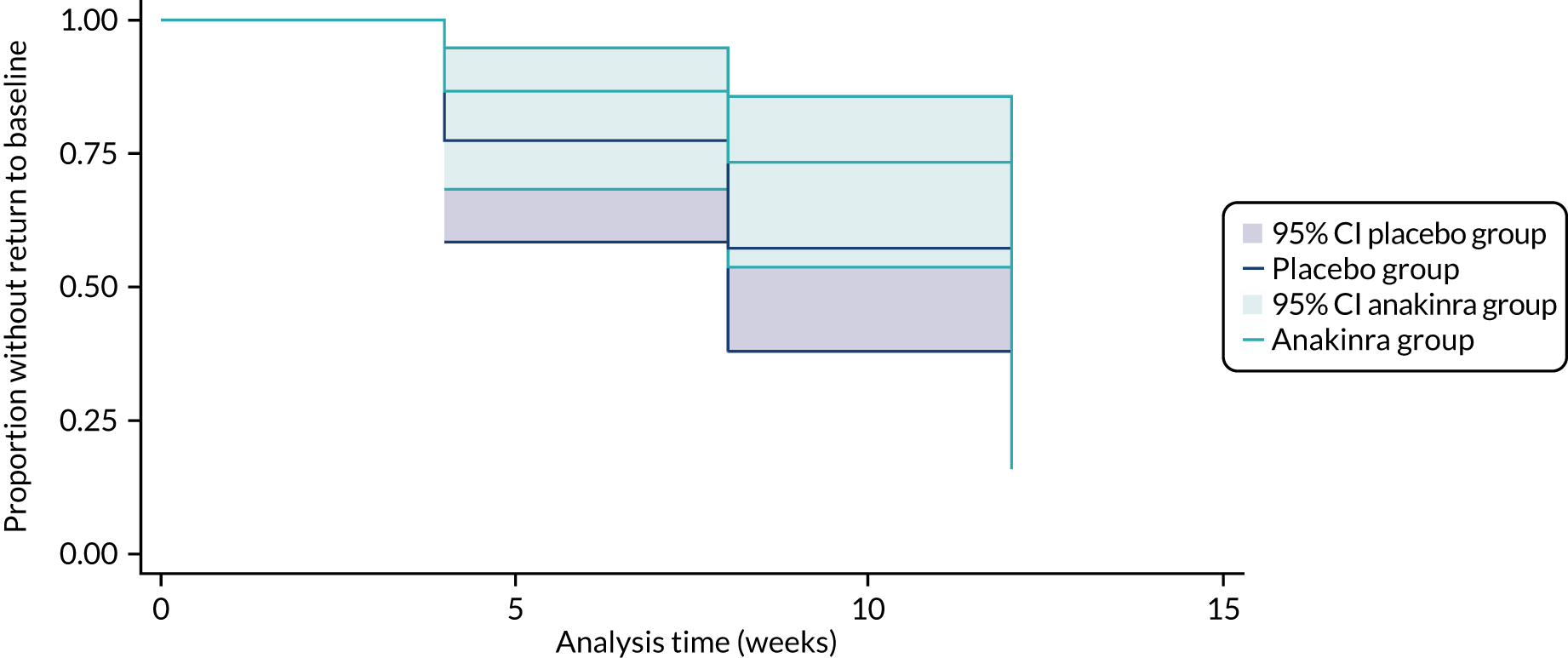

Kaplan–Meier curves were plotted for time to response and time to relapse outcomes. Given that outcomes were observed at a relatively few discrete time intervals (weeks 4, 8 and 12), complementary log–log models were fitted to estimate the treatment effect for the time-to-event outcomes, as this is an analysis model suitable for discrete survival time data. The time-to-event models included a fixed effect for treatment group and a random intercept for centre (stratification variable).

Adverse event analysis

Data concerning AEs were collected during study visits from reports of testimony from study participants, clinical observations, clinical examinations and blood tests.

Local clinicians rated the relationship of each AE to the study medication as none/unlikely/possible/likely/definite. From this classification, adverse reactions were the subset of non-serious AEs considered to have a possible/likely/definite relationship with the study medication. Serious adverse reactions (SARs) consisted of the subset of SAEs considered to have a possible/likely/definite relationship with the study medication. Furthermore, if an event was considered related to the study IMP, local clinicians also rated whether or not the reaction was unexpected.

All AEs were coded using terms referencing the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) at the ‘preferred terms’ level. These were also summarised by MedDRA system organ class and intensity (when subjectively assessed by local clinicians as mild/moderate/severe).

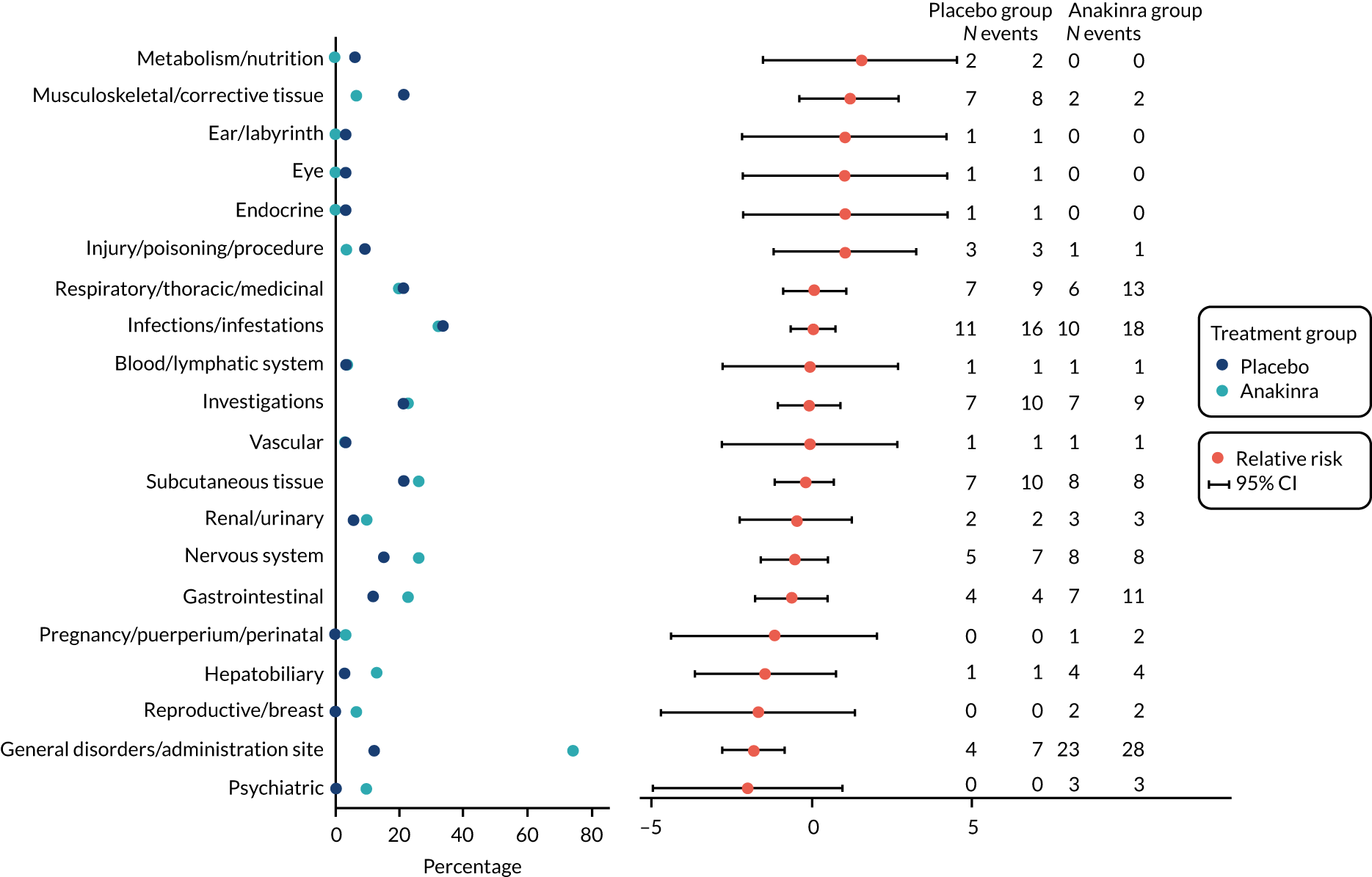

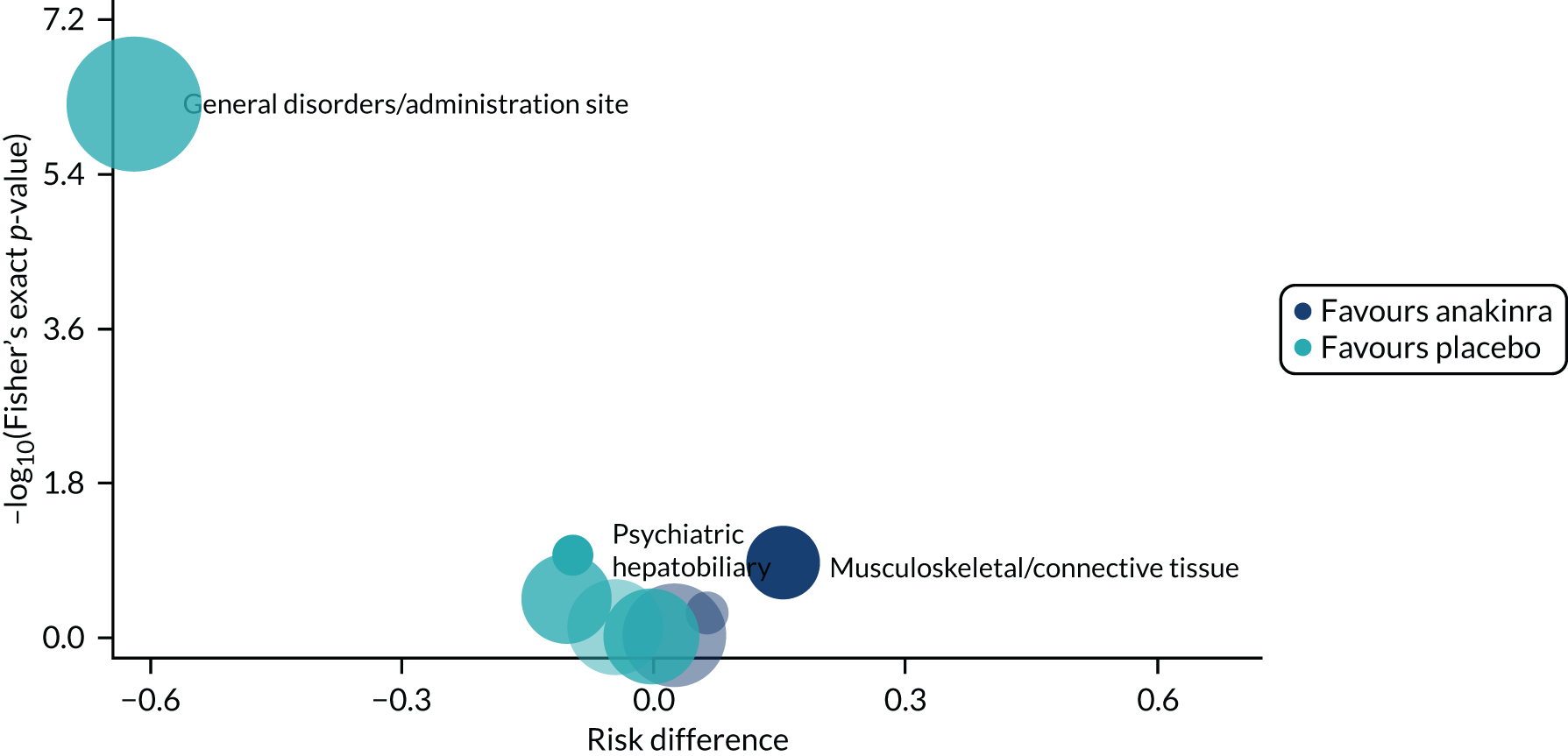

Adverse events were tabulated by treatment group for both the number of events and the number of participants with each type of event. AEs were also listed individually by MedDRA preferred term level and intensity (subjectively assessed by local clinical investigators as mild/moderate/severe) and summarised by MedDRA system organ class level. To identify the events with the strongest evidence for between-group difference, we constructed a volcano plot, in which the difference between treatment groups in the risk of non-serious AEs and reactions, by MedDRA system organ class, was plotted against the p-value from a Fisher’s exact test. 36 To further aid interpretation, AEs were also summarised visually in a dot plot, which displayed the proportions of individuals experiencing each type of event, by group, and the relative difference with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). The number of events related to an infection was also tabulated.

Exploratory analysis

A longitudinal analysis was undertaken using a linear (Gaussian) mixed model to determine the treatment difference in PP-PASI scores at week 12. The analysis model was the same as in the primary analysis, but included additional data at week 12. The treatment effect for PP-PASI scores at week 12 was estimated and reported with a 95% CI. Given that it was hypothesised that palmar disease may respond more quickly to anakinra than plantar disease, pre-planned exploratory analysis separately estimated the efficacy of anakinra on (1) disease activity at week 8, measured using fresh pustule count on the palms, adjusted for baseline, compared with placebo, and (2) disease activity at week 8, measured using fresh pustule count on the soles, adjusted for baseline, compared with placebo. For each of the palms and soles fresh pustule count, a linear mixed-effects model was used, which included fixed effects for treatment group, time (weeks 1, 4 and 8), treatment group by time interaction and baseline value of the associated outcome. A random intercept for participant and centre was also included in each of the models.

Post hoc analysis

The treatment group difference in ≥ 50% improvement in PP-PASI (PP-PASI 50) scores and ≥ 75% improvement in PP-PASI (PP-PASI 75) scores at week 8 was assessed using a mixed-logistic binary model that included centre as a random intercept and fixed effects for treatment group and baseline PP-PASI scores. We also examined the treatment group difference in the PP-PASI pustule subscale scores at week 8, separately for palms and soles, using a mixed-ordered logistic model that included participant and centre as a random intercept and fixed effects for time, time by treatment group interaction and baseline PP-PASI pustule subscale scores. For each participant and region (i.e. palm or sole), the maximum severity pustule rating across the left or right component of the region was utilised in analyses.

Mechanistic samples

Genetic analyses, including whole-exome sequencing, bulk ribonucleic acid (RNA) sequencing, pathway enrichment analyses and upstream regulator analysis, were used on mechanistic samples obtained during the trial to investigate the pathogenic involvement of IL-1 in PPP.

Open-label extension analysis

The number of participants who entered the OLE was summarised by original randomised treatment group. Baseline characteristics of all participants in the original double-blind period were descriptively compared against those of the participants entering the OLE period.

In the OLE, some participants continued their medication (some following a 4-week break and some with a longer break) and some participants started the medication for the first time. For this reason, it was not possible to undertake a randomised comparison for this extended follow-up period. Therefore, this was treated as an observational intervention period.

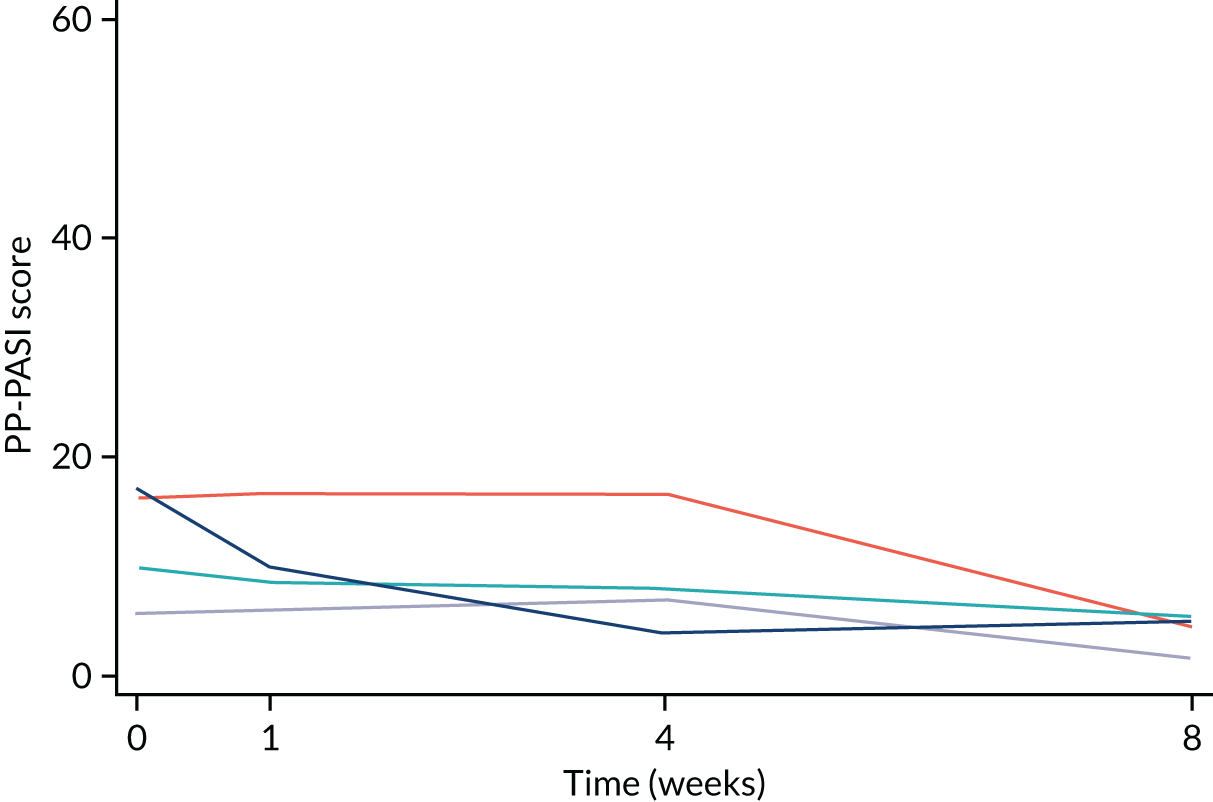

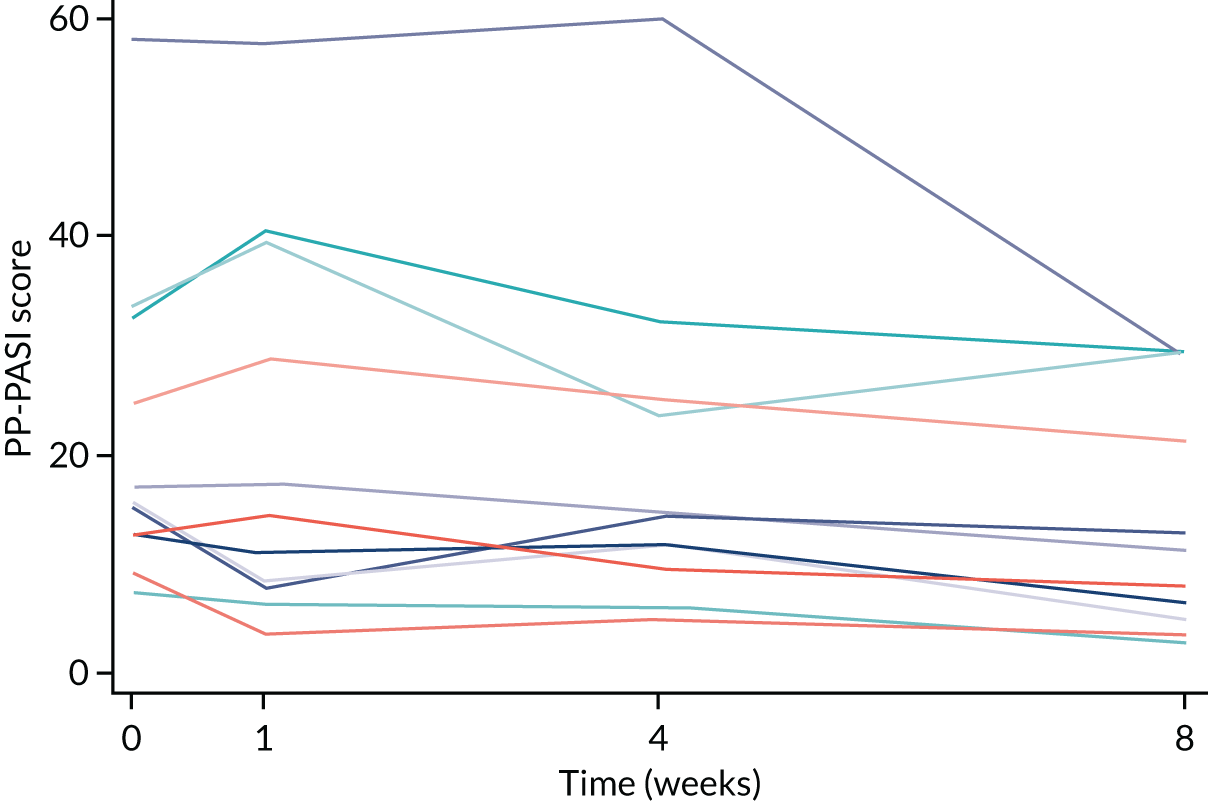

For the population of participants who continued into the OLE stage, descriptive statistics were presented for the open-label outcomes recorded at the OLE baseline visit and 8 weeks after OLE treatment initiation (fresh pustule count, total pustule count, PP-PASI scores, PPP-IGA, clearance on PPP-IGA and PASI) by original randomised treatment.

The week 8 outcomes of the participants originally randomised to the active group from the double-blind part of the trial were combined with the week 8 outcomes of participants originally randomised to the placebo group from the OLE to form a first-time exposure group. Descriptive statistics were presented for the first-time exposure group.

Adverse events were recorded for all participants in the OLE until the final follow-up visit.

No statistical testing was performed because of the open-label study design and because some participants commenced OLE anakinra treatment immediately following the week 12 visit (of the randomised double-blind placebo-controlled study), whereas others had previously completed the full double-blind trial schedule.

Trial oversight

Trial Management Group

The Trial Management Group (TMG) was chaired by Professor Catherine Smith (chief investigator of the study) and consisted of the co-applicants of the trial grant, a patient representative (Helen McAteer, Chief Executive of the Psoriasis Association) and the trial manager, and was responsible for decisions on the day-to-day running of the trial. The TMG provided the forum and mechanism through which the opinion of the central co-ordinating team (at Guy’s Hospital) and co-applicant on study matters was sought and discussed. The TMG met monthly and reported to the Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and the DMC.

Trial Steering Committee

The TSC comprised an independent chairperson (Professor Edel O’Toole, Queen Mary University of London), two independent members [Professor Hervé Bachelez, Consultant Dermatologist (with internationally recognised clinical and academic expertise in pustular forms of psoriasis), University Paris Diderot/Saint-Louis Hospital; and Dr Stephen Kelly, Consultant Rheumatologist, Barts Health NHS Trust], an independent patient representative (Mr David Britten), the chief investigator of the study (Professor Catherine Smith) and the trial statistician (Dr Victoria Cornelius, Imperial Clinical Trials Unit).

The TSC met as required and was the main decision-making body for the study. It had overall responsibility for scientific strategy and direction while also providing supervision and advice to study members.

Data Monitoring Committee

The DMC was chaired by an independent chairperson [Professor Deborah Symmons, Consultant Rheumatologist (who provided pharmacovigilance expertise in rheumatological interventions including anakinra), University of Manchester] and was responsible for monitoring evidence for treatment harm. The DMC also included an independent member (Dr Mike Ardern-Jones, University of Southampton), an independent statistician (Professor Simon Skene, University of Surrey), the chief investigator of the study (Professor Catherine Smith), the trial statisticians (Dr Suzie Cro, Imperial Clinical Trials Unit, and Dr Victoria Cornelius, Imperial Clinical Trials Unit) and the APRICOT trial manager. The DMC also collated data reports and reviewed all decisions pertaining to the safety aspects of the study.

The DMC met on initiation of the project and at specific study milestones thereafter, with the opportunity to convene extraordinary meetings to discuss SAEs if necessary.

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement (PPI) has been central to the APRICOT study throughout its course. In this section, we summarise the different ways in which participants and the public have been involved and have had an impact on the study. A detailed description is provided in Appendix 7.

Aim

We convened patient and public partners, including people with pustular psoriasis and representatives from the Psoriasis Association (Northampton, UK), to provide input and support into all aspects of the study, including study design and ethics issues, patient support materials and questionnaires, delivery, results interpretation and communication of study outcomes.

Methods

From the outset (pre-funding preparation), Helen McAteer, Chief Executive of the Psoriasis Association, partnered with the study group as a co-applicant to ensure that we effectively engaged with participants and the public in the design, implementation, evaluation and communication of programme of research. She was also a member of the TSC and the TMG. When the outline application was being made, one-to-one discussions were held with participants (n = 3, two with APP requiring systemic therapy and personal experience of participating in placebo-controlled RCTs) to seek their advice on the study design and outcome measures. For the development of the full application, a formal Patient and Lay members Group (PLAG) meeting was held that consisted of one patient with APP, one patient with GPP, one patient with psoriasis, a NICE psoriasis guideline committee member, Helen McAteer, the Biomedical Research Centre PPI co-ordinator and (the chief investigator) Catherine Smith. A patient representative (David Britten) was part of the TSC and regularly attended and actively participated in these meetings to provide guidance and support to the APRICOT study. The APRICOT study was regularly mentioned at all of the PPI events held by the St John’s Institute of Dermatology (at Guy’s and St Thomas’ NHS Foundation Trust), and in Manchester and Newcastle. During these events, participants were asked for their feedback and suggestions about the trial experience (for themselves) and how it could potentially be improved. These findings were fed back to the central co-ordinating team for consideration by the TMG/TSC.

Impact of patient and public involvement

The study design involved a RCT with a placebo. The discussions held with participants about the outline application led to the decision to limit the trial treatment duration to 8 weeks and to extend the scope of the patient-orientated outcome measures for the study to include the pustular psoriasis-specific quality of life. The PLAG meeting shaped the trial design and led to amendments (e.g. the inclusion of rescue topical corticosteroid) that were applied to the full application prior to formal submission. With respect to samples for mechanistic studies, the PLAG considered and approved the planned sampling strategy, including skin biopsies.

During the trial, the removal of some visits in substantial amendment 4 (see Appendix 4) was heavily informed by PPI to help to boost study recruitment. Patient feedback suggested that some were concerned about missing out on treatment if they were in the placebo group, and this became a concern that was instrumental in devising and implementing the OLE to help to boost study recruitment. Furthermore, in response to feedback from the TSC patient representative, various sites and potential participants, staff at study sites were encouraged to ensure that it was made clear to all potential and actual participants that travel expenses would be reimbursed in full. This was important given that a number of participants had to travel significant distances to attend study visits.

Discussion and conclusions

The PPI in the APRICOT study enabled the study to recruit to target. The input gained from the PPI was important in designing the study and in shaping the trial once running. PPI was also crucial in the promotion of the trial, which ultimately generated study awareness and helped to enhance recruitment.

Reflections/critical perspective

The Psoriasis Association participated regularly in discussions about recruitment strategies and was extremely helpful in advertising the APRICOT study via social media, its magazine and its website. It helped to guide participants, directing any queries to the study website and e-mail address (where interested parties could self-refer). It also helped with the review and amendment of study materials. The PPI could have been enhanced by including more than one formal lay patient representative in the study infrastructure to more accurately reflect the PPP patient population and to enable more diverse conversations and guidance during the trial. A recent PPI event on psoriasis held during the COVID-19 pandemic over Zoom (Zoom Video Communications, San Jose, CA, USA) had more than 120 attendees; the question and answer format worked well, suggesting that virtual formats may be efficient and cost-effective ways of engaging a wider audience that would appeal to participants. We have opted to use this format to disseminate the findings once published and will also utilise the Psoriasis Association and its social medial channels to facilitate this.

Chapter 3 Results

Recruitment and participant flow

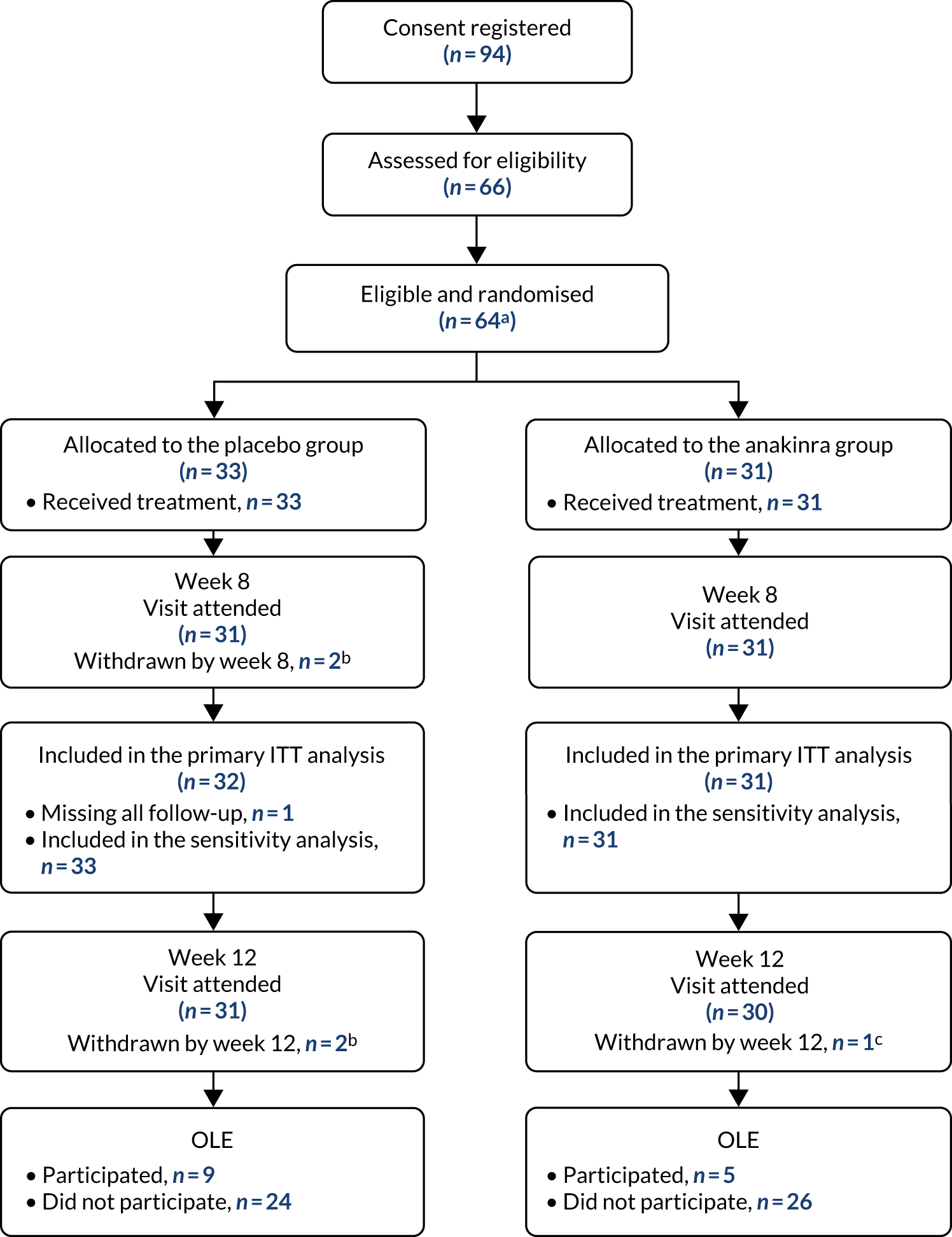

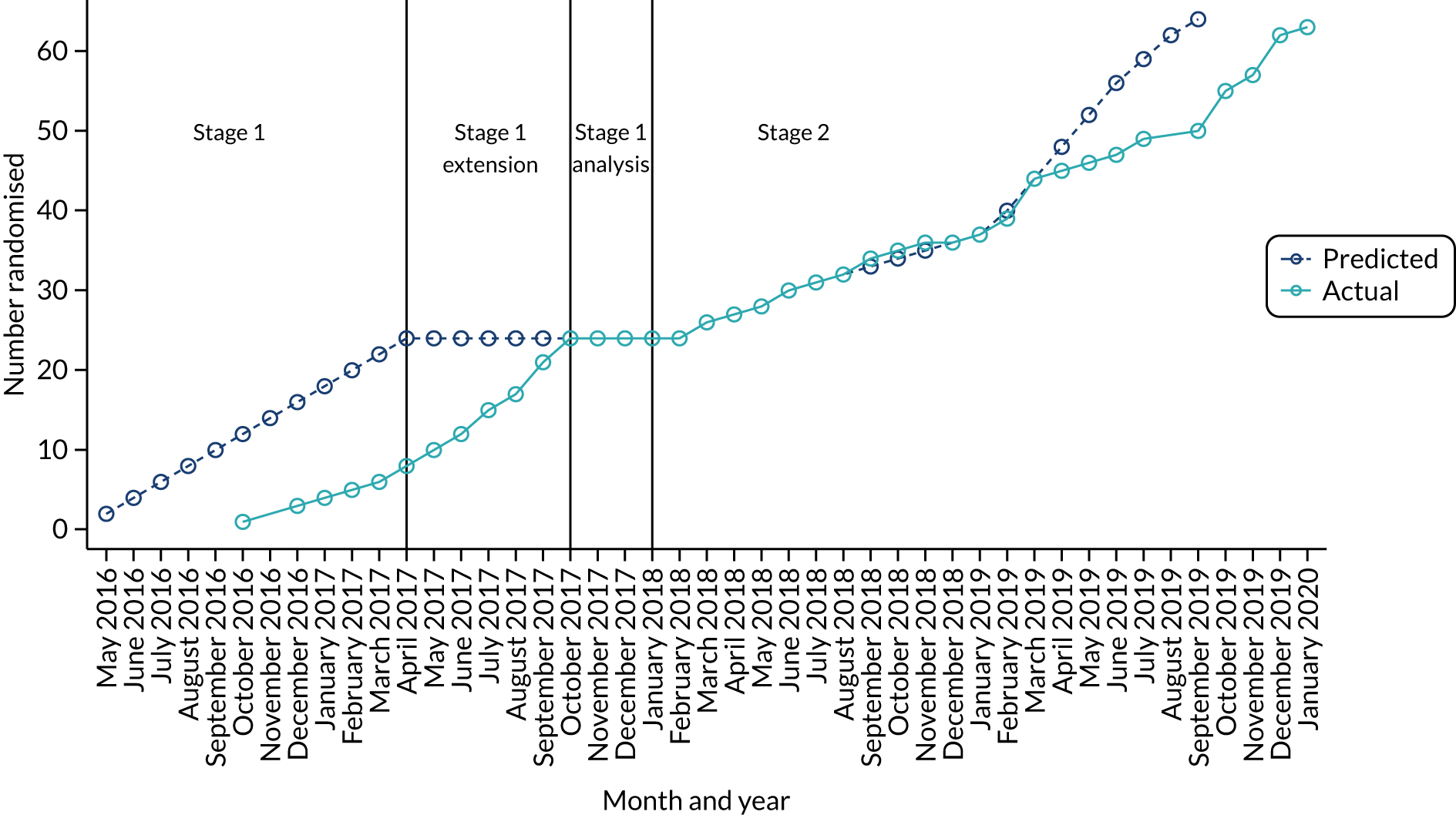

Between October 2016 and January 2020, a total of 64 eligible participants were enrolled: 33 were randomly allocated to the placebo group and 31 to the anakinra group (see Appendix 6, Tables 40 and 41, and Figure 20). An additional two consenting participants were randomised in error and never received any treatment and are excluded from all analysis. Figure 2 is the CONSORT flow chart for the trial, which summarises the participant flow through the trial. A total of 64 participants received treatment (placebo group, n = 33; anakinra group, n = 31), of whom 62 (placebo group, n = 31; anakinra group, n = 31) attended the week 8 visit and 61 attended the week 12 visit (placebo group, n = 31; anakinra group, n = 30). A total of 14 participants entered the OLE (placebo group, n = 9; anakinra group, n = 5).

FIGURE 2.

The CONSORT flow chart. a, An additional two participants were randomised, making a total of 66 randomised; however, these two participants were randomised in error, as they were ineligible. They were not offered treatment and were immediately withdrawn and excluded from all analysis. b, One participant withdrew in week 1. One participant was lost to follow-up and withdrawn post week 4. c, One participant withdrew at week 8. Note: numbers withdrawn from the trial are cumulative.

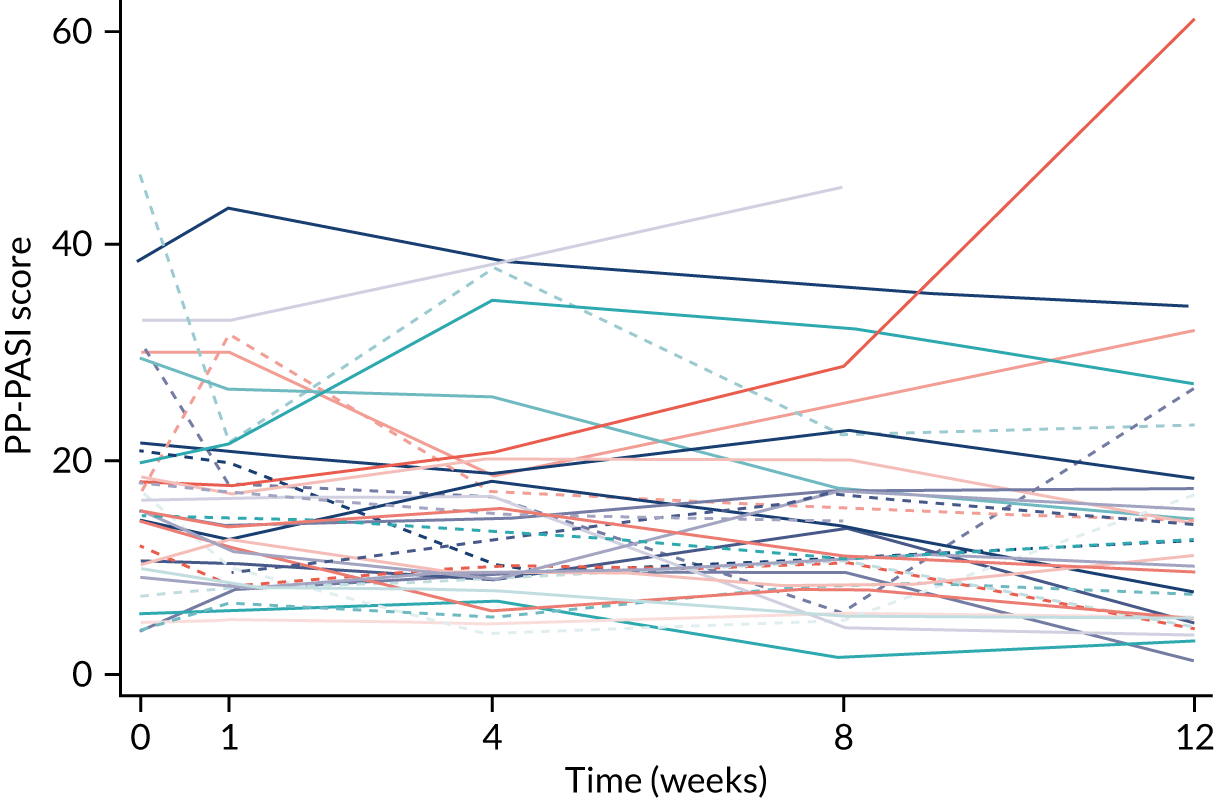

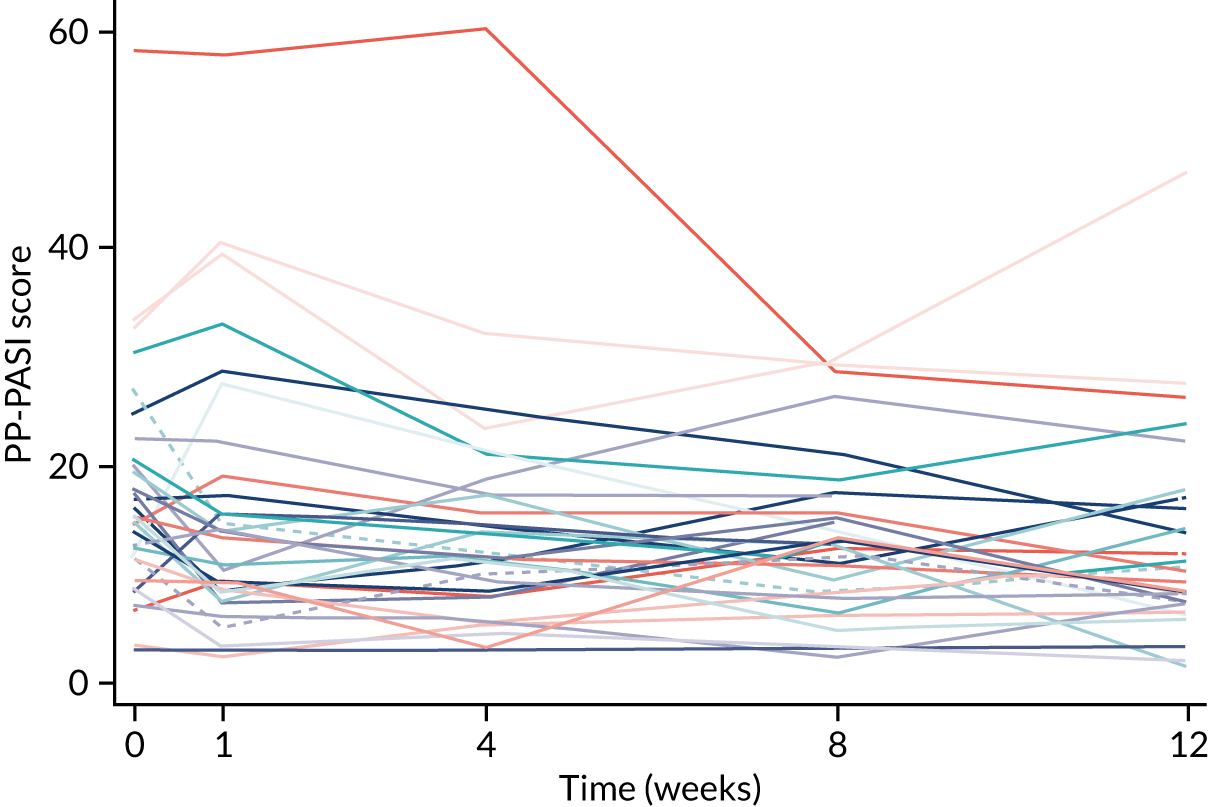

Stage 1

Recruitment began in October 2016 and the pre-planned interim stage 1 analysis was performed in January 2018 after the first 24 participants had been followed up for 8 weeks (placebo group, n = 13; anakinra group, n = 11). The unadjusted PP-PASI score averaged over weeks 1–8 was 16.2 points (SD 11.1 points) in the placebo group and 12.9 points (SD 7.9 points) in the anakinra group. The baseline-adjusted treatment group difference in PP-PASI scores averaged over weeks 1–8 was –1.2 points (95% CI –5.5 to 3.1 points), and the point estimate was in favour of anakinra. The unadjusted fresh pustule count averaged over weeks 1–8 was 47.2 points (SD 59.4 points) in the placebo group and 61.6 points (SD 76.9 points) in the anakinra group. The baseline-adjusted treatment group difference in the fresh pustule count averaged over weeks 1–8 was 16.5 points (95% CI –51.0 to 49.6 points), and the point estimate was in favour of placebo. Given that one outcome was in favour of anakinra (PP-PASI score), the trial met the criteria to progress to stage 2.

The mean difference in agreement between the fresh pustule count assessed at sites and the fresh pustule count assessed centrally using photography was 27 pustules (95% CI –131 to 185 pustules). The ICC was used as a measure of agreement for fresh pustule count between the site assessor and the photographic central assessor, and was found to be 0.13 pustules. The mean difference in agreement in PP-PASI scores between the first and the second site assessors was –0.56 points (95% CI –5.9 to 4.8 points). The ICC for fresh pustule count between two independent site assessors was 0.73 pustules. Overall, the DMC decided unanimously to recommend PP-PASI score as the primary outcome variable for stage 2 because this outcome was judged to be more reliable than fresh pustule count; the agreement (ICC) between the two PP-PASI independent assessors was considerably higher (0.73 points) than the agreement between the site and the central photo fresh pustule count assessments (0.13 points). Additional results from stage 1, including the unadjusted standardised mean differences between the treatment groups for the stage 1 outcomes by time point, can be found in Appendix 9, Table 42, and Figures 23 and 24.

Baseline characteristics

Table 1 summarises baseline demographics by randomised group. The baseline characteristics of the placebo and anakinra treatment groups were generally well matched, including demographics and the severity and impact of participants’ disease.

| Baseline demographic | Treatment group | Total (N = 64) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo (N = 33) | Anakinra (N = 31) | ||

| Age (years), mean (SD) | 51.7 (13.6) | 49.9 (11.9) | 50.8 (12.7) |

| Sex, n (%) | |||

| Male | 6 (18) | 4 (13) | 10 (16) |

| Female | 27 (82) | 27 (87) | 54 (84) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |||

| White | 31 (94) | 28 (90) | 59 (92) |

| Asian/Asian British | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Black/black British | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Chinese/Japanese/Korean/Indochinese | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Other | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Smoker, n (%) | |||

| Current smoker | 19 (58) | 16 (52) | 35 (55) |

| Ex-smoker | 9 (27) | 12 (39) | 21 (33) |

| Non-smoker | 5 (15) | 3 (10) | 8 (13) |

| PP-PASI score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 18.0a (10.4) | 17.5 (10.8) | 17.8 (10.5) |

| Median (IQR) | 15.9 (10.4–21.3) | 15.4 (11.7–20.7) | 15.6 (10.6–21.0) |

| Fresh pustule count (palms and soles) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 36.1 (33.1) | 39.8† (46.3) | 37.9 (39.6) |

| Median (IQR) | 28.0 (18.0–45.0) | 25.5 (11.0–58.0) | 27.0 (15.0–49.0) |

| Fresh pustule count (soles) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 25.9 (23.4) | 29.6a (43.2) | 27.7 (34.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 23.0 (4.0–36.0) | 15.0 (5.0–37.0) | 19.0 (4.0–37.0) |

| Fresh pustule count (palms) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 10.2 (19.2) | 10.2a (16.5) | 10.2 (17.8) |

| Median (IQR) | 2.0 (0.0–13.0) | 2.5 (0.0–13.0) | 2.0 (0.0–13.0) |

| Total pustule count (palms and soles) | |||

| Mean (SD) | 116.9 (96.4) | 154.3a (198.7) | 134.7 (153.7) |

| Median (IQR) | 97.0 (45.0–169.0) | 89.0 (45.0–157.0) | 95.0 (45.0–169.0) |

| PPP-IGA,b n (%) | |||

| Moderate | 16 (48) | 16 (52) | 32 (50) |

| Severe | 17 (52) | 15 (48) | 32 (50) |

| Participant global assessment, n (%) | |||

| Almost clear | 0 (0) | 2 (6) | 2 (3) |

| Mild | 3 (9) | 3 (10) | 6 (9) |

| Moderate | 14 (42) | 14 (45) | 28 (44) |

| Severe | 13 (39) | 7 (23) | 20 (31) |

| Very severe | 3 (9) | 5 (16) | 8 (13) |

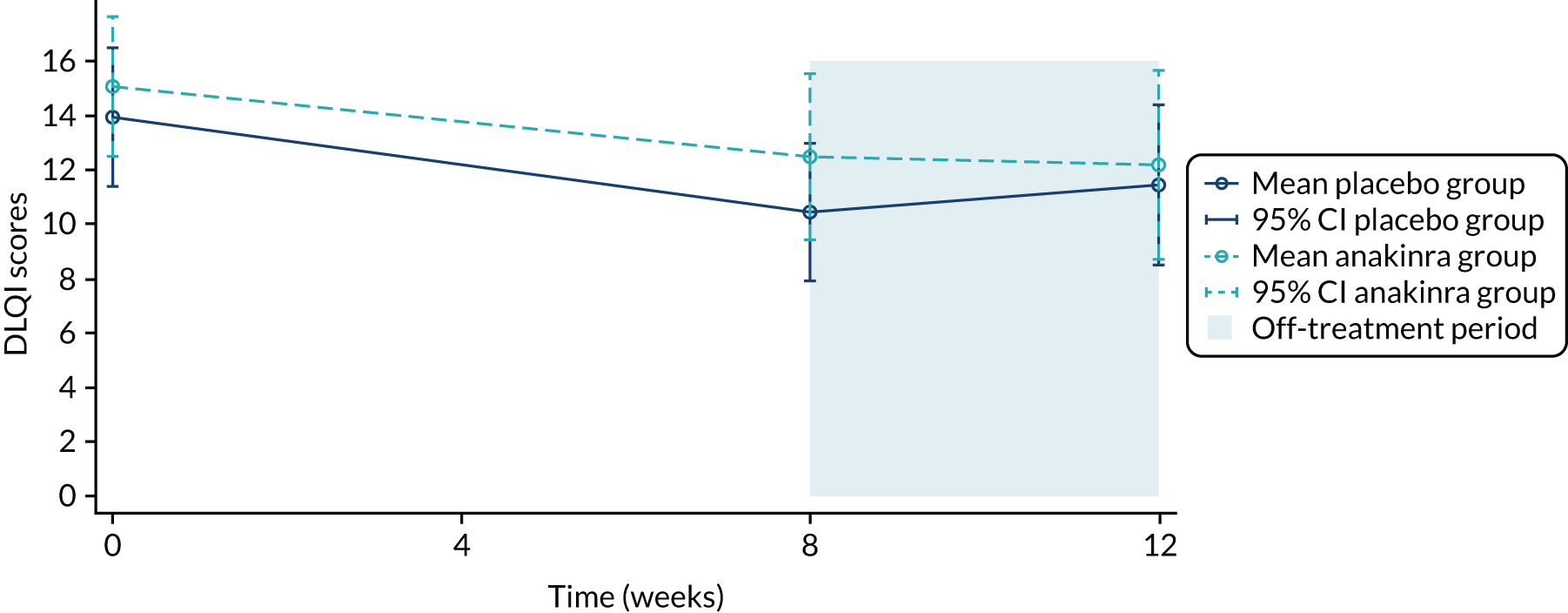

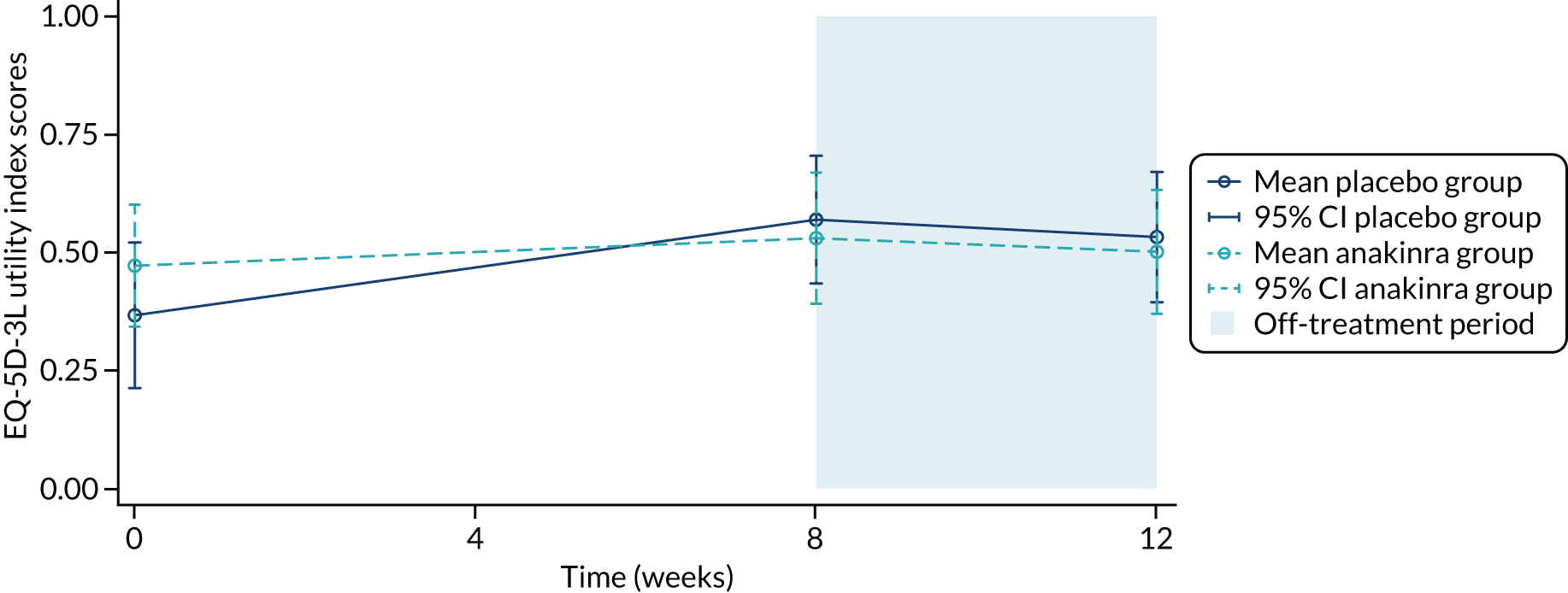

| DLQI | |||

| Mean (SD) | 13.9 (7.2) | 15.1 (7.0) | 14.5 (7.1) |

| PASIc | |||

| Mean (SD) | 2.1 (5.4) | 1.1 (1.6) | 1.6 (4.1) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.0 (0.0–1.8) | 0.2 (0.0–1.6) | 0.0 (0.0–1.6) |

| PP-QoL | |||

| Mean (SD) | 46.4 (13.8) | 45.5 (14.8) | 46.0 (14.2) |

| EQ-5D utility score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 0.37 (0.43) | 0.47 (0.35) | 0.42 (0.40) |

| Median (IQR) | 0.62 (0.09–0.73) | 0.62 (0.16–0.73) | 0.62 (0.09–0.73) |

| EQ-5D-VAS score | |||

| Mean (SD) | 57.7 (27.7) | 68.4d (18.3) | 62.5 (24.4) |

| Median (IQR) | 65.0 (45.0–80.0) | 75.0 (55.0–80.0) | 70.0 (50.0–80.0) |

The mean age of the participants was 50.8 years; 84% were female and 92% were of white ethnicity. Current smokers made up 55% of participants and ex-smokers made up 22%. The mean disease severity at baseline, as measured by the PP-PASI, was 17.8 points (SD 10.5 points). The median fresh pustule count including both the palms and soles was 27.0 pustules (IQR 15.0–49.0 pustules) and total pustule count across the palms and soles was 9.0 pustules (IQR 45.0–169.0 pustules).

Withdrawals from treatment and from the study

During the trial, a total of 11 participants (17%) withdrew from study treatment: six from the placebo group and five from the anakinra group (Table 2).

| Time of and reason for withdrawala | Number of withdrawals (%) | Total (N = 64) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo group (N = 33) | Anakinra group (N = 31) | ||

| Point of treatment discontinuation | |||

| Baseline (n = 64) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Week 1 (n = 63) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Week 2 (n = 63) | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Week 3 (n = 63) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Week 4 (n = 63) | 3 (9) | 3 (10) | 6 (9) |

| Week 5 (n = 63) | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Week 6 (n = 62) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | 2 (3) |

| Week 7 (n = 62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Week 8 (n = 62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Reason for permanent trial treatment discontinuation | |||

| AE | 1b (3) | 4c (13) | 5 (8) |

| Withdrawal of consent | 2 (6) | 1 (3) | 3 (5) |

| Lack of response | 2 (6) | 0 (0) | 2 (3) |

| Condition worsening wants other treatment | 1 (3) | 0 (0) | 1 (2) |

| Total (n = 64) | 6 (18) | 5 (16) | 11 (17) |

Retention in the study was high (see Figure 2). Only three participants (5%) who withdrew from treatment also withdrew entirely from the study. One participant who withdrew from treatment in the placebo group prior to the end of week 1 did not attend any further follow-up appointments and was withdrawn from the study because of non-compliance with the visit schedule. Two further participants who withdrew from treatment early continued in the trial immediately following treatment cessation, but were later withdrawn: one placebo participant was withdrawn post week 4 prior to week 8 due to loss to follow-up and one anakinra participant was withdrawn at the week 8 visit prior to week 12 due to a wish to start other therapies.

Temporary treatment discontinuations, after which trial treatment was recommenced, occurred more frequently in the anakinra group than in the placebo group. There was a total of nine participants recorded to have temporarily discontinued treatment, with 3 out of 33 (9%) in the placebo group and 6 out of 31 (19%) in the anakinra group (Table 3). Temporary discontinuations were mainly as a result of AEs, except for one discontinuation in the anakinra group from an individual who wanted to start other treatments because their condition was worsening. The larger number of discontinuations in the anakinra group was driven by injection site reactions. The temporary treatment numbers include one participant in the placebo group and one in the anakinra group who later permanently withdrew from treatment and who are also included above.

| Time of and reason for temporary treatment discontinuationa | Number of discontinuations (%) | Total (N = 64) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Placebo group (N = 33) | Anakinra group (N = 33) (N = 31) | ||

| First point of treatment discontinuation | |||

| Baseline (n = 64) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Week 1 (n = 63) | 1b (3) | 1c (3) | 2 (3) |

| Week 2 (n = 63) | 0 (0) | 2d (6) | 2 (3) |

| Week 3 (n = 63) | 1 (3) | 2e,f (6) | 3 (5) |

| Week 4 (n = 63) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Week 5 (n = 63) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Week 6 (n = 62) | 1 (3) | 1g (3) | 2 (3) |

| Week 7 (n = 62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Week 8 (n = 62) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) |

| Reason | |||

| AE | 3h (9) | 5i (16) | 8 (13) |

| Condition worsening wants other treatment | 0 (0) | 1 (3) | 1 (2) |

| Total | 3 (9) | 6 (19) | 9 (14) |

Adherence to treatment

Adherence to trial treatment was recorded by using the responses to daily text messages [from a short message service (SMS)], self-reporting from participants using a paper trial diary (issued at the baseline visit and checked at each study visit) and verbal self-recall at study visits. For those who used the SMS service (see Table 4), a daily SMS was sent out to enquire about whether or not the participant had administered their dose that day and required a response of ‘yes’. Unfortunately, an operational incident (which was discovered in January 2019 and was rectified during mid-March 2019) meant that the SMS service was not utilised by all participants (six participants were affected during this period). After excluding the known treatment withdrawals using SMS (Table 4), out of a maximum of seven injections per week, the placebo group reported, on average, 5.7 injections per week at both week 1 and week 8, and the anakinra group reported, on average, 5.8 injections per week at week 1 and 5.4 injections per week at week 8.

Table 4 also summarises the average number of injections received weekly, as self-reported at each clinical visit; these adherence data were self-reported using either a paper trial diary or verbal self-recall: it was not possible to separate the two methods of measurement. For those with self-reported adherence data (see Table 4), after excluding withdrawals, an average of 6.5 injections was reported per week in week 1 and 6.4 in week 8 in the placebo group, compared with 6.9 at week 1 and 6.7 at week 8 in the anakinra group. When combining the SMS and self-recalled adherence data (taking the mean weekly adherence where both measurements were reported per participant), reported adherence was similar in both groups, with the average number of injections received per week being 6.3 at week 1 and 6.2 at week 8 in the placebo group and 6.7 at week 1 and 6.4 at week 8 (after excluding withdrawals) in the anakinra group. However, when including the withdrawals data from the participants who were known to receive no injections following treatment withdrawal or during temporary withdrawal periods to get an overall picture of adherence per week (Table 5), the adherence was a little lower in the placebo group than in the anakinra group: an average of 6.1 injections per week at week 1 and 4.8 injections per week at week 8 in the placebo group, compared with 6.7 at week 1 and 5.3 at week 8 in the anakinra group.

| Treatment perioda | Number of doses per week | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMS datab | Self-reported datac | Mean of SMS and self-reported data | ||||||||||

| Placebo group | Anakinra group | Placebo group | Anakinra group | Placebo group | Anakinra group | |||||||

| n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | n | Mean (SD) | |

| Week 1 (N = 63) | 10 | 5.7 (1.8) | 13 | 5.8 (1.4) | 28 | 6.5 (1.5) | 29 | 6.9 (0.3) | 29 | 6.3 (1.6) | 29 | 6.7 (0.6) |

| Week 2 (N = 60) | 12 | 6.3 (1.2) | 11 | 6.5 (0.9) | 27 | 6.4 (1.8) | 27 | 6.9 (0.6) | 28 | 6.4 (1.5) | 27 | 6.8 (0.6) |

| Week 3 (N = 57) | 12 | 6.5 (0.7) | 10 | 6.5 (0.7) | 26 | 6.6 (1.4) | 24 | 6.8 (0.5) | 28 | 6.6 (1.4) | 24 | 6.8 (0.5) |

| Week 4 (N = 58) | 12 | 6.3 (1.8) | 13 | 6.2 (0.8) | 26 | 6.6 (1.5) | 25 | 6.9 (0.4) | 28 | 6.5 (1.5) | 25 | 6.7 (0.5) |

| Week 5 (N = 53) | 12 | 6.3 (1.4) | 13 | 6.5 (0.9) | 24 | 6.7 (1.4) | 23 | 7.0 (0.0) | 26 | 6.5 (1.4) | 23 | 6.9 (0.3) |

| Week 6 (N = 51) | 12 | 6.3 (1.2) | 12 | 5.9 (1.8) | 22 | 6.5 (1.5) | 22 | 7.0 (0.2) | 24 | 6.4 (1.5) | 22 | 6.7 (0.7) |

| Week 7 (N = 50) | 12 | 5.8 (2.0) | 12 | 6.1 (1.4) | 22 | 6.5 (1.6) | 23 | 7.0 (0.2) | 24 | 6.4 (1.7) | 23 | 6.7 (0.6) |