Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the EME programme as project number 14/150/03. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The final report began editorial review in May 2022 and was accepted for publication in September 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The EME editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2023 Moakes et al. This work was produced by Moakes et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2023 Moakes et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Clinical background

Ectopic pregnancies (EPs) occur when the embryo implants outside the endometrial cavity, most commonly in the fallopian tube. It complicates 1–2% of all pregnancies and is a life-threatening emergency because it can cause the tube to rupture, eliciting a catastrophic maternal haemorrhage. 1 EPs are a significant contributor to maternal morbidity and mortality in both the developed and developing world. 2,3

Around 98% of EPs occur in a fallopian tube. Risk factors incurring the highest odds of an EP are those associated with pre-existing tubal injury, such as a previous EP, tubal ligation, tubal pathology (often resulting from pelvic infections) and prior tubal surgery. 4,5 Other risk factors include conception via in vitro fertilisation, smoking and the presence of an intrauterine device in situ. 4,5

Because of the emergent nature of an EP, prompt management is required. In most cases, laparoscopic surgery is carried out to remove the pregnancy, ideally before it ruptures. Laparoscopic excision will often involve en bloc removal of the affected fallopian tube. Urgent surgical management is mandated when there are clinical or ultrasound suspicions that the ectopic implantation has ruptured and there is active bleeding. However, if the EP is stable and there is no evidence of bleeding, medical management may be considered (as detailed below).

Laparoscopic excision of EP can be carried out safely. However, there are some rare risks, such as injury to internal viscera during the operation and small risks associated with having a general anaesthetic. Furthermore, there are many regions in the world where surgery is not easily accessed. Hence, there is an important clinical role for effective medical options to treat EP.

Current medical management of ectopic pregnancies with methotrexate

First proposed in 1991,6 medical management with a single intramuscular (IM) injection of methotrexate (MTX) is a recognised treatment for women with tubal EP without signs of rupture. 7

Medical management centres on the use of the chemotherapeutic agent MTX. MTX is a folate antagonist and this induces cell death because folate is a necessary ingredient of DNA synthesis (a substrate for the nucleoside thymidine). 8 For decades, it has been long recognised that trophoblast tissue is very sensitive to MTX. Since the late 1950s it has been used to treat choriocarcinoma (placental tumours). 8

The MTX treatment protocol involves an initial IM injection of MTX (50 mg/m2), following which serum human chorionic gonadotrophin (hCG) levels (uniquely secreted from gestational tissues) are monitored until it drops to <15 international units/litre (IU/l), which indicates a non-pregnant state. 9 If the serum hCG is not falling appropriately, a second dose of MTX may be given.

Low-grade evidence on the resolution rate of MTX treatment for EP suggests it is around 70% effective. 10 Treatment failure carries around a 21% risk of requiring a second dose of MTX and the subsequent risk of emergency laparoscopic surgery (where there are inherent risks of damage to visceral organs and an impact on subsequent fertility). In addition, EPs with higher hCG levels (>1000 IU/l) at the start of treatment with MTX, take a significant length of time to resolve and require multiple outpatient monitoring visits. There is a need for more effective medical treatments for tubal EP to reduce the need for additional MTX, to reduce the need for emergency surgery and to reduce the time to resolution associated with MTX management.

Gefitinib as a possible new treatment for ectopic pregnancies

Over the past decade we have generated preclinical11 evidence, and data from small clinical trials12–15 suggesting adding oral gefitinib to IM MTX may improve its effectiveness. 16

Gefitinib is an epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) inhibitor. 17,18 It could plausibly disrupt the ectopic implantation site, because placental tissue exhibits very high expression of EGFR and the developing placenta seems critically dependent on this cellular pathway for survival. 19–22

Gefitinib is used to treat non-small cell lung cancer where it is prescribed indefinitely after the primary cancer treatment. In 2004 postmarketing surveillance of 31,045 people exposed to gefitinib was reported to the Food and Drug Administration. 23 Common side effects include skin rash and diarrhoea. Gefitinib is associated with a rare but concerning side effect of interstitial lung disease (ILD) (0.3% incidence). However, it is possible that developing gefitinib-related ILD mainly happens when there is coexisting lung cancer. Also, the median time to developing related ILD is 42 days and major risk factors include being older than 55 and male sex. 23 Offering it to women who are younger (and unlikely to have lung cancer) and limiting the dose to 7 days would avoid all these risk factors. A short course of the drug is therefore likely to be very safe as a treatment option.

Preclinical studies

In preclinical experiments, we found combining MTX and gefitinib appeared to be significantly more potent in inducing placental cell death in vitro compared to treatment using either drug alone. 11 Combining them induced a more potent blockade of EGFR signalling, and more apoptosis compared to either drug on its own. Compared to MTX alone, adding gefitinib to MTX induced significantly greater shrinkage in the volume of tumours comprising immortalised placental cells (JEG3-placental cell line) grafted subcutaneously on immunocompromised (NOD/SCID) mice. 11 Hence our preclinical data identified the possibility that combining gefitinib with MTX may be a promising treatment for EP.

Early phase clinical studies

We also reported a phase I single arm, open label study of 12 participants diagnosed with EP and a pretreatment serum hCG of <3000 IU/l. 12 Participants were administered MTX and 250 mg of oral daily gefitinib in a dose escalation protocol: one dose for the first three participants, three doses for the second three participants, seven doses for the last six. Treatment appeared safe with no clinical or biochemical evidence of serious toxicity.

The trial also produced early efficacy data that was encouraging. Median serum hCG levels by day 7 after treatment among our study participants were less than one-fifth of the levels observed among 71 historic controls who had been treated with just MTX. The median time for the EP to resolve among our participants treated with MTX and gefitinib was 34% shorter compared to MTX alone (21 days compared with 32 days). 12

We subsequently reported a case series of eight women with extra-tubal EP treated with 7 days of oral gefitinib and IM MTX. 13 Five were interstitial (cornual) EP and three were caesarean section scar EP. Pretreatment serum hCG levels ranged between 2458 and 48,550 IU/l and six women had pretreatment hCG levels > 5000 IU/l. For all eight cases, their extra-tubal EP resolved without need for surgery. Furthermore, a case report has been published of a woman with an interstitial EP and contraindications to surgery. Treated with gefitinib and MTX, her EP resolved without the need for surgery. 15

We have also reported a phase II single arm trial, administering combination gefitinib and MTX to 28 women with stable EP of larger size, defined as a pretreatment serum hCG between 1000 and 10,000 IU/l. 14,24 With this treatment, 24 of the 28 participants had their EP resolve without requiring surgery. This met our a priori statistical analysis cut off, which allowed us to conclude that the efficacy of gefitinib and MTX to treat EP is 70% or more. 14

Collectively, our preclinical studies and our early phase trials suggested combining gefitinib and MTX showed promise as a new medical treatment to treat EP. However, this needed to be demonstrated in a large randomised, placebo-controlled trial.

In the ‘Gefitinib for Ectopic pregnancy Management’ (GEM3) study, which is detailed in this monograph, we evaluated the efficacy and safety of combining MTX and gefitinib to treat tubal EP, compared with MTX alone.

Chapter 2 Methods

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from May et al. 25 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Trial design

The GEM3 trial was a placebo-controlled randomised, blinded, multicentre trial of a combination of MTX and gefitinib versus MTX and placebo as a treatment for EP. The trial had a favourable ethical opinion from Scotland A Research Ethics Committee (ref: 16/SS/0014).

Recruitment

GEM3 participants were recruited from early pregnancy units (EPU) in 50 of the 74 National Health Service (NHS) participating sites across the UK. Firstly, potential participants were referred to the local research teams by their attending clinician with their permission. All referred women were then approached by researchers who were trained in Good Clinical Practice and specifically in taking consent for this trial. Potential participants were provided with a Participant Information Sheet and given time to consider their involvement. All patients were told that participation in the trial was completely voluntary and that once recruited they could withdraw at any stage in the trial. Reassurance was given that participation or withdrawal would not affect their normal clinical care. If patients expressed an interest, written informed consent was sought and they were assessed for eligibility.

Eligibility criteria

Participants were assessed for eligibility by an appropriately trained doctor. The participants needed to meet the following criteria:

-

women aged between 18 and 50 years;

-

clinical decision made for treatment of tubal EP with MTX;

-

able to understand all information (written and oral) presented (using an interpreter if necessary) and provide signed consent;

-

diagnosis of either:

-

definite tubal EP [extrauterine gestational sac with yolk sac and/or embryo, without cardiac activity on ultrasound scan (USS)];

-

clinical decision of probable tubal EP [extrauterine sac-like structure of inhomogenous adnexal mass on USS with a background of suboptimal serum hCG concentrations (on at least 2 different days)];

-

-

pretreatment serum hCG level of 1000–5000 IU/l (within 1 calendar day of treatment);

-

clinically stable;

-

haemoglobin between 100 and 165 g/l within 1 calendar day of treatment;

-

able to comply with treatment and willing to participate in follow up. Participants could not be included if any of the following criteria were applicable:

-

pregnancy of unknown location;

-

evidence of intrauterine pregnancy;

-

breastfeeding;

-

hypersensitivity to gefitinib;

-

EP mass on USS greater than 3.5 cm (mean dimensions);

-

evidence of significant intra-abdominal bleed on USS, defined by echogenic free fluid above the uterine fundus or surrounding one ovary within 1 calendar day;

-

significant abdominal pain, guarding/rigidity;

-

clinically significant abnormal liver/renal/haematological indices within 3 calendar days of treatment;

-

galactose intolerance;

-

significant dermatological disease, for example, severe psoriasis/eczema;

-

significant pulmonary disease, for example, severe/uncontrolled asthma;

-

significant gastrointestinal illness, for example, Crohn’s disease/ulcerative colitis;

-

participating in any other clinical trial of an investigational medicinal product (IMP);

-

previous participation in GEM3;

-

Japanese ethnicity, due to higher risk of ILD from use of gefitinib in this population.

-

Randomisation method and minimisation variables

Once final eligibility was confirmed and consent obtained, participants were randomised to GEM3 by the research staff at sites using a secure online randomisation service provided by the Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit. Participants were randomised in an equal (1:1) ratio to gefitinib or placebo and a bottle number was allocated. The bottle number was sent via email to the local Principal Investigator (PI), the trial pharmacist and the research nurse performing the randomisation. A ‘minimisation’ procedure, incorporating a random element, using a computer-based algorithm, was used to avoid chance imbalances in important prognostic variables. Strata used in the minimisation were as follows:

-

baseline hCG levels (<1500 IU/l, ≥1500 to 2500 IU/l, ≥2500 IU/l);

-

body mass index (BMI) (<25 kg/m2, ≥25 kg/m2);

-

ectopic mass size (<2 cm, ≥2 cm);

-

recruiting centre.

Interventions

Investigational medicinal product information

The IMP was gefitinib, as a tablet. Each tablet contained gefitinib 250 mg.

The placebo was lactose powder, in the same format as the IMP to be identical in colour, shape and weight. The treatment regime was exactly the same as in the gefitinib group.

Interventions were supplied by Astra Zeneca and packaged and distributed by Sharp Clinical Services, UK. These companies had no role in the design, conduct, analysis or reporting of the trial.

A clinical trial pharmacist prepared the trial treatment bottle for dispensing. Each trial treatment bottle contained seven tablets. Bottles were then dispensed at the baseline visit. The labels on the bottle instructed participants to take one tablet each day for 7 days as directed, at the same time each day and they had to be taken orally with a drink of water. A drug instruction card was also given to each participant with the following instructions:

-

Tablets should be taken orally with a glass of water.

-

You take ONE tablet ONCE a day at around the same time for 7 days.

-

First dose will be on the same day you have your MTX injection.

-

Avoid taking antacid medicines 2 hours before taking the tablet and for 1 hour afterwards.

-

If you take TOO MANY tablets by accident, let the trial team know straight away.

-

If you FORGET to take a tablet, if you are less than 12 hours late take the missed tablet as soon as you remember and take the next one at the usual time.

-

If you are more than 12 hours late skip the forgotten tablet and take the next one at the usual time.

-

If you vomit then just take your next dose as planned. Do not take an extra tablet that day.

-

Don’t take a double dose to make up for the forgotten dose.

-

If in doubt then please contact the research team.

Non-investigational medicinal product information

The non-IMP was MTX as an IM injection. The dose was 50 mg/m2 calculated according to the participant’s body surface area. Women were given one injection of MTX on the day of randomisation. It was anticipated that some women would require a second dose of MTX as per clinical requirement. The MTX was taken from clinical stock.

Treatment allocations

Participants were commenced on the trial intervention on the day they were randomised. They commenced on one tablet of 250 mg gefitinib or matched placebo each day for 7 days (or until resolution of EP if this occurred prior to 7 days).

Blinding

Participants, investigators, research nurses and other attending clinicians all remained blind to the trial drug allocation for the duration of their participation.

In case of any serious adverse event (SAE), the general recommendation was to initiate management and care of the participant as though the woman was taking gefitinib. Cases that were considered serious, unexpected and possibly, probably or definitely related to the trial intervention [suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction (SUSAR)], were unblinded as appropriate, if deemed necessary. In any other circumstances, participants, investigators and research nurses and midwives remained blind to drug allocation whilst the participant remained in the trial.

The trial statisticians were unblinded to the trial drug allocation following approval of the Statistical Analysis Plan (SAP) and after the database had been locked for analysis.

Trial appointments

Trial participants attended routine clinical care appointments as per their local Trust policy for the treatment of an EP. Most EPUs advised review on day 4, 7 and then weekly post randomisation. At each visit, adverse events (AEs), symptoms, extra visits to hospital, further doses of MTX and need for surgery were captured and recorded on the database.

Adherence monitoring

Adherence to treatment was assessed by both participant’s self-reported account of total number of tablets taken and clinician reported data on whether the MTX injection was given. We predefined adherence as participants who received their initial MTX injection and at least 75% of their allocated treatment (gefitinib or placebo) prior to resolution (up to a maximum of 7 daily doses if resolution had not occurred by 7 days post randomisation). Women who were considered adherent as per this definition comprised the per-protocol cohort.

Co-enrolment

Participants were not permitted to participate in other IMP trials but were permitted to take part in non-IMP (e.g. questionnaire/tissue collection) studies.

Participant withdrawal

A participant was considered for withdrawal from the trial treatment if, in the opinion of the investigator or the care providing clinician or clinical team, it was medically necessary to do so. Participants could also voluntarily withdraw from treatment at any time, however, women were encouraged to continue follow-up following withdrawal from trial treatment to minimise attrition bias.

Participants could voluntarily withdraw their consent to study participation at any time. If a participant did not return for a scheduled visit, attempts were made to contact her and where possible, review adherence and safety data. Reasons for withdrawal were captured where possible. If a participant explicitly withdrew consent to have any further data recorded their decision was respected and recorded on the electronic data capture system. All communication surrounding the withdrawal was noted in the patient’s medical notes and no further data collected for that participant.

Outcomes and assessments

Primary outcome measures

The primary outcome measure was surgical intervention for the treatment of EP (salpingectomy or salpingostomy by laparoscopy or laparotomy).

Secondary outcome measures

Secondary outcomes were as follows:

-

need for further treatment with MTX;

-

number of days to resolution of pregnancy (hCG ≤ 15 IU/l);

-

number of hospital visits associated with treatment;

-

patient satisfaction measured by a Likert scale;

-

return to menses (assessed 3 months after resolution of EP);

-

safety/tolerability (AEs).

Outcome assessment details

The schedule for outcome assessment is given in Table 1. Details of how outcomes were generated are given in Table 2.

| Day of treatment | Standard clinical care visits | Day 14–21 (during scheduled clinical care visits) | Month 3 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Consent | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Clinical assessment | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Serum hCG | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| AEs | ✓ | ✓ | ||

| Adherence | ✓ | |||

| Return to menses and acceptability | ✓ |

| Outcome assessed | Timepoint | Method | Reported by |

|---|---|---|---|

| Serum hCG | Clinical care visits | Routine clinical blood sample | NHS laboratory results |

| Full blood count, urea and electrolytes, liver function tests | Clinical care visits | Routine clinical blood sample | NHS laboratory results |

| AEs | Clinical care visits | Clinical assessment of participant at follow-up visit and medical records | Research nurse/doctor |

| Adherence | Clinical care visits | Clinical assessment of participant at follow-up visit | Study participant reported |

| Return to menses and acceptability | 3 months postresolution of EP | Paper case report form | Study participant and research nurse/doctor |

Relevant trial data was transcribed directly onto a secure web-based database. All personal information was treated as strictly confidential. Source data comprised of the case report forms, questionnaires and hospital notes. Women were encouraged to report AEs occurring between clinic visits or presenting at non-participating hospitals to the research nurse. Self-reports were verified against clinical notes. There were validation methods built into this system to ensure data consistency and quality.

Adverse events and serious adverse events

All AEs, from consent until resolution of EP (hCG ≤ 15 IU/l or surgical intervention), whether observed directly or reported by the patient, were collected and recorded. Common known side effects of gefitinib were not reported as AEs (unless they met the definition of seriousness) but were captured directly onto the database at each visit. These common side effects were abdominal pain, diarrhoea, nausea, vomiting, rash, fatigue, dizziness and mouth ulcers. Trial participants were asked about the occurrence of AEs and SAEs at each study visit. All SAEs were emailed or faxed to the sponsor’s office within 24 hours of the research staff becoming aware of the event and onward reported to Astra Zeneca. The local PI (or other nominated clinician) had to assign seriousness, severity, causality and expectedness (if deemed related) to the SAE before reporting. SAEs categorised by the local investigator as both suspected to be related to the trial drug and unexpected were classified as SUSARs, and were subject to expedited reporting. In the case of any SAEs, management and care of the women was initiated as though the woman was taking gefitinib. All AEs and SAEs have been MedDRA coded (version 24.1) for consistency of reporting.

Statistical considerations

Sample size

The sample size was based on data taken from the GEM2 phase II study,14 published cohort data13 and an unpublished audit of women undergoing usual care at two participating sites (2012). These data suggested 30% of women would require surgical intervention in the MTX only group, with a halving of this proportion plausible in the gefitinib and MTX group (a 50% relative reduction). A sample size of 322 participants was required to provide 90% power with an alpha error rate of 5% to detect this size of difference. We planned to include 328 participants in the trial to account for up to 2% attrition.

Statistical analysis

A comprehensive SAP was drawn up prior to any analysis. In brief, categorical data were summarised with frequencies and percentages. Continuous variables were summarised with means and standard deviations unless there was evidence of skew, where medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) were presented. In the first instance, participants were analysed in the treatment group to which they were randomised [intention to treat (ITT)], irrespective of adherence with the treatment protocol. All estimates of differences between groups were presented with 95%, two-sided confidence intervals (CIs), adjusted for the minimisation variables (where possible).

The primary outcome was analysed using a mixed-effects log-binomial model to generate an adjusted risk ratio (RR) and an adjusted risk difference (RD) (using an identity link function), including centre as a random effect. Statistical significance of the treatment group parameter was determined (p-value generated) through examination of the associated chi-squared statistic (obtained from the log-binomial model, which produced the RR).

Binary secondary outcomes were analysed as per the primary outcome. Time to hCG resolution was considered in a competing risk framework to account for participants who had surgical intervention for their EP. 26 A cumulative incidence function was used to estimate the probability of occurrence (hCG resolution) over time. A Fine-Gray model was then used to estimate a subdistribution adjusted hazard ratio (HR) directly from the cumulative incidence function. In addition, a further Cox proportional hazard model was fitted and applied to the cause-specific (non-surgical resolution) hazard function and used to generate an adjusted HR. 27 Return to menses was analysed using a Cox regression model. Number of hospital visits associated with treatment was analysed using a Poisson regression model, including centre as a random effect to generate an adjusted incidence rate ratio (IRR). Acceptability of treatment was analysed using an ordinal logistic regression model, including centre as a random effect to generate an adjusted odds ratio (OR).

Sensitivity and supportive analyses of the primary outcome included a per-protocol analysis, an analysis that excluded any women found to violate the inclusion/exclusion criteria post randomisation and an analysis to investigate the small amount of missing primary outcome data by means of a ‘tipping point’ approach, which explored the possibility that missing responses were ‘missing not at random’. Unadjusted models were utilised. Firstly all women with missing outcome data were considered as having not met the primary outcome (i.e. surgical intervention was no). Two scenarios were then considered. In the first scenario, in women who had missing data in the gefitinib group, ‘events’ (i.e. surgical intervention was changed from no to yes) were sequentially added to this group until the number of events added was equal to the number of women with missing outcome data in that group. With the addition of each event, an unadjusted model was run and the RR stored. The tipping point for the gefitinib group occurred when enough events have been added such that the upper/lower limit of the CI from the corresponding model differed from that of the primary ITT finding (in regards to whether the CI crossed the null value of one), should the tipping point exist. A second scenario was then considered, which repeated this process in the placebo group. A sensitivity analysis for time to hCG resolution was also conducted where the threshold for resolution was considered as 30 IU/l.

Preplanned subgroup analyses (limited to the primary outcome measure only) were completed for the following: baseline serum hCG levels (<1500 IU/l, ≥1500 to <2500 IU/l, ≥2500 IU/l), BMI (<25 kg/m2, ≥25 kg/m2) and ectopic size on ultrasound (<2 cm, or ≥2 cm). The effects of these subgroups were examined by adding the subgroup by treatment group interaction parameters to the regression model. p-values from the tests for statistical heterogeneity were presented alongside the effect estimate and estimates of uncertainty within each subgroup. In addition to this, ratios were provided to quantify the difference between the treatment effects estimated within each subgroup.

Interim analyses of effectiveness and safety end points were performed on behalf of the Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee (DMEC) on an approximately annual basis during the period of recruitment. These analyses were performed with the use of the Haybittle–Peto principle28 and hence no adjustment was made in the final p-values to determine significance.

All analyses were performed in SAS® (version 9.4 SAS Institute Inc., Cary, North Carolina 27513, USA) or Stata® (version 17.0 StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

Amendments to the project

During the course of the trial we submitted 22 substantial amendments and six non-substantial amendments. Please see details in Table 3.

| Number and ethics date | Amendment type | Summary of changes made |

|---|---|---|

| 01_3 March 2016 | Following ethical review | Changes as per feedback from ethics |

| 02_8 March 2016 | Non-substantial | Questionnaire v3_typos corrected Protocol, timescales clarified, unblinding, randomisation process detailed, minor clarifications to inclusion/exclusion as per clinician’s feedback |

| 03_10 October 2016 | Non-substantial | Correction of typo on page 19, Japanese ethnicity added for consistency |

| 04_15 January 2019 | Non-substantial | Extension to recruitment period |

| 05_31 January 2020 | Non-substantial | Extension to recruitment period |

| 06_4 June 2021 | Non-substantial | Change of PI at Addenbrookes |

| 01_1 September 2016 | Substantial protocol v5 | Clarification of terms following co-investigators, TSC and DMC meetings |

| 02_6 October 2016 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 03_1 December 2016 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 04_12 April 2017 | Substantial protocol v6 | Clarification of processes. Update of SmPC. Update TSC change of Chair and DMC change of statistician. Update contact details of trial team |

| 05_12 May 2017 | Substantial | Change of PI and addition of sites |

| 06_16 June 2017 | Substantial | Change of PI |

| 07_5 October 2017 | Substantial | Addition of sites, update of contact details |

| 08_30 October 2017 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 09_1 December 2017 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 10_17 April 2018 | Substantial protocol v7 | Change to SmPC gefitinib Change in contact details, TMG and TSC members and change in statistician Clarification of terms |

| 11_17 April 2018 | Substantial | Addition of sites Change of PI at South Tees and Aberdeen |

| 12_26 June 2018 | Substantial | Addition of site |

| 13_29 August 2018 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 14_3 January 2019 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 15_27 February 2019 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 16_2 April 2019 | Substantial | Addition of sites |

| 17_26 July 2019 | Substantial protocol v8 | Change of address for Sharp Clinical UK Removal of mechanistic study Addition of information re long-term follow up Change in staff information Addition of data management section 9 |

| 18_18 October 2019 | Substantial | Addition of site Change of PIs |

| 19_9 March 2020 | Substantial | Addition of sites Change of PIs |

| 20_6 July 2020 | Substantial | Change of PIs |

| 21_11 February 2021 | Substantial | Change of PIs |

| 22_19 February 2021 | Substantial protocol v9 | Change to SmPC – gefitinib and methotrexate Minor changes to analysis section for clarification Minor administrative changes for clarification |

Trial oversight

Study oversight was provided by a Trial Steering Committee (TSC), chaired by Professor Ying Cheong (University of Southampton) and a DMEC, chaired by Professor Usha Menon (University College London). The TSC provided independent supervision for the trial, providing advice to the Chief and Co-Investigators on all aspects of the trial throughout the study. The DMEC adopted the DAMOCLES charter29 to define its terms of reference and operation in relation to oversight of the GEM3 trial.

Public and patient involvement

We have been supported throughout the trial by the Ectopic Pregnancy Trust (EPT) and, in particular, its chair. Public and patient involvement was crucial in improving the acceptability of the GEM3 trial and promoting engagement of gynaecologists. We engaged with EPT throughout, improving our understanding of the needs of patients with EP. Members of the EPT commented on all patient-facing materials to ensure that they were clear and comprehensive. We organised three research site team training days during the course of the trial and EPT patient representatives spoke at each of these meetings (e.g. on how best to counsel participants when approaching them about the trial). We will engage with the EPT regarding the dissemination of our results, providing a plain English summary of the findings. This will be distributed via the EPT’s website and on their social media channels. Any future research groups taking forward the research recommendations from this project would benefit from engaging with the EPT.

Chapter 3 Results of the clinical trial

This chapter reports the results of the randomised controlled trial.

Recruitment

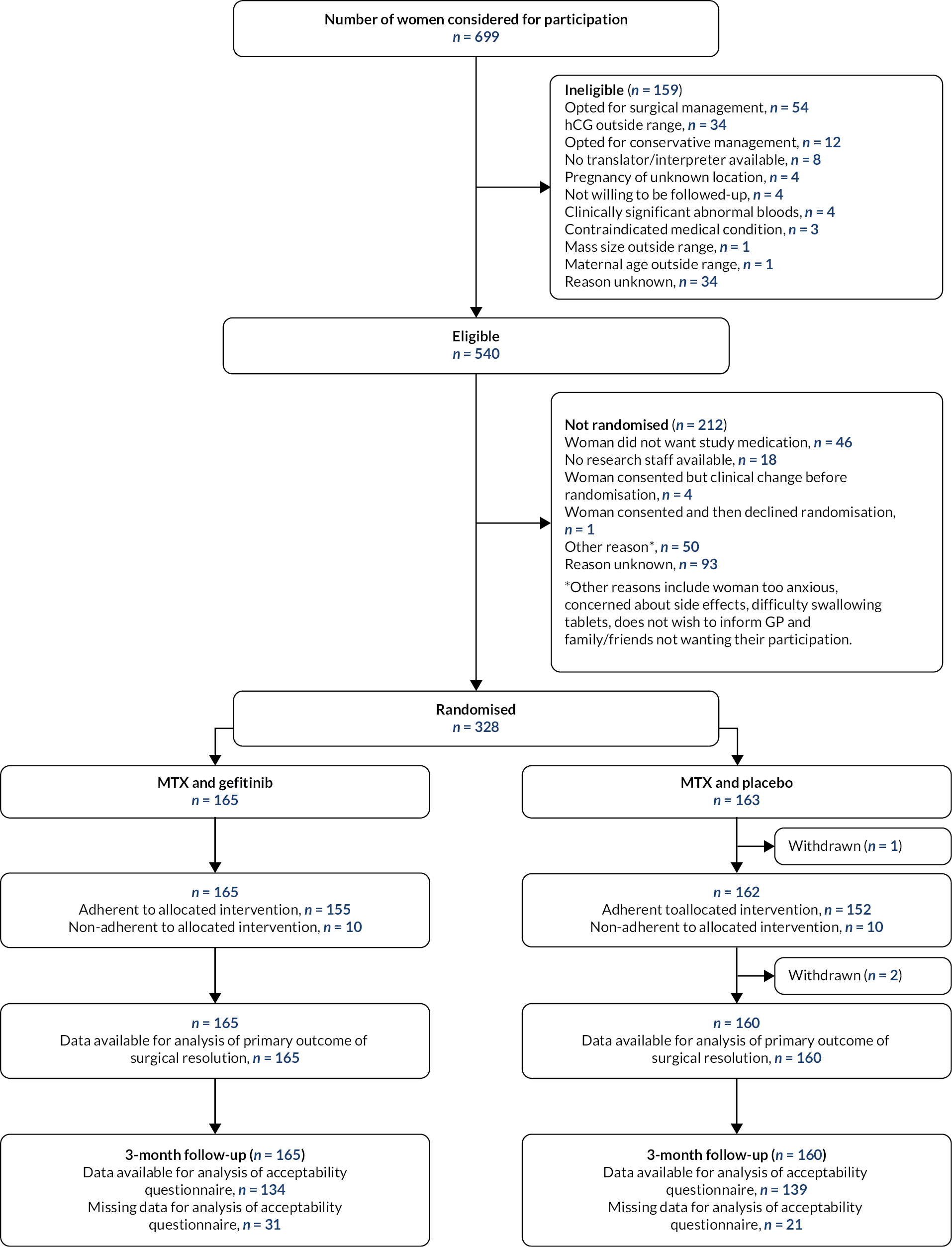

Screening of participants commenced on 2 November 2016 and the last woman was randomised on 6 October 2021 (Figure 1). Recruitment was paused during the COVID-19 pandemic from 20 March 2020 until 2 June 2020 but otherwise the pandemic had limited impact on the trial process and data collection. Three hundred twenty-eight women were recruited from 50 sites, the contribution from each site can be seen in Table 4. The complete flow of participants through the GEM3 trial is shown in Figure 1. Initially, 699 were considered for participation, of which, 540 women were considered eligible. Of these women, 328 women were randomised, 212 were not randomised for various reasons (details in Figure 1). A total of 165 participants were assigned to gefitinib and 163 to placebo. Three women withdrew from GEM3 and there were no deaths. Reasons for trial withdrawal are provided in Table 5.

FIGURE 1.

CONSORT diagram.

| Recruiting hospital | All participants – no. (%) (N = 328) |

|---|---|

| University College Hospital | 35 (11) |

| West Middlesex University Hospital | 33 (10) |

| St Thomas’ Hospital | 28 (9) |

| Burnley General Hospital | 27 (8) |

| Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh | 20 (6) |

| Glasgow Royal Infirmary | 13 (4) |

| Addenbrooke’s Hospital | 11 (3) |

| King’s College Hospital (Denmark Hill) | 11 (3) |

| Darent Valley Hospital | 11 (3) |

| University Hospital Coventry (Walsgrave) | 10 (3) |

| Queens Hospital, Romford | 10 (3) |

| St Peters Hospital | 10 (3) |

| Birmingham Heartlands Hospital | 8 (2) |

| Frimley Park Hospital | 7 (2) |

| Stoke Mandeville Hospital | 7 (2) |

| Ninewells Hospital | 6 (2) |

| Manchester Royal Infirmary | 5 (2) |

| Forth Valley Royal Hospital | 5 (2) |

| The James Cook University Hospital | 4 (1) |

| Chesterfield Royal Hospital | 4 (1) |

| Royal Hampshire County Hospital | 4 (1) |

| Queens Medical Centre | 4 (1) |

| St Michael’s Hospital | 3 (1) |

| Basildon Hospital | 3 (1) |

| Sheffield Teaching Hospitals | 3 (1) |

| Hinchingbrooke Hospital | 3 (1) |

| Peterborough City Hospital | 3 (1) |

| East Surrey Hospital | 3 (1) |

| Victoria Hospital | 3 (1) |

| University Hospital of North Durham | 3 (1) |

| St Helier Hospital | 3 (1) |

| Gloucestershire Royal Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Worcestershire Royal Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Queen Charlotte’s & Chelsea Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Norfolk & Norwich University Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Crosshouse Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Tameside General Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Queens Hospital, Burton | 2 (1) |

| Princess Alexandra Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Sunderland Royal Hospital | 2 (1) |

| Homerton University Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| West Suffolk Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| Royal Stoke University Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| Scunthorpe General Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| Warrington Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| Wishaw General Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| Aberdeen Royal Infirmary | 1 (<1) |

| Birmingham Women’s Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| Leighton Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| Poole General Hospital | 1 (<1) |

| MTX and gefitinib (N = 165) | MTX and placebo (N = 163) | |

|---|---|---|

| Withdrawalsa – no. (%) | 0 (-) | 3 (2) |

| Reason for withdrawal – no. | ||

| Intrauterine pregnancy detected | - | 2 |

| No consent obtained | - | 1 |

Pregnancy

Two participants were found to have intrauterine pregnancies following randomisation to the trial. These pregnancies were found to be unviable. These participants were withdrawn from the trial.

Participant characteristics

At enrolment, baseline characteristics were well balanced between groups (Table 6). The mean age was 31.7 years (SD 5.5 years), mean BMI was 26.8 kg/m2 (SD 6.1 kg/m2), the median pretreatment hCG levels were 1994.0 (IQR 1487.0–2819.0), and 25% had a starting ectopic size ≥ 2 cm measured on USS.

| Participant characteristics | MTX and gefitinib (N = 165) | MTX and placebo (N = 162a) |

|---|---|---|

| hCG level (IU/l)b – no. (%) | ||

| <1500 | 44 (27) | 40 (25) |

| ≥1500 to <2500 | 64 (39) | 65 (40) |

| ≥2500 | 57 (34) | 57 (35) |

| Median (IQR, N) | 1972 (1457–2820, 165) | 2023 (1523–2809, 162) |

| BMI (kg/m2)b – no. (%) | ||

| <25 | 79 (48) | 78 (48) |

| ≥25 | 86 (52) | 84 (52) |

| Mean (SD, N) | 26.7 (5.9, 165) | 26.9 (6.3, 162) |

| Ectopic size (cm)b – no. (%) | ||

| <2 | 121 (73) | 124 (77) |

| ≥2 | 44 (27) | 38 (23) |

| Woman’s age (years) | ||

| Mean (SD, N) | 31.7 (5.6, 165) | 31.7 (5.3, 162) |

| Minimum–maximum | 18.3–45.5 | 19.0–48.1 |

| Per vaginum (PV) bleeding – no. (%) | ||

| No PV loss | 57 (34) | 77 (48) |

| Light bleeding | 89 (54) | 73 (45) |

| Moderate bleeding | 17 (10) | 10 (6) |

| Heavy bleeding | 1 (1) | 2 (1) |

| Clots or flooding | 1 (1) | 0 (-) |

| Ethnicity – no. (%) | ||

| White | 122 (74) | 126 (78) |

| Asian | 19 (12) | 19 (12) |

| Chinese | 1 (1) | 3 (2) |

| Black | 12 (7) | 9 (6) |

| Mixed | 10 (6) | 2 (1) |

| Otherc | 0 (-) | 2 (1) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Smoking status – no. (%) | ||

| Current smoker | 38 (24) | 36 (23) |

| Ex-smoker | 27 (17) | 32 (21) |

| Never smoked | 95 (59) | 86 (56) |

| Missing/unknown | 5 | 8 |

| Previous Chlamydia infection – no. (%) | 25 (17) | 21 (15) |

| Missing/unknown | 21 | 21 |

| Number of presumed patent tubes – no. (%) | ||

| 0 | 0 (-) | 1 (1) |

| 1 | 24 (15) | 24 (15) |

| 2 | 140 (85) | 137 (85) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Nulliparous – no. (%) | 91 (55) | 85 (52) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Number of previous presumed EPs/pregnancies of unknown location – no. (%) | ||

| 0 | 138 (84) | 133 (82) |

| 1 | 22 (13) | 21 (13) |

| 2 | 3 (2) | 7 (4) |

| ≥3 | 1 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Missing | 1 | 0 |

| Current IVF pregnancy – no. (%) | 5 (3) | 2 (1) |

| Missing/unknown | 1 | 1 |

| USS finding – no. (%) | ||

| Inhomogenous mass | 82 (50) | 75 (46) |

| Extrauterine sac like structure | 47 (28) | 48 (30) |

| Extrauterine gestation sac with yolk sac | 31 (19) | 33 (20) |

| Extrauterine gestation sac with embryo/foetal pole | 5 (3) | 6 (4) |

Adherence to treatment

Nearly all women received their initial MTX injection (99%), of the three women who did not receive their initial injection reasons can be seen in Table 7. The median number of tablets taken was 7.0 (IQR 7.0–7.0) in both groups. One hundred fifty-five of 165 (94%) women in the gefitinib group were considered adherent, in comparison to 152 of 162 (94%) women in the placebo group.

| MTX and gefitinib (N = 165) | MTX and placebo (N = 162a) | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial MTX injection received – no. (%) | ||

| Yes | 163 (99) | 161 (99) |

| No | 2 (1) | 1 (1) |

| Reason initial MTX injection not given – no. | ||

| Woman ruptured and required surgery before MTX could be given | 1 | 0 |

| Woman was found to be ineligible postrandomisationb (MTX not required) | 1 | 0 |

| Woman was found to be ineligible postrandomisationc (surgery required) | 0 | 1 |

| Number of tablets received | ||

| Median (IQR, N) | 7.0 (7.0–7.0, 165) | 7.0 (7.0–7.0, 162) |

| Minimum–maximum | 0–7.0 | 0–7.0 |

| Adherent – no. (%) | ||

| Yes | 155 (94) | 152 (94) |

| No | 10 (6) | 10 (6) |

Primary outcome

For the primary ITT analysis, there was no evidence of a difference in the primary outcome. The surgical intervention rate in the gefitinib group was 30% (50/165) and 29% (47/160) in the placebo arm (adjusted RR 1.15, 95% CI 0.85 to 1.58; adjusted RD −0.01, 95% CI −0.10 to 0.09; p = 0.37) (Table 8).

| MTX and gefitinib | MTX and placebo | RRa (95% CI) | RDb (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgical interventionc – n/N (%) | ||||

| ITT analysis | 50/165 (30) | 47/160 (29) | 1.15 (0.85 to 1.58) | −0.01 (−0.10 to 0.09) |

| Per-protocol analysisd | 48/155 (31) | 45/151 (30) | 1.05 (0.67 to 1.64) | 0.00 (−0.10 to 0.10) |

| Eligible populatione | 50/164 (30) | 46/159 (29) | 1.17 (0.86 to 1.60) | 0.00 (−0.10 to 0.10) |

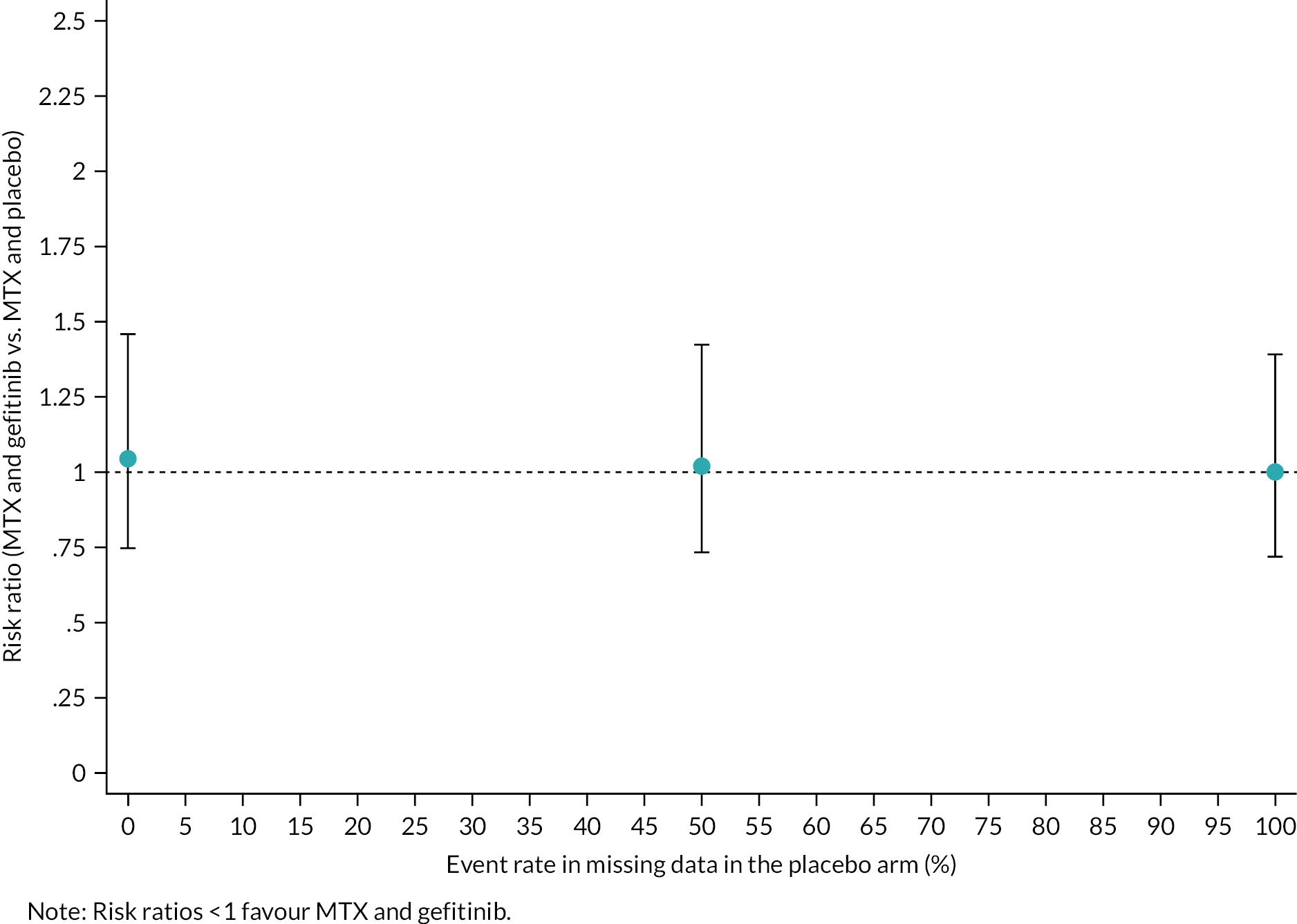

Sensitivity and supportive analyses had minimal impact on effect estimates as described below. In the per-protocol analysis of the primary outcome comparison, including only the 306 women defined as adherent who had primary outcome data available, the effect estimates changed only marginally. Similarly, when the analysis population was limited to women who were not found to violate the inclusion/exclusion criteria (post randomisation), the point estimates and CIs were almost identical to the ITT analysis. Finally, the sensitivity analyses to assess the impact of missing data using a ‘tipping point’ approach (as summarised in Figure 2) support the conclusion that our primary outcome analysis was robust to the small amount of missing data. A tipping point analysis was not conducted in the gefitinib group since there were no missing primary outcome data in this group.

FIGURE 2.

Tipping point analysis in the placebo group.

Subgroup analysis was performed for the three prespecified variables used in the minimisation algorithm, namely baseline hCG levels (key subgroup), BMI and ectopic size. There was no evidence for varying effective in each subgroup analysis performed. The proportion of women who required surgical intervention in each subgroup is shown in Table 9.

| MTX and gefitinib | MTX and placebo | Interaction, p-value | Adjusted risk ratioa (95% CI) | Ratiob (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Key subgroup | |||||

| hCG level (IU/l) | |||||

| <1500 | 7/44 (16) | 9/40 (23) | 0.60 | 0.83 (0.35 to 2.01) | 0.62 (0.00 to 1.24)c |

| ≥1500 to <2500 | 21/64 (33) | 20/64 (31) | 1.07 (0.66 to 1.72) | 0.80 (0.25 to 1.34)d | |

| ≥2500 | 22/57 (39) | 18/56 (32) | 1.34 (0.82 to 2.19) | REF | |

| Exploratory subgroups | |||||

| BMI (kg/m2) | |||||

| <25 | 24/79 (30) | 24/76 (32) | 0.95 | 1.13 (0.71 to 1.80) | 0.98 (0.34 to 1.62)e |

| ≥25 | 26/86 (30) | 23/84 (27) | 1.15 (0.73 to 1.81) | ||

| Ectopic size (cm) | |||||

| <2 | 42/121 (35) | 37/122 (30) | 0.32 | 1.22 (0.87 to 1.73) | 1.57 (0.18 to 2.96)f |

| ≥2 | 8/44 (18) | 10/38 (26) | 0.78 (0.35 to 1.76) | ||

Secondary outcome results

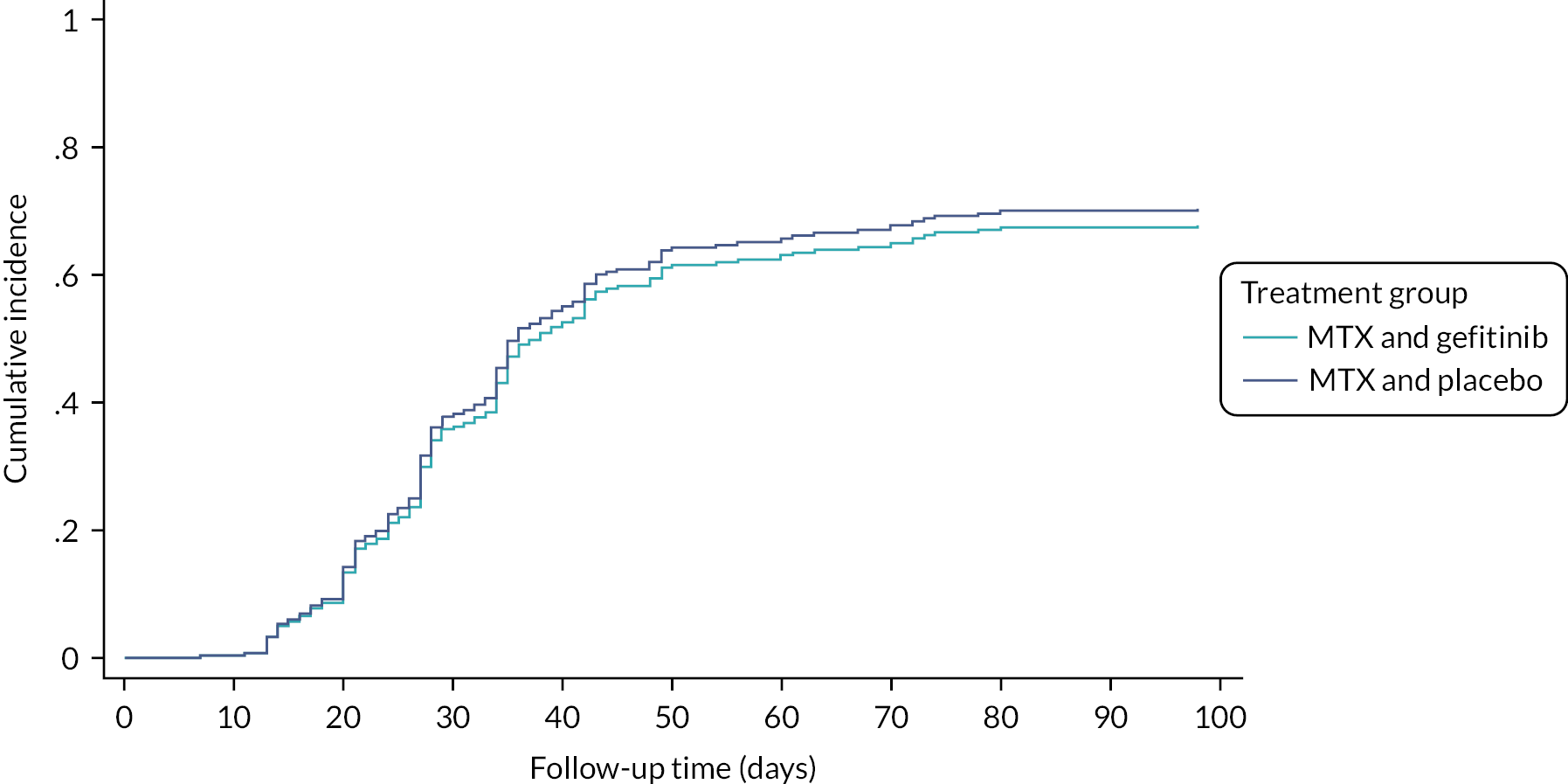

There were no differences in the secondary outcomes (Table 10). The median time to resolution of the EP (defined as serum hCG declining to ≤ 15 IU/l) for those where medical management successfully resolved the EP was 28.0 days (IQR 23.5–36.0, n = 108) in the gefitinib group and 28.0 (IQR 21.0–36.5, n = 108) days in the placebo group (cause specific HR of 0.96, 95% CI 0.69 to 1.33; subdistribution HR 1.03, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.40) (Figure 3). A second dose of MTX was administered to 12% (20/165) of participants in the gefitinib group and 14% (23/162) in the placebo group (adjusted RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.57 to 1.28). The number of hospital visits was similar in both groups. The median number of days before a return to menses was similar in both groups: 24.0 days (IQR 24.0–38.0, n = 132) in the gefitinib group versus 24.0 (IQR 24.0–38.0, n = 134) in the placebo group (adjusted HR 1.08, 95% CI 0.83 to 1.40). Both treatments had high rates of satisfaction (percentage of women who were very, or mostly satisfied was 77% in the gefitinib group and 76% in the placebo group).

| MTX and gefitinib (N = 165) | MTX and placebo (N = 162a) | Estimate (95% CI) | Estimate (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Secondary outcomes | ||||

| Additional MTX – n/N (%) | 20/165 (12) | 23/162 (14) | 0.86b (0.57 to 1.28) | 0.01c (−0.07 to 0.09) |

| Time to hCG resolution (≤15 IU/l) (days)d – median (IQR, N) | 28.0 (23.5–36.0, 108) | 28.0 (21.0–36.5, 108) | 0.96e (0.69 to 1.33) | 1.03f (0.75 to 1.40) |

| Time to hCG resolution (≤30 IU/l) (days)g – median (IQR, N) | 27.5 (20.0–35.0, 112) | 27.0 (20.0–35.0, 111) | 1.14e (0.83 to 1.58) | 1.08f (0.79 to 1.46) |

| Number of hospital visits – median (IQR, N) | 5.0 (4.0–7.0, 163) | 5.0 (3.0–6.0, 162) | 1.01h (0.92 to 1.12) | - |

| Satisfaction with effects of treatment – no. (%) | ||||

| Very satisfied | 59/134 (44) | 72/138 (52) | 0.89i (0.71 to 1.12) | - |

| Mostly satisfied | 44/134 (33) | 33/138 (24) | ||

| Neither satisfied nor dissatisfied | 24/134 (18) | 23/138 (17) | ||

| Mostly dissatisfied | 3/134 (2) | 4/138 (3) | ||

| Very dissatisfied | 4/134 (3) | 6/138 (4) | ||

| Acceptability of study treatment – no. (%) | ||||

| Very acceptable | 78/134 (58) | 87/138 (63) | 0.79j (0.49 to 1.28) | - |

| Mostly acceptable | 32/134 (24) | 32/138 (23) | ||

| Neither acceptable nor unacceptable | 19/134 (14) | 13/138 (9) | ||

| Mostly unacceptable | 3/134 (2) | 4/138 (3) | ||

| Very unacceptable | 2/134 (2) | 2/138 (2) | ||

| Likely to recommend study treatment – no. (%) | ||||

| Very likely to recommend | 78/134 (58) | 93/139 (67) | 0.6j (0.37 to 1.01) | - |

| Fairly likely to recommend | 32/134 (24) | 33/139 (24) | ||

| Neither likely to recommend or recommend against | 15/134 (11) | 4/139 (3) | ||

| Fairly likely to recommend against | 4/134 (3) | 6/139 (4) | ||

| Very likely to recommend against | 5/134 (4) | 3/139 (2) | ||

| Time to return to menses (days) – median (IQR, N) | 24.0 (24.0–38.0, 132) | 24.0 (24.0–38.0, 134) | 1.08k (0.83 to 1.40) | - |

FIGURE 3.

Cumulative incidence function plot for time to hCG ≤ 15 IU/l (by treatment group).

Adverse events

The number of women who experienced a SAE was 3% (5/165) in the gefitinib group and 4% (6/162) in the placebo group (p = 0.74). One woman in the gefitinib group experienced a SUSAR as a result of a likely reaction to MTX. The proportions of women who reported diarrhoea or a rash were higher in the gefitinib group compared to the placebo group (Table 11). Further details of all AEs and SAEs are presented below in Tables 12 and 13.

| MTX and gefitinib (N = 165) | MTX and placebo (N = 162a) | |

|---|---|---|

| Reported symptoms – n/N (%) | ||

| Abdominal pain | 135/162 (83) | 133/160 (83) |

| Dizziness | 72/160 (45) | 61/160 (38) |

| Nausea | 104/161 (65) | 97/160 (61) |

| Diarrhoea | 75/160 (47) | 39/161 (24) |

| Rash | 97/159 (61) | 36/160 (23) |

| Mouth ulcers | 42/160 (26) | 24/160 (15) |

| Fatigue | 127/161 (79) | 115/161 (71) |

| Vomiting | 32/160 (20) | 33/160 (21) |

| MTX and gefitinib (N = 165) | MTX and placebo (N = 162a) | |

|---|---|---|

| AEs – n/N (%) | ||

| Number of women who experience an AE | 37/165 (22) | 38/162 (23) |

| Number of AEs – no. | 52 | 63 |

| Details of AEs (MEDRA coded v2.4) – no. | ||

| Blood and lymphatic system disorders | 2 | 1 |

| Cardiac disorders | 1 | 0 |

| Ear and labyrinth disorders | 2 | 0 |

| Eye disorders | 0 | 2 |

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 3 | 10 |

| General system disorders and administration site conditions | 0 | 3 |

| Immune system disorders | 0 | 2 |

| Infections and infestations | 5 | 7 |

| Investigations | 2 | 7 |

| Metabolism and nutritional disorders | 1 | 1 |

| Musculoskeletal and connective tissue disorders | 5 | 3 |

| Nervous system disorders | 5 | 6 |

| Neurological disorders NEC | 3 | 0 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 8 | 6 |

| Psychiatric and behavioural symptoms | 2 | 1 |

| Renal and urinary disorders | 2 | 0 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 4 |

| Respiratory disorders | 0 | 3 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 1 | 0 |

| Skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders | 6 | 6 |

| Surgical and medical procedures | 3 | 1 |

| Vascular disorder | 1 | 0 |

| SAEs – n/N (%) | ||

| Total number of women experiencing a SAE | 5/165 (3) | 6/162 (4) |

| Number of SAE’s reported – no. | 5 | 6 |

| Details of SAEs (MEDRA coded v2.4) – no. | ||

| Gastrointestinal disorders | 1 | 1 |

| Immune system disorders | 1 | 0 |

| Infections and infestations | 1 | 0 |

| Investigations | 2 | 2 |

| Pregnancy, puerperium and perinatal conditions | 0 | 1 |

| Reproductive system and breast disorders | 0 | 1 |

| Respiratory, thoracic and mediastinal disorders | 0 | 1 |

| MTX and gefitinib |

|---|

| MTX and placebo |

| Seen in EPU – abdominal pain. Admitted and scan arranged. Urology in surgical triage. Seen for a CT scan. Showed no renal calculi and pain settling. Discharged with no clinical diagnosis. |

| Patient attended out of hours with abdominal pain. There was no evidence of rupture of ectopic (as she did not have ultrasound at attendance). It was a clinical decision to proceed with laparoscopic salpingectomy, which was uncomplicated with evidence of drop in serum hCG levels. Patient was discharged and follow-up bloods obtained. Normal. |

| *Hyperventilated after MTX injection. Blood pressure and pulse and O2 sats stable throughout the episode. However, as patient was very worried about reaction, she was admitted overnight and given antihistamines. Following this reaction, the patient declined to take IMP. |

| Seen in gynae assessment unit with increase in lower right sided abdominal pain radiating down leg and unable to sit down. Admitted overnight and scanned. Initial diagnosis was potential rupture of ectopic. Increase in free fluid but no mass seen therefore ruled out. Settled slightly and admitted home. Seen in clinic – pain still there but not as extreme. |

| Participant seen for follow-up visit. Distressed due to lower abdominal pain. Decision then made to hospitalise later that day for analgesia, IV antibiotics, fluids, and further investigations due to previous history of pelvic inflammatory disease. Investigations continuing to confirm diagnosis, has also history of ovarian cyst. |

| Patient attended accident and emergency with difficulty in breathing, coughing green/brown sputum. Kept overnight for IV antibiotics. |

| UTI and sepsis, abdominal pain requiring laparoscopy lap negative IV antibiotics as inpatient discharged home on oral antibiotics in patient for 4 days FOLLOW-UP Abdominal pain – raised CRP, septic bundle commenced, inpatient for 4 days. Diagnostic laparoscopy or ovarian cyst. Antibiotics. Seen, feels recovered physically. |

| Admitted with increasing abdominal pain. Known right ovarian cyst and ectopic. Managed conservatively with analgesia. Diagnosed with urinary tract infection and treated with antibiotics. |

| Reattended with pain left iliac fossa pain. Repeat USS shows – free fluid, left ectopic and new right sided multicystic structure. hCG dropped and haemoglobin stable. Allowed home. |

| Rising hCG levels. Laparoscopy did not show any EP, intrauterine pregnancy of uncertain viability seen on USS. Review of USS – definitely no intrauterine pregnancy seen. Laparoscopy – no EP seen. Heterotopic pregnancy not ruled out yet. |

| Admitted to gynae with severe pain. Scanned. Ruptured ectopic. Emergency laparoscopy. Procedure actually confirmed ruptured ovarian cyst on opposite side. However, tubal pregnancy removed surgically at same time. Overnight stay on gynae ward. Discharged. |

Chapter 4 Discussion

This is the first randomised placebo-controlled clinical trial to evaluate the treatment of tubal EP with a combination of MTX and gefitinib. It conclusively demonstrates that adding oral gefitinib to standard medical treatment in women with a tubal EP does not reduce surgical intervention. Combination treatment may also cause symptoms, such as a rash or gastrointestinal upset.

Our preclinical and three previous single arm clinical studies suggested that the addition of gefitinib to standard medical treatment with MTX could have been a better medical treatment capable of resolving most EPs. 11–14 While we were aware of the potential limitations associated with our earlier non-randomised clinical studies, we believed that the use of a complimentary combination chemotherapeutic drug was a very reasonable approach and we proceeded to our phase III clinical trial.

Nonetheless, the robustness of our trial design, including our large sample size, blinding to treatment allocation, near complete capture of the primary outcome and high adherence rates, ensures internal validity and enables our findings to be interpreted with certainty. In addition, we minimised with respect to serum hCG concentrations, BMI and EP size: all factors that are potentially prognostic for the success of MTX treatment. While it is possible that the excess number of reported symptoms known to be associated with gefitinib, particularly the facial rash, could have led to unblinding in some participants, it is unlikely that the decision to perform surgery would have been influenced by anything other than clinical need. Furthermore, the CIs around our comparative estimate exclude a small relative reduction of 15% or more, so we can conclude that gefitinib is not clinically effective.

It is possible that our trial has failed due to the dose of gefitinib being too low, or due to poor drug penetration. ‘Precision dosing’, based on drug penetration, has been suggested to outcomes in cancer trials. 30 However, this approach would have required state-of-the-art techniques that are out with the scope of our study. 31–33 If poor drug penetration was the reason for our negative findings, it may mean that combination treatment with gefitinib and MTX may still prove useful for other placental-related disorders where drug penetration may be better, such as molar or extratubal pregnancies.

Our trial provides useful information for counselling patients and to support recommendations in guidelines for EP. Specifically, we show that women with EP (with a pretreatment hCG of 1000–5000 IU/l) treated with IM MTX alone take a median of 28 days (IQR 21.0–36.5 days) to resolve (when medical treatment is successful), require a second dose of MTX in 14% of cases (95% CI 9% to 20%), require surgery in 29% (95% CI 22% to 36%) of cases, return to normal menstruation after a median of 24 days (IQR 24.0–38.0 days), and are highly satisfied with their treatment.

In summary, our results show that the combination of gefitinib with MTX is not clinically effective for the treatment of tubal EP. The addition of gefitinib does not reduce subsequent surgical intervention and is associated with higher rates of reported symptoms than placebo.

Equality, diversity and inclusion

As this trial took place in a semi-emergency setting with restrictive inclusion criteria we were unable to target specific under-represented groups. However, we were open to recruitment across 74 sites in Scotland, England and Wales, some rural and some inner city, and the ethnic diversity of the PIs and research staff at these sites was broad. In addition, we had PIs ranging from experienced consultants to nurse practitioners, encouraging nurses to take on PI roles as the EPUs (where the recruitment was carried out) were often managed by nursing staff. Of the 328 women recruited to this trial 248 of these were White (76%); 38 were Asian (12%) and 21 were Black (6%).

Implications for practice

The key findings of GEM3 are clear: women with a tubal EP should not be offered combination of gefitinib and MTX because it is no more effective than treatment with MTX alone. However, our trial has generated high-quality evidence on the success rates of IM treatment with MTX – how long it takes for the EP to resolve and how many will need rescue surgery (failed medical treatment). These data will be immediately useful for patient counselling (to help them choose either surgery or medical management) and for inclusion in early pregnancy guidelines.

Recommendations for future research

In our opinion, no further research is required to evaluate the role of gefitinib in the management of women with tubal EPs. Questions that remain unaddressed relate to the use of combination treatment for other extrauterine and uterine EPs, such as caesarean scar pregnancies, or in the management of choriocarcinoma.

Acknowledgements

Contributions of authors

Catherine A Moakes (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-0473-0532) (Trial Statistician) performed the analyses for the trial, contributed to the interpretation of the trial and the drafting of the report.

Stephen Tong (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-2319-0586) (Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology) contributed to the design, delivery, analysis and interpretation of all components of GEM3, the first draft and overall editing of the final report.

Lee J Middleton (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-4621-1922) (Senior Statistician) contributed to the design of GEM3, oversaw the statistical analysis, contributed to the interpretation of the trial and the drafting of the report.

W Colin Duncan (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7170-5740) (Professor of Reproductive Medicine and Science) contributed to the design, delivery, analysis and interpretation of all components of GEM3, the first draft and overall editing of the final report.

Ben W Mol (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8337-550X) (Professor of Obstetrics and Gynaecology) contributed to the design, delivery, analysis and interpretation of all components of GEM3, the first draft and overall editing of the final report.

Lucy H R Whitaker (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-7678-6551) (NES/CSO Clinical Lecturer in Obstetrics and Gynaecology) contributed to the editing of the final report.

Davor Jurkovic (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-6487-5736) (Consultant Gynaecologist) contributed to the editing of the final report.

Arri Coomarasamy (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3261-9807) (Professor of Gynaecology) contributed to the editing of the final report.

Natalie Nunes (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-1801-6281) (Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist) contributed to the editing of the final report.

Tom Holland (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5727-0659) (Consultant Gynaecologist) contributed to the editing of the final report.

Fiona Clarke (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-0298-9601) (Consultant Obstetrician and Gynaecologist) contributed to the editing of the final report.

Lauren C Sutherland (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-5465-8586) (Trial Co-ordinator) was responsible for the day-to-day management, delivery of the trial, drafting the report and overall editing of the final report.

Ann M Doust (https://orcid.org/0000-0001-8726-7186) (Research Manager) contributed to the design of GEM3, was responsible for the day-to-day management and delivery of the trial, contributed to drafting the report and overall editing of the final report.

Jane P Daniels (https://orcid.org/0000-0003-3324-6771) (Professor of Clinical Trials) contributed to the design, delivery and interpretation of the trial and editing of the final report.

Andrew W Horne (https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9656-493X) (Professor of Gynaecology and Reproductive Sciences and Chief Investigator) contributed to the design, delivery, analysis and interpretation of all components of GEM3, the first draft and overall editing of the final report.

Members of the GEM3 Collaborative Group

Co-investigators

Stephen Tong, Co-investigator, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Ben Mol, Co-investigator, Monash University, Melbourne

Colin Duncan, Co-investigator, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Jane Daniels, Co-investigator, University of Nottingham, Nottingham

Professor Arri Coomarasamy, University of Birmingham, Birmingham

Mrs Alexandra Peace-Gadsby, Ectopic Pregnancy Trust

Lee J Middleton, University of Birmingham, Birmingham

Mr Davor Jurkovic, University College Hospital, London

Miss Cecilia Bottomley, Chelsea and Westminster Hospital, London

Professor Tom Bourne, Imperial College, London

Trial Management Group

Andrew W Horne (Chair), Chief Investigator, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Stephen Tong, Co-investigator, University of Melbourne, Melbourne, Australia

Jane Daniels, Co-investigator, University of Nottingham, Nottingham

Ben Mol, Co-investigator, Monash University, Melbourne

Colin Duncan, Co-investigator, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Catherine A Moakes, Statistician, University of Birmingham, Birmingham

Lee J Middleton, Senior Statistician, University of Birmingham, Birmingham

Ann M Doust, Research Manager, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Frances Collins, Trial/Lab Manager, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Lauren Sutherland, Trial Co-ordinator, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Clive Stubbs, Team Lead, Birmingham Clinical Trials Unit, University of Birmingham, Birmingham

Jordan Doust, Data manager, University of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Principal Investigators and recruiting sites

Sherif Saleh, Aberdeen Maternity Hospital, Aberdeen

Miriam Baumgarten, Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge

Ben Galea, Addenbrookes Hospital, Cambridge

Sinha Sanjay, Furness General Hospital, Barrow-in-Furness

Malar Raja, Basildon University Hospital, Basildon

Thangamma Katimada-Annaiah, Bedford Hospital, Bedford

Pratima Gupta, Heartlands Hospital, Birmingham

Justin Chu, Birmingham Women’s Hospital, Birmingham

Faye Rodger, Borders General Hospital, Melrose

Fiona Clarke, Burnley General Hospital, Burnley

Satya Duvvur, Queen’s Hospital, Burton-On-Trent

Monique Latibeaudiere, Cardiff Royal Infirmary, Cardiff

Natalie Nunes, West Middlesex Hospital, Isleworth

Victoria Finney, Countess of Chester Hospital, Chester

Janet Cresswell, Chesterfield Royal Hospital, Chesterfield

Feras Izzat, University Hospital Coventry, Coventry

Rebecca Thompson, Leighton Hospital, Crewe

Sonal Anderson, University Hospital Crosshouse, Kilmarnock

Fouzia Memon, Cumberland Infirmary, Cumberland

Jerry Oghoetouma, Darlington Memorial Hospital, Darlington

Gabriel Awadzi, Darent Valley Hospital, Dartford

Manju Sindhu, Doncaster Royal Infirmary, Doncaster

Binita Pande, Ninewells Hospital, Dundee

Velur Sindhu, University Hospital of Durham, Durham

Lucy Whitaker, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Mayank Madhra, Royal Infirmary of Edinburgh, Edinburgh

Sangeetha Devarajan, Epsom and St Helier Hospitals, Epsom

Jananki Putran, Princess Alexandra Hospital, Harlow

Shahzya Huda, Forth Valley Hospital, Larbert

Sridevi Sankharan, Frimley Park Hospital, Camberley

Chitra Kumar, Princess Royal Maternity Hospital, Glasgow

Kelly Bingham, Gloucestershire Royal Hospital, Gloucester

Shruti Mohan, Hillingdon Hospital, Hillingdon

Hema Nosib, Hinchingbrooke Hospital, Hinchingbrooke

Sandra Watson, Homerton Hospital, Homerton

Kate Stewart, Raigmore Hospital, Inverness

Jackie Ross, King’s College Hospital, London

Punukollu Durgadevi, Victoria Hospital, Fife

Penny Robshaw, Liverpool Women’s Hospital, Liverpool

Ursula Winters, St Mary’s Hospital, Manchester

Gautam Raje, Norfolk and Norwich University Hospital, Norwich

Shilpa Deb, The Queen’s Medical Centre, Nottingham

Rebecca McKay, Peterborough City Hospital, Peterborough

Joanne Page, Derriford Hospital, Plymouth

Krupa Madhvani, Poole Hospital, Poole

Tom Bourne, Queen Charlotte and Chelsea Hospital, London

Mona Sharma, Queen’s Hospital, Romford

Radwan Faraj, Rotherham General Hospital, Rotherham

Emma Kirk, Royal Free Hospital, London

Renee Behrens, Royal Hampshire County Hospital, Winchester

Gourab Misra, Royal Stoke Hospital, Stoke-On-Trent

Sujan Sen, Scunthorpe General Hospital, Scunthorpe

Jo Fletcher, Royal Hallamshire Hospital, Sheffield

Pinky Khatri, James Cook Hospital, South Tees

Umo Esen, South Tyneside District Hospital, South Tyneside

Sundararajah Raajkumar, Southend Hospital, Southend-On Sea

Susannah Hogg, Southmead Hospital, Bristol

Abigail Oliver, St Michael’s Hospital, Bristol

Ngozi Izuwah-Njoku, St Peter’s Hospital, Chertsey

Tom Holland, St Thomas’ Hospital, London

Sucheta Iyengar, Stoke Mandeville Hospital, Aylesbury

Amna Ahmed, Sunderland Royal Hospital, Sunderland

Catherine Wykes, East Surrey Hospital, Redhill

Millicent Anim-Somuah, Tameside Hospital, Tameside

Davor Jurkovic, University College Hospital, London

James Davis, Manor Hospital, Walsall

Vinita Raheja, Wansbeck General Hospital, Wansbeck

Helena Nik, Warrington Hospital, Warrington

Rita Arya, Warrington Hospital, Warrington

Suganya Sukumaran, Warwick Hospital, Warwick

Barkha Sinha, West Suffolk Hospital, Bury St Edmunds

Sandhya Rao, Whiston Hospital, Whiston

Rajalakshmi Rajagopal, University Hospital Wishaw, Wishaw

Sakunthala Tirumuru, New Cross Hospital, Wolverhampton

Mamta Pathak, Worcestershire Royal Hospital, Worcester

Geeta Kumar, Wrexham Maelor Hospital, Wrexham

Sponsor

ACCORD – NHS Lothian and University of Edinburgh

Monitoring and Audit team led by Elizabeth Craig and Lorn MacKenzie

Ethics statement

The trial was approved by Scotland A REC committee (ref: 16/SS/0014) on 29 February 2016.

Data-sharing statement

All data requests should be submitted to the corresponding author for consideration. Access to anonymised data may be granted following review.

Patient data

This work uses data provided by patients and collected by the NHS as part of their care and support. Using patient data is vital to improve health and care for everyone. There is huge potential to make better use of information from people’s patient records, to understand more about disease, develop new treatments, monitor safety and plan NHS services. Patient data should be kept safe and secure, to protect everyone’s privacy, and it is important that there are safeguards to make sure that it is stored and used responsibly. Everyone should be able to find out about how patient data is used. #datasaveslives. You can find out more about the background to this citation here: https://understandingpatientdata.org.uk/data-citation.

Disclaimers

This report presents independent research. The views and opinions expressed by authors in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the NHS, the NIHR, the MRC, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care. If there are verbatim quotations included in this publication the views and opinions expressed by the interviewees are those of the interviewees and do not necessarily reflect those of the authors, those of the NHS, the NIHR, the EME programme or the Department of Health and Social Care.

References

List of abbreviations

- AE

- adverse event

- BMI

- body mass index

- CI

- confidence interval

- CONSORT

- Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials

- DMEC

- Data Monitoring and Ethics Committee

- EGFR

- epidermal growth factor receptor

- EP

- ectopic pregnancy

- EPT

- Ectopic Pregnancy Trust

- EPU

- Early Pregnancy Unit

- EudraCT

- European Clinical Trials Database

- hCG

- human chorionic gonadotropin

- HR

- hazard ratio

- ILD

- interstitial lung disease

- IM

- intramuscular

- IMP

- investigational medicinal product

- IQR

- interquartile range

- IRR

- incidence rate ratio

- ISRCTN

- International Standard Randomised Controlled Trial Number

- ITT

- intention to treat

- MedDRA

- Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities

- MTX

- methotrexate

- NHS

- National Health Service

- OR

- odds ratio

- PI

- Principal Investigator

- RD

- risk difference

- RR

- risk ratio

- SAE

- serious adverse event

- SAP

- Statistical Analysis Plan

- SUSAR

- suspected unexpected serious adverse reaction

- TSC

- Trial Steering Committee

- USS

- ultrasound scan