Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/01/24. The contractual start date was in September 2017. The final report began editorial review in August 2021 and was accepted for publication in February 2022. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Hassiotis et al. This work was produced by Hassiotis et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Hassiotis et al.

Chapter 1 Background and study overview

Challenging behaviour and outcomes in adults with intellectual disabilities

Adults with intellectual disabilities (also known as learning disabilities in the UK) constitute around 1% of the population. 1 Substantial research shows that these adults have higher rates of mental ill-health,2 and many display challenging behaviour such as aggression towards others, property destruction and self-injury. 3–7 A whole-population epidemiological survey found that ≈ 18% of adults with intellectual disabilities living in the community present with new-onset or relapse of serious challenging behaviour. 8

Challenging behaviour may be the precursor to abuse and/or the implementation of restrictive practices by health-care staff looking after adults with intellectual disabilities. 9 The most recent examples of institutional abuse of adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour came to light in 2011 at Winterbourne View hospital,10 followed by Whorlton Hall in 2018. 11 In England, the Transforming Care programme12 was published shortly after as a national response to the Winterbourne View scandal to improve the lives of adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour by setting transparent monitoring procedures, conducting regular service audits, employing qualified health-care professionals and promoting advocacy. The interim government report published following the scandal emphasised that the quality of lives of adults with intellectual disabilities and their families improved following deinstitutionalisation. 12 However, the Learning Disability Census Report13 indicated minimal change over the years 2013–15 in relation to the number of inpatient admissions in England, length of inpatient stay, out-of-area placements and use of antipsychotic medication to manage challenging behaviour. This confirmed concerns about the pace of progress in the care provided for this population by community intellectual disability services (CIDSs) across the country. Similarly, data from inpatient services for adults with intellectual disabilities and/or autism showed a very gradual decrease in the number of admissions over time between March 2015 (admissions, n = 2895) and September 2020 (admissions, n = 2060). 14

Data collected by the Department of Health and Social Care indicated that 24,000 adults with intellectual disabilities would be at risk of being admitted to assessment and treatment units, which are often hundreds of miles away from their home, because of challenging behaviour. 6,15,16 These studies indicate that younger male adults with intellectual disabilities and history of previous admissions appear to be at an increased risk of re-admission, such that they should be a population of focus for intervention. 17 Previous concerns about the overprescription of medication were confirmed by a recent study that reported increased figures of psychotropic drug prescription by general practitioners (GPs) to adults with intellectual disabilities. 18,19 The ‘Stopping The Over-Medication of People with an intellectual disability, autism or both’ (STOMP) programme20 was launched by NHS England in 2016 to support adults with neurodevelopmental conditions (including intellectual disabilities) remain well and have a good quality of life. A recent study published by Public Health England reported changes that were in the desired direction over a 7-year period (January 2010–December 2017). 21 The study findings revealed that GPs’ prescription of psychotropic medication to adults with intellectual disabilities to manage challenging behaviour appeared to have decreased since the launch of the STOMP programme in June 2016,20 but it was too early to attribute any observations in prescribing trends to the programme. 21

Out-of-area prolonged hospitalisations and overprescription of psychotropic medication to adults with intellectual disabilities remain an excessive financial cost to the NHS, ranging from £96,000 to £222,000 per person annually, because of the need for more intensive support. 3,13,22 Failure to effectively address a display of challenging behaviour before it reaches a crisis point causes significant distress and burden to families and the consequent breakdown of placements. 23,24 Cumulative studies in Canada indicated that adults with intellectual disabilities were more likely to visit the emergency department,25 return to the emergency department within 30 days of discharge,26 have delayed discharge, be in long-term inpatient care and die prematurely. 27

The concept of intensive support teams in the UK

Specialist intensive services for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour appear to have operated internationally since 1985. 28 From as early as 1993, published literature from the UK has advocated for intensive support teams (ISTs) to support the effective management of challenging behaviour within the community and to prevent inpatient admissions. 29–31 In 1993, 65 specialist teams were operating in England and Wales. 32 ISTs were developed as specialist services that were expected to support people with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour in their local communities following deinstitutionalisation. 32 A number of terms are used to describe ISTs, including ‘peripatetic teams’, ‘assertive outreach teams’ and ‘specialist behaviour teams’. 29,33

A recent survey29 identified 46 peripatetic services for people with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour in England (teams, n = 40), Scotland (teams, n = 4), Wales (teams, n = 1) and Northern Ireland (team, n = 1). These teams aim to help carers manage such behaviours by delivering a range of multidisciplinary specialist support and interventions [e.g. positive behaviour support (PBS), positive psychology, behavioural, eclectic and proactive work) that aim to improve independence skills and mental and physical ill health; to reduce other risks; and, more recently, for those who are inpatients, to prompt timely discharge planning. 29 ISTs are seen as having a significant role in recovery and, therefore, as leading to a better quality of life and a reduction in the frequency and severity of further episodes of crisis.

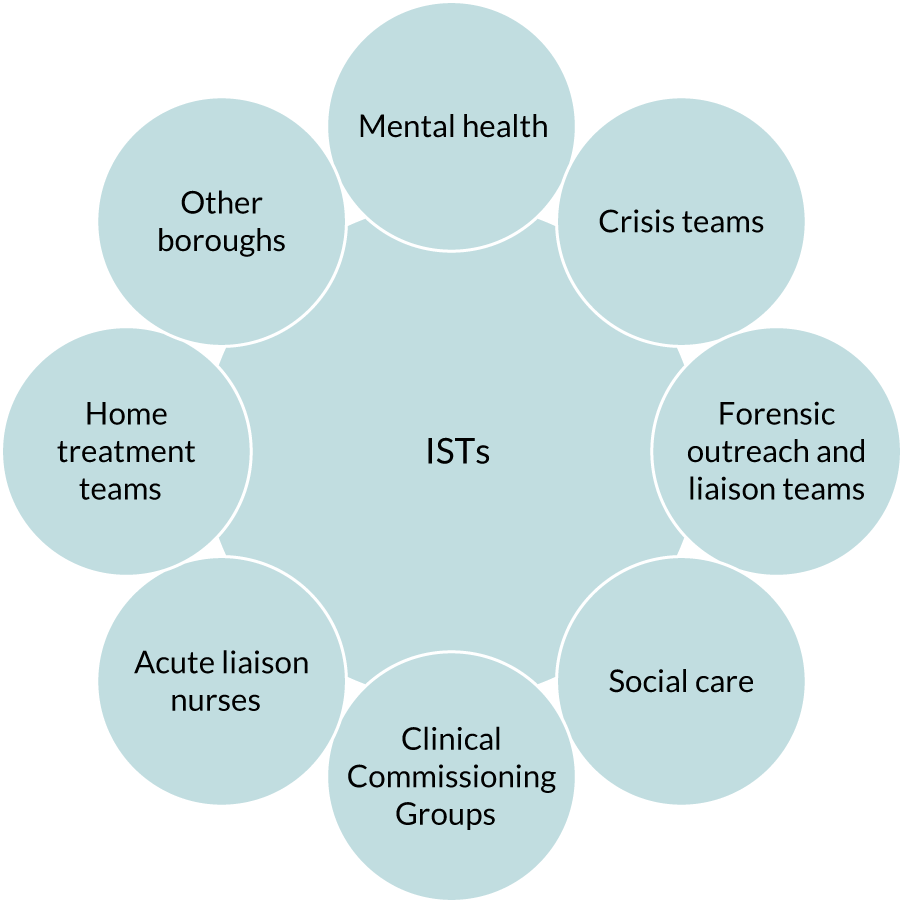

Widespread concerns about the mental health, social and financial outcomes of inadequately supporting adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour over the years were highlighted by NHS England in 2015 and 2017. 34,35 In Transforming Care: a National Response to Winterbourne View Hospital,12 ISTs were recommended to provide specialist, proactive and responsive care, aimed at avoiding unnecessary inpatient admissions, supporting adults within the community or reducing inpatient length of stay. In the main, ISTs are community-based, specialist, multidisciplinary (e.g. psychology, nursing, psychiatry) health-care teams that deliver interventions such as PBS or other support 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (24/7), when necessary, as part of their operation. 34,35

The announcement of the national ‘Building the Right Support’34 plan aimed to complement the previous policy initiative of 201212 by developing more community services to reduce the number of inpatient admissions for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour. 34 NHS England funded six services to act as pilot sites and reinvest any savings in enhancing their community services, including ISTs. In 2017, a total of 48 Transforming Care Partnerships were established in different areas of England to improve the quality of care and quality of life of adults with intellectual disabilities; they aimed to adapt their services in a way that would make a real difference to the lives of adults with intellectual disabilities. 35 Since 2015, the establishment of care and treatment reviews (CTRs) contributed to a sharp reduction in the number of unnecessary inpatient admissions. Data from inpatient services for adults with intellectual disabilities and/or autism showed that this resulted in a 30% decrease in the number of admissions between March 2015 (n = 2895) and September 2020 (n = 2060). 14 Similarly, > 70% (403/552) of CTRs for adults with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour were not admitted to hospital in 2016–17. 36

The Systemic, Therapeutic, Assessment, Resources, and Treatment (START) programme model was identified as best practice by the National Academy of Sciences Institute of Medicine in the USA. 37 It provides community-based, person-centred crisis intervention 24/7 for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour; this is delivered by a multidisciplinary team that collects outcome measures routinely and develops partnerships with local service providers. 38,39 Non-randomised research studies emphasised that adults with intellectual disabilities who received support from the intensive START clinical team reported less challenging behaviour, and fewer psychiatric emergency department visits and hospitalisations at 12 months. 38,39 Although the data suggest that the START programme has the potential to improve outcomes for adults with intellectual disabilities in crisis, a randomised controlled trial is yet to test if the START programme is effective for adults with intellectual disabilities who also experience a behavioural or mental health issue, especially as such issues often coexist with physical health comorbidities.

Different models of intensive support teams in the NHS

There is currently little evidence regarding the preferred IST model to meet the complex needs and challenging behaviour of adults with intellectual disabilities in the community. Previous research has demonstrated the positive contribution of standalone specialist behaviour support compared with standard treatment for adults with intellectual disabilities to improve the presentation of challenging behaviour over time (e.g. over 3 and 6 months). 40 On the other hand, Inchley-Mort et al. 41 reported that, at 6 and 12 months, the challenging behaviour of adults with intellectual disabilities who received standalone specialist behaviour support improved compared with the behaviour of those who received usual care from professionals based within a CIDS who were trained to deliver behavioural interventions.

Although there may be a rationale for standalone ISTs,40 there is currently no substantial evidence on long-term outcomes. This has led to scepticism about IST provision and concerns that devoting a large number of resources to specialist services will detract from offering good-quality care universally, especially as emerging evidence suggests that alternatives (e.g. embedded teams) may also be effective. 41 Furthermore, adults with intellectual disabilities and their carers may face disruption and discontinuity in care due to frequent changes in service provision and they may be dissatisfied with what they perceive as the less ‘expert’ service provided by CIDSs. 42 A pilot study found that placing IST staff within a CIDS for 6 months increased staff confidence and understanding of working with adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour. 43 In addition, the findings of the service redesign pilot project reported that the CIDS team described the support from IST colleagues as beneficial to improving clinical outcomes for adults with intellectual disabilities, enhancing the IST’s visibility and providing clarity on the existing resources to manage challenging behaviour. 43

The national plan aspires to develop better community services for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour (and/or other complex needs) to reflect the diversity of this population. 34 The suggested service redesign focused on presenting adults with intellectual disabilities as living satisfying, valued lives and being treated with dignity and respect. 34 However, it does not distinguish between mental health and challenging behaviour functions, nor does it give any guidance on the duration of engagement with the individual with intellectual disability. This contrasts with the high-fidelity models that have been in operation in adult mental health, specifically home treatment teams, crisis teams and assertive outreach services. As a result, there is confusion about whether ISTs should follow the principles of operation found in mental health crisis resolution and home treatment teams or assertive case treatment teams. Clarification on these points is particularly important as it has direct consequences on how adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour can be best supported in the short- and longer-term. Therefore, despite the roll-out of the Transforming Care programme,44 to the best of our knowledge, there has not been a systematic evaluation of ISTs in terms of characterisation, patient outcomes and relationships with other services in the areas in which they operate. Other potential challenges in establishing ISTs are the lack of a mandate to develop such services, the lack of specification of the approach to follow and the multiple configurations of CIDSs across England and other UK countries.

The literature from other populations (e.g. dementia care45) suggests that home treatment teams appear to offer effective management of crises and to reduce the number of admissions. Wheeler et al. 46 reported limited evidence of the clinical impact of crisis teams on hospital admissions in adults with acute mental health problems, but adults with acute mental health problems, carers and health-care professionals emphasised that accessibility, continuity of care, time to talk, practical help and treatment at home were valuable features of good practice by crisis resolution teams in adult mental health. Thus far, there has been limited reporting on stakeholder experiences of ISTs; however, two studies showed that adults with intellectual disabilities, family carers and care home (paid) carers find the involvement of IST staff and the frequency of contact helpful. 42,47

In addition, although the Building the Right Support34 plan was much needed, it was developed to improve care for adults with intellectual disabilities based on multiple-stakeholder consensus (including adults with intellectual disabilities, their families, service providers and clinicians), rather than on evidence-based information and high-quality research. However, NHS commissioners require robust information on the most efficient service model for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour to fund appropriate services. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guideline 11 on challenging behaviour3 reports the state of evidence thus:

It is widely recognised that locally accessible care settings could be beneficial and could reduce costs but there is no strong empirical evidence to support this.

NICE. 3

In short, an inquiry into ISTs’ characteristics and their ability to deliver positive outcomes to foster long-term investment in them is an important and pressing clinical question. In line with NHS England guidance15 for locally and effectively managing adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour, this work will provide commissioners and clinicians with the evidence they need to deliver high-quality care to an underserved population. The project maps onto principles 7 (‘I can access specialist health and social care support in the community’) and 8 (‘If I need it, I get support to stay out of trouble’) of the plan outlined in the service model for commissioners of health and social care services in England. 34 This project is also in accordance with The NHS Long Term Plan,48 which aims to ‘improve community-based support so that adults can lead lives of their choosing in homes not hospitals; further reducing our reliance on specialist hospitals’ (Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0. URL: www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/3/).

Study aims and objectives

The overall aim of this study was to systematically examine the clinical and cost characteristics of different IST care models in England to ensure that ISTs are appropriately funded and implemented within the NHS.

The study objectives were to:

-

describe the geographical distribution and provision of IST services in England

-

create a typology of IST service operation in England

-

compare the clinical effectiveness of different IST models for service user outcomes, including challenging behaviour, mental health status, risk, satisfaction with care, quality of life and hospital admissions

-

estimate the costs of different IST models and investigate cost-effectiveness

-

understand how ISTs impact the lives of adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour, their families and the local services

-

generate evidence to inform and support decision-making on commissioning ISTs for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour.

Our key research questions were:

-

What models of IST are currently in operation?

-

Which models perform better in achieving positive outcomes for service users?

-

What are the costs and cost-effectiveness of the different IST models and how do they compare?

-

How does the local service context support or hinder these processes?

-

What are service users’ and family carers’ experiences of ISTs and do they differ between models?

-

What are the views of multiple stakeholders on the strengths and limitations of ISTs and the processes that support or hinder their functioning?

Study design

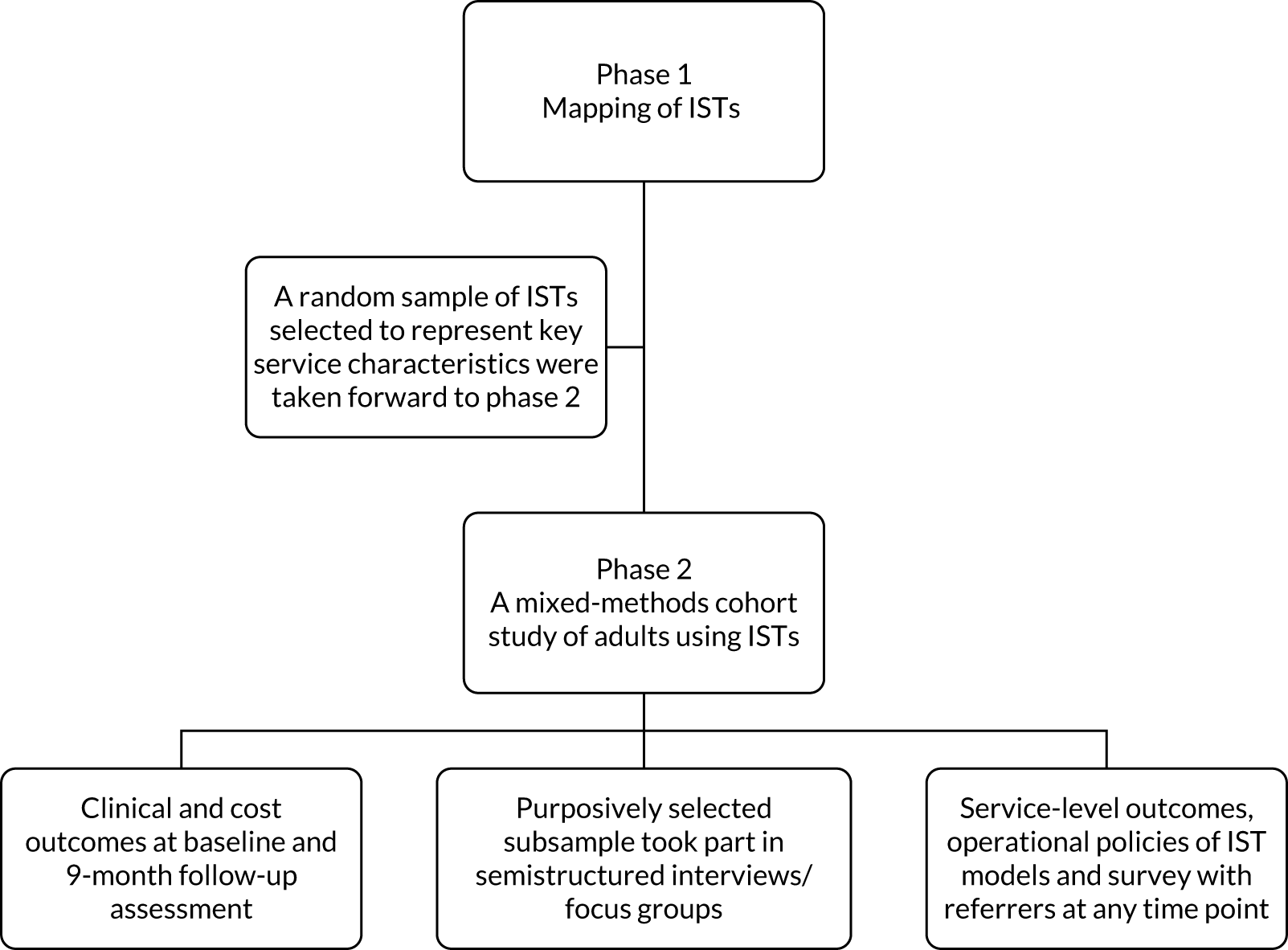

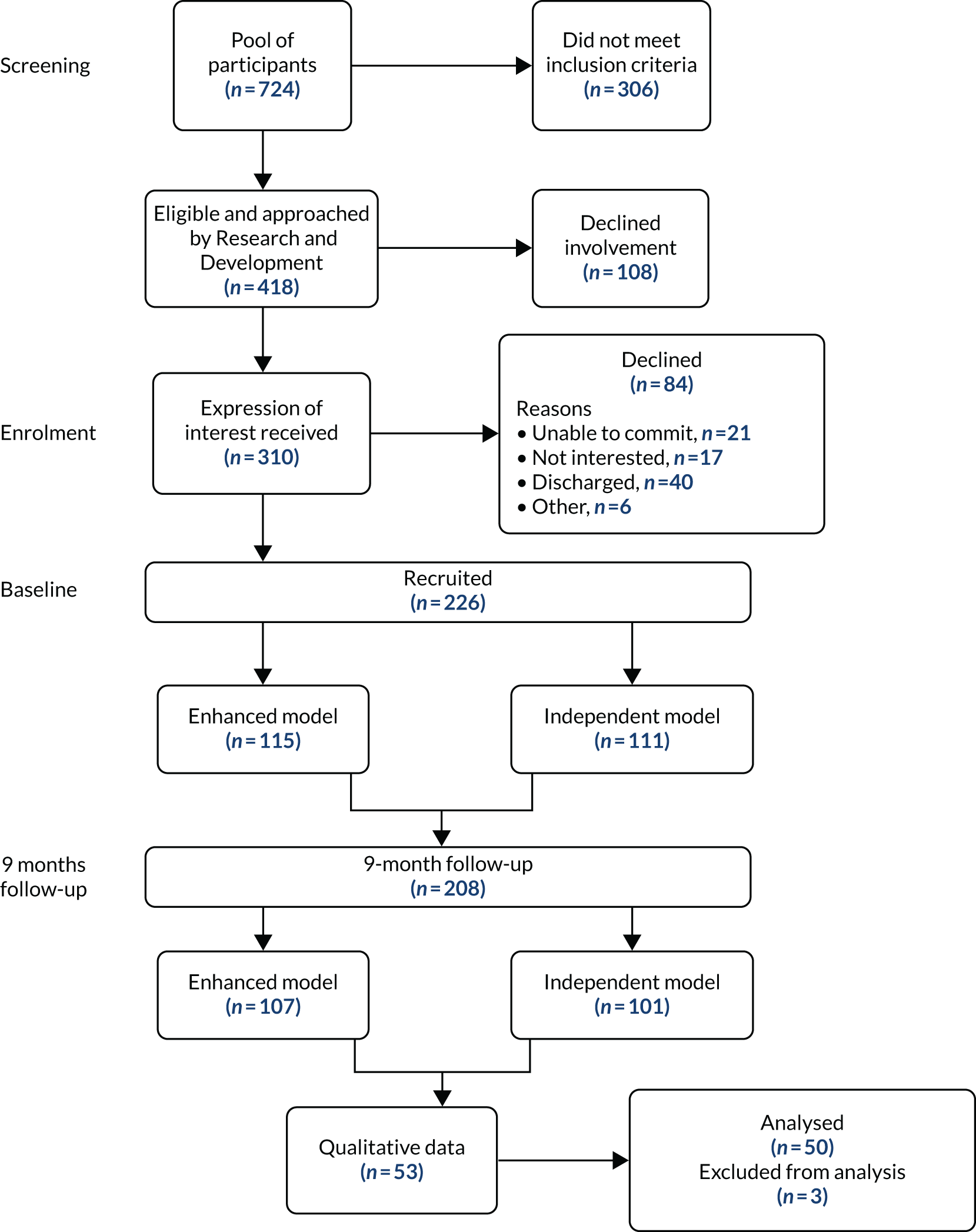

A two-phase mixed-methods design was implemented to address these research questions. Figure 1 illustrates the overall design and flow of the study.

FIGURE 1.

Study overview.

Phase 1 was a quantitative study that identified IST services in the 48 Transforming Care Partnerships in England, described their service characteristics and created a typology of different IST models.

Phase 2 was a mixed-methods cohort study that conducted a survey of health-care professionals’ experiences of the referral process to ISTs and investigated the:

-

clinical and cost outcomes of the identified IST models at 9 months from baseline

-

experiences of multiple stakeholders of ISTs

-

service-level outcomes and operational policies of the identified IST models.

Ethics approval

The Health Research Authority reviewed and approved the study and all amendments (substantial and non-substantial). The Research Ethics Committee reference number is 18/LO/0890.

Amendments to study protocol

The following changes were made to the original study protocol:

-

substantial amendments –

-

revised study exclusion criteria for phase 2

-

revised sample size and power calculations

-

additional information about qualitative interview transcriptions

-

number of teams changed from 16 to as many as needed to reach recruitment target; data collection for people who refer to ISTs extended to include self-completed survey (e-mail/online/paper or combination)

-

topic guide for adults with intellectual disabilities and relevant study documents [e.g. participant information sheets (PISs) and informed consent forms (ICFs)] updated to reflect staff changes.

-

-

non-substantial amendments –

-

addition of new research sites

-

addition of new research sites and revised GP letter

-

addition of new research site

-

withdrawal of research site and addition of new research site

-

change of local collaborator in one research site

-

addition of new research sites

-

updated study documents to reflect staff changes, use of digital platforms and telephone call to respond to the COVID-19 pandemic

-

costed study extension.

-

Deviation from the study protocol

The protocol for the study has been published. 49 The study diverged from the Health Research Authority-approved protocol to complete the qualitative evaluation of IST models, recruiting from 10 ISTs instead of seven ‘case study’ sites. The aim of conducting interviews in seven ‘case study’ sites was to link the perspectives of stakeholders to specific service context. Owing to problems recruiting from these seven sites during the COVID-19 pandemic, we extended our efforts to other sites with similar service characteristics.

Adverse events

No adverse events were reported to the study.

Data management

All aspects of data management of the study complied with the UK’s Data Protection Act 1998,50 good clinical practice and the General Data Protection Regulation. 51 Data from phase 1 were collected electronically using online survey software (Opinio; ObjectPlanet AS, Oslo, Norway) or on paper forms that did not contain identifiable information and were marked with an anonymised participant identification number only. The paper files from this project were stored on secure University College London (UCL) premises in a locked cupboard accessible to members of the UCL research team only. We followed all aspects of data protection as per research governance and social care and NHS policies. Any data stored at UCL was registered for data protection (Z6364106/2018/04/09) and participant records were anonymised. Identifiable data that constitutes the identification key to link consent forms to case report forms and audio-recordings of consent obtained by telephone/video were stored in the UCL secure platform Data Safe Haven.

Patient and public involvement

In the course of preparing the application, a number of consultations were carried out with two adults with intellectual disabilities and five family carers and paid carers of adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour to select and discuss the topic of the funding proposal. They were unanimous in their praise for the accessibility and communication that they had with the IST and they stated that it should be a resource for all services for people with intellectual disabilities who are likely to display challenging behaviour. They emphasised the support that the IST provided in the community, at the person’s home and to the caregivers. They also talked about other aspects of the team, such as the teaching and training functions, that had been useful to them.

We were able to speak with two service users who had direct experience of working with the team; they mentioned that the professionals had helped them with ‘managing their anger’ and that they were very fond of them as they ‘visited often and could talk to staff’. All were supportive of the application because they thought that it was important to find out more about the teams and whether or not commissioners may be more interested in funding ISTs ‘if they know more about the benefits’. The feedback received from the adults with intellectual disabilities and the family carers was overwhelmingly positive and ISTs were seen as an important resource for reducing the number of admissions and maintaining these adults in the community.

In addition, a co-applicant gave a presentation on IST at an educational meeting for trainees and consultants in intellectual disability. The psychiatric audience considered issues such as evidence, the wider context of the teams and the need to have robust data on what works best, as they recognised that we need to improve the existing evidence base and value for money for CIDS practice.

Post award, we liaised with two London-based service user groups to decide the involvement of service users in the project. We enlisted interested adults who wished to be members of the Project Advisory Group. We conducted interviews to appoint people with a range of different experiences and carried out a 3-hour training session in research skills and tasks over the duration of the project using easy-read formats based on National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) guidance. 52 The Project Advisory Group had two facilitators in case of illness or leave. We also sought input from family carers through local carer groups in co-applicants’ sites.

The Family Carer Advisory Group included four family carers recruited through the Challenging Behaviour Foundation (Chatham, UK), an independent charity of experts by experience.

The specific tasks of the service user and family carer advisors’ input to the Project Advisory Group were to (1) develop participant information resources and pilot instruments and topic guides; (2) contribute to the interpretation of the findings; (3) have an overview of the study processes, advise on recruitment and contact with potential participants and carers; and (4) report and disseminate the research findings.

Meetings with both expert-by-experience groups took place every 3 months. The Project Advisory Group remained actively engaged in all of the tasks listed above. In particular, their views during the qualitative coding and analysis of transcripts directed the final presentation of study findings. When physical or virtual presence in meetings was challenging, a telephone call was arranged to discuss the study progress and record each member’s comment.

Last, there was service user and family caregiver representation in the Study Steering Committee that oversaw the study. Thus, the interests of all parties and the views of those involved have been fully represented in the conduct of the study.

Chapter 2 Identification of intensive support models in England

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Hassiotis et al. 53 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Introduction

Phase 1 of the study was required to proceed to the model evaluation phase and comprised a national survey that aimed to investigate the operation of ISTs in England.

The key objectives of the survey were to:

-

examine the geographical distribution and characteristics of ISTs in England

-

develop a typology of IST service models

-

describe the IST model profiles and contextual characteristics.

The phase 1 study has been published elsewhere. 53

Methods

A screening questionnaire (see additional files; www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/160124/#/documentation; accessed 3 March 2022) was initially developed to identify the geographical distribution of ISTs, with reference to national guidance;30 it was sent to all specialist CIDSs in England. CIDSs were identified through multiple routes, including Clinical Commissioning Groups, online searches, previous research and the list of 48 Transforming Care Partnerships. The screening questionnaire included a list of the terms that are used to describe specialist intensive care in England (see Chapter 1).

The responses to the screening questionnaire were reviewed by members of the Project Management Group (PMG) to check whether or not the identified intensive teams fulfilled the IST criteria and should be contacted for the IST-specific survey. Any discrepancies regarding team assignment were resolved by discussion with all PMG members. The criteria were broad: (1) identification of IST function separate from CIDSs, (2) a referral pathway for challenging behaviour and/or (3) staff trained to deliver interventions for challenging behaviour.

The managers of all ISTs identified from the screening survey were invited to take part, and those who agreed to take part were sent a detailed online questionnaire using the Opinio platform (see additional files; www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/160124/#/documentation; accessed 3 March 2022). The questionnaire was divided into 13 sections, including 62 open- and close-ended questions that covered information about service type and location, caseload and referral numbers, opening hours, response target times, staffing, management and funding, services provided by the IST, service user characteristics, use of outcome measures, interventions and assessments, and the intensity of support, as well as concluding questions. There were free-text questions that addressed the model and philosophy of IST care, suggested changes to the service, challenges faced by the IST and priorities for improving the service.

A number of strategies were adopted to achieve a high completion and return rate, such as having both an online and a hard-copy version of the survey, regular e-mail prompts and the option of completing the questionnaire by telephone. The survey response data were managed using the Opinio software.

Data analysis

The IST characteristics and geographical location of ISTs were summarised using descriptive statistics [i.e. count and percentage for categorical measures or median and interquartile ranges (IQRs) for continuous outcomes which were not normally distributed].

A hierarchical cluster analysis was performed using six grouping variables to develop a typology of ISTs and classify services on prespecified variables into a number of groups, with similar services being placed in the same group. These were:

-

setting of service

-

team composition

-

caseload

-

operating hours

-

type of referral permitted

-

use of outcome measures.

All factors were defined as binary measures for each of these variables. IST staff were grouped into professional categories such as nursing psychology, psychiatry, social work and other. The total number of health-care professionals was calculated for each team. Teams were defined as multiprofessional if they consisted of two or more professional staff categories. The caseload per team member was calculated as the number of service users per full-time equivalent (FTE) member of staff. A large caseload was defined as 2.5 or more clients per FTE staff member (excluding trainees), which is in line with guidance from the UK Department of Health and Social Care about mental health crisis teams. 54

The operating hours of ISTs were defined as extended hours of operation if they offered services outside working hours (09.00–17.00) on weekdays or offered any weekend services. Those ISTs that accepted referrals directly from service users eligible to receive specialist intellectual disability services, or from their family carers and paid carers, were defined as allowing self-referrals to their service. On the other hand, there were ISTs that accepted referrals exclusively from services such as GP services, mental health services or police or third-sector organisations, and not self-referrals. The remaining two grouping factors, setting (e.g. embedded within CIDSs or independent service separate from CIDSs) and whether or not the service used outcome measures, were based on direct responses to the relevant questions in the survey.

The six grouping variables were used to perform a hierarchical cluster analysis employing Ward’s method,55 with squared Euclidean distance as the dissimilarity measure. The accumulation of individual services into larger clusters was illustrated with a dendrogram. The dendrogram was carefully reviewed, taking into consideration the dissimilarity of measures for different clusters, a visual inspection of the dendrogram and a discussion about the clinical validity of the proposed models with the co-applicant experts. All analyses were carried out using Stata/IC, version 14.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA).

The qualitative data from free-text responses were analysed thematically. 56 Data were extracted into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft, Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet to organise responses to each question into basic topic- and opinion-based themes. Two researchers independently conducted the initial coding and analysis under the supervision of a qualitative expert to ensure clarity and consistency among findings. Preliminary outputs were reviewed by all members of the research team.

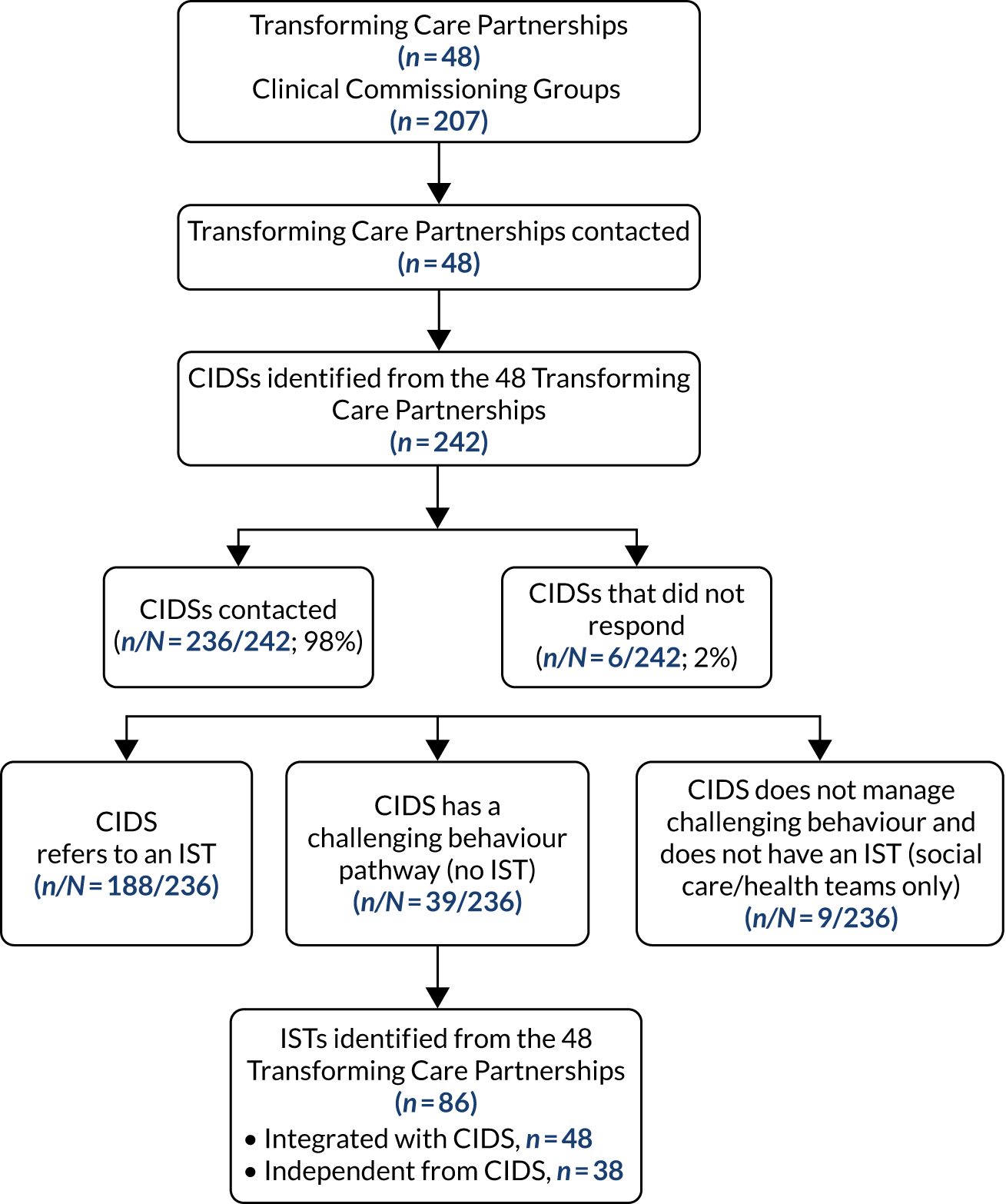

Results

Two-hundred and thirty-six out of 242 (98%) CIDSs completed and returned the screening questionnaire to identify ISTs. Of those, 188 CIDSs declared that they referred to 80 ISTs; the managers of these ISTs were sent a web link or hard copy of the detailed survey (Figure 2). In total, 73 (91%) IST managers returned their questionnaires.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of the identification of ISTs during the screening survey with CIDSs. Reproduced with permission from Hassiotis et al. 53 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Service characteristics of all intensive support teams

The main IST service domains are presented below.

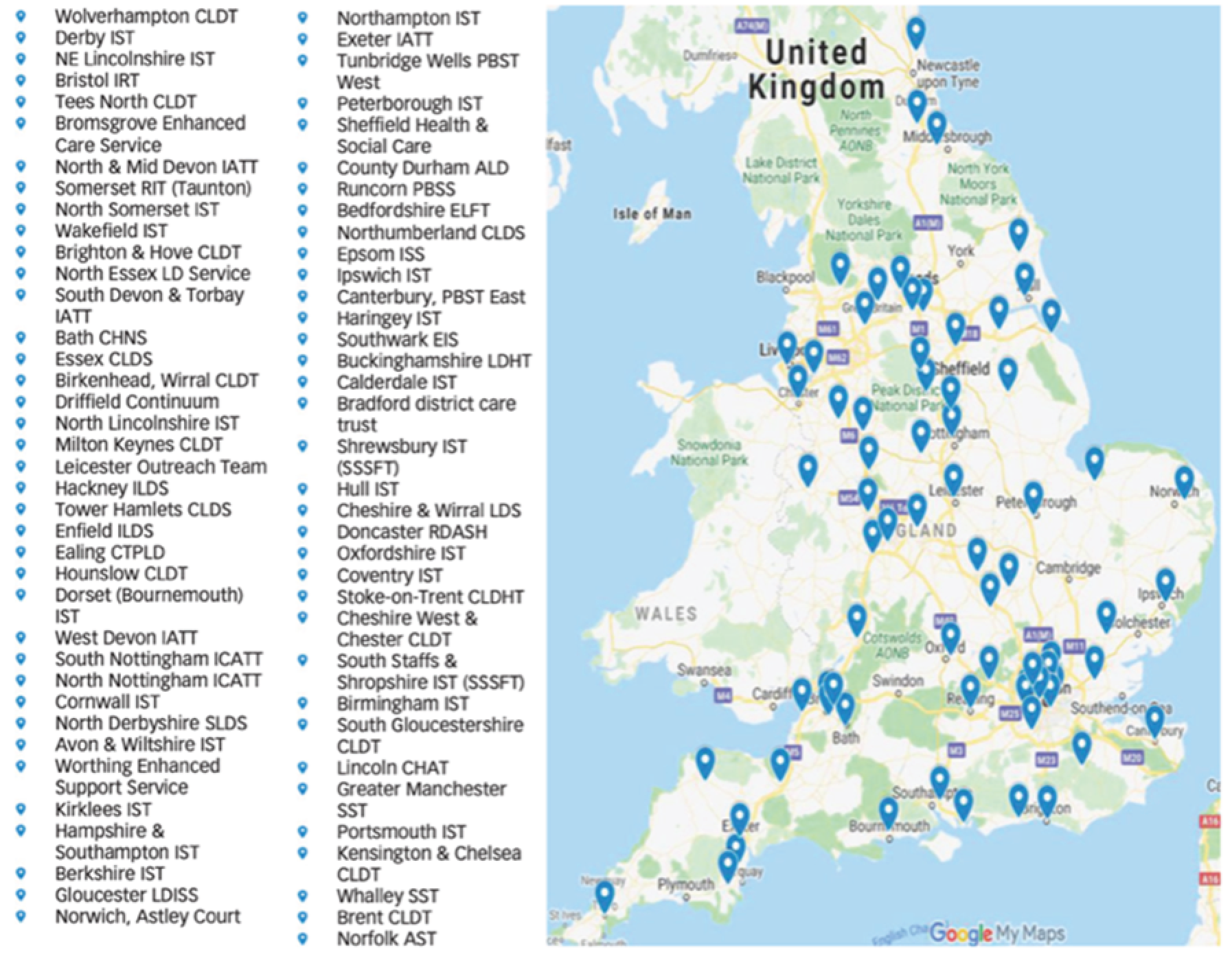

Service location and setting

The ISTs was equally distributed geographically throughout Northern England, the Midlands and Eastern England, and Southern England (Figure 3). The majority of the ISTs were funded by the NHS, although the lead organisation may have differed by area, including services that were funded by the local authority. Very few ISTs were part of social enterprises. Social enterprises are private businesses (usually registered as charities) that use their surplus money from selling/trading goods and/or providing services to reinvest in their services. They are autonomous from the NHS and financially viable, although they are considered part of the NHS by the public.

FIGURE 3.

Geographical location map of ISTs. ALD, Adult Learning Disability; AST, Adult Support Team; CHAT, Community Health Assessment Team; CHNS, Complex Health Needs Service; CLDHT, Community Learning Disability Health Team; CLDS, Community Learning Disability Service; CTPLD, Community Team for Adults with Learning Disabilities; CTPLS, Community Team for People with Learning Disabilities; EIS, Early Intervention Service; ELFT, East London Foundation Trust; IATT, Intensive Assessment and Treatment Team; ICATT, Intensive Community Assessment and Treatment Team; ILDS, Intensive Learning Disability Service; IRT, Intensive Response Team; ISS, Intensive Support Service; LD, Learning Disability; LDHT, Learning Disabilities Health Team; LDISS, Learning Disability Intensive Support Service; LDS, Learning Disability Service; NE, North East; PBSS, Positive Behaviour Support Service; PBST, Positive Behaviour Support Team; RDASH, Rotherham Doncaster and South Humber; RIT, Rapid Intervention Team; SLDS, Specialist Learning Disability Service; SSSFT, South Staffordshire and Shropshire Foundation Trust; SST, Specialist Support Team. Map data © 2019 Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). Reproduced from Hassiotis et al. 53 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Interventions used

Intensive support teams offer a range of interventions, including PBS, psychoeducation and other psychosocial interventions. A detailed summary of all of the key IST characteristics is shown in Table 1. 53

| Characteristic | ISTs (N = 73), n (%) |

|---|---|

| Location and setting | |

| Region | |

| Northern England | 19 (26) |

| Midlands and Eastern England | 22 (30) |

| Southern England | 23 (32) |

| London | 9 (12) |

| Setting | |

| Mainly funded by NHS (Clinical Commissioning Groups) | 67 (92) |

| Mixed funding, including from local authority | 20 (27) |

| In social enterprise | 3 (4) |

| Standalone service | 25 (34) |

| Length of time in operation (months), median (IQR) | 48 (24–96) |

| Service users | |

| Size of current caseload, median (IQR) | 25 (15–50) |

| Number of service users on at-risk register, median (IQR) | 6 (2–15) |

| Average visit duration | |

| 30–60 minutes | 25 (35) |

| 60–120 minutes | 43 (60) |

| > 120 minutes | 4 (6) |

| Extended working hours | 48 (66) |

| IST operates a duty/crisis line | 38 (52) |

| Outcome measures used | 55 (75) |

| Staffing, training and skills | |

| Multiprofessional staff team | 65 (89) |

| Intellectual (learning) disability nurses | 62 (85) |

| Clinical psychologists | 57 (78) |

| Speech and language therapists | 38 (52) |

| Occupational therapists | 33 (45) |

| Psychiatrists | 31 (42) |

| Social workers | 59 (81) |

| Trainee staff (e.g. student nurses, trainee associate practitioners) | 38 (52) |

| One or more team members trained as an approved mental health practitioner | 6 (8) |

| Perceived need for additional training or skills (e.g. additional professional roles or additional skills such as intervention and prevention strategies) | 50 (68) |

| Eligibility and referrals | |

| Lower age limit | |

| IST accepts adults only (people aged ≥ 18 years) | 59 (81) |

| IST accepts young people (aged 14–17 years) | 12 (16) |

| No lower age limit | 2 (3) |

| Upper age limit | |

| None | 71 (97) |

| IST accepts patients in contact with the criminal justice system | 65 (89) |

| IST accepts patients experiencing mental health problems | 71 (97) |

| IST accepts patients with intellectual disabilities and challenging behaviour who are not in crisis but who need support | 64 (88) |

| IST provides early hospital discharge support | 72 (99) |

| IST accepts self-referrals | 41 (56) |

| IST accepts referrals without further assessment from trusted assessors | 14 (19) |

| Target time to respond to referrer (days), median (IQR) | 5 (1–14) |

| Target time to commence assessment (days), median (IQR) | 5 (1.5–14) |

| Target time to complete assessment (days), median (IQR) | 7 (3–28) |

| IST operates a waiting list | 7 (10) |

| Interventions used | |

| PBS | 72 (99) |

| Psychoeducational interventions with service users’ family carers or paid carers | 68 (94) |

| Other evidence-based psychosocial therapies (e.g. anger management, mindfulness, counselling, cognitive behavioural therapy) | 68 (94) |

Caseload

The ISTs’ median caseload was 25 (range 15–50) adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour, whereas the median number of adults considered to be at risk of admission was 6 (range 2–15). The average duration of an IST staff member’s visit to a service user was usually 1–2 hours. In total, 66% of the ISTs reported working extended hours and 52% operated a duty/crisis line.

Staffing, training and skills

A common feature of ISTs was their multidisciplinary nature. A number of health and care professionals worked together in ISTs; the most common type of professional was nursing staff, followed by social workers. More than 65% of IST managers described a perceived need for additional training or skills in their service.

Referrals and eligibility

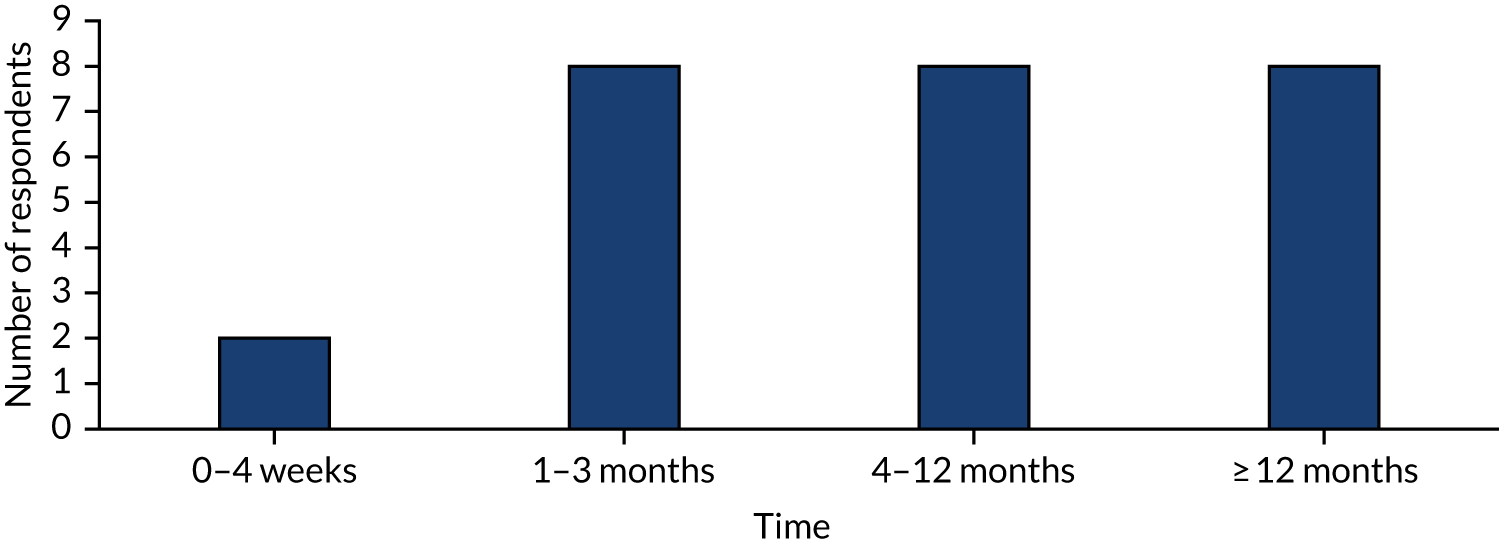

Most ISTs operated with few or no limitations on accepting referrals for adults with intellectual disabilities relating to challenging behaviours, or for mental ill health either in the acute phase or for ongoing care. Self-referral was accepted by 41 ISTs. The IST managers reported that assessments take place within 5 days and are completed within 7 days. In total, 19% of ISTs accepted referrals for young people aged 14–17 years, ensuring a smooth transition to adult specialist services, with 3% of those ISTs indicating that they had no lower age limit and worked across the lifespan.

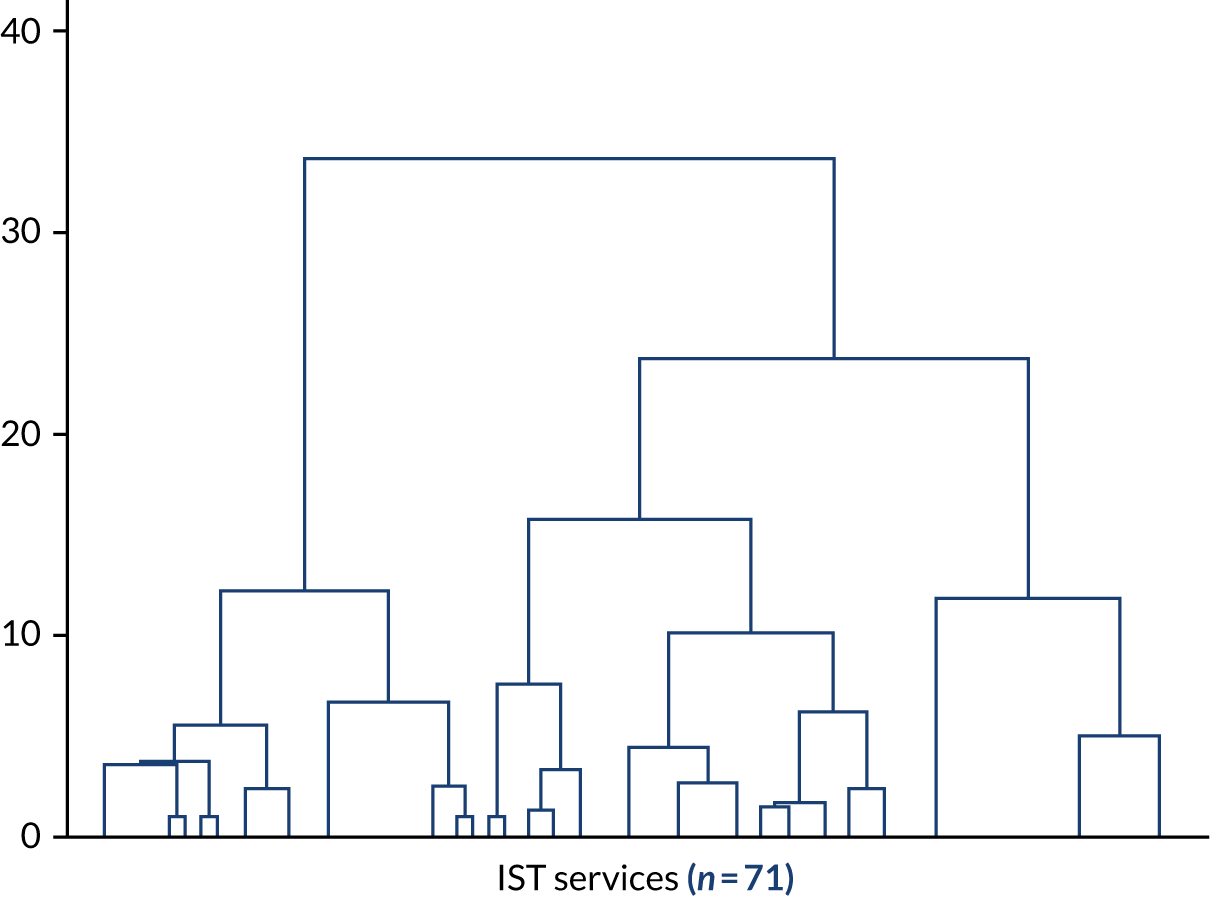

Cluster analysis

The cluster analysis included data from 71 ISTs because we were unable to obtain data on FTEs from the IST managers of two teams. A two-cluster typology was preferred over a three-cluster typology on the basis of distance dissimilarity statistics from the cluster analysis and discussion among experts. The three-cluster typology split the independent provision cluster into two clusters of fairly equal size (n = 27 and n = 19, respectively). These two subclusters were differentiated most strongly on whether or not they were a standalone service, whether or not they had a large caseload, and whether or not self-referral was permitted. Information about the factor clustering is shown in the dendrogram (Figure 4), which illustrates the agglomeration of individual services into ever-larger clusters. Horizontal lines at zero indicate clusters of services that are identical in relation to the grouping factors. Horizontal lines nearer the bottom of the dendrogram represent the merging of clusters that are similar to each other. Horizontal lines nearer the top of the dendrogram represent the merging of more heterogeneous clusters, with larger distance values. Long vertical lines indicate that two clusters that are dissimilar to each other are being combined and suggest that the clusters represent distinct types of services.

FIGURE 4.

Dendrogram illustrating cluster agglomeration. Reproduced from Hassiotis et al. 53 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. This figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

We named the two models the enhanced model and the independent model. Enhanced ISTs were more likely to (1) accept self-referrals, (2) have a large caseload, (3) be integrated with the CIDS function and (4) provide longer-term support than independent ISTs. Enhanced ISTs were less likely to use outcome measures than independent ISTs. A detailed presentation of the characteristics of each IST model is shown in Table 2. Based on the data, there is limited evidence that service models were sufficiently distinguished by whether or not they employ a mix of health and social care professionals (i.e. multidisciplinary teams) or if they operate extended opening hours.

| Characteristic | Model, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced (N = 25) | Independent (N = 46) | |

| Self-referral permitted | 25 (100) | 16 (35) |

| Large caseload | 23 (92) | 15 (33) |

| Outcome measures used | 13 (52) | 41 (89) |

| Standalone service | 3 (12) | 21 (46) |

| Multiprofessional staff team | 21 (84) | 43 (93) |

| Extended working hours | 16 (64) | 31 (67) |

| Other service characteristics | ||

| Working hours | ||

| Monday–Friday only, 7–8 hours | 9 (36) | 15 (33) |

| Monday–Friday only, ≥ 8 hours | 9 (36) | 8 (17) |

| Monday–Friday, ≥ 7 hours, and weekends | 5 (20) | 13 (28) |

| Monday–Friday, 24 hours, and weekends | 2 (8) | 10 (22) |

| Staffing (FTE), median (IQR) | 5.6 (3.6–9.6) | 10.2 (6.8–15.0) |

| Level of intellectual disability | ||

| All levels (mild/moderate/severe/profound) | 18 (72) | 38 (83) |

| All except profound | 2 (8) | 4 (9) |

| All except mild | 4 (16) | 2 (4) |

| Other combination | 1 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Clients with a neurodevelopmental disorder, mean (SD) | 62.1 (21.5) | 51.1 (22.5) |

| Frequency of contact with clients | ||

| Less than once per week | 1 (4) | 2 (4) |

| Once per week | 8 (33) | 9 (20) |

| Twice per week | 5 (21) | 6 (13) |

| Three or more times per week | 6 (25) | 14 (30) |

| Other | 4 (17) | 15 (33) |

| Duration of contact with clients | ||

| 1–3 months | 0 | 7 (15) |

| 3–6 months | 7 (29) | 20 (33) |

| 6–12 months | 13 (54) | 20 (43) |

| ≥ 12 months | 4 (17) | 4 (9) |

Philosophy of care, perceived challenges and priorities for improvement for intensive support teams

Respondents mentioned that the intervention model they used was pivotal to the success of their approach:

The service advocates a PBS approach to supporting service users. The evidence from the team supports that early identification of service user difficulties significantly reduces the likelihood of placement breakdown.

Team manager, independent IST

Others referred to the care the service provides as:

Person-centred, holistic ethos, use of positive behaviour support.

Team manager, enhanced IST

Intensive support team managers’ responses suggested that specialist care from the IST was valued, leading to plans to expand the skill mix of the IST staff. In addition, recruiting qualified and/or experienced health-care professionals to ISTs was described as a positive development:

Restructuring of joint LD [learning development] services and appointment of PBS specialist to lead internal and external support staff.

Clinical nurse specialist, independent IST

We are going to be enhancing the team and increasing working hours.

Lead behaviour nurse, enhanced IST

A lack of resources, high staff turnover, variable expectations from accommodation providers and the quality of care provided to adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour were the most commonly identified challenges:

Clinical demands high – team have not been fully resourced since its start date. Retention of staff and recruitment problematic. Long periods without team manager in place. Difficult to function as an ‘intensive’ support team and meet referral needs and manage risks and trust targets/expectations.

Team manager, independent IST

Working with specialist residential providers who do not obviously have the degree of specialism that they advertise in winning support contracts (e.g. little to no specialist training for staff around autism, communication, challenging behaviour and/or mental health), who then become reliant on our team for longer than we are able to lead on all aspects of mental health/behavioural assessment and support.

Team manager, independent IST

Intensive support team managers reported that the service priorities were the implementation of national policies, a provision of intensive care outside of usual working hours and liaison with other local agencies to improve communication and referral procedures:

Improving links with mainstream services and inputting on reasonable adjustments. Improving awareness in out-of-hours services to avoid hospital admissions out of hours.

Team manager, independent IST

. . . addressing the STOMP (overmedication with antipsychotics) agenda, develop service user involvement in the IST work and improving risk management.

Team manager, enhanced IST

Clinical pathways were noted as areas requiring improvement for some ISTs, as were enhancement of IST workforce skills through specialist training and adopting evidence-based practice. Staff training in PBS was identified as an important part of delivering person-centred care:

Increase up-skilling of staff teams to reduce ongoing reliance on service (e.g. skills, etc.).

Team manager, enhanced IST

Expanding the IST function to work with an all-age service user population, particularly those aged ≤ 18 years, or patients with autism and other populations, such as those with borderline intellectual functioning, were identified as potential future additions to ISTs.

Summary

Phase 1 was a comprehensive description of the geographical distribution, characteristics and service models of IST care in England. Specialist services for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour appeared to be operational across England, although London had the smallest number of ISTs. Following careful consideration of the clinical utility of the findings from the cluster analysis, we found that there were two IST models (enhanced and independent). The role of ISTs encompassed many different components of care, from the management of challenging behaviour in adults with intellectual disabilities to the facilitation of the discharge of inpatients with intellectual disabilities, the assessment and treatment of adults with intellectual disabilities, autism diagnostic assessments and often the support of adults with intellectual disabilities involved in the criminal justice system. Just over half of ISTs (52%) reported operating a daily help line (also called a duty line) staffed by health professionals with the capacity to respond immediately to crises, and one-third of the ISTs provided 24-hour and weekend support to adults with intellectual disabilities and families in distress. However, IST managers across the two models reported that the system appeared to lack flexibility when an individual was in crisis because of the limited/lack of alternative services to avoid admission and the small number of skilled social care providers.

Chapter 3 Clinical evaluation of intensive support team models

Introduction

There is currently little evidence about whether different models of ISTs for challenging behaviour (i.e. dedicated vs. alternative) achieve better clinical outcomes for adults with intellectual disabilities who display challenging behaviour. There is a need for a systematic evaluation of whether or not a specific model of IST is optimal for treating and managing challenging behaviour in local communities, and able to deliver positive outcomes for patients and their families. For more information, please see the published protocol. 49

Methods

We conducted a cohort study of adults with intellectual disabilities, with a nested case–control comparison of two IST models. We included a random selection of 21 ISTs in England representing one of two models: enhanced or independent (Table 3). Random sampling ensured representation of different sizes of teams/caseloads, and both rural and urban services (where possible) for the second stage of the study.

| Grouping variable | Model | |

|---|---|---|

| Enhanced | Independent | |

| Design | Embedded with CIDS | Standalone teams |

| Support length | > 6 months | 3–12 months |

| Referrals | Self-referral | Professional referral only |

| Caseload | ≥ 20 service users | ≈ 15 service users |

| Outcome measures | Limited use of outcome measures | Outcome measure use |

Inclusion criteria

Service

The inclusion criteria for services were as follows: the IST adheres to one of the identified models, it has been operational for ≥ 12 months, there is commitment to fund it for the study duration, and it has the capacity and capability to recruit the required number of participants.

Service users

The inclusion criteria for service users were as follows: participants were adults with mild to profound intellectual disabilities based on clinical diagnosis, aged ≥ 18 years and eligible to receive support from an IST service.

Exclusion criteria

Service

The exclusion criteria for services were as follows: the IST has been operational for < 12 months at selection or there are plans to dissolve it.

Service users

The exclusion criteria for service users were as follows: a primary clinical diagnosis of personality disorder or substance misuse, or a decision by the clinical team that a referral to the study would be inappropriate (e.g. because of ongoing legal challenges to the service or because the person was acutely unwell).

Procedures

Participant consent and enrolment

Potential participants were identified by each IST professional either at the first clinical assessment or from the IST services’ caseloads. IST professionals gave potential participants brief verbal information about the study and those agreeing to speak to the researcher had their contact details shared with the researcher. For those who were referred to the study but who did not have the mental capacity to consent, consent was sought from their family and paid carers, who acted as (family/nominated) consultees. For service users with decision-making capacity, the researcher spoke to the potential participant over the telephone or in person, and sent or gave the service user the PIS (in easy-read format) to inform them of the reasons for undertaking the study, the kind of questions we would be asking their carer, and that we would ask for information from their notes to check details, such as the number of service contacts, which we would undertake twice (first at baseline and then at the 9-month follow-up).

If the service user agreed to take part in the study, they completed a written consent form or consent was taken by telephone/video call and audio-recorded for purposes of verifying consent. The researcher then repeated the above process (using the carer PIS) with the service user’s paid carer or family carer to seek their consent to take part and complete the study questionnaires. At the time of referral and/or treatment, some participants did not have the decision-making capacity to consider participation. For those service users lacking decision-making capacity, the researcher approached their personal or nominated consultee (using the consultee PIS) and sought written or audio-recorded (by telephone/video) assent to include the service user in the study. Reasons for ineligibility and/or exclusion of eligible service users were documented. Participants were allowed to withdraw from the study at any point. (The service user, paid carer and family carer, and personal consultee PISs and ICFs can be accessed at URL: www.fundingawards.nihr.ac.uk/award/16/01/24.)

Outcome measures

Participants were either new referrals or existing IST cases. A baseline assessment was carried out, with follow-up at 9 months (± 4 weeks) after the baseline. The follow-up assessment time point reflected the period of involvement of the IST, which lasted ≥ 12 months and was a pragmatic reflection of clinical practice. At the time of completion, the country was in the first COVID-19 lockdown and in-person assessments were not allowed. The end of the study was the date of the last video/telephone follow-up with the last participant.

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was change in challenging behaviour as measured by the Aberrant Behaviour Checklist-Community, version 2 (ABC-C). 57 This is an established and internationally used carer-administered measure of challenging behaviour that measures psychiatric symptoms and behaviour across five domains: irritability, lethargy, stereotypic behaviour, hyperactivity and inappropriate speech. It was adopted as the primary outcome measure as reduction in challenging behaviour is the main remit of ISTs.

Secondary outcomes

-

Mental health comorbidity: the carer-reported Psychiatric Assessment Schedule for Adults with Developmental Disabilities (PAS-ADD) Clinical Interview58 is used for screening for a mental disorder, but it is not diagnostic.

-

Clinical risk: the Threshold Assessment Grid (TAG)59 measures clinical risk and previous research has found associations between perceived risk and hospital admission. 60

-

The Quality of Life Questionnaire (QoL-Q). 61 This is a widely used measure with good psychometric properties that has been developed specifically for adults with intellectual disabilities and can be proxy completed.

-

Health-related quality of life: the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L),62 is a standard measure for health economic evaluations and it is used to generate quality-adjusted life-years (QALYs) as a result of IST input. Two versions were administered where possible. If the service user had capacity, a self-report version of the EQ-5D-5L was utilised. If the service user lacked capacity, the proxy version of the measure was completed by their carer. In the case of the service user having capacity, the carer was also asked to complete the proxy version and the responses were compared.

-

Service use: the Client Service Receipt Inventory (CSRI)63 (adapted for the study, 6-month retrospective service use at each assessment point) is a widely used service use questionnaire and has been validated for use in mental health and intellectual disabilities services research.

We collected sociodemographic information, the number of hospital admissions and maintenance of accommodation at follow-up.

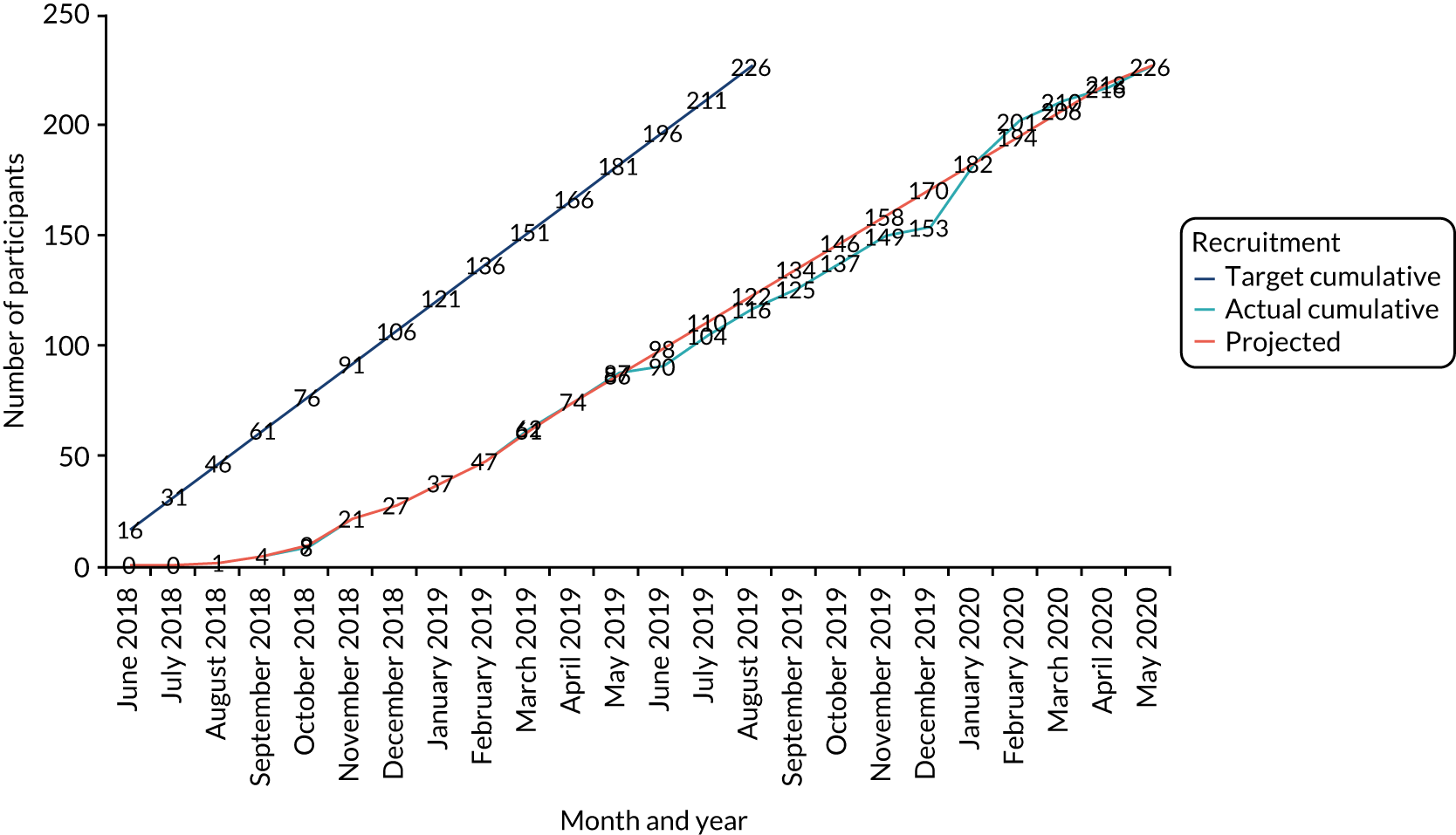

Sample size

Assuming two IST models, detecting a difference of 0.45 standard deviations (SDs) in primary outcome score would require 96 participants per group (192 in total) with 5% significance (two-sided) and 80% power and an interclass correlation coefficient of 0.02. 40,64 After inflation for 15% loss to follow-up, the estimated sample size was 113 participants per model (226 participants in total).

Statistical analysis

The data analysis plan follows an a priori developed statistical analysis plan (see additional files; www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/160124/#/documentation; accessed 3 March 2022).

Data cleaning

Prior to performing analyses, basic checks were performed by the statistician (LM) to ensure the quality of the data. Each outcome (primary and secondary) variable was checked for the following: missing values, values outside an acceptable range and other inconsistencies. If missing values or other inconsistencies were found, the data in question were sent to the study manager for checking and were confirmed as correct and left unchanged, corrected or deemed to be missing, as appropriate.

Baseline characteristics

The baseline characteristics of participants are summarised separately for the two types of service identified in phase 1 of the study. Categorical variables are reported as counts and percentages, whereas continuous variables are summarised as means and SDs or medians and IQRs as appropriate, depending on the distribution of the data.

Primary outcome analysis

All analyses were conducted using Stata, version 16. The primary outcome was the change in challenging behaviour, as measured by a change in ABC-C score between baseline and the 9-month follow-up. Change in ABC-C total score from baseline to the 9-month follow-up was calculated for each participant. The mean difference in ABC-C change score between the two IST models identified in phase 1 of the study was estimated using a mixed-effects linear regression model with change in ABC-C score as the outcome, a fixed effect of service type as the main exposure, and a random effect of IST to account for clustering within services. For ABC-C and the domains, a positive coefficient denotes improvement.

The potential confounders identified were age; sex; accommodation type; level of intellectual disability [i.e. Short Adaptive Behaviour Scale (SABS) score]; level of risk (baseline TAG); presence of autism and/or attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD); number of physical comorbidities; and PAS-ADD Clinical Interview organic condition, affective or neurotic disorder and psychotic disorder scores. These were specified as covariates in the adjusted multilevel linear regression models, which were similar to the unadjusted model described above. The estimated difference in change in ABC-C total score from both unadjusted and adjusted models was reported with accompanying 95% confidence interval (CI), and the p-value was reported for the unadjusted model only.

Owing to the data collection window of 9 months ± 4 weeks, the length of time between the baseline and 9-month follow-up measures may vary between participants. To ensure that effect sizes were not biased as a result of this, we performed a sensitivity analysis by adding a fixed effect for the length of follow-up to the above models.

Model checking

The statistical model for the primary outcome analysis included an assumption that the residuals were normally distributed. This assumption was checked through the construction of appropriate histograms and normal quantile plots.

Missing data

The potential for bias due to missing data was assessed by exploring the number of missing observations in key variables and considering potential missingness mechanisms. Predictors of missingness analysis was carried out, in which the outcome was presence or absence of ABC-C at 9 months. Each baseline characteristic was univariately included as a fixed effect in mixed-effects logistic regression models, with a random effect for IST. The only variable accounting for missing data was ‘physical health problems’ (see Appendix 1, Table 20).

Secondary analyses

The secondary outcomes detailed above were analysed using statistical models analogous to those used for the primary outcome. Where change in TAG was the outcome, TAG at baseline was not included as a covariate. For TAG scores, a positive coefficient indicates improvement, and for QoL-Q scores, a negative coefficient indicates improvement. Binary outcomes were analysed using mixed-effects logistic regression models and were not adjusted for covariates owing to limited power. The p-values are not reported for secondary outcomes. The analyses of secondary outcomes are considered exploratory, and these outcomes were analysed using available data only.

Results

Intensive support team recruitment

Twenty-one ISTs across England agreed to participate in the study; 11 were enhanced ISTs and 10 were independent ISTs.

Participant enrolment

Recruitment of participants began in September 2018 and was completed in May 2020 (19 months). In total, 724 participants were screened, with 306 not meeting the inclusion criteria. Following review of the inclusion/exclusion criteria, 418 adults with intellectual disabilities were eligible to participate in the study and were approached by the IST or research team of each research sites and/or us. Just over one-quarter (n = 108) of eligible adults with intellectual disabilities declined participation and 310 adults with intellectual disabilities expressed an interest in the study. From this, a further 84 adults with intellectual disabilities declined involvement because of an inability to commit, lack of interest, health problems, or discharge by the time the researchers contacted them (Figure 5). In total, 226 participants were recruited to the study, with 115 adults with intellectual disabilities in the enhanced model and 111 in the independent model.

FIGURE 5.

The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) diagram.

Follow-up

Follow-up data collection took place 9 months post baseline data collection for each participant and was conducted between May 2019 and January 2021 (20 months). In total, 18 participants were lost to follow-up (attrition rate 8%). The reasons for loss to follow-up were as follows: declined follow-up assessment, for example because of hospitalisation, imprisonment, change of care provider, excessive stress during the pandemic, or because they had withdrawn since the first assessment (n = 9); participants were non-contactable (n = 5); the follow-up assessment window was breached (n = 2); or death (n = 2). In total, 208 (92%) adults with intellectual disabilities completed the follow-up assessment (enhanced, n = 107; independent, n = 101). See Figure 5 for the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) diagram.

Characteristics of participants

The baseline demographic characteristics of the entire sample are shown in Table 4 by IST model. The median age of the overall sample was 29 years. Most participants were male, of white ethnicity and single. A larger percentage was in education, day centre, looking after family or ‘other’ in the enhanced model than in the independent model (45% vs. 32%, respectively; p = 0.035). A larger percentage of adults had sensory problems in the independent model than in the enhanced model (68% vs. 52%, respectively; p = 0.018; Table 5). There were no other significant differences between models. The characteristics at the 9-month follow-up can be found in Appendix 1, Tables 18 and 19.

| Characteristic | Total (N = 226) | Model | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced (N = 115) | Independent (N = 111) | ||||||

| n/N | % | n/N | % | n/N | % | ||

| Age (years) | |||||||

| Median (IQR) | 29 (23–39) | 30 (24–41) | 28 (22–38) | 0.183 | |||

| Aged ≥ 25 | 151/226 | 67 | 81/115 | 70 | 70/111 | 63 | 0.239 |

| Sex | |||||||

| Male | 155/226 | 69 | 80/115 | 70 | 75/111 | 68 | 0.746 |

| Female | 71/226 | 31 | |||||

| Ethnicity | 0.382 | ||||||

| White | 181/226 | 80 | 90/115 | 78 | 91/111 | 82 | |

| Black | 23/226 | 10 | 11/115 | 10 | 12/111 | 11 | |

| Asian | 17/226 | 8 | 12/115 | 10 | 5/111 | 5 | |

| Other | 5/226 | 2 | 2/115 | 2 | 3/111 | 3 | |

| Marital status | 0.498 | ||||||

| Single | 224/226 | 99 | 113/115 | 98 | 111/111 | 100 | |

| Married | 2/226 | 1 | |||||

| Living situation | 0.354 | ||||||

| Alone or with partner (with or without children) | 45/226 | 20 | 23/115 | 20 | 22/111 | 20 | |

| With parents or relatives | 58/226 | 26 | 34/115 | 30 | 24/111 | 22 | |

| Other (e.g. sheltered accommodation, group living, hospital) | 123/226 | 54 | 58/115 | 58 | 65/111 | 59 | |

| Accommodation | 0.279 | ||||||

| Median (IQR) (months) | 47 (12–144) | 48 (12–132) | 36 (11–146) | ||||

| Family home | 68/225 | 30 | 38/114 | 33 | 30/111 | 27 | |

| Supported living | 81/225 | 36 | 34/114 | 30 | 47/111 | 42 | |

| Residential | 60/225 | 27 | 33/114 | 29 | 27/111 | 24 | |

| Independent | 16/225 | 7 | 9/114 | 8 | 7/111 | 6 | |

| Length of time in current accommodation < 6 months | 32/226 | 11 | 13/115 | 11 | 19/111 | 17 | |

| Main source of income | |||||||

| Salary/wage | 1/226 | 0.4 | 0/115 | 0 | 1/111 | 1 | 0.491 |

| Family support | 62/226 | 27 | 35/115 | 30 | 27/111 | 24 | 0.303 |

| State benefits | 226/226 | 100 | 115/115 | 100 | 111/111 | 100 | a |

| Occupational status | |||||||

| None | 140/226 | 62 | 67/115 | 58 | 73/111 | 66 | 0.245 |

| Any employment | 4/226 | 2 | 2/115 | 2 | 2/111 | 2 | 0.972 |

| Education, day centre, looking after family, other | 87/226 | 38 | 52/115 | 45 | 35/111 | 32 | 0.035 |

| Voluntary work | 12/226 | 5 | 6/115 | 5 | 6/111 | 5 | 0.950 |

| Characteristic | Total (N = 226) | Model | p-value | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enhanced (N = 115) | Independent (N = 111) | ||||||

| Mean or n/N | SD or % | Mean or n/N | SD or % | Mean or n/N | SD or % | ||

| Neurodevelopmental disorder | |||||||

| Neither ASD nor ADHD | 66/226 | 29% | 33/115 | 29% | 33/111 | 30% | 0.628 |

| ASD or ADHD | 144/226 | 64% | 72/115 | 63% | 72/111 | 65% | |

| Both ASD and ADHD | 16/226 | 7% | 10/115 | 9% | 6/111 | 5% | |

| Ability level (SABS) | 52 | 24 | 50 | 25 | 56 | 22 | 0.079 |

| Aetiology of intellectual disability | 0.385 | ||||||

| Down syndrome | 10/225 | 4% | 6/114 | 5% | 4/111 | 4% | |

| Fragile X syndrome | 2/225 | 1% | 1/114 | 1% | 1/111 | 1% | |

| Unknown | 181/225 | 80% | 95/114 | 83% | 86/111 | 77% | |

| Other | 32/225 | 14% | 12/114 | 11% | 20/111 | 18% | |

| Physical health problems | 197/226 | 87% | 99/115 | 86% | 98/111 | 88% | 0.621 |

| Mobility problems | 85/226 | 38% | 45/115 | 39% | 40/111 | 36% | 0.631 |

| Sensory problems | 135/226 | 60% | 60/115 | 52% | 75/111 | 68% | 0.018 |

| Epilepsy | 58/226 | 26% | 33/115 | 29% | 25/111 | 23% | 0.288 |

| Incontinence | 76/226 | 34% | 41/115 | 36% | 35/111 | 32% | 0.512 |

| Cancer | 2/226 | 1% | 0/115 | 0% | 2/111 | 2% | 0.240 |

| Overweight | 18/226 | 8% | 7/115 | 6% | 11/111 | 10% | 0.289 |

| Diabetes | 13/226 | 6% | 6/115 | 5% | 7/111 | 6% | 0.725 |

| Overweight or diabetes | 27/226 | 12% | 12/115 | 10% | 15/111 | 14% | 0.476 |

| Cardiovascular related | 7/226 | 3% | 4/115 | 3% | 3/111 | 3% | > 0.999 |

| Respiratory related | 11/226 | 5% | 6/115 | 5% | 5/111 | 5% | 0.803 |

| Other physical health problem(s) | 68/226 | 30% | 33/115 | 29% | 35/111 | 32% | 0.642 |

| ABC-C total | 63 | 33 | 64 | 34 | 62 | 32 | 0.607 |

| Irritability | 20 | 11 | 21 | 11 | 20 | 11 | 0.660 |

| Lethargy | 14 | 9 | 14 | 9 | 14 | 10 | 0.784 |

| Stereotypic behaviour | 5 | 5 | 6 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 0.116 |

| Hyperactivity | 19 | 12 | 19 | 13 | 18 | 11 | 0.363 |

| Inappropriate speech | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 0.288 |

| PAS-ADD Clinical Interview | |||||||

| Organic condition | 30/226 | 13% | 14/115 | 12% | 16/111 | 14% | 0.620 |

| Affective or neurotic disorder | 48/226 | 21% | 22/115 | 19% | 26/111 | 23% | 0.430 |

| Psychotic disorder | 15/226 | 7% | 4/115 | 3% | 11/111 | 10% | 0.063 |

| TAG | 14 | 5 | 14 | 5 | 13 | 5 | 0.307 |

| QoL-Q | 70 | 10 | 70 | 11 | 69 | 8 | 0.581 |

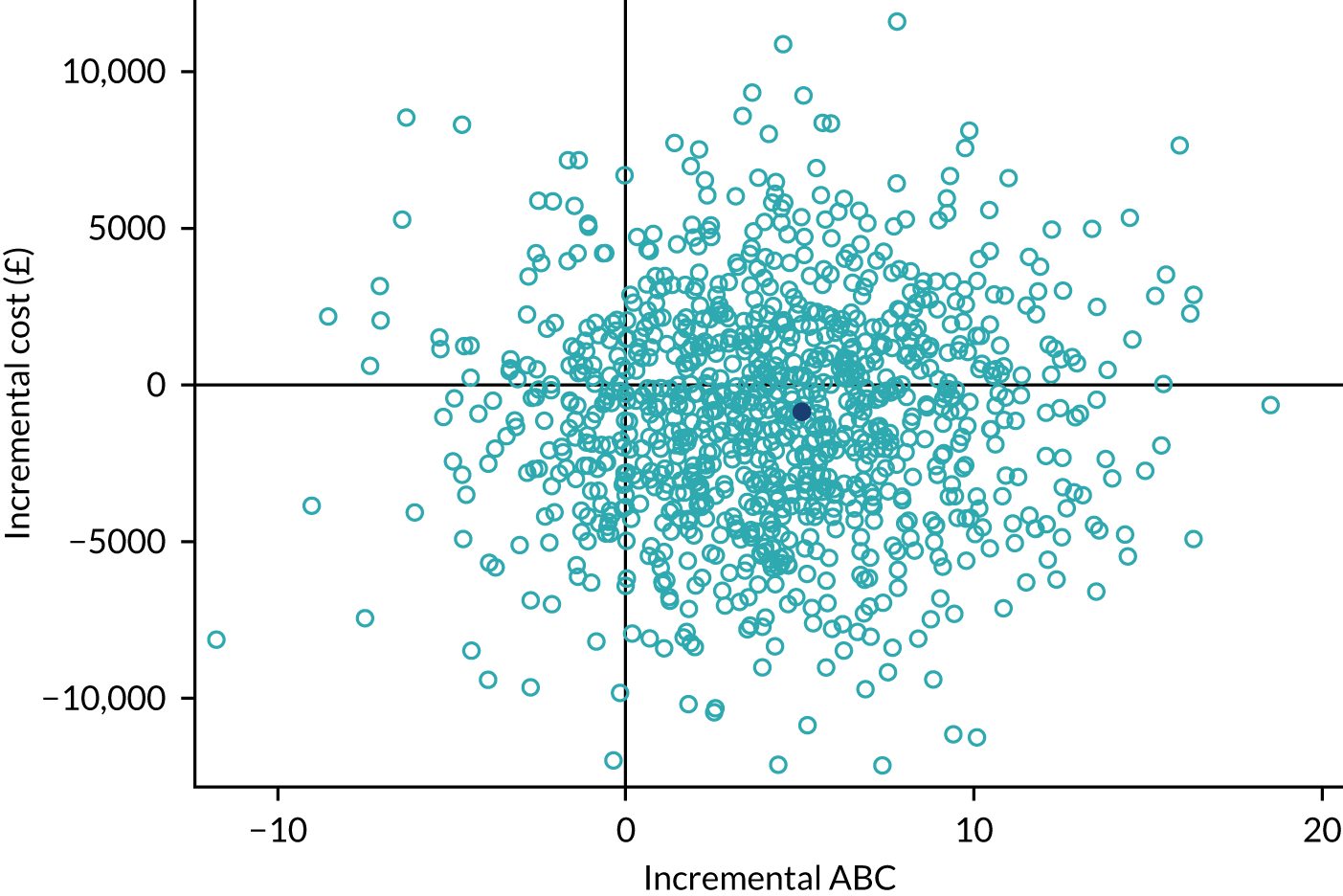

Primary outcome

The primary outcome was a change in ABC-C score between baseline and the 9-month follow-up. The results can be seen in Table 6. All primary outcome analyses showed a positive outcome (i.e. improvement) in change in ABC-C total score from baseline to 9 months. However, unadjusted analyses found no difference between the IST models for change in the ABC-C total score from baseline to 9 months (β 3.08, 95% CI –7.32 to 13.48; p = 0.561). This held true for adjusted analyses (β 4.27, 95% CI –6.34 to 14.87; p = 0.430), and time between baseline and 9-month data collection and other covariate-adjusted analyses (β 3.62, 95% CI –6.99 to 14.22). The only predictors of missingness were physical health conditions (see Table 20). The adjusted models included the number of physical health problems.

| Outcome | Model | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||||

| Number | Coefficient | 95% CI | Number | Coefficient | 95% CI | |

| Change in ABC-C total | 208 | 3.08 | –7.32 to 13.48 | 163 | 4.27 | –6.34 to 14.87 |

| Adjusted for length of follow-up | 204 | 2.75 | –7.56 to 13.06 | 160 | 3.62 | –6.99 to 14.22 |

| Change in ABC-C | ||||||

| Irritability | 208 | 1.14 | –2.41 to 4.69 | 163 | 2.09 | –1.67 to 5.86 |

| Lethargy | 208 | 1.40 | –1.77 to 4.58 | 163 | 1.31 | –1.82 to 4.44 |

| Stereotypic behaviour | 208 | –0.05 | –1.44 to 1.34 | 163 | 0.69 | –0.77 to 2.14 |

| Hyperactivity | 208 | –0.07 | –3.54 to 3.39 | 163 | –0.11 | –3.68 to 3.45 |

| Inappropriate speech | 208 | 0.83 | –0.10 to 1.77 | 163 | 0.37 | –0.86 to 1.60 |

Secondary outcomes

Secondary outcomes are presented in Table 7. No significant differences were found between the IST models for any secondary outcomes from baseline to 9 months. No significant differences were found between the IST models for the subscores of the PAS-ADD Clinical Interview scale [organic condition (odds ratio 1.09, 95% CI 0.39 to 3.02), affective or neurotic disorder (odds ratio 0.91, 95% CI 0.32 to 2.59), psychotic disorder (odds ratio 1.08, 95% CI 0.21 to 5.50)], change in TAG score (adjusted β 1.12, 95% CI –0.44 to 2.68) or change in QoL-Q score (adjusted β –2.63, 95% CI –5.65 to 0.40) from baseline to 9 months.

| Outcome | Model | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted | Adjusted | |||

| Estimate | 95% CI | Estimate | 95% CI | |

| PAS-ADD Clinical Interview (odds ratio) | ||||

| Organic condition | 1.09 | 0.39 to 3.02 | ||

| Affective or neurotic disorder | 0.91 | 0.32 to 2.59 | ||

| Psychotic disorder | 1.08 | 0.21 to 5.50 | ||

| Change in TAG score between baseline and 9 months (β) | 1.11 | –0.35 to 2.57 | 1.12 | –0.44 to 2.68 |

| Change in QoL-Q score between baseline and 9 months (β) | –0.75 | –3.62 to 2.11 | –2.63 | –5.65 to 0.40 |

Summary

Overall, analyses showed an improvement in ABC-C score from baseline to 9 months. However, unadjusted and adjusted analyses found that there was no significant difference between the IST models in ABC-C score at 9 months. In addition, there were no significant differences between IST models for any of the secondary outcomes at 9 months. It is possible that the function of the two models overlapped, including patient profiles and treatments delivered.

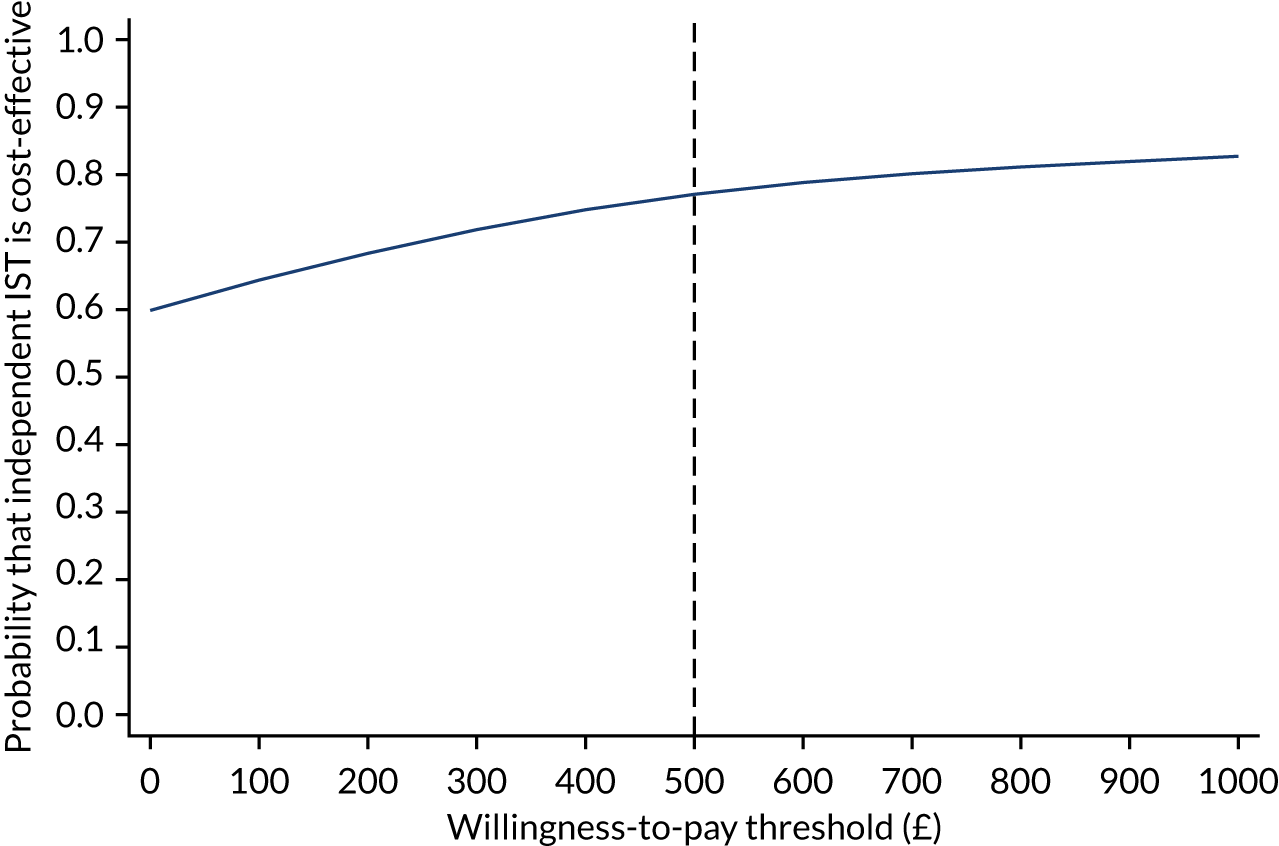

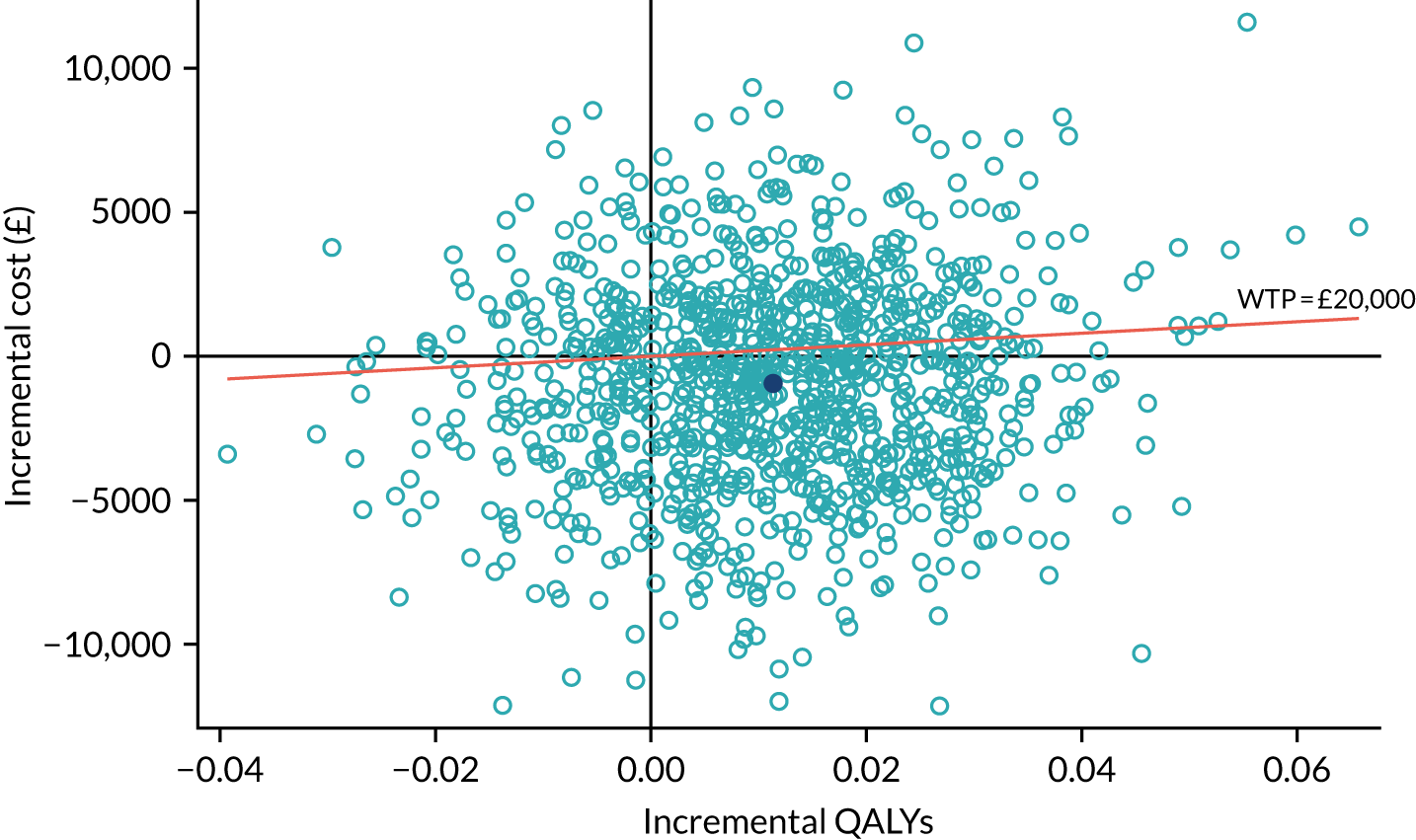

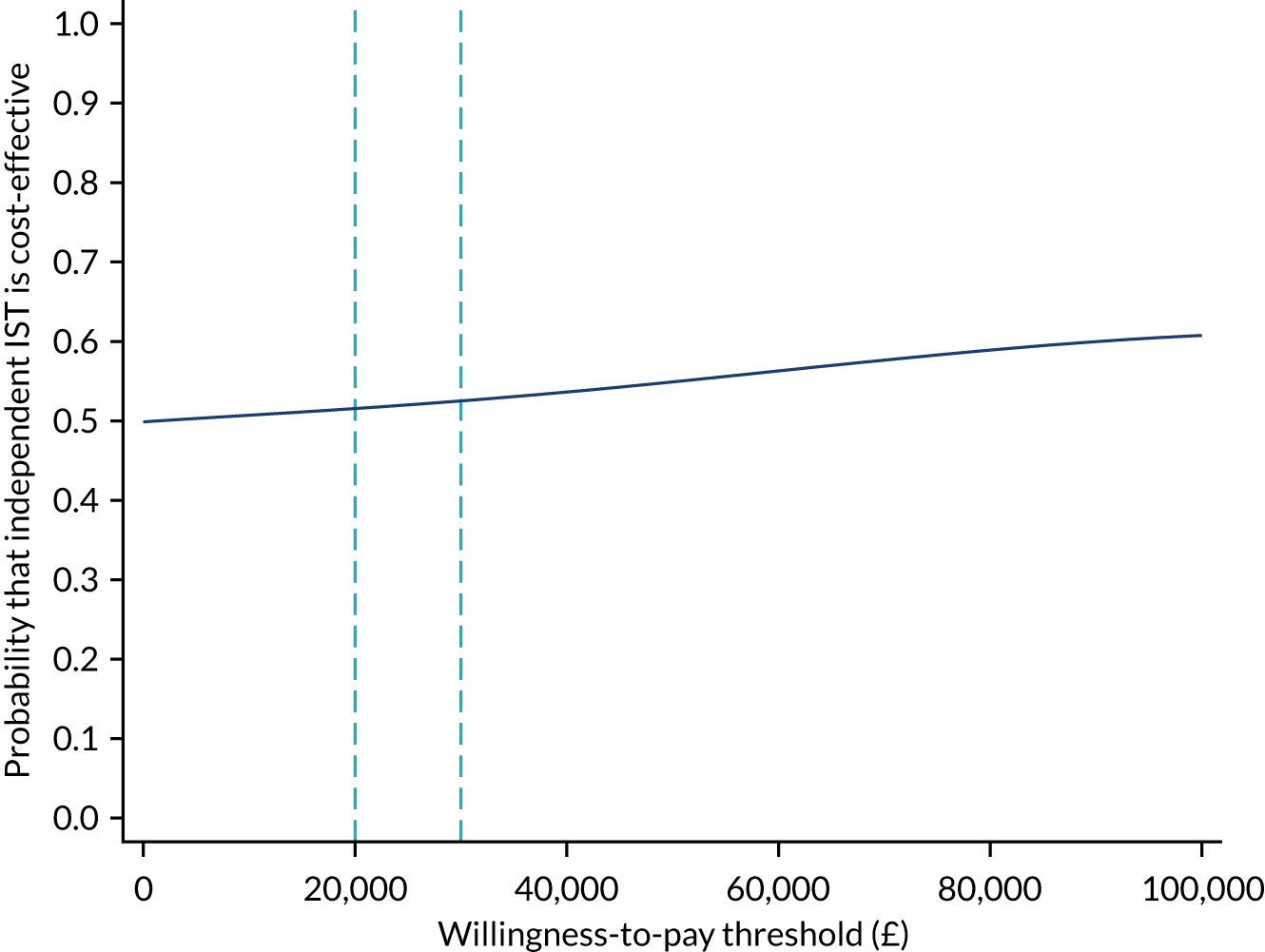

Chapter 4 Cost evaluation of intensive support team models

Introduction

The Transforming Care programme12 is aimed at enabling adults with intellectual disabilities and/or autism who display challenging behaviour to remain in their local communities, access the right support and reduce the number of costly inpatient admissions. Intensive community support, such as that provided by ISTs, is seen as a way to mitigate these challenges; however, there are a number of models of provision and, despite the prioritisation of ISTs and substantial financial backing by the government, no available economic evidence exists on the value for money for these services. The aim of the health economics component of the study was to derive and report the costs of each IST model and to investigate the cost-effectiveness of the IST care models (using two outcome measures in turn). The health economic component was carried out alongside the clinical evaluation. For more information, see the published protocol. 49

Methods

The inclusion/exclusion criteria for the IST service models and service users are described in Chapter 3. The study procedures, including recruitment, consent and outcome measures, were the same as those described in Chapter 3.

Economic analysis

The data analysis plan follows an a priori developed health economics analysis plan (HEAP) (see additional files; www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/160124/#/documentation; accessed 3 March 2022).

Economic perspective

The economic evaluation adopted two perspectives. In the first instance, the analysis took a health and social care perspective that covered hospital and community health and social care services. Other voluntary-sector provision was also included, as most support from outside the family is funded by social services and provided by not-for-profit organisations. In addition, as family members and carers provide the majority of support for most people with intellectual disabilities, a wider societal perspective was also considered, one that included not only the cost to health and social care, but also the cost of unpaid support to the study participant from family and friends.

Cost of intensive support teams

The costs of each IST service model were calculated using established approaches to service costing. 63 Informed by this approach, the research team obtained a description of each IST model (phase 1 of the study) and collected financial information from the service managers in each of the IST models that took part in the evaluation phase (defined in Chapter 2). In addition, service managers were asked to record details on staffing by Agenda for Change (AfC) band, working hours of staff in different professions, the average percentage of time spent with clients (face to face and non-face to face), whether or not the role involved travel, the number of sessions with clients per case, and the size of the caseload and the number of referrals over 12 months. These data were combined to give an overall average annual cost per study participant for each IST model. The annualised average cost per study participant for each model was then weighted to derive a cost per study participant for each IST model over 9 months.

The costing relates to all care functions or activities provided by the IST, as it was not possible to carry out microcosting by function or activity (e.g. assessment, postassessment activities within the ISTs) because all ISTs were unable to provide such detailed activity-based information. Adopting this approach to costing the IST models, which covered all care activities by each service, was less intrusive. In cases where the numeric data required from service managers were missing, median imputation was adopted to avoid distributional concerns from using the mean values.

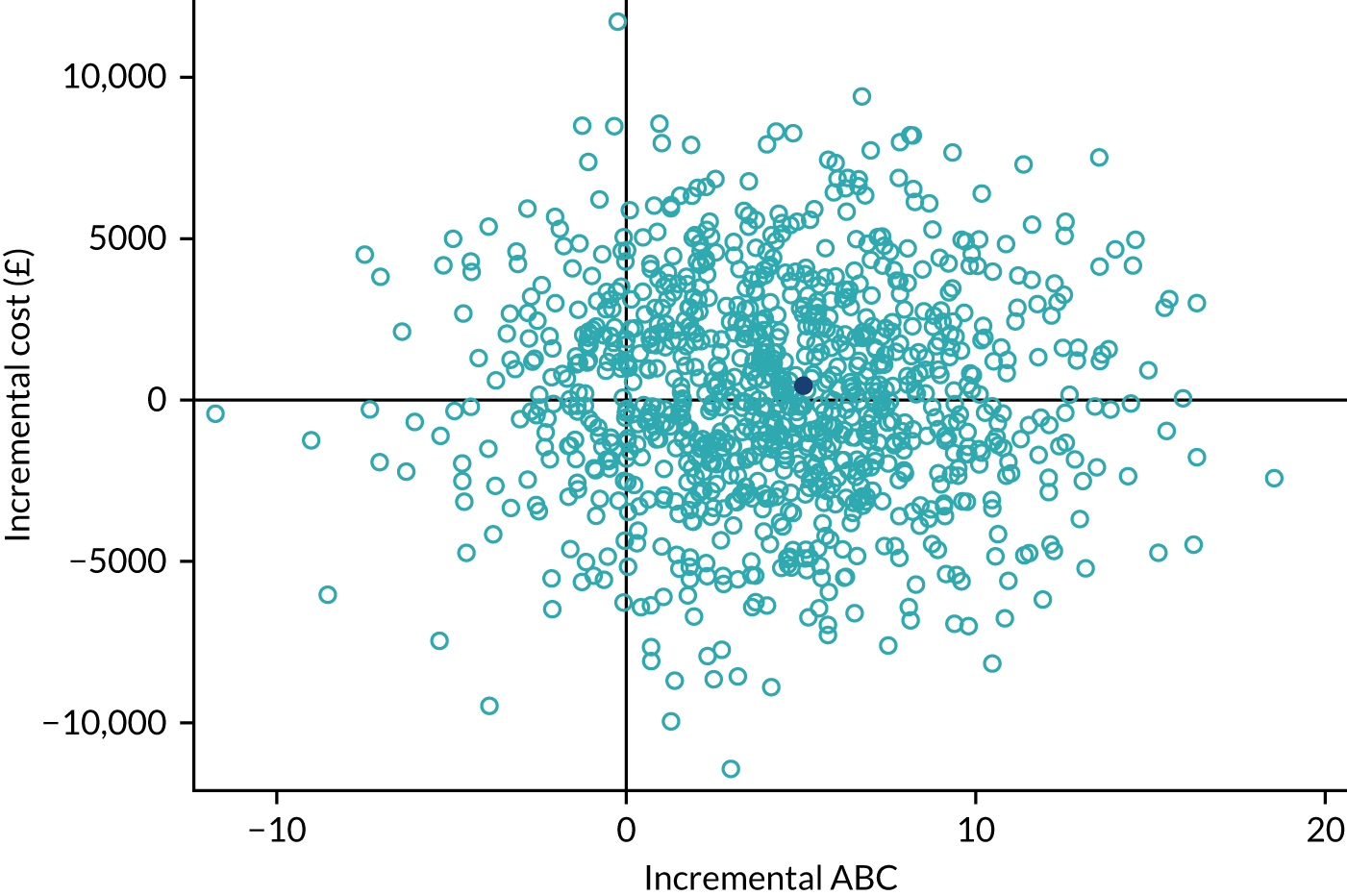

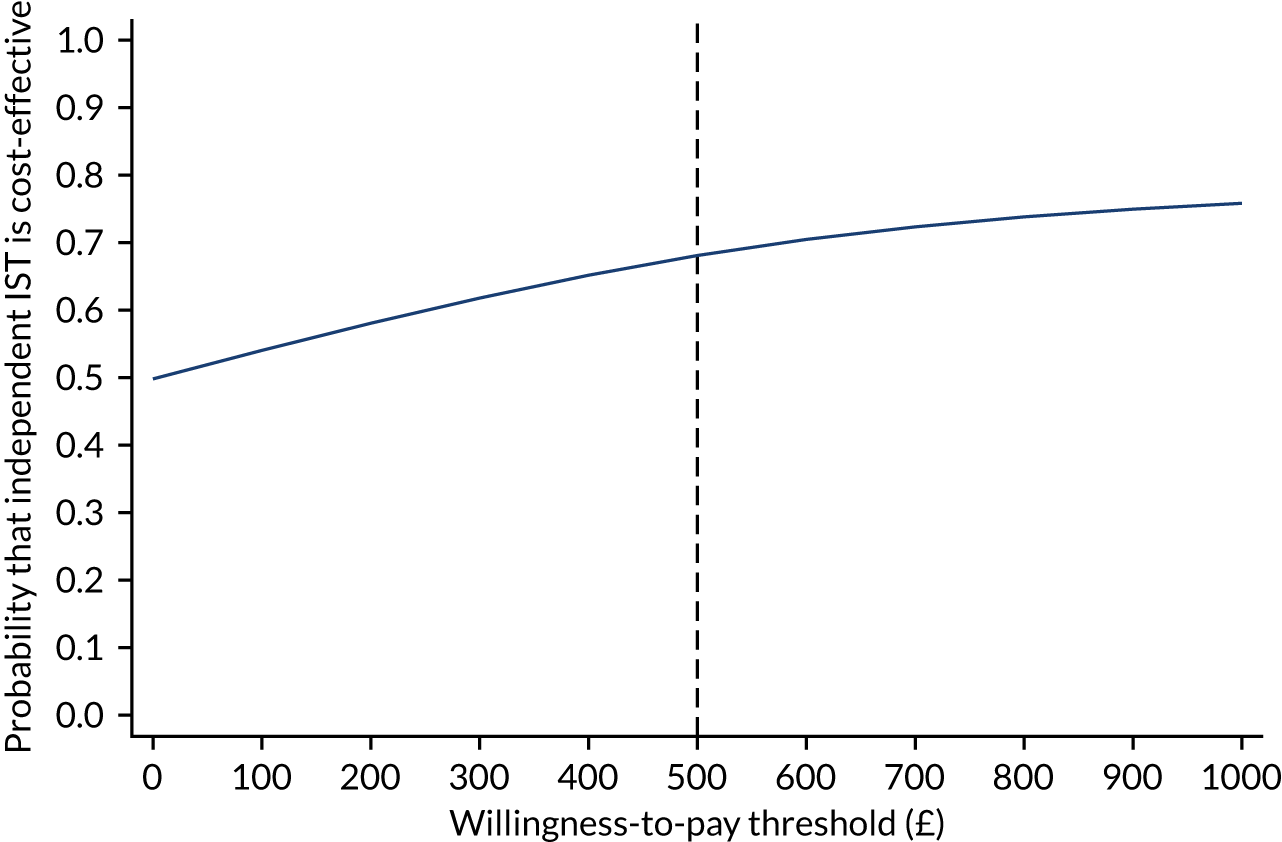

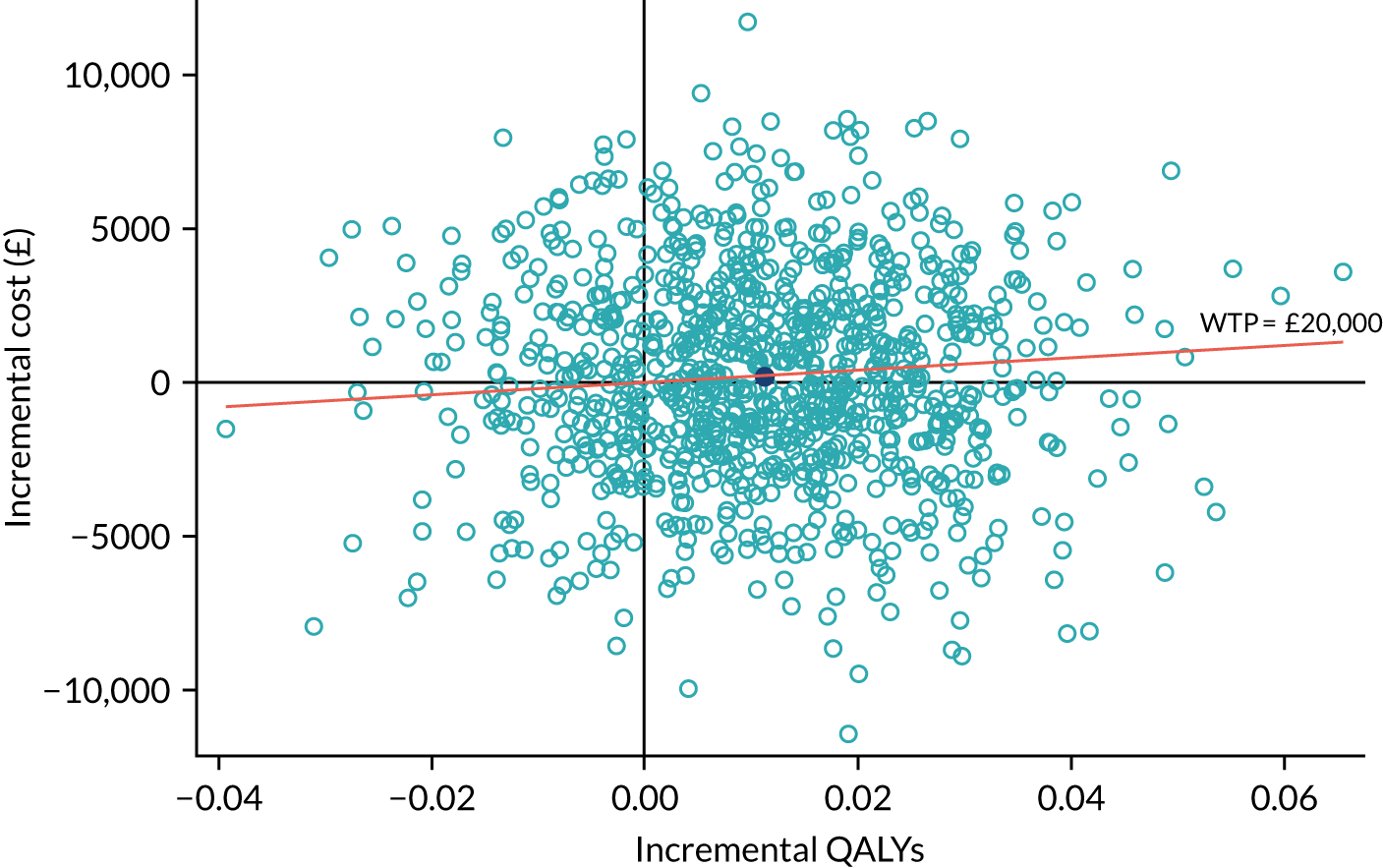

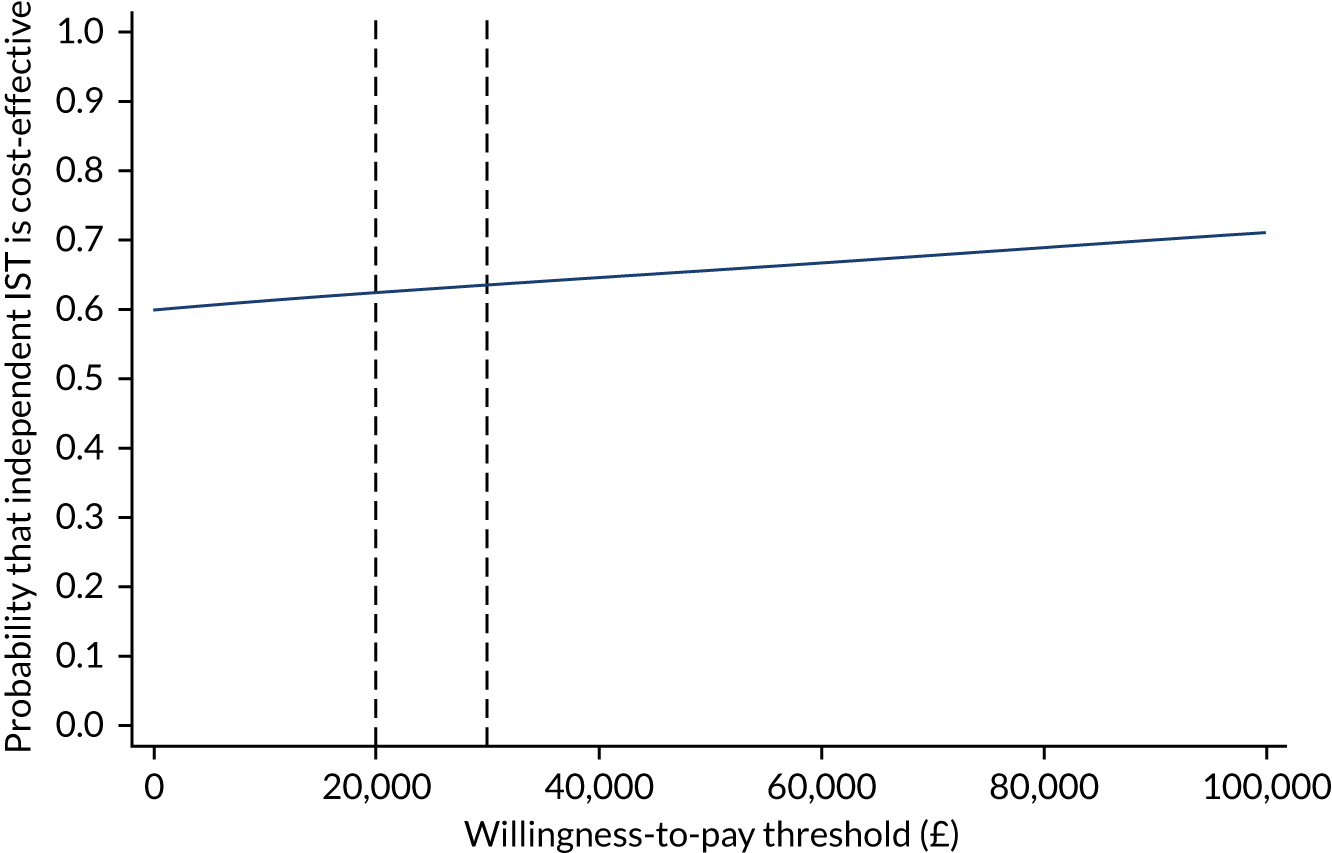

Costing service and support external to intensive support teams