Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 16/52/23 . The contractual start date was in February 2018. The final report began editorial review in December 2020 and was accepted for publication in June 2021. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2022 Latter et al. This work was produced by Latter et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaption in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2022 Latter et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background and rationale

Patient/carer access to medicines at end of life (EoL) is critical for control of symptoms, including pain and distress, and recent evidence confirms that medicines optimisation at EoL is a research priority area for patients and carers. 1,2 The symptom of pain is a leading cause of concern among patients and the public in relation to EoL and dying, and analgesic use is a crucial part of effective symptom management. 3 Although, to the best of our knowledge, there are no detailed studies, research in related areas conducted over the last few years suggests that prescription, dispensing, supply and associated information given about medicines (see Glossary, Medicines access) are often considered difficult, complex, demanding, lacking co-ordination and involving a multiplicity of health-care professionals (HCPs) by patients using these services. 4,5 In one of the only few related studies,6 patients in the USA experienced barriers to accessing medicines, resulting in insufficient medication and delays in pain relief, or ‘diligent pain management efforts by multiple clinicians in multiple settings resulted in an oversupply of pain medications for some patients and raised issues related to communication, co-ordination, and safety’. In addition, we have accounts from community nurses (CNs) that they expend much effort in ensuring that patients on their caseloads are able to access medicines (e.g. by collecting prescriptions from general practices and delivering them to patients). 7 The British Medical Association (London, UK) highlighted three areas (i.e. system, professional and patient) where barriers specific to accessing pain relief at EoL can operate. 3 System barriers revolved around regulation and guidance, use of opioids and the nature of palliative care service provision. A review of UK cancer registry and primary care patient data by Ziegler et al. 8 highlighted EoL patients’ lack of access to opioids and suggested that this was strongly associated with hospital death. 8 The authors concluded that ‘to date no UK research has systematically charted and evaluated patient experience of medicines access during the last year of life’. 8

Internationally, research has repeatedly highlighted patients’ and carers’ needs for information regarding medicines in the EoL context,9,10 and a recent systematic review evaluating educational interventions to help carers manage medicines on behalf of patients in the home indicated that solutions remain elusive. 2 Recent work by this report’s authors focused on developing and testing education-focused interventions for pain and related medicines management in the home. 4,5,11 However, our experience during these studies has suggested that the information patients and carers receive about medicines at a key point earlier in the patient pathway (i.e. when medicines are prescribed, dispensed and supplied to them) has a critical influence on their ability to self-manage medicines in the home. Data generated from these studies suggested that, not just in relation to information given, these patients’ and carers’ experiences of prescribing, dispensing and supply were in themselves key influences on patient/carer medicines management, symptom control and subsequent unplanned use of out-of-hours (OOH) services and, yet, their experiences were problematic. In the UK context, little is known about this important aspect of patient and carer experience.

The delivery of EoL care is characterised by the involvement of a number of different professional groups and organisations. Typically, a patient’s care may include the involvement of palliative care specialists, along with generalists, and primary, secondary and community care specialists, as well as care from the voluntary sector (e.g. charity-funded hospice care). Although it is acknowledged that there may be patient and carer access problems with traditional systems, including general practitioner (GP) services (a significant provider of EoL care at home), little is known about these problems from the perspective of HCPs. Nurses take a lead role in providing community-based EoL care, but limited evidence suggests that here too there might be problems (e.g. nurses find it difficult to access GP services for EoL prescriptions8,12 and prescribing by palliative care nurses may not have been exploited to its full potential13,14). Moreover, community pharmacists’ (CPs) expertise in palliative care medicines optimisation remains underdeveloped. 15,16 There is a lack of in-depth research into the underlying context or causes of these issues, as well as their wider impact on patient experience of access to medicines. The National Institute for Health and Care Research’s (NIHR) themed review of EoL care research highlighted the need for innovative models of care. 17 Although there are some promising innovations in EoL care, such as pharmacist-attached palliative care teams, OOH support and community pharmacy-commissioned palliative care medicines services, the impact of these innovations on patient access to medicines, as well as their cost-effectiveness comparative to more traditional delivery models, remains largely unevaluated.

Our recent research suggests that the supply chain ‘upstream’ may be a contributing factor to the complexity and problems with access experienced by patients. 4,5 For example, patients and carers report a disconnection between prescriber choice of medicine/formulation/strength and pharmacy stocks, with prescriptions written without knowledge of currently available stock. Even when staff at a patient’s regular pharmacy make efforts to ensure stocks of a patient’s ‘usual’ medicine, rapid changes during EoL care may lead to newly prescribed medicines not being stocked. For medicines not in stock at the time the prescription is presented, the impact of a medicines wholesaler’s opening hours and delivery times OOH may block timely patient access. Previous research with wholesalers and distributors into the supply chain of medical products to patients concluded that ‘The consequences of supply disconnection revealed haphazard supply, unmet user needs and lack of information transfer between player groups’, including lack of patient feedback to wholesalers and distributors on the impact of their practices on patient access. 18 However, to our knowledge, the CP, wholesaler and distributor perspectives on the supply chain of EoL medicines have not been investigated. Therefore, they warrant examination to understand the contribution these different groups make to service delivery and the patient experience of medicines access.

A series of key reports has stressed the pressing need to improve EoL services because of unacceptable variation in access to, and experience of, care. 19,20 NIHR research has also identified poorly co-ordinated services and limited access to specialist palliative care. 17 Our recent research suggests that good access to, and information about, medicines at EoL remains a variable and often burdensome experience for many, affecting symptom control, quality of life and use of unplanned and OOH services. 4,5 At the same time, there are gaps in our knowledge about HCPs’ views on this, and why potential workforce solutions (e.g. use of nurses and pharmacists) to improving medicines access are apparently underutilised. Zeigler et al. ’s14 small survey found that there is potential to improve nurse prescribing in palliative care and recommended further research into patients’ views of this innovation in service delivery. Savage et al. 15 reported significant scope for improving access to, and interaction with, CPs for people with cancer pain and their families. The number of nurse and pharmacist prescribers is rising, with > 53,000 nurses21 and 880622 pharmacists now trained as independent prescribers. In addition, there are significant changes to community pharmacy services as the national integration agenda is driven forward, including commissioning of palliative care medicines access services, higher use of summary care records (SCRs) by community pharmacies, primary care-based pharmacists employed in general practices and community pharmacy-integrated urgent/emergency care services.

To the best of our knowledge, there are other innovations in EoL service provision emerging that offer the potential to improve medicines access experiences, but, to date, their impact on this important aspect of patient experience and their cost-effectiveness remains largely unexplored. Edwards et al. ’s23 study of patients with cancer showed that consultations about medicines provided by community pharmacy services, whether face to face or by telephone, were considered acceptable. Recent guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (London, UK) addressed the delivery and organisation of EoL care services and detailed expectations around OOH pharmacy services, including access to medicines for symptom management in adults approaching the end of their life and effective mechanisms for care co-ordination among the community and primary care team. 24 Dedicated OOH EoL care advice lines have been developed for people in the last year of life and are now a recommended part of OOH service provision nationally. 24 From a Welsh perspective, in 2018, the Royal Pharmaceutical Society (RPS) (Cardiff, UK) issued a set of recommendations25 aimed at making sure patients who require palliative and EoL care can access a range of pharmacy expertise. Eleven recommendations, designed to strengthen pharmacy’s contribution to improved patient care, were made across four areas: (1) supporting and informing patients, (2) timely access, (3) workforce and (4) education and training. 25 At a time when EoL care remains a NHS delivery, professional and research priority, there is an urgent need to provide a systematic and detailed evaluation of these issues in the current national context to inform policy, service delivery and organisation, research and practice going forward.

We hypothesise that patients’ experiences of access are influenced by the characteristics of service provision. To better understand the influence of a range of different characteristics of service provision, a comparison of experiences across different service models would enable distillation of the features that lead to good- or poor-quality medicines access for patients. To the best of our knowledge, no research has systemically studied patient experience of medicines access against the backdrop of differing features of service delivery, such as GP-led care, community palliative care, specialist nurse team-led care and centralised OOH advice lines (currently operating in England), and/or the perspectives of HCPs and pharmaceutical wholesalers/distributors (WDs) involved in prescribing, dispensing, supplying and providing associated information about medicines.

National policy on EoL care has framed this study in that it examines a key issue (i.e. access to medicines) that exemplifies a current concern and imperative, including variation in service delivery and choice of care, as well as the principles outlined in Ambitions for Palliative and End of Life Care: A National Framework for Local Action 2015–202020 (i.e. fair access to services, maximising comfort and well-being, and co-ordination of care). 19,20 This research has aimed to contribute to the understanding of the effectiveness of recommendations and guidance for EoL service delivery that pertain to medicines access, by incorporating evaluation of models of care delivery that include care co-ordination, shared records and 24 hours per day, 7 days per week (24/7) cover, as well as other distinctive features.

Chapter 2 Methods

Study aim

We aimed to provide an evaluation of patient and carer access to medicines at EoL within the context of models of service delivery.

Objectives

-

To produce a critical overview of existing research on experiences and outcomes of medicines access within EoL models of service delivery through a systematic literature review (phase 1).

-

To undertake a large-scale survey to evaluate EoL care professionals’ current practices, as well as to:

-

identify factors influencing professionals’ contributions

-

assess the potential of the community-based nurse and pharmacist workforce to improve patient access to medicines at EoL

-

provide an overview of current models of service delivery (phase 2).

-

-

To evaluate and compare patient and carer experiences of medicines access within models of EoL service delivery, including those featuring innovations in care, through undertaking mixed-methods case studies of practice (phase 3).

-

To estimate the cost-effectiveness of service models (phase 3).

-

To map patient ‘access to medicines pathways’ at EoL, including timelines of problems, decisions, actions and use of services (phase 3).

-

To identify barriers to and facilitators of maximising the contribution of the nurse and pharmacist workforce to medicines access at EoL (phases 2 and 3).

-

To interview CPs, wholesalers and distributors to evaluate supply chain processes and identify challenges in providing access to EoL medicines (phase 4).

-

To convene an expert consensus-building workshop to review study findings and generate recommendations on key characteristics of EoL service delivery that support medicines access (phase 5).

Design and theoretical framework

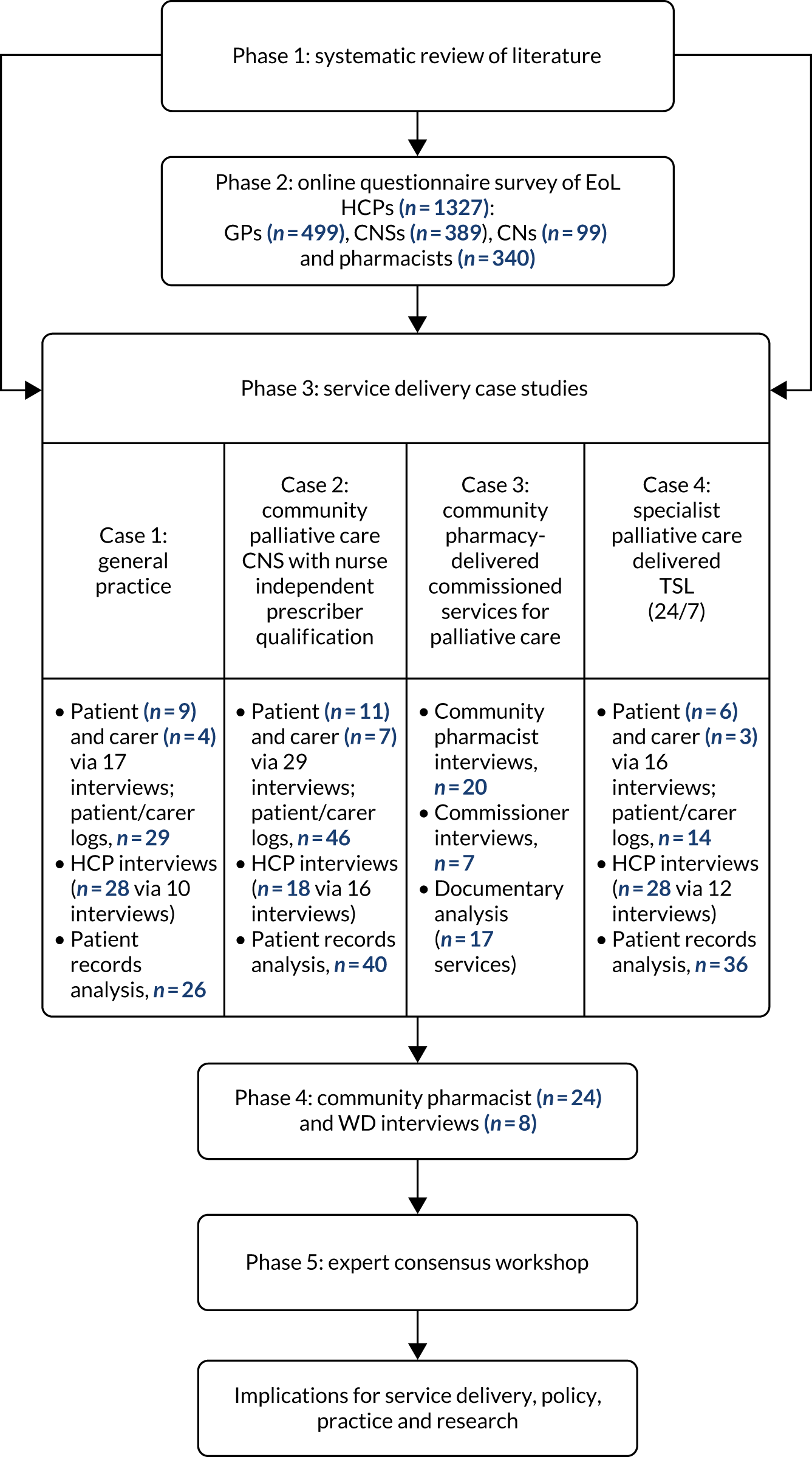

The study used a multiphase mixed-methods design with sequential linked phases, where initial phases informed subsequent phases (Figure 1). 26 The study drew on systems thinking, acknowledging the complexity and multiplicity of actors, the ever-changing health-care context and that systems interact over time to create new patterns. 27 A whole-systems approach framed consideration of medicines access. This approach assumed that services are responsive to the needs of the individual patient/carer, stakeholders accept their interdependency and that action by any one stakeholder may have an impact on the whole system, those using the system do not experience gaps or duplication in provision, and relationships and partnerships are enhanced. 28 These theoretical assumptions informed data collection (e.g. sampling of multiple stakeholders and investigating issues of interdependency in data collection tools), as well as data analysis and interpretation (i.e. through frameworks derived from data collection tools, logic models and sensitivity to systems thinking and complexity).

FIGURE 1.

Study design and methods flow chart. CNS, clinical nurse specialist; TSL, telephone support line.

Research plan

Phase 1 (objective 1)

Phase 1 comprised a systematic review of research evaluating medicines access experiences, influences and outcomes across EoL service delivery models.

Phase 2 (objectives 2 and 6)

Phase 2 comprised an online questionnaire survey of GPs, community-based nurses and pharmacists practising in EoL care contexts.

Phase 3 (objectives 3–6)

Phase 3 involved an in-depth contextual evaluation of medicines access experiences, service costs and outcomes in EoL service delivery models, drawing on multiple stakeholder perspectives within multiple embedded mixed-method case studies (n = 4).

Phase 4 (objective 7)

Phase 4 comprised interviews with CPs and pharmaceutical WDs.

Phase 5 (objectives 8 and 9)

Phase 5 involved a stakeholder workshop with invited EoL care experts to review study findings and generate implications pertaining to EoL medicines access.

More detailed description of the methodology for each phase is provided in individual phase chapters. Standards for reporting qualitative research29 are used to report the qualitative elements of the study throughout.

Ethics

Phase 2 of the study was approved by the NHS Health Research Authority (IRAS reference 231837). Phases 3 and 4 were approved by the NHS Health Research Authority South Central – Hampshire A Research Ethics Committee (reference 18/SC/0675). All participants were informed that they were free to withdraw from the study at any time.

Patient and public involvement in the research

Patient and public involvement (PPI) was integral to the study. Three PPI participants acted as patient and carer representatives on the Study Steering Committee (SSC) and were recruited via the NIHR People in Research website [URL: www.peopleinresearch.org/ (accessed 8 November 2021)], one of whom (LR) was also a study co-applicant. The SSC met four times over the course of the study. In addition, PPI participants were supported before and after meetings by members of the research team, including the study PPI lead (AB). PPI participants were paid an honorarium per meeting for their time and contribution, and travel expenses were also paid. The SSC PPI participants contributed to all aspects of the research, commenting on study processes and findings, and ensured that the study focused on the issues of relevance to key stakeholders. In addition, two SSC PPI members presented their experiences of accessing medicines as part of the phase 5 workshop.

Chapter 3 Phase 1: systematic review and narrative synthesis of research evaluating medicines access experiences, influences and outcomes within end-of-life service delivery models

This chapter describes the first phase of the study (i.e. a systematic review and narrative synthesis of research).

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Ogi et al. 30 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Our aim was to systematically search for and critically review international research studies for evidence of (1) patient, carer and HCP experience of medicines access within the context of different models of EoL service delivery, and (2) patient and carer outcomes associated with medicines access experiences. Phase 1 addresses study objective 1. Key issues identified from the review were used to inform phases 2–4 of the study.

Method

The systematic review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines. 31 A search of research, policy and grey literature was undertaken.

Information sources

Expert advice was sought from library specialists to generate relevant search terms and, in March 2019, four electronic databases (MEDLINE, PsycInfo, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature and EMBASE) were searched for published literature from January 2006 to March 2019, using keywords, synonyms and Boolean operators. (As an example, the description and search terms for MEDLINE are shown in Appendix 1.) A citation search was conducted on the included articles for further relevant material. The Cochrane Library was searched to acquire relevant systematic reviews. PROSPERO (a database of international prospectively registered systematic reviews) was also searched to identify relevant ongoing systematic reviews. For information regarding relevant ongoing trials, ISRCTN and ClinicalTrials.gov were searched. Grey literature sources were searched for unpublished materials from January 2006 to June 2019. To obtain further relevant published or grey literature, members of the study’s SSC were asked for their top five references on this issue.

Study selection

Eligibility

The inclusion and exclusion criteria are summarised in Box 1. The search period began with 2006, as, at this point, nurses and pharmacists in the UK gained the legal ability to independently prescribe any medicine from the British National Formulary. 32

-

Studies evaluating patients’, carers’ and HCPs’ experiences and outcomes of medicine access processes specific to, or inclusive of, palliative and EoL care being provided to adult patients living in their own homes.

-

EoL: the last year of life.

-

Medicine access: prescribing, dispensing, supplying and providing associated information about medicines.

-

Prescribed medicines (excluding diagnostic tests, medical devices and materials).

-

Studies published in the English language.

-

Studies published between January 2006 and March 2019 (or June 2019 for The Cochrane Library and grey literature sources).

-

Services for, or related to, children.

-

Services for inpatients or not-at-home care (e.g. nursing home, hospital wards).

-

Services or support for medicines management at home.

-

Evaluation related to anticipatory, or ‘just-in-case’, medicines.

-

Geographical medicine access in low-economic countries not transferable to the UK.

-

Evaluation of professional capacities in medicines access processes.

Reproduced with permission from Ogi et al. 30 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The box includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original box.

Selection process

Studies were selected for inclusion using a two-step process. One researcher (MO) screened titles (and abstracts when necessary) to remove duplicates, using data management software (EndNote X8.2, Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA). Following deduplication, titles and abstracts were screened to determine study eligibility. To ensure the validity of the process, two reviewers (MO and NC) each independently screened a random sample of 10% of abstracts and screening results were double-checked by a third reviewer (SL). After resolving disagreements and achieving consensus, screening proceeded by a single reviewer (MO). Following initial decisions on papers for inclusion, two reviewers (MO and SL) each independently reviewed full-text articles against all inclusion and exclusion criteria and resolved disagreements through discussion to achieve consensus.

Data extraction

Data extraction was conducted for each eligible study by a single reviewer (MO) and was checked against the original manuscript by another reviewer (SL). Quality appraisal using the mixed-methods appraisal tool, which is appropriate for systematic reviews that include qualitative, quantitative and mixed-method research studies,33 was undertaken by a single reviewer (MO), recorded on a data extraction sheet and then checked by another reviewer (SL). Data management software (EndNote) was used to organise the search results and references.

Synthesising and interpreting results

The search identified that studies included qualitative, quantitative, and mixed-methods research. Therefore, the framework for a mixed-studies review was utilised, with the thematic analysis of qualitative data within a data-based convergent synthesis design. 33 In this design, qualitative and quantitative data can be analysed and synthesised together. Overlaying this, however, and in keeping with the study focus, we structured the review according to models of service delivery that we found in the literature reviewed.

Findings

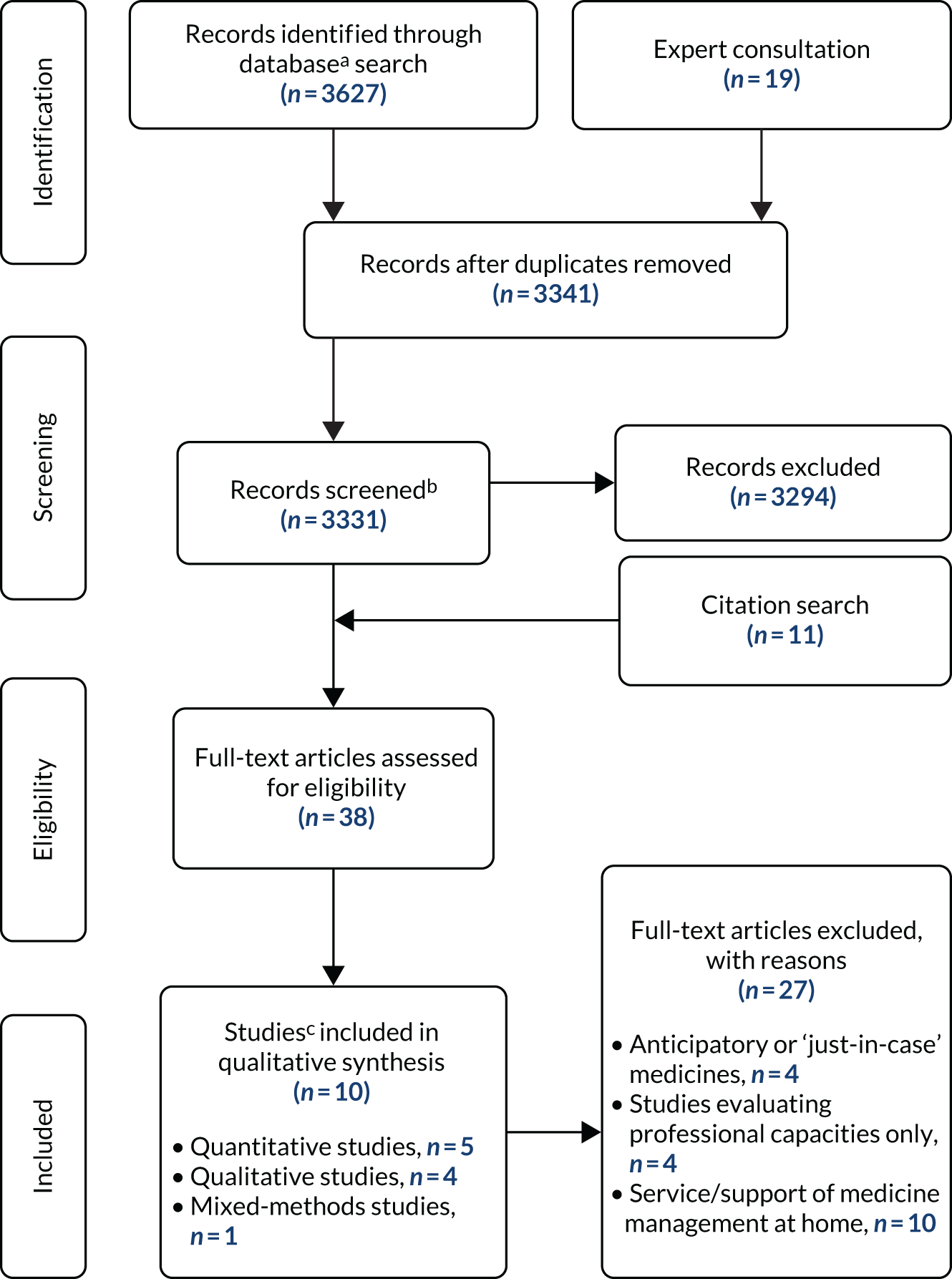

The electronic database search produced 3627 records and 19 records were identified through expert consultation, as shown in the PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 2. Ten studies (five quantitative studies, four qualitative studies and one mixed-methods study) were included in the review. There was one case of multiple reports of the same study,34,35 which were linked together for the purposes of the current review. The studies were from the UK (n = 4), the USA (n = 3), Ireland (n = 1), Australia (n = 1) and Japan (n = 1). Studies were predominantly inclusive of community pharmacy (n = 6), and other types of service delivery were specialist palliative home care medicines kits (n = 3), general practice (n = 1) and community-based clinical nurse specialist (CNS) prescribers (n = 1). In general, the quality of each study was rated as being moderate in terms of methodological rigour. Limitations included that samples were often insufficiently described, making conclusions about generalisability or transferability difficult; the development of data collection tools often lacked detail; and surveys had low response rates, making response bias difficult to rule out. There were no randomised controlled trials or large-scale studies.

FIGURE 2.

A PRISMA flow diagram for systematic reviews. 31 a, Databases: MEDLINE (n = 1306), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (n = 167), PsycInfo® (n = 968) and EMBASE (n = 1186); b, the reason for reduction: sources were not accessible (n = 10); and c, two papers34,35 reporting the same study were counted as one study. 34,35 Reproduced with permission from Ogi et al. 30 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

Medicines access and community pharmacy services

Four studies focused exclusively on investigating medicines access experiences related to community pharmacy,16,36–38 of which two studies16,38 included pharmacies providing commissioned palliative medicine services. Two further studies12,39 included evaluations of community pharmacy medicines access as part of investigating the broader model of community service provision for patients receiving home-based specialist palliative care. Two studies16,36 focused exclusively on the perspectives of CPs in providing access, whereas three other studies12,38,39 also included patients and other HCPs. Bennie et al. 37 focused solely on patients’ views of community pharmacy access. Overall, findings from all six studies12,16,36–39 revealed a picture of delays and problems with accessing medicines from community pharmacies.

Controlled drugs and pharmacy stock of palliative care medicines

Ise et al. 36 provide some quantitative data on access, with data indicating less than comprehensive provision. For example, in Ise et al. ’s36 nationwide survey in Japan, 77% of the 1036 community pharmacies reported holding a ‘narcotics’ (opioid) licence, but only 50% of the community pharmacies reported involvement in monthly provision of opioids. It is unclear why the other 23% of pharmacies did not hold a licence or how this affected the patient experience of accessing opioids, but Ise et al. 36 comment that a system whereby all community pharmacies can supply opioids to all patients who need them has clearly not been established. Certainly, lack of community pharmacy stock of palliative care medicines generally is also reported as problematic in other studies. 12,16,38 A study by Miller38 found that although 80% of 55 patients reported receiving palliative medicines on their first visit, one in five patients had to travel to more than one pharmacy before accessing their medicines, despite 73% of medicines being reported as ‘needed urgently’. In a study by Lucey et al.,12 although 54% of 22 patients (n = 22) reported medication changes during the study period were characterised by no delay, the numbers of patients were small (n = 12) and nurses reported 12 delays across 57 patients over a 12-week period, with the majority of these being a wait of > 48 hours. In 50% of cases, the main reason for delays was no stock in the community pharmacy. The proportion of all medicines acquisition episodes these nurse-reported delays represent is not clear. Although not measured quantitatively, CPs in Akram et al. ’s study16 of four localities in Scotland also reported delays in being able to provide palliative care medicines, and these pharmacies were part of an enhanced service and specialist network to provide these medicines to patients in the community.

Information provision

Data on community pharmacy information provision for patients is available in three studies36,37,39 and, again, these data show scope for improvement. Patients and carers in Bennie et al. ’s37 focus groups saw the pharmacist (as well as GPs) as a source of medicines information if they had a relationship with them. However, some patients and carers reported little contact with a CP and overall knowledge of services offered was poor, with patients often acquiring knowledge in an unplanned way through family and friends or when in a crisis situation. Patients and carers wanted a more proactive role from pharmacists, in particular information regarding prescription and supply processes of controlled drugs (CDs) or when a new medicine was prescribed. The sample in Bennie et al. ’s37 study was small, with 14 patients and 13 carers from one city in Scotland. Nevertheless, findings from Ise et al. ’s36 national survey also highlight gaps in information provision, with 50% of the 1036 pharmacists in the study reporting that they did not counsel patients about their palliative care medicines, primarily because they lacked information about the patient, and < 5% reporting that they had a room to counsel the patient privately. In an Australian study by Kuruvilla et al. ,39 carers and patients felt that sometimes the information provided was inadequate for them to manage their medications appropriately.

Influences on accessing medicines from community pharmacies

Four studies12,16,36,38 reported on influences that challenge or support the access process. Many of these influences can be classified as centrally concerned with communication between the pharmacist and other members of the health-care team. Communication into the pharmacy was reported as problematic, causing delays in supplying medicines, through a mismatch between prescriptions received and stocks held and/or a lack of information on the palliative care status of the patient. 16,36,38 The latter was due to either the pharmacist seeing unfamiliar patients who had been referred by another network pharmacist16 or HCPs’ reluctance to share information. 38 A finding reported by both studies that included enhanced or commissioned services also related to communication, that is medicines access was adversely affected by HCPs’ lack of knowledge about these services. 16,38 Miller38 concludes that this lack of knowledge found in her study resulted in patients and carers not always being able to access medicines promptly and that HCPs need to routinely be made aware of such services and their locations. Similarly, patients and carers in Bennie et al. ’s study37 also reported a lack of awareness of more general pharmacy services.

Further obstacles were also identified. For example, 33% (19/57) of pharmacists completing questionnaires in Lucey et al. ’s12 study reported difficulties in accessing stock and 49% reported that medicines not being on state reimbursement schemes caused delays. In addition, Lucey et al. 12 reported another factor that caused delays was having no one to courier prescriptions/medication to and from the GP, pharmacy and patient. The difficulty of patients or carers picking up medications from a community pharmacy was also noted by Miller. 38

Few data were available on factors supporting good access, related to the fact that studies highlighted poor access experiences. However, pharmacists in one study16 stated that pre-emptive communication from CNs about medicines likely to be required by patients was helpful, as well as being part of a network of pharmacists from whom medicines and advice could be accessed. Miller38 reported that the range of palliative medicines stocked was a key facilitating factor in access, although pharmacists reported practical difficulties keeping them in stock. Seventy per cent of pharmacists in Ise et al. ’s36 survey also said that being able to have a swift supply from, and ability to return opioids to, wholesalers would be useful, as well as being able to get stock from other local pharmacies. Akram et al. 16 also found that CPs wanted better training of counter staff and of locum pharmacists, as well as resources for pharmacists to support clinical practice. In a study by Kuruvilla et al. ,39 family involvement and delivery services seemed to be helpful, although the latter were not always available and, occasionally, there would be a financial burden for some patients when delivery was not free. In addition, patients and families receiving medicines in this way seldom interacted directly with pharmacists.

Outcomes of community pharmacy medicines access

There are few data on outcomes reported in the studies reviewed. One study38 reported that commissioned service pharmacies stocking an agreed list of palliative care medicines could shorten the time required to obtain urgently needed palliative medication compared with medication being provided by a non-commissioned service pharmacy. The median time taken for accessing urgent palliative care medicines was significantly longer for non-commissioned service pharmacies (5 hours) than for pharmacies commissioned to hold stock of palliative care medicines (10 minutes) (p = 0.002). In addition, compiling tailored lists of palliative care medications through communication between pharmacists and GPs resulted in a similar time-saving in commissioned pharmacies. 38 However, the impact of this on outcomes such as symptom control, patient and carer distress or use of emergency health services was not evaluated.

Overall, findings are suggestive of problems with accessing medicines from community pharmacies and a number of issues that delay access have been identified, many of which focus on either pharmacy stock or communication between the pharmacy and HCPs and patients. However, with the exception of one study,36 sample sizes were small and pertained to only a few localities, and there is a lack of data on outcomes of access experiences.

Medicines access and general practitioners

Only one study12 included data on GPs’ experiences of providing medicines access, focusing on delays and the causes of these. Questionnaires were sent to 268 GPs in one city, asking them to select the most common causes of delay from a prespecified list. A total of 111 questionnaires were returned (41% response rate). ‘No delay’ (the only ‘delay’-focused response option) was reported by only 34% of GPs. The most commonly cited factor causing delay was the need to clarify the advice given by the home care team (30.6%), followed by the inability of someone to collect the prescription (23.4%) and 18.9% of respondents reported the patient being unable to attend the surgery as a cause of delay.

Medicines access and community specialist nurse independent prescribers

One interpretive phenomenological study34,35 conducted interviews with six independent nurse prescribers employed as community palliative care CNSs. The study was conducted in one region in England and aimed to understand the lived experience of these nurses prescribing for palliative care patients in the community. The ‘most significant’ perceived benefit of nurse prescribing, reported by all six nurses, was that it enabled patients to access medication quickly, particularly ‘near the end of their life’, leading to effective symptom management. 34,35 The majority of the nurses also considered that it was during OOH that the ability to prescribe independently had the most impact, preventing delays by avoiding the need to call an OOH doctor, which could reportedly take many hours. The authors concluded that ‘[t]he ability of community palliative care CNSs to prescribe can facilitate rapid access to medicines, particularly during OOH periods’. 34,35

Medicines access and hospice emergency medication kits

Three studies40–42 from the USA evaluated the outcome of hospice emergency medication kits (HEMKs) with regard to use, impact and cost. Kits are typically ordered by a physician on referral to hospice care and are kept in the patient’s home. These kits allow the patient access to small quantities of medication that can be administered immediately on nurse instruction. Unlike just-in-case boxes, which are typically used in the UK to manage symptoms in the last few days of life, HEMKs are designed for potential use over a longer period of EoL care, including, for example, antibiotics. Emergency medication kits contain sufficient medications for 12–72 hours, thereby avoiding the immediate need for pharmacy and physician involvement after hours. 41 All studies included an evaluation of the perceived impact of HEMKs, which shed light on their effect on access to medicines. In all studies,40–42 clinicians providing care were asked about the impact of HEMKs on unplanned health-care resource use, with the majority of clinicians suggesting that kits averted use of other services. For example, 93% of the 78 home hospice nurses completing a questionnaire survey in one study42 reported that an emergency department visit or hospitalisation was avoided by having a kit in the home, with 26.1% of hospice nurses reporting that this was ‘often’ and 40.6% reporting that this was ‘very often’. Clinician views on helpfulness and patient satisfaction were also positive across the two studies41,42 measuring this, with 59% of nurses considering HEMKs to be helpful 100% of the time and 100% (n = 13) of the hospices using HEMKs in the other study reporting that it increased both patient and nurse satisfaction. In a comparison of a hospice using HEMKs for some patients with a hospice not using them, Walker and McPherson41 reported that after-hours nurses perceived that caller (i.e. patient/family) satisfaction was significantly higher in hospice patients with a kit than in both the non-kit hospice patients and the HEMK hospice patients without a kit (95%, 75% and 82%, respectively; p < 0.001). This study41 also measured the impact of HEMKs on perceived symptom relief time. Nurses in the hospice using HEMKs estimated that 56% of after-hours callers received symptom relief within 30 minutes, whereas nurses reported that none of their callers from the hospice without kits was treated satisfactorily in < 30 minutes.

Overall, although HEMKs were found to have a positive impact on a number of medicines access indicators in all three studies, including, perhaps notably, shorter time to symptom relief and reduced use of emergency services, all were small scale. Two studies40,41 were confined to a state-wide hospice survey and one study42 focused on a sample from one medical centre only, resulting in overall small numbers of hospices, clinicians and patient records included. In addition, the majority of the data from all studies were limited to clinicians’ perceptions only, with limited objective data and no patient or carer experiences captured.

Discussion

Our review found sparse research in this area. Nine16,34,35,37–42 of the 10 studies were small scale or pilot studies and local samples. Although it is difficult to generalise the results, this review identified several problems in current models and also highlighted potential approaches to improving medicine access.

Studies revealed that issues of medication stock availability at community pharmacies are likely to contribute to access problems. Pharmacies commissioned to provide stocks of locally agreed palliative medicines lists reduced these delays in medicine access. 38 However, the study by Miller38 evaluated only one local service and city area. This confirms that evaluation of these services on a wider scale is warranted. Alternatively, improvements upstream within the supply chain into community pharmacies might also be effective to avoid potential delays, and this is investigated further in Chapter 7. Studies also suggested that a number of problematic issues were linked to communication between pharmacists and patients (e.g. patients’ lack of awareness of services and of information provision about medicines) and/or between pharmacists and other HCPs (e.g. pharmacists’ lack of awareness of patients’ palliative care status and HCPs’ lack of awareness of commissioned pharmacy services).

Three studies40–42 in this review suggested that HEMKs, which comprise a number of palliative care medicines stored in the patient’s home that could be used in an emergency, can avert hospital admissions and emergency department visits and improve quality of care at home by providing timely access during OOH. HEMKs are not used in the UK at present, although the broad principle of anticipatory prescribing was explored in the study.

Community palliative care specialist nurse prescribers were also reported to provide OOH support and quicker medicine access in times of crisis. However, data were confined to one small-scale study34,35 and, therefore, further evidence, including larger-scale samples and insights of other stakeholders, is needed to endorse the value of nurse and pharmacist prescribing in this context.

Overall, conclusions are limited by the quantity and quality of the research conducted to date. Only a few models have been studied and only one study12 used a systems approach, studying different components of service delivery as a whole, with all other studies focussing on only one component. Medicines access provision by professionals such as a generalist CNs and GPs are understudied, as well as more recent initiatives such as specialist-delivered telephone support lines (TSLs) available OOH. Most studies focused on HCP self-report data and only four studies12,37–39 included views of patients. There was very few data on outcomes of medicine access experiences and so comparison between models in this respect was not possible.

Summary

Despite suggestions that accessing palliative care medicines to manage symptoms at home is problematic for patients, the review confirmed that there is very little large-scale or in-depth research into these experiences and how models of service delivery influence access. However, the review was useful in sensitising us to potential issues influencing access to medicines in different service delivery models. These issues are investigated further in phases 2–4, which also included evaluations of both established and more recent service delivery models, and patient and carer perspectives.

Chapter 4 Phase 2: online survey of health-care professionals

This chapter addresses objective 2 of the study. A large-scale online survey was conducted to evaluate professionals’ current practices, identify factors influencing professionals’ contributions and assess the potential of the community-based nurse and pharmacist workforce to improve patient access to medicines.

Parts of this chapter have been reproduced with permission from Latter et al. 43 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Method

An online questionnaire survey was designed using the Checklist for Reporting Results of Internet E-Surveys. 44

Questionnaire design

The systematic narrative review (see Chapter 3) informed questionnaire design. Considering the limited research in this area, we also consulted with clinical and academic experts in the field to identify key issues. The final questionnaire, administered via Online Surveys [URL: www.onlinesurveys.ac.uk (accessed 9 November 2021)], comprised sections that included roles in access provision, in-hours and OOH medicines provision, interprofessional medicines communication, nurse and pharmacist prescribing and, to estimate service effectiveness, impact of access on pain control. Items (one to three per page) comprised closed-ended response formats, including Likert scales, and open-ended items. Questionnaire submission required completion of key filter questions, with descriptive responses optional.

Sample

The target sample comprised a convenience sample of representatives from the main professional (generalist and specialist) groups providing community-based EoL care in England, including GPs, pharmacists working in community pharmacies (i.e. CPs), pharmacists who are employed in general practices [i.e. primary care pharmacists (PCPs)], nurses who specialise in community palliative care (i.e. CNSs) and nurses delivering a range of care in patients’ homes, including palliative care (i.e. CNs).

Recruitment process and access

A survey website link was distributed via e-mail to GPs and pharmacists via research leads employed as part of NIHR Clinical Research Networks (CRNs). Based on estimated numbers of health professionals in a typical CRN, and our target response of 200 participants in each professional group, the link was distributed to GPs in registered research-active general practices in four CRNs (two in the north of England and two in the south of England) and to pharmacists in all 15 CRNs in England. Distribution to pharmacists occurred via various local pharmacist networks operating within the CRNs. Clinical leads for all hospices in England with teams of CNSs delivering community-based palliative care (146/167 hospices in England) distributed the survey via e-mail to their CNS teams, as did clinical leads in seven community trusts that employ CNSs directly. Based on estimated numbers of CNs in a typical community trust, local collaborators in four community trusts (two in the north of England, one in the south of England and one in the east of England) distributed the e-mail survey link to all CNs in the trust. In addition, the survey link was posted on relevant interest groups’ websites [e.g. Association of Supportive and Palliative Care Pharmacy (URL: www.aspcp.uk), ehospice (URL: https://ehospice.com) and the Association for Prescribers (Essex, UK) (URL: https://associationforprescribers.org.uk)] and distributed via newsletters [e.g. Hospice UK’s (London, UK) newsletter]. For general practices, community pharmacies and community trusts, organisational-level participation was captured via NIHR processes, which contributed to overall payments to the CRNs and to the general practices that participated.

Data collection

Data were collected from July to October 2018. Up to three reminders were distributed to maximise responses.

Analysis

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics. For the analysis of the pain control data, we conducted tests of differences in proportions, comparing question 1 (current pain levels) and question 2 (estimated pain levels with improvement to medicines access) responses. We also created a weighted estimate from question 1 data (i.e. pain level estimates across a typical 100 EoL patients who use the service) by multiplying the pain category (no = 0, mild = 1, moderate = 2 or severe = 3) by the proportion of individual respondents estimated would be in those categories (and, therefore, higher values represented higher levels of pain). We then conducted linear regression with the weighted variable as the dependent variable, controlling for the role of the respondent. Statistical analyses were conducted using Stata® (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). A directed content analysis approach was undertaken (by NC and JB) to analyse free-text responses, including quantification. 45

Results

Respondents

A total of 1327 responses from eligible HCPs were received [GPs, n = 499; CNSs, n = 389; CPs, n = 219; PCPs, n = 151; and CNs, n = 99 (note that 30 HCPs were employed as both CPs and PCPs)]. Missing data were very low (< 1% for most questions). All responses provided were used (i.e. there was no case-wise deletion) and no imputation was carried out. All percentages are calculated from responses provided (i.e. excluding missing data).

Medicines access practices

Methods of providing new prescriptions in-hours

Access routes to new prescriptions for palliative care medicines during working hours are shown in Table 1. (These medicines were defined as regular and as-necessary medicines, administered via all routes for symptom management during the last year of life, excluding ‘just-in-case’ boxes. 46) Most nurses and GPs were providing home visits for patients to issue new prescriptions. Large numbers of all professional groups were also providing consultations by telephone and a significant minority also reported using e-mail. Over 93% of all professional groups used referral to a GP as a route for patients to access medicines. Large proportions of all professionals also cited referral to a nurse prescriber. Table 1 also shows a relatively high level of engagement in helping to provide new scripts by PCPs. Fifty-two per cent (79/151) of the PCP sample also reported advising patients/carers about palliative care medicines [43% (65/151) did not] and 63% (95/151) reported engagement in systematically reviewing medicines prescribed for palliative care patients [32% (49/151) did not].

| Which of the following are you able to provide for patients to obtain new prescriptions during working hours? Please select all options you use: | Survey respondent, n (%) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | CN | GP | PCP | CP | |

| Personal home visits | 349 (92) | 82 (93) | 484 (98) | 52 (43) | 49 (35) |

| Telephone consultations | 335 (88) | 78 (91) | 498 (100) | 134 (96) | 147 (85) |

| E-mail consultations | 79 (24) | 8 (10) | 169 (35) | 32 (28) | 63 (43) |

| GP practice appointments | 168 (51) | 43 (56) | 496 (100) | 122 (91) | 44 (38) |

| Community pharmacy appointments | 37 (12) | 11 (15) | 118 (29) | 28 (29) | 131 (73) |

| Referral to nurse prescriber | 194 (58) | 69 (78) | 286 (65) | 102 (78) | 101 (62) |

| Referral to pharmacist prescriber | 64 (20) | 21 (26) | 149 (34) | 66 (65) | 81 (53) |

| Referral to GP | 375 (97) | 92 (96) | 351 (95) | 147 (100) | 185 (93) |

Overall, many respondents were satisfied with their ability to support patients to obtain new prescriptions during working hours. Fifty-seven per cent (762/1327) of respondents were extremely or very satisfied, especially GPs (386/499, 77%); however, 43% (567/1327) of the sample were somewhat, slightly or not at all satisfied.

Nurse and pharmacist prescribing

Of nurse and pharmacist respondents, 42% (160/386) of CNSs, 27% (27/99) of CNs, 76% (114/151) of PCPs and 16% (36/219) of CPs were qualified as independent prescribers. The most common reasons for not training as a prescriber were the cost of training (155/508, 31%), lack of employer/colleague support (122/508, 24%), no backfill of their post available while attending training (92/508, 18%) and no designated clinically based trainer available (80/508, 16%).

Of the nurse and pharmacist respondents, CNSs prescribed most frequently, with two-thirds (86/130, 66%) of CNSs prescribing at least two or three times per week, whereas two-thirds of the CNs (14/22, 64%), PCPs (60/87, 69%) and CPs (12/20, 60%) prescribed only once per month (or less). Analgesics, antiemetics and laxatives were identified as the most frequently prescribed medicines by all the nurse and pharmacist prescriber professional groups. For all respondent groups, the majority (206/244, 84%) prescribed CDs, ranging from 96% (125/130) of CNSs to 69% (60/87) of PCPs.

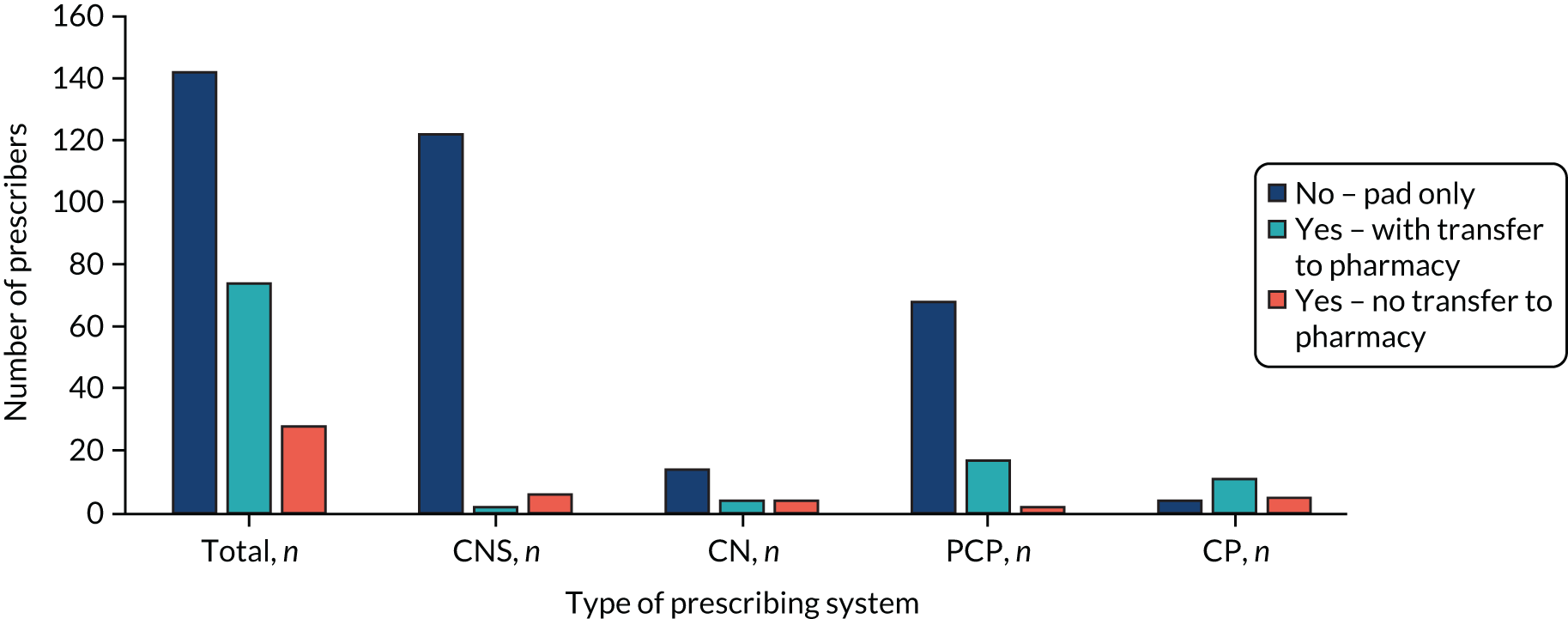

The majority (142/244, 58%) of prescribing nurses and pharmacists were not able to use an electronic prescribing system (Figure 3). Most CNS prescribers were restricted to writing prescriptions by hand via a paper prescription pad. Only a minority of all nurse and pharmacist respondent groups were able to prescribe electronically and transfer this electronically to the pharmacy.

FIGURE 3.

Nurses’ and pharmacists’ ability to prescribe electronically.

Out-of-hours services for medicines access

When asked if there was CNS service provision 7 days per week in their area, overall, 49% (656/1327) of respondents responded yes, 18% (239/1327) stated no provision and 33% (434/1327) were unaware whether or not there was provision. Of note, 76% (166/219) of CPs, 72% (109/151) of PCPs and 33% (167/499) of GPs were not aware. Twenty per cent (76/389) of CNS respondents reported covering 18.30 to 08.00 weekdays and 71% (276/389) reported covering weekends and bank holidays. For CNs, cover was 43% (43/99) and 67% (66/99), respectively.

Respondents were also asked how effective CNS 7 days per week cover was at facilitating OOH access to medicines for patients. Overall, 43% (280/656) of respondents rated CNS cover as extremely or very effective, 36% (235/656) reported cover as somewhat effective and 22% (141/656) reported cover as only slightly or not at all effective. Analysis of comments indicated that CNSs’ ability to prescribe medicines seemed to be critical in their perceived effectiveness, and, for some, this also interacted with access to pharmacy stocks to influence speed of access.

When asked about confidence in their ability to advise patients how to best access palliative care medicines OOH, nurses, particularly CNSs, tended to rate themselves as most confident. Seventy-nine per cent (307/389) of CNSs were extremely or very confident, as were 61% (61/99) of CNs. Pharmacists were less confident, with 30% (45/151) of PCPs and 39% (86/219) of CPs rating themselves as extremely or very confident. Although 47% (236/499) of GPs reported being extremely or very confident, 35% (177/499) were only somewhat confident and 18% (86/499) were slightly or not at all confident.

Community pharmacy-commissioned service provision

Table 2 shows the provision of commissioned palliative care medicines services by CP respondents (n = 219).

| If you are a CP in a community pharmacy, do you provide a commissioned service for palliative care (e.g. on-demand availability of specialist drugs)? | Yes, n (%) | No, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Commissioned servicea | 67 (31) | 148 (68) |

| Of those with a commissioned service | ||

| Stocking a locally agreed list of core palliative care medicines | 62 (93) | 5 (7.5) |

| OOH availability of palliative care medicines from your pharmacy | 32 (48) | 35 (52) |

| OOH availability of palliative care medicines from other linked pharmacies in your area | 19 (28) | 48 (72) |

| Provision of information on the service to other pharmacy contractors plus HCPs to signpost patients to the service | 47 (70) | 20 (30) |

| Provision of information on the service to patients plus carers directly | 41 (61) | 26 (39) |

Most services included stocking a core list of agreed palliative care medicines. A smaller proportion of services – approximately half – reported providing OOH medicines from their own pharmacy and 28% (19/67) via a linked pharmacy in their area. Around two-thirds of the sample reported providing information on the service to HCPs (47/67, 70%) and directly to patients and carers (41/67, 61%).

In contrast, when asked whether or not they were aware of commissioned services for palliative care medicines, overall, 39% (517/1327) of all HCPs stated yes, 9.2% (122/1327) reported no provision and 52% (690/1327) were unaware. GPs, especially, lacked awareness (340/499, 68%). However, when respondents were aware, the vast majority (433/517, 84%) considered that the service facilitates speed of access to medicines for patients.

Factors influencing medicines access service provision

Prescribing competence

Overall, just under two-thirds (518/819, 64%) of the sample reported feeling very competent (373/819, 46%) or extremely competent (145/819, 18%) in prescribing palliative care medicines, with 27% (217/819) feeling somewhat competent and 10% (84/819) reporting feeling slightly or not at all competent. CNS respondents reported greatest competence, with 84% (132/157) feeling very or extremely competent. Seventy per cent (347/498) of GPs reported feeling very or extremely competent, with almost one-third (142/498, 29%) rating themselves as somewhat competent. Over one-third (10/25, 40%) of CNs reported feeling very or extremely competent, with 48% (12/25) reporting that they were somewhat competent. Pharmacists reported less competence, with only 22% (24/109) of PCPs and 14% (7/49) of CPs reporting feeling extremely or very competent.

Access to patient records

Experience of access to shared patient records for communicating about medicines is shown in Table 3.

| Do you have access to shared patient records for communication about medicines access between health professionals? Tick all that you are able to access | Survey respondent | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CNS | CN | GP | PCP | CP | |||||||||||

| Paper, n (%) | Electronic, n (%) | None, n (%) | Paper, n (%) | Electronic, n (%) | None, n (%) | Paper, n (%) | Electronic, n (%) | None, n (%) | Paper, n (%) | Electronic, n (%) | None, n (%) | Paper, n (%) | Electronic, n (%) | None, n (%) | |

| GP records | 22 (5.7) | 203 (52) | 173 (44) | 5 (5.1) | 77 (78) | 18 (18) | 14 (9.3) | 145 (96) | 2 (1.3) | 10 (4.6) | 62 (28) | 149 (68) | |||

| GP OOH records | 8 (2.1) | 117 (30) | 264 (68) | 1 (1.0) | 60 (61) | 38 (38) | 72 (14) | 349 (70) | 86 (17) | 13 (8.6) | 100 (66) | 39 (26) | 6 (2.7) | 21 (9.6) | 192 (88) |

| CN records | 77 (20) | 218 (56) | 105 (27) | 39 (7.8) | 281 (56) | 186 (37) | 7 (4.6) | 97 (64) | 48 (32) | 1 (0.5) | 15 (6.9) | 203 (93) | |||

| Hospice/palliative care specialist records | 3 (3.0) | 66 (67) | 30 (30) | 46 (9.2) | 154 (31) | 304 (61) | 20 (13) | 58 (38) | 77 (51) | 3 (1.4) | 12 (5.5) | 204 (93) | |||

| CP records | 2 (0.5) | 18 (4.6) | 369 (95) | 1 (1.0) | 8 (8.1) | 90 (91) | 12 (2.4) | 29 (5.8) | 458 (92) | 4 (3.3)a | 9 (7.4)a | 108 (89) | |||

| SCRs | 23 (5.9) | 153 (39) | 219 (56) | 2 (2.0) | 60 (61) | 37 (37) | 26 (5.2) | 417 (84) | 59 (12) | 6 (4.0) | 138 (91) | 8 (5.3) | 13 (5.9) | 198 (90) | 8 (3.7) |

Data revealed a variable picture. Those based in general practice (i.e. GPs and PCPs) had relatively high levels of access. However, CNSs reported limited access to others’ records, whether paper or electronic, with 44% (173/389) reporting no access to GP records and 68% unable to access GP OOH records.

Satisfaction with access to shared records to facilitate medicines access reflected these results. Thirty-nine per cent (507/1327) of respondents, overall, were either not at all or only slightly satisfied. CNSs and CPs were especially likely to rate access as not at all satisfactory, with half (193/389, 50%) of all CNSs reporting that they were either not at all or only slightly satisfied.

Impact of nurse and pharmacist prescribing

Overall, just over half of respondents considered that prescribing by a nurse or pharmacist consistently had a beneficial impact on palliative care medicines access, with 21% (283/1327) and 34% (445/1327) of respondents considering prescribing by a nurse or pharmacist as always or often beneficial, respectively. However, one-quarter of GPs (124/499, 25%), 29% (44/151) of PCPs and 26% (58/219) of CPs reported that they did not know about the impact of this initiative on access to medicines, with comments reflecting their lack of, or limited experience of, these services.

Community pharmacy provision of palliative medicines

Table 4 shows the results of CP respondents’ opinions on issues identified in our review of the literature that may, potentially, have an impact on their ability to facilitate access to medicines, confirming that several issues were problematic in practice.

| How frequently do you | Never, n (%) | Rarely, n (%) | Sometimes, n (%) | Often, n (%) | Always, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Undertake medicines optimisation reviews for palliative care patients | 61 (28) | 65 (30) | 52 (24) | 26 (12) | 13 (6.0) |

| Feel that lack of awareness of patients’ palliative status influences your ability to help patients access medicines | 13 (6.0) | 22 (10) | 71 (33) | 87 (40) | 25 (11) |

| Encounter a discrepancy between palliative care medicines prescribed and the stock you hold | 12 (5.5) | 36 (17) | 76 (35) | 79 (36) | 14 (6.5) |

| Limit your stock of palliative care medicines because ‘use by’ dates are likely to expire | 27 (12) | 37 (17) | 47 (22) | 67 (31) | 40 (18) |

| Limit your stock of palliative care medicines because of lack of storage space | 63 (29) | 59 (27) | 38 (18) | 41 (19) | 15 (6.9) |

| Experience problems receiving Rx electronically from patients’ general practices | 28 (13) | 40 (18) | 65 (30) | 51 (23) | 34 (16) |

| Encounter carers not having satisfactory ID, seeking to collect CD prescriptions for patients | 16 (7.3) | 68 (31) | 73 (33) | 51 (23) | 10 (4.6) |

Service delivery solutions

A total of 909 (69%) respondents responded that there were solutions to problems with service delivery. Seven hundred and three of these respondents provided an analysable description of proposed solutions, with between one and six (mean 1.55; median 1) solutions in each response, generating 1087 ‘solutions’, which were thematically coded. Solutions were coded within 17 themes and ranged from 173 respondents (i.e. the most frequently cited) to four respondents (i.e. the least frequently cited). The top four themes (all cited by ≥ 145 respondents) are highlighted in Table 5 (note that the next most cited theme was notably lower with 96 respondents).

| Are there possible solutions to any gaps or problems with service delivery? | Number of respondents |

|---|---|

| Theme 1: improved pharmacy provision | 173 |

| Improved community pharmacy-delivered commissioned services for palliative care | |

| 24-hour community pharmacy provision, local availability, sufficient stocks and improved delivery from distributors | |

| Improved use of PCPs | |

| Theme 2: more non-medical prescribers | 162 |

| Palliative care specialist nurses, CNs and pharmacists (i.e. palliative care specialist pharmacists and PCPs) | |

| Increased funding, training places and support | |

| Greater availability OOH | |

| Systems to support non-medical prescribers to be active | |

| Theme 3: shared electronic records | 148 |

| Universal integrated systems and access, and timely updating | |

| Sharing across health-care providers (i.e. generalist and specialist palliative care, primary and secondary care, and in-hours and OOH) | |

| Theme 4: integrated HCP working | 145 |

| Between generalists (GPs, OOH GPs, CNs, PCPs, CPs) and specialist palliative care | |

| Between prescribers and CPs (regarding formularies and stock levels) | |

| Between CCGs/LPCs and community pharmacies and prescribers (regarding improved strategic management/guidance for medicine shortages) | |

| Signposting to community pharmacy OOH services |

A total of 173 respondents focused on the need for improved pharmacy provision to aid medicines access. Of these respondents’ solutions, 107 were specific to commissioned services for palliative care, including adequate incentives for provision (e.g. comprehensive reimbursement of costs), more pharmacies with this provision and related locality-based provision (e.g. one commissioned service pharmacy per locality), signposting of these services to HCPs and patients/carers (facilitating wider awareness of the services), improvements in stock availability (and related formularies to enable adequate stock levels), improved OOH access to services, audits of service provision and palliative care training of commissioned pharmacist service providers.

A total of 162 respondents addressed the need for greater numbers of palliative care specialist nurses, CNs and pharmacists to be prescribing. Responses from GPs appeared to demonstrate support for greater levels of nurse and pharmacist prescribing, particularly by palliative care specialist nurses. This was viewed as aiding faster access to medicines, as the prescription is provided as part of the patient assessment visit, while also improving care and prescribing safety through not having to relay messages about prescribing between different services.

A total of 148 respondents stated the need for access to shared electronic records to facilitate good practice in prescribing and informed patient assessment, as well as improved information-giving to patients/carers about medicines and related access. Record-sharing was key to providing timely access to medicines. Record-sharing was particularly important for CPs who desired shared electronic records access to be aware of an individual’s palliative status, enabling them to ‘answer quite a lot of the questions that can be raised’ by patients/carers about medicines and access to them.

Access to shared electronic records was also a crucial component of integrated HCP working (as stated by 145 respondents). Fragmented care delivery led respondents to state solutions that focused on the need for integrated working between all members of the multidisciplinary team (MDT) (including CPs), generalist and specialist palliative care providers (including methods of achieving this, such as joint patient visits and palliative care register-related meetings), prescribers and CPs (to ensure pharmacist awareness of local palliative care prescribing recommendations and appropriate stocks to meet needs), and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)/Local Pharmaceutical Committees (LPCs), community pharmacies and prescribers (to enable strategic management of medicine shortages).

Perceived effectiveness of service and impact of barriers

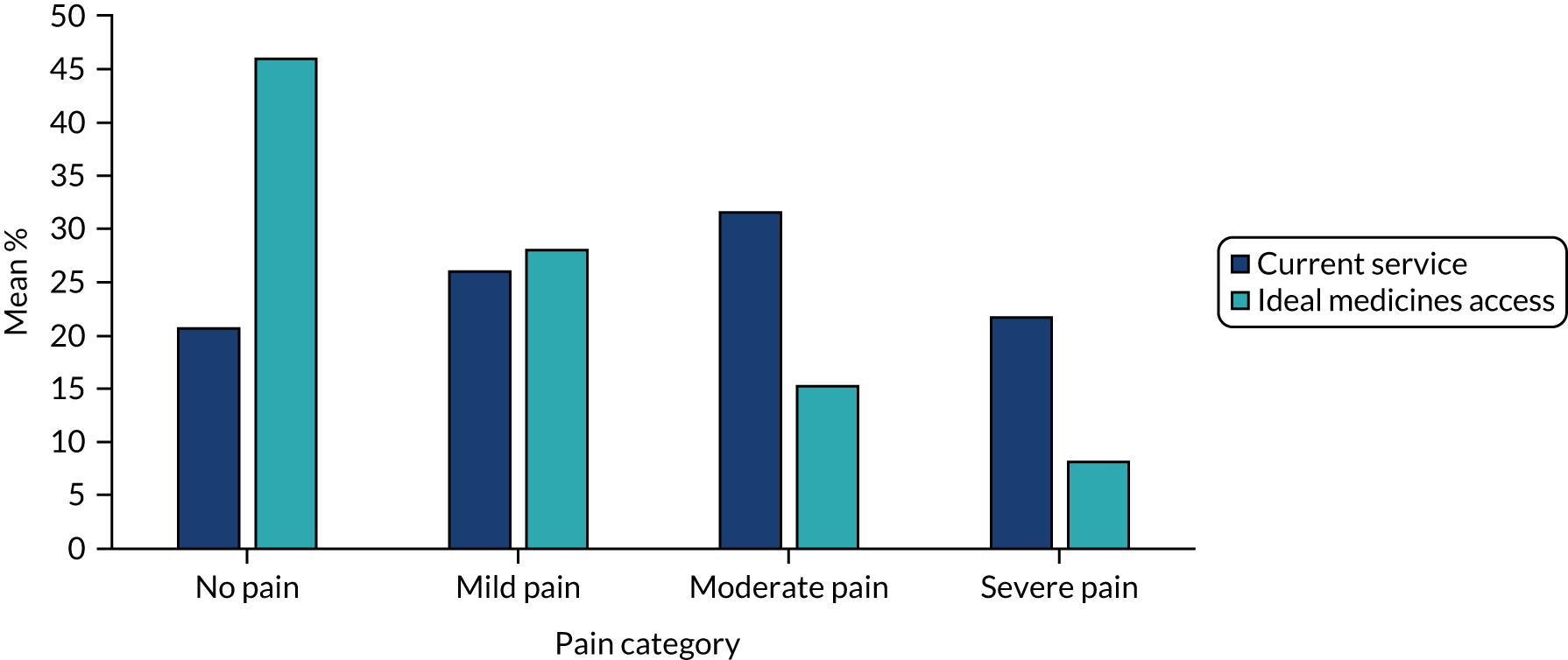

Respondents were asked to estimate the proportion of their patients who currently experienced no, mild, moderate and severe pain (question 1). Respondents were then asked to re-estimate these proportions following removal of barriers to medicines access (question 2). Figure 4 shows that there would be a significant perceived improvement in pain control with better medicines access (no pain, p = 0.0018; mild pain, p-value not significant; moderate pain, p = 0.026; severe pain, p = 0.047). However, missing data for these questions were higher than for other questions (18% and 23%, respectively) and a further 10% of respondents provided invalid answers to both questions (i.e. data that did not sum to 100).

FIGURE 4.

Mean proportions of responses across pain categories for the estimated effectiveness of current and improved medicines access. 43 Reproduced with permission from Latter et al. 43 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The figure includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original figure.

There was a clear impact of respondent role in data from questions 1 and 2, with pharmacists indicating that they see higher proportions of patients with poor pain control. This was likely an artefact of ‘case mix’ rather than service effectiveness. We tested the impact of various service factors on weighted question 1 response. After controlling for role, there were few statistically significant predictors of pain control outcomes. However, respondents within services with access to GP records or SCRs47 reported significantly lower pain estimates than respondents without access (p = 0.005 and p = 0.009, respectively).

Summary

Although only indicative, our results are suggestive of an impact of access to medicines on patient outcomes (e.g. level of pain control). The results also show that a range of HCPs and routes are currently being used to support patient access to palliative care medicines, but there is potential to increase the scale and effectiveness of these through addressing the barriers highlighted. These include training larger numbers of the nursing and pharmacist workforce to prescribe using electronic systems, as well as ensuring better access to shared electronic patient records across professional groups. This needs to take place alongside attention to tackling the impediments that currently reduce the effective provision of community pharmacy and community pharmacy-commissioned medicines services. Finally, greater team integration and communication, including improved awareness (among GPs and pharmacists in particular) of existing service provision, is warranted.

Chapter 5 Phase 3: case studies of service delivery models

Parts of this chapter are reproduced or adapted with permission from Campling et al. 48 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

This chapter addresses objectives 3–6, utilising comparative case study design with an analytic focus on service delivery models, specifically patient and carer experience of medicines access, cost-effectiveness, patient medicine access pathways, and barriers to and facilitators of maximising the contribution of the nursing and pharmacist workforce to medicine access. The chapter begins with an overview of the methods utilised across the sites, followed by a detailed description of each service delivery case study, together with the application of methods and the findings from each case.

Method

Sampling of case sites

Four service delivery models were purposively selected, informed by survey results:

-

general practice

-

community palliative care CNS with a nurse independent prescriber (NIP) qualification

-

community pharmacy-delivered commissioned services for palliative care

-

palliative care 24/7 TSL.

This ensured that a range of service delivery models were included, covering traditional models of service delivery (i.e. case 1) and those with more innovative characteristics (i.e. cases 2–4).

Sampling, data collection and analysis of subunits

Cases 1, 2 and 4

The sample size was determined by the goal of analytical, rather than statistical, generalisability and based on a requirement to achieve data saturation within the case (interviews) and pattern match data in the patient records. 49 Internal generalisability within each case was maximised by sampling patients/carers who were considered to be representative of others in the case. 50

The unit of analysis was the service delivery model, with embedded subunits of analysis.

Prospective data from up to 10 patients (and their carers, when appropriate) were sampled within each case study service model. The eligibility criteria for patients were as follows:

-

no longer receiving curative treatment (e.g. individuals listed as palliative on a palliative care register or CNS caseload)

-

in receipt of prescribed medicines for symptom management

-

living in their own home or in a home of a relative (but not a nursing or care home, or hostel, or individuals who are homeless)

-

survival could be reasonably anticipated to be no less than 12 weeks

-

able to give informed consent

-

able to speak and write English.

Patients/carers were asked to complete a structured log on medicines access experiences over an 8-week period from recruitment into the study. The logs collected data regarding obtaining prescriptions and medicines, plus supporting information, both in-hours and OOH. These logs supplemented and/or were an aide memoire to sequential interviews with patients/carers conducted at study entry and at 4 and 8 weeks. Interview guides and log data collection were informed by PPI feedback. Interview data were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using a framework analysis (see Appendix 2). 51 An initial coding framework was constructed from the interview guides and then developed inductively from the data to identify main themes (NC at site 1, JB at sites 2 and 4, and NC and ZE at site 3).

Health-care professionals who were providers of EoL care in the case study service model were purposively sampled and invited to take part in a semistructured interview, either individually or in a group. HCPs were asked about their experiences of facilitating access to medicines, including barriers and facilitating factors. Interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and analysed using a framework analysis51 (see Appendix 2).

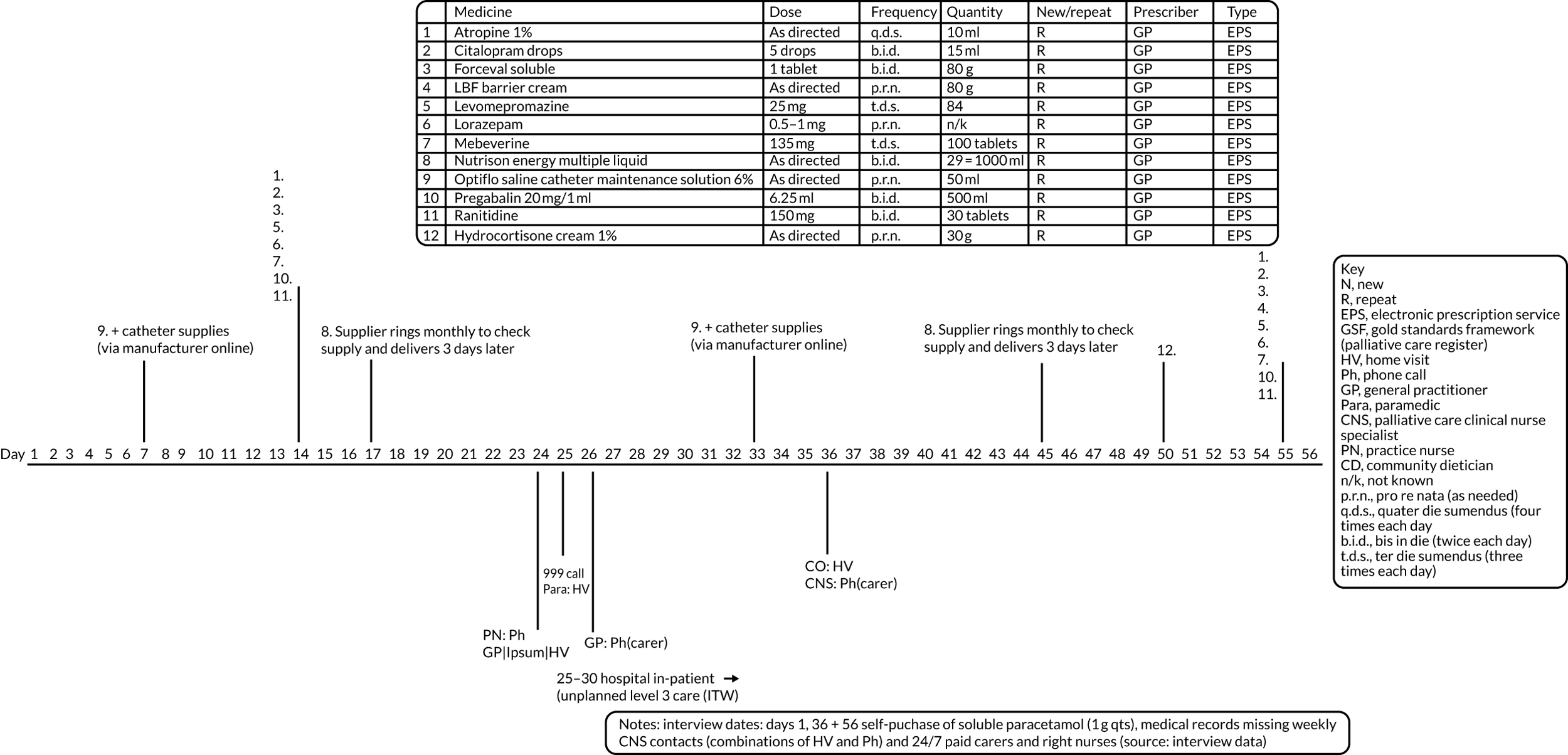

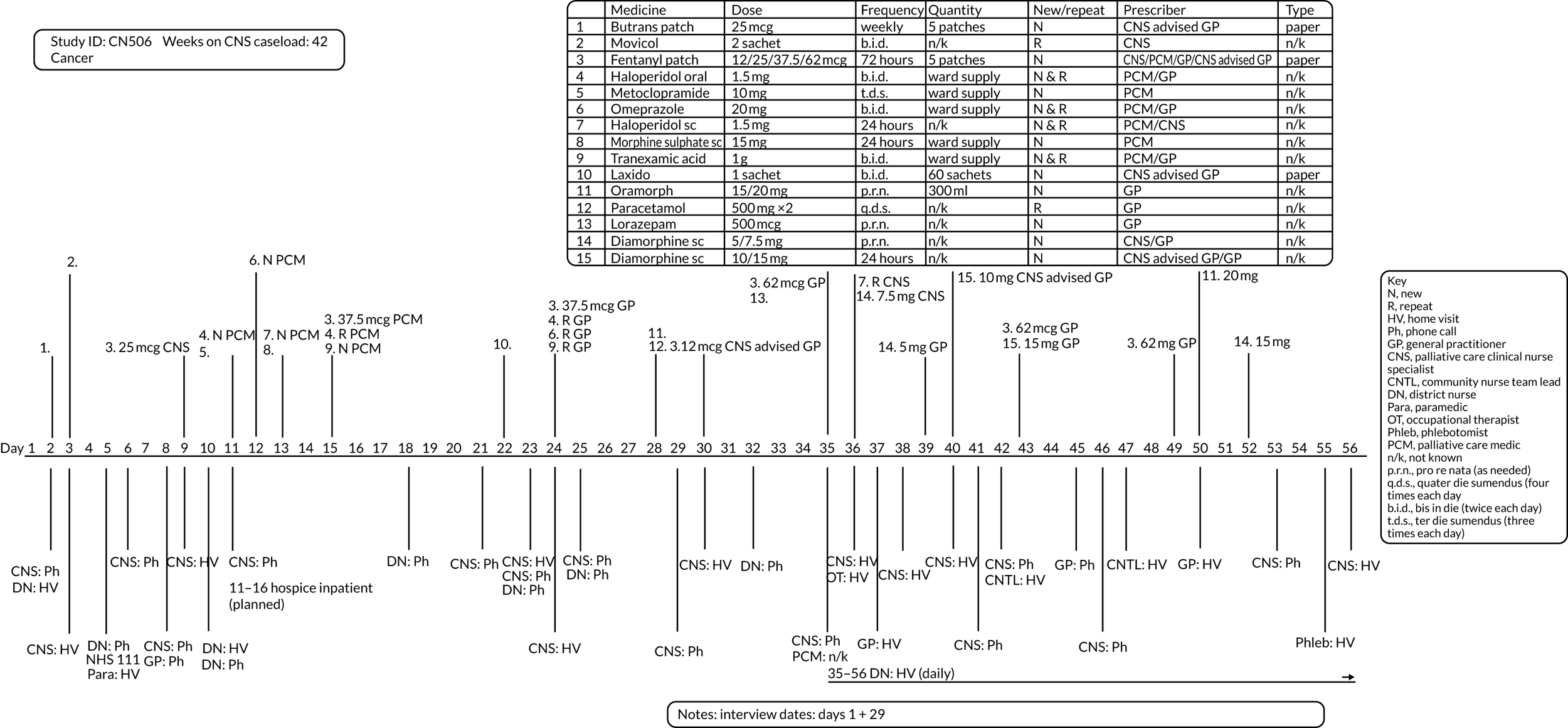

A retrospective convenience sample of up to 40 patient records (including patients taking part in recording logs and interviews) were reviewed. Data were extracted on medicines prescribed (including when and by whom) and services used (including OOH, unplanned or emergency services, and hospice or hospital admissions). For health economics analysis, see Chapter 6. Annotated timelines for each patient were also constructed when possible, with HCPs accessed, prescribing decisions and services used, to understand medicines access processes. 52

Case 3

Case 3 focused on community pharmacy-delivered commissioned services for palliative medicines. The data collection methods for this case differed from cases 1, 2 and 4. Data from phases 1 and 2 indicated that this was an important model to evaluate in more depth. However, scoping work highlighted that it was not feasible to identify and recruit patients using these services from general practices. For example, a palliative care patient from the typically small number registered with any one general practice is likely to use more than one community pharmacy, and/or patients using a particular commissioned service pharmacy are likely to be registered with a large number of general practices. In addition, our data suggested that CPs are often unaware which patients using their service are receiving palliative care. We were aware that documentary data on these services were publicly available, and that service commissioners were likely to have important insights into how these services have an impact on access to medicines. Therefore, this case focused on qualitative interviews across three sample groups, supplemented by documentary analysis. Sample groups were (1) CPs providing commissioned services, (2) commissioners of these services and (3) community-based HCPs [e.g. palliative care CNSs, CNs, CPs (not providing commissioned services) and GPs].

For details of the health economic evaluation, please see Chapter 6.

Case study data analysis

Data from within each case were triangulated (i.e. data source and method triangulation) to build in-depth contextual understanding of medicines access experiences in each delivery model. 53

Cross-case comparison

On completion of data analysis for each case, cross-case comparison was utilised for pattern matching and theory-building. 49 This comparative evaluation was developed through the construction of logic models for each case and against a framework of indicators characterising good practice in medicines access. This framework was informed by the phase 1 systematic review, the phase 2 survey, our PPI consultation and relevant national standards. 20,24 The framework included indicators such as speed of access to medicines; patient and carer burden (e.g. time, travel, cost, psychological distress) experienced in accessing medicines; number and type of contacts required before a medicine is supplied; accessibility, ease of use and comprehensiveness of information sources; and use of OOH, unplanned or emergency services. The framework was used to help evaluate each case and to enable systematic comparisons across service delivery types (see Appendices 8, 16, 19 and 24 for logic models for each case).

Case 1: general practice

Method

The case

The unit of analysis was services in which GPs were the main (usually sole) community-based prescriber. This unit of analysis was selected as representative of typical service delivery for community-based palliative patients.

Sampling