Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HSDR programme or one of its preceding programmes as award number 17/05/26. The contractual start date was in August 2019. The draft manuscript began editorial review in August 2022 and was accepted for publication in June 2023. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HSDR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ manuscript and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the draft document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this article.

Permissions

Copyright statement

Copyright © 2024 Bellass et al. This work was produced by Bellass et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This is an Open Access publication distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution CC BY 4.0 licence, which permits unrestricted use, distribution, reproduction and adaptation in any medium and for any purpose provided that it is properly attributed. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. For attribution the title, original author(s), the publication source – NIHR Journals Library, and the DOI of the publication must be cited.

2024 Bellass et al.

Chapter 1 Introduction

The prison population in England and Wales has almost doubled since 1990 to just under 80,000 people,1 with Government projections suggesting that this figure will continue to rise, reaching 98,700 by 2026. 2 People who enter prisons have often experienced multiple social and economic disadvantages which contribute to significantly higher levels of substance use, mental illness, infectious diseases and long-term conditions than in the population as a whole. 3,4 Although English prisons represent an opportunity to reduce these health inequalities,5 their failure to provide equivalent standards of care and achieve equivalent health outcomes – principles enshrined in international standards6 – has led to calls by the UK Government for the development of quality indicators to measure the extent of inequities between prison and community populations. 7

Multiple challenges exist, however. At the time of writing, performance measurement in prisons utilises the Health and Justice Indicators of Performance (HJIPs) framework, which somewhat increases the transparency of prison healthcare delivery8 and enables assessment of performance across prisons, but inhibits comparability with community primary care. Further, use of the quality and outcomes framework (QOF), which incentivises the achievement of evidence-based (EB) quality indicators through linked remuneration in community primary care,9 is not contractually mandated in prisons through commissioning frameworks. QOF monitoring activities are therefore reliant on individual clinicians’ motivation,10 leading to variability in performance measurement across the prison estate and constraints on the ability to compare community and prison populations. Finally, while the logistics of performance measurement and comparison are challenging in themselves, questions also remain about the interpretation of the principle of equivalence, and how the balance between measurement of care processes and health outcomes should be struck. Selecting sets of performance indicators requires rigorous and transparent consultative processes, yet little has been published on the prioritisation of prison healthcare indicators, and within this limited body of literature, selection processes are largely obscure.

Relatively little research has examined the quality of primary care provided in prisons11 to allow comparisons to the general population, or to explore ‘routine’ primary care rather than focusing on health issues commonly associated with the prison population, such as substance use or mental illness. Exceptions include Silverman-Retana et al. ,12 who found lower achievement on process of care indicators for a cohort of men with diabetes or hypertension in Mexico City compared to when they lived in the community, and McConnon et al. ,13 who found that people in Ontario who had been incarcerated were more likely than people who had not to be overdue for colorectal screening and breast cancer screening. As the UK prison population ages (the proportion of over 50s has risen from 7% in 2002 to just under 17% in 2021),2 reflected in the fact that non-communicable diseases (NCDs) have superseded suicide as the leading cause of mortality in English and Welsh prisons,3 a greater focus on routine primary care is warranted.

Similarly, there are limited data available on National Health Service (NHS) national screening or risk-assessment programmes in prison,14 yet prison leavers are more likely to be disproportionately affected by risk factors for NCDs,10,15,16 face barriers for care continuity across the prison–community interface10 and to have poorer health outcomes. 17,18 Further, there is limited evidence on factors affecting uptake of health care, although existing research suggests that the prison environment, patient gender, length of stay and ethnicity can all impact on patterns of utilisation. 19–21 Understanding variability across prisons, and how health care may perpetuate or exacerbate health inequalities, will provide important insights into how quality could be improved and inequalities reduced for this vulnerable population.

The Understanding and Improving the Quality of Primary Care in Prison (Qual-P) study was commissioned by the National Institute for Health and Care Research (NIHR) to explore gaps and variations in the quality of primary care for people in prison and identify quality-improvement interventions to promote high-quality prison care. The objectives were:

-

to identify candidate quality indicators based on current national guidance which can be assessed using routinely collected data through a stakeholder panel;

-

to explore perceptions of quality of care, including barriers to and enablers of recommended care and quality indicators, through qualitative interviews involving both ex-prisoners and prison healthcare providers;

-

to assess the quality of primary care provided to prisoners through quantitative analysis of anonymised and routinely held prison healthcare records;

-

to integrate the above findings within a stakeholder consensus process in order to prioritise and enhance quality-improvement interventions which can be monitored by our set of quality indicators.

In addition, the study team responded to a call from the NIHR for researchers to conduct further analyses of existing data pertaining to mental health (MH). The team was subsequently awarded an extension to the original project to conduct a secondary analysis of the qualitative interview data, and to compare achievement on physical health indicators for people diagnosed with mental illness and/or receiving psychotropic medication with achievement for people with no coded mental illness or prescription for psychotropic medication.

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 reports the findings of the scoping review of quality indicators in the prison setting.

Chapter 3 outlines an expert consultation process on indicator prioritisation.

Chapter 4 presents the findings from the qualitative work package (WP) (objective 2), exploring barriers and enablers to quality care from the perspectives of healthcare staff and people who have lived in prison.

Chapter 5 describes findings relating to the third objective, the quantitative analysis of healthcare records from 13 prisons in the North of England.

Chapter 6 integrates the findings from all prior WPs.

Chapter 7 describes the findings from the additional MH workstream, involving supplementary quantitative and qualitative analyses.

Chapter 8 brings the findings from across all WPs together and discusses what they mean on a higher level, with reference to the literature, and briefly concludes the whole report.

Chapter 2 Scoping review

Introduction

A scoping review was undertaken to identify and synthesise previous work conducted on quality indicators and performance measurement in the prison setting. The focus of the review was on the selection, development, implementation and review of quality indicators and performance measures. Our research question was: what is known from the research literature about the development and selection of quality indicators for primary health care in the prison setting?

Some material from this chapter has been reproduced from Bellass et al. (2022).

Bellass S, Canvin K, McLintock K, Wright N, Farragher T, Foy R, Sheard L. Quality indicators and performance measures for prison healthcare: a scoping review. Health Justice 2022;10(1):13. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40352-022-00175-9

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CCBY 4.0) which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Method

Scoping reviews are increasingly being used in health research to map the contours of knowledge on a particular topic. 22,23 However, in comparison to systematic reviews, which benefit from clearly articulated and replicable procedures, scoping review methodology has historically been less well-defined, resulting in considerable variability in approach and rigour. 23–27 In addressing the lack of consensus around scoping review methods, Arksey and O’Malley24 established a six-stage framework for conducting a scoping review, comprising identifying the research question, literature searching, selection of studies, charting the data, collating and reporting the results, and an optional stage of validating the review findings through stakeholder consultation. In comparison to systematic reviews, they suggest, scoping reviews typically have broader, more exploratory questions, are more inclusive in terms of study designs, and do not exclude studies based on an assessment of methodological rigour.

Other authors since have sought to expand Arksey and O’Malley’s work,24 offering further detail to the stages within the framework,25,27 for example, emphasising clarification of the focus of the question and the rationale of the study, and recommending a combination of independent reviews and team discussions to enhance the rigour of the process. Tricco et al. 26 called for standardised reporting of scoping reviews to increase transparency, which has resulted in the publication of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews [PRISMA-ScR (www.prisma-statement.org/Extensions/ScopingReviews)],28 an adaptation of the PRISMA statement originally created for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (www.prisma-statement.org/). The PRISMA-ScR items were used to guide the scoping review reported here.

Eligibility criteria

The following criteria were developed to determine which sources would be eligible for inclusion in the review:

Inclusion criteria:

-

any type of literature that relates to the selection, development, implementation or review of quality indicators in the prison setting (either adult or juvenile);

-

in empirical papers, any research method employed;

-

any health condition;

-

published between January 2004 and December 2019;

-

English language only;

-

international literature.

As the specific focus of the review is performance measurement and the use of quality indicators in prisons, literature meeting the following criteria were excluded:

Exclusion criteria:

-

community criminal justice settings;

-

literature relating to the transition from prison to the community.

Information sources and search strategy

A published search strategy aimed at identifying primary care quality indicators for people with serious mental illness using three key concepts (primary care, quality indicators and serious mental illness)29 was adapted by an Information Specialist to include search terms relating to prison settings and exclude those relating specifically to serious mental illness. Hence, the search strategy (see Appendix 1 for the MEDLINE and CINAHL versions) was structured around three key concepts: quality indicators, primary care and prison. Boolean operators were used to combine synonyms in the concept groups with OR prior to combining the three groups of search results with AND.

It should be noted that in American literature, the term ‘prison’ is used differently to the UK context. In the USA, ‘prison’ typically refers to a confinement facility operated by the state or the Federal Bureau of Prisons, and usually houses people convicted of serious crimes. In contrast, jails in the USA are governed locally and accommodate people on remand or convicted of less serious crimes who are therefore likely to have short stays. The term ‘corrections’ is used in the USA to encompass both prisons and jails. The use of the term ‘prison’ in this review relates to the UK context and acts as an equivalent to the US word ‘corrections’.

Six databases were selected by the Information Specialist for their likelihood to index articles relating to quality indicators or to health quality in prisons: CINAHL, MEDLINE, Criminal Justice Abstracts, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Scopus. Searches were conducted separately for each database, using the Ebsco search for Criminal Justice Abstracts, the Ovid search for PsycInfo and EMBASE, and then adapting the search syntax for Scopus. Searches were conducted up to April 2021 by the Research Fellow (SB).

Additional methods of literature identification were conducted to augment the electronic search strategy. Four key journals (International Journal of Prisoner Health, Journal of Correctional Health Care, The Prison Journal and British Journal of General Practice) were hand-searched. In addition, the institutional profiles of seven key authors were examined for further relevant publications. Finally, forwards and backwards citation tracking was conducted on an initial group of 12 influential papers.

Search results were managed and de-duplicated in EndNote X9.

Study selection

The de-duplicated search results were divided equally between the Research Fellow (SB) and the Programme Manager (KC). Both researchers reviewed the abstracts of papers excluded by the other. As an additional check, a further search using the EndNote Quicksearch function was undertaken in the excluded groups using keyword/key phrase searches (e.g. performance measurement, quality indicators) to ensure that no papers containing these terms had been erroneously excluded.

Abstracts of literature that were identified from supplementary searches, that is, journal searches, author searches and citation tracking, were reviewed by both researchers. Where there was disagreement over the selection of sources, an inclusive approach was taken and the paper was put through to the full-text review stage. Both researchers reviewed the full-text articles, resolving any disagreements through consultation with a co-Principal Investigator (LS).

In accordance with the inclusive stance of scoping review methodology,23,24 and in contrast to systematic review methodology,30 papers were not excluded on the basis of a formal critical appraisal of study methodology, since the purpose of this review was to provide a descriptive overview of the literature on quality indicators in the prison setting, rather than to assess the robustness of clinical evidence underpinning the indicators.

Data charting and data items

A data charting table (see Appendix 2), was constructed using generic study features informed by the Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual https://wiki.joannabriggs.org/display/MANUAL/11.2.7+Data+extraction), and bespoke elements informed by detailed reading of six of the texts selected after full-text review. The chart was constructed by the Research Fellow and reviewed by the Programme Manager and a co-Principal Investigator (LS), and was adapted in an iterative process by the Research Fellow following further reading. The charting table facilitated comparison between studies.

Data items relating to the features of the study were extracted, such as the country of origin, the year, the study type and the funder. In addition, contextual elements relating to the development of quality indicators were charted, including drivers for the development of performance measurement, the challenges and constraints of the prison environment, issues relating to the transfer of performance measures from a community setting, and stakeholder engagement in decision-making processes.

Synthesis

Results were synthesised into the following groups, studies that: (1) reviewed quality indicators, (2) developed or recommended the use of explicit quality indicators or less explicit performance measures and (3) implemented quality indicators. Additionally, trends in performance measurement over time were synthesised.

Findings

Study selection

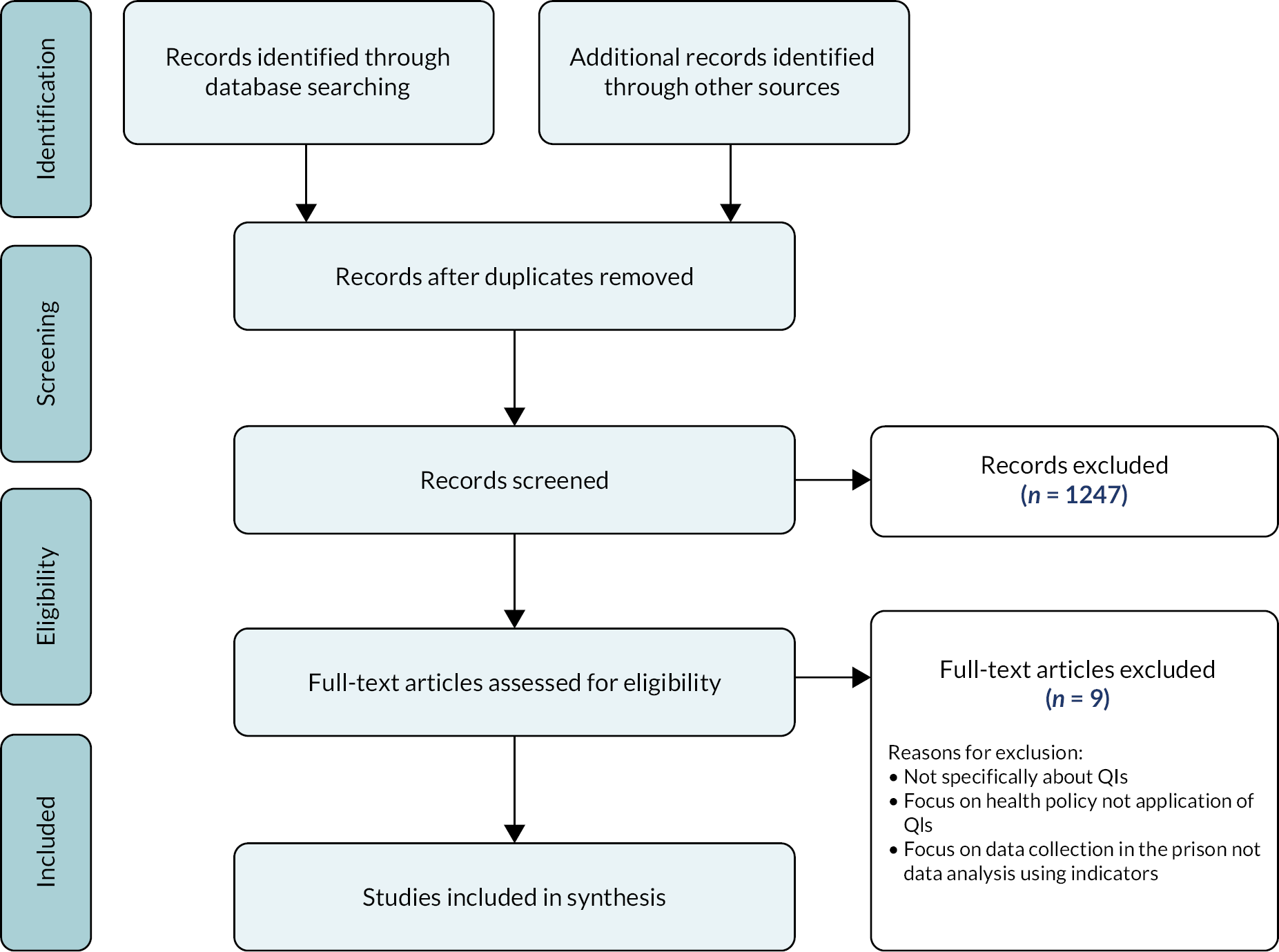

A PRISMA flow chart of the study selection process is shown in Figure 1. Of the 1271 sources identified from electronic searches and supplementary searches, 24 were assessed as eligible for full-text review following abstract screening. Nine of these were excluded due to lack of a focus on quality indicators, being policy- rather than care-oriented, or for focusing on data collection rather than analysis. Fifteen sources were included in the final synthesis.

FIGURE 1.

Selection of sources of evidence: Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram. QI, quality indicator.

Study characteristics

The characteristics of the included studies are shown in Appendix 3, Table 14. All the studies were American in origin, bar one UK study. 31 Six studies developed quality indicators or performance measures,32–37 two sources reviewed indicators or approaches to performance measurement,38,39 while a further two described implementation,31,40 and one commentary paper advised on implementation. 41 One study developed and implemented indicators in a prison setting,42 while two described approaches to developing and testing indicators across US prisons,43,44 and one tested performance measurement of diabetes screening in one prison. 45

Three studies originated from the same research programme and were published in the same 2011 issue of the Journal of Correctional Health Care. The programme aim was to assess quality of healthcare measurement in California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) and other prison systems and to recommend a portfolio of performance measures. The three studies were: an expert consultation process (reported in Asch et al. ,35 with the resulting list of indicators published by Teleki et al. 39) interviews, site visits and document reviews within CDCR,39 and a review of performance measurement activities in six correctional systems. 38

Types of quality indicators and performance measures

Most of the literature included quality indicators or performance measures, although the content varied widely from a few illustrative examples,32,35,40,41,43 to extensive lists. 33,34,36,39,44 Further variation was found in the format of measures, with some authors providing ‘explicit’ quality indicators33,35,39,40,44 – defined by Damberg et al. 38 as objective, EB measures that provide a standardised means of measuring quality across prisons – while others provided more broadly stated performance measures. 32,34,36,41,43 Explicit indicators, Damberg et al. 38 suggest, are distinguishable by their format; they have a clearly expressed denominator, that is, the number of people eligible for a particular measure, and a specified numerator, that is, the number of people from the denominator who satisfy the measure. Further parameters are often included, such as a reporting period, for example, the last 12 months, or particular diagnostic codes. The measure is then expressed as a percentage, calculated by dividing the numerator by the denominator and multiplying by 100. Explicit quality indicators are typically classified as ‘process’ indicators, that is, those focusing on care delivery, or outcome indicators, which measure the achievement of a particular health outcome, as demonstrated in Table 1.

| Process indicator | |

| Numerator | Number of prisoners from the denominator who received at least one serum potassium and either a serum creatinine (Cr) or a BUN therapeutic monitoring test in the measurement year |

| Denominator | Total number of prisoners who received at least a 180-day supply of ACE inhibitors, ARBs or diureticsa during the measurement year38 |

| Outcome indicator | |

| Numerator | Number of prisoners from the denominator having low-density lipoprotein < 100 on or between 60 and 365 days after discharge for an acute cardiovascular event |

| Denominator | Total number of prisoners aged 18–75 years as of 12/31 of the reporting year who were discharged alive in the year before the reporting year for acute MI38 |

In this body of literature, performance measures provided ways to assess prison healthcare quality, but the numerators, denominators and reporting periods were typically not specified, though often implied. For example, Greifinger36 appended a list of questions that could identify areas for clinical performance improvement through the interrogation of randomly selected small samples of healthcare records. For example, taking 10 records of people with positive tests for syphilis, gonorrhoea and chlamydia, Greifinger suggested that a measure of quality would be those who had received an appropriate prescription to treat their condition within 3 days. Similarly, Hoge et al. 34 suggested that people in prison who screen positive on a validated suicide risk assessment measure should ‘receive a referral to a MH staff member for evaluation. All inmates deemed to be an acute risk should be placed on suicide watch immediately and be immediately referred to the MH team’ (p. 643). Thus, the numerators and denominators are implicit in these measures of healthcare quality, but further work would be required to clarify the parameters of the metrics before they could be implemented in practice; clarifying denominators in the prison population, for instance, is particularly challenging given the transience of the population as people move between the community and the prison estate, or are transferred between prisons.

Studies focused on chronic care quality measurement

Four studies (Kountz and Orsetti,42 Castro,45 Booles31 and Kintz)37 were included in this review to give specific insights into quality assessment of chronic condition (CC) management in prison settings. Booles31 and Castro45 focused solely on diabetes, exploring, respectively, care processes and risk assessment. Booles31 conducted a survey of diabetes care quality in UK prisons, with 19 respondents, while Castro45 retrospectively analysed 50 health records of people diagnosed with diabetes during their prison term and held a consultation exercise to choose the most appropriate clinical guidelines for diabetes screening in prisons.

Kountz and Orsetti42 and Kintz37 explored quality of care for diabetes and other CCs [asthma and hypertension42 and asthma, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV)/acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS), hypertension/cardiovascular disease (CVD), lipid disorders, seizures, hepatitis, severe mental illness (SMI) and hepatic cirrhosis]. 37 Kountz and Orsetti42 developed and implemented a quality assessment tool, and Kintz,37 following Damberg et al. ,38 conducted a study of prison nurses’ perceptions of quality of care for chronic health conditions.

All of the authors identified the lack of standardised guidelines or their inconsistent application as causes of variability in care processes, which contributed to increased risks of sentinel events42 and diabetic complications. 31,45 Booles,31 for instance, in his survey of diabetes care in UK prisons, found that only 14 of the 19 prisons that responded were conducting routine monitoring of the diabetic patients, and only 37% of the sample had provided a mobile retinal screening service. Similarly, Kountz and Orsetti,42 when extracting a random sample of 10 medical charts, found that four people with diabetes were not receiving standard care. They also found that the lack of baseline data on CCs hampered efforts to identify high-risk patients and prevent sentinel events.

Castro,45 in her dissertation study on retrospectively identifying diabetes risk in 50 people subsequently diagnosed with diabetes in a US correctional facility (CF), found a lack of consistency in diabetes screening. For example, only 3 of 13 people with prediabetic impaired fasting glucose had subsequent HbA1c tests, although whether appointments were arranged but not attended is unclear.

Kintz,37 in her interview study with eight prison nurses, offered some insights into the barriers to quality health care for people in prison with CCs. Alongside confusion about which standards to apply, nurses reported that constrained resources resulted in acute care taking priority over long-term condition care. Inadequate data systems and poor levels of staff retention, education and appreciation of the value of performance measurement were other barriers that impeded efforts to provide quality of care. Kountz and Orsetti42 similarly found a reluctance among staff to employ the audit method they devised, with only two-thirds of the charts being completed on intake.

Methods of selecting performance measures or quality indicators

Several papers in the review described methods of selecting performance measures or quality indicators,32–36,44 with the quality indicators resulting from Asch et al. ’s35 consultation process being reported in the sister Teleki et al. 39 paper. There was noticeable variation in methodological rigour. For example, work that selected quality indicators varied significantly in the approach taken; there was a sharp contrast between the robust expert consensus processes employed by Asch et al. 35 and single individuals recommending indicators in Greifinger36 and Laffan. 41 None of the papers included in this review explicitly included the patient perspective, drawing instead on researcher, care provider or care manager input. However, it was noted by one group of authors, Asch et al. ,35 that people on the receiving end of care may have different priorities for performance measures, perhaps placing more value on outcome indicators which measure changes in health status, than those relating to care processes.

Non-rigorous approaches

Greifinger’s36 performance measures are oriented towards improving the safety of people in prison. Drawing on national and international prison healthcare standards, community patient safety standards relevant to prison settings, and his own experience of reviewing correctional health care, he compiled a guide of measures covering 30 domains of prison health care, including (but not limited to) access to care, chronic disease management, MH assessment and treatment, medical record-keeping, sexually transmitted infections (STIs) and mortality reviews.

Watts44 reports on the development of a quality indicator set based on the Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) metrics, the work conducted by the RAND organisation in 201135,38,39 and the Vermont Department of Corrections internal measurement system. However, very little information is given on the processes through which some of the measures were adapted for the prison setting. Similarly, Laffan,41 Bisset and Harrison43 and Raimer and Stobo40 provide short lists of measures but only minimal detail on the origin or development of the indicators.

Consensus approaches

Other authors described consensus approaches to select indicators. Asch et al. ,35 for instance, utilised a modified Delphi method, drawing on the expertise of a panel comprising nine senior people with clinical experience in correctional health care as well as relevant experience in other areas such as prison directorships, court-appointed monitorships and membership of clinical guideline committees. Following a review of health condition prevalence in prison populations, mortality statistics, and findings from qualitative interviews with healthcare providers and people responsible for quality measurement in correctional health,38,39 16 healthcare topics were chosen for further investigation. From accessing 29 community or correction-specific standards relating to the topics, and asking study participants to recommend indicators, 1731 indicators were identified. Of these, 662 were eliminated for being non-specific, leaving 1069 for further scrutiny. Following classification of indicators using the Donabedian structure–process–outcome taxonomy, content reviewers evaluated groups of indicators using criteria including importance to prison health care, scientific evidence base, implementability and interpretability. Indicators relating to specialist care were removed to retain a focus on primary care processes that were perceived to be within the jurisdiction of prison health care. As a result of this process, and a review of indicators rejected by the content reviewers, 111 indicators were presented to the panel for validity and feasibility assessment, with a 0–9 rating requested from panel members both before and during the meeting, and the level of agreement and disagreement being discussed at the meeting. Ultimately, 79 measures were retained, of which 62 were process indicators, 10 outcome indicators and 7 access indicators. The panel remarked that while these quantitative measures were a valuable means of assessing quality, they needed to be augmented by implicit quality measures such as mortality reviews and patient experience surveys.

While others have used similar consultation methods to identify quality indicators and performance measures, none match Asch et al. ’s35 rigorous multistaged approach. Stone et al. ,33 for instance, in their development of a quality indicator matrix for the Missouri Department of Corrections, appeared to rely only on the research team to identify the domains of healthcare delivery for which to identify standards and quality indicators, although administrators and medical staff were involved in selecting the final 32 indicators from an original list of 150. Where Stone et al. ’s33 work differed from Asch et al. ’s35 was in their attempts to select performance benchmarks (BMs) based on community BM data for similar indicators. This involved some modification of the indicators, for example, age range adjustments, to more closely align the prison population with the population as a whole.

Another study that sought to adapt community indicators for the prison setting was Hoge et al.’s34 selection of performance measures for MH care in prisons. Twenty-nine participants, including for-profit and independent MH practitioners and researchers, participated in a 6-hour roundtable discussion to reach consensus on meaningful indicators drawn from national standards. According to the authors, consensus was reached on nearly every subject.

Wright32 reports on the Association of State Correctional Administrators’ (ASCA) preliminary efforts to identify eight domains across the spectrum of activities in correctional systems that could be subject to a national performance measurement system that would enable a greater degree of transparency and accountability. Using seven comprehensive prison performance models, an ASCA subcommittee selected the eight most pertinent areas of correctional performance to assess, two of which were health-related: ‘substance abuse and MH’ and ‘health’. The subcommittee then selected three of the eight for their preliminary performance measurement system, including ‘substance abuse and MH’ but excluding ‘health’. Following some debate, the subcommittee decided upon performance indicators for each domain; for substance abuse and MH, they chose average daily rates of people receiving treatment for both conditions to be the indicators of performance.

Challenges and constraints of implementing quality assessment in the prison setting

Authors of papers in this review described a range of challenges to the implementation of performance measurement in prisons, including changing demographics of the prison population, the functionality of the data system, staffing and resourcing issues, and challenges to standardising quality of care measurement across different organisations.

Data system functionality

The inadequacies of existing data systems in prison settings were highlighted by most of the authors in this review, with key issues being poor co-ordination and a lack of functionality in key areas, such as capture and extraction of data,34,37,44,45 interface with other prison systems,38 prison pharmacies39,45 and community healthcare settings. 44 A lack of co-ordination with community healthcare settings leads to prison clinicians having to rely on patient self-report, which can compromise measures of prison healthcare quality. However, integrating prison health systems with those of community healthcare settings can be, as Bisset and Harrison43 noted, ‘unfamiliar and daunting territory’ (p. 3). Inconsistency in data input was also noted as a problem that could adversely affect the quality of analyses. 38,39,42,43

The absence of prison-specific BM data was cited as an inhibiting factor to quality assessment. 32,33,38 Additionally, the capacity of the data collection system was also perceived to be problematic, with requirements to collect data for legal purposes competing with the collection of data for quality-monitoring purposes:39,44 Teleki et al. 39 observed that there are ‘too many metrics being tracked for too many different purposes’ (p. 110), which can dilute performance measurement efforts. The same authors also identified difficulties clarifying the numerator and denominator, and a concern that the amount of data for some conditions would be too small to conduct a meaningful analysis. 39

Organisational issues

A few authors highlighted the difference in priorities between the medical staff and the prison administrators,31,34,41 noting that healthcare budgets may be managed by people lacking experience of healthcare delivery and that effective quality assessment of health care required collaboration between the two systems. 44

High staff turnover,34,37 under-staffing42 and the need to employ a data analyst to write and run queries38 were seen as difficulties that could jeopardise attempts to measure the quality of health care. In addition, the lack of a feedback loop for staff to gain insights into under-performing services can impede quality-improvement activities. 39

A further issue raised is whether standardisation should occur when institutions have varying mission statements, legal structures, and populations. 32 Standardisation can also be compromised by the lack of universal agreement on disease management for chronic health conditions. 37

Conclusion

While this review found limited evidence on the development and implementation of quality indicators and performance measurement in prison health care, and the evidence was virtually entirely restricted to the US context, a number of significant issues have been identified. These include the demographics of the prison population, the functionality of the data system, the format of quality indicators, stakeholder engagement, the choice of standards, target setting and staff engagement.

Chapter 3 Identification/development of quality indicators

Introduction

Measurement is a cornerstone of quality improvement in health care. Measures of the quality of care can be used to identify priorities for improvement, drive change through feedback to clinicians and healthcare organisations, and assess the impact of improvement strategies. In WP1, we set out to identify and select quality indicators that could be assessed using routinely collected data for use in the prison estate. We subsequently applied and analysed achievement of the selected indicators in our statistical analysis WP (see Chapter 5). This chapter describes the process by which we identified and developed the indicators.

Methods

Design

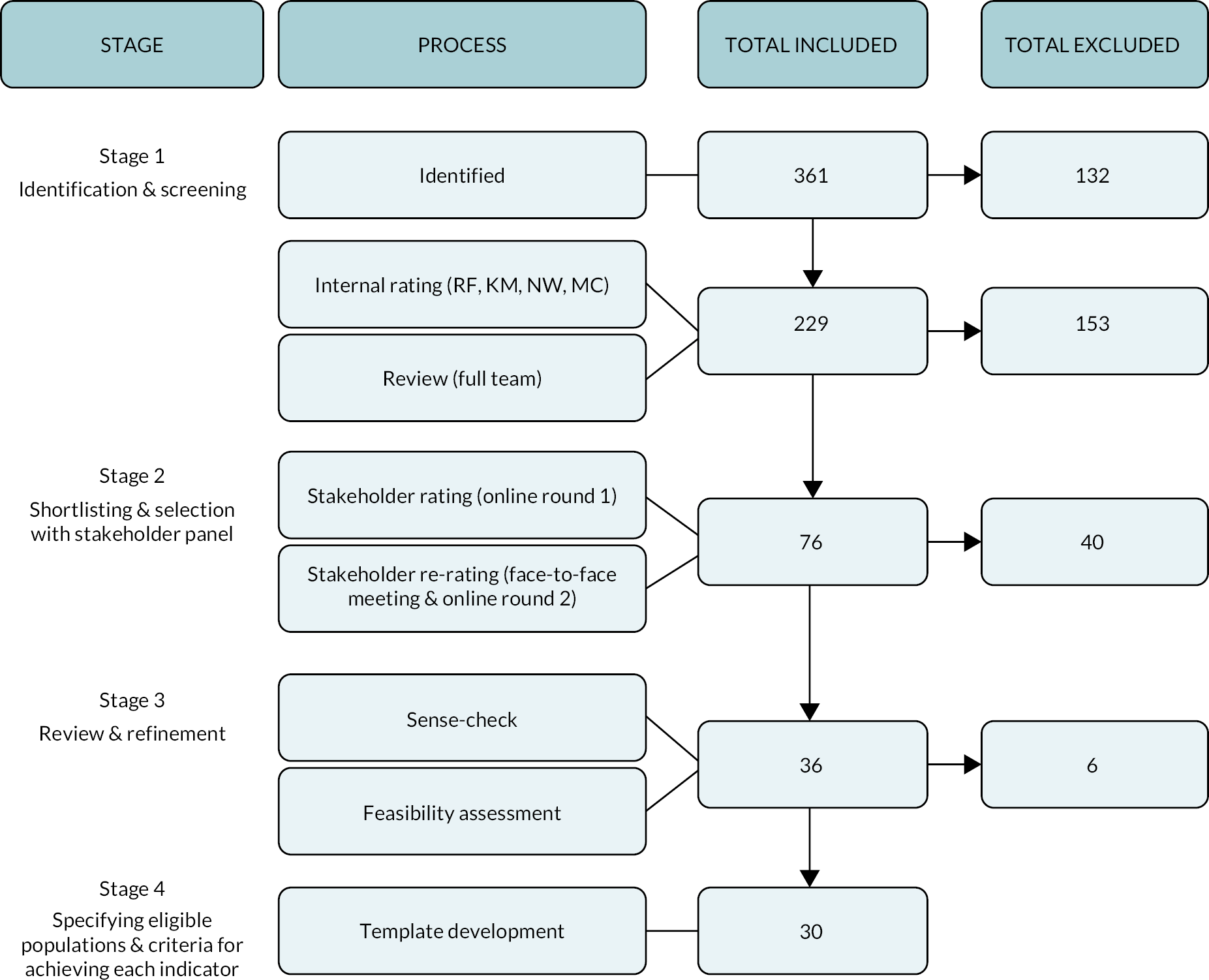

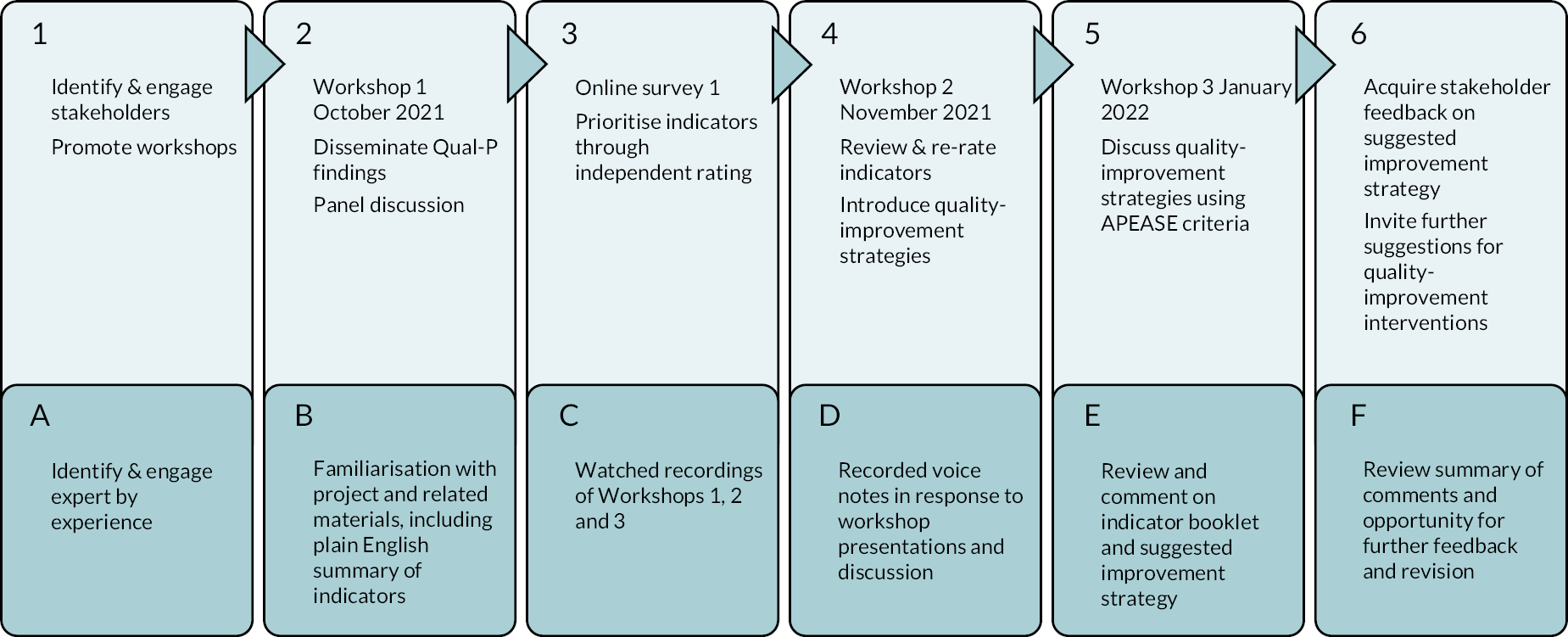

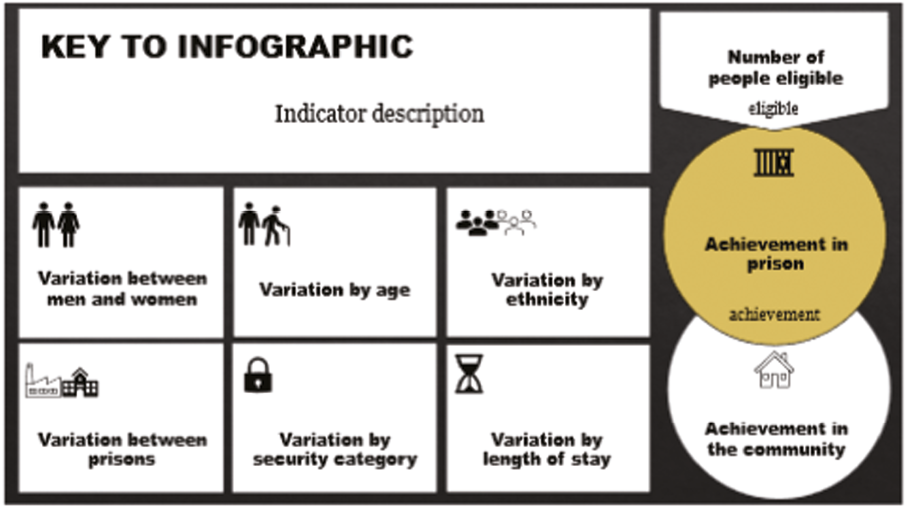

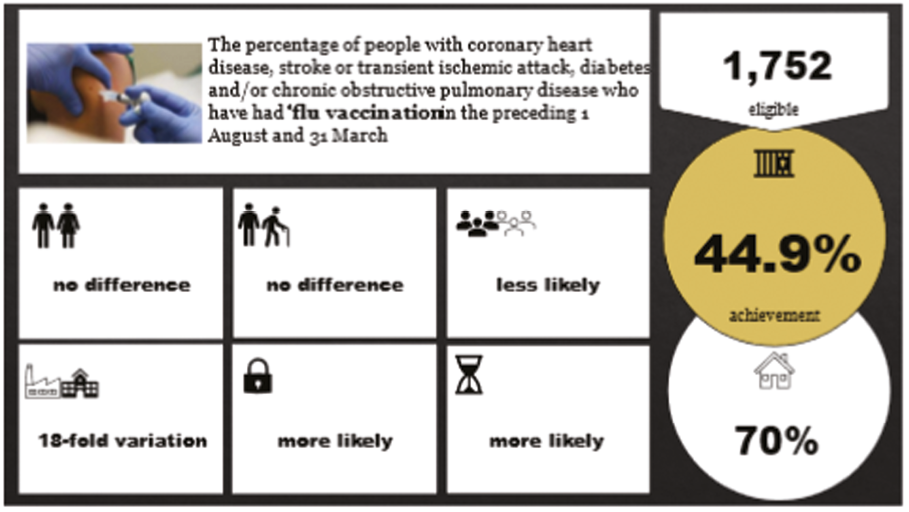

Our four-stage process comprised (1) identification and screening of candidate indicators from guidance and wider literature, (2) shortlisting and selection with a stakeholder consensus panel, (3) specifying eligible populations and criteria for achieving each indicator and (4) piloting data extraction to assess feasibility and refine indicators (Figure 2). We chose a modified RAND consensus process for shortlisting and selection to promote transparency in decision-making, and because it allowed interactions between participants which can help judgements requiring some degree of deliberation. 46

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of the four-stage indicator selection and development process.

Stage 1: identification and screening of candidate indicators

We identified candidate indicators from guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) including the QOF,47 clinical guidelines48–50 and the General Medical Service contract,51 and local quality indicators selected from local quality requirements from the NHS Standard Contract for prison health care 2019–20 for the North East, North West, and Yorkshire and Humber (set by the Commissioning Team under Schedule 4). We also drew on three studies that produced lists of indicators for use in primary care settings. 29,52,53 Our indicators were intended to measure individual-level care rather than organisational-level features and performance, which we allowed for in the analysis. Therefore, we did not draw upon Care Quality Commission (CQC) inspection standards.

We screened candidate indicators to prevent placing an excessive burden on the stakeholder consensus panel. An academic general practitioner (GP) (RF) conducted a preliminary screen of the full list of indicators and excluded those that were not relevant to primary care or had been superseded by new indicators. Four clinical team members, comprising RF, a former prison nurse and healthcare manager (MC), and two prison GPs (KM and NW), further screened the indicators. In an online survey, they independently screened according to two criteria: (1) likely amenability to measurement using routinely collected data and (2) potential for significant patient or population benefit. We collated the scores assigned by the clinical team members and then ranked the indicators. The full project team then systematically worked through the list of indicators during an internal workshop and discussed borderline indicators, discrepant ratings, and options for composite (combined) indicators.

Stage 2: shortlisting and selection with consensus panel

We had planned to recruit a panel of 11 participants, with a range of prison-specific, clinical and academic experience, recognising that consensus groups gain relatively little in reliability beyond this number. 46 We aimed to balance familiarity with day-to-day decision-making in community primary care with an appreciation of issues specific to the delivery of health care in the prison setting and the needs of the prison population. We invited several people with lived experience of prison to join the panel, but none accepted. Eight professionals from a range of criminal justice, health and MH backgrounds (including general practice, psychiatry, clinical psychology and nursing) accepted the invitation to participate.

We asked panellists to rate each candidate indicator independently online using a 1–9 Likert scale (where one is low and nine is high) according to the single criterion of ‘potential for significant patient benefit’. We provided instructions on rating and the list of indicators in a PDF by e-mail with a printed copy by post to use as a reference. To make the process accessible for panellists without relevant clinical training or former knowledge of quality indicators, we constructed a glossary of terms and plain-language descriptions of the indicators. We encouraged stakeholders to rate every indicator but provided a ‘don’t know’ option for all indicators. We piloted the functionality of the online survey with a project team member prior to sending to panellists. We also shared the original long list of indicators with the panel so they could highlight any indicators screened out earlier by the research team for reconsideration and asked them to suggest any indicators that we had not identified. We briefed the panel that we were ultimately aiming to provide a balanced suite of indicators which covered different aspects of primary care in prisons.

We calculated median scores for each rating using Microsoft Excel. We ordered indicators according to their median score for ‘potential for significant patient benefit’ and levels of discordance for presentation at a face-to-face panel meeting. We presented median ratings for each indicator. One of the authors (RF) facilitated a structured discussion which focused on indicators with the most discordant ratings. Low discordance was defined as all ratings for each indicator being three or fewer points apart, medium discordance at all ratings being between four and six points apart, and high discordance as at least two ratings between seven and nine points apart.

We gave panellists the opportunity to seek clarification about any aspects of indicators and to discuss their reasons for low or high ratings. Immediately after this discussion, panellists independently rated each indicator again. Five panellists completed both rounds, one of whom could not attend the face-to-face meeting and therefore completed ratings remotely. Our smaller than planned panel still collectively possessed a diverse range of perspectives,54 despite the difficulty in attracting busy clinicians and professionals to take part in this half-day exercise.

Stage 3: review and refinement

We reviewed and updated the list of indicators, considering them both individually and as a set. We disaggregated composite indicators and removed duplicates and low-rated indicators. We also conducted a sense-check to review face validity for individual indicators and as a set of indicators. Before moving to stage four, we conducted initial feasibility investigations; to be eligible for inclusion in our suite of indicators, data had to be routinely collected and coded in templates. If not, they could not be operationalised.

Stage 4: specifying eligible populations and criteria for achieving each indicator

We developed a template for each indicator which specified the eligible population (the denominator) and what criteria would need to be met for achieving the indicator (the numerator). The templates further included information on indicator sources and notes on development. We held several clinical team meetings (involving RF, KM and NW) to refine the indicators and monthly ‘troubleshooting’ meetings (involving RF, NW, KM, KC, PH, SR and TF) to develop and agree the data queries for each indicator. We designed data searches based upon existing algorithms, such as those used for QOF, wherever possible, to permit later comparisons with indicator achievement in community settings. The data specialist (SR) extracted anonymised individual patient-level data for the 13 prisons where health care was provided by Spectrum Community Health Community Interest Company (CIC) from SystmOne electronic health records. We reviewed descriptive summaries of the extracted data prepared by the statistician (TF) for apparent anomalies and discrepancies at the troubleshooting meetings. The data specialist subsequently refined searches until final versions were agreed.

Results

Stage 1: identification and screening of candidate indicators

We identified an initial ‘long-list’ of 361 candidate indicators (see Appendix 4) from the following sources:

-

55 from the NICE guideline for the physical health of people in prison;48

-

21 selected from local quality indicators from the NHS Standard Contract for prison health care 2019–20 for the North East, North West, and Yorkshire and Humber; and

-

17 opioid and related indicators from National Health Service England (NHSE) and Public Health England (PHE) guidance for prescribers55 and published work. 56

Preliminary screening excluded 132 indicators, including duplicates and indicators not relevant to primary care. Of the remaining 229 indicators, the clinical team rated 103 as measurable and of potential significant patient benefit: these indicators had full consensus for both criteria, or full consensus for one criterion and 75% consensus for the other (Table 2).

| Rated as measurable | Rated as of potential benefit to patient | Combined rating (%) | Number of indicators |

|---|---|---|---|

| 4 | 4 | 8 (100) | 43 |

| 4 | 3 | 7 (87.5) | 25 |

| 3 | 4 | 35 | |

| 3 | 3 | 6 (75) | 33 |

| 4 | 2 | 3a | |

| 2 | 4 | 19a | |

| 3 | 2 | 5 (62.5) | 9a |

| 2 | 3 | 49a | |

| 2 | 2 | 4 (50) | 13a |

| 229 | |||

Further review by the project team led to the promotion of 14 indicators from the 126 lower-rated indicators and their inclusion in Round 1 of the stakeholder survey. We also discarded 41 higher-rated indicators from the original 103, removing duplicates and indicators with substantial overlap. Following this internal rating and review process, we took forward a total 76 out of 229 indicators to the stakeholder panel.

Stage 2: shortlisting and selection with consensus panel

In the first round of online rating, seven of the eight stakeholder panel members rated 76 indicators. Panel discussions led to several single indicators around blood pressure control and lipid management being grouped into composites for the second round of rating, taking the number of indicators from 76 to 60. Five stakeholders then re-rated these 60 indicators. Discordance between ratings reduced following the face-to-face meeting (Table 3). In the first round, two (2.6%) indicators had low discordance (ratings ≤ 3 points apart), but this increased to 17 (28.3%) in the second round. Similarly, those with high discordance fell from 28 (36.8%) to 11 (18.3%).

| Level of discordance | Number of indicators | |

|---|---|---|

| Initial online rating (%) | Re-rating face-to-face and online (%) | |

| Low discordance Ratings are ≤3 points apart |

2 (2.6) | 17 (28.3) |

| Medium discordance Ratings are between 4 and 6 points apart |

46 (60.5) | 32 (53.3) |

| High discordance At least two panel members’ ratings were between 7 and 9 points apart |

28 (36.8) | 11 (18.3) |

| Total | 76 | 60 a |

The panel rated 31 (51.6%) indicators as having high potential for significant patient benefit (with median scores of 7–9), 22 (36.6%) as having medium potential (with median scores of 4–6), and seven (11.6%) as having low potential (with median scores of 1–3; Table 4).

| Potential for significant patient benefit measure (median scores) | Communicable disease | MH | Routine primary care | Prison-specific | Number of indicators (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| High 7–9 | 3 | 4 | 17 | 7 | 31 (51.6) |

| Medium 4–6.5 | 4 | 2 | 15 | 1 | 22 (36.6) |

| Low 1–3.5 | 0 | 3 | 4 | 0 | 7 (11.6) |

| Total | 7 | 9 | 36 | 8 | 60 |

Stage 3: review and refinement

We discarded all seven of the lowest-rated indicators and 18 of the medium-rated indicators. We began indicator development with 31 indicators rated as having high potential for significant patient benefit but discarded nine of these because they could not be operationalised reliably, often because data were not routinely coded. This included various local quality indicators from the ‘prison-specific’ category relating to the number of individuals with complex mental or physical health problems or those on clinical substance-misuse pathways arriving without communication, and another regarding pre-release appointments with a nurse. Our enquiries suggested that staff typically used ‘free text’ rather than coded templates to enter data. Therefore, any search would significantly underestimate adherence to these indicators. Additionally, it was not possible to determine whether the denominator in the MH indicator should include anyone on the MH in-reach team caseload (i.e. the secondary care team) or only those who are subject to transfer to secure hospital. We also changed or discarded indicators where the additional complexity of devising and applying searches was likely to exceed the marginal benefits of measuring them in the prison population, such as one for chronic kidney disease (CKD) where recommended blood pressure control levels depended on the assessment of urinary albumin–creatinine ratios. The remainder were excluded as they overlapped with other indicators. We discarded a total of 34 indicators and were left with 26 (4 medium-rated and 22 high-rated).

We then disaggregated two composite indicators which would otherwise have added to the complexity of measurement and interpretation. We disaggregated one recommendation to offer equivalent health checks to those offered in the community, for example, the NHS health check programme, learning disabilities annual health check, relevant NHS screening programmes, such as those for abdominal aortic aneurysm (AAA) and bowel, breast and cervical cancer. This was to ensure that the three indicators taken forward (NHS screening for AAA and breast cancer respectively and the NHS health check programme) were specific to each programme. From these we constructed three separate indicators for AAA screening, breast screening and CVD risk assessment for the NHS health check programme.

We also disaggregated the indicator that we constructed for Round 2 of the stakeholder screening which comprised 10 separate blood pressure indicators to create two new composite indicators (each including four subindicators) covering blood pressure control in CVD, one for patients aged 79 and under and one for patients aged 80 and over.

We retained other composites, typically grouped together in planning and assessing care, such as measuring eight processes of care for type 2 diabetes (e.g. records of foot examination and smoking status). This resulted in a final total of 30 indicators, comprising 25 indicators rated by the panel as of high potential benefit to patients and 5 rated as of medium potential (after accounting for disaggregated indicators). A summary of ratings and refinements to the shortlist of 30 indicators can be found in Appendix 5.

Stage 4: specifying eligible populations and criteria for achieving each indicator

We took forward 30 candidate indicators. We made several decisions in defining the indicator denominators. First, we generally applied indicators over 12-month periods from 1 April to 31 March, so that we measured processes or outcomes of care over a year coinciding with the QOF reporting period. For certain indicators, such as those concerning opioid prescribing, our measurements were based upon an 8-week period up to 31 March. Both these approaches allowed us to make later, indirect comparisons with community data. Second, we generally disregarded any ‘exception reporting’ used for QOF. In the community, this allows practices to exclude eligible patients from the denominator of an indicator if patients refuse to attend for treatment or if the treatment covered by that indicator is likely to be inappropriate for an individual patient. There are concerns about ‘gaming’, whereby patients might be excluded to inflate apparent achievement, although this is unlikely to be widely misused. 57 QOF does not operate in prison general practice. We decided to include all eligible patients in denominators to ensure that we took a complete population perspective. Anecdotally, we had also learnt that patients in prison may miss healthcare appointments for reasons other than personal choice, such as unavailability of an escorting officer. Third, when considering care received over a given period, we measured the care received by an individual over that whole period whether or not she or he had been transferred to a different prison. In that way, our findings reflect care received by individuals rather than the care provided by individual prisons. However, we were unable to include any records of care provided in community general practice within the indicator period. Therefore, for example, an individual in prison for 6 months who had received appropriate diabetes checks in community primary care in the preceding 6 months would be coded as not meeting diabetes checks unless these also occurred in prison.

We resolved several queries after the research team sense-checked the emerging data. We made further decisions on how to operationalise and typically simplify indicators. For example, the original hepatitis B and C indicator was a complex composite that covered screening, vaccination and communication of results for hepatitis B and C, and which duplicated aspects of another indicator on screening for hepatitis B and C. We therefore focused on numbers of vaccinations given at prison population level and also for higher-risk groups (people coded as currently or recently using drugs). We also simplified a composite indicator on antipsychotic monitoring to focus on monitoring for risks of cardiometabolic disease [e.g. lipid levels, body mass index (BMI)].

In summary, we modified the wording of 7 indicators (simplified 3, expanded 4) out of our final list of 30 indicators (see Appendix 5). Our final list comprises:

-

nineteen indicators drawn from QOF;47

-

one indicator from advice for prescribers on the risk of the misuse of pregabalin and gabapentin;55

-

one from guidelines regarding the physical health of people in prison;48

-

three from guidance for the General Medical Services contract;51

-

one NICE Clinical Commissioning Group indicator;58

-

one from PHE Guidance. 61

The list encompassed the following domains: communicable disease; MH; prison-specific; diabetes, asthma and epilepsy care, screening and CVD.

Interpretation of findings

Our suite of indicators includes topics especially relevant to the prison population (MH, drug misuse and communicable diseases) and covers potentially overlooked ‘mundane’ aspects of primary care, such as the management of hypertension and asthma. Our indicators consider equity explicitly (e.g. in including those uniquely relevant to women and older people) and implicitly (e.g. analyses can examine differences in achievement according to age, coded ethnicity and sex). We recognise that the indicators cannot cover all aspects of care, including processes and outcomes which are not routinely captured and coded in electronic health records and important features of holistic care (such as communication skills). Therefore, their application needs to be complemented by other sources of data on quality of care.

We generally balanced three other characteristics of our indicators. First, we had a range of process and outcome indicators. Process indicators should ideally have a strong evidence base so that following the process predictably leads to improved outcomes [e.g. prescribing of secondary preventive treatment following myocardial infarction (MI)]. 62 The evidence base for several process indicators is less certain, but these can still be recognised as signals of good-quality care (e.g. processes of care for diabetes). 63 Indicators solely focusing on processes of care rather than health outcomes may not help overcome therapeutic inertia – the failure to intensify treatment in patients not meeting clinical goals of treatment (e.g. recommended blood pressure control in diabetes). 64 Outcome indicators are subject to higher ‘noise to signal’ ratios, whereby a range of factors beyond professional practice influence outcomes (e.g. varying patient concordance with blood pressure treatment). 65 Second, we included a range of single and composite indicators. We generally used composites for indicators assessing several, closely linked processes of care (e.g. for diabetes) and disaggregated them when considering outcomes (e.g. blood pressure control). Offering a battery of single, simpler indicators is more likely to be feasible in practice compared to more complex indicators and better direct specific actions to improve quality of care (e.g. in specifying gaps in attainment of specific aspects of diabetes care such as blood pressure control). 66 Third, most of our indicators focused on relatively common conditions or problems affecting people in prison (e.g. drug misuse). However, we recognised that solely focusing on common problems might marginalise rarer but clinically important needs. We therefore included some indicators that were important to the management of long-term conditions for older people (e.g. dementia, heart failure).

Summary of main findings

We have identified and developed a set of indicators, largely drawn from EB guidance, to assess the quality of primary care delivered in prisons. They are largely drawn from evidence-based guidance and, if followed, can deliver population benefits. The indicators cover both specific priorities for the prison population and core priorities of community primary care, thereby allowing assessments of care equivalence across settings. The indicators are based upon routinely collected data, thereby allowing efficient and scalable application beyond the research context to inform and drive quality-improvement strategies.

Chapter 4 Qualitative interview study with prison leavers and prison healthcare staff

Introduction

The qualitative study aimed to explore perceptions of the quality of prison health care from two perspectives: prison leavers (hereon referred to as patients) and prison healthcare staff. Specifically, the study aimed to identify barriers and facilitators of care delivery in prison, and to map these data to a multilayer theoretical framework to develop detailed understandings about prison healthcare quality.

Some material from this chapter has been reproduced from Sheard et al. (2023):

Sheard, L, Bellass S, McLintock K, Foy R, Canvin K. (2023) Understanding the organisational influences on the quality of and access to primary care in English prisons: A qualitative interview study. British Journal of General Practice, 100166

This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (CCBY 4.0) which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, provided the original work is properly cited. See http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Methods

Ethics approval

We gained approval for the qualitative WP from the University of Leeds School of Medicine Research Ethics Committee (SoMREC) on 17 July 2019 (ref. no. 18-093), which permitted us to interview recently released people who were not on probation. Early engagement with agencies, however, identified that restricting eligibility to people not on probation would be likely to impede recruitment. We therefore sought approval from Her Majesty’s Prison and Probation Service (HMPPS) National Research Committee (NRC) to enable us to recruit people on probation. HMPPS NRC approved the study on 24 December 2019 (ref. no. 2019-383). As a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, HMPPS NRC suspended approval for all research studies on 20 March 2020. Fieldwork resumed in mid-July 2020.

Sample

Recruitment

We aimed to recruit around 15 participants in both of the participant groups, which was initially felt to be sufficient to ensure heterogeneity. Discussions with stakeholders resulted in a decision to extend the sample sizes in both groups to 20–25, to enable the inclusion of a wider range of healthcare professionals and a more diverse sample of patients. In particular, we were advised to ensure that women and those with chronic physical health conditions were represented in the patient sample. Ethical approval to increase the sample sizes was obtained. Prior to the pandemic, we had planned to conduct face-to-face recruitment of patients, and face-to-face interviewing of participants in both groups. Instead, virtually all recruitment and fieldwork were conducted using remote methods, that is, by telephone or video call.

Patient participants were recruited with the help of PPI consultants (n = 9), via local service providers (n = 6), Twitter (n = 3), a lived-experience panel (n = 2) and snowballing (n = 1). We monitored participant characteristics throughout recruitment. As the fieldwork progressed, we identified two key characteristics that were either absent or under-represented: women, and people with long-term physical health conditions. We made further recruitment efforts to address this limitation. Following advice from project team members, we contacted over 25 organisations, including hostels, third-sector organisations and theatre companies. Four women, two of whom had physical long-term conditions, were ultimately recruited to the sample, along with a further two men with long-term conditions.

Healthcare staff were recruited to the study via a range of routes. Facilitated by project team members, a global e-mail was circulated amongst Spectrum healthcare staff, which recruited 11 people, with a follow-up e-mail generating a further 3 participants. Heads of health care at another prison healthcare provider, Practice Plus Group, distributed information within teams, which resulted in two staff joining the study. A further two people responded to study promotion on Twitter, and one person was recruited via snowball sampling.

The sample was continuously monitored during the recruitment process, and project team members were asked to approach people performing prison healthcare roles that had not been included in the sample. A further three people participated in the study following approach by project team members.

Data collection

We interviewed 21 prison leavers and 22 prison healthcare staff. Data collection took place between November 2019 and March 2021. All interviews were conducted one-to-one, with two interviews conducted face-to-face before the pandemic, and the remaining 41 interviews conducted remotely via telephone or video call (staff), or by telephone (patients). Interviews with patients were between 18 and 73 minutes long (average = 35.4 minutes), and with prison healthcare staff between 31 and 61 minutes (average = 46.5 minutes).

Due to approximately all of the data collection being remote, and in line with guidance provided by SoMREC, most participants gave audio-recorded consent (n = 36), following discussion of the consent process with the researcher. The two patients who took part in pre-pandemic face-to-face interviews gave written consent, and five staff chose to e-mail completed consent forms which were then signed by the researcher and returned.

Although we informed participants that notes could be taken instead of audio-recording the interview, all participants consented to being recorded. Audio consent recordings and completed consent forms were stored on a separate server (or in a locked cabinet) to interview recordings. All audio recordings were stored in encrypted format, with the decryption key known to only three researchers (SB, KC and LS). Interview recordings were sent via a secure delivery service to a transcription company where they were stored on a secure server and deleted within 14 days of transcription.

Participants’ names were rarely mentioned in the interview recordings, but participants would frequently name prisons, NHS organisations, voluntary services, local areas or, very rarely, the names of prison staff. To ensure anonymity, names of individuals were deleted from the transcript, and the names of organisations or areas were replaced by codes stored in a password-protected spreadsheet, with the password known only to SB, KC and LS. A total of 48 prison establishments were mentioned in participant accounts, including open and closed female prisons (n = 8), adult male prisons (categories A–D, n = 38) and male young offenders’ institutions (n = 2).

Data analysis

Data from both groups have been mapped to a multilayer barriers and facilitators matrix which has been informed by Ferlie and Shortell’s67 approach to improving quality of care. In brief, Ferlie and Shortell67 argue that quality improvement in health care requires attention to four levels – the individual, the group or team, the organisation, and the larger system and environment within which the organisation is embedded. These layers are to some degree artificial due to myriad interdependencies: several issues operate at multiple levels. Nevertheless, it provides a useful heuristic to attempt to understand the complexity of care delivery and receipt in the prison setting.

It is important to outline how the model has been interpreted for the analysis. We have understood the individual level to pertain to psychological phenomena, including motivations, intentions, attitudes, beliefs and responsibilities. Examples include professional identity for staff, and a lack of autonomy or control for patients. These data account for a relatively small proportion of the full data set.

Data have been mapped to the group/team level where they relate explicitly to interpersonal processes within and between healthcare staff, prison officers and patients. Examples of data mapped to this level are intersubjective decision-making processes regarding care and the creation and maintenance of reputation. A substantial proportion of the data set was mapped to this level.

The organisational level accounts for most of the data collected. We understood this level to relate to perceptions of organisational culture, the organisation and delivery of health care as part of the prison regime (including access to health care), quality assurance, continuity of care as people move between prisons or in and out of prisons, material resources and contractual issues.

Finally, the larger environment/system level was understood to refer to forces beyond the prison environment, such as national or regional data infrastructure, clinical policies, standards and codes of conduct, national screening programmes and decisions made at national level regarding prison funding. Data mapped to this level were relatively sparse.

The data did not map in a straightforward way to the participant groups. Data presented here capture participants’ perceptions of barriers and facilitators and are not intended to represent factual accounts of policy or practice. A unique identifier is attached to each excerpt in the following format: gender, age, prison category(ies) (patients); healthcare professional (HCP)/prison category(ies) (staff).

Findings

Participant characteristics

Participant characteristics are presented in Table 5.

| Characteristics | Patients | Healthcare staff | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender | Male | 18 | 16 |

| Female | 4 | 6 | |

| Age group | 20s | 3 | 3 |

| 30s | 7 | 2 | |

| 40s | 10 | 9 | |

| 50s | 0 | 6 | |

| 60s | 1 | 1 | |

| Ethnicity | Black African | 1 | 0 |

| Black English | 1 | 0 | |

| British Asian | 3 | 0 | |

| White | 0 | 1 | |

| White British | 12 | 18 | |

| White English | 2 | 0 | |

| White Scottish | 0 | 1 | |

| White/Black Caribbean | 1 | 0 | |

| Arabic/English | 0 | 1 | |

| Not stated | 1 | 1 | |

| Male/female estate | Male | 18 | 18 |

| Female | 4 | 3 | |

| Both | – | 1 | |

| Prison category: male | A–D | 1 | 0 |

| A | 0 | 3 | |

| B | 4 | 5 | |

| C | 0 | 3 | |

| D | 0 | 2 | |

| A/B | 0 | 1 | |

| B, C | 10 | 1 | |

| B, C, D | 2 | 1 | |

| B, D | 0 | 1 | |

| C, D | 0 | 2 | |

| Prison category: female | Closed | 2 | 3 |

| Closed/semi-open | 2 | 0 | |

| No. of sentences in last 5 years | 1 (but many previously) | 1 | – |

| 1 | 10 | – | |

| 2 | 3 | – | |

| 3–4 | 2 | – | |

| Many | 2 | – | |

| Years in prison health care | 1–3 | – | 6 |

| 4–7 | – | 7 | |

| 8–10 | – | 2 | |

| More than 11 | – | 6 | |

| Not stated | – | 1 | |

| Profession | Administrator | – | 1 |

| Associate practitioner | – | 1 | |

| GP | – | 2 | |

| Health promotion worker | – | 1 | |

| MH nurse | – | 1 | |

| Nurse – band 5 | – | 2 | |

| Nurse prescriber | – | 1 | |

| Occupational therapist | – | 2 | |

| Pharmacy technician | – | 1 | |

| Physiotherapist | – | 1 | |

| Recovery worker | – | 1 | |

| Recovery/service development | – | 1 | |

| Senior clinical manager | – | 3 | |

| Senior nurse | – | 4 | |

| Years in current role | 1–3 | – | 9 |

| 4–7 | – | 7 | |

| 8–10 | – | 5 | |

| 11+ | – | 1 | |

Barriers and facilitators analysis

For a brief summary of the barriers and facilitators, see Table 6.

Individual level

Data that were mapped to the individual level related to psychological processes and internal attributes such as emotions, knowledge, autonomy, personal responsibilities and motivation. Barriers at this level relate to the impact of the system on autonomy and emotions that can hamper access to or delivery of care: facilitators to participants’ motivations or attitudes that enable them to work within or around the system.

Barriers

Lack of control

A recurring theme in the interviews with patients was a sense of lack of autonomy and control over their access to health care or to over-the-counter medications. Although some prisons have self-service kiosks where patients can request healthcare appointments and medication electronically, other prisons rely on a system involving paper applications (‘apps’), which patients complete and deposit in a box on the wing. Compared to care in the community, health care in prison was less likely to be viewed as something which could be influenced by individual agency, as one participant explained:

There might be a waiting time [in the community] but you know where you stand, you get to talk to the people that you want to talk to, you can speak to the doctor, they ring you within 24 hours … you can raise your concerns, you can get an emergency appointment.

M49/B

Furthermore, there was a sense that the more a patient tried to exercise control over access to care, the less likely it was to be successful. Several participants perceived that repeated requests for help could irritate officers and therefore be counterproductive, as one person explained: ‘You keep putting apps in and you will just piss the officers off. They will see an app and put it in the bin’ (M27/BC). This sense of a lack of control was more broadly embedded in the perception of not having equivalent human rights to people living in the community; participants described feeling like ‘second-class’ (M29a/BC) or ‘lower-class’ (M43b/BC) citizens. This could translate into demeaning or frustrating experiences such as not having the opportunity to shower before a healthcare appointment, having appointments cancelled with little warning, not having access to pain medication perceived to be commensurate with clinical need, or having complaints ignored.

Emotional responses

Experiencing frustration was not the sole province of patients: staff also described dealing with similar emotions caused by a range of factors including perceptions of laziness in other staff, inconsistency in the quality of nursing care and lack of co-operation from prison officers. In part, frustration could be caused by an inability to provide care in a manner consonant with their sense of professional identity. Recounting trying to deal with a very distressed patient without support from the MH team, one nurse working in a category C prison noted:

I felt useless, because we just couldn’t do anything for him. And it’s awful to watch, because I’d known him for years, known him since he was a sprog, been coming in and out since he was a juvie.

HCP-12/C

Wishing to support patients, but being constrained from doing so by lack of support, the regime, or occasionally by patients themselves: ‘you think, we’d just got that wound looking really nice, and then you got upset, and now it’s back to square one again’ (HCP-16/A), could lead to feelings of burnout.

Feelings of resignation were occasionally expressed by people in both participant groups – a perception that both staff and patients would have to manage the best they could in an enduring system. One patient, describing problems gaining access to his diabetic medication, observed that it was ‘literally just usual prison difficulties getting things you’re supposed to have’ (M36/B). Similarly, a GP noted that:

I’m so busy when I’m in there, I don’t feel that I have the time to report every little thing that is frustrating about the job …. So we let things go and I suppose eventually you’d develop a mentality of ‘Oh flip, nothing is ever going to happen, I’ll just cope with the way things are’.

HCP-05/CD

Patient knowledge and literacy

Several staff perceived patients to have minimal engagement with healthcare services outside prison, and to have limited knowledge of health conditions, which could impact their likelihood of accessing health care. This is potentially compounded by ‘invisible’ conditions, such as diabetes and by low levels of literacy. Low levels of literacy could not only hinder people from attending appointments, but could prevent them from using the application system altogether, as one GP explained: ‘first of all they have to put their problem in writing which is very difficult for some of them because they can’t write properly’ (HCP-05/CD).

Facilitators

Patients emphasised individual traits which could help them to obtain health care. Typically, participants in this group perceived that being assertive, persistent and articulate would facilitate their access to health care. One woman observed:

I am lucky in a way that I’m able to advocate for myself … I have a very good understanding of medical situations … and I can explain them … the time and the setting would make it difficult for people who didn’t have that ability … my overall experience is that health care is something you almost have to argue for and fight for and to a certain extent is associated to privileges.

F48/Closed

Despite the challenges of working in prison, several staff expressed their commitment to what was perceived to be a unique healthcare landscape, with some remarking that they would not wish to work elsewhere. One senior nurse, for instance, noted that:

I would just like to say that I absolutely love my job and I can’t see me going anywhere before retirement. I said they will take me out of there in a box … I don’t think I would fit anywhere else now.

HCP-18/C-D

This sense of the ‘specialness’ of working in prison health care led some participants to discuss the skills needed for clinical practice. The following were seen as skills particular to the prison environment:

-

Being able to cope with the constraints of working in a setting where security, rather than care, is given primacy.

-

The ability to adapt communication to people who may be distressed, abusive and disadvantaged.

Engaging with patients provided opportunities to make a difference to people’s lives, as the two quotes below exemplify:

I love working in prisons, I love it. I love working with prisoners, they are the most motivated, engaged, enthusiastic, grateful, everything that people wouldn’t think that they are. They are just the most endearing group of people … that I’ve ever worked with, so I stick with it because they are amazing. The rest of it is utterly hideous, to be honest.HCP-20/B

I feel it’s a place where I can really achieve things. It’s not like going into a well-run general practice where … patients are lovely and everything works perfectly. It is a place where you can really make changes and where you can, on an individual basis, you can really help these people.

HCP-09/BCD, Closed

The sense of fitting into the prison environment also required staff to present themselves in particular ways. One senior nurse, for example, stated that ‘if you are really, really soft and fluffy I think you would get walked on’ (HCP-18/C-D). Poor levels of staff retention were commonly attributed to individuals not being personally suited to working in prisons; in contrast, some staff who had intended to stay for a short time found high levels of job satisfaction.

The ability to provide care in the context of a strict regime was perceived by staff to be facilitated by individual proactivity and creativity. Identifying opportunities to improve care, being motivated and having confidence to make changes, and finding ways to work around the system were described by some of the staff. However, such innovative working could be vulnerable to being drawn away to perform other clinical tasks, as one recovery worker explained:

Our IDTS (Integrated Drug Treatment System) nurse is very good …. She has great plans for being proactive with the vulnerable population of men that also have substance misuse problems …. She will even do things like building a therapeutic alliance and run a detox group pre-COVID. She … receives no support for that. Although her role is part of health care, because she is a nurse she gets pulled to do an awful lot. She is just seen as an extra primary care person. She is not.

HCP-01/C

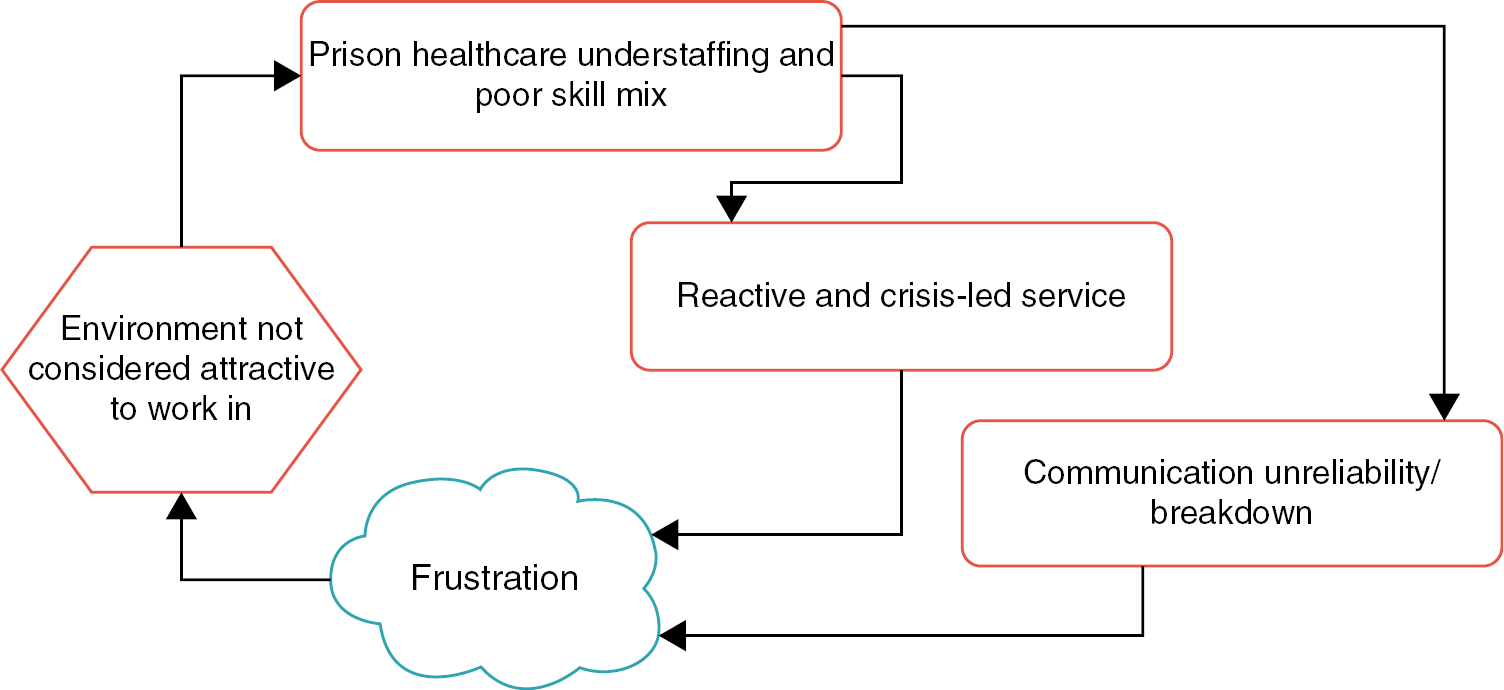

Group/team level