Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1808/238. The contractual start date was in January 2009. The final report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Buchanan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Aims, background and methods

The subtitle of this project concerns ‘the realities of middle and front-line management work’. The problems of defining middle management, in any sector, and the ambiguities surrounding the location of front-line hospital managers, led to us drop ‘and front-line’ from this report. Role titles (ward sister, divisional nurse, operations manager), although not always accurate or consistent, offer a better guide to the nature of the work and responsibilities of post holders than ‘middle’ or ‘front-line’ designations

Things can only get different

You'll hear people say ‘management’ in inverted commas. And I'll say, but you all manage. I think that there's always been quite a hierarchy in the NHS. And I do not believe we've done as much as we can to break that down. I want everyone to take accountability and responsibility.

Modern matron, Netherby hospital

How do hospital managers in the NHS handle the demands of a constantly changing service? How do managers affect the quality of patient care and clinical outcomes? Patient safety is a national priority, but changing working practices following serious incidents can be problematic. Why? We know surprisingly little about the work experience, practices and attitudes of hospital managers, who are key to implementing local strategy and national initiatives. However, when things go wrong, this is the group that often takes the blame. This study seeks to build on what we know about management, change and leadership, and relate this to current trends.

This chapter describes the research questions and aims of this study, explains the background to the project and provides an overview of the research process and methods. This project began in 2009. By 2012, however, the service had changed in a number of significant ways. Two events in particular had an impact on acute hospital management roles during this period.

Economic crisis

The first of these events was the collapse of the investment bank Lehman Brothers, which filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in America on 15 September 2008. With debts of over US$600B, this was the largest corporate failure in American history, triggering a global financial crisis. This in turn led to massive government spending around the world to recapitalise other banks that were close to collapse because of their exposure to Lehman's debts.

In the UK, financial support for the banking sector increased UK public sector net debt to £845B by the end of 2009, prompting action to reduce government spending. Government policy was to ‘protect’ the NHS budget (> £100B a year). Nevertheless, cost inflation in the health service is historically higher than general inflation, and flat funding or small rises amounting to real decreases in annual NHS spending can generate deficits for individual provider organisations.

In 2010 the chief executive of the NHS, Sir David Nicholson, thus set the service the target of generating £20B of efficiency savings (one-fifth of annual spending) by 2014–15. Known as ‘the Nicholson challenge’ or ‘the NHS recession’, all health-care providers had to consider radical cost improvement programmes (CIPs) while maintaining the level, quality and safety of services.

New government

The second event was the election of a Conservative–Liberal Democrat coalition government following the general election in May 2010. The new Secretary of State for Health published his first White Paper in July 2010. 1 This set out proposals to abolish primary care trusts (PCTs) and strategic health authorities, give most of the NHS budget to clinical commissioning groups and create a National Commissioning Board. Trusts were also expected to achieve at least 3.5% cost improvements annually over 3–5 years while improving quality of care. The Secretary of State also proposed a 45% cut in the management costs of the service by 2014–15. Government ministers depicted health-care managers as ‘costly, pen-pushing bureaucrats’, and the service was now to be run by clinical staff: general practitioners, hospital doctors, and nurses.

These and other structural and regulatory changes were consolidated in a Health and Social Care Bill introduced to Parliament in January 2011. The lengthiest piece of legislation in British history, the bill's provisions were controversial. The uncertainties surrounding these proposals, how they would operate in practice and the implications for funding created a challenging management agenda. As one participant in this project observed:

Netherby is a £250 million hospital. Over the next three years, we're looking at inflated costs and deflated income. If we do nothing, in three years’ time, we will be losing up to £30 million a year, so we need to do something now. We have a transformation steering group whose remit is to design a programme to prevent the trust running up an annual £30 million loss. We want to avoid ‘slash and burn’, but we do need to lose staff and cut management layers. This means big change.

Director, Netherby hospital

Budget cuts, new structures, tighter regulation, fresh priorities, negative stereotyping – some participants in this study said that they ‘had seen it all before’. The NHS, which celebrated its 60th anniversary in 2008, has been subject to changes of this nature throughout its history. But for the majority of participants, this was new; one manager observed, ‘it feels different this time’. The scope of the structural and regulatory changes, the severity and pace of funding cuts, the need to improve quality and safety, and the job insecurities were unprecedented. Following Lehman's collapse and the shift in government policy, for health-care managers it was no longer ‘business as usual’. The acute hospital model was challenged with strategies for moving care into the community, focusing on prevention (alcohol abuse, obesity) and on self-management of long-term conditions (asthma, diabetes). From 2011, changes to tariffs meant that hospitals would no longer be remunerated in full for increases in emergency department attendances, and would be penalised for (among other breaches) emergency readmissions within 30 days. Management confidence in the ability of the service and individual provider trusts to deliver the necessary savings was low. 2

The NHS was thus passing through a further period of rapid and radical change during the life of this project. The context in which management work is carried out is crucial. The management implications of the changing institutional context are explored in Chapter 3. The local organisational contexts of the trusts participating in this project are discussed in Chapter 4. As institutional and organisational contexts change, management roles change too. As the chief executive of The King's Fund observed, ‘things can only get different’ (p. 14). 3

Research questions

Interviewer: What outputs would you like to see from this project?

Respondent: I want to understand what we can do to support and help those in increasingly challenging roles, because we need to get it right. Otherwise, they will do it badly or won't do it. I want to gain a better understanding of their motivation, so that we can help provide meaningful careers.

Senior executive, Greenhill hospital

This project addressed three sets of questions:

-

Realities: What are the pressures and demands facing middle managers in health care? What are the implications of these trends?

-

Changes: What roles do middle managers play in implementing changes? How are changes arising from serious incidents implemented, and how can this process be improved?

-

Contributions: How does management practice affect clinical and organisational outcomes? What factors influence management contributions to performance? How can the components of an ‘enabling environment’ for management work be assembled and sustained?

Realities

We can claim some understanding of the nature of general management roles,4 the realities of management work,5 rewards and pains6 and how managers spend their time. 7 Is that knowledge relevant to health care today? This project sought to understand how current pressures have affected the realities of middle management work in acute settings. Convention has managers running things as they are while leaders drive change. But managers at all levels in the NHS could be excused a cynical response to that distinction, having implemented a series of major changes affecting all aspects of the service – culture, structures, priorities, governance, working practices – and more.

Changes

There is a widespread perception that the management of change in health care is especially problematic. 8 This has led to a renewed emphasis on medical engagement in leadership and change. 9,10 Recent evidence suggests, however, that many radical changes are implemented, not by small groups of senior managers and doctors, but by distributed groups of middle managers and others, including clinical staff. 11 Several studies undermine the distinction between leaders who drive change and managers who maintain order, emphasising middle management roles in strategy, and in change ‘under the radar’. 12–14 The development of distributed change leadership, based on the spontaneous concertive action of staff at all levels, is evident in health care. 15,16 Clark et al. 17 note that ‘Enhanced clinical engagement should work towards a model of diffused leadership, where influence is exercised across a complex set of relationships, systems and cultures’ (p. 32, italics added for emphasis).

Change is thus a central aspect of middle management work. 18,19 Following serious incidents, the recommendations from investigations are sometimes adopted rapidly. However, despite efforts to ‘learn the lessons’, these recommendations often lead to little or no action. 20 Noting that the pace of change in improving patient safety had been slow, Donaldson21 cited the distinction between passive learning (identifying lessons) and active learning (implementing changes), noting that the latter does not follow automatically. This project thus explored the processes of change following serious incidents, to identify the conditions that respectively block and promote change in such contexts.

Contributions

One research tradition has sought to understand what managers do. 4,22 Another line of research concerns the contributions that middle managers make to clinical and wider organisational outcomes. This project sought to identify the conditions that enable, support and strengthen those contributions. Evidence suggests a systemic link between management practices and outcomes. 23–25 Management competencies are key, but organisational context is also crucial in determining receptiveness,26 setting priorities and incentives, focusing attention and energy and establishing an environment that either enables or stifles service improvement. What does an ‘enabling environment’ look like? How can the components of an enabling environment be assembled and sustained? One of the outcomes of this project (see Chapter 7) is a ‘contributions-based’ model of management work.

Why middle management?

The ward leaders – sisters and charge nurses – make or break the hospital's reputation. We have over fifty wards on two sites. Each has a team of twenty to thirty staff operating 24/7. It's where the costs arise, and where patients and visitors make judgements about standards, depending on staff approach and discipline. That's where the key business of patient care is.

Senior executive, Greenhill hospital

The NHS has since the mid-1980s focused attention on chief executives and trust boards. One manifestation of this was the Leadership Qualities Framework. 27 When it was first published, the principal investigator for the current project was working with a hospital in the Midlands. The human resources director was running management development sessions for new clinical directors and business managers – a group of ‘senior middle’ managers. She telephoned the Leadership Centre (part of the NHS Modernisation Agency) and requested 20 copies. She was asked about the use to which these would be put. When she explained, she was told that copies could not be provided. Why not? Because the framework was designed for board-level directors and not for less senior staff.

This anecdote is symptomatic of what appear to be deep-rooted attitudes towards leadership and management in the NHS. Since 2009 there has been a National Leadership Council. There was no National Management Council. There was an elite top leaders programme for those in roles deemed to be ‘business critical’. There was no top managers programme. The NHS had developed several leadership competency frameworks. There were no management competency frameworks. An NHS Leadership Academy was launched in November 2011. There was no Management Academy.

The updated version of the Leadership Qualities Framework28 does suggest that the framework applies to staff at all levels – except for two of the seven domains, ‘creating the vision’ and ‘implementing the strategy’, which are the preserve of ‘a relatively small group of people who hold designated positional roles, and are required to act as leaders in formal hierarchical positions. These two domains focus more on the contribution of individual leaders rather than the general leadership process’ (p. 8). If this ‘general leadership process’ means middle managers, then this implicit division of leadership labour ignores two decades of compelling research evidence. 29,30

One consequence of the focus on senior leadership is that less is known about the roles, experiences, contributions and motives of middle managers. 31 The presumption that their contributions are less ‘business critical’ has passed unchallenged. The Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) research programme had funded previous studies on leadership, organisation cultures, performance management and service reconfiguration. Those studies, however, did not explore directly the work of middle managers. There was, therefore, a pressing need for research into the challenges facing management in health care and this was recognised as a priority theme for research. 32

Have conditions changed so dramatically since 2007 as to render the findings from this project obsolete? On the contrary. The impact of institutional and organisational context remains central to our understanding of management roles and contributions. For acute hospitals, change agendas are complex and challenging, and middle managers are key to implementation. Although other issues have surfaced and generated additional research questions, the challenges that the NHS has faced since 2007, and will face from 2012 onwards, have only reinforced the importance of this theme.

Research methods

This project used a multimethods collaborative design involving set-up interviews, focus groups, a management survey, documentation from participating sites, serious untoward incident narratives based on documentation and interviews, and management briefings (see details in Appendix 8). The aim throughout was to engage participants as co-researchers, in formulating the original proposal, in survey design and in selecting case incidents. The project stages are summarised in Table 1.

| Project stage | Timing | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Stage 1: set-up | January–October 2009 | Project launch, recruit research fellow, ethical approvals, advisory group, set-up interviews to gather background information on participating sites |

| Stage 2: management focus groups | January–October 2010 | Focus groups at each of six sites: identify motives, trends, contributions |

| Stage 3: management survey | August–October 2011 | Survey trust management populations: realities, changes, contributions |

| Stage 4: management briefings | June 2011–March 2012 | Feed back findings in briefing groups; explore implications for practice |

| Stage 5: managing extreme events | January 2010–March 2012 | Incident narratives, focusing on change following extreme or serious events |

| Stage 6: publication and dissemination | Ongoing, final report June 2012 | Final report, further dissemination |

Timescale and participating trusts

The project was based in six acute hospitals, selected to provide geographical spread and variation in size and status. To maintain anonymity and confidentiality, they were given pseudonyms. These hospitals are profiled in Table 2. A trust is a public sector corporation and is not a trust in the legal sense. This model was introduced in 1990 as part of the plan to develop an internal market in health services, with general practice fund holders buying care from independent providers. Trusts have a board with a chief executive and executive directors, and non-executive directors including a chairperson. Trusts are required to appoint an audit committee comprising non-executive directors (excluding chairpersons) to oversee finance and corporate governance.

Following controversy and trade union resistance, the ‘foundation trust’ concept was introduced in 2004. Foundation trusts have greater operational and financial autonomy, under a licence granted by the foundation trust regulator, Monitor. The organisation structures and governance arrangements of foundation trusts encouraged them to operate like businesses, with close links to local communities through boards of governors comprising members drawn from the populations that they served. All NHS trusts were expected to achieve foundation status by 2013–14. 33

| Trust | Sites | 2011–12 (£)a | Staffa | Bedsa | FTb | CEsc | Big issued |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnside | 1 | 120M | 2400 | 400 | No | 2 | PCT relations |

| Clearview | 1 | 590M | 7000 | 1150 | Yes | 2 | Site development |

| Greenhill | 2 | 420M | 8000 | 1100 | Yes | 1 | Emergency targets |

| Netherby | 2 | 240M | 4200 | 600 | No | 5 | Ageing estate |

| South Netley | 2 | 490M | 9000 | 1150 | No | 2 | One site by 2014 |

| Wattle Park | 1 | 240M | 3400 | 700 | No | 2 | Merger plans |

In 2010–11 there were 258 hospitals in England,34 but only 172 acute trusts (of which around 140 had foundation status). The discrepancy is explained by the wave of mergers in the first decade of the 21st century, creating several trusts that combined more than one hospital, such as Greenhill, Netherby and South Netley, which each operated two hospitals at different locations.

The selection of those trusts cannot be seen as a representative sample in the traditional, statistical sense. However, the aims of developing theory and practical guidance rely on the more powerful concepts of analytical refinement and naturalistic generalisation, rather than on statistical generalisation. 35–37 With regard to understanding the problems of implementing change following serious incidents, statistical generalisation is irrelevant, but ‘isomorphic learning’ is important. 38 Sample size is not a concern in the context of these research and practice-related aims. Nevertheless, those six trusts can be regarded as broadly representative of the acute sector as they operate in the same policy, regulation and funding environment, facing the same government demands and public expectations, with similar internal structures, working conditions and terms of employment. Empirical support for a claim to representativeness comes from the observation that the middle management experience displayed broad similarities across those six trusts, despite their differences in size, structure, location, status and problems. There were differences, of course, but the similarities were more striking.

Collaborative research design

Collaborative research designs, although not without problems, have been shown to be effective in translating research into practice in health care. User engagement contributes to the development and dissemination of findings, and to building research capacity among those involved. 39 This project adopted a collaborative design, with five aspects. First, in negotiating access to participating trusts, the draft research proposal was circulated to chief executives and other board-level directors for comment. The draft was altered as a result of feedback received. Second, one of the questions asked in management set-up interviews concerned desirable outputs from this project. Recurring themes included the value of fresh evidence to support leadership and management development, managing a complex and contradictory agenda and implementing change to improve patient safety. Third, we ran a project launch event followed by three update workshops at which findings were fed back to participants for critical comment, focusing also on the implications for practice. Fourth, project findings were fed back to individual trusts in management briefings, triggering discussions around interpretation and emphasis and practical implications. Finally, this project was assisted by a SDO management fellow, on full-time secondment from Clearview for 8 months and attached to the project part-time over 2 years.

We also established an advisory group with eight members (see Appendix 2). Two were senior academics with experience of health-care management research. The other six included two in senior national NHS roles, an acute trust research and development manager, two freelance consultants specialising in health-care management development and our SDO management fellow who came from an operational management role at Clearview. The managers in this group outnumbered the academics. Together they provided a valuable sounding board and source of ideas and advice on project methods and focus, interpretation of findings and applications, and dissemination methods.

Data collection

Information came from five main sources: interviews, focus groups, survey, briefings and incident narratives. That information was complemented by documentation (annual plans, strategy documents, reports and accounts, board agendas and minutes, NHS staff survey results and trust newsletters), much of which was in the public domain and available from trust websites. Table 3 summarises the numbers of participants involved in each stage of the project, at each of the six acute trusts.

| Trust | Set-up interviews | Focus groupsa | Incident interviewsb | Survey | Briefingsc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Burnside | 10 | 47 (5) | 15 | 108 | 16 |

| Clearview | 24 | 52 (12) | 14 | 250 | 78 |

| Greenhill | 13 | 33 (7) | 2 | 77 | 85 |

| Netherby | 17 | 38 (9) | 6 | 86 | 40 |

| South Netley | 12 | 23 (2) | 0 | 90 | 2 |

| Wattle Park | 17 | 41 (5) | 9 | 0 | 0 |

| Total | 93 | 234 (40) | 46 | 611 | 221 |

| Total project participants | 1205 | ||||

The project stages involved the following activities.

Stage 1: set-up

-

Collection of background information on research sites through set-up interviews and internet downloads.

-

Recruiting, orienting and equipping research fellow.

-

Collating and reviewing literature on middle management, the management of ‘extreme’ change and management contributions to health-care organisation outcomes.

-

Ethical approvals, governance checks and research passports.

Set-up interviews had three objectives (see agenda in Appendix 2): first, to establish the key groups of middle and front-line managers with whom it would be appropriate to run focus group discussions; second, to gather background on each trust and its management agenda; and third, to establish logistical arrangements for distributing project information.

Stage 2: management focus groups

The original proposal was to run four focus groups at each participating site, involving around 100 managers in total. These discussions generated information concerning the changing nature of middle management work, and issues arising in those discussions also contributed to the design of the survey (see participant information and topic guide in Appendix 2). As Table 3 shows, however, over 230 managers participated in 40 focus group discussions. The main reason for exceeding the original target lay with replies to the interview question concerning the middle management groups to involve in this project and who would not be covered with only four focus groups. The widely distributed nature of the management population in an acute trust is explored in Chapter 2. At two trusts, South Netley and Wattle Park, arranging focus groups proved to be a logistical problem. Only two groups were run at South Netley and, although five were run at Wattle Park, one relied on interviews with clinical directors with whom we were never going to be able to meet as a group.

Stage 3: management survey

The aim of the management survey was to build on the qualitative information from interviews and focus groups, and to generate evidence from a larger sample on the nature of emerging pressures and demands, and the implications for management practice. The aim was to survey the entire middle management populations in the six participating trusts, but this was not possible. The plan was to use a ‘60–40’ design with around 60% of survey items common to all sites, for comparison and benchmarking purposes, and 40% tailored to local priorities. However, as the survey was being designed early in 2011, pressures on trust managers' time increased sharply, and three trusts decided not to complement the survey with their own questions. Findings are explored in Chapter 5 and full details of the survey design, administration and analysis are provided in Appendix 3.

Stage 4: management briefings

Starting in the second quarter of 2011, we offered management briefings to give participants an opportunity to assess the findings and their implications. These were also opportunities for respondent validation, to check interpretations and to explore implications for practice. The limited amounts of time that managers were able to give to these meetings meant that there was often little chance for extended discussion. However, the broadly favourable responses to these presentations did provide reassurance with regard to the main findings.

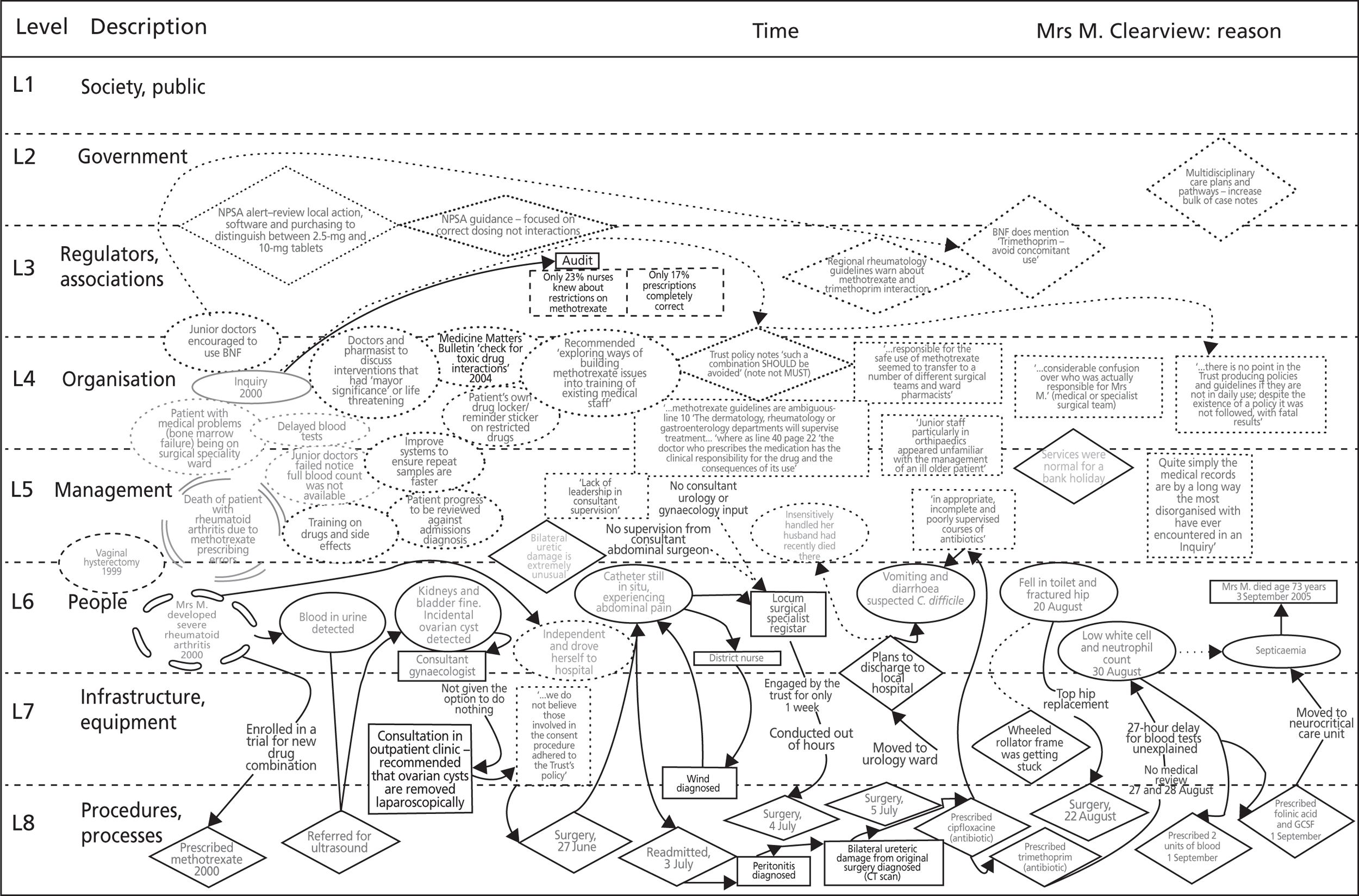

Stage 5: managing extreme events

This stage of the project focused on the management processes involved in implementing change following serious or ‘extreme’ incidents. 40 The aims included developing an understanding of processes that have rarely been investigated from a change management perspective, and developing frameworks of practical value in such settings. Patient safety and serious incident investigation are areas in which considerable amounts of work – theoretical and practical – already exist. However, the focus of that commentary concerns investigation methods to understand incident causality, and protocols to improve safe practice. The implementation of changes to practice is rarely automatic or straightforward, and there are gaps in our understanding of the potential problems. The aim, therefore, was to document narratives of successful and less successful attempts to implement change following serious incidents, to identify the conditions that shape the outcomes.

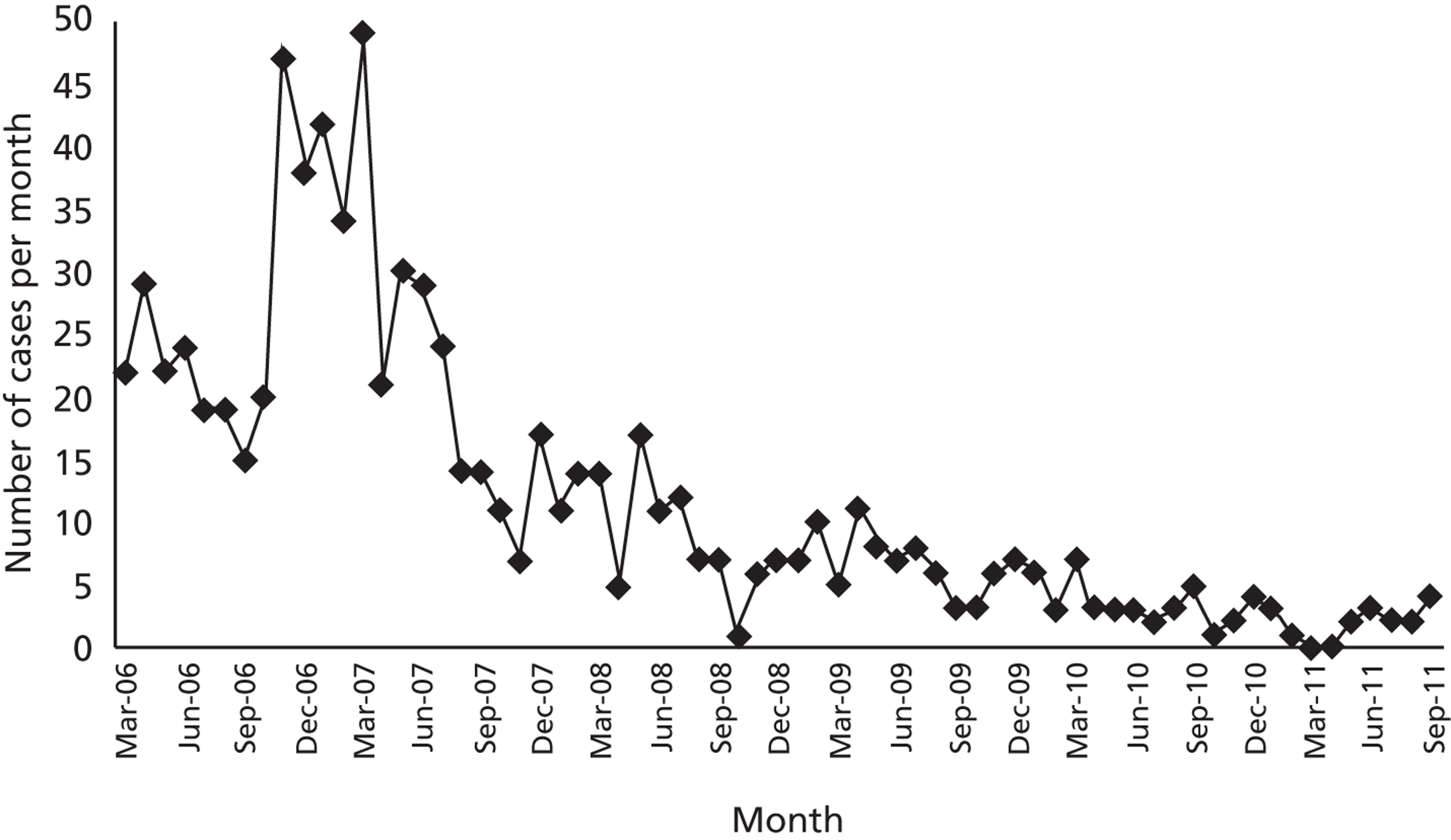

The incidents discussed in this report are listed in Table 4. The outcome in one of these incidents, concerning the handling of the Clostridium difficile outbreak at Burnside, was sustained success. Change following the other incidents, however, was problematic. Because of space constraints, four of these incidents are discussed in Chapter 6 and one is reported in Appendix 4.

| Serious incident | Trust |

|---|---|

| C. difficile outbreak | Burnside |

| Patient death, drugs interaction | Clearview |

| Mental health patient suicide | Clearview |

| Surgical patient misidentification | Clearview |

| Norovirus outbreak (see Appendix 4) | Wattle Park |

Stage 6: publication and knowledge transfer

Publication and dissemination traditionally follow project completion. In this case, however, the intent was to develop outputs from the project from an early stage, particularly when these had implications for management practice. We wanted to generate high-impact, readily accessible modes of communication, which nevertheless maintained the integrity and, where appropriate, the complexity of the issues at stake and implications for management practice. Outputs have included a series of research briefings, a podcast, a magazine article, a contribution to the Health Service Journal online resources section and conference and seminar presentations (see Appendix 5).

Data analysis

Table 5 summarises the approach to data analysis, linking information sources to the project themes.

| Stage, link to themes | Analysis, what this revealed |

|---|---|

| 1. Set-up interviews | Context profiling, of participating trusts |

| Managing realities | Outcomes: identify local priorities and management agenda, factors shaping management realities |

| 2. Focus groups | Content analysis, identifying recurring themes |

| Managing realities | Outcomes: identify pressures, trends affecting middle management, suggestions for strengthening management contribution |

| Managing change | |

| 3. 60–40 survey | Statistical analysis: descriptive statistics and frequency distributions; content analysis of open responses (one trust only) |

| Managing realities | Outcomes: sample characteristics, motives and values, incidence and experience of new challenges and trends, factors and practices impacting effectiveness, components of ‘enabling’ and ‘disabling’ environments for management work, changing patterns of management activity |

| Managing change | |

| Managing contribution | |

| 4. Briefing groups | Content analysis, identifying recurring themes |

| Managing contribution | Outcomes: respondent validation, practitioner check on analysis, interpretations, and implications for practice |

| 5. Extreme events | Visual mapping and event sequence analysis, of incident narratives |

| Managing change | Outcomes: identify recurring success and problem patterns in extreme change processes, contingency framework based on comparisons of incidents and contexts |

| Managing contribution |

Methodology assessment

This study has a number of limitations. First, data collection was uneven across the six participating trusts, mainly because of the growing pressures on hospital management and the difficulties in arranging meetings. Second, the extended time frame potentially jeopardises the relevance of information gathered towards the beginning of the project (although many of the pressures raised at that stage have intensified since). Third, coverage of this range of themes across six trusts has perhaps been achieved at the expense of depth; it was not possible to follow up many interesting issues because of time pressures on both researchers and participants. Fourth, this qualitative study of management contributions develops conclusions that would benefit from quantified support.

Problems arose more with regard to the context in which this project was conducted than with the project design. The context involved changes that were unprecedented in scale and pace, and which made exceptional demands on NHS staff time, particularly those with management responsibilities. We attempted to arrange 1-hour interviews with individuals and 1-hour focus group meetings with around half a dozen managers at a time, when operational pressures were already requiring them to work well beyond contract hours. It was also difficult to arrange for the distribution of, and encourage responses to, the survey because of pressure on resources. Although we were able to generate outputs from an early stage, the slower than expected accumulation of data delayed the data analysis process. Major outputs have thus also been delayed, and developing the publications stream further is a priority following the completion of this project report.

Nevertheless, the project design and methods allowed us to construct rich pictures of the changing realities of middle management work in acute settings and management contributions to organisational and clinical outcomes and how those contributions could be strengthened. The incident narratives have generated fresh insights, theoretical and practical, for streamlining change processes and contributing to patient safety. Participants saw this project as valuable and timely, and none refused to be interviewed. Focus groups invariably ran beyond their scheduled hour as participants wanted to continue discussion. We were invited to incorporate management briefings in trust leadership development programmes. We were asked to run additional management skills sessions, particularly with regard to the development of influencing and political skills, and on implementing change after serious incidents. Informal feedback from managers on project outputs has been highly favourable. We have also developed interesting and valuable suggestions for further research.

Chapter 2 The NHS management population

Names, ranks and numbers

We want to turn this into a great organisation, a great place to work. We need to engage people or lose talent, especially in general management roles. Retaining talent in management roles is going to be a problem. They could just walk away to other sectors.

Director, Greenhill

There is a widespread perception that the NHS is bureaucratic and overmanaged by ‘pen-pushers’ and ‘grey suits’. 31,41,42 Management costs were thus a popular target for politicians during the life of this project, particularly approaching the general election in May 2010. 43,44 In exploring the NHS management population, this chapter reaches four conclusions:

-

Evidence suggests that the NHS is undermanaged, despite claims about disproportionate increases in management numbers, and the composition of the NHS workforce is stable.

-

The proportion of staff with managerial responsibilities is much higher than suggested in official statistics, which do not recognise many middle managers or those whose roles combine clinical and managerial responsibilities.

-

Acute trust management includes ‘pure plays’ with managerial roles and ‘hybrids’ with combined clinical–managerial duties; hybrids outnumber pure plays by four to one.

-

The obsession with management numbers and costs overlooks more significant issues concerning management capacity and the contributions that middle and front-line management make to clinical and organisation outcomes.

Management numbers

The NHS Information Centre collates annual workforce census figures (www.ic.nhs.uk). The overview in March 2011 reported that, on 30 September 2010, as fieldwork for this study began, the NHS in England had nearly 1.2 million employees (full-time equivalent or FTE, Table 6), including 40,094 ‘managers and senior managers’ (Table 7).

| 2000 | 2010 | % increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headcount | 1,118,958 | 1,431,557 | 28.0 |

| FTE | 892,620 | 1,186,571 | 32.9 |

| 2000 | 2010 | % increase | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Headcount | 25,256 | 41,962 | 66.1 |

| FTE | 24,253 | 40,094 | 65.3 |

Between 2000 and 2010, management numbers increased by 65%. The same calculation for 1999–2009 revealed a rise in management numbers of 84%. Total NHS employment rose by 30% over this period. Although the press made an issue of this ‘80–30’ disparity, basic arithmetic suggests a more prosaic conclusion. The disparity arises from the difference in the bases of the calculation, which is over a million in one case and around 20,000 in the other. Percentage calculations produce higher figures with smaller bases. For example, when team membership grows by only one person from two to three, that is a 50% increase. When team numbers swell to 101 from 100, that is a 1% increase.

The Information Centre figures (Table 8) show that managers represented just under 3% of the NHS workforce (FTEs) in 2000 and just over 3% in 2010 – hardly a dramatic increase. The census published in 2012 shows that total employment fell to 1,193,334 (headcount) by November 2011 and the number of managers and senior managers also fell to 3.2% of the total.

| 2000 | 2010 | |

|---|---|---|

| Headcount | 2.3 | 2.9 |

| FTE | 2.7 | 3.4 |

It is, however, appropriate to explain the increase in management numbers since 1999. Part of the explanation lies with the 30% increase in the numbers of staff requiring recruitment, selection, coaching, mentoring, supervision, appraisal, discipline, development – management. The increase was also likely to have arisen as a result of other demands:45

-

pursuit of foundation trust status, developing service-line management

-

waiting times and other targets, outcomes, performance standards

-

Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) agenda

-

world-class commissioning, creation of clinical commissioning groups

-

patient choice, electronic booking, independent treatment centres

-

payment by results, changes to tariffs, fines

-

making £20B efficiency savings by 2015

-

constantly changing regulatory, auditing and accreditation regimes

-

serious incident and ‘never event’ investigation and reporting systems

-

Monitor and Care Quality Commission (CQC) compliance processes and quality accounting.

Drawing from Binley's Database of NHS Management, Walshe and Smith31 arrive at similar conclusions. Although using information gathered for commercial purposes, with different inclusion criteria, Binley's data have been collected in a consistent manner for a considerable period, and reveal trends similar to those in the Information Centre figures. According to Binley's Database, NHS management numbers in the UK rose by 28% between 1997 and 2010 (Table 9). Walshe and Smith note that NHS spending over this period increased by 105% in real terms, from £60B in 1996–7 to around £123B in 2010–11 (at 2011 prices). They conclude that the management workforce has not expanded disproportionately, having not only more staff, but also more money, to manage. Binley's Database also shows that management numbers in acute services (across the UK) have been relatively stable, with 14,810 in 1997, 12,642 in 2000 and 13,985 in 2010.

| Year | England | UK |

|---|---|---|

| 1997 | 20,029 | 24,822 |

| 2000 | 18,462 | 22,366 |

| 2010 | 27,413 | 31,871 |

How does the NHS compare with other sectors? The Office for National Statistics Labour Force Survey shows that around 15% of the total UK workforce are designated ‘managers and senior officials’. This proportion has changed little in the past decade, rising from 13.6% of all those in employment in 2001 to 15.6% in 2010 (www.statistics.gov.uk/statbase/product.asp?vlnk=14248). With only 3% of the workforce in management roles, the NHS may be short of management expertise.

Management costs

The question of management numbers is linked to costs, which, in a climate of global recession and domestic austerity, were the subject of debate. This debate was not new. In 2001, Appleby46 reported on ‘government's war on management costs (synonymous with managers/bureaucrats)’, asking, ‘what level of management costs should the NHS expect to bear in order to have a well-managed service?’ The ‘New Labour’ administration wanted to cut NHS management costs by £1B over 5 years from 1997. Appleby46 also noted that ‘Managers are not seen by most of the public as adding any value to the NHS or patient welfare. Indeed, most would like to see fewer managers and, yes, more doctors, more nurses, more beds.’ Reducing ‘bureaucracy’ is perennially popular.

McLellan47 noted that management costs were around 3% of the annual service budget in 2010. In comparison, US charities spend between 4% and 8% of revenue on management. The estimate for UK charities is between 5% and 13%. 48 McLellan47 cites these figures as evidence that the NHS is undermanaged, a situation that would be exacerbated, he argued, by the policy of cutting management costs by 45% by 2014–15, pointing to ‘the scale of the financial challenge facing the service and the potential lack of management capacity to deal with it’ (p. 3).

Drawing on an analysis by McKinsey, Santry43 reports that management accounted for 1.5% of the total NHS budget in 2009, putting the UK at number 18 in a list of 23 global health systems. Management in other countries consumed much higher proportions of their health-care budgets, including in Mexico (11.8%), the USA (7%) and France (6.8%). Santry was responding to a claim by the Secretary of State for Health that there was no comparative international evidence to show that the NHS had low management costs.

An undermanaged service?

The NHS Confederation49 argued that, as one of the largest employers on the planet, spending over £2B a week and meeting the health-care needs of around 60 million people, the proportion of managers in the NHS is low. The evidence indeed suggests that the NHS has ‘lean management’. The wisdom of policy to cut management numbers and costs is thus in doubt, as this weakens the motivation and commitment of managers, and dilutes the management capacity to implement change. The King's Fund42 commission on management in the NHS concluded that, ‘It might just as sensibly be asked, how can it be run effectively with only 45,000 managers?’ (p. 4).

Pure plays and hybrids

Other evidence shows that the official figures underestimate the numbers of those with either a ‘pure’ management role or a ‘hybrid’ role combining clinical duties with managerial responsibilities:

-

pure plays: roles that are wholly managerial

-

hybrids: roles that combine clinical and managerial responsibilities.

The NHS Information Centre data do not count as managers any clinical and scientific staff holding hybrid managerial roles; however, if hybrids as well as pure plays are counted, then the proportion of NHS staff in management positions is not 3% but around 30%.

Beyond the G matrix

Employment figures compiled by the NHS Information Centre50 were based on the Occupational Code Manual Version 9. Managers were covered in the ‘G matrix for administration and estates staff’. This included those with ‘overall responsibility for budgets, staff or assets, or who are held accountable for a significant area of work’. This included chief executives, board directors and deputies, and service managers reporting to them. However, managers who had to be qualified as doctors, nurses, therapists, scientists or ambulance personnel were coded in their professional area, such as clinical directors, modern matrons and ward sisters, and laboratory supervisors. Trust chairpersons and non-executive directors did not appear in the management numbers either. They were coded in the ‘Z matrix for general payments’ along with Macmillan and Marie Curie nurses.

Other line managers, team leaders and supervisors were coded as ‘clerical and administrative’. They were excluded from management numbers because they ‘do not have responsibility for a significant area of work/budget’, including ‘line managers for whom management is only a portion of their role who may also act as analysts or in some other administrative or clerical capacity’. This understates the significance of such roles – ward managers, outpatient department management, the management of diagnostic units and cleaning, catering and portering supervisors. Those staff can have a major impact on hospital performance and reputation.

Staff coded in the ‘clerical and administrative’ category in the G matrix, including those with managerial responsibilities, appeared in the census as ‘support to clinical staff’. In 2010, support staff accounted for 26.5% of all NHS employees in England, a proportion that had also been stable for a decade. The proportion of staff in ‘central functions’ – finance, personnel, information – was also relatively stable, at 8% of employees in 2010.

Who are these ‘uncoded middle managers’? One of the questions in the project set-up interviews was: ‘Who would you include in the middle management population of the trust – the key categories and/or groups to whom we should be speaking?’ Responses included hybrid roles (medical director, clinical director, senior/lead nurse, midwifery manager, modern matron, ward sister, specialty lead, laboratory team leader) as well as pure plays (deputy/assistant director, general manager and department head). Using an organisation's own definition of middle management is a strategy advocated by Currie and Procter,51 and adopted in this project.

The workforce information departments (who collate the census figures for the NHS Information Centre) in Clearview and Greenhill were asked to estimate the total management populations of their trusts, counting pure plays and hybrids. This was based on a briefing on the traditional definition of management in terms of planning, organising, supervising, directing, co-ordinating, reporting and budgeting, or POSDCoRB,52 and also taking responsibility for human resource management, and the implementation of service improvement, into account. If a role includes some or all of those activities then it is categorically a management role. The estimates are shown in Table 10. In both trusts, around one-third of staff had managerial roles, with pure plays accounting for 6% of the total. It is also important to note that hybrids in both cases outnumbered pure plays by four or five to one. The head of leadership and organisation development at Greenhill felt that these estimates were low. Asked to make an informed guess about the actual figure, she replied, ‘I think we're looking at 35 to 40 per cent’.

| Clearview | Greenhill | |

|---|---|---|

| Total staff (FTE; 2011a) | 7137 | 6254 |

| No. with management responsibilities | 2380 | 1940 |

| No. with management responsibilities as percentage of total staff | 33.3 | 31.0 |

| No. of pure plays | 398 | 405 |

| Pure plays as percentage of total staff | 5.6 | 6.5 |

| Pure plays as percentage of all management | 16.7 | 20.9 |

An overmanaged service?

The NHS may be viewed as undermanaged, with only 3% of its 1.4 million employees in management roles. Knowing that at least one-third of staff (in acute trusts) have managerial roles, can we conclude that the service is overmanaged? This raises the question of management capacity.

Management capacity can be defined as the ability of the function as a whole to respond effectively to the demands placed on it at any given time. The management agendas of the trusts collaborating in this study were lengthy, complex and fluid (see Chapter 4). Different profiles of pure plays and hybrids may be equally effective in the context of different local conditions, past histories and current agendas. It is not possible to assess capacity simply by comparing numbers. Fewer pure plays may mean lower management costs, but that could increase the burden on hybrids, reducing time for patients, professional development and innovative service improvements. That may in turn lead to the appointment of more clinical staff to compensate, cancelling the cost advantage of having fewer professional managers.

With regard to the ‘3% versus 30%’ question, at least four other factors impinge on the management capacity of an acute trust. First, ‘the other 30%’ are not all FTEs; most are hybrids. One senior hybrid asked about the mix of clinical and managerial responsibilities in nursing roles replied:

Head nurses are ‘50–50’. They're responsible for the managerial nursing aspects in their directorate. But I hold them accountable for nursing professional issues as well. For a matron, I would expect that to be very much more clinical. And probably it should be 75–25, clinical – managerial. For a ward sister, the ideal is that they should have two days a week where they can deal with the managerial elements of their role, but it's also about making sure standards are adhered to. So probably a 60–40 split.

In your judgement, are some of those staff spending more time on their management responsibilities than they should?

No. I would say it's the other way around. They don't get enough management time.

Director, Netherby

Interviews with modern matrons elsewhere suggest that this balance of responsibilities varies from trust to trust, and fluctuates over time, depending on the management agenda.

Second, despite our previous definition, some ‘pure plays’ have specialist non-managerial responsibilities and so they are not necessarily each a ‘full’ FTE. For example, one manager commented as follows about her managerial specialist responsibilities:

Question: Is my profession ‘manager’ or ‘trainer/coach’? Answer: Trainer/coach. Therefore, when answering what percentage do I ‘manage/lead’ versus what is ‘practical/specialist’, I'd say 70–30. I do have a practical/specialist role I fulfil that is not management. There is clear water between the two, and I suspect that many others will say the same. Few of them will see themselves as NHS managers wholly, rather a specialist first, in a management role, but their loyalties are often to the profession they trained hard in.

Senior manager, Greenhill

Thus, 100 pure plays does not necessarily equate to 100 FTE managers. Although no longer employed full-time in a clinical capacity, many pure plays have a clinical background (such as nursing) that they bring to their relationships with clinical staff, and use to inform decisions and judgements. Some maintain their registration, and ask their workforce information offices to code them with their profession in the annual census figures, and not in the G matrix as managers.

Third, most hybrids have had limited management education, beyond short courses. Pointing to the piecemeal ‘on the job’ management development of medical staff, Gillam53 argues that ‘the idea that all doctors can just “manage” is hopelessly naive’ (p. 1). Short courses include The King's Fund management and leadership for clinicians course, which runs over 5 days, and Leading an Empowered Organisation (LEO), which was a 3-day course (now discontinued) for staff (including nurses) in management and supervisory roles. A master’s degree in business administration takes a year of full-time study to complete; few clinical staff have the desire, time or financial resources to obtain this qualification. During this project, Clearview, Greenhill and South Netley implemented their own leadership and management development programmes. But these still amounted to more ‘short courses’, albeit intensive and tailored. The management capabilities of many hybrids are thus dependent on limited educational input and considerable on-the-job learning:

We don't have any managerial training and lots of work is left to us. I expect that in the future we will be left to make more decisions. There is more workload. You have to do appraisals, you are asked to create a new policy and deliver presentations and you are expected to do more.

Mixed focus group, Greenhill

I've been in post for three years, and I want promotion. Are they developing me into a matron's role? There is no ongoing development. Ward managers are just left to get on with it. You are left on your own. Find your own development. The one-to-one meetings that we have with more senior management are all about operations and finance.

Ward sister, Netherby

Fourth, many hybrids do not view themselves as managers or they use the label reluctantly. In 2010, ward managers at Netherby voted to change their job title – to ward sister. Other examples included:

I've been a consultant nephrologist since 2003, and I've been involved with the emergency department project since 2005. The role of clinical lead is managerial if you want to call it that. In the emergency department project, this has involved structure change. But ‘management’ has connotations among clinicians relating to stick not carrot. Managers are people who withhold resources rather than try to improve services. My role is more of a leadership and organisation development role, much wider than management.

Clinical director, Greenhill

I would describe my role as clinical leadership. I'm not nursing, not hands on. I am not at all managerial. My role is professional leadership. But this does influence behaviour, practice, change, service improvement, so managerial in those senses. The senior staff on the wards have managerial responsibility; ward sister, charge nurse are front-line managers. Matrons and head nurses are middle management. I have a manager role, but I have professional accountability, so the emphasis of my role is with professional leadership.

Senior nurse manager, Netherby

These participants were more comfortable describing themselves as ‘leaders’. Before fieldwork commenced, we were instructed by a senior manager at South Netley to change the subtitle on the project documentation, from ‘middle and front-line managers’, so that this would appear as a study of ‘managerial and clinical leads’. These views reflect a trend in the public sector to value and promote leadership at the expense of mere management. 54,55

Mintzberg4 offers a straightforward resolution to the ‘leadership versus management’ debate. Asking if one would like to be managed by someone who doesn't lead, or led by someone who doesn't manage, he concludes that, ‘We should be seeing managers as leaders, and leadership as management practiced well’ (p. 9, italics in original). With a similar view, and using ‘managers’ and ‘leaders’ interchangeably, Quinn et al. 56 argue that, ‘we want to distinguish between individuals who happen to have management positions and individuals who truly display leadership in their management of others’ (p. 333). The evidence from this project demonstrates that, if the distinguishing features of leadership concern designing, inspiring and driving change, then middle management roles in the NHS are indeed a blend of management and leadership.

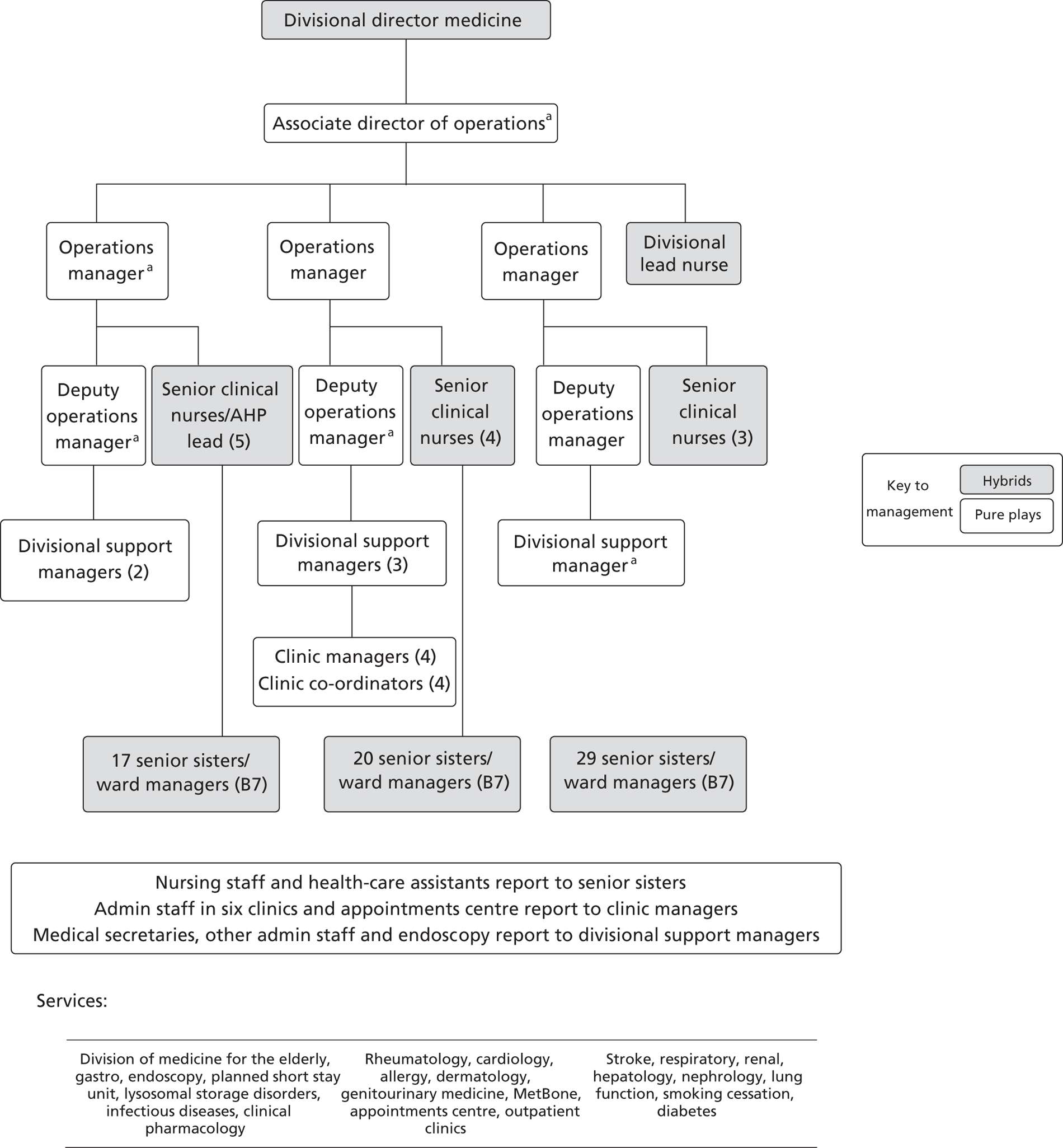

To illustrate how pure plays and hybrids populate a hospital management structure, Figure 1 shows the organisation chart for the medicine division at Clearview. This division had 350 beds in 16 wards, employing 1200 staff (headcount). The division's budget in 2010–11 was over £80M, with target savings of around £5M. The organisation chart identifies 21 pure plays and 80 hybrids. In other words, as indicated previously with regard to what appears to be the typical balance of roles at trust level, the ratio of hybrids to pure plays in this division was around 4 to 1.

FIGURE 1.

Clearview Hospital medicine division organisation chart (October 2011). a, Managers with clinical backgrounds. AHP, allied health professional.

Finding the front, defining the middle

For the purposes of this project it proved difficult to define unambiguously ‘the front line’ in relation to ‘the middle’. Definitions provided by various commentators suggest that this should not be a problem. However, three considerations apply. First, in acute care, the management ‘front line’ is mobile. Second, the hybrids who occupy this ‘fluidic space’ have onerous managerial responsibilities that influence quality of patient care, as well as organisational performance. Third, the distinctions between roles in this ambiguous zone are more important than whether they are defined as ‘middle’ or ‘front line’. We have thus dropped the phrase ‘front line’ from discussion. The term ‘middle management’ relates to anyone with managerial responsibilities who does not sit on a hospital board of directors. Distinctions between roles will be drawn with reference to specific job titles.

There are particular reasons for viewing ward sisters as middle, not front-line, managers. First, their roles are similar to those of matrons and senior nurses, to whom they report. Second, they are ‘mini-general managers’, controlling a budget, overseeing the development and morale of nursing staff, supporting medical staff, delivering service improvements and supporting and improving the patient experience. 57 Third, the ‘manager–subordinate’ relationship they have with other nurses is blurred, as staff nurses routinely ‘step up’ to cover for ward sisters in their absence. Fourth, with their operational experience, they act as intermediaries between senior management and day-to-day patient care. 58–60 Finally, it has been suggested that management regulation should not stop at board members, but should include ward managers. 61 The ward sister's experience is a middle management experience.

Conclusions and implications

Composition and capacity

The official census shows that around 3% of NHS employees are managers and senior managers. In contrast, when middle managers and those holding hybrid clinical-managerial roles are included, the actual proportion of staff in an acute trust with managerial responsibilities is around 30%. Management is a widely distributed function, not confined to a small cadre or elite.

There is little or no evidence to suggest that the NHS is overmanaged. The proportion of staff in management roles is (officially) much lower than the all-sector UK average. The (official) cost of management is similar to or lower than management costs in comparable settings, and is low on international comparisons. Support for the argument that the service is overmanaged relies on a flawed understanding of the arithmetic of percentage calculations. However, numbers and costs are less significant in relation to patient care, service improvement and overall performance than the management capacity of acute trusts.

NHS management has been equated with unnecessary bureaucracy. As later chapters reveal, this caricature is inaccurate. Cuts in the numbers of pure plays in acute settings could have serious consequences for the workloads of hybrids who would have to cover the resultant gaps, unless the scope of trust management agendas were to be reduced and simplified, and there is little sign of that happening. A policy of cutting management costs could thus jeopardise the effective implementation of other structural, regulatory and financial reforms, and could also jeopardise patient safety through increasing the management pressures and demands on those with hybrid responsibilities.

The denigration of NHS management, while resonating with public sentiment, damages the reputation, engagement, goodwill and motivation of a group that is key to implementing government policy, meeting national targets and maintaining the efficiency, quality and safety of day-to-day patient care. Although derogatory comments are presumably aimed at pure plays, the resultant image of management is a deterrent to clinical staff who may be invited to take on management roles. Potential candidates see through the ambiguous terminology of ‘leadership’, and have a clear understanding of the nature and perception of the management positions that they are being asked to assume. National rhetoric thus reinforces the perception of medical staff that colleagues who have taken management roles have ‘gone over to the dark side’. As it is government policy to encourage clinical staff to accept greater management responsibilities, this consequence is perverse.

Implications for practice

One implication for practice concerns the issue of management capacity, which in an acute trust, and based on the evidence from this project, can be seen as a product of:

-

management numbers

-

individual capabilities

-

engagement and motivation

-

organisational resources and infrastructure – the ‘enabling environment’

-

the quality of clinical-managerial collaboration

-

the ability to generate requisite variety.

Ashby's law of requisite variety62 argues that the management function must be able to generate at least the same levels of variety and complexity as the system being managed can adopt. Variety and complexity are required to deal effectively with variety and complexity; responses to complexity are often mistakenly aimed at simplification. The lack of multiple perspectives and diversity in thinking has been shown to reduce organisational resilience and contribute to system failures. 63 A management function whose members come from a range of different backgrounds should be able to generate greater diversity than a more homogeneous group; the quality of their collaboration is therefore a key factor. Echoing the notion of distributed leadership, forms of ‘management in the plural’, with multiple collaborators, can thus contribute significantly to capacity. 64 This issue will be explored further in Chapter 7.

This assessment assumes that it is possible to measure those factors, to operationalise the formula. This is problematic in practice, as each set of factors has multiple dimensions, and the understandings and definitions of those terms will differ from one setting to another. Nevertheless, in principle, this model – summarised in Figure 2, distinguishing individual and organisational dimensions – offers a starting point for exploring management capacity at system and trust levels.

FIGURE 2.

Dimensions of management capacity.

The management capacity six

| Individual dimensions | Organisational dimensions |

|---|---|

| Capabilities | Resources and infrastructure |

| Engagement and motivation | Clinical–managerial relationships |

| Numbers | Ability to generate requisite variety |

Most of the evidence from this study suggests either that acute trusts lacked management capacity or that available capacity was underutilised. Symptoms of undercapacity that were observed included problems arranging meetings due to busy diaries, meetings cancelled at short notice, regular evening and weekend working, managers saying that they could not cope with the workload, comments about ‘our firefighting culture’ and hiring external management consultants to help manage crises.

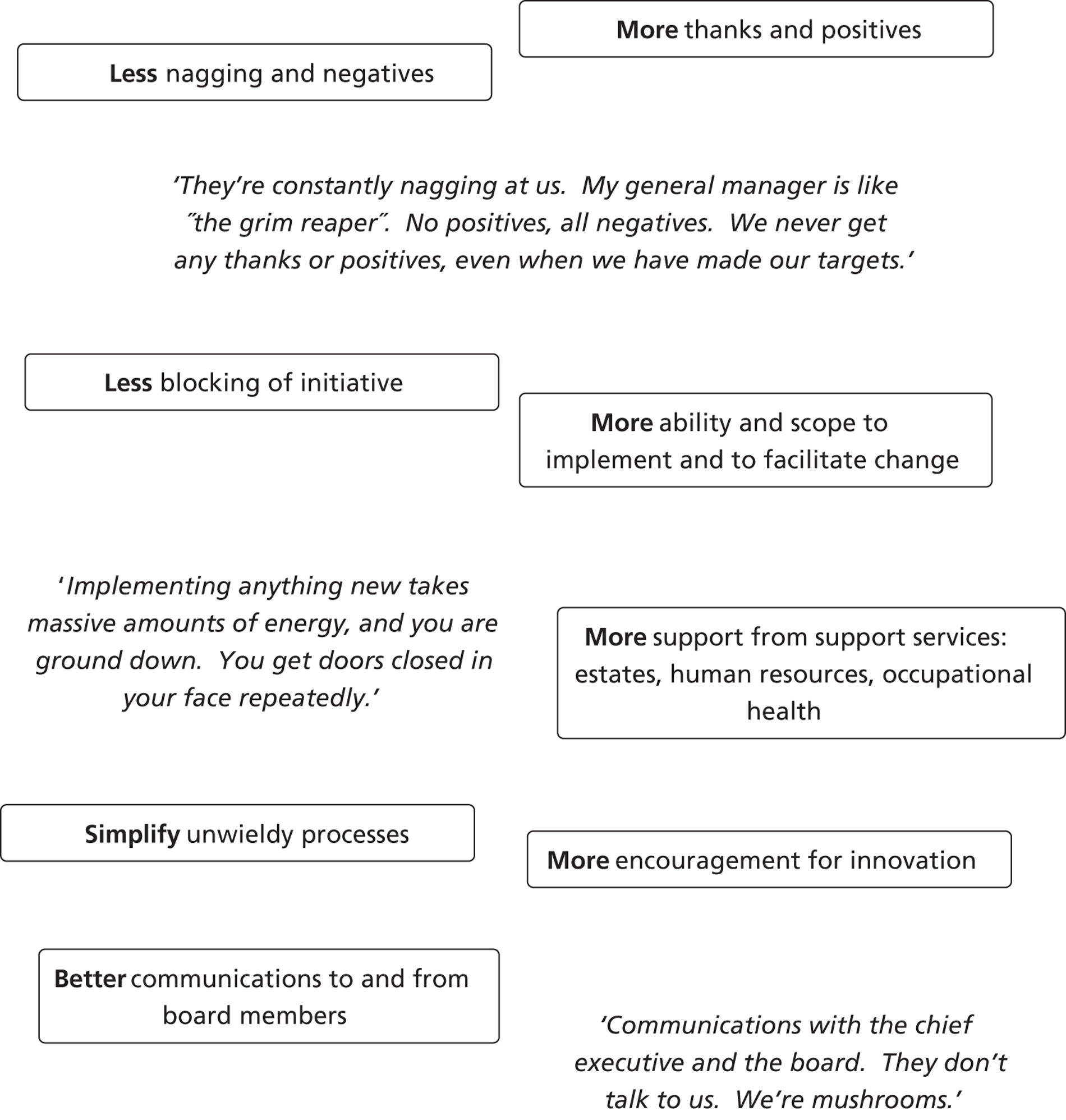

Symptoms suggesting that capacity was not being used effectively included the circulation of irrelevant and duplicated e-mails, staff performance issues not addressed, multiple unplanned interruptions throughout the day, minuted actions from meetings outstanding for months, frustration at bureaucracy impeding simple service improvements, managers criticised for decisions within their remit, experienced clinical and managerial staff carrying out basic administration, penalties for minor failures to achieve goals or targets and managers complaining, ‘just let me run my business’. Ideally, responses to an assessment suggesting that a trust or division is underutilising management capacity include:

-

redesign of cumbersome and dated systems and procedures

-

clear corporate e-mail policy to avoid duplication and overload

-

more preplanning, no ‘crisis of the day’, less ‘firefighting’

-

streamlined, simplified decision-making processes

-

increased autonomy for managers implementing service improvements

-

redesigned information technology (IT) systems to provide timely and useful information

-

shift senior management style away from ‘only blame, avoid praise’

-

shift senior management style to ‘high trust – high autonomy’.

Implications for research

Assessment of management capacity should be a fruitful area for further research, exploring the nature, source, assessment and implications of varying capacity levels. Improved understanding of capacity would provide a useful counterbalance to crude arguments about the value and contributions of management based on numbers and costs. As capacity is an organisational construct (incorporating individual dimensions), this suggests a shift in the research agenda with theoretical implications for health-care management, and with regard to management theory in general. This shift in emphasis is summarised in Table 11.

| Conventional approach | Complementary perspective |

|---|---|

| What individual managers do | What the management function contributes |

| Management roles | Management processes |

| Management numbers and costs | Management capacity |

These recommendations are not particularly novel. Management and organisation studies research has been working in these directions for some time. However, a more thorough exploration of management function, process and capacity in health care would have potential practical benefits for the service and the sector, as well as implications for the development of general management theory.

Chapter 3 The institutional context

The nature and significance of context

The NHS, like any other organisation, is embedded in a historical, sociocultural, economic and political context which shapes the norms, values and expectations that in turn influence the structures and processes of the health-care system. 65 The nature of, and relationships between, the dimensions of the institutional context are critical to understanding the demands that are placed on the management function, and the changing nature of managerial roles.

Context is not simply a stage on which action takes place. The context of an organisation is fluid and dynamic, influencing and in turn shaped by organisational events. 66 These inter-relationships do not necessarily generate a state of constant flux and indeterminacy. The institutional context is also responsible for reinforcing and perpetuating organisational characteristics, for maintaining patterns of continuity. For example, the so-called postmodern trend for flat, fluid, agile organic structures that was supposed to sweep away traditional, rigid, slow-moving bureaucratic structures has barely touched the NHS in its 60-year history. 67

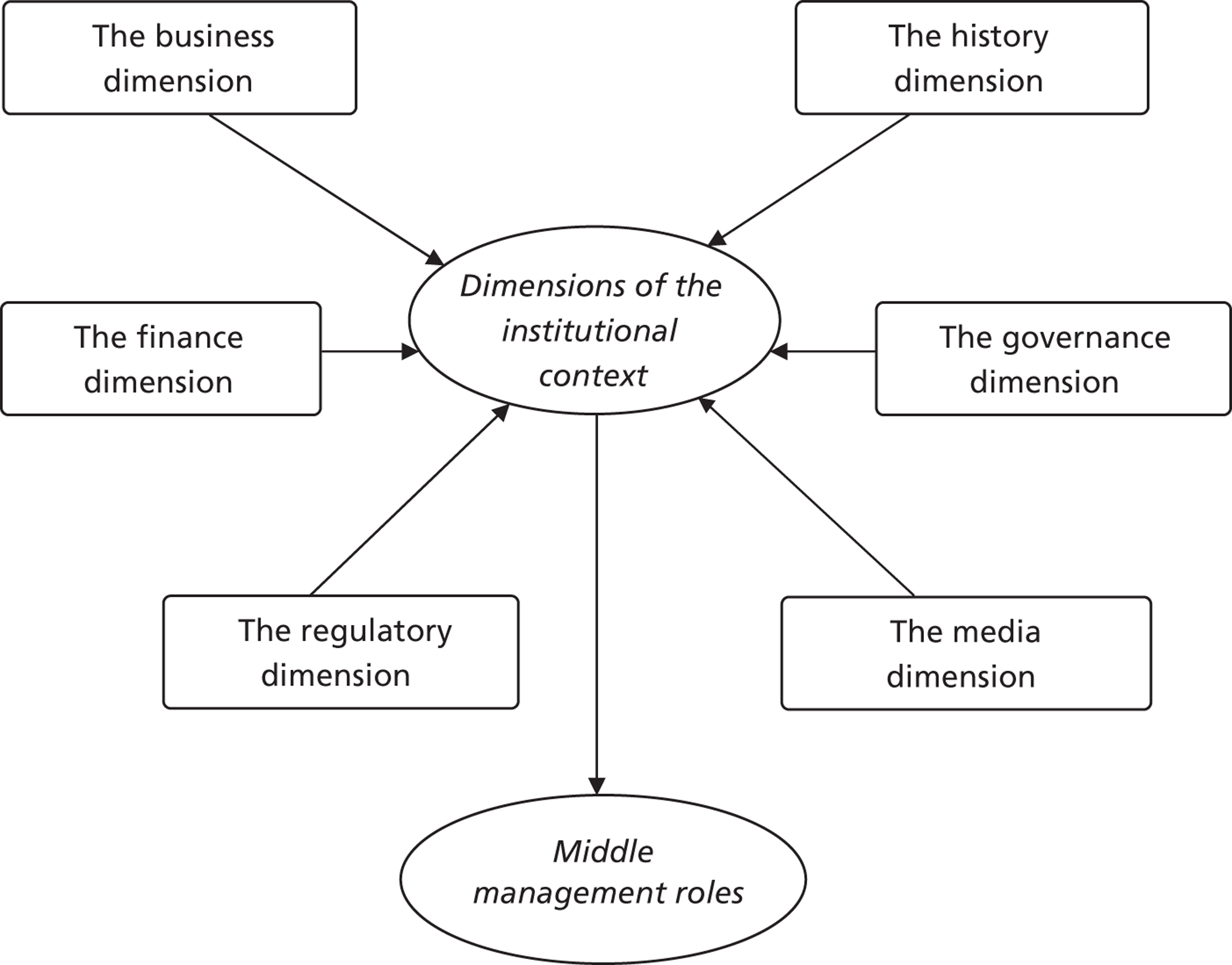

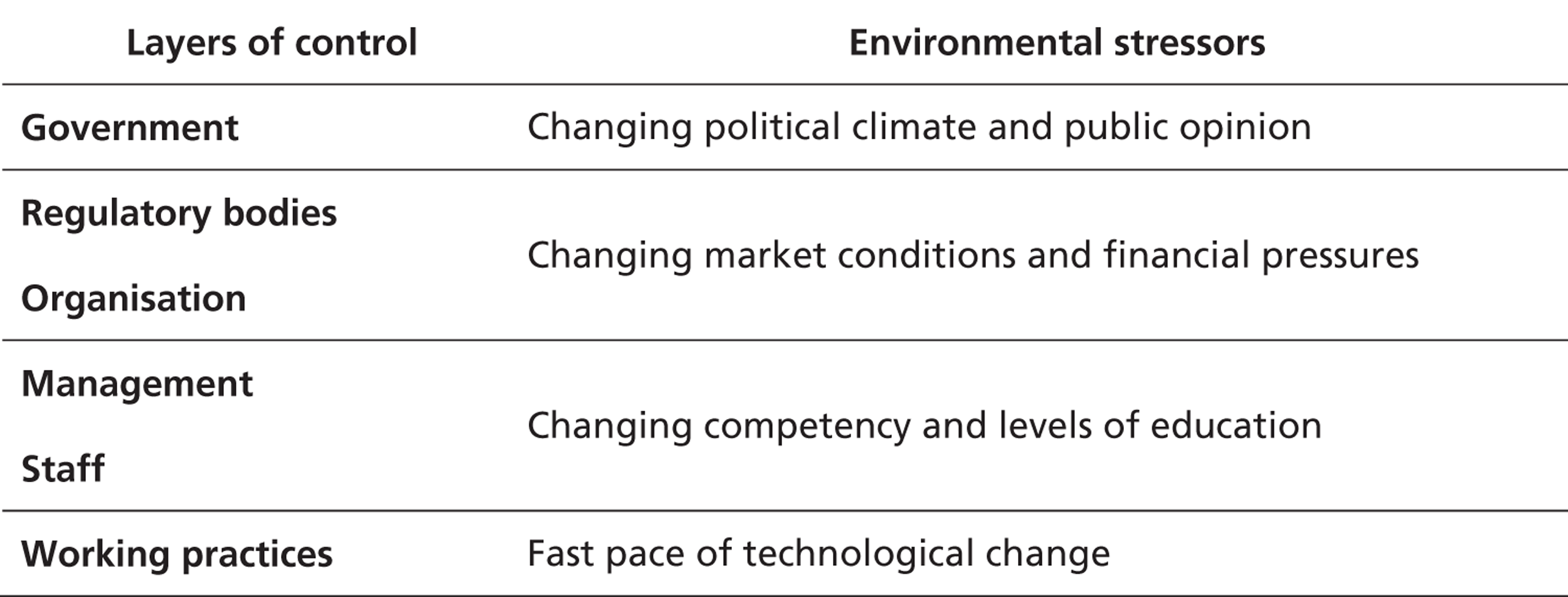

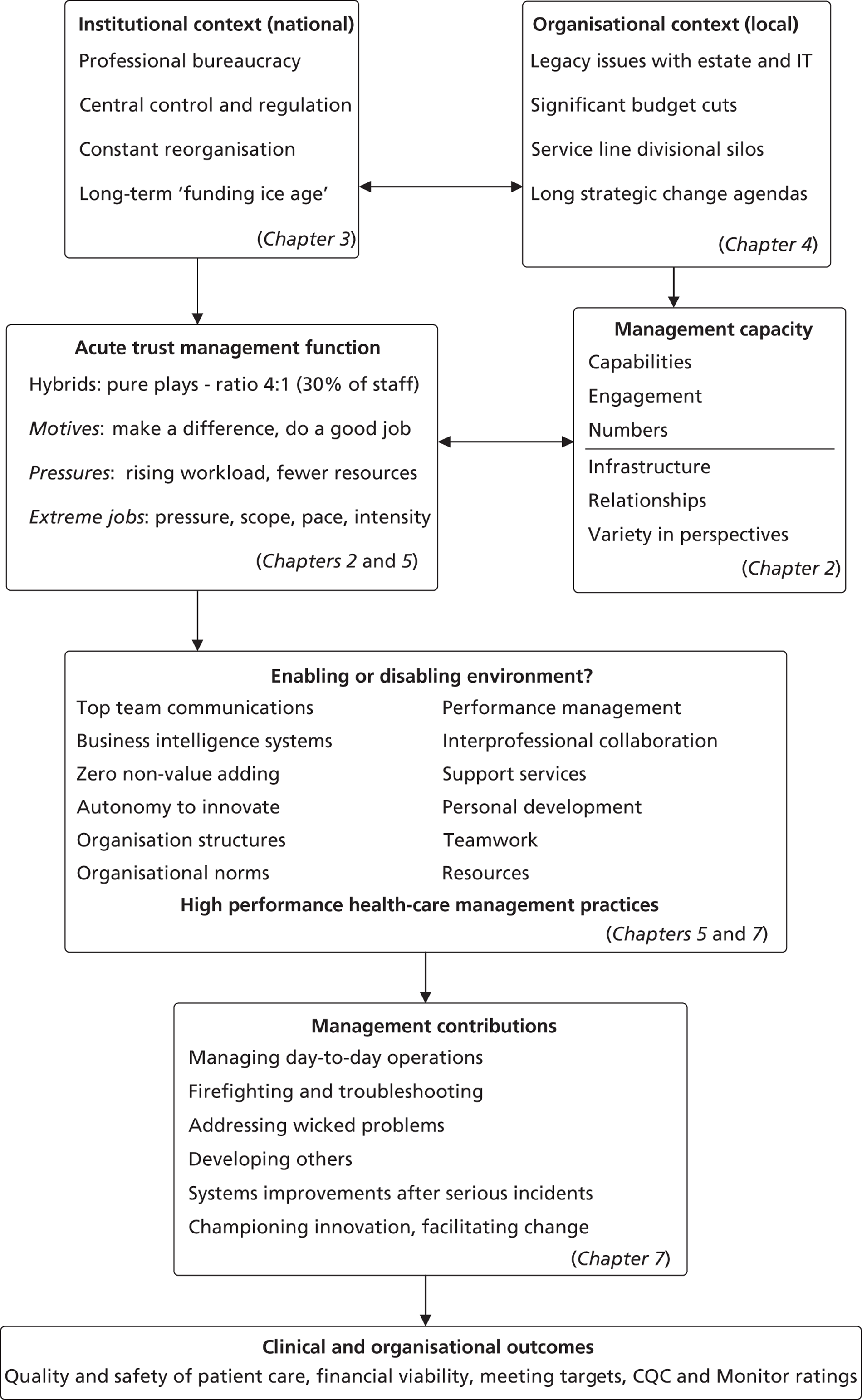

Six dimensions of the context in which the NHS operates are identified (Figure 3). These concern the history of the service, the contemporary business of health care, governance, regulation, finance and the role of the media. These dimensions overlap; discussion of regulatory regimes could equally belong with ‘governance’, and discussion of health care as a business with ‘finance’. The overarching aim of this discussion, however, is to explore relationships between the institutional context and middle management roles. The main conclusions from this analysis are:

-

History dimension. Although subject to constant reorganisations, core features of the hierarchical, centrally controlled professional bureaucracy appear to be relatively stable. Rules, regulations and slow decision processes can be beneficial, offering predictability and consistency, but can also impede innovation and rapid change. The current regulatory regime is a legacy from a series of ‘high-profile’ failures, the most recent concerning events at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust (‘Mid Staffs’). The global financial crisis that began in 2008 led to ongoing national austerity budgeting and to pressure on health care to make major efficiency savings, of approximately one-fifth of the annual spend of the service.

-

Business dimension. The private and public health-care sectors are now closely intertwined. In hospitals, clinical services are structured and run as ‘businesses within the business’. Clinical and managerial staff are encouraged to adopt a more commercial orientation and to develop new business models, managerial and process innovations, inventive uses of new technologies, public–private collaborations and competitive strategies. A key challenge concerns balancing efficiency and productivity with quality and safety of patient care. The NHS is also expected to generate revenue from innovations and exports.

-

Governance dimension. The government elected in 2010 embarked on a complex, rapid and controversial reorganisation of NHS structures. Some existing bodies were abolished (strategic health authorities and PCTs) and new ones were created, including a National Commissioning Board and local clinical commissioning groups. Policy to cut management costs generated considerable resentment. The promised liberation, autonomy and empowerment were difficult to spot, and ‘micromanagement’ continued.

-

Regulatory dimension. Providers answer to many regulators, auditors, inspectorates and accreditation agencies (RAIAs), whose information demands overlap and can be burdensome. Regulation has improved aspects of performance, but has not prevented systemic failures in care. The regulatory regime extends to innovation, where the call for a more creative, commercial approach is accompanied by a compliance framework, standardised efficiency measures, fines and an implementation board. In the wake of the Mid Staffs inquiry, some form of regulation of health-care management was expected to emerge during 2012–13.

-

Finance dimension. ‘The Nicholson challenge’ to find £20M efficiency savings between 2010–11 and 2014–15 was described as a ‘NHS recession’, a ‘funding ice age’ and a ‘perfect storm’. Trusts from 2010 had to implement CIPs generating recurrent savings of 3–4% per annum, raising anxiety about job security among all staff including management. Although cutting costs and improving productivity were over-riding issues, these actions had to be balanced with the priorities of improving the quality and safety of patient care. Middle managers in particular felt the need for financial management skills.

-

Media dimension. The press ‘rules of production’ mean that sensational, dramatic ‘bad news’ stories are more likely to be reported than good news. The constant ‘bad press’ influences public perceptions of the service and its staff, and also affects government policy. Commentary supportive of management is rare; poor management is typically blamed for system faults and failures, and a negative stereotype of managers as costly pen-pushing bureaucrats prevails, potentially inhibiting motivation and recruitment.

FIGURE 3.

Dimensions of the institutional context of the NHS.

The six dimensions

The history dimension

The history of the NHS is a history of change. An organisation of this size and cost is unlikely ever to be free from political intervention. As governments in the UK change at least every 5 years, the potential for turbulence is high. During this project, the service witnessed shifting government priorities, new organisational arrangements and regulatory systems and more ‘high-profile’ events including failures in care for the elderly,68 Winterbourne View69 and failures in care at Mid Staffs. 70

Subject to constant change, has the NHS now developed the agile, flexible, non-hierarchical, organic, responsive attributes of the post-bureaucratic archetype? Commentators have been predicting ‘the dinosaur scenario’, the extinction of bureaucracy, for a century. Buchanan and Fitzgerald67 argue that the NHS has become an ‘accessorised bureaucracy’. This has meant acquiring some fashionable new practices and private sector terminology while maintaining central control, complex structures, multiple regulatory bodies and the proliferation of performance metrics. This echoes a previous study which concluded that, although the ‘fur coat’ of structures had changed, the ‘knickers’ of the power relations that underpin the professional bureaucracy were intact. 71

The accessories, however, have improved access to and the quality of patient care and contributed to reductions in waiting times and infection rates. 72 Bureaucracy brings the benefits of unity, co-ordination, precision, predictability, consistency, impartiality, organisational memory and continuity across governments. 73,74 The accessorised bureaucracy provides a stable, predictable system that also features innovation and change, and may thus be a good hybrid solution.

In terms of recent history (2009–11), four sets of events were significant. First, Next Stage Review was published in June 2008,75 with a review 1 year later. 76 This review noted the challenges posed by demographic trends, rising public expectations and the rapid development of new technologies, and stressed the importance of improving the quality and safety of care, putting fresh emphasis on the role of clinical leadership.

Second, the financial crisis forced the UK government to support domestic banks, at considerable cost, leading to austerity measures to reduce the resultant deficit. The NHS was asked to find £20B of savings by 2014–15 through a quality, innovation, productivity and prevention programme. 77 Developing cost improvements to reduce spending on the required scale consumed considerable time and energy. Finding savings within one financial year was difficult; making recurring annual savings of 3–4% was a major challenge.

Third, the mortality rate at Mid Staffs since 2005 led to an investigation78 and then to an independent inquiry,70 followed by a public inquiry. Problems were attributed to failures in leadership and management, as well as to lapses in clinical care. This incident led to demands to regulate health-care managers. 61

Fourth, the general election in May 2010 returned a coalition government that proposed a radical reorganisation of the structure, funding and regulation of the service. New legislation was to scrap existing bodies – strategic health authorities, PCTs – and create others – a National Commissioning Board, clinical commissioning groups and Healthwatch England (a ‘consumers' champion’). The White Paper1 also indicated a 45% reduction in management costs. One participant in this study described the Department of Health as ‘a hyperactive child’, overloading staff with untested ideas disseminated in vast amounts of unco-ordinated documentation that nobody had time to read (clinical director, Netherby). Many commentators questioned the wisdom of introducing such a major reorganisation, accompanied by massive budget cuts, while reducing the numbers and costs of managers – within 4 years. 79

The business dimension

We need to learn better how to compete. We've got to run as a business now, we're beginning to get there, and pathology is at the forefront. We have a well equipped lab, we have senior management support, we deliver on targets, our finance is OK, half of our business is with the trust and other hospitals, and the other half of our business is with general practitioners. In 2009, microbiology and immunology started to offer fourteen new services. This is a growth business.

Clinical director, Netherby

Our future survival will depend on our ability to adopt a more business orientated way of thinking and working whilst being appraised for the quality of our patient services delivered through effective managerial practice.

Management development programme brochure, South Netley

When I speak to nurses and clinicians about ‘the business’, they physically recoil. It does not come naturally to doctors and nurses to see that they are part of a business when they have signed up for a vocation.

Operations manager, Clearview

Foundation trusts have greater autonomy than non-foundation trusts and are encouraged to operate as businesses. Payment by results was introduced in 2002 to promote competition, allowing low-cost providers to retain surpluses. Clinical services are now organised as autonomous ‘business units within the business’, which involves clinical staff in activity reviews, costing and budgeting, service improvement and developing business plans. The House of Commons Health Committee80 concluded that the foundation trust application process had ‘forced NHS organisations to operate in a more business-like way’ (p. 36). Commercial practices such as process redesign, quality improvement and ‘lean’ have become common practice across the service. 81–83

The private sector now plays a key role in public sector services. 84 The public services industry (PSI) involves private and third sector businesses providing services under government contract. The PSI in Britain employs 1.2 million people, generating annual revenues of around £80B, covering services such as maintenance and cleaning, computing and other business processes, social care facilities, services for the elderly, children and people with disabilities, custodial services, leisure services, waste management, and clinical care provided by independent treatment centres. Health is the largest component of government spending on the PSI, totalling £24B in 2007–8, followed by social protection (£18B), defence (£10B) and education (£7B). The Julius review84 concluded that subjecting providers to competition reduces costs without affecting quality, and advised that public service markets should be exposed to further competition.