Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1809/230. The contractual start date was in February 2009. The final report began editorial review in August 2012 and was accepted for publication in December 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Senior et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Older prisoners are the fastest growing subgroup in the prison estate in England and Wales. 1–4 In spite of the rapid increase in numbers and the complex and costly health and social care needs of older prisoners,5 their service provision is currently often suboptimal. 6 Emerging evidence has suggested that there are particular service provision and integration deficits at key transition points for older prisoners, such as on entry to and discharge from prison. 7

This programme of research examined the health and social care needs and current service provision for older male adults entering and leaving prison, and evaluated a model for systematic needs assessment and care planning for these groups. Women have been excluded from the study because of the low number of older female prisoners. In June 2011 there were only 63 female prisoners aged ≥ 60 years in England and Wales compared with 2952 male prisoners in this age group [National Offender Management Service (NOMS), 2011, personal communication].

Objectives

The specific objectives of the current study were:

-

to explore the lived experiences and needs of older people entering and leaving prison

-

to describe current provision of services, including integration between health care and social care services

-

to pilot and evaluate an intervention for identifying health and social care needs on reception into prison and ensuring that these are systematically addressed during older people's time in custody.

Methods

The research programmes was a mixed-methods study divided into four parts:

-

a study of all prisons in England and Wales housing adult men, establishing the current availability and degree of integration of health and social care services for older adults

-

establishing the health and social care needs of older men entering prison, including their experiences of reception into custody

-

the development, implementation and evaluation of an intervention to identify and manage the health care, social care and custodial needs of older men entering prison

-

exploration of the health and social care needs of older men released from prison into the community.

Ethical considerations

Ethical approval to conduct the study was obtained from South Staffordshire Local Research Ethics Committee (09/H1203/47) and the University of Manchester's Research Ethics Committee. To access Her Majesty's Prison Service (HMPS) establishments, governance approval was obtained from the NOMS National Research Committee and from individual prison governors/directors. For each establishment, site-specific approval was obtained from the relevant NHS primary care and mental health trusts. Research staff had NHS research passports and letters of access.

To ensure informed consent, all participants were provided with a participant information sheet (see Appendix 11). The information detailed on the sheet was also verbally imparted to ensure comprehension and allow for any literacy difficulties. Participants were provided with the opportunity to ask questions and were given at least 24 hours to consider their participation. Participants were frequently reminded of their right to withdraw from the study at any time. All written consent was obtained by researchers rather than prison or health care staff.

All participants had issues of confidentiality explained to them and were aware that the informationthey provided would be treated in confidence unless we were concerned for their immediate safety, or the safety of others. In such circumstances the appropriate individuals at prison establishments were informed. In some instances this led to the opening of Assessment, Care in Custody and Teamwork (ACCT) documents to ensure that prisoners who were at risk of self-harm were appropriately supported by prison and health care staff.

The safety of researchers was also prioritised and appropriate strategies were in place for conducting interviews in prison and in the community. Interviews were conducted in public places when possible. When this was not plausible because of interviewees' mobility difficulties, two researchers were present.

The University of Manchester and NHS protocols for data protection were strictly adhered to.

The authors have no competing interests to report.

Chapter 2 Background

The growing number of older prisoners

It has been well documented that the number of older prisoners is increasing rapidly in England and Wales. 1 In December 2012 there were 85 women in prison aged ≥ 60 years in England and Wales, compared with 3292 male prisoners in this age group (NOMS, 2013, personal communication). The proportion of male prisoners aged ≥ 60 years has steadily increased from 2% in 2002 to 4% in 2011 (NOMS, 2011, personal communication). This trend is also evident in both Canada and the USA. 8,9

There are a number of factors contributing to this increase, including changes to sentencing practices, for example an augmentation in mandatory sentencing, the pursuit of convictions in later life for historical offences, the use of indeterminate imprisonment for public protection and an increased number of life sentences. 7 Furthermore, the general population are living longer, thus there are a greater number of older people in society to commit crimes. 10–12

The Ministry of Justice projections (2011) estimate that the overall prison population may increase to 94,800 by June 2017 (NOMS, 2013, personal communication). Such projections take into account a number of factors, including the age of defendants entering the system. NOMS figures show that prisoners aged ≥ 50 years were the only age category subgroup to increase year on year since 2006 (NOMS, personal communication). The projected increase of this subgroup of prisoners will undoubtedly affect many aspects of the system, including creating increased pressure on prison-based health care provision as services attempt to address the complex health needs of older prisoners. 13 It has been argued that prisoners aged ≥ 50 years acquire age-related health problems 10 to 15 times faster than their peers in the general population. 14–16 As a consequence, the cost of health care for older prisoners is significantly higher than that for younger prisoners, with costs estimated to be between three- and eightfold higher. 13,16–18

Defining older prisoners

In the general population the definition of an older person is wholly socially constructed, with different age-dependent events, for example pension and benefit entitlements, occurring at different age points. Similarly, the age at which a person in custody is regarded as an older prisoner is, to some degree, arbitrary. Throughout this study the minimum cut-off age of 60 years is used to define an older person. This is in line with the lower cut-off age generally used by social services.

Policy and legislation

Currently, there is no national strategy for the care of older prisoners, despite repeated recommendations for one to be developed. 7,19 The provision of services for older prisoners across the English and Welsh prison estate has been under formal review since 2004, at which time an independent inspection of 15 prisons housing adult men by Her Majesty's Inspectorate of Prisons (HMIP) found that the physical design of establishments often restricted older people from accessing many areas of the prison. 19 Older prisoners were observed to be excluded from taking part in a full range of activities as a result. Some older prisoners reported feeling unsafe within establishments, and specific staff training to deal with issues affecting older prisoners was found to be sparse. 19 A follow-up inspection of 29 establishments in 2008 found that only three prisons had a policy specifically addressing the needs of older prisoners. The later inspection did, however, find that older prisoners were less fearful than had been identified previously and that the majority were happy with the care they received. 7 Her Majesty's Chief Inspectorate of Prisons' (HMCIP) review of older prisoner care raised grave concerns that older prisoners' needs were not planned or provided for after release. 7 Only four prisons could be identified as providing specific resettlement help for older prisoners. The recommendation from the previous review that the specific resettlement needs of older prisoners should be accurately assessed and provided for on release was thus reiterated. 7

Stemming from findings of the reviews of 2004 and 2008, and updates to the Disability Discrimination Act (now replaced by the Equality Act 2010), HMPS published Prison Service Order (PSO) 285520 relating to prisoners with disabilities, including reference to older prisoners. The overall standard stated that, ‘The Prison Service ensures that all prisoners are able, with reasonable adjustment, to participate equally in all aspects of prison life without discrimination’. 20 The PSO outlined the requirement for prisons to ensure that offending behaviour courses, work and education were accessible to older prisoners, and that prisons should consider having a lead member of staff for older prisoners. It also emphasised the need to have continuity in managing chronic physical health problems through effective multidisciplinary working and information sharing, reflective of the care of older people in the community. It is a well-established principle that prison-based health care provision should be equivalent in quality and range to health care provided in the community and that all national standards for health care apply equally in prison and community settings. 21 Thus, the National Service Framework for Older People22 applies in prison. The framework focuses on providing person-centred care to older people, whether in their own home or in a residential setting. It aims to diminish age discrimination and promote independence among older people as well as ensuring that care provided is relevant to older people's needs. It focuses particularly on health conditions relevant to older people, such as stroke and specific mental health problems associated with ageing. 22

The Department of Health produced a toolkit for good practice for older prisoner care in 2007. 23 The toolkit made specific recommendations aimed at bringing prison-based care into line with national policy and community practice. The document stipulated that older prisoners should be assessed using a health and social care assessment specifically designed for their needs and that this should be repeated every 6 months, with care plans made and reviewed accordingly. The Department of Health’s A Pathway to Care for Older Offenders23 emphasised the importance of comprehensive and systematic identification of the needs of older prisoners on entry into custody.

Currently, the provision of health care services in prison relies heavily on information elicited at reception from a generic screening instrument. 24 There are specific versions of the instrument for men and women; however, there are no specific questions relevant to assessing age-related needs, for example relating to memory, cognition or level of independence with daily living skills. Previous studies have shown that, if health problems are not elicited at reception, they are unlikely to be detected later during a person's detention;25 thus, it is appears unlikely that, without tools specifically designed to identify age-related health needs, such deficits would be routinely detected later during the custody period.

As part of A Pathway to Care for Older Offenders,23 the Department of Health has also made recommendations around preparation for release and follow-on support in the community, which are particularly pertinent to this study. The Department of Health stipulates that release planning for older prisoners should involve the following:

-

a health and social care needs assessment history being forwarded by the health care team to the offender manager

-

the conduction of a pre-release health and welfare assessment

-

an assessment by a social worker, conducted face-to-face

-

collaboration with external organisations

-

the organisation of a care package

-

formal arrangements for loans of occupational therapy equipment

-

a pre-release course specifically for older and retired prisoners. 23

In 2009, the National Association for the Care and Resettlement of Offenders (Nacro), in conjunction with the Department of Health, produced a training pack for prison staff working with older prisoners. 26 The purpose of this document was to raise awareness among staff of the common health difficulties experienced by older offenders. It intended to set out good practice guidelines and encourage the commencement of specialised activities for older prisoners such as older prisoner groups, in-cell work for those with mobility difficulties and appropriate exercise opportunities. Furthermore, it aimed to encourage staff working with older prisoners to contact community-based specialised agencies for older people to obtain information and support. 26 Throughout, the training pack attempted to pursue the principle of equivalent services for prisoners as for older people in the community.

The health and social care needs of older prisoners

Older prisoners have complex health needs. 27 The physical health needs of older prisoners are greater than those of both younger prisoners and those of a similar age living in the community. 14 Kingston et al.,3 in their UK sample of 121 prisoners aged ≥ 50 years in four prisons in and around Staffordshire, found that participants each had an average of 2.26 physical health problems. Approximately 85% of older prisoners have one or more major illness. The most frequently reported health conditions among older prisoners are cardiovascular diseases (35%), arthritis and/or back problems (41%), respiratory diseases (15%), endocrine disorders (21%) and sensory deficits (12%). 13,28

The mental health needs of older prisoners have been found to vary significantly from those of their younger counterparts in prison. 2 Older prisoners are at a greater risk of becoming isolated within the prison environment and are less likely to have social support, putting them at a greater risk of developing mental health difficulties. 29 In the aforementioned study by Kingston et al.,3 half of prisoners in the sample (n = 60) were identified as having a mental disorder, with depression being the most frequently diagnosed. Furthermore, 12% (n = 15) had symptoms of cognitive impairment. Strikingly, Fazel et al. 6 found that 86% of their sample showing signs of depression were not receiving antidepressant medication nor was depression documented in their medical records. In addition, alcohol is the most commonly misused substance among older prisoners. 30,31

There is a dearth of research regarding older prisoners' social care needs. Previous studies have shown that older prisoners have high levels of unmet need in the domains of accommodation release planning and daytime activities. 4 A comprehensive study carried out by Hayes et al. 32 in 2010 found that, of the sample of 262 prisoners aged ≥ 50 years, more than one-third had some level of functional need in activities of daily living and 14% had mobility difficulties. Nearly half were imprisoned far from their home area, which made contact with family and friends difficult; 15% had no contact at all with family or friends.

The provision of social care is an area often overlooked within the prison environment, largely because there is an apparent lack of understanding of what constitutes ‘social care need’ within a prison institutional setting. 33 The result is that the provision of social care becomes, by default and through a sense of necessity, the responsibility of health care services rather than being regarded as a wider, multi-agency responsibility. 7

There is currently very limited research focused on the specific issue of identifying and meeting the health and social care needs of older prisoners on entry into prison. It has been established that, within the general prison population, just over one-quarter of all self-inflicted deaths occur within 1 week of prison entry. 34 Furthermore, previous research conducted by Crawley35 suggested that older prisoners entering prison for the first time experience a number of distressing phenomena, labelled ‘entry shock’. Contributing factors included high levels of noise, lack of privacy, indigent facilities, claustrophobic conditions, perplexing rules and regulations and hostility from younger prisoners and uniformed staff. Within Crawley's study, many older prisoners reported that, in the absence of any support in prison, they were able to recall previous difficult experiences such as induction into the army or a childhood in care and that they used these as an, albeit imperfect, ‘blueprint’ for how to cope in the prison. 35

As well as the risks associated with reception into prison and the early weeks spent adapting to custody, some limited research has identified that the period post release is also risky in terms of prisoners' physical and mental health. 36 There have been a small number of studies that have explored, prior to discharge, older prisoners' concerns and issues about release,37–39 suggesting that older prisoners struggle disproportionately with community resettlement because of reduced support networks and the increased likelihood that they are suffering from health and mobility problems. 39 Crawley38 and Crawley and Sparks37 explored older prisoners' concerns regarding their release from prison, concluding that they often experienced intense anxieties about release and inadequately understood the resettlement process. Key concerns included where they were going to live and how they were going to get there; their physical safety on release (for those convicted of sexual offences in particular); loss of personal possessions and support networks; and access to health care for support with chronic illness. Their concerns prior to discharge were so intense that many of them felt that it would be better to stay in prison than be released into the community.

There is an increased risk of suicide among recently released prisoners in England and Wales, with the greatest elevation in risk identified in those aged ≥ 50 years. 40 Despite these increased needs, older prisoners' resettlement needs are often ignored; it has been suggested that, in spite of evidence to the contrary, this is because they are generally considered to be of lower risk than their younger peers,38 which is exacerbated by their being less assertive. 38 Crawley38 advocated the need for an emphasis on effective, proactive communication with older prisoners to reduce severe feelings of anxiety leading up to release. No studies have been published to date that have followed up older prisoners after their release to examine the barriers to and facilitators of successful community reintegration.

Assessing older prisoners' health and social care needs

There are challenges to effectively conducting health and social care assessments of older people in the community. 41 Problems have included the under-reporting of need, variations in assessments across disciplines and geographical areas and disagreement between different professionals. 41 The National Service Framework for Older People22 set out plans to improve the assessment of all older people's needs, including the introduction of the Single Assessment Process (SAP). The aims of the SAP were to standardise the assessment process across organisations and geographical areas, raise the standard of assessment, assist information sharing, prevent duplication of assessment processes and ensure holistic assessment of need. 22

Implementation of the SAP should result in an individual care plan that clearly describes the help to be provided and who should be contacted in case of emergency or should a person's needs change. 22 Additionally, the guidelines specify that care plans be agreed with the older person and that the older person should hold a copy of his or her own care plan. 22 Findings from an evaluation of the SAP suggested that its implementation had been uneven and that full implementation will be a long process. 42 Elsewhere, it has been suggested that statutory social services assessments have improved since the introduction of the SAP; however, the extent to which these improvements can be attributed to the SAP is unclear. 41

Health and social care services for older prisoners

The provision of services for older prisoners varies considerably between establishments. 7 HMCIP's 2008 review of 29 adult establishments7 found that few establishments had an older prisoner lead (OPL) responsible for co-ordinating the care of older prisoners. When in operation, the role was often given to the disability liaison officer (DLO), in addition to their already full workload. However, and more encouragingly, a further large-scale survey in 2010 of staff working in 92 establishments in England and Wales, conducted on behalf of the Prison Reform Trust,43 found that over one-third of prisons now had an older prisoner group/forum running at their establishment. It is also becoming evident that voluntary agencies are increasingly involved with older prisoners in some establishments, providing befriending services and help on release and running groups for older prisoners. 26 Specific older prisoner clinics were reportedly established in many prisons; however, the frequency of clinics varied considerably. Prison buddy schemes set up to help prisoners with tasks such as fetching meals or keeping cells tidy were also operational in some establishments. In certain prisons, older prisoners are housed together because of their differing psychosocial needs to those of their younger counterparts. 11 In summary, services available to older prisoners appear to be increasing, albeit in an ad hoc informal manner, lacking organisation or adherence to an overarching model of best practice but with some examples of apparent good practice. 44

Prisons are, for the most part, designed for younger, able-bodied prisoners. 7 Many prison establishments in England and Wales are of Victorian design and construction. Narrow staircases and cell doors and long corridors mean that those with mobility problems struggle to physically access many parts of prisons. 7 This frequently results in older prisoners with mobility problems being housed routinely in prison inpatient wards, simply because of a lack of appropriate facilities in other wing locations rather than because of a need for continuous nursing care. 7 It is noteworthy that, where adaptations have been made, such as the installation of chairlifts, equipment has often been found to be out of order. 7 Nacro and the Department of Health suggest that some simple adaptations should be made to care appropriately for older prisoners, for example doors and windows should be easily opened; less harsh lighting should be installed; radiators should be easily adjustable; special cutlery, plates, bowls and trays should be provided for older prisoners; and lower television shelves and appropriate seating should be made available in cells. 26

The commissioning of health and social care services

Historically, HMPS, through the existence of the Prison Medical Service, latterly renamed the Prison Health Service, was responsible for the provision of the majority of health care services for prisoners. Almost all services were provided ‘in house’, ranging from primary care for everyday physical complaints to inpatient care for those with severe mental health problems. HMPS directly employed doctors as prison medical officers, and part-time medical practitioners were also employed, usually local general practitioners (GPs). Other health care staff consisted largely of qualified nurses, usually with general or mental health qualifications, and prison health care officers, usually non-nurse-qualified personnel who undertook in-service training to assume duties traditionally associated with nursing staff.

Following sustained criticism of both standards of care provided to prisoners and the relative expense of such services, a clinical improvement partnership between the NHS and HMPS was established in 1999. 21 Initially, HMPS maintained control of the costs of health care services but, by 2006, budgetary control for health care provision in all public sector prisons was transferred to primary care trusts (PCTs).

The Health and Social Care Act 2012 heralded the transfer of the majority of NHS commissioning responsibilities across England from PCTs to clinical commissioning groups (CCGs), largely controlled by GPs. However, from April 2013, the responsibility for commissioning prison-based care will transfer from PCTs to the national NHS Commissioning Board, along with a number of other ‘specialist’ services. The national Commissioning Board will be supported across England by 27 local area teams (LATs) and it has been announced that 10 of the 27 LATs will develop specific expertise and lead on matters relating to the commissioning of offender health care including, but not limited to, prison-based services.

Although prison-based health care services within public sector prisons are now a fully integrated part of the wider NHS, the involvement of local authority social services with prisoners in need of social care remains underdeveloped. Anecdotally, particular issues seem to arise when requests are made to NHS services, and perhaps more markedly social services, to provide assessments or services for prisoner-patients not deemed to fall within the geographical boundaries of a particular area's service. For example, when a prisoner requires admission to secure mental health care, NHS commissioners for the prison where the person is housed may argue that they are not responsible for the care costs as the person's last known address outside custody is determined to be elsewhere in the country. Similarly, social services departments have frequently failed to accept that the populations of prisons within their geographical catchment area are ‘proper’ residents. Our study discusses these matters in detail throughout.

In future, again as part of the organisational changes contained within the Heath and Social Care Act 2012, a local health and well-being board (HWB) will be established in each of England's 152 upper-tier local or unitary authority areas, to co-ordinate commissioning across health, public health and social care. Each HWB will comprise representatives from the CCG, a director of public health, a director of children's services, a local Healthwatch England representative and other key stakeholders at the discretion of the local authority (Healthwatch England is the new independent ‘consumer champion’ for health and social care in England).

Each HWB is charged with co-ordinating a Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) to identify the health and well-being needs of the local population, and producing an annual Joint Health and Wellbeing Strategy (JHWS) to outline how partners will address the needs of the local community through their commissioning of NHS, social care and public health provision. Most of the 152 local authorities in England have now formed shadow HWBs that are already developing the JSNAs and JHWSs for 2013–14. The need to undertake JSNAs for the whole of a local population may serve as a way of including prisoners' social care needs in a much more widespread and routine way than has previously been the case, although the success of this is currently unknown and will need to be reviewed when JSNAs and JHWSs are published and can be evaluated.

Integration between health care and social care services for older prisoners

The effective integration of health and social care services in the community has been a policy goal for over four decades. 45 The Department of Health's National Service Framework for Older People22 highlighted the importance of adequate integration between prison and community social care agencies to ensure that prisoners receive an adequate standard of care. 22 Successful integration between health care and social care services is challenging within prisons. 46 Accountability for the provision of social care services for older prisoners is a particular problem. 46 This is often because there is an overlap of service provision between prison, health and local authorities accompanied by high levels of uncertainty around which local authority is responsible for an older prisoner's care on release, particularly when older prisoners are discharged into different geographical areas from those of their prison establishment. 46 According to the Department of Health's recent publication entitled Caring for our Future; Reforming Care and Support,47 preparations are ongoing to address this dilemma. HMCIP's review in 20087 found little evidence of multidisciplinary working within prison environments, with particular deficits observed in the resettlement of older prisoners. In the main, prison staff considered the social care of older prisoners to be the responsibility of health care staff. In an overwhelming majority of cases, social care arrangements were found not to be in place for older prisoners. 7,44

Summary

The current study will identify whether or not any improvements have been made to service provision for older prisoners. It will also build on the existing literature to explore the barriers to and facilitators of integrative working between health care and social care services. Furthermore, it will aim to address the established deficit in systematically addressing the health and social care needs of older prisoners through the development, implementation and evaluation of a needs assessment and care-planning intervention for older prisoners.

Chapter 3 Determining the availability and integration of health care and social care services for older adults in prison

Introduction

Previous research suggests that provision of health and social care services specifically for older prisoners is ad hoc7,19 and that successfully integrating services is challenging. 7 The first part of this study aimed to establish current levels of service provision for older men in prison across England and Wales. It also aimed to ascertain how well health and social care services were integrating currently and identify common facilitators of and barriers to more effective integrative working.

Methods

Mixed methods were adopted in this part of the study, comprising a national questionnaire and semistructured interviews with a range of professional respondents.

Questionnaire

Development of the questionnaire

A questionnaire was designed to ascertain what health and social care services were available for older male prisoners in England and Wales and how well these services were currently integrated. A copy of the questionnaire is included in Appendix 2. The topics included in the questionnaire were drawn from the recommendations for good practice made in the Department of Health's older offender toolkit23 and HMCIP's review,7 supplemented by examination of additional key themes identified across the wider published literature base. The final version of the questionnaire examined the following areas:

-

details of staffing levels and training on issues related to ageing

-

absence/presence of an identified lead for older men

-

services available to older men

-

details of chronic disease and/or older adult clinics

-

details of work/activities and environmental adaptations for older men

-

access to, and engagement with, local social services departments and other specialist older adult services.

As part of the development process the questionnaire was piloted at 13 prisons. Findings from the pilot resulted in some minor alterations to the wording and structure of the questionnaire.

Distribution of the questionnaire

It was decided that, in the likely absence of an identified OPL in each prison, the health care manager at each establishment would be the most appropriate member of staff to complete the questionnaire, providing a consistent approach. An up-to-date list of names and contact details of all health care managers was obtained from the Offender Health Division at the Department of Health and cross-checked against records held by regional offender health leads.

A complete list of all prisons in England and Wales housing adult men (n = 97) at the time of the questionnaire distribution (October 2010) was created through HMPS sources, and questionnaires were distributed by post and email to the health care managers of all of these establishments. Sites were followed up by email 2 weeks after the initial distribution of questionnaires; by telephone after a further 2 weeks; and by letter after an additional 2 weeks for those still outstanding. If they wished, health care managers were given the option of completing the questionnaire by telephone interview with a member of research staff.

Questionnaire data analysis

Questionnaire data were entered into the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) version 19 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Descriptive statistics were generated from these data and analyses by prison type were conducted. Data were examined to identify whether or not there were any differences between geographical regions; none was observed and thus the data are presented here without any regional stratification.

Semistructured interviews

Semistructured interview sampling

Data from the questionnaire were used to identify prisons that reported particular successes or challenges in integrating health and social care services. A coding system was devised and responses to key questions about the integration of health and social care services were tallied. These questions identified whether or not contact with social care services occurred, by what means and how successful this contact was. Prisons that scored the highest and those that scored the lowest were identified and then approached for inclusion in the semistructured interview process.

In total, 32 staff members from the four highest-scoring and four lowest-scoring prisons, holding the following roles, were invited to participate in the semistructured interviews: health care manager, OPL, general nurse, health care assistant, offender manager, DLO, education employment and training officer, equalities/diversity officer, prison officer, social worker, social care worker, probation officer, specialist older adult worker, specialist older prisoner worker and housing worker.

Semistructured interview procedure

Staff members were approached in the first instance by the health care manager at each establishment to introduce the study and ask permission to pass their professional contact details on to the research team. A research assistant then contacted the prospective interviewees by telephone to discuss the study further. Information sheets and consent forms were sent electronically to all participants (see Appendix 11). Consent forms were signed by each participant and returned to the research assistant before interviews were conducted. All interviews were conducted between October 2011 and May 2012. Interviews were conducted over the telephone by a research assistant and recorded digitally. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes. Questions enquired about joined-up working, communication and information-sharing practices. At the end of the interview participants were thanked for their time and co-operation and informed of the next stages of the research and the timetable, outputs and methods of dissemination. The interview schedule is provided in Appendix 3.

Semistructured interview data analysis

Data from the interviews were transcribed verbatim and analysed using the constant comparison method. 48 Constant comparison analysis is one of the most widely used qualitative methods of analysis. 49 The method is rooted within the grounded theory approach developed by Glaser48 during the 1960s. Constant comparison ensures that theory stays rooted in the data,50 resulting in emerging theories developing from the data rather than already existent literature. 51 It is most appropriate for studies in which little is known about the topic or a new perspective is required and was therefore highly relevant to all aspects of this study.

Constant comparison methods involve both the fragmenting and the subsequent connecting of data. Pieces of data are coded and separated from their original interview transcript. Extracts are then compared and combined with other fragments until connections are made to help the researcher understand the overall picture of what the interviewee has said. 50 According to Glaser,48 there are four stages involved in the constant comparison method of analysis. For the purpose of our research these stages were followed in the context of our research questions. The first stage involved identifying provisional themes and comparing incidents that apply to such themes. The second stage involved comparisons between interviews. The third stage involved delimiting and integrating categories/concepts into themes. Overlapping categories/concepts or undefined categories/concepts were re-examined until final versions emerged. Stage four involved clarifying ideas, which leads to the formulation of a theory or multiple theories.

NVivo (version 8; QSR International, Southport, UK), a qualitative software package, was used to analyse transcripts. Such programs aid the researcher to store, sort and code qualitative data and increase the rigour of a qualitative study. 49 Two researchers conducted qualitative analysis for this study and there was therefore the opportunity for one researcher to take the role of a ‘peer debriefer’. This involved periodical discussions between the researcher conducting the analysis and the peer debriefer regarding matters of methodology and analytical procedures. This provided an opportunity to test emerging themes and increases the credibility of the findings. 49

Results

First, the questionnaire response rates and the numbers of older prisoners at establishments are presented. Second, questionnaire findings are presented under two broad topic areas: service availability and the integration of health and social care services. Third, findings from the semistructured interviews are presented to augment the questionnaire findings with more detailed information about key points.

Questionnaire response rates

The questionnaire was distributed to the health care managers of the 97 establishments housing adult males in England and Wales. Following rigorous follow-up processes, 78 health care managers returned a questionnaire, resulting in an overall response rate of 80%. Response rate by prison type ranged between 73% and 92% (Table 1). There was no difference in response rate between public sector prisons and private finance initiative prisons.

| Prison type | Adult male establishments in England and Wales, n | Adult male establishments that returned the health care questionnaire, n (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Local prisons | 36 | 33 (92) |

| Open prisons | 9 | 7 (78) |

| Training prisons | 52 | 38 (73) |

| Private prisons | 10 | 8 (80) |

| Public prisons | 87 | 70 (80) |

| Total sample | 97 | 78 (80) |

Numbers of older prisoners

Table 2 shows the total numbers of older prisoners across the 78 prisons and the proportion of the overall population that they constitute. Overall, older prisoners aged ≥ 60 years accounted for 4% of the population in the 78 establishments. These 78 establishments held 77% of the male prison population in June 2011. Prisons holding only sentenced prisoners had a higher proportion (5%) of older prisoners than local (3%) and open (3%) prisons. The private and public prisons had similar proportions of older prisoners.

| Prison type | Total number of prisoners held at establishments in this sample | Prisoners aged ≥ 60 years held at establishments in this sample | % of prisoners aged ≥ 60 years held at establishments in this sample |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local prisons | 27,779 | 824 | 3 |

| Open prisons | 3027 | 94 | 3 |

| Training prisons | 24,719 | 1265 | 5 |

| Private prisons | 7168 | 202 | 3 |

| Public prisons | 48,357 | 1981 | 4 |

| Total sample | 55,525 | 2183 | 4 |

A breakdown of older prisoners by specific age group and conviction status is shown in Table 3. Almost three-quarters (71%) were aged between 60 and 69 years. One-fifth (20%) of older prisoners were aged between 70 and 79 years and three (< 1%) prisoners were aged ≥ 90 years. Examination of the conviction status of older prisoners showed that the majority had been sentenced (84%) with fewer convicted but unsentenced (2%) or on remand (6%).

| Local prisons, n (%) | Open prisons, n (%) | Training prisons, n (%) | Private prisons, n (%) | Public prisons, n (%) | Total sample, n (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age group (years) | ||||||

| 60–69 | 603 (73) | 81 (86) | 974 (77) | 107 (53) | 1551 (78) | 1559 (71) |

| 70–79 | 167 (20) | 13 (14) | 252 (20) | 43 (21) | 389 (20) | 432 (20) |

| 80–89 | 30 (4) | 0 (0) | 18 (1) | 13 (6) | 35 (2) | 48 (2) |

| 90+ | 2 (0.02) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 3 (0.2) | 3 (0.1) |

| Conviction status of total sample | ||||||

| Sentenced | 524 (64) | 76 (81) | 1219 (96) | 174 (88) | 1654 (85) | 1828 (84) |

| Convicted unsentenced | 39 (5) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 12 (6) | 27 (1) | 39 (2) |

| Remand prisoners | 121 (15) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 16 (8) | 105 (5) | 121 (6) |

Service availability for older prisoners

Questionnaire findings

Details of health care department staffing levels and training

The percentage of health care staff trained in the care and assessment of older prisoners within particular staff groups is shown in Table 4. Specific training in the care and assessment of older people was provided to health care staff in less than half of prisons in this sample (41%, 32).

In primary care and inpatient services, 8% (135) of health care staff had received training in the care and assessment of older people. A similar proportion of staff in mental health and in-reach services (7%, 28) had received training in this area.

Comparatively, training prisons contained a higher percentage of trained staff, both in primary care and inpatient services (14%, 78) as well as in mental health and in-reach teams (15%, 22). The proportion of staff trained in open prisons was lower (2% and 0% respectively). There was a significant difference in the number of staff trained in primary care and inpatient services between private and public prisons [χ2 (1, n = 135) = 8.34, p = 0.004].

| Local prisons | Open prisons | Training prisons | Private prisons | Public prisons | Total sample | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary care and inpatient services | ||||||

| Staff employed, n | 1084 | 59 | 567 | 174 | 1536 | 1710 |

| Staff trained in the care and assessment of older people, n (%) | 56 (5) | 1 (2) | 78 (14) | 4 (2) | 131 (9) | 135 (8) |

| Specialist mental health/in-reach team | ||||||

| Staff employed, n | 224 | 12 | 143 | 33 | 346 | 379 |

| Staff trained in the care and assessment of older people, n (%) | 6 (3) | 0 (0) | 22 (15) | 2 (6) | 26 (8) | 28 (7) |

Older prisoner strategy and specific services for older prisoners

Table 5 outlines the specific services available to older prisoners across prison types. Overall, of the 78 establishments, 44 (56%) had a written older prisoner care policy. Only two of the seven open prisons (29%) had such a policy compared with 19/33 local prisons (58%). The majority of prisons (81%, 63/78) had an identified OPL in their health care department. The percentage of prisons with an identified OPL was higher within local prisons (88%, 29/33) than in open prisons (71%, 5/7). However, of the 63 designated OPLs, only 28/78 (36%) had received any specific training to support them in their role. In establishments where there was no identified OPL, 64% (n = 9) of health care managers stated that there was an intention to introduce one.

A prisoner helper/buddy/peer support scheme was most commonly found in training prisons, although they were not available in the majority of such establishments (45%, 17/38). None of the private prisons had an older prisoner helper/buddy scheme. The majority of prisons had a chronic disease clinic (89%, 69/78) but just over half operated a specific older adult clinic (53%, 41/78).

| Local prisons, n/N | Open prisons, n/N | Training prisons, n/N | Private prisons, n/N | Public prisons, n/N | Total sample, n/N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Older prisoner strategy | ||||||

| Written older prisoner care policy | 19/33 | 2/7 | 23/38 | 5/8 | 39/70 | 44/78 |

| Identified lead for older prisoners within the health care department | 29/33 | 5/7 | 29/38 | 6/8 | 57/70 | 63/78 |

| OPL received training to support them in this role | 14/33 | 2/7 | 12/38 | 3/8 | 25/70 | 28/78 |

| Specific services available for older prisoners | ||||||

| Prisoner helper/buddy scheme | 9/33 | 1/7 | 17/38 | 0/8 | 27/70 | 27/78 |

| Reception screening tool for older prisoners at reception | 6/33 | 1/7 | 6/38 | 0/8 | 13/70 | 13/78 |

| Screening tool following transfer from another establishment | 12/33 | 1/7 | 15/38 | 2/8 | 26/70 | 28/78 |

| First night arrangements for older prisoners | 7/33 | 1/7 | 4/38 | 0/8 | 12/70 | 12/78 |

| Protocol for forwarding reception screening information to health care | 8/33 | 0/7 | 4/38 | 1/8 | 11/70 | 12/78 |

| Chronic disease and older adult clinics within prisons | ||||||

| Chronic disease clinic | 30/33 | 6/7 | 33/38 | 7/8 | 62/70 | 69/78 |

| Older adult clinic | 19/33 | 4/7 | 18/38 | 4/8 | 37/70 | 41/78 |

Specific activities for older prisoners

Just over half of the establishments (55%, 43/78) provided one or more activities specifically for, and accessed only by, older prisoners. Within these 43 establishments such services included social groups (26%, 11/43), gym and exercise sessions (42%, 18/43) and in-cell work (2%, 1/43). Activities specifically for older prisoners with mobility problems were provided by 33% (26/78) of prisons. Health care managers were asked what type of factors affected access to certain activities/areas for prisoners with mobility problems. Of those who responded, 64% (14/22) reported that there was a lack of lifts/ramps available where access to activities required prisoners to use stairs and 14% (3/22) stated that door dimensions were not large enough for wheelchairs. Where this was the case, two-thirds of respondents noted that no alternative activities were provided for those negatively affected.

The integration of health and social care services for older prisoners

Questionnaire findings

Over half of establishments (64%, 50/78) reported having some form of contact with external social care services. However, only 31% (24/78) of health care managers stated that there was a co-ordinated approach between their health care department and local social services, with only 15% (12/78) holding meetings to discuss older prisoner cases. Only 51% (40/78) had contact with other types of specialist older adult organisations (Table 6).

| Local prisons, n/N | Open prisons, n/N | Training prisons, n/N | Private prisons, n/N | Public prisons, n/N | Total prisons, n/N | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Contact with social care services | ||||||

| Establishment has contact with local social care services | 21/33 | 2/7 | 27/38 | 6/8 | 44/70 | 50/78 |

| Co-ordinated approach between health care and social services regarding older prisoners with social care needs | 11/33 | 2/7 | 11/38 | 2/8 | 22/70 | 24/78 |

| Sufficient communication from social services | 9/33 | 1/7 | 5/38 | 2/8 | 13/70 | 15/78 |

| Written protocol between health care and social services regarding older prisoners | 1/33 | 0/7 | 2/38 | 0/8 | 3/70 | 3/78 |

| Meetings held with staff from social services to discuss older prisoner cases | 7/33 | 0/7 | 5/38 | 3/8 | 9/70 | 12/78 |

| Contact with specialist older adult services | ||||||

| Contact with specialist older adult organisations | 18/33 | 5/7 | 17/38 | 3/8 | 37/70 | 40/78 |

| Co-ordinated approach between health care department and specialist older adult services | 11/33 | 1/7 | 10/38 | 2/8 | 20/70 | 22/78 |

| Specialist older adult services currently unavailable (but deemed necessary) | 7/33 | 1/7 | 9/38 | 2/8 | 15/70 | 17/78 |

Semistructured interview findings

Thirty-two interviews were conducted to investigate levels of integration between prison, prison health care and social care services staff. The overall aim of the interviews was to provide supplementary in-depth information to add context to the questionnaire findings, in particular to identify specific barriers to and facilitators of the integration of prison and community-based health and social care services.

Three overarching themes were identified and explored during the analysis. Themes and subthemes are shown in Table 7.

| Theme | Subtheme |

|---|---|

| 1. Responsibility and accountability | Ambiguity |

| Budget constraints | |

| Geographical limitations | |

| 2. Information sharing | Confidentiality of health care information |

| Focus on risk | |

| 3. Working practices | Staff attitudes |

| Restrictive prison regime |

Theme 1: responsibility and accountability

A prominent theme that emerged during interviews was the ambiguity that staff felt around who, or which disciplines/agencies, was properly responsible for providing social care to prisoners.

Problems around the integration of prison and community-based services was a recurring theme and integration was felt, in the majority of cases, to be non-existent. Even when they existed, relationships between prisons and social services were generally considered to be strained. One interviewee described how prison staff often considered the social care of older prisoners to be the responsibility of other prisoners rather than staff and therefore other prisoners would be left to assist older prisoners with their social care needs without adequate training to undertake such tasks:

‘Oh you [social care worker] shouldn’t have to do that [change incontinence pads]. Just leave . . . we’ll get the prisoners to do that.’ But it was giving our knowledge and expertise over to the prisoners to deal with the situations that they were dealing with in a safe manner, because they [other prisoners] were dealing with incontinence, and not dealing with it properly. So the spread of infection could have been quite high. So passing that knowledge over to them [other prisoners] from our point of view, we thought was quite . . . you know, it needed to be beneficial for them, because they [prisoners] were very much left by the prison officers [to care for older prisoners].

Social care worker, p1:32

Ambiguity over responsibility for social care was also evident among staff working within the prisons:

Because there is a social care aspect to some of it [care of older prisoners] there’s ambiguity over where that falls and who is responsible for delivering that. There is the belief by, I think a cultural belief, that older people, if they have a social care need or maybe need help with getting dressed or washed, that that should fall to health care because prison staff aren’t here to do that.

Health care manager, p1.9

Funding restrictions, in particular depleted local authority and social care service budgets, reportedly led to services not taking accountability for older prisoners' health and social care. This was reported by many interviewees as a major issue facing the sector as a whole:

Unfortunately, social services won’t get involved in prisons, because they say they don’t have the budget for it. And we’ve tried, even in cases where we’ve had people terminally ill, it’s been very difficult to get social services involved. We’ve had a chap who’s got quite . . . he’s quite disabled, mobility wise, and we had to pay for the assessment of that patient ourselves, whereas in the community he wouldn’t have to do that.

Health care manager, p1.23

Geographical limitations were highlighted as a significant barrier to effective integrative working. Many prisoners, particularly those serving long sentences, do not reside in prisons in their home area. Additionally, people are often routinely transferred between a number of establishments during their sentence and ongoing care from outside or prison-based agencies is often not considered to be a sufficient priority to keep an older person in one particular establishment. This can create tension between the prison and local social care services. A social worker in the mental health in-reach team illustrated this by detailing an experience of contacting a local authority on behalf of a prisoner, outside of the area in which his current prison was situated. He described a laborious process of trying to get staff in the person's home local authority area to accept that the prisoner was originally from their area. The local authority instead stated that the prisoner should be released to the area in which the prison was located, an area in which the prisoner had no home or family ties to help with successful community reintegration:

But certainly the local authority weren’t fully accepting of that individual and say, ‘yes this man’s from [our area] and therefore he can come back to us’.

Social worker, p1.31

One interviewee described a perverse situation whereby only by seemingly creating or allowing social care needs to arise through deliberate inaction could a prisoner be helped by social services:

[What the local authority says] He’s not a resident in our area – even though he may have been, it doesn’t matter. The usual thing – I’ve come across this several times when I visit [prison name]. The [local] authorities tend to say, okay, well, he’s in a residence already, he’s in prison. When he’s released and he’s homeless then we have a responsibility to pick him up. So they have to make themselves homeless before the local authority will respond.

Older prisoner organisation worker, p1.22

Theme 2: information sharing

Within the prison environment, as in the community, health care records are maintained in confidence; thus, information contained therein is not routinely shared with non-health care staff. With regard to meeting the social care needs of older men, this situation can have many repercussions, given that prisoners routinely live on residential wings under the day-to-day care of prison officers. Health care records can contain a wealth of information that would make the day-to-day support of older prisoners easier for prison discipline staff to manage, for example issues around incontinence management, mobility difficulties and maintaining personal and environmental cleanliness. Such information was generally not imparted to prison staff, and discipline staff in particular noted this as problematic:

Yes, giving information about people’s particular social needs, a lot of nursing staff will not give that information out because of medical confidence.

DLO, p1.4

A lack of adequate information sharing and effective integration was attributed to assessment and IT systems not being linked:

It’s integrating the assessment process but, at the moment, the IT systems just don’t talk.

Older prisoner organisation worker, p1.22

According to staff, information sharing was primarily focused on risk and public protection rather than the health and social care information needed to support individuals. Interviewees explained that appropriate links and communications were made when liaising with agencies involved in managing risk, for example the police and probation services; however, sharing around care issued was not considered to be of the same importance or as valuable an activity. It was evident that information-sharing practices were possible to develop and operate; however, to make progress integrating health and social care services to improve the meeting of individuals' needs, a greater importance needed to be placed on routine practices rather than on only higher-level risk-based information-sharing practices:

It’s not the health they look at, they look at the risks, it’s risk focused.

Older prisoner organisation worker, p1.22

We’re well aware, particularly in my department, of the need to protect the public. So we will always information share and contact the appropriate people.

Offender manager, p1.20

Theme 3: working practices

Staff were fully aware that the professional styles and attributes of individual staff directly affected how well staff worked together across professional and prison/community boundaries. Staff who adopted positive attitudes and proactively nurtured working relationships created an environment in which different agencies operated effectively together. Conversely, negative staff attitudes severely impeded the effective integration of health and social care services. A further barrier to integration and the meeting of individual needs was noted to be the time-bound and institutional fixed routines of all prisons, which frequently curtailed imaginative work and hampered new initiatives as they became caught up in, and were rendered inoperable by, overly burdensome security procedures.

A number of staff noted that forming positive working relationships improved integrative working. It resulted in staff having the ability to approach each other in an appropriate manner when seeking assistance:

But what oils the wheels if you like is the relationships, getting to know people, getting to know who you can ask about what and, if I say knowing how to approach them that’s perhaps not quite right, but if you know somebody and you’re able to just have a chat to them and they can put a face to the name and whatever, then it does make life a lot easier if you’re just talking to folk and trying to get what you want from them.

Probation officer, p1.30

The approach that a staff member takes when meeting the needs of older prisoners was seen to be an integral part of working. One interviewee emphasised that some prison staff had a very negative attitude towards the needs of less able prisoners:

Prison officers don’t really care about things like that [social care needs]. Prison officers felt that we [social care workers] shouldn’t have been in there [the prison] caring for the person that we were caring for.

Social care worker, p1.32

The prison regime was described as ‘time bound’. This caused problems as staff were continuously under pressure to maintain the strict prison regime. A social worker highlighted that it remains difficult for external agencies to gain access to prison establishments because of the limited time available to access prisoners. This inhibits effective integrative working, possibly leading to inequality of care provided to those in prison in comparison with older people in the community:

As a social worker, I have to work within the constraints of the prison regime, it’s difficult for outside agencies to gain access [to prisoners].

Social worker, p1.31

A lack of face-to-face contact between prison staff and staff working for external agencies was identified as a barrier to integrative working. There were limited opportunities for staff from outside agencies to meet with prison staff as a result of the strict prison regime. Face-to-face meetings were considered an essential part of multi-agency working but were held infrequently because of the practical difficulties faced:

I guess, the difficulty, again, that I’ve found is, you can make good links, with people, on the phone, but, ideally, it’s so much more effective, if you can go out and introduce yourself, to people, and they get to know a face and, you know, they put a face to a name, and vice versa.

Housing officer, p1.14

Summary

In this cross-sectional national survey an 80% response rate was achieved. Older prisoners represented 4% of the prison population within our sample; this is in line with national figures (4%; NOMS, 2012, personal communication).

Over half of the establishments had a written older prisoner policy and 80% of prisons had a designated OPL; however, only a minority of these staff had received any specialist training to undertake their role. An investigation of integration between health and social care services showed that 64% of establishments had contact with local social care services; however, only 33% believed that there was a co-ordinated approach between health care and social care services. Furthermore, only 16% of health care managers reported holding meetings with social services to discuss the care of older prisoners.

Qualitative interviews highlighted the nuanced institutional factors and working practices that facilitate the effective integration of health and social care services for older prisoners, and the barriers that staff face. Positive staff attitudes were highlighted as a prerequisite to effective working. Barriers to success included the lack of clarity felt by many staff regarding where responsibility and accountability for providing social care to prisoners actually lay. Locating people in prisons away from their home area impeded the ability, and indeed willingness, of social services to become involved in the very important tasks around resettling an older person in the community. Information sharing was felt to be successful only in terms of managing risks rather than in the equally important and, of course, very closely inter-related area of meeting individual need.

Chapter 4 Establishing the met compared with the unmet needs of older people entering prison

Introduction

Older prisoners' complex health and social care needs are often unmet. 4,6 The second part of this study aimed to establish the met and unmet needs of recently incarcerated older prisoners, as well as capture their experiences of being received into prison custody.

Methods

This part of the study employed mixed methods including structured and semistructured interviews with prisoners on entry into prison.

Sampling strategy

This part of the study involved ‘local prisons’ only. Local prisons hold people awaiting trial, those convicted of short sentences and those at the early stage of a long sentence. All local prison establishments in four geographical regions were approached to take part in this part of the study. The geographical regions were selected as a result of their close proximity to the research base and comprised North East England, Yorkshire and Humberside, the North West and the West Midlands.

Nine establishments out of 12 agreed to take part. The sample included three private prisons and six public prisons. Prisons were located in both rural and urban areas.

Inclusion criteria

Participants meeting the following criteria at the nine local prisons were invited to participate in this part of the study:

-

age ≥ 60 years

-

newly received into the prison (i.e. received from court rather than another prison establishment).

Participants

The overall sample was a consecutive sample of 100 prisoners aged ≥ 60 years received into the nine prisons between February 2010 and December 2011. The required sample size for the needs assessment phase of the study was discussed several times at the early steering group meetings. It was decided that a series of formal statistical sample size and power calculations would not be necessary, or appropriate, in the context of an exploratory descriptive needs assessment. The assessment tool [Camberwell Assessment of Need – Short Forensic Version (CANFOR-S52)] yields purely descriptive information regarding a series of met compared with unmet needs (expressed as percentage values) and from these data we felt that there was no purpose in generating inferential statistics such as confidence intervals or p-values. Therefore, we had no basis for making formal sample size and power calculations in relation to hypothesis-testing parameters or required levels of statistical precision. The CANFOR tool also assesses an array of widely different types of unmet need, some of which are fairly common and some of which are very rare. Given the novelty of our needs assessment work for this particular subgroup of prisoners, and the lack of prior knowledge on which to predict the levels of unmet need observed, we opted for a pragmatic sample size of 100 older male prisoners. It was felt that this would be sufficiently large for estimating levels of unmet need across most of the CANFOR domains, whilst also being of a manageable and feasible size in terms of what could be achieved given the resources available and the time scale.

Of those older prisoners approached, 18 refused to participate. The participation rate across all nine establishments was 85%. Twenty-seven of the 100 older prisoners (27%) were invited to participate in the semistructured interviews and all consented. Semistructured interviews were conducted until data saturation was reached and no new themes emerged. All interviews were conducted during the initial 10 weeks in prison custody.

Interview procedure

On a weekly basis a nominated member of prison staff identified prisoners aged ≥ 60 years entering the prison using the Computer – National Offender Management Information System (C-NOMIS). The research team at the University of Manchester contacted the named contact at each prison weekly or fortnightly (depending on the preference of the prison contact) to inquire about new receptions into the prison. The research assistant travelled to the prisons to inform potential participants of the study. Prisoners were given at least 24 hours to consider their participation and written informed consent was obtained. Interviews were conducted in interview rooms or cells in each prison. The structured and semistructured interviews lasted approximately half an hour each (a total of 1 hour combined). The semistructured interview was audio recorded when approval from the security department and the participant was obtained.

Structured interview tools

The following structured assessments were used:

-

CANFOR-S measures health and social need experienced over the last month across 25 domains. Each domain is scored as not applicable, no need, met need or unmet need. The CANFOR-S was specifically designed for use in forensic services and is appropriate for use in prison settings.

-

The Geriatric Depression Scale short form (GDS-15)53 contains 15 questions, which are answered yes or no. Items indicative of depression carry a score of 1. A total scale score of ≥ 5 is suggestive of mild depression and scale guidelines suggest that further investigation is warranted. A total score of ≥ 10 almost always indicates severe depression. In this study the GDS-15 had a Cronbach's alpha score of 0.85, suggesting good internal consistency.

-

The Brief Psychiatric Rating Scale (BPRS)54 consists of 24 seven-point ordered category rating scales. Items 1–14 are based on interviewees' answers to the interviewers' questions, while items 15–24 are based on the interviewers' observations of the participants' behaviour during the interview.

-

The UK minimum data set (MDS) for home resident assessment and care screening background (adapted version)55 recodes information from participants themselves and participants' health care records. The participant section collects information in 13 sections ranging from daily routine in the previous 12 months to psychological well-being in the previous 7 days. The staff section contains four sections collecting information on an older person's cognitive patterns, communication/hearing patterns, mood and behaviour patterns, mobility and activities of daily living. The final section records information contained in an older person's health care records. It contains seven subsections recording all aspects of an older person's health; it also details what medication is currently being prescribed and what external medical intervention was previously required. This was adapted by the research team for the prison environment.

-

Audit – A data sheet to collect information from prisoners' clinical records was designed by the research team. Information recorded during a prisoner's initial 4 weeks of custody was collected. Data were gathered from electronic and paper health care records. Data collected included details of the assessments that were carried out by health care staff on reception and subsequent follow-up assessments; what referrals or contacts with prison/health care/external agency staff were made; and individual interventions received.

Semistructured interview guide

The semistructured interview aimed to capture older prisoners' experiences of reception into custody (see Appendix 4). The interview ascertained the difficulties faced by older people entering prison, in particular how their health, social care and custodial needs were addressed. Participants were asked how their needs could have been more appropriately met and to comment on any additional services that they feel would have been beneficial.

Data analysis

Quantitative data analysis

Data were entered into SPSS version 19. Initial descriptive statistics were computed for all scales used. Missing data were treated by omitting cases for which data were incomplete (listwise deletion). Fourteen participants declined to complete the GDS-15 because this caused them distress and one participant's BPRS data were missing. Health care record data for 12 participants and audit data for 15 participants were unobtainable.

Results

Quantitative findings

Demographics

All demographic information is presented in Table 8. Participants' ages ranged between 60 and 81 years with a mean age of 65.5 years [standard deviation (SD) 5.35 years]. Prisoners were categorised into four age ranges with the majority aged between 60 and 69 years and only a small percentage aged > 75 years. The majority were white British (95%). Similar proportions of participants were single, married and divorced. In relation to offences committed, 19% were incarcerated for violent crimes, 28% for crimes of a sexual nature and 36% for other crimes, which varied from fraud to acquisitive crimes to drug offences, and 17% refused to disclose their offence. This is not dissimilar to national statistics of prisoners aged ≥ 60 years. In 2011, 20% of prisoners > 60 years were detained for violent crimes, 58% for crimes of a sexual nature and 22% for other crimes (NOMS, 2011, personal communication).

The majority of participants had their own private accommodation and lived independently of health/social service support before entering prison. In total, 25% of participants were serving sentences of < 12 months and 25% were serving sentences of between 1 and 5 years. Over half of the sample had not been in prison previously. The majority of interviews with participants took place during their initial 6 weeks in custody.

| Demographics | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Participant age (years) | |

| 60–64 | 59 (59) |

| 65–69 | 25 (25) |

| 70–74 | 8 (8) |

| 75+ | 8 (8) |

| Ethnicity | |

| White British | 95 (95) |

| Other mixed background | 1 (1) |

| Other Asian background | 1 (1) |

| Other background | 3 (3) |

| Marital status | |

| Single | 35 (35) |

| Married | 29 (29) |

| Divorced | 28 (28) |

| Separated | 5 (5) |

| Widowed | 3 (3) |

| Offence | |

| Violent | 19 (19) |

| Sexual | 28 (28) |

| Other | 36 (36) |

| Not disclosed | 17 (17) |

| Conviction status | |

| Convicted – sentenced | 58 (58) |

| Remand | 33 (33) |

| Licence recall | 6 (6) |

| Convicted – unsentenced | 2 (2) |

| Missing | 1 (1) |

| Sentence length | |

| < 12 months | 25 (25) |

| 1–5 years | 25 (25) |

| > 6 years | 10 (10) |

| Unsentenced | 40 (40) |

| Number of previous times in prison | |

| 0 | 51 (51) |

| 1–3 | 29 (29) |

| > 3 | 20 (20) |

| Length of time in prison at time of interview (weeks) | |

| 0–2 | 9 (9) |

| 3–4 | 38 (38) |

| 5–6 | 30 (30) |

| 7–8 | 15 (15) |

| 9–10 | 4 (4) |

| Missing | 4 (4) |

| Wing location | |

| Vulnerable prisoner unit | 43 (43) |

| Sentenced prisoners wing | 28 (28) |

| Remand/induction wing | 5 (5) |

| Health care | 14 (14) |

| Unknown | 5 (5) |

| Drug-free wing | 3 (3) |

| Detox wing | 2 (2) |

| Admitted from (at prison entry) | |

| Private home/flat with no health/personal social services | 72 (72) |

| Private home/flat with health/personal social services | 1 (1) |

| Sheltered housing | 8 (8) |

| Other | 19 (19) |

| Lived alone prior to entry | 40 (40) |

| College/apprenticeship | 39 (39) |

| University-level education | 10 (10) |

Camberwell Assessment of Need – Short Forensic Version

The CANFOR-S results are shown in Tables 9 and 10. Mean total need among this sample was 5.24 (SD 2.81) with a median of 5.00; mean met need was 2.51 (SD 1.51) and mean unmet need was 2.74 (SD 2.65), both with a median of 2.00.

The CANFOR-S contains five domains that can be scored as not applicable: accommodation, transport, childcare, sexual offending and arson. These items are not relevant to some respondents and are excluded when the scale is administered. Therefore, the number of cases analysed varies for these items. Table 10 shows that the highest proportions of unmet need were in the domains of information about condition and treatment (38%), psychological distress (34%), daytime activities (29%), benefits (28%) and food (22%).

| Met need | Unmet need | Total need | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 2.51 | 2.74 | 5.24 |

| SD | 1.51 | 2.65 | 2.81 |

| Median | 2.00 | 2.00 | 5.00 |

| Interquartile range | 1 | 3 | 4 |

| CANFOR-S domain | Cases analysed, N | Older prisoners with unmet need, n (%) | Older prisoners with met need, n (%) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Information about condition and treatment | 100 | 38 (38) | 12 (12) |

| Psychological distress | 100 | 34 (34) | 14 (14) |

| Daytime activities | 100 | 29 (29) | 28 (28) |

| Benefits | 100 | 28 (28) | 6 (6) |

| Food | 100 | 22 (22) | 65 (65) |

| Physical health | 100 | 21 (21) | 46 (46) |

| Telephone | 100 | 13 (13) | 5 (5) |

| Money | 100 | 13 (13) | 3 (3) |

| Company | 100 | 10 (10) | 0 (0) |

| Accommodationa | 57 | 9 (16) | 7 (12) |

| Looking after the living environment | 100 | 8 (8) | 14 (14) |

| Treatment | 100 | 8 (8) | 11 (11) |

| Alcohol | 100 | 7 (7) | 5 (5) |

| Self-care | 100 | 6 (6) | 9 (9) |

| Intimate relationships | 100 | 6 (6) | 4 (4) |

| Basic education | 100 | 5 (5) | 3 (3) |

| Transporta | 57 | 5 (9) | 2 (4) |

| Childcarea | 4 | 0 (0) | 4 (100) |

| Psychotic symptoms | 100 | 2 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Safety to self | 100 | 2 (2) | 6 (6) |

| Sexual expression | 100 | 1 (1) | 0 (0) |

| Sexual offendinga | 74 | 1 (1) | 4 (5) |

| Drugs | 100 | 0 (0) | 2 (2) |

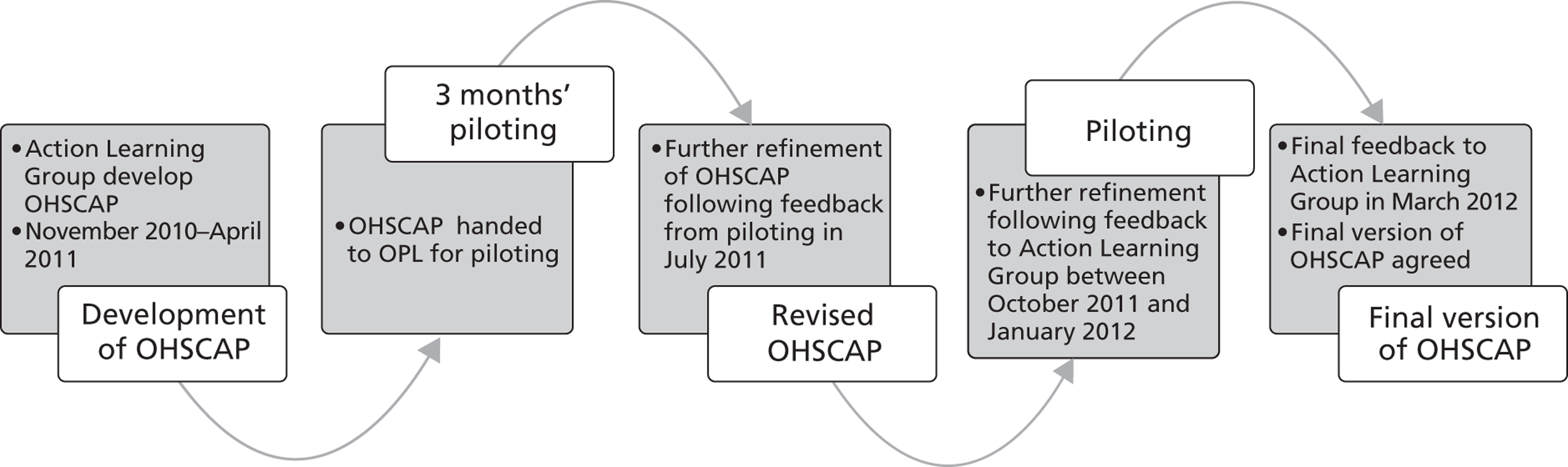

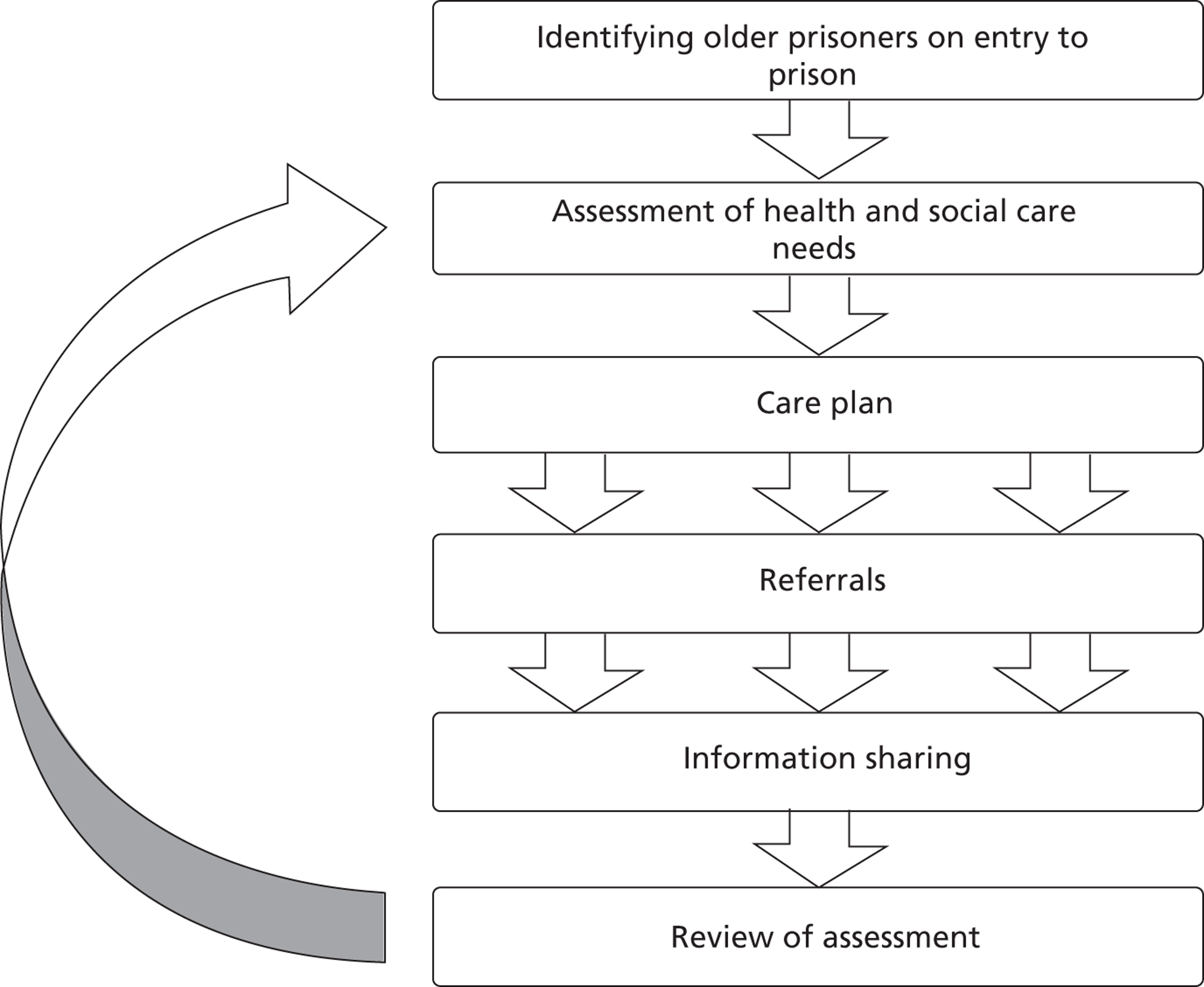

| Arsona | 2 | 0 (0) | 2 (100) |