Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1012/03. The contractual start date was in July 2011. The final report began editorial review in July 2012 and was accepted for publication in December 2012. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Chambers et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction, approach, rationale and method

Introduction

How boards set direction, exercise control and shape culture in their organisations is once more in the spotlight with the high-profile failure of Barclays Bank PLC to rein in their traders and their senior staff, and the hugely missed opportunity of G4S to employ sufficient security staff to support the Olympics. 1 In the NHS, the Kane Gorny case at St George's Hospital in Tooting2 illustrates that despite the architecture of governance, including extensive board oversight and a full panoply of clinical risk management arrangements, organisations, including illustrious teaching and research institutions such as St George's Hospital, that have been established to care for patients can still do them harm. Desperate for water, Kane Gorny rang 999 from his hospital bed. The ward staff mistook his medical condition for an attention-seeking mental health problem, with fatal consequences.

Interest in how boards can control and influence organisations as complex as those that make up the NHS is likely to continue, and indeed increase, particularly in the light of recent failings in patient safety, the events at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust and the forthcoming findings from the Francis Inquiry and the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Performance (QIPP) agenda, and as the scale of efficiencies required begins to bite. There is a need to reduce the variation in organisational performance across the NHS (e.g. as measured by the quality and safety of care provided and efficiency and productivity), for which boards hold ultimate responsibility. By exploring how effective boards can add value it is hoped that this research will both benefit patients and improve service efficiency. In the wake of the publication of the first Francis report3 into the failings at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, the chief executive of the NHS has emphasised the role of boards as guardians of patient safety. The NHS Confederation, which represents the NHS board member community, has expressed the need for more detailed analysis of the complex issues around the cultures and characteristics of boards. 4

There are some clues from a selective literature review about what boards in the wider UK public sector might do well to pay attention to. 5 There is, for example, evidence that smaller boards with well-functioning subcommittees are associated with better performance. Board focus on the three areas of strategy, use of resources and talent management appears to be important. Board dynamics is emerging as a significant element, with a triadic proposition of working relationships that combine the three elements of (1) high trust between board colleagues, (2) high challenge by non-executives to executive proposals and (3) high levels of engagement in and out of board meetings. 5 The energy and expertise of non-executive directors are argued to be important in partnering with managers to shape strategy and in tracking performance. 5 These programme or middle-range theories around the structure, focus and dynamics of boards are examined in more detail within the review reported here.

As the latest wide-ranging structural reforms in the NHS bed down, we envisage that the findings of this evidence synthesis will also be highly relevant for clinical commissioning consortia as they begin to enact their own governance arrangements. The study uses and builds on a developing body of knowledge in relation to health-care governance, organisational culture and performance, which have been the subject of other funded National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) studies (e.g. Sheaff et al. ,6 Davies et al. ,7 and Mannion and House8).

The approach that we have taken is a theory-based realist review emanating from our judgement that the effectiveness of boards is likely to be highly context dependent. We start from an exploration of theories and frameworks about boards in general, including underlying assumptions about their purpose, composition, role and behaviours. We then examine the literature relating to non-profit, state and health-care boards to ascertain sectoral or domain-specific distinguishing contextual features. We proceed to analyse the available guidance for boards to determine the experiences of boards, the dominant discourse and the gaps as a result of certain ideas and theories being foregrounded. We examine and assess the empirical evidence for the effect of boards on organisational performance and end with a mapping and assessment of board development approaches. Our conclusions offer the beginnings of an explanatory framework for use by NHS boards and identify areas for further research.

The four objectives of this literature synthesis are:

-

objective 1: to explore the main strands of the literature (e.g. in corporate governance, behavioural economics, organisational studies, organisational strategy, organisational psychology, public management, health-care management) about boards and to identify the main theoretical and conceptual frameworks that relate to the structure, purpose, functions, behaviours and effectiveness of boards

-

objective 2: to understand to what extent the experiences of NHS boards match these theories and to provide an explanatory framework for understanding the characteristics of effective boards in the NHS

-

objective 3: to assess the empirical evidence relating to how NHS boards can contribute to organisational performance

-

objective 4: to map and evaluate different approaches to board development including diagnostic tools, models of assessment and facilitation, and to identify how these approaches relate to theories about board effectiveness and their impact on organisational performance.

Approach

The study is an evidence synthesis of a diffuse literature relating to boards and organisational performance with particular reference to health-care boards and with special emphasis on the NHS. A literature review on board effectiveness commissioned for the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement9 concluded that:

there is no agreement among researchers on the best framework for identifying, measuring and discussing characteristics of effective boards . . . There has been a lack of clear definition of concepts and a reliance on incomplete research models. This means that there is little convergence on terminology, definitions and findings.

p. 5

The terrain is characterised by some complexity in terms of the multiple locations of the evidence across different disciplinary traditions, by weakness and ambiguity in terms of association and causation (and direction of causation) and by the influence of contextual factors on board characteristics, performance and effectiveness. Given this complexity, a conventional systematic review, with its emphasis on a hierarchy of evidence and randomised controlled trials as the research design of choice to address questions of effectiveness, would not be appropriate. Indeed, a traditional systematic literature review would almost certainly be unable to take account of the multiple and interconnected variables that influence boards and their performance.

A realist angle on the other hand emphasises the contingent nature of the evidence and addresses questions about what works in which settings, for whom, in what circumstances, how and why. 10 It is suited to the investigation of complexity for evaluations of either complex interventions or complex causal pathways. 11 Given that boardroom practices have been described as a ‘black box’,9 this seems a sensible approach to take: the study aims to open that ‘black box’. A realist synthesis also emphasises an iterative approach between programme theory and predicted theory and we therefore chose this for our overarching research design. Jagosh et al. 12 offer useful definitions of terms used in realist reviews and a summarised version is provided in Box 1.

Middle-range theory: Middle-range theory is an implicit or explicit explanatory theory that can be used to assess programmes and interventions. ‘Middle range’ means that it can be tested with the observable data and is not abstract to the point of addressing larger social or cultural forces (i.e. grand theories).

Context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) configurations: CMO configuring is used to generate causative explanations pertaining to the data. The process draws out and reflects on the relationship between context, mechanism and outcome of interest in a particular programme. A CMO configuration may pertain to either the whole programme or only certain aspects. Configuring CMOs is a basis for generating and/or refining the theory that becomes the final product of the review.

Context: Context often pertains to the ‘backdrop’ of programmes and research. Examples of context include cultural norms and history of the community in which a programme is implemented, the nature and scope of existing social networks, or built programme infrastructure. They can also be trust-building processes, geographical location effects, funding sources, opportunities or constraints. Context can be broadly understood as any condition that triggers and/or modifies the behaviour of a mechanism.

Mechanism: A mechanism is the generative force that leads to outcomes. It often but not always denotes the reasoning (cognitive or emotional) of the various actors in relation to the work, challenges and successes of the partnership. Mechanisms are linked to, but not synonymous with, the programme's strategies (e.g. a strategy may be a rational plan, but a mechanism involves the participants' display of responses to the availability of incentives or other resources). Identifying the mechanisms advances the synthesis beyond describing ‘what happened’ to theorising ‘why it happened, for whom and under what circumstances’.

Outcomes: Outcomes are either intended or unintended and can be proximal, intermediate or final. Examples of intervention outcomes are improved health status, increased use of health services and enhanced research results.

Demiregularity: Demiregularity means semipredictable patterns or pathways of programme functioning. The term was coined by Lawson13 who argued that human choice or agency manifests in a semipredictable manner – ‘semi’ because variations in patterns of behaviour can be attributed partly to contextual differences from one setting to another.

Adapted from Jagosh J, Macaulay AC, Pluye P, Salsberg J, Bush PL, Henderson J, et al. Uncovering the benefits of participatory research: implications of a realist review for health research and practice. Milbank Q 2012;90:311–46. Copyright © 2012 John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. Reproduced with permission of Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Realist synthesis belongs to the family of theory-driven inquiry. This is an approach rather than a strict technical procedure. 14 It starts with knowledge and theory and ends with more refined knowledge and theory, along the way ‘stalking and sifting’ ideas and empirical evidence. It continuously searches for and refines explanations of programme effectiveness. 10,14 It draws from Campbell and Russo's15 notion of organised distrust and ambition to secure methodological advances and trustworthy reporting (p. 143). In our case, the synthesis addresses, in particular, questions about how boards operate, in what circumstances and why, the influence that boards may have on organisational performance and the appropriateness and relevance of tools and techniques for board development. The focus is therefore very much on mechanisms rather than on boards per se. Realist review learns from, rather than controls for, real-world phenomena, thereby providing an acknowledgement, for our study, that no two boards are the same in human composition, context or stage of development.

The limitation of realist synthesis is that it is a method which is still in development with a relatively small number of studies under its belt and there can be shortcomings in investigations of context–mechanism–outcome configurations, some confusion between context and mechanism and a lack of a proper explanatory focus. 11,14,16 Standards for realist and meta-narrative evidence syntheses (Realist and Meta-review Evidence Synthesis: Evolving Standards; RAMESES) are under development and are not due to be published until 2014. 17 However, from the reviews and literature published to date, it is an approach that appears to address the limitations of more traditional systematic review methods when dealing with complex social interventions across different circumstances, with varying underlying beliefs and assumptions. 18 Its focus is on offering explanations rather than judgements and developing principles and guidance rather than making rules. For the purposes of this review, we believe that this is a more appropriate course of action to take – it will offer insights for practitioners to take note of and make use of and will offer a valuable addition to the armamentarium currently available to members of NHS boards.

In considering alternative approaches we are mindful of an analysis of alternative approaches to systematic review (Table 1) which underlines that only realist synthesis meets the criteria for focusing on mechanisms rather than whole programmes. In our case, this allowed us to look at discrete aspects of boards (composition, methods of working, governance arrangements and so on) rather than having to consider ‘the board’ as the overall unit of analysis.

| Approach | Unit of analysis | Focus of observation | End product | Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Meta-analysis | Programme | Effect sizes | Relative power of like programmes | Whole-programme application |

| Narrative review | Programme | Holistic comparisons | Recipes for successful programmes | Whole or majority replication |

| Realist synthesis | Mechanisms | Mixed fortunes of programmes in different settings | Theory to determine best application | Mindful employment of appropriate mechanisms |

One of the principles of realist synthesis is the importance of sense-making. The meta-narrative mapping approach to synthesising evidence is attractive because it acknowledges different disciplinary traditions and changes to dominant narratives over time. 20 It explores paradigmatic assumptions and the story of how empirical studies build on one another. This approach was deployed to illuminate changing paradigms across different disciplines in understanding about the diffusion of innovations. 20 Board governance is also a good example of where the dominant narrative has changed, with a shift away from the discourse of agency theory within the political science discipline to a more hybridised one in which, inter alia, board dynamics within the organisational behaviour discipline is now playing a significant contribution. We therefore adopted a meta-narrative mapping approach within a realist framework to identify and explain the rise and fall of dominant theories about the composition, role and functioning of boards.

The caveat here is the challenge of the very diverse nature of the sources of evidence on which the review is based and the relative infancy of the realist synthesis method; hence, detailed guidance around the processes of data extraction and appraisal is limited. Given the diversity of literature on boards and governance, we have purposely drawn on evidence from a broad range of peer-reviewed journals, books and reports. We are not claiming to be exhaustive in the search strategy employed; rather, we have focused on literature that helps to shed light on the theoretical propositions that drive the review and the relevance and rigour of the literature are judged in relation to the particular proposition under consideration, regardless of its source.

A key test for NIHR-funded studies is that the research questions and subsequent research findings are relevant and usable for the target audience who are responsible for the organisation and delivery of health care. Realist review stresses the importance of intensely practical theorising with programme practitioners to guide the inquiry of what works in what circumstances, how and why, eliciting, articulating and formalising hypotheses as to why outcomes are so varied (pp. 180–1). 14

Accordingly, in line with realist review principles, we tested, honed and refined the research questions with a joint expert advisory and stakeholder group of 23 people, made up of seven researchers active in the relevant discipline areas together with 16 representatives of the target audience of NHS board members and managers, including four board chairpersons, four non-executive directors/governors, two NHS chief executive officers (CEOs) and six corporate governance experts from the legal profession and from management consultancy. We convened this group once on a face-to-face basis in Manchester and ran a facilitated workshop early on in the study to elicit programme theories about board structures, processes, dynamics, development and impact on organisational performance and to guide the development of the research questions. The outcome of the workshop was a list of testable propositions and questions of interest to this stakeholder group, which are outlined in the following section. The provisional findings of the study were shared with the same expert advisory group and a number of comments were received. This embeds the ‘linkage’ between practitioners and researcher communities, which is advocated as a key characteristic of realist synthesis and helps to move findings from research into practice. 12,21

Focus of the review

There are four main steps in a realist review,10 which we have broadly followed. These include, first, clarifying the scope; second, searching for evidence; third, extracting the data and appraising the evidence; and, fourth, synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions. Chapters 2 and 3 are concerned with theory comparison and reality testing and complete the scoping by articulating the main theories to be explored, Chapters 4–6 focus on the appraisal and use of the evidence and Chapter 7 draws conclusions from a synthesis of the material.

Drawing from the realist approach to clarifying the scope of the study, our research questions at the start, which came from the main objectives described above, were amplified by the stakeholder group and a number of underlying testable propositions were also developed. These are outlined in full in the following sections.

Research question 1

Where are the main disciplinary sources of ideas about boards and what are the principal theories, conceptual frameworks and main paradigms?

Research question 2

How can theories and evidence about how boards operate in general help NHS boards in their work, in particular in the light of recent and forthcoming changes to the structure and governance arrangements in the NHS?

Additional questions of interest to members of the advisory group

-

What is the role and purpose of NHS boards? In what ways are these the same as or distinct from those of other boards?

-

To what extent are diffusions of governance models, for example in relation to financial performance from other sectors (e.g. commercial sector), applicable to the NHS? What is not transferable?

-

What is and could be the role and function of the board of governors in foundation trusts in comparison to the role and function of the board of directors?

-

What is the range of contributions that board members can usefully make?

-

What are the respective roles of specialists/experts (e.g. clinicians) and generalists and the contributions that they can make?

-

What is the role of the chairperson in running the meeting, framing the discussion, ordering the agenda?

-

How important is diversity (style, gender, background, knowledge and ethnicity) for dynamics and effective board working? When?

-

What constitutes effective board challenge (including how it is constructed and how it is handled)?

-

What is the distinctive contribution of informal board seminars (compared with formal board meetings)?

-

How do board subcommittees operate and how do they report to and influence the main board?

-

What questions should this study be asking in the light of forthcoming changes in the NHS (e.g. for foundation trusts, clinical commissioning groups)? What are the lessons from the evidence about effective boards that are applicable to clinical commissioning groups?

Testable propositions

-

Size is less important than balance and composition of the board.

-

The functioning of board committees has an impact on effective board working.

-

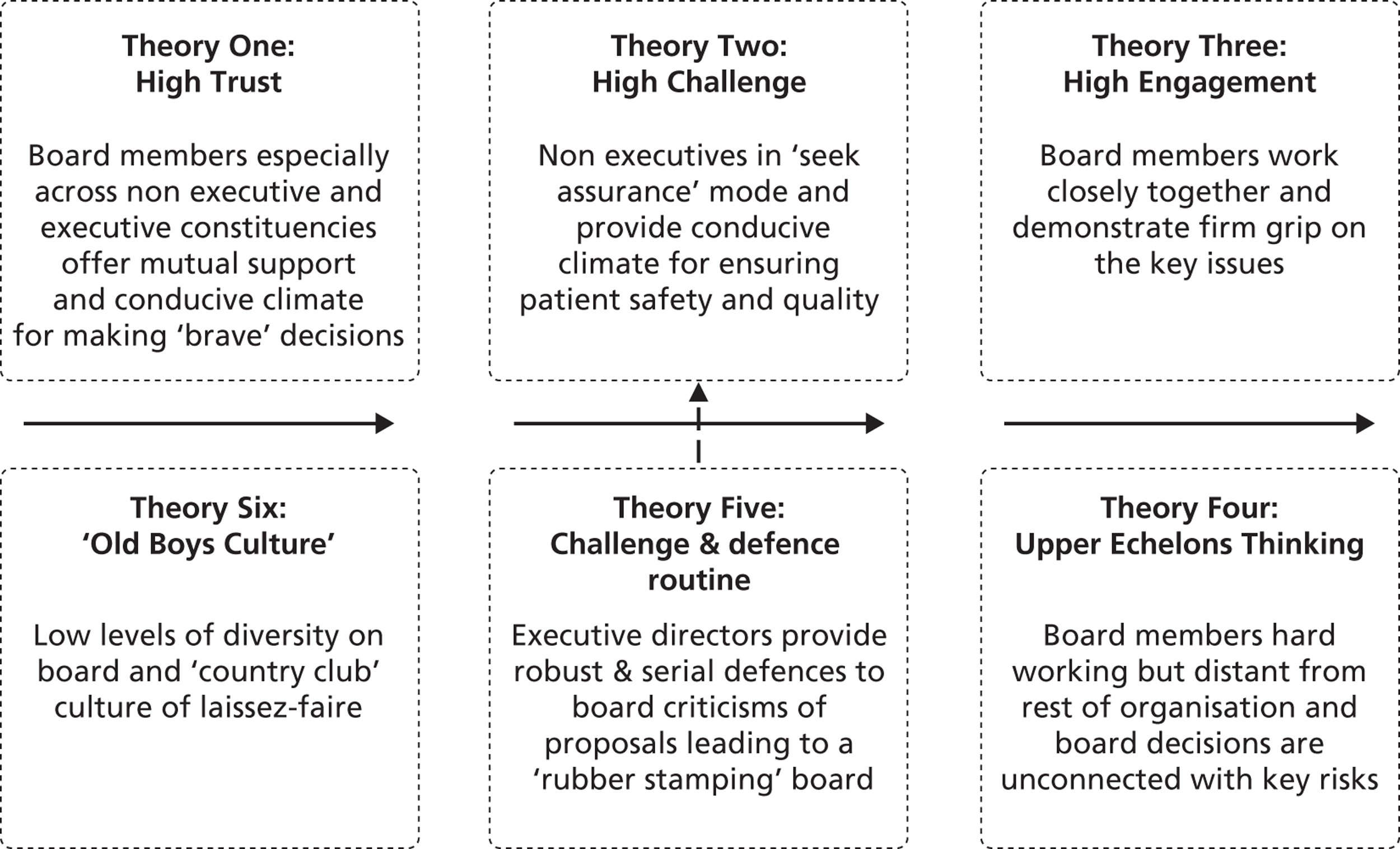

Triadic proposition that effective NHS boards exhibit dynamics of high trust + high challenge + strong grip/assurance.

Research question 3

What is the empirical evidence (positive and negative) in relation to the impact of NHS boards on performance, including at different stages in the performance cycle?

Additional questions of interest to members of the advisory group

-

How does the focus of organisational performance vary depending on the type of NHS body?

-

How do boards reflect on what aspects of performance they decide to focus on?

-

How is the balanced scorecard (where this is used) developed and who sets the benchmarks?

-

How do boards create a culture of patient safety?

Testable propositions

-

High-performing boards take a critical perspective on how they measure and control for organisational performance.

-

Boards prioritise quantifiable and more easily measurable areas of performance.

-

Hearing and using patient and staff perspectives and patients' stories is important in framing board business.

-

Boards in the NHS may have more influence on financial than on clinical performance (does finance trump quality?).

-

‘Greater’ (however measured) contribution of non-executive directors on boards is associated with higher organisational performance.

Research question 4

What are the different approaches to health-care board development and which are likely to work best in different contexts and types of NHS organisations?

Additional research questions of interest to members of the advisory group

-

What kinds of board development are effective and in what circumstances?

-

What is a good balance between individual and collective board development?

-

What are the respective roles of management consultants and (in-house and outsourced) organisational development practitioners?

-

What are the advantages/disadvantages of customised compared with off-the-shelf approaches to board development?

-

To what extent is board development in itself another assurance exercise?

-

How does appraisal of board members by the chairperson work in practice in the NHS and elsewhere?

Testable propositions

-

Board development is more than board development programmes and is an approach that includes appraisal, periodic review and so on.

-

Board diagnostic tools and board development activities can make a difference to effective board working.

-

Board development programmes have variable impact on improved organisation outcomes.

Research methodology

A literature synthesis using a realist approach is neither a systematic review nor a meta-analysis. The PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses; www.prisma-statement.org) 2009 checklist, nevertheless, contains important steps regarding the structure and content of a review that we have followed where relevant. In particular, we have taken note of the need for a clear rationale, objectives, study selection and data collection processes, data extraction reporting, synthesis of results, summary of the evidence, limitations and conclusions.

The detailed plan of investigation is summarised in Table 2 with more detail about the search strategy provided in Table 3 as this lies at the heart of the study. It is important to note that the four objectives with their associated research questions are closely inter-related. For example, in attempting to arrive at an understanding about different approaches to board development (the final objective), the material is correlated with findings from the literature on theories about boards, their application in NHS contexts and evidence about how boards affect organisational performance. Equally, although Table 2 suggests a sequential set of phases, in realist review there is an iteration between the phases so, for example, theories about boards and explanations about the characteristics of effective boards in NHS contexts are shaped and reshaped throughout the course of the study.

Data extraction and inclusion/exclusion processes are less linear than in traditional systematic reviews and decisions do call for pre-existing knowledge of the subject area and the exercise of judgement on what to include/exclude from the review, drawing on advice from the research team and stakeholder group as required. Examples of data extraction forms used are provided in Appendix 1.

| Phase | Actions |

|---|---|

| Define the scope of the review (research question 1: theories about boards; research question 2: experiences of NHS boards; research question 3: impact of boards on performance; and research question 4: board development) |

|

| Search for, extract and appraise the evidence (see also Table 3) |

|

| Synthesise findings |

|

| Draw conclusions and make recommendations in relation to the original objectives of the study (objective 1: explanation of theoretical and conceptual frameworks about boards; objective 2: application of frameworks to understand characteristics of effective boards in NHS contexts; objective 3: assessment of the evidence of how boards affect organisational performance; and objective 4: evaluation of approaches to board assessment and development) |

|

| Phase | Actions |

|---|---|

| Decide purposive sampling strategy |

|

| Define search sources, terms and methods |

|

| Develop data extraction forms |

|

| Test for relevance and rigour |

|

| Set thresholds for saturation |

|

Literature search

A search was conducted from 1968–2011 across relevant library and external sources as outlined in the following sections.

Full text

-

ABI/INFORM® (ProQuest, Ann Arbor, MI, USA): > 3000 leading peer-reviewed management journals and business publications.

-

Business Source Premier (EBSCO Industries, Inc., Ipswich, MA, USA): > 2800 leading peer-reviewed management journals and business publications.

-

Emerald (Emerald Group Publishing Limited, Bingley, UK): > 500 peer-reviewed business journals covering subject areas such as leadership, corporate governance, organisation studies, general management, industry and public sector management.

-

SAGE Management & Organization Studies/Health Sciences: > 40 peer-reviewed management journals and 50 health sciences titles.

-

SciVerse® ScienceDirect® (Elsevier, Amsterdam, the Netherlands): > 2400 peer-reviewed titles covering various disciplines including business and management disciplines, health sciences, life sciences and physical sciences.

-

Wiley Online Library: > 1500 titles covering various disciplines including business and management and health sciences.

Indexes and abstracts

-

ISI Web of Knowledge: abstracts and citations for > 8000 science and social science journals.

-

Scopus: abstracts and citations for > 15,000 science and social science journals.

-

Zetoc: British Library's electronic table of contents – abstracts and indexes for > 20,000 journals.

-

PubMed: citations for biomedical journals.

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL): indexes for 3800 journals covering nursing and allied health literature.

-

Ovid: access to various collections including EMBASE (3500 medical journals), Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), MEDLINE and PsycINFO.

-

Applied Social Science Index and Abstracts (ASSIA): spans > 500 journals for health, social services, psychology, sociology, economics, politics, race relations and education.

Practitioner literature

-

Social Science Research Network (SSRN): > 300,000 working papers covering various management and business disciplines; many working papers available in full text.

-

Service and Delivery and Organisation (SDO) studies.

-

NHS NIHR reports.

-

NHS Leadership Academy.

-

NHS Confederation.

-

Department of Health research and publications.

Books

-

Nielsen Books in Print: > 15 million records for internationally published books (including out-of-print books)

Specific titles

The following titles specified by the research team were covered by the Business Source Premier, ABI/INFORM, Emerald, SAGE and Wiley databases:

-

British Journal of Management (1990+, Business Source Premier)

-

Corporate Governance: An International Review (1993+, Wiley Online Library)

-

Corporate Reputation Review (1997+, ABI/Business Source Premier)

-

Economic Development Review now Economic Development Journal (1984+, Business Source Premier)

-

Health Services Management Research (1987+, ABI/Business Source Premier)

-

Health Affairs (1994+, ProQuest)

-

Human Relations (1947+, SAGE)

-

Journal of Business Ethics (1987+, ABI)

-

Journal of Healthcare Management (1987+, ABI)

-

Leadership & Organization Development Journal (1980+, Emerald)

-

Nonprofit Management and Leadership (1998+, Business Source Premier)

-

Public Administration and Development (1998+, Wiley Online Library).

The following titles were searched individually:

-

Journal of Business Ethics (1982–7, JSTOR)

-

Health Care Management Review (1976+, Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins journals)

-

Corporate Governance (1994–2006, Emerald).

A combination of selected keywords within title/abstract/subject terms, shown in Box 2, was used to identify references.

Title: board* and framework* or theor* or model* or literature

Title: board* and (success* or effective* or performance*)

Subject: board* or governance

Title: board*

Abstract: success* or effective* or performance

Subject: board or governance

Title: board* or governance*

Title: framework* or theor* or model* or literature

Subject: board*

Title: board* or corporate governance*

Abstract: board* or corporate governance*

Abstract: theor* or framework* or model* or literature

Subject: board or governance

Title: board* or governance

Abstract: board*

Abstract: success* or effective* or performance*

Abstract: firm* or company* or organisation* or organization*

Subject: board* or governance

Health-related boards literatureTitle: nhs or national health service

Title: board* or governance

Subject: board* or governance

Title: nhs or national health service

Abstract: board* or governance

Subject: board* or governance

Title: board* or corporate governance* or clinical governance

Title: health or healthcare or health service or public health or nhs or national health service or emergency service* or hospital* or care trust* or clinical care or care

Subject: board* or governance

Title: board* or corporate governance* or clinical governance

Title: health or healthcare or health service or public health or nhs or national health service or emergency service* or hospital* or care trust* or clinical care or care

Abstract: board*

Subject: board* or governance

Title: board* or governance* or clinical governance

Abstract: health or healthcare or health service* or public health or nhs or national health service* or emergency service* or hospital* or care trust* or clinical care or care

Abstract: theor* or framework* or literature or model*

Subject: board* or governance

To aid the management of references, the results were exported to EndNote X5 (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA), a standard reference management tool, which allows references to be sorted by type, for example articles, papers and websites, and provides an efficient method to review relevance. Two EndNote libraries were created, one for general literature and one for health-care-related literature. References were tagged to allow results in each EndNote library to be filtered by the four main research questions.

In the first phase of the literature review, all journal abstracts, book summaries and papers were read and allocated for potential interest to the four research questions by the principal investigator or discarded. A second member of the research team viewed a random sample of abstracts to check the decision-making. In phase two, full articles and texts were viewed before a judgement was made to select for full examination or to discard. In the final phase, further hand searching and snowballing took place to augment and in some cases update the literature under scrutiny.

Studies excluded from the review

The following study topics were excluded from review as these were deemed not to be related to our research questions, nor were they topics of interest to the advisory group members or relevant to our testable propositions:

-

small firms

-

founder director firms

-

CEO pay

-

corporate social responsibility

-

specific industry sectors, for example sports, banking, technology-intensive firms, in which findings pertain only to that sector

-

in-country articles in which findings relate only to that country

-

anecdotes of single company experiences.

Studies included in the review

In total, 618 general articles, 209 health-care-related articles, 252 textbooks and 54 reports were identified as a result of the initial search. After screening and tagging for links to the four research questions, 22 textbooks, 21 reports and the following numbers of articles were reviewed to assess their relevance for full examination:

-

374 (general) + 50 (health-care related) for research question 1 on general theories and frameworks for boards

-

28 (general) + 29 (health-care related) for research question 2 on experiences of health-care boards

-

70 (general) + 20 (health-care related) for research question 3 on the impact of boards on organisational performance

-

47 (general) + 9 (health-care related) for research question 4 on approaches to board development.

After eliminating duplicated references and application of criteria for exclusion, and the inclusion of additional material from hand searching, snowballing and updating, 670 articles and other texts were selected for full review.

Chapter 2 Theories about boards

Disciplinary sources of ideas about boards

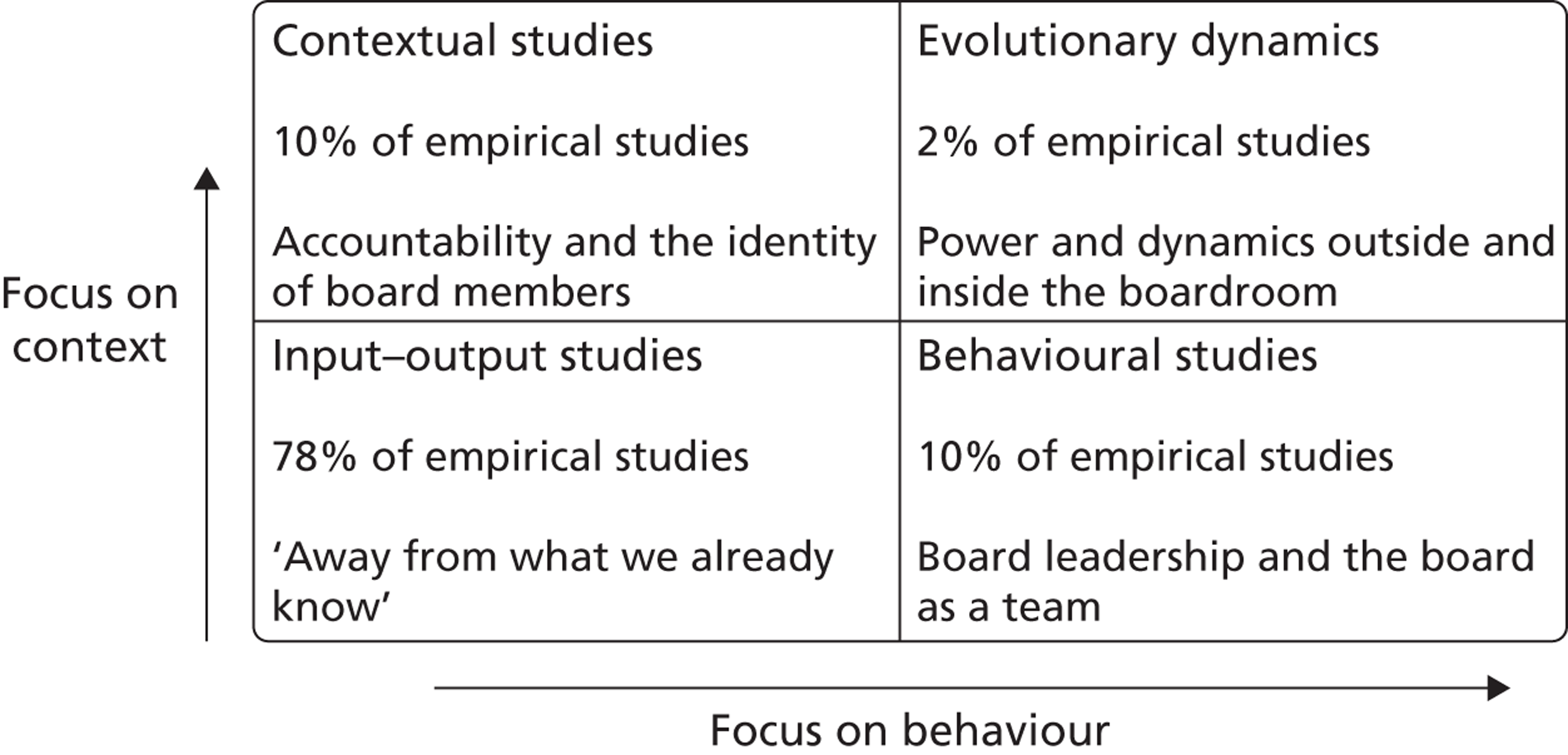

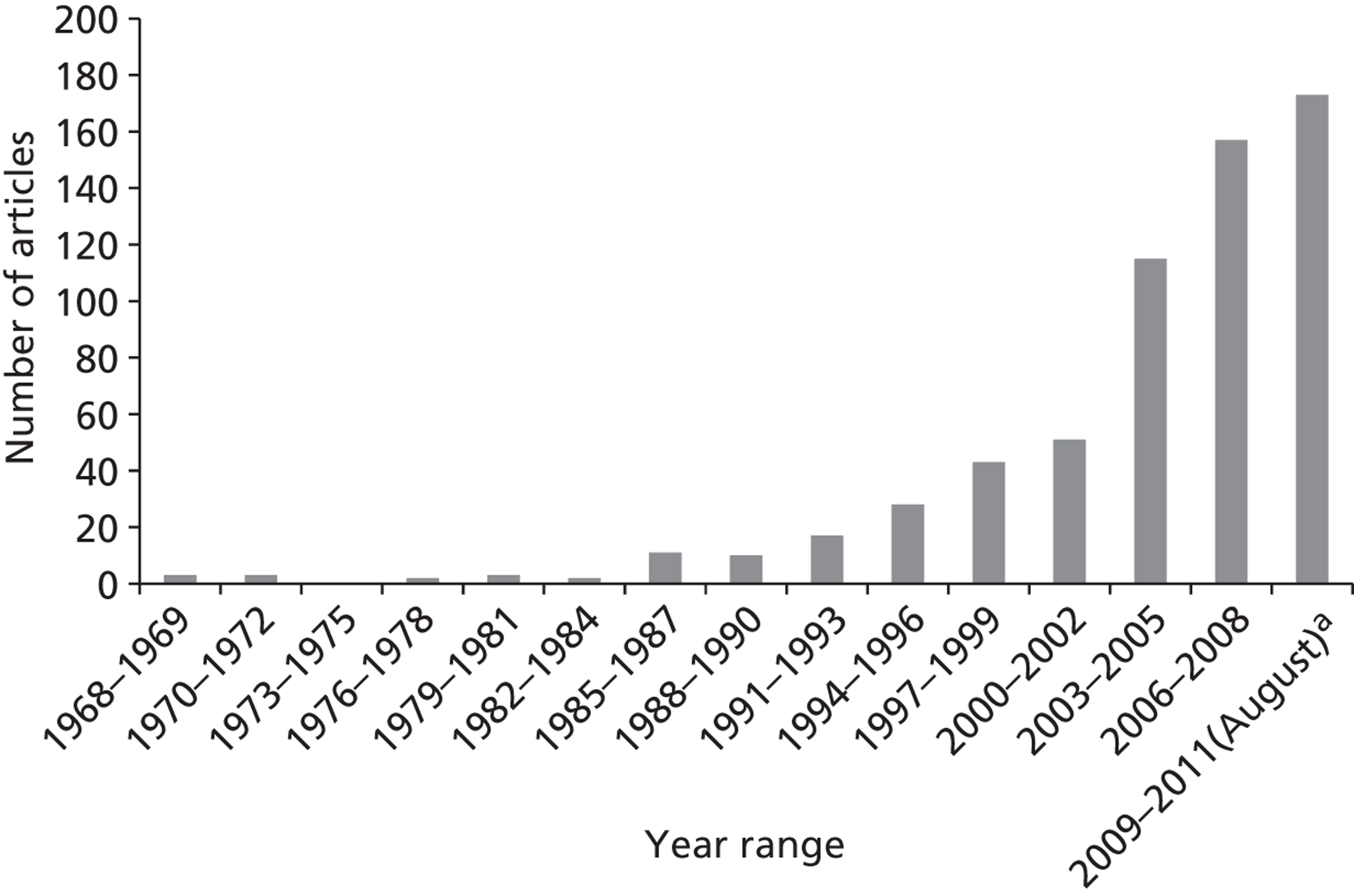

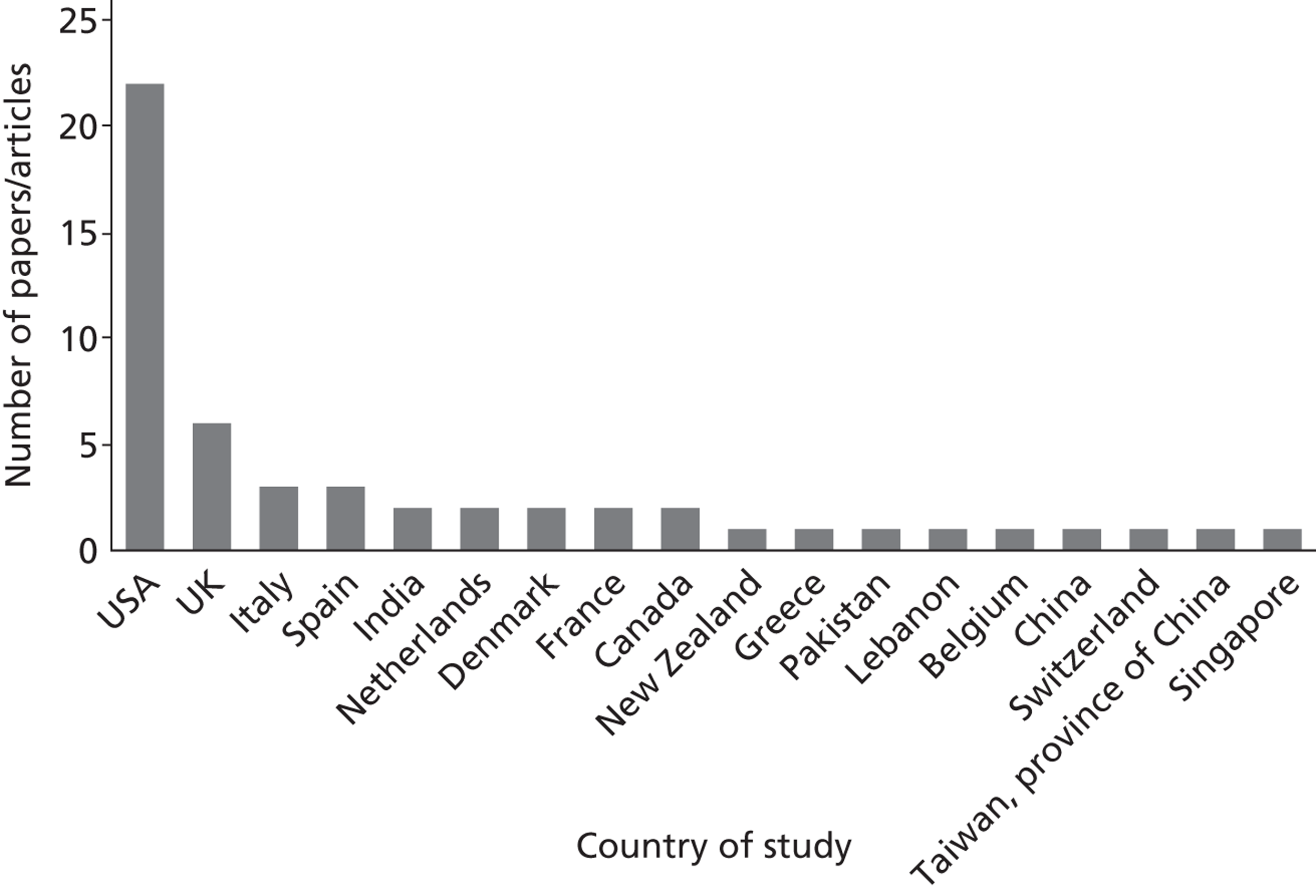

What are the main disciplinary sources of ideas about boards and what are the principal theories, conceptual frameworks and main paradigms? Interest in board governance is growing. In our trawl of 618 general (as distinct from health-care-specific) articles from 1968 to 2011 we found a significant and steady recent increase in relevant material (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Publication timeline. a, Search undertaken in August 2011.

| No. | Journal | No. of articles |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Corporate Governance | 49 |

| 2 | Corporate Governance: An International Review | 46 |

| 3 | British Journal of Management | 13 |

| 4 | Journal of Financial Economics | 13 |

| 5 | Corporate Ownership and Control | 12 |

| 6 | Nonprofit Management and Leadership | 12 |

| 7 | Long Range Planning | 11 |

| 8 | Journal of Corporate Finance | 9 |

| 9 | Journal of General Management | 9 |

| 10 | Nonprofit and Voluntary Sector Quarterly | 9 |

| 11 | SSRN Working Paper Series | 9 |

| 12 | Academy of Management Journal | 8 |

| 13 | Journal of Business Ethics | 8 |

| 14 | Journal of Management Studies | 8 |

| 15 | Strategic Management Journal | 7 |

| 16 | Academy of Management Annual Meeting Proceedings | 6 |

| 17 | International Journal of Business Governance and Ethics | 6 |

| 18 | Journal of Management and Organization | 6 |

| 19 | The International Journal of Accounting | 6 |

| 20 | Administrative Science Quarterly | 5 |

| Other titles with less than five articles (totalling 267 journals) | 366 | |

| Total | 618 |

Table 4 shows the top 20 journals in terms of numbers of articles and, as discerned from terms used in the titles and abstracts, these articles largely relate to ‘corporate governance’ and ‘management’, although economic, legal, strategic, behavioural and organisational frames are also significant (Table 5 shows the main disciplinary themes). A number of key texts are characterised by interdisciplinary synthesis, for example legal (Berle22) and economic (Means22).

| Theme | No. found |

|---|---|

| Corporate governance | 272 |

| Management | 171 |

| Strategy | 57 |

| Organisation | 33 |

| Law | 25 |

| Economics | 14 |

| Psychology | 3 |

Huse23 distinguishes between general theories (contingency and evolutionary), the role of boards (e.g. agency, stewardship and so on) and process theories (e.g. norms, decision-making culture and interactions). Selim et al. 9 refer to the interaction of structures, processes and behaviours in affecting board effectiveness. We have adapted these, which we would identify as middle-range theories, by starting with theories about the role of boards, proceeding to process theories, which we have termed board practices, and concluding with a conjunction of the two.

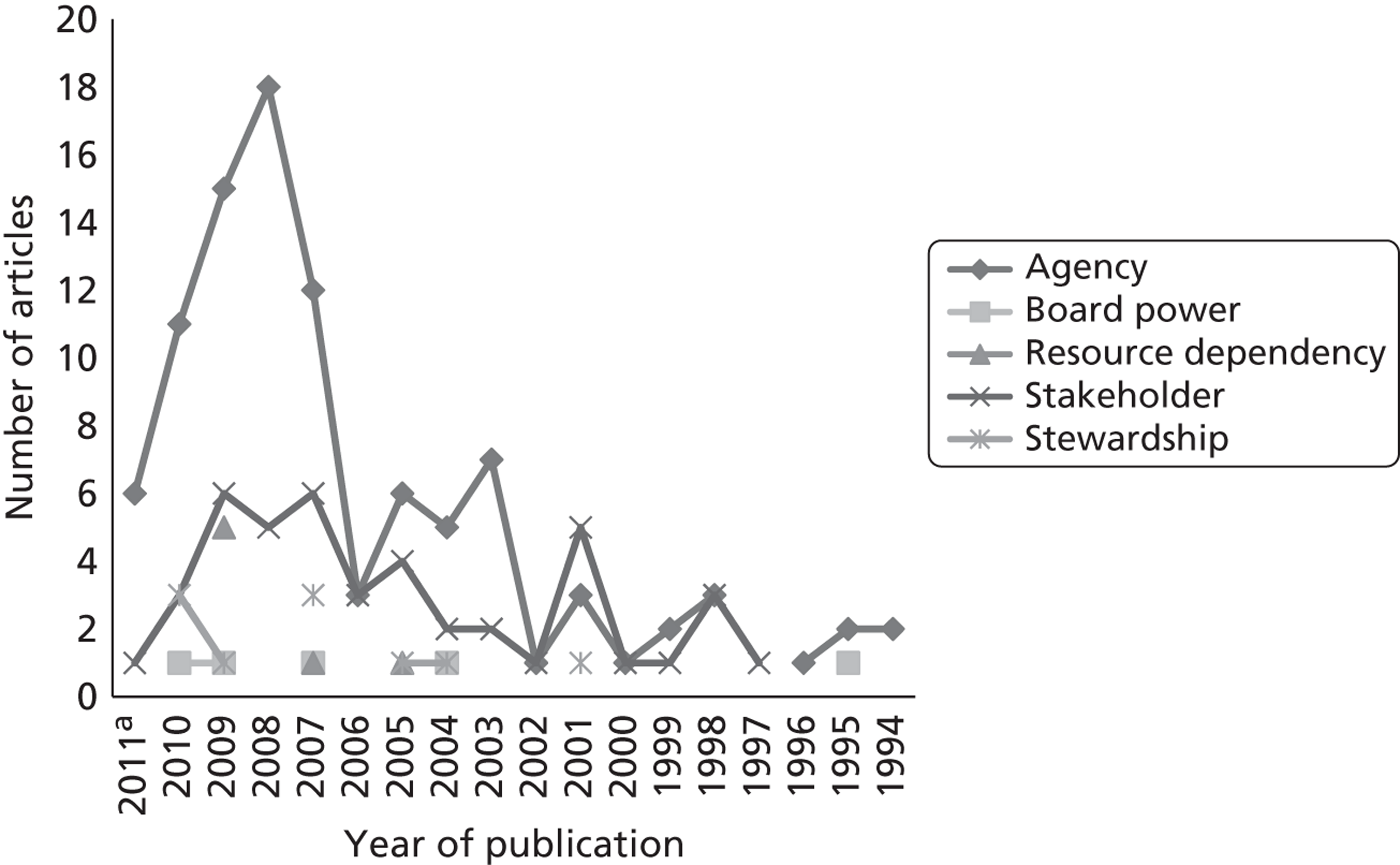

Principal corporate governance theories

Figure 2 outlines the numbers of articles relating to the main theories about boards and, therefore, shows the relative dominance of the main theories over time. In addition, the texts in Table 6 were selected as landmark texts because of frequency of citations, influence on corporate governance theory and theory development and relevance for the research questions in this study.

FIGURE 2.

Timeline for the main board theories (from 618 general references about boards). a, Search undertaken in August 2011.

| Study | Contribution | Citation ratea |

|---|---|---|

| Pfeffer and Salancik 200324 | Resource dependency theory | 13,826 |

| Berle and Means 193222 | Agency theory | 10,609 |

| Ferlie et al. 199625 | New public management and boards | 1417 |

| Davis et al. 199726 | Stewardship theory | 1401 |

| Dalton et al. 199827 | Meta-review | 953 |

| Carver 200628 | Policy governance theory | 687 |

| Roberts et al. 200529 | Role of non-executive directors | 249 |

| Huse 200523 | Board behavioural framework | 199 |

| Stiles and Taylor 200130 | Boards at work | 181 |

| Cornforth 200331 | Non-profit governance | 173 |

| Chait et al. 200532 | Non-profit governance | 161 |

| Garratt 199733 | Board tasks | 147 |

| Brown 200534 | Non-profit governance | 124 |

| Clarke 200435 | Philosophical foundations of governance | 111 |

| Clarke 199836 | Stakeholder theory | 109 |

| Hillman et al. 200937 | Resource dependency theory | 67 |

| Vinnicombe et al. 200838 | Women on boards | 64 |

| Gabrielsson 200739 | Board behaviour | 21 |

| Heracleous 200840 | Meta-review | 19 |

| Brown and Guo 201041 | Non-profit governance | 14 |

| Capezio 200942 | Behavioural agency theory | 7 |

Agency theory

History of agency theory

Boards of commercial corporations were developed as a result of the industrial revolution, the growing commercial complexity of business and the gradual separation of ownership, and risk, from control. Trading, banking, transport and utility companies led the way before manufacturing in assuming corporate form. The significance of this silent revolution is eloquently outlined by Berle and Means22 in the preface to their classic text:

It is of the essence of revolutions of the more silent sort that they are unrecognized until they are far advanced. This was the case with the so-called ‘industrial revolution’ and is the case with the corporate revolution through which we are at present passing.

The translation of perhaps two-thirds of the industrial wealth of the country [USA] from individual ownership to ownership by the large, publicly financed corporations vitally changes the lives of property owners, the lives of workers, and the methods of property tenure. The divorce of ownership from control consequent on that process almost necessarily involves a new form of economic organization of society.. . .

When these subjects are thought through there will still remain the problem of the relation which the corporation will ultimately bear the state – whether it will dominate the state or be regulated by the state or whether the two will coexist with relatively little connection. In other words, as between a political organization of society and an economic organization of society which will be the dominant form? This is a question which must remain unanswered for a long time to come.

(pp. lii–liv)

The influence on society of how business is conducted is undisputable: ‘With 50 of the world's largest economies being companies, and the 500 largest corporations controlling 25% of the world's economic output, the impact of business on society is undeniable’ (p. 96). 30

The earliest fully developed theory about boards was thus agency theory, at the heart of which lies questions about the organisation and ownership of property and the distribution of power that goes along with that. Over the past few centuries, the holding of property has moved from being an active to being a passive affair. Evolution of control has been classified by Berle and Means22 as (1) control through ownership, (2) majority control, (3) control through legal device, (4) minority control and (5) management control (p. 67). When ownership is held by a very large number of individuals and bodies with none holding a significant proportion, control is effectively handed over from owners to managers. A total of 44% of the largest 200 US corporations in Berle and Means's study22 were found to be under management control in 1929 (p. 106), rising to 84% by 1963. Agency theory is predicated on the notion that the shareholders' and managers' interests are likely to be different and that the behaviours of both sets of actors are characterised by self-interested opportunism. 22 Those in control ‘can serve their own profits better by profiting at the expense of the company than by making profits for it’ (p. 114). 22

There is a prehistory here that it is worth examining. Germane to the public sector focus of this study, before the industrial revolution, charities and municipal authorities were the earliest examples of corporations. In 1614, Sir Edward Coke confirmed both the legal personality and the abstract nature of corporations and remarked in the case of a contested estate in relation to which funds were vested in Sutton's Hospital:

the Corporation itself is only in abstracto, for a Corporation aggregate of many is invisible, immortal, & resteth only in intendment and consideration of the Law; and therefore it cannot have predecessor nor successor. They may not commit treason, nor be outlawed, nor excommunicate, for they have no souls, neither can they appear in person, but by Attorney. A Corporation aggregate of many cannot do fealty, for an invisible body cannot be in person, nor can swear, it is not subject to imbecilities, or death of the natural body, and divers other cases.

Coke 1614, cited in Coke and Shepherd43

Although boards were supposed to represent the interests of absent owners or shareholders (the principals), and management became the agents of the board, Adam Smith44 highlighted what he saw as the hazards of diverting the control of company resources away from the owners:

The directors of such companies . . . being the managers rather of other people's money than of their own, it cannot well be expected, that they should watch over it with the same anxious vigilance with which the partners in a private copartnery frequently watch over their own.

p. 439

Analysis of agency theory

Coming now to the present day, agency theory, with its emphasis on conformance, suggests that the monitoring role of the board, supported by processes such as external audit and reporting requirements, is likely to reduce problems of management pursuing their own interests or performing poorly (Box 3 provides a summary of the implications of agency theory for an understanding of board governance). The emphasis is on avoiding performance problems stemming from poor management or inappropriate use of managerial discretion. The theory is underpinned by a belief derived from neoclassical economics that, as both principal and agent are utility maximisers, the latter is not likely to always act in the interest of the former. Agency costs are incurred in acting to minimise the gap between the two sets of interests. Jensen and Meckling45 elaborate on the three sources of agency costs: monitoring expenditure, bonding costs (to tie the agent in) and residual loss (the costs of agents' decisions which diverge from those that are in the best interests of principals). These authors also emphasise the generality of the agency problem, both at all levels of management and also across different types of organisations, including non-profit organisations (NPOs), government corporations and co-operatives. This is derived from a view that most organisations (private firms, NPOs, government bodies) serve as a nexus for a set of contracting relationships among individuals. 45

Fama and Jensen46 further explicate the value of agency theory by explaining the circumstances in which a separation of decision management (generation and implementation of proposals) and decision control (ratification and monitoring processes) is indicated. This includes large corporations, and also most NPOs and government bodies when there is a degree of complexity or size which means that there is a hierarchy and a diffusion of decision management and when important decision-makers are not exposed to significant risk by the financial effects of their decisions, which is indeed a distinctive characteristic of NPOs and government bodies.

Eisenhardt47 urges the use of agency theory to investigate problems that have a principal–agent structure, for example information asymmetry, outcome uncertainty and risk, offering an empirically testable perspective on the challenges of co-operative effort. Rather than wholesale adoption or rejection, this author advocates its deployment when there are particular contracting problems, goal conflict or lack of clarity, and in tandem with other organisation theories.

Agency theory carries with it certain assumptions about human behaviour and, for public sector bodies, certain assumptions that governments make about human behaviour. For health care, the assumption behind agency theory is about the need to rein in the self-serving behaviour of managers and clinicians, as well as the need to mitigate against poorly performing managers, which has also been termed ‘honest incompetence’. 48

Recent critiques of agency theory claim that it downplays the complexity of individual motivations and permutations of organisational life and that it relates to a view about the self-centredness of human behaviour in organisations which is now contested. 26,49 Huse et al. 50 challenge a core assumption behind agency theory, which is the possibility of complete contracting ex ante for all stakeholders. Without this, and with the probability of incomplete contracting, other theories emerge naturally. In a meta-analysis, Deutsch51 found little support for agency theory's prediction about the impact of board composition, particularly the proportion of outside directors, on critical decisions, for example around CEO compensation, risk and control, that involve a potential conflict of interest between managers and shareholders. Relating closely as it does to the monitoring and compliance aspect of the board role, which is commonly regarded as a cornerstone of board work, agency theory nevertheless continues to hold sway and dominates the literature about board theories (see Figure 2 for a timeline: out of 174 articles accessed relating to different board theories over the past 17 years, 105 discussed agency theory, although the backlash against agency theory was most notable around 2004–6).

One possible reason for the continued primacy of agency theory is the development of a modernising behavioural variant. This argues that in some circumstances boards may opt for behaviour-based rather than outcome-based incentive schemes for its executives to achieve alignment and optimal contracting. 47,52,53 Behavioural agency theory proposes that the traditional advocacy of incentives based on firm-level outcomes may, particularly in view of the impossibility of complete ex-ante contracting, lead to unintended consequences. 53 Behavioural agency theory proposes that incentive alignment can be achieved through outcome-based contracts, behaviour-based contracts or a combination of the two. 47,52,53 Whereas outcome-based contracts link CEO pay to firm-level performance, behaviour-based contracts link pay to the board's direct supervision of CEO behaviour, decisions and actions, which, in turn, are assumed to have a positive, if indirect, influence on firm performance. 53 Capezio et al. 42 argue the case for behavioural agency theory to mitigate against the potential weaknesses of outsider directors who may suffer from information asymmetry and who may be excessively influenced by institutional emulation or social identity issues in their approach to the setting and controlling of organisation targets, performance and executive incentives.

-

Boards have a responsibility to mitigate the risks inherent in the separation of ownership from management

-

Managers may not always act in the interests of the organisation either as a result of self-seeking behaviour or because of incompetence

-

There may be damaging information asymmetry between the knowledge held by the management and the knowledge that is available to the representatives of the owners (in health care this would be the non-executive directors or lay members or governors on behalf of the public) on the board

-

The main role of the board is to obtain the necessary information to monitor the performance of the company and to hold the managers to account

Stewardship theory

Stewardship theory was developed as a challenge to beliefs that managers are always self-interested rational maximisers, first by Donaldson54 with later development by Davis et al. 26 and Cornforth31 (Box 4 provides a summary of the implications of stewardship theory for an understanding of board governance). According to stewardship theory, the goals of board directors and of their managers are aligned, with the latter being intrinsically motivated to act in the best interests of the organisation and to focus on intangible rewards such as opportunities for personal growth and achievement. The theory relates to a very different human relations perspective from the one that underpins agency theory, one in which, in general, people are motivated to do good and to act unselfishly, as long as a number of organisational and cultural preconditions are satisfied. 26 In this model, managers and owners share a common agenda and work ‘side by side’; the emphasis is on the board's role in developing strategy rather than on monitoring performance and a preponderance of internal (or executive) directors with high levels of access to information is favoured. 31 Implicit in stewardship theory is the understanding that the owners (principals) are prepared to take risks on how managers will run their business and provide a return on their investment, indicating a level of trust that is absent in agency theory.

The theory was explicated in a large empirical study covering 658 corporate directors in four countries. Anderson et al. 55 found that boards of directors were evolving into an active partnership with management, positioning themselves as a strategic asset to the organisation. This partnership role is more in keeping with a model of stewardship rather than an agency model of the board as monitor. Importantly, this co-operative role requires that the board develop closer ties with management. The board's shift to sit closer to management might otherwise have created an oversight vacuum but for the move toward activism by institutional investors. In the view of the authors, this evolution of the board to strategic partner of management, combined with increased investor monitoring, offers the potential to produce a more effective governance regime.

Davis et al. ,26 although proponents of stewardship theory, argue that, given the mixed empirical evidence, neither agency theory nor stewardship theory represents a ‘golden bullet’ for corporate governance. Other critiques of stewardship theory also indicate that there is, at best, mixed evidence to support this theory56 and that its application can lay organisations open to risks of governance failure, strategic drift or inertia. In addition, there is a danger of ‘groupthink’57 or ‘upper echelons’-dominated thinking,58 in which there is not enough independent challenge on the board. A study of 768 US company directors showed that non-executive directors experienced acute role conflict in having to serve the interests of shareholders while at the same time maintaining camaraderie on the board. 59 The same directors reported that non-executive directors who were members of a remuneration committee felt compelled to appease the CEO.

-

Managers on the whole direct their efforts to the well-being of the organisation that they are serving

-

Managers and owner representatives (outsider directors, non-executive directors, lay members or governors) on boards work together to develop strategy and to monitor performance

-

The value of directors lies in using their knowledge to advise their executive colleagues on the board

Resource dependency theory

Resource dependency theory derives from economics and sociology disciplines concerned with the distribution of power in the firm and was developed particularly by Zahra and Pearce60 and Pfeffer and Salancik24 (Box 5 provides a summary of the implications of resource dependency theory for an understanding of board governance). According to resource-based theory, the organisation is an amalgam of tangible and intangible assets and capabilities. 61 Strategic resources in particular are those that are valuable, rare, inimitable and non-substitutable. 62 In this context, the board can be seen as a strategic resource. Given that all organisations depend on others to survive and thrive, resource dependency theory24 suggests that managing external relationships to leverage influence and resources is the prime purpose of the board, and hence board members are selected for their background, contacts and skills in ‘boundary-spanning’. 63 Mintzberg64 called the board the mediator between internal and external coalitions, facing in to management and out to shareholders. The use of the board as a co-optative mechanism (also known as co-optation theory) reflects the potential of the board in fostering long-term relationships with key external constituencies, thereby co-opting important elements of the organisation's external environment. This is also evidenced by multiple board membership known as board interlocks. 65 The theory focuses on how uncertainty caused by external environmental factors and dependence on outside organisations can be minimised. Four benefits that board directors can bring include advice, access to information, preferential access to resources and legitimacy. 24

Allied to resource dependency, and drawing from Marxist sociology, is class hegemony theory, according to which the members of boards and governing bodies, even in a culturally diverse society, seek to perpetuate a ruling elite. Here, a small group of people head or direct all of the large companies and organisations through the exercise of political, social and economic power66 and imposition of a ruling-class world view. 67,68 The justification of the approach is that the world view taken is beneficial to all and not just to the ruling class. In relation to board governance, this amounts to an inner circle who constitute a distinct recursive semi-autonomous powerful network deeply embedded in community and society. 30

A recent review of resource dependency theory37 confirmed theoretical support and the existence of empirical evidence for this lens for understanding boards and emphasised its contingent and dynamic nature and its particular utility early in the life cycle of organisations and in times of stress or decline. The theory can be criticised for an overfocus on an external locus of control construct. 69 It underplays views of the board role in determining its own future through strategising, and in exercising oversight of internal management actions and performance.

-

Organisations depend on others for survival

-

Board members add value because of their background, skills and contacts

-

The main role of the board is leveraging and managing external relationships

-

Board members may belong to a network of other powerful people who exercise control over the direction of public life in a series of board interlocks

Stakeholder theory

Stakeholder theory comes from nineteenth-century developments of alternative forms of organisation and control in the shape of mutuals and co-operatives (for a review with specific interest for the health-care sector see Gregory70). Recent thinking on stakeholder theory has been developed in particular by Blair71 and Clarke36 (Box 6 provides a summary of the implications of stakeholder theory for an understanding of board governance). There is a view that an exclusive focus on shareholder interests has not held the key to good corporate performance and effective accountability. In an age of vocal consumer groups, employee activism, media monitoring and now social networking, the assumption that only shareholders are capable of effective monitoring looks increasingly flawed. 36

According to stakeholder theory,72 board members work to understand and represent the different interests of individuals and groups who have a ‘stake’ in the organisation. Stakeholders are all those whose participation is critical to the survival of the organisation. 73 These include managers, employees, customers, suppliers (contractual stakeholders) and the community, that is, consumers, regulators, government, pressure groups, media and local communities. 73 The argument runs that the inclusion of a range of different stakeholders drives an inclusive approach that represents a wide spectrum of societal opinions, balances competing priorities and avoids dominance by one group with particular interests. Among the myriad of stakeholders, stakeholder theory also argues that boards have to identify the critical stakeholders (e.g. key staff groups) whose commitment is essential for long-term value creation. According to stakeholder agency theory, managers are seen as the agents for all of the stakeholders, not just the owners. 74

The genesis of stakeholder theory can be traced back to the co-operative movements of the nineteenth century. Although Berle and Means' classic text22 is cited as the leading proponent of agency theory, their conclusions actually herald the notion of corporate social responsibility, and the importance of a community theory for how corporations should be managed, and they begin to address the broader question of what corporations (and therefore boards that manage them) are for:

This third alternative offers a wholly new concept of corporate activity. Neither the claims of ownership nor those of control can stand against the paramount interests of the community. . .it seems almost essential if the corporate system is to survive. . .that the ‘control’ of the great corporations should develop into a purely neutral technocracy, balancing a variety of claims by various groups in the community and assigning to each a portion of the income stream on the basis of public policy rather than private cupidity.

pp. 312–13

Penrose75 developed the intellectual foundation of stakeholder theory in her proposition that the company can be seen as a bundle of human assets and relationships. Blair71 argues that, if organisations are viewed as institutional arrangements for managing relationships between all of the parties that contribute to the wealth of the enterprise, not just the shareholders, management has to take into account the effect of corporate decisions on all stakeholders. Thus, the control rights should be allocated according to all of the stakeholders who provide the sources of firm value creation and who bear risk. In some interpretations of stakeholder theory,71 a hierarchical distinction is made between ‘taking into account’ the views of stakeholders and ‘being responsible to’ the shareholders.

Blair further argues that there developed an accommodation of the classic property conception of the corporation with a newer social entity conception, backed by developments in US law that protected companies which engaged in socially responsible behaviour that might not directly, in the short term, maximise profits for shareholders but that benefited shareholders in the long run, on the premise that the well-being of communities in which companies operate was considered good for business.

In practice, given that knowledge is these days the pre-eminent resource and that knowledge is generated by individuals, elements of the stakeholder approach are increasingly utilised. Only by creating great relationships with employees, customers, suppliers, investors and the community will organisations learn and change fast enough. 36 This argument is backed by Kaufman and Englander76 in their advocacy of the ‘team production’ model of corporate governance, which draws from a stakeholder view for board membership to include representation from those who add value, assume risk and possess strategic information.

Stakeholder theory has been challenged by some, for example Von Hayek,77 who argues that allowing management to use company resources for ends other than a direct increase in shareholder value confers on them ‘undesirable and socially dangerous powers’ (p. 100). Other arguments against the stakeholder view include diversity of and lack of clarity about stakeholder expectations, complexity of trade-offs if stakeholder interests are to be taken account of and the need for a simple focus of the bottom line for managers. 78

Despite the fact that stakeholder governance models are deeply embedded in some countries in Europe, notably Germany, and in Japan, and that claims for these countries' industrial and social success are often based on this model, the empirical evidence for stakeholder theory is weak. In a study of 250 firms and more than 3000 directors, Hillman et al. 79 found no association between the presence of stakeholder directors on the board and organisational performance. The theory can be criticised for encouraging risk-averse, inoffensive but bland and lowest common denominator decision-making. It can lead to large and unwieldy boards with people recruited for whom they represent rather than for their board-level skills. 80

-

The role of the board is to ensure the longer-term survival and value creation for the organisation and is dependent on the commitment of key stakeholders not just shareholders

-

The role of board members is to understand and represent the views of all those with a stake in the organisation

-

The board may have to manage complex trade-offs between the interests of shareholders and those of stakeholders (in the case of health care the latter may be the wider public and the former may be the patients and the staff of the hospital)

Theories about the exercise of board power

Berle and Means,22 in relation to agency theory, delineate between the three main aspects of enterprise: (1) having power with ownership and taking action, (2) the diverse situations of owners without appreciable power and (3) having power without appreciable ownership (p. 112). Power can be defined as the ability to influence others and, in relation to boards, Huse et al. 50 argue that the literature on power can usefully be divided into four main groups. These are direct power, indirect power, conscience-controlling power and institutional power. Power differentials between members of the board affect both processes and outcomes (Box 7 provides a summary of the implications of board power theory for an understanding of board governance). Mace81 found that the gap between expectations of boards and actual practices could at least in part be explained by power relations.

Models of board behaviour and exercise of power can be related to the main theories about boards: for example, agency theory is connected to a ‘challenge and compliance’ set of behaviours, whereas stewardship theory relates to a high-trust partnership style of working, and in a stakeholder model board members tend to be most vocal when articulating the interests of ‘their’ constituency. 80 Power boards are those to which influential boundary spanners have been recruited, in a model closely related to a resource dependency view of the board. 30

In an amplification of their view that one size does not fit all, Davis et al. 26 propose that participative, empowered, involvement-oriented management culture with lower power distance is more likely to produce principal–steward relationships, and that a control-oriented management, with individualist culture and transactional leadership characteristics and high power distance, will, conversely, produce principal–agent relationships. The authors further indicate that both the principal and the agent (manager) are psychologically predisposed to one or other relationship but do have a choice. They conclude that, if there is an agreed mutual stewardship relationship, the potential performance of the firm is maximised and, if there is an agreed mutual agency relationship, risks and costs are minimised.

In his influential piece on the exercise of power by independent directors of the board, Mace82 argues that, at least at the time of writing, there is a substantial gap between the myths of business literature and the realities of business practice. Directors do give advice, set discipline and provide decision-making in times of crisis but are less likely to exercise influence over strategy or to ask discerning questions or in reality take charge of the CEO selection process. This all suits CEOs who, according to the managerial hegemony frame, do not want the directors too involved in the company. In a more nuanced contribution, Lorsch and MacIver83 chart the rise and fall and rise again of the potential power vested in the independent director. This has to do with the increase in the proportion of outside directors, and the multiple sources of power, which include legal authority, stakeholder expectations and personal confidence as well as the power of unity of purpose amongst board members. Kosnik84 argues for merging agency and managerial hegemony theories to clarify the contingencies that might affect board performance in corporate governance. The argument runs that one is not more valid than the other but that the switching rules need to be identified.

Related to this are theories about the sources and use of board power, including the power of the chief executive,85 the exercise of managerial hegemony,35 the discretionary effort and skill exercised by non-executive board members86 and the increased role of the board in periods of crisis or transition,83 which can be followed by ‘coasting’ according to the stress/inertia theory. 87 Critiques of models of board power argue that there is a sometimes mistaken assumption that board members are able to exercise influence over senior management, and that it is through this influence on management that they are able to bring about change and influence organisational performance. 5

Three main rules governing the proper exercise of power by management have been developed and tested legally: a decent amount of attention to business, loyalty to the interests of the business and reasonable business competence (p. 197). 22 Managerial power theory argues that board structures set the conditions for board control. Boards dominated by managers are seen as weaker monitors and compromised, as the CEO can exercise inappropriate influence over his or her own, and fellow executives', compensation and career advancement. 88 Further, managerial power theory proposes that a CEO who is also a board chairperson (chairperson–CEO duality) has the power to influence board decisions in general and to create the conditions for board ‘capture’. 89–92

Power circulation theory explains political dynamics amongst elites93 and was extended to the corporate governance context by Ocasio,94 Shen and Cannella95 and Combs et al. 96 The theory suggests that top management in organisations is inherently political, characterised by shifting coalitions and continual power struggles. 94 Power circulation challenges the notion that CEOs can perpetuate their power. 94,97 Instead, it suggests that managerial power ebbs and flows because of political obstacles and triumphs arising from the shifting allegiances of colleagues and rivals. Combs et al. 96 argue that a board with a majority of outside directors is only important to control a powerful CEO and that a weaker CEO can be adequately controlled by the other executives.

Finally, in relation to Huse et al.'s allusion to conscience-controlling power,50 corporations may transgress because, although they have power, they lack the conscience to do good, as they have ‘no soul to be damned and no body to be kicked’ (Edward 1st Baron Thurlow, English Lord Chancellor 1778–92, quoted in Coffee,98 p. 386). This begins to indicate the requirement for an agency theory in reverse – the need to consider who controls or regulates the decisions and actions of the board, and a revisiting of Berle and Means' question22 about whether the political or the economic organisation of society should dominate (p. liv).

-

The holding and exercise of power on the board changes over time and power distance between members on the board can also vary

-

Power on boards often rests with managers not with outsider or non-executive directors or lay members or governors

-

Board members add value by understanding the circumstances in which managerial hegemony is beneficial to the organisation and the circumstances in which it is not

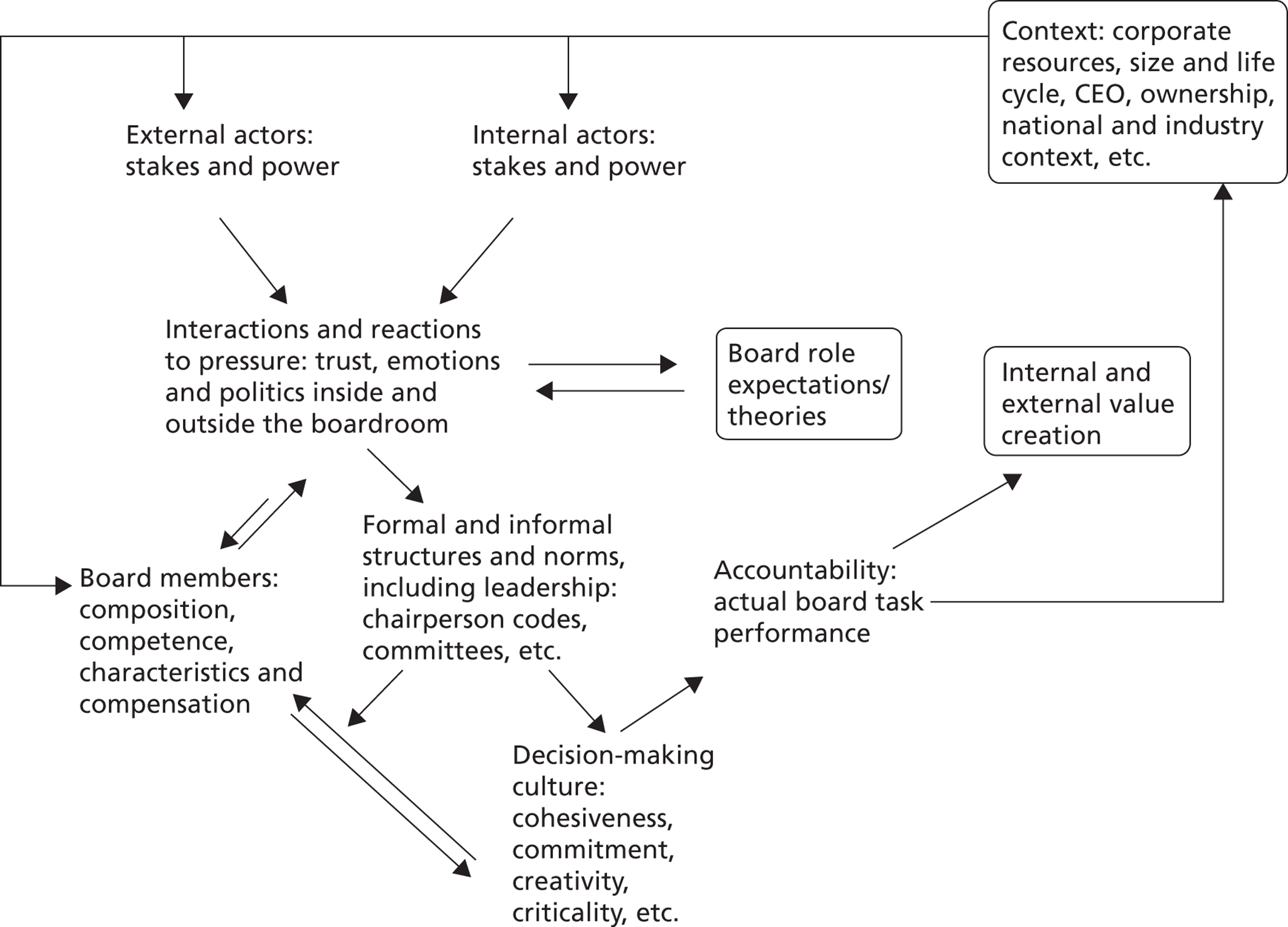

Developing a realist interpretation framework of board theories, contextual assumptions, mechanisms and intended outcomes

The terrain is characterised by some complexity in terms of the multiple locations of the evidence across different disciplinary traditions. Drawing together these theories is a daunting task. Within a realist frame, the focus is on offering explanations rather than judgements, and developing principles and guidance rather than making rules. 16 In line with a realist view, it seems to us that underpinning the main theories about the role of boards is a series of contextual assumptions, mechanisms and intended outcomes. These are summarised in Table 7.

The theories suggest that boards face choices. If the main intended outcome is for the minimisation of risk (e.g. patient safety), it follows that the main mechanism should be monitoring, predicated on agency theory. This may come at the expense of innovation, however, which is predicated on stewardship theory, with a mechanism of collaborative working on the board. When there is an issue around power (e.g. in health care, the power of the professions, or the power of the regulator), the mechanism of power differentials may need to be deployed to ensure equilibrium. In the context of long-term service commitment in a health-care system, a multi-stakeholder approach involving collective effort may be indicated, with an outcome of long-term added value.

| Theory | Contextual assumptions | Mechanism | Intended outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Agency | Low trust and high challenge and low appetite for risk | Monitoring and control | Minimisation of risk for owners |

| Stewardship | High trust and less challenge and greater appetite for risk | Partnership between managers and owners | Excellence in performance |

| Resource dependency | Importance of social capital of board | Boundary spanning | Inward investment and greater reputation |

| Stakeholder | Importance of collective effort; risk is shared by many | Collaboration | Long-term added value |

| Board power | Power relations foregrounded; rests on human desire for control | Use of power differentials | Equilibrium |

Board practices

What do boards actually do, what should they do and how does this relate to theories about boards? There have been calls for frameworks that combine the insights of different theories. 31,99 One useful model has been proposed by Garratt,33 drawing on an earlier model by Tricker. 99 Garratt suggests that there are two main dimensions of the board's role, what he calls ‘conformance’ and ‘performance’. Conformance involves two main functions: external accountability, including compliance with legal and regulatory requirements and accountability to shareholders or other stakeholders, and supervision of management through oversight, monitoring performance and making sure that there are adequate internal controls. This conformance dimension matches quite closely with the agency theory perspective on governance. In contrast, the performance dimension is about driving the organisation forward to better achieve its mission and goals. This again consists of two main functions, policy formulation and strategic thinking, to take the organisation forward. The performance dimension is in keeping with stewardship theory of corporate governance. This framework (depicted in Table 8) suggests that boards need to be concerned with both the conformance and the performance dimensions of corporate governance.

| Focus | Short-term focus on ‘conformance’ | Long-term focus on ‘performance’ |

|---|---|---|

| External focus | Accountability:

|

Policy formulation:

|

| Internal focus | Supervision:

|

Strategic thinking:

|

Carver100 proposes a ‘policy governance’ model. He claims this to be a universally applicable theory of governance that, with the board as servant-leader, and a strict separation of governance from management, is a conceptually coherent paradigm of principles and concepts encompassing ends, executive limitations, governance processes and board–ownership and board–staff linkages. The model can be criticised for similar reasons as the weaknesses exposed in agency theory, which it draws from: the distance between the board and the management of the organisation can mean that essential monitoring does not take place, and it might not be fit for purpose during turbulent times in the life cycle of the organisation.

As an alternative, and of particular relevance, but not exclusively, to the non-profit sector, Chait et al. 32 propose a hierarchy consisting of three essential components of governance: fiduciary, strategic and generative. Fiduciary duties, or the monitoring and compliance aspects, relate to the legal responsibilities of trustees and to the agency theory of governance. The strategic component relates to the work of the board in setting direction and is closer to the ‘performance’ aspect of Garratt's33 two main dimensions of board work. Generative governance is also about performance but it encapsulates leadership through governance and thereby aims for organisational renewal as well as tasks relating to strategy. Boards exercising generative governance can help organisations to unlearn organisational practices that have become unhelpful101 by diagnosing new opportunities, new performance measures and new control systems.