Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 10/1012/09. The contractual start date was in September 2011. The final report began editorial review in October 2012 and was accepted for publication in March 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors' report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen's Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Hanney et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

The research question

This evidence synthesis responds to a call by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme in 2010 that requested a synthesis ‘which maps and explores the likely or plausible mechanisms through which research engagement might bear on wider performance at clinician, team, service or organisational levels’. 1 The invitation to tender (ITT) called for a review of the relevant research literature to see what empirical support exists for any theoretical mechanisms, and stated that ‘A theoretically and empirically grounded assessment of the relationships, if any, between research engagement and performance should explore issues of causation’. 1 These statements led us originally to formulate the research question we intended to address in this review as follows: Engagement in research: does it improve performance at a clinician, team, service and organisational level in health-care organisations?

We found there was a widely held assumption that research engagement improved health-care performance at the various levels, as, for example, expressed in the 2010 White Paper, Equity and excellence: liberating the NHS2 and in a 2010 briefing from the NHS Confederation. 3 The briefing reported possible explanations, expert comments and some evidence to support this view, including reference to the web site of the Association of UK University Hospitals (AUKUH) which had issued a press release showing that university hospitals on average did better than non-AUKUH hospitals in the quality of service scores produced by the Care Quality Commission. 4 However, this AUKUH analysis was very brief and did not take into account other possible factors. In practice, in our early explorations at the time of the ITT in mid-2010, we could identify very little direct empirical evidence to support this assumption. Nevertheless, we identified diverse bodies of knowledge that we thought might help to address the question.

Given these circumstances, we knew that this review would not be straightforward and that we would have to think constructively about both its scope and our methodological approach as we explored the field, making revisions to our proposed approach where needed. These changes are discussed in more detail in Chapter 3. Below we set out the interpretation we put on key terms, the scope of the study we eventually conducted, and provide a brief guide to the contents of the remainder of this report.

Interpretation of key terms

We started the overall evidence synthesis by making the initial scoping, planning and mapping stage as wide as possible in an attempt to maximise our chances of capturing any coherent bodies of empirical evidence relating to the question or to any mechanisms that might be relevant. This wide scope also included our initial interpretations of the terms ‘research engagement’, ‘engagement in research’, ‘performance’ and ‘mechanisms’ that had been used in the ITT.

‘Research engagement’ and ‘engagement in research’

In line with discussions about reforms to health research systems which illustrated the Government's desire to involve the health-care system in research,5 we initially interpreted the term ‘research engagement’ broadly. We also recognised the need to look for both positive and negative impacts of research engagement.

Driving this ITT was a concern to improve understanding of the impact on health-care performance of engagement in research. With this in mind, we took ‘engagement in research’ to mean a deliberate set of intellectual and practical activities undertaken by health-care staff and organisations. These include the following:

-

Health-care staff (as individual clinicians and as teams):

-

being involved in actively undertaking research studies

-

playing an active role within the whole research cycle, including research design and commissioning

-

undertaking research training for a research degree

-

playing an active role in research networks, partnerships or collaborations.

-

-

Health-care services and organisations:

-

supporting health-care staff in the activities outlined in (a) above

-

playing an active role in research networks, partnerships or collaborations, either internally (within the particular service or organisation) or externally (with other organisations and researchers).

-

The ITT explicitly and prominently highlighted the literature on engagement in medical leadership as being a different but related domain to that of research engagement, implying, we assumed, that it might potentially make an important contribution to the requested evidence synthesis. Our interpretation of ‘engagement in research’ as an active process undertaken by health-care staff ties in with the literature on medical/workforce engagement and impact on performance. 6–9 For example, Bakker8 defines work engagement as a ‘positive, fulfilling, work-related state of mind that is characterised by vigour, dedication, and absorption’ (p. 51).

In a recent paper relating medical engagement to organisational performance, Spurgeon et al. 9 talk about ‘the active and positive contribution of doctors within their normal working roles to maintaining and enhancing the performance of the organisation which itself recognises this commitment in supporting and encouraging high quality care’ (p. 115) (our italics). Thus, health-care services and organisations also have an active role to play. The relation between workforce engagement and performance is dependent on a symbiosis between organisations and those who work within them. 10,11 This organisational support and encouragement is a two-way process involving organisations working to engage employees and the latter having a degree of choice as to their response. 12,13

Although such insights were helpful, the literature on medical/workplace engagement did not, as we initially hoped, prove a fruitful source of empirical findings on our own narrower question. There were two main reasons. First, ‘engagement’ is a complex term that means different things to different people. It is variously interpreted in the literature and there is no universal definition:13 this can impede the identification and interpretation of empirical findings. Thus, while many authorities advocate physician engagement as the key to organisational performance,14 a common theme in papers discussing this issue is that there is limited empirical evidence about the positive impact of enhanced medical engagement on organisational performance,7,9,15 although it has been demonstrated that lack of engagement presents significant problems in the organisational pursuit of change and improvement. 7 Spurgeon et al. 9 summarise the current position, describing ‘engagement’ as a multifaceted construct whose complexity has probably contributed to the lack of clarity in understanding the links between levels of engagement and performance. This study did find a correlation between medical engagement and service improvement.

Second, the literature on medical/workplace engagement takes little heed of research activity as a factor in improving performance, and the ability to ‘engage in research’ (however defined) is not seen as one of the core competencies in medical professionalism. Thus, it is claimed that there ‘is increasing acknowledgement by the medical profession that doctors need to be competent managers and leaders at all stages of their careers’ (p. 3) (our italics) but engagement in research as a possible part of those careers is not mentioned in this paper. 7 In fact, research is only mentioned once – the authors discuss the skills required to enable doctors to function efficiently and effectively within complex systems and quote Tooke's16 view that ‘the doctor's role as diagnostician and the handler of clinical uncertainty and ambiguity requires a profound educational base in science and evidence-based practice (EBP) as well as research awareness’ (p. 17). Tooke's16 insight is confirmed by others. In a broad ranging discussion of the changing nature of medical professionalism in the context of practice innovation, Mechanic17 talks about ‘practicing in an evidence-based way that acknowledges and takes account of current medical research and understanding’ (p. 329). However, there is no discussion in these key papers (or to our knowledge in the medical engagement literature more generally) of what this research awareness is or should be, of how it is to be achieved and maintained, or how it might (in the context of medical engagement more generally) be a factor that contributes to improved performance.

In this context we note that the terms ‘engagement in research’ and ‘engagement with research’ are sometimes used interchangeably in the literature. Given this, it seemed relevant at the start of our review to explore how far a broader definition of research engagement could also include engagement with research, taking this term to mean a less substantial involvement at individual and team level related more to receiving and transmitting the findings of research. It could therefore include aspects of activities such as continuing medical education (CME) and knowledge mobilisation, which often focus on encouraging research utilisation alone, and not on research utilisation as an integral phase in the whole research cycle. This is an important distinction between ‘engagement with research’ and ‘engagement in research’, and since our brief was to explore the whole pathway from research engagement to performance we finally decided to concentrate our resources primarily on the interpretation of research engagement as ‘engagement in research’ in the sense given above.

‘Performance’

In health care, the case for the universal measurement of clinical and organisational performance is well established,18 but the specific nature of performance measurement is a contested topic and there is no neat prescription for the design of performance measurement systems in the NHS, or more generally. 19 A wide range of measures has been used: ‘there exists, for any organisation, a range of possible measures. This is true especially of health care, with measures of clinical process, health outcomes, access, efficiency, productivity and employee variables all offering some potential’ (p. 107). 20

Complicating the picture further, Mannion et al. 21 suggest that different channels of communication may convey different performance information.

A variety of systems to assess aspects of NHS performance have been used in recent years – including the star rating system for NHS trusts, clinical governance reviews, National Service Framework reviews, national and local audits, performance monitoring by strategic health authorities, and Quality Accounts. 21,22

Reflecting the origins of performance measurement in industry, much of the literature on health-care performance initially focused on health-care organisations and on their use of measures of activity and cost. 23 Over time health-care organisations' need to demonstrate clinical quality as well as efficiency24,25 led to the development of measures of clinical output and outcome and a move to a balanced scorecard approach. 23 Within the context of the 2008 Darzi review,26 and subsequent Government White Papers,2 in the NHS in England this emphasis on the measurement of the quality of care delivered has continued. The development of clinical audit has also focused attention on the measurement of clinical performance against measures of clinical process and health outcome. In some clinical fields in the NHS in England, clinical audit is now mandatory and the participation of health-care organisations in these clinical audits is monitored through the Quality Accounts that NHS health-care providers are required to produce annually. Despite all these changes there has, until the relatively late arrival in 2010 of the Quality Accounts, been a marked absence of indicators relating to research activity or engagement in research in NHS trusts. If Pettigrew et al. 27 are right in their contention that performance measurement systems are an important determinant of organisational performance in their own right [‘you get what you measure’ (p. 8)], then this earlier failure to develop research indicators suggests that although medical research has generally been seen as a good thing, it took a shift to a quality agenda for research activity and research engagement in trusts to be seen as potential drivers of improved organisational performance.

Given all this, we decided that exploring improvements in health-care performance at all levels across all possible measures in a focused review would have been a very large and perhaps impossible task. Reflecting the quality agenda, we therefore decided to concentrate our focused review on papers that discussed improvements in clinical processes and outcomes.

‘Mechanisms’

In a broad sense ‘mechanisms’ have been defined as ‘underlying entities, processes, or [social] structures which operate in particular contexts to generate outcomes of interest’ (p. 368). 28 However, in this review we took a simpler interpretation related to our notion of engagement in research as a set of activities, and defined ‘mechanisms’ as levers that instigate or sustain a relationship between those activities and improved health-care performance.

Scope of the review

In an attempt to identify the nature of whatever evidence might already have been collated, we initially explored and mapped a wide range of bodies of knowledge. These are listed in Chapter 3. However, it became clear that no single, readily identifiable area of knowledge would comprehensively address the review question. The lack of direct evidence about research engagement in these bodies of knowledge indicated that, in any overall assessment of how health-care performance might be improved, many other factors are analysed ahead of research engagement. It also suggested that our search for evidence about the impact of research engagement would be complex. Furthermore, within the many bodies of research that explore the diffusion of innovations and were reviewed by Greenhalgh et al. ,29,30 not only does research engagement appear to play a limited direct role in the explanations discussed, but also there is a great variability of circumstances in which innovations can be adopted. We assumed that there was likely to be a similar variability in the mechanisms through which research engagement might improve health-care performance, and in the circumstances in which those mechanisms would succeed.

In the next chapter, we highlight findings from a number of existing reviews of varying degrees of relevance to our evidence synthesis. Of these, one review impacted directly on the structure and scope of our evidence synthesis. This was a systematic review by Clarke and Loudon published in 201131 (i.e. after proposals for our project had been submitted). It focused on the narrower topic of the effect on patients of their health-care practitioner's or institution's participation in clinical trials. It concluded that there might be a ‘trial effect’ of better outcomes, greater adherence to guidelines and more use of evidence but, crucially, went on to state ‘the consequences for patient health are uncertain and the most robust conclusion may be that there is no apparent evidence that patients treated by practitioners or in institutions that take part in trials do worse than those treated elsewhere’ (p. 1).

Given this uncertainty about whether or not research engagement improves performance, we decided first to address this question in a focused review before moving on to questions about the mechanisms through which such changes might come about. It was also apparent that it would be impossible to conduct comprehensive systematic database searches in all the bodies of knowledge we had covered in our original scoping and mapping exercise. Therefore, although we wanted a broader coverage than Clarke and Loudon,31 we decided to concentrate on the central question of whether or not research engagement (tightly defined to cover engagement in research rather than the broader engagement with research) led to measurable improvement in actual health-care processes and outcomes. The second half of this definition (‘measurable improvement in health-care processes and outcomes’) was also tightly defined. It excluded studies that considered whether or not research engagement led merely to steps along the path to improved performance (such as increased research utilisation, changes in attitudes towards research, or gains in efficiency), but did not go on to consider if these led to improvements in the quality of care.

After the initial mapping phase we also decided the scope of our review was already too wide to include the slightly separate but equally important topic of whether or not engaging the public and patients as partners in research improved health-care performance. 32 We recognise the importance of this issue, and also that there are ways in which patients can engage with research and then press their clinicians to provide what might be seen as research-informed treatments. Nevertheless, the steer in the original brief was to focus on health-care professionals and organisations. We also noted that the topic of patient involvement in health research was being covered by a separate review by Evans et al. , also commissioned by the NIHR SDO programme: Public involvement in research: assessing impact through a realist evaluation.

Considerable benefits from health research have been demonstrated using various approaches, including the Payback Framework. 33–36 We assumed, however, that we should interpret our research question to focus on whether or not any identified improvements in the performance of clinicians or health-care organisations had resulted in some way from the processes of their being engaged in research, whether or not that improvement occurred concurrently with the conduct of research or subsequently. In our search for papers it proved challenging to establish the precise inclusion criteria to enable us to focus on this interpretation, and we return to this issue at several points in this report. Nevertheless, our analysis of the papers from the focused review provided an answer to the question of whether research engagement improves performance.

Finally, in order to address the question of the mechanisms that might cause research engagement to lead to improved health care, we recognised that it would be important to draw on a wider range of papers than just those that met the inclusion criteria for the focused review. We therefore decided to supplement the focused review with a wider but more informal review of a more extensive range of papers. In the searches for the focused review we identified many papers, but finally included in that review only those that met our inclusion criteria (i.e. included empirical data and covered in a single paper the whole pathway from research engagement to improved health-care performance; see Chapter 3, Methods for more details). The starting point for the wider review was all the papers that reached the full-paper review step of the focused review, plus some additional papers that we had identified in the mapping exercises. Using criteria, again set out in Chapter 3, we identified a broad range of papers, and in particular included those that provided important descriptive or theoretical accounts, and/or provided evidence about progress along some of the steps between research engagement and anticipated improvement in health-care performance, and/or supported (or challenged) the findings from the focused review about whether or not engagement in research improves health-care performance. We drew on the papers from the wider review to supplement those from the focused review to enable us to conduct a fuller analysis of causation in the links between research engagement and performance by exploring evidence about potential mechanisms and about the theories underpinning their development and adoption.

A road map of the report

We have attempted to write this report as a coherent whole, but inevitably in addressing the complexity of the subject matter we have followed various theoretical and empirical pathways. Therefore, in Box 1 we provide a brief summary of what is covered in each of the remaining chapters.

Chapter 1 sets out the background to the review including our interpretation of the research question and of various key terms (research engagement, performance, and mechanisms), and the scope of the review

Chapter 2 describes the existing theories, reviews and analyses on which our review draws and uses them to develop a matrix to help us analyse the variety of mechanisms through which research engagement might improve health-care performance. Inevitably the relationship between the theories and the subsequent methods and data collection was iterative and so the matrix reported here is the final version after revisions during the review

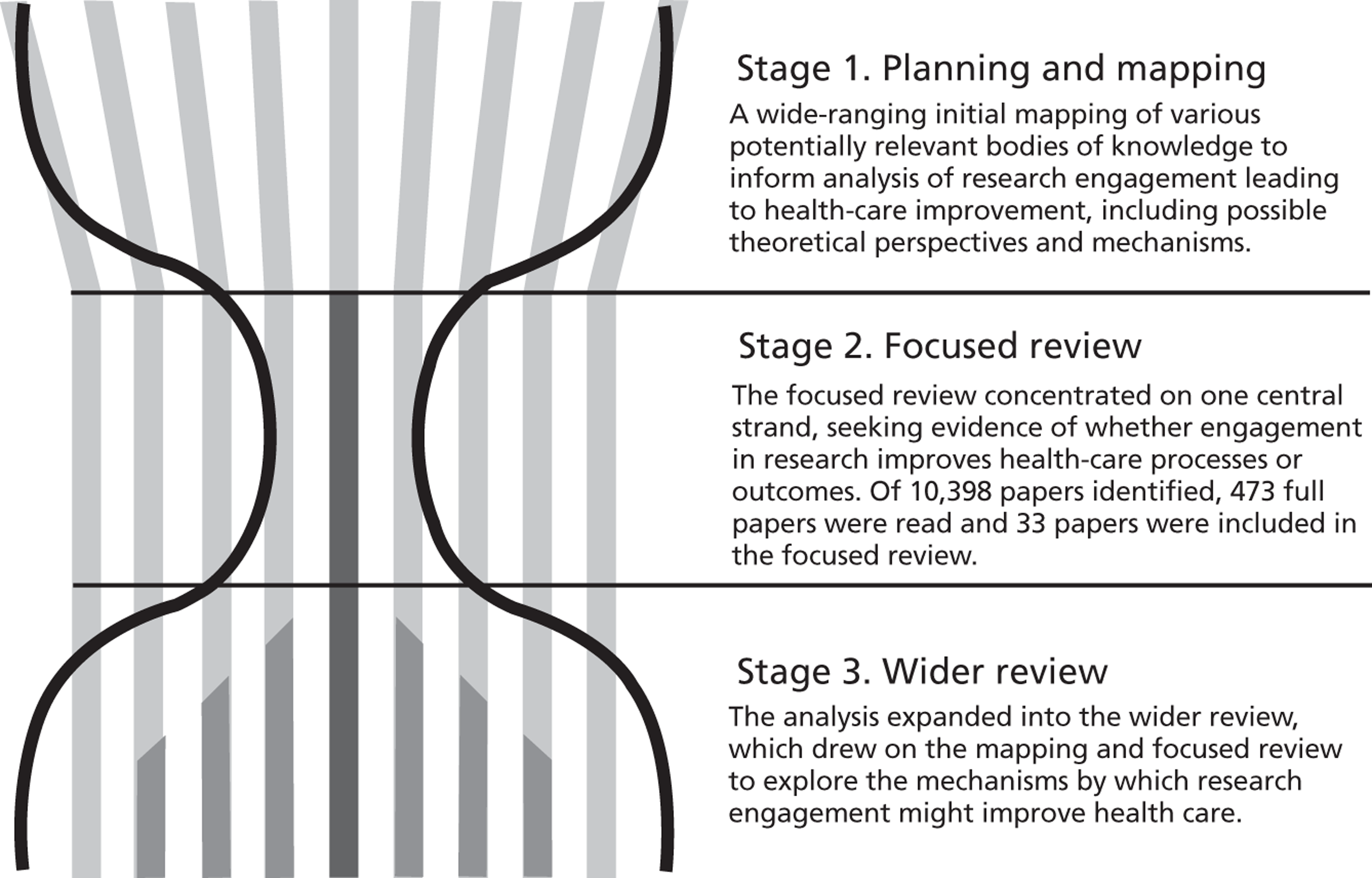

Chapter 3 describes the methods used in what we have christened an ‘hourglass’ review that consists of three main stages: Stage 1: Planning and mapping; Stage 2: The focused review; and Stage 3: Wider review and report

Chapter 4 presents the findings from the focused review on the question of whether or not research engagement improves health-care performance

Chapter 5 analyses the relationships between research engagement and performance by drawing on empirical and theoretical evidence, including evidence on potential mechanisms, from both the focused review and the wider review

Chapter 6 draws on both the focused review and, especially, the wider review to analyse how organisational support for research engagement from health-care organisations can improve performance

Chapter 7 presents our discussion and conclusions, including implications for practice and recommendations for research

Chapter 2 Key theories, reviews and analyses – developing an analytic matrix

Key theoretical positions that informed the review

As noted, the ITT for this review requested a ‘theoretically and empirically grounded assessment’. Therefore, our initial planning and mapping exercise explored several major theoretical approaches that could, potentially, contribute to informing the conduct of the review and to building a framework within which to analyse the mechanisms through which engagement in research can improve performance. Here we are describing existing theories and reviews that count as part of the background to the project. The process by which we selected those existing theories and reviews, described below, and drew on them to help build the matrix, inevitably involved iteration and was informed by the Stage 1 planning and mapping exercise. Initially in the mapping stage we were as inclusive as possible. However, what drove the selection of these specific included theories was the decision (described in Chapter 1) to concentrate on research engagement as ‘engagement in research’ and not go for a wider version that would also have included ‘engagement with research’.

Research engagement as a way of increasing ability and willingness to use research: the theory of absorptive capacity, and theories about the characteristics of research adopters

Absorptive capacity

The concept of ‘absorptive capacity’ as described by Cohen and Levinthal in the context of industrial research37,38 (see also Rosenberg39) suggests that conducting research and development (R&D) within a firm helps that firm to develop and maintain its broader capabilities to assimilate and exploit externally available information from research. Further, they claim that ‘absorptive capacity may be created as a byproduct of a firm's R&D investment’ (p. 129). 38 Subsequent authors also used the concept in the analysis of industrial development, noting, for example, that ‘Japanese firms, which were importing many technologies from Europe and North America, were exceptionally good at the improvement of both processes and products but they were only able to do this because of their own strengths in R&D’ (p. 120). 40

The original theory could apply at different levels, including individual and organisational levels. Various authors developed the concept further in relation to organisations. In particular, Zahra and George41 broadened understanding of this concept beyond the original view that an organisation's engagement in research is the key issue. In 2006 Lane et al. 42 reviewed the use of the concept of absorptive capacity in the many subsequent articles claiming to be drawing on it. Lane et al. 42 suggest that much of the later writing has followed the approach of Zahra and George. 41 This has also occurred in the health field where, for example, a study exploring the capacities of health-care organisations to absorb research defined absorptive capacity in terms of environmental scanning, collection of satisfaction data, and the level of workforce professionalism. 43 The result is that the simpler interpretation of absorptive capacity being a by-product of research is sometimes overlooked.

Nevertheless, and returning to the original by-product concept, it can still be argued that when clinicians and managers in a health-care system are seen as stakeholders in the research system then their engagement in research can be a way of boosting their ability and willingness to use research from wherever it might originate. For example, drawing on parallels from the literature on industrial research, Buxton and Hanney44–47 include this increased capacity to use research as one of the benefits identified in their multidimensional categorisation of benefits from health research, and this approach is replicated in other health research impact assessment frameworks that build on the Payback Framework,48,49 and when the development of health research systems in low- and middle-income countries is being considered. 50 Part of the theoretical underpinning behind the idea that research engagement contributes to building absorptive capacity is the notion that, in practice at least, knowledge is not a pure public good but instead requires a level of understanding of research before it can be absorbed. 51 Such understanding can be built up by undertaking research.

Characteristics of research adopters

Rogers52 identifies 26 ways in which those who are early adopters of innovations differ from those who are later adopters of research, but being engaged in research is not included. Greenhalgh et al. ,30 adapting earlier work,53 list the personal characteristics of those who adopt innovations. Personal values are included in the list, and Greenhalgh et al. cite the work of one study54 that suggests actors adopting medical innovations include those motivated by values, for example ‘“academic” doctors feel the need to align with evidence from research trials’ (p. 111). 30

The above discussion relates to the absorption and/or adoption of research findings by a wider group of people than those who originally undertook the research. It is, however, relevant to consider if aspects of these theories also relate to those who produce specific research findings, and might then be in a position to adopt them in their regular practice. Both Rogers52 and Greenhalgh et al. 30 draw on the work of Ryan and Gross55 to set out a model of the stages in the process of adoption, and the first stage is knowledge (i.e. awareness of the innovation). However, although participating in research evaluating a specific innovation is a highly effective way of accessing knowledge about it, and this increased knowledge can be seen as a by-product of that participation, this point is not specifically made in the model (and clearly not everyone whom it is hoped will adopt an innovation could be involved in a trial).

The co-ordination of research engagement to enhance its effectiveness: a role of research networks

Research networks are increasingly important in several countries, including the USA and the UK. In the USA, practice-based research networks (PBRNs) have been in existence for several decades. They not only provide a means for community practitioners to become involved in research, but can also facilitate the ‘downstream’ dissemination and implementation of research results into community-based clinical practice by:

. . . enhancing providers' acceptance of research results and strengthening their commitment to acting on research findings. This level of participation also often encourages practice organizational changes that facilitate the research and allows participants access to more or earlier information compared with others who did not participate in the research.

p. 444156

As they mature, it becomes clear that research networks can have more than one goal. Some have evolved from structures whose primary purpose is to involve clinicians and health-care organisations in clinical trials to become structures that also aim to spread information about research and research findings. In addition, research networks can encourage members to identify research needs in order to make the research undertaken more relevant,11 and to this extent they use the collaborative approach described below.

In the UK, clinical research networks are a central pillar in the development of the English NIHR. 57 The objectives of the Clinical Research Network Coordinating Centre58 are more restrictive than those described above for the research networks in the USA and focus on aspects such as increasing the efficiency of clinical research processes and increasing the number of NHS trusts that are involved in clinical research. This might suggest that any improvements in health care that result from the research engagement would be far from the main purpose of the network, but in fact such impacts were identified as possible outcomes. The Cancer Research Network led the way because it was hypothesised that:

. . . if more patients could have access to late phase clinical trials, not only would their outcomes improve as they gained access to novel therapies, but the inculcation of a research culture across all hospitals delivering cancer care would also lead to a general improvement in the standard of care.

p. vii2959

This claim does suggest some theorising about how these networks are a mechanism through which such impacts might arise. It is also compatible with statements about the PBRNs in the USA. As such it is of interest not only to know what research networks can achieve, but also how they do so.

There are some overlaps between the thinking in the ‘stages of innovation’ model promoted by Rogers,52 and the basic role of research networks. The first step of the ‘stages of innovation’ model is that those adopting an innovation have to have knowledge about it, and then be persuaded to believe they should use it. We suggest that the knowledge and trust about an innovation that comes from being involved in research helps explain the adoption process. Rogers52 also argues that trialability and observability are important characteristics of innovations that are adopted. Although this might appear to be the same as having knowledge about an innovation, Rogers52 was here talking about characteristics of the innovation rather than the adopter. However, we believe this concept could be adapted to help explain how an increase in the number of clinicians undertaking research (perhaps through research networks) might increase adoption of evidence-based approaches. Thus, and to use and perhaps reinterpret terms used by Rogers52 when describing the characteristics of innovations, research networks can promote ‘trialability’ (here defined as giving clinical staff and health-care organisations the opportunity to gain experience of an innovation on a limited basis in the context of a clinical trial) and ‘observability’ (here defined as giving clinical staff and health-care organisations the opportunity to observe the impact of innovations in other parts of the network).

Research engagement as a way of ensuring the research produced has more likelihood of being used to improve the health-care system: theories of collaboration and of action research

Under this heading we examine several partially overlapping theories that focus on ways of engaging potential users from the health-care system in aspects of research processes with the aim of improving the relevance of research to users, and increasing the likelihood of research being used.

Collaborative research

In 2003 Denis and Lomas60 traced the development of a collaborative approach to research in which researchers and potential users work together to identify research agendas, commission research, and so on. They identified the 1983 study by Kogan and Henkel61 of the R&D system of the health department in England as a key early contribution. According to Kogan and Henkel61 a critical feature of the collaborative approach, as applied to research on policy-making, is that researchers and policy-makers should join forces ‘to identify research needs against policy relevance and feasibility’ (p. 143). They developed their theories about the collaborative approach not only from their own extensive 7-year formative evaluation of developments in the health department's R&D division, but also from models of social research impact developed by Carol Weiss,62 including an interactive model which they claimed reinforced the notions that the boundaries between science and society are permeable.

Work to analyse and operationalise this collaborative approach has been undertaken in the Canadian Health Services Research Foundation (CHSRF), led by Jonathan Lomas. 63,64 His concept of ‘linkage and exchange’ between users and researchers has been particularly influential. The belief that collaborative research is more likely to be relevant to potential users is a key concept. Collaborative approaches to research somewhat mirror the concept of ‘Mode 2’ research (i.e. research that is context-driven, problem-focused and interdisciplinary). 65,66 The applicability of ‘Mode 2’ concepts to health research was analysed by Ferlie and Wood. 67

One early and successful example of developing and promoting collaborations between researchers and health-care staff to maximise engagement in research, and encourage wider use of the findings of research, was the post-war childhood leukaemia trials in the UK (and the USA). However, as Moscucci et al. 68 demonstrate, this success was very dependent on the context in which this collaboration developed at the time. But, in addition to being applied in one-off situations, there are now efforts to go further than the institutional developments described by Kogan and Henkel61 and build long-term collaborative approaches that, it is hypothesised, will lead to research that is more likely to meet needs of a health-care system, and hence be used and improve performance. (Some of these are described in Chapter 6. )

Greenhalgh et al. 30 also build aspects of the collaborative approach into their model for considering the determinants of diffusion of innovations in the organisation and delivery of health services. Again drawing on the work of Rogers,69 they suggest that successful adoption of an innovation is more likely if developers or their agents are linked with potential users at the development stage in order to capture and incorporate the user perspective.

The collaborative approach is generally more interventionist than the absorptive capacity concept, but sometimes they can be brought together. In current initiatives and writings about the health research system there is often overlapping emphasis: first, on collaborative working with users of research so as to produce applied research that is more likely to be adopted by potential users because of its relevance to them; and second, on engaging users in the wider research enterprise in a variety of ways and through various networks to encourage the uptake of research findings more generally. This second approach can be interpreted as an attempt to build absorptive capacity. In 2008 Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRCs) were introduced by the English NIHR to boost the effectiveness and translation of health research, and the following definition of CLAHRCs70 highlights their complex remit:

The collaborations have three key interlinked functions: conducting high quality applied health research; implementing the findings from this and other research in clinical practice; and increasing the capacity of local NHS organisations to engage with and apply research.

p. 10870

Initiatives such as the CLAHRCs also illustrate how collaboration can work at various levels, with one aim of collaboration at an organisational level being to help foster collaboration at other levels within the participating bodies. (We discuss this further in Chapter 6. )

Action research

The notion that research users should be closely involved in research activity in order to produce research that meets their needs also overlaps with theories underpinning action research, or participatory action research (PAR). The action research model was first conceptualised by Lewin71 and has been described and developed in much subsequent writing. It consists of a spiral of cycles of action and research, with four phases: planning, acting, observing and reflecting. The aim is to enable investigators to link theory with practice using a participatory and consensual approach towards investigating problems and developing plans to deal with them.

A realist review published in 2012 by Jagosh et al. 72 looks at the benefits of participatory research and examines the coconstruction of research through partnerships between researchers and people affected by and/or responsible for action on the issues under study. Building on the work of Lasker et al. ,73 they adopted the theory of ‘partnership synergy’ to hypothesise that equitable partnerships with stakeholders' participation throughout the project succeed largely through synergy.

Research engagement at an organisational level to improve the performance of the health-care organisation

Given the wide scope of our original brief and the diversity of the fields of study involved, our decision to focus on engagement in research rather than also include engagement with research was necessary to give our review sufficient focus. However, there are limitations to this approach. One of these is that it cuts across some of the major theoretical approaches that underpin efforts to improve organisational performance in health care, such as promoting learning organisations, adopting an organisational approach to quality improvement (QI), and knowledge mobilisation. However, we found that in all these fields, research-related discussion tends to be largely about research utilisation, EBP and translation gaps: research engagement as a term is rarely used, and further refinements of that term not considered.

These issues are illustrated in a recent review of knowledge mobilisation and research utilisation by Crilly et al. 74 They note that there is a well-established literature on the utilisation of clinical evidence in health care, but that there has been less consideration of the utilisation of management evidence and research by health-care organisations. Their review aimed to redress this imbalance and paid particular attention to the management literature, identifying 10 large domains or thematic categories in that literature. Their subsequent search of the health and social science literature identified two further domains: the evidence-based movement and ‘super structures’ – defined as ‘the infrastructure of institutions and funding that commission health-care research’ (p. 45). However, it was only in relation to this last domain that this large review found any literature in which research and engagement were considered together as a means to promote change. In a discussion of the various ‘structures’ developed by the English health R&D system to boost the translation of research, Crilly et al. 74 quoted the Department of Health's High Level Group on Clinical Effectiveness recommendation about increasing the effectiveness of clinical care through promoting the development of new models to encourage relevant research, engagement and population focus and embed a critical culture that is more receptive to change. 75

Crilly et al. 74 also made a further and more general point. They noted that although learning processes and their relationship with organisational design emerged as an important theme in their review, the whole question of organisational form had received little attention in health-care literature, despite major reorganisations designed to promote bench to bedside research translation and organisational learning. We were therefore especially interested in our own review to identify health-care organisations that have given particular attention to engagement in research in their overall approach to improved performance, and explore the theoretical underpinnings of those approaches.

We found several examples, many of them from the USA. Thus, the Veterans Health Administration (VHA) in the USA included various aspects of research engagement as part of a comprehensive re-engineering exercise designed to improve the quality of health care provided. 76 According to a former Undersecretary for Health at the United States Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), the fact that VA investigators are nested in a fully integrated health-care delivery system with a stable patient population that has an exceptionally high prevalence of chronic conditions provides them ‘with unparalleled opportunities to translate research questions into studies and research findings into clinical action’ (p. I–9). 77 One high profile way in which this integration has been achieved is through the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) programme, which was launched in 1998 to accelerate the implementation of new research findings into clinical care by creating a bridge between those performing research and those responsible for health systems operations. In a recent evaluation of QUERI, Graham and Tetroe78 highlight how this comprehensive approach has successfully incorporated some of the theoretical approaches described above, referring to a ‘paradigm shift to an action-oriented approach that meaningfully engages clinicians, managers, patients/clients, and researchers in research-driven initiatives to improve quality’ (p. 1). This shift, they claim, is towards coproduction of knowledge or ‘Mode 2’ knowledge production.

In QUERI, and in other complex initiatives such as the CLAHRCs in the UK (the ‘community wide academic health centres’ referred to above), various theoretical approaches overlap, and detailed evaluations of such initiatives provide useful pointers to the different mechanisms through which research engagement might lead to improved health care. (We return to these issues in Chapter 6. )

Previous reviews and analyses

The findings from a range of previous reviews are relevant to our evidence synthesis to varying degrees and shaped our thinking about its scope. As we discuss these previous reviews below, we attempt to assess their relevance to our own review, but even the most relevant were not included in our focused review because of the danger of double counting.

Practitioner or institution participation in clinical trials

The systematic review by Clarke and Loudon published in 201131 has already been mentioned and is important for several reasons. First, its findings can be interpreted as highlighting the need for a further focused review to update, and if possible expand, the search in an attempt to identify if there is sufficient evidence to come to a somewhat firmer conclusion about whether or not research engagement is likely to improve health-care performance. Second, it addresses the boundary between studies on practitioner or institutional participation and those exploring whether or not patients who are involved in trials achieve better health outcomes.

Patient involvement in trials

Previous reviews, noticeably by Vist et al. ,79 indicate that, on average, ‘the outcomes of patients participating and not participating in RCTs were similar, suggesting that participation in RCTs, independent of the effects of the clinical interventions being compared, is likely to be comparable’ (p. 2). However, an earlier review by Stiller80 concluded that: ‘referral to a specialist centre or to a hospital treating many patients with the disease, or inclusion in a clinical trial, is often linked with a higher survival rate for the cancers which have been studied’; and he went on to suggest that there was ‘no evidence that centralised referral or treatment according to protocols leads to lower survival rates’ (p. 360).

These reviews are of particular importance to our evidence synthesis because they provide a complex, but partial, mirror image to the evidence about whether or not research engagement by clinicians and organisations leads to improved health care. Their unit of analysis is patients, whereas the reviews by Clarke and Loudon,31 and by ourselves, examine the care provided by clinicians and by institutions. However, there are potential overlaps, for example, Vist et al. 79 claim that the differences in care that were identified in some studies ‘might be due to differences in adherence to a protocol by participating clinicians’ (p. 4). This is another reason why we had to be very careful in devising the inclusion criteria for our study.

Health outcomes in teaching hospitals

There is a growing literature on whether or not the patients treated in a teaching hospital have better health-care outcomes than those treated in non-teaching hospitals. If this was shown to be the case, then it could potentially be important evidence about whether or not research engagement leads to improved performance. Although most research-intensive hospitals are likely to be teaching hospitals, teaching hospitals are not necessarily research-intensive. This makes it difficult to interpret the findings. Furthermore, the largest systematic review we found81 – of 132 PubMed studies – identified a great deal of variability in the results between the studies but that overall no link could be confirmed. Also, although some papers did find a positive relationship, many warned about the difficulty of coming to any clear conclusions about this correlation given the large number of confounding factors. 82,83

Medical academics

The idea of medical academics being motivated to engage in research to improve the health care of their own patients is a powerful one. This most often takes the form of clinicians leading or participating in traditional clinical trials. In some instances, however, clinicians set out to conduct research not to test the general efficacy of one therapy compared with an alternative approach, but rather to identify the best treatment for an individual patient through multiple crossover studies conducted in single individuals. A review of such N-of-1 trials84 concluded that they ‘are a useful tool for enhancing therapeutic precision in a range of conditions and should be conducted more often’ (p. 761). Despite this conclusion, such trials are resource-intensive and unlikely to occur in more than a small minority of cases.

Collaborative approaches

The reviews of Clarke and Loudon31 and of Vist et al. 79 focus on trials of new therapies, and do not include papers describing specific interventions such as collaborative approaches. Among the reviews that have explored these approaches, Lavis et al. 85 concluded that, taking study design, study quality and consistency of findings into consideration, the most rigorous statement they could make about factors that encourage the use of research by health managers and policymakers was that ‘interactions between researchers and health care policy-makers increased the prospects for research use by policy-makers’ (p. 39). This finding came, however, from a relatively small number of papers, and it is not clear how far the interactions were collaborative prior to and during the research activity and would, therefore, meet our inclusion criteria for engagement in research. Focusing specifically on health policy-making, Innvær et al. 86 reviewed the literature on factors that led to research utilisation and showed that personal contact between researchers and policy-makers was the factor most often identified. Again, it is not clear how far this represents policy-maker engagement in agenda setting and the processes of research, or how far it is restricted to dissemination activities and is therefore engagement with, but not in, research.

Action research and participatory action research

Through action research health-care professionals (often nurses or therapists) work with researchers to explore locally identified problems. Given the nature of the process, it is not easy to maintain the distinction between these forms of research and direct implementation/improvement initiatives. Several reviews have examined action research but have found that the impacts on patient care and health outcomes are often not covered. For example, Soh et al. 87 reviewed action research studies in intensive care settings but of the 21 studies included only one described improved health-care outcomes. 88 Munn-Giddings et al. 89 reviewed studies of action research in nursing published between 2000 and 2005. Munn-Giddings et al. 89 identified 62 studies, but ‘Only 13% could be defined as having their focus on a direct impact on patient care’ (p. 474).

Assessing research impact

A systematic review of previous attempts to assess research impact found comparatively few comprehensive categorisations of the impacts of health research that attempted to include any analysis of whether or not research engagement led to improved health care as a by-product. 33 The studies that had considered this were mostly limited to a few of the studies that used the Payback Framework in which research engagement leading to benefits as a by-product is one of the explicit categories of impact.

Assessing research utilisation

Some reviews cover the step in the pathway from research engagement to research utilisation. These are often more about engagement with research than engagement in research. For example, there are extensive reviews of knowledge transfer and exchange,90,91 diffusion of innovations,29,30 and research utilisation and knowledge mobilisation. 74 All of them cover aspects of researchers interacting with potential research users, which can in some cases, but not all, overlap with the collaborative approach. Mitton et al. 90 start their review by stating that: ‘Knowledge transfer and exchange (KTE) is an interactive process involving the interchange of knowledge between research users and researcher producers’ (p. 729). Some reviews of research utilisation include consideration of whether or not engagement in research is important in encouraging research utilisation, but the findings are often inconclusive. For example, a review of studies of research utilisation by nurses found that only 13 out of 55 papers examined research participation as a possible factor. 92 Although these studies described various forms of research involvement and a total of 13 individual characteristics were identified, each one of these characteristics (including the one most related to our concept of engagement in research) was assessed in fewer than four studies. This, the authors claimed, prevented them ‘from drawing conclusions on the relationships between individual characteristics typical of involvement in research activities and nurses' use of research findings in practice’ (p. 12).

Additional analyses published in 2011

The final body of work we cover in the ‘background’ is a supplement to the Annals of Oncology that was published in late 2011 during the course of our own review. This supplement built on the work of a 2009 workshop addressing the question of ‘The impact of the process of clinical research on health service outcomes’. 93 In the introduction, Selby93 notes that the Vist et al. review79 (cited above) examined a ‘substantial literature’ evaluating the benefits for individual patients of trial participation, but that there was a lack of convincing evidence. Of more relevance to our own review is the conclusion of the workshop that there is an even less extensive literature on the impact of research activity on the quality of health-care outcomes within research-active institutions and health-care systems in general and that there ‘is a pressing need for more research in this area’ (p. vii3).

The focus of the papers in this Annals of Oncology supplement varied. In setting out the key question the workshop thought should be addressed in future research, Pater et al. 94 claim that their question:

. . . has been deliberately phrased to indicate our concern with benefits that occur contemporaneously with the research activity. We do not directly address the question of whether institutions that participate in a particular research project are more likely to implement the results once they become known.

p. vii5894

Other papers in the supplement did, however, take a broader perspective and began to analyse some of the factors that might cause research engagement to lead to health-care improvement. 95 (We draw further on this set of papers in later chapters.)

Learning from previous studies and developing a matrix for analysing the potential mechanisms

These various theoretical perspectives and systematic reviews provided an important starting point for our own review. Taken overall they highlighted five key points:

-

There appeared to be no firm answer to the question of whether or not research engagement does improve health-care performance.

-

Research engagement is often subsumed within larger, more complex interventions.

-

Studies often focus on steps along the pathway from research engagement to health-care outcomes and not the whole pathway.

-

There are many studies that might contribute to a synthesis of possible mechanisms by which research engagement might improve health care, but also a large number of disparate activities described.

-

There would be value in developing a matrix to help organise the data analysis, categorise studies and unpick which mechanisms operate in the very different circumstances described by the various papers.

From the above accounts we identified two main dimensions along which to categorise studies that assess whether or not research engagement leads to improved performance. We have called these two dimensions the degree of intentionality and the scope of the impact (Table 1).

| Broader impact (e.g. as a result of their research engagement, health-care staff are more willing/able to use research produced by others to improve health care) | Specific impact (e.g. the findings from studies are used more rapidly and/or extensively by those involved in the research engagement that led to them) | |

|---|---|---|

| Least intentionality – by-product | Research engagement involves participating in research studies, and the absorptive capacity concept could be important in helping explain the ability to adopt research conducted elsewhere | Research engagement involves participating in research studies, and the mechanisms would be associated with knowledge, etc., about the specific research and its conduct |

| Some intentionality – research networks | Research engagement involves network membership which can include regular participation in research studies and, in addition, network communication about the conduct and findings from research studies in the field covered by the network | Research engagement involves network membership which can include regular participation in research studies and network communication about the conduct of those specific trials |

| Greatest intentionality – interventions | Research engagement here might include programmes to give clinicians/managers/policy-makers some experience of identifying research needs and participating in research. As a result they might then be more willing/able to use research from wherever it comes | Research engagement here can involve collaborative research, QI research initiatives, participatory and action research, and aspects of organisational initiatives. As a result the specific research produced is more relevant to the needs of those involved and they are more likely to use it |

The first dimension involves the degree of intentionality in the link between research engagement and health-care performance. Inevitably there are overlaps, but three main categories could be identified and viewed as forming a spectrum:

-

The end of this spectrum involving least intentionality includes the improved health-care performance resulting from engagement in research that can be categorised (to adapt Cohen and Levinthal's term37,38) as a by-product of a trial or other research which has been conducted to test a specific therapy or approach. This does not of course mean the improvement happens by accident, but rather that the production of these by-product benefits was not the primary aim of the research study in which the clinicians were engaged.

-

Research networks can broadly be seen as somewhere near the middle of this spectrum. They exist primarily to promote the conduct of research on specific therapies in a particular field, but often have additional wider remits of informing network members about the conduct of, and findings from, research in a field more generally, and addressing the identified research needs of network members.

-

The other end of the spectrum involves greatest intentionality: here there are various interventions such as the collaborative approach, participatory and action research, and organisational approaches where the intention is explicitly to produce improved health-care performance as a direct consequence of research engagement.

The second dimension in the proposed matrix is the scope of the impact made by research engagement. Here there are two categories, broader and specific, and the studies of these focus on different issues. Studies included in the ‘broader impact’ category take various forms, including:

-

studies assessing whether or not those clinicians and health-care organisations who engage in research are more likely than those who do not engage in research to apply the findings of research studies conducted elsewhere

-

studies assessing the more general health-care performance of clinicians, teams, and organisations who engage in research, and comparing the performance with those who do not.

The ‘specific impact’ category covers two circumstances:

-

studies assessing whether or not improved health-care performance arises as a result of the subsequent rapid application of the findings from the specific research by those who engaged in the research that produced the findings

-

studies assessing whether or not improvement in health-care performance arises concurrently with the specific research activity (or subsequently) as a result of those conducting the research applying the evidence-based processes/protocols (but not the intervention regimens) associated with the research activity to a broader range of patients than just those participating in that particular research project.

The difficulties of applying the matrix include the fact that some of the papers in our focused review have features that fit into more than one category on a certain dimension. Nevertheless, it is important to attempt to make such categorisations because of the potentially very different mechanisms that may be at work in these different circumstances on the two dimensions.

Chapter 3 Methods

The review involved the three stages set out in Figure 1. This is described as an hourglass review to reflect the scope of the conceptual analysis and the number of papers considered in detail (rather than the sheer volume of titles reviewed) at each stage. The three parts of the review were a broad mapping stage, followed by a focused or formal review on the core issue of whether or not research engagement improves health care, and a final stage which involved an exploration of a wider literature to help identify and describe plausible mechanisms.

FIGURE 1.

The hourglass three-stage review.

We consulted an international expert advisory group and patient representatives at key points in the review process. Given the international nature of the advisory group the consultation was mostly by e-mail. However, we met face-to-face with the patient representatives.

Ethical approval was obtained from Brunel University's Research Ethics Committee.

Stage 1: planning and mapping

We made the initial scoping and planning phase as wide as possible in an attempt to ensure we captured any coherent bodies of empirical evidence relating to the question and any plausible mechanisms. We examined a large number of bodies of knowledge as listed in Box 2.

Twelve bodies of knowledge were explored in the initial mapping stage:

-

the organisation of health research systems and of collaborative approaches to the conduct of health research including linkage and exchange

-

the role of in-house industrial research, including concepts such as absorptive capacity

-

diffusion of innovations/absorptive capacity in health-care systems

-

performance at clinician, team, service and organisational level in health-care organisations, approaches to the measurement of such performance, and overlaps with the concept of medical engagement

-

the role of medical academics in translational research

-

assessing the impacts of research and how the utilisation of research improves health-care performance

-

quality improvement

-

knowledge mobilisation and management, and knowledge transfer

-

organisational processes and learning organisations

-

medical education, continuing professional development, and critical appraisal

-

evidence-based medicine

-

the role of patient engagement in research

For this exercise we drew on our existing knowledge, team meetings and brainstorming sessions, and consultation with the advisory group. We also started with an open mind about the types of research on research that might have addressed our question, following the Institute of Medicine's definition of health services research as a: ‘multidisciplinary field of inquiry, both basic and applied, that examines the use, costs, quality, accessibility, delivery, organization, financing, and outcomes of health care services to increase knowledge and understanding of the structure, processes, and effects of health services for individuals and populations’ (p. 3). 96

Our initial explorations presented us with a dilemma. Discussions with the project's information scientist confirmed that it would be impractical to conduct a focused search of all the bodies of knowledge that might have something relevant to say on the topic. Yet, as far as we could tell, none of them appeared to contain a sufficiently large number of relevant papers to make it sensible to focus explicitly on that area in order to explore the various mechanisms involved.

We therefore decided to extend the initial stage to enable us to map the field as widely as possible so as to inform the later more detailed database search. This mapping phase continued the approaches described above, plus hand-searching of journals, searching of relevant web sites, and searching the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care Cochrane database. The journals on which we conducted a preliminary hand search at this stage specialise in aspects of the relationship between research engagement and improved health-care performance. They included: Journal of Health Services Research & Policy; The Milbank Quarterly; Evidence & Policy; Implementation Science; and Health Research Policy & Systems. Preliminary internet searches were conducted on the following websites: English Department of Health; NIHR; National Institute for Health and Care Excellence; World Health Organization; numerous Canadian health research organisations (including CHSRF); and the University of Birmingham Centre for Health Services Management library.

Papers considered to be particularly relevant for the study were given a designated ‘KEY’ status, and we used snowballing to explore further potentially relevant references cited in these papers.

The findings from this informal but extensive searching were used to develop initial maps of each of the bodies of knowledge from the diverse range listed above, and to inform the search terms used in the next stage – the focused review.

Stage 2: the focused review

The search strategy

The focused, or formal, review concentrated on the specific question of whether or not engagement in research improves health-care performance. We wanted a comprehensive search of as many databases as possible. The search terms we used for the MEDLINE searches are given in Appendix 2. The search terms were similar for the other databases (modified to meet the requirements of each). We were seeking to identify empirical research studies where the concept of ‘involvement in research’ was an input and some measure of ‘performance’ was an output. We included the VHA as a search term because our initial mapping, and expert advice, highlighted the importance of the VHA as a rare example of an organisation that had explicitly attempted to integrate research fully into its operations in order to improve health-care performance. The initial broad interpretation of our terms was tightened as we progressed through the review.

The search strategy covered the period January 1990 to March 2012 as the mapping phase suggested that this was the most fruitful period for addressing the review topic. We used English-language terms, although identified papers not published in English were considered for inclusion, and consideration was given to terms used in other English-speaking countries (e.g. the use of the term ‘community’ in North America can be noticeably different from its use in the UK). We sought papers containing empirical data from a whole range of research approaches, both quantitative and qualitative, in line with our broad interpretation of health services research. Our search was not, therefore, limited to clinical trials. We searched MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), Web of Science, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA), British Nursing Index, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC) and System for Information on Grey Literature in Europe (SIGLE) databases. The search strategy was developed by members of the research team and a senior information scientist from King's College London. These database searches were supplemented with more focused hand-searches of the five journals initially searched in Stage 1 (as listed above), papers suggested by our expert advisors and patient representatives, further searching of several national and international websites (as listed above) and snowballing of papers considered to be key for the discussion. Searches were conducted by an information scientist working closely with the review team.

Steps in the focused review

First step – title review

This step involved examination of the title of each paper, and occasionally the abstract when the title provided too little detail, to quickly exclude documents clearly not relevant to the review. The predominant aim here was to be inclusive, only excluding papers clearly not relevant. Reasons for exclusion at this step were: not health related, not a human study, no mention of research (or related terms), no clinical outcomes or processes. At first papers were reviewed by two reviewers independently, but this was reduced to one reviewer after a short time as the numbers of abstracts to be studied was large and a test indicated that the agreement between the reviewers was considered to be satisfactory.

Second step – abstract review

In the second step of the review, we studied the titles and full abstracts in greater depth to assess the eligibility of each paper that had not been excluded at the title review. A first reviewer conducted this exercise and then passed the paper (and, where appropriate, comments) to a second reviewer. The aim of the first reviewer was to be inclusive: the aim of the second reviewer was to be more selective. Where the two reviewers disagreed they met to discuss the title and abstract. If agreement was still not possible then the paper was taken through to the third step of the review for a study of the full paper, along with the papers where there was agreement on inclusion.

Reasons for exclusion were: not health related, not a human study, no mention of engagement in research (or related terms), no clinical outcomes or processes. Reasons for inclusion were: mention of engagement in research or of research in combination with collaboration, multicentre, organisational, or other related terms, mention of clinical outcomes or processes in the form of empirical data.

Third step – full-paper review

The third step was a further relevance and initial quality check of all the included papers from the second step to determine which papers were suitable to proceed through to the data extraction stage.

Determining the inclusion criteria for this step was complicated because the special relationship between research engagement and improved health care had to be demonstrated in some way in the included papers. So, for example, in relation to clinical research, just because researchers who had been involved in a particular trial were now using the findings of that trial was not, by itself, sufficient. Instead, and as far as possible, we attempted to include only studies that examined in some way whether or not those clinicians/institutions who had been engaged in the research were adopting the findings more rapidly and/or extensively than other clinicians/institutions, i.e. we were looking for some measure of control within the study. For collaborative and action research, slightly different considerations had to come in to play because, by the very nature of the research, it was intended to be most relevant for those engaged in the research.

During the earlier parts of the review we identified some potentially important papers describing activities such as participation in research networks or action research that we considered to be a form of engagement in research and that in some instances seemed to lead to improved health care. Therefore, while we had, as noted, defined research engagement quite tightly to refer to engagement in research, we also wanted to make sure we captured the full range of activities that might come under that term and not restrict ourselves to looking just at clinical trials as Clarke and Loudon31 had explicitly done. Therefore, to add precision to our inclusion criteria, we explicitly set out some of the activities that we believed could be considered to be included under the heading ‘engagement in research’. Our final inclusion criteria are set out in Box 3.

Our final inclusion criteria were:

(a) Includes empirical data

(b) Explicitly includes engagement in research in any way including:

-

agenda setting

-

conducting research

-

action research

-

research networks where the research involvement is noted

OR, implicitly includes engagement in research through membership of a research network and, even though participation in a specific study is not noted, there is a comparison of health care between such settings and other settings (could be the comparison shows a difference or no difference)

BUT NOT

-

solely engagement with research, for example continuing medical education, evidence-based medicine, implementation efforts, critical appraisal, etc.

-

patient engagement in research

(c) Includes assessment of health-care processes/outcomes including, for example, use of clinical guidelines

BUT NOT

-

just research utilisation; or

-

just adoption of research in policy-making, with no follow through into improved health care in organisations or services; or

-

just improvements such as staff satisfaction or morale

We applied broadly similar inclusion principles across all categories of papers, and, where possible, reflected the spread of approaches we saw in the literature by including studies in organisational settings, and collaborative and participatory studies. This meant, for example, seeking to include studies that made some attempt to show that the use of the findings from engagement in collaborative or action research resulted in improvements in health-care performance, and that the clinician/institution behaviour was sustained beyond the period of the intervention. In other words, we attempted to distinguish a sustained impact from a more temporary study effect. Ideally such studies would also show some evidence of differential uptake of findings by the clinicians/institutions involved in the research, as measured against control groups not involved. But we found that this was rarely studied: collaborative or action research is often undertaken in response to the specific needs of the clinicians/institutions engaged in that research, and frequently does not include any control.

All three reviewers agreed on the papers taken through to the final data extraction stage of the review, and a data extraction sheet was completed by one reviewer for each of these papers. A quality check was informed by checklists available as part of the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme or similar, but the diversity of methods used in the papers meant that no one quality appraisal tool could be rigidly applied.

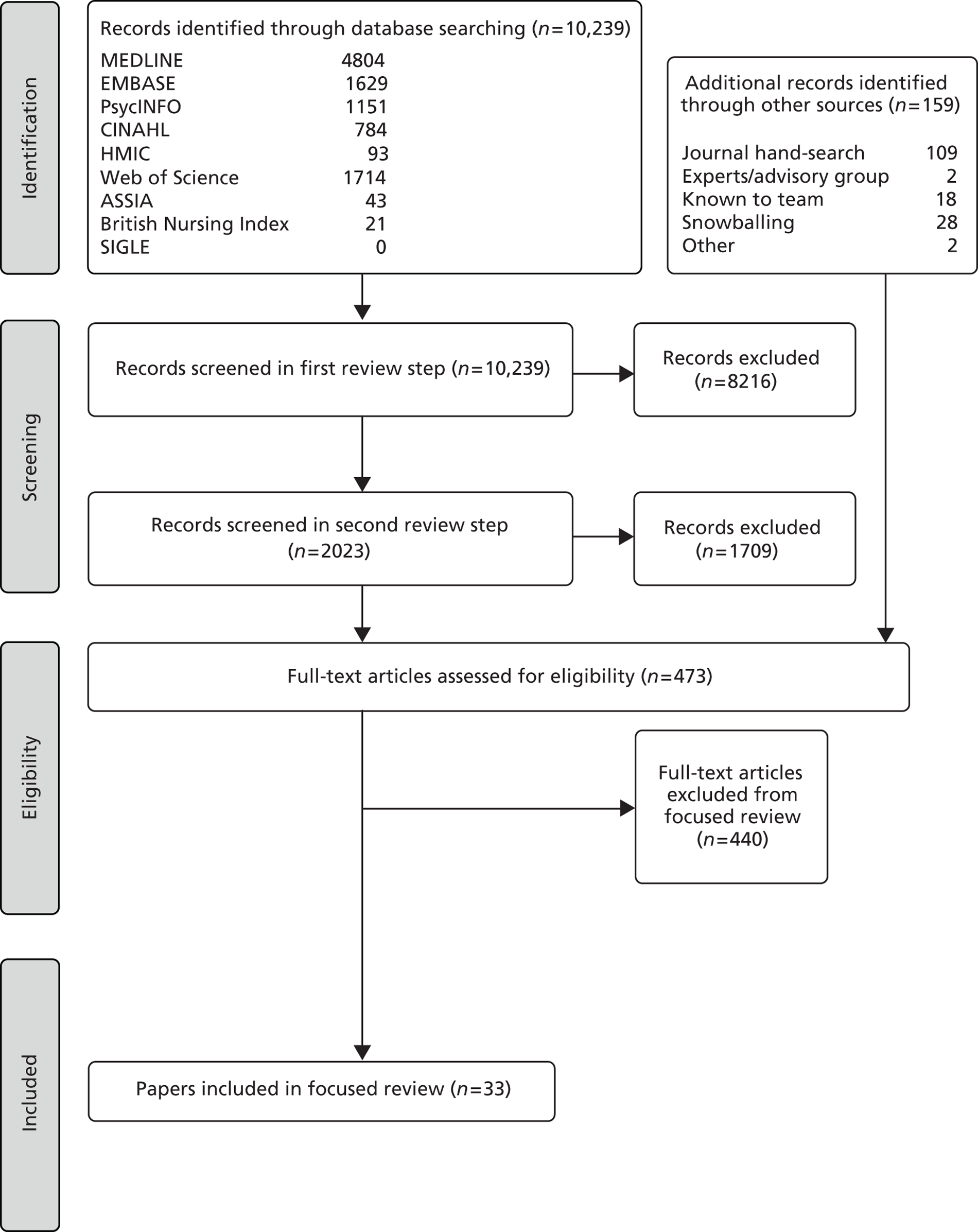

The number of papers involved at each step of the focused review is set out in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram of the literature search for the focused (or formal) review.

Analysis in the focused review

The papers in our focused review are even more diverse than the 13 papers in the Clarke and Loudon review,31 which did not involve a meta-analysis because the papers were too heterogeneous. Therefore, we too decided not to conduct a meta-analysis, but instead to provide an account of each paper in tabular form. Each paper that reached the final data extraction stage was also analysed in relation to:

-

Its importance to this review based on quality (especially the level of control in the study), size of the study and relevance to our review question.

-

Whether the findings were positive (showing research engagement did improve health care) or negative (showing no positive impact) or mixed. Under this interpretation, a ‘negative’ finding did not necessarily mean that health care worsened, it might have remained unchanged over the course of the study. Some papers provided mixed data about improvement that were inconclusive and difficult to interpret. Findings that were partially positive and partially inconclusive we labelled ‘mixed/positive’; findings that were partially negative and partially inconclusive we labelled ‘mixed/negative’.

-

The degree of intentionality of the link between research engagement and health-care performance (by-product, research network, or intervention).

-

The scope of the impact made by research engagement (broader impact/specific impact).

-

The level of engagement discussed (clinician or organisational). We initially intended to analyse papers according to the four levels of engagement mentioned in the ITT – clinician, team, service or organisational – but eventually used the two levels of clinician and organisation because, at levels above that of individual clinicians, there is little consensus about the reporting terms used and we could not readily apply the separate categories of team, service and organisation.

Finally, each of the papers was examined to identify any factors that the authors were proposing as possible causes of the improvement in health-care performance.

This analysis was supplemented by the wider review described below.

Stage 3: wider review and report