Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/2001/09. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The final report began editorial review in November 2012 and was accepted for publication in February 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2013. This work was produced by Toye et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Aims

The aims of this study were to:

-

increase our understanding of patients’ experience of chronic non-malignant musculoskeletal (MSK) pain and therefore have an impact on quality of care

-

utilise existing research knowledge to improve understanding and, thus, best practice in patient care

-

contribute to the development of methods for qualitative research synthesis.

Chapter 2 Background

Chronic pain is common and universal; it occurs at all ages and in all populations and has been reported throughout recorded history.

p. 31

The alleviation of pain is a key aim of health care,2 yet pain can often remain a puzzle. 3 Chronic pain persists beyond the expected healing time and, by definition, is not amenable to routine treatments such as non-narcotic analgesia. 4 This is further complicated by the finding that pain is not always explained by a specific pathology and, even if a pathology is identified, the person will not necessarily develop pain. 3 Some suggest that chronic pain be acknowledged as a condition in its own right, rather than as a symptom of specific underlying disease. 3,5

Each year over 5 million people develop chronic pain. 6 Population estimates suggest that around 25% of adults around the world suffer with moderate or severe pain,1,7–10 and for between 6% and 14% of these adults the pain is severe and disabling. 3,11 We know that pain has a high impact on the individual’s physical, psychological and social well-being. 12 For example, 49% of patients with chronic pain experience depression, 25% lose their jobs and 16% feel that their chronic pain is so bad that they sometimes want to die. 6 Not only does pain have a major impact on participation in life, it also has an impact on ‘the economic balance-sheet of populations’ (p. 3). 1 Estimates suggest that the cost of chronic pain to the national economy may run into tens of billions of pounds each year. 2 Demographic changes leading to an increase in the older population are also likely to increase the need for appropriate health care. 3,13 MSK pain (notably back and joint pain) and headache are possibly the most predominant kinds of chronic pain. 3 MSK pain is pain associated with muscles, ligaments, tendons and bones. It can range from local pain (e.g. knee pain) to widespread bodily pain (e.g. fibromyalgia), making it difficult to accurately estimate how many people have chronic MSK pain. To further complicate this, those with severe MSK pain are also likely to suffer with pain in other parts of their body. 3,13 However, we know that the prevalence of MSK pain in the population is high and appears to be increasing,14 and this may have an impact on the provision of health care for those in pain. A greater understanding of patients’ experience of chronic pain could help to shape future health care for this group.

There are some signs that chronic pain is now being seen from a public health perspective. 1,15–17 The first English Pain Summit took place in November 2011, bringing together parliamentarians, health-care professionals, commissioners and patient groups to discuss chronic pain and pain services in the UK. 2 Chronic pain is also one of the four clinical priorities of the Royal College of General Practitioners for 2011–14. 18 The policy landscape suggests that access to effective pain relief is a fundamental human right that is often denied to those in chronic pain. However, there is a growing awareness that more could be done to support people in chronic pain to achieve the goal of living well with their pain. Recent policy published in England2 and further afield in the USA19 has begun to call for a cultural transformation in the way that people in chronic pain are viewed and treated and this meta-ethnography is set within this policy context.

One of the aims of qualitative research in health care is to understand the experience of illness and make sense of the complex processes involved. It aims to generate concepts that allow us to understand behaviour. 20 Qualitative interpretations allow us to ‘anticipate’ rather than predict what might happen in a particular situation. 20 It can thus lead to substantial improvements in health-care and policy decisions by enabling clinicians and policy-makers to understand the appropriateness and meaningfulness of interventions. The Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group acknowledges the importance of including qualitative findings within evidence-based health care and stresses that ‘evidence from qualitative studies can play an important role in adding value to systematic reviews for policy, practice and consumer decision-making’ (p. 571). 21 Syntheses of the existing body of qualitative research can also help to identify gaps in knowledge and to target these gaps. Insights from several meta-ethnographies in health care have contributed to a greater understanding of complex processes such as medicine taking,22 adherence to treatments for diabetes23 and use of antidepressants. 24 Excluding qualitative research from evidence-based practice may mean that we omit vital information from decisions related to policy and practice. 25

However, the proliferation of studies exploring the experience of chronic non-malignant MSK pain makes it difficult for clinicians and policy-makers to use this knowledge to inform practice and policy, and increases the danger that these findings are ‘doomed ultimately never to be visited’ (p. 786). 26 There is a growing body of qualitative research exploring patients’ experience of chronic MSK pain, yet there has been no attempt to systematically search the qualitative literature with the aim of increasing our conceptual understanding. The aim of qualitative synthesis is to systematically review and integrate the findings of qualitative research to increase our understanding.

Chapter 3 Methods

There are various methods for synthesising qualitative research. 27–30 Studies range from those aiming to describe qualitative findings to those that aim to be more interpretive and generate theory. As qualitative synthesis generally aims to move beyond description,31 it may be more useful to see these two approaches as two poles on a continuum. Meta-ethnography is an interpretive form of knowledge synthesis, proposed by Noblit and Hare,20 that aims to develop new conceptual understandings. As we aimed to produce a conceptual synthesis of qualitative findings related to chronic non-malignant MSK pain, we chose to use meta-ethnography as our method of qualitative synthesis. Some authors argue that meta-ethnography is more suited for synthesising a small number of studies. 23,32 Reviews of published qualitative syntheses show that, in the majority of syntheses using meta-ethnographic methods, the number of studies included ranges from 3 to 44. 25,28,32 There are only a very small number of meta-ethnographic syntheses that include a larger number of studies than this. 25,28 However, we knew that we were likely to find a large number of relevant studies and aimed to see if meta-ethnography could be used to synthesise when there is a large body of qualitative research.

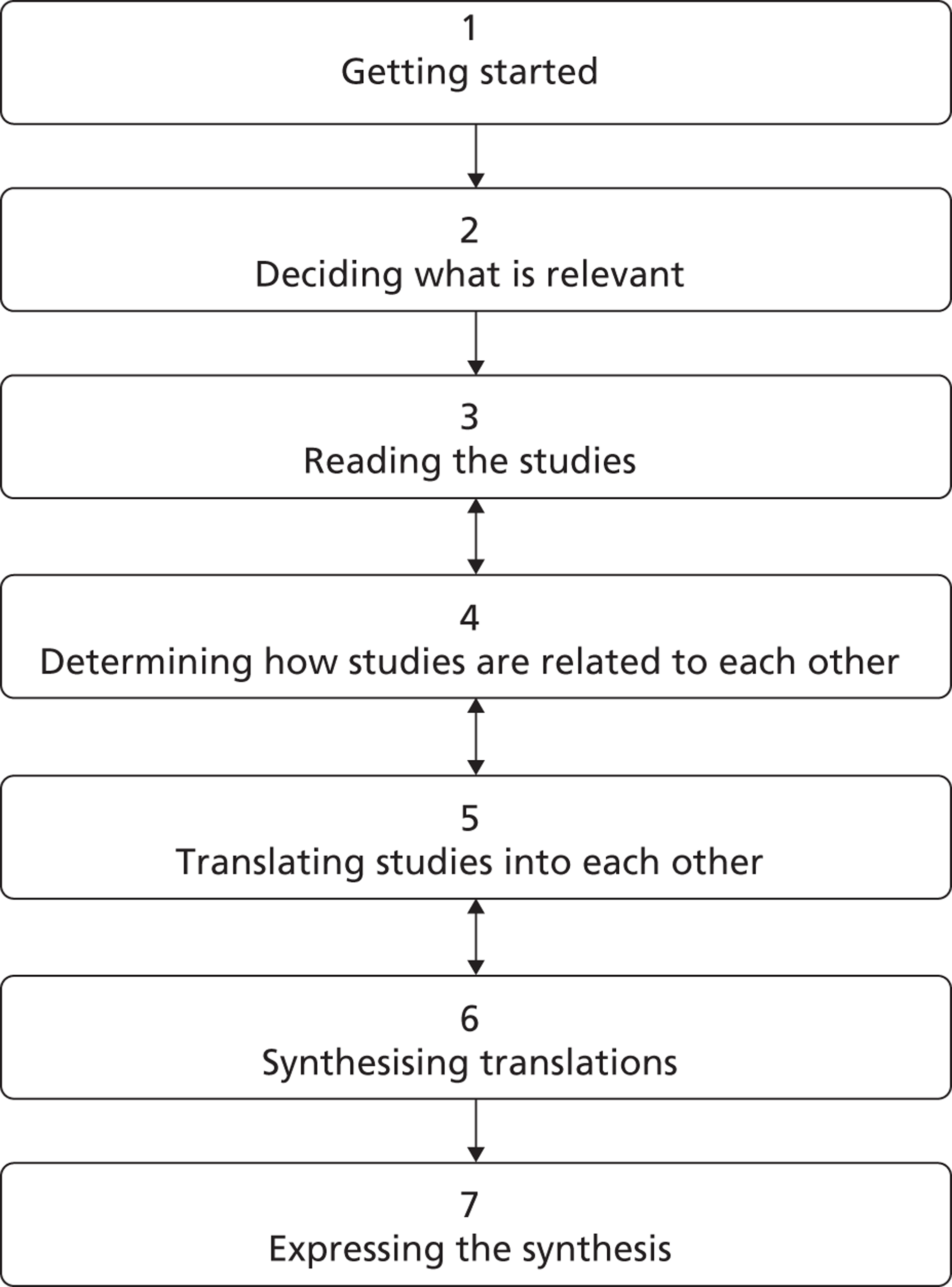

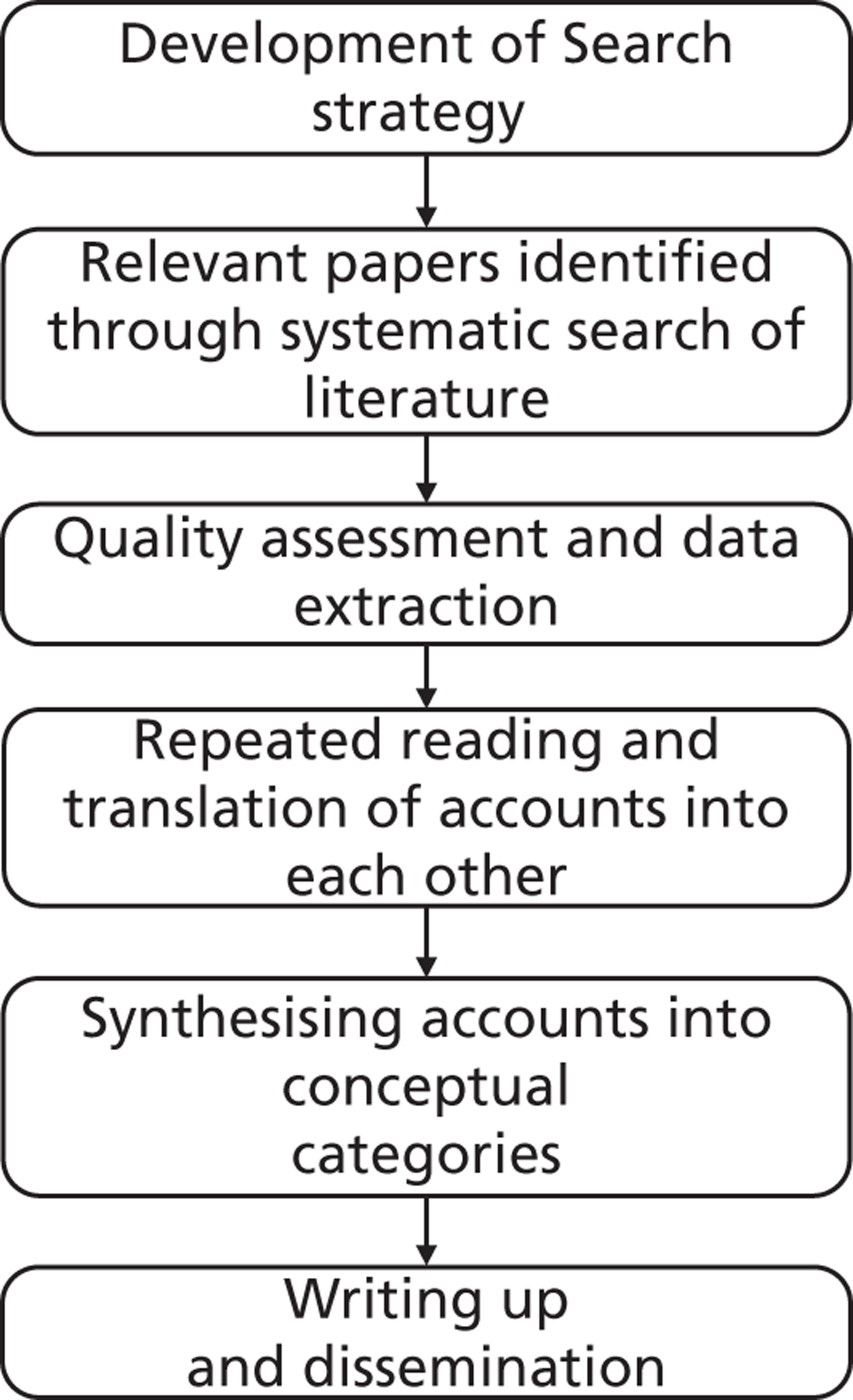

Meta-ethnography has been successfully used to synthesise qualitative studies in health care. In a recent Health Technology Assessment (HTA) report evaluating meta-ethnography, Campbell and colleagues28 identified 41 qualitative syntheses. Six of these explicitly employed meta-ethnography to synthesise findings and a further 16 described their method as meta-ethnographic. Other reviews of qualitative syntheses suggest that the number is much larger than this and increasing dramatically. 25,32 For example, Hannes and colleagues32 demonstrated that the number of qualitative syntheses in 2008 had doubled within 4 years, and that the most commonly used method of synthesis is meta-ethnography. We searched the medical databases [Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED), EMBASE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), MEDLINE, PsycINFO, British Nursing Index (BNI) and Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL)] using the terms meta AND ethnography (in title and abstract) and found 19 additional health-care studies published between 2009 and 2012 that explicitly used meta-ethnography. 24,33–50 This limited search may underestimate the number of qualitative syntheses now using meta-ethnography, but it seems clear that a growing number of researchers are using meta-ethnography to synthesise qualitative findings. Noblit and Hare20 propose seven stages to a meta-ethnography synthesis, which take the researcher from formulating a research idea to expressing the findings of research (Figure 1). These stages are not discrete but form part of an iterative research process.

1. Getting started

This stage of the research involves ‘finding something that is worthy of the synthesis effort’ (p. 27). 20 The decision to develop a conceptual synthesis of patients’ experience of chronic non-malignant MSK pain was an iterative process that was sparked at the British Pain Society Annual General Meeting in 2009 when two of the research team (FT and KS) first met. From here we approached other members of the team with a specific interest and expertise in chronic pain, qualitative research and research synthesis (Box 1). We began with informal meetings and telephone discussions, which culminated in a successful application to fund the project. The study protocol is provided in Appendix 1.

-

FT has a master’s degree in Archaeology and Anthropology and is also a qualified physiotherapist with an interest in chronic pain management. She has expertise in qualitative health research and methodology.

-

KS has a quantitative and qualitative health and pain research background and has used mixed methods in most of her research. She has experience of systematic reviews and qualitative research synthesis using meta-ethnography. Her professional background is in nursing.

-

NA is a doctoral-qualified nurse academic and practising pain nurse. He has completed syntheses of qualitative research using Joanna Briggs Institute Qualitative Assessment and Review Instrument (JBI-QARI) methodology.

-

MB has broad experience in systematic reviews. She has completed syntheses of qualitative research using JBI-QARI methodology. Her professional background is in nursing.

-

EC qualified as a nurse and throughout her 25-year research career has utilised mixed methods in her pain research.

-

KB is a qualified physiotherapist with 20 years of experience of running chronic pain management programmes. She is also an experienced researcher and uses mixed methods in most of her research.

The development of this meta-ethnography was both iterative and collaborative. Team members felt free to agree, disagree or change their mind within the safety of the group. The aim of considering alternative views within a team is not necessarily to agree on an interpretation but rather to enter into a dialectic process whereby our ideas are challenged and modified. This can lead to greater conceptual insight by challenging the boundaries of our own interpretations, just as a single word from another person can jog our memory or spark off insight when we had not expected it.

Throughout the project the project team met monthly either face-to-face or in Skype™ meetings (Skype Ltd Rives de Clausen, Luxembourg). We also met regularly with an advisory group that included two patient representatives and three NHS clinicians with experience in pain management (Box 2). The terms of reference for the advisory group are shown in Box 3.

-

A patient who has recent experience of treatment for non-malignant MSK pain from a NHS trust.

-

A patient with an interest in research from University/User Teaching and Research Action Partnership (UNTRAP) based at the University of Warwick. UNTRAP is a partnership between users of health and social care services and carers, the University of Warwick and the NHS. It aims to support the involvement of service users and carers in teaching and research.

-

A consultant in pain management who has been actively involved in policy decisions for chronic pain.

-

Two members of NHS staff working in chronic non-malignant pain.

-

To advise the project team and partner institutions on the project plans, including scope and range.

-

To review objectives and progress against plans and objectives.

-

To discuss and recommend any variations and developments.

-

To monitor the relationships between the current partners and any future additional institutions.

-

To review and discuss the quality of the research.

-

To help the researchers contribute to knowledge at a European and an international level.

2. Deciding what is relevant

This stage involved systematically searching for, screening and appraising potential studies to decide which to include in the synthesis. Qualitative syntheses do not aim to summarise the entire body of available knowledge, or make statistical inference from it. Qualitative syntheses are concerned with conceptual insight. Noblit and Hare20 strongly suggest that it is not necessary to include all published reports in a meta-ethnography: ‘Unless there is some substantive reason for an exhaustive search, generalizing from all studies of a particular setting yields trite conclusions’ (p. 28).

Campbell and colleagues28 also suggest that ‘omission of some papers is unlikely to have a dramatic effect on the results’ of qualitative synthesis (p. 35). However, for several reasons we decided to undertake a systematic search of published qualitative studies reporting patients’ experience of chronic MSK pain. Importantly, this project provided funding and the unique opportunity to identify the qualitative studies published in this area, and identify any gaps in knowledge. We wanted to produce a conceptual analysis with a weight of evidence that would have resonance with the health research community who were more used to quantitative systematic reviews. Finally, whereas previous meta-ethnographies in health care have included small numbers of studies,28 we knew that a systematic search in our chosen area would allow us to apply the methods of meta-ethnography to a large number of studies. Although Campbell and colleagues28 suggest that trying to include too many studies in a qualitative synthesis is unwieldy, we wanted the opportunity to see whether meta-ethnography could be useful in synthesising a large body of qualitative knowledge. With the ever-expanding body of qualitative research, qualitative syntheses are increasingly likely to identify large numbers of studies.

Scope of the search

-

Inclusions. Fully published reports of qualitative studies that explored adults’ experience of chronic non-malignant MSK pain. Chronic pain was defined as pain lasting for ≥ 3 months.

-

Exclusions. Cancer pain, neurological pain (e.g. stroke, multiple sclerosis), phantom pain, facial pain, head pain, dental/mouth pain, abdominal/visceral pain, menstrual/gynaecological pain, pelvic pain, samples in which the experience of the patient cannot be disentangled from that of others (e.g. carers, clinicians, partners), studies that explore chronic illness not explicitly chronic pain (e.g. rheumatoid arthritis studies that do not explicitly explore the experience of pain), samples that include conditions other than chronic MSK pain, auto-ethnography and studies that report individual case studies.

Search strategies

Strategies for identifying qualitative research may be unwieldy and often ‘trade-offs’ between recall and precision are necessary. 51 For this study we employed a qualified research librarian to help conduct the search. We chose several strategies:

Electronic databases

First, using a combination of free-text terms and thesaurus terms or subject headings we searched for relevant qualitative studies using six electronic bibliographic databases (MEDLINE, EMBASE, CINAHL, PsycINFO, AMED and HMIC). Studies were included up until the final search in February 2012 and there were no exclusions for dates. We used search terms available from the InterTASC Information Specialists’ Sub-Group (ISSG) Search Filter Resource (see www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/intertasc/; accessed June 2013) to develop our search strategy. The ISSG is a group of information professionals supporting research groups producing technology assessments for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). The search was limited to studies of adults. As meta-ethnography relies on identifying and defining concepts within each study, we also chose to limit the search to English-language studies. The search syntax used for MEDLINE is shown as an example in Box 4 and the syntax for the other electronic databases is shown in Appendix 2.

Hand-searching

Hand-searching journals is an important strategy for comprehensively identifying relevant qualitative studies. 51–53 At an early team meeting we identified specific journals reporting significant numbers of qualitative research studies in full. These journals were Journal of Advanced Nursing, Social Science & Medicine, Qualitative Heath Research, Sociology of Health and Illness and Arthritis Care and Research. We subsequently added three additional journals for hand-searching (Disability and Rehabilitation, Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences and BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders) as these contributed the highest numbers of potential hits in the database searches (40, 20 and 15 studies respectively). We hand-searched the contents lists of these journals for 2001–11.

Reference lists

Finally, we searched the reference lists of all relevant qualitative studies for further potential studies. We did not specifically search the grey literature as we wanted to include fully published research reports only.

-

RESEARCH, QUALITATIVE/

-

ATTITUDE TO HEALTH/

-

INTERVIEWS AS TOPIC/

-

FOCUS GROUPS/

-

NURSING METHODOLOGY RESEARCH/

-

LIFE EXPERIENCES/

-

(qualitative OR ethno$OR emic OR etic OR phenomenolog).mp

-

(hermeneutic$OR heidegger$OR husserl$OR colaizzi$OR giorgi$OR glaser strauss).mp

-

(van AND kaam$OR van AND manen OR constant AND compar$).mp

-

(focus AND group$OR grounded AND theory OR narrative AND analysis OR lived AND experience$OR life).mp

-

(theoretical AND sampl$OR purposive AND sampl$OR ricoeur OR spiegelberg$OR merleau).mp

-

(field AND note$OR field AND record$OR fieldnote$OR field AND stud$).mp;

-

(participant$adj3 observ$).mp

-

(unstructured AND categor$OR structured AND categor$).mp

-

(maximum AND variation OR snowball).mp

-

(metasynthes$OR meta-synthes$OR metasummar$OR meta-summar$OR metastud$OR meta-stud$).mp

-

“action research”.mp

-

(audiorecord$OR taperecord$OR videorecord$OR videotap$).mp

-

exp PAIN/

-

exp ARTHRITIS, RHEUMATOID/

-

exp FIBROMYALGIA/

-

exp OSTEOARTHRITIS/

-

MUSCULOSKELETAL DISEASES/

-

exp ARTHRITIS/

-

1 OR 2 OR 3 OR 4 OR 5 OR 6 OR 7 OR 8 OR 9 OR 10 OR 11 OR 12 OR 3 OR 14 OR 15 OR 16 OR 17 OR 18

-

19 or 20 or 21 or 22 or 23 or 24

-

25 AND 26

-

cancer.ti,ab

-

27 NOT 28

-

29 [Limit to: English Language and Humans and (Age Groups All Adult 19 plus years)];

Screening

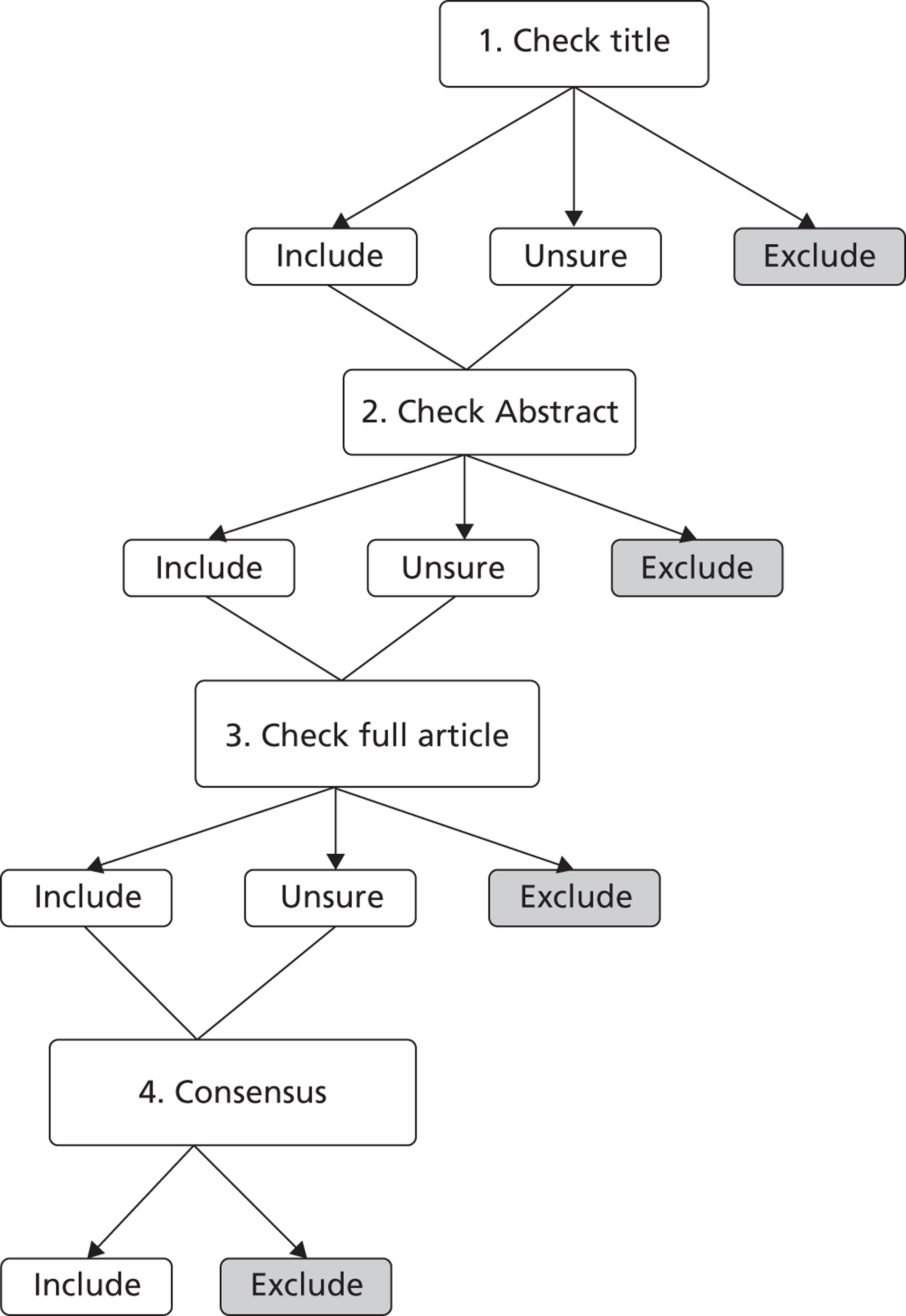

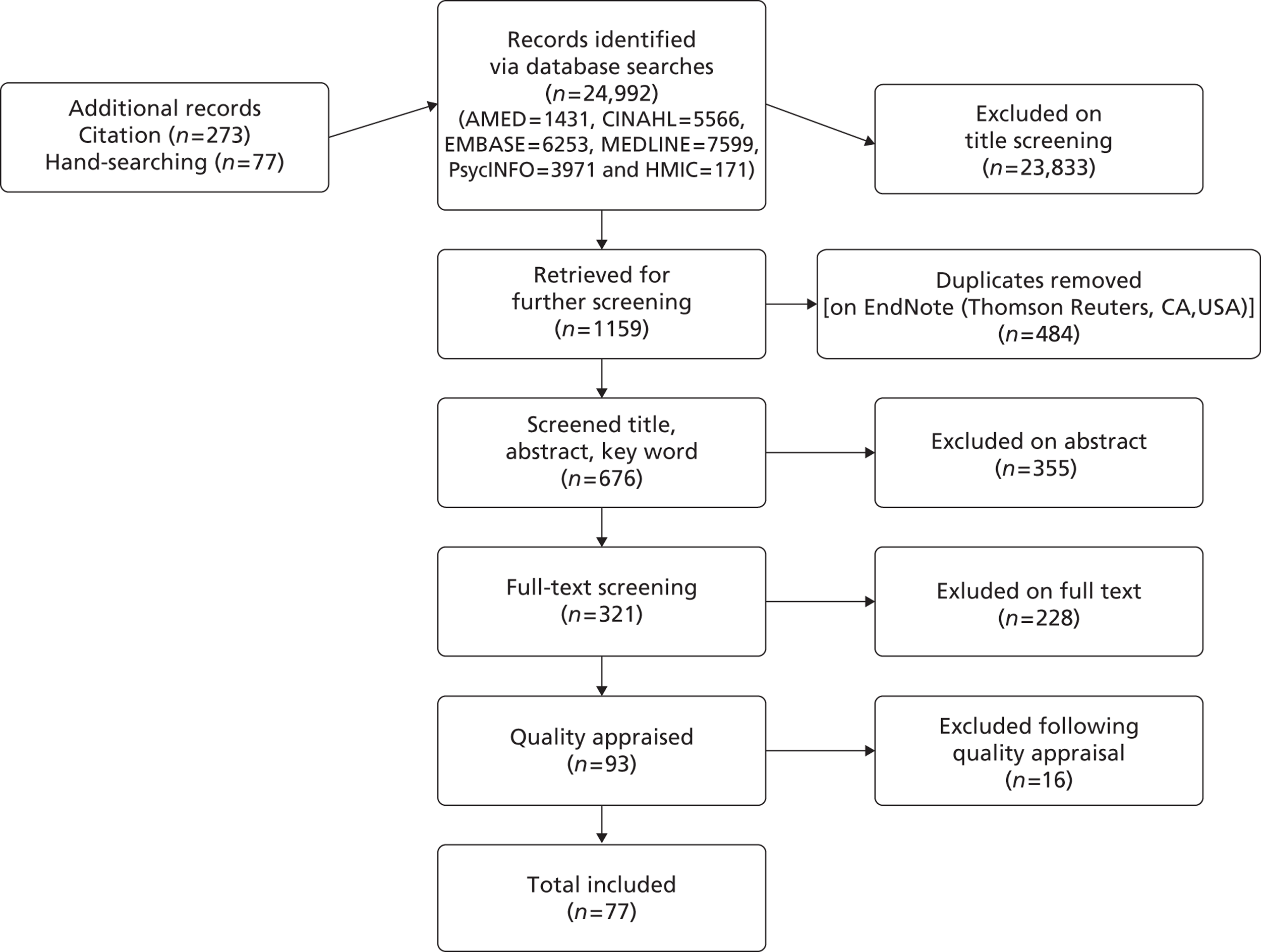

Once we had identified potential studies we adapted the process as outlined by Sandelowski and Barroso27 to exclude articles that did not meet the inclusion criteria. The stages of screening are shown in Figure 2. A research librarian and researcher (FT) screened the titles of the identified articles. If they were uncertain whether to include a study after reading the title, FT read the abstract. If she was still uncertain about inclusion, the full text was checked by two researchers. If they remained uncertain the article was sent to the full team for a consensus decision.

FIGURE 2.

Process for screening articles from the searches.

Quality appraisal

The use of quality criteria for qualitative research is widely debated. 54–58 There are now many suggested frameworks for appraising the quality of qualitative research, yet no consensus on what makes a qualitative study ‘good’ or ‘good enough’. 28,57 Although it is clear that structured checklists do not produce consistent judgements in qualitative research appraisal,57 these checklists may be useful in providing a focus for discussions. 28 Some researchers suggest that we attempt to distinguish ‘fatal’ methodological flaws in qualitative systematic reviews. 57,58 Others argue that quality appraisal should not be used at all to exclude studies from qualitative synthesis. 31 As appraisal tools tend to focus on method, some argue that excluding studies on this basis may mean that insightful studies are excluded. 28 However, although Campbell and colleagues28 suggest that studies should not be excluded on the grounds of quality, they do not recommend ‘abandoning appraisal’ altogether.

To be utilised within a meta-ethnography, a study must provide an adequate description of its concepts (Pope C, Britten N. Workshop on qualitative synthesis and meta-ethnography, course on meta-ethnography at Oxford Brookes University, June 2009, personal communication with FT, and references 20 and 28). We agreed that conceptual insight was fundamental to meta-ethnography, but also felt that papers should be reported ‘well enough’ methodologically to allow us to make a judgement about the inductiveness of the findings. In summary, we felt that we needed some assurances that a report was inductive and grounded in patients’ experience. To provide a focus for team discussion, the team decided to use checklists to assist quality appraisal. We did not intend to use a particular score as a cut-off point, but wanted to explore the utility of these scores for quality appraisal in qualitative synthesis. We used three methods of appraisal. First, we used the questions developed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for appraising qualitative research59 (Box 5), which have been used for appraising the quality of studies for meta-ethnography. 23,60,61 The CASP tool consists of 10 questions to consider when appraising qualitative research. Although it was not designed to provide a numerical score, we wanted to explore whether a score could be used to assist quality appraisal for meta-ethnography. After some discussion, the team agreed to assign a numerical score to each question to indicate whether we felt that the CASP question had (1) not been addressed, (2) been addressed partially or (3) been extensively addressed. This gave each paper a score ranging from 10 to 30.

Second, as two team members (NA and MB) were experienced in the use of the JBI-QARI in systematic reviews of evidence,62 we used this alongside the CASP tool as an alternative appraisal tool to stimulate discussion. The JBI-QARI also consists of 10 questions, which are rated as ‘yes’, ‘no’ or ‘unsure’ (Box 6). After rating each question the reviewer then makes the decision to include or exclude the paper. Early in the appraisal process we agreed that the JBI-QARI did not add anything further to the CASP tool with regard to the final decision on inclusion. However, for completeness we continued to grade each paper.

Finally, we categorised each paper as a key paper (conceptually rich and could potentially make an important contribution to the synthesis), a satisfactory paper, a paper that is irrelevant to the synthesis or a methodologically fatally flawed paper. 57 This method has also been used to determine inclusion of studies into meta-ethnography. 24 The concepts ‘fatally flawed’, ‘satisfactory’ and ‘key paper’ have not been defined but are global judgements made by a particular appraiser that comprise several unspecified factors.

-

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

-

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

-

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

-

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

-

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

-

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

-

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

-

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

-

Is there a clear statement of findings?

-

How valuable is the research?

-

Is there congruity between the stated philosophical perspective and the research methodology?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the research question or objectives?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the methods used to collect data?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the representation and analysis of data?

-

Is there congruity between the research methodology and the interpretation of results?

-

Is there a statement locating the researcher culturally or theoretically?

-

Is the influence of the researcher on the research, and vice versa, addressed?

-

Are participants, and their voices, adequately represented?

-

Is the research ethical according to current criteria or, for recent studies, is there evidence of ethical approval by an appropriate body?

-

Do the conclusions drawn in the research report flow from the analysis, or interpretation, of the data?

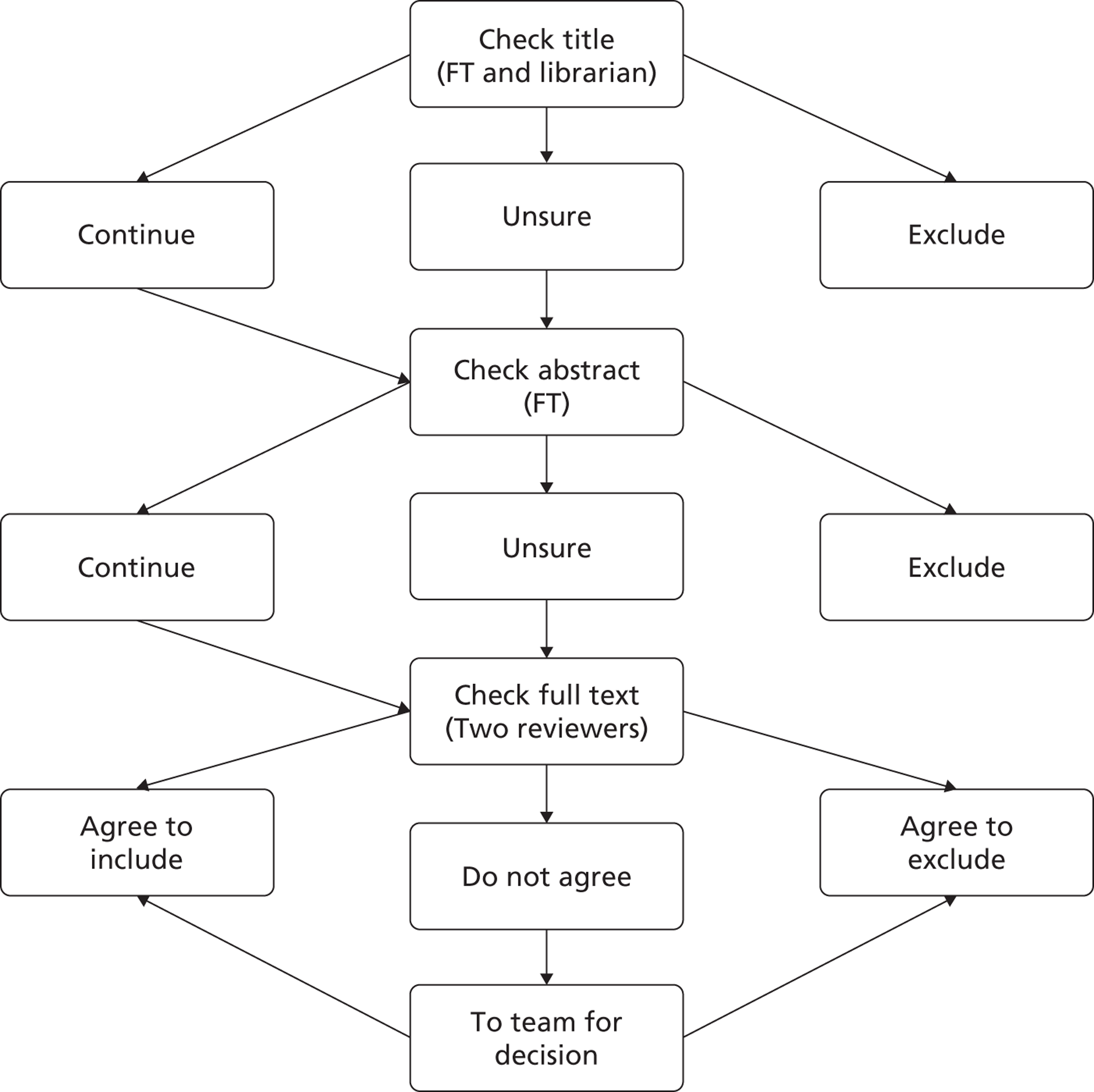

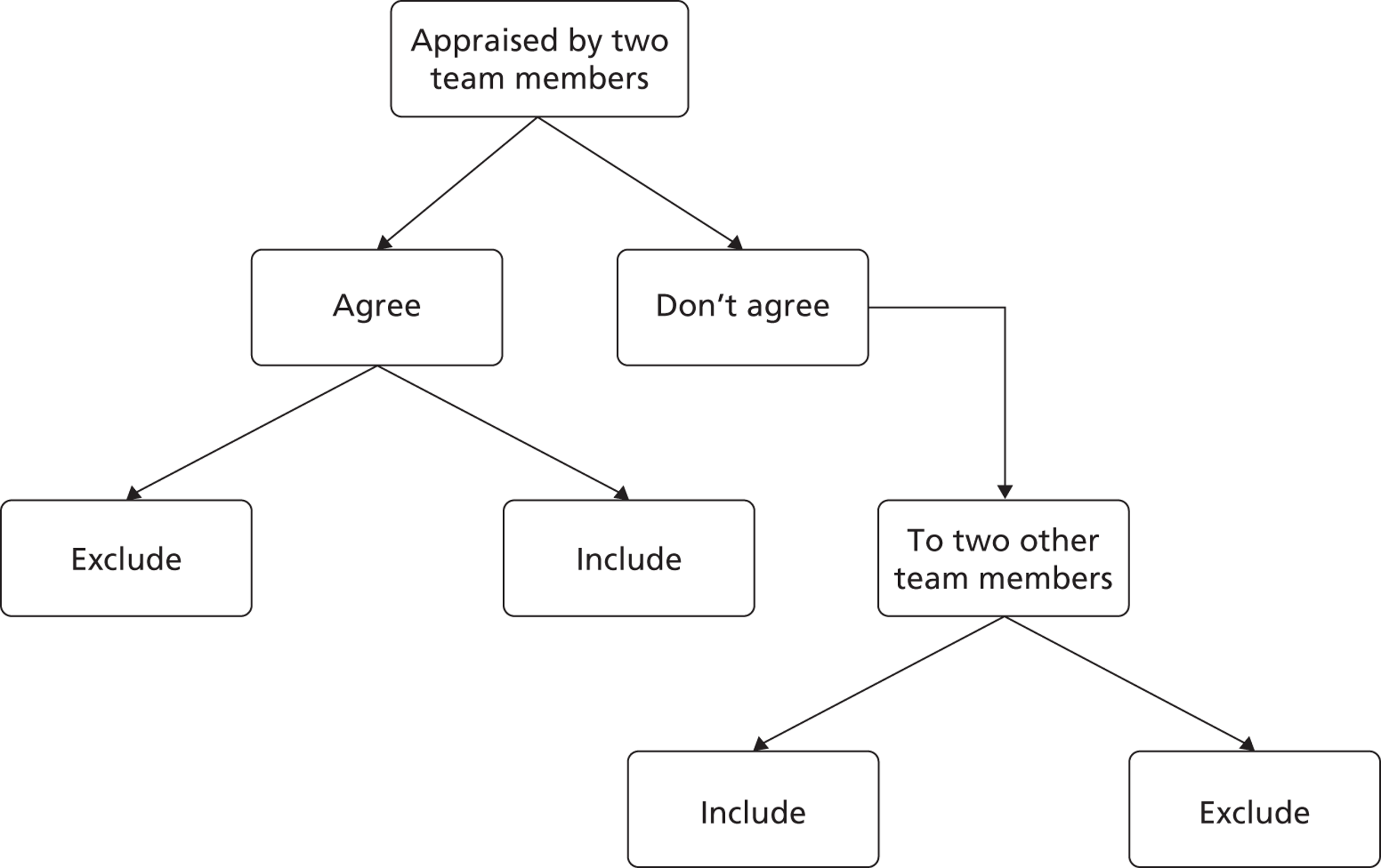

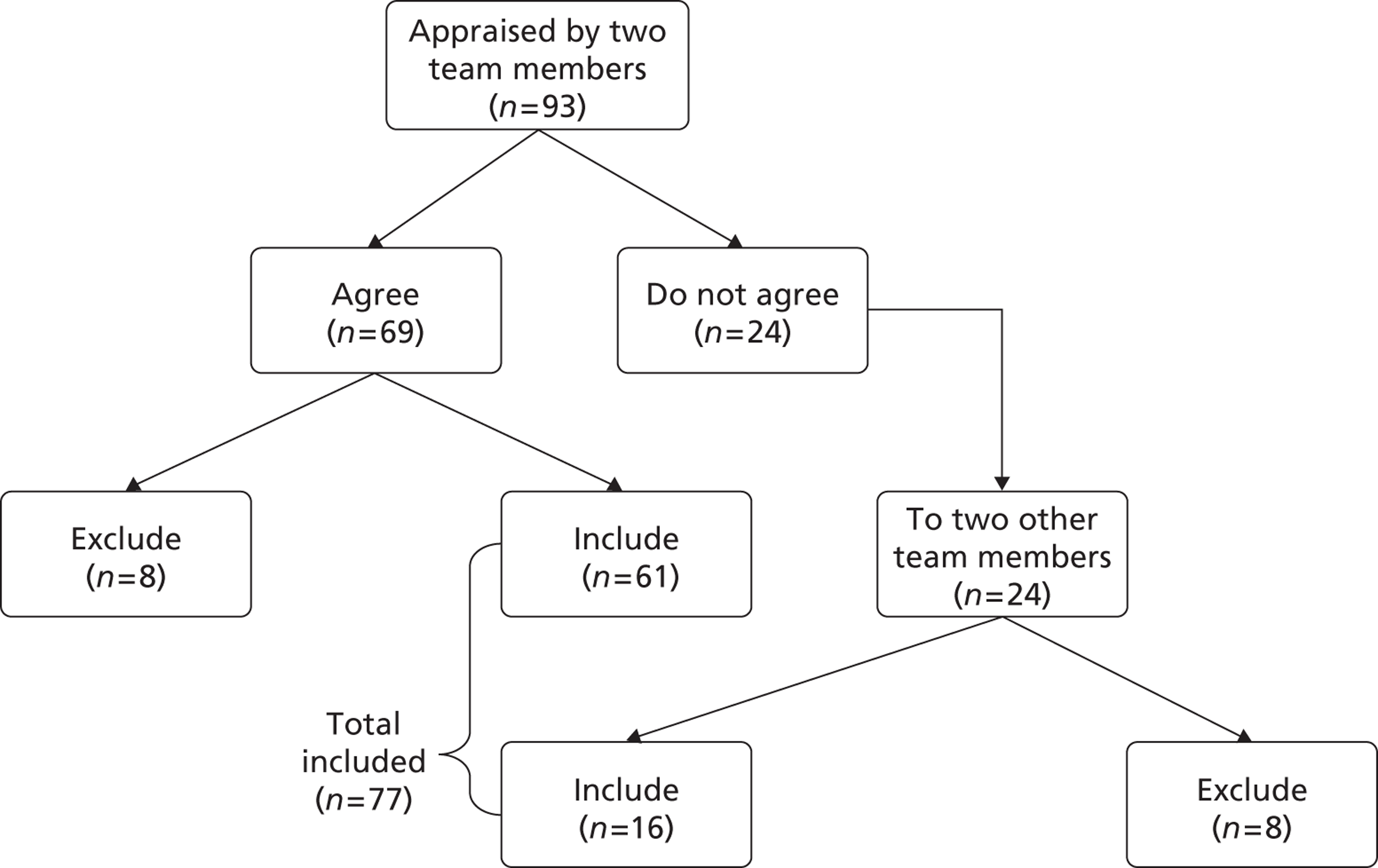

To test and refine the appraisal process each team member independently appraised the first 10 relevant studies identified and met to discuss their decisions. Two team members (FT and JA) appraised all subsequent papers and, if they were unable to reach an agreement, the paper was sent to two other team members to make a final decision (Figure 3). Team members were rotated so that they did not always appraise papers with the same person.

FIGURE 3.

Process for appraising papers.

3. Reading the studies

This stage of meta-ethnography involves thoroughly reading and rereading the studies to identify and describe the concepts. This requires ‘extensive attention to the details in the accounts’ (p. 28). 20 Thorough reading continues throughout all phases of meta-ethnography rather than being a discrete phase.

After the first reading, FT uploaded a PDF version of each complete study into NVivo 9 software (QSR International, Southport, UK) for analysing qualitative data. This allowed her to reread the primary research findings throughout all stages of analysis and compare the original interpretations to developing ideas. NVivo 9 allowed FT to collect, organise and analyse a large body of knowledge by ‘coding’ findings from the results and discussion sections of papers under ‘nodes’. Findings can be coded under several nodes simultaneously and the overlap between coding can be easily observed. This is particularly useful for team analysis as it allows the researcher to easily make a record of how each team member has coded data, whilst continuing to return to the original articles. NVivo 9 also allows researchers to write memos and link these memos to specific data to keep track of developing ideas and theories. FT classified each study on NVivo 9 so that the team could identify the following study characteristics: author, journal, year of publication, type of pain, number and age of participants, source and country of participants (e.g. pain clinic in UK), method of data collection (e.g. interviews) and methodological approach (e.g. grounded theory).

4. Determining how studies are related to each other

The purpose of careful reading in meta-ethnography is to identify and describe the ‘metaphors’ or concepts in studies and ‘translate’ or compare them with those in other studies. This is fundamental to meta-ethnography because concepts are the raw data of the synthesis. This stage involves creating ‘a list of key metaphors, phrases, ideas and/or concepts’ (p. 28). 20 However, although meta-ethnography requires clearly articulated concepts, it can sometimes be difficult to decipher these concepts through the description, in other words to see ‘the wood through the trees’. For example, the reader may find him- or herself attempting to recode findings or to condense them into higher conceptual categories to make sense of them. One of the aims of qualitative analysis is to develop conceptual categories that help us to understand an experience, rather than just describe that experience. 63 We describe a concept as a meaningful idea that develops by comparing particular instances. Fundamentally, concepts must explain not just describe the data.

However, as the act of description itself requires a level of interpretation, it can be difficult to decipher a concept; it may be more useful to understand ‘description’ and ‘concept’ as two poles on a spectrum. Campbell and colleagues28 recognise this difficulty: ‘It became apparent that the distinction between findings and concepts was neither simple to make nor useful, and because it was felt to be unnecessary it was abandoned’ (p. 55).

Sandelowski and Barroso27 also recognise the complexity of synthesising qualitative findings when levels of interpretation can range from thematic surveys, which make some effort to ‘move beyond a list’, to ‘fully integrated explanations’ of social phenomena (p. 145). Schütz’s64 concept of first- and second-order constructs is frequently used in meta-ethnography studies to distinguish the data of meta-ethnography. 28 Schütz makes a distinction between (1) first-order constructs (the participants’ ‘common sense’ interpretations in their own words) and (2) second-order constructs (the researchers’ interpretations based on first-order constructs). The ‘data’ of meta-ethnography are second-order constructs. In meta-ethnography, these second-order constructs are then further abstracted to develop third-order constructs (the researchers’ interpretations of the original authors’ interpretations). However, the distinction between first- and second-order constructs is somewhat ‘unclear’. 60 Importantly, although first-order constructs are often presented in meta-ethnographies to represent the patients’ ‘common sense’ interpretations in their own words, it is important to remember that these words are chosen by the researchers to illustrate their second-order interpretations. Our approach deviates from that of other meta-ethnographies in that we chose to base our synthesis entirely on second-order constructs. Specifically, we made the decision to only include concepts that we felt were clearly articulated. We did not attempt to ‘reorganise’ findings, but excluded data from analysis if we could not decipher a concept. We made this decision because of the methodological issues surrounding the reorganisation of data from qualitative research. The second-order interpretation is based on a body of knowledge accessed through fieldwork. Therefore, attempts to reorganise findings without access to the wider body of knowledge might not illuminate the conceptual interpretation originally intended. In other words, we could argue that attempts at reorganisation are not grounded in the body of knowledge. We therefore made the decision to define the second-order constructs and not to include findings for which we could not decipher a concept.

A collaborative approach to interpreting second-order constructs

A fundamental issue with deciphering second-order constructs is that readers interpret concepts in light of their own experience. Thus, different readers may suggest different interpretations. 20 Thus, a meaningful idea for one researcher may not be meaningful for another; one reader might see a concept whereas another might see no more than a description. The reader makes a personal judgement about whether there is a relevant concept and how to describe it. The unique methodological variance of our approach was to take a collaborative approach to interpreting second-order constructs and, thus, challenge our individual interpretations. In this way we aimed to consider alternative interpretations and ensure that interpretation of second-order constructs from the primary papers remained grounded in the originating studies. Paterson and colleagues65 advocate the benefits of collaborative endeavours for qualitative syntheses, as collaboration ‘requires that researchers be willing and able to risk voicing opinions not shared by everyone else in the group’ (p. 28). In short, the interpretation of each second-order construct entering the analysis was negotiated and constructed collaboratively.

To do this, three members of the team (FT, JA and one other team member selected on rotation) read each paper to identify and describe their interpretation of each construct. The team then discussed and developed a collaborative interpretation of each second-order construct. Because of the scale of the study and the potential number of second-order constructs, our interpretations needed to combine clarity and precision in as few words as possible. We therefore used a combination of the authors’ description of the second-order construct (when it briefly and clearly described the construct) and our interpretation of the original construct (if the original was unclear or lengthy). Our collaborative interpretations form the raw data of our synthesis in the same way that interview narrative forms the ‘data’ of qualitative analysis. This approach allowed us to compile an inventory of concise interpretations of second-order constructs that we felt confident were grounded in the primary studies.

Untranslatable concepts

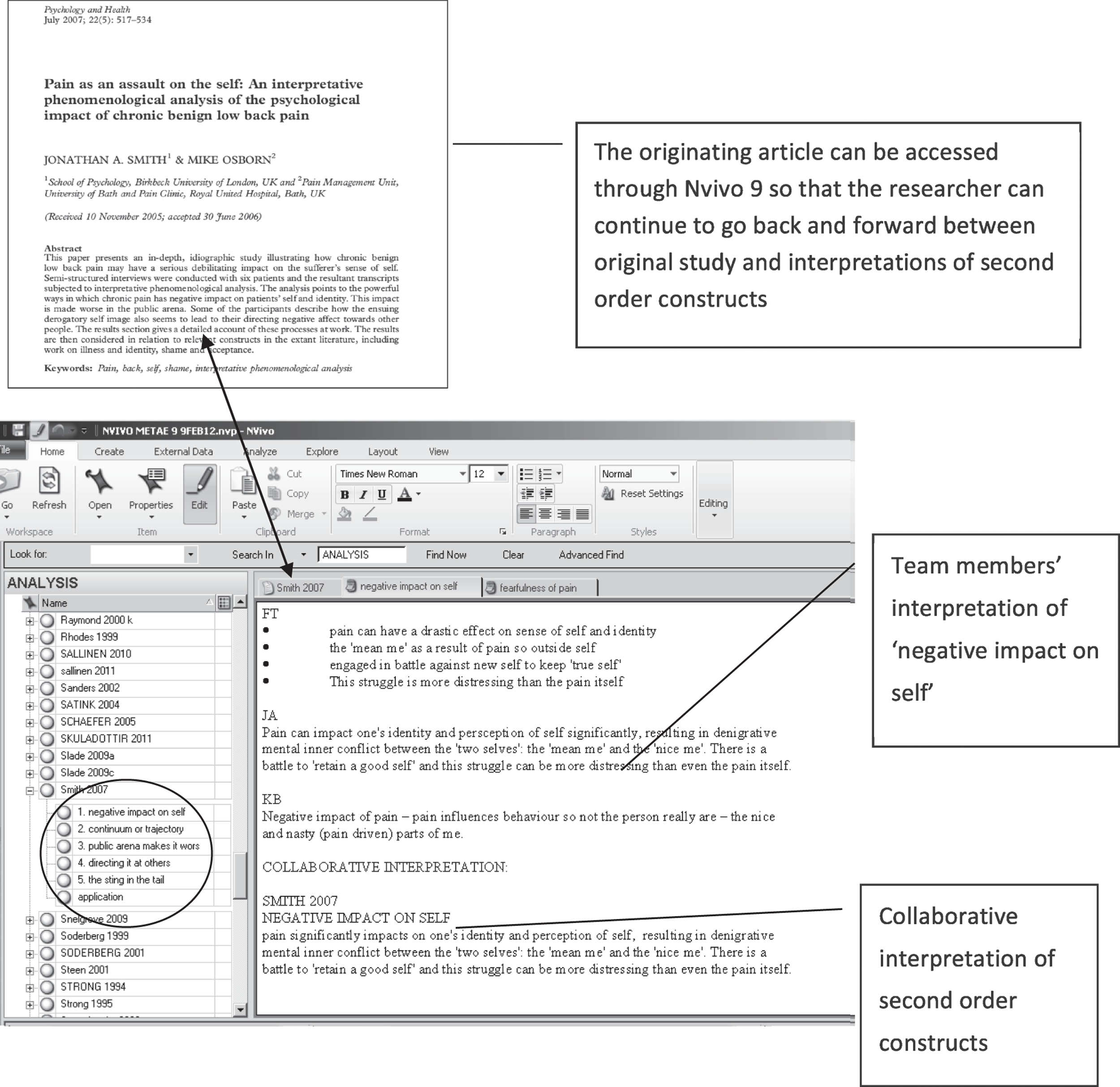

If team members agreed that there was no clear concept articulated, we labelled it ‘untranslatable’ and did not include it in the analysis. For example, in some cases the construct consisted of a descriptive account or list of items that we felt the urge to ‘recode’. In other words, there was no central idea pulling the description together. This did not mean that the study was rejected in its entirety; some studies combined clearly defined and ‘untranslatable’ concepts. If one team member deciphered a concept, we included it in the analysis, even if another member did not. Our aim was to challenge our interpretations, rather than reach consensus. Although this process was labour intensive, we wanted to be confident that the concepts were grounded in the original studies. We spent time reading and rereading the original papers to be certain that our interpretations were grounded in the original studies. The three individual interpretations and resulting collaborative interpretations were uploaded onto NVivo 9 (Figure 4). NVivo 9 allowed us to easily access the original studies whilst reading the attached memos and developing ideas.

FIGURE 4.

Developing collaborative interpretations of second-order constructs using NVivo 9. Published with permission from QSR International. The left window shows how each study was set up as a ‘node’ on NVivo 9, with each of its concepts as subnodes. For example, Smith 2007 contains the concepts ‘negative impact on self’, ‘continuum or hierarchy’, ‘public arena makes it worse’, ‘directing it at others’ and ‘the sting in the tail’. The right window shows a memo attached to the concept ‘negative impact on self’. This memo shows three team members’ interpretations of the concept and the final interpretation of this concept used in the analysis. Reproduced with permission from Taylor & Francis Ltd, URL: www.tandfonline.com: Smith JA, Osborn M. Pain as an assault on the self: an interpretative phenomenological analysis of the psychological impact of chronic benign low back pain. Psychol Health 2007;22 :517–35. 66

5. Translating studies into each other

The next stage in meta-ethnography involves exploring how the second-order constructs are related to each other, thus translating studies into each other. 20 This is achieved through the constant comparative method of grounded theory. 67 By constantly comparing constructs we begin to see similarities and differences between them and organise them into further abstracted conceptual categories with shared meanings. In other meta-ethnographies, for example those of Campbell and colleagues,28 researchers have used an index paper as a way of orienting the synthesis. 68 In these examples, concepts from an early or ‘index’ paper are compared with concepts from subsequent studies. However, there are methodological issues with using an index paper to begin analysis. One could argue that using an index paper is comparable to being constrained by a priori concepts. There is also the problem of how to decide which paper to use as an index paper. The chosen index paper can potentially have a dramatic effect on the resulting interpretation. How do we define a ‘classic’ paper? There is no consensus about what makes a study ‘good’,28,57 and suggested criteria for appraising quality vary considerably. 69 We also need to consider that we will not necessarily find the conceptually rich papers first. Qualitative analysis does not start when the full body of data is collected but continues alongside data collection; the process of searching and analysing is iterative. The decision to use an index paper may rest on the number of studies to be synthesised. We knew that this meta-ethnography would include a large number of studies and comparing concepts across studies from an index paper in this way was likely to be unwieldy.

All team members were given the full list of second-order constructs and asked to organise them, through constant comparison, into categories or ‘piles’ that shared meaning. Each team member wrote a description for each category or ‘pile’. This process of categorisation using constant comparison is integral to qualitative research. The team met to discuss their categories and definitions. We did not aim to reach consensus, but to collaboratively develop our interpretations over time. At team meetings members broke into separate groups and then regrouped to discuss findings. Conceptual categories were written up on a whiteboard and discussed. Although team members gave different labels to their categories, it became clear through discussion that there was an encouraging overlap in the definitions of categories. Table 1 gives the team categories for the MSK second-order constructs and illustrates the overlap in team categories. For example, the concept that later developed as ‘struggling to affirm self’ was labelled as ‘self and body’, ‘body in pain’, ‘body is alien’, ‘pain as alien’, ‘altered body’ and ‘body self’. If we found that second-order constructs did not ‘fit’ our developing conceptual categories, we went back to the original studies to challenge our interpretations and discussed the constructs within the group. We also went back to the original studies after the final model was developed to check for fit. If we still felt that a construct did not ‘fit’, we did not include it in the analysis.

| Conceptual categories for MSK | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| FT | JA | KB | KS | NA | EC |

| Health-care professionals The system Medication |

The medical system | Expectations of health-care professionals | The system Health-care professionals Medication |

Health care as barrier | Health-care professionals |

| Self and body I am not me Relationship to body |

Body in pain Perceptions of self |

Body is alien Mind body image esteem Normal vs. abnormal |

Pain as alien Altered body Loss of self Normalising |

Body self Dualism |

Striving to be normal Who am I – sense of self |

| Thinking about future | Challenges of pain | Hope vs. despair | Hope vs. resignation Unpredictability |

Unpredictability and fear emotions | Impediments (various) |

| Making sense of pain | Patient explanations for pain | Medical model | Cause and treatment medical model Make sense of pain |

Making sense of pain | |

| Negotiating reciprocity and capability | Impact on relationships | Community Family Communication |

Relationships Social disruption |

Relationships Dependence Social withdrawal Isolation |

|

| Proving credibility | Perceptions of others | Stigma Acceptance |

Proving credibility Moral narrative |

Lack of understanding Validation and representation |

|

| Work benefits | Dealing with benefits system | Work and benefits | Work Benefits |

Work | Work |

| Trusting myself – becoming expert | Community Pain management Road to accepting new self |

Acceptance and self-management | Being with others is supportive Do it despite pain Moving forward |

Being strong Competence Learning to cope |

Managing self and moving forward Living alongside pain |

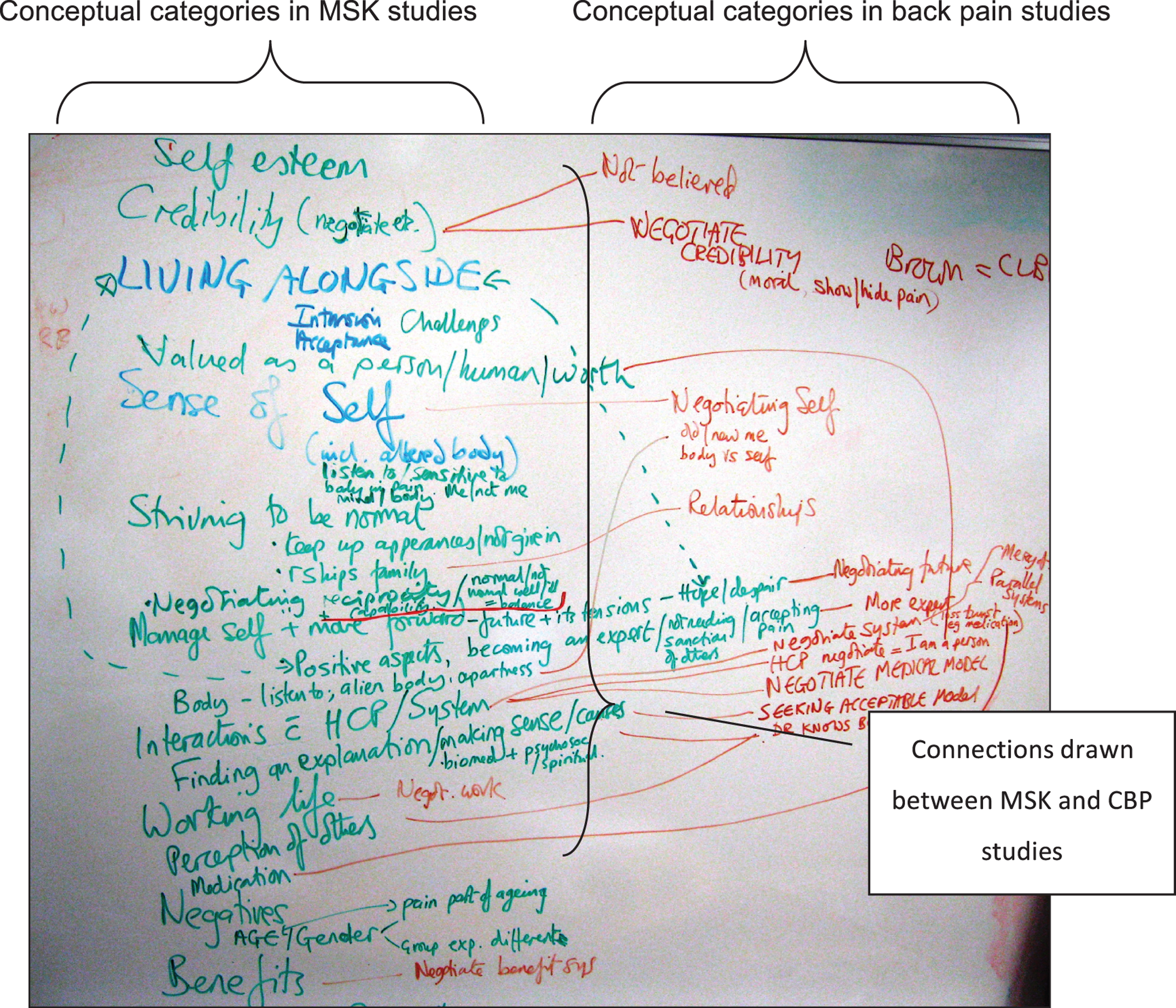

We kept the second-order constructs for fibromyalgia, chronic back pain (CBP) and all other MSK studies separate from each other so that we could explore any differences in conceptual categories between these groups. The process of categorising second-order constructs was repeated for MSK, fibromyalgia and CBP. After several team meetings we agreed to amalgamate MSK and CBP studies as the categories overlapped considerably. However, we decided to keep the fibromyalgia studies separate in the analysis as there were some differences in categorisation. Figure 5 shows how we compared and contrasted categories for MSK and CBP using a whiteboard. The same process was repeated for MSK and fibromyalgia.

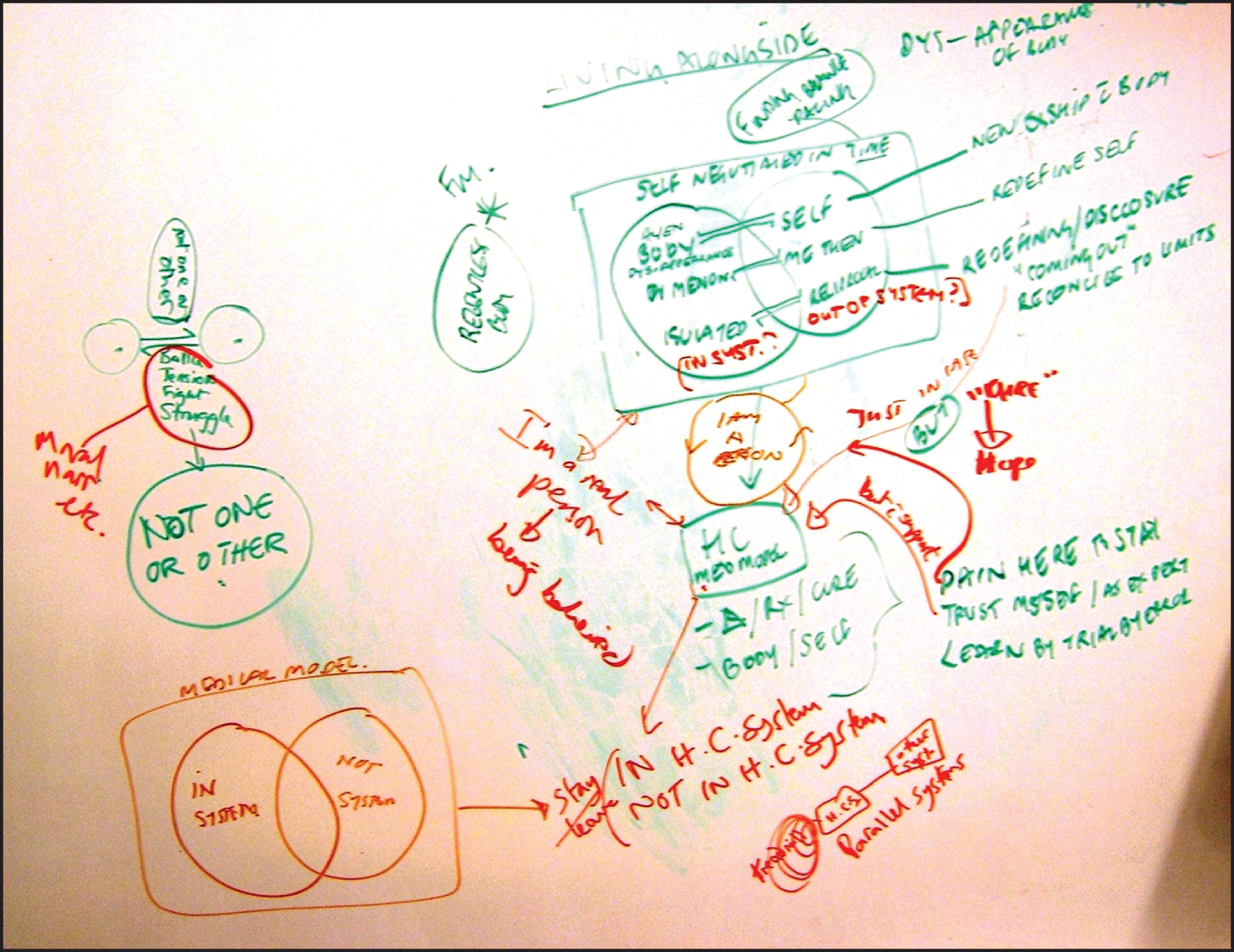

FIGURE 5.

Comparing the conceptual categories from CBP and MSK studies during team meetings using a whiteboard. This shows how the team compared categories that were developed from MSK and CBP second-order constructs. MSK categories are shown on the left and CBP categories are shown on the right. Connecting lines show links between categories.

Using NVivo 9 to assist analysis

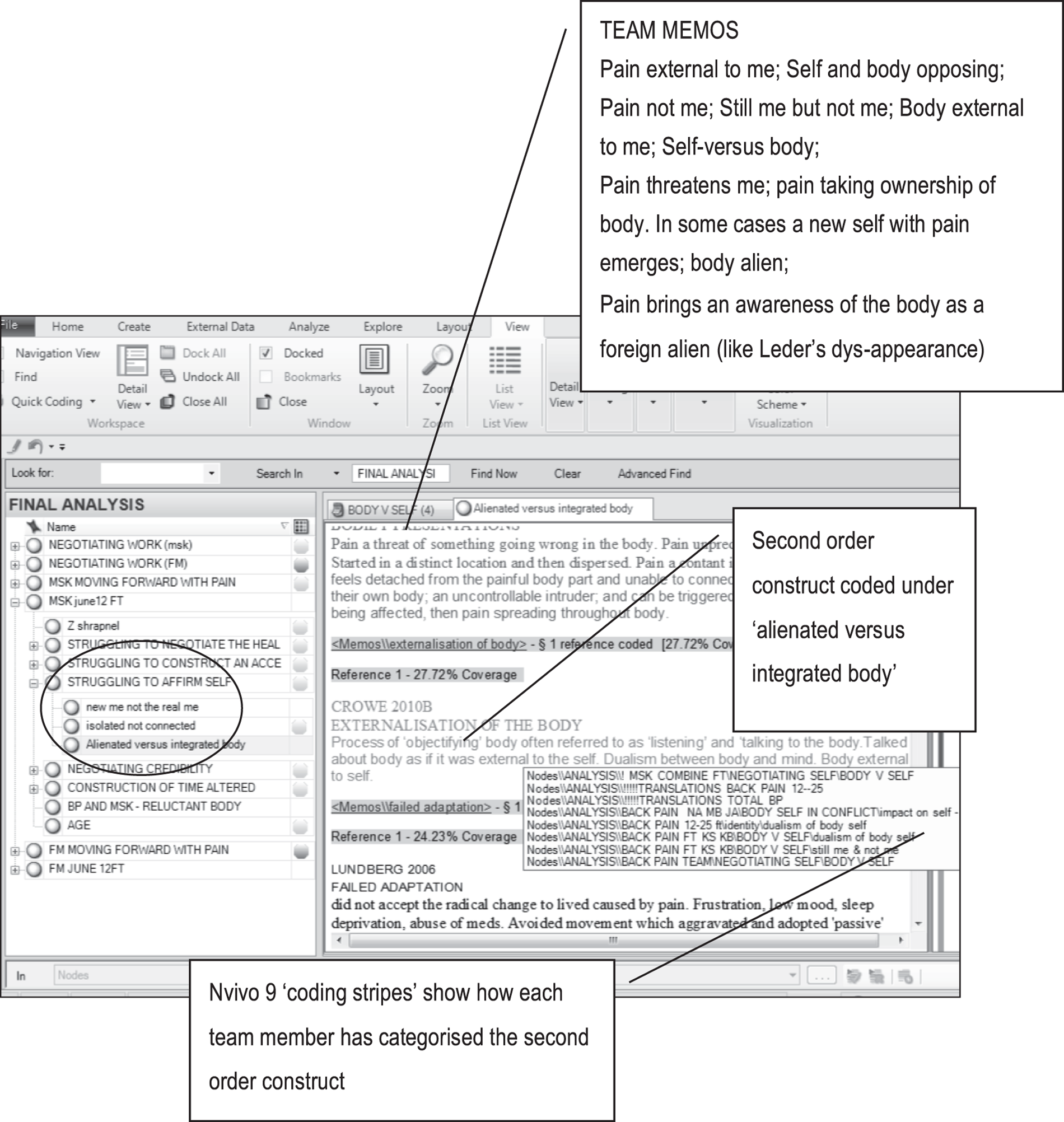

We combined the benefits of face-to-face team discussions with the benefits of using NVivo 9 software for qualitative analysis. NVivo is commonly used by qualitative researchers to assist analysis. However, not all qualitative researchers would choose to use computer software to organise their thoughts. We do not advocate a ‘right’ way of doing this, as it is a matter of personal preference. Some researchers prefer to use a more ‘hands-on’ approach with pen, paper and scissors; we also needed to consider that not all team or advisory group members had access to the computer software. Although NVivo 9 has the capacity to allow multiple researchers to simultaneously code onto a single database, we felt that because of the scale of the study this would be unwieldy, and therefore the principal investigator (FT) maintained and organised the NVivo 9 database. FT found it useful to code and organise the second-order constructs using NVivo 9. After each team meeting FT transferred the coding, categorising and supporting definitions and notes for each team member onto the NVivo 9 database (Figure 6). This allowed her to compare how each team member had categorised and defined conceptual categories and to return to the original article. Although the software has the capacity to produce models and graphics to support analysis, we found it more useful for team analysis to use a whiteboard when developing our conceptual models.

FIGURE 6.

Transferring team coding and team memos onto a NVivo 9 database. Published with permission from QSR International. The left screen shows the developing team categories for MSK second-order constructs. For example, the category ‘struggling to affirm self’ incorporates ‘new me not the real me’, ‘isolated not connected’ and ‘alienated vs. integrated body’. The right screen shows how NVivo 9 ‘coding stripes’ are used to identify how each team member has coded a particular second-order construct. In this example the construct ‘externalisation of the body’ has been coded by team members as ‘body vs. self’, ‘body–self in conflict’, ‘dualism of body–self’, ‘still me but not me’ and ‘negotiating body–self’. The team categories were brought together into the conceptual category ‘alienated vs. integrated body’.

6. Synthesising translations

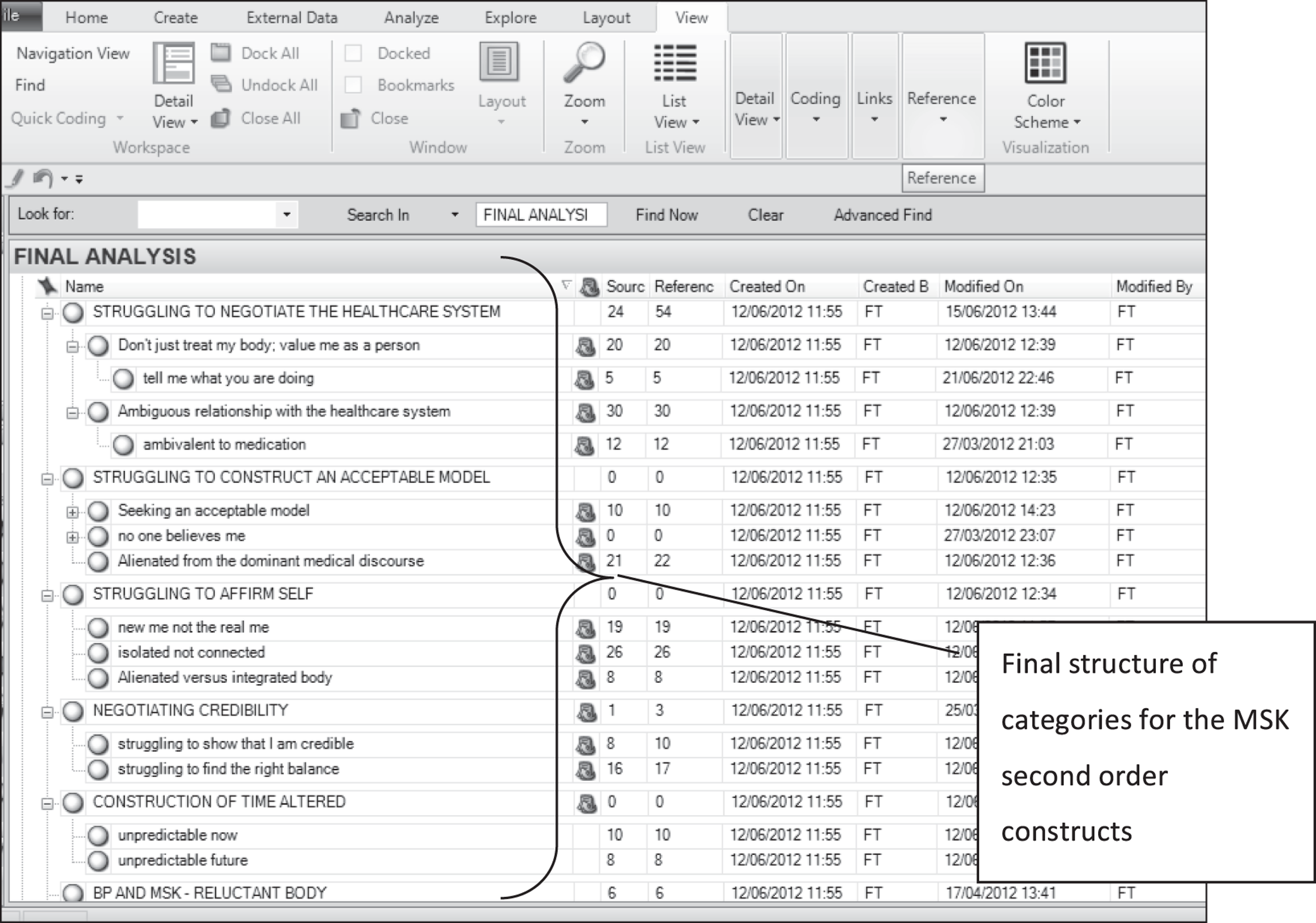

The next stage of meta-ethnography is to synthesise or make sense of the process of translation. Noblit and Hare20 suggest three genres of synthesis for meta-ethnography: (1) refutational (in which findings contradict each other), (2) reciprocal (in which findings are directly comparable) and (3) findings are taken together and interpreted as a line of argument. This third type of synthesis involves ‘making a whole into something more than the parts alone imply’ (p. 28). We intended to develop a line of argument synthesis. This is achieved by constantly comparing concepts and suggesting an interpretive order. In the words of Noblit and Hare:20 ‘We first translate the studies into one another. Then we develop a grounded theory that puts the similarities and differences between studies into interpretive order’ (p. 64).

Drawing on team discussions, and using NVivo 9 to continually compare concepts, categories and team memos, we developed a structure of categories that ‘made sense’ of the developing team analysis. Each team member then considered whether or not the structure reflected the discussions that had taken place. If a team member did not think that a particular second-order construct fit, we discussed this in meetings and made any necessary changes. Figure 7 shows how the final list of categories was developed using NVivo 9.

FIGURE 7.

Team coding structure for MSK using NVivo 9. Published with permission from QSR International. This illustrates the final structure of categories for the MSK second-order constructs on NVivo 9.

We found it useful to construct a diagram to develop and refine our line of argument. This diagram was developed collaboratively over time and was the focus for team discussions during this phase. Figure 8 illustrates the development of this model in team meetings using a whiteboard. Several amended versions of this diagram were created until we arrived at a model that reflected our final interpretation.

FIGURE 8.

Developing a line of argument using a whiteboard.

7. Expressing the synthesis

This phase concerns the dissemination of the research findings to maximise their impact.

Chapter 4 Results

Deciding what is relevant

Search and screening

The results of the systematic search are shown in Figure 9. We screened the full text of 321 potentially relevant studies and excluded 228 for the following reasons:

-

chronicity of pain was not explicit in the sample description82–122

-

did not explicitly state that it was specifically about MSK pain173–209

-

included perceptions of others such as family members, carers, clinicians210–243

-

did not meet the specific scope, for example explored perceptions of fatigue or exercise266–280

-

explored the experience of chronic disease rather than chronic pain. 281–295

FIGURE 9.

Results of the search strategy.

Ninety-three studies66,296–387 met the study scope and were appraised (see Figure 9).

Quality appraisal

Figure 10 shows that we appraised 93 studies and excluded 16,296–311 meaning that we included 77 studies66,312–387 in the meta-ethnography. There was a wide range in CASP scores between FT and JA, from –12 to 5. Table 2 shows the scores and ranks given to all papers appraised by the team.

FIGURE 10.

Results of quality appraisal by the team.

| Study | FT CASP score | FT rank | JA CASP score | JA rank | Difference in CASP score | Agree | Final decision |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aegler 2009312 | 26 | SAT | 25 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Allegreti 2010313 | 21 | SAT | 20 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Bair 2009314 | 22 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Campbell 2007315 | 23 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 1 | Yes | In |

| Campbell 2008316 | 25 | SAT | 23 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Cook 2000317 | 20 | SAT | 25 | SAT | – 5 | Yes | In |

| Coole 2010318 | 22 | SAT | 21 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Coole 2010319 | 24 | SAT | 22 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Coole 2010320 | 23 | SAT | 21 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Cooper 2009321 | 21 | SAT | 22 | SAT | – 1 | Yes | In |

| Cooper 2008322 | 21 | SAT | 23 | SAT | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Crowe 2010323 | 21 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 3 | Yes | In |

| De Vries 2011324 | 23 | SAT | 27 | KP | – 4 | Yes | In |

| Dickson 2003325 | 23 | SAT | 23 | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Dragesund 2008326 | 22 | SAT | 23 | SAT | – 1 | Yes | In |

| Gustaffson 2004327 | 23 | SAT | 23 | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Hallberg 1998328 | 22 | SAT | 20 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Hallberg 2000329 | 23 | SAT | 20 | SAT | 3 | Yes | In |

| Harding 2005330 | 25 | SAT | 25 | KP | 0 | Yes | In |

| Hunhammar 2009331 | 21 | SAT | 21a | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Johansson 1996332 | 23 | SAT | 21 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Johansson 1997333 | 20 | SAT | 21 | SAT | – 1 | Yes | In |

| Johansson 1999334 | 20 | SAT | 21 | SAT | – 1 | Yes | In |

| Lachapelle 2008335 | 24 | SAT | 22 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Liddle 2007336 | 22 | SAT | 27 | SAT | – 5 | Yes | In |

| Lofgren 2006337 | 21 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 3 | Yes | In |

| Lundberg 2007338 | 24 | SAT | 25a | SAT | – 1 | Yes | In |

| Madden 2006339 | 22 | SAT | 22 | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Mannerkorpi 1999340 | 22 | SAT | 22a | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Mengshoel 2004341 | 23 | KP | 25 | KP | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Osborn 1998342 | 28 | KP | 24 | KP | 4 | Yes | In |

| Osborn 2006343 | 25 | KP | 22 | SAT | 3 | Yes | In |

| Osborn 2008344 | 27 | SAT | 27a | KP | 0 | Yes | In |

| Patel 2007345 | 20 | SAT | 20 | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Paulson 2002346 | 26 | SAT | 27 | KP | – 1 | Yes | In |

| Paulson 2002347 | 20 | SAT | 23 | SAT | – 3 | Yes | In |

| Raheim 2006348 | 24 | SAT | 23 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Raymond 2000349 | 20 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 4 | Yes | In |

| Rhodes 1999350 | 20 | KP | 22 | KP | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Sallinen 2010351 | 22 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Sallinen 2011352 | 22 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Sanders 2002353 | 24 | KP | 23 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Satink 2004354 | 19b | SAT | 25 | SAT | – 6 | Yes | In |

| Skuladottir 2011355 | 20 | SAT | 22a | SAT | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Slade 2009356 | 21 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 3 | Yes | In |

| Slade 2009357 | 22 | SAT | 24 | SAT | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Smith 200766 | 28 | KP | 24 | KP | 4 | Yes | In |

| Snelgrove 2009358 | 25 | KP | 23 | KP | 2 | Yes | In |

| Soderberg 1999359 | 20 | SAT | 23 | SAT | – 3 | Yes | In |

| Soderberg 2001360 | 20 | SAT | 23 | SAT | – 3 | Yes | In |

| Sturge-Jacobs 2002361 | 22 | SAT | 24 | KP | – 2 | Yes | In |

| Teh 2009362 | 22 | SAT | 25 | SAT | – 3 | Yes | In |

| Toye 2010363 | 23 | SAT | 22 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Toye 2012364 | 23 | SAT | 22 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Toye 2012365 | 23 | SAT | 22 | SAT | 1 | Yes | In |

| Undeland 2007366 | 22 | SAT | 20 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Walker 1999367 | 22 | SAT | 26 | KP | – 4 | Yes | In |

| Walker 2006368 | 21 | SAT | 21 | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Werner 2003369 | 24 | KP | 22 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Werner 2003370 | 24 | KP | 22 | SAT | 2 | Yes | In |

| Werner 2004371 | 21 | KP | 21 | SAT | 0 | Yes | In |

| Afrell 2007372 | 19 | FF | 20 | SAT | – 1 | No | In |

| Arnold 2008373 | 18 | FF | 22 | SAT | – 4 | No | In |

| Crowe 2010374 | 18 | FF | 24 | SAT | – 6 | No | In |

| Cunningham 2006375 | 19 | FF | 20 | SAT | – 1 | No | In |

| De Souza 2011376 | 18 | FF | 23 | SAT | – 5 | No | In |

| Gullacksen 2004377 | 18 | FF | 19 | SAT | – 1 | No | In |

| Hellström 1999378 | 22 | SAT | 19 | FF | 3 | No | In |

| Holloway 2007379 | 22 | SAT | 17 | FF | 5 | No | In |

| Kelley 1997380 | 14 | FF | 18 | SAT | – 4 | No | In |

| Lempp 2009381 | 18 | FF | 21 | SAT | – 3 | No | In |

| Liedberg 2002382 | 18 | FF | 22 | SAT | – 4 | No | In |

| Paulson 2001383 | 18 | FF | 25 | SAT | – 7 | No | In |

| Schaefer 2005384 | 14 | FF | 22 | SAT | – 8 | No | In |

| Steen 2001385 | 18 | FF | 21 | SAT | – 3 | No | In |

| Strong 1994386 | 17 | FF | 23 | SAT | – 6 | No | In |

| Strong 1995387 | 17 | FF | 20 | SAT | – 3 | No | In |

| Busch 2005296 | 19 | FF | 19 | FF | 0 | Yes | Out |

| Chew 1997297 | 16 | FF | 19 | FF | – 3 | Yes | Out |

| De Souza 2007299 | 17 | FF | 19 | FF | – 2 | Yes | Out |

| Holloway 2000310 | 16b | FF | 14 | FF | 2 | Yes | Out |

| May 2000309 | 13 | FF | 19 | FF | – 6 | Yes | Out |

| Morone 2008301 | 17 | FF | 19 | FF | – 2 | Yes | Out |

| Silva 2011305 | 17b | FF | 19 | FF | – 2 | Yes | Out |

| Sokunbi 2010306 | 19 | FF | 19 | FF | 0 | Yes | Out |

| Cudney 2002298 | 18 | FF | 21a | SAT | – 3 | No | Out |

| Liedberg 2006300 | 19 | FF | 22 | SAT | – 3 | No | Out |

| Raak 2006302 | 16 | FF | 20 | SAT | – 4 | No | Out |

| Reid 1991303 | 16 | FF | 22 | KP | – 6 | No | Out |

| Schaefer 1995304 | 12 | FF | 24 | SAT | – 12 | No | Out |

| Schaefer 1997311 | 17 | FF | 20 | SAT | – 3 | No | Out |

| Tavafian 2008307 | 14b | FF | 20 | SAT | – 6 | No | Out |

| Wade 2003308 | 18 | FF | 25 | SAT | – 7 | No | Out |

Following study appraisal, FT and JA agreed on 69 of the 93 studies (61 included, eight excluded). We did not use a cut-off score for inclusion. FT and JA did not agree on 24 studies and these were sent to be appraised by two other members of the team (16 included, eight excluded). Table 3 shows the percentage agreement between FT and JA for each method of appraisal. Agreement between FT and JA ranged from 52% to 74% for the CASP questions and from 29% to 82% for the JBI-QARI questions. Agreement for the rankings ‘fatally flawed’, ‘satisfactory’ or ‘key paper’ was 62%. The median (range) scores for papers rated as ‘fatally flawed’, ‘satisfactory’ and ‘key paper’ are shown in Table 4. FT and JA agreed that five studies were key papers; FT graded a further five as key papers and JA graded a further seven as key papers (Table 5). Because of this low level of agreement, the category ‘key paper’ was not useful for the purpose of analysis. Although we had discussed the possibility of performing a form of ‘sensitivity analysis’ to determine whether or not our findings were altered if we included only key papers, lack of agreement over what a key paper was made this impossible; we also could not use the other scores to determine any particular level of evidence.

| Appraisal tool questions | % agreement between reviewers 1 and 2 |

|---|---|

| CASP 1 | 59 |

| CASP 2 | 74 |

| CASP 3 | 52 |

| CASP 4 | 57 |

| CASP 5 | 65 |

| CASP 6 | 67 |

| CASP 7 | 52 |

| CASP 8 | 60 |

| CASP 9 | 63 |

| CASP 10 | 55 |

| FF, SAT, KP ranking | 62 |

| JBI-QARI 1 | 50 |

| JBI-QARI 2 | 78 |

| JBI-QARI 3 | 82 |

| JBI-QARI 4 | 61 |

| JBI-QARI 5 | 57 |

| JBI-QARI 6 | 61 |

| JBI-QARI 7 | 29 |

| JBI-QARI 8 | 42 |

| JBI-QARI 9 | 66 |

| JBI-QARI 10 | 60 |

| JBI-QARI final decision | 74 |

| Rating | FT | JA |

|---|---|---|

| Fatally flawed | 17 (12–19) | 18 (14–19) |

| Satisfactory | 22 (19–27) | 22 (18–27) |

| Key paper | 24 (20–28) | 25 (22–27) |

Included studies

We included 77 papers in the meta-ethnography reporting 60 individual qualitative studies. The studies that produced more than one paper are indicated in Tables 6 and 7. Forty-nine papers (37 individual studies) explored the experience of people with chronic MSK pain. 66,312,323,325,326,330–334,336,338,342–345,350,353–358,362–365,367,372,374,376,379,385–387 Twenty-eight papers (23 individual studies) explored the experience of people with fibromyalgia. 324,327–329,335,337,339–341,346,349,351,352,359–361,366,373,375,377,378,380–384 A description of these studies is provided in Tables 6 and 7, showing for each study the age range and source of participants, the country where the study was carried out, the method of data collection and the methodology used.

| Study | Age range (years) | Source of participants | Condition | Country | n | Male, n | Data collection | Methodologya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Aegler 2009312 | 29–61 | PMP | MSK | Switzerland | 8 | 3 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Afrell 2007372 | 30–72 | PC, PMP, pain clinic | MSK | Sweden | 20 | 7 | Semistructured interviews | Phenomenology |

| Allegreti 2010313 | 28–72 | PC | CBP | USA | 23 | 12 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Bair 2009314 | 27–84 | RCT | MSK | USA | 18 | 7 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis |

| Campbell 2007315 | 34–78 | PMP | CBP | UK | 16 | NK | Focus groups | Thematic analysis |

| Campbell 2008316 | 36–66 | Non-service users | MSK | UK | 12 | 3 | Interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Cook 2000317 | 22–63 | Back pain rehab | CBP | UK | 7 | 3 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bCoole 2010318 | 22–58 | Back pain rehab | CBP | UK | 25 | 12 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bCoole 2010319 | 22–58 | Back pain rehab | CBP | UK | 25 | 12 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bCoole 2010320 | 22–58 | Back pain rehab | CBP | UK | 25 | 12 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bCooper 2009321 | 18–65 | PT | CBP | UK | 25 | 5 | Semistructured interviews | Framework analysis |

| bCooper 2008322 | 18–65 | PT | CBP | UK | 25 | 5 | Semistructured interviews | Framework analysis |

| bCrowe 2010374 | 25–80 | Adverts and PT | CBP | New Zealand | 64 | 33 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bCrowe 2010323 | 25–80 | Adverts | CBP | UK | 64 | 33 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| De Souza 2011376 | 27–79 | Rheumatology | CBP | UK | 11 | 5 | Unstructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Dickson 2003325 | 63–80 | PC | MSK | USA | 7 | 0 | Interviews and observation | Thematic analysis |

| Dragesund 2008326 | 26–68 | PT | MSK | Norway | 13 | 5 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis |

| Harding 2005330 | 29–71 | PMP | MSK | UK | 15 | 3 | In-depth interviews | Framework analysis |

| Holloway 2007379 | 28–62 | pain clinic | CBP | UK | 18 | 12 | Semistructured interviews | IPA |

| Hunhammar 2009331 | 19–58 | PC | MSK | Sweden | 15 | 6 | In-depth interviews | Grounded theory |

| bJohansson 1996332 | 21–60 | PC | MSK | Sweden | 20 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| bJohansson 1997333 | 21–60 | PC | MSK | Sweden | 20 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| bJohansson 1999334 | 21–60 | PC | MSK | Sweden | 20 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| Liddle 2007336 | 20–65 | University | CBP | Northern Ireland | 18 | 4 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis |

| Lundberg 2007338 | 30–64 | PT | MSK | Sweden | 10 | 5 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| Osborn 1998342 | 25–55 | Back pain rehab | CBP | UK | 9 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | IPA |

| bOsborn 2006343 | 36–52 | Pain clinic | CBP | UK | 6 | 4 | Semistructured interviews | IPA |

| Osborn 2008344 | 36–52 | Pain clinic | CBP | UK | 10 | 5 | Semistructured interviews | IPA |

| Patel 2007345 | 29–62 | Benefits office | MSK | UK | 38 | 15 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Rhodes 1999350 | 25–65 | Health-care plan | CBP | USA | 54 | 20 | In-depth interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Sanders 2002353 | 51–91 | Survey | MSK | UK | 27 | 10 | In-depth interviews | Grounded theory |

| Satink 2004354 | 42–70 | PMP | CBP | Netherlands | 7 | 3 | Narrative interview | Phenomenology |

| Skuladottir 2011355 | 35–55 | Adverts | MSK | Iceland | 5 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Grounded theory |

| bSlade 2009356 | 26–64 | Adverts and university | CBP | Australia | 18 | 2 | Focus groups | Grounded theory |

| bSlade 2009357 | 26–65 | Adverts and university | CBP | Australia | 18 | 2 | Focus groups | Grounded theory |

| bSmith 200766 | 36–52 | Pain clinic | CBP | UK | 6 | 4 | Semistructured interviews | IPA |

| Snelgrove 2009358 | 39–66 | Pain clinic | CBP | UK | 10 | 3 | Semistructured interviews | IPA |

| Steen 2001385 | Adults | RCT | MSK | Norway | 48 | NK | Semistructured interviews | Phenomenology |

| Strong 1994386 | 30–75 | Adverts | CBP | Australia | 7 | 3 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis |

| Strong 1995387 | 30–75 | Adverts | CBP | New Zealand | 15 | 4 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis |

| Teh 2009362 | 63–86 | Pain clinic | CBP | USA | 15 | 5 | In-depth interviews | Grounded theory |

| bToye 2010363 | 29–67 | PMP | CBP | UK | 20 | 7 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| bToye 2012364 | 29–67 | PMP | CBP | UK | 20 | 7 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| bToye 2012365 | 29–67 | PMP | CBP | UK | 20 | 7 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| bWalker 1999367 | 28–80 | Pain clinic | CBP | UK | 20 | 12 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| bWalker 2006368 | 28–80 | Pain clinic | CBP | UK | 20 | 12 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| bWerner 2003369 | 26–58 | PC and PMP | MSK | Norway | 10 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| bWerner 2004371 | 26–58 | PC and PMP | MSK | Norway | 10 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| Werner 2003370 | 31–53 | PMP | MSK | Norway | 6 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| Study | Age range (years) | Source of participants | Condition | Country | n | Male, n | Data collection | Methodologya |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Arnold 2008373 | 31–72 | Rheumatology | FM | USA | 48 | 0 | Focus groups | Grounded theory |

| Cunningham 2006375 | 30–70 | University | FM | Canada | 8 | 1 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bHallberg 1998328 | 22–60 | Insurance hospital | FM | Sweden | 22 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| bHallberg 2000329 | 22–60 | Insurance hospital | FM | Sweden | 22 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| Hellström 1999378 | 32–50 | FM group | FM | Sweden | 10 | 1 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| Kelley 1997380 | Mean 50 | PMP | FM | USA | 22 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Narrative analysis |

| Lempp 2009381 | 20–69 | Rheumatology | FM | UK | 12 | 1 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Liedberg 2002382 | 26–64 | Questionnaire survey | FM | Sweden | 39 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Lofgren 2006337 | 30–63 | PMP | FM | Sweden | 12 | 0 | Diaries, focus groups, interviews | Grounded theory |

| Madden 2006339 | 25–55 | Hospital databases | FM | UK | 17 | 1 | Semistructured interviews | Induction/abduction |

| Mannerkorpi 1999340 | 29–59 | FM group | FM | Sweden | 11 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| Mengshoel 2004341 | 37–49 | PMP | FM | Norway | 5 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bPaulson 2001383 | 41–56 | Rheumatology | FM | Sweden | 14 | 14 | Narrative interviews | Phenomenology |

| bPaulson 2002346 | 41–56 | Rheumatology | FM | Sweden | 14 | 14 | Narrative interviews | Phenomenology |

| bPaulson 2002347 | 41–56 | Rheumatology | FM | Sweden | 14 | 14 | Narrative interviews | Phenomenology |

| Raheim 2006348 | 34–51 | PC, PT, FM group | FM | Norway | 12 | 0 | Life-form interviews | Phenomenology |

| Raymond 2000349 | 38–47 | FM association | FM | Canada | 7 | 1 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bSallinen 2010351 | 34–65 | PMP | FM | Finland | 20 | 0 | Narrative interviews | Thematic analysis |

| bSallinen 2011352 | 34–65 | PMP | FM | Finland | 20 | 0 | Narrative interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Schaefer 2005384 | 37–59 | Adverts | FM | USA | 10 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| bSoderberg 1999359 | 35–50 | Rheumatology | FM | Sweden | 14 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| bSoderberg 2001360 | 35–60 | Rheumatology | FM | Sweden | 25 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Sturge-Jacobs 2002361 | 20–57 | PMP | FM | Canada | 9 | 0 | Unstructured interviews | Phenomenology |

| Undeland 2007366 | 42–67 | FM group | FM | Norway | 11 | 0 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis |

| De Vries 2011324 | 31–60 | Adverts and FM website | FM and MSK | Netherlands | 21 | 9 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis |

| Gullacksen 2004377 | 23–55 | PMP | FM and MSK | Sweden | 18 | 0 | In-depth interviews | Phenomenology |

| Gustaffson 2004327 | 23–59 | Pain management | FM and MSK | Sweden | 18 | 0 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory |

| Lachapelle 2008335 | 23–75 | Adverts | FM and MSK | Canada | 45 | 0 | Ethnography and focus groups | Ethnography |

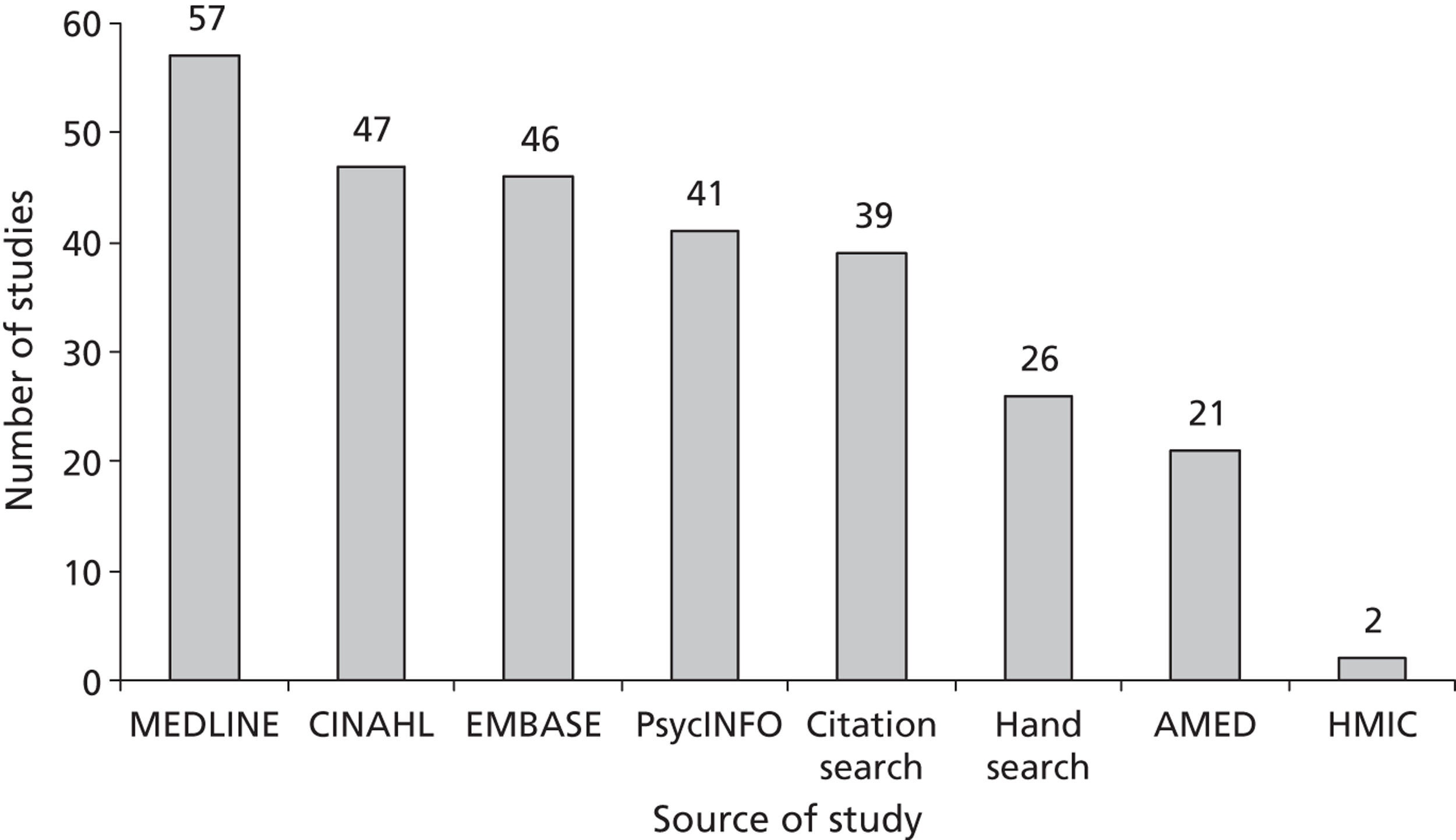

Figure 11 shows the sources of the included studies. In total, 74% of the included studies (n = 57) were identified from MEDLINE and 95% of the studies (n = 73) were identified by combining MEDLINE, CINAHL and PsycINFO. EMBASE and AMED added only one additional study each and HMIC added no extra studies. Hand-searching and citation searching added three additional studies. Included studies came from 40 different journals (Table 8). The highest contributors were Disability and Rehabilitation (7), Scandinavian Journal of Caring Sciences (7), Social Science & Medicine (5) and Qualitative Health Research (5).

FIGURE 11.

Sources of included studies.

| Journal | Papers, n |

|---|---|

|

|

Determining how studies are related

A glossary of all of the collaborative interpretations of each second-order construct is given in Appendix 3. These represent the raw data of our meta-ethnography.

Table 9 shows findings that were not included in the meta-ethnography because the team agreed that they were ‘untranslatable’. In other words, we felt that there was no central idea that pulled together the original findings. We did not attempt to reorganise these findings to include them in our analysis.

| Study | Author descriptor of theme used in primary study |

|---|---|

| Allegretti 2010313 | Convergence with physician |

| Arnold 2008373 | Other |

| Bair 2009314 | Barriers to self-management – ‘other’ |

| Cook 2000317 | Cognitive perceptual factors |

| Cook 2000317 | Patient experiences |

| Cook 2000317 | Quality of life |

| Cook 2000317 | Relationship with health-care professional |

| Cook 2000317 | Experience of active rehabilitation |

| Coole 2010320 | Assistance from employer |

| Coole 2010320 | Fewer options if working alone |

| Coole 2010320 | Pros and cons of working for oneself |

| Cooper 2009321 | Not self-managing, awaiting further investigation |

| Crowe 2010323 | Low-impact exercise |

| Cunningham 2006375 | Ongoing process of managing fibromyalgia |

| De Souza 2011376 | Friends and family |

| Dragesund 2008326 | Associations about body |

| Dragesund 2008326 | Aware of body |

| Dragesund 2008326 | Feeling for the body |

| Hallberg 2000329 | Diverse pain coping |

| Hallberg 2000329 | Subjective pain language |

| Kelley 1997380 | Depression |

| Kelley 1997380 | Feeling good |

| Kelley 1997380 | Needs |

| Lachapelle 2008335 | It could be worse |

| Lachapelle 2008335 | Realising no cure |

| Lachapelle 2008335 | Receiving a diagnosis |

| Lempp 2009381 | Life before and after diagnosis |

| Liddle 2007336 | Effect on individual |

| Liddle 2007336 | Limitations to recovery |

| Liddle 2007336 | Physiotherapy recommendations |

| Patel 2007345 | Painful condition |

| Schaefer 2005384 | Coming to grips and making changes |

| Schaefer 2005384 | Managing symptoms |

| Slade 2009357 | Participant suggestions |

| Snelgrove 2009358 | Painful body and self |

| Snelgrove 2009358 | Physical coping strategies |

| Strong 1994386 | Domestic |

| Strong 1994386 | Mobility |

| Strong 1994386 | Negative emotions |

| Strong 1994386 | Positive emotions |

| Strong 1994386 | Relationships |

| Strong 1994386 | Treatment |

| Strong 1995387 | What do you do when in pain |

| Teh 2009362 | Involved in quality of care |

| Walker 1999367 | Challenging the medical model |

Translating studies into each other: developing the conceptual categories

This section describes the team’s final conceptual categories, illustrated by examples of second-order constructs. We have chosen particular second-order constructs to illustrate our conceptual categories in the same way that primary qualitative research studies use narratives as exemplars of concepts or themes. The second-order constructs supporting each conceptual category are presented in Appendix 4. These tables show the team memos describing each category. Table 10 shows an example of the team memos and second-order constructs supporting one conceptual category (‘alienated vs. integrated body’).

| Team memos: pain external to me; self and body opposing; pain not me; still me but not me; body external to me; self vs. body; pain threatens me; pain taking ownership of body; in some cases a new self with pain emerges; body alien; pain brings an awareness of the body as a foreign alien (like Leder’s dys-appearance of body388) | |

| MSK | Fibromyalgia |

|---|---|

| Osborn 2008:344

fearfulness of pain Rhodes 1999:350 anatomical body Johansson 1999:334 bodily presentations Crowe 2010:323 externalisation of the body Lundberg 2007:338 failed adaptation Osborn 2006:343 living with body separate from self Snelgrove 2009:358 crucial nature of pain – body/self/pain as a threat Afrell 2007:372 acceptance typologies – rejecting the body |

Raheim 2006:348

theoretical interpretation – lived body Raheim 2006:348 typologies – powerlessness Paulson 2002:346 body as obstruction – reluctant body Sturge-Jacobs 2002:361 thinking in a fog Raheim 2006:348 typologies – coping |

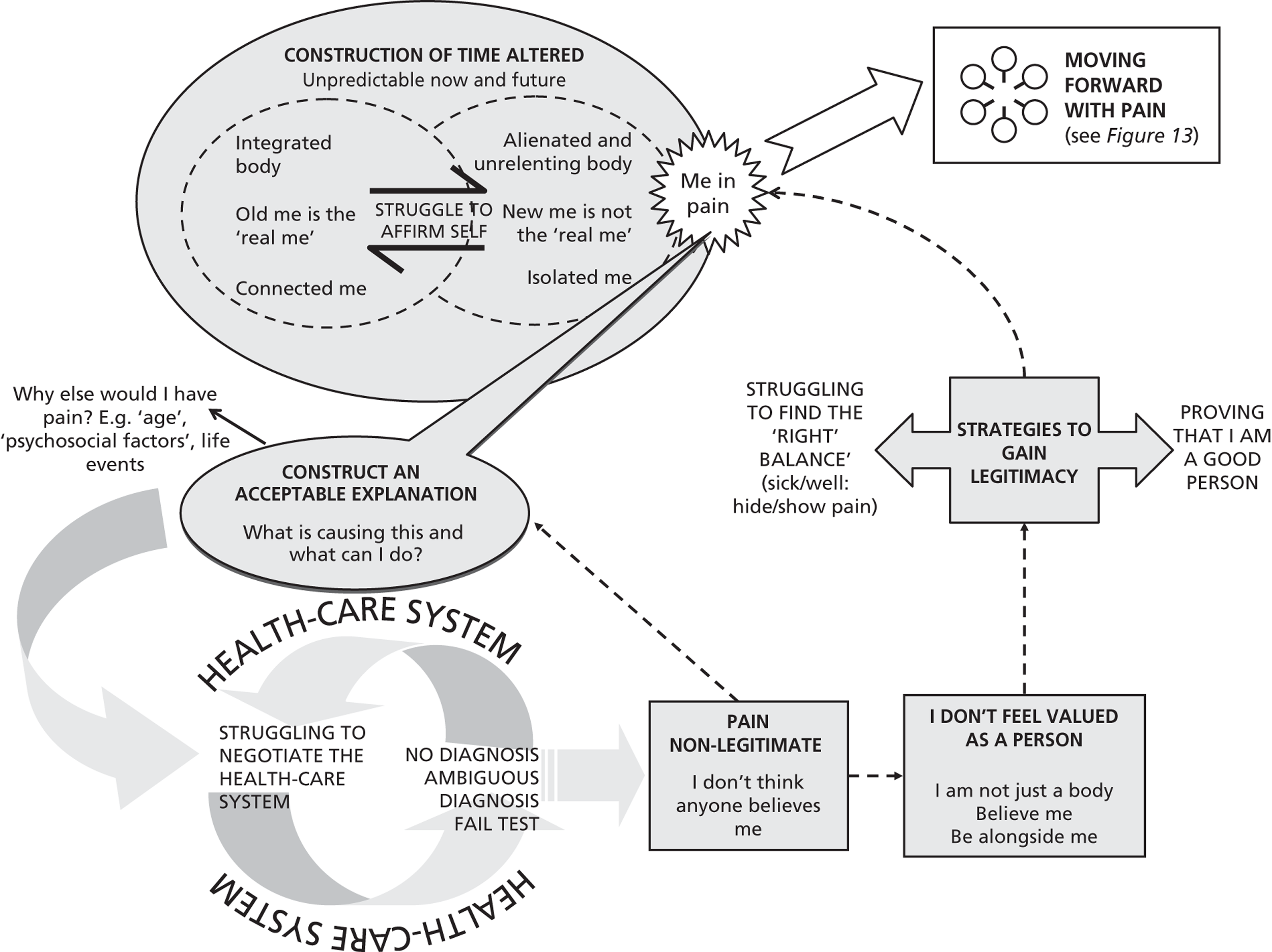

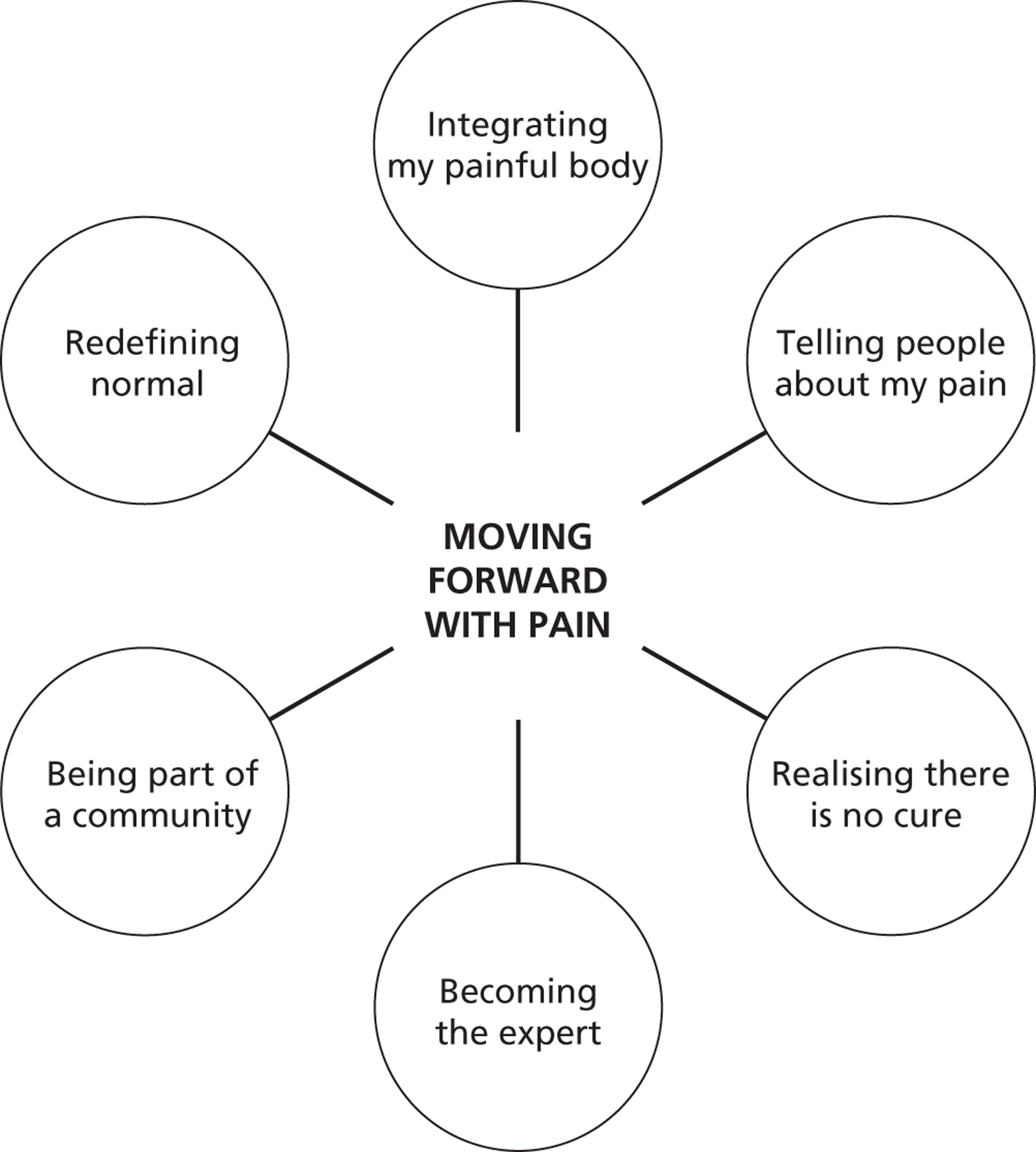

Fundamental to the patients’ experience of chronic MSK pain is a constant struggle: (1) struggle to affirm myself; (2) struggle to reconstruct myself in time; (3) struggle to construct an explanation for suffering; (4) struggle to negotiate the health-care system; and (5) struggle to prove legitimacy. The over-riding theme of these categories is adversarial, giving a sense of being guilty until proven innocent. However, in spite of this constant struggle there is also a sense of (6) moving forward alongside my pain. We discuss differences in category descriptions for fibromyalgia and MSK studies throughout the following sections.

1. Struggling to affirm myself

The category ‘struggling to affirm myself’ describes a struggle to hold on to the ‘real self’, which is threatened by continuing pain. It incorporates three concepts: (a) alienated versus integrated body, (b) the ‘new me’ is not the ‘real me’ and (c) isolated not connected me.

1(a) Alienated versus integrated body

The alienated body describes how a person with chronic pain experiences a fragmentation of body and self. Chronic pain makes a person become aware of their body when before they were not. Body and self are no longer integrated, and the painful body becomes it, as opposed to me. Pain takes ownership of the body and is experienced as a malevolent presence. 343 Crowe and colleagues323 describe this as the ‘externalisation of the body’, in which self and body come apart and the body becomes external to the self.

Second-order construct: Osborn and Smith 2006:343 living with body separate from self

Pain has made me aware of my body now. Separation of painful body from self. Self and body opposing entities. Painful part not me. Unpleasant and relentless presence of a body that is ‘not me’. Living with pain affects who I am [self]. New body alien. I feel powerless against an alien body. Dysfunctional part of body not me. Distinction made between the original self and that self which had emerged due to pain.

Paulson and colleagues346 describe the body in pain as ‘a reluctant body’ that is unresponsive to the demands of meaningful participation. This altered relationship with the body, if antagonistic, can make a person feel ‘homeless’ in his or her own body.

Second-order construct: Raheim 2006:348 theoretical interpretation – lived body

Participants describe dualism of body in pain with a distinction between self and body. No longer unconscious of the body but more aware of it, while paradoxically feeling ‘homeless in one’s own body’, and wanting to escape from it. Some do not report feelings of disintegration, but rather view the body in pain as a ‘problematic friend’ with which they can cope. Dialogue between self and body is either positive or negative: (a) impossible enemy – antagonistic (parasitic) dualism; homeless in body, (b) friendly dialogue – symbiotic dualism; at home in my body

Negotiating an unrelenting body

The category ‘unrelenting body’ is linked to the change in the way that the person experiences his or her own body. This category developed from the fibromyalgia studies. The unrelenting body overwhelms and drains a person’s resources. This concept includes second-order constructs that describe the tangible bodily presence of chronic pain and its wide-reaching effects. Chronic pain is physically ‘agonising’ and its impact goes beyond the physical body to become emotionally unrelenting. The concept describes the powerlessness of the person in pain against an unrelenting body.

Second-order construct: Lachapelle 2008:335 barriers to acceptance – unrelenting pain and fatigue

Unrelenting pain and fatigue – women drained of physical and emotional resources.

Second-order construct: Lempp 2009:381 change in health identity

Illness became increasingly intrusive in life and began to undermine their confidence and sense of self. Self-esteem undermined. Fear of not being able to rely on body and the unpredictability of the illness.

Integral to the unrelenting bodily experience of fibromyalgia pain is an engulfing and insurmountable fatigue.

Second-order construct: Sturge-Jacobs 2002:361 fatigue invisible foe

Fatigue engulfing, insurmountable and overwhelming, insidious, unseen and uncontrollable. Affects all aspects of life. Activities had to be avoided or prioritised. Fear of becoming a burden on friends and family (i.e. non-reciprocal relationships). Always receiving help and not giving.

Fibromyalgia studies also describe the cognitive effects of unrelenting pain, a ‘fibro-fog’. Living in this fog a person becomes forgetful, lacks motivation and finds it difficult to focus or to articulate his or her thoughts. 373

Second-order construct: Sturge-Jacobs 2002:361 thinking in a fog

Brain ‘in a fog’; unable to concentrate or think clearly. Difficulties with problem solving, abstract thinking, and the inability to make appropriate judgement calls or on-the-spot decisions were areas of concern for all participants. Mind and body ‘constantly at odds’. Sense of being in a dark place. Could affect ability to continue meaningful employment.

As we were surprised not to find this concept developed in the MSK papers, we searched for second-order constructs that supported this category in the MSK papers and found only three papers. 331,358,368 In short, there was more focus on the experience of the body in pain in fibromyalgia studies.

1(b) ‘New me’ not the ‘real me’

This describes the discrepancy and ensuing struggle between a past ‘real me’ and a present ‘not real me’ with pain. A person in pain struggles to balance this deficit and to prevent the erosion of the real self. The new me is described as ‘not real’ and the old me as ‘real’. There is now a chasm between what other people think that I am (the new me in pain) and what I think I am (the past me). In this way Osborn and Smith342 describe how a person compares their self now with a past self. A person in pain looks back nostalgically to the ‘real me’ of the past.

Second-order construct: Osborn and Smith 1998:342 comparing this self with other selves

Compared self with others and past/future self.

a. I am not like the old me who was fit and able to work hard. Some defined themselves as bereaved. Grieved for the old self. I am not my happy previous self – look back nostalgically. Painful reminder of loss. Past self considered to represent the real self replaced by new false persona. Pain denies me my right to be me.

b. Fear what future will bring. Feelings of uncertainty.