Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/2001/21. The contractual start date was in November 2010. The final report began editorial review in October 2012 and was accepted for publication in May 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Stephen T Green is a NHS consultant and director of QHA Trent. QHA Trent is a British company delivering accreditation and consultancy services for hospitals and clinics located internationally.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Lunt et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Section 1 Background

Chapter 1 Introduction

This study explores the role and impact of medical tourism, defined here as travel by patients to non-local providers incurring out-of-pocket and third-party payments for medical treatments but excluding state-funded cross-border care available under the European Union (EU) directive. 1 Our focus is on both inward and outward flows of medical tourists seeking treatments to and from the UK. The study examines the implications of medical tourism for the NHS across a range of specialties and services including dentistry, bariatric surgery, fertility services and cosmetic surgery. The multidisciplinary research team worked across four analytical streams of activity to examine:

-

consumerism and patient decision-making

-

quality, safety and risk (including in the clinical context)

-

economic implications

-

medical tourism provider and market development.

Beyond anecdotal reports and media speculation, relatively little is known about the implications for the NHS of inward or outward out-of-pocket medical tourism. This is despite an estimated 50,000 UK patients travelling overseas for treatment annually2 and significant numbers of overseas patients using UK NHS private and independent sector facilities. The study sought to understand these flows in greater detail and to explore the opportunities and risks. The study provides insights for NHS policy-makers, managers, regulators, commissioners, providers, clinicians and consumer interest groups. The study contributes to a better understanding of macro and local factors: costs; quality and safety; administrative and legal dimensions; decision-making; and unintended and unforeseen consequences for the NHS of inward and outward medical tourists.

Background

The impact of globalisation in health and health care has paralleled emerging trends towards increased reliance on individualised health-care provision and ‘consumer’-led access to ‘health-related’ information. Wider system developments include the growth of the cross-border supply of health-related goods and services, greater overseas investment in domestic provision and increased movement of professionals and health providers, as well as trends towards consumption of health care abroad and discounted travel incentives included as part of medical assessment and treatment packages. 3–8 One increasingly popular form of consumer expenditure is what has become commonly known as ‘medical tourism’, a type of patient or ‘consumer’ mobility in which individuals travel outside their country of residence for the consumption of health-care services abroad. 9

Medical tourism takes place when individuals opt to travel overseas with the primary intention of receiving medical (usually elective surgery) treatment. These journeys may be long distance and intercontinental, for example from Europe and North America to Asia, and cover a range of treatments including dental care, cosmetic surgery, bariatric surgery and fertility treatment. 10–12 Some speculate that medical tourism is a US$60B industry internationally. 13

A medical tourist may be defined in two ways depending on the type of health system and how it is funded. First, there are medical tourists who can be categorised as ‘consumers’ because they use purchasing power expressed through the market to access a range of dental, cosmetic and elective medical treatment. There are related questions about access to insurance, the portability of insurance and whether or not voluntary insurance systems extend to the choice of overseas services. Within the USA, for example, several domestic private insurers have looked towards purchasing services overseas. In addition, there are increasing numbers of underinsured consumers who need to pay out of pocket for treatments. 14–17

Second, at a European level, medical tourism may involve exercising citizenship rights to receive medical treatment in another EU member state (better known as cross-border care) and request their national purchaser to reimburse the cost of treatment (see European Court of Justice judgments18–20). The European Parliament and the Council of Ministers formally adopted the patients’ rights to cross-border health care directive1 in March 2011 in an attempt to codify development and clarify the situation for EU citizens (see Appendix 1).

However, although current knowledge of the demand and supply of cross-border health care is growing at European and national levels,21–24 there are no comprehensive data on inward and outward out-of-pocket and third party-funded flows (including government-sponsored) and their health and economic impact. 8 This study therefore contributes to further understanding of patient mobility and its implications for the NHS. 7,25,26 The study was particularly timely given the current global financial context and the likely implications for health expenditure and national health budgets,27,28 and also attempts to encourage NHS institutions to be more outward looking through the launch of NHS Global in 2010:29

While there are already strong examples of NHS Trusts and organisations successfully sharing their ideas and products abroad, we want to create a more systematic approach to this work, and in doing so bring benefits back to the NHS and the UK taxpayer . . . It is now more important than ever to maximise the international potential of the NHS.

NHS foundation trusts will also have more opportunity to undertake international activities should they wish to, including treating international patients (as inward medical travellers are known). Under the 2012 Health and Social Care Act30 the pre-existing cap on non-NHS income, which varied across foundation trusts, was increased. This allowed all foundation trusts to earn 49% of income from non-NHS work, including international patient activity within private activities (in force from 1 October 2012).

How the increase in private activity impacts on the NHS and its patients is not clear and is dependent on whether or not the particular foundation trust is operating close to capacity and whether additional capacity is generated to treat private patients or existing capacity is used. 31 NHS patients may receive benefits if new or enhanced facilities are shared between private and NHS patients. However, if private patients are of greater priority there will – all things unchanged – be a growth in waiting lists and waiting times for NHS patients (Section B155–B156). 31 There is currently no evidence to judge whether or not this will be the case.

A number of factors have possibly contributed towards the growth in outward medical tourism. These include improved disposable incomes, increased willingness of individuals to travel for health services, lower-cost air travel and the expansion of internet marketing – which is a major platform of information for those seeking and providing such treatments. Why do patients choose to travel overseas for treatments when evidence suggests that most patients prefer to be treated closer to home?32,33 Before this research was conducted, purported reasons to travel were said to include cost (e.g. dentistry), availability of treatment, privacy, perceived quality and for the purposes of combining treatment with an overseas vacation (especially for diaspora populations). For instance, UK patients may have to wait to meet NHS criteria on age or circumstance before being offered some treatments, or may be ineligible according to the current criteria [e.g. in vitro fertilisation (IVF), gender reassignment surgery, renal transplantation], and private treatment in the UK may be costly and not offer the range of preferred techniques and technology. Conversely, the reputation of private providers in the UK, and the perceived or actual quality of care in many countries, mean that in some areas of medical activity there is a desire for foreign nationals to seek treatment in the UK. Having completed the project, the evidence about decision-making and drivers is now on a far firmer footing.

Currently, medical tourism for the UK is limited to the private, out-of-pocket sector. However, there are important implications for a publicly funded and provided system such as the NHS. For instance, there may be a range of beneficial and detrimental consequences, such as cost savings from those voluntarily seeking care abroad, costs of follow-up care for those who have been treated overseas, and costs and benefits associated with patients travelling into the UK for paid treatments. There will also be a range of associated health impacts.

Research objectives

Media reports and speculation notwithstanding, we knew little about the historical and likely future development and impact of medical tourism for the UK NHS. The objectives of our study were to:

-

generate a comprehensive documentary review of (1) relevant policy and legislation and (2) professional guidance and legal frameworks governing inward and outward flows of medical tourists to and from the UK

-

better understand the information, marketing and advertising practices used in medical tourism, within both the UK and provider countries of Europe and beyond (and the benefits and drawbacks of them)

-

examine the magnitude and economic and direct health-related consequences of inward and outward medical tourism for the NHS

-

understand how decision-making frames, assessments of risk and associated factors shape health treatments for patients (including how prospective medical tourists assess provider reputation and risk) and to collate evidence on the role of intermediaries and brokers in facilitating medical tourism

-

better understand treatment experience, continuity of care and postoperative recovery for inward and outward flows of patients

-

elicit the views and perspectives of professionals and key stakeholder groups and organisations with a legitimate interest in medical tourism (exploring patient and professional choice, benefit, safety, harm and liability)

-

map out the medical tourism industry and chart its development within the UK and assess the likely future significance for the NHS.

Research streams

A preliminary scope of the literature and practical issues identified four streams of evidence that would inform a better understanding of medical tourism and advise policy-makers on strategies to capitalise on its benefits and minimise risks it may present:

Stream 1: consumerism and patient decision-making

We knew little about how patients made their decisions concerning treatments and destinations and what forms of hard intelligence (performance measures, quality markers, safety information) and soft intelligence (website information, friends, internet chat rooms) they use. What role do networks play in decision-making? How informed are patients when making their choices?34 Are factors that encourage cross-border exchanges (including type of care, reputation of provider, urgency of treatment, gender, age, location and socioeconomic status of patient) (e.g. reference 21) similar to those that shape out-of-pocket exchanges? What is the role of general practitioners (GPs) and web-based resources in encouraging or discouraging UK residents considering undertaking medical tourist treatments?

Stream 2: quality, safety and risk

Modern health care is an inherently risky undertaking with the potential for clinical errors and medical incompetence and malpractice, particularly in treatment areas that are not regulated by national laws and guidelines. How do patients understand the elements of risk involved in undertaking treatment overseas? There are also potential ethical, legal and insurance issues, which can influence the patient decision-making procedure. Research was needed to collect evidence on the experiences and outcomes of treatment abroad (benefits, satisfaction, unintended and dysfunctional clinical consequences). The importance of communication between professionals and aftercare, privacy and confidentiality vis-à-vis information sharing, the use of information technology (IT) information by professionals, and how patient information flows are all important areas in which data are needed. What attempts are being made to regulate the industries – by national governments or organisations themselves? What is the use of independent international health-care accreditation in European settings, such as that provided by Joint Commission International (JCI)?

Stream 3: economic implications

What are the economic implications of medical tourism for the UK NHS? There are no routinely collected data concerning inward and outward flows of medical tourists to and from the UK; however, we sought to explore what information existed [within the International Passenger Survey (IPS) and within foundation trusts themselves] and to examine the implications of such data.

Stream 4: medical tourism providers and market development

There has been a steady rise in the number of companies and consultancies offering brokerage arrangements for services and providing web-based information for prospective patients about available services and choices. This can be attributed to the transaction costs associated with medical tourism, which patients would want to reduce. Typically brokers and their websites tailor surgical packages to individual requirements: flights, treatment, hotel and recuperation. Some brokers or concierges offer medical screening. A series of inter-related questions arose with regard to the precise role of brokers and intermediaries in arranging overseas surgery. How do organisations determine their market? How do medical tourism facilitators source information, select providers and subsequently determine the most appropriate advice? Further, what are the relationships between clinical providers and such intermediaries? What are the implications of the majority of medical tourism websites being commercially driven and intermediaries relying on advertising revenues and commission?

Chapter 2 Methods and structure

Research approach and methodology

The study involved integrating policy analysis, desk-based work, economic analysis and treatment case studies. We used a mixed-method approach of qualitative and quantitative data collection and the study included both primary and secondary data collection/analysis. Activity comprised a preliminary systematic review and broad data collection to address the four research streams. In this chapter we focus on the broad methodology, outlining why a number of data sources were required to understand medical tourism, and the challenges of implementing a project of this nature (see Appendix 2 for the study protocol). The research conducted for this project has been ambitious in that it was trying to establish the level of current evidence and knowledge in an area in which robust routine data are lacking. This required innovative approaches, including in the recruitment of patients but also in obtaining data on inward medical tourism through freedom of information requests. Specific issues with regard to the research process and sample sizes are addressed in this chapter. The entire research project adopted an iterative approach, with authors regularly reviewing methods for data collection. Data collected were triangulated with other sources to ensure that findings presented are an accurate reflection of the data.

The NHS fieldwork was undertaken in the English NHS [with primary care trusts (PCTs) and foundation trusts] although the medical tourists that we interviewed were located UK-wide (including Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland). The IPS data relate to the UK whereas our trust data for economic costs relate to England. A number of the broader issues regarding outward medical travel and patient decision-making, safety and experience are common to the wider UK population but there are differences between how the English NHS and non-English NHS are organised (e.g. with regard to foundation trust status and commissioner/provider relationships). The policy directions on potentially expanding private care and the directive on NHS Global do not extend outside of the English NHS.

Preliminary systematic review activity

The study was underpinned by a systematic overview [based on NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination (CRD) guidelines for systematic review35] of previously published literature on medical tourism (reported fully in Chapter 3). Although the research project overall drew on grey literature and industry surveys to triangulate findings when required (and as specified), the systematic review focused on published literature. This was to ensure the robustness of findings and to retain feasibility, given the overwhelming quantity of data published on the subject.

Secondary data analysis

Data provided by the IPS and foundation trusts’ responses to freedom of information requests were analysed to understand patient flows and their financial consequences.

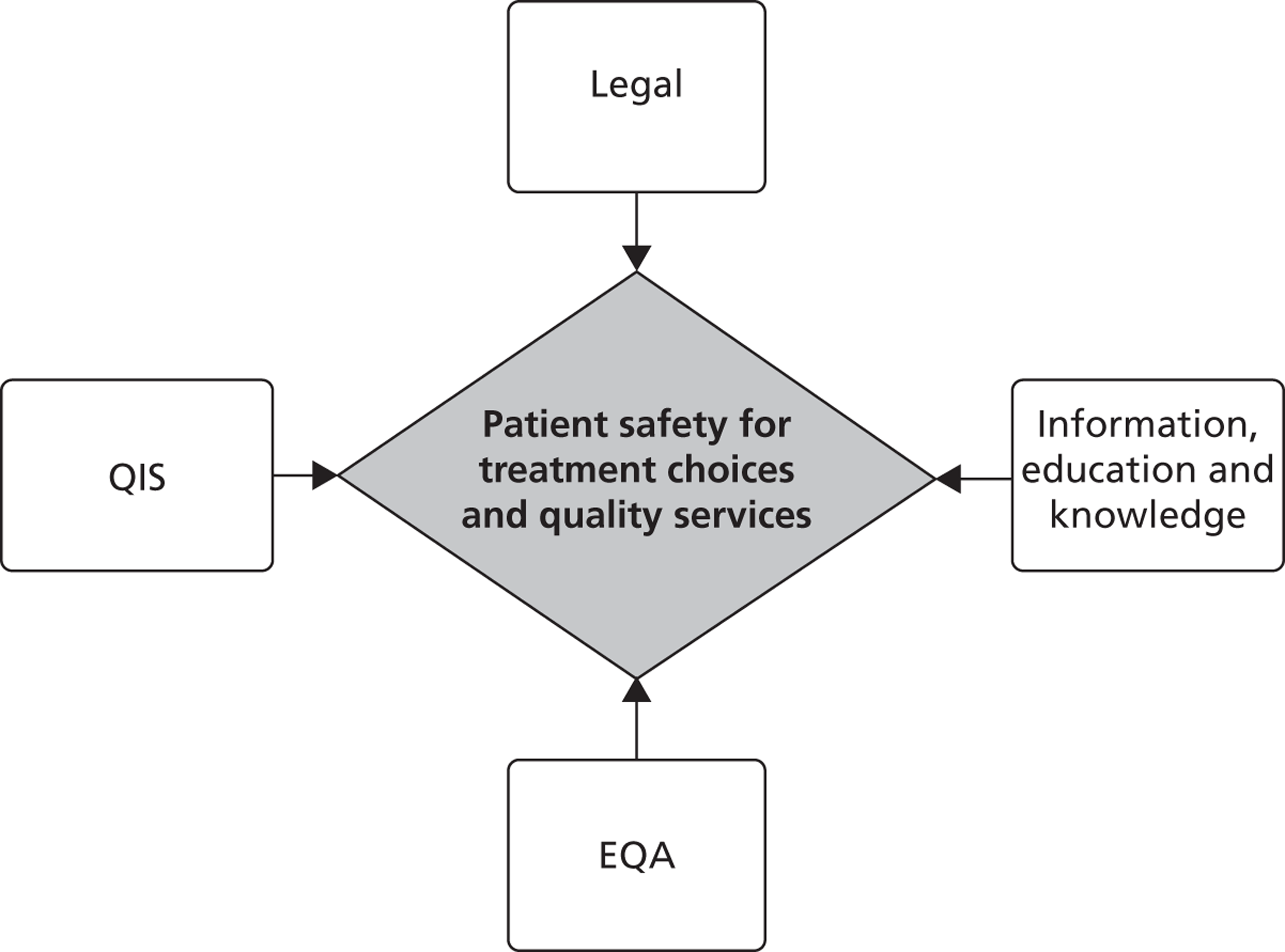

Desk-based activity

Desk-based activity was undertaken to collect both primary and secondary data around patient safety and service quality – legal dimensions, education and information, external quality assessment (EQA) and quality information systems (QISs). The methods and results are reported fully in Chapters 6–8.

Interviews

We undertook in-depth interviews with a range of key stakeholders and interests involved with medical tourism (n = 134 plus 23 overseas providers) between March 2011 and August 2012. All interview schedules are provided in Appendix 3. Interviews were conducted with the following groups.

Professional associations and stakeholders

Individuals representing a range of professional associations, clinical interests and representative bodies were interviewed. This ranged from the Royal Colleges to bodies concerned with quality control and those representing nurses and doctors. Overall, we interviewed 16 individuals across this range of interests, including from legal, cosmetic, dental, fertility, primary care and travel health services. The project team drew up a list of key interests and individuals and discussed their coverage. Individuals were invited to be interviewed, either in a personal capacity or as spokespeople of their clinical specialty or organisation. There was also an element of further snowball recruitment. Interviewees were typically interviewed face to face; interviews lasted for between 30 and 60 minutes and were recorded and transcribed.

Medical tourism businesses and employees

Individuals representing the perspectives of businesses and employees within medical tourism (including facilitators, website operators, insurance providers, private fertility counsellors) were interviewed. The project team drew up a list of key interests and undertook a review of recent conference speakers, literature and websites to identify medical travel interest. The recruitment net was cast widely and we sought to understand the wider dynamics, drivers and aspirations of the individuals and companies. Overall, we interviewed 18 individuals across this range of interests, including from legal, cosmetic, dental, fertility and travel health services.

Individuals were interviewed over the telephone or using Skype™ (Skype Ltd, Rives de Clausen, Luxembourg), although a number were also interviewed at trade fairs and conventions. There was also an element of further snowball recruitment. Interviews lasted for between 20 and 60 minutes and were recorded and transcribed.

NHS managers

We sought to interview individual managers within PCTs and foundation trusts who could illuminate our understanding of the inward and outward flows of patients and the impact of such flows on the NHS. An element of snowball and convenience recruitment was used. To access individuals with commissioning insights, the study was publicised by listservs to those with commissioning knowledge and interest in overseas/cross-border patients. Individuals who had attended a cross-border health-care seminar at which the research team was present were also contacted. The NHS Confederation circulated our call for interviewees to members and, of our 23 NHS interviewees, six held commissioning roles.

For NHS providers, we identified trusts that were seen to have a longstanding interest in, or aspiration to further develop, international patient work. There is a strong network of interests (particularly around London) focused on private and international services by the NHS; individuals were approached to participate. Interviews were conducted face to face and lasted for 25–60 minutes. Interviews were usually recorded and transcribed. The NHS Confederation circulated our call for interviewees to members. We interviewed 13 NHS providers, which along with the six commissioners and four relevant practitioners, gave us a total sample of 23 NHS interviewees.

Patient interviews

A total of 46 people were categorised to our medical tourist and diaspora samples across four treatment case studies and ‘other treatment’ categories. In addition to these respondents, we also spoke to a total of 31 individuals as part of our ‘diaspora’ category (Table 1). Not all of these individuals provided interviews, instead opting to take part in a more communal discussion appropriate to the cultural dynamics of the group.

| Treatment type | Number of respondents | Procedures covered | Locations of treatment |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fertility | 9 | IVF, intracytoplasmic sperm injection, egg donation, sperm donation | Czech Republic, Ukraine, Sweden, Spain, Cyprus |

| Bariatric | 11 | Gastric band, gastric bypass, gastric wrap, gastric sleeve, duodenal switch, pancreatic diversion and duodenal bridge | Belgium, France, Czech Republic |

| Dental | 11 | Crowns, bridges, routine work and check-ups, fillings, braces, dental plates, implants | Hungary, Germany, Croatia, India, Poland, Italy, Lithuania |

| Cosmetic | 9 | Facelift, liposuction, tummy tuck, minimal access cranial suspension facelift, nose, face and eyes | Belgium, Poland, Czech Republic, Pakistan |

| Other | 6 | Nerve surgery, gynaecology, ultrasound, immunotherapy, shoulder stabilisation, needle for Dupuytren's contracture | France, Greece, Belgium, Germany, USA |

| Diaspora | 31 | Diagnostic, dental | Germany, India |

Our core sample of 46 medical tourists was sourced through a variety of means. In the first instance we posted a call for interviewees on our medical tourism project website as well as trialling an advert in a local newspaper. The advert was unsuccessful and over the 18 months of the project our online contact form yielded four responses. We came to increasingly rely on posts made to online support or information forums. This proved particularly successful, especially in terms of our bariatric and fertility samples (Appendix 7 details the range of sites and networks that we utilised for recruitment). In some cases we made contact with those whose stories had been reported elsewhere, for example in media publications or as patient testimonials. A sample of 46 is clearly not a representative sample, although the team attempted to source a wide range of travel experiences, including major and more minor procedures, a range of treatments and those who perceived themselves as having good and less successful outcomes. Attracting respondents proved extremely difficult, especially the dental sample as there appeared to be no online ‘community’.

Our diaspora sample consists of individuals from three community groups (two urban Somali groups and one Gujarati group). Access to these groups involved the support of individuals who acted as informal gatekeepers to the communities, often organising meetings with interviewees, a location in which to meet and, in some instances, interpreters.

Individuals were approached to participate and interviews were conducted face to face or, when a preference was expressed, by telephone and Skype. Interviews lasted for between 30 and 100 minutes and were recorded and transcribed. The interviews explored a range of dimensions including drivers, decision-making, treatment experience and postoperative care. They also asked about the costs that were incurred during travel abroad, including for treatment, accommodation, insurance, recuperation and aftercare.

Overseas providers

A total of 23 people were interviewed regarding overseas provision. Here, a range of recruitment and interview techniques was adopted. We undertook five full interviews by telephone and face to face, but also used opportunities at trade shows and conferences in the UK and Europe to meet and talk with overseas providers, taking field notes. These contacts and discussions went far beyond our initial expectation of 10 providers.

Interview process

As already described the recruitment of patients evolved and we revised the recruitment strategy several times. The different kinds of treatments that formed the basis for the case studies developed in the analysis were informed by findings from the initial systematic review of the literature. This identified bariatric, fertility, dental and cosmetic treatment and diaspora travel as types of procedures for which patients travel to receive treatment.

Initially, we had anticipated hip and heart patients as a further group of patients travelling for higher-risk and higher-cost procedures but, although these were targeted in our initial recruitment strategy, they proved much harder to identify. This is a likely reflection of the project’s UK focus as patients resident in the UK are unlikely to travel for high-cost and complex procedures given that these are available for free on the NHS. This is opposite to the case in the USA where patients may feel more compelled to travel for treatment for complex procedures given the high costs and much larger associated savings.

We made a conscious effort to interview similar numbers of patients across the different groups to maintain a balance within the findings across different treatment types and ensure that the findings can reflect on medical tourism overall, rather than specific conditions. Attempts to identify specificities and commonalities across treatment conditions also informed the analysis process described below.

Although the number of interviews gathered was in part determined by constraints in timing and challenges faced in recruitment, especially of patients, we stopped the interviewing process only once a saturation point was reached and no new themes were emerging from the interviews. Although the sample is not representative of all medical tourists, clear commonalities in motivation and experiences of patients emerged across the sample of interviews.

Interview analysis

Both quantitative and qualitative data analysis involves the common steps of data reduction (and data cleaning), data organisation and data interpretation. The study interview data were analysed using the ‘framework method’ of thematic analysis. 36,37 This allowed a search for conceptual definitions, typologies, classifications, form and nature (process, system, attitudes, behaviours) and explanations. 38 The study had clear research streams and specific questions that it sought to explore. We examined the data for particular ‘outliers’, searching for negative or disconfirming evidence that appeared to be inconsistent with the emerging analysis.

When consent was provided, all interviews were recorded and transcribed (see transcriber confidentiality agreement in Appendix 4). Transcripts were reviewed by four authors undertaking primary data collection and analysis (NL, DH, HK, JH). Interviews were grouped into categories defined in the study framework (e.g. professional associations or patients.). Patient interviews were further grouped into the following categories: bariatric, cosmetic, fertility, dental, diaspora and ‘other’ tourism. Authors read all transcripts and met to generate initial themes for the analysis. Themes were specific to groups of transcripts, for example themes for the analysis of fertility tourists differed from those used for professional associations. Once themes were agreed, one author took the lead on thematic analysis of the specific group of interviews and drafting of texts. These were then cross-checked by a second author to ensure accuracy and avoid bias. As a final step, completed drafts of the texts were reviewed and commented on by all authors.

Given the highly sensitive nature of the patient and provider data, we endeavoured to ensure the confidentiality and anonymity of individuals and organisations when reporting the findings.

Case study synthesis

The research design included treatment case studies that would allow the team to synthesise findings across the range of data sources (qualitative and, when possible, quantitative) and to draw together primary and secondary knowledge. Five case studies were developed: bariatric, fertility, dental, cosmetic and diaspora (see Section 3). Case study selection was informed by the review of the literature, which indicated that these areas were likely to be of value in understanding medical travel.

This method allows a better understanding of the varying specialties within medical tourism and the dynamics of patient consumer decision-making, risk-taking, and quality and safety of particular treatments. Multiple case study analysis also provides insight over and above that of individual case studies and has advantages over simply seeing the whole data set ‘in the round’. 39

Each case comprises around 10 interviews with patients to illuminate decision-making processes and treatment experiences (e.g. dentistry or bariatric). Cases included quantitative data analysis where possible, based on descriptive statistics covering aspects such as expenses incurred. Case studies also introduced analysis of relevant website and print advice (commercial and professional sources) for that particular specialism. The case studies drew on interview data from industry and clinical interests with a view to assessing current and emerging developments.

The case studies helped facilitate understanding of aspects of medical tourism that were treatment specific and those that were common across different types of treatment. This proved particularly valuable for the analysis of patient motivation and in the costing work. It also helped validate the data.

Ethics

We sought NHS ethical approval to interview representatives of NHS purchaser and provider organisations in the localities selected (managers and non-clinicians within PCT or foundation trust settings). The full ethics application ‘Implications for the NHS of inward and outward medical tourism’ was submitted to the Sheffield Research Ethics Committee for consideration and approval (11/H1308/3). Local research and development approval and appropriate letters of access were then gained for each of our final fieldwork locations (11 sites in total). Sampling for medical tourism patients did not require access to the NHS, nor patient records or materials. We sought clarification with the local National Institute for Health Research Research and Design Service and local NHS research ethics committee and ethics approval for patient recruitment was not required. We recruited ‘medical tourists’ through networks and snowball recruitment, not through the NHS.

Informed consent was a fundamental part of the study approach. Each interviewee was provided with details of the study (which they could retain) and asked to complete a consent form (see Appendices 5 and 6, respectively, for examples of these).

Fieldwork challenges

The project had a number of challenges. It included data collection in familiar health services territory (including NHS managers and professional associations and use of NHS financial information). But it also required fuller engagement with non-NHS interests and groups (non-NHS patients, commercial interests beyond the NHS). A range of data sources was required for the research team to meet its objectives and offer insight around decision-making, patient safety, economic implications and market and provider development.

Sourcing and completing interviews with medical tourists required significant effort, as well as intensive networking, patience and substantial persistence. In some areas of activity (e.g. cosmetic treatment) we recruited in a context in which media outlets would pay hefty fees for patient stories and testimonials. We were also talking about potentially sensitive issues across a range of treatment areas. Each strategy, network and site (detailed extensively in Appendix 7) contributed some part towards meeting our final sample target. The project team was supported by an advisory group (see Appendix 8 for advisory group terms of reference and membership).

For NHS managers, particularly those on the purchasing side, the impending reorganisation of PCTs provided recruitment obstacles. In two sites where we gained ethics approval, interviewees were unable or unwilling to participate in the research. Given the number of recruitment sites (up to 15), obtaining local research and development approvals and access was very time-consuming but necessary under existing governance arrangements.

Changes from protocol

There were two main departures from the envisaged study design. First, the proposal envisaged undertaking a survey in addition to the in-depth qualitative interviews. This would collect more detailed demographic and financial information from a larger number of travellers. Although we were successful in securing the qualitative interviews, recruitment numbers were not high enough to allow for a survey element. Some indicative financial information was collected in the detailed patient interviews, some of which is detailed in the treatment pathways (see Appendix 9).

Second, we anticipated recruiting 10 inward medical tourists within our overall figure of 50. However, given the typically high-end treatment focus and government-sponsored nature of these patients, this proved difficult. There were also no support forums and clear gatekeepers through which such patients could be accessed. Time constraints did not allow us to build the necessary relationships with embassies and health attachés that may have provided these recruitment opportunities. Aside from this we were able to collect data on the context within which these patients travelled to the UK. These data were collected by talking to a range of managers within the NHS foundation trusts and those working within the independent sector. Table 2 summarises our data collection process.

| Data collection method | Description | Collected by | Research objective | Report coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Interviews | ||||

| Patients (treatment groups n = 46; diaspora n = 31) | Treatment groups: cosmetic, dental, bariatric, dental, cultural, other | DH, JH, LM, HK, NL | Understand decision-making frames, assessments of risk and associated factors; better understand treatment experience, continuity of care and postoperative recovery | Chapters 9 – 14 |

| NHS (n = 23) | Purchaser and provider roles | NL | Elicit the views and perspectives of key stakeholder groups | Chapters 9 – 15 |

| Stakeholders (professional associations n = 16) | Representatives of professional associations | NL/JH | Elicit the views and perspectives of key stakeholder groups; map out the medical tourism industry and chart its development | Chapters 9 – 15 |

| Stakeholders (businesses, employees n = 18) | Individuals working within the private sector of medical tourism | LM, DH, JH | Map out the medical tourism industry and chart its development | Chapter 4 |

| Overseas providers (n = 23) | Country strategies | JH/DH/NL | Map out the medical tourism industry and chart its development | Chapter 4 |

| Desk-based work | ||||

| Review of websites | 100 sites reviewed, guideline search | DH, HK, NL, RS, JH | Better understand information, marketing and advertising practices | Chapters 6 and 8 |

| Review of quality and safety accreditation | 150 sites reviewed | NL/HK | Understand decision-making frames, assessments of risk and associated factors | Chapters 6 and 8 |

| Secondary data analysis | ||||

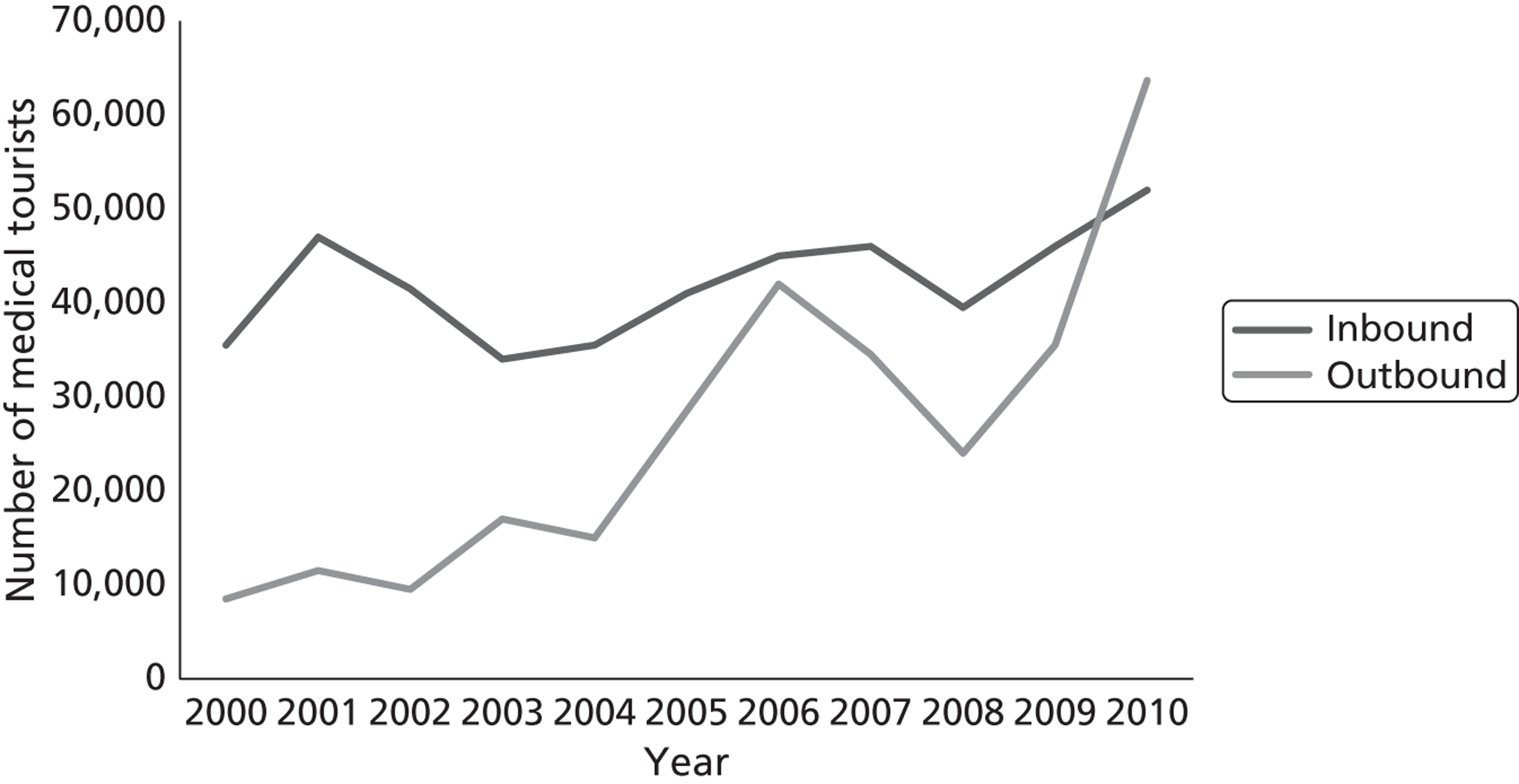

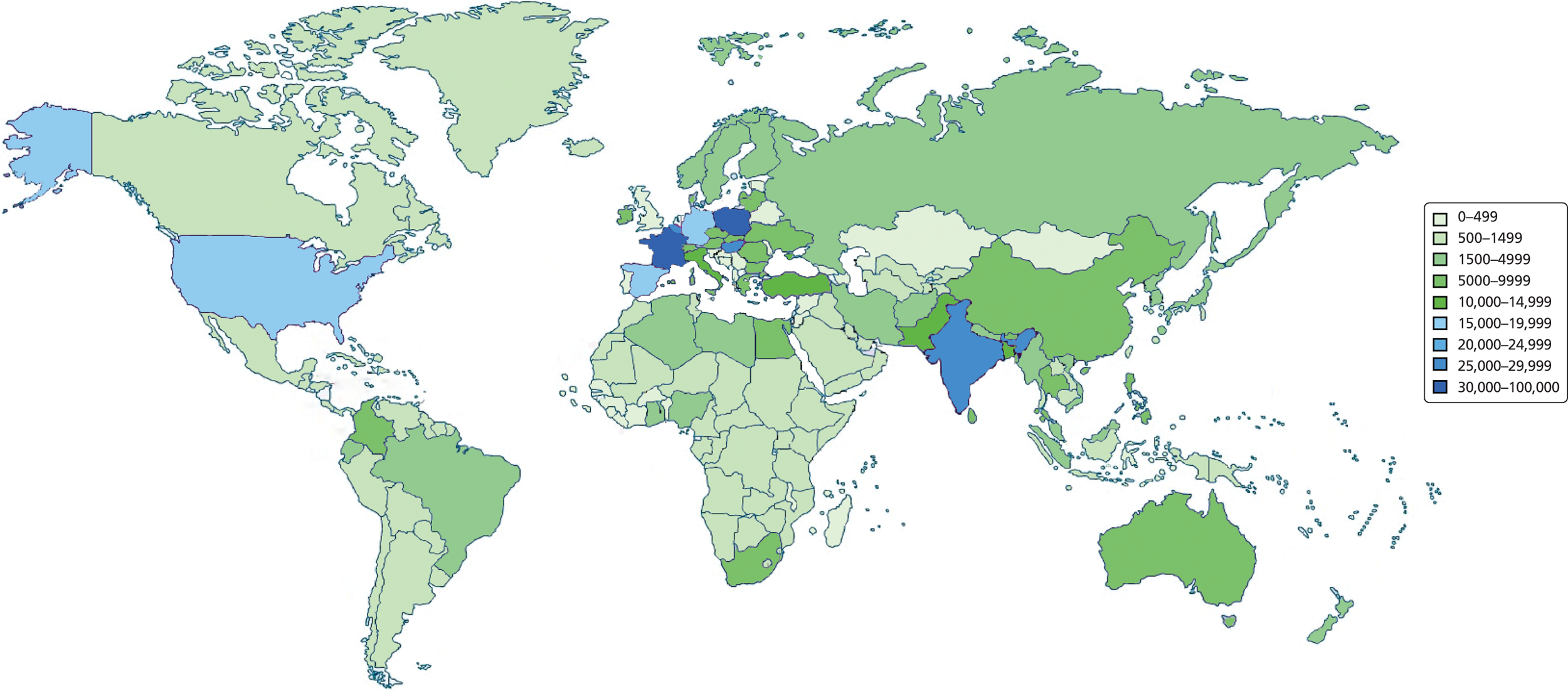

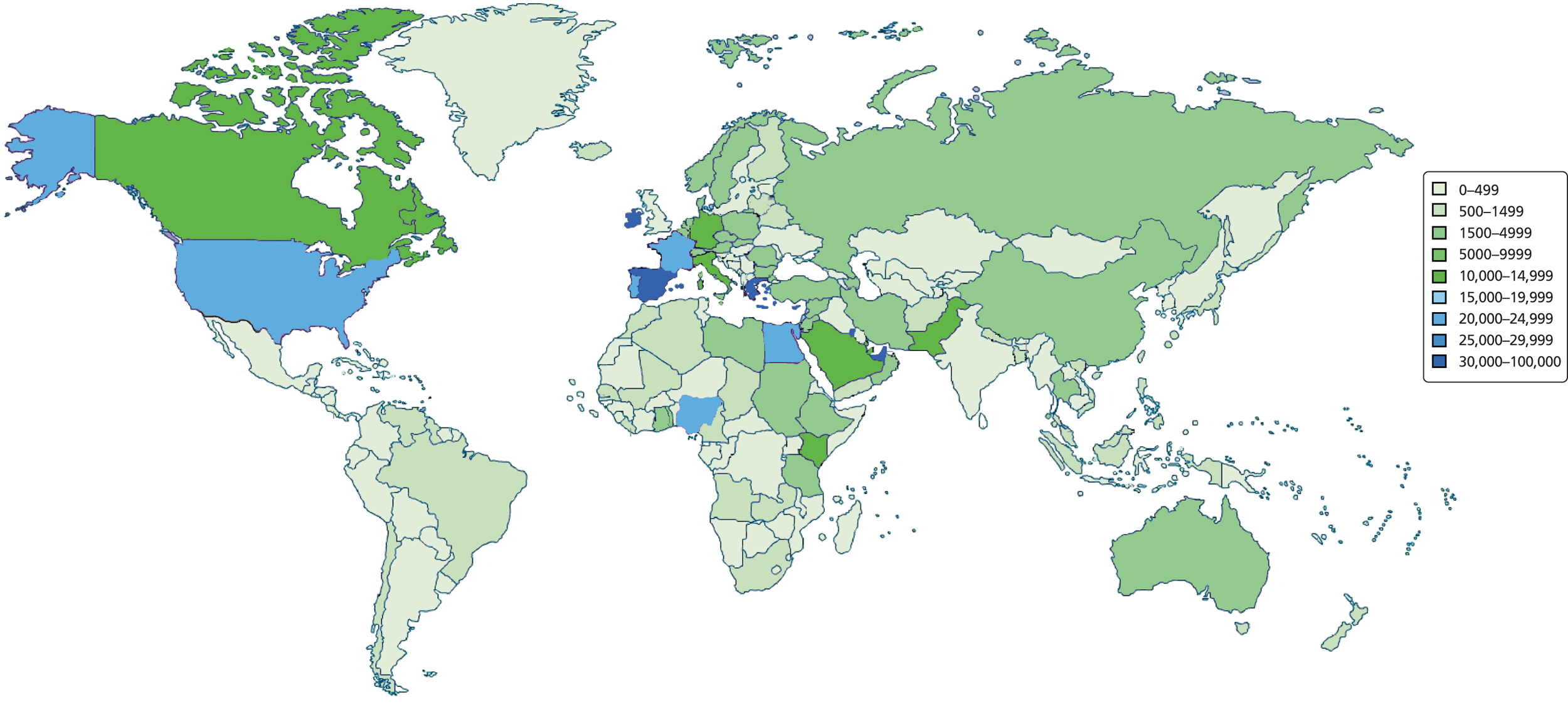

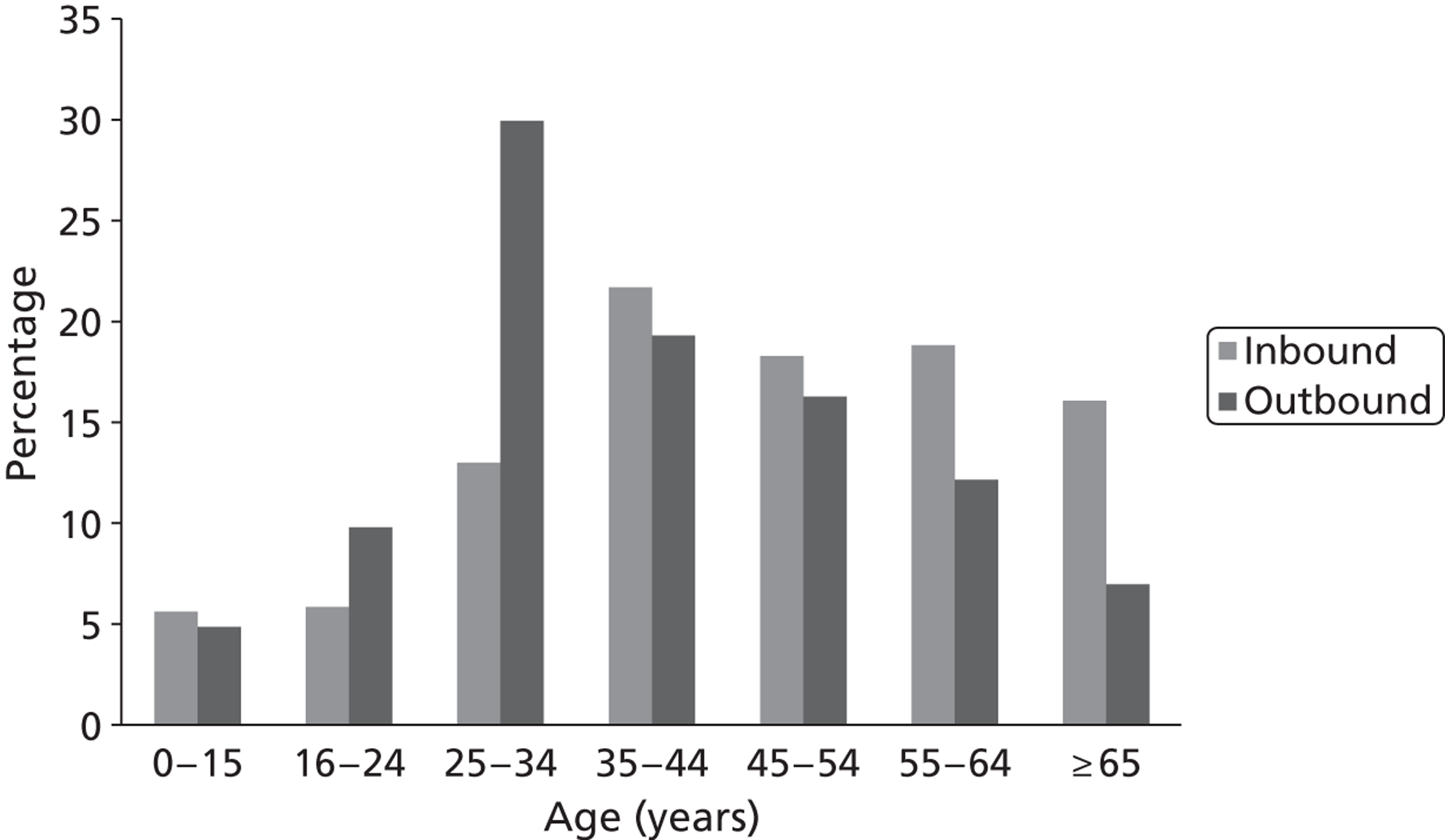

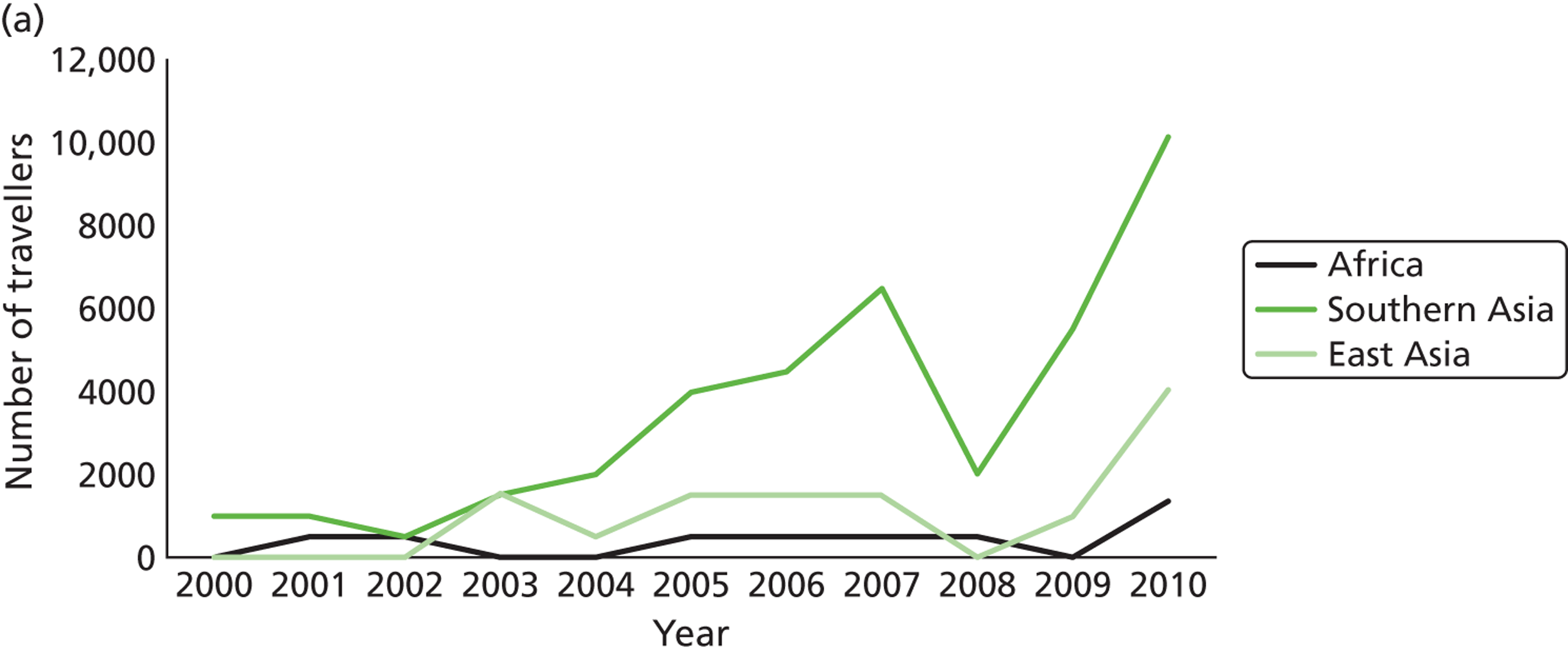

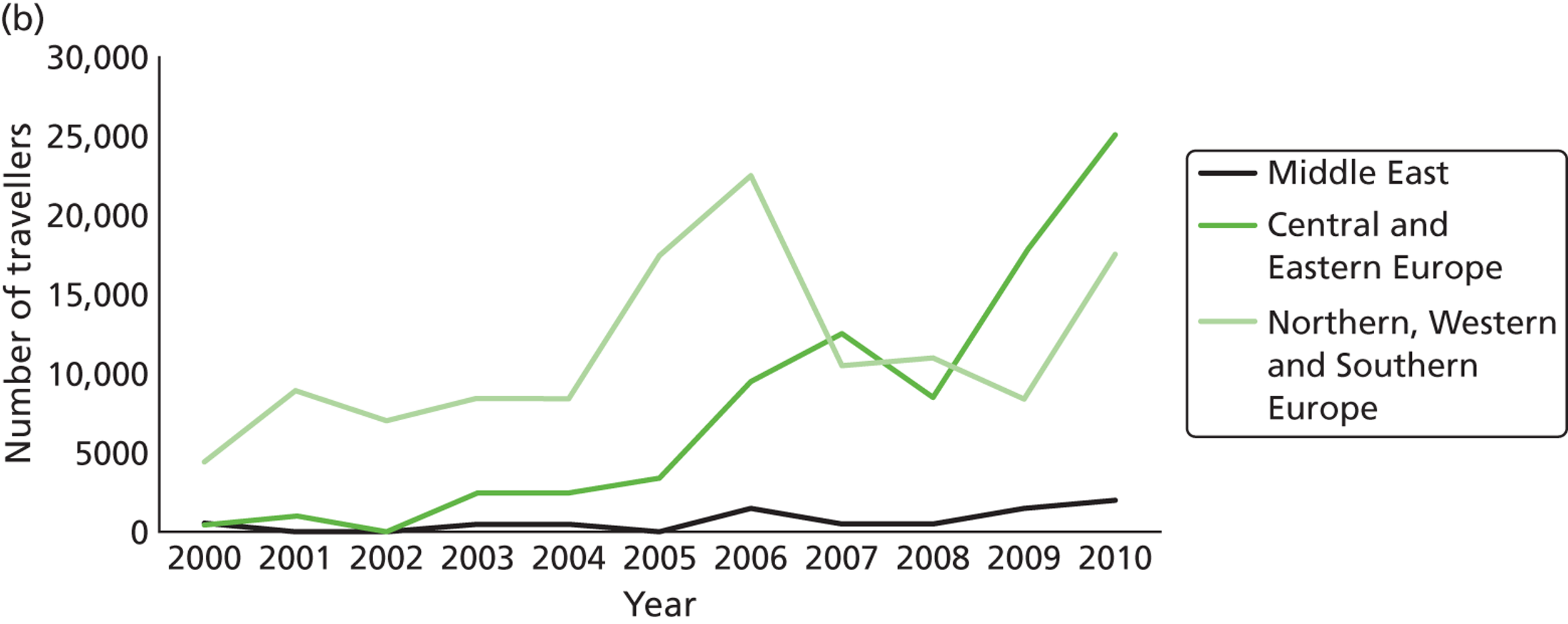

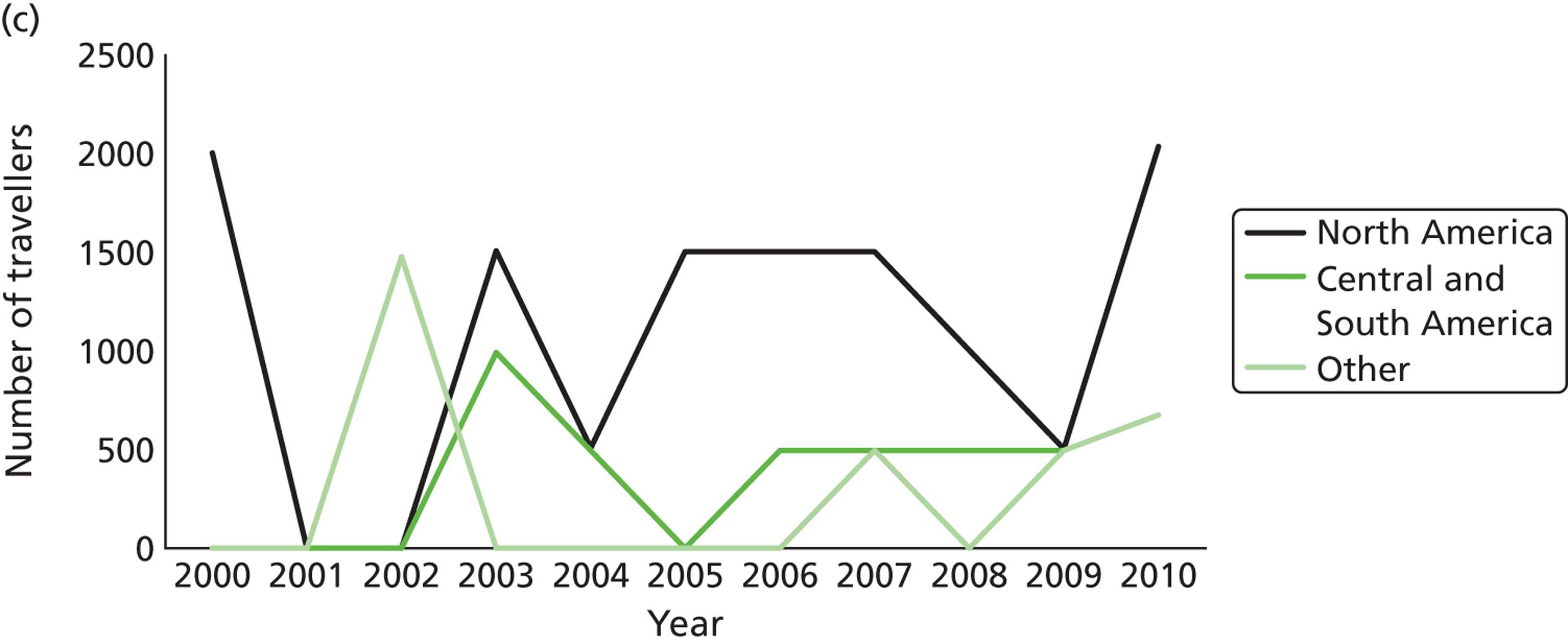

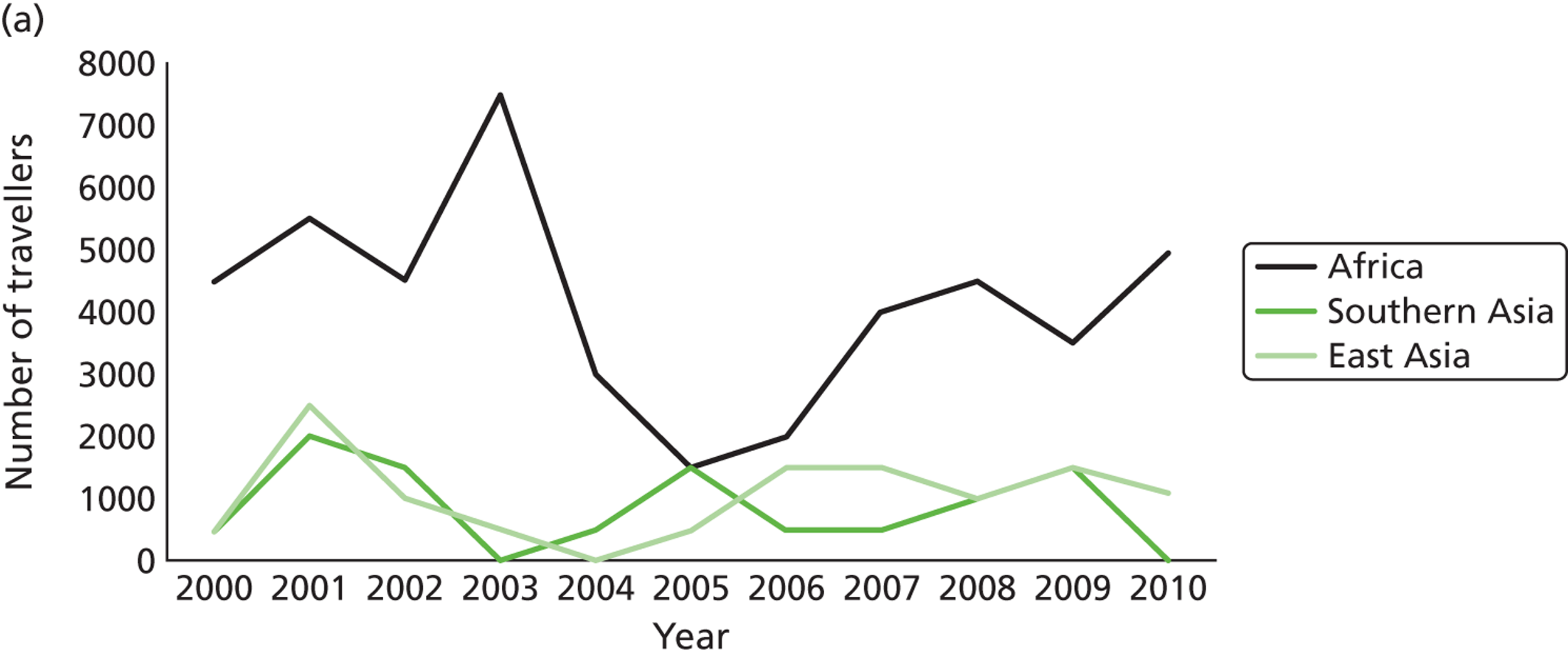

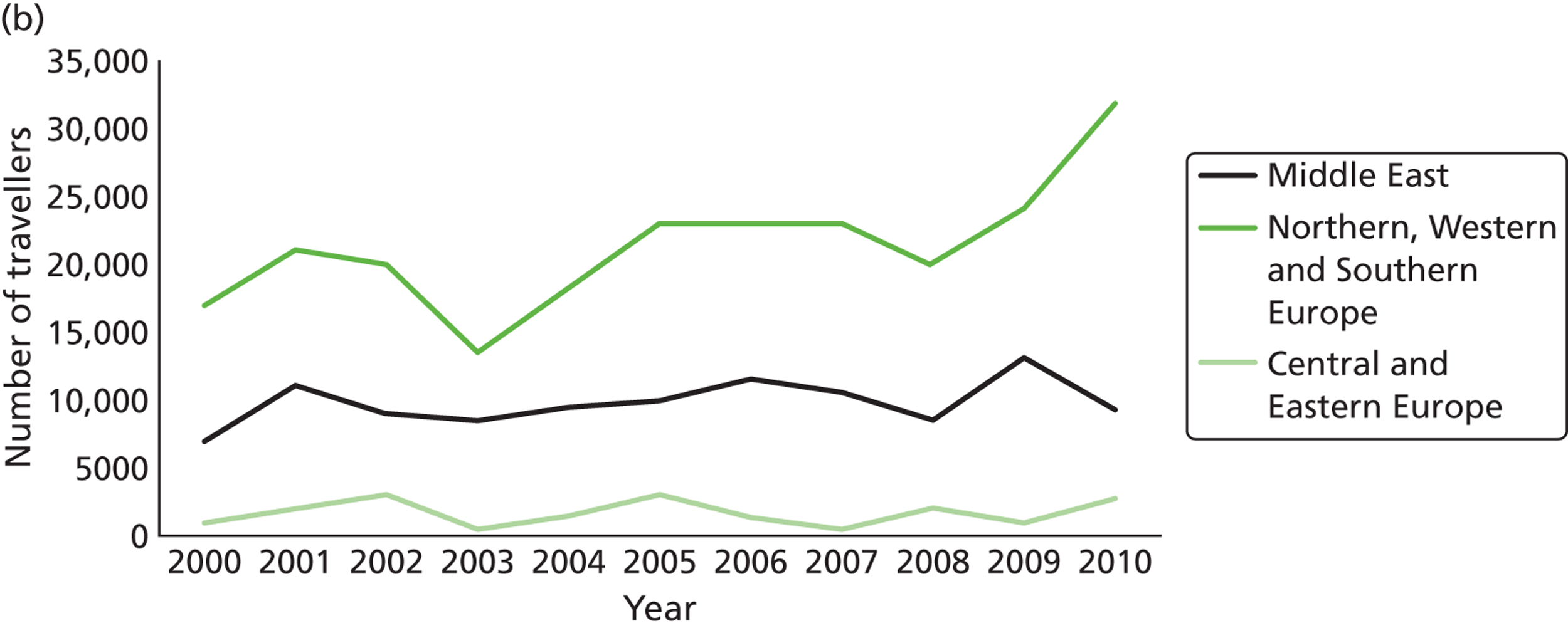

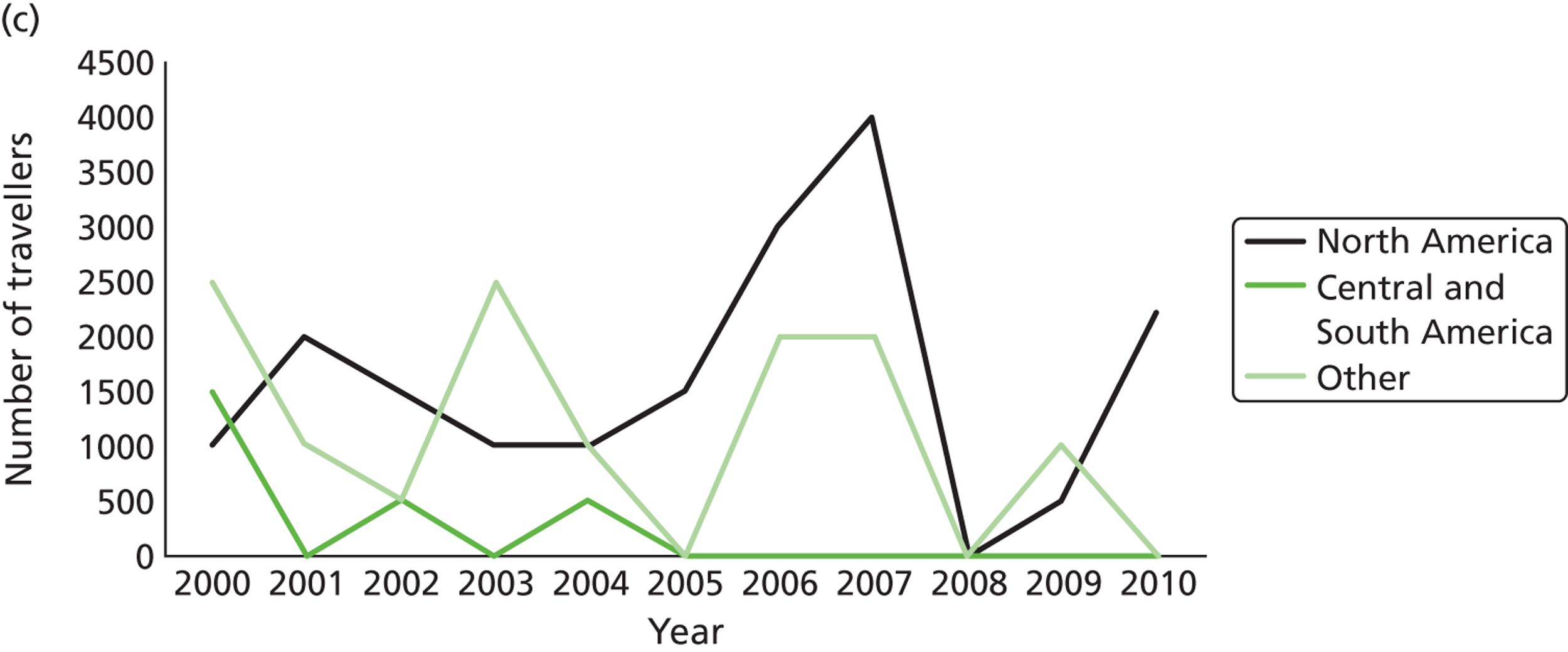

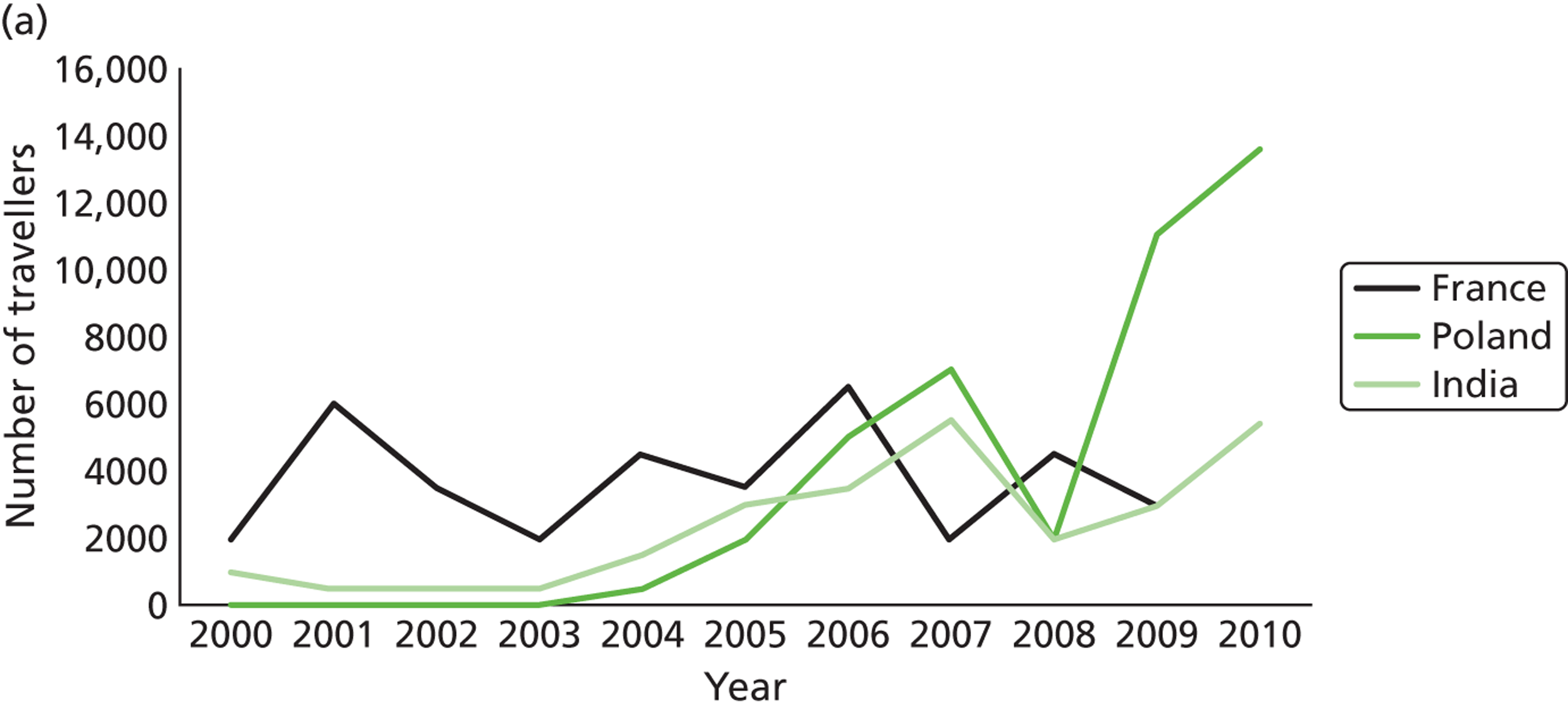

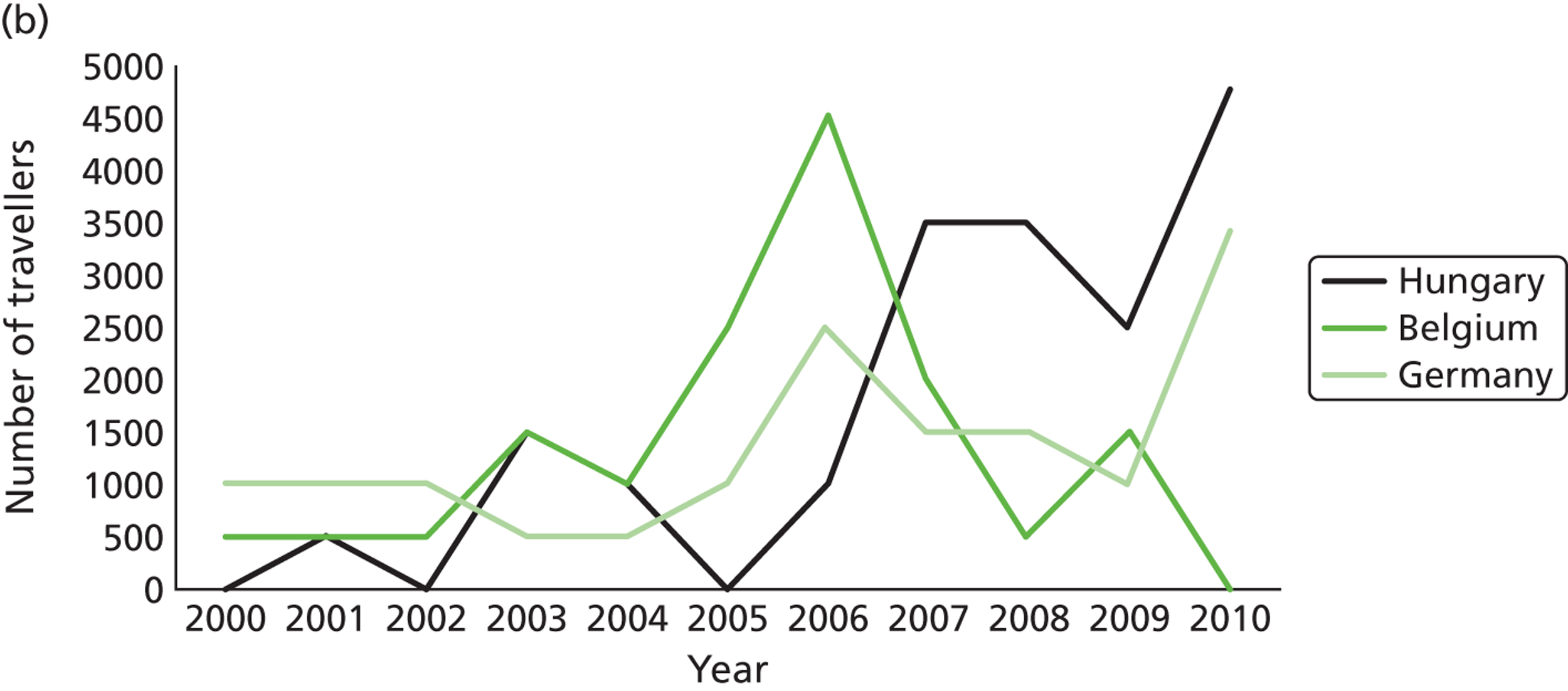

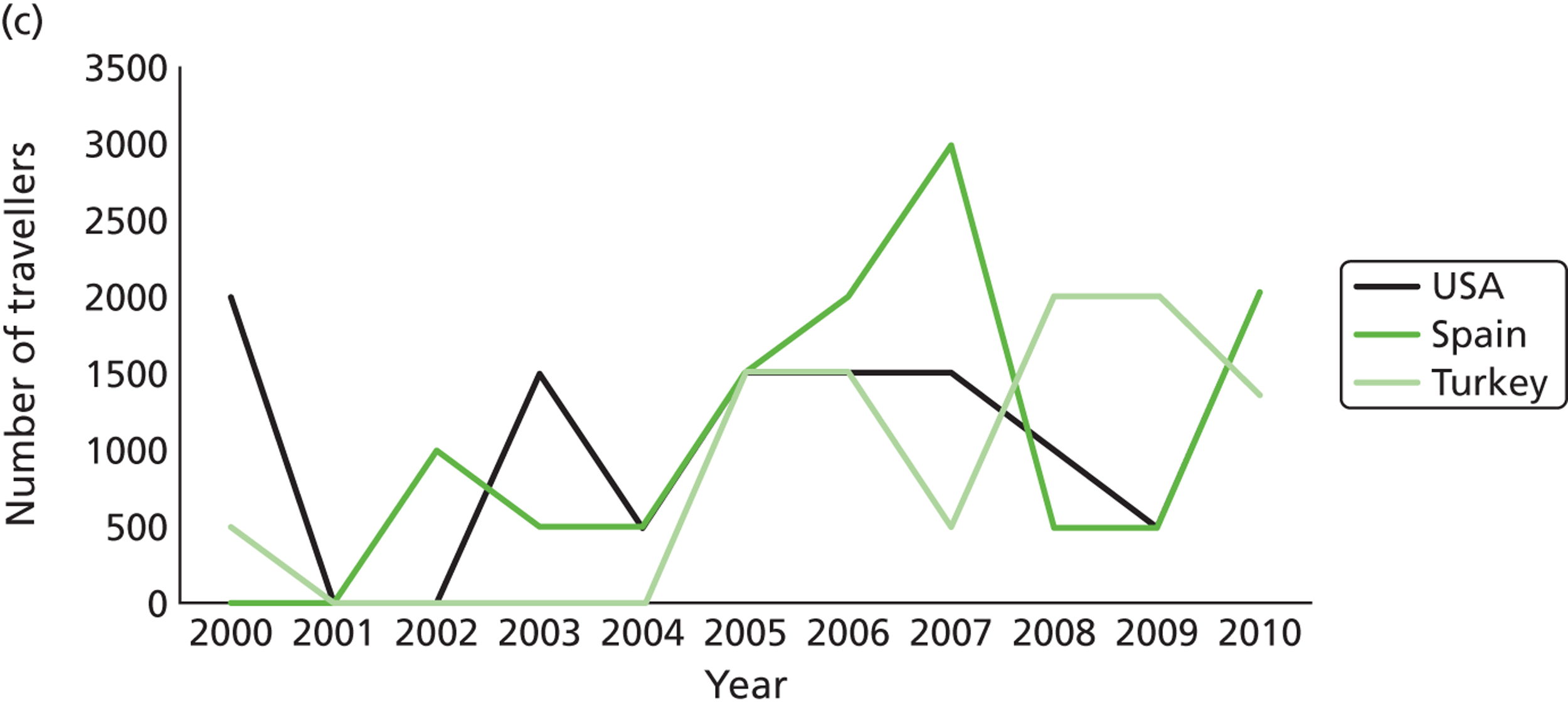

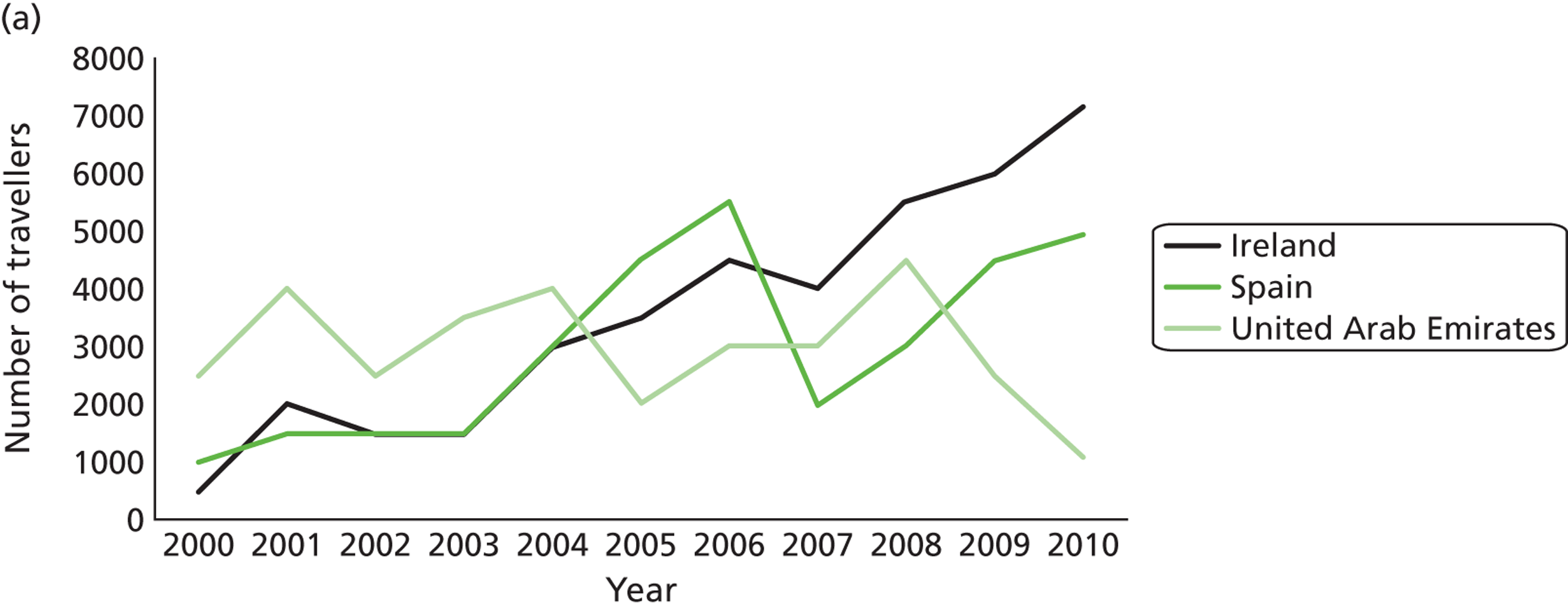

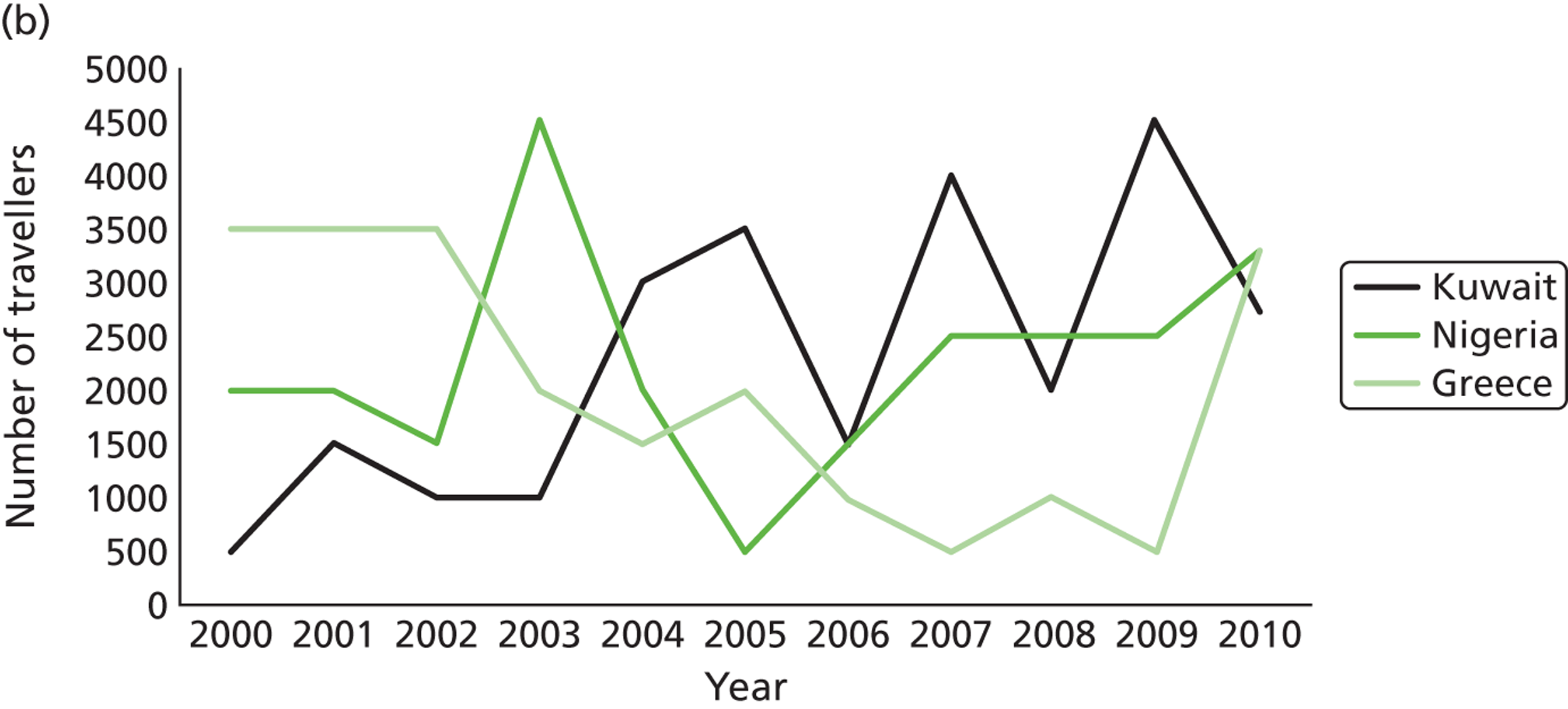

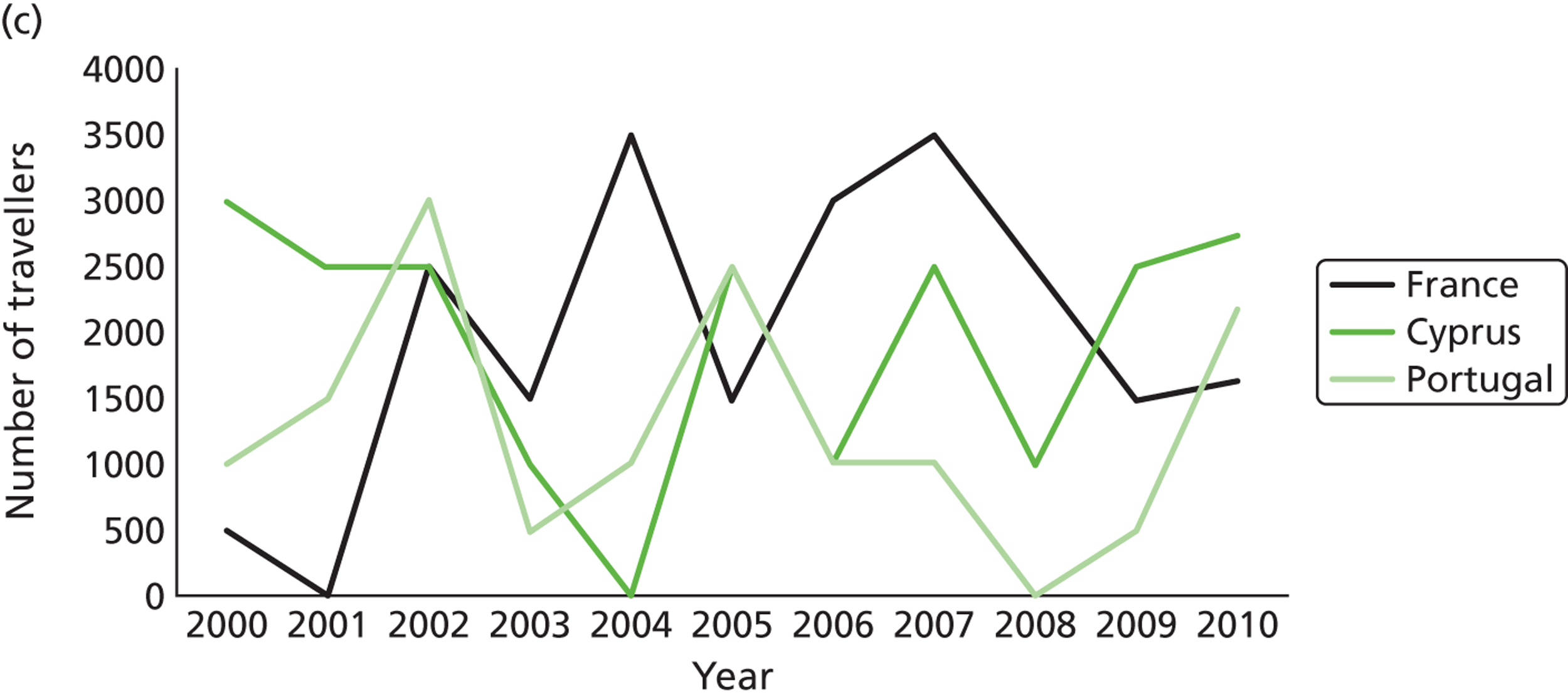

| IPS | 2000–11 | DH, JH, RS | Examine the magnitude of inward and outward medical tourism | Chapter 5 |

| Costing | Freedom of information requests 28 NHS trusts | JH/RS/NL | Examine the economic and direct health-related consequences of inward and outward medical tourism | Chapter 16 |

| Systematic review | ||||

| Review of medical tourism literature | JH/RS | Comprehensive documentary review | Chapters 3 and 7 | |

The impact of departure from the protocol on findings

In light of the challenges reported and the obvious further insights that could be gained by having a greater number of cases or interviews, for example of NHS managers, we have been careful not to overstate the findings and potential weaknesses resulting. We addressed challenges in data collection through innovative data collection methods, for example the freedom of information requests to fill in the limited information available on inbound UK tourists.

For the subgroups for whom data were collected, a saturation point was reached in the interviews as themes repeated themselves. The lack of interviews with inbound medical tourists to the UK means that research findings do not address motivation and limit the insights offered of their experiences of the NHS. There is also a need for further research to better understand the effects of inbound medical tourism on the NHS.

In addition, a large-scale survey (had it yielded statistically significant results) may have enabled further quantitative analysis of medical tourism. However, as the study interviewed the largest sample of UK medical tourists to date, we feel strongly that it presents the most valid insights and the most robust data on patient motivation and experience available to date. We carefully triangulated all findings and recommendations to ensure the validity of the findings stated.

Report structure

The report is structured as follows. The remainder of Section 1 provides a systematic review of the medical tourism literature (see Chapter 3), highlighting where major gaps in knowledge exist. Chapter 4 provides an introduction to the medical tourism industry. Drawing across all interview data (industry, overseas providers and professional associations, and medical tourists) it undertakes broader conceptualising to explore services involved, the ways in which information is sought, and supply/provider chains. Chapter 5 provides a critique of existing estimates and extrapolations around medical tourist flows and an analysis using IPS data provided by the Office for National Statistics (ONS).

Section 2 examines issues related to patient safety and service quality including the legal and policy context (see Chapter 6), education (see Chapter 7) and EQA and QISs (see Chapter 8), and synthesises interviews from professional associations and NHS managers.

Section 3 includes the treatment case studies. This section contains an initial synthesis (see Chapter 9) followed by five case studies of different treatments (bariatric, fertility, dental and cosmetic; see Chapters 10–13) and diaspora travel (see Chapter 14). The cases include patient interview data, wider interview data relevant to the treatment case (professional, industry, overseas) and material drawn from earlier sections.

Section 4 presents the data and discussion on inward patient flows of international patients into the NHS (policy and background, processes and perspectives) (see Chapter 15), outlines the economic considerations (see Chapter 16) and draws together the policy, management and research implications (see Chapter 17).

Chapter 3 Systematic review: what do we know about medical tourism?

Introduction

Medical tourism – people travelling abroad with the expressed purpose of accessing or receiving medical treatment – is a growing phenomenon associated with processes of globalisation. 40 This includes cheaper and more widely available air travel and cross-border communication through the internet, which allows medical providers from one country to market themselves to patients in another. At the same time, increased movement of health workers for education means greater consistency of care offered in origin and destination countries. This has been coupled with an increase in foreign direct investment in health-care providers in destination countries, including by private medical insurance companies. In some instances, US private insurers now allow patients to have treatment abroad. The increasing acceptance of health-care portability is evident in Europe where greater patient mobility led to a EU directive1 on cross-border health care. Together with a rise in out-of-pocket expenditures for health in many high-income countries at a time of economic crisis, these factors (travel, communication, consistency of care, cost and an increased acceptance of the portability of health care) conspire to form a perfect storm for medical tourism.

As a consequence, even in countries with a universal public health-care system, such as the UK NHS, patients are now travelling abroad to receive medical treatment. Data from the ONS indicate that in 2010 63,00041 people travelled abroad for medical treatment.

However, understanding of medical travel is limited. Little is known about which patients choose to travel and why. Details of the volume of patient flows and resources spent remain uncertain. This has hampered efforts to understand the economic costs to and benefits for countries experiencing inflows and outflows of patients. 8 Similarly, the medical tourism industry and the role of private providers, brokers and marketing remains a ‘black box’. 40 Although interest in the issue has grown over the past decade, the effects on patients and health systems are not fully understood. Given the emerging nature of medical travel research, the evidence base is not yet clearly mapped.

This review of the literature aims to outline the current level of knowledge on medical tourism and to better understand this phenomenon, including its impact on the UK NHS. Specific objectives are to better understand patient motivation, the medical tourism industry, the volume of medical travel and the effects of medical tourism on originating health systems. These objectives informed the search strategy and review criteria set out in Appendix 10. The results of the literature review are reported and discussed with reference to subthemes that emerged; special attention is devoted to findings directly relevant to the NHS. Conclusions are presented on current levels of knowledge, critical gaps and future research priorities on medical travel.

Methods

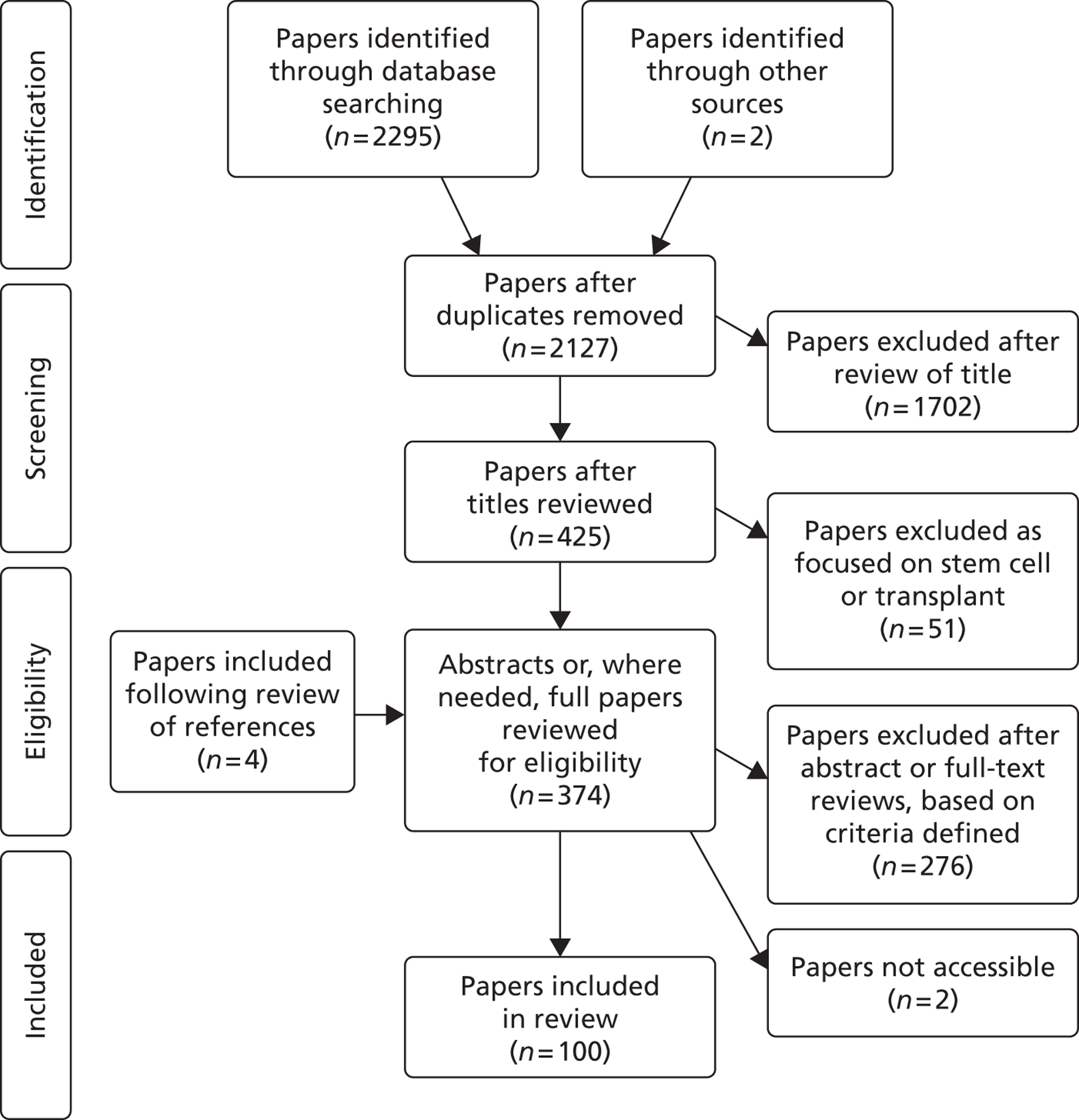

The review was conducted between September and December 2011, considering all papers published by this date, and adapted the strategy employed by Smith et al. 42 The strategy was reviewed and amended by a project advisory board consisting of academics, policy-makers and practitioners. The search strategy and inclusion criteria for the review are provided in Appendix 10 and the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart is provided in Appendix 11. In total, 100 papers were selected for inclusion in the review. 8,10–12,17,26,40,42–134

Results

An increase in medical tourism research is evident from the prominence of the issue. In 2010 and 2011, five journals devoted special editions to medical tourism: Global Social Policy, Body and Society, Anthropology and Medicine, Tourism Review and Signs.

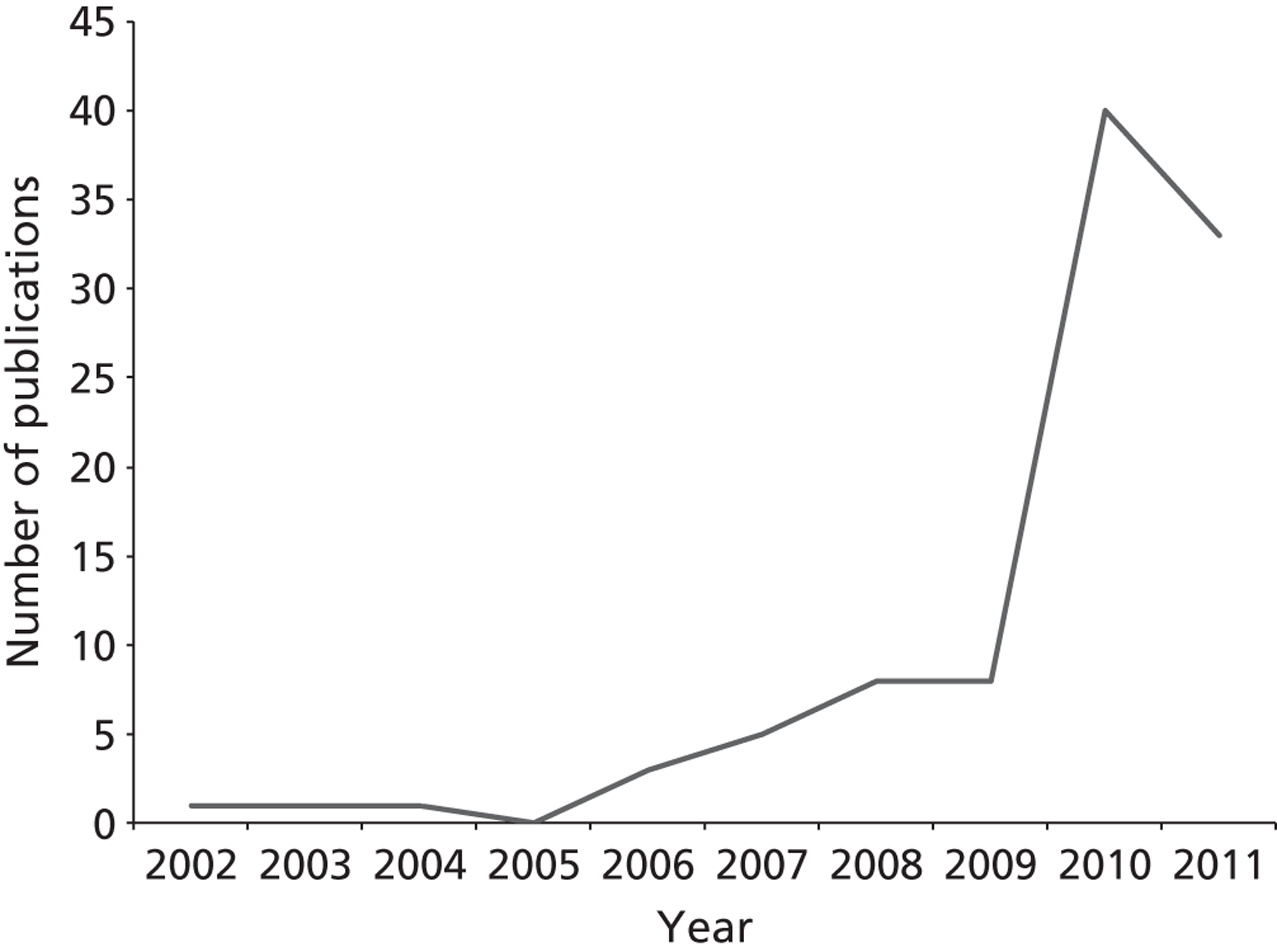

A rapidly expanding literature over the past 5 years (with an ‘explosion’ in 2010 and 2011) is reflected in the publication dates of papers reviewed, as evident from Appendix 12 (see Figure 9); 73 papers were published in 2010 and 2011. 40,42–45,47,50–52,54–57,59–61,64,67–78,80–95,97,99,102–104,107–121,123,125–127,129–133 This underlines the increase in medical travel and its importance as an issue in UK health-care provision.

Types of studies reviewed

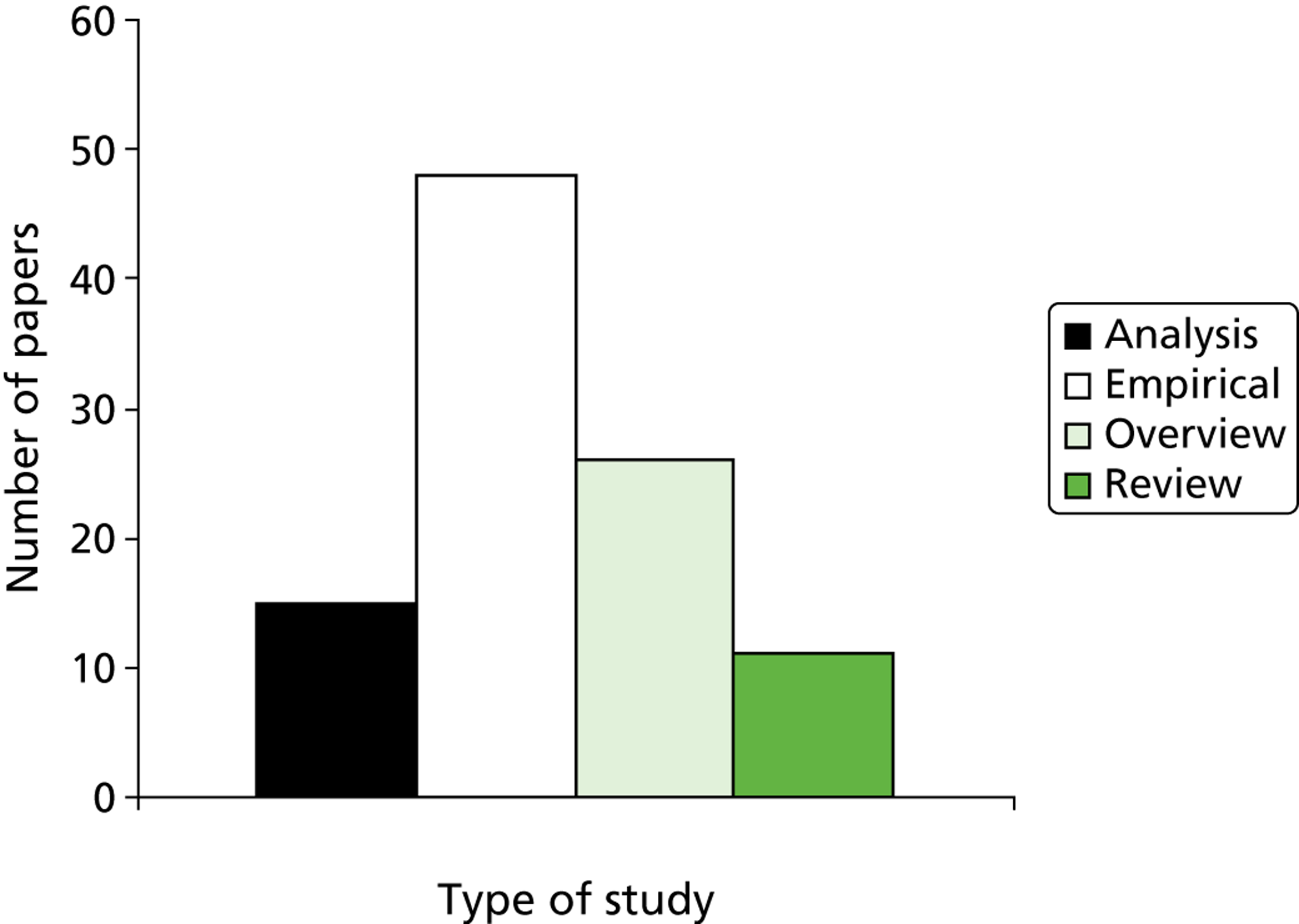

Papers included in the review were classified into the following categories:

-

empirical: denoting papers based on primary research, interviews, surveys, analysis of data sets, or the calculation of revenue and tourist flows, and case studies of patients

-

reviews: literature, scoping and systematic reviews of medical tourism websites

-

analysis: papers that, although drawing on secondary sources, provide substantive new insights or conceptualise medical tourism in a new way (a number of papers presented frameworks)

-

overview articles: papers that give an introduction to the issue of medical tourism.

The results are summarised in Appendix 12 (see Figure 10). In total, 47 papers17,43,44,47–49,51,57,62,65,66,68,71,76,78,81–83,85–87,93,94,96–100,103–106,110–114,116,118–120,124,126,127,132,133 presented findings from empirical research, 25 provided an overview of issues,10,11,26,46,50,52,53,58–60,63,67,73,79,80,91,97,100,115,120,122,128,130,135,136 15 were classified as analysis8,54,56,61,69,75,84,88,108,109,119,123,125,129,131 and 11 were reviews. 40,42,55,70,72,78,89,90,92,95,133 Of the 47 empirical studies, 19 reported findings from quantitative research12,17,43,47,76,81,85,93,96,98,99,103–106,110,114,116,124 (in most cases a survey), 15 were qualitative studies,44,57,62,68,71,74,82,87,94,112,113,116,118,120,132 eight reported case studies of patients51,66,83,101,102,111,119,127 and a further five48,49,65,86,93 reported the results of an experiment, cost calculation or evaluation of an intervention. In total, 32 of the empirical findings were published between 2010 and 2011, underlying the provenance of the issue.

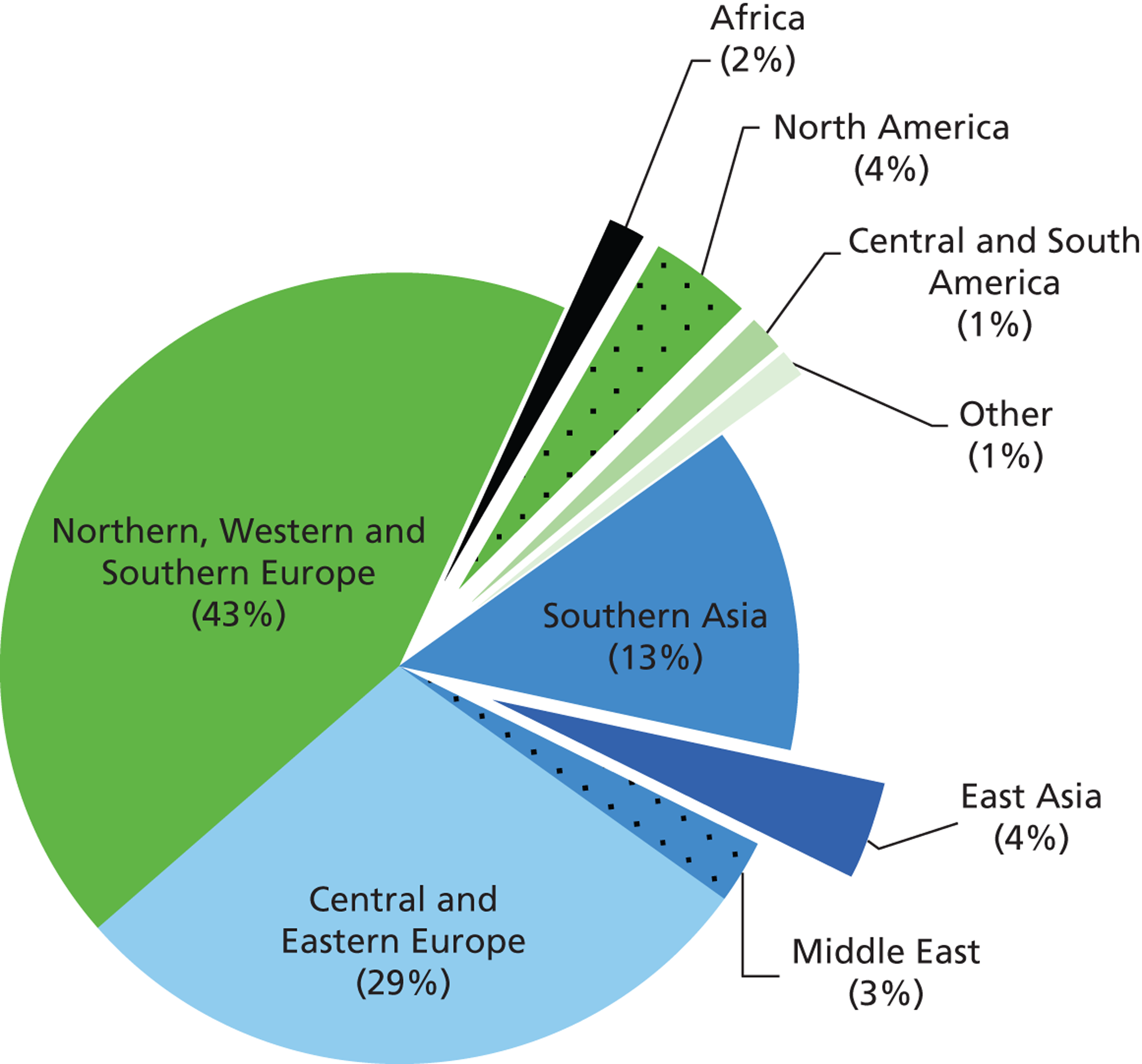

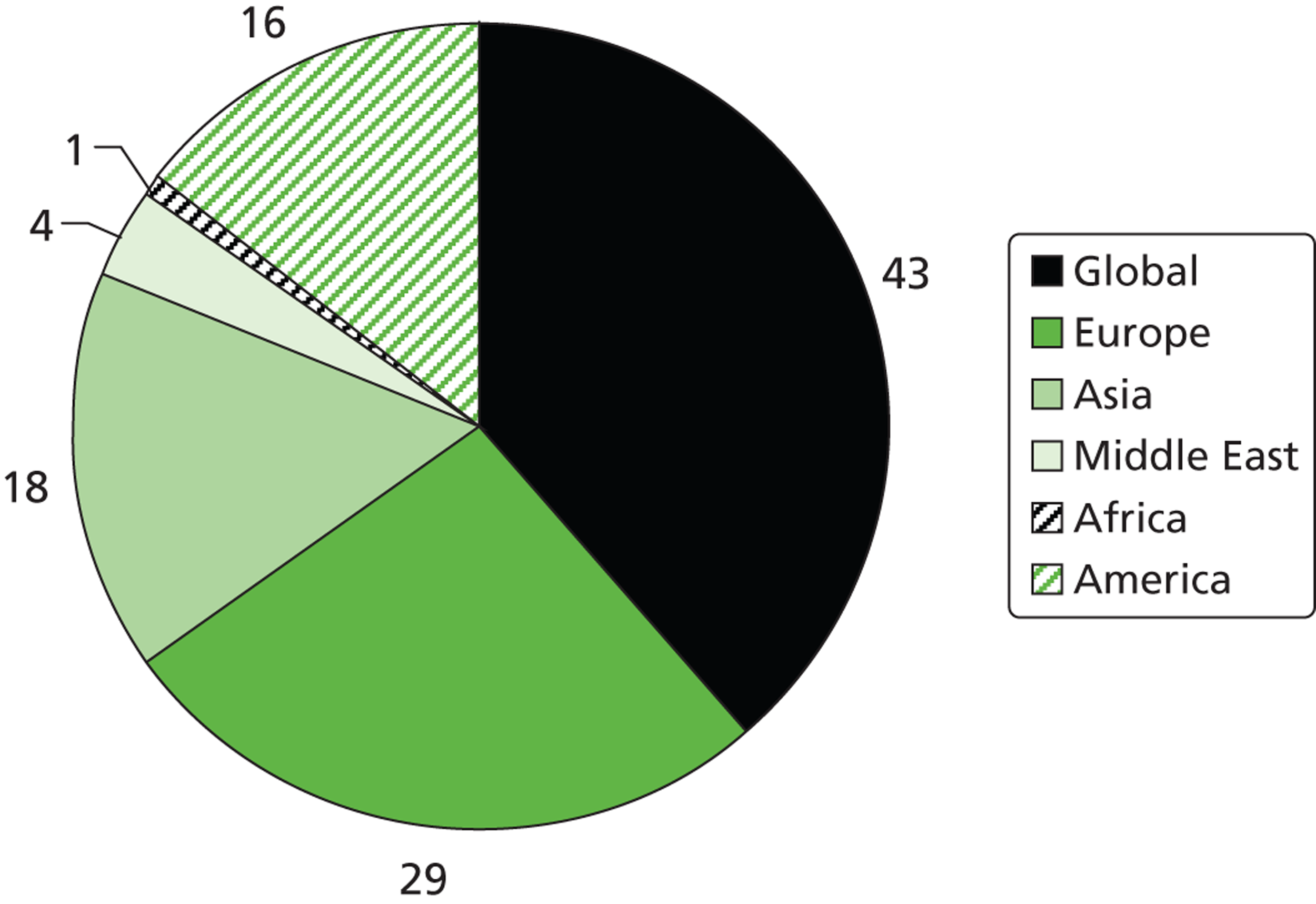

Geographical focus

Papers were grouped according to which region the research investigated. Papers that provided a general overview that was not focused on a specific region or country were classed as global. A total of 43 papers fell into this category. 8,10–12,17,26,45–47,52–55,58,59,63,64,67,69,70,72,73,78–81,89,90,92,93,95,107,111,119,121–123,129–133,135 Europe was the focus of 27 papers,40,42,44,48–50,57,60–62,65,66,75,76,83,84,91,94,98,100–102,104–106,114,126 with 13 explicitly focusing on the UK42,57,62,65,66,76,83,94,98,101,102,104,114 in their study design and a further 11 papers10,40,43,50,53,90,91,99,105,106,119 from across the entire sample referring to either UK patients or the NHS. The geographical distribution of papers is summarised in Appendix 12 (see Figure 11).

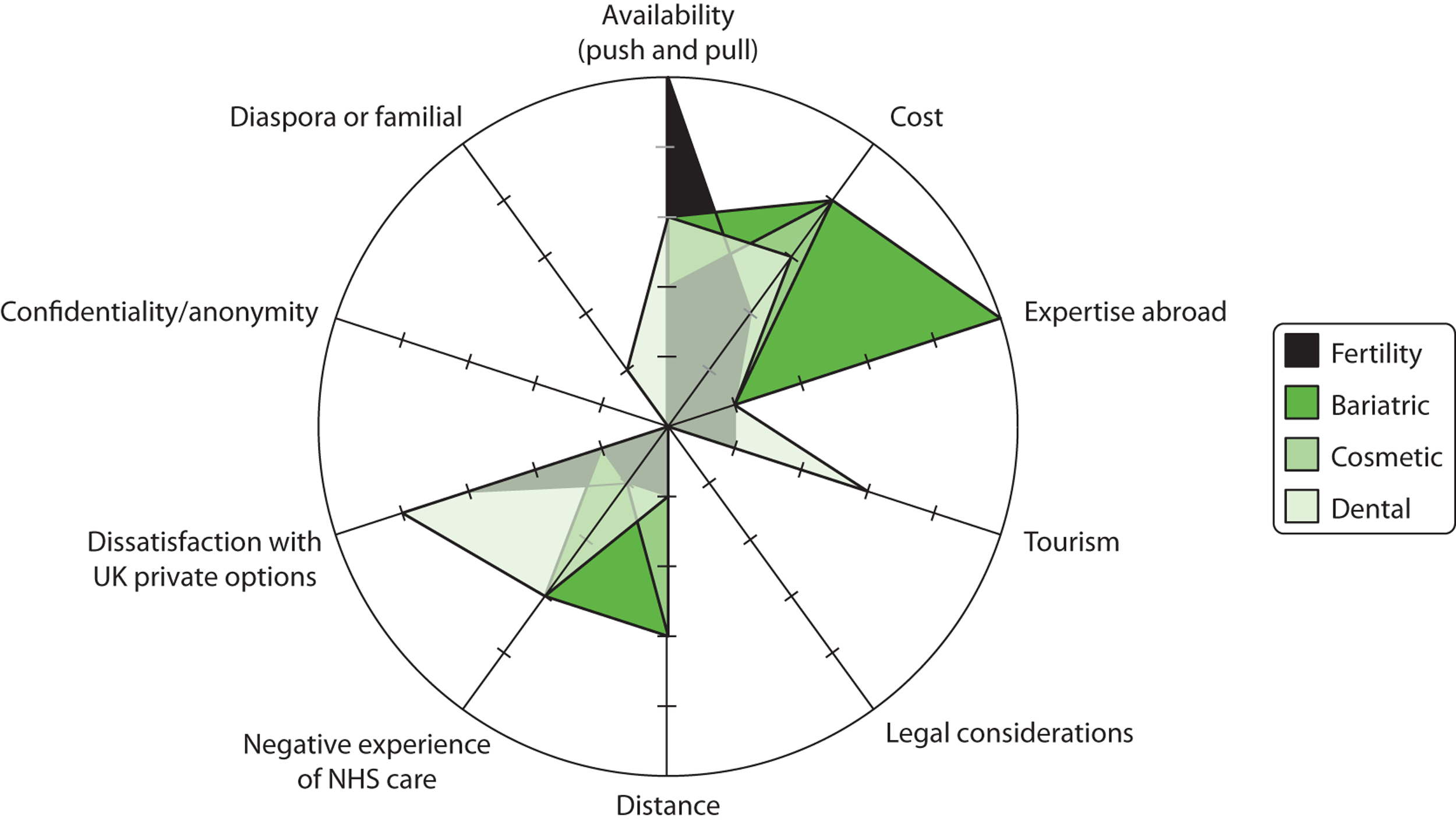

Evidence from studies reviewed suggests a regional dimension to medical tourism. Japanese companies send their employees to Thailand10 or to countries in the Gulf. 43,116 A study of medical tourists in Tunisia found that these were from neighbouring countries. 85 Thailand, Singapore, Malaysia109 and India8 and others have marketed themselves as medical tourism destinations. Countries are known for specific areas of medicine: Singapore for high-end procedures,86 Thailand for cardiac, orthopaedic and gender reassignment surgery,11 Eastern Europe for dental tourism108 and Spain for fertility treatment. 72

Although some destinations were recognised as being popular with UK patients, for example Budapest for dental treatment, proximity alone does not appear to explain preference for one destination over another.

Issues covered

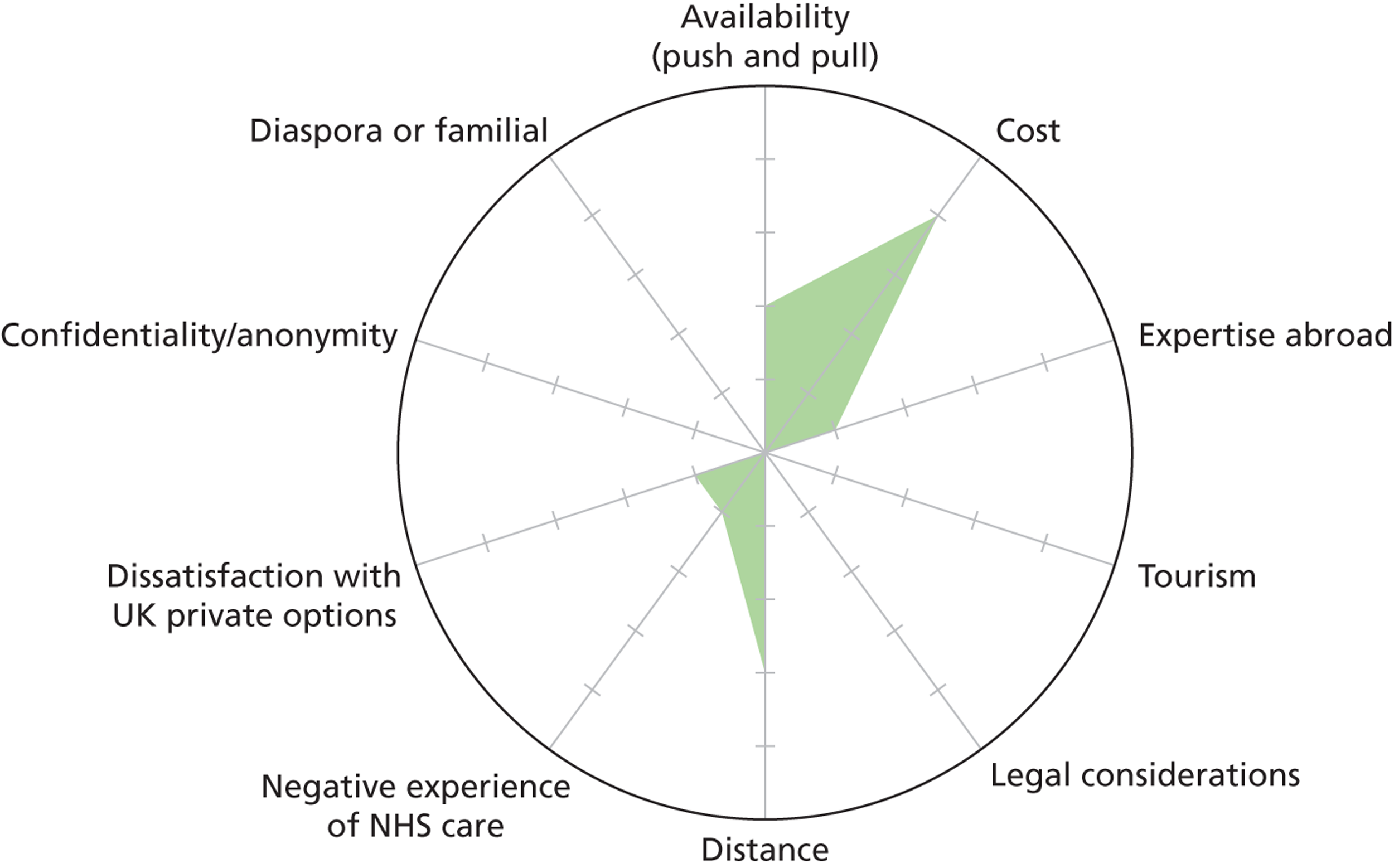

Most papers made reference to push and pull factors determining patients’ decision to travel. These relate to cost, perceived quality, familiarity, waiting lists or delays in treatment or the lack of availability of certain treatments in the country of origin. 61 As this list demonstrates, these are often complex57 and may vary according to the treatment for which a patient travels. A patient travelling for cosmetic surgery, for example, may enjoy the anonymity of a destination far from their country of origin,53 whereas migrants may prefer to travel to their country of origin to feel more comfortable with the language or type of care provided. 87

A subset of papers reviewed focused on specific types of medical tourism.

Diaspora travel

A number of studies refer to a group of medical travellers classified as diaspora travellers. Studies describe this in relation to India, China, Korea and Mexico, with recent migrants returning to their ‘home’ country to access treatment that is either not available or perceived to be not available in their country of residence, or perceived to be more effective in their ‘home’ country. 43,71,87,94

Glinos et al. 61 developed a typology for patient motivation (availability, affordability, familiarity, perceived quality of care), cross-referenced with whether a patient has funding or not. The authors applied this typology to understand patient motivation in a range of case studies from the literature and found that diaspora patients return because of reasons of familiarity with the system, as well as affordability.

Fertility tourism

Reproductive or fertility tourism is comparatively better documented than other forms of medical tourism. 40 Sixteen papers44,47,57,59,60,72,74,79,98,100,106,113,114,129,130,132 were identified for inclusion in this review; seven59,74,79,113,129,130,132 focused on equity and ethical issues relating to fertility tourism, including the rights of women in recipient countries.

Four papers57,98,106,114 specifically examined cross-border reproductive care (CBRC) in Europe. Two106,114 of these papers presented findings of surveys monitoring patient flow and services accessed across Europe and a third paper98 presented the results of the effects of such travel on patients giving birth in a central London hospital. One57 provided a qualitative, in-depth study of UK patients and their motivations for travelling abroad.

One paper47 presented findings from an online survey of prospective and actual tourists. Four papers44,60,79,100 provided a general overview of the issues relating to fertility tourism. Hudson et al. 72 presented a review of the literature on CBRC. Results included the consistent gap in empirical research; of 54 papers reviewed only 15 were based on findings from empirical investigation. The authors note the absence of studies and knowledge about patients’ backgrounds and factors motivating their travel, and a gap in the research on the industry.

Three papers57,98,114 explicitly explore the effects on the NHS. The study by McKelvey et al. 98 of multiple births over the past 11 years found that over one-quarter of high-order pregnancies in a UK foetal medicine unit occurred in patients who had travelled abroad to access fertility treatment. The qualitative study by Culley et al. 57 showed the complex motivations for travelling abroad, but concurred with other research that cost of treatment and the greater number of gametes available abroad or more easily accessible gametes played a part in decision-making. This was echoed by the results of a survey114 in which UK respondents were most likely to name difficulty in accessing fertility treatment as motivation for travel.

Dental, bariatric and cosmetic tourism

A further area of medical tourism is dental tourism. 137 Three papers101,105,122 focused on the issue of patients travelling for dental treatment. These indicated that this is likely to be an area of increasing travel by UK residents given the high cost of dentistry in the UK private sector, limited availability in the public sector and the lower cost in Eastern Europe. 101 Some countries, such as Hungary and Poland, have marketed themselves as dental centres of excellence. 137 A survey of dental clinics in Western Hungary and Budapest105 showed the largest group of patients (20.2%) originating from the UK, with lower prices being cited as the main motivating factor.

Two papers focused in depth on issues surrounding bariatric surgery. One explored the ethical challenges117 and the other was a case study of complications experienced by a US patient. 127

Papers by Birch et al. 134 and Miyagi et al. 102 focused on complications from cosmetic tourism in UK patients. A poll conducted amongst members of the UK public found that 92% would consider travelling abroad for cosmetic surgery. 104 The possibility of a large number of UK patients seeking cosmetic surgery abroad appears to be supported by a survey conducted by the British Association of Plastic, Reconstructive and Aesthetic Surgeons (BAPRAS),76 which found that 37% of respondents had seen patients in the NHS with complications from overseas surgery.

Risks

The issue of risks to the patient in terms of health outcomes was covered in 30 papers. 11,26,40,51,53,55,63,64,66,67,70,72,76,77,79,83,91,92,99,102,104,107,111,114,115,117,119,127,128,135 Perhaps surprisingly, only seven of these51,64,83,91,99,102,111 focused exclusively on the issue; 10 studies51,55,65,98–101,117,127,132 mentioned longer-term health outcomes of patients. Four papers51,66,83,111 reported cases of infection that resulted from patients travelling to receive medical treatment. Three51,83,111 described the recent outbreak of NDM-1-producing Enterobacteriaceae following patients receiving treatment in India, which highlighted some of the dangers of medical tourism and microbial resistance. The fourth66 described an outbreak of hepatitis B in a London hospital traced to a patient recently returned from surgery in India.

Effect on recipient country health system

As summarised in Appendix 12, 36 papers8,17,42,43,48,49,51,56,65,68,71,74,78,83,85–88,92,94,97,102,103,105,106,108,109,113–116,120,124,125,128,132 focused on the effects on the recipient country health system. Issues highlighted include the potential for medical tourism to result in the retention of doctors in, or attraction of doctors to, low- and middle-income countries, thus preventing or reversing a brain drain, and to generate foreign currency. 86 Also considered is the danger of creating a two-tiered health system, resulting in increasing inequities in access and quality of health care for the local population in destination countries. 78,125 Explanations are twofold: first, a rise in price in countries that do not provide public health services free at the point of use and, second, the potentially greater concentration of doctors in the private sector. 103

A total of 34 papers8,17,42,47–49,56,57,65,66,71,76,77,81,83,87,91,94–96,98–101,104,106–108,114,117,118,127,129,132 focused on potential effects on the health system of originating countries. These referred to factors leading to travel by patients, including a rise in costs. Studies documented patients returning with complications,99 including to the NHS. 102 Research highlighted the need for regulation, the lack of quality control of overseas providers and the cost (potential or real) arising to the originating country from treating complications. Two papers94,96 calculated the potential cost savings and benefits of sending patients abroad. When papers focused on the effects on the health system of originating countries, this was mainly on perceived negative consequences.

Industry

Thirty-nine of the papers reviewed8,10,11,17,43,44,50,53,56,57,60,62,68,69,71,72,76,81,85,88–92,95,97,98,103,104,106,107,109,113,116,122,124,128,132,135 focused at least partly on providers of medical tourism. Less attention was paid to facilitators (n = 19). 47,50,56,57,59,70,77,81,89–92,104,113,117,118,132,133,135 A subset of 19 papers8,50,56,62,68,69,76,81,88–90,92,95,107,109,118,124,132,133 studied the medical tourism industry in a more focused way. This included reviews of websites,90 market analysis,82 qualitative analysis of the role of medical tourism facilitators118 and a more general review,92 as well as a model for tourism development. 69 Articles examining communication materials and websites highlighted the limited information on follow-up care and redress in case of complications. 79 They also pointed to an emphasis on testimonies from patients rather than formal accreditation or qualification of clinicians and the great focus on tourism aspects of the destination and offering services ‘as good as at home’. 80 In addition, the low cost of treatment was used as a selling point.

There were two qualitative studies of medical tourism facilitators (interview samples included nine118 and 1282 interviewees, respectively); facilitators were presented as a heterogeneous group with a range of motivations.

Studies tended to mention regulation but only two123,130 reviewed this more systematically; both pointed to a vacuum in regulation.

Many studies mentioned individual hospitals or recounted an example of a medical tourism provider at the country level to give a flavour of the industry. 53,82 However, only four studies85–88 reported findings of a more systematic assessment of the industry and its operations. One study,40 evaluating past experiences of EU cross-border care, examined contracting arrangements and their effects on health outcomes.

Trade in health services: revenue and volume

Medical travel – the consumption of health services abroad – is defined as a trade under the General Agreement on Trade in Services (GATS) mode 2 and the majority of papers included in this review implicitly or explicitly focused on this form of trade in health services. 8 A subset of seven papers75,85,94,103,116,125,128 included a detailed discussion of other forms of trade in health services, including cross-border provision of services (GATS mode 1) and movement of health workers (GATS mode 4). Many overview papers mentioned the investment by US providers in Asian hospital groups without explicitly exploring this (GATS mode 3). Four papers8,46,75,94 analysed policy processes and challenges to trade in health services.

The actual volume of trade (the flow of medical patients) was referred to in many papers but investigated in few. 74,85,105,114,116 Studies by the United Nations Economic and Social Commission for Asia and the Pacific124 and Leng88 all provided further estimates or trends. The studies by Lautier,85 Siddiqi et al. 116 and NaRanong and NaRanong103 were the only ones that calculated the total volume of trade in health services (for 13 countries), including the actual costs and effects on recipient country health systems. For example, NaRanong and NaRanong103 calculate the contribution of medical tourism to the Thai gross domestic product (GDP) (0.4%), with medical tourists with their higher purchasing power likely to increase the cost of health services and lessen access in the public sector.

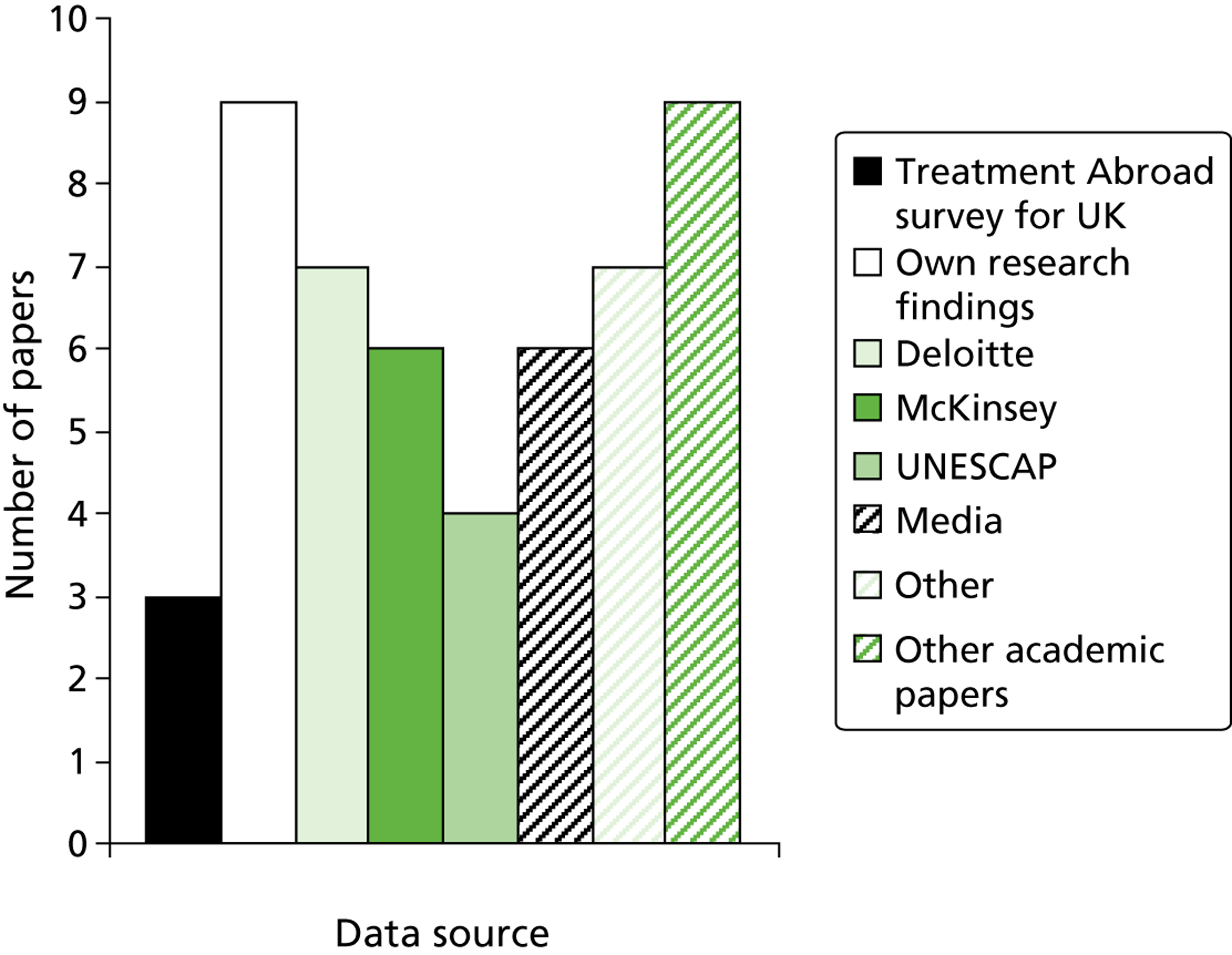

Most papers cited similar figures for patient flow but often sources were not accessible or figures were based on media reports or on other academic papers, which in turn quoted inaccessible sources. When sources for patient numbers were cited these have been summarised in Appendix 12.

One of the most commonly cited sources for patient flows was other academic papers. Seven papers67,81,92,93,108,129,131 referred directly to a report by Deloitte17 and six10,40,50,58,67,68 referred to a report by McKinsey;12 the exact ways in which figures in these reports were calculated remain unclear. Even when these reports were not referenced, the figures cited suggest that these two reports were used as sources. For example, a paper by Nassab et al. 104 cites the Economist, stating that 750,000 US patients travelled abroad for treatment in 2007. This is the figure provided in the report from Deloitte17 in 2008. Eight papers85,88,103,105,106,114,116,124 had either generated or collected their own data on patient flows.

Discussion

Perhaps the most surprising finding was the increase in number of papers presenting findings from primary research – a shortfall or gap that had been noted by the earlier literature reviews. 42,55,70 The recent publication date of many papers confirms the increasing amount of research being carried out on medical travel.

Medical tourism is a phenomenon in the private health-care market, which makes it hard to monitor and regulate patient flows. 137 Despite the rapid increase in number of publications over the past 2 years, reliable calculations of the actual volume of patient flow remain rare. This confirms findings from an earlier review,42 which also noted the lack of information on how the figures in the reports by Deloitte Consultancy17 and McKinsey12 were calculated.

The body of literature focusing on medical tourism as a trade in health services indicates that further research investigating levels of such trade is needed. Data on costs and benefits of medical tourism are rare and this limits accurate assessments of its effects to inform policy decision-making. Studies are also needed to empirically observe the effects of medical tourism in practice. The definitions of trade in health services provided,8 together with the framework for measuring its level provided by Siddiqi et al. ,116 set out a methodology for such research.

Understanding of the industry is limited. None of the research-driven papers captured the entire value chain of medical tourism. It is not evident how different industry actors (e.g. referring clinician, websites, facilitators, travel agents and receiving clinicians or hospitals) link together and how their relationships may influence patient experiences and health outcomes. Three papers referred to the role of medical tourism facilitators, drawing on small samples, demonstrating the need for further research in this area, especially to enable regulation or to address the ethical dimensions discussed in the papers reviewed. 118,131,133

Types of medical tourism

The literature reviewed clearly indicates that medical tourism is no unified phenomenon. Subthemes as distinct areas covered by research were evident from the review, such as diaspora or fertility travel or travel for bariatric surgery or dental or cosmetic work. The papers on diaspora travel highlight that medical tourism and decisions by patients to travel are not simply guided by cost considerations or even clinical outcomes. Rather, the literature points to a complex matrix of perceptions of care, waiting times, cost and other factors.

The different types of medical travel allow some inferences about patient motivation, for example cost or availability in cosmetic procedures, regulation in the case of fertility and so on. However, a lack of information about patients’ characteristics limits a deeper understanding of push and pull factors.

Impact on the NHS: lack of studies focusing on long-term health outcomes

Evidence demonstrates that patients travelling abroad to receive treatment and returning to the UK may face complications or infections requiring follow-up in the public sector. Seven papers65,66,76,83,98,101,102 reported on patients who were treated in the NHS as a result of complications resulting from treatment abroad. Based on the literature reviewed, cosmetic procedures appear to be an area of growth for medical travel by UK patients and are likely to result in costs to the NHS from resulting complications. This underlines the need for further research to ascertain the potential impact and costs for the NHS arising from medical tourism.

In addition, little is known about the longer-term health outcomes of medical tourists beyond these incidental reports of complications. No literature on inward medical travel and its effects on the NHS was identified, pointing to a gap in knowledge.

Conclusions

This review provides a map of current knowledge on medical tourism and identifies a series of subthemes. The reviewed papers demonstrate the multidisciplinary nature of medical tourism research. There has been an ‘explosion’ in research on medical tourism over the past 2 years. This review clearly identifies limits to current knowledge; many papers remain hypothetical and there are many areas in which further research is needed.

There is still a lack of information on the background of patients and the numbers of patients travelling abroad for treatment. This limits insights into why some patients travel and others do not and restricts evidence about the possible costs and benefits of medical travel.

The absence of information on patients’ social, economic and demographic backgrounds hampers the ability to understand patient decision-making and determinants of travel. The studies reviewed indicate that motivation is complex. Further information is needed to fully understand this decision-making process. It is especially relevant to gain insight into why patients from countries with public health-care systems such as the UK choose to travel abroad.

Little is known about the industry beyond reviews of information materials and websites. Further research, especially qualitative and survey-based research, is needed to better understand how the sector operates and what its motives are to ultimately understand how it drives or affects trade in health services and health outcomes of medical travellers.

Although case studies of patients returning from treatment abroad with complications were reported, these did not quantify the potential cost of medical travel to the patients’ ‘home’ health systems. Given the evidence of an increase in medical travel such research is urgently needed.

There is no research examining the long-term health outcomes of UK medical tourists. Further qualitative and quantitative research, beyond immediate clinical outcomes, is needed to truly understand the effect of medical travel on patients and its cost to the health system.

Implications for the NHS

-

There is a need to collect data on the number of patients who return from treatment abroad and are treated within the NHS.

-

There is a need for additional surveys and quantitative research to understand more fully the volume of patients who travel abroad and their social and economic characteristics. This will enable a more accurate understanding of the scale of the issue and factors determining patient travel. These ‘push factors’ may in themselves hold valuable lessons that reflect on the NHS.

-

There is a need for research to assess the long-term health outcomes of medical travellers to fully understand the effects on individual and population health.

Chapter 4 The context of medical tourism

This chapter provides an introduction to medical tourism services, processes, providers and countries’ strategies. Drawing across the composite data set, including interview data (encompassing commercial interests, overseas providers, professional associations and stakeholders, and medical tourists) supported by the desk-based activity (e.g. website review), we seek to conceptualise and typologise, unravelling the bigger picture of medical tourism, as viewed through the perspective of respondents. The chapter is structured around four themes:

-

services: highlighting the range of treatment and ancillary services within medical tourism (offered by providers, marketed on the internet and purchased by patients)

-

information: conceptualising the ways in which information is made available

-

clinical provision: outlining the range of clinical providers within medical tourism and their supply chains

-

country strategies: a review of five country strategies aimed at growing medical tourism and their perspectives on UK market opportunities.

The chapter summarises the emerging implications for the NHS.

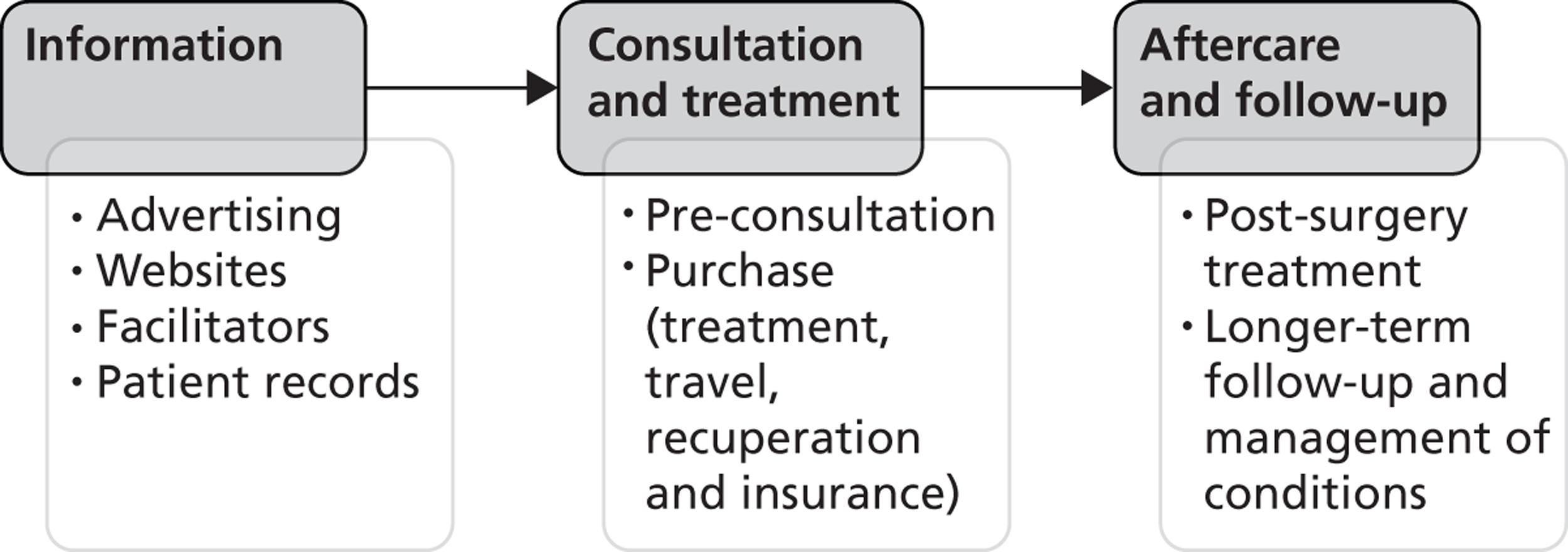

Services

Medical tourism treatment pathways involve a number of services (both clinical and ancillary) that together give an overall experience. Although not all of these services are integrated in each and every patient journey, the variety of services illustrates the full range of possibilities:

-

conferences and media activities: for example fertility trade fairs that market, inform and connect potential travellers with overseas services

-

websites: prospective travellers use the internet to find out about medical travel and to support decision-making, including clinic websites, portals (which may contain details of numerous clinics) and consumer-driven sites such as chat rooms and discussion boards

-

intermediaries: (facilitators and brokers) provide information (web-based and one-to-one) for prospective patients about treatments and services and make arrangements for treatment and services

-

preconsultation: this may take place in the UK or abroad at a preliminary clinic undertaken by the surgeon or doctor, or screening may be provided by a contractor based within the UK

-

treatment: (provided by clinics and hospitals) may involve outpatient treatment, day surgery or longer-stay hospital admission

-

forms of accreditation: (available to clinics, hospitals and facilitators) seek to offer assurance around the quality and safety of products; accreditation is itself typically a commercial activity with competing accreditation bodies offering their services

-

financial products: available to patients to fund the costs of travel and treatment

-

insurance products: developed to insure for travel and loss, and seek to cover the costs of further treatments that may be required as a result of complications and dissatisfaction following surgery abroad

-

travel, hotel and concierge: flights, accommodation (for accompanying family and companions, or for patient recuperation) and support services (e.g. translation) are purchased

-

tourism and wellness: for some medical tourist destinations and treatments, attempts are made to promote the cultural, heritage and recreational opportunities

-

aftercare: may be arranged within the treatment country or within the home country (including dressings, stitches, pharmaceutical arrangements, monitoring and follow-up).

There are particular stages in the treatment pathway during which issues arise that have a bearing on the NHS. First, can individuals obtain appropriate information to ensure that they are able to make an informed choice and ensure their safety? For example, is non-commercial advice and input available at trade fairs and on websites, for example travel guidance and checklists? Second, what advice should the Department of Health, commissioning bodies and GPs provide to individuals seeking to travel abroad? Finally, are appropriate aftercare arrangements made, given that there may be expectations of receiving NHS care and financial implications if aftercare services are required.

Information

Searching for information may be time-consuming, confusing and overwhelming. Individuals may be unclear how best to go about finding and validating trustworthy sources of information. Looking across the range of patient, commercial and stakeholder interviews, analysis identified three idealist models whereby prospective medical tourists gather information and source their destination and provider (see Appendix 13).

Model 1: facilitator-enabled provision

A range of intermediaries – known as brokers or facilitators – arrange services and phases of treatments. Such intermediaries may specialise in particular target markets or procedures or destination countries (e.g. from our own interviews these included sites focused on fertility treatment or on a particular destination for a range of treatments). Facilitators may be physically located in a home country, have a presence overseas or both. As well as e-mail and telephone communication, they may undertake chaperoning and translation functions during the travel and treatment phases. The potential for intermediaries can be attributed to the transaction costs associated with medical tourism.

Model 2: consumer-driven access to information and provision

In the consumer-driven model individuals use various forms of soft/hard intelligence to inform decision-making around medical and ancillary products, relying on marketing imagery, or evidence on quality and outcomes. They take the lead in searching and arranging. Our patient interview data suggest that individuals consult websites to compare costs and to reduce their own transaction costs when putting together a particular treatment journey (particularly related to search and information costs). As outlined in Section 3, decisions are likely to vary for different treatments (e.g. fertility treatments, for which patients are likely to be health literate about success rates and risks). Decisions to be made include selecting country, clinic and clinician and arranging travel insurance or specialist insurance, finance, travel, accommodation and concierge, and aftercare.

Model 3: networked access to information and provision

The final type of access to medical travel information relies predominantly on network dynamics. 138 Individuals source information through treatment-based, cultural-based and professional networks.

Cultural- or treatment-based networks involve patients drawing on the advice, relationships and socialisation influence of a wider group:

-

Cultural-based networks: for example, Section 3 outlines how British residents and citizens with cultural and historic ties to Indian and Somali populations travel to India and Germany, respectively, for dental treatment and diagnostics based on informal recommendations from close friends and within the wider community network.

-

Treatment-focused networks include organised discussion forums and self-help groups that cohere around treatments/conditions such as bariatric, fertility and cosmetic treatment. As Section 3 outlines, these networks may also be enmeshed in delivering treatments themselves, including offering services for support and aftercare (e.g. bariatric and fertility support groups).

Professional networks involve professional ties and connections mediating information and choice:

-

Professional networks can involve clinicians and professionals advising and linking individuals to clinicians and hospitals across national boundaries. For example, as detailed in Section 3, some private fertility clinics have links to partner clinics overseas (where perhaps wider treatment choices are available). Clinicians will also directly recommend amongst their own networks (reflecting education, training and experiences). As Chapter 15 outlines, when overseas governments are paying for NHS treatment, the choice of provider is explained by network knowledge and strong ties (e.g. where referring clinicians trained or undertook postqualifying training or where attachés have strong links).

These three network configurations sharply contrast simple market relationships of buyer and seller making trade-offs around price/quality.

To reiterate, these three idealist models (facilitators, individuals and networks) explain how information is sourced for medical tourism. These three types are clearly evidenced within our patient stories and wider interviews. As ideal types they are not mutually exclusive, and patient stories will contain one or more such sources of information, for example there is overlap between models 2 and 3 with regards to consumers’ engagement with professionals.

There are also clear advantages and disadvantages of such sources of information. In Appendix 13 we develop an analysis of the potential advantages and drawbacks of these three information sources, informed by what medical tourists and commercial interests suggested during interviews.

Clinical provision

Within medical tourism there is a diversity of participating clinics and providers [as Ackerman139 suggests, ‘cottage industries and transnational enterprises’ (p. 405)]. Providers are primarily from the private sector but are also drawn from public sectors. Relatively small clinical providers may include solo practices or dual partnerships, offering a wide range of treatments in areas such as cosmetic surgery. At the other end of the scale are extremely large medical tourism facilities in which clinical specialism is the order of the day. Hospitals may be part of large corporations or wider affiliations of general and specialist clinics. Although there are smaller independent, specialist clinics, it is these large complexes that dominate the Spanish industry.

Larger clinics and providers have moved to offer a range of services (financial products, insurance, hotel, translation, accommodation, aftercare) within a horizontally integrated supply chain. Services may be more loosely or fully integrated and emphasise upstream integration (finance, preconsultation, travel), downstream integration (recuperation, aftercare, follow-up) or both.

Country strategies