Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1809/1075. The contractual start date was in January 2010. The final report began editorial review in April 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

John Powell is a member of the NIHR Journals Library Board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Scarbrough et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and aims

The Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) initiative was developed by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) in response to a new research and development (R&D) strategy in the NHS: ‘Best Research for Best Health’. This response focused on the ‘second gap in translation’ identified by the Cooksey review;1 namely, the need to translate clinical research into practice. As specified by the NIHR’s briefing document on CLAHRCs, a crucial stage in translating research into practice was seen to be ‘the evaluation and identification of those new interventions that are effective and appropriate for everyday use in the NHS, and the process of their implementation into routine clinical practice’ (p. 1).

The research presented in this report was funded by the NIHR as one of four uniquely focused projects aimed at evaluating the CLAHRC initiative. The ‘external evaluation’ reported here was designed to complement the internal evaluations being carried out within each CLAHRC. Its particular focus was on CLAHRCs as a new form of ‘networked innovation’. Following a start-up meeting of the evaluation projects in October 2009, our study commenced January 2010.

Aims of the Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care initiative

The NIHR established nine CLAHRCs as partnerships between at least one university and surrounding NHS and other organisations in October 2008. The CLAHRCs were selected through open competition, by an independent international selection panel. The objectives for the CLAHRCs as set out in the original call for proposals were as follows:

-

to develop an innovative model for conducting applied health research and translating research findings into improved outcomes for patients

-

to create a new, distributed model for the conduct and application of applied health research that links those who conduct applied health research with all those who use it in practice across the health community covered by the collaboration

-

to create and embed approaches to research and its dissemination that are specifically designed to take account of the way that health care is increasingly delivered across sectors and across a wide geographical area

-

to increase the country’s capacity to conduct high-quality applied health research focused on the needs of patients, and particularly research targeted at chronic disease and public health interventions; and

-

to improve patient outcomes across the geographic area covered by the collaboration.

The core funding for this initiative was around £50M, with each CLAHRC being funded £5–10M over 5 years by the NIHR, with added ‘matched funding’ by local partners.

Aims of our study

Our research design was developed in response to a call for proposals issued by the Service Delivery Organisation (SDO) of the NIHR (www.nets.nihr.ac.uk/__data/assets/pdf_file/0005/81572/CB-09-1809-1072.pdf). While certain broad areas were identified within this call, it did not specify particular research questions but exhorted researchers ‘to capitalise on the opportunity provided by the CLAHRCs to evaluate this new initiative and in doing so to make a substantial contribution to learning for the CLAHRCs themselves and for the NHS as a whole’ (p. 5). The call specified that evaluations should be well theorised, and should be able to contribute to ‘the wider evidence base on how best to foster the application of research findings in practice settings’. In response to this call, the aims for our study were specified as follows:

-

to provide an independent and theory-based evaluation of CLAHRCs as a new form of networked innovation in the health sector

-

to support the organisational learning and improvement of CLAHRCs by providing comparative evidence and insights on their innovation capabilities within both a national and an international context

-

to support improved patient outcomes by adding to the evidence base on networked innovation within the UK health sector, especially with respect to management and governance mechanisms, and how this compares with leading international examples

-

to increase the NHS’s capability for networked approaches to innovation by developing a more comprehensive theoretical framework

-

to make recommendations on improving the evaluation of KT through greater appreciation of the role of networks; and

-

to contribute to the international knowledge base on research use through cross-national comparisons, and the cross-fertilisation of academic literatures.

These aims have remained unchanged since the beginning of the study.

Chapter 2 Review of existing literature

The knowledge translation problem in health care

As outlined above, the challenge facing the CLAHRCs was defined in terms of overcoming a ‘translational gap’ between research and practice. This notion of a gap between the knowledge developed by research communities in health care and health-care practice itself is the subject of an extensive literature. 2–5 A perceived gap between research and practice is not confined to health-care organisations; other work has identified it more broadly as a major societal and organisational challenge. 6 The implications of such a gap, however, are seen as extremely serious in the health-care setting where the ‘non-adoption’ of new research evidence and/or the lack of spread of new forms of improved practice may have significant adverse consequences for patient well-being. 3,7,8 These concerns were articulated by the Cooksey report,1 which sought to address the relationship between research and practice as a continuum of activities. As noted above, Cooksey’s analysis of the translational gap within that continuum helped to inform the establishment of the CLAHRC initiative.

The analysis of the knowledge translation (KT) challenge in health care in terms of a metaphorical ‘gap’ has had important implications for the development of theoretical models and, beyond that, policy initiatives in this area. While it has long been argued that the translation of research into practice is problematic, traditionally this has been viewed in terms of linear and unidirectional movement, from the production of research (and other forms of knowledge) to its use in practice. 9 In effect, there was an assumption that research findings would be disseminated from the laboratory through applied research and development and then into practice.

This assumed linear path from the production of knowledge to its use – signified in the term ‘gap’ – has since been subject to lengthy debate and criticism in the health-care sphere. 10–12 Some scholars have even questioned the continued use of the term ‘translation’, given the one-way direction of knowledge flow and conversion that it often implies. 13 In the period leading up to the establishment of the CLAHRCs, then, a new set of approaches were emerging that highlighted the importance of ongoing interaction and trust-based relationships between researchers and practitioners in meeting the challenge of translation. 14–16 These approaches moved away from a linear view of translation to one which gave greater recognition of the complex, multifaceted interactions involved in developing and implementing research in practice. 17,18 At the same time, within the wider literature of organisation studies, a further stream of research focused on explaining the processes and practices through which knowledge is translated across different settings. 19,20 Leaving aside any notational issues, such approaches depict KT as crucially important for improving health care as this is the process whereby research evidence comes to inform and impact health-care policy and practice and vice versa. 21

In the health-care setting, the notion of KT was given greater prominence among policy makers by the work of the Canadian Institutes for Health Research (CIHR). The World Health Organization subsequently adapted the CIHR’s work and defined KT as ‘the synthesis, exchange, and application of knowledge by relevant stakeholders to accelerate the benefits of global and local innovation in strengthening health systems and improving people’s health’ (p. 2).

Responding to the knowledge translation problem: policy interventions

Policy-makers now recognise that, as collaborative working practices facilitate the process through which research findings can come to inform policy and practice,22 deliberate institutional strategies for collaboration can be used to support the utilisation of knowledge. 5 Policy interventions designed to support KT in health care, and to connect innovations with practical improvements, have taken a wide variety of forms. One approach taken by health research funding agencies has been to commission collaborative entities in which academic researchers work closely with other stakeholder groups (such as health-care practitioners, patients, industry and policy representatives). Canada has been at the forefront of such initiatives. An early example was a grant programme developed by the Quebec Social Research Council (CQRS) in the 1990s to encourage the building of research partnerships between researchers, decision-makers and practitioners. 23 A second Canadian example is the Need to Know project funded by the CIHR. 24 A notable example in the USA has been the Quality Enhancement Research Initiative (QUERI) of the US Veterans Administration. 25

These policy interventions represent examples of system-level KT interventions, where an environment is created to support the production and application of health-care evidence in influencing policy and practice. 26 In the UK, various centres and networks (including CLAHRCs, Biomedical Research Centres, Patient Safety Translational Research Centres and, most recently, Diagnostic Evidence Co-operatives) already form a crucial part of the NIHR infrastructure, and the recently established academic health science networks are intended to play a major role in connecting innovation with improvement in the NHS, and have a brief to work with CLAHRCs on translating research and learning into practice. Each programme is characterised by a strategic approach of assembling mechanisms and processes to support KT across the boundaries of stakeholder groups, such as between the ‘producers’ (i.e. academic researchers) and the ‘users’ (i.e. practitioners, commissioners and patients) of health-care evidence in policy and practice. While it is the ‘external-directed’ boundary between the diversely different communities of the ‘producers’ (academics) and ‘users’ (practitioners and policy makers) of health-care research27 that is most often recognised as the focus of these interventions, they can also be directed ‘internally’, such as within the boundaries of a profession28,29 and/or between members of the same organisational entity. 30

These kinds of policy interventions, while being many and varied, are all premised on the assumption that supporting new forms of highly networked, collaborative working across boundaries (organisational and/or epistemic) will result in better knowledge sharing and, as a result, the speedier translation of new ideas into (and from) actionable solutions. These interventions, including the CLAHRCs, can be framed, then, as initiatives aimed at ‘networked innovation’; that is, ‘innovation that occurs through relationships that are negotiated in an ongoing communicative process, where control cannot rely on either market or hierarchy alone’ (p. 916). 31 Our evaluation of the CLAHRCs is thus able to be positioned, more broadly, as an evaluation of an initiative aimed at networked innovation.

The premise underpinning networked innovation initiatives is that network-based organisational forms are more effective at knowledge sharing and, therefore, better for innovative performance, than either markets or hierarchies. The features which enable such effectiveness, however, are the subject of ongoing research. Work on some of the recent initiatives highlighted above, for example, has highlighted features such as the importance of leadership, culture, and context (e.g. CQRS);23 the need to build relationships between groups to support KT (e.g. Need to Know);24 and the long time scales needed to show health benefit (QUERI). 25 Even the benefits of the network form itself are open to question. A recent systematic review of knowledge mobilisation in health-care organisations found that the superiority of networked organisation designs for knowledge sharing and performance rested on the quality of the relationships more than the network structure. 32 For example, low-trust relationships in networks can lead to poorer knowledge sharing than high-trust relationships in hierarchies. 32 Put simply, ‘relationships trump design’ (p. 173). 32 The broad conclusion of this review was that the benefits of network arrangements for KT cannot be taken for granted.

We need, then, to better understand what it is that makes networks actually work. This means asking questions about the social relationships and boundary-spanning activities underpinning knowledge sharing in networked settings, the beliefs and interests of those involved, and the governance and management mechanisms deployed in specific contexts for particular ends.

Conceptual framework

Our perspective involved viewing the work of the CLAHRCs and their partners as involving a process of networked innovation. 31 This perspective begins from the important point that the KT efforts of the CLAHRCs are aimed, ultimately, at achieving innovative outcomes. They exist, in other words, for a specific purpose, which is to encourage the sharing of knowledge aimed at translating new ideas into improved practices. As is well recognised, however, this innovation task is problematic. 33 The requisite knowledge is distributed across the boundaries of expertise, professional groups and organisations. 20,34 As a result, innovation requires the progressive exchange, transformation and ‘co-production’ of knowledge by collaborating groups. 16 Moreover, because the CLAHRCs entail novel forms of collaboration, the roles, accountabilities and management of these groups also need to be worked out. Our conceptual framework thus needed to incorporate particular processes found in previous research to shape the ability of such distributed groups to work together in KT endeavours. These include the following.

Overcoming boundaries to access distributed knowledge

As work in the innovation field has highlighted, the knowledge required to develop and implement innovation is increasingly distributed across different groups and organisations. 35 This finding is also echoed in studies within health care. McAneney et al. ,36 for example, note that ‘the knowledge which is needed to solve problems and bring about changes is likely to be distributed throughout organisations and to come from many different sources’ (p. 1498). Recognition of the need to span boundaries is a long-established theme in innovation studies, and research has focused to a great extent on organisational boundaries. 37 However, the importance of accessing distributed forms of knowledge underlines not only the need for translation between different organisations, but also the need to circumvent what recent work has termed the ‘knowledge boundaries’ that constrain the flow of knowledge between different epistemic groups and communities.

Knowledge boundaries naturally arise, according to Carlile, because of the embeddedness of knowledge in practice – knowledge sticks at the boundaries of practice and is shared where practices are shared. 20 Such boundaries can be analysed in terms of syntactic (shared or different language), semantic (shared or different meanings) and pragmatic (shared or different practices) dimensions. 20 The value of this analysis is that it highlights the multifaceted and relational character of KT. 38 It thus provides a broader view of the challenges of translation that highlights the extent to which particular groups, such as researchers, policy-makers and practitioners, are connected or divided by their respective contexts, language and (politically invested) practice. These different groups can be viewed as ‘epistemic communities’, which are characterised by shared language, values and world views. 39

A number of studies have sought to establish the types of mechanisms and processes that can be used to support KT across knowledge boundaries in health care. 27,40 These studies build on an understanding that knowledge cannot easily be translated into a comprehensible form from one community for utilisation by another dissimilar community:41,42 knowledge, in other words, is embedded or ‘sticky’,43 as the producers and users of knowledge inhabit different worlds. 44 Knowledge is also politically invested,20,45 so there is a pressure within networked innovation initiatives for more collaborative forms of knowledge production to revert to (or even be undermined by) long-established modes of producing knowledge based on professional demarcations. 46

Given that the challenges of translating knowledge across the boundaries of diverse groups and communities are especially stark within the health-care field, attention has been placed on developing, managing and evaluating interventions that can facilitate this process. Among the mechanisms highlighted in the existing literature is the creation of boundary-spanning or ‘knowledge broker’ roles for individuals to link discrete communities;47–49 organisational-level activities (such as using forums and meetings) as places for the exchange of ideas between groups;50,51 and integrated KT processes and end-of-grant activities in which findings are translated for other audiences. 52

Considerable attention has been placed on understanding the process of ‘boundary spanning’ across organisational and epistemic groups within health care. While some research has highlighted the importance of material objects in bridging diverse groups,39 boundary spanning can also be achieved by individuals who, either formally or informally, enact a ‘knowledge broker’ role. Such individual boundary spanners have been described as performing functions such as acting in leadership and network-building roles, fostering relationships, and contributing an innovative perspective,53,54 suggesting that boundary-spanning individuals are those with experience of and credibility in both ‘camps’, such that they can move back and forth and broker understandings between different thought worlds. Such knowledge-brokering strategies can be used to address the language and cultural barriers between the worlds of research and decision-making by translating research and other evidence into different vocabularies. 55 The knowledge-broker role is designed so that individuals can act as facilitators of collaboration and ‘translators’ of knowledge from one community to another. Indeed, as the use of interpersonal contacts and good communication skills in the context of partnerships and research collaborations is emphasised in knowledge brokering, it has been described as particularly suitable for linking upstream research with downstream practice. 48 Therefore, one important strand of our work is on roles enacted by individuals to support the translation of knowledge across groups.

While much attention has been given to individuals performing boundary-spanning activities as brokers between diverse groups, previous studies also indicate that knowledge brokering can be enabled by organisations and structures, such as a whole network of ties or collaborative strategies. 56 These types of boundary-spanning mechanisms are about structures, activities or processes that an initiative may develop in order to facilitate KT within a collaborative community. For example, explicit strategies that have been described include initiative-wide activities developed to provide a ‘space’ for face-to-face interaction and discussion, such as consultation sessions, interactive multidisciplinary workshops, steering committees and the formal creation of networks and communities of practice. 57 The CIHR’s influential global integrated KT approach represents an organisational-wide strategy to support activities that are conducive for KT across the boundaries of the producers and users of research. 58 This approach is about building a structure and interlinking activities at the level of a whole initiative that is able to facilitate sharing knowledge across the boundaries of a wide range of actors, including health professionals, researchers, the public, policy-makers and research funders. 59 It may also include the formal allocation of resource to individual knowledge brokers.

Developing social networks to enable the translation of knowledge

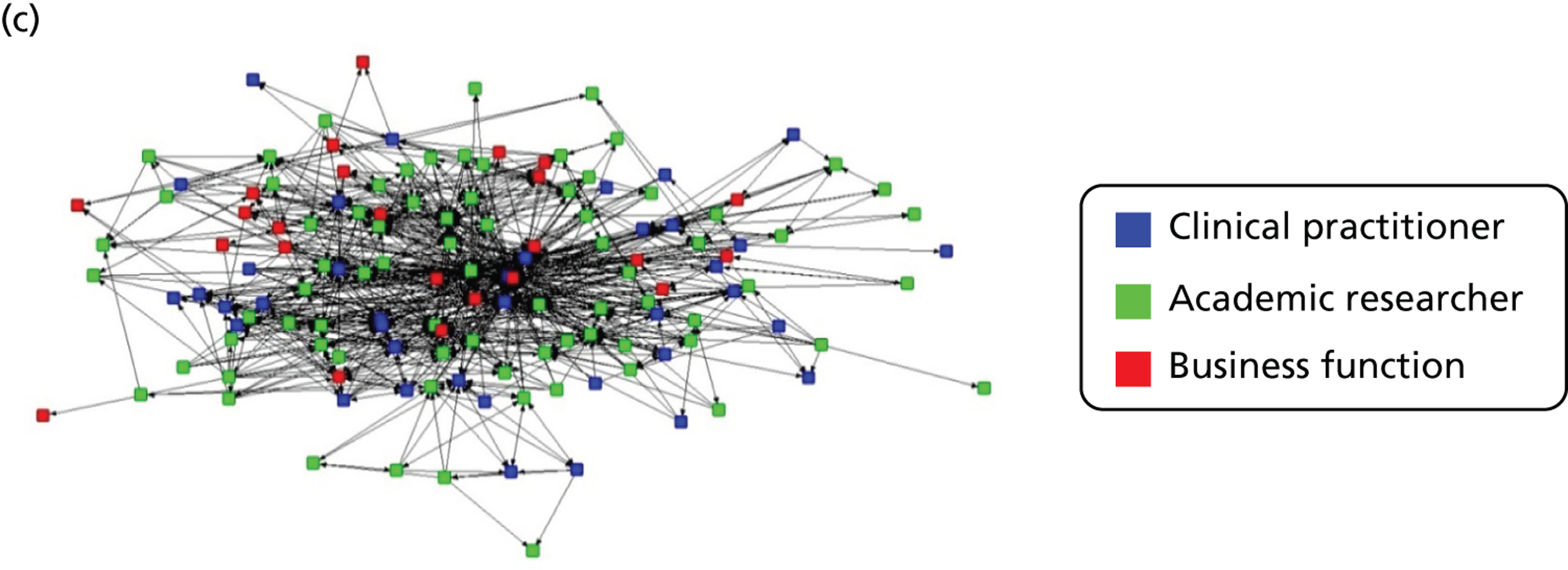

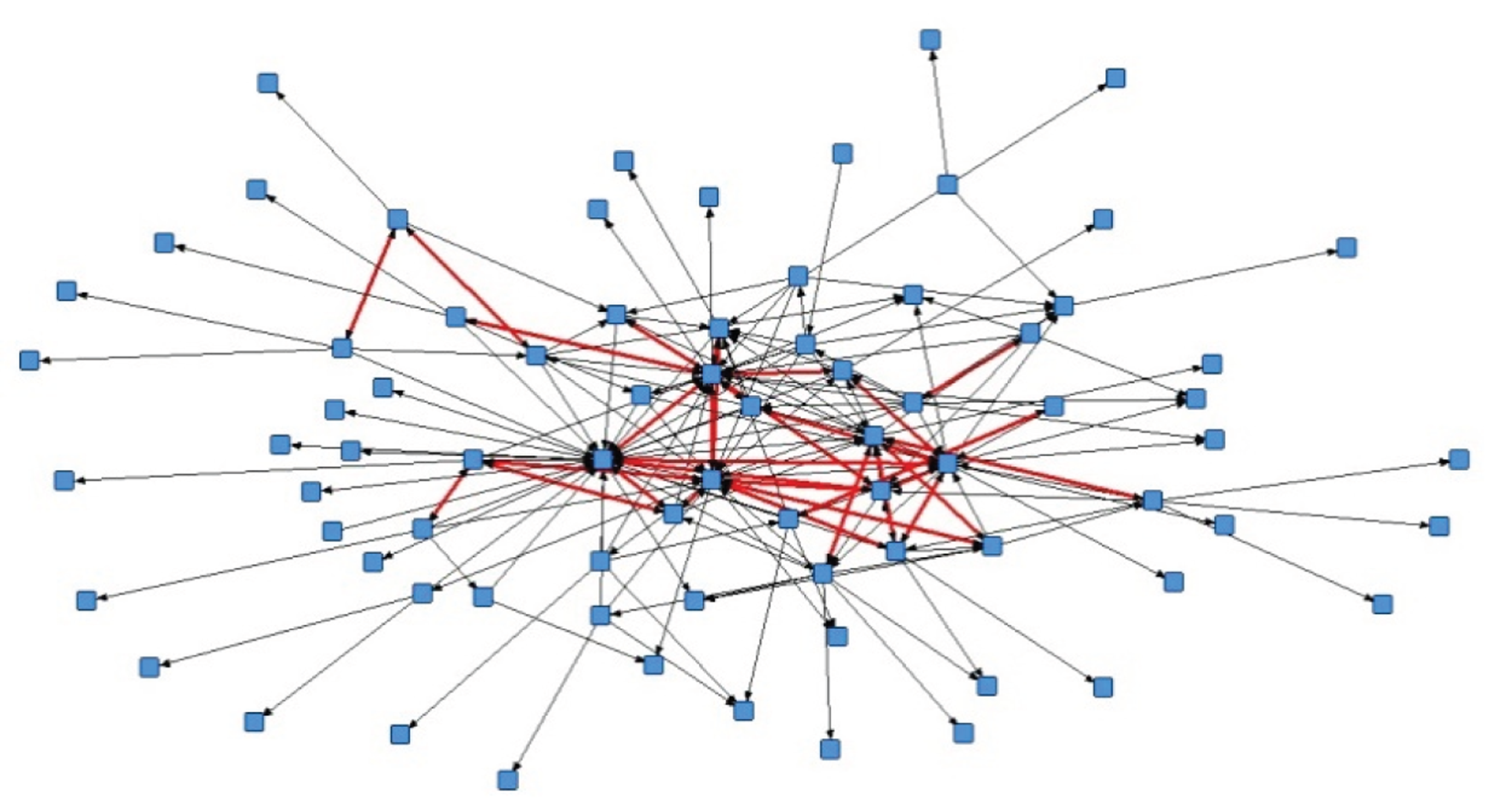

In the recent period, recognition of the importance of boundaries between groups has been complemented by greater awareness of the central importance of social networks in enabling innovation that spans communities or practice groups. 31 Studies focusing on the analysis of network ties have highlighted the importance of network structures in shaping the flow of knowledge and information within and between organisations. 34,60 Here, the focus is less on individuals and more on the nature of the relationships and information flows across individuals and groups: their interconnectedness, in other words. Network analysts use a range of well-developed concepts (e.g. ‘nodes’ to denote position or location, and ‘ties’ to denote relationships or links among these positions) and methods [in particular, social network analysis (SNA)] to link the patterns of relationships in the network to the behaviours that arise from it. 61 Such tools allow analysts to reveal and represent the informal social relationships within and across organisations that shape work-related outcomes. This now-extensive body of work links helps to underline the impact, for example, on innovation of brokering across ‘structural holes’62 between different groups, as well as the pivotal roles of boundary-spanning groups and gatekeepers. It also highlights the different roles played by different kinds of social ties in knowledge sharing, with weak ties being linked to the sourcing of information and strong ties being linked to the establishment of trust and the sharing of tacit knowledge. 63 Importantly, social networks provide a relational form of governance (the ‘informal structure’) whereby an individual or group’s position (centrality) in a network relative to others plays a key role in their ability to exercise power. This informal structure has been found to be especially important in networked innovation settings (such as the CLAHRCs) where the exercise of power requires extensive boundary spanning and where sources of power influence innovation outcomes. 64

The attention paid to social networks in studies of innovation more generally has not so far been matched by work in the health-care management field. Here, recent studies, with relatively few exceptions, have focused on networks as formal, quasi-organisational entities, frequently associated with policy interventions. 65 As McAneney et al. 36 note, relatively few studies have addressed the implications of network structure for KT. Only in more recent work do we find social network analytical techniques being applied to uncovering the latent structure of ties between groups and individuals. Thus, a study by Currie and White66 uses SNA to identify the interplay between knowledge brokering and professional hierarchy. The authors argue that such brokering both is influenced by, and helps to mitigate, the impact of such hierarchy on knowledge mobilisation. They also highlight the role of groups in such brokering as against the actions of specific individuals.

Bringing together different interpretations: the role of cognitive maps

The importance of cognition and the underlying belief structures that groups and individuals bring to their interpretation of new situations has been identified as central to networked innovation and collaborative work. 67,68 Furthermore, work has shown how underlying cognitive structures or belief systems – sometimes termed ‘cognitive maps’ – are implicated in sense-making and decision-making processes. 69 However, while a number of studies have addressed the role of such cognitive maps in the actions of managerial groups,70 less attention has been paid to their importance in health-care settings. One exception here is the work of Sutherland and Dawson,71 who adopt a ‘sense-making’ approach to behavioural change among clinicians. They use the notion of cognitive maps to highlight the way in which actors ‘apportion meaning to situations, relationships, roles, and objects, and store such interpretations and understanding in cognitive structures, often in the form of “taken-for-granted” knowledge’ (p. 53). 71 Such structures or maps in turn influence how novel events or ‘equivocal’ situations are interpreted. 72

The arguments coming from this strand of work effectively underline the relevance of cognitive structures to the outcomes of networked innovation initiatives such as the CLAHRCs. As we highlighted at the beginning of this report, the notion of KT, which informed the original funding initiative for the CLAHRCs, was broadly defined and ‘equivocal’ in the sense that it was open to multiple interpretations. Organisational models and mechanisms of KT and its effectiveness within different contexts remain highly debated. It follows from this that the cognitive maps which different CLAHRC groups bring to this KT endeavour – what it means, and how it can or should be operationalised – may vary significantly across CLAHRCs, and may have important consequences for the way in which policy-inspired models are interpreted and enacted. A crucial question here has to do with participants’ ‘causal maps’ – that is, the associations they make between particular phenomena and particular outcomes. This is because such causal maps and their characteristics (e.g. cognitive complexity) have been closely linked to strategic visions and intentions and decision-making. 70 We recognise, of course, that intentions and cause–effect beliefs do not necessarily translate directly into behaviours and actions. 73 However, drawing the role of cognition and cognitive maps into our conceptual framework provides a useful complement to the emphasis on social interaction seen in previous research on networked innovation and collaborative work.

Management, governance and organisation

Much of the literature on KT tends to focus on the process by which this occurs, thus emphasising the micro-dynamics of interactions between individuals and groups. Viewing this process in the abstract, however, tends to neglect the important, if often antecedent, effect of the way in which that process is designed, directed and resourced.

Previous work has shown that efforts to engineer a process of KT may fail because management and governance are inappropriate to the task at hand. Relevant here is a study of the management and organisation of the Genetics Knowledge Parks initiative – a policy intervention designed to speed the translation of genetics and genomics science into clinical practice through the establishment of regionally based ‘knowledge parks’, where academic researchers, health-care practitioners and industry would work collaboratively. 74,75 This study found that the ambiguity that was inherent in these novel forms of collaboration generated uncertainties about its evaluation and the extent to which it was delivering against broadly defined, but extremely ambitious, objectives. This uncertainty prompted governing bodies (funders and policy bodies) to try to more tightly monitor and evaluate the work, thus creating burdensome reporting requirements and constraints on innovation.

This example raises an important issue of governance – that is, management practices often assume a linear model of innovation (i.e. planning and monitoring against predefined objectives and targets) whereas networked innovation is inherently an emergent and iterative process. 76,77 Equally, this example may reflect inappropriate forms of accountability and organisation being applied to a policy intervention. 74 The importance of management and organisation was fully recognised in the CLAHRC call for proposals, however, which highlighted the need to specify a director, management arrangements and explicit strategies for managing the collaborative partnerships involved in the CLAHRC.

The impact of the institutional and policy context

The example of the Genetics Knowledge Parks, outlined above, shows how the translation work occurring at the micro level within networked innovation initiatives is shaped by the wider institutional and policy context. The impact of the institutional and policy context on innovations in health care is widely reflected in the existing literature. 40,65,78,79 One conclusion here, then, is that, while much can be learned from models of KT in other nations, we must also be sensitive to the need to adapt and appropriate such models for the UK health-care setting.

Complementing this recognition of the importance of context at a macro level, there is a growing body of work on the ways in which context may shape more localised efforts to translate knowledge into health-care practice. Studies have shown, for example, that the same evidence may lead to different outcomes in different decision-making contexts,80 or that some translational activities, such as knowledge-broker roles, may be adaptable to different contexts. 49 At the same time, there remains a gap within the existing literature on how contextual features influence the KT process. This has driven calls for further research to address the influence of context as a prerequisite for developing more effective approaches in this area. 81,82

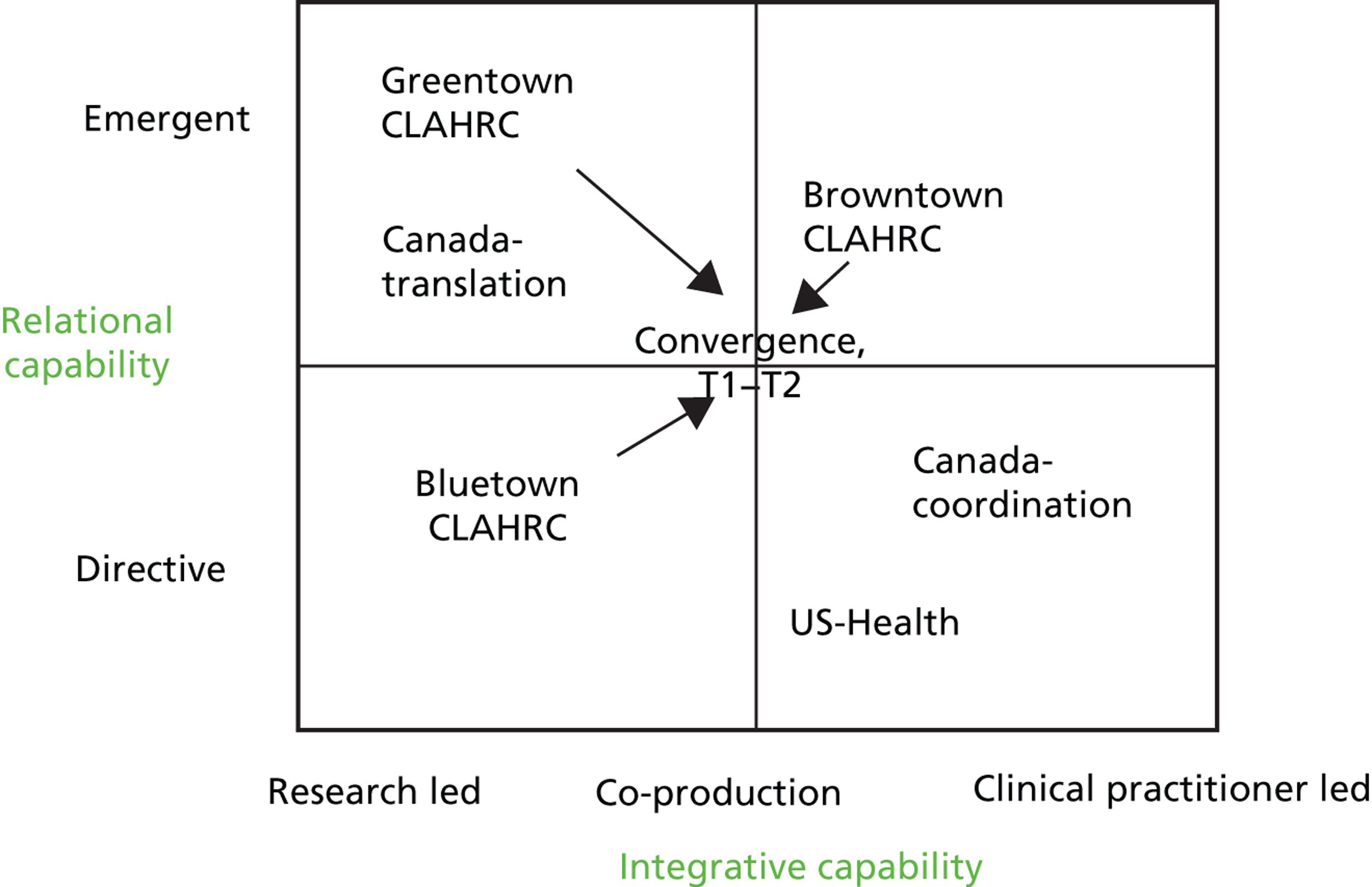

Development of capabilities for networked innovation

One perspective on the influence of context which has emerged in the literature focuses on the development of capabilities for networked innovation. Such innovation is seen as taking place at the interstices of organisations and of professional communities, thereby demanding new capabilities on the part of participating organisations. 61 Two forms of capability have been identified as crucial to the translation of scientific research and evidence into practical applications. ‘Relational capability’ denotes an organisation’s ability to work with diverse others in an innovation system. ‘Integrative capability’ is defined in terms of the ability of individuals and groups to move back and forth between science and the locus of practice. 83

The emergence of these capabilities is seen as being influenced by the institutional context for innovation. A study of networked forms of biomedical innovation, for example, highlights the influence of the national institutional context on UK firms’ capabilities as compared with their US counterparts, highlighting in particular the constraints on the development of more ‘hybrid’ roles that combine scientific and entrepreneurial skills. 79

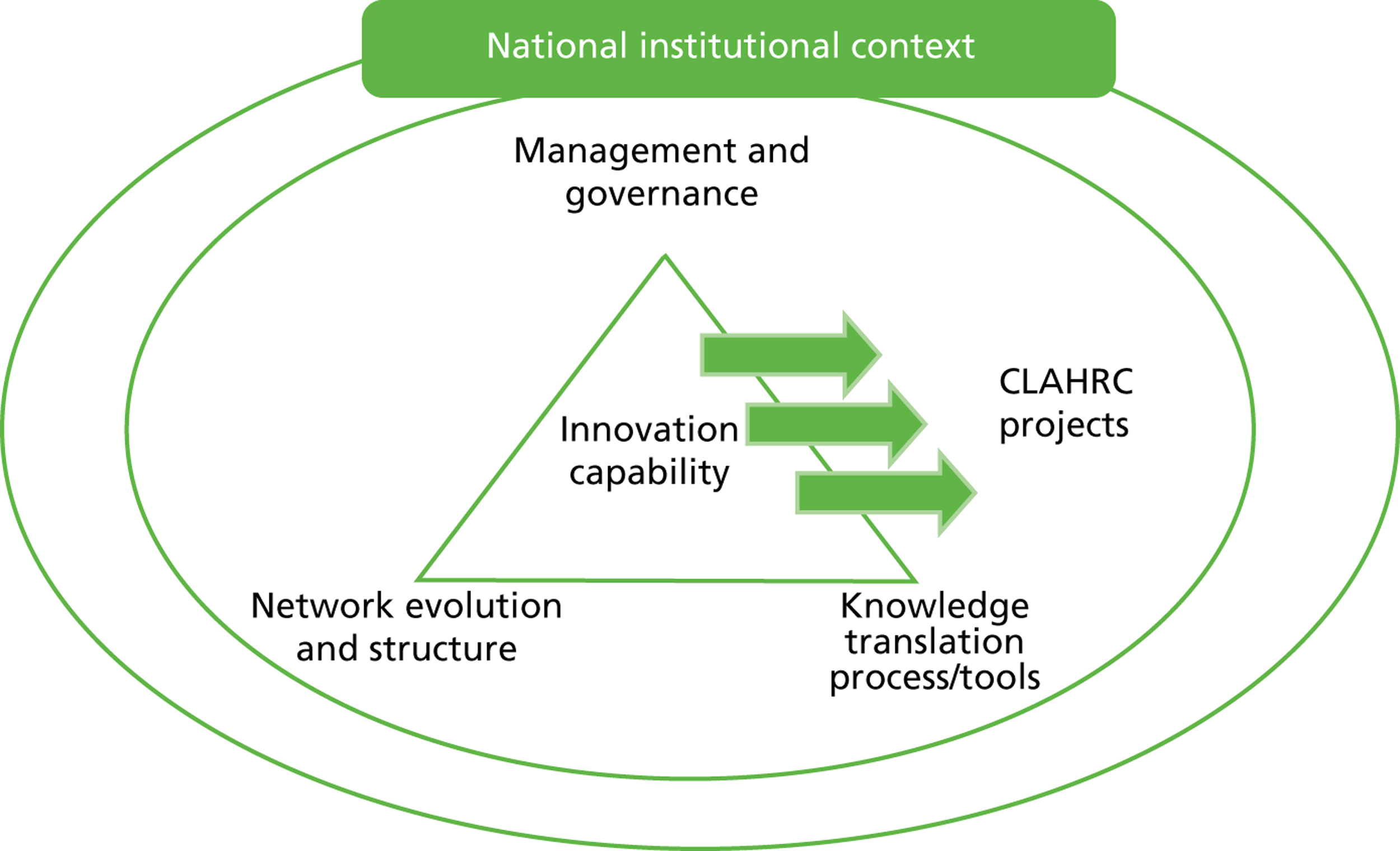

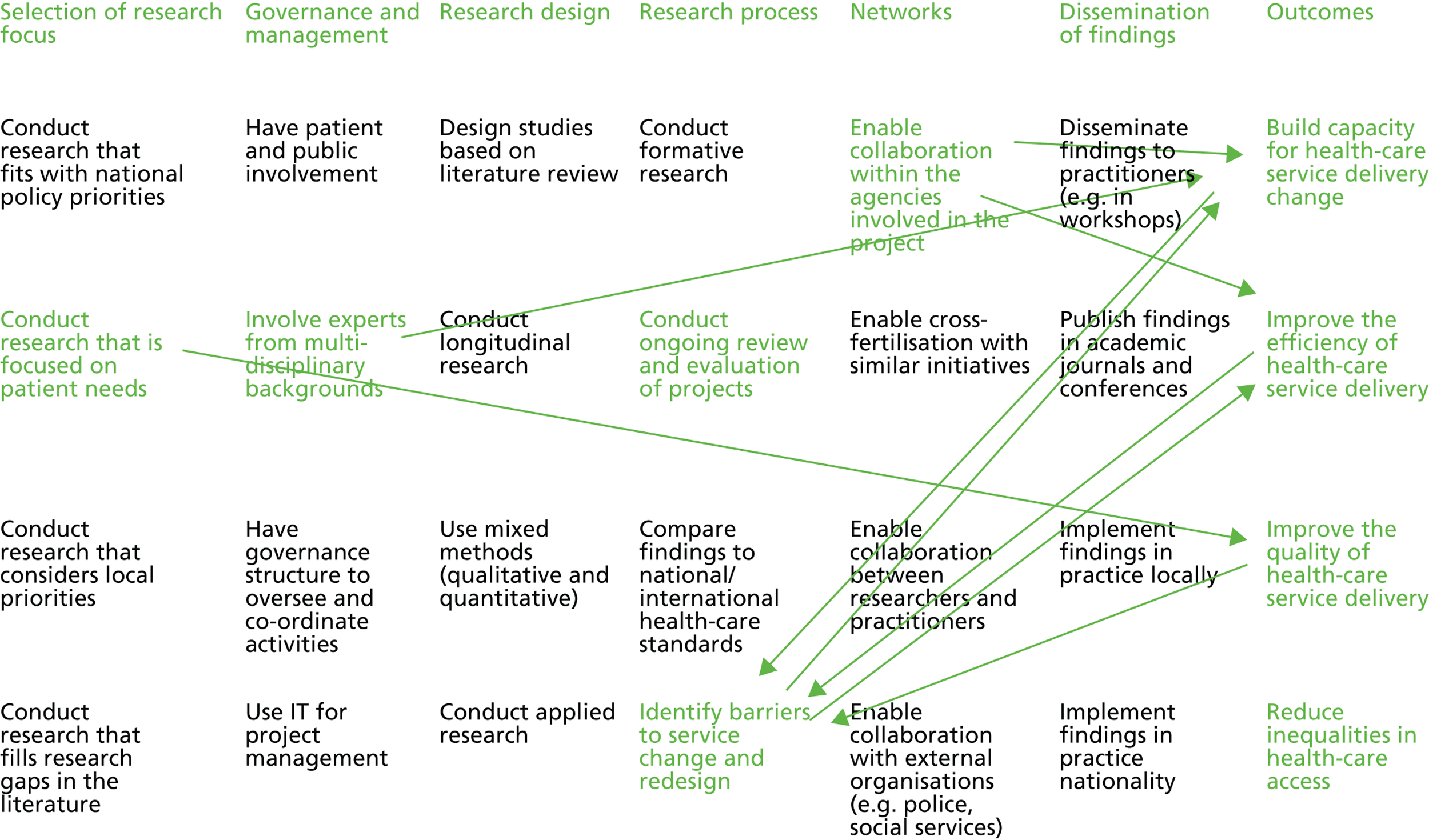

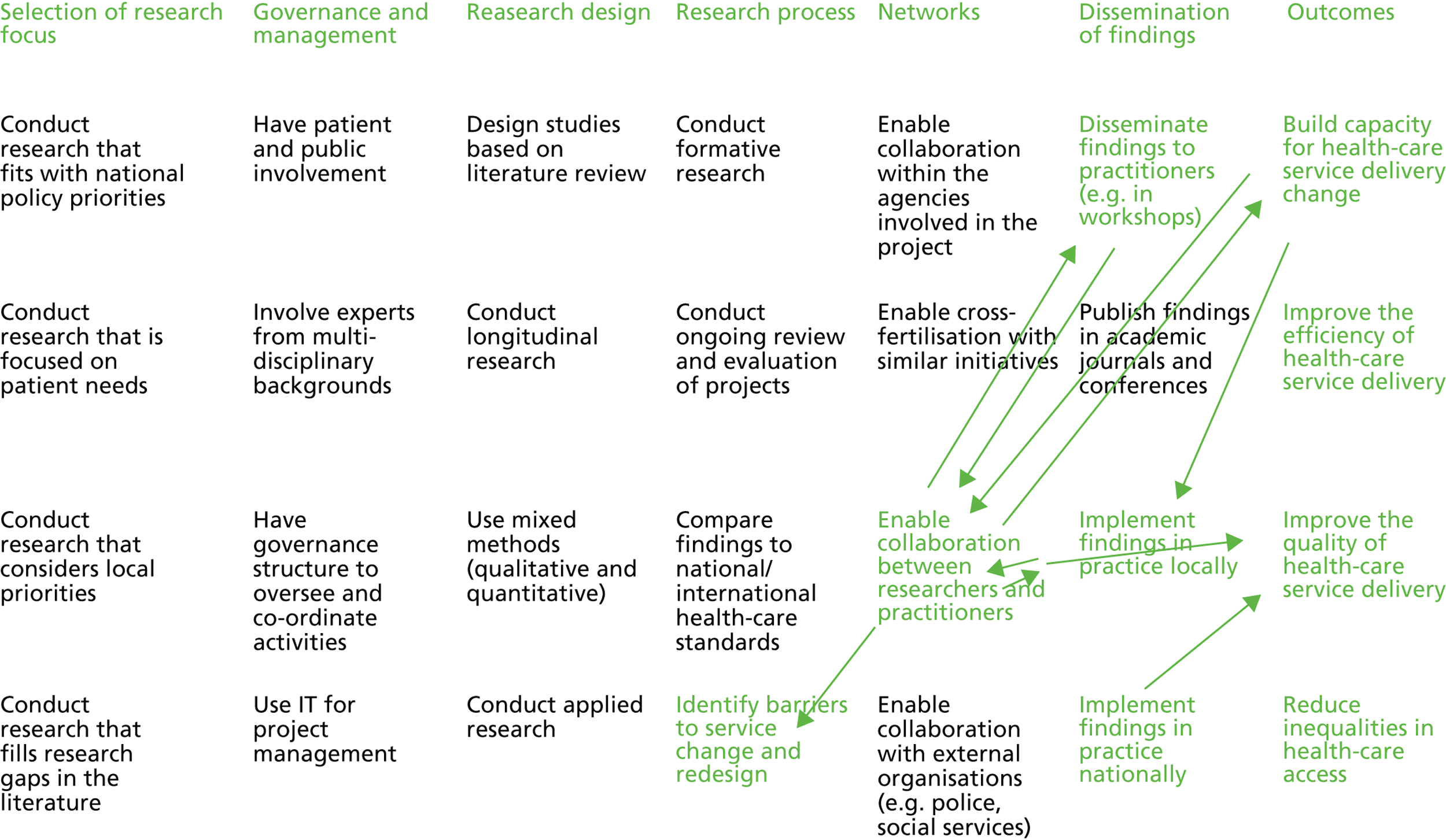

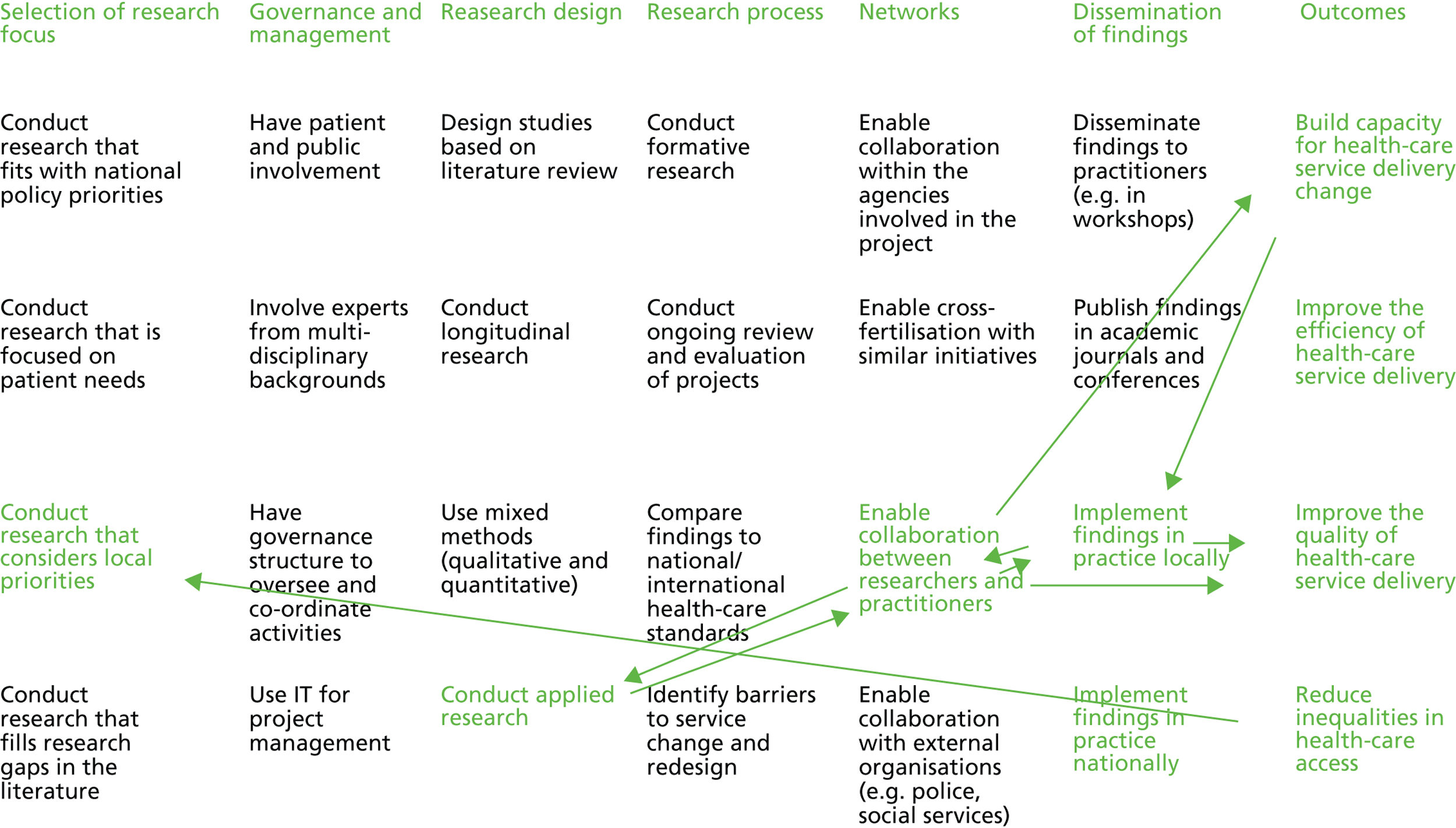

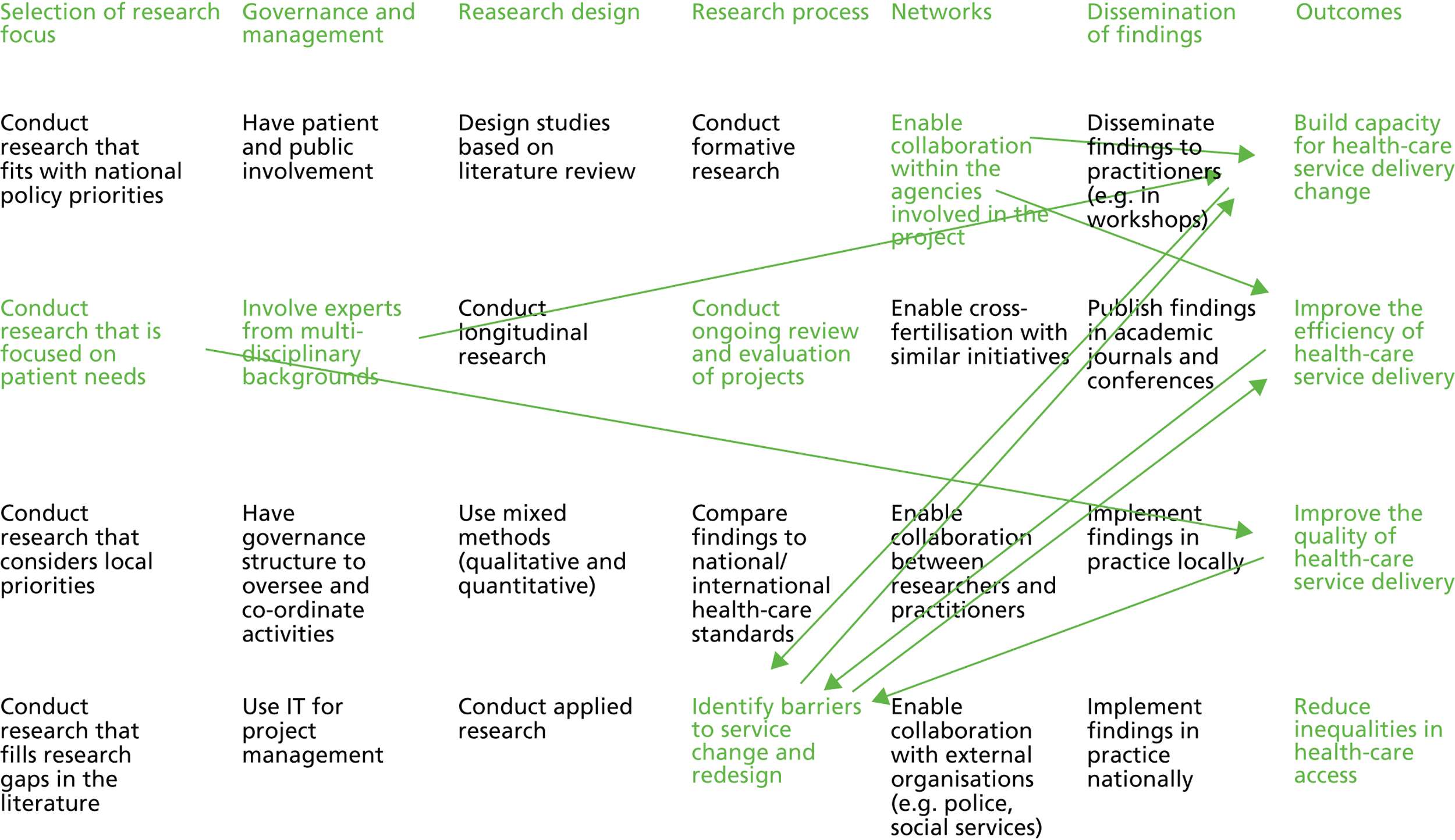

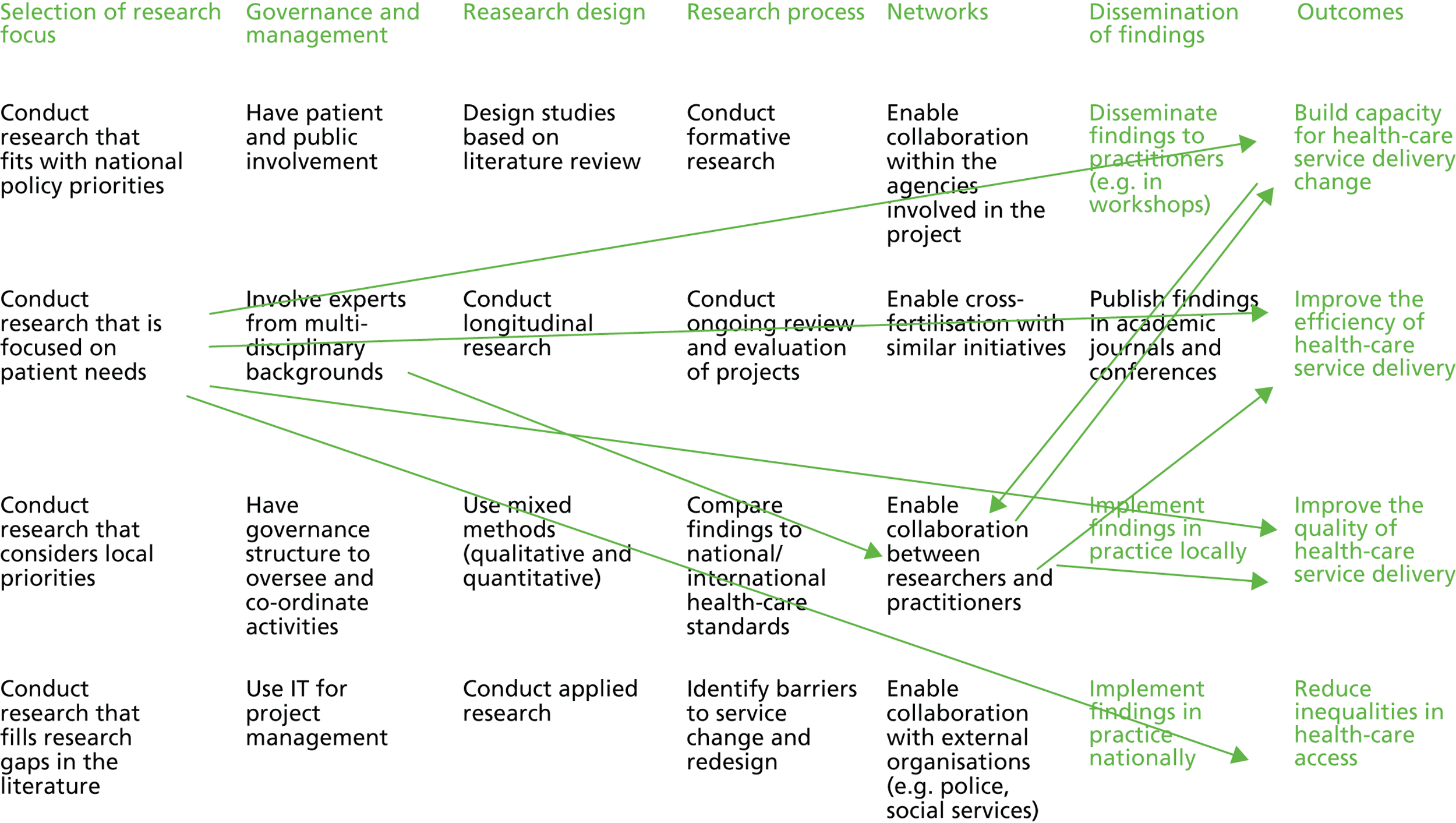

Taken together, these different strands in our analysis of the literature helped us to develop a conceptual framework for our study, as outlined in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

Conceptual framework.

Research objectives of the empirical study

Integrating this conceptual framework with the wider aims identified for the study helped us to frame the specific research objectives to be addressed by the empirical study. These were specified as follows:

-

Identify the micro-level relationships between researchers, intermediary groups and practitioners which enable the translation of knowledge from research into practical settings.

-

Map the evolving structure of social and interorganisational networks that underpin CLAHRCs, including the emergence of boundary-spanning groups and gatekeeper individuals, and brokering across ‘structural holes’ between communities.

-

Examine the impact of policy and governance arrangements within which such networks are situated on translations of knowledge between research and practice.

-

Compare the UK CLAHRC initiative with similarly intentioned networked innovation initiatives in the USA and Canada, with a view to learning from these experiences while also recognising their distinctive institutional contexts.

Chapter 3 Research methods

The study uses a mixed-methods approach for a comparative case study of six collaborative initiatives designed to facilitate the translation of research evidence into health-care policy and practice. This chapter describes the research design that was used and reflects on the methodological considerations of our approach, including how we applied our networked innovation conceptual framework to support the amalgamation and analysis of the data collected from the different components of this study.

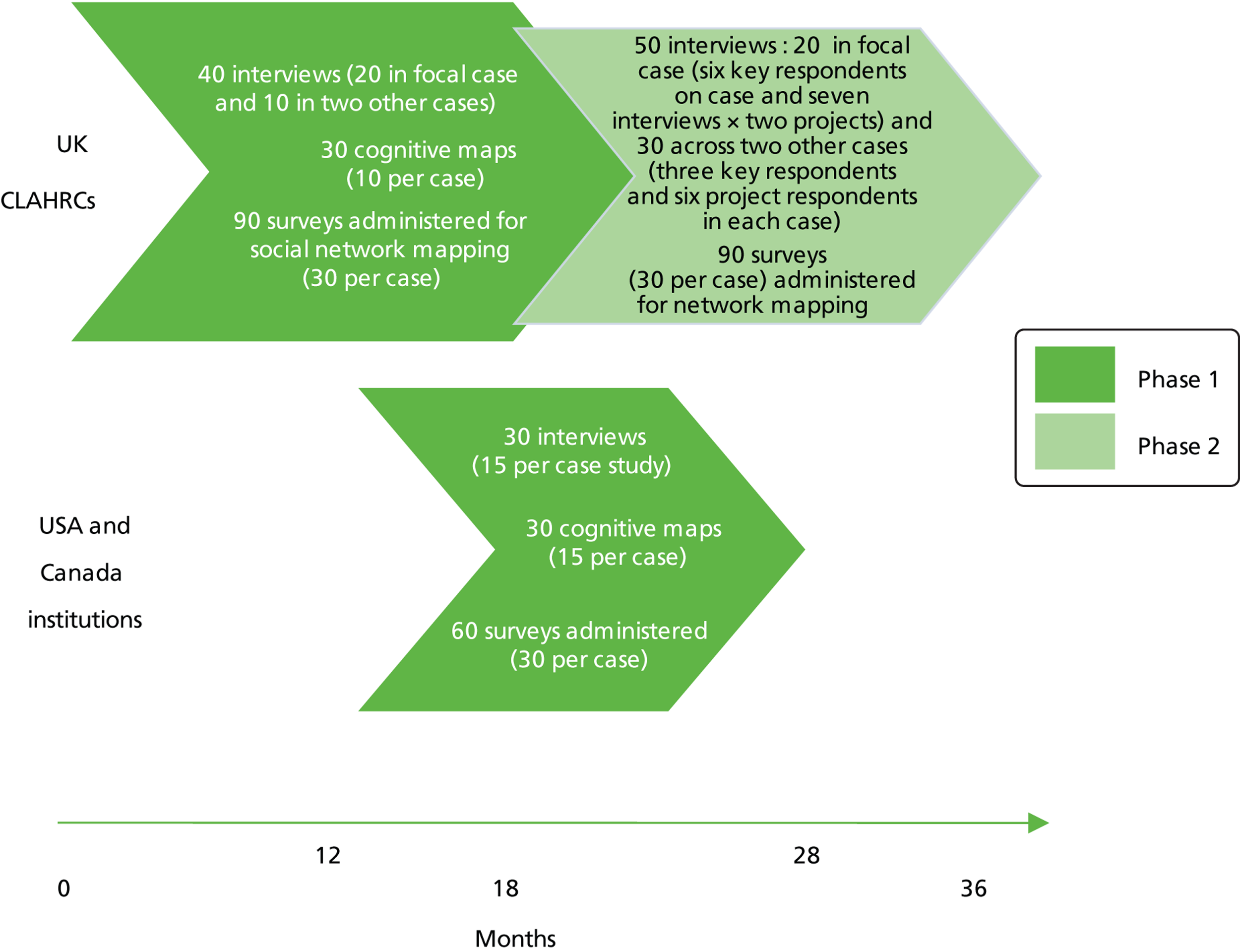

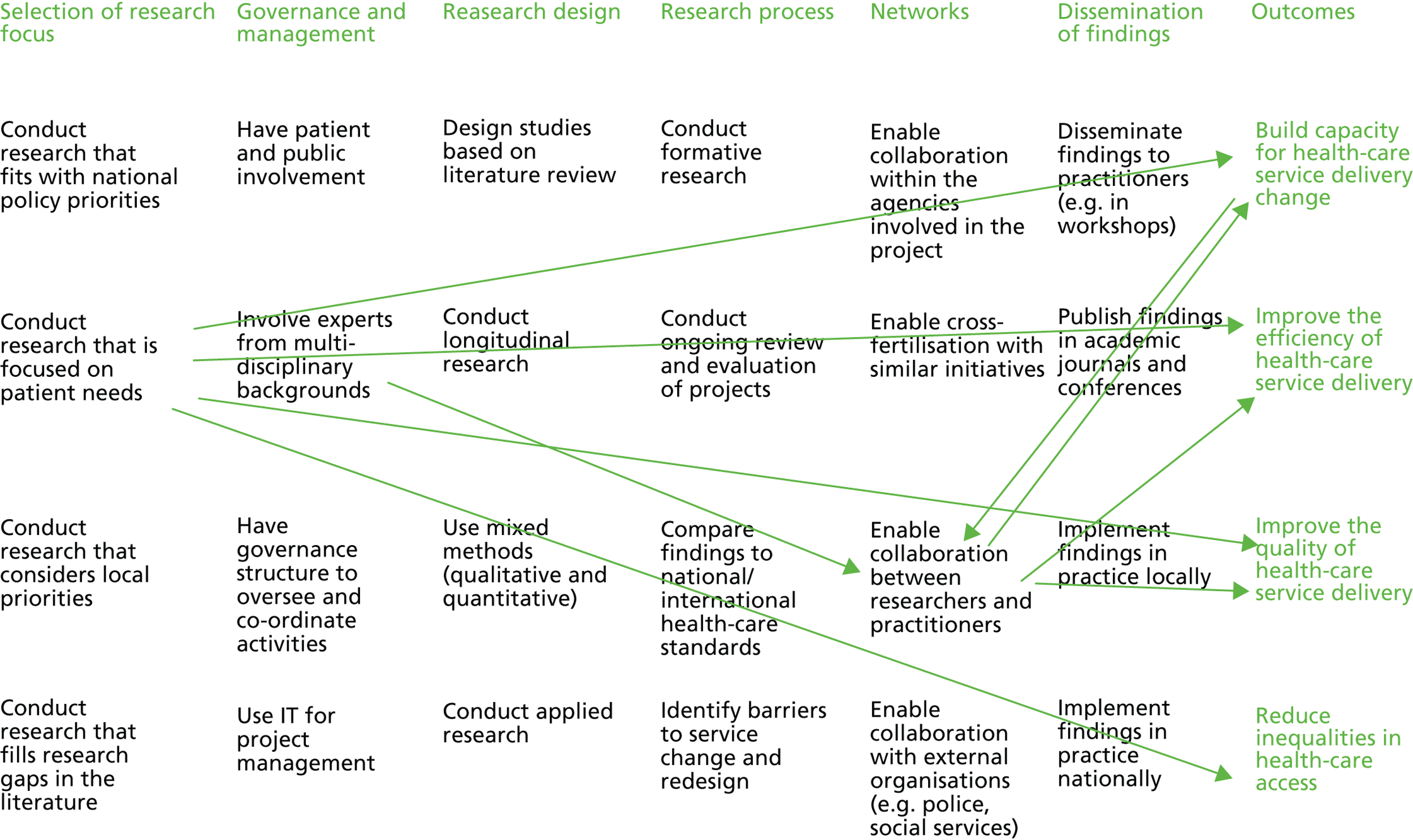

Stages of the research process

The overall study design was comparative case study involving a temporally phased data collection process conducted across three case sites based in the UK and three sites in North America over a period of 36 months ( Figure 2 ). The UK fieldwork was conducted over two partially overlapping phases of work in order to support our research objectives of mapping the evolving structure and social relationships that underpinned the development of the CLAHRCs over time (objectives 1 and 2, Chapter 2 ), as well as the impact of different models of governance and management implemented by the CLAHRCs (objective 3, Chapter 2 ). The two phases allowed us to identify how, under ostensibly the same policy initiative, the CLAHRCS developed different types of structures, relationships and activities and to trace the ways in which these supported or engendered different elements of their vision(s) and the KT process.

FIGURE 2.

Research plan.

The fieldwork in North America was conducted in one phase. The data collection here was designed to meet objective 4 – that is, to allow a comparison of the CLAHRC initiative with similarly intentioned networked innovation initiatives in the USA and Canada, with a view to learning from these experiences while also recognising their distinctive contexts.

Before we commenced the study, the protocol was reviewed by the University of Warwick ethics committee. In addition, before the data collection with NHS participants commenced, the UK study was reviewed by the West Midlands research ethics committee (REC) and received a favourable opinion in July 2010 (REC ref. 10/H1208/30) allowing data collection to include employees of NHS organisations in addition to those holding university contracts.

The study was also guided by a scientific advisory board, whose membership included individuals with direct experience of CLAHRC operations, external experts, and a service user representative.

To operationalise our comparative case study design, we utilised three major sets of research methods:

-

qualitative investigation based on a comparative approach and involving the use of semistructured interviews with key participants across cases

-

social network analysis via the use of survey instruments

-

analysis of cognitions via the use of a cognitive mapping tool (Cognizer®, Mandrake Technology Limited, Leeds, UK).

The rationale and application of these different methods is outlined next.

Qualitative investigation

Data were collected using a case study approach, comprising three sites based in the UK and three based in North America. A case study design was considered appropriate for this study as this method supports the exploratory aims of this study, which are ‘how’ and ‘why’ questions related to the development of organisations over time through the interaction and relationships between individuals and communities within programmes of work. 84 In particular, this approach allows evaluation of the contextual conditions (at both the micro and the institutional level) that influence how the different modes of organising developed and deployed by CLAHRCs are able to support their KT endeavours.

It is important to note that the aim of our study was not to compare the CLAHRCs in terms of their overall ‘success’; it was recognised from the outset that, given the very broad remit of the CLAHRCs, and the different originating contexts, what counted as ‘success’ would be context-specific and would require a different kind of evaluation. 78 Rather, the aim of the comparison was exploratory and developmental – that is, to trace the ways in which different kinds of activities with similar objectives could support (or sometimes constrain) particular aspects of KT and innovative performance within certain contexts, and to compare lessons learned across cases. Thus, it is appropriate for this type of exploratory study to use a purposive sampling frame to select cases, as the aim is to use the distinctive features of each case to support our analysis by highlighting the role of particular case attributes and context in influencing how innovation is achieved, and the challenges and issues experienced.

The international dimension of the study was motivated by the (then) SDO call itself and by the benefits of international comparison in this field. We selected reference sites in the USA and Canada because these countries were highlighted in the Cooksey report8 as relevant international comparators for the UK. These are also countries that are recognised as leaders in health-care innovation, but which are facing, or have recently faced, similar challenges in terms of demands for translation. In addition, both the USA and Canada have undergone significant institutional reforms in recent years aimed at achieving more effective translation.

The three UK cases selected had all successfully bid for funding under the UK NIHR CLAHRCs programme. However, each initiative had enjoyed extensive flexibility in how they interpreted the remit. As a result, the visions which their leaders brought to the CLAHRC mission, and the associated governance and management structures which were put in place, varied significantly. We chose the three case study sites as they each represented different ‘experimental’ models of how institutional support can be used to develop collaborative networks to facilitate translational research. This allowed us to explore how the different approaches and attributes of each model related to the development of different types of capabilities for supporting innovation within a networked context. In particular, it allowed an analysis of how the characteristics of each case – such as its vision, its management approach, its structure and organisation – related to the capabilities it had for supporting an innovative programme of work. In addition, by conceptualising each case study as a ‘network of connections’, this approach enabled comparative study of how social ties supported KT between actors involved with the initiative.

To support our aim of identifying the interplay between the national or institutional context and the micro-level relationships which enable KT, within each case site it was important to contextualise how macro-level attributes of each initiative (e.g. management, governance, structure, vision) shaped how the various programmes of work within each initiative were achieved in practice. Therefore, for each UK case site, we selected three to four clinical projects to act as ‘micro-cases’ for us to explore in greater detail how project teams were able to achieve their work within the context of how each initiative was envisaged. In order to select projects that would be complementary across all three case sites, we first developed a selection framework tool to collect information about the background and aims of each clinical project, such as whether or not the project was developed from a pre-existing area of work, the type of organisations involved with the team, and the type of innovation the project work involved. The tool was completed by the CLAHRC core management, and projects were selected that fitted into three broad clinical topic areas (mental health, stroke and community services), as they represented complementary features across the three case studies.

The three North American initiatives are not part of the same funding programme. Instead, they were funded by different regional entities and by foundations (as per the two Canadian initiatives) or by federal money (as per the US initiative). Further details about the funding programs of each North America initiative are provided in the next section (see Qualitative data collection). In terms of the selection of specific clinical projects, the criteria varied across the initiatives. The Canada–Coordination initiative is a relatively small project that focuses on improving co-ordination among four health-care players located in the Ottawa metropolitan area and the clinical focus is on improving the quality of care of children with complex care problems. The Canada–Translation initiative involves a number of clinical themes ranging from mental health to the management of the relationships between doctors and patients. For this second case, we decided to focus on the creation of processes and practices promoting KT due to the fact that the initiative is relatively young and tangible research output on specific themes was not available at the time of our fieldwork. The US–Health initiative includes a broad range of clinical themes. In our qualitative analysis we present examples involving the management of the relationships between health-care structures and end users (i.e. the patients).

Qualitative data collection

Semistructured interviews were conducted face to face with individual members from three CLAHRC organisations within the UK as well as from the three North American initiatives. This was guided by an interview schedule, which was framed in terms of discussion of the three broad topics captured by the theoretical framework depicted in Figure 1 – that is, management and governance, KT processes/tools, and the development of social networks and relationships. Questioning encouraged interviewees to discuss specific examples of collaborative working (e.g. prompts such as ‘tell us about a situation where you have worked together well/where you have found it challenging’). The length of interviews was approximately 45–60 minutes, and the audio recordings were subsequently transcribed, providing texts of data for analysis. The interviews were supplemented by observational data and the collation of key documents, for the purpose of providing greater insight into the work taking place within the initiatives. This included attending meetings, including core management meetings, knowledge exchange, dissemination and engagement events. In addition, with respect to the UK CLAHRCs, original bid documents and NIHR interim reports were also collected. At the project level, in addition to attending project meetings, where opportunity arose, we also observed other activities, such as advisory board meetings and engagement events. We also collected written information about the projects, such as project outlines, information for participants, publications and other outputs.

In terms of the UK CLAHRCS, the first interviews conducted were with core members/founders of each CLAHRC initiative, such as the director, programme managers and other core members, and these members were reinterviewed in phase 2. Interviews were also conducted with members of the sample ‘micro-case’ project teams, which focused on three or four of the projects from each CLAHRC. The interviewees selected for phase 1 purposively targeted data collection from those in a variety of different types of roles (team leaders, managers, research and clinical professionals). Additional interviews were conducted with members of ‘specialist support services’, which were areas where each CLAHRC demonstrated particular types of expertise, such as academic advice in the form of economics and statistics support, KT and implementation expertise, and practitioner insight into areas of clinical services, commissioning, policy-making and capacity building. Depending on the different model of each CLAHRC, some of these members belonged to the clinical project teams, with others positioned in other parts of the initiative, such as central support and ‘cross-cutting themes’. Because of this variation, interviews with individuals in these types of roles were particularly important for understanding the distinctive ‘flavour’ of the vision of each CLAHRC model. In phase 2, follow-up interviews were targeted to be conducted with, primarily, the same representatives as from phase 1. However, owing to changes in personnel, particularly at the researcher level, these interviews typically focused on those in leadership and managerial positions from both central CLAHRC and project level, and also clinical professionals involved in project work.

In the first phase, interviews focused on the start-up of each CLAHRC, such as its set-up, aspirations, plans and initial formation of contacts. Documentary evidence, such as the NIHR funding application forms, website information and project-specific documents (such as study protocols), was used to provide additional information on these aspects and to reduce potential problems of retrospective accounting. In the second phase, interviews focused on what types of outcomes had been achieved, and the discussion focused on reflection about the experience of conducting a work programme within the CLAHRC context. In addition, textual information, such as interim reports and examples of outputs and dissemination activity, were used to supplement examination of the types of outcomes being demonstrated by each CLAHRC. In total, 67 interviews were conducted in phase 1 (Bluetown, 24; Greentown, 21; Browntown, 22) and 42 in phase 2 (Bluetown, 16; Greentown, 12; Browntown, 14).

In terms of the North American initiatives, we conducted a few preliminary interviews with the leaders of each initiative. Following a snowball approach, we were able to gain access to additional people involved in the various projects and to collect documents including presentations from steering and working committees and minutes of meetings. We were also able to attend (and record and transcribe) several meetings. The North American fieldwork was conducted in a single phase spanning September 2010 to March 2012. In total, we conducted 49 interviews and observations (27 with Canada-Coordination, 11 with Canada-Translation and 11 with US-Health). The criteria to select the sample followed the UK CLAHRCs (as one aim of the North American study is to compare the results with the UK CLAHRCs). Therefore, we adopted similar criteria and focused on people who were involved in the initiatives from the beginning, having a broad view of the overall initiative and, in most cases, decision-making responsibility.

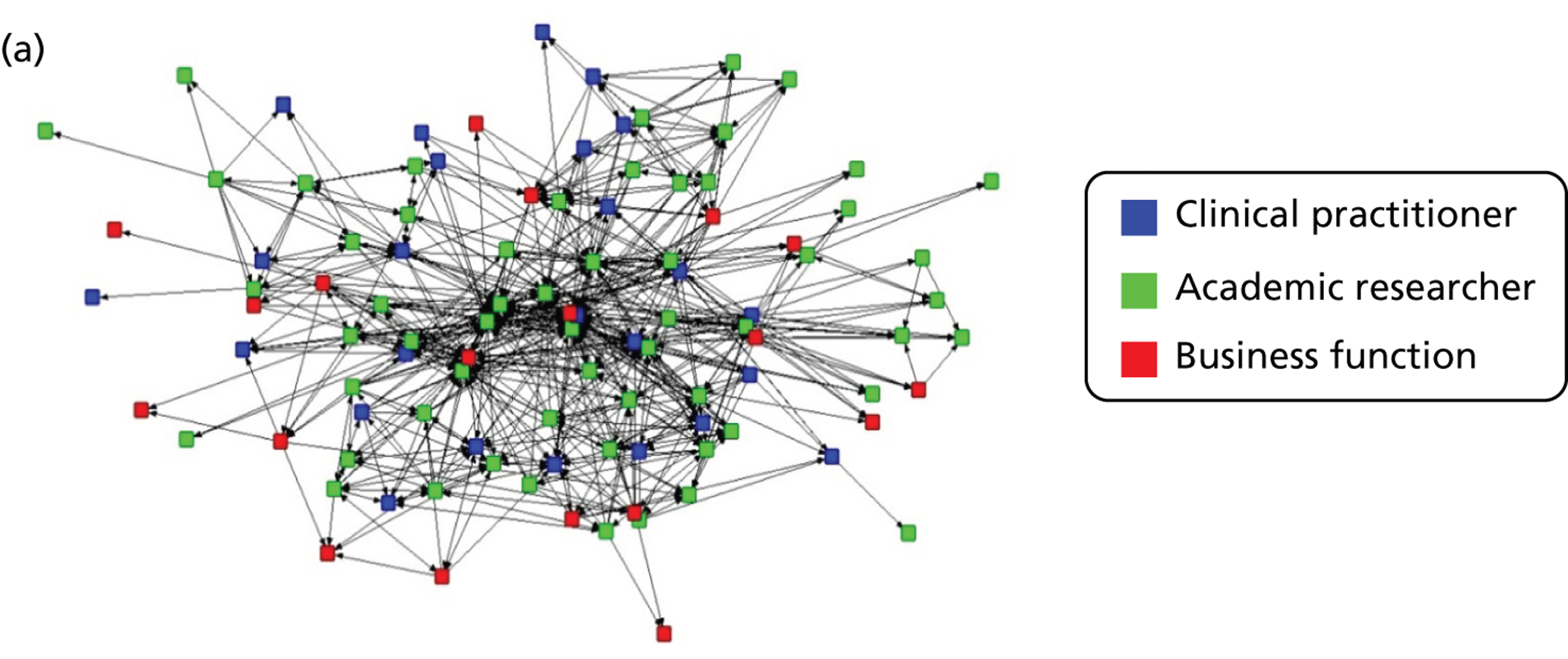

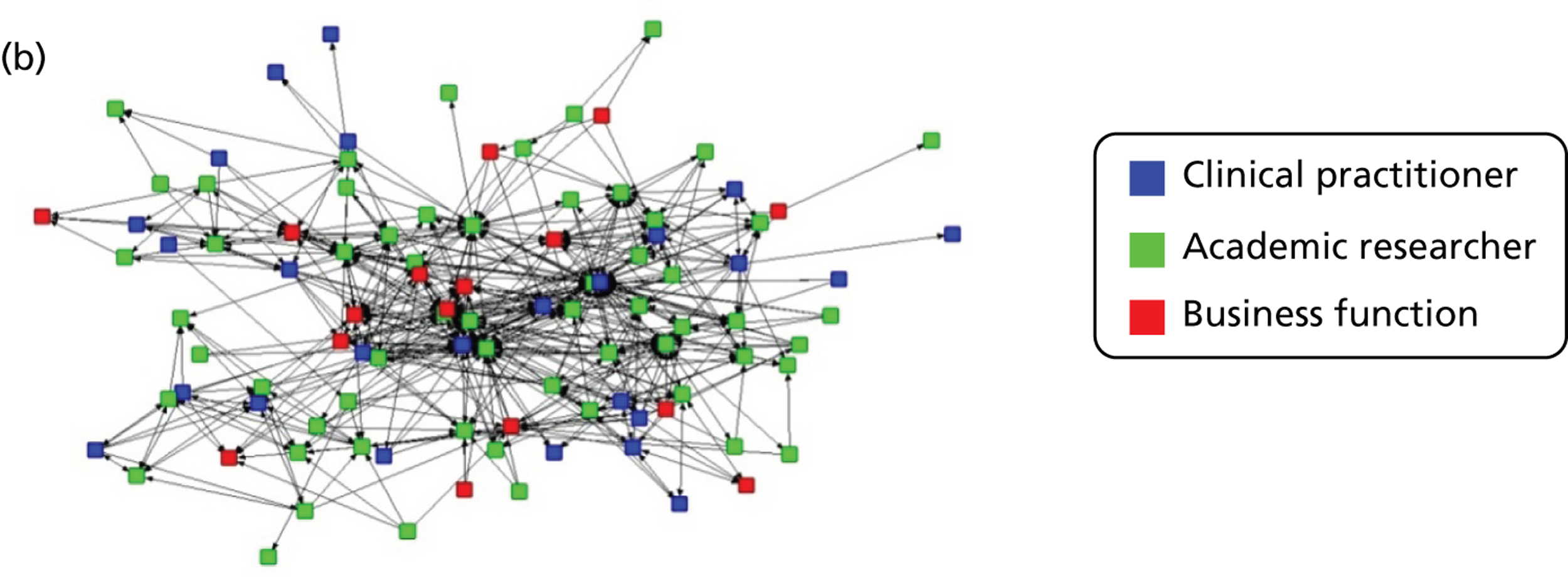

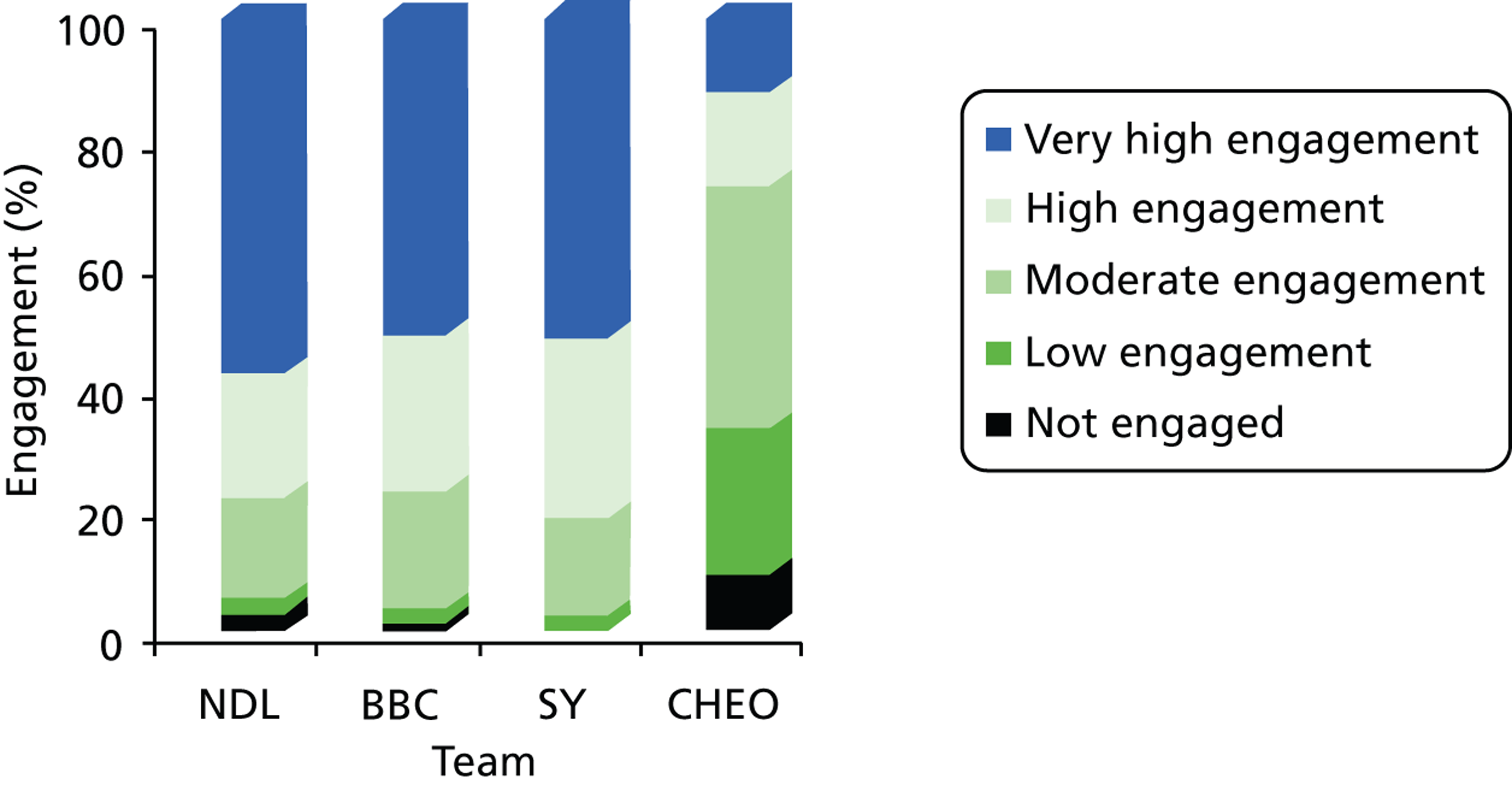

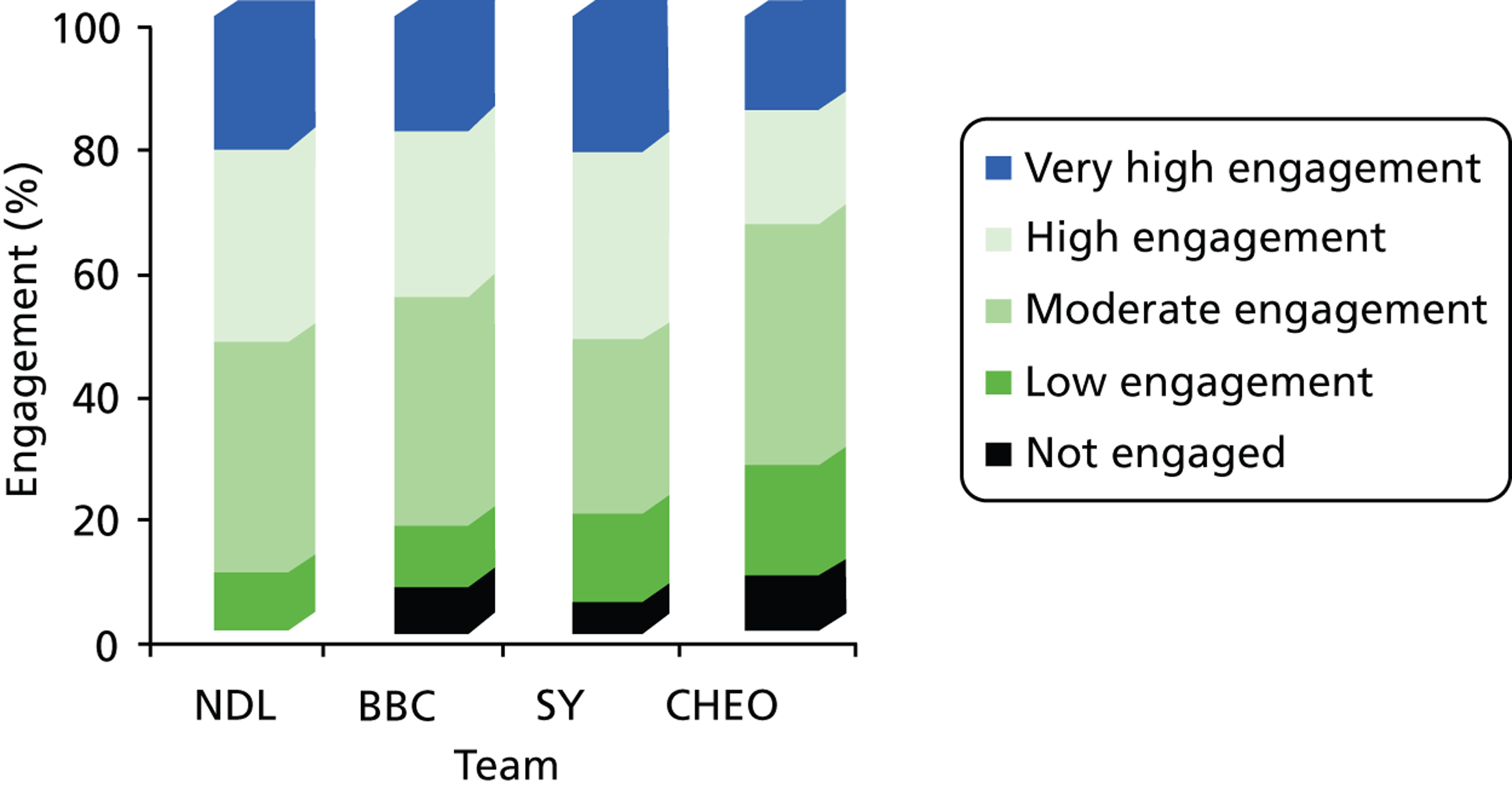

Social network survey and research design

The use of SNA as an analytical tool within health-care research is still relatively limited, though there is growing recognition of the effect of social networks on the spread of certain medical conditions. 85 To inform our social network survey design, therefore, we drew primarily on a critique of the existing literature in the organisational and management studies fields. 86,87 In relation to the UK CLAHRCs, we wanted to know with whom CLAHRC individuals translate knowledge relevant to their CLAHRC work and from this construct an informal knowledge network for each CLAHRC organisation within the context of formal management structures. The following name generator question was used to yield a list of knowledge contacts: ‘Who are the most important (people) for you to have contact with in order to be effective in your CLAHRC work?’. We invited respondents to name contacts within their CLAHRC team, in the CLAHRC as a whole and external to the CLAHRC, with up to five names per category.

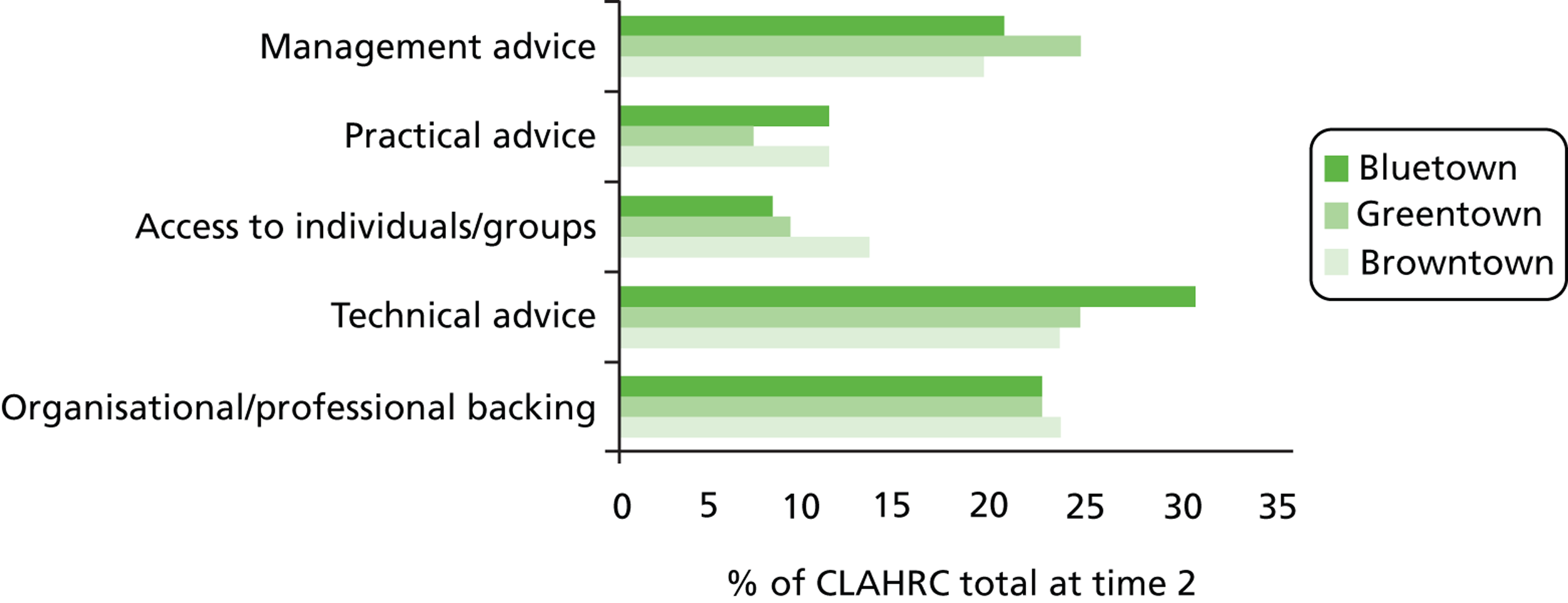

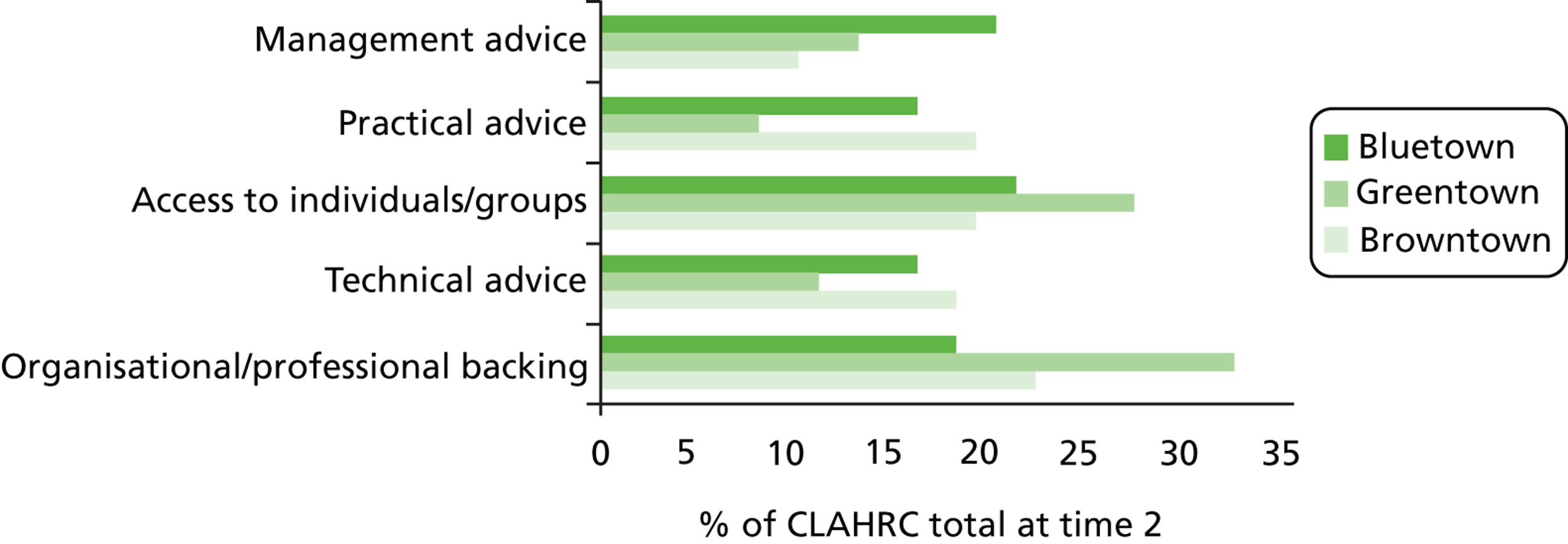

Following other studies of informal advice-giving and -seeking activities as the key processes of KT in professional settings,38,88 we also investigated the type of knowledge resources provided by CLAHRC network contacts. We asked respondents to describe the type of benefit provided by their contacts using the following knowledge resource categories: organisational/professional backing, technical advice, access to groups and/individuals, practical advice, management advice, or other. The survey also questioned the intensity/quality of knowledge-related ties based on emotional closeness and frequency of interaction and previous collaboration between contacts.

Our original proposal did not include undertaking SNA in North America, but we took the opportunity to conduct a SNA study at Canada-Coordination. To ensure comparability and validity, we adopted similar design and sample criteria to the CLAHRC study.

Collecting network data

The first task was therefore to identify individual members of each KT initiative through discussion with the health-care initiatives. Administrators of each KT initiative provided a membership roster. These lists were checked to remove individuals for whom participation in the study was not relevant. This included individuals who were no longer involved or employed by the organisation or who were on leave (i.e. sick/maternity/sabbatical). Delineation of each network sample was therefore defined by the criteria of CLAHRC membership. We then surveyed all individuals who we believed to be members of each CLAHRC. The same method was applied to our Canadian case site, Canada–Coordination.

With knowledge of who was in the network as well as demographic information on these individuals, it was then possible to assess the structure of KT between individuals in each health-care setting. An online survey was developed and individuals were sent an e-mail containing a web-link to access. The roster of CLAHRC member names was built into the electronic survey so that respondents were able to see the names of other CLAHRC members via a drop-down menu. Respondents were also able to name external contacts so that we were able to study KT relations beyond the CLAHRC. To show the development and changes of CLAHRC knowledge networks over time, the SNA survey ran for two data collection waves, providing data snapshots, which we refer to as time 1 and time 2.

Piloting

Prior to the official online release date, the survey was piloted, including testing and retesting, by a subsample of CLAHRC members and also members of the research team not involved with the SNA component of the study.

Response rates

The social network survey was sent to a total of 325 individuals across three CLAHRC health-care initiatives in the UK and 39 members of the Canada-Coordination initiative. The average response rate for the CLAHRCs was 71% at time 1 and 63% at time 2. The response rate from Canada-Coordination was lower than for the CLAHRCs. A breakdown of the response rates is provided in Table 1 .

| Health-care initiative | Time 1 | Time 2 | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respondents/sample (n/N) | Response rate (%) | Respondents/sample (n/N) | Response rate (%) | |

| Greentown | 75/109 | 69 | 68/102 | 67 |

| Bluetown | 93/123 | 76 | 54/100 | 54 |

| Browntown | 93/135 | 68 | 89/131 | 68 |

| Canada-Coordination | 39/77 | 51 | N/A | N/A |

Non-response and partial completions

Reminder prompts were sent to individuals who had not responded or who had provided a partial completion of the survey. The use of personalised e-mail prompts, telephone calls and reminders by CLAHRC leadership helped to achieve an increased response rate from members.

Validity

Our interim feedback reports and presentations to the KT initiatives allowed us to cross-check that the network ‘story’ that was being built made sense and resonated with CLAHRC members. In all cases, we received positive responses and helpful critical questions from the CLAHRCs. We also triangulated SNA and qualitative data sources.

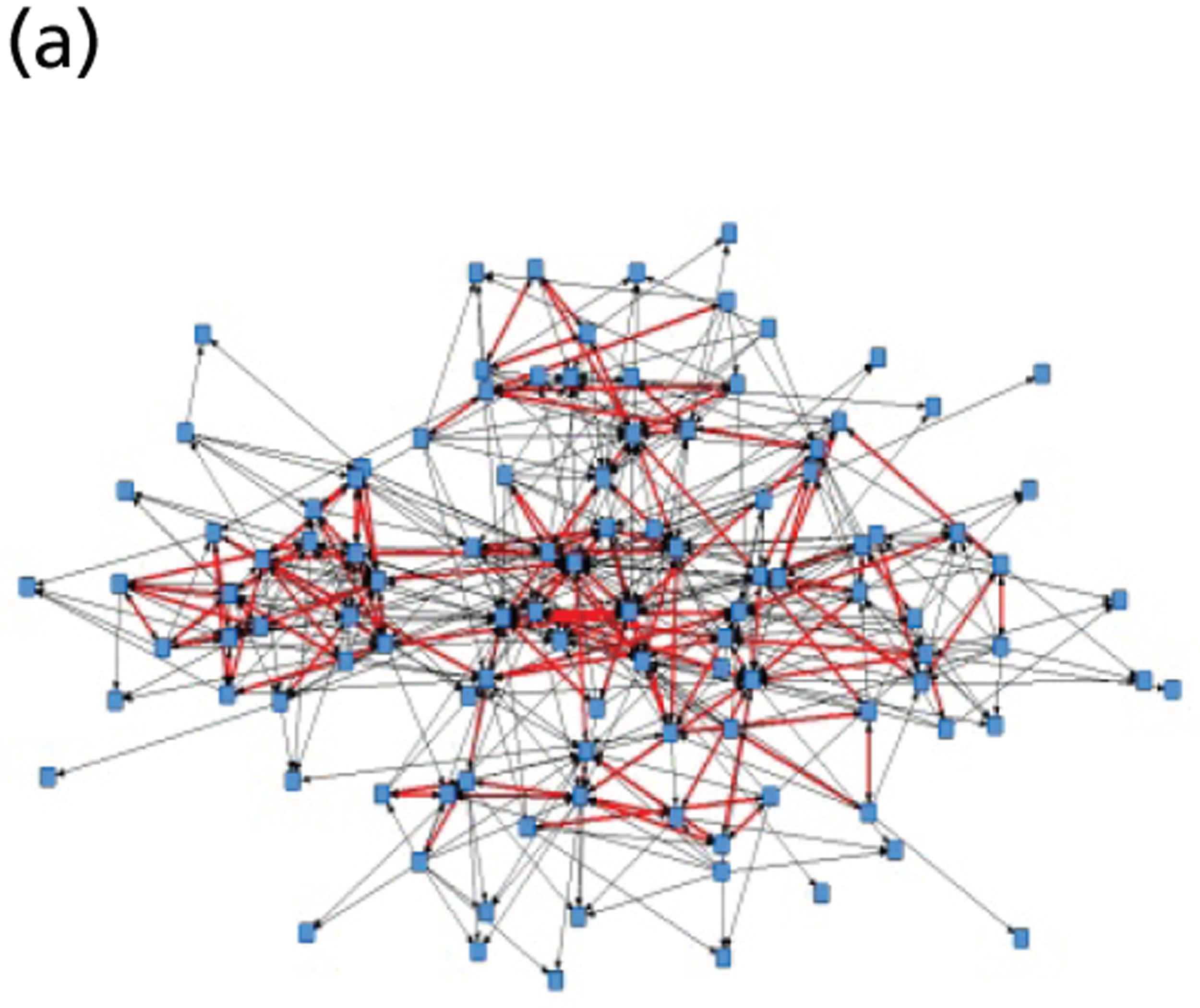

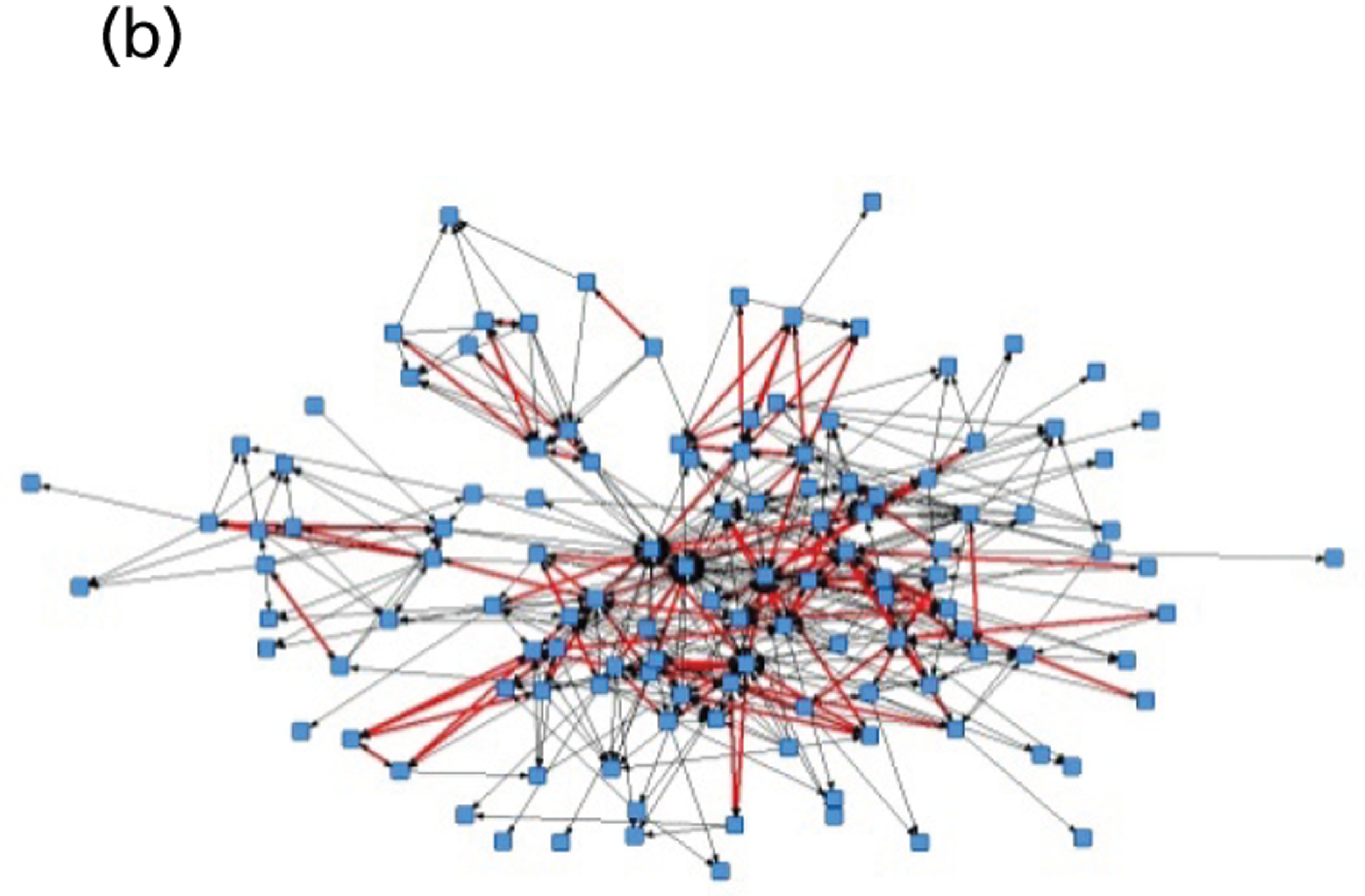

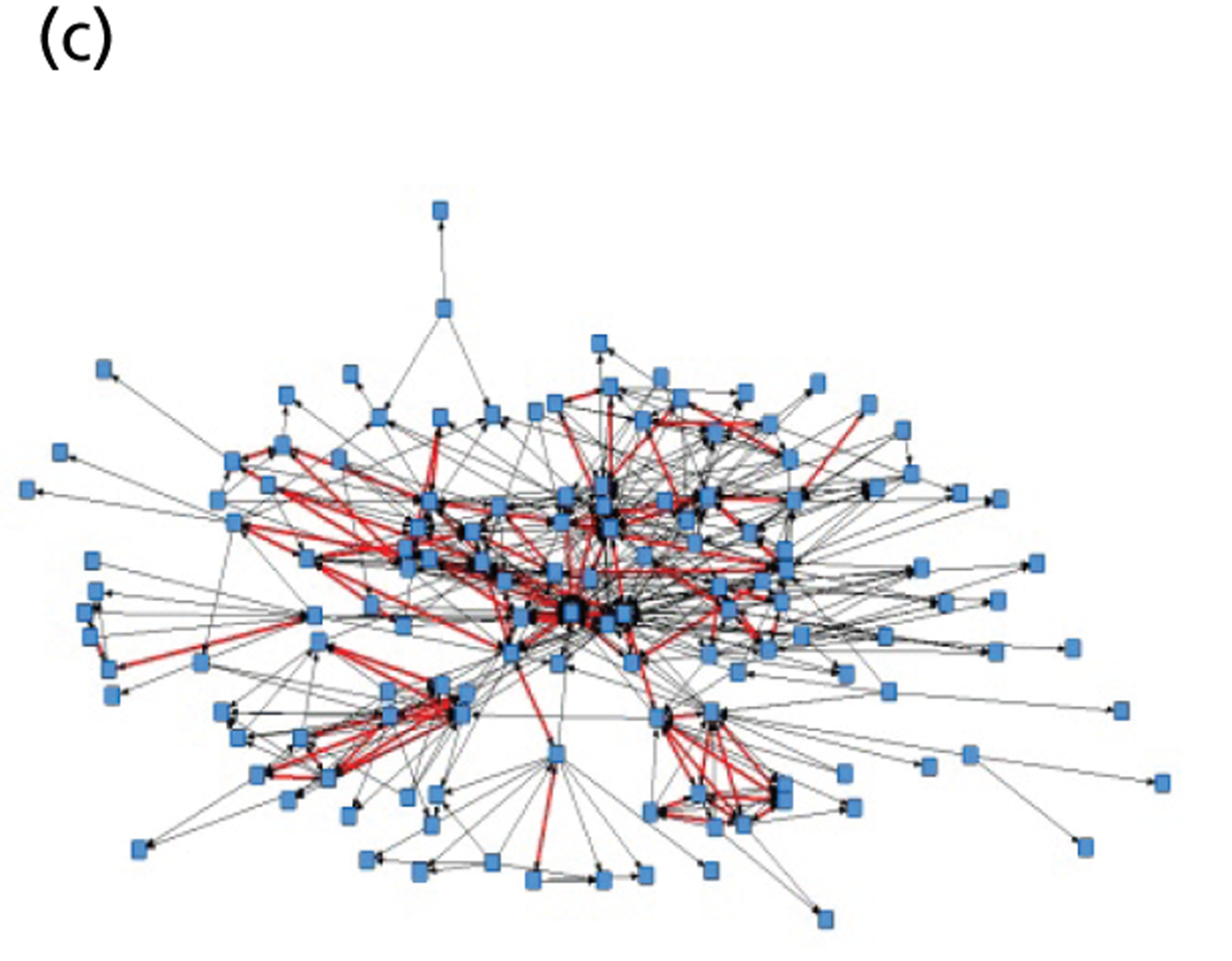

Visualisation and analysis

Social network analysis was conducted using UCINET (Analytic Technologies, Lexington, KY, USA), with descriptive statistics and graphs in SPSS (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) and Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). In network visualisations, each ‘node’ represents a survey respondent/KT initiative member.

Limitations

Generalisability

We attempt to provide comparative analysis of the KT networks but, as per our research design, we do acknowledge that KT activities may be influenced by specific contexts.

Missing data and network size

Social network analysis is sensitive to missing data,88 and this inevitably impacts on our study (more so for time 2 data). Social network data are notoriously difficult to collect. The study was ambitious and we relied on building and maintaining strong, positive relationships with the CLAHRCs and frequent communication and interim feedback of findings. Time 2 data collection occurred during the period prior to CLAHRC refunding, which may help to explain the lower response rate. To help overcome the issue of missing data we assumed symmetry for relations where it made sense to do so in our analysis. 89 We acknowledge the effects of network size on other structural metrics such as density,90 particularly for the smallest Canada-Coordination network.

Other issues

Beyond general issues related to inaccurate survey response (i.e. respondent misunderstanding questions), we highlight that network studies can be affected by the accuracy of respondent recall. 91 However, omission of contacts seems to be an issue for studies on weak or distant ties92 and this study focuses on ‘most important’ ties for KT activities, relations which are likely to be more obvious.

The boundary specification problem is a common issue when studying social networks with unclear boundaries, that is, where it is not entirely clear who is in the network. For this study, the network boundary was defined by CLAHRC membership. Our survey also permitted the inclusion of external knowledge contacts if these people were deemed important to respondents in the context of their CLAHRC KT work. A fixed vertex degree research design limited the number of contacts respondents were able to name to up to five external contacts. This restriction was chosen to yield data on the most important ties in KT contexts both internal and external to the CLAHRC, and to prevent people from simply recalling contacts from memory, which would likely result in bias towards most frequent and recent ties.

We considered the trade-off between respondent fatigue and a survey of the whole organisation and concluded that asking for relations between all CLAHRC members would have been too burdensome on respondents. Our fixed vertex research design urged respondents to think about whom to include and exclude rather than freely name everyone, or name too few.

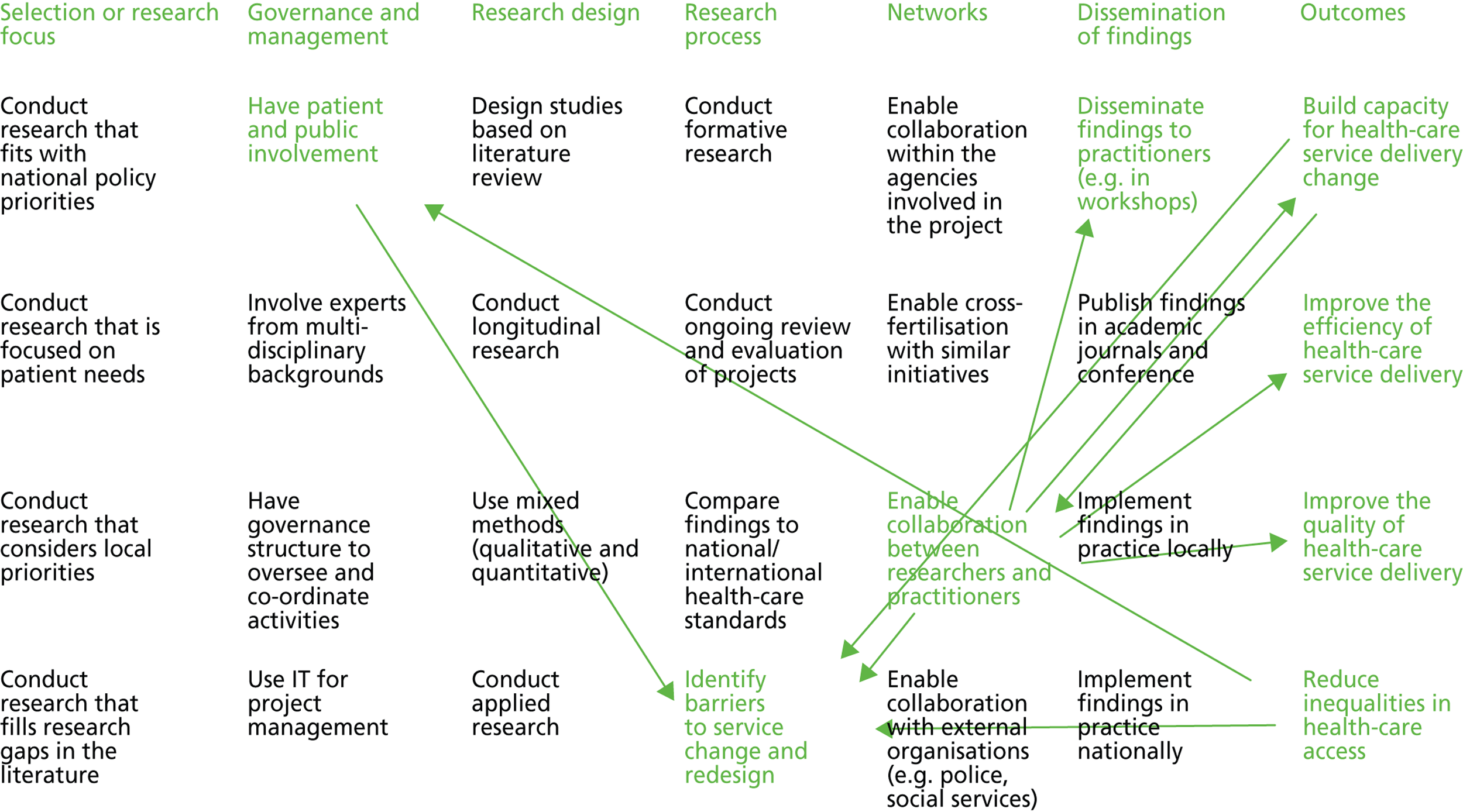

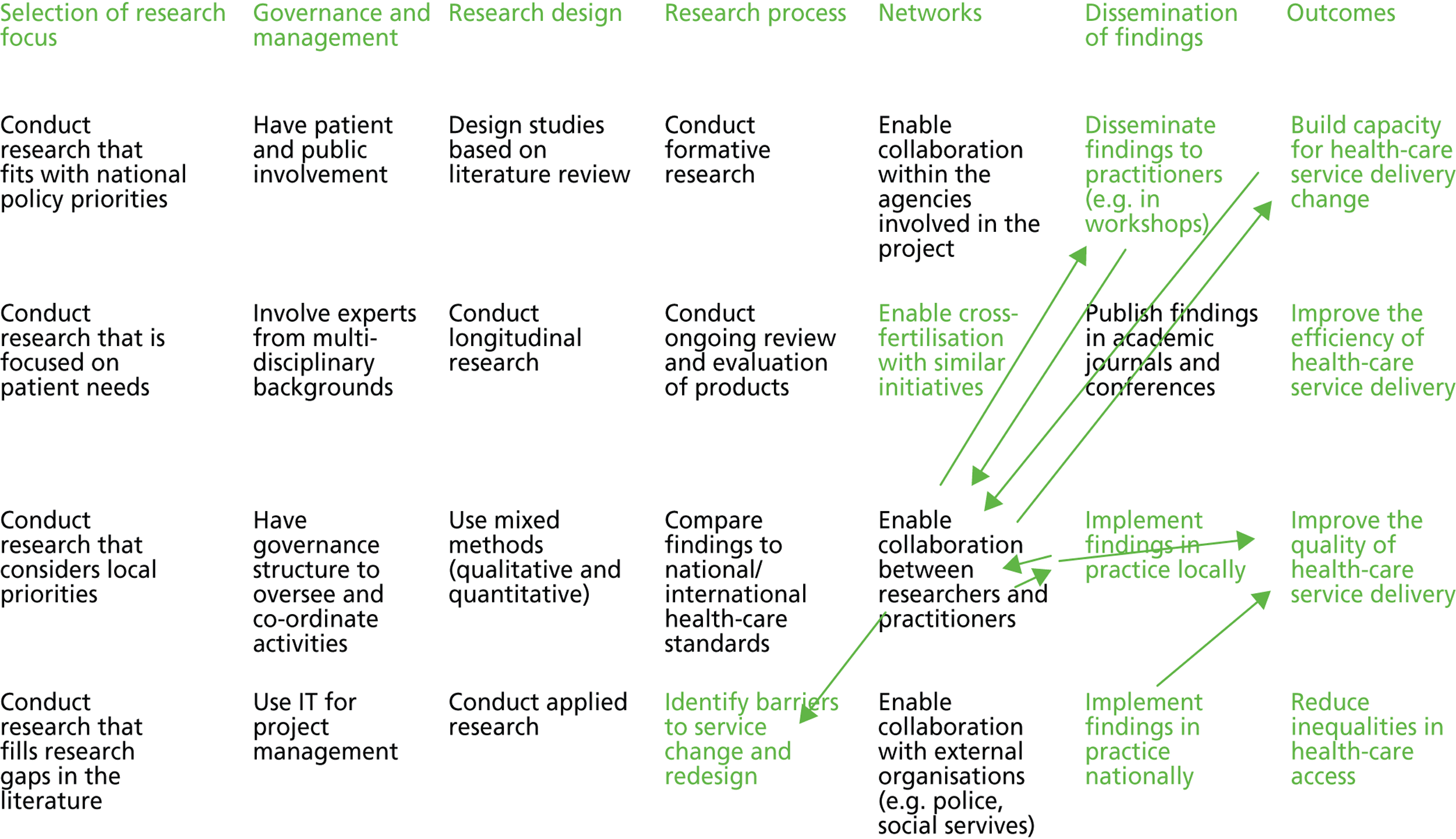

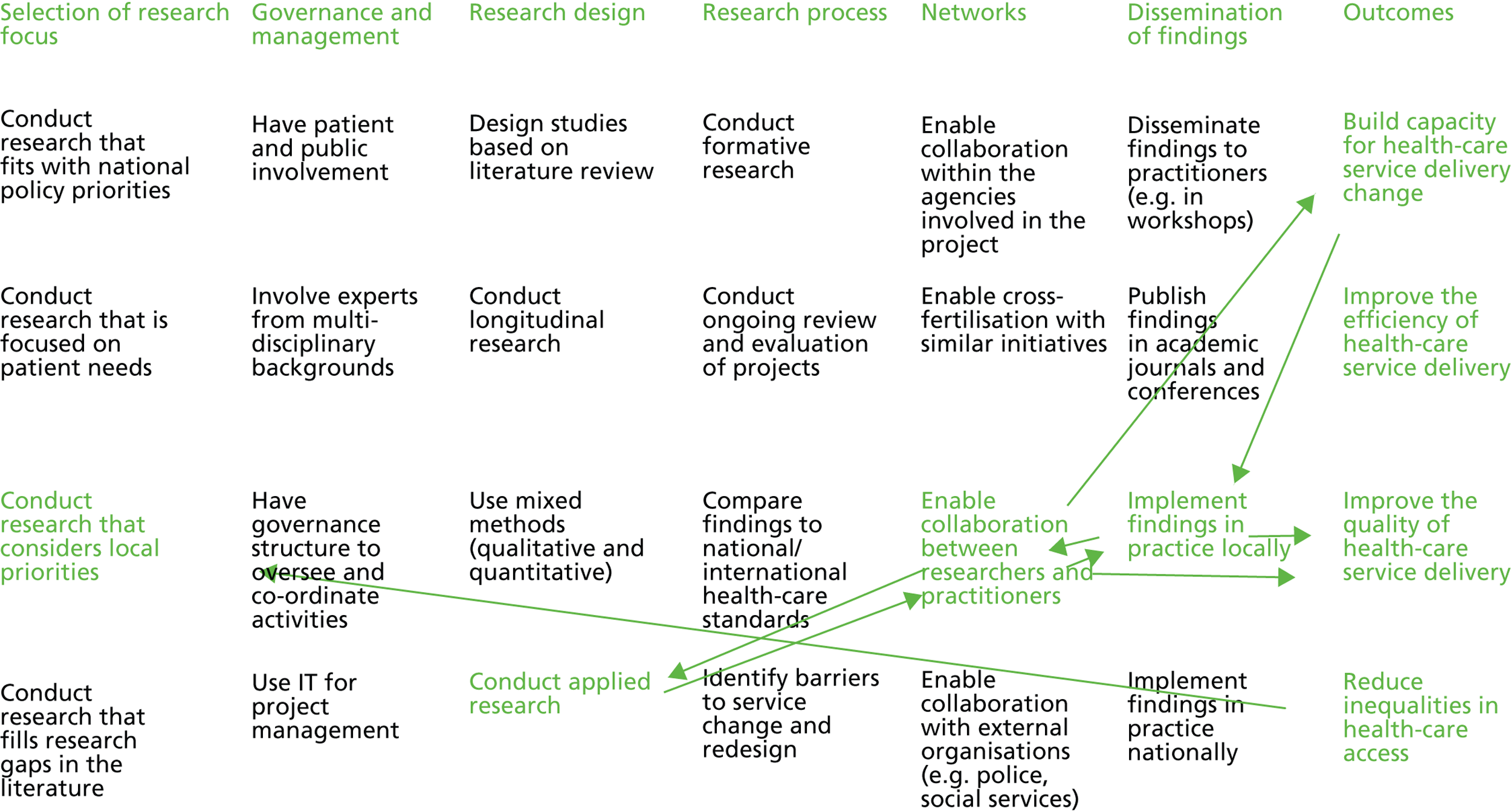

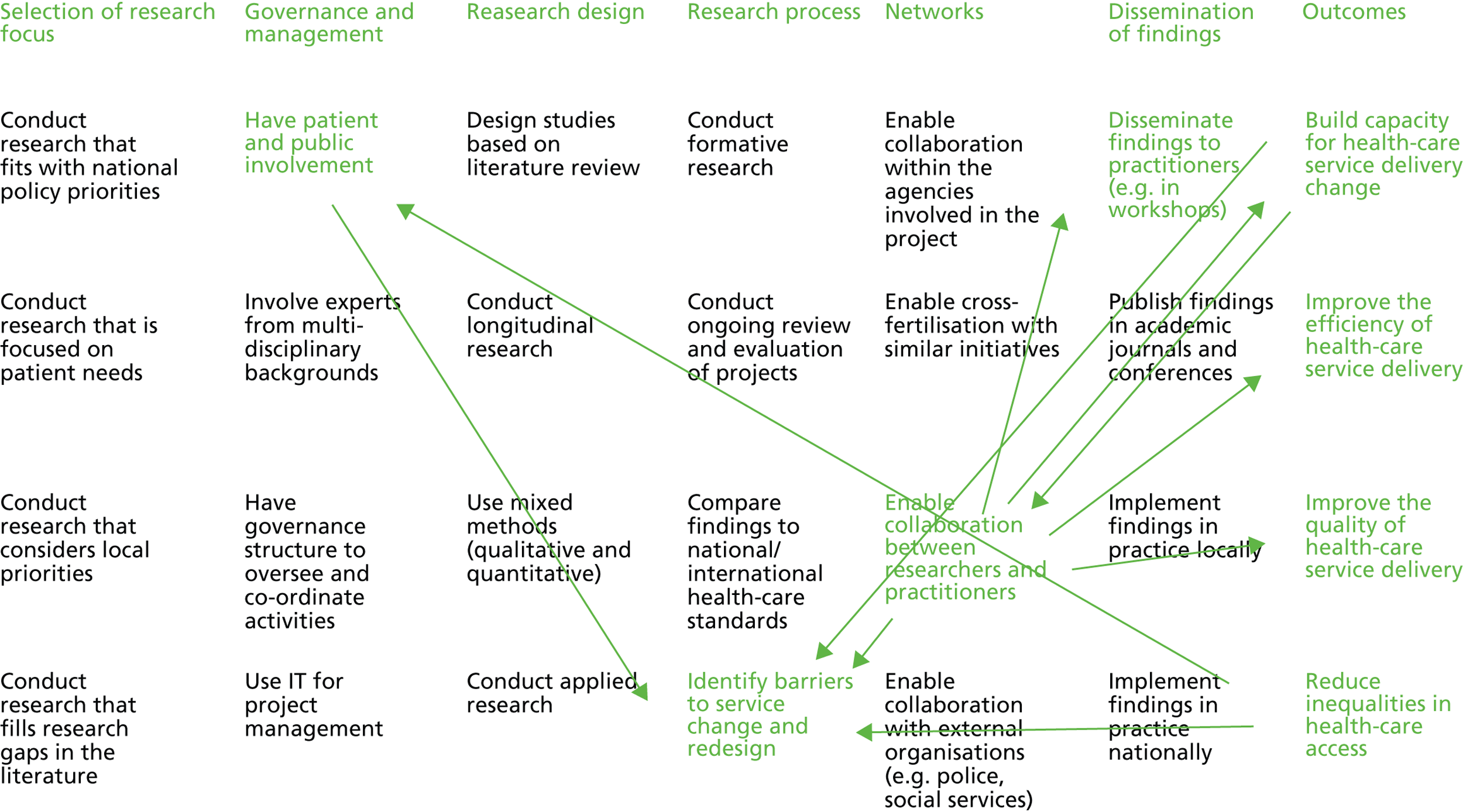

Cognitive and causal mapping approach

A number of studies on cognitive mapping highlight that this technique allows the identification of frames, schemas, and mental paths that characterise individuals as well as groups of people. 93,94 Causal maps (the tool adopted in this research) are a particular cognitive mapping method that highlight cause–effect relationships between a priori established ‘entities’ (or constructs) that play a role in a project/initiative. A common approach,95 and one followed in this study, is to identify inputs (i.e. drivers, factors or triggers) and outputs (i.e. aims, objectives or targets) of a project. The inputs are those elements that contribute towards reaching the outputs. It is clear that both inputs and outputs can vary and might be not clear to (or shared among) all participants in the project.

Scholars who apply causal mapping techniques are interested in knowing more about the beliefs of the participants in order to establish, for example, whether or not there is alignment between inputs and outputs. Alignment (or misalignment) of the participant’s beliefs does not always mirror the success (or the failure) of a project. However, knowing more about collective beliefs (as we do in this research) might help in understanding the development of a project. Therefore, we chose to adopt the causal mapping tool to (1) identify (common) perceptions of inputs and outputs of the five initiatives that we studied and (2) map perceived causal links between inputs and outputs.

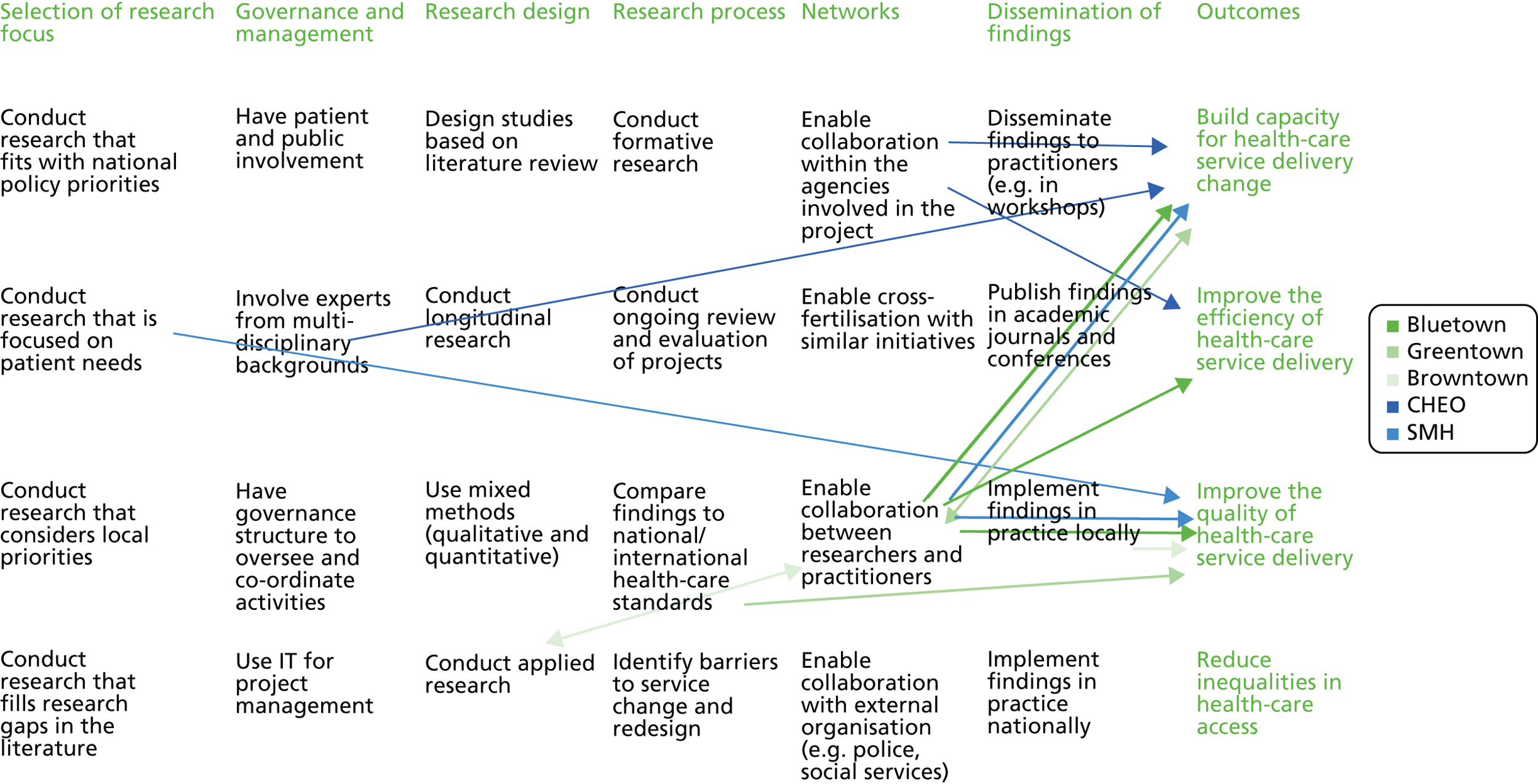

As outlined in Table 2 , we were able to identify 28 constructs using a content analysis method applied to official documents of the three CLAHRCs (the bids) and similar documents of the two Canadian initiatives supplemented with data drawn from initial interviews with those involved in the initiatives. We used these constructs to develop individual and then collective causal maps for each initiative, using Cognizer®, a software tool that manages the causal mapping exercise.

| Focus | Governance and management | Design | Processes | Networks | Dissemination of findings | Outcomes |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conduct research that fits with national policy priorities | Have patient and public involvement | Design studies based on literature review | Conduct formative research | Enable collaboration within the agencies involved in the project | Disseminate findings to practitioners | Build capacity for health-care service delivery change |

| Conduct research that is focused on patient needs | Involve experts from multidisciplinary backgrounds | Conduct longitudinal research | Conduct ongoing review and evaluation of projects | Enable cross-fertilisation with similar local initiatives | Publish findings in academic journals and conferences | Improve the efficiency of health-care service delivery |

| Conduct research that considers local priorities | Have governance structure to oversee and co-ordinate activities | Use mixed methods (qualitative and quantitative) | Compare findings to national/international health-care standards | Enable collaboration between researchers and practitioners | Implement findings in practice locally | Improve the quality of health-care service delivery |

| Conduct research that fills research gaps in the literature | Use information technology for project management | Conduct applied research | Identify barriers to service change and redesign | Enable collaboration with external organisations (e.g. police, social services) | Implement findings in practice nationally | Reduce inequalities in health-care access |

Below, we provide a detailed description of the method adopted. The four steps follow Clarkson and Hodgkinson. 95

Step 1: We performed content analysis of a number of documents and interviews [using NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK)] of the three CLAHRCs and the two sites in Canada. The content analysis concentrated on gathering information regarding two main themes: (1) What are the factors that will lead to the success of the particular health-care initiative? and (2) What will constitute success for the particular initiative? We focused the content analysis on input–output constructs and identified unique codes (initially 516) for each sentence that corresponded to a statement linking an input and an output.

Step 2: We reduced the 516 codes to 28 constructs, cross-matching multiple sources of data. We performed a confirmatory test involving two academics experts in health care as well as six health-care practitioners from the various initiatives involved in this research, obtaining 95% overlapping results.

Step 3: Three independent researchers grouped the 28 constructs into seven categories, including four outcome constructs. As these are derived from a process of analysis of documents and interviews of the five initiatives where health-care systems are sufficiently different (Canada vs. the UK), we can argue that the identified constructs could be applied to most health-care service redesign innovation initiatives. In terms of using these constructs in a causal mapping exercise, the following process was undertaken (step 4).

Step 4: Using Cognizer®, software designed to produce causal maps, we involved people across the three CLAHRCS and the two Canadian initiatives. Following the approach identified in previous studies,96 we selected people who (1) led the initiative, (2) were decision makers and (3) were involved in one or more project committees. The participants to the causal mapping exercise were asked to (1) select 8 of 28 constructs (we removed the four outcome constructs from the list of available constructs), (2) rank order these selected constructs in terms of their importance to the initiative (we refer to this as the survey part of the exercise); and (3) rate the relationship between the selected constructs (we refer to this as the causal mapping part of the exercise). In terms of this last task, we elicited causal maps using Cognizer®, following the steps outlined by Clarkson and Hodgkinson. 95

Chapter 4 Empirical analysis and findings: qualitative investigation

Introduction

As noted previously, to be able to address the different dimensions of CLAHRC activity relevant to our study, we adopted a ‘multilevel’ approach in our fieldwork and analysis97 that sought to integrate evidence from both our CLAHRC-level and our project-level data collection to provide a coherent, narratively structured account of the CLAHRCs’ development.

The overall approach that we adopted to data analysis incorporated a hybrid process combining both inductive and deductive thematic analysis of interview data. 98 At a basic level, thematic analysis of interview data is simply where coding ‘is used to break up and segment the data into simpler, general categories and expand and tease out the data in order to formulate new questions and levels of interpretation’ (p. 30). 99 It was important to recognise that, in building our study on a theoretical concern with networked innovation,31,79 we had already made assumptions and developed ideas about the focus for the analysis. However, it was also important to allow our analysis to be data driven to allow new ideas to emerge during the process of coding. Therefore, we needed to develop an approach that allowed us to make use of our preconceived ideas and theoretical underpinning, while still maintaining the inductive flexibility of an approach that supports the generation and development of new ideas.

As interpretive research still needs to demonstrate credibility and trustworthiness through being founded on a systematic evidence of the research process, our data analysis was supported by a structured method that combined steps in which we were ‘data driven’ and inductively developed codes based on interesting ideas and themes that emerged from our study of transcripts, together with incorporating phases of review in which we reflected on how these ideas fitted in with the overall objectives of our study. Therefore, although our research analysis was based on a linear ‘step-by-step’ procedure, this still facilitated an iterative and reflexive process. 98 However, in following a structured approach, we were able to continually reframe our analysis both based on ideas from inductive study, and allowing our theoretical grounding to be an integral part of the generation of codes.

We used NVivo to support our data analysis. While NVivo can be used to support a more objective and logical categorisation of codes, we should recognise that this is only an aid to the organisation of the material and is not in itself an interpretive device.

To structure the individual case narratives outlined below, we have adopted three major headings which reflect our conceptual framework and support critical concerns around the development of the CLAHRCs. These headings are as follows: governance, management and organisation; collaboration and networks; and KT. To begin our account, however, we focus on the way in which the goals of the CLAHRC initiative were appropriated by individual CLAHRCs in terms of the vision which they defined for themselves.

The vision of the Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

As the three case sites of translational initiatives within the UK were all created through the same UK NIHR funding programme, they were all designed to meet the same aim and generic mission. However, there was significant flexibility in the way in which this mission was interpreted by the leaders of different CLAHRCs. We term these interpretive acts of leadership as different ‘visions’ of collaborative translational research. Within our study we have explored how the vision of each CLAHRC has emerged from and interacted with the structuring of the initiative, particularly in terms of management and governance. By studying the CLAHRCs’ development over time, then, the qualitative fieldwork has been able to explore how these distinctive features of each CLAHRC influence their approach to KT.

Bluetown Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care

The Bluetown CLAHRC is based on a partnership with organisations from a large urban area. It is led by a university hospital with an established strong reputation in conducting research. The health-care partners are representative of a range of organisation types, including acute hospital, primary care and mental health trusts, which includes both organisations with extensive research experience and those that have been previously less involved. The CLAHRC was originally established around a simple ‘hub-and-spoke’ model of a small central management team and nine clinical project teams. The core of the CLAHRC, including its management team and several of the clinical project teams, is centred on a traditional medical school public health department with high-profile academic expertise in clinical sciences research, and historic links with the lead NHS site. Each project team is largely composed of members based in the same geographical base, with a number of teams based at the university, and other clinical project teams are located within one of the health-care partnership organisations. Specialist support services were included as a CLAHRC-wide resource, providing each clinical project team with access to people who could contribute medical sociology, health economics, methods such as systematic reviewing, and statistical expertise.

The director was integral to developing the vision for this CLAHRC and for embedding this within the different clinical projects. Throughout the development of this CLAHRC, his vision has been strongly influential on the form that the work programmes within the CLAHRC have taken as they have progressed. In particular, a clinical scientific tradition was incorporated into the design of study protocols at the start of the programme, with particular attention being placed on scientific methodological rigour, especially the production of outputs suitable for top-quality, peer-reviewed academic publication. In particular, all of the clinical projects were designed as prospective evaluation clinical-academic research studies and, therefore, constituted a set of work programmes all linked by a common scientific approach.

It’s to prospectively evaluate service delivery as it happens. And where possible to interact, you know, with managers and how the service delivery takes place. So that the product will be examples where this has happened prospectively and good examples that have been published in good places. In the process of doing that to export the idea or develop the idea in the local area.

BLUETOWN001

This illustrates a cornerstone of the Bluetown CLAHRC model: the vision emphasises that the quality of the evidence being produced is crucial to its ultimate impact. As a result, the vision of this CLAHRC was founded on the view that any programme of work should first be grounded in a rigorous scientific approach, as only high-quality evidence should be taken up within health-care policy and practice.

Management, governance and organisation

The CLAHRC was originally formed around a small central leadership team, with the vision of the director strongly influencing the focus and direction of the CLAHRC model. As the director had a historically strong reputation in the local area, this helped to legitimise the CLAHRC as something that was perceived as of value by those in senior positions within the partner organisations.

The vision of the core management team has been strongly influential on the approach that each programme of work uses. Each programme of work is expected to use a rigorous scientific design and methodology in order to produce robust evidence that is suitable for publication in high-quality academic journals. Therefore, the model builds on the approach to scientific work that was historically conducted by the lead organisations, with the CLAHRC emphasising that through these work programmes the teams should foster collaborative relationships with relevant service areas. This vision is emphasised through the role of the leaders within each of the project teams, who provide scientific and methodological direction to the programme of work. However, although there is recognition of the overarching objectives expected from each team by the central management, there is no CLAHRC-wide strategy for how each team should be structured or how collaborative relationships should be formed and developed. As a result, the lead of each project team has been provided with extensive flexibility on how their individual programme is organised. As a consequence, each team tended to foster relationships with particular groups and communities as relevant to the local services on which they were gathering evaluative evidence. The influence of the CLAHRC was important here in formalising and legitimising this collaboration between clinical academics and targeted groups in the NHS.

Without CLAHRC, we would have some of those connections but I think the momentum, thrust and energy that’s going into current programme really wouldn’t be there . . . associating with individuals from other fields, groups that we wouldn’t normally be part of. This has really allowed us to reflect more objectively on work, and the direction we’re going.

BLUETOWN022

Structural features of the CLAHRC were used to communicate the overarching objectives of central management to the clinical project teams. This involved regular interactions between the centre and projects, management representation at project team meetings, and programmed meetings for project leaders and project managers. The positions which project members held in other environments (i.e. outside of their own team environment) were typically construed as ‘honorary’ – that is, not part of the main role which project members perform within their clinical team or central management group ( Box 1 ).

Observation of the interactions within a project meeting illustrated how the vision of the overall initiative is emphasised through the presence of a member of the core management at clinical project meetings. The core of the project team is based in a different location to the central CLAHRC. However, the team also have a number of affiliated members who contribute different types of expertise, such as health economics and clinical-academic insight. At the outset of the meeting, the advisory member recounted how she had earlier met with members of the central CLAHRC and discussed the overall objectives of the CLAHRC. She was asked to stress the core management group’s strategy and approach for the CLAHRC, and in particular the need for the team to consider where findings from the programme of work could be published in academic journals. She describes her role within the project meetings as ‘to remind the project team of central management’s priorities and viewpoints for the vision of the initiative’.

Although the majority of clinical project team members share similar types of disciplinary expertise, with most having clinical–academic experience, the structural organisation of the initiative provides access to other types of expertise. The extent of the CLAHRC-wide resources means that individuals with expertise such as health economics, statistics, systematic reviewing, sociology and communication are easily available for project teams to access. With the sociology theme, for example, each project team allocated a small proportion of their own resources to support the employment of a select number of people with this type of expertise. Although these team members come from different working cultures from the majority of the CLAHRC members, it is clear to the clinical project teams that the director values and respects the expertise that these individuals can provide. This helps to legitimise their contribution within the teams, even in sociological territory, which such teams would not normally view as part of their remit. At the start of CLAHRC, the cross-cutting activity for sociology was an undefined programme of work, but this provided an opportunity for these members to liaise with the clinical project teams to identify how they could support their programme of work. As relationships were built up, they quickly identified certain project teams where they could add value to the other work that was already planned by the team lead.

We are officially termed as a cross-cutting theme but we’re also embedded in the individual research, as in our jobs are paid out of individual projects.

BLUETOWN003

This cross-cutting work has become an embedded part of a proportion of the clinical project teams. Although they provide a different type of expertise to the clinical projects, the members of this cross-cutting theme enact their role in such a way as to fit in with the overall work programme. While, overall, the cross-cutting theme constitutes only a small part of the CLAHRC, resources were deliberately allocated so that the members of this group would be highly skilled and experienced, and therefore able to achieve this. They have also been able to contribute guidance to more junior members of the project teams who are involved with areas that overlap with their area of expertise, such as qualitative components. Observation from in-depth studies of the four clinical themes indicates that this approach has facilitated the ‘embedding’ of the cross-cutting theme members within the project teams.

Networks and collaboration

The qualitative interviews demonstrated that from the early stages of the CLAHRC’s development, a clear objective was understood to focus on working with stakeholder groups, such as collaborating with NHS practitioners and managers within the clinical project work. There was also acknowledgement that this required some compromise with established academic work practices, with some effort being required to produce work that is suitable for practitioners.

Getting researchers to understand practitioners is a covert aim of CLAHRC. So that you don’t go away for five years and then tell them what they should have done in the first place because practitioners don’t want to hear that.

CMBLUETOWN007

The activity of each of the clinical project teams means that they create links to defined health-care organisations involved in the CLAHRC partnership. The interaction between members of the project team (e.g. the project lead) is integral to fostering the relationships among the official partner organisations of the CLAHRC. As many senior CLAHRC members had pre-existing collaborative relationships with NHS trusts, they were able to enact ‘senior’ boundary-spanning roles. Many of the theme leads were in clinical–academic dual activity roles and held honorary contract positions with NHS organisations. However, their leadership typically reflected the wider ‘epistemic’ community of a university setting, emphasising academic values rather than the practical concerns seen in the health service environment. For university-based teams, the collaborative interaction was framed by the values of the academic community, with high-level academic publication considered as important for demonstrating value to these groups. This was seen as consistent with the vision of the CLAHRC, in that the collaboration is seen as creating a culture within health-care settings which is more receptive to high-quality scientific evidence.

It’s nonsense to say . . . the PCT health, local authority or the voluntary sector don’t consider evidence. They do. They just consider evidence perhaps in a different way than you or I perhaps might consider evidence . . . The CLAHRC process is about the better, the optimal decision making that we can bring, the greater rigour, to set different parameters for making the decision. That is the value.

BLUETOWN014