Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1801/1066. The contractual start date was in August 2010. The final report began editorial review in March 2013 and was accepted for publication in October 2013. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Corrections

-

This article was corrected in March 2016. See Drennan VM, Halter M, Brearley S, Carneiro W, Gabe J, Gage H, et al. Corrigendum: Investigating the contribution of physician assistantsto primary care in England: a mixed-methods study. Health Serv Deliv Res 2016;2(16):137–138. http://dx/doi.org/10.3310/hsdr02160-c201603

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Drennan et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

This study addresses questions of the implications of the changing workforce in primary care. It is focused, in the first instance, on providing information that addresses the questions of general practitioners (GPs), managers and those involved in commissioning services and education programmes in the UK. This chapter provides the background and rationale to the study by presenting contextual information about primary care, the workforce in general practice, mid-level practitioners including physician assistants (PAs) and the evidence at the point the study was commissioned (December 2009). The aims and objectives of the study are presented, followed by brief detail of the advisory mechanisms and public involvement to the study team. The chapter concludes with an outline of the rest of the report.

Rationale

Primary health care has a pivotal role in the NHS, as in other countries. 1 In all countries of the UK, the policy direction over the past 20 years has been to increase the delivery of health care outside hospitals at the same time as addressing issues of effectiveness, accessibility, equity, patient choice and affordability in primary care. 2–8 This policy stream, together with views from within the profession of general practice itself, argues that the delivery of services will require differently skilled and different types of health professionals working in general practice. 9 The changing demands on health-care systems combined with financial pressures and/or shortages of professionals raise questions of effectiveness and efficiency in all health-care workforce structures and/or staff deployment. 10 Task-shifting from one occupational group to another, substitution of one professional for another and the growth of support workers (in direct health-care and administrative roles) are three strategies evident in primary and secondary care in many countries. 11–14 These strategies are evident in the changes in the UK general practice workforce, including the use of ‘mid-level’ providers. ‘Mid-level’ health practitioner is a term that has been used to describe a qualified health professional (non-medical and non-dental) practising at a level above that of the basic level of qualification for most health professionals in the UK and with authority to assess, investigate and commence or change treatment within the agreed scope of practice with their employer and/or clinician supervisor. 15 PAs and nurse practitioners (NPs) are two examples of mid-level practitioners among a diversity of titles and roles worldwide. 16

We outline first of all the developments in the general practice workforce before providing information on PAs in primary care and the rationale for the study.

Developments in the UK general practice workforce

There are about 10,000 general practices in the UK and, as a sector, these have been characterised by entrepreneurial developments in service delivery as well as in practice organisational forms. 17,18 Many of these developments have arisen through individual enthusiasms and values19,20 and others have developed in response to incentives and health professional labour market fluctuations. 21,22 The flexibilities created both by the new General Medical Services Contract23 and other forms of contracts for primary care24,25 created opportunities for different organisational forms and skill mixes appropriate to the needs of patient populations and to the provision of out-of-hours and extended hours services. GPs, as both health-service professionals and employers, exemplify the human resource policy stream articulated first in the human resource strategy for the NHS Improvement Plan in 2002: ‘more staff working differently‘. 26 The GP workforce has, in the last 10 years, both grown and diversified, with increased numbers of part-time and salaried, rather than partner, GPs. 27–30 However, it should be noted that shortages of GPs and their distribution are not uniform across the country. For example, the number of GPs per 10,000 population in England in 2011 ranged from 6.3 in the east of England region to 7.7 in the south-west region. 27 There have also been changes in the types and volume of consultations undertaken in general practice, with shifts of responsibilities from secondary care to primary care, for example in chronic diseases management and the development of GPs with special clinical interests. 31

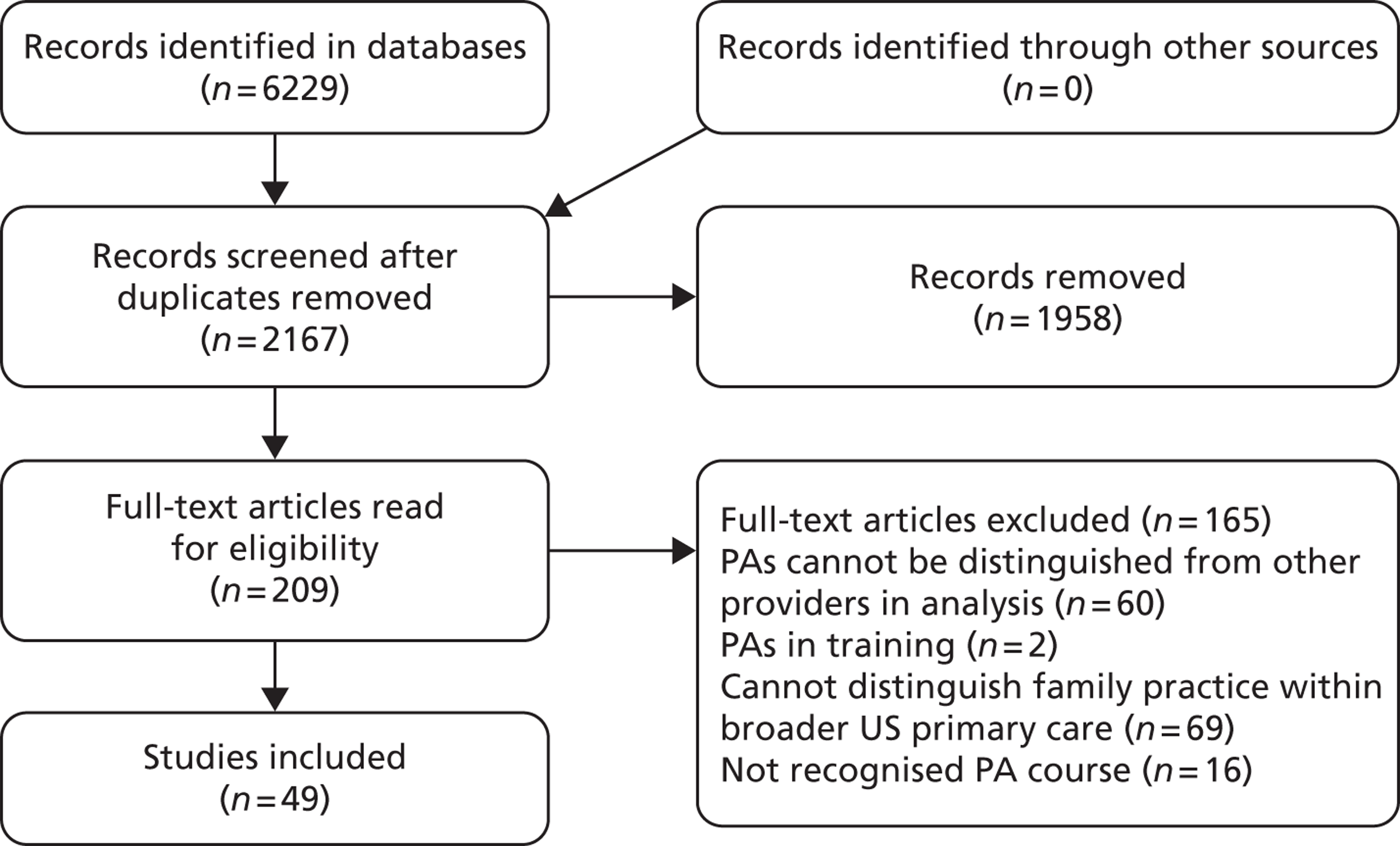

These shifts have been accompanied by GPs moving to employ a wider skill mix within general practice teams. 29 Such a development is evident in the growth over the past 25 years in numbers of administrative staff, nurses and others providing direct care. 27,28 Current statistics for general practice staff in England are illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Composition of general practice workforce in England, 2011. FTE, full-time equivalent. Data source: NHS Information Centre. 32

In the UK, the solo GP with only a receptionist is an organisational model of the past. 33 However, debates continue within the profession of general practice regarding the appropriate mix of staff and skills for a general practice team. 20,34 It is evident from annual surveys in general practice in Scotland that nurses, together with direct care staff such as health-care assistants (HCAs), account for increasing volumes of patient consultations (30% in 2011). 35 Analysis indicates that these are not consultations in which patients present with undifferentiated diagnosis but are follow-up consultations for monitoring or review activities. 35 This suggests that the nursing and direct care staff are both supplementing the work of the doctor and undertaking delegated tasks. Outside general practice itself there are suggestions, such as from a HM Treasury-commissioned report, that NPs could provide a form of substitution, undertaking at least 25% of the work undertaken by GPs. 36 A Cochrane Review published in the same year37 suggested that the evidence was more nuanced. Previous systematic reviews indicated that patient health outcomes were broadly the same for NP and doctor consultations but that patient satisfaction was higher, the length of consultation was longer and the rate of investigative tests was higher for nurse consultations than for consultations with doctors. 38,39 The Cochrane Review excluded observational studies and also separated analysis between those studies in which the nurses were taking ongoing responsibility for chronic disease management and those in which they substituted for the doctor in first-contact, urgent consultations. 37 It was reported that in the studies of ongoing chronic disease management ‘there were no appreciable differences between doctors and nurses in health outcomes for patients, process of care, resource utilisation or cost’. 37 In the five included studies of first-contact, urgent consultations, broadly similar health outcomes for patients were reported for nurses and doctors. Differences reported between the two were lengthier nurse consultations, greater rates of recall by nurses, but higher satisfaction scores for nurse consultations than for doctor consultations. 37 The authors reported that the ‘impact on physician workload and direct cost of care was variable’. 37

By the turn of the twenty-first century there was a policy impetus for a redesigned workforce, particularly in primary care and first-contact services,21 an acute shortage of nurses and doctors applying to work in primary care and encouragement to develop and test new roles from a national body for service innovation known as the NHS Modernisation Agency. 40 At this point, some GPs with others who were looking for workforce solutions began to consider the contribution that another type of ‘mid-level’ practitioner, the PA, working in the USA, could make to the NHS. Before examining this occupational group in the UK, the following section provides contextual information on PAs in the USA and other countries.

Physician assistants

Physician assistants were introduced as a new professional group in the USA in the 1960s in response to medical shortages and misdistribution. 41 PAs are ‘graduates of an accredited PA educational program who are nationally certified and state licensed to practice medicine under physician supervision’. 42 The 170 educational programmes in the USA last an average of 27 months and require applicants to have qualifications in basic science and behavioural sciences and experience of health care. 42 The courses are based on medical education programmes and include 2000 hours of clinical experience practice. 42 Each qualified PA is required to undertake continuing medical education and recertification every 6 years. 42 PAs undertake physical examinations, investigations, diagnosis, treatment, and prescribing within their scope of practice as agreed with their supervising doctor. 43 They have to be registered in the state in which they want to work, and each state has separate regulations and limitations on the prescribing authority of PAs. There are similar numbers of PAs44 and NPs45 in the USA, and about one-quarter of PAs work in family medicine settings46 (Table 1).

| Role | Total number practising in the USA | Percentage practising in family medicine |

|---|---|---|

| Doctors of Medicine (2009) | 766,836144 | 1244 |

| NPs (2006) | 81,43345 | 2545 |

| PAs (2009) | 62,960144 | 2646 |

Studies have demonstrated that PAs, as an occupational group in the USA, provide equivalent and safe care to physicians for the case mix they attend and are acceptable to patients. 47,48 PAs have been shown to have the same task productivity of between 50% and 80% of a physician, dependent on practice setting and experience of the PA, with attendant cost savings to the organisation dependent on the remuneration levels of both the PAs and the physicians they are replacing. 49–51

A number of other countries have PAs in their health-care systems and have developed PA educational programmes. Hooker et al. 52 provide an overview of international developments. Canada introduced PAs in the military in 1984 and in the civilian health service in 1999. Taiwan (Province of China) converted a group of nurses to PAs in 1997 and introduced a PA programme, as did the Netherlands in 2001. The health services in Australia ran pilot projects in rural and remote areas in Queensland starting in 2009, developed the first PA education programme in 201053 and are looking to develop this workforce further. 54 New Zealand has also run a demonstration project and is about to commence a second in rural areas and in primary care. 55 The International Association of PA Educators reported that in 2012 there were 12 countries with PA education programmes: Australia, Canada, England, Germany, Ghana, India, Kenya, the Netherlands, Saudi Arabia, Scotland, South Africa and the USA. 56 Key issues in all countries have been how to achieve recognised accreditation and regulation mechanisms as well as authority for prescribing. 52 The earliest record of GPs in the UK exploring the use of PAs was in 1980. 57 We will now describe the UK experience of PAs from 2000 to 2009.

Physician assistants in the UK

In undertaking a review of the literature, it became evident that in the UK setting the term ‘physician assistant’ was being used in two ways. The first was by some hospital trusts in the UK to describe medical technicians with national vocational qualifications (NVQs) at level 2 or 3. The second was in relation to PAs either trained in the USA or trained in the UK at postgraduate level to the American model. This study is concerned with the second group.

Under the auspices of the policy for the modernisation of the workforce, many developments in new roles were encouraged in the first decade of the century. Small-scale, local pilots of training for roles such as PAs (although often under different role titles) were developed in many parts of the country. 58 The central government health department interest in exploring the utilisation of PAs was evident in two ways. The first was the support of the development of the anaesthetist practitioner programme, later PAs (Anaesthesia), with the Royal College of Anaesthetists in 2003. 59 The second was the funding of pilot projects deploying PAs in support of a wider range of medical teams. Two large-scale pilot projects were funded from central health departments in which USA-trained PAs were employed in a variety of health-care settings: primary care, emergency departments, intermediate care, orthopaedics and surgical specialties in England (2002–5)60 and Scotland (2005–8). 61 The pilot in England arose specifically out of the difficulties of recruiting GPs to deprived communities and the interest in the PA role as a potential solution from a nurse partner in a personal medical services practice, some local GPs and the local primary care trust managers. 60 The evaluations reported that they were very well received by patients, received without problems by other professionals, worked at the level of either a NP or a doctor in training and were reported to be safe in clinical practice. Caveats were noted; for example, demands on mentors were higher than anticipated and a tendency towards slightly longer consultations was reported. 60,61 The evaluation study in England reported on eight USA-trained, experienced PAs working in GP practices. 60 Mixed methods were used including interviews, electronic appointment data and PA- and supervisor-completed forms of types of patients seen and their clinical activities over specified weeks. The PAs were found to provide a similar number of consultations a day (an average of 16.5 per day) to GPs (17 per day) and see, broadly, the same types of patients, with variations between individuals according to prior experience, subspecialisation and practice organisation. 62 Issues that were reported included a period of acclimatisation to the NHS and medical practice in the UK being necessary for American PAs, and a lack of prescribing rights resulting in a greater demand on supervising GP time than would be usual in the USA. 62 It was also noted that the PAs expanded the scope of types of services offered in some practices and allowed others to increase their numbers of registered patients. 62 The Scottish pilot evaluated supernumerary PA posts, of which five were in general practice. Mixed methods were used, including interviews with staff and patients and self-completion work activity by the PAs and events diaries by the PAs and their supervisors. 61 In the primary care setting, the findings concurred with the reports of the English pilot. 63 In their conclusions, both evaluations pointed to the need for research that considered cost-effectiveness more systematically. 60,61

Concurrent with these pilots, PA educational programmes were initiated62 and then further developed by the Department of Health, involving the Royal Colleges of Physicians and General Practitioners. Together these organisations have agreed a competency and curriculum framework for PAs’ education,64 modelled closely on that of the USA. By 2009, postgraduate diploma courses for PAs had commenced in four English universities and a further three trained PAs in the specialty of anaesthesia only. 59 The first of their students had graduated by 2009. These developments were supported by national PA networks and structures. The PAs in anaesthesia established an Association of Physicians’ Assistants (Anaesthesia), which has an agreed curriculum and competency framework with the Royal College of Anaesthetists and the Association of Anaesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland, and holds a voluntary managed register of qualified PAs (Anaesthesia). 65 The UK Association of Physician Assistants was established in 2005. 66 Together with the UK and Ireland Universities Board for Physician Assistant Education (UKIUBPAE), it established the Physician Assistant Managed Voluntary Register (PA MVR) in 2010. 67 The Department of Health agreed an updated version of the competency and curriculum framework64 to reflect this last development. 68

Although both the medical and the nursing professions have in the past been hostile to the introduction of the PA role,59,69,70 there has been increasing acceptance that the addition of PAs to multidisciplinary teams, such as first-contact services, can enhance the delivery of care. 71 At the same time, the number of general practices employing PAs, although small, is growing. 72 In an interview study of 20 GPs, respondents reported that they were motivated to employ PAs in order to increase the practice capacity to manage patient demand within government targets for access, while considering value for money and broadening the skill mix in their teams. 72 The GPs reported that the PAs were primarily being used to see ‘same-day’ and ‘urgent’ appointment patients, although some had also forward-booked appointment clinics and chronic disease management clinics, and some undertook home visits. That study did not quantify or collect details on the work activity of PAs. 72

It was evident that there was growing interest from potential employers in PAs and a potential supply of UK-trained PAs. The UK evidence was limited in 2009 as to the effect of introducing PA personnel into general practice on issues of patient outcomes, service efficiency and safety. This study aimed to address the knowledge gap and provide information to inform decision-makers in health services, commissioning and higher education institution (HEI) settings.

Study aims and objectives

This study aimed to investigate the contribution of PAs to the delivery of patient care in primary care services in England. The research questions addressed were:

-

How are PAs deployed in general practice and what is the impact of including PAs in general practice teams on the patients’ experience and outcomes?

-

What is the impact of including the PAs in general practice teams on the organisation of general practice, the working practices of other professionals, relationships with these professionals and the practice costs?

-

What factors support or inhibit the inclusion of PAs as part of English general practice teams at the local and macro levels?

The full protocol has been published on the National Institute of Health Research (NIHR) Health Service and Delivery Research Programme website. The study team had the benefit of both an advisory group and a patient and public involvement group (see Appendix 1). Both of these groups met during the course of the study to help inform study tool development and research processes, and participated in the seminar in which emerging findings were presented and discussed. In between meetings, communication was electronic, using a newsletter and a website. In addition, the study team were successful in applying for a NIHR management fellow to work alongside the team, allowing synergy between the NHS management community and the research community. Further details are provided in Appendix 2.

The following chapters provide details of the study methods (see Chapter 2) and the findings reported in four chapters. The report concludes with the discussion and recommendations.

Chapter 2 Methods

This investigation employed an evaluative framework suggested by Maxwell73 to examine the contribution that PAs make to the effectiveness, appropriateness, equity, efficiency, acceptability and costs of primary health care. The study had two phases of enquiry. The first investigated the research questions at the macro and meso level of health-care systems through (a) a review of evidence, (b) a scoping survey74 of key informants at national and regional levels and (c) a survey of the current work deployment of PAs in UK general practice. The second phase used a comparative case study design75 of 12 general practices to investigate the research questions at the micro level of the health-care system. Each of these phases is described in detail below. The evidence from each of these elements was then synthesised by the research team and brought to a wider consultative group of people who had participated in the study, including the advisory group and public and patient involvement group.

Phase 1: investigating at the macro and meso levels of health systems

This phase had three elements: (1) a review of evidence, (2) a scoping survey74 of key informants at a national and regional level and (3) a survey of current work deployment of PAs in UK general practice.

The review of evidence

In this element we undertook three review activities. The first was a review of empirical evidence using a rapid review methodology76 for empirical evidence of the deployment and impact of PAs (research questions 1 and 2; see Chapter 1, Study aims and objectives). The second was a narrative review77 of published commentaries and opinions of the PA role in the UK setting. The third was a narrative review77 of national and international policy and developments on health-care workforce planning in relation to PAs and primary care. The last two activities addressed the question as to factors supporting or inhibiting the presence of PAs in the primary care workforce.

The review of empirical evidence

A review78 was conducted to investigate the evidence of the contribution of PAs to primary care as applicable to a European model. The European model of general practice/family medicine was that given by the European region of the World Organization of Family Doctors79 (WONCA Europe). Seven databases [British Nursing Index, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Scopus] were searched from 1967 (or start date if later) to September 2010. A broad range of search terms was used singly and in combination: physician assistant, primary health care, family practice, general practice, family physician, general practitioner (see Appendix 3).

The inclusion criteria were defined as follows:

-

The PA role was one with a recognised PA qualification.

-

The setting was of general practice/family medicine (including community paediatrics in the USA) or the data were identified as pertaining to ‘family medicine’ within other findings from broader ‘primary care’.

The exclusion criteria were defined as follows:

-

Settings of secondary care, in-patient care ambulatory or outpatient care.

-

Health care provided by primary care specialists in the USA (obstetrics, gynaecology, internists or primary care physicians) that would be regarded as secondary care in the UK.

-

The personnel were student PAs or nurses/others who had received special training as medical assistants (that is, without a recognised PA course) for a particular disease condition.

-

The data presented did not distinguish either between PAs and other professionals or between the general practice/family medicine setting from ‘primary care’ overall in its presentation of results.

Retrieved abstracts were screened and full papers, where available, were obtained. Each full paper was assessed for inclusion by two researchers independently and a third (HG, SdeL, VMD, and MH) in cases of indecision or disagreement. A data extraction framework was developed which included categories of PA activities, study methods and key findings. Study outcome measures were categorised using Donabedian’s80 framework of structure, process and outcome. Owing to the wide range of methods used in the retrieved studies, a broad quality assessment of the studies was undertaken using critical appraisal tools81 appropriate to the papers’ methods (e.g. qualitative, cohort, health economic) with additional questions derived from the British Medical Journal’s guidance for peer reviewers. 82 The heterogeneity of the retrieved studies precluded any pooling of data and a narrative synthesis was undertaken using the Donabedian80 framework.

Review of commentaries

A documentary analysis83 was undertaken of published commentaries and opinion pieces about PAs in the UK health-care system or addressed to UK audiences. The published material was identified in two ways: first, through the electronic database search described in the previous section and, second, by an internet search using the Google™ (Mountain View, CA, USA) search engine. The internet search used a combination of terms: physician assistant, physician assistants, National Health Service (NHS), primary care, secondary care, England, Scotland, Wales, Northern Ireland, pilots and workforce, and was repeated at intervals by WC from April 2011 until December 2012. ‘Published’ was defined as in print and electronic formats including online forums between 1980 and 2012. The lower date was determined by our previous knowledge of the first paper published on the experience of a PA in UK primary care. 58 A data extraction framework was developed which included a categorisation of the author (journalists, doctors, nurses, health service managers, etc.), the intended audience, any catalyst for the item (e.g. another published item), inclusion of any empirical evidence and from which country, evidence of support, resistance or neutrality in the publication. The items were recorded chronologically with the data extraction in a Microsoft Excel (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. A narrative synthesis was drawn from the data.

Review of workforce policy and developments

The purpose of this review was both to identify policy and developments pertaining to PAs in the primary health-care workforce in the UK and internationally in order to both help the research team contextualise the study and to identify supporting or hindering factors in the development of the PA profession in the English health-care workforce. The review drew on the methods of the documentary review. 83 Publications were identified through the searches described above. Additional searches were performed to identify polices and reports on health-care workforce planning and development relevant to, primarily, the education and employment of PAs and, secondarily, primary care. The time period covered was from the mid-1990s to the present day. The searches were conducted by:

-

visiting key websites in the UK, for example government health departments in each of the four countries, the Centre for Workforce Intelligence (CfWI) and Strategic Health Authority (SHA) websites

-

using keyword searches in the Google search engine for open source materials related to the topics of interest, for example ‘primary care workforce’, ‘physician assistant/s’ (and other titles to describe this profession, such as medical care practitioners) and ‘health care workforce’

-

snowballing techniques of references and website links.

The documents identified in this way were screened to include only those with relevance to health-care workforce in primary care. Research team alerts of new policy or reports relevant to the study were generated by one researcher (WC). A data extraction framework was developed to classify the document by country, type of author, type of document (e.g. policy, analysis of primary data, opinion and evaluative reports), any reference or absence of reference to PAs and key points from or about the document. The information was saved on an electronic database with full references, any URLs and electronic copies of the original. A narrative synthesis was undertaken addressing the questions of interest.

Scoping survey

A scoping survey74 was undertaken to address research question 3: what supports or inhibits the use and development of PAs in the primary care? (See Chapter 1, Study aims and objectives. ) The method is one element of a scoping review74 and allows for data to be gathered from those knowledgeable in the issue of interest, providing a range of perspectives to ensure breadth in the analysis. 84 It is an approach that has been widely used, most recently in exploring European perspectives on human health resource issues. 85 A purposive sample of key informants at national and regional levels in England and Wales was approached to participate. These were individuals at a senior level from central departments of health, professional organisations, regulatory organisations, patient organisations, and commissioning bodies who are concerned with the development of primary care services, workforce development and health professional regulation. At the point of the design of the study (2009) the Department of Health and Social Services (Wales), unlike the Departments of Health for England and Scotland, had not explored the use of PAs. In order to consider diversity in national environments, individuals were approached to participate in England and Wales. Individuals were identified for approach through an internet search of public domain organisational sites, suggestions of the study advisory group and members of the research team, and snowball techniques from participants. An aide-memoire was developed of topic areas, based on the issues of interest, to be used in semi-structured interviews83 which were offered either face to face or by telephone, dependent on participant preference. The aide-memoire explored knowledge of mid-level practitioners, PAs and perceptions of the factors that currently and will in the future support or inhibit their use and development in the UK settings. Notes were taken during the interview and, with permission, digitally recorded. These were transcribed, anonymised and the recordings deleted. The transcriptions and notes were analysed using the constant comparison method86 by two researchers (WC and VMD) independently, compared and further analysis confirmed with a third researcher (JG). The analysis of the early interviews assisted in identifying further stakeholder groups from whom views were sought. This element of the study was deemed service evaluation by the NHS ethics query service and as such not for research ethics review. It conformed to all university requirements.

Survey of current use of physician assistants in general practices in England

An online, anonymous, self-completion survey was developed and piloted with two PAs who had previously worked in general practice in England. It posed questions of career history, work environment, work activities and estimates of volumes of work. PAs known to working in primary care were invited to participate in 2010 through e-mails sent out by the UK Association of Physician Assistants (UKAPA), course leaders of PA courses in English universities and practices identified as employing PAs in previous research. 72 All invitation e-mails included a link to the survey website and requested forward distribution to any other PAs thought to be working in primary care. UKAPA estimated that there were about 25 of their member PAs employed in primary care. The electronic survey was open for responses for 7 weeks (7 October to 30 November 2010). It addressed three areas: the activities and role of PAs in the primary care team, their primary care setting and their qualifications. Those interested in volunteering for the second phase of the study were given an opportunity to give their contact details at the end of the survey. The survey did not require NHS ethical review and fulfilled all university requirements for the ethical conduct of research. Descriptive analysis of the data was undertaken using Statistical Product and Service Solutions (SPSS) (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA).

Phase 2: the micro level

A comparative case study design75 was used to address the three overarching research questions at the micro level of analysis through examination of 12 case studies: six general practices currently employing PAs and six matched practices not including PAs in their staffing. A mixed-methods approach87 allowed for both description and the quantification of the impact of PAs in the context of general practice. This element of the study addressed specific additional questions:

-

How are PAs deployed and supervised in general practice and how do their roles and responsibilities compare with those of the doctors, NPs and practice nurses?

-

How do PA outcomes of care differ from those of GPs, specifically with respect to prescriptions rates, referrals, investigations, reattendances for the same problem within 2 weeks, patient safety, and patient satisfaction?

-

How do patients understand the role of PAs and what is the experience of patients when consulting PAs?

-

How does employment of PAs affect practice organisation, staffing configurations and costs?

-

What are the factors that support or inhibit the employment of PAs?

The six practices employing PAs were identified either by the PAs initially volunteering through the survey (see Survey of current use of physician assistants in general practices in England) or by an expression of interest from a practice. The volunteering PA practices achieved diversity in features such as general practice size, practice population sociodemographic characteristics, rural and urban coverage, and in the country in which the PAs had qualified. The comparative that was designed required some similarity between PA and comparator GP practices. Following the agreement to participate from PA employing practices, comparison practices were sought in the same health economy and with similar characteristics and patient population size. After the adoption of the study by the UK Clinical Research Network (UKCRN) Primary Care Research Network (PCRN), officers in five local PCRNs made the initial approaches and requests for comparison general practices. Practices expressing interest were then contacted and provided with information, and an initial meeting was set up between the researchers (VMD and MH) and the GP, the practice manager and, in those employing practices, the PA. A summary description of the practices is provided at the end of Chapter 2 (see Table 5).

The general practices and staff likely to be included in the study were provided with full participant information sheets for all research activities. Written agreement and consent for the practice to participate was obtained from the senior partner GP. Procedures for obtaining individual informed consent for each of the research activities are described below.

Data were gathered through the activities detailed in the following sections in this chapter. The analysis is described in each section and the economic analysis in Economic analysis. Analyses were then combined and synthesised to address the research questions as outlined in Table 2.

| Research questions | Data |

|---|---|

| (a) How are PAs deployed and supervised in general practice and how do their roles and responsibilities compare with those of the doctors, NPs and practice nurses? | Interviews with practice staff |

| Work activity diaries | |

| Administrative data | |

| Observation of consultations/meetings | |

| (b) How do PA outcomes of care differ from those of GPs, specifically with respect to prescriptions rates, referrals, investigations, reattendances for the same problem within 2 weeks, patient safety and patient satisfaction? | Consultation record review and patient survey |

| Clinical review of reconsultations | |

| Observation of consultations | |

| (c) How do patients understand the role of PAs and what is the experience of patients when consulting PAs? | Patient interviews |

| Patient survey | |

| (d) How does employment of PAs affect practice organisation, staffing configurations and costs? | Interviews with practice staff Work activity diaries |

| Administrative data | |

| (e) What are the factors that support or inhibit the employment of PAs? | Interviews with practice staff |

Semi-structured interviews with practice staff

Semi-structured interviews83 were undertaken with PAs, GPs, practice managers, receptionists and practice nursing staff. A purposive sample in each practice was approached, provided with information and invited to participate. Aide-memoires for each professional group were developed addressing the questions (a), (b), (d) and (e), above, but allowing flexibility to explore new issues or ideas raised in the interview. GPs, PAs and nurses were also asked to describe their responsibilities and activities within the practice. In addition, practice managers and GPs were invited to provide any practice documents that would provide the research team with information about the practice, its working practices, services provided, staffing and planning. If documents on staffing were not available, the practice managers were asked to provide this information verbally. The interviews were conducted face to face or by telephone as preferred by the participant, digitally recorded with consent, transcribed and erased after analysis. Thematic analysis was undertaken88 initially by one researcher (RL), with further analysis by two other researchers (VMD and MH) and interpretative discussion with the wider research team. Documentary evidence on staffing was read and data extracted as relevant to providing contextual information for each practice.

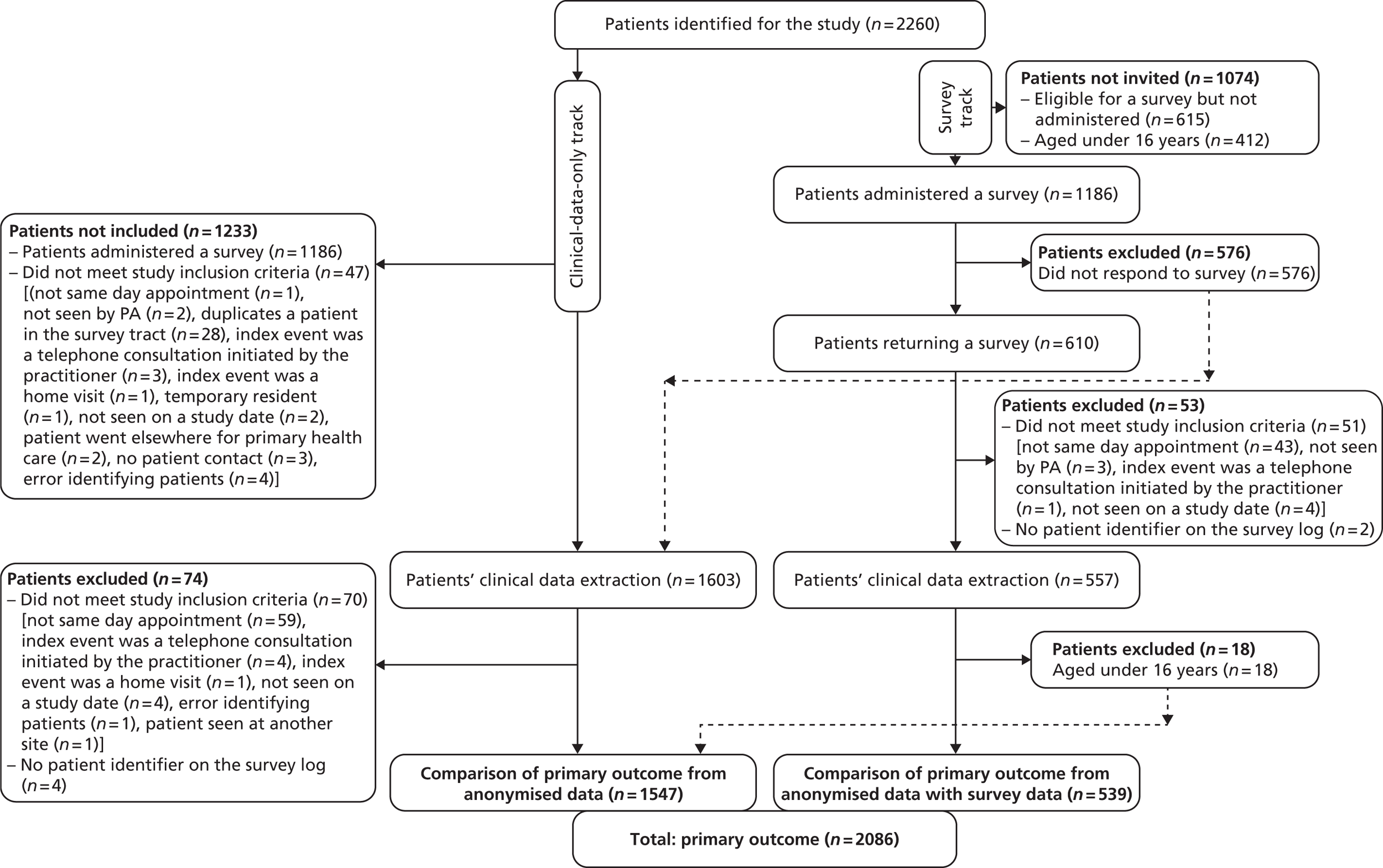

Consultation record review and linked patient survey

The consultation record review and linked patient survey, which addressed question (b) above, was of patients presenting in urgent or same-day surgeries. This was the type of surgery that PAs were predominately working in as identified from the national survey (p. 9). Each practice identified time periods in summer and winter periods (known as reference periods) during 2011 and 2012 in which they were able to assist the research team in data gathering. The length of time periods were based on the practice’s estimation as to the number of surgeries required to reach the sample size. Each practice made staff and patients aware of the research during the reference periods in keeping with their usual practice, for example via notices at the reception desk.

The patient surveys

The validated General Practice Assessment Survey (GPAS)89 focuses on patient outcomes and consultation experience and was used with permission (Paula Metcalfe, GP Patient Survey Team, 12 October 2010, personal communication). During a meeting of the study’s public and patient participation group (see Chapter 1, Study aims and objectives) the GPAS was scrutinised and amendments suggested to improve the clarity of the wording and to specifically address the experience of a consultation with a PA. The amended, self-completion GPAS (see Appendix 4) was then to be offered to adult patients in each designated surgery during the reference periods. The method of distribution and collection varied in each practice, according to their working practices. In some practices, the GP or PA handed the patient a sticker to return to the receptionist, following the consultation, to collect a survey pack (containing a questionnaire, participant information sheet, and business reply envelope). In other practices, the survey pack was sent by post either the same day or the next. All completed questionnaires could be returned in a sealed envelope to a collection box in the practice reception or by post to the research team. The questionnaire did not include any information that could identify the person. Each questionnaire had a unique study identifier (study ID). Practice staff kept a log of the dates of survey administration (the index event) and recorded the unique practice identifier of the patient against the study ID. Practice staff were asked to send out a research team prepared reminder and duplicate survey pack to all those who had taken or been sent a questionnaire who had not responded. The practice staff did not have any access to any of the completed questionnaires, ensuring that anonymity was protected. Data were entered onto a SPSS spreadsheet and descriptively analysed. The data were then also added to the data drawn from the consultation record review as described below.

In the PA-employing practices, the survey pack included additional material inviting patients to participate in a face-to-face or telephone interview. A separate consent form and business reply envelope were provided to respond to the invitation.

Consultation record review

This review addressed the primary outcome of the study: the rate of reattendance in general practice or an urgent care facility defined for the study as GP out-of-hours care, emergency department, walk-in centre, minor injury unit or other direct entry emergency unit (e.g. early pregnancy assessment unit) within 2 weeks of the initial consultation (the index consultation) with a PA or GP, and questions of whether or not the initial consultation activity by the PA or GP was appropriate in the light of the subsequent reattendance. The consultation records also provided the data for the process measures of advice, investigations, treatments, referrals and prescriptions.

The sample

The sample size required for the primary outcome was based upon randomised controlled trial data which compared the rate of reattendance in general practice within 2 weeks and outcomes of care delivered by NPs and GPs in the UK for patients attending ‘same-day appointments’. These studies reported figures ranging from a self-reported 18.2%90 through to extracted medical records 28.4%91 and 29%92 for patients seeing GPs and 20.4%, 31% and 37.2% for NPs, respectively. Taking Venning et al. ’s91 analysis as the most robustly adjusted of these, the reattendance rate within 2 weeks of the consultation for this sample size calculation was taken as 28.4% for GPs and 37.2% for NPs. Assuming an OR of 1.5 and adjusting for slight multicollinearity as reported by Venning et al. ,91 we estimated that a sample size of 205 in each group (consultations with a PA or a GP) was needed to give 80% power at a significance level of 5% for a logistic regression using the covariates of age, gender and general practice. We estimated that anonymised clinical records data might be required for up to approximately 600 patients each attended by PAs and GPs in the 12 practices in the data collection periods in order to meet the required sample size, assuming a response rate of 30% to the patient survey. However, in conducting the study, two problems arose. The first was that a condition of the research ethics approval was that child consultations were excluded from the survey element but could be included in the review of clinical records. We therefore included all child consultations in the designated surgeries in the reference periods as our review and survey had shown that PAs were consulted by children and their parents. The second problem arose through inaccurate research team and practice staff estimates of patient survey return rates in their practice (i.e. lower than our assumptions) resulting in more surgeries being designated for survey distribution. In some practices, clinical records were passed to the research team some months after the designated surgeries and only then did it become apparent to the research team that these had much greater numbers than anticipated. In addition, in some practices, there was a lack of fidelity to the protocol in that not all eligible patients were offered the survey (in some instances only 30% were offered). This was apparent to the research team staff only when they returned to discuss the participant numbers and check that the reference periods were similar to those of the preceding weeks for the practice. As the possibility of selection bias could not be eliminated, the research team decided to include all of the clinical records sent by the practices. This resulted in a larger sample than in the study design.

The data

Data from the electronic records of those patients who consulted in the designated surgeries during the reference periods were extracted and all patient identifiers removed in the practice. These data were then passed to the research team using the unique study ID number only. The data extraction occurred at a time point more than 2 weeks after the end of the reference period. The data extracted by the practice staff for the index event included the consultation date, person consulted (PA or GP) and length of consultation; the patient’s age, gender, ethnicity and postcode; the patient’s presenting conditions; number of prescriptions from the consultation; the number and type of Quality and Outcome Framework93 chronic conditions registers the patient was entered on; the number of repeat prescriptions; and the number of times the patient had contact with the practice in the three months preceding the index event. For any consultations in the following 2-week period, the location of consultation, the professional consulted, presenting condition(s) and number of prescriptions issued were recorded. The research team used the postcode on each record to assign the Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD)94 and then deleted the postcode. The practice records varied in the extent to which Read codes95 were used for the presenting problem or diagnosis. The research team subsequently reviewed each record and assigned Read codes95 to presenting problems that were documented but not coded by practice staff and assigned study codes for groups of diagnostic tests, referrals, procedures, certificates, medicine management and advice given (see Appendix 5). Each consultation record was coded by one member of the research team and then checked by a second. Uncertainties were discussed and resolved with a third member of the team. A categorisation of the presenting problems in the index consultation was also assigned to each patient record in order to examine the case mix of the consulting patients. This classification of acute, chronic, minor/symptoms, prevention and processes was an adaptation of that used by de Jong et al. ,96 developed by the research team in which the GP in the research team (SdeL) made the final decisions on categorisation and assignment. The method of assignment of a condition category to each patient is presented in Appendix 6.

Each index consultation that had subsequent consultations was identified. Each subsequent consultation was coded by two research team members to identify whether it was for exactly the same, a linked or a different problem to that of the index consultation. The method for designation was developed and refined with the GP research team member (SdeL).

All data were entered into a SPSS spreadsheet, to which the data from the patient survey (where available) could be matched by the study unique identifying number.

The data were then analysed descriptively, involving summary measures of location (e.g. means /medians/proportions) and dispersion [standard deviations (SDs)/percentiles] appropriate for the type and distribution of the individual variables. Differences in processes and outcome between those practices with and without PAs were assessed by generalised estimating equation models. 97 The resulting ORs or rate ratios were adjusted for the case mix and IMD variables where they were significant predictors or notably confounded the relationship between practice type and the dependent variable. The correlation matrix was set to be exchangeable, that is to say patients were assumed to have some shared characteristics within each practice, whether from demographics or organisation of the practice.

The clinical review of reconsultations records

All records in which a patient had reconsulted within 2 weeks for the same or a linked problem were assigned to clinical record review. The review of medical records, or ‘chart review’, is a longstanding method of assessing the consultation98 used in assessing overall quality99 and considered reliable in detecting prescribing errors. 100

An anonymised printout of the computerised medical record system was reviewed to assess the quality of the record and to assess the appropriateness and safety. The data on whether it had been a GP or PA who had conducted the index consultation were removed, as well as any other references that might identify the practice or its geographical area (e.g. hospital name). A clinical review process, which addressed the question as to whether or not, in the light of the subsequent consultation(s), the first consultation had been appropriate, was developed by the GP member of the research team (SdeL) in consultation with the clinical review team of four GPs. The four GPs all had experience of assessing the quality of the consultation and, to a more limited extent, of the medical record. They were all active in education: one was a trainer while the other three took medical students in their practices; two were research active; two were male, two were female. They were trained in two 2-hour training sessions led by SdeL.

Based on the problem-orientated medical record format,101 the experienced GP reviewers were asked to judge each element of the consultation, the overall appropriateness and whether a GP or a PA had been consulted. Weed’s taxonomy,101,102 for the elements of a problem-orientated medical record, was used as an measure of quality of the record, and the opinion of experienced GPs about appropriateness of the content of each part was used for the problem presented. The GP raters also gave an overall assessment. Weed’s101,102 approach was to suggest that there were four key elements of the record, described by the acronym SOAP:

-

Subjective: what the patient complains of, the problem from the patient’s perspective.

-

Objective findings from the consultation (e.g. blood pressure measurement).

-

Analysis by the clinician of the problem.

-

Plan for future action, including follow-up.

We modified this by making it explicit that the plan could have different elements: investigations, prescriptions and other aspects of the plan, such as referral or follow-up (Table 3).

| Weed’s SOAP | Modified SOAP | Includes | Explanation | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Subjective | Subjective | History | Patients’ complaint(s) |

| 2 | Objective | Objective | Exam | Objective findings (e.g. blood pressure recording) |

| 3 | Analysis | Analysis | Problem | May include diagnosis, recorded as the problem or reason for encounter |

| 4 | Plan | Investigation | Tests | Laboratory tests, X-rays, other tests initiated in primary care |

| 5 | Prescription | Acute, repeat or recommendation for over the counter | ||

| 6 | Other aspects of the plan | Referral |

Each record was assessed by a GP and 20% by two GPs independently using a study-designed form (see Appendix 7). Data were entered into a SPSS spreadsheet, analysed descriptively and inter-rater reliability was assessed. Inter-rater reliability is a measure of the extent to which the reviewers agreed with each other in their responses. Fleiss’s kappa103 is a simple measure of this inter-rater reliability. A kappa score of 0 indicates no more agreement than one would expect to occur simply by chance, and a score of 1 indicates complete agreement on all the data that were rated. Negative scores indicate agreement that is worse than chance. It is often said that a kappa score of 0.0–0.2 is ‘poor’, one of 0.21–0.4 is ‘fair’, 0.41–0.6 is ‘moderate’, 0.61–0.8 is ‘good’, and 0.81–1.0 is ‘very good’. 104 The raters assessed one case/medical record as a group. Next, they analysed three cases on their own and checked back afterwards. They then did a further 10 cases, which were assessed for inter-rater reliability.

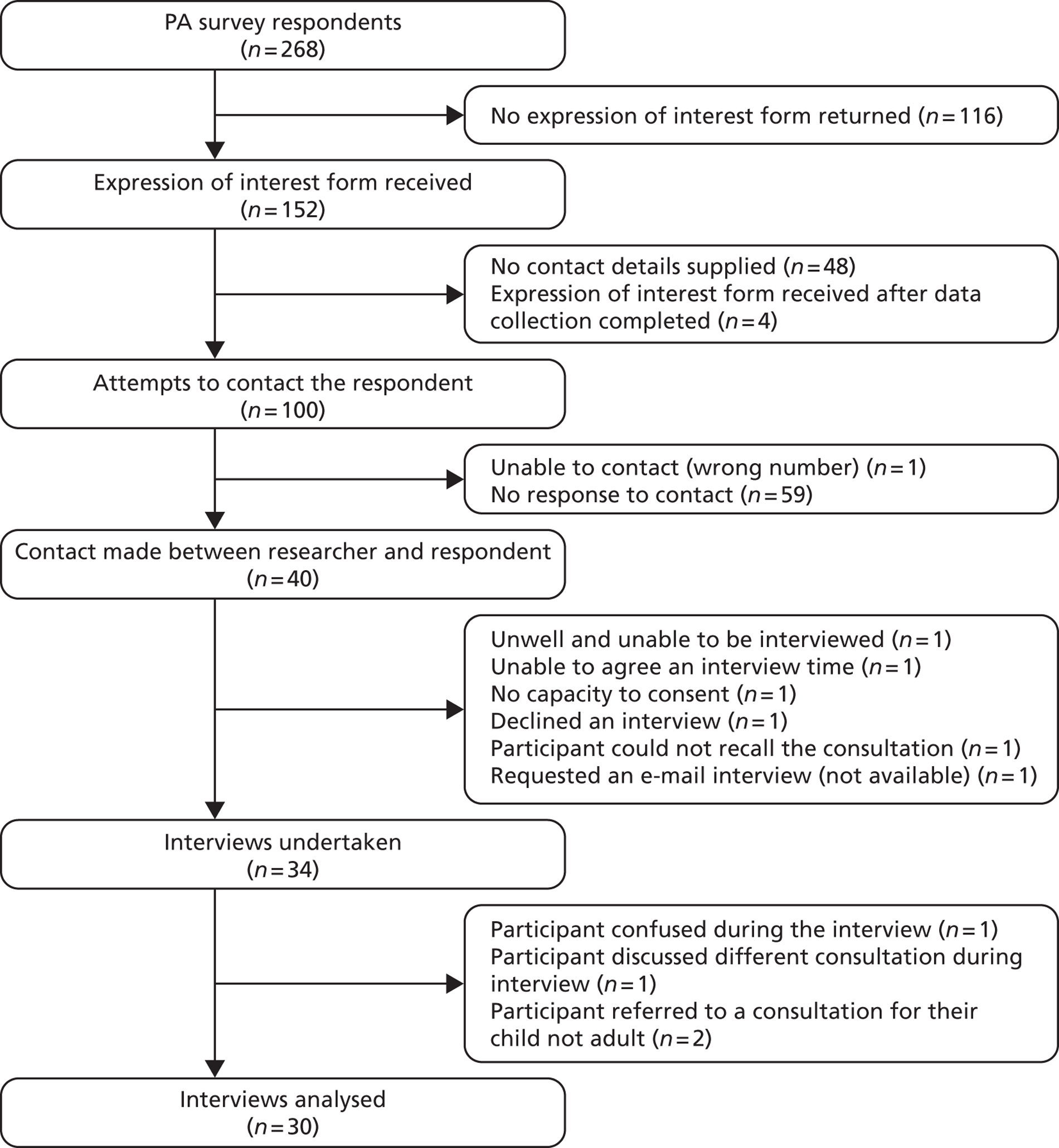

Patient interviews

Patients who had consulted PAs and received a survey were also invited to participate in telephone or face-to-face interviews. This was designed to address question (c): how do patients understand the role of PAs and what is the experience of patients when consulting PAs? An aide-memoire was developed to explore issues not captured by the patient survey such as patient choice, understanding of the role of the PA, perceptions of the consultation with regard to communication and perceived expertise. A researcher (WC) contacted those who responded to the invitation as soon after the index consultation as possible. With consent, the interviews were digitally recorded, transcribed and analysed thematically88 by three researchers (LJ, MH, WC) using the NVivo software programme (QSR International Pty Ltd, Doncaster, Australia) (LJ, MH).

Observation of physician assistants and general practitioners

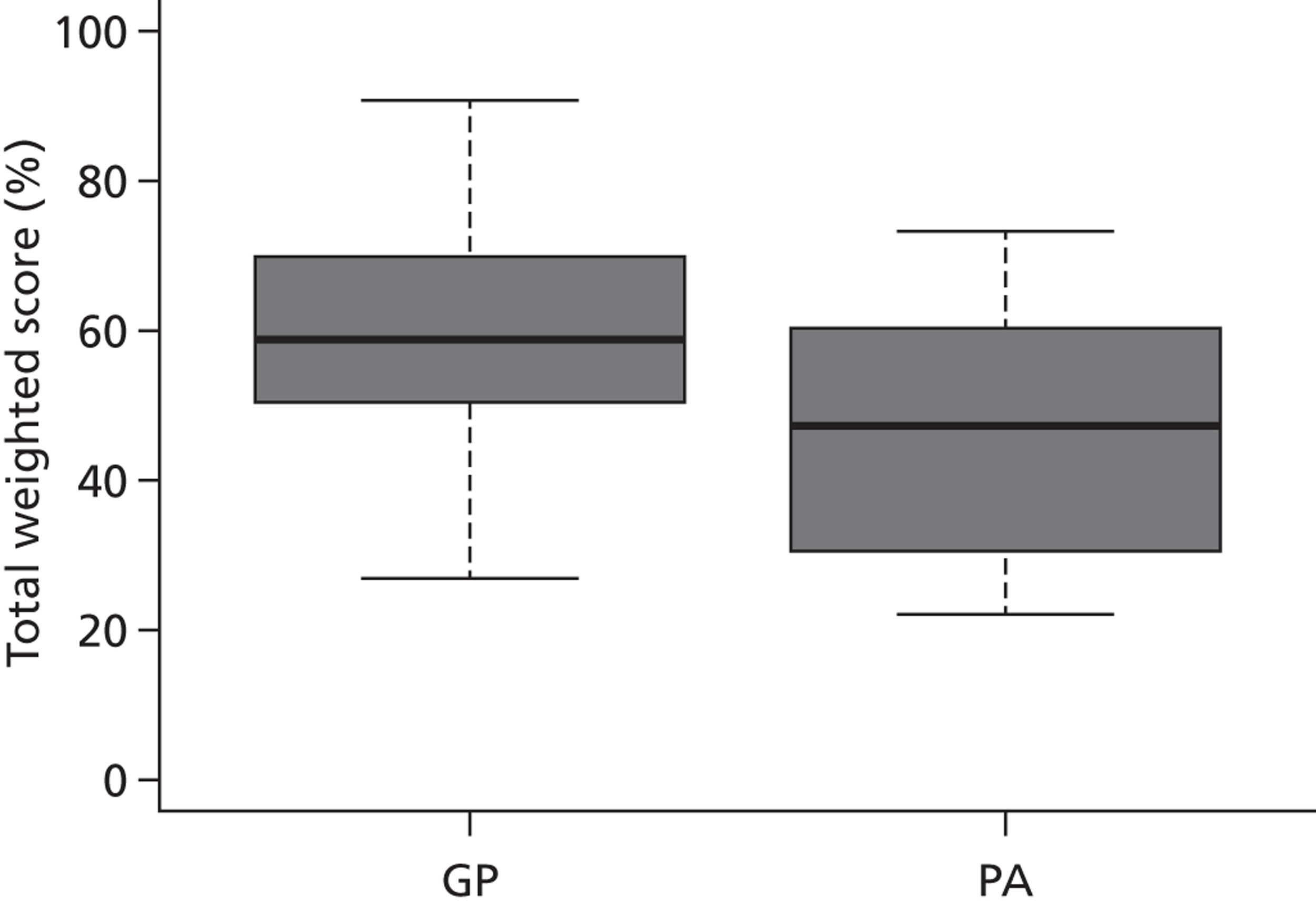

Patient consultations were video recorded, with consent of the practitioner and the patients, during one surgery per PA and GP. This element addressed questions (a), (b) and (e). We recorded GPs and PAs using two video channels, and assessed competence at consulting using the validated Leicester Assessment Package (LAP) rating scale. 105 Video recording is an established method of assessing the consultation106 and the use of two channels was a compromise between the multichannel recording we planned106 and what we could gain the NHS REC permission for.

Patients in the designated surgeries were provided with information and consent was sought in writing by a researcher in the waiting room before recording commenced. Recording was stopped at the end of each consultation. Patients were then asked whether they continued to give consent or would prefer that it was withdrawn and the recording deleted. Practitioners also reconsented to the inclusion of each recording or could ask for a recording to be withdrawn at the end of the surgery. The recordings were made using ALFA: a computer-mediated consultation observation technique developed to provide an analysable overview of the consultation. 107 Each consultation was assessed by two GPs independently using the LAP105 for assessing competence in general practice on dimensions of interviewing and history taking, patient management, problem solving and behaviour and relationship with patients.

The LAP for video consultation is a tool for measuring competence by direct observation. It was initially developed in the 1990s and demonstrated to have validity108–110 and reliability across levels of clinical competence. 107 Testing of reliability found a range of mean scores between 51.3% and 70.2% in one study, depending on levels of experience,110 and between 45% and 75% in another looking at the effect of interruption. 109 Although it has been criticised, no better package has been developed. 111,112 The LAP has also been used in a range of clinical contexts – assessment of cancer patients,112 the needs of caregivers113 and in the assessment of psychosexual problems. 114 This package has also been used in an international setting, where a 50% pass mark was included,115 for assessing practice nurses116 and medical students. 117

Grades were given by the four raters, using the seven main categories of the assessment package, and the results were then analysed. The seventh element of the package, the record, could not be rated as it could not be properly observed from the two-camera set-up used. Record keeping referred to how the health-care professional (HCP) interacted with the computer. It was not possible to view the detail of the individual record being collected by the HCP owing to the fact that only two channels of video were being recorded, and an additional channel is required for recording video directly from the HCP’s computer screen. Three of the seven categories – interview/history taking, patient management and problem solving – are given a double weighting, and count for 20% of overall marks (Table 4). When combined, this means that the LAP scale total is 100, allowing final results to be expressed as a mean score (out of 5 for each category) or be expressed as a total percentage score.

| LAP105 component | Weighting (%) |

|---|---|

| Interview/history taking | 20 |

| Physical examination | 10 |

| Patient management | 20 |

| Problem solving | 20 |

| Behaviour/relationship with patients | 10 |

| Anticipatory care | 10 |

| Record keeping | 10 |

A workshop was held to discuss the findings with the raters (unblinded) which was video recorded and transcribed.

Observation was also undertaken in a sample of practice clinical meetings in which PAs and GPs were both present to understand more broadly how the PAs interact with the GPs in clinical decision-making in the practice. Permission and invitations was sought from the practice manager, the GPs and the PA. Permission and consent to observe was sought at each meeting that the research team was invited to. Field notes were made of only the activity and interaction of the team members. Analysis of these notes was used to complement data from the staff interviews (see Semistructured interviews with practice staff) and consultation video observations.

Work activities of physician assistants and general practitioners

Work activity diaries, using the 2006–7 general practice workload survey,118 were offered to PAs to complete for 1 week in the summer and winter. This addressed question (a), above. Early discussions with GPs made it evident that these diaries were unlikely to be completed by practice professionals other than the PAs and the data were therefore sought through interviews (see Semi-structured interviews with practice staff) and administrative systems. Data were entered onto a SPSS spreadsheet and analysed descriptively.

Economic analysis

The economic analysis was conducted at two levels:

-

The resource implications and costs of different team configurations were explored using practice-level data on staffing. Skill mixes, and the relative contribution of different practitioners, were compared within and between practices that do and do not employ PAs, after consideration of case mix differences. Nationally validated scales119 were used to calculate total human resource costs and costs per patient.

-

The impact of PAs, compared with GPs, on consultation processes (e.g. prescribing, referral and investigations), consultation outcomes (e.g. reattending, consultation satisfaction) and length, at individual patient level, as analysed in the clinical record element were incorporated in a high-level analysis of costs and effectiveness.

Practice level

Data

Each of the 12 practices (six with and six without a PA) was asked in November 2012 to provide information about their staffing configurations – headcounts and whole-time equivalents (WTEs) of:

-

clinical personnel

-

– GPs (partners and salaried/other)

-

– mid-level professionals – PAs and NPs

-

– nursing and other staff engaged in direct patient care – practice nurses (PNs), HCAs, phlebotomists

-

-

support staff

-

– managers and professionals [e.g. for information technology (IT), finance]

-

– secretarial, reception, clerical.

-

The number of patients on the list of each practice and the proportions aged > 65 years and < 15 years were obtained from the Department of Health NHS Commissioning Board. 120 IMD 2010 for each practice was obtained from the NHS Information Centre. 121

Costs

Unit costs of clinical personnel were obtained from validated national sources. 119 These unit costs provide a value, per annum, that covers remuneration, on-costs, qualifications (where relevant), training, capital and other overheads associated with each role (see Appendix 8). PAs were costed as Band 7 nurses (secretary of UK Association of PAs, 2012, personal correspondence). The same costs were applied to GP partners and salaried GPs because evidence on this was contradictory. One study suggested that partners cost less than salaried GPs122 and others argued partners cost slightly more123 or the same. 124

The remuneration levels of management and other support staff were obtained by looking at several job vacancies within the NHS for each role (outside London rates) in January 2013, and inferring an average salary. The on-costs and overheads associated with each role were assumed to be equivalent to those of clinical NHS staff working in general practice with the same remuneration. For example, the salary of a NP was £38,800 and job advertisements for practice managers were around the same level, so the on-costs and overheads of the NP were used to estimate the costs of a practice manager.

Analysis

The numbers of WTE staff in each category, and numbers of patients per GP, were calculated and compared within and between practices with and without a PA. Reported vacancies were included in the calculations.

Staffing costs were calculated for each category in each practice on an annual basis by multiplying the WTE by the unit cost. Total staff costs for each practice per annum were obtained by summing across all staff categories. An average cost per patient per practice was calculated, and compared within and between practices with and without a PA.

The sample of practices included in the study in both the PA and no-PA groups were compared with national staff headcount data from the NHS Information Centre 2012125 with respect to the proportions of GPs who were salaried (vs. partners), and the numbers of administrative/clerical staff and nurses/direct patient care staff per GP.

Patient level

Analysis

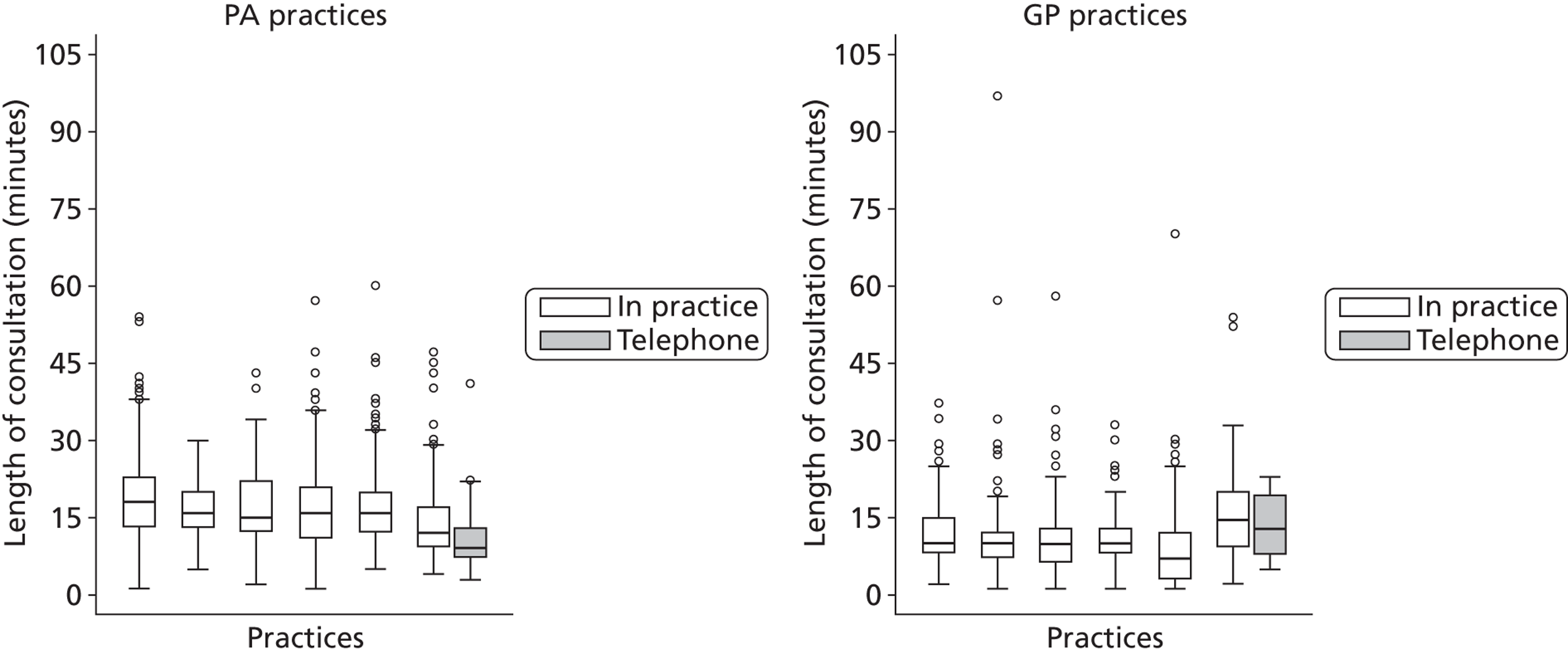

The patient-level analysis used findings from the analysis of consultation records and the patient survey to compare the costs and effectiveness of consultations by PAs and GPs. The mean length of consultations in minutes for PAs and GPs was calculated from available data recorded by the ‘time enter’ and ‘time leave’ functions on practice management systems. Nationally validated unit costs119 were applied to mean consultation lengths to explore differences between PA and GP practices in the cost of consultations. Other ways in which the use of PAs may affect practice costs were also considered, such as GP time spent in supervision and training, but could not be quantified as data were not available. The relative effectiveness of PAs and GPs was judged by rates of reconsultation (primary outcome), patient satisfaction, and rates of referring, prescribing, testing, fitness to work certification, procedures and advice giving (process outcomes). Adjusted values of variables were used, after controlling for covariates.

Ethics and research governance

Phase 2 of the study required a number of types of reviews and agreements. The research ethical review was undertaken by NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) South East Coast – Surrey who gave approval but required that child patients were not included in some elements (REC reference number: 10/H1109/28). Local NHS primary care research governance approvals were obtained using different local processes from five different bodies. The procedures for local agreement of the UKCRN NHS service support costs to research in general practice varied in each area. Agreements were obtained for each participating general practice.

The case study settings

Twelve practices participated in the study in the south-west, east and south-east of England. They were diverse in the sociodemographic features of their locale, the number of practice partners and the size of their registered patient population. These data are presented within ranges, to ensure anonymity for the practices, in Table 5.

| Practice study ID | Type of locationa | IMD | Practice partners (WTE) | Patient list size | Employing a PA |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Rural-50 | 11–15 | 1–3 | 5001–10,000 | Yes |

| 2 | Rural-50 | 6–10 | 4–6 | > 10,000 | No |

| 3 | Rural-80 | 6–10 | 4–6 | > 10,000 | No |

| 4 | Rural-50 | 11–15 | 4–6 | 5001–10,000 | No |

| 5 | Rural-50 | 16–20 | 1–3 | 5001–10,000 | Yes |

| 6 | Significant rural | 16–20 | 4–6 | > 10,000 | Yes |

| 7 | Significant rural | 11–15 | 4–6 | > 10,000 | No |

| 8 | Major urban | 31–35 | 1–3 | < 5000 | No |

| 9 | Major urban | 31–35 | 1–3 | 5001–10,000 | No |

| 10 | Major urban | 31–35 | 4–6 | < 5000 | Yes |

| 11 | Other urban | 11–15 | 1–3 | > 10,000 | Yes |

| 12 | Major urban | 46–50 | 1–3 | 5001–10,000 | Yes |

The report now turns to presenting the findings.

Chapter 3 Findings: evidence at the macro and meso levels

In this chapter we report on the findings from the first phase of the study: (a) the review of evidence, (b) the scoping survey74 of key informants at a national and regional level and (c) the survey of current work deployment of PAs in UK general practice.

The review of evidence

In this section we report on our rapid review76 of different types of documentary evidence. This includes a systematic review of empirical evidence, a review of commentaries and a review of workforce policies (see Chapter 2, The review of evidence for the method).

The systematic review of empirical evidence

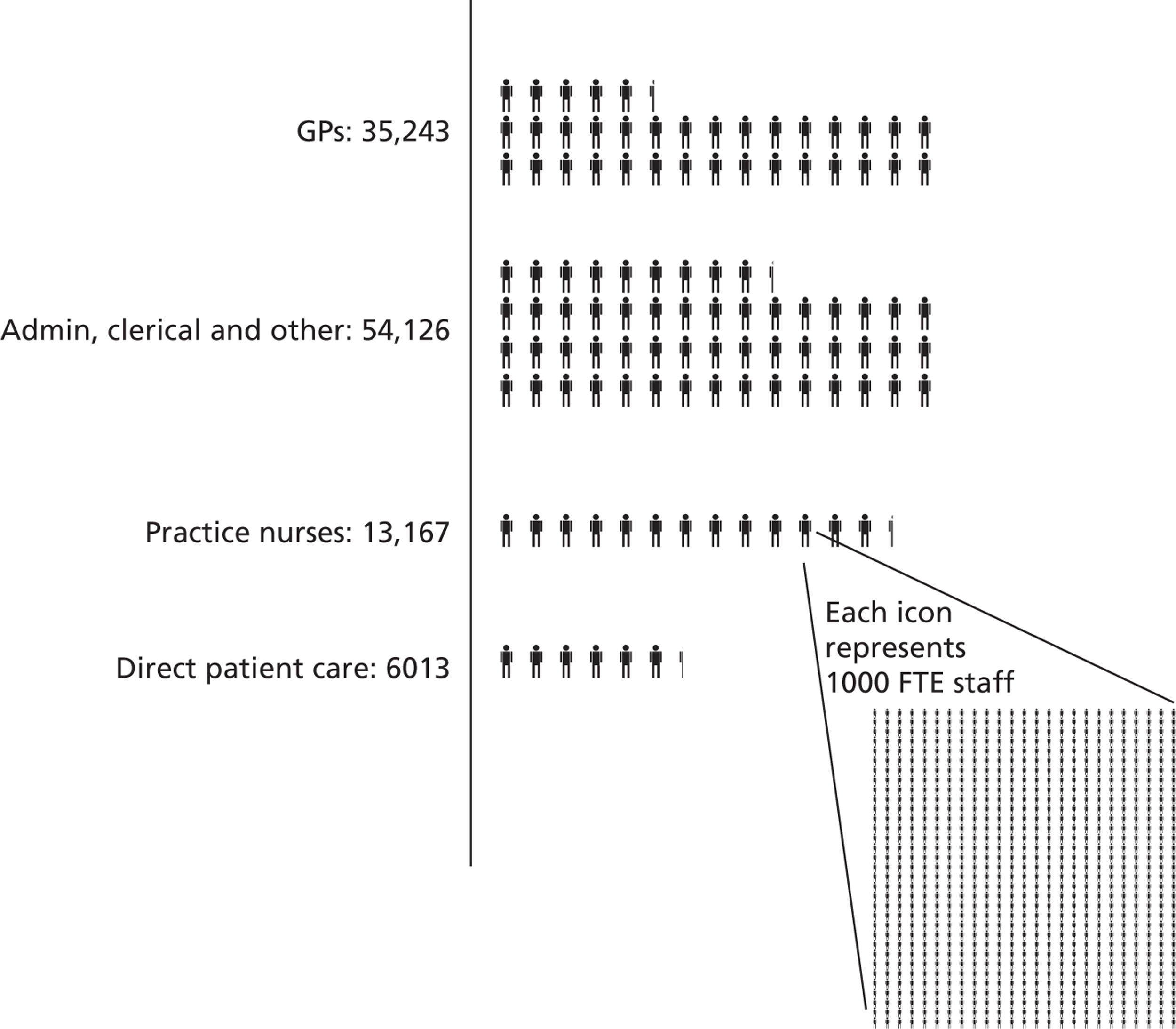

Of the 2167 publications identified and screened, 49 met the inclusion criteria49,62,127–161 as presented in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA)162 diagram in Figure 2.

Of these included studies, 46 were from the USA, and one each was from the UK,62 Australia,163 and the Netherlands. 164 The heterogeneity of the types of studies (Table 6) and their outcome measures mean that any meta-analysis was not possible and a narrative review is presented. The overall judgement of the quality of the research was that it was weak to moderate with few studies providing comparative data about other occupational groups.

| Method and data source | Number of studies |

|---|---|

| Quantitative surveys | 27 (five are secondary analyses) |

| Medical record review | 5 |

| Structured/quantitative observations of practice | 3 |

| Individual or focus group interviews | 4 (three qualitative analysis) |

| Administrative cost data analysis | 1 |

| Mixed methods | 9 |

Evidence regarding structural aspects of PAs in primary care was found in 24 studies62,127–149 ranging in date from the late 1970s to 2007. These studies focused predominantly on PAs as a human resource in primary care, investigating questions as to the numbers employed in primary care, the willingness of physicians and managers to employ PAs, perceptions of barriers to employment and issues in retention rates. In the USA, the numbers of PAs are seen to have grown over time. Although studies vary in their findings, several suggest that approximately half of those with PA qualifications work in primary care. 128–132,139 Support for the concept is mostly reported to be high among family doctors,62,142–148 with the potential for releasing the doctors’ time to allow them to focus on more complex patients (and thereby increase practice productivity)143–146 being one of the most prominent reasons, alongside perceptions of patient satisfaction. 146,147 Retention is not considered problematic. 140,141

Aspects of the process of care were reported in 24 studies49,62,134,137,140,144,147,151–161,164–168 ranging from the late 1970s to 2009. The majority of these studies describe the work activities of the PA and the patient groups who consult them. The greater part of the PA work is reported to be in consultations with patients with acute presentations. 140,150,151,153–155,158,160 Two studies suggest that doctors who are in the same primary care facility as PAs attend more patients with chronic conditions49,153 and one suggests that the doctors attend more patients with more serious problems. 140 The evidence indicates that, while PAs can be consulted by patients of all types, primary care facilities have systems which direct particular groups of patients to the PA. 156 The activity level of PAs’ work is reported in a number of studies but without conclusive evidence. Varying levels of PAs’ productivity in patient throughput have been reported compared with those of family physicians, suggesting that there is near equivalency62 and up to 60% physician whole-time equivalence. 164 PAs are consistently reported to require supervision from physicians, although this is low in actual patient care episodes154,165,166 apart from when PAs are not afforded prescribing rights. 62 Some evidence suggests that the employment of PAs provides greater capacity and efficiency in the provision of primary care. 62,149,153,164 Seven papers49,154,155,157,158,167,168 report on investigations in the USA about the issue of cost and the impact on practice finances. Only one provides data after the year 2000. 49 Again, no conclusive evidence is provided, with four suggesting that the employment is not financially advantageous for the practice49,155,156,168 and four suggesting otherwise. 38,154,158,167

Evidence about the outcomes of care was found in 14 papers. 140,141,144,154,155,160,163,168–173 Overall, PAs were reported as acceptable to patients,141,155,160,168–171 although this decreased in a rural setting in which patients were not offered the choice to see a doctor. 141 One study involving hypothetical scenarios suggested that patients were less willing to consult a PA in primary care if they had more complex conditions. 173 The evidence on technically appropriate care provided by PAs was weak and mainly from the 1970s. 140,144,154,155,168,169,174 While evidence was mainly positive regarding the appropriateness of care, some less favourable comparisons with other providers were also reported. 155,175 It is noteworthy that most of these studies were concerned with care for people with chronic conditions, for example diabetes; however, the evidence suggests that this patient group are in the minority in the PA workload.

Despite 40 years of studies, the evidence pertaining to PAs in family practice remains descriptive and weak, accentuated by poor reporting. While the review provides some evidence of the consequences of changing from physicians to PAs, it also makes it clear that research questions remain which would benefit from country-specific, good-quality investigation.

The findings of this systematic review are reported in full elsewhere. 176

Review of commentaries

This section reports on the findings of the review of commentaries and published opinions. This was one element of the study that contributed to investigating the question as to what supports or inhibits the development of PAs in primary care in the UK. The review was undertaken as reported earlier (see Chapter 2, The review of evidence). One hundred and seventeen published (print and electronic) commentaries and opinions were found that met the criteria for the review and these are listed in Appendix 9. They were found in sources with public, medical and nursing audiences (Table 7).

| Source type | Number |

|---|---|

| Journals and magazines targeted primarily to medical audiences (print and electronic) | 65 |

| Journals and magazines targeted primarily to nursing audiences (print and electronic) | 28 |

| Journals and magazines targeted to health-service managers | 9 |

| National newspapers | 7 |

| Other types of journals | 8 |

| Total | 117 |

The commentaries ranged in date from 1980 to 2012, with the greatest number published between 2004 and 2006 (Table 8). This was the period in which a Department of Health-funded pilot project was being conducted in England. 60

| Time period | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pre 2000 | 2000–3 | 2004–6 | 2007–12 | |

| Published commentaries (n) | 6 | 28 | 58 | 25 |

Journalists were the most frequent type of author (n = 28), followed by medical staff (n = 24), including those with clinical backgrounds and senior medical practitioners, and by academics (n = 20). A notable absence was a patient or public perspective. Only one member of the public177,178 pointed out that the public were not asked for their views and questioned the need for new roles in the NHS. Many of the commentaries were unclear as to the competencies of a PA. In some, the author confused a PA trained in the USA model with a similarly named role in the UK in which individuals are trained to undertake only technical tasks such as taking bloods under the direction of a doctor.

Fifty-one of the commentaries gave a positive view of PAs, 24 gave negative opinions and the remainder were neutral, often suggesting that more information was required to help inform opinion. The positive opinions were authored for the most part by senior medical practitioners and academics. The doctors were mainly from the acute setting and, either from direct experience or from consideration of their current staffing issues, could envisage a place for PAs in their teams. Some of the more recent opinions relate to the potential for PAs to provide solutions to contemporary health policy requirements such as those found in the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention programme174,179 and as support to GPs in the new commissioning structure. 180 The majority of the negative opinions were authored by GPs and nurses. None of these had direct experience of PAs. Issues raised included the transferability of a US model to a UK setting; confusion for the public when faced with multiple roles; concern that PAs were not cost-effective in general practice when compared with GPs; and a viewpoint that nurses and NPs fulfilled this role in the UK health-care workforce and offered greater value to patients than another professional trained in the medical model. Conflicting views were authored from junior doctors; some reported that PAs made their working lives better as they could delegate routine tasks, while others questioned whether or not they would be in competition for jobs for which PAs would be seen as preferable by managers because they were cheaper.

There was little citation of empirical publications to support opinions in the commentaries, with most referring to other opinion pieces. It is possible to detect a trend over time to more positive, or at least neutral, opinions as more direct experiences of PAs in the UK were reported.

We turn now to the findings from reviewing the workforce policy documents and associated material.

Review of workforce policies and developments

One hundred and thirty-three documents were identified. Those concerned with international developments regarding PAs in primary care informed the context for the study (reported in Chapter 1). Twenty documents were published after 2010 (the year of the election of the Coalition government) by central government departments or regional bodies responsible for NHS workforce and education planning. There was a lack of reference to PAs in all of the English policy documents and, similarly, in the House of Commons Health Committee Report into the workforce and education. 181 At a local level we did identify a few NHS trusts in England with plans to employ PAs (e.g. see University Hospitals of Leicester NHS Trust Annual Operational Plan 2011–12182). The only mention of PAs in Welsh documents was in reference to the health workforce in rural areas, but no commitment to develop or support the role of PAs in this context was made. 183 In contrast, there was more evidence of recognition for PAs in Scotland where they were cited in central government policy documents both as an example of workforce efficiency184 and as a potential addition to the remote and rural health-care workforce. 185 To this end, NHS Grampian, as the lead NHS organisation for workforce development, was working actively with the University of Aberdeen to establish and recruit to a PA education programme. 185 There was little reference to PAs in other types of workforce review documents which were intended to inform decision-making bodies.

Support for PAs was, however, evident in the medical colleges. The support of the Royal College of Anaesthetists for PAs (A) was noted earlier in Chapter 1, as was the support of the Royal College of General Practitioners and the Royal College of Physicians (RCP) in establishing competency and curriculum frameworks. More recently, the Royal College of General Practitioners referred to PAs in their review of general practice34 and also included PAs in their membership via their General Practice Foundation. The Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh also offered foundation membership to PAs. 186 PAs were also cited by the Director of the Medical Workforce Unit at the RCP187 as one of the solutions to the problems facing medical workforce planning, medical training and complying with the European Working Time Directive. 188

Against this backdrop of limited recognition in policy, we go on to report the findings from the scoping survey.

The scoping survey