Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1806/261. The contractual start date was in November 2009. The final report began editorial review in August 2013 and was accepted for publication in March 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Peckham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

It is estimated that some 15 million people in England have a long-term condition (LTC) and that this number will continue to increase. People with a LTC have, to varying degrees, a long-standing relationship with local health services. Concern about whether or not the NHS meets the needs of people with LTCs emerged in the 1990s. 1 The previous Labour government emphasised the need for better services developing a national strategy for people with LTCs, service developments, improved patient and public involvement (PPI) and supporting new service developments. 2,3 PPI was a key element of policy responses to developing services for people with LTCs, with a particular emphasis on PPI in commissioning. 4

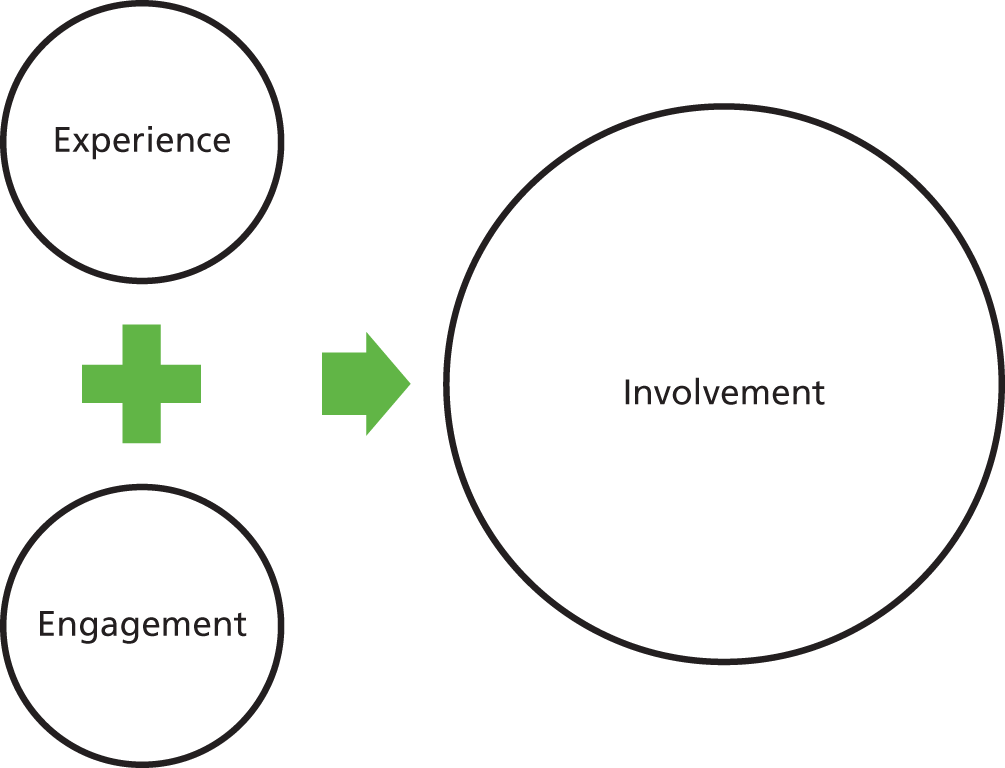

Importantly, however, the emphasis on PPI has been continued by the current government and the NHS Mandate5 places a responsibility on the NHS to improve the co-ordination of care for people with LTCs. In particular, NHS England and Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) are required to improve services and, in particular, develop commissioning strategies that address the needs of people with chronic LTCs, support strategies for self-help and engage them in decisions about the services they receive. 6 In Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS,7 the coalition government explicitly set a key task for the new NHS commissioning board (NHS England) to champion patient and carer involvement, and stated that the Secretary of State would hold it to account for progress. This represents a significant challenge, not only for NHS England but also for local CCGs. However, there has been an important change in language and terminology. Equity and Excellence refers to engagement as a key route for clinical commissioners to take rather than involvement, which was a term used previously in policy documents and guidance. While such a change may, in reality, be semantic, meanings are quite important; as we shall discuss later in this report, a problem exists of terms being used interchangeably while, at the same time, different stakeholders and individuals confer different meanings to the same terms. 8 Involvement and engagement were terms used interchangeably in the data. We have used the term PPI where it was clear that it related to PPI. Patient and public engagement and involvement (PPEI) has been used in this report as an overarching term to describe activities involving engagement and involvement.

In 2007, government proposals for people with LTCs suggested that user groups were to be key to increasing the devolution of decisions to practice-based commissioners (now abolished) and the development of ‘strategic commissioning’ between health and social care agencies. 9 Guidance for commissioning agencies, published in 2007, placed great importance on how commissioners could procure care that promoted the health and well-being of individuals in consultation with local people. 10 These were incorporated into the commissioning competencies, needs assessment frameworks and performance regimes across health and social care, and there was a clear emphasis on increasing the role of the third sector. 11–13 The NHS Next Stage Review14 highlighted changing public expectations related to ‘control, personalisation and connection’, and building partnerships with patients and LTC user groups.

While the policy direction for commissioning was clear, implementation was variable as primary care trusts (PCTs) coped with a complex blend of incentives and regulatory arrangements. Practice-based commissioning (PBC) was seen as integral to the success of commissioning strategies for LTCs but remained underdeveloped, had little significant effect on the redesign of services and did not sufficiently engage most general practitioners (GPs) in commissioning. 15,16 Good commissioning for people with LTCs requires not only developing a set of skills for commissioning responsive and appropriate patient pathways that provide relevant choices for service users, but also developing approaches to sustaining user engagement. Research on engaging users in the NHS and on user involvement in change management in health services has demonstrated a willingness and commitment to engagement, but few, if any, concrete examples of effective influence by users or evidence of change. 17,18

While the importance of PPI in commissioning has been recognised since the initial development of NHS purchasing in the 1990s, there has not been any significant evidence that such engagement has influenced commissioning decisions. 8,17–19 In 2007, a Picker Institute survey found that, while PCTs had a number of mechanisms and defined management responsibilities for PPI, ‘. . . there is a disconnect between these activities and the relatively low expectation that patient, public and community groups will have significant influence on commissioning decisions’ (p. 15). 18 Key barriers identified were difficulties in reaching marginalised, isolated or deprived groups, a lack of understanding among the public of ‘commissioning’ and a lack of reliable data about patients’ experiences. However, when respondents to the Picker survey were asked what approaches PCTs were considering for future engagement, there was a continued emphasis on methods such as formal consultations, patient panels, citizens’ juries and surveys.

It was in this context that our original proposal to the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) was developed. The research brief highlighted a number of areas for research relating to the organisation and processes of commissioning, with particular reference made to commissioning for people with LTCs. Our project responded to these general issues and explicitly focused on the question in the brief related to PCTs and their PBCs to ensure that ‘voice’ and community engagement, as set out in both Our Health, Our Care, Our Say White Paper and World Class Commissioning, are achieved.

Aims and objectives

The projects initial aim was, therefore, to examine how commissioners enable voice and engagement of people with LTCs and identify what impact this has on the commissioning process and pattern of services. A key outcome of the research will be guidance on the skills and expertise needed by different commissioners, what actions are most likely to lead to responsive services and the most effective mechanisms and processes for active and engaged commissioning for people with LTCs. Our specific objectives were to:

-

critically analyse the relationship between the public/patient voice and the impact on the commissioning process

-

determine how changes in the commissioning process reshape local services

-

explore whether or not any such changes in services impact on the patient experience

-

identify if and how commissioners enable the voice and engagement of people with LTCs

-

identify how patient groups/patient representatives get their voice heard and what mechanisms and processes patients and the public use to make their voice heard.

While the specific aim of the research did not change, the specific focus on methods had to be adapted to undertaking the research within a dynamic and rapidly changing context. However, this did provide the opportunity to investigate how PPI developed at this time of transition and what specific processes and structures for PPI were being developed within the new emerging commissioning architecture of the English NHS. As such, the aims and objectives remained the same but we have adapted our research protocol to address this changing context (see Chapter 3).

The study

Over the last 10–15 years, there has been an increasing recognition that the NHS needs to improve the support and service that it provides to people with LTCs. The current context for this is within a framework where commissioners are expected to develop stronger roles in shaping and planning local services that are responsive to local needs. In relation to LTCs, policies of choice and PPI are key to how this will be achieved. The key objectives of this study were to examine processes – how people were involved in local commissioning decisions – and impact – what was the result of that involvement.

However, the study was undertaken during a period of extensive change within the English NHS. In particular, the abolition of PCTs and development of CCGs created an ever-changing local context for our case study research, but this was only part of a much wider and far-reaching reorganisation of the English NHS introduced by the coalition government and enshrined in the Health and Social Care Act 2012 (discussed further in Chapter 2). 20 This had a significant impact on the conduct of the research in terms of both the activities we initially intended undertaking and conducting the case study research which was designed to incorporate interviews with key informants on a regular basis.

In 2009, when the project commenced, PCTs were the main commissioning organisations within the NHS, with practice-based commissioners having been developed in some areas. The original study design was focused on case studies of PCTs and our case studies were selected to reflect differences between PCTs (rural, urban, strong PBC presence, etc.). At this time it was clear that increasing emphasis was being placed on the role of PBCs and, as a result of reduced management cost funding and stronger PBCs, some PCTs were already merging into larger commissioning organisations. 21 With the election of the new coalition government in 2010 and publication of Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS,7 the pace of change increased, with proposals for a major restructuring of the English NHS. In particular, commissioning responsibilities, which had predominantly been invested in PCTs, were now redistributed across new GP-led commissioning groups, NHS England and local authorities (see Appendix 11). The reforms led to further PCT mergers into clusters and the development of new GP commissioning groups, with a formal Pathfinder CCG programme launched at the end of 2010. 22 By April 2012, all areas of the country had emerging CCGs and PCT clusters were beginning to reform into commissioning support organisations. During 2012–13, these groups then went through an authorisation process to become statutorily responsible for NHS commissioning from April 2013.

Patient and public involvement has been a key theme in health policy in the UK since the introduction of the internal market by the Conservative government in the early 1990s and continues to be prominent in the current coalition government policy. 7 The changes introduced by the Health and Social Care Bill also involved further reorganisation of PPI structures. The government has dismantled much of the PPI infrastructure of the previous Labour government, replacing it with new developments at the primary care level and in the role of local authorities. The only aspect of previous PPI structures that has been retained is the governance of NHS foundation trusts with the emphasis on membership from staff, patients and the public. CCGs, which will be led by GPs, will be commissioning health care to meet the needs of their local population. They ‘will need to engage patients and the public on an ongoing basis as they undertake their commissioning responsibilities, and will have a duty of public and patient involvement’ (p. 7). 7 Key changes to the role of local authorities in health care aim to align PPI with the ‘democratic oversight’ role of councils.

We planned to undertake a scoping review of PCT PPI activities across England. We commenced this work to plan in late 2009, drawing data from websites and then selecting a sample of PCTs to follow up in more detail where we identified particular good practice (see Chapter 2 for details). However, with the abolition of PCTs, this information has become redundant, and it was decided, and agreed with NIHR, that we would not produce a scoping review report. We also faced problems in case study site recruitment and access, given the extent of the reorganisation. During the research, many of the NHS staff we initially interviewed left their jobs, and new staff, in new organisations, took over responsibilities. This created a number of difficulties tracking developments in case study areas. While the research was being undertaken, we had the opportunity to collaborate with research being undertaken by the Policy Research Unit in Commissioning and the Healthcare System (PRUComm). This involved surveys of all CCGs (in December 2011 and May 2012) and case study research in eight CCGs. We negotiated and discussed questions on PPI in order to enrich our data collection. We discussed this and agreed the change with NIHR.

However, the delays in case study recruitment meant that we needed further time for data collection. The team also felt that it would be most useful if we could have sufficient time to explore changes being introduced by the new CCGs. We approached NIHR to ask for an extension to July 2013. This would allow us to undertake an analysis of CCG approaches to PPI in authorisation plans and draw on the PRUComm data. This was agreed and the end date for the research was changed from November 2012 to July 2013.

As an integral element of our study, we responded to a call to apply for funding for a management fellow to work with the project team. We were successful in being awarded funding for a NHS manager from one of our case study sites to work part-time with the research team and who undertook further research training.

Thus, the study draws on data from a literature of commissioning and PPI as well as PPI related to LTCs, case study data collected as part of this research, survey and case study findings from the PRUComm research (see Chapters 4–7) and an analysis of CCG authorisation plans.

Structure of this report

This report presents the key findings of the research and sets these within the context of the recent changes to the organisation and structure of the English NHS and key conceptual frameworks relating to PPEI. Chapter 2 discusses the background to the project and a summary of the key NHS changes that occurred during the period within which the research was undertaken. In Chapter 3, we set out the methods used, and challenges faced, in the process of undertaking the research. Chapters 4–6 present the findings from our three case studies. Chapter 7 discusses the organisational changes in the NHS in more detail, focusing on the development of CCGs and the extent to which PPI has been prioritised and embedded in practice. This chapter draws on data from surveys and case study research undertaken by PRUComm (directed by Peckham) and undertaken at the same time as the research in this study, as well as an analysis of authorisation plans of a sample of CCGs. Chapter 8 discusses our findings. In Chapter 9, we summarise the main conclusions of our research in relation to the key research objectives. In order to provide some summative assessment of the impact of PPEI, we also include here the responses from an expert reference group who independently reviewed three selected exemplars drawn from our case study research. Drawing on the findings of the research, we then identify key guidance points for national and local organisations and make recommendations for future research.

Chapter 2 Background

Introduction

The treatment and management of LTCs is one of the greatest challenges facing health systems around the world today and is recognised as being of particular importance within the UK NHS. 23 The strategies used by health professionals to engage, support and empower people with LTCs have an important role in improving health outcomes. 24–26 However, there is continued recognition that the NHS has not provided sufficient support for people with LTCs or managed their care to their, or the NHS’s, benefit.

It is suggested that there are around 15 million (almost one in three) people who have one or more LTCs in England and this accounts for in excess of 70% of the total health and social care budget. 27 This relates to around 50% of all GP visits, 64% of all hospital outpatient appointments and 70% of all inpatient bed-days. 28 People with LTCs experience poor co-ordination of care, leading to adverse events and increased hospitalisations. International comparisons suggest that the UK lags behind other countries in supporting people with LTCs. 29,30 While it is difficult to identify exact numbers of people with specific conditions given the rise in multimorbidity, the numbers of people with diabetes, neurological problems or rheumatoid arthritis (RA) do differ, with the first of these three conditions comprising the largest number of patients. It is currently estimated that 2.5 million people in England are living with diabetes, and a further 850,000 people in the UK have diabetes but either are unaware or have no confirmed diagnosis. 31 The NHS spends approximately £10B per annum on treating diabetes and 80% of NHS spending on diabetes goes into managing avoidable complications. People with diabetes account for around 19% of hospital inpatients at any one time, and have a 3-day-longer stay on average than people without diabetes. Most type 2 diabetes costs are due to hospitalisation. 31

Taken together, neurological conditions are common. For example, 8 million people in the UK suffer from migraine. 32 Altogether, approximately 10 million people across the UK have a neurological condition. 33 These account for 20% of acute hospital admissions and are the third most common reason for seeing a GP. Around 17 people in a population of 100,00034 are likely to develop Parkinson’s disease and two people in a population of 100,000 experience a traumatic spinal injury every year. 32 An estimated 350,000 people across the UK need help with daily living because of a neurological condition and 850,000 people care for someone with a neurological condition. 33

Rheumatoid arthritis affects some 580,000 people in England. There are around 12,000 children under the age of 16 with the juvenile form of the disease. The total cost to the UK (including indirect costs and work-related disability) are estimated to be between £3.8B and £4.75B per year. 35 Uncontrolled RA increases mortality through an increased risk of cardiovascular disease such as heart attacks and strokes; thus, early detection and treatment and good management of the disease are important. 35

Government policy on long-term conditions

Since the NHS Plan, the government has been committed to improving support for people with LTCs and set public service agreements in 2005 to reduce emergency bed use and introduce case management for high intensive service users. 1,36–38

The Department of Health policy Your Health, Your Way39 identified five key outcomes for people with LTCs: an improved quality of life, health and well-being and more independence; better supported self-care; more choice and control, with services built around their needs; influence over the design of services that would be more integrated, proactive and responsive; and high-quality, efficient and sustainable services.

This builds on the quality requirements for people with LTCs set out in the National Service Framework for Long-Term Conditions38 that provided a framework for commissioning and service delivery.

A key policy theme has been enabling ‘person-centred’ or ‘personalised’ care. 2 Commissioning is central to this process and to the achievement of policy on LTCs. 9 Yet commissioning for health, and in particular, commissioning in the NHS has received much criticism. 40–42 Research highlights the need for substantial management investment and a range of needs assessment, clinical, contracting and relationship management skills. 40,41,43,44

Commissioning for long-term conditions

When the study commenced, it was already clear that additional investment in expanding commissioning management was unlikely, given concerns about whether or not the additional cost would produce sufficient gains in productivity. 42 In fact, in 2009, it was already identified that savings would need to be made in management costs in the NHS as part of a package of measures to address future NHS funding shortfalls. 45,46 With the introduction of changes outlined in Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS7 and enacted in the Health and Social Care Act 2012, the challenges facing commissioners have intensified. In particular, reductions in the overall management allowance mean that there are fewer resources available to support commissioning activities, including PPI. In addition, the proposals, which involved the largest restructuring of the NHS since its inception, created a more complex commissioning structure than that which existed prior to 2010, with responsibilities now spread between a number of local and national agencies (see Appendix 13).

Equity and Excellence set out the rationale behind the proposed changes to commissioning, arguing that the closer involvement of GPs in the commissioning of care would ensure more effective dialogue between primary and secondary care; decision-making ‘closer to the patient’; and increased efficiency. 7 The White Paper argued explicitly that ‘we will learn from the past’ (p. 28)7 and claimed that the government had built upon lessons learned from previous clinically-led commissioning initiatives, including GP Fundholding and Total Purchasing Pilots from the 1990s. 47,48 The reforms were set out in the Health and Social Care Bill which became the 2012 Act following a controversial passage through parliament with a substantial number of amendments. 22 With the Health and Social Care Act 2012 passed by parliament, additional guidance was published by the Department of Health (and subsequently by the shadow NHS Commissioning Board) (Box 1). A timetable was set out for CCGs to apply for full ‘authorisation’ as statutory bodies from July 2012, with the first CCGs taking full responsibility for commissioning from April 2013.

-

Developing Clinical Commissioning Groups: Towards Authorisation. 49

-

The Functions of GP Commissioning Consortia. A Working Document. 50

-

Commissioning Support: Clinical Commissioning Group Running Costs Tool. A ‘Ready Reckoner’. 51

-

Towards Establishment: Creating Responsive and Accountable Clinical Commissioning Groups. 52

-

Developing Commissioning Support: Towards Service Excellence. 53

-

Clinical Commissioning Group Governing Body: Roles Outlines, Attributes and Skills, in April 2012. 54

Two hundred and eleven CCGs worked towards becoming authorised by the National Commissioning Body, NHS England, by the end of March 2013 (see Chapter 7 for a discussion of the authorisation process). Since April 2013, they have been responsible for contracts with providers of health care in their communities amounting to around £65B per annum.

In relation to commissioning services for people with LTCs, commissioners need to demonstrate how they can achieve maximum benefit within existing resource levels by focusing activities on those that bring most patient benefit. This approach is central to the Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) agenda for LTCs. 55 One approach currently under discussion is greater integration of health services along the lines of the USA’s integrated purchaser/provider models or making greater use of soft methods of persuasion. 1,42 The previous government placed an emphasis on developing choices by engaging local users and organisations for people with LTCs, rather than individual patients, to ensure an appropriate range of services that meet people’s needs. The 2007 Department of Health consultation on choices for people with LTCs focused on shifting away from a ‘one size fits all’ model to one maintaining independence and providing people with more choice and control over their care with benefits for patients and the NHS. 4 With regard to people with LTCs, the emphasis was on developing clinical pathways and care management programmes. 1,42 However, evidence of the effectiveness of such approaches in many chronic conditions is limited,56–59 and there is no evidence of significant service user input influencing the development of such pathways. 60,61 The development of pathways may also create tensions with policies on choice and it would seem critical that to develop responsive pathways that provide meaningful choices will require significant service user input as well as collaboration with health-care commissioners and providers. 4,62,63 Current policies focus more on individual management through approaches such as the Year of Care model with flexible commissioning and self-management programmes. 4,31

The current emphasis on developing integrated pathways for managing LTCs reflects the need to address issues of comorbidity and fragmented service models. Recent policy, together with the structural reforms introduced in the Health and Social Care Act 2012, have also highlighted the need for more generic, integrated pathways for LTCs, as these might prove more successful in generating cost savings. 64 However, the evidence is not conclusive and it could take a number of years to show any meaningful impact. 65,66 This changing context in which commissioners have to operate is a complex and turbulent environment presenting significant challenges for health-care commissioners. 55 Prior to April 2013, the NHS LTCs QIPP work stream managed by local PCTs promoted a holistic model for management of LTCs – and was focused not just on specific diseases but also on providing support for patients to co-manage multiple conditions. This programme of work has now been taken over by NHS England and it is not clear how they will be taking forward this work or what direction they will be headed, as they were still in the process of developing their work programme during our study. Outcomes from the QIPP work stream included risk stratification, integrated teams and co-managed care for people with LTCs. It also introduced the Year of Care model as an alternative to Payment by Results.

Despite the large consultation undertaken in 2012 to develop a cross government LTC strategy, the new government has placed the responsibility for developing a strategy around LTCs5 with the new national commissioning board, NHS England. The strategy67 will seek to see a change in the quality of life for people with LTCs (NHS outcome framework domain 2). However, the final output from this has not been published and is now part of the work of NHS England – who may, or may not, develop their own strategy for LTCs. This is interesting as there was a long consultation in 2012 with a number of user groups and organisations but at the present time it is not clear what is being done with this information. 64 Elements of the LTC model (risk stratification/integrated pathway/maximising numbers with co-managed care) are being used to develop Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) for general practice to place an emphasis on ‘patient-centred care’. However, there are criticisms of QOF regarding both patient-centred care and how it relates to quality of care. 68,69

Patient and public involvement: variety of organisations

While there have been numerous changes to structures and processes for PPI in the NHS, there have been no formal mechanisms for PPI established since the 1970s. 8,62,69,70 Recent changes to the English NHS have reformed many previous structures but continue to emphasise the importance of engagement and involvement. 22 At a local level, there are a wide variety of patient and user organisations. 71 Patients, users and carers with a collective illness identity have long organised themselves, often independently of government, but these organisations are diverse and hence difficult to categorise and analyse. 72 Research suggests that local organisations are often patchy in coverage,71,72 although at a national level, groups such as Carers UK, National Voices [formerly the Long Term Medical Conditions Alliance (LMCA)] and the Patients Forum [replaced by the Local Involvement Networks (LINks) and recently replaced by local Healthwatch] are closely involved in the policy process and some support local group engagement with the NHS and social services. 72,73 Specific case studies of HIV (human immunodeficiency virus)/AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) groups, maternity, physical disability and mental health users suggest that local groups do get engaged in policy and service issues and that patient/advocacy and voluntary organisations are important in promoting PPI with the NHS. 74–77 Such investigations have, however, paid relatively little attention to the outcomes of PPI. 17

Recent policy on patient and public involvement

Recent policy (since 2001) identifies that the NHS needs to be responsible to patients and service users and more accountable to citizens who fund it. 20 This rhetoric is further played out within the recent NHS reforms of the coalition. The Health White Paper7 detailed intentions around shared decision-making – ‘nothing about me without me’ – through choice and increased voice of local people, service users and patients. Responses from consultations suggested that there needed to be a stronger voice of the public78 and recent NHS reform planning echoes this ambition. 79

The 2012 Health and Social Care Act made clear the duties of the new organisations established under the Act, such as the NHS Commissioning Board and CCGs, around implementing proposals to give patients and the public more say and greater involvement in care and treatment decisions within the new health-care system, holding the board to account for delivery through its NHS mandate. 5 However, much of the recent policy vocabulary on involvement or engagement is patient centred and individual, with a focus on empowerment in decisions about own care rather than about patients and the public having a strategic role, either collectively or individually, in helping to shape health care. 49 Examples of this approach can be seen in the emphases on embedding care planning, shared decision-making and support for people to manage their own conditions – including a pledge to care planning written into the NHS constitution, roll-out of personal health budgets and support for telehealth/telecare, as well as producing a compendium of information to support commissioning LTC care, aimed at commissioners. It appears to be more about patient engagement (in own care) rather than public involvement in commissioning health care.

Patient and public involvement/engagement in commissioning health care

The recent health reforms present a new set of issues and challenges for PPI in commissioning health care. The majority of health-care services in England will now be commissioned by CCGs led by GPs. This is not the first approach to primary care-led commissioning in the UK, with GP fundholding introduced in 1991 and followed by a number of variants of engaging GPs in health-care commissioning. 80 Research suggests that in these previous approaches to primary care-led commissioning there has been little involvement of patients and the public. 80

Patient and public: there is little evidence to suggest that practices engaged patients and public in their commissioning activities in a meaningful way. Across the different schemes since 1990, GPs believed that, by definition, they had an excellent understanding of patient needs and could act as reliable proxies for their patients; as a result, they did not think of formal PPI as a priority. 81–83 Where efforts to consult patients were made, this was often seen as a box-ticking exercise. 82 In primary care groups, where approaches to involve patients and public had been initiated, this was more at the informing rather than at the participatory level. It has been suggested that PPI is relatively underdeveloped in primary care and GPs need to be educated about its value. 84

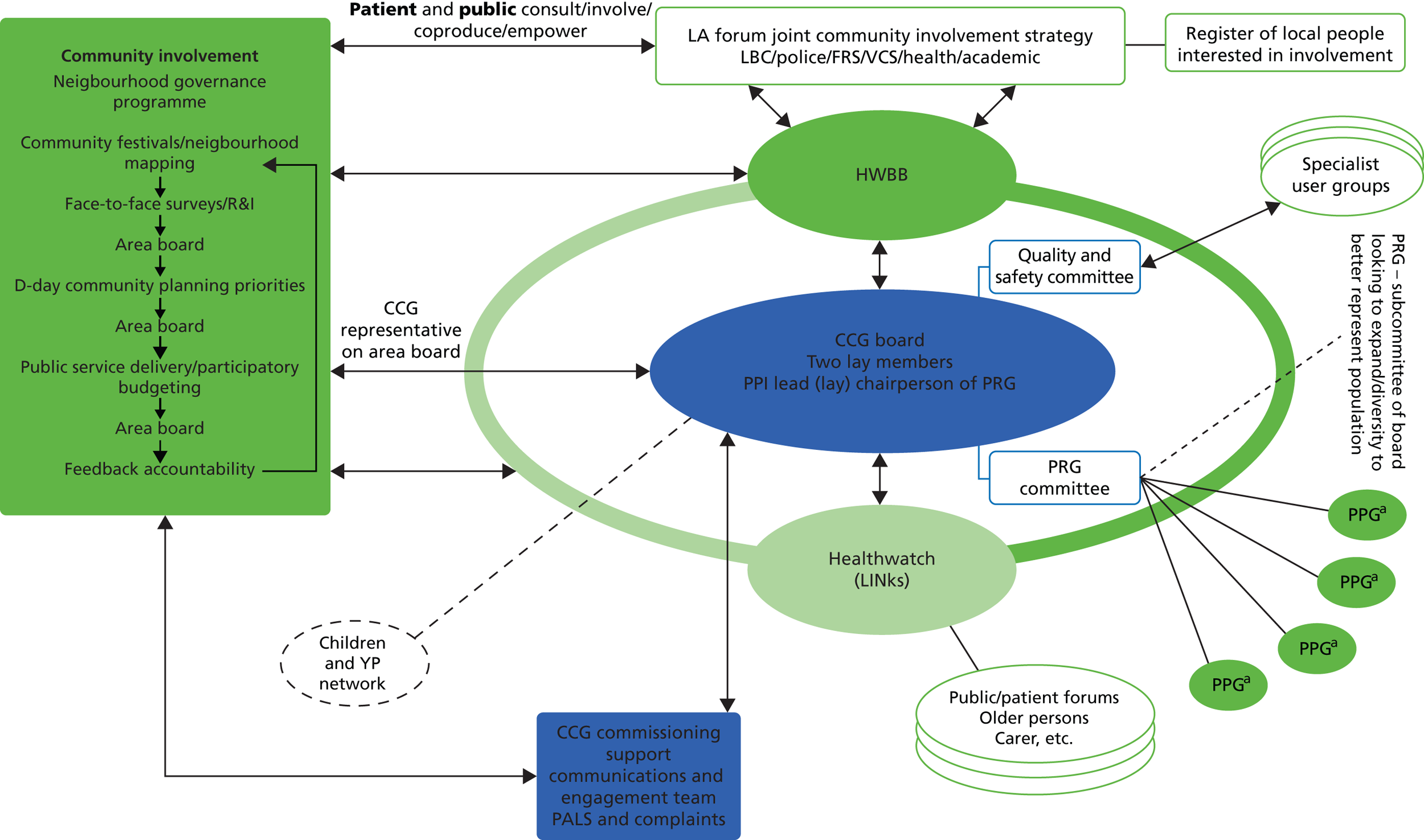

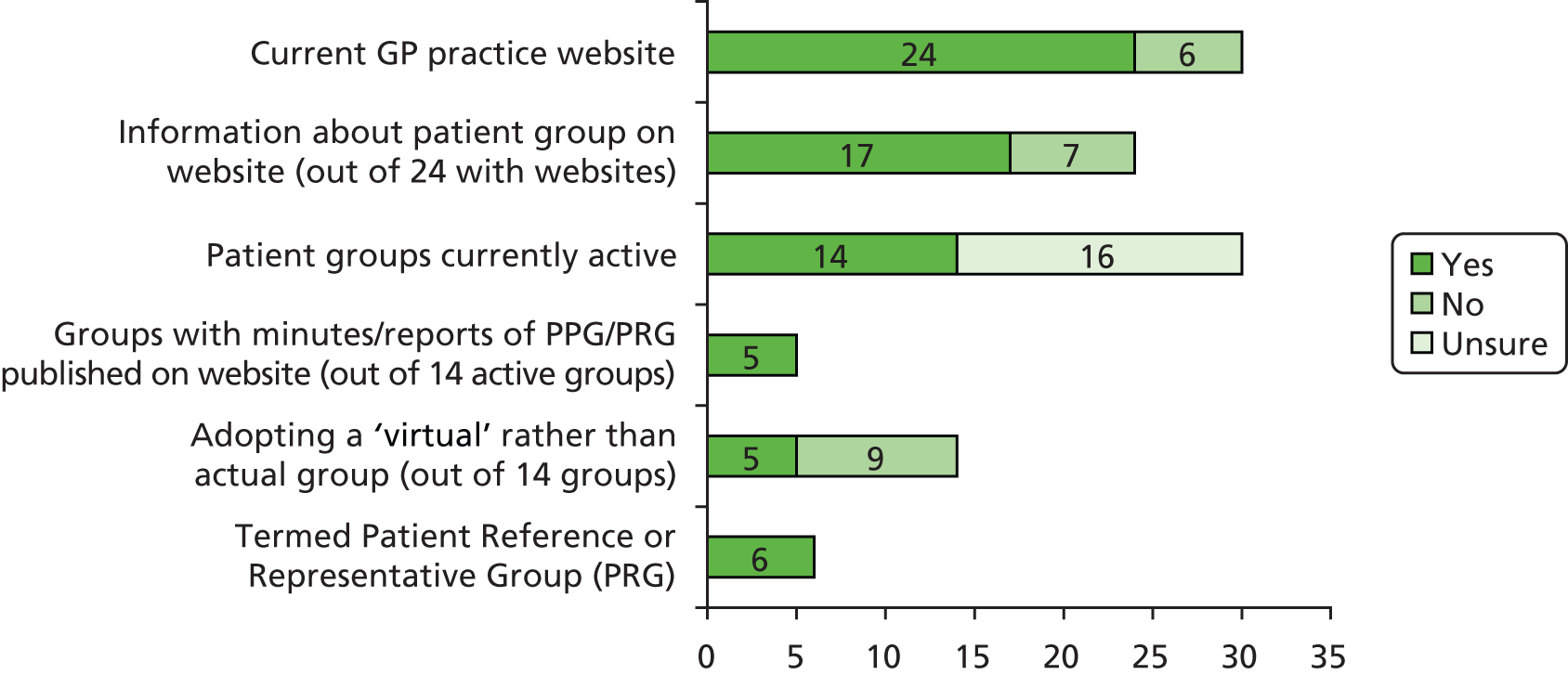

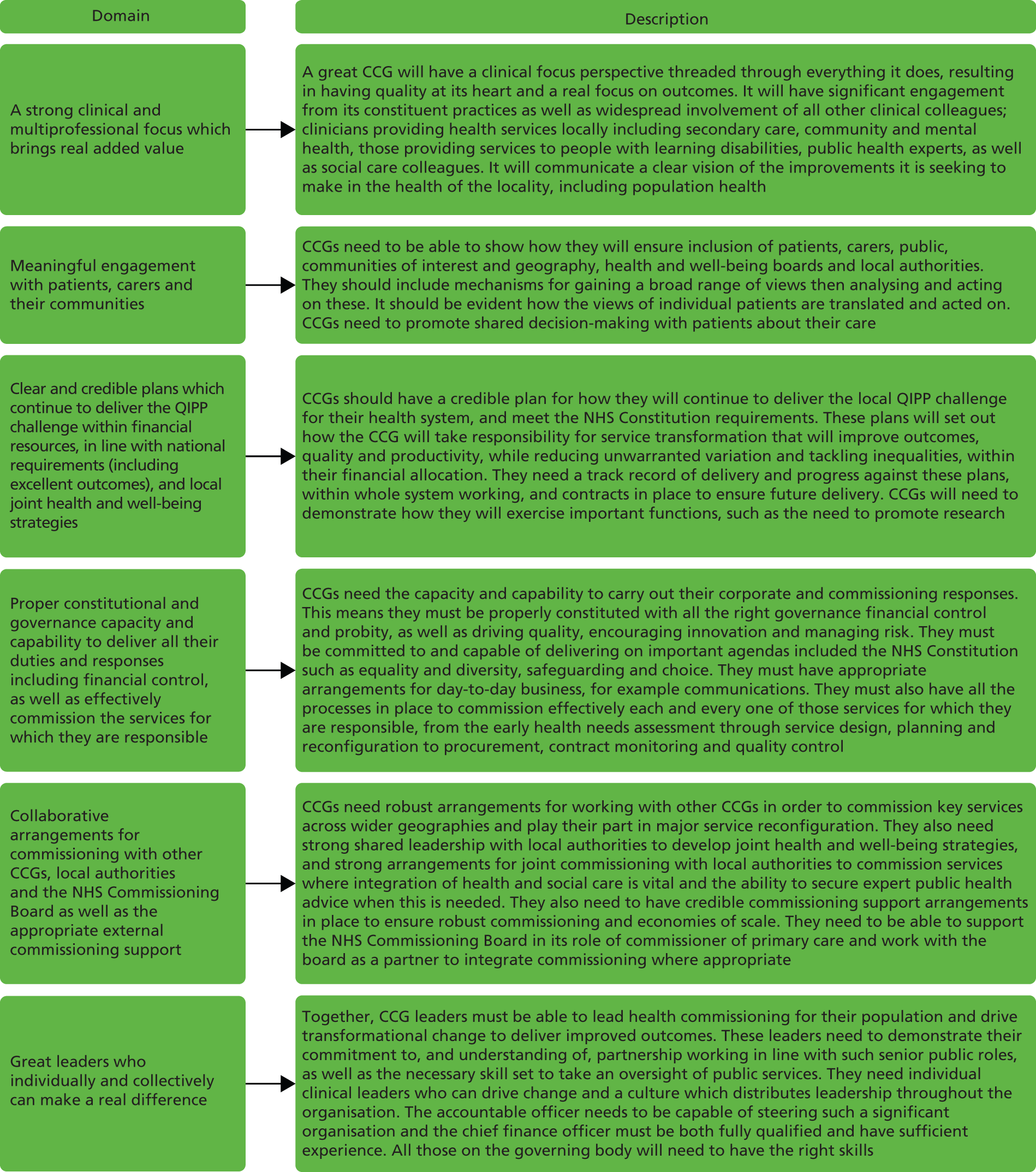

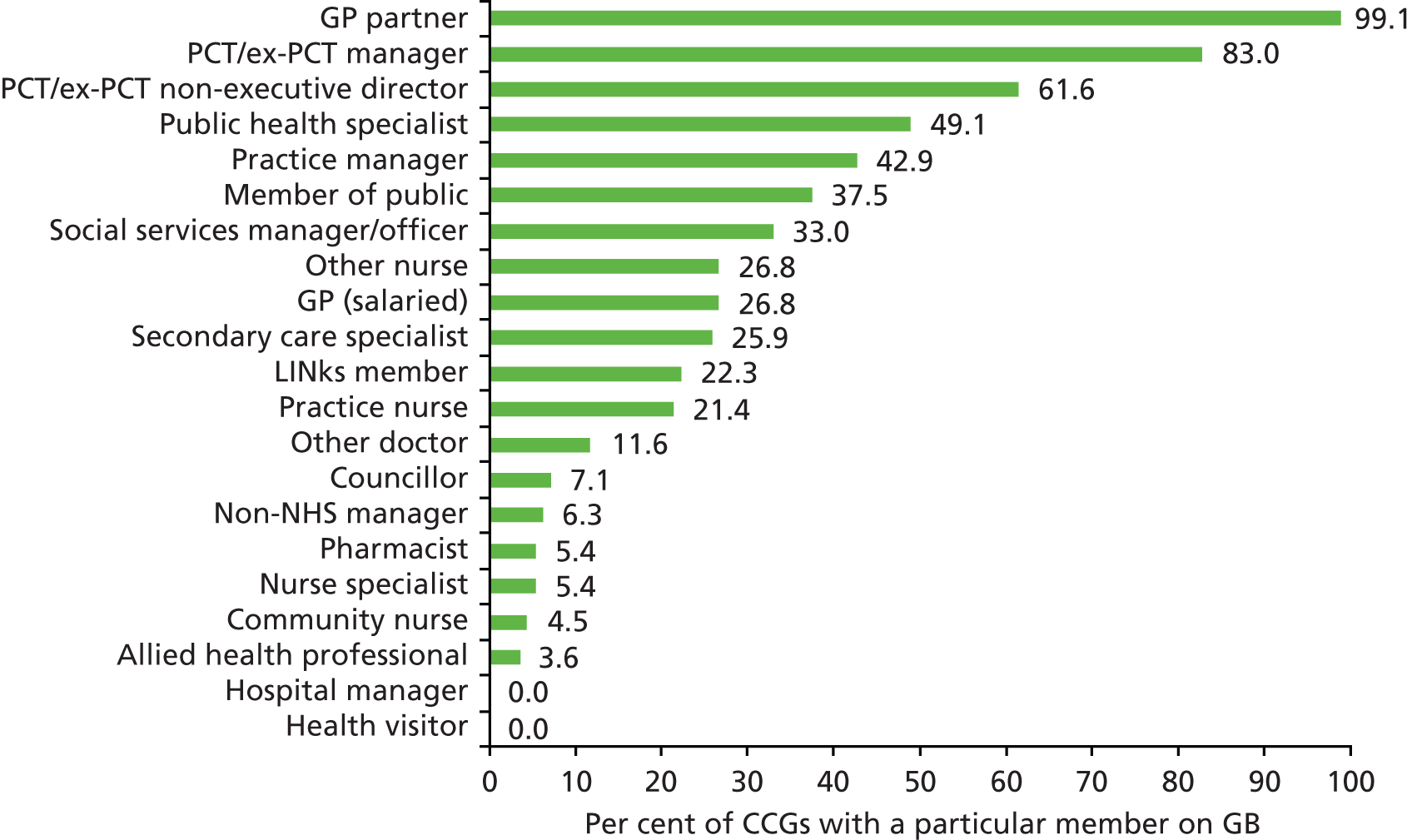

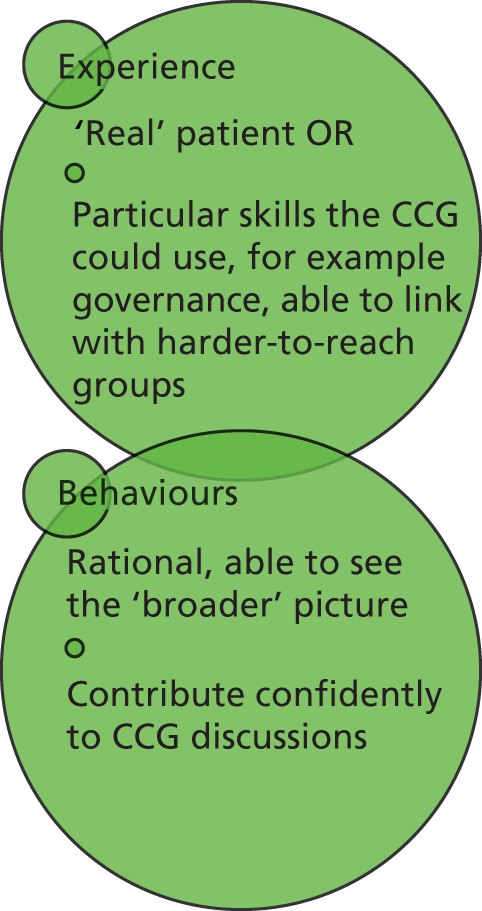

Clinical Commissioning Groups are held accountable by a National Commissioning Board, NHS England, which formally authorises CCGs. Currently, there are 211 CCGs authorised to commission NHS services as of April 2013. Despite a number of policy levers and local incentives to develop PPI,49,67,85 it is unclear whether or not CCGs will be able to fully embrace PPI within their culture. Given the lack of evidence of effective models of PPI in commissioning, as well as a lack of reliable data on patient involvement18,86 and the fact that many CCGs are likely to buy in commissioning support services from ex-PCT personnel, this lack of a creative PPI culture looks likely to continue. Many do not have the skills, time or resources. A recent study of CCG leaders for patient and public engagement87 revealed that, although CCG leads were keen to engage with patients and public, there was some lack of understanding of what engagement was and how it might be used within the whole commissioning cycle, particularly for procurement and monitoring. Commissioning, particularly for LTCs, is resource intensive. 88 However, the new health-care landscape involves CCGs developing strategic alliances and partnerships with existing and new organisations such as the Health and Well-Being Board (HWBB) and Healthwatch, which, in the case of the HWBB, requires the development of joint strategies with their local authority, who have a culture of public/community engagement, thereby providing some direction and potential for cross-learning.

Patient and public involvement influencing commissioning decisions: is it working?

The importance of PPI in commissioning has been recognised since the initial development of NHS purchasing in the 1990s. However, there has been no significant evidence that such engagement has influenced commissioning decisions. 8,17–19 In 2007 the Picker Institute published the results of a survey of PCTs examining PPI in commissioning. They found that while PCTs had a number of mechanisms and defined management responsibilities for PPI, there was a disconnect between the emphasis on processes and structures for PPI and the relatively low expectation that patient, public and community groups would have any significant influence on commissioning decisions. 18 Key barriers identified were difficulties in reaching marginalised, isolated or deprived groups, a lack of understanding among the public of ‘commissioning’ and a lack of reliable data about patients’ experiences. However, when asked what approaches PCTs were considering for future engagement, there was a continued emphasis on methods such as formal consultations, patient panels, citizens’ juries and surveys. These approaches did not identify engagement or involvement of user and patient groups for people with LTCs, despite this approach being promoted by the government’s policy on choice for people with LTCs. 4,9 Guidance for commissioning agencies placed great importance on how care that promotes the health and well-being of individuals in consultation with local people was procured10 forming the basis for commissioning competencies, needs assessment frameworks and performance regimes across health and social care. 10,12 There was also a clear emphasis on increasing the role of the third sector. 13 The NHS Next Stage Review also highlighted changing public expectations related to ‘control, personalisation and connection’, and building partnerships with patients and LTC user groups. 14 At the start of this research project (November 2009), we undertook an extensive scoping exercise of national changes in commissioning for LTCs. The project protocol highlighted a number of key areas for investigation: Department of Health pilot sites and demonstrators, website analysis [PCTs, strategic health authorities (SHAs) and national patient organisations] and documentary analysis (associated policies, budgets, commissioning power and choice sets). Websites were traversed using key words (identified via project objectives, research questions, literature review, health policy, commissioning models) with a search for key documents associated with LTCs/PPI and/or commissioning. Key documents were identified as Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA); World Class Commissioning Panel reports; LTC strategies; commissioning strategy; communication and engagement strategies; PPI strategies; and a 5-year strategic plan.

We found that many PCTs recognised the need to improve data collection, knowledge management and address intelligence gaps in relation to needs assessment. PPI within this context was variable; methods included the use of existing PPI mechanisms, steering group membership, workshops, stakeholder events and facilitation by social enterprise organisations. LTCs were addressed in all JSNAs reviewed and was referenced, either explicitly or implicitly, in all key documents. Correlations between an ageing population and LTCs were highlighted, with such conditions often described as a disease burden. Emphasis was placed on effective management; this included care closer to home, patient education, self-care, capacity building in general practice, targeted risk assessment, the reduction of emergency admissions and exploiting new technologies. As such, we found that in general the localised strategic viewpoint mirrored Department of Health-related documentation and LTC models. Of particular relevance – especially given the changes to commissioning that occurred during the period of research – was that PBC was seen as a key vehicle for LTC commissioning; however, organisational development at this time was variable, with limited PPI evident.

Generally, PCT PPI strategy focused on well-recognised methods, with one-third of the PCTs having a panel or membership schemes in operation and otherwise an emphasis on expert patient programmes, volunteering, Patient Advocacy Liaison Service (PALS) and reader panels. However, specific involvement in relation to LTCs was more limited.

A lack of innovative approaches could explain World Class Commissioning panel report results for competency 3 (influence on local health opinions, PPI, improvement in patient experience). In 2008–9, no PCT (n = 114) had obtained the highest level 3 competency (67% operating at level 2 and 33% at level 1). In 2009, assessments of the quality of commissioning published on the NHS Choices website showed that only 2% of PCTs were coded as excellent, the majority gaining ‘good’ at 51%. PPI in specialised commissioning groups was even less well developed, with 50% having no visible ‘involvement’ section on their website. Data collection and analysis were terminated in August 2010 following changes in health policy and the planned abolition of PCTs.

A search for recent evidence of impact of PPEI within LTCs health care revealed limited literature, particularly in relation to the specific LTCs relating to this project, as well as a lack of robust evaluative data. This reflects Sullivan and Skelcher’s89 view that lay representatives may be marginalised and have less influence than senior executives and NHS decision-makers. Nevertheless, from the small number of varied qualitative studies appraised (n = 9), a number of themes emerged. Involvement initiatives led to some positive outcomes for the service users involved: increasing knowledge, self-confidence and self-esteem,90–92 with a resulting increased capacity to become involved with decision-making. 92,93 Much of involvement or engagement was limited to sharing information, through helping the development or design of patient information material or commenting on experience of a service, rather than helping to actively plan and shape services,91,93,94 and were largely professional rather than service-user led or codesigned. Service users also demonstrated broader ‘critical awareness’ but were unlikely to be involved at a strategic or active level, such as that of service development. 95 As most studies lacked robust evaluative data, it was difficult to attribute service improvements to PPEI specifically, even though many reported positive outcomes in some areas. In addition, levels of involvement varied between studies; while some showed that there was involvement at a limited, consultation level,94,96 others were more in-depth,95,97 and this made between-study comparisons meaningless.

Our findings reflected those of the Picker Survey as well as contemporary research on PBC which also highlighted its integral role for the success of commissioning strategies for LTCs, although these remained underdeveloped and ‘yet to have a significant effect on the redesign of services’ and that ‘the incentives and infrastructure to support PBC are not currently sufficient to engage most GPs in commissioning’, a finding supported by research on PBC. 15,16 While PBC provided much of the stimulus for the development of CCGs, early research on their development does not suggest significant differences in their approach to PPI – as is discussed later in this report.

The challenges for PPI in the NHS are well discussed in the wider literature. Research has identified key contextual factors that pose challenges for effective PPI such as lack of time and resources, lack of interest among professionals and the public, and lack of knowledge of how to translate PPI into changes in health services. 98 Tritter and McCallum’s99 analysis of the state of play in user involvement suggested three areas of weakness: time and expertise for developing trust, capacity to participate effectively, and a lack of consensus on agenda and goals. Commissioners may also face the problem of who exactly to involve (e.g. patient groups or the general public), how to achieve proper representation, and the difficulty of reconciling different agendas (e.g. between organisational and professional interests and the variety of interests of the public). Some researchers draw attention to the importance of clinical champions for successful PPI. 100 Past research indicates that it is unlikely that new commissioning groups will have the required skills, resources, time or inclination to develop PPI. 81

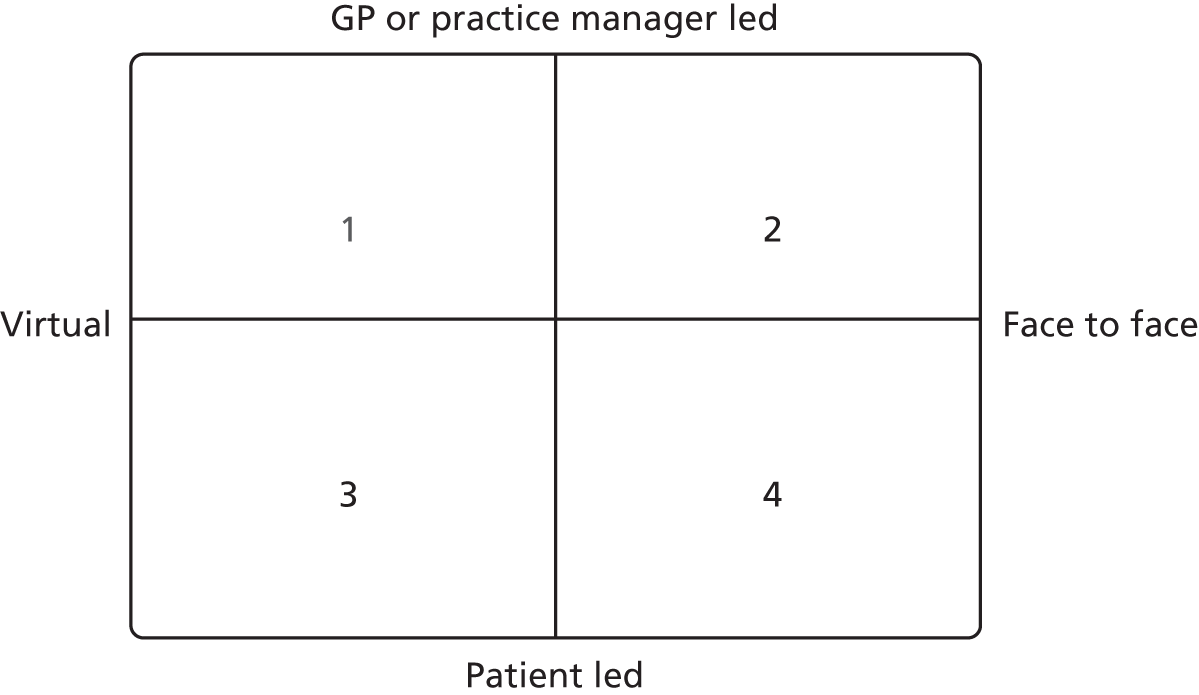

Patient and public involvement can employ a variety of mechanisms of involvement depending on the degree of actual power invested in the public. 101 Direct/indirect involvement refers to the absence or presence of mediating agents (e.g. GPs in health care are mediating agents for patients). Passive/active involvement refers to whether it is health professionals or the public who are setting the agenda or are being instrumental in actual decision-making. 72,100,102 Deliberative/non-deliberative involvement refers to the presence or absence of face-to-face interaction with the public. Examples of deliberative mechanisms are focus groups, health panels and citizens’ juries, while non-deliberative approaches include postal questionnaires and public consultations through postal or electronic voting.

Research has yielded scant evidence about concrete outcomes achieved by PPI in commissioning. The impact of PPI on services is often not clear, acting potentially as a disincentive to engage. Limited tools exist for measuring or assessing patient involvement. 103 When evaluating impact of user involvement strategies we should look at indicators of success that include both process and outcomes including economic evaluation. 104 Evaluating outcomes, however, is not easy, as it may take years before the outcomes of PPI can be measured. Equally, outcomes of PPI may be difficult to disentangle from other interventions. Some benefits are easier to prove, such as user satisfaction, opportunities of meeting others in a similar situation and increased knowledge about the availability of services related to their condition. 94 Gibson et al. 105 identify a series of key questions to be addressed in assessing the impact of PPEI:

-

Does the new system allow a plurality of public arenas where the service user voice can be heard?

-

Which areas of decision-making will be open to influence by PPI and which will not?

-

Which proposed solutions will be acceptable and unacceptable to the various stakeholders?

-

Is the host organisation prepared to change to accommodate some of these solutions?

These also link to what Barnes106 and others106–110 refer to as emotional and figurative deliberation based on experiential knowledge. They argue that patient and public experience is as important as more purposive-rational deliberations.

It is not surprising, therefore, that PPI has often remained a ‘window dressing’ exercise, with actual implementation of policy by local managers being rather lukewarm and unsuccessful. Involvement, if it happens, tends to be passive. 111,112 When it is active, it tends to relate more to existing service users than to members of the broader community. 100,113 One review concluded that ‘primary care-led commissioning organisations have struggled to engage patients and the public in a meaningful way’ (p. 3). 114 Despite some guidance available on skills development, such as in the Smart Series guide for commissioning,115 there would appear to still be a need to develop the required culture for PPI, and, until there is evidence available about what is working/effective etc., it is going to be difficult to create that culture. 86 The previous World Class Commissioning and central guidance on commissioning was not specific for GP practice which may explain why, in the past, there has not been enough work or guidance on skills development around PPI for GPs. This is gradually being developed and the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Centre of Commissioning competencies for clinically led commissioning (August 2011) include engaging the public. 116

Conclusion

Good commissioning for people with LTCs requires not only developing a set of skills for commissioning responsive and appropriate care that provides relevant choices for service users, but also developing approaches to sustaining user engagement. While previous research on engaging users in the NHS and on user involvement in change management in health services has demonstrated a willingness and commitment to engagement, there are few concrete examples of effective influence by users or evidence of change. 17

It was against this background that this study was developed. As described in the previous chapter, the study was undertaken at a time of substantial change in the NHS which commenced in 2009 with moves to reduce NHS management costs through PCT mergers,46 an increasing focus on integrated care and approaches to self-management2,14 and substantial organisational reform introduced by the coalition government in 2010 which developed from the end of 2010 and formally came into practice in April 2013.

With agreement from NIHR, the research period was extended to enable the research team to explore some of the early impacts of this changing commissioning environment during 2012 and early 2013 (reported in Chapter 7). However, the key aim of the study remained an examination of how commissioners enable voice and engagement of people with LTCs, and to identify what impact this has on the commissioning process and pattern of services. Our key research questions were:

-

What kinds of relationships existed, and were developing, between the public/patients and commissioners?

-

What impact did the public/patient voice have on the commissioning process and decisions made by commissioners?

-

To what extent did any changes in the commissioning process reshape local services?

-

Did any such changes in services impact on the patient experience?

-

How did, if at all, commissioners enable the voice and engagement of people with LTCs in the commissioning process?

-

How did patient groups/patient representatives get their voice heard and what mechanisms and processes did patients and the public use to make their voice heard?

The findings of this project will contribute to supporting the development of relevant skills and mechanisms for engagement for commissioners and service users and representatives within this new health-care landscape.

Chapter 3 Methods

Research design

The aim of this project was to develop an understanding of some of the complex issues of involving patients and the public in commissioning health care. In order to investigate this phenomenon, a case study design was adopted in order to develop an in-depth analysis of the processes, structures and context of PPI. Case study methods are a recognised and well-established approach to conducting research in a variety of ‘real life’ settings including health care. 117 Yin defines case study research as ‘an empirical study that investigates contemporary phenomena within a real-life context, when the boundaries between the phenomena and context are not clearly evident and which multiple sources of evidence are used’ (p. 18). 118 This approach allowed us to employ a range of social science research techniques and designs, mainly qualitative, to gain some in-depth understanding of the nature of engagement between service users, the public and local NHS organisations within their specific organisations. It also provided the methodological flexibility to generate some theoretical insights from our results. 119 We were thereby able to adopt an interactive approach to data collection and analysis, allowing theory development grounded in empirical evidence, a main strength of this design. 120,121

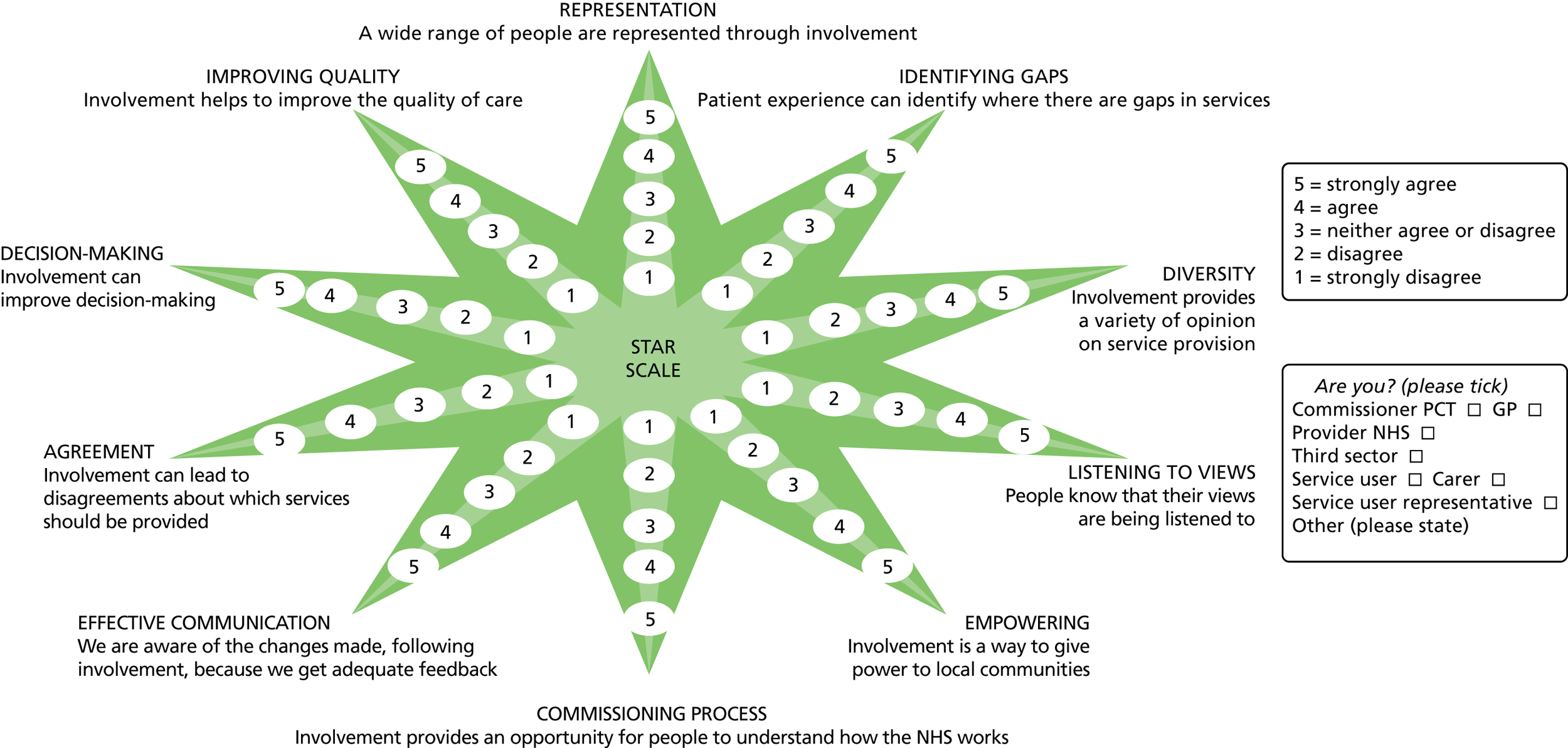

A multilayered approach was used, combining mapping of activity at national and local levels, analysis of local context and detailed case studies in three locations. Specific methods were employed including interviews, focus groups and workshops with a range of stakeholders, observation of key commissioning and PPEI meetings, and analysing documentary data, as well as using an adapted Likert Scale ‘Star Chart’ to measure perceptions of engagement and involvement over time.

Recruitment

As this study was undertaken during a period of great change within the NHS, recruiting NHS personnel became a challenge. This was particularly significant during the tracking phase of the study, as respondents moved on to different organisations and roles and responsibilities were not always clearly defined during the transition to CCG stage. We therefore had to adapt our methodology during the tracking stage of the study to ensure that we collected relevant data from those who were in the appropriate posts. In some cases, this meant interviewing new personnel in the latter stages of the study, including some who had new PPEI roles and responsibilities in the new health-care structures. This is explained more fully in our findings (see Chapter 3). To support the iterative process, and enable comparisons between each site during the course of the study, the case study sites were recruited in turn (Figure 1).

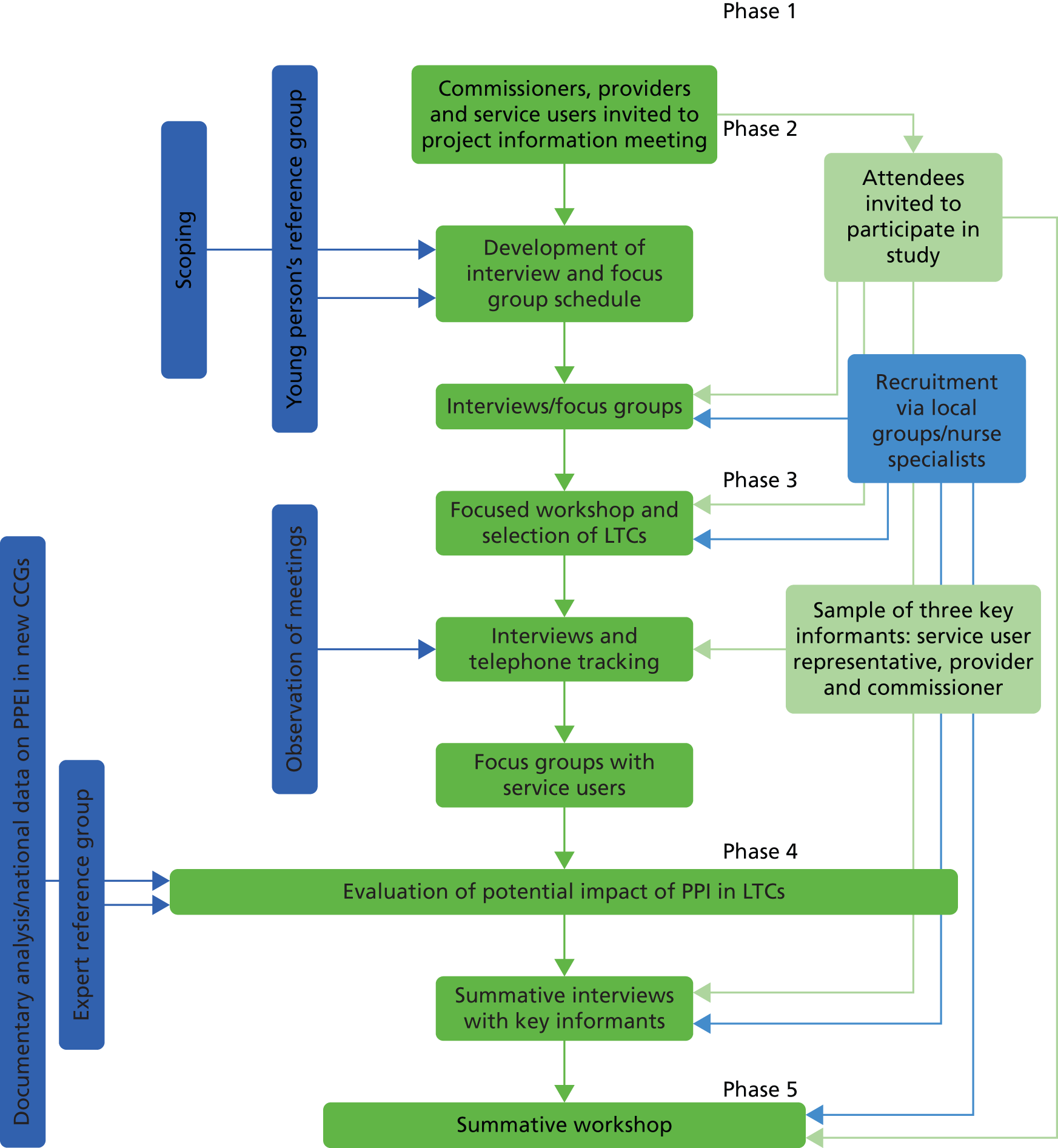

FIGURE 1.

Plan of research.

Ethics

This project had NHS approval [Research Ethics Committee (REC) reference 10/H0713/24] obtaining favourable approval by the REC on 6 July 2010 with minor protocol changes agreed by ethics (Table 1). The project was originally funded for 3 years and the main focus was to investigate PPEI within the PCT commissioning structure. An extension of 9 months was granted to enable data collection within the transition stages of the new commissioning environment. A revised research plan to reflect the extension was written. All changes to the research protocol were also reported to, and agreed with, NIHR.

| Protocol | Detail of amendment | Date approved by REC |

|---|---|---|

| Initial protocol | 6 July 2010 | |

| Amendment 1 | To allow young persons option of being interviewed face to face or by telephone or within a focus group. Amendments to interview schedules, consent forms and information for participant forms made to reflect changes | 7 February 2011 |

| Amendment 2 | Amendment to age of consent for interview for young person to be reduced from 13 to 12 years. No changes to interview schedules/information/consent forms required | 7 February 2011 |

Methodology

The research was carried out in five distinct phases from October 2009 to July 2013. The project flowchart (see Figure 1) illustrates the phases of the research and methods employed.

Phase 1: scoping national changes in commissioning and case study selection

As referred to earlier in this report, we were unable to complete this phase of the study due to the abolition of PCTs. However, we did look at public information available from PCTs and this was used to inform case study selection and to initially draft the Star Chart tool (see Appendix 15) used in agreement with Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR).

Phase 2: contextualisation

Aim

This phase was to establish detailed information on the three local case study sites selected for the study. The aim was to contextualise the specific range, type and actions of the three tracer condition based groups that would be examined in more depth in phase 3.

Sampling strategy: selection of case study sites

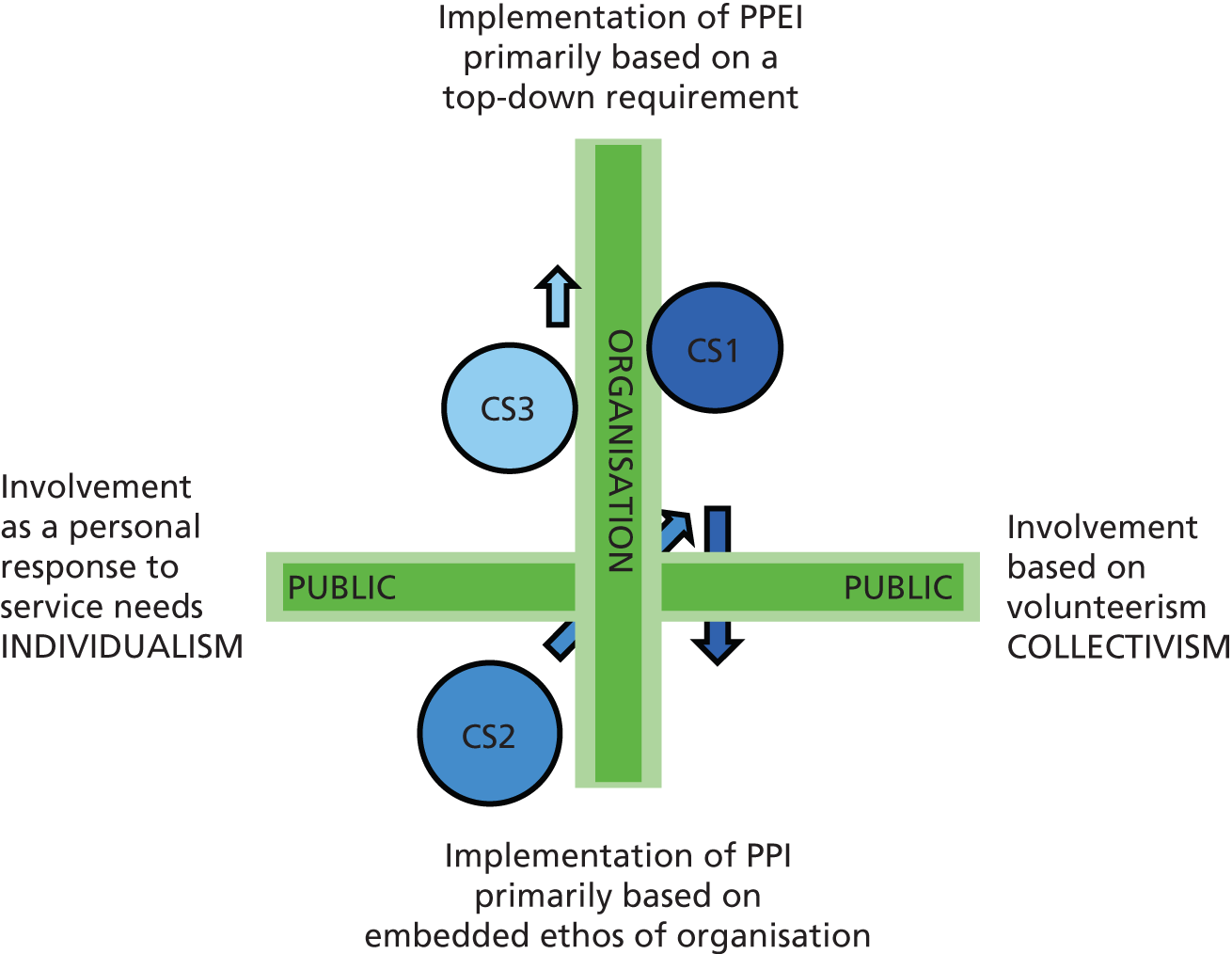

Three case study areas (PCTs) were purposefully selected to provide a range of demographic and geographical variation to include urban/rural, different cultural and ethnic populations as well as including a range of local NHS agencies (see Table 2). During the course of the research, the PCT in case study 1 (CS1) merged with other adjacent PCTs into a larger cluster. However, the emerging single CCG within CS1 covered the original PCT population. In case study 2 (CS2) and case study 3 (CS3), the PCT remained a single entity and these were replaced during 2012 by single CCGs.

Table 2 lists the main characteristics of the three sites.

| Case study | Setting | Population/ethnicity | Secondary care provider | PBC/CCGs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS1 | Mixed urban/rural | Some ethnic minority groups, but mainly white | District general hospital | Single CCG |

| CS2 | City based | Average-size BME population | Teaching hospital | Well-developed PBC, single CCG |

| CS3 | Urban | High BME population | Foundation trust district general hospital | Single CCG |

Sampling strategy: selection of tracer long-term conditions

Three LTCs, reflecting varying known relationships across the health and social care divide as well as demand for services, were chosen for study in each location (Table 3). It was anticipated that by selecting diverse populations and levels of engagement and involvement we would identify a range of different levels of PPI. Previous studies suggest that people who participate in local health-care decision-making are generally older, wealthier and better educated than the general population and are less likely to be from black and minority ethnic (BME) communities or from other vulnerable communities. 122,123 These patient groups were specifically selected as they reflected a wide age range for study, including children and young people with LTCs, who are less likely to have a voice in their care than adults with LTCs. In addition, we purposively selected one case study with an ethnically diverse and large BME population (see CS3). The research design was structured to avoid only examining decision-making and service changes where the process was framed by the health service and its approach to engaging patient or user involvement. 124

| LTCs | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Diabetes | Vocal patient groups, large population, established services |

| RA | Less established patient groups and services |

| Neurological conditions | Variety of patient groups and services with substantial local variation in services |

Sampling

Purposeful sampling was employed to target practice-based and PCT commissioners and public involvement staff, provider organisations and patient representatives for each of the tracer conditions. Interview targets were set, with each site aiming to recruit up to seven PCT, PBC and PPEI leads, one provider from each tracer condition and around five patient and public representatives, including adults as well as young people and carers, from each tracer condition. In order to address problems of recruiting only patient representatives who were already involved with local health agencies, we recruited participants via local voluntary groups and support groups as well as through advertising in clinics and practices and identifying participants who were not in formal groups. 123,124 For example, in one case study, site participants with RA were not involved in any group or health-care organisation approaches to PPI. Theoretical data saturation also guided sampling, in that sampling relevant cases would continue until no new theoretical insights emerged from the data. One case study site exceeded the target sample due to staff reorganisation as a result of the health reforms, necessitating targeting the new ‘PPEI’ staff and patient/public leads. A total of 102 participants were interviewed for the study across phases 2 and 3. Table 4 shows the total number and range of participants interviewed in each site. Table 5 shows the full range of roles.

| Case study | Service users and representatives | Commissioners (PCT, GP, CCG/LA and PPEI leads) | Providers | Total number of interviews |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CS1 | 33 | 11 | 4 | 48 |

| CS2 | 11 | 9 | 5 | 25 |

| CS3 | 11 | 13 | 5 | 29 |

| Total interviewed in range | 55 | 33 | 14 | 102 |

| Role | CS1 | CS2 | CS3 |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCT commissioners | 2 | 1 | 2 |

| PCT PPEI leads | 1 | ||

| GP commissioners | 1 | 2 | |

| GP practice managers | 1 | 2 | |

| PCT/CCG transition PPEI project leads | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| CCG PPEI executive leads | 1 | ||

| CCG PPEI representatives | 8 | 1 | |

| CCG medical director | 1 | ||

| Local Healthwatch | 1 | ||

| HWBB | 1 | ||

| Service providers | 3 | 3 | 3 |

| Service users and representatives | 12 | 10 | 9 |

| PCT/LA diversity lead | 1 | ||

| CCG clinical lead (diabetes) | 1 | ||

| Local authority PPEI executive | 1 | 1 | |

| GP commissioning support (SHA) | 1 | ||

| PCT/LA commissioning (YP) | 1 | ||

| Provider PPEI lead | 1 |

In addition to the people interviewed, the local workshops involved other service users and their representatives, providers and commissioners. For example, initial workshops were attended by between 30 and 40 people in each case study, with service users from a wide variety of age ranges and backgrounds. In the second workshops, 76 people attended across the three case study sites and 30 people attended focus groups structured to address the tracer topics, with two of these being with people from BME communities. There was some overlap between those attending initial workshops in phase 1, the follow-up workshops in phase 2, focus groups and interviewees.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We set out to include as many local service users and their representatives as possible through running local workshops which were advertised to as many people and organisations in each of the three tracer groups, proactive work to recruit young people and use of snowballing techniques to reach as wide a population as possible. Overall, in the study we included:

-

service users and representatives from age 12 (no upper age limit), with diabetes or RA or a neurological LTC receiving services in the case study site (PCT)

-

informal carers

-

parents of children 0–16 years old.

We excluded:

-

younger people whose parents/guardians did not consent to their participation

-

service users and informal carers who were unable to speak or read English and for whom translation services within the research team or locally were unavailable

-

informal carers of adult patients who had not consented for the carer to be approached.

Data collection

Initial meeting and workshop

An initial set-up meeting was organised by the research team with key stakeholders from the PCT in each case study site. This was carried out with those leading on commissioning and providing services for people with LTCs. The aim of this meeting (alongside providing information about the study and an invitation to participate) was to discuss local provision for the three tracer conditions and how patients and the public are currently involved. Information gathered from this meeting, along with additional local scoping of patient and public groups, was used to identify and map the key organisations and groups, as well as the institutional structures for local commissioning of health care for the three tracer conditions. Representatives from these organisations and groups, including primary, community and secondary providers, health-care commissioners as well as patient and public representatives, were purposefully selected to represent the tracer conditions and to reach as many people with an interest in the research topic as possible; they were invited to attend an initial workshop, or information meeting, within each case study site. We specifically mapped as many relevant patient groups and organisations, voluntary groups related to people with diabetes, neurological conditions and RA in each area as possible (including support groups run by services, local groups of national organisations), as well as contacting some specific individuals identified through a snowballing technique to ensure that we reached as wider patient/user community as we could. 122–124 The aim of this meeting was to map the terrain of local PPEI to understand the contextual features impacting on each case study. It was also used to identify any key issues, projects or mechanisms for PPEI, which we aimed to follow up in more depth in the next phase.

Interviews

Following the initial workshop, a series of mainly individual in-depth semistructured interviews were carried out with a purposive selection of commissioners, providers and service users and representatives for each site (see Table 5 for total numbers interviewed in each site). Data saturation guided the sample limit. The interview aimed to elicit views on the issues, processes and current activity relating to commissioning health care for people with LTCs across the three tracer conditions. Interviews were carried out face to face, normally at the participant’s place of work or leisure, or by telephone if requested, following the researcher’s obtaining of full consent. The interview schedule, information on interview and consent forms are attached at Appendices 3–6. Following interview, the participant was asked to complete the Star Chart tool to obtain some assessment of the individual’s understanding and experience of PPEI.

Data from young people

It was planned to hold a series of focus groups with young people to obtain their perspectives on involvement during this phase of the research. The research team consulted guidelines for the operation of research with young people125–127 and these were taken into account, especially to ensure that the principles of how to conduct fieldwork with young people with age-appropriate sensitivity were adhered to. 128,129 However, the project represented an attempt to include young people within a project adopting an inclusive approach across the life course and in a new area, that of patient-led commissioning. Moreover, we encountered a number of gatekeeper issues that were unanticipated. The team had difficulty recruiting young people to a focus group (see Chapter 8, Power and control). In discussions with our young person reference group, it was agreed that individual telephone interviews might result in more success in recruitment. Following approval of this revision to the protocol by the REC and NIHR, a total of 10 young people and their carers were interviewed in this phase of the study.

Follow-up workshop

Focused, or follow-up, workshops (one in each case study site) were held at the end of phase 2 to explore local issues and approaches to commissioning people with LTCs in more depth. Examples or issues around PPEI, identified during earlier interviews and discussions with stakeholders, were used to guide some of the discussion. PCT, local authority and practice-based commissioners as well as clinical leads (commissioner, provider) and representatives from user groups and patient organisations from the three tracer conditions, plus key representatives from consumer and patient organisations, were invited to attend. In total, 76 participants attended these workshops across the three sites. These represented a mix of commissioners, service users/representatives and providers. The workshop also served to identify specific exemplars of PPEI practice suitable for follow up as ongoing in-depth analysis over time in phase 3 of the project. For CS1, this was identified as a third-sector targeted approach to support local commissioning of neurological conditions and a schools-based diabetes project, for CS2 an integrated diabetes service with PPEI input and for CS3 a proposed community diabetes service for the local BME population.

Dissemination of findings

It was originally intended that we would share results and outcomes of these workshops with participants through a shared website. We developed a project-specific website at the beginning of the project. This was a secure site in order to share documents, resources and findings within the project team, who had intended to use this as a method of dissemination with participants. However, following discussions with participants during workshops and interviews, a process of e-mailing workshop reports out to participants was considered preferable to requiring people to engage with another ‘internet site’, particularly in the current climate of change and turmoil.

Phase 3: evaluation of the impact of involvement on local health policy processes

Aim

In this phase, we aimed to identify the impact of involvement on local health policy processes such as service reconfiguration, service delivery and service development. This was through an exploration of public/patient views and perceptions of how the public voice is heard and if/how it impacts on change. Processes relating to the potential exemplars of PPEI practice identified in phase 2 were focused on, with the aim of exploring the extent to which participants felt that they were able to successfully influence local health policy processes in the past year, as well as issues that they were currently trying to place on local policy agenda or attempts to influence current commissioning policy/strategies on LTCs. Their development was tracked during this phase. (See Appendices 6–8 for exemplars.)

Methods of data collection

Interviews (phase 3 interviews and telephone tracking)

A purposive sample of three key informants (service user representative, commissioner and service provider) were selected for each case study site. They were interviewed soon after the exploratory focused workshop in phase 2. The original plan was to carry out a series of short tracking telephone calls as well as a further two interviews (one in the middle of the 18-month tracking and one at the end), with the purpose of tracking case study site activity and to explore any impact of PPEI on local health policy process. At the end of each interview, measurement of the interviewee’s perception of changes in user involvement was to be made through the Star Chart tool. However, staff changes (with key commissioning informants lost from all three of the sites at varying stages of the study) meant that tracking could not be undertaken in the manner it was intended and the Star Chart tool was of limited use. Tracking was, nevertheless, carried out with those who were still in place and further interviews were undertaken with some of the new commissioning and PPEI personnel where available. (See the case study site findings in Chapters 4–6 for further information.)

Focus groups

A number of focus groups were held with a selection of service users within this phase to complement the data collected from interviews and observation. Focus groups are group discussions that are carried out to examine a specific set of topics. 130 This was done in order to hear issues which may not readily emerge from interviews or observations alone, and to capture the shared, lived experience with the possibility, through the synergy of conversation, of developing unique data or ideas. 131 As Ivanhoff and Hultberg suggest, the strength of the focus group method is that researchers are provided with an opportunity to appreciate the way people perceive their own reality and get ‘closer to the data’ (p. 126). 132 Focus groups also provide a safe environment for some individuals or groups, such as those from similar socioeconomic or ethnic backgrounds, who might find interviews intimidating, and can serve to provide a voice from seldom-heard or marginalised groups. We had originally planned to carry out focus groups with young people in phase 2 but had to adapt our plans, as emerging data from interviews indicated that this would not be the preferred option for this group and we had to amend our protocol to include interviews as an option. No focus groups were held with young people in phase 2 or 3 of this project.

A selection of service users were recruited using convenience or snowball sampling methods to ensure adequate coverage of a range of patient groups.

Four focus groups with service users were carried out in this phase, with a total number of 30 participants (Table 6 gives a breakdown of numbers and characteristics of participants). The focus groups were facilitated by two members of the research team, with one acting as main facilitator and the other taking notes. The focus group discussions were recorded with consent and transcribed verbatim. Notes taken during the focus group were used to clarify the discussion and aid analysis.

| Case study | Number of participants and focus groups | Characteristics of focus group |

|---|---|---|

| CS1 | Six participants in one focus group | Service users (adult) with neurological LTCs |

| CS2 | Four participants in one focus group | Service users (adult) with RA |

| CS3 | Twenty participants in two focus groups | Service users (adult BME) with diabetes |

Some of the issues or findings emerging from the initial workshop and interviews were used to explore further in the focus group. As previously discussed earlier, many of the statements contained within the Star Chart tool were no longer valid as commissioning had changed so much. However, the statements that were still meaningful in the new context were used to guide some of the discussion within the focus groups. In two of the focus groups, vignettes developed from phase 2 interviews were used to trigger discussion on their involvement in LTC service commissioning. In one of the case study sites, focus groups were carried out with groups with very little or no spoken English and were therefore conducted through a translator. (See Appendices 9 and 10 for focus group topic guides and information provided to participants.)

In total, 10 key commissioning and PPEI meetings were observed across all the case study sites and relevant documents collected for analysis during phases 2 and 3. The central aim was to observe the nature of PPEI within these meetings, how and in what way the lay voice is heard and acted upon. Field notes of the meetings were recorded and used as appropriate for analysis.

In order to better understand the position of PPI within the emerging new health structures, data were obtained on PPEI processes and structures from a national survey on emergent CCGs (via PRUComm) as well as from a selection of CCGs undergoing authorisation (refer to Checkland et al. 22 for details of methods in the PRUComm study). (See Chapter 7 for further information and findings.)

Phase 4: confirmation of outcome measures

Aim

Following an initial analysis of data in phases 2 and 3, the aim of this phase was to identify outcome measures related to commissioning including direct evidence of service change, changes in investment, satisfaction with changes and processes of engagement.

Methods of data collection

An expert reference group was formed, consisting of a number of external key people with a wide variety of expertise and experience relating to patient involvement, clinical skills and knowledge and clinical practice around LTCs in general and/or specific to the tracked tracer conditions. These acted as a virtual panel to provide comments on the identified exemplars of PPEI practice tracked in phase 3. The aim was to bring some external verification of whether or not the interventions, services or processes, developed through PPEI, were likely to lead to improvements and benefits for patients. (See Appendix 9 for expert reference group list.)

We had originally planned to carry out a number of summative focus groups with a purposive sample of commissioners, providers and service users to discuss outcomes of commissioning. However, in the rapidly shifting staff turnover, focus groups were not possible and individual as well as small group interviews (as in CS1) were carried out instead. These were conducted with a purposive sample of commissioners, service users, providers and PPEI staff to discuss changes in services and process of engagement. This was also supplemented by participant and non-participant observation of specific related commissioning meetings where field notes were made about evidence of service changes, including changes in investment, processes of PPEI as well as any perceived satisfaction with any changes.

Phase 5: summative workshop

Aim

The aim of this phase was to present the findings from the study to date to a range of stakeholders, assess the current situation and discuss the way forward. The summative workshop formed part of the initial analysis and synthesis stages of the research and was used for both the presentation of findings and also to explore the validity of our preliminary analysis of the data.

Methods

A summative workshop, with patient and public representatives, commissioners, PPEI executive/lay leads and providers from all three case study sites, was held in London in April 2013. Over 40 stakeholders attended this meeting. Preliminary analysis was presented to the audience for discussion and clarification. The workshop was chaired by the chair of the Engagement and Voice in Commissioning (EVOC) advisory group and facilitated by a lay representative who had experience in supporting emerging CCGs on PPEI at the SHA level and was involved in assessing the PPEI part of the CCG authorisation process for a number of CCGs. Data obtained from this workshop was used to refine the analysis. A report from the workshop was written and circulated as a project output (see Appendix 10).

Analysis and synthesis

Comparative case study analysis was used to identify and explain patterns across and within organisations and case study sites. The strategy for analysis was to:

-

observe, describe and explain the interaction between commissioning approaches identified and the way that patients and the public are engaged in these processes

-

identify and explain patterns of commissioning LTC services in each case study

-

examine the relative influence of patient and public views on LTC commissioning processes to identify lessons for future development of policy and practice.

Extensive notes were made of workshops and workshop material collected and analysed by the research team. Interviews and focus groups were transcribed verbatim and explored to uncover main themes. Transcripts were analysed using qualitative software (NVivo, QSR International, Warrington, UK) to enable thematic coding. Documents were coded to identify key themes and decisions were made. Framework matrices were developed using coded themes to summarise and condense data sources by codes and themes. Visual Star Charts were translated into Likert scale measurements and interpreted numerically. National and local contextual information was obtained from undertaking a discourse analysis of key policy documents and data from a range of national patient and public organisations. Data from a national survey of emerging CCGs were extracted to provide further information on the direction of travel for PPEI within the new health structures, and a selection of first wave CCGs undergoing authorisation were analysed thematically in relation to the evidence supplied around PPEI.