Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 09/1801/1029. The contractual start date was in October 2010. The final report began editorial review in November 2013 and was accepted for publication in April 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Richard Baker reports grants from the National Institute for Health Research during the conduct of the study.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Tarrant et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Summary of the study

Providers of primary care services do not always respond to the needs of diverse groups of patients, and certain groups of patients may be underserved and, therefore, disadvantaged. General practitioner (GP) practices are increasingly being encouraged to become more responsive to the needs of their patients in order to address these inequalities. Our aim in this study was to develop a patient-report questionnaire that could be used as a measure of patient experience in the context of efforts to improve responsiveness. We aimed to develop a questionnaire that could be used by diverse patient groups (including those with learning disabilities, and those who do not read or write English) and that was suitable for use by a range of different primary care organisations (PCOs), including GP practices and walk-in centres.

This involved, first of all, finding out what responsiveness means. To this end, we conducted a literature review, and interviews and focus groups with patients and staff in 12 PCOs in the East Midlands. We developed a questionnaire and tested it with patients from six of these PCOs. We then asked 15 PCOs across three different regions in England to distribute it to a large sample of patients. We checked the questionnaire for validity and consistency. We refined the questionnaire for different PCO settings and for specific patient groups. We investigated existing ways of population mapping which GP practices could use to increase their understanding of the needs of their populations in relation to responsiveness.

Summary of this chapter

This background chapter describes evidence for inequalities in patient experience in primary care. Within English policy, ‘responsiveness’ has been identified as a possible solution to this problem. The meaning of responsiveness in the current context of English primary care is explored. The existing measures of responsiveness and their deficiencies are summarised, and the need for a specific patient-report questionnaire on responsiveness that will allow the voice of all patients to be heard is identified.

Background

Inequalities in patient experience in primary care

One consistent finding across primary care patient experience surveys is that certain patient groups tend to report less positive experiences. 1 Patients from black and minority ethnic (BME) backgrounds, patients with poor health status, poor mental health or disabilities, less affluent patients, and younger patients tend to report poorer experiences of accessing and using primary care. 2–5 The reasons for this variation in experiences across different patient groups are not well understood. 1,5 In the case of patients from BME groups, some of this variation may be explained by the fact that these patients tend to be clustered in generally poor-performing practices, although many BME patients report less positive experiences than other patients within the same practice. 5 The variation in patients’ experiences of care between practices and across different patient groups has been described as unacceptable. 6 These inequalities are a cause for concern, as poorer experience of primary care is likely to impact on and perpetuate inequalities in health across diverse patient groups.

Responsiveness as means of addressing inequalities: an emerging concept

These concerns led to a focus in English policy from around 2008 onwards, under the Labour government, on efforts to improve access and responsiveness in primary care. Primary care providers were encouraged to work to be more ‘responsive’ – to move from a ‘one size fits all’ approach to delivering their services, towards a more flexible and responsive approach that takes into account the specific needs of their local populations. Guidance from the Department of Health (DH) underlined this aspiration, stating that, ‘there is no “one size fits all” model, it is for practices to personalise their services to meet their patients’ preferences’7 (see Chapter 3, Inequalities and the needs of diverse groups).

The concept of responsiveness was seen as closely linked with access, with the DH explicitly conceptualising practice responsiveness as a component of patient experience of access in primary care. 5 Definitions of the concept incorporate communicating and engaging with patients and carers, making efforts to identify and meet their non-clinical needs (i.e. their needs in terms of accessing and using services, rather than health needs or needs relating to the consultation or the clinician–patient relationship) and engaging in efforts to support patients from specific groups who may be vulnerable or experience particular difficulties in using primary care.

Practice responsiveness is the way in which a practice communicates and engages with its patients and their carers and responds to their non-clinical needs and preferences, reflecting the different ways in which they might prefer to access the service and an appropriate clinician, book, or indeed cancel an appointment. It includes the practice’s attitude to customer service and friendliness of staff, the environment in which patients wait to be seen and the way in which they interact and support patients from particular groups, such as those with hearing or sight loss or people from a black or minority ethnic background. 7

p. 15

The importance of supporting patients from diverse groups to access and use primary care services was underlined by a subsequent report on improving the experience of BME patients. 8 The report identified multiple reasons for the poorer access and experience of primary care of patients from BME groups; these included language and culture barriers, poorer health status, variable quality of GP services, and different expectations of BME patients. The report suggested that practices needed to work in partnership with BME patients, plan for their needs and ensure that the services were personalised to meet identified needs, and concluded that, ‘more responsive and personalised care will mean benefit for all members of the community – black and white – through the lessons learnt in service development’ (p. 3). 8

This focus on identifying and responding to the non-clinical needs of patients from diverse groups represented a shift in thinking, in that much of the work on inequalities and patient experience in primary care has tended to be concerned with clinical or health needs, and features of the consultation. This has included research into communication skills and barriers, patient-centredness and cultural competence, and issues such as patient–physician gender and race concordance. 9–11

Improving responsiveness

A review of key English policy and discussion documents highlights the key domains of service which have been identified in policy and guidance as those that GP practices should attend to in improving their responsiveness. These include engagement and communication with patients; practice opening hours; ease of contacting the practice; the ability of patients to easily make appointments that meet their needs for urgency, timing, and choice of practitioner; equity of access; alternative modes of consultation; the use of information technology (IT) to facilitate information and access; availability of premises and appropriateness of the physical environment, including accessibility; customer care; and adjustments for specific groups, including minority ethnic groups, disabled people, young people and carers. 7,12–15

Policy directives on responsiveness from 2008 onwards were accompanied by efforts to support and incentivise primary care providers to become more responsive. In 2008–9, a Primary Care Service Framework for accessible and responsive primary care13 was developed, setting out standards for care provision to improve responsiveness, and providing guidance for primary care trusts (PCTs) as to how practices might demonstrate their responsiveness. Under this framework, GP practices could claim financial reward for demonstrating their uptake of elements of responsiveness set out in the framework. Alongside this, the Practice Management Network produced extensive guidance on how to improve access and responsiveness in the form of a ‘how to’ manual,14 and a DVD to train reception staff on improving the patient experience. 15 These guides remain available, and give examples of good practice, and advice for practices in improving customer care, improving access for groups who are disadvantaged, and effectively engaging with patients. At the time that these resources were launched, they were accompanied by a training programme organised by the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP).

Responsiveness in the current context of primary care

Responsiveness was a highly prominent theme in English primary care policy under the Labour government (predominantly between 2003 and 2010). Despite significant political changes and NHS reorganisation, responsiveness remains a core aspiration for primary care. The DH White Paper Equity and Excellence, produced under the coalition government, calls for a ‘genuinely patient-centred approach in which services are designed around individual needs, lifestyles and aspirations’. 16 The new Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) have a constitutional duty to reduce inequalities between patients in relation to their ability to access primary care services, and the outcomes achieved,17 and as such, issues of accessibility and responsiveness of local primary care providers are likely to be of concern to them. There have been some slight shifts in focus. Under the coalition government, responsiveness has become associated with the personalisation and choice agenda:16

In future, patients and carers will have far more clout and choice in the system; and as a result, the NHS will become more responsive to their needs and wishes.

p. 16

In recent years there has also been a growing emphasis on the role of patient engagement and involvement in promoting responsiveness. Interest groups such as the National Association for Patient Participation (NAPP) have taken a keen interest in responsiveness, emphasising the importance of ‘effective patient participation [in] ensuring the quality and responsiveness of services and health outcomes for patients and the wider community continuously improve’. 18

Responsiveness has also been highlighted as a key element of ‘the right culture’ post Francis, with a focus on responding to patients’ needs and preferences, encouraging a patient-centred philosophy, responding to complaints, and listening to patients. 19

A range of initiatives and programmes continue to be made available to support efforts to improve responsiveness in primary care. These include the ongoing RCGP Quality Practice Award programme; its ‘patient centred care module’20 sets standards relevant to responsiveness, and indicates evidence that practices can provide to demonstrate their performance in these areas. Initiatives such as Productive General Practice (developed by the now defunct NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, and still in use),21 and The King’s Fund’s experience-based codesign toolkit,22 provide guidance and support for primary care providers in involving patients in the task of identifying unmet needs within local populations, and aligning the design and delivery of services with the needs of the patients. There remains a need for research to inform approaches to addressing inequalities on health care in cost-effective ways; research into access, quality, cost and effectiveness of services for disadvantaged groups has been identified as important. 23

Measures of responsiveness

Responsiveness can best be understood as a feature of the PCO: the extent to which the organisation (1) has processes and systems in place to help them to understand the non-clinical needs of patients and how best to address them; (2) designs their services in ways that are directed at meeting these identified needs; and (3) takes a flexible and personalised approach to delivering services and helping patients gain access to the services they need.

It is evident that responsiveness of a PCO can be assessed through relatively ‘objective’ measures of these efforts, for example the extent to which the practice has clearly-defined strategies to identify the needs of their patient population, or the extent to which the practice provides different routes for patients to book appointments that are appropriate to the needs of the local population.

Alongside this, it is also important that the views of patients are sought. Responsiveness is ultimately reflected in patients’ perceptions of whether or not the service provided actually meets their non-clinical needs. Users of a service will have a range of needs and preferences, and the patterns of these will vary across services and localities; changes in service provision targeted at improving responsiveness may meet the needs of some groups of patients, but fail to address the needs of others, meaning that groups who are disadvantaged may be no better served.

While there are a number of validated and widely used patient experience questionnaires for primary care, including the annual national GP patient survey,24 there are currently no patient-report questionnaires that are designed specifically as measures of patient experience of responsiveness in primary care. Existing questionnaires include some non-clinical aspects of care (primarily issues relating to access and the behaviour of reception staff), but also include more extensive questions on the clinical aspects of care (quality and experience of the consultation).

There is extensive evidence on what matters to patients (across clinical and non-clinical domains of primary care25,26). A useful distinction has been made between relational aspects of care (e.g. dignity, empathy), and ‘functional’ aspects (e.g. access, waiting):1 non-clinical aspects of care may fall within both of these dimensions. The recent NHS Patient Experience Framework brings together evidence on patient experience and sets out the key elements of patient experience across the NHS. 27 The framework includes some ‘non-clinical’ elements, particularly access, privacy, and transition and continuity.

The framework is designed to be used flexibly, and it is acknowledged that, ‘different areas of the framework will be more significant in particular settings for different groups of patients and therefore demographics, equality, and environment will need to be considered when applying the framework’. 28 It is not clear, however, which non-clinical features of primary care are most salient for patients from different groups in judging the responsiveness of primary care services to their needs.

It is important to recognise that the boundary between clinical and non-clinical needs may be blurred, but the focus on responsiveness brings attention to the specific issues of whether or not patients find services easy to access and use, and whether or not they feel that services are aligned with their personal, cultural or lifestyle-related needs. If a questionnaire is to act as a valid measure, it is essential that it cover these issues.

A further consideration is that existing patient experience measures tend to achieve a low response rate from patients from traditionally disadvantaged groups. The term ‘seldom heard’ has been used to describe these groups, defined as those who do not have an effective voice in relation to public and voluntary service providers, and who are the most vulnerable to ill health because of social and economic disadvantage. This includes minority ethnic groups, people with disabilities or mental health problems, refugees, travellers, homeless people, ex-offenders, migrants who do not speak English and others who are socially excluded. 29,30 Accessing the views of these ‘seldom-heard’ groups is critical in assessing whether or not practices are responding fairly to the needs of all. There has been some recognition of the need to find ways of gathering more targeted and detailed information about experiences across patients from different groups. 1

In this study, we aim to develop a measure of patient experience of responsiveness that includes the non-clinical needs identified as most important for patients across diverse groups; is worded to tap into responsiveness in terms of ease of getting needs met (rather than simply measuring experience); and is designed to be appropriate for use with patients who are traditionally seen as ‘hard to reach’ and hence ‘seldom heard’.

Diversity of primary care providers

We aim to develop approaches to measuring responsiveness across a range of primary care providers. While the GP practices remain core providers of primary care, there is a diverse set of organisations that fall under the umbrella of primary care, and these organisations differ in the types and nature of services they deliver. Walk-in centres, minor injury units and urgent care centres all provide primary care services which are accessible without appointments and are open to patients outside traditional working hours. Traditional general practices have diversified, with the emergence of specialist practices providing services to vulnerable groups such as asylum seekers and homeless patients; large health and social centres enable patients to access a wide range of services under a single roof. In addition, patients consult pharmacists for advice, and pharmacies commonly offer extended health services such as health checks. There may be specific challenges to responsiveness across these different types of organisations, and patients are likely to have different expectations of the types of services they can access and the way in which these will be organised and delivered across the different providers. These differences have implications for approaches to measuring responsiveness in primary care.

Summary and discussion

Responsiveness in primary care continues, across two governments, to be seen as an important element in reducing inequalities and, thus, providing equitable quality care. Understanding how responsiveness can be measured and improved requires an understanding of the needs of the primary care population. In the absence of an existing way to measure their non-clinical needs, the requirement to develop a patient-report questionnaire is clearly identified. Existing objective measures may contribute to understanding how responsive a PCO may be, but alongside these we need to assess patients’ own perceptions of whether or not their non-clinical needs are met.

The need to hear from those who are traditionally ‘seldom heard’ is essential in any effort to measure and increase responsiveness, as it is traditionally these disadvantaged groups who provide the greatest challenge in terms of ‘access’ but who also may have the most to benefit from a responsive primary care system.

Measures of responsiveness need to take into account the specific challenges and contexts of different types of primary care provider.

Chapter 2 Methods

Summary of this chapter

The primary aim of this study was to develop a measure of patient experience of the responsiveness of primary care providers to their needs. The study involved a review of policy documents and literature, and qualitative research with patients (see Chapter 5) and primary care staff (see Chapter 4), in order to define and operationalise responsiveness. Based on this work, a questionnaire was drafted and piloted (see Chapter 6) across a range of primary care service providers before final testing, including how to optimise the use of the questionnaire to access the views of diverse patient groups (see Chapter 7).

A secondary aim was to explore the mapping of diversity in primary care. It became clear that the aim of developing guidance for practices on mapping their patient populations would not be feasible, and that there would be more value in exploring of the significant barriers and challenges to practices in undertaking this (see Chapter 8).

Summary of methods

Development and testing of the questionnaire had three main stages. The overall study design is described below and in Figures 1–4. Further details of the methods are provided for each part of the study in the corresponding chapter of this report.

Stage 1: literature review and interviews with patients and staff

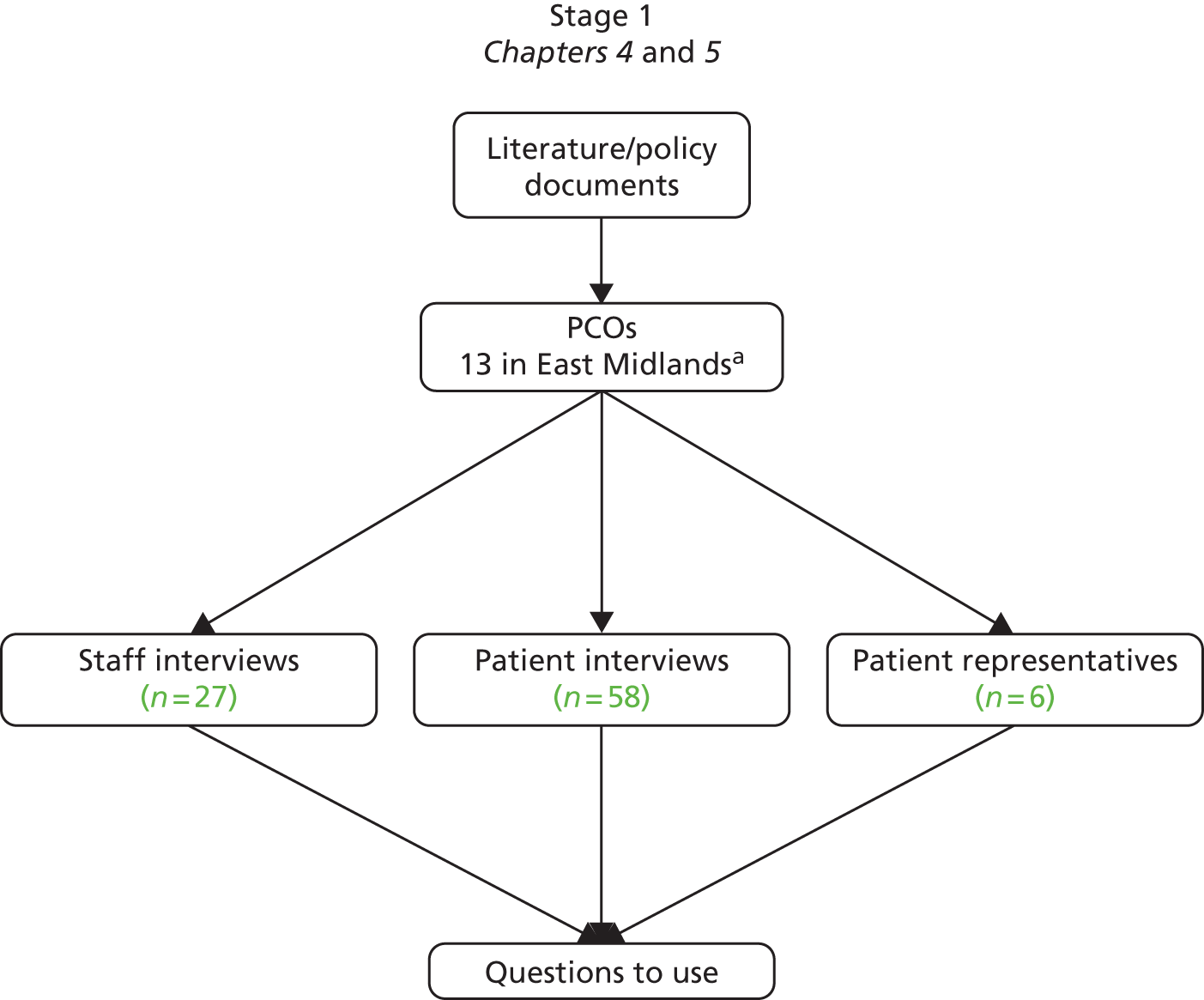

This stage commenced with a literature review on the meaning and measurement of responsiveness (Figure 1). Different fields in which responsiveness has emerged as a core concept were scoped, and from this literature we identified key items and followed narrative threads.

FIGURE 1.

Stage 1: literature review and qualitative interviews. a, In 12 PCOs both staff and patient interviews were conducted, while in one PCO only staff interviews were conducted.

We then conducted qualitative work with patients and professionals in order to understand how patients experienced responsive primary care, the ways in which practices had attempted to deliver responsive service, and the barriers and facilitators to this. We also explored the important features of a questionnaire on responsiveness for patients and for PCOs. We conducted semistructured interviews with staff (n = 27), patient representatives (n = 6) and patients (n = 58) from 13 PCOs in the East Midlands. Recruitment was supported by the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) for the East Midlands and South Yorkshire; practices in the South Yorkshire region were not included. Thirteen PCOs were identified through the PCRN and were selected to include mainstream GP practices of varying size, population demographics and location, as well as other types of PCO, including a walk-in centre, pharmacies and a specialist GP practice for homeless patients (Table 1).

| PCO | Type | Location | Sizea | Region | Deprivation decileb | Stage 1 | Stage 2 pilot 1 | Stage 2 pilot 2 | Stage 3 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 01 | GP surgery | Urban | Large | East Midlands | 5 | ✓c | – | – | – |

| 02 | Pharmacy | Inner-city | Large | East Midlands | 4 | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 03 | Pharmacy | Rural | Large | East Midlands | 10 | ✓ | – | ✓ | ✓ |

| 04 | GP surgeryd | Town centre | Large | East Midlands | 5 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| 05 | GP surgery | Rural | Medium | East Midlands | 10 | ✓ | – | – | – |

| 06 | GP surgery | Inner-city | Small | East Midlands | 4 | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| 07 | Homeless GP surgery | Inner-city | Small | East Midlands | 2 | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| 08 | Health and social care centred | Inner-city | Large | East Midlands | 1 | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| 09 | WIC | Urban | Large | East Midlands | 4 | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| 10 | GP surgery | Urban | Large | East Midlands | 4 | ✓ | – | ✓ | – |

| 11 | GP surgery | Urban | Medium | East Midlands | 6 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| 12 | GP surgery | Rural | Small | East Midlands | 8 | ✓ | ✓ | – | – |

| 13 | GP surgeryd | Inner-city | Small | East Midlands | 3 | ✓ | – | – | ✓ |

| 14 | Pharmacy | Inner-city | Large | Greater London | 1 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 15 | Pharmacy | Inner-city | Large | Greater London | 2 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 16 | GP surgerye | Inner-city | Small | Greater London | 1 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 17 | WIC | Inner-city | Large | Greater London | 1 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 18 | GP surgery | Urban | Medium | Greater London | 1 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 19 | GP surgery | Recruited for stage 3 but withdrew prior to data collection | |||||||

| 20 | GP surgery | Rural | Small | Northern & Yorkshire | 10 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 21 | GP surgery | Rural | Medium | Northern & Yorkshire | 8 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 22 | GP surgerye | Town centre | Small | Northern & Yorkshire | 2 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 23 | WIC | Town centre | Large | Northern & Yorkshire | 2 | – | – | – | ✓ |

| 24 | Pharmacy | Town centre | Large | Northern & Yorkshire | 3 | – | – | – | ✓ |

Based on the analysis of these interviews, we generated descriptions of the key components of responsive primary care as experienced by patients, and used these to develop a set of potential questions for the questionnaire.

Stage 2: developing the questionnaire

We conducted three patient focus groups specifically targeted at patients from ‘seldom-heard’ groups, to explore and validate understanding and acceptability of the questions. As a result of the focus groups, the questions were refined. Although we had intended to develop a short, generic questionnaire that would be applicable to all primary care providers, including GP practices, pharmacies and walk-in centres, the findings from the interviews and focus groups suggested this would not be feasible or acceptable to patients. We elected to lead with the development of a questionnaire for GP practices, which would then be adapted and modified to make it more appropriate to other specific primary care settings.

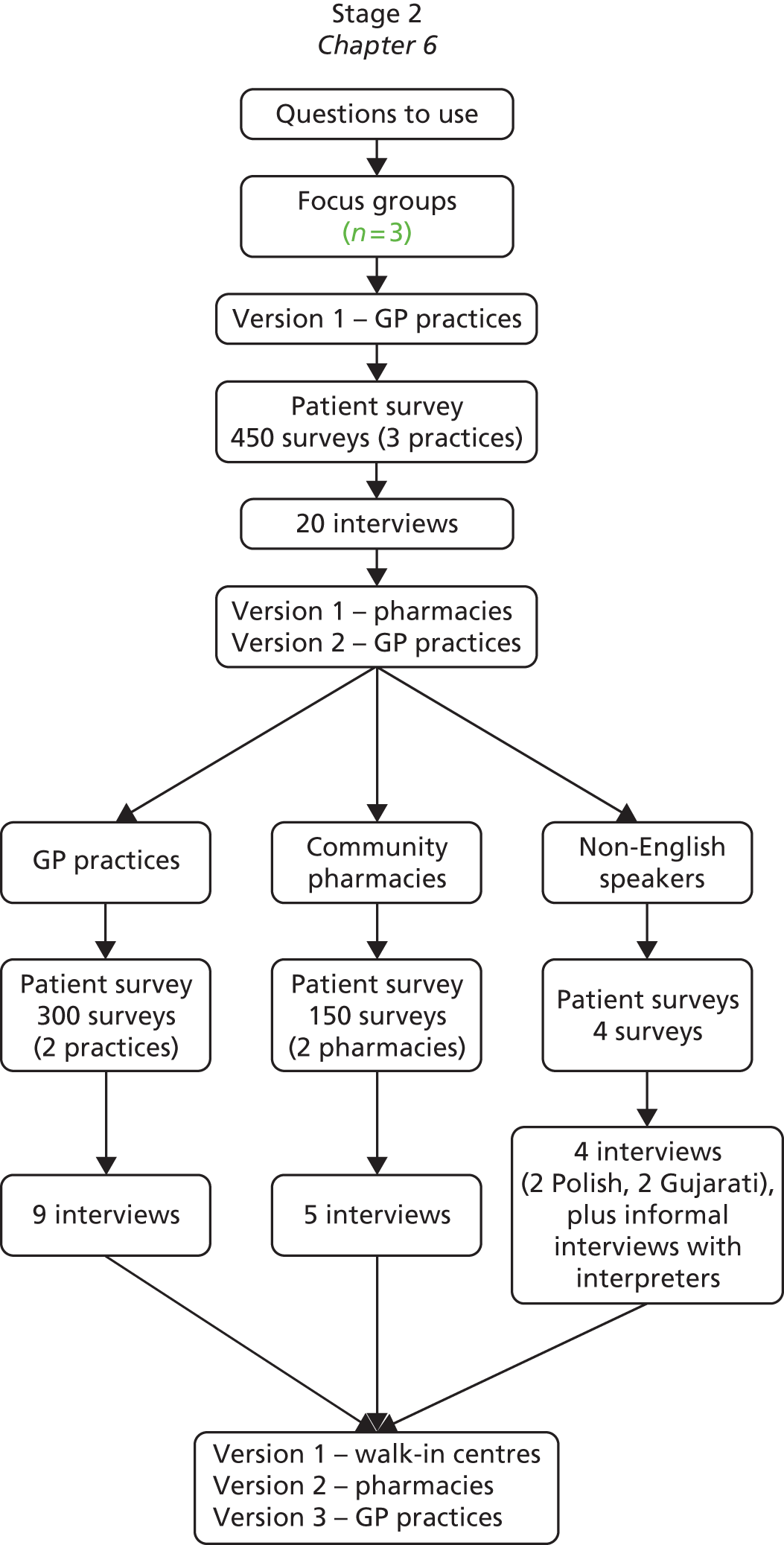

A draft questionnaire was developed including the revised questions, open questions to allow comments, and sociodemographic questions. A version was produced in paper and another online. The draft questionnaire was subject to two rounds of piloting, involving administration of the questionnaire to patients in primary care, semistructured interviews with responders to assess face validity and acceptability to patients, and cognitive interviews to assess comprehensibility. Piloting informed the refinement of questions, and provided insight into the feasibility of use of the questionnaire across different service providers (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Stage 2: piloting of the questionnaires.

Version 1 of the questionnaire related to GP surgeries only, with the plan to adapt for other primary care providers. The first pilot was conducted in three GP practices selected from the 12 PCOs remaining after stage 1 (one practice withdrew during stage 1). A patient survey was handed out to 150 patients in each practice and a purposive sample of responders who expressed an interest were invited to take part in semistructured interviews to assess face validity and acceptability. The questions were modified and a pharmacy version was developed. The second pilot was conducted in a different set of two GP practices and in two pharmacies. In this second pilot, 450 patients received a questionnaire and cognitive interviews were conducted with a sample of responders to identify problems with question wording or questionnaire design.

We also conducted a consultation with relevant groups and individuals, using contacts through the advisory group (e.g. learning disability organisations, community organisations representing patients from ethnic minority groups, people with visual impairment) to identify preferences for a range of formats, and approaches to administering the questionnaire; members of the project team also contributed to this.

The questionnaire and the approaches to administering the questionnaire were revised iteratively in the light of the findings from the pilots. Version 1 of the GP surgery questionnaire was tested in pilot 1, and then amended to version 2 in pilot 2. Version 1 of the pharmacy questionnaire was developed for pilot 2. In stage 3 (see Figure 3), version 3 of the GP surgery questionnaire and version 2 of the pharmacy questionnaire were tested, and version 1 of the walk-in centre questionnaire was developed and tested.

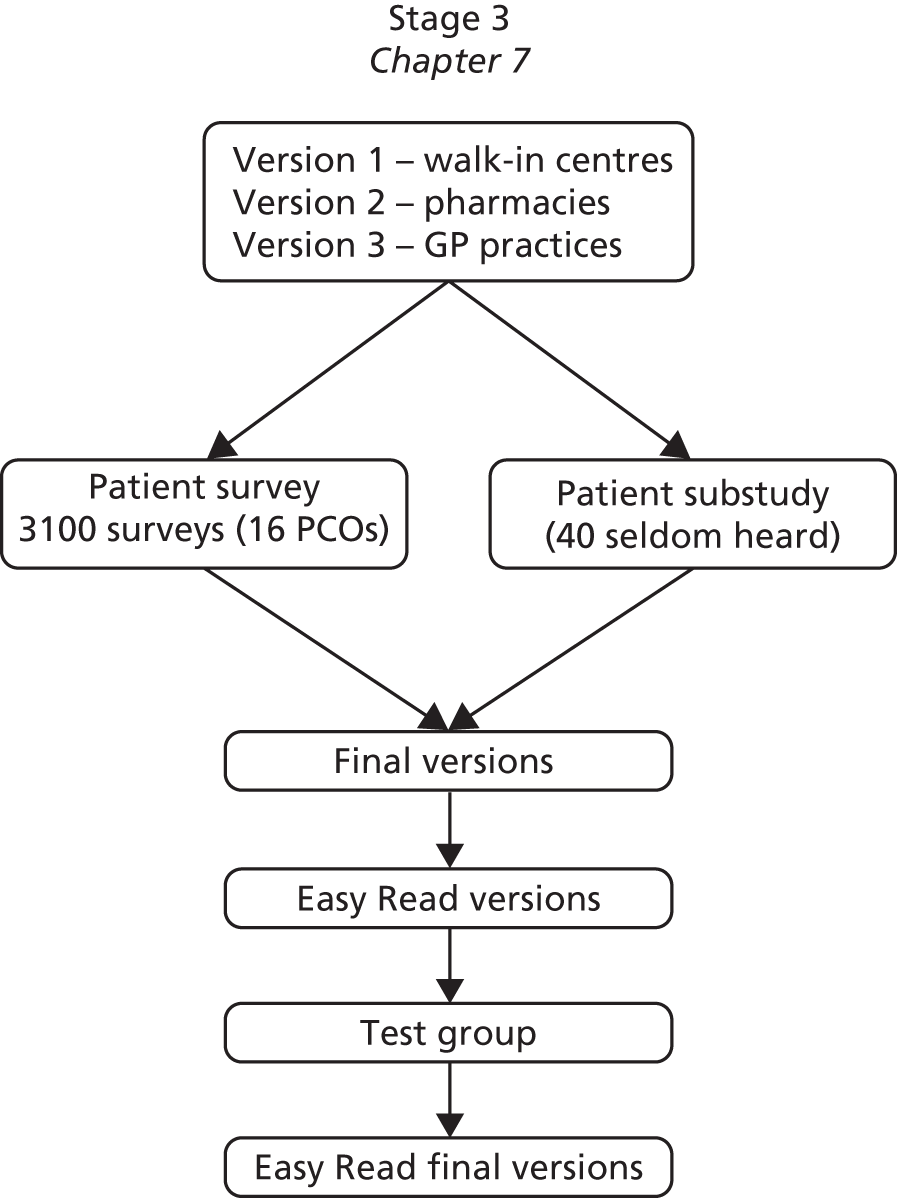

Stage 3: testing the questionnaire

To assess the reliability, validity and acceptability of the questionnaire, a large-scale pilot was undertaken in 16 PCOs across three regions in England: six of the PCOs recruited for stage 1 of the study, five new PCOs from the Northern and Yorkshire/North West region, and five new PCOs from Greater London (Figure 3). PCOs were selected to ensure a diverse sample, and included eight GP surgeries, five pharmacies, three walk-in centres and one Health and Social Care centre (Table 1). The questionnaire was handed to a sample of up to 200 users attending most PCOs, except the two pharmacies and a small specialist homeless practice recruited from stage 1 that handed out 100 each. As one practice withdrew before it had handed out any patient packs, these 200 were split between four other practices; hence four GP practices were asked to hand out 250. Two practices did not manage to hand out their full quota during the time scale of the study. Responders who expressed an interest were mailed a second copy of the questionnaire, to enable test–retest reliability to be assessed. Feedback was gained from staff in participating PCOs on their experiences of administering the questionnaire, and the value of the data to them in informing changes to practice.

FIGURE 3.

Stage 3: large-scale testing of the questionnaires.

As part of stage 3, we worked with a sample of PCOs to explore ways of including patients from ‘seldom-heard’ groups in the survey process. We conducted informal interviews with staff co-ordinating the survey to identify the ‘seldom-heard’ groups within their patient population and to discuss ways of supporting these patients to become involved. The study team provided support and resources to practices to enable them to undertake additional work to include ‘seldom-heard’ groups in the survey, in ways that were tailored to the needs of specific patient groups. We also engaged a specialist in Easy Read materials to produce an Easy Read version of the questionnaire. This was subject to small-scale testing with people with learning disabilities.

The questionnaire developed as a result of this process is available in three versions: a GP surgery version, a pharmacy version and a walk-in centre version. The majority of questions are common across the three versions, but each contained some questions specific to the particular type of PCO. The questionnaire was designed as a self-completion paper questionnaire in standard and Easy Read formats, but can also be interviewer-administered (including via an interpreter) or completed online.

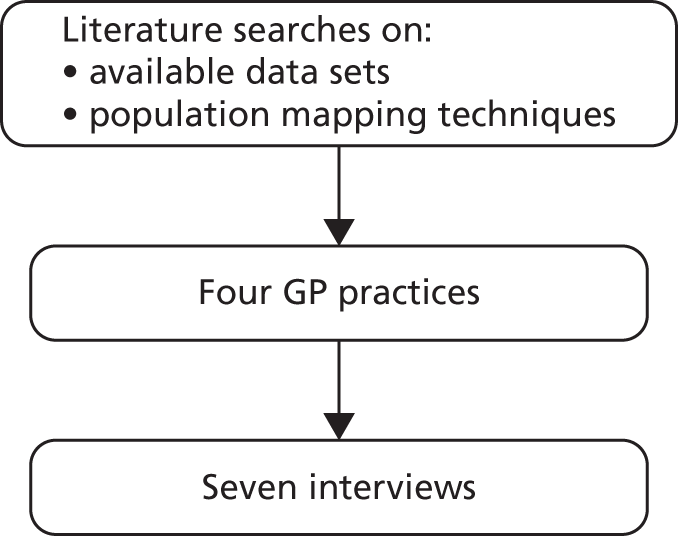

Mapping population diversity substudy

We also undertook a substantial substudy to explore approaches to and attitudes towards mapping diversity in primary care. This involved a review of available methods for population mapping and the challenges to this, and interviews with staff in four participating GP surgeries about their experiences of and attitudes to exploring the characteristics of their patient populations (Figure 4).

FIGURE 4.

Population mapping.

Data analysis

For the initial staff and patient interviews, and for narrative interviews in pilot 1, data were analysed using a combination of framework analysis and the constant comparative approach, which involved both deductive and inductive elements. An initial coding frame was generated from the research questions, which acted to guide, but not constrain, the analysis; themes and subthemes were added and iteratively revised as additional interviews were coded. The cognitive interviews were coded and charted with a focus on comprehension and response selection. NVivo 8 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to organise the qualitative data.cr.

For pilots 1 and 2, we used SPSS (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) to generate descriptive statistics for each question. In pilot 3, we carried out an exploratory factor analysis to investigate the structure of the GP questionnaire, and to identify key questions to form the basis of scores for the questionnaire which could be used as a measure of patient experience of responsiveness. We conducted analysis to provide initial evidence about reliability and validity. 32,33 We used Cronbach’s alpha coefficients to assess internal consistency for scores from identified subfactors. Pearson correlations were calculated between the scale scores from our questionnaire, and three indicators of construct validity. Kappa and intraclass correlation coefficients (ICCs) were calculated for the test–retest questionnaires to assess test–retest reliability.

Ethical considerations/governance

An advisory group was convened at the start of the project (see Appendix 1). We sought to include a variety of members with an interest in responsiveness in primary care, including academics, policy-makers and commentators, representatives from disadvantaged and traditionally ‘seldom-heard’ groups, and members of professional bodies. The remit for the group was to provide an insight into the meaning of responsiveness from their individual perspectives, and to provide feedback on our work in progress. The group’s advice and views have been invaluable throughout the project, and we are extremely grateful for their participation.

The study received a favourable opinion from the Nottingham Research Ethics Committee 2 on 28 May 2010. Research management and governance (RM&G) approval was received from all localities where the study was taking place. Seven substantial amendments were submitted throughout the course of the project, and all received a favourable ethical opinion and RM&G approval.

Assessment of the method

Strengths of the method

Our greatest success was ensuring we received the views from ‘seldom-heard’ patients. Given our focus on developing a questionnaire that reflected the needs and preferences of all patients, it was paramount that we both sought the views of these patients and tested the questionnaire with them. We achieved this using a combined approach. First, we ensured a diverse membership of the advisory group, including patient representatives from organisations that sought to promote the well-being of people with hearing and sight loss and learning difficulties, and ethnic minorities. Second, we included a specialist GP practice for homeless patients throughout the study, and recruited PCOs with diverse patient populations. Third, we devised a substantial substudy with two GP surgeries, to target two groups of ‘seldom-heard’ patients: Turkish speakers, and vulnerable (often homeless) patients attending a community group.

Another success was our sample of participants in all stages of the study, which was both large and diverse. The PCOs taking part in stage 1 were drawn from a variety of surgery locations (rural, suburban and urban; deprived and affluent; mixed ethnicities) with both large and small practice list sizes. In addition, we sought to include patients who were not well represented in the main sample. We recruited patients and patient representatives through charities supporting non-English speakers, people with learning difficulties, and people with hearing and sight loss both through the advisory group and by cold-calling organisations directly.

We also feel that exploring the meaning of the concept of responsiveness from a range of perspectives (through a literature review across different fields, from the perspective of staff across different PCOs, and from the perspectives of diverse groups of patients) has allowed us to generate a deep understanding of the complexities of the concept, and has generated valuable learning to inform work to improve responsiveness.

Methodological challenges

The greatest challenge was to provide the time and material resources to support the PCOs in their participation. As with most primary care research, there was a continuum of commitment and engagement from the participating PCOs. Some were extremely keen and contributed quickly and efficiently, with little input from the research team. At the other extreme were PCOs that needed regular reminders and prompting to ensure their continued participation. Some required material input, such as having ready-printed letters provided for use rather than printing the letters themselves on their headed paper. Unfortunately, one GP practice withdrew due to internal staffing changes during stage 1 (after the staff interviews, prior to the patient interviews). Another practice that agreed to participate in stage 3 eventually withdrew after many failed attempts on behalf of the research team to get data collection started.

Ensuring that the ‘seldom heard’ were included in stage 3 pilot was difficult. The two practices that engaged with the substudies to reach out to ‘seldom-heard’ groups were keen to participate and found the experience extremely rewarding. However, other PCOs were less interested in committing the time and resources. Administration of the substudy required additional administrative time and constant management.

Some of our methods were iterative and reactive to previous experience. During the 3-year project, we submitted seven substantial amendments to the research ethics committee and associated RM&G offices. These were time-consuming in terms of both preparation and approval processes. Although all amendments were ultimately successful, the project was held up on several occasions while we waited for approvals.

Two further methodological challenges arose. The first related to our aim of developing a measure of patient experience of responsiveness. Our initial intention was to design this to include a small number of generic, high-level and relatively abstract questions which would produce a single score. However, testing this approach with focus groups demonstrated that this was not acceptable to patients, and was unlikely to be valid. Patients wanted concrete questions that they could relate to their experiences. As a result, the questionnaire we developed was more specific and detailed than planned. However, our work in pilot 3 demonstrates that, despite this, it can be used to produce responsiveness ‘scores’.

The second methodological challenge relates to our aim of producing a measure that would be generic. For the reasons described above, this was not seen as acceptable to patients, so we instead developed a core questionnaire for GP practices and adapted this for pharmacies and walk-in centres. This means that the additional versions were not subject to the same level of development and testing as the GP questionnaire and are likely to require more work before they are ready for use.

Summary and discussion

This chapter has provided an overview of the methods we have used in the project. The qualitative interviews and focus groups, and the subsequent development of the questionnaires, are described. The methods of piloting of the questionnaires are introduced. Description of each of these methods is expanded within each of the following chapters of the report. We have also described the ethical considerations and governance arrangements employed during the study, provided a critique of our methods, and shared our main successes and challenges.

Chapter 3 Literature review: meaning and measurement of responsiveness

Introduction

We conducted a literature review on the meaning and measurement of responsiveness. The aim of this was to describe the range of work around the concept and to identify common and divergent themes. This provides a contextual background to our work to develop a measure of patient experience of responsiveness in the specific field of primary care.

A systematic search provided a starting point for scoping out the different fields in which responsiveness has emerged as a core concept; from this literature, we identified key items and followed narrative threads. We do not claim this to be a comprehensive and systematic review, and do not cite all papers identified through systematic searches. Rather, we draw on the literature to present a narrative overview of the diverse ways in which responsiveness has been conceptualised, and the implications of this.

Methods

We conducted systematic searches of MEDLINE and Web of Knowledge from January 2001 to March 2011 for papers relating to the meaning and measurement of responsiveness. This initial search was supplemented with searches of the internet and of reference lists of identified reports and papers, to identify relevant ‘grey’ literature. Identified abstracts were screened for relevance. The paper/reports were summarised into a chart which was used to generate an overview of the range and nature of work on this concept. The search strategy and methods for review and analysis are described in Appendix 2.

We present a narrative scoping review of the literature on the key fields of work relating to the meaning and measurement of responsiveness, and identify the themes that have emerged within these fields. In writing the narrative review we have referenced wider literature that was ‘signposted’ by papers identified through the core search.

Findings

Our review of the literature indicated that responsiveness is a rather fuzzy concept, with a range of meanings and definitions evident across different fields of the literature. We identified three distinct but overlapping conceptualisations of responsiveness in the literature, corresponding to domains of literature relating to service quality; inequalities and the needs of diverse groups (in health or other services); and consumerism and patient involvement.

Service quality

Responsiveness has a long history of being considered as a core element of service quality. 34 Service quality has been defined as the ability of the organisation to meet or exceed customer expectations. 35 Parasuraman and colleagues’ widely accepted model of service quality includes five key dimensions: tangibles (features of the service environment); reliability; responsiveness; assurance (the extent to which the organisation and its employees are perceived as credible and trustworthy); and empathy. Within this context, responsiveness has been defined as an organisation’s employees’ ‘willingness to help customers and provide prompt service’ (p. 23). 35

Service quality is seen as important for customer-serving organisations in marketing,36 achieving success and profitability through helping to attract and retain customers,37 and promoting customer satisfaction. Responsiveness is recognised as particularly important to the public image of customer-serving organisations; in the UK, the Institute of Customer Service38 makes a high-profile annual People’s Choice award for ‘Most Responsive Organisation’.

The notion of responsiveness as an element of service quality also features in the health literature. Several papers speak of responsiveness as part of a high-quality service, and as a feature of customer service or interactions between staff and patients. For instance, in a qualitative study of patients’ expectations and experiences of public and private providers, patients were found to expect more responsiveness and better quality of care and to be willing to pay for it. 39 A study of predictors of hospital patient satisfaction ratings in the USA found that nursing staff communication with patients had an important bearing on perceived responsiveness. 40

The field of work on service quality has generated a number of measures; the most widely used of these is the SERVQUAL scale. 35,41 This incorporates the five dimensions of service quality described above. The SERVQUAL scale includes a subscale of four questions to measure responsiveness:

-

P10: employees of XYZ tell you exactly when services will be performed

-

P11: employees of XYZ give you prompt service

-

P12: employees of XYZ are always willing to help you

-

P11: employees of XYZ are never too busy to respond to your requests.

SERVQUAL has been used extensively across a wide range of settings to measure service quality, either in its original form or adapted to the specific setting. 42,43

The SERVQUAL dimensions have been found to be applicable and stable in the measurement of service quality in health care,44–46 and specifically in primary care,47 with responsiveness remaining a core element of service quality in this context. SERVQUAL has been adapted and used in studies of service quality in a range of health-care settings48–51 but has not found wide application in the context of primary care. A version of SERVQUAL designed to assess the quality of hospital services has been developed,52 and SERVQUAL has been adapted for use in a primary care clinic in the USA. 53 The revised scale was assessed for factor structure, reliability and validity; responsiveness remained a core element of the scale. Four questions on responsiveness were included, relating to prompt service; employee willingness to help; staff never too busy to respond to requests; and convenient opening hours.

The conceptualisation of responsiveness as an element of service quality has several key implications. First, responsiveness is tied to customer service – the quality and promptness of interactions between employees and customers (or between staff and patients) – rather than other features of the organisation. Second, the notion of service quality focuses on improving customer experience, exceeding expectations, increasing satisfaction, and even ‘delighting’54 the customer. It is seen as a route to attracting and retaining customers, and increasing market share. Within this literature, responsiveness is not seen as a ‘duty’ or essential feature of an organisation, but as a ‘value adding’ feature of service. Third, the focus is not on diverse or disadvantaged groups, but on improving the experience of all customers/patients.

Inequalities and the needs of diverse groups

The concept of responsiveness is also prominent in the field of work relating to health inequalities. Seminal work undertaken by the World Health Organization (WHO) in the late 1990s and early 2000s identified responsiveness as one of the three intrinsic goals of health systems (along with good health and fair financing). 55 Responsiveness involves health systems meeting the needs of the patients they serve, and is based on the idea that there are fundamental needs, or basic human rights, that health systems should meet for all patients. These needs are seen as relating to the non-clinical domains of health service provision. Responsiveness is defined as ‘how well the health system meets the legitimate expectations of the population for the non-health enhancing aspects of the health system. It includes seven elements: dignity, confidentiality, autonomy, prompt attention, social support, basic amenities, and choice of provider’ (p. 1). 56 It is suggested that if a health system is responsive, the interactions that people have within the health system may improve their well-being, irrespective of improvements to their health. 57

The WHO argues that the measurement of responsiveness is essential to assessing the performance of health systems, and importantly, involves measuring ‘both the overall level of achievement (average over the whole population) as well as the distribution (equitable spread of this achievement to all segments of the population)’ (p. 1). 56 It is clear that this conceptualisation of responsiveness involves fairness and avoiding inequalities across the patient population.

By their definition, the WHO sought to measure responsiveness objectively by looking at how patients perceive what happens in their experience of using health care. 56 They developed a responsiveness instrument58 and tested it across 35 countries. Factor analysis revealed the seven elements used in their definition, above. 59 Levels of responsiveness were measured using a patient-report questionnaire, split into two sections: patients were asked, first, to rate their experience with the system, and second, to rate how important each element was to them. Each element comprised 3–7 questions. 56 Questions were formatted to assess the extent to which patients felt their needs for each dimension were met, for example:

-

In the last 12 months, how often did the office staff, such as receptionists or clerks there, treat you with respect?

-

always

-

usually

-

sometimes

-

never.

-

Data on inequalities in distribution of responsiveness were generated through surveys completed by key informants in each country; informants were asked about whether or not they felt that particular patient groups were discriminated against with regard to responsiveness in their country. 60

The WHO responsiveness measure has been widely used in studies to assess health system responsiveness internationally. 61,62 This has included work to identify predictors of health system responsiveness; evidence suggests that health-care expenditures per capita, and educational development, are positively associated with responsiveness, while public sector spending is negatively associated with responsiveness. 63 The WHO definition has also been used as the basis of work to identify unmet needs in disadvantaged groups, including a literature review to identify the extent to which people who access mental health services were not having their needs met. 64

The WHO work focuses on responsiveness of health systems, rather than individual providers such as GP practices. The WHO definition was adapted for primary care by Canadian researchers to produce a definition of responsiveness as the ‘ability of the primary care unit to provide care that meets the non-health expectations of users in terms of dignity, privacy, promptness, and quality of basic amenities’ (p. 341). 65 They argued that the operationalisation of responsiveness was problematic due to lack of distinctness from other concepts such as whole-person care. Their earlier work to develop national indicators suggested two core questions to ask about responsiveness: ‘Are patients satisfied that the Primary Health Care organization and providers respect their right to privacy, confidentiality and dignity? Are patients confident that PHC organizations and providers are responsive to their culture and language needs?’66

The focus in health on responsiveness as involving providing services equitably and meeting the needs of all, across diverse groups, is echoed in work on responsiveness in the field of education. Responsiveness to learners’ needs has been considered in terms of meeting individual student needs, information, support, respect and opportunities to air views; these dimensions have been included in the National Learner Satisfaction Survey. 67

As discussed earlier, arguments for the need to promote responsiveness in primary care tend to draw heavily on the inequalities agenda with a recognition that responding to specific groups’ needs might help to reduce inequalities. 68 However, needs are framed in a slightly different way from the notion of universal legitimate expectations that is central to the WHO work. Instead, the focus is on the diverse needs of different patient groups, and ensuring that individual patient needs are met through individualised and proactive care. 69,70 Alignment with the needs of different patient groups is seen to be important, and there has been particular focus on the need for cultural alignment with minority groups. Research has shown how cultural self-reflection and self-awareness on the part of staff can be helpful, and how developing a reciprocal understanding of needs can lead to a flexible responsive service. 71 However, the evaluation of a human immunodeficiency virus mental health service that actively valued cultural responsiveness (acknowledging clients’ cultural identities, taking their beliefs, norms and values into account in the interventions) struggled to separate out whether cultural responsiveness or integrated care affected observed findings independently or in combination. 72

With responsiveness defined as an approach to reducing inequalities, the onus is on providers to ensure that they understand their practice populations, and can segment them based on need. 13,73 There is also an emphasis on finding proactive ways to reach out to marginalised groups who may find it difficult to access health care. 74,75

One challenge raised within this field relates to the nature of needs, expectations and demands. A distinction has been made between needs and demands in the context of health needs assessment, and this distinction may be useful in conceptualising needs in relation to non-clinical aspects of care. Under this framework, needs have been described as areas in which there is capacity to benefit, and as ‘normative’, i.e. they should be met. 76 Demands are what patients ask for (implicit in this is the notion that it may or may not be appropriate for providers to respond to demands). One study, exploring the views of staff about needs and demands in relation to public services, concluded that responsiveness related to identifying unmet needs (with a focus on cultural needs), and finding the right balance of managing needs and demands. 77 The authors define needs as rational demands (consistent and evidence-based) as opposed to demands as ‘desires’. They argue that public services should try to meet users’ demands, but that other forms of demand management may be required to realign these demands with users’ needs. They suggest that practical demand management in needs-based public service requires knowledge of users’ demand for services; content analyses of users’ demands to identify any misinformed demands; conversion of any misinformed demands into evidence-based specifications of needs; and formulating coherent evidence-based demands on behalf of users who cannot do so themselves. They acknowledge the tension between needs assessment being professionally controlled rather than responsive to users. 77

The key implications of considering responsiveness as relating to inequalities include, first, that responsiveness relates to a broad set of non-clinical features of service organisation and delivery. Second, responsiveness is seen as a core duty of an organisation – providing a level of service that meets patients’ needs fairly across all patient groups (although there are some differences in emphasis in relation to whether this refers to basic universal needs or specific needs of different patient groups or individual patients, and a recognition that responsiveness may involve managing demands). Third, the focus is on diverse groups and ensuring that no patient groups are disadvantaged in their experiences of receiving services. Under this definition, achieving responsiveness requires more than just good customer service; it requires an understanding of population characteristics, and proactive planning to meet needs and avoid disadvantage. Finally, measures of responsiveness need to pick up on differentials between different groups, and identify whether or not certain groups are disadvantaged (e.g. BME groups, deprived groups, males, females).

Consumerism and patient involvement

The focus on responsiveness has been linked with the shift towards consumerism and consumer demand for services that are tailored to individual needs. Responsiveness is seen as a way of bringing the NHS in line with other services such as retail and banking, which are geared towards being adaptable to individual needs, and offering more convenience, choice and flexibility. Fundamental to this shift is the idea that services should be geared to the interests of users rather than the convenience of producers. 78 Increasing user participation is described as core to this; an advisory document reporting on group discussions and a citizens’ forum found that:

Overall, people think that a responsive public service is one that: provides easy and appropriate access to services; encourages the individual to use and shape services in ways that suit them; actively seeks to learn from public involvement and develop services accordingly. 70

p. 5

People’s ideas on how public services could be made more responsive included making communication simple and obvious, keeping people informed throughout, involving people as early as possible, and shared responsibilities and shared outcomes. 70 User ‘choice’ and ‘voice’ are also seen critical: exit and voice (communicating user demands) have been described as two ‘recuperation’ mechanisms for making organisations responsive. 79

In the context of public service and administration literature, responsiveness has been contrasted with collaboration. 80 The authors described responsiveness as responding to requests for action or information. They viewed responsiveness as a mostly passive, unidirectional reaction to people’s needs and demands, whereas collaboration was a more active, bidirectional act of participation, involvement and unification of forces between two or more parties. Some definitions of responsiveness in primary care and patient involvement literature are more in line with this notion of collaboration.

Responsiveness in primary care has been defined as synonymous with patient participation, engagement and involvement. 81 NAPP suggest that being responsive requires practices to engage with patients; that patient experience is a key part of a responsive practice; and that improved communication and responsiveness are needed for a successful practice and patient participation group (PPG). 81 A discussion piece summarising the meaning of responsiveness included involving patients with service planning. 74 The authors found two ways that this was enacted. First, some seek to involve patients in the planning of care. Second, others make attempts to reach out to groups who find it difficult to access health care. A Scottish study of Local Health Care Co-operatives highlighted the need to engage patients and local communities, and defined responsiveness in terms of proactively engaging patients in planning services. 82

The close link between responsiveness and patient engagement is highlighted by the inclusion in a directed enhanced service (DES) framework on responsiveness of an eligibility criteria relating to engagement with patients,13 as the report states:

Improving access and responsiveness needs to be strongly founded on engagement with patients and should be a dynamic process. Providers should be required to demonstrate active engagement with people and local communities in developing services . . . Providers should demonstrate how they respond to patient feedback and this is to be used to shape and improve services . . . Local Involvement Networks (LINks), the voluntary sector and patient advocacy organisations are all further mechanisms to seek active involvement in service planning, delivery and monitoring.

p. 6

There are limitations to the conceptualisation of responsiveness as dependent on choice, voice and patient involvement. Changing providers is not always cost-neutral for users, and exercising voice adds practical burdens with little reward, hence users who exercise voice may be few, self-selected and apparently ‘unrepresentative’. 79 Many people with common health conditions, such as mental health problems, are reluctant or unable to engage in the ‘user movement’, hence undermining the effectiveness of patient involvement. 69

The key implications of definitions of responsiveness within the consumerism/patient engagement literature are, first, responsiveness framed in this way is about patients as consumers taking responsibility for defining78 and asserting their needs. The implication of this is that less responsibility is placed upon providers to proactively plan for and support disadvantaged groups. This is in tension to some extent with the notion of responsiveness as a duty of providers and as a way of reducing inequalities (as discussed above). Reliance on patient choice and voice may result in responsiveness to those who are most eloquent and demanding, at the expense of the vulnerable and needy. There has been much focus on the need for groups who are disadvantaged to have a voice, and on providers working to involve, and hear the voices of, ‘seldom-heard’ groups. Second, a distinction can be made within this literature between the notion that responsiveness can be defined as the extent to which providers engage with patients and enable choice and voice, and the view that patient involvement and engagement is a key means of achieving or improving responsiveness (by helping providers better understand patient characteristics and needs, particularly those of groups who are disadvantaged). Third, this suggests that measures of responsiveness should assess aspects of patient choice and engagement, and the extent and quality of dialogue between providers and patients.

Summary and discussion

We have demonstrated that the literature on responsiveness falls into three broad, overlapping themes. Service quality literature speaks of responsiveness as part of a high-quality service. Responsiveness is closely linked with good customer service – providing for customer needs in a quick, efficient and polite manner. Literature on inequalities casts responsiveness as a duty of providers and as involving meeting the needs of all patients across different patient groups. A third body of literature links responsiveness to the shift towards consumerism and patient participation: being a responsive GP practice means engaging with patients, for example, through working with PPGs and involving patients in planning services.

These three distinct conceptualisations of responsiveness have different implications and connotations. With responsiveness conceptualised as service quality, it is seen as something that adds value to a service, and as a way of attracting customers and building market share. It is not seen as a ‘duty’ or essential feature of an organisation, but as a ‘value adding’ feature of service. This conceptualisation has a focus not on diverse or disadvantaged groups, but on improving the experience of all customers/patients. When responsiveness is defined as relating to inequalities, it becomes seen as a core duty of an organisation, and the focus shifts to considering the needs and experiences of disadvantaged patient groups. Conceptualising responsiveness as relating to patient involvement shifts the responsibility away from the provider and sees it as held by or shared with the patient.

In English policy, definitions of and debates about responsiveness reflect the different conceptualisations emerging from these three bodies of literature, as can be seen in the definition presented in the report Improving GP access and responsiveness:7

Practice responsiveness is the way in which a practice communicates and engages with its patients and their carers and responds to their non-clinical needs and preferences, reflecting the different ways in which they might prefer to access the service and an appropriate clinician, book, or indeed cancel an appointment. It includes the practice’s attitude to customer service and friendliness of staff, the environment in which patients wait to be seen and the way in which they interact and support patients from particular groups, such as those with hearing or sight loss or people from a black or minority ethnic background.

It is potentially problematic that the definition of responsiveness in primary care draws on all three conceptualisations of responsiveness, all with different implications about how responsiveness might be achieved and measured, meaning that responsiveness in primary care remains a fuzzy and poorly delineated concept. In subsequent qualitative work, this study sought insight into what responsiveness in primary care actually means to staff and patients, and how it can be measured and then improved.

Chapter 4 Staff interviews

Summary of this chapter

We conducted interviews with a purposive sample of clinical, management and administrative staff from GP practices, pharmacies and walk-in centres. We aimed to gain insight into the meaning of responsiveness for PCOs, the strategies and approaches to improving responsiveness to diverse patient needs in primary care, and the key barriers and challenges. We also explored what measures PCOs currently used to assess their responsiveness, and their preferences for features of a new questionnaire.

Methods

Recruitment

Semistructured interviews were conducted with members of staff recruited from 13 PCOs in the East Midlands of England (see Table 1). Purposive sampling ensured that a range of PCO staff (management, clinical and reception) were involved. Staff were approached directly by a study researcher, with permission from a senior member of staff, or were approached by our main contact at the PCO. Two members of staff were invited to be interviewed at each PCO. One PCO was a practice managed by a large national company; here, we invited a member of staff at the head office, in addition to the practice staff.

Interviews

Most of the interviews were conducted by EA or JW on PCO premises, and one was conducted over the telephone. A topic guide was developed and used flexibly to guide the conduct of the interviews. Participants were asked to give their views on what responsiveness meant to them and their PCO, how responsiveness was enacted in their PCO, and successes and difficulties they had faced in their attempts to be responsive to patients’ needs and preferences. The topic guide for the GP surgery and walk-in centre staff is included in Appendix 3; this was adapted slightly for pharmacy staff. Interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim.

Analysis

Analysis progressed alongside the interviews using NVivo to organise the data. Data were analysed using a combination of framework analysis83 and the constant comparative approach, which involved both deductive and inductive elements. An initial coding frame was generated from the research questions and focused on the meaning of responsiveness, examples of implementation, meeting the needs of different groups, and barriers and facilitators to providing a responsive service. We used this coding frame to map staff descriptions of the strategies available to them to develop responsive primary care services. The coding frame acted to guide and bound the analysis of staff interviews to ensure a focus specifically on ‘responsiveness’, not just broad experiences of primary care (e.g. ensuring that the focus remained on ‘non-clinical’ aspects of care). However, we were careful to ensure that the coding frame did not unduly constrain the analysis; themes and subthemes were added and iteratively revised as additional interviews were coded. As such, themes were tested and developed inductively to produce a description of the strategies PCOs use to be responsive, grounded in staff’s views and experiences. In interpreting the data, we drew on concepts around market orientation and customer orientation developed in the marketing literature. 84,85

In the initial part of the findings, we focus on data from the GP practices; we reflect on similarities and differences in the accounts of walk-in centre and pharmacy staff in a separate section.

Findings

Twenty-seven members of staff were interviewed, including GPs, practice and pharmacy managers, administrators, receptionists, and a nurse (Table 2). We interviewed six men and 21 women: 22 white British, four South Asians and one Filipino. Staff had worked at their respective PCOs for between 8 months and 25 years (median 4 years, mean 6 years) (see Table 2).

| Job role | Sex | Age group (years) | Total | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 18–24 | 25–34 | 35–44 | 45–54 | 55–64 | |||

| GP | M | – | 1 | 1 | 1 | – | 3 |

| F | – | 1 | 1 | – | – | 2 | |

| Nurse | F | – | – | 1 | – | – | 1 |

| Practice manager | M | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| F | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 6 | ||

| Receptionist | F | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 8 |

| Head office | F | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| Pharmacy manager | M | – | 1 | – | – | – | 1 |

| F | – | – | – | 1 | – | 1 | |

| Pharmacy staff | F | – | – | – | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Total | 2 | 7 | 6 | 7 | 5 | 27 | |

General practitioner practices

Meaning of responsiveness

Responsiveness was seen by the majority of staff to be about how the practice meets the needs of their patients, particularly around gaining access to the care they need. Staff commonly talked about meeting the needs of vulnerable groups who may need additional support to access the services they need, and ensuring that patients from diverse groups were treated fairly. These groups included patients with particular characteristics (e.g. older people, people from a BME background, non-English speakers); illnesses, conditions and disabilities (such as the blind or partially sighted, deaf or hard of hearing, and those with specific conditions such as cancer, diabetes and epilepsy); and situation, location and lifestyle (busy or working people, carers, people living in deprivation or who are homeless, travellers).

Giving appointments that the patients require, they are getting the telephone access that they require, they are getting the treatment that they require. [. . .] It’s aligning with the patient’s agenda I think.

S09, GP

From my point of view, responsiveness is being there for the patients and responding to what their needs are, and making sure the surgery provides what the patient population needs. [. . .] The needs of the patients here are a lot different to [our other practice]. [. . .] Here, you have got a mixture of young Asian families and elderly white folk, at [our other practice] I would say 99.9 of the population are Muslims.

S25, practice manager

Some staff, particularly practice managers and reception staff, understood responsiveness in terms of how they dealt with individual patients’ needs at the point at which the patient used the service.

So responsiveness is dealing with the problem I think as fast and as promptly as you can.

S03, practice manager

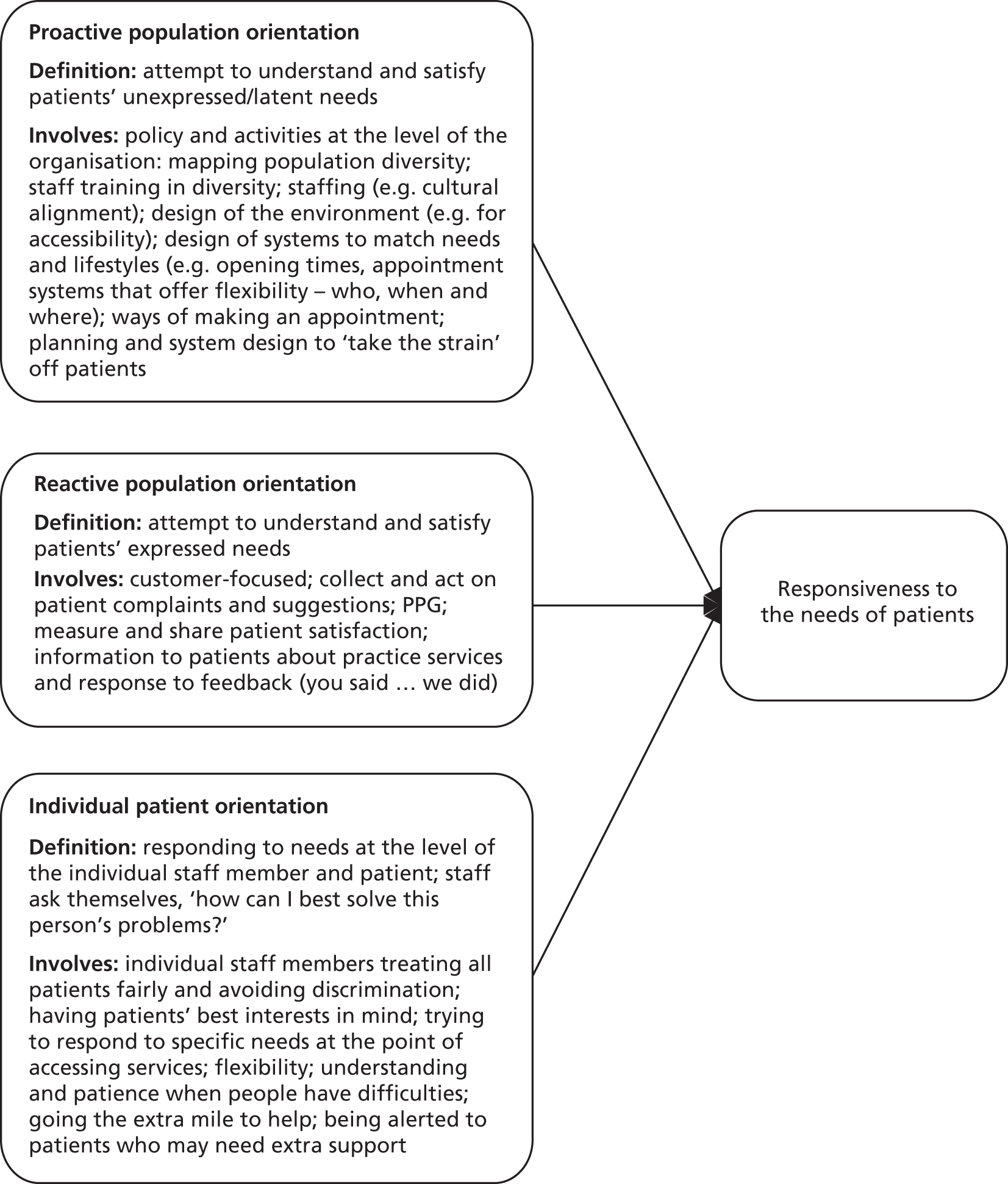

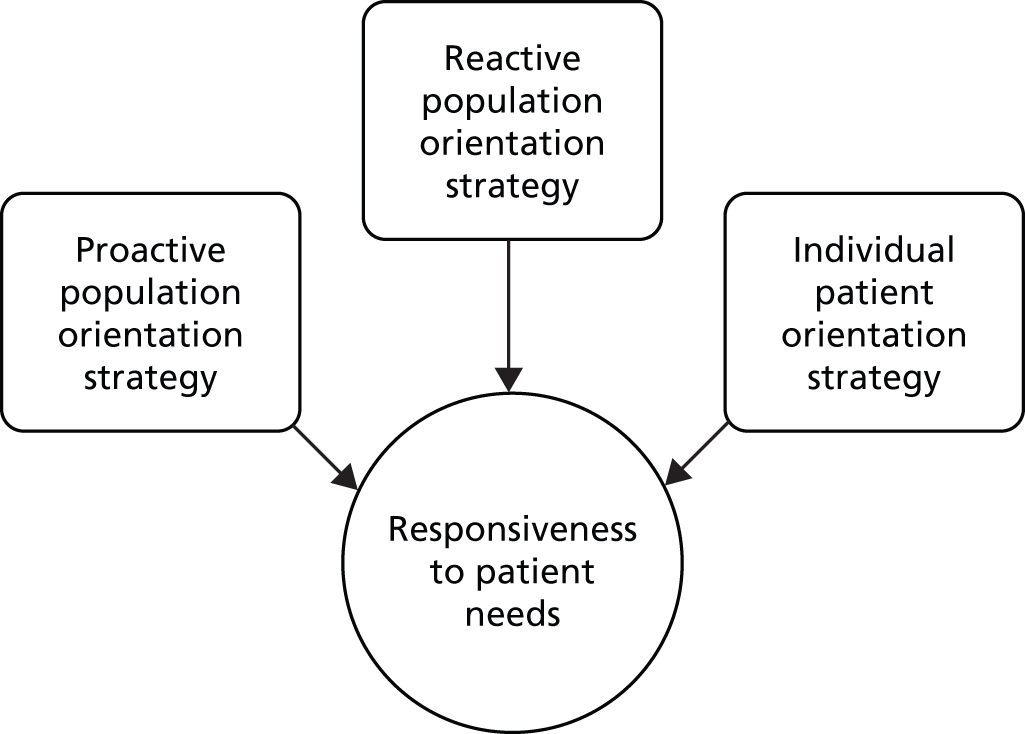

What approaches do primary care organisations use to make their services more ‘responsive’ to the needs of patients?

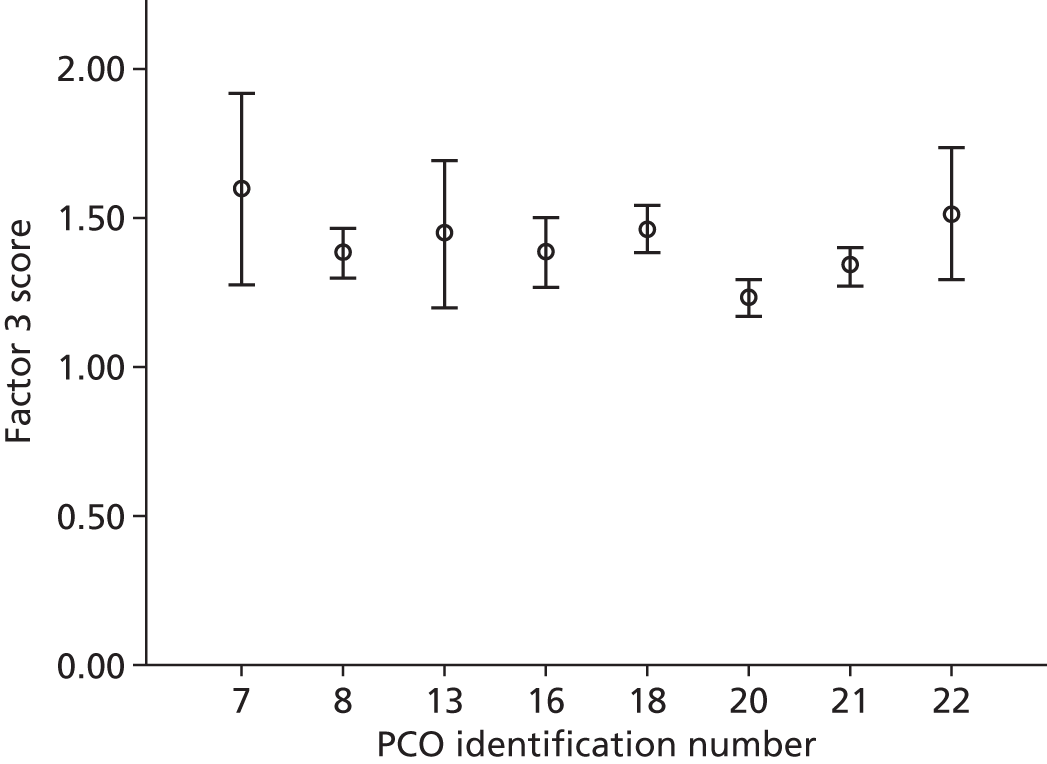

Staff described various activities undertaken at their PCO to improve the extent to which they could meet the needs of their patients. From these descriptions we developed a typology of approaches to providing a responsive primary care service. We found that approaches fell into three distinct categories that varied in the extent to which they were proactive or reactive, and the extent to which they were focused at the level of the practice population or the individual patient. These categories were (1) proactive population orientated approaches (approaches that involved PCOs planning ahead to design systems and services around the anticipated needs of the different groups of patients that used their services); (2) reactive population orientated (attempts to elicit and respond to patients’ expressed needs, feedback and complaints); and (3) individual patient orientated (providing flexibility and support at the level of the individual patient), which is also primarily reactive. These themes are summarised in Figure 5.

FIGURE 5.

Strategies for responsiveness: themes.

Proactive population-orientated strategies

One prominent theme in staff accounts of strategies for responsiveness reflected the attempts of practices to develop an awareness of the diverse patient groups they served and their specific needs, and to proactively design and organise their services so that they could respond to the needs of specific patient groups.

It’s looking at different groups of people and trying to work out what they want and need, and looking at ways to provide that, . . . it’s trying to find ways to firstly kind of identify the problems and then work out ways to change things.

S15, GP

A minority of practices had developed an understanding of their patient populations through formal mapping, but the majority described their understanding as based on informal staff knowledge of the local patient population. (The issue of practices’ awareness of the characteristics of their patient population is explored in more detail in Chapter 8. )

[Site 1] has a lot of Muslim patients and South Asian patients, [site 2] has some as well but less . . . a lot of Polish patients as well. I don’t know about our Afro-Caribbean population, no idea. There definitely are some but I have no idea what proportion we would have.

S02, GP

The steps that practices took to proactively plan for and support the needs of diverse groups included adapting the physical environment and technology, providing interpreters and other communication support, staff training on diversity, considering the design of appointment and booking systems, and using tailored approaches to contacting specific groups of patients and delivering services to meet their needs.

The physical environment was talked about commonly in the context of how improvements to the building had been made in ways that met the needs of diverse groups. This was particularly in relation to patients with disabilities, although staff also talked about how consideration had been given to the way the environment could be set up to better meet the needs of other groups, including teenagers and families with young children.

One of the things when we had the building refurbished was improving disabled access, because we used to have a horrible desk where . . . the receptionist [was] standing behind a chest-high hatch with a grill, whereas we have got that low desk now.

S12, practice manager

The teenage population . . . for them, . . . as you come just inside the surgery, there is a huge notice board there and we put things there, because we feel that the teenagers coming in might not want to come fully into the surgery, they can just come into that first bit the foyer, see what they need to see and if anything there, does interest them, then they can come in further.

S14, receptionist

Staff also talked about provision for communication support for specific patient groups, including non-English speakers and patients with a sensory impairment:

We have got quite a lot of patients who don’t speak English as their first language. So things like the screen that patients use to book in when they arrive at the surgery: . . . if they speak a different language then that is all written in the language that they speak.

S15, GP

Staff training in diversity issues, and in supporting the specific needs of specific patient groups, was also seen as critical to providing a responsive service.

I think probably [we need] more training and awareness for staff . . . It’s maybe that education about the range of issues that may be faced from mental disabilities, visual impairment, hearing impairment, physical disabilities . . . to make sure that we try and consider things from the perspectives of every one of our patients.

S27, head office

For some groups of patients, the key issue was seen to be planning to enable diverse patient groups to access the services, particularly groups of patients who would be disadvantaged by standard opening times and appointment systems. Staff described ways that their practice had adapted the systems for appointments around the needs of these patient groups.

We have obviously got some surgeries that support care homes, you know, you have got people that have mobility issues, so we tend to do regular GP visits, . . . we will say the GP is going to be here on a Monday afternoon and a Thursday afternoon. [. . .] So we do try to accommodate the needs that we have.

S27, head office

Many staff recognised that tailored approaches could be required to help patients from disadvantaged groups to access services and have their needs met. Being responsive often involved practices ‘doing things differently’ in the way that they communicated and engaged with patients.

We have got a few [patients] in [location] that couldn’t read or write. So we were sending out absolutely loads of letters, for all chronic diseases, for immunisations, follow-ups for smears. Our postage was extortionate, but I think we were having no results [. . .]. So then we started to actually telephone, to actually ring them up . . . and that was quite successful.

S03, practice manager

We do the learning disability health checks here . . . and they gave us literature for people with learning disabilities and told us how to set things out, for somebody with a learning disability . . . Just sending them a standard letter, they are going to think ‘oh no’, but this had pictures and things on it so that was very useful.

S25, practice manager

In some practices, initiatives that had been developed to help improve the services or support provided to specific groups within the practice population. Setting up registers of patients with specific needs could help practices to identify patients who might benefit from additional support and to direct them to appropriate services.