Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1809/255. The contractual start date was in December 2009. The final report began editorial review in July 2013 and was accepted for publication in February 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paula Whitty has been employed as Director of Research, Innovation and Clinical Effectiveness at one of the research study’s mental health trust study sites since April 2011 (and by the trust’s predecessors as Consultant in Medical Care Epidemiology since 1998). David Hunter is an appointed governor of one of the acute foundation trust hospital study sites involved in this research project and was a member of the commissioning board for the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation programme between 2009 and 2012, and the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research programme between 2012 and 2014. Jonathan Erskine was a non-executive director of one of the primary care trust study sites until October 2011. Martin Eccles received a salary one day a month as a senior mentor for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Fellows and Scholars programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Hunter et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Policy context and background

The North East Transformation System (NETS) was a unique experiment in the adoption of transformational change in a complex system, namely the NHS in North East England. If the initiative had been allowed to evolve and mature, it might have become a blueprint for other regions to copy. However, it was unexpectedly interrupted and required to take a different direction following the UK coalition government’s proposals to reorganise the NHS, announced in July 2010. 1 In this scene-setting introductory chapter, we locate the NETS in its broader policy context.

Launched in 2007, the NETS was both pioneering and novel in terms of its purpose and scope. However, it did not exist in isolation from other quality initiatives that also sought to improve service delivery and quality of care, while also reducing waste and variation. Government policy during this period was influenced by several factors. First was the election of a Labour government that sought to distance itself from its predecessor’s health-care reforms, which emphasised internal markets and competition as a mechanism to stimulate health service improvements. In addition, the appointment in 1999 of Liam Donaldson as Chief Medical Officer for England proved both timely and significant. Donaldson had been a major proponent of patient safety in his previous role as Regional General Manager of the former Northern and Yorkshire Regional Health Authority. He was also a principal architect of clinical governance arrangements. Clinical governance has been defined as ‘a framework through which NHS organisations are accountable for continuously improving the quality of their services and safeguarding high standards of care by creating an environment in which excellence in clinical care will flourish’. 2 Many of the concerns and concepts embraced by clinical governance were encompassed in the NETS.

The NETS therefore evolved and took root within a policy context that was sympathetic and receptive to its overall aims, purpose and approach. This introductory chapter sets out the key elements of the government’s focus on quality improvement (QI) which formed the broad policy context for, and background to, the NETS. Chapter 3 provides a brief history of the origins and evolution of the NETS, which formed the backdrop to the evaluation of its evolution and its impact over the period of the study.

A focus on quality and QI has been a central feature of NHS policy since 1997, although the interest in quality goes much further back. The Labour government, elected in May 1997, invested heavily in a range of initiatives intended to improve quality. In a White Paper published in 1997 (The New NHS: Modern, Dependable), it stated: ‘The new NHS will have quality at its heart . . . Every part of the NHS, and everyone who works in it, should take responsibility for working to improve quality’3 [© Crown copyright 1997, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0 (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2)].

The government expressed concern about the unacceptable variations in performance and practice. It sought to address the problem by putting quality at the top of the NHS agenda. The objective was to align local clinical judgements with clear national standards that incorporated best practice. This was described in detail in an important consultation document published by the Department of Health in 1998, A First Class Service: Quality in the new NHS. 4 The plan was for national standards to be set through national service frameworks and through the establishment of a new body, the National Institute for Clinical Excellence (NICE) (in April 2013 this became the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence).

At local level, standards were to be delivered by a clinical governance system that was informed by the latest evidence and guidance on what worked best for patients. The approach was also supported by lifelong learning for staff and modernised professional self-regulation. Clinical governance is the process by which each part of the NHS assures its quality and ensures that clinical decisions are aligned with its principles. The intention was to introduce a system of continuous improvement into the operations of the whole NHS. Quality was to be everybody’s business and was based upon partnerships within health-care teams comprising health professionals and managers. The new emphasis on quality was to be established at all levels of the NHS. It was stressed that the drive to place quality uppermost on the NHS agenda was concerned with changing thinking, rather than merely ticking checklists.

Central to the government’s focus on quality was the clinical governance framework which included a comprehensive programme of QI activity and processes for monitoring clinical care. Developing a structured and coherent approach to clinical quality was central to the whole endeavour. This included an emphasis on attracting, developing, motivating and retaining high-calibre health-care professionals, managers and staff. Continuing professional development was viewed as central to continuous QI, which was termed ‘action for quality’. The 10-year strategy acknowledged that the issues were complex and could not be tackled overnight. The vision for quality aimed to create a NHS culture that encouraged innovation and success, and one that fostered a learning culture which made good use of best practice exemplars. This was seen as the bedrock of continuous improvement, as well as a focus on partnership working rather than competiton. 4

The drive to improve quality was considered to involve major cultural change for all. Part of supporting such a change in culture entails developing organisations to deliver change. 4 The crucial elements to achieve success were excellent leadership and the involvement of staff. These were important because, in some QI work, there has tended to be a separate focus on either clinically led improvement or improvement led from a management perspective. The result was discrete, parallel activities within organisations with misaligned objectives, duplication of effort and a lack of focus. 5 The challenge for health-care organisations is to improve both clinical and managerial quality, as in practice they interact – or should do. The government acknowledged this in 1998. When the NETS was conceived nearly 10 years later, it was similarly informed by such an approach.

Many of the ideas set out in the government’s 1998 consultation document were lost in the subsequent series of NHS reforms that started with the NHS Plan in 2000. 6 Further waves of structural and other changes to various NHS organisations proved both disruptive and distracting. Quality and patient safety only came back into vogue as a result of two particular developments. First, the period of increased investment in the NHS came to an end in 2007 owing to the global economic slowdown and the subsequent collapse of the banking system. Attention therefore focused on using resources more efficiently and effectively. The Quality Innovation Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) initiative was introduced specifically with this aim in mind. It was intended to avoid a retrenchment response to spending pressures through adopting a more intelligent approach to commissioning decisions that avoided putting quality at risk. Initiatives like the NETS were seen by some NHS leaders at the Department of Health as being especially important for the whole NHS, and were being looked to as pioneers providing lessons for the rest of the system. This was because they offered the potential to improve services without sacrificing staff or losing any of the gains resulting from previous additional investment stemming from the Wanless report. 7 The second factor which reinstated QI as a central objective of government policy was Lord Darzi’s next stage review of the NHS. 8 Commissioned by the then prime minister, QI was given particular prominence by Darzi, an eminent cardiac surgeon. In his view, one of the ‘core elements’ of leadership was a focus on continuous improvement. Aligning clinical and managerial approaches to quality was seen as critical.

A review of QI in health care published in 2008 concluded that having an improvement method is important to achieve outcomes, but the particular method adopted is not important. 9 Failures are usually due to intractable problems in relationships or leadership rather than in the tools or methods adopted. These conclusions are supported by our research. The architects of the NETS approach saw it as a transformational change initiative that sought to achieve a change in overall culture. It specifically addressed the issues of leadership and relationships through the Vision and Compact. The evidence demonstrates that it is important for leaders to adopt and commit to whichever tool or method is chosen ‘for as long as it takes to deliver the results for patients’8 (Our NHS Our Future: NHS Next Stage Review – Leading Local Change, © Crown copyright 2008). Øvretveit provided evidence that leadership is associated with, and influences, successful improvement and is a factor contributing to slow, partial or failed improvement. 10 However, the highly contextual nature of change makes generalisation difficult.

The early development of the NETS initiative was informed by these findings, although how far this was explicit or implicit is unclear. The origins of the NETS are described in Chapter 3, drawing on a scoping review conducted in 2008 which formed the basis for the main study. 11 Before doing so, however, we set out why the NETS was important, its particular features which set it apart from other QI initiatives, and our research aims and objectives.

The generalisation of results is an important, if often contested, issue in research that investigates complex adaptive systems of the type to be found in the NHS. 12 Walshe13 commented that with QI research

the aim is not to find out ‘whether it works’, as the answer to that question is almost always ‘yes, sometimes’. The purpose is to establish when, how and why the intervention works and to unpick the complex relationship between context, content, application and outcomes.

Having undertaken these tasks, the issue remains one of how far it is reasonable to offer generalisable findings, as the precise combination of factors making for success may be particular to that setting and not possible to replicate elsewhere. On the other hand, it is likely that the presence of some features will serve as generic drivers of change which can be usefully highlighted and disseminated more widely. Of course, how they are then applied in practice in varying settings will determine their precise configuration and impact. The Health Foundation’s work on spreading improvement demonstrates that with the right learning and support systems, the NHS has the potential to spread good practice across the system to the universal benefit of staff and patients. However, realising this potential is far from straightforward. 14

The North East Transformation System: key features, research aims and objectives

The NETS is of national and international importance because NHS North East (NHS NE), until its demise in March 2013, was the first Strategic Health Authority (SHA) to adopt a region-wide strategy that aimed to transform an entire health-care system. The initiative was bold and ambitious because the SHA served a population of 2.4 million people and the NHS in the region employed 77,000 staff. Up until that time, the implementation of lean and similar tools and methods in the NHS had involved relatively small-scale interventions confined to particular hospital departments and support services. 15 However, NHS NE was committed to addressing more complex system-wide issues, including addressing transformational change, culture and the relationship between clinicians and managers. Many aspects of the NETS were aligned with Darzi’s NHS next stage review conclusions about how best to ensure service redesign. 16

The NETS started with seven pathfinders that represented a wide range of NHS organisations, including the SHA, primary care trusts (PCTs), acute trusts and mental health trusts. These pathfinders constituted wave 1 of the NETS initiative. Subsequent waves included other NHS NE organisations that were programmed to undertake NETS training at regular intervals of around 12 months. The NETS took much of its inspiration and guidance from the Virginia Mason Production System (VMPS) whose lean method was derived from the Toyota Production System (TPS).

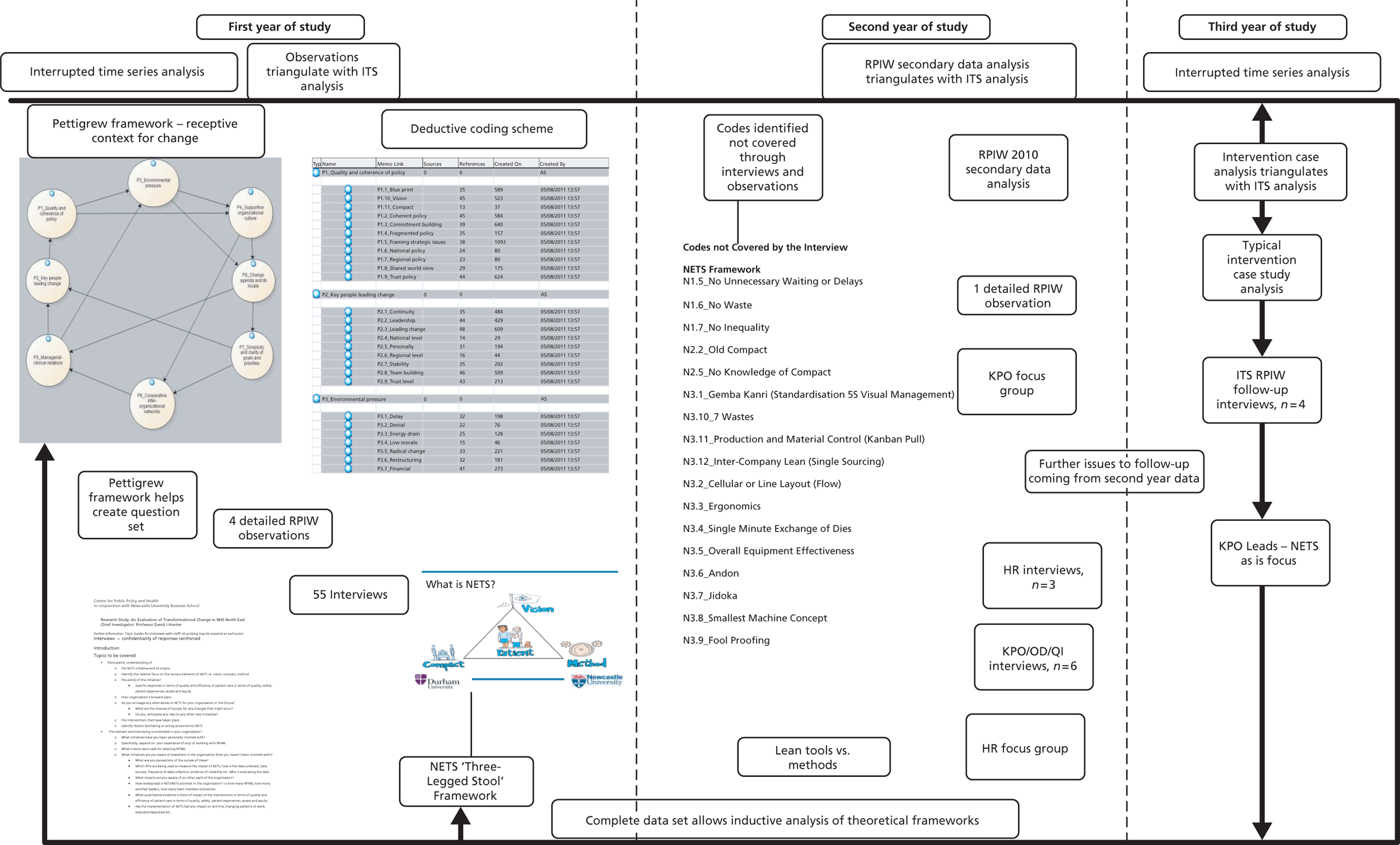

Although NHS NE was committed to supporting a full evaluation of the NETS, it was anxious to capture the learning from its early experiences. To this end, a 6-month scoping study of the background and initial steps was commissioned from Durham and Newcastle Universities. 11 The scoping study took place between January and July 2008 and investigated the NETS, its aims and objectives and the initial developments that had occurred in the seven first-wave pathfinder organisations. It prepared the ground for the main study, whose aims and objectives are described below.

Research aims and objectives

This research has:

-

Produced a literature review that focused upon change management in health systems; the adoption of TPS/lean in health-care organisations; and learning from lean in manufacturing. This builds on the literature review undertaken for the scoping study. 11

-

Evaluated the impact of the NETS (comprising Vision, Compact, Method) and its evolution over time, including the impact on NHS organisational and clinical cultures (including staff engagement and empowerment); the quality and efficiency of health care in respect of technical quality, safety, patient experience, access and equity; reduced waiting times and waste; and reduced variation across specialties, departments and hospitals.

-

Identified the factors facilitating (or acting as barriers to) successful change, including an evaluation of rapid process improvement workshops (RPIWs).

-

Evaluated the role of the NETS project team in co-ordinating progress and supporting the transfer of learning, including the mechanisms used for identifying and disseminating best practice.

-

Investigated the extent to which the changes introduced through the NETS (and through other means in the case of non-NETS study sites) have become embedded and sustained.

-

Assessed the impact of the NETS on service users, for example patients or carers and/or family and friends.

Conducting the North East Transformation System study

The NETS research team was drawn from Durham and Newcastle Universities. Members of the team included health professionals, and academics who were specialists in health policy, human resource management, operations management, strategy and statistics. Project management was provided by one of the co-investigators (Erskine) who was located with the principal investigator (PI) at Durham University. Part of this important role was to organise and support team meetings. These occurred frequently and rotated between Durham’s Queen’s Campus on Teesside and Newcastle University Business School. In addition, and apart from regular e-mails and telephone calls, the team set up a password-protected virtual research environment on a secure server for sharing key documents and managing communications. Second, an external advisory group (EAG) was established to guide and support the study throughout its duration. Membership of the group and its terms of reference are provided in Appendix 1. Between them, EAG members possessed a wealth of experience of managing and researching health-care services and of improvement science methods. The EAG met approximately every 6 months and members provided useful guidance and advice on various aspects of the study during its data gathering and writing-up stages.

The third feature to note was that the study was allocated a Management Fellowship. The Management Fellowship scheme was established by the former Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme to address concerns about translating research into practice. A part-time management fellow (MF) was seconded from the NHS and commenced work in April 2010. A report on her activities, and the way the role evolved during the course of the study, is included in Appendix 2.

Chapter 2 Literature review

A literature review was undertaken for the scoping study. This involved searching a wide body of published work that included professional and managerial tribalism in health systems, organisational culture, leadership styles and the evolution of lean thinking in manufacturing, public services and the NHS. 11

The review of literature on professional–managerial relations, organisational culture, leadership styles and complex adaptive systems is only briefly reported here. The review focuses on the evolution of lean and its application to the NHS and how this can relate to the NETS. The section Lean in health care has been updated to reflect how this particular area has developed since the original scoping study was produced.

Management–profession interface

The tension between managerial and professional values is well documented in the literature and underpins the rationale for a Compact. A BMJ editorial in 2001 posed the question: why are doctors unhappy?17 It suggested that the causes were multiple, although one in particular was highlighted: ‘the mismatch between what doctors were trained for and what they are required to do’. 17 Trained in some specialty or field of medicine, ‘doctors find themselves spending more time thinking about issues like management, improvement, finance, law, ethics, and communication’. 17 In an article in the BMJ the following year, Edwards et al. suggested that the cause of doctors’ unhappiness ‘is a breakdown in the implicit compact between doctors and society: the individual orientation that doctors were trained for does not fit with the demands of current healthcare systems’. 18 They described the old compact and why it is no longer regarded as legitimate, and outlined what a new compact might look like. The old compact comprised two aspects: what doctors give and what they get in return (see lists below). The mismatch between these has been the cause of dissonance over what doctors might have reasonably expected the job to be and how it now is. Some commentators have suggested that the psychological contract – or compact – is a useful concept to explain this problem. 18–20

What doctors give:

-

sacrifice early earnings and study hard

-

see patients

-

provide ‘good’ care as the doctor defines it.

What doctors get in return:

-

reasonable remuneration

-

reasonable work/life balance later

-

autonomy

-

job security

-

deference and respect.

A new and more sustainable Compact is required because the old promise to doctors is either no longer valid or can act as a barrier to modernisation. Among the new imperatives to be addressed in a revised Compact are the following:18

-

greater accountability (e.g. guidelines)

-

patient-centred care

-

becoming more available to patients, providing a personalised service

-

working collectively with other doctors and staff to improve quality

-

evaluation by non-technical criteria and patients’ perceptions

-

a growing blame culture.

Edwards et al. asserted that it was not possible to return to the old compact and that clinical leaders and managers must create ‘a new compact that improves care for patients, improves the effectiveness of the healthcare organisation, and helps create a happier workforce’. 18 The following year, once again in the BMJ, Davies and Harrison returned to the theme of the discontented doctor and argued that a principal reason for the dissatisfaction doctors experienced was their relationship with managers. 21 This manifests itself in a perceived sense of diminished autonomy and reduced dominance. The authors argued for ‘better alignment between doctors and the organisations in which they provide services’ while noting that the extent of ‘cultural divergence between managers, doctors, and other professional groups suggests that such a realignment will be far from easy’. 21 They concluded by insisting that there is no practicable alternative to doctors engaging with management. Yet, despite such calls, the unease felt by many doctors and their lack of being valued has persisted. 22 This was a major reason for inviting a surgeon, Ari Darzi, to lead the next stage review of the NHS, which had clinicians and other front-line staff at the heart of the change process – change that is ‘locally-led, patient-centred and clinically driven’16 (High Quality Care For All: NHS Next Stage Review Final Report, © Crown copyright 2008).

For their part, managers are also unhappy with their lot. They can appear beleaguered functionaries in a system that is more politicised than ever and whose political heads regard themselves as its leaders. 23 A major exponent of lean in the UK, Seddon, considered that distortions in the health system ensure that the patient is not put first. 24 The result is an elaborate set of managerial ploys which are, in effect, forms of cheating or gaming to arrive at the results desired by their political masters. But it is a further contributor to the unhappiness felt on both sides of the management–medicine divide.

The awkward and often dysfunctional relationship between managers and professions is far from being a new phenomenon. In their study of hospital organisation in 1973, Rowbottom et al. 25 noted that

the position of doctors . . . presents a fascinating, and possibly unique, situation to any student of organisation. Never have so many highly influential figures been found in such an equivocal position – neither wholly of, nor wholly divorced from, the organisation which they effectively dominate.

The work of Degeling et al. 26,27 demonstrated the importance of getting professionals and managers to:

-

recognise interconnections between the clinical and financial dimensions of care

-

participate in processes that will increase the systematisation and integration of clinical work and bring it within the ambit of work process control

-

accept the multidisciplinary and team-based nature of clinical service provision and accept the need to establish structures and practices capable of supporting this

-

adopt a perspective which balances clinical autonomy with transparent accountability. 27,28

The findings from Degeling’s work pointed to significant profession-based differences on each of the four elements of the reform agenda. 26–28 They also demonstrated the barriers that face those seeking to introduce changes in the delivery of health care. For those changes to happen there needs to be a common sense of purpose and a set of core values shared by the key stakeholders. These prior conditions do not exist. Degeling’s work showed that all attempts to impose managerial controls on clinical work are doomed to failure unless a different approach to managing change and engaging with clinicians and other health-care staff is adopted. 26,27

Organisational culture and leadership styles in health care

Culture is something of a weasel word that may simply be empty rhetoric. It is often invoked too readily and simplistically in a health-care context, the belief being that if culture change can occur then issues of organisational performance will be resolved. Despite this, culture does matter. Many commentators such as Schein29 and Mannion et al. 28 have emphasised the importance of culture in shaping organisational behaviour and hence achieving improved performance. However, change can be stifled by culture. As Mannion et al. stated, culture constitutes the informal social aspects of an organisation that influence how people think, what they regard as important, and how they behave and interact at work. 28 Organisational culture has been defined by Schein29 as:

the pattern of shared basic assumptions – invented, discovered or developed by a given group as it learns to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration – that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.

Culture is therefore not merely that which is observable in social life but also the shared cognitive and symbolic context within which a society or institution can be understood. 28 But Mannion et al. 28 resisted the temptation of searching for a ‘magic bullet or simple cultural prescription for the ills of the NHS’ (pp. 214–15). In their view, ‘what works’ is contingent upon context ‘and on how and by whom efforts targeted at culture reform are evaluated and assessed’ (pp. 214–15). They counselled against the adoption of a ‘one size fits all’ approach to culture management in the NHS and ‘encourage[d] the adoption of more nuanced strategies which seek to deploy a judicious mix of instruments and supporting tactics depending on setting and application’ (pp. 214–15). One of the principal components of effective culture management relates to leadership styles. 30 Much has been written about leadership and hundreds of definitions offered but, as Goodwin observed, ‘it is principally local context that largely determines the leadership approach to be adopted, meaning local challenges, the history and relative strength of local relationships, local resource issues and local ways of doing things’ (p. 330). 31

Some writers on leadership subscribe to a trait or competency approach, i.e. one size fits all, which ignores context. The NHS competency framework is an example of this. Competencies have been criticised for being overly reductionist, overly universalistic or generic, focusing on past or current performance, focusing on measurable behaviours and outcomes, and resulting in a limited and mechanistic approach to development. 32 Critics also believe that ‘such frameworks reinforce the underlying assumption that leadership resides in the individual’ (pp. 32–3). 33 They are regarded as too generic and ignore ‘the context of a situation and the complexity of running very challenging and diverse workplaces’ (pp. 32–3). As Western argued, ‘the experience on the ground may be that there is little room for seizing the future and empowering others when the context feels disempowering due to a production-line atmosphere where success is measured against meeting targets and deadlines’ (pp. 32–3). 33 Situational leadership is therefore regarded as more appropriate in the context of complex adaptive systems.

In their study of the impact of leadership on successful change in the NHS, Alban-Metcalfe and Alimo-Metcalfe found that competencies did not predict effectiveness but that ‘engaging’ leadership styles significantly predicted motivation, satisfaction, commitment, reduced stress and emotional exhaustion, and team effectiveness/productivity. 34 For them, leadership was viewed as a shared or distributed process and one that was embedded in the culture.

Like other writers on leadership, Goodwin30,31 also noted that leadership is not a characteristic of one person but rather is a process ‘played out between leaders and followers, without whom leadership cannot exist’ (p. 330). 31 Not all commentators believe that leadership and management are entirely separate entities, but those who do consider that leaders are different from managers because they view people from an emotional perspective, seeing them as individuals. 33 But managers can demonstrate leadership and a leader can have managerial skills. Bennis defined leaders as those who ‘master the context’ whereas managers ‘surrender to it’ (p. 45). 35 Leadership is about passion, vision, inspiration, creativity and co-operation, rather than control, which is the hallmark of management. 33 A variant on this view is that a leader creates change whereas a manager creates stability. Running through all these definitions is the derogatory assumption that management is the ‘other’ to leadership; a view of the manager as an outdated mechanistic functionalist. Leadership is very clearly in vogue and ‘sexy’; whereas managers are regarded as transactional in their approach, leaders are seen as transformational.

In keeping with this view of leadership as being about emotions and meaning rather than control, Goodwin claimed that leadership is a dynamic, relationship-based process that uses a twofold approach:

-

creating an agenda for change using a strong vision; and

-

building a strong implementation network to get things done through other people. 30

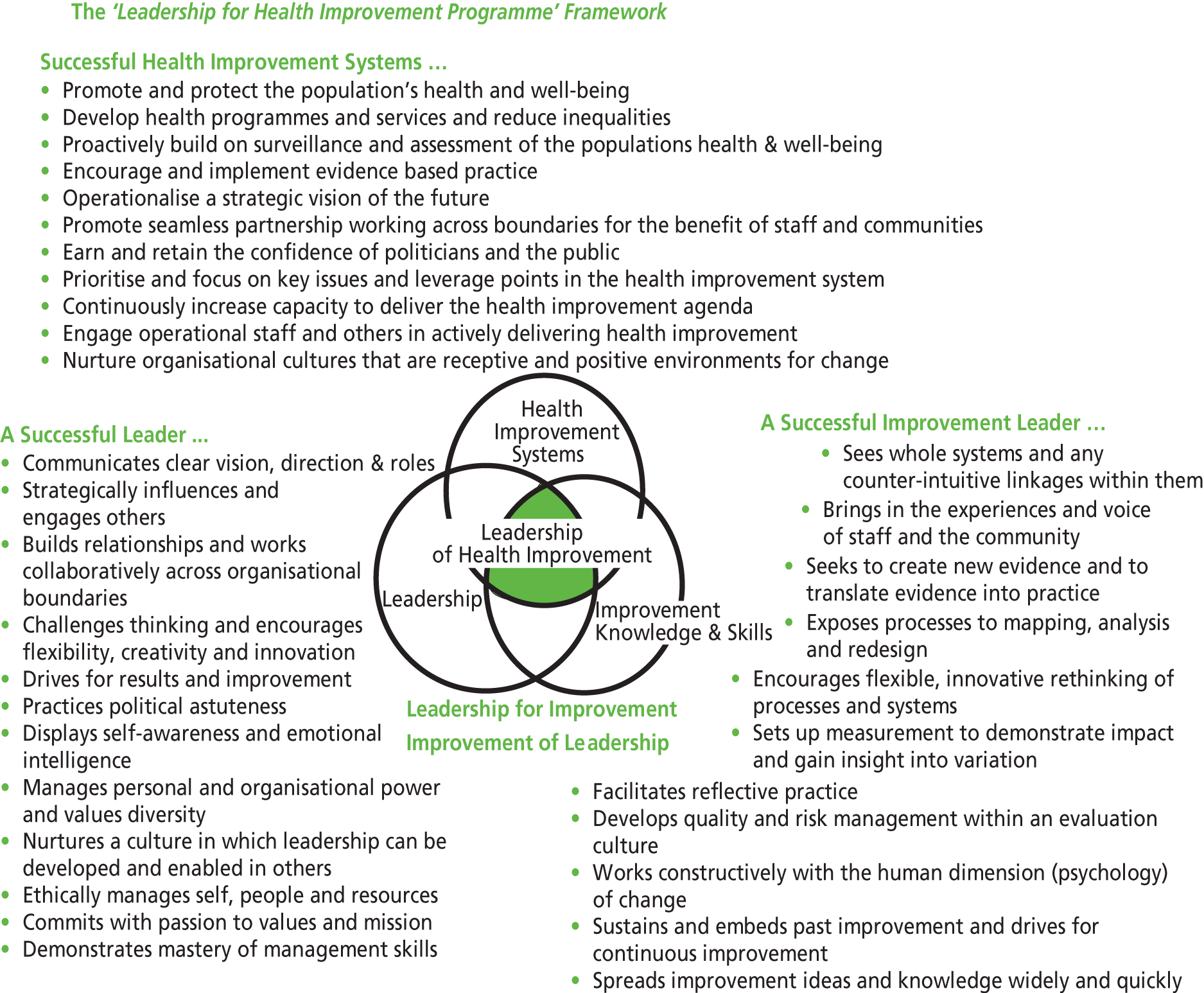

In their Leadership for Health Improvement framework, Hannaway et al. 36 applied improvement science thinking, which borrowed many of its ideas and principles from lean. The approach has been applied in the NHS as a result of the work of the former NHS Modernisation Agency and its successor, the NHS Institute for Innovation and Improvement, which has been superseded by the NHS Leadership Academy. The 10 High Impact Changes for Service Improvement Delivery includes the optimisation of flow and the reduction of bottlenecks, the application of systematic approaches, improved access and role redesign. 37

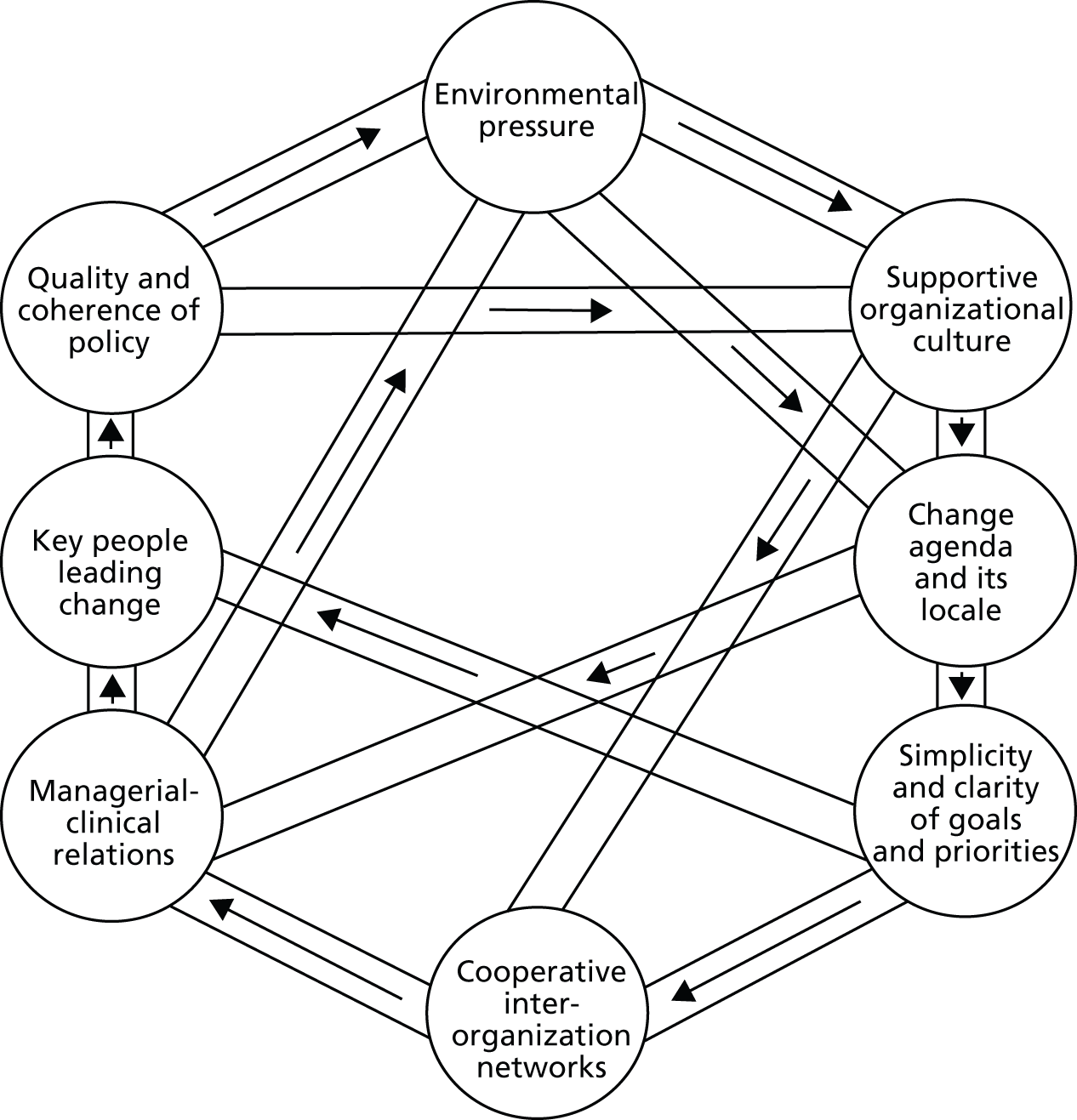

Complexity and health

It is generally accepted that leading and managing a health system is a complex business where there are few certainties and where ambiguity and paradox are often present. These need to be managed rather than denied or obscured by an inappropriate managerial model. Failure in public policy and public services occurs, according to Chapman, because ‘assumptions of separability, linearity, simple causation and predictability are no longer valid’ (p. 65). 38 Under such conditions of growing complexity, it is essential that those responsible for managing and governing take on a wider, more holistic perspective, ‘one that includes complexity, uncertainty and ambiguity’ (p. 65). 38 Systems thinking marks a shift away from regarding the entities being managed as if they were linear, mechanical systems. As Plsek (Paul E. Plsek & Associates, Inc., 2003) commented in materials distributed at a Leadership for Health Improvement workshop held in York in 2006, ‘existing principles of management and leadership are based on old metaphors that fail to describe adequately or accurately complex situations’ (© 2003 Paul E. Plsek & Associates, Inc.; reproduced with permission from Plsek P. An Organisation is not a Machine! Principles for Managing Complex Adaptive Systems. Materials prepared for Leadership for Health Improvement programme. York: Unpublished; 2006). In a complex system, the complex adaptive manager and/or leader:

-

manages context and relationships

-

creates conditions that favour emergence and self-organisation

-

lets go of ‘figuring it all out’

-

relies on ‘good enough’ analysis of the problem and its solution

-

requires minimum specifications to act rather than prescribing actions in advance.

Plsek, in the workshop materials referred to above, defined a complex adaptive system as ‘[a] collection of individual agents with freedom to act in ways that are not always totally predictable, and whose actions are interconnected so that one agent’s actions changes the context for other agents’ (© 2003 Paul E. Plsek & Associates, Inc.; reproduced with permission from Plsek P. An Organisation is not a Machine! Principles for Managing Complex Adaptive Systems. Materials prepared for Leadership for Health Improvement programme. York: Unpublished; 2006).

The remainder of the literature review presented below focuses on lean thinking and tools, as these have been central to the NETS initiative and, in particular, in demonstrating that successful change is possible and motivational for staff. The sections The evolution of lean, Fordism and Toyota Production System focus on the origins and evolution of lean in the manufacturing sector, including its impact in the North East region of England. Lean in the UK examines the recent take-up of lean thinking in the UK NHS as well as the public services sector more widely.

The evolution of lean

Lean production evolved from established production management approaches. These include the concept of interchangeable parts devised by Eli Whitney, scientific management developed by Taylor, Henry Ford’s mass production and the TPS. 39–41

Taylor found that in craft systems, skills and knowledge were transferred through the apprentice model. 39 Braverman considered that management was buying knowledge which was the workers’ capital. 42 There were variations in the volume and quality of work performed by different individuals as they had different ways of performing tasks. Taylor used the term ‘soldiering’ to describe workers who deliberately did work slowly. 40 He noted that there was conflict between management and workers fighting over the control of work and pay. There was a lack of standardised working methods and training. The end result was that there was waste, which was to the detriment of both the workforce and management. 43

The scientific management movement was very influential in the development of modern institutions which carry out labour processes. 42 Taylor stated that: ‘the principal object of management should be to secure the maximum prosperity for the employer, coupled with the maximum prosperity for each employee’ (p. 9). 39 Taylor believed that this required each individual to maximise efficiency by producing the greatest possible daily output.

Taylorism is based upon four principles:

-

It is necessary to systematically analyse work through time and motion studies to develop standardised methods.

-

Organisations should train employees in best practice approaches rather than leaving them to train themselves.

-

Workers should be provided with detailed instructions that prescribe how to undertake standardised tasks.

-

There should be a separation between ‘planning’, undertaken by managers using scientific management principles, and ‘doing’, performed by workers. 44,45

The core elements of Taylorism are (1) that operations should be standardised and optimised scientifically using time and motion studies and (2) the division of labour between managers and workers. 46 Taylor highlighted the importance of training as a mechanism for ensuring that individuals were able to work at maximum efficiency. 39

Taylorism has several limitations. 45 It creates non-value-adding supervisors and other indirect workers, which increases costs. Flexibility is reduced by the reliance on semiskilled workers and high levels of demarcation. However, new workers can be integrated quickly into the production process, which increases numerical flexibility. It becomes unattractive to work on the shop floor. Taylorism is widely considered to be anti-worker. 42

Fordism

Ford developed mass production at the Highland Park plant in 1913. His approach incorporated many aspects of Taylorism. He automated the production of standard parts using repetitive processes and introduced a continuously moving assembly line. 40 The pace of work and the volume of production were determined by the line speed. The combination of Taylorist approaches and assembly lines, together with a rigorously controlled and well-paid workforce, became known as ‘Fordism’,43 which achieved economies of scale through the division of labour. The objective was to minimise the unit cost through high-volume manufacturing. Production workers were not responsible for quality; there were specialist inspectors and repair staff. There was also a strict separation between the planning and execution of work, and a high division of labour. 46

Toyota Production System

The TPS was developed by Taiichi Ohno. 41 He identified several barriers to implementing mass production approaches in Japan. After the Second World War there was limited domestic demand. Furthermore, customers required a large variety of vehicles, so there was a requirement for low volume and high variety. Workers were reluctant to work in a system that considered them to be a variable cost, owing to legislation that strengthened workers’ rights during the period of American occupation. Japanese companies were starved of capital and foreign exchange; therefore, companies were unable to purchase expensive Western equipment. There was intense competition from overseas manufacturers that were keen to enter the Japanese market while defending their established markets. 47 Toyota could not afford to fund the working capital required to maintain the buffers that would be needed to maintain the high utilisation of production lines that were subject to line imbalances, quality problems and other sources of variability. Toyota therefore developed an alternative solution, which was to operate with minimum inventory while simultaneously maintaining high resource utilization. 48 The TPS is based upon two concepts. First, costs are reduced through the elimination of all forms of waste (those things that do not add value to the product). Second, there is a need to fully utilise workers’ capabilities. 49

The TPS may be viewed as a set of tools for reducing waste or as the set of principles that led to the development of the tools. 50 Liker51 identified 14 principles associated with four themes: (1) long-term philosophy; (2) the right process will produce the right results; (3) add value to the organisation by developing people; and (4) continuously solving route problems drives organisational learning.

Lean in the UK

In the 1980s and 90s inward investment by Japanese automotive companies exposed the uncompetitiveness of many UK automotive components suppliers. 52,53 The Society of Motor Manufacturers and Traders collaborated with the Department of Trade and Industry to form the Industry Forum in 1996. 54,55 This initiative was supported by major automotive companies. They seconded staff with expertise in improving manufacturing processes, who became ‘master engineers’. 56,57 Their role was to train UK engineers in the use of ‘best practice’ manufacturing tools and techniques in order to increase the competitiveness of the UK suppliers. The Industry Forum developed training programmes that used a ‘Common Approach Toolkit’. The ‘building blocks’ included clear out, configure, clean and check, conformity, custom and practice (5C)/sorting, set in order, systematic cleaning, standardising and sustaining (5S),58 the seven wastes,59 standardised work and visual management. The workshops also included training in data analysis, problem solving, set-up improvement and line balance. 56 Skills, knowledge and delivery techniques were disseminated through ‘Master Classes’,60,61 which included training and practical, shop floor-based process improvement activities. The aim of the Master Class is to introduce staff to best practice approaches and to improve performance in terms of quality, cost and delivery. 56

The superior performance of Japanese exemplars encouraged the dissemination of lean principles and tools to other contexts, including service industries and health care. However, Western organisations have often been able to adopt specific lean tools but have found it difficult to change the organisational culture and mindset. The impact of lean interventions is often localised. Organisations often fail to achieve the desired improvements to the overall system. 62

Lean philosophy and strategies

The TPS was developed in Japan by Ohno and Shingo and forms the basis of lean manufacturing. 63 Vollmann et al. 64 considered the goal of lean to be zero inventories, zero defects, zero disturbances, zero set-up time, zero lead time, zero transactions and routine operations that operate consistently day to day. Transactions consist of (1) logistical transactions (ordering, execution and confirmation of material movement); (2) balancing transactions, associated with planning that generates logistical transactions (production control, purchasing, scheduling); (3) quality transactions (specification and certification); and (4) change transactions (engineering changes, etc.).

In lean manufacturing, waste may be viewed as any activity that creates cost without producing value. 65,66 Ohno outlined seven forms of waste:67

-

Overproduction, i.e. making too many items or making items before they are required. The result is extended lead times and increased inventory, which incurs carrying costs.

-

The waste of waiting, i.e. time when materials or components are not having value added to them.

-

The waste of transportation, i.e. the movement of materials within the factory, which adds cost but not value.

-

The waste of inappropriate processing describes the use of a large, expensive machine instead of several small ones leads to pressure to run the machine as much as possible rather than only when needed.

-

The waste of unnecessary inventory, which increases lead times, reduces flexibility and makes it difficult to identify problems. This form of waste increases carrying costs and may cause waste through obsolescence.

-

The waste of unnecessary motions relates to ergonomics. If operators become physically tired it is likely to lead to quality and productivity problems.

-

The cost of defects is caused by internal failures within the factory, including scrap, rework and delay, as well as external failures that occur outside the manufacturing system (repairs, warranty cost and lost custom).

Bicheno59 identified additional ‘new’ wastes: untapped human potential; inappropriate systems that add cost without adding value; wasted energy and water; wasted materials; wasted customer time; and the waste of defecting customers – it may cost many more times to acquire a customer than it does to retain one.

Lean comprises a philosophy, a way of thinking that focuses upon value. Often this is considered in terms of cost reduction:62

This migration from a mere waste reduction focus to a customer value focus opens essentially a second avenue of value creation . . . Value is created if internal waste is reduced, as the wasteful activities and the associated costs are reduced, increasing the overall value proposition for the customer . . .

The other main emphasis is on continuous improvement that is usually based upon teamwork undertaken by empowered employees.

Lean initiatives in the North East of England

In 2000, the level of productivity (measured in terms of gross value added, i.e. the value of outputs minus the value of inputs) in the North East was 25% lower than the national average. 68 This situation had made the support of manufacturing companies a major policy objective of One North East (ONE), the regional development agency (RDA) (RDAs were abolished in 2012 as part of the government’s deficit reduction programme). In 2002, ONE funded the North East Productivity Alliance (NEPA), which aimed to improve the productivity of regional companies by training employees in lean tools using the Master Class approach.

The NEPA Master Classes selectively trained employees in the following tools: (1) 5S/5C; (2) standard operations; (3) skill control; (4) Kaizen; (5) visual management; (6) process flow; (7) problem solving; (8) Single-Minute Exchange of Dies (SMED); (9) production-led maintenance; (10) work measurement; (11) failure mode effect analysis; (12) poka-yoke (mistake-proofing); (13) value stream mapping (VSM); and (14) advanced problem solving. 69

The NEPA approach was further developed in 2008 through the European Regions for Innovative Productivity (ERIP) project. Research led by Newcastle University developed an improved lean implementation approach for small business that aimed to standardise processes and reduce costs while improving quality and delivery performance. 70 This approach was applied in 25 small- and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) across the North Sea Region of Europe. Policies for improving the productivity and efficiency of SMEs had not been fully resolved by any of the European member states. Therefore, a transnational approach was advocated to develop a transferable solution. Building on the research highlighted above, a grant was awarded by the European Regional Development Fund (Interreg funding) to support the transfer of lean into SMEs across the North Sea Region. The objective of the ERIP project was to develop a methodology, using the knowledge developed in the North East of England (building on the NEPA work), which could be used by SMEs across the North Sea Region of Europe to implement lean to become more competitive. A key challenge identified through the research was that SMEs found it difficult to allocate the necessary time and resource to undertake the improvement activities. To address this, a new approach was developed through the research, called bite-sized lean. 70 This demonstrated that while lean could be applied in various contexts, it needed to be tailored. The next sections review research relating to lean in the public and health-care sectors respectively.

Lean in the public sector

McNulty and Ferlie71 argued that the UK’s new public management (NPM) reforms, which began in the early 1980s, eventually evolved, by the mid-1990s, into what they termed ‘NPM 4’. NPM 4 is characterised by a melange of private and public sector management ideas, emphasising a value-driven approach, concerned with the quality of service, and a continuing commitment to a distinctive public sector ethos of collective provision. Although McNulty and Ferlie had reservations about the application of private sector models such as business process re-engineering (BPR) to public sector settings (within the context of NPM 4), they concluded that the shift to a NPM model has made the public sector more receptive to ideas of process redesign. Lean is focused on process rather than product, and to this extent McNulty and Ferlie’s observations are highly relevant. For example, they found that a number of public sector organisations experience a problem over organising their work with regards to process and functional principles. 71 This is precisely the tension described by Seddon72 when he criticised local government for setting up ‘front office/back office’ call centres to process the various requests and demands from local citizens.

Although BPR and total quality management (TQM) have certainly attracted considerable attention in the public sector – including health care – there is evidence from recent literature that lean management and the TPS are currently more in vogue in a variety of public service settings. 73 For example, Hines and Lethbridge74 reviewed a project that implemented a lean value system in a university. The authors found a number of case studies relating to lean initiatives in academic settings, and they engaged in a 3-year initiative to embed lean methods and thinking in a client university. 74 Radnor and Bucci75 investigated the use of lean in UK business schools and universities. They found that the application of lean in UK universities was still relatively new and primarily applied in support and administrative functions.

Hines et al. 76 explored the use of lean in the Portuguese and Welsh legal public sectors, particularly in court services. McQuade77 discussed the organisational transformation brought about by lean thinking in a UK social housing group. Erridge and Murray78 reported on the application of lean principles to local government procurement processes, using the example of procurement contracts drawn up by Belfast City Council. The authors concluded that ‘lean supply’ was compatible with the best value approach to procurement, as long as characteristics of lean that are most closely aligned to manufacturing are adapted to fit the culture of local government. Scorsone79 considered the implementation of lean by the city government of Grand Rapids, MI, USA, in the face of fiscal restrictions and a dwindling workforce. Radnor and Bucci80 evaluated a lean programme undertaken in Her Majesty’s Court Services. The programme sought to focus on administrative functions as part of the operational aspects of court services. The underlying challenge of the project was to improve the delivery of service through a waste elimination programme, as well as simplify processes and free up capacity to be able to do more work. The outcome of the evaluation found that the programme had created impact within the court services. Leadership played a key role along with the dedicated project team. Other findings identified the understanding of why there is a need to change, changing and updating practices which had not been revisited, and engaging with the workforce in a manner that promotes a desire to change. Radnor and Bucci provided a framework to support the implementation of lean in public services. This framework requires an understanding of an organisation’s processes, customer requirements and types of demand. These factors are identified as key to ensuring that any lean programme can be successful. 80

One of the most wide-ranging evaluations of lean in the public sector – in terms of the scope of the research undertaken – is the report titled Evaluation of the Lean Approach to Business Management and Its Use in the Public Sector. 81 This document aimed to provide a comprehensive assessment of the success of the lean philosophy and tools in transforming a number of public sector organisations in Scotland. The report, commissioned by the Scottish Executive, covered eight case studies and three pilot sites, including local authorities, health agencies and a government (Royal Air Force) agency. It described a range of levels of engagement with lean, from full implementation (acceptance of lean thinking across all levels of an organisation, and use of lean tools and techniques, together with some likelihood of sustainable transformation) to light-touch lean [adoption of a ‘quick win’, toolkit approach, usually based on rapid improvement events (RIEs)]. These case studies collectively warn against a lean implementation approach that relies too heavily on the lean/TPS ‘toolbox’ without a complementary commitment to lean thinking at all levels of the organisation. The implication is that the tools of lean/TPS (RIEs, 5S, Kaizen blitz, etc.) are less likely to become embedded and have sustainable value unless they are part of a wider package of organisational reform. Furthermore, Radnor and Walley82 suggested that many public sector organisations lack an understanding of process management. Organisations that only gain quick wins, usually via RIEs [or rapid process improvement workshops (RPIWs) in VMPS parlance], find it difficult to sustain improvement in the long term. In a number of cases, the authors found a lack of alignment between the lean/TPS implementation and the organisations’ strategic objectives.

An over-reliance on the lean/TPS toolbox can make it difficult to embed process-oriented thinking. Radnor et al. 81 found that a common public sector response has been to avoid specific, transformational, quick win tools, believing these to be unwelcome imports from a manufacturing environment and inappropriate for use in public service. The message here is that balance is required. The case studies showed that the success of lean/TPS implementation was context dependent, and relied to a large degree on a number of organisational and cultural factors. When lean is not fully aligned with the strategy of a public sector organisation, there is a risk that it will not be sustainable in the long term. Having a critical mass of people who are trained in lean and accepting of it as a transformational agent is also essential.

As a brief summary, Radnor et al. 81 identified the following critical success factors for implementing lean in public service organisations:

-

organisational culture and development

-

organisational readiness

-

management commitment and capability

-

external support from consultants (at least initially)

-

having a strategic approach to service improvement

-

teamwork and whole-systems thinking

-

timing – setting realistic timescales and making effective use of staff commitment and enthusiasm

-

effective communication channels across the whole organisation.

These points were reinforced by a range of papers in a special issue of Public Money & Management (February 2008). These considered the relevance of lean in improving public sector services; aspects of lean thinking that ‘fit’ public service organisations; the transfer of lean experience from other sectors; and the extent to which lean is a distraction or a panacea.

Lean in health care

Most of the research on lean in health care has focused on hospitals. Spear83 highlighted a series of avoidable medical errors and patient safety issues in the US hospital sector. He advocated the use of the TPS to remove ambiguities in processes and to empower health-care workers to solve problems as they arise, rather than opting for work-around solutions. Spear pointed out that ‘No organisation has fully institutionalised to Toyota’s level the ability to design work as experiments, improve work through experiments, share the resulting knowledge through collaborative experimentation, and develop people as experimentalists’. 83

Radnor et al. 84 investigated the introduction of lean in four UK NHS hospital trusts. They found a widespread use of lean tools that led to small-scale and localised productivity gains and highlighted significant contextual differences between health care and manufacturing that made it difficult to move towards a more system-wide approach. In particular, some of the principles proposed by Womack et al. 47 do not apply. ‘Customer value’ in health care is different to manufacturing because the patient is normally a recipient of treatment and does not commission or pay for the service. The provision of health care is often subject to budgetary constraints that make it capacity led; there is limited ability to influence demand or reallocate resources saved by improvement measures.

Fillingham15 described the use of the TPS for improving patient care at the Royal Bolton Hospital in the UK, which has been widely considered to be an exemplar case. He reported a 42% reduction in paperwork, better multidisciplinary teamworking, a reduction in length of stay by 33% and a 36% reduction in mortality. Ballé and Régnier85 reported on the use of lean to reduce medication distribution errors, nosocomial infection rates and catheter infections in a French hospital. Although the initiative was deemed successful, the authors identified resistance to the standardisation of clinical and nursing practices. Gowen et al. 86 investigated the application of continuous QI, Six Sigma and lean in US hospitals. They concluded that lean was significant in reducing the sources of errors, but that it did not improve organisational effectiveness. Chiarini87 researched an improvement project utilising lean and Six Sigma tools to reduce safety and health risks to nurses and physicians who managed cancer drugs in an Italian hospital. The author identified that the tools helped improve health and safety and reduced pharmaceutical inventory. Yeh et al. 88 looked at the application of lean thinking and Six Sigma and how they could be used to improve processes in treating an acute myocardial infarction. The outcome was that the medical quality improved, as did market competitiveness. Esain and Rich89 focused on improving patient flow through hospitals to reduce waiting times.

Outside the hospital sector, Boaden and Zolkiewski90 conducted a process study of the non-clinical aspects of a UK general practice, with particular attention to the relationship between the patient and the managerial and administrative aspects of the organisation. Endsley et al. 91 considered process and flow issues in family medical practice in the USA. They focused upon understanding patient needs and administrative procedures, which led to reduced waste. Endsley et al. made a good case that, from the patient’s perspective, many of the frustrations involved in accessing general practitioner (GP) services arise not from direct contact with the physician, but from missing paperwork, unacceptably long waiting times, and poorly managed hand-offs between doctor, practice nurse and receptionist. 91

One of the most frequently cited exemplars of lean in health care is the Virginia Mason Medical Center (VMMC). It adopted the TPS to create the VMPS. The research on VMMC has included work by Weber,92 who investigated how improved logistics and productivity reduced costs and defects; Furman and Caplan,93 who outlined the patient safety alert system; Nelson-Peterson and Leppa,94 who described the elimination of waste in nursing procedures; McCarthy95 on the application of the TPS; Bush96 on eliminating waste; Kowalski et al. 97 on nurse retention and leadership development; and Pham et al. 98 on the redesign of care processes.

The next chapter considers the origins and evolution of the NETS, which was supported by consultancy from VMMC and Amicus.

Chapter 3 The origins and evolution of the North East Transformation System

In this chapter, the key influences and factors that led to the introduction of the NETS and the pivotal role of NHS NE are considered. The NETS comprised three principal components: Vision, Compact and Method. It drew heavily on the seminal influence of the VMPS which was derived from the TPS and from Amicus.

Why the North East Transformation System?

In the North East of England the NHS performs well in terms of meeting targets and performance measures, but the population has poor health due to the region’s industrial heritage and socioeconomic factors. 99 Although this might seem to be a paradox at first glance, it is not really, as good health is determined by factors that lie outside the health-care system. 100 The social and economic circumstances in which people live and work can have a significant impact on their state of health, as Marmot’s work on the social determinants of health and the life course amply demonstrates. 101,102 Nevertheless, while in existence, NHS NE believed that the NHS could do much better by focusing on quality and patient safety and adopting a whole-systems approach to an individual’s and community’s health state. 11

The NETS was instigated as a result of the SHA board’s conviction that a new approach to the way in which it conducted its business was both required and essential. At a meeting held to share information about lean activities across trusts in the North East of England in February 2011, the SHA’s medical director, one of the chief champions of the NETS, commented that the solution was no longer simply doing ‘the same thing but harder’, but doing it smarter. Merely doing what had always been done would deliver exactly the same result. To shift the paradigm or do something genuinely different required changing the rules of the game and transforming the culture of the system. This is something Don Berwick and his colleagues at the Boston-based Institute for Healthcare Improvement in the USA had known for a long time. 103 It was a central theme in his report to the coalition government on the lessons to be learned from the failures at Mid Staffordshire hospitals. 104 NHS NE sought to achieve system-wide rather than localised transformation through a major change programme that would engage all parts of the health system in the North East, including commissioners as well as providers of services. There was an early intention to encourage GPs to undertake training in the principles of the NETS, but it was recognised that GP practices were unlikely to form part of the vanguard, as they lacked the required resources to do so.

Throughout the NHS there was considerable interest in organisational change and the tools available to embed and sustain it. These were reviewed in a National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded study by Isles and Sutherland,105 intended for health-care managers, professionals and researchers. The study concluded that change in the NHS will not be straightforward. The NHS was an example of a ‘complex adaptive system’, which Plsek and Greenhalgh defined as ‘a collection of individual agents with freedom to act in ways that are not always predictable, and whose actions are interconnected so that one agent’s actions changes [sic] the context for other agents’. 12 Complex adaptive systems invariably have fuzzy boundaries, with changing membership and members who simultaneously belong to several other systems or subsystems. In such contexts, tension, paradox, uncertainty and ambiguity are natural phenomena and cannot necessarily or always be resolved or avoided. Instead, they need to be embraced by the various stakeholders and harnessed in such a way that they result in sustainable solutions to complex problems. Arising from such concerns, the term ‘whole-systems thinking’ is now routinely used by managers and clinicians to capture the particular features of a complex health-care system and reflect the following features:

-

an awareness of the multifactorial nature of health care and an acknowledgement that complex health problems – often termed ‘wicked problems’ because they have no simple or easy solutions – lie beyond the ability or capacity of any one practitioner, team or agency to fix106

-

an interest in designing and managing organisations as dynamic interdependent systems committed to providing safe, integrated care for patients. 105

The NETS and its evaluation was informed by systems thinking. A system cannot be considered in isolation from its context and overall environment,107 nor do systems constitute neat chains of linear cause-and-effect relationships which can be isolated and understood in their own terms. In health-care systems, complex networks of inter-relationships are the norm. 108

Isles and Sutherland’s 2001 review noted that the problems and situations that occur cannot be resolved through the use of a single tool or strategy. 105 Consequently, NHS managers had to acquire the ability to diagnose different situations, as well as the skill to find the right tool to use in the particular circumstances that they face. NHS NE’s choice of the NETS and its three main components was certainly informed by such a diagnosis as well as exposure to the VMMC’s adoption of a change programme. The VMPS was derived from TPS principles and methods that were subsequently adapted to suit the North East context.

The NETS comprises three components, familiarly known as the ‘three-legged stool’: Vision, Compact and Method. These components are not individually pioneering. It is the combination that constitutes the NETS approach to transformational change and lends it particular novelty as far as the NHS is concerned.

Vision

The Vision adopted by NHS NE was for it to be a leader in excellence in health improvement and health-care services. To achieve this, the SHA adopted a zero tolerance approach and proceeded to articulate a powerful, uncompromising vision for health-care services in the North East, underpinned by the ‘seven no’s’:99

-

no barriers to health and well being

-

no avoidable deaths, injury or illness

-

no avoidable suffering or pain

-

no helplessness

-

no unnecessary waiting or delays

-

no waste

-

no inequality.

The sheer bravura of such a list had an immediate impact which made staff in the NHS take stock. The NETS was seen as one of the pillars for implementing the Vision set out in NHS NE’s strategy, Our Vision, Our Future. 99 Of course, achieving the Vision was to prove immensely challenging, but the SHA board, led by its chairman, wanted to set the bar high. The Vision set out the fundamental objectives and direction of the NHS in the region and it was intended to be a living document with which all staff could engage. It was shared with other public bodies, embedded in a suite of local strategy documents, promoted by local managers and cascaded down to front-line staff. The architects of the NETS intended each NHS trust in the North East to draw on the regional Vision for inspiration, but also to create their own Vision, relevant to their organisation’s purpose and values and ‘owned’ by their staff. Otherwise, the Vision risked being imposed from on high, which could have resulted in resistance from front-line staff.

Compact

The Compact arose from the enduring tension between managerial and professional values and the attempt to find some accommodation between the two groups with their differing cultures. It was influenced by the Physician Compact introduced by the VMMC at an early stage of its change journey. The concept of a compact was simple enough: an explicit deal between two parties which, in the case of the VMMC, comprised the clinicians and the VMMC organisation. 109 The intention was to move from an implicit compact to a new explicit one which reflected changes in health care and its management.

Such tensions were not confined to the VMMC or even the USA. In the UK, successive governments have sought to change the way the NHS operates and is managed. Central to these efforts has been shifting the frontier between medicine and management in favour of the latter. It was a development that began in earnest with the first major reorganisation of the NHS in 1974 and has been an enduring theme ever since. However, the effect of a growing managerial encroachment into medicine was not unanimously welcomed by clinicians. Many were suspicious of such developments and opposed to what they perceived to be an erosion of their clinical freedom. An editorial in the BMJ in 2001 posed the question: why are doctors unhappy?17 It suggested the causes were multiple, but highlighted one in particular, which concerned the training doctors received and the nature of the work they were subsequently required to perform. Despite their medical training in a particular specialty, the reality of life on the front line required doctors to think about other matters, including management, finance, ethics and communication. 17 Edwards et al. 18 suggested that the cause of doctors’ unhappiness lay in a breakdown between them and society at large. Doctors were trained to function as individuals with a fair degree of autonomy, but the demands of modern health-care systems required them to be accountable for their actions and to operate as members of a team. They described the old compact which underpinned the NHS and why it was no longer regarded as legitimate, and outlined what a new compact might look like. The old compact comprised two aspects: what doctors gave and what they got in return (Table 1). The mismatch between these was the cause of the dissonance over what doctors might have reasonably expected the job to be and what it now was. Some commentators have suggested that the psychological contract – or compact – is a useful concept to explain this problem. 18–20 Jack Silversin from Amicus, an international consultancy specialising in health-care system improvement, was an influential figure during this period on both sides of the Atlantic. His contribution to the debate was significant because he had worked on the Physician Compact at VMMC and subsequently provided an input into the NETS and its development of the Compact.

| What doctors give | What doctors get in return |

|---|---|

| Sacrifice early evenings and study hard | Reasonable remuneration |

| See patients | Reasonable work/life balance later |

| Provide ‘good’ care as the doctor defines it | Autonomy |

| Job security | |

| Deference and respect |

A new and more sustainable compact was required because the old promise to doctors was either no longer valid or could act as a barrier to modernisation. Among the new imperatives to be addressed in a new compact were those listed in Box 1.

-

Greater accountability (e.g. guidelines).

-

Patient-centred care.

-

More available to patients, providing a personalised service.

-

Work collectively with other doctors and staff to improve quality.

-

Evaluation by non-technical criteria and patients’ perceptions.

-

A growing blame culture.

Edwards et al. 18 were of a view that returning to the old compact was not possible and that doctors and managers should work together to devise a new compact that: was fit for modern health-care systems, sought to improve patient care and the effectiveness in which they worked, and would result in a happier workforce. Apart from the issues with patients and their care, a principal reason for the discontent among doctors was the dissatisfaction they experienced in their relationship with managers. It manifested itself in a perceived sense of diminished autonomy and reduced dominance. To address these concerns, Davies and Harrison21 argued in favour of a better alignment between doctors and the organisations in which they worked. However, given the tensions and cultural differences that existed between doctors, managers and their professional groups, they were under no illusions that such a task would be easy or straightforward. They concluded by insisting that there was no practicable alternative to doctors engaging with management. Despite such calls, there was still unease felt by many doctors who perceived that they were not valued. 22 This was a major reason for Ari Darzi being invited by the government to lead the next stage review of the NHS. As noted in Chapter 1, this was an attempt to re-engage clinicians in the reform effort together with other front-line staff so that they were at the heart of the change process – change that was ‘locally-led, patient-centred and clinically driven’. 16

However, the unhappiness felt was, and is, not confined to clinicians. Managers are also unhappy with their lot, a situation that has arguably, and for many, deteriorated further in recent years as a result of being subjected to continuous organisational change whose precise purpose is often unclear and whose impact often falls short of expectations. Combined with a culture of fear and ‘terror by targets’,110 the outcome is an environment which, as the Berwick report put it, ‘is toxic to both safety and improvement’. 104 The ‘harvest of fear’ evident at Mid Staffordshire resulted in

a vicious cycle of over-riding goals, misallocation of resources, distracted attention, consequent failures and hazards, reproach for goals not met . . . A symptom of this cycle is the gaming of data and goals; if the system is unable to be better, because its people lack the capacity or capability to improve, the aim becomes above all to look better, even when truth is the casualty.

Berwick 2013104 [A Promise to Learn – A Commitment to Act: Improving the Safety of Patients in England, © Crown copyright 2013, contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v2.0 (www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/doc/open-government-licence/version/2/)]

Managers in such a dysfunctional environment can appear beleaguered functionaries in a system that seems more politicised than ever and whose political heads regard themselves as its true leaders. 23 Indeed, critics of the waves of reform under the Labour government between 1997 and 2010 hold that the ‘terror by targets’ regime was largely responsible for distortions in the health system which, unintentionally, ensured that the patient was not put first. 110 The result, as Berwick noted, is an elaborate set of managerial ploys, often labelled ‘gaming’, to arrive at the results desired by their political masters and mistresses.

The term ‘culture’ is often invoked too readily and simplistically in a health-care context, especially in the aftermath of the Francis report into the events at Mid Staffordshire Hospital between 2005 and 2009. 111 It is assumed that culture change will address issues of organisational performance. Culture is important in terms of shaping organisational behaviour and improving performance. 28 Change can also be stifled by culture. Mannion et al. 28 commented that culture comprises the informal social aspects of an organisation that influence how people think, what they regard as important, and how they behave and interact at work. Organisational culture has been defined as29

the pattern of shared basic assumptions – invented, discovered or developed by a given group as it learns to cope with its problems of external adaptation and internal integration – that has worked well enough to be considered valid and, therefore, to be taught to new members as the correct way to perceive, think, and feel in relation to those problems.

Culture is therefore not merely that which is observable but also the shared cognitive and symbolic context within which a society or institution can be understood. 28 But Mannion et al. counselled against the adoption of a ‘one size fits all’ approach to culture management in the NHS and encouraged ‘the adoption of more nuanced strategies which seek to deploy a judicious mix of instruments and supporting tactics depending on setting and application’ (pp. 214–15). 28 These issues were very much at the heart of the NETS and how it sought to win ‘hearts and minds’ across the North East region. Those leading the initiative recognised the importance of establishing shared goals, cultural change and collaborative working.

As the literature review in Chapter 2 revealed, a principal component of effective culture management is leadership style. 30 Perhaps the key factor to note is that leadership entails much more than the actions or behaviour of an individual, as such a focus ignores the importance of both context and complexity. Situational leadership is therefore regarded as more appropriate in the context of complex adaptive systems. Alban-Metcalfe and Alimo-Metcalfe,34 in their study of leadership and successful change in the NHS, found that a culture of ‘engaging’ leadership significantly predicted motivation, satisfaction, commitment, reduced stress and emotional exhaustion, and team effectiveness/productivity. Leadership, then, is not about control but about co-operation and creating an agenda for change using a strong vision.

In their Leadership for Health Improvement framework (Figure 1), Hannaway et al. 36 employed a mix of improvement science concepts together with softer notions of emotional intelligence and political astuteness.

FIGURE 1.

The ‘Leadership for Health Improvement’ framework (reproduced with permission from Figure 7.2 in Hunter DJ, editor. Managing for Health. London: Routledge; 2007. p. 158). 36

Method

We now turn to the third leg of the stool – the Method. The particular method used within the NETS approach was considered less important than the commitment to QI. It is important to adopt a contingency approach to achieve fit between the local context, the needs of the organisation and the Method. However, the VMPS was by far the preferred approach and was strongly supported by the SHA, which invested resources in it to encourage wider engagement and commitment.

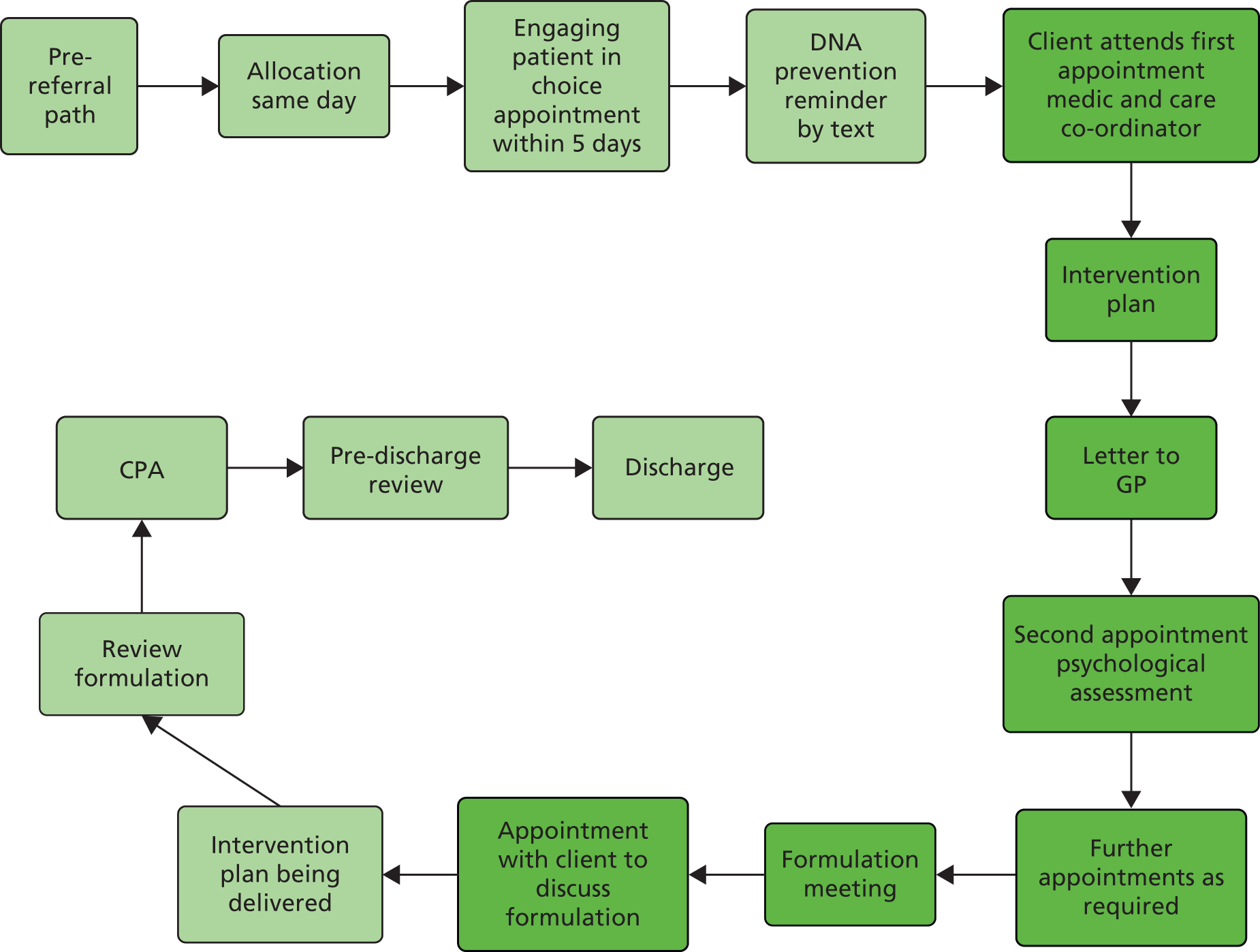

The NHS NE’s desire was to develop and roll out across the region a NE Production System modelled on the VMPS. The SHA anticipated that the VMPS would enhance patient safety and increase capacity through making better use of existing resources. The objective was to increase patient and staff satisfaction, shorten the patient pathway, stimulate continuous improvement and encourage a new culture of clinical care. 11 This was to be achieved by making full use of the potential skills and strengths of all team members.