Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 08/1909/251. The contractual start date was in September 2009. The final report began editorial review in December 2012 and was accepted for publication in January 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Funding received from the South East Coast Dementias and Neurodegenerative Disease Research Network and the NHS South East Coast.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Gage et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Parkinson’s disease

Parkinson’s disease (sometimes referred to as Parkinson’s) is a degenerative neurological condition that affects mainly older people, but there are also significant numbers with young onset. 1 Globally, it is the second most common neurological condition. 2 Within the UK, it is estimated that 1% of people over the age of 65 years have Parkinson’s, with the prevalence rising to 2% among those over 85 years. 1 Parkinson’s disease is caused by the destruction of cells in the substantia nigra of the brain, resulting in a lack of the neurotransmitter dopamine, and hence difficulties with movement. The main motor symptoms are bradykinesia (slowness of movement) and muscle rigidity. Tremor is also experienced in about 70% of people with Parkinson’s. Although frequently designated a movement disorder, Parkinson’s disease additionally inflicts a range of distressing non-motor symptoms, including pain, sleep disturbance, postural instability (leading to falls), and problems with speech, swallowing, constipation, incontinence and sexual dysfunction. 3–5 Difficulties with communication and impaired cognitive function can result in social isolation, and many people with Parkinson’s suffer depression. About 25% will develop dementia. 6

There is currently no known cure for Parkinson’s disease. Symptoms usually appear gradually on one side of the body first and worsen over time. As the disease progresses, people with Parkinson’s become increasingly dependent, and a considerable burden is carried by family carers. Treatment revolves around maintaining quality of life through symptom relief, and may involve a large number of different professionals and services (specialist neurology, primary care, nursing, physiotherapy, occupational therapy, speech and language therapy, pharmacy, dietetics, continence, psychiatry, mental health and social care). 7

Four stages in the development of Parkinson’s disease have been identified, each requiring different types and levels of care. Around the time of diagnosis, when the symptoms are mild, patients and carers need information and support to help them understand the nature of the condition and services available. As symptoms gradually worsen, patients enter a maintenance stage, when minor disability is managed effectively by a drug regimen and input from a range of therapists. In the complex stage, when medications are less effective, symptoms become difficult to manage and a variety of complications arise, new medicines have to be added and carefully adjusted to control for side effects, and additional non-pharmacological treatment input is required. At the palliative stage, when drugs may no longer be effective, relieving distress, pain and other symptoms and providing support for the patient and family are the sole remaining options. 8

The mainstay of management of Parkinson’s disease is a pharmacological regimen, which gradually becomes less effective and more complicated as the disease progresses. This is supported by rehabilitative therapies, assistive technologies and, occasionally, surgery. The range of pharmacological options has increased over time, and centres around levodopa (which acts through replacing depleted dopamine stores in the brain), dopamine agonists, (typically used early in the disease to stimulate the production of dopamine) and monoamine oxidase type B (MAO-B) inhibitors and catechol-O-methyltransferase (COMT) inhibitors (to prolong the effect of levodopa). 9

Parkinson’s is a complex condition and affects people differently, so individual assessment, and treatments tailored to specific needs, are required. 9 In particular, Parkinson’s medications need to be titrated to balance symptom relief with significant side effects, including nausea, daytime sleepiness, vivid dreams and hallucinations, increased libido and compulsive behaviours (gambling, shopping and other repetitive activities). 2 When drugs are working, the patient is said to be ‘on’, but as the effect of a dose wears off, symptoms return (the patient is ‘off’), and the prevention of large and rapid swings in functioning requires careful adjustment of the timing and size of doses. Over time, the efficacy of medications diminishes, and increases in the dosage need to be managed carefully to reduce the risk of dyskinesia (large uncontrollable limb movements). Rehabilitative therapies have a role in primary and secondary prevention, and to optimise health, functioning and quality of life, at all stages of the disease. 10

Rationale for Specialist Parkinson’s Integrated Rehabilitation Team Trial

Given the range of symptoms and the complexity of managing Parkinson’s disease, a collaborative multidisciplinary team (MDT) approach to rehabilitation is recommended in order to provide a co-ordinated and seamless package of care to people with Parkinson’s, and is accepted best practice. 3,10–13 However, the effectiveness of the MDT approach has not been widely researched. 3,13–18 Active management within a co-ordinated multidisciplinary Parkinson’s disease centre had a positive impact on functioning over 12 months,19 and two community-based studies have identified short-term benefits of treatment. 20,21 One self-management programme has been found to have positive effects on health-related quality of life at 6 months,22 but another study found that short-term effects were not sustained. 23 A need has been expressed for studies that identify cost-effective service delivery models that reduce disability and dependency and prevent admission to long-term care. 12–16,24,25 The Specialist Parkinson’s Integrated Rehabilitation Team Trial (SPIRiTT) investigates the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of two alternative models of specialist rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s in a community setting.

SPIRiTT builds on the findings of a previous multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme, co-ordinated by a Parkinson’s nurse specialist (PNS) in a day-hospital setting. 26 This intervention resulted in significant immediate gains for patients in mobility, independence, well-being and health-related quality of life,21 but, in the absence of continuing input, these benefits had largely dissipated 4 months after the intervention ended. 26 Some patients were excluded because they could not get to the day hospital. Moreover, the accompanying economic evaluation showed that day-hospital treatment incurred facility overhead costs and involved the use of expensive hospital transport for patients with more advanced disease. 27

SPIRiTT specifically addresses the issue of patient transport raised by the day-hospital model by delivering rehabilitation to people in their own homes. Moreover, it evaluated whether or not the fading of benefit when specialist input is withdrawn (a common feature of time-limited rehabilitation interventions)27 can be avoided in a cost-effective way by providing continuing support from specially trained care assistants. Participants in SPIRiTT received an equivalent package of specialist rehabilitation to that used in the day-hospital study so that valid comparisons could be drawn between the models of domiciliary and day-hospital provision.

Policy context

The SPIRiTT model of service delivery is grounded in the recommendations of several recent policy documents of the English NHS. These promote the integration of health and social care services,28 provision of services closer to patients’ homes,28 co-ordination of care for particular patient groups by specialist disease-specific nurses,29 supported self-management29 and personalised care planning, rehabilitation and carer support in order to reduce costly unplanned hospital admissions. 30 Moreover, guidelines from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) for the management of Parkinson’s disease12 recommend regular patient review, comprehensive care plans, a central role for PNSs and regular access to physiotherapy, occupational therapy, and speech and language therapy. PNSs are deployed in many parts of the NHS, supporting specialist neurology teams in acute settings, or as part of community services. Evaluations of PNS roles suggest that they do not improve outcomes, compared with doctors, but that their input is highly valued by patients and carers because they are accessible, and for the information and support that they provide. 31,32 PNSs are key to the organisation of a MDT, being pivotal to the co-ordination of care around the patient.

Many people with Parkinson’s do not routinely see PNSs or individual therapists, and even fewer receive co-ordinated MDT input. 33,34 Inequalities in care, shortages of specialist nurses and therapists, poorly integrated services, and inadequate information provision and signposting are key features of the gap between established standards of care and the care received, that have recently been identified. 33,35–38

SPIRiTT investigates the impact of implementing a proactive approach to Parkinson’s management, in line with recent recommendations. Other research has shown routine assessment and support for older people living in the community, with a variety of conditions, can have positive effects on mortality and admission to long-term care. 39 Evaluations have been conducted in a range of countries, including the USA,40–43 Canada,44 Australia,45,46 Denmark,47,48 Italy49 and Switzerland,50 but overall evidence on outcomes (such as physical functioning and health-related quality of life), service use and costs is inconsistent. 46,51,52 Through a focus on outcomes for people with Parkinson’s, SPIRiTT seeks to extend the current evidence base.

Workforce issues

Capacity constraints in the form of high PNS caseloads and shortages of therapists were identified by NICE as barriers to the delivery of their guidance for management of Parkinson’s disease,12 and these have been confirmed by a recent survey of PNSs. 53 While NICE recommends a caseload of 300 patients, over half of PNSs have lists in excess of 500, with adverse effects on the amount of routine support that they can provide to patients. In common with other advanced practice nurses in the community, PNSs report undertaking a variety of tasks (some of which do not require advanced skills), and that time pressures create a need to risk stratify patients. Their focus is on ‘crisis’ management rather than ongoing advice and support. 54,55 The use of care assistants, trained in the special features and management of Parkinson’s, working with PNSs and MDTs of health-care professionals in the community on assigned tasks appropriate to their skill level and knowledge, is one way in which resources for delivering care and support to people with Parkinson’s can be increased.

Competency-based training enables non-registered staff to properly complement the activities of professionals,28,56 and professionals to appropriately meet supervision, delegation and accountability challenges. 57 Trained care assistants have been shown to be effective at underpinning professional working and to have a positive impact on nurses’ ability to provide high-quality care, their work experiences, and the cost-effectiveness of service delivery. 58 The use of trained assistants is consistent with NHS policy for the health and social care workforce which advocates the integration of non-registered health and social care workers with enhanced roles in MDTs, to implement and deliver therapy and monitor and support patients,30,59 as a means of increasing the flexibility, efficiency and responsiveness of services. 60,61

Aims, objectives and hypotheses

The aims of the SPIRiTT study were to evaluate two models of specialist MDT rehabilitation for people with Parkinson’s in the community, to add to the existing evidence base, to inform future service development and commissioning, and ultimately to improve the quality of care and outcomes for patients and live-in carers (i.e. family, friends and paid carers living in the same household). The specialist rehabilitation was based on a multidisciplinary service that works with the patient and family to resolve problems, through a process of goal setting, care planning, intervention and evaluation, to achieve outcomes that maximise functioning and social participation with minimum distress to patient or family carer. 62 The research set out to explore not just the multidisciplinary professional input, but also budgetary and management arrangements, and barriers and facilitators to cross-sector working, that may impact on future implementation of the model.

The specific objectives were to:

-

implement a specialist neurological rehabilitation service for people with Parkinson’s and their live-in carers, delivered in their own homes, comprising MDT assessment, care planning and treatment (following the protocol previously evaluated in a day-hospital setting)

-

provide ongoing support from specially trained care assistants to half (randomly selected) of those receiving the specialist rehabilitation

-

evaluate the clinical effectiveness of the specialist rehabilitation service, and the value added by ongoing support from trained care assistants embedded in the MDT, compared with usual care (which is largely non-specialist and non-team based), across a range of patient and carer outcomes

-

assess the costs of the specialist rehabilitation intervention and of the ongoing care assistant support, and calculate relative cost-effectiveness, including the consideration of savings from service use offsets

-

investigate the acceptability of the new service delivery models (specialist domiciliary rehabilitation with and without ongoing support from trained care assistants) from the perspectives of all stakeholders including commissioners, MDT members, care assistants, service managers, patients and live-in carers and

-

deliver guidance for commissioners, providers and policy-makers about the acceptability, clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of different models of specialist neurological rehabilitation.

The hypotheses were that:

-

a package of domiciliary multidisciplinary specialist rehabilitation would benefit:

-

people with Parkinson’s in terms of maintaining mobility and independence (primary outcome for patients) and improving well-being and health-related quality of life

-

live-in carers in terms of reduced strain (primary outcome for carers) and improved health-related quality of life and

-

society through reduced use of other health and social care services, including hospitalisations and admissions to long-term care

-

-

the addition of 4 months of ongoing support from trained care assistants would help to maintain the benefits of the specialist team rehabilitation, and avoid the fading of effects that typically accompanies the withdrawal of input

-

the intervention would be acceptable to major stakeholders, and barriers and facilitators to wider implementation would be identified.

Chapter 2 Methods

Design

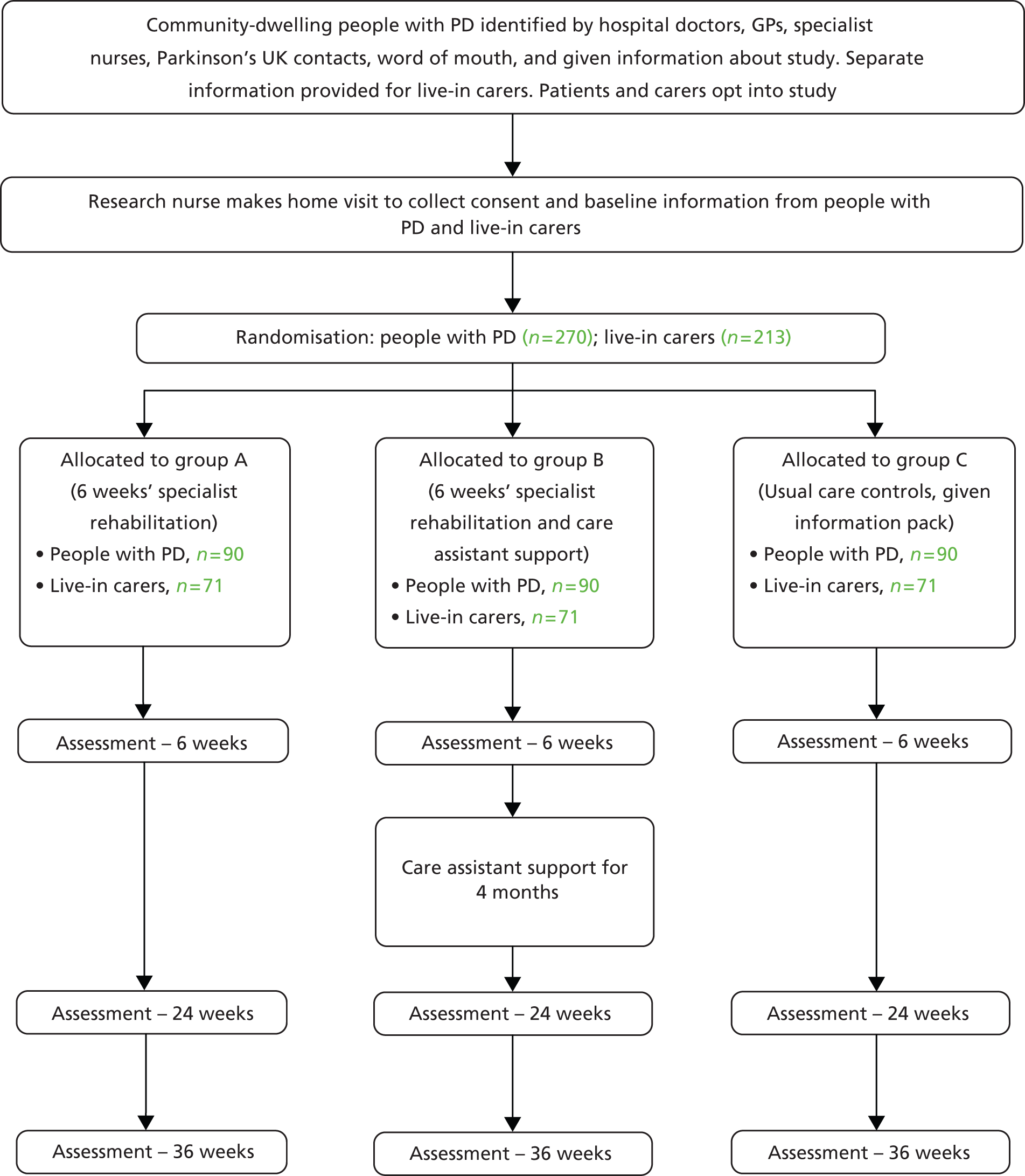

The study consisted of a pragmatic three-parallel group randomised controlled trial (RCT). People with Parkinson’s in group A were assessed and managed by a specialist MDT for 6 weeks according to a care plan that was agreed among the professionals and with the patient and carer. Group B had the same MDT assessment and management, and additionally received ongoing support for 4 months from a trained care assistant. Group C received normal care (i.e. no co-ordinated MDT assessment and care planning, and no ongoing support). Follow-up was conducted at three points (6, 24 and 36 weeks) over 6 months to determine the impact and relative cost-effectiveness of the two interventions. Qualitative interviews were undertaken with providers (MDT members, care assistants), and patients and carers in groups A and B, to gain feedback about the acceptability of the interventions. The Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials (CONSORT) flow diagram63 summarises the study design (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Consolidated Standards of Reporting Trials flow chart for SPIRiTT. GP, general practitioner; PD, Parkinson’s disease.

Setting

Contiguous communities around three district general hospitals in the county of Surrey, England. The study area contains urban, suburban and rural localities and a broad mix of socioeconomic and ethnic groups.

Participants

The project sought to recruit people with Parkinson’s, at all stages of the disease, and their live-in carers (where applicable). People with Parkinson’s were identified by a variety of means, including hospital clinic lists; general practitioners (GPs); Parkinson’s UK contacts; PNSs; community-based therapists; and word of mouth. Research nurses from the Primary Care Research Network (PCRN) and the Dementias and Neurodegenerative Diseases Research Network (DeNDRoN) assisted with the identification of people with Parkinson’s through general practices and specialist Parkinson’s hospital clinics, respectively. Any interested person with Parkinson’s was given a leaflet which included a brief description of the study and the contact details of the research team (see Appendix 1). Posters (see Appendix 2) were sent to relevant organisations with a request that they be displayed in areas visible to people with Parkinson’s.

People with Parkinson’s could volunteer to take part in the study by contacting the research team by telephone, post or e-mail. An initial eligibility screen was undertaken by a researcher by telephone (see Appendix 3). Volunteers who met the inclusion criteria (Box 1) were sent full information about the trial, and a consent form. A separate information sheet and consent form was provided for people with Parkinson’s and live-in carers (family, friends, and paid carers living in the same household), where appropriate (see Appendix 4).

People with Parkinson’s (any stage of the disease) were included if they:

-

were 18 years of age, or over

-

had a clinical diagnosis of Parkinson’s disease

-

lived in the community (own home or minimally sheltered accommodation) with their own living areas

-

lived in the catchment areas of three district hospitals in the county of Surrey

-

were able to read and write English in order to complete the self-report questionnaires

-

had not received a multidisciplinary package of care over the last 6 months

-

had not taken part in rehabilitation research in the last 6 months.

Live-in carers were included if they were:

-

18 years of age, or over

-

able to read and write English in order to complete the self-report questionnaires.

Recruitment

Following telephone screening, a pool of eligible volunteers was built up. The MDT intervention was started once this pool contained 180 people with Parkinson’s, a process that took about 3 months (June to August 2010). The establishment of this pool of patients ensured that the 6-week intervention could be delivered continuously to six cohorts of 30 patients, without any delays. Volunteers were informed during the telephone screening that it could be a few months before their turn for starting the trial came around. While the early volunteers were receiving treatment, recruitment of further people with Parkinson’s continued until the study target sample size of 270 (see sample size calculations below) was achieved. In this way, the research team ensured that the next cohort of patients was assembled for the MDT in a timely manner, and that the MDT professionals had no idle periods pending recruitment of participants.

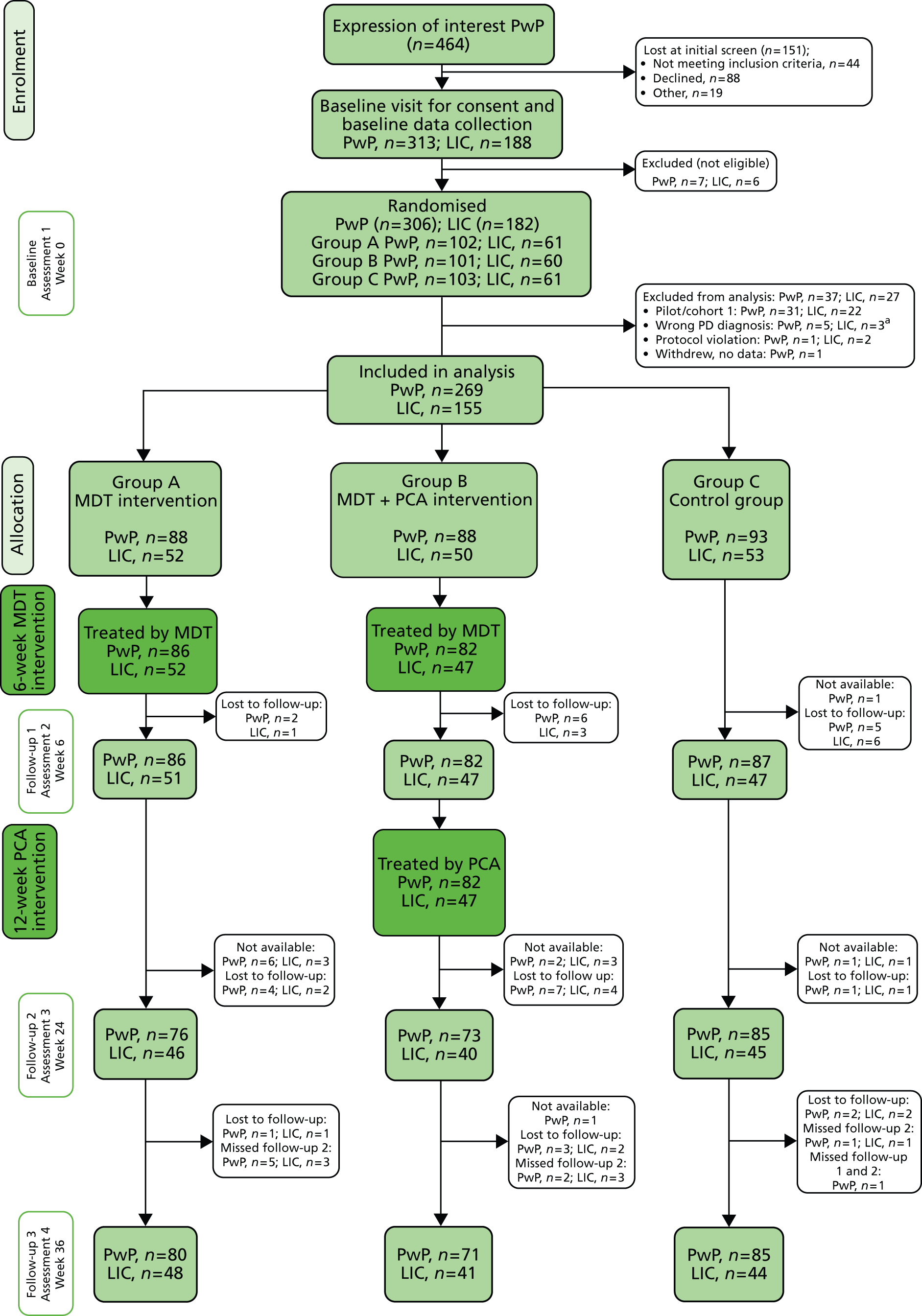

Treatment of the first cohort started in September 2010. An ex post decision was made to consider the first cohort as a pilot, and recruitment was increased to 306 people with Parkinson’s so that an additional cohort could be treated and any volunteers found ineligible at baseline could be replaced. The MDT rehabilitation programme for the final cohort ended December 2011, with PCA support for that cohort finishing in April 2012, and final assessments completed in July 2012.

Consent and baseline data collection

Volunteers were entered into the trial in blocks (cohorts) of 30. These blocks were initially defined on the basis of participants’ home addresses, in order to reduce the time and costs of travel to participants’ homes for the delivery of the intervention and collection of the research data. In the later cohorts, geographical grouping was no longer possible as the last volunteers were spread around the whole catchment area.

When a volunteer was assigned to a cohort, an appointment was made for a research nurse to make a home visit to answer further questions, receive consent (person with Parkinson’s and carer separately), and collect baseline information (see Appendix 4). If a live-in carer did not want to take part in the research, the person with Parkinson’s could still join the trial. However, carers were not accepted if the person with Parkinson’s did not want to participate. When live-in carers opted out of taking part in the research, they were still invited to be part of the MDT treatment programme. The baseline visit was arranged as close as possible to the start of the intervention for any cohort. However, with 30 volunteers (and live-in carers) in each cohort to be assessed, the visits had to be spread over a period of 4 to 6 weeks.

Baseline information

People with Parkinson’s self-reported details of their age, sex, ethnicity, education, housing tenure, living situation (alone or with others), caring arrangements, employment status, income, benefits, smoking, height and weight [for body mass index (BMI)], and comorbidities (see Appendix 5). The abbreviated Lubben Social Network Scale was used to screen for social isolation. 64 This asks respondents to report on frequency of contacts with friends (three items) and relatives (three items), each scored on a scale of 0 to 5, and summed; total scores of ≤ 12 deem the respondent to be at risk of social isolation. The research nurse assessed time since Parkinson’s diagnosis, MDT service use, falls, disease stage [using the six-category modified Hoehn and Yahr scale (0, no sign of disease to 5, wheelchair bound/bedridden without help, but not using the 0.5 increments that are not clinimetrically tested)]65 and cognitive function [using the 30-item Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE),66 which includes simple tests of arithmetic, memory and orientation (see Appendix 5)]. Background information requested from live-in carers included age, sex, ethnicity, education, employment status, smoking, height and weight (for BMI), comorbidities (see Appendix 5), and relationship to, and time spent caring for, the person with Parkinson’s. The baseline assessment included the outcome measures selected for the trial (see Table 2). If participants found the baseline data collection process tiring, some items suitable for self-completion were left with them, and the research nurse made a second visit a few days later to collect the remaining questionnaires.

Exclusion

Baseline data were examined at the research office to confirm eligibility for the trial, and some volunteers were excluded at this stage (Box 2). Specifically, people with Parkinson’s with a MMSE score of < 24 were excluded because it was judged that they would not be able to follow instructions associated with the rehabilitation intervention. People with Parkinson’s and live-in carers were excluded if they scored at the most favourable end of all outcome scales as the trial would not be able to demonstrate improvement, and, in 6 months, had little likelihood of demonstrating reduction in any expected decline; provided that they scored under the maximum on at least one measure, they were included. They were informed of the decision by letter (see Appendix 6), and were replaced by another volunteer, whenever possible, in order to keep the cohort sizes at 30 people with Parkinson’s.

People with Parkinson’s were excluded if they:

-

scored at the most favourable end of all outcome scales (i.e. had no limitations)

-

scored < 24 out of 30 on the MMSE,66 to ensure that those recruited could follow instructions associated with the rehabilitation intervention.

Live-in carers were excluded if they:

-

scored at the most favourable end of all outcome scales (i.e. had no limitations).

Registration and randomisation

After consent and baseline data had been collected, volunteers were given a unique registration number by the project administrator. Those that were eligible were randomised to either group A – specialist rehabilitation; group B – specialist rehabilitation and ongoing care assistant support; or group C – usual care, control group. A separate randomisation sequence was prepared by the study statistician prior to the commencement of the study for patients without live-in carers and for patients with live-in carers. In each instance, blocked randomisation was used to formulate the sequence involving the three comparison groups. With three groups in the study, there are six possible sequences (ABC, ACB, BAC, BCA, CAB, CBC). A die was thrown to determine the group order within any block of three. Hence, any of the six possible group sequences in a block were equally possible, and group sizes were kept even (10 people with Parkinson’s per group, provided that the cohort had the full complement of 30 people). Only the project administrator and the study statistician had access to each randomisation sequence.

The project administrator informed all participants of the group to which they were randomised, and provided a schedule of dates indicating when they might expect the treatment visits (groups A and B only) and research visits (all groups) (see Appendix 7). Contact details of the participants randomised to either of the treatment arms were passed to the MDT. The GPs of all participants were informed of their involvement in the trial and the group to which they had been randomised (see Appendix 8).

Interventions

Specialist rehabilitation intervention (groups A and B)

A MDT comprising two PNSs, two physiotherapists (PTs), one occupational therapist (OT) and two speech and language therapists (SLTs) was assembled from local professionals. They worked part-time for the trial from a base in the University of Surrey, and were employed by other health-care providers for the rest of the week. Friday was assigned (for the convenience of all concerned) for the delivery of the intervention, and for team meetings. Some team members also conducted treatment visits on Thursdays as the workload required. An administrative assistant in the research office provided support, to confirm MDT schedules and appointments with participants (by mail and telephone), organise team meetings, keep records and arrange travel expenses.

Team members visited the homes of participants to deliver a specialist rehabilitation package, tailored to individual needs. In order to make the outcome from the trial comparable with that of the previous study set in a day hospital,21,23,26 a similar programme of specialist rehabilitation was provided comprising an initial assessment and the formation of an agreed care plan reflecting the needs, wishes and expectations of the person with Parkinson’s and carers. A group education and relaxation component in the day-hospital trial could not be replicated in the domiciliary setting. As a substitute, the MDT provided participants with a folder containing 11 fact sheets produced by Parkinson’s UK and the research team, and discussed these with participants according to individual needs. Topics included various aspects of living with Parkinson’s, such as medications, physiotherapy exercises, foot care, diet and nutrition, speech and language, sleep and fatigue, continence and bowel care, welfare rights and benefits, advice for carers, and relaxation techniques (see Appendix 9).

The rehabilitation intervention was co-ordinated by the PNSs, and involved specialist input from each professional, over a period of 6 weeks. Most patients received one visit from one of the professionals each week. The team met face to face twice in each 6-week cycle to discuss patient plans and progress, and communicated by e-mail and telephone at other times. Two hospital consultants (a neurologist and a gerontologist), both with a special interest in movement disorders, were available to the MDT, and provided patient-specific advice as required. Referrals to other professionals were made when indicated, including to a neurologist, a community mental health team and a Parkinson’s UK support worker. Further treatment for people with ongoing needs beyond the end of the 6-week intervention was arranged through referrals to local community services. The MDT input was expected to be about 9–12 hours of individualised patient-facing nursing and therapy input, which was largely equivalent to that delivered in the previous day-hospital trial, so that findings could be compared. However, it was recognised that some people may need more, and others less, time than this. Including patient-related non-patient-facing time spent in travel, writing case notes, meetings, etc., 3 days of professional time was allowed for each person with Parkinson’s in the trial.

Ongoing support (group B)

In addition to the programme of specialist MDT rehabilitation, participants randomised to group B received ongoing support for 4 months from a care assistant trained in Parkinson’s [Parkinson’s care assistant (PCA)], starting at the end of the 6-week MDT intervention. Three PCAs were employed over the period of the trial (Table 1). The main one had sole responsibility for five cohorts, and shared three other cohorts with another PCA. The other PCAs had sole responsibility each for one other cohort. The PCAs were embedded in the MDT and worked under the supervision of the PNS. About 1 hour per week per patient was allowed for ongoing support, and contact was via a mix of home visits and telephone contacts, through which the PCA monitored progress in the implementation of the agreed care plan and reported back to the MDT. If required, MDT members continued to provide input. Care assistants were recruited to the project from local health and social care employers.

| PCA | Cohort | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | |

| PCA 1 | ||||||||||

| PCA 2 | ||||||||||

| PCA 3 | ||||||||||

Usual care/control (group C)

Participants in the control group continued to receive care as usual (no co-ordinated MDT care planning or ongoing support). When informed of their group allocation, people with Parkinson’s and their live-in carers (as appropriate) were sent generic information (available from Parkinson’s UK) about Parkinson’s disease (see Appendix 10). This was a small enhancement on the service they were likely to be receiving. In order to measure the impact of the interventions, this information was also given to the participants in groups A and B by the MDT (additional to the educational fact sheets that they received). At the end of the trial, people in the control group were offered an assessment by a member of the MDT (of their choice), and the educational fact sheets provided to groups A and B were provided for them at that time. The assessment was the same as that provided by the MDT to the intervention groups, and advice and referrals were provided as indicated.

Cross-contamination between groups was minimised through recruiting people with Parkinson’s individually, and giving treatments tailored to their specific needs. Moreover, the intervention and research assessments took place in participants’ homes, which were geographically dispersed over the catchment areas of three large district general hospitals.

The MDT treatment started for the first cohort in September 2010 and ran continuously for 10 cohorts (cohort 1 was a pilot) until December 2011, with the PCA input to the last cohort ending in April 2012. On completion of the intervention, or the assessment for the control group, a detailed report was written about each participant and sent to their GP. All participants continued to receive care as usual during their time in the trial, attending for routine outpatient appointments or contacting their GPs, as required.

Multidisciplinary team processes and monitoring

Members of the MDT met prior to the trial to discuss and agree the details of the intervention, including the roles and protocol to be followed by individual therapists (see Appendix 11). A client record form (CRF) was designed comprising sections for (1) general information about the patient [age, sex, contact details, GP’s name and telephone number, description of home (e.g. steps), services received, driving status, date of Parkinson’s diagnosis, falling history, other health problems]; (2) PNS assessment, based on the Movement Disorder Society (MDS) Unified Parkinson’s Disease Rating Scale (UPDRS),67 and review of non-motor symptoms, medication and side effects; (3) PT assessments of balance, posture, gait and mobility; (4) OT assessment of activities; and (5) SLT subjective and objective assessment of speech, voice and swallowing. Each professional had space to record problems, actions and recommendations for the patient (see Appendix 12). The goals of the agreed care plan were reviewed and ratified at team meetings and summarised in the CRF, which also contained instructions for the care assistant (group B only). The start and end time of each contact (visit and telephone call), all referrals and recommendations made were recorded in summary form on the front cover.

The CRF was left in the participant’s home for the duration of the 6-week intervention, and was completed by each professional at each visit. At the end of each visit, each professional sent a brief report by e-mail to the MDT administrator, who compiled a master document for team meeting discussions which took place in the third and sixth week of each cohort, in a meeting room at the university (team base). The purpose of the meeting in week 3 was to review the professionals’ assessments for each patient and agree on the subsequent treatment plan. The meeting at the end of the cohort was to confirm individualised future recommendations, to provide guidance for the care assistants who would take over supporting participants in group B, and to plan the schedule of visits in the first 3 weeks of the next cohort. In addition to patient-related business, team meetings were used to further interdisciplinary understanding and working. Early in the project, each professional provided training insights for team members from the other disciplines. These presentations were often based around case studies of individual patients in the trial, and served to improve knowledge and interprofessional co-ordination.

Training

A one-day MDT training event was held before the launch of the intervention. Led by the PNS, the team focused on the UPDRS,67 using a training video from the MDS. Two people with Parkinson’s [members of the patient and public involvement (PPI) group] attended the session and each professional was able to test out and refine their component of the CRF. Each PCA was individually trained by the PNS using the training pack previously developed by the research team,68 fact sheets and a training video published by Parkinson’s UK. They then shadowed each individual therapist. The PNSs accompanied the PCAs on the early visits made by the PCAs.

Intervention pilot

The finally agreed CRF and MDT processes reflect some minor changes that were implemented, in the light of experience, at the end of the first cohort. In particular, the original plan for three team meetings per cohort (weeks 3, 5 and 6) was revised, and the meeting in week 5 was dropped because it was found to be time-consuming and unnecessary. A decision was made to leave the CRF in participants’ homes and send summary reports of each contact to the MDT administrator, because the original plan to transfer the CRF between professionals proved impractical. It was also agreed that only the PNS would assess the patient using the UPDRS, whereas the original idea had been that this would be undertaken by whichever professional met the patient first. Owing to these changes, and because the recruitment of professionals was still under way and the team was under-resourced during the treatment of the first cohort, it was decided to extend the trial to include a tenth cohort (a total of 300 people with Parkinson’s, instead of 270), and to consider the first cohort to be a pilot.

Outcome measures

Instruments which reflect the needs of people with Parkinson’s (functional outcomes, disease-specific and generic health-related quality of life, psychological well-being, self-efficacy, mobility, falls and speech) and carers (strain, stress, health-related quality of life, psychological well-being, and functioning), and which had been found sensitive in previous rehabilitation studies undertaken by the research team,21,23,26,27 were included in the list of outcomes selected for the study. All instruments are widely used and well validated for use with older people and in intervention studies (Table 2). Measures of relevance to daily functioning were chosen as the primary outcomes: the Self-Assessment Parkinson’s Disease Disability Scale (patients report ease or difficulty of doing 25 general activities on a five-point scale)69,70 and the Modified Caregiver Strain Index. 71 Information on use of other health and social services was also collected as part of the economic evaluation (see below) to explore whether or not expenditure on the intervention was offset by reductions in the use of other health and social services. The instrument battery was developed and piloted in collaboration with patient and carer representatives in the PPI group. It took about 1 hour to complete.

| Category | Instrument | Description and scoring | Range |

|---|---|---|---|

| Participant: people with Parkinson’sa | |||

| Disability (primary outcome) | Self-Assessment Parkinson’s Disease Disability Scale69,70 | Self-reported ease of or difficulty in doing 25 activities in general (e.g. getting out of bed, getting dressed, cutting food, writing a letter), scored on five-point scale: 1 (able to do it alone) to 5 (unable to do it at all). Original scale contained 24 items and suggested two factors – gross mobility and fine co-ordination69 – but a later paper concludes that the items form a unidimensional hierarchy70 | 25–125 (highest disability) |

| Parkinson’s specific | PDQ-872,73 | Summary index reflecting overall impact of Parkinson’s disease on patients for use in trials. Eight items related to self-perceived health (getting around in public, getting dressed, feeling depressed, embarrassed in public, problems with close personal relationships, concentration, communication and muscle cramps) over the last month are each scored on five-point scale: 0 (never) to 4 (always). The total score is summed and transposed to a scale of 0 to 100 (worst). PDQ-8 is derived from the more extensive PDQ-39 and was selected to reduce participant burden | 0–100 (worst perceived health) |

| Non-Motor Symptoms Questionnaire74,75 | Self-report of 30 non-motor symptoms (e.g. bowel, pain, concentration, falling, sleep, dreams, sweating, dribbling) in the last month (scored yes = 1, no = 0) | 0–30 (worst symptoms) | |

| Participant: people with Parkinson’sa | |||

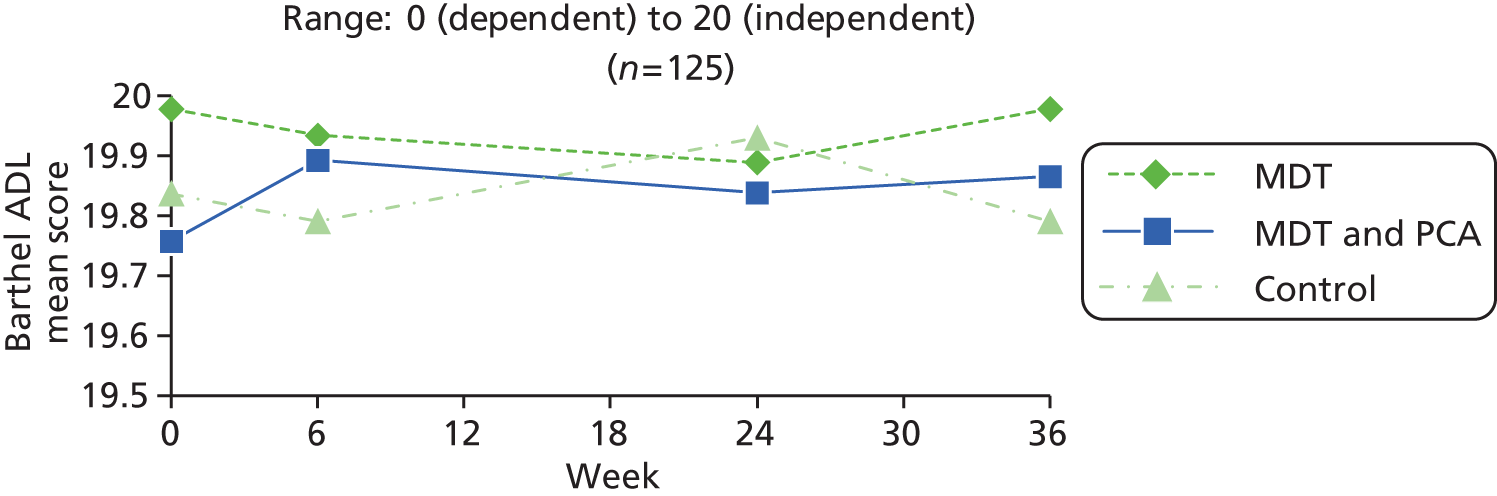

| Activities | Barthel ADL76 | Widely used instrument to establish the degree of independence in 10 activities (e.g. mobility, bathing, dressing, toilet, feeding), scored 0 for unable or totally dependent. Some items are binary while others have three or four points on the scale; maximum score 20 (totally independent) | 0 (dependent) to 20 (independent) |

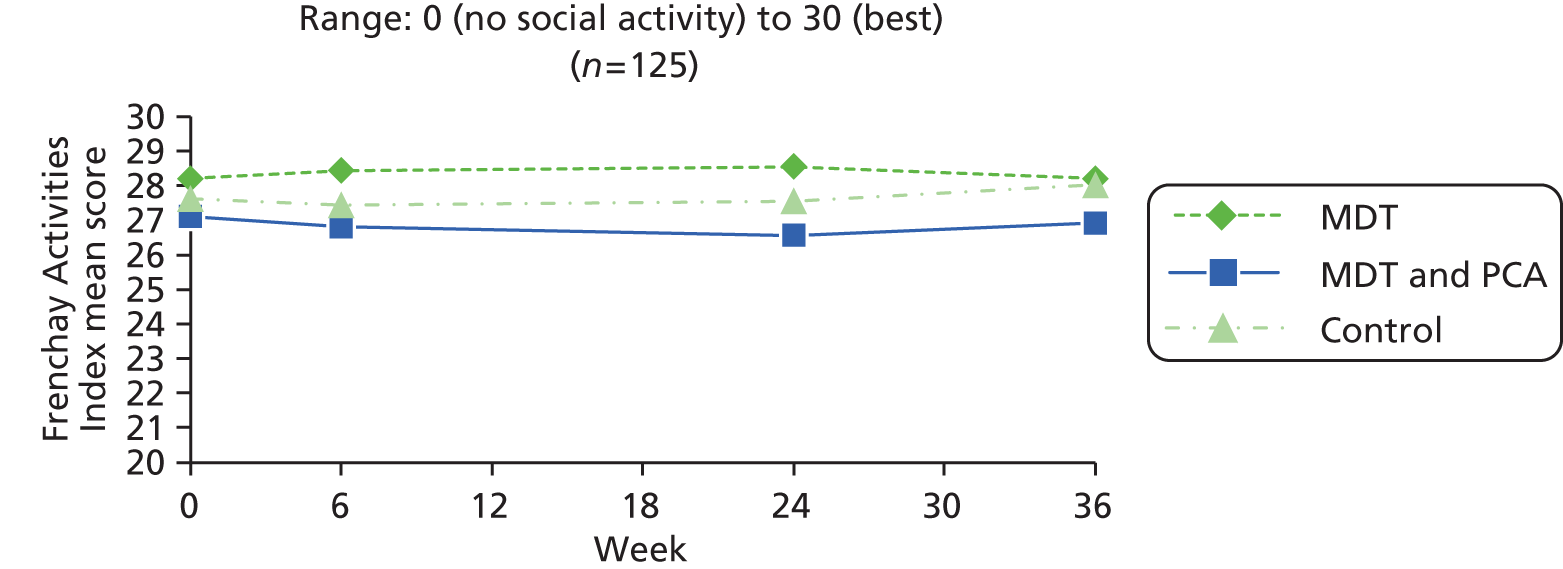

| Frenchay Activities Index77–79 | The Frenchay Activities Index is a short questionnaire that is widely used to measure lifestyle after stroke. The first of two parts was used – frequency of 10 everyday activities in the last 3 months; each scored 0 (never) to 3 (most days) (for meal preparation and washing-up) or at least weekly (for other items such as washing clothes, housework and hobbies). The third part of the index was not used as it relied on 6-month recall and this was not suitable for more frequent assessments | 0 (no social activity) to 30 (best) | |

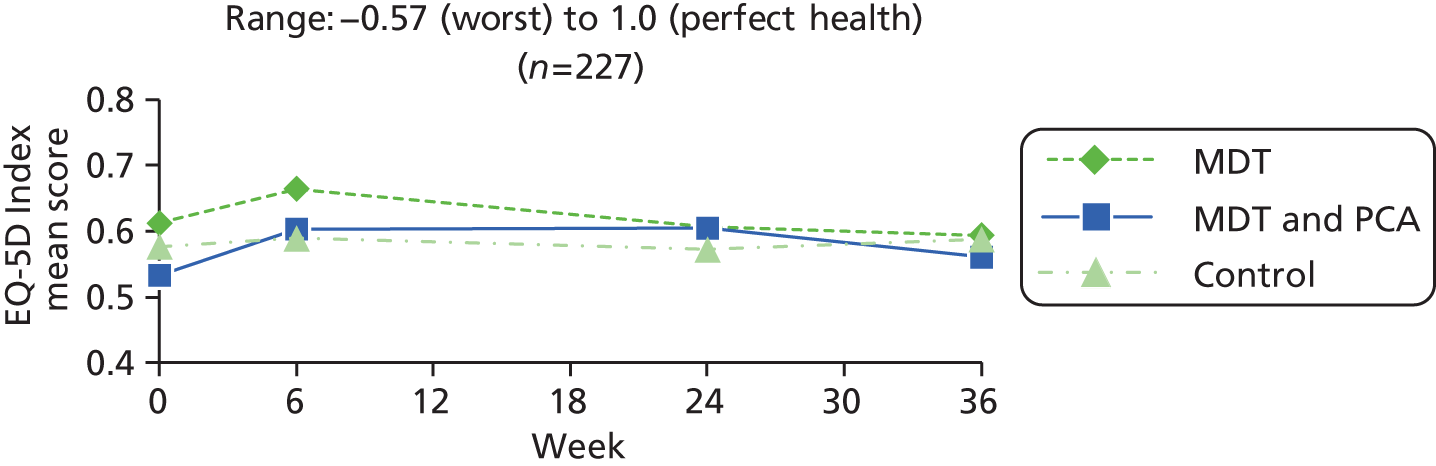

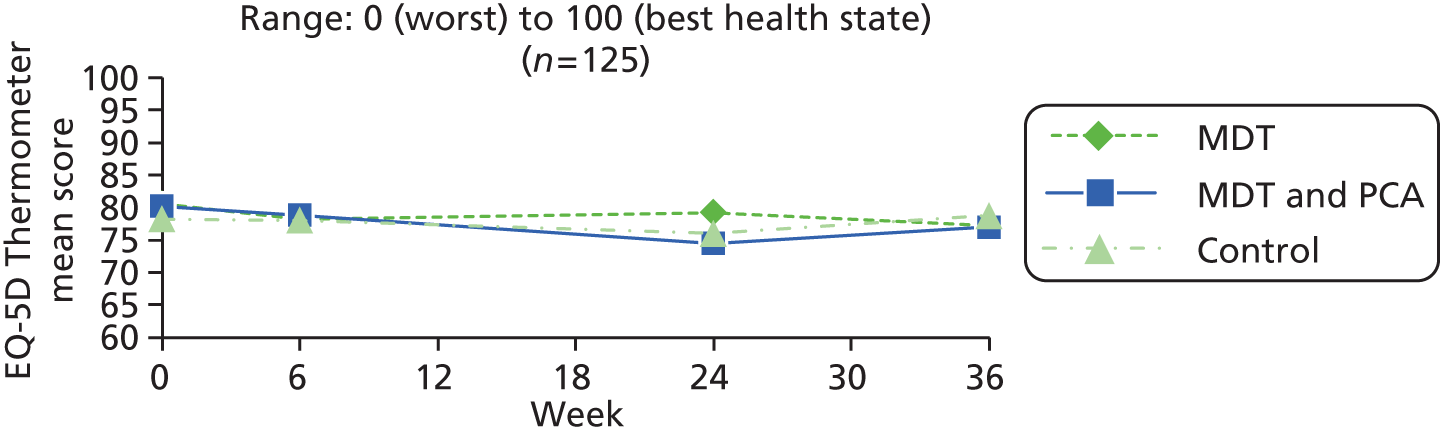

| HRQoL (generic) | EQ-5D Thermometer80,81 | EQ-5D is a simple standard measure, designed for self-completion and applicable to a wide range of health conditions. It provides a descriptive profile [five dimensions – mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression – each measured on a three-point scale (no, some and extreme problems)], transformed to a single index for use in economic evaluations. There is also a VAS (thermometer) recording the respondent’s self-rated health on a vertical scale (end points – best and worst imaginable health state, 0–100) | 0 (worst) to 100 (best health state) |

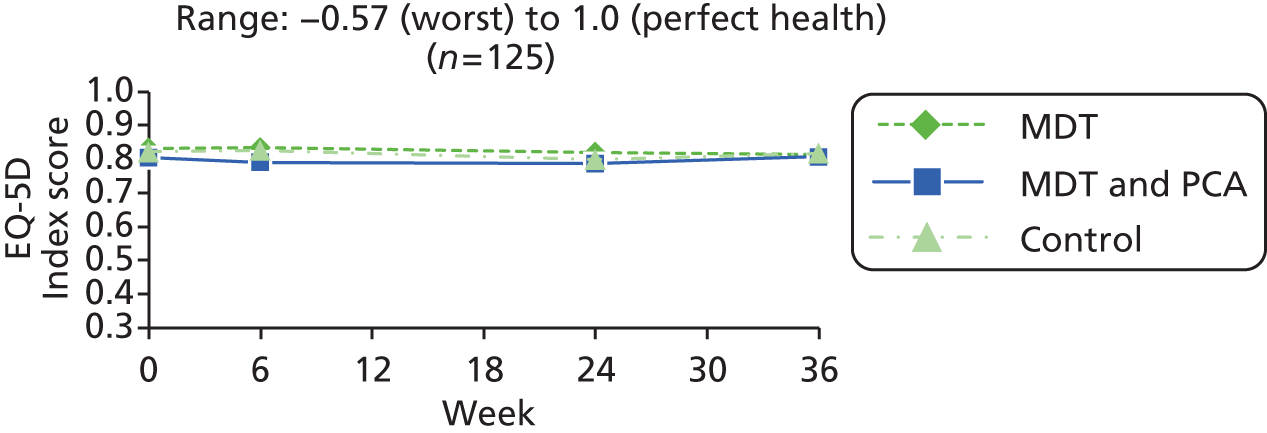

| EQ-5D Index80,81 | –0.57 (worst) to 1.0 (perfect health) | ||

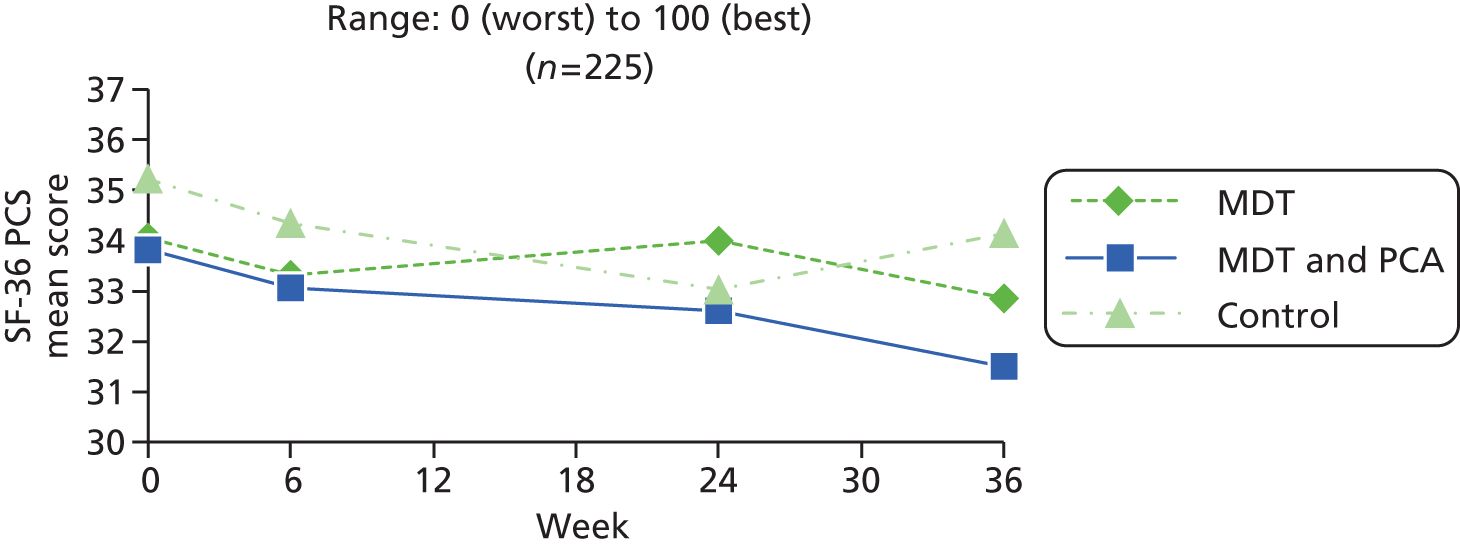

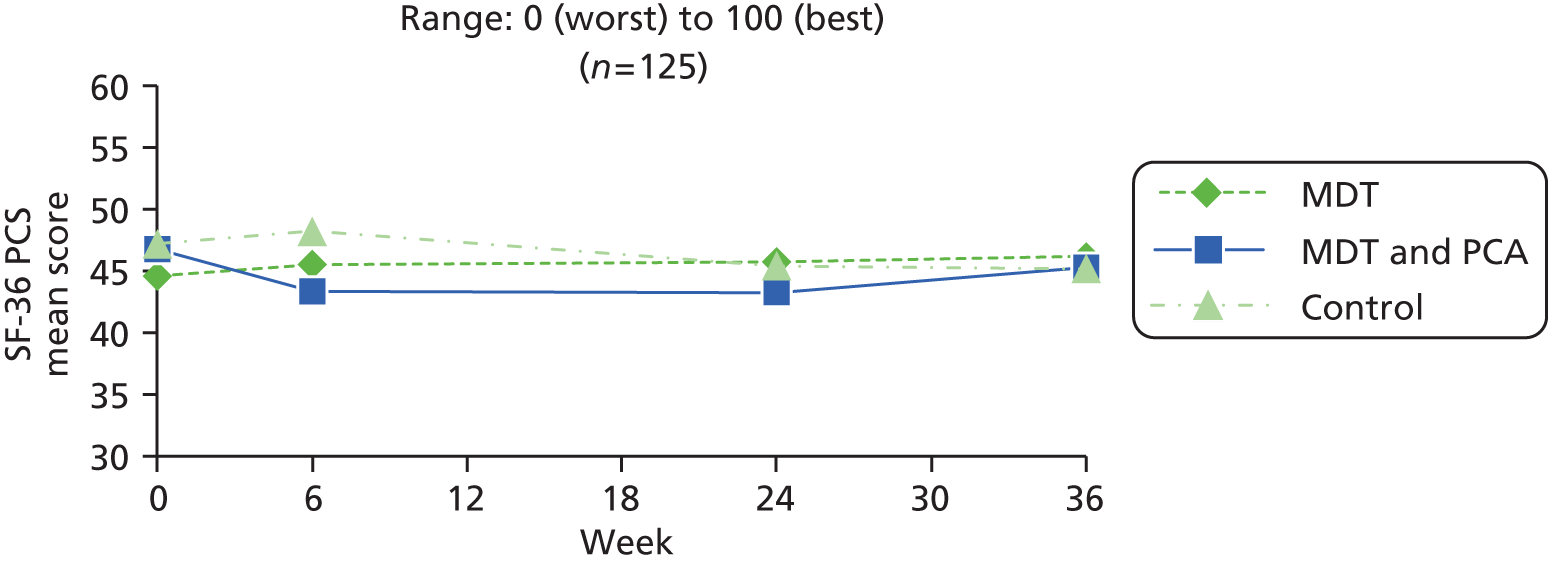

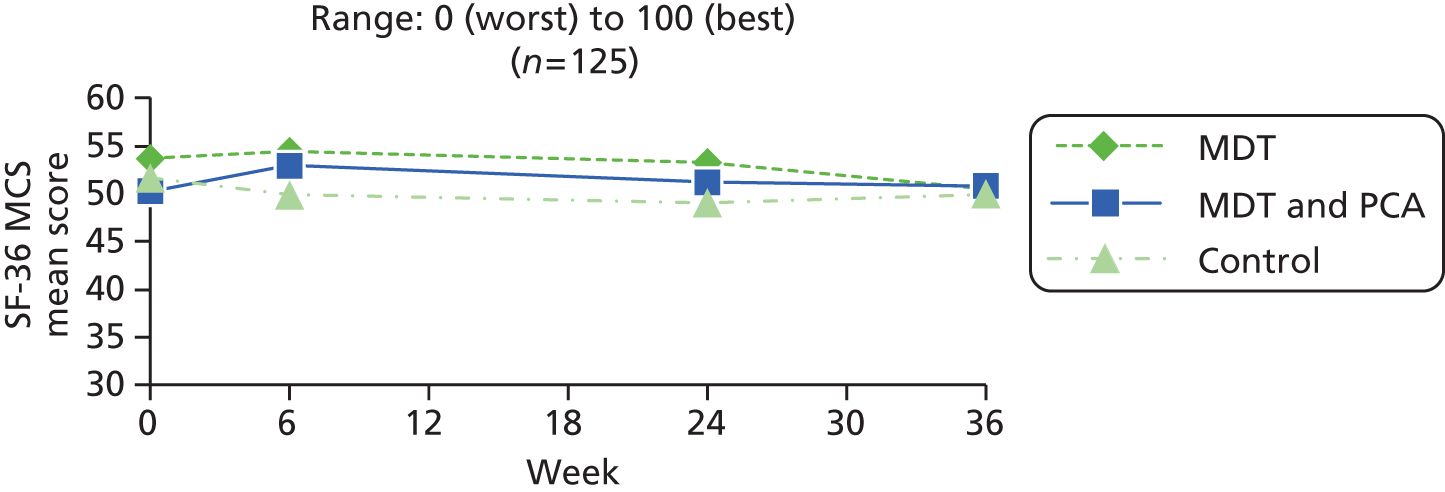

| SF-36 PCS82 | SF-36 is a widely used scale assessing eight health domains (limitations in physical activities, usual activities, roles and social activities, bodily pain, mental well-being, vitality and general health). The instrument was constructed for self-report or use by interview. Scoring is by algorithm, range 0 (worst) – 100 (best) and set to US population norm, mean of 50, SD of 10. The eight subscales form two distinct higher-order clusters: the PCS and the MCS | 0 (worst) to 100 (best) | |

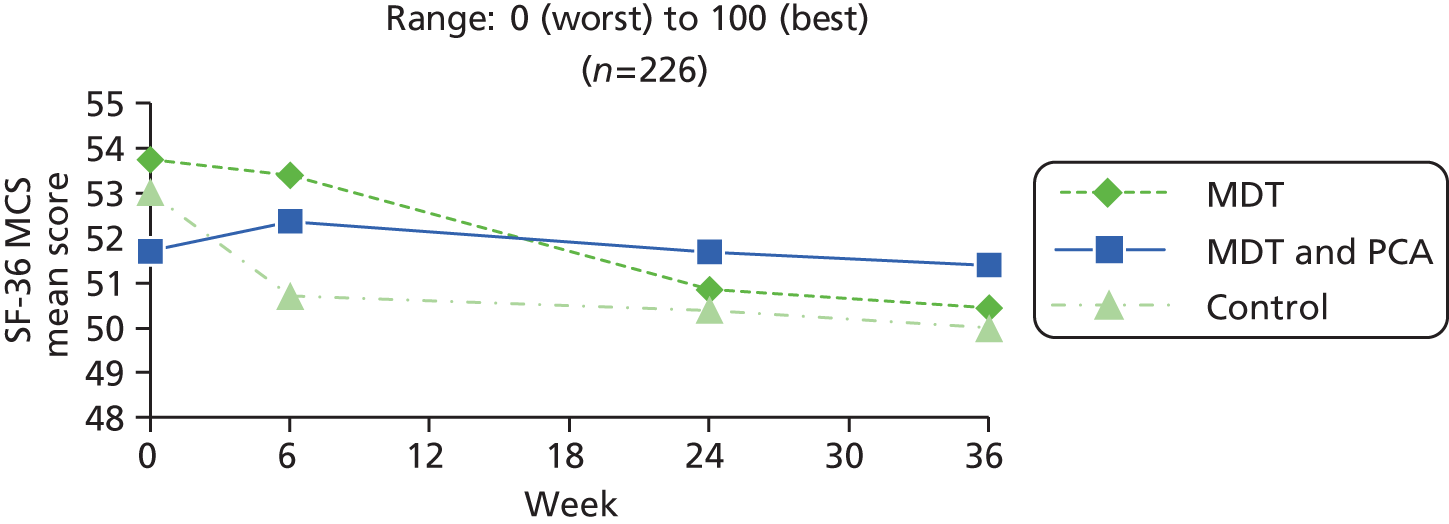

| SF-36 MCS82 | 0 (worst) to 100 (best) | ||

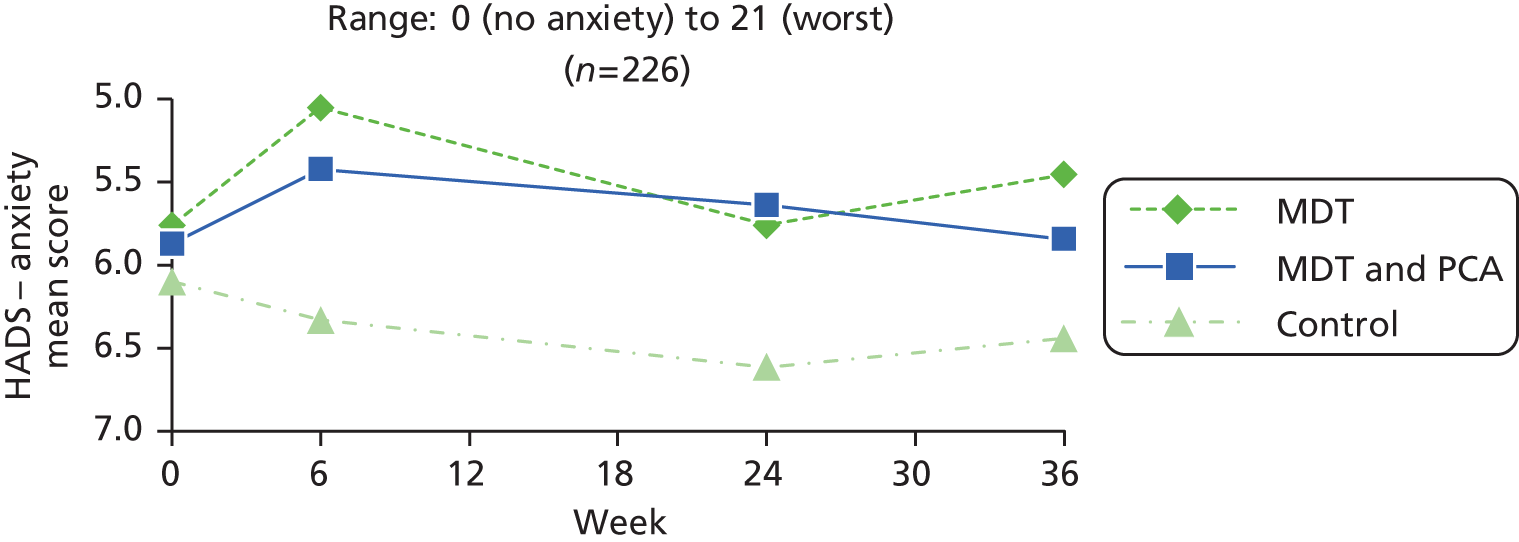

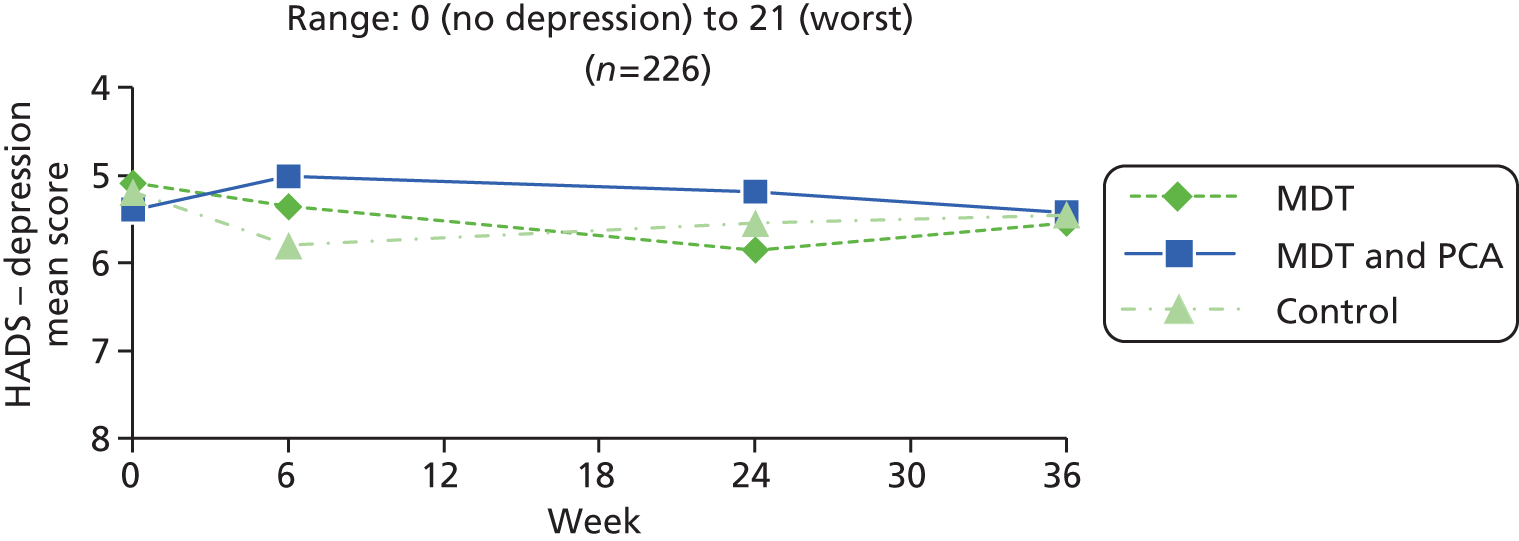

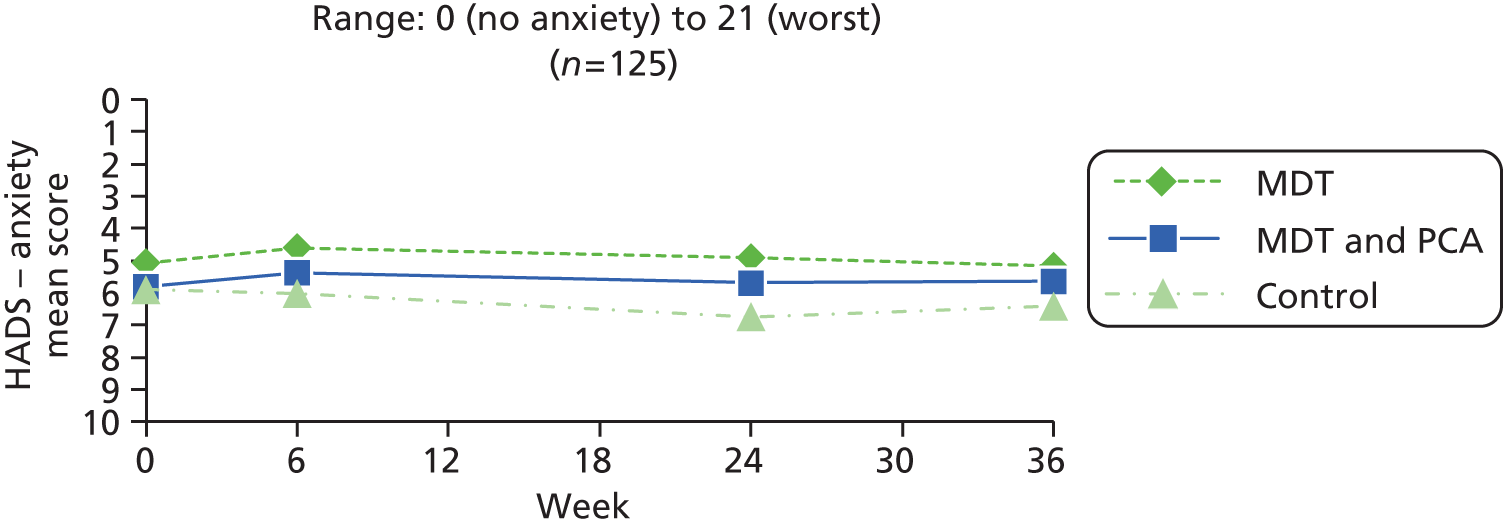

| Psychological well-being | HADS – anxiety83 | HADS is a self-assessment scale developed to detect states of depression and anxiety in a hospital outpatient setting. It contains 14 questions (seven each for depression and anxiety), scored 0–3: total range 0 (no anxiety/depression) to 21 (high anxiety/depression). Cut-offs: 0–7 = normal; 8–10 = borderline; 11–21 = abnormal | 0 (no anxiety) to 21 (worst) |

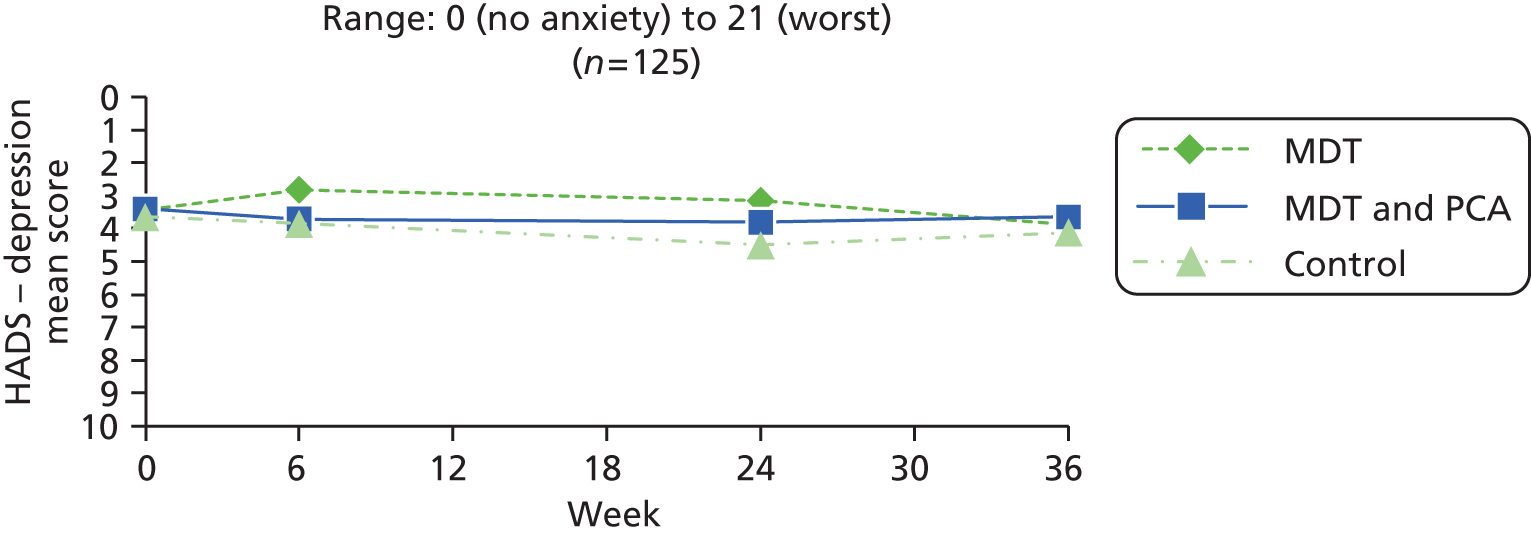

| HADS – depression83 | 0 (no depression) to 21 (worst) | ||

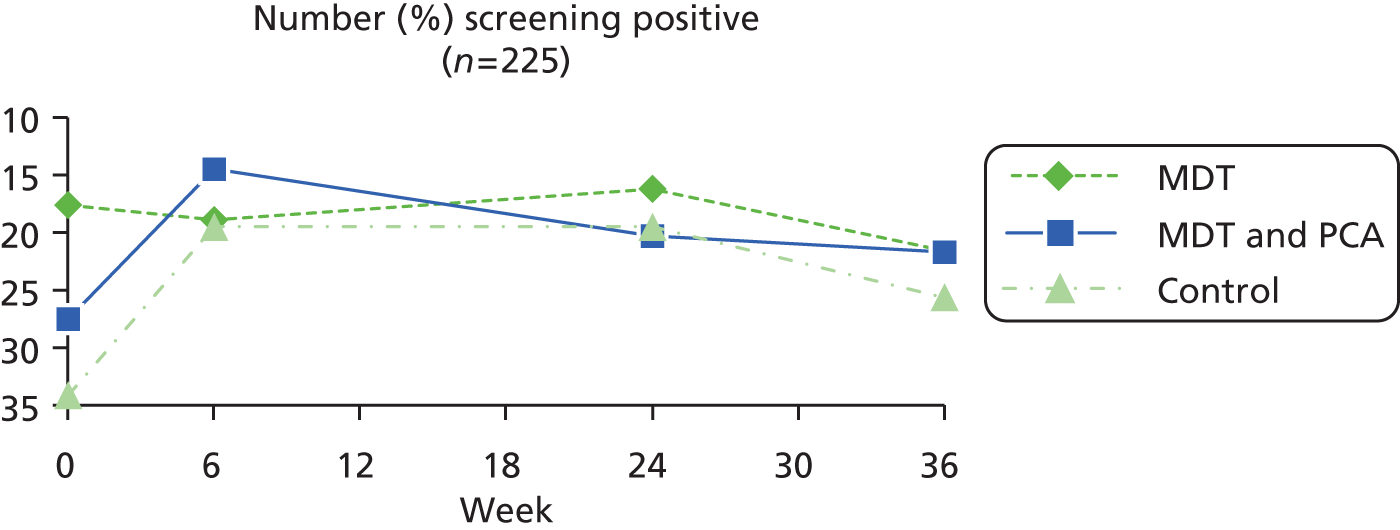

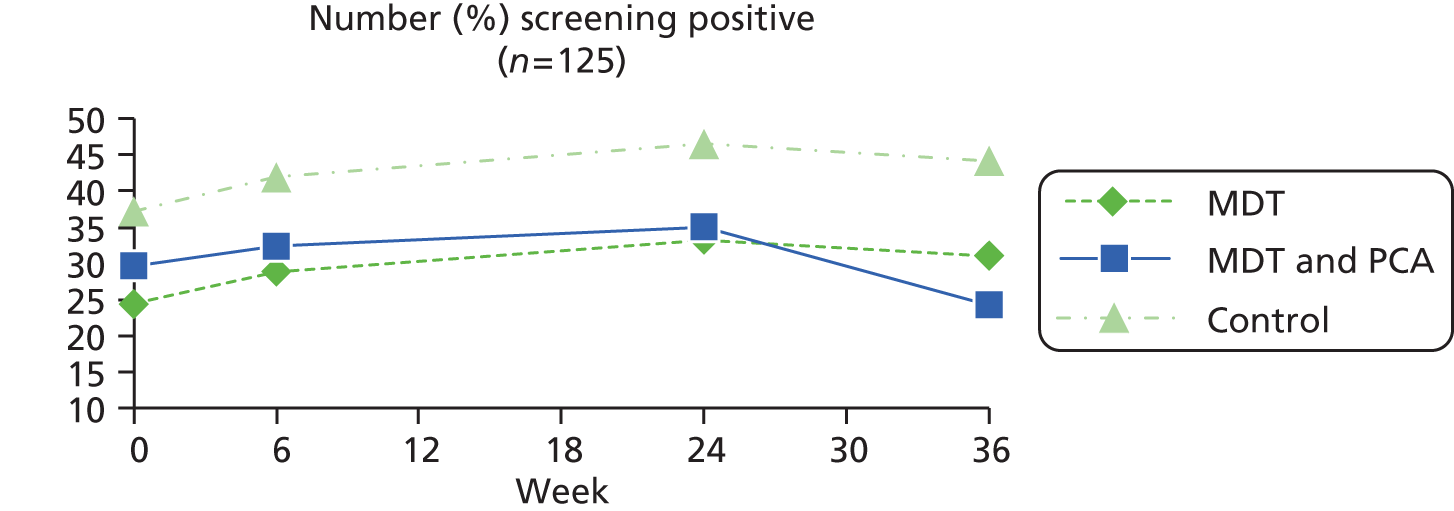

| Yale Depression Screen84,85 | This is a single-item tool with reasonable reliability and validity that can be administered by non-registered staff to screen for depression in the community: In the past 4 weeks, have you often felt sad or depressed? (Yes = 1, no = 2) | Yes = 1, no = 0 | |

| Participant: people with Parkinson’sa | |||

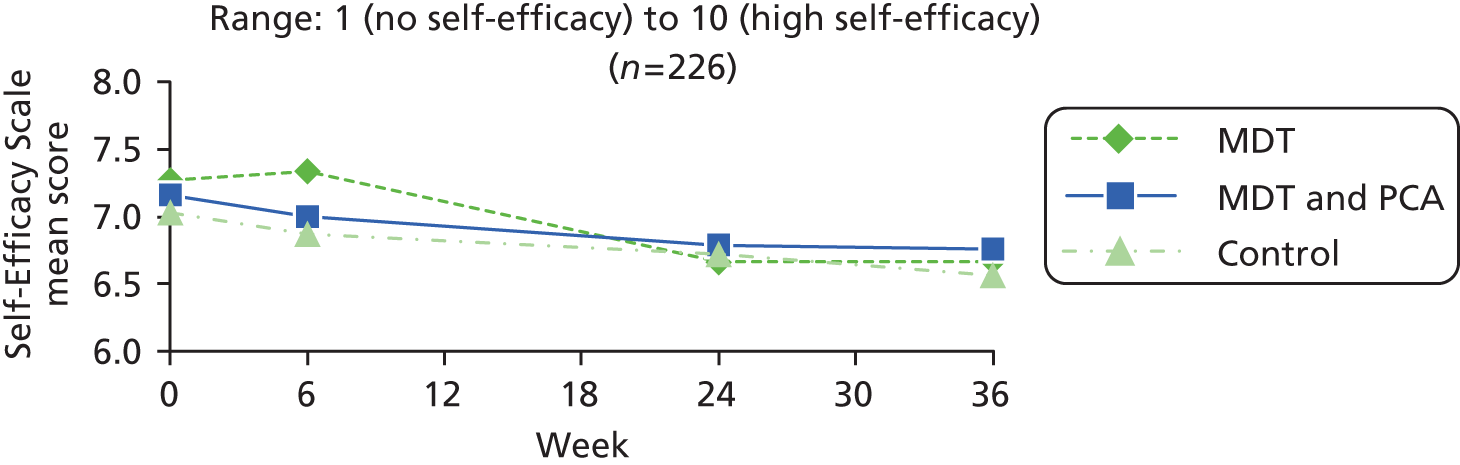

| Self-efficacy | Self-Efficacy Scale86 | Self-efficacy for managing chronic diseases six-item scale measures confidence in doing certain activities such as managing pain, fatigue and medications, each scored from 1 (not confident at all) to 10 (totally confident) and summed, and the mean calculated | 1 (no self-efficacy) to 10 (high self-efficacy) |

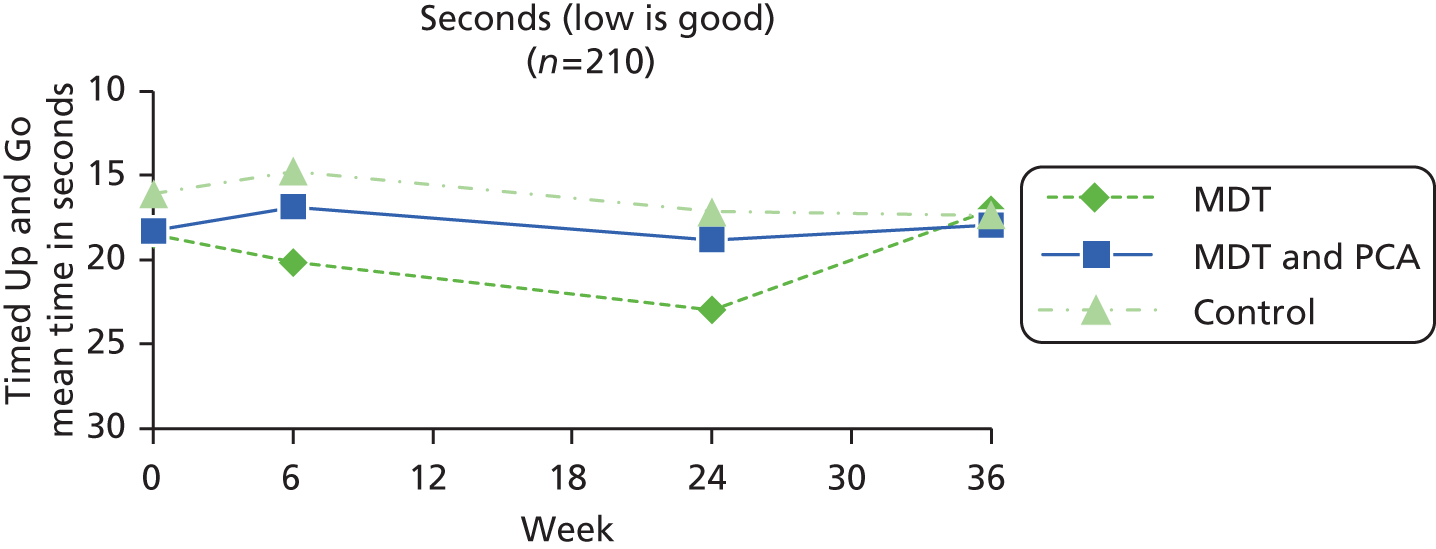

| Mobility | Timed Up and Go87,88 | Quick and simple nurse-measured indicator of ability to perform sequential locomotor tasks that incorporate walking and turning. Subject stands from a standard armchair, walks (a measured) 3 metres, turns, walks back and sits. The same chair should be used in repeated tests. Timed with stopwatch. Recorded mean, SD ‘off’ (‘on’): 17.2, 7.3 (13.7, 3.9) | Seconds (low number good) |

| Falls (self-report) | In last 3 months, have you fallen? Yes = 1, no = 0. If yes, asked how many times; if hurt themselves; if able to get up off the floor/ground; if saw doctor; if falls related to freezing | Yes = 1, no = 0 | |

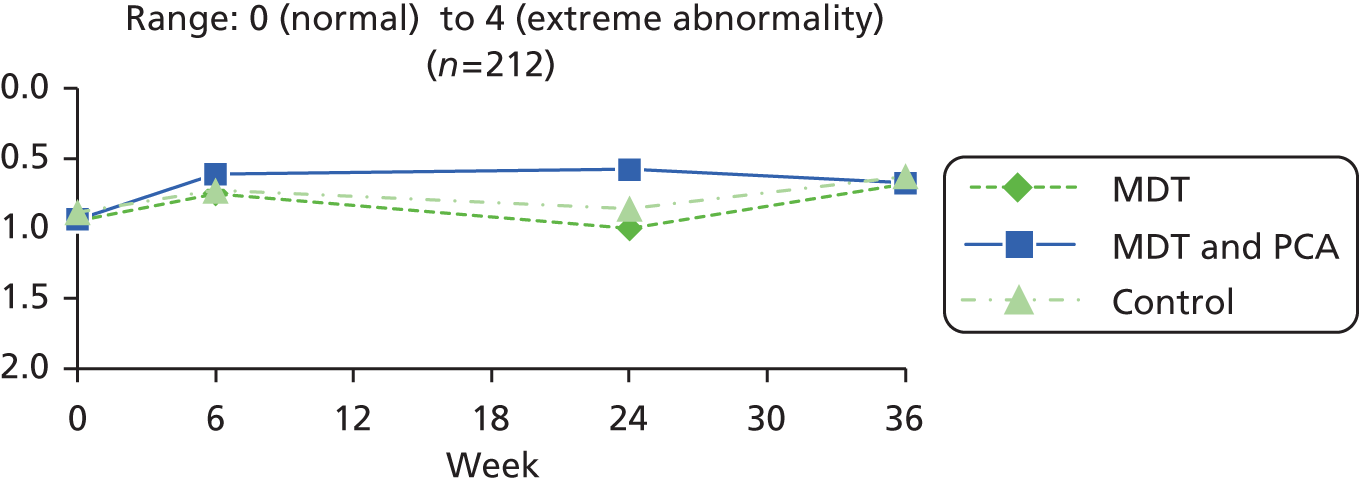

| Mobility | UPDRSb – posture item from motor examination part of the scale89 | 0: normal erect 1: not quite erect, slightly stooped posture; could be normal for older person 2: moderately stooped posture, definitely abnormal; can be slightly leaning to one side 3: severely stooped posture with kyphosis; can be moderately leaning to one side 4: marked flexion with extreme abnormality of posture |

0 (normal) to 4 (extreme, abnormal) |

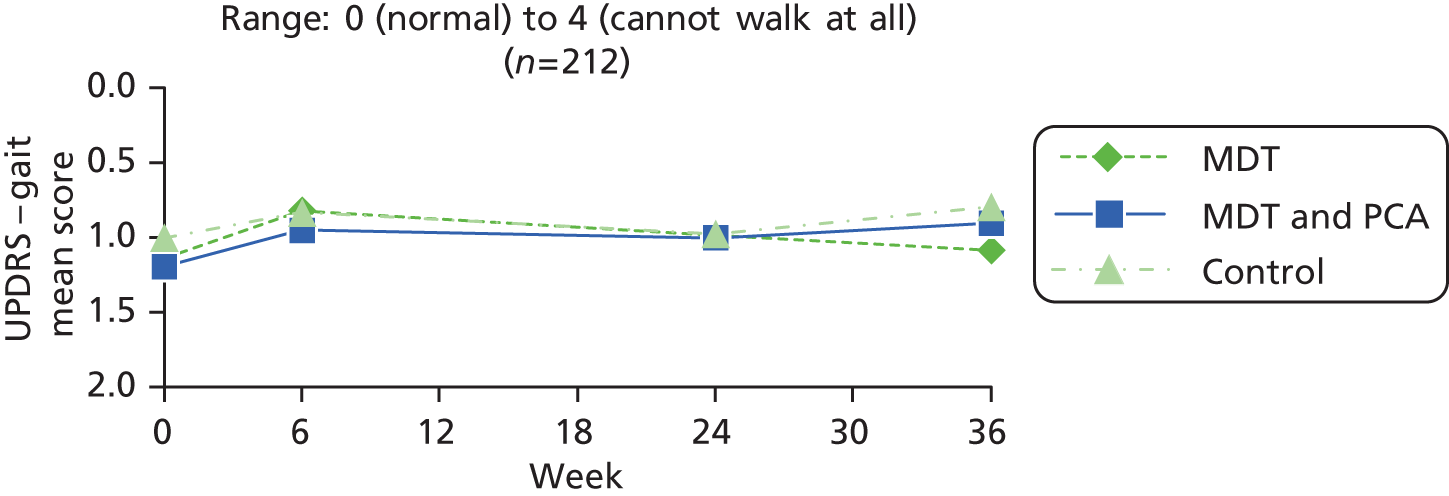

| UPDRSb – gait item from motor examination part of the scale89 | 0: normal 1: walks slowly, may shuffle with short steps, but no festination or propulsion 2: walks with difficulty, with little/no assistance; may have some festination, short steps, or propulsion 3: severe disturbance of gait, requiring assistance 4: cannot walk at all even with assistance |

0 (normal) to 4 (cannot walk at all) | |

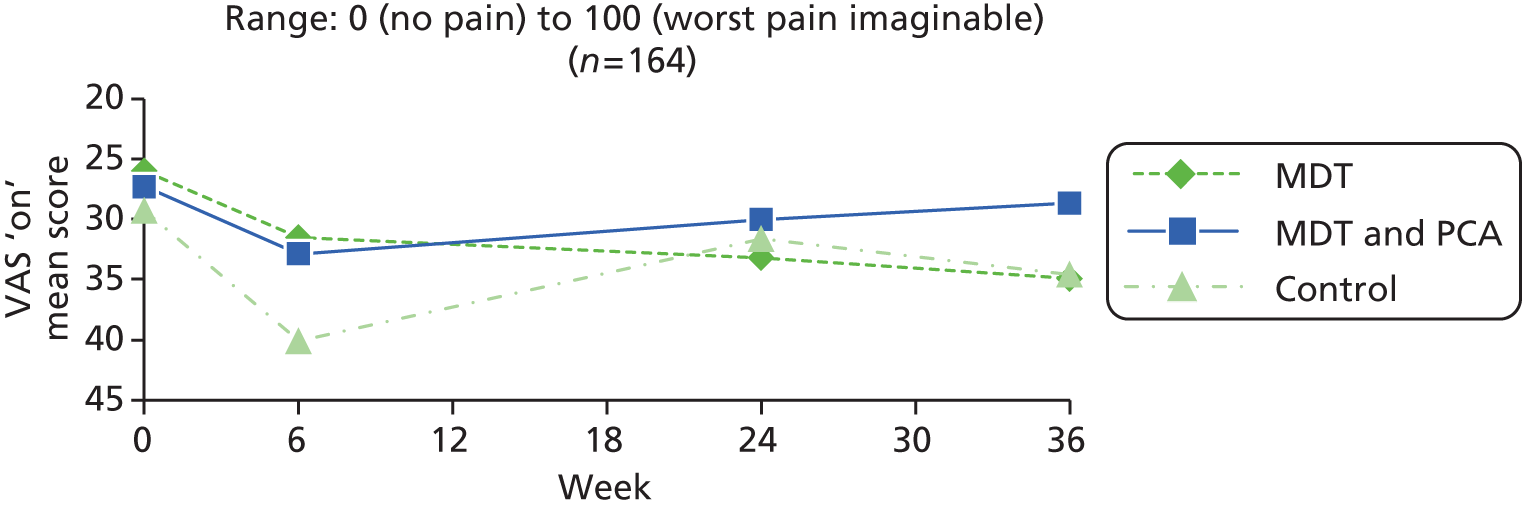

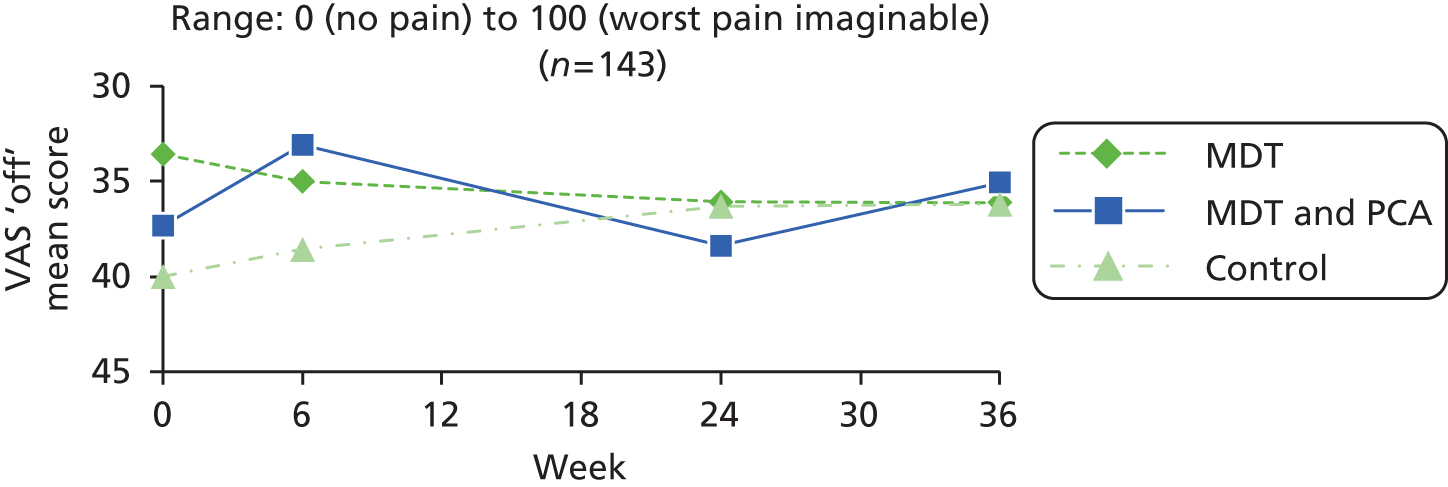

| Pain | VAS, in ‘on’ and ‘off’ states90–93 | Unidimensional measure of pain intensity, with low respondent burden, and widely used in diverse adult populations. The VAS is shown as a continuous 10 cm horizontal line anchored by verbal descriptors: 0 (no pain at all) to 10 (worst pain imaginable). Participants were asked to mark two VAS scales, one to show pain in the ‘on’ state and one for the ‘off’ state when pain ratings are typically higher. Measured by ruler in millimetres | 0 (no pain) to 100 (worst pain imaginable) |

| Participant: people with Parkinson’sa | |||

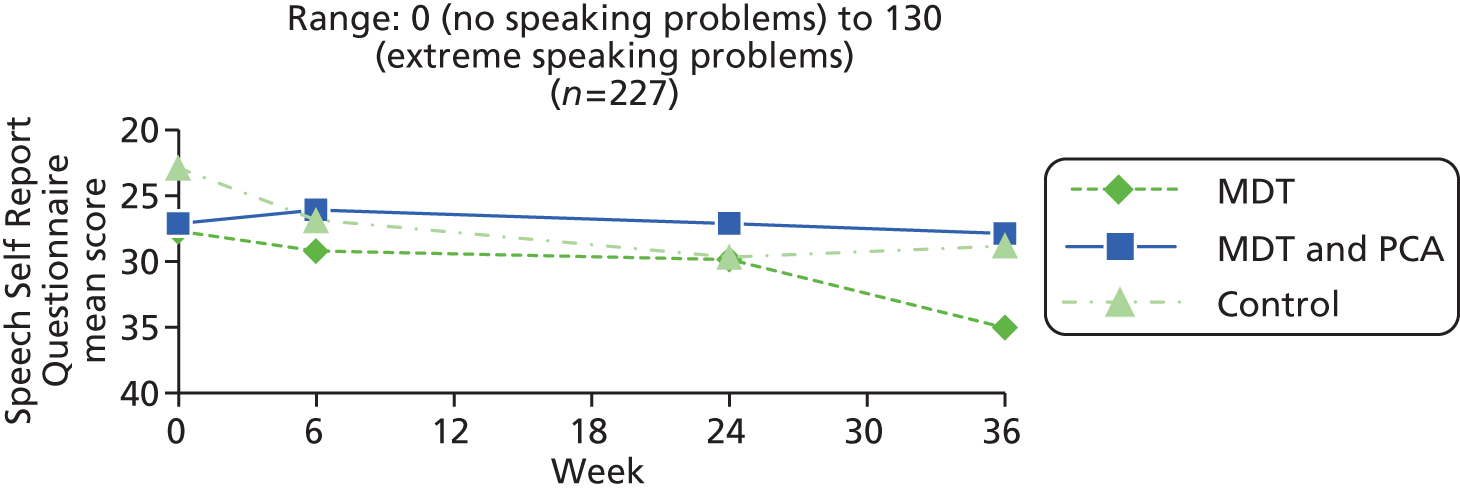

| Speech | Speech Self Report Questionnaire (reproduced in Appendix 13; available from authors) | Non-validated patient-centred questionnaire used successfully in previous trial.21,23,26,27 Used in clinical practice by SLT to identify problems encountered by patients, and comprises 11 statements about speech problems (e.g. voice is weak, husky, hesitant), and 15 statements about situations avoided (e.g. making telephone calls, ordering in a café, participating in a meeting), each scored 0 (never) to 5 (always) and summed, giving total score range of 0 (no speaking problems) to 130 (extreme speaking problems) | 0 (no speaking problems) to 130 (extreme speaking problems) |

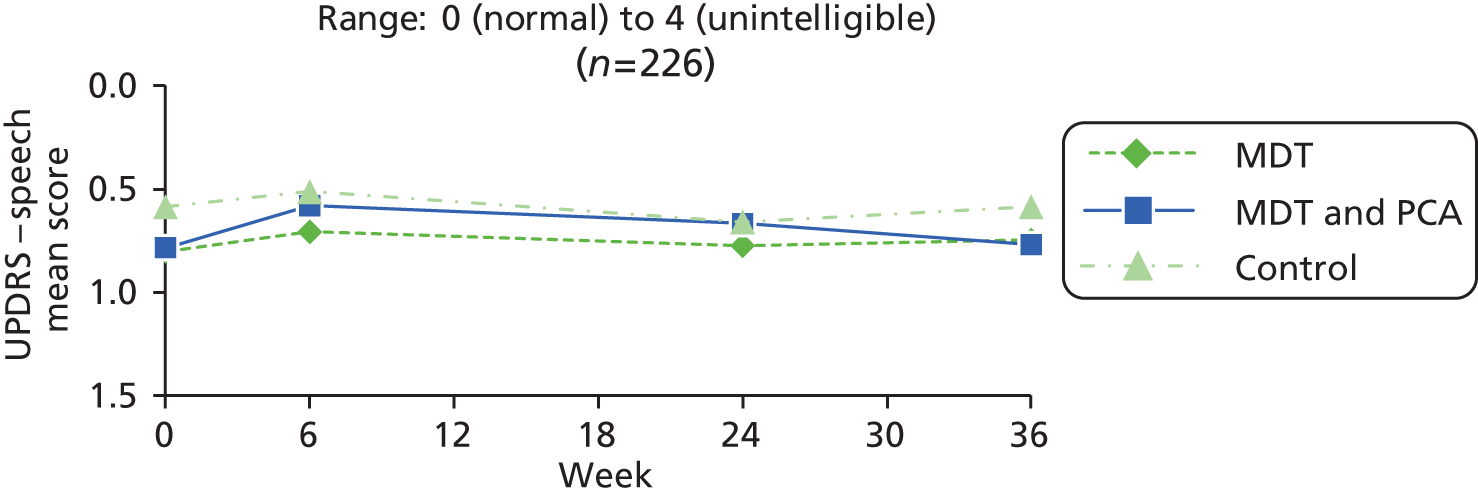

| UPDRSb – speech item in the ADL section89 | 0: normal 1: mildly affected, no difficulty being understood 2: moderately affected, sometimes asked to repeat statements 3: severely affected, frequently asked to repeat statements 4: unintelligible most of the time |

0 (normal) to 4 (unintelligible) | |

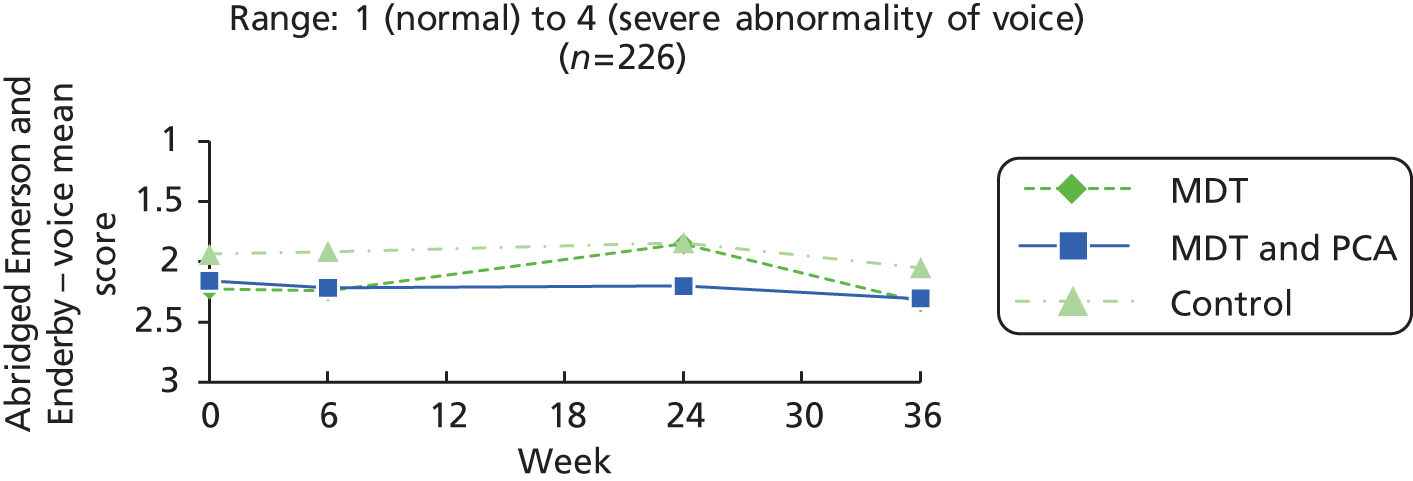

| Speech | Abridged Emerson and Enderby Screening Assessment Rating Scale – voice94 | 1: no impairment, voice normal for age and sex 2: slight impairment, slight abnormal nasality, quality or volume 3: moderate impairment, abnormal nasality, quality or volume 4: severe impairment, severely abnormal nasality, quality or volume |

1 (normal) to 4 (severe abnormality of voice) |

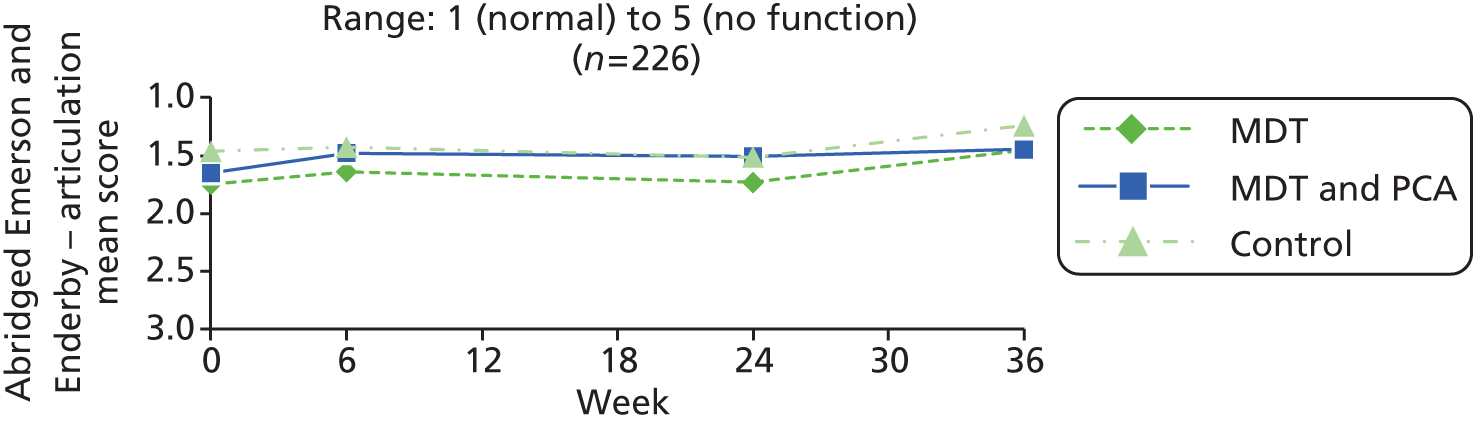

| Abridged Emerson and Enderby Screening Assessment Rating Scale – articulation94 | 1: no impairment, normal 2: slight impairment, a few articulatory substitutions, not usually affecting intelligibility 3: moderate impairment; abnormal articulation noticeable, sometimes affects intelligibility 4: severe impairment, many sounds articulated abnormally, intelligibility markedly affected |

1 (normal) to 4 (severe abnormality of articulation) | |

| Participant: live-in carersa | |||

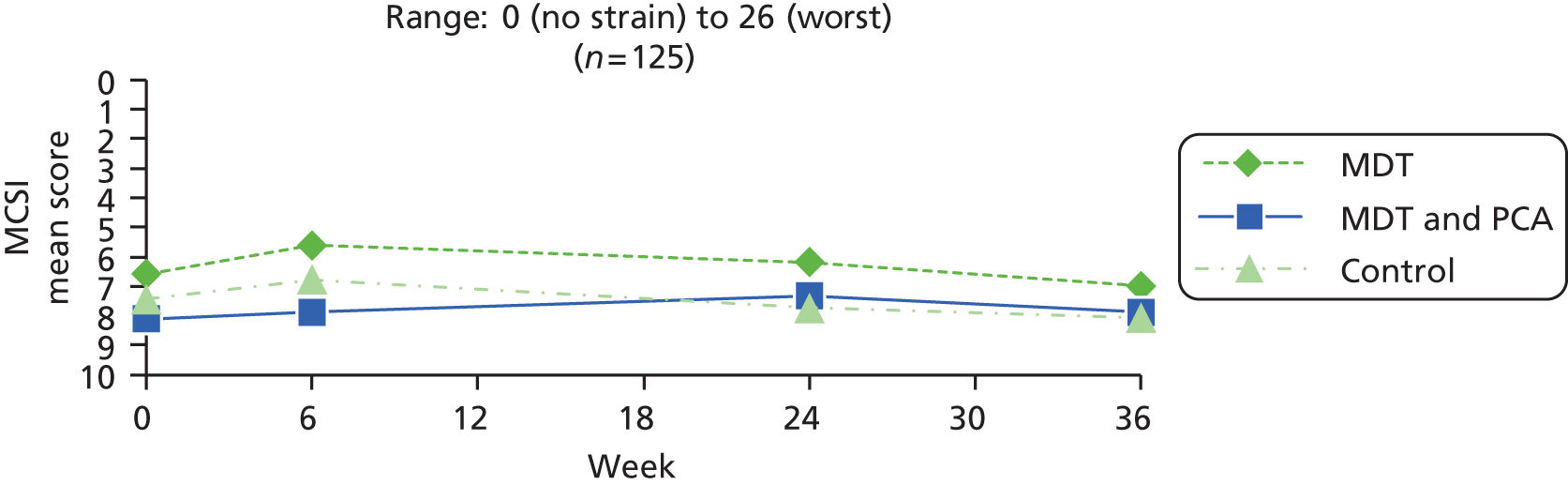

| Strain (primary outcome) | Modified Caregiver Strain Index71 | Fifteen items that caregivers can find difficult (e.g. disturbed sleep, financial strain, work adjustments), each rated on a three-point scale: 0 = no; 1 = yes, sometimes; 2 = yes, on a regular basis | 0 (no strain) to 26 (worst) |

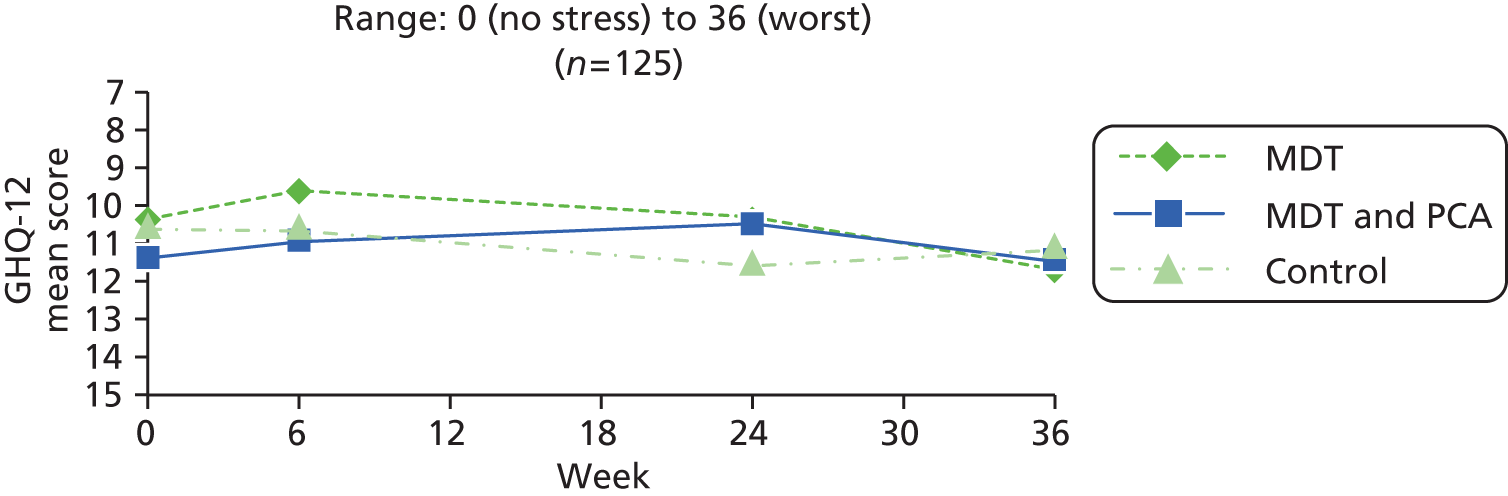

| General health | General Health Questionnaire –1295 | Widely used questionnaire to assess stress in carers, with 12 questions about their emotional state over the last 4 weeks (e.g. ability to concentrate, enjoyment of day-to-day activities, feeling happy, under strain, lost sleep), scored on four-point scale: 0 = better than usual/no problem; 1 = as usual; 2 = worse than usual; 3 = much worse than usual, and summed to give total 0 (no stress) to 36 (worst) | 0 (no stress) to 36 (worst) |

| Activities | Barthel ADL76 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | |

| Frenchay Activities Index77–79 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | ||

| HRQoL (generic) | EQ-5D Thermometer80,81 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | |

| EQ-5D Index80,81 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | ||

| SF-36 PCS82 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | ||

| HRQoL (generic) | SF-36 MCS82 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | |

| Psychological well-being | HADS – anxiety83 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | |

| HADS – depression83 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | ||

| Yale Depression Screen84,85 | As in people with Parkinson’s (above) | ||

Outcome assessments

Participants in all groups were assessed in their homes by a research nurse, at baseline, week 6 (at the end of the 6-week rehabilitation intervention), week 24 [4 months (18 weeks) after the end of rehabilitation, coinciding with the end of ongoing support for group B], and week 36 (for final follow-up). For each cohort of 30 people with Parkinson’s (and live-in carers), baseline assessments took place in the 6-week period prior to the start of the treatment phase. Assessments after the end of the 6-week treatment phase took place during the subsequent 6 weeks. The assessments at 24 and 36 weeks after baseline were arranged as close as possible to those stages for individual participants. In the event that participants were unavailable owing to holidays, illness or other reasons, visits would be arranged up to 6 weeks beyond the stipulated time. Beyond that, the assessment was deemed missed. Those unavailable at 24 weeks were contacted for their final 36-week follow-up assessment. The time between assessments was analysed on a per-patient basis.

When follow-up research assessments were due (cohort by cohort), participants were telephoned by the research office to make an appointment at a time convenient to them. A letter confirming the day and time of the visit was mailed, together with some of the outcome measures that were suitable for self-completion. To save time during the research nurse visits, participants (people with Parkinson’s and carers) were asked to complete these questionnaires in advance (see Appendix 13). At the visit, the research nurse checked or assisted with the self-completion questionnaires (which included the reporting of service use for the economic evaluation) and undertook the remaining assessments of the people with Parkinson’s: single-item depression screen; measures requiring clinical judgement (Timed Up and Go,87,88 posture, gait and speech items); and falls reporting (also for trial safety monitoring) (see Appendix 14). All questionnaires were checked for completeness before the research nurse left the participant’s home, and again in the research office. Any missing or unclear data were checked with participants as soon as possible after each assessment.

Inter-rater reliability

One full-time research nurse conducted assessments throughout the trial. Prior to starting data collection, visits to the home of members of the PPI group were arranged (a person with Parkinson’s and a live-in carer) so that the battery of assessments could be practised. The research nurse was accompanied on these visits by the research manager, so that any problems could be addressed. In particular, this enabled guidance for the safe conduct of the Timed Up and Go test to be established. It also served to identify the need for laminated sheets to be prepared with response options (in large print) for different questionnaires for use when participants could not self-complete and that data needed to be collected from them in an interview.

During the middle period of the trial, when several cohorts were at different stages of assessment, two part-time research nurses were employed to assist with the data collection. To ensure consistency of processes, the assistants were trained by the main research nurse through shared assessment visits. The first assessments undertaken by the assistant nurses were observed by the senior research nurse and followed by a debriefing discussion after it was completed.

Blinding

Group allocation was not known at baseline assessment, which took place prior to randomisation. Databases showing group allocations were not available to the research nurses. Moreover, the research nurses did not answer the office telephone because participants often called in to alter MDT appointments, and this would have compromised the nurses’ blinding. Participants were asked not to discuss aspects of the trial and treatments with the research nurses, and were reminded of this at each assessment visit. Despite this, some participants did disclose that they had been treated by mentioning MDT members or the care assistant during the second and third research assessment visits.

Blinding was broken at the end of the third (24-week) assessment, when research nurses collected feedback on the acceptability of the interventions (from groups A and B only). It was not possible to collect data on acceptability separately. Thus, the acceptability questionnaires were placed at the back of the pack of self-completion instruments that were mailed in advance to participants for the 24-week visit. Nurses collected and checked completeness of these packs prior to leaving the participant’s home, and were thus made aware of whether or not the participant had received the MDT intervention by the presence or absence of acceptability questionnaires. Research nurses might have remembered patients’ groups when they returned for the final 36-week assessment. However, they reported poor recall of group allocations because there were over 300 participants in the trial, they were undertaking contemporaneous assessments of several cohorts at any point in time, and there was a gap of 3 or 4 months between the follow-up assessments.

Acceptability of the intervention

Participants

Semistructured questionnaires were designed to gather feedback on the acceptability of the interventions from group A and B participants at the end of the 24-week research assessment (separate forms for people with Parkinson’s and live-in carers) (see Appendix 15). This part of the study sought to capture the patient and carer voice and experience of the rehabilitation interventions relative to perceived needs and priorities. The questionnaires contained rating scales and open-text fields regarding how helpful, or how successful, participants found different aspects of the programme or the programme as a whole, and how they thought it could be improved. Items on value for money were included.

However, the research nurse found that many participants were having problems recalling the MDT phase, which had been completed 4 months earlier. As a result, a decision was taken to send the questionnaire (with questions relating to the PCA component removed) to participants by mail (to protect blinding) at the 6-week assessment point. Participants were sent a stamped addressed envelope for the return of the questionnaires. The research office reminded participants by telephone to ensure a good response rate. This change was implemented from the fourth cohort onwards (i.e. it did not apply to the pilot cohort or the first two cohorts that are included in the analysis). The acceptability questionnaires continued to be distributed at the 24-week assessment point to collect feedback on ongoing benefit and the PCA input.

Multidisciplinary team professionals and Parkinson’s care assistants

All members of the MDT and the PCAs were asked to provide reflective feedback (in the form of open comments) on integrated team working, team functioning and their individual role, and the delivery of the intervention at the end of cohorts 2, 6, and 8 (see Appendix 16). In addition, a structured feedback form was circulated at the end of the intervention, asking for Likert scale ratings and comments on communication and support within the team, delegation of responsibilities, involvement of patients and carers in care planning, and examples of good practice and challenging situations that they had encountered (see Appendix 16).

‘Exit’ interviews were also conducted with all team members, and PCAs, to learn about their views and experiences of MDT working. The interviews were conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher, who was a member of the project team but who had minimal contact with the day-to-day working of the MDT. The interview took the form of a conversation, guided by a list of topics (see Appendix 17). The main points were noted by hand. In addition, during the analysis phase of the study, the lead PNS wrote a report on the intervention, including observations on team working and illustrative participant case studies.

Stakeholder interviews

It was originally intended that service providers and a selection of commissioners would be asked for their views about the intervention, to identify strengths and weaknesses, and barriers and facilitators to its wider implementation. However, during the project period, significant organisational changes were put in place within the NHS (replacement of primary care trusts with local commissioning groups) to take effect shortly after the project ended. This made it difficult to identify the relevant stakeholders. Following discussion with the external advisory group, it was decided that this part of the project would be integrated into dissemination activities.

Sample size calculations

Patient sample size calculations were based on detecting clinically meaningful differences in the primary patient outcome measure. Carer sample sizes reflected the findings of previous work that suggest that 79% of people with Parkinson’s have a carer. 21

It was planned to recruit 270 people with Parkinson’s over a 12-month period across the three areas, with 90 randomly allocated to each of the three groups. This calculation was based on the numbers of people with Parkinson’s needed to detect differences between groups in changes in the primary outcome: Self-Assessment Parkinson’s Disease Disability Scale. 69,70 Assuming a similar level of variation as in the day-hospital trial,23 in order to detect a difference in the changes in the disability score of 1.25 [with standard deviation (SD) = 2.5, size = 5%, power = 80% and a two-sided test], 64 subjects with Parkinson’s disease were needed in each of the three groups.

Assuming a similar level of variation in the primary outcome – Modified Caregiver Strain Index71 – as in the day-hospital trial,23 in order to detect a difference between groups in the changes in the Modified Caregiver Strain Index of 0.535 (with SD = 1.07, size = 5%, power = 80% and a two-sided test), 64 carers were needed in each of the three groups. In the previous study, 79% of community-dwelling people with Parkinson’s had a live-in carer. 21 Thus, if there were 64 carers per group, this necessitated 246 [(64 × 3)/0.79 = 243.04] Parkinson’s subjects, i.e. 82 per group.

In the previous day-hospital trial, the loss to follow-up/non-completion/missing data rate between recruitment and the 6-month assessments was 26%. However, in that trial, participants attended the day hospital for treatment (six visits) and research assessments (four visits), and difficulties with transport and intercurrent illness accounted for missing data and drop-out. We expected less attrition in the SPIRiTT trial because participants would receive both treatment and the research assessments in their own homes, at times convenient to them.

Allowing for 10% loss to follow-up/non-completion/missing data rates for people with Parkinson’s, 243.04/0.90 = 270.04 patients were required = 90 per group. With 90 patients per group, we expected to recruit 71 carers per group. These group sizes would also ensure that the samples for patients and carers would both remain above the critical values of 64 if there was a loss of 5% of carers (and associated patients) and an independent loss of 5% of people with Parkinson’s.

Withdrawals

Participants could withdraw from the study due to illness or personal reasons. They were made aware (via the information sheet and consent form) that withdrawal from the study would not affect their future care, and that data collected to date would still be used in the final analysis. Volunteers who were not randomised because they failed eligibility criteria at baseline were replaced, but participants who withdrew from the trial for any other reason were not replaced.

Data management

Data were entered into IBM SPSS Statistics version 19 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) databases using the trial unique patient identification number. Separate databases were constructed for:

-

information collected at baseline and on outcomes (all four assessments), by cohort, and combined for the analysis at the end of the trial

-

the data from the patient and live-in carer acceptability questionnaires

-

items from the CRF that were needed (a) for the calculation of the costs of the treatment programme (number and duration of therapist visits and telephone calls) for the economic evaluation, and (b) to illustrate MDT activity (quantifiable variables only, i.e. referrals made, medication changes recommended, recommendations made by the OT for aids and adaptations).

Contact details and GP details of participants were kept in an administrative database separate from the research information. All paper data were stored in locked cabinets, and all computer data were stored on a secure server.

Data were entered by one person and checked by a second, with random checking (using random numbers and ID numbers) of five persons with Parkinson’s and five carers in each cohort. If errors were found, the rate of checking was increased. The statistician, who was blinded to group allocation until all databases were completed, undertook further data cleaning.

Statistical analysis

Data relating to people with Parkinson’s and carers were analysed separately.

The analysis started with an intention-to-treat (ITT) approach, based on group assignment (excluding the pilot cohort), and including participants who had provided information at baseline assessment but had subsequently withdrawn, had not been available for assessments or were lost to follow-up. Some participants completing a baseline assessment had dropped out prior to treatment. A per-protocol analysis (PPA) was, therefore, also conducted, restricted to participants who fulfilled the protocol in terms of eligibility, interventions and all outcome assessments.

Baseline data (week 0) were analysed to describe the characteristics of the participants and to check for significant imbalance between the three groups with respect to background characteristics and outcomes, using appropriate statistical tests. The characteristics of the participants who were lost in the PPA were compared with those of the full ITT sample.

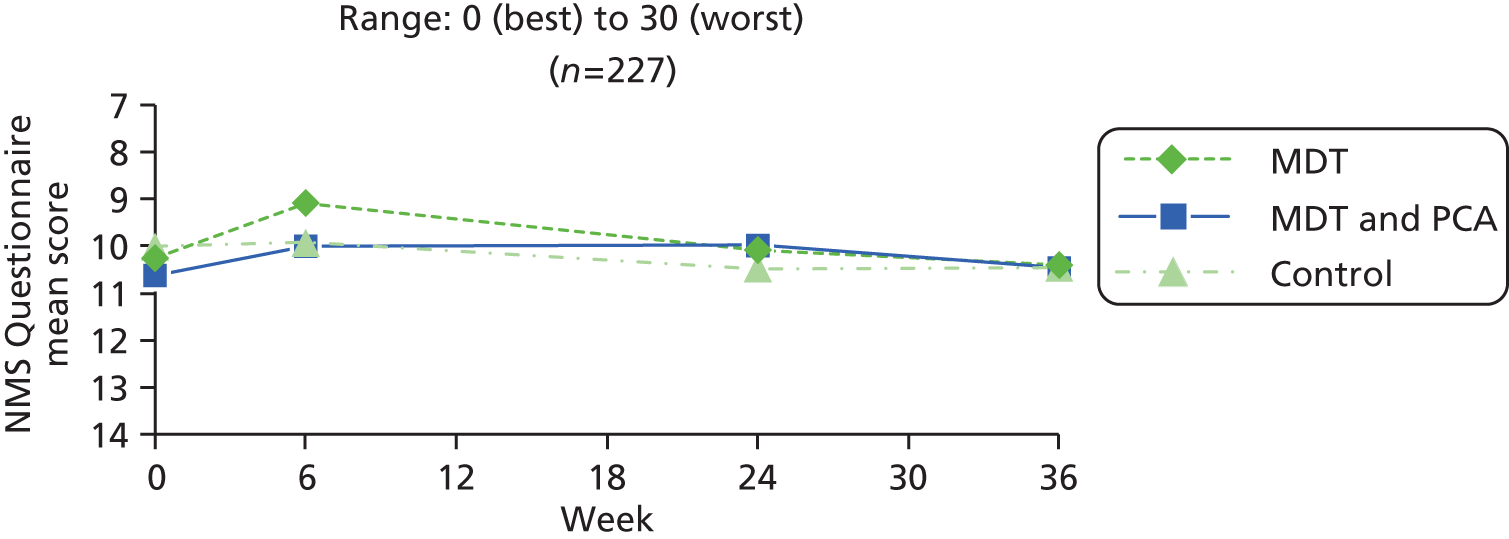

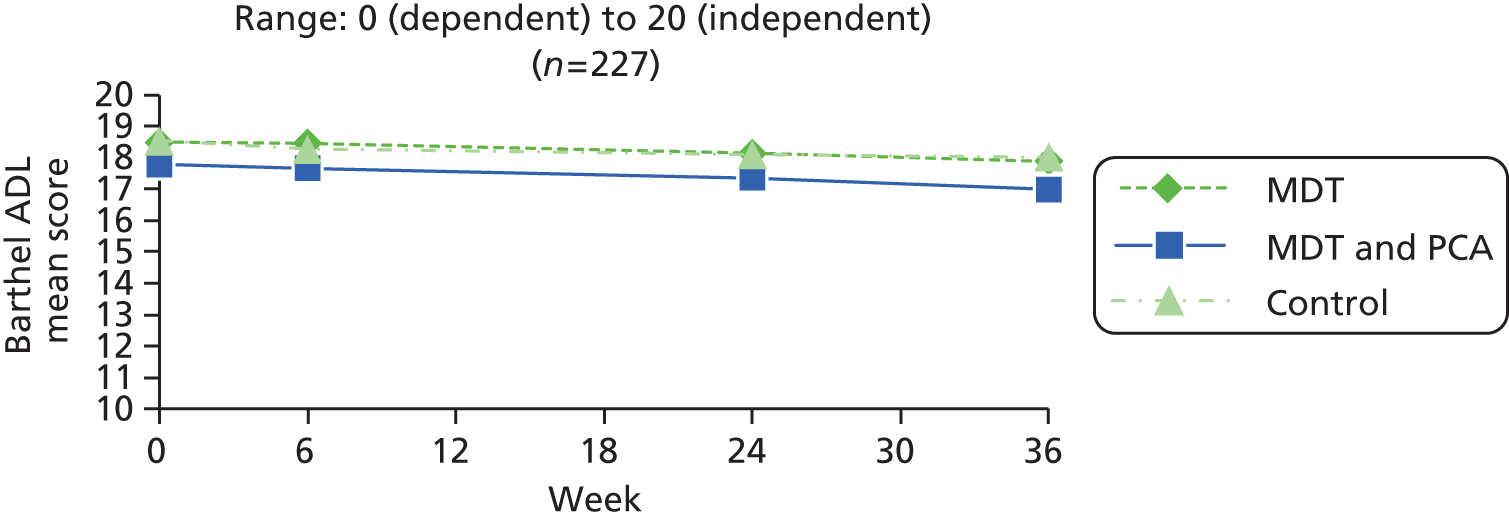

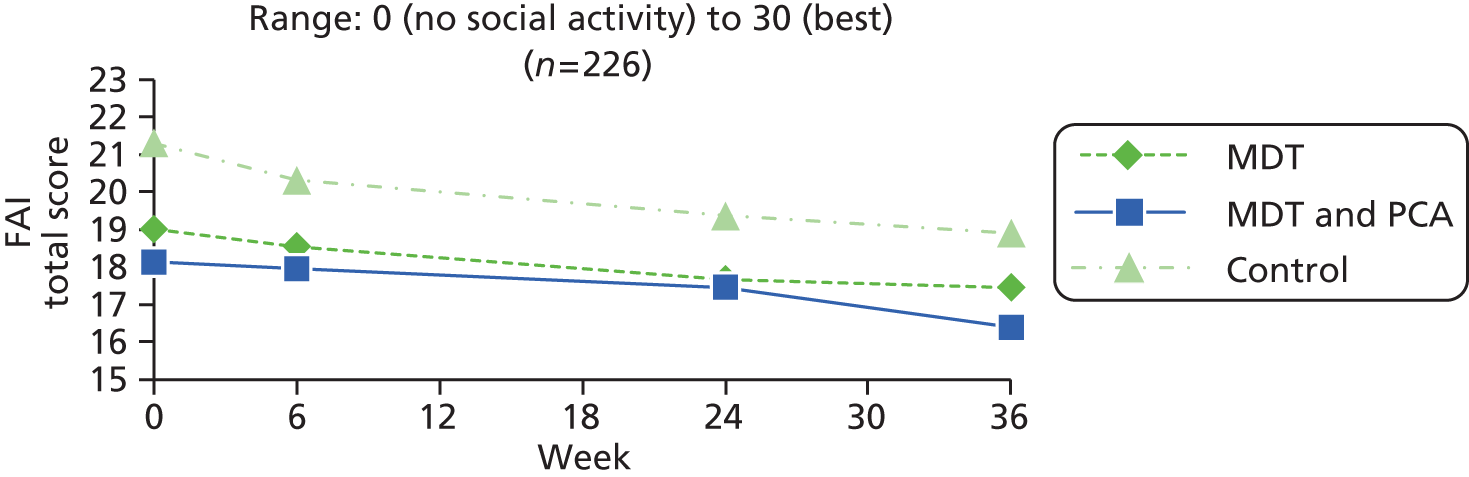

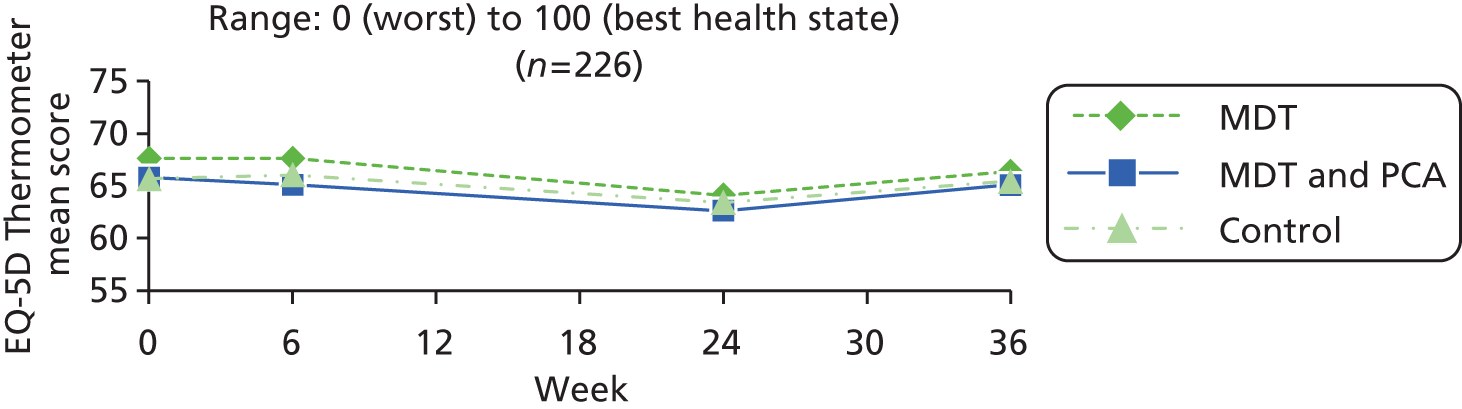

All outcomes were analysed at each follow-up assessment point [6 (post MDT treatment), 24 (post PCA) and 36 weeks (final end point)]. A series of null hypotheses were set out a priori for testing. Groups were compared with respect to changes in outcome measures between assessment points.

In order to identify short-term effects arising from the MDT intervention, change scores (week 6 minus week 0) of each participant in the specialist rehabilitation groups (A and B) were compared with those of participants in the control group (group C). The null hypotheses tested were that there were no differences between the groups (A + B vs. C) with respect to change in any outcome.

The impact of the PCA support for group B from week 6 to week 24 was assessed by comparing changes in outcomes for group A versus group B between week 6 (end of MDT intervention for both groups) and week 24 (end of PCA intervention for group B). The null hypotheses tested were that there were no differences between the groups (A vs. B) with respect to change in any outcome (week 24 minus week 6). This analysis was designed to show loss or maintenance of effects arising from the PCA support after the MDT input ceased.

Medium-term effects were further investigated through a comparison of all groups at 24 weeks (A vs. B, A vs. C, and B vs. C) using participants’ change scores from baseline (week 24 minus week 0). The null hypotheses tested were that there were no differences between the groups with respect to change in any outcome.

In order to identify long-term effects, groups were compared at 36 weeks (A vs. B, A vs. C, and B vs. C) using participants’ change scores from baseline (week 36 minus week 0). The null hypotheses tested were that there were no differences between the groups with respect to change in any outcome.

An additional exploratory analysis was performed using each participant’s change score for all outcomes between week 24 and week 36 (36 minus 24). This analysis provides evidence of trends in each group, and differences between groups, over the follow-up period after all interventions ceased in week 24.

Although multiple statistical tests were undertaken, adjustments for multiple testing were not made because a priori hypotheses were specified. Results are presented in full and selective reporting of significant results has been avoided. Furthermore, most outcomes are independent.

For all of the above analyses of changes, distributions were inspected to identify major aberrations from normality which could preclude the use of parametric tests. In most cases, raw data failed normality tests, but change scores were close to normal and parametric tests were used. One-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) tests were used for comparisons between all three groups, and unpaired t-tests were used for comparisons between pairs of groups. Within-group changes between assessment points were also explored using paired t-tests. In each case, a two-sided test was used.

Missing data

Stringent attempts were made to minimise missing data through checking questionnaires as they were completed, and returning to participants to retrieve missing items. If more than two responses were missing from an instrument, the whole instrument was disregarded for that individual. As a result, remaining missing responses within instruments were minimal, averaging 0.40% for people with Parkinson’s and 0.06% for live-in carers (see Appendix 18). These missing items were filled using the established procedures for that scale (if available), or else setting the value of the missing item to zero (or normal), i.e. the most favourable value. Some participants found it difficult to complete some outcome measures [e.g. the pain visual analogue scales (VASs)], and this resulted in non-response for that instrument and a smaller sample size in the analysis. The research nurses did not carry out the Timed Up and Go test if the participant was in an ‘off’ state during the assessment or was immobile due to injury or surgery.

Loss to follow-up

Collection of research data from participants in their own homes minimised the loss to follow-up. If participants could not be reached, or were away from home, or hospitalised at one follow-up point, they were contacted and asked to complete later assessments.

Analysis of the acceptability questionnaires

Responses from people with Parkinson’s and live-in carers were analysed separately and mainly focused on those sent by mail at 6 weeks (at the completion of the MDT intervention) from cohort 4 onwards. Questionnaires completed at 24 weeks were not fully analysed due to concerns about participant recall. Research nurses reported that by 24 weeks (4 months after the end of the MDT intervention), some participants found it difficult to remember the input of different professionals, sometimes confusing trial therapists with regular health and social care professionals who they had seen in the meantime. Two issues from the acceptability questionnaire distributed at 24 weeks were analysed: a question asking about continuing benefit beyond the end of the MDT intervention (at 6 weeks); and two items that specifically gave participants in group B an opportunity to comment on the PCA input over weeks 7–24.

Quantitative items (rating scales) were analysed descriptively and results were presented as proportions, means and SDs, depending on the nature of the questions. Text responses were transferred to a Microsoft Excel database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) for analysis. These questions asked, at the 6-week assessment, how helpful participants found the treatment; the most successful aspects of the programme; the least successful aspects of the programme; ways in which the programme could be improved; and for other comments about the treatment and the study overall. For each of these questions, the written responses were printed out and read several times by a researcher. Irrelevant comments that did not address the question were removed, including comments that were illegible and those relating to the research process (e.g. that there were too many forms to fill in). Main themes in the responses were then identified. The question from the 24-week assessment about continuing benefit from the MDT intervention was analysed in the same way. The process was independently checked by a second researcher.

Analysis of feedback from the multidisciplinary team and Parkinson’s care assistants

Notes taken during the ‘exit’ interviews were combined with reflections provided by team members during the trial and subjected to thematic analysis98 by the researcher who undertook the interviews. The analysis was checked by a second researcher.

Economic evaluation

The economic evaluation adopted a NHS perspective. Participants were treated in their own homes and incurred no costs in accessing treatment.

The resources used in the delivery of the intervention (both MDT and PCA components) were recorded in the individual participant CRFs. Information relating to patient contact [number and duration (in minutes) of visits and telephone calls to participants by individual therapists] was transferred to a patient-level SPSS database, and descriptive statistics were calculated. Time spent with individual professionals was summed to determine total minutes of contact with the MDT and with the PCA (group B). Data on total contact time were checked for normality (using histograms) and for variance. Variation was explored between groups A and B, and within cohorts, with respect to total MDT contact duration and PCA input (group B only), using appropriate statistical tests.

The costs of the intervention were calculated in Great British pounds (GBP) for 2011, at the level of individual patients, as the sum of the costs of (1) patient contact time (home visits and telephone calls) with all members of the MDT and with the PCA (group B), including an allowance for non-patient-facing follow-up tasks arising from visits or telephone calls, such as writing notes, arranging referrals, and discussion at MDT meetings; (2) travel expenditures and time spent in travel for home visits; and (3) a fixed 1 hour spent by the PNS in writing a letter to the GP of each participant to report on what care had been given to their patient.

Costs of staff time were obtained from validated national sources99 (see Appendix 19). The hourly rates used are inclusive of all on-costs, and management office/administrative support and facilities overheads. Following discussion with the professionals, an extra 30 minutes per home visit and 15 minutes per telephone call were added for time spent in non-patient-facing follow-up. The distances from the MDT base to the home postcodes of all participants in the study were obtained, and the median distance taken as the basis for calculating the travel costs for all home visits, and the NHS mileage reimbursement rate was applied. Professional time spent in travel was costed on the basis of an assumed 20 miles per hour (which was judged appropriate for the suburban/rural nature of the catchment area). Unit costs used in the calculations are shown in Appendix 19. Costs of the MDT intervention were compared between groups A and B, and between cohorts, to confirm uniformity of delivery.

The use of health and social care services [hospital in- and outpatient, accident and emergency (A&E), GP and a range of other community health and social services, respite care in residential settings, personal social services] were collected by self-report at baseline, 24- and 36-week assessments by recall for the previous 3 months. Participants were also asked about informal (unpaid care from family and friends). Service use was analysed descriptively at group level. The costs of health services were calculated at each assessment point using unit costs obtained from national sources99 (see Appendix 20), multiplied by the number of units used. Weekly day-care use was multiplied by 12 to give the cost over 3 months. Contacts with GPs at home and in the surgery were combined as one category, but the appropriate unit cost was applied to each component. Where participants reported self-paying for services, the costs were excluded from the calculations. Costs of service utilisation in the intervention groups (A and B) were compared with each other and with the usual-care group (C) to assess the extent to which the costs of the interventions may be offset by savings elsewhere in the health and social care system. The costs of tests, social and informal care reported by participants were not calculated due to insufficient details about the type and frequency of the service.

Clinical results were inspected to assess the value of conducting a cost-effectiveness analysis. If statistically significant differences in change scores between groups were found for either the patient or carer primary outcome measures, or European Quality of Life-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) Index scores (for quality-adjusted life-years), at the final end point (6 months), a full cost-effectiveness/cost–utility analysis would be conducted. Otherwise, the costs of the intervention would be evaluated in relation to the broader range of patient and carer consequences/outcomes. 100

Risks and adverse events

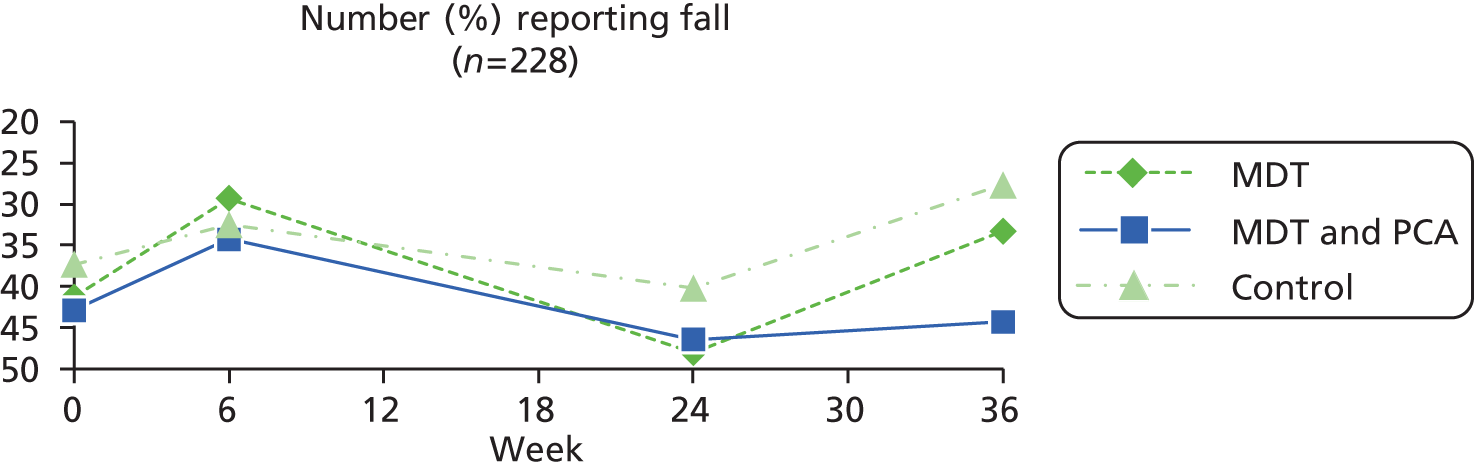

Risks to participants from the trial were considered small, and no higher than those of usual care. The MDT intervention was delivered by experienced professionals and was based on standard practices that aim to improve self-awareness and management. It included assessment of home safety and aids and adaptations, and recommendations made to participants were intended to result in overall improvements in safety. The care assistants were fully trained, and worked under the instruction of team professionals, in the support of patients and carers and the implementation of the agreed care plan. However, it is possible that encouragement to exercise could result in falls that might not otherwise have occurred. Accordingly, falls were closely monitored and analysed on an ongoing basis. Fall rates reported during the trial were compared between groups and with baseline falls data. The external advisory group reviewed falls data at each meeting to ensure that the incidence of falls in intervention groups had not increased significantly since baseline, or in comparison with the control group. Other potential harms to the experimental groups included depression if raised expectations were not met, distress when additional input was stopped, and loss of support from family and friends if the additional care was perceived to reduce the need for informal support.

All adverse events (any unfavourable or unintended sign, symptom, syndrome or illness that developed or worsened during the period of the trial) and serious adverse events (life-threatening or resulting in hospitalisation, disability or death) were recorded. The information was gathered from various sources, including report by MDT, research nurses, telephone messages from participants, obituary notices, and information from doctors. All reported events were reviewed by the project manager, and assessed for seriousness, expectedness and causality by clinical members of the research team. Any serious adverse event deemed to be directly related to, or suspected to be related to, the intervention, and unexpected, was to be reported to the study external advisory group and the ethics committee.

Management and governance

The research team was run on a day-to-day basis by a full-time manager, with help from an administrative assistant. All aspects of data collection and management were under the supervision of the research manager, and analysis was undertaken by a statistician. The research team was supported in the delivery of the trial by an external steering committee, which met twice per year to review progress and ensure timely completion of milestones. Membership included clinical experts, experienced researchers, representatives from Parkinson’s UK and the European Parkinson’s Disease Association, local service providers and commissioners, and people with Parkinson’s and carers.