Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its proceeding programmes as project number 11/1014/06. The contractual start date was in April 2012. The final report began editorial review in June 2013 and was accepted for publication in February 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2014. This work was produced by Panagioti et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Background

In the context of the increasing prevalence and impact of long-term conditions,1 and increasing numbers of patients reporting multiple conditions,2 there is worldwide interest in innovations in service delivery that can better manage patients with long-term conditions in a way that is effective, patient-centred and efficient. 3

Current NHS policy for long-term conditions has been influenced by work done at Kaiser Permanente in the USA, and envisages care for long-term conditions based around three tiers representing three broad groups of patients with different needs. Care for patients in those tiers is supposed to be qualitatively different in content and process – the various aspects of care in each tier are shown in Box 1.

Designed for the highest users of unscheduled care, care at this tier may involve a ‘community matron’ or similar professional who adopts a case management approach, proactively intervening to anticipate potential crises and to co-ordinate the care from multiple agencies.

Disease-specific care managementDisease-specific care management may be focused on general practice teams identifying patients with long-term conditions through disease registers, following clinical protocols through regular clinical review and supporting self-management.

Supported self-managementThis involves assisting patients with conditions to manage their care through the development of appropriate confidence, skills and attitudes.

Adapted from Department of Health. Supporting People with Long Term Conditions: An NHS and Social Care Model to Support Local Innovation and Integration. London, HMSO; 2005. 4

Supported self-management

For the purposes of this report, the terms ‘self-care’ and ‘self-management’ will be considered synonymous.

Many different types of self-management have been described, including regulatory self-management (e.g. eating, sleeping and bathing), preventative self-management (e.g. exercising, dieting and brushing teeth), reactive self-management (e.g. responding to symptoms) and restorative self-management (e.g. adherence to treatment regimens). 5

Although different long-term conditions have varying requirements, across conditions a number of key tasks have been defined, including response to symptoms; response to acute episodes and emergencies; using medication; managing diet, exercise and giving up smoking; managing emotions, using relaxation and stress reduction; interacting effectively with health professionals; seeking information and appropriate community resources; adapting to work; and managing relations with significant others. 6

Self-management can involve a very wide range of activities, from basic health literacy and self-management skills, through to broader social activities (public engagement, and social capital). 7 There are also debates in the literature about the relative importance of self-management behaviours (e.g. changes in diet or exercise) and more general attitudes, such as self-efficacy, as it has been argued that the benefits of programmes such as the Stanford Chronic Disease Self-Management Programme (CDSMP) are mediated through self-efficacy changes. 8 Comprehensive models of self-management9,10 highlight the fact that self-management cannot be divorced from influences at other ‘levels’, such as health services, family and wider social networks,11 and the physical and sociocultural environment.

Formal self-management support in England is provided through a number of different models. 12 These include:

-

increasing access to health information13

-

deployment of assistive technologies such as telehealth and telecare14,15

-

facilitation of community-based skills training and support networks, such as the Dose Adjustment For Normal Eating (DAFNE)16 and Diabetes Education and Self-Management for Ongoing and Newly Diagnosed (DESMOND)17 courses for particular conditions and the NHS version of the CDSMP (the Expert Patients Programme)18 for generic long-term conditions

-

interventions led by health professionals. 9

The benefits of self-management

Despite a developing evidence base, there is a lack of clarity concerning the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-management interventions. A large metareview of 46 existing reviews of self-management interventions reported:

Despite the large number of studies . . . the evidence base still has large gaps. Long-term outcomes, cost-effectiveness, the comparative effectiveness of different . . . strategies, and which components of complex interventions provide the greatest benefit have not been adequately evaluated. 13

The limited effectiveness of self-management support reflects a number of factors. It may reflect intrinsic problems with the design of such interventions, or that the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness is moderated by patient characteristics or contextual factors such that only some populations (patterned by demography, clinical conditions or other factors) show benefit. Equally, it may reflect problems in the implementation of self-management support, such as limited engagement from patients and professionals,19 lack of reach into marginalised groups who have most capacity to benefit and a lack of integration with other long-term condition initiatives. 20 Self-management support interventions are unlikely to reflect the considerable inputs and mobilisation of resources undertaken by others in a personal social network. 21

Self-management and demand management

Self-management is an attractive proposition to the management of long-term conditions for a number of reasons. As well as the potential benefits for health, self-management offers a more participatory approach to health care, with patients making a critical contribution to achieving health gain and making decisions to ensure that their care is personalised to their needs.

However, a key part of the driver for health policy is the potential of self-management to make a significant contribution to the efficient delivery of health care. The influential Wanless report suggested that the future costs of health care would be related to the degree to which people became engaged with their health and its management. 22 Although the health costs associated with ageing are a matter of controversy,23 health services are facing major challenges in terms of the projected increases in those aged ≥ 65 years, the consequent prevalence of multimorbidity and concomitant increases in demand associated with these demographic changes.

The global financial crisis and central government pressure for major savings has meant that even greater focus is being placed on efficiency in health-care delivery. The Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) initiative in the NHS is designed to identify efficiencies through service redesign. Increasing self-management support is a major focus of the programme. 24

Although self-management support has been highlighted as having a significant contribution to make to efficiency, there are uncertainties about the scale of that contribution. Initial reports of major effects of self-management support on health-care utilisation25 have not always been replicated26 and the fact that the main impact of some interventions is on intermediate outcomes (such as self-efficacy) rather than health and health-care utilisation has led to controversy over the overall impact of self-management. 27,28 Some implementation of self-management support may have inadvertently driven up demand in populations to which self-management is directed. 29

Economic analysis in health services is based on the principle of opportunity cost, i.e. any one use of resources involves a ‘cost’ associated with the lost potential from alternative uses. Efficiency involves maximising outcomes for a given cost or minimising costs for a given level of outcome.

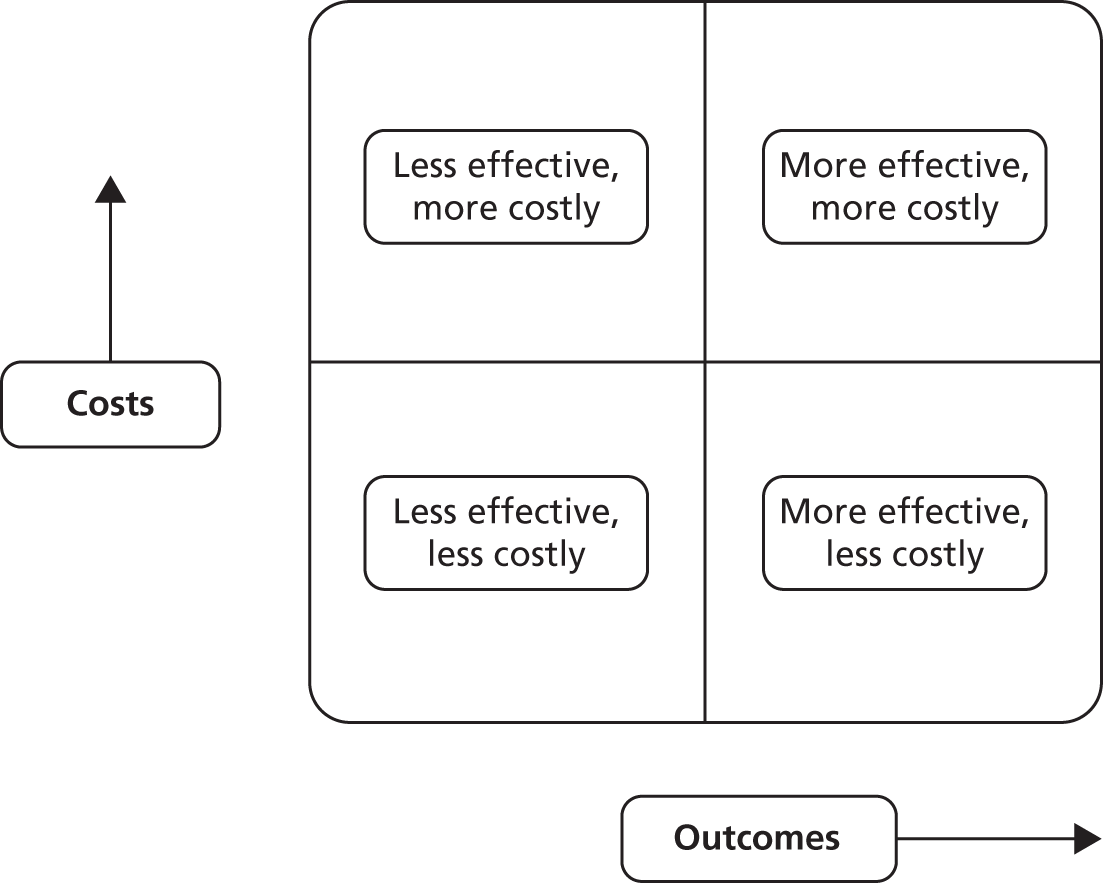

However, many health-care interventions improve outcomes and increase costs, which means decision-makers are faced with decisions about ‘allocative efficiency’: additional resources are required to provide the new service, which incurs an opportunity cost for other groups of patients. 30 Economists use the concept of the cost-effectiveness plane to illustrate the relationships between costs and outcomes (Figure 1). Many health-care interventions are placed in the ‘top right’ quadrant of the cost-effectiveness plane and raise such ‘allocative efficiency’ questions for decision-makers.

FIGURE 1.

Cost-effectiveness plane.

However, the financial pressures faced by health systems means that there is increasing interest in interventions that are ‘technically efficient’. This is defined as an intervention which is less costly and at least as effective as current treatments. 30 An implicit assumption underlying interest in self-management support is that delivering care in this way has the potential to be technically efficient, by shifting some activity from health services to the patient and by more effective management of problems to avoid crises and the need for more extensive health service intervention.

Assessing the technical efficiency of self-management support is best achieved through comprehensive economic analyses using an assessment (and quantification) of both quality of life (QoL) and costs, to assess the location of the intervention on the cost-effectiveness plane. Although there are increasing numbers of full economic analyses, many self-management studies have not conducted such a full economic analysis, but many have included data on outcomes and costs, which may allow placement on the plane.

The aim of this review is to conduct a comprehensive assessment of the current evidence around self-management support to judge the degree to which current models of support reduce utilisation without compromising outcomes.

The results of the Reducing Care Utilisation through Self-management Interventions (RECURSIVE) review need to be considered alongside the Practical Systematic Review of Self-management support for long-term conditions (PRISMS) study,31 which is a broader assessment of the role of self-management support in long-term conditions using a variety of metareview techniques. 31

Chapter 2 Research questions

What models of self-management support are associated with significant reductions in health services utilisation (including admissions) without compromising outcomes, among patients with long-term conditions?

-

Population: patients with long-term conditions.

-

Intervention: self-management support.

-

Comparison: usual care.

-

Outcomes: service utilisation (including admissions) and QoL.

-

Study design: randomised controlled trials (RCTs).

What are the key recommendations for service commissioners and research funding bodies on delivery of self-management support and future research priorities?

Chapter 3 Review methods

Population

We included studies of patients with long-term conditions.

There is no definitive list of such conditions and we adopted the generic definition of a long-term condition as one that cannot be cured but can be managed through medication and/or therapy. This included common conditions such as diabetes, asthma, coronary heart disease, as well as more rare disorders and mental health conditions such as depression, anxiety and psychosis. We also included studies recruiting patients with a mixture of long-term conditions, as well as those recruiting on the basis of multimorbidity.

As well as using clinical and diagnostic labels reported in the studies, we also structured aspects of our review on potentially important characteristics of long-term conditions discussed at the first PRISMS workshop (Table 1). 31

| Cluster | Exemplar conditions |

|---|---|

|

Asthma, low back pain, type 1 diabetes, chronic pain, depression, schizophrenia, inflammatory bowel disease, migraine, endometriosis |

|

Hypertension, type 2 diabetes, epilepsy, allergy/anaphylaxis, atrial fibrillation, chronic kidney disease |

|

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, congestive heart failure, multiple sclerosis |

|

Osteoarthritis, dementia, chronic fatigue syndrome, progressive neurological conditions (Parkinson’s, multiple sclerosis, motor neuron disease) |

We excluded subjects < 18 years of age and studies conducted in the developing world.

Intervention

For the purposes of the review, we defined a self-management support intervention as:

An intervention primarily designed to develop the abilities of patients to undertake management of health conditions through education, training and support to develop patient knowledge, skills or psychological and social resources.

Categories of support of relevance to the review are outlined in Table 2. It is important to note that we excluded self-management undertaken without input, guidance or facilitation by services. Although an enormous amount of self-management is undertaken without any support from services, it is rarely the subject of intervention studies.

| Type | Examples |

|---|---|

| Education/training for providers | Training programmes which help providers counsel patients more skilfully, particularly in relation to behaviour change |

| Education/training for patients/carers | Disease-specific education or behaviour change interventions. Modes of education delivery may include online, paper based, face to face or through audio/visual technologies |

| Decision support | Support to make shared decisions about treatment options |

| Monitoring and feedback | Telehealth, such as telephone-, mobile phone- or computer-based monitoring methods, with monitoring by professionals and potential access to a wider team |

| Environmental adaptations | Supported living equipment and home modification, or telecare |

| Care or action plans | Discussion and negotiation between patients and professionals about management and goals, often involving a written plan |

| Exercise | Training and formal exercise programmes |

| Psychological support | Peer support (face to face or online, or more formal supportive counselling or therapy) |

| Financial interventions | Personal health budgets or payments for achieving treatment tasks or goals |

We included all formats and delivery methods (group or individual, face to face or remote, professional or peer led).

In line with the original brief, we included interventions across the pyramid of care for long-term conditions. After initial screening of a proportion of the studies, we distinguished the following types post hoc:

-

‘pure’ self-management, with self-management materials provided without any additional support beyond that provided in usual care

-

supported self-management (with up to 2 hours of additional support in total from a health professional or trained peer)

-

intensively supported self-management (with more than 2 hours of additional support from a health professional or trained peer)

-

case management (with more than 2 hours of additional support from a health professional or trained peer, and support from a multidisciplinary team as part of the intervention protocol).

The adoption of the 2-hour threshold was an arbitrary empirical threshold that provided a reasonable distribution of studies among the different categories.

Two authors independently assessed the type of intervention and disagreements were identified and resolved through discussion. For analytical purposes we combined the first three categories into a broad ‘self-management’ category and compared that with ‘case management’.

Comparisons

We included studies for which a self-management support intervention was additional to usual care and compared this against usual care alone or against studies for which the self-management support intervention was compared with a more intensive ‘usual care’ intervention (e.g. ‘hospital at home’ vs. conventional hospital use). We excluded studies for which two versions of self-management support interventions were compared, as such comparisons did not allow assessment of the impact of the self-management support per se.

Outcomes

We extracted data on the effect of self-management interventions on core types of health-care utilisation. Our focus was on comprehensive measures of costs (i.e. summaries including multiple sources of cost) or major cost drivers (i.e. hospital use). Other, more minor, costs (such as medication and primary care visits) were identified but not analysed. Our focus was on hospital use and total costs.

We also separately extracted data on outcomes relating to patient QoL and health outcomes. These included standardised measures of disease-specific outcomes, generic QoL and depression/anxiety. We excluded measures of psychological or clinical variables that did not provide a direct assessment of health or QoL, such as self-management behaviour, self-efficacy, glycosylated haemoglobin (HbA1c) or forced expiratory volume (FEV), as these are likely to be unreliable indicators of health-related quality of life (HRQoL). 32

Study design

We included only RCTs in the review, as these studies give optimal protection against selection bias, and excluded quantitative studies lower down the hierarchy of evidence about clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness (non-randomised trials, longitudinal studies and cross-sectional studies).

Review protocol

The review protocol – Reducing Care Utilisation through Self-management Interventions (RECURSIVE): a quantitative review of self-management support to reduce utilisation without compromising outcomes (registration number CRD42012002694) – is available as part of the PROSPERO database and is provided in Appendix 1. We have been explicit about any deviations from the published protocol in this report.

Identification of studies

We began the process of identifying eligible studies by checking published reviews, including those identified by the PRISMS study. 15,33–81

We complemented searches of existing reviews with a primary search of multiple databases, conducted in 2012. Databases included the Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health (CINAHL), EconLit (the American Economic Association’s electronic bibliography), EMBASE, Health Economics Evaluations Database, MEDLINE (the US National Library of Medicine’s database), MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) and the PsycINFO (the behavioural science and mental health database).

A search strategy was developed in MEDLINE, using an iterative approach and a set of existing studies known to be relevant. This strategy was then adapted to run on the remaining databases.

The actual search strategies (developed in conjunction with an information specialist at the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, University of York, York, UK) and details of the searches are listed in Appendix 2.

The titles and abstracts of all the studies identified were screened for eligibility. More than 40% of all the studies (n = 5000) were independently screened by two members of our research team. Disagreements were dealt with by discussion and the involvement of a third reviewer. Because high levels of inter-rater reliability were achieved (κ = 87%), the abstract screening of the remaining studies was completed by one reviewer.

Studies had to fulfil three inclusion criteria to be eligible for full-text screening:

-

RCTs

-

long-term conditions

-

self-management or case management intervention.

If the studies did not meet one or more of these three criteria, they were excluded from the review. Those studies that did not provide sufficient information to rate their eligibility on the basis of the above criteria were retained for full-text screening.

Approximately one-third of the full texts were screened by two reviewers independently. Disagreements were dealt with by discussion and the involvement of a third reviewer. Because high levels of inter-rater reliability were achieved (κ = 85%), the remaining full texts were screened by one reviewer. The full texts had to fulfil five inclusion criteria to be eligible for inclusion in the review:

-

RCTs

-

diagnosis of a long-term condition

-

self-management or case management intervention

-

adults (aged ≥ 18 years)

-

report quantitative data on costs/rates of health-care utilisation and health outcomes (QoL, depression and anxiety).

All the studies that were rated as eligible or as potentially eligible (if no clear decision could be reached) were discussed in group meetings by three members of our research team (MP, NS, PB).

Data extraction

We designed a data extraction sheet to collect data on the studies and the interventions included within them. We were unable to seek additional data from authors in the time frame of the review.

We extracted data on study quality. We chose a dichotomous measure based on allocation concealment, as this is the aspect of trial quality most consistently associated with treatment effect,82,83 and is particularly relevant when outcomes are subjective, such as QoL. 84 Other measures of trial quality in the risk of bias tool, such as blinding, are generally less useful in trials of self-management interventions because it is difficult to meet the conditions required for effective blinding. Allocation concealment was judged as adequate or inadequate according to the relevant section from the Cochrane risk of bias tool. We analysed intervention effects on all outcomes (QoL, hospitalisation and costs), grouping by risk of bias (based on the dichotomous measure of the quality of allocation concealment) to assess if results varied by study quality.

We extracted data on the effect of self-management interventions on health-care utilisation and total costs. We also separately extracted data on the methods used in the subset of studies reporting formal cost-effectiveness, cost–utility and cost–benefit analyses. A previously used checklist was employed to assess the quality of the literature. 85 This checklist is based on the Drummond checklist for assessing economic evaluations86 and has been adapted to capture more fully the quality of economic evaluations in self-management interventions (see Appendix 3).

Descriptive data on studies, populations and interventions were extracted by two members of the research team working independently. Coding of the type of intervention was conducted on the basis of those extractions by two members of the research team working independently, with disagreements dealt with by discussion. A subset of data on quantitative outcomes were extracted by two members of the research team working independently (n = 50 studies), with the rest of the data extracted by one member and checked by a second.

We also extracted published data on the ‘reach’ of each model of self-management support, in terms of the proportion of eligible patients who did not take part in the study, and whether or not long-term conditions additional to the index condition (with the exemption of severe psychosis and dementia) were used as exclusion criteria.

Analyses

Accurate placement of studies on the cost-effectiveness plane requires accurate quantification of the magnitude of both effects on costs and outcomes, which requires particular forms of data beyond simple text descriptions of significance and p-values.

We sought data that would allow us to report a standardised mean difference (or ‘effect size’) for health outcomes and costs (Box 2). This generally requires reporting of means, standard deviations (SDs) and sample sizes, although other presentations of those data can be used (such as mean difference statistics), and other presentations (i.e. use of dichotomous outcomes such as rates rather than means) can be translated to a standardised mean difference through appropriate transformation. 91 When single parameters were missing (such as a SD, or a sample size at follow-up), we imputed based on other data in the review, or heuristics (e.g. assuming that 70% follow-up would be achieved from numbers of participants randomised at baseline). We excluded studies that lacked data if there were no other studies in the review to allow imputation.

A RCT assesses the effect of a treatment by comparing the outcomes in the treatment and control groups. Many measures of QoL are continuous, providing a score that varies from 0 up to a maximum based on the number and response range of the items.

Comparing the mean scores of patients in the treatment and control groups gives a good indication of the impact of the treatment. For example, if patients in the treatment group have a mean score at the end of the study of 20, and the controls have a mean of 15, the mean difference is 5 points (i.e. treatment leads to an improvement in QoL of 5 points on average). One difficulty is that it takes an expert to know whether or not a difference of 5 points is important or trivial. A second problem is that studies often use different measures. Knowing that a treatment causes a mean improvement of 5 points when QoL has been measured on two completely different scales makes comparison impossible.

Effect sizes overcome these difficulties by standardising. Essentially, this involves dividing the mean difference from each trial by a measure of the underlying variability of the scores on that outcome (the so-called SD). If scores are generally very variable, then a large mean difference would be required to demonstrate that treatment was better than control. If scores do not vary markedly, then a small mean difference may still represent an important effect of treatment. The mean difference divided by a measure of variability in this way is often described as an effect size.

Standardising in this way means that the difference between treatment and control groups can be described in terms of the same unit (i.e. units of SD). So, if one RCT finds a mean difference of 5 points and the SD is 10, then the effect size is 0.5 (and the difference in QoL is half a SD). A second trial using a different measure might report a larger mean difference of 15 but, if the SD of scores in that trial is 25, then the effect size is actually only slightly increased (15/25 = 0.6) even though the mean difference is much larger.

A convention has emerged to judge the magnitude of effect sizes calculated in this way. An effect size of around 0.2 is often described as ‘small’, an effect size of 0.5 as ‘medium’ and an effect size of 0.8 as ‘large’. 87 These are convenient labels with some validity88,89 and they provide a useful rule of thumb to assess the effect of interventions in the context of the wider literature. Nevertheless, decision-makers need to be careful in their interpretation.

Outcomes reported on dichotomous scales (such as proportion of patients using a hospital following treatment) are often reported using different metrics (such as odds ratios, relative risks and NNT). However, they can be translated to an equivalent effect size. For example, a ‘small’ effect size (0.2) is equivalent to a NNT of approximately 18, while effect sizes of 0.5 and 0.8 are equivalent to NNTs of approximately 4 and 2.5, respectively. 90

NNT, number needed to treat; SD, standard deviation.

It is generally the case that many measures of utilisation (e.g. hospital length of stay) and data on costs demonstrate significant skew (where many patients report low costs, but a small proportion have disproportionately large values). In line with published reviews,92 we identified those outcomes for which the SD multiplied by two was greater than the mean, as in these cases it is argued that the mean is not a good indicator of the centre of the distribution,93 although skewed data are less problematic if the sample size is large.

We explored statistical heterogeneity through the I2 statistic,94 which provides an estimate of the percentage of total variation across studies that can be attributed to heterogeneity rather than chance. We labelled levels of heterogeneity as ‘low’ (1–25%), ‘moderate’ (26–74%) and ‘high’ (≥ 75%). Caution should be applied in the interpretation of pooled effects in meta-analyses with ‘high’ levels of heterogeneity.

A minority of self-management support trials use cluster allocation to reduce bias associated with contamination. Such studies were identified and the precision of analyses adjusted using a sample size/variation inflation method recommended by the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care group of the Cochrane Collaboration,95 assuming an intraclass correlation of 0.02.

Some studies reported multiple self-management support interventions against a single control. In these cases, we extracted each self-management support intervention as a separate comparison and entered them where relevant in the meta-analysis, dividing the control group sample size appropriately to avoid double counting in the analysis (although this method assumes effect sizes are independent).

The aim of the analysis was to conduct a quantitative systematic review to identify self-management support interventions associated with significant reductions in health services utilisation (including hospital admissions) without compromising outcomes.

The primary analysis was structured by type of long-term condition, with a separate analysis for studies including mixed groups of patients with varying long-term conditions. We also conducted sensitivity analyses to explore the PRISMS categories of conditions (see Table 1) as an alternative typology, restricting those analyses to the two most prevalent categories (PRISMS 1 and 3) (see Table 1).

For each condition category, we present a description of the search and identification of the studies, including the total number identified and the subset of studies including analysable data on QoL, on utilisation and costs and on both outcomes. Our primary interest was on studies reporting both forms of data, because studies that reported only one outcome cannot formally be placed in the cost-effectiveness plane.

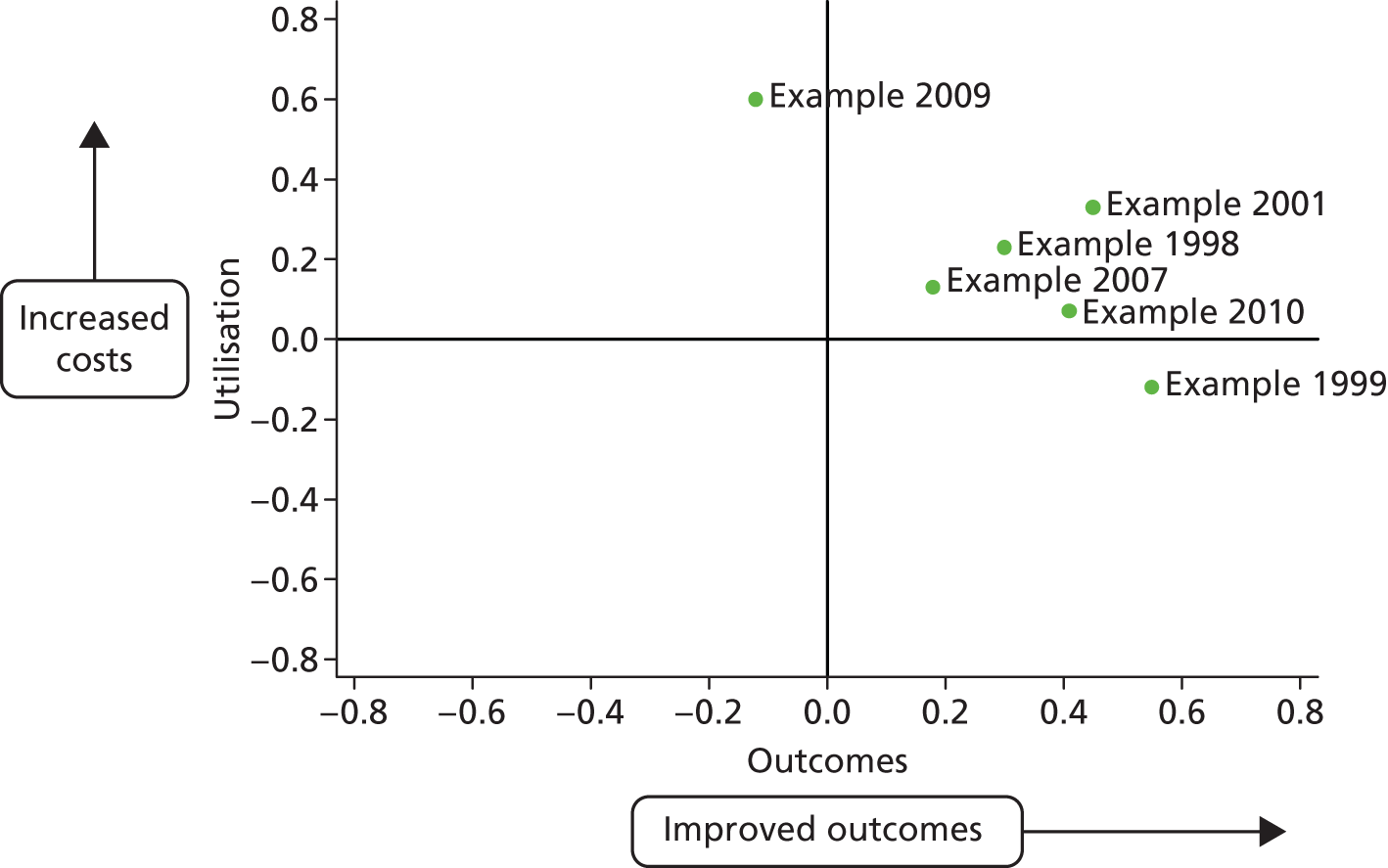

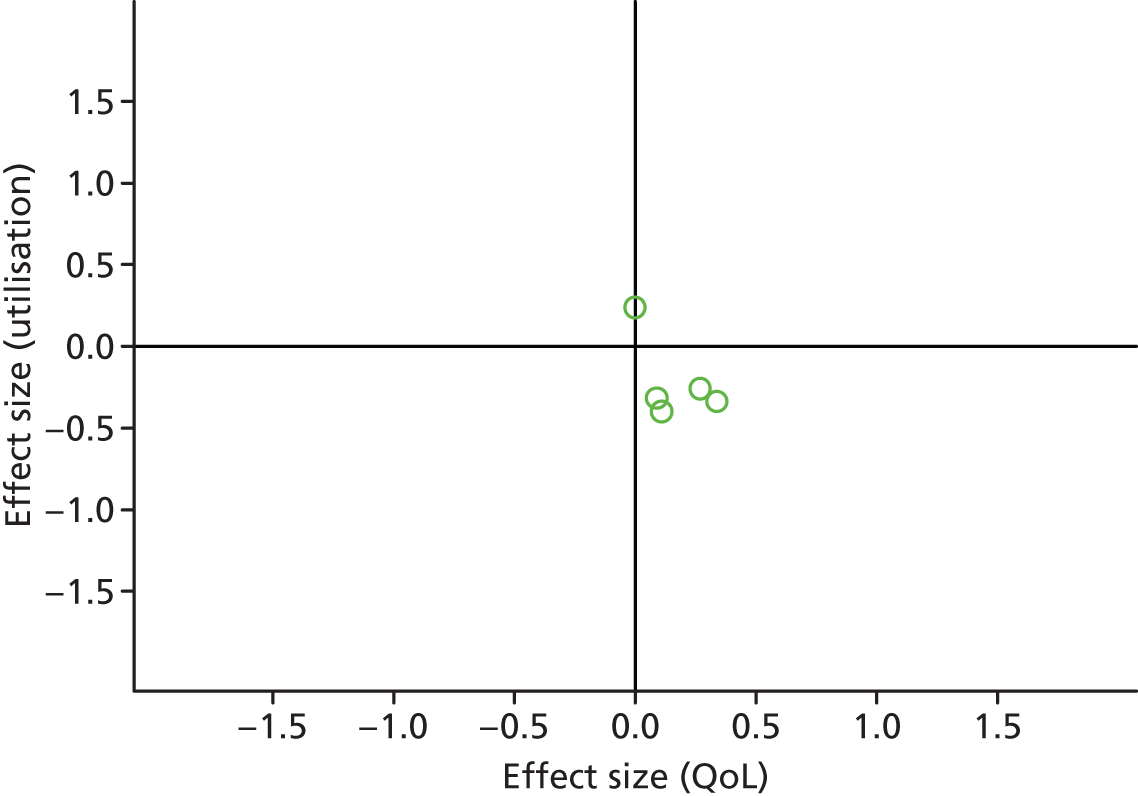

We present the results of the included studies for each condition group according to a permutation plot for all studies reporting both outcomes (i.e. QoL and hospital use and QoL and costs), plotting the effect of interventions on utilisation and outcomes simultaneously and placing them in quadrants of the cost-effectiveness plane depending on the pattern of outcomes (Figure 2). The plot shows the pattern of results at the level of the individual study, gives a visual impression of the distribution of studies across the cost-effectiveness plane, and identifies studies in the appropriate quadrant (i.e. those that reduce costs without compromising outcomes) and those in problematic quadrants (i.e. those that reduce costs but also compromise outcomes, or those that compromise both outcomes and costs).

FIGURE 2.

Example permutation plot showing utilisation and health outcomes.

Small-study bias

There are a number of forms of bias that can occur in the identification and inclusion of trials in systematic reviews and meta-analyses. For example, publication bias is defined as a bias that reflects differences in the characteristics and results of studies that have been identified for a systematic review, and those that have not been identified. 96

Funnel plots97 using standard errors98 (with associated regression tests) can be used to detect what is called small-study bias. These plot effect size estimates against study sample size. The expectation is that the results from smaller studies will be more variable than larger studies and the plot will resemble a funnel. If the plot is asymmetrical and skewed, this may reflect the fact that some small studies have not been published or identified. It should be noted that funnel plots may identify problems that relate to issues other than publication bias.

It is possible that studies reporting data amenable to meta-analysis differ in systematic ways from those that do not. As reporting of data amenable to meta-analysis was a criterion for inclusion, we did not extract data on the characteristics of studies that were not amenable to our analytic methods and are, therefore, unable to conduct a formal comparison of studies included or excluded for this reason.

We presented two permutation plots, one based on studies reporting a measure related to hospital use, and one based on total costs. Hospital use was the primary outcome measure defined by the brief and generally represents a significant driver of total costs in most health-care systems. However, focusing on a single source of utilisation leaves the analysis vulnerable to cost shifting, when benefits found in terms of reductions in hospital use mask increases in costs elsewhere (e.g. primary care, or patient out of pocket costs). We therefore repeated the permutation plot using the subset of studies that provided data on total costs.

Analysis proceeded as follows.

For each condition, we conducted separate meta-analyses of the effects of self-management interventions in trials reporting utilisation outcomes (separately for total costs and hospital use outcomes) and in trials reporting QoL outcomes.

As a secondary analysis, we then identified the subset of trials of self-management interventions reporting both utilisation and QoL outcomes and conducted a meta-analysis of the effects of self-management interventions on utilisation and QoL outcomes, in the subset of trials reporting both outcomes. We conducted these sensitivity analyses in those long-term conditions for which there were at least 10 studies with both outcomes.

We repeated each of these analyses for all types of self-management support and compared the three types of self-management support, combined, with case management. ‘Self-management’ interventions were defined as either those that did not include any support from health-care professionals or those for which limited support (≤ 2 hours) or more extensive support (> 2 hours) was provided by one or more health-care professionals. ‘Case management’ was defined as supported self-management interventions that involved both > 2 hours of support and input from multidisciplinary health-care teams.

Major deviations of the review from the protocol published in PROSPERO are outlined in Table 3.

| Original protocol | Deviation |

|---|---|

| All data extraction will be conducted by two members of the research team working independently, with disagreements dealt with via discussion | Data on studies, populations and interventions were extracted by two members of the research team working independently. Coding of the type of intervention was conducted on the basis of those extractions by two members of the research team working independently, with disagreements dealt with by discussion. A subset of data on outcomes was extracted by two members of the research team working independently, with the rest of the data extracted by one member and checked by a second |

| We will extract data to assist in the quality assessment of primary studies according to the Cochrane risk of bias tool | We restricted our assessment of risk of bias to allocation concealment |

| We will explore the characteristics of models of self-management showing favourable patterns of outcomes in the matrix through narrative review or through formal meta-regression techniques if the data are amenable | We structured the core analyses by condition and restricted secondary analyses to univariate analyses of the impact of risk of bias and type of intervention |

Patient and public involvement

Patient and public involvement in the review was provided through the stakeholder workshops conducted as part of the PRISMS study, for which representatives from the RECURSIVE team attended the initial meeting to help develop the frameworks and priorities for the PRISMS review, which fed through into the analyses for RECURSIVE.

Chapter 4 Results

Study characteristics

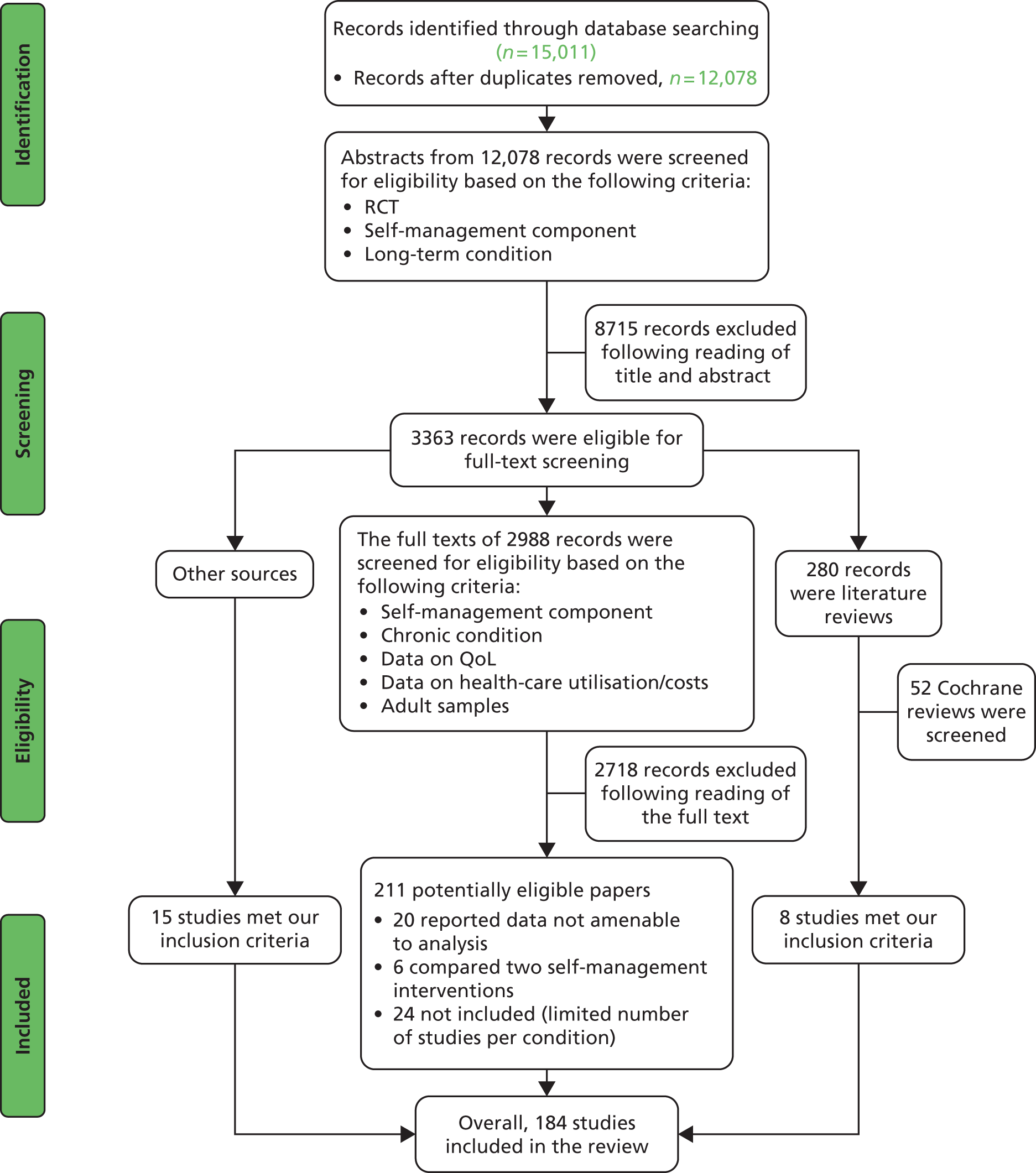

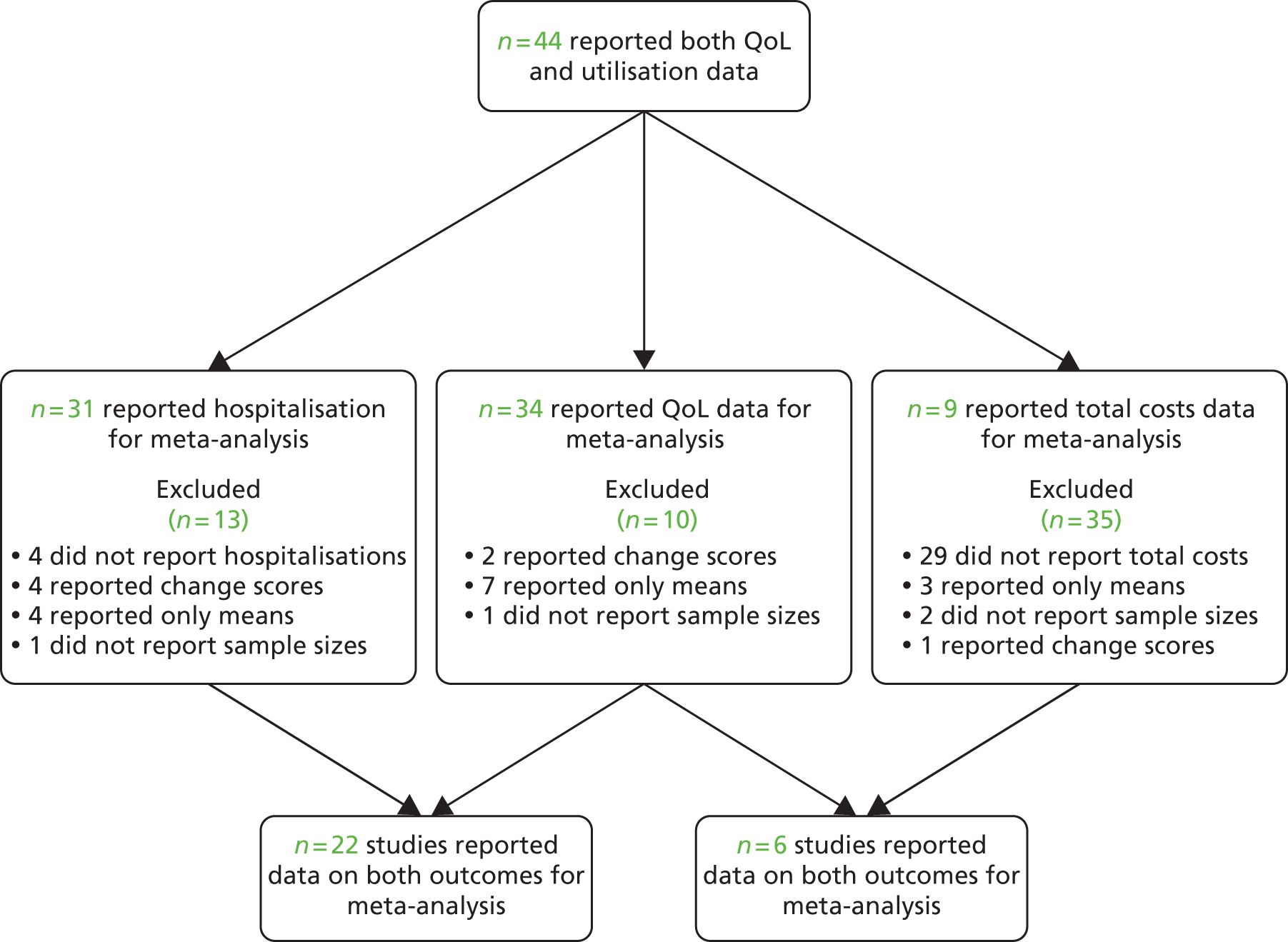

Overall, we screened 12,078 titles and abstracts for eligibility in the review. The flow of studies through the search process is outlined in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) 2009 flow diagram: entire review. Overall pattern of the results.

Full details of data extracted from individual studies (population, conditions, comparisons, risk of bias, economic analyses) are provided in Appendices 4–8.

We also identified 24 studies reporting data on QoL and health-care utilisation in other long-term conditions,99–122 such as hypertension (n = 5), inflammatory bowel disease (n = 6), lung disease (n = 3), multiple sclerosis (n = 2), chronic kidney disease (n = 1), Parkinson’s disease (n = 1), migraine/headache (n = 2), insomnia (n = 1), psoriasis (n = 1), acid-peptic disease (n = 1) and ulcerative colitis (n = 1) (Table 4). Although these studies met the eligibility criteria of the review, we excluded studies where there were very low numbers in particular condition categories, where our analytic methods were unlikely to be productive.

| Category | Characteristics | n (%); (N = 184) |

|---|---|---|

| Context | Country | |

| UK | 43 (23) | |

| USA | 65 (35) | |

| European | 44 (24) | |

| Other | 32 (17) | |

| Patients | Condition | |

| Arthritis | 14 (8) | |

| Cardiovascular | 53 (29) | |

| Diabetes | 11 (6) | |

| Mental health | 29 (16) | |

| Mixed disease | 13 (7) | |

| Respiratory | 44 (24) | |

| Pain | 20 (11) | |

| Mean age (years) (SD) | 58 (13) | |

| % male | 49 | |

| Intervention | Content | |

| Pure SM | 9 (5) | |

| Supported SM | 36 (20) | |

| Intensive SM | 87 (47) | |

| Case management | 52 (28) | |

| Technology involved | 43 (23) | |

| Mean (SD, range) | 275 (202, 23–1801) | |

| External validity | Excluded patients with other long-term conditions | 65 (35) |

| Proportion of eligible patients who did not take part in the study | ||

| Not clear | 48 (26) | |

| < 20% | 40 (22) | |

| 21–40% | 55 (30) | |

| 41–60% | 25 (14) | |

| 61–80% | 14 (8) | |

| 81–100% | 2 (1) | |

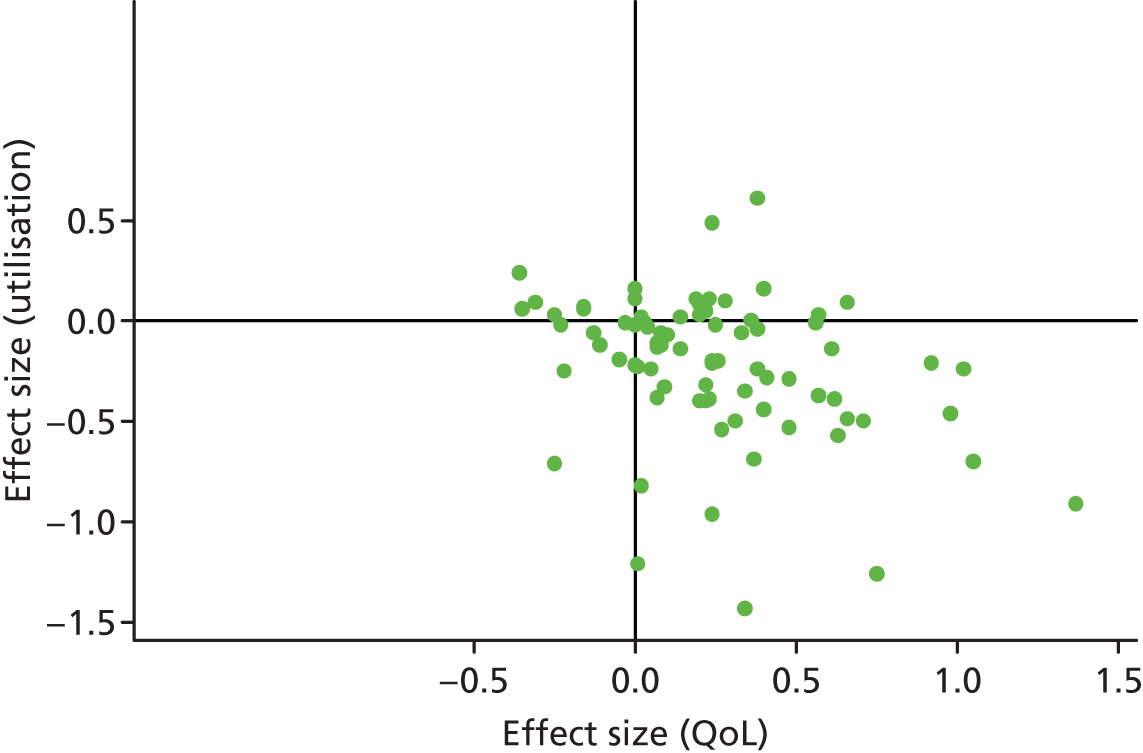

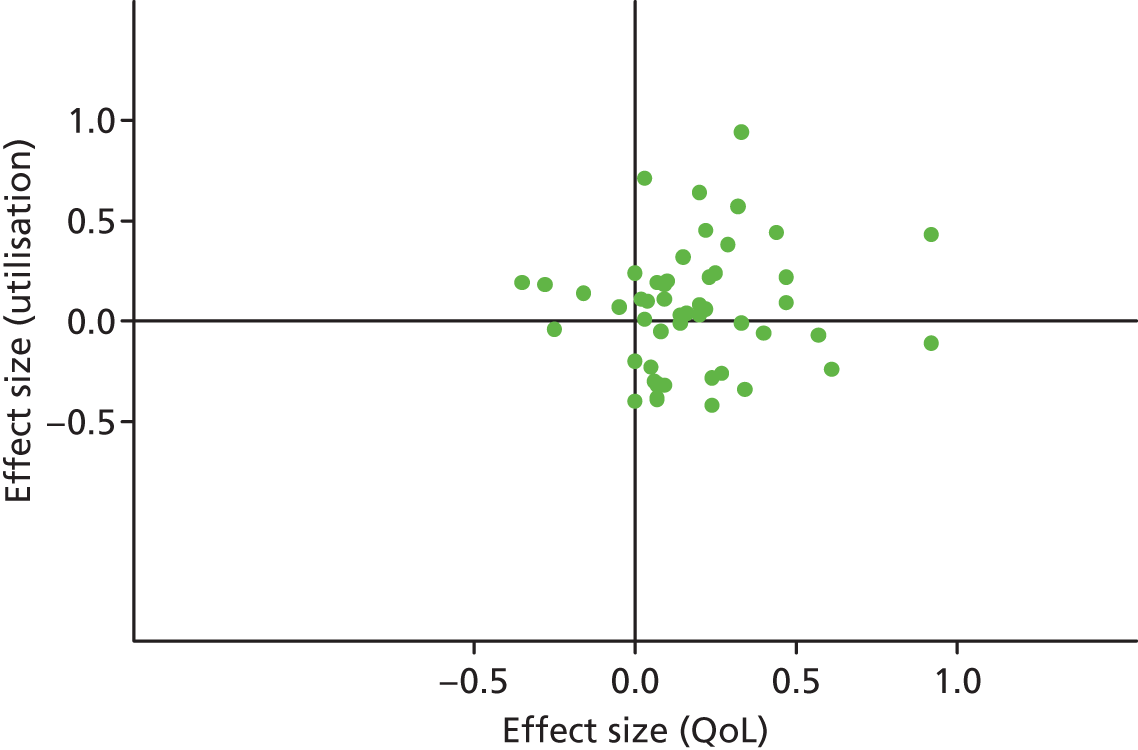

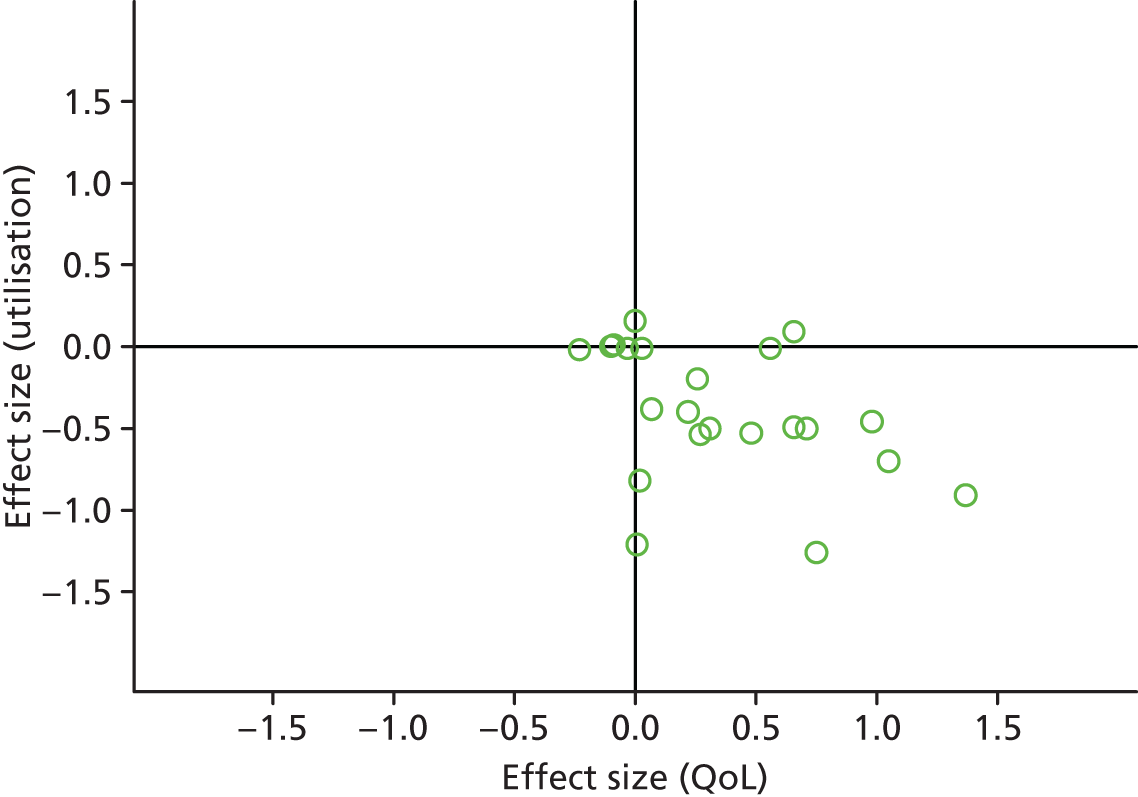

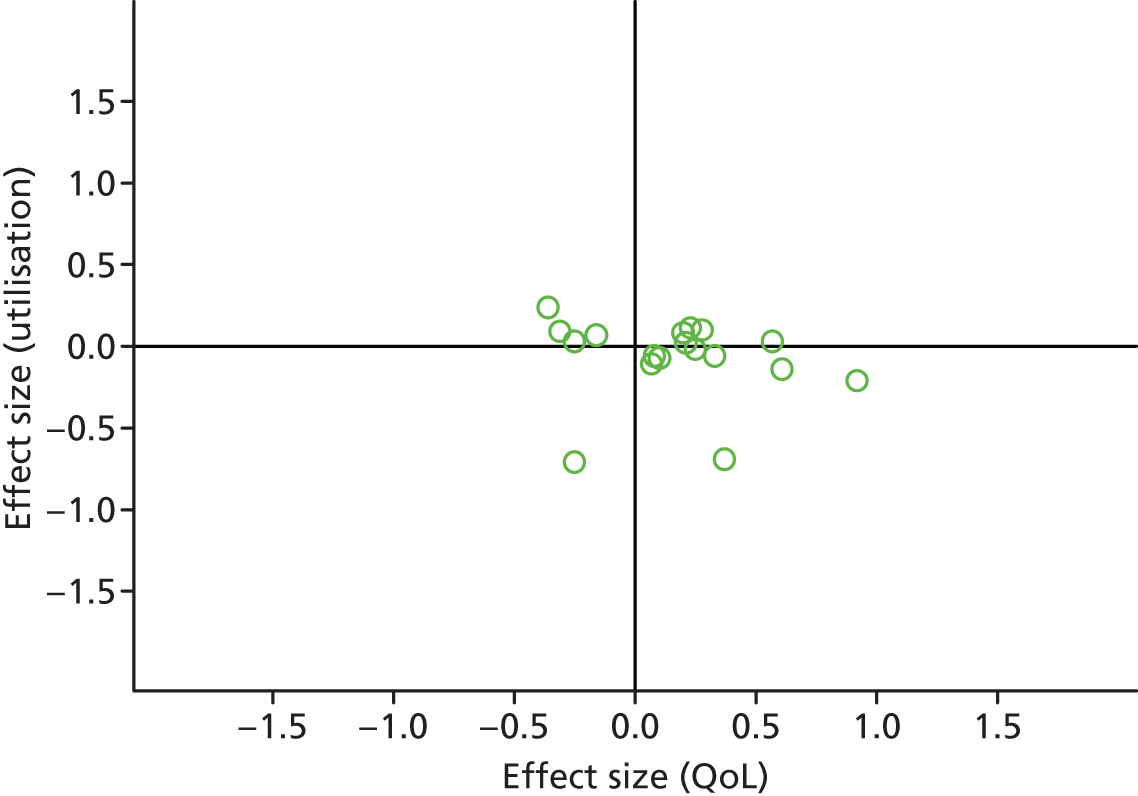

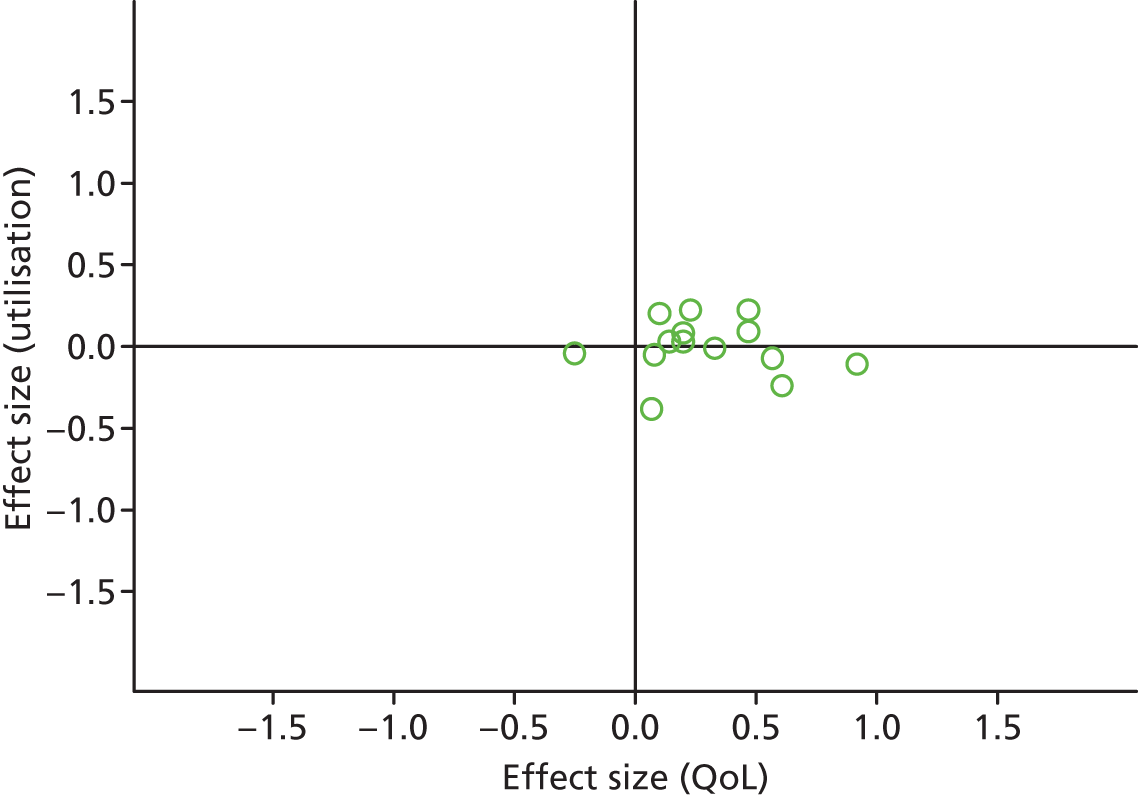

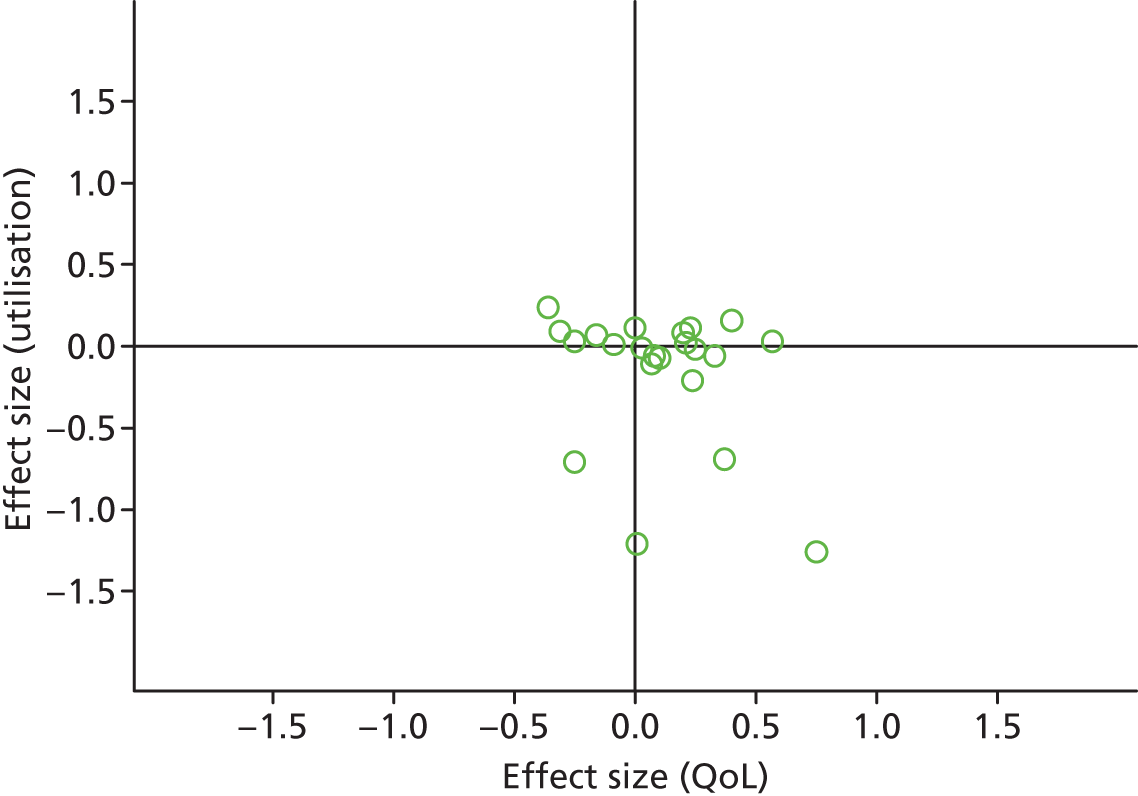

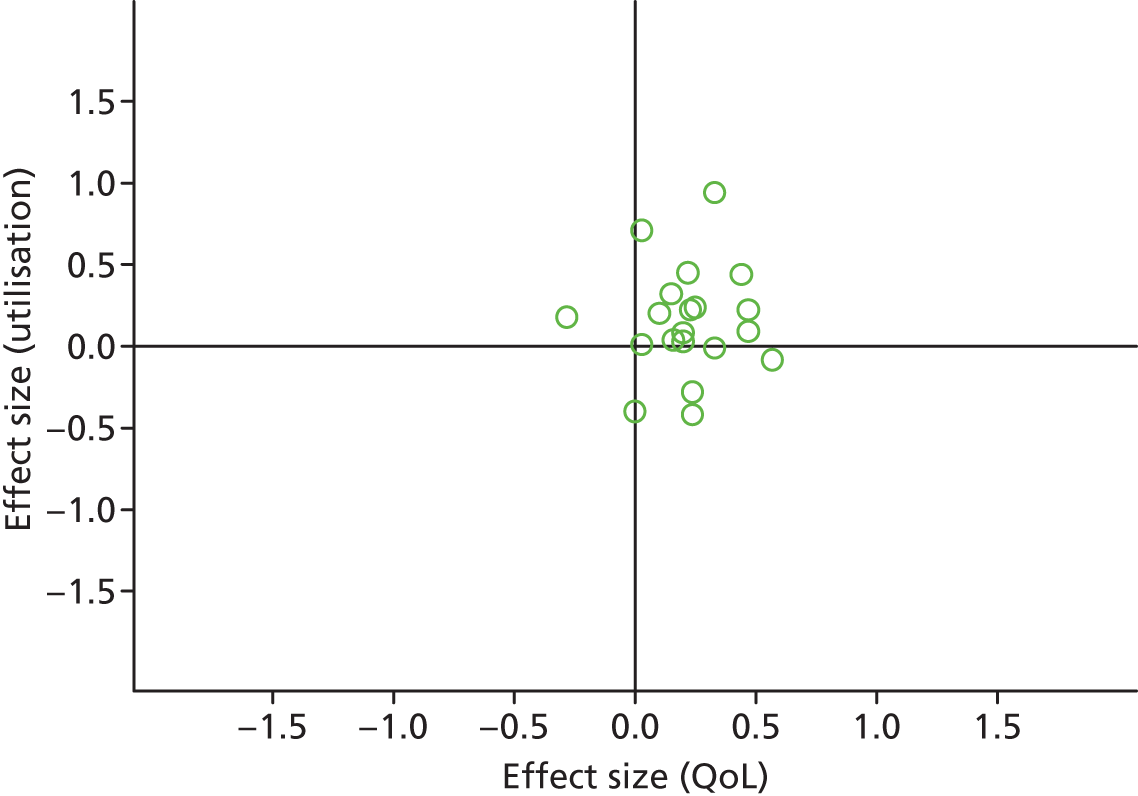

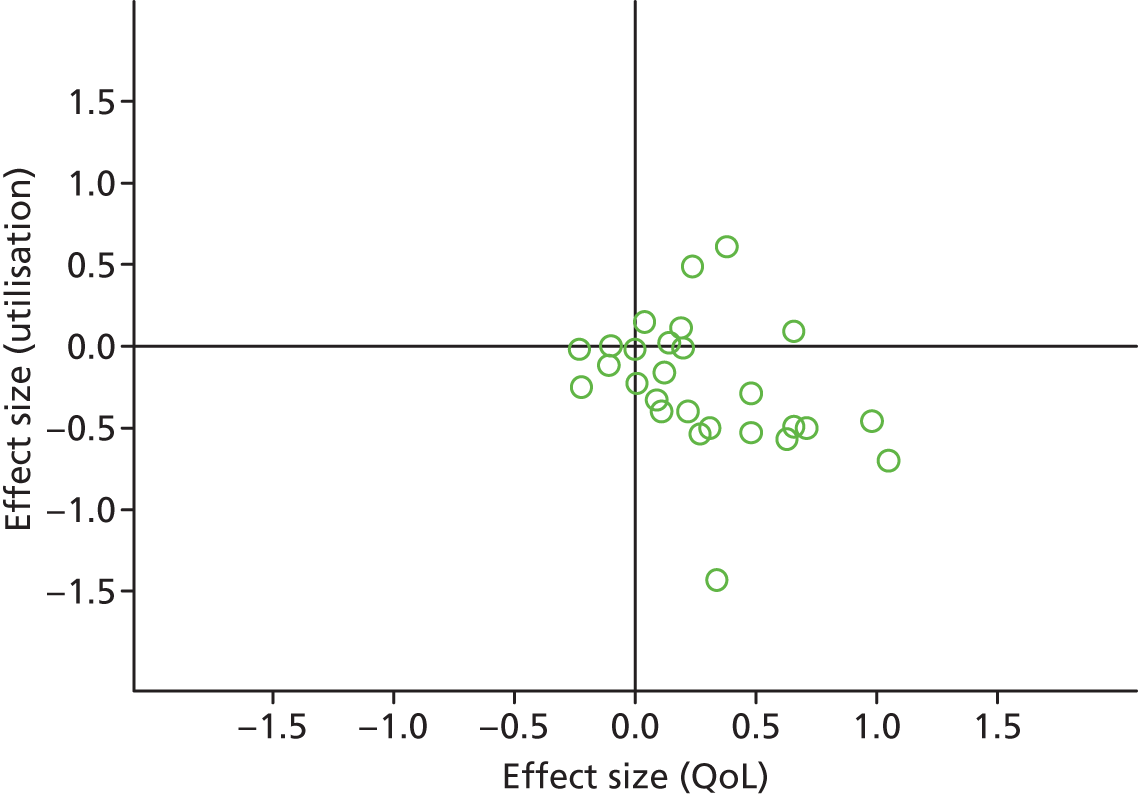

Figures 4 and 5 show the overall permutation plots, plotting QoL and hospital use outcomes (see Figure 4) and QoL and costs (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 4.

Permutation plot (all studies): QoL and hospital use outcomes.

FIGURE 5.

Permutation plot (all studies): QoL and total costs.

In terms of hospital use, the bulk of studies are in the lower right quadrant (i.e. they are associated with improvements in QoL and reductions in utilisation). Only a minority of studies report decrements in QoL and a smaller proportion of studies report improved outcomes with increases in utilisation.

In terms of costs, the picture is more mixed with more studies in the top right quadrant, reporting improved outcomes with increases in utilisation. Of the studies reporting costs, almost all demonstrated significant skew (i.e. the SD multiplied by two was more than twice the mean).

Note that the plots do not represent the uncertainty around point estimates, which in many studies would be considerable.

Formal economic analyses

The formal economic analyses are listed in Appendix 8 with comments on design and results, with formal extraction of details relating to study design in Appendix 3. 123–165

Although the formal economic analyses represent a more limited data set than those meta-analysed, the broad pattern of the results was similar. A small number of self-management support interventions were dominated by usual care, including studies in diabetes and pain. A significant proportion of studies reported that self-management support was dominant (when the intervention was associated with increases in QoL and reductions in costs). Dominant self-management support interventions were found in a number of conditions, including respiratory, cardiovascular, mental health and arthritis and other pain conditions. The remainder represented studies showing that self-management support was associated with improvements in QoL and increases in costs, with a proportion of those studies going on to show that the ratio between costs and benefits was at levels likely to appeal to decision-makers.

Some of the analyses were sensitive to the perspective taken, with results different when analysis was restricted to health costs or extended to include wider societal costs.

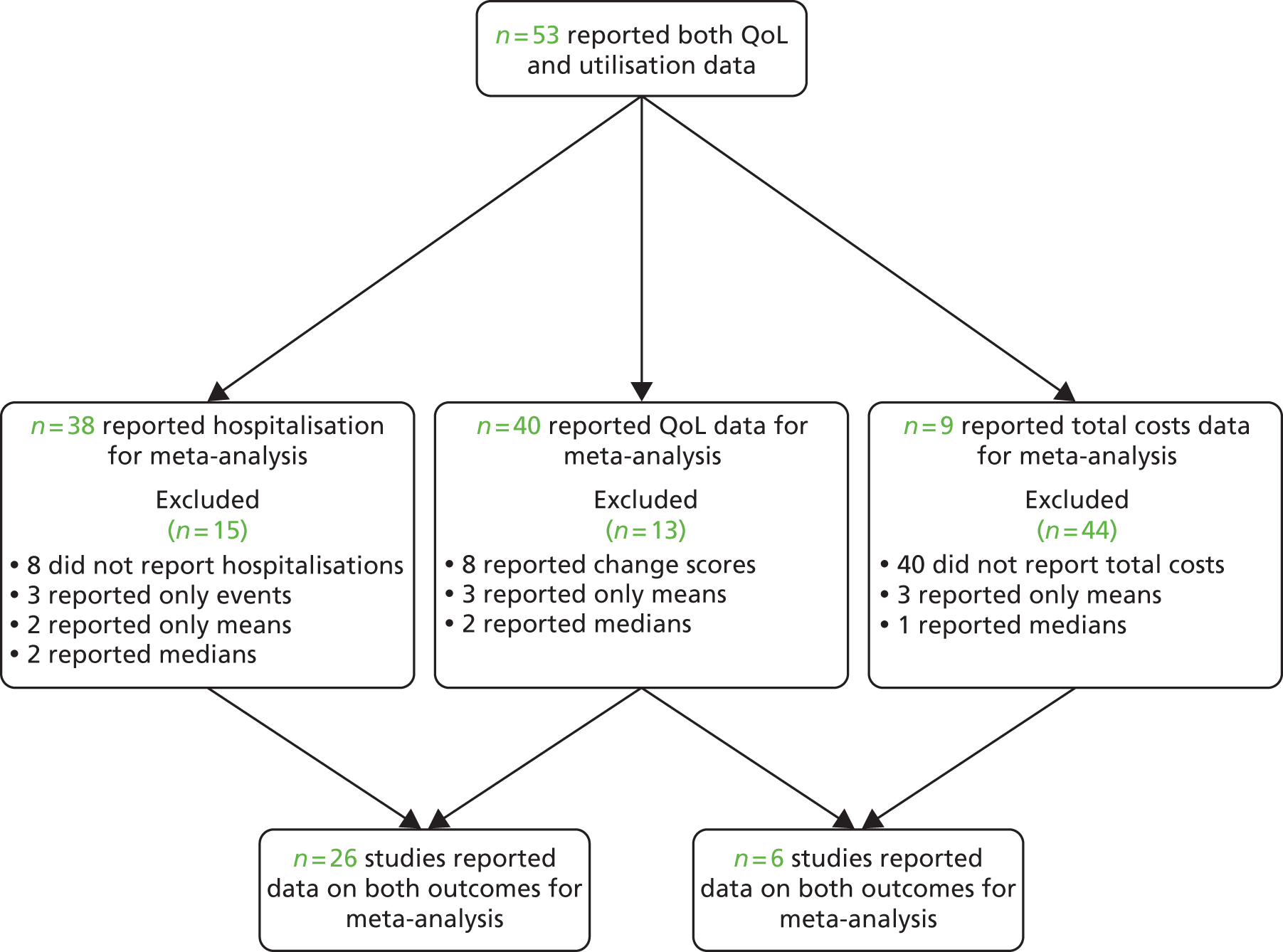

Analyses of studies for patients with respiratory problems

The studies identified in respiratory problems are detailed in Figure 6. 118,123–129,166–200

FIGURE 6.

Flow chart of studies in patients with respiratory problems.

Figures 7 and 8 show the permutation plots for interventions for patients with respiratory problems.

FIGURE 7.

Permutation plot: respiratory (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 8.

Permutation plot: respiratory (total costs and QoL).

Most studies reporting hospital data were in the bottom right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements or no differences in QoL and hospital use. Benefits in utilisation were less pronounced in total costs.

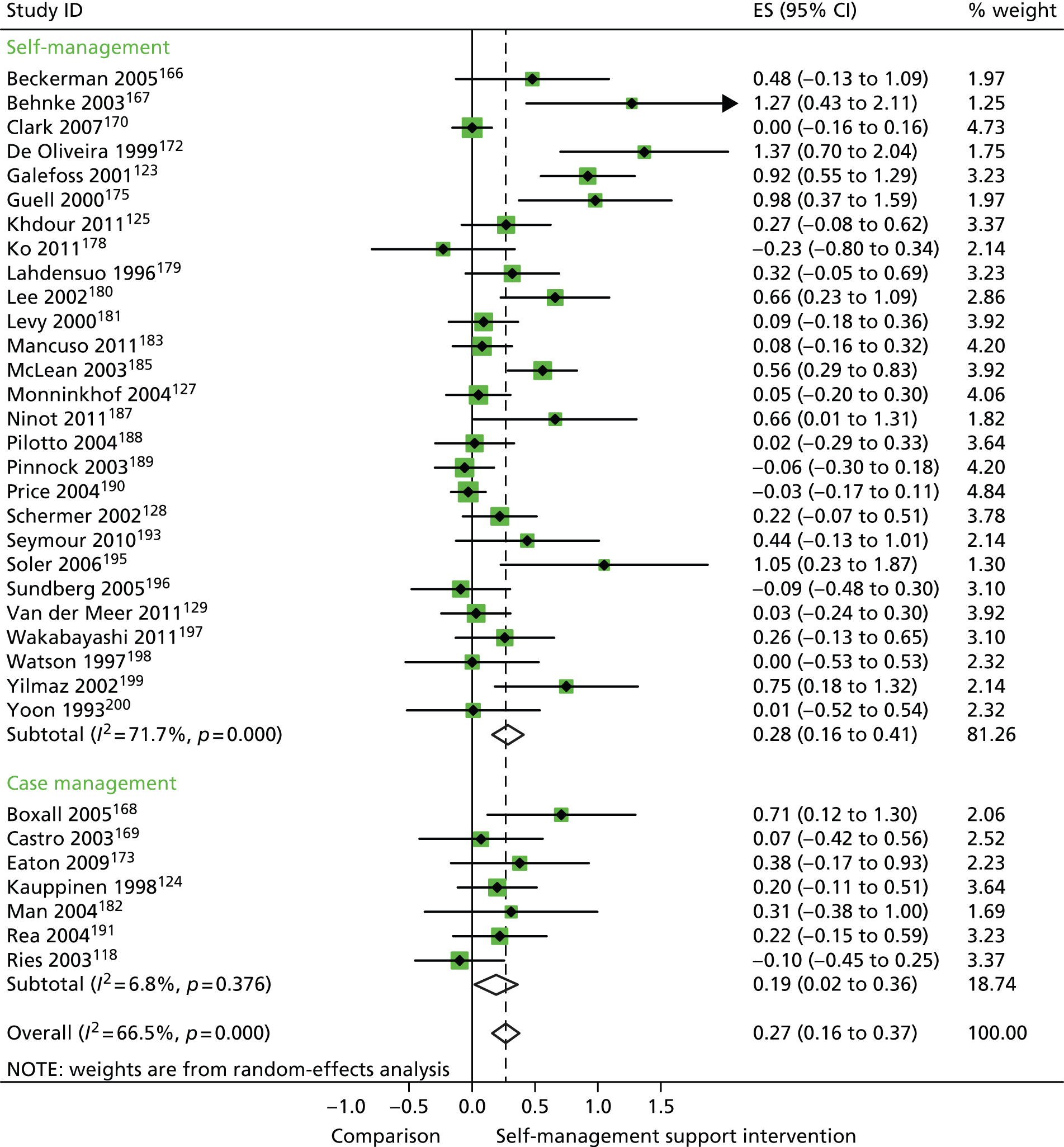

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with respiratory problems were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 9).

FIGURE 9.

Forest plot: respiratory (QoL). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

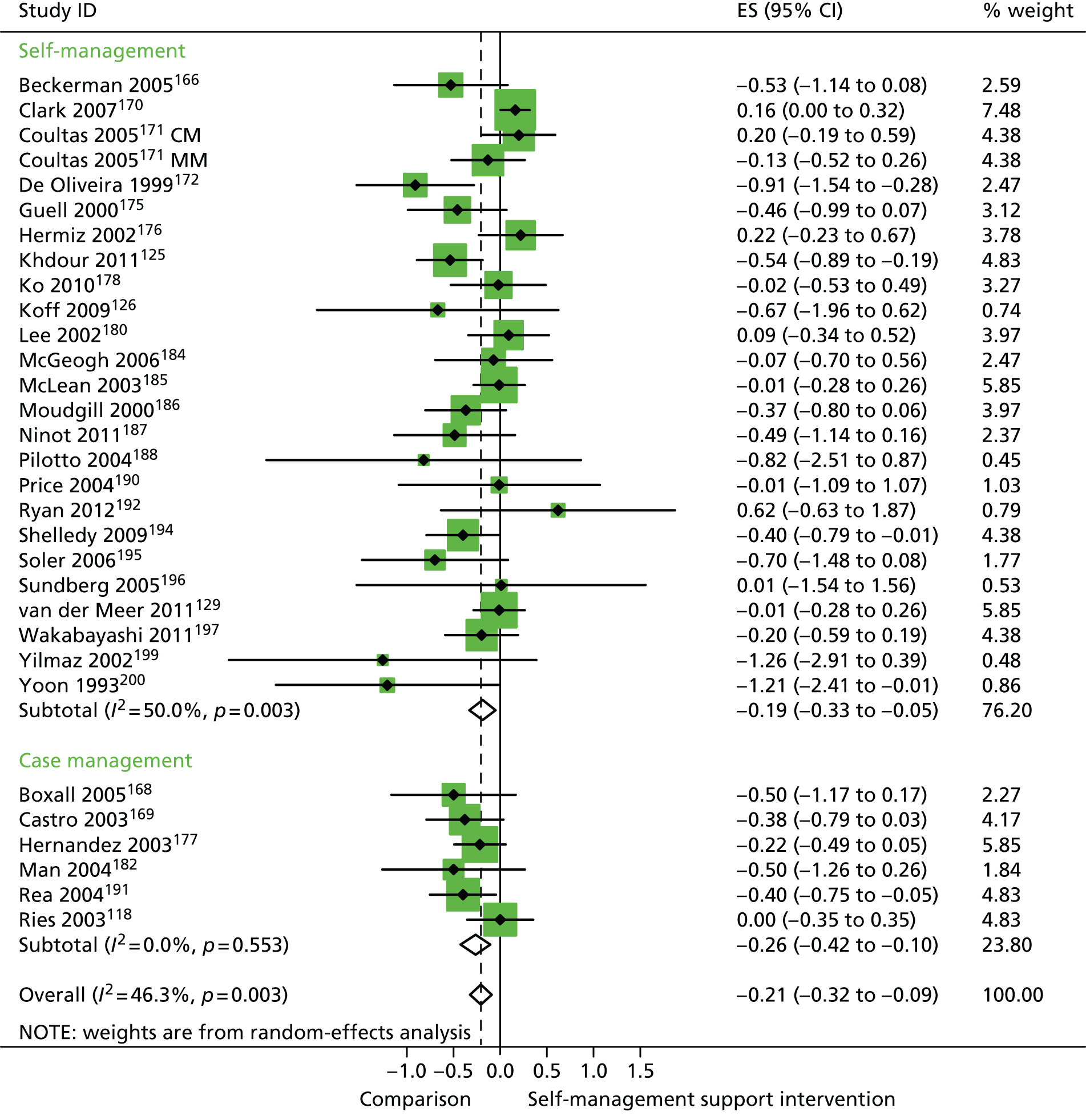

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with respiratory problems were associated with small but significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 10).

FIGURE 10.

Forest plot: respiratory studies (hospital use). CI, confidence interval; CM, nurse-assisted collaborative management; ES, effect size; MM, nurse-assisted medical management. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

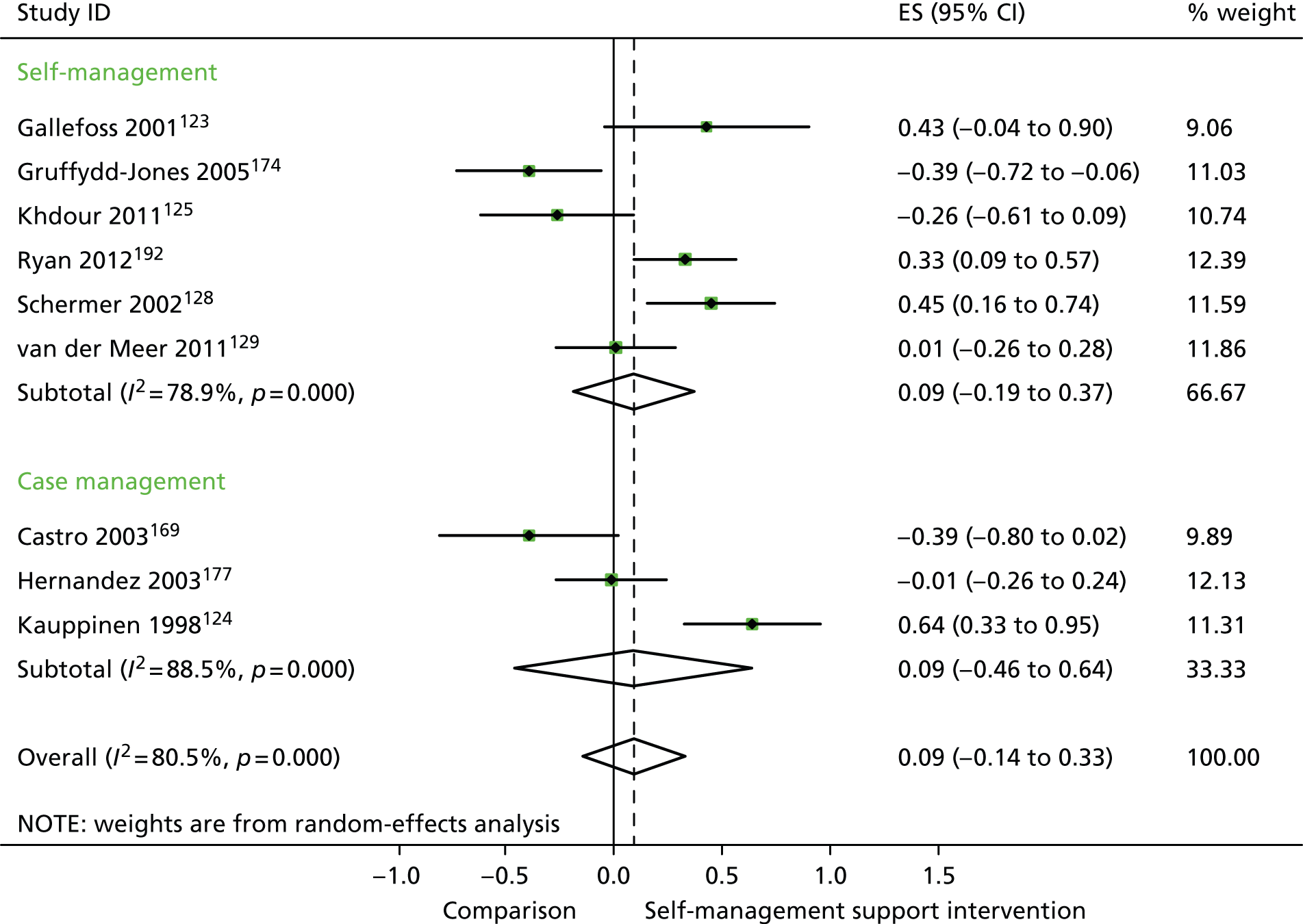

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with respiratory problems were associated with non-significant increases in costs. Variation across trials was high (Figure 11).

FIGURE 11.

Forest plot: respiratory studies (costs); CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, there was evidence that ‘case management’ interventions produced small but significant improvements in QoL and small but significant reductions in hospital use, but no significant difference in costs. ‘Self-management’ interventions showed small but significant improvements in QoL and small but significant reductions in hospital use, but no significant difference in costs.

Analyses of studies for patients with cardiovascular problems

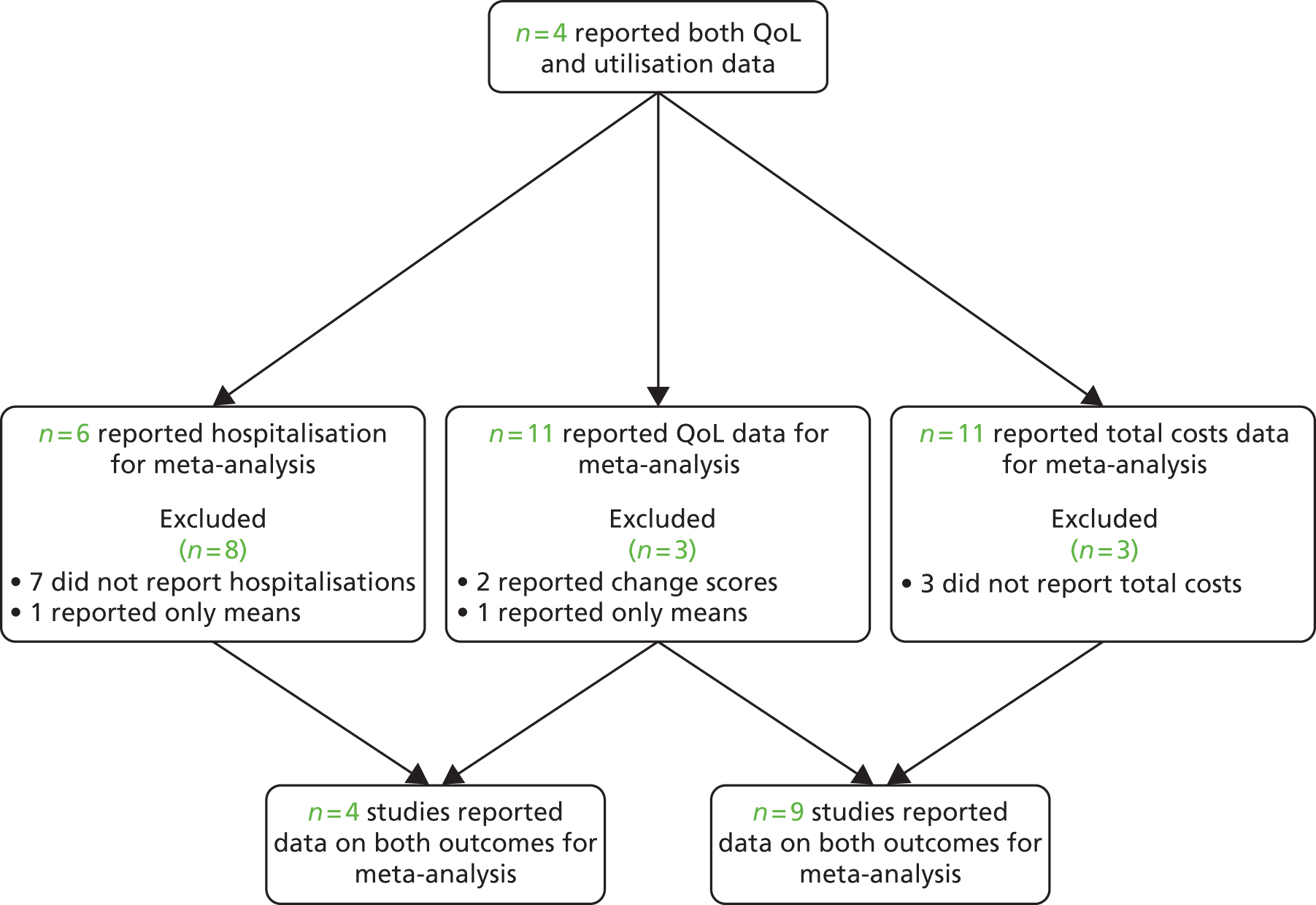

The studies identified in cardiovascular problems are detailed in Figure 12. 134–137,201–247

FIGURE 12.

Flow chart of studies in patients with cardiovascular problems.

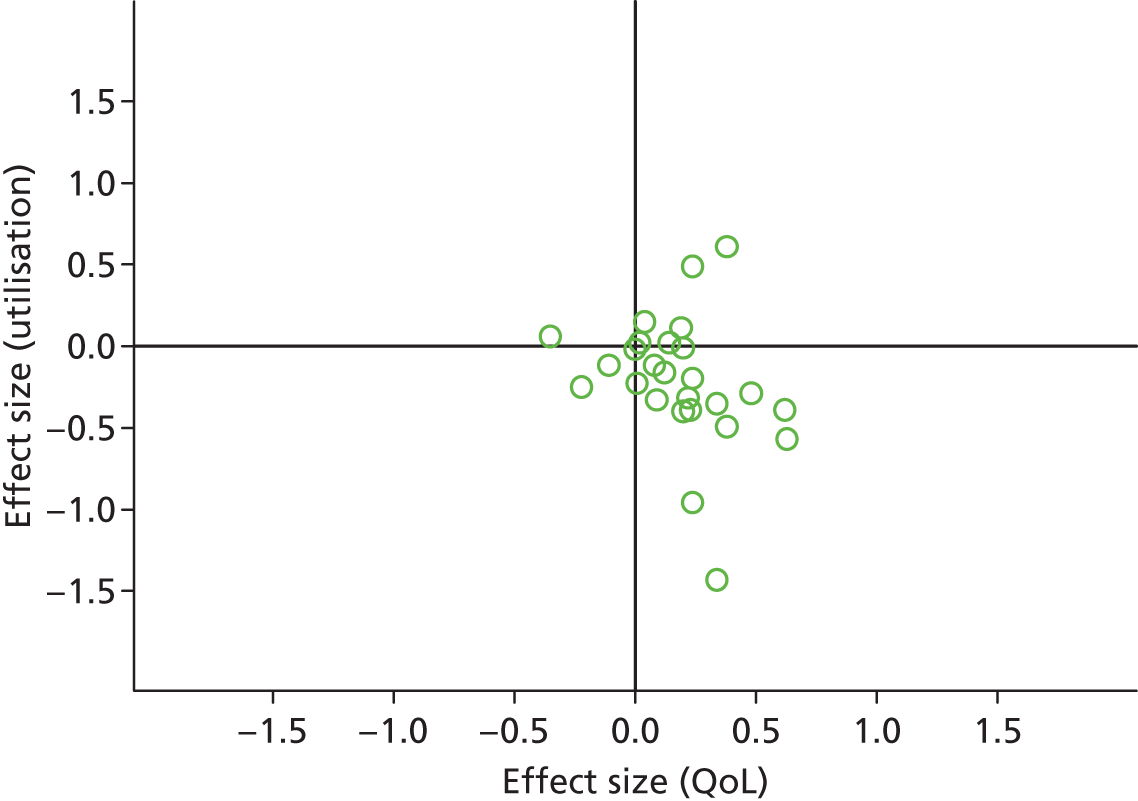

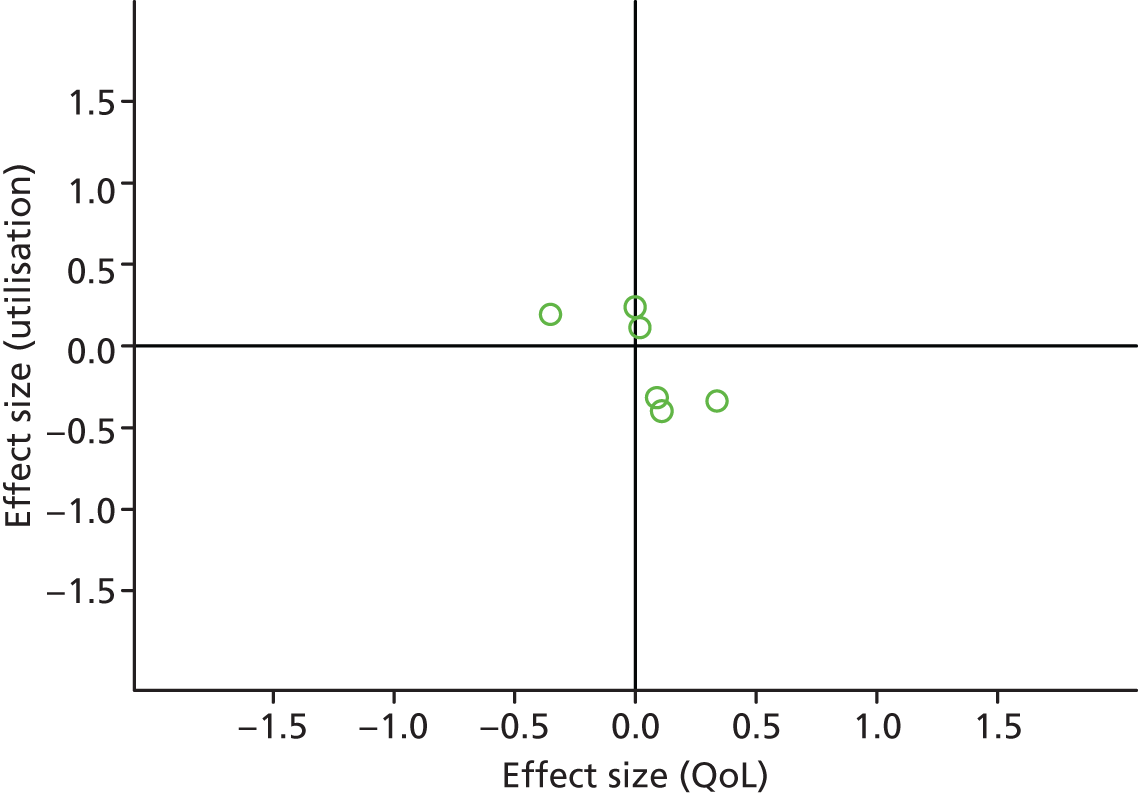

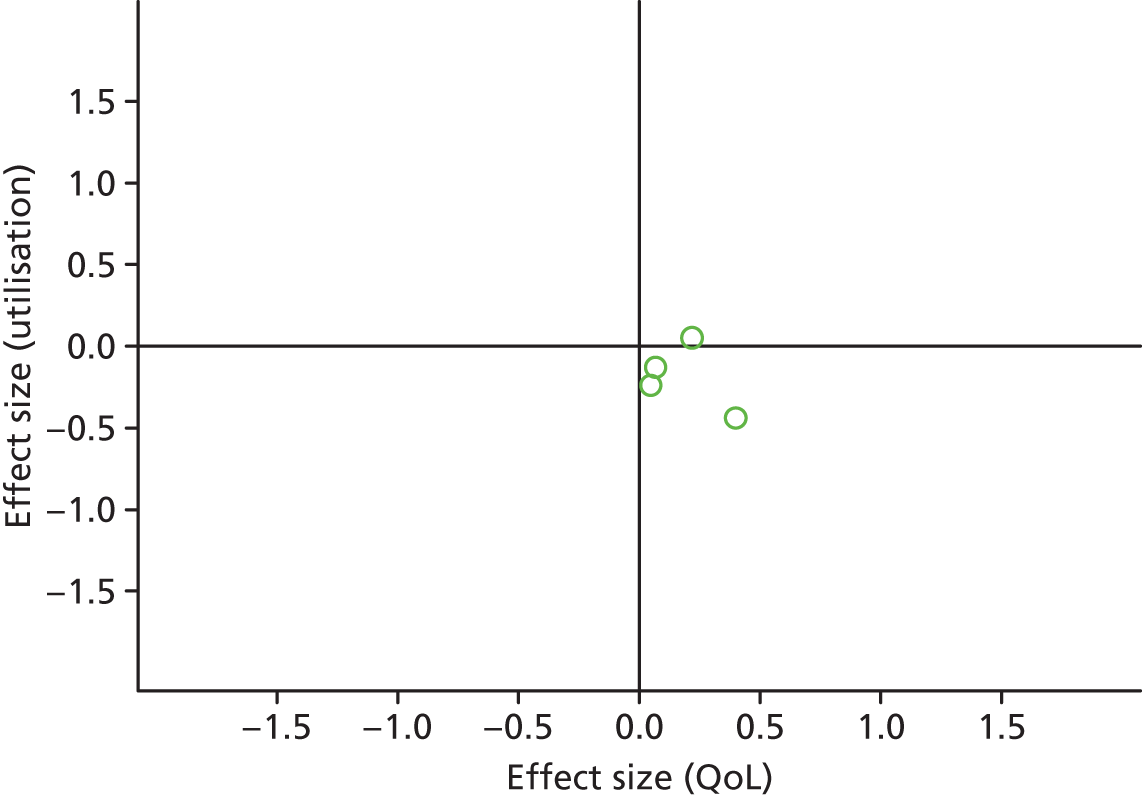

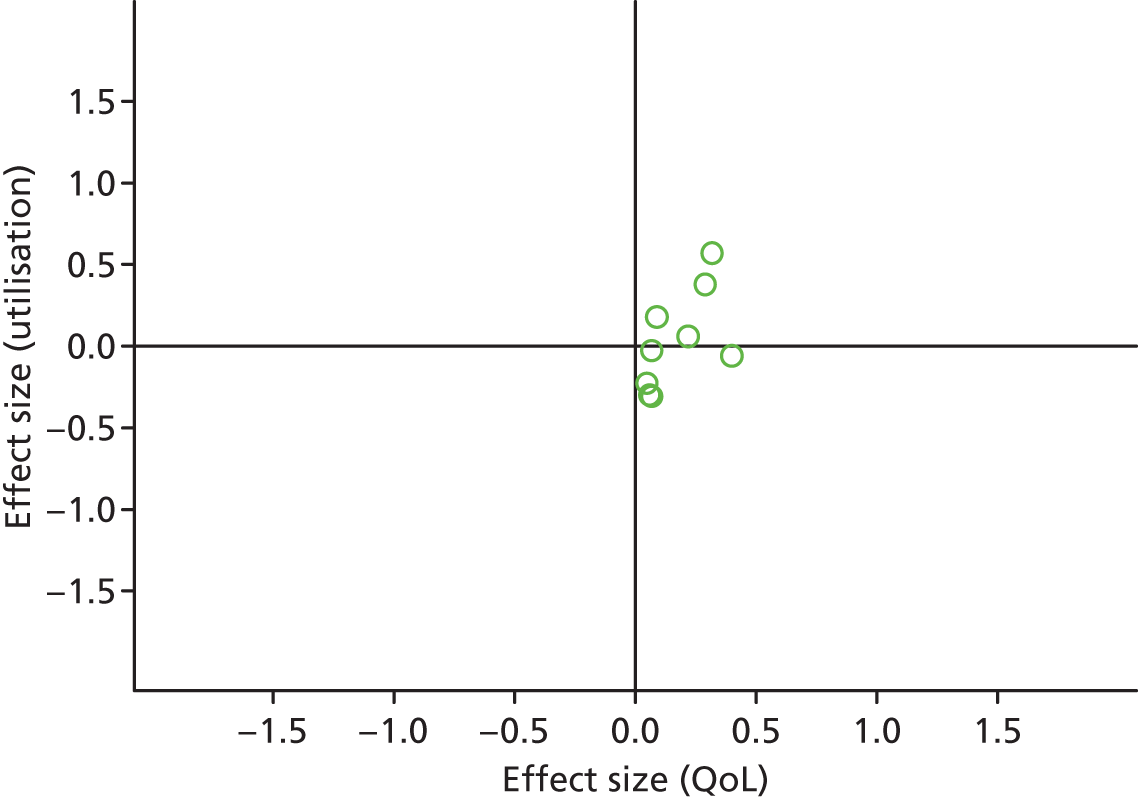

Figures 13 and 14 show the permutation plots for patients with cardiovascular problems.

FIGURE 13.

Permutation plot: cardiovascular (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 14.

Permutation plot: cardiovascular (costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the bottom right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements or no differences on QoL and hospital use.

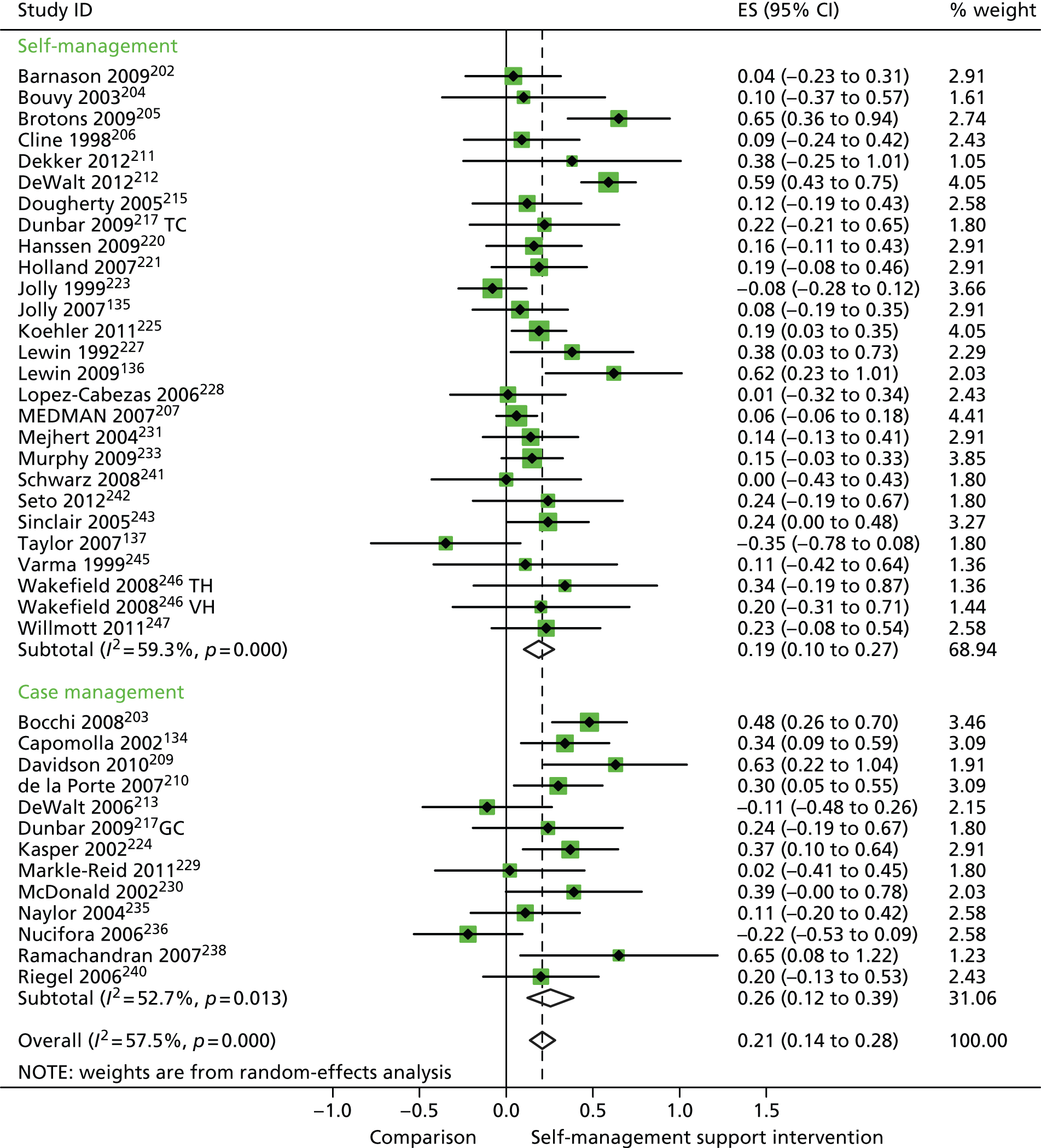

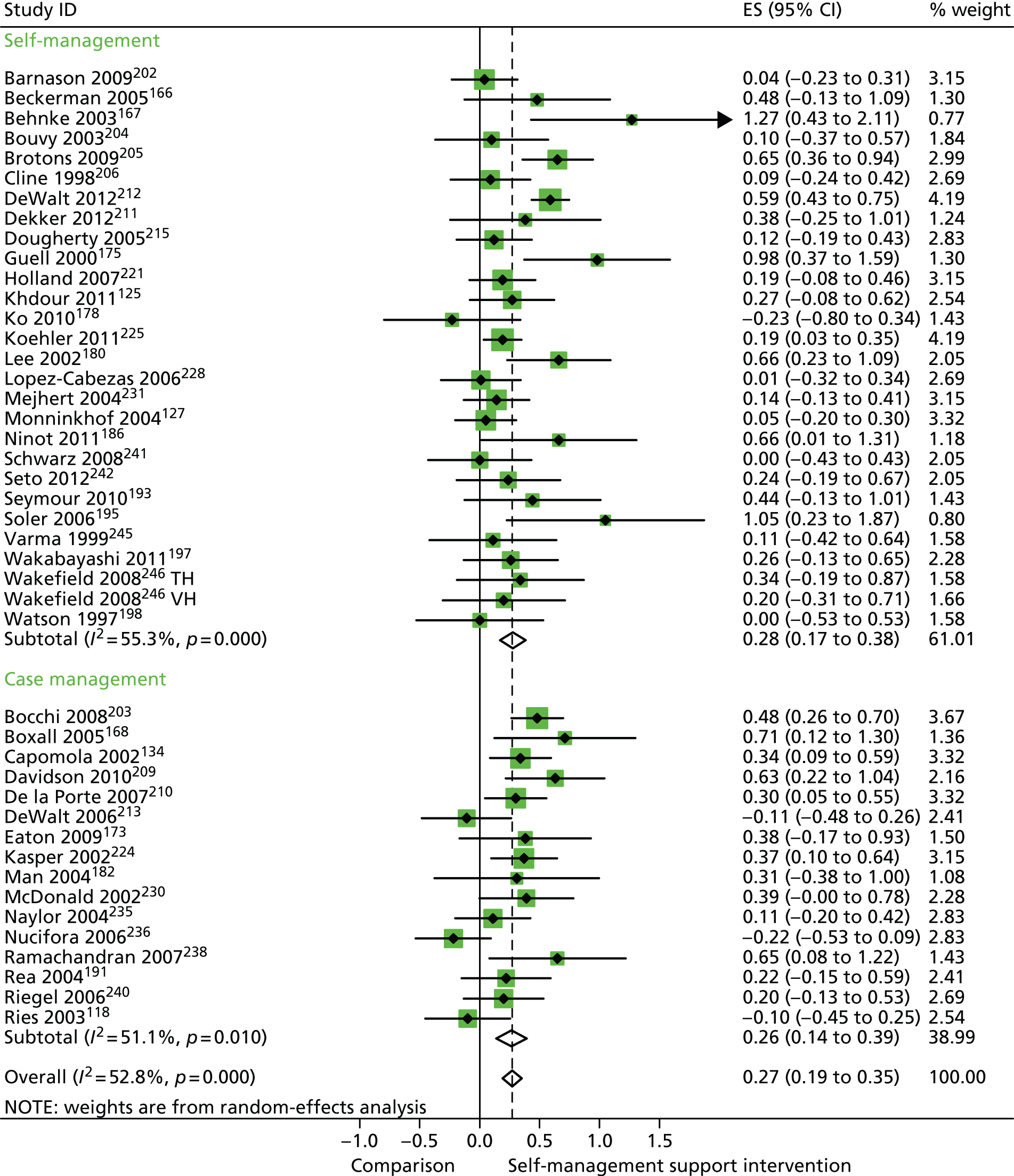

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cardiovascular problems were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 15).

FIGURE 15.

Forest plot: cardiovascular (QoL). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; GC, group counselling intervention; TC, individual telephone counselling intervention; TH, telehealth post-discharge support; VH, video health post-discharge support. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

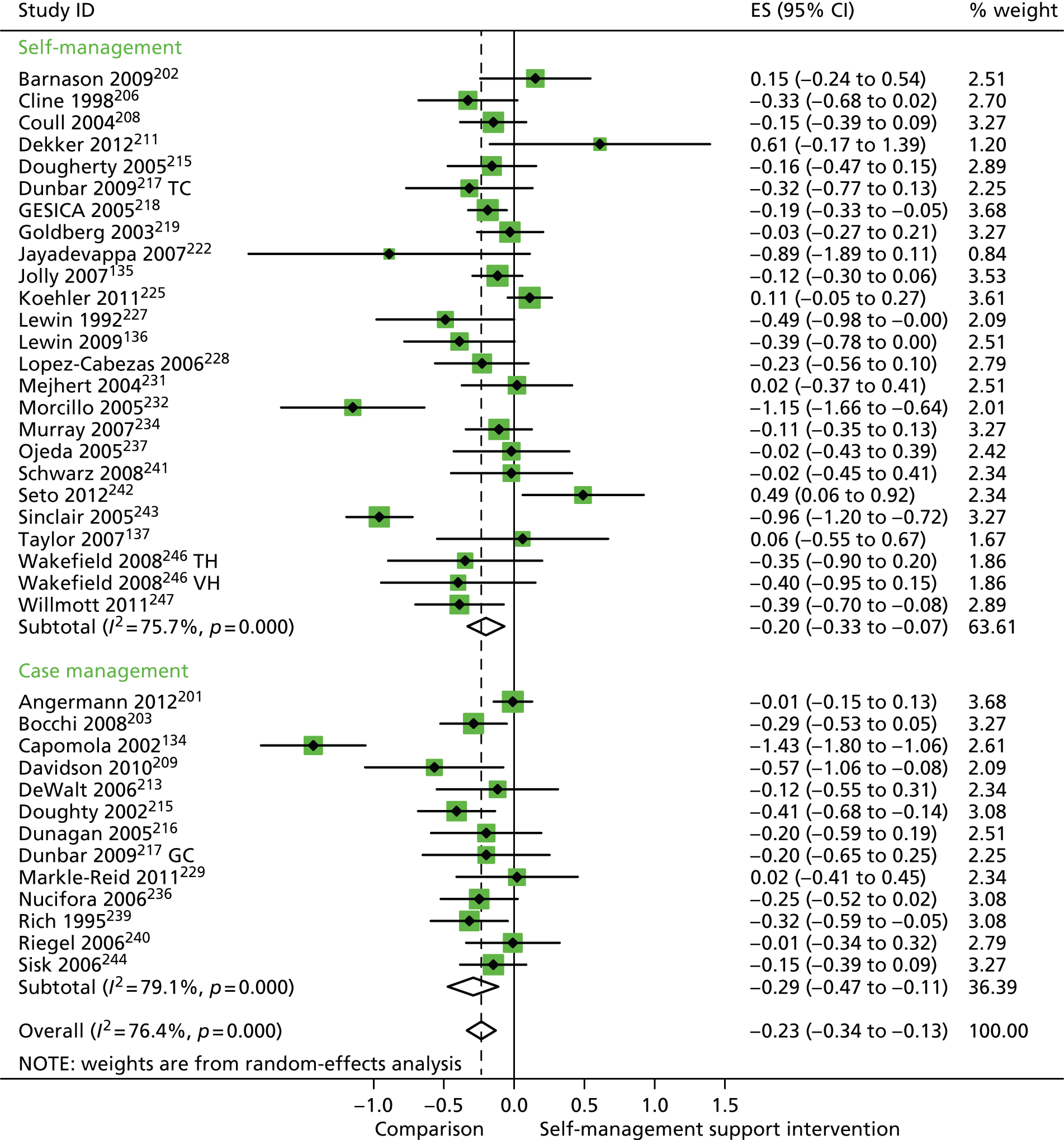

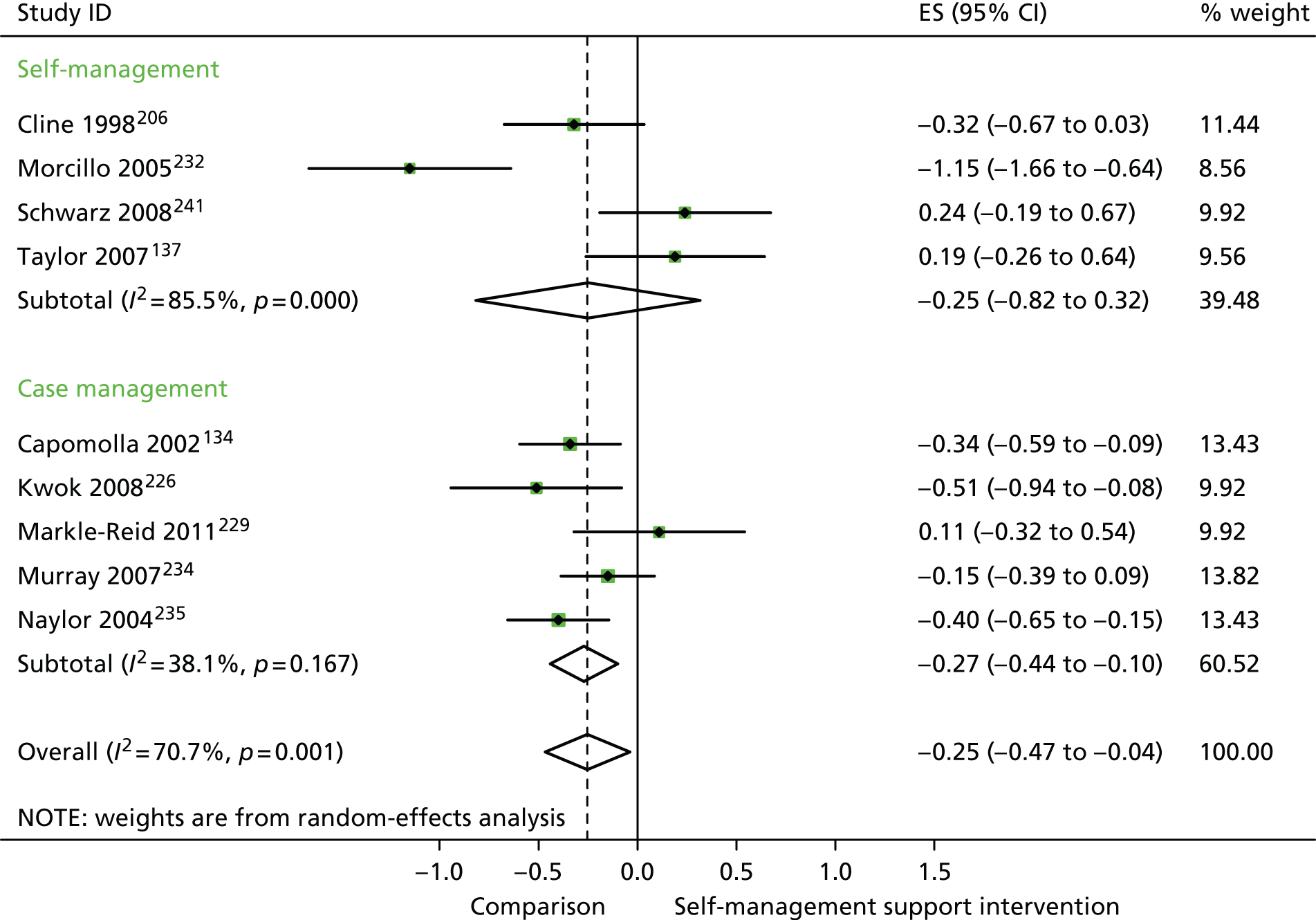

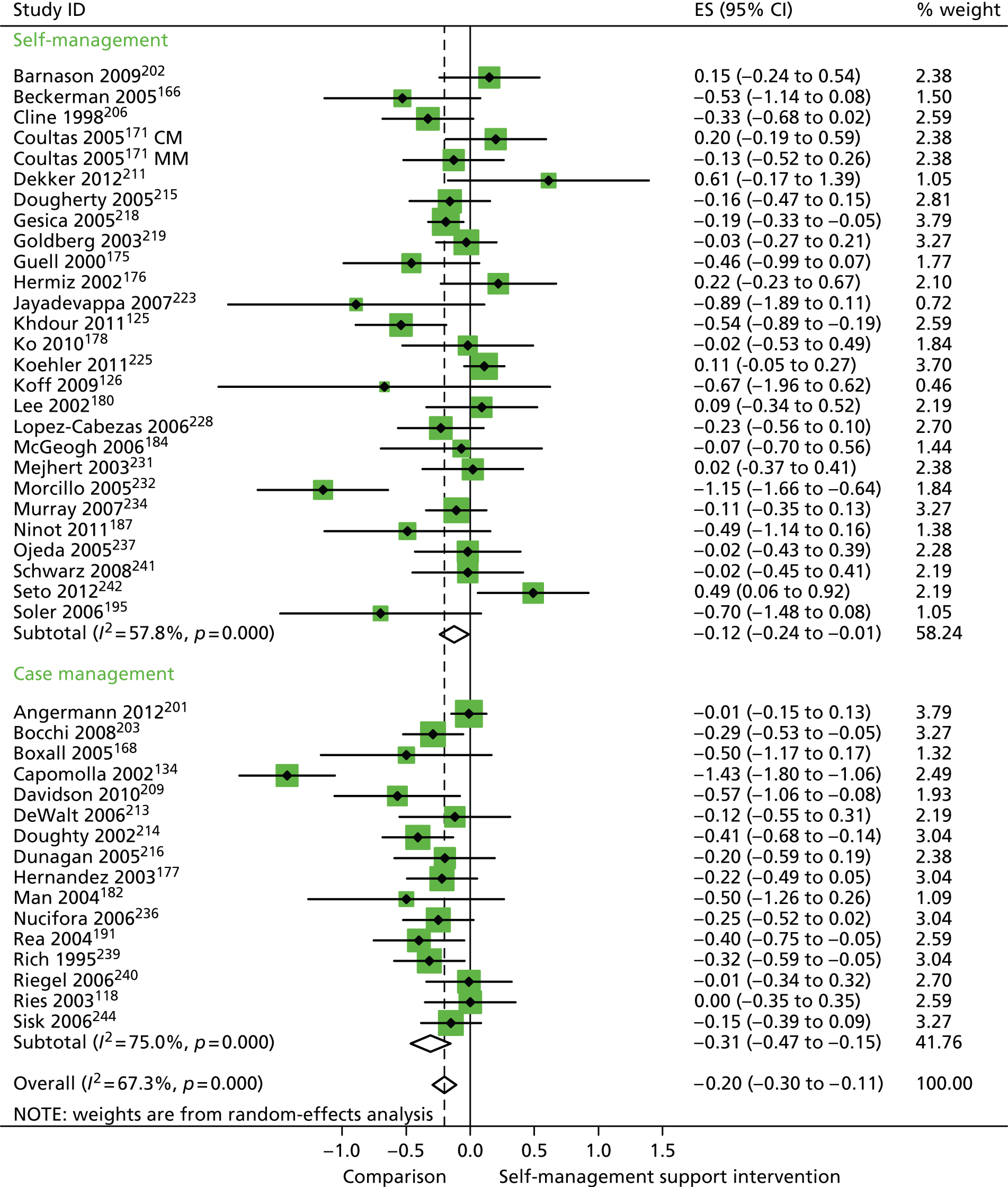

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cardiovascular problems were associated with small but significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was high (Figure 16).

FIGURE 16.

Forest plot: cardiovascular (hospital use). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; GC, group counselling intervention; TC, individual telephone counselling intervention; TH, telehealth post-discharge support; VH, video health post-discharge support. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

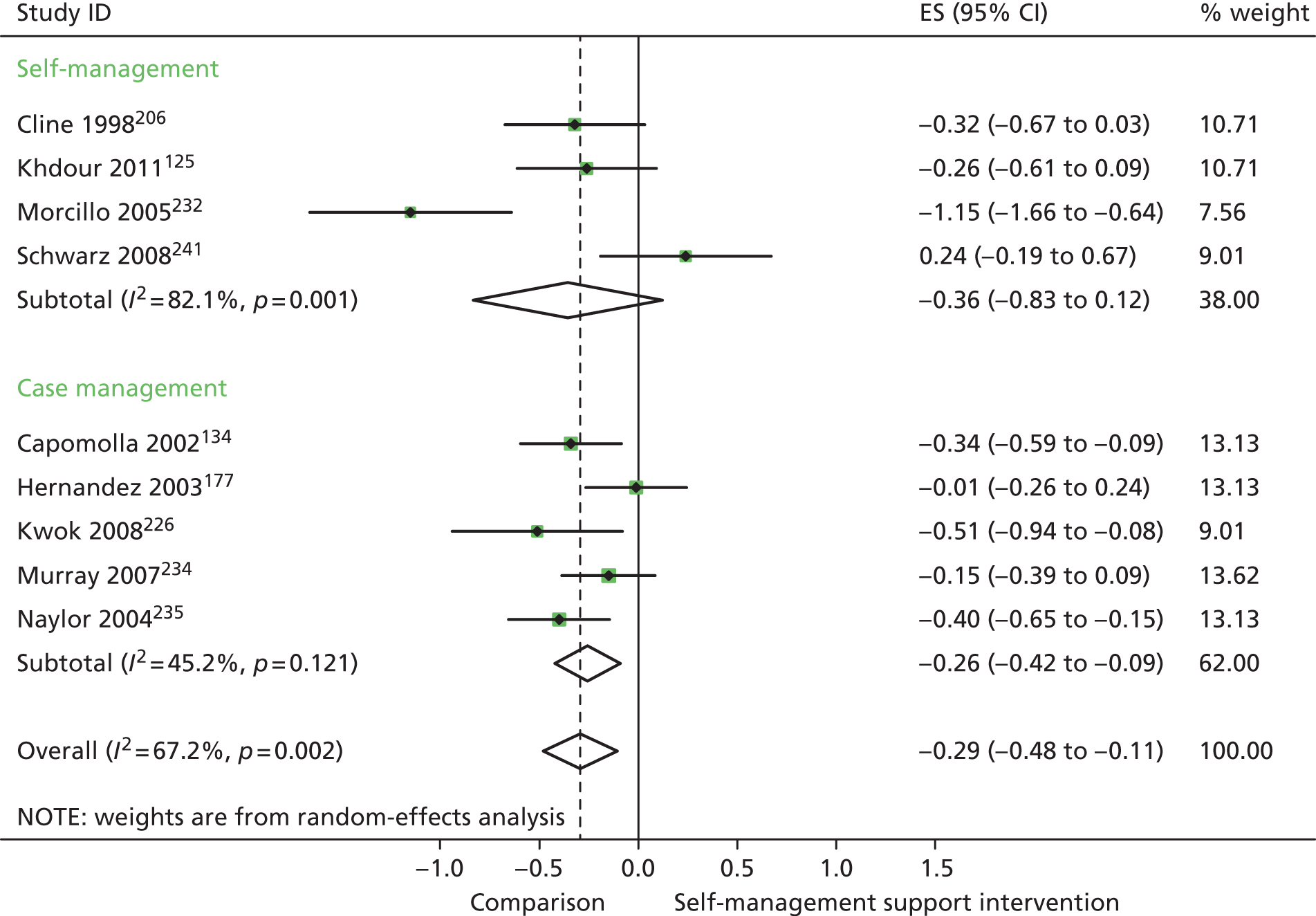

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cardiovascular problems were associated with small but significant reductions in costs. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 17).

FIGURE 17.

Forest plot: cardiovascular (costs). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, there was evidence that ‘case management’ interventions produced small but significant improvements in QoL and reductions in hospital use and costs. ‘Self-management’ interventions showed small but significant improvements in QoL and reductions in hospital use, but no significant reductions in costs.

Analyses of studies for patients with arthritis problems

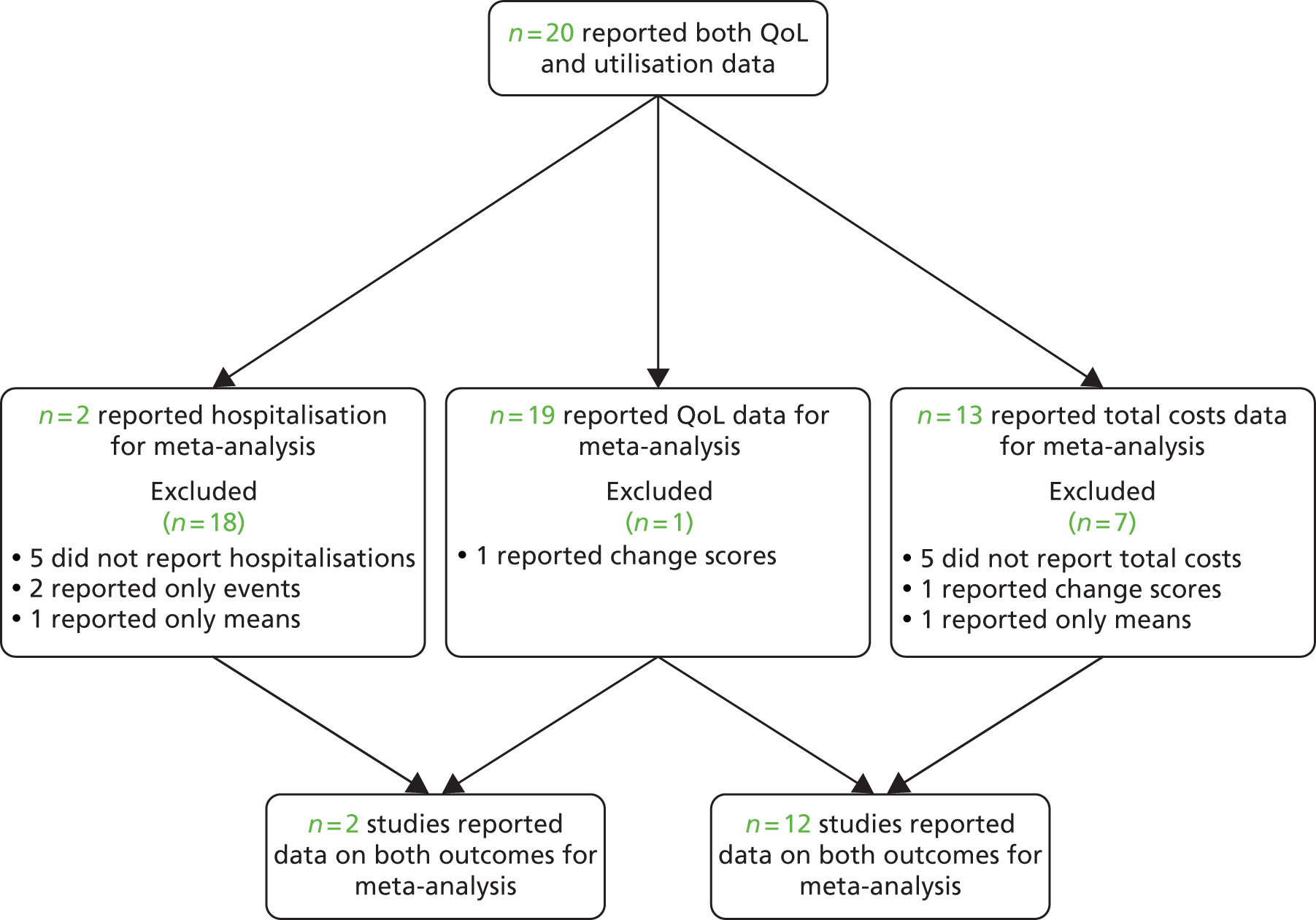

The studies identified in respiratory problems are detailed in Figure 18. 146,148–151,153–155,248,249

FIGURE 18.

Flow chart of studies in patients with arthritis problems.

Figures 19 and 20 show the permutation plots for patients with arthritis problems.

FIGURE 19.

Permutation plot: arthritis (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 20.

Permutation plot: arthritis (total costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the top right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements in QoL and increases in costs.

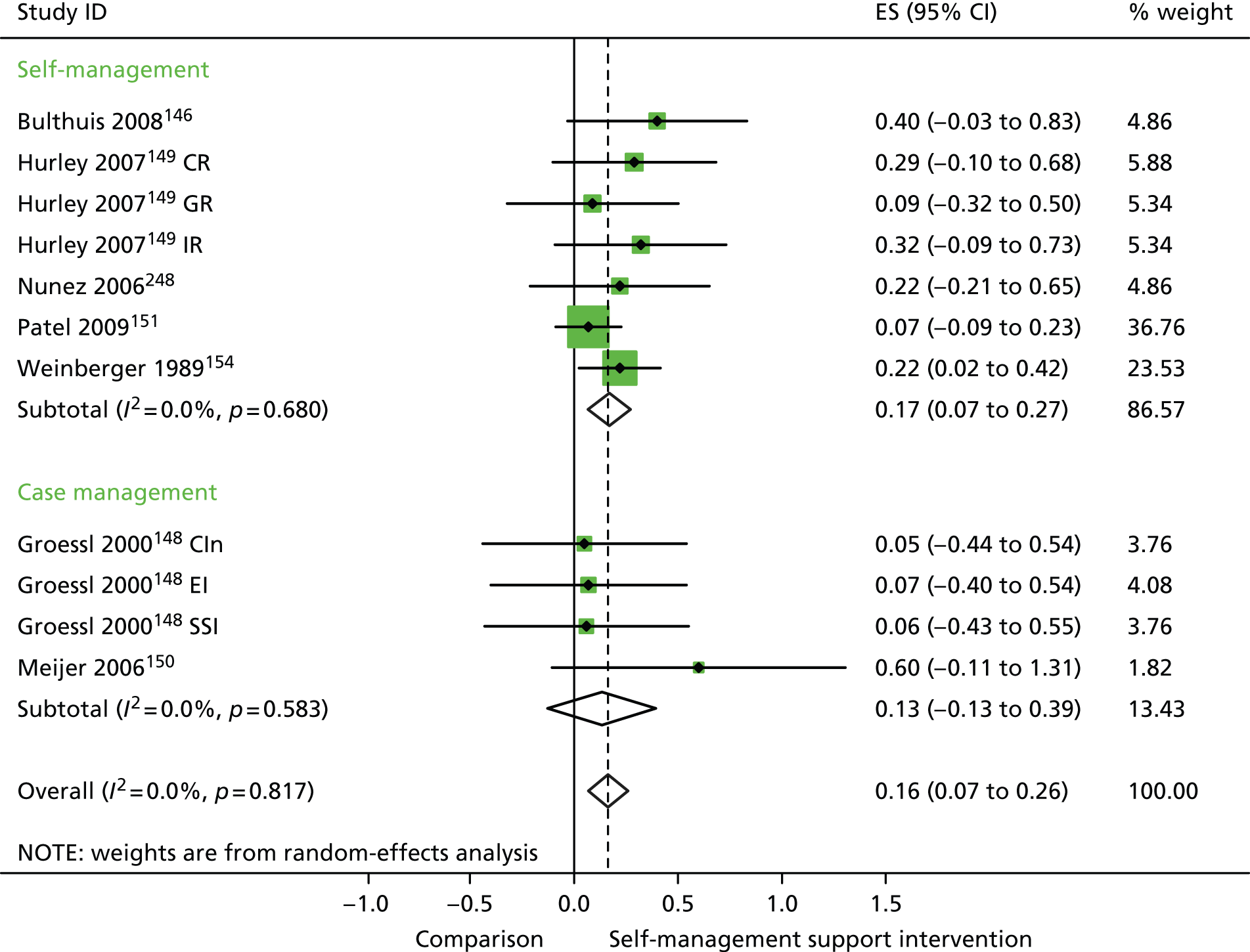

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with arthritis problems were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. There was no significant variation across trials beyond that expected by chance (Figure 21).

FIGURE 21.

Forest plot: arthritis (QoL). CI, confidence interval; CIn, combined (education and social support) intervention; CR, combined (group and individual) rehabilitation; EI, educational intervention; ES, effect size; GR, group rehabilitation; IR, individual rehabilitation; SSI, social support intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

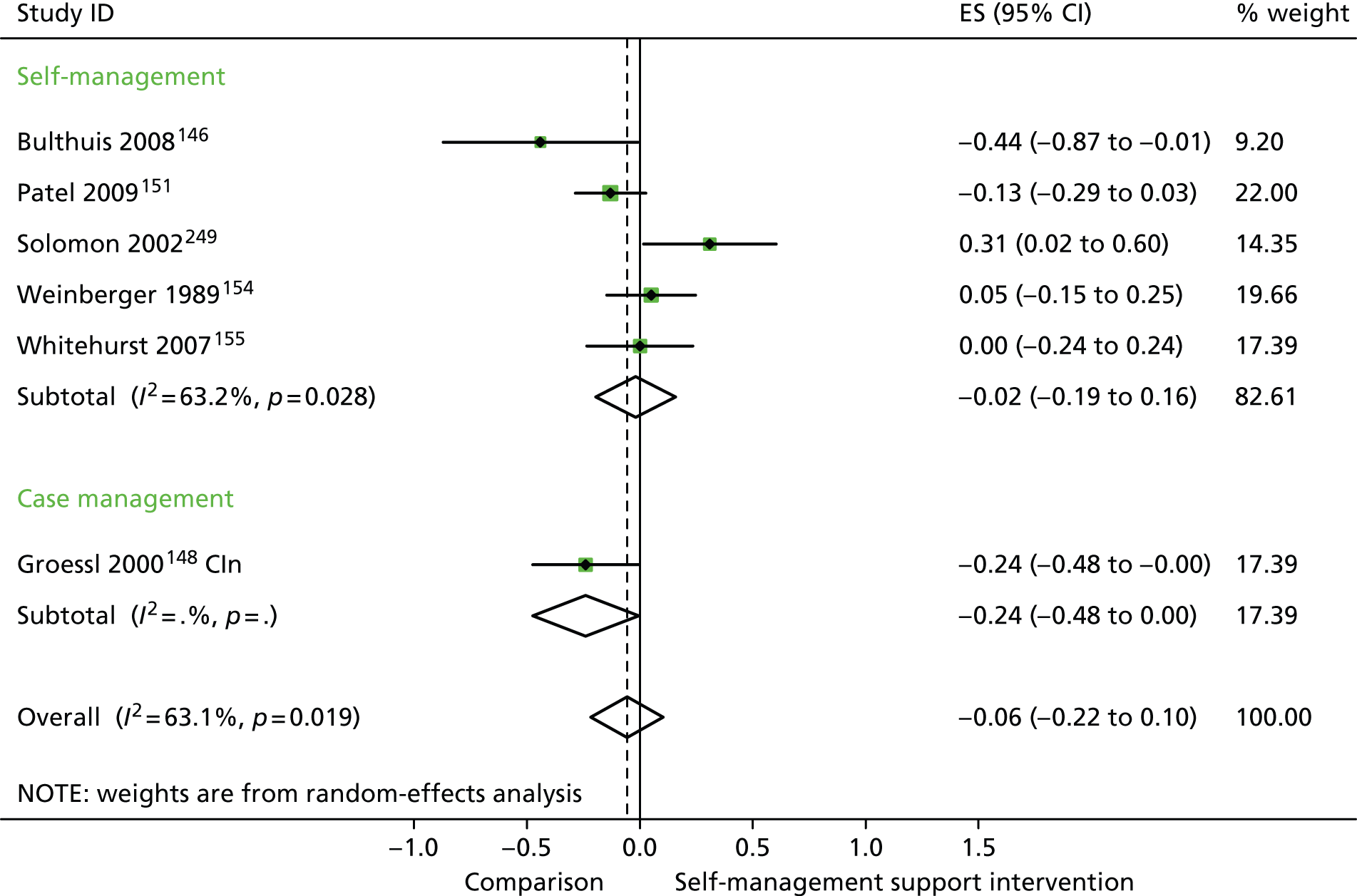

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with arthritis problems were associated with non-significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 22).

FIGURE 22.

Forest plot: arthritis (hospital use). CI, confidence interval; CIn, combined (education and social support) intervention; ES, effect size. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

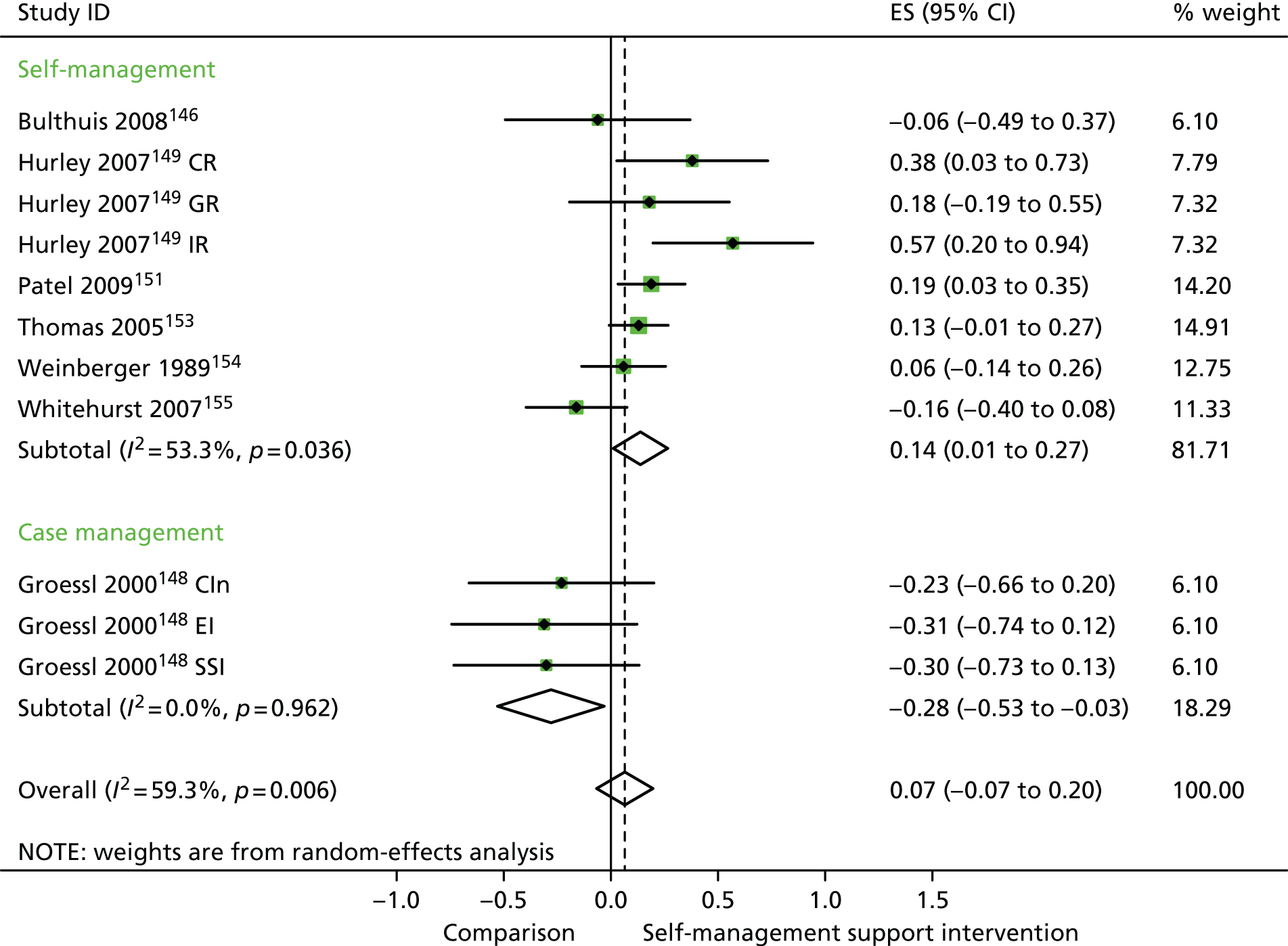

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with arthritis problems were associated with non-significant increases in costs. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 23).

FIGURE 23.

Forest plot: arthritis (costs). CI, confidence interval; CIn, combined (education and social support) intervention; CR, combined (group and individual) rehabilitation; EI, educational intervention; ES, effect size; GR, group rehabilitation; IR, individual rehabilitation; SSI, social support intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, there was evidence that ‘case management’ interventions produced non-significant improvements in QoL and small but significant reductions in hospital use and costs, while ‘self-management’ interventions had small but significant benefits on QoL, non-significant effects on hospital use and small but significant increases in costs.

Analyses of studies for patients with pain problems

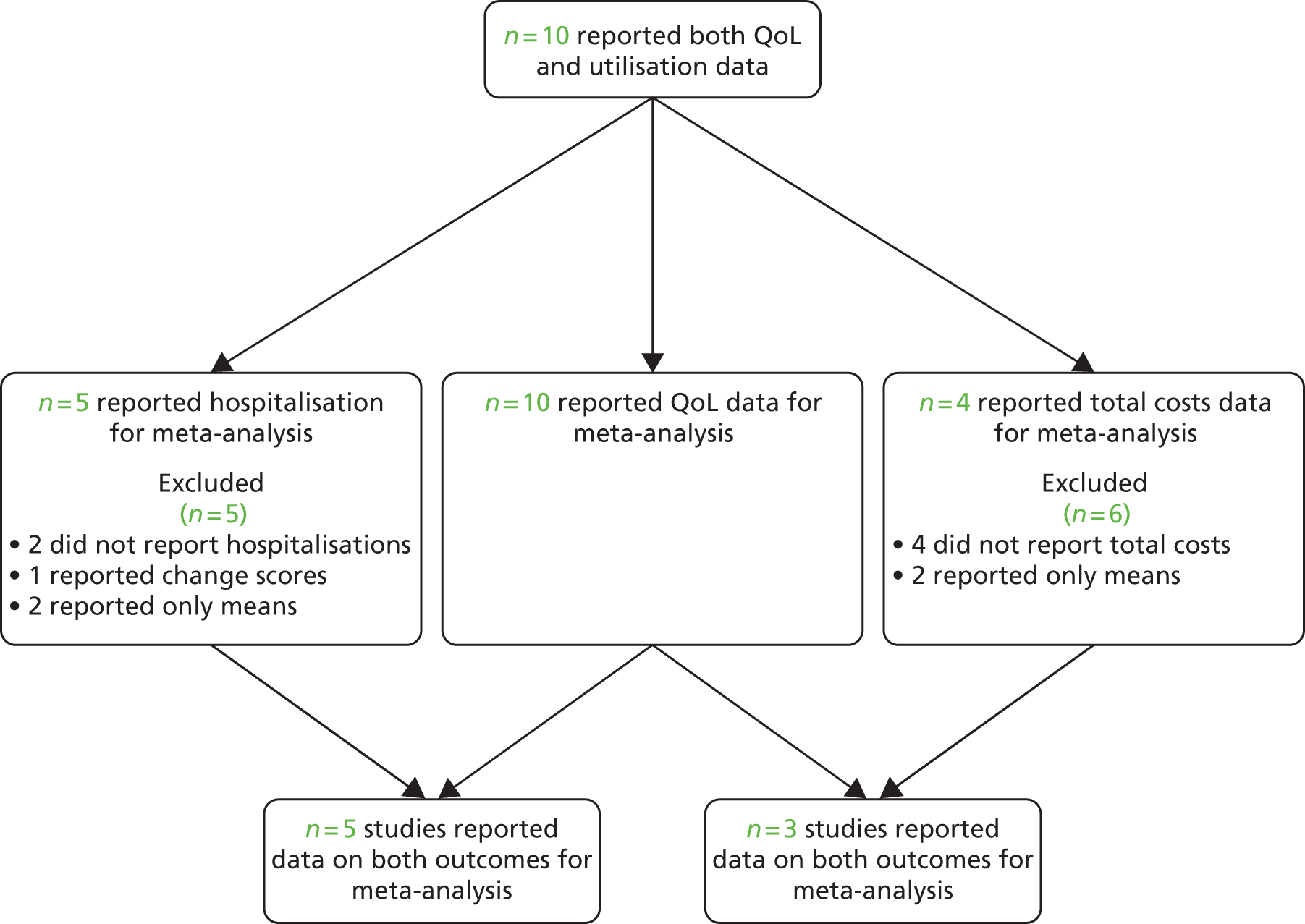

The studies identified in pain problems are detailed in Figure 24. 156–160,250–256

FIGURE 24.

Flow chart of studies in patients with pain problems.

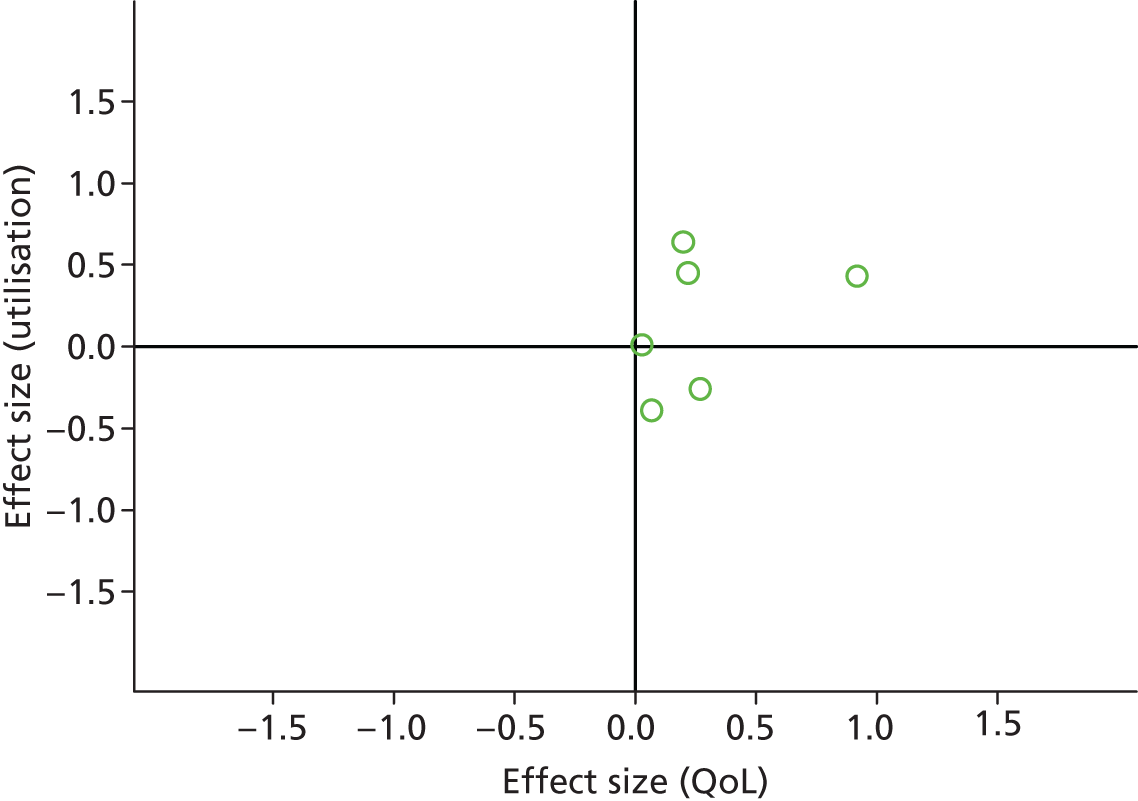

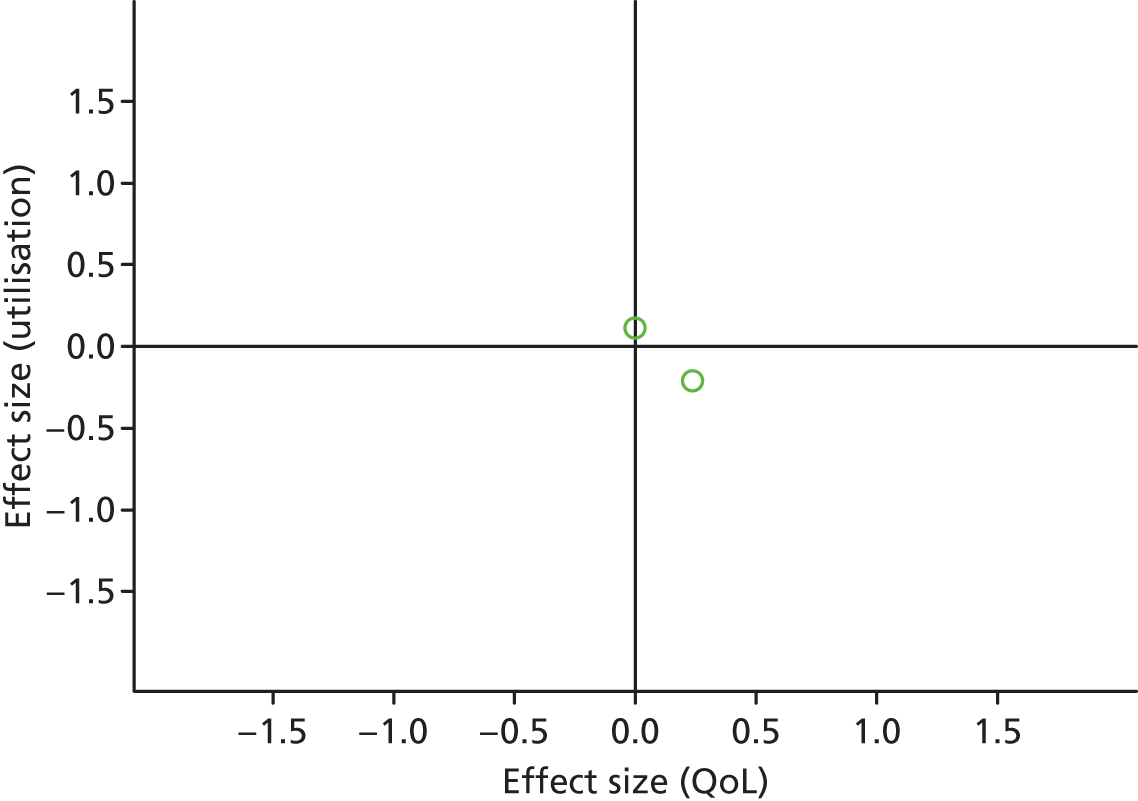

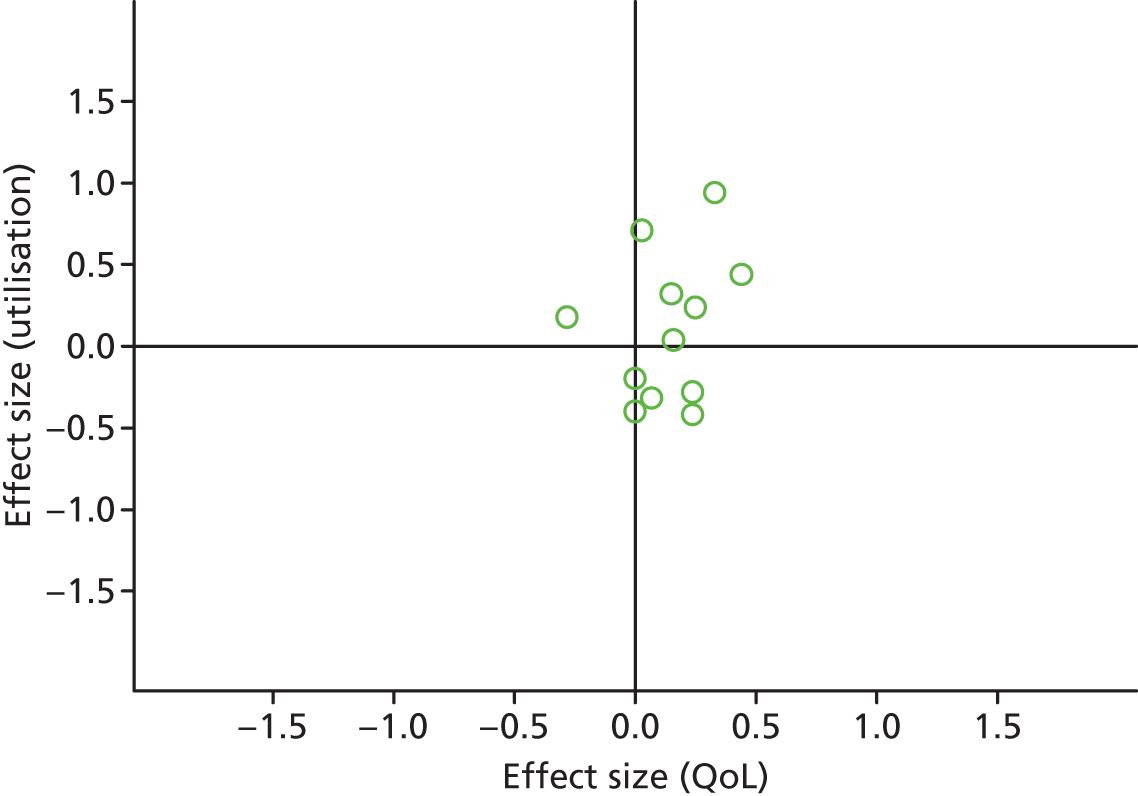

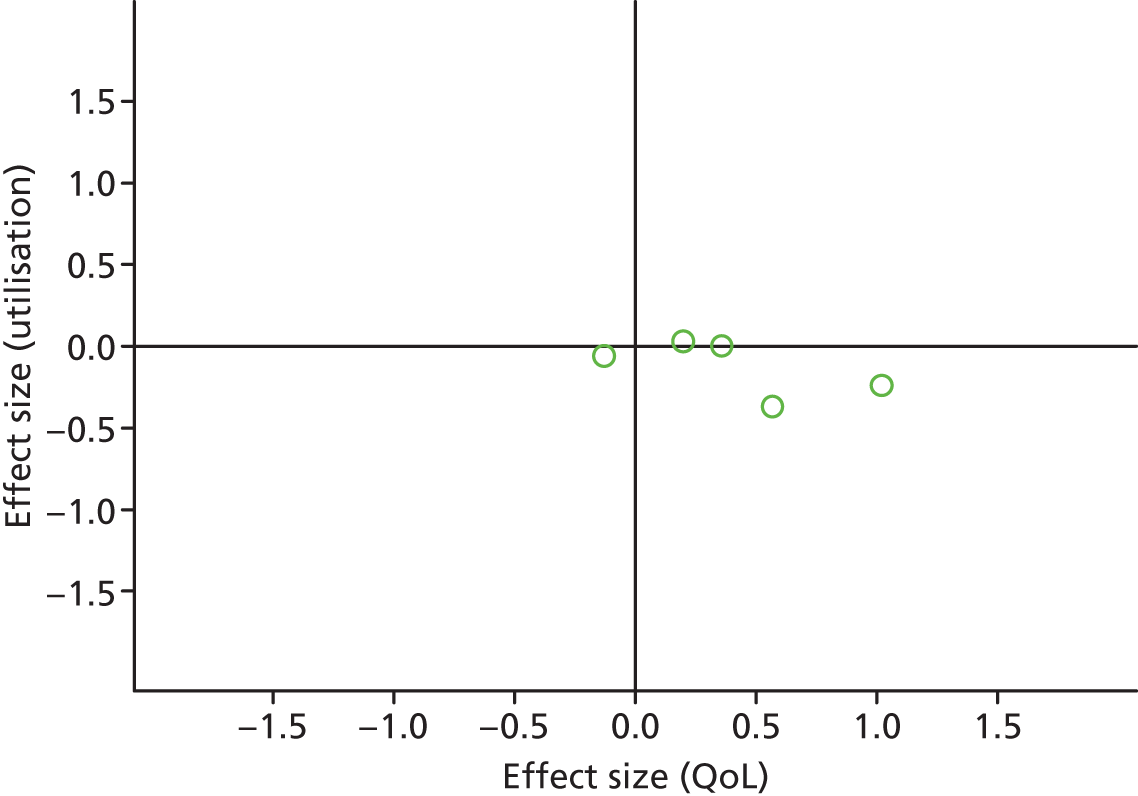

Figures 25 and 26 show the permutation plots for patients with pain problems.

FIGURE 25.

Permutation plot: pain (hospital use and QoL).

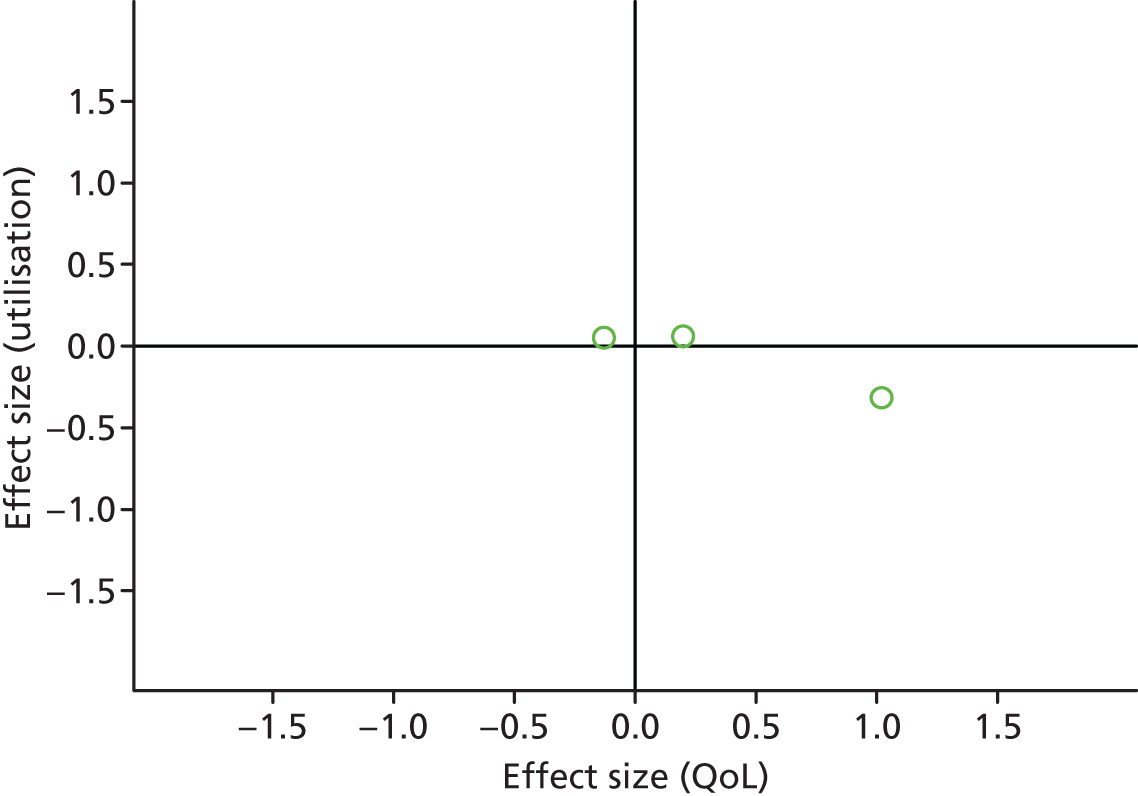

FIGURE 26.

Permutation plot: pain (total costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the top right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements in QoL and increases in utilisation.

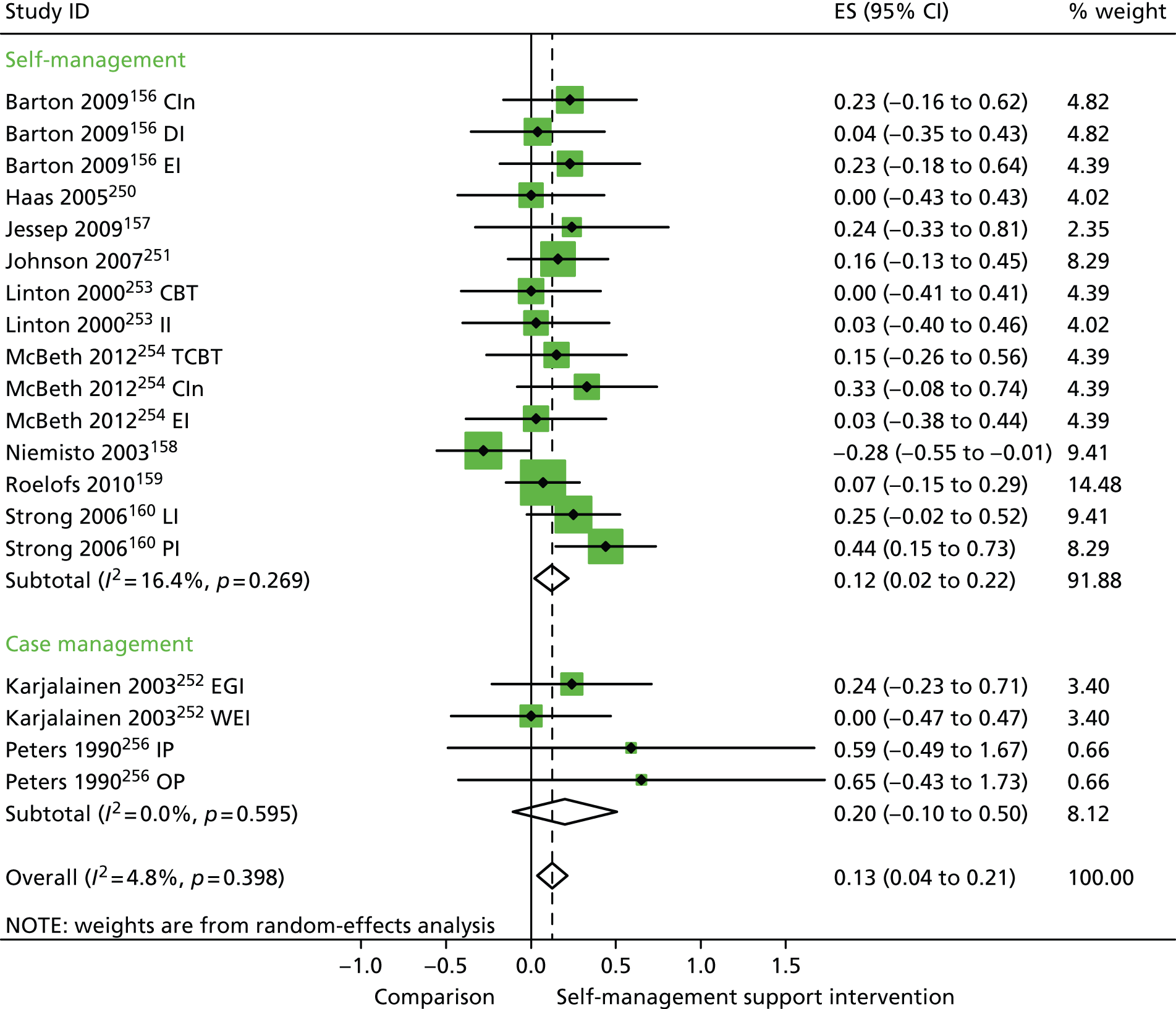

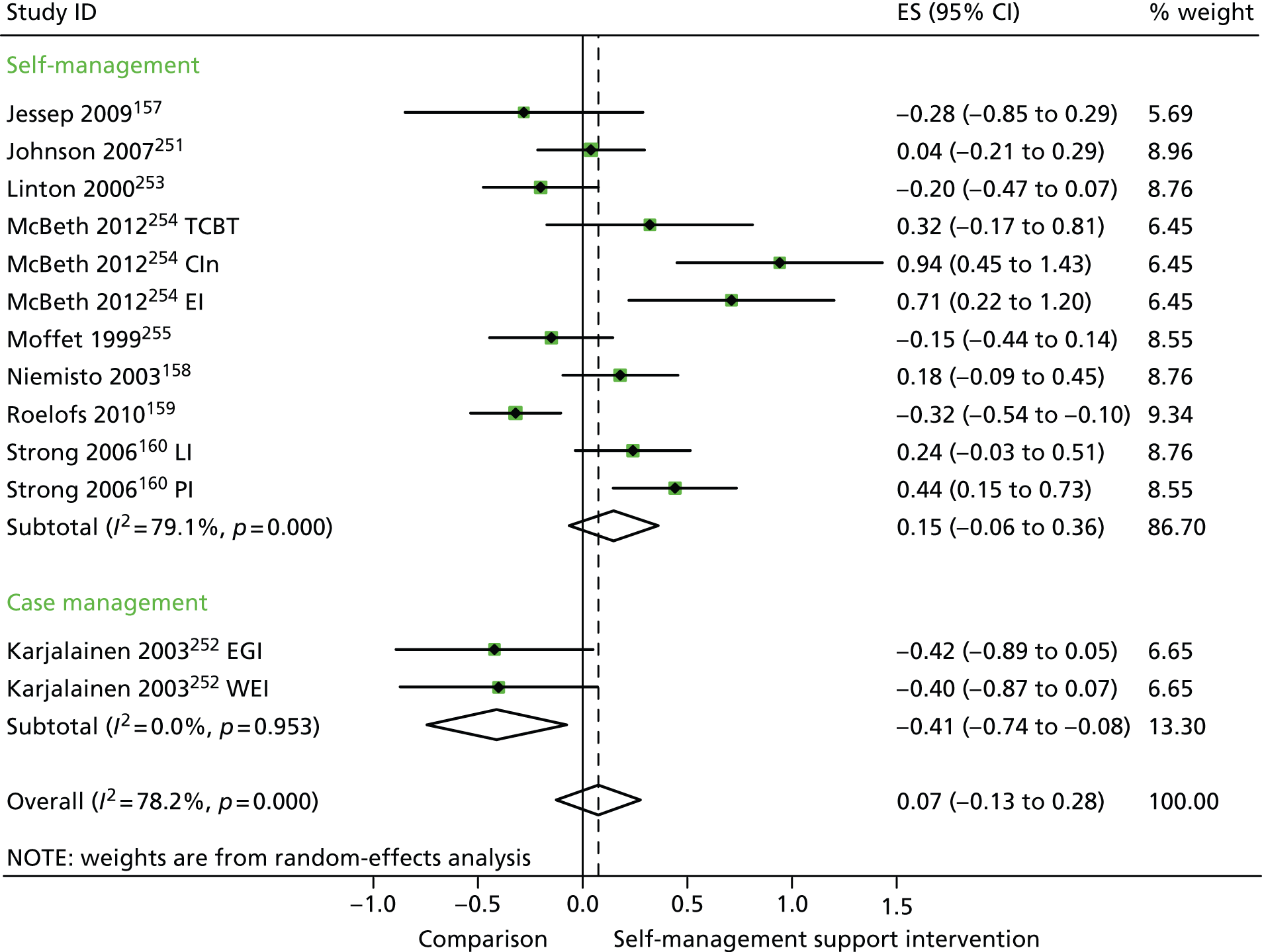

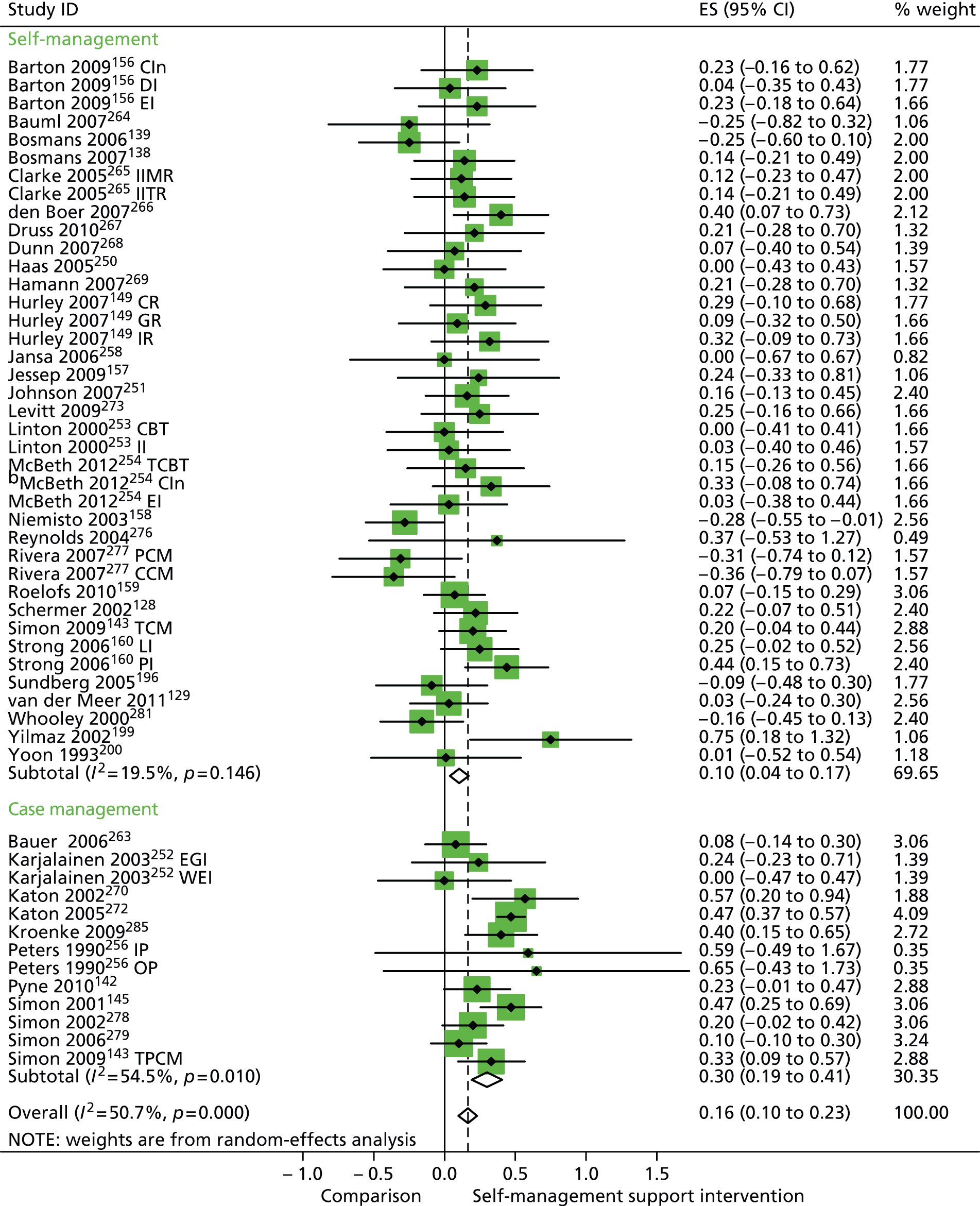

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patient with pain problems were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was low (Figure 27).

FIGURE 27.

Forest plot: pain (QoL). CBT, group cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention; CI, confidence interval; CIn, combined intervention; DI, dietary intervention; EGI, exercise and graded activity intervention; EI, exercise intervention; ES, effect size; II, information-only intervention; IP, inpatient pain management programme; LI, lay-led self-care intervention; OP, outpatient pain management programme; PI, psychologist-led self-care intervention; TCBT, telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy; WEI, work-based exercise and graded activity intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

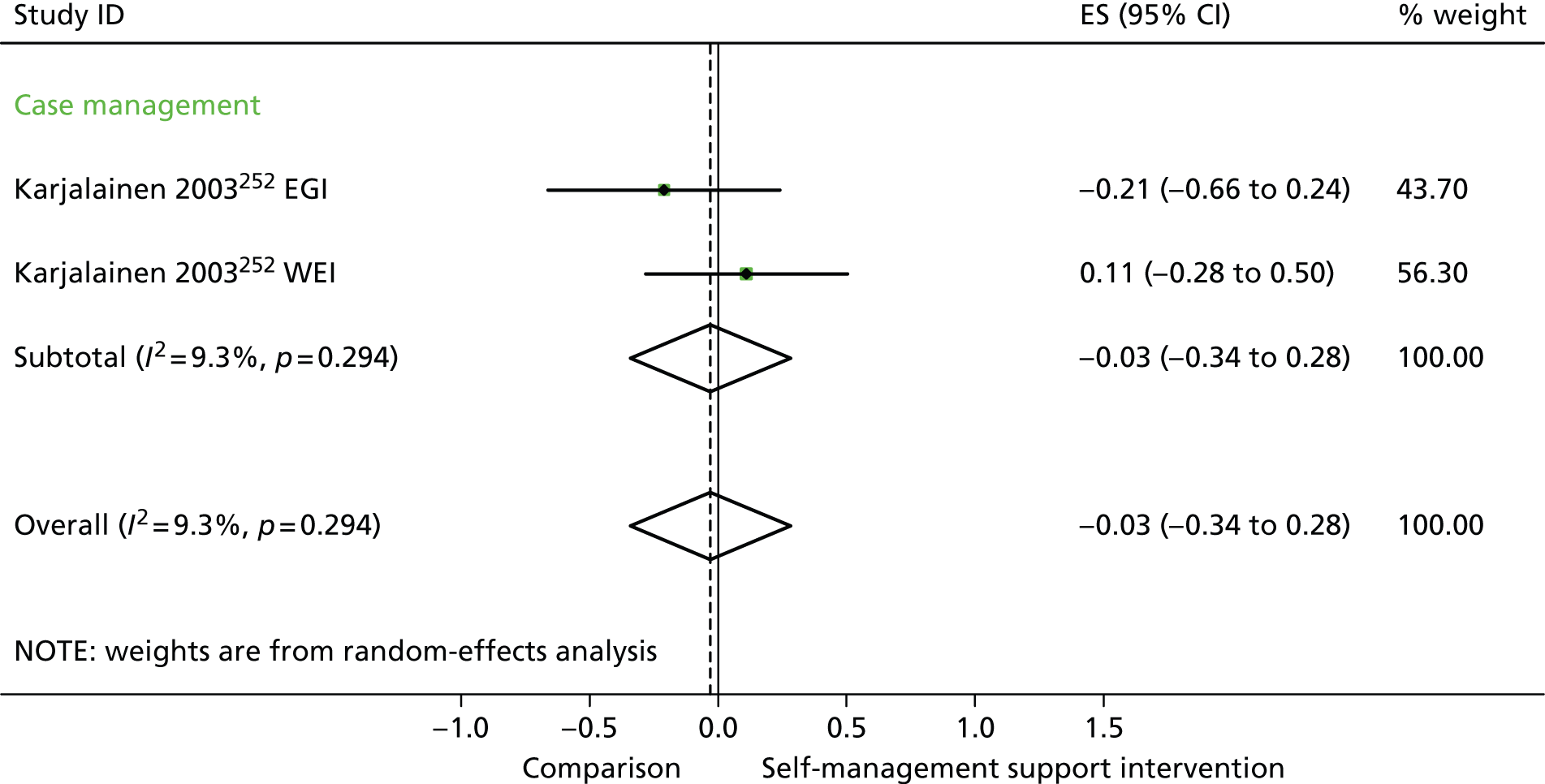

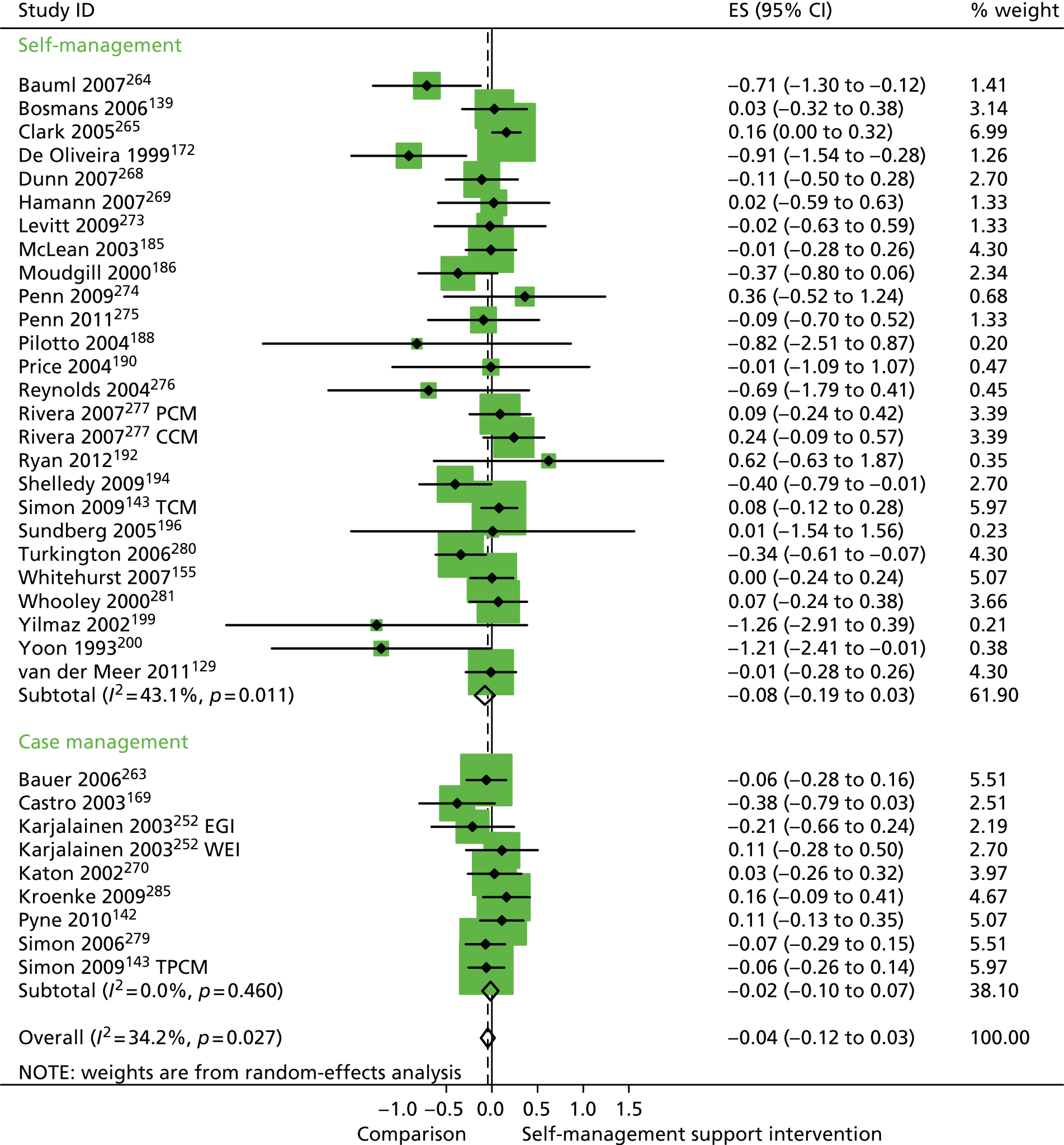

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with pain problems were associated with non-significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was low (Figure 28).

FIGURE 28.

Forest plot: pain (hospital use). CI, confidence interval; EGI, exercise and graded activity intervention; ES, effect size; WEI, work-based exercise and graded activity intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

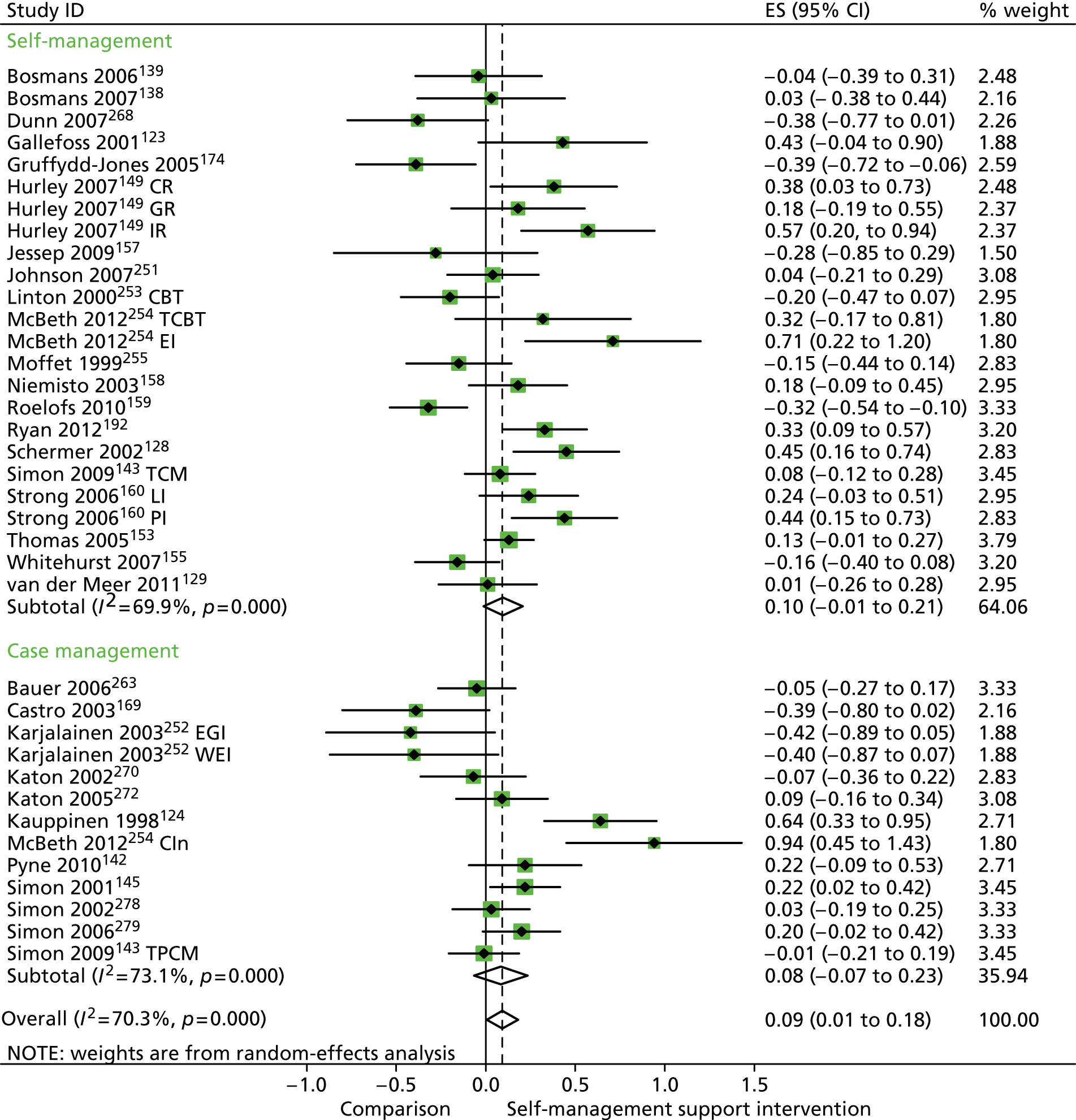

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with pain problems were associated with non-significant increases in costs. Variation across trials was high (Figure 29).

FIGURE 29.

Forest plot: pain (costs). CI, confidence interval; CIn, combined (telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy and exercise) intervention; EGI, exercise and graded activity intervention; EI, exercise intervention; ES, effect size; LI, lay-led self-care intervention; PI, psychologist-led self-care intervention; TCBT, telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy; WEI, work-based exercise and graded activity intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, the effects of ‘case management’ interventions on QoL and hospital use were non-significant, but showed moderate and significant reductions in costs. ‘Self-management’ interventions showed small but significant improvements in QoL but non-significant effects in costs.

Analyses of studies for patients with diabetes problems

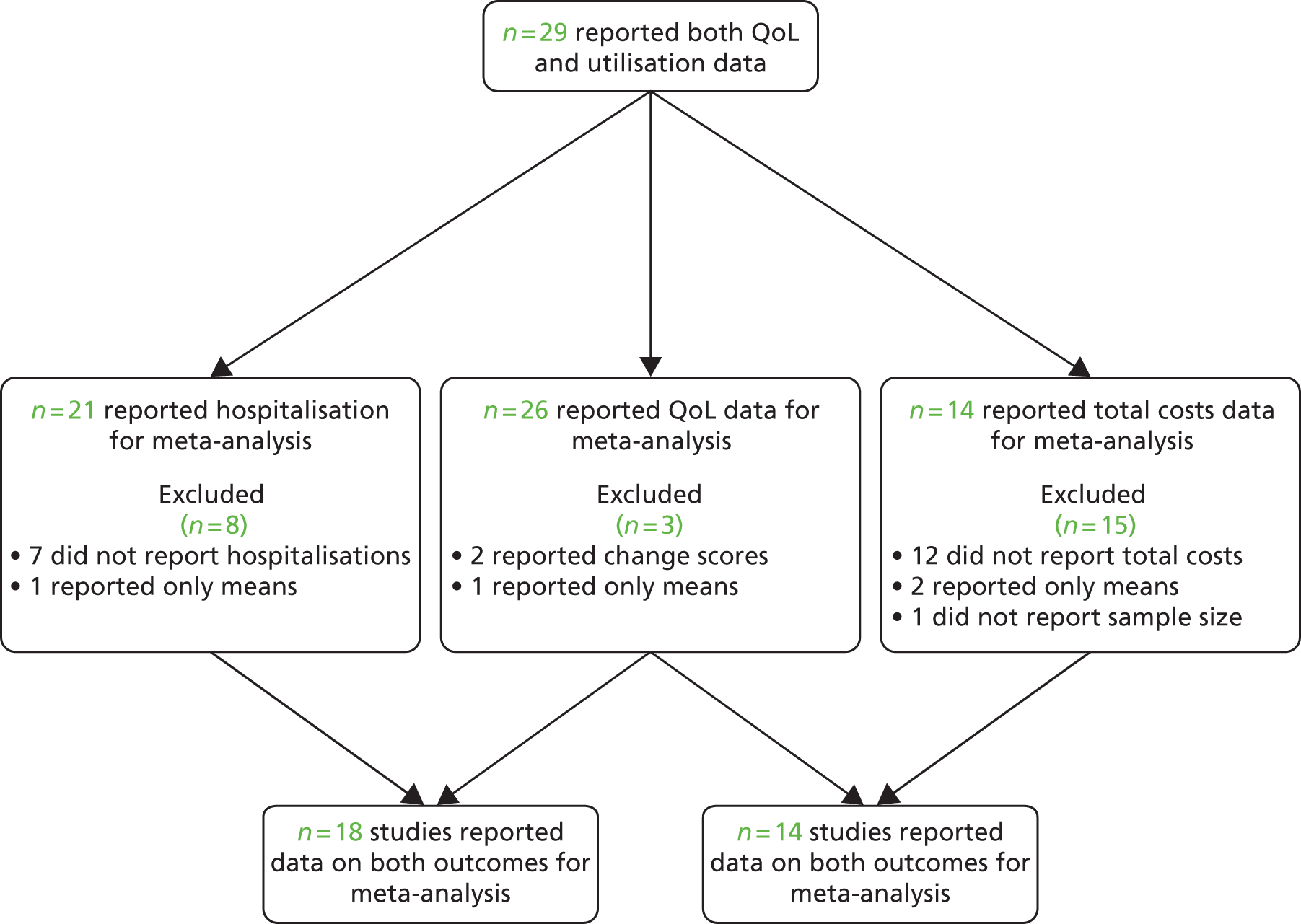

The studies identified in diabetes problems are detailed in Figure 30. 130–133,257–262

FIGURE 30.

Flow chart of studies in patients with diabetes problems.

Figures 31 and 32 show the permutation plots for patients with diabetes problems.

FIGURE 31.

Permutation plot: diabetes (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 32.

Permutation plot: diabetes (total costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the bottom right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements in QoL and equal or decreased utilisation.

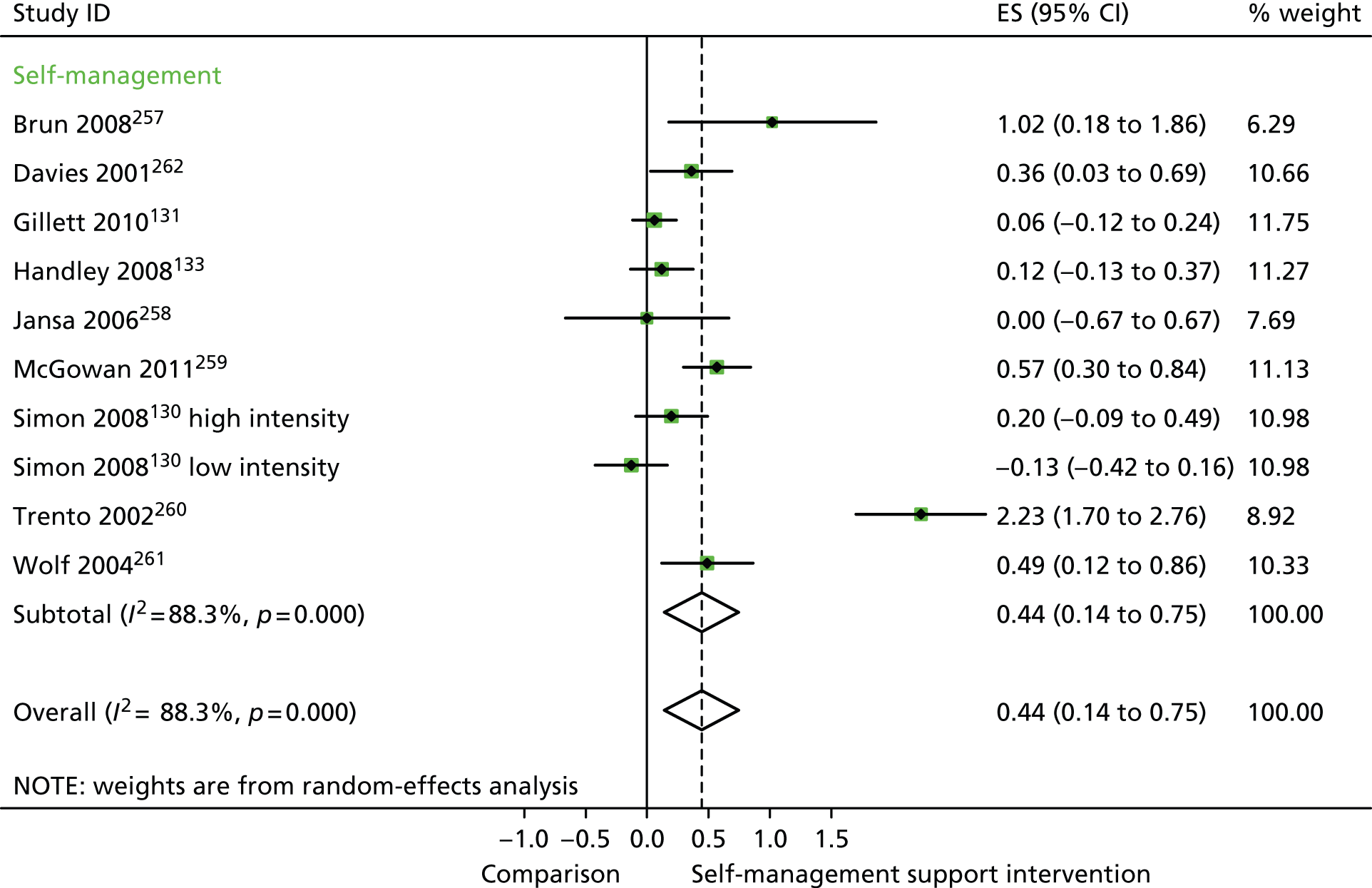

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with diabetes problems were associated with significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was high (Figure 33).

FIGURE 33.

Forest plot: diabetes (QoL). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study. ‘Low intensity’ is use of blood glucose meter and advice to contact GP for interpretation; ‘high intensity’ is use of blood glucose meter and training to interpret results.

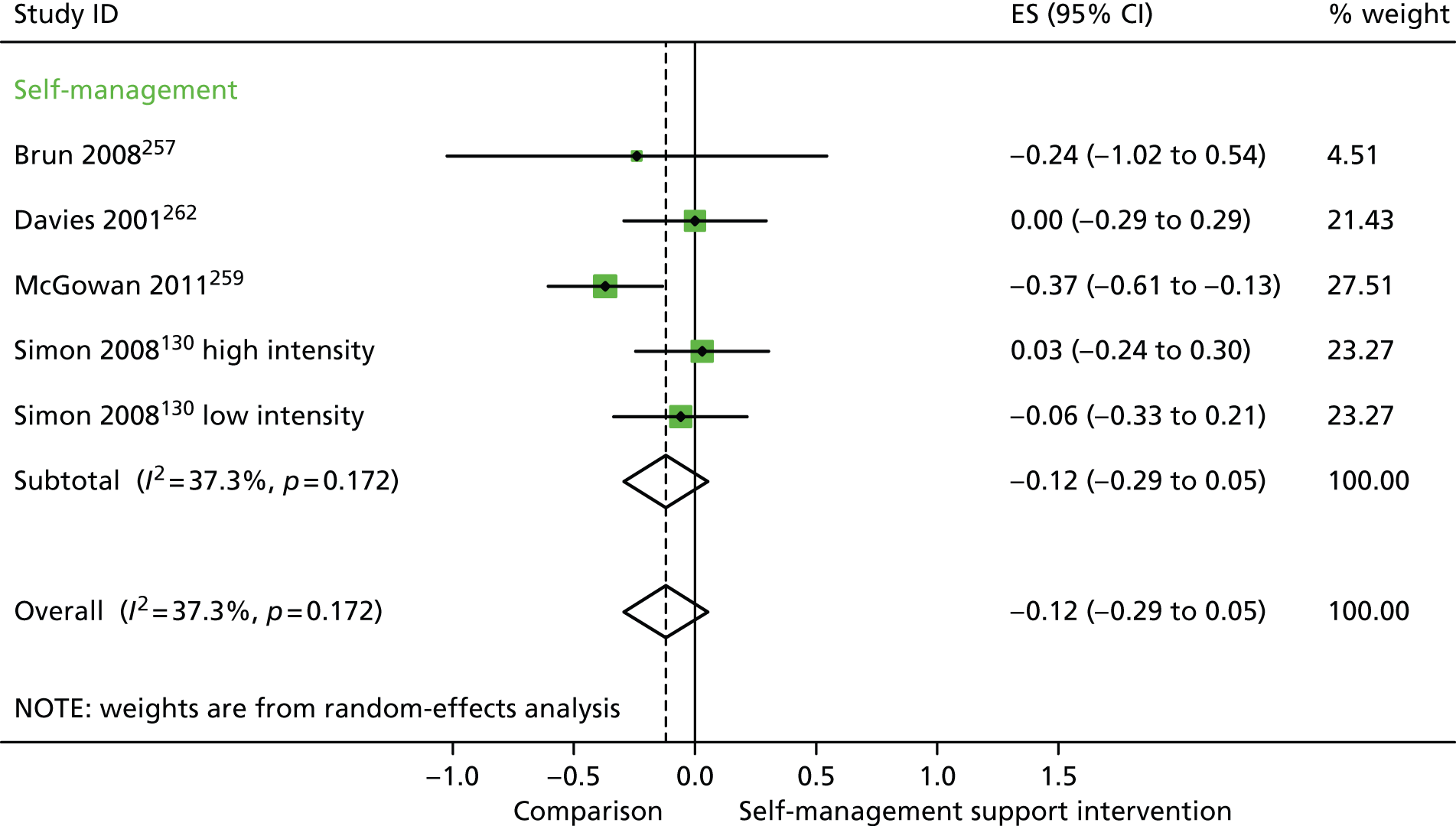

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with diabetes problems were associated with non-significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 34).

FIGURE 34.

Forest plot: diabetes (hospital use). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study. ‘Low intensity’ is use of blood glucose meter and advice to contact GP for interpretation; ‘high intensity’ is use of blood glucose meter and training to interpret results.

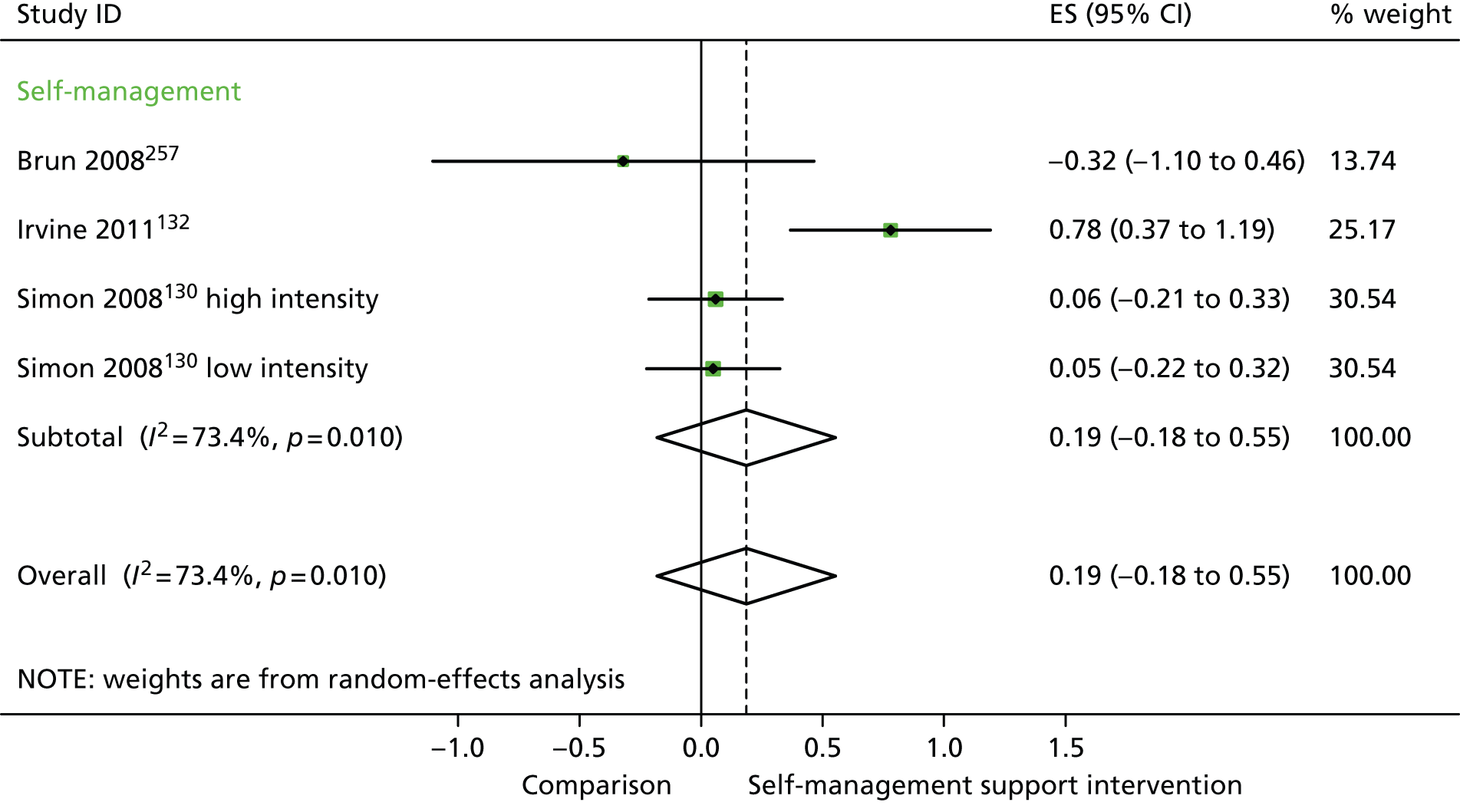

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with diabetes problems were associated with non-significant reductions in costs. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 35).

FIGURE 35.

Forest plot: diabetes (costs). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size. ‘Low intensity’ is use of blood glucose meter and advice to contact GP for interpretation; ‘high intensity’ is use of blood glucose meter and training to interpret results.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, ‘self-management’ interventions showed significant improvements in QoL but non-significant reductions in hospital use or costs.

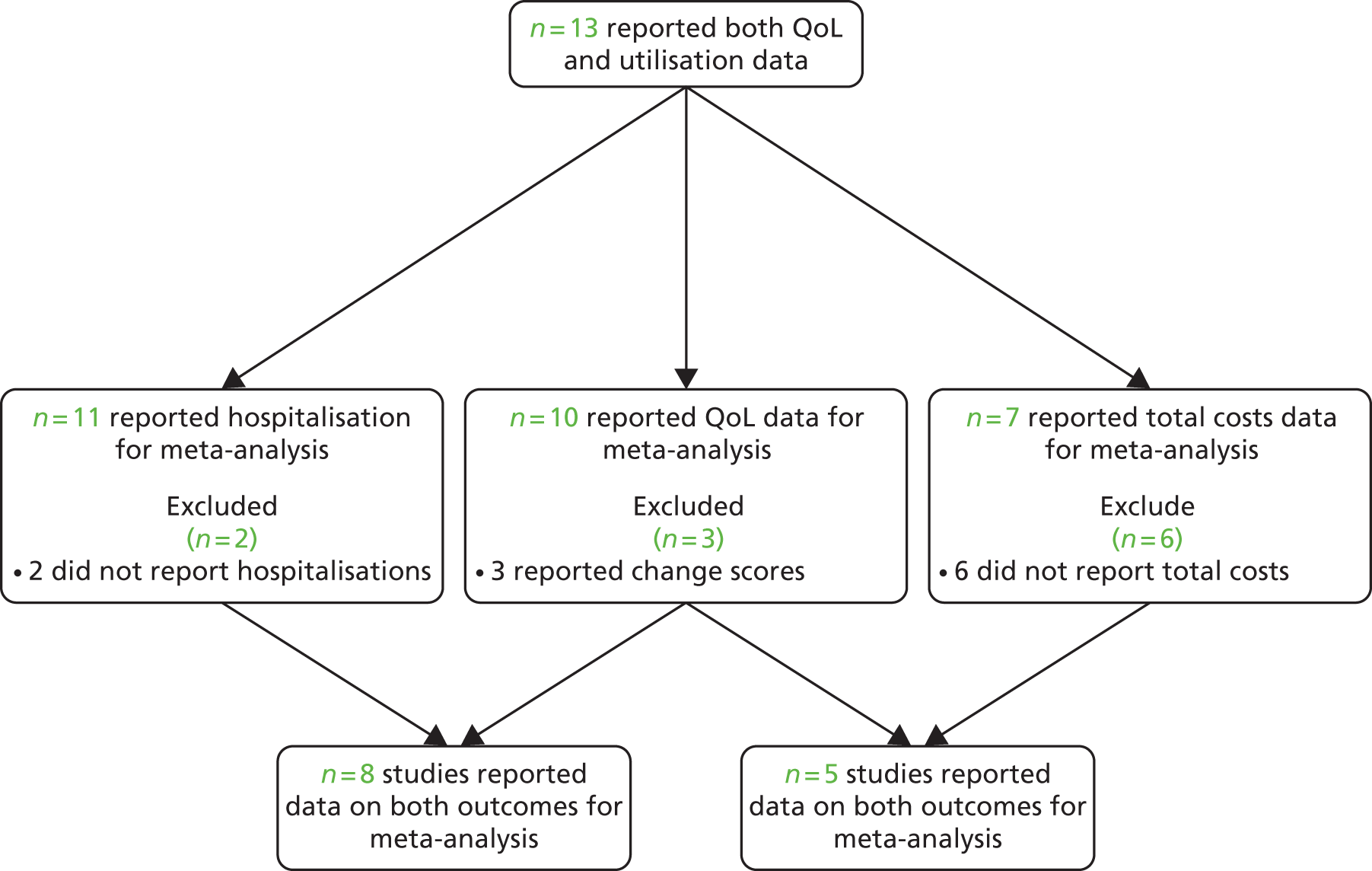

Analyses of studies for patients with mental health problems

The studies identified in mental health problems are detailed in Figure 36. 138–143,145,165,263–281

FIGURE 36.

Flow chart of studies in patients with mental health problems.

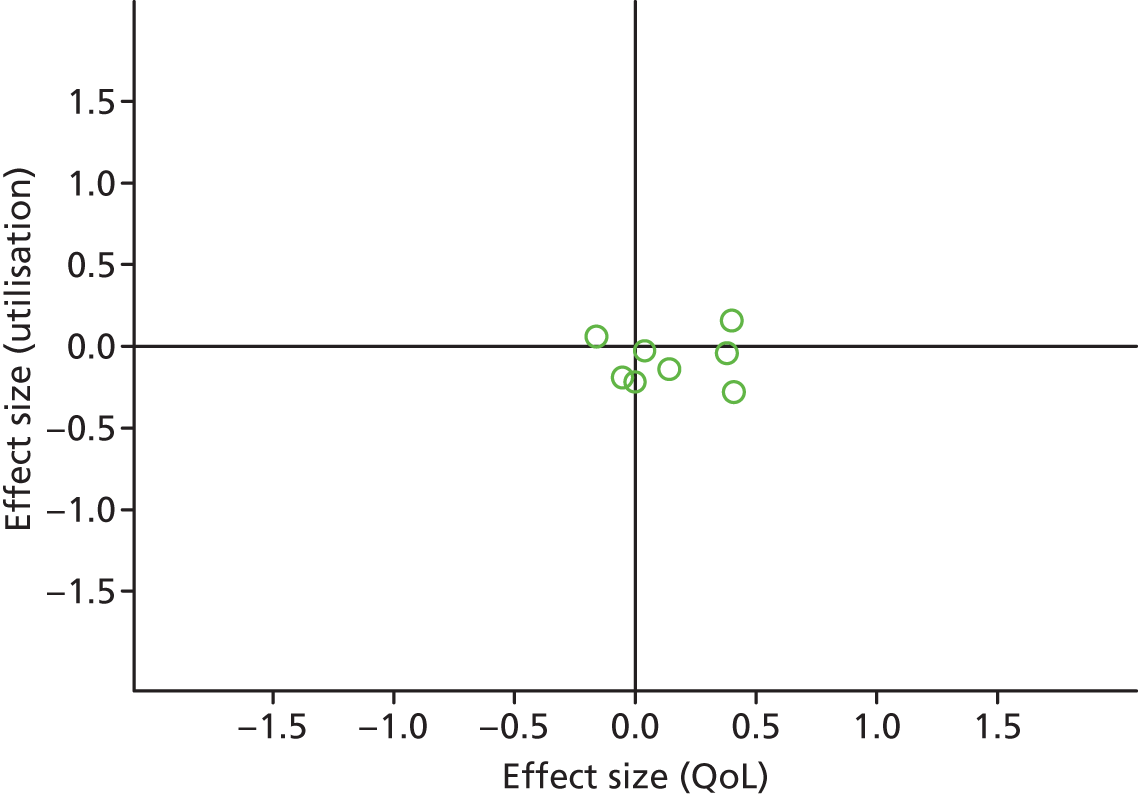

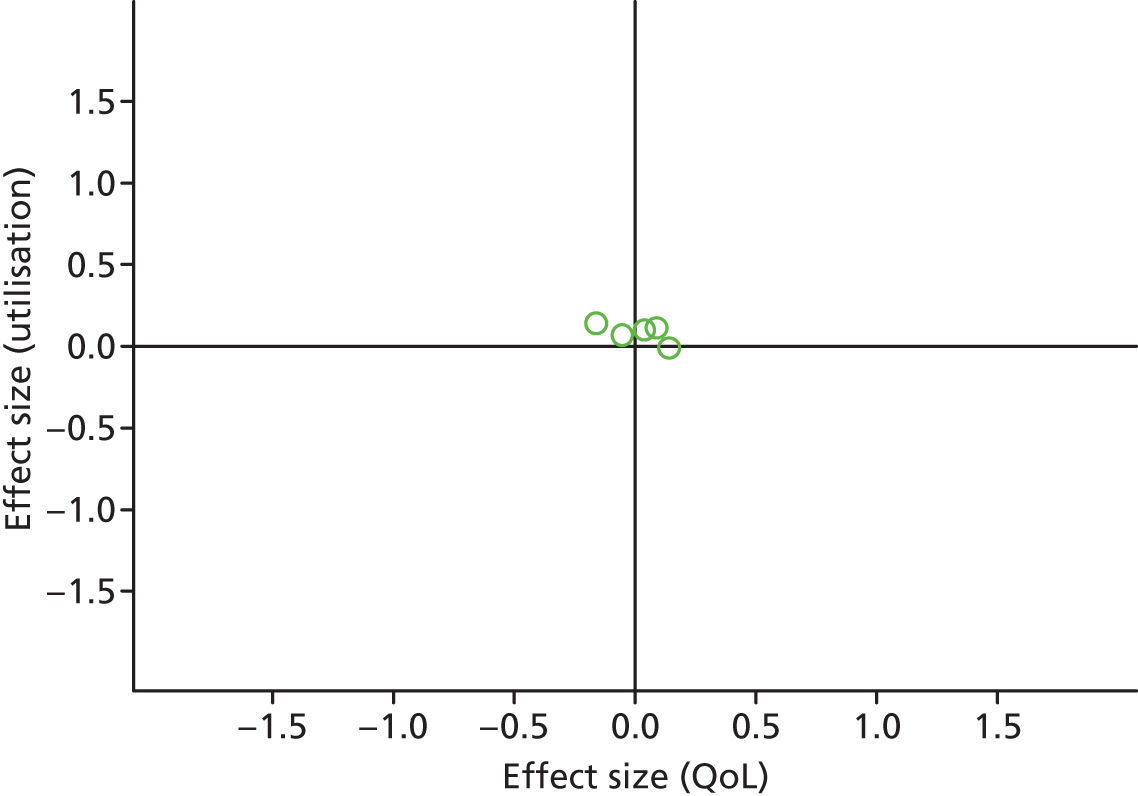

Figures 37 and 38 show the permutation plots for patients with mental health problems.

FIGURE 37.

Permutation plot: mental health (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 38.

Permutation plot: mental health (total costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements in QoL with varied effect on utilisation or costs.

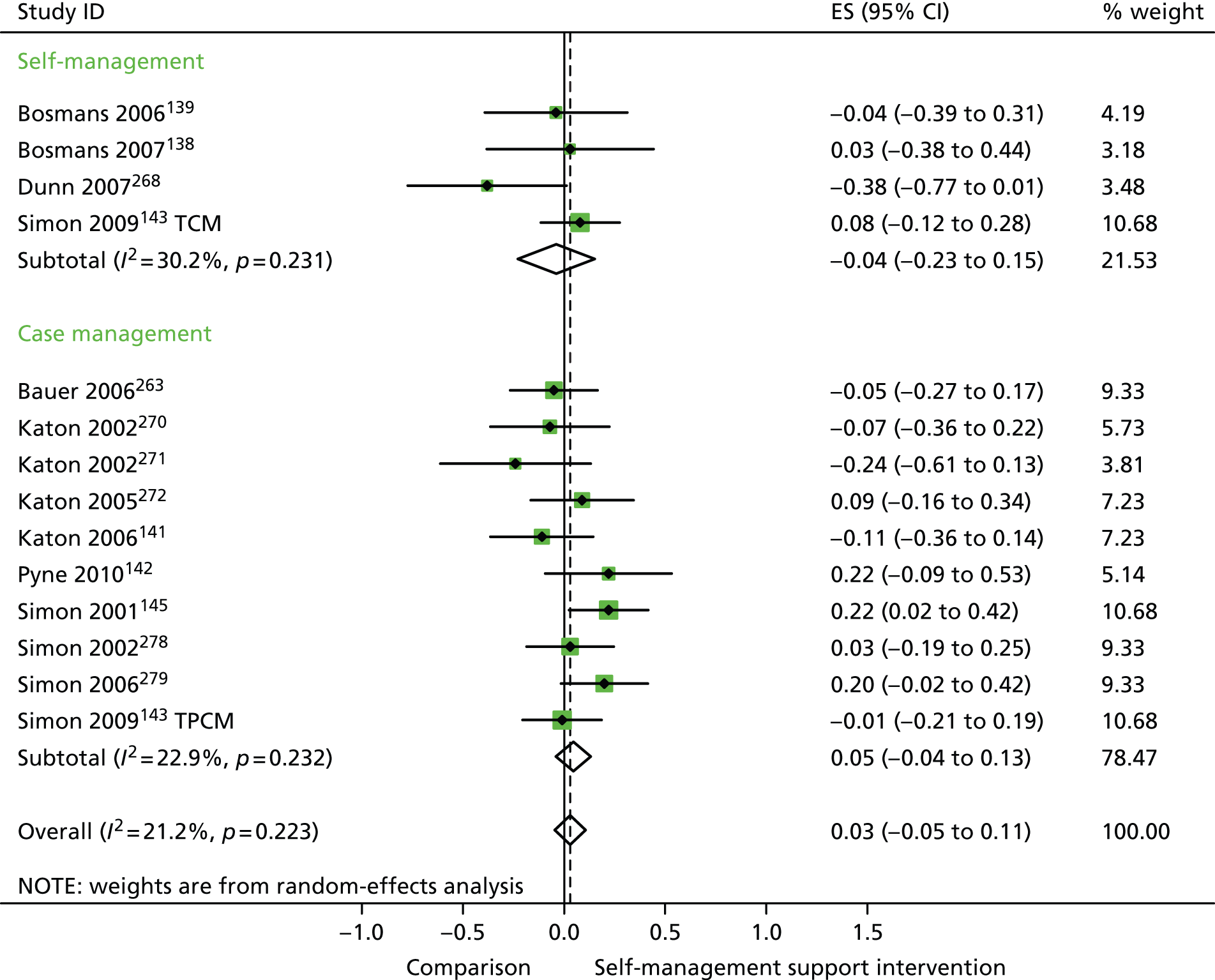

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with mental health problems were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 39).

FIGURE 39.

Forest plot: mental health (QoL). CCM, case management supported by a consumer; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; mail, internet self-help and mailed reminders; PCM, case management supported by a professional; TCM, telephone care management; tel, internet self-help and telephone reminders; TPCM, telephone psychotherapy and care management. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

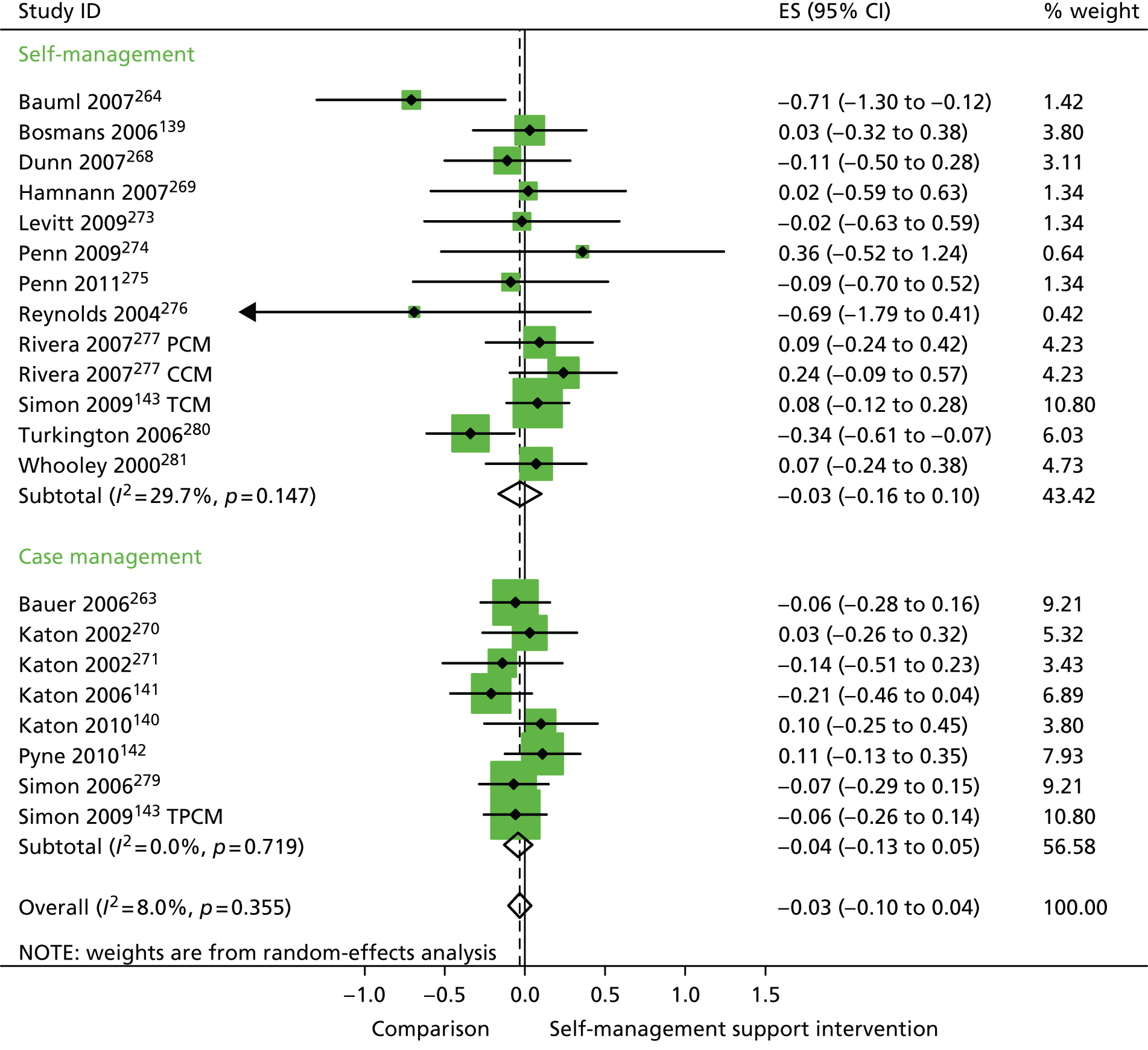

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with mental health problems were associated with non-significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was low (Figure 40).

FIGURE 40.

Forest plot: mental health (hospital use). CCM, case management supported by a consumer; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; PCM, case management supported by a professional; TCM, telephone care management; TPCM, telephone psychotherapy and care management. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with mental health problems were associated with non-significant increases in costs. Variation across trials was low (Figure 41).

FIGURE 41.

Forest plot: mental health (costs). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; TCM, telephone care management; TPCM, telephone psychotherapy and care management. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, there was evidence that ‘case management’ interventions produced significant improvements in QoL but no significant reductions in hospital use and costs. ‘Self-management’ interventions showed no significant improvements in QoL and no significant reductions in hospital use or costs.

Analyses of studies for patients with mixed problems

The studies identified in mixed problems are detailed in Figure 42. 162,163,282–290

FIGURE 42.

Flow chart of studies in patients with mixed problems.

Figures 43 and 44 show the permutation plots for patients with mixed problems.

FIGURE 43.

Permutation plot: mixed (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 44.

Permutation plot: mixed (total costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements in QoL with no effect on utilisation or costs.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with mixed problems were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 45).

FIGURE 45.

Forest plot: mixed (QoL). CDSMP home, peer-led, face-to-face CDSMP variant; CDSMP phone, telephone-based CDSMP variant; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

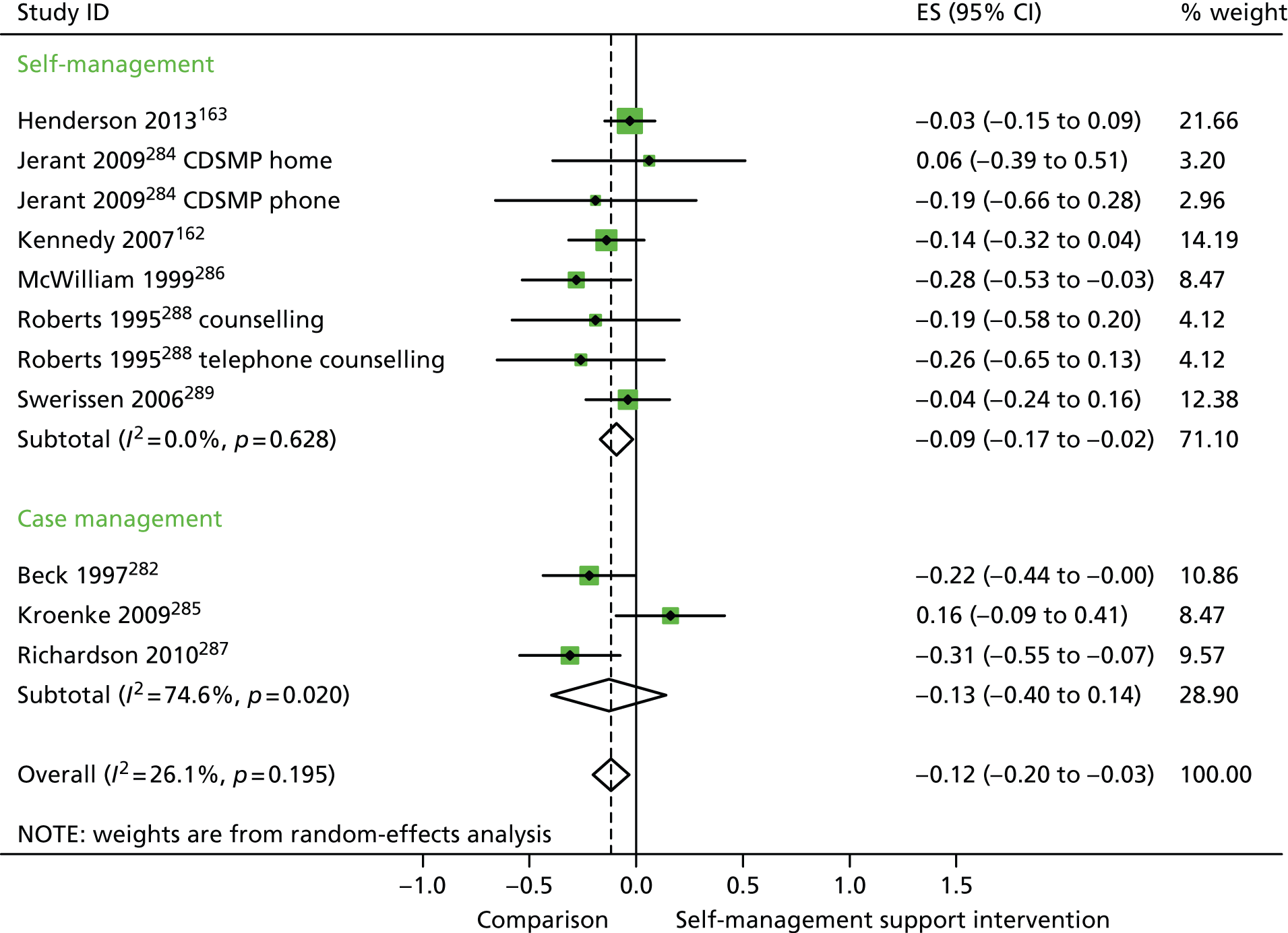

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with mixed problems were associated with small but significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 46).

FIGURE 46.

Forest plot: mixed (hospital use). Counselling, face-to-face counselling with a nurse; CDSMP home, peer-led, face-to-face CDSMP variant; CDSMP telephone, telephone-based CDSMP variant; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; telephone counselling, telephone counselling with a nurse. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

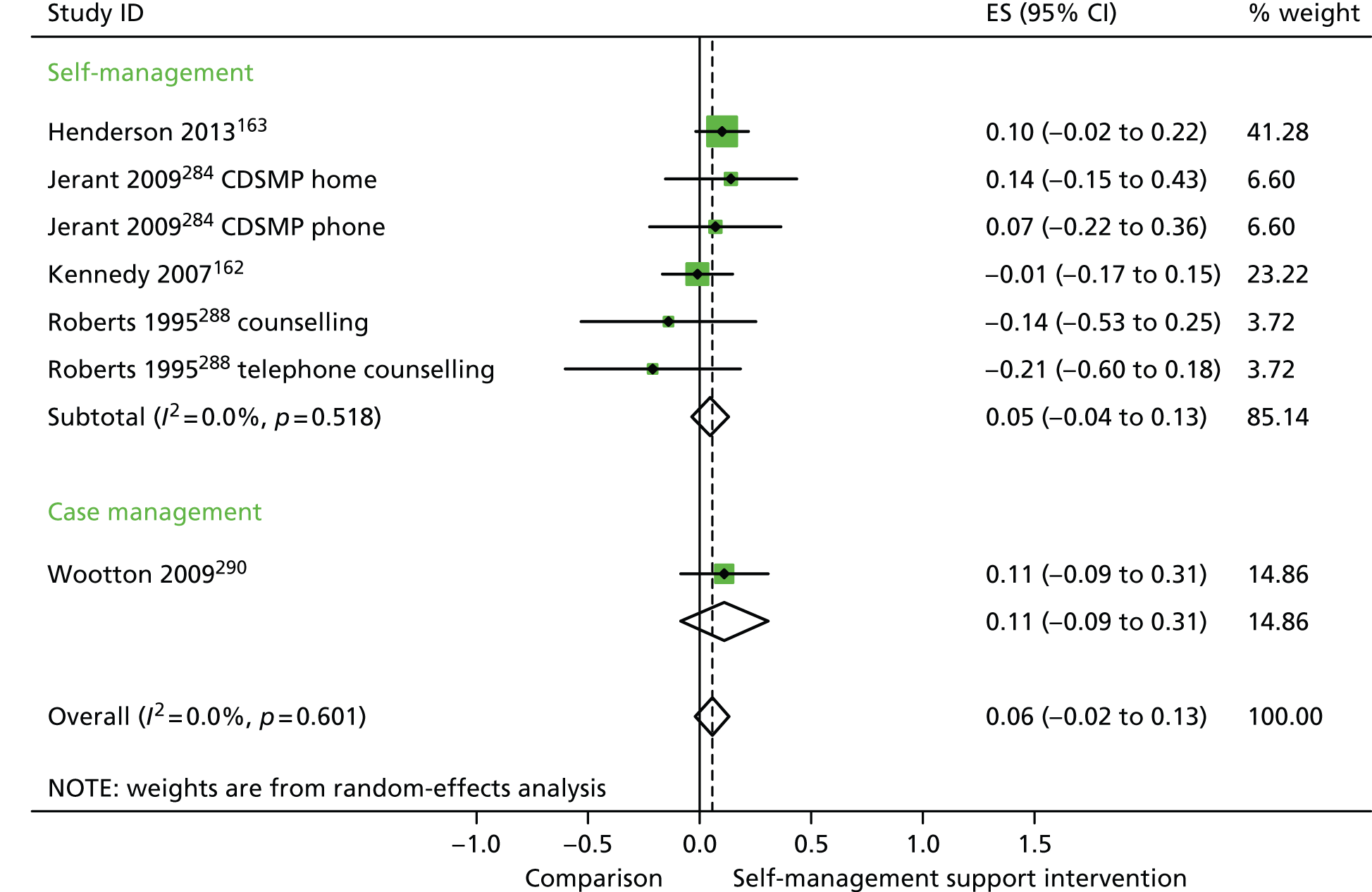

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with mixed problems were associated with non-significant increases in costs. There was no significant variation across trials beyond that expected by chance (Figure 47).

FIGURE 47.

Forest plot: mixed (costs). Counselling, face-to face counselling with a nurse; CDSMP home, peer-led, face-to-face CDSMP variant; CDSMP telephone, telephone-based CDSMP variant; CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; telephone counselling, telephone counselling with a nurse. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, ‘case management’ interventions produced non-significant effects on QoL, hospital use and costs. ‘Self-management’ interventions showed non-significant improvements in QoL, small but significant reductions in hospital use and non-significant increases in costs.

Analyses of studies for patients with long-term conditions in PRISMS cluster 1: long-term conditions with marked variability in symptoms over time (see Table 1)

Figures 48 and 49 show the permutation plots for patients in PRISMS cluster 1: long-term conditions with marked variability in symptoms over time.

FIGURE 48.

Permutation plot: PRISMS cluster 1 (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 49.

Permutation plot: PRISMS cluster 1 (total costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements in QoL with mixed effects on utilisation or costs.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cluster 1 conditions were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 50).

FIGURE 50.

Forest plot: PRISMS cluster 1 (QoL). CBT, group cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention; CCM, case management supported by a consumer; CI, confidence interval; CIn, combined intervention; CR, combined (group and individual) rehabilitation; DI, dietary intervention; EGI, exercise and graded activity intervention; EI, exercise intervention; ES, effect size; GR, group rehabilitation; II, information-only intervention; IIMR, internet self-help intervention with mail reminders; IITR, internet self-help intervention with telephone reminders; IP, inpatient pain management programme; IR, individual rehabilitation; LI, lay-led self-care intervention; OP, outpatient pain management programme; PCM, case management supported by a professional; PI, psychologist-led self-care intervention; TCBT, telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy; TCM, telephone care management; TPCM, telephone psychotherapy and care management; WEI, work-based exercise and graded activity intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cluster 1 conditions were associated with non-significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 51).

FIGURE 51.

Forest plot: PRISMS cluster 1 (hospital use). CCM, case management supported by a consumer; CI, confidence interval; EGI, an exercise and graded activity intervention; ES, effect size; PCM, case management supported by a professional; TCM, telephone care management; TPCM, telephone psychotherapy and care management; WEI, work-based exercise and graded activity intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cluster 1 conditions were associated with non-significant increases in costs. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 52).

FIGURE 52.

Forest plot: PRISMS cluster 1 (costs). CBT, group cognitive–behavioural therapy intervention; CI, confidence interval; CIn, combined (telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy and exercise) intervention; CR, combined (group and individual) rehabilitation; EGI, exercise and graded activity intervention; EI, exercise intervention; ES, effect size; GR, group rehabilitation; IR, individual rehabilitation; LI, lay-led self-care intervention; PI, psychologist-led self-care intervention; TCBT, telephone-delivered cognitive–behavioural therapy; TCM, telephone care management; TPCM, telephone psychotherapy and care management; WEI, work-based exercise and graded activity intervention. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, ‘case management’ interventions produced small but significant improvements in QoL and had no significant effects in hospital use and costs. ‘Self-management’ interventions showed very small but significant improvements in QoL and no significant effects in hospital use or costs.

Analyses of studies for patients with long-term conditions in PRISMS cluster 3: ongoing long-term conditions with exacerbations (see Figure 4)

Figures 53 and 54 show the permutation plots for patients in PRISMS cluster 3: ongoing long-term conditions with exacerbations.

FIGURE 53.

Permutation plot: PRISMS cluster 3 (hospital use and QoL).

FIGURE 54.

Permutation plot: PRISMS cluster 3 (total costs and QoL).

Most studies were in the bottom right quadrant of the plots, reporting improvements in QoL with reductions in utilisation or costs.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cluster 3 conditions were associated with small but significant improvements in QoL. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 55).

FIGURE 55.

Forest plot: PRISMS cluster 3 (QoL). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size; TH, telehealth post-discharge support; VH, video health post-discharge support. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cluster 3 conditions were associated with small but significant reductions in hospital use. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 56).

FIGURE 56.

Forest plot: PRISMS cluster 3 (hospital use). CI, confidence interval; CM, nurse-assisted collaborative management; ES, effect size; MM, nurse-assisted medical management. Note: when studies are reported twice, this refers to different arms within the same study.

In analyses including all studies, self-management support interventions for patients with cluster 3 conditions were associated with small but significant reductions in costs. Variation across trials was moderate (Figure 57).

FIGURE 57.

Forest plot: PRISMS cluster 3 (costs). CI, confidence interval; ES, effect size.

In analyses exploring the impact of different types of self-management support, there was evidence that ‘case management’ interventions produced small but significant improvements in QoL and small but significant reductions in hospital use and costs. ‘Self-management’ interventions showed small but significant improvements in QoL and reductions in hospital use but no significant reductions in costs.

Summary of the results

The core results are summarised in Tables 5–7.

| Condition | Combined QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Self-management QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Case management QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Combined hospital use, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Self-management hospital use, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Case management hospital use, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | 0.27 (0.16 to 0.37, 34, moderate) | 0.28 (0.16 to 0.41, 27, moderate) | 0.19 (0.02 to 0.36, 7, low) | −0.21 (−0.32 to −0.09, 31, moderate) | −0.19 (−0.33 to −0.05, 25, moderate) | −0.26 (−0.42 to −0.10, 6, zero) |

| Cardiac | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.28, 40, moderate) | 0.19 (0.10 to 0.27, 27, moderate) | 0.26 (0.12 to 0.39, 13, moderate) | −0.23 (−0.34 to −0.13, 38, high) | −0.20 (−0.33 to −0.07, 25, high) | −0.29 (−0.47 to −0.11, 13, high) |

| Arthritis | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.26, 11, zero) | 0.17 (0.07 to 0.27, 7, zero) | 0.13 (−0.13 to 0.39, 4, zero) | −0.06 (−0.22 to 0.10, 6, moderate) | −0.02 (−0.19 to 0.16, 5, moderate) | −0.24 (−0.48 to 0.00, 1, N/A) |

| Pain | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.21, 19, low) | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.22, 15, low) | 0.20 (−0.10 to 0.50, 4, zero) | −0.03 (−0.34 to 0.28, 3, low) | No data reported | −0.03 (−0.34 to 0.28, 3, low) |

| Diabetes | 0.44 (0.14 to 0.75, 10, high) | 0.44 (0.14 to 0.75, 10, high) | No data reported | −0.12 (−0.29 to 0.05, 5, moderate) | −0.12 (−0.29 to 0.05 5, moderate) | No data reported |

| Mental health | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.33, 26, high) | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.17, 15, moderate) | 0.38 (0.24 to 0.51, 11, high) | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.04, 21, low) | −0.03 (−0.16 to 0.10, 13, moderate) | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.05, 8, zero) |

| Mixed | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.24, 10, moderate) | 0.11 (−0.03 to 0.24, 7, moderate) | 0.22 (−0.03 to 0.48, 3, moderate) | −0.12 (−0.20 to −0.03, 11, moderate) | −0.09 (−0.17 to −0.02, 8, zero) | −0.13 (−0.40 to 0.14, 3, moderate) |

| Combined QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Self-management QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Case management QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Combined costs, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Self-management costs, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Case management costs, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory | 0.27 (0.16 to 0.37, 34, moderate) | 0.28 (0.16 to 0.41, 27, moderate) | 0.19 (0.02 to 0.36, 7, low) | 0.09 (−0.14 to 0.33, 9, high) | 0.09 (−0.19 to 0.37, 6, high) | 0.09 (−0.46 to 0.64, 3, high) |

| Cardiac | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.28, 40, moderate) | 0.19 (0.11 to 0.27, 27, moderate) | 0.26 (0.12 to 0.39, 13, moderate) | −0.25 (−0.47 to −0.04, 9, moderate) | −0.25 (−0.82 to 0.32, 4, high) | −0.27 (−0.44 to −0.10, 5, moderate) |

| Arthritis | 0.16 (0.07 to 0.26, 11, zero) | 0.17 (0.07 to 0.27, 7, zero) | 0.13 (−0.13 to 0.39, 4, zero) | 0.07 (−0.07 to 0.20, 11, moderate) | 0.14 (0.01 to 0.27, 8, moderate) | −0.28 (−0.53 to −0.03, 3, zero) |

| Pain | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.21, 19, zero) | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.22, 15, low) | 0.20 (−0.11 to 0.51, 4, zero) | 0.07 (−0.13 to 0.28, 13, high) | 0.15 (−0.06 to 0.36, 11, high) | −0.41 (−0.74 to −0.08), 2, zero) |

| Diabetes | 0.44 (0.14 to 0.75, 10, high) | 0.44 (0.14 to 0.75, 10, high) | No data reported | 0.19 (−0.18 to 0.55, 4, moderate) | 0.19 (−0.18 to 0.55, 4, moderate) | No data reported |

| Mental health | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.33, 26, high) | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.17, 15, moderate) | 0.38 (0.24 to 0.51, 11, high) | 0.03 (−0.05 to 0.11, 14, low) | −0.04 (−0.23 to 0.15, 4, moderate) | 0.05 (−0.04 to 0.13, 10, low) |

| Mixed | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.24, 10, moderate) | 0.11 (−0.03 to 0.24, 7, moderate) | 0.22 (−0.03 to 0.48, 3, low) | 0.06 (−0.02 to 0.13, 7, zero) | 0.05 (−0.04 to 0.13, 6, zero) | 0.11 (−0.09 to 0.31, 1, N/A) |

| Disease, outcome, analysis | Combined QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Self-management QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Case management QoL, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Combined utilisation, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Self-management utilisation, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) | Case management utilisation, overall ES (95% CI, n, I2) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Respiratory, hospital use, all | 0.27 (0.16 to 0.37, 34, moderate) | 0.28 (0.16 to 0.41, 27, moderate) | 0.19 (0.02 to 0.36, 7, low) | −0.21 (−0.32 to −0.09, 31, moderate) | −0.19 (−0.33 to −0.05, 25, moderate) | −0.26 (−0.42 to −0.10, 6, zero) |

| Respiratory, hospital use, both | 0.28 (0.14 to 0.43, 22, moderate) | 0.31 (0.14 to 0.48, 17, high) | 0.18 (−0.07 to 0.43, 5, moderate) | −0.26 (−0.41 to −0.11, 22, moderate) | −0.25 (−0.44 to −0.07, 17, moderate) | −0.29 (−0.48 to −0.09, 5, zero) |

| Cardiac, hospital use, all | 0.21 (0.14 to 0.28, 40, moderate) | 0.19 (0.10 to 0.27, 27, moderate) | 0.26 (0.12 to 0.39, 13, moderate) | −0.23 (−0.34 to −0.13, 38, high) | −0.20 (−0.33 to −0.07, 25, high) | −0.29 (−0.47 to −0.11, 13, high) |

| Cardiac, hospital use, both | 0.17 (0.08 to 0.26, 26, moderate) | 0.15 (0.06 to 0.23, 18, low) | 0.21 (0.00 to 0.41, 8, moderate) | −0.23 (−0.38 to −0.08, 26, high) | −0.18 (−0.35 to 0.00, 18, high) | −0.36 (−0.66 to −0.05, 8, high) |

| Pain, costs, all | 0.13 (0.04 to 0.21, 19, zero) | 0.12 (0.02 to 0.22, 15, low) | 0.20 (−0.11 to 0.50, 4, zero) | 0.07 (−0.13 to 0.28, 13, high) | 0.15 (−0.06 to 0.36, 11, high) | −0.41 (−0.74 to −0.08, 2, zero) |

| Pain, costs, both | 0.13 (0.00 to 0.25, 12, moderate) | 0.13 (−0.01 to 0.27, 10, moderate) | 0.12 (−0.21 to 0.45, 2, zero) | 0.10 (−0.12 to 0.31, 12, high) | 0.18 (−0.05 to 0.41, 10, high) | −0.41 (−0.74 to −0.08, 2, high) |

| Mental health, hospital use, all | 0.22 (0.11 to 0.33, 26, high) | 0.05 (−0.07 to 0.17, 15, moderate) | 0.38 (0.24 to 0.51, 11, high) | −0.03 (−0.10 to 0.04, 21, low) | −0.03 (−0.16 to 0.10, 13, moderate) | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.05, 8, zero) |

| Mental health, hospital use, both | 0.18 (0.02 to 0.33, 18, high) | −0.04 (−0.20 to 0.12, 10, moderate) | 0.38 (0.18 to 0.57, 8, high) | −0.01 (−0.08, 0.06, 18, zero) | 0.03 (−0.10 to 0.15, 10, low) | −0.04 (−0.13 to 0.05, 8, zero) |

Table 5 shows the impact of self-management support on hospital use and QoL. Results are highlighted in the table that show an effect size of 0.2 (at least a ‘small’ effect by current convention), for which the effect is statistically significant. As can be seen from Table 5, such impacts are found in a number of cells in relation to QoL, but are restricted to interventions in respiratory and cardiovascular populations in relation to hospital use.

Table 6 is structured in the same way, but details the impact of self-management support on costs and QoL. Significant reductions in costs are found only in relation to cardiovascular problems overall, and in case management interventions in cardiovascular, pain and arthritis problems.

It should be noted that some of the differences between Tables 5 and 6 reflect changes in the number of studies included in the analysis and associated precision of the estimates.

Table 7 represents a sensitivity analyses, testing whether or not the broad results in Tables 5 and 6 endure when analyses are restricted to studies which report both QoL and utilisation/cost data. The results were very similar, suggesting that the main analyses were robust.

Study outcomes and risk of bias

Table 8 shows the effects of self-management support on the three core outcomes, grouped according to our risk of bias measure (based on reported allocation concealment). Studies judged at high risk of bias reported better effects on QoL and greater reductions in hospitalisation and costs than those judged at low risk of bias, although they were also associated with increases in total costs.

| Outcome | Overall effect size (I2, 95% CI) | Effect size (high risk of bias) (I2, 95% CI) | Effect size (low risk of bias) (I2, 95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | 0.22 (0.17 to 0.26) | 0.23 (0.18 to 0.29) | 0.18 (0.12 to 0.25) |

| Hospital use | −0.16 (−0.20 to −0.11) | −0.18 (−0.24 to −0.11) | −0.10 (−0.16 to −0.04) |

| Costs | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.08) | 0.07 (−0.05 to 0.18) | −0.01 (−0.09 to −0.07) |

Small-study bias

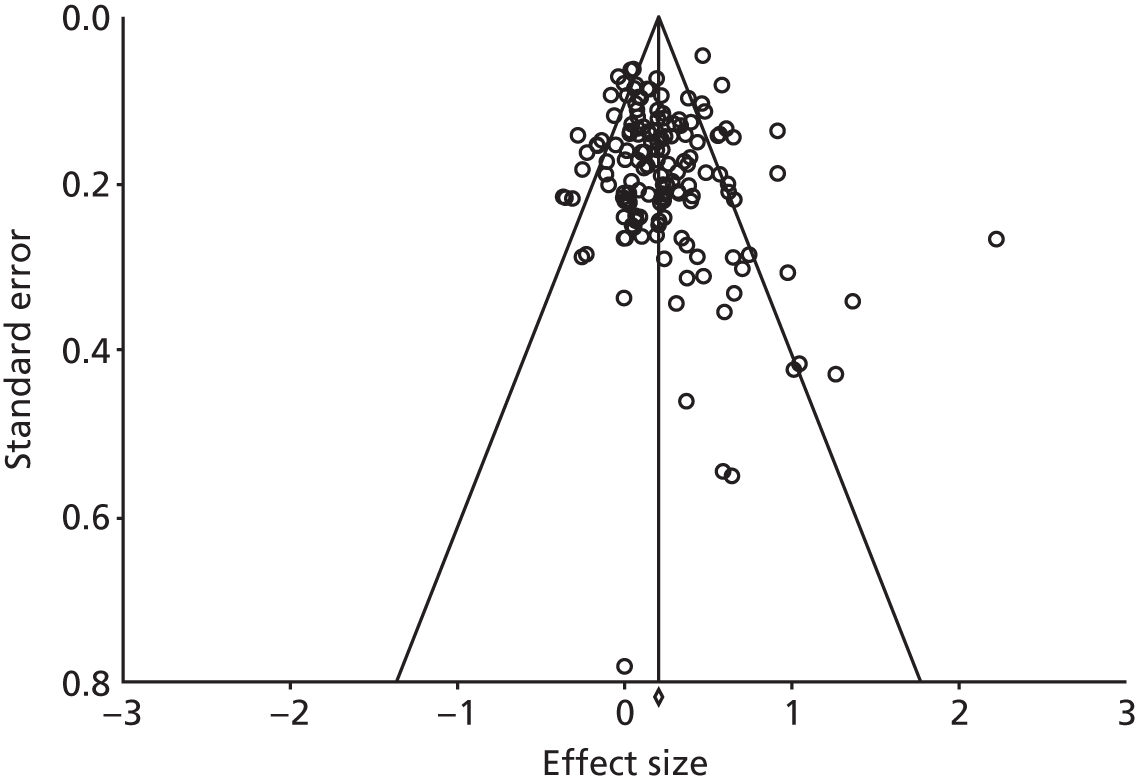

The funnel plot for the studies reporting QoL outcomes is presented in Figure 58. The plot was symmetrical and the regression statistics did not show evidence of small-study bias [intercept 0.47, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.16 to 1.10; p = 0.14].

FIGURE 58.

Funnel plot: QoL.

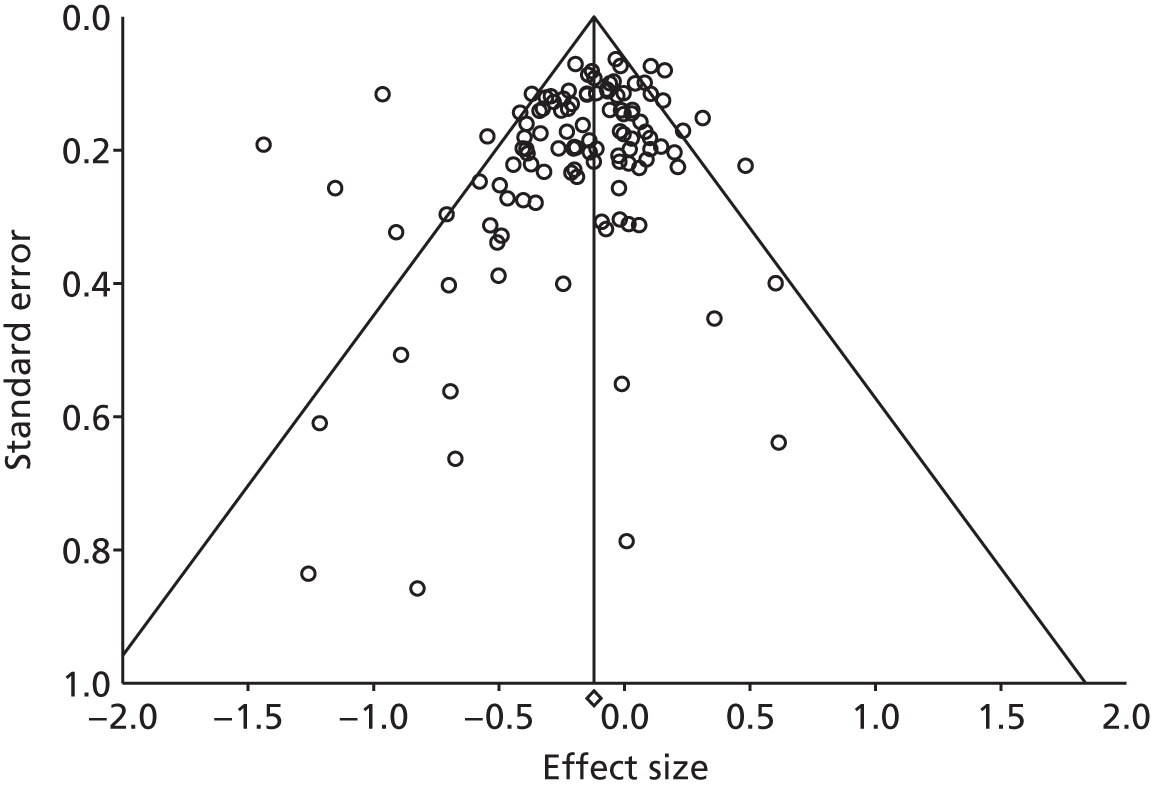

The funnel plot for the studies reporting hospital use outcomes is presented in Figure 59. The plot was not symmetrical and the regression statistics showed evidence of small-study bias (intercept –0.91, 95% CI –1.55 to –0.27; p = 0.01).

FIGURE 59.

Funnel plot: hospital use.

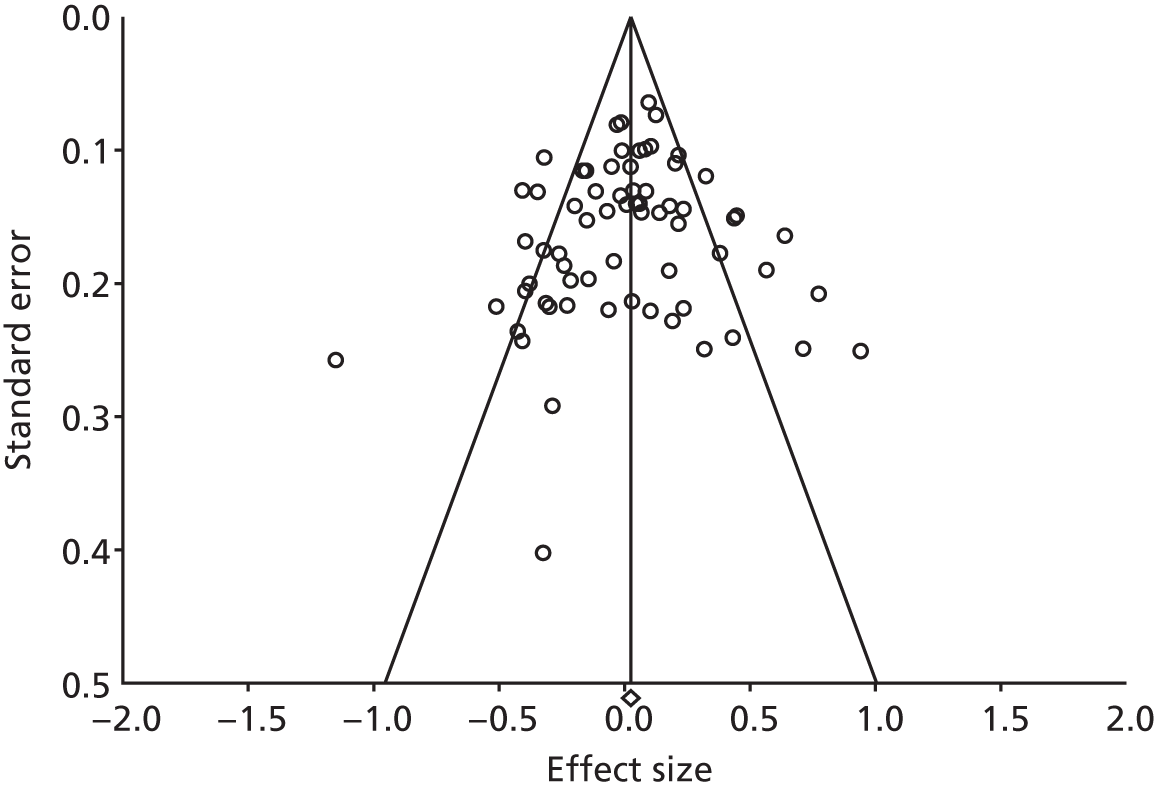

The funnel plot for the studies reporting costs is presented in Figure 60. The plot was symmetrical and the regression statistics did not show evidence of small-study bias (intercept –0.46, 95% CI –1.71 to 0.79; p = 0.47).

FIGURE 60.

Funnel plot: total costs.

External validity and reach

The degree to which the results of a trial conducted in a particular setting can be generalised to a different setting (that is the external validity) is always an issue in the interpretation of findings of systematic reviews. The impact of variation in context may be greater when considering complex service-related interventions that are designed to impact on individual behaviour, or when the focus is on utilisation outcomes that may themselves reflect important differences in the context in which the study is run.

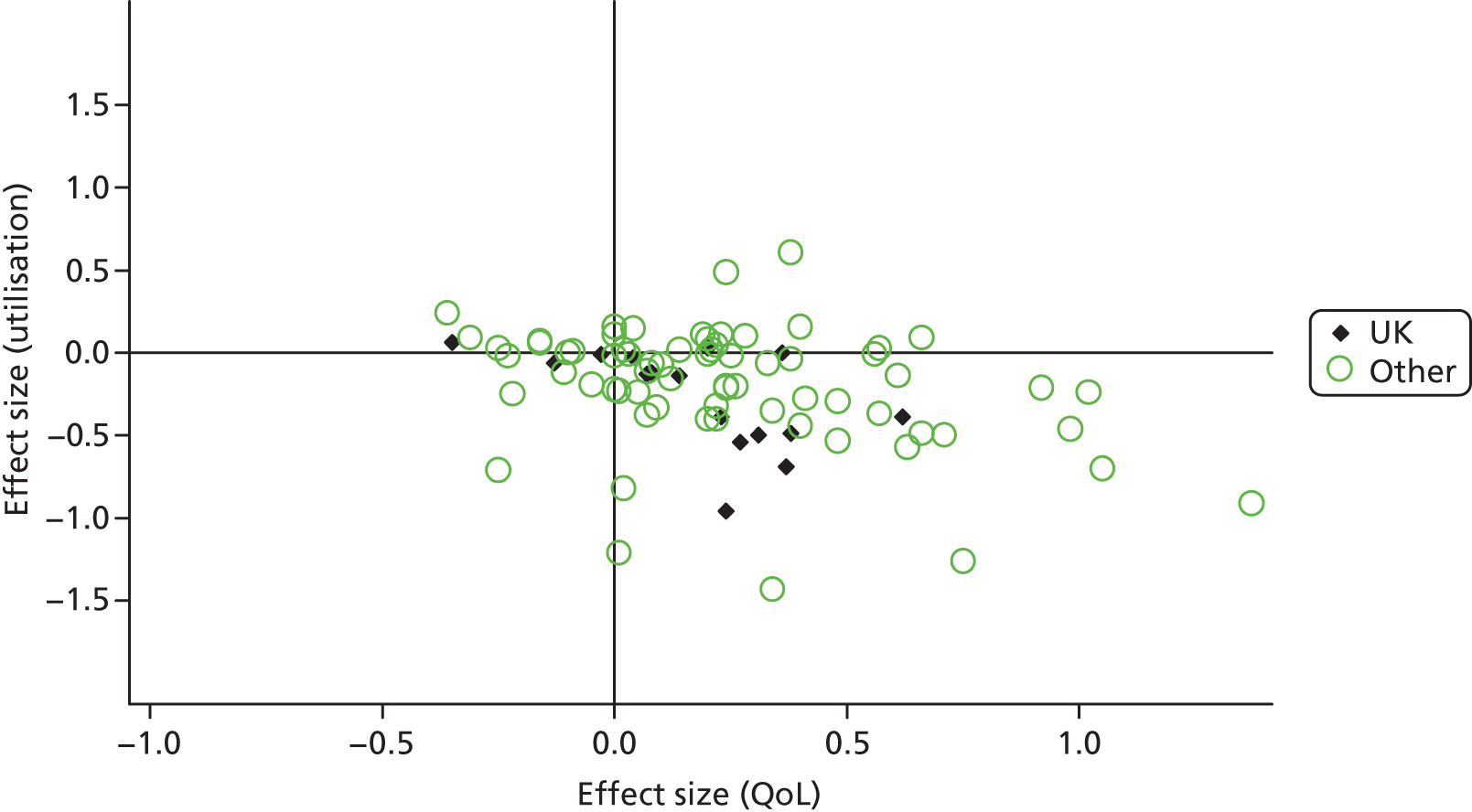

To explore this issue, we calculated a permutation plot for the hospitalisation data, identifying UK studies in the plot to assess whether the pattern of results was different. The plot is shown in Figure 61.

FIGURE 61.

Permutation plot: hospitalisation (UK vs. other studies).

The comparison is somewhat crude, as there may be similarities in the systems of care between the UK and other countries (e.g. the Dutch health-care system is similar in having a strong primary care focus). Nevertheless, there was no strong evidence from the plot that the pattern of findings about the relationship between QoL outcomes and utilisation was markedly different in UK studies from the wider international literature.

We also calculated the overall effect sizes for QoL, hospitalisation and total costs by country, to assess whether or not the effect of self-management interventions on these individual outcomes varied markedly in UK and non-UK settings. The results are shown in Table 9.

| Outcome | Overall effect size (95% CI) | Effect size, UK studies (95% CI) | Effect size, non-UK studies (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | 0.22 (0.17 to 0.26) | 0.10 (0.05 to 0.14) | 0.25 (0.19 to 0.30) |

| Hospital use | −0.16 (−0.20 to −0.11) | −0.23 (−0.35 to −0.11) | −0.14 (−0.19 to −0.09) |

| Costs | 0.02 (−0.05 to 0.08) | 0.13 (0.02 to 0.24) | −0.04 (−0.12 to 0.04) |