Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 09/1001/52. The contractual start date was in February 2011. The final report began editorial review in January 2013 and was accepted for publication in July 2014. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2015. This work was produced by Peckham et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

Chapter 1 Introduction

Since the 1970s there has been a growing policy and practice interest in the public health role of primary care. The 1978 World Health Organization Alma Ata declaration1 set the context for exploring the relationship between primary care and its role in prevention and population health. In the UK, the government highlighted the importance of health promotion in general practice in its 1987 White Paper Promoting Better Health2 and the introduction of health promotion payments in the 1990 general practitioner (GP) contract. This introduced, for the first time, specific payments for health promotion activities and provided the first key national policy interest in the public health role of general practice. Despite this, very little formal attention was paid to the public health role of general practice in the UK until the turn of the century. The introduction of the new General Medical Services (GMS) contract and the Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) in 2004, and recommendations in the Wanless Review3 on public health, provided a new impetus and focus on the role of general primary care and, more specifically, general practice.

Alongside an interest in how services were to be delivered, there was also an increasing focus on the effectiveness of interventions delivered in public health. However, much of the research on effectiveness has produced equivocal outcomes and, on the whole, has not addressed the contextual issues that might affect the final outcome of such interventions. Understanding how public health services are delivered and organised has been highlighted as an important area for public health research. 4 Concern about the public health role of primary care has been identified as an area of concern in the UK since the mid-1990s, with professional bodies exploring the extent to which the professional practice of GPs and nurses should include prevention. 5–7 A number of commentators have also specifically addressed the extent to which prevention and health improvement should be an integral part of general practice. 8–15

In order to explore the role of general practice and primary care in health improvement activities, this project was developed with an explicit focus on the delivery and organisation of such activities. The project was designed to examine who delivers these interventions, where they are located, what approaches are developed in practices, how individual practices organise such public health activities within general practice and how these contribute to health improvement. Our focus was on health promotion and prevention activities. However, these are contested concepts and their meanings are often confused and unclear,16 and they are frequently used as a synonyms for ‘public health’, which also lacks clarity and certainty as a descriptor of activity. 4,17 It is important, in carrying out a review of health-promoting and health improvement activities, to be as clear as possible about what is understood by such terms.

The need for this scoping study has been identified based on previous and existing research being undertaken by the research team members and discussions with practitioners in primary care. The need to develop public health in primary care was highlighted by Derek Wanless3 in his report on public health. Current research on the QOF has also shown that there are important changes in the activities and roles of practice-based staff in relation to health-promoting activities. The recent King’s Fund review of GP quality highlighted the need to examine the wider role of the primary health-care team in general practice and their contribution to health improvement. 18 In a recent review of health promotion opportunities for general practice, Watson15 noted that ‘there has been a dearth of information about the effectiveness of health promotion in the primary care setting’ (p. 180). In advocating a health-promoting general practice model, he concludes that there is a need for further research to demonstrate ‘health benefits for local communities . . . and also a need to identify potential practical and organisational difficulties’. Finally, Health England has identified that ‘there are significant gaps in the evidence base for primary prevention interventions in primary medical care’. 19

The aim of this scoping exercise was to identify the current extent of knowledge about the health improvement activities in general practice and the wider primary health-care team. The key objectives were to provide an overview of the range and type of health improvement activities, and to identify gaps in knowledge and areas for further empirical research.

Our specific research objectives were:

-

to map the range and type of health improvement activity undertaken in general practice and primary care

-

to scope the literature on health improvement in general practice and identify gaps in the evidence base

-

to synthesise the literature and identify effective approaches to the delivery and organisation of health improvement interventions in a general practice setting

-

to identify the priority areas for research as defined by those working in general practice.

The focus of this scoping review and evidence synthesis was to identify where further research on the provision of public health in general practice is needed. To this extent the review seeks to identify areas of practice where there is evidence to support health improvement, and areas of practice that lack research evidence or where the current evidence base is incomplete. Our aim was not to provide a systematic review of the evidence base or provide a comprehensive and detailed account of all areas of public health practice in primary care.

The purpose of this research was, therefore, to identify areas where there is good evidence of effective approaches to the delivery of interventions in general practice and areas where there is an insufficient evidence base to support practice and where further research will support the development of practice. In particular, we focused on identifying:

-

the range and type of activities that are best suited to the general practice context

-

the roles and responsibilities of practice-based staff in relation to what they should be doing

-

community-focused (rather than individual-focused) health improvement activities

-

the efficacy of incentivised and non-incentivised health improvement activities and how these affect health improvement activity in the practice

-

other interventions that primary care staff can undertake that contribute to health improvement that are currently not universally undertaken.

So that the review findings provide a substantive evidence base for the implementation of effective health improvement programmes, we adopted two approaches to the review. The first focused on assessing the quality and strength of the research evidence while the second examined the extent and nature of the literature to identify where additional research is required. Given that our focus was on service delivery and organisation, we have drawn on a broader assessment of study quality than is used in systematic reviews and also incorporated papers where there was some description of services. While more weight has been given to studies and papers with some evaluative component, we also felt it important to include more descriptive studies to provide an overview of the delivery and organisation of health improvement activities in general practice. However, it became clear from very early on in the study that providing a comprehensive overview and identifying approaches supported by evidence of effectiveness would be complex. An initial review of Cochrane studies relevant to this review suggested that we would not find significant numbers of studies that included assessments of the way that interventions were delivered and organised. In addition, the range and nature of the studies was enormous as was the breadth of topics.

Rather than make a systematic assessment of the evidence, we have attempted to draw together an assessment of quality, relevance, theory, integrity of interventions, context and sustainability of interventions and outcomes. While randomised controlled trials (RCTs) are considered a gold standard of quality of evidence, we have also examined, and included where relevant, non-RCTs, such as controlled before-and-after studies, interrupted time series and comparisons with historical controls or national trends. These may not always represent the best available evidence. Relevant qualitative research has also been included in order to help identify the factors that enable or impede the implementation of an intervention, describe the experience of the participants receiving it and their subjective evaluations of outcomes, and understand the diversity of effects across studies, settings and groups. 20

It was recognised from the beginning that the task of assembling information and evidence on the delivery and organisation of health improvement activities in general practice would create a number of challenges in terms of developing the search strategy and identifying papers that provided details of service and delivery of health improvement activities. Substantial investment was made in trying to refine a search that would provide a wide range of information that when synthesised would contribute to improving knowledge and understanding of current practice. This involved refining our research protocol and approach. We narrowed our searches to review UK papers only. This was partly driven by the volume of studies identified in our literature searches but was also to ensure relevance, taking into account the different context of UK general practice from the delivery and organisation of primary care in other countries. Following early discussions with practitioners in practices and public health agencies, we also changed our approach to consultations with practitioners. Originally we planned to hold stakeholder events but, because of the unprecedented upheavals in the NHS during the period of the research, arranging meetings was extremely difficult. In addition, the substantial task of dealing with the extensive literature meant that we had to allocate more staff resources to this element of the study, further limiting our ability to undertake an extensive practitioner scoping study as outlined in our original application. It was, therefore, agreed with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Service Delivery and Organisation (SDO) programme that we would instead draw on discussions with individual practitioners in practices and public health agencies and in group discussions with GPs when these could be arranged.

Structure of this report

The main elements of the report provide details of the literature review. The review was developed from a reading of all selected papers, but not all these are referred to in the report because of the substantial amount of material. Chapter 3 provides details of how we approached the literature and dealt with the complexities of conducting the review. Chapters 4–6 provide details of the literature. Chapter 4 describes the main aspects of the literature including the quality, topic areas and extent of the literature found. The chapter also includes a brief outline of some of the key themes emerging from discussions with practitioners. Chapter 5 provides details of the range of activities identified in the literature. Chapter 6 provides details of the evidence about effective ways to organise and deliver health improvement interventions in general practice or by the primary health care team. Given the changes currently being introduced in the English NHS, in Chapter 7 we examine how these changes impact on the public health role of general practice. The aim of this chapter is to set the findings of the scoping review within the context of the recent changes to the organisation of public health and health-care services in England resulting from the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 21 Finally, in Chapter 8 we identify some of the key messages arising from the review and set out the implications for practice and further research.

Chapter 2 Background

Since the 1970s there has been a growing interest in the role of primary care, and general practice in particular, in public health activities. The main focus of attention has been the important health promotion role of general practice. General practice has traditionally been the first point of contact with the NHS and there are 300 million patient consultations in England every year. 22 The role of general practice is to act as the gatekeeper to the NHS, managing the health care for the practice population and referring relevant cases to secondary care services. This places general practice in a unique position not just to provide medical care but also to promote the health and well-being of the practice population.

This chapter provides a brief overview of the key themes and discusses a number of concepts relating to the public health role of general practice health improvement activities associated with the practice and primary health-care team. It is not intended to be a detailed review of the issues, as there have been a number of previous studies that have explored the relationship between general practice and public health18 and the broader relationship between public health and primary care. 23,24 The aim of this review is to examine how health improvement activities are organised and delivered within general practice, and this chapter provides a discussion of those issues which focused the proposal on this aspect of general practice activity.

Organisationally, the history of UK public health is complex, involving a number of changes in the responsibility, structure and roles of different professionals engaged in public health practice. 25–27 Over the past 20 years there has been a shift towards highlighting the role of primary care in public health alongside a renewed focus on partnerships, and the development of a multidisciplinary workforce and the introduction of public health targets such as those for reducing health inequalities, improving detection rates for cancer and smoking cessation. However, despite a policy focus on reducing health inequalities, the infant mortality gap has widened and, while life expectancy is increasing overall, it is increasing more slowly in socially and economically deprived areas. 28 The Wanless Report3 on improving the public health function in England argued that public health activities at a local level needed to be prioritised and adequately resourced in order to develop long-term sustainable action to improve population health and that there is a need to evaluate existing activities against a common framework (including their cost-effectiveness). The report identified the need to develop incentives, shared local targets and performance management in primary care trusts (PCTs) to enable them both to prioritise public health issues and to work in partnership with local authorities (LAs) on public health. In response, policy-makers began to focus on specific public health measures, such as doubling the capacity of smoking cessation interventions, targeting prevention of cardiovascular disease (CVD) by increasing coverage of antihypertensives and statins, and improving the detection of cancer. These more clinical interventions are delivered at a primary care level, making the role of GPs and practice nurses in particular crucial to the delivery of public health improvements and reductions in health inequalities. This expansion of activities has been supported in a number of ways through contractual mechanisms and by wider debate about public health roles of practice staff.

The public health role of primary care was also highlighted by the Marmot Review29 on health inequalities. There is good evidence to suggest that people from lower socioeconomic groups have their cancer diagnosed at a later stage and are less likely to participate in cardiovascular screening affecting treatment options and outcomes – areas where the general practice role is critical. 30,31 In examining how to reduce inequalities, the Marmot Review29 focused attention on the role of general practice and reiterated the important leadership function of GPs and the NHS in tackling health inequalities. 32 The task-group report on priority conditions highlighted a number of key areas relevant to general practice including CVD, obesity, alcohol and drug misuse, mental health, and the health and well-being of older people. 33 In addition, the delivery systems and mechanisms task group32 highlighted the key role of primary care and the use of incentive systems such as the QOF. The Marmot Review29 paid specific attention to the impact of the QOF and its role as a mechanism for contributing towards reductions in health inequalities. It was recognised, however, that the QOF had limitations, and Exworthy et al. in the Task Group 7 report cautioned that the QOF is mainly concerned with secondary prevention for existing chronic disease (Exworthy M, Marmot Review. Task Group 7: Delivery systems and mechanisms Topic 3: Structural reorganisations and their impact on the ability of the health system to focus on population health. Unpublished; 2009). There are therefore few indicators which relate to primary prevention (10 of the 146 indicators). There is therefore a risk that primary preventative activities will be overlooked. It is significant that Marmot29 therefore made a specific recommendation about extending the use of the QOF to include more primary prevention activities, while recognising that the QOF should not be viewed as the only vehicle for promoting primary prevention within general practice.

Introduced at the same time as the QOF, the Local Enhanced Service (LES) element of the 2004 GMS contract has made a significant contribution to supporting public health in general practice. LESs have been particularly effective in involving GPs in locally driven public health efforts supporting a wide range of evidence-based public health activities, such as identifying CVD risk and providing long-acting contraceptives, and in 2009/10 they accounted for some £370M. 34 Having the option of LESs in the contract has provided a way for GPs to reduce preventable morbidity, and it could continue to do so in the future. This option would be especially helpful in the context of a more diverse provider landscape.

With the election of the new government in 2010, there have been a number of key developments that have an impact on the public health role of general practice. The 2010–15 coalition government’s programme published in May 2010 made explicit reference to proposals to restructure the NHS and specifically to incentivise GPs to tackle public health problems. 35 These proposals were further developed with the publication of two White Papers, Equity and Excellence: Liberating the NHS36 and Healthy Lives, Healthy People: Our Strategy for Public Health in England,37 which signalled substantial organisational changes in the NHS and a shift in public health policy. With the Health and Social Care Act 2012,21 PCTs and strategic health authorities have been abolished. Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and the new NHS Commissioning Board (NHS England) took on responsibility for health-care commissioning from April 2013. Of particular significance are the role of NHS England as the contractor for general practice and the transfer of public health responsibilities to LAs. Many of the activities previously funded through LES, including sexual health, smoking cessation, prevention and treatment of alcohol misuse, falls prevention and mental health promotion, are now commissioned through the public health budget of LAs, while the GP contract is currently the responsibility of NHS England. These shifts are likely to affect the role of general practice in public health and are discussed later in this report (see Chapter 7).

Other developments include an expanded role for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) with an increasing emphasis on the development of public health guidance and its new responsibility for developing QOF indicators. To date, NICE has published 39 potentially relevant guidance documents covering topics such as accidents and injuries, alcohol, behaviour change, CVD, child health, diabetes, maternal health, obesity and diet, physical activity, sexual health, smoking and tobacco, vaccine-preventable diseases, and working with and involving communities (see list at www.nice.org.uk/guidance/published?type=ph). However, reference to general practice and the wider primary health-care team is limited in this guidance. For example, NICE Public Health Guidance number 21, Reducing Differences in the Uptake of Immunisations38 identifies the practice and its staff as key practitioners as well as other key primary care settings within the community and also, for young people, the important role of schools, nurseries and social care settings involving health-care, social care and education staff. This guidance draws on international evidence, which may limit applicability to a UK general practice context.

Of particular relevance to this review is the fact that such evidence rarely takes into account the different international or local contexts of evidence. For example, a systematic review of RCTs on lifestyle interventions in primary care39 included seven studies: three from the UK as a whole, one from England, one Finnish, one Australian and one from New Zealand. No account is taken of different payment, organisational or system contexts. The only key delivery variable referred to is whether it was undertaken by a nurse or a physician, although these are stated without any further detail. Similarly, a systematic review of brief alcohol interventions40 included 24 studies across north America, Europe, Africa and Australia; and a systematic review of interventions in routine clinical practice on nutrition and physical activity for reduction of diabetes risk41 included 12 studies, with three from the UK, one Japanese, one Italian, two Swedish, three from the USA, one Finnish and one Australian. Routine clinical practice locations varied and, while they were predominantly delivered by physicians, this was not always clear. The aim of this review is to examine the delivery and organisation of health improvement activities in UK general practice or by the primary health-care team from the practice. The context of the practice or location and the way the activity is organised, who delivers it, etc. are critical to providing an overview of such activity. One key problem in examining the public health role of primary care is the lack of single, stable and bounded definitions of both health improvement and primary care.

Defining public health and primary care

There is some ambiguity about whether the term ‘public health’ is primarily about NHS activity or something wider. This ambiguity reflects a longstanding debate about the nature of public health itself. The most widely used definition of public health is that provided in 1988 by Acheson,42 who defined public health as ‘the science and art of preventing disease, prolonging life, and promoting health through the organised efforts of society’ (p. 1). The UK Faculty of Public Health endorses this definition; it suggests that public health is population based; it suggests that there is a collective responsibility for health, protection and disease prevention; it accepts the key role of the state; and it suggests that tackling public health problems involves a concern for the underlying socioeconomic and wider determinants of health as well as disease, and involves partnerships between all those who contribute to the health of the population. The faculty identifies three key domains of public health practice:

-

health improvement

-

inequalities

-

education

-

housing

-

employment

-

family/community

-

lifestyles

-

surveillance and monitoring of specific diseases and risk factors

-

-

improving services

-

clinical effectiveness

-

efficiency

-

service planning

-

audit and evaluation

-

clinical governance

-

equity

-

-

health protection

-

infectious diseases

-

chemicals and poisons

-

radiation

-

emergency response

-

environmental health hazard.

-

In the 2010 Public Health White Paper,37 the government set out five domains of public health which were to be covered by a public health outcomes framework:

-

domain 1 – health protection and resilience: protecting people from major health emergencies and serious harm to health

-

domain 2 – tackling the wider determinants of ill health: addressing factors that affect health and well-being

-

domain 3 – health improvement: positively promoting the adoption of ‘healthy’ lifestyles

-

domain 4 – prevention of ill health: reducing the number of people living with preventable ill health

-

domain 5 – healthy life expectancy and preventable mortality: preventing people from dying prematurely.

The scope of this review falls mainly in the area of health improvement and domains 3 and 4 outlined in Healthy Lives, Healthy People. 37 However, identifying clear-cut public health activities or responsibilities is complex, and many activities overlap the domains defined by the Faculty of Public Health and those in the public health outcomes framework. For this review, the definition of health improvement draws on that used by the World Health Organization, first outlined by Leavell and Clark in 1958. 43

Primary prevention: activities designed to reduce the incidence of an illness in a population and thus to reduce, as far as possible, the risk of new cases appearing and to reduce their duration. Primary prevention can be defined as the action taken prior to the onset of disease, which removes the possibility that the disease will ever occur. It signifies intervention in the pre-pathogenic phase of a disease or health problem. It includes the concept of ‘positive health’, a concept that encourages achievement and maintenance of an acceptable level of health that will enable every individual to lead a socially and economically productive life. Primary prevention may be accomplished by measures designed to promote general health and well-being, and quality of life of people, or by specific protective measures.

While not all of these areas of activity relate to primary care or even specifically general practice, key activities such as lifestyle advice, nutrition and health are as much part of practice as immunisation, safe use of drugs, etc.

Secondary prevention: activities aimed at detecting and treating pre-symptomatic disease. It is defined as an action which halts the progress of a disease at its incipient stage and prevents complications. Secondary prevention attempts to arrest the disease process, restore health by seeking out unrecognised disease and treating it before irreversible pathological changes take place, and reverse communicability of infectious diseases.

There is an obvious and clear link between the role of general practice and primary medical care, and secondary protection. The individual focus of general practice, especially in the UK, places the primary care practitioner in a key position to identify areas for secondary prevention and, where relevant, undertake action.

Tertiary prevention: activities aimed at reducing the incidence of chronic incapacity or recurrences in a population, and thus to reduce the functional consequences of an illness; including therapy, various rehabilitation techniques and interventions designed to assist the patient to return to educational, family, professional, social and cultural life. This level involves the treatment and monitoring of people with disease, and general practice plays a key role in this in the UK. For the purposes of this review we have categorised this as treatment and outside our review.

However, strict demarcation between levels is not always possible, as some activities cut across these levels. For example, protecting others in the community from acquiring an infection can involve providing secondary or even tertiary prevention for the infected and primary prevention for their potential contacts. Some activities do not differentiate between levels so promoting smoking cessation is directed at those without any health problems as well as those already identified as having a specific disease. Froon and Benbassat44 have argued that, given the inconsistencies in the way the different definitions of levels of prevention are used in practice, this approach should be abandoned. They argued that interventions should be defined by their objective, target population and type of intervention.

This refocusing of health promotion frameworks has already been promoted in government public health policy. In Choosing Health: Making Healthy Choices Easier,45 the government set out proposals for more integrated approaches to prevention and health promotion for children through Children’s Trusts and Children and Family Centres, and using schools as settings for health promotion working with children and their families. Primary care was also seen as an integral part of a community-based approach to health promotion. It is not clear, however, how far the shift has permeated current policy thinking in relation to primary care and public health activities of general practice. Current policy appears to have demarcated general practice with a stronger emphasis on the GP role and using consultation opportunities to address individual lifestyle issues. The 2010–15 coalition agreement The Coalition: Our Programme for Government35 announced that the Department of Health (DH) would strengthen the role and incentives for GPs and GP practices on preventative services, both as primary care professionals and as commissioners. As primary care professionals, GPs and GP practices play a critical role in both primary and secondary care prevention. They have huge opportunities to provide advice, brief interventions and referral to targeted services through the millions of contacts they have with patients each year. It is clear that current government policy continues to emphasise the important role of general practice and primary care that cut across the different levels of intervention and domains of practice.

Similarly, there is a longstanding debate about the nature of primary care. 46–49 In the UK, ‘primary care’ generally refers to services provided by general practice, dental practice, pharmacists and opticians. There is little discussion about the range of services that this encompasses. In 1994 the US Institute of Medicine defined primary care as the provision of ’integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community’ (p. 15). 50 Starfield47 has discussed the parameters of primary care, focusing on the role of primary care in dealing with the whole person in a holistic way over the long term and providing co-ordination of care for individuals. Starfield47 identified four unique features of a primary care service: first contact access, person-focused care over time, comprehensiveness and co-ordination. Hogg et al. 51 suggest that other important aspects of primary care include patient–provider relationships as defined by communication, holistic care and an awareness of the patient’s family and culture. They also argue that primary care performance needs to be set within a broader structural environment that recognises the wider health-care system, the practice context and the organisation of the practice. This reflects an increasing acceptance of the role of the health-care delivery system, including issues of governance and accountability, resources, inter-relationships between primary care and other health and social care services, and person-centred care. 52,53 Kringos et al. 53 undertook a systematic review to identify the core dimensions of primary care, identifying 10 core dimensions. The review identified preventative and health promotion activities as elements of primary care and, in particular, how such activities are underpinned by dimensions such as co-ordination of care and equity. However, they concluded that a primary care system can be defined and approached as a multidimensional system contributing to overall health system performance and health. The broad nature of primary care and the difficulty of providing a clear definition were highlighted by Peckham and Exworthy. 48 In the UK, primary care is variously equated with general practice, the primary health-care team and a broader view of a wide variety of community-based services. For the purposes of this review we identified our focus as those health improvement activities that are undertaken in general practice or by staff located in practices but which are delivered outside the practice. This definition was not without its problems, and relating definitions to search terms was complex (see Chapter 3). There are, however, specific aspects of policy and practice that directly relate to the organisation and delivery of health improvement within general practice and primary care settings and are directly relevant to this review, including contractual issues in general practice, pay for performance, its organisation and staffing, and relationship to professional public health practice.

The general practitioner contract

Historically, GPs’ status as independent contractors to the NHS has meant general practice has been relatively free of direct management and monitoring compared with other parts of the NHS and has predominantly provided a demand-led sickness service. Thus, any focus on public health has tended to be more focused on a secondary level of prevention, although GPs have always provided general lifestyle advice, vaccination, etc., as a normal part of good practice. 48,54 GPs’ income was based on allowances, capitation and fees for a limited set of services, and the nature and quality of care was undefined and left to professional discretion. 54 There is a range of general incentives for GPs and the wider primary health-care team to engage in public health activities. Capitation payment systems (such as that for UK GPs) provide a general incentive for health promotion and managing long-term care problems to minimise inappropriate use of primary care services – particularly when compared with fee-for-service payment systems. 55,56 However, practice in the UK falls short of this aspiration. 57,58 In addition, wider influences such as national policy frameworks, guidelines, professional competencies, and practice guidelines and educational programmes seem to influence physician practice and encourage more preventative health interventions and practice, but the evidence is limited. 59

Before the introduction of the latest GMS contract in 2004, practices were given financial incentives to provide health promotion. For example, cervical cancer screening is undertaken predominantly within general practice by GPs and practice nurses. Target payments (for achieving 50% and 80% coverage rates) were introduced in 1990 as part of the revised GP contract and, while provision of this financial incentive increased coverage from 53% to 83% of GPs achieving the 80% target, these improvements bore no relation to local need. 60,61 However, for GPs and practices which found it difficult to achieve even 50% coverage, there was no real incentive to try and maximise the uptake of screening. 60

The new GMS contract of 2004 continued the trend of increasing regulation of clinical practice to improve quality of clinical care, with a pay-for-performance system rewarding practices for the quality of their services. 62 The main principles of the new contract were:

-

a shift from individual-GP to practice-based contracts

-

contracts based on workload management, with core and enhanced service levels

-

a reward structure based on the new QOF and annual assessments

-

an expansion of primary care services

-

modernisation of practice infrastructure (especially information technology systems).

The contract is not universal, as there are alternative contract types alongside the GMS contract, including Personal Medical Services, which cover about 30% of practices and were developed in the 1990s; Alternative Provider Medical Services aimed at contracting private sector companies to run GP practices; and Specialist Provider Medical Services contracts for specific GP services such as those for homeless people. The core contract includes general patient care, with prevention seen as an integral part of the provision of such care. Over the years, specific aspects of prevention have been identified beyond clinical care, such as health checks for new patients. LESs also provided a way for PCTs to contract for specific areas of health promotion such as drug and alcohol services, extending stop-smoking services, breastfeeding initiatives and dealing with other locally identified public health problems. By 2009, LES expenditure represented a significant investment in locally defined services. 63

The QOF has also been used to target some preventative activities, although to date their extent has been limited. There were recommendations in the Marmot Review29 for greater use to be made of the QOF for reducing health inequalities. Currently, despite the inclusion of key clinical areas and an increasing emphasis on prevention, there is little evidence to support any substantial beneficial impact of the QOF on either preventative activities or reducing health inequalities. 64,65 However, there is some evidence to show that the QOF has contributed to a reduction in the delivery of clinical care related to area deprivation,66 and a systematic review of the impact of pay-for-performance schemes on health inequalities concluded that inequalities have largely persisted since the introduction of schemes. 67 The Healthcare Commission report68 noted that the QOF is unlikely to encourage practices to try and include the most ‘hard to reach’, since no further points are received once 90% coverage has been achieved. Typically, QOF points are awarded to reflect workload and consist of both a minimum performance threshold (payments beginning once 40% of eligible practice population have been treated) and a maximum threshold (e.g. 90% of those eligible) with graduated payments in between.

Few QOF indicators directly address health outcomes and primary prevention. The evidence suggests that the QOF has improved health outcomes for some conditions, but has had a limited impact on others, including adverse effects for population subgroups and non-incentivised activities. Current research also highlights the limitations of the QOF scores awarded in improving health outcomes, due to the indicators’ ceiling thresholds and the suboptimal clinical targets set compared with national clinical guidelines. 69,70 One key exception has been the inclusion of smoking targets. These were included in early versions of the scheme and was associated with the universal uptake by GPs for recording the smoking status and providing smoking cessation advice for patients with various comorbid factors [coronary heart disease (CHD), stroke or transient ischaemic attack, hypertension, diabetes, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) or asthma and, from 2008, chronic kidney disease, schizophrenia, bipolar disorder or other psychoses]. Notably, the original QOF threshold for intervening with smokers without comorbidity factors was simply that status was recorded at any time. This was changed in 2006, when recording smoking status in non-morbid patients was required periodically (every 27 months), rather than ‘ever’, to attract payment. However, only one indicator is solely focused on the achievement of an actual health outcome (i.e. the number of epilepsy patients who have been seizure free in the last 15 months), whereas the remaining intermediate outcomes relate to targets which are an indirect measure of one’s health (e.g. cholesterol < 5 mmol/l). The QOF points available are also weighted towards particular conditions such as diabetes (88 points) and CHD secondary prevention (69 points), compared with scores available for COPD (30 points), depression (31 points) and other mental health conditions (40 points).

The QOF also allows GPs to ‘exception report’ to ensure that they are not penalised by patients who do not attend reviews of their medication or where patients are unable to tolerate medication, possibly because of side effects. Exception reporting is supposed to ensure that GP performance is measured only against a viable practice population. However, it is possible for reporting to be ‘gamed’ to exclude high-risk patients or those for whom GPs have missed targets, thereby decreasing the patient pool and maximising QOF scoring. 71

The organisation of preventative activities in primary care settings

A Cochrane review72 on the secondary prevention of ischaemic heart disease stated it succinctly: while the benefits of individual medical and lifestyle interventions are established, the effectiveness of interventions which seek to improve the way secondary preventative care is delivered in primary care or community settings is less so. A review by The King’s Fund18 examining the quality of general practice identified that a key challenge to improving the quality of public health and ill-health prevention is that there is a lack of evidence about the effectiveness of interventions carried out by primary care practitioners. The authors concluded that:

Evidence about the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of public health interventions is growing . . . However, more needs to be done to help understand how general practice can effectively tackle ill-health prevention. General practice, public health practitioners and academics all have the responsibility to work together to improve this evidence base.

p. 3118

While it is clear that there is a substantial commitment, in terms of both policy and practice, for general practice to be engaged in public health activities, the literature tends to discuss this in one of three ways. The first way is in the focus at a conceptual level examining the links between primary care and public health. The second is the focus on the public health role of primary care professionals. Finally, the literature has examined the role of the practice as a location for public health activity. We examine each of these areas in turn.

Primary health care as public health

There has been a longstanding debate within general practice about the extent to which ‘primary health care’ has both a community and an individual orientation. 47,48 There is good evidence to demonstrate that primary care can effectively contribute to individual health. Health promotion activities can be categorised as individual, practice and community based, and these may be primary or secondary prevention activities.

The development of public health policy and practice in the second half of the twentieth century was marked by two major inter-related tensions: whether public health is a largely medical domain or a multidisciplinary one, especially given the wider determinants of health, and whether public health is a specialist or generalist activity. 27 These two tensions are central to discussions about the role of general practice in public health. Primary care has been seen as a logical location for local public health action, and its role was specifically identified in the Alma Ata declaration. 1 However, in many Western industrial countries this link has not been so clearly identified and a more individualistic, medicalised system of primary medical care has developed. This is particularly true in the UK. 48,73 Since the late 1970s there has been an increasing recognition that primary care should encompass a population health perspective and that prevention and health improvement are key constituents of high-quality primary health care. 1,47,53

Experience suggests that, while the public health activity of practices is located in the community, primary care professionals do not necessarily engage with the community about public health issues and about the relevance of their activity to the community’s health priorities. 12 Generally, the structures and cultures of primary care organisations reflect the dominant medical model, which inhibits the development of community perspectives on health. 12,74 Many professionals, then, confine their public health activity to a strictly clinical agenda. Those who do engage with the community on wider public health issues go beyond their formal role,8,10,12,75 although there is a tradition of public health within UK general practice, and of activist doctors addressing health inequalities in deprived communities. 13,14 Direct policy support for public health came with the 1990 GP contract, which introduced the first payments for reaching cervical screening and immunisation targets, and for running ‘health promotion’ clinics. The development of primary care organisations in the 1990s shifted the focus towards population approaches, seemingly building on incentives for health promotion and education, as well as secondary prevention, that already existed in UK general practice. 48,76,77 However, none of these incentives succeeded in drawing GPs ‘beyond the surgery door’, and they still focused on what were essentially clinical activities. 10,78 Generally, GPs focus prevention interventions on patients at high risk rather than taking a population approach or maximising opportunities for health promotion advice to all patients who might benefit. 79 Nevertheless, prevention is seen as an important element of the role of primary care practitioners. 80,81

Professional public health practice in general practice and primary care

The range of professionals engaged in general practice and primary care include all staff who work within the practice, are based or located at the practice or are part of the primary health-care team linked to the practice. There has been discussion about the public health role of such professionals for many years. Policy tends to focus on the role of the practitioner, with the main emphasis on the GP, although there has been an increasing recognition of the roles of other practitioners based in general practice or providing primary care services. However, the main funding mechanism for general practice remains the GMS contract, which is negotiated with the GP principals in the practice, and most payment mechanisms are historically associated with GP activities. For example, while the QOF is essentially a reward system for GPs to undertake specific activities with patients, it is practice nurses who actually undertake much of the work. 82

Tannahill83 has argued that public health in primary care incorporates clinical and non-clinical dimensions and that it challenges GPs to more proactively address their patient population’s needs. This view was supported by the coalition government of 2010–15, which identified the need to extend the public health role of GPs and further incentivise public health activity through the QOF. 37 The Royal College of General Practitioners also supports a stronger, proactive role for GPs in carrying out public health activities and interventions, with health promotion representing a core element of the general practice curriculum (Box 1). 7

-

A wide knowledge of the public’s health and prevalence of disease.

-

The ability to judge the point at which a patient will be receptive to the concept and the responsibilities of self-care.

-

Knowledge of patient’s expectations and the community, social and cultural dimensions of their lives.

-

Understanding the importance of ethical tensions between the needs of the individual and the community, and to act appropriately.

-

Working with other members of the primary health-care team to promote health and well-being by applying health promotion and disease prevention strategies appropriately.

-

The ability to work as an effective team member over a prolonged period of time and understand the importance of teamwork in primary care.

-

Understanding the role of the GP and the wider primary health-care team in health promotion activities in the community.

-

Understanding approaches to behavioural change and their relevance to health promotion and self-care.

-

Changing patients’ behaviour in health promotion and disease prevention.

-

Helping the patient to understand work–life balance and, where appropriate, help patients achieve a good work–life balance.

-

Describing the effects of smoking, alcohol and drugs on the patient and his or her family.

-

Promoting health on an individual basis as part of the consultation.

-

Negotiating a shared understanding of problems and their management (including self-management) with the patient, so that the patient is empowered to look after his or her own health and has a commitment to health promotion and self-care.

-

Giving information on acute and chronic health problems, on prevention and lifestyle, and on self-care.

Source: Royal College of General Practitioners. Healthy People: Promoting Health and Preventing Disease. 2007. URL: www.rcgp-curriculum.org.uk/pdf/curr_5_Healthy_people.pdf (accessed 10 June 2010). 7

At the heart of the relationship between general practice and public health is an ethical balance between individual and collective freedom. For primary care practitioners, the roles of patient’s advocate and population planner may conflict with one another. 84 Many practitioners are ambivalent about the place of health promotion alongside their more central clinical caring role. Some GPs question the idea that they should be vested with responsibilities for social engineering that are really the proper role of government. 85 General practitioners are also often untrained as health educators, and may have a narrow view of health promotion and limited experience of community development activities. The potential for primary care practitioners to influence public health is also shaped by the role of local health purchasers, which redistribute resources between geographical areas, clinical disciplines and practices to support a public health agenda. However, the GP contract has for nearly 20 years included a number of aspects of health promotion, and more recently the Marmot Commission on health inequalities29 has focused some attention on developing the performance elements of the contract, within the QOF.

There has also been a longstanding debate about the public health role of nurses and allied health professionals. 86 In particular, the health promotion role of nurses has long been recognised by professional and regulatory bodies that have advocated a stronger public health role in nursing. 87 Following the publication of Making a Difference: Strengthening the Nursing, Midwifery and Health Visiting Contribution to Health and Healthcare,88 there has been an increasing policy emphasis on developing the public health role of nurses. However, there has been an increasing trend towards more clinical specialisms, and concerns have also been raised about supporting the public health roles of key groups such as health visitors and school nurses. 89–91 There has been less discussion about the public health role of district and other specialist nurses. 86 However, over the last 20 years, practice nurses have experienced a substantial change in their involvement in public health activities. The introduction of health promotion banding payments in the 1990s, the focus on screening and the introduction of the QOF in 2004 have had a significant impact on the role and workload of practice nurses and also led to the introduction of more health-care assistants working in general practice. 92,93 Practice nurses are undertaking a substantial amount of the screening and monitoring activities in general practice for blood pressure, diabetes, asthma, etc., creating a stronger health promotion role with symptomatic patients. There has also been an increase in practice nurses undertaking smoking cessation work. 94,95

Changes in the role of health visitors in the past 20 years have involved a more targeted focus on disadvantaged groups and families. This has involved closer working with developments such as Sure Start and family/children centres. 96 While the specific role of the public health nurse (as in Scotland) has not been developed in England, health visitors remain the most public-health-focused nursing role. 97 However, the coalition government of 2010–15 was committed to increasing the health visiting workforce by 4200 health visitors by 2015. This commitment was supported by the Health Visiting Implementation Plan,98 which uniquely set out the government’s determination for health visitors to be the key drivers for child and family public health through the vehicle of the Healthy Child Programme. 99 This is on target to be achieved, although the evidence base for health-visiting interventions remains relatively weak. 100

More broadly, however, there has been a clear shift in thinking about practitioner roles that increasingly highlights a health promoting role and one that also emphasises the practitioner’s role as a facilitator as well as medical or health professional expert. The growing emphasis on self-care, coproduction and supporting self-management has influenced approaches to health promotion. However, in general practice the emphasis appears to have been an increasing focus on individual lifestyle and clinical interventions with patients identified with specific risk factors or with existing morbidities. The shift has been reflected in the definition of core professional values and the incorporation of population health as a core professional value80,81 but does not appear to incorporate core public health skills such as those identified in the public health skills framework. 101 This has been developed by Public Health England (PHE) to provide a clear structure for public health practice and professional development in public health.

There has also been a growing interest in the roles of non-nursing, non-practice-based community staff such as community pharmacists. 102,103 Agomo undertook a scoping study exploring the range of roles that community pharmacists were providing in public health. 104 Dominant activities were smoking cessation, healthy eating and lifestyle advice, provision of emergency hormonal contraception, infection control and prevention, promoting cardiovascular health and blood pressure control, and prevention and management of drug abuse, misuse and addiction. However, the study identified gaps in the UK evidence base and in knowledge of what activities were being undertaken in some geographical areas (e.g. London).

General practice as a location for public health activity

General practice has been seen as an ideal location for health promotion activities, as it is the location of most individual contacts with the health service in the UK. In 2008/9 there were just over 300 million GP consultations in England. The average number of patient consultations each year has been gradually increasing from 3.9 in 1995/6 to 5.5 in 2008/9. Since 2004 in particular, there has been a change in the proportion of patients seen by nurses in primary care, with the proportion of nurse consultations increasing from 21% to 34%, and consultations with GPs reducing from 75% to 62%, reflecting changing workload patterns. This shift may reflect a change in recording of nurse consultations as well as an increase in the numbers of patients seen. This represents a high degree of contact with practice populations. While recent changes in out-of-hours care, increased advice roles for pharmacists and the development of telephone advice lines and walk-in centres have provided alternative points of contact, general practice remains the main first point of contact and ideally placed to develop and support health improvement activities.

However, in many ways the boundaries of the practice have changed, as many community activities are linked to general practice through the activities of community nurses and there is a recognition that some activities traditionally associated with general practice may be better provided in other community locations including people’s homes, schools and community pharmacies. In addition, there is a greater expectation that the role of general practice is to refer people to preventative activities such as specialist stop-smoking services, weight loss services and exercise activities. Developing closer links with schools – for sexual health and other health support services for young people – has led to not just school nurses but other health professionals working in schools. With changes to the structure and delivery of health services, some activities traditionally seen as part of general practice can now be delivered by a range of agencies such as community organisations delivering the NHS Health Check.

Watson15 has suggested that, rather than focus attention on general practice as a location for health promotion, the development of the concept of a health-promoting practice should be employed. Drawing on ideas in the World Health Organization Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion,105 Watson argues that it is possible to conceptualise the practice as a setting. While the focus of ‘settings’ has been on the community or schools and workplaces, the principles of the ‘settings’ concept can be applied to primary care. ‘Settings’ literature has emphasised key central concepts that involve the desire to act on policies, reshape environments, build partnerships and develop empowerment and ownership as well as developing personal competencies for public health. 106,107 There is also a shift from medical expert to change facilitator for health promotion. This broadens the perspective of activities and who undertakes them, where they are undertaken and how they are delivered. It shifts attention away from specific interventions for individuals and places health promotion practice in general practice within a broader social and environmental context. In undertaking this review we have drawn on this concept to structure our data collection and analysis.

Conclusion

The discussion of current issues raises a number of concerns about examining the public health role of general practice and primary care. These relate to two broad themes. The first is methodological. While there has been a substantial number of research papers and reviews on health promotion in general practice, the focus has been on the intervention. Very little attention appears to have been paid to the way interventions are delivered or organised. Reviews, in particular, have not addressed this organisational context. The second is that many reviews draw on international evidence and this raises important questions about their relevance to UK general practice. While not unique in terms of its structure and organisation, UK general practice has a particular organisational form, tradition and funding structure which are different from most other countries. Such differences – the QOF being a good example – are likely to create different incentives and contexts within which health promotion takes place.

It is also clear that much of the literature and research on health promotion focuses on the relationship between the practitioner and the individual patient. UK general practice operates within an individualised medical model. 48 Developments in recent years have tended to strengthen this focus, with an emphasis on individual, clinical (predominantly pharmaceutical) preventative interventions. Broader, more community-based approaches – such as those advocated by Julian Tudor-Hart,14 for example – tend not to be supported by policy or professional and regulatory guidelines. Following the Marmot Review29 there has been more policy interest in developing the public health role of general practice, and new QOF criteria to promote preventative activities are being developed by NICE. However, there remains a degree of uncertainty within general practice itself about its public health role and how preventative interventions are best delivered.

Chapter 3 Methods

Introduction

Our methodological approach was based on the standard methodology for scoping reviews. 108,109 It consisted of two components: (1) literature review and (2) consultation with key stakeholders. The findings from these components were integrated to establish how well current knowledge mapped onto priorities and issues identified by stakeholders, to identify gaps in knowledge and future priorities.

The aim was to conduct a synthesis of the research evidence and wider literature on public health and primary care. Reviews of health improvement interventions pose numerous challenges due to multicomponent interventions, diverse study populations, multiple outcomes measured, the wide range of approaches and study designs used, and the effect of context on intervention design, implementation and effectiveness. 110 An initial scoping of the literature identified in excess of 20,000 papers that may be relevant to the topic area, and we developed strategies designed to manage paper selection and data extraction. The aim was to undertake a review of the extant literature on health improvement and primary care, focusing on the contribution of activities undertaken in or associated with general practice, wider practice and the primary health care team. However, following changes to the NHS and developments in public health service provision in England, the scope of the review was extended to include non-practice-based health improvement activity. This included exploring the roles of primary health care team members in the community and schools, and community pharmacists. However, the focus remained primarily on those activities associated with general practice, and our search strategies were based upon this central premise.

The review focused on examining the health improvement role of general practice in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. We initially intended including English-language papers on health improvement roles in health systems with similar general practice organisational arrangements (e.g. Holland, Sweden, Canada, New Zealand), however, the initial literature searches identified a substantial number of papers and, given the specific nature of UK general practice and the need to produce findings relevant to the delivery and organisation of public health activities in UK general practice, it was decided to restrict the searches to UK studies only.

This study was not a systematic review of the literature but, in order to provide a comprehensive synthesis of the evidence, the team approached the review drawing on systematic methods. The conceptual complexity of both public health and primary care raised a number of initial problems in identifying key words for the literature search. In addition, the team also recognised that a focus on service delivery and organisation would create difficulties in identifying relevant literature. It was decided to approach the review in a number of stages including a hand search of selected primary care/public health journals and NHS public health reports. This was to be followed by an initial search of key databases and then broadened to cover all relevant databases. Dependent on the number of papers found, we would then develop a strategy for paper selection.

Ethics

Formal NHS ethical approval was not required, as the study sought information only on current service delivery. The study was classified as service evaluation as defined by current National Research Ethics Committee guidelines: Defining Research, published by the NHS Health Research Authority. 111 The research was conducted in line with ethical standards relevant to applied research and had approval from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine ethical committee.

Preliminary hand searches

To facilitate the development of search terms for the literature search, preliminary hand searches of key journals and PCT public health reports were undertaken. The purpose of this preliminary work was to create a more useful list of keywords for our search. We selected two recent director of public health reports from each strategic health authority: one from a rural PCT and one from an urban PCT (based on calculated population density). The reports were reviewed for references to ‘GP’, ‘general practice’, ‘primary care’ and ‘primary health care’. Each report was also skimmed to make sure relevant references were identified. We recorded any discussion of health problems in relation to general practice and any mention of general practice interventions as well as noting the common words or phrases used.

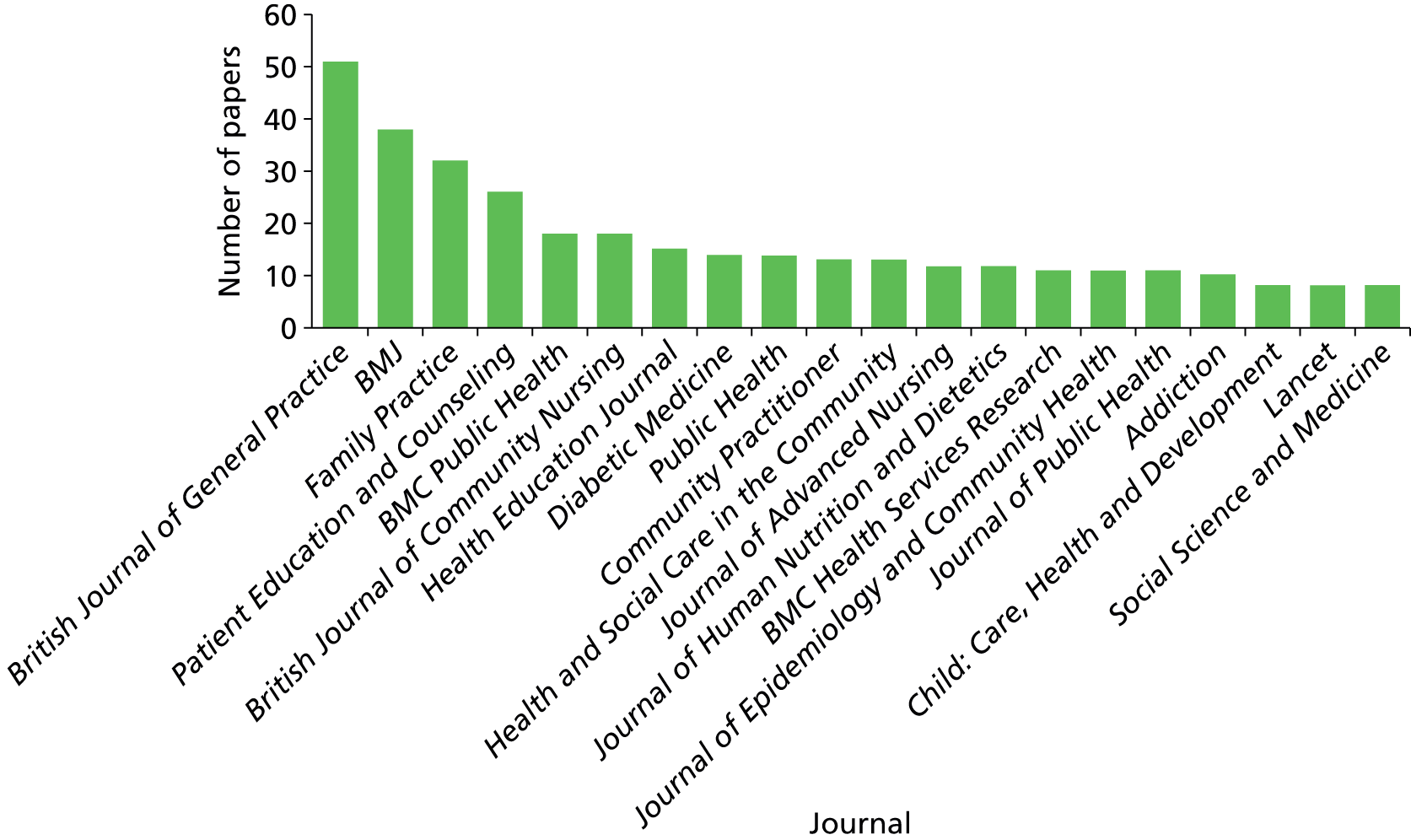

Journals included in the hand search were the British Journal of General Practice, Health Promotion International, the Journal of Public Health and Primary Health Care Research and Development. Tables of contents from 1990 to the present were skimmed for titles relating to health promotion or disease prevention services delivered in general practice or by general practice staff. Broad selection criteria were used, and all study types were considered. Full-text papers were downloaded and skimmed and, if the paper still fitted our topic, three pieces of data were recorded for each paper: relevant keywords used, health problem discussed and type of intervention discussed.

In addition to these hand searches, the research team met with public health experts, local public health managers and staff in general practices. The aim of these discussions was to help focus the review and provide a rationale for paper selection. As a result it was decided that we would categorise papers that were selected for review into one of four categories:

-

include for evidence synthesis of approaches to delivery/organisation of health improvement

-

include because tells us about health improvement activities undertaken in primary care

-

mark as a paper ‘of interest’

-

reject paper.

While the evidence synthesis focused on the first category, we also decided to include papers in the second category in the review, as they provided useful information about the range of activities being undertaken in general practice.

Preliminary results

There was a wide variation in the amount that GPs were mentioned in PCT public health reports. Several reports did not mention general practice at all while others listed innovative measures that general practices were implementing to tackle public health problems.

Four journals were searched for papers on general practice provision of public health services between 1990 and 2010. Numbers of relevant papers from each journal were 75 from the British Journal of General Practice, six from Health Promotion International, 15 from the Journal of Public Health and six from Primary Health Care Research and Development.

Based on this list of terms, we undertook a MEDLINE search, which yielded over 100,000 hits. A rapid review of a small selection of abstracts showed that few papers were likely to be relevant. This result suggested that our search strategy was too wide. However, we also found that a number of the papers that we uncovered in our hand search had not been detected by this broad search strategy. Our next step was the practical one of narrowing our search finding to a manageable number of papers. We developed a second search strategy that identified specific keywords that appeared to generate substantial relevant hits from within our original list of terms. We also restricted our search to the UK to try to identify a manageable pool of references. See Appendix 1 for the literature search strategy.

Initial literature search

Thus, an initial search of Ovid MEDLINE, informed by the keywords obtained from the hand searches, was conducted by combining synonyms for primary care, public health and the UK. The search strategy is listed in Appendix 1. Results were limited to academic papers published in the English language between 1990 and 2010. The search yielded 14,948 references. Bearing in mind that the final literature search was planned to be conducted on four databases, this high number of papers from one database was deemed to be unmanageable for paper selection. Steps were therefore taken to further refine this search.

Refinement of literature search

The initial search was refined by replacing the public health search terms with synonyms for three areas of public health highlighted in the Healthy Lives, Healthy People White Paper. 37 These were ‘prevention’, ‘health improvement’ and ‘health promotion’. Thus the search was a combination of synonyms for these three areas of public health, primary care and the UK. The search was run on four databases, namely MEDLINE, EMBASE, Global Health and CINAHL Plus, using strategies designed specifically for each database, described in Appendix 2. Results were limited to academic papers published in the English language between 1990 and 2010. This search yielded 7209 results in total after duplicate references were removed using EndNote X4 software (Thomson Reuters, CA, USA).

The discrepancy between 7209 results from four databases in the refined search and 14,948 results from one database in the initial search led to concerns that the refined search may have missed relevant papers. In order to investigate this, a sample of references published in June of each year from 1990 to 2010 which were retrieved by the initial search but not by the refined search were examined. From this, eight additional areas to supplement the refined search were identified. These were alcohol and drug addiction, brief interventions, exercise therapy, immunisation, lifestyle, risk reduction, screening and smoking cessation. Synonyms for the eight areas were combined with search terms for primary care and the UK, and limited to academic papers published in English between 1990 and 2010, as before. The search strategies for each of the four databases are shown in Appendix 2.

The final literature search results consisted of references retrieved by combining the search strategies used in our refined search (see Appendices 1 and 2). Duplicate references were removed using EndNote X4 software. The process was repeated on 12 May 2012 to identify papers published in 2011 and early 2012. The total number of references retrieved for the years 1990–2012 was 16,791.

Paper selection

Paper selection was conducted in three sequential stages: by title, by abstract and by full text. At each stage, the following inclusion criteria were used:

-

Is it focused on primary care?

-

Is it health improvement (defined as primordial, primary, secondary or tertiary prevention, and also encompassing health promotion)?

-

Is it, or could it be, related to service delivery or organisation?

-

Does it report research findings or, alternatively, does it contain a description of health improvement activities undertaken in practice?

If the answers to all four questions were yes, the paper was progressed to the next stage. Where abstracts were unavailable or did not provide sufficient information to assess the paper’s relevance, the full text was obtained in order to assess relevance.

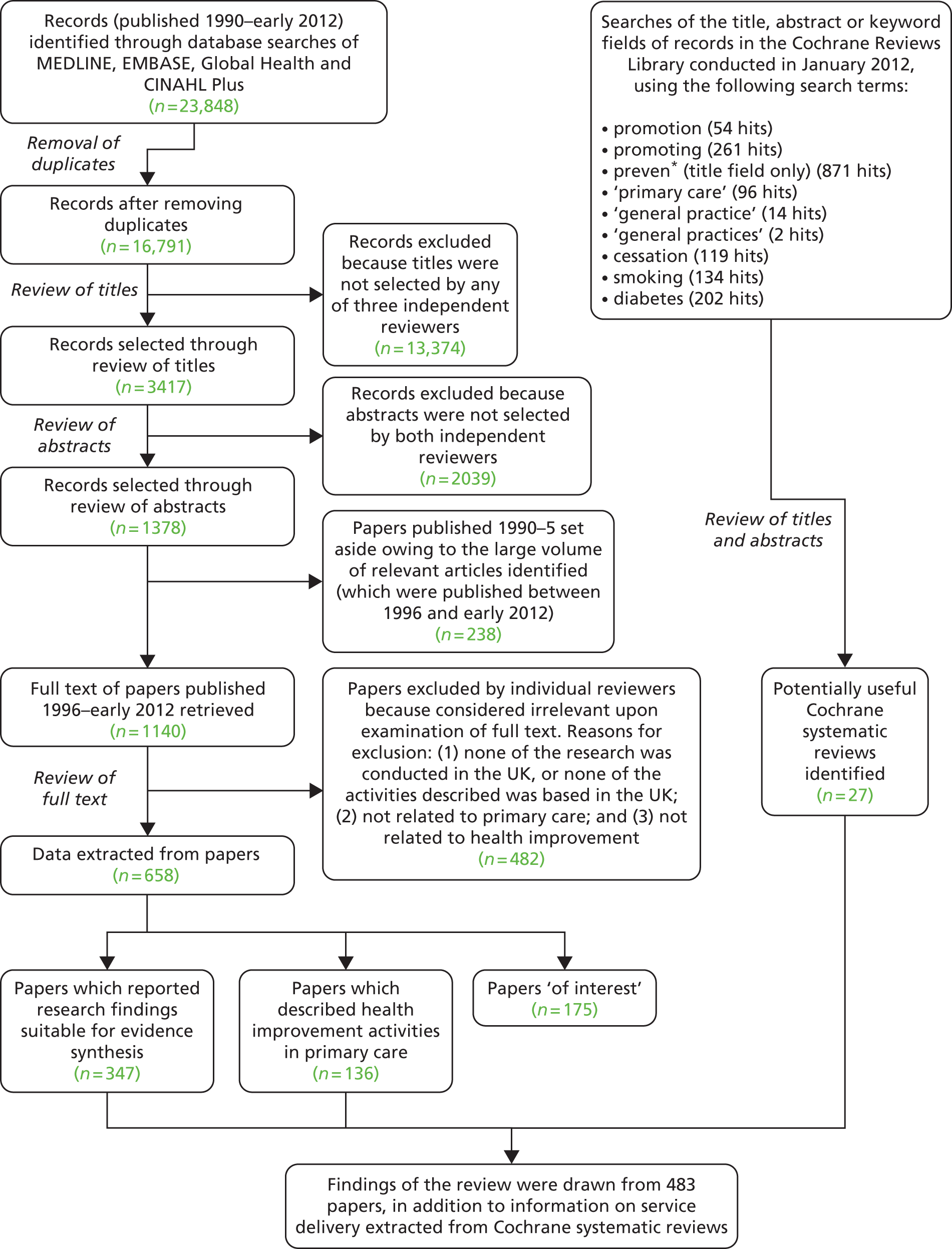

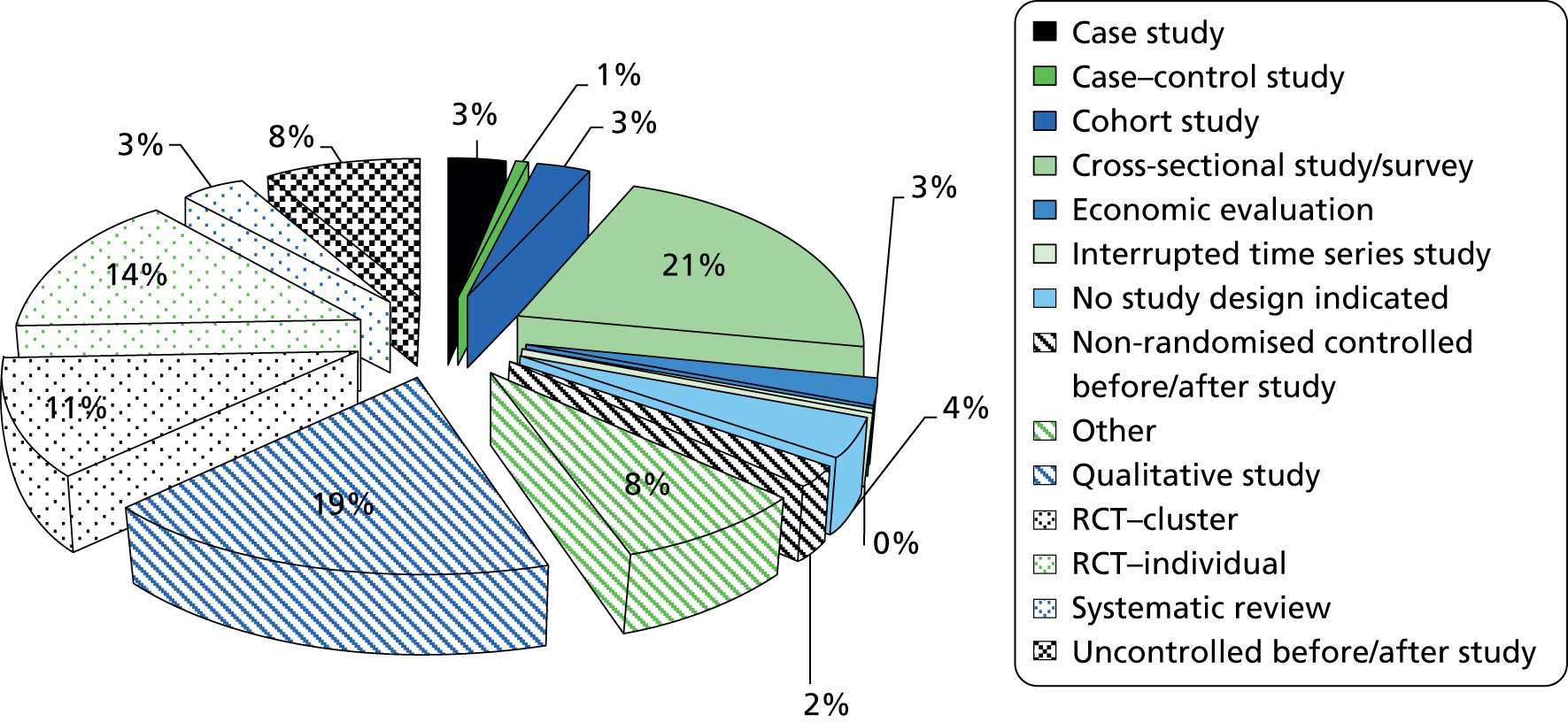

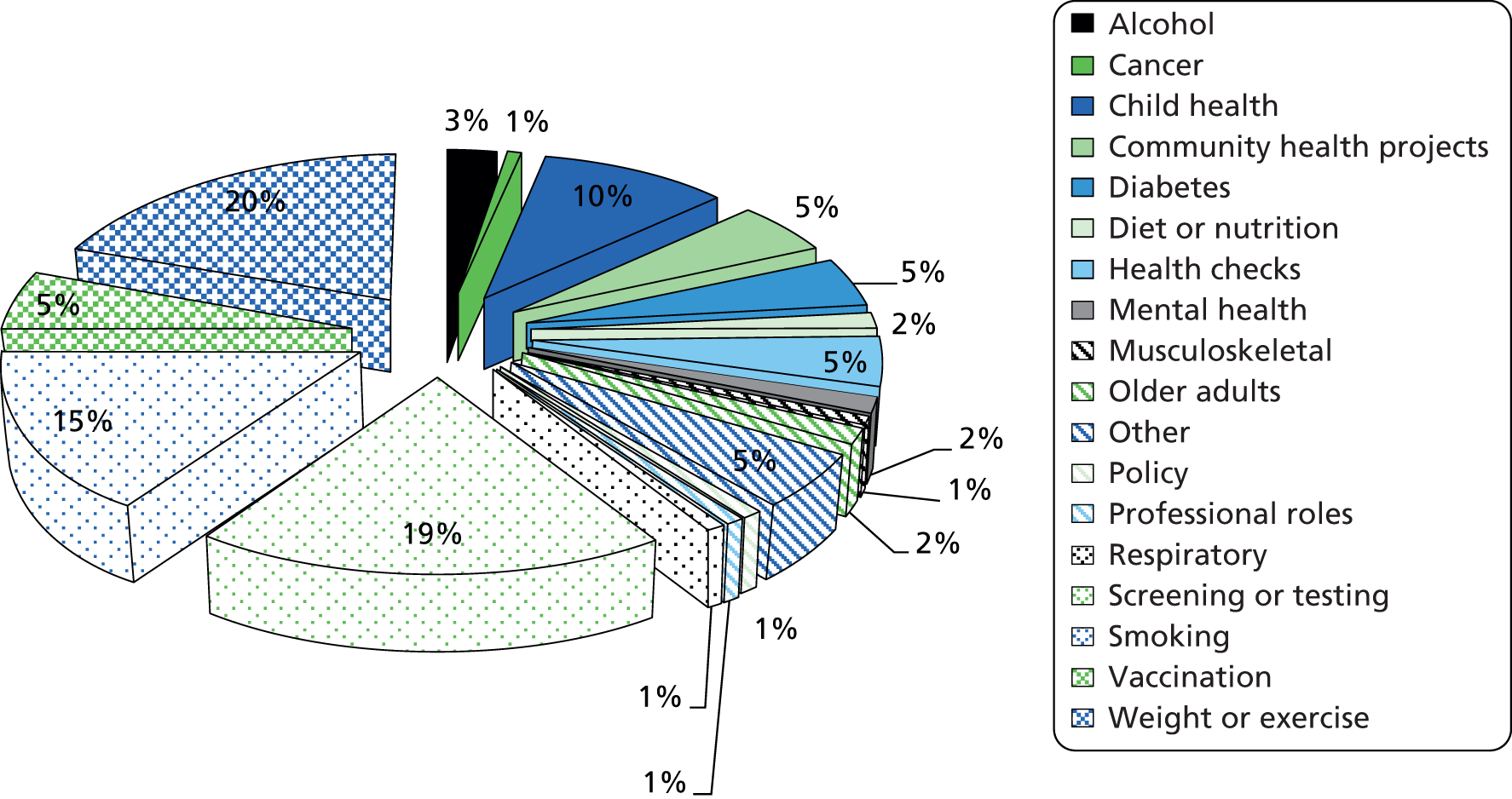

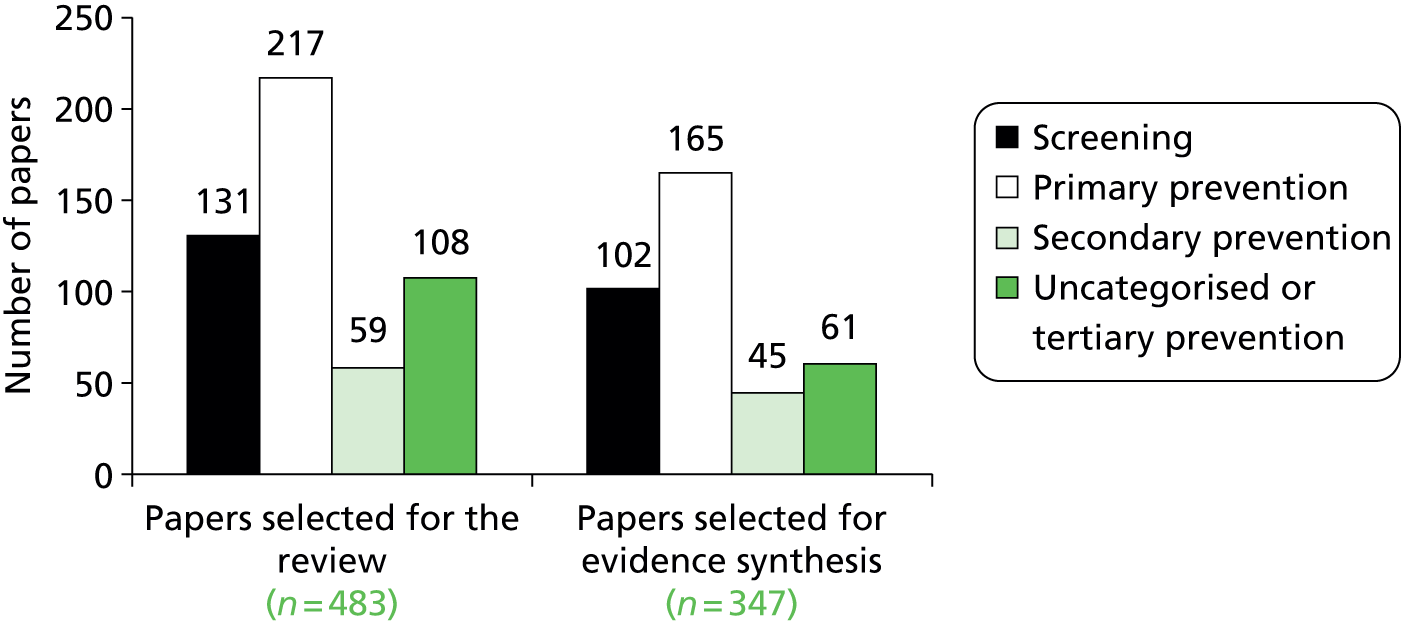

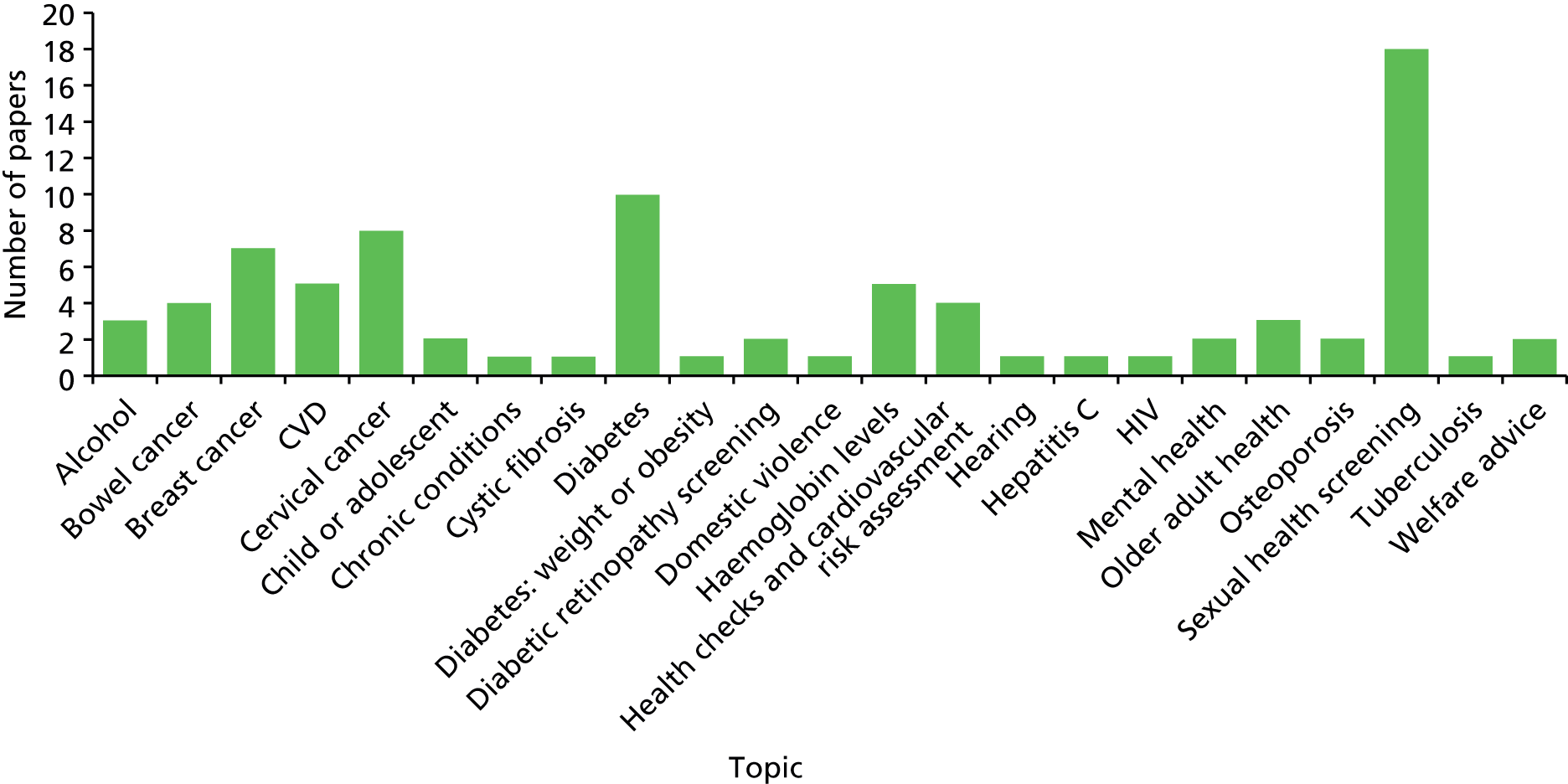

The 16,791 references were divided so that, in the title selection stage, the title of each paper was reviewed separately by three reviewers. If any one reviewer considered a paper to be relevant, it was progressed to the abstract selection stage. In the abstract stage, references were divided so that each abstract was reviewed separately by two reviewers. If both reviewers considered a paper to be relevant, it was progressed to the full-text stage. In the full-text stage, data from each paper were extracted by individual reviewers. There was also an opportunity to discard papers at this stage, if considered to be irrelevant upon examination of the full text. The overall search and paper selection process is shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of review process.

Supplementary searches

In addition to our database searches we undertook a search of The Cochrane Library to identify potential reviews that might have relevance to our review. Searches of the title, abstract or keywords of reviews in The Cochrane Library were performed in January 2012 using the search terms listed below:

-

promotion – 54 results

-

promoting – 261 results

-

preven* (search restricted to title field only) – 871 results

-

‘primary care’ – 96 results

-

‘general practice’ – 14 results

-

‘general practices’ – 2 results

-

cessation – 119 results

-

smoking – 134 results

-

diabetes – 202 results.

The results were manually reviewed to identify potentially relevant reviews.

We then examined each of the final results for any information relating to public health service delivery and organisation in primary care. We identified 27 potentially useful reviews (see Appendix 3). In addition there were three reviews in progress that were possibly relevant and we also identified a review on Interventions to implement prevention in primary care that was registered in 2001 but then withdrawn in 2005 owing to a lack of resources available to undertake the review.

The results of these reviews were incorporated into the findings from our literature search. While there is inevitably some overlap of papers, we conducted a brief cross-check. Given the differences in search strategies, review focus and quality assessment, this was limited.

We also examined NICE guidance on public health and primary care but this was more limited. NICE started undertaking public health reviews only recently. However, where relevant, the guidance is referred to in this review.

Finally, we searched for other reviews that focus on public health and primary care. Two key reviews were identified. The first was undertaken in Canada23 and the other was by the Committee on Integrating Primary Care and Public Health Board on Population Health and Public Health Practice, US Institute of Medicine. 24 Both these reviews examined the relationship between primary care and public health. The first of these had a very broad focus and had little direct relevance to general practice or actual health improvement activities. The US review was very specific on the US context and the potential for developing public health in primary care. Neither review added anything substantial to our own searches but they are referred to where relevant.

Data extraction

Given the large volume of relevant papers identified, a decision was made to perform data extraction on a subset of papers published from 1996 to early 2012. We identified that older papers tended to be selected less and decided that we would therefore restrict full data extraction to after 1995. We retained the selected references for 1990–5 and, where relevant, examined and included papers in the review where they added additional information. The topic ranges for these papers focused on a small number of themes including health checks for older people, smoking cessation, health promotion payments (under the 1990 GMS contract) and CVD. There was a large number of papers describing activities in general practice and the community. There has been a substantial number of changes to the funding and organisation of primary care since the mid-1990s, and therefore we focused mainly on the more recent papers. Details of selected papers are given in Chapter 4.

Data were extracted from each relevant paper into an Access 2010 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) database using a standardised form, which is included in Appendix 4. The form had been designed by the research team and contained fields to capture information on the type of study, outcomes, population targeted, service provider and main results. For intervention studies there were fields for describing the intervention and how it related to service delivery or organisation. Designing a single data extraction form for use across all types of studies was complex and the final format did not provide a single structured way to extract data from qualitative studies. The limitations of the data extraction form were:

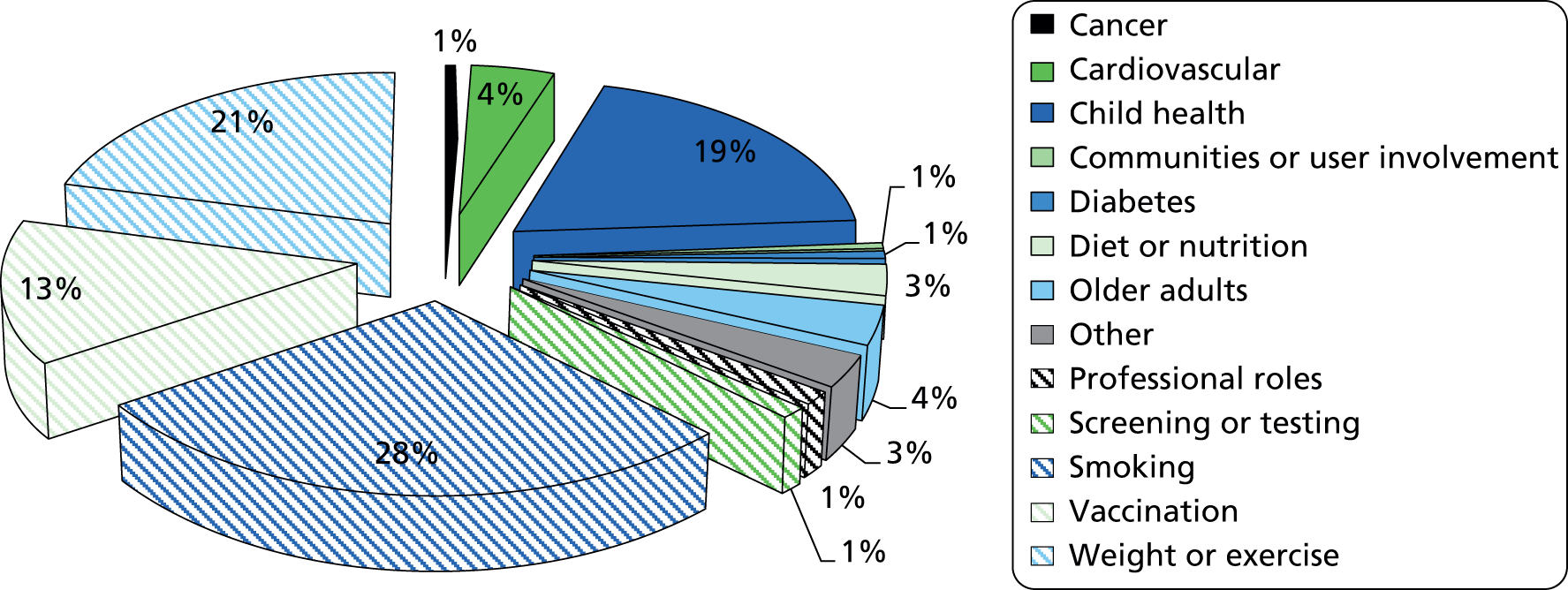

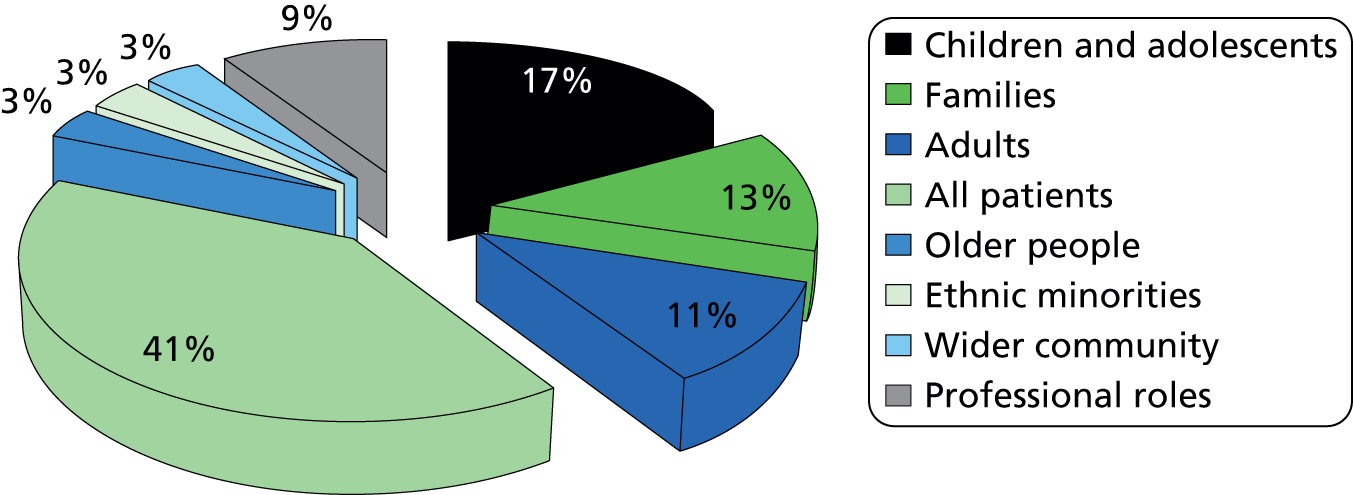

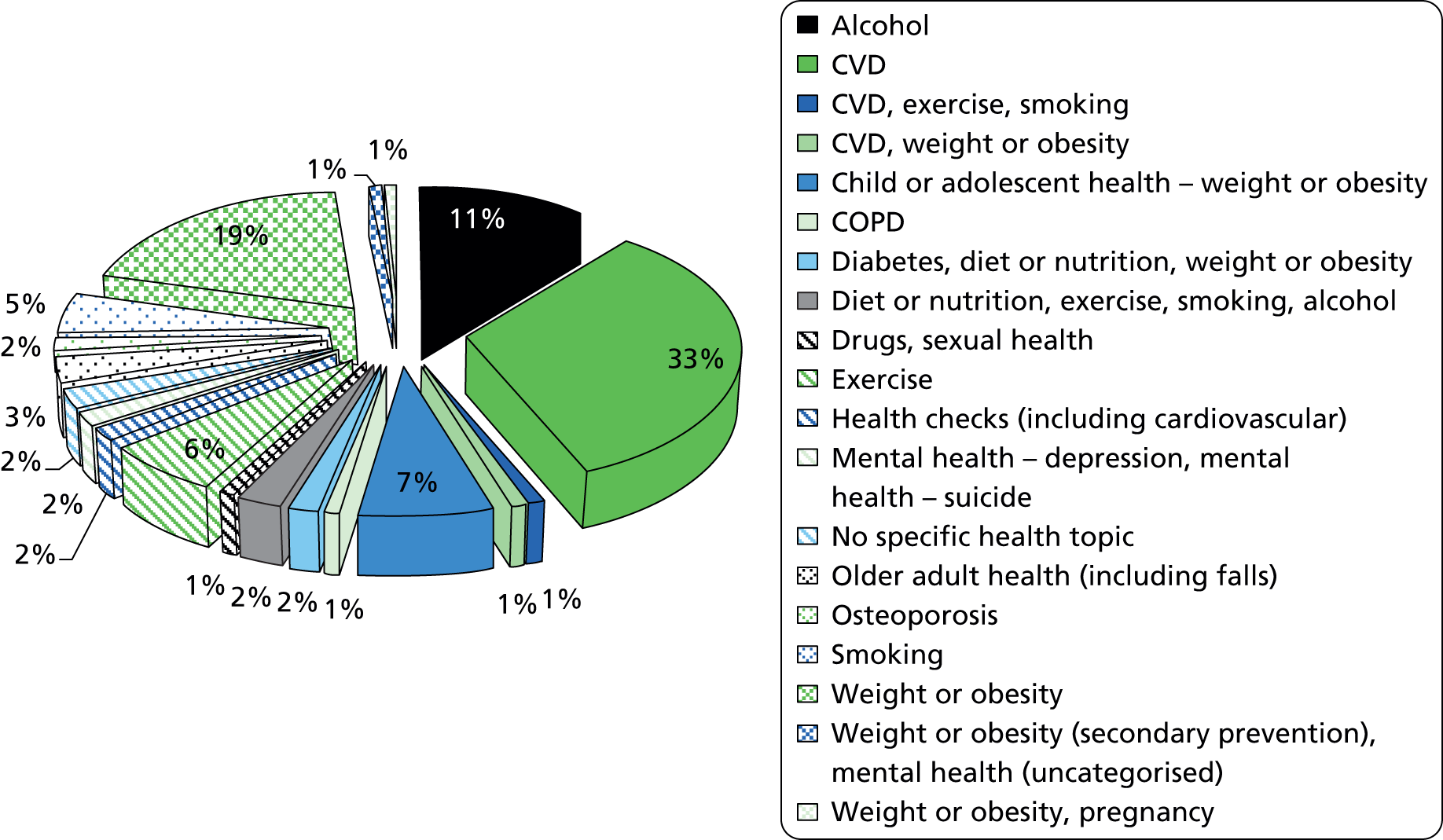

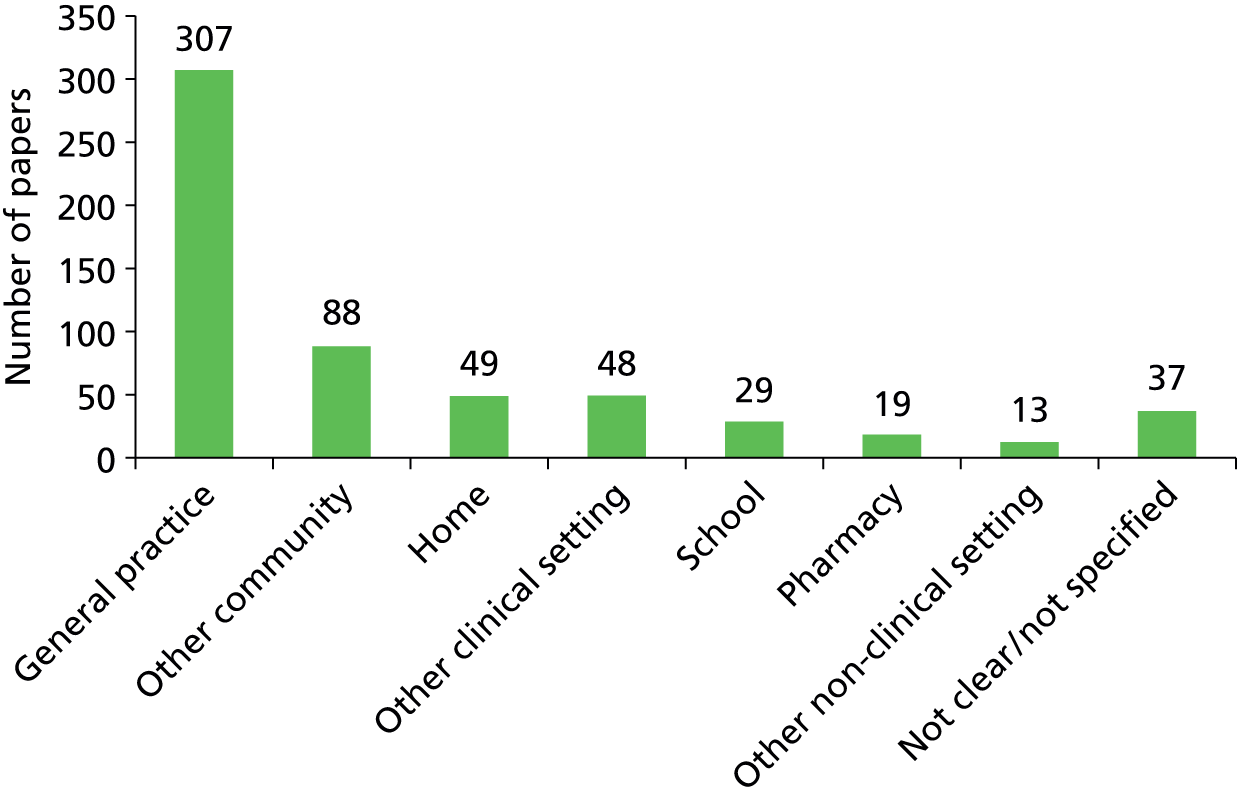

-