Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/19/51. The contractual start date was in March 2015. The final report began editorial review in October 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Bee et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Foreword

Parent member, REfOCUS advisory panel

It’s simple, being the parent of a child with a long-term condition is tough. You watch your child struggle. You have very little to offer. It is their burden, and as a parent, you want to carry it. Doctors tell us what to do and what should happen. But it doesn’t really work that way. Families manage in unique ways. Sometimes, self-care is our only way to take control. We care for our kids, we look things up, we try alternative solutions and we do our best. Often, it’s not enough, and that can leave us frustrated. We are the ones awake at night, holding our children’s hands, giving them medication and contemplating their futures. Parents of children with long-term conditions want everything for their children. On good days, we are rational, we appreciate everything we are offered and we understand the limitations of a burdened health service. We understand our own role and we embrace our situation. During the tough times, we just want to carry the burden and we don’t know how. We know that ‘throwing money’ at the problem won’t solve it, but we are tired and sad, and we expect more. Using self-care support to reduce unnecessary health service use is important. Finding out which types of self-care support can reduce service use without compromising our own children’s health is crucial.

Terminology

Throughout this report, we use the term ‘parent’. This term is intended to cover a breadth of roles and has been chosen in preference to alternative and lengthier terms such as ‘parent/guardian’ or ‘adult caregiver’. We acknowledge that not all adults who are parenting children are biological parents.

Chapter 1 Background

Context

The global burden of disease is shifting to long-term conditions (LTCs)1 and there is increasing international emphasis on developing effective, efficient and person-centred models of service delivery to meet the needs of this client group. 2–4 Self-care support interventions constitute a central aspect of this agenda5–12 and are intended to empower individuals and enhance their self-care capacities and capabilities, while simultaneously reducing the fiscal burden on health-care systems. 13,14

The Department of Health defines a LTC as one ‘that cannot be cured but can be managed through medication and/or therapy’. 11 Underpinning the policy emphasis on self-care support for LTCs are a number of philosophical and patient-centred drivers. The shift in illness patterns from acute conditions to LTCs has coincided with a change in philosophy from ‘cure’ to ‘care’. Growing dissatisfaction with impersonal services, greater desire for personal control in health interactions and enhanced awareness of the potential impact of lifestyle on longevity and well-being have all complemented the drive to optimise health outcomes, without exacerbating rising health-care costs. 8,15 The English strategy for the NHS, the Five Year Forward View,3 emphasises the importance of health promotion, ill-health prevention and early intervention for sustainable health-care services, and mandates new models of care, including self-care, to facilitate efficiency savings alongside improved patient outcomes.

A global economic crisis means that substantial effort continues to be invested in improving the efficiency of health-care systems. Yet, despite self-care being advocated as a key way in which to increase efficiency, there remains uncertainty regarding the scale of the contribution that can be made. 16,17 Evidence for the success of self-care support has predominantly focused on individually centred outcomes of behavioural change and, until recently, ambiguity has surrounded the impact of these models on health service utilisation and costs. Initial reports of the effects of self-care support on health-care utilisation have not been consistently replicated across studies17–23 and the focus of interventions on enhancing intermediate outcomes such as self-efficacy has generated debate regarding the relevance of existing evidence to service commissioners. 24,25

A previous National Institute for Health Research-funded systematic review, REducing Care Utilisation thRough Self-management InterVEntions (RECURSIVE),26 successfully responded to this challenge by attempting to determine which models of self-care support were associated with significant reductions in health service utilisation without compromising the health outcomes of adults with LTCs. This review concluded that self-care support in adults is associated with small but significant improvements in quality of life (QoL) and, importantly, that only a minority of self-care support studies report reductions in health-care utilisation in conjunction with reductions in health status. However, patterns of health- and social-care utilisation in children and young people may be qualitatively and quantitatively very different from adults, and potential differences in the factors and systems influencing engagement in self-care support across the lifespan27–30 make it difficult to extrapolate these findings to younger populations. This review applies the approach employed by RECURSIVE26 to this different population. It builds on two previous National Institute for Health Research-funded reviews31,32 that investigated the effectiveness and acceptability of self-care support interventions for children and young people with long-term physical and mental health conditions, both updating and integrating them into a single data set.

Self-care and self-care support

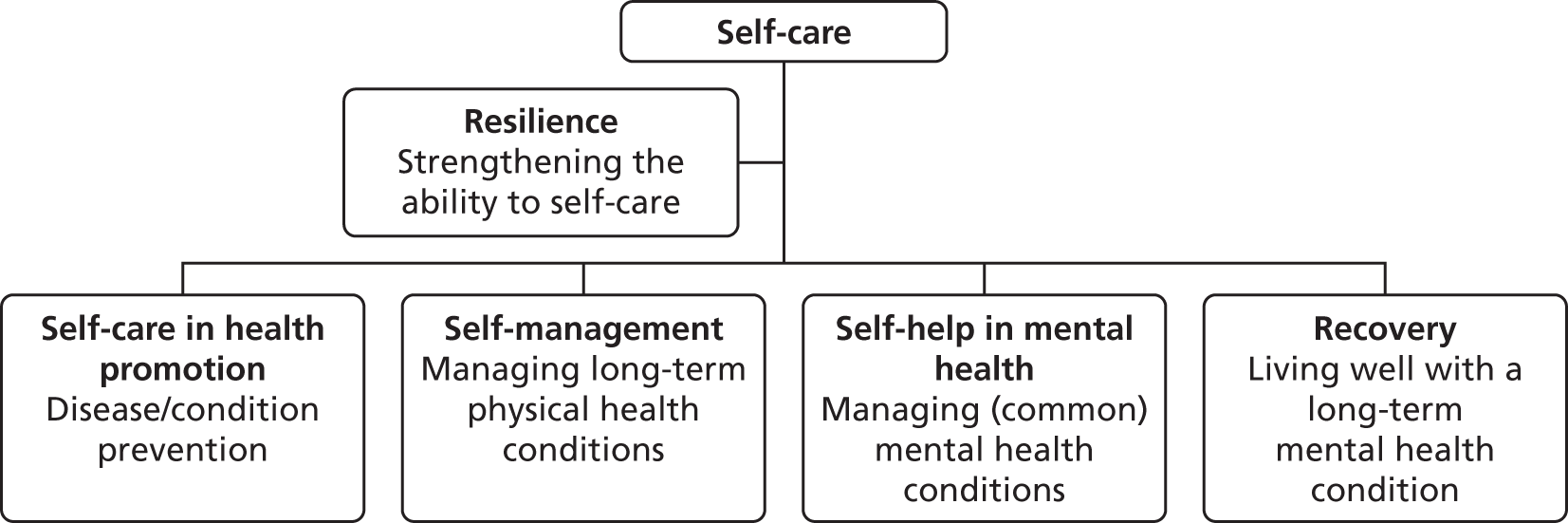

There is some conceptual blurring in the literature, with ‘self-care’ and ‘self-management’ often being used interchangeably in physical health, and terms such as ‘self-help’ and ‘recovery-centred care’ being preferred in mental health. 31–34 Resilience is often associated with self-care and is seen as a means of strengthening an individual’s capacity to self-care or as a buffer to the stresses associated with LTCs. 35 For the most part, however, self-care is regarded as the overarching term, with the alternative terms reflecting different variants of self-care or its influencing factors (Figure 1). A commonly accepted definition of self-care8 is:

The actions people take for themselves . . . to stay fit and maintain good physical and mental health; meet social and psychological needs; prevent illness or accidents; care for minor ailments and long-term conditions; and maintain health and wellbeing after an acute illness or discharge from hospital.

Department of Health. 8 © Crown copyright 2005. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v1.0

FIGURE 1.

Relationship of self-care concepts.

Whatever the terminology that is used, self-care ultimately refers to an approach in which control (and responsibility) shifts from the health-care professional (HCP) to the individual (or to the individual and their families/carers in the case of children and young people). This shift in control has implications for HCPs in that, within a philosophy of self-care, professionals work with patients, services users and their families as partners. 13

Partnership working introduces the notion of support for self-care (or self-care support). Support for self-care refers to HCPs (or other self-care support ‘agents’, such as a teachers or peers), supporting the individual and/or their families to take control of their health condition through developing their confidence, knowledge and skills. 8,36,37 This may occur via a variety of methods and techniques (e.g. information provision, psychoeducation and skills training) delivered in a variety of formats (e.g. online, face to face or by telephone) to individuals or groups. 8,32,33

In this study we have chosen to use the term self-care support rather than self-management support because this broader term incorporates self-management, self-help, recovery and resilience support. Furthermore, the term self-care support is more appropriate in describing the interventions examined.

Self-care support in children and young people

‘Whole-systems’ guidance advocates modernisation of the health-care system to improve the quality and efficiency of the services that children, young people and their families receive. 38 International childhood mortality data, combined with evidence of substantial variation in LTC management in this younger population, attest to how much additional effort is still required to achieve this goal. Compared with other nations, evidence points to a disproportionate number of UK children dying from non-communicable diseases and a rapid increase in the number of children and young people living with LTCs. 38,39 Fifteen per cent of children aged between 11 and 15 years experience long-term illness or disability and 10% have a mental health problem. 40–42 Over the last decade, child health policy has highlighted the vulnerability of these children and emphasised the need for health services to engage with them and support them effectively in self-care behaviours. 38,39,43–45

The case for early intervention in LTCs is compelling. Children diagnosed with LTCs face a lifetime of symptom management, and the extent to which they and their families negotiate this in childhood is likely to influence their longer-term health outcomes, life chances and subsequent patterns of health service utilisation. 31,39 Providing optimal, evidence-based support for self-care thus has the potential to make a significant and sustained contribution to NHS efficiency, as well as improving care quality and delivering direct benefits to patient health.

The role and effectiveness of different forms of self-care support in adults has been explored. An already extensive evidence base includes rigorous evaluations of the Expert Patients Programme and assistive technologies through the Whole System Demonstrator programme. To date, however, wholesale transfer of adult models to children and young people’s services has failed. 46,47 Comprehensive models of self-care48,49 argue that self-care cannot be divorced from the broader context in which it occurs. In children and young people, self-care knowledge, attitude and behaviour change50 are open to influence from health services, parents and peers. 51–53 Adolescence, in particular, is often characterised by increased risk-taking, lack of adherence to treatment regimens and a greater than normal deterioration in health status. 27,29,54–56 The importance of developing child- and young person-centred models that are developmentally appropriate and reflect the roles of parents and peers is increasingly being recognised. 31

Studies investigating the effectiveness of self-care support interventions designed for children and young people suggest positive effects on health status, QoL, self-efficacy, condition-related knowledge and coping. 31,32,57,58 For some interventions, acceptability has also been demonstrated. Qualitative studies reveal that children, young people and parents all value the opportunities that group-based self-care support provide to interact with others in similar situations to themselves. Interventions that use e-health methods to deliver self-care support have been judged to be feasible and applicable. 31,32

Yet, despite a developing body of evidence on the clinical effectiveness of self-care support interventions for children and young people, key knowledge gaps remain. There has been insufficient synthesis of quantitative data on health-care utilisation and the comparative effectiveness of different self-care support strategies. Previous reviews and meta-analyses have focused almost exclusively on intermediate or clinical outcomes, and rigorous evaluations of the cost-effectiveness of self-care interventions and their impact on health-care utilisation are lacking. Moreover, existing reviews do not explore associations between content and outcomes; they typically treat outcomes and costs as separate concepts and rarely have an explicit focus on the joint effects of outcomes and costs. This makes it difficult to identify technically efficient interventions capable of reducing unnecessary health-care use [such as avoidable emergency department (ED) visits and hospital admissions] without potentially compromising children and young people’s health.

Assessing the efficiency of self-care support

Commensurate with trends in the adult population, long-term physical and mental health conditions in children and young people are increasing. 59–61 Self-care support offers these young people and their families the opportunity to work collaboratively with professionals, actively participate in health-care decision-making and ensure that care is personalised to their needs. An implicit assumption underlying the use of self-care support is that it can successfully shift LTC management from health services to the patient, avoid unnecessary crises and prevent more extensive health services utilisation by managing patients’ problems more effectively. This has the potential to improving patient outcomes while simultaneously reducing resource utilisation and costs.

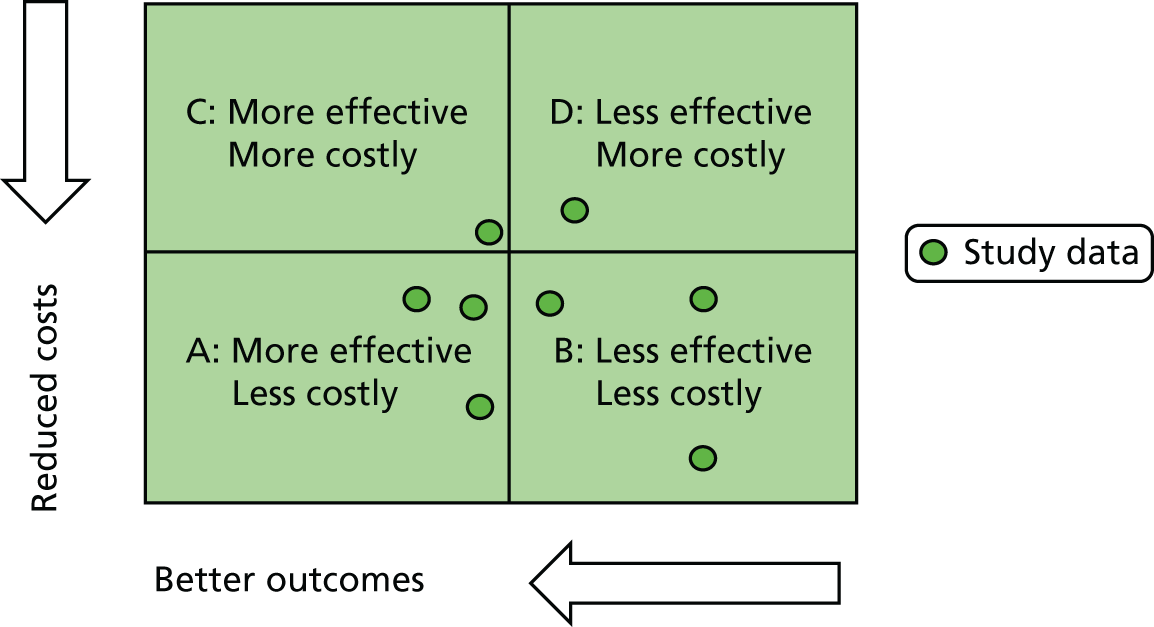

In health care, resource utilisation typically refers to as the number and type of health-care resources or services that are used, for example health professionals’ time, medicines, diagnostic tests/investigations and treatment appointments. Each aspect of resource utilisation incurs a cost. Rigorous and comprehensive evaluation of the effects of self-care support for children and young people thus demands concurrent evaluation of patient outcomes and health-care costs. As shown in Figure 2, plotting these effects against each other can identify models of self-care that are able to reduce costs without comprising outcomes for children and young people (quadrant A) and distinguish these from models that reduce both outcomes and costs (quadrant B), or improve outcomes at increased cost (quadrant C).

FIGURE 2.

Example matrix showing effects on utilisation and outcomes. Adapted from Panagioti et al. 26 Contains information licensed under the Non-Commercial Government Licence v2.0.

Systematic reviews and meta-analyses bear witness to the number of trials of self-care support for children and young people that have been conducted. Although not always designed to enable a full economic analysis, many present sufficient data to enable the intervention to be placed on the cost-effectiveness plane. Systematic synthesis of these data is required to inform evidence-based decision-making and the commissioning of high-quality, technically efficient services.

Review aim

The review reported here aimed to take account of health-care utilisation and costs in conjunction with health outcomes to provide evidence-based guidance on the provision of cost-effective self-care support for children and young people with long-term physical and mental health conditions.

Our objectives were to:

-

identify and integrate into one data set, eligible data from existing reviews on the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of self-care support interventions for children and young people with long-term physical and mental health conditions

-

update and expand existing search strategies to increase their sensitivity to a broader range of measures of health-care utilisation in children and young people

-

conduct a quantitative systematic review of the available evidence to identify those models of self-care support for children and young people that are associated with reductions in health services utilisation and cost, without compromising health outcomes

-

provide evidence-based recommendations for service commissioners regarding the optimal delivery models for self-care support interventions

-

provide key recommendations for research funding bodies on future research priorities.

Chapter 2 describes the review methods.

Chapter 2 Review methods

The review reported here was a quantitative systematic review that sought to answer three key questions:

-

What models of self-care support are associated with significant reductions in health-care utilisation without compromising health outcomes for children and young people with LTCs?

-

What are the key recommendations for service commissioners regarding the delivery of self-care support for LTCs in children and young people?

-

What are the priorities for research funding bodies regarding self-care support in children and young people?

Our review was conducted in line with current systematic review guidance. 62,63

Study eligibility criteria

Studies were assessed for inclusion in the review according to a standard set of eligibility criteria. These criteria are summarised in Box 1 and described in full below.

Children and young people aged 0–18 years with a long-term physical health condition evidenced through clinical diagnosis, contact with health services or scores above clinical cut-off points on validated screening measures.

InterventionSelf-care support delivered in a health, social care or educational setting.

ComparatorUsual care, including more intensive usual care (e.g. clinic or inpatient management).

OutcomesGeneric, HRQoL, or disease-specific symptom measures or events and health service utilisation (i.e. hospital visits and admissions, additional service use and costs).

DesignRandomised trials, non-randomised trials, CBAs, ITS designs.

Exclusion criteriaAt-risk populations or preventative interventions; self-care interventions lacking active support (e.g. pure self-care, passive instruction); intermediate health outcomes (e.g. self-efficacy, HbA1C levels, FEV recordings) and health outcomes of adult caregivers.

CBA, controlled before-and-after study; FEV, forced expiratory volume; HbA1c, glycated haemoglobin; HRQoL, health-related quality of life; ITS, interrupted time series.

Population

We defined children and young people as individuals aged < 18 years. Although the transition to adult services is not always immediate and key elements of development may continue beyond 18 years of age, this cut-off point aligned with our earlier reviews on the clinical effectiveness of self-care support interventions for children and young people. In accordance with the inclusion criteria of our previous reviews, we included studies with participants aged up to 25 years as long as the mean age of the sample, and/or the majority of participants, remained under the age of 18 years.

We restricted our review to LTCs. To be eligible for inclusion in the review, participants were required to have a diagnosis of a LTC, defined through clinical assessment, contact with health services or symptom scores above clinical cut-off points on validated screening instruments. We excluded preventative studies that looked at a population at ‘high risk’ of developing a LTC.

There is no definitive list of LTCs and hence we adopted the Department of Health’s generic definition of a LTC as one ‘that cannot be cured but can be managed through medication and/or therapy’. 11 We included studies recruiting patients with a mix of LTCs.

Both mental and physical health conditions were eligible for inclusion in the review. This included common conditions such as diabetes, asthma, coronary heart disease, depression, anxiety and psychosis. Comprehensive lists of eligible conditions are provided in Box 2. In line with the views of our patient and public involvement (PPI) advisory panel, we excluded autism spectrum disorder, intellectual disabilities, substance misuse (unless comorbid with another LTC) and cancer in long-term recovery or remission, as these conditions were deemed to fall outside our working definition of a long-term physical or mental health condition.

Asthma, diabetes, congenital heart disease, stroke, musculoskeletal disorders, epilepsy, chronic fatigue syndrome, sickle cell disease, cleft palate, cystic fibrosis, chronic skin conditions, inflammatory bowel disease, thalassaemia, HIV infection/AIDS.

Mental healthConduct disorder, ADHD, anxiety (including panic), phobia, school refusal/phobia, depression, OCD, traumatic stress (PTSD), self-harm, psychosis including schizophrenia, eating disorders (including anorexia and bulimia).

Ineligible for the reviewAutism spectrum disorder, intellectual disabilities, substance misuse, cancer in long-term recovery or remission, obesity.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder; AIDS, acquired immunodeficiency syndrome; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; PTSD, post-traumatic stress disorder.

Interventions

Self-care can be defined in different ways according to who engages in the self-care behaviour (e.g. individual, family, community) and the intervention context (e.g. health promotion, illness prevention, illness impact limitation or restoration of health). To meet the definition of self-care support, an intervention needs to include an agent other than the self, typically a health professional, peer group, voluntary sector representative or information technology platform.

The goal of self-care support has previously been defined as the enablement of patients to perform three discrete sets of tasks: medical management of their condition (e.g. taking medication); carrying out normal roles and activities; and managing the emotional impact of their condition. 64 For the purposes of our review, we defined a self-care support intervention as:

. . . any intervention primarily designed to develop the abilities of children and young people (and/or their adult carers) to undertake management of their long-term health condition through education, training and support to develop their knowledge, skills or psychological and social resources.

Example categories of self-care support of relevance to this review are outlined in Box 3. We included all formats and delivery methods for self-care support (e.g. group or individual, face to face or remote, professional or peer led). Interventions delivered in health, social care, educational or community settings were included. Interventions that targeted the child or young person, or their adult caregiver, were included.

Education or training, for example disease-specific education or behaviour change interventions for CYP and/or their adult caregivers. Education or training may be delivered online, paper based, face to face or through audio/visual technologies.

Decision support, for example support to help CYP and their families to make decisions about their treatment options.

Monitoring and feedback, for example real-time telephone or computer-based monitoring methods, with active monitoring from professionals, feedback response and potential access to a wider care team.

Environmental adaptations, for example supported living equipment or home modification.

Collaborative care planning, for example discussion and negotiation between professionals and CYP and/or their adult caregivers regarding illness and care management and goals.

Psychological support, for example face-to-face or online peer support, or formal counselling/therapy from a health professional.

CYP, children and young people.

Written action plans, developed in collaboration with children and young people or their families, were eligible for the review, but were excluded if there was no evidence of self-care discussion or negotiation. Self-care support, by definition, is designed to offer a more participatory approach to health care, with patients making a critical contribution to achieving health gain and making decisions to ensure that their care is personalised to their needs. We excluded all interventions where the target of the intervention was not actively engaged and/or remained a passive recipient of knowledge or instructions.

We excluded self-care undertaken without any input, guidance or facilitation by services. Although self-care can be, and often is, undertaken without service support, it is rarely the subject of intervention studies. We excluded studies where the effects of self-care support could not be distinguished from broader interventions for LTCs. We excluded studies evaluating service development or quality improvement initiatives in which self-care support was not the predominant component of the intervention.

Comparators

We included studies in which a self-care support intervention was additional to usual care and compared against usual care alone, or in which a self-care support intervention was compared against a more intensive usual care intervention (e.g. home- vs. clinic-based monitoring). We excluded studies in which two versions of self-care support were compared and the two interventions were of comparable intensity and content, because such comparisons did not allow for an assessment of the impact of self-care support per se.

Outcomes

To meet our research objectives, we required evidence of effectiveness of validated self-care support to reduce health-care utilisation without compromising children and young people’s outcomes. We restricted our analysis to studies of self-care support that reported quantitative data on patient outcomes and health-care utilisation, as these were the only studies that could answer our brief.

Eligible patient outcomes included standardised measures of health-related or generic QoL or disease-specific symptom measures or events. We excluded intermediate outcomes and measures of psychological or clinical variables that did not provide an assessment of subjective health status or QoL [e.g. self-care behaviours, self-efficacy, glycated haemoglobin (HbA1C) levels or forced expiratory volume recordings]. In adult populations, such variables are known to be unreliable indicators of health-related quality of life (HRQoL). 65 We extracted data on the health outcomes of the child/young person and excluded the health outcomes of adult caregivers.

Eligible outcomes for health-care utilisation comprised data on hospital visits and admissions, emergency care, primary care visits, other scheduled or unscheduled health-care use, patient costs and total costs. Our primary foci were comprehensive measures of health service costs (i.e. summed totals of multiple sources of cost) and/or major cost drivers (i.e. hospital admissions). Other, more minor, costs (such as medication use) were identified but not formally analysed. The rationale for this is discussed further in Data preparation and analysis.

Design

We included randomised controlled trials (RCTs), non-randomised controlled trials (nRCTs), controlled before-and-after studies (CBAs) and interrupted time series designs, as defined according to the Effective Practice and Organisation of Care (EPOC) criteria63 (Box 4). UK and non-UK studies were included. Translation of non-English-language studies was undertaken.

Investigators allocate participants to the different groups that are being compared using a method that is random. Randomisation ensures that participants in each comparison group should differ only in their exposure to the intervention. Randomisation can occur at an individual or cluster (site/region) level.

Non-randomised controlled trialsInvestigators allocate participants to the different groups that are being compared using a method that is not random.

Controlled before-and-after studiesDecisions about allocation to the different comparison groups are not made by the investigators. Outcomes of interest are measured in both the intervention and control groups before the intervention is introduced and again after the intervention has been introduced.

Interrupted time series designProvides a method of measuring the effect of an intervention when randomisation or identification of a control group are impractical. Multiple data points are collected before and after the intervention and the intervention effect is measured against the pre-intervention trend.

Search methods

In accordance with the review protocol, our search strategies included electronic database searches, reference list searches, targeted author searches and forward citation searching.

Electronic databases

We began the process of identifying eligible studies by checking published reviews, including those previously undertaken by the research team. 26,31,32 We complemented our searches of existing reviews with a primary search of multiple electronic databases, conducted in March 2015.

We updated and expanded our existing search strategies to ensure that they were sensitive to a broad range of health-care utilisation beyond formal cost-effectiveness analyses. Search terms relating to the key concepts of the review were identified by scanning the background literature and browsing the MEDLINE medical subject heading thesaurus, and through discussion with collaborating colleagues at the University of York’s Centre for Reviews and Dissemination.

A search strategy was developed in MEDLINE, using an iterative approach tested against a set of 15 studies known to be relevant to our review. This MEDLINE search strategy was adapted to run on all other databases designated in our protocol.

Electronic searches were undertaken on the following health and allied health databases:

-

MEDLINE (accessed 18 March 2015 via OvidSP; www.ovissp.ovid.com)

-

EMBASE (accessed 18 March 2015 via OvidSP; www.ovissp.ovid.com)

-

PsycINFO (accessed 17 March 2015 via OvidSP; www.ovissp.ovid.com)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL; accessed 19 March 2015 via EBSCOhost; www.search.ebscohost.com)

-

ISI Web of Science, including Social Sciences Citation Index (SSCI) and Science Citation Index Expanded (accessed 19 March 2015 via Web of Science; www.wos.mimas.ac.uk)

-

NHS Economic Evaluation Database (NHS EED) (accessed 18 March 2015 via Wiley Online Library)

-

The Cochrane Library, including Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (CDSR), Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) and Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (accessed 18 March 2015 via Wiley Online Library)

-

Health Technology Assessment database (accessed 18 March 2015 via Wiley Online Library)

-

Paediatric Economic Database Evaluation (PEDE) (accessed 31 March 2015 via http://pede.ccb.sickkids.ca/pede/index.jsp)

-

the IDEAS database of economic and finance research (accessed 31 March 2015 via http://ideas.repec.org).

All databases were searched from inception. No language or design restrictions were applied. Full details of the search strategies, search terms and the specific dates of individual searches are reported in Appendix 1.

Additional search strategies included scanning the bibliographies of all relevant retrieved articles, targeted author searches (for additional publications and/or unpublished data identified in conference abstracts) and forward citation searching. No studies were identified that had not been retrieved by other means.

Changes to the search protocol

All searches were conducted as specified in the original review protocol with the exception of the Health Economic Evaluations Database (HEED). HEED ceased publication prior to study commencement and was not searched as part of the final review. Coverage of the relevant economic evidence base was ensured through searches of the NHS EED, the Health Technology Assessment database, the PEDE and the IDEAS database of economic and finance research. The potential impact of this protocol change was judged to be minimal.

Study screening and selection

With the exception of the IDEAS database, all records retrieved from the electronic searches were imported into a bibliographic referencing software program (EndNote X5; Thomson Reuters, CA, USA) and duplicate references identified and removed. Review screening and eligibility judgements were managed in Covidence systematic review software (Veritas Health Innovation, Melbourne, VIC, Australia). Pairs of reviewers independently screened all titles and abstracts for eligibility using prespecified inclusion criteria described below. Additional economic abstracts located through IDEAS were managed as hard-copy records and independently screened for eligibility by two reviewers using identical eligibility criteria.

To be eligible for full-text screening, search records (titles and abstracts) had to fulfil three initial inclusion criteria:

-

RCT, nRCT or eligible quasi-experimental design

-

children or young people with a LTC as participants/possible participants

-

a potential self-care support intervention.

Where both reviewers agreed that the studies did not meet these criteria, studies were excluded from the review. When both reviewers agreed on inclusion, or when there was conflict, full-text articles were retrieved for review. All studies without abstracts were retained for full-text screening unless they could be reliably excluded on the basis of their title alone.

Two reviewers independently assessed all full-text articles against the review’s full list of eligibility criteria (see Box 1). Any remaining disagreements were resolved by third party discussion.

Data extraction and quality assessment

Data extraction used prespecified data extraction sheets designed and piloted specifically for this study. We extracted data on the study author, year of publication, study design and setting, and relevant characteristics of the population, intervention(s), comparison(s) and outcomes reported. We separately extracted data on the methods and economic perspective used in the subset of studies reporting formal cost-effectiveness, cost–utility or cost–benefit analyses. Where available, we extracted published data on the ‘reach’ of self-care interventions, defined according to Reach, Effectiveness, Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance (RE-AIM) guidance. 66 Intervention reach was defined in terms of (1) the proportion of eligible patients who did not take part in the study; and (2) the presence or absence of LTCs additional to the index condition in the study exclusion criteria.

Data extraction for study context was undertaken by one reviewer and independently verified by a second reviewer. Study outcomes were extracted independently by two reviewers using separate outcome extraction sheets. Discrepancies in the extracted data were resolved by referral to the original studies and, where necessary, arbitration by a third reviewer.

Where multiple outcomes were reported by the same study, we used a decision rule to determine, in advance, the most relevant outcome for meta-analysis. Our priority was on children and young people’s own subjective assessment of QoL. Where this was not reported, we extracted, in order of priority, parent-reported QoL, patient-reported symptoms or parent-reported symptoms. If two or more outcomes of equal priority were available, we selected the one with most complete reporting and prioritised continuous over dichotomous data.

When there were multiple publications for the same study, data were extracted from the most recent and complete publication. In cases where the duplicate publications reported additional relevant data, these data were also extracted.

Methodological quality appraisal

Methodological quality appraisals were undertaken by one reviewer and independently verified by a second reviewer. Studies were assessed for methodological quality using the Cochrane Collaboration Risk of Bias Assessment Tool for RCTs62 or the Cochrane guidance for non-randomised designs. 62 Economic studies were assessed using a critical appraisal checklist for economic evaluations. This checklist was based on Drummond’s checklist for assessing economic evaluations67 and was adapted to capture more fully the quality of economic evaluations in self-care support interventions (see Appendix 2).

Quality ratings for randomised studies were based on a dichotomous measure of allocation concealment (i.e. adequate or inadequate/unclear). Allocation concealment is the aspect of trial quality most consistently associated with treatment effect. 68,69 Other indicators may be less relevant in trials of behavioural interventions where participant, personnel and outcome blinding are often difficult to achieve.

Data preparation and analysis

The aim of our review was to establish which models of self-care support (if any) were associated with significant reductions in health service utilisation without compromising outcomes for children and young people with long-term physical or mental health conditions. To answer this question, studies needed to quantify the effect of an intervention on both costs and health outcomes.

Accurate placement of studies on a cost-effectiveness plane requires detailed data beyond a simple text description of statistical significance. We sought data that would enable the calculation of standardised effect sizes (ESs) for both health outcomes and costs. ES calculations are possible when primary research studies report appropriate statistics which can be translated into a common metric, such as a standardised mean difference. 70

We selected outcomes closest to a 12-month follow-up. Our choice of follow-up point was, to an extent, arbitrary, balancing analysis of longer-term effects with the consistency of data between studies. Continuous measures were translated to a standardised mean difference [the mean of the intervention group minus the mean of the control group, divided by the pooled standard deviation (SD)]. Outcomes were coded so that negative ESs always represented improvements for the intervention compared with control. Outcomes reported as dichotomous variables were translated to a standardised mean difference using the logit transformation.

We assumed a 70% follow-up from the number of participants randomised at baseline, where sample size could not be ascertained. This was an arbitrary imputation that sought to maximise the inclusion of data, using a value below that usually considered as an indicator of primary study quality (80%).

Where single parameters were missing (e.g. a SD), we imputed these where there was other comparable data in the review. We excluded studies that lacked data and where there were no other studies in the review to allow meaningful imputation. Calculation of ESs was not possible for all outcomes.

Measures of health-care utilisation (e.g. length of hospital stays) and costs can often demonstrate significant skew because many patients report low costs, but a small proportion can have disproportionately high levels of use. In line with other published reviews,26,71 we identified all outcomes where the SD multiplied by two was greater than the mean, as in these cases it is argued that the mean is not a good indicator of the centre of the distribution. 72

When studies reported multiple comparisons that were eligible for the same meta-analysis (e.g. two types of intervention vs. control), both comparisons were included, but sample sizes in the control group were halved to avoid ‘double counting’ of participants in the control group and thus inappropriate precision in the relevant meta-analysis. This method assumed independent ESs. We conducted the sample size modification in all cases where a study included two or more intervention groups compared with control and where more than one of those intervention groups was included in the same meta-analysis.

A minority of self-care support trials (n = 10) used cluster allocation to reduce bias associated with contamination. We identified cluster trials and adjusted the effective sample size (and thus the precision) of these comparisons using methods recommended by the EPOC group of the Cochrane Collaboration. 63 We assumed an intraclass correlation of 0.02.

Where sufficient data were reported for particular comparisons, and when populations and interventions were considered sufficiently homogeneous, we pooled effects. We pooled QoL and subjective symptom measures and did not explore differences in the effects of self-care support observed with different outcome measures.

Owing to marked heterogeneity in the interventions and outcomes, meta-analyses used random-effects modelling, with the I2 statistic to estimate heterogeneity. 73 We labelled ESs as minimal (an ES of < 0.2), small (an ES of 0.2 < 0.5), moderate (an ES of 0.5 < 0.8) or large (an ES of ≥ 0.8) and levels of heterogeneity as ‘low’ (I2 statistic 1–25%), ‘moderate’ (I2 statistic 26–74%) or ‘high’ (I2 statistic ≥ 75%). These categorisations are arbitrary distinctions. However, caution should be applied in the interpretation of pooled effects in meta-analyses where heterogeneity is ‘high’.

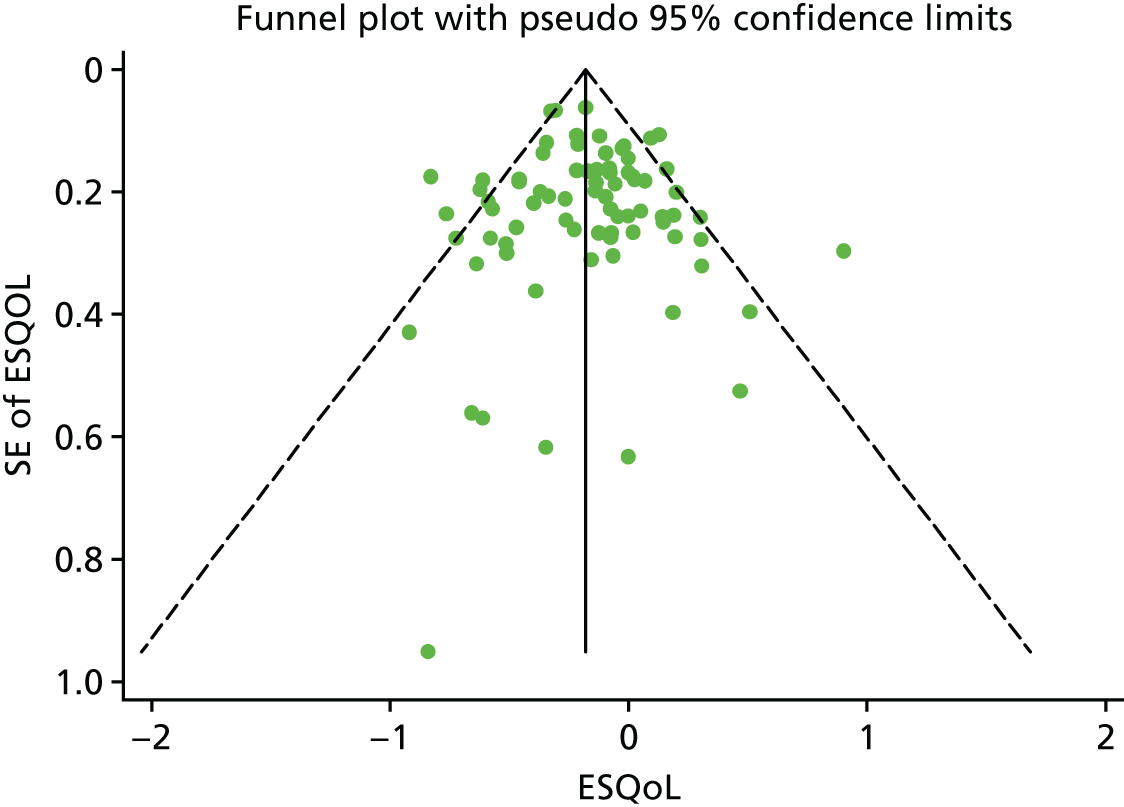

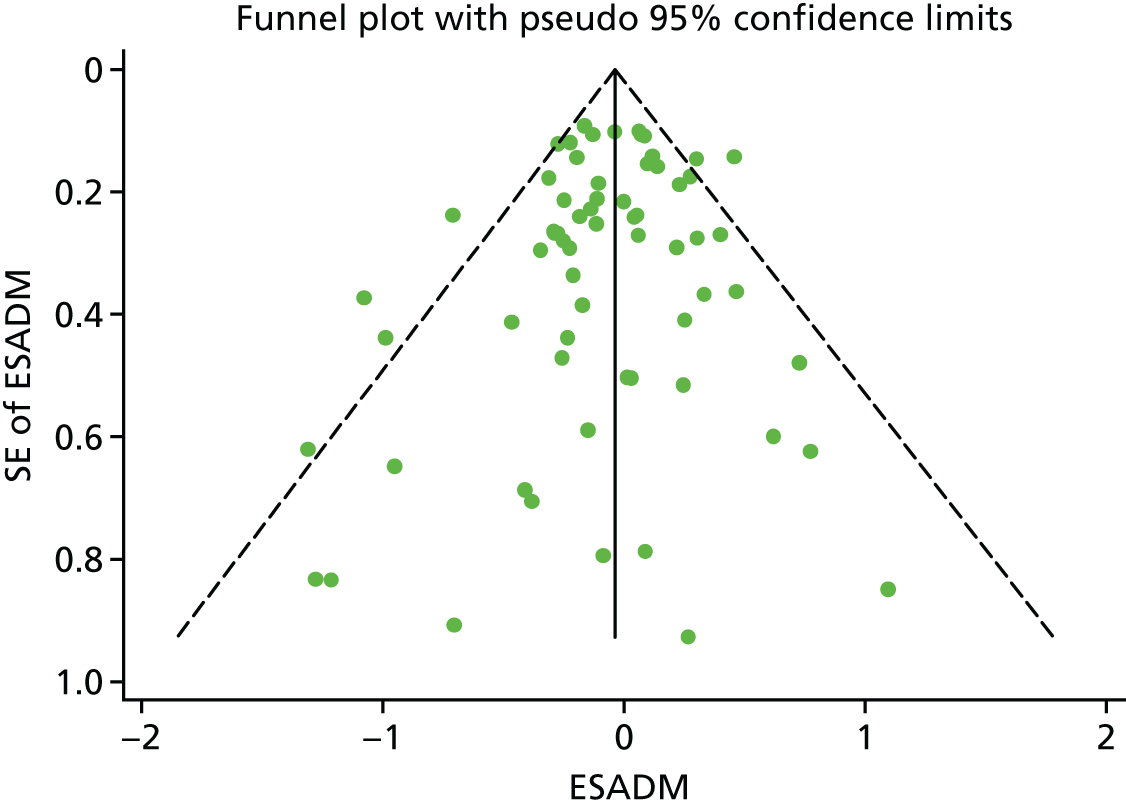

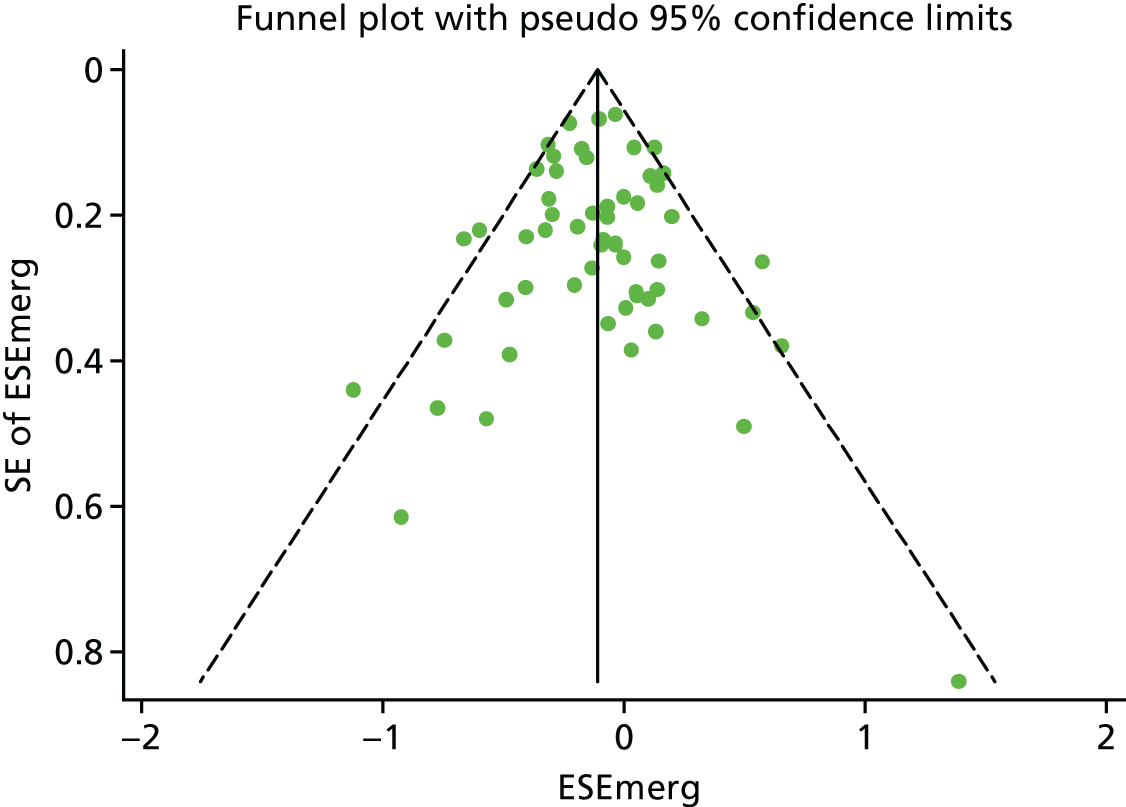

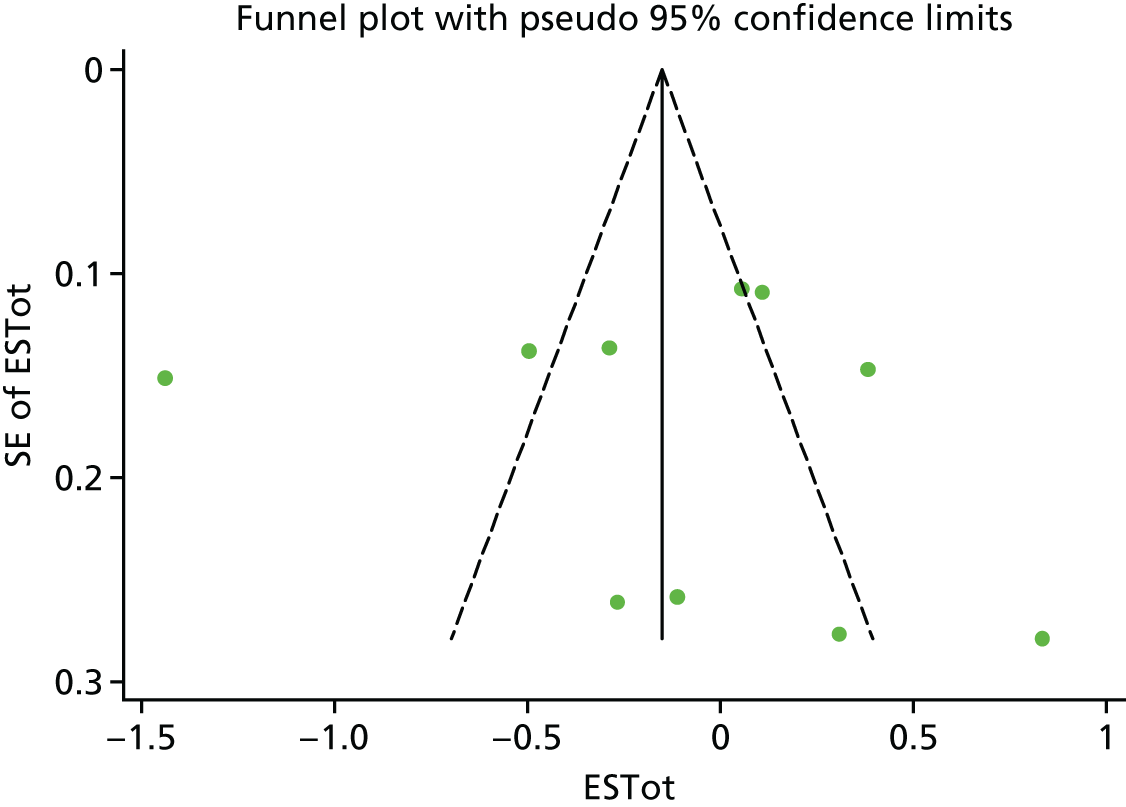

Small study bias

Funnel plots74 using standard errors75 and associated regression tests were used to explore small-study bias where sufficient data were available. The purpose of a funnel plot is to map standardised ESs from individual studies against their standard error (i.e. the underlying precision of the observed effect). A funnel plot is based on the premise that precision in an ES estimate will increase as sample size increases. Effect estimates from smaller studies with larger standard errors should, therefore, scatter more widely at the bottom of the plot. Larger studies with smaller standard error should display a narrower spread. Bias is suggested by an asymmetrical plot and statistical testing of a potential relationship between treatment effect and precision. An absence of smaller studies without statistically significant effects is an indicator of potential publication bias. In this situation, the effect calculated in a meta-analysis may overestimate the intervention effect.

Changes to the analytical protocol

Our analysis was designed to consider the ability of models of self-care to reduce health-care costs without compromising patient outcomes. Our primary analysis was on total costs. Our protocol stipulated that our secondary analyses would, where data allowed, consider all other major types of resource use and cost. This included inpatient, outpatient, primary care, community care and patient out-of-pocket expenditures.

Meaningful analysis requires that sufficient, comparable data are reported across the primary studies. Lack of consistent measurement and ambiguity in some of the outcomes that were reported prevented accurate demarcation of primary, secondary and community health-care costs. More usually, outcome data were presented as urgent (non-scheduled) compared with scheduled service use. Definitions of scheduled resource use varied according to illness type and context.

Our PPI advisory panel identified hospital admissions, ED visits and patient and families’ out-of-pocket expenses as the three outcomes that they would like to be prioritised in our review. An insufficient number of studies reported out-of-pocket expenses. Our secondary analyses thus focused on hospital admissions and ED use.

Hospital use represents a significant driver of total costs in most health-care systems. However, focusing on a single source of utilisation leaves the analysis vulnerable to cost shifting, where any benefits found in terms of reduced hospital use may mask increased costs elsewhere in the health-care system (such as in community care). Our primary analysis thus remained focused on total costs.

Data presentation

We present the results of included studies according to a permutation plot (see Chapter 1, Figure 2). The permutation plot presents data from all studies reporting both outcomes (i.e. QoL and total costs, QoL and hospital admissions, and QoL and emergency care). Each plot shows the pattern of results at the level of the individual study and gives a visual impression of the distribution of studies across the cost-effectiveness plane. The plot distinguishes between studies in the appropriate quadrant (i.e. those that reduce costs without compromising outcomes), from those in problematic quadrants (i.e. those that reduce costs but also compromise outcomes, or those that compromise both outcomes and costs).

We analysed data for included studies as a whole and then conducted meaningful subgroup analyses. A priori subgroup analyses were conducted for level of evidence quality (defined as the adequacy of allocation concealment) and the age of the children and young people. Subgroup analyses for age classified studies according to whether they delivered self-care support to children (aged < 13 years), adolescents (aged ≥ 13 years) or a mixed child–adolescent age group.

Additional subgroup analyses were conducted for the type of LTC and the setting and type of self-care support intervention that was evaluated (i.e. intervention target, format, delivery method and intensity). The subgroups that we used for these preplanned analyses were determined post hoc, based on the nature and distribution of the evidence.

Post hoc classification by long-term condition

We grouped different LTCs post hoc into four conceptually and clinically relevant categories. These categories were asthma, other (non-asthma) physical health conditions, behavioural disorders and mental health.

Our a priori intention was to also aggregate data across subtypes or ‘clusters’ of conditions, based on a similar typology to that developed by the Practical systematic RevIew of Self-Management Support for long-term conditions (PRISMS) study for adults with LTCs. 26 We did not aggregate our data in this way, as all but four studies focusing on behavioural disorders fell into the same condition cluster (cluster 1: LTCs with marked variability in symptoms over time).

Post hoc classification by intervention type

Existing typologies of self-care support for children and young people with LTCs highlight the importance of considering different aspects and characteristics of the intervention, including its target, location, facilitation and delivery methods. 31

We conducted subgroup analyses based on intervention target (child and/or young person, adult or both), format (individual, group or mixed) and delivery method (face to face, remote or mixed model). We also conducted subgroup analyses on intervention setting, defined as inpatient, outpatient/clinic, school or community, home or mixed location.

In line with our previous review of self-care support for adults with LTCs,26 we included interventions across the spectrum of care and distinguished post hoc between the different intensities and types of self-care support that were provided.

We used a similar approach to classify intervention intensity as we used in our previous review, with post hoc amendments to accommodate the level and type of intervention descriptions provided in our primary studies. Our final classification system was informed and approved by our PPI advisory panels and distinguished between four different categories of self-care support:

-

‘Pure’ self-care support for interventions providing self-care support through a stand-alone resource (e.g. interactive mobile application or educational online program).

-

Facilitated self-care support for interventions providing fewer than four sessions or < 2 hours of face-to-face or remote self-care support. Support is provided by a designated self-care agent (e.g. health professional or peer) and usually targets a single group (e.g. children or parents). The support provided will often be (but is not limited to) self-care education, feedback or care plan review.

-

Intensively facilitated self-care support for interventions providing regular and repeated contact exceeding more than four sessions or 2 hours’ support in total. Support is provided by a designated self-care agent health professional or peer and often targets multiple groups (e.g. children and parents or children and teachers). The support provided will often be multifaceted and may include some co-ordination of a patient’s primary or standard care.

-

Case management for interventions providing more than four sessions or 2 hours of additional support from a designated agent, with additional support from a multidisciplinary team and explicit referrals or care co-ordination as part of the intervention protocol.

Two authors independently assessed the type, and content, of each self-care support intervention. Disagreements were identified and resolved via team discussion.

Changes to the review protocol

The review protocol is available as part of the PROSPERO database: A Rapid Evidence synthesis of Outcomes and Care Utilisation following Self-care support for children and adolescents with long-term conditions (REfOCUS): reducing care utilisation without compromising health outcomes (registration number CRD42014015452). We have been explicit about any deviations from the published protocol in the relevant sections of this report. Deviations of the review from the protocol published in PROSPERO are summarised in Box 5.

We will search specialist economic databases including the NHS EED, the HEED, the Health Technology Assessment database, the PEDE and the IDEAS database of economic and finance research.

-

The HEED was not searched as part of the final review.

We will structure our synthesis according to the LTCs prioritised by previous reviews (i.e. diabetes, asthma, cystic fibrosis, anxiety and depression). We will include other LTCs in our synthesis where we identify eligible economic evidence (e.g. epilepsy, juvenile idiopathic arthritis, ADHD, eating disorders and self-harm).

-

We structured our synthesis according to the availability of data. We grouped studies in a way that was conceptually and clinically relevant.

Our primary analysis will be on total costs. We will repeat this analysis for all major types of costs (e.g. inpatients, outpatients, primary care, community care and out-of-pocket expenditure).

-

As stipulated, our primary analysis was on total costs. We only conducted secondary analyses where data allowed and where the costs were sufficiently similar to make meta-analyses appropriate and interpretable. Our secondary analysis focused on hospital admissions and urgent care.

We will extract data to assist in the quality assessment of primary studies according to the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool criteria for RCT and nRCT designs.

-

In line with other published reviews, we restricted our assessment of risk of bias to allocation concealment, independently assessed by two members of the research team.

We intend to aggregate data at several different levels (i.e. within a condition, across subtypes or ‘clusters’ of conditions and across all conditions).

-

We aggregated data across all conditions and within four post hoc categories of LTCs. Data did not allow for meaningful aggregation at the level of condition clusters.

We will distinguish between groups of interventions differing in content (e.g. psychological support, skills training, health monitoring and feedback).

-

We classified interventions post hoc into four broad categories of intervention types. Insufficient data were available to enable meaningful analysis at the level that was originally specified.

ADHD, attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

Patient and public involvement

This review was conducted in collaboration with two PPI advisory panels: an adult panel composed of eight parents and health professionals working with children and young people with LTCs; and a children and young people’s panel composed of 12 young people living with a long-term physical or mental health condition. Panel members were recruited from local NHS trusts, children and young people’s physical and mental health services, user and carer organisations (e.g. YoungMinds, Asthma UK, Diabetes UK), allied organisations (e.g. the Mental Health Research Network’s Young Person’s Mental Health Advisory Group) and existing networks within the research team. All lay members were reimbursed for their time and travel expenses.

Four panel meetings were held for 1–2 hours on each occasion throughout the course of the review. Meetings took place on university premises and were attended by members of the research team. Two representatives from the children and young people’s panel attended the adult PPI panel meetings to provide a link between the two groups and ensure coherence and continuity in topic discussions.

The initial meeting for both panels was focused on establishing relationships, orientating panel members to the project, and developing and agreeing terms of reference for participation. The second meeting was led by the children and young people and was, at their own request, focused on developing a patient-centred logo and tagline for the project. The final logo and tagline, ‘Our Services, My Health’ were selected by PPI consensus and feature on all project resources and dissemination materials.

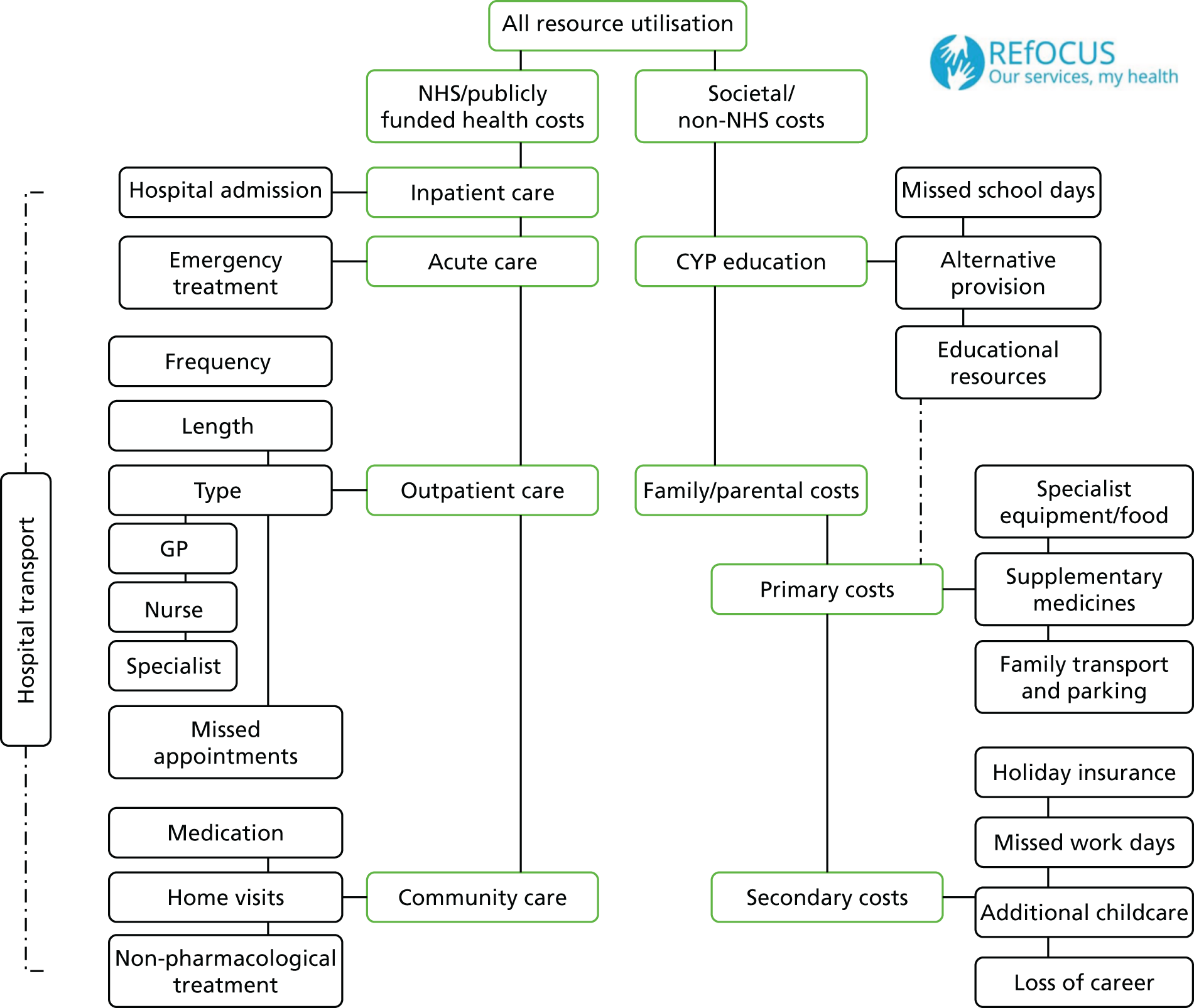

The third meeting was dedicated to developing the frameworks and priorities for the review. This process included PPI approval of the taxonomies used to classify self-care support interventions and the clusters of LTCs that fed through into the analyses. In collaboration with members of the research team, PPI panel members participated in an interactive discussion designed to explore lay interpretations of a systematic review simultaneously assessing patient outcomes and health-care costs. PPI panel members developed a framework depicting the impact of living with a LTC from the perspective of children, young people and their families (Figure 3). This was used to select meaningful patient-centred outcomes for extraction and analysis in the review and may be used to contextualise the remit and scope of this report within a broader sphere of the potential costs incurred by LTC management. This issue is discussed further in Chapter 4.

FIGURE 3.

Key determinants of resource utilisation in children and young people with long-term physical and mental health conditions: a PPI perspective. CYP, children and young people; GP, general practitioner.

At the fourth and final meeting, advisory panel members discussed the findings of the review and interpreted their meaning for services and for children, young people and their families. Panel members assisted in formulating and prioritising evidence-based recommendations for service commissioners and research funding bodies, ensuring that these remained relevant to stakeholder priorities. All recommendations arising from this review are detailed in Chapter 4.

Chapter 3 presents the review’s results.

Chapter 3 Results

Overview of the evidence base

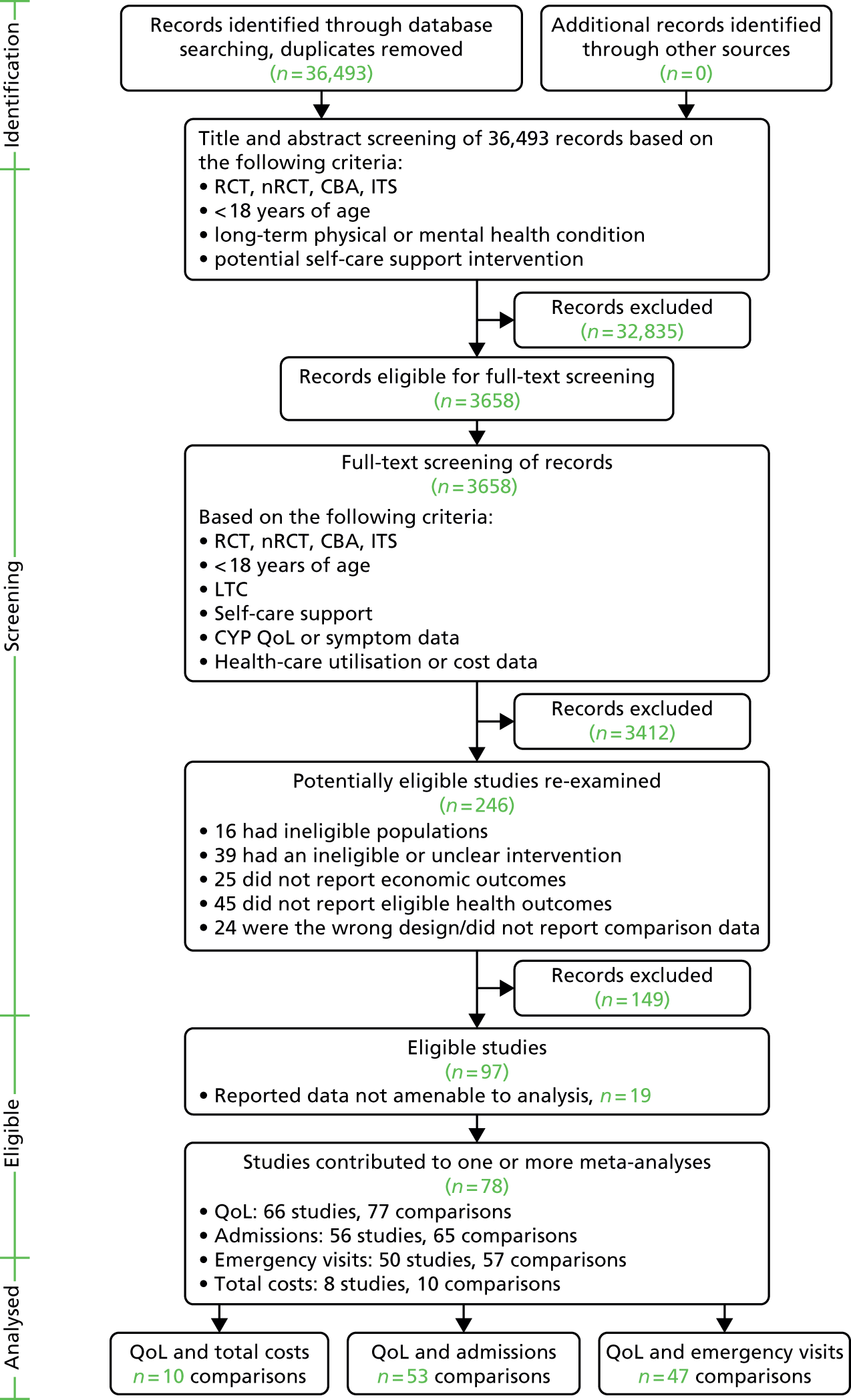

We screened 36,493 unique records for eligibility; 127 papers reporting on 97 studies were included. 20,21,76–200 Figure 4 presents the flow of studies through the review. A full list of the included studies and their study reference details is provided in Appendix 3. Excluded studies and the reasons for their exclusion are provided in Appendix 4.

FIGURE 4.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses flow diagram: flow of studies through the review. CYP, children and young people.

The included studies comprised 77 RCTs, 10 cluster RCTs, four nRCTs and six quasi-experimental (CBA) designs. Thirty-seven trials (38%) were rated as high quality (i.e. at low risk of bias) on the basis of adequate randomisation and allocation concealment procedures. Fourteen studies (14%) were conducted in the UK. Full details of the data extracted from individual studies (i.e. population characteristics, conditions, comparisons and design) are provided in Appendices 5–8 and summarised in Table 1. Formal economic analyses were reported by a subset of studies (n = 35, 36%). This subset is listed in Appendix 9, which provides detailed information on the design and quality of the economic analyses.

| Category | Characteristic | n (%) or mean (SD) |

|---|---|---|

| Study context | UK | 14 (14.4) |

| European | 18 (18.6) | |

| US/Canadian | 54 (55.7) | |

| Mixed/other | 11 (11.3) | |

| Baseline sample size | Mean (SD) | 215 (209) |

| Range | 10–1316 | |

| Quality rating | Adequate allocation concealment | 37 (38.1) |

| Population | Asthma | 66 (68.0) |

| Diabetes | 6 (6.2) | |

| Other physical health | 2 (2.1) | |

| Mental health | 18 (18.6) | |

| ADHD/behavioural difficulties | 5 (5.2) | |

| Children (aged 0–12 years) | 32 (33.0) | |

| Young people (aged 13–18 years) | 23 (23.7) | |

| Mixed children and young people | 42 (43.3) | |

| Mean (SD) CYP age (years) | 10.12 (3.9)a | |

| % CYP male | 53.4b | |

| Intervention contentc | Pure | 5 (4.3) |

| Facilitated | 26 (22.8) | |

| Intensively facilitated | 74 (64.9) | |

| Case managed | 9 (7.9) | |

| Intervention targetc | CYP | 32 (28.0) |

| Parents/adult caregivers | 9 (7.9) | |

| Mixed | 73 (64.0) | |

| Intervention settingc | Health (inpatient) | 6 (5.3) |

| Health (outpatient/clinic) | 49 (43.0) | |

| Home | 31 (27.2) | |

| School/community | 18 (15.8) | |

| Mixed | 10 (8.8) | |

| Intervention deliveryc | Face to face | 94 (82.5) |

| Remote | 13 (11.4) | |

| Mixed | 7 (6.1) | |

| Intervention formatc | Individual | 77 (67.5) |

| Group | 25 (21.9) | |

| Mixed | 12 (10.5) |

The vast majority of included studies recruited children and young people with physical health conditions (n = 77, 76%), predominantly asthma (n = 66, 68%). Long-term mental health conditions were also represented (n = 18, 19%), split between depression and anxiety (n = 6), psychosis or schizophrenia (n = 3), self-harm or suicide (n = 6) and eating disorders (n = 3). Most studies (n = 42, 43%) recruited across a broad age continuum (e.g. included both children and young people).

The majority of the interventions that were evaluated were intensively facilitated self-care support or case management, requiring more than four sessions or 2 hours of total contact from a health professional and/or other self-care agent. As might be expected in this population, the majority of interventions targeted adult caregivers, either together or in parallel with children and young people. Self-care support interventions were most typically delivered face to face to individuals or individual families, in either an outpatient setting or a patient’s home. Most studies delivered self-care support in addition to usual care and compared its effects with usual care alone.

Overall pattern of the results

Sixty-four studies, reporting on 77 comparisons, provided QoL outcome data in a form suitable for meta-analysis. The number of studies contributing data to a meta-analysis of health service costs was limited (n = 10 comparisons), restricting the utility of our primary analysis. A greater number of studies contributed data on hospital admissions (65 comparisons) and ED visits (57 comparisons), facilitating more meaningful interpretation of these outcomes (Table 2).

| Outcome | ES | 95% CI | I2 statistic (%) | Number of comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | –0.17 | –0.23 to –0.11 | 48 | 77 |

| Hospital admissions | –0.05 | –0.12 to 0.03 | 35 | 65 |

| Emergency visits | –0.11 | –0.17 to –0.04 | 38 | 57 |

| Total costs | –0.11 | –0.47 to 0.25 | 92 | 10 |

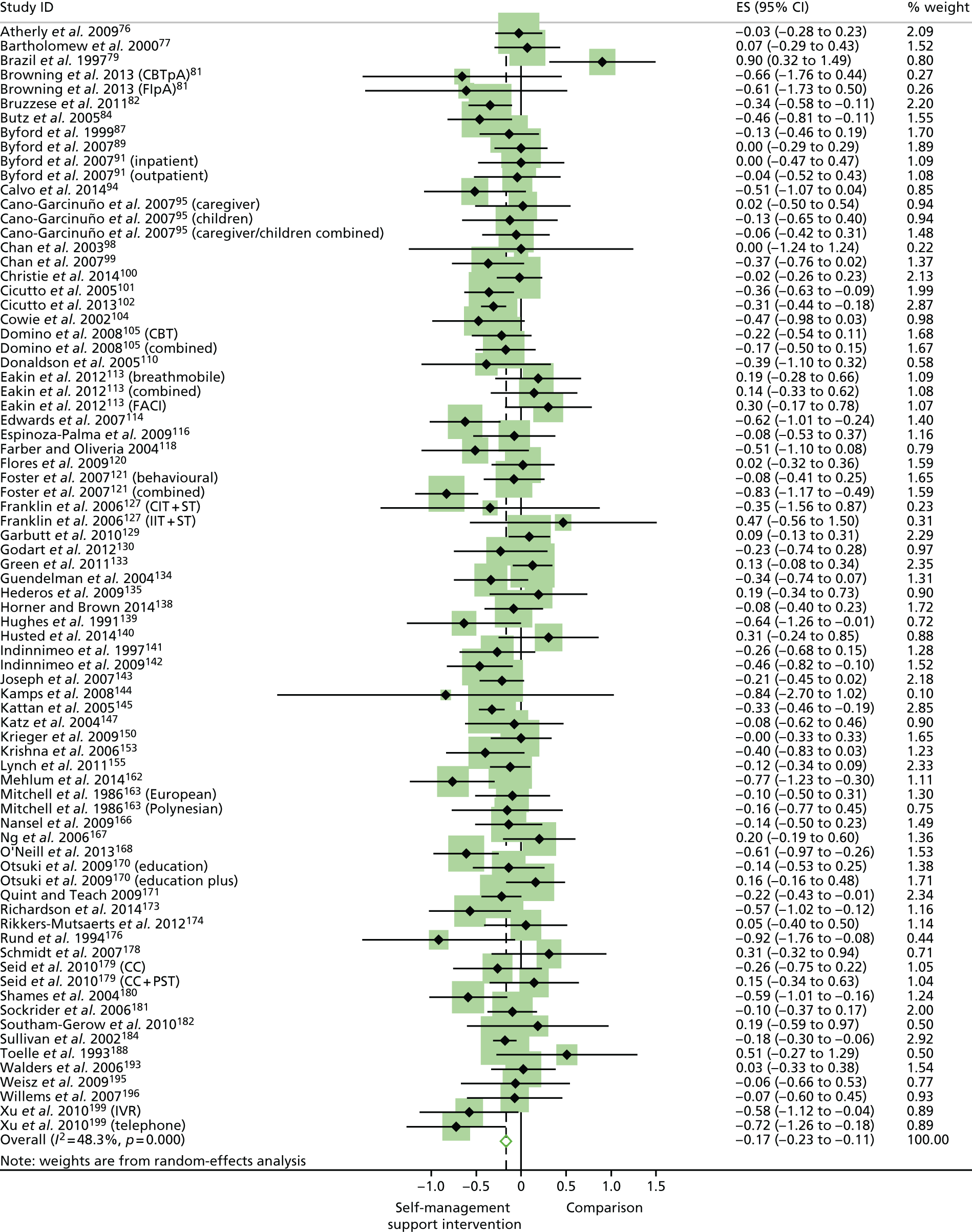

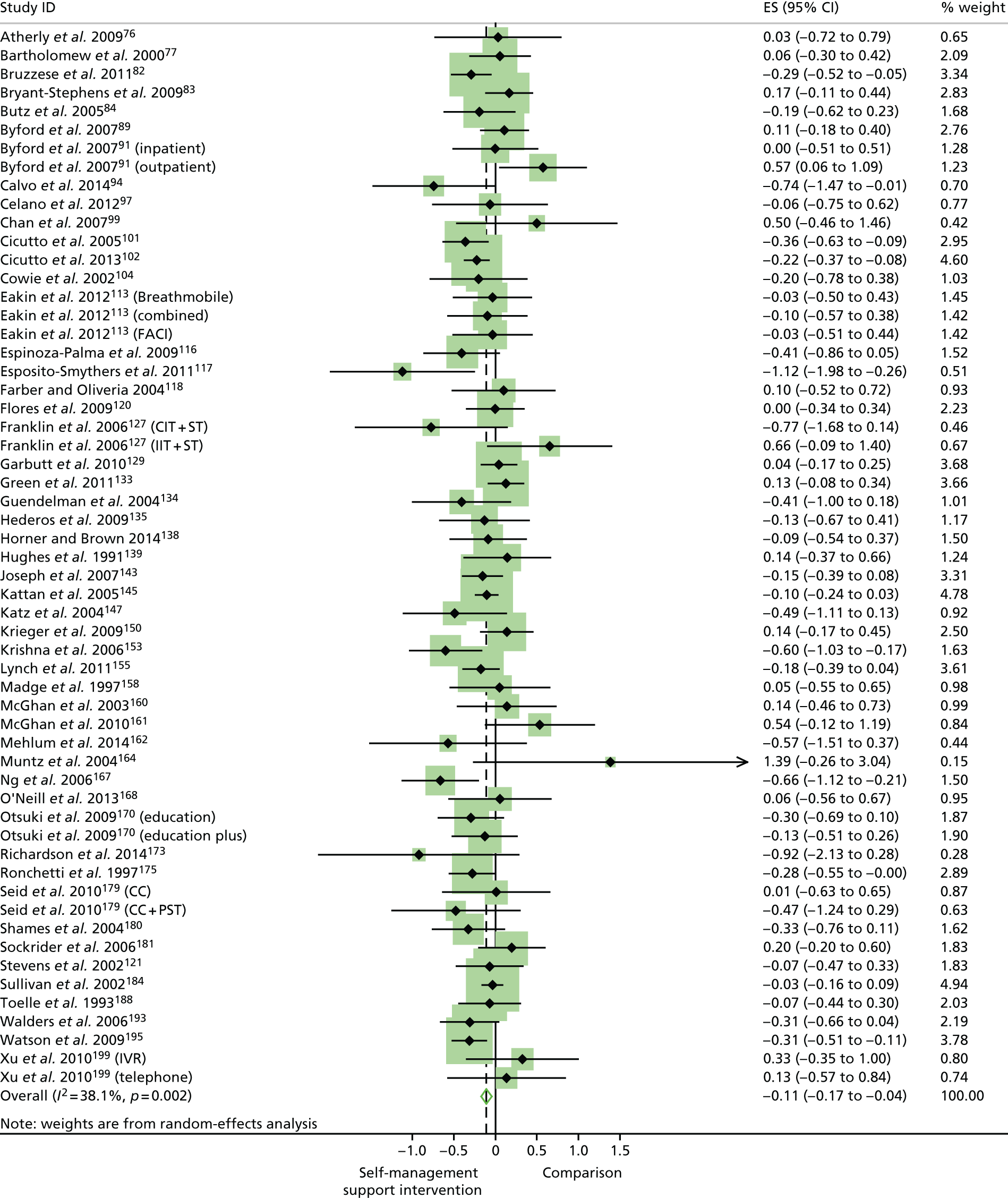

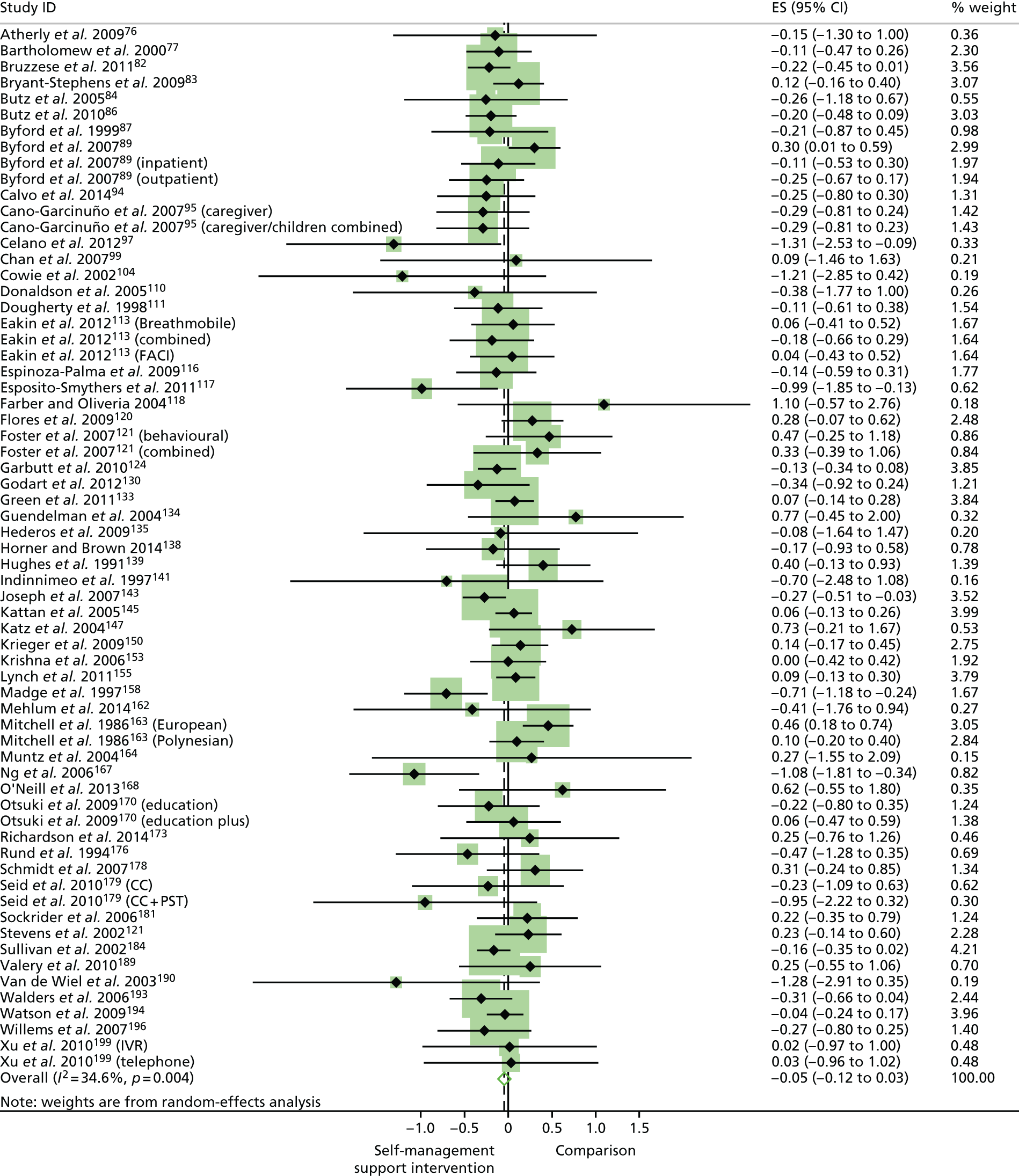

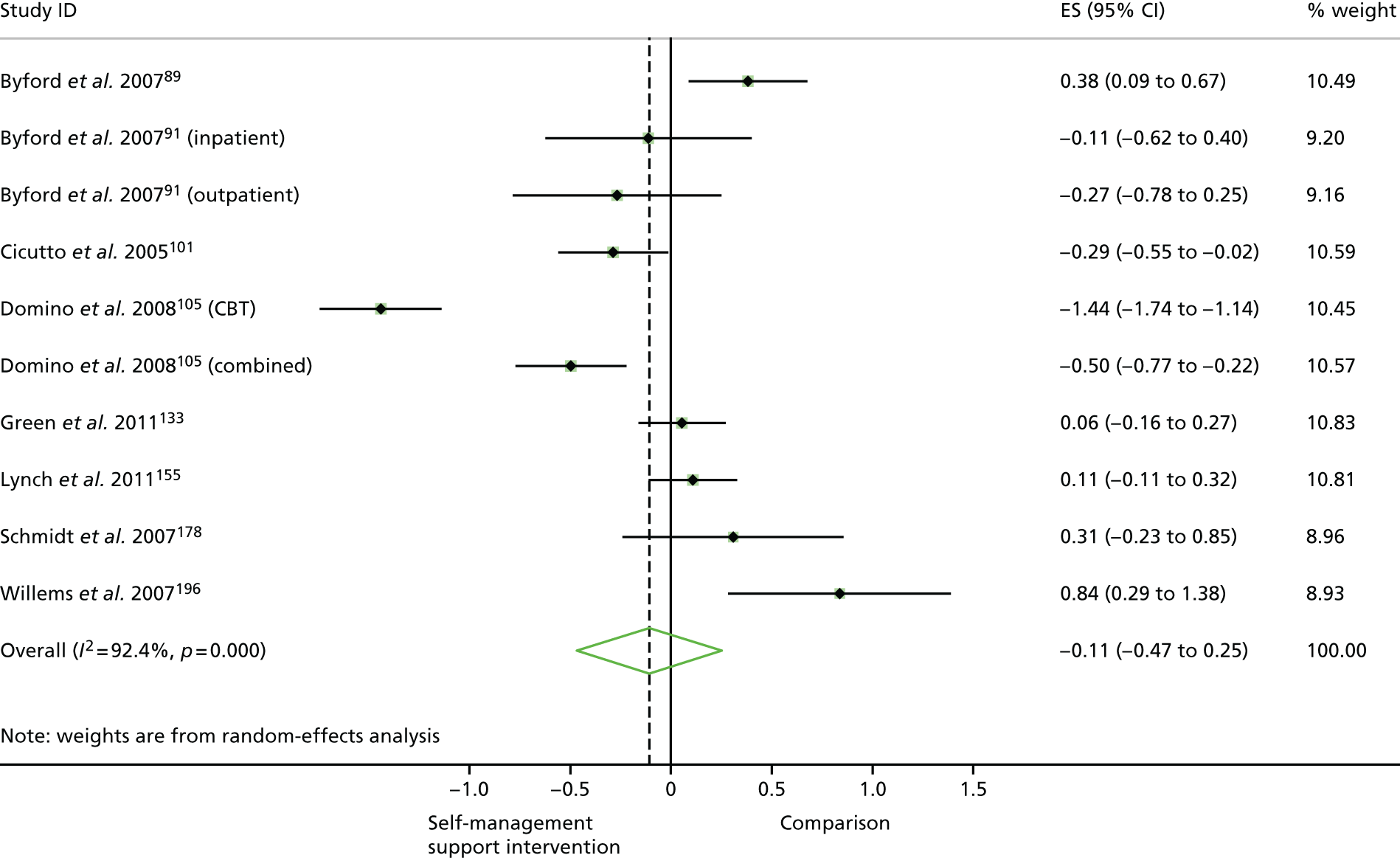

The meta-analysis of all study data demonstrated that self-care support was associated with statistically significant but minimal improvements in QoL [ES –0.17, 95% confidence interval (CI) –0.23 to –0.11], with moderate variation across trials (Figure 5). Self-care support was associated with minimal but statistically significant reductions in ED use (ES –0.11, 95% CI 0.17 to 0.04) (Figure 6). Meta-analyses showed minimal, statistically non-significant reductions in hospital admissions (ES –0.05, 95% CI –0.12 to 0.03) (Figure 7) and total health service costs (ES –0.11, 95% CI –0.47 to 0.25) (Figure 8). Pooled estimates for total health service costs were based on a small number of comparisons with high variation across trials. Subgroup analyses were used to explore the different characteristics of self-care support that may be associated with each of these outcomes (these are detailed in Analyses of different types of self-care support, Table 9).

FIGURE 5.

Forest plot: QoL. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy; CBTpA, Cognitive Behavioural Therapy for Adolescents with Psychosis; CC, care co-ordination; CIT, conventional insulin therapy; FACI, Facilitated Asthma Communication Initiative; FipA, family intervention in adolescent inpatients with psychosis; IIT, intensive insulin therapy; IVR, interactive voice response; PST, problem-solving skills training; ST, Sweet Talk.

FIGURE 6.

Forest plot: emergency visits. CC, care co-ordination; CIT, conventional insulin therapy; FACI, Facilitated Asthma Communication Initiative; IIT, intensive insulin therapy; IVR, interactive voice response; PST, problem-solving skills training; ST, Sweet Talk.

FIGURE 7.

Forest plot: hospital admissions. CC, care co-ordination; FACI, Facilitated Asthma Communication Initiative; IVR, interactive voice response; PST, problem-solving skills training.

FIGURE 8.

Forest plot: total costs. CBT, cognitive–behavioural therapy.

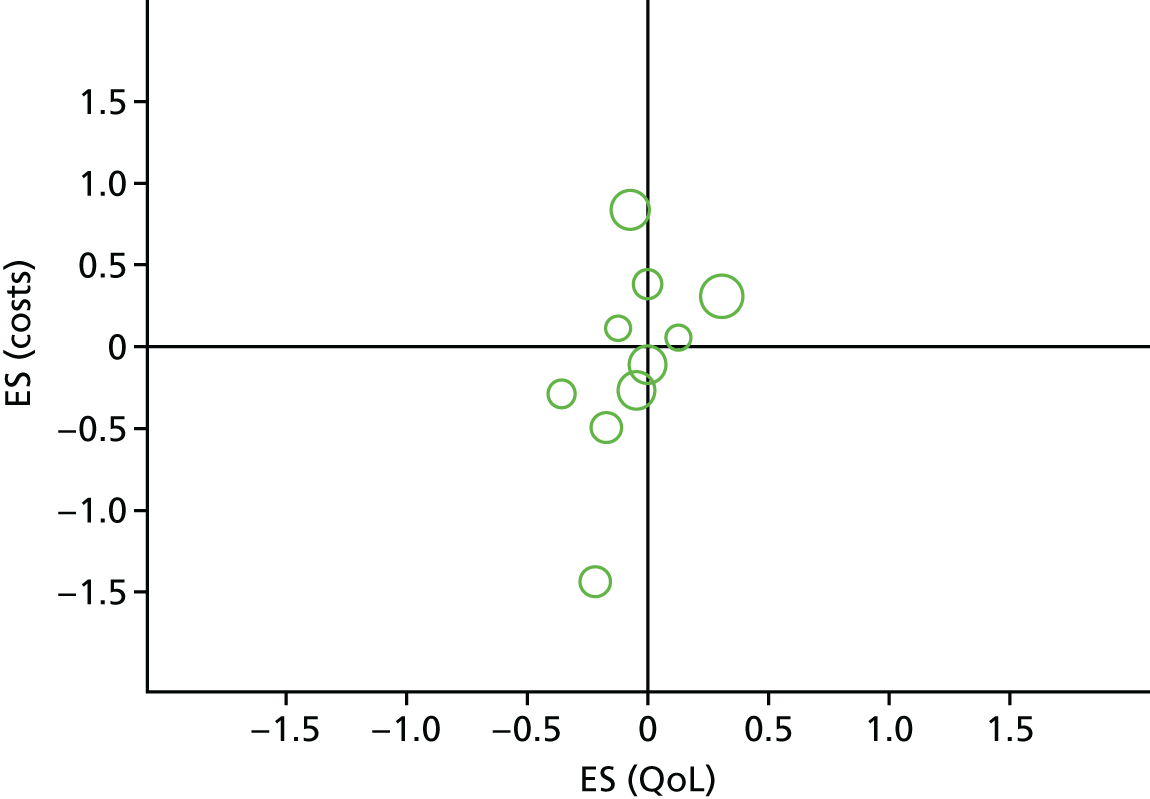

Primary analysis: quality of life and total health service costs

Total health service costs were infrequently reported. Only eight studies reporting 10 comparisons were eligible for inclusion in a permutation plot that simultaneously charted the effects of self-care support on children and young people QoL and total health-care costs (Figure 9). Six of these comparisons were rated as being at a low risk of bias.

FIGURE 9.

Permutation plot of QoL and costs.

When effects were plotted against each other, the comparisons were primarily distributed across the left-hand quadrants of the plot, suggesting that self-care support interventions currently demonstrate high variability in terms of economic effect, but typically confer minimal to small improvements for QoL. This conclusion is based on limited data and must be treated with caution. The circles in the permutation plots are an illustrative indicator of their relative ‘weight’ in the analysis. Permutation plots do not consider uncertainty around individual study point estimates which, in some instances, may be marked. Almost all studies reporting total costs (eight comparisons) demonstrated significant skew in either control or intervention outcome data.

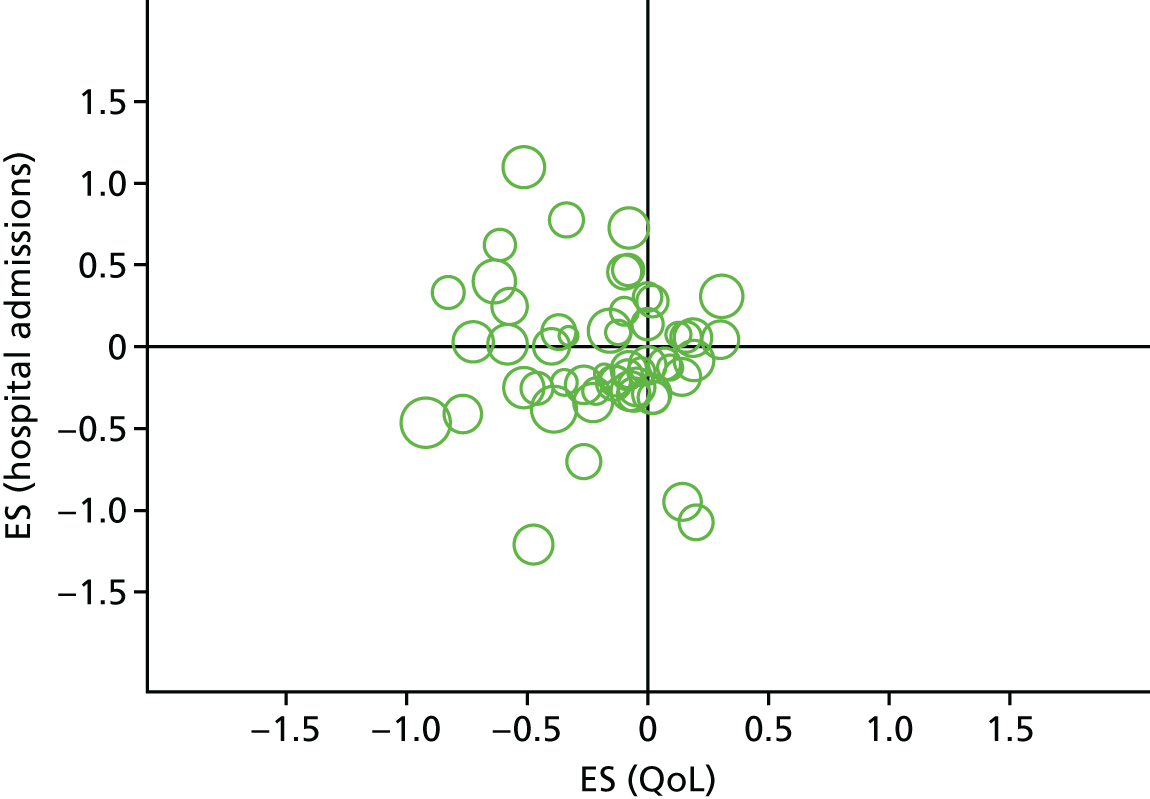

Quality of life and hospital admissions

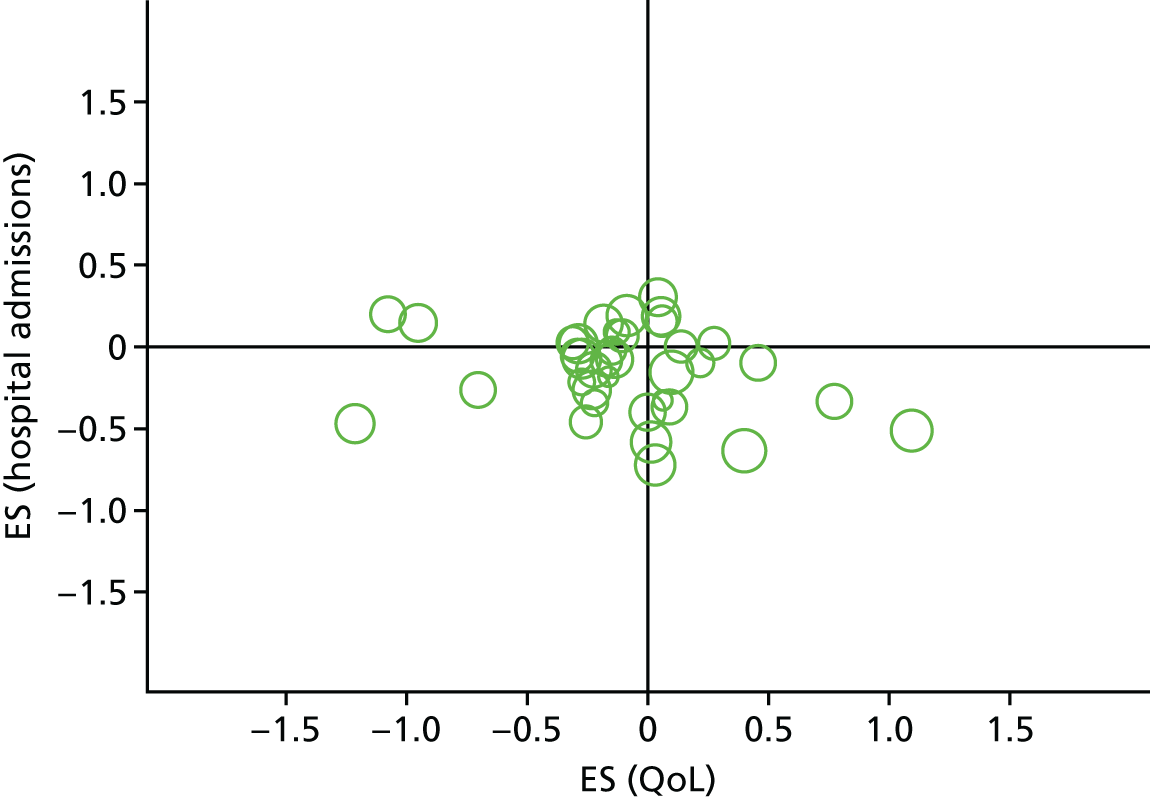

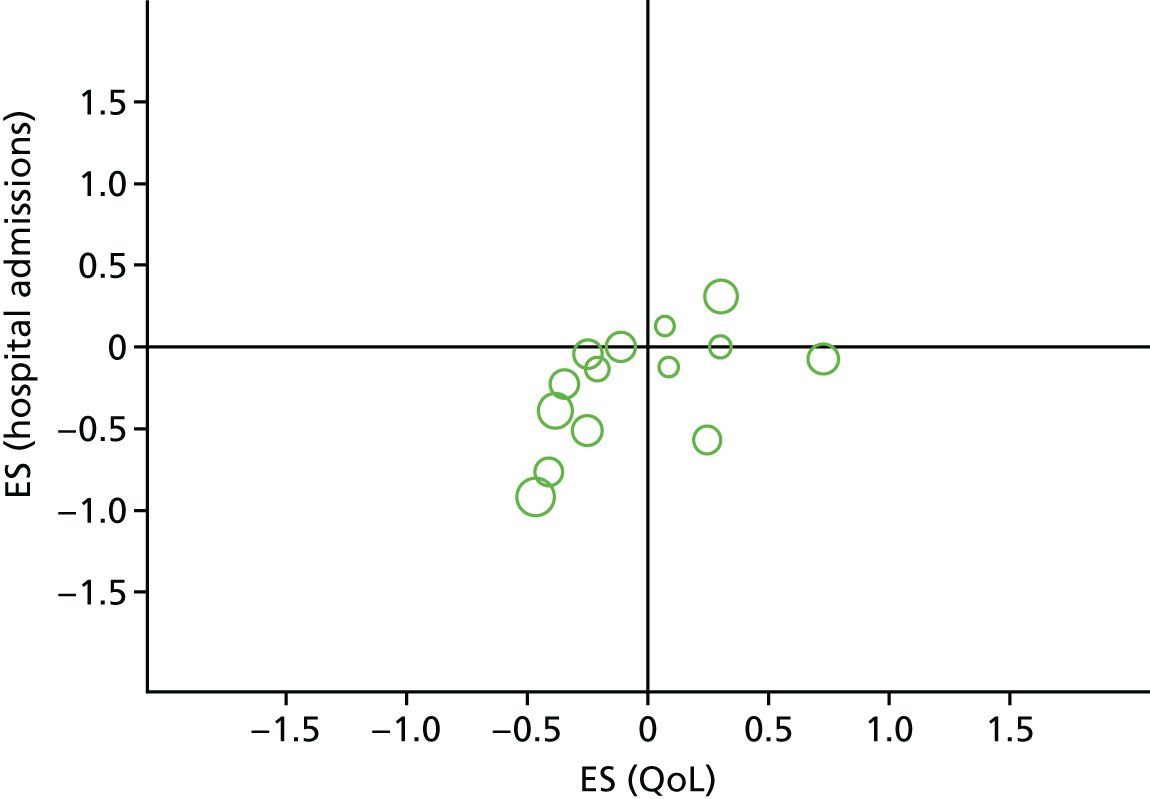

Fifty-three comparisons were eligible for inclusion in a permutation plot charting the effects of self-care support on QoL and hospital admissions (Figure 10); 29 of these comparisons originated from RCTs with adequate allocation concealment.

FIGURE 10.

Permutation plot of QoL and hospital admissions.

When hospital admissions were plotted against patient outcomes, most comparisons were distributed on the left-hand side, spanning both the lower and upper left-hand quadrants. This suggests that, on the basis of the available evidence, self-care support for children and young people is likely to be associated with improvements in QoL, but variable effects on hospital admissions. A minority of studies was located in the lower right-hand quadrant, suggesting reduced hospital admissions, but a marginally compromised QoL. As stated previously, permutation plots do not consider the magnitude of uncertainty around individual study point estimates and, for some studies in the current analysis, this uncertainty may be marked.

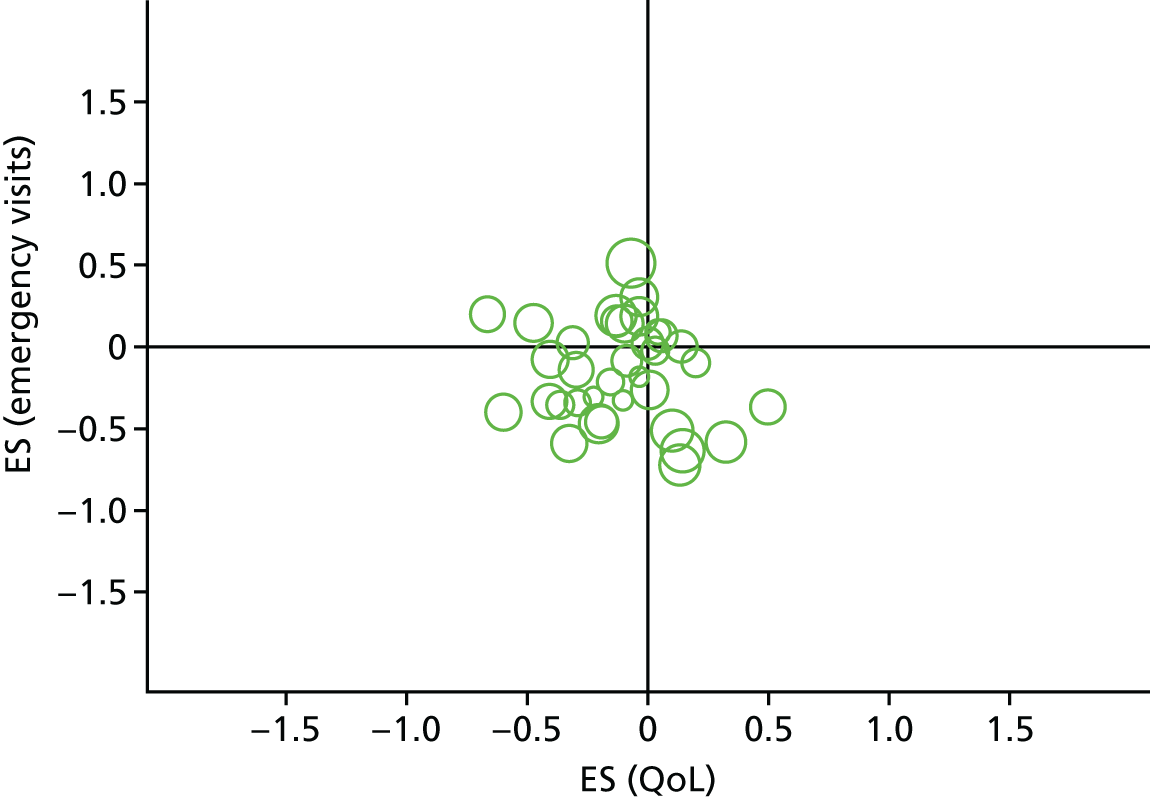

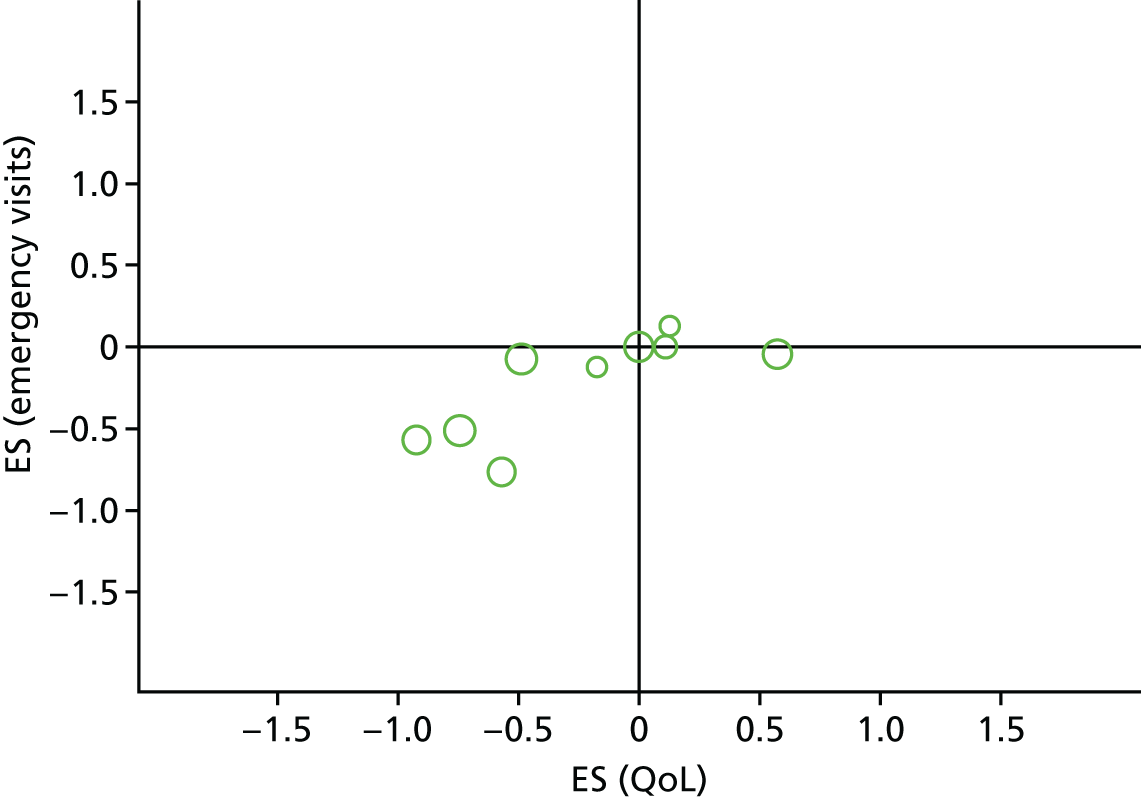

Quality of life and emergency department visits

Emergency department visits were identified by our PPI panel as a particularly important aspect of health service utilisation for children, young people and their parents. Forty-seven comparisons were eligible for inclusion in this permutation plot (Figure 11); 24 were from RCTs with adequate allocation concealment.

FIGURE 11.

Permutation plot of QoL and emergency visits.

When emergency visits were plotted against patient outcomes, the majority of studies fell in the lower left-hand quadrant, demonstrating that self-care support can reduce ED use without routinely compromising children and young people’s QoL. Fewer studies report reduced emergency visits with decrements in QoL (lower right-hand quadrant) or significant improvements in QoL associated with increased service use (upper left-hand quadrant).

Analysis by long-term condition

Included studies were categorised into one of four broad groups based on the type of LTC: asthma, other physical health, mental health and behavioural difficulties. These groups were determined post hoc according to the nature of the evidence that was identified.

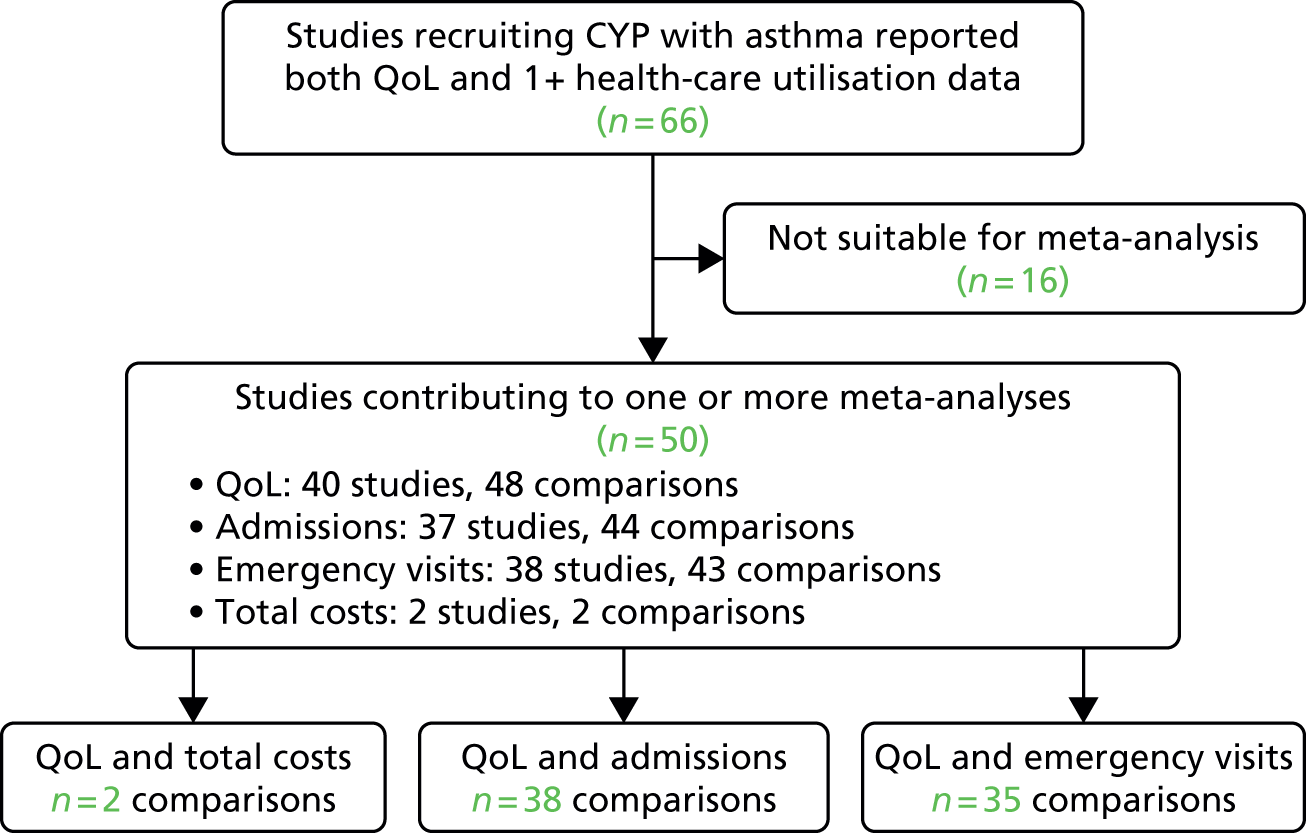

Asthma

Sixty-six studies evaluated self-care support for children and young people with asthma. The flow of studies through the review is depicted in Figure 12. Pooled effects for each outcome are reported in Table 3. Meta-analysis of all asthma studies demonstrated that self-care support was associated with minimal but statistically significant improvements in QoL, with moderate variation across trials. Self-care support was associated with minimal but statistically significant reductions in ED use, with low variation across the studies. Meta-analyses showed no significant effects on hospital admissions. Meaningful interpretation of total cost data was limited by the small number of comparisons (n = 2).

FIGURE 12.

Analyses of studies for patients with asthma. CYP, children and young people.

| Outcome | ES | 95% CI | I2 statistic (%) | Number of comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | –0.15 | –0.22 to –0.08 | 45 | 48 |

| Hospital admissions | –0.06 | –0.15 to 0.02 | 38 | 44 |

| Emergency visits | –0.12 | –0.18 to –0.06 | 22 | 43 |

| Total costs | 0.25 | –0.85 to 1.35 | 92 | 2 |

Owing to a lack of data, permutation plots were not calculated for total costs. Thirty-eight comparisons were eligible for inclusion in a permutation plot charting the effects of self-care support on QoL and hospital admissions for asthma (Figure 13); 16 of these comparisons originated from RCTs with adequate allocation concealment.

FIGURE 13.

Permutation plot of QoL and hospital admissions (asthma).

When hospital admissions were plotted against patient outcomes, most comparisons were distributed across the lower right- and left-hand quadrants. This suggests that self-care support interventions that reduce the number of hospital admissions for children and young people with asthma will not routinely compromise QoL but, on the basis of the current evidence, such compromises cannot be ruled out.

When emergency visits were plotted against QoL for children and young people with asthma (Figure 14), the majority of studies fell in lower left-hand quadrant, demonstrating that self-care support can reduce ED use without compromising children and young people’s QoL. A notable number of studies in other quadrants suggested that self-care support interventions may reduce emergency visits with decrements in QoL (lower right-hand quadrant) or improve in QoL but increase service use (upper left-hand quadrant).

FIGURE 14.

Permutation plot of QoL and emergency visits (asthma).

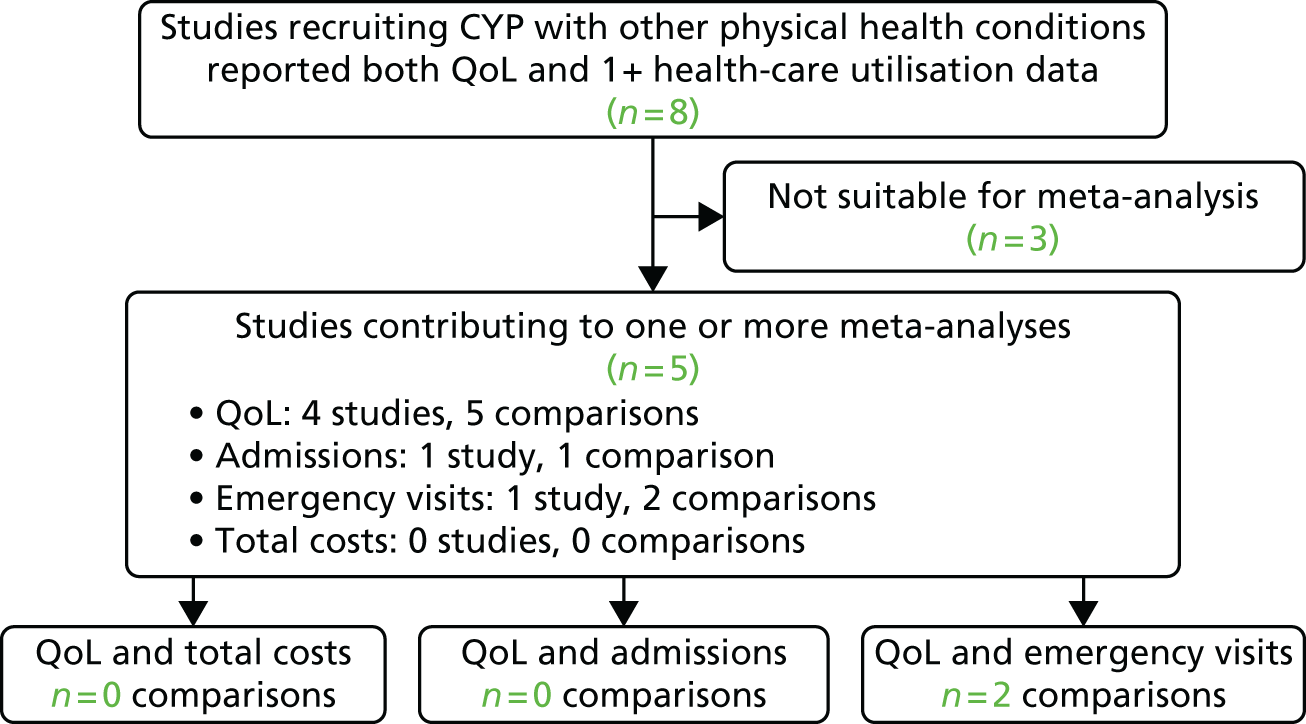

Other (non-asthma) physical health conditions

Eight studies evaluated self-care support for children and young people with other physical health conditions. The flow of studies through the review is depicted in Figure 15. Owing to the small number of data available for meta-analysis, meaningful interpretation of the evidence base for non-asthma physical health conditions is limited. Pooled ESs are presented in Table 4 for completeness. Permutation plots are not presented.

FIGURE 15.

Analyses of studies for patients with other (non-asthma) physical health conditions. CYP, children and young people.

| Outcome | ES | 95% CI | I2 statistic (%) | Number of comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | 0.00 | –0.18 to 0.19 | 0 | 5 |

| Hospital admissions | –0.11 | –0.61 to 0.38 | – | 1 |

| Emergency visits | –0.03 | –1.43 to 1.37 | 82 | 2 |

| Total costs | – | – | – | 0 |

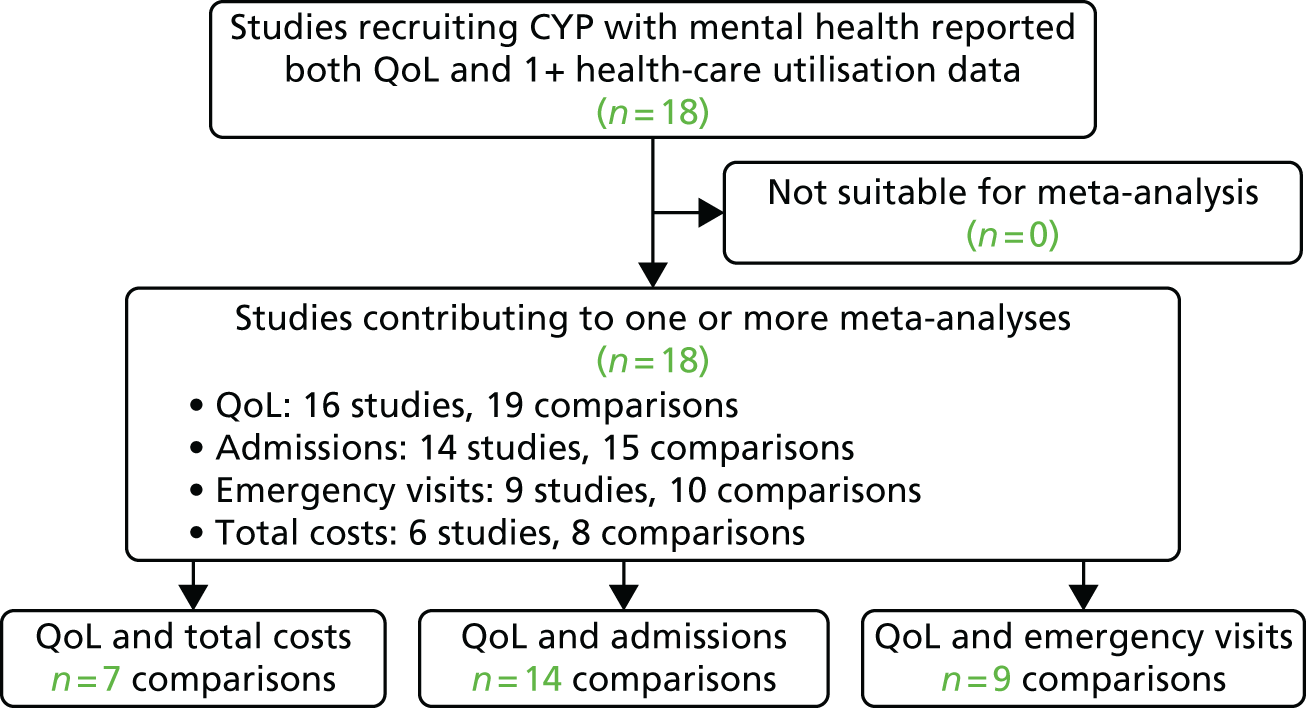

Mental health conditions

Eighteen studies evaluated self-care support for children and young people with mental health conditions. The flow of studies through the review is depicted in Figure 16. Pooled effects for each outcome are reported in Table 5. Meta-analysis of all mental health studies demonstrated that self-care support was associated with minimal but statistically significant improvements in QoL, with moderate variation across trials. The meta-analyses showed no significant effects on hospital admissions, ED visits or total costs. Meaningful interpretation of total cost data was limited by a small number of comparisons (n = 8) and high variation across trials.

FIGURE 16.

Analyses of studies for patients with mental health conditions. CYP, children and young people.

| Outcome | ES | 95% CI | I2 statistic (%) | Number of comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | –0.17 | –0.29 to –0.05 | 33 | 20 |

| Hospital admissions | –0.02 | –0.17 to 0.14 | 30 | 15 |

| Emergency visits | –0.15 | –0.39 to 0.09 | 64 | 10 |

| Total costs | –0.19 | –0.61 to 0.23 | 93 | 8 |

Owing to a lack of data, permutation plots were not calculated for total costs. Fourteen comparisons were eligible for inclusion in a permutation plot charting the effects of self-care support on QoL and hospital admissions for mental health (Figure 17); 10 of these comparisons originated from RCTs with adequate allocation concealment.

FIGURE 17.

Permutation plot of QoL and hospital admissions (mental health conditions).

When hospital admissions were plotted against patient outcomes, the majority of comparisons were located in the lower left-hand quadrant, suggesting that self-care support can reduce utilisation for children and young people with mental health conditions without compromising QoL. A minority of studies were located in the lower right-hand quadrant, suggesting reduced hospital admissions but a marginally compromised QoL. As stated previously, data were limited and findings must be treated with caution.

Nine comparisons were eligible for inclusion in a permutation plot charting ED visits against patient outcomes (Figure 18); seven were from RCTs with adequate allocation concealment. When emergency visits were plotted against patient outcomes, the majority of studies fell in lower left-hand quadrant, demonstrating that self-care support can reduce ED use without routinely compromising children and young people’s QoL. Limited data mean that these results must be treated with caution.

FIGURE 18.

Permutation plot of QoL and emergency visits (mental health conditions).

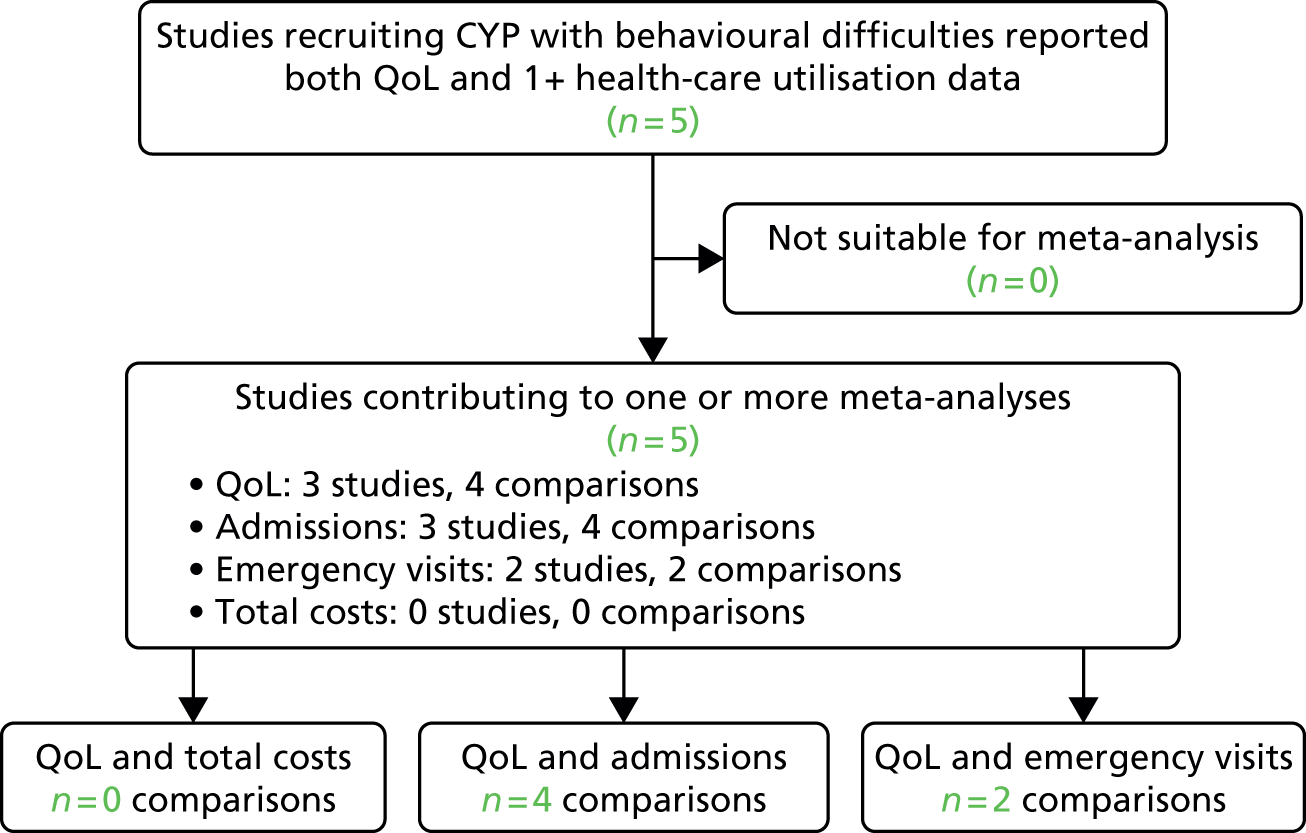

Behavioural difficulties

Five studies evaluated self-care support for children and young people with behavioural difficulties. The flow of studies through the review is depicted in Figure 19.

FIGURE 19.

Analyses of studies for patients with behavioural difficulties. CYP, children and young people.

Owing to the small number of data available for meta-analysis, meaningful interpretation of the evidence base for non-asthma physical health conditions is limited. Pooled ESs are presented in Table 6 for completeness. Permutation plots are not presented. Table 7 summarises the results of all meta-analyses, presented according to LTC type.

| Outcome | ES | 95% CI | I2 statistic (%) | Number of comparisons |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | –0.53 | –0.86 to –0.20 | 71 | 4 |

| Hospital admissions | 0.30 | –0.14 to 0.75 | 3 | 5 |

| Emergency visits | 0.49 | –0.73 to 1.72 | 55 | 2 |

| Total costs | – | – | – | 0 |

| Outcome | LTC type | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asthma | Other physical health | Mental health | Behavioural disorders | |

| QoL | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.15 | 0.00 | –0.17 | –0.53 |

| 95% CI | –0.22 to –0.08 | –0.18 to 0.19 | –0.29 to –0.05 | –0.86 to –0.20 |

| n | 48 | 5 | 20 | 4 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 45 | 0 | 33 | 71 |

| Hospital admissions | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.06 | –0.11 | –0.02 | 0.30 |

| 95% CI | –0.15 to 0.02 | –0.61 to 0.30 | –0.17 to 0.14 | –0.14 to 0.75 |

| n | 44 | 1 | 15 | 5 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 38 | – | 30 | 3 |

| Emergency visits | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.12 | –0.03 | –0.15 | 0.49 |

| 95% CI | –0.18 to –0.06 | –1.43 to 1.37 | –0.39 to 0.09 | –0.3 to 1.72 |

| n | 43 | 2 | 10 | 2 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 22 | 82 | 64 | 55 |

| Total costs | ||||

| Pooled ES | 0.25 | – | –0.19 | – |

| 95% CI | –0.85 to 1.35 | – | –0.61 to 0.23 | – |

| n | 2 | – | 8 | – |

| I2 statistic (%) | 92 | – | 93 | – |

Analysis by age

Subgroup analyses were carried out on the basis of children and young people’s age. Studies were categorised according to whether the self-care intervention targeted children (aged 0–12 years), adolescents (aged 13–18 years) or both (Table 8). Across all three age groups, self-care support had statistically significant but minimal effects (ES of < 0.2) on QoL. Self-care support was associated with a statistically significant but minimal reduction in ED use for children. Irrespective of the target age group, self-care support had no statistically significant effects on hospital admissions or total costs. Variation in the magnitude of ESs observed across the three subgroups will in part reflect differences in the number of studies available and the precision of the pooled estimates.

| Outcome | Age group | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Children | Adolescents | Mixed | |

| QoL | |||

| Pooled ES | –0.19 | –0.17 | –0.13 |

| 95% CI | –0.30 to –0.08 | –0.28 to –0.07 | –0.23 to –0.04 |

| n | 23 | 23 | 31 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 66 | 40 | 27 |

| Hospital admissions | |||

| Pooled ES | –0.06 | –0.08 | –0.04 |

| 95% CI | –0.14 to 0.03 | –0.22 to 0.06 | –0.19 to 0.10 |

| n | 21 | 18 | 26 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 0 | 42 | 49 |

| Emergency visits | |||

| Pooled ES | –0.10 | –0.14 | –0.11 |

| 95% CI | –0.17 to –0.04 | –0.31 to 0.03 | –0.25 to 0.04 |

| n | 22 | 14 | 21 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 9 | 55 | 47 |

| Total costs | |||

| Pooled ES | –0.29 | –0.19 | 0.84 |

| 95% CI | –0.56 to –0.02 | –0.61 to 0.23 | 0.29 to 1.38 |

| n | 1 | 8 | 1 |

| I2 statistic (%) | – | 93 | – |

Analyses of different types of self-care support

When different intensities of self-care support were compared, intensive facilitation conferred limited benefit over and above other forms of self-care support (Table 9).

| Subgroup | Outcome | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| QoL | Hospital admission | Emergency visits | Total costs | |

| Intervention intensity | ||||

| Pure/facilitated | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.20 | –0.08 | –0.12 | 0.84 |

| 95% CI | –0.29 to –0.10 | –0.24 to 0.09 | –0.29 to 0.05 | 0.29 to 1.38 |

| Number of comparisons | 22 | 17 | 16 | 1 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 25 | 38 | 44 | – |

| Intensive/case managed | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.16 | –0.04 | –0.10 | –0.20 |

| 95% CI | –0.23 to –0.08 | –0.12 to 0.04 | –0.17 to –0.03 | –0.57 to 0.16 |

| Number of comparisons | 55 | 48 | 41 | 9 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 56 | 25 | 37 | 92 |

| Intervention target | ||||

| CYP | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.09 | –0.00 | –0.12 | –0.11 |

| 95% CI | –0.20 to –0.02 | –0.18 to 0.17 | –0.28 to 0.04 | –0.61 to 0.38 |

| Number of comparisons | 23 | 12 | 12 | 7 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 37 | 49 | 51 | 95 |

| Parents | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.20 | –0.05 | 0.02 | – |

| 95% CI | –0.57 to 0.17 | –0.22 to 0.12 | –0.15 to 0.19 | – |

| Number of comparisons | 5 | 6 | 5 | – |

| I2 statistic (%) | 48 | 0 | 38 | – |

| Mixed | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.20 | –0.06 | –0.12 | 0.02 |

| 95% CI | –0.27 to –0.13 | –0.15 to –0.15 | –0.20 to –0.04 | –0.17 to 0.22 |

| Number of comparisons | 49 | 47 | 40 | 3 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 37 | 36 | 37 | 5 |

| Intervention format | ||||

| Individual | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.16 | –0.02 | –0.09 | –0.10 |

| 95% CI | –0.22 to –0.09 | –0.10 to 0.06 | –0.18 to 0.00 | –0.59 to 0.39 |

| Number of comparisons | 54 | 55 | 40 | 8 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 29 | 34 | 37 | 94 |

| Group | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.11 | –0.15 | –0.12 | –0.11 |

| 95% CI | –0.29 to 0.07 | –0.28 to –0.02 | –0.27 to 0.02 | –0.44 to 0.23 |

| Number of comparisons | 12 | 8 | 10 | 2 |

| I2 statistic (%) | 75 | 0 | 54 | 75 |

| Mixed/unclear | ||||

| Pooled ES | –0.25 | –0.70 | –0.13 | – |

| 95% CI | –0.42 to –0.09 | –1.77 to 0.37 | –0.25 to 0.00 | – |

| Number of comparisons | 11 | 2 | 7 | – |