Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/178/22. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The final report began editorial review in September 2016 and was accepted for publication in March 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Paul Aylin and Alex Bottle report that the Dr Foster Unit at Imperial College London is partially funded through a research grant by Dr Foster, a commercial health-care information company (wholly owned by Telstra Health) that provides health-care analytics solutions to NHS organisations. Paul Aylin and Alex Bottle are part-funded by a grant to the unit from Telstra Health (formerly Dr Foster Intelligence) outside the submitted work. Charles Vincent reports funding from the Health Foundation for research and from Haelo (a commercial innovation and improvement science organisation) for consultancy work.

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Aylin et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

The purpose of Chapter 1 is to establish the context in which this evaluation of a national surveillance system for mortality alerts is set. It covers the background to the surveillance system, controversies around the use of hospital mortality and the rationale for the study.

Background

Background of the monthly mortality alerting system

The origins of the Imperial College monthly mortality alerting system lie in analyses commissioned by the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry in 1999 examining paediatric cardiac surgical outcomes at Bristol Royal Infirmary. Our group confirmed serious concerns around the surgical outcomes at Bristol,1,2 and established the usefulness of routine administrative data [Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)] in helping to identify quality of care issues. In further research commissioned by the Shipman Inquiry and published in 2003,3,4 our group established the role that statistical process control charts [specifically, log-likelihood cumulative sum (CUSUM) charts], and other routinely collected data (from death certificates) could play in the continuous surveillance of health-care outcomes, and, in this specific case, the detection of unusual patterns of patient mortality within general practices. Since then, we have demonstrated that the coverage and completeness of routinely collected administrative data is comparable with (or better than) that of clinical audit data. 5,6 We have used mortality rates (because these are well recorded) as a potential reflection of quality of care, with the inference that possibly more, less serious complications underlie them. We have subsequently published other indicators on safety,7 stroke care8 and returns to theatre9 based on administrative data.

Our work on appropriate statistical techniques in mortality surveillance in general practice3 established the utility of statistical process control charts in surveillance of health-care performance. This led to the application of these methods to secondary care administrative data in the development of a surveillance system to detect high mortality rates, emergency readmission and long length of stay in 256 diagnosis groups and 120 surgical procedure groups in collaboration with a commercial company, Dr Foster (Dr Foster Limited, London, UK; www.drfoster.com). 10 The system is now used in 70% of acute hospital trusts in England. A similar system based on our work is in use in the Netherlands, the USA, Belgium and Italy.

Following the development of the surveillance system, it became apparent that we were identifying a number of alerts each month, some of which were generated in trusts that did not have access to Dr Foster analytical tools. In 2007, we created a system whereby, each month, we notified trusts by letter (regardless of whether or not they were Dr Foster customers) if they had alerted for a subset of diagnoses and conditions at a high alarm threshold (see Appendix 1 for an example of the alert letter). In this letter, we are explicit in the range of possible reasons for a signal, including random variation, poor data quality or coding problems and case-mix issues, and we emphasise that we draw no conclusions as to what lies behind the figures. We worked closely with the Healthcare Commission [which was to be taken over by the Care Quality Commission (CQC)] in setting up this mortality alerting and surveillance system (MASS), and agreed to notify them about the letters we sent. The Healthcare Commission subsequently set up their own alerting system, based on similar methods, but their data were originally less current and based around Healthcare Resource Groups. Within the first 8 months of running our monthly alerts, one hospital had a series of six mortality alerts in a range of conditions and procedures. This helped to trigger an inspection of care at Stafford Hospital, which was within Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. The initial inspection team found ‘appalling’ failures of emergency care within the trust, and a number of inquiries, culminating in the public inquiry led by Robert Francis, confirmed a litany of failings. The inquiry report recognised the role that our surveillance system of mortality alerts had to play in identifying Mid Staffordshire as an outlier. 11 A key recommendation reflecting our unit’s work was that all health-care provider organisations should develop and maintain systems that give effective real-time information on the performance of each of their services, specialist teams and consultants in relation to mortality, patient safety and minimum quality standards.

Controversy in using hospital mortality in investigating quality of care

There is some controversy over the value of analyses looking at hospital mortality in relation to quality of care. Many arguments concern summary measures of hospital mortality such as the hospital-standardised mortality ratio (HSMR) and the summary hospital-level mortality indicator (SHMI),12,13 whereas the mortality alerting system we describe focuses on specific diagnosis and procedure groupings. Even Hogan et al. 14 acknowledge the value of standardised mortality ratios for specific groups of patients.

However, it is useful to review the criticisms of the use of mortality indicators (even if that criticism does tend to focus on summary measures of hospital mortality) in relation to quality of care. Several arguments have been made:

-

inconsistent relationship between mortality measures and quality of care

-

avoidable deaths

-

weak signals

-

case mix and coding.

Inconsistent relationship between mortality measures and quality of care

An often cited argument put forward by critics12,15,16 against the validity of mortality measures is that there is poor agreement between process measures and mortality outcomes. One widely quoted ‘systematic review’17 reviewed 36 studies and 51 processes of care and found a correlation between better quality of care and lower risk-adjusted mortality ‘in under half the relationships (26/51 51%) but the remainder showed no correlation (16/51 31%) or a paradoxical correlation (9/51 18%)’. 17 The authors concluded that the relationship between risk-adjusted mortality and quality of care was neither ‘consistent nor reliable’. Aside from an obvious point that 51% is not ‘under half’, the study undertakes no review of the quality of papers and makes no comment on sample size. Many of the studies in which no relationship was found were simply too small to detect an effect with any statistical significance. Additionally, it is entirely plausible that some process measures of care either are unrelated to mortality or have a relationship too small to detect without detracting from the validity of hospital mortality measures as an indicator of quality of care. Despite the weaknesses of the review, the paper has been cited many times in support of criticisms of the validity of mortality measures, even though there were a substantial number of studies that found a relationship. In our study, we have looked for relationships between some structure and process measures (agreed a priori in the study protocol) and alerting and non-alerting trusts.

Avoidable deaths

Although we have never made the claim that the MASS is a measure of avoidable deaths, it has been suggested that ‘avoidable deaths’ identified through case note reviews might be a more useful tool for exploring quality of care issues in relation to death; they have been proposed,14 and are being advocated,18 to be used routinely in NHS organisations. Case note reviews are by no means a gold standard. Studies trying to identify avoidable deaths find only low to moderate levels of agreement between reviewers19–21 with typical intraclass correlation coefficients in the range 0.4–0.6. Higher rates of reliability can be achieved by setting strict criteria for the reviewers as to what should be considered avoidable. However, the stricter the criteria, the more likely that important cases will be excluded. In one study,22 125 categories of avoidable death were listed, but there were still events that qualified as avoidable deaths that did not fall within them.

There is also some evidence that reviewers of case notes are less likely to classify avoidability among more sick and vulnerable patients. In a recent retrospective case note review of 1000 deaths, the observation was made that the fact that ‘patients were more likely to experience a problem in care if they were less functionally impaired, were elective admissions and had a longer life expectancy on admission was inconsistent with studies in other countries and might reflect a bias among reviewers towards discounting problems in the most frail, sick patients’. 23

The idea of avoidability as determined through a case note review is limited when considering the impact of quality of care on mortality. As an example, a study examining hospital admissions resulting from acute myocardial infarction (AMI)24 found that in-hospital mortality was lower with shorter door-to-needle times. Patients waiting > 45 minutes for fibrinolytic therapy had 37% higher odds of death than those waiting ≤ 30 minutes. There was no cut-off point at which delay becomes fatal, but on average a patient who waits longer for treatment is less likely to survive than one who is treated in < 30 minutes. It is rarely possible to say for any given patient that extra time waited contributed to their death. However, we know that, in aggregate, across a group of patients who wait longer, more of them will die and that some of them would have survived if treatment had been provided earlier.

Hogan et al. 14 attempted to relate estimates of avoidable deaths to HSMRs. Using only one reviewer per case, they looked at 34 hospital trusts, and reviewed 100 case notes in each. With an average of just over three ‘preventable’ deaths per hospital, with such small numbers, it is not surprising that they found no significant difference in the proportion of avoidable deaths across the trusts they examined. However, despite this, Hogan et al. 14 go on to examine the relationship of the tiny numbers of avoidable deaths in each trust with HSMRs. It is, again, no surprise, given the small numbers, that no significant relationship was found. In fact, one statistician commented that, given the study weaknesses, ‘the authors were trying to detect not just an implausibly large, but an impossibly large effect size’. 25 However, Hogan et al. 14 then make the bold assertion that ‘the absence of a significant association between hospital-wide standardised mortality ratios and avoidable death proportions suggests that neither metric is a helpful or informative indicator of the quality of a trust’. 14 As the same statistician commented, ‘robustly inferring the validity of hospital mortality indicators based on the findings of this study is impossible’. 25 To make any conclusion about the quality of other indicators based on case note reviews, particularly involving such small numbers, would seem to go way beyond the evidence in hand.

Weak signals

It is the low proportion of preventable deaths arising from these case note reviews that critics of mortality indicators use to argue that there are too few preventable deaths to account for the degree of variation in HSMRs. The extent to which any indicator is useful depends on the degree of ‘signal’ versus ‘noise’. With mortality measures, noise could be due to random variation or due to other factors such as unadjusted for case-mix or coding issues. The mortality alert surveillance system attempts to tackle the problem of random variation by setting high alarm thresholds, giving a very low false alarm rate as a result of simple random variation (probability of false alarm is < 0.001 over a 12-month period). Despite this high threshold, signals still arise.

The signal-to-noise ratio relates to the positive predictive value of an indicator. The true positive predictive value for HSMRs is unknown. There is some indication in the Keogh mortality review, where, of the 14 trusts inspected for quality of care on the grounds of high mortality rates by Sir Bruce Keogh in 2013,26 11 were regarded as being sufficiently poor to warrant being placed in special measures. This would equate to a positive predictive value of 0.79. This evidence is anecdotal and relates to HSMRs rather than to specific diagnosis and procedure mortality alerts. Part of the motivation to carry out this National Institute for Health Research-funded study was to go beyond anecdote and examine, more systematically, the relationship between mortality alerts and other external indicators, and to look at the findings and impact of our alerting system.

Case mix and coding

Case-mix adjustment based on administrative data has been criticised12,13,27 because for some variables it depends on the accuracy of clinical coding secondary diagnoses for comorbidity and palliative care. Some potentially valid theoretical concerns have been raised, particularly but not exclusively regarding case-mix adjustment, but little robust quantitative evidence has been presented as to the size of their effect. 28 The well-cited paper by Mohammed et al. ,27 which points to these methodological biases (specifically in HSMRs), uses a hypothetical example to illustrate the potential effect size. The paper focuses on at least two mechanisms that might contribute to this so-called ‘constant risk fallacy’: the first involves differential measurement error and the second involves inconsistent proxy measures of risk. In their analysis of real data, the authors argue that inconsistencies in risk of death for emergency admissions support their assertion. They suggest that large variations in the proportions of elective/non-elective patients with zero length of stay indicate that systematically different admission policies were being adopted across hospitals. Unfortunately, their data seemed to erroneously include day cases, which explains the low crude death rates and mean length of stay and affects the proportion of admissions that are emergencies. A paper published subsequently29 attempted to actually quantify the effect of coding and other concerns on the HSMR, including palliative care, short-stay observation patients, multiple admissions per patient and a failure to capture post-transfer or post-discharge deaths. The study concluded that, despite theoretical concerns about bias, HSMRs in most hospital trusts were in practice usually only modestly affected by the differences in the predictive models incorporated into this sensitivity analysis. There were a few notable exceptions, particularly relating to palliative care and timelier linkage with out-of-hospital deaths, although the paper also referred to improved coding guidelines that may address some of these issues.

Given the potential limitations to administrative data, the argument has been made for making better use of the increasing number of specialised sources of data, in particular those used to support national clinical audits. 13 Our group has carried out comparisons of administrative data with clinical audit data in the past, comparing risk prediction models and quality. One study compared the performance of risk prediction models for death in hospital based on administrative data with published results based on data derived from three clinical databases. 6 This concluded that routinely collected administrative data can be used to predict risk with similar discrimination to clinical databases, and that could be used to adjust for case mix for monitoring health-care performance. Two other papers looked at coverage and completeness of surgical procedures in colorectal surgery30 and vascular surgery5 in two clinical audit databases compared with hospital administrative data. They found between twice and four times as many cases recorded in the administrative data as in the audit data sets, suggesting significant under-recording. They also found that 39% of patients within the colorectal cancer database had missing data for risk factors used for risk adjustment. Although these papers were published in 2007 and 2008, more up-to-date reports from even well-established and reputable audits such as the Myocardial Ischaemia National Audit Project (MINAP) suggest that poor data quality, particularly on patient characteristics, renders the risk adjustment of mortality rates unreliable. 31 Given that the accuracy of administrative data appears to be improving and that clinical coding is now regarded as predominantly of good quality,32 the argument for abandoning it in favour of much more expensive, and often less complete, audit data seems rather less tenable.

Rationale for the study

The mortality alerting systems run by the CQC and the Imperial College London unit have already had some success in detecting hospitals delivering poor-quality care, such as the identification of problems at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. 1,11,33 Given the controversy, there is clearly still uncertainty about the sensitivity of systems based on the analysis of routinely collected hospital data and health-care providers’ responses following alerts. 14,34

As the mortality alerts provided by Imperial College London and CQC are for specific diagnoses or procedures, they are potentially more actionable than summary (overall) measures of mortality such as the HSMR or the SHMI. 35 The MASS demands significant resources from CQC and Imperial College London, and also from hospital staff following up the alerts; so although the CQC is continually evaluating its surveillance programme, this project will both complement and build on the CQC’s activity. 36

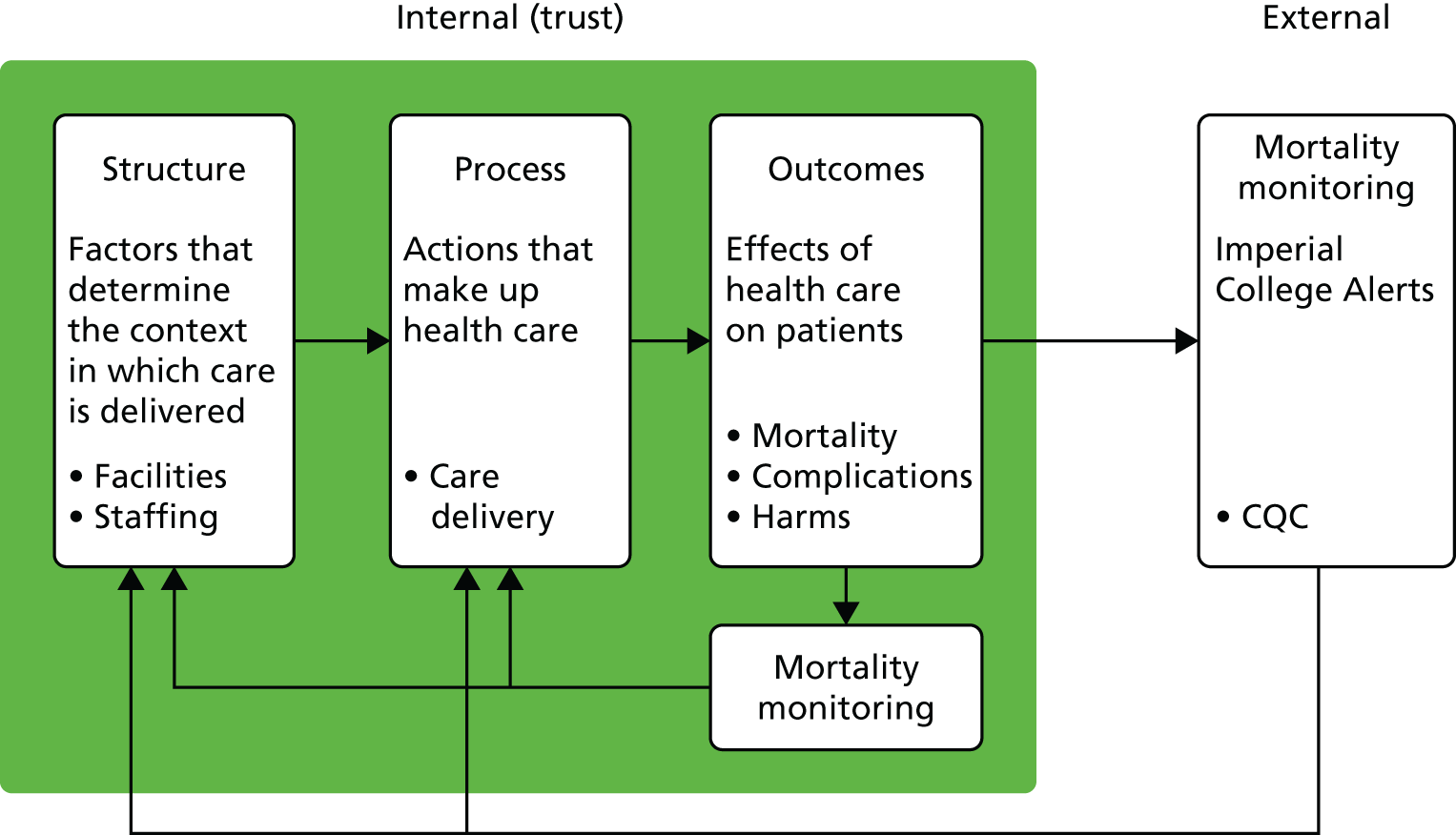

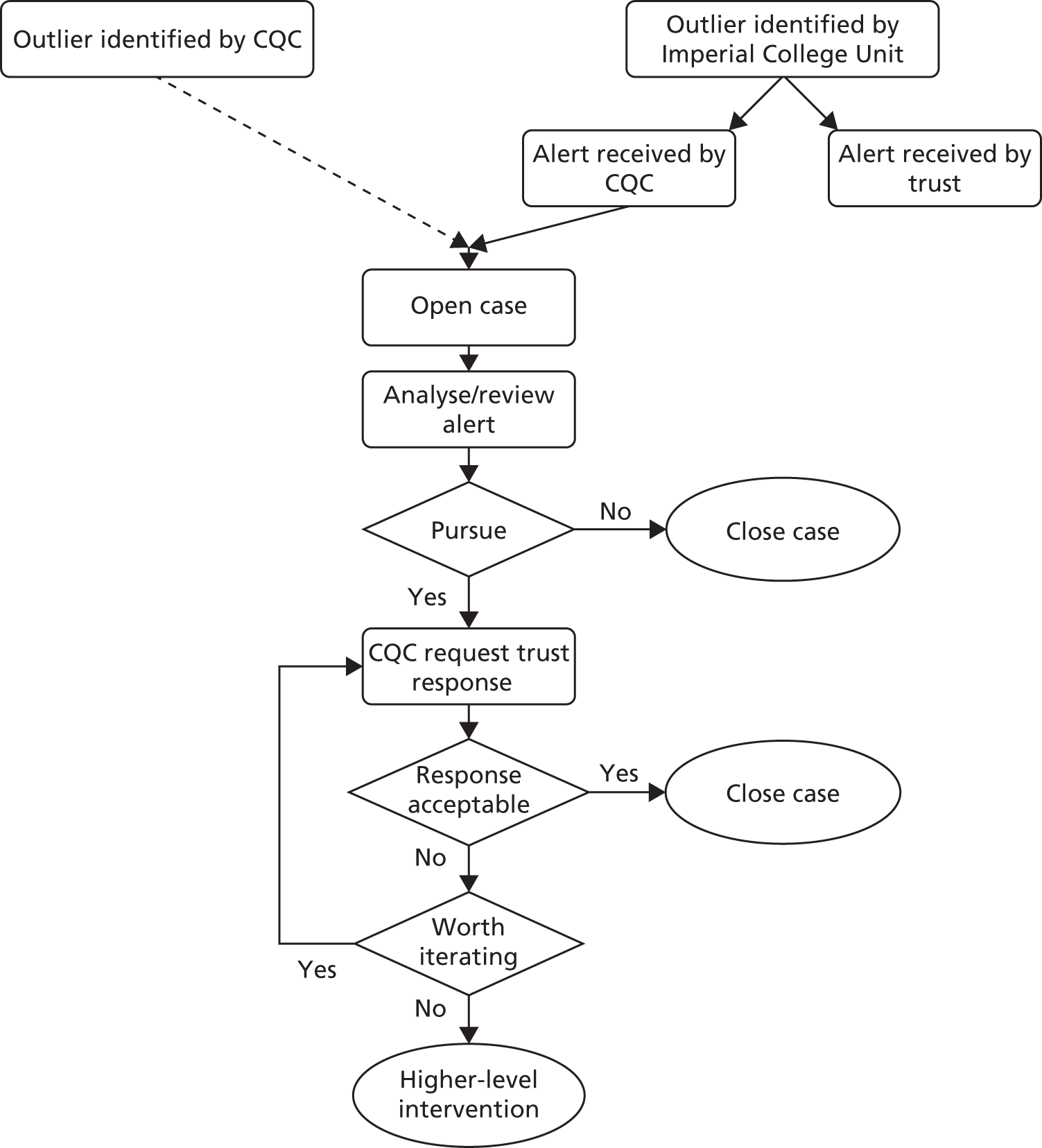

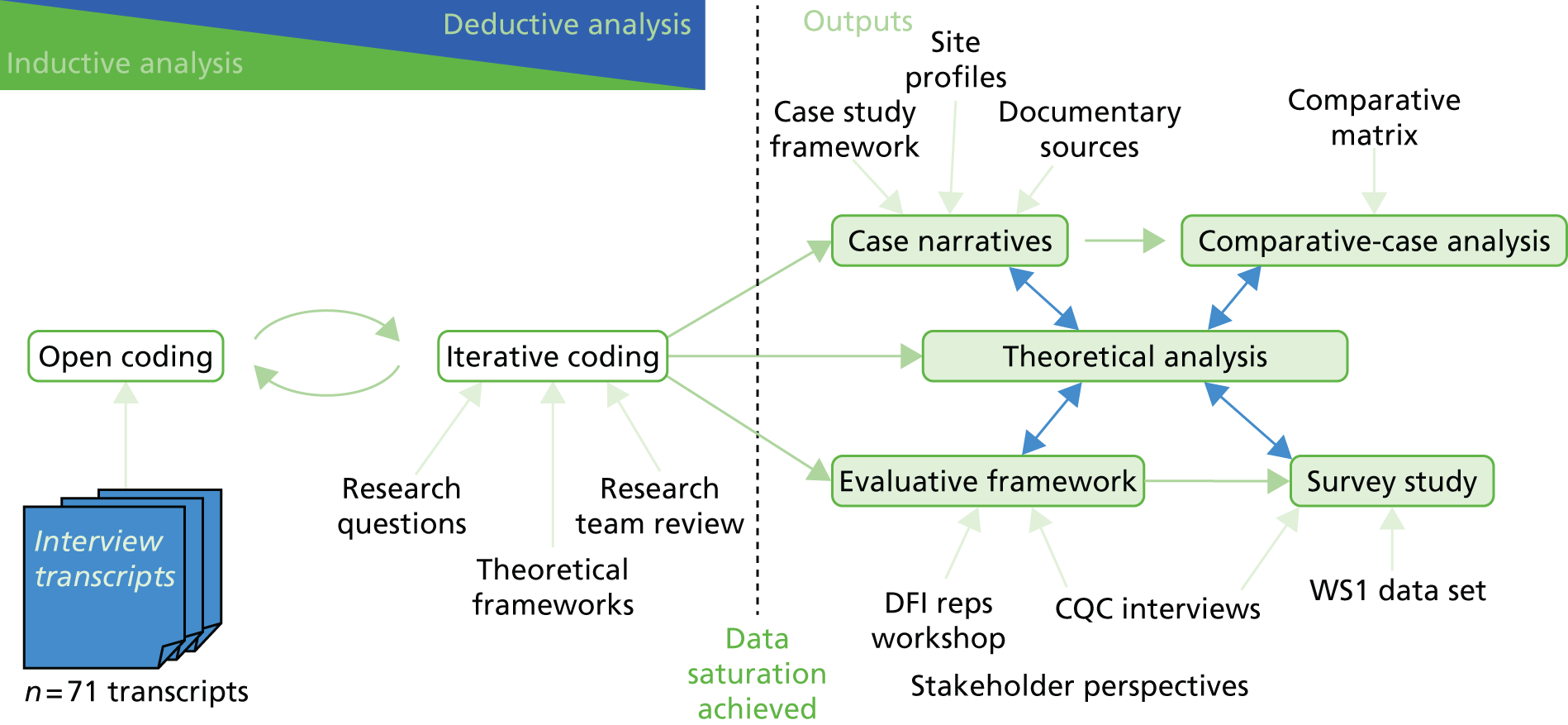

We based our evaluation of this MASS on the prior hypothesis that a mortality alert might be an indication of poor quality of care. By notifying a trust of a higher-than-expected death rate, we have made the assumption that efforts to investigate the alert resulting in changes to the structure and processes within the trust may result in improved outcomes. This hypothesised feedback mechanism triggered by a mortality alert is displayed in a simple theoretical model (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Theoretical model displaying hypothesised feedback mechanism following mortality monitoring.

If a mortality alert is a reflection of quality of care issues, one might expect to see:

-

quality of care issues confirmed after further investigation

-

associations with factors related to care structure and processes within the trust that might impact on quality of care, including resources such as bed occupancy and staffing or care provision

-

associations with patient outcomes including patient satisfaction, harms or death

-

differences in care provided between frequently alerting trusts and trusts that rarely alert

-

a reduction in mortality following actions to improve quality of care.

According to CQC reports,37 500 mortality alerts were processed between 2007 and 2011 (approximately 100 each year38). However, there has been no systematic empirical research to determine whether the Imperial College London unit and the CQC joint national MASS is any better at detecting quality of care issues than other less focused approaches (e.g. HSMR or SHMI), or if alerts are associated with reductions in mortality rates. It is also unclear what the most appropriate actions are for trusts after they receive an alert.

Previous studies on effective interventions have tended to be small scale and descriptive, with methodological limitations restricting the control of confounding factors, interpretation of results or causality. Research evaluating interventions to reduce mortality has highlighted difficulties in attributing effects to specific interventions due to multiple concurrent schemes, and has produced equivocal results. 39–41 Similarly, internationally there is very little evaluation of other monitoring/regulatory systems on whether or not regulation (e.g. accreditation) leads to better outcomes. 42

National mortality surveillance could be potentially efficient to manage, as data are routinely collected. Computer algorithms are adaptable and can be refined more easily than employing additional staff and/or training for similar activities. The surveillance system requires minimal specialist equipment and it is not affected by potential delays due to policy changes in the provision or commissioning of health services.

Chapter 2 Research objectives

Chapter 2 outlines our research objectives and defines an overview of our approach to the evaluation of a national surveillance system for mortality alerts.

Through a detailed assessment of the Imperial College Unit/CQC mortality surveillance system, our project aims to improve understanding of mortality alerts and to evaluate their impact as an intervention to reduce mortality within English NHS hospital trusts. To achieve our aim, we focused on six objectives:

-

to describe the findings and impact of a national mortality surveillance system as a feedback mechanism for quality improvement

-

to determine the relationship of alerts to other potential indicators of quality

-

to determine the temporal patterns of alerts and whether or not they are associated with subsequent changes in mortality rates at trusts

-

to describe trusts’ responses to receiving mortality alerts and the impact on safety/quality improvements, including organisational and staff behaviour

-

to determine whether or not there are differences in the delivery of care between frequently alerting trusts and trusts that alert rarely for two conditions that commonly generate mortality alerts – AMI and sepsis

-

to determine, at trusts where mortality decreased after alerts, whether or not they were more likely to apply common safety/quality interventions than trusts that repeatedly alert.

Overview of approach

We applied a mixed-methods approach, which naturally fell into two workstreams: the first employed quantitative research methods and the second employed qualitative research methods.

In workstream 1, we described trends in mortality alerts and carried out a descriptive analysis of CQC investigations into the Imperial College mortality alerts (objective 1); examined the statistical relationships between mortality alerts and measures of quality of care that relate to the trust care structure, processes and outcomes (objective 2); and applied an interrupted time series model to examine the impact of mortality alerts on subsequent mortality, using national hospital administrative data on admissions (objective 3).

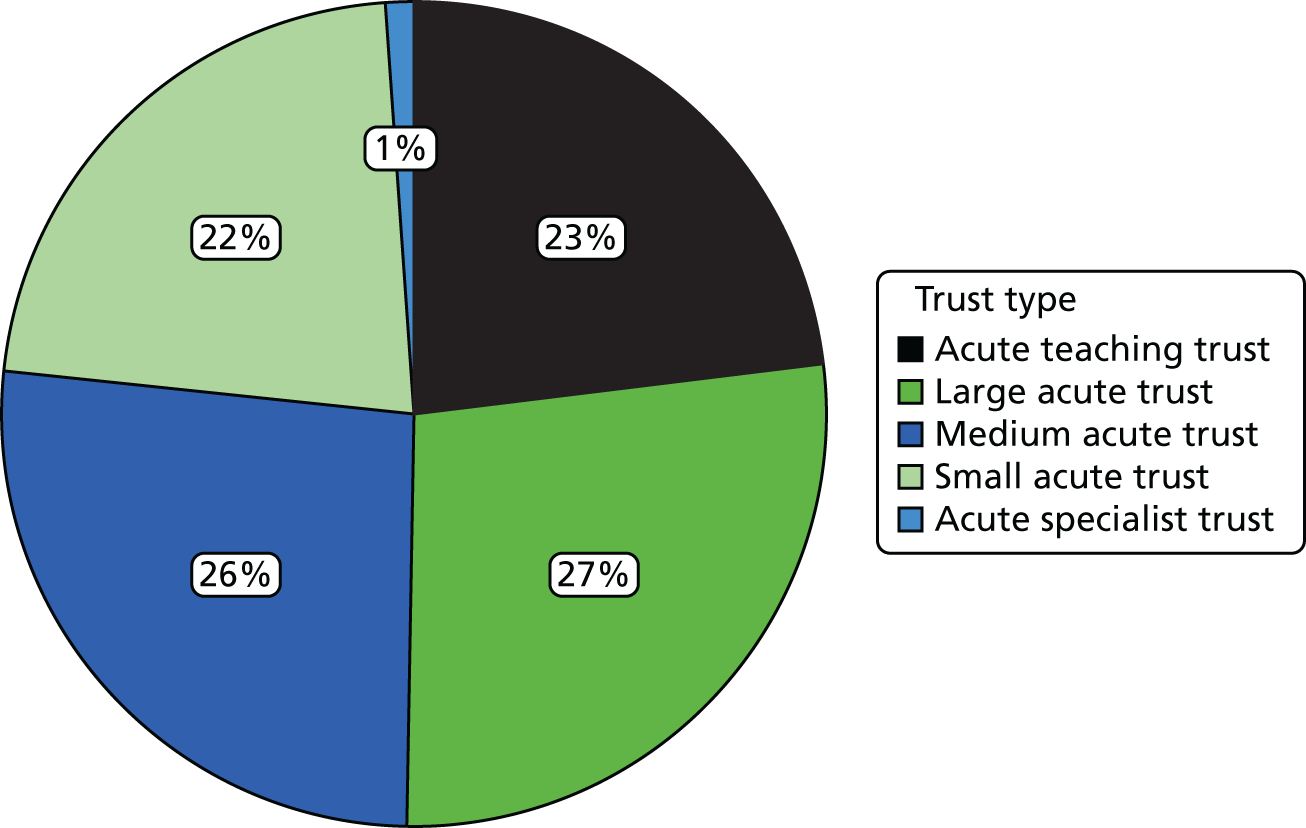

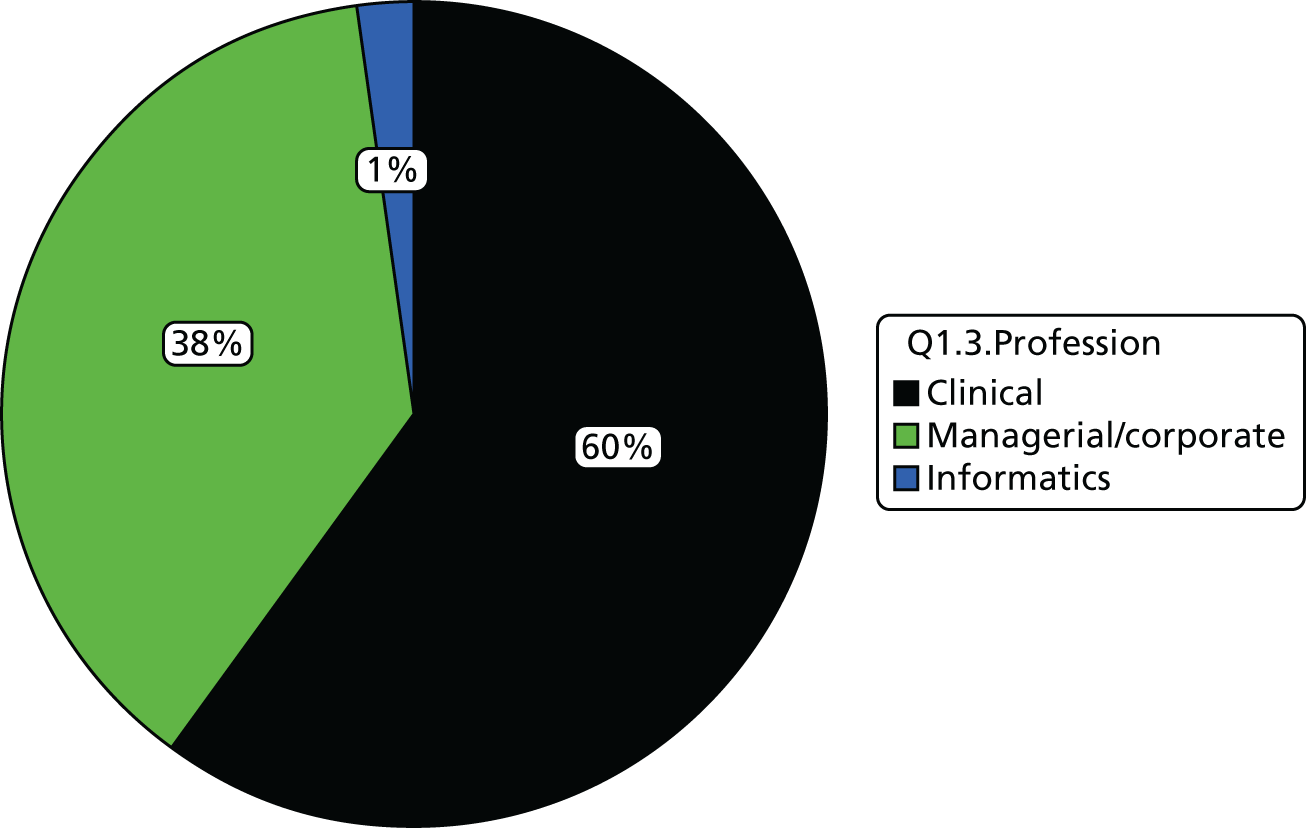

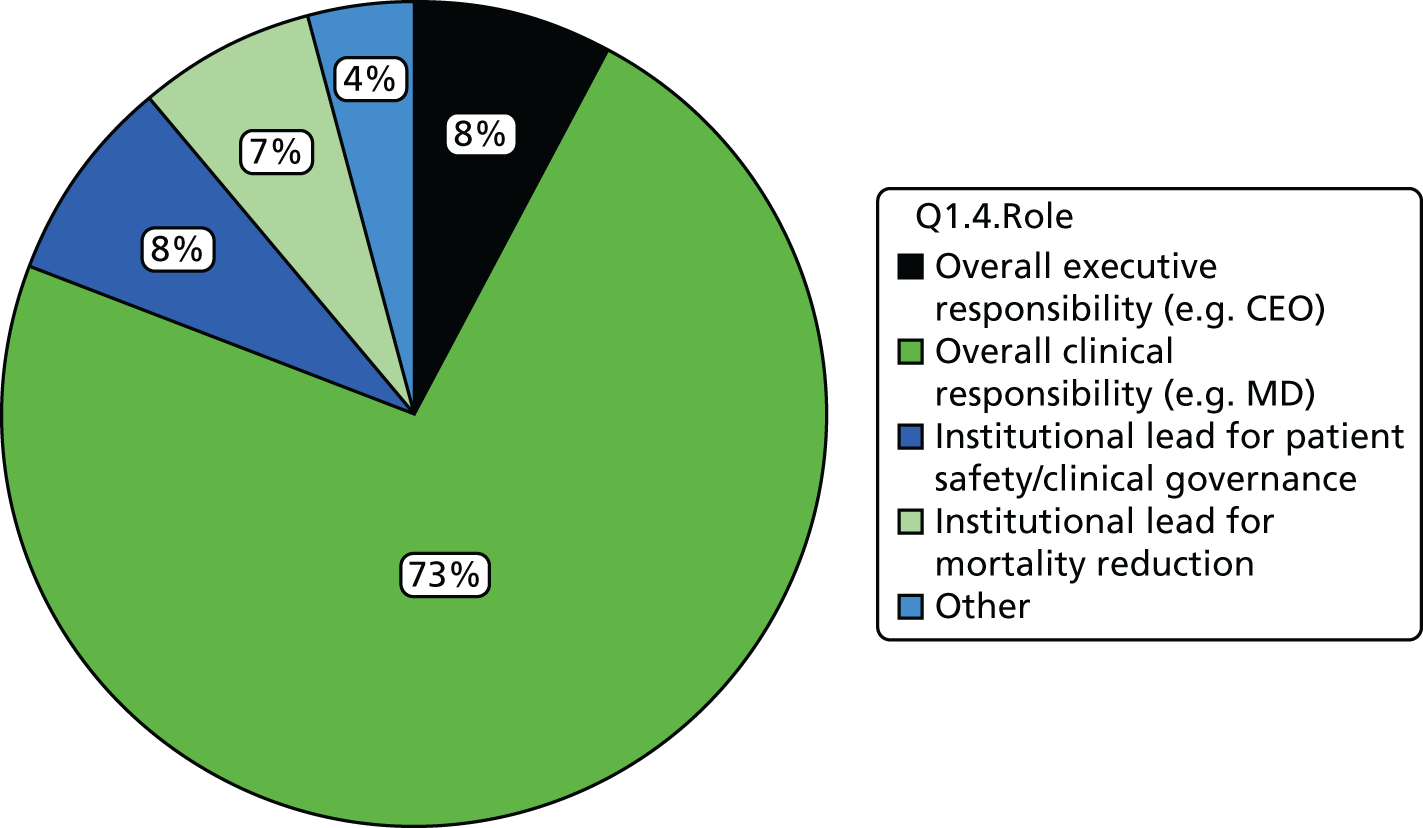

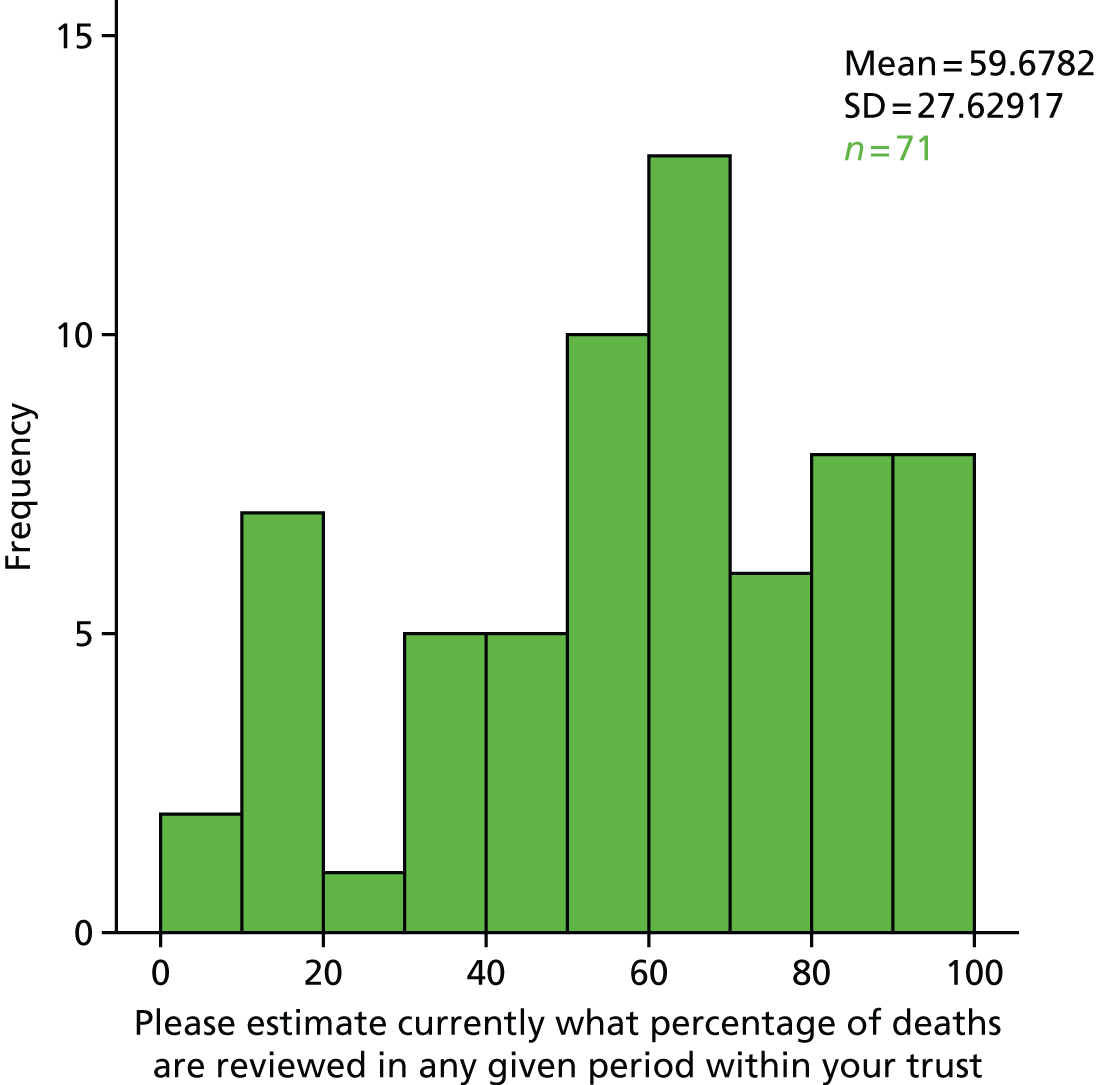

In workstream 2 we undertook in-depth qualitative case studies to understand the local impact of receiving an alert and the institutional behaviour that resulted. Adopting a realist evaluative stance, we aimed to generate rich descriptions of how the alerts, as a form of feedback intervention, instigated interactions between local context, institutional behaviour and institutional outcomes (objectives 1 and 4). We identified 11 sites that had alerted in one of two areas, sepsis or AMI, during the 2011–14 period, stratified by single or multiple alerting conditions and historical statistical trends in relative risk (objectives 5 and 6). We used principles of grounded theory and structured framework analysis to apply both inductive and deductive logic to our analysis and interpretation of the case study data, including a comprehensive review of organisational theory to ensure that our sense-making process was theoretically informed. A subanalysis of qualitative data was undertaken to support the development of an evaluative framework and survey instrument, which was subsequently used in a national cross-sectional survey of the perceptions of mortality leads at alerted trusts. The survey aimed to describe variance in organisational structures and processes concerning mortality governance (objective 1) and to capture evaluative perceptions concerning the efficacy of the current mortality surveillance and alerting system (objective 4).

Chapter 3 Literature review

In this chapter, we carry out a literature search and review to identify the current knowledge on the use of mortality surveillance systems as an indicator of quality. We then go on to review the literature for several areas of theory that are relevant to the institutional response to mortality alerts, namely institutional theory and neo-institutional theory, organisational readiness for change, absorptive capacity, normalisation process theory and sense-making, among others.

Mortality surveillance systems as an indicator of quality

Methods

In this project, we set out to understand how hospitals react to mortality alerts and whether or not outcomes improve as a consequence. We carried out an electronic literature search within three research databases to describe how our study fits into existing evidence. We aimed to identify literature that specifically examined clinical performance through hospital mortality assessment or monitoring.

The studies included people of any age who had been admitted for any hospital treatment living in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) country. The reason for excluding studies from non-OECD countries was partly to limit the search, and partly because non-OECD countries will have different health-care systems and, specifically, different health-care information systems. We limited the studies to only those written in English. We included exploratory, descriptive and quasi-experimental study designs.

Search strategy

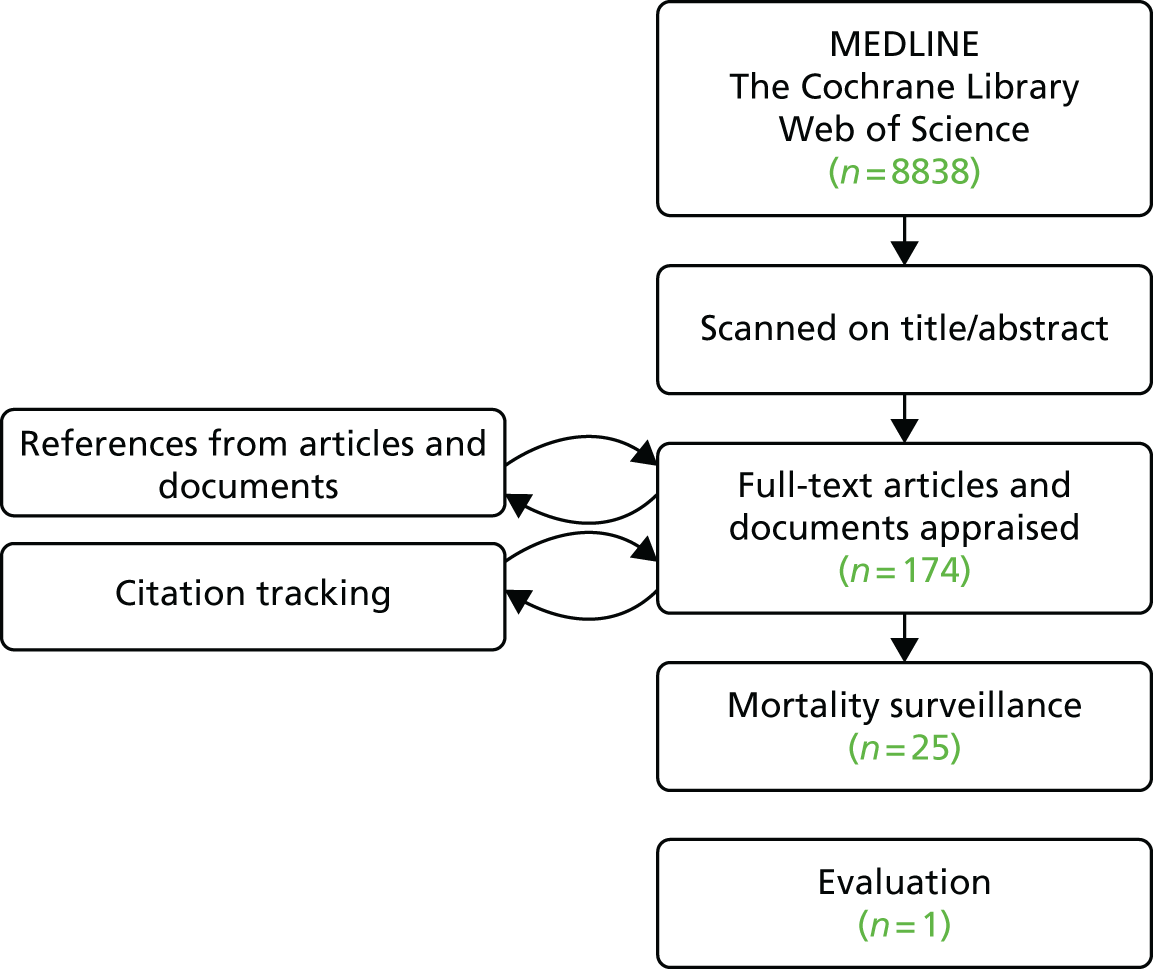

Our search terms (within the title and abstract) were Hospital AND (Monitor* OR Surveillance) AND (Death OR Mortality). We adapted our search for MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library and Web of Science. Literature was also retrieved using article references and citation tracking.

Data collection, analysis and reporting

We screened initially on the title; a second screen was on the abstract and the final screen was on the full papers. One reviewer carried out screening, a second reviewer checked the final screen and both reviewers reached a consensus on which studies to include in the review.

Results

There were > 8000 research papers/documents identified in MEDLINE, The Cochrane Library and Web of Science combined. We isolated 174 relevant articles and documents on the first two screenings. We appraised individual text articles/documents and identified further articles using referenced literature and citation tracking. Twenty-five studies were included for this final review. Figure 2 shows the flow chart for the process.

FIGURE 2.

Flow chart of process identifying articles and documents on hospital mortality surveillance evaluations.

Monitoring mortality is an integral part of health care43 and originally focused on specific departments such as the intensive care unit (ICU),44 or surgical procedures,45 for which data were collected through audits. Although our literature search focused on mortality monitoring using administrative data, we did include literature in which there was mortality monitoring using audit data.

Government bodies in the UK and USA have a long history of publishing mortality statistics. 46 One of the first articles that used routine hospital data to investigate hospital mortality and to suggest their use as a mechanism to identify patterns of potentially poor quality of care was a US report by the RAND Corporation and sponsored by the Health Care Financing Administration at the US Department of Health and Human Services, which was published in 1989. 47 In this study, admissions were extracted from hospital discharge data for all acute care hospitals treating Medicare patients. Admissions were over a 1-year period between October 1983 and September 1984, and included Medicare patients aged ≥ 65 years. The admissions were grouped by the diagnosis-related group and mortality rates were directly standardised for age, sex and race. The authors found that variation in hospital mortality rate was unlikely to have arisen through chance. The authors acknowledged that these large differences could have differed as a result of severity of the condition (the analysis did not adjust for comorbidity as they questioned the quality of the recording of secondary diagnoses) and highlighted that rates must be interpreted with caution. However, the authors did suggest that the data could be used as a screening tool to point to institutions or cases that appear to warrant more in-depth review.

Jarman et al.’s48 paper in 1999 was the first English study to use administrative, routinely collected data to investigate standardised hospital death rates. The authors were unable to adjust for severity but utilised a case-mix model (including a comorbidity score) as a proxy measure. The strength of this study was the population coverage. It used national public hospital administrative data in which the population was all patients admitted to NHS hospitals between April 1991 and March 1995. Previous mortality studies used regional, individual hospital or insurance-based populations. A major limitation with this study is that only inpatient deaths could be measured, as at that time there was no linkage to death registry data. This meant that the study missed deaths that occurred shortly after discharge but that may have been related to the hospital stay. The paper did, however, introduce a standardisation methodology that was to later be adapted (and further developed) for use by Dr Foster Intelligence, a commercial health-care information company that published performance indicators on NHS hospital services.

Table 1 lists the studies identified in the literature search on mortality surveillance as an indicator of quality. Hospital mortality monitoring studies were international, covering the UK,2,14,35,51,53 the USA,49,52,59,64,67,68,70 the Netherlands,57,63 Canada55,69 and Australia and New Zealand. 50,54,56,58,60–62,65,66 Studies were for a range of conditions and settings; these included surgical,2,51,59,64,66,70 intensive care,50,52,54,61,63,65 transplantation53,67,68 and all cause. 14,49,55,57,58,60

| Authors | Title | Year | Country | Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hofer and Hayward49 | Identifying poor-quality hospitals. Can hospital mortality rates detect quality problems for medical diagnoses? | 1996 | USA | All cause |

| Aylin et al.2 | Comparison of UK paediatric cardiac surgical performance by analysis of routinely collected data 1984–96: was Bristol an outlier? | 2001 | UK | Surgical |

| Cook et al.50 | Monitoring the evolutionary process of quality: risk-adjusted charting to track outcomes in intensive care | 2003 | Australia | Intensive care |

| Aylin et al.51 | Paediatric cardiac surgical mortality in England after Bristol: descriptive analysis of hospital episode statistics | 2004 | England | Surgical |

| Afessa et al.52 | Evaluating the performance of an institution using an intensive care unit benchmark | 2005 | USA | Intensive care |

| Rogers et al.53 | Cumulative risk adjusted monitoring of 30-day mortality after cardiothoracic transplantation: UK experience | 2005 | UK | Cardiothoracic transplantation |

| Cook54 | Methods to assess performance of models estimating risk of death in intensive care patients: a review | 2006 | Australia | Intensive care |

| Canadian Institute for Health Information55 | HSMR: A New Approach for Measuring Hospital Mortality Trends in Canada; 2007 | 2007 | Canada | All |

| Bottle and Aylin35 | Intelligent information: a national system for monitoring clinical performance | 2008 | UK | 172 conditions/procedures |

| Coory et al.56 | Using control charts to monitor quality of hospital care with administrative data | 2008 | Australia | AMI |

| Heijink et al.57 | Measuring and explaining mortality in Dutch hospitals; the hospital standardised mortality rate between 2003 and 2005 | 2008 | Netherlands | All cause |

| Ben-Tovim et al.58 | Measuring and reporting mortality in hospital patients: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; 2009 | 2009 | Australia | All cause |

| Hall et al.59 | Does surgical quality improve in the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program: an evaluation of all participating hospitals | 2009 | USA | Surgical |

| Ben-Tovim et al.60 | Routine use of administrative data for safety and quality purposes – hospital mortality | 2010 | Australia | All cause |

| Pilcher et al.61 | Risk-adjusted continuous outcome monitoring with an EWMA chart: could it have detected excess mortality among intensive care patients at Bundaberg Base Hospital? | 2010 | Australia | Intensive care |

| Cook et al.62 | Exponentially weighted moving average charts to compare observed and expected values for monitoring risk-adjusted hospital indicators | 2011 | Australia | AMI |

| Koetsier et al.63 | Performance of risk-adjusted control charts to monitor in-hospital mortality of intensive care unit patients: a simulation study | 2012 | Netherlands | Intensive care |

| Cohen et al.64 | Optimising ACS NSQIP modelling for evaluation of surgical quality and risk: patient risk adjustment, procedure mix adjustment, shrinkage adjustment, and surgical focus | 2013 | USA | Surgical |

| Moran and Solomon65 | Statistical process control of mortality series in the Australian and New Zealand Intensive Care Society (ANZICS) adult patient database: implications of the data generating process | 2013 | Australia/New Zealand | Intensive care |

| Smith et al.66 | Performance monitoring in cardiac surgery: application of statistical process control to a single-site database | 2013 | Australia | Cardiac surgery |

| Sun and Kalbfleisch67 | A risk-adjusted O-E CUSUM with monitoring bands for monitoring medical outcomes | 2013 | USA | Liver transplantation |

| Snyder et al.68 | New quality monitoring tools provided by the scientific registry of transplant recipients: CUSUM | 2014 | USA | Transplantation |

| Hogan et al.14 | Avoidability of hospital deaths and association with hospital-wide mortality ratios: retrospective case record review and regression analysis | 2015 | UK | All cause |

| Lesage et al.69 | A surveillance system to monitor excess mortality of people with mental illness in Canada | 2015 | Canada | Mental health |

| Cohen et al.70 | Improved surgical outcomes for ACS NSQIP hospitals over time: evaluation of hospital cohorts with up to 8 years of participation | 2016 | USA | Surgical |

Mortality monitoring methods

There are two types of methods reported in the literature for monitoring hospital mortality. The first uses a cross-sectional measurement of condition-specific standardised mortality ratios2 and HSMRs (all-cause mortality) in Canada,55 the Netherlands57 and Australia. 60 Using this method, assessment is achieved through benchmarking, whereby hospitals are assessed against set standards or using interhospital comparisons. The Australian Institute of Health and Welfare commissioned a report on measuring and reporting mortality in hospital patients to determine whether or not it was possible to produce accurate and valid indicators of in-hospital mortality using Australian administrative data. 58 Risk-adjusted modelling predicted or explained the variation in mortality rates to a similar extent as in international literature, and authors concluded that high or rising HSMRs could be used to signal a potential problem within a hospital.

The second method investigates cumulative measures over time using statistical process control charts. Steiner et al. ,71 in 2000, introduced the idea of using risk-adjusted CUSUM charts for monitoring mortality in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Since then, there have been several international papers investigating the use of control charts to monitor the quality of hospital care in other settings;56,62,66,68 however, these studies were on clinical audit data and not on administrative hospital data. Bottle and Aylin35 published a paper in 2007 that investigated the use of statistical control charts for monitoring clinical performance, including in-hospital mortality. The methodology described was the basis for the national surveillance system for mortality alerts that is evaluated in this report. Pilcher et al. 61 investigated whether or not the use of a statistical process control chart could have detected the high death rate in the ICU at Bundaberg Base Hospital, around which there was considerable publicity because of perceived excess mortality between 2003 and 2005. The authors concluded that the methodology was able to detect fluctuations in relative risk of death in the Bundaberg ICU that were not apparent when standardised mortality ratios were used.

Validation

Two papers used the methodology to identify hospitals in which there were reported failings in quality as outliers. The paper by Aylin et al. 2 examined paediatric cardiac surgery and confirmed high mortality rates identified through surgical audits, and a large public inquiry, while Pilcher et al. 61 investigated the use of statistical process control chart methodology compared with previous reports of high death rates at an ICU, although it is not clear from their paper how the initially high rates were determined. Hogan et al. 14 attempted to use case note reviews as a gold standard. They reviewed 100 case notes of deceased patients in 34 hospital trusts. They found an average of just over three ‘preventable’ deaths per hospital. The authors then went on to examine the relationship of these small numbers of avoidable deaths in each trust with HSMRs. The study was woefully underpowered and no significant relationship was found. Despite this, the authors claimed that ‘the absence of a significant association between hospital-wide SMRs [standardised mortality ratios] and avoidable death proportions suggests that neither metric is a helpful or informative indicator of the quality of a trust’. 14

Evaluations

Many health-care systems internationally use routine administrative data to monitor quality indicators, including hospital mortality. Examples of these are the analytic toolkits, provided by commercial companies such as Dr Foster (UK), Telstra (Melbourne, VIC, Australia; www.telstra.com.au) and 3M (Maplewood, MN, USA; www.3m.com). However, we did not find published literature on evaluations of these toolkits.

Clinical audits (or databases) have been used for a number of years to monitor outcomes such as mortality in a range of settings and conditions, but particularly in surgery. 43,45 Audits involve data collection and analysis that is time-consuming and expensive to compile. However, we identified one evaluation of a study using clinical audit data in our literature search. The study was on the American College of Surgeons National Surgical Quality Improvement Program® (ACS NSQIP®). 64 ACS NSQIP collects data from participating hospitals and analyses them, and participating hospitals are provided with reports that permit risk-adjusted comparisons, including 30-day mortality, with a surgical quality standard. Cohen et al. 70 carried out an ‘evaluation’ of the surgical outcomes over time, and found a decreasing trend in mortality in 62% of participating hospitals and an average of 0.8% annual reduction in mortality rate. There are, however, limitations to this study. There are no control (non-ACS NSQIP participating) hospitals, and the reported trends could have been influenced by secular trends unrelated to ACS NSQIP. The authors do acknowledge this limitation, yet they still classify the article as an evaluation.

Limitations

We are aware that limiting the search to papers written in English may have resulted in some literature being missed; for example, one paper, by Stausberg et al.,72 was written in German. We also understand that not all evaluations are published in peer-reviewed journals; however, we feel that those studies that have been scrutinised by other experts in the same field are a more robust subset to include in our review.

Conclusions

Our literature search has highlighted that although there has been literature on the methodology for monitoring hospital mortality, there is little literature on evaluation, and the only study that attempted to evaluate a benchmarking system for surgical outcomes in the USA is weak. To our knowledge, there has never been an evaluation of a hospital mortality surveillance system using routinely collected administrative data. 2

Institutional theory

Institutional theory provides conceptual frameworks to analyse and compare the response of organisations working in the same field with demands placed on them by external institutions. 73–75 In this section, an overview of the relevant aspects of these theories is described in relation to hospital trusts (organisations) working in the English NHS (the field), considering their response to the demand placed on them from Imperial College London/Dr Foster and the CQC (external institutions) through the receipt of a mortality alert letter. We review several areas of theory that are relevant to the institutional response to mortality alerts, namely institutional theory and neo-institutional theory,74–78 organisational readiness for change,79–81 absorptive capacity,82–87 normalisation process theory88–90 and sense-making,91–93 among others. We include areas of institutional theory that were identified a priori in the initial research protocol, but have complemented these perspectives with a review of theories that emerged as relevant during the course of interaction with case study data. Rather than providing a comprehensive literature review, we consider each theory in terms of its specific relevance as a potential explanatory model for the operation of the MASS. In this sense, the following subsections define the theoretical lenses that will be used as frameworks in subsequent analyses and the parent theories from which we extract concepts to aid in the understanding and interpretation of the processes and mechanisms of interaction between the MASS and institutional behaviour in each of our case study sites.

Response to multiple competing influences

The structure and distribution of power among institutional actors at the field level within health-care systems is considered an important determinant of how organisations such as hospitals respond to external demands (Table 2). In fields such as health care, where there are multiple influential institutional actors, each without adequate power to clearly dominate but with enough power to constrain the actions of organisations, the leadership task in hospitals is considered even more complex. 95–97 Pache and Santos76 describe this external environment as a ‘moderately centralized field’. In health care, this is found where there are, for example, strong medical societies, government regulators and commissioners all making demands on health-care organisations.

| Field | Description |

|---|---|

| Highly centralised fields | Typically rely on one principal constituent whose authority in the field is both formalised and recognised.94 This principal constituent can resolve disagreements between disparate players and impose relatively coherent demands on organisations |

| Moderately centralised fields | Characterised by the competing influence of multiple and misaligned players whose influence is not dominant, yet is potent enough to be imposed on organisations |

| Decentralised fields | Institutional pressures are rather weak and, when incompatible, they can be easily ignored or challenged by organisations as the referents have little ability to monitor or enforce them |

NHS trusts have multiple competing influences from external institutions, not least from commissioners and financial regulators,98 and in this respect the English NHS can be described as a moderately centralised field. A broad range of external factors, such as policy-level initiatives, professional bodies seeking to change practice, local pressure from commissioning groups for service development and reconfiguration, and others, may influence the internal governance agenda within a health-care organisation, in addition to internal factors. Mortality alerts, therefore, compete with other priorities and demands placed on NHS trusts by external institutions, such as to reduce cancer and other waiting times, to improve infection control, to introduce standard operating procedures to reduce surgical ‘never events’ or to deliver specific local commissioning priorities. Investigating the local causes of mortality alerts, developing a formal response to regulators regarding the mortality trend and implementing actions to reduce avoidable mortality are all resource-intensive activities. Each has the potential to detract from effort and to divert resources that trusts may otherwise allocate to respond to these competing pressures.

Pache and Santos76 also suggest that the nature of external demands conditions the response of organisations. For example, responses may differ depending on whether the demands take the form of goals for the organisation to pursue or of the specific means or courses of action to achieve those goals. MASS letters take the form of information, indicating an area that the trust may wish to investigate. The letters are deliberately outcome focused, in that they focus on the observed significant trends in mortality without suggesting an underlying cause or course of action. The Imperial alert letters, therefore, do not set specific objectives for the response, and trusts are free to decide how they respond. When alerts are followed up by the CQC, the form of the response, its timescale and components are specified; however, the degree to which the focus of the planned actions is specified varies as a function of ongoing interactions between the alerting trust and the CQC and the results of local investigations into the origins of the alert.

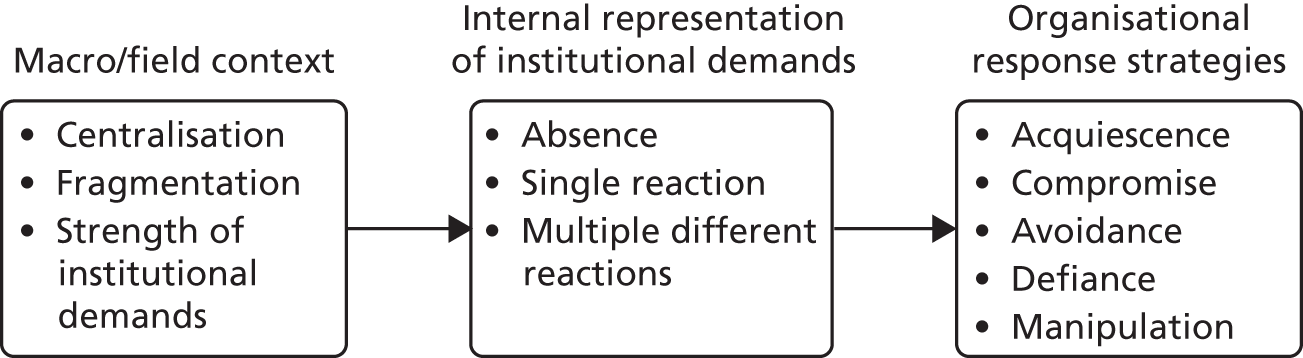

Other institutional analysts have highlighted how organisational responses to external institutional pressures and resource dependencies may vary across contexts and how organisational leaders exercise a range of strategic choices. 99 A model outlining organisational responses to institutional demands and resource dependencies identified a continuum of organisational responses ranging from acquiescence, compromise and avoidance to defiance and manipulation (Box 1). 77

-

Acquiescence refers to how organisations comply with institutional demands whether consciously or unconsciously arising from habit, imitation or voluntary accession.

-

Compromise refers to when an organisation partially conforms to institutional demands by adjusting those institutional demands and/or adjusting internal organisational responses.

-

Avoidance strategies involve attempts by the organisation to adjust conditions so as to make it possible for the organisation to comply with institutional demands. Avoidance tactics include concealing non-conformity by pretending to acquiesce; by preventing technical monitoring of compliance (buffering); or by changing the organisational function so as to make compliance unnecessary (escaping).

-

A defiant strategy may occur when the organisation rejects at least one institutional demand and may be manifested as dismissal of a demand, overtly challenging a requirement or aggressively attacking the institutional demand.

-

A manipulation strategy refers to the deliberate attempt to actively change the content of institutional demands. Manipulation tactics include co-opting sources of institutional pressure, influencing norms by active lobbying and controlling the source of pressure.

Adapted from Oliver. 77

In relation to mortality alerts, acquiescence relates to trust accession to the institutional demand from the CQC or Dr Foster to accept the mortality alert as intended (i.e. as a valid and valuable signal worthy of investment of resources in a response). Compromise may take various forms in the context of the MASS, but may involve, for example, negotiation with the CQC over the components of the expected response itself or correcting erroneous coding of cases that it has been agreed are unduly affecting the ratio of observed to expected mortality. Avoidance strategies might include closing a problematic service or deliberately reducing monitoring in specific areas.

Defiance may see the trust actively challenging Imperial College/Dr Foster over the validity of the information content of the alert: the accuracy of the data themselves or the adequacy of the risk-adjustment model on which the alerts are based. Manipulation might include more deliberate attempts to recode cases so as to artificially reduce outliers.

The organisational (trust) response to the MASS may be governed, in part, by alignment between the alerting issue and parallel demands for organisational resources. In their analysis of how hospitals respond to competing demands for quality improvement and financial balance, Burnett et al. 98 grouped the responses into four categories. These ranged from (1) organisations that were more likely to respond to requests from regulators by using expedient, short-term measures, regardless of whether or not this would achieve sustainable change in the longer term, to (4) organisations that had invested in, and embedded, quality improvement into everyday work, and had worked with external institutions to align quality and cost requirements. Two factors were found to be important in this research: first, the organisational pre-conditions, and, second, the ability of senior leaders to align external demands with internal requirements into a coherent strategy that achieved both cost and quality requirements.

Legitimacy

Meyer and Rowan73 propose that organisations are more likely to respond to external demands, in ways that support the organisation’s legitimacy:

[O]rganisations are driven to incorporate the practices and procedures defined by prevailing rationalized concepts of organisational work and institutionalized in society. Organisations that do so increase their legitimacy and their survival prospects, independent of the immediate efficacy of the acquired practices and procedures.

Meyer and Rowan73

Meyer and Rowan73 propose that, in deciding how to respond, organisations adopt the practices of other organisations working in the same field, in a process of ‘ceremonial conformity’. They argue that this occurs regardless of whether or not the adopted practices conflict with the efficiency criteria or requirements of the other organisations. Organisations, it is argued, copy and incorporate these practices in order to gain legitimacy and enhance their survival prospects by being seen by external institutions to comply with current norms. Organisations seeking such legitimacy will conform to these practices, regardless of whether or not they are likely to achieve a desired outcome, and regardless of impact of these practices on other pressures and on costs. In this way, the practices spread, and organisations, and their structures, become isomorphic with the myths of the institutional environment. Applying this to mortality alerts, the question arises as to whether or not organisations’ responses to alert letters have become isomorphic over time, such that there is now an established way in which trusts are expected to respond. Furthermore, one may ask whether or not these new practices have the desired impact on reducing mortality and whether or not they are cost-effective. Alternatively, are they more ‘ceremonial’ so that trusts can be seen to be doing something, and hence complying with what is expected, regardless of the outcome?

Intraorganisational context and organisational change

Greenwood and Hinings100 proposed that the nature and pace of change within organisations in the same field varies because of the political dynamics among intraorganisational groups, and the degree to which organisations are socially and professionally embedded within their contexts. Pache and Santos76 build on these ideas to specify, more clearly, how the nature and degree of internal representation of, or support for, competing pressures within an organisation will result in mobilising the specific types of responses identified by Oliver. 77 For example, in hospitals, medical, nursing and managerial groups may have different priorities for, and conceptions of, the requirements in an alert letter, and here conflict may arise regarding what needs to be done and when. There may additionally be multiple interpretations of the validity of an alert, or the attributable causes of above-expected mortality rates. Pache and Santos76 suggest that when there is a single, common reaction shared across different internal groups this may lead to a unified resistance to an external pressure, for example in refuting the data in an alert letter or questioning coding. In contrast, when internal groups offer differing reasons for resisting an external pressure, they are likely to compete for their preferred course of action. In situations when there is an absence of internal representation or support, internal groups will usually exhibit indifferent commitment and the external pressures will tend to induce at least minimally compliant actions by the organisation. 76 This is summarised in Figure 3.

Neo-institutional theory

Neo-institutional theory is concerned with how organisations orientate themselves within the institutional environment and is concerned with three properties, or pillars, of organisational life, as follows:75,78,101–104

Institutions exhibit stabilising and meaning-making properties because of the processes set in motion by regulative, normative, and cultural-cognitive elements. These elements are the central building blocks of institutional structures, providing the elastic fibres that guide behaviour and resist change.

Scott,104 p. 57

Table 3 sets out the definitions of these elements in relation to each other and how they manifest themselves within organisations.

| Regulative | Normative | Cultural–cognitive | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Basis of compliance | Expedience | Social obligation | Taken-for-granted |

| Basis of order | Regulative rules | Binding expectations | Shared understanding |

| Mechanisms | Coercive | Normative | Constitutive schema |

| Logic | Instrumentality | Appropriateness | Mimetic |

| Indicators | Rules | Certification accreditation | Common beliefs |

| Laws | |||

| Sanctions | Shared logics of action | ||

| Affect | Fear guilt/innocence | Shame/honour | Certainty/confusion |

| Basis of legitimacy | Legally sanctioned | Morally governed | Comprehensible |

| Recognisable | |||

| Culturally supported |

Regulative influences on how trusts regard the Mortality Alerting and Surveillance System

The role of the CQC as the regulator is important in the MASS. Institutional theory suggests that the external institutions that are able to enforce their demands most effectively are usually those that possess greater power and influence over a particular set of organisations either through control of financial and material resources or through their authority over legal and professional sanctions. 75 Regulatory influences include rule-setting, monitoring and sanctioning activities,104 designed to impact on and influence the behaviour of an organisation. Theorists argue that the costliness of the sanctions governs how organisations will respond to regulative pressures. 105 Foucault introduced the concept of ‘governmentality’, whereby organisations self-govern in response to perceived surveillance and/or the coercive power of external organisations. 106

Applying these theoretical perspectives to the MASS, several factors are important. First, the CQC has considerable (actual) power over English NHS trusts through its role in licensing trusts to deliver health care. Institutional responses may, therefore, be governed by the threat of real sanctions or adverse repercussions for non-compliance. In addition, the subject of the letters (higher-than-expected death rates) has potential (if not real) implications for the reputation of the hospital (both locally and nationally) and the reputation of the medical professionals, not least the trust’s medical director.

Normative influences on how trusts respond to external pressures

Normative influences are related to social obligation, consisting of values and norms that develop over time and become embedded in organisational life as routines and roles. Norms relate to how things should be done, defining the legitimate means to achieving goals. Values relate to practices and actions that are considered desirable or preferred. 104 Normative influences, therefore, define the legitimate means of the pursuit of valued ends; for example, in this study, bundles for diagnosing and treating sepsis or for diagnosing or preventing AMI. Scott104 summarises this as:

The central imperative confronting actors is not ‘What choice is in my own best interests?’ but rather, ‘Given this situation, and my role within it, what is the appropriate behaviour for me to carry out?’

Scott,104 p. 65

Tendency towards specification of the response to mortality alerts may be regarded as a normative influence on institutional behaviour following an alert, just as the alerts themselves embody norms for risk-adjusted mortality across institutions.

Cultural–cognitive influences and sense-making

Cultural–cognitive influences focus on the meanings, beliefs and perception of people within the organisation and how they respond to these. Scott,104 in summarising extensive research by psychologists, describes how cognitive frames are part of the range information-processing activities, from determining what information will receive attention, and how it is encoded and retained in an organisation’s memory, to how it is interpreted. Together, these determine how an organisation will respond. In addition, Scott104 describes how cultural systems operate at multiple levels, from the shared definition of local situations to those that constitute an organisation’s culture. These cultural systems shape organisational life and, in our analysis, we examine these influences on how trusts respond to mortality alerts, for example the extent to which responses to the MASS are ‘taken for granted routines’, such as case note review: ‘the way we do things here’. This is built on in the next section on ‘sense-making’.

Sense-making

‘Sense-making’ is the process of giving meaning to experience. 91–93 Sense-making involves the ongoing development of plausible explanations that rationalise human behaviour when the current state of the world deviates from the expected state. 92 ‘Reasons’ or explanations for disruptions in the flow of activity are sought from frameworks such as institutional constraints, traditions, plans and acceptable justifications.

With regard to the MASS, we use this theory to consider how participants make sense of the alert letters, how they talk about them and how they rationalise the messages within. This leads to consideration of the actions taken in response to participants’ rationalisation of the messages in the alert letters.

Organisational receptivity and readiness for change

Responding to intelligence on avoidable mortality involves changes to the process of care delivery and, to a greater or lesser degree, organisational change. Organisational receptivity, or readiness for change, was found to be important in the course of change programmes that aimed to improve quality and safety of care. 81 Weiner et al. 107 frame organisational readiness for change (as opposed to individual readiness) as collective behaviour change in the form of systems redesign: multiple, simultaneous changes in staffing, workflow, decision-making, communication and reward systems. 29,30

Weiner et al. 107 set out the features of a receptive and non-receptive context for organisational change. Organisational readiness factors found to be important for successful change include senior management and board commitment, fostering receptivity to change, clinicians’ engagement in quality improvement, quality reporting processes and fostering processes for improvement that engaged frontline staff. 108–110 Other work has identified factors such as stakeholder support, team climate and individual attitudes and preferences. 111,112 Exemplars of past successful change are also considered important in giving those involved a sense of confidence that the proposed change can and will be achieved. 113

Research reported in 2006110 concluded that NHS organisations showed high variability in some of these important readiness factors, for example in the infrastructure for improvement and the use of improvement tools and techniques. The research also found financial targets to be the main drivers of improvement in the NHS, with these efforts largely project based and not part of routine operations.

Periods of uncertainty, for example trust mergers and management changes, have been found to have a negative influence on the course and success of change programmes. 114,115 Pettigrew et al. 97,116 described these as ‘receptive’ and ‘non-receptive’ contexts for change (Box 2).

Quality of ‘policy’ at the local level is important in terms of both the quality of analysis (e.g. importance of data in making argument) and the quality of the process (e.g. broad vision important).

Availability of key people leading changeNot individual, ‘heroic’ leadership, but leadership that is distributed and exercised in a more subtle and pluralist system. Continuity of leadership is very important and lack of continuity is highly detrimental.

Environmental pressure: intensity, scale and orchestrationCan be both positive and negative. Excessive pressure can drain energy from the system, but, if orchestrated skilfully, environmental pressure can produce movement (e.g. financial crisis can be seen as threat or can be leveraged to achieve change).

A supportive organisational culture‘Culture’ refers to deep-seated assumptions and values far below surface manifestations, officially espoused ideologies or even patterns of behaviour. The past can be very influential in shaping these values, which may be both a strength and a weakness. In health care, the array of subcultures is important. Aspects of culture found to be associated with high rate of change: flexible working across boundaries rather than formal hierarchies; open, risk-taking approach; openness to research and evaluation; strong value base giving focus to loose network; and strong positive self-image and sense of achievement.

Effective managerial/clinical relationsRelations better when negative stereotypes broken down (e.g. as a result of mixed roles such as hybrids). Important for managers to understand what clinicians value and have good understanding of health-care operational issues.

Co-operative interorganisational networksBetween health-care organisations and between health-care and other organisations. Most effective networks informal and purposeful, but vulnerable to turnover. Factors that can facilitate networks include financial incentives, shared ideologies or history and existence of boundary spanners.

Simplicity and clarity of goals and prioritiesA fewer number of priorities pursued over a long-time period associated with achieving change. Need to insulate from constantly shifting short-term pressures.

The fit between the change agenda and the localeHow factors in local environment, which may be outside control (e.g. nature of local population, presence or absence of teaching hospitals), are anticipated as potential obstacles of change.

Based on Pettigrew et al. 116

Organisational readiness factors are considered to be both psychological and behavioural. For example, those involved need to be motivated to implement the change,80 and they are often described as being dissatisfied with the status quo or believing that the change is beneficial either personally or to patients. A study of readiness to change in 58 general practice organisations in Australia found that staff were more ready to change when there was a low overall team climate. 117 They were also more ready to change when job satisfaction was considered low, supporting the findings elsewhere that staff are more ready to change if they are dissatisfied with the status quo.

In a recent targeted review examining which common implementation factors are associated with improving the quality and safety of care, eight success factors were found. 118 These included the preparations made for the change, staff capacity for implementation, and resources. Obstacles to implementation were the opposite: ‘for example, when people fail to prepare, have insufficient capacity for implementation or when the setting is resistant to change, then care quality is at risk, and patient safety can be compromised’. 118

Applied to the MASS, organisational readiness factors may affect the capacity of a trust to successfully implement change in care systems for key areas that are commonly alerted, such as sepsis or AMI, and to implement improvement actions more generally in response to mortality alerts. Specifically, organisational readiness for change theory would suggest that an optimal response requires the right culture, including teamwork, leadership and multiprofessional engagement, among other factors. Compatibility with existing goals and priorities, minimal resistance to change and effective intraorganisational communication may all be implicated in an effective organisational response.

Theories relating to implementation of quality improvement practices

Normalisation process theory

Normalisation process theory examines how new technology and routines become ‘normalised’ into the routine processes within an organisation. 88,119 It uses neo-institutional theory to explain how individuals in an organisation react to macro influences.

Normalisation process theory is described as a sociological ‘toolkit’ to understand the embedding of practices such as an innovation or the implementation of an innovation. Normalisation process theory is concerned with two areas:

-

process problems – about the implementation of new ways of thinking, acting and organising in health care

-

structural problems – about the integration of new systems of practice into existing organisational and professional settings.

Normalisation process theory focuses on the practices that occur through four generative mechanisms: coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring.

Coherence is defined as the sense-making that people do both individually and as a collective when they are faced with operationalising a particular set of practices. Coherence is divided into four subset processes including an examination of the work people do together to build a shared understanding of what is required. Cognitive participation is the relational work that people do to initiate change. This includes how key participants of the practice work to engage key participants and drive the change. Collective action is the operational work that people do to enact a set of practices. Finally, ‘reflexive monitoring’ is the appraisal work that individuals do to assess how the new or modified practices affect them and the people around them (note that this is not an appraisal of the practise itself but of the way it affects the individuals). Reflexive monitoring may lead attempts to redefine procedures or modify practice in the longer term.

Absorptive capacity

Absorptive capacity is concerned with the contribution of knowledge processes to organisational performance. 83–86 According to absorptive capacity theory, the success of an organisation is a result of the degree to which its internal processes are effective in aligning the organisation with its changing external environment. 84

Absorptive capacity has three components:83,84

-

Exploratory learning: the process through which new knowledge is recognised and understood. The capability of this process is based on prior knowledge in the organisation as well as value judgments.

-

Transformative learning: those processes that affect the way in which new knowledge is assimilated into and combined with prior knowledge.

-

Exploitive learning: how assimilated knowledge is translated into actions that will benefit the organisation. This includes the implementation of policies and plans.

The capacity for learning within an organisation will depend, according to absorptive capacity theory, on investment in these knowledge processes. Organisations that invest more in knowledge processes are considered more likely to increase their performance than those that fail to invest. Furthermore, those that fail to invest may find it hard to catch up and are likely to become ‘permanently failing organisations’. 120 The value of absorptive capacity as a theoretical framework lies in its focus on internal knowledge management within an organisation and organisational capacity to continuously embody that knowledge in its systems and processes. Failure to effectively manage knowledge to achieve this undermines the ability of public sector organisations to perform. 84

In the context of MASS, the mortality alerts represent externally generated intelligence on potentially harmful variations in care that, in turn, act as stimulus for internal investigation, monitoring and action. The process by which the organisation assimilates the information and knowledge generated is one of organisational learning governed by absorptive capacity. Furthermore, developing a repeatable process for responding to mortality alerts and understanding the local institutional value of a MASS involves processes of exploratory, transformative and exploitative learning.

Organising for quality

Organising for quality is a theoretical approach steeped in empirical evidence that aims to understand the processes involved in achieving quality. The theory is highly practical and was born out of an international study of European and US hospitals. Although the researchers found that there were many different paths by which quality improvement can be achieved, they identified unique unifying features that stretched across all of their case studies. Rather than focus on when things went right, organising for quality seeks to illustrate the challenges that are faced when implementing quality improvement. The approach recognises six unifying challenges to the process of organising for quality, shown in Box 3.

-

Structural: structuring, planning and co-ordinating quality efforts.

-

Political: addressing the politics and negotiating the buy-in, conflict and relationships of change surrounding any quality improvement effort.

-

Cultural: giving ‘quality’ a shared, collective meaning, value and significance within the organisation.

-

Educational: creating and nurturing a learning process that supports continuous improvement.

-

Emotional: inspiring, energising and mobilising people for the quality improvement effort.

-

Physical and technological: designing physical systems and technological infrastructures that support improvement and quality of care.

Added later in the QUASER research study:121

-

Leadership: providing clear, strategic direction.

-

External demands: responding to broader social, political and contextual factors.

Chapter 4 Data sources

This chapter focuses on external data sources relating to our evaluation. We first discuss HES, the data source used to create the mortality alert. We then consider other hospital indicators of quality of care used in our evaluation that relate to hospital (or trust) structure, process and outcomes. Data collected during the qualitative analysis (workstream 2) will be discussed in Chapter 5 (see Workstream 2).

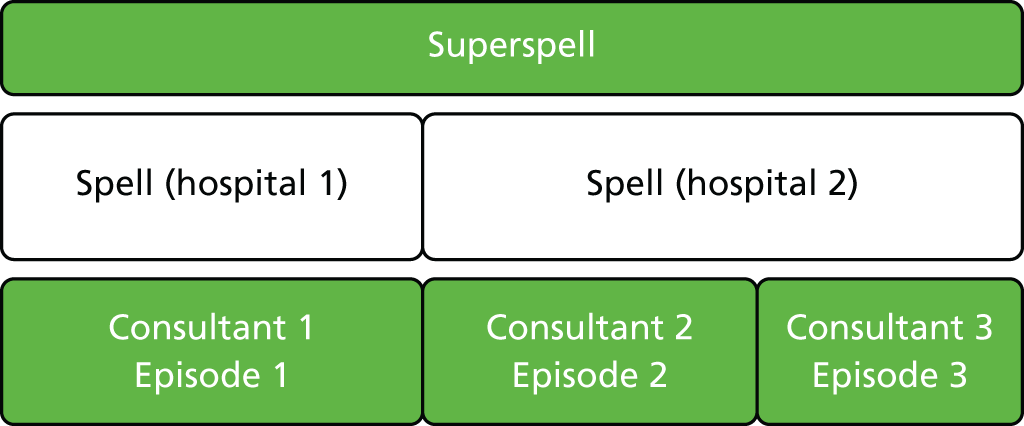

Hospital Episode Statistics data

Hospital Episode Statistics is a national administrative database containing information on all admissions to public (NHS) hospitals in England. 122 Each record in HES contains data on patient demographics, such as age, ethnicity and socioeconomic deprivation based on postcode of residence; data on the episode of care, such as hospital name, date of admission, date of discharge and discharge destination, which includes a code for death; and clinical information. 123 Diagnoses for each patient are recorded using the International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10),124 and the information is divided into the primary diagnosis (main problem treated) and various secondary diagnoses (including comorbidities and complications). Procedures performed during an episode are coded using the Office of Population, Censuses and Surveys Classification of Surgical Operations and Procedures, Fourth Revision (OPCS-4). 125 There is a unique identifier (HESID) for each patient in HES, which makes it possible to link a patient’s historical medical records. The Imperial College Unit holds provisional HES data provided monthly by NHS Digital. HES monthly data are used to generate the mortality alerts. The Imperial College Unit also holds the final annual publication of HES data. The data cover a financial year and the resulting snapshot of health-care activity will differ from the monthly HES extracts, as changes to the data may occur in the interim period. The Imperial College Unit combines episodes (periods of patient care under a single consultant) to form patient ‘spells’ to a single hospital; in turn, spells are linked together to account for interhospital transfers, creating ‘superspells’, as shown in Figure 4. In this report, we refer to a continuous period of care (whether a spell or superspell) as an admission.

FIGURE 4.

A patient’s stay in hospital (admission) in terms of episodes, spells and superspells.

Calculating risk of death

The Imperial College Unit calculates the probability of death using a logistic regression model based on national data and incorporating information on method of admission, patient age, patient gender, year of discharge, month of admission (for respiratory disease such as asthma), previous emergency admissions (in the last year), socioeconomic deprivation, comorbidities and palliative care. 126 The risk factors are further defined in Table 4. The relative risk for a specific diagnosis/procedure for each trust is the ratio of the observed number of deaths (the total number of finished provider admissions that resulted in a death) to the expected number of deaths (based on the probability of death from a risk-adjusted model).

| Risk factors | Definition |

|---|---|

| Method of admission | Elective or emergency |

| Patient age | Age at start of admission field in HES. Values were recoded to < 1, 1–4, 5–9 and 10–14 years, followed by 5-year bands |

| Patient gender | Gender |

| Year of discharge | The financial year of date of discharge at the end of the admission |

| Month of admission | The calendar month at the beginning of the admission |

| For respiratory diseases only | |

| Previous emergency admissions (in the last year) | From method of admission field in HES (values 21–28) in the admission records in the previous 365 days for the same patient |

| Socioeconomic deprivation | Carstairs and Morris127 |

| Comorbidities | Charlson score derived from secondary diagnosis fields of the admission128 |

| Palliative care | If any episode in the spell has the treatment function code 315 or contains Z515 in any of the diagnosis fields, then ‘palliative’; else, ‘non-palliative’ |

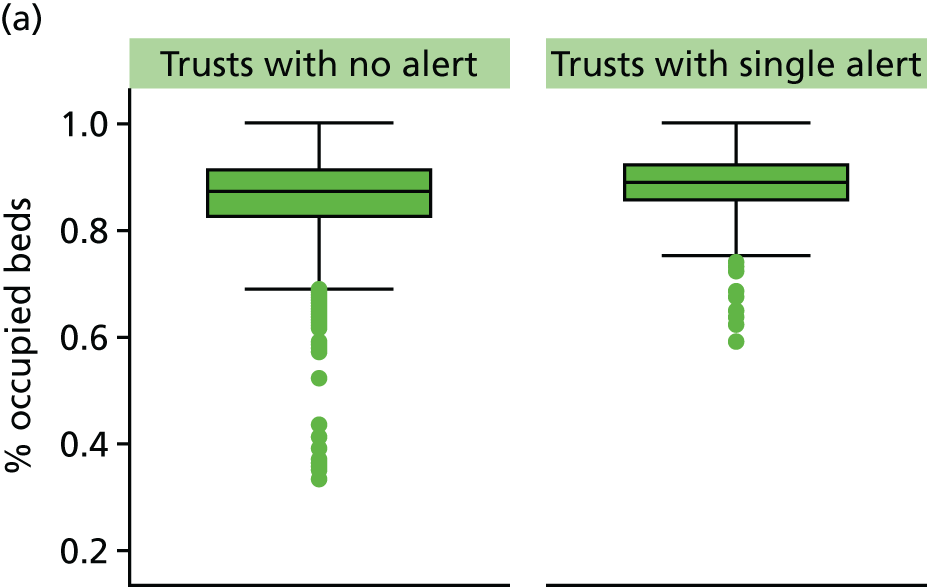

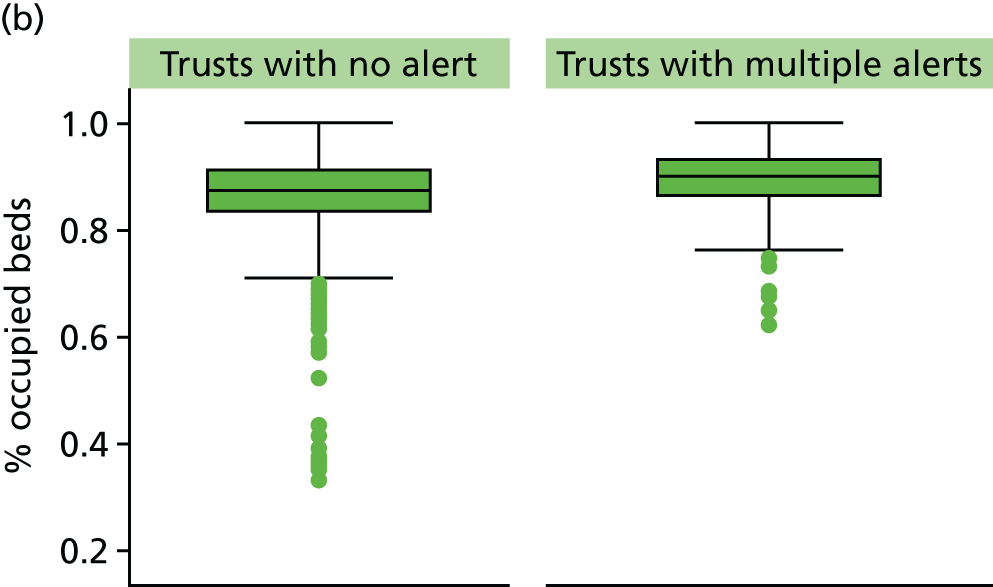

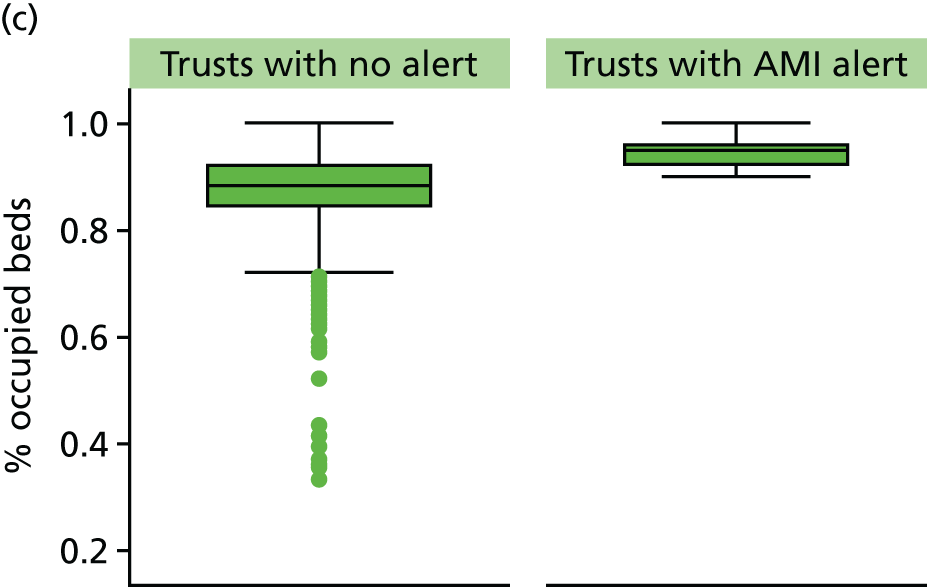

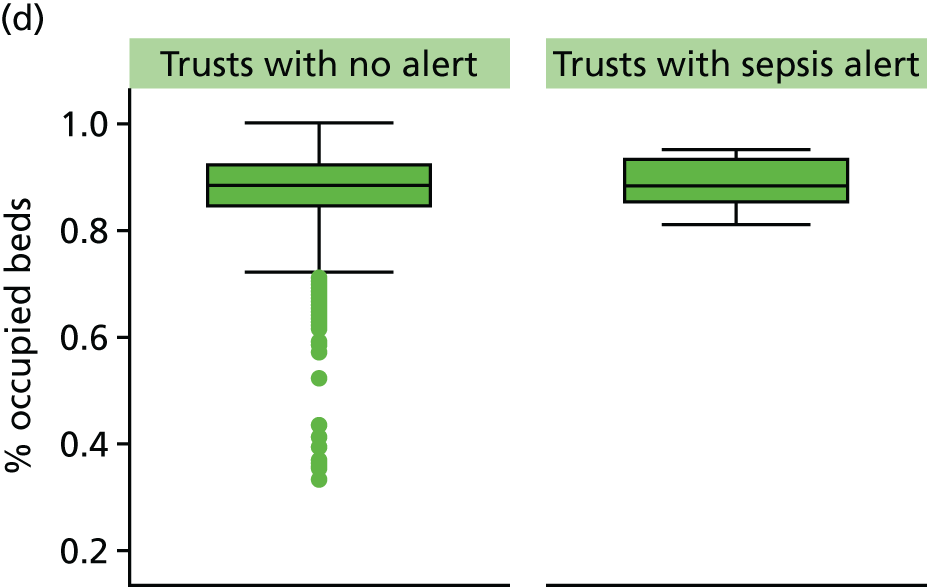

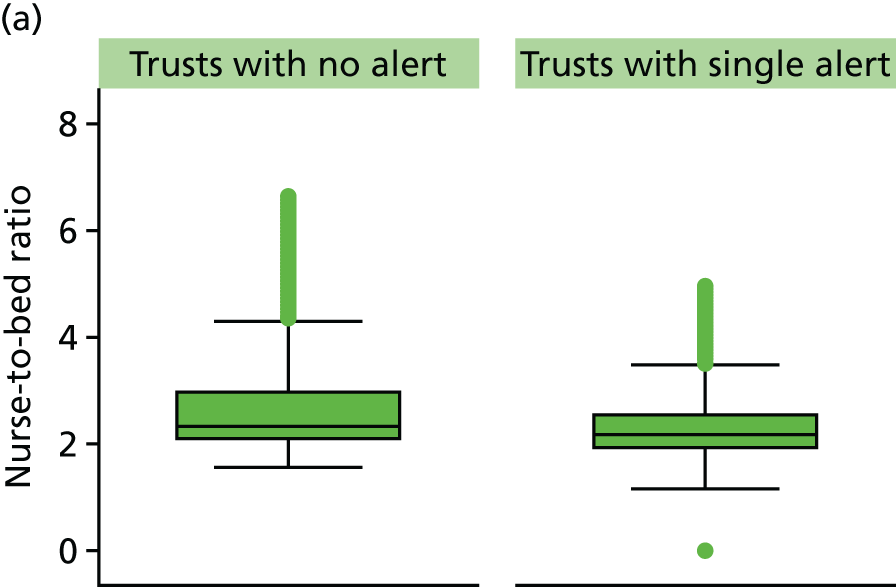

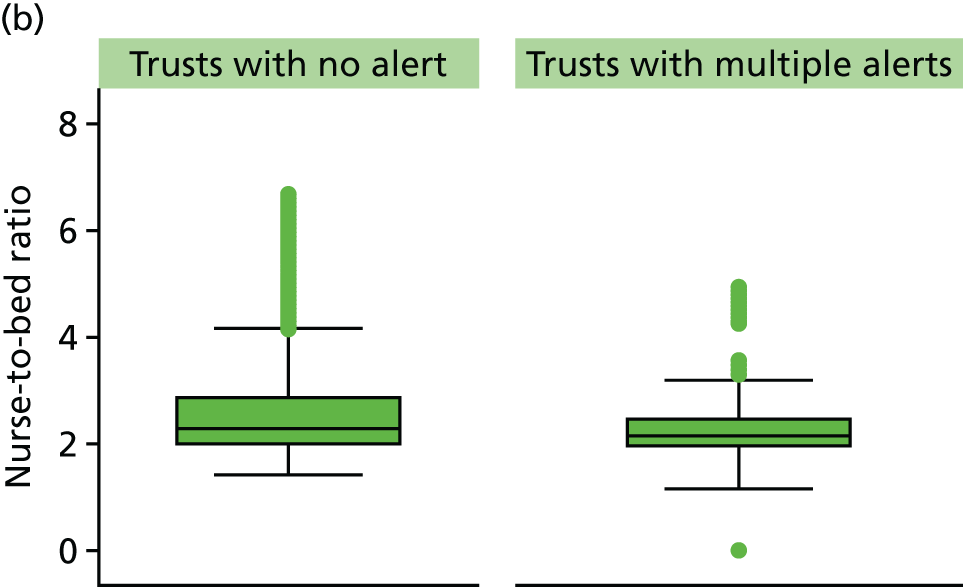

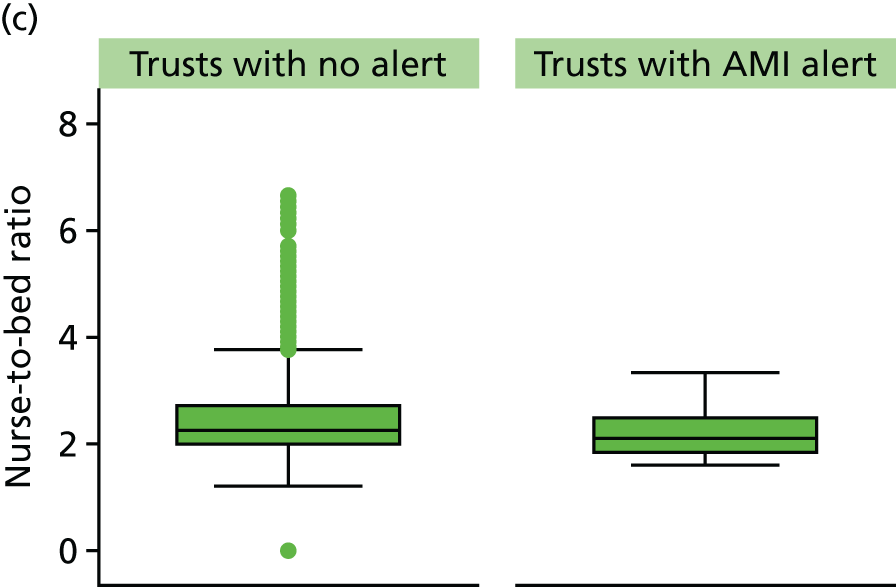

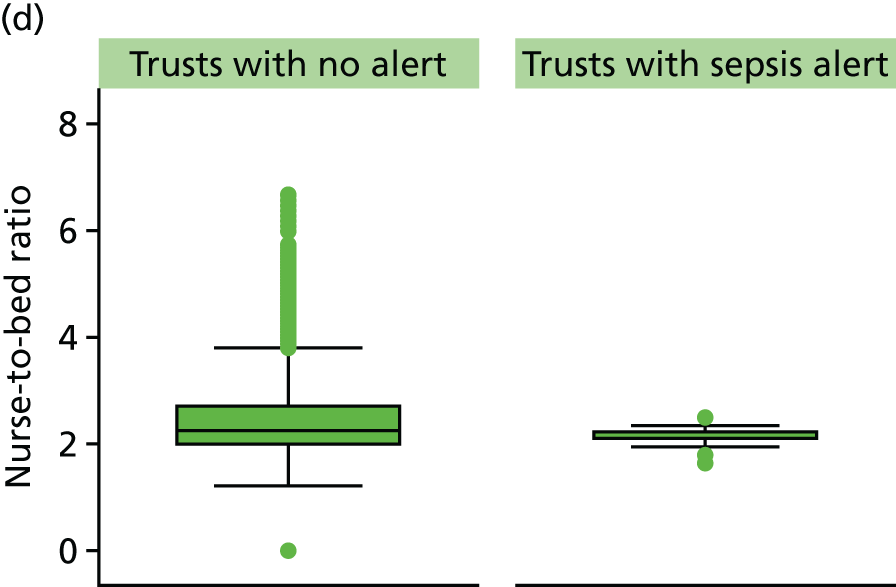

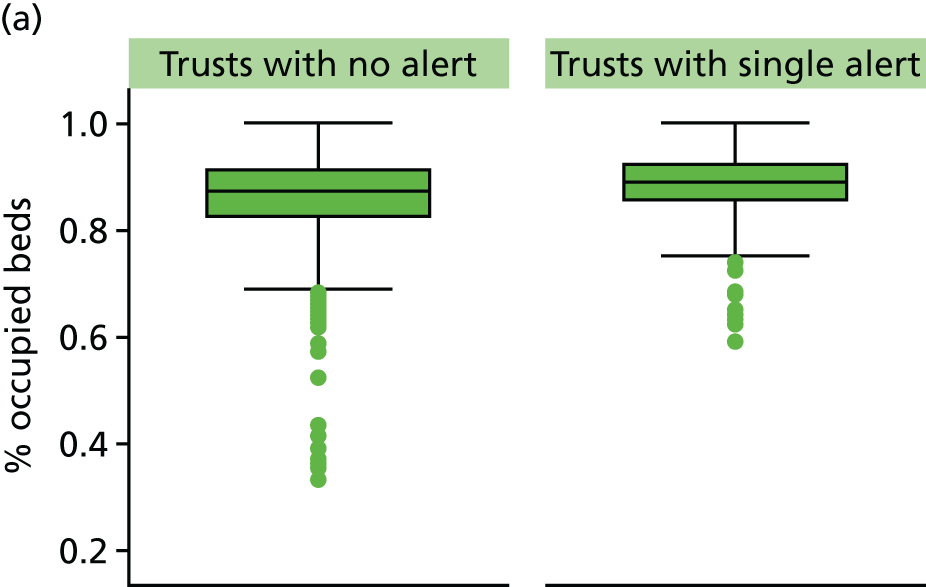

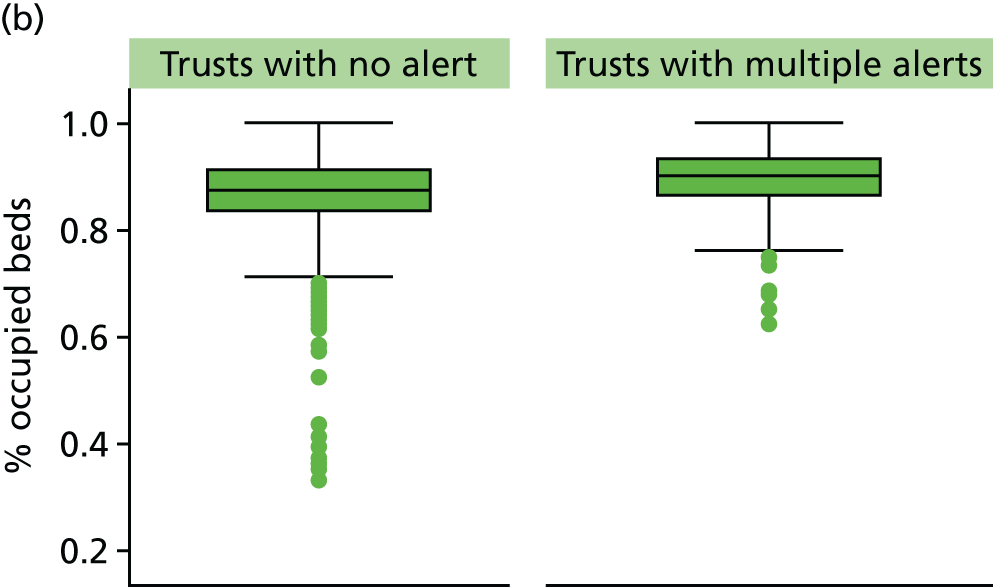

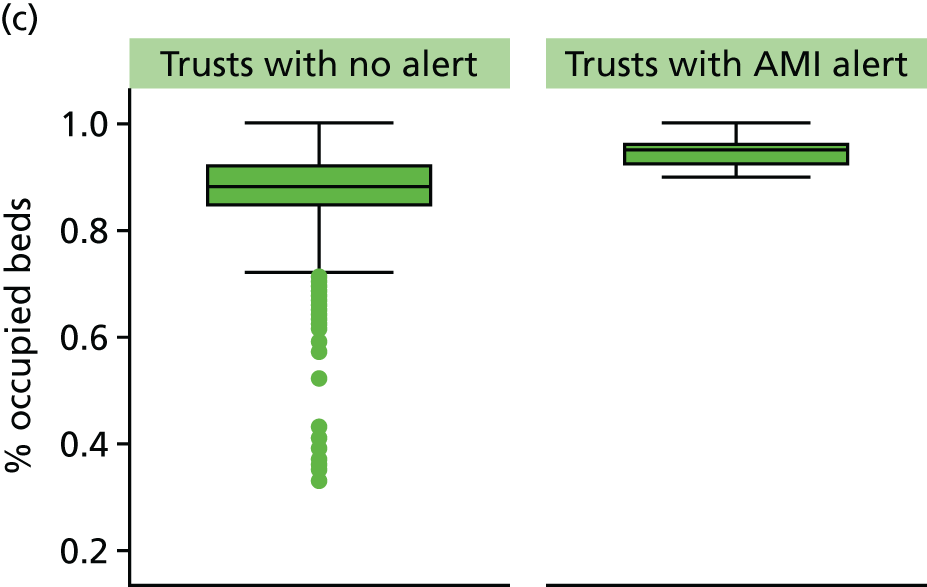

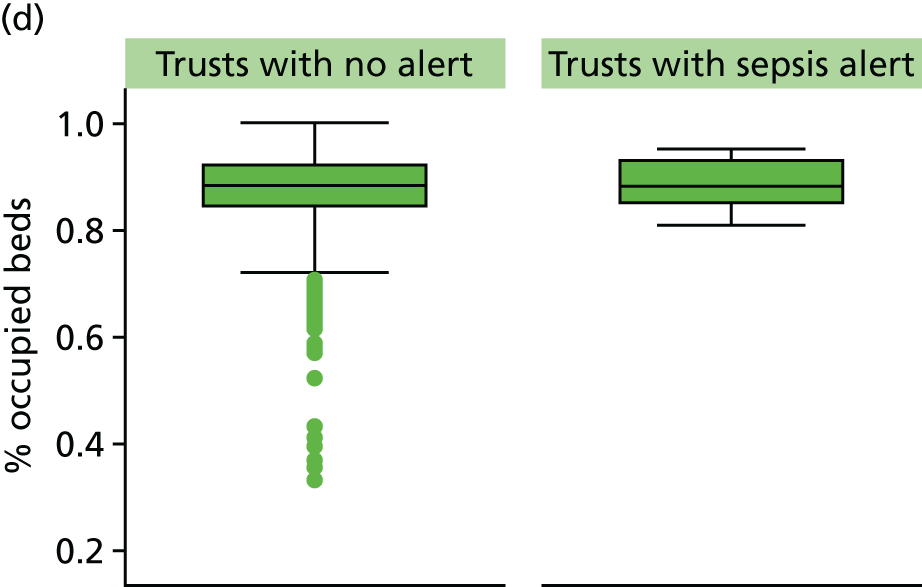

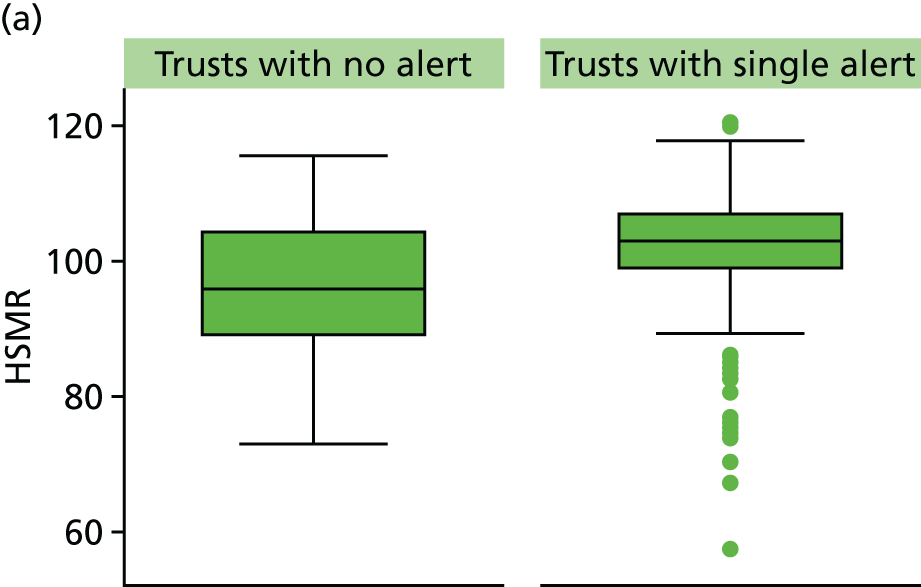

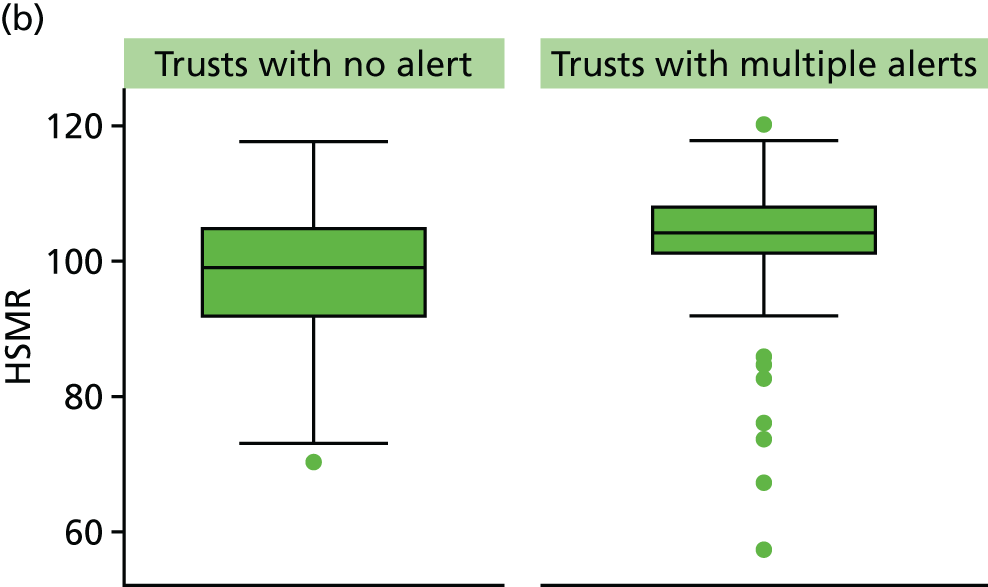

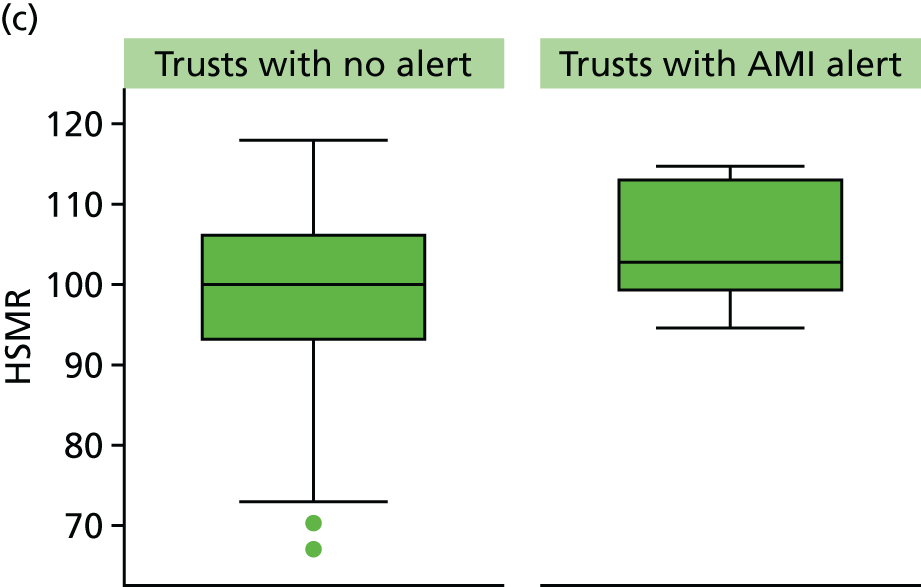

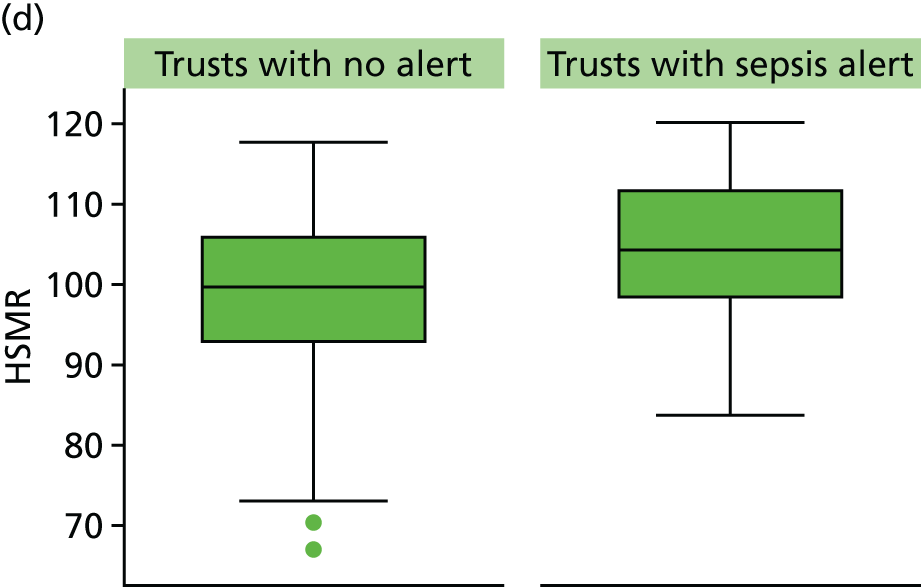

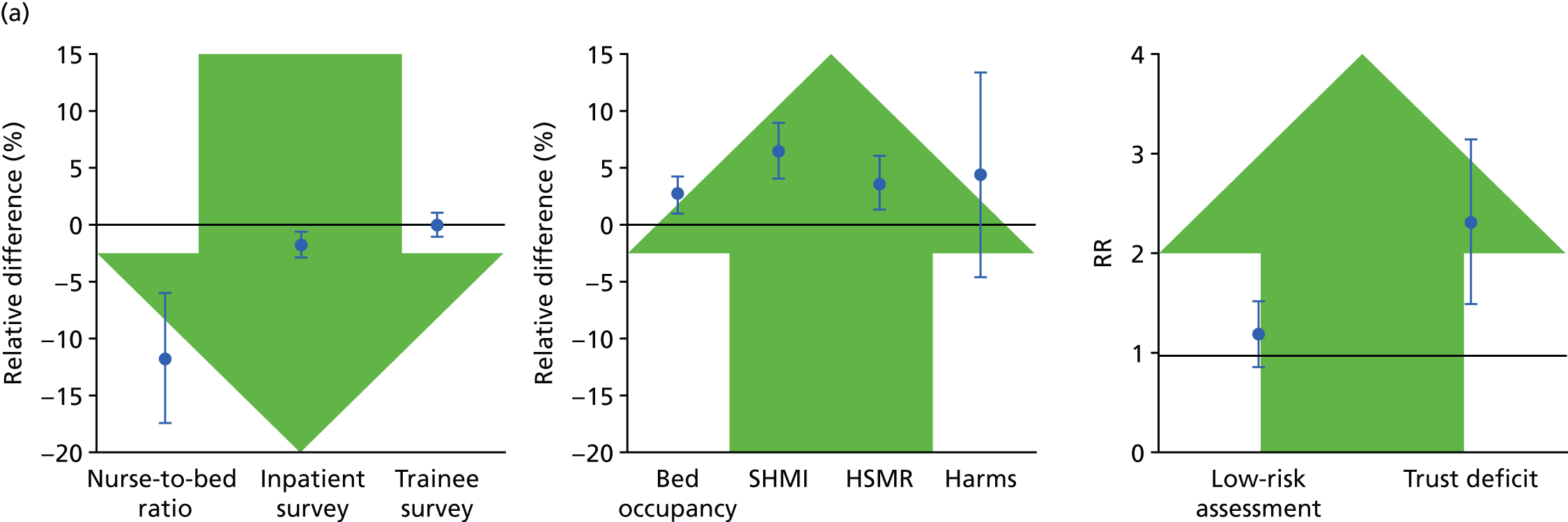

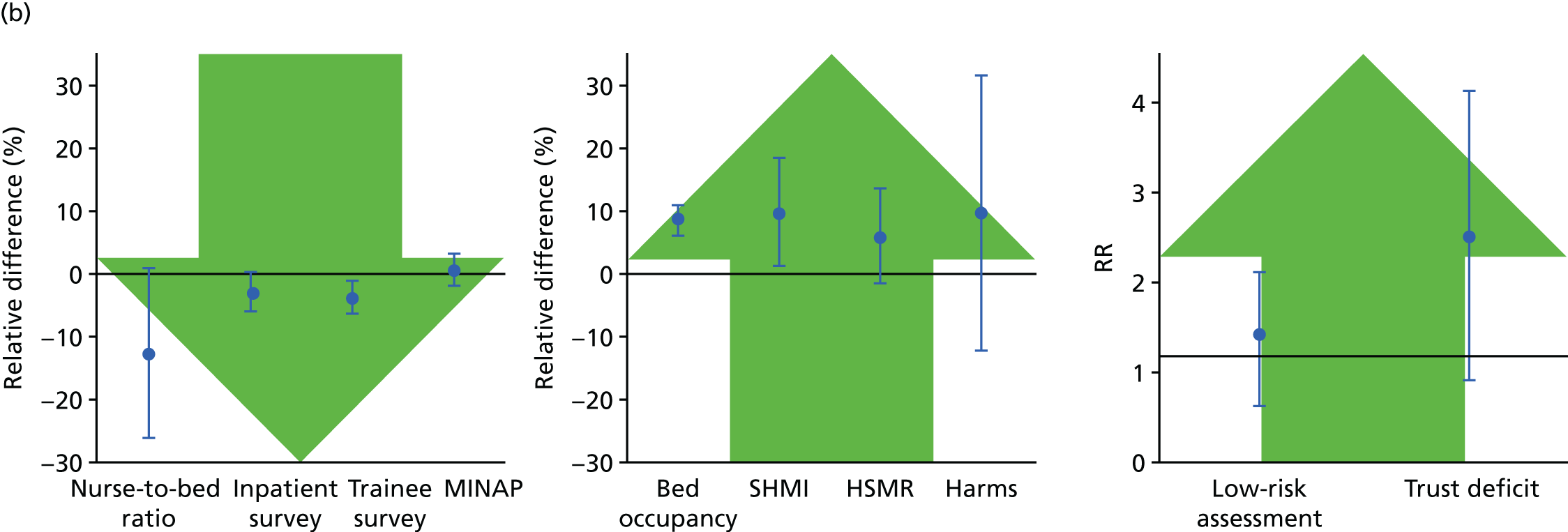

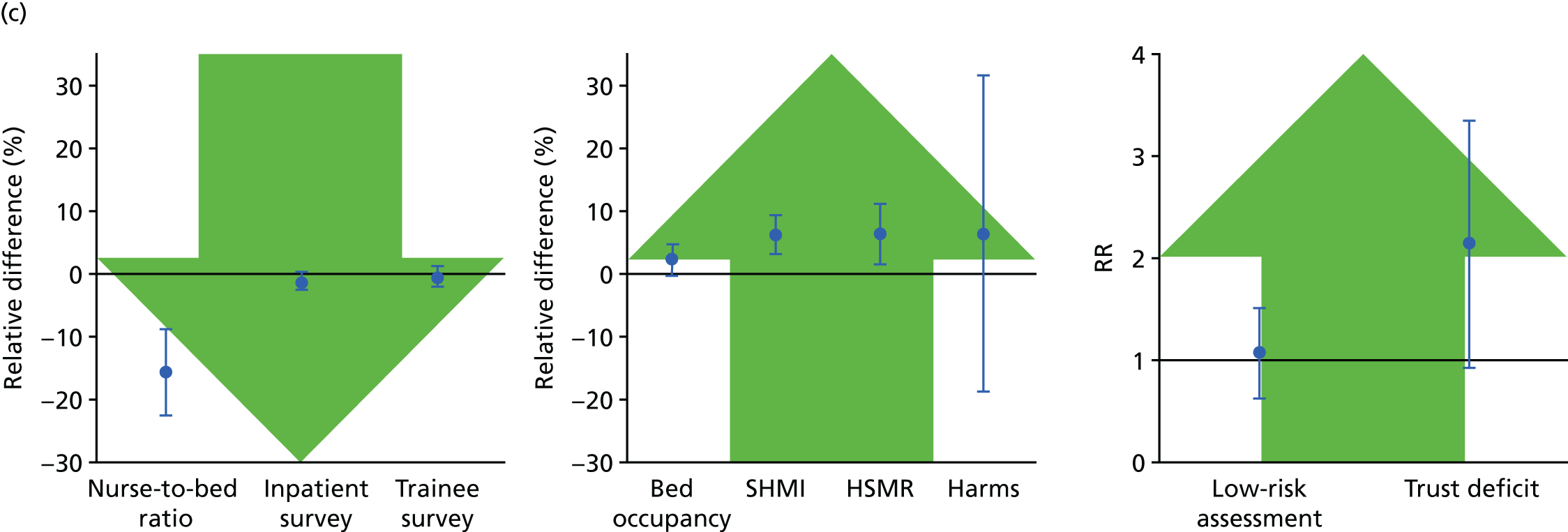

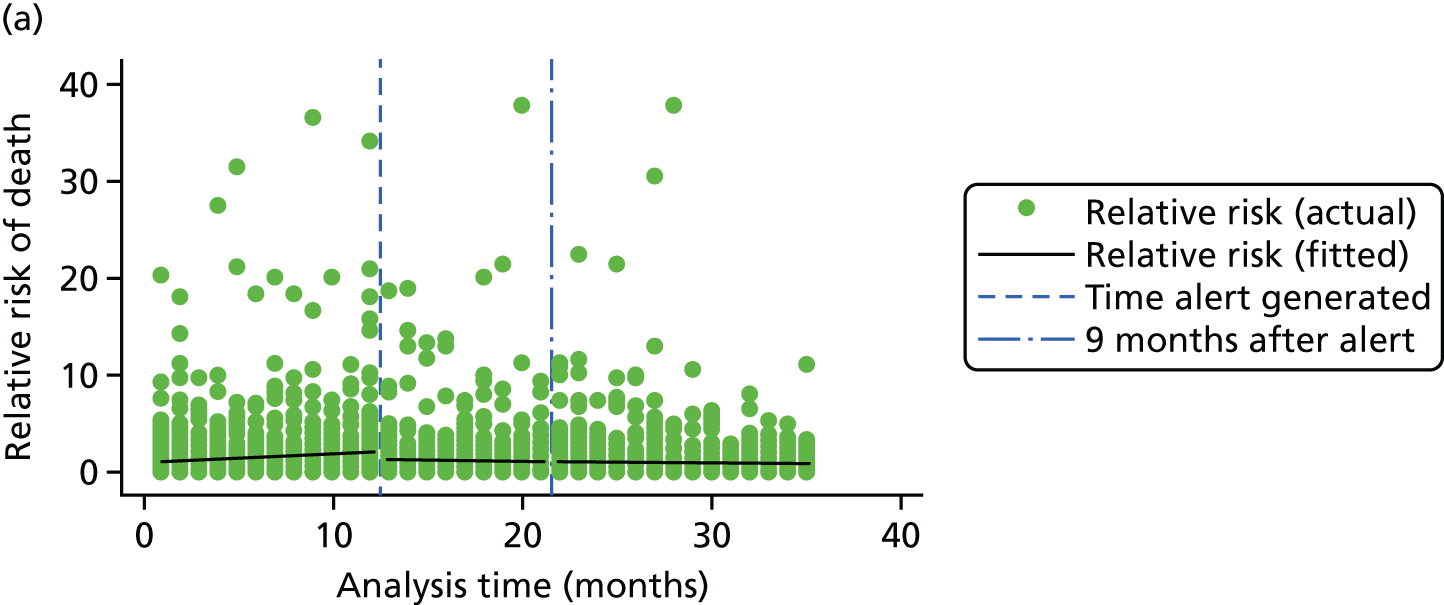

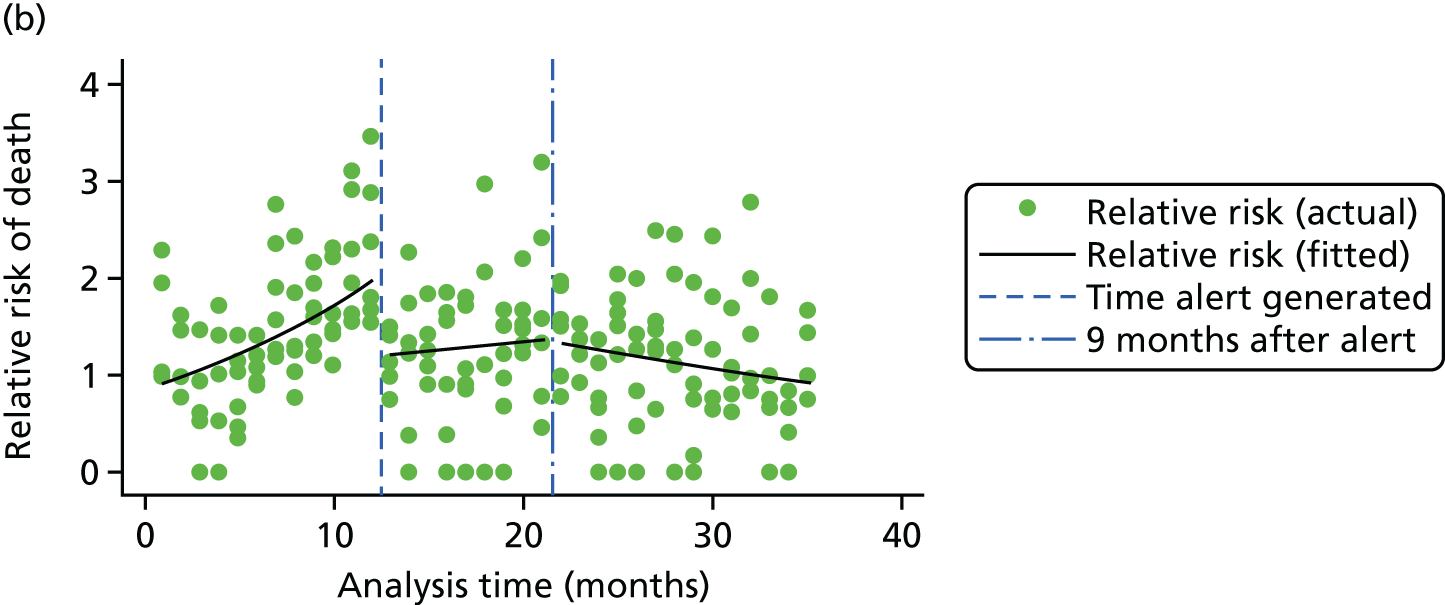

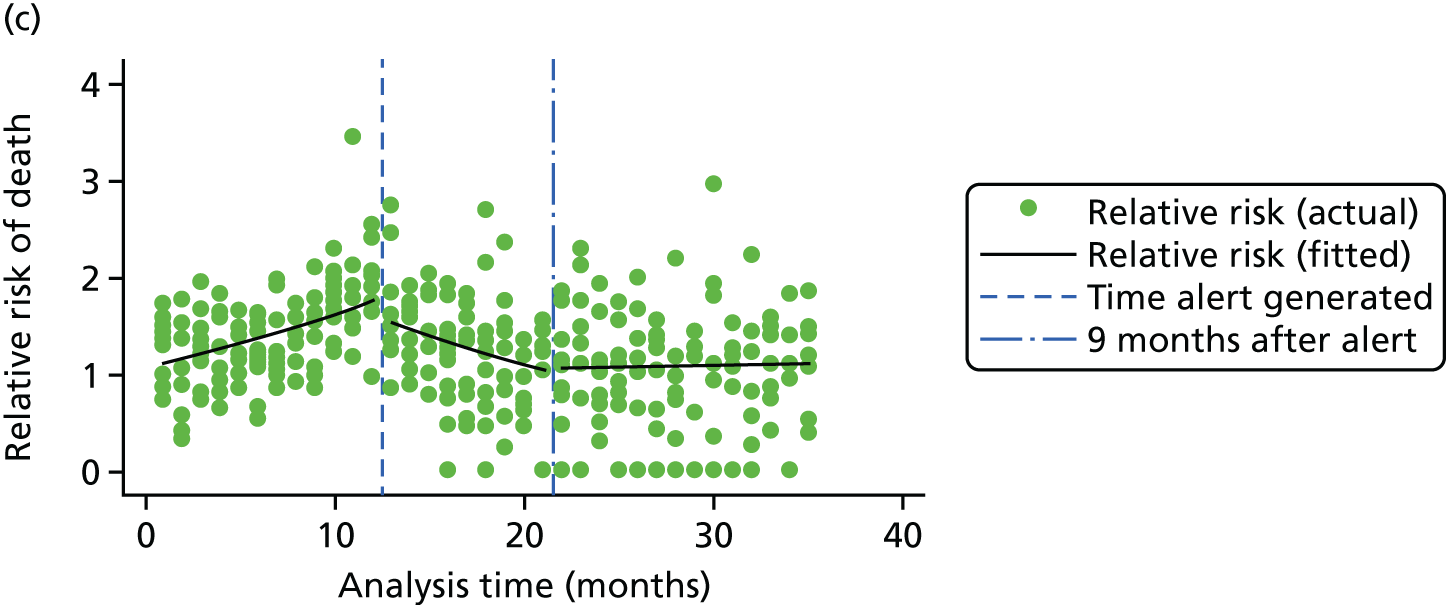

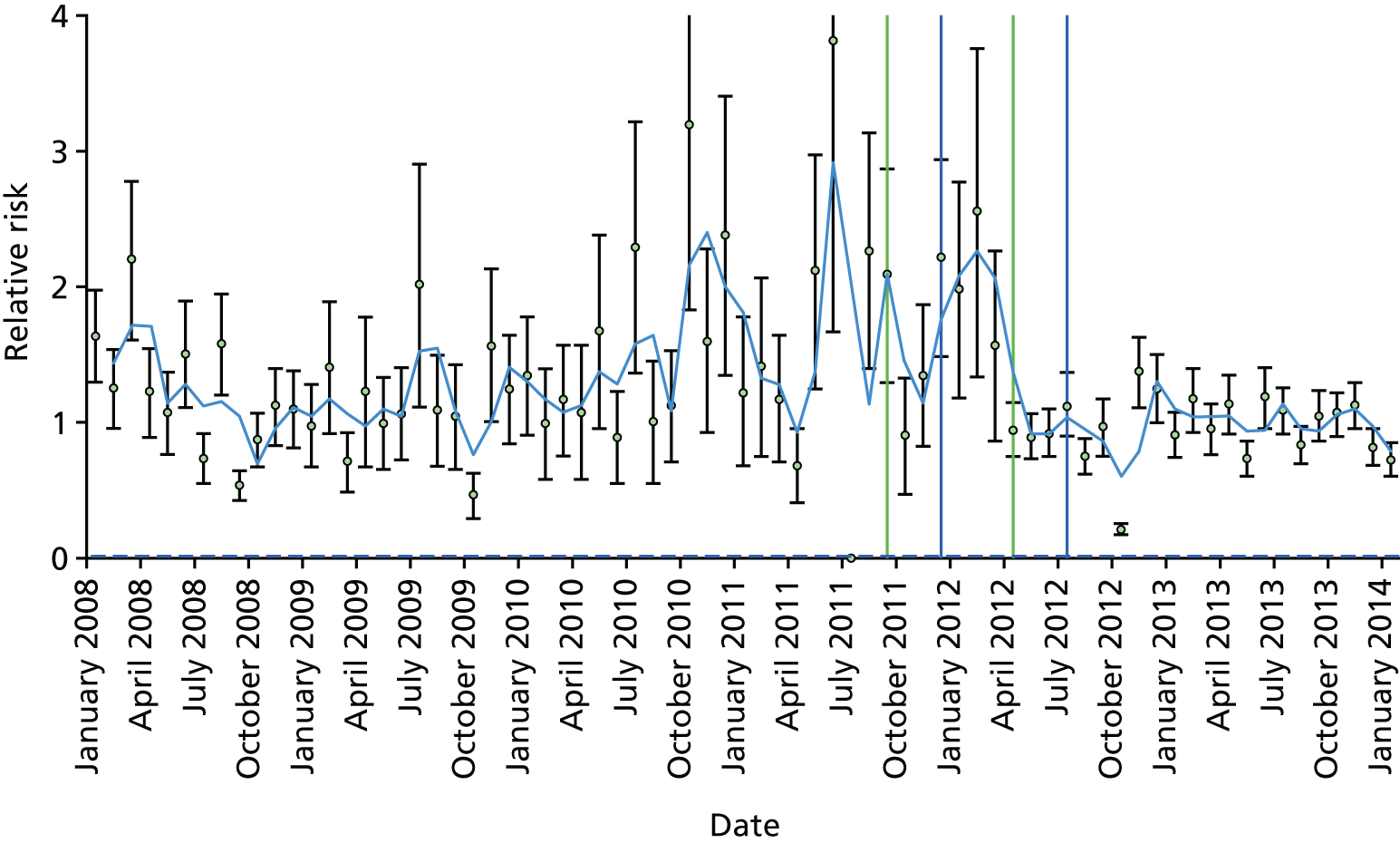

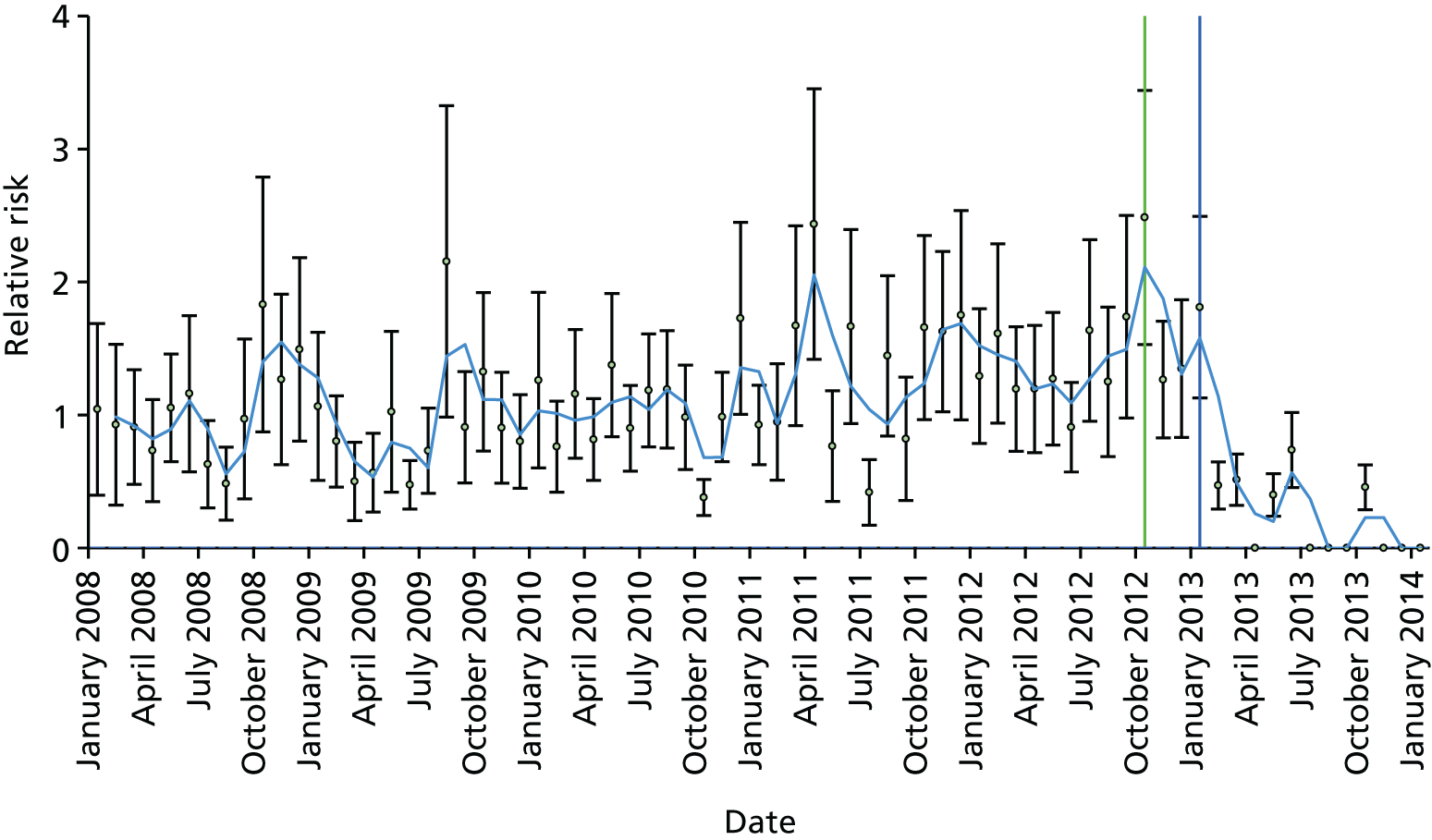

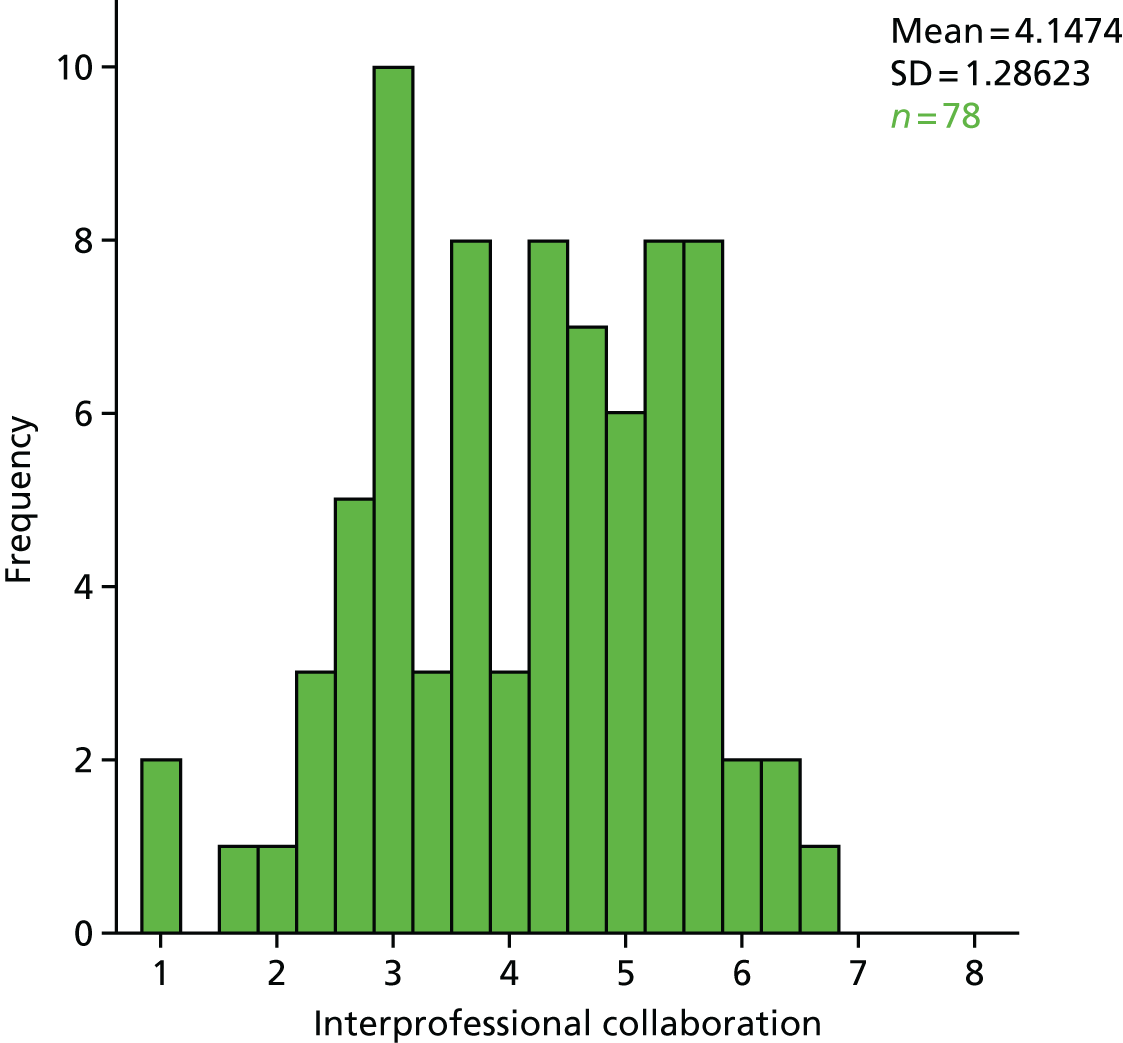

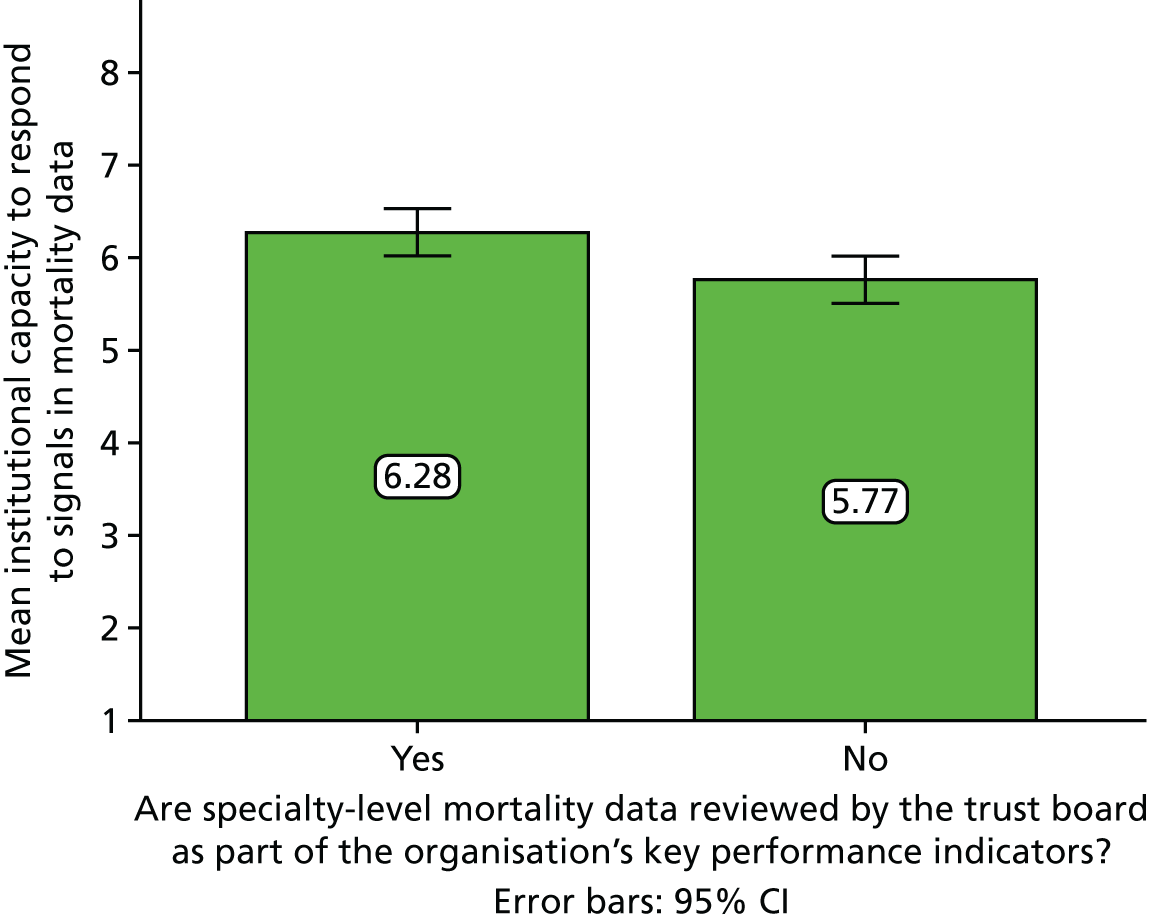

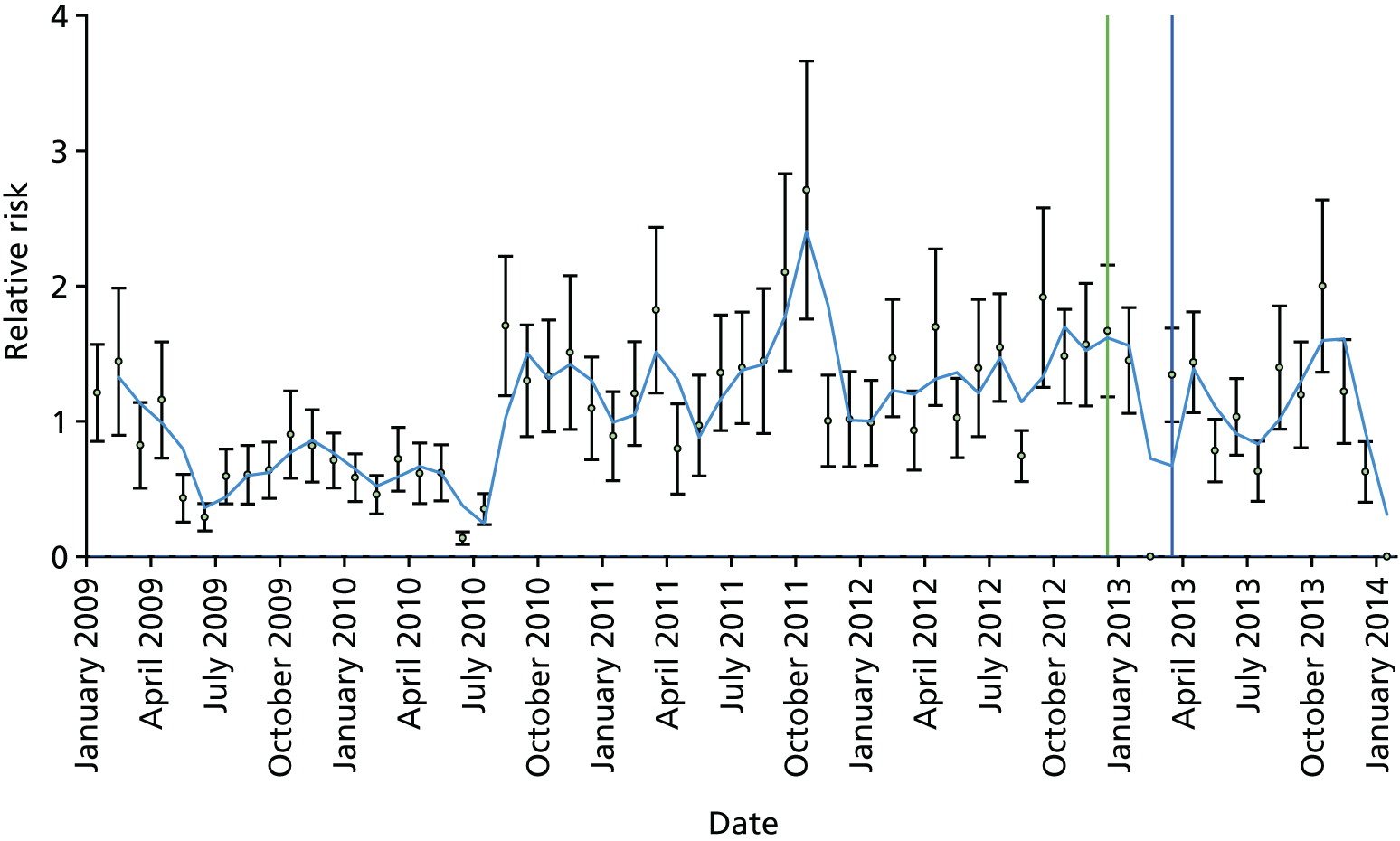

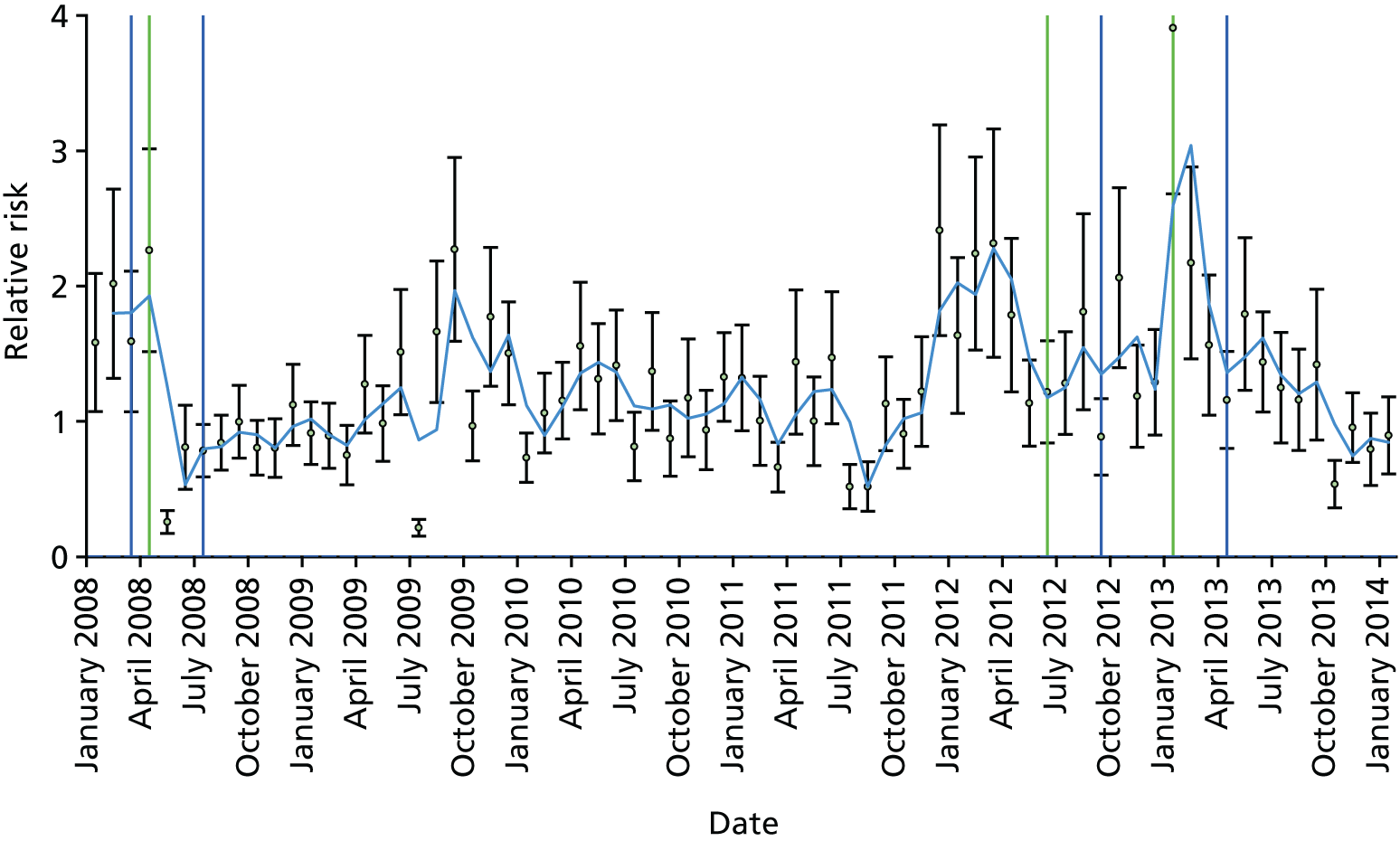

Alerts data