Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/209/51. The contractual start date was in May 2014. The final report began editorial review in August 2016 and was accepted for publication in April 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Frances E Griffiths and Anne-Marie Slowther are funded for other research by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme (14/156/20 and 13/10/14), the NIHR Programme Grants for Applied Research programme (RP-PG-1212-20018) and the NIHR Research Design Service (PR-RD-0312-1001).

Disclaimer

This report contains transcripts of interviews conducted in the course of the research and contains language that may offend some readers.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Griffiths et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Our overall research question was: what are the effects, impacts, costs and necessary safeguards for digital clinical communications (DCCs) for young people living with long-term conditions (LTCs) and engaging with specialist NHS providers?

Digital clinical communication

Our definition of DCC is one in which the clinician and/or young person is (or could be) mobile when sending or receiving the communication. It has two-way functionality and can be initiated by either party. It may be synchronous or asynchronous and is for the purpose of delivering or receiving clinical care. Examples of such digital communications take place using e-mail, text messaging, mobile phone, web portals or personal health record (PHR) systems (e.g. Patient Knows Best), voice over internet protocols (VoIPs) [typically Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and FaceTime (Apple Inc., Cupertino, CA, USA)] and social media [e.g. Facebook (Facebook, Inc., Menlo Park, CA, USA) and Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA)].

The health burden of young people with long-term conditions and the health service factors

Young people living with LTCs are vulnerable to service disengagement and this endangers their long-term adult health. Poor transition between paediatric and adult services can lead to disengagement from health services and poorer health outcomes. 1–5 Among young renal transplant recipients, 35% had lost their transplants by 36 months after transfer to adult renal care and there is a large peak of graft loss between the ages of 20 and 24 years. 6 The introduction of transition co-ordinators for paediatric liver transplant recipients and integrated paediatric–adult clinical services for patients with kidney failure have led to improved outcomes in young people transitioning from paediatric to adult care. 7–9 Transition co-ordinators and integrated paediatric–adult clinical services have been associated with improved adherence and reduced rates of graft failure. 7,8 However, the use of these services at present is limited. A systematic review of 13 studies found that large numbers of young patients with congenital heart disease were lost to follow-up or experienced gaps in their care after transitioning from paediatric to adult cardiology services. 4 With sickle cell disease, during the period of transition to adult services, regular attendance at outpatient clinics and adherence to medical regimens, in particular penicillin prophylaxis, declines. 10–12 This is a worrying trend, especially because it is estimated that 25% of deaths reported in young people are linked to infection and poor compliance with penicillin prophylaxis. 13 Compared with adults, children and young people living with diabetes mellitus are less likely to have their glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) levels measured. 14 Young people in their early twenties are less likely to have their HbA1c levels measured than those aged 10–19 years. 14 Furthermore, adolescents and young adults (aged 15–24 years) tend to have poorer diabetes mellitus control than younger children (aged 0–14 years). 15 This disengagement from services results in a considerable health burden for the young people and their families and an economic burden for the NHS. Health service factors affecting young people’s engagement with health care include poor patient–clinician communication, inflexible access to people and information, lack of person-centred health care and the need for continuity and relationship development. 4,16–19

Digital communication and its use for health care in the UK

In the UK, 66% of adults own a smartphone. Among young people aged 16–24 years smartphone ownership is 90% and almost all young people who own a smartphone use it to access the internet. 20 Although people of all ages use digital technologies in relation to health and health care,21–27 several studies have reported requests from young people for e-mail, text messages and social media communications with their health-care team. 16,28 At the start of the study we saw young people using the NHS as providing the best current opportunity for understanding how, why and with what effect, DCC can be used by NHS providers. At the time of initiating our research we were aware of a number of clinics using digital communication with young people. For example, clinical teams were using digital communication with young people with bipolar disorder29 and diabetes mellitus,30 and personal contacts confirmed use of e-mail, text messages or web portals in conditions including liver disease and sickle cell disease. These innovators provided opportunities to learn how to best harness digital communication in the NHS to the benefit of the young people for whom it provides care.

The research started at a time when UK policy and technological solutions were developing in relation to the use of digital communication in health care. Government policy on clinical information was to improve access to information31 and to have systems in place for digital communication between clinicians and patients by 2015. 31 One aspect of this was the NHSmail 2 project. 32 The then-ongoing Caldicott 2 review was seeking the appropriate balance between protection of personal information and sharing of information to improve care. 33 The imperative to digitalise the NHS has accelerated during our study. For example, in October 2015 the National Information Board’s Workstream Roadmaps was published. 34 NHSmail 2 was launched in July 2016, providing e-mail that is now secure for use with patients and Dame Fiona Caldicott published her review of data security, consent and opt-outs in the summer of 2016. 35 In the autumn of 2015, the National Information Board successfully negotiated, in the Treasury spending review, for £4.2B to digitalise the NHS. Professor Robert Wachter was appointed in November 2015 to chair a review of the NHS on its digital future and make recommendations. 36 This review was published in September 2016. 36

In his presentation to The King’s Fund Digital Health Congress in July 2016, Professor Wachter highlighted what is termed the productivity paradox – digitalisation has not resulted in a change in productivity – and suggested two factors for unlocking this for the NHS: the improvements in the technology and reimagining the work. 37

Professor Wachter’s review36 considered all aspects of digitalisation for the NHS, including electronic medical records, communication between clinicians and communication between clinicians and patients. Our study is limited to communication between clinicians and young people with LTCs about clinical issues. For our study, the key improvement in the technology is the smartphone, able to support all forms of digital communication: mobile phone infrastructure-supported voice and text communication (mobile phone and text messaging) and internet-supported voice and text communication (VoIP, such as Skype, e-mail and other social media), while people are on the move. Our study examines how clinicians have reimagined their work.

Evidence for the impact of digital clinical communication on health outcome

In the last two decades a wide range of digital communication systems have been developed in relation to health. There is a large research literature, including several dedicated peer-review journals and many reviews. In this section we discuss systematic reviews of evaluations of DCC and LTCs that were published prior to 2014 and so provided the rationale for our research. The evidence base has continued to grow and later evidence relevant to our research question is reviewed within this project report in Chapters 11–13. The published systematic reviews varied in how they defined their focus. Some focused on a specific technology (e.g. Ye et al. ,38 Blackburn et al. 39 and de Jongh et al. 40) and others specified both disease and technology (e.g. Holtz and Lauckner41). There were reviews in which the focus was the nature of the content of the communication, such as symptom reporting before a first appointment or between appointments (e.g. Johansen et al. 42) or the communication of diagnostic tests (e.g. Meyer et al. 43). Most reviews included studies from across all ages, except our own reviews on diabetes mellitus and mental health,44,45 which focus specifically on young people.

Evidence of the effectiveness of DCC from systematic reviews was equivocal, although all reviews reporting effects found either in favour of the intervention or no differences when compared with usual care. No trials reported poorer outcomes in the experimental digital communication arm. There was an almost unanimous finding from review authors of poor-quality intervention reporting alongside varying methodological quality of included studies. The reviews found study populations to be generally more educated, with higher socioeconomic status than population norms. 41,46,47 Several reviews found that patient engagement with health-care providers increased, as assessed by access data, contact data or health-care professional workload data (e.g. Ye et al. ,38 Sutcliffe et al. ,44 Martin et al. 45 and McLean et al. 48). A review that considered the possible impact of this increased engagement49 included 90 trials of synchronous and asynchronous communications in diabetes mellitus care. The authors found that the effect sizes of these interventions had remained static over the 16-year period covered by their review, despite increasing normalisation of the technologies across the populations and emphasis on higher-quality research designs. They found that asynchronous communications led to greater improvements in glycaemic control and self-care outcomes, with synchronous interventions being more user-friendly and more cost-effective for patient and provider. Combined interventions led to greatest quality-of-life improvements. Alongside these positive findings were negative impacts. Depression increased, parental relationships deteriorated and information overload was reported in some included studies.

Many reviews of the impact of DCC on health outcome also identified evidence gaps. To ensure that our research filled these gaps we systematically summarised these evidence gaps. We included in this summary reviews that (1) investigated asynchronous and/or synchronous communication between patients and clinicians using digital communication technologies; (2) had been published from 2010 onwards, as older reviews were unlikely to capture the types of digital communication usage patterns commonly experienced in 2014 when we wrote the summary; and (3) included children and young people or young adult populations only, or young people as well as older adults or if it concerned a condition commonly affecting young people. Seventeen published reviews were identified and their recommendations and justifications for future research were identified. We included one review from 2009 because of its focus on training and support for health professionals. Table 1 presents the list of research priorities identified along with details of the reviews and whether or not our research has tackled each one.

| Priority topics for future research identified in systematic reviews | Number of reviews recommending research on the topic | Research tackled topic: yes/no |

|---|---|---|

| Factors important to patients, public and clinicians | 940,41,43–46,49,51,52 | Yes: for patients and clinicians |

| Cost and/or cost-effectiveness/resource use | 838,40,42,44,46,51,53,54 | Yes |

| Research to identify moderators, mediators, active ingredients, theoretical basis for intervention and link with outcomes (MRC framework50) | 640,42,48,51,55,56 | Yes: qualitatively |

| Harms and risks (including privacy and data security) | 540,43,46,48,51 | Yes |

| Qualitative research designs | 443,46,48,49 | Yes |

| Research generic to multiple long-term-condition populations such as use of generic scales or outcomes of interest, measures to facilitate meta-analysis and/or comparisons across conditions (e.g. health economics, medication use, quality of life and service engagement) | 438,42,48,54 | Yes: a range of LTCs included with qualitative and health economics comparison; identification of a potential generic measure |

| Need for research to inform policy and practice in a range of digital communication aspects to inform implementation/roll out | 342,43,53 | Yes |

| Impact on contact frequency and on A&E attendance, hospitalisation and clinical outcomes | 344,49,53 | Yes: case based |

| Health-care professional–patient relationship within this digital communication context | 343,47,57 | Yes: via interviews |

| Broaden socioeconomic and ethnic diversity of research to assess access and inequalities and uptake/usage | 341,46,47 | Case studies include conditions common in ethnic minorities |

| Telephone counselling vs. e-mail counselling | 146 | Specific comparison not made, but one case study undertook text-based counselling |

| Function of communication (e.g. timely advice) in digital communications rather than technological mode of communication | 148 | Yes |

| Focus on widely used digital communication intervention not just future focused | 154 | Yes |

| Effects of age on use, impact, outcome | 144 | No: proposal is focused on young people |

| Patient and clinician training and preparation | 145 | Yes |

| Use in symptom monitoring | 145 | Symptoms monitoring not specifically studied but was talked about by participants |

| Investigation of the motivational/fun elements of health technology toys | 142 | No examples found |

| Smartphone applications to support web-based interventions | 149 | No specific examples found |

| Content of communication | 151 | Yes: via interviews |

Of the 17 reviews, nine mentioned the need to understand what was important to patients, the public and clinicians. 40,41,43–46,49,51,52 Eight reviews identified cost as a priority for research on DCC. 38,40,42,44,46,51,53,54 Specific areas identified were health-care resource use by patients and health professional workload. Several reviews reported increased communication with patients when digital communication channels were available. This led to concerns about the costs of meeting patient demand. 44,46 One of our own reviews44 identified clinician training and ongoing support as a potential hidden cost, as clinicians may not be as familiar with, and confident in, the use of these technologies as their younger patients. Five reviews indicated the importance of exploring risks and harms, information security and privacy issues. 40,43,46,48,51 Several reviews felt that it was time to develop an evidence base across conditions and clinical contexts38,42,48,54 as there are many commonalities across LTCs,42 but evidence was concentrated in a small number of LTCs, such as diabetes mellitus and asthma. Six reviews suggested the need for a deeper understanding of how these interventions work to produce the desired outcome40,42,48,51,55,56 and three specifically identified the relationship between the patient and clinician. 43,47,57 Outcomes suggested by three review teams were frequency of contact using the digital communication on offer, accident and emergency (A&E) attendance, hospitalisation and clinical outcome. 44,49,53 Several reviews indicated that the majority of research had been undertaken in more affluent, educated and ethnic majority populations. 41,46,47

Aims and objectives

In response to the identified evidence gaps we developed the following aims and objectives.

Aims

-

To evaluate the impacts and outcomes of DCCs for young people living with LTCs. Many young people disengage from health services between the ages of 16 and 24 years, resulting in poor health, but they are prolific users of digital communications. As such, young people using the NHS present the best current opportunity for addressing our second research aim.

-

To provide a critical analysis of the use of DCCs by NHS specialist care providers. DCCs are being widely embraced by clinicians working with young people, but the NHS is currently underserved by research evidence to prepare it for this development.

Objectives

-

To engage young people in the implementation of the research.

-

To observe and explore with young people with LTCs – and where appropriate a parent/carer, clinicians and managers – the use of DCC in the NHS for a variety of clinical conditions, how it is used and with what impact and issues related to ethics and patient safety.

-

To investigate the impact of DCCs on health outcomes for young people with LTCs and on their engagement with, and use of, health services.

-

To describe the cost of implementation and ongoing provision of DCC and how it varies across different clinical conditions, and to understand the value of this service to patients and clinicians.

-

To identify and explore the use of patient-reported outcome measures (PROMs) for future cost-effectiveness studies, which can be used across disease areas to capture the impact of DCC.

-

To evaluate and synthesise published evidence on the use of DCC by health professionals with young people with LTCs.

-

To develop and disseminate guidance for NHS providers and commissioners on the use of DCC, to provide insights for policy-makers from current NHS use of DCC and to consider the need for future research.

We chose not to specify a specific technology to study in order to future-proof the study and to avoid limiting the utility and validity of the results. The digital communication ecosystem is rapidly changing. 20 For example, the introduction of smartphones is changing the way people access information and use communication channels. The use of communication channels also evolves. For example, Twitter was initially used primarily for broadcasting, but then became used for communicating between individuals or within small groups. 58 We studied the use of DCC via whatever medium was being used by the patients and clinicians we studied, in order to draw out results that are transferable across technologies. This allowed us to learn from a small number of established systems for DCC for young people in the NHS, and from the informal, unregulated development of this means of communication between clinician and patient.

The research focused on young people (aged 16–24 years) who have LTCs such as diabetes mellitus, cancer, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease and other conditions that require engagement with specialist (secondary or tertiary) clinical services. We studied NHS providers of specialist clinical services. We were concerned with communication between patients and specialist (secondary or tertiary care) clinicians/clinic teams who have already been in contact with each other in the clinical setting, where communication was, or there was potential for it to be, in both directions – patient to clinician and clinician to patient. We did not include specifically the delivery of therapeutic interventions via digital communication media59 [such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT)],60 nor digital communication that solely involves the delivery of information on disease prevention and health promotion. 61 However, where the use of a digitally delivered intervention or the delivery of disease prevention and health promotion information formed part of ongoing patient–clinical team communication, they were included.

Research questions

Our data collection, analysis and synthesis addressed the following prespecified research questions. These questions are grouped according to the approach to data analysis taken to answer the questions [or for Chapter 9 on information governance (IG), the perspective of the research participant]. These analysis approaches correspond to chapters in the report as indicated below.

Chapter 3: what works for whom, where, when and why?

-

What works for whom, where, when and why?

Chapter 4: ethical implications of using digital clinical communication to support young adults with long-term conditions

-

What concerns do patients and clinicians have about confidentiality in relation to DCC?

-

How does this form of communication affect the patient–clinician relationship and the clinician’s duty of care?

-

What regulatory framework is needed to reassure patients and clinicians regarding its use?

Chapter 5: patient safety

-

What are the significant risks to patient safety associated with the use of DCC in the context of supporting young people with chronic disease?

Chapter 6: health economic analysis

-

What value do patients place on DCC?

-

What are the direct resource use implications for the NHS of implementing it?

-

How does the direct resource use vary when used with different patient groups?

-

What are the resource implications for scaling up in the NHS?

Chapter 7: information governance

This chapter analyses the data from the interviews with IG officers with reference to the research questions for Chapters 4–6.

Chapter 8: impacts on health-related outcomes

-

How is the impact on the health status of patients currently evaluated?

-

Using existing clinical data, what is the impact on health status of patients?

Chapter 9: generic patient-reported outcome measures

-

What generic outcome measures are available to assess the impact of DCC?

-

In the future, how can its effectiveness be measured across health conditions?

Chapters 10–12: scoping reviews

-

What is the evidence in the literature to support, refute or add value to the case study findings?

Chapter 13: discussion

-

What are the risks to patients and to NHS specialist care providers from its use?

-

What policy and procedural changes are needed for gaining benefit and limiting harm?

-

In which clinical areas is benefit most likely and how is benefit most likely to be achieved?

-

What future evaluation is needed and how should it be undertaken?

In response to requests from NHS England and NHS Digital (formerly the Health and Social Care Information Centre) for assistance with the development of their policies and procedures, we undertook the analyses reported in Report Supplementary Material 1. The consensus conference, which also contributes to the above research questions, is also reported in Report Supplementary Material 1.

We tackled the following question through our internet search described in Chapter 3 in order to form our sampling frame.

-

How, and for what purpose, is this form of communication taking place (or not) in the UK?

We tackled the following question through maintaining awareness of developments in the ethical, legal, policy and governance landscapes relevant to DCC in the UK to ensure that our research took account of this.

-

What is the ethical, legal, policy and governance framework for DCC?

In Appendix 1, we provide a report on all our patient and public involvement (PPI) activity and the impact it had on the research, except for PPI activity linked to the identification of a generic outcome measure which is reported in Chapter 9. Our appendices also include copies of the quick reference guides produced in response to discussions with NHS Digital, from our data analysis. These are A4 leaflets available to freely download from www2.warwick.ac.uk/fac/med/research/hscience/sssh/research/lyncs/ (accessed 5 March 2017). The NHS Digital website carries a link to these guides.

Ethical considerations in planning this study

The key ethical issue in this study was confidentiality in both recruitment and data collection. During data collection we were asking clinic staff to reveal their clinical activities that may have been in breach of IG policies. This was a difficult issue, as these clinicians are rich sources of data. We drew up a protocol for action for serious breaches of confidentiality, but did not take action for activity that we found to be common practice. This approach was approved by the ethics committee (see Chapter 2). Data collection was planned across 20 different sites so preserving anonymity is possible.

Chapter 2 Methodology and methods of case studies and the characteristics of the cases

This chapter reports the methodology and methods for the case studies, and describes these case studies. Methods for the systematic scoping reviews, review of PROMs and consensus conference are reported in the relevant chapters.

The main empirical work for this study utilises a case study approach. Robert Yin describes a case study as ‘an empirical inquiry that investigates a contemporary phenomenon in depth and within its real-life context, especially when the boundaries between phenomenon and context are not clearly evident’ (p. 18). 62 In this research, the contemporary phenomenon we study is the use of DCC and the context is specialist NHS care provision for young people with LTCs. In-depth study allows us to simultaneously focus on several different elements of care provision, such as patient safety and ethical concerns. When conducting a case study, one of the first steps is to develop propositions to identify what to study. 62 Our propositions are that DCC fits with young people’s day-to-day mode of communication and, therefore, they would prefer it to other means of communication with their clinical team; and clinicians use DCC to encourage young people with LTCs to engage with their health care and improve their health outcomes (even if this puts other aspects of clinical service provision, such as record-keeping, at risk). Based on these propositions, we need to look for evidence to answer our research questions from the young people and clinical teams. The young person with a LTC in communication with their clinical teams (i.e. young person–communication–clinical team) is our unit of analysis. This unit of analysis is embedded within the wider clinic, the NHS and contemporary society. 62

Ethics and research governance permissions

The study was approved by the National Research Ethics Service Committee West Midlands, The Black Country on 5 March 2014 (reference number 14/WM/0066). A substantial amendment was granted on 26 February 2015 to allow the following changes to the invitation letters and participant information sheets: offer a £20 voucher as a thank you for participating in the study; include information regarding the study’s insurance and indemnity; and include information about whom participants should contact to make a complaint. In addition, the amendment approved a further two ‘invitation to interview’ letters specifically aimed at young people who did not attend (DNA) their appointments. A second amendment approved on 18 June 2015 covered the following amendments: (1) change to the protocol to make recruitment of parents/carers easier, enabling the researcher to contact a participant’s parent/carer directly once the consent of the participant was given; (2) taking the burden of recruitment away from research nurses by enabling the research team to contact the parent/carer; (3) extending the £20 voucher as a thank you for participation to parents/carers; (4) changes to the patient information leaflet to reflect the above changes; (5) changes to the recruitment poster to include information about the £20 voucher (which we had in error omitted from this participant information); (6) changing the term ‘long term’ to ‘health’ in patient information leaflets in cancer care clinics as the clinicians felt that the term ‘health condition’ would better reflect the patients’ view of their condition; and (7) request permission for a number of students undertaking health-related graduate and undergraduate studies to undertake data analysis. Research governance approvals were awarded by 16 participating NHS trusts hosting our 20 research sites. Details of these NHS trusts are withheld from this report to protect the identities of participating health professionals, many of whom were using digital communication methods at the time of interview under the radar of their NHS trust IG policies and procedures.

Clinical case site recruitment

Case site inclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria for clinical sites were as follows.

-

The clinic provided specialist care for young people with LTCs.

-

The LTC was currently expensive to the NHS.

-

The clinical team expressed interest in the use of two-way digital communications to a minimum, moderate or large extent.

We sampled clinical teams for diversity of long-term health conditions experienced by young people.

Case site recruitment

As a relatively large number of case sites were required, multiple recruitment strategies were used. An extensive internet search of grey literature was conducted to identify technology being used for clinical communications in the UK. An internet search using the search engine Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) was undertaken between December 2013 and February 2014. The keywords used were e-health, telehealth, telemedicine, digital communication, young people and young persons. Combined, the searches returned 24,626,063 hits. The first 35 pages of each search were scrutinised for relevance. In the case of potentially relevant projects, detailed information was sourced from individual trust websites, documents and reports. Further details were obtained by contacting key individuals and project leads. This search identified 71 projects involving DCC, running at 38 different NHS trusts, health-care organisations and universities. We tried to contact 14 sites that seemed eligible for participation (the search was not limited to young people with LTCs). Additionally, one clinical team was identified via the internet and approached.

Snowball recruitment was also used: the research co-applicants sent out recruitment e-mails to their colleagues and asked that they pass the information on to anyone else who may be interested; in addition, specific clinical teams were suggested by the research co-applicants, based on the known use of communication technology in their usual practice. The research team contacted 51 different clinical teams using this approach. Research team members attending academic and applied health conferences advertised the study with poster presentations and recruited potential case sites through networking sessions. Seven contacts were made this way. Finally, the research team was approached by seven NHS trusts that had seen the study listed in the National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR’s) portfolio. A further 24 contacts were made after people already in discussion with the research team snowballed the study information to others they thought would be interested. Overall, we made initial contact with a total of 104 different clinical teams.

Interview participant recruitment

We aimed to conduct brief interviews with members of the clinical team, up to 15 patients aged 16–24 years and an IG officer at each site. Where the clinical team was < 15 patients, we aimed to interview all members of staff. Parents/carers/household members of young people with a LTC were also invited to participate in an interview.

Two weeks prior to fieldwork commencing, a research nurse from the local clinical research network or NHS trust identified eligible patients attending the clinic on days when a Long-term conditions Young people Networked Communication (LYNC) study researcher was present. These patients were sent (via post, or e-mail if appropriate) a study information sheet and given an option of contacting the researcher in advance to express interest in participating. Patients were also recruited by the researcher during their time in clinic, usually while waiting for their appointment. Patients were asked to bring examples of recent DCCs to inform interview discussion. The research nurse also identified patients who frequently DNA clinic appointments from clinic records and sent a separate recruitment letter to these patients. Young people were given a choice of medium for their interviews: in the clinic, over the telephone or via other technology chosen by the participant (including e-mail and Facebook). The researcher asked for consent either during recruitment or prior to commencement of the interview. For telephone interviews, consent was given verbally and a dated note was made by the researcher. All participants were offered a £20 high-street voucher as a thank-you token. At the end of the interview, researchers asked the patient if they were willing for their parent/carer/household member to be interviewed for the study. If they agreed, they provided contact details for the research nurse to send out an invitation letter. These interviews were conducted over the telephone, at a time convenient for the participant.

Clinic staff were recruited on an ad hoc basis during fieldwork. Prior to the start of fieldwork the researchers attended a team meeting to introduce themselves and the research, and to make staff aware of their presence on site. We aimed to interview any clinic staff who used (or would potentially use) DCC, such as nurses, doctors, professions allied to medicine and administrative staff. We specifically sampled for diversity of job role and experience of, and opinion about, DCC within each case study. Within each clinic we aimed to interview as many team members as were willing to participate, up to 15 members of staff. In small clinics we interviewed all relevant team members. In large clinics we aimed to get representation across all specialties and grades of staff. Interviews took place over the telephone, or in a location chosen by the participant (clinic space, offices, cafes, etc.). Participants were reassured that the information they provided would be confidential and that it would not be possible to identify specific clinics or staff members from our research report. It was also explained that if a concern arose about unethical or unsafe clinical practice, the researcher would need to report this to a principal investigator (PI) who would decide if it was necessary to initiate action through normal professional channels. However, no such practice was reported. During data collection we were asking clinic staff to reveal activities that may breach IG policies. This was a difficult issue, as these clinicians were likely to be rich sources of data. We therefore drew up a protocol of action for serious breaches of confidentiality (see Appendix 2). However, we did not expect to take action for activity that we found was common practice.

At each case site we aimed to interview a trust-wide IG officer. We aimed to conduct this interview prior to fieldwork commencing, so that the researcher would not inadvertently disclose clinic practices that may be out of step with trust IG policies. Additionally, this enabled an understanding of the local context in which the clinical staff operated. Interviews with IG officers took place on site in trust offices or over the telephone.

Data collection

Non-participant observation

Non-participant observation of the clinic and shadowing of clinic staff took place at each clinical site. Using an observation pro forma, the researchers noted how the clinic functioned, how DCC was used and monitored within the team and what evidence there was for more widespread use of digital communication within the clinic space (e.g. clinic staff using computers, patients using smartphones in waiting rooms). When shadowing members of the clinical team, the researchers reported if, and how, digital communication was used for clinical purposes, describing the context and content of the dialogue. Shadowing lasted for up to 2 hours, whereas clinic observation lasted for the duration of the clinic (up to 8 hours) and were designed to note the use of digital communications between appointments. When possible, observations preceded interviews. The researchers made patients and staff aware of their presence in the clinic by wearing a T-shirt identifying them as LYNC study researchers and putting up posters advertising the study. Observation schedules are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Semistructured interviews

All interview schedules focused on how digital communication was used for clinical purposes and the advantages and concerns participants had about this use, specifically identifying risk and ethical concerns. The interview schedules were a guide and we covered the part of the schedule relevant to each interviewee. Based on initial analysis of interviews we adjusted interview schedules to ensure that we obtained the richest possible data (e.g. altering question wording). During individual interviews we adjusted the words we used to refer to digital communication according to the words used by the interviewee in response to early questions.

Additional data on ethics, safety and the generic PROMs were collected from specific sites. Data from a cancer and liver conditions site were initially analysed with a focus on ethical concerns. Based on this analysis, the interview schedule was amended to focus on emerging ethical issues, such as equity in access, consent, privacy and confidentiality, risks/benefits to staff, patient–clinician relationship, patient autonomy and duty of care. This interview schedule was used to collect data from a further three sites (renal, cystic fibrosis and mental health). These sites were chosen based on their use of DCC and diversity in health condition. Additional data on safety were collected from two clinics (diabetes mellitus and cancer) which used DCC. The diabetes mellitus clinic was chosen as the self-management of diabetes mellitus involves the young person making decisions several times a day about their dose of insulin and errors in these decisions can quickly lead to adverse events. The cancer clinic was chosen as these young people are likely to be on medication with potentially serious side effects and are coping with psychological distress as a result of their life-threatening diagnosis. At these two sites, the interview schedule was amended to focus on important safety issues, such as risks, the importance of risks to patients, how risks are accepted or reduced, engagement with treatment regime, adverse events, unintended outcomes and benefits. In the later sites, the interview schedule was revised to focus on undertaking cognitive interviews to assess the two generic PROMs identified in the literature review and from PPI activity. This interview schedule was used with seven patients and seven clinicians.

A specific interview schedule was developed for use with IG officers, with input from our IG co-applicants. This focused on if, and how, technology was used within the trust for communication about clinical issues, what policies instruct the use of technology, recorded DCC-related incidents and their professional opinions on the use of digital technologies in their respective NHS trusts. When DCC was not used, the key professionals were asked whether or not there were any future ambitions to introduce these types of communication, and if there were any barriers to, and enablers of, this introduction. Interview schedules are available in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Collection of impact data

Data are broadly categorised in two groups: (1) the cross-clinic and condition outcome data and (2) clinic-specific outcomes. Cross-clinic outcomes are appointment status (attended, cancelled or not attended), A&E attendance and hospital admission. Such outcomes, from most sites, were obtained from the information technology (IT) departments of trusts, with contact initiated by the site contact (PI, consultant, etc.) or the service manager. For tertiary care case study sites, A&E attendance and hospital admission data for their clinic patients were not available, as the patients would attend their local A&E department or hospital for emergencies.

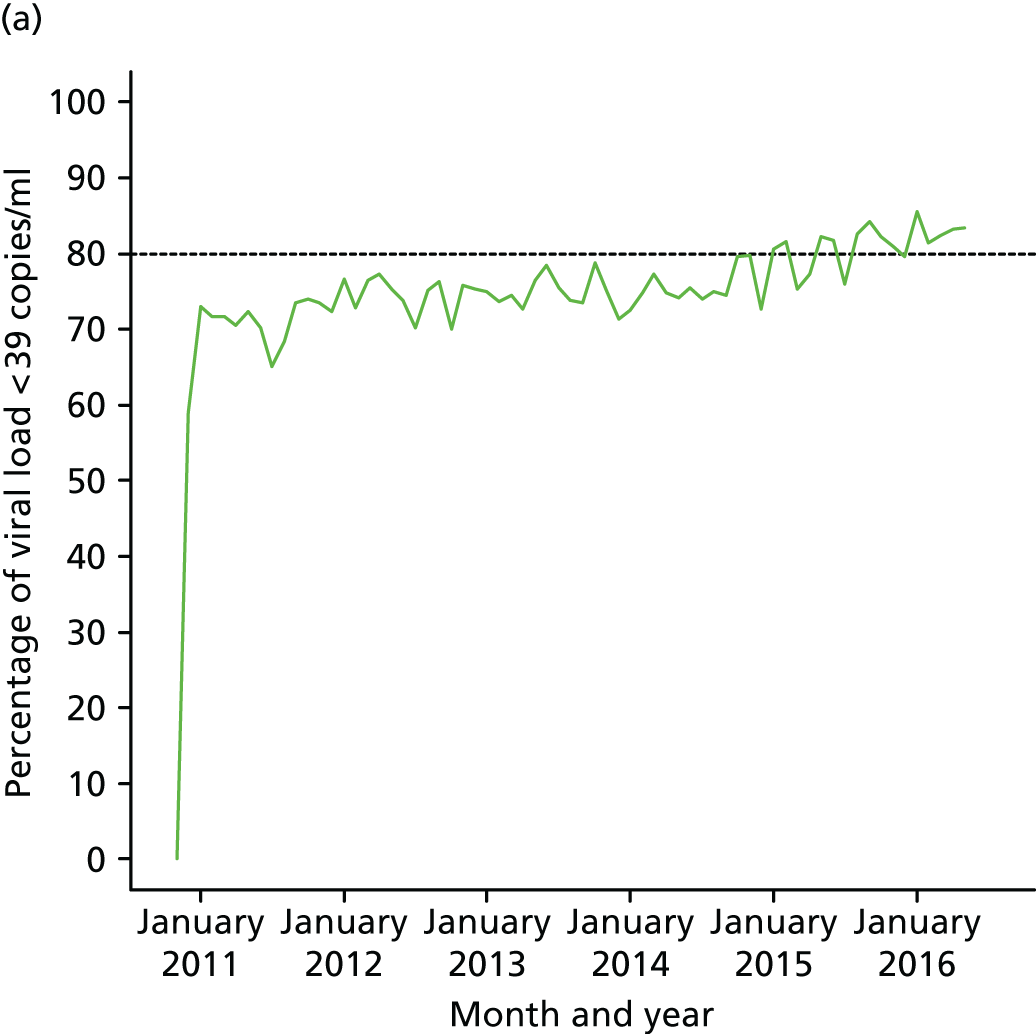

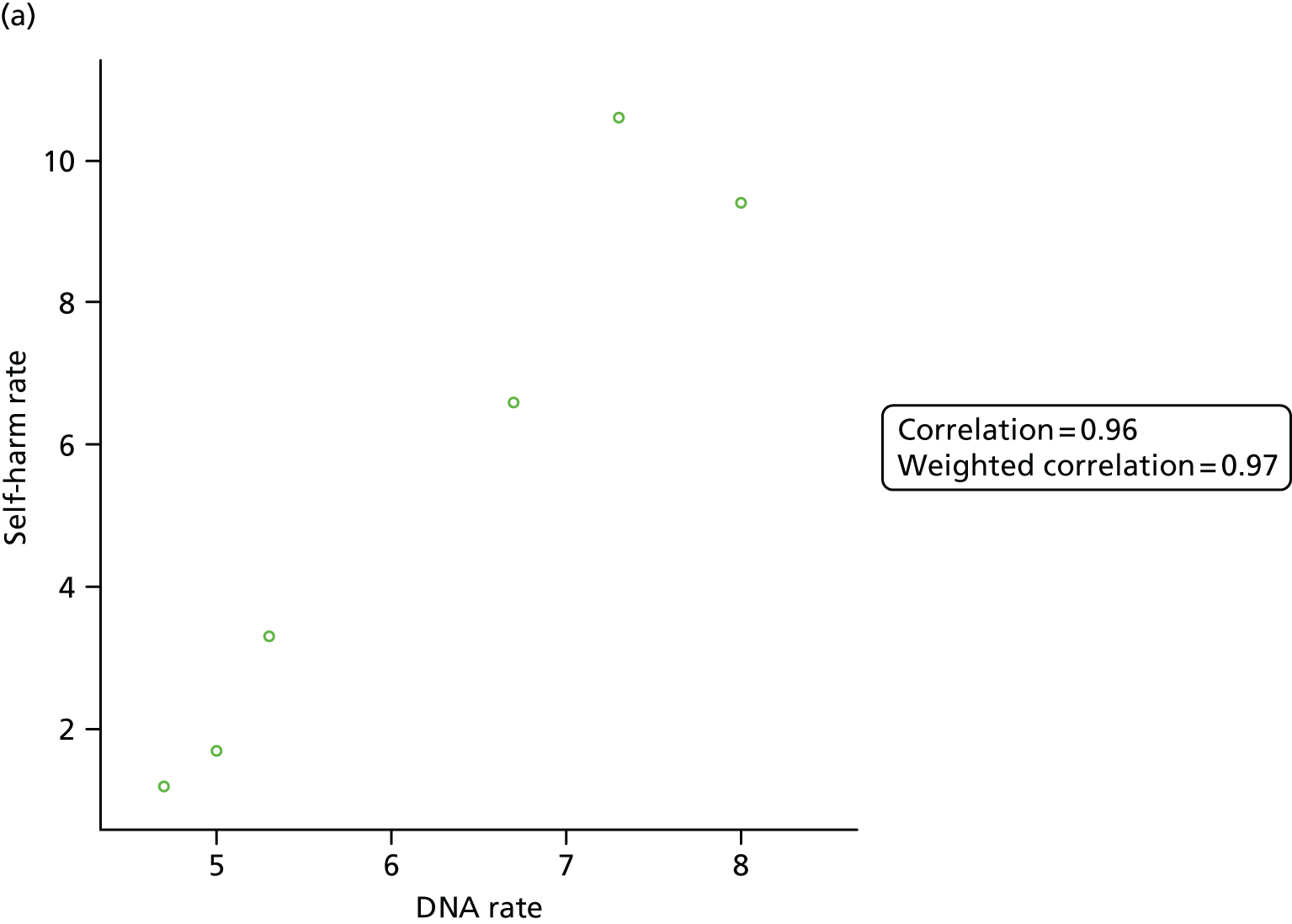

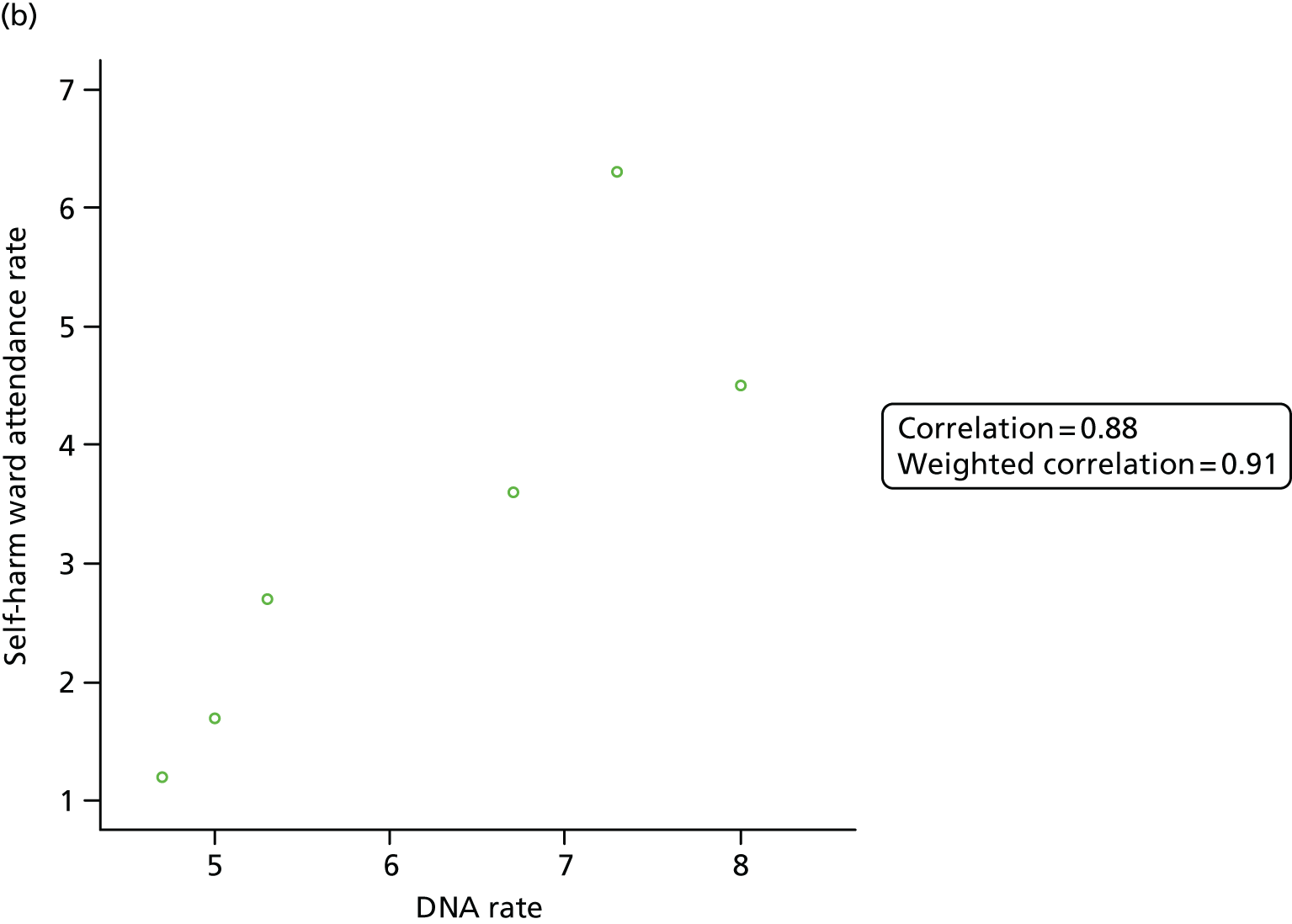

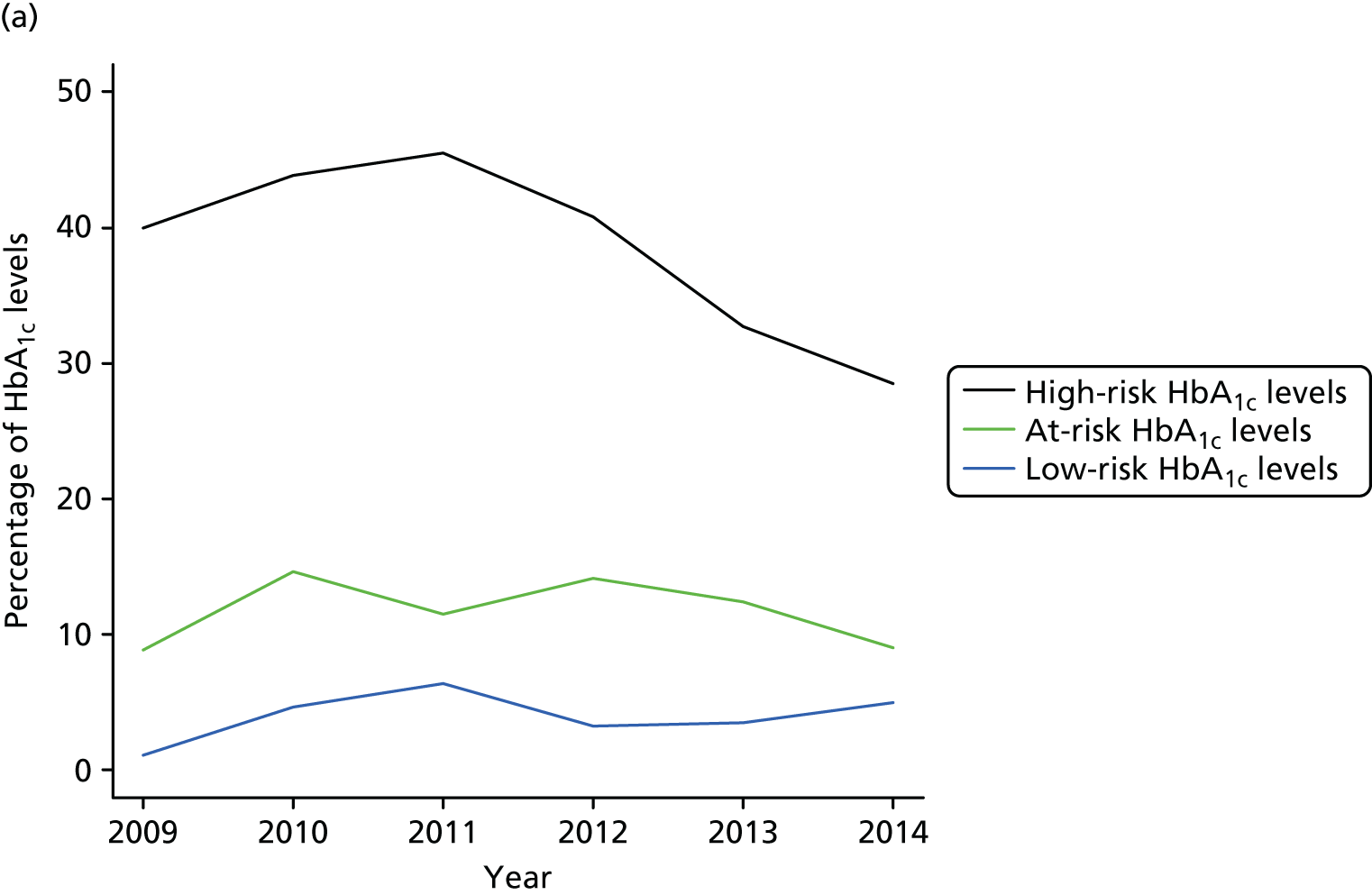

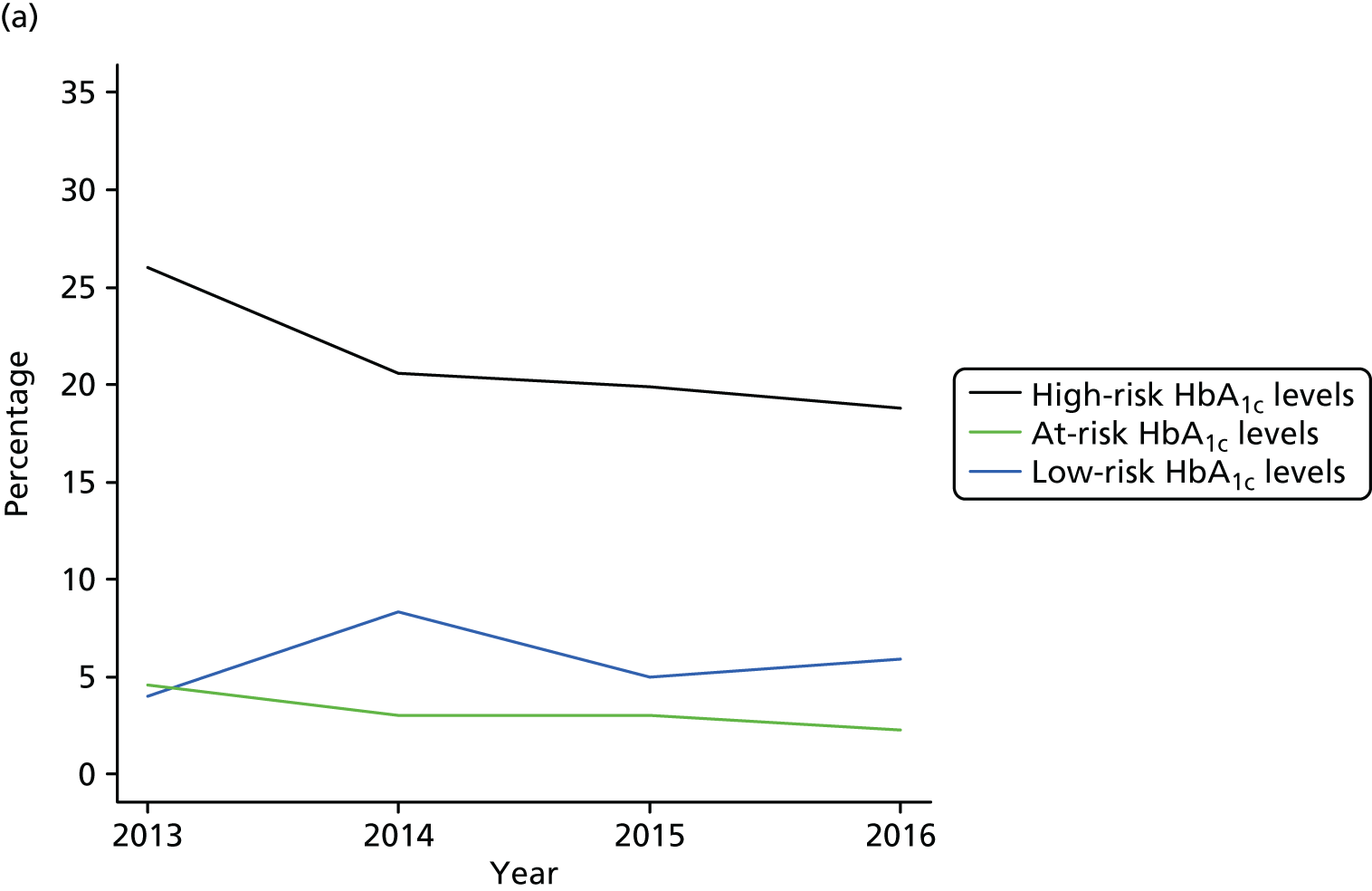

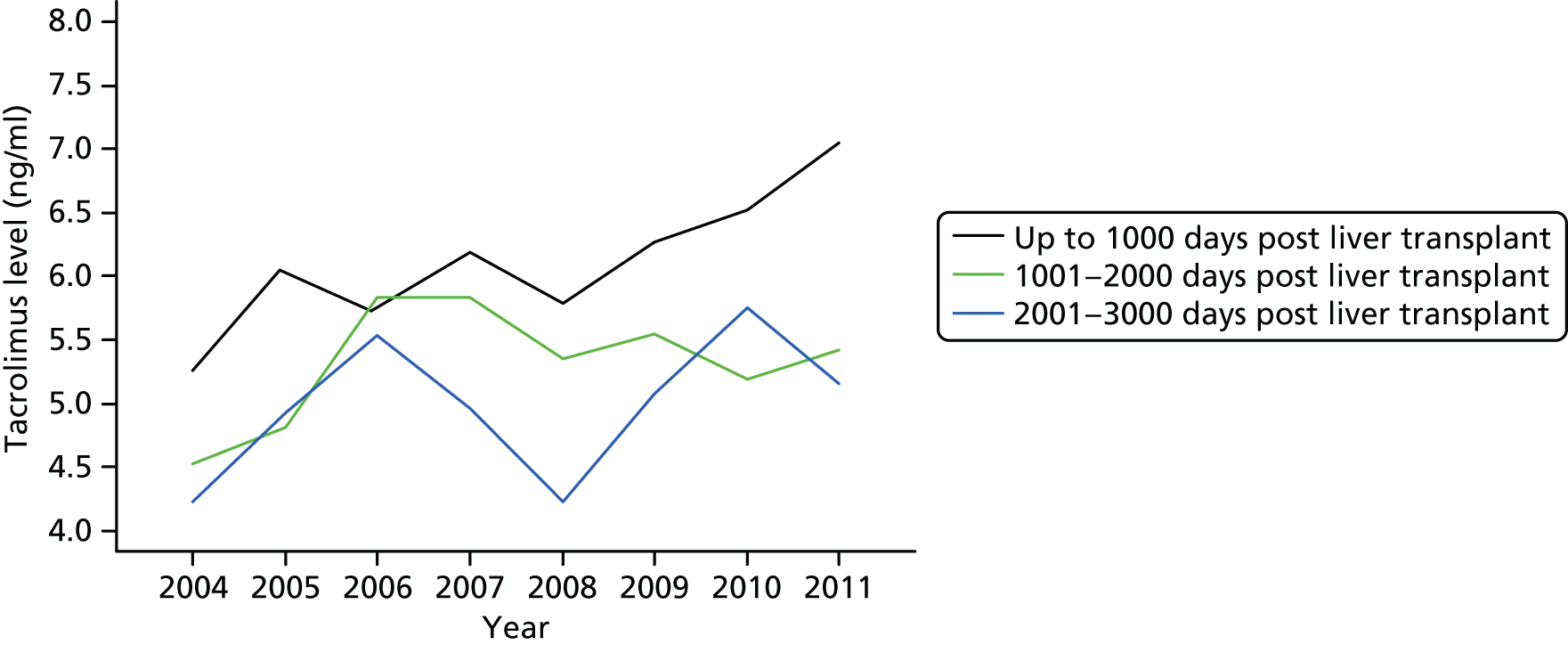

Clinic-specific outcomes are outcomes specific to the various health conditions and sites studied. These were identified in discussion with the clinical team as being key indicators of patients’ health. These outcomes were HbA1c and glucose levels for diabetes mellitus sites; body mass index (BMI); forced expiratory volume in 1 second (FEV1) as a percentage of predicted (FEV1% predicted); bed-days to receive intravenous (i.v.) therapy for cystic fibrosis sites; time to discharge for a dermatology site, where patients are discharged from the service when the skin condition is successfully treated; tacrolimus level for a liver cancer site; viral load for a human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) site; urine protein and serum creatinine levels for a renal site; and self-harm incidents and self-harm ward attendances for mental health sites. Tacrolimus level data from the liver cancer site, and BMI and FEV1% predicted data from one of the cystic fibrosis sites, were extracted by the clinic staff, whereas all the other clinic-specific outcomes were provided by IT specialists from trusts. These aggregated data were collected for all patients in the age range of our study on these cross-clinic and clinic-specific outcomes. Data collection periods were for the year prior to the escalation of DCC in each service and every year following to the point of fieldwork commencement.

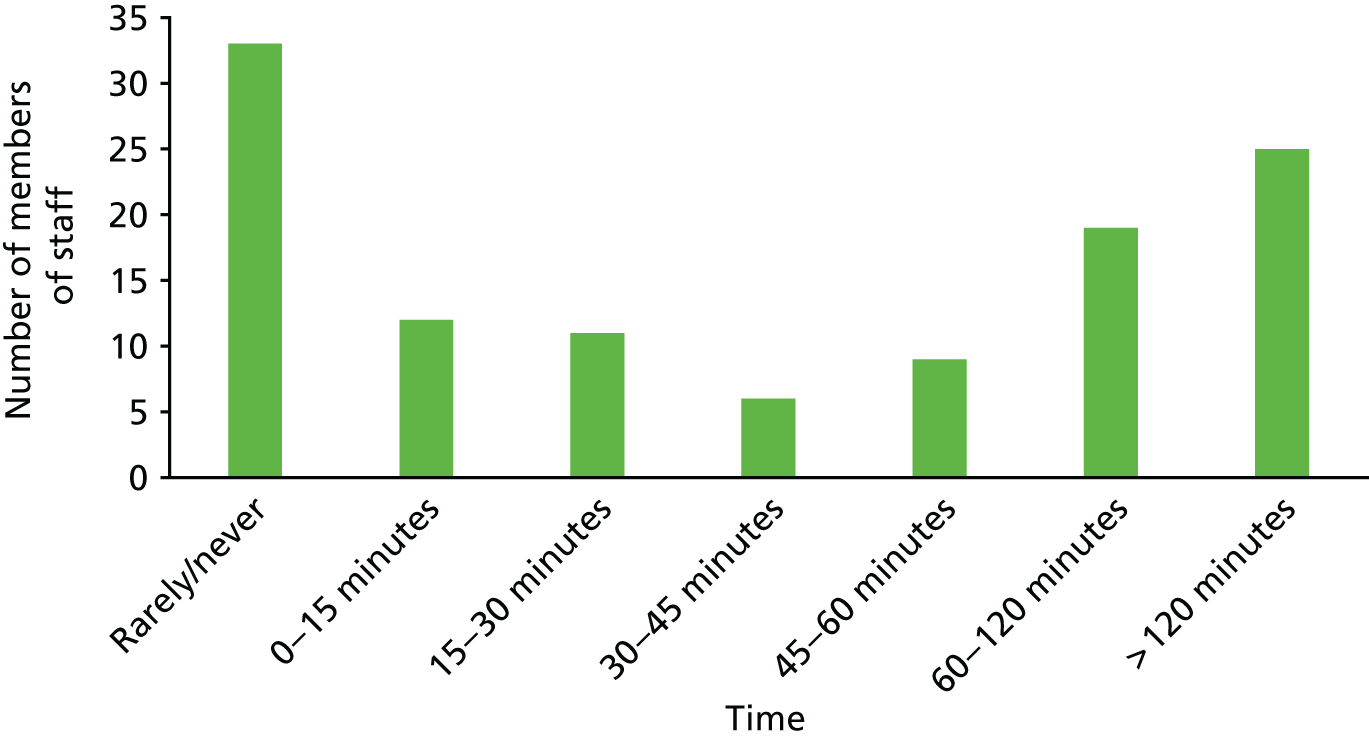

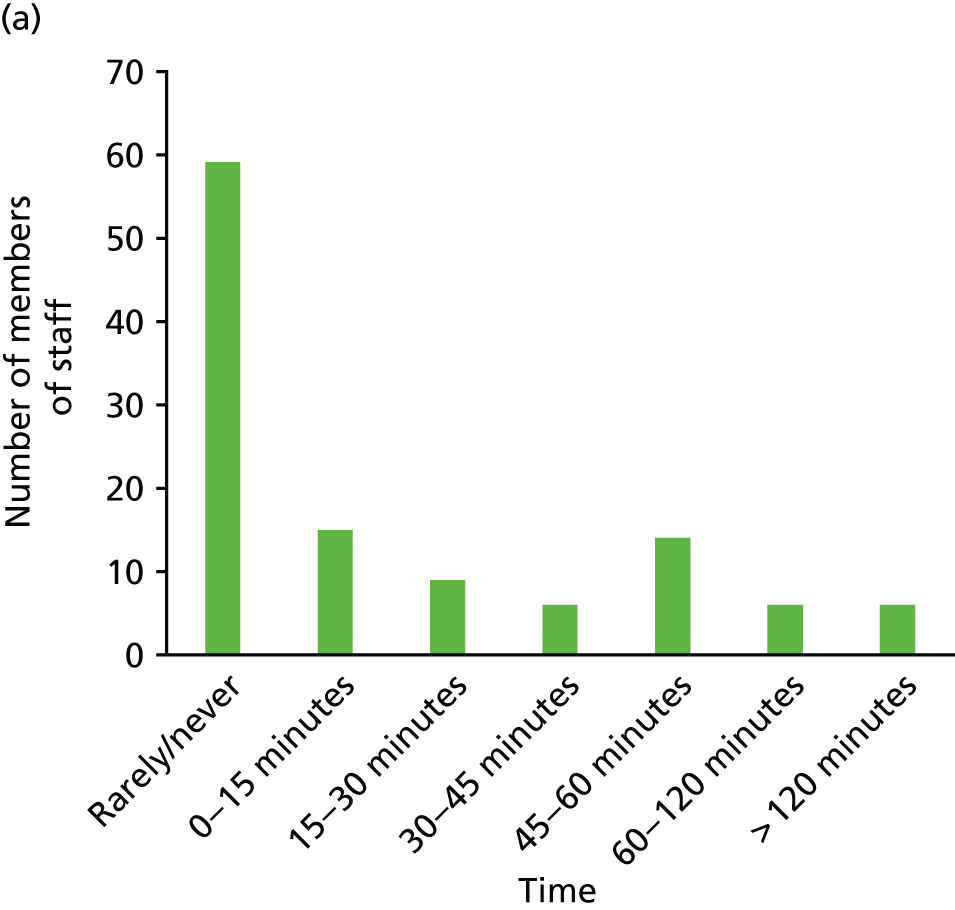

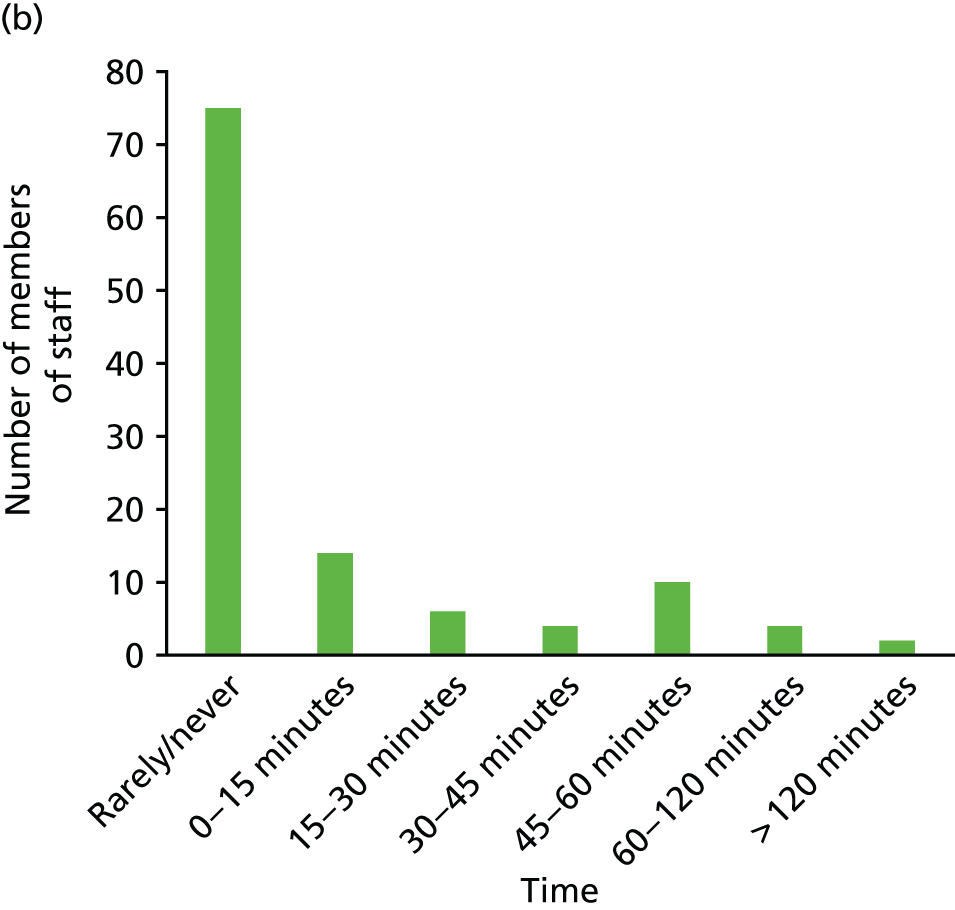

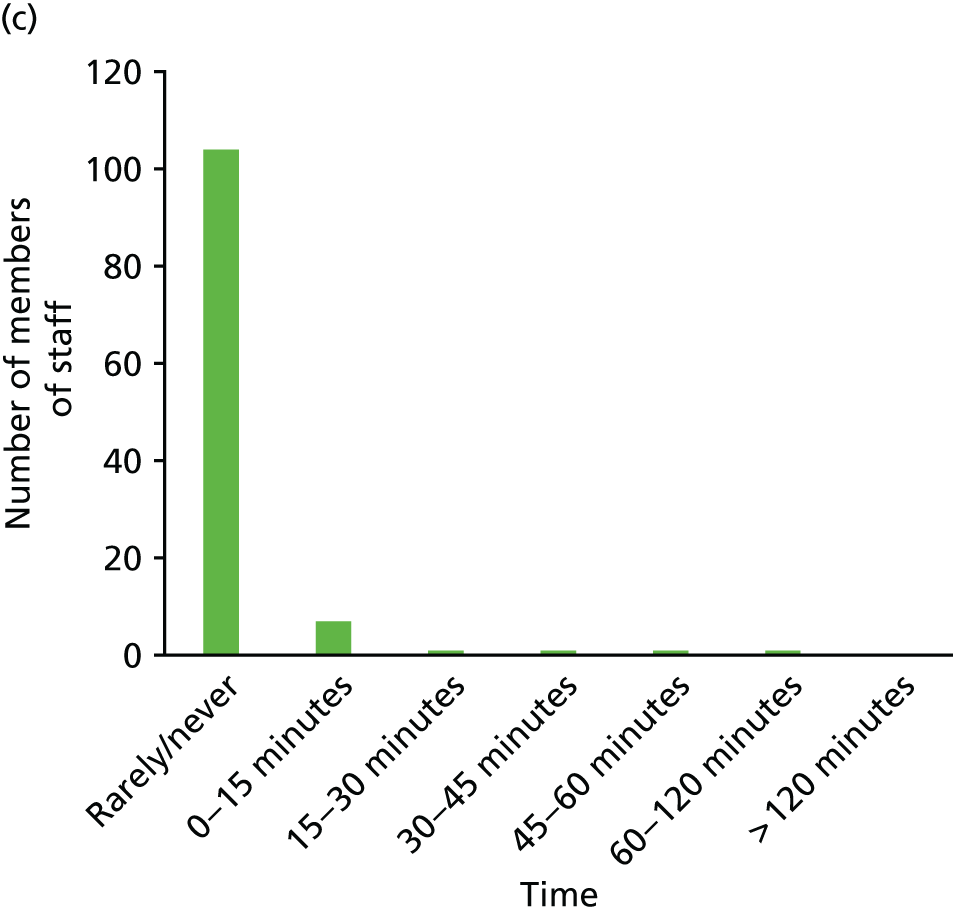

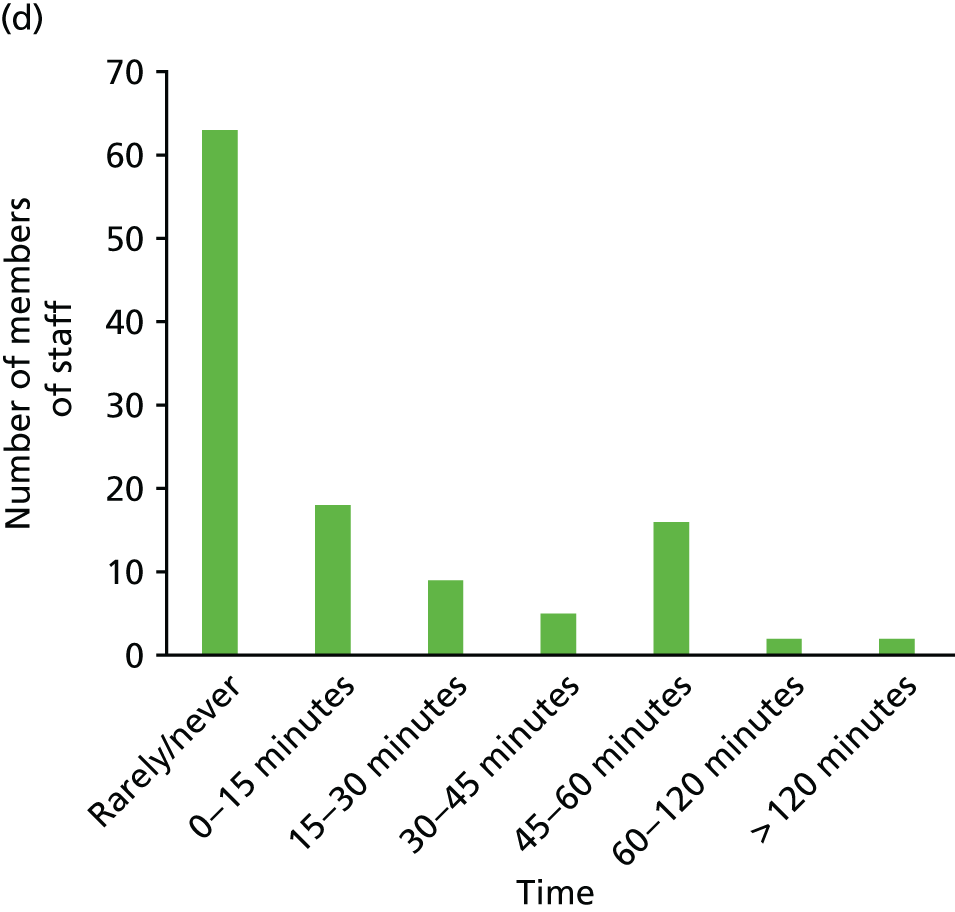

Collection of economic data about the digital communication system

A structured questionnaire was developed to collect data on resource use associated with DCC (see Report Supplementary Material 1), during staff interviews. The questionnaire was based on initial case study observation and semistructured interviews with staff. All staff, at each case study site, who participated in an interview, and whose role involved any degree of contact with patients, were asked to complete the questionnaire. Where possible, the questionnaire was given during the interview, otherwise it was sent by e-mail after the interview had taken place. The questionnaire asked staff members to report the time they spent each day on DCC-related activities, broken down by the channel of communication used (e-mail, mobile phone calls, text messaging or other, such as VoIP). Staff were not asked to report a precise figure; instead they were asked to report usage for each channel by selecting from boxes corresponding to time intervals (e.g. 0–15 minutes, 15–30 minutes). The questionnaire also asked staff to report what technology they used for DCC (laptop, desktop personal computer, mobile phone or tablet) and who provided this equipment (i.e. whether it was provided by the clinic or themselves). Data were obtained from a site administrator, or suitable equivalent, at each site on the grade of each staff member and the number of days worked per week.

A further aim of the LYNC study was to explore, qualitatively and quantitatively, the value DCC provided service users, and how this value might be elicited. A number of ‘value’ questions were explored in the interview schedule, whereby patients at each site were asked how much they would hypothetically be willing to pay for a service which used DCC compared with one which did not. After interviews at the first two case sites, the question focusing on value to patients was changed from a willingness-to-accept format (as cited in the protocol) to a willingness-to-pay format, as patients struggled to understand the original question. An open-ended question was used, but where patients struggled to respond, we tried using prompts suggesting values ranging from £5 to £50 in order to understand what values respondents might consider plausible. In sites where technology was not used for clinical communication, clinic staff and patients were asked about how they currently communicated, how happy they were with the current situation and what DCC they would find useful in the future.

Documents collated

Current trust policies and procedures were collated with help from lead clinicians and IG managers. These documents were used to inform the IG interviews. IG managers were asked to tell us about any adverse events relating to the use of DCC.

Data management

All interviews were audio-recorded. At each case site, individual participants were given a unique code to identify all data collected from them. After each case site visit, field notes were typed up and interviews transcribed and anonymised. Qualitative data were managed by NVivo 11 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) and all files were stored on a secure server.

Impact data were supplied in Microsoft Excel® spreadsheets (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). For each Excel file provided, a copy to be analysed was made. Both the original Excel files and analysed copies were stored in a secure project folder. Some analyses, such as computing the DNA appointment rates, involved computing rates in the Excel file copies. Other analyses consisted manipulating Excel files data using syntaxes written in the SPSS (version 23; IBM SPSS Statistics, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA) statistical program and this generated new formats of data. The generated data files were similarly stored in the secure project folders. Some plots were generated using the R statistical program (The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria). The R scripts written to make the plots were also stored securely.

Analysis

All qualitative data were initially coded in NVivo for the different analysis approaches within the project (what works for whom, where, when and why; ethics; patient safety; and health economics). The IG officer interviews were coded and analysed separately, as these interviews covered the use of DCC in the whole NHS trust in which the officer worked, not just the clinic we had studied. This provided a different perspective on our research questions. Further analysis of the qualitative data is described in the following sections on What works?, Ethics, Safety, Health economics and Information governance.

Survey and impact data were analysed as described in the following sections on analysis for Health economics and Impact.

Emerging findings from each analysis were discussed and shared with the project team and the Project Management Group (PMG).

What works?

Research question: what works for whom, where, when and why?

Qualitative interviews with patients and staff at 20 clinics across England and Wales, along with data from clinic observations, were analysed. This analysis stream focused on clinics’ current use of digital communications and did not consider that which was planned or wanted in the future. As per protocol, data from the first clinic were analysed line by line by using Pawson and Tilley’s configurations of context + mechanism > outcome, to produce a table which was further categorised into themes. 63 Attempting to identify these configurations at a ‘micro level’ (individual actions and interactions) was repetitive and distracted from understanding the variations in how DCC works. This led to the analysis team concluding that the idea of configurations of context + mechanism > outcome is useful, but at the level of the clinical team plus their patients. As a result, context was provided for each clinic through working with each site PI to capture the clinic purpose, mechanism became the main focus of this analysis and outcome was planned to be covered by the quantitative data derived from clinical outcome data.

Building on the codes identified in the first clinic, a coding structure was devised beneath the broad code of ‘what works’. These codes were refined with each subsequent clinic analysed, resulting in a structure with top-level codes under which was a series of subcodes that captured the similarities and differences between clinics. Codes were discussed and refined by team members (including a young PPI member of the PMG), working on the ‘what works’ analysis, at regular meetings as each subsequent clinic was analysed.

During the development of the initial coding structure, data from each clinic were coded by two members of the research team, who compared coding and discussed differences. This process enabled the team to reach consensus on the meaning and understanding of each code. After coding was completed for the first five clinics, one member of the research team took responsibility for coding the remaining sites.

Rather than develop propositions, as envisaged in the protocol, the analysis developed a number of key themes which answer the research question ‘What works for whom, where, when and why?’. Some themes focused on the perspectives of certain participants (e.g. clinicians or patients), others focused on time or technical differences in digital communication. The analysis incorporated context and outcome through comparison across clinics. The clinic-level approach gave us analytical gain that was missing when the first site was analysed for micro context + mechanism > outcome configurations. Rather than devise logic models from these configurations, one thread of the analysis analysed the data to produce scenarios illustrating which type of digital communications are most useful in the context of ‘what works for whom, where, when and why?’ These scenarios will be useful to clinicians who are proposing to use DCCs for the first time or who are planning to introduce different or new methods of communicating digitally.

Overall, 14 sites were analysed fully to produce the main themes in the ‘what works’ analysis. Data saturation had been reached by this point, meaning that no new substantive themes were identified in the data. The final six sites were analysed at the macro code level, with the data identified as ‘what works’ reviewed for differences from the case sites already analysed, or to give additional depth and understanding to the previously defined codes.

Ethics

Research questions: what concerns do patients and clinicians have about confidentiality in relation to DCC? How does it affect the patient–clinician relationship and the clinician’s duty of care? What regulatory framework is needed to reassure patients and clinicians regarding its use?

Data analysis followed the method described by Ives and Draper for ‘normative policy oriented empirical ethics’. 64 This approach recognises the need for ethical policy (in this case policy on the use of DCC) to be informed by both a theoretical analysis of the ethical concerns and the moral intuitions of the relevant stakeholders. Transcripts from two early sites were initially read to identify examples of explicit articulation of ethical issues; areas of conflict or disagreement; expressions of discomfort with current or perceived practice; or examples of avoidance of an ethical issue. A refined interview schedule focusing on prompts to elicit reflection on ethical issues was developed and used alongside the general interview schedule in a further three sites. The transcripts from these five sites were discussed in a series of five analysis meetings and initial themes relating to ethical concerns and issues were identified. All transcripts for these sites were coded against the initial themes with further discussion and refinement of the themes in analysis meetings in which consensus was reached on the ethical interpretation of the data. Ethical issues and values identified were then considered in relation to ethical, professional and legal normative frameworks. The discussions were recorded and transcribed to ensure that the range and nuance of the identified ethical issues were captured. The process was then repeated with a sample of transcripts from the remaining sites to look for any new themes/issues arising and to consolidate consensus on the initially agreed themes.

Safety

Research question: what are the main risks associated with the use of DCC in the context of young people with chronic conditions?

Data that had been macro coded as patient safety were analysed further in NVivo. These sections were first read in their entirety to allow familiarisation with the data.

Data were then coded using descriptive coding based on an established safety science framework for analysing and describing risk. 65 This framework describes risk qualitatively based on the hazard (i.e. a situation that carries risk); the potential consequences of the hazard; the potential causes that might lead to the hazard; and possible mitigation strategies to reduce the risk. Data were coded by two researchers.

In a second cycle of analysis, the descriptions of risk were clustered around similar hazards to identify the main risks. Clustering of hazards and identification of main risks were discussed and refined during 1- or 2-weekly analysis meetings. The findings were presented to members of the project team during methodology group meetings and to the wider advisory group during PMG meetings in order to validate the findings and to receive feedback.

Health economics

Research questions: what value do patients place on DCC? What are the direct resource use implications for the NHS of implementing it? How does the direct resource use vary when used with different patient groups? What are the resource implications for scaling up in the NHS?

Scope and aims of the health economic component of the Long-term conditions Young people Networked Communication study

The scope and aims of the LYNC study health economic component follow on from the design of the main study, which is an in-depth qualitative assessment of the use and impact of digital communications, defined broadly and evaluated across a diverse collection of case studies. This context does impose significant limitations on what could be achieved in terms of formal economic evaluation within the LYNC study. Specifically, the case studies provide cross-sectional data on current practice in diverse clinical settings, rather than information on specific interventions that could be subjected to economic evaluation. Furthermore, the scope of the LYNC study does not include longitudinal data collection or well-defined case and control groups that might be used to identify incremental costs and benefits. Given the restrictions imposed by the nature of the LYNC study, our aim was not to attempt estimation of the cost-effectiveness of digital communication use at each site, but instead to motivate future formal economic evaluations in this area and provide reflections that might be useful in the design of such studies. We aim to inform service delivery as well as research by considering what challenges might arise from the implementation and monitoring of practices around digital communication, and whether or not economic evidence might be required to inform decision-making around the adoption of digital communication in routine practice.

Data from the health economic questionnaire were used to calculate, for each respondent, the annual absolute costs associated with DCC usage. We refer to absolute cost as the data do not allow us to distinguish between additional activity occurring because of the adoption of digital communication usage, which is an incremental cost of digital communication, and activity which would have taken place even if digital communication had not been adopted, which is therefore not an incremental cost of digital communication. Time responses were converted into costs using the mid-point for the time interval and for the salary as given by the NHS Agenda for Change Pay Scales for 2014–15. 66 Costs for equipment were taken from price lists provided by IT services at the University of Warwick and annualised assuming a 3-year lifespan for the technology and a discount rate of 3.5%, in line with methods guidance from the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE). 67 A health services perspective was adopted for costing, which meant that equipment costs were only included if the equipment had been provided by the employer primarily to facilitate DCC. Where data were available on all staff members at a site who interacted with service users, this costing was used to estimate the total costs of DCC-related activity at the site. For sites where one or more staff did not complete the questionnaire, an attempt was made to identify a staff member in a similar role who had completed the questionnaire, from whom the missing information could be extrapolated. This was used to estimate the total clinic costs related to DCC activity, but only if the overall completion rate for the site was over 50% (if more than half the questionnaires were not completed at a site, no attempt was made to estimate clinic-level costs). For sites where it was possible to estimate annual DCC-related direct costs, information was sought from the clinic on the size of its patient list. Where this information was available, it was used to estimate the cost per patient supported by the service of DCC.

In order to identify the consequences of DCC use at each site in terms of the impact on patient health and well-being, and clinic costs and efficiency, the health economics team reviewed the transcripts of interviews carried out with staff members at each site. Quotes were extracted that provided information on the purpose and content of DCC between clinic staff and patients, either in terms of specific examples or general experience, the consequences that arose from such communications and the counterfactual (what would have happened if DCC was not available in this situation). The aim was to identify the route to impact on outcomes that were intrinsically valued by patients – this includes the health outcomes which the service is intended to improve, but could also include outcomes relating to patient well-being more broadly. It would also include outcomes related to service efficiency, utilisation and costs. Data were also extracted on intermediate or process impacts of DCC that could lead to such outcomes. Data extraction was carried out by one health economist for all transcripts. For each site, a sample of transcripts were reviewed independently by a second health economist and comparison made for quality assurance. Once data had been extracted from all transcripts at a site, the findings were compared to identify and combine, within a thematic analysis table, quotes relating to the same use of DCC. The health economics team reviewed this table to identify gaps in the information. A follow-up interview was carried out with a senior clinician at each site to elicit information on the consequences and counterfactuals of DCC examples identified from staff interviews, where the information provided at the initial interview was incomplete.

Information governance

All IG manager interviews were entered into NVivo 10 and analysed on the basis of systematic coding recommended by Saldana. 68 This method of analysis breaks down data to identify relevant patterns and, ultimately, groups coded segments into categories which are linked to overarching themes and concepts. Two investigators coded three interviews concurrently to develop preliminary codes. Subsequently, two transcripts and the preliminary codes were reviewed, discussed, amended and agreed between two IG co-investigators, a clinician, a member of the PPI and the researchers. These final codes were then applied to the remaining interview transcripts. Additional codes were developed and applied as appropriate and a 20% subset of all clinician and patient interviews were coded using these IG codes and contributed data to the analysis.

Inductive thematic analysis69 was adopted to identify themes that were strongly linked to the data (data driven) and equally served the purpose of eliminating the influence of the researcher’s analytic preconceptions. The identification of themes was explicitly achieved at a semantic level70 on the basis of the key patterned responses provided by the IG officers. Line-by-line analyses of transcripts were undertaken to identify recurring topics. These were then sorted, identifying similarities and differences. 71 The analysis provides a descriptive account of the emergent themes.

Impact

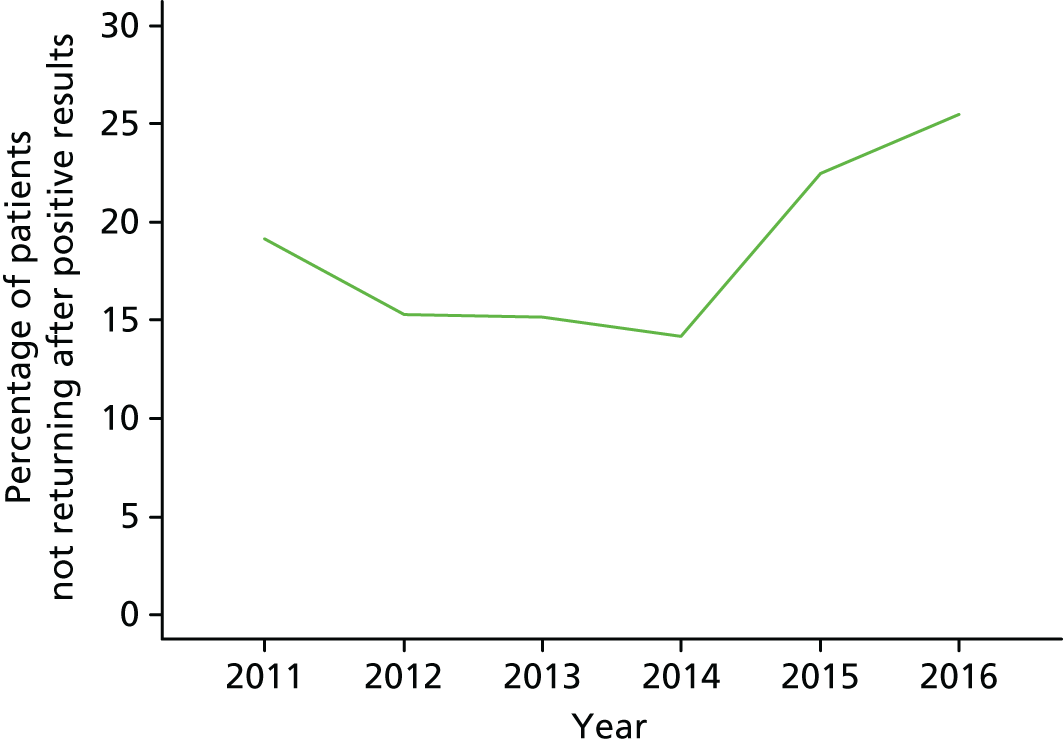

Research questions: how is impact of DCC on health status of patients currently evaluated? Using existing clinical data, what is the impact of DCC on health status of patients?

Analysing cross-clinic outcomes data

For the appointment status, DNA rates for each year were calculated to assess the trend over time. Most appointment data were provided in Excel spreadsheets giving a breakdown of how many were attended (attended), how many were cancelled (cancelled) and how many were not attended (DNA). DNA rates were calculated in Excel spreadsheets using the formula DNA/(attended + cancelled + DNA). In some sites, data were provided indicating appointment status for each individual appointment. In such instances, SPSS syntaxes were written to manipulate the data and calculate the DNA rate.

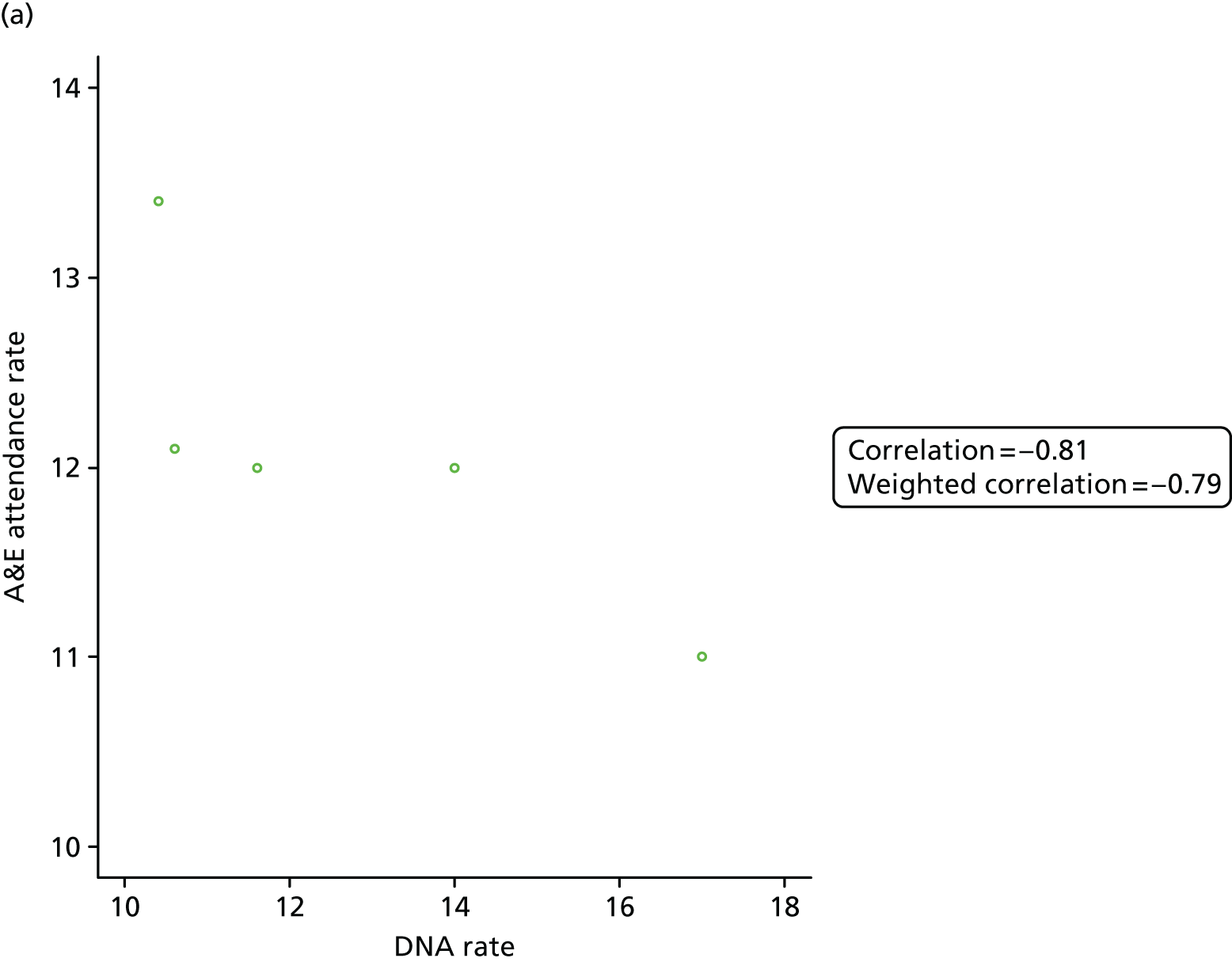

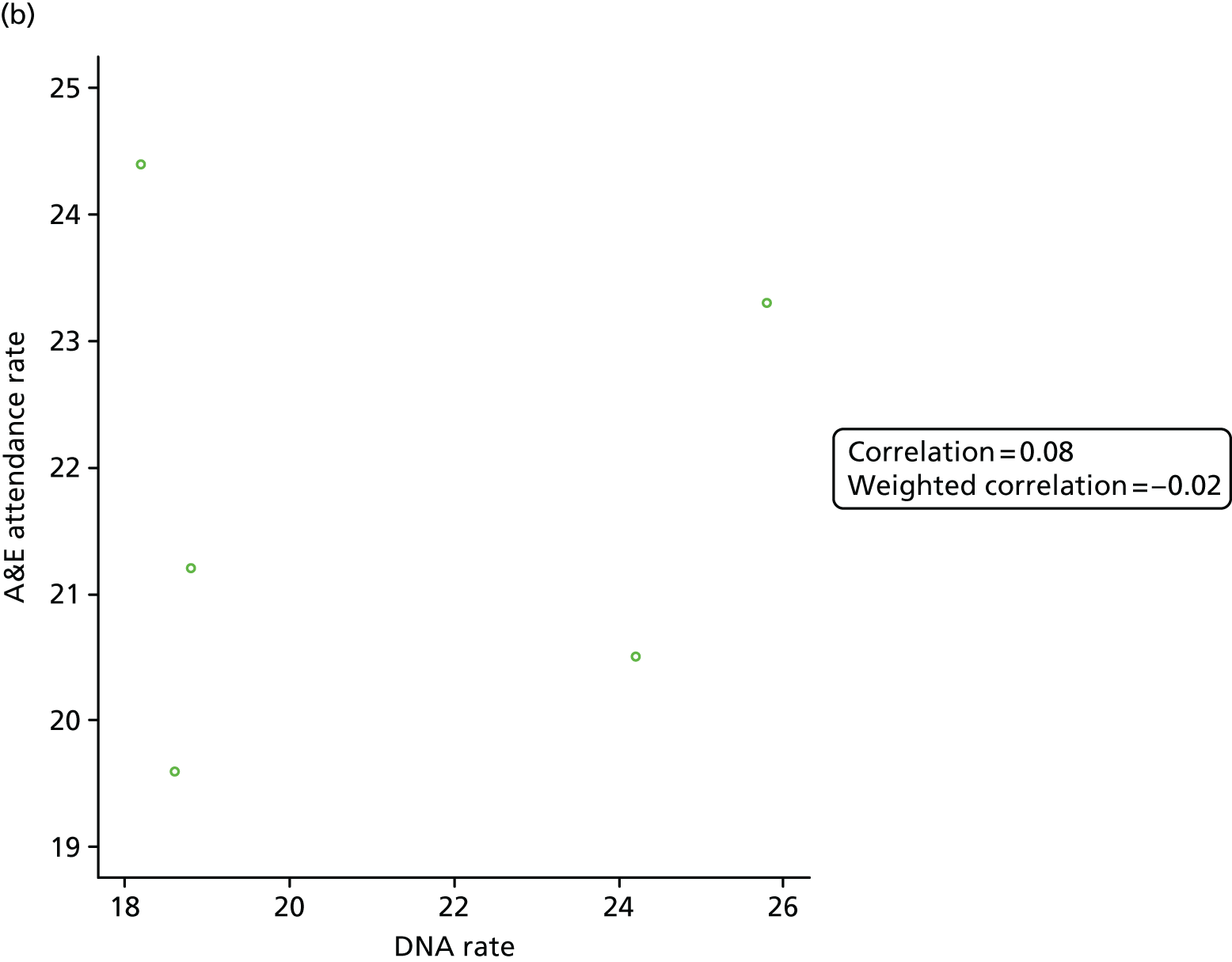

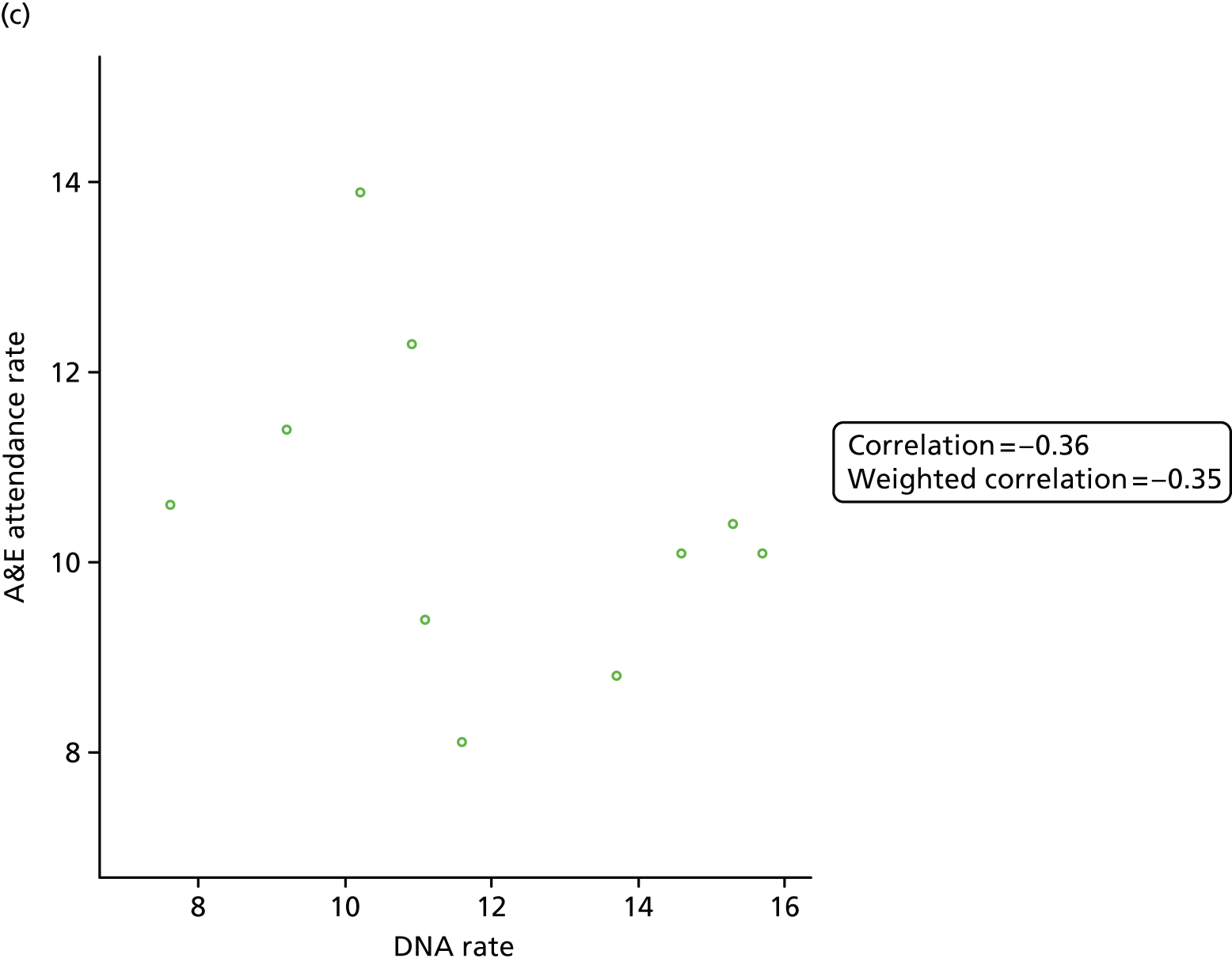

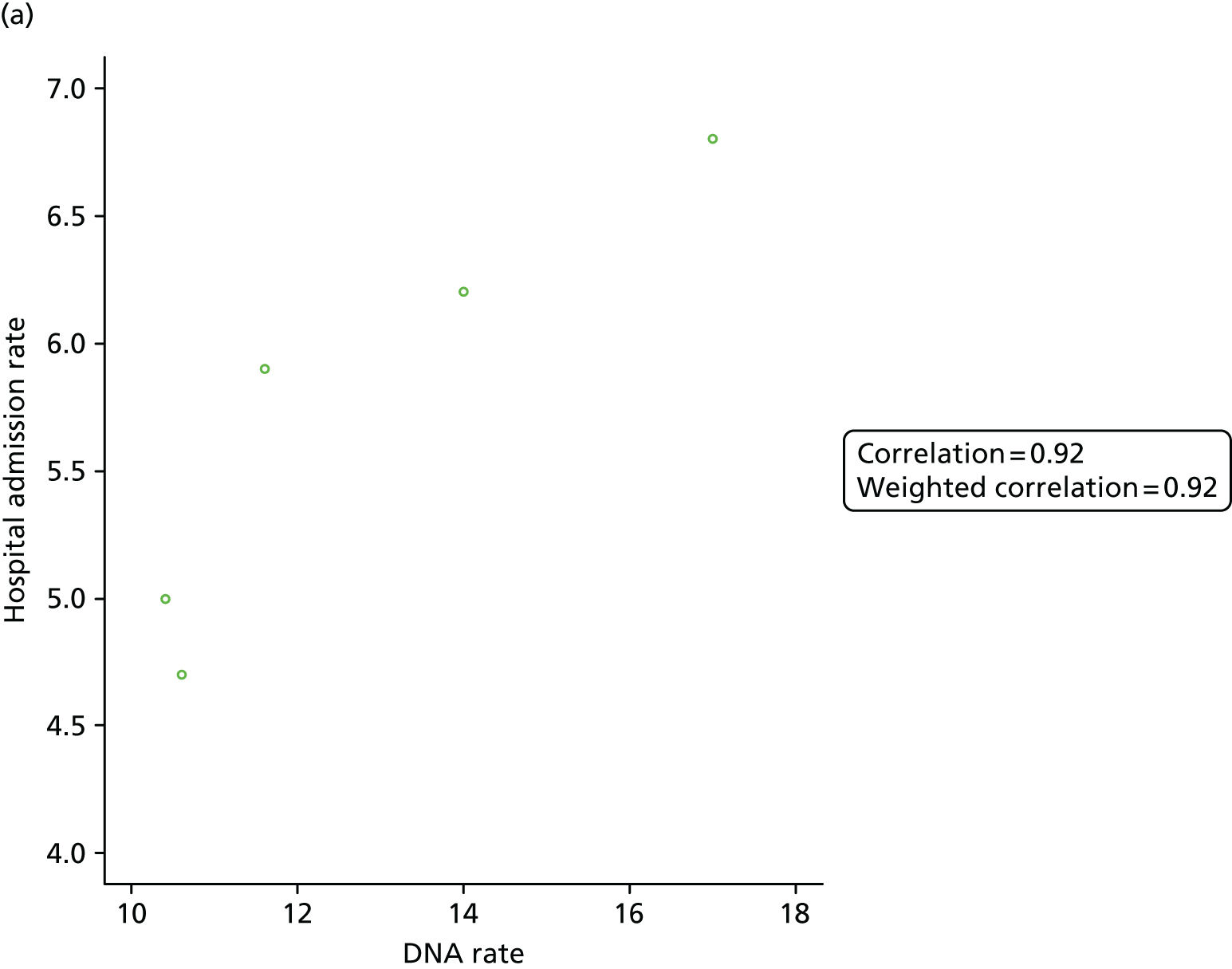

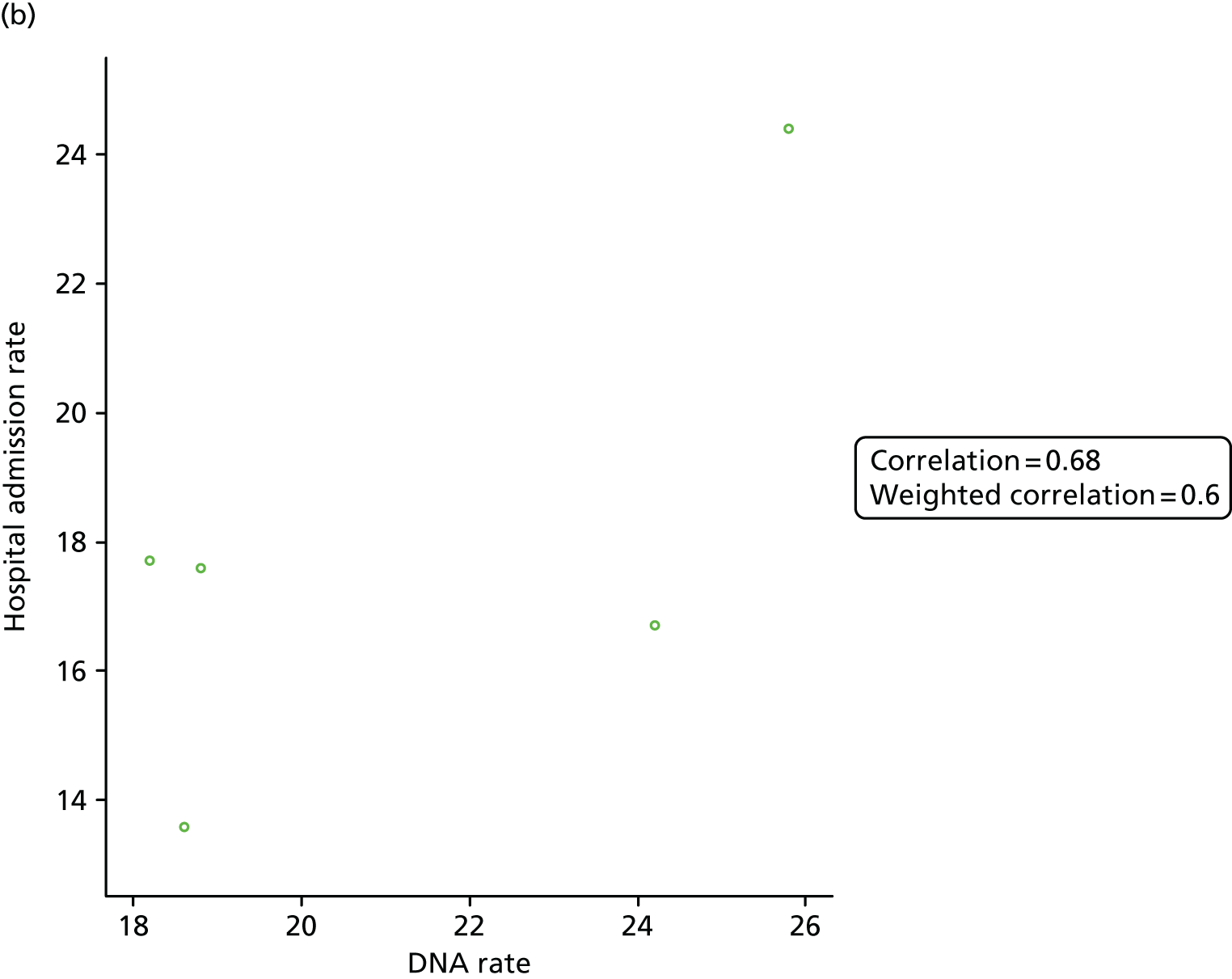

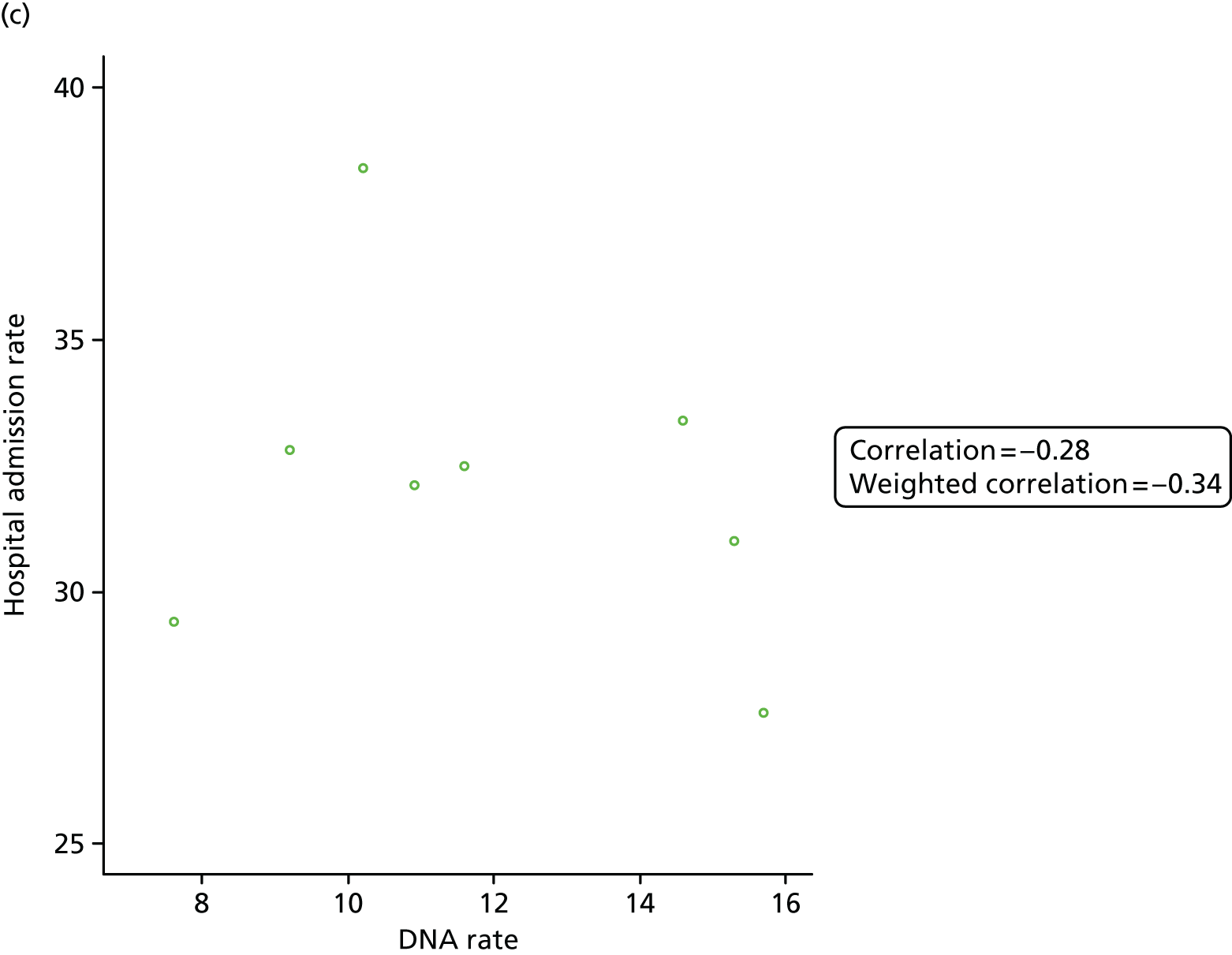

For A&E attendance, rates of at least one attendance in each year were calculated. These were used to assess trend over time. A&E attendances were reported for each episode. SPSS syntaxes were written to calculate A&E attendance rates. Hospital admission data were analysed similarly.

For all these cross-clinic impact outcomes, instances where there was a change associated with DCC use, or any other major change in practice, were noted so that their effects could be taken into account in interpretation.

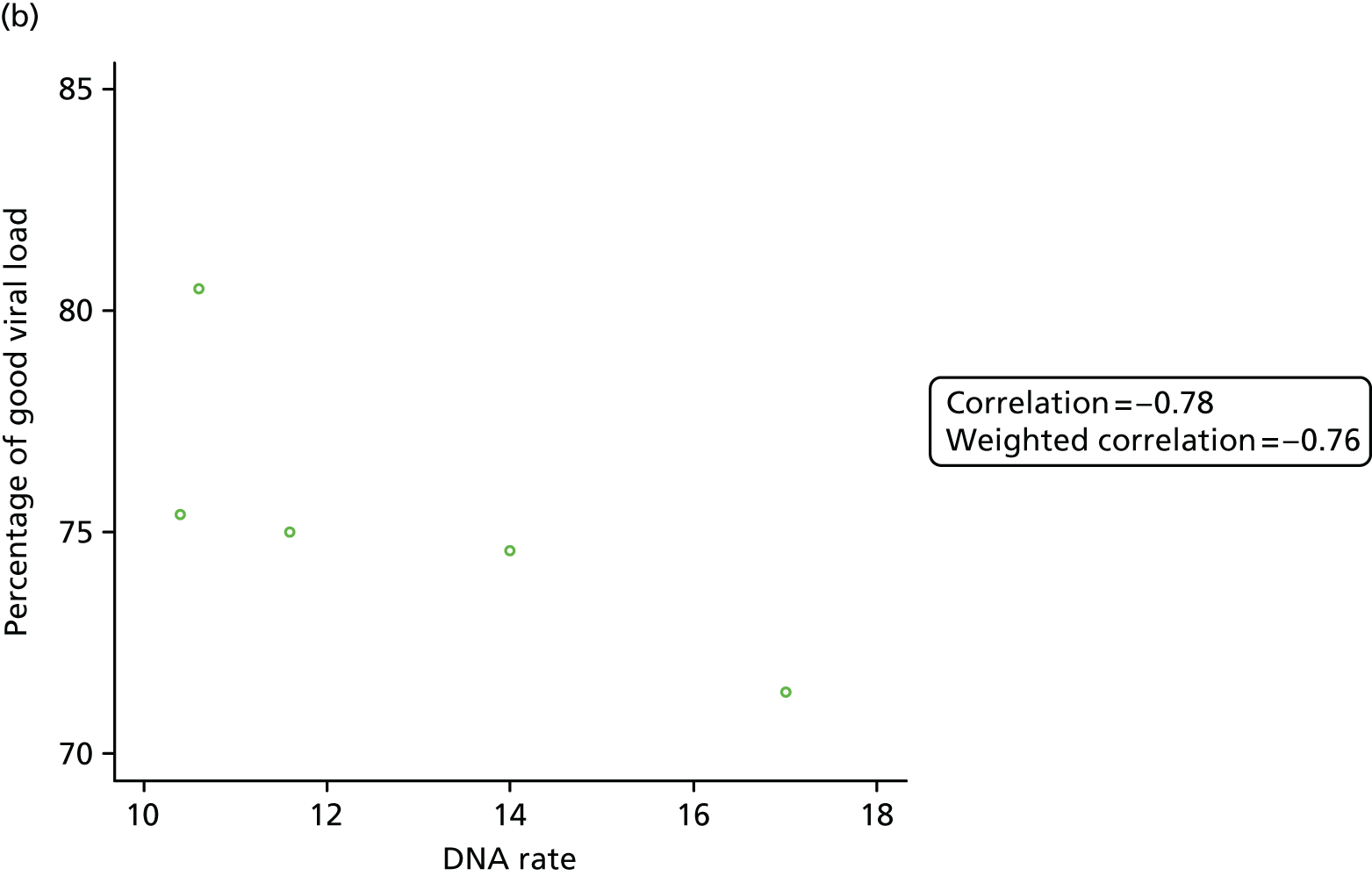

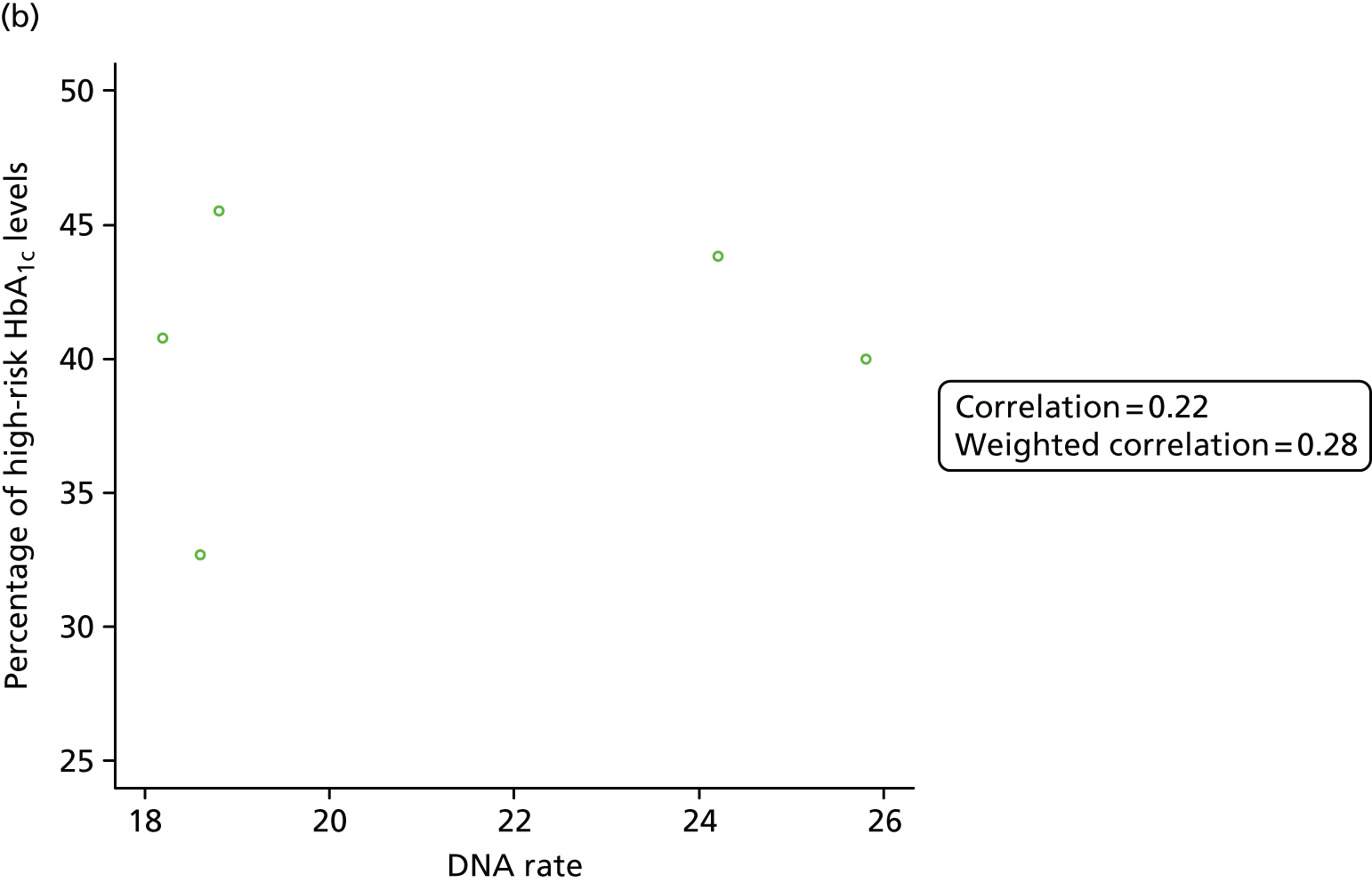

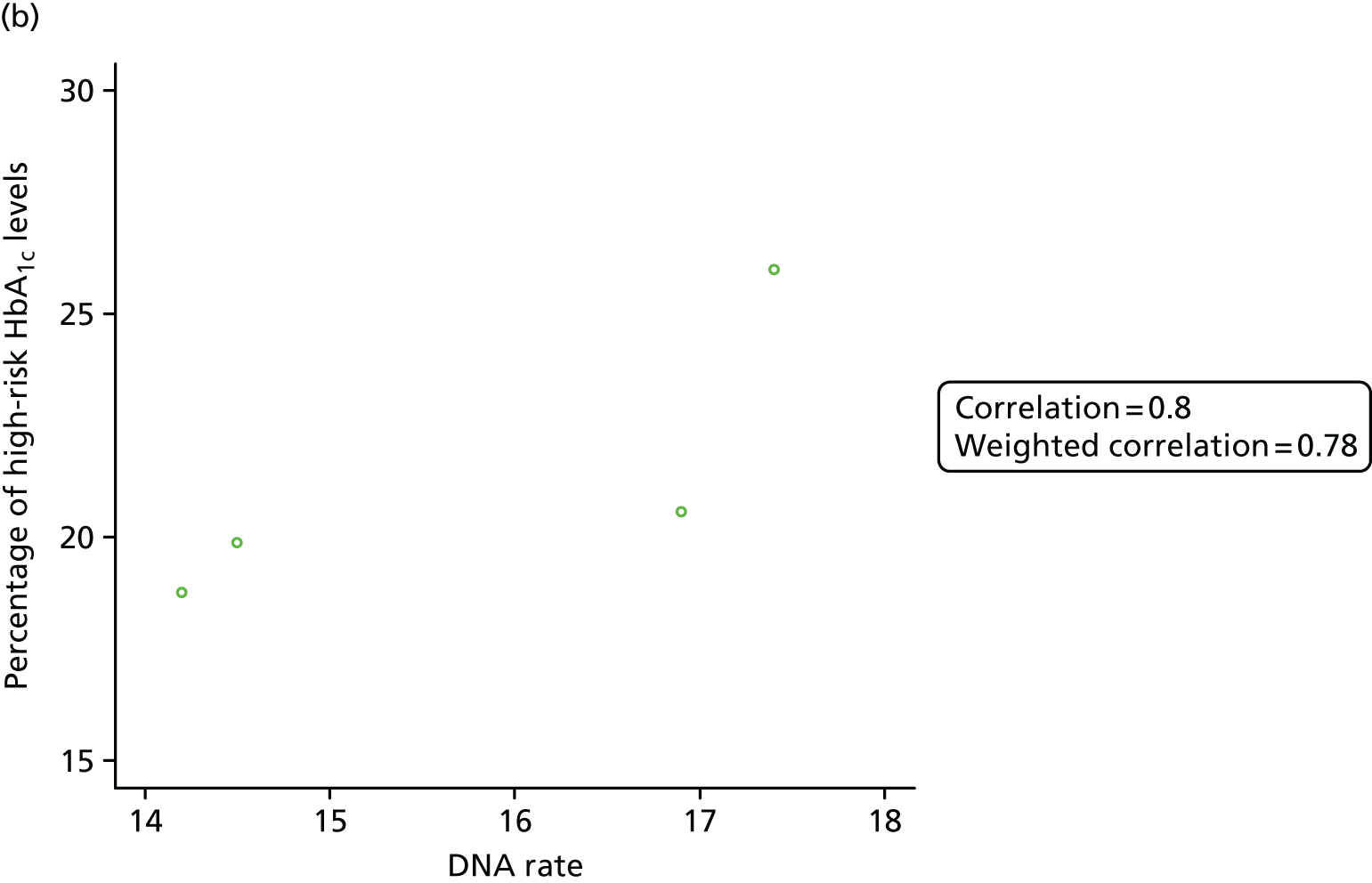

Scatterplots and Pearson’s correlations (weighted and unweighted) between annual DNA rates and each of annual A&E attendance rates and hospital admission rates were used to assess if lowering DNA rates affects A&E rates and hospital admissions. Weights used for weighted correlations were proportional to the number of registered young persons.

Analysing clinic-specific impact data

Most clinic-specific outcomes were measurements taken continuously over time to monitor the management of a condition. For example, continuously monitoring viral load and HbA1c level for young people in HIV and diabetes mellitus sites, respectively. Change over time for such outcomes was assessed by plotting individual young patients’ profiles over time and also the mean profile. The profiles were compared with the target set by the site.

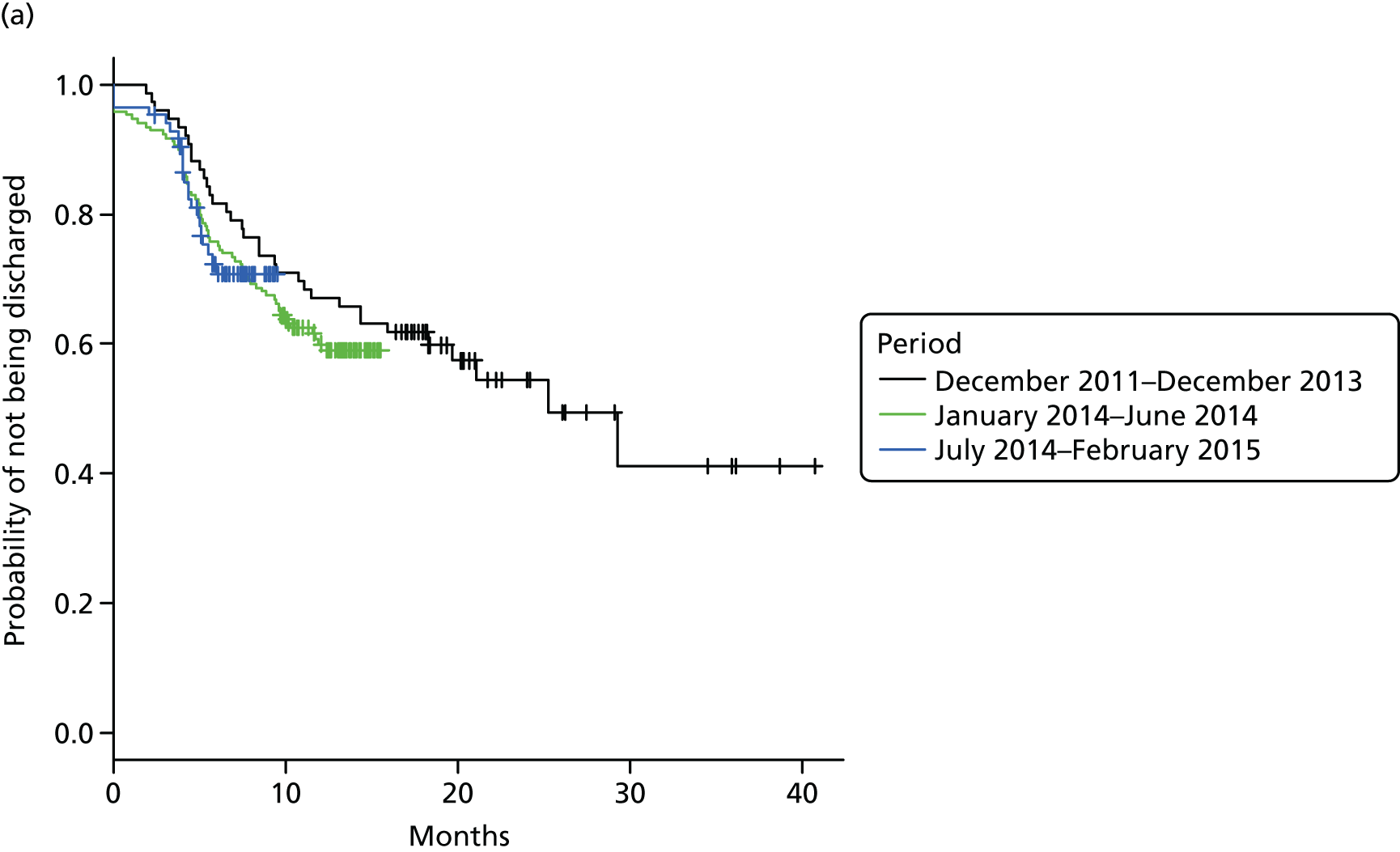

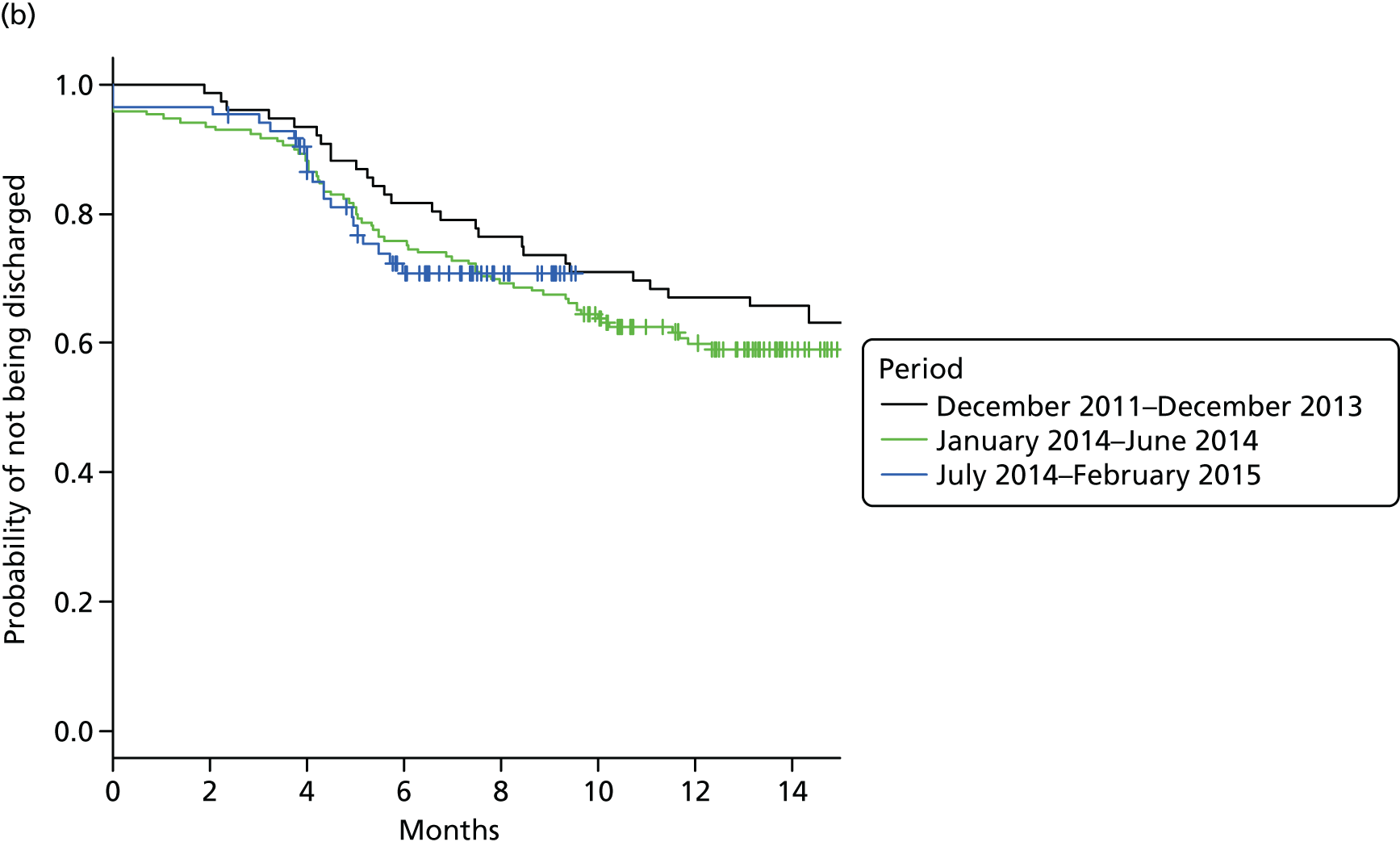

Time to discharge data have a different form, so these were summarised using Kaplan–Meier plots. To assess effect over time, patients were categorised into groups based on the period when they were registered in a clinic, with a Kaplan–Meier plot obtained for each category. An example of a clinic-specific outcome is i.v. infusion rates. For this outcome, rates of patients requiring at least one i.v. infusion per year were calculated.

Again, instances where there was a change associated with DCC use (or any other major change in practice) were noted, although, where possible, the impact of DNA rates on other outcomes was assessed using scatterplots and Pearson’s r correlations.

Additional analyses

In response to policy-maker requests (NHS Digital and NHS England), we undertook a thematic analysis of our qualitative data on the use of personalised medical records and on information governance managers regarding the use of Skype for clinician–patient communication. This is reported in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Consensus conference

We held a consensus conference to consider our key findings. This is reported in Report Supplementary Material 1.

Results

Description of case sites

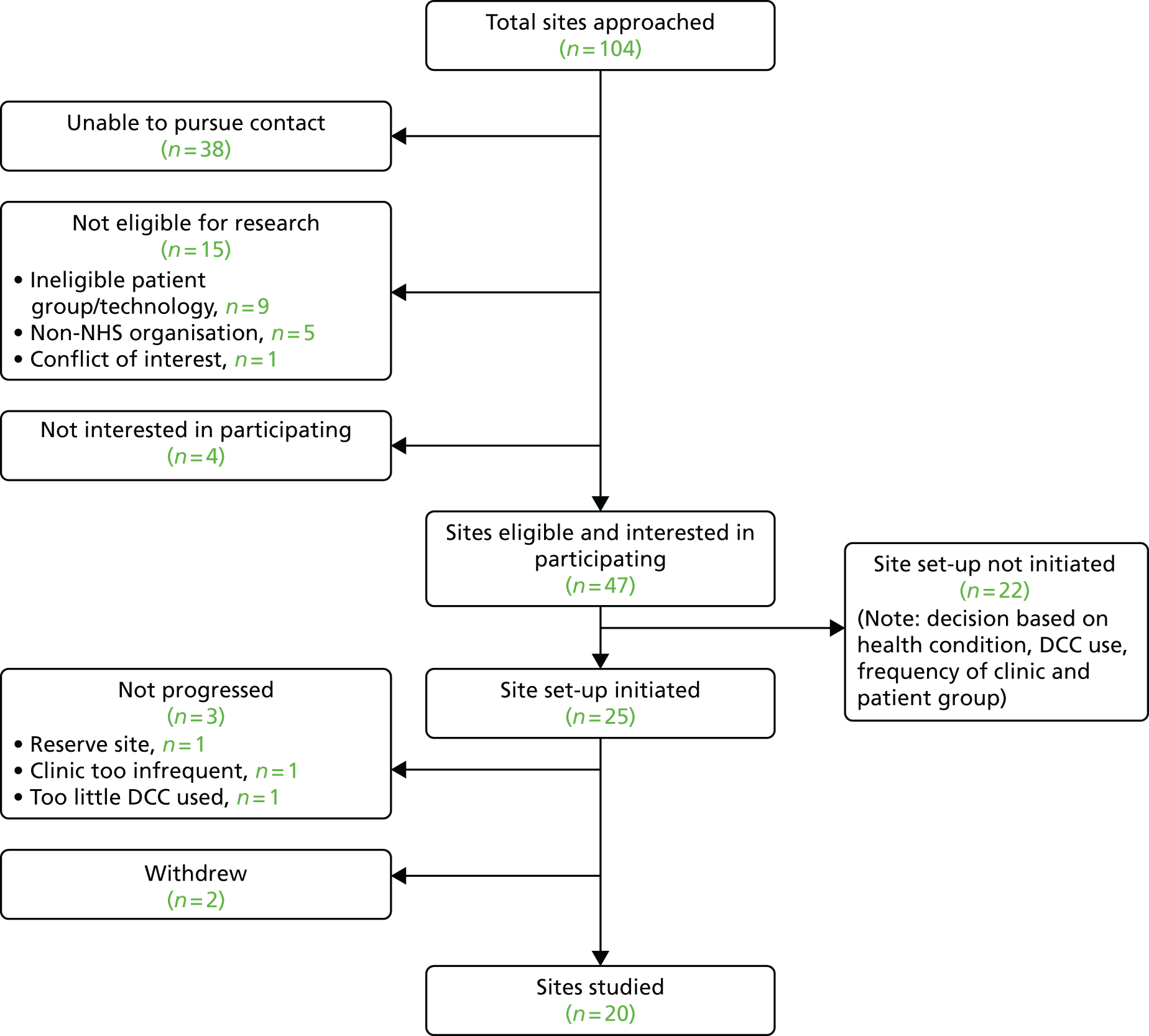

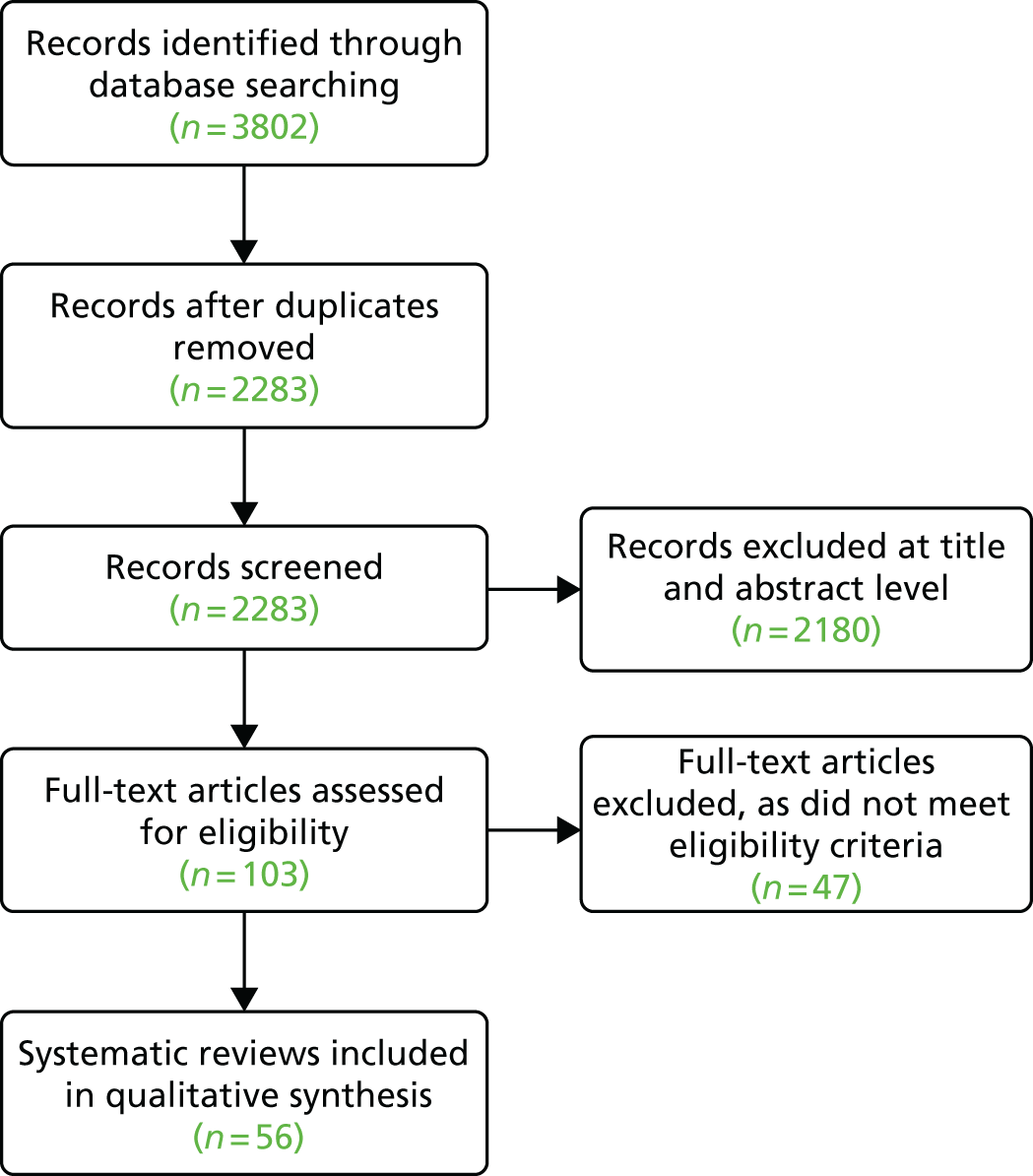

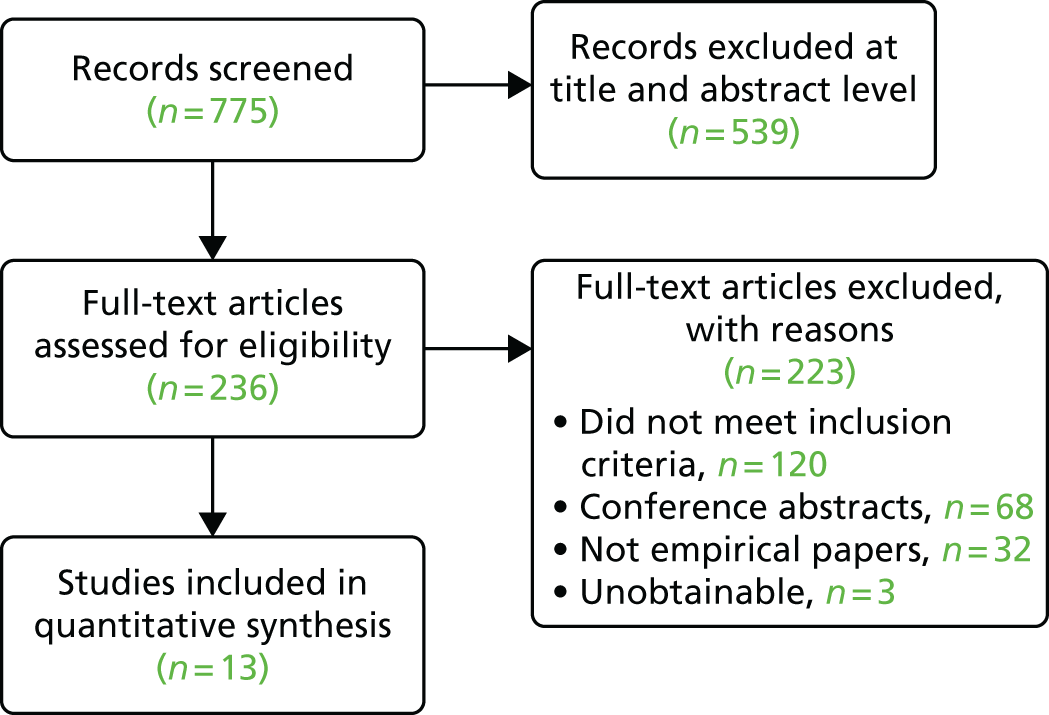

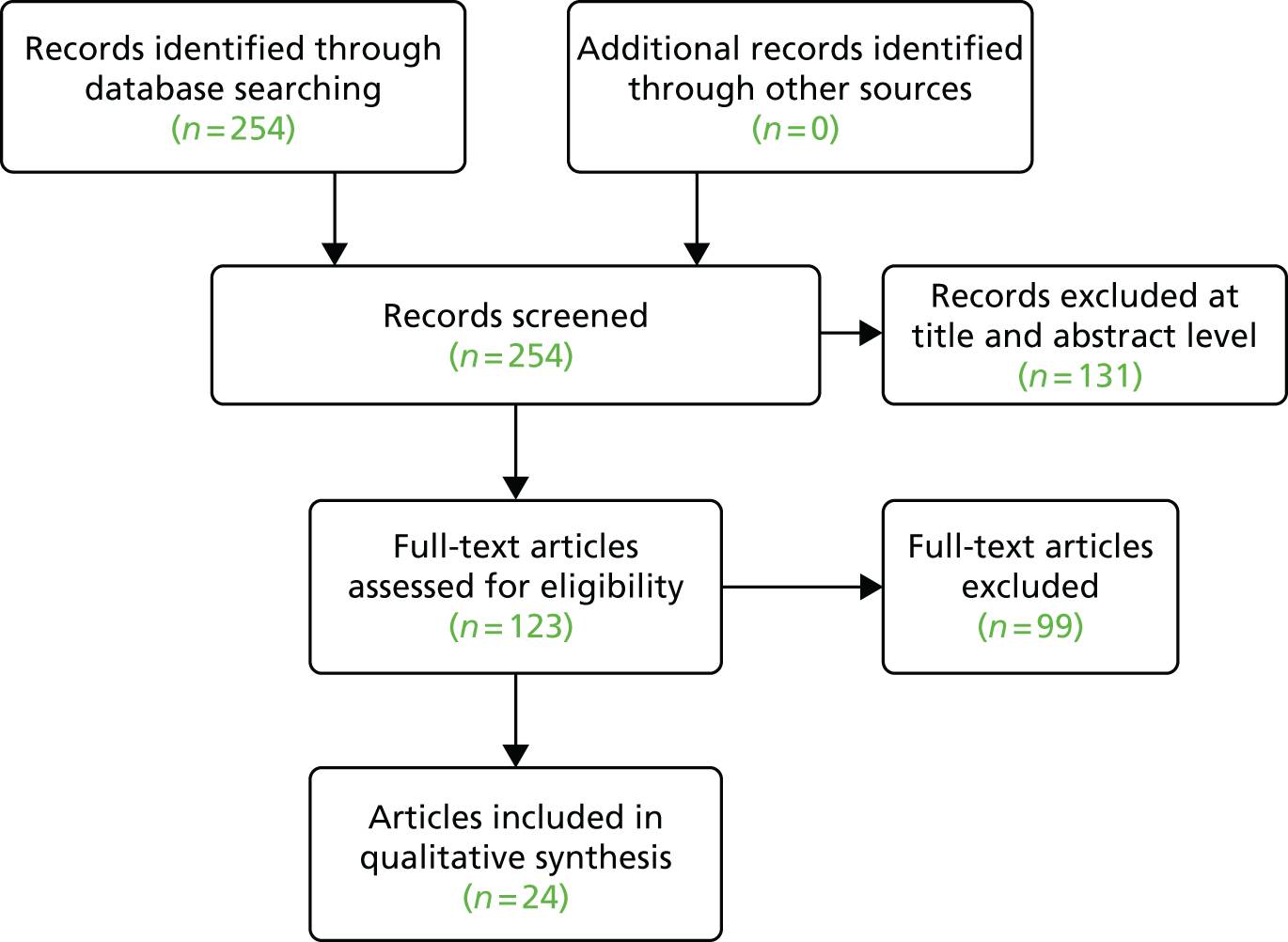

Of the 104 clinics contacted, 47 were eligible for the research and interested in participating (Figure 1). Sampling of eligible sites aimed to achieve diversity in health condition, DCC used, the frequency of the clinic, the size of the patient group cared for and geographical location, so that each case site was unique. We initiated site set-up at 25 sites. Of these, two withdrew and three were not progressed beyond initial set-up, giving a total of 20 case sites studied.

FIGURE 1.

Flow chart showing case site recruitment.

The case sites studied focused on 14 different health specialties: cancer, cystic fibrosis, dermatology, diabetes mellitus, HIV, inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), liver conditions, mental health [both Child and Adolescent Mental Health Services (CAMHS) and Early Intervention in Psychosis Teams (EIPTs)], renal conditions, rheumatology, sexual health, sickle cell disease (a condition experienced mostly by those from ethnic minorities) and a school nurse service which covered a range of different health conditions. Clinic populations varied from children and adolescent services, to transition populations, young adult services and adult services. Clinical teams were based in a range of locations around England and Wales: nine were in the south and east of England, seven were in the Midlands, three were in the north of England and one was in Wales. The types of geographical location served by the clinics included rural areas, major industrial cities, market towns, industrial towns and London. A range of DCCs was used in these clinics; some were heavy users, whereas others did not communicate digitally with patients in any way (Table 2 provides case study site descriptors).

| Site ID/health condition | Clinic population (as described by the clinic) | Patient age (years), range | Digital technology used in clinic |

|---|---|---|---|

| Liver conditions | Transition | 12–25 | Text messaging and e-mail |

| Sickle cell disease | Transition | 12–24 | Mobile phone and text messaging |

| Mental health 4 (early intervention) | Youth | 14–35 | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Cancer 1 | Teenage and young adult | 15–24 | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Diabetes mellitus 2 | Transition | 16–25 | Mobile phone and VoIP |

| IBD 1 | Adult | > 16 | Web portal and e-mail |

| IBD 2 | Adolescent | 13–23 | |

| HIV infection | Adult | > 18 | None |

| Sexual health | Adult and young people | > 16 | Testing kits ordered online |

| Cancer 2 | Teenage and young adult | 15–24 | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Diabetes mellitus 1 | Transition | 12–19 | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Mental health 1 (early intervention) | Age independent | > 16 | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Cystic fibrosis 1 | Adult | > 16 | |

| Dermatology | Adult | > 18 | |

| Mental health 2 (CAMHS) | Child and adolescent | < 18 | None |

| Mental health 3 (outreach team) | Child and adolescent | < 18 | Mobile phone, text messaging and VoIP |

| Arthritis | Transition | 16–25 | None |

| Paediatric | < 18 | None | |

| Cystic fibrosis 2 | Adult | > 16 | Mobile phone, text messaging and VoIP |

| School nurse service | Young people | 14–19 | Text messaging and VoIP (pilot) |

| Renal conditions | Young adult | 16–22 |

Description of interview participants

A total of 367 participants took part in an interview. Of these, 165 were patients, 173 were clinic staff, 13 were parents/carers and 16 were IG officers (Table 3).

| Health condition | Participants recruited (n) | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Case sites | Patients | Staff | Parents | IG officer | Staff shadowed | |

| Cancer | 2 | 23 | 18 | 3 | 2 | 11 |

| Cystic fibrosis | 2 | 15 | 16 | 1 | 1 | 4 |

| Dermatology | 1 | 7 | 4 | 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Diabetes mellitus | 2 | 23 | 14 | 0 | 2 | 7 |

| Mental health: CAMHS | 2 | 9 | 22 | 1 | 2 | 7 |

| Mental health: EIPT | 2 | 5 | 17 | 0 | 2 | 10 |

| HIV infection | 1 | 9 | 12 | 1 | 0 | 4 |

| IBD | 2 | 14 | 13 | 2 | 1 | 7 |

| Liver conditions | 1 | 15 | 12 | 2 | 2 | 7 |

| Renal conditions | 1 | 7 | 7 | 1 | 0 | 3 |

| Arthritis | 1 | 16 | 8 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Sexual health | 1 | 12 | 10 | 0 | 0 | 3 |

| Sickle cell disease | 1 | 10 | 13 | 0 | 2 | 9 |

| School nurse service | 1 | 0 | 7 | 0 | 1 | 4 |

| Total | 20 | 165 | 173 | 14 | 16 | 79 |

Patient recruitment ranged from 0 to 16 people per clinic. The largest number of patients was recruited from cancer and diabetes mellitus clinics. It was not possible to recruit any patients from the school nurse service and no patients who frequently DNA appointments volunteered to participate in the study. Only 16 patients chose to share examples of their digital communication with a clinician with us. Interviews with patients were primarily conducted over the telephone (n = 82), but also in person (n = 41), by e-mail (n = 35), via Facebook (n = 4), via Skype (n = 2) and by text messaging (n = 1). Synchronous interviews (taking place in person, or via telephone or Skype) took between 20 and 60 minutes, with most taking approximately 30 minutes. Asynchronous interviews took longer to complete; the longest, via e-mail, took 2 weeks. Overall, few parents/carers were recruited; none was recruited from 11 individual sites. Parent interviews took place primarily via telephone (n = 7), but also by e-mail (n = 4) and in person (n = 2).

Between 3 and 12 members of clinic staff were recruited from each site. The largest number of clinic staff were recruited from CAMHS teams and the fewest from dermatology. This reflects the size of the clinical teams being studied and the number of sites focusing on each health condition. Clinic staff had a range of clinical and clerical roles, including consultants, registrars, community nurses, advanced nurse practitioners, psychiatrists, psychologists, dietitians, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, pharmacists, secretaries and administrators. Interviews with staff took place in person (n = 148) or by telephone (n = 25). Interviews lasted up to 2 hours, but the majority took approximately 45 minutes. A total of 79 staff members were also shadowed across the clinical teams. Shadowing usually lasted between 1 and 2 hours, but lasted longer (the maximum was 7 hours) if the clinician felt that it was appropriate.

Information governance specialists and Caldicott Guardians were also interviewed. Two were interviewed in each of five trusts and one was interviewed at each of six trusts. It was not possible to interview an IG officer or Caldicott Guardian at nine sites. The majority of interviews were conducted in person (n = 10), with the remainder conducted by telephone. All interviews were audio-taped and lasted between 20 and 45 minutes.

In the results chapters that follow we include illustrative quotations from our qualitative data. These are each labelled with the condition the clinic manages, participant type and participant number. We present our analysis of qualitative data by thematic focus: ‘what works’, ethics and patient safety.

Chapter 3 ‘What works, for whom, where, when and why?’

In this chapter we report the thematic analysis of our case study data that addressed this research question. The context of the thematic analysis is the clinic and its purpose. This was described by each clinical team lead and is summarised in Table 4. The table includes a list of the digital communications that were in use in each clinic.

| Site ID/health condition | Clinic purpose | Use of digital communications |

|---|---|---|

| Diabetes mellitus 1 | Maintain good control of diabetes mellitus through maintaining blood glucose levels, with an aim to prevent or delay long-term complications. This is achieved through diet, exercise and insulin dosage | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Mental health 1 (early intervention) | Planned recovery approach following first episode of psychosis. Aim is to discharge after a maximum 3 years in the service. Care is through coping skills and medication monitored through CAARMS, which assesses mental health status | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Cystic fibrosis 1 and 2 | To maintain health status and prevent decline. This is achieved through regular clinic review to assess weight, diet, lung function and adherence to medication |

Cystic fibrosis 1 site: mobile phone Cystic fibrosis 2 site: mobile phone, text messaging and VoIP |

| Dermatology | To halt progression of condition and alleviate psychological distress. Regular reviews to monitor hair loss and blood monitoring for those on oral medication | |

| Mental health 2 (CAMHS) | Provides specialist assessment and treatment for young people with moderate to severe mental health needs and associated risks. Treatments include CBT, systemic and family therapy, psychodynamic therapy, art therapy and pharmacotherapy | None |

| Mental health 3 (outreach team) | Patient group is young people being discharged into the community from psychiatric care or on the verge of being admitted. Aim is to avoid admission and provide immediate help at a time of crisis. Deliver dialectic behavioural therapy through weekly meeting and telephone support. Also deal with young people displaying emotional or behavioural difficulties that are concerning to agencies | Mobile phone, text messaging and VoIP |

| Arthritis | Optimise health and well-being. This is achieved through regular reviews for physical and psychological health. No single measure of health as complex medical management. Regular checks of joint affected and regular eye checks are given | None |

| School nurse service | Service for 11- to 19-year-olds to get advice on health-related topics and as access point for services. Young people have the option to remain anonymous while accessing advice, but must give up anonymity to access services. The purpose is to provide information and advice and to provide a route to access services | Text messaging and VoIP (pilot) |

| Renal conditions | To preserve kidney function as long as possible. Regular monitoring of kidney function. Diet is particularly important as is psychological support. Rapid deterioration is a possibility | |

| Liver conditions | The aim is to improve young people’s self-management skills and, ultimately, improve health outcomes considering both physical health and psychological well-being. This is done through improving the process of transition from the paediatric to adult service for young people living with chronic liver disease. The service aims to achieve this through meeting young people’s development needs at this time | Text messaging and e-mail |

| Sickle cell disease | To empower young people to manage their care. This is done through imparting knowledge and giving skills to enable effective management of their condition in the community. The aim is to have fewer hospital admissions. Requires frequent blood monitoring | Mobile phone and text messaging |

| Mental health 4 (early intervention) | Aim to identify and treat as many people with the first episode of psychosis as possible. This is done through delivering a multidisciplinary package of care for up to 3 years | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Cancer 1 | This is a tertiary service the aim of which is to provide one environment where young people aged 16–24 years diagnosed with any form of cancer can come and get access to a multidisciplinary team. The service enables peer support and access to teenage cancer trusts | Mobile phone, text messaging and e-mail |

| Diabetes mellitus 2 | The aim is to assess, guide and support patients to attain and maintain good control of their diabetes mellitus. This is done through good maintenance of blood sugar levels aided by regular diet and lifestyle review. The purpose of the multidisciplinary team is to support and prepare individuals to live with diabetes mellitus. Regular reviews help to mitigate any untoward consequences and the team proactively intervenes to avoid hospital admission where possible | Mobile phone and VoIP |

| IBD 1 and 2 | To try and capture clinical remission measured as mucosal healing. From the patient perspective, the goal is to relieve symptoms and to avoid further flare-ups. Those who are considered stable enough are monitored remotely |

IBD 1 site: web portal and e-mail IBD 2 site: e-mail |

| HIV infection | The aim of the clinic is to maintain patients’ health and well-being. This is done by ensuring patients are aware of the condition and are encouraged to adhere to their treatment | None |

| Sexual health | The aim is to enable early and rapid diagnosis and treatment of sexually transmitted infections. A further aim is the prevention of unwanted conceptions | Testing kits ordered online |