Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/97/24. The contractual start date was in June 2015. The final report began editorial review in December 2016 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Geoff Wong is a member of the Health Technology Assessment Primary Care, Community and Preventive Interventions Panel. Mark Pearson’s role was supported by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Collaboration for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care South West Peninsula.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Papoutsi et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

A post-antibiotic era—in which common infections and minor injuries can kill—far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.

Antimicrobial resistance is a very real threat. If we have no suitable antibiotics to treat infection, minor surgery and routine operations could become high risk procedures.

The rise of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) has been described as a global crisis. Infections with bacteria such as Klebsiella pneumoniae, Staphylococcus aureus and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, which were once routine to treat, can now be untreatable. The urgency of this problem is reflected in policy developments and campaigns at an international level (e.g. World Antibiotic Awareness week). Recently, a United Nations declaration has garnered widespread commitment by countries to raise the level at which AMR is discussed politically and pave the way for an internationally co-ordinated approach. 3 The UK government has already taken action by establishing the Global AMR Research Innovation Fund together with China and contributing to the Fleming Fund for AMR surveillance in low- and middle-income countries, among other steps. 4–6

These steps followed initial recommendations by a high-profile AMR review, commissioned by the UK government, which estimated that there will be 10 million deaths a year globally as a result of drug resistance by 2050. 7 Beyond this very significant human cost in terms of morbidity and mortality from previously treatable infections, the consequences of drug resistance extend past patients who present with infections. Many surgical procedures (when antibiotics are given prophylactically in the hope of preventing infections) may be harder to justify as the risk and consequences of infection become more likely and serious. Cancer chemotherapy is potentially facing an equally significant burden because of AMR. 8

There is also a substantial financial cost resulting from increased use of expensive second- and third-line drugs, extended health-care stays and the inevitable complications of failed treatments. AMR has been estimated to cost US$21B–34B per annum in the USA. 1 The recently completed AMR review in the UK calculated that the cost of lost global production would amount to a total of US$100T by 2050 if no action is taken. 7 These numbers reinforce the argument that a focus on strategies to curtail the emergence and spread of AMR is vital.

In terms of suggested solutions, substantial emphasis is currently being placed on developing new antibiotic treatments and promoting access to diagnostic tests in a range of clinical settings. 7 With few new antibiotics currently in the pipeline or recently licensed, it is unlikely that we will encounter major developments in this area in the near future, despite new incentives for pharmaceutical firms, and resistance will redevelop quickly. 7 Diagnostic tests have been suggested as a solution that can help safeguard the effectiveness of antibiotics currently available. 7 It is assumed that better access and use of diagnostic tests will lead to better-informed decisions and more appropriate use of antimicrobial agents. However, studies in clinical settings show that this may not always be the case and a more nuanced understanding is needed. 9,10

Another way to achieve antimicrobial stewardship, that is, to promote optimal care for patients while preserving the effectiveness of antimicrobials and minimising the threat of drug resistance (see Glossary), has been through interventions in primary and secondary care. The aim of these interventions has been to ensure that health professionals are prescribing antimicrobials only when indicated, and that they are using the right drug, at the right time, at the right dose and for the right duration. 11,12 Antimicrobial prescribing interventions have been broadly classified into three categories according to the intervention strategy pursued (1) persuasive interventions mainly include educational and promotional strategies, (2) restrictive interventions refer to changes in the prescribing processes or efforts to introduce barriers such as approval processes and (3) structural interventions refer to changes in the way laboratory tests are provided and computerised systems are used in prescribing. 13 Given that up to 50% of antibiotic usage in hospitals is inappropriate, significant change is required by all specialties and professions involved in antimicrobial prescribing and administration. 14

In the UK, a broad range of such antimicrobial stewardship interventions have been implemented, including the Hospital Pharmacy Initiative15 and the Medical Schools Council’s Safe Prescribing Working Group. 16 Interventions have comprised distribution of educational materials,17–19 lectures and seminars,20,21 audit and feedback on performance19,22 and manual and automated reminders. 23,24 More recently, the TARGET toolkit has been introduced in primary care to influence prescribing choices, taking into account the role of patient expectations. 25,26 In secondary settings, the Start Smart Then Focus approach has been proposed to help prescribers make informed decisions and to encourage them to review their decisions when appropriate. 11,25 Top-down interventions aiming to invoke the power of social norms for behaviour change have also been employed,27 along with more grassroots approaches (e.g. the Antibiotic Guardian initiative). 28 The upcoming AMR Commissioning for Quality and Innovation payments framework will attempt to consolidate the impact of previous initiatives by monitoring hospital trust performance on a number of indicators and a similar benchmarking exercise is being carried out in primary care. 29

Previous systematic reviews have compared the effectiveness of different intervention strategies, favouring interventions that restrict prescribing options (e.g. compulsory order forms or expert approval) over purely educational or feedback programmes. 13 However, these reviews focus primarily on calculating effect sizes,13,30 rather than identifying how antimicrobial prescribing interventions work, for whom, how and why, so that they can be more effectively transferable across settings. When interventions have had variable levels of success, there was little explanation as to why. Qualitative studies on antimicrobial prescribing paid less attention to specific groups of prescribers, such as doctors in training. 31–33 With social norms and informal influences increasingly recognised as important in antimicrobial prescribing,34,35 uncertainty exists about which intervention types to implement for trainees and what refinements are needed for local circumstances. There is also less understanding of how antimicrobial prescribing interventions should be tailored to address the specific needs of doctors in training, as most studies assume that doctors are a uniform body of health professionals with similar needs. 36

Doctors in training and antimicrobial prescribing

After graduating from medical school in the UK, new doctors enter the 2-year foundation programme, which mostly takes place in hospital settings. They then undertake a further 5 years as a core/specialty trainee in hospitals or 3 years in general practice. Postgraduate trainees across all stages are classed as independent prescribers and will prescribe for patients, typically on a daily basis. In their first 2 years in clinical training, trainees rotate between hospitals and across specialties, commonly between every 3–6 months. In specialty training (after completion of the foundation programme), the duration of rotations varies depending on the area and the career path.

Doctors in training are an important target group, both as numerically the largest prescribers in the hospital setting in the UK and as a key part of a future generation of antimicrobial prescribers. 37 For many trainees, decisions around antimicrobial prescribing make up a significant part of their daily practice (e.g. general practice, paediatrics or emergency medicine training). Developing effective antimicrobial stewardship requires that we understand more about the antimicrobial prescribing behaviours of doctors in training.

The importance of education for prescribing behaviour change has been described as self-evident. 12 Evidence indicates that it is unclear if current educational prescribing behaviour change interventions have any consistent effect, particularly for new prescribers. 38 For example, a systematic review of prescribing behaviour change educational interventions for new prescribers in hospital settings found that the impact of particular types or combinations of interventions was highly variable as a result of the complex environments in which these interventions are embedded. 36,39 A systematic review focusing on behaviour change interventions in all prescriber types reported similar findings. 40 This raises the question as to why some prescribing interventions are successful in some contexts but not in others. Answering this question is important if we are to design interventions that are more effective. 12

This knowledge gap has partly come about because much of the current literature has not taken sufficient account of the wider context in which doctors in training prescribe antimicrobials. Prescribing is a complex mix of knowledge, skills and behaviours, with no simple relationship between them. 41,42 Prescribing the right antibiotic at the right time is not just about having the correct knowledge about, for example, local formularies, resistance patterns and dosages, but also understanding a patient’s expectations, concerns, comorbidities and social context. Hospital context and processes play an equally important role. 43 The antimicrobial prescribing challenges faced by foundation doctors include cognitive knowledge deficits (not knowing what to do in certain situations), practical issues of not knowing that local prescribing protocols exist on a ward, and professional challenges of having to ‘take sides’ when more senior health-care professionals disagree on prescribing decisions. 43 For example, Ross et al. 39 point out that doctors in training work within a strict medical hierarchy in complex organisations and that their prescriptions are often influenced by other doctors. McLellan et al. 44 report that a technical focus on isolated prescribing competencies is unlikely to support doctors in training to become safe prescribers.

The implication is that any review that seeks to understand antimicrobial prescribing interventions for doctors in training needs to look beyond just educational interventions and seek to make sense of the role of wider contexts. This review on IMProving Antimicrobial presCribing for doctors in Training (IMPACT) adds to a growing literature that acknowledges the importance of the wider context and attempts to explain how and why trainee prescribing practices differ under different circumstances.

Review questions

The IMPACT realist review aimed to understand how interventions to change antimicrobial prescribing behaviours of doctors in training produce their effects. The review was structured around the following objectives and review questions.

Objectives

-

To conduct a realist review to understand how interventions to change antimicrobial prescribing behaviours of doctors in training produce their effects.

-

To provide recommendations on the tailoring, implementation and design of strategies to improve antimicrobial prescribing behaviour change interventions for doctors in training.

Review questions

-

What are the mechanisms by which antimicrobial prescribing behaviour change interventions are believed to result in their intended outcomes?

-

What are the important contexts that determine whether or not the different mechanisms produce the intended outcomes?

-

In what circumstances are such interventions likely to be effective?

Chapter 2 Review methods

To make sense of the context in which antimicrobial prescribing decisions are made, we followed a realist approach for evidence synthesis. A realist review is an interpretive, theory-driven approach to synthesising evidence from qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods research. Its main strength comes from providing findings that coherently and transferably explain how and why context can influence outcomes. This is particularly relevant to complex programmes characterised by significant levels of heterogeneity. The plan of investigation followed a detailed protocol based on Pawson’s five iterative stages for realist reviews: (1) locating existing theories, (2) searching for evidence, (3) selecting articles, (4) extracting and organising data and (5) synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions. 45 To this, we have added an additional step 6: highlighting the importance of the write up in realist analysis and placing further emphasis on what counts as quality in realist research. The review ran for an 18-month period from June 2015 until November 2016. The protocol has been published in BMJ Open46 and the review has been registered with PROSPERO (CRD42015017802). 47 We were granted ethics clearance by the Central University Research Ethics Committee at the University of Oxford.

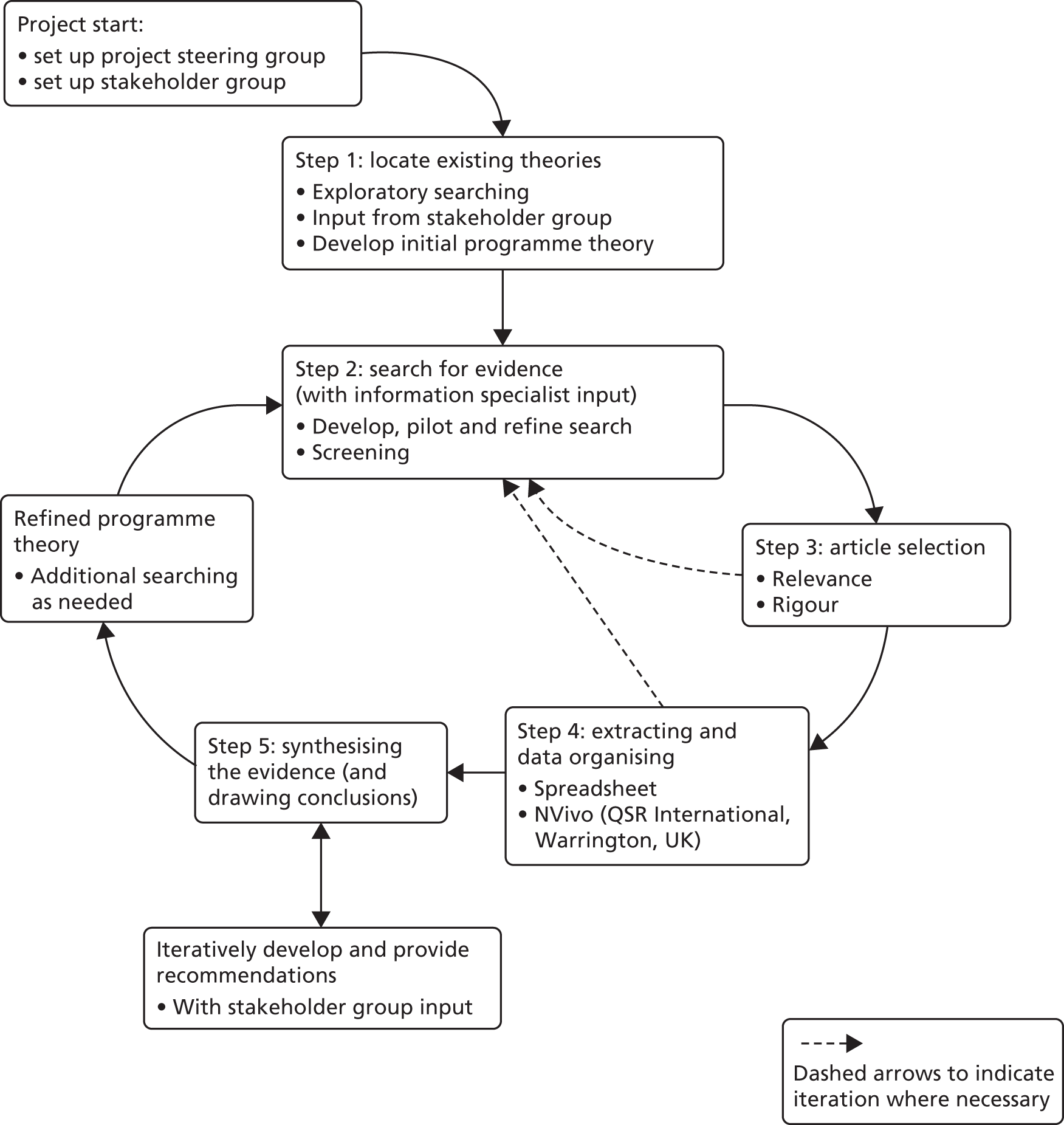

During the course of this project, the team sought to maximise learning from existing evidence to identify ‘what works, for whom, under what circumstances and why’, according to realist principles. This allowed increased emphasis on the mechanisms driving antimicrobial prescribing behaviour of doctors in training within specific contexts. Rather than defining effectiveness in terms of effect size, the review examined how the responses of doctors in training to the resources offered to them (mechanisms) were triggered in particular circumstances (contexts) to generate certain behaviours or outcomes for antimicrobial prescribing. In doing this, we focused first on developing an understanding of wider processes related to antimicrobial prescribing for doctors in training, rather than targeting and isolating particular interventions or groups of interventions for analysis. Having understood how the process of antimicrobial prescribing works for doctors in training, we then examined how particular families of interventions or intervention strategies may (or may not) address the contextual challenges identified. The review design and methodology is explained in more detail in the sections below and illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of the project.

Stakeholder group

A diverse stakeholder group was recruited for the IMPACT review to provide content expertise for programme theory refinement. A total of 21 people were consulted throughout the review, including patient representatives/carers, consultants, doctors in training at different stages, pharmacists, microbiologists, academics and policy-makers. Consultations with stakeholder group members took place as part of 2-hour meetings at regular intervals throughout the project, but also through individual telephone calls if stakeholders were not able to attend meetings (n = 6) and e-mail exchange. Table 1 provides a detailed list of the meetings that took place, including the number of participants and the topics discussed.

| Date | Stakeholder group members | Key topics discussed |

|---|---|---|

| 17 September 2015 | Eleven participants:

|

Explored the role of social dynamics and informal influences in guiding prescribing behaviours for doctors in training, different conceptualisations of the problem of AMR, as well as the gap between patient expectations and the actual uncertainties of prescribing in practice |

| 3 December 2015 | Eight participants:

|

Discussed initial findings from the review of the literature and explored how these reflected stakeholders’ experiences with antibiotic prescribing |

| 18 March 2016 | Seven participants:

|

Continued the discussion of emerging findings from the review and started generating ideas on potential outputs from the project and optimal dissemination strategy |

| 17 June 2016 | Eight participants:

|

Finalised the programme theory and discussed actionable findings emerging from the review |

Following the first stakeholder meeting in September 2015, we carried out further recruitment to participant groups that were under-represented (e.g. junior doctors) in order to include a range of views and opinions on the topic. Although in the second and third stakeholder meetings we engaged fewer individuals in total (as per the numbers presented in Table 1), the diversity of the group was such that it allowed us to address the aspects of programme theory that were in need of refinement. Stakeholder meetings took place at the University of Exeter and usually started with a brief slide presentation by our project team to introduce stakeholders to the topic under discussion. Iterations of the programme theory were presented to the group in the form of statements, accompanied by relevant quotations from the literature, to obtain their feedback. Discussions were designed to be more open ended in the early stages of the review, but focused on particular aspects of the programme theory as the project progressed. Later stakeholder groups focused on actionable findings and dissemination of the study. Facilitation of the meetings ensured that everyone was able to contribute and voice their opinion, whether in agreement or disagreement. With the verbal consent of participants, discussions were audio-recorded and detailed minutes drafted, which were then shared with the stakeholder group. These data were used only to set direction for the review and to refine programme theory, rather than as primary data for analysis, and the report does not include any data excerpts from these meetings.

Discussions with stakeholders helped ground the review in the practical reality experienced by participants and the challenges they faced in their respective roles. ‘Translation’ of realist review terms into everyday language became necessary to avoid methodological jargon, while still adequately conveying the nuances of the review findings. Stakeholder involvement also contributed significantly to the development of actionable findings in a form that would be usable and engaging. More details on actionable findings emerging from the review are presented in Chapter 3.

Patient and public involvement

The stakeholder group included strong patient and public involvement (PPI) throughout the project. Mark Pearson led the PPI component of the review and invited patients and members of the public who would be part of the stakeholder group (n = 5 in total) to attend a preparation meeting, at which they discussed the terms of their involvement and any key issues that needed to be addressed to facilitate meaningful participation. In the stakeholder meetings, patients and members of the public provided significant input to programme theory development, often highlighting aspects and questioning assumptions that the rest of the group were taking for granted (e.g. how prescribing norms differ between hospitals). The Plain English summary for this report has been reviewed by two patient representatives from our stakeholder group.

Steering group

A separate steering group of three academics with expertise in realist review approaches was set up for the project. The steering group was updated about the progress of the study, provided scientific and budget oversight and made sure that the project was delivered as proposed in the protocol.

Step 1: locating existing theories

In the first stage of the review we carried out exploratory searching to identify initial literature sources on antimicrobial prescribing interventions and antimicrobial prescribing more generally. The aim of this initial search was to identify explanations about how antimicrobial prescribing interventions work for doctors in training at different levels and why they may work in particular circumstances and not in others. 48,49 In line with previous systematic reviews,36 this exploratory search identified a range of articles but found that few of those specifically discussed doctors in training. In this limited number of articles on doctors in training, antimicrobial prescribing interventions were often primarily educational, were not described in enough detail or were mainly evaluated using pre-/post-study designs. On their own, these articles did not provide enough information to adequately develop and refine a programme theory of antimicrobial prescribing interventions in a way that would generate an in-depth understanding of how the intervention components contributed to particular outcomes.

Therefore, we supplemented our focus on antimicrobial prescribing interventions for doctors in training with explaining how antimicrobial prescribing works for trainees as a process more generally. This enabled us to reach the same results through a less direct route: first looking at how antimicrobial prescribing is done and how specific mechanisms are driving particular antimicrobial prescribing behaviour in certain contexts, and then looking at whether or not current intervention strategies address these challenges. In this way, we were able to overcome limitations of poor reporting and lack of detail in the description and evaluation of interventions.

The exploratory searching of step 1 differs from the more formal search for data described in step 2, in that it aims to sample the literature to quickly identify the range of possible explanatory theories that may be relevant. We used methods such as keyword-, author- and project-based searches in MEDLINE/PubMed and Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), elicitation of key studies from expert recommendations, citation tracking and snowballing from relevant systematic reviews. 50 Keywords included ‘antimicrobial’, ‘prescribing’, ‘junior doctors’, ‘stewardship’ and synonymous terms. This was supplemented with grey literature searches [which identified reports and policy documents from key organisational websites such as Public Health England (PHE), WHO, UK government], along with searching for relevant theories based on the articles already retrieved. 51

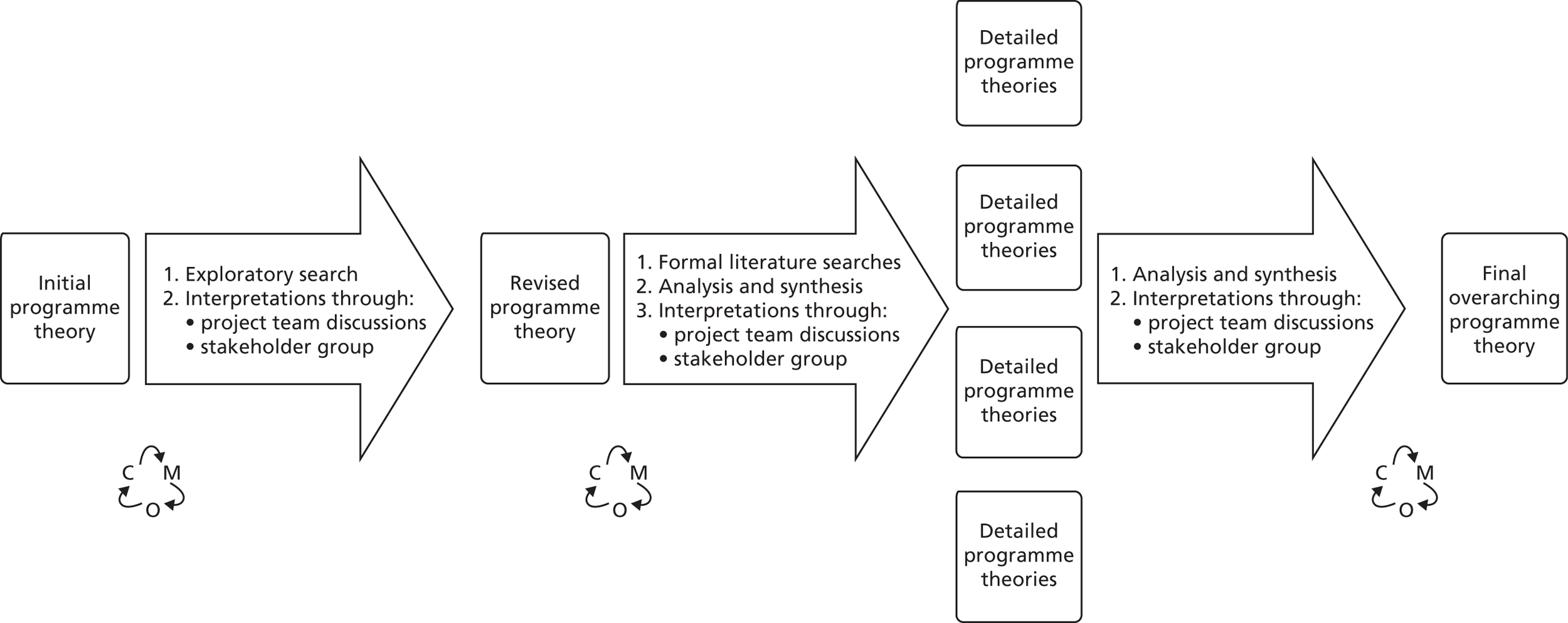

This initial search led to key documents that were used as a starting point to refine the initial programme theory devised at the outset of the project. Before any literature searching had taken place, Geoff Wong developed a ‘rough’ programme theory through experiential, professional and content knowledge. This initial programme theory included a number of assumptions about how the process of antimicrobial prescribing works for doctors in training and what mechanisms may interact with important contexts to produce certain outcomes. These initial assumptions were then discussed between the team at the outset of the project in order to develop a guide for literature searching and programme theory development (Figure 2 shows the process of programme theory development). For example, initial focus on ‘uncertainty’ as a potential core mechanism driving antimicrobial prescribing behaviour led to an informal review of relevant literature to examine whether or not and how this assumption could be embedded into the programme theory under development.

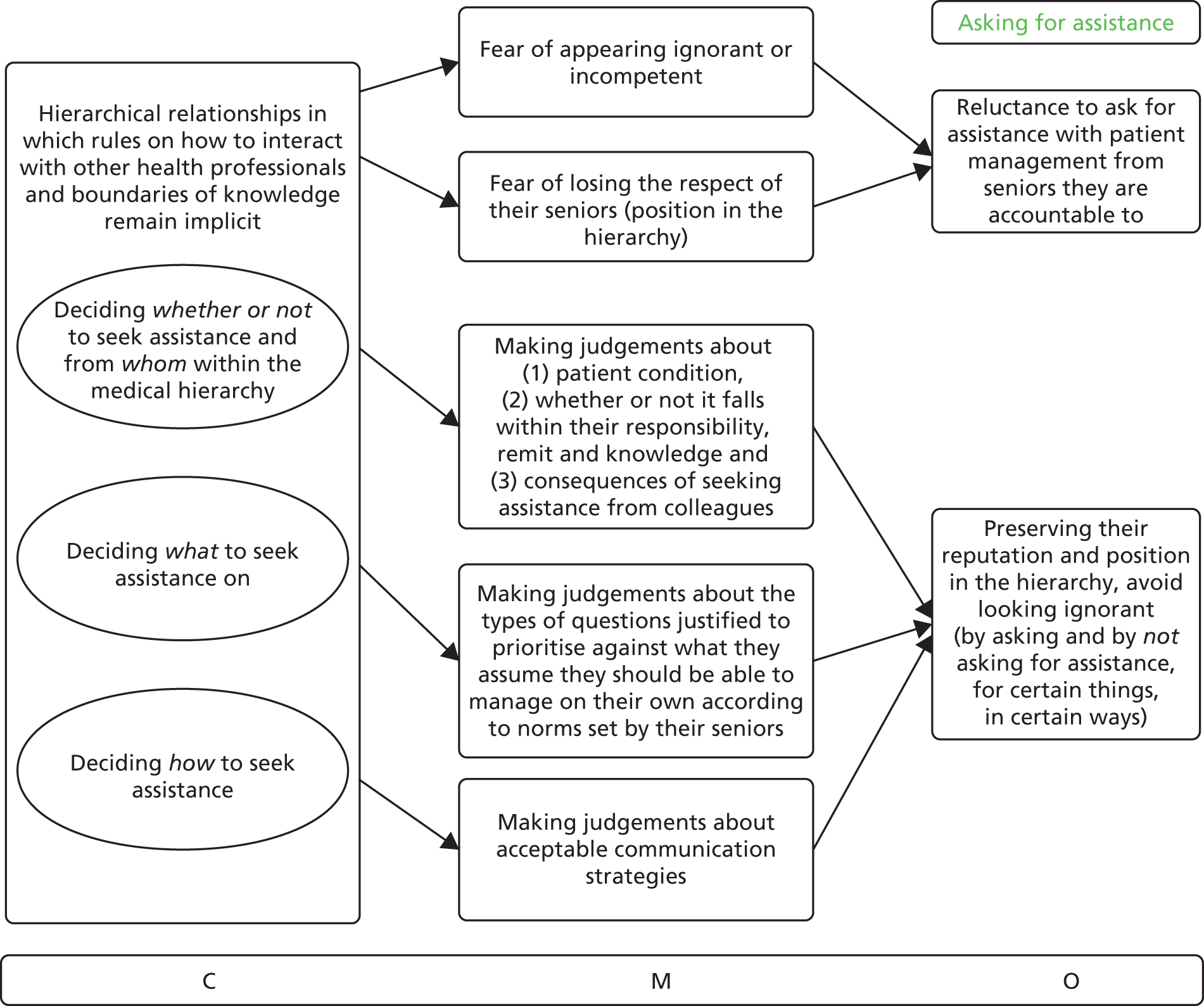

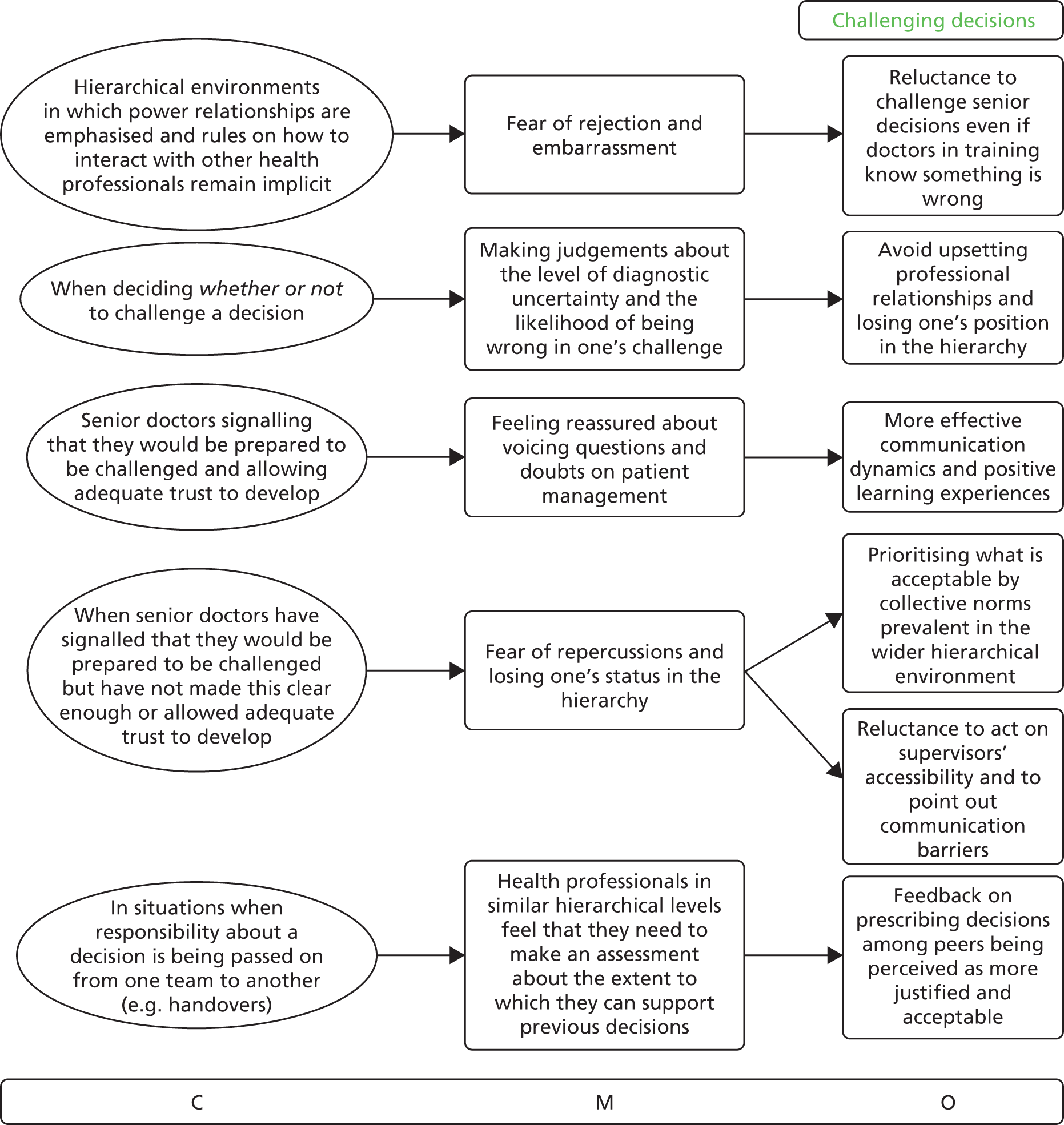

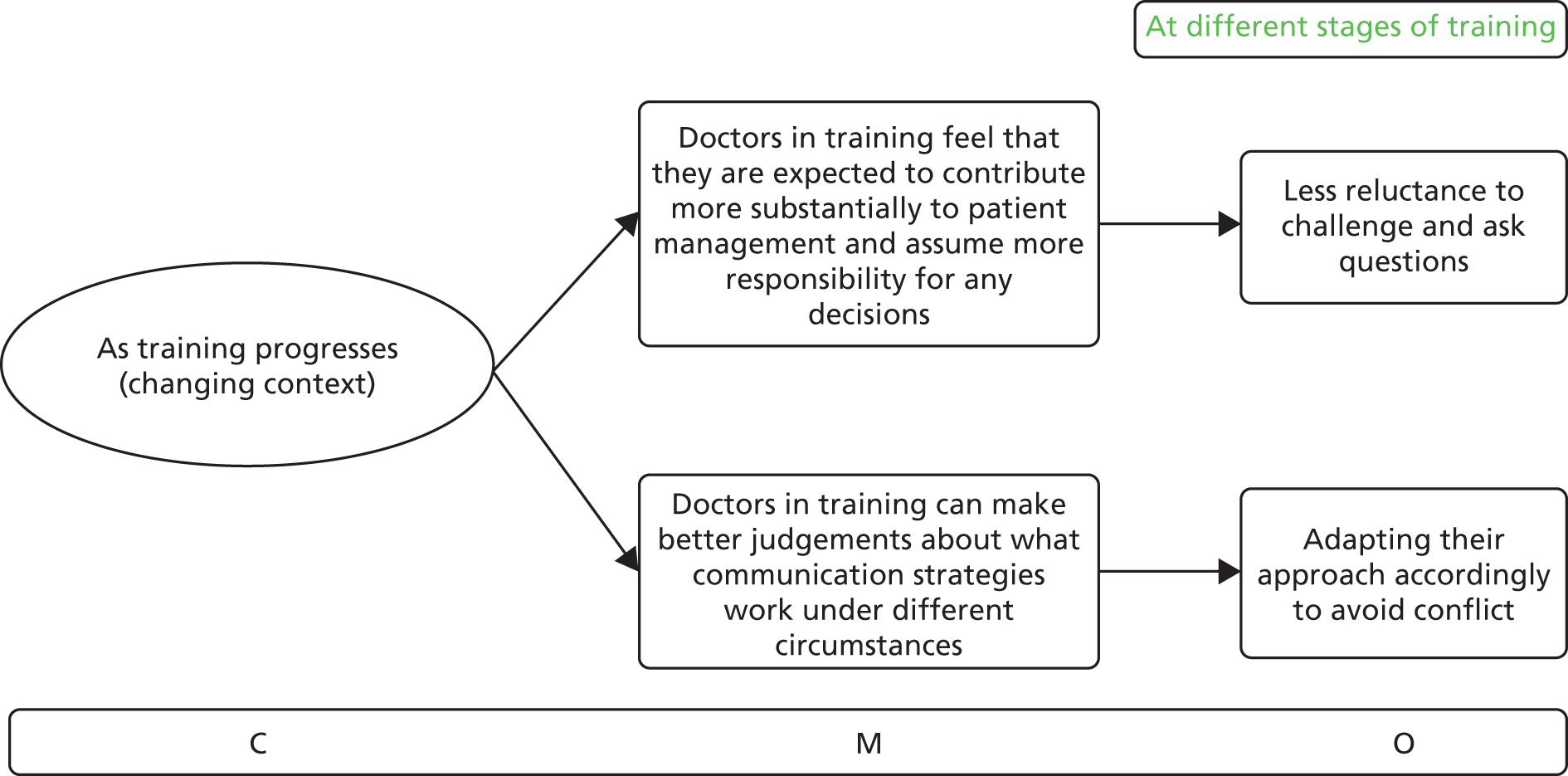

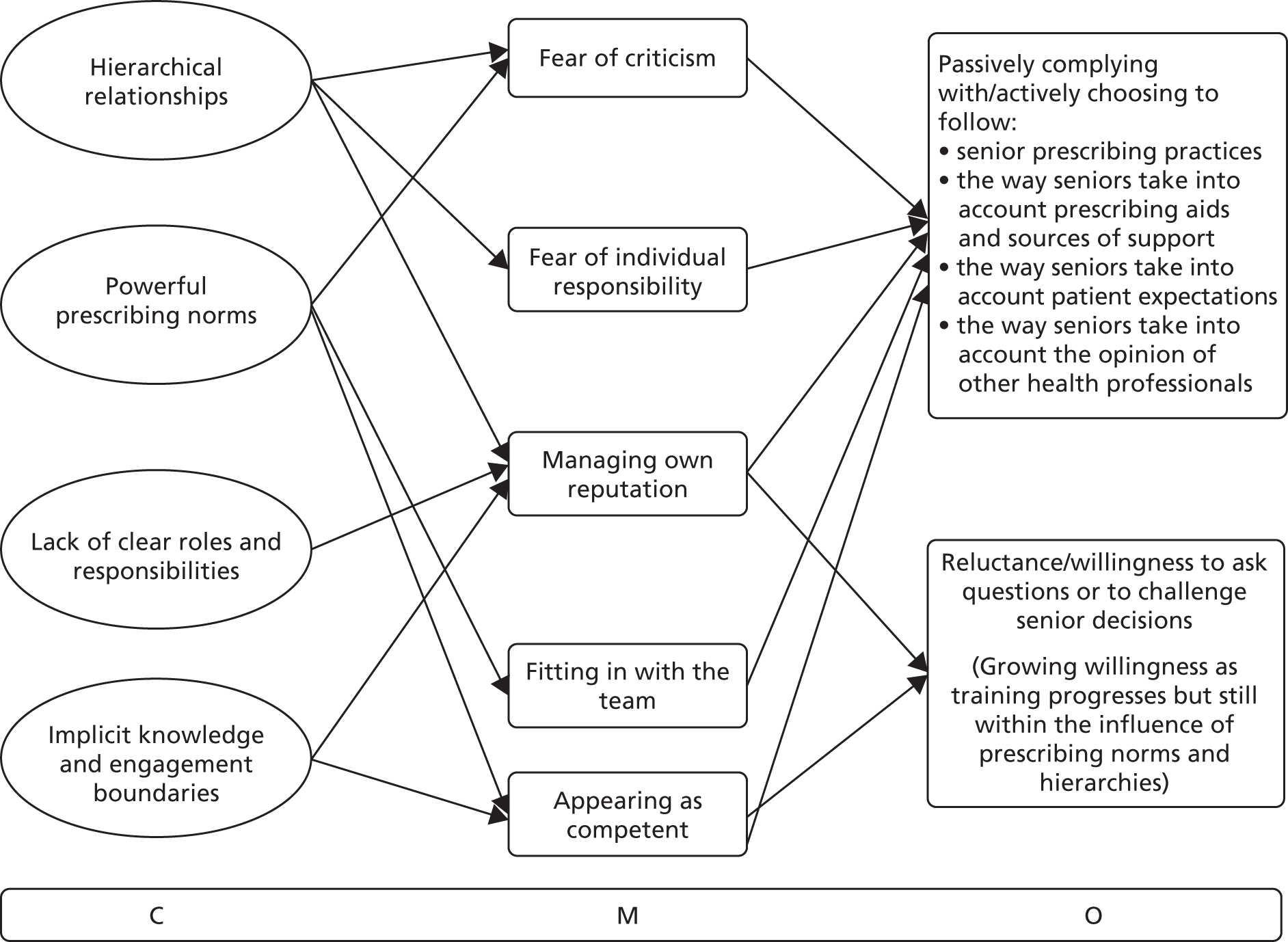

FIGURE 2.

Programme theory development. C, context; M, mechanism; O, outcome.

Building a programme theory required iterative discussions within the team to make sense of, interpret and synthesise the different components. We also consulted with key experts from our stakeholder group through face-to-face meetings, telephone calls and e-mail throughout the review (see Stakeholder group).

Step 2: searching for evidence

Main search

After completing initial exploratory searches and drafting a first version of the programme theory, we proceeded with more formal searches for relevant data in the research literature. The purpose of step 2 was to find a relevant ‘body of literature’ with which to further develop and refine the programme theory from step 1. Searching was designed, piloted and conducted by an information specialist (SB) with experience of conducting searches for complex systematic reviews. The search strategy was initially guided by a related systematic review by Brennan and Mattick36 on educational interventions to change the behaviour of new prescribers in the hospital setting. However, we needed to make modifications to the search strategy used by Brennan and Mattick to include search terms for doctors up until the end of their training and to focus specifically on antimicrobial prescribing. This resulted in a different body of literature that we analysed using a realist logic, as described in steps 3 and 4.

The search strategy was developed in MEDLINE (via Ovid) using an iterative process of adding, removing and refining search terms in order to retrieve a set of search results with an appropriate balance of sensitivity and specificity (i.e. the search was configured to retrieve a wide range of relevant literature and to minimise the retrieval of irrelevant literature). A combination of free text and indexing terms was used. Sample sets of results were screened by Chrysanthi Papoutsi as the search developed, which helped with the selection of relevant search terms. In addition, relevant studies identified by the review team through online keyword searching in Google Scholar and PubMed were used to benchmark or test the search strategy. The final search strategy used a range of search terms for the concepts ‘doctors in training’, ‘prescribing’ and ‘antimicrobial’, which were combined using the AND Boolean operator.

In September 2015, we searched the following nine bibliographic databases: EMBASE (via Ovid), MEDLINE (via Ovid), MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via Ovid), Web of Science core collection limited to Science Citation Index Expanded (SCIE) and Conference Proceedings Citation Index – Science (CPCI-S) (via Thomson Reuters), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL), Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the Health Technology Assessment (HTA) database (all via The Cochrane Library) and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (via ProQuest). The search syntax and indexing terms were translated from the original MEDLINE search as appropriate for use in these databases. The search results were exported to EndNote X7 (Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and deduplicated using the automatic deduplication feature and manual checking by the information specialist (SB). The search strategies for each database are reproduced in full in Appendix 1.

We also undertook forward citation chasing (using Google Scholar) and manually searched citations contained in the reference lists of important articles included in the review and in relevant grey literature. Google alerts were set up to update the literature with papers published after September 2015. Articles received from content experts were included in the data set for screening.

For the main search, our inclusion and exclusion criteria were broad as we sought to find quantitative, qualitative and mixed-methods studies.

Inclusion criteria

-

Aspects of antimicrobial prescribing: all studies that focused on one or more aspects of antimicrobial prescribing (or when combined with other types of prescribing). A comprehensive definition of prescribing proved challenging to identify in the existing literature. Therefore, we viewed prescribing as the act of determining what medication a patient should have and the correct dosage and duration of treatment. We also acknowledged how prescribing requires a ‘mixture of knowledge, skills and judgement’ as there is ‘no simple relationship between knowledge and behaviour’. 43

-

Study design: all study designs.

-

Types of settings: all studies that were conducted in hospital or primary care settings.

-

Types of participants: all studies that included doctors in training (any specialty and at any level).

-

Types of intervention: interventions that focus on changing/developing antimicrobial prescribing behaviour or studies discussing how doctors in training engage with antimicrobial prescribing.

-

Outcome measures: all prescribing-related outcome measures.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies focusing only on drug administration (no prescribing decision).

All citations were reviewed by Chrysanthi Papoutsi to ensure that they matched the exclusion and inclusion criteria. A 10% random subsample was reviewed independently by Geoff Wong to ensure consistency around the application of the inclusion criteria. One small inconsistency was identified as a result of different interpretations of junior doctor roles, but this was easily resolved through discussion.

Additional search

An important process in realist reviews is searching for additional data to inform programme theory development and refinement. A second search was undertaken in January 2016 to allow the review to focus on issues that emerged as significant after the literature from the main search had been analysed. As outlined in the original protocol for the project, we anticipated that our programme theory would need to take into account the influence of the wider context in hospitals and primary care on the prescribing behaviour of doctors in training. During the course of the review, and through consultations with the stakeholder group, more specific contextual dynamics of hierarchies, teamworking and decision-making were identified as important in explaining how and why antimicrobial prescribing works in certain ways, for certain groups of doctors in training. Therefore, the supplementary search focused more specifically in those three areas: hierarchies, teamworking and decision-making.

Our approach to search-strategy development was similar to that used for the main search. A small set of articles was initially identified through hand-searching and expert opinion. These were then used by the information specialist (SB) to develop and pilot the search strategy for the additional search. The results of early versions of the search were discussed by e-mail between the project team and decisions were made on how best to refine the terms to be used in the search. This additional search was not intended to be exhaustive, but to purposefully draw together literature from different disciplines that could provide an explanatory backbone for the sociocultural influences identified as important. This also meant that the additional search did not focus on antimicrobial prescribing, per se, but in understanding the wider context in which doctors in training practise and prescribe.

The final search strategy used a wider range of search terms for the concepts ‘hierarchy’, ‘decision making’, ‘team work’ and ‘junior doctor’ – departing from a strict focus on the prescribing literature. A combination of free text and indexing terms were used for each concept. The search was developed in MEDLINE (via Ovid) and adapted for use in other databases, including (in toto) MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via Ovid), CENTRAL, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, the HTA database (all via The Cochrane Library) and ASSIA (via ProQuest). The search strategies for each database are reproduced in full in Appendix 1. The results of the searches were exported to EndNote X7 and deduplicated using automated and manual checking.

We also undertook forward citation searching (using Google Scholar) and manually searched citations contained in the reference lists of documents included in the review. Articles received from content experts were also screened for relevance. Google alerts were set up to update the literature with papers published after January 2016.

For the additional search, two members of the team (GW and CP) met to discuss inclusion and exclusion criteria, which were then confirmed in discussions with the rest of the group. Although we had a primary interest in qualitative studies that could provide rich contextual information on hierarchical and team dynamics, we did not exclude any study designs from the search.

Inclusion criteria

-

Studies discussing the role of hierarchies, teamwork and decision-making, in relation to doctors in training.

-

Study design: all study designs.

-

Types of settings: all studies that were conducted in hospital or primary care settings.

-

Types of participants: all studies that included doctors in training (any specialty and at any level).

Exclusion criteria

-

No prespecified exclusion criteria.

All citations were reviewed by Chrysanthi Papoutsi to ensure that they matched the inclusion criteria. A 10% random subsample was reviewed independently by Geoff Wong to ensure consistency in how the inclusion criteria were applied. There were no differences between reviewers.

Step 3: selecting articles

The selection process primarily focused on the extent to which articles included data that could contribute to the development and refinement of programme theory. Using Endnote X7, Chrysanthi Papoutsi screened the titles and abstracts of all articles resulting from the two searches in reverse chronological order, to exclude articles that did not contain information relevant to antimicrobial prescribing. Chronological order was important to be able to trace changes in the way medical education was delivered and to take into account the influence of culture.

Having completed the title and abstract screening, if the relevance of a reference could not be ascertained, the full text was obtained. Chrysanthi Papoutsi read the full texts of all remaining articles and classified them into categories of high and low relevance.

Articles from the main search were deemed to be of lower relevance when their findings were not as specific to the current situation in the NHS and the wider UK context, or if they were not specific enough for the target group of this review. For example, articles from the main search were classified as being of lower relevance when they:

-

referred to aspects of health care in low- and middle-income countries that are not as relevant to the way the health service is organised in the UK (but articles on low- and middle-income countries were included when of direct relevance to the review question)

-

referred to conditions that are not as common in the UK (e.g. tropical diseases)

-

involved all prescribers without making specific mention to doctors in training

-

fulfilled the search terms but were published before 1990 (as these articles were less likely to reflect recent changes to clinical training in the UK and contemporary challenges in clinical work).

Position or other background papers resulting from the main search were stored separately in case it was necessary to draw on them for additional data required for programme theory refinement.

For the additional theoretically driven search, articles were classified as being of lower relevance when they:

-

discussed hierarchies and teamwork but not in the context of junior–senior relationships, instead focusing primarily on interprofessional dynamics or on single non-medical professional groups (e.g. nurses, physiotherapists)

-

fulfilled the search terms but were published before 2000 (as cultural dynamics in the training environment would be better reflected in more recent literature, as identified after reviewing post-1990s papers resulting from the main search).

Directly relevant position or other background papers were included in the highly relevant category for the additional search, as the nature of the data in these position papers was much more useful for programme theory refinement, compared with the position papers emerging from the main search. This is likely because of the nature of the search, as the additional literature focused on sociocultural dynamics that are more likely to be discussed critically in position papers.

A random sample of 10% of documents selected was assessed and discussed between Chrysanthi Papoutsi and Geoff Wong to ensure that screening and selection decisions were made consistently.

At the point of inclusion based on relevance, the trustworthiness and rigour of each study were also assessed. 49 For example, if data had been generated using a questionnaire, then the trustworthiness of the data was considered to be greater if the questionnaire had been previously tested and shown to be reliable and valid, and had not been altered (or if alterations had been made, subsequent testing had been undertaken). Considerations of rigour and relevance were often inter-related, as papers were more likely to include data useful for programme theory refinement when they had followed their chosen methodology to the standard required. This means that studies were not excluded on the basis of rigour alone, but it was often the case that lack of rigour also meant lack of data useful enough for programme theory development. A qualitative study would provide richer data if a wide range of experiences were sought up to the point of data saturation (i.e. no new information would arise), and those experiences were analysed adequately and presented in detailed, contextualised quotations. Table 10 in Appendix 2 provides an overview of how particular aspects of the programme theory are supported by data from specific sources, and the strength of the arguments we were able to make based on our judgements about the trustworthiness of each study.

Step 4: extracting and organising data

Once article selection was finalised and the core data set was established, Chrysanthi Papoutsi reread the full texts of the included articles chronologically, starting with the most recent, and carried out initial manual coding. During this familiarisation stage, parallel notes were kept on potential contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, as well as their relationships with the initial programme theory, to prepare the ground for more in-depth work.

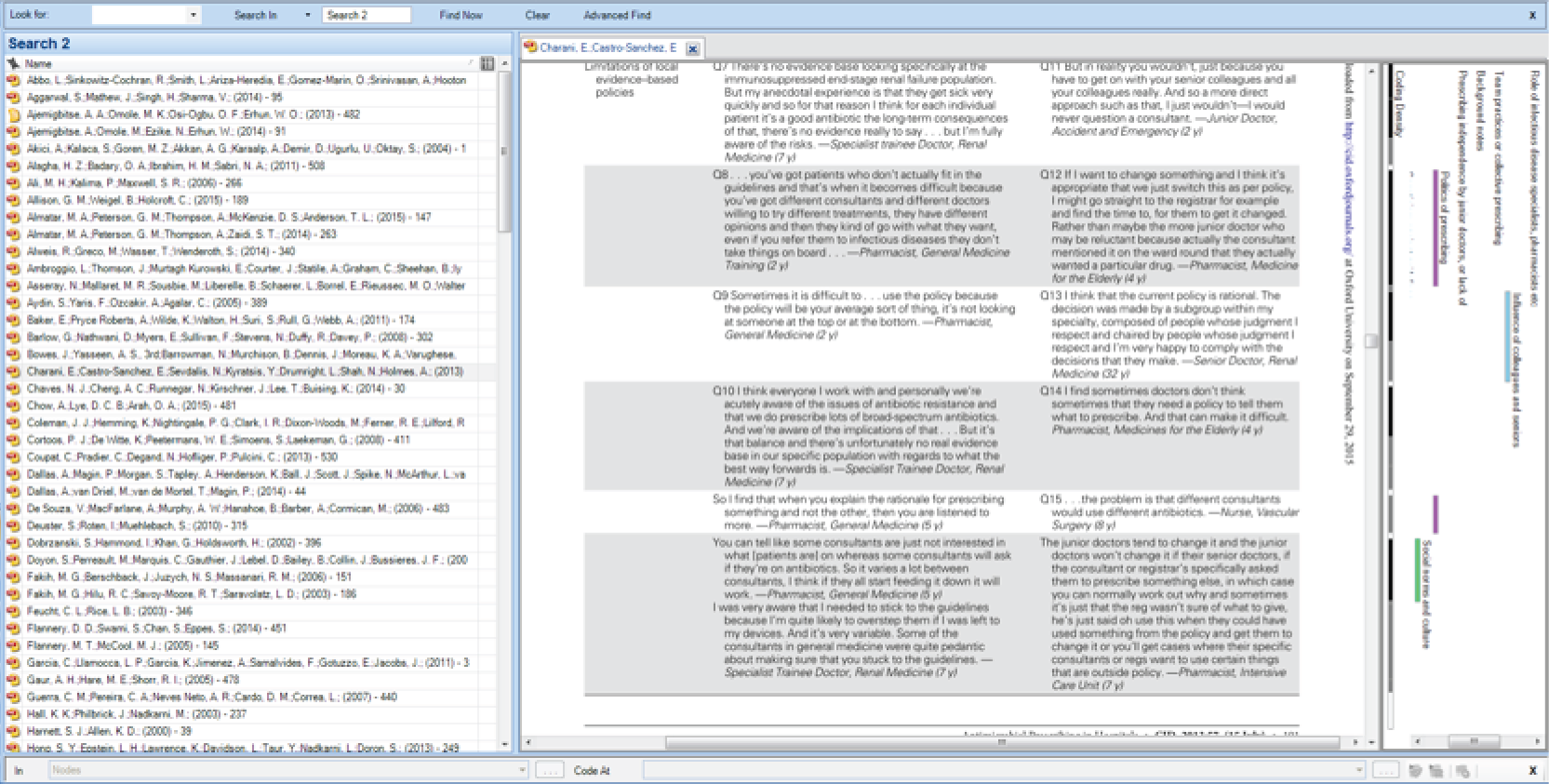

The electronic versions of the articles were then uploaded into NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) (qualitative data analysis software) for further analysis (see snapshot of NVivo coding in Figure 3). At this stage, the analysis focused on the richest sources, that is, articles that had been identified in the familiarisation stage as having the most potential to inform the programme theory. In some cases, the manual coding from the familiarisation stage was transferred into NVivo intact. In other cases, additional or different codes were applied to correspond to how the understanding of the literature had changed since the familiarisation process. The first rounds of coding focused on the conceptual level, classifying content in analytical categories, to be able to refine these further. We added this initial stage as we have found from past experience that it is easier to make sense of data when they have been categorised into related categories. This means that we did not immediately categorise data into contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, but approached coding with an open mind to understand what issues are coming up in the data (e.g. difficulties working with guidelines, time pressures, hierarchical environment). The data within these initial categories were reread and, when needed, recoded and reclassified. It was only after conceptual coding was completed that we started to consider whether or not each of these categories (or subcategories within them) included sections related to contexts, mechanisms and their relationships to outcomes. We continued refining the coding framework in NVivo and used relationships (a NVivo function) to create links between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes where possible across the NVivo data set, so that these links could be reviewed further.

FIGURE 3.

Screenshot from the analysis process in NVivo. Screenshot using NVivo version 10 software, reproduced with permission from QSR International Pty Ltd. NVivo Qualitative Data Analysis Software; QSR International Pty Ltd. Version 10, 2012. NVivo is a trademark and registered trademark of QSR International Pty Ltd. Patent pending, www.qsrinternational.com.

Coding followed both an inductive (codes emerging from the analysis of the literature) and a deductive (codes created in advance informed by the initial programme theory, stakeholder group discussions and exploratory literature searching) mode. The coding framework resulting from the analysis of the richest papers was subsequently applied to the rest of the articles, moving from more relevant and specific to less relevant and specific papers (from the most potential to contribute to programme theory refinement to least) [see Appendix 3 for an overview of the codes applied to each document (Tables 11–14)].

Having identified conceptual categories and, subsequently, potential contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, the analysis continued under a realist, explanatory logic. Starting from relevant outcomes, we sought to interpret and explain how different groups of doctors in training responded to resources available in their environment (the mechanisms) with regard to antimicrobial prescribing and to identify the specific contexts or circumstances when these mechanisms were likely to be ‘triggered’. For each step, we applied a realist logic of analysis, so as to explain how the (intermediate) outcome for each step might be achieved in realist terms, that is, what interaction between context(s) and mechanism(s) might lead to that outcome. For each step in the sequence, we sought to identify what mechanism(s) generates the outcome and in what contexts this mechanism might be triggered. Such an analysis was repeated throughout the review and enabled us to build sets of context–mechanism–outcome configurations (CMOCs) that explained the antimicrobial prescribing behaviours of doctors in training.

Realist reviews are used to synthesise data from qualitative, quantitative and mixed-methods studies. This means that different types of data were used to identify contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Often, quantitative data illustrated the outcome patterns evident, such as error rates among different grades of doctors in training or proportions of trainees reporting use of guidelines to inform their decisions. Qualitative data were used to explain these patterns in more detail.

We compared and contrasted emerging CMOCs with the evolving programme theory, so as to understand the place of and relationships between each CMOC with the programme theory. As the review progressed, we iteratively refined the programme theory, driven by interpretations of the data included in the literature (see Figure 2 for process of programme theory development).

With new iterations of the programme theory, already-included studies were rescrutinised to search for data relevant to the revised theory that may have been missed initially (e.g. three more papers were added to the core data set from the main search). Relevant articles cited in the included papers were followed up for additional data as described in Step 3: selecting articles. Memos and annotations were used to make sense of the data, especially in relation to inferring mechanisms and relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. We also coded articles for more descriptive categories, such as relevant background information, study characteristics and recommendations provided. The characteristics of the documents were extracted into a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet separately for the results of the main search, the additional search and studies identified outside the database searches (see Appendix 2). A sample of the coding for 10% of the papers included in the review was independently checked by Geoff Wong for consistency.

The aim of the analysis was to reach theoretical saturation, in that sufficient information had been captured to portray and explain the wide range of experiences of doctors in training with antimicrobial prescribing in primary and secondary care. Excerpts coded under specific concepts in NVivo were then exported into Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) documents. Drawing on the analysis of the literature done in NVivo, Word documents were used as coding reports, to provide a more flexible space to test the viability of different CMOCs and build the narrative of the synthesis. This included adding explanatory text through abductive and retroductive reasoning (see Step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions). A diary was kept throughout the analytical stages to record processes followed and decisions made at different points during the review.

Step 5: synthesising the evidence and drawing conclusions

Lack of adequate reporting of intervention characteristics and implementation processes, along with limited measures of success, posed obstacles in directly comparing interventions against each other to understand how context had influenced outcomes. Instead, as explained in the beginning of Chapter 2, we focused on developing a programme theory of the antimicrobial prescribing experiences of doctors in training to try and understand how and why they made particular prescribing decisions. For instance, we compared the circumstances under which doctors in training may or may not be driven to comply with prescribing decisions made by their seniors without asking any questions.

To do this, we moved iteratively between the analysis of particular examples, stakeholder interpretations, refinement of programme theory and further iterative searching for data to test particular subsections of the programme theory. A realist logic of analysis was used to analyse and synthesise the data. During our analyses we developed and refined the initial programme theory by drawing on the coding carried out within and outside NVivo (e.g. Word document coding reports, memos, other notes) to configure relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. This entailed asking a series of questions and making judgements about the relevance and rigour of content within included articles, as set out below.

-

Relevance:

-

Are the contents of a section of text within an included document referring to data that might be relevant to programme theory development?

-

-

Judgements about trustworthiness and rigour:

-

Are these data sufficiently trustworthy to warrant making changes to the programme theory?

-

-

Interpretation of meaning:

-

If the section of text is relevant and trustworthy enough, do its contents provide data that may be interpreted as being context, mechanism or outcome?

-

-

Interpretations and judgements about CMOCs:

-

What is the CMOC (partial or complete) for the data?

-

Are there data to inform CMOCs contained within this document or other included documents? If so, which other documents?

-

How does this CMOC relate to CMOCs that have already been developed?

-

-

Interpretations and judgements about programme theory:

-

How does this (full or partial) CMOC relate to the programme theory?

-

Within this same document, are there data that inform how the CMOC relates to the programme theory? If not, are there data in other documents? Which ones?

-

In light of this CMOC and any supporting data, does the programme theory need to be changed?

-

Abductive reasoning (see Glossary) was employed at the analysis and synthesis stage, particularly to infer and elaborate on mechanisms (which often remained hidden or were not articulated adequately). This means that we followed a process of constantly moving from data to theory, in order to infer and refine explanations about why certain behaviours are occurring, and we tried to frame these explanations at a level of abstraction that they could cover a range of phenomena or patterns of behaviour.

Relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes were sought not just within the same articles, but across sources (e.g. mechanisms inferred from one article could help explain the way contexts influenced outcomes in a different article). Synthesising data from different sources was often necessary to compile CMOCs, as not all parts of the configurations were always articulated in the same source.

In summary, the process of evidence synthesis was achieved by the following analytic processes, as modified from the original version:52

-

Juxtaposition of data sources – comparing and contrasting data presented in different articles. For example, data about prescribing experiences from an in-depth qualitative source enabled insights into how outcomes are achieved as described in a quantitative study.

-

Reconciling ‘contradictory’ or disconfirming data – when outcomes differ in apparently similar circumstances, further investigation was necessary to find explanations for why these different results occurred. This involved a closer consideration of context and what counts as context for different types of ‘problems’, in order to understand how the mechanisms triggered can explain differences in outcomes.

-

Consolidation of sources of evidence – when there are similarities between findings presented in different sources, a judgement needs to be made about whether these similarities are adequate to form patterns in the development of CMOCs and programme theory, or whether there are nuances that need to be highlighted, and to what end.

Engagement with substantive theory

Theory in realist research operates at a number of different levels to substantiate the inferences made about mechanisms, contexts, outcomes and the configurations between these elements. Theory is also useful in adjudicating findings with what is already known on the topic under research, to enhance the plausibility and coherence of the arguments made.

The first step we took in understanding what theoretical frameworks and ideas would be relevant to the review was to look at existing work on antimicrobial prescribing. Our starting point was the literature collected as part of the exploratory search in step 1, described in Chapter 2. This enabled us to consider a wide range of theoretical understandings that could be of potential relevance. We compiled a list of theories used in previous research and looked for updated frameworks that could further inform this work. As we retrieved literature more specific to the review questions from the main and additional literature searches in step 2, we focused on a smaller set of potentially relevant theories. Throughout the analysis and synthesis of data from the articles included in the review, we sought links between the different theoretical frameworks and emerging CMOCs. This was done with a view to extend the explanatory potential and usefulness of the overall programme theory developed out of the CMOCs.

Some of the theoretical ideas that informed the development of the programme theory derived from papers retrieved from the literature search – especially from the additional theoretically driven search (e.g. Broom et al.,53 who used Bourdieu’s practice theory). Other theoretical frameworks were sought specifically to cover particular aspects of the phenomena we were attempting to explain. For example, as it became evident that the need to belong in the clinical team emerged as an important mechanism driving antimicrobial prescribing behaviour, we sought substantive theory that would help us to think through what this mechanism means and how it can be conceptualised in the context of our data. This led us to group reference theory and its application from a realist perspective, which enabled us to both validate use of ‘group reference’ as a mechanism and to extend what this may mean by working across data and theory. 54 Substantive theory used in this work is further discussed in Chapter 3, Drawing on substantive theory.

Step 6: writing up and quality considerations

Writing up the results of the analysis and the CMOCs into programme theory has been an important step in fine-tuning our explanations. Our analyses (when we made interpretations by comparing data, evolving programme theory and substantive theoretical frameworks) were not abstract thought experiments, but involved drafting several diagrams and writing up numerous versions of the programme theory. We developed and refined several iterations of the CMOCs and narrative for the review, until we felt that all data were adequately accounted for and inferences were coherent with existing literature. Through drafting CMOCs and reviewing these between team members, along with supporting data, we were able to fine-tune our interpretations and achieve shared understanding of the arguments made. This process was necessary to unpack different assumptions and to distinguish between the nuances underpinning CMOCs. We found that simply verbally discussing our evolving interpretations did not enable us to fully engage with the data, their interpretation and the inferences made. Writing things down in detail and drawing diagrams enabled us to achieve greater explanatory depth in our analyses and resulted in recognition of more mechanisms than those immediately visible in the ‘raw’ data.

Each section in Chapter 3 of this report has been structured to provide:

-

a brief narrative on how and why doctors in training engage with antimicrobial prescribing

-

the realist analysis underlying each of these narratives, that is, the CMOC developed as the data from the literature was interpreted in realist terms

-

data excerpts from the literature that support the CMOC along with their reference and any additional explanatory text needed.

We have chosen to present text excerpts relevant to each CMOC to demonstrate the strength of the argument made in each of the sections and to increase the transparency of reporting (illustrative examples are included under each CMOC and all data extracted from the literature are available on request from the authors). Setting out the ‘raw’ data in this way allows closer scrutiny of the interpretations made to configure contexts, mechanisms and outcomes, which adds to the transparency and trustworthiness of the process undertaken.

Table 2 outlines how the review has fulfilled the quality standards for realist review according to the recently published RAMESES quality standards.

| Quality criteria | How the criteria were fulfilled |

|---|---|

| The research topic is appropriate for a realist approach | The review is focusing on antimicrobial prescribing for doctors in training, which is a complex issue as trainees have to navigate hierarchical dynamics, variability in prescribing practices and contradicting advice, as well as clinical uncertainty |

| The research question is constructed in such a way as to be suitable for a realist synthesis | The research question broadly asks how, why, to what extent, for whom and in what circumstances do interventions to improve antimicrobial prescribing work for doctors in training. To reach an in-depth understanding, this was extended in the process of the review to look at how trainees engage with antimicrobial prescribing more widely |

| The review demonstrates understanding and application of realist philosophy and realist logic that underpins a realist analysis | The data have been collected and analysed using a realist logic of analysis to provide explanations that contain CMOCs |

| The review question is sufficiently and appropriately focused | The review question was further focused in the first stages of the review, by specifically looking at hierarchical dynamics in more depth, led by initial findings in the literature |

| An initial realist programme theory is identified and developed | The first project meeting for the review discussed an initial programme theory, which was then further developed and refined |

| The search process is such that it would identify data to enable the review team to develop, refine and test programme theory or theories | The search strategy used terms that would maximise the potential for returning data relevant to the programme theory. The additional search performed was specifically driven by the programme theory |

| The selection and appraisal process ensures that sources relevant to the review containing material of sufficient rigour to be included are identified. In particular, the sources identified allow the reviewers to make sense of the topic area; to develop, refine and test theories; and to support inferences about mechanisms | Sources containing rich data and of adequate rigour were identified and allowed reviewers to configure CMOs and to support their inferences about relevant mechanisms. Illustrative quotations have been included in Chapter 3 to allow for transparency in the inferences made and in the way CMOCs have been developed. All quotations are available from the authors on request |

| The data extraction process captures the necessary data to enable a realist review | Data coding and extraction were iterative to enable all relevant data to be captured in support of specific CMOCs. As the programme theory developed, sources were revisited to ensure supporting or refuting data had not been missed |

| The realist synthesis is reported using the items listed in the RAMESES reporting standard for realist syntheses55 | This report and the publication planned out of this work have both followed the reporting standards for realist synthesis |

Results of the review

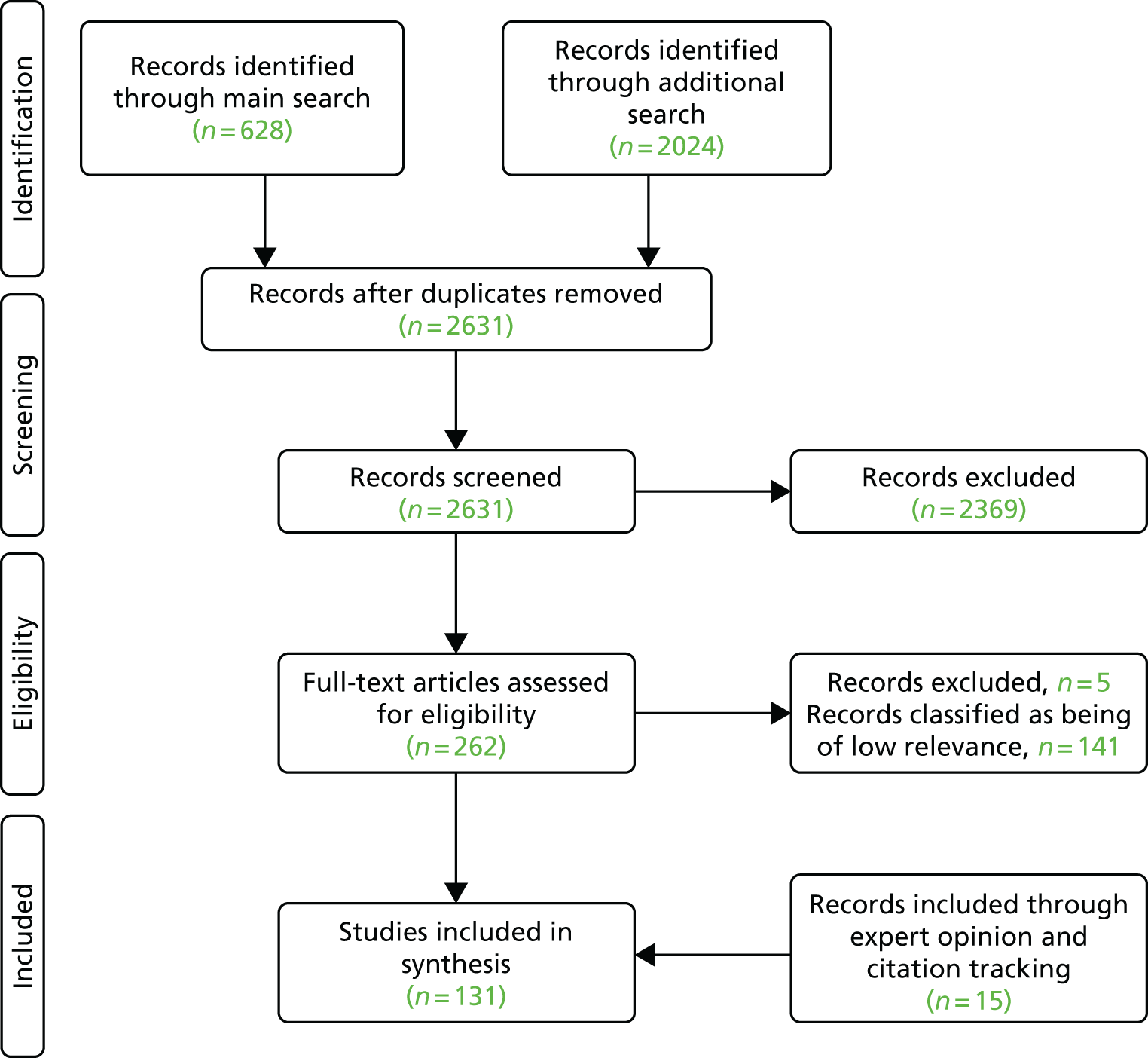

The process of screening and article selection resulted in 131 references. Of those, 81 references came from the main literature search and 35 references from the additional search. The remaining 15 articles resulted from citation tracking, targeted searches and expert suggestions, on the basis of relevance to programme theory.

Of the 131 references, 78 used quantitative methods, 37 used qualitative methods, 12 were mixed-methods papers and there were also three position papers and one report (for more details, see Appendix 2 on included studies).

The Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) diagram (Figure 4) provides more detail on the screening and selection process.

FIGURE 4.

The PRISMA diagram.

Main search

In more detail, the main literature search retrieved a total of 628 articles. Of those, 12 articles were duplicate records and 293 were not relevant to the purposes of this review. From the 81 titles accompanied only by conference abstracts, two full-text publications were identified, and these were already included in the data set. There were also 21 records for which the full text could not be retrieved. These records were saved separately to decide whether or not it was necessary to pursue other means of retrieving the full text. However, once the rest of the articles had been screened and analysed, it became obvious that these records had limited potential for informing programme theory and could be of questionable rigour. As theoretical saturation had been reached, a decision was made not to pursue full-text retrieval any further. Only studies published in English were included, to take account of the UK context. When non-English papers provided abstracts in English (in the majority of cases), these were reviewed by a member of the team who found that there was no clear mention of doctors in training or little relevance to programme theory development.

The screening process resulted in 97 papers being classified as being of low relevance to programme theory development and 81 articles being classified as comprising the core data set for the review. An additional 19 position and background papers were stored separately in case it became necessary to draw on them to supplement our interpretations of the data.

Additional search

From the additional, theory-driven search, a total of 2024 articles were identified. Of those, 1646 were excluded at title screening, and 302 at abstract screening, as irrelevant to the purposes of the review. Nine citations were already included in the data set from the main search and for two articles the full text was not available. As in the main search, a judgement was made about the potential added value of retrieving full texts when unavailable, which resulted in the decision that they would be of limited potential for informing programme theory. Another five articles were excluded as irrelevant at full-text screening.

The screening process for the additional search resulted in 25 papers classified as being of low relevance to programme theory development and 35 articles as core sources providing a necessary explanatory backbone to the review. Directly relevant position or other background papers (n = 3) were included in the highly relevant category for the additional search, as they were of sufficient relevance to inform the programme theory directly.

As explained in Chapter 2, two members of the team worked jointly to ensure consistency at different stages of the screening and coding process. For both searches, Geoff Wong independently reviewed a 10% random sample of the set of articles retrieved to ensure that they corresponded to the review aims, and a 10% sample of the articles selected to ensure that screening criteria were applied consistently. In addition, at the coding stage, Geoff Wong reviewed the coding for 10% of included papers out of both searches to ensure accuracy and consistency.

There were no major disagreements between the two reviewers (CP and GW). There was only one small discrepancy in the coding process, but this was easily resolved and ongoing discussions enriched data analysis.

Tables 7–9 in Appendix 2 provide more details on the characteristics of the studies included in the data set for the review.

Chapter 3 Findings

This realist review moves beyond identifying barriers of and facilitators to appropriate antimicrobial prescribing for doctors in training to reach an explanation of how and why trainees engage with antimicrobial prescribing differently under different circumstances. To do this, we focus on situations where antimicrobial prescribing decisions appear more challenging and there is increased uncertainty about what course of action to take (compared with when the diagnosis is clear-cut and it is widely accepted that an antimicrobial is appropriate – such as with a feverish patient with confirmed bacteraemia on blood cultures).

It is well recognised in the literature that doctors in training often find antimicrobial prescribing decisions challenging, either because of inherent diagnostic uncertainty, or because they have not yet developed relevant experience and knowledge. These barriers were discussed extensively in the set of articles included in this review. This has guided our focus in looking at what trainees do, in the presence of uncertainty, inexperience and lack of knowledge, to reach antimicrobial prescribing decisions. In other words, as guided by our data, we recognise that these factors will always limit prescribing decisions and place more emphasis on solutions that can work in the face of uncertainty, inexperience and lack of knowledge. For the same reasons, our analysis draws less attention to uncertainty about technical aspects of the process of prescribing,56–59 poor dissemination of information or conflicting guidelines and lack of awareness,43,60–65 and operational inefficiencies and pressures. 43,62,66–70 Instead, we are looking to understand what drives the behaviour of doctors in training in the presence of these limitations – namely uncertainty, inexperience and lack of knowledge.

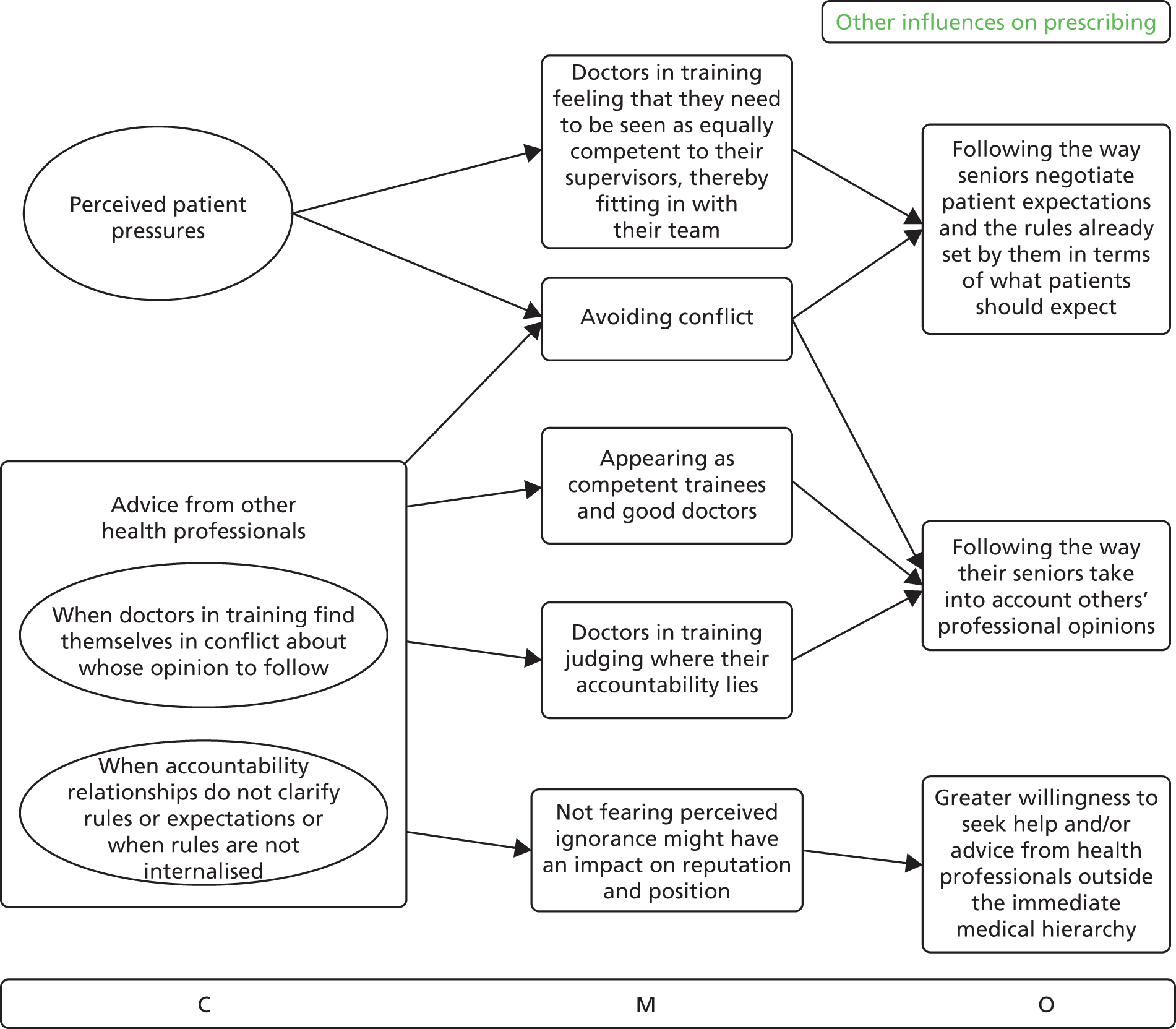

The rest of this chapter sets out the findings from the analysis and synthesis of the literature reviewed. There are two parts to this findings chapter. Part A focuses primarily on antimicrobial prescribing decisions, use of guidelines and other decision support aids, receiving support from other health professionals and managing patient expectations. Part B presents data from the literature on seeking assistance and challenging decisions made by senior supervisors. In each of these two parts, there are a number of subsections organised as follows:

-

First, we provide a narrative of findings based on our analysis of the data found within the literature.

-

This is then followed by a detailed realist analysis that contains one or more CMOCs.

-

Illustrative data (i.e. extracts from manuscripts) that we have used to make our interpretations and inferences for each of the CMOCs are also provided in each of the subsections. Some of these data derive from quotations presented in relevant articles, other data come from interpretations or conclusions drawn by the authors of these articles (rather than being primary data), or data extracts are presented in other forms (e.g. survey results), depending on the study design. The full list of quotations extracted from the literature is available from the authors on request.

For some CMOCs there is a larger number of supporting quotations from the literature included in the review, while other CMOCs are supported by a smaller set of data. This would provide some indication of the strength with which arguments can be made out of the data included here, but quantity would not be the only consideration. The level of detail and depth within each of the quotations and the confidence with which we can draw inferences from the data also plays a role. Some articles presented a wealth of data (possibly because of reporting flexibility in some journals) whereas other articles were constrained in the data they could present, therefore limiting the number of data we had available to us to interpret. However, this does not mean that arguments cannot be made with adequate strength for CMOCs supported by a smaller set of data, especially when substantiated by relevant theory (see Chapter 3, Drawing on substantive theory).

In some of the CMOCs presented, lack of adequately detailed data in included papers means that we have not been able to fully determine the fine-grained relationships between contexts, mechanisms and outcomes. Limitations of the review are presented in more detail in Chapter 4.

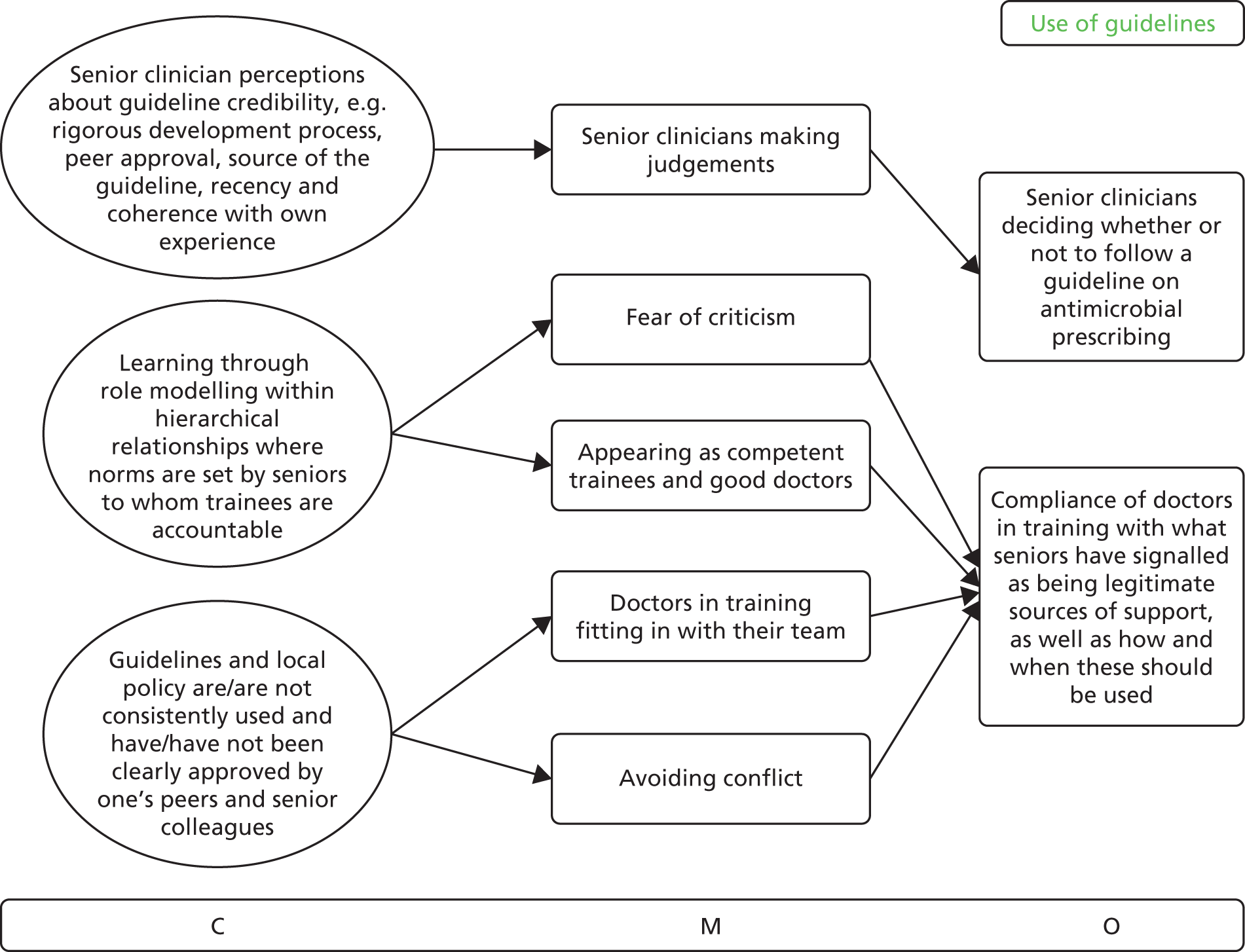

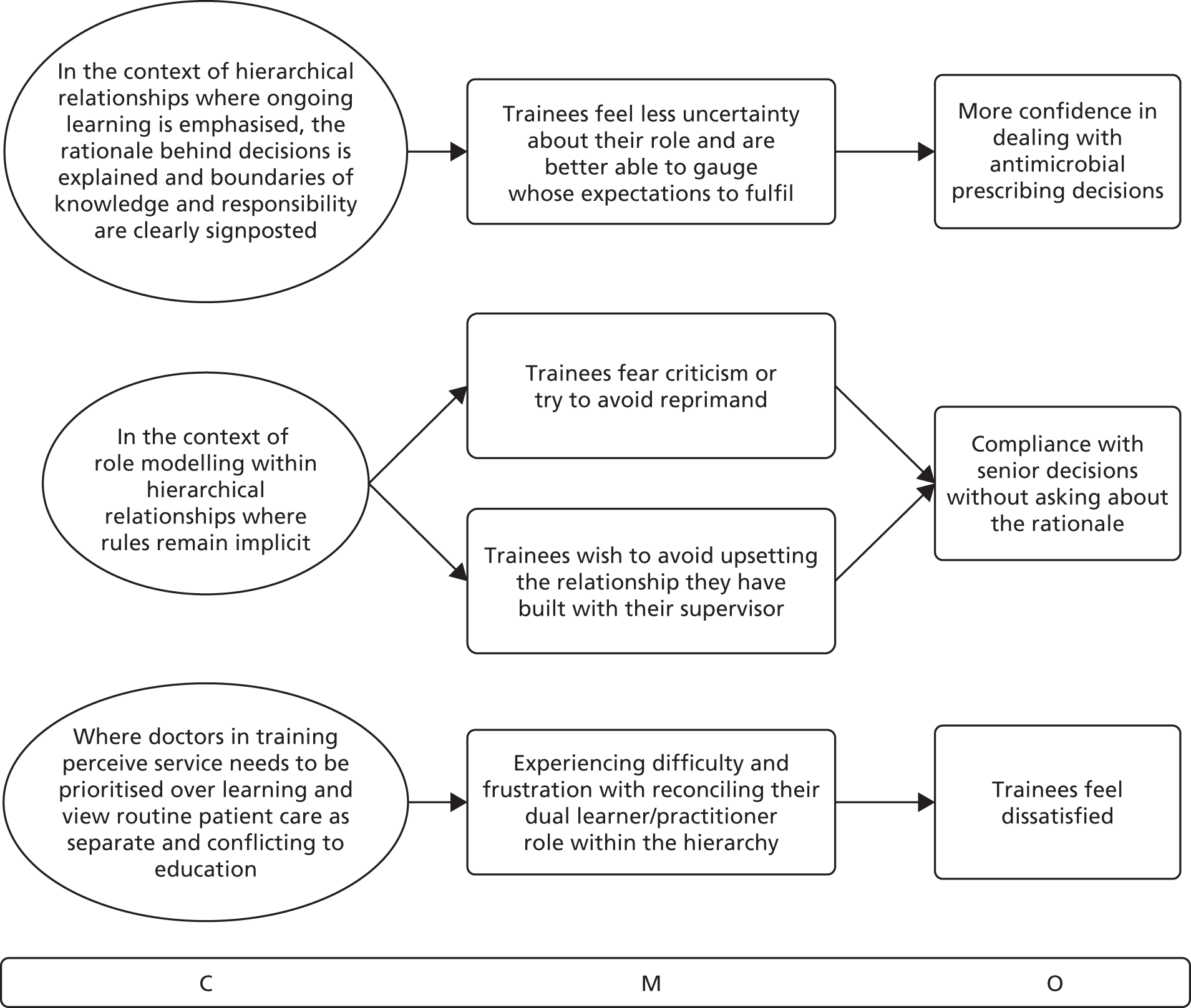

Part A: making decisions about antimicrobial prescribing and prescribing support

Influence of the formal medical hierarchy

The literature describes hierarchies as a core and pervasive aspect of professional socialisation in medicine in the UK, particularly in the context of explicit and implicit role modelling of appropriate clinical and prescribing behaviours from senior to junior members of the clinical team. One of the professional values communicated through role modelling within hierarchical relationships by senior experienced practitioners is that of decision-making autonomy. More senior clinicians set the norms about what is appropriate prescribing in practice (i.e. what is and is not acceptable) and about how to manage conflicting priorities. Doctors in training largely comply with the specific prescribing etiquette(s) and behaviours considered legitimate by the formal prescribing hierarchy (medical ‘chain of command’) at any given instance. This compliance results primarily from fear of criticism and fear of individual responsibility for patients deteriorating, although inertia sometimes also plays a role in junior doctor responses. Some specialties are described as significantly hierarchical in the literature, such as surgery, in which status differences and authority gradients are particularly pronounced and continuously enacted (i.e. surgeons set the rules and permissions).

Doctors in training also try to sustain positive relationships and manage the impression of others, in the context of their seniors’ role in evaluating their performance and influencing career progression. They are fitting in with the teams they are working with by adopting an identity of a competent trainee (which often means that you do as you are told so that you are perceived as a ‘safe pair of hands’). As decision-making autonomy is understood to be an important professional marker of experienced practitioners, doctors in training try to balance their respect for the decision-making autonomy of their seniors with learning how to be a competent doctor themselves.

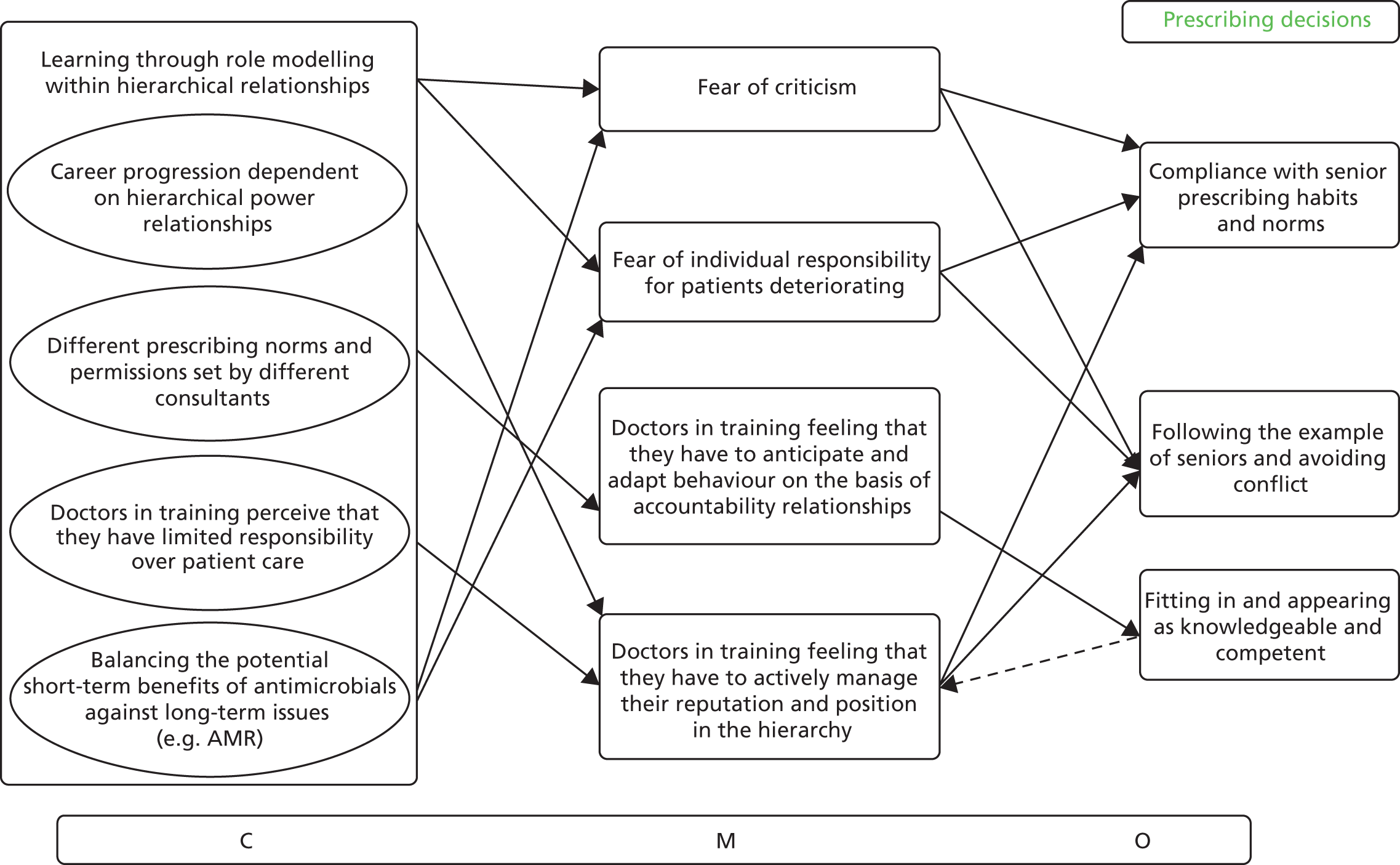

Realist analysis

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration 1

In a context of learning through role modelling within hierarchical relationships [context (C)], junior doctors passively comply with the prescribing habits and norms set by their seniors [outcome (O)], because of fear of criticism [mechanism (M)] and fear of individual responsibility for patients deteriorating (M).

Context–mechanism–outcome configuration 2

In a context in which career progression depends on hierarchical power relationships (C), junior doctors feel that they have to preserve their reputation and position in the hierarchy (fitting in) (M), by actively following the example of their seniors and avoiding conflict (O).

To provide one example of the process of interpreting data to develop CMOCs from the papers reviewed, we are drawing on Toulmin’s model of argumentation. 71 Toulmin suggests that an argument consists of a number of elements: a claim, which is the conclusion drawn; grounds for the claim, which are the data or evidence to support the claim; a warrant, which connects the evidence to the claim; backing, to support the warrant; a qualifier for the claim to show degree of certainty; and a rebuttal to recognise any limiting factors that apply to the claim being made. 71 On this basis, to develop a CMOC (what we have interpreted as being a claim in Toulmin’s model) we need a number of elements to substantiate our argument. For example, in CMOC 1 above:

-

The grounds for our claim are provided by data constituting context, mechanisms and outcome. From the data extracts below, quotation 1 provides evidence for ‘role-modelling within hierarchical relationships’ as a relevant context. Quotation 3 provides evidence for fear of criticism as a mechanism: ‘I actually have been criticized by a staff because of not covering somebody [with antibiotics . . . ]’70

-

And quotation 4 for fear of individual responsibility for patients deteriorating as a second mechanism: ‘Because if you make a mistake, it is going to be the primary concern of the patient, of course, and something bad is going to happen to them’. 70

-

A large number of quotations indicate the outcome, which is compliance with the prescribing habits and norms set by their seniors (e.g. quotation 9).

-

The warrant is what links data to the claim and, in the case of CMOCs, can be conceptualised as the relationships between the Cs, Ms and Os identified in the different quotations. This means that the warrant relates not to the individual data behind the claim, but to the connections between the data that allow the claim to be validated. For example, quotation 2 provides a warrant for the relationship between the context ‘Whatever attending [physician] you are with is the attending who you learn from . . .’70

-

and outcome ‘. . . and if I see them continuously not prescribe antibiotics over and over again, then I feel comfortable not prescribing antibiotics. But if they always do it, then I feel the need to do it.’70

-

Backing is provided by substantive theory, as discussed in Chapter 3, Drawing on substantive theory. Hierarchies are a pervasive aspect of medicine and have long been a topic of theoretical analysis.

-

Qualifiers link back to the strength of the argument and the degree of certainty we can have in the claim being made. CMOC 1 and CMOC 2 show that there is a fine difference between passive compliance and actively choosing to follow the decisions made by senior clinicians, which cannot be adequately resolved with the data included in this synthesis, although further CMOCs draw a more nuanced picture.

-

A rebuttal can be made in that, under some circumstances, or when doctors progress in their training, there is less fear of criticism, as trainees are more comfortable with understanding the prescribing practices in their context. This is further highlighted in CMOCs 27 and 28 towards the end of Chapter 3.

Relevant extracts from papers included in the review

‘I think it goes from the top down so everybody has to do the same thing. If the consultant or registrar doesn’t set a good example, the junior will certainly not follow it [the good example].’ (Specialist Trainee Doctor, Stroke)

‘Whatever attending [physician] you are with is the attending who you learn from, and if I see them continuously not prescribe antibiotics over and over again, then I feel comfortable not prescribing antibiotics. But if they always do it, then I feel the need to do it’. (Resident interview)

‘I actually have been criticized by a staff because of not covering somebody [with antibiotics . . . ] I was suspicious for endocarditis but they were clinically stable and so I wanted to get multiple blood cultures and monitor . . . The next morning I was pretty severely reamed out for not covering the patient [with antibiotics], although the person did fine and did not have a bad clinical result.’ (Resident interview)

‘Because if you make a mistake, it is going to be the primary concern of the patient, of course, and something bad is going to happen to them. And then you have your personal reputation to think about, too.’ (Resident interview)

The data [included in this paper] tell us, however, that junior doctors’ decisions and behaviours are also influenced by the prevailing culture of the organisation and the juniors’ perceptions of the hierarchy within which they work.

When focusing on the role of the supervisors, both internal medicine and surgical residents emphasized their importance as role models because supervisors’ practice strongly determined the subsequent prescribing behaviour of residents.

The most significant influence on prescribing practices was the opinion of more senior colleagues in the team to which the NCHD [Non-Consultant Hospital Doctor] was assigned. This was especially important in the earlier years of one’s medical career when doctors (particularly pre-registration house officers) have limited autonomy. [. . .] Instructions from seniors 1. ‘I did what I was told, like all interns do’ (Male Specialist Registrar, Anaesthesia) 2. ‘It’s a good system because he (Senior colleague) probably knows better than you; he may have a good reason’ (Male Registrar, Ear, Nose and Throat)

‘Some registrars described feeling undermined or criticised by their supervisors for their prescribing decisions. [. . .] ‘It’s a big power differential . . . You’re still at the mercy of the training provider coming and doing visits, and your supervisor giving input on if you do what you’re told or not’. (Registrar)

For some registrars, there are concerns that they need to ‘do what they’re told’ or fit in to a particular practice culture to prevent conflict and ensure career progression [. . .]

‘The origin of my practice came from supervisors during residency training, but the supervisors practised differently with respect to indication, dose, and number of doses. Thus, I chose to imitate the credible supervisors with good results of postoperative infection and my personal inclination.’ (Resident)

Influence of implicit and explicit rules or ‘norms’

When rotating in different environments, doctors in training encounter a number of different ‘rules’ or norms depending on the hierarchical relationships they become embedded within. According to the literature, junior doctors experience changes in prescribing norms not just between departments and hospitals, but also between different consultants in the same setting. Apart from differences between prescribing practices, the strength of norms may also differ according to how fluid or stable hierarchies are perceived to be (e.g. when doctors in training are members of multiple teams in different departments working on different wards vs. when doctors in training are primarily based within one department and on the same ward). At any given point in time, doctors in training seem to comply with the norms set by the consultants towards whom they feel most accountable.