Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal. The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/05/11. The contractual start date was in November 2016. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Dalton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

Introduction

Mental health care for armed forces personnel in the UK while they are still in service is commissioned by the Defence Medical Services (DMS) (but inpatient mental health services are currently provided by a NHS consortium). Services on discharge are mainly the responsibility of the local NHS [Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs)] in terms of payment and provision. However, a few services, including ones that have been initiated by the DMS, may be provided by the DMS for 6 months. The transition of the individual from one service to another may create a reason for reticence to present for help. In the UK, the Armed Forces Covenant exists as a formal commitment and moral obligation to the armed forces community that no one will face disadvantage compared with other citizens in relation to the provision of public and commercial services, and special considerations are appropriate in some cases (e.g. the injured or bereaved). 1

In 2011, it was reported that only 23% of UK veterans suffering symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) went on to access support services. 2 More recently, it has been reported that half of the armed forces veterans with PTSD now seek help from NHS services, but also that individuals are rarely referred to the correct specialist care. 3

The background to this research arises from current thinking about the anticipated rise in demand for psychological trauma services in the UK, with particular reference to armed forces veterans with PTSD. 4 In 2014, there were 2.8 million ex-service personnel in the UK, and it was envisaged that requirements for specialist support would grow as a result of armed forces restructuring and ever more complex needs arising from recent conflicts. 5,6

Given the transitionary arrangement and the anticipated rise in demand for services, there is a need to explore the adequacy and suitability of current and planned mental health services to treat PTSD to meet the specific requirements of armed forces veterans. Our research maps out key services currently being provided in the UK and evaluates the empirical evidence on the effectiveness of models of care and the effectiveness of available treatments.

Veterans and post-traumatic stress disorder

Definitions of ‘veteran’

In the recent NHS England stakeholder engagement survey questionnaire, a veteran is referred to as follows:

We use ‘veteran’ to mean anyone who has been a serving member of the British armed forces for a day or more. It means the same as ‘ex-service personnel’ . . . when we say ‘veteran’ or when we talk about armed forces’ experiences, this includes reservists as well as regulars.

p. 2 of the questionnaire7

Other definitions exist. For example, in the USA, a veteran is ‘a person who served in the active military, naval, or air service and who was discharged or released under conditions other than dishonourable’ (Title 38 of the Code of Federal Regulations). 8

In our research we aimed to capture definitions of ‘veteran’ in the international research literature and adopt a consistent approach to reporting.

Post-traumatic stress disorder and ‘complex post-traumatic stress disorder’

Post-traumatic stress disorder is an anxiety disorder following very stressful, frightening or distressing events. People with PTSD can experience nightmares and flashbacks; they can feel isolated, irritable and guilty. Various sequelae, such as insomnia and poor concentration, can have a significant impact on day-to-day living. NHS standard treatments for PTSD currently include watchful waiting, psychotherapy, trauma-focused cognitive–behavioural therapy (TFCBT), eye movement desensitisation and reprocessing (EMDR), group therapy and counselling, and medication (antidepressants). 9

Post-traumatic stress disorder is not a static condition. Many people leave the armed forces with undiagnosed PTSD, and the condition often manifests after they have left the service. Expert opinion suggests that veterans will commonly (around 50% of the time) suffer from ‘complex PTSD’ (or complex presentations of PTSD). There is currently no agreed diagnostic code for this condition, and ‘complex PTSD’ is not a universally agreed term in the research literature.

‘Complex PTSD’ is described by field experts as PTSD compounded by comorbidities such as substance misuse and depression. It is linked to multiple (as opposed to single) traumatic events, although it does not always arise from active military service; for example, the condition may result from repeated trauma/sexual abuse in childhood. 10,11 ‘Complex PTSD’ is interpreted by some medical professionals as PTSD with additional syndromes, such as pathological disassociation, emotional dysregulation, somatisation and altered core schemes about the self, relationships and sustaining beliefs. 12 The US Department of Veterans Affairs National Center for PTSD describes ‘complex PTSD’ as a condition arising from repeated trauma over a number of months or years, manifesting as a cluster of symptoms that may require special treatment consideration. 13

Despite the absence of a clear definition and a diagnostic mechanism for ‘complex PTSD’, it appears to be distinguished from PTSD by its link with exposure to multiple traumatic events. Therefore, for the purposes of our work we assumed that PTSD in the veteran population was synonymous with ‘complex PTSD’.

It is thought that the context, severity and complexity of PTSD in armed forces veterans may require different approaches13 (i.e. treatments or models of care) from those offered to the general population; these are, as yet, not fully understood. Veterans appear to have higher levels of adverse childhood events before they join, seem to drink more alcohol than the general population and are more likely to have been exposed to multiple traumatic events that may produce different challenges for treatment when compared with treatment for single events or occasions of sexual/domestic abuse and rape. It is also thought that veterans are more willing to admit to combat-related PTSD as a less-stigmatised form of mental illness. 10

Relevant ongoing research

Current National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) guidance on the management of PTSD (CG26, March 2005) is being updated and is due for completion in August 2018. 14 Early in 2016, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) released a Health Technology Assessment programme call: ‘Treating mental health problems with a history of complex traumatic events’. In response to this call, ongoing work now includes: INterventions for Complex Traumatic Events (INCiTE). 15

Brief overview of current policy context and commissioning for veterans’ mental health in the UK

In England, most NHS health-care services (including mental health services) for veterans are currently commissioned locally by CCGs. NHS England has specific duties (and separate funding) to commission a small number of specialised mental health services (such as online and specialised residential services and specific psychological therapies), prosthetic services, assisted conception, online psychological support for veterans and families, and inpatient PTSD services. 16 A number of third-sector organisations collaborate in service provision.

The NHS England strategic review of commissioning intentions for Armed Forces and their families for 2016/17 reports priorities to improve care for veterans with mental health issues, specifically in relation to (1) people with complex PTSD, including comorbidities linked to substance misuse and (2) when stigma is a barrier to accessing care. 16 Alongside the strategic review, NHS England conducted a stakeholder engagement exercise between January and March 2016, focusing on mental health services for veterans currently provided across 12 sites in the UK. 7,17 The findings of this engagement were published in September 2016. 18 In the final report, there is reference to three pilots for enhanced models of care for veterans’ mental health services conducted between November 2015 and March 2016.

In general, mental health services for veterans in England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland are provided by (1) the mainstream NHS services, (2) bespoke NHS-funded specialist clinics (including those for PTSD), (3) the Veterans and Reserves Mental Health Programme (for those who have been deployed since 1982 and are experiencing mental health problems as a result of military service) via the Ministry of Defence and (4) third-sector organisations, for example Combat Stress, Help for Heroes and Walking with the Wounded. 19 In Scotland, veterans are eligible for priority treatment as determined by their general practitioner (GP),20 and a network of specialist help is currently being established to mirror geographic coverage of the regional health boards. In Northern Ireland, medical and other support services for former full-time and part-time Ulster Defence Regiment (UDR) and Royal Irish Regiment (R IRISH) (home service) soldiers and their families are provided by the charity Aftercare. 21 In Wales, each of its seven local health boards appoints a veteran therapist (VT) with an interest in, or experience of, military mental health problems. This is part of a Welsh government-funded service called Veterans NHS Wales. Referrals to the VT come from health-care staff, GPs, veteran charities and self-referral. 22

Commissioning decisions across the UK are supported by detailed mental and related health-needs assessments across each country; these assessments also outline key messages for research and practice. The most recent reports are available for England in 2015,23 Wales in 201624 and Scotland in 2016. 25 The review for Northern Ireland was published in May 2017 and did not form part of our analysis. 26

Objectives

Against this background, our research sought to explore the adequacy and suitability of current and planned mental health services in the UK to treat PTSD in relation to the specific requirements of armed forces veterans. To do this, we reported what is known about current provision of services in the UK and brought this together with a rapid evidence review to indicate which models of care and which treatments may be effective.

The research answered four research questions, as follows:

-

What services are currently provided in the UK for UK armed forces veterans with PTSD (stage 1 of this report)?

-

What is the evidence of effectiveness of models of care* for UK armed forces veterans with PTSD (as described above), including impact on access, retention, clinical outcomes, patient satisfaction and cost-effectiveness (stage 2 of this report)?

-

What treatments show promise for UK armed forces veterans with PTSD? (stage 3 of this report)?

-

What are the high-priority areas for further research?

*We adopted the working definition of a model of care suggested by the Government of Western Australia Department of Health:27 models of care should outline the best-practice care and services for a patient, population or cohort in their progression through the stages of a condition, injury or event and should aim to ensure that people receive appropriate care at the right time and in the right setting by the right team.

The project is a rapid evidence review. There is no universally accepted definition of this term and a number of other terms have been used to describe rapid reviews incorporating systematic review methodology modified to various degrees. Our intention was to carry out a review using systematic and transparent methods to identify and appraise relevant evidence and produce a synthesis that goes beyond identifying the main areas of research and listing their findings. We foresaw that the process would be less exhaustive and the outputs somewhat less detailed than might be expected from a full systematic review.

Chapter 2 Methods

Scope of the review

We had a limited timeframe (3.5 months) so we adopted a pragmatic approach with regular reviews to adjust the scope and content of our work as necessary.

We conducted the rapid evidence review in four stages:

-

Stage 1: a brief overview of current practice in the UK for the treatment of PTSD in armed forces veterans.

-

Stage 2: a rapid evidence review on models of care for armed forces veterans with PTSD.

-

Stage 3: a rapid metareview evaluating the effectiveness of treatments for PTSD in armed forces veterans.

-

Stage 4: a narrative synthesis of the evidence on potentially effective models of care (stage 2) and treatments (stage 3), using the overview of current practice (stage 1) as a guiding framework, highlighting priority areas for further research.

Inclusion criteria

Population

We included armed forces veterans with PTSD after repeated exposure to traumatic events. We did not generalise to PTSD caused by single trauma events.

Intervention

For stage 2 (see Stage 2: a rapid evidence review on models of care) we included models of care for PTSD in armed forces veterans. As part of the brief from our research commissioners, we were asked to pay specific attention to peer support types of interventions. To help explore the elements of care models, we gathered information on current service provision in the UK (see Stage 1: a brief overview of current practice in the UK).

For stage 3 (see Stage 3: a rapid metareview of treatments) we included treatments for PTSD in armed forces veterans.

Setting

We focused on the NHS across the UK. We considered models of care and treatments in the international literature (e.g. US Department of Veterans Affairs) if deemed applicable to the NHS in the UK.

Comparator

Not applicable.

Outcomes

We identified any outcomes reported in the included studies, but focused on those considered relevant and important by stakeholders.

Study design

For stage 2 we did not restrict by study design. For stage 3 we included only systematic reviews. In stages 2 and 3, systematic reviews were included only if they met the minimum quality criteria for entry to the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects (DARE) produced by the Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 28

Stage 1: a brief overview of current practice in the UK

We provided a brief overview of arrangements currently in place in the UK for the treatment of PTSD in UK armed forces veterans. Particular attention was paid to peer support-type interventions, including those supported by the third sector. Using a pro forma list of questions (see Appendix 1), we carried out the following activities:

-

We contacted the 12 service providers17 referred to in the NHS England stakeholder engagement survey,7 and we also contacted selected service providers in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland to find out what is provided specifically for armed forces veterans in relation to PTSD. We contacted (as appropriate) third-sector organisations involved in the provision of services across the UK.

-

We drew on the knowledge of expert contacts to help with information gathering. Individuals and organisations were identified through existing links and contacts.

Stage 2: a rapid evidence review on models of care

We undertook a rapid evidence review of the effectiveness of models of care for armed forces veterans with PTSD. Although we adhered to the principles of robustness and transparency, our approach was less exhaustive and outputs less detailed than would be the case in a full systematic review.

Searching

The aim of the search was to identify relevant systematic reviews, primary research, guidelines or grey literature on models of care for PTSD in veterans. A search strategy was developed in MEDLINE (via Ovid) and included terms for veterans, PTSD and models of care. No geographical, language, date or study design limits were applied. The MEDLINE strategy was adapted for use in the other resources searched.

The searches were carried out in November/December 2016. The following databases were searched: MEDLINE (including: Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations); PsycINFO; and PILOTS (Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress database).

In addition, a search for relevant guidelines was undertaken via NHS Evidence, the National Guideline Clearinghouse and the US Department of Veterans Affairs. The research report sections of the following websites were searched to identify additional relevant reports or grey literature:

-

US Department of Veterans Affairs – Health Services Research and Development [www.hsrd.research.va.gov/ (accessed 10 November 2016)]

-

Australian Government Department of Veterans Affairs [www.dva.gov.au/about-dva/publications/research-and-studies (accessed 10 November 2016)]

-

Government of Canada Veterans Affairs Canada [www.veterans.gc.ca/eng/about-us/research-directorate/publications/reports (accessed 11 November 2016)]

-

National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine [www.nationalacademies.org/hmd/Reports.aspx (accessed 11 November 2016)]

-

Forces in Mind Trust [www.fim-trust.org/reports/ (accessed 8 December 2016)]

-

King’s Centre for Military Health Research [www.kcl.ac.uk/kcmhr/publications/Reports/index.aspx (accessed 8 December 2016)].

The results of the searches for stages 2 (review of models of care) and 3 (metareview of treatments) were imported into EndNote X7 [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA], deduplicated and then screened for inclusion in either review. Full search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

Study selection

We included any study design relevant to models of care for armed forces veterans with PTSD, but only when it was possible to extract findings separately for this population. Particular attention was paid to peer support-type interventions, including those supported by the third sector. We assessed studies from the international literature when this was deemed relevant to UK armed forces veterans. We prioritised evaluations (when available), followed by descriptive/observational research. We anticipated that not all reviews would be systematic reviews (i.e. using objective and transparent methods to identify, evaluate and summarise all relevant research evidence). Therefore, reviews were included only if they met the minimum quality criteria for DARE. It was mandatory that they demonstrated adequate inclusion/exclusion criteria, literature search and synthesis. In addition, formal quality assessment of primary studies and/or sufficient study details must have been reported. Full details of the DARE process are available. 28

As a result of the short time frame to complete this evidence synthesis, studies were excluded if we were unable to locate a full-text copy by 13 January 2017.

We used EPPI-Reviewer (EPPI-Centre, Social Science Research Unit, Institute of Education, University of London, UK) and EndNote X7.4 to screen titles and abstracts. Study selection was carried out by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer when necessary.

Data extraction

Data were extracted on participants, models of care, outcomes (when applicable) and any other characteristics we considered helpful to our work.

We created data extraction tables in Microsoft Word (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA). Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer, with disagreements resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer when necessary.

Quality assessment

We assessed systematic reviews using the DARE critical appraisal process. Based on the quality criteria used to select studies (see Study selection), a judgement was made on the overall reliability of the review and its findings. For evaluative primary research, we used the EPOC (Effective Practice and Organisation of Care) risk-of-bias tool for controlled studies29 and the CASP (Critical Appraisal Skills Programme) critical appraisal tool for qualitative research. 30 See Post-protocol decisions relating to stage 2 for further details of quality assessment.

Quality assessment was carried out by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer when necessary.

Synthesis

We synthesised the evidence narratively and highlighted potentially effective models of care. During the regular reviews, as the project progressed, we made adjustments to the scope and content of the work.

Post-protocol decisions relating to stage 2

Our working definition of ‘models of care’ (see Chapter 1, Objectives) was helpful in shaping initial parameters for stage 2. However, during screening and selection of studies it became clear that the term ‘model of care’ could be interpreted in more than one way. For example, we found studies that described a specific method or mechanism by which an intervention was delivered (e.g. telehealth, smartphone applications, group support) and others that adopted a broader organisational or systems perspective (e.g. integrated care, community outreach). This important distinction turned our thoughts to what might be the most helpful perspective for readers of our rapid evidence synthesis. Given the ongoing UK policy focus to achieve sustainable new models of care (i.e. how services can be optimally organised and structured), we decided to focus on the broader ‘systems’ interpretation. Based on this interpretation, we developed a coding list (see Appendix 3) to help organise the evidence and to shape the data extraction and synthesis going forward. Two reviewers independently assigned codes to individual studies. Disagreements were resolved by consensus or through discussion with a third reviewer.

The number of included studies was much larger than expected. Given the short time frame and resources, we had to make pragmatic decisions at the data extraction stage to ensure that there was sufficient time to adequately synthesise the studies. We therefore chose to data extract in full and critically appraise more robust study designs, conventionally considered to be systematic reviews, randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and controlled trials. We also chose to extract data in full qualitative studies that provide insight from a service user perspective. The remaining studies were predominantly single-group designs, which are typically considered less methodologically robust. These studies had more limited data extraction (e.g. study design, sample size, code and description of model of care, list of outcomes and a summary of authors’ conclusions and recommendations). Although these single-group studies were not formally assessed for methodological quality, we considered the adequacy and clarity of reporting on context, methods and impact.

Stage 3: a rapid metareview of treatments

We undertook a rapid metareview of systematic reviews evaluating the effectiveness of treatments for PTSD in armed forces veterans.

Searching

The aim of the search was to identify relevant systematic reviews of treatments for PTSD in veterans. A search strategy was developed in MEDLINE (via Ovid) and included terms for veterans and PTSD. No geographical, language or date limits were applied. Study design search filters were used in the strategy (when appropriate) to limit retrieval to systematic reviews.

The searches were carried out in November 2016. The following resources were searched: Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, DARE and the Health Technology Assessment database. PROSPERO was also searched to identify any ongoing reviews. In addition, searches of MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and CINAHL (Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature) were carried out to identify any relevant systematic reviews published since the closure of DARE in 2015.

The results of the searches for stages 2 (review of models of care) and 3 (review of treatments) were imported into Endnote X7, deduplicated and then screened for inclusion in either review. Full search strategies can be found in Appendix 2.

Study selection

We included systematic reviews on treatments for armed forces veterans with PTSD. We assessed reviews from the international literature when this appeared to be relevant to UK armed forces veterans. Systematic reviews were included only if they met the minimum quality criteria for DARE (see stage 2). If, in the course of searching for treatments, we found additional systematic reviews on models of care, we assessed them for inclusion in stage 2 (see Stage 2: a rapid evidence review on models of care).

We used EPPI-Reviewer and Endnote X7.4 to screen titles and abstracts. Study selection was carried out by two reviewers independently, with disagreements resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer when necessary.

Data extraction

Data were extracted on participants, treatments, comparators, outcomes (when applicable) and any other characteristics we considered helpful to our work. Data extraction was carried out by one reviewer and checked by a second reviewer; disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer when necessary. We created data extraction tables in Microsoft Word.

Quality assessment

We assessed systematic reviews using the DARE critical appraisal process (see Stage 2: a rapid evidence review on models of care). Quality assessment was carried out by two reviewers independently and disagreements were resolved by consensus or by a third reviewer, when necessary.

Synthesis

We presented a brief narrative overview to highlight potentially effective treatments.

Stage 4: narrative synthesis of all stages

We synthesised the evidence narratively on potentially effective models of care (stage 2) and treatments (stage 3), using the overview of current practice (stage 1) and the models of care coding list (see Appendix 3) as a guiding framework. We adopted a ‘best evidence approach’ (i.e. highlighting the best-quality and most-promising evidence) to inform future research and practice.

Public and patient involvement

As a result of the short timescale for this project, we used findings from the NHS England stakeholder engagement survey as a starting point to represent service user input. 18 We also contacted a veteran (who was also a service user) to provide additional input. We aimed to use this input to help explore patterns in the NHS England public and patient engagement data and to provide supplementary insights, as appropriate.

Advisory group

We called on existing links and contacts to establish an advisory group of people who have a specific interest in this topic area. The advisory group comprised representatives with academic, military and service commissioning experience who we anticipated would be able to help (1) strengthen our background knowledge on policy context and current research and practice, and (2) develop further contacts. Further detail is provided in Acknowledgements, External advice, at the end of this report.

Chapter 3 Results

Stage 1: what services are currently provided in the UK for UK armed forces veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder?

We provide a brief overview of arrangements currently in place in the UK for the treatment of PTSD in armed forces veterans. Information was gathered from the following sources: we sent (by e-mail) a pro forma list of questions (see Appendix 1) to the 12 service providers in England referred to in the NHS England stakeholder engagement survey;17 and we also approached the main contacts for service provision in Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland. In addition, we contacted selected third-sector organisations known to offer UK-wide coverage. Prior to sending out the questions, we identified a named contact at each organisation who was willing to assist with the information gathering. A number of experts helped us to identify contacts, particularly in the third sector.

We received 17 responses out of 21 service provider contacts (81% response rate) and details are presented in Appendix 4. We spoke with five experts selected to provide key perspectives of importance to our work. These included representation from NHS England (one person), public health/local authority (two people), and academia/clinical practice (two leading academics with experience in military operations and/or clinical practice).

Development of a coding framework on models of care

Using the information gathered from the service providers, we developed a set of codes to represent descriptions of how services were organised and delivered (models of care). The list was expanded and codes were clarified using information from the literature in stage 2. Given our decision to distinguish care delivery mechanisms (models with a narrower focus) from systems-based models, we divided the list into two sections. The list of codes is presented in Appendix 3.

Overview of current service arrangements in the UK for veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder

Most providers report a range of mental health services for veterans, and many are delivered as part of a wider package of interventions across the NHS and third sector. Various models of care are employed to deliver services for veterans. Collaborative working across sectors is commonplace. Peer support and ‘Veterans Champions’ are also in place. Referrals to services occur via many different routes and access via self-referral is available as an option in most cases. Multiple (clinical and non-clinical) professions are involved in the delivery of services and these services are available to veterans beyond the clinical setting. Several organisations mention specific support for veterans with PTSD. This does not necessarily mean that other providers do not provide targeted services for PTSD; rather, it appears that specialist treatment for this condition can be embedded in wider mental health services and assistance for comorbid conditions. Factors affecting the successful implementation of services and treatments for veterans with PTSD appear to be (1) inadequate funding and resources, (2) wider system challenges, (3) lack of research and development and (4) the inherent complexities of the target population. Evaluation of services and treatments appears to be taking place, but sporadically and to varying degrees. Responses were not received on all questions from every provider; therefore, the information set out below reflects where detail was offered to us. The findings are presented grouped by geographical area, reflecting the NHS England document. 17

North of England (four service providers)

What services and treatments are provided/how are clients referred?

Veterans’ mental health services in the north of England are currently provided by NHS foundation trusts (or partnership trusts) in Greater Manchester West; Greater Manchester and Lancashire; Yorkshire and Humberside; and Northumberland, Tyne Wear and Esk Valleys. All except Yorkshire and Humberside report that they have collaborative working arrangements with third-sector organisations, namely Combat Stress, Walking with the Wounded and Royal British Legion. A variety of services and treatments are offered across the area, including specific trauma-focused activity [e.g. TFCBT; prolonged exposure (PE); cognitive restructuring; EMDR] and Improving Access to Psychological Therapies (IAPT) services for those with less complex trauma. Other (more generic) services include case management across health and social care pathways; signposting to other psychological-related problems such as substance misuse; and linkages with services tackling wider determinants of well-being such as housing and financial and social needs. Yorkshire and Humberside offers an outreach service delivered by four specialist therapists trained in mental health and with experience of working with ex-military personnel. Referrals to services occur through many routes, including referral from health-care professionals (GP and other), self-referral, family members and carers, third-sector organisations and prisons. In Greater Manchester and Lancashire, 74% of referrals arrive via non-NHS routes; this site provides specific support for veterans with PTSD and was the location for one of three 6-month NHS England pilots for enhanced models of care in 2015/16 (‘Overcoming the barriers’, a model to address some of the issues that veterans experience when accessing mental health services). 18

Where and how services and treatments are provided/who provides them?

Access to services in the north of England appears to be largely in the community setting. For example, in Greater Manchester and Lancashire, access routes involve a number of community venues as close to home as possible, from football grounds to libraries, but also in the client’s own home where this is more appropriate. Individuals involved in the delivery of services in this part of England include various types of specialist psychological therapist (some with military experience), mental health nurses and counselling staff; others are peer support workers, case managers and those from non-psychological specialisms such as art therapy and employment mentoring.

Midlands (three service providers)

What services and treatments are provided/how are clients referred?

All services are provided by NHS foundation trusts and all have some level of working arrangement with Combat Stress. Geographical coverage is North Essex, East Midlands and West Midlands.

Services and treatments include packages of care reflecting a holistic approach to mental health needs including assistance with housing, employment and social integration, in addition to specialist mental health support. Veteran support groups with input from third-sector organisations are also offered. Other providers report on broader models of care, such as integrated community mental health, early intervention and veterans’ liaison services. Specific psychological therapies are available [including those recommended by NICE such as cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) and EMDR]. Referral routes to services include GPs, local authorities and third-sector organisations; referrals to specialist services are through the NHS or criminal justice system. The West Midlands Military Veterans’ Hub (part of South Staffordshire and Shropshire NHS Foundation Trust) takes a proactive approach to recruitment. It asks service users if they wish to be seen by the Veterans Service and automatically notifies the service regarding those who are interested. This service is a collaboration of eight NHS mental health service providers, each with its own ‘Veterans Champion’ to link with existing teams and providers. Veterans First (Essex), which is part of the North Essex Partnership University NHS Foundation Trust, provided two of the three 6-month NHS England pilots for enhanced models of care in 2015/16. 18 One pilot programme was a joint substance misuse and mental health service model; the second was an outpatient service for veterans with moderate to severe PTSD.

Where and how services and treatments are provided/who provides them?

Treatments and services can be accessed at the NHS trusts, in the veteran’s own home or at a location agreed (as appropriate) with the service user.

Delivery of services in this area of England calls on the skills of clinical nurses and psychologists with specialist training in trauma-focused interventions and therapists conversant with CBT and EMDR. Other staff also attend Veterans Awareness training and have access to specialist lead clinicians.

South of England (five service providers)

What services and treatments are provided/how are clients referred?

Services for veterans in the south of England are provided by NHS foundation trusts (or partnership trusts) in all cases except for Surrey. Here, arrangements for veterans are provided by Virgin Care on behalf of Surrey County Council. Some providers report close working arrangements with third-sector organisations. Geographical coverage is London, Berkshire, Avon and Wilshire (South West), Surrey and Sussex. Interventions range from signposting services to comprehensive multidisciplinary assessment, case management and specific trauma-focused services (including NICE-approved CBT and EMDR). Specialist PTSD services are offered at two locations (London Veterans Service and South Central Veterans Mental Health Service delivered by the Berkshire Healthcare NHS Foundation Trust). Surrey Engagement and Veterans Emotional Support (SERVES) offers a range of services including advice and information (signposting to third-sector organisations), drop-in centres, crisis helplines and ‘emotional gyms’. In Sussex, the Sussex Armed Forces Network is led by CCGs in partnership with the NHS Foundation Trust. Partnership working with a range of organisations (including local authorities) facilitates a pathway for veterans covering various sources of help on wider determinants of health (including mental health) and Veterans Champions are trained to work in secondary care. The main sources of referral are self-referral, GPs and other health professionals, IAPT services, third-sector organisations and family members.

Where and how services and treatments are provided/who provides them?

The delivery of services and treatments across the south of England takes place in various settings, including NHS clinics, community outreach, prison inreach, third-sector-run facilities and GP surgeries. People involved in providing services include specialist health professionals (clinical psychologists, clinical nurse specialist, psychiatrists and VTs) and non-clinical staff such as art therapists and social workers.

Scotland

What services and treatments are provided/how are clients referred?

Veterans First Point (V1P) Scotland is the government-funded NHS provider that facilitates a network of NHS–third-sector partnerships to support veterans across Scotland. This service is supported specifically with the help of libor-funding (a commitment by the government to use banking fines to fund services). At present, services include drop-in centres, peer support, psychological therapy, community outreach, prison inreach, occupational therapy, brokerage and identification of individuals with complex needs. An Individual Placement Model is also offered to help promote mental health recovery through work. Self-referral appears to be popular; other referrals occur via existing psychology services.

Where and how services and treatments are provided/who provides them?

In 2016, eight newly funded V1P centres were established and services for veterans continue to develop within each of the following locations, reflecting the Scottish health boards: Ayrshire and Arran, Borders, Fife, Grampian, Highland, Lanarkshire, Lothian (the largest) and Tayside. Services and treatments are provided by peer support workers, occupational therapists, psychological therapists and other clinicians.

Wales

What services and treatments are provided/how are clients referred?

Services and treatments for veterans in Wales are facilitated by Veterans NHS Wales, which is funded by the Welsh Government. Each of the seven local health boards in Wales has an appointed VT. The organisation offers multiple options for treating individuals with PTSD [including TFCBT, EMDR, cognitive processing therapy (CPT) for couples and cognitive and behavioural conjoint therapy]. One-to-one peer mentoring is offered through the service charity ‘Change Step’, while peer mentoring through ‘Care After Combat’ is specifically for veterans released from prison. The organisation also signposts people to various third-sector organisations. Self-referrals are accepted and others arrive from primary and secondary care and third-sector organisations.

Where and how services and treatments are provided/who provides them?

Veterans NHS Wales has 14 mental health professionals with wide-ranging backgrounds, from occupational psychology to social work. All have been trained to deliver EMDR.

There are seven local health boards, each employing between one and four VTs. Services are provided via a ‘hub and spoke’ model (the hub being the University Hospital of Wales in Cardiff).

Northern Ireland

What services and treatments are provided/how are clients referred?

From the information we received, veterans in Northern Ireland are looked after by the UDR and R IRISH (home service) Aftercare Service, funded by the Ministry of Defence. Services are limited to veterans who have served in either the UDR or R IRISH. This organisation offers access to a specific trauma-focused psychological therapy intervention comprising an initial assessment followed by 10 sessions of one-to-one counselling. The main source of referral is via case workers who have responded to requests for home visits by veterans; other referrals come from GPs, health trusts and third-sector organisations.

Where and how services and treatments are provided/who provides them?

Case workers offer a holistic approach to medical, welfare and benevolence. They also help with completion of referral forms. The specific intervention (above) offered by this organisation is initiated in Belfast, followed by sessions delivered locally to the individual by a network of contract counsellors.

UK-wide third-sector organisations

What services and treatments are provided/how are clients referred?

We contacted four UK third-sector organisations, three of which reported that they deal specifically with mental health/PTSD in armed forces veterans.

The first of these, Combat Stress, claims to be the leading mental health charity for veterans in the UK. The influence of this organisation is reflected in our summary of service provision so far, Combat Stress being the most frequently mentioned collaborator with the NHS. Combat Stress is best known for its stepped-care intervention dealing with three stages of recovery: (1) stabilisation, (2) trauma therapy and (3) reconnecting veterans with their lives. PTSD treatment is the focus of trauma therapy in the second stage. This stage is characterised as the intensive treatment programme (ITP), based on work from the Australian Department of Veterans Affairs. The programme was commissioned by the NHS in 2011 and is free for veterans with severe PTSD. Activity within the ITP is based on TFCBT, psychoeducation and well-being, using group and individual delivery formats, and art therapy is offered throughout. In the third stage, part of reconnecting veterans with their lives involves family member involvement in psychoeducation about PTSD and reducing stigma. The organisation also offers a crisis helpline, community clinics, residential treatment centres and case management for substance misuse.

The organisation PTSD Resolution Ltd offers a model of care incorporating counselling and psychotherapy for veterans with PTSD based on Human Givens therapy. 31

Walking with the Wounded operates the ‘Head Start’ Programme, which is offered to people with mild to moderate common mental health disorders, including PTSD. Specifically for PTSD, the organisation offers access to NICE-recommended approaches such as TFCBT and EMDR.

Help for Heroes does not offer direct clinical interventions, but instead provides a variety of other services to help with recovery and welfare. Part of the organisation ‘Hidden Wounds’ offers free individual support for mental health and associated comorbidities such as adverse drinking habits. Help for Heroes also directly commissions services from the NHS, Walking with the Wounded and Combat Stress.

Referral routes to third-sector organisations appear to be similar to those found among the NHS service providers we contacted. Walking with the Wounded appears to connect with multiple agencies, but most referrals are received via GPs. This organisation has also assisted Public Health England in a national programme of GP training for veteran mental health matters.

Where and how services and treatments are provided/who provides them?

Multidisciplinary teams with wide-ranging clinical, non-clinical and military backgrounds make up the general profile of those who provide third-sector services for veterans. PTSD Resolution has a network of 200 therapists all trained in Human Givens therapy; these therapists are registered and the list is accredited in the UK by the Professional Standards Authority for Health and Social Care. Services and treatments from third-sector organisations are generally delivered in various locations, including an inpatient setting, a community setting and in the person’s own home. Walking with the Wounded has a national network of accredited therapists and guarantees that clients receive support within 10 days of returning consent forms and within 10 miles of their home.

Other service providers

Two other organisations in the north of England were contacted on the basis that they did not appear to fit with either the NHS or third-sector delivery models. The St Johns and Red Cross Defence Medical Welfare Service is available across Greater Manchester hospitals. It does not provide treatment but instead provides support and signposting for veterans across the referral pathway. The service is specifically for veterans aged ≥ 65 years.

Liverpool Veterans appears to be an independent organisation developed by Breckfield and North Everton Neighbourhood Council in conjunction with the Foundation for Art and Creative Technology (FACT). It provides links to services, research and fundraising events for veterans and their families in the Liverpool area. Of particular note is that the organisation signposts individuals with PTSD to Tom Harrison House (a specialist facility for addiction recovery). 32

Factors affecting implementation

Several challenges to the implementation of services and treatments for veterans with PTSD were reported by the service providers we contacted. These are summarised in the following sections.

Funding and resources

Inadequate funding to meet current demand was frequently cited, particularly for trauma services. Availability of appropriate clinicians and venues was also seen to be problematic. Lack of resources was reported to result in lengthy waiting lists for services and treatment in some areas. In Northern Ireland, restriction of eligibility to those only with previous service in the UDR or R IRISH (home service) or a veteran discharged via the Personnel Recovery Unit was seen as a limitation.

Wider system challenges

Perhaps as a consequence of inadequate funding and resources, further challenges to implementation were difficulties in negotiating appropriate longer-term treatments (such as psychotherapy) within the NHS. Service providers also mentioned that NHS IAPT can be slow to provide definitive treatment. As veterans often present in crisis because of pressure from partners, employers or the criminal justice system, such delay is at odds with the pressing needs and expectations that require prompt attention in this population group.

Poor co-ordination of care between agencies was also cited as a hindrance to successful implementation of services and treatments. For example, veterans with comorbid substance misuse were described by one service provider as ‘. . . a football between services’. The difficulty, in their view, appears to be about where to place the veterans’ needs on the continuum of care. Indeed, veterans are often viewed as too risky for well-being services but not unwell enough for secondary psychological services.

Research and development: knowledge base

Inadequate research and treatment development was cited by one service provider as being at odds with the increased drive to deliver evidence-based interventions with appropriate assurances in place. A concern expressed by another service provider was that a particular delivery model delivered by them was not understood sufficiently by commissioners, resulting in the inability to achieve full implementation of the intervention.

Complexities of the client group

Successful implementation of services and treatments for veterans with PTSD is affected, generally, by the fact that this is a highly challenging client group. They are described by service providers as unstable, unreliable and generally hard to engage because of inherent difficulties they tend to experience with help seeking. On referral, clients often arrive with testing social, financial and premorbid disposition. They can also feel let down because of problems already mentioned in relation to long waiting lists, unsatisfactory previous treatment and wider system challenges.

Evaluation of services and treatments

Evaluation of current service provision for veterans is clearly taking place across the UK. However, activity appears to be sporadic and is discharged to varying degrees. NICE evidence-based therapies are being implemented, and several service providers referred to various types of evaluation (past or present).

Ongoing activity includes unspecified projects and research relevant to particular organisations; standard assurance processes such as inspections by the Care Quality Commission and the Friends and Family Test; and general audits of medical services covering clinical governance and client satisfaction. Other providers refer to regular reporting mechanisms providing feedback to NHS England on key performance indicators.

More specific and detailed evaluations were reported by other organisations, such as the 1-year evaluation of the Veterans Wellbeing Assessment and Liaison Service (North East). In Wales, an annual report is published reflecting on services provided by Veterans NHS Wales; a specific evaluation was carried out in 2014 by Public Health Wales on behalf of the Welsh Government. 33 This evaluation contained pre–post intervention clinical measures and patient satisfaction (measured by questionnaires and focus groups with veterans and their partners). In its March 2016 newsletter,34 V1P Scotland reports on the evaluation of its services (‘The Transformation Station’), which is a collaboration between NHS Lothian and Queen Margaret University working with V1P Scotland.

Publications relating to specific programme evaluation using observational study designs were cited by two service providers: PTSD Resolution Ltd and Combat Stress. 35,36 The latter organisation has a large repository of research available on its website.

Collaboration with academic institutions was reported. King’s College London (King’s College Mental Health Research) is currently evaluating the Head Start programme at Walking with the Wounded. Standardised and reliable measures are being used {Patient Health Questionnaire – 9 items (PHQ-9), Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7-item scale (GAD-7), Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT), PTSD Checklist – Civilian Version (PCL-C), and Work and Social Adjustment Scale (patient-reported outcome measure) [WSAS (PROMS)]} at the start, middle and end of therapy. Client evaluation for West Midlands Veterans Hub takes place through the University of Worcester, with IAPT measures taken to measure client progress.

Stage 2: what is the evidence of effectiveness of models of care for UK armed forces veterans with post-traumatic stress disorder?

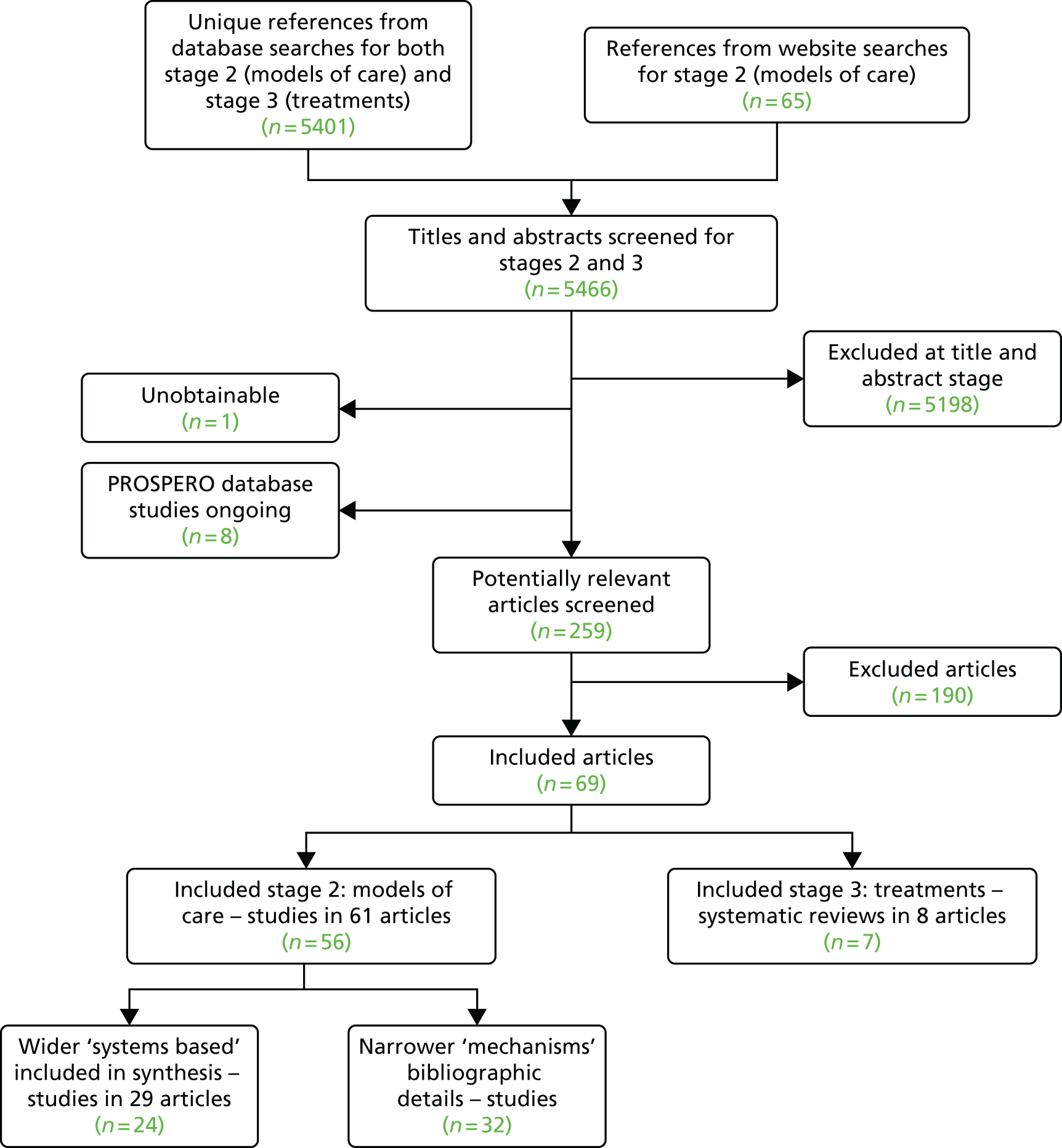

We included 61 articles (56 studies) (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart.

Thirty-two studies reported on types of care delivery with a narrower focus (e.g. delivery mechanisms such as telehealth and triage assessment). We identified these studies using the coding framework developed from stage 1 (see Appendix 3). No further analysis was carried out on these studies as they were not the main focus of our rapid evidence review (see Chapter 2). For completeness, the 32 studies are listed bibliographically in Appendix 5.

We focused on models of care adopting a wider or ‘system-based’ perspective (e.g. integrated care, settings-based delivery, etc.). Twenty-four studies (29 articles) were selected (using the stage 1 coding framework in Appendix 3) (Table 1). Within these studies, three RCTS (four papers) were prioritised to represent evidence from a conventionally more robust study design. 37–40 In addition, a qualitative study41 was identified as potentially important to provide insight from a service user perspective. The four studies underwent full quality assessment. All were connected to the Veterans Health Administration, US Department of Veterans Affairs.

| First author, year, reference | Study design | Partnership, cross-sector, liaison work, co-location | Co-ordinated, integrated, collaborative, networks, multidisciplinary care | Inpatient | Outpatient | Day care | Residential | Primary care | Peer support | Multicomponent treatment programmes | Family systems model | Community outreach | Use of IAPT | Prison inreach | Case management | Stepped-care model | Early intervention | Crisis management |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| RCTs (USA) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Schnurr, 2013;37 VA | RCT | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| McFall, 2010;38 and McFall, 2007;39 VA | RCT | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| McFall, 2000;40 VA | RCT | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Qualitative study (USA) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Hundt, 2015;41 VA | Qualitative | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Other study designs | ||||||||||||||||||

| Australia | ||||||||||||||||||

| Pietrzak, 2011;42 McGuire, 2011;43 Bredhauer, 201144 | Critical review and analysis (guideline) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Forbes, 200845 | Survey | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||

| Creamer, 200246 | Quasi-experimental observational study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| UK | ||||||||||||||||||

| Burdett, 2016;35 PTSD Resolution charity | Service evaluation | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Murphy, 2015;36 and Murphy, 2016;47 Combat Stress – NHS funded third sector | Observational | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| USA | ||||||||||||||||||

| Ohye, 201548 | Descriptive article | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Sniezek, 201249 | Descriptive article (guest editorial) | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| USA, conducted or funded via VA | ||||||||||||||||||

| Baringer, 1990;50 VA | Before-and-after intervention pilot study | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Brawer, 2011;51 VA | Observational | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Bohnert, 2016;52 VA | Observational system evaluation | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||

| Chan, 2007;53 VA | Descriptive article (thesis) | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Donovan, 2001;54 and Donovan, 1999;55 VA | Before-and-after treatment study | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Fontana, 1997;56 VA | Quasi-experimental observational | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Forman, 1990;57 Department of Public Health and Massachusetts Department of Veterans Services | Descriptive article | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Jain, 2014;58 Jain, 2016;59 and Jain, 2015;60 VA | Observational study | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Joseph, 2015;61 VA | Letter describing programme | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Otis, 2009;62 VA | Before-and-after study (pilot) | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Plagge, 2013;63 VA | Before-and-after | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | ||||||||||||||

| Randall, 201564 | Observational | ✓ | ||||||||||||||||

| Walter, 2014;65 VA | Non-randomised comparison | ✓ | ✓ | |||||||||||||||

| Total number of studies | 2 | 11 | 5 | 4 | 2 | 5 | 7 | 3 | 4 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

The 20 remaining studies (24 articles) used designs typically regarded as less methodologically sound. These were primarily single-group designs, comprising the following: five observational studies (eight articles),36,47,51,52,58–60,64 five descriptive pieces,48,49,53,57,61 four before-and-after studies (five articles),50,54,55,62,63 two quasi-experimental studies,46,56 a critical review/guideline,44 a survey,45 a service evaluation35 and a non-randomised comparison. 65 Although these studies were not formally assessed for methodological quality, they were carefully considered and retained as important contributors to the evidence picture on models of care.

Across the total number of included studies (24 studies, 29 articles) in our review, publication years ranged from 1990 to 2016. Eighteen studies (23 articles) were conducted in the USA37–41,48–65 (17 of these were connected to the Veterans Health Administration, US Department of Veterans Affairs), three studies were conducted in Australia44–46 and two studies (three articles) were carried out in the UK. 35,36,47

Models of care

The majority of studies focused on integrated/collaborative care, or primary care models, to deliver services for veterans with PTSD. Other popular models were settings based, such as residential, inpatient, outpatient or day-care delivery. Multicomponent programmes, partnership working, peer mentoring, family systems models and community outreach were also described. Some studies reported more than one model of care (see Table 1).

Outcomes

Clinical measures related to PTSD were the most frequently reported. Others included intervention access and uptake, service use, and perspectives or satisfaction related to the intervention. Various measurement tools were used.

The next section of this chapter begins with an examination of studies that were subject to full quality assessment. We then provide an overview of the remaining studies. For all studies, we review the setting, the model of care (guided by the stage 1 framework, see Appendix 3) and the outcomes as reported in the studies. When possible, we identify the authors’ conclusions and, for the more robust study designs, we provide our assessment of reliability. We signpost any material differences in coverage between the more robust and less methodologically sound study designs. We conclude with a summary of the evidence, identifying where this best demonstrates effectiveness of models of care for UK armed forces veterans with PTSD.

Evidence from the randomised controlled trials

Three RCTs (four papers)37–40 were included. One RCT was well conducted and was rated as being at a minimal risk of bias; the other two trials had risks of bias which may affect the reliability of their findings. 37 Full details of the RCTs and their quality are presented in Tables 2 and 3.

| Study details (first author) | Stage 1 category and characteristics of models of care as described by authors | Outcomes, measures and summariesa | Commentaryb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care | |||

|

Schnurr, 201337 Country: USA Setting: primary care/VA clinic/multiple sites Evaluative/descriptive: evaluation Type of publication: RCT Participants: n = 195 |

Stage 1: co-ordinated, integrated, collaborative, networks, multidisciplinary care; primary care Comparisons: 3CM (collaborative care) including telephone care management vs. usual care 3CM: education and tools for primary care clinicians and staff; telephone care management for patients by a centrally located care manager to answer questions and promote treatment adherence; support from a psychiatrist who supervises care managers by telephone, provides consultation to primary care clinicians and facilitates mental health care referral; content specific to PTSD (not specified) Programme adapted from RESPECT-D for treatment of depression Usual care: not defined All primary care providers received 1-hour training on PTSD (diagnostic criteria, assessment, treatment) |

Outcomes and measures (at baseline, 3 and 6 months): primary outcome – PTSD symptom severity (measured by PDS). Secondary outcomes – depression (Hopkins Symptom Checklist-20), functioning [SF-12 or SF-36 (text and table 2 differ in the paper)], perceived quality of care (5-point scale), utilisation (electronic patient records, clinician consultation, technology codes, VA Decision Support System) and costs (VA Decision Support System, Fee Basis programme) Summary of results as reported by the author: veterans in the 3CM group were more likely to have mental health visits (p = 0.04), antidepressant prescriptions (p = 0.05) and refills (p = 0.03), and higher outpatient pharmacy costs (p < 0.001). Over a 6-month period, no differences were found between 3CM and usual care for PTSD symptoms, depression or functioning. 3CM was associated with a lower perceived quality of PTSD care Treatments within each intervention package were delivered at the provider’s discretion. Summary of authors’ conclusions: careful examination of the way in which collaborative care models to treat PTSD are implemented is needed. Primary care providers need additional support to encourage them to manage PTSD Authors’ research recommendations: not reported |

|

|

McFall, 2010;38 and McFall 200739 Country: USA; multisite VA clinics Single/multiple provider: single provider Evaluative/descriptive: evaluation Type of publication: RCT Participants: n = 943 |

Stage 1: co-ordinated, integrated, collaborative, networks, multidisciplinary care Comparison: IC vs. SCCs IC: individual smoking cessation treatment integrated within mental care for PTSD. Delivered by mental health clinicians (largely psychologists and social workers). Training was provided to those delivering the intervention SCC (usual care): VA smoking cessation clinics Full details of the interventions are provided in the paper |

Outcomes and measures: primary outcomes – 12-month prolonged abstinence from tobacco between 6 and 18 months post randomisation (self-report with bioverification when possible). Secondary outcomes – 7- and 30-day point prevalence abstinence (self-report with bioverification when possible), severity of PTSD (CAPS and PCL), depression (PHQ-9), number of treatment sessions (VA electronic records), use of cessation medications (self-report) Summary of results as reported by the author: IC was more effective than SCC for prolonged abstinence (adjusted OR 2.26, 95% CI 1.30 to 3.91; p = 0.004). Differences in 7-day and 30-day point prevalence abstinence (favouring IC) were largest at 6 months (16.5% vs. 7.2%, p < 0.001; 13.8% vs. 5.9%, p = 0.001, respectively) and remained statistically significant at 18 months. The number of counselling sessions and days of cessation medication explained 39.1% of the treatment effect. Psychiatric status (including improvements in PTSD symptoms in both groups) did not differ between the groups at 18 months’ follow-up The authors reported that a small minority of IC clinicians did not deliver the treatment as designed, which may have led to less favourable IC outcomes. There were no significant differences in adverse events between IC and SCC groups Summary of authors’ conclusions: among smokers with military-related PTSD, integrated care involving smoking cessation treatment and mental health care resulted in greater prolonged abstinence than specialised cessation treatment alone Authors’ research recommendations: not reported |

|

| Community outreach | |||

|

McFall, 200040 Country: USA Single/multiple provider: single provider – large urban VA medical centre Evaluative/descriptive: evaluative Type of publication: RCT Participants: n = 594 |

Stage 1: community outreach Intervention group: mailing followed by direct telephone contact. The mailing included information about locally available PTSD treatment services, an invitation to seek care and details of how participants could respond. Direct telephone contact (by the study co-ordinator 1 month after the mailing) included a 15-minute survey covering treatment history, awareness of mental health resources, barriers to access and willingness to receive further information about specialised services Control group received the telephone survey 6 months after the intervention group received the mailing |

Outcomes and measures: participant enquiries (return of postcards, telephone calls), arrangement of an intake appointment with a mental health provider (verbal agreement with the study co-ordinator), attendance at intake assessment session at the VA centre and attendance at one or more VA treatment follow-up sessions (medical centre electronic records). Outcomes were measured within 6 months of mailing to the intervention group Summary of results as reported by the author: compared with the control group, veterans in the intervention group were significantly more likely to arrange an intake appointment (28% vs. 7%; p < 0.001), attend the appointment (23% vs. 7%; p < 0.001) and to attend at least one follow-up treatment session (19% vs. 6%; p < 0.001). Barriers to accessing treatment were identified as personal obligations, inconvenient clinic hours and receipt of treatment from a non-VA provider Summary of authors’ conclusions: an inexpensive outreach intervention can increase use of mental health services by underserved veterans with PTSD. This model may be useful for other populations with chronic mental illness Authors’ research recommendations: not reported |

|

| First author, year | (1) Was the allocation sequence adequately generated? | (2) Was the allocation adequately concealed? | (3) Were baseline outcome measurements similar? | (4) Were baseline characteristics similar? | (5) Were incomplete outcome data adequately addressed? | (6) Was knowledge of the allocated interventions adequately prevented during the study? | (7) Was the study adequately protected against contamination? | (8) Was the study free from selective outcome reporting? | (9) Was the study free from other risks of bias? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Collaborative care | |||||||||

| Schnurr, 201337 | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Low | Unclear | Low | Low |

| McFall, 2010;38 and McFall, 200739 | Low | High | Low | Low | High | High | High | Low | Unclear |

| Community outreach | |||||||||

| McFall, 200040 | Low | Unclear | Unclear | Low | Low | Unclear | High | Low | Unclear |

Models of care covered collaborative primary care-based delivery, integrated mental health care and lifestyle behaviour treatment and community outreach. Outcomes comprised clinical outcomes (including PTSD-related outcomes and smoking abstinence), intervention access and service uptake. All studies were conducted in the USA in the context of the Veterans Health Administration (US Department of Veterans Affairs).

Collaborative/integrated types of care were the focus in two RCTs (three articles). 37–39 The first RCT by Schnurr et al. 37 (195 participants) focused on a three-component model (3CM) (a programme of education and support for primary care clinicians and staff across multiple sites) with additional telephone care management for patients and staff. 3CM included PTSD-specific content, but this aspect was not described in detail. The combined intervention was compared with usual care (not defined), and all interventions were delivered at the provider’s discretion. Results for health care use showed that veterans in the 3CM group had higher numbers of mental health visits, higher numbers of antidepressant prescriptions, higher numbers of refills and higher costs relating to outpatient pharmacy. There were no differences between 3CM and usual care in PTSD symptoms, depression or functioning over a 6-month period, but 3CM was associated with lower perceived quality of PTSD care. This was a well-conducted trial with low risk of internal bias; however, generalisability may be limited to a US Veterans Affairs (VA) population of middle-aged males. The study authors emphasised the need to support primary care providers in managing PTSD; they also suggest that future attention to intervention fidelity (how interventions are delivered in practice) is required. The authors’ conclusion seems reliable.

Another form of collaborative/integrated care was investigated in the second RCT by McFall et al. 38,39 (943 participants). In this study, individual smoking cessation treatment was integrated with mental health care for PTSD and compared with services delivered by VA smoking cessation clinics (usual care). The authors stated that not all treatments were delivered as designed. Integrated care was associated with greater prolonged abstinence from smoking, and also with higher rates of prevalence abstinence at 6 months, which remained statistically significant at 18 months (although this was mediated by the number of counselling sessions and days of cessation medication). Improvements in PTSD symptoms did not differ between the study groups at 18 months and there were no significant group differences in adverse events. The authors suggest that integrated mental health care and smoking cessation in veterans with PTSD is a promising intervention. This conclusion reflects the evidence presented, but some potential bias in the conduct of the trial may limit its reliability. Generalisability beyond older male Vietnam-era veterans with chronic PTSD and co-occurring depression may be limited; mediation or contamination by concurrent intervention was possible; and issues of variable implementation may affect claims to intervention effectiveness.

The remaining RCT conducted by McFall et al. 40 focused on 594 participants receiving community outreach from a large urban US VA medical centre. The intervention group received mailed information about available PTSD treatment and an invitation to seek care, followed by telephone contact and a survey 1 month later. This group was compared with a control group receiving only the telephone survey 6 months after the intervention group mailing. Access to (and uptake of) treatment was higher in veterans in the intervention group; these participants were also more likely to attend follow-up treatment sessions. Barriers to accessing care included personal obligations, inconvenient appointment times and receipt of treatment from elsewhere. The authors suggested that low-cost outreach can increase mental health service use by underserved veterans with PTSD. The reliability of this conclusion may be limited because of potential bias arising in the conduct of the trial. Generalisability beyond male Vietnam veterans in receipt of VA disability benefits for PTSD may be limited.

Qualitative evidence

Service user perspectives on peer support (defined as ‘. . . a model of care in which patients “in recovery” from an illness provide emotional, instrumental, and informational support to patients with the same disorder’) was the focus of a well-conducted qualitative study by Hundt et al. 41 The views of 23 participants were sought on perceived benefits, drawbacks and favoured programme characteristics of peer support (reported primarily as group delivery) when incorporated into existing PTSD programmes at a US VA PTSD clinic. In general, views about peer support were positive at all stages of the care process. Perceived benefits included improved social support and understanding, purpose and meaning (for peer supporters); normalisation of PTSD symptoms; and feelings of hope and therapeutic benefit as a result of talking to others. Peer support also helped to initiate professional treatment. Reported drawbacks were largely related to uneasiness about group dynamics and trusting others. Preferences were expressed for strong leadership and separate peer support provision according to type of conflict, trauma (combat or sexual) and gender. The authors’ conclusion, suggesting that peer support is an acceptable complement to other PTSD treatments, seems reliable. Generalisability to a wide range of veterans (including those beyond the VA system) is plausible. Details of this study and quality assessment are presented in Tables 4 and 5.

| Study details (first author) | Stage 1 category and characteristics of models of care as described by authors | Outcomes, measures and summariesa | Commentaryb |

|---|---|---|---|

| Peer support | |||

|

Hundt, 201541 Country: USA Single/multiple provider: single provider – VA PTSD clinic Type of publication: qualitative study Participants: n = 23 |

Stage 1: peer support Peer support incorporated into existing PTSD programmes Peer support is defined as: |

Outcomes and measures: perceived benefits, drawbacks and desired programme characteristics (one-time qualitative interview in person or by telephone) Summary of results as reported by the author: overall, veterans were positive about peer support. Benefits included improved social support and understanding, the provision of purpose and meaning (for peer supporters), normalisation of PTSD symptoms and feelings of hope, therapeutic gain through the process of opening up to others and helping to initiate professional treatment. A few perceived drawbacks were largely related to uneasiness about peer group dynamics, fears about prejudice and difficulties trusting others. In general, peer support was considered valuable at all points in the care process (before care to increase initiation of treatment, during care to encourage adherence and after care to help maintain skills learned). Strong leadership was considered important and separate peer support groups were preferred according to type of conflict, type of trauma (combat or sexual) and gender Summary of authors’ conclusions: veterans found peer support to be highly acceptable as a complement to existing PTSD treatments, with only a few drawbacks Authors’ research recommendations: future focus on patient satisfaction with peer support and effectiveness; more attention to the most effective structure and format of peer support |

|

| First author, year | (1) Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research? | (2) Is a qualitative methodology appropriate? | (3) Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research? | (4) Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research? | (5) Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue? | (6) Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered? | (7) Have ethical issues been taken into consideration? | (8) Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous? | (9) Is there a clear statement of finding? | (10) How valuable is the research? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Peer mentoring | ||||||||||

| Hundt, 201541 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Cannot tell | Yes | Yes | Yes | Contributions to research and practice are reported |

In summary, limited evidence suggests that the most promising model of care is a collaborative arrangement that provides staff and patient support, and additional help to facilitate good care management, resulting in improved uptake of health care by veterans. The positive impact on smoking abstinence of integrated care, incorporating mental health care with smoking cessation treatment, is encouraging but less well substantiated, as is the effect of community outreach on increasing treatment access and uptake. Generalisability of these systems of care outside the VA setting and to younger, female veterans returning from conflicts other than Vietnam may be limited. There appears to be good evidence suggesting that peer support can be an acceptable complement to other PTSD treatments and this type of care delivery may be generalisable to a range of veteran populations. There was no clear evidence of effect for models of care on PTSD symptoms or other mental health outcomes.

Overview of the remaining included study designs

Twenty studies (24 articles) provided further information on models of care. 35,36,44–65 Various study designs (primarily involving single groups) were used, including quasi-experimental, before-and-after studies, observational designs and descriptive pieces. Sample sizes (when reported) ranged from 6 (patients) to 696,379 (administrative data). These studies were not assessed for methodological quality, but were considered important contributors to the evidence picture and are reviewed below.