Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal.The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/05/12. The contractual start date was in March 2016. The final report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Preston et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

The emergency department (ED) setting has long been acknowledged as a complex setting in which to deliver care to older people. The difficulties of delivering care have to be viewed alongside the more general challenges that are facing NHS EDs. In 2013, NHS England set out a strategy for an urgent care system that was:

more responsive to patients’ needs, improves outcomes and delivers clinically excellent and safe care.

This strategy also needs to be viewed alongside the UK government target of 95% of all ED patients being discharged, transferred or admitted within 4 hours of presenting at an ED.

The delivery of safe and appropriate care to older patients in the ED has a number of challenges. Older patients are not a homogeneous group. They encompass a wide age range and are a diverse group in terms of their general health and presenting complaints. The National Service Framework: Older People2 describes older people as being in one of three groups: entering old age (still living an active and independent life), transitional (between healthy active life and frailty) and frail older people (vulnerable as a result of health problems or social care needs).

This review is focused on the delivery of care to this last group (frail older people). Set within the context of increasing demand and pressure on the delivery of care in the ED, frail older people are a group who present a specific challenge to the ED. First, older people are more likely to present to the ED and, second, once they are in the ED, they present a specific set of challenges to the delivery of safe and effective care.

In terms of the volume of demand that older people place on the ED, this is in part a result of the ageing population. There has been an increase in the absolute and relative numbers of older people in the general population as people are living to an older age. The University of Sheffield undertook a rapid review on urgent care for the National Institute for Health Research, which found that frail older people use emergency care more frequently (especially those who are aged > 80 years and those who are acutely unwell or in the last year of life). 3 Gruneir et al. 4 report on the disproportionate use of the ED by older age groups compared with younger age groups. However, this disproportionate use is not inappropriate: both medical and non-medical reasons underpin the reliance of this group on the care provided in EDs. A recent literature review commissioned by the NHS Confederation,5 which examined the evidence on how to improve urgent care for older people, found that demand on the ED from older people is not simply related to their need for urgent and emergency care; it is also related to the care that they receive (or do not receive) elsewhere in the health-care system. Examples of the types of interventions that might reduce demand on EDs include preventing ED admission through ambulatory triage, referring older people directly to a ward, a medical assessment unit or elderly care unit, delivering appropriate care within a home/community setting (a nursing home or their own home) and preventing readmissions when older people are discharged from acute medical care through interventions delivered in the home.

Once older people present to the ED, they present a specific set of challenges in terms of their management and care. Older people are more likely to have long-term conditions and multiple morbidities and they are often taking multiple medications. They may have disabilities that make the fast-moving nature of the ED highly unsuitable. They are also more likely to have dementia, or present with delirium, and this is often alongside the presenting complaint that has required them to seek emergency care. Older patients can also often present non-specifically5 and are therefore difficult to diagnose and treat accordingly. Underlying all of this is that a number of older patients are frail and the ED faces difficulties in identifying those who are frail and delivering appropriate care to them. Once frail older people are in the ED, it becomes critical to manage their presenting complaint in the context of their frailty. A recent Lancet editorial6 outlined the four issues facing EDs in their management of frail older people: (1) timely recognition of frail patients is difficult; (2) there is no standard definition for frailty; (3) frail older people need to be treated in the context of their frailty as opposed to treating them only according to their presenting complaint; and (4) there are a lack of clinical guidelines for treating frail older people in the ED.

Identifying frail older people is highly challenging and this challenge is acknowledged widely in the academic literature: ‘. . . there is no single operational definition of frailty that can satisfy all experts’. 7 There is no set age threshold for when an older person becomes frail; however, Dent et al. 8 suggest that frailty is present in around one-quarter of people aged > 85 years. Carpenter et al. 9 discuss how chronological age is often seen as synonymous with biological age and the majority of research studies consider people aged ≥ 65 years as a homogeneous population. In an evidence review examining discharge interventions, Lowthian et al. 10 found three groups of older people in the literature: (1) patients stratified by age (which varied from ≥ 65 years to ≥ 75 years); (2) vulnerable people within these age categories; and (3) older people who had been screened and were considered to be at high risk.

Some clinicians and academics believe that frailty can be defined using a set of clinical indicators (e.g. patients with multimorbidity or an increased risk of falls). Others believe that frailty is more closely linked to changes in the physiology of older people (accumulated deficits). However, what is widely acknowledged in the literature is the need to manage these patients with their frailty considered alongside their presenting complaint. 8,11 There are numerous reasons for this, such as the need to avoid polypharmacy,12 the need for follow-up care for patients and the high rate of readmission of frail patients. 13 It is known that frail patients have worse outcomes than the general population of older people if they attend the ED. Maile et al. 14 cite 46% mortality for frail older people within a year of them attending the ED.

Therefore, the scope of this review is how best to manage frail older people within the ED. This will allow us to map interventions to identify frail older people and those at high risk of adverse outcomes, study the management of frail older people in the ED and examine the potential for improvements in both patient and health service outcomes.

The research questions for the review were as follows:

-

What is the evidence for the range of different approaches to the management (identification and service delivery interventions) of frail older people within the ED?

-

Is there any evidence of their potential and actual impact on health service and patient-related outcomes, including impacts on other services used by this population and health and social care costs?

Additional research questions included:

-

What specific approaches to the management of frail older people exist within the ED?

-

What evidence is there that these approaches to management within the ED could influence attendance and/or reattendance rates in frail older people, hospital admission and/or readmission rates in frail older people, patient-centred outcomes in frail older people and costs to the health service?

-

What evidence is there that these approaches to management within the ED could influence other health service outcomes (as reported in the literature and as mentioned as important by the clinical academics/topic experts) and is there evidence of any unintended outcomes (such as the displacement of care) as a result of how frail older people are managed in the ED?

Chapter 2 Review methods

This chapter describes the methods utilised in our evidence synthesis. These are:

-

protocol development

-

literature search

-

choice of review methodology

-

study selection

-

study classification

-

data extraction

-

synthesising evidence

-

assessment of the evidence base

-

use of internal and external experts.

Protocol development

The protocol was developed following the suggestion of the review topic by the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) review commissioners. The protocol was developed by the team at the School of Health and Related Research (ScHARR), led by the review author. The protocol was shared with our internal team and our topic experts, as well as with the HSDR team. Suggested changes were made and the final protocol was produced in June 2016. Following this, the review was registered with PROSPERO (reference number CRD42016043260).

Literature search

The review started with the search for evidence and three search iterations were undertaken to efficiently identify relevant evidence for the review. The review team was already aware that the topic had a substantial evidence base in terms of the quantity of evidence, with a number of evidence reviews already published. Therefore, the search strategy had to be designed in light of these considerations and in light of the fact that the aim of the review was to systematically map the current evidence base.

Stage 1: search of evidence retrieved for earlier review and scoping search

An initial search (in May 2016) was undertaken using the evidence base retrieved for the Turner et al. 3 review. These references were filed in an EndNote library (version 8; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and this was searched using terms for older people and frail older people. The purpose of this search was to provide an initial idea of the size and scope of the available literature and to refine search terms for the database search. The following keywords were searched for in the title of the references: ‘ageing’, ‘aged’, ‘elderly’, ‘frail’, ‘old’ and ‘geriatric’.

Additionally, a search was conducted in May 2016 in MEDLINE (via OvidSP) for reviews and other relevant literature; it was developed using pre-existing search strategies, used for reviews in the same topic area, devised by information specialists at the University of Sheffield. The search was structured using terms for population (frail older people) and setting (ED). The search was not limited by intervention type as an a priori decision about which interventions were to be included could have limited our understanding of the scope of the topic. The search was limited to evidence published from 2005 to 2016 to ensure currency of the included research and limited to English-language-only papers as time constraints meant that it would not have been feasible to translate non-English-language papers. The search was not limited to any specific geographical region as published search filters to identify evidence from specific countries are not always successful. The MEDLINE search strategy is provided in Appendix 1.

Stage 2: search of health and medical databases

The second search, undertaken in July 2016, involved a wider range of health and medical databases. The following databases were searched, with the MEDLINE search adapted appropriately for the different databases:

-

EMBASE via OvidSP

-

The Cochrane Library via Wiley Online Library

-

Web of Science via Web of Knowledge via ISI

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCOhost

-

Health Management Information Consortium via OpenAthens

-

PROSPERO.

Stage 3: complementary searching

We also undertook a number of complementary searches (in autumn 2016) to ensure that we had retrieved all relevant evidence for the review. These included scrutiny of reference lists of included papers and relevant reviews. Any relevant papers that were within our date range were obtained and, if they met the inclusion criteria, were included in the review. The reviews used for this exercise are detailed in Appendix 2. In addition, we undertook citation searching of included primary studies that focused on a frail or at-risk population.

Choice of review methodology

Based on our knowledge of the volume of evidence on interventions for older people in the ED and the need to generate a useful review product for the HSDR programme and the ED/frailty community, a systematic mapping review was selected as the most appropriate evidence product. 15 The appropriateness of the mapping review methodology was based on the diverse and diffuse evidence base and the need to ‘collate, describe and catalogue available evidence relating to a topic or question of interest’. 15 The aim of a mapping review is to ‘map out and categorize existing literature from which to commission further reviews and/or primary research by identifying gaps in research literature’. 16

Study selection

Studies were included in the review according to the inclusion and exclusion criteria in Table 1.

| Category | Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria |

|---|---|---|

| Population |

|

Aged < 65 years |

| Intervention |

|

Interventions that are delivered wholly outside the ED |

| Outcome | The study had to report either patient or health service outcomes. Qualitative studies that report service user views or experiences of specific interventions would be included | Studies that do not report an outcome of an intervention; for example, a study that reported only the mean age of people being treated in an EFU would not be included. Qualitative evidence providing general experiences of ED care of (frail) older people would not be included, unless relating to a specific intervention |

| Setting | Delivered within the ED or units embedded in the ED | Delivered in community/home settings or ambulatory care |

| When patients are admitted (e.g. medical assessment units and frailty units) | ||

| Study type |

|

|

Screening criteria

We limited the evidence included in our review to that published from 2005 to 2016. The reason for this was related to the volume of evidence in the area and the need to retrieve a manageable evidence base. In addition, earlier evidence would have been identified and included in the many evidence reviews published in this area. Restricting the date ensured that the evidence included was relevant to the current clinical environment.

Notably, the review does not include ‘frail older people’ as an inclusion criteria. Throughout the process of the review, from the development of the protocol onwards, it became clear that identifying papers that had a population of frail older people according to predefined criteria would be challenging. Had we included only evidence from papers in which the authors had defined their population as frail, or their intervention as targeted at frail older people, then we would have limited the review, as scrutiny of titles and abstracts often did not reveal the population included. Therefore, we took the approach at the screening stage to include all studies in which the population was aged ≥ 65 years and then, at a later stage, further divided these studies into those including frail older people and those including a general population of older people.

Screening process

Screening was undertaken by three reviewers (LP, AC and DC). All titles and abstracts retrieved by the searches were entered into EndNote and EndNote was used for screening. All titles and abstracts were screened by one reviewer (either LP or AC), with DC screening 50% of the titles and abstracts screened by LP and 50% of the titles and abstracts screened by AC (i.e. 50% of all titles and abstracts). The decisions made about whether articles should be ‘included’, ‘excluded’ or ‘queried’ were noted in EndNote. Any queries were discussed with a fourth reviewer (JT) until consensus was reached. The inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to guide this discussion. Queries tended to be around the setting of an intervention and whether or not it was delivered in an ED setting. Articles that met the inclusion criteria that were (systematic) reviews were also marked as ‘include’ and background articles were also identified. To check the screening consistency of the two reviewers, a third reviewer screened approximately 50% of the references as detailed above and a kappa coefficient was calculated.

Study classification

Following the screening process, a list of included studies was drawn up. Full-text papers were obtained for all of the included studies and an examination of titles, abstracts and full texts was undertaken. As this review was a systematic mapping review, it was important to classify the evidence in order to develop a better understanding of the evidence base. It became clear that there was not a clear definition of the population of frail older people and so the review would need to include evidence on a wider population of older people (generally aged ≥ 65 years). In addition, this classification allowed the review team to divide articles into two categories: (1) those looking at the identification of frail older people or older people at high risk and (2) those looking at service delivery interventions to better manage older people and frail older people in the ED.

Data extraction

Once the final list of included studies had been determined, data extraction was undertaken by one of four reviewers (AC, LP, DC and FC). As this review was a mapping review, the focus was on extracting data that described interventions and their outcomes, rather than on numerical estimates of effectiveness. Therefore, single data extraction was an appropriate method as it can be undertaken with limited risk to the interpretation of results and findings from individual studies.

A standardised approach was developed and a data extraction form was developed for all of the three types of data extraction undertaken. These were:

-

full data extraction for all studies on population groups defined as frail older people or older people at ‘high risk’ by the study authors

-

brief data extraction for all studies on a population of older people, normally aged ≥ 65 years, without any specific risk criteria

-

brief data extraction for all relevant reviews that met our review inclusion criteria.

All of these data extraction tables were tested and refined by the review team. When it was clear that a conference abstract was related to a study that was published later, the data from these publications were extracted together.

Bearing in mind the complexity involved in defining frailty and the varying views about how it should be measured and applied in clinical care, our approach was to use the definitions of frailty described by study authors, but to also include older patients defined by study authors as being at high risk alongside frail patients. This approach was required partly because of the lack of clear definitions in the literature about which groups were frail and which groups consisted of all older people, for example whether or not the existence of a specific condition (e.g. patients aged ≥ 65 years with a fall) meant that patients were considered to be frail, and partly because of the lack of research into older people with frailty both generally and specifically in terms of their use of Emergency and Urgent Care. 17

Therefore, the approach adopted by this review was to undertake a full data extraction on evidence that was clearly about frail or at-risk older people. However, as it became clear that focusing solely on this evidence would not allow the development of understanding about how different approaches might influence outcomes, a brief data extraction was undertaken on the interventions that targeted a general older population, aged ≥ 65 years. This approach extends what was outlined in the review protocol. The approach described in the review protocol was that ‘where evidence exists for other elderly populations, this may be extracted into evidence tables (depending on the volume of evidence retrieved) but not used in the evidence synthesis’. However, the review used this evidence in a more thorough manner to better map the range of interventions that may potentially be used for older people in the ED.

Synthesising evidence

Data were extracted and tabulated and summary tables were created. These were used to inform the narrative synthesis presented in Chapter 4. Because of the heterogeneity of study interventions and outcomes, it was not possible to undertake any formal meta-synthesis. Data were synthesised by intervention type: interventions to identify patients as being frail or at high risk and interventions that changed the delivery of care to patients (service delivery innovations).

Assessment of the evidence base

This review aimed to map the evidence on interventions to identify and manage frail older people. Mapping reviews seek to characterise an evidence base, not compare interventions on the basis of their effectiveness. Although formal quality assessment is appropriate within the systematic review process to examine whether or not included studies may be at risk of bias, it is not required in a mapping review, as a mapping review does not interpret evidence to inform specific clinical questions or decisions. Indeed, use of a standard tool would not have been possible in this review because of the diversity of the study designs.

Rather than a formal quality assessment, we carried out a bespoke assessment of the evidence base using three distinct methods:

-

an examination of the research designs used and the strengths and limitations of those designs

-

an examination of the self-reported limitations included in the articles relating to frail or high-risk older people

-

an assessment of the relevance of the evidence to the contemporary UK NHS setting.

Use of internal and external experts

Our review used internal and external experts. Within ScHARR, three very experienced professors of emergency medicine, who are also practising ED consultants, advised on the research questions and the protocol and commented on the summary documents for the final report. In addition, we were aided by the Sheffield Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust Clinical Research Office Online Patient Advisory Panel who read and commented on our plain English summary and scientific summary.

Changes from the protocol

The protocol was developed prior to extensive literature searching and the choice of a mapping review methodology was made by the research team once the volume of evidence, diversity of study designs and heterogeneity of the evidence was clear. The choice of a mapping review impacted on two main areas: how evidence from other systematic reviews was used and how quality assessment was handled.

A more methodical approach to handling evidence from relevant reviews was adopted. Rather than simply mapping reviews against primary studies, as per the protocol, we used relevant reviews (whether systematic or not) as a source of evidence to locate additional papers for this review. In addition, when reviews matched the inclusion criteria for this review, these data were extracted and review findings were summarised in the results.

The review protocol stated that the Cochrane risk-of-bias tool would be used for quality assessment. However, this tool is appropriate only for a selected number of study designs, few of which were used by the studies reported in the review. As stated earlier, formal quality assessment using a validated checklist is not a standard feature of a mapping review. Therefore, we developed criteria to assess the evidence base, which are described in Chapter 4, Assessment of the evidence base.

Chapter 3 Results: included and excluded studies

This chapter details the studies that were included in, and excluded from, the review.

Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses

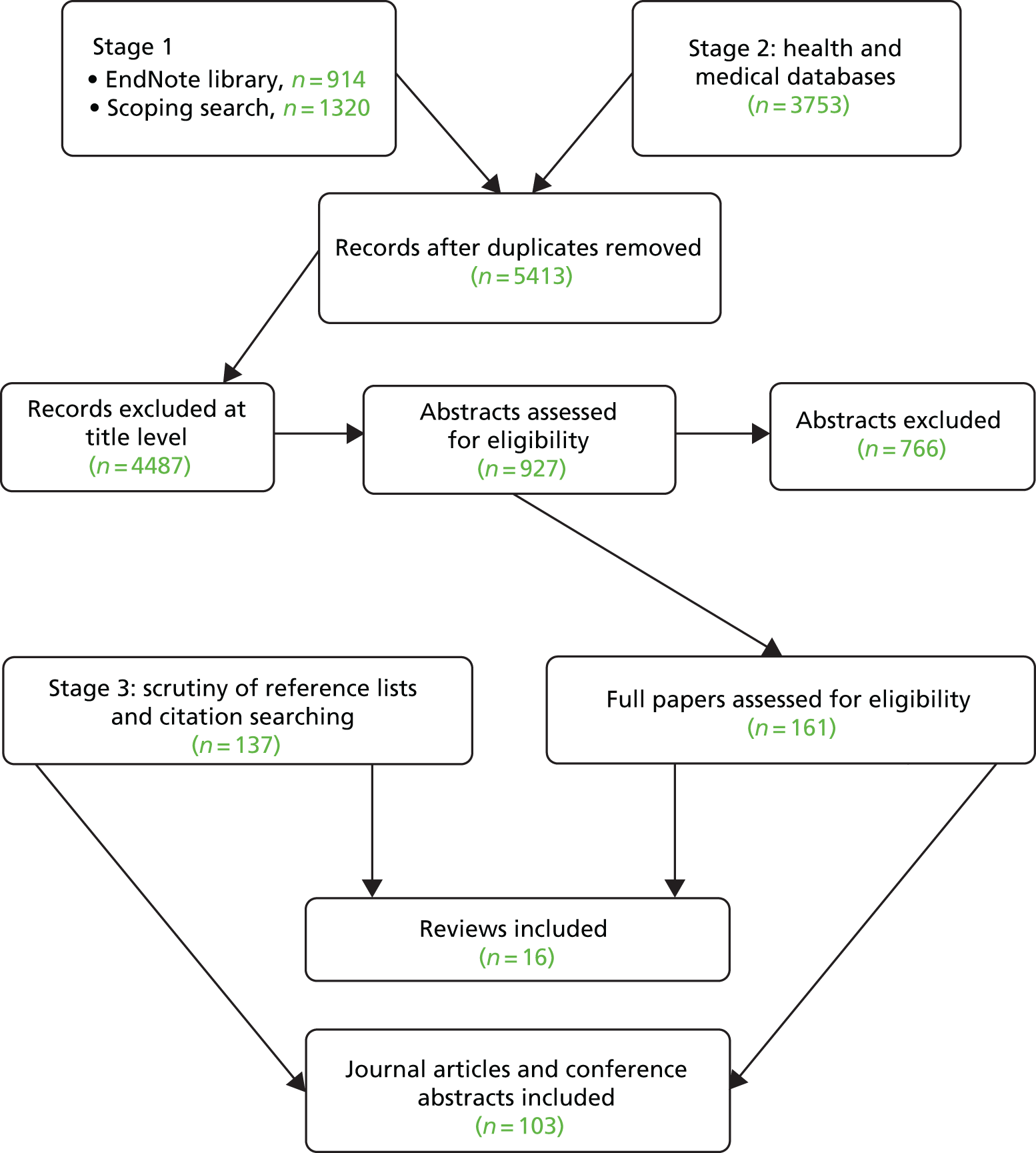

The full papers, conference abstracts and reviews identified as a result of the literature search are described in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow diagram in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Modified PRISMA flow diagram.

Second screening of retrieved references

A kappa coefficient was calculated for the double screening process, demonstrating good agreement between the reviewers [κ = 0.794, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.665 to 0.929].

Studies included in the review

A total of 103 papers (full journal articles and conference abstracts) and 16 reviews were included in the review. Further details of the characteristics of these studies are provided in Chapter 4.

Studies excluded from the review

A list of the full-text studies and conference abstracts excluded from the review and the reasons for their exclusion is available in Appendix 3.

Chapter 4 Results of the review

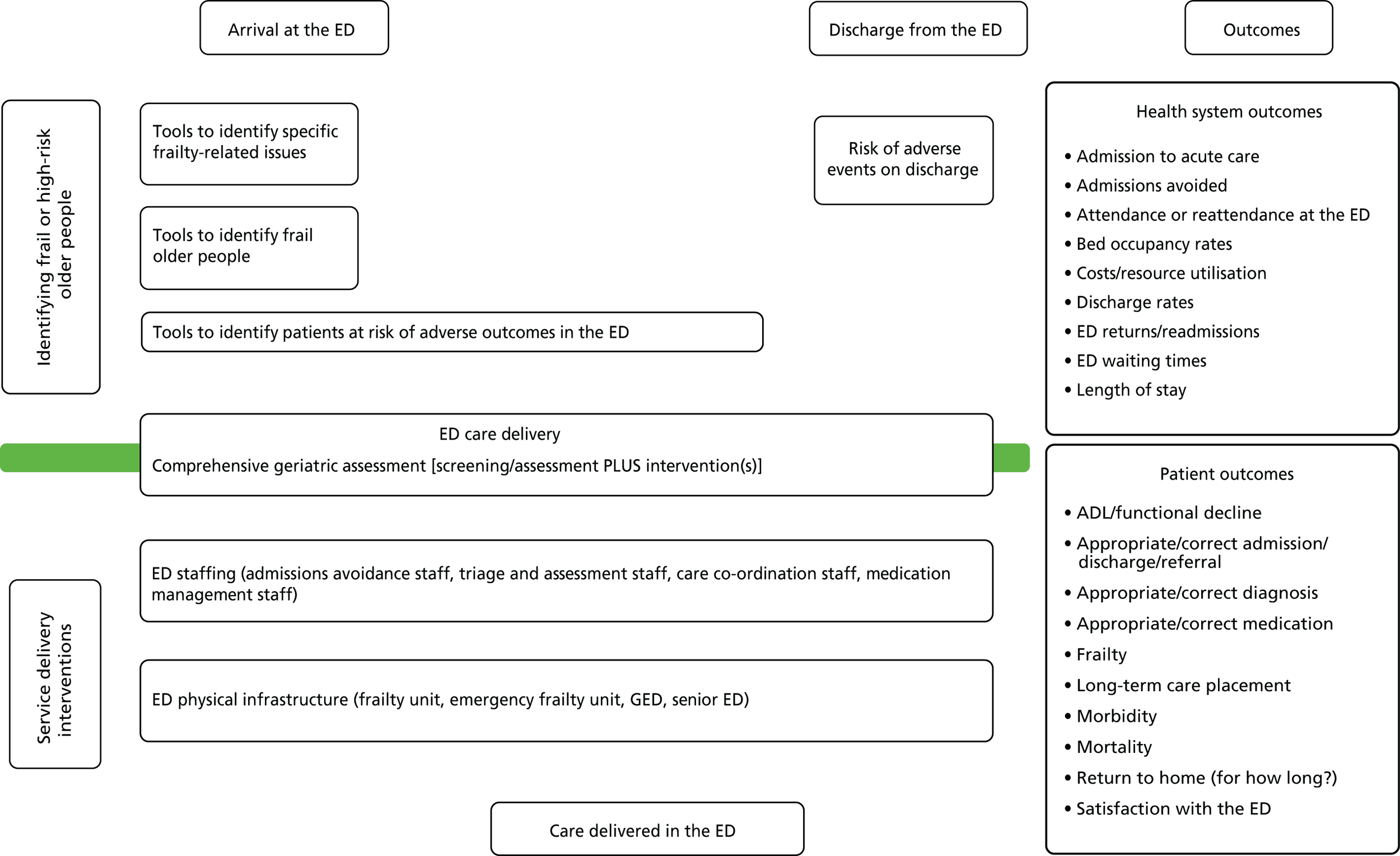

This chapter presents the main results from the review, related to:

-

the overall evidence base

-

the characteristics of included studies (identification of frail/at-risk older people and service delivery innovations for this group)

-

a narrative summary of the evidence

-

a patient pathway diagram

-

an assessment of the evidence base.

Characteristics of the overall evidence base

In total, 103 articles,18–120 representing 90 studies, were included in this systematic mapping review. Detailed data extraction tables of included studies are provided in Appendices 2, 4 and 5.

There were 61 full papers,19,21,23,27–29,33,35,36,38–43,49–61,63–65,68,69,71–73,76–82,86,88–90,93,95,101,106,108,110,112–117,119,120 38 conference abstracts18,20,22,25,30,32,34,37,45–48,62,66,67,70,74,75,83–85,87,91,92,94,96–100,102–105,107,109,111,118 and four papers24,26,31,44 classified as ‘other’ (letters to the editor and editorials containing data).

Of the 92 studies reported in the 103 articles/conference abstracts, 32 included a frail or high-risk population21–25,27,29,30,49,50,52–54,61,62,67,68,71–75,78,83,86–90,98,99,102–104,106,112,114,118,119 and 60 included a population of older people. 18–20,23,26,28,31–48,51,55–60,63–66,69,70,76,77,79–82,84–97,100,101,105,107–111,113,115–117,120

Thirty-seven studies18–23,27–60 reported on interventions to identify frail or high-risk older people. These comprised diagnostic tools to screen for frailty-related issues (n = 720,22,27–33), diagnostic tools to screen for frailty (n = 718,34–39), prognostic tools to measure the risk of adverse events in the ED (n = 523,40–43) and prognostic tools to measure the risk of adverse events on discharge (n = 1819,21,44–60).

Interventions to manage older people and frail older people in the ED were reported in 53 studies: 21 examined changes to ED staffing,26,61–85 11 examined changes to the physical infrastructure of the ED,86–97 18 examined changes to how care was delivered24,25,98–117 and other interventions were reported in three studies. 119–121

The majority of the studies were undertaken in the USA (n = 2718,19,35,36,38–40,45,46,48,57,59,64,66–68,70,84,91–94,96,97,113,114,116,119,120), the UK (n = 1420,61,62,72,74,83,86,88,89,95,98,102–106,117) and Australia (n = 1026,44,60,63,73,76–80,82,110). The UK studies were more likely to focus on frail or high-risk older people (n = 11). Other studies were undertaken in Italy (n = 721,27,49,58,90,111,118), Canada (n = 628,37,47,51,52,65), Ireland (n = 534,69,71,75,107), Switzerland (n = 322,33,42,53,54), the Netherlands,32,55 Singapore,112,115 Hong Kong,25,108,109 Spain,87,99 Sweden24,31 and France41,81,85 (all n = 2) and Belgium,56 Germany,50 New Zealand,29,30 South Korea,23 Taiwan100,101 and Turkey43 (all n = 1).

A wide number of study types were utilised. Table 2 gives the study designs and number of studies of each type. No studies on the cost-effectiveness of interventions to identify and manage older people in the ED were located in the evidence base.

| Experimental studies | Observational studies | Unclear |

|---|---|---|

|

|

|

Table 3 highlights that the main group that interventions were targeted at was adults aged > 65 years with no specific condition.

| Age category | Studies (n) |

|---|---|

| ≥ 65 years | 44 |

| ≥ 65 years with trauma/acute condition | 4 |

| ≥ 65 years with fall/chronic condition | 3 |

| ≥ 65 years with positive diagnosis of ‘at risk’ | 3 |

| ≥ 65 years with, or ≥ 70 years without, chronic condition | 4 |

| ≥ 70 years | 5 |

| ≥ 72 years | 1 |

| ≥ 75 years | 11 |

| ≥ 75 years, frail/multiple comorbidities | 2 |

| ≥ 80 years with syndromes described as geriatric | 2 |

| ≥ 85 years | 1 |

| No age category | 10 |

| Total | 90 |

Although it was not possible to undertake a numerical analysis of the mean or median age of the population of older people studied in the review, because of the incomplete reporting of data, it is possible to say that, although interventions tended to be targeted at those aged > 65 years (considered to be older people in the literature), the average age of study participants (and, therefore, those benefiting from interventions) was much higher, generally around 80 years of age.

Studies were categorised as being related to either the identification of frail older people or changes to how ED services were configured or delivered. The classification of the service delivery interventions was based on how studies were reported in the included articles and the elements of service delivery that were researched. Fifty-eight of the studies focused on service delivery interventions and 37 on screening (diagnostic and prognostic). A further breakdown of these categories is given in Table 4.

| Category | Description | Studies (n) | Articles (n) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Screening | Diagnostic tools to identify frailty | 7 | 7 |

| Diagnostic tools to screen for frailty-related issues | 7 | 9 | |

| Prognostic tools to measure risk of adverse events in the ED | 5 | 5 | |

| Prognostic tools to measure risk of adverse events on discharge | 18 | 19 | |

| Service delivery interventions | Individual or team changes to ED staffing | 21 | 26 |

| Changes to the physical infrastructure of the ED | 11 | 12 | |

| Care delivery and assessment interventions (CGA) | 18 | 22 | |

| Miscellaneous | Various | 3 | 3 |

Characteristics of included studies: screening

Thirty-seven studies (40 publications18–23,27–60) dealt with strategies aimed at identifying patients with frailty or distinguishing higher- from lower-risk patients in the ED. The great majority of these studies assessed the diagnostic or prognostic accuracy of tools using a prospective or retrospective cohort design, which is an appropriate design for this type of study. Only one study (published as a conference abstract) used a randomised trial design18 and one was a secondary analysis of data from a randomised trial. 19 Both of these studies were conducted in the USA.

The largest group of studies came from the USA (n = 1218,19,35,36,38–40,45,46,48,57,59), followed by Canada (n = 528,37,47,51,52). Among European countries, the largest numbers of studies were performed in Switzerland (n = 322,33,42,53,54) and Italy (n = 421,27,49,58). The Netherlands (n = 232,55) was the only other European country with more than one included study. The only study included from the UK was a study of a screening tool that was reported in abstract form only. 20 Outside Europe, studies were included from Australia,44,60 New Zealand,29,30 Turkey43 and South Korea. 23

The numbers of patients included in screening studies ranged from 6918 to 2057. 21 Two other studies22,23 recruited > 1000 patients. Most studies recruited patients aged ≥ 65 years, but the average age of patients actually recruited was considerably older, typically in the mid-seventies or older (see data extraction tables in Appendices 4 and 5). The proportions of men and women included varied among the included studies.

Characteristics of included studies: interventions

Fifty-three studies (63 articles24–26,61–120) examined changes made to how ED services were delivered to populations of (frail) older people. These studies tended to investigate changes to the structure of the ED (n = 1186–97), changes to staffing in the ED (n = 2126,61–85) or changes to how care is delivered (n = 1824,25,98–117), such as the introduction of comprehensive geriatric assessment (CGA) or similar assessment-type interventions. There were also a number of unique interventions (n = 3119–121), which are also reported here.

The majority of the studies reported here were observational studies; predominantly before-and-after studies or cohort studies. Three studies reported results from randomised controlled trials (RCTs). 24–26

All of the studies reported either patient or health service outcomes that were derived from patient data, with the exception of one study,120 which reported changes in ED clinician prescribing behaviour. The main patient-related outcome measures were mortality, functional status, frailty and place of residence (own home or residential/nursing care). The main health service outcomes were admissions, readmissions, ED reattendance and length of stay.

The largest group of studies came from the USA (n = 1564,66–68,70,84,91–94,96,97,113,114,116,119,120), followed closely by the UK (n = 1361,62,72,74,83,86,88,89,95,98,102–106,117). Nine studies were undertaken in Australia. 63,73,76–80,82,110

Most studies reported outcomes for patients aged ≥ 65 years, as these patients were considered to be ‘older people’ and, therefore, the target age for identification of frailty or at risk of adverse outcomes. However, when a mean age was reported, this tended to be > 75 years (see Appendix 6; more detailed reporting of age is not possible because of variable reporting in the included articles). The proportion of men and women included varied among the studies.

Detailed analysis of study and intervention characteristics was hindered by the limited data in the included papers, many of which were conference abstracts.

Narrative synthesis of screening papers

The objective of using a diagnostic or prognostic screening tool as a supplement to clinical judgement is to improve the health-care provider’s ability to distinguish older people who are frail or at high risk of adverse outcomes from those who are not. Older people who are identified as frail can then be considered for specific management in the ED. A test to identify older people as frail in the ED setting needs to be both accurate and feasible to apply. The interventions that may be delivered to these groups are described in Diagnostic tools to identify frailty.

The evidence identified in this review showed that screening tests were used on both populations of older adults aged > 65 years and on populations that were already considered to be at high risk. We distinguished between:

-

studies that compared the findings of the test with those of a more comprehensive test (reference standard, i.e. diagnostic accuracy studies); these tended to be related to the identification of frailty or frailty-related issues

-

studies that evaluated the ability of the test to predict adverse outcomes during a period of follow-up (i.e. prognostic studies); these tended to be screening tests to identify older people at risk of adverse events in the ED or adverse events following discharge from the ED.

Further details of all of the studies can be found in the data extraction tables (see Appendices 2, 4 and 5).

Diagnostic tools to identify frailty

We included seven studies (nine publications20,22,27–33) of diagnostic tools to identify frailty (Table 5). These were studies that recruited a sample of older people attending the ED and assessed the accuracy of a screening tool against a reference standard.

| Study | Participants (n) | Tool | Reference standard | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Salvi et al.27 | 200 | ISAR | DAI | The ISAR tool had sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 63%. The ISAR tool is a useful screening tool for frailty and identifies patients who are at risk of adverse outcomes after an ED visit as well as those who are likely to benefit from a geriatric intervention |

| Asomaning and Loftus28 | 525 | ISAR | No reference standard | 271 patients (representing 51.6% of those eligible for screening) were screened with the ISAR tool. Low compliance by staff was a barrier to implementation of the tool |

| Boyd et al.29,30 | 139 | BRIGHT | CGA | The BRIGHT tool successfully identifies older adults with decreased function and may be useful in differentiating patients in need of comprehensive assessment |

| Eklund et al.31 | 161 | FRESH | Frailty indicators | Both sensitivity (81%) and specificity (80%) of the FRESH tool were high. The tool is simple and rapid to use, takes only a few minutes to administer and requires minimal use of energy by the patient |

| Wall and Wallis20 | 118 | CFS | Validated frailty scales | Analysis of ROC curves showed that the CFS accurately identified frail patients compared with other well-established frailty scales (AUC 89–91%) at appropriate cut-off points. Its implementation in the ED could increase the proportion of frail patients admitted directly to a geriatric ward |

| Lonterman et al.32 | 300 | ED screening tool | Safety management screening bundle | The ED screening tool has moderate validity compared with the screening bundle and can identify most older ED patients at high risk of adverse outcomes |

| Schoenenberger et al.22,33 | 1547 | EGS | ED diagnosis | Introduction of the EGS was associated with an increase in the detection of potentially overlooked geriatric problems. Adaptations to enhance feasibility and to ensure clinical benefit are needed |

The included studies evaluated a wide variety of screening tools. The Identification of Seniors at Risk (ISAR) tool was the only tool to be evaluated in two studies. 27,28 A diagnostic accuracy study27 reported that the ISAR tool had a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 63% relative to a frailty measure, the Deficit Accumulation Index (DAI). The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve was 0.92, indicating a good performance in identifying frailty based on the DAI definition. However, a study of the implementation of the ISAR tool in a Canadian ED setting found that only 51.6% of eligible patients actually received an ISAR screen. 28 This was attributed to the fast-paced nature of emergency care and lack of staff resources at night.

Other screening tools have been evaluated in single diagnostic accuracy studies. The Brief Risk Identification for Geriatric Health Tool (BRIGHT), developed in New Zealand, is an 11-item tool that showed a good ability to identify older people with ‘decreased function’ relative to a reference standard of CGA. 29,30 The limitations of this study, identified by the authors, include that it was a small, single-centre study and that 18% of patients who completed BRIGHT were lost to follow-up, raising the possibility of follow-up bias. BRIGHT is designed to be suitable for completion by the patient or a carer and used in combination with a particular type of CGA.

The only other fully published study of this type evaluated FRESH, which is a five-item tool (subsequently reduced to four items) that was specifically designed to screen for frailty. 31 FRESH was evaluated using a range of frailty indicators as reference standards and performed well, with both sensitivity and specificity being around 80%. The test takes only a few minutes to administer and requires minimal input from the older person. However, the tool has been evaluated in only one small study to date (n = 161) and the data were not collected during the ED visit but during a subsequent visit to patients at home. 31

Finally, of three diagnostic accuracy studies published only as conference abstracts, one was carried out in a UK setting. 20 This study used the Clinical Frailty Scale (CFS), a rapid and simple case-finding tool, to assess 118 older patients admitted to geriatric wards from the ED. The CFS performed well in comparison with established frailty scales at appropriate cut-off points. The authors suggested that use of the CFS as a triage tool in the ED could increase the proportion of frail older people admitted directly to geriatric wards (i.e. admitted earlier rather than later). However, although this was a study of a relevant population, data were not actually collected in the ED and patient management and outcomes were not evaluated. Thus, the value of this study by itself appears to be limited.

The other two conference abstracts evaluated an ED screening tool32 and an emergency geriatric screen (EGS). 22,33 The ED screening tool performed well, with an area under the curve (AUC) of 0.83 relative to a reference standard, described as a safety management screening bundle. However, few details of either tool were reported in the abstract. The second study used actual ED diagnoses as the reference standard and reported an increase in the detection of potentially overlooked geriatric problems compared with a control period.

Overall, the evidence for the diagnostic accuracy of tools for identifying frail older people is limited. None of the tools has been evaluated extensively using this methodology and differences in terminology make it unclear whether or not different studies are examining the same phenomenon. In addition, individual studies have different methodological features and settings, which may limit their internal or external validity. However, the evidence base using follow-up to evaluate the predictive abilities of these tools is more extensive and the evidence summarised here should be read alongside Prognostic tools for adverse events after discharge.

Diagnostic tools to identify specific frailty-related issues

We identified seven diagnostic accuracy studies of tools to screen for specific frailty-related issues (as distinct from frailty as a general overall condition) in the ED (Table 6). All of the studies evaluated screening for cognitive impairment/dysfunction and most used the Mini Mental State Examination (MMSE) as a reference standard. Two studies did not use a standard diagnostic accuracy design. 18,34 In a randomised trial published as a conference abstract,18 physicians were either informed or not informed of the results of screening for mental status and delirium. The study found that information about screening results did not appear to influence physicians’ decisions in relation to documentation, disposition or management. 18 This is a potentially important finding, but the study was small (69 patients).

| Study (issue) | Participants (n) | Tool | Reference standard | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Carpenter et al.18 (geriatric syndromes) | 69 | MMSE/CAM | N/A (RCT of screening) | Screening did not appear to influence the decisions made by physicians |

| Carpenter et al.35 (cognitive dysfunction) | 169 | Ottawa 3DY; Brief Alzheimer’s Screen; SBT; and caregiver-completed AD8 | MMSE | Brief screening instruments such as the SBT can rapidly identify patients at lower risk of cognitive dysfunction |

| Carpenter et al.36 (cognitive dysfunction) | 371 | SIS and caregiver-completed AD8 | MMSE | The SIS was superior to the caregiver-completed AD8 for identifying older adults at increased risk of cognitive dysfunction |

| Eagles et al.37 (impaired mental status) | 260 | Ottawa 3DY | MMSE | Ottawa 3DY is a simple screening tool that has been shown to be feasible for use in the ED |

| Hadbavna et al.34 (cognitive impairment) | 117 | TRST and SIS | N/A | A high proportion of older patients attending the ED met criteria for cognitive impairment. There was considerable variation in the implementation of the screening instruments between nurses, despite training |

| Wilber et al.38 (cognitive impairment) | 352 | SIS | MMSE | The sensitivity of the SIS (63%) was lower than in earlier studies. Further research is needed to identify the best brief mental status test for ED use |

| Wilber et al.39 (cognitive impairment) | 150 | SIS and Mini-Cog | MMSE | The SIS had a sensitivity of 94% and specificity of 86%. The test is short, easy to administer and unobtrusive, allowing it to be easily included in the initial assessment of older ED patients |

Hadbavna et al. 34 also did not use a conventional diagnostic accuracy study design in their study evaluating the six-item screener (SIS) test and triage risk screening tool (TRST). Instead, repeat screening with the SIS was used to confirm whether or not patients met the criteria for cognitive impairment. The authors found that there was considerable variation between nurses in the implementation of screening. 34 This adds to the study of Asomaning and Loftus28 in identifying potential problems in administering screening tools in normal clinical practice.

Prognostic tools for adverse events within the emergency department

We included five studies evaluating the accuracy of screening tools for assessing patients’ risk of adverse events within the ED itself (Table 7). Each study used a different tool, suggesting that there is currently no consensus around which tools to use. Follow-up was limited to the time that the patient was in hospital, with the exception of one study that included a 30-day follow-up. 40 This study40 found that a delirium prediction rule based on age, prior stroke or transient ischaemic attack, dementia, suspected infection and acute intracranial haemorrhage had good predictive accuracy for delirium determined by the confusion assessment method (CAM).

| Study | Participants (n) | Tool | Follow-up | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Beauchet et al.41 | 424 | BGA | In hospital | The combination of a history of falls, male sex, cognitive impairment and aged < 85 years identified older ED patients at high risk of a long hospital stay |

| Dundar et al.43 | 939 | REMS/HOTEL | In hospital | The REMS, REMS without age and HOTEL scores cannot be used to identify GED patients requiring hospital admission, but they are of value for predicting in-hospital mortality and intensive care admission |

| Grossmann et al.42 | 519 | Emergency Severity Index | In ED | The Emergency Severity Index level showed good validity for resource consumption, disposition, ED length of stay and survival |

| Kennedy et al.40 | 700 | Delirium prediction rule | 30 days | The delirium prediction rule had good predictive accuracy (area under the ROC curve = 0.77) |

| Lee et al.23 | 1903 | CTAS | In ED | The CTAS is a triage tool with high validity for older patients and is especially useful for categorising severity and recognising those who require an immediate life-saving intervention |

One study carried out in France used a brief geriatric assessment (BGA) method to identify patients in the ED who were at high risk of a long hospital stay. 41 The BGA consisted of six items and the authors concluded that a history of falls, male sex, cognitive impairment and age of < 85 years identified patients at increased risk of a long hospital stay (≥ 13 days). The authors noted that this group of patients would require geriatric care and planning for discharge. Further evidence on the management of patients following geriatric assessment in the ED is presented in Narrative synthesis of service delivery intervention papers.

The other studies in this group evaluated tools for predicting the risk of hospital or intensive care unit (ICU) admission or the need for an immediate life-saving intervention. Emergency Severity Index level 1 had low sensitivity (46.2%) but high specificity (99.8%) for predicting the need for a life-saving intervention. 42 The index level was also correlated with resource consumption, disposition, ED length of stay and survival. The Canadian Triage and Acuity Scale (CTAS) showed both high sensitivity (97.9%) and high specificity (89.2%) for the need for life-saving intervention. 23 The results of a Turkish study evaluating the Rapid Emergency Medicine Score (REMS) and Hypotension, Oxygen saturation, low Temperature, ECG changes and Loss of independence (HOTEL) tools indicated that these tools cannot be efficiently used to identify older ED patients requiring hospital admission. 43 However, the tools had reasonable validity for predicting ICU admission and in-hospital mortality. The HOTEL score was a stronger predictor than REMS or REMS without taking age into account.

These studies focus on the short-term outcomes of older patients attending the ED. The exception is the study by Beauchet et al. ,41 which may be read alongside other studies of geriatric assessment in the ED. The limited number of studies identified makes it difficult to draw conclusions about which tools may be of most value in the setting of the UK NHS.

Prognostic tools for adverse events after discharge

Eighteen studies (19 publications19,21,44–60) assessed the ability of screening tools to predict adverse outcomes following a patient’s discharge from the ED (Table 8). The studies evaluated a wide range of tools, with follow-up ranging from 28 days to 12 months. The ISAR tool and TRST were most commonly evaluated, with one study44 evaluating a tool derived from the ISAR tool. None of the included studies was performed in the UK. Four studies were published as conference abstracts only. 45–48

| Study | Tool | Follow-up | Findings |

|---|---|---|---|

| Studies of ISAR | |||

| Hegney et al.44 (n = 2139) | Screening tool adapted from the ‘Screening Tool for Elderly Patients’, which in turn was developed from the ISAR tool | 28 days (study used a before-and-after design) | There was a decrease in re-presentations. It is suggested that this is because of increased referral to other community-based services (i.e. diverting patients elsewhere) |

| Salvi et al.49 (n = 200) | ISAR | 6 months | The ISAR tool was a reliable and valid predictor of death, long-term care placement, functional decline, ED revisit or hospital admission at 6 months’ follow-up |

| Singler et al.50 (n = 520) | ISAR | 28 days | The ISAR tool with a cut-off score of ≥ 3 is an acceptable screening tool for use in German EDs |

| Studies of TRST | |||

| Fan et al.51 (n = 120) | TRST | 120 days | The TRST cannot be used as a single diagnostic test to predict whether or not Canadian ED elders will have an ED revisit, hospital admission or long-term care placement at 30 or 120 days |

| Hustey et al.19 (n = 650) | TRST | 120 days | The TRST is a valid proxy measure for assessing functional status in the ED and may be useful in identifying patients who would benefit from referrals or surveillance after discharge |

| Lee et al.52 (n = 788) | TRST | 12 months | The TRST demonstrated only moderate predictive ability and, ideally, a better prediction rule should be sought |

| Studies comparing ISAR with TRST | |||

| Carpenter et al.45 (n = 225) | ISAR and TRST | 3 months | Neither the ISAR tool nor the TRST distinguish older ED patients at high or low risk for 1- or 3-month adverse outcomes |

| Graf et al.53,54 (n = 375) | ISAR, modified ISAR and TRST | 12 months | The screening tools may be useful for identifying older patients who can be discharged from the ED without further geriatric evaluation, thus avoiding unnecessary CGA |

| Salvi et al.21 (n = 2057) | ISAR and TRST | 6 months | Risk stratification of older ED patients with the ISAR tool or TRST is substantially comparable for selecting older ED patients who could benefit from geriatric interventions. The ISAR tool had slightly higher sensitivity and lower specificity than TRST |

| Studies comparing several tools | |||

| Buurman et al.55 (n = 381) | ISAR, TRST, questionnaires of Runciman et al.123 and Rowland et al.124 | 120 days | None of the screening tools was able to discriminate clearly between patients with and without poor outcomes |

| Moons et al.56 (n = 314) | ISAR, TRST, questionnaires of Runciman et al.123 and Rowland et al.124 | 90 days | Repeat visits in older persons admitted to an ED seemed to be most accurately predicted using the Rowland questionnaire, with an acceptable number of false positives. This instrument can be easily integrated into the standard nursing assessment |

| Studies of other tools | |||

| Baumann and Strout57 (n = 929) | ESI | 1 year | When used to triage patients aged > 65 years, the ESI algorithm demonstrates validity. Hospitalisation, length of stay, resource utilisation and survival were all associated with ESI categorisation in this cohort |

| Di Bari et al.58 (n = 1632) | ISAR, Silver Code | 6 months | Prognostic stratification with the Silver Code is comparable with that obtained by direct patient evaluation |

| Dziura et al.46 (n = 250) | Rapid screening assessment | 30 days | Rapid screening assessment provides a rapid and accurate method for identifying older patients in the ED who are likely to return to the ED |

| Eagles et al.47 (n = 504) | TUGT | 6 months | TUGT scores were associated with frailty, functional decline and fear of falling. TUGT scores were associated with falls at the initial ED visit but were not predictive of falls at 3 or 6 months |

| Post et al.48 (n = 250) | GRAY | 30 days | The ED GRAY can be quickly performed in the ED to initially assess disability and identify issues that need to be addressed. Combined with other data, it provides good discrimination of the risk of ED readmission within 30 days |

| Stiffler et al.59 (n = 107) | SHARE-FI | 30 days | The SHARE-FI tool appears to be a feasible method to screen for frailty in the ED |

| Tiedemann et al.60 (n = 397) | Two-item screening tool (falls) | 6 months | The two-item screening tool showed good external validity and accurately discriminated between fallers and non-fallers. The tool could identify people who may benefit from referral or intervention after ED discharge |

The ISAR tool was developed in Canada in the 1990s. 122 It is a self-report screening tool with six questions related to functional dependence, recent hospitalisation, impaired memory and vision and polypharmacy. A score of ≥ 2 (i.e. positive answers to two or more items) is the normal cut-off point for being considered high risk. Two studies in this review evaluated the ISAR tool alone for screening older patients in the ED. 49,50 Both studies concluded that the ISAR tool was a valid and reliable screening tool in their setting. Singler et al. 50 used a cut-off point of ≥ 3 rather than ≥ 2 in their study, which would have the effect of increasing the specificity of the tool. A study of a screening tool derived from the ISAR used a before-and-after design and found a decrease in re-presentation to the ED after introduction of the tool. 44 The authors suggested that this was attributable to an increase in referrals to community-based services, which diverted patients away from attending the ED.

The TRST is a risk-screening tool designed to be applied to patients aged ≥ 75 years in the ED. Like the ISAR tool, it includes six items and a score of ≥ 2 indicates high risk. Three studies in the review evaluated the TRST alone and two of them51,52 cast doubt on the predictive ability of the tool. By contrast, a study in the USA concluded that the TRST was a valid measure for assessing functional status in the ED and may be useful in identifying patients requiring referral or monitoring after discharge. 19 Thus, the evidence base for the TRST when evaluated alone is limited and mixed.

Although evaluation of single screening tools appears most feasible for delivery in the ED and the least burdensome for patients, many studies have compared two or more tools using the same sample of patients. Three studies compared the ISAR tool and the TRST. Salvi et al. 21 and Graf et al. 53,54 both concluded that the tools are useful for risk stratification in the ED and have similar properties. However, Salvi et al. 21 emphasised use of the screening tools to select patients who could benefit from geriatric interventions, whereas Graf et al. 53,54 favoured their use to avoid unnecessary intervention. By contrast, a US study45 found that neither tool successfully distinguished patients at high and low risk for adverse outcomes at 1 and 3 months. Once again, it is difficult to draw firm conclusions from this group of studies.

Two further studies compared the performance of ISAR and TRST with that of two other tools, the Runciman123 and Rowland124 questionnaires. Moons et al. 56 highlighted the value of the Rowland questionnaire for predicting repeat ED visits, whereas Buurman et al. 55 found that none of the screening instruments distinguished between patients with and without poor outcomes over 120 days of follow-up. These similarly designed studies were carried out in Belgium and the Netherlands, respectively, and so their relevance to UK settings is uncertain.

Other screening tools have been evaluated in single studies. We included seven studies of this type, all of which reported positive results. The emergency screening instrument (ESI),57 rapid screening assessment46 and Survey of Health, Aging and Retirement in Europe Frailty Instrument (SHARE-FI)59 are short question-based tools similar to those discussed above. Eagles et al. 47 evaluated the timed up and go test (TUGT) and reported that scores were associated with frailty, functional decline and fear of falling. Limited details of this study are available as it was published as a conference abstract only. Two studies described tools to predict specific frailty-related outcomes: falls60 and ED readmissions. 48 Finally, the Silver Code differs from other risk screening tools by being derived from administrative data. When compared with the ISAR tool, the Silver Code showed a similar ability to predict ED return visits, hospital admission and mortality over 6 months of follow-up. 58 The concept of using administrative data to support initial triage in the ED seems attractive, but in this study the Silver Code was derived retrospectively several months after the patient was enrolled for the study. As noted by the authors, improved processing and flow of administrative data would be necessary for the data to be used for real-time triage in the ED.

Summary of screening papers

The evidence on tools to support the identification and management of patients with frailty in the ED is extensive but inconclusive. The ISAR tool and the TRST are the most extensively evaluated tools, but many other tools are available, including non-question-based tests and, potentially, tools using administrative data. Limitations of the included studies include the small sample sizes, that most were conducted at a single centre and that many were published as conference abstracts with limited details. Contradictory results obtained in different prognostic studies using the same tool reflect the fact that health service use-related outcomes, in particular outcomes such as repeat ED visits and hospital admission, will be influenced by the health and care system as well as by patient factors. Hence, the results of studies performed in one country cannot be readily generalised to another country. The lack of UK studies in this body of evidence limits the relevance of the evidence to NHS settings. There are other studies that examine screening tools for conditions that are common in frail older people; however, these have not been included in the review as they were not identified through the literature searches as they were not specifically limited to a frail or older population.

Narrative synthesis of service delivery intervention papers

This section reports papers that describe changes to how care is delivered to frail and older patients within the ED. The service delivery interventions that are reported here were targeted at both frail older people and a more general population of people aged > 65 years. Differentiating between the groups at whom interventions were targeted was often difficult. Data extraction tables for these service delivery interventions are available in Appendices 4 and 5.

Overall, the intervention reporting was descriptive rather than analytical, with limited data on the feasibility and acceptability of interventions. Therefore, this section aims to map, classify and describe the interventions delivered and the outcomes on which they are reported to have had an impact.

To present the synthesis in a clear and logical manner, interventions were classified as follows:

-

ED staffing initiatives (21 studies reported in 26 articles26,61–85)

-

changes to the physical infrastructure of the ED (11 studies reported in 12 articles86–97)

-

care delivery interventions (18 studies reported in 22 articles24,25,98–117)

-

other interventions (three studies reported in three articles119–121).

Emergency department staffing initiatives

We identified 21 studies (26 publications26,61–85) reporting on instances in which the staffing of the ED had been modified to better meet the needs of an older population. These staffing modifications varied; there were examples of initiatives in which a single individual was located in the ED or added to an existing multidisciplinary team (MDT) or in which a new MDT was established. Differentiating between staffing initiatives and care initiatives (e.g. when CGA was introduced to an ED and delivered by a newly established geriatric liaison nurse) was problematic. The description of the interventions was often brief, reflected in the fact that a number of the studies were reported in conference abstracts only. Details of these interventions are given in Table 9.

| Intervention | Staff | Study, population | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Frail older | General older | ||

| Staffing initiatives: individual | Admissions avoidance geriatrician | Jones and Wallis,61 Jones et al.62 | |

| Aged care pharmacist | Mortimer et al.63 | ||

| Clinical pharmacy specialist | Shaw et al.64 | ||

| EDCCs | Bond et al.65 | ||

| Geriatric nurse practitioner | Argento et al.66 | ||

| Nurse liaison | Aldeen et al.,67 Aldeen et al.68 | ||

| Aged care nurse liaison | Basic and Conforti26 | ||

| Triage nurse | Fallon et al.69 | ||

| Geriatric nurse liaison | Dresden et al.70 | ||

| Staffing initiatives: team | Geriatric medicine liaison | Tan et al.71 | |

| ATOP | Leah and Adams72 | ||

| ASET | Ngian et al.73 | ||

| Geriatric liaison team | Thompson et al.74 | ||

| FITT | O’Reilly et al.75 | ||

| CCT (falls) | Harper et al.76 | ||

| CCT (general) | Arendts et al.77,78 | ||

| Allied health staff (falls) | Waldron et al.79 | ||

| MDT CCT | Corbett et al.80 | ||

| MGT | Launay et al.81 | ||

| CCT | Arendts et al.82 | ||

| Acute care of the elderly service | Bell et al.83 | ||

| Patient liaison service | Berahman et al.84 | ||

Individual initiatives

We identified nine studies (across 11 articles26,61–70) of interventions in which a single clinician was introduced to the ED setting or added to an existing team. A variety of clinicians were introduced (geriatric consultants, pharmacists and nurses) in addition to other roles such as emergency department care co-ordinators (EDCCs).

Jones and Wallis61 and Jones et al. 62 reported on an admissions avoidance consultant geriatrician. The geriatrician worked in conjunction with allied health professionals and also provided follow-up, which was required by one-third of the patients in the cohort. The geriatrician’s role was to provide medication advice and follow-up planning. Outcomes for this intervention were broadly positive compared with ‘hospital averages’. However, the authors cautioned that reducing admissions among more-stable patients may lead to wards having a higher proportion of less-stable patients and, therefore, the outcomes of the admitted patients may appear to be negatively affected by the intervention.

Admissions avoidance was also the primary aim of the matched pairs study reported by Bond et al. 65 EDCCs aimed to reduce admission rates through better linkages with home care and community services. The study did not show any difference in any of the outcomes measured (admission rates, revisit rates or readmission rates) between those who received the EDCC intervention and those who did not, although the design of the study may have contributed to this.

Two studies reported on the role of a geriatric pharmacist. 63,64 A prospective evaluation of an aged care pharmacist was undertaken by Mortimer et al. 63 The aged care pharmacist’s role was to examine medication history, review medication orders and liaise with medical staff about medication-related issues. The aged care pharmacist was effective at reducing medication errors compared with the control group receiving usual care, the intervention was acceptable to patients and there was no difference in terms of re-presentation following discharge between the aged care pharmacist group and the control group. Shaw et al. 64 described a new role of a clinical pharmacy specialist, who delivered medication review and management. The study found that clinical outcomes were not improved as a result of the intervention.

Nursing interventions were also common. Argento et al. 66 reported a pilot study of a geriatric nurse practitioner intervention. The geriatric nurse practitioner provided specific care to older people, with the study finding positive outcomes. As part of the wider Geriatric Emergency Department Innovations through the Workforce, Informatics and Structural Enhancements (GEDI-WISE) programme, one of the innovations was to develop the geriatric assessment and care co-ordination skills of ED nurses, as reported in the study by Aldeen et al. 67 The nurse liaison undertook screening tests, liaised with the wider MDT, created safe discharge plans and followed up patients. Preventable admissions in high-risk patients were reduced (although admissions were increased in those with a less severe presentation, perhaps because of underlying problems being identified). Length of stay in the ED was increased for patients seen by the nurse. Basic and Conforti26 reported on a RCT of an intervention for high-risk older people involving early geriatric assessment by an aged care nurse, who assessed, monitored and referred patients with high-risk criteria. They found that the intervention did not significantly reduce any of their outcomes of interest (admission, functional decline or length of stay), with the authors arguing that this was because the intervention did not influence patient care and management following discharge or have any influence over the care provided once patients had been admitted.

Fallon et al. 69 reported on a triage nurse initiative, which involved screening with the TRST. The intervention was delivered in the ED and patients were admitted to the acute medical assessment unit (AMAU) if it was deemed necessary. The TRST identified patients as being at risk of an adverse outcome. Although the outcomes of these patients are unknown, the study identified characteristics of the frail older population and suggested that geriatric AMAUs may better meet their needs.

Dresden et al. 70 undertook a prospective cohort study of a geriatric nurse liaison intervention (GNLI) involving assessment and care co-ordination in the USA. The GNLI group (n = 829) had significantly improved outcomes compared with the control group (n = 873) with regard to hospitalisation, 30-day readmission rates and length of stay. However, no data were collected past 30 days and no information on ED readmissions was collected.

Team initiatives

We identified 12 studies across 15 publications71–85 that reported team initiatives. Staff interventions also took the form of initiatives that involved the establishment of new MDTs for older patients. Six interventions71–73,83 were identified for frail or high-risk patients.

Three papers77,78,82 reported findings from an Australian study that established a care co-ordination team (CCT) to deliver comprehensive allied health assessment/intervention to older patients to improve patient outcomes. The CCT comprised a minimum of one physiotherapist, occupational therapist or social worker, all of whom had geriatric experience. The intervention included functional assessment to identify patients’ needs and direct them to appropriate care and services. Further details are provided in Table 10.

| Study and type | Sample characteristics and size | Outcome measured | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arendts et al.78 (matched pairs study) |

|

28-day ED reattendance, readmission and mortality | No difference in mortality between the intervention group and the control group. The intervention group had a slightly increased ED reattendance rate and a much higher risk of hospital readmission compared with the control group |

| Arendts et al.77 (non-randomised, prospective pragmatic study) |

|

Hospital length of stay for patients admitted | No difference in length of stay (median 88 vs. 87 hours) in unadjusted (log-rank p = 0.28) or adjusted (IRR 0.97, p = 0.32) analysis |

| Arendts et al.82 (non-randomised, prospective study) |

|

Admission to inpatient beds | 72.0% for the intervention group and 74.4% for the control group – borderline statistical significance (OR 0.88, 95% CI 0.76 to 1.00; p = 0.046) |

The work of the CCT in the same setting was reported by Harper et al. ,76 who looked at the role of the CCT specifically for older falls patients. Patients referred by ED clinicians were given targeted falls support. The study reported the changes over 3 years since the introduction of the CCT, with regression modelling demonstrating a decrease in re-presentation and readmission rates, although these results were not significant. Another falls prevention intervention, also delivered in Australia by allied health professionals, was reported by Waldron et al. 79 A prospective before-and-after study of 313 geriatric falls patients demonstrated that allied health staff significantly increased the proportion of patients reviewed and significantly increased referrals for comprehensive guideline care, with a consequent increase in the average quality-of-care index score.

Patients with multiple diagnoses or aged > 80 years were referred to an ED geriatric medicine liaison service in a pilot study undertaken in Ireland. 71 A MDT approach to assessment, led by a senior geriatrician, dealt with 285 patients over a nearly 3-year period. Although study numbers were relatively small, analysis was undertaken on the data collected, with the finding that mean length of stay was significantly shortened for the ED geriatric medicine patients compared with usual care patients. This did not adversely affect repeat attendances or readmission rates.

An assessment team for older people (ATOP) was established in a UK hospital to meet the needs of an increasingly frail population. 72 The focus of the team was to provide CGA to patients with two or more markers of frailty, with assessment not simply based on age alone. The ATOP consisted of a geriatrician, six senior nurses, a senior social worker and assistant, a senior occupational therapist and assistant and a health-care assistant. The aim of the ATOP was to prevent admissions and, in the 4 months of the study, 178 admissions were prevented in patients who the ED team would otherwise have admitted. A basic cost analysis stated that ‘the potential cost saving from preventing the admission of the 89 patients aged 80 years and above seen in the study period could be more than £500,000’. 72

Seven studies73–75,80,81,83–85 examined interventions delivered to general geriatric populations. An aged care service emergency team (ASET) was established in Australia to reduce missed diagnoses in the ED and prevent inappropriate discharges (and, therefore, ED re-presentations). A study by Ngian et al. 73 examined these discordant cases (i.e. cases in which the ASET had recommended the admission of patients who were considered suitable for discharge by the ED). The study looked at what additional evidence was measured by the ASET and found that it was more likely to measure functional, cognitive and mobility impairments as well as identifying acute medical conditions. The data collected were largely qualitative and did not have a comparator; however, the study demonstrated the additional information that might be useful when planning the discharge or admission of frail older patients.

A conference abstract of a UK study carried out in the John Radcliffe Hospital ED reported findings from a newly established geriatric liaison team undertaking CGA. 74 The limited data reported indicated that, over 6 months, and for the 35 patients studied, the length of stay was reduced by 4.8 hours.

An intervention targeted specifically at frail older people was reported by O’Reilly et al. 75 The frail intervention therapy team (FITT) combined allied health professionals to identify all frail patients who presented to the ED and then deliver MDT assessment to them. To analyse the outcomes of the FITT, data were compared for the first quarter of 2015 and 2016 (after the FITT was established). The study reported an 11.6% increase in patients presenting to the ED, a 59% increase in patients discharged and a 42% increase in patients transferred to a ward in < 9 hours.

The formation of a care co-ordination programme in 2005 in Australia was reported by Corbett et al. 80 This MDT, with an emphasis on allied health professional input, was set up to reduce avoidable admissions and inappropriate re-presentations to the ED. Positive study outcomes confirmed a statistically significant reduction in the proportion of patients admitted as well as improvements in the mean quality-of-life score and user satisfaction following the introduction of the care co-ordination programme.

A brief report of a mobile geriatric team (MGT) was provided by Launay et al. 81,85 The intervention consisted of medical assessment (termed geriatric assessment by the study authors) followed by geriatric (medical) and gerontological (medical and social) discharge recommendations. Although outcomes for a small number of patients were evaluated (n = 168), the study authors reported that only the geriatric recommendations were associated with early discharge from the ED [odds ratio (OR) 4.38; p = 0.046].

In another study, an acute care of the elderly (ACE) service was developed that focused on the establishment of a team (consultant, junior doctor and nurse) to deliver CGA to patients aged > 80 years with complex problems or frailty. 83 Data from 10 months of the service showed that 459 out of 662 inappropriate admissions were avoided.

A patient liaison service to better meet the needs of the older patient was evaluated and reported by Berahman et al. ,84 with the main outcome of the study being the measurement of patient satisfaction with the patient liaison service. Comparing the satisfaction of patients who had and had not received the intervention, there was a non-significant slight trend towards improved scores when a patient liaison was present.

Overall, mapping these studies showed that there were few similarities between them. Staffing interventions that added a single member of staff to an ED tended to focus on improving processes and outcomes related to medication management (whether they were delivered by a pharmacist or by another clinician) and improving care co-ordination, follow-up and linkages between the ED and home. Interventions that added a new team to the ED tended to have more of a focus on frail older people, perhaps indicating that, for care to be focused on the frail older person, a variety of health-care professionals need to be included. There were fewer similarities across all of the studies in the outcomes that were assessed, although avoiding admissions and mortality were most frequently measured.

Changes to the physical infrastructure of the emergency department