Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/198/07. The contractual start date was in July 2015. The final report began editorial review in May 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Fran Toye, Kate Seers and Karen Barker authored two studies that are included in this qualitative evidence synthesis. Kate Seers is a Health Services and Delivery Research board member and a Health Services Research Commissioning board member.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Toye et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

A recent systematic review1 of population studies indicates that as many as 28 million adults in the UK are affected by chronic pain. Population estimates suggest that around 25% of adults around the world suffer with moderate or severe pain,2–6 and for between 6% and 14% of these adults this pain is disabling. 6,7 We know that living with chronic pain can be challenging and that patients do not always feel valued or believed by health-care professionals (HCPs). 8 To improve these patients’ experiences of health care, we need to understand what is going on from the perspective of the HCP. In particular, we need to understand why it is that working with people with chronic non-malignant pain can result in patients experiencing this as an adversarial relationship. If we can understand what it is like to be a HCP providing health care to people with chronic non-malignant pain, and in particular its challenges and rewards, this understanding can facilitate improvements in the experience and quality of health care for this large group of people.

Chronic pain can be particularly challenging for HCPs to treat because it persists beyond the expected healing time and is not amenable to routine methods of pain control. 9 This is complicated by the finding that pain is not always explained by a specific pathology. 6 HCPs find working with patients with chronic pain very complex. For example, HCPs describe feeling ‘bombarded by despair’ under the pressure of not being able to fix the person in pain. 10 They can also find it a challenge to balance empathy with ‘not getting too involved’. 10 Allegretti and colleagues11 describe the challenges for general practitioners (GPs) and highlight mismatches in patients’ and clinicians experiences of health care. Others report feelings of frustration and discord in the patient–clinician relationship. 12 It is not uncommon for patients to report dissatisfaction with their HCP interaction and this is likely to influence their decisions and actions. 13 The rationale for this study is underpinned by the need to facilitate ‘patient-centred medicine’. 14 Mead and Bower15 identified five key dimensions of patient-centred medicine: (1) taking a biopsychosocial perspective; (2) framing the ‘patient-as-person’; (3) sharing power and responsibility; (4) therapeutic alliance, which hinges on an effective personal relationship; and (5) ‘doctor-as-person’, which recognises the influence that HCPs’ personal characteristics and responses can have on care. Mead and Bower15 indicate that patient-centred care requires HCPs to be self-aware of their emotional responses and reactions: ‘sensitivity and insight into the reactions of both parties can be used for therapeutic purposes’. Thus, understanding the experience of providing health care to people with chronic non-malignant pain from the perspective of the HCP can have important implications for delivery of health care, decision-making and health-care quality. The findings will allow HCPs and their managers to understand, in detail, the challenges of providing health care to this complex group of patients and, thus, facilitate improvements to the quality of health care. In addition, a mutual understanding of what it is like to provide and receive health care for chronic non-malignant pain can facilitate a therapeutic partnership from the perspective of both patients and their HCPs.

The aim of qualitative evidence synthesis (QES) in health care is to systematically review and integrate findings in order to increase our understanding of the complex processes of health care and, thus, improve the experience and quality of that care. The proliferation of qualitative studies can make it difficult to access and utilise qualitative knowledge to inform practice and policy. 16 The Cochrane Qualitative Research Methods Group acknowledges the importance of including qualitative findings within evidence-based health care,17 and insights from several meta-ethnographies have contributed to a greater understanding of complex processes in health care, for example medicine-taking,18 diabetes,19 antidepressants,20 chronic musculoskeletal pain8 and chronic pelvic pain. 21 There are various methods for synthesising qualitative research. 16,22–25 An important distinction made in synthesis approaches is between (1) those that aim to describe or ‘aggregate’ findings and (2) those that aim to interpret these findings and develop conceptual understandings or ‘theory’. 26 Our aim is to develop conceptual understanding. We will use the methods of meta-ethnography developed, refined and reported by Toye and colleagues8 in a previous meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of chronic musculoskeletal pain.

Objectives

-

To undertake a QES (meta-ethnography)26–28 that will increase our understanding of what it is like for HCPs to provide health care to people with chronic non-malignant pain and, thus, to inform improvements in the experience and quality of health care.

-

To make our findings easily available and accessible through a short film.

-

To contribute to the development of methods for QES that aim to bring together qualitative research findings so that health care can be improved.

Chapter 2 Methods

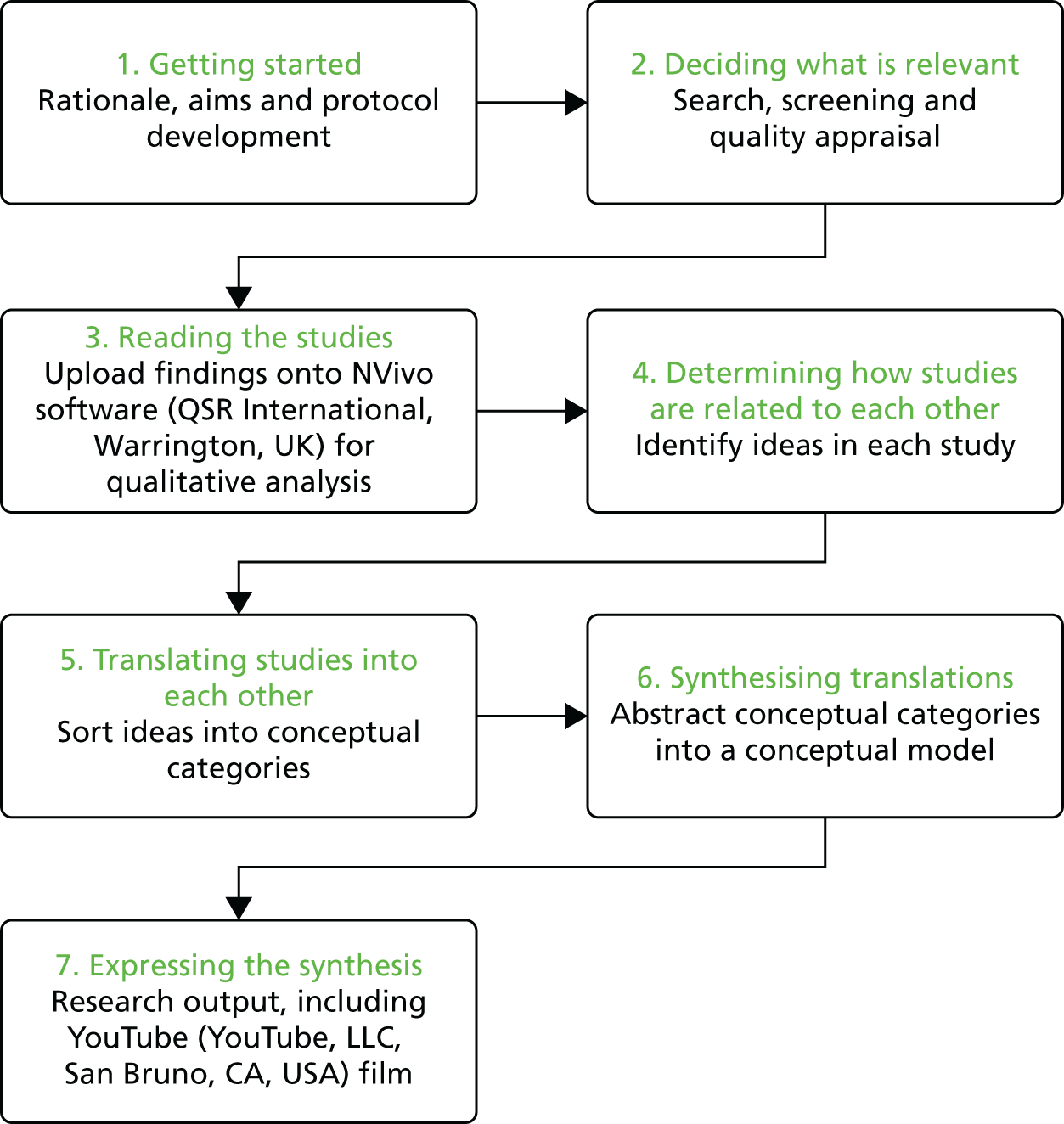

There are seven stages to meta-ethnography (outlined in Figure 1). Stage 1 incorporates the rationale, aims and protocol development. Stage 2 involves deciding what is relevant to the synthesis through a systematic search, screening and appraisal. The analytical stages in meta-ethnography involve overlapping research activities: reading the studies (stage 3), determining how the studies are related (stage 4), translating the studies into each other (stage 5) and synthesising the translations (stage 6). The final stage (stage 7) involves the output and dissemination of findings.

FIGURE 1.

The stages of meta-ethnography.

Stage 1: getting started

This stage incorporates the background, rationale, aims and protocol development.

Stage 2: deciding what is relevant

In their original text on meta-ethnography, Noblit and Hare26 do not advocate an exhaustive literature search, and the number of studies included in meta-ethnographies ranges widely. 22,24,27 The aim of meta-ethnography is not to perform statistical analyses but to draw on knowledge for conceptual development. Some argue that including too many studies makes the analysis ‘unwieldy’. 27,29 However, we aimed to produce a conceptual analysis with a weight of evidence that has resonance with the health research community and thus undertook a systematic search of the published literature. Our previous meta-ethnography has demonstrated the value of undertaking a systematic search and including a larger number of studies into a QES. 28

Searching and screening

Inclusions

We included studies that explored HCPs’ experiences of providing health care to adults with chronic non-malignant pain.

Exclusions

We excluded studies of acute pain, head pain, arthritis (including osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis) or patient experience, and studies in which HCPs’ experiences could not be disentangled from the experiences of others (e.g. patients, carers or family members).

We searched five electronic bibliographic databases [MEDLINE, EMBASE, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), PsycINFO and Allied and Complementary Medicine Database (AMED)] using terms adapted from the InterTASC Information Specialists’ Sub-Group search filter resource. 30–33 The InterTASC Information Specialists’ Sub-Group is a group of information professionals supporting research groups producing technology assessments for the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (URL: www.york.ac.uk/inst/crd/intertasc/; accessed 24 July 2017).

We developed the search strategy with an information specialist and used a combination of specific subject heading terms and free-text terms (Table 1). We did not use the ‘clinical query limits’ option for qualitative research in our searches, as we had found that this can filter out relevant qualitative studies. To ensure value for money, we did not include citation checks, hand-searching, grey literature or Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) searches. Previous experience has shown us that these strategies do not necessarily add significant conceptual value to large meta-ethnographies. 28 Two reviewers screened the titles, abstracts and full texts of potential studies for relevance.

| Database | Terms | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Qualitative research | Pain | |||

| Subject heading | Free text | Subject heading | Free text | |

| MEDLINE | ATTITUDE TO HEALTHCARE/INTERVIEWS AS TOPIC/FOCUS GROUPS/NURSING METHODOLOGY RESEARCH/ATTITUDE TO HEALTH |

Qualitative ADJ5 (theor* OR study OR studies OR research OR analysis)/ethno*/emic OR etic/phenomenolog*/ hermeneutic*/heidegger* OR husserl* OR colaizzi* OR giorgi* OR glaser OR strauss OR (van AND kaam*) OR (van AND manen) OR ricoeur OR spiegelberg* OR merleau/constant ADJ3 compar*/focus ADJ3 group*/grounded ADJ3 (theor* OR study OR studies OR research OR analysis)/narrative ADJ3 analysis/discourse ADJ3 analysis/(lived OR life) ADJ3 experience*/ (theoretical OR purposive) ADJ3 sampl*/(field ADJ note* ) OR (field ADJ record* ) OR fieldnote*/ participant* ADJ3 observ*/action ADJ research (digital ADJ record) OR audiorecord* OR co AND operative AND inquir* /co-operative AND inquir* (semi-structured OR semistructured OR unstructured OR structured) ADJ3 interview*/(informal OR in-depth OR indepth OR ‘in depth’) ADJ3 interview*/(‘face-to-face’ OR ‘face to face’) ADJ3 interview*/’IPA’ OR ‘interpretative phenomenological analysis’/’appreciative inquiry’ social AND construct*/poststructural* OR (post structural*) OR post-structural* /postmodern* OR (post modern*) OR post-modern*/ feminis*/humanistic OR existential OR experiential |

BACK PAIN/CHRONIC PAIN/PAIN/PAIN MANAGEMENT/FIBROMYALGIA/ |

(chronic* OR persistent* OR long-stand* OR longstand* OR unexplain* OR un-explain*) ADJ5 pain Fibromyalgia ‘back ache’ OR back-ache OR backache ‘pain clinic’ OR pain-clinic* pain adj5 syndrome* |

| PsycINFO | QUALITATIVE RESEARCH/INTERVIEWS/GROUP DISCUSSION/GROUNDED THEORY/CONTENT ANALYSIS/LIFE EXPERIENCES/PHENOMENOLOGY/ETHNOGRAPHY/ | CHRONIC PAIN/LOW BACK PAIN/MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN/PAIN/PAIN CLINIC/BACKACHE/FIBROMYALGIA/ | ||

| EMBASE | QUALITATIVE RESEARCH/QUALITATIVE RESEARCH/PHENOMENOLOGY/PERSONAL EXPERIENCE/ATTITUDE | BACK PAIN/CHRONIC PAIN/LOW BACK PAIN/MUSCULOSKELETAL PAIN/PAIN/PAIN CLINICS/FIBROMYALGIA/PAIN MANAGEMENT/ | ||

| CINAHL | QUALITATIVE STUDIES/QUALITATIVE VALIDITY/PHENOMENOLOGY/PHENOMENOLOGICAL RESEARCH/ETHNOGRAPHIC RESEARCH/ANTHROPOLOGY, CULTURAL/OBSERVATIONAL METHODS/PARTICIPANT OBSERVATION/LIFE EXPERIENCES/LIFE HISTORIES/ATTITUDE TO LIFE/ETHNOLOGICAL RESEARCH/ETHNONURSING RESEARCH/NATURALISTIC INQUIRY/FOCUS GROUPS/GROUNDED THEORY/PURPOSIVE SAMPLE/THEORETICAL SAMPLE/SNOWBALL SAMPLE/FIELD STUDIES/FIELD NOTES/CONSTANT COMPARATIVE METHOD/CONTENT ANALYSIS/DISCOURSE ANALYSIS/THEMATIC ANALYSIS/ | PAIN/PAIN CLINICS/CHRONIC PAIN/FIBROMYALGIA/PAIN CLINICS/ | ||

| AMED | ATTITUDE/INTERVIEWS/ | PAIN/FIBROMYALGIA/BACKACHE/ | ||

Quality appraisal

Although there are many frameworks suggested for appraising the quality of qualitative research, there is no consensus on what makes a study ‘good’. 27,34 However, a growing number of researchers are appraising studies for the purpose of QES. 24

Although we did not intend to use rigid guidelines for determining inclusion, we used three methods of quality appraisal to frame our discussions:

-

The questions developed by the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme (CASP) for appraising qualitative research (Box 1). 35 We assigned a numerical score to each question to indicate whether we felt that the CASP question (1) had not been addressed, (2) had been addressed partially or (3) had been extensively addressed, thus giving a possible score range of 10–30. 8 We used the CASP in this way in a previous meta-ethnography of patients’ experience of living with chronic non-malignant pain, in which we found that satisfactory papers scored at least 19. 8

-

A list of seven themes (Table 2) developed from a qualitative study embedded in a previous meta-ethnography funded by the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme. 36 Unlike CASP, these themes were developed specifically for meta-ethnography. For example, CASP does not focus specifically on conceptual clarity as a facet of quality, which is a distinguishing feature of meta-ethnography.

-

We categorised, as suggested by Dixon-Woods and colleagues,34 a ‘key paper’ that was ‘conceptually rich and could potentially make an important contribution to the synthesis’; a ‘satisfactory paper’; a paper that is irrelevant to the synthesis; and a paper that is methodologically fatally flawed.

-

Was there a clear statement of the aims of the research?

-

Is a qualitative methodology appropriate?

-

Was the research design appropriate to address the aims of the research?

-

Was the recruitment strategy appropriate to the aims of the research?

-

Were the data collected in a way that addressed the research issue?

-

Has the relationship between researcher and participants been adequately considered?

-

Have ethical issues been taken into consideration?

-

Was the data analysis sufficiently rigorous?

-

Is there a clear statement of findings?

-

How valuable is the research?

Reproduced from CASP. 35 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for non-commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/3.0/.

| Question | Response |

|---|---|

| 1. Is the background/rationale/aim described? | Yes/no/not clear |

| 2. Is the sample described? | Yes/no/not clear |

| 3. Is the researcher’s perspective clear | Yes/no |

| 4. Has the researcher challenged their own interpretation? | Yes/no/not clear |

| 5. Does the researcher’s interpretation come from the original data? | Yes/not clear |

| 6. Can you identify the ideas in this study (or do you find yourself recoding)? | Yes/no/not always |

| 7. Has this changed your thinking/made you think? (Describe in what way) | Yes/no |

Two reviewers appraised each paper, and if they were unable to reach an agreement the study was sent to a third reviewer for the final decision.

GRADE-CERQual

We also utilised the Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research (GRADE-CERQual) framework37 (URL: www.cerqual.org/; accessed 24 July 2017), which aims to help reviewers to assess and describe how much confidence readers can place in review findings, in other words ‘the extent to which the review finding is a reasonable representation of the phenomenon of interest’. 37 GRADE-CERQual proposes four distinct areas to rate for each review finding before assessing overall confidence. We aimed to explore how these domains were useful in assessing the confidence in a conceptual QES.

Methodological limitations

In GRADE-CERQual, methodological limitations are the ‘extent to which there are problems in the design or conduct of the primary studies that contributed evidence to a review’. 37 Reviewers are required to provide an evaluation of the methodological quality of the studies supporting each of the review findings.

Relevance

In GRADE-CERQual, relevance is the ‘extent to which the body of evidence from the primary studies supporting a review finding is applicable to the context specified in the review question’. 37 Reviewers are required to provide an evaluation of the relevance of the studies supporting each of the review findings.

Adequacy of data

In GRADE-CERQual, adequacy of data is an ‘overall determination of the degree of richness and quantity of data supporting a review finding’. 37 Rich data provide ‘sufficient detail to gain an understanding of the phenomenon we are studying’. 37 Reviewers should describe the adequacy of data for each finding.

Coherence

In GRADE-CERQual, coherence considers whether or not the finding is well grounded in the primary studies. Reviewers should demonstrate that there has been no ‘attempt to create findings that appear more coherent through ignoring or minimising important disconfirming cases’,37 in other words demonstrate that they are not cherry-picking evidence to support an a priori concept. They should describe consistency and inconsistency along with possible explanations for any variations found across studies or cases.

Overall confidence

Finally, GRADE-CERQual reviewers give an overall rating of confidence for each individual review finding. The suggested ratings are high, moderate, low or very low. Lewin and colleagues37 indicate that ‘it may be difficult to achieve “high confidence” for review findings in many areas, as the underlying studies often reveal methodological limitations or there are concerns regarding the adequacy of the data’.

Stage 3: reading the studies

This stage of meta-ethnography involves thoroughly reading and re-reading the studies to identify and describe the ideas or concepts. 26 The raw data of meta-ethnography are ideas or concepts in the primary studies. To allow us to refer to the original studies, we uploaded the study findings onto NVivo 11 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK) for qualitative analysis. NVivo is particularly useful for collaborative analysis as it allows the team to keep a record and compare the reviewers’ unique interpretations. NVivo 11 also allows the researchers to write memos and link them to data in order to keep track of developing analysis. We maintained a Microsoft Excel® database (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) of study demographics, appraisal and decisions on inclusion or exclusion. We read the studies in batches related to the topic/professional group and in the order in which they were retrieved, and did not use an index paper. In other meta-ethnographies, for example those of Campbell and colleagues,27 researchers have used an index paper as a way of ‘orienting the synthesis’. 38 In these examples, concepts from an early or index paper are used for comparison with concepts from subsequent studies. However, we felt that there were methodological issues with using an index paper:

-

How do we decide which paper to use as an index paper?

-

How do we define a ‘classic’ paper with no consensus about what makes a study good?

-

An index paper can have a dramatic effect on the resulting interpretation.

-

Using an index paper can mean that we become constrained by a priori concepts. This is important because we will not necessarily find the conceptually rich papers first. The process of searching and analysing is iterative and analysis does not start when the full body of data is collected but continues alongside data collection.

-

When synthesising a large number of studies, comparing concepts across these studies from an index paper can become unwieldy.

Stage 4: determining how studies are related to each other

Determining how studies are related to each other involves creating ‘a list of key metaphors, phrases, ideas and/or concepts’ (p. 28). 26 The purpose of careful reading in meta-ethnography is to identify and describe the ‘metaphors’/ideas/concepts in each study and ‘translate’ or compare them to those found in other studies. This is fundamental to meta-ethnography because concepts are the raw data of the synthesis. However, at times it can be a challenge to decipher the concepts from primary studies. 36 Two reviewers read each paper to identify and describe the concepts and compiled a list of concepts from the original papers. Our analysis was based on clearly articulated concepts from the originating papers. Schütz39 distinguishes between (1) first-order constructs (the participants’ ‘common sense’ interpretations in their own words) and (2) second-order constructs (the researchers’ interpretations of first-order constructs). In meta-ethnography, the ‘data’ are second-order constructs that are further abstracted to develop third-order constructs (reviewer’s interpretations of second-order constructs). However, the distinction between first- and second-order constructs is not clear-cut:40 primary authors choose narrative exemplars to illustrate a second-order construct. Meta-ethnography attempts to identify themes not from original narrative data but from the reported concepts. We did not recode narrative data as any attempt to recode is not embedded in the primary research process. Rather, we excluded data from analysis if both reviewers could not decipher a clear concept.

Owing to the scale of the study and the potential number of second-order constructs, our interpretation of each concept needed to combine clarity, precision and brevity. We therefore used a combination of the author’s description of the second-order construct (which briefly and clearly described the construct), and our interpretation of the construct (if the original was unclear or lengthy). In some cases, we found that there was a section of narrative exemplar provided by the original authors that was enough to give the essence of the concept. Our aim was to compile a list of concise interpretations of second-order constructs that were grounded in the primary studies.

Stage 5: translating studies into each other

The next stage in meta-ethnography involves exploring how the concepts are related to each other and, thus, sorting concepts into conceptual categories. 26 All three reviewers organised, discussed and then reorganised the concepts into categories. ‘Translation’ is achieved through the constant comparative method41 through which the reviewers begin to see similarities and differences and organise concepts into further abstracted conceptual categories.

Stage 6: synthesising translations

The next stage of meta-ethnography is to synthesise, or make sense of, the conceptual categories by developing overarching themes and integrating these themes into a conceptual model. This is part of an ongoing process in which findings are further abstracted to form a conceptual framework. We planned to develop a line-of-argument synthesis, which involves ‘making a whole into something more than the parts alone imply’ (p. 28). 26 In our experience of performing large meta-ethnographies, a line of argument can incorporate reciprocity and refutation into a useful conceptual model. This is achieved by constantly comparing concepts and developing ‘a grounded theory that puts the similarities and differences between studies into interpretive order’ (p. 64). 26 We described and printed conceptual categories on postcards and sent these to our advisory group members to read and sort into thematic groups. Then, during the next advisory group workshop, members formed small groups to discuss and reorganise the postcards together. Each of the groups then chose a spokesperson to describe its themes. The complete advisory group then discussed and agreed on the final overarching themes. The aim of the workshop was to develop thematic groups that would underpin a conceptual model. Once the thematic groups had been finalised at the advisory group meeting, all three reviewers discussed and agreed on a conceptual model that they felt was greater than the sum of the individual themes.

Stage 7: expressing the synthesis

The final stage of meta-ethnography involves output and dissemination of findings. Our outputs included a short YouTube film (YouTube, LLC, San Bruno, CA, USA) (see Report Supplementary Material 1; URL: www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1419807/#/documentation). The script for the film was woven together from narrative exemplars from the primary studies to illustrate each overarching theme. The reviewers worked closely alongside a media company, RedBalloon (URL: www.redballoon.co.uk/; accessed 24 July 2017), which specialises in outputs from qualitative research. The team had worked successfully together to produce a film from a previous HSDR-funded meta-ethnography that explores patients’ experiences of living with chronic musculoskeletal pain (www.youtube.com/watch?v=FPpu7dXJFRI; accessed 24 July 2017).

Chapter 3 Findings

This is a full report of findings reported in Toye and colleagues42 (Reproduced from Toye et al. 42 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/) and Toye and colleagues43 (Reproduced from Toye et al. 43 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

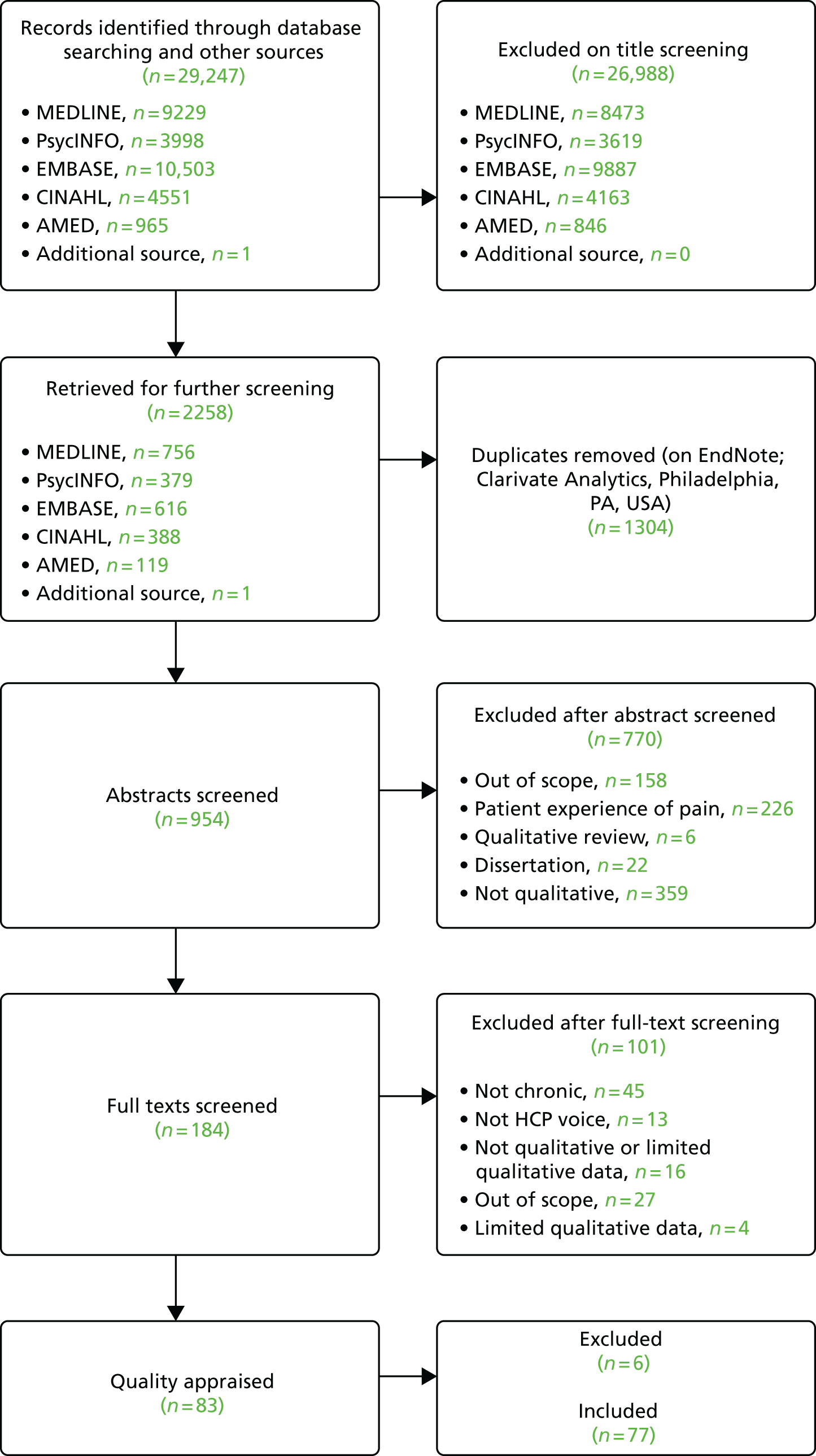

Search results

The results of the systematic search are shown in Figure 2. We screened 954 potentially relevant studies and excluded 770 after screening the abstracts. We retrieved 184 full-text articles and excluded 101 for the following reasons:

FIGURE 2.

Systematic search results.

Of the 83 potential studies, we unanimously excluded six on the grounds of methodological report. 144–149 We included 77 published studies reporting the experiences of > 1551 HCPs. 11,150–225 Table 3 provides the author, year of publication, professional/topic group, geographical context, number of participants, data collection and analytical methods for each study. HCPs included a diversity of doctors, nurses and allied health professionals in various contexts and geographical locations. Not all of the studies reported the number of participants from specific professional groups, which meant that it was not possible to give the exact sample number from each profession. The majority of studies were from the USA, the UK, Canada and Sweden. The sample size from the studies ranged from 6 to 103 (average 22). One focus group study165 and three ethnographic studies156,200,223 did not report their sample size.

| First author and year | Location | n | Data collection | Analytical approach | Professional group/topic |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Afrell 2010151 | Norway | 6 | Focus groups | Phenomenology | Specialist physiotherapists |

| Allegretti 201011 | USA | 13 | Semistructured interview | Immersion–crystallisation | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| Åsbring 2003152 | Sweden | 26 | Semistructured interview | Grounded theory | Fibromyalgia |

| aBaldacchino 2010153 | UK | 29 | Focus groups and interviews | Framework analysis | Opioid prescription |

| Barker 2015154 | UK | 7 | Semistructured interviews | Action research | Specialist physiotherapists |

| aBarry 2010155 | USA | 23 | Semistructured interview | Grounded theory | Opioid prescription |

| Baszanger 1992156 | France | NK | Ethnography | Grounded theory | Chronic pain services |

| aBerg 2009157 | USA | 16 | Semistructured interview | Thematic analysis | Opioid prescription |

| Bergman 2013158 | USA | 14 | Interviews | Thematic analysis | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| Blomberg 2008159 | Sweden | 20 | Focus groups | Grounded theory | Nursing |

| Blomqvist 2003160 | Sweden | 52 | Interviews | Content analysis | Older adults |

| aBriones-Vozmediano 2013161 | Spain | 9 | Semistructured interview | Discourse analysis | Fibromyalgia |

| Cameron 2015162 | UK | 13 | Semistructured telephone interviews | Thematic analysis | Older adults |

| Cartmill 2011163 | Canada | 10 | Semistructured interview | Grounded theory | Chronic pain services |

| Chew-Graham 1999164 | UK | 20 | Semistructured interview | Grounded theory | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| Clark 2004165 | USA | NK | Focus groups | Ethnography | Pain in aged care facilities |

| Clark 2006166 | USA | 103 | Semistructured interviews | Content analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| Côté 2001167 | Canada | 30 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Pain-related work disability |

| Coutu 2013168 | Canada | 5 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Pain-related work disability |

| Dahan 2007169 | Israel | 38 | Focus groups | Immersion–crystallisation | Guidelines |

| Daykin 2004170 | UK | 6 | Semistructured interviews | Grounded theory | Physiotherapists |

| Dobbs 2014171 | USA | 28 | Focus groups | Content analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| Eccleston 1997172 | UK | 11 | Q-analysis | Q-analysis | Mixed professionals |

| Espeland 2003173 | Norway | 13 | Focus groups | Phenomenology | Guidelines |

| aEsquibel 2014174 | USA | 21 | Interviews | Immersion–crystallisation | Opioid prescription |

| aFontana 2008175 | USA | 9 | Semistructured interview | Emancipatory research | Opioid prescription |

| Fox 2004176 | Canada | 54 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| aGooberman-Hill 2011177 | UK | 27 | Semistructured interview | Thematic analysis | Opioid prescription |

| Gropelli 2013178 | USA | 16 | Semistructured interviews | Content analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| Hansson 2001179 | Sweden | 4 | Interviews | Grounded theory | Pain-related work disability |

| Harting 2009180 | The Netherlands | 30 | Focus groups | Content analysis | Guidelines |

| Hayes 2010181 | Canada | 32 | Focus groups and interviews | Grounded theory | Fibromyalgia |

| Hellman 2015182 | Sweden | 15 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Pain-related work disability |

| Hellström 1998183 | Sweden | 20 | Interviews | Phenomenology | Fibromyalgia |

| Holloway 2009184 | Australia | 6 | Semistructured interviews | Constant comparison | Pain in aged care facilities |

| aHolloway 2009185 | Australia | 6 | Semistructured interviews | Constant comparison | Pain in aged care facilities |

| Howarth 2012186 | UK | 9 | Interviews and focus groups | Grounded theory | Chronic pain services |

| aKaasalainen 2007187 | Canada | 66 | Interviews and focus groups | Grounded theory | Pain in aged care facilities |

| Kaasalainen 2010188 | Canada | NK | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| aKaasalainen 2010189 | Canada | 53 | Interviews and focus groups | Case study analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| aKilaru 2014190 | USA | 61 | Semistructured interview | Grounded theory | Opioid prescription |

| aKrebs 2014191 | USA | 14 | Semistructured interview | Immersion–crystallisation | Opioid prescription |

| Kristiansson 2011192 | Sweden | 5 | Interviews | Narrative analysis | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| Liu 2014193 | Hong Kong | 49 | Interviews and focus groups | Content analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| Löckenhoff 2013194 | USA | 44 | Focus groups | Content analysis | Mixed HCPs |

| Lundh 2004195 | Sweden | 14 | Focus groups | Constant comparison | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| MacNeela 2010196 | Ireland | 12 | Critical incident interview | Thematic analysis | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| McConigley 2008197 | Australia | 34 | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| aMcCrorie 2015198 | UK | 15 | Focus groups | Grounded theory | Opioid prescription |

| Mentes 2004199 | USA | 11 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Pain in aged care facilities |

| O’Connor 2015200 | USA | NK | Ethnography | Constant comparison | Chronic pain services |

| Øien 2011201 | Norway | 6 | Interviews, focus groups, observation | Case study | Physiotherapists |

| Oosterhof 2014202 | The Netherlands | 10 | Interviews and observation | Thematic analysis | Chronic pain services |

| Parsons 2012203 | UK | 19 | Semistructured interviews | Framework analysis | Mixed professionals |

| Patel 2008204 | UK | 18 | Semistructured interview | Thematic analysis | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| aPatel 2009205 | UK | 18 | Semistructured interview | Thematic analysis | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| Paulson 1999206 | Sweden | 21 | Interviews | Phenomenology | Fibromyalgia |

| Poitras 2011207 | Canada | 9 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Guidelines |

| aRuiz 2010208 | USA | 21 | Focus groups and interviews | Grounded theory | Older adults |

| Schulte 2010209 | Germany | 10 | Semistructured interview | Thematic analysis | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| Scott-Dempster 2014210 | UK | 6 | Semistructured interviews | Interpretative phenomenological analysis | Specialist physiotherapists |

| aSeamark 2013211 | UK | 22 | Interviews and focus groups | Thematic analysis | Opioid prescription |

| Shye 1998212 | USA | 22 | Focus groups | Immersion–crystallisation | Guidelines |

| aSiedlecki 2014213 | USA | 48 | Interviews | Grounded theory | Nursing |

| Slade 2012214 | Australia | 23 | Focus groups | Grounded theory | Physiotherapists |

| Sloots 2009215 | The Netherlands | 4 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Chronic pain services |

| Sloots 2010216 | The Netherlands | 10 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Chronic pain services |

| aSpitz 2011217 | USA | 26 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Opioid prescription |

| aStarrels 2014218 | USA | 28 | Telephone interview | Grounded theory | Opioid prescription |

| Stinson 2013219 | Canada | 17 | Focus groups | Thematic analysis | Chronic pain services |

| Thunberg 2001150 | Sweden | 22 | Interviews | Grounded theory | Chronic pain services |

| Toye 2015220 | UK | 19 | Focus groups | Grounded theory | Mixed professionals |

| Tveiten 2009221 | Norway | 5 | Focus groups | Content analysis | Chronic pain services |

| Wainwright 2006222 | UK | 14 | Interviews | Thematic analysis | Primary care physicians/GPs |

| Wilson 2014223 | UK | NK | Interviews, documents | Ethnography | Guidelines |

| Wynne-Jones 2014224 | UK | 17 | Semistructured interviews | Constant comparison | Pain-related work disability |

| Zanini 2014225 | Italy | 17 | Semistructured interviews | Thematic analysis | Chronic pain services |

Quality assessment and inclusion

Table 4 provides the outcome of appraisal: the CASP score from each reviewer [from 10 (low) to 30 (high)]; the difference in CASP score between reviewers; the seven themes developed from a previous meta-ethnography;8 the global quality score (key, satisfactory, uncertain, irrelevant or fatal flaw); and reviewers’ assessment of potential value based on CASP question 10 (‘how valuable is the research?’). The difference in CASP score between two reviewers ranged from –4 to 2 (a possible score of 10–30). They did not agree about the inclusion of four studies,172,178,196,201 which were subsequently included by a third reviewer. Two reviewers agreed that 89% of primary authors had reported their study aim and 84% had described their sample. They agreed that 89% of the authors had not reported their perspective and its potential influence on findings and 69% had not reported methods for challenging their interpretation. Reviewers also agreed that only 65% of authors had provided clear examples to demonstrate that their findings were drawn from the data and only 55% of authors had clearly described all their findings. Twenty-eight studies11,150,151,153,154,156,157,159,165–167,174,176,179,187,190,195,204,207–209,211–214,221–223 were reported as having ‘changed the thinking’ of at least one reviewer. However, reviewers’ appraisal comments (see Appendix 1) suggested that, even if they did not change their thinking, the primary studies encouraged reviewers to think. Two reviewers unanimously appraised five studies150,151,214,222,223 as ‘key papers’ and 72 as ‘satisfactory’ (see Table 3). At least one reviewer appraised 26 studies11,150,151,154,156,157,160,170,171,176,187,190,191,195,198,204,205,210,211,214,219–223,225 as potentially making a ‘valuable’ contribution to the analysis. They agreed on 21 of 26 of the valuable studies. To allow readers to evaluate the transferability of findings, Table 5 shows the reviewers’ assessment of relevance (direct, indirect, partial or uncertain) and aim of each study. We rated 60 studies11,150,152–164,168–171,173–178,180,181,183–188,190–193,195,196,198,200–211,214,215,217,218,221,222,224,225 as directly relevant, seven151,165,166,197,219,220,223 as indirectly relevant, nine172,179,182,189,194,199,212,213,216 as partially relevant and one167 as uncertain.

| In/out | First author and year | Reviewer 1 CASP score | Reviewer 2 CASP score | Difference between CASP scores | Theme | Global quality and value score (CASP question 10) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Rationale/aim described? | 2. Sample described? | 3. Researcher’s perspective clear? | 4. Challenged interpretation? | 5. Does interpretation come from the data? | 6. Can you identify the ideas? | 7. Has this changed your thinking? | ||||||

| In | Thunberg 2001150 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N (Y) | Y (N) | KP and V2 |

| In | Slade 2012214 | 28 | 29 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | KP and V2 |

| In | Wainwright 2006222 | 28 | 28 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y (N) | KP and V2 |

| In | Afrell 2010151 | 29 | 29 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y (N) | Y | KP and V2 |

| In | Wilson 2014223 | 29 | 30 | –1 | Y | Y | N (Y) | Y | Y | Y | Y | KP and V2 |

| In | Tveiten 2009221 | 26 | 28 | –2 | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT and V2 |

| In | Kaasalainen 2007187 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT and V2 |

| In | Kilaru 2014190 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT and V2 |

| In | Krebs 2014191 | 27 | 28 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT and V2 |

| In | Lundh 2004195 | 27 | 29 | –2 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N (Y) | SAT and V2 |

| In | Fox 2004176 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | SAT and V2 |

| In | Allegretti 201011 | 28 | 29 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | SAT and V2 |

| In | Baszanger 1992156 | 28 | 27 | 1 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y (N) | SAT and V2 |

| In | Daykin 2004170 | 28 | 28 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y (N) | N | SAT and V2 |

| In | McCrorie 2015198 | 28 | 29 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y (N) | N | SAT and V2 |

| In | aPatel 2008204 | 28 | 29 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | SAT and V2 |

| In | Zanini 2014225 | 28 | 28 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT and V2 |

| In | Barker 2015154 | 29 | 29 | 0 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N (Y) | SAT and V2 |

| In | Berg 2009157 | 29 | 29 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT and V2 |

| In | Scott-Dempster 2014210 | 29 | 29 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT and V2 |

| In | Toye 2015220 | 29 | 29 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT and V2 |

| In | Blomqvist 2003160 | 26 | 28 | –2 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | SAT and V1 |

| In | Dobbs 2014171 | 27 | 28 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT and V1 |

| In | Seamark 2013211 | 27 | 26 | 1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT and V1 |

| In | Stinson 2013219 | 27 | 25 | 2 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT and V1 |

| In | aPatel 2009205 | 28 | 28 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | SAT and V1 |

| In | Cameron 2015162 | 22 | 22 | 0 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | SAT |

| In | Chew-Graham 1999164 | 22 | 23 | –1 | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Coutu 2013168 | 22 | 21 | 1 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | Löckenhoff 2013194 | 22 | 22 | 0 | N (Y) | Y | N | N | N | N | N | SAT |

| In | Åsbring 2003152 | 23 | 24 | –1 | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Shye 1998212 | 23 | 24 | –1 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y (N) | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Siedlecki 2014213 | 23 | 24 | –1 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Baldacchino 2010153 | 24 | 23 | 1 | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y (N) | Y | SAT |

| In | Côté 2001167 | 24 | 25 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Hellström 1998183 | 24 | 25 | –1 | Y | Y | N | N | Y (N) | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Kristiansson 2011192 | 24 | 24 | 0 | Y | Y | N (Y) | N | N | N | N | SAT |

| In | Parsons 2012203 | 24 | 25 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Fontana 2008175 | 25 | 24 | 1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Clark 2004165 | 25 | 26 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | SAT |

| In | Harting 2009180 | 25 | 25 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | SAT |

| In | Hayes 2010181 | 25 | 26 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | McConigley 2008197 | 25 | 26 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y (N) | N | SAT |

| In | Poitras 2011207 | 25 | 26 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Ruiz 2010208 | 25 | 25 | 0 | Y | Y | N (Y) | Y | Y | Y | N (Y) | SAT |

| In | Sloots 2010216 | 25 | 25 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | Wynne-Jones 2014224 | 25 | 25 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | Bergman 2013158 | 26 | 25 | 1 | Y | Y | N (Y) | Y | Y | Y (N) | N | SAT |

| In | Cartmill 2011163 | 26 | 26 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Clark 2006166 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | SAT |

| In | Dahan 2007169 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | Gooberman-Hill 2011177 | 26 | 28 | –2 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N (Y) | N | SAT |

| In | Hansson 2001179 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | N (Y) | Y | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Holloway 2009184 | 26 | 26 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Holloway 2009185 | 26 | 26 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Kaasalainen 2010189 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | O’Connor 2015200 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Schulte 2010209 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N (Y) | Y | N | Y | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Sloots 2009215 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N | N (N) | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Starrels 2014218 | 26 | 27 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Barry 2010155 | 27 | 26 | 1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Blomberg 2008159 | 27 | 28 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Briones-Vozmediano 2013161 | 27 | 28 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y (N) | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Espeland 2003173 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | Y (N) | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | Esquibel 2014174 | 27 | 28 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y (N) | SAT |

| In | Hellman 2015182 | 27 | 28 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Howarth 2012186 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Kaasalainen 2010188 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Liu 2014193 | 27 | 28 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y (N) | N | SAT |

| In | Mentes 2004199 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Oosterhof 2014202 | 27 | 26 | 1 | Y | Y | N (Y) | Y | Y | N | N | SAT |

| In | Paulson 1999206 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | N (Y) | N | N | SAT |

| In | Spitz 2011217 | 27 | 27 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | SAT |

| In | Eccleston 1997172 | 20 | 25 | –5 | Y (N) | Y | N (Y) | Y (N) | Y | N | N | SAT/FF |

| In | MacNeela 2010196 | 21 | 22 | –1 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | SAT/FF |

| In | Øien 2011201 | 23 | 24 | –1 | Y | Y | N | Y (N) | N (N) | N (N) | N | SAT/FF |

| In | Gropelli 2013178 | 21 | 21 | 0 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N (N) | N | SAT/FF |

| Out | Kotarba 1984149 | 14 | 13 | 1 | N | N (N) | N | N | N | N (N) | N | FF |

| Out | Dysvik 2010148 | 18 | 17 | 1 | N | N (Y) | N | N (N) | N | N | N | FF |

| Out | Hadker 2011147 | 19 | 19 | 0 | N (Y) | N (Y) | N | N (N) | N | N | N | FF |

| Out | Schofield 2006144 | 19 | 19 | 0 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | FF |

| Out | Crowe 2010146 | 21 | 25 | –4 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | FF |

| Out | Corbett 2009145 | 23 | 23 | 0 | Y | Y | N | Y | N (Y) | N (N) | N | FF |

| Out | Corrigan 2011116 | 21 | 21 | 0 | N (Y) | N (Y) | N | N | N | N (N) | N | Irrelevant |

| Out | Coutu 2013168 | 24 | 25 | –1 | N (Y) | N | N | N | N (Y) | N | N (N) | Irrelevant |

| First author and year | Relevance | Study aim |

|---|---|---|

| Afrell 2010151 | Indirect | To find out how physiotherapists experienced the influence of systematically prepared key questioning on their relation to, and understanding of, patients with long-standing pain |

| Allegretti 201011 | Direct | To explore shared experiences among chronic low back pain patients and their physicians |

| Åsbring 2003152 | Direct | To investigate:

|

| Baldacchino 2010153 | Direct | To describe physicians’ attitudes and experience of prescribing opioids to people with chronic non-cancer pain and a history of substance abuse |

| Barker 2015154 | Direct | To evaluate the implementation of acceptance and commitment therapy to physiotherapy-led pain rehabilitation programme |

| Barry 2010155 | Direct | To examine physicians’ attitudes to and experiences of treating chronic non-cancer pain |

| Baszanger 1992156 | Direct | To examine how physicians, specialising in pain medicine, work at deciphering chronic pain |

| Berg 2009157 | Direct | To explore providers’ perceptions of ambiguity and then to examine their strategies for making diagnostic and treatment decisions to manage chronic pain among patients on methadone maintenance therapy |

| Bergman 2013158 | Direct | To understand the respective experiences of patients with chronic pain and primary care practitioners communicating with each other about pain management in the primary care setting |

| Blomberg 2008159 | Direct | To explore district nurses’ care of chronic pain sufferers and to create a theoretical model that can explain the variation in district nurses’ experiences of caring for these patients |

| Blomqvist 2003160 | Direct | To explore nursing and paramedical staff perceptions of older people in persistent pain and their day-to-day management of pain |

| Briones-Vozmediano 2013161 | Direct | To explore experiences of fibromyalgia management, namely diagnostic approach, therapeutic management and the health professional–patient relationship |

| Cameron 2015162 | Direct | To explore current attitudes and approaches to pain management of older adults from the perspectives of HCPs representing multidisciplinary teams |

| Cartmill 2011163 | Direct | To explore the experience of clinicians during the transition from working as an interdisciplinary team to providing a transdisciplinary model of care in a programme for chronic disabling musculoskeletal pain |

| Chew-Graham 1999164 | Direct | To understand how GPs understood chronic low-back pain, how they approached the consultation and how they conceptualised the management of this problem |

| Clark 2004165 | Indirect | To describe the kinds of pain assessments nursing home staff use with nursing home residents and the characteristics and behaviours of residents that staff consider as they assess pain |

| Clark 2006166 | Indirect | To explore the perceptions of a nursing home staff who participated in a study to develop and evaluate a multifaceted pain management intervention |

| Côté 2001167 | Uncertain | To explore the views of chiropractors about timely return to work, to identify the approaches used and to learn about perspectives on the barriers to, and facilitators of, successful return to work with musculoskeletal disorders |

| Coutu 2013168 | Direct | To define and describe scenarios depicting the differences between clinical judgement, workers’ representations of their disability and clinicians’ interpretations of these representations |

| Dahan 2007169 | Direct | To identify the barriers to, and facilitators of, the implementation of low-back pain guidelines from family practitioners’ perspective |

| Daykin 2004170 | Direct | To explore physiotherapists’ pain beliefs with the purpose of highlighting the nature of their beliefs and the role they played within their management of chronic low-back pain |

| Dobbs 2014171 | Direct | To explore:

|

| Eccleston 1997172 | Partial | To explore how sense is made of the causes of chronic pain |

| Espeland 2003173 | Direct | To identify and describe:

|

| Esquibel 2014174 | Direct | To explore the experiences of adults receiving opioid therapy for relief of chronic non-cancer pain and those of their physicians |

| Fontana 2008175 | Direct | To critically examine subjective factors that influence the prescribing practices of registered nurses for patients with chronic non-malignant pain |

| Fox 2004176 | Direct | To identify barriers to the management of pain in long-term care institutions |

| Gooberman-Hill 2011177 | Direct | To explore GPs’ opinions about opioids and decision-making processes when prescribing ‘strong’ opioids for chronic joint pain |

| Gropelli 2013178 | Direct | To determine nurses’ perceptions of pain management in older adults in long-term care |

| Hansson 2001179 | Partial | To elucidate life lived with recurrent, spine-related pain and to explore the development from work to disability pension |

| Harting 2009180 | Direct | To gain an in-depth understanding of the determinants of guideline adherence among physical therapists |

| Hayes 2010181 | Direct | To explore knowledge and attitudinal challenges affecting optimal care in fibromyalgia |

| Hellman 2015182 | Partial | To explore and describe health professionals’ experience of working with return to work in multimodal rehabilitation for people with non-specific back pain |

| Hellström 2015183 | Direct | To explore the clinical experiences of doctors when meeting patients with fibromyalgia |

| aHolloway 2009184 | Direct | To explore the experiences of nursing assistants who work with older people in residential aged care facilities (chronic pain example) |

| aHolloway 2009185 | Direct | To explore the experiences of nursing assistants who have worked with older people in residential aged care facilities who are in pain |

| Howarth 2012186 | Direct | To explore person-centred care from the perspectives of people with chronic back pain and the interprofessional teams that cared for them |

| Kaasalainen 2007187 | Direct | To explore the decision-making process of pain management of physicians and nurses and how their attitudes affect decisions about prescribing and administering pain medications among older adults in long-term care |

| Kaasalainen 2010188 | Direct | To explore the perceptions of health-care team members (regulated and non-regulated staff) and nurse managers (management staff) regarding the nurse practitioner role in pain management in long-term care |

| Kaasalainen 2010189 | Partial | To:

|

| Kilaru 2014190 | Direct | To identify key themes regarding emergency physicians’ definition, awareness, use and opinions of opioid prescribing guidelines |

| Krebs 2014191 | Direct | To understand physicians’ and patients’ perspectives on recommended opioid management practices and to identify potential barriers to, and facilitators of, guideline-concordant opioid management in primary care |

| Kristiansson 2011192 | Direct | To understand and illustrate what GPs experience in contact with chronic pain patients and what works and does not work in these consultations |

| Liu 2014193 | Direct | To explore nursing assistants’ roles during the process of pain management for residents |

| Löckenhoff 2013194 | Partial | To examine how perceptions of chronological time influence the management of chronic non-cancer pain in middle-aged and older patients |

| Lundh 2004195 | Direct | To explore and describe what it means to be a GP meeting patients with non-specific muscular pain |

| MacNeela 2010196 | Direct | To examine how GPs represent chronic low-back pain in an applied context, especially in relation to psychosocial care |

| McConigley 2008197 | Indirect | To develop recommendations and a related implementation resource ‘toolkit’ to facilitate implementation of pain management strategies in Australian residential aged care facilities |

| McCrorie 2015198 | Direct | To understand the processes that bring about and perpetuate the long-term prescribing of opioids for chronic non-cancer pain |

| Mentes 2004199 | Partial | To evaluate whether or not information from family members/friends about patients’ lifelong pain behaviour improves pain detection in cognitively impaired residents and to evaluate pain information from caregivers |

| O’Connor 2015200 | Direct | To explore patterns of communication and decision-making among clinicians collaborating in the care of challenging patients with chronic low-back pain |

| Øien 2011201 | Direct | To describe communicative patterns about change in demanding physiotherapy treatment situations |

| Oosterhof 2014202 | Direct | To explore which factors are associated with a successful treatment outcome in chronic pain patients and professionals participating in a multidisciplinary rehabilitation programme |

| Parsons 2012203 | Direct | To explore beliefs about chronic muscular pain and its treatment and how these beliefs influenced care seeking and ultimately the process of care |

| aPatel 2008204 | Direct | To explore GPs’ experiences of managing patients with chronic pain from a South Asian community |

| aPatel 2009205 | Direct | To explore the experiences of and needs for management of people from a South Asian community who have chronic pain |

| Paulson 1999206 | Direct | To explore the experiences of nurses and physicians in their encounter with men with fibromyalgia |

| Poitras 2011207 | Direct | To identify barriers and facilitators related to the use of low-back pain guidelines as perceived by occupational therapists |

| Ruiz 2010208 | Direct | To explore the attitudes of primary care practitioners towards chronic non-malignant pain management in older people |

| Schulte 2010209 | Direct | To understand the factors that influence whether or not referrals from GPs are made, and at what stage, to specialised pain centres |

| Scott-Dempster 2014210 | Direct | To explore physiotherapists’ experiences of using activity pacing with people with chronic musculoskeletal pain |

| Seamark 2013211 | Direct | To describe the factors influencing GPs’ prescribing of strong opioid drugs for chronic non-cancer pain |

| Shye 1998212 | Partial | To gain understanding about why a controlled intervention to reduce variability in lumbar spine imaging test rates for low-back pain patients was ineffective |

| Siedlecki 2014213 | Partial | To explore and understand nurses’ assessment and decision-making behaviours related to the care of patients with chronic pain in the acute care setting |

| Slade 2012214 | Direct | To investigate how physiotherapists prescribe exercise for people with non-specific chronic low-back pain in the absence of definitive or differential diagnoses |

| aSloots 2009215 | Direct | To explore which factors lead to tension in the patient–physician interaction in the first consultation by rehabilitation physicians of patients with chronic non-specific low-back pain who are of Turkish and Moroccan origin |

| aSloots 2010216 | Partial | To explore which factors led to dropout in patients of Turkish and Moroccan origin with chronic non-specific low-back pain who participated in a rehabilitation programme |

| Spitz 2011217 | Direct | To describe primary care providers’ experiences of and attitudes towards, as well as perceived barriers to, and facilitators of, prescribing opioids as a treatment for chronic pain among older adults |

| Starrels 2014218 | Direct | To understand primary care providers’ experiences, beliefs and attitudes about using opioid treatment agreements for patients with chronic pain |

| Stinson 2013219 | Indirect | To explore the information and service needs of young adults with chronic pain to inform the development of a web-based chronic pain self-management programme |

| Thunberg 2001150 | Direct | To explore the way HCPs perceive chronic pain |

| Toye 2015220 | Indirect | To understand the impact on HCPs of watching and discussing a short research-based film about patients’ experience of chronic musculoskeletal pain |

| Tveiten 2009221 | Direct | To develop knowledge of the dialogue between the health professionals and the patient in the empowerment process at a pain clinic |

| Wainwright 2006222 | Direct | To explore the dilemma of treating medically explained upper-limb disorders |

| Wilson 2014223 | Indirect | To understand both the meaning of a clinical practice guideline for the management of non-specific low-back pain and the sociopolitical events associated with it |

| Wynne-Jones 2014224 | Direct | To explore GPs’ and physiotherapists’ perceptions of sickness certification in patients with musculoskeletal problems |

| Zanini 2014225 | Direct | To identify aspects important to address during a consultation to build a partnership with patients with chronic pain |

Coding and conceptual categories

We coded batches of studies in the following order according to topic/professional grouping:

-

Ten studies reported the experiences of primary care physicians/GPs. 11,158,164,192,195,196,204,205,209,222

-

Four studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs. 172,194,203,220

-

Three studies explored the experiences of physiotherapists. 170,201,214

-

Three studies explored the experiences of physiotherapists specialising in chronic pain management. 151,154,210

-

Five studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs providing health care to people with fibromyalgia. 152,161,181,183,206

-

Eleven studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs working in specialist chronic pain services. 150,156,163,186,200,202,215,216,219,221,225

-

Five studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs working in pain management related to employment. 167,168,179,182,224

-

Twelve studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs prescribing opioids to patients with chronic pain. 153,155,157,174,175,177,190,191,198,211,217,218

-

Six studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs utilising guidelines for chronic pain. 169,173,180,207,212,223

-

Three studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs working with older adults. 160,162,208

-

Thirteen studies explored the experiences of a mixed group of HCPs working with older adults in long-term care facilities. 165,166,171,176,178,184,185,187–189,193,197,199

-

Two studies explored nurses’ experiences of providing health care to people with chronic non-malignant pain. 159,213

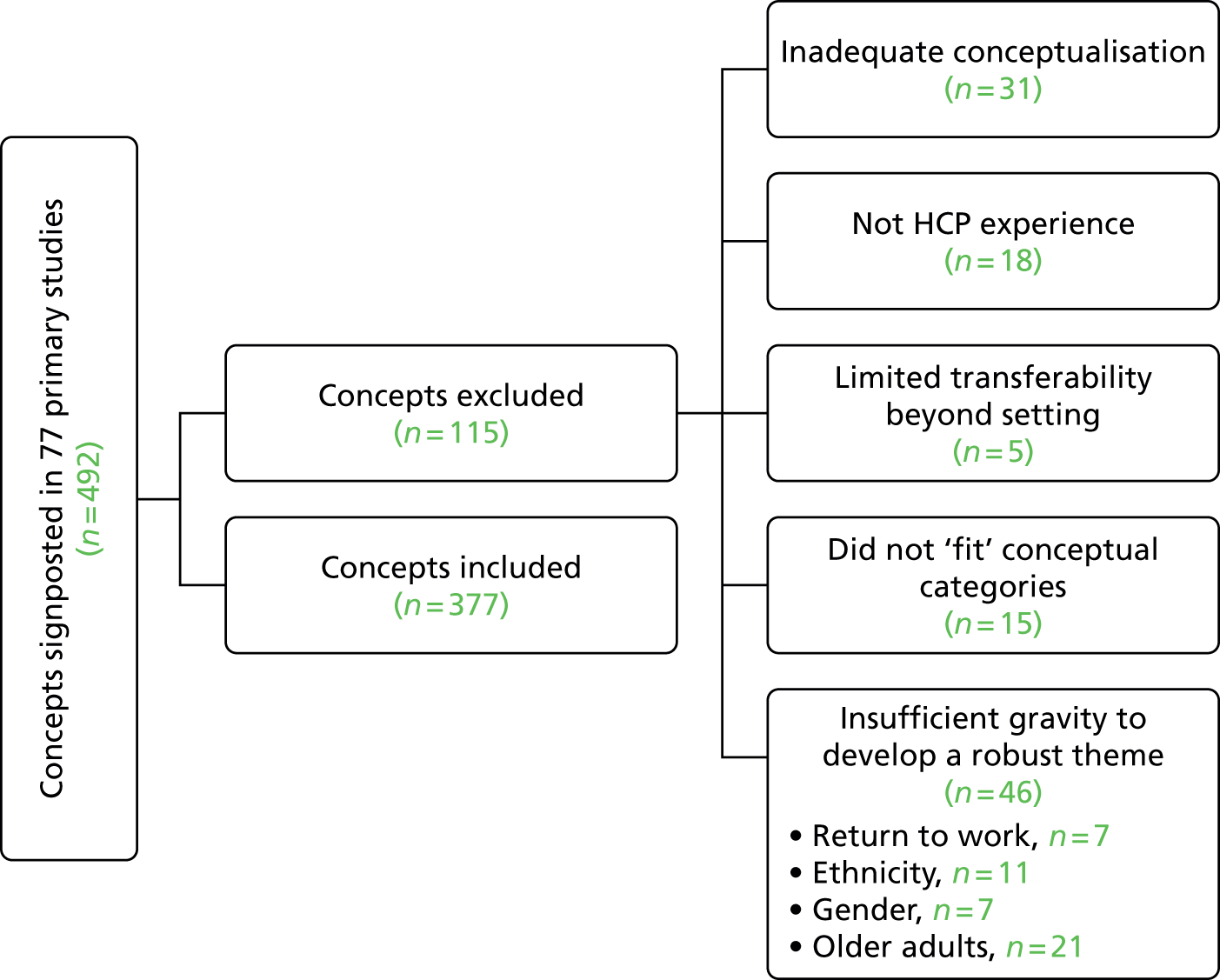

Appendix 2 provides a coding report of included and excluded concepts. Two reviewers identified 492 potential concepts in 77 primary studies (Figure 3). They excluded 115 potential concepts for the following reasons: inadequate conceptualisation (31 concepts in 17 studies11,150,155,160,162,169,173,178,181,188,192,196,197,206,208,219); did not explore HCP experience (18 concepts in seven studies168,174,198,202,203,215,223); and explored a topic with limited transferability beyond a specific context (five concepts in five studies166,167,197,208,223). We agreed that for some topics there were insufficient concepts to allow us to develop robust conceptual categories: return to work (seven concepts in two studies167,182), ethnicity (11 concepts in five studies171,204,205,215,216), gender (seven concepts in one study206) and older people (21 concepts in nine studies159,160,162,165,176,187,194,199,208). Fifteen potential concepts did not fit our developing conceptual analysis (Table 6).

FIGURE 3.

Concepts that were included and excluded.

| First author and year: qualitative finding | Description of finding |

|---|---|

| Barry 2010:155 logistical factors – ancillary staff | Physicians expressed concern that they had an insufficient number of qualified staff to implement pain management |

| Barry 2010:155 logistical factors – insurance coverage | Concerns about the logistics of insurance coverage for pain management services and the difficulty in characterising patients’ pain status because of restrictions from insurance companies |

| Fontana 2008:175 critical analysis | Conflicts of interest in which the patients’ best interests are given a low priority. Nurses did not see prescribing decisions as ethical ones and, as a result, did not recognise the conflicts that were at work when they made these decisions |

| Holloway 2009:184 initiating clinical care | The ability to provide pain management for residents when needed varied considerably between facilities; for some it involved basic care such as emotional support, positioning and using hot-packs, whereas in other facilities they administered pain medication and had responsibility for monitoring the effectiveness of the pain management interventions and documentation |

| Holloway 2009:185 perfect positioning (rewards of getting it right) | Assistants felt sustained and fulfilled by the rewarding aspects of caring. All spoke of their passion for, enjoyment of and love for their work (and this is why they stayed in it). Despite the emotional distress associated with observing people in pain, assistants gained satisfaction from seeing residents relieved of pain. Discussed poor financial remuneration |

| Kaasalainen 2010:188 interactions with long-term care staff and managers | Nurse practitioner was viewed as a nurse with added skills who assisted other health-care team members with managing uncontrolled pain and was often used as an additional resource for nurses |

| Liu 2014:193 instigator implementing non-pharmacological interventions | Skills in distraction, reassurance and being gentle. Nursing assistants explained how they distracted or reassured residents who were in pain |

| Löckenhoff 2013:194 age differences in time horizons (treatment planning) | Consistently reported that they planned and administered pain management regimens for the long term |

| Lundh 2004:195 variation 1 | I can feel very curious! What do these symptoms stand for? |

| Oosterhof 2014:202 experiences concerning the treatment outcome (learning new behaviour) | HCPs recognised that change takes effort and a combination of explanation and practice. Some managed to learn and implement new behaviour because they have always been active or because of good body awareness or physical preference. Others find it difficult to keep up effort because of personal problems and poor social support |

| Scott-Dempster 2014:210 ‘It’s not a One Trick Pony’ | Physiotherapists regarded activity pacing as part of the pain management tool box. Activity pacing was not described as something that was clearly definable or had fixed parameters. Achieving this flexibility could be challenging, as it meant that the physiotherapist had to adapt activity pacing for each individual |

| Seamark 2013:211 cost | Some did not consider cost and prescribed what was needed. Others felt that it was important to bear in mind |

| Siedlecki 2014:213 core concepts/taking ownership | Some did not take ownership of the problem and saw it as someone else’s problem |

| Stinson 2013:219 barriers to care (patient-specific barriers) | Difficult to maintain a consistent pain management regimen because of time commitments and reluctance of younger people |

| Stinson 2013:219 pain management strategies (support systems) | HCPs recognised the importance of peer support for patients |

All reviewers organised the remaining 377 concepts into 42 conceptual categories. Table 7 gives an example of one of the conceptual categories (‘is the pain real?’) and its included concepts. Our description of the concepts that formed the raw data of analysis were a combination of the primary author’s description of the second-order construct (in which they briefly and clearly described the construct), and our interpretation of the construct (if the original was unclear or lengthy). In some cases we found that there was a section of narrative exemplar provided by the original authors that adequately described the essence of the concept.

| First author/year and qualitative finding | Description of finding |

|---|---|

| Åsbring 2003:152 illness vs. disease | HCP scepticism for conditions characterised by a lack of objective measurable values that would make it possible to establish cause. Fibromyalgia and chronic fatigue described as illness not disease. There was some doubt regarding this scientific ideal |

| Åsbring 2003:152 moral judgement of illness | Biomedical disease was regarded as more threatening to self than ‘illness’. Suggestion that patients think they cannot live with it because they have not experienced something ‘really threatening’. An individual who claims to be sick must also look sick to be accepted as such. Sometimes doubted legitimacy of person |

| Bergman 2013:158 acknowledgement of the reality of pain and the search for objective evidence (primary care practitioners) | Search for objective evidence of pain is a crucial part of evaluation (particularly with opioids). Struggled with the dilemma of how to respond in the absence of physical findings. Looked for behavioural and non-verbal cues to indicate presence/absence of pain. Doubted legitimacy in the absence of evidence. Others acknowledged the subjective nature of pain and importance of believing patients |

| Esquibel 2014:174 effect of chronic opioid therapy on doctor–patient relationship – examples of chronic opioid therapy embittering the doctor–patient relationship | Opioid therapy can become the source of conflict and mistrust. Clinical encounters can become largely overshadowed by opioid medication discussion or controversy. Physicians tend to question the validity of their patient’s pain and do not approve of opiate pain medication as treatment |

| Hayes 2010:181 definition and diagnosis | Questioned the validity of fibromyalgia itself and recognised the impact of this doubt. Doctors did not like clinical situations in which they did not feel in control: The patients tell me with a smile on their lips that they are suffering immensely from all kinds of bodily disorders. How on earth can they look so terribly healthy? |

| Holloway 2009:184 clinical decision-making | Assistants relied on their knowledge of the resident. They spent time with residents and knew their behaviours and moods, so were able to detect changes. They made personal judgements that influenced clinical decisions about pain. Some felt that residents exaggerated pain and changed pain report to ‘more appropriate’ level |

| Kaasalainen 2010:189 health-care providers | Staff did not always believe residents’ reports of pain, or felt that they were overstating their pain. At times, staff felt they needed to ‘second guess’ the residents’ reports |

| Lundh 2004:195 an inconsistent patient | She had ten different symptoms and looked totally healthy! Then you are surprised! |

| MacNeela 2010:196 representing the person’s experience (work and legal issues) | Return to work was synonymous with recovery and successful adjustment, but work avoidance and ulterior motives were part of the script for chronic low-back pain. Could highlight doubt and risk rather than person’s ‘plight’: I mean that could be genuine . . . You’d have to be on guard this man isn’t laying it on |

| Siedlecki 2014:213 nurse characteristics – discernment | Nurses described the importance of knowing their patients to discern appropriate pain management:You can look at that patient and many times what they tell you verbally may not be consistent with what we see . . . they may be very calmly in bed or fall asleep as they’re talking to you but they tell you their pain is a 10/12 |

| Stinson 2013:219 barriers to care (societal barriers) | HCPs described the societal tendency to cast doubt on the veracity of chronic pain: This isn’t something that people can see and so a lot of people, I think, feel like they’re not believed either by their friends or by their family or their health care practitioners um and that is also I guess a big issue |

Once the reviewers had agreed on a description of each conceptual category, Fran Toye wrote a statement of this finding in the first person.

For example:

This conceptual category described how endless paperwork eats into HCPs’ limited patient time

became:

This endless paperwork eats into my limited patient time.

We have found that writing concepts in the first person is a powerful way for reviewers and their advisory group members to fully engage in the meaning and sentiment of each concept. It also facilitates the use of accessible language for a diverse audience in both analysis and dissemination.

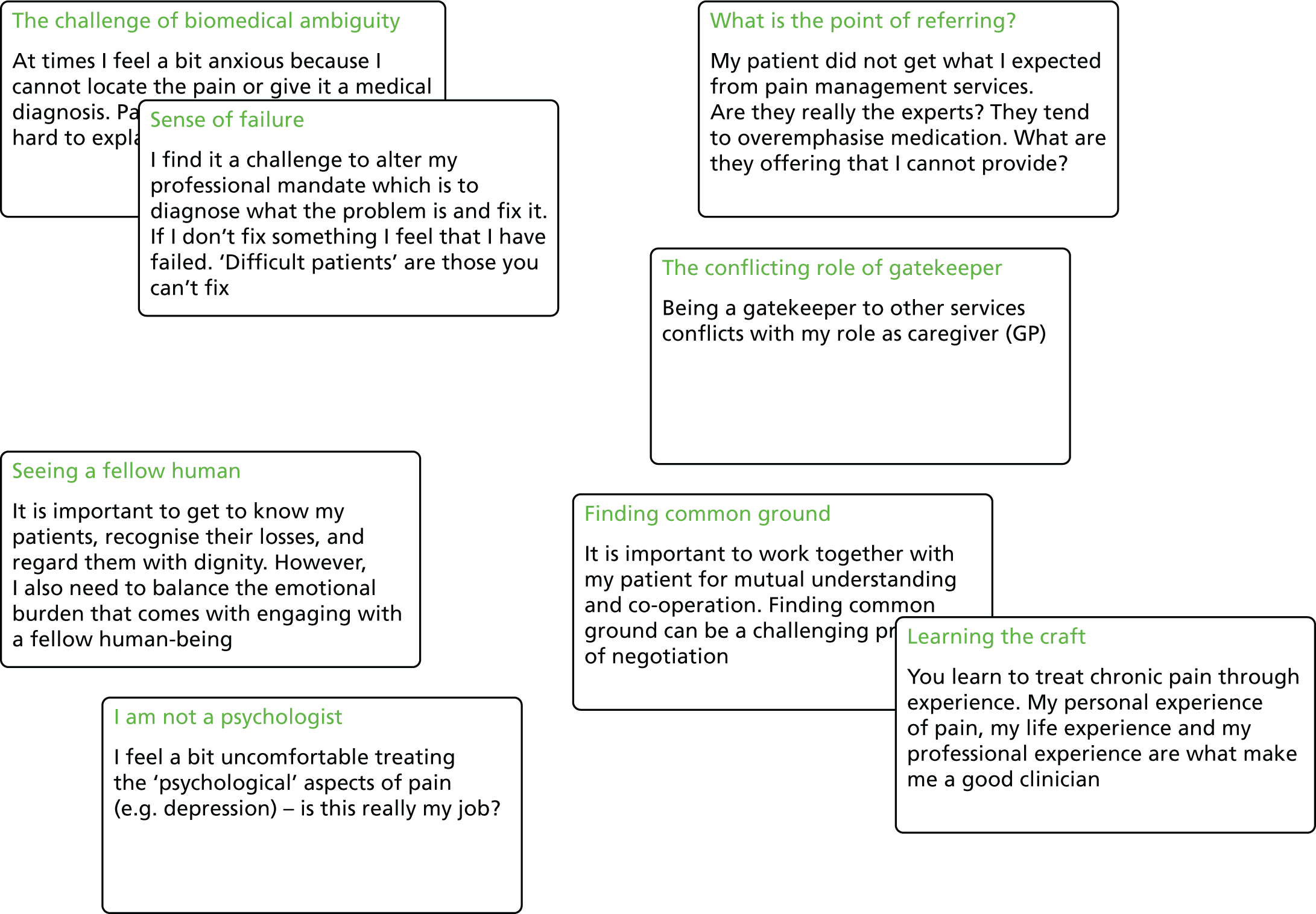

Table 8 provides a description of each of the 42 conceptual categories written in the first person. The reviewers worked with a research fellow and a project advisory group that included patients and HCP members to further abstract these 42 conceptual categories, printed on postcards, into six overarching themes that underpin HCPs’ experience of providing health care to people with chronic non-malignant pain (Figure 4). Table 9 provides a list of the conceptual categories underpinning each of the six final themes. Table 10 shows the number of studies and concepts for each theme organised by topic/professional group. It also indicates the global appraisal score given for individual studies supporting the theme.

| Conceptual category title | Description of conceptual categorya |

|---|---|

| My professional duty | It is my professional duty to provide the care that I see fit and my patient’s duty to follow my professional advice. Professional competence is paramount. Do not let your patient dictate what to do |

| This endless paperwork takes time | This endless paperwork eats into my limited patient time |

| It takes time to get to know someone | I need to get to know my patient if I am going to help them, but this takes time. Because my time is restricted I tend to focus on the person’s physical body rather than on the person sitting in front of me. Sometimes I even avoid seeing patients with chronic pain |

| I am my patient’s advocate | I am an advocate for my patient and it is my job to mediate between them and other staff and organisations. This advocacy makes our relationship strong but it can come with personal risks of loss or failure |

| Seeing a fellow human | It is important to get to know my patients, recognise their losses and regard them with dignity. However, I also need to balance the emotional burden that comes with engaging with a fellow human being |

| The conflicting role of gatekeeper | Being a gatekeeper to other services conflicts with my role as caregiver (GP) |

| Learning the craft of pain management | You learn to treat chronic pain through experience. My personal experience of pain, my life experience and my professional experience are what make me a good clinician |

| We did not learn this in class | I didn't learn how to treat chronic pain in my clinical education. I am underskilled in chronic pain management, particularly psychological strategies and medication |

| Guidelines: take them or leave them | The guidelines for back pain just give me more paperwork to read. I can take them or leave them |

| Guidelines: support psychosocial model | The guidelines for back pain are useful because they give weight to a psychosocial explanations rather than overemphasising biomedical explanation |

| Guidelines: to convince others about my decisions | Sometimes I use the guidelines for back pain to convince patients and other clinicians that I am making the right decision; ‘look I am following this to the letter!’ |

| Guidelines: constrain expert knowledge | The guidelines for back pain challenge or even constrain my expert knowledge |

| Guidelines: prevent individualised care | The guidelines for back pain do not allow me to provide individualised treatment for my patient |

| Exhausted by the sense of loss | I am a ‘helpless helpoholic’. I have a strong yearning to help but am constantly frustrated and disappointed. I am on a hiding to nothing and whatever I do is not enough. I am overwhelmed and exhausted by the sense of loss |

| A sense of failure | I find it a challenge to alter my professional mandate, which is to diagnose what the problem is and fix it. If I do not fix something I feel that I have failed. ‘Difficult patients’ are those you cannot fix |

| I am not a psychologist | I feel a bit uncomfortable treating the ‘psychological’ aspects of pain (e.g. depression) – is this really my job? |

| The challenge of biomedical ambiguity | At times I feel a bit anxious because I cannot locate the pain or give it a medical diagnosis. Pain remains ambiguous and hard to explain |

| It is difficult to access specialist services | It is really difficult to access specialist pain (and addiction) services |

| What is the point of referring to other services? | My patient did not get what I expected from pain management services. Are they really the experts? They tend to overemphasise medication. What are they offering that I cannot provide? |

| Finding common ground | It is important to work together with my patient for mutual understanding and co-operation. Finding common ground can be a challenging process of negotiation |

| Conflicting agendas | If you and your patient do not have a shared agenda this can cause tension. Patients often expect a cure, a specific test or a referral when this is not on my agenda |

| Show them you believe them | I need to show patients that I believe them |

| It’s a matter of give and take | I sometimes provide things that my patients ask for in order to maintain our relationship, even when I know there is little point. My decisions are not always taken on clinical grounds. At times you need to balance long- and short-term gains |

| Patient empowerment is easier said than done | It is difficult to navigate between professional and patient expertise. When do I let my patient make the decision (especially when I think they are making a mistake)? Although I should let them be in control, it can be easier to take charge |

| Feigning diagnostic certainty | My patients cling ‘tenaciously’ to the biomedical model and sometimes I ‘feign diagnostic certainty’ so that they continue to trust me. However, I sometimes worry that this is dishonest |

| Healing supersedes fixing | Healing is a journey that I take in partnership with my patient. Sitting alongside rather than constantly trying to diagnose and fix can take away the sense of failure for both of us |

| Betwixt biomedical and psychological explanations | Patients do not want to shift from a biomedical explanation to a psychosocial one. The biomedical model is more socially acceptable in our culture. Trying to shift my explanation can make it very difficult for me to maintain a good relationship with my patient |

| Bridging biomedical and psychosocial | When I shift from biomedical explanation to a psychosocial explanation I use strategies to avoid alienating my patient. This does not resolve the uncertainty but circumvents the problem by using other labels or treatments that can be ambiguous |

| I am in the best position to know the patient but no one listens to me | Even though, on the front line, I am in a ‘the perfect position’ to get to know the patient and help manage their pain, I am ignored or undermined by my colleagues who do not listen to what I have to say |

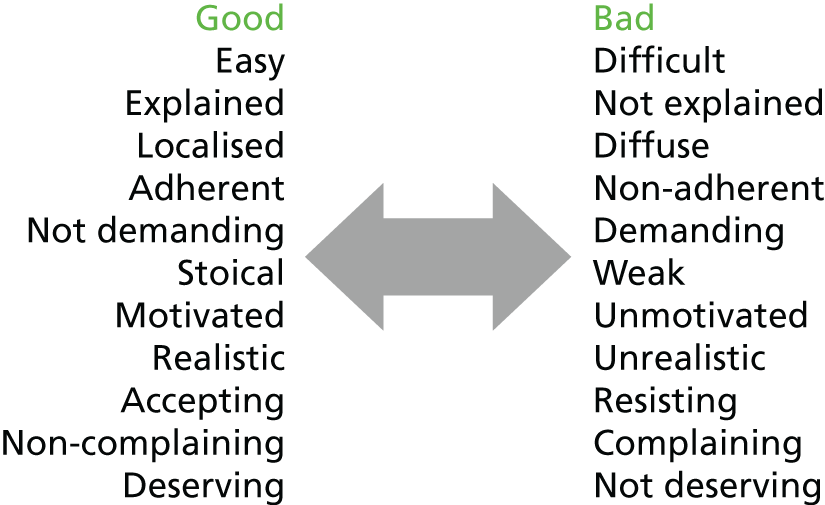

| Mutual professional respect facilitates care | A mutual and respectful relationship with my colleagues can facilitate the kind of communication that underpins effective pain management |