Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/209/02. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The final report began editorial review in January 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Lizanne Harland reports personal fees from Bristol Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) and Gloucestershire CCG outside the submitted work. Lesley Wye is a member of the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Prioritisation Commissioning Panel. Chris Salisbury is a board member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) HSDR programme, which funded this project. He is also a board member of the NIHR School for Primary Care Research.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Horrocks et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction, background and aim of the study

This chapter provides the rationale for the study, outlines the policy context for community nursing service provision and describes some of the challenges in measurement of service quality within community nursing.

Introduction

Public perceptions and trust in the medical and nursing profession were shaken by the Bristol Royal Infirmary inquiry in 20011 and the failings in care at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust,2 both of which related to care quality in hospitals. NHS England (NHSE)3 responded with The 6Cs and Compassion in Practice, a paper characterising provision of high-quality nursing under the categories of the six ‘Cs’ – ‘care’, ‘compassion’, ‘courage’, ‘communication’, ‘commitment’ and ‘competence’– that could be applied to nursing in any health-care setting, and that has since been rolled out to include all practitioners in the NHS. The importance of having well-educated, graduate practitioners providing leadership at the front line in the nursing workforce to ensure the care and safety of patients has also been confirmed. 4 Since 2016, Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC) revalidation has been introduced for registered practitioners to ensure that adherence to the code of professional standards for nurses in care delivery is being upheld. 5 However, the setting and monitoring of care standards is somewhat easier in the acute sector than in the community, and it is notable that the majority of work in relation to assessing nursing care quality has been undertaken in a hospital setting. Given the comparative invisibility of care delivery in patients’ homes, it is crucial that care quality can be monitored to protect patients.

Nurses constitute the largest service group within community-based health provision and work in a range of roles supporting patients in their homes to prevent unnecessary hospital admission and facilitate timely discharge. They may work in specialist roles, such as palliative care or heart failure, or as part of nursing teams (e.g. district nurses and community matrons), providing a full range of nursing care to people who are housebound, therefore serving the most vulnerable and frail NHS users. 6 Care provided in the home is largely invisible to planners and managers and, therefore, it is crucial to understand how quality measures for community nursing are identified and their usefulness for assuring service quality. 7,8 Although an understanding of how to measure the quality of services is growing in the hospital and primary care sectors, comparatively little is known about how best to measure service quality in the community nursing sector,9 or how patients perceive the value of current quality indicators.

The setting and measurement of quality standards have been formally incorporated into community health service commissioning decisions since 2009 and a database of quality indicators (QIs) has been published for use in community services. 10 The use of standardised QIs across community services should, in theory, enable similar services to be compared. Despite substantial investment in QI schemes, however, little is known about how quality measures are used in practice and their usefulness in improving and monitoring quality in nursing. A recent report by The King’s Fund found that community care providers still lacked ‘robust, comparable national indicators that would enable them to benchmark their performance’ and that information technology (IT) and infrastructure were underdeveloped to support quality measurement. 11 The report covered the full range of community services; however, many community services actually take place in clinic and health centre settings and provide time-limited episodes of care for which outcome measures may be readily identified. In contrast, quality measurement in community nursing is complicated by the fact that the majority of service users are cared for in the home and have complex and long-term health problems or deteriorating conditions, making suitable outcome measures difficult to design. 12,13

Quality indicators are measures that aim to numerically describe a service to enable comparison or to assess improvement. 10,14,15 They can come from multiple sources, including Transforming Community Services,10 Community Information Data Set16 and National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) quality standards,17 in addition to local derivation. 18 The concept of quality measurement in health care incorporates a range of different dimensions,19–21 and perspectives on quality measurement can vary between commissioners, providers and service users. 18 Donabedian’s health-care quality framework19 comprises three domains, namely structure (the organisational system or environment under which care is provided, e.g. training of staff, staffing levels), process (e.g. components of service provision) and outcome measurement (the consequences for health of the care delivered). There has been debate about the relative importance of process and outcome measures in quality assurance. 21 Although outcomes represent the ultimate goals of health care and are more easily measured and understood by service users, they can be affected by extraneous factors outside the control of the health service and may not be apparent at the time of care delivery, so are more difficult to attribute. For this reason they may be mistrusted by service providers. 7,18,22 Process indicators, in contrast, are likely to be within the scope of the health-care provider and less likely to be influenced by external factors, but are less easily measured or understood by those outside the service. 22

More recently, NHS quality of care assessment has reflected an emphasis on efficient use of resources and effectiveness, the latter reflecting both clinical outcomes and user experience. 21 This approach was incorporated and further developed within the current NHS quality domains, namely patient experience and clinical effectiveness, with the addition of patient safety. 23 At the time of the current study, these quality domains were incorporated into an annual, nationally mandated quality scheme called Commissioning for Quality and Innovation (CQUIN). The CQUIN scheme, included within the NHS standard contract, offers community services providers additional income to meet quality goals (e.g. improvements in end-of-life care planning) by measuring quality outcome indicators (such as the number of people with a record of death in a preferred place). 24 The intention was to allow commissioners to negotiate with health-care providers on developing services to meet local priorities, while operating within a broader national framework based on national and international best practice. The scheme has the potential to provide information for comparison purposes and incentivise innovative practice and higher-quality aspirations locally. However, a national evaluation of the scheme (which included both acute and community providers) found that few of its interviewees consulted national indicators when developing their CQUIN schemes and that the variety of local indicators that emerged were often unclear or lacking in precision, making it difficult to follow up performance or benchmark services. 25 Several recommendations were made, including reducing the number of local CQUINs schemes and the provision of a small number of benchmarking QIs with a menu of appropriate indicators for use in acute and community settings. Since the changes following the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act 2012,26 it is unclear how, if at all, use of the CQUIN scheme has changed under Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) led by general practitioners (GPs) and how useful it is in the context of measuring quality in community nursing.

The delivery of NHS community nursing services is also subject to a number of quality requirements or key performance indicators (KPIs) incorporated within the standard NHS contract for monitoring and accountability purposes. 27,28 National quality requirements applicable for community nursing include ‘duty of candour’ and ‘never events’, that is, the need for staff to speak up if they are aware of ‘near miss’ incidents of potential harm to patients in order that learning can be gained to prevent similar harms from happening in future. A medication error involving insulin (much of which is administered by community nurses in patients’ homes) would be designated a ‘never event’, as its impact on the patient could be catastrophic. 29 The duty of candour states that staff should be honest and transparent in their communications with patients and their relatives when things go wrong. 30 The contract also includes locally agreed incentive schemes and requires reporting on service quality issues, such as complaints, serious incidents, staff numbers and skill mix, all of which can provide a regular snapshot of real-time feedback on service quality. In addition, providers are required to provide feedback from patients and staff on a regular basis.

Regular approval from the Care Quality Commission (CQC)31 is another requirement of community nursing service providers. CQC inspection overlaps with several areas incorporated in the NHS standard contract, but also includes quality standards related to ‘caring’. Caring is defined as the degree of dignity, respect and compassion while receiving care, people being involved as partners in their care and people who use the services receiving support to cope emotionally with their condition, none of which is directly monitored by the NHS contract. Another key difference relates to the approach to monitoring quality, which always involves an observation of practice and assessment of leadership, as well as an inspection of relevant documentation and talking directly to front-line staff and patients. Taken together, there appears to be a battery of quality assurance requirements on which community service providers report, suggesting a large workload to set, monitor and report on indicators of service quality, without evidence of their perceived usefulness for community nursing from the perspectives of commissioners or service providers and those in receipt of nursing care.

Quality indicator schemes have the potential to improve care quality by provision of feedback to clinicians to improve performance and reduce variation between services, yet there is a body of evidence that suggests that there can be unintended consequences of their use. 32 Unintended consequences documented in the literature included data collection using IT interfering with patient interactions and demotivation of clinicians when they felt their professional judgement being over-ruled. A study exploring primary care professionals’ experiences of the GP Quality and Outcomes Framework, a pay-for-performance quality scheme, suggested that the nature of professional and patient consultations had changed since its introduction, with patient centredness and continuity negatively affected. 33,34 Rambur et al. ,35 reporting on UK studies that included nurses, found evidence of ‘measure fixation’, that is, inappropriate attention on isolated aspects of care conflicting with patient-centred care. 36,37 Although the nurses referred to above tended to work in general practice or acute settings, little is known about the impact of incentivised QIs such as CQUINs on care delivered by community nurses. Furthermore, incentivised QIs for nursing that have been applied in acute care have been rolled out into the community, taking little account of the differing care context for nurses,38 and it is not clear how useful these are for assessing quality from the perspectives of commissioners, providers, patients or front-line community nursing staff.

In this report, findings are presented from a study comprising a collaboration between four universities (University of the West of England, Bristol; University of Bristol; London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine; and University of Manchester) and a NHS partner (the NHS Bristol CCG). Patient and public involvement in the study was integrated firmly at the outset by the inclusion of a lay co-applicant, who instigated the initial research question of how the use of performance indicators might affect nurses’ delivery of personalised care. The study aimed to understand how QIs were being selected and applied in the community nursing context, whether or not these were considered useful by patients, commissioners and providers, and how they could best be used to confer benefit to patients being cared for by community nurses.

Background

The recent background for community nursing provision has been one of continuing organisational change and financial pressure. The NHS is expected to make £22B in efficiency savings by 2020. 39 A key factor in meeting this target is to shift care from acute service provision to the community, placing increased pressure on community services to reduce avoidable hospital admissions and enable the timely discharge of patients. The following section presents the key themes from our review of the literature, which drew on both a structured search of research relating to quality and community nursing and the knowledge of relevant literature within the research management group (see Appendix 1 for the search strategy). It outlines recent policy in the arena of commissioning and community service provision, including the drive to integrate health and social care services, workforce issues and the care context for community nursing, against which the measurement of service quality takes place.

Policy context for community nursing services

The study commenced in 2014, soon after the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act 2012,26,40 with the newly formed CCGs having been in place just over 1 year. Alongside the new commissioning organisations, Transforming Community Services had required NHS organisations in England to be either commissioner or provider. 40 New models of community services providers, for example social enterprises and community foundation trusts, were announced in the Next Stage Review as well as a flexible standard contract to enable commissioners to:

hold community health services to account for quality and health improvement.

p. 4441

Many of these organisations were only created in 2010/11 with 3- to 5-year contracts. A quality framework for community services was also published, which identified 76 QIs reflecting the six areas contained in Transforming Community Services. 10 Community teams were expected to choose and implement a few of these indicators, adapting them to their local circumstances, but at least one commentator expressed doubts that nurses would be given full budgetary control to implement them. 42

The increased integration of health and care services and funding to improve the quality of services for older and disabled people was announced in the Better Care Fund (BCF) spending review (£3.8B worth of funding in 2015/16). 43 In theory, the programme would directly affect the delivery of community nursing, as community nurses play a key role in looking after older and disabled people in their homes. The establishment of new models of care, such as multispecialty community providers, which are vehicles for integrating health and social care, was encouraged in the Five Year Forward View;39 these models are likely to impact on the way that community nursing provision is delivered in future. The main challenges facing commissioners have been identified as the need to consult and engage with patients, and the use of competitive tendering and outcomes-based contracts as organisations move to the new models of care. 44 Furthermore, a major problem hampering community services commissioning was said to be a lack of reliable data and suitable outcome measures, both essential components of outcomes-based commissioning. 44 These components must be in place to allow the benchmarking and evaluation of value-for-money services.

Community nursing services are central to effective integrated care provision, but appropriate outcome measures to assess the impact of integrated care require co-production across organisations and tailoring to those organisations’ priorities for service delivery. 45 The development of meaningful outcomes can be a lengthy process, and this is currently at an early stage. A survey of health and social care managers found that interprofessional working (IPW) for older people, an aspect of integrated care, tended to focus on time-limited, problem-specific interventions, with intermediate care services the most frequently identified model of provision. 46 Intermediate care services are short-term, high-input nursing and therapy care provided to patients at risk of hospital admission or post discharge from hospital, with a focus on support and rehabilitation. The avoidance of hospital admission and recovery from acute episodes of ill health are valid health-care outcomes for intermediate care service input, but they do not reflect continuity of care, which is arguably a better indicator of high-quality integrated care, particularly from the perspective of patients with long-term conditions and their carers. 18 Time, resources and good communication between front-line clinicians and managers are all required to facilitate effective integrated care, but disparities have been reported between, on the one hand, the expectations of leaders in terms of the speed of change required and, on the other hand, the expectations of front-line staff in terms of the feasibility of such change in practice. 47 It is not known how the impact of individual services, such as community nursing, will be attributed for quality monitoring purposes in the developing integrated care context.

Workforce issues

A responsive and high-quality community nursing service is vital for meeting the policy aims of reducing pressure on acute services and, therefore, reducing NHS costs. Historically, decisions about the structure and deployment of nursing teams have been based on tradition and so can be inconsistent and non-systematic. 48 Longstanding issues include a large number of vacancies and a lack of consensus on the most appropriate way to use staff to meet patient need (i.e. whether the service should be generalist or specialist led, or the level of skill mix required in teams). Shortages in community nurse staffing levels have been claimed to lead to patients being readmitted to hospital. 49 The Royal College of Nursing (RCN) has repeatedly stressed that, despite the policy drive to move care into the community and closer to people’s homes, community nursing numbers have declined. There was a 42% fall in district nurse-trained nurses between 2004 and 2014,50,51 and the overall proportion of nursing staff employed to provide general nursing care to people in their own homes has changed little. 52

Patient safety is a fundamental NHS quality measure. A new commissioning framework for community nursing,53 produced following the recommendations of the Francis report,2 takes into account safe staffing. The quality measures incorporated in the framework include access to professional development, use of evidence-based metrics for patient outcomes and experience, and KPIs to demonstrate evidence of workforce planning. District nursing providers, however, still require evidence-based operational scheduling tools to determine the requisite numbers and skill mix of staff needed to deliver care to patients at home. These, in turn, need to be compatible with a population needs-informed community nursing workforce forecasting tool before outcomes and performance can be compared across organisations. 48 Without such tools, it is difficult to know how to benchmark organisational performance and measure quality improvement in community nursing.

The staffing of community nursing teams has been bolstered by the introduction of skill mix, that is, the inclusion of nursing assistants to undertake specific roles in patient care. A National Institute for Health Research-funded study found that nursing assistants made up one-quarter of the community nursing workforce. The study found that senior managers appreciated the breadth of skills offered by skill mix and the consequent freeing up of registered nurse time for more complex nursing care. 54 When nursing assistants have been used effectively in relation to medication visits, they have been shown to improve access, reduce the pressure on qualified staff and have the potential to reduce costs. 29–40,42–55 Despite the positive evidence for skill mix, a survey conducted by the RCN Eastern suggested that nearly half of the 139 respondents found that skill mix in their teams was insufficient to meet patient need. 49 However, the use of skill mix with nursing assistants working within tightly defined roles in the community could result in increased delivery of task-focused nursing care as, from a patient perspective, those with complex morbidities might experience more than one nurse from the same team calling to provide different aspects of care, with a detrimental impact on continuity of care and, therefore, on perceived quality.

Measuring quality in community nursing

The policy drive for clinical effectiveness quality outcomes and increased provider competition has required community nursing services to adopt some of the commercial approaches associated with private sector organisations to demonstrate that the commissioners’ requirements are being met, for example production of evidence about patient and GP satisfaction with the service, regular updating of practice to demonstrate adherence to international best practice and demonstration of value for money. 56 Measuring clinical effectiveness in community nursing, however, is challenging; patients are generally older and frail, with deteriorating conditions and comorbidities that make it difficult to establish meaningful indicators (e.g. wound care outcomes depend on a number of factors such as the physical, social and environmental context of the patient). 57 A further challenge is attributing a change in health status to a particular intervention delivered by nurses, as community nurses tend to work alongside other services, agency staff and informal carers. Unlike in a hospital or a nursing home setting, community nurses are not able to oversee patients continuously to ensure compliance with best practice. 57

Measures of productivity, such as nurse–patient contacts and fulfilment of visits within designated time limits, have been used as a measure in district nursing as a proxy for clinical effectiveness. Such measures are comparatively easy to draw down from clinical databases. With the adoption of assessment and monitoring tools that measure clinical effectiveness for outcomes such as end-of-life care, patient safety and patient satisfaction, the need for accurate documentation has become an even greater necessity. Such tools are completed in the home by community nurses themselves in the context of clinical care and now serve the dual purpose of populating service quality databases. The new commissioning framework for community nursing recommends investment in new technology to both increase patient independence and enable community staff to record care activity more efficiently. 53 The importance of having an appropriate IT infrastructure in place in the community to deliver the intended aims of the quality schemes has been emphasised and is driving forward the implementation of mobile technology in the community. 58,59 However, there is a risk that the use of technology will facilitate the collection of outcomes that are not necessarily meaningful in relation to community nursing service quality, simply because it is possible to capture the data.

Summary

Despite recent progress in developing a framework for commissioning community nursing, there remain a number of practical challenges in measuring community nursing service quality. The impact of workforce issues and organisational changes such as IT implementation may not be fully understood in relation to community nursing. The nature of the work community nurses do, frequently over a lengthy time scale, makes finding suitable quality measures difficult. Moreover, it is not known how suitable or valid it is to use measures developed in acute settings for the purposes of assessing service quality in the community. There is a gap in the literature about the type of quality measures in use by commissioners and their effectiveness in really monitoring and improving the quality of community nursing care. Recent drives to encourage new forms of integrated organisations are likely to involve community nursing, and hence appropriate measures of quality will need to be determined.

In this study, we aimed to investigate how quality metrics are selected and agreed between commissioners and providers of community nursing services, as well as how these metrics are subsequently used in practice with the purpose of understanding how to improve them for the benefit of patients. We also focused on the perceived usefulness of current measures in improving quality of care provision, including patient and carer perspectives, and explored the challenges facing service providers in collecting information relating to quality of care.

Chapter 2 sets out the methodology of this three-phase, mixed-methods study. For clarity, this is immediately followed in Chapter 3 by the findings of the first phase, the national CQUIN survey. The following five chapters (see Chapters 4–8) report the case study findings. Chapter 9 draws together the findings from all of the data streams, which are then discussed in the final chapter (see Chapter 10) of the report.

Chapter 2 Study objectives, design and methodology

This chapter details the design and methodology of this mixed-methods study. The overall aims and objectives of the study are introduced below, followed by information about components of the study design and conduct. The chapter also includes information on how patient and public involvement contributed to and informed many aspects of both design and methodology; the process for gaining NHS ethics and research and development (R&D) approvals for the study; and a summary of deviations from the original protocol.

Aims and objectives

The study aimed to investigate the selection, application and usefulness of quality measures in use for community nursing from April 2014 to June 2016 in order to identify how they are used and the factors that influence their usefulness in achieving their intended goals of ensuring high-quality care for patients.

The research questions developed for the study were:

-

Which QIs are selected locally, regionally and nationally for community nursing?

-

How are they selected and applied?

-

What is their usefulness to patients, commissioners and community provider staff?

The associated study objectives were to:

-

map QIs in use for community nursing

-

identify the processes for the selection of QIs for community nursing at local, regional and national level

-

clarify the processes for introducing and applying QIs into community nursing services and to explore how data are collected, analysed and quality assured

-

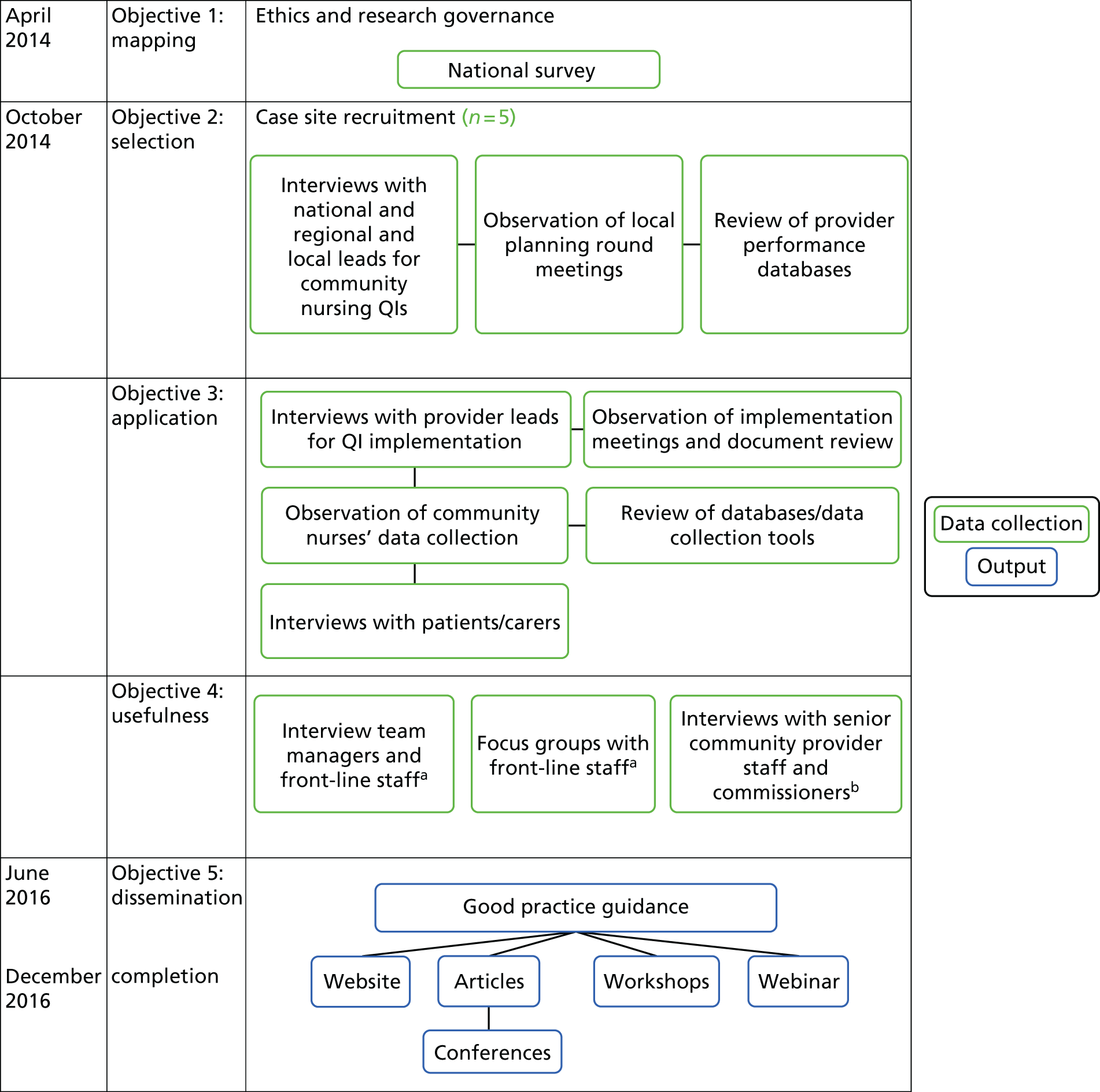

explore the usefulness of indicators in terms of meeting priorities, assessing the quality of services, influencing commissioning decisions and bringing about changes in service delivery from the perspectives of patients, front-line teams and commissioners (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Flow diagram of study methodology. a, Interviews will also explore selection; b, interviews will also explore selection and application.

A mixed-methods design in three phases was utilised, which comprised:

-

phase 1 – a national cross-sectional survey of QI schemes

-

phase 2 – an in-depth qualitative case study of the selection, application and usefulness of quality measures in use for community nursing in five study sites

-

phase 3 – a series of stakeholder engagement workshops to validate and check the transferability of our findings.

Mixed-methods design and conceptual framework

The study used a pragmatic mixed-methods design involving an integrative approach of ‘connecting’ quantitative and qualitative data rather than ‘merging’ or ‘embedding’. 60 Mixed methods were employed sequentially to provide both breadth (phase 1) and depth of description of QI use in community nursing (phase 2). Quantitative data were collected first to describe the range of QI and incentive schemes in use nationally in community nursing during 2014/15, and then to give a sample of providers from which to purposively select five sites for the case study. Case study research enables an in-depth exploration of contemporary events using a combination of qualitative data collection methods. Such methods include interviews, non-participant observation and documentary analysis. 61,62 One of the strengths of the case study approach is that it enables the triangulation of data, thus supporting the validity of the overall analysis. Our case study in multiple sites built on the survey findings by exploring in depth the relationship between policy directives on quality measurement and influences on local implementation. It enabled the identification and probing of the processes of selection and application of QI schemes and other quality measures currently used by community nurses, as well as an insight into the perceived effectiveness of such measures for the purpose of assessing service quality.

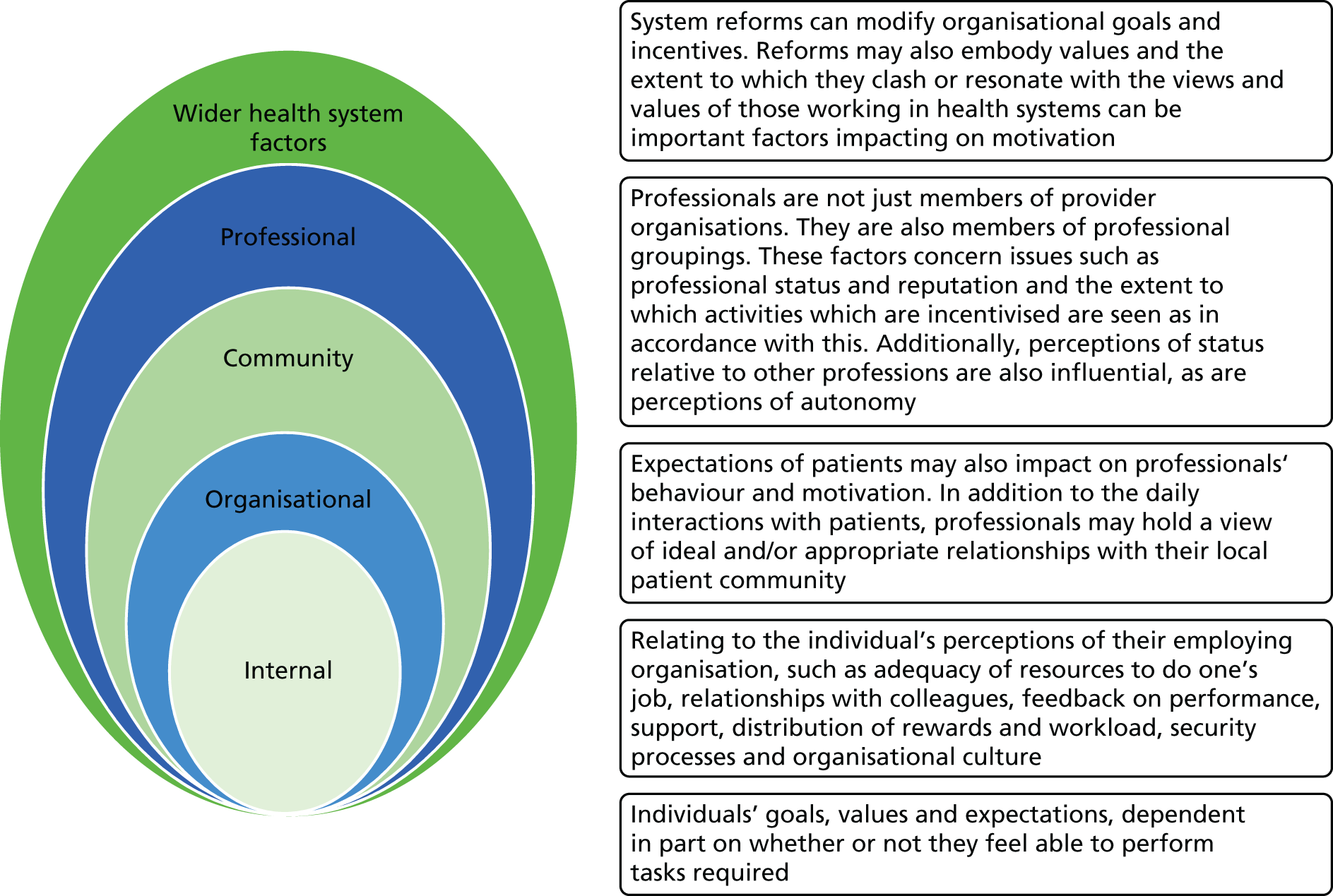

Individual and local factors can affect the success of national policy implementation, so an understanding of the interplay between these is fundamental in ensuring that any benefits from national initiatives, such as QI schemes, are obtained. To conceptualise our study, we used a framework originally developed by Franco et al. ,63 which had been utilised successfully in our earlier work. 32 This multilevel framework includes factors that influence individual behaviour and attitude, and incorporates organisational and wider health system contexts and relationships, helping explain the interplay between them. These contexts are all likely to have a bearing on which QIs get selected, as well as how they are applied in practice.

We ‘co-produced’ this project by working in partnership throughout the research process with patient and carer representatives, commissioners and community nurses, who were part of the larger study team. This included drawing on their expertise and knowledge when formulating the research question(s), scoping the literature, collecting and analysing data, and identifying the key messages, mediums and target audiences for dissemination. In a subsequent phase (phase 3), we held engagement events with commissioners, health-care practitioners, patients and carers in 10 locations nationally to check our analyses and interpretation of evidence to improve the dependability and transferability of our findings and also to support the development of good practice guidance (see Appendices 2–4).

Setting

The study provided a national snapshot of QI schemes applying to community nursing, followed by an investigation of the selection, application and implementation of QI schemes in five sites across England. Each case site comprised a dyad of a community nursing service provider contracted to provide NHS services and their associated CCG. At least one case study site was an independent provider. The included community nurses were registered nurses providing home-based nursing care to adults. A geographical spread of case sites and different types of community nursing provider enhanced the reach of the project and transferability of findings.

For clarity, the methodology of the national survey will be reported first, followed by the case study.

Phase 1: national survey

Design and sampling

The original intention was to conduct an electronic cross-sectional survey of all 211 CCGs across England in order to identify their community nursing service providers and associated QI schemes. The first step was to identify potential respondents by using the CCG information and contact details available online from NHSE to identify departments and/or commissioners responsible for quality or commissioning community nursing services. It became clear quickly that the requisite information was generally not available online. Although using the telephone number given occasionally resulted in correctly identifying a potential respondent, this was a laborious and time-consuming approach. In April 2014, at the time of the survey, the CCGs were comparatively new organisations, having only recently been established after the implementation of the Health and Social Care Act 2012. 26 Often it was not easy for the local administrators answering the telephone to identify the correct personnel responsible for commissioning community nursing, and they frequently suggested that the researcher submit the questions through a Freedom of Information (FOI) request; this was therefore adopted as the main method of data collection.

Data collection

Once the appropriate avenue for submitting a FOI request to a CCG was identified, the following three questions were asked.

-

Who commissions community nursing services for your CCG and what are their contact details?

-

What QI scheme(s) covering community nursing services are being used for 2014/15?

-

Which organisation provides your community nursing services and what is the nature of this provision, for example NHS, social enterprise, voluntary organisation or private?

Data comprising a mix of CQUINs, local QIs and KPIs were received in a variety of formats – electronic spreadsheets, word documents and copies of contracts – all with varying degrees of completeness. As the second phase of the project aimed to examine, in detail, the processes around quality measurement in community nursing, and as the aim of the current phase was to gain a broad national quality snapshot, it was decided to focus on CQUINs only for the analysis. CQUINs were also submitted in a format sufficiently consistent to allow a cross-organisation comparison, and allowed variation and local priorities to be identified nationally. All of the organisational details and CQUINs data were entered onto a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet, and were cleaned by checking for anomalies or inconsistencies across fields.

Analysis

For each CQUIN, we recorded the NHS region and CCG area and, when supplied, the indicator name, its descriptor and the rationale for its use. The CQUINs were then categorised as ‘national’ (pertaining to the national indicator scheme) or ‘local’ (reflecting local needs and conditions), as defined by the NHSE CQUIN guidance. As the CQUINs documentation we received only rarely specified community nursing services in the title, it was necessary to identify which CQUINs applied to nursing. To identify and code community nursing CQUINs, three researchers with professional experience of either community nursing or commissioning, working in pairs, scrutinised the associated description and rationale to determine whether or not the CQUIN applied to nursing. At least one of the following criteria had to be met for this purpose:

-

Community nurses are directly involved in gathering data about quality.

-

Community nurses’ activities constitute an essential contribution to the achievement of the CQUIN.

There is significant variation in the configuration of community services,11 which could affect the above coding. To be inclusive, when it was not possible to be certain whether or not the CQUIN applied to community nursing, the CQUINs were coded as ‘possible’ (e.g. if a CQUIN applied to a reablement service and it was not clear if the local service included a community nurse) or ‘definite’ (e.g. if it clearly related to community nursing service provision, or if such nurses collected data for the purposes of quality measurement).

Next, community nursing CQUINs were further coded by applying the following quality dimensions to each:

-

patient safety, clinical effectiveness and patient experience, or a combination of these dimensions23

-

structure, that is, contributing to the underpinning service requirements (e.g. staff numbers, appropriate training, infrastructure, building and equipment); process, that is, activities carried out by staff in relation to service delivery; or outcome, that is, the assessment of the impact of health activities on patients. 19

Initial coding was conducted by one researcher, with a 10% sample recoded by a second researcher; any differences were resolved by discussion prior to completion of coding.

Since the national evaluation of CQUINs25 had recommended the promotion of the use of a Pick List and evidence-based indicators, a final exercise investigated whether or not the community nursing CQUIN indicators had identifiable sources: indicator names, descriptors and rationales were searched for mention of particular documents (e.g. NHS Outcomes Framework)27 and for particular organisations (e.g. NICE). Exact wording drawn from community indicators in the CQUINs Pick List (a database of evidence-based QIs for users of the CQUIN scheme),24 was also used as a search term to identify any local CQUINs which had incorporated indicators from the Pick List. When a source was identifiable, the CQUIN was coded accordingly. Three researchers, two of whom had professional health-care backgrounds, collaborated to produce these coding schemes.

The resulting data were descriptively analysed using IBM SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY, USA). The methods and emerging findings of the survey were made available on the project website.

The next section describes the design and methodology of the case study.

Phase 2: case study

A case study is a preferred method for examining, in detail, contemporary events over which it is not possible or desirable to exert control. 61,62 It constitutes an in-depth exploration of a ‘bounded system’ (p. 61),62 or ‘case’, over time, through the use of multiple data sources, rich in context and detail. The proposed case study was to explore in depth the processes in use for measuring quality in community nursing services in England. The aim was to collect data over the duration of the annual commissioning cycle, focusing on agreeing contracts and quality monitoring and evaluation in order to understand the processes involved. We also aimed to investigate the impact on front-line staff and patients and their carers of the application of quality measures in practice, and the perceptions of all participants of the usefulness of such measures for determining the quality of nursing. Following the Health and Social Care Act 201226 and the implementation of clinical commissioning organisations, and in discussion with the research management group, it was decided to explore whether or not the new organisational context might determine or help to explain any variations found across different sites. A multisite case study approach was therefore deemed appropriate and we recruited five case sites across the country.

Sampling

Purposive sampling enables researchers to select sites on the basis of their potential to provide data on the contextual factors considered to be significant for the investigation. 64 In discussion with the research management group, a shortlist of 10 potential case sites was identified, from which seven were approached and five were recruited. Once identified as potential sites, both the commissioning and the provider organisation were approached separately, but concurrently, via the people named as responsible for commissioning and managing community nursing in the organisations. Each organisation was advised that it could not be used as a case site if the other organisation chose not to participate. The case sites were identified on the basis of the findings of the survey, selected using the following inclusion criteria:

-

variation in geographical location across England

-

range and number of QI schemes in operation across community nursing services

-

range of provider organisation type (NHS and independent).

Although there is no consensus on the number of case sites to include in a multisite case study, five sites enabled depth of study, while also enabling sufficient cross-comparison to check for consistency. 65 One of three researchers was allocated to be the main contact for data collection within each site to enable trust to be established and an in-depth knowledge of the site to be developed. The nurse researcher visited all the sites in which front-line observations took place. This arrangement enabled sufficient depth of knowledge in relation to commissioning at each site and cross-case understanding of evidence relating to front-line staff, patients and informal carers.

Participant inclusion criteria

-

National and regional quality leads from NHSE in a position to provide understanding about the influence of national and regional quality directives on local implementation of quality schemes.

-

Commissioners and community service provider managers directly responsible for community nursing services and, in particular, agreeing and implementing QI schemes.

-

Registered community nurses delivering nursing care to people aged ≥ 18 years in their own homes. This criterion included district nursing teams, integrated care teams, integrated community nursing teams, community matrons and community nurses for older people, who provide home-based care for adults with multiple and advanced long-term conditions requiring nursing and palliative care services. The service aims for these community nurses are to enable people with long-term or deteriorating conditions to live independently for as long as possible, reduce avoidable hospital admissions by timely nursing interventions and facilitate the discharge of patients not requiring hospital care.

-

Patients (adults aged ≥ 18 years) or their carers receiving care from community nurses in their own homes were also recruited to the study for interview. Interpreters were available if required.

Participant exclusion criteria

-

Community nurses providing children’s, mental health and learning disabilities nursing were excluded as joint commissioning arrangements often apply in relation to these services and these would have broadened the scope of the project significantly, causing a loss of focus.

-

Patients were excluded from this study if they were aged < 18 years, in the final stages of terminal illness, or could not give informed consent (or, in the case of reduced mental capacity, consent could not be gained from their legal representative).

Case study sites

Each site comprised a CCG and a service provider. Community nursing services were provided by four NHS organisational types (community trusts, combined acute and community trusts or community foundation trusts) and one social enterprise. In all of the case sites, community nurses were located in geographically based teams of various configurations serving a number of general practices. They are accessed by a single point of entry system, whereby there is one centralised telephone number for referrers and other patients.

Pseudonyms have been used and any similarity with existing place names is unintentional. A summary of the characteristics of each case site is provided in Table 1.

| Characteristic | Site | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alderton West | Beechbury | Cedarham | Dogwoodheath | Elmhampton | |

| Type of area | Urban | Urban | Urban | Urban | Rural |

| Deprivation relative to the national average | Higher than average | Higher than average | Higher than average | Higher than average | Lower than average |

| Approximate number of general practices covered by case site CCG | 50 | 40 | 50 | 60 | 80 |

| Approximate size of population served by case site CCG | 1,000,000 | 300,000 | 300,000 | 300,000 | 500,000 |

| Total number of CCGs in the area | 4 (3 commission jointly) | 3 (all commission jointly) | 2 (both commission jointly) | 3 (all commission independently) | 1 |

| Approximate size of population served by provider | > 1,000,000 | 800,000 | 600,000 | 300,000 | 500,000 |

| Type of provider | NHS community foundation trust | NHS community trust | NHS acute and community foundation trust | Social enterprise | NHS foundation trust |

Once permission was granted for the case study to be carried out, local senior managers (commissioners and providers) identified suitable meetings for the researchers to observe, as well as members of their organisation who could assist us in recruiting individuals from the requisite staff groups. With the assistance of administrative staff in the case study sites, potential participants were sent study information sheets so that they could decide whether or not to participate. The methods for recruiting service users to the study are explained below.

Data collection

Observations, interviews and focus groups were the main methods of data collection. Semistructured interviews were used as they enable sufficient focus on the topic under investigation while allowing flexibility for the participants to introduce new ideas and experiences for study. These were audio-recorded and undertaken using purpose-designed interview schedules guided by the research questions and advice from members of the research management group. In particular, the patient reference group provided advice on the interview schedule designed for patients and carers. Four experienced researchers with varying backgrounds, including two with experience of professional practice in the NHS, collected data. The data collection methods used in each site are shown in Table 2.

| Research question | Objective | Data collection method |

|---|---|---|

| How are QIs selected and applied? | Selection: to identify the processes for the selection of QIs for community nursing at local, regional and national level |

Semistructured interviews with national, regional and local community QI leads in each case study site Non-participant observation of local commissioning/contract meetings where QIs were discussed, selected, developed and/or monitored. Documentary review |

| Application: to clarify the processes for introducing and applying QIs into community nursing services and to explore how data are collected, analysed and quality assured |

Semistructured interviews with provider leads responsible for QI implementation Observation of meetings between provider leads responsible for implementation and front-line provider staff Shadowing of community nursing staff to observe QI data collection. Documentary review |

|

| What is their usefulness to patients, carers, commissioners and community provider staff? | Usefulness: to explore the usefulness of indicators in terms of meeting priorities, assessing the quality of services, influencing commissioning decisions and bringing about changes in service delivery from the perspective of patients, front-line teams and commissioners |

Semistructured interviews with patients and carers Focus groups and semistructured interviews with clinical team managers and front-line clinicians Semistructured interviews with senior community provider and commissioners |

One-to-one semistructured interviews were conducted with commissioners and provider managers. Observations of internal meetings or combined CCG/provider meetings (where QIs for community nursing were on the agenda) were also undertaken. Joint meetings between the commissioners and their service provider managers and internal quality meetings within the local service provider organisations were observed. The aim of the observations was to learn about the local priorities and contextual quality issues for commissioners and provider managers, and to understand the professional roles and relationship between staff in the different organisations. Interviews for commissioners and service providers covered the processes used for identifying suitable QIs and the policy-drivers underpinning their choices; perceived usefulness of QIs for service quality improvement; characteristics of effective schemes and perceptions of how well CQUIN schemes have worked for community nursing.

One-to-one semistructured interviews were conducted with nurse team leaders and an observation of team meetings was undertaken when the monitoring or application of QIs was on the agenda. Interview topics included perceptions of how front-line staff feed into the process of selection and implementation of QIs; systems for recording data; the extent to which selected indicators are under the control of the clinician; barriers to implementation; and benefits or service improvements deriving from indicator use.

Focus groups were conducted with front-line staff to explore their views and experiences of QIs being used for community nursing. In addition, front-line observations were undertaken by a community nurse-trained researcher to observe processes of QI data collection and recording during patient visits. Indicative topics for focus groups with front-line staff included awareness of current indicators; the extent to which staff feel able to influence or participate in selection of QIs; confidence in QIs as a reflection of service quality; extent to which staff are in control of factors that could influence achievement of particular QIs; how quality data are recorded; challenges for front-line teams in implementing indicators; and perceptions of impact on patient care. Front-line staff were recruited via their managers, or through newsletters to the organisation.

Table 3 details the number of participants contributing data in interviews and focus groups, and meetings observed in each case site.

| Data collection | Number of events (number of participants) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alderton West | Beechbury | Cedarham | Dogwoodheath | Elmhampton | |

| Interview | |||||

| Commissioners | 3 (3) | 4 (4) | 4 (4) | 4 (5) | 4 (5) |

| Provider managers | 3 (3) | 7 (7) | 2 (2) | 5 (5) | 5 (5) |

| Community nursing team leaders | 2 (2) | 2 (2) | 1 (1) | 1 (2) | 3 (3) |

| Patients (patients, carers) | 3 (1, 2) | 1 (0, 1) | 4 (4, 0) | 2 (2, 0) | 3 (2, 1) |

| Total | 10 (11) | 14 (14) | 11 (11) | 12 (14) | 15 (16) |

| FG | |||||

| Front-line staff | 1 FG (6) | 2 FGs (5) | 3 FGs (11) | 1 FG (15) | 2 FGs (8) |

| Meetings observed | |||||

| Commissioners and provider managers | 4 (35) | 3 (34) | 2 (38) | 2 (14) | 3 (34) |

| Commissioners only | 2 (9) | ||||

| Provider managers only | 2 (9) | 1 (8) | 2 (37) | 1 (11) | 1 (11) |

| Community nursing managers/team leaders | 2 (33) | 1 (9) | 1 (11) | ||

| Total | 8 (77) | 4 (42) | 4 (75) | 6 (43) | 5 (56) |

Many of the data that inform quality measurement in community nursing are collected by front-line nurses themselves. Observation and shadowing of front-line staff was therefore undertaken to observe how data for QIs were documented during the course of delivering and recording patient care in the home. A researcher with a professional community nursing, albeit not district nursing, background (SH), undertook all the shadowing. The choice of using a registered nurse who was not a district nurse but had a community background was made to preserve the balance between ‘insider’ and ‘outsider’ status of the researcher to understand and identify with the front-line teams and preserve patient dignity, but also to maintain the professional distance that permits adequate observation and data collection. 66 Participating case sites identified members of nursing teams who were prepared to be shadowed and visits were arranged at times to suit the nurses, avoiding the winter pressures period. Handover meetings or safety briefings were also attended and the use of computer software for documenting activity and outcomes of care was observed. A contemporaneous diary was written and evidence from shadowing nursing staff in the home was recorded separately on purpose-designed observation schedules. In each case site, any key documents detailing the selection, monitoring and evaluation of quality measures in use for community nursing, such as CQUINs, NHS contract sections 4 and 6, and community dashboards, were requested. Table 4 shows the number of front-line nurses shadowed and the number of home visits made in each case site.

| Front-line observation | Site | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alderton West | Beechbury | Cedarham | Dogwoodheath | Elmhampton | |

| Number of shadowing sessions (community nurses shadowed) | 3 (3) | 2 (2) | 4 (4) | 0 | 4 (3) |

| Total number of home visits undertaken | 12 | 11 | 21 | 0 | 22 |

| Assessment | 1 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Assessment and follow-up | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Follow-up visits | 11 | 11 | 18 | 0 | 19 |

| Assessment and discharge | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Discharge visits | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

See Appendix 5 for interview, focus group and observation schedules used to collect data from commissioners, provider managers and front-line staff.

A combination of approaches was used to identify patient (patient and/or carers) participants. We aimed to conduct one-to-one semistructured interviews with people initially identified from the shadowing of front-line staff. This strategy had limited success owing to the age and infirmity of such patients and their carers. To ensure sufficient representation from patients and carers in the study, we supplemented one-to-one interviews with a locally derived focus group. Patient and carer interviews included questions about their perceptions and understanding of high-quality nursing care. The current QIs applying to community nursing were then explained and patients and carers were asked their views on these for assessing community nursing service quality. Any further areas that patients and carers felt were important indicators of nursing quality were noted.

See Appendix 6 for interview and focus group schedules used to collect data from patients and carers.

Data analysis

The case study generated multiple sources of qualitative data from the sites, including interviews with patients, local senior managers (commissioner and providers) with a role in quality implementation, community nursing team leaders, focus groups with front-line nurses, observations of front-line nursing staff and quality meetings, and documentation relating to the selection, application or monitoring of quality. Interview data were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim, and contemporaneous notes were made during the observation of meetings and the shadowing of front-line staff. Data were anonymised and entered into NVivo 10 software (QSR International, Warrington, UK), or, in the case of front-line observations, into a Microsoft Excel® spreadsheet to aid comparison.

Qualitative data analysis drew on constant comparison techniques by which analysis proceeded with and informed data collection,67 with members of the research team liaising regularly to share their interpretations of findings from the case sites. Data were open coded initially to generate concepts that were then validated by comparison and discussion with members of the research team, whose composition reflected key audiences. Once the codes were agreed, these were used to construct a coding framework within NVivo and a team approach to coding proceeded, with each member of the team taking responsibility for coding a particular set of data across the sites [e.g. one member of the team coded all of the provider manager interviews (KP) and another coded all of the commissioner manager interviews (CP)]. All members of the team coded the meetings that they themselves had observed. Front-line team focus group data were analysed by one researcher (LD) and the service user interview, shadowing and observation data were analysed by the nurse researcher (SH). In this way, the research team gained a cross-site perspective. The individual coding databases were merged regularly into an NVivo master database to check progress and assess whether or not there were any differences in the way codes were being applied. The resulting codes were then further analysed to determine their attributes and dimensions, resulting in themes relating to selection, application and usefulness of QIs in the case study sites.

An adapted version of the five-level analysis theoretical framework developed by Franco et al. 63 was used to aid our interpretation of the interview and focus group data (Figure 2). This framework was developed in previous work that examined the relationship between financial incentives and behaviour in a range of primary care and community settings in health care. 32 It is applicable to the selection and implementation of all types of QI schemes, not only those that include financial incentives. The framework assisted in enabling the matching of codes and emerging themes with potential contextual facilitators and barriers to use of quality measures in terms of meeting priorities, assessing service quality, influencing commissioning and bringing about changes in service delivery. To increase the rigour of the analysis, use of multiple sources of data provided opportunities for comparison and contrast across accounts. For example, patients’ views, expectations and experiences demonstrated an alternative perspective on the values driving selection and application of QIs by commissioners and health-care providers.

Documentary analysis was limited due to the relative paucity and incompleteness of documents supplied to the research team across the case sites. The standard NHS contract was analysed to assess the degree of content relating to quality of community nursing services. When it was possible to obtain documents containing information about QIs, these were analysed to identify which QIs were being used for contracting community nursing in 2015/16. Documents included quality reports, ‘dashboards’ and schedules 4 and 6 of the NHS contract from the case sites (see Chapter 4). The analysis compared how, or if, quality measures related to the professional standards set out in Vision and Strategy for Nursing, Midwives and Care Staff 3 and CQC quality criteria now being applied to community services. The documentary analysis was undertaken by a member of the research team who was actively working as a community nurse at the time of the study.

The next section describes the organisation of the stakeholder engagement events.

Phase 3: stakeholder engagement

Evidence suggests that research is most effectively disseminated using multiple vehicles, ideally with face-to-face interaction. 68 Dissemination events were an integral part of the study design and were planned to start towards the final few months of the project. We planned to hold workshops across the country, both putting on special events ourselves and contributing to other organisations’ meetings and conferences in order to check the study’s emerging findings and develop our good practice guidance with a wider audience. These events were intended to include a mixed group of commissioners, service managers, front-line staff, patients and carers. Owing to the time constraints on NHS staff, these were timetabled to last either a morning or an afternoon, when possible, and attendees were able to hear about emerging findings from the study and discuss the good practice guidance.

Researchers contacted participating case sites and used personal and professional contacts and networks in different parts of the country to identify other organisations that might be interested and willing to assist in holding a workshop locally. Once a workshop was agreed in principle, a key local lead for community nursing was identified and asked to give an introduction to the day. An experienced facilitator with a commissioning background, a member of the core research team and one other member of the wider team involved in the project facilitated the workshops. To gain stakeholder feedback about some of the study findings as well as statements from the draft good practice guidance, a key activity during the workshop was to engage small delegate groups in a deliberative dialogue exercise. 69 These small group discussions were distinct from focus groups in so much as data were not collected with which to inform the study; rather they were designed to discuss our findings in relation to delegates’ own experiences. Each workshop produced feedback on emerging findings and draft good practice guidance. Nursing participants received certificates of attendances for professional revalidation purposes. Participants completed evaluation forms and facilitators reflected on each workshop, making adjustments to timing and materials in response to feedback (see Appendix 2).

Projected outputs

-

Development of a project website on which outputs based on emerging findings of the study have been published (www.QuICN.uk). As our NHS co-applicants stressed the importance of getting findings out early, we began to disseminate emerging findings via our website within 6 months of starting the project, with the analysis of the national QI database and publication of discussion papers (www.quicn.uk).

-

Publications, including the full report, evidence summaries for participants and other stakeholders, peer-review journals, local NHS newsletters and A5 laminates, are in progress.

-

Using the findings of our project we have developed good practice guidance (see Appendix 4) on how best commissioners and managers can approach the selection and application of appropriate quality measures for community nursing and their perceived usefulness from the patient and carer perspectives.

Patient and public involvement

There has been substantial input from service users (patients, carers and/or members of the public) throughout the study. In earlier work to develop local QIs for community services in Bristol, a service user expressed concern that the administration and collection of data for QIs would distract community nurses from delivering patient-centred care. This individual was a co-applicant on the successful proposal and has been the co-lead on the user aspect of this study. As a former performance manager and member of the local community health forum, he contributed to designing the study and recruiting other lay people to become involved by sitting on the research management group and/or being part of a service user reference group (SURG) for the study. The SURG has contributed to the design of data collection tools for patients and carers, including an aide-memoire to assist researchers in covering topics thought by members to be important (see Appendix 6), the interpretation of findings and the content of the final report. SURG members have also been involved in the development and delivery of the stakeholder engagement workshops. In addition, a member of SURG was involved in interviewing and selecting research staff.

Patients and carers have attended workshops where emerging findings have been discussed and contributed to the interpretations of evidence and development of good practice guidance.

Ethics and NHS permissions

We considered our project to be low risk (as it is not an intervention study and we were not recruiting patients unable to give informed consent for interviews). Therefore, on advice received from NHS ethics, we initially submitted via the proportionate review process. On their closer scrutiny, the project was deemed to involve risk as it involved the shadowing of front-line staff during patient visits, and the submission was, therefore, forwarded to the next full NHS ethics meeting. At this meeting, the proposal to include the shadowing of front-line staff was considered to be intrusive to patients. Moreover, the frailty of community nurse patients, some with fluctuating mental capacity to give informed consent for an observer to be present, led to the project then being referred to a specialist NHS Ethics Committee. Approval for the study was finally obtained in July 2014 (National Research Ethics Service Committee Yorkshire & The Humber – Leeds West 14/YH/1059). The process for shadowing front-line staff to observe documentation of quality data in the field (i.e. patients’ homes) required that nurses visiting patients a few days before the day of the observation visit took a study information sheet to patients in order to allow them to consider the nurses’ involvement in this aspect of the study. On the day of shadowing, the visiting nurse was consented to the study and went into the home alone to see the patient to ask if they would agree to a nurse researcher being present to observe their nurse for that visit. If they answered positively, the researcher was admitted. The researcher then obtained verbal permission from the patient to observe the nurse. Formal written consent to take part in the study was not required from patients themselves, as they were not study participants and no identifiable data were collected from or about them. We subsequently sought and received additional ethics permission to recruit patients to a focus group when we found that we were unable to recruit enough patients via front-line observation visits. These participants were recruited through the SURG.

We were unable to start NHS R&D permissions until we had identified potential case sites from the survey findings. Recruitment entailed initial contacts to both a community services provider and a commissioner from the local CCG, and approval to participate from both partners was required before an application for NHS permissions could be sought (this was sometimes a time-consuming process). Commissioning organisations were comparatively new and there were difficulties identifying the appropriate person within the organisation to give approval. Moreover, community nursing services provider organisations have a range of types (e.g. NHS community trust, combined acute and community organisations, independent or private), meaning that it was sometimes difficult to find the person who could take responsibility for signing up to the project. The NHS permissions process was lengthy and involved duplication and slight variation of requirements across the sites, where each application was considered separately. Owing to the multiplicity of data collection methods and range of participants in a mixed-methods study, there was a large amount of related paperwork for R&D departments to review. This created a lot of extra work for both the R&D departments and the research team. Overall, the administration involved in the permissions process was time-consuming for each organisation, and, on one occasion, having just achieved successful sign-off from R&D in one site, permission was suddenly withdrawn by the provider without explanation. One other case site took several months to obtain internal agreements, having initially expressed interest to the researcher, so we eventually withdrew and selected another site from the list in a similar area. We were eventually able to recruit and obtain permission for all 10 organisations constituting the five case sites, although we were late starting data collection in two sites.

Deviation from the original protocol

Given the degree of organisational change and workforce pressures present during the course of this study, we were fortunate to have established good links with our case sites and to be allowed access to undertake data collection. However, the following small changes to the protocol had to be accepted.

The number of national and regional NHSE quality leads we interviewed was comparatively small. The interviews we conducted suggested that their strategic role with CCGs and current priorities tended towards the acute rather than the community sector and, although they were knowledgeable, their actual role in relation to quality process implementation in community settings appeared to be more limited. These interviews were, however, very useful for informing subsequent data collection in the case sites.

As explained earlier in this chapter, we took a pragmatic decision to alter our means of data collection for the national survey in response to the incompleteness of the CCG data available online at the time of the survey. We had planned to undertake an electronic survey, but the requisite e-mail addresses were not provided online owing to data protection, and the telephone numbers supplied usually went to a local administrative assistant who did not know to whom our enquiry should be directed. We were frequently asked to go through FOI channels to access the information we required, as these departments were set up to provide advice on a range of topics, so we used this as our main method of data collection. We also decided to focus our analysis on CQUIN data only for this part of the study, as only these data were provided in a form that was sufficiently comparable across organisations.

One case site did not allow us to shadow their front-line staff. As it had been hoped to recruit patients for interview from the shadowing exercise, this led to the provider organisation helping us with the identification of patients by offering us access to their local patient group, with limited success. There was considerable similarity in the findings from the four sites where front-line shadowing did take place, and evidence from the focus group of front-line staff that was held there confirmed that the same contextual pressures and views on quality measurement found in other sites pertained.

The supporting documentary analysis we had planned was constrained by the variation in the documents supplied to us by the case sites. We were able to compare CQUINs across the sites again, but, owing to the changes in the CQUIN schemes over time and current policy-drivers, the variation in what sites were doing nationally and locally had reduced. There may also have been some concerns in case sites at the potential sensitivity of documents being used.

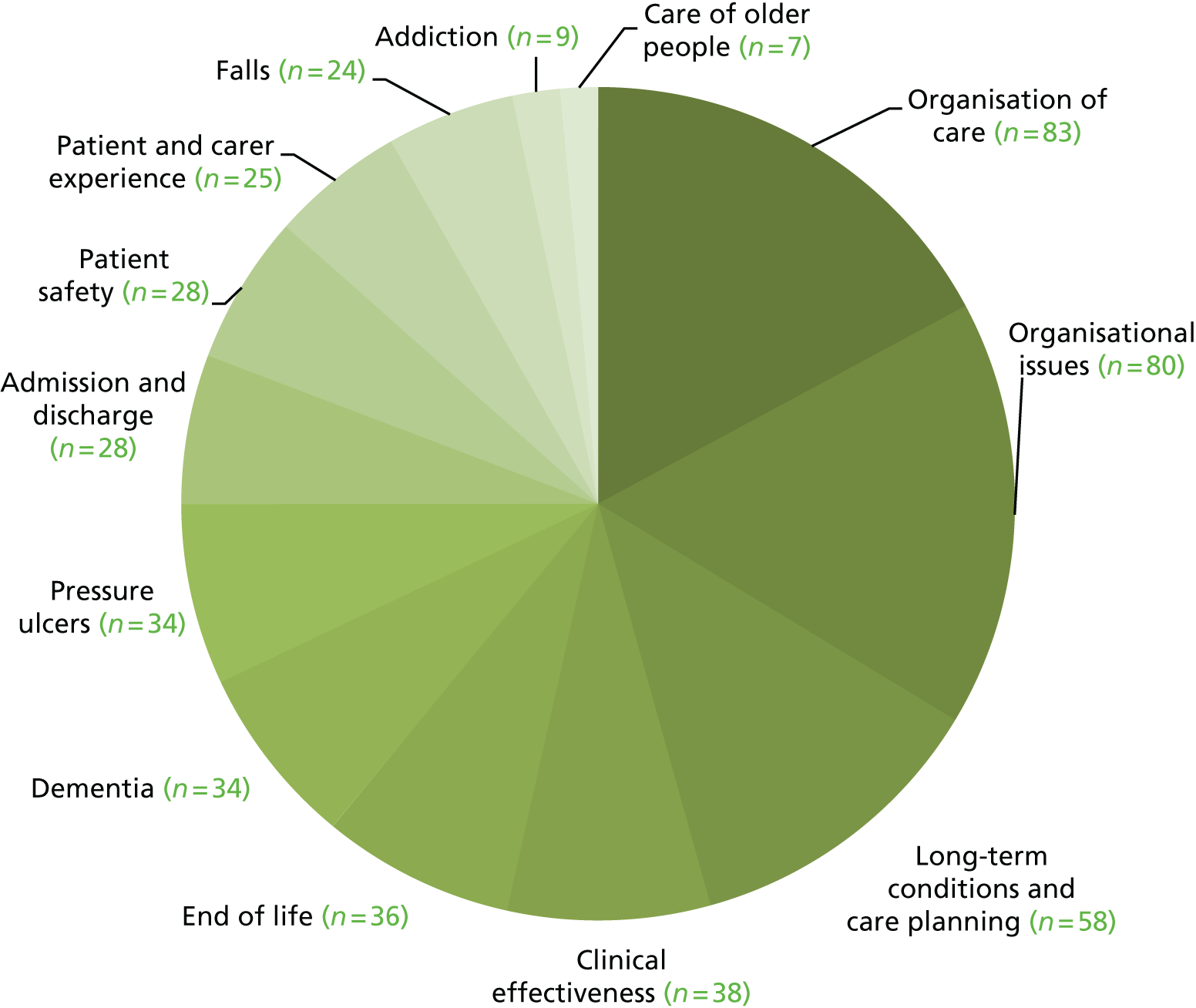

Chapter 3 National survey findings

In this and the next five chapters (see Chapters 4–8) we present our findings. In this chapter, we present the findings from the national survey of CCGs that aimed to identify the number and variety of CQUIN QIs in use for community nursing in 2014–15, conducted across all of the CCGs in England. The first section of the chapter presents the findings from the descriptive statistical analysis; the second section details the findings arising from the content analysis of the data.

Descriptive statistical analysis of data

Response rate

All the CCGs contacted (n = 211) acknowledged our initial approach.

Of these, 25 CCGs either had no information ready to send us, or replied that they were unwilling to send us any. A further 27 CCGs sent us only information about KPIs or other QIs. A total of 159 (75%) CCGs sent us CQUIN data. The response rate by region was North, n = 56 (82.3%); Midlands and East, n = 49 (81.7%); South n = 36 (69.2%); and London, n = 18 (58.1%).

The CQUIN scheme entails organisations meeting both national and local QIs. At the time of data collection, national CQUINs comprised the Friends and Family Test (FFT), National Safety Thermometer (NST) and, in acute settings, The National Dementia and Delirium CQUIN. As all providers were obliged to meet the criteria set within the national CQUINs, the findings presented here relate to only local CQUINs that definitely involved community nursing services (community nursing CQUIN). These included CQUINs focused on the prevention and treatment of pressure ulcers (PUs), which extended the requirements of the NST, and dementia (not nationally mandated for community settings). Of the 159 respondents who sent us CQUIN data, 145 (68.7% of all those contacted) sent information about at least one local CQUIN definitely related to community nursing. The findings concerning those local CQUINs that possibly applied to community nursing can be found on the project website (www.quicn.uk). The following sections of this chapter focus only on the 145 CCGs that sent us definite community nursing CQUINs.

Organisation of care information

The 145 CCGs that provided information on local community nursing CQUINs commissioned community nursing services from 78 provider organisations. Of these, NHS trusts providing both community and acute services were the predominant form of organisation (n = 36, 46.1%), with NHS community health-care trusts the second most dominant type of organisational structure (n = 27, 34.6%). Social enterprises (n = 13, 16.7%) and private providers (n = 2, 2.6%), both comparatively new entities in community provision, together constituted < 20% of community nursing service provision. Table 5 shows the regional variation in the number of CCGs associated with each of these 78 community nursing service providers.

| Number of CCGs served by each provider | Region, n (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| London | Midlands and East | North | South | |

| 1 | 5 (50.0) | 6 (30.0) | 17 (51.5) | 7 (46.7) |

| 2 | 3 (30.0) | 7 (35.0) | 9 (27.3) | 2 (13.3) |

| 3 | 1 (10.0) | 2 (10.0) | 5 (15.2) | 3 (20.0) |

| 4 | 0 | 4 (20.0) | 2 (6.1) | 2 (13.3) |

| 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 (6.7) |

| 6 | 1 (10.0) | 1 (0.5) | 0 | 0 |

| Total number of providers | 10 (100) | 20 (100) | 33 (100) | 15 (100) |

Commissioning support units or other suppliers such as private consultants provided commissioning advice and support to CCGs as they assumed their new role. One hundred and thirteen (78%) CCGs provided information linking them with a commissioning support unit. It was not possible to discern details of any commissioning support unit support for 32 CCGs.

Number of local community nursing CQUINs set

From the 145 CCGs in our data set, we received details of 484 local community nursing CQUINs. The average number of local community nursing CQUINs set by CCGs was three, with a minimum of one and a maximum of 12.

The picture looked different for community nursing service providers as, in many of these cases, they were providing services for more than one CCG. On average, providers were implementing four to six local CQUINs. Twelve providers were each associated with only one local community nursing CQUIN. Fifteen of the 82 providers in the data set had to deliver on relatively high community nursing CQUIN numbers (> 10).

Analysis of local community nursing CQUINs

As the focus of the wider study is on process, including an exploration of the way in which CCGs and providers collaborate to select and implement CQUINs, findings are presented for the total number of local community nurse CQUINs (n = 484). The majority of local community nurse CQUINs (n = 309) were uniquely worded, suggesting that they were tailored to local circumstances. First, the local community nurse CQUINs were analysed for their fit with the main quality domains used by CQUIN schemes.

Quality dimensions

The local community nurse CQUINs were analysed for their fit with the main quality domains used by CQUIN schemes, namely patient safety, patient experience and effectiveness of care (quality dimension 1),23 and Donabedian’s domains for measuring health-care quality, namely structure, process and outcome (quality dimension 2). 19 The complexity of community nurse CQUINs in use was made evident by the fact that 143 (29.6%) community nurse CQUINs addressed a combination of two or three aspects of quality dimension 1. Similarly, 122 (25.2%) community nurse CQUINs focused on more than one aspect of quality dimension 2. Owing to a lack of information, six (1.2%) community nurse CQUINs were undetermined with respect to quality dimension 1, and eight (1.7%) could not be related to a specific aspect of quality dimension 2. The aspect of quality dimension 1 most frequently addressed was effectiveness of care (417 community nurse CQUINs, 86.2%). The aspect of quality dimension 2 most frequently addressed was process (336 community nurse CQUINs, 69.4%) (Table 6).

| Quality dimension aspect | Number of community nursing CQUINs (%)a (N = 484) |

|---|---|

| Effectiveness of care | 417 (86.2) |

| Patient safety | 116 (24.0) |

| Patient experience | 93 (19.2) |

| Process | 336 (69.4) |