Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/59/08. The contractual start date was in November 2014. The final report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in June 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Helen Atherton has received fellowship funding from the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) School for Primary Care Research (SPCR) during the conduct of the study. Chris Salisbury is a member of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Atherton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Communication technologies are routinely used by the public in everyday life, and there is an expectation that this should extend to health care.

Globally, the use of such technologies in health care is variable. In Denmark, the use of e-mail for consultations in general practice became mandatory in 2009, a measure intended to raise the quality of services delivered to patients, and in 2013 there were four million consultations conducted this way. 1,2 The USA has well-established options, including patient portals for online access to clinicians and routine telephone consultations, which are offered by several of the large health maintenance organisations, under fee for service arrangements. 3

In Finland, e-mails between doctors and patients have been a routine part of care for over a decade. 4 Mobile devices in parts of Africa have vastly increased access to the telephone, as well as to the internet; the potential impact on health care is arguably more transformational than in countries with pre-existing landline networks. 5

In the UK, policy-makers have suggested that alternatives to face-to-face consultations in the general practice setting could have a transformative impact by alleviating staff workload and improving patient access. 6,7 Policy has reflected this, and there has been sustained interest in encouraging general practice to adopt alternatives to the face-to-face consultation. In 2012, the UK Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) produced a target:

All patients should be able to communicate electronically with their health and care team by 2015.

DHSC. 6

However, this target for implementation was not met. A 2014 policy document from the DHSC and NHS England outlined government proposals8 and suggested that the introduction of alternative methods, such as e-mail or internet video [e.g. Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)], to provide consultations could improve the current provision of primary care in the UK. NHS England has consistently pursued a digital agenda for primary care. Patient Online9 is a NHS England programme, which encourages general practices to:

offer and promote online services to patients, including access to coded information in records, appointment booking and ordering of repeat prescriptions.

NHS England. 9

The scope of Patient Online is set to be extended to the use of online consultation. Most recently, in 2016, General Practice Forward View,7 published by NHS England, outlined an investment of ‘£45 million for a multi-year programme to support the uptake on online consultation systems’7 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0), although the nature of these was unspecified. This agenda has not been limited to England. The NHS in Northern Ireland devised an eHealth and care strategy, which encourages citizens to ‘interact with health care electronically’10 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0), and NHS Scotland has set a target to encourage practices to offer online services to patients, in particular to increase rates of video-consultation use. 11 In Wales, the NHS strategy is for patients to:

use the internet, email and video conferencing to connect with clinicians and care professionals in a way that suits them, potentially reducing delays and costs to the service and service users.

Welsh Assembly. 12

In 2014, GP Access Fund supported 20 pilot projects, to the value of £50M over 1 year, to test new approaches to improve access to general practices. 13,14

An evaluation of the first wave of projects has been published. 15 This evaluation reported that six pilot sites intended to introduce video-consultation tools and six pilot sites trialled e-mail consultations. The conclusion of the report was that non-traditional modes of contact (e.g. video or e-mail consultations) have yet to prove any significant benefits and have had low rates of patient uptake. 15 A second wave of funding under the GP Access Fund has now been released. 14 Several of these pilots also include the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations, including e-mail consultations, Skype consultations and/or greater use of telephone consultations. Despite the second wave commencing in 2015, the findings from the evaluation have not yet been published by NHS England.

There is pressure on general practice to offer alternative methods of consulting with patients. However, apart from the increased use of telephone consultations, most practices have been slow to adopt alternatives. 16–18 This reflects concerns expressed by GPs about the impact of introducing additional consultation methods and, particularly, concerns about increased workload and achieving safe use. 19,20

Although professional bodies are now making tentative steps towards embracing some of the newer technologies, and supporting practitioners21–23 who wish to use alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, this support has been slow to arrive. This reflects the uncertainty arising from a lack of evidence in the general practice setting, and wider concerns about the general practice workload. This view was supported by the recent report by the Primary Care Workforce Commission,24 which stated that more evidence is required before e-mail or internet video consultations can be recommended as a routine part of primary care.

Given that some general practices have already adopted alternative methods of consulting,17,25 and that there is an increasing expectation that they should be available, this provides an opportunity to provide GPs with guidance for using these new methods, based on best evidence and existing experiences, encouraging those taking them up to do so as safely and effectively as possible, and bringing the maximum benefit for patients and the NHS. 26

Evidence explaining why this research is needed now

The underlying assumptions that drive the policy rhetoric relate to convenience and accessibility for patients and an efficient use of practitioners’ time. 27,28 However, there is little evidence to support such assumptions. The Nuffield Trust,29 among others, have identified the potential for the use of remote consultation in primary care, but also the need for more evidence on the impact of remote consulting.

Evidence to date has assessed the potential impact of some alternatives on clinical outcomes. 30,31 Although trial evidence for some types of alternatives is poor, observational data have pointed towards some clinical benefits, such as improved outcomes from e-mail communication for those with diabetes mellitus and hypertension32 and better monitoring of health concerns with online access to records,33 at least in market-driven health systems. When combined with self-monitoring, telephone and e-mail consultation have been effective in the management of hypertension and diabetes mellitus. 34,35

Studies have sought opinions from patients and health-care professionals on whether or not, and how, they would use alternatives,20,36,37 but these data have been based on hypothetical opinions rather than experience. Other studies have attempted to assess the impact of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation on workload and consultation numbers in primary care settings;38–40 however, these studies have been of low quality,30 or have assessed impact in the context of a patient portal that offers additional functionality,33,41 making it difficult to draw conclusions about the impact of the alternative to the face-to-face consultation alone.

Recent years have seen a plethora of small and local pilot projects and commercial initiatives around specific systems,42,43 which proliferate in an environment of patchy and inconclusive evidence.

What the existing literature does not tell us is under what conditions, with which patients and in which ways alternative methods of consultation actually work. This project addresses this need and builds on previous research by focusing on the experiences of patients and practitioners who have used these alternatives to the face-to-face consultation with different groups of patients for different purposes. 19,44

Where GPs have started to use alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, we can learn from their experiences and from their rationale for introducing them, as well as their reasons for persisting with or discontinuing use. The feasibility of these alternatives to the face-to-face consultation is likely to rely on factors that are identifiable only when they are used in practice (e.g. patient characteristics or the purpose of consultation). Barriers to, and facilitators of, use become apparent as patients and practitioners navigate their way through use. The existing literature on experience can be utilised to develop a picture of how alternatives might be expected to work. 45–47

Existing research has demonstrated a limited understanding of the fact that consultation methods are complex interventions. 30 The lack of good quantitative evidence on technologies such as e-mail and video consultation reflects the difficulties of testing them in trials, as their use has not been clearly defined. 48 Often, distinct elements of the consultation have not been taken into consideration. By developing a theoretical framework, we hope to deconstruct what makes alternatives different from face-to-face consultations, allowing us to assess if and how they should be tested, in relation to the appropriate populations, outcome measures and methodological approach.

This research builds on the previous literature in related fields on how new technologies are adopted and implemented in health care. There has been some research in relation to telehealth interventions to support patients in their own homes. For example, the application of the normalisation process theory to the implementation of telehealth has demonstrated that it is the work involved in adopting new approaches that influences whether or not they normalise in practice; that is, they must fit in with health-care professionals and their roles for successful implementation. 49,50 Other work using the technology acceptance model has highlighted the importance of both usefulness and perceived ease of use in influencing behavioural intentions to use new technology. 51

Work by Greenhalgh et al. 52 on the failed introduction of the HealthSpace communication platform also highlighted the importance of ensuring that the technology used meets people’s perceived needs and fits with their other health-care arrangements. 52 We will take account of these related theoretical perspectives, including insights from the normalisation process theory, the technology adoption model and the diffusion of innovations theory, but we do not propose to base our analysis on any of these specific models.

Health-care needs differ between patient groups. Evidence around how different groups are affected by the introduction of new consultation methods is sparse. Studies have included patient populations in general practice, and this has not tended to include consideration of different patient groups. For telephone consulting, there has been some consideration of the effects on different patient groups, such as patients with brain injuries. 53 However, for other alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, little is known about the impact on different groups of patients. 19,46,54 Existing data from a range of countries and settings indicate that young people, those with tertiary education, the employed and students are more likely to use alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, along with those in poor health. 55,56 It is important to understand more about the use of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation by different patient groups in general practice and whether or not they provide better access to care in relation to need, and, subsequently, their influence on health inequalities.

What is the problem being addressed?

It is important to understand how these alternatives work for patients, and to determine the benefits, advantages and disadvantages for different groups of patients and for a practice as a whole. Some groups are likely to benefit more than others. 55,57 Although attempts have been made to determine the impact of some alternatives on clinical outcomes,30,31,58,59 there has been a lack of focus on appropriate application and implementation, and this is key if we are to inform safe use and to be able to successfully evaluate their use in practice.

Use of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation

The study was designed to explore the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations, including telephone consultations (but not those used to triage all requests for consultations before offering any face-to-face appointments), e-mail, structured e-consultation systems (e.g. eConsult, Hurley Innovations Ltd, London, UK; askmyGP, GP Access Ltd, Leicester, UK) and internet video [e.g. Skype™ (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)]. It was expected that in many practices, different combinations of these alternatives to the face-to-face consultation would be offered to varying extents; for example, practices offering internet video consultations are likely also to offer telephone and e-mail consultations.

Furthermore, several methods of communication may be used over the course of one illness. For example, a patient with asthma may have a regular review by completing a structured review form online (which is checked later by the practice nurse), may send an e-mail with a query about their medication, might make a telephone consultation to assess if they need to be seen urgently during an acute attack or may make a face-to-face consultation if their attack does not resolve.

Practices may also offer the same technology for different purposes; for example, most practices allow patients to contact the GP by telephone (most commonly by leaving a message and the doctor telephoning them back), but some practices encourage patients to use telephone consultations as the usual first form of contact. This study explores the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations for any clinical purpose, including consultations for initial assessment of symptoms or triage, follow-up, chronic disease management and/or discussion of test results. This excludes remote monitoring of health conditions not involving a consultation and also excludes administrative purposes, which do not usually involve direct contact with a clinician (e.g. making an appointment or requesting a repeat prescription).

On the practice side, examples of models of delivery include those that are very simple (e.g. e-mails being routed to the patient’s chosen individual GP for a response) and those that are structurally more complex (e.g. the use of a duty doctor who conducts all telephone and e-mail consultations on any given day).

It is important to note that although we are examining alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, they are not replacements – rather, they are additional methods of consultation. The different type of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation that will be considered are described next.

Types of technology

Telephone consultations

Telephone consultations have been in use for a long time; therefore, the issue for our study is not plausibility but, rather, optimal application. This includes gaining a greater understanding of how practices have addressed potential problems, such as concerns about increased workload or safety.

Several telephone-based initiatives have been introduced in general practice, with a view to reducing GP workload, for example, telephone triage. 60 Some practices offer a system of care in which almost all patients are offered a telephone consultation initially (variously labelled GP Access61 or Doctor First62); however, as the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) has funded another parallel study that specifically looks at this model of care, we will exclude these approaches from our study.

E-mail consultation

The application and use of e-mail consultation are varied. Some GPs offer e-mail consultations using conventional e-mail programs, whereas others favour asynchronous consultations via a structured online form. 63 There are commercial providers that offer website services to general practices, which can act as a secure host for e-mail consultations (e.g. MySurgeryWebsite). 64 In the case of e-mail communication with patients, NHS Digital has supported NHS policy with the introduction of NHSmail 2. 65 This system allows clinicians to engage in secure e-mail communication with patients, but NHS Digital does not provide guidance on how this might be done.

E-mail consultation includes secure messages sent using webmail. The most commonly described method of applying practice-wide access is via a secure website, whereby patients log in to the practice website and are given the option to send online messages. Responses are received via the patient’s e-mail inbox or an inbox they can access via the website. These sites also tend to offer appointment-booking and repeat prescriptions in the manner of a patient portal, and there is speculation that they could also offer access to medical records. UK policy-makers draw on examples of these sites from the USA, for example, from Kaiser Permanente and the Mayo Clinic, where patient portals are in use. 3,32,66 Thus, UK policy-makers appear to believe that a patient portal system is the most plausible model for the introduction of online consultation,7 despite the fact that this is not backed by robust evidence and has not been tested in a UK setting. Even in the USA, the uptake rate of electronic communication is low and it has not achieved widespread adoption. 67

E-consulting

In this study, e-consulting refers specifically to consultations mediated by software provided by two commercial providers (eConsult, previously known as WebGP,68 and askmyGP69), which claim to manage demand by allowing patients to complete a ‘structured online consultation’. 70 Patients enter information about their symptoms and, in some cases, leave an electronic message for the GP. This provides the GP with a history to enhance the subsequent contact, which is usually made by telephone. eConsult68 software is linked into the practice website and supported by Egerton Medical Information Systems (EMIS; EMIS Web, EMIS Health, Leeds, UK), a main supplier of electronic medical record software in the UK. 71 NHS England has openly supported the roll-out of these software systems in its plans for how general practice will deliver care in the next 5 years, providing:

£45 million [for a] national programme to stimulate uptake of online consultations systems for every practice.

NHS England. 7

Video

There are some examples of the use of internet video to provide consultations in general practice. 42 The use of video consultation is much less well known in UK primary care. There are many reports of practices taking it up (including projects funded by the GP Access Fund, NHS England),14 but little evidence of its feasibility and effectiveness. As described previously, despite six practices piloting video-consultation tools, there was in fact a low level of uptake by practitioners and patients; thus, conclusions could not be drawn about their use. 15 Facilities are emerging to support this type of consultation. For example, EMIS has recently introduced a feature into its systems that provides video consultations, and the feature offers secure communications. 72

Aim

To use a theory-based evaluation approach to understand how, under what conditions, for which patients and in what ways alternatives to face-to-face consultations may offer benefits to patients and practitioners in general practice, and to use this understanding to develop guidance for general practices and a framework for subsequent definitive evaluation.

Objectives

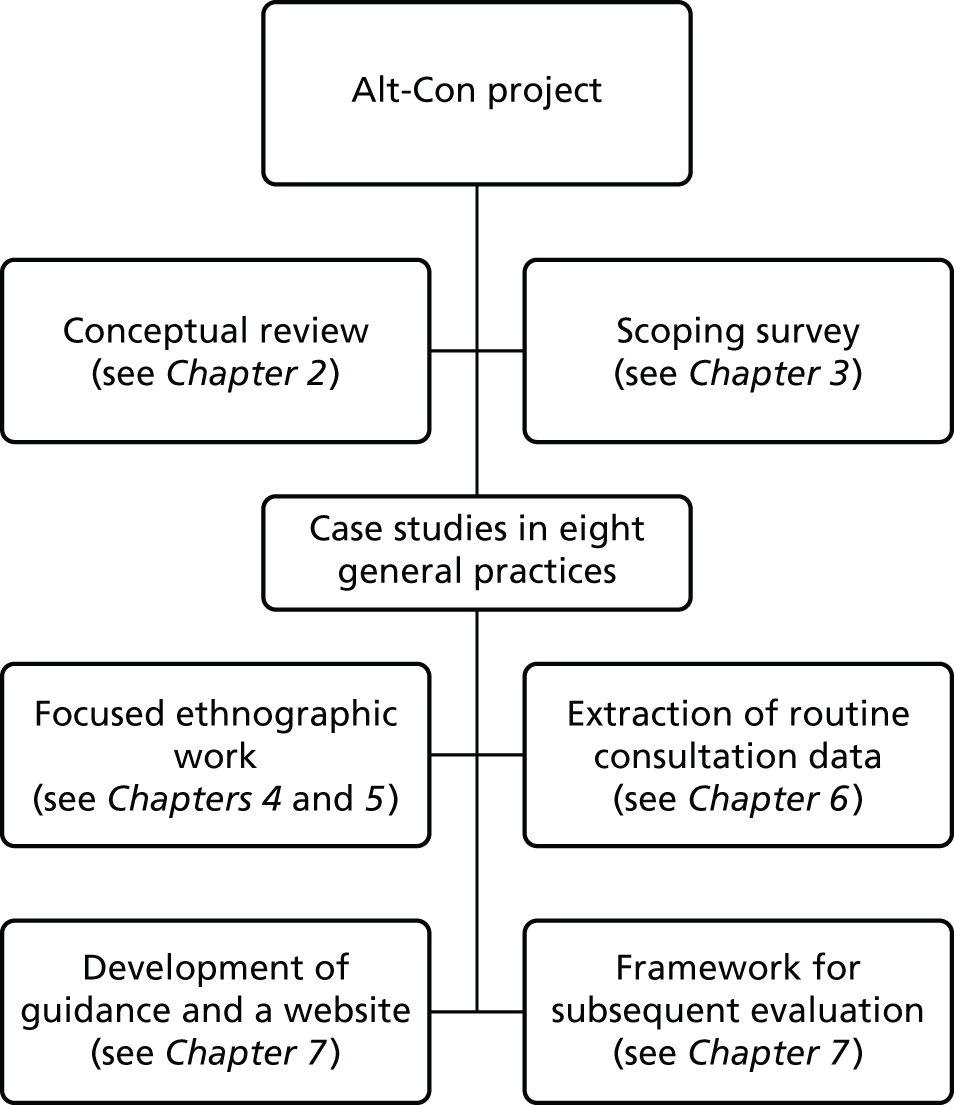

Our study covers the first stages of the MRC’s complex intervention framework, that is, identifying the evidence base, identifying/developing a theory and modelling the process and outcomes. 73 It utilises a mixed-methods case study design. 74 Figure 1 shows a chart outlining the various elements of the project and their relationship.

FIGURE 1.

Different elements of the study and their relationship.

Identifying the evidence base

Objective 1: to conduct a conceptual review, synthesising the literature (qualitative and quantitative) on patients’ and practitioners’ experiences of alternatives to face-to-face consultations, with a particular focus on the views of different groups of patients and factors that promote or hinder the wider implementation and uptake of these alternative forms of consultation.

Developing a theory

Objective 2: to use a scoping exercise to identify the range of ways in which general practices in England and Scotland are currently providing alternatives to face-to-face consultations in order to create a typology of these alternatives.

Objective 3: to identify and recruit approximately eight practices with varied experience of implementing alternatives to face-to-face consultations to act as focused ethnographic case studies.

Objective 4: in the case study practices, to explore how practice context, patient characteristics, the type of technology and the purpose of the consultation appear to interact to determine the feasibility and impact of alternatives to face-to-face consultations, from the perspectives of both patients and staff. This includes the impact on the clinician–patient dynamic. The impact for people living in isolation, people with disabilities, disadvantaged groups and other vulnerable or hard-to-reach groups will be a particular focus.

Objective 5: to identify the factors that act as the main barriers to, and facilitators of, wider use of these alternatives.

Modelling the process and outcomes

Objective 6: to use the findings to develop guidance and a website resource for general practice, detailing the most promising applications of alternatives to face-to-face consultations for different patient groups and different purposes, and in different practice and population contexts.

Objective 7: to treat the provision of alternatives to face-to-face consultations as an intervention, in order to develop a framework for a subsequent evaluation. We will clarify the target population, appropriate outcome measures and best methodological approach for this evaluation.

The research is focused to fill the gaps in the existing evidence base in a way that leads to practical and applicable findings, and provides a framework for future evaluation. It is hoped that the research findings will broaden the scope for research in this area.

Conceptual framework

This study uses a theory-based evaluation approach, which ‘examines the conditions of program implementation and mechanisms which mediate between processes and outcomes as a means to understand when and how programs work’. 75 There are a number of other related approaches to intervention development and evaluation, including logic models,76 realist evaluation,77 intervention mapping78 and causal modelling. 79 Although these approaches have different emphases, they have many ideas in common, including the importance of context in determining outcome and the need to clarify the underlying theory about how an intervention leads to change and clearly specify the intended outcomes. In addition, May et al. 80 have developed the normalisation process theory in order to understand the processes of implementation and integration that lead to innovations becoming embedded in everyday work.

Weiss75 distinguishes between programme theory, which specifies the mechanism of change (the theoretical causal chain for how an intervention leads to intended outcomes), and implementation theory, which describes how the intervention is carried out. This theory-based evaluation approach is helpful in identifying factors that are deemed to be key mediating processes through which an intervention achieves its aims and moderating factors that influence the extent to which process and outcomes are achieved.

In order to develop the programme theory, we drew on a realist approach81 to describe the provision of alternatives to face-to-face consultations in terms of:

-

context [e.g. characteristics of the general practice, the target patient population, the policy framework and the information technology (IT) infrastructure]

-

the theory and assumptions underlying the introduction of an alternative to the face-to-face consultation (how and why different staff members thought that alternatives to face-to-face consultations might lead to benefits)

-

the flow of activities that comprise the intervention (the key processes that occur when patients make use of these alternatives)

-

intended benefits/outcomes (those deemed important to different groups of patients and practitioners).

The implementation theory explored moderating factors that influence the extent to which the process and outcomes are achieved, such as factors acting as barriers to, and facilitators of, practices offering alternatives to face-to-face consultations or to different groups of patients using them.

By focusing on practices that have tried to offer alternatives, including some that deemed their use successful, we aimed to learn lessons about how practices have overcome problems, such as barriers to implementation, and the key factors that made this possible. We will also gain an understanding of the motivations of practitioners who have or have not offered alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, the experience of different groups of patients who have had the opportunity to use these alternatives, the benefits and disadvantages from the perspectives of patients and practitioners, and the problems that remain.

A key focus of interest will be which groups of patients make use of, and have the most to gain from, these alternative forms of access and whether these new approaches are increasing or reducing inequalities of access. This includes consideration of which groups are currently disadvantaged by the limited provision of alternatives to face-to-face care. We will explore the impact of provision of these alternatives on patient satisfaction with access to general practice. We will also explore clinicians’ perceptions of the impact of new forms of consultation on their workload and the appropriateness of the content of patient contacts, as well as factors that would facilitate the wider implementation of these new models of care.

The recently published Wachter report,82 commissioned by the UK DHSC, focused on making IT work in the health service in England, and was largely concerned with implementation at the secondary care level. However, some of the findings were pertinent for the introduction of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation in primary care: ‘digitise for the correct reasons’, and ‘it is better to get digitisation right than to do it quickly’82 (both of these quotations contain public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). This study will explore both the reasons that practices have introduced alternatives to the face-to-face consultation and how they have done it, allowing us to explore perceptions about the ‘right’ way to do this.

Team

The project team was deliberately diverse and was situated across four different universities. Table 1 provides an outline of team member contributions and backgrounds.

| Role in the project | Description of role | Background |

|---|---|---|

| 1. PI (CS) | Led and oversaw the project | GP, background in mixed methods, expert in the field |

| Led and conducted the scoping survey (see Chapter 3) | ||

| Led the analysis of quantitative data from the case study sites (see Chapter 6) | ||

| 2. Co-investigator (BM) | Local PI for two focused ethnographic case study sites | GP, background in mixed methods, expert in the field |

| 3. Co-investigator (JC) | Clinical and methodological input into all elements of the project | GP, background in mixed methods, expert in the field |

| 4. Co-investigator (AG) | Led and conducted the PPI throughout the study (see Chapters 2, 4, 5 and 8) | Patient and public involvement expert |

| 5. Co-investigator (SZ) | Senior lead of focused ethnographic case studies (see Chapters 4, 5, 7). Conducted the conceptual review with HA (see Chapter 2) | Medical sociologist, background in qualitative research |

| 6. Co-investigator (HA) | Day-to-day lead of focused ethnographic case studies and local PI for three focused ethnographic case study sites (see Chapters 4, 5, 7) | Health services researcher, background in mixed methods, expert in the field |

| Conducted conceptual review with SZ (see Chapter 2) | ||

| 7. Project manager and researcher (HB) | Oversaw and managed the entire project | Health psychologist, background in nursing and mixed methods |

| Conducted the scoping survey with CS (see Chapter 3) | ||

| Focused ethnographer for three case study sites | ||

| 8. Researcher (TP) | Focused ethnographer for three case study sites | Medical anthropologist, background in qualitative methods |

| 9. Researcher (AB) | Focused ethnographer for two case study sites | Health services researcher, background in social anthropology and mixed methods |

Structure of the report

Chapter 2 outlines the conceptual review of the literature. Chapter 3 presents the scoping study, which informed identification of the case study sites for recruitment. Chapter 4 details the methods of the focused ethnographic work in our case study sites and Chapter 5 presents the results of this. Chapter 6 describes the routine consultation data obtained from the electronic medical record in each case study site.

Chapter 7 synthesises the different elements of the study, both qualitative and quantitative, and describes how the guidance for the practical application of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation was developed. It includes the framework for future evaluation. The report concludes with the discussion in Chapter 8.

Chapter 2 Conceptual review

This chapter is based on material previously published in Atherton H, Ziebland S. What do we need to consider when planning, implementing and researching the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations in primary healthcare? Digit Health 2016;2:1–13. 83 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 3.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/3.0/. The text below includes minor additions and formatting changes to the original text.

Background

This conceptual review was informed by realist review, which is a method for synthesising research evidence that is particularly useful in examining complex interventions. 81,84 The methods offer a useful framework for identifying and managing syntheses of existing research and have been applied in such fields as lean thinking in health care,85 internet-based medical education,86 social diffusion in health care,87 social networks and social capital in the self-management of chronic illness88 and the potential health effects of accessing online patient experiences. 89

Policy and practice initiatives need to build on collective wisdom about the successes and failures of previous initiatives; in this review, we sought to identify explanations of why and how various alternatives to face-to-face consultations might work (or not) in primary care.

Aim

To identify and synthesise articles that explore, or test, the effects of alternatives to face-to-face consultations in relation to patient and staff experiences, or describe theories or ideas about the potential effects.

Methods

The review methods drew on Ziebland and Wyke 201289 (Box 1). The review was conducted by HA and SZ.

-

Finalised the review question (see aim).

-

Developed an initial matrix to record the cumulative results from the literature.

-

Drew on considerable existing knowledge of the literature based on our own and colleagues’ bibliographic databases.

-

Conducted a wide-ranging search (with assistance from a librarian) to identify any studies that have explored, or tested, the effects of alternatives to face-to-face consultations in relation to experiences, or described theories or ideas about the potential effects.

-

We examined all resulting titles and abstracts and selected potentially promising papers that could inform thinking.

-

More sources were identified by ‘snowballing’ from reference lists as ideas emerged.

-

A final search for additional studies was made when we had nearly completed the review. Studies were also added when encountered, for example, through discussions and seminars.

-

Each full paper was read by either HA or SZ. No formal quality appraisal tools were used but each paper was considered in relation to its:

-

relevance – does the research address the topic and enable the adding to, adaption or amendment of the initial matrix developed in step 1b?

-

rigour – does the research support the conclusions drawn from it by the authors?

-

-

We identified papers containing important ideas and discussed their relevance during regular meetings throughout the review.

-

This matrix was the main data extraction framework, with new categories incorporated where relevant during the initial reading.

-

The initial ‘map’ or overview identified potential positive and negative effects of alternatives to face-to-face consultations, with particular focus on the impact on inequalities and access, effect on patients and all staff working in primary care, and the potential mechanisms through which each effect might work.

-

A constant comparison approach between reading and the working table was applied. This identified the point at which no new ideas were emerging and ‘saturation’ was reached.

-

We presented the findings at a full project team meeting.

-

We presented and discussed the findings at the Society for Academic Primary Care conference in 2015.

-

At the end of the case study period we presented the findings of the conceptual review and the case studies to the case study practices as part of our stakeholder event.

-

The review was published in a peer-reviewed journal.

Types of studies

The review included material from any study design or article type. Given the changing nature of the field, the review focused on recently published articles (2012 onwards), but included sources from before 2012 where relevant.

Setting

The setting of interest for this review was primary care, but material from related settings (e.g. e-mail consultation between patients and specialists) was included where it provided lessons directly relevant to primary care.

Types of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation

We sought material on the following technologies: telephone consultations (but not those used to triage all requests for consultations before offering any face-to-face appointments), e-mail, e-consultations and internet video (e.g. Skype) technologies, short messaging service (SMS), telehealth and any other ‘care at a distance’ application.

Search for material

Our search was devised in conjunction with an information specialist at the University of Oxford. It was designed to identify articles that have explored, or tested, the effects of alternatives to face-to-face consultations in relation to how patients or staff experience their use, or described theories or ideas about the potential effect.

The search was intended to identify a wide range of study designs and articles. A sensitive search was designed, which yielded a high number of retrieved articles. Databases searched included the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature, Cochrane Register of Controlled Trials, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, EMBASE, MEDLINE, PsycINFO, Science Citation Index, Social Science Citation Index and Conference Proceedings Citation Index (see Appendix 1 for search strategies). We searched the databases from date of inception to 2015, and then a filter was applied to limit the retrieved articles to those from 2012 onwards.

We used additional sources: (1) key systematic reviews in the field and included studies, (2) papers identified by HA and SZ in the course of our work, (3) papers suggested by experts in the field (including the project team) and (4) papers identified by snowballing from the references lists of interesting and relevant studies.

The news archives of several related news websites and eHealth Insider, Pulse and GP Magazine were all searched for relevant material.

Selecting material

Within the articles identified using the database search, we examined all articles. A two-phase approach was taken; first, titles were examined, before looking at selected abstracts in more depth. Selected articles were then read in full. We checked the reference lists of full studies as we read them. When a ‘key’ paper was identified, we examined the references. The process was iterative, with further material sought as the matrix was populated.

Collation of material and identification of themes

For the purposes of collating material for the review we devised a matrix, which allowed for identification and extraction of key ideas and provided a constant comparison framework.

Either HA or SZ, and sometimes both, read articles. Where useful information was present in a study or article, it was added to the matrix. The matrix template was developed iteratively as material was extracted. For an example of the matrix template see Appendix 2.

Using a matrix allowed us to extract material according to the participants we were interested in, in line with the aims of the wider study: reception staff, nurses, GPs, practice managers, patients (particularly disadvantaged groups) and carers. Additional detail was added as extraction commenced; this meant including other groups (secondary care clinicians, policy-makers, professional bodies) and also acknowledging roles that apply outside a UK setting (e.g. service manager and primary care physician).

We extracted information from the studies by technology type, and initially split it into two categories: positive effects and negative effects. We added a further two categories once the extraction process commenced. These were ‘positive speculation on effects’ and ‘negative speculation on effects.’ This reflected the studies and articles that provided opinion on the technology, and also the studies and articles that included both empirical data and speculation.

Collating material in this way allowed us to identify the potential mechanisms through which each effect might work. Early in the process we (SZ and HA) met to compare the extraction into the matrix and to discuss key themes arising. We continued extraction of material until saturation was reached for the emerging themes.

Appraisal of articles

We did not apply formal quality appraisal tools in this conceptual review; however, each article was considered in relation to:

-

relevance – does the research address the topic and enable us to add to, adapt or amend the initial matrix?

-

rigour – does the research support the conclusions drawn from it by the authors?

When articles were not relevant, we excluded them from those used to develop the matrix. When rigour was in question, we did not exclude the article, but, instead, this was noted for the purposes of interpreting the data.

Synthesis of findings

We identified the main themes from the matrix and put these into an initial ‘map’, using the OSOP90 (one sheet of paper) method for grouping the material. From this point, we used a constant comparison approach: reading the articles and expanding the themes. We met regularly to discuss the data, and this often involved going back to key articles and revisiting themes that were identified earlier in the extraction process.

At this stage, the contents of the matrix and the initial map were shared at a team meeting to obtain input as the analysis progressed. The main themes were also discussed at a patient and public involvement (PPI) workshop (described below).

Theoretical framework

We based our development of the eventual conceptual map on input gained from the wider team and further meetings between the review team (HA and SZ). In organising and structuring the conceptual map, we used the Halford91 sociological framework of health-care work and organisation for information and communications technology (ICT) initiatives.

Halford’s framework91 views that the introduction of new ICT applications threatens to disrupt health-care work and organisation by disrupting social orders mediated by inter-relations of power, knowledge and identity. The analytical framework positions ICT initiatives within orderings of health-care work and organisation, with ICT applications posing three potential disruptions to the organisational, professional and spatial dimensions of health-care work and organisation.

This framework was chosen because it helps to understand, at a general level, how ICT initiatives disrupt the prevailing order of health care. The dimensions of the framework were used to structure the conceptual map, with the acknowledgement that the processes presented are inter-related, shaped by health-care work and organisation, but do not occur independently.

Development of the conceptual map

Once the material had been mapped, we developed it into a series of key questions to be asked when ‘planning, implementing and researching’ alternatives to face-to-face consultations, guided by Halford’s framework. 91 The conceptual map was also used, along with the protocol for the study, to devise a case study guide for the ethnographers to use while conducting the fieldwork. The guide was designed to align the information in the protocol with the information emerging from the review, to ensure that the data collected were in line with the aims of the study and built on existing research. The ethnographic team used it as a supporting guide when conducting the fieldwork.

Patient and public involvement workshop

In order to refine the emerging findings of the review, we held a workshop with patient and public participants. The workshop was facilitated by Andy Gibson. It lasted approximately 3 hours and was attended by five members of the public. We shared the themes from the review, and then members of the research team worked in small groups with the workshop participants to discuss the themes, followed by a whole-group discussion.

Results

Material from 149 separate articles was used in this review, obtained from database searches or snowballing, or via recommendations from team members. They included articles on telephone consulting (29 articles), e-mail/online consulting (34 articles), video consulting (21 articles) and SMS (one article) and articles describing themselves as being about ‘telehealth,’ ‘telecare’ or ‘teleconsultation’ (38 articles). The remainder discussed a combination of communication methods. We found 36 articles that explicitly stated that they were set in primary care, although some were set in multiple health settings. There was a mixture of study and article types, from systematic reviews to commentaries. In total, 56 of the 149 articles were relevant and used when identifying the key themes and devising the conceptual map, and these are each cited at the relevant places in the conceptual map. See Appendix 3 for a full list of the 149 articles identified.

Initial themes

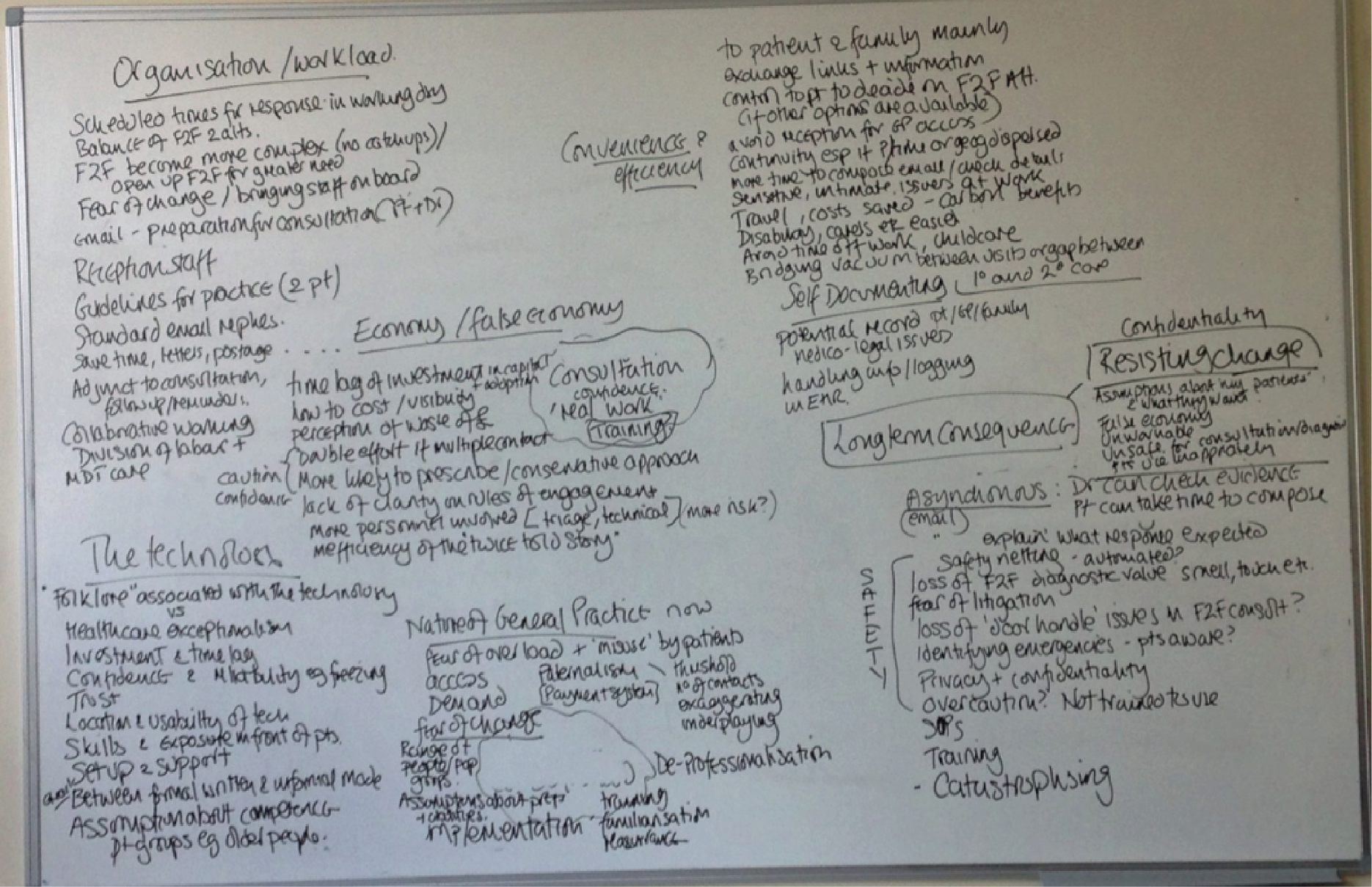

In the initial map, we identified the positive and negative effects of alternatives to face-to-face consultations, the effect on patients and staff working in primary care and other health-care settings and the potential mechanisms through which each effect might work. We identified nine main themes: organisation/workload, convenience and efficiency, the self-documenting nature of alternatives, economy/false economy, the technology itself, the nature of general practice, fear of change, asynchronicity and safety (Figure 2). This map provided the basis for the analysis.

FIGURE 2.

Map of initial themes.

Patient and public involvement workshop

Throughout the discussions, the themes from the review were compared with the perspectives of those attending the workshop. We further explored any differences or possible new ideas within the review material to see if they could add to the conceptual map.

Conceptual map

The final conceptual map covered 10 themes under three headings: organisational disruptions and dynamics, professional disruptions and dynamics and spatial disruptions and dynamics.

Organisational disruptions and dynamics

Uptake and awareness

In settings in which the availability of alternative forms of consultation is a matter for individual practices, rather than being required by policy directives (as in Denmark), then the question is raised as to how patients find out what is available to them at their practice. In a survey of patients’ reasons for not consulting their doctor by e-mail,92 the lack of awareness of the possibility of an e-mail consultation was one of the main reasons for non-use. Primary care professionals have described selectively offering alternatives to patients who they feel are able to use them appropriately. 19,93 Awareness will clearly affect uptake, as will the attitudes of members of the primary care team towards offering these alternatives. There was a lack of material relating to the perspectives of reception staff and their contribution to the uptake and awareness of alternatives, despite their patient-facing role.

Organisation of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation in the health-care setting

Several of the misgivings that have been raised about alternative consultations relate to the organisation and administration of the practice rather than to the consultation itself. Common concerns include what will happen if a part-time member of staff does not pick up an urgent e-mail and if alternatives to the face-to-face consultation will introduce inefficiencies for the practice. 67 Staff sometimes express concerns about whether or not patients will exercise their options responsibly, fearing that the relative ease of sending an e-mail (or a stream of e-mails) may mean that some patients will overconsult or misrepresent their symptoms. 94,95 Although the evidence is limited, in settings in which e-mail consultations have been introduced, they have not, as yet, opened the floodgates for patient demand. 96 Even in practices and health systems in which patients have had the right to e-mail their family doctors for some time, these alternatives are not widely used. 55,97 In Denmark, where e-mail consultations are a standard part of primary care, some doctors admit to managing their patients’ expectations by deliberately delaying their responses to non-urgent e-mails. 44

Primary care is set up to deliver the face-to-face consultation. As yet, there is little evidence about how best to time, conduct and record other forms of consultation. 94,98,99 These uncertainties make changes to service delivery difficult. 30,48 Potential inefficiencies include duplicated consultations if patients consult remotely and then attend the practice or need a home visit. 60,100,101 A study of telephone triage in general practice found that, where telephone triage led to a face-to-face consultation, the duration of this subsequent face-to-face consultation was no shorter, despite a clinician speaking with the patient during the telephone encounter. 102

Making arrangements for recognising and reimbursing some of these alternatives to the face-to-face consultation is an ongoing process. 103,104 In the USA, problems have arisen where reimbursement for Medicare patients is at the discretion of individual insurers, with many patients not being reimbursed for alternative types of communication with their health-care provider. 105

Different alternatives to the face-to-face consultation also differ in their impact on practice organisation. The face-to-face consultation is usually booked via reception staff. This is also the case for most telephone consultations. E-mail can allow patients to bypass the gatekeeping role of the reception staff and obtain direct contact with the primary care professional, or whoever is allocated the task of replying to the e-mail. 19,106 This prospect is sometimes viewed as unacceptably disruptive by clinicians. 107 There is a lack of evidence relating to the roles of team members, such as reception staff, in delivering alternatives to the face-to-face consultation.

Safety

Patient safety is crucial in any form of consultation, but alternatives to the face-to-face consultation present an unknown in terms of what these issues might be. Despite patient safety being cited as a reason to be wary of introducing alternatives to the face-to-face consultation,108 there is very little documentation of what these concerns are. Patient privacy and confidentiality are described as being important, but reports of privacy and confidentiality breaches are few, and collection of these data is uncommon. The Cochrane review of trials relating to e-mail for consultation found that the trials did not report any harms, but this is not the same as stating with confidence that no harms occurred. 30 There is much work to be done in identifying potential patient safety issues and mitigating the risk associated with these.

Organisation of space

As a visual method of consultation, there are considerations to be made when using video conferencing. To benefit from video conferencing, practices may need to allocate a well-lit, private area for the staff to use, as well as reliable connections, so that screens do not freeze mid-consultation. 107,109 This also applies to the systems that the patients are using. 110 A reliable contingency arrangement may be needed in case of technological failure. The potential for ‘freezing’ or image breakdown during a video consultation may have clinical consequences – for example, it can be particularly disturbing for people with mental illness. 109

Professional disruptions and dynamics

Proximity in the consultation

The common feature of all alternatives to the face-to-face consultation is that they are not face to face. A different medium inevitably changes some aspects of the performance of the consultation; these elements may be lost, or may need to be expressed in a different way or performed at a different time, for core elements of the doctor–patient relationship to be maintained. 111,112 There is particular uncertainty around the ‘rules of engagement’ for e-mail and video consultations. 19,44,113 The proximity with the patient that is afforded in the traditional face-to-face consultation permits diagnostic cues, such as smelling the patient’s skin and breath, noting how the patient walks into the room and using casual contact, such as shaking hands, to assess skin temperature and tone. 114,115 The health-care professional may lose some of their ability to check the patient’s understanding, which is often conveyed via non-verbal communication. 116,117 As yet, there is little research indicating whether misunderstandings are increased or diminished with alternatives to the face-to-face consultation.

Professional indemnity

Related to the lack of guidance or consensus on best practice, patient safety and the risk of litigation are often raised when alternatives to the face-to-face consultation are proposed. 93,118 This could be understood as a proxy reason, given that highlighting safety concerns is undoubtedly a more ‘acceptable’ form of resistance than voicing concerns about threats to professional identity and power. However, there is also some evidence that clinicians’ safety concerns are leading to safety-netting, demonstrated by prescribing behaviour; for example, primary care doctors are more likely to prescribe antibiotics during an e-visit than when they consult face to face. 119 This may reflect uncertainty around the medicolegal consequences of this type of prescribing. In trying to understand how alternatives are working, it is necessary to be alert to how safety-netting procedures are enacted.

Health-care professional attitudes

When health-care professionals are asked about their views on using alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, concerns tend to focus on whether or not their clinical duty to provide safe and effective care might be compromised. 37,45 Much of this concern relates to the potential impact of these additional consultation methods on their workload. Fears expressed include increases in consultation volume24,120 and increased administrative load. 20

Those with experience of successfully using alternatives to the face-to-face consultation in their own practice raise similar issues: still feeling uncertain about the long-term effects on their workload and, consequently, their patients. 19 Research suggests that any new technology needs to be seen to enhance what the professional sees as their core role,121 otherwise it is unlikely to be accepted into practice. 122,123

There have been far fewer studies collecting the views and experience of practice nurses on alternatives to the face-to-face consultation, but there is evidence that nurses feel that their role requires proximity to the patient. 111,124–126 In a study of a telehealth self-care support system for people with chronic health problems, the nurses who were providing the service positioned their work as ‘proper nursing’, whereas nurses who were using the telecare system suggested that the calls with patients were ‘just chat’ and doubted that real nursing could be delivered via the telephone. 127 A Norwegian study of nurses working in emergency medicine found that the approach of nurses changed when they consulted remotely: they were more assertive and gave more advice.

Health-care professional skills

An important consideration is whether the technology is familiar and easy for both parties to use or whether it requires new skills. Some health-care professionals worry that their lack of confidence with technology may be exposed, and that such exposure might undermine their authority. 128,129 In a study of breastfeeding support via video consultation, lactation consultants were concerned about technical issues, such as the quality of images, but patients were very satisfied with the remote consultation. The lactation consultants were not confident about undertaking clinical assessments via video – a concern that the authors concluded could be addressed by specific training in using the medium. 110 Although the balance of power within the consultation may change if the primary care professional’s skills come under patient scrutiny,130 this is not necessarily damaging and could even be a helpful shift in longer-term relationship dynamics.

Spatial disruption and dynamics

The nature of the communication medium

There are already many different technologies that patients could use to consult their doctor without meeting face to face, for example telephone, e-mail, SMS and video communication. Although specific platforms are likely to be superseded in a fast-changing field, it is possible to differentiate according to whether the method provides (moving) images, audio or written content, and whether the exchange is in real time or asynchronous. Asynchronicity allows both patients and health-care professionals to send and act on contacts at a time that suits them. For the health-care professional, they can draw upon external resources or check evidence, perhaps providing sources of information for the patient. 67,131 For patients, it allows them time to construct an enquiry, perhaps with help from family or friends, and to send follow-up questions that occur after a consultation. E-mail allows patients to upload images. Methods that allow video connection give health-care professionals the opportunity to view the patient, including visual symptoms (such as a rash) and also, potentially, the patient’s home setting. All of these factors allow for the collection of information on the state of the patient, beyond that communicated verbally.

Patient interface with alternatives to the face-to-face consultation

Where patients have been offered an alternative to the face-to-face consultation, they usually report liking them. 132,133 E-mail and telephone consultations remove the need to attend the GP or nurse’s professional space, which tends to be viewed as a benefit by patients. 67,106,119 Other reported benefits include the convenience of being able to consult while at work,134 to choose when and how to consult and the perceived advantage of avoiding the practice receptionist. 44,124 The ability to communicate with a doctor via e-mail means that the patient can compose a message when something is bothering them, which may be outside office hours. The patient (and their family) may like to exchange information relevant to health and care decisions within their personal contacts. Parents can photograph, record and attach digital files with images of a child’s rash, or recordings of an infrequent cough or breathing difficulty. 44,128 For patients preparing for a visit to hospital, or recovering at home afterwards, these methods can provide a way to keep in touch without necessitating a visit. 111

E-mail exchanges can provide a consultation record, and possibly clearer explanations and subsequent understandings than information obtained during face-to-face contact. 111 This may be particularly advantageous to those who are less articulate or confident in person, those who wish to discuss their consultation with others and those who need help with translation. 94 Some patients may be more willing to disclose intimate or sensitive information via an e-mail than in person or over the telephone – especially if they are at work or in a public place. 44 For others, the reverse will be true, not least because of concerns about confidentiality in e-mails.

Health professionals raise concerns that older patients, disabled patients, people without literacy skills and patients who are less educated3,55 may be disadvantaged through alternatives to the face-to-face consultation. 45 There is some evidence that, for those who have internet access, patients who are disabled, elderly, less confident or living at some distance from the practice are often among those who are particularly keen to use e-mail consultations. 56 Patient skills in using these technologies should be considered. Providing information or training may not be enough on its own. Varsi et al. 131 recommend that patients should be shown how to use a system at a point when it is relevant to them, rather than as part of a general induction to their health-care organisation. If the information does not come at the right time, the patient may not remember the system, or (as is likely in a fast-moving field) the system may have changed by the time they come to use it.

Although there is a lot of speculation about the potential benefits and disadvantages for patients, and particular subgroups of patients, much of it has been written from the health-care professional perspective, and credible empirical evidence from patients is very limited. The perspectives and experiences of patients (and especially those from groups who are assumed to be disadvantaged by the introduction of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation) clearly need further attention when designing, implementing and evaluating systems.

Unintended consequences

It is important when studying alternatives to the face-to-face consultation to consider the potential for unintended consequences. There are numerous examples of technologies that have been tinkered with and adapted in the field,121 some to the extent that their initial purpose is barely recognisable. Changes in one element of care provision can have an impact on other elements of care and the role of other staff. An example is Winthereik and Langstrup’s study,135 in Denmark, of patient and professional behaviours in response to a new portal for pregnant women. The portal was introduced to help women with uncomplicated pregnancies to self-manage, with aims to free up resources for patients with more complicated conditions. They found that, although only a minority of participants engaged in the portal, those who did enacted their active and responsible involvement at the clinic rather than at home. The use of the portal, therefore, provided both more and less than was anticipated: it reconfigured relations in a way that is likely to alter the meaning of care, but not in a manner that was likely to free up resources. In addition, the health-care practitioners, who were supposed to be using the portal to maintain a complete and shared electronic record, were instead printing a paper record and adding their own hand-written notes. The health-care professionals ended up doing more work than before.

Key questions

As the conceptual map was developed, a series of key questions was created (Box 2). These questions were used to form the basis of an essay: ‘What do we need to consider when planning, implementing and researching the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations in primary healthcare?’. The essay was submitted to and accepted by the Journal of Digital Health and published in September 2016. 83 The content of the essay overlaps with the material presented in this chapter, although the essay was designed for broader application beyond the study.

-

How could patients find out what methods of consultation are offered by their doctor?

-

How will alternatives to the face-to-face consultation be scheduled into existing practice?

-

What impact will alternatives to the face-to-face consultation have on reception and administrative staff work patterns?

-

What are the agreed rules of engagement for the use of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation?

-

What contingency is in place to ensure that communication by asynchronous methods is responded to, and in a timely fashion?

-

How will the expectations of all parties be managed?

-

How can consultations be appropriately administered to avoid duplication of effort?

-

How will alternatives to the face-to-face consultation be documented in the medical record, especially when consulting remotely from the practice?

-

Is reimbursement for alternatives to the face-to-face consultation appropriate? What are the arrangements for reimbursement?

-

What are the potential patient safety issues?

-

How are these (or might these be) mitigated?

-

Are there risks to patient privacy and confidentiality?

-

What are the contingency arrangements for technology failure?

-

What did the designers intend it to do – and (more importantly) how is it used in practice?

-

Does it allow eye-to-eye contact? Is it in real time or is it asynchronous?

-

What is lost in comparison with the copresent consultation?

-

What is the effect on valued aspects of primary care, such as the relationship and continuity of care?

-

What is the alternative to the face-to-face consultation appropriate for? Is it offering a replacement for the face-to-face consultation or is it complementary?

-

Is there a risk of misunderstanding as a result of the change in medium, and can this be accounted for?

-

Will alternatives to the face-to-face consultation change how patients communicate?

-

How are the roles of different team members affected by their use?

-

Are there implications for staffing in the practice?

-

How is medicolegal protection in relation to alternatives to the face-to-face consultation organised and understood in the practice setting?

-

What are the views and concerns of different members of the team about alternatives to the face-to-face consultation?

-

What skills are needed? Is training and support available?

-

Will patients require training or guidance in using alternatives to the face-to-face consultation?

-

Will the introduction of alternatives to the face-to-face consultation allow for flexible working?

-

If so, might this have an impact on primary care staffing recruitment and retention?

-

Are there cost implications?

-

Who was involved in setting up the system and whose work was considered?

-

Is the rationale for introducing an alternative to the face-to-face consultation clear and understandable to all staff members?

-

What impact does it have on all of the different members of the team?

-

Whose core values and interests are served?

-

How is resistance enacted, and by whom?

-

How will patient experiences be collected and recorded?

-

Are there types of consultation that are preferred face to face?

-

What about patients from groups who are often assumed to be disadvantaged in relation to alternatives to the face-to-face consultation (older, disabled, less educated, those with language difficulties)?

-

How might patients use the opportunity to share digital files with their doctors?

-

Are there consequences (either positive or negative) for other elements of the practice, or other aspects of care provision?

-

Are there consequences for other parts of the health system (use of emergency helplines, hospital emergency departments, etc.)?

-

Do (and how do) staff and patients modify new forms of consultation to better meet their needs?

-

How else might the planner, implementer or researcher identify unintended consequences?

Case study guide

The findings of the review fed directly into the case study guide. The case study guide was produced to guide the focused ethnographers in their understanding of the required scope of data collection across the three case study sites. Each ethnographer came from a different background, and two had not conducted research in general practice settings before. The guide was used to ensure that they understood the scope of the focused ethnography and felt confident going into the field.

The guide outlined specific areas of interest, including the staff members they should consider observing (e.g. focusing on reception staff as well as clinical staff), things they might want to look out for (e.g. dynamics within the clinic between staff members) and where they might look (e.g. areas where team members interact beyond the consultation areas) in this particular setting.

The 13-page guide was written systematically, and began by reiterating the objective of the case studies and outlining the participants of interest. Then, for each group of interest, such as reception staff, the tasks required (observation, interview) and the per-protocol approach to conducting the tasks were outlined, and the factors to explore were detailed. These factors were derived from both the protocol and the review findings. The guide finished with a summary of each technology type and the specific factors to explore in relation to these. This was helpful for the ethnographers at the beginning of the study when they were unfamiliar with the research questions. They were told that it was a guide and not a checklist and that it was for their personal reference only. For the case study guide, see Appendix 4.

Conclusion

This conceptual review has identified and synthesised material relating to patient and staff experiences of alternatives to the face-to face-consultation, along with theories and ideas about the potential effects. Key questions to be asked when researching alternatives to the face-to-face consultation have been applied in devising a case study guide, which was used by the focused ethnographers in guiding data collection at case study sites.

The conceptual map and key questions devised here are applied to the interpretation and synthesis of all data collected in this study; this included the focused ethnography and the routine consultation data. The use of the conceptual map and the key questions is demonstrated in the case study results chapter (see Chapter 5) and the synthesis chapter (see Chapter 7), respectively.

Chapter 3 Scoping study

The material in this chapter is republished with permission from the British Journal of General Practice. 136

Introduction

The main aim of this project was to recruit case study practices across three study sites: in and around Bristol; in and around Oxford; and in Lothian and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland. Case study practices had to be using or considering introducing, or to have recently ceased using, alternatives to face-to-face consultations, such as telephone consultations, e-mail consultations, video consultations or e-consultations. We employed a scoping study to identify practices fitting these criteria which could be invited to participate in the main study.

Our secondary aim was to understand the extent of the use of these alternatives to the face-to-face consultation in contemporary general practice.

Methods

The scoping study utilised a number of methods to identify the practices. The main approach was to send a postal survey to all of the practice managers, GP partners and salaried GPs (n = 2719) at all the practices in and around Bristol, Oxford, Lothian and the Highlands and Islands of Scotland (n = 421). This was supplemented by four further approaches: (1) exploring the practices’ websites, (2) contacting companies that offer support in providing alternatives to face-to-face consultations, (3) utilising local and national links with those working in primary care and (4) utilising existing knowledge within the team.

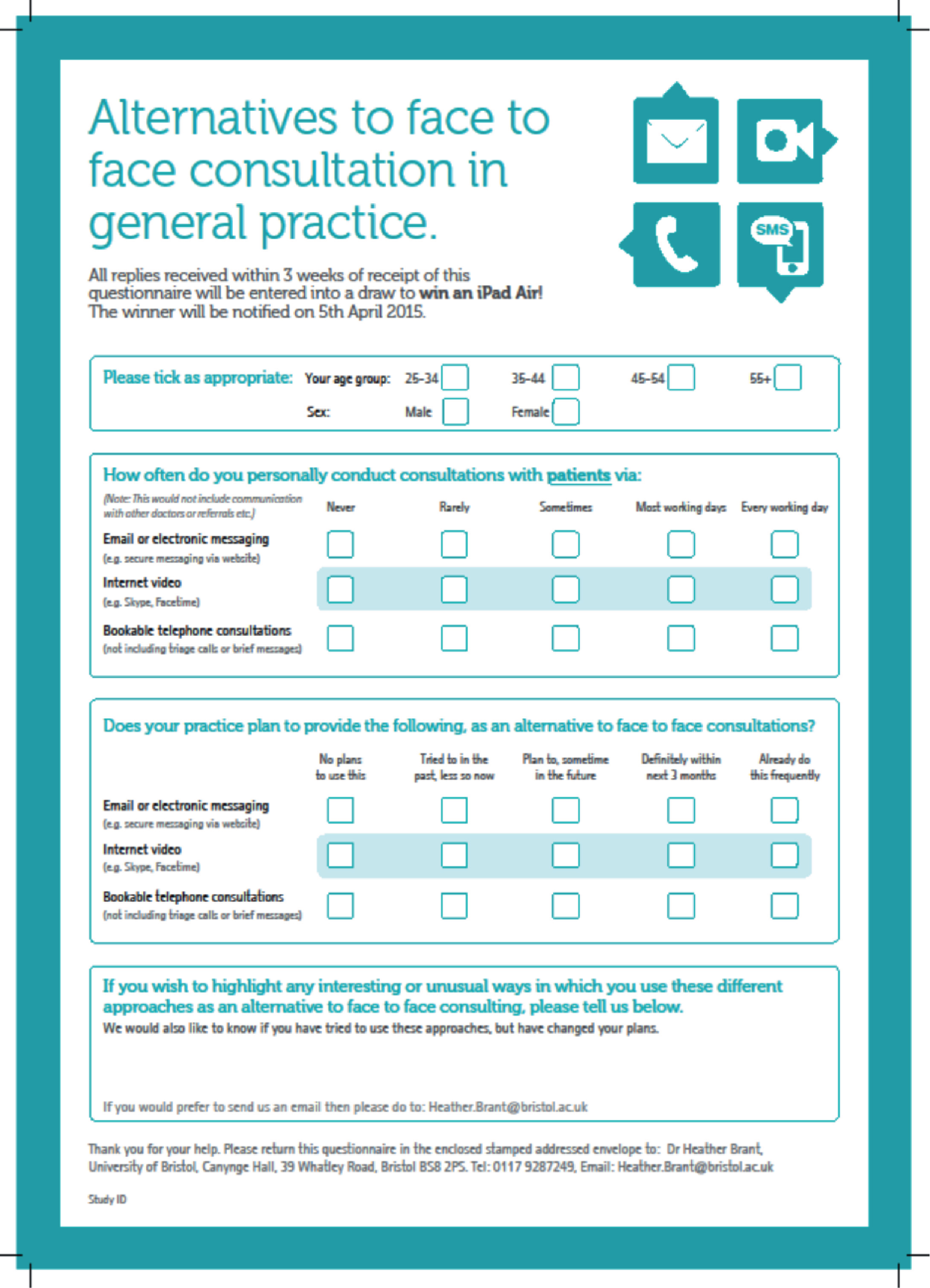

The postal survey

The single-page survey opened with questions about the age and sex of the respondent, followed by two groups of questions. In one group, participants were asked whether their practice currently provided or planned to provide consultations with patients via e-mail or electronic messaging, internet video or telephone. We excluded telephone triage, as this constitutes a contact rather than a consultation and telephone triage is being assessed in an ongoing project funded under the same call. 137 In the other group of questions, participants were asked how often they personally conducted consultations using each of these approaches. Each question in both groups was scored on a 5-point Likert scale. The questionnaire closed with the opportunity for respondents to add information ‘about any interesting or unusual ways in which you use these different approaches’ in a free-text box (Figure 3).

FIGURE 3.

Questionnaire.

Practices within the English study sites were identified through the relevant Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) websites. For the practices in Scotland, we retrieved details from the Information Services Division Scotland website. Information about the practice managers, GP partners and salaried GPs were accessed via the practice website if one existed. For those practices without a website [53/421 (13%)], we gained the information through a telephone call to the practice.

We posted questionnaires to each of the practice managers, GP partners and salaried GPs. As the focus of this study was on provision of care at a practice level rather than individual GP attitudes, our aim was to receive at least one response from each practice. If no response had been received following a period of 2 weeks, a postal reminder was sent to all of the GPs and the practice manager within the practice, and 2 weeks after this a telephone reminder was made, if appropriate, to the practice manager. We also offered an incentive, with all those who returned a completed questionnaire within a specified time being entered into a raffle for a tablet computer.

Ethics and research governance permissions

The Health Research Authority and the University of Bristol Faculty of Medicine and Dentistry Research Ethics Committee deemed that no ethics permission was needed.

Analysis

We conducted the primary analysis at the practice level, and then subsequently analysed GPs’ personal use of alternative forms of consultation at an individual level. Numerical data were analysed using simple statistical methods supported by Microsoft Excel® 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) and Stata® 13 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX, USA). Where different responses were given by respondents within the same practice, we used the mean result at practice level, rounding to the nearest whole number (since each response was scored from 1 to 5 on a Likert scale). We explored the extent of variation in response by different individuals within the same practice, using the within-practice standard deviation (SD) and the intraclass correlation (ICC) coefficient. Responses regarding GPs’ own use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations were analysed at the individual respondent level. Responses from practice managers were excluded from the individual-level analyses, as they do not consult with patients.

We analysed the results from the free-text box thematically, using NVivo 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK), and visual mind-mapping was carried out to examine themes and patterns in the data. 90

Exploring practice websites

An attempt was made to access each of the 421 practice websites in our three study areas (186 English and 235 Scottish practices) to see if there was any reference to the use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations. However, websites were not identified for 53 out of 421 practices (13%) at the time of searching (51 of the 53 were in Scotland).

Contacting commercial organisations

A number of companies market software systems to general practices to support them in providing alternatives to face-to-face consultations. We drew up a list of these companies through existing knowledge of the team and extensive searches of the internet. Eight companies were approached to enquire whether or not there were any practices using their technology within our study sites. Although four companies responded, no practices were identified because either the technology was outside our remit, they were reluctant to provide details of the practices that were using their technology, or there were no practices in our study areas.

Utilising local and national links with those working in primary care

In addition to the above methods, we also approached the local CCGs, Health Boards and Primary Care Research Networks in our study areas to ask if there was any awareness of practices adopting any form of alternatives to face-to-face consultations. We were also able to identify any practices or local consortiums that may have been funded by the GP Access Fund. 14 Unfortunately, this approach did not yield any further information, as either we had already identified the sites or there was little knowledge of the local use of alternatives to face-to-face consultations. Our enquiries also demonstrated that, although many sites receiving funding from the GP Access Fund14 had said that they would implement alternatives to face-to-face consultations, such as video-consultation, we were not able to identify any that had actually done so at that point in time.

Results

Postal survey

Of the practices approached, 163 out of 186 practices (88%) in England and 156 out of 235 practices (66%) in Scotland responded, giving an overall practice response rate of 76% (n = 319/421). In addition, 40% of English and 25% of Scottish surveys were returned with an overall individual response rate of 33% (n = 889/2719). The number of responses per practice ranged from 1 to 11.

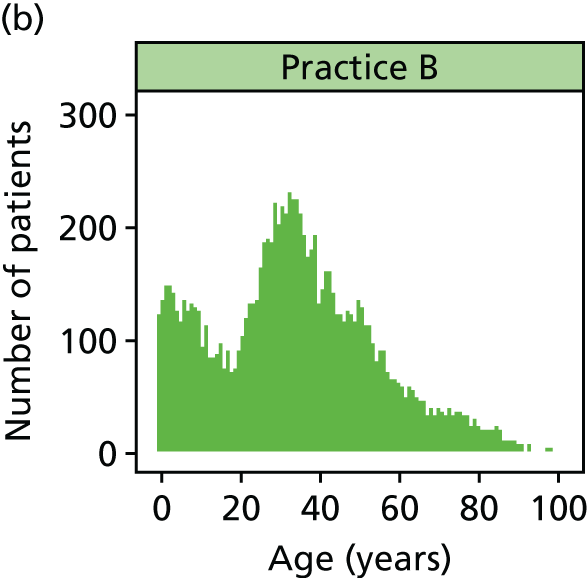

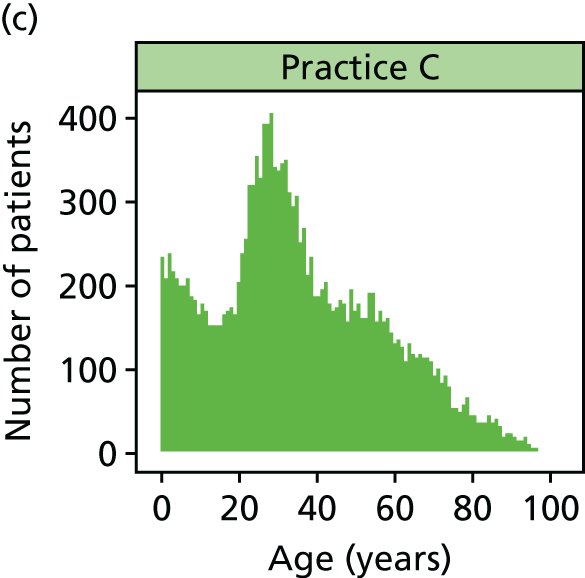

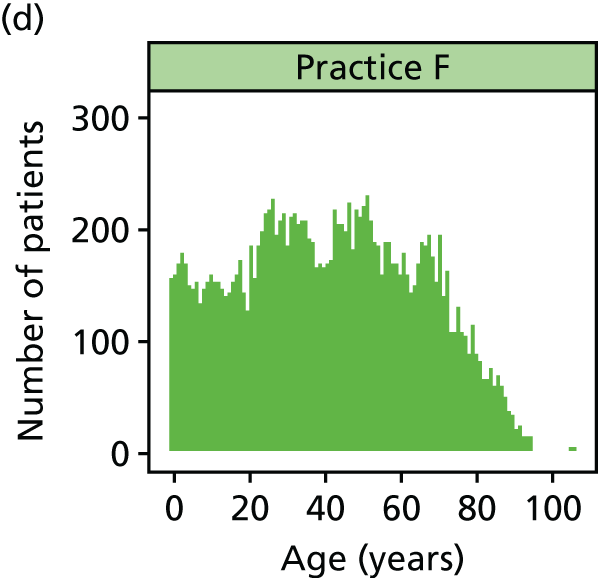

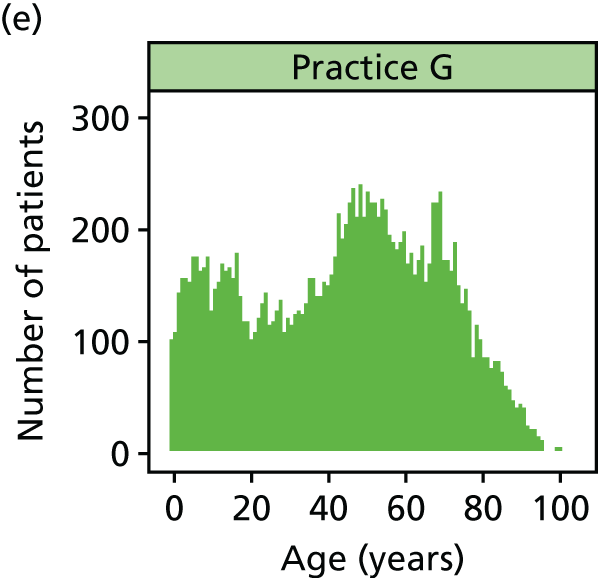

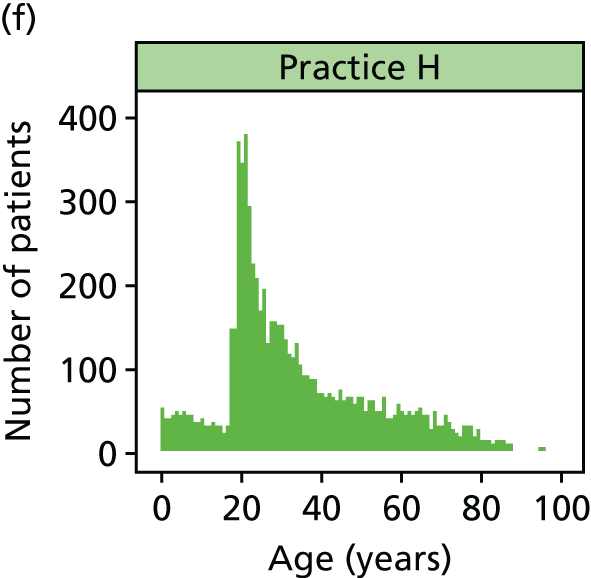

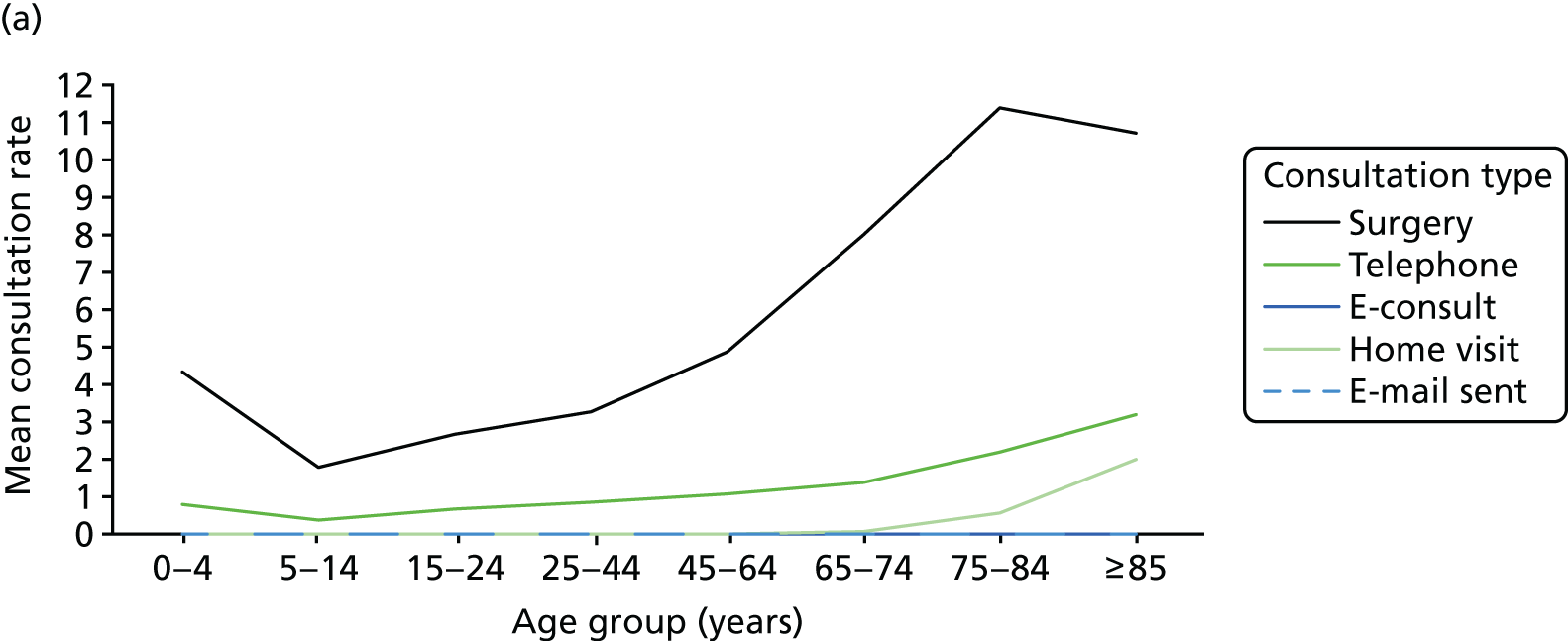

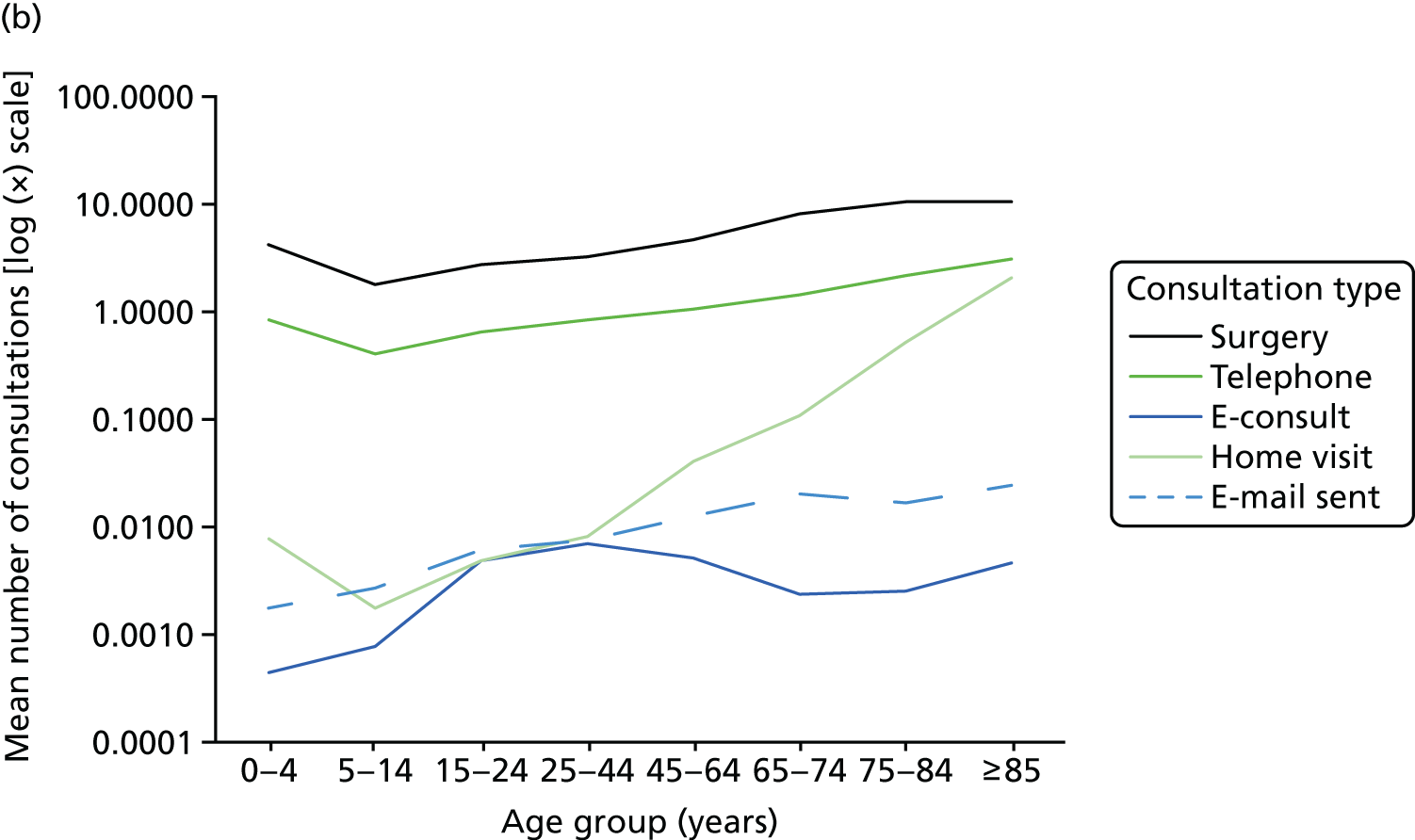

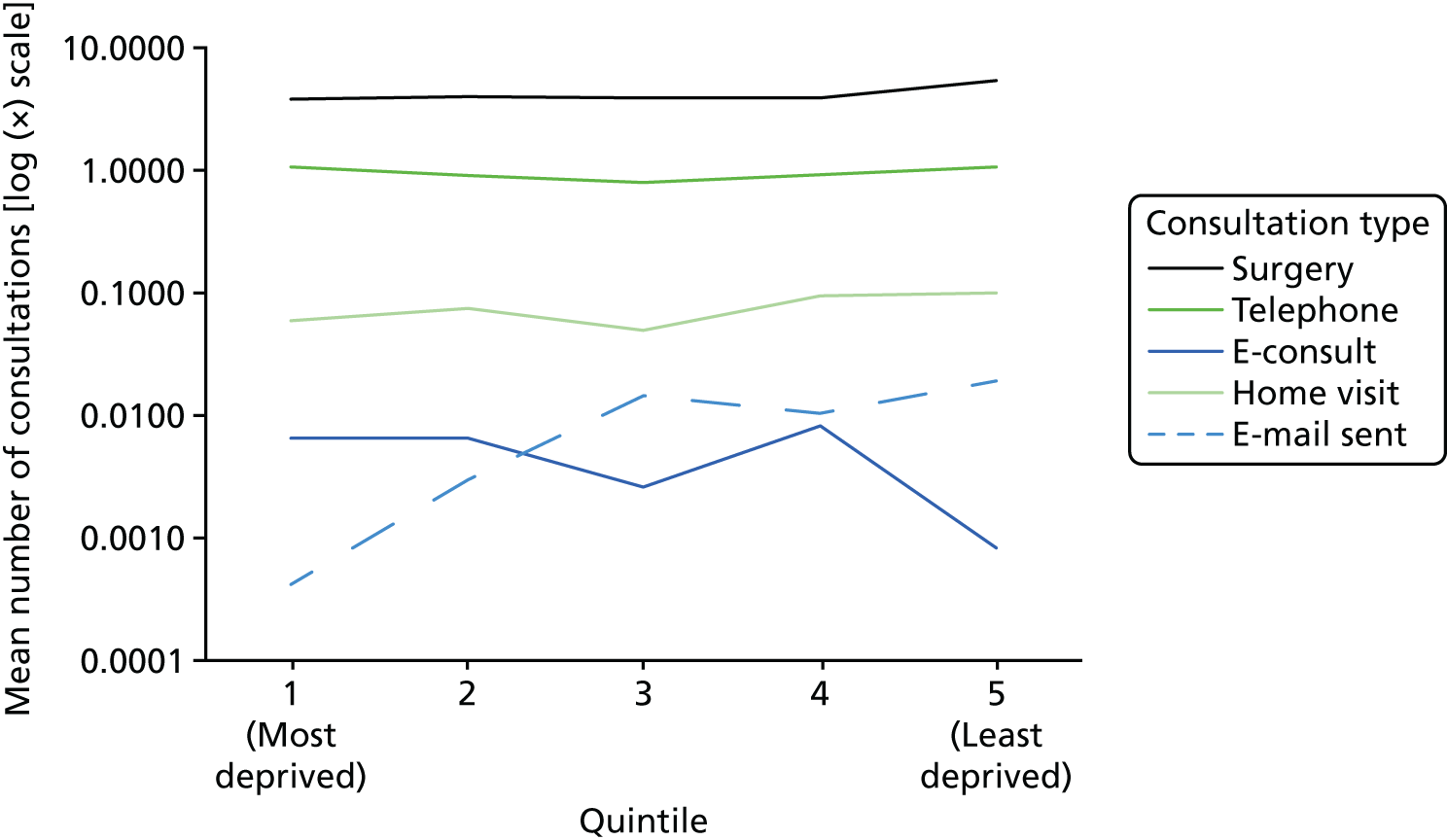

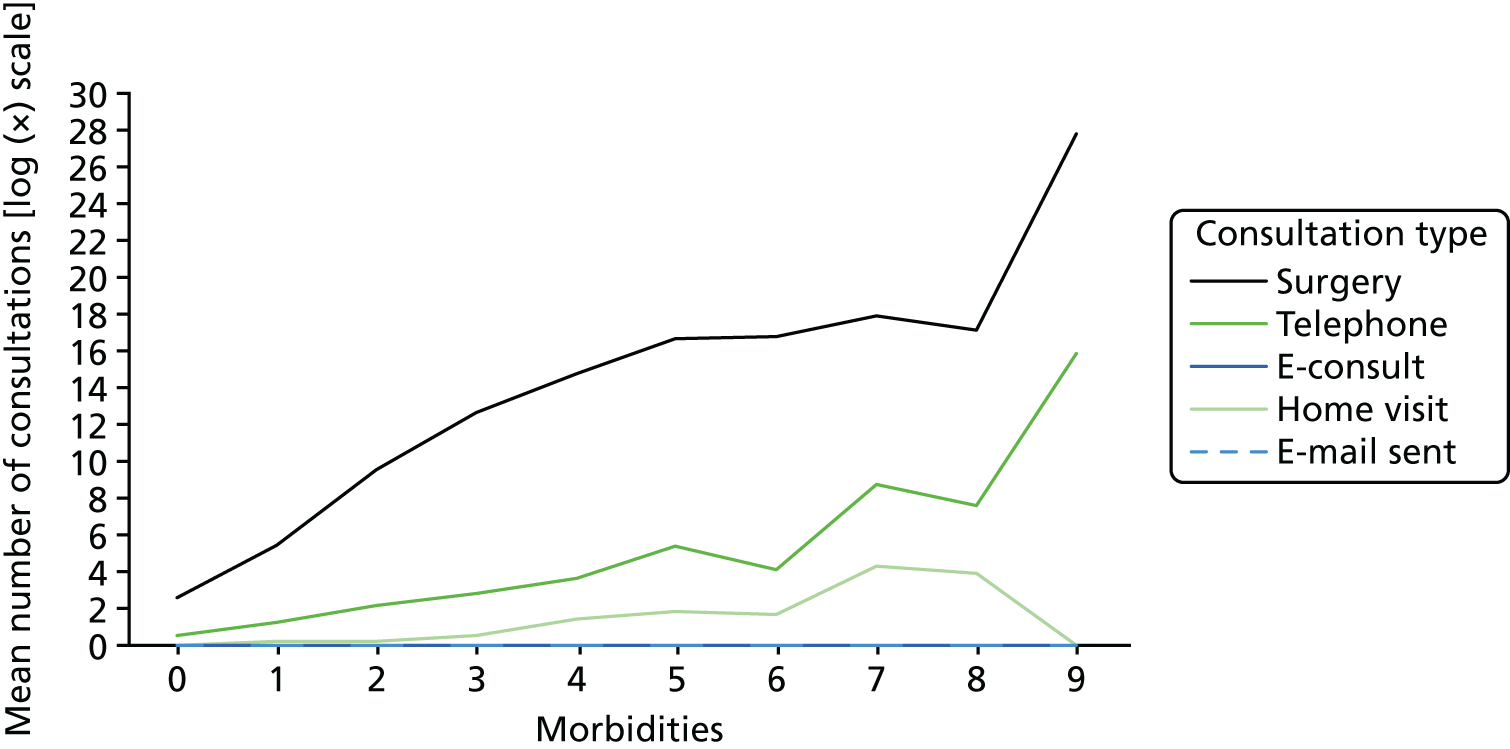

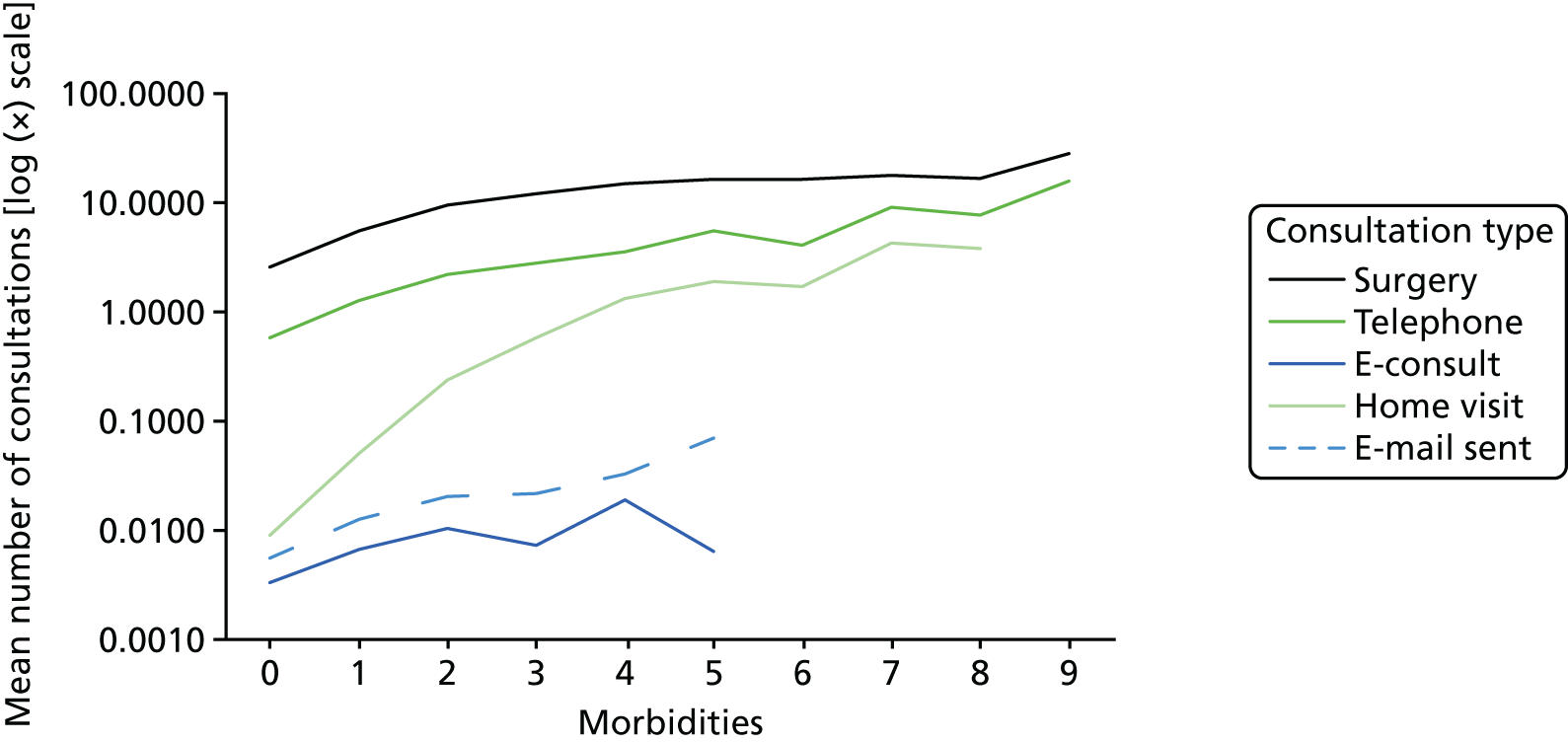

Profile of respondents