Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 11/1017/18. The contractual start date was in February 2013. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Godfrey et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

In this chapter, we set out the background to and rationale for the study. We review evidence on the meaning of person-centred care, considered a benchmark of care quality, with reference to the care of people with dementia on acute hospital wards. We then describe the development of an intervention to improve the care of hospitalised older people with dementia, the theory of change underpinning it and the objectives of the research to evaluate it.

Improving care of people with dementia in hospital: a policy priority

Improving the care of people with dementia has been identified as a policy priority in the UK and internationally over the last decade. This has resulted in the development of national dementia strategies in England1, Wales2 and Scotland. 3,4 Similar initiatives have been introduced in other European countries5 and in Australia6,7 and New Zealand. 8 In the UK, the policy and strategic objectives include improving care quality for people with dementia in acute hospitals (objective 8 of the English strategy1 and target 2 of the 1000 Lives Plus campaign for Wales2); and making hospitals more ‘dementia friendly’. 3 Both objectives are prioritised in the Prime Minister’s Dementia Challenge. 9,10

Older people are the main users of acute hospital beds, and around half of patients who are aged ≥ 70 years have a cognitive impairment, including dementia, delirium and delirium on dementia. 11–13

The needs of people with dementia in hospital are multiple and complex. They include care needs relating to functional impairments, a consequence of physical comorbidities common among those in advanced older age; expressive, emotional and communication needs, which vary depending on the nature, severity and impact of their cognitive impairment; and medical needs resulting from the type of acute event precipitating hospital admission, which may also exacerbate the dementia (e.g. pain and infection).

People on hospital wards living with dementia are at heightened risk of unintended adverse events. These events include delirium and falls that contribute to increased mortality, longer length of hospital stay and poor health outcomes such as loss of independence and new care home admissions,11,12,14,15 with the attendant resource implications. 16,17 Being in hospital may be experienced as frightening and engender feelings of anxiety, distress and agitation18–22 as a consequence of the busy and unfamiliar environment. Features of physical design, organisational structure, care climate and care processes that do not take account of individuals’ vulnerability and reduced resilience may exacerbate distress and contribute to poor outcomes. 21,22

The dominance of older people on acute wards and the prevalence of dementia among those hospitalised means that care delivery to people with a cognitive impairment is a litmus test of the quality of hospital care. Yet, despite the frequency with which people with dementia utilise acute care, evidence from systematic reviews,21,22 recent in-depth studies18,23,24 and national audits25,26 suggests that the needs of people in this group are often under-recognised and inadequately addressed.

Care of hospitalised older people with dementia

Studies have identified the organisational and cultural features of acute care delivery that have a negative impact on the care of patients with dementia. These include inflexible care routines that privilege the performance of medical and physical care tasks over time spent with patients,27,28 and physical environments that are difficult to navigate. 21,22,25 The nature and quality of staff interactions with patients has been regarded as problematic, with staff encounters that are primarily task focused and involve limited engagement of the person at a personal level;17–19,21,22,24,25,29–33 and communication practices that are poorly responsive to the emotional needs of patients17,21–25,27,30–32 and/or lead to a failure to ‘see’ and act on behavioural cues that might indicate distress or pain. 34,35 Studies have reported stigmatising and negative attitudes towards people with dementia among some staff and that such patients should not be admitted to acute wards. 27,29–32 Often conveyed as ensuring their safety and that of other patients, the consequence is to see people with dementia as ‘other’. Conversely, staff with knowledge of dementia express lower perceived strain in caring for a person with dementia and less negative attitudes. 32 Research with caregivers has reported inadequate support for their relative with nutrition and hydration,17 both risk factors for delirium;36 the person with dementia not being treated with dignity and respect;17,22,24,27,37,38 and limited engagement in decision-making, for both the person with dementia and the caregiver. 17,22,37 A key factor, contributing to poor care delivery from UK studies, is lack of knowledge and skill in dementia care. 20,22,25,38

Person-centred care: a marker of care quality

What is person-centred care?

‘Person-centred’ care has become ubiquitous in UK health and social care policy discourse as synonymous with care quality. Prioritised in the National Service Framework for Older People,39 it is viewed as key to upholding dignity in care40 and forms one of the key Principles of Nursing Practice developed by the Royal College of Nursing (RCN). 41 However, either its meaning in policy is implicit or there is varying emphasis on different domains. It is commonly conveyed as individualised care, holistic care, choice, autonomy and dignity; and the use of the term, and the particular emphasis attached to it, has varied over time and in relation to wider policy interests (see Appendix 1 for a document review).

From research, there is a similar lack of clarity on what is person-centred care. Two systematic reviews examined its meaning in health,42,43 although they adopted different perspectives. Kogan et al. 42 explored research relating to older people, and Sharma et al. ’s43 review of reviews addressed understanding of person-centeredness in nursing and medicine. Both concluded that there was no consensus on meaning, posing difficulties in operationalising the concept. Neither included studies in acute care, and only 3 out of 132 papers in Kogan’s review related to people with dementia, all of which were conducted in long-term care. To explore this further, we consider theoretical conceptions of personhood and person-centred care in dementia and draw on research evidence to explore what quality care might look like for people with dementia on acute wards.

Theoretical conceptions of person-centred care in dementia

Personhood in dementia

Kitwood’s44 theoretical model of ‘personhood’ has been enormously influential as the basis for ‘person-centred’ care in dementia. He drew attention to the way in which people’s experience, behaviours and actions do not simply arise as a consequence of neurological deficits. They are also shaped by interactional processes that result in the erosion of personhood and the consequent invisibility and diminishing of the person; in essence, loss of cognition is equated with being a non-person, with a deleterious impact on the individual. Similarly, Sabat45 has explored how the social positioning of people with dementia affects how they are related to, considered and conceptualised, and which in turn affects their personhood, their behaviour and their interactions with others. This theory projects the malign impact of ‘others’ (whether at institutional, organisational, social or interpersonal levels) on the person’s sense of self.

Based on humanistic values and person-centred psychotherapy,46 Kitwood suggests that a person with dementia can sustain relative well-being if personhood is maintained. Drawing on empirical research in long-term care, he defines five psychological needs (not unique to people with dementia) to establish the main foci of interventions for sustaining personhood: comfort, attachment, inclusion, occupation and identity. Although the concept of ‘person-centred’ has been criticised for its ‘individual’ emphasis,47 ‘personhood’ as articulated by Kitwood and Sabat is relational, the underpinning assumption being that the person is embedded in relationships in a social world. Person-centred care, therefore, is care that meets the person’s psychological and social needs, informed by values of respect and concern for others, and that has been summarised in the VIPS model. 48 Here, person-centred care comprises four elements: valuing people with dementia and those who care for them (V); treating people as individuals (I); looking at the world from the perspective of the person with dementia (P); and positive social environment such that the person can experience well-being (S). The significance of the quality of the relationship with persons with dementia is uncontested. Less evident is how to operationalise an appropriate response to the psychological and social needs identified by Kitwood44 into settings that are temporary, geared to specific purposes and where relationships are short-lived and transient, as are acute wards. Indeed, it is argued that operationalising person-centred care will vary with the nature of the setting in which it is delivered. 49

Embodiment and dementia

Recent developments in understanding dementia have drawn on theories of embodiment. 50–53 Kontos50 directs attention at the way in which people with dementia express selfhood through their embodied way of ‘being in the world’ (i.e. through activity and engagement rather than reflection or contemplation). She contends that selfhood that resides in the pre-reflective body has two origins. The first is primordial, whereby ‘selfhood emanates from the body’s power of natural expression, and manifests in the body’s inherent ability to apprehend and convey meaning’. 50 This is seen, for instance, in how people, including those with severe dementia, communicate with gestures, body movements and facial expressions, which carry meaning in interpersonal communication; they are reflective of agency or intentionality. The second origin of selfhood is the sociocultural dimension of the pre-reflective body: people’s actions and interactions convey deeply internalised, socioculturally specific ways of being in the world. For example, people with severe dementia may converse with each other following normative rules of engagement (e.g. turn-taking), although the content may seem unintelligible to the listener. She argues that the notion of embodied selfhood refers to the complex inter-relationship between primordial and social characteristics of the body, which reside below the threshold of cognition, are grounded in the pre-reflective level of experience and are manifest primarily in corporeal ways. Understanding the ways in which people are embodied is to challenge the assumption that there is loss of agency with cognitive impairment. The conception of embodied communication as meaningful has implications for engaging with people with dementia in acute care. Hughes53 considers that if one is to share, if not fully understand, the world of a person with dementia, one must draw on myriad non-verbal and expressive cues, and to make sense of them requires knowledge of the person.

Practice of person-centred care on acute wards

Research relating to older people with dementia on acute wards primarily highlights difficulties in care practice, and evidence reviews conclude that a chasm exists between the rhetoric of ‘person-centred care’ and actual delivery. 21,22 Apart from a recent study,24 this research does not draw on a theoretical conception of ‘person-centred’ care in dementia, although several studies offer insight into what person-focused practice might look like.

Studies on the quality of care delivery on acute wards have been mainly small scale, employing ethnographic18–20,30,33 or mixed methods, including interviews with caregivers. 23,24,29,31,32,54 Two20,54 drew out components of good practice from observation, interviews and conversations with patients. Tolson et al. ,54 employing critical incident interviewing with patients (possible with only a small number) and caregivers, identified four themes within a temporal frame around which components of quality practice could be delineated. ‘Settling in’ referred to the process of adjustment involving responsiveness to emotional signifiers and acknowledgement of the person as valued and part of a family/social network. Its significance stemmed from the person’s need for reassurance, given the disorientation and distress resulting from being in an unfamiliar environment. ‘Visible love’ by engaging with the affective dimension of caring, including the connections between the patient and family, generated a sense of the person’s worth. ‘Reaching me, reaching you’ related to the interactional quality of encounters in which sharing and knowing assumed central importance. ‘My condition’ embraced the acute illness, existing health problems and the cognitive impairment. Quality practice meant achieving a ‘balance of care’ based on understanding the inter-relationship between these three. ‘Best’ practice in acute care required attention to the particular needs of people consequent on the cognitive impairment; strategies that promoted ‘settling in’, thereby enabling people to feel valued; and proactive communication that facilitated connections with the person’s biography and significant relationships in providing care.

Norman20 identified two further components pertinent to ‘good’ practice. First, patients were viewed not just as passive ‘recipients’ of care but as active agents, conveying a sense of ‘self’ in their actions and interactions. When staff viewed what patients did as meaningless or problematic, it resulted in a construction of patients as reduced and dependent. Conversely, seeing patients’ actions and interactions as meaningful drew forth a staff response that reinforced the person’s individuality and sense of self. Second, a distinction was drawn between two types of nursing work, ‘practical’ and ‘emotional’, similar to that in recent literature between ‘task-centred’ and ‘person-centred’. ‘Practical’ work was defined by minimal collaboration in which a provider/recipient relationship prevailed; ‘emotional’ work involved higher levels of collaboration, including prioritising patients’ needs. However, this binary conception of forms of work in the context of people with dementia on acute wards appears limited. Instead, employing the conception of Tolson et al. 54 of the ‘balance of care’, it would seem more useful to consider ‘practical’ and ‘emotional’ work not as polar opposites, but as infused, one with the other.

Nilsson et al. ’s32 ethnographic study on a cardiology unit offers negative evidence in support of Tolson’s ‘balance of care’ conception. The overarching category, ‘falling behind’, refers to the way in which patients’ needs associated with dementia went largely unnoticed until they escalated and emerged as problems that disrupted the usual flow or threatened safety issues in the unit. The response generated was reactive and not proactive, with negative consequences for patients, relatives and staff. Clissett et al. 24 employed Kitwood’s44 conception of the basic needs necessary to sustain personhood as an a priori framework to determine what was person-centred care, namely care that offered comfort, attachment, inclusion, occupation and identity. They concluded that although staff promoted attachment and inclusion, there was little evidence that they supported patients’ sense of identity, occupation and comfort; and that practice was poor in these areas. Their conclusions and interpretations do not flow unambiguously from the empirical data presented. First, the content of what was contained within these domains appeared somewhat arbitrary. Second, the way findings were presented (conveying accounts of how these needs were met followed by missed opportunities) meant that the weight given to positive aspects of practice, in relation to lost opportunities, is unclear from the illustrative data. Third, what shaped these positive and negative features of practice were not elucidated, as the focus was on the interpersonal level of staff–patient engagement. Fourth, there is an assumption that needs conceived of as necessary to secure well-being developed in a care homes context are equally relevant to acute care.

Another recent qualitative comparative study of care delivery to people with a cognitive impairment on a specialist medical and mental health unit and standard care wards within a randomised controlled trial33 provides further clarity on what person-centred practice might look like on acute wards. This involved a subsample of 60 (30 in each group) out of 90 trial participants observed using dementia care mapping and unstructured observation captured in fieldnotes. Many aspects of practice were similar across specialist and standard care wards: crowded, noisy physical environments; delivery of care in a routine and task-oriented fashion; communication that was usually brief or absent when meeting physical care needs; and the prioritisation of physical over emotional needs. Some features of person-centred care were observed, described as care that included personal communication during routine care tasks, validating patient concerns, facilitating independence and delivering care at a relaxed pace. The main difference between standard care and the specialist unit related to the work carried out within the activities room, with designated activities co-ordinators in the specialist dementia unit. The authors concluded that the profile of patients on both ward types was similar (high dependency resulting from acute illness, functional dependency, behavioural and psychological problems with increased cognitive impairment). Although the activities programme was very successful for some people, severity of illness and impairment meant that others could not participate. The trial,55 of which this qualitative study was a component, is the only published research to date that has examined the outcomes of care practice on specialist medical and mental health units compared with standard care. The findings reported increased satisfaction among caregivers on the specialist unit but no significant differences in organisational or clinical outcomes.

In summary, although person-centred care is presented as a marker of care quality in health research, there is no consensus on its meaning. Although the humanistic values underpinning person-centeredness offer a guide for practice, further work is needed to concretise what this person-centred practice might look like in an acute ward environment, and what methods and tools might be effective in improving practice.

Developing the observation tool

The Person, Interactions and Environment (PIE) observation tool was developed for use in the first national audit of dementia on NHS hospital wards25 during a 3-year research study (2008–10). The aim was to develop and feasibility test an easy-to-use tool to:

-

enable local observers (staff or volunteers) to view care from the perspective of the person with dementia

-

provide observers with a means (and vocabulary) to report on care quality based on the findings

-

enable the care provided to be compared with that of other hospitals nationally

-

produce data for use by ward staff to develop action plans to improve practice.

The study was overseen by a steering group for the National Audit of Dementia (NAD), comprising professional and ‘experiential’ dementia experts (including individuals with dementia, and caregivers).

Process of Person, Interactions and Environment tool development

The first phase involved iterative scoping reviews to examine the concept of person-centeredness, and the observation tools used to measure it in an acute setting that could potentially be adapted for the audit. The literature review identified several potential candidate tools. However, these were based on nursing models and not dementia specific;56,57 or they were dementia specific but not tailored for use in an acute setting;58–60 or the complexity, level of expertise required and cost involved in using the tool made it impractical. 59,60 It was agreed to develop a new observation tool for the audit.

A subsequent systematic search of the literature was undertaken to explore the dimensions of care valued by hospitalised older people generally and by those with dementia specifically. The findings from this review were discussed through a process of stakeholder consultation via focus groups with staff and patient representatives from different specialties in four hospitals, and a patient and public involvement group. The purpose was to inform the content and structure of the proposed tool and how it might be used in hospital.

The PIE tool has three dimensions: person, interactions and environment. These represent the elements of knowing and using information about the patient as a person in care delivery, the quality of staff–patient interaction, and the effect of the immediate organisational and physical environment. They reflect inter alia the personhood of the individual, including their subjective experience (incorporating biography, values, life preferences and significant relationships); the interactional or relational character of the social world in which the person is embedded and that shapes sense of self and identity; and the nature of the surrounding physical, social and care environment that provides the context in which care is delivered. Drawing on interactionist44 and social positioning45 theories of dementia, it was understood that the type and severity of the cognitive impairment both have an impact on the individual’s experience of the interpersonal, social and physical world, which in turn affects the person with the condition. This dynamic has implications for the care delivery of people living with dementia on acute wards.

The feasibility of the draft tool and guidance was tested in seven hospitals (18 wards) and through further consultation with the advisory group. Key criteria were that it should be acceptable to staff and feasible for use with minimal resources.

Following modifications and refinements, the PIE tool and guidance were presented in the form of a workbook manual and a one-day workshop to train hospital staff in its use. For audit purposes, PIE involved gaining informed consent to observe the care of up to six patients with dementia or problems in a ward area in real time. Observations were conducted by two staff (one external to the ward), who paired up to observe different patients for at least two periods of 2 hours (one in the morning and one over lunchtime). Following reflection and feedback with the ward team, each ward identified one aspect of good practice and one requiring improvement, with achievable short-term and longer-term actions to be undertaken at ward, directorate and trust/health board levels.

Use of Person, Interactions and Environment in the National Audit of Dementia

An enhanced audit component of the NAD was conducted in a subsample of 55 hospitals (145 wards), and included PIE. The findings from PIE observations, conveyed in the published report,25 were that care and communication were generally reactive and based on an organisationally set, task-driven routine rather than being person-focused, flexible and proactive. Although there were ‘pockets’ of positive, individualised care in the practice of individual staff, or as elements of ward practice, only a handful of wards (5/105) reported practices that were consistently focused on the person. There were periods of care-based activity interspersed with inactivity, leading to lack of attention and stimulation. The environment was often impersonal and dementia unfriendly, with a lack of orienting cues, dementia aids or areas for socialising.

Although the findings were not novel, the breadth of coverage underscored the nature and extent of the problem of care delivery to patients with dementia. Furthermore, a comparison between wards offered preliminary evidence of ‘propellers’ or features of staff–patient interaction that supported person-focused communication, suggesting scope to enhance care.

As the primary purpose of the audit was to document current practice, the process of translating action-planning at ward level to effect organisational change, and the systems and mechanisms required to support and sustain it, was not developed. Nor was there an attempt to examine whether action plans derived from observation affected staff practice, patients’ care experience or health outcomes. These conclusions prompted the current study: the development of PIE as a generalisable practice development process in conjunction with the PIE observation tool (PIE Programme), and an evaluation of its effectiveness in improving care for people with dementia on acute wards.

From the Person, Interactions and Environment observation tool to the Person, Interactions and Environment programme

The PIE Programme (referred to henceforth as PIE), tools, guidance, implementation process, manual and ‘theory of change’ were elaborated on as part of this current study.

This further development involved an iterative review of the literature on implementing change, a workshop with staff across the Yorkshire and the Humber region who had used PIE in the NAD, and participation in workshops with NHS hospital staff (RW, JC and MG). These workshops were conducted as part of a Quality Mark for Elder-Friendly Hospital Wards, launched by the Royal College of Psychiatrists in partnership with the Royal College of Physicians, the British Geriatrics Society, the RCN and Age UK. Within these fora, we tested out the further acceptability and use of PIE as a strategy and process to support cultural and practice change on acute wards to meet the needs of patients with dementia.

The Person, Interactions and Environment intervention and implementation process

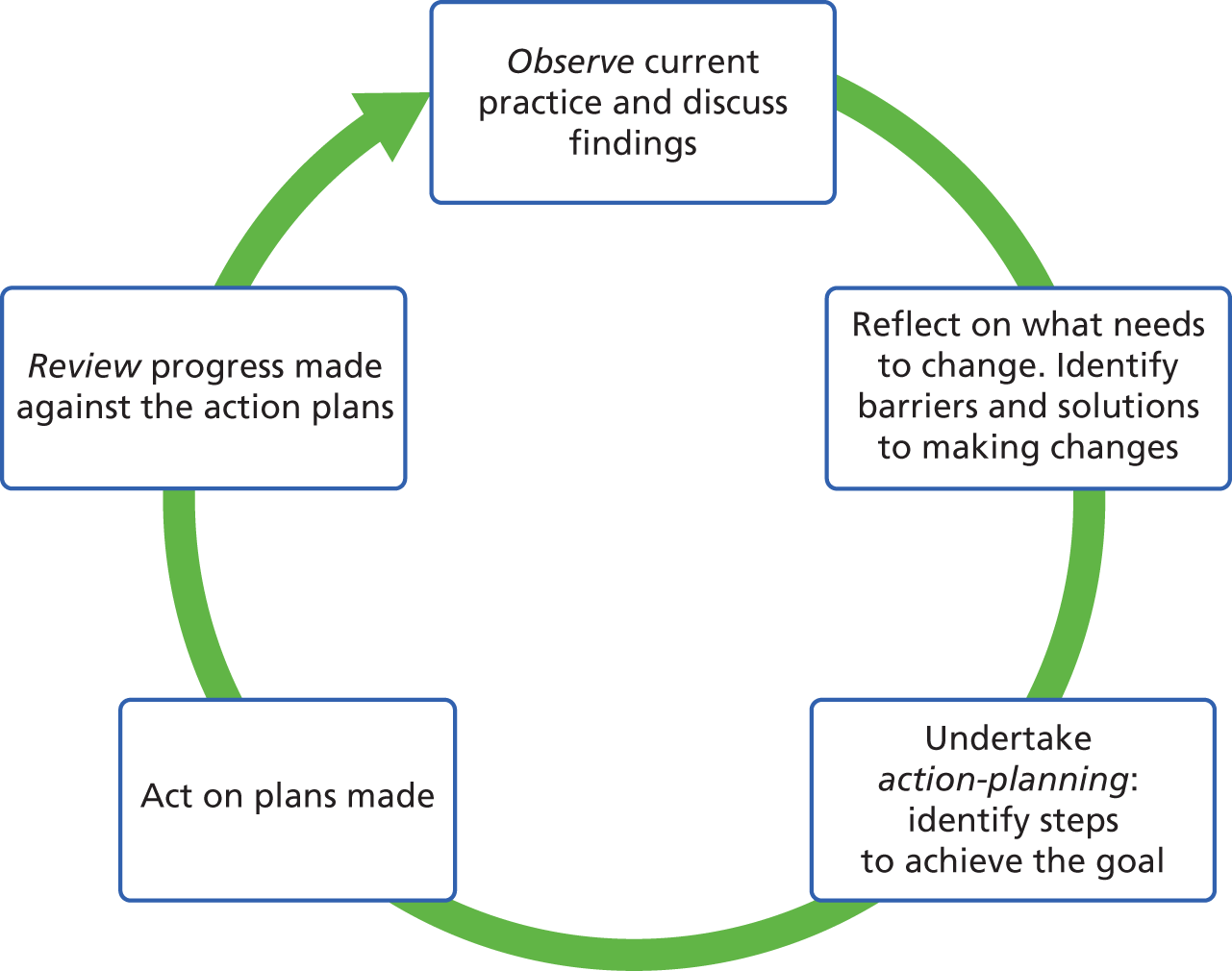

PIE adopts a systematic approach, using a set of steps to implement and embed change in routine care on hospital wards, each step being supported by tools and guidance. Implementation is a cyclical process comprising observation of current practice (observation tool and guidance). Observation is a means to, first, document care as delivered and, second, consider the impact of the care on patients with dementia to promote fresh insights and potentially challenge existing practice. Reflection on observations is the basis for identifying goals and action plans to improve practice (action-planning tool and guidance). Goals for change are prioritised and action plans are formulated. Action plans specify steps to move from current practice towards achieving goals; how these will be taken forward and by whom; and how they will be communicated to the wider staff group to extend the programmes’ reach and engage them in action. A review of progress against planned action, including an appraisal of barriers to and facilitators of change (review tool and guidance), enables an adjustment of action and/or a review of goals. The process is illustrated in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PIE service improvement process.

Implementation team

An additional mechanism to effect change is the establishment of an implementation team to lead it. Its core membership comprises a ward manager or senior nurse with the authority and legitimacy to drive the programme; a matron or practice development lead outside the ward to provide organisational and facilitative support, and act as a conduit between ward-based initiatives and dementia strategies at the departmental and hospital levels; and ward staff involved in directly providing care to patients, such as nurses, therapists and health-care assistants (HCAs). Within these parameters, the size and make-up of the team is flexible.

This conception synthesises a top-down and bottom-up approach to change:61 the active involvement of senior staff to secure organisational commitment to introducing and embedding the programme; and the engagement of those directly in delivering it, to ensure that their views and experiences inform the pace and direction of change. 62–64 The responsibilities of the team include:

-

raising awareness of PIE among the whole staff group

-

organising observations, action-planning and review of progress

-

engaging ward staff in change through discussion of priorities and action plans

-

reviewing what systems and mechanisms need to be put in place to support sustainability.

Strategies to support implementation

Several strategies are in place to support implementation: a PIE manual, and an interactive training workshop to introduce participants to PIE.

Person, Interactions and Environment manual

The manual is organised as a workbook and comprises three sections. Section 1 describes the PIE purpose and rationale, specifically why people with acute illness living with dementia require a tailored and dementia-sensitive approach to meet their care needs and facilitate recovery. Section 2 provides an overview of the cyclical process of change involving observation, reflection, action-planning, action and review. Section 3 details each step in the implementation process (observation, action-planning and review), the tools for each step, guidance on using the tools and a flow chart to indicate what should happen and when. Worked-out exemplars of observations, action plans and reviews are provided.

Person, Interactions and Environment introductory workshop

PIE is introduced in a one-day workshop to familiarise participants with the programme. The first part of the workshop conveys, through various media (role play, drama, video clips), how the social and spatial environment of an acute ward may be perceived by persons with a cognitive impairment. This is aimed at sensitising staff to how people with dementia may experience the world around them. Observation of encounters between professionals and people with dementia are presented via drama and video clips, for example the ‘Come feel with me’ DVD (digital versatile disc). 65 The purpose is to elicit critical refection on how people with dementia may express agency through embodied action, thereby directing attention on ‘knowing the person’ to interpret behaviour and action. The second part of the workshop takes participants through each step in the observation, action-planning, action and review cycle, preparatory to introducing PIE on their ward.

Theory of change

In designing the PIE implementation process, we drew on normalisation process theory (NPT)66 as a sensitising framework. From the range of theories available on implementation,67,68 our use of NPT stems from its sociological focus and the utility of the broad constructs that constitute it. In contrast to psychological theories of change that address individual behaviour, NPT focuses on microsocial processes that affect the implementation of a practice (or technique) in an organisation or clinical setting to account for how individuals and organisations understand and make sense of the new practice, engage with it, participate in the work relating to it, and reflect or appraise its effects in relation to valued goals. NPT appeared most apt for PIE implementation. PIE is a whole-ward intervention; it does not simply involve change in individual behaviour, but also requires organisational, cultural and team-level change. Furthermore, the PIE intervention uses and alters roles and patterns of communication among staff and between staff and patients. Changed meanings, practices, roles and relationships are intended to become part of ‘the way we do things here’ (ward culture).

Within NPT, ‘normalisation’ refers to the work of individuals as they engage in activities that become routinely embedded in knowledge and practice. NPT postulates four generative mechanisms that operate individually and collectively to explicate how practices become ‘normalised’ within routine care: coherence, cognitive participation, collective action and reflexive monitoring. New practices, the theory contends, become routinised when:

-

the work that defines and organises a practice or intervention is understood as meaningful and invested in, in respect of the knowledge, skills, behaviours and actions required to implement it at an individual and collective level (coherence)

-

the work is perceived as worthwhile and appropriate for the commitment of individual time and effort in order to bring about the intended outcome (cognitive participation)

-

work practices, and the division of labour through which these are carried out, are modified or adapted to incorporate the change or intervention into the social system of the host organisation (collective action)

-

those engaged appraise the effects as attributable to the intervention and congruent with valued goals (reflexive monitoring).

In PIE, the work of generating coherence begins with the introductory workshop, with its content and participatory nature focused on a range of ways for participants to ‘see the world’ from the perspective of the person with dementia. This continues with the first step in the improvement cycle, namely staff’s real-time observation of patients with dementia. Taking a ‘step back’ from work roles to observe ‘persons, practice and context’ for a short time, as an ‘outsider’ looking in, will, it is assumed, help staff to ‘see’ things in a different way (coherence). This is the prerequisite to reflect on, and examine, what may have been taken-for-granted assumptions, activities and practices. In contrast to the use of the PIE observation tool in the NAD, the number of observations, by whom and when, are flexible, to facilitate local buy-in. Collective discussion of observations within the PIE team further reinforces coherence, and by establishing the need for, and possibility of, change, will secure cognitive participation. These reflections form the starting point for identifying goals for change and the necessary steps or action plans to achieve the goals. Action-planning, including who does what and how it will be communicated and discussed within the wider team, is intended to pursue the work of collective action. A review of progress and reappraisal of goals and actions in the light of what works will, it is assumed, act as leverage to continue the process (reflexive monitoring).

The PIE implementation process is systematic and tools are provided for each step (observation, action plans and reviews). However, the content – how observations are conducted (the number conducted, and for how long, by whom and when they are conducted), the goals identified and the action plans pursued – is flexible and tailored to individual wards. Implementation is conceived of as a process and not a one-off event. 69 A significant dimension of PIE implementation is temporality. Change through successive observation, action-planning, action and review cycles mean that the process is likely to be non-linear and multidirectional,70,71 the success (or failure) of action plans creating the conditions for subsequent review and new/reworked action plans. The commitment and skill of those leading the change and in working through each phase of the improvement cycle will affect implementation and outcomes, so that there is a degree of unpredictability of the process (and the outcomes).

PIE is an exemplar of a complex intervention. 72 It contains multiple interacting components; the levels at which change is directed are several (individual, collective and organisational); and there is flexibility in delivering it. The change process is emergent and non-standardised. 73 The ward setting within which the intervention is being introduced, and with which it interacts, is also dynamic, adding another level of complexity. 74

The research study

The overall research purpose was to examine whether or not PIE enhanced the care of older people on acute wards living with dementia, how this was achieved, and whether or not, and in what ways, this had an impact on ward practice, patient and caregiver experiences and selected clinical outcomes.

The objectives of the process and outcomes evaluation of PIE were to:

-

provide a descriptive and explanatory account of how staff engaged with PIE in the real-life context of acute ward delivery

-

test out and refine the causal assumptions underpinning PIE (the theory of change)

-

explore the impact of PIE on practice, patient and caregiver experiences and clinical outcomes.

The research questions posed address the PIE process and outcomes at several levels. The specific questions were as follows.

Process of change

-

How is delivery of PIE achieved, and what is actually delivered?

-

How does PIE produce change, or, conversely, if the intended changes do not occur, is this because of poor/inadequate theory or poor implementation?

-

How and in what ways is PIE implementation (and outcomes) affected by the organisational and resource context of acute care delivery?

Outcomes

-

Does PIE change ward staff practice in ways that are consistent with person-focused care?

-

Is PIE effective in improving care for people with a coincidental dementia on acute wards, as experienced by those patients and/or observed by their relatives/caregivers?

-

Is there preliminary evidence of effectiveness of PIE in improving selected clinical outcomes (days in delirium and falls rate)?

Chapter 2 Evaluating Person, Interactions and Environment: methodology and methods

Introduction

This chapter elucidates the methodology and methods employed in performing a process and outcomes evaluation of PIE. It includes the rationale for the design, sampling strategy, data collection methods and analysis; the ethical issues posed; and how public and patient participation was pursued.

Methodology

We performed a comparative, longitudinal, mixed-methods case study. Case-based research75–79 is characterised by the depth and detail of information collected within naturally occurring, bounded settings, in which the boundary between the setting and focus of interest is permeable. 78 In this study, the analytic lens was care delivery to older people with dementia hospitalised on NHS acute wards. This is one facet of ward work, which is also affected by contextual factors outside the ward.

The distinctiveness of the approach is its systemic and holistic perspective. Ragin and Becker75 argue that:

The . . . case oriented approach places cases, not variables centre stage. But what is a case? Comparative social science [answers this question] . . . Boundaries around places and time periods define cases.

Ragin and Becker, p. 575

Embedded in this conception is that cases are complex systems in which:

[T]rajectories and transformations depend on all of the whole, the parts, the interactions among parts and whole, and the interactions of any system with other complex systems among which it is nested and with which it intersects.

Ragin and Becker, p. 275

The rationale for adopting a case study design flowed from the nature of PIE and the setting in which change was introduced. PIE exhibits several features of complex interventions:72 the number and difficulty of behaviours and practices required to implement and deliver it; the levels at which change is required (individual, collective and organisational); the degree of flexibility permitted in delivering it; and the dynamic environment in which it is being implemented. The setting for initiating and implementing PIE is the acute ward; the evaluation of effectiveness requires an understanding of ‘how’ and ‘why’ change occurs within this organisational context. The comparative focus enables the exploration of commonalities and differences between cases to develop an explanatory account that extends beyond the specificity of each case.

We sought to provide a rich description of care delivery to patients with dementia in the spatial, temporal and organisational setting of the hospital ward; to understand how, and the conditions in which, PIE effects change over 18 months; and, conversely, why change occurs in some circumstances and not in others. An embedded process evaluation examined how PIE was understood and enacted by staff in real time.

Methods

Sampling strategy

Our intention was to recruit eight wards in four acute NHS trusts. Cases were sampled purposively. Wards with a substantial proportion of older people with dementia among their patient intake were identified in trusts (care of older people wards, dementia wards and trauma orthopaedic wards), varying in size and type of catchment locality in three English regions. We employed criteria of ‘readiness’ to implement PIE,80 informed by previous research on delirium prevention:81

-

interest expressed among senior acute hospital staff in taking part in research to improve person-centred care for people with dementia

-

agreement of senior ward staff to engage in a practice improvement programme over 18 months

-

commitment from a clinical lead at directorate level or an individual with responsibility for practice development to assume a leadership role in initiating and facilitating PIE.

Site recruitment

Using networks developed through the NAD, letters of invitation were sent to named individuals (directorate leads, practice development leads and ward managers) in 13 NHS hospital trusts in different English regions, and followed up with telephone conversations. Those indicating interest in taking part were sent an ‘expression of interest’ pro forma, which encapsulated the ‘readiness’ criteria. This was a signed commitment by a ward manager, directorate matron and practice development lead to take part and to assume responsibility for initiating and facilitating PIE.

Meetings with staff at ward and directorate level were organised in each of five acute trusts that expressed interest. These offered diversity in their size (small, medium or large), type of catchment locality (small towns with rural hinterland, large city, metropolitan area, and a geographically dispersed locality of large towns and villages) and geographical location (north, central and south English regions). They spanned 11 wards: three medical, care of older people wards; two dementia wards; four acute trauma wards; one acute stroke ward; and one older people’s rehabilitation ward. All trusts and wards agreed to participate in the research, returning their signed forms. Based on initial meetings with directorate and ward staff during recruitment, wards varied in their degree of ‘dementia awareness’ (reinforced in data collection).

We agreed to oversample and include these trusts and linked wards; prior experience of research in acute hospitals suggested that organisational turbulence was common (e.g. changes to ward models, ward reorganisation and bed closures). This proved prescient. Before fieldwork began, one of the sites (an orthopaedic trauma ward) dropped out because of staffing difficulties. Appendix 2 provides a summary of the structure of participating sites.

Data collection methods

A common set of data was collected for each ward over a 7- to 8-week period at baseline, and at 9 and 18 months following PIE implementation for those wards that pursued PIE.

We collected qualitative data via interviews with staff to examine their views on care delivery and the meaning of person-centred care; explored how routine care was accomplished in time and space using ethnographic observations and informant interviews with staff; conducted in-depth case studies with patients and their relatives or caregivers to understand how people with dementia experienced care through observation of patients over their acute episode and conversations ‘in the moment’ with them, and interviews and conversations with relatives/caregivers; and built up a picture of how their journey into and through the ward unfolded in time, via case notes and observations of handover and multidisciplinary team (MDT) meetings.

Quantitative data relating to ward structure (trust policy, resources and priorities) and physical environment; organisation (staff and patient profiles) and care culture (staff questionnaire), which shape care delivery and patient experience, were collected. Outcome data to examine the impact of PIE were collected at baseline and at 9 and 18 months for selected clinical outcomes (days in delirium and falls), although the systematic collection of these data across all implementation sites proved problematic (see below).

Ward structure and organisation

Physical environment

A description of the physical environment of each ward was constructed from observation.

Patient profile

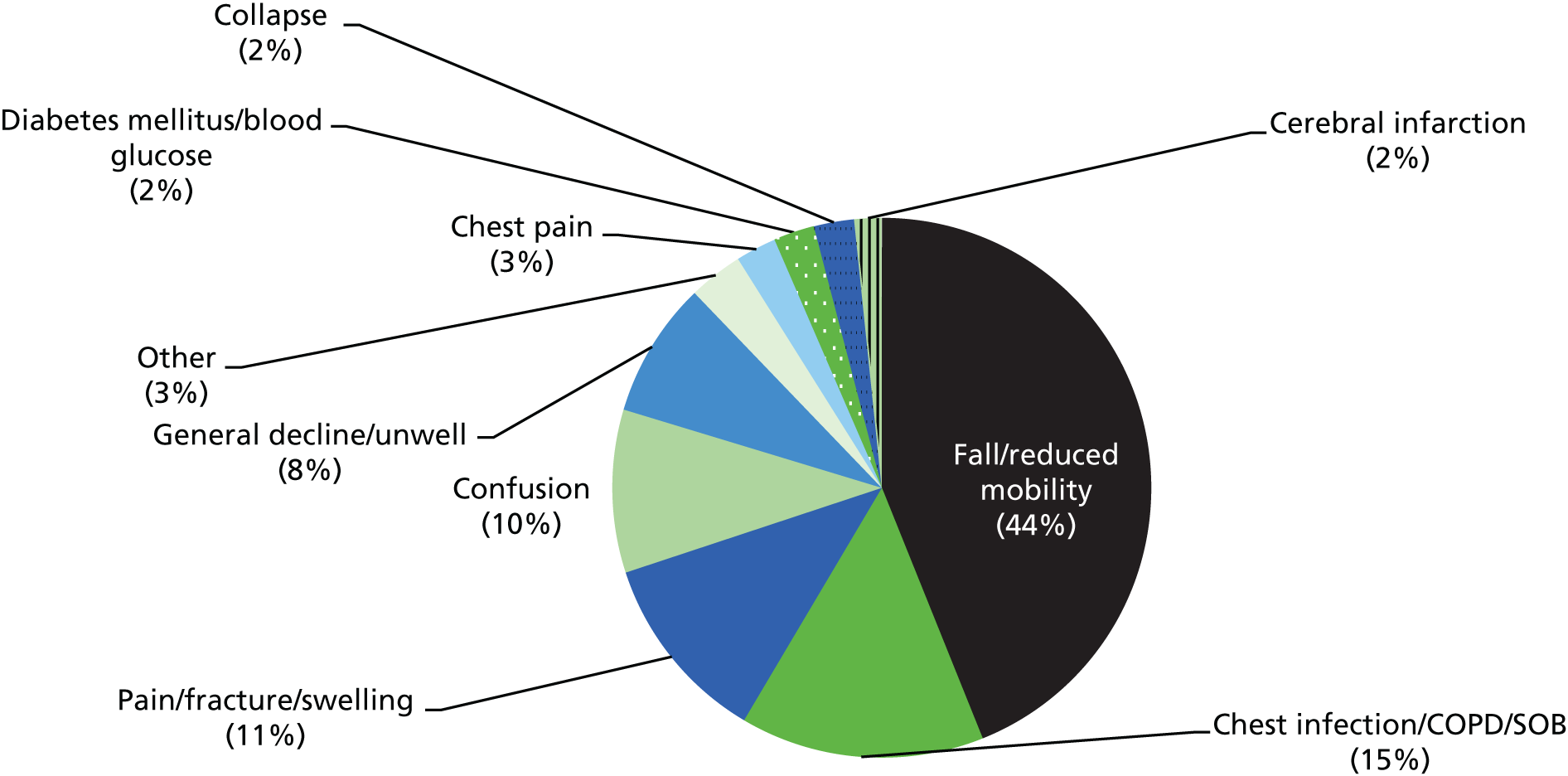

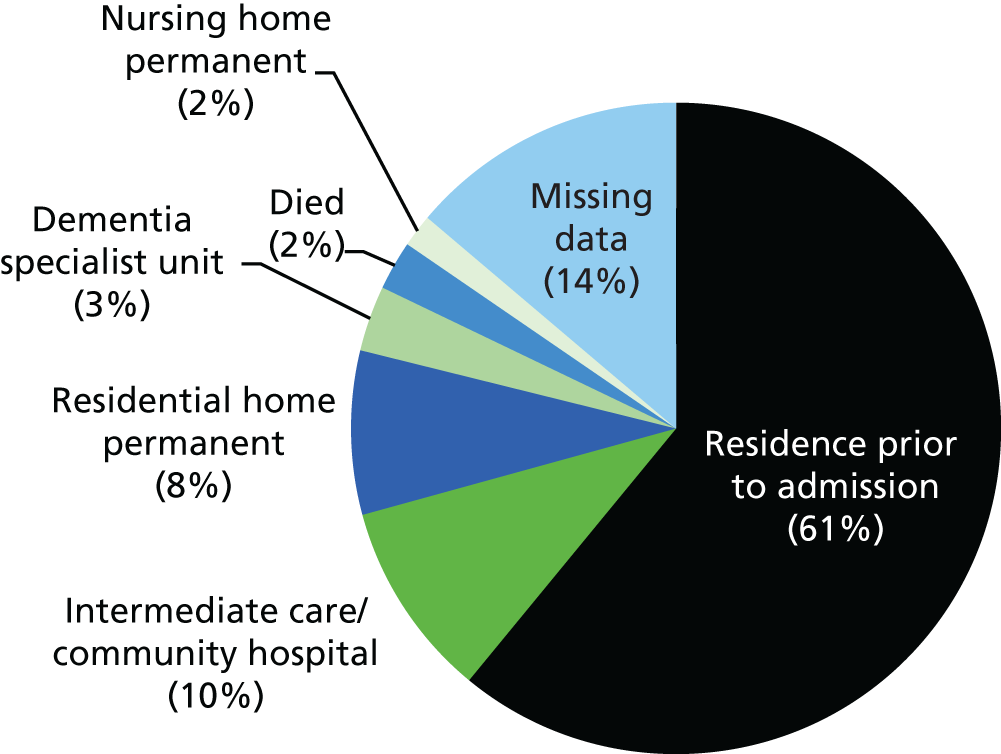

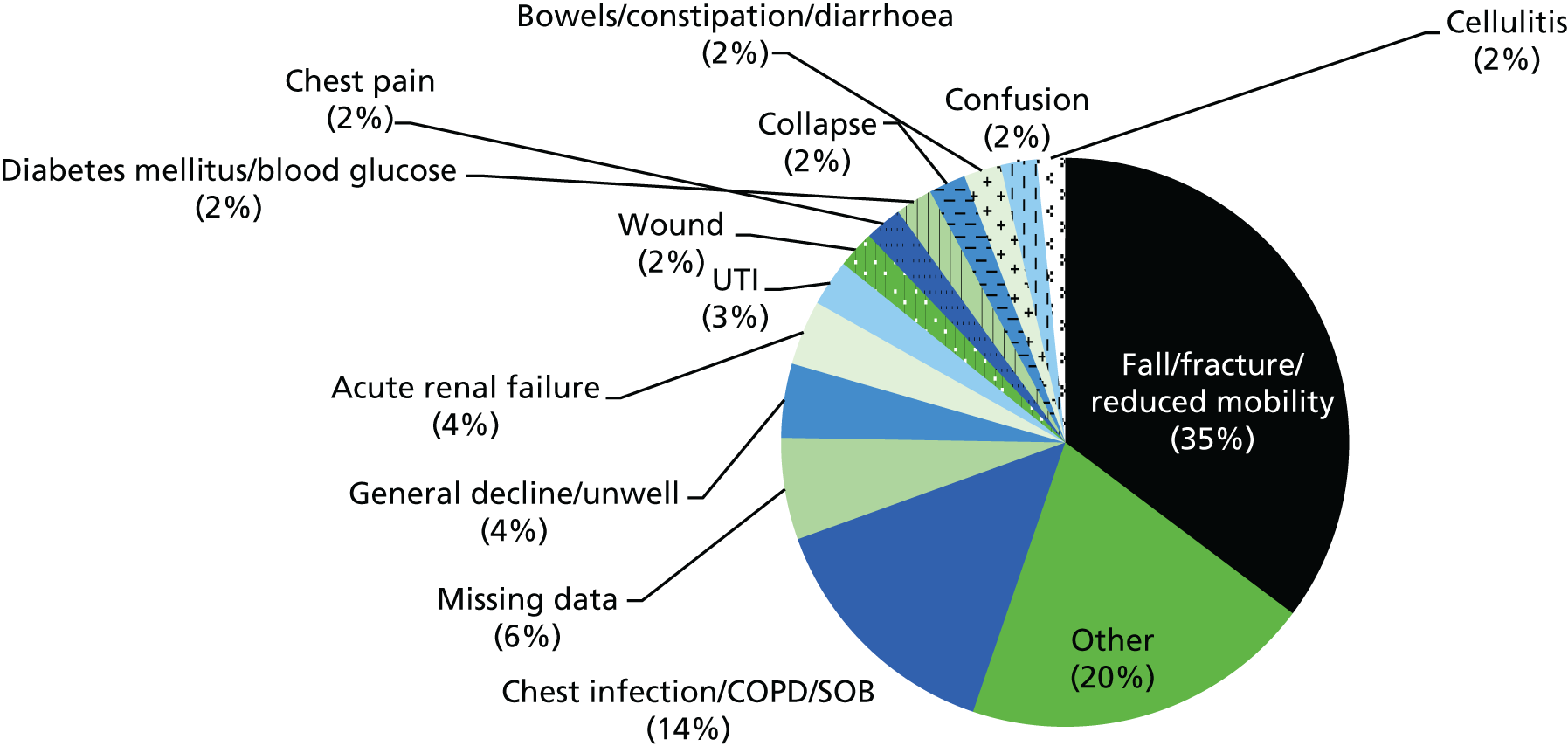

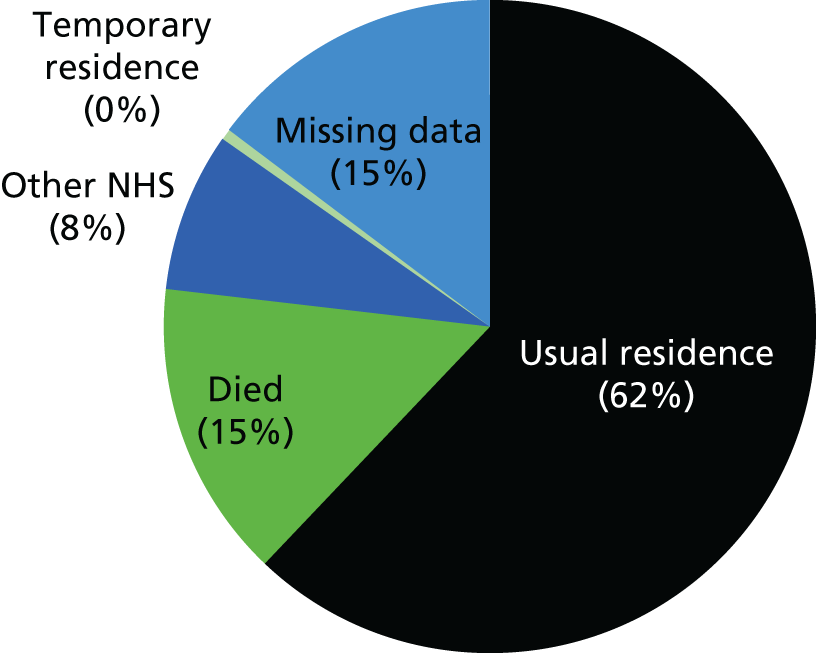

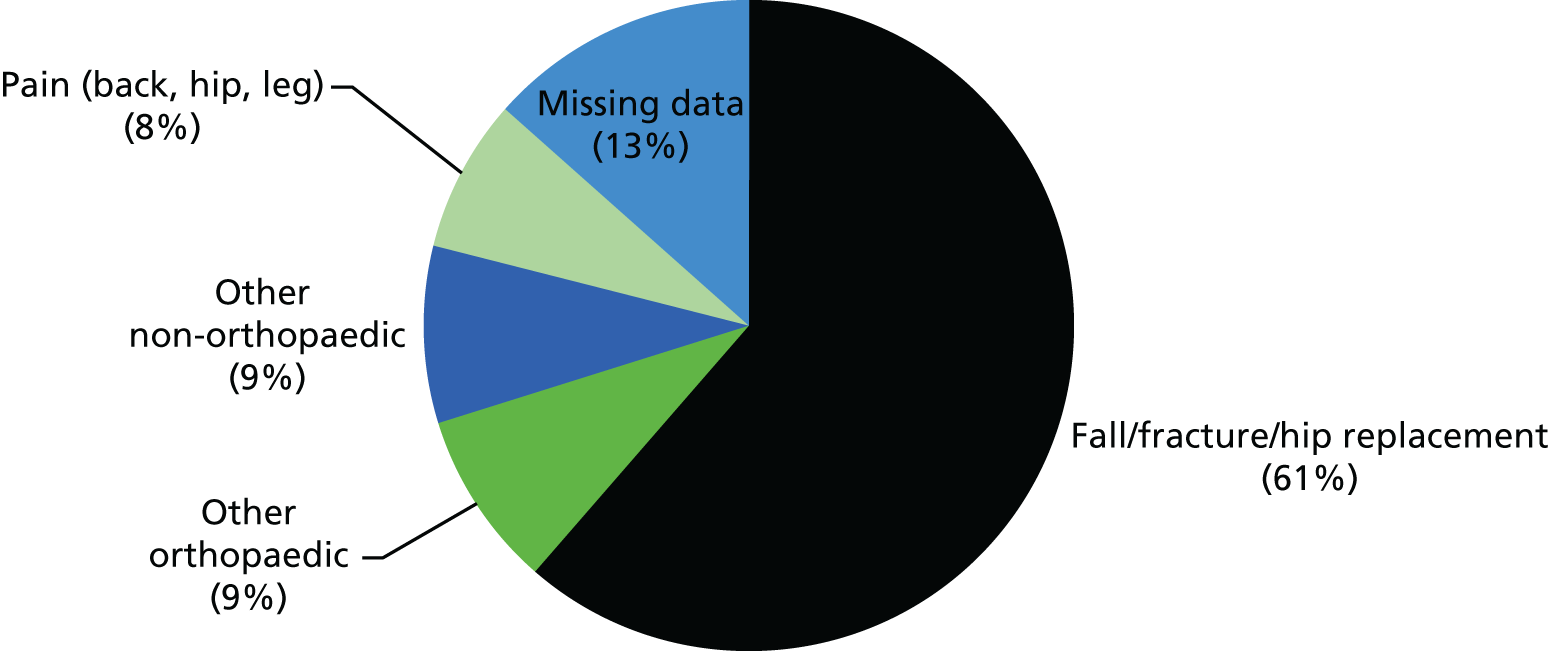

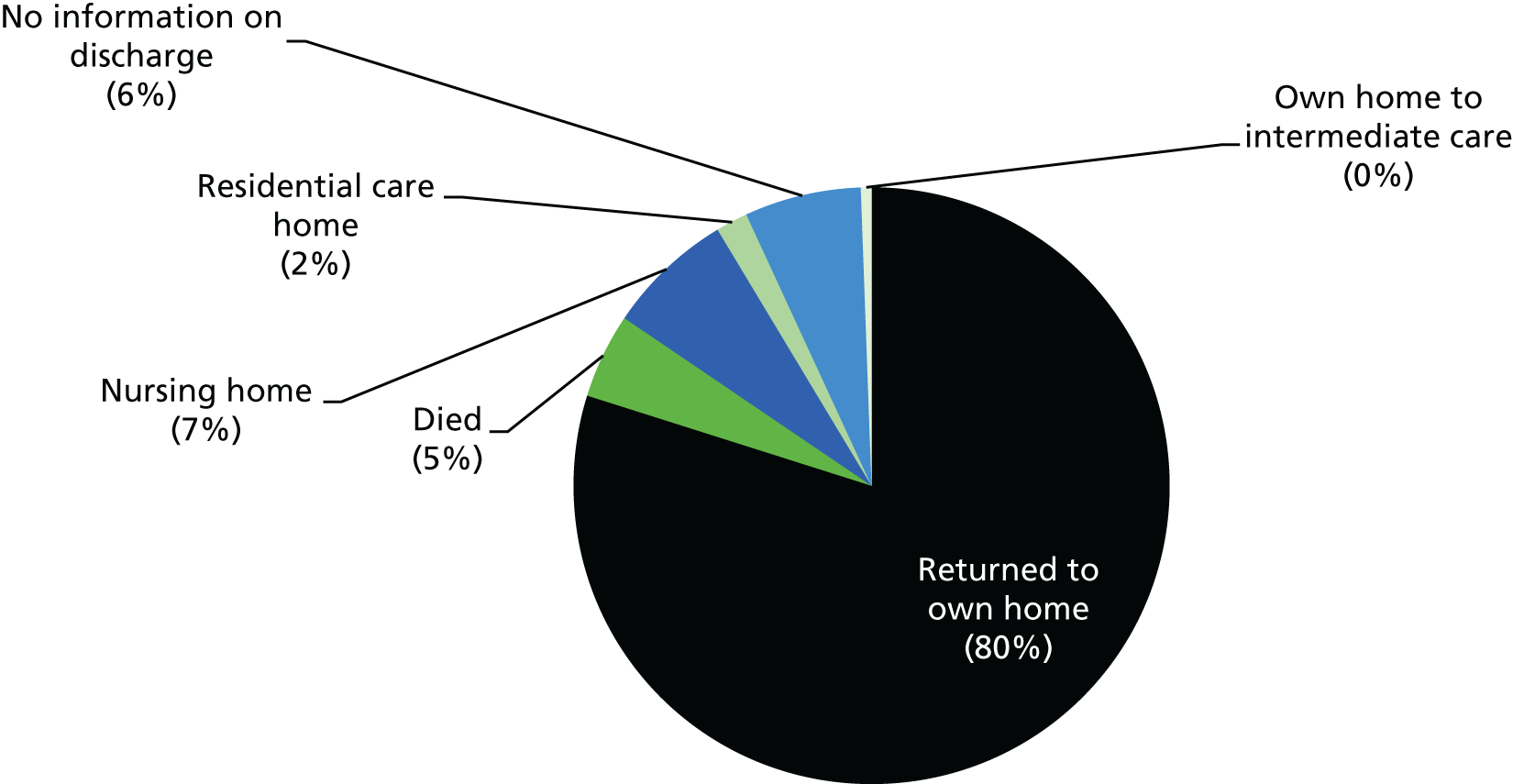

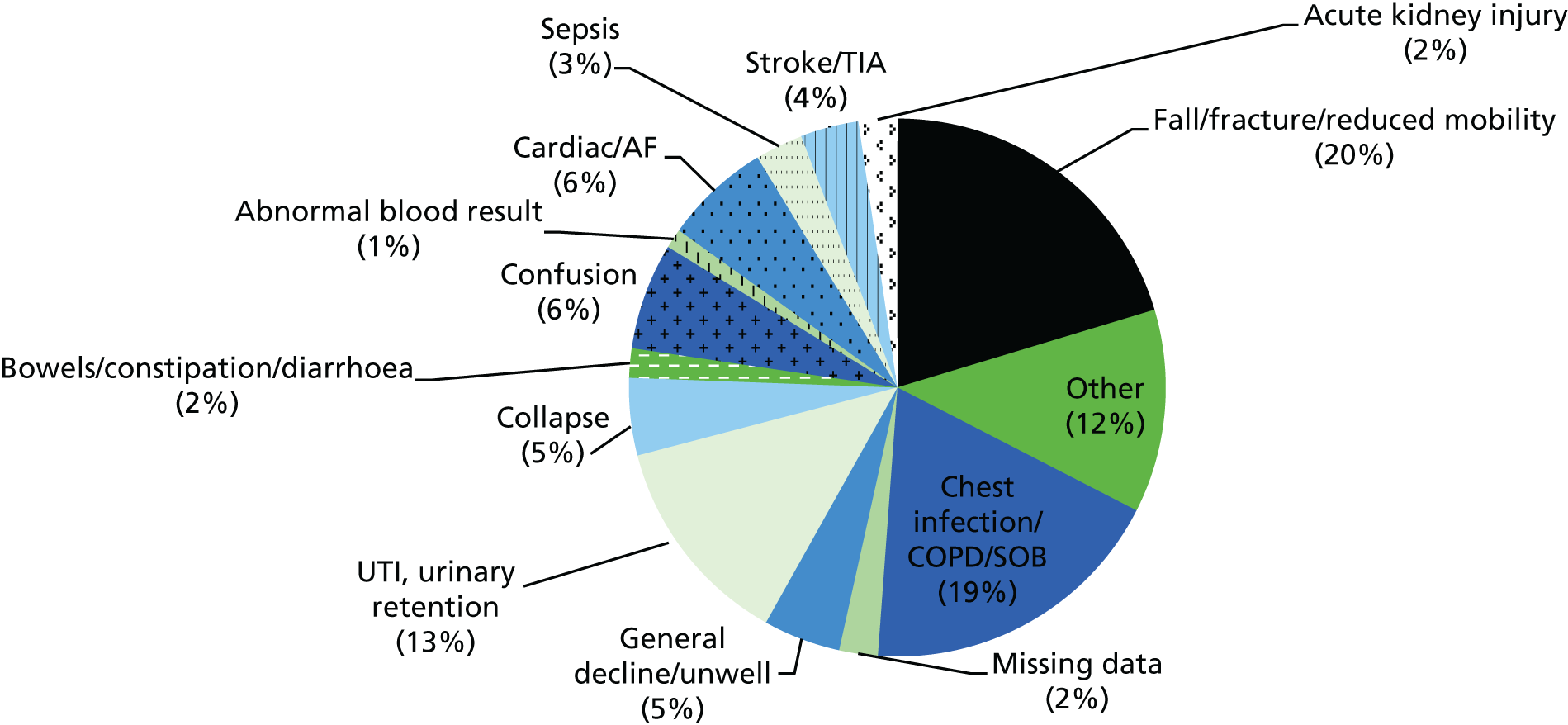

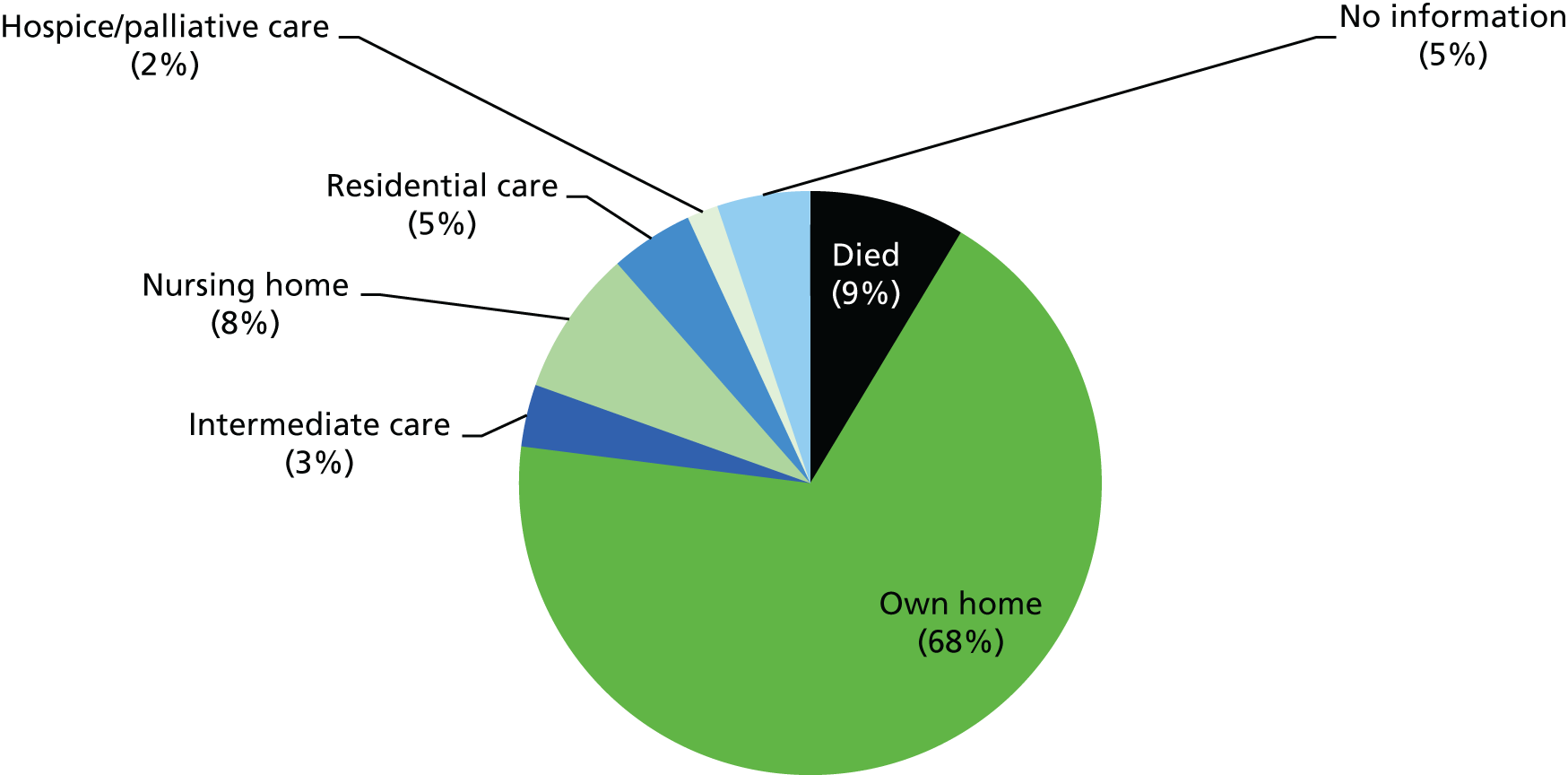

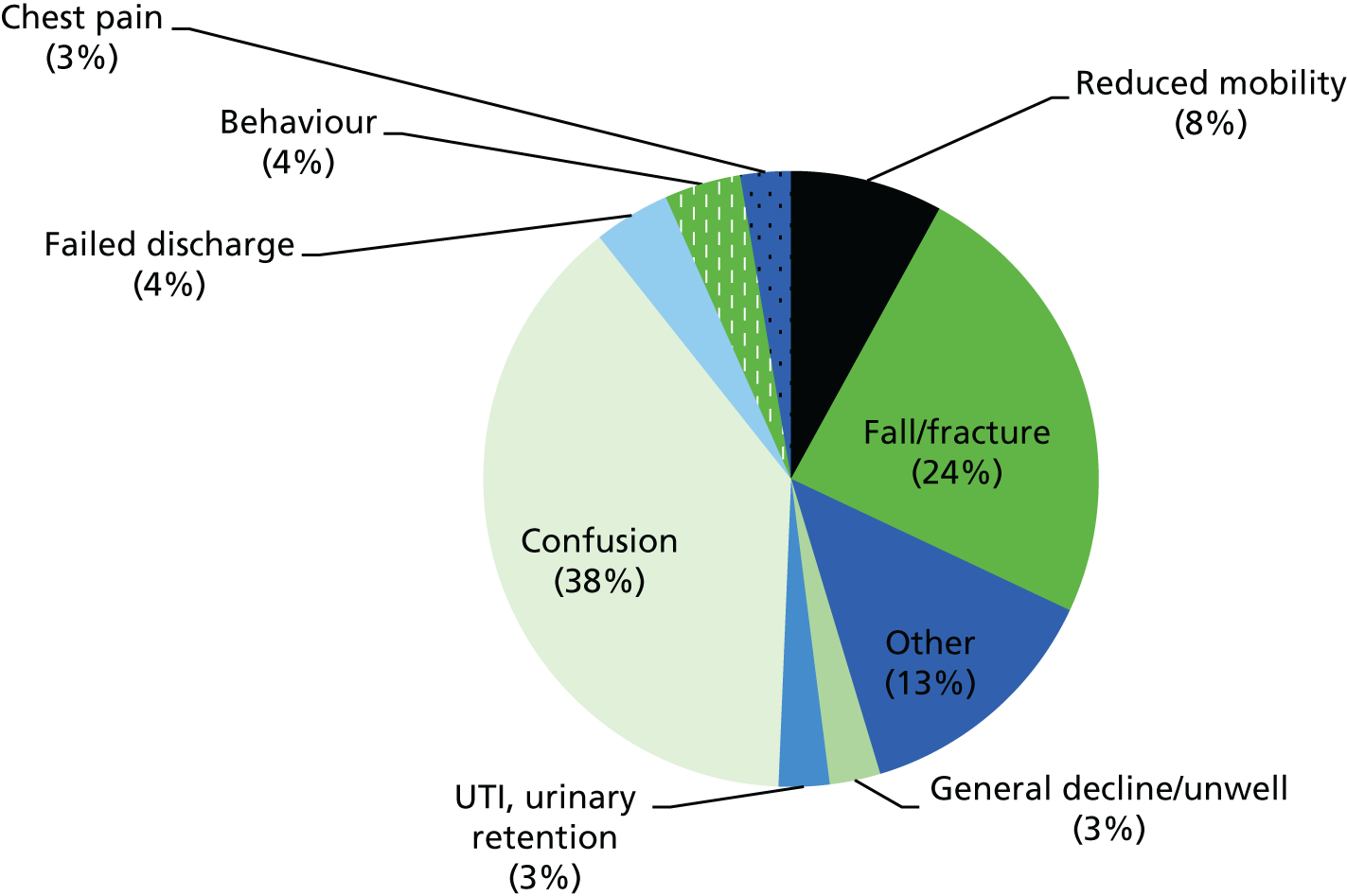

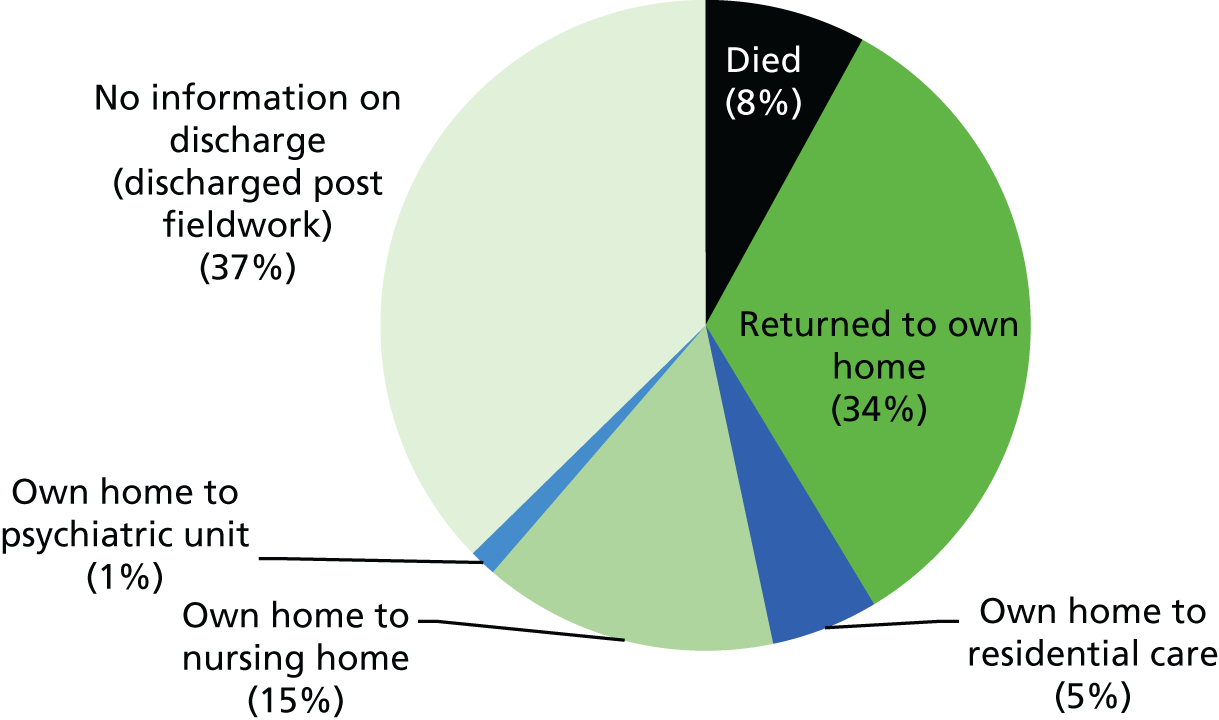

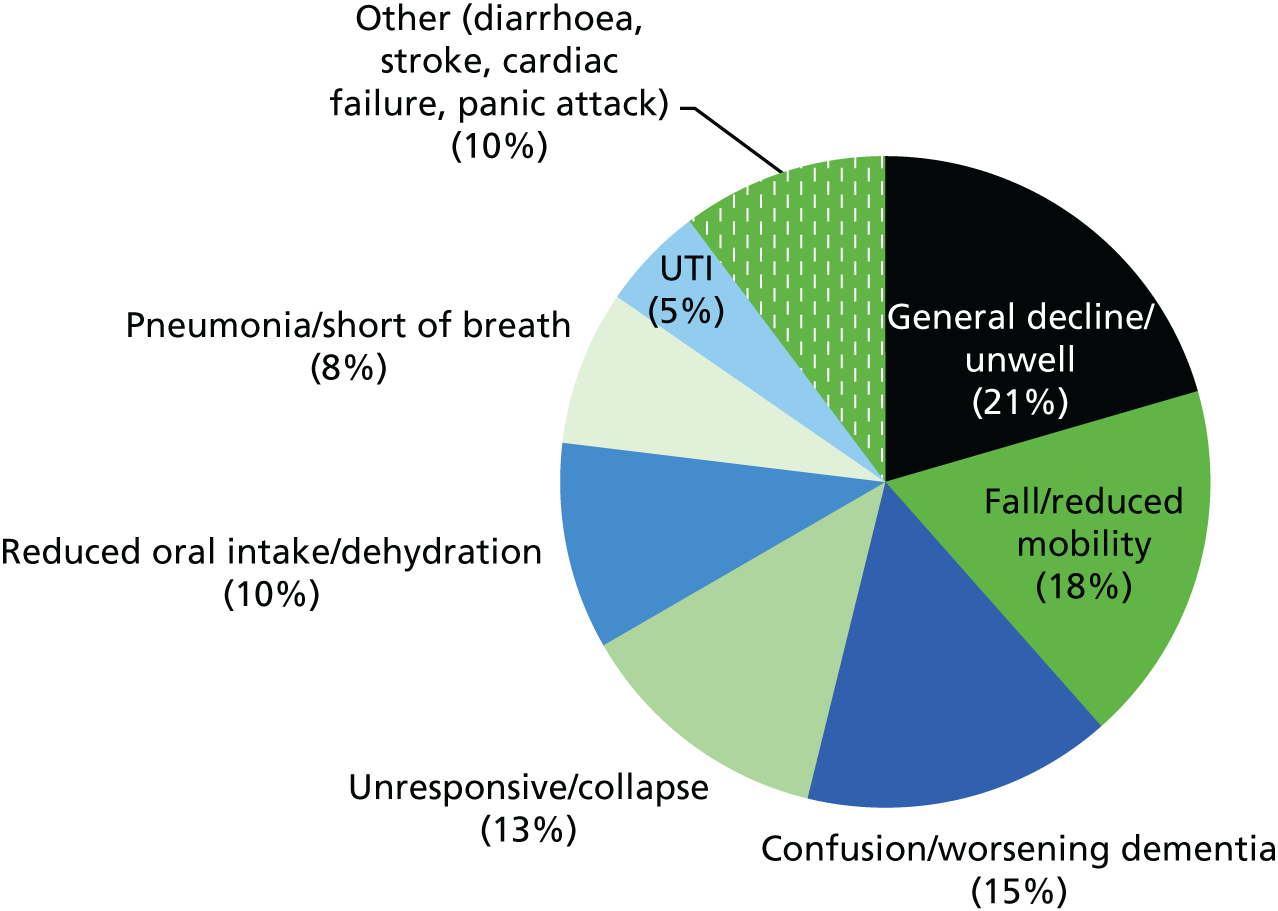

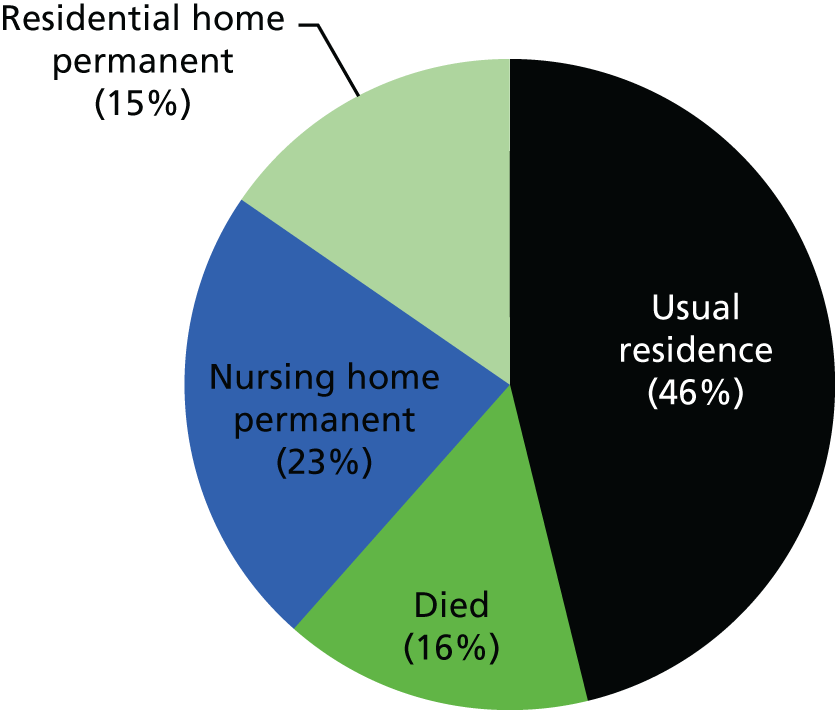

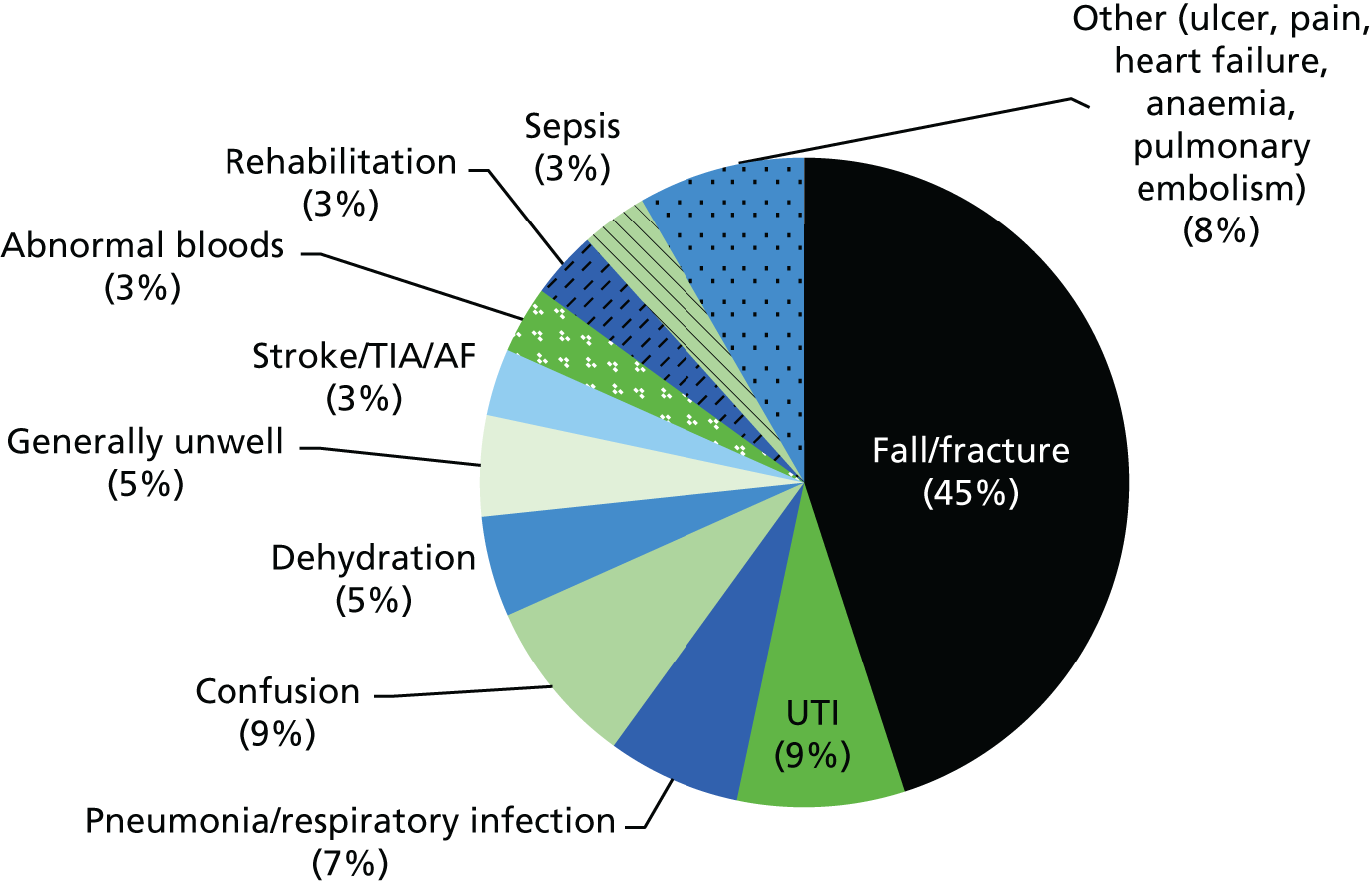

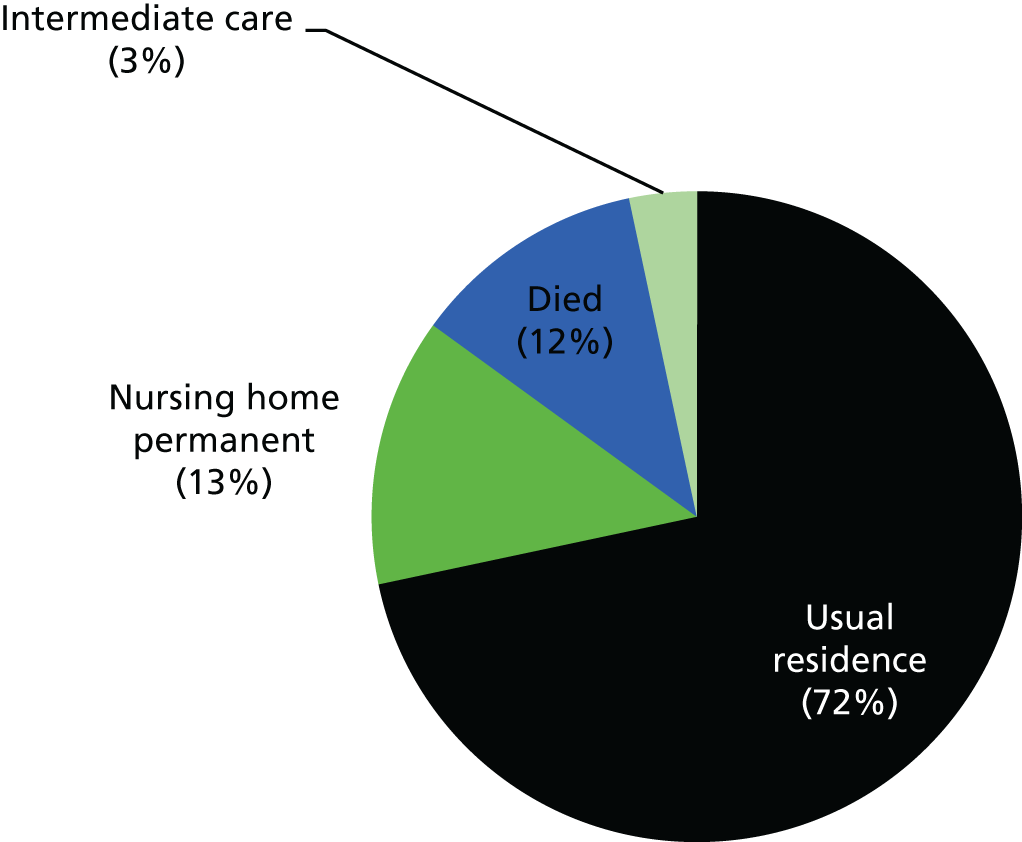

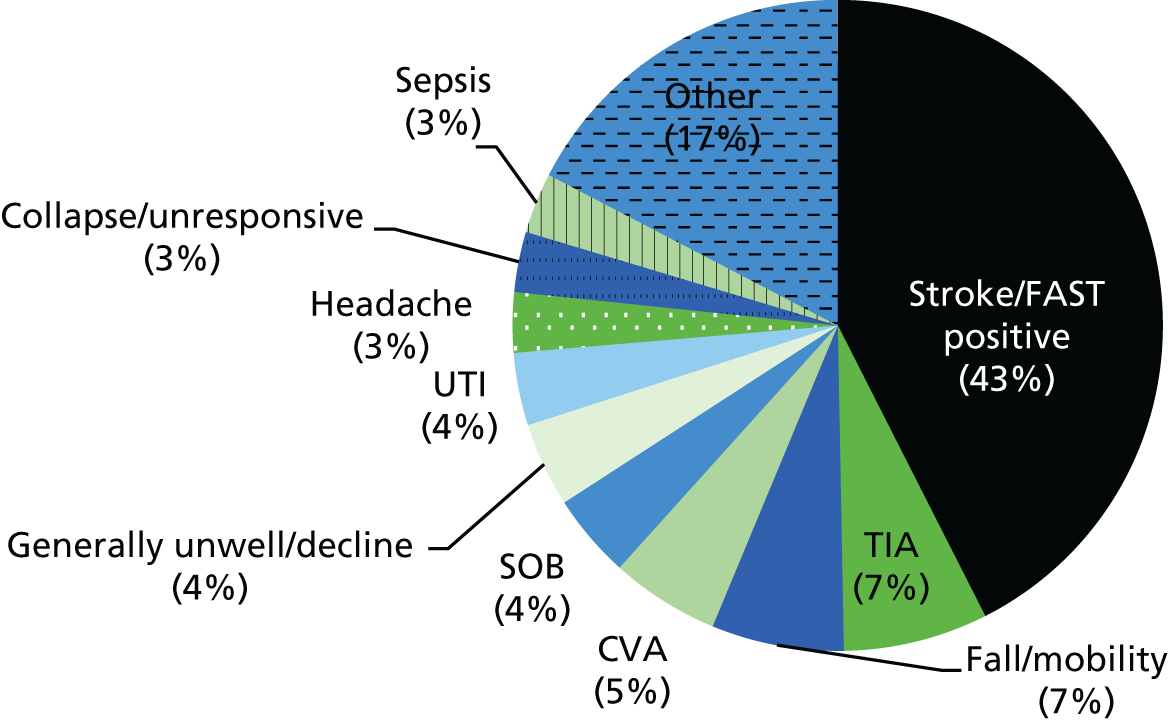

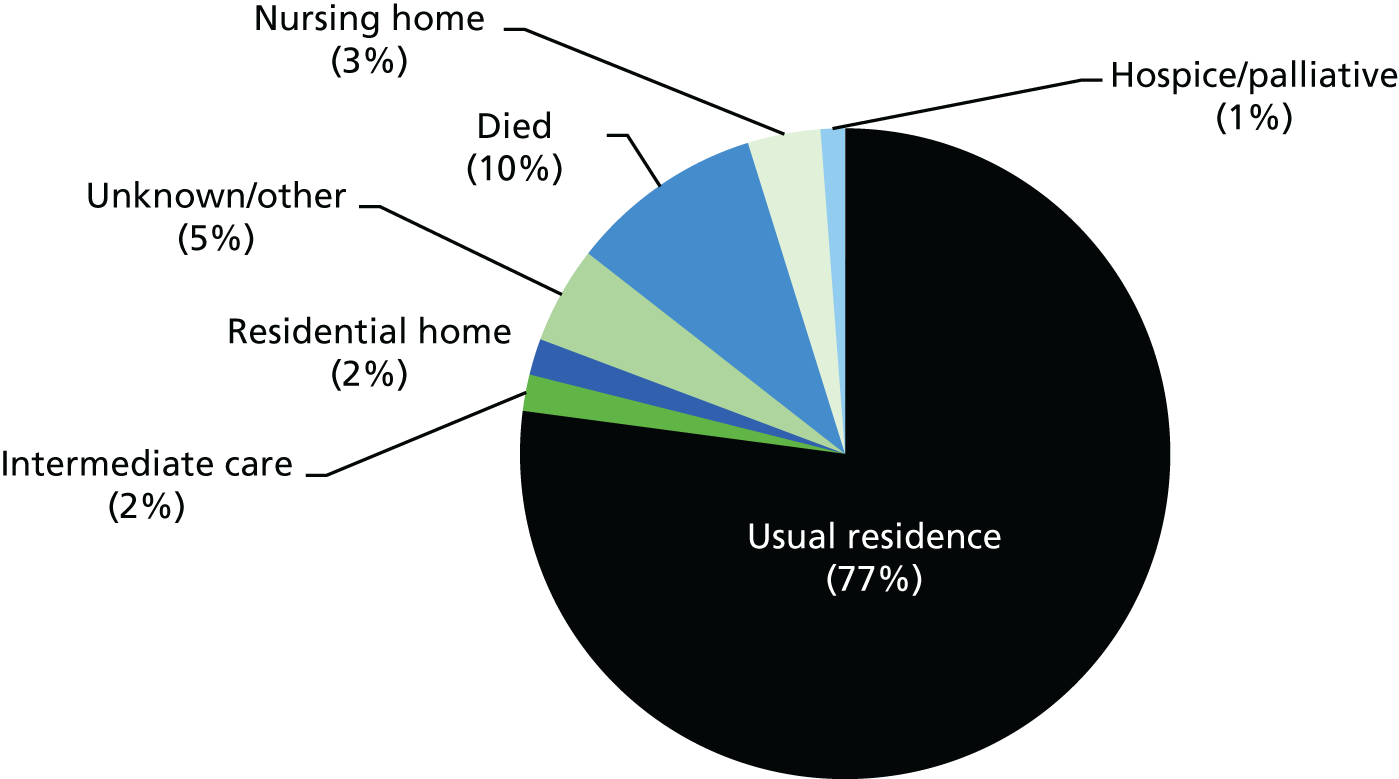

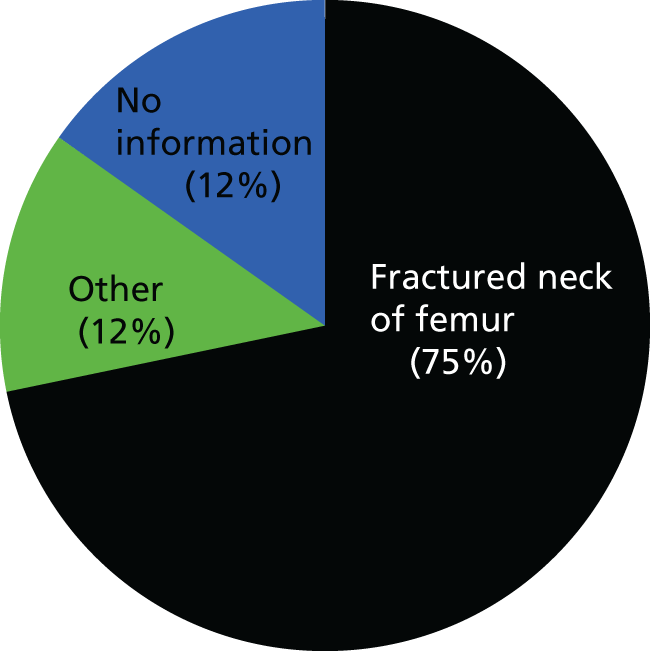

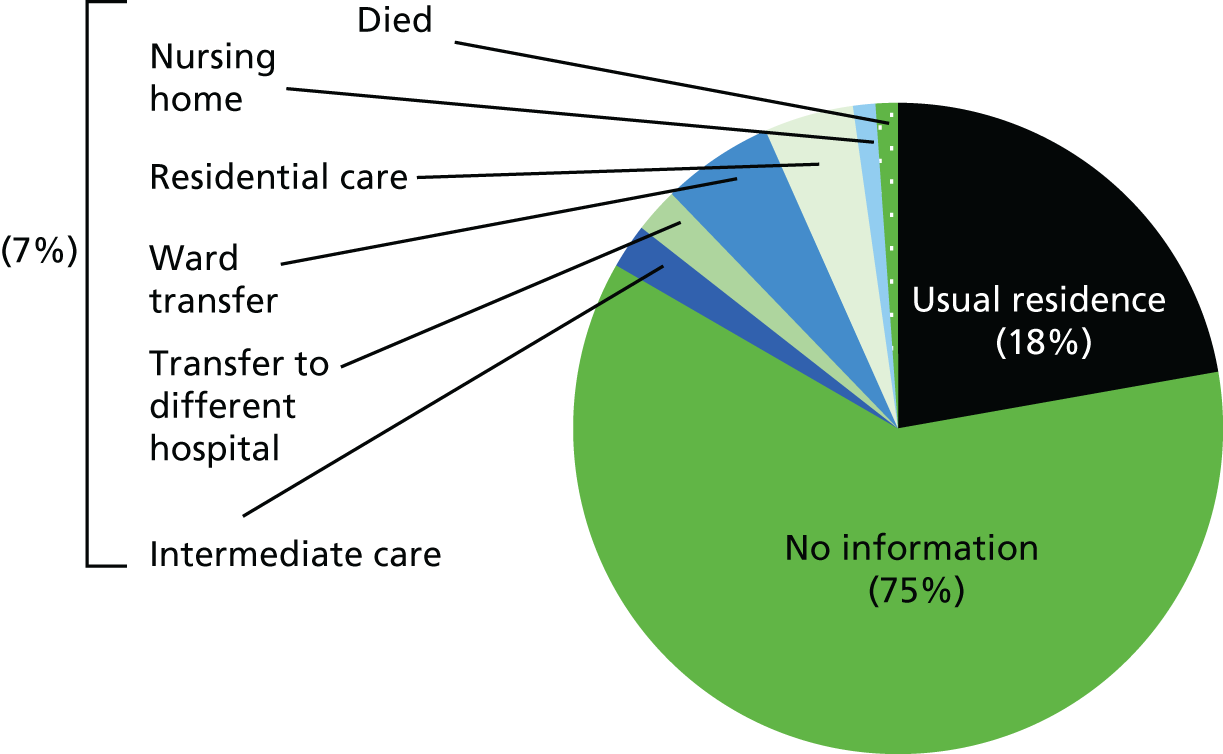

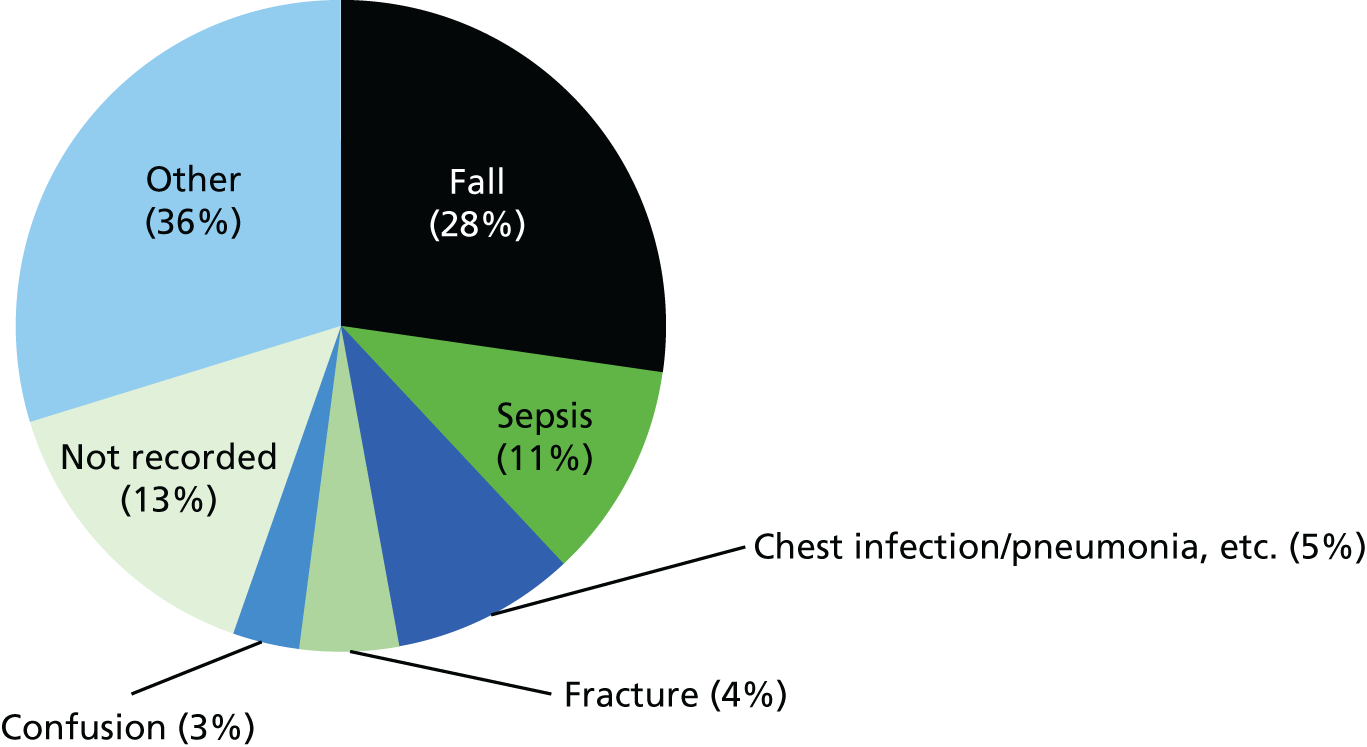

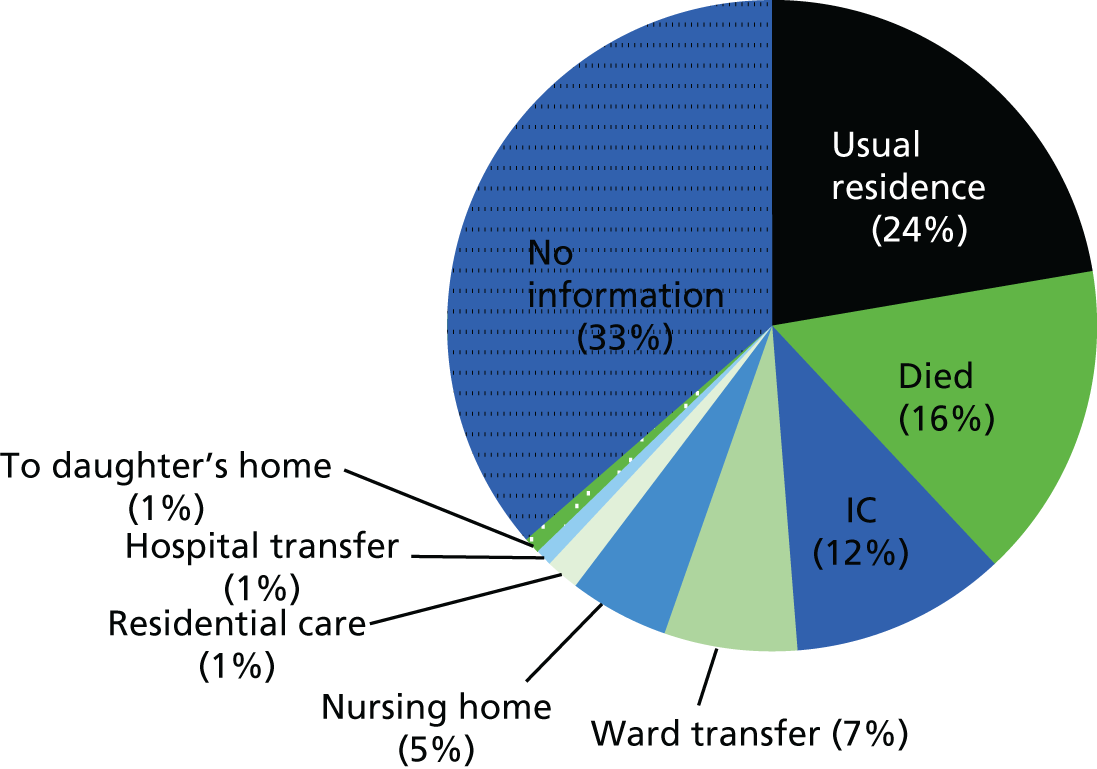

A patient profile was created using a common pro forma for all wards in a Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) spreadsheet. All patients on the ward and all new admissions during each data collection period were included. For each patient, we collected demographic (age, gender, and residence prior to admission), clinical (reason for admission, dementia diagnosis, probable dementia/memory problems and delirium) and service variables (date of admission and discharge, length of inpatient stay, discharge destination and readmission within 30 days). We adopted a pragmatic approach to the problem of poorly diagnosed dementia25 by classifying patients with a formal diagnosis and those assessed during their admission with probable dementia. In the report, we use ‘dementia’ to include both.

The collection of patient profile data required negotiation with trusts and wards to facilitate completion, as the data had to be provided in anonymised format and input by trust staff. Researchers made strenuous efforts to ensure that the pro forma was completed as fully and accurately as possible – a not inconsiderable task – and some funding was provided to wards to support this. The resulting data set provides a picture of variation in the patient journey between ward types and across trusts from admission to discharge.

Staffing profile

As well as collecting information on staff mix and staffing complement, researchers noted actual staff numbers during observed shifts and whether these staff were permanent, temporary, Bank or agency. This provided a more accurate picture of the meaning of staff shortages and difficulties than simple reference to the designated staffing levels that should occur.

Care culture, staff knowledge and understanding of person-centred care

The Climate for Care Questionnaire28 comprised 38 items relating to staff views on the shared philosophy of ward care, adequacy of resources, mutual support, feeling safe, improving practice, involvement, developing skills, time pressures and team working. It was slightly modified to include core MDT members such as therapists and medical staff (see Appendix 3).

All staff were asked to complete the questionnaire anonymously; responses were voluntary and were returned by being placed in a sealed envelope in a box file kept in a shared area where the researcher could collect them. Most returns were from nurses and HCAs. Completion rates varied between wards, with an overall response rate of just under 50% among nursing and care staff. It is difficult to be precise in that the calculation was based on staff complement, but the level of vacancies carried by wards varied between wards and over time. We sought to maximise response using different methods: ward managers were asked to remind staff during handovers; ward clerks were approached to keep the box for completed questionnaires in a prominent place (staff room or nurses’ station); and researchers gave out questionnaires to individual staff present during observation. It was notable that wards in which fieldwork revealed poor staff morale had a low response rate. In total, there were 104 respondents.

We conducted qualitative interviews, using a topic guide, with a purposive sample of ward staff at different levels of seniority and discipline (e.g. medical, nursing, therapy and care staff) and different roles (ward clerk, housekeeping and domestic staff). The topic guide was employed as an aide-memoire and interviewees were invited to discuss issues of importance to them. Conducted prior to PIE implementation, the purpose of the interviews was to explore how staff understood the meaning of person-centred care for people with dementia and the factors from their perspective that affected care delivery. The interview times varied between 30 minutes and 1 hour; they were subject to interruptions, and were often rescheduled and resumed opportunistically in gaps between frenetic activity. Interviews were audio-recorded (with a few exceptions when staff declined) and fully transcribed. In total, 56 interviews were conducted.

These included trust strategies and performance, ward-based assessment and care protocols for patients with cognitive impairment (dementia and delirium), treatment and care planning documentation, care pathways for dementia and delirium, and policies and procedures.

Organisation of care, ward routines and practices

Ethnographic observation was employed to develop an understanding of the pattern of ward activity and routines and how care for people with dementia was accomplished. This incorporated informant conversations with staff to clarify issues raised in the observation and to seek their perspective (albeit sensitive to staff’s work demands). 82 It provided a richer account of what was happening, including what people took for granted or were unable to articulate.

Each ward was visited by a researcher before fieldwork began to acquire familiarity with the spatial environment and to develop an initial observational strategy: where to observe, when to observe and the key actors involved. This provided an opportunity for the researchers to acquaint staff with the study and to respond to any questions about it.

Observation occurred over approximately 8 weeks in each of 10 wards at baseline. Researchers covered a variety of shifts: early morning, afternoon and night, weekdays and weekends. They observed the daily pattern of work, regular routines (ward rounds, multidisciplinary meetings and handovers) and special events (staff away-days). Field notes captured descriptions of settings, events, interactions and activities. Contemporaneous jottings in the field were written up as expanded accounts as soon as possible after observation (observation sessions usually occurred over a 3-hour period to facilitate this). 83–85 A field note journal was maintained in chronological order. It included initiatives introduced at hospital or ward level relating to care of people with dementia or pertinent to the ward case study (e.g. discussion and proposals around ward moves, staffing and hospital/trust performance). The researchers’ impressions and reactions to interactions, activities and episodes were recorded separately, as adopting such methods of reflexivity is an important quality check when undertaking such research. 85

For general observation, the focus was on routine practice. Observational notes did not record the names of individuals, only whether they had a professional role or if they were a patient or visitor. Neither did the researcher engage in observations of one-to-one clinical encounters between staff and patients; in cubicles where clinical examinations were being carried out; in spaces deemed private, such as behind curtains, in toilets or bathrooms; or in other spaces considered inappropriate by senior staff.

During observation, researchers were often asked for assistance by patients. Our approach was to respond to such requests by explaining the researcher’s role and by alerting a staff member, except when the request involved normal courtesies (e.g. opening a carton of juice left on a tray, moving a drink closer to the patient or providing directions) and did not require medical or functional knowledge (as in providing assistance with standing or walking). This generally worked well.

Approximately 30 hours’ general observation occurred on each of 10 wards at baseline (this varied somewhat with the size of the ward). A total of 295 hours’ observation was carried out.

Further observation for the same duration and over the same time periods occurred at interim (four wards) and at follow-up (two wards), reflecting the stage to which PIE implementation was pursued. A total of 175 hours of further observation was carried out.

Patient case studies

We intended to recruit up to six patients with a cognitive impairment on each ward, at each data point, for in-depth study. The purpose was to explore patients’ experience of care and their relatives’ or caregivers’ views about the care and their involvement in decision-making. Through conversations ‘in the moment’ with the patient during observation, we sought to include people with moderate to severe impairment in ways that were meaningful and ethical, as the method does not require verbal facility or the ability to recall. This would also enable us to locate individuals’ care experiences in the context of staff communication practices with them and the organisational, social and spatial environment of their ward. Additionally, we intended to conduct qualitative interviews with the patient’s relative or caregiver, review medical and care notes, and observe multidisciplinary meetings at which the person’s care and discharge plan was discussed.

Early on, it was evident that triangulation of data for patient case studies was very time-consuming. Because of the length of time these patients spent on the ward, and the depth and quality of data as a result of following patients to discharge, the research team proposed (supported by the Health Services and Delivery Research programme) to reduce the number of patient case studies, so as not to sacrifice depth for breadth of coverage. Purposive sampling was pursued to identify two patients at each site at each data point, selected as critical exemplars of those with dementia in acute wards. They included people unable to communicate verbally or perceived as challenging for staff to manage. The observation of selected patients enabled us to expand understanding of care routines that were not easily accessible through general observation but could be explored through the prism of individual patient journeys, for example the often convoluted process of discharge planning. Each patient/case study involved 5 or 6 hours’ additional focused observation. Appendix 4 provides pen-pictures of two of them. A total of 31 patient case studies were completed: 156 hours’ observation and conversations ‘in the moment’, and 28 interviews with relatives.

A summary of qualitative data by ward for different phases of data collection is presented in Appendix 5.

Person, Interactions and Environment process evaluation methods

An embedded process evaluation86 addressed the following research questions derived from NPT concepts, using a similar approach to that we employed in two recent studies. 87,88

-

Were the strategies employed to engage staff (interactive workshops and manual) sufficient to engender a sense of purpose around the beliefs and values that inform person-focused care for people with dementia (coherence)?

-

Was the process for leading and implementing PIE (team and service improvement cycle) perceived as worthwhile and feasible to invest in to effect change in ward culture and practice (cognitive participation)?

-

Was the work involved in pursuing PIE implementation (observation, action-planning and review) conceived of as necessary and effective in engaging staff in implementing and sustaining change (collective action)?

-

Did staff individually and collectively appraise PIE as worthwhile for themselves and their patients in benefits or outcomes achieved (appraisal)?

We utilised mixed methods to examine how delivery was achieved, what was actually delivered, the mechanisms of change and the effect of contextual factors on delivery. 89,90

-

Observation of PIE action-planning and review meetings to provide a contemporaneous account of the intervention: how it was activated, who was involved, problems encountered and solutions developed. Given the locally determined nature of the content (flexibility) within a systematic process, the question relating to fidelity is couched in terms of how precisely each step in implementation was pursued and proceeded to the next phase. 91

-

Conversations/informant interviews with implementation team members to explore how the programme was understood and communicated to the wider ward team; how different programme components were implemented (tools and guidance); and whether they were perceived as necessary, sufficient and of value in facilitating change. These took place at intervals of around 3 weeks within full and partial implementation wards.

-

Collection and analysis of PIE documentation: observation, action-planning and review tools to examine the content of the programme as enacted.

-

Staff narrative accounts of the process: interviews with a sample of PIE team members at the conclusion of implementation provided retrospective reflection on the process and impact of change. Additionally, we conducted interviews with individuals in sites that had not implemented PIE to explore implementation barriers (29 interviews with 37 staff).

-

Events ‘log’: a contemporaneous ‘events’ log was maintained by researchers to capture change in policies, systems and procedures outside PIE implementation that might affect the change process and outcomes. This included initiatives undertaken by the trust aimed at improving the care of people with dementia.

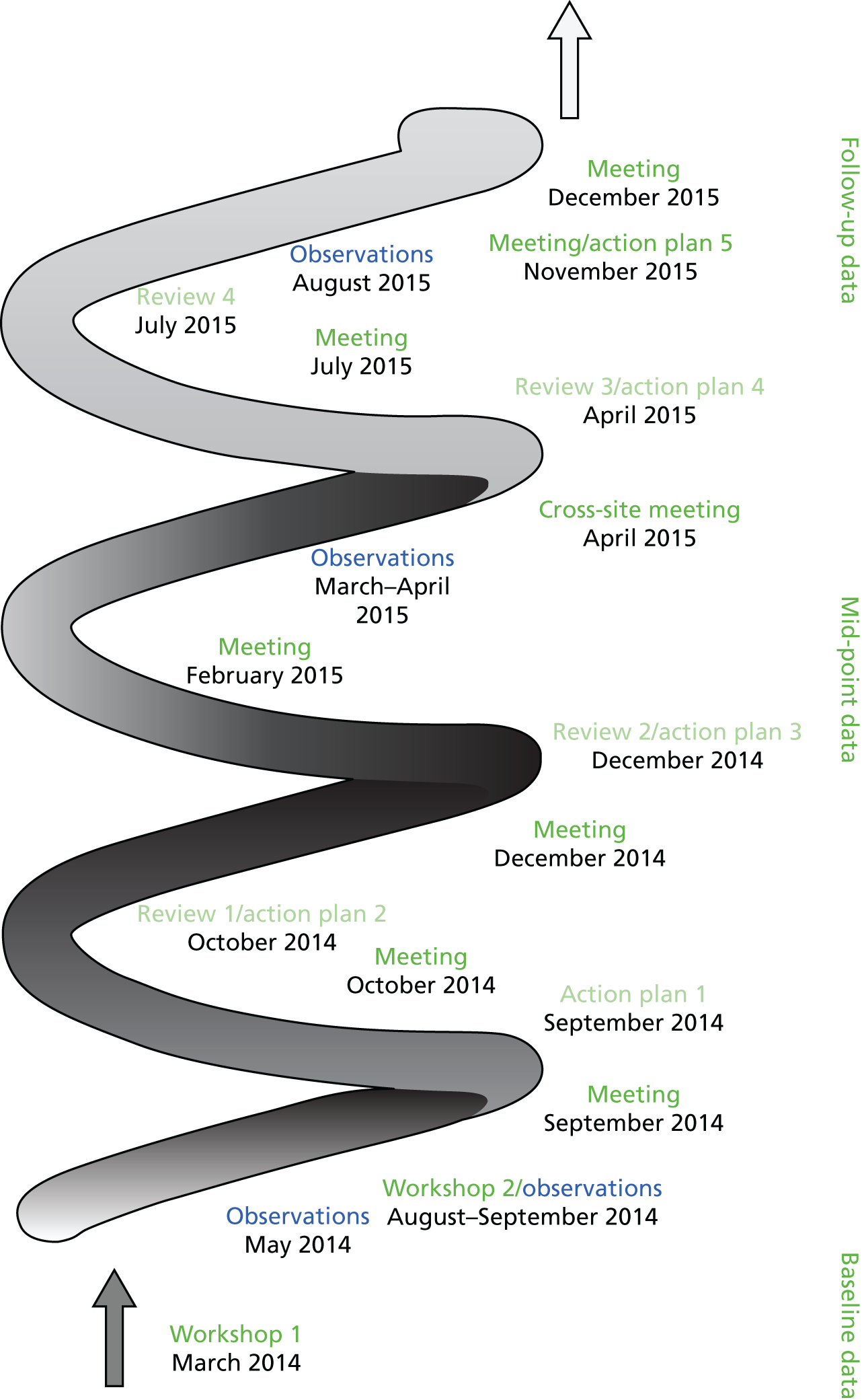

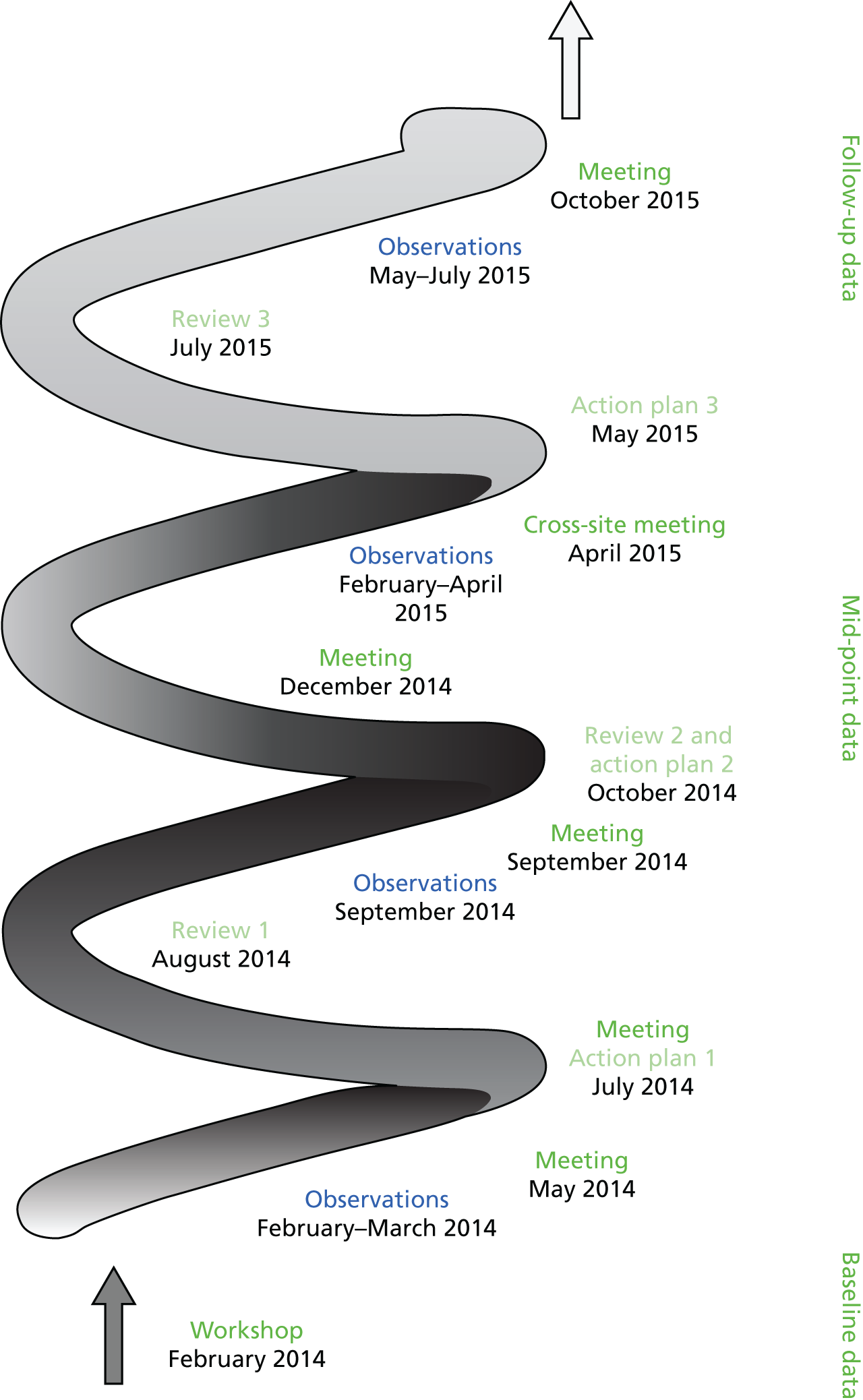

We had intended to organise two cross-site workshops at interim and conclusion of implementation to compare experiences and the contextual factors influencing these. Because of the unevenness of PIE implementation and the wide geographical location of sites, this did not prove feasible. One cross-site meeting occurred of staff in wards in two geographically distant hospitals within Seaford Trust (see Chapter 5).

Impact of Person, Interactions and Environment

Ward staff practices

Ethnographic observations and interviews with staff (as above) were conducted at 9 and 18 months where PIE implementation occurred.

Patient and relative/caregiver experiences of care

The sources of data were ethnographic observations and patient case studies.

Clinical outcomes

We sought to collect quantitative data on delirium incidence, days in delirium and falls at baseline and at 9 and 18 months. Delirium and falls are the most common unintended adverse events affecting older people admitted to hospital. We hypothesised that the rate of falls and days in delirium would be affected by improvements in care practice.

Delirium is a common, serious and unrecognised condition on acute wards;13,36,92,93 dementia is a risk factor for delirium36,94,95 and delirium accelerates cognitive decline. 96 Delirium incidence is associated with environmental (e.g. setting, lighting, and sensory overload) and care-related factors (e.g. fluid and nutritional intake, mobilisation and cognitive stimulation) that interact with patient vulnerability,36,97 and is regarded as a critical marker of care quality. 36,97 Data on delirium incidence and occurrence are not routinely collected in hospital, in part reflecting poor knowledge of the condition. 93,97,98 In this study, we employed the validated Delirium Observation Screening (DOS) scale,99 a 13-item scale developed to facilitate the early recognition of delirium, which is based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders-Fourth Edition100 criteria. It comprises a single sheet completed at least once daily by nurses as they attend to patients, with a score of > 3 indicating delirium (see Appendix 6).

We negotiated for the DOS scale to be incorporated into ward practice so as to prospectively collect information to monitor delirium rates and days spent with incident delirium. Although the completion of the DOS was reported to take < 1 minute, and therefore was not resource-intensive, staff found that it took considerably longer. The DOS scale was not consistently completed, with wards citing staffing difficulties as a reason for lack of completion. Several wards on which staff were already sensitive to the observational cues of ‘acute confusion’ and valued the information to inform practice (including both dementia wards) completed DOS. A high incidence of delirium and of days in delirium on these wards did not (from observation) reflect poor care quality.

Regarding falls, systematic reviews101,102 suggest a modest reduction in the falls rate with multifactorial interventions in hospital settings. The National Patient Safety Agency103 concluded that the most useful measure of falls is the number of falls per 1000 occupied bed-days. Reported falls for patients admitted during each phase of data collection were recorded as one of the patient profile variables on the Microsoft Excel datasheet, and a calculation was made of the rate of falls per 1000 occupied bed-days. Unfortunately, there was a considerable number of missing patient profile data, including those on falls for the two wards that successfully implemented PIE. When such data were available, we have reported them. However, the interpretation of the data is not straightforward. Not only do risk factors for falls relate to the actions of ward staff, but there are also patient-specific factors that give rise to variability in rates. Thus, risk increases with advanced age, presence of dementia, delirium and frailty, so that ward patient profile will affect the falls rate. 104 Similarly, as hospital-related falls occur as a consequence of mobilising and recovering from illness, practices regarding the balance of risk, promoting rehabilitation and respecting autonomy will also affect the falls rate. 104 Overall, the data obtained on falls were patchy across sites. On both clinical outcome measures, then, we were unsuccessful in securing reliable and consistent data for all wards. The attempt to do so has raised useful questions regarding feasibility, which we consider in Chapter 6.

Service outcomes (length of stay, readmissions within 30 days and discharge destination) were collected as part of the patient profile data set.

Analysis

Qualitative data (interview transcripts and ethnographic field notes) were analysed using grounded theory methods,105 including simultaneous data collection and analysis, constant comparison, searching for negative cases and memo writing. Descriptive and analytic codes were developed into higher-order categories through processes of data reduction and reassembly. First, an analysis was pursued for each data set (interviews, observations, patient case studies) within individual wards (the case study). We then compared analytic themes across these data sets, drawing out, for example, similarities and differences between staff interviews and observations on the understanding and practice of person-centred care. Through regular research team meetings, the emerging data from individual case studies, and reflections on them, were discussed. The similarities and differences between wards were drawn out, and we identified topics for more focused observation and ideas of analytic interest to pursue. Hypotheses were generated to explore and account for variation between cases; these were tested out through a cross-case comparison and search for alternative explanations.

Regarding ward practices with respect to patients with dementia, we proceeded as follows. From initial observations, we focused on aspects of practice relating to the work of communication, routine care tasks, responses to different types of distress, the strategies adopted and the attitudes and knowledge that informed them. For each case study, all incidents and episodes relating to this work were mapped, alongside the environmental, organisational and interactional contexts in which they occurred and the physical and emotional responses of patients. Through a comparison between the incidents and episodes captured in memos, we identified patterns of action and interaction. These patterns and what shaped them were refined through cross-case comparison. For example, the open code ‘distress’ was explored through a perusal of all incidents and episodes pertaining to it. Through constant comparison, different forms of distress were identified, which varied by how the distress was manifested, the perceived need giving rise to it and the persistence of its expression. Staff responses were similarly coded and categorised based on the type of response and the context in which it occurred. The relationship between the varied forms of distress and the responses to them were interrogated to identify patterns, which were further refined through a comparison between cases.

A similar analytic process was pursued in relation to PIE implementation. Qualitative data from interviews, workshop notes, observation of action-planning and review meetings, and examination of completed documentation were drawn together for each ward in chronological order. This provided a within-case descriptive account of implementation over time, the nature of the engagement of staff with each step in the cycle and the barriers encountered, using NPT as a sensitising framework. The emphasis was on delineating the sequence of implementation steps over time and in the context of events within the hospital and trust; the conditions that had an impact on the temporal flow of action, and their consequences, whether persisting with or abandoning PIE. We then examined implementation processes, through a cross-case comparison, to discern generalisable features that might account for variation. An analysis of the qualitative data was conducted manually, moving iteratively between the empirical data, sense-making in relation to the data and reflection on the literature.

Quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics.

Research team

Three investigators conducted the case studies with the academic support of the lead author (an experienced qualitative researcher and teacher in qualitative methods). The three attended a 5-day module on the theory and practice of qualitative research at the University of Leeds, which included ethnographic methods and analytic strategies. All four met regularly (at least monthly) to consider emerging findings and problems encountered. Between meetings, telephone conversations and e-mail discussions facilitated dialogue and mutual support, as the observations made heavy demands on researchers both practically and emotionally. The wider research team, including the chief investigator, met every 2 months to discuss progress. This was in addition to receiving support and advice from the Programme Management Group.

Ethics

Ethics approval for the study was obtained from the National Research Ethics Committee Yorkshire & The Humber Bradford (reference 12/YH/0442). The main ethical issues were securing the consent of patients to take part in specific ward observations, conversations and interviews, especially those who might have dementia or delirium, and not seeking formal consent for the general observations of ward routines.

Patient consent

The consent procedures adhered to the Mental Capacity Act 2005106 and accompanying Code of Practice. 107 First, when an individual was identified by staff as having a cognitive impairment, we considered how best to approach that person, with advice from ward staff (e.g. times when the person might be more alert, or when their relative was present). Second, the researcher explained the study in clear terms and ascertained whether or not the person understood the information. Third, if the person was deemed unable to make a decision about participating in the research, we sought information regarding a suitable personal consultee (close relative or friend), either from the patient or from a staff member. Every effort was made to secure a suitable personal consultee, or, in their absence, a nominated consultee to give patients without next of kin the opportunity to participate. If the consultee advised that a patient who lacked capacity would be willing to take part in the study, then that person was included, providing that they showed no signs of unwillingness (e.g. becoming distressed, upset or anxious in the presence of the researcher or when discussing the study). Consent was ongoing. The researchers checked that people were willing to continue, and were sensitive to signs of distress, including verbal and non-verbal cues.

General ward observations

The decision not to seek research consent for the general observations of ward routines was carefully considered. As observations were unobtrusive, carried out in public or semipublic spaces, and did not identify individual staff, patients or visitors by name, we considered that it would be impractical, and probably more intrusive, to seek formal written consent from all those present. Instead, we sought informal, verbal consent. Before each observation, the researcher reported to a senior staff member and introduced themselves to any staff they had not previously met, doing this at an opportune moment that did not interfere with the workflow. At the end of each observation period, the researcher ‘signed out’ with the senior staff. It should be emphasised that, throughout the study, observations were conducted with the full knowledge, support and co-operation of ward staff. If anyone appeared unhappy, distressed or uncomfortable by our presence on a particular occasion, we did not include them in the observation. This happened rarely. There were several instances when a patient became annoyed with the researcher when she indicated that she was unable to help the patient leave the ward and return home (call a taxi or get their coat). More often, when a patient was distressed and no staff member was available, the researcher sat with the person and sought to provide reassurance.

In the report, we have used pseudonyms throughout – for trusts, wards, staff, patients and caregivers – and have altered some biographical details to protect anonymity, privacy and confidentiality.

Patient and public involvement

There were several strands to our patient and public involvement strategy.

We involved our well-informed local older person’s group (approximately 15 people), with whom we have a longstanding relationship. This is a subgroup of a forum, established by the local authority, that comprises approximately 300 retired local people who are consulted on health and social policy issues. The subgroup has been acting as an advisory body in all aspects of our delirium and dementia research since July 2007. Three meetings of the group took place: at the beginning to inform data collection methods and contribute to the ethics application; following the conclusion of baseline data collection in the first two sites to reflect on the emerging findings and their implications for further data collection; and at the end of the study to discuss issues around PIE implementation.

Two meetings were held with people with dementia, one of which also involved caregivers. One meeting occurred with people with dementia and/or memory problems (n = 5). This ‘memoires’ group is a longstanding group of people who meet weekly for social, leisure and arts-based activities, and is organised by one of the locality-based neighbourhood networks for older people in inner-city Leeds. We held another meeting with people with dementia and their caregivers, hosted by another neighbourhood network in an outer suburb (n = 34). In both meetings, we discussed our emerging findings in relation to people’s experiences of acute care (i.e. people with dementia and their relatives). These meetings were organised to include the voices of people with dementia in the study, especially given that the cross-site workshops did not happen.

Two caregivers of relatives with dementia, recruited through the Alzheimer’s Society Research Network, were engaged as co-applicants and played a key role at all stages of the research. Our steering group also included a person with dementia and his caregiver, both of whom participated in discussions about direction and progress.

Chapter 3 Case study profiles

Introduction

This chapter describes the structural, organisational and cultural context of the study wards prior to PIE implementation. It also situates each ward within the wider hospital and trust environment, with specific focus on the policies in place, and the priority attached to, and investment in, services for older people with dementia. At the same time, direction and resource deployment at trust (and hospital) level is shaped by national policy priorities, regulatory requirements and resource constraints. The interactions between these levels create a fluid and dynamic environment for service delivery in wards and to patients.

National policy context: dementia

When the study began, in early 2013, the timing seemed propitious. National policy on improving the care of people with dementia had been given impetus with publication of the Prime Minister’s Challenge on Dementia 2015. 9 This coalesced with other policy drivers: the report of the Francis inquiry, published in March 2013,108 on the failings in Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust, particularly around the care of frail, older patients; and the findings of the first National Audit of Dementia Care on acute wards. 25

Interest in improving hospital care for patients with dementia was reflected across the five trusts. All had in place, or were in the process of developing, dementia strategies, although the content of these varied.

City NHS Trust

Organisation

City Trust is a long-established foundation trust, being among the first wave to achieve foundation status. It provides services to a core population of around 500,000, and employs > 5000 staff. Acute services are mainly located within a 900-bed hospital, with an 80-bed facility providing rehabilitation and outpatient provision from a separate site. It is a large, busy trust, with > 120,000 accident and emergency (A&E) department attendances annually. Situated in a region with a post-industrial heritage and a diverse culture, its diversity has contributed to an increased demand on health and social care provision at both ends of the age spectrum.

Since attaining foundation status, City Trust had generated an annual surplus. However, annual reports noted the challenge of securing improvements in quality and performance, managing reduced income growth, identifying efficiency savings and responding to the demands of a multiethnic population within one of the most deprived English local authorities.

Up until 2011, the trust was assessed as meeting the performance targets set by the national regulator, Monitor. During 2012 and 2013, performance targets on waiting times for treatment were breached, resulting in a review by the NHS Support Team, the launch of a comprehensive turnaround programme, and a return to compliance in April 2013. In January 2014, the Care Quality Commission (CQC) issued a report on an unannounced inspection the previous October on the main hospital site and assessed that action was needed in several areas, including respecting and involving people who use services and assessing and monitoring the quality of provision. A warning notice was issued on staffing because of staff vacancies carried. Strategic action centred on making improvements in problem areas, including the recruitment of staff, for implementation during 2014. A CQC inspection in October 2014 assessed the trust as ‘requiring improvement’; medical care was ‘good’ at both hospital sites. A change in leadership at board and senior management level at this time created some organisational instability. This was the context in which the strategic priorities around the care of people with dementia were established.

Care of people with dementia

A strategic trust priority from 2011 to 2012 was improving the physical environment for patients with dementia. City Trust was successful in securing external funding for this purpose, augmented by investment through its capital improvement programme. The design and execution of the changes on several older people’s wards was described as ‘exemplary’ in the CQC’s 2014 inspection report. The 2013/14 annual report announced the extension of the improvement programme to the second hospital.