Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/77/15. The contractual start date was in June 2016. The final report began editorial review in June 2017 and was accepted for publication in December 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Alison Turner reports membership of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Dissemination Centre Advisory Group. The Strategy Unit (NHS Midlands and Lancashire Commissioning Support Unit) was commissioned to support the Dudley Multispecialty Community Provider (MCP) vanguard, and Alison Turner has been involved in providing evidence analysis in support of the local evaluation of the vanguard. Abeda Mulla reports membership of the NIHR Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Prioritisation Panel (researcher led); The Strategy Unit was commissioned by the Dudley Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG) to deliver a primary care development programme, and Abeda Mulla is involved in providing general practices with service improvement and change support, and evaluating the programme workstreams. The Strategy Unit was also commissioned by NHS England to conduct a rapid research study in the context of General Practitioner (GP) Access, and Abeda Mulla was the technical lead for the project, overseeing all aspects of the analysis and writing the report. Andrew Booth reports being a principal investigator on a NIHR HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre contract and membership of the NIHR Complex Reviews Research Support Unit Funding Board. Shiona Aldridge works for The Strategy Unit, which was commissioned by NHS England to conduct a rapid research study in the context of GP Access, and she was involved in undertaking the qualitative analysis; she was also involved in providing evidence analysis in support of the local evaluation of the Dudley MCP vanguard. Sharon Stevens reports being involved in providing evidence analysis in support of the local evaluation of the Dudley MCP vanguard and undertaking the evidence review for the NHS England-funded review of managing access in English general practice. Mahmoda Begum reports that, in relation to The Strategy Unit being commissioned by the Dudley CCG to deliver a primary care development programme, she is involved in providing general practices with service improvement and change support, and evaluating the programme workstreams; she was also involved in undertaking the qualitative interviewing and analysis for the NHS England-funded review of managing access in English general practice. Anam Malik reports that, in relation to The Strategy Unit being commissioned by the Dudley CCG to deliver a primary care development programme, she is involved in providing general practices with service improvement and change support, and evaluating the programme workstreams; she was also involved in undertaking the qualitative interviewing and analysis for the NHS England-funded review of managing access in English general practice.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Turner et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Multispecialty community providers as new care models

The publication of the Five Year Forward View (FYFV)1 formally introduced the NHS England (NHSE) strategy for delivering new integrated models of care: ‘the NHS will take decisive steps to break down the barriers in how care is provided between family doctors and hospitals, between physical and mental health, between health and social care’1 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). At the time of publication, the NHS was facing significant financial pressures; in 2013–14 there was a £90.6M deficit across acute trusts and Clinical Commissioning Group (CCGs),2 and this increased financial burden was exacerbated with a 6.4% fall in public spending in adult social care between 2009–10 and 2015–16. During this period, the population aged ≥ 65 years grew by 15.6%3 and the health-care costs of managing long-term conditions was forecasted to increase by £5B between 2011 and 2018. 4

These cost pressures served to add urgency to the migration of English health and social care economies towards integrated care delivery. 5 The FYFV outlined five pioneering new models of integrated care, to be delivered through a systematic approach of large-scale transformation, with the ambition of providing better quality and experience of health care. These models differed in their involvement of different health and care agencies, but shared one main aim: to reduce the high level of avoidable hospital admissions (20% in 2013),6 while offering improved health-care quality, outcomes and patient satisfaction, which were all becoming increasingly challenging to deliver. 1,7–10

This evidence synthesis concerns itself with the 14 multispecialty, community-based provider vanguards, that is, the multispecialty community provider (MCP) model of care. The MCP focus was a result of the local health economy context; two MCPs requested support from The Strategy Unit (where all but one of the study authors were based), and MCP programme leads (national and local) expressed interest in participating as advisors for the synthesis to ensure relevance to their needs. We follow NHSE’s definition of MCPs:

It is a new type of integrated provider . . . combines the delivery of primary care and community-based health and care services – not just planning and budgets. It also incorporates a much wider range of services and specialists wherever that is the best thing to do.

NHSE. Contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.011

The model was intended to provide accessible, co-ordinated services for patients through professional integration in community settings: ‘one new option to permit groups of general practitioners (GPs) to combine with nurses, other community health services, hospital specialists and perhaps mental health and social care to create integrated out-of-hospital care’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 1

The distinction between the primary and acute care systems (PACSs) and MCP new models of care can be characterised by the role of the acute sector; inherent within MCPs was the emphasis on primary care focus and leadership, whereas PACSs, by definition, required acute and primary care collaboration. As such, the MCP vanguards chosen had the necessary focus on general practice, with primary care development being the priority for local health economies to drive the shift towards transformation of primary care services. This transformation included extended primary care services; innovative care delivery; application of digital technologies; new skills and roles; greater community involvement and collaboration with the voluntary sector; and greater convenience for patients. Through becoming ‘the focus of a far wider range of care needed by their registered patients’,1 the expectation was that MCPs would eventually become the providers of out-of-hospital care delivering a patient-focused model12 within an integrated system that has aligned commissioning and provider incentives. 13

As the vanguard MCPs started their journey, standard principles for operation were provided with the flexibility to adapt for the local context. 11 The emerging care model and contract framework for MCPs14 described the core features of MCPs and ways of contractually supporting a MCP. This included stipulations to:

-

serve the whole population, not just a specific subset (e.g. those aged > 65 years)

-

operate at four different tiers: (1) whole population, (2) people with self-limiting conditions, (3) people with ongoing care needs and (4) patients deemed to be at risk of unscheduled care or high utilisation

-

deliver the MCP through community ‘care hubs’, with each hub serving a community of around 30,000–50,000 people

-

demonstrate financial integration, potentially through a single, multiyear whole-population budget for all MCP services

-

deploy the MCP budget flexibly to reshape the local care delivery system, including incentives and risk-/gain-share agreements.

As a model of care, the emphasis is on system-wide improvement across multiple dimensions of health care,15 often expressed as the triple aim (improving population health, patient experience and cost-effectiveness) or as the quadruple aim16,17 (which also incorporates staff or provider experience). Reflecting the association between staff experience and quality of care,18 we use the term quadruple aim in this review.

Legacy integrated care models

National policy in England has for some time advocated a stronger role and increased accountability for primary care in delivering integrated care. Most notably, Lord Darzi’s High Quality Care For All. NHS Next Stage Review Final Report19 gave rise to integrated care pilots, community-based polyclinics with a primary care function and a renewed focus on practice-based commissioning. The subsequent integrated care and support pioneers were a result of a national partnership, through which an integration plan set out how local structures, such as health and well-being boards, could facilitate health and care agencies to make further steps towards integration. 20 Within this, primary care was said to have:

. . . a key role to play in supporting the local delivery of integrated care, by providing continuity across primary, community and secondary settings, focusing on preventative care and facilitating access to social care, including for carers, through effective coordination of care planning and management and risk stratification.

National Collaboration for Integrated Care and Support20

In parallel to the selection of the integrated care and support pioneers, the Better Care Fund programme was launched, providing the means by which pooled budgets could be used to deliver agreed NHS and local government integration plans. Over time, the integrated care and support programme was absorbed by NHSE and is now simply known as NHSE Pioneers.

At the time of the introduction of the new care models, the evidence base on health-system integration was variable, characterised by a lack of consensus on what constitutes integrated care,21,22 with no single model or approach to integrated care that was feasible for universal application. 23,24 However, although a universal model may not exist, the evidence base of legacy integrated care models offers the prospect of important lessons for what might be considered the ‘active ingredients’ for MCP models of care. 25–29 The ‘critical ingredients’ for integrated care had already been identified as relationship management, staff development and staff retention. 29 There is also a recognition that understanding integrated care requires a framework of the micro (e.g. clinical integration), meso (e.g. professional and organisational integration) and macro (e.g. system integration). 30

Several of the current MCPs began their integrated care journey as pilots, pioneers or GP Access Funds31 (previously known as the Prime Minister’s Challenge Fund) recipients. Although the integrated care pilots/pioneers specifically followed an integrated care agenda, the GP Access Fund31 schemes took a more indirect route to integration, as the focus was ‘to help improve access to general practice and stimulate innovative ways of providing primary care services’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0). 32 In parallel, in some localities, a more bottom-up approach to community integration developed, such as ‘Healthy Villages’ in Birmingham,33 where community partnerships were established with the NHS and the local authority, again as a result of the combined pressures of demographic and financial challenges. 34 Lack of formal evaluation, compared with the vanguards, means that the learnings and outcomes are difficult to access.

The evaluation of the UK Integrated Care Pioneers found some convergence of activities towards a similar set of specific interventions, including primary care-centred features of multidisciplinary teams (MDTs) and care navigation. 35 It was also noted that these pioneers became less ambitious and more pragmatic in their efforts to achieve horizontal local integration as delivery progressed. 35

Table 1 provides some examples of what might be considered to be the main legacy models of MCPs, such as integrated care approaches, either in England or internationally. The models we have listed in Table 1, and described below, were identified to be of interest to MCP vanguards. These models were mentioned in the ‘value propositions’ that each vanguard was requested to submit with their programme logic models (to request funding from the NHS Transformation Fund in 2016/17). 42 These legacy or international models were mentioned because they resonated with MCP vanguards in their design or aspirations. The Strategy Unit had access to these materials, as we supported the development of the vanguard logic models, and the new care models team gave permission to further use the materials for the purpose of this synthesis. As such, the international models discussed here are not intended to be an exhaustive assessment by the review authors, but rather a reflection of models that were known to, and thus likely to influence, MCP vanguards.

| Name | Location | Timeline | Evaluation/overview |

|---|---|---|---|

| Predecessors to the MCP | |||

| Integrated Care Pilots | England | 2008–10 | RAND Europe, and Ernst and Young LLP (2012)36 |

| Integrated Care Pioneers | England |

First wave: 2014 Second wave: 2015 |

Erens et al. (2016)35 |

| GP Access Funds | England |

First wave: 2014 Second wave: 2015 |

SQW and Mott MacDonald (2016)32 |

| Other models of care that have influenced MCPs | |||

| ACO | USA |

Pioneers: 2012–16 Next generation: 2018 |

L&M Policy Research (2016)37 |

| Alzira | Spain |

First 15-year contract in 1999 Second 15-year contract in 2003 |

de Rosa Torner (2012)38 |

| Buurtzorg | The Netherlands | Founded in 2006 | Gray et al. (2015)39 |

| Gesundes Kinzigtal | Germany | Founded in 2006 | Hildebrandt et al. (2010)40 |

| Nuka | USA – Alaska | Founded in 1999 | Southcentral Foundation (2016)41 |

Accountable care organisations

Of the international models, arguably the key influencer of the new care models was the US accountable care organisation (ACO) approach. ACOs were introduced in 2012, following new legislature for health-care reform in the USA, which directed the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) Innovation Centre to develop and test new payment and service delivery models through the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. 43 ACOs are described as a group of providers that are contractually responsible to a commissioner to provide all of the care for a given population over a defined period of time, and to uphold pre-agreed quality outcomes within a given ‘capitated’ budget or ‘fee-for-service’ agreements. 44 The programme theory for ACOs is that if providers have an opportunity to share in financial rewards (or face penalties), then ACOs will reduce fragmentation and duplication in medical care. It is suggested that the improved communication and co-ordination across providers, physicians and patients will improve the quality of services and reduce spending. 45 The Pioneer ACO programme started in 2012, with 32 pioneer sites chosen by the CMS to participate, and ended in 2016 with eight organisations. 45 Forty-four next-generation ACOs have been selected by the CMS and will begin the programme in 2018. 45

Gesundes Kinzigtal

Gesundes Kinzigtal (meaning ‘healthy Kinzigtal’ – the town in south-west Germany where the model was introduced) is an accountable network of physicians, partnering with a health-care management company, driven by the needs of multimorbid patients requiring co-ordinated care. 46 Long-term contracts were put into place in 2006 with two German non-profit sickness funds to integrate health and care services for their insured populations. The integrated system covers a population of 60,000, of which Gesundes Kinzigtal is in charge of the health-care budget of 31,000 ‘assureds’. 40 It has a responsibility to deliver regionally integrated health and care services, covering all age groups and care settings, with the explicit triple aims of improving the health of the population, enhancing the patient care experience and reducing the per capita costs of care. To date, improved population health outcomes,40 potential cost-effectiveness,47 more appropriate access (decline in overuse, underuse and misuse of health care) and an increase in health-care quality have been reported. In early 2017, the lessons from Gesundes Kinzigtal were applied to the launch of a new integrated care model in a city in northern Germany, which was designed to improve access to health services in two of Hamburg’s disadvantaged suburbs: Billstedt and Horn. We discuss the underpinning evidence around access in integrated systems in Chapter 4.

Alzira

The Spanish ‘Alzira’ model (named after the town where the model was first implemented) is akin to the financially led model of the US ACOs. However, it has a unique feature of private and public contracting, such that the private sector finances the construction and operation of the health-care infrastructure and delivers clinical services through a capitation fee. This reduces the public sector partner role to that of commissioner of health care. 48 The regional government entered into a long-term contract in 1999 for 15 years, and cost-effectiveness benefits were widely reported. 38 Acerete et al. ,49 however, dispute some of the claims, stating that ‘the precise level of cost savings achieved has never been subject to public scrutiny and remains controversial, with a true like-for-like comparison impossible’. 49 The financial innovations of both the ACO and the Alzira models have influenced the vanguards’ contracting and budgeting mechanisms, and we explore this further in Chapter 5.

Nuka

The Nuka System of Care50 is built on the premise that the relationship between the primary care team and the patient/customer-owner is the single most important tool in managing chronic disease, controlling health-care costs and improving the overall wellness of a population. It was developed in the late 1990s by the Southcentral Foundation, a non-profit health-care organisation serving a population of around 60,000 Alaska Native and American Indian people in Southcentral Alaska. 41 The accountability for improved health outcomes in Nuka lies with the partnership of providers and people in the Native Alaskan community, who changed from being the ‘recipients of services’ to the ‘owners’ of their health system, so that they could co-design services and oversee implementation. The Southcentral Foundation’s annual progress report documents outcomes that include increased patient satisfaction and significant reductions in the use of specialist and hospital-based treatment. 51 The key to the success of this model of integrated care is suggested to be the transfer of the partnership ‘power’ to the recipients of services. 51 We explore partnerships for integrated care further in Chapter 6.

Buurtzorg

The Dutch Buurtzorg (neighbourhood care) not-for-profit model was born out of a desire to improve the staff experience of community nurses delivering integrated home care. It aimed to provide an accountable partnership with social innovation, ‘humanity over bureaucracy’, at its core,52 by attempting to shift the care delivery mindset from managerial protocols and administration to clinical autonomy and accountability. 53 Buurtzorg Nederland was founded in 2006, with a small team of professional nurses, and following 10 years of operation, the model has extended to encompass 10,000 nurses in 850 teams in towns and villages all over the Netherlands, and has spread to a further 24 countries. 54,55 In response to criticisms of ‘cherry-picking’ of patients in its reporting of cost-effectiveness, the Dutch Ministry of Health, Welfare and Sport commissioned the consulting firm Klynveld Peat Marwick Goerdeler (KPMG; Amstelveen, the Netherlands) to compare Buurtzorg with other home-care providers. This evaluation showed that, even after controlling for differences in patient characteristics, Buurtzorg remained a low-cost provider of home-care services; the addition of patients’ total costs (nursing home, physician and hospital costs) resulted in Buurtzorg’s total per-patient costs being around average for the Netherlands. 39 Moreover, the quality of care was deemed efficient, as demonstrated by patient satisfaction56 and a high level of staff experience, as shown by Buurtzorg being named the best national employer in 2010–12. 39 Chapters 4–6 provide further support for the inclusion of staff experience as a health-care aim.

Multispecialty community provider progress

As a result of reductions in agency/locum staffing at trusts and commissioner underspends, the Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View57 reported a context of ‘improved financial grip’ in 2017 compared with 2014. A further contributor was the deployment of funding to manage local emergency activity pressures. Here, the MCP and PACS were highlighted as having lower growth in emergency hospital admissions and emergency inpatient bed-days than the rest of England, in the period of January–December 2016, compared with the October 2014–September 2015 vanguard baseline. Of the MCP vanguards, Principia Partners in Health reported absolute reductions in emergency admissions per capita. 57

The Next Steps on the NHS Five Year Forward View57 notes that sample sizes and the duration of implementation may limit the applicability of the results. The same document suggests that vanguards, in particular, are expected to ‘earn their passage’ and take clearer financial accountability for reducing emergency hospitalisation growth in their area, in order to be deemed a success and earn accountable care system (ACS) status. 57 Thus, the definition of vanguard ‘success’, and a more general pressure to report a positive impact, through the measurement of emergency hospital admission growth in the short term, was noted by some commentators to signal a change from a model that is ‘coherent, patient-centric and focused on prevention’, which takes time towards delivering a more tangible measure of success, to one which has to justify central investment. 58 The scaling-down of ambition – ‘the original Forward View vision of PACS and MCPs, as embodied by the vanguards, is still relevant but its collision with reality has produced a more modest set of ambitions and a less all-encompassing definition of success’58 – resonates with the previous assessments of integrated care pioneers. 35

However, this might not be the case for all vanguards; those that are more established and moving from being experimental to business as usual – ‘A few areas (particularly some of the MCP and PACS vanguards) in England are on the road to establishing an ACO, but this takes several years’57 (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0) – may become more ambitious, with the formation of ACSs initiating ‘the biggest national move to integrated care of any major western country’. 57 The first eight candidates for ACSs were announced in June 2017,59 with the remit to retain existing health and social care structures (this is different from ACOs), to deliver integrated care with increased financial accountability, negating the need for burdensome annual transactional negotiations. 57,60

Aim and objectives

The aim of this synthesis was to provide decision-makers in health and social care with an ‘actionable’ evidence base for the MCP model of care. We believe that this synthesis, based on realist principles, can serve as a ‘blueprint’ with ‘active ingredients’ to inform the design and delivery of current and future iterations of the MCP model. 61

Specifically, the objectives of the synthesis were to:61

-

articulate the underlying programme theories of the MCP model of care, by mapping the logic models of the 14 MCP vanguards, selecting and prioritising significant theories for investigation

-

identify sources of theoretical, empirical and practice evidence to test selected programme theories

-

appraise, extract and analyse evidence, reconciling confirmatory and contradictory evidence

-

develop the synthesis, explaining how the mechanisms used in different contexts contribute to outcomes and process variables

-

consult with key stakeholders to validate the findings and to test their applicability to different contexts

-

finalise the synthesis, incorporating stakeholder feedback

-

disseminate the findings, preparing a series of practical tools to support knowledge.

Chapter 2 Review methodology: stakeholder engagement, programme theory elicitation and analysis of the literature

On initiation, the review team registered a review protocol with the PROSPERO database and published an expanded version within a peer-reviewed journal. 61 This chapter first describes how we analysed existing logic models to identify programme theories and then engaged with stakeholders in order to verify and elucidate these potential programme theories. Subsequently, we conducted a systematic search of the relevant literature, supplemented by further purposive explorations for evidence, underpinning each programme theory component. Key to the review strategy was our realisation that we needed to prioritise programme theory that could most inform the current development of MCPs. A two-level approach was used to populate, first, full programme theory reviews (R1–3), and then, second, a larger range of programme theory maps (M4–7), which seek to identify the key evidence underpinning additional important programme theory components prioritised by the stakeholders. Just as an intervention may have multiple intervention components, each triggering one or more mechanisms, so too a programme theory can be seen to have multiple theory components, each engaging with one or more mid-range theories. In actuality, when a programme is delivering against the intended outcomes, all of the programme theory components operate synergistically and interactively. However, for evaluation purposes, theory components are best dissected as separate entities and explored, in this report, via either programme theory reviews or programme theory maps. By programme theory component, we therefore refer to the most meaningful level of granularity for the overarching programme theory to be examined, by mapping and assembling the literature.

This chapter seeks to follow the reporting standards advocated by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR)-funded Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) project. 62 We describe how we carried out our review, following the steps outlined in comparable projects. 63 We have found it helpful to follow Pawson’s64 time and task template for a realist synthesis. Specifically, with regard to searching for evidence, we have broadly followed the six principal elements identified in a forthcoming chapter on the ‘realist search’. 65

As stated in the previous chapter, the aim of our realist synthesis was to provide decision-makers in health and social care with a practical evidence base relating to the MCP model of care.

Justification for the choice of a realist/best-fit framework synthesis

Best-fit framework synthesis

We took the innovative approach of using a best-fit framework synthesis as a means of organising and mapping data, as a prequel to a formal realist synthesis. A best-fit framework synthesis offers a rapid tool by which to facilitate data extraction and analysis, and thus maximise the value of the interpretive synthesis in a way that is amenable to the production of practical recommendations. 66 Framework synthesis is considered ‘especially suitable in addressing urgent policy questions where the need for a more fully developed synthesis is balanced by the need for a quick answer’. 67 A best-fit framework synthesis offers a pragmatic variant of framework synthesis. Instead of spending a disproportionate amount of time in developing a definitive conceptual framework with stakeholders, a best-fit framework synthesis uses the best-available conceptual or instrumental frameworks as a starting point for extracting and analysing the data. In doing so, it harnesses ‘the recognised strengths of both framework and thematic synthesis’. 68 Furthermore, in this project, we specifically sought frameworks with ‘practitioner credibility’ with those working within a rapidly developing area of models of care. Framework synthesis was thus selected as a vehicle for the future dissemination of findings. A best-fit framework synthesis was subsequently combined with a synthesis following realist principles, which is particularly suited to exploring what works, when, for whom and in what circumstances.

The realist principles used in this project derive from the need to use methods that acknowledge the inherent complexity within programmes of change and their evaluation. 69 Although the initial development of the realist methodology focused on realist evaluation, using purposely collected and readily available primary data, Pawson64 subsequently identified the need for, and documented, a corresponding process within the emerging science of reviews. The realist synthesis approach has been consolidated and explored more fully, as demonstrated by Rycroft-Malone et al. 70 in 2012. Particularly influential is the trend to combine elements of realist evaluation and synthesis in order to optimise relevance and transferability. The realist approach acknowledges that interventions do not necessarily transfer easily from one setting to another, and offers deeper insights into the contextual factors involved in change. Realist approaches have been demonstrated as having particular utility within the NIHR’s Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme-funded projects. 63,71,72

Programme theory development and refinement requires undertaking a series of activities. These activities do not necessarily take place sequentially, and are typically iterative. However, we present them serially for transparency and ease of understanding. We undertook the following activities, reinterpreted from Pawson64 and others in a forthcoming book chapter (due for publication in June 2018):65

-

formulating specific questions as lines of inquiry73

-

exploring a proposed area of research to identify previously published research and, if necessary, refining the research question (the background search)64

-

identifying theories as hypothetical explanatory accounts (initial programme theories) of how an intervention works (the search for programme theories)64

-

identifying empirical evidence to test and refine the initial programme theory (the search for empirical evidence)64

-

responding to new information needs that emerge during testing and refining the initial programme theory (the final search to refine programme theories)64

-

documenting the search process in an explicit and transparent manner. 62,74

A realist synthesis is theory driven and seeks to unearth ‘the unseen elements of a programme (the mechanisms) that lead to its success or failure’. 72 Configurations of contexts, mechanisms and outcomes are mapped to show how particular contexts or conditions trigger mechanisms to generate outcomes. Multiple mechanisms may be activated within each intervention, each representing a ‘pathway from resource to reasoning and response’. 75 The reasoning and response may derive from the perspectives of the receivers, the organisers or those delivering the programmes. 76

Programme theory ‘describes the theory built into every programme’,62 being expressed as ‘if we provide these people with these resources it may change their behaviour’. 77 A strength of realist synthesis is its facility to accommodate diverse sources of evidence when ‘reconstructing’ programme theories. It draws from a systematic process that includes stakeholder engagement, an overview of relevant extant theory62 and close examination of primary research. 64 Such an approach faces three challenges: (1) many commentaries may not articulate a programme theory, or at least may not make a particular programme theory explicit; (2) programme theories may be expressed in a variety of forms and formats, making translation and comparison problematic; and (3) the non-standardisation of format makes it difficult to prioritise theories for further exploration.

However, important adaptations from the classic realist approach acknowledge our ready access to an explicit source of programme theory (i.e. the logic models produced by the local MCP teams). Although programmes of change (i.e. New Care Models programmes) may be considered to be ‘theories incarnate’;69 these theories truly ‘take on flesh’ when realised within the structure of logic models. In this review, we developed a theory by analysing the definitive published logic models, along with their associated narratives, as a source of articulated theories about ‘what works’ in MCP models and the conditions that might result in the achievement of programme success.

For the purposes of this review, a MCP was considered to be ‘a new type of integrated provider’ that ‘combines the delivery of primary care and community-based health and care services’ with the result that ‘services previously based in hospitals’ (e.g. outpatient clinics, diagnostic, day surgery, etc.) may be delivered in the community. It may also involve the integration of ‘mental and physical health services and, potentially, social care provision, together with NHS provision’ [adapted from NHSE (2016);11 contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0].

As this definition implies, successful implementation and transformational change are contingent on diverse factors that must be acknowledged within a review approach that accommodates complexity and contingency. As a consequence, we selected a theory-driven approach to evidence synthesis, underpinned by the realist philosophy of science and causality. 78

Review questions

Our original review questions were as follows:61

-

What are the foremost theories of change inherent within the MCP model of care?

-

What seem to be the ‘active ingredients’ that should inform the design of MCP models of care?

-

What are the social and cultural conditions that influence (enabling and blocking) change within MCP models of care, and how do these mechanisms operate in different contexts?

-

What are the key knowledge gaps and uncertainties in relation to the design, implementation and evaluation of MCP models of care?

Changes to the review process

No major changes to the review process were made subsequent to the publication of the review protocol. 61 However, to maximise the utility of the realist synthesis for project stakeholders, and to enhance its value for NIHR, we decided to complement our approach to full realist reviews of key programme theory components with a broadly analogous process of ‘mapping’ for other components identified during the identification of a programme theory.

This mapping approach combines elements of the realist review process,64 rapid realist review approaches79 and features utilised in systematic mapping. 80 Specifically, rapid realist methodology seeks to incorporate the theory specification of a realist review,64 with the boundary clarification aim of a scoping review. 81 In contrast to a systematic review, systematic mapping does not aim to answer a specific question. Instead, it ‘collates, describes and catalogues available evidence (e.g. primary, secondary, quantitative or qualitative) relating to a topic of interest’. 80,82 Included studies are used to develop a greater understanding of concepts and to identify knowledge gaps and knowledge clusters. Systematic mapping aims to share the same characteristics of being systematic, explicit and reproducible that are possessed by systematic reviews, but can be used to address open-framed questions on broad topics. Systematic mapping is particularly valuable for broad, multifaceted questions, as revealed by our identification of programme theory components, whereby a topic of interest is not considered suitable for systematic review.

Identification of programme theories

A ‘classic’ realist synthesis begins with the identification of opinions and commentaries as a source of programme theories for which evidence is later sought.

Multispecialty community providers as new care models represent complex social programmes, involving multiple stakeholders or actors, structures and organisations. We were able to harness a ready source of programme theory, in the form of logic models developed by 12 of the 14 MCPs. These logic models were submitted to NHSE as part of its programme documentation in the first year of new care model funding. Although falling short of a standardised format, all were informed by the conventions of logic model presentation. 83 Logic models ‘outline the inputs, processes, outputs and outcomes of a programme’84 in an accessible diagrammatic form, typically with accompanying notation and/or explanatory text. The logic models developed by the vanguards typically follow the model recommended in The Magenta Book: Guidance for Evaluation,85 which lends itself to the CIMO (context, intervention, mechanisms, outcomes)73 framework within which we planned the search strategy.

An initial rapid desk-based analysis of the MCP vanguard applications identified that multiple interventions and mechanisms are being developed at the micro, meso and macro levels [e.g. extensivist primary care, multidisciplinary community teams, social prescribing (interventions), community assets and social capital (mechanisms)]. Resources can be ‘material, cognitive, social or emotional’. 77 Resources identified within NHSE’s MCP Framework: Working Document86 include design, evaluation, integrated commissioning, patient and community empowerment, technology, workforce, leadership and engagement.

Formulating specific lines of inquiry

In many realist reviews, the research team needs to ‘surface’ programme theories from interviews with stakeholders, and from the published literature and more ephemeral contributions, such as blogs and newspapers. Our access to the formal logic model submissions submitted by vanguards as a requirement for applications for funding allowed us to explore a full spread of interventions, as identified by the vanguards, against a backdrop of different contextual characteristics. The selection of vanguard sites holds an inherent advantage in offering a form of ‘intensity sampling’. However, from a methodological point of view, the concept of a ‘vanguard’ holds an inherent risk of selection bias (i.e. the likelihood that sites have been selected according to their readiness for new care models). So, although we sought to explore the implementation of new care models across a diverse sample of care providers, the total sample itself had been preselected. Such caution is particularly important when looking to apply review findings to roll out and sustainability for ‘failed’ vanguard applications and for those sites that could not aspire to a vanguard application. Nevertheless, existing MCP vanguards represent significant diversity of both contexts and target populations, as acknowledged in our choice of an approach that emphasises ‘what works for whom under what circumstances’,69 and offer the potential to identify context-specific issues and constraints at a particular level, even where a general pattern of successful implementation appears to prevail. Under these conditions, it becomes particularly important to implement a series of validation checks and balances within the strategy for data synthesis.

Strategy for programme theory identification

The extraction and articulation of programme theories offers a foundation for the entire realist synthesis project. We analysed all available MCP logic models (12 of the 14 sites), supplemented by related documentation available in the public domain (via vanguard websites and the NHSE website). We worked systematically through all of the available logic models, extracting causal links in the form of ‘if–then’ statements. 87 We then grouped these if–then statements thematically within a spreadsheet (Table 2) and sought to reconstruct the causal pathways into an aggregated logic model that represented the integrated programme theory from across multiple sites (see Chapter 3).

| Statements | |

|---|---|

| If . . . | Then . . . |

| Commissioners fund new community facilities | Community services will increase capacity |

| Commissioners fund new community facilities | Acute services will discharge patients to community facilities (step-down) |

| Commissioners fund new community facilities | Health-care professionals will treat more patients closer to or at home |

| Commissioners fund new community facilities | Practitioners can support the patients most likely to need acute care |

| Commissioners fund paramedic practitioner roles to support home visiting | Fewer patients will attend A&E departments |

| Commissioners fund paramedic practitioner roles to support home visiting | GPs will refer fewer patients for emergency admissions |

| Commissioners fund paramedic practitioner roles to support home visiting | Commissioners will negotiate disinvestment in acute beds |

When causal links were incomplete, an attempt was made to verify these links from the logic model of an alternative source. When this was not possible, these orphan links were ‘parked’ for later review and rationalisation. Logic models are sometimes criticised for being ‘rigid’ and for not making explicit the causal pathways through which change occurs. 84 Closer examination of our data source confirmed these complexities – sometimes nodes or links between logic model components were imperfectly articulated; in other instances, intermittent links were omitted, resulting in incomplete causal pathways.

An investigation of the full set of available logic models was intended to reveal the diversity of the different programme theories underlying MCPs, while also uncovering fundamental local differences in approach or emphasis. The resultant set of programme theories was compiled for discussion with the advisory group.

At the same time, team members were sensitising themselves to different interpretations of the new care models initiatives through official documents, local guidance, independent commentaries and blogs and current awareness services, such as the Health Service Journal, The Commissioner Newsletter and NHSE’s New Care Models Bulletin. Broader exploration of the wider historical and political context also took place; for example, via the literature on large-scale transformation. 42,88

As a model of care comprising a broad range of interventions, the MCP model generated multiple programme theory components. The richness of the data is significant – we extracted, in total, 1394 if–then statements. All statements were coded using the agreed best-fit framework and then grouped into themes that emerged from the data. This allowed us to compare the MCP programmes in terms of context, mechanism and outcome configurations efficiently and rapidly within the subsequent realist synthesis. 79

We developed twelve draft theories:

-

innovative services deliver sustainable care

-

community-based, co-ordinated care is more accessible

-

collective responsibility improves quality and safety outcomes

-

multidisciplinary teams provide continuity of care

-

local MCP contracting delivers ACOs

-

pooled budgets incentivise integrated care providers

-

fostering relational behaviours builds resilient communities

-

integrated care navigators increase workforce capacity

-

engaged and trained staff lead cultural change

-

new ways of working enable staff resilience

-

evaluation activities sustain transformational change

-

information-sharing enables effective collaboration.

By cataloguing the different programme theories underlying MCPs, as identified from the logic models (reported in Chapter 3 of this report), we were able to identify underpinning mechanisms by which different programme components achieve their effect, as perceived by those actively involved in designing and implementing the New Care Models programmes across the vanguard sites.

Agreeing the focus of the review

To agree the focus of the review, we presented our initial programme theory components and a basic overview of constituent if–then statements at a 1-day stakeholder meeting. Our stakeholder event included the following people:

-

an academic, who was the chief investigator of another HSDR programme-funded New Care Models project (reference number 15/77/10)

-

the accountable officer/chief clinical officer of a CCG, which was a MCP vanguard site

-

the chief officer of a CCG, which was a MCP vanguard site

-

a communications consultant and fellow

-

the Director of Primary Care in a CCG

-

an evaluation lead in NHSE

-

an executive director of a MCP vanguard site

-

a regional manager of the New Care Models programme in NHSE

-

two patient and public representatives

-

the Director of Strategy of a community health-care foundation trust.

We presented our initial programme theorising as ‘propositions about how new care models are intended to work’, and invited participants to comment on these ideas and refine, extend and prioritise them.

Contribution of the project advisory group

A detailed assessment of the area under study identified a lack of a single appropriate framework. In June 2016, the project advisory group was briefed on the aims, objectives, scope and approach of the study, with a specific focus on the best-fit framework synthesis approach, sharing with them a tentative framework with which the review team intended to support the realist synthesis. The discussion proved to be extremely fruitful, as the review team were made aware of a forthcoming framework from NHSE.

Working with the advisory group allowed us to test the proposed approach and programme theories with key stakeholder groups. It also made us aware of relevant work within the New Care Models programme and the vanguard sites. For example, the review team secured early sight of an implementation matrix being developed by NHSE, which sets out the key characteristics and expectations of new care models.

Creation of a metaframework

Subsequently, we identified five existing frameworks to cover the various aspects relevant to the MCP model of care. These were derived from three relevant guidance documents for MCPs (a, b and e) and two integrated care frameworks (c and d):

-

the eight enablers of transformation in The Forward View into Action: New Care Models: Update and Initial Support89

-

MCP Framework: Working Document 86

-

Framework on Integrated, People-Centred Health Services 90

-

System Leadership: Lessons and Learning from AQuA’s Integrated Care Discovery Communities 91

-

The Multispecialty Community Provider (MCP) Emerging Care Model and Contract Framework. 11

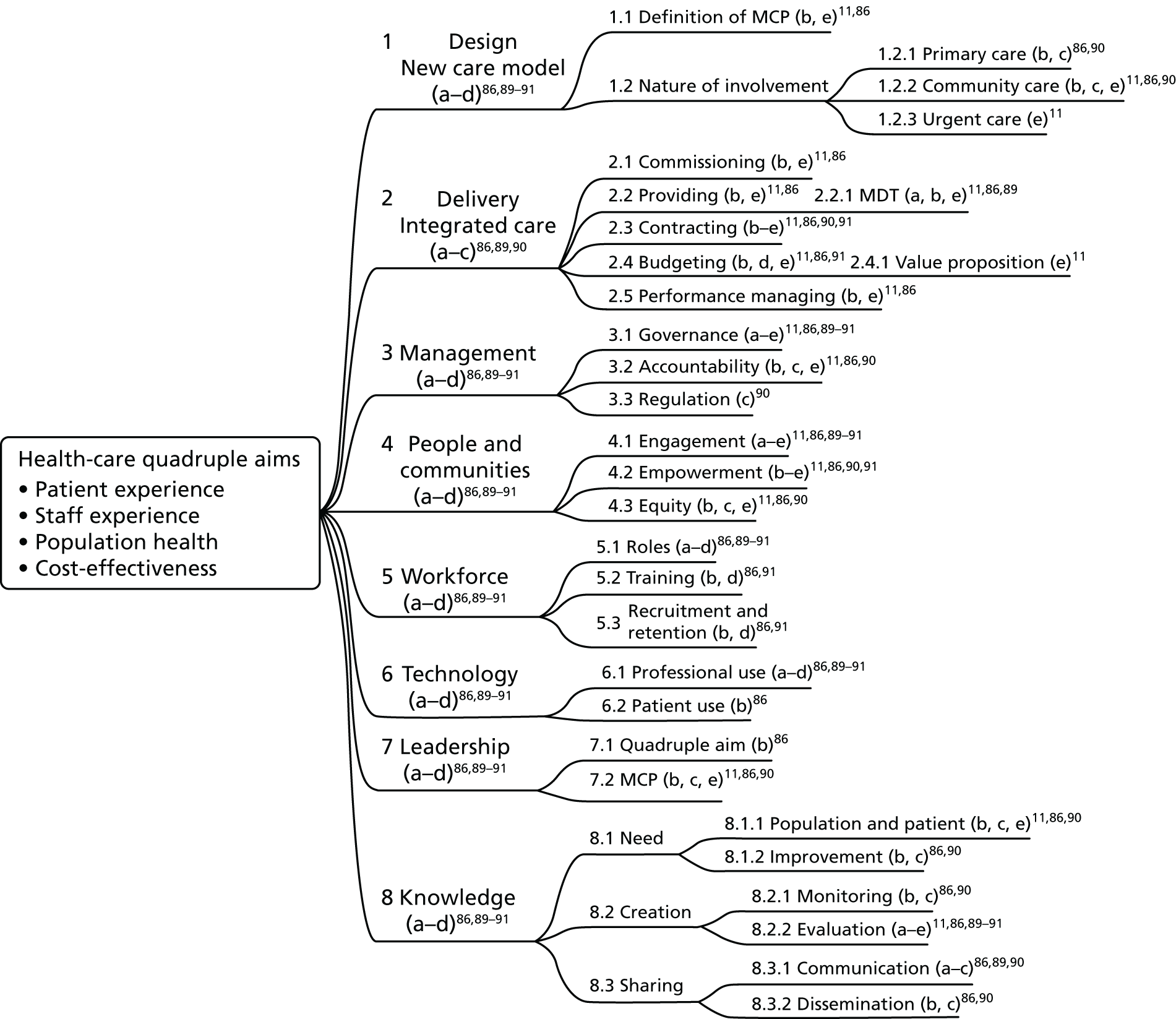

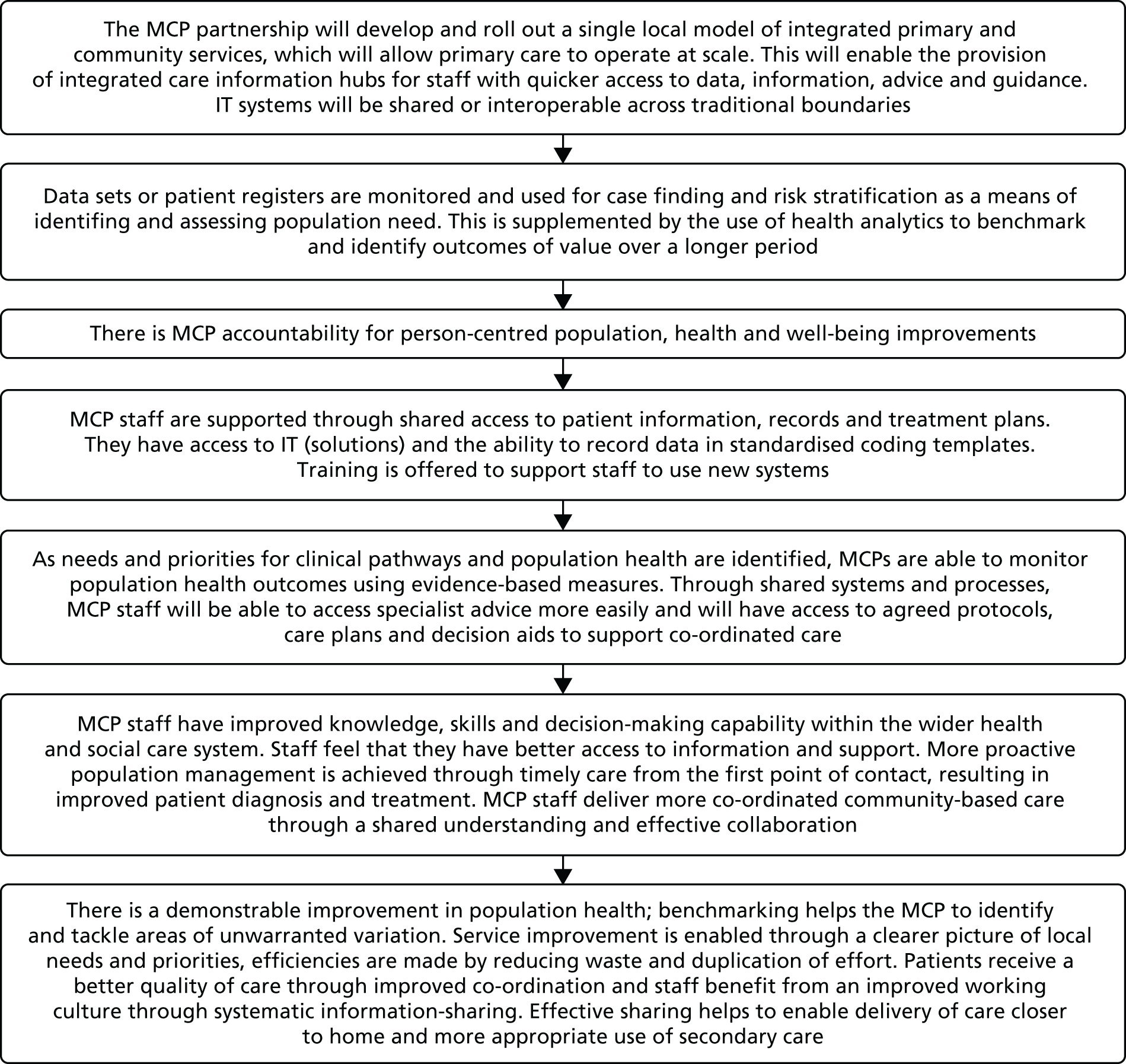

Finally, a sixth quadruple aim framework was identified to capture the intended outcomes, namely, patient experience; the health of the population; health-care costs; and staff experience. 17 The chosen frameworks each contributed unique elements, and so we followed the approach, previously reported by Carroll et al. ,68 of merging the six frameworks into a single metaframework. Essentially, the best-fit framework provided an additional analytical lens for the data, separate from the realist terminology and principles, and offered resonance with the world view of the stakeholders. By combining the six frameworks within a single metaframework, we constructed both a conceptual map and a vehicle for the organisation and extraction of data (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

Best-fit framework.

Strategy for prioritisation and finalisation of the candidate programme theories

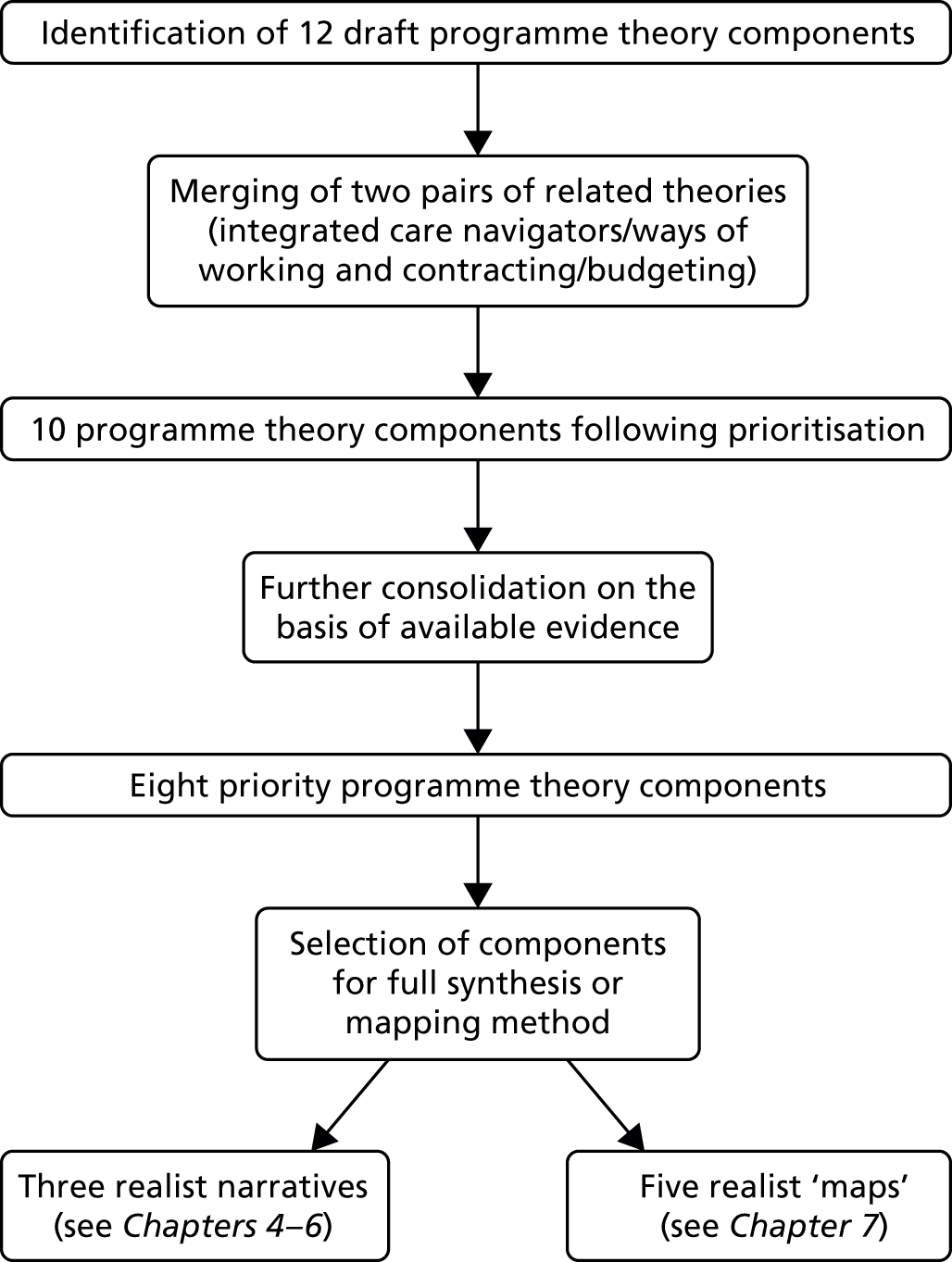

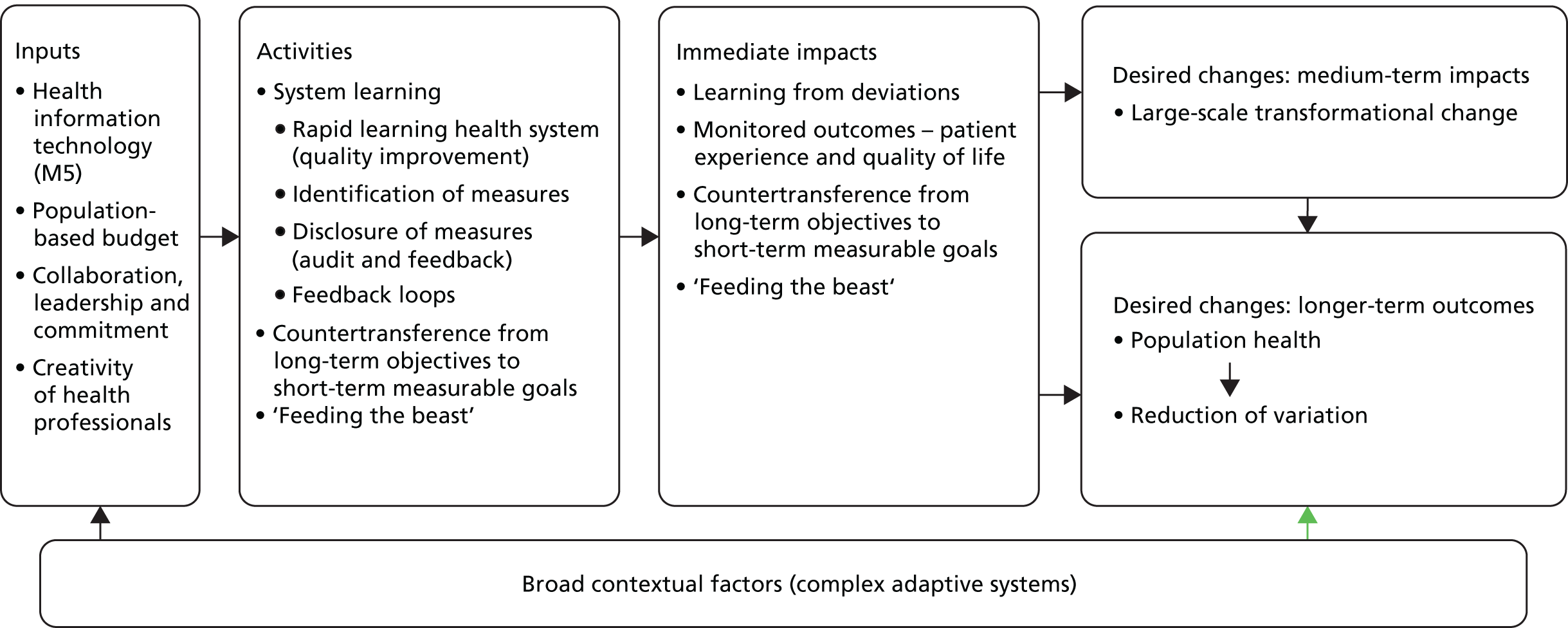

Following the stakeholder workshops, we held a review team meeting to reflect on the issues raised and to agree the focus of the review. We chose not to utilise a formal method of prioritisation, recognising that our stakeholder event had not been organised on representation principles; instead, stakeholders offered valuable perspectives on the 12 individual programme theory components and the composite programme theory (Figure 2). It was interesting to observe a strong consensus on priorities across professional and lay representation, even when more overtly public- or patient-focused programme theory components featured in the candidate list.

FIGURE 2.

Identification and prioritisation of programme theories.

As a result of the stakeholder event, the review team:

-

merged several related programme theory components in which synergies were identified

-

refined the wording of several programme theory components to make them more accurate or salient

-

prioritised several theory components for full realist review, while allocating the remaining theories to a broad focused mapping approach (see Box 1).

The stakeholder group had also initiated an informative discussion on the possible unintended consequences of specific elements of the MCP model; for example, how moving diagnostic services into the community might stimulate increased locality demand with a consequent effect on false positives, referrals and admissions.

A flow diagram and narrative was developed for each draft theory (see Chapters 4–7), which were reviewed with the project advisory group in October 2016. The group was asked to validate theories and to prioritise those appropriate for realist review. This conversation was supplemented with telephone interviews with each of the three MCP leads on the advisory group. From working with the group, we were able to merge two of the theory components (integrated care navigators and ways of working) into one and prioritise three theory components for realist review (see Chapters 4–6 and Figure 2). The group opted to prioritise theory components that represent the more innovative aspects of the MCP model, typically those for which coverage by existing reviews is more limited. We proposed to conduct mapping reviews for the remaining theory components (see Chapter 7) to provide realist-oriented overviews of the key review literature.

We subsequently merged the two theories relating to contracting and budgeting, resulting in 10 theories (four prioritised for realist review, with the remaining six subject to mapping review; see Figure 2). Finally, a detailed examination of the respective evidence bases underpinning the programme theories indicated further commonalities in arriving at the following programme theories (Box 1) for exploration through the theoretical literature and the empirical evidence (three for review and five for maps).

If primary care providers grow (new/expanded roles, additional services, hubs, extended hours) to deliver place-based services, then patients will access more specialist care within community settings.

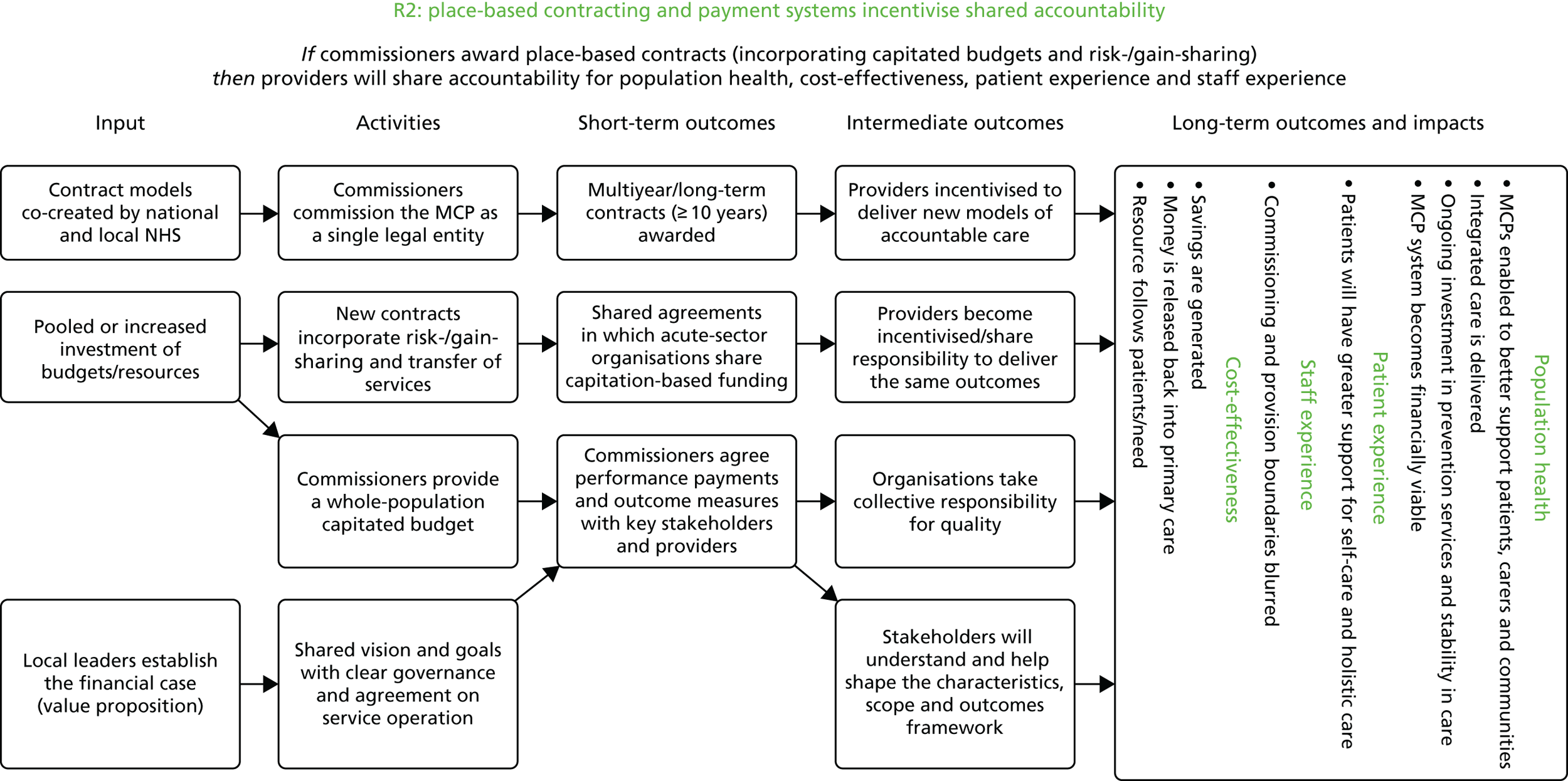

R2: place-based contracting and payment systems incentivise shared accountabilityIf commissioners award place-based contracts (incorporating new accountability and governance models, capitated budgets and risk-sharing), then providers will adopt integrated working.

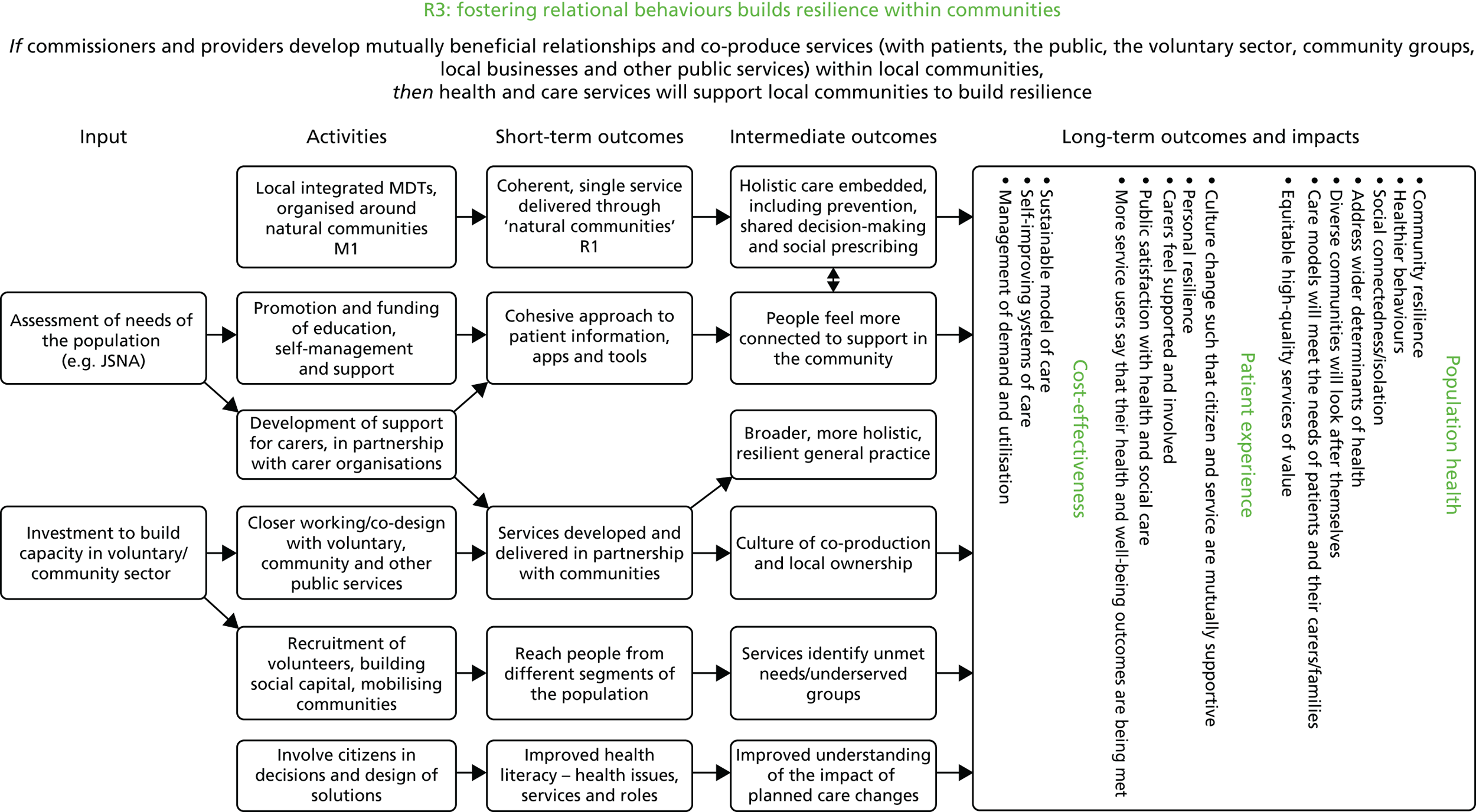

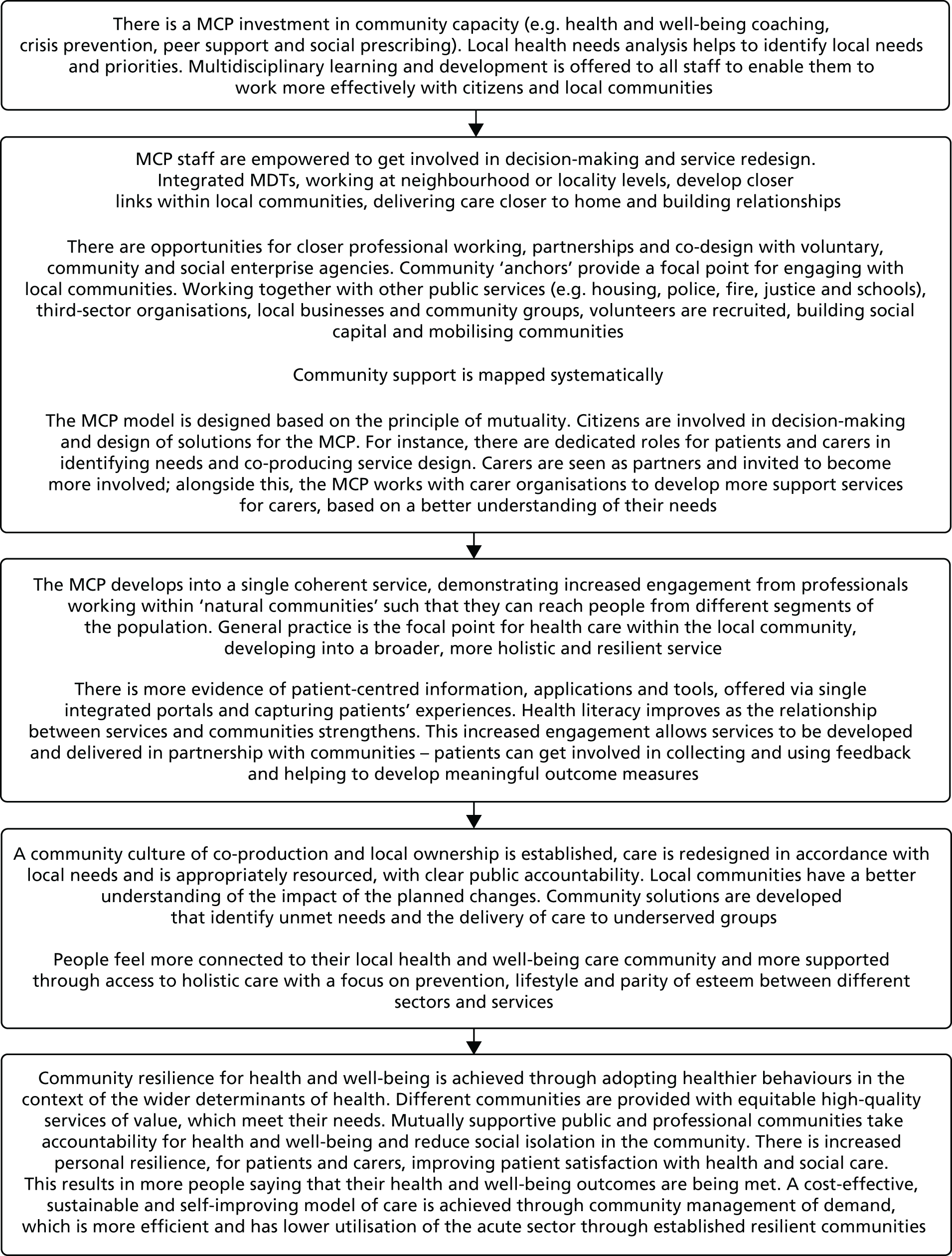

R3: fostering relational behaviours builds resilience within communitiesIf commissioners and providers develop mutually beneficial relationships and co-produce services (with patients, the public, the voluntary sector, community groups, local businesses and other public services) within local communities, then health and care services will support local communities to build resilience.

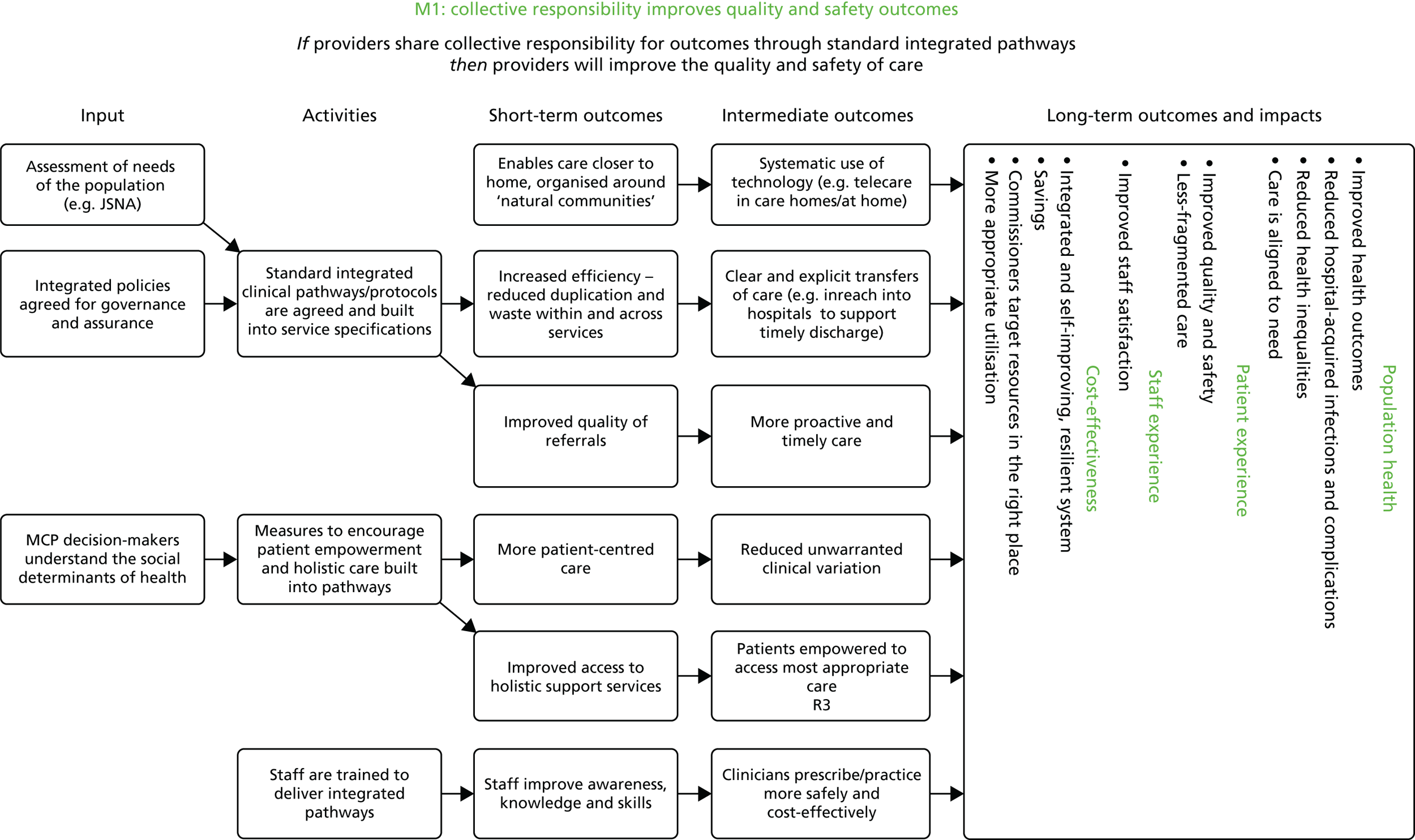

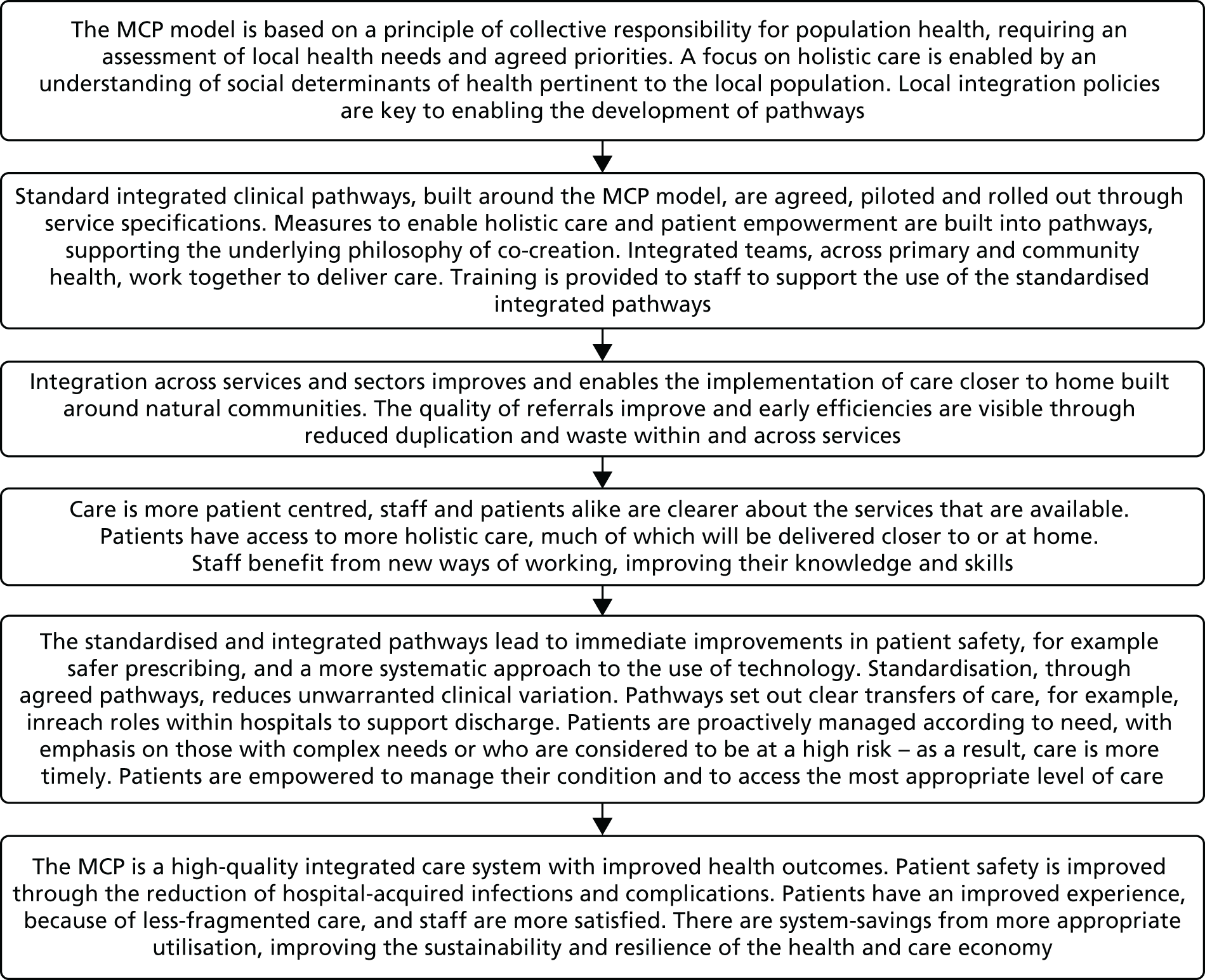

Programme theory component maps M1: collective responsibility improves quality and safety outcomesIf providers share a collective responsibility for outcomes through standard integrated pathways, then providers will improve the quality and safety of care.

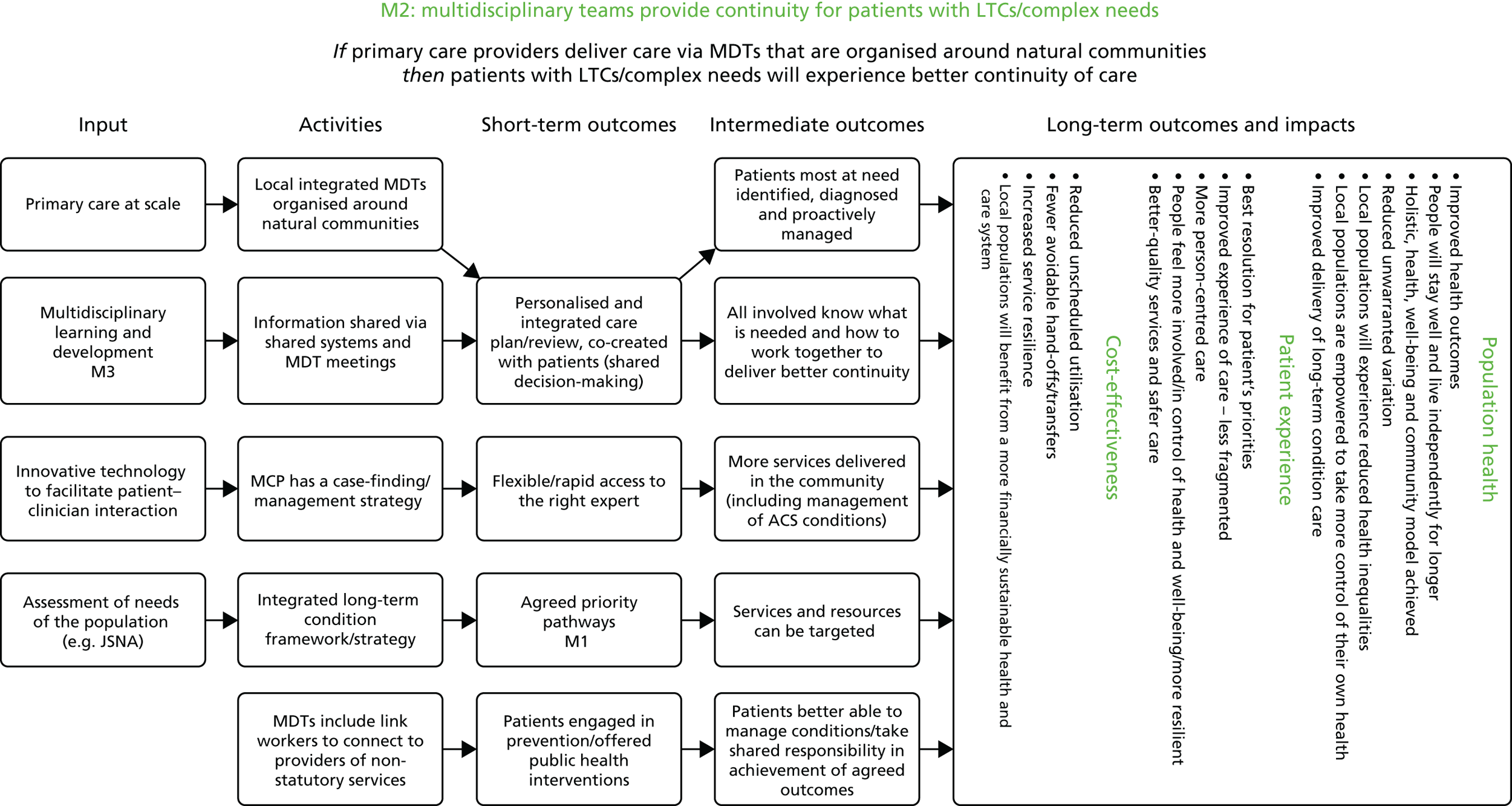

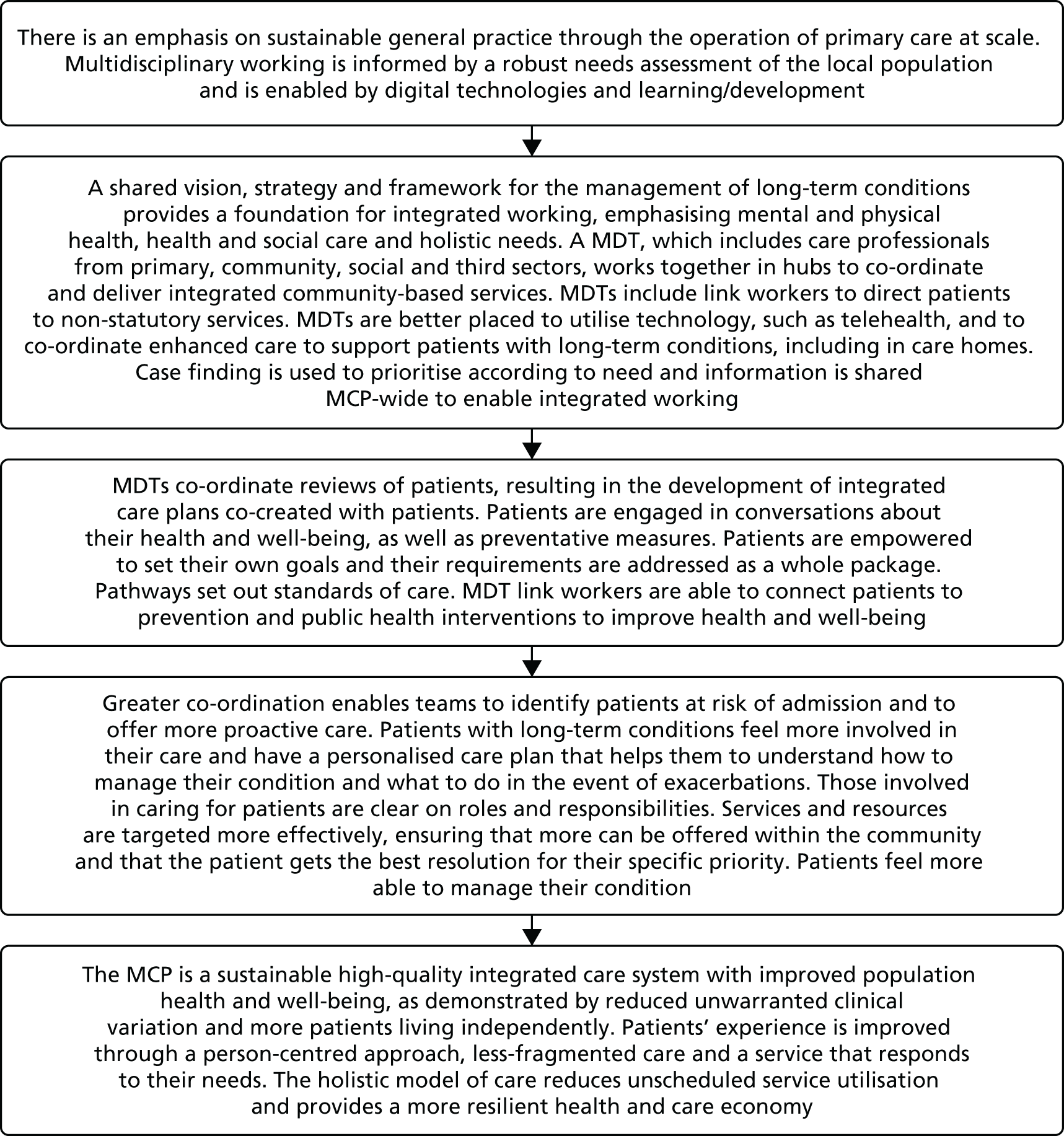

M2: multidisciplinary teams provide continuity for patients with long-term conditions/complex needsIf primary care providers deliver care via MDTs (organised around natural communities), then patients with long-term conditions/complex needs will experience better continuity of care.

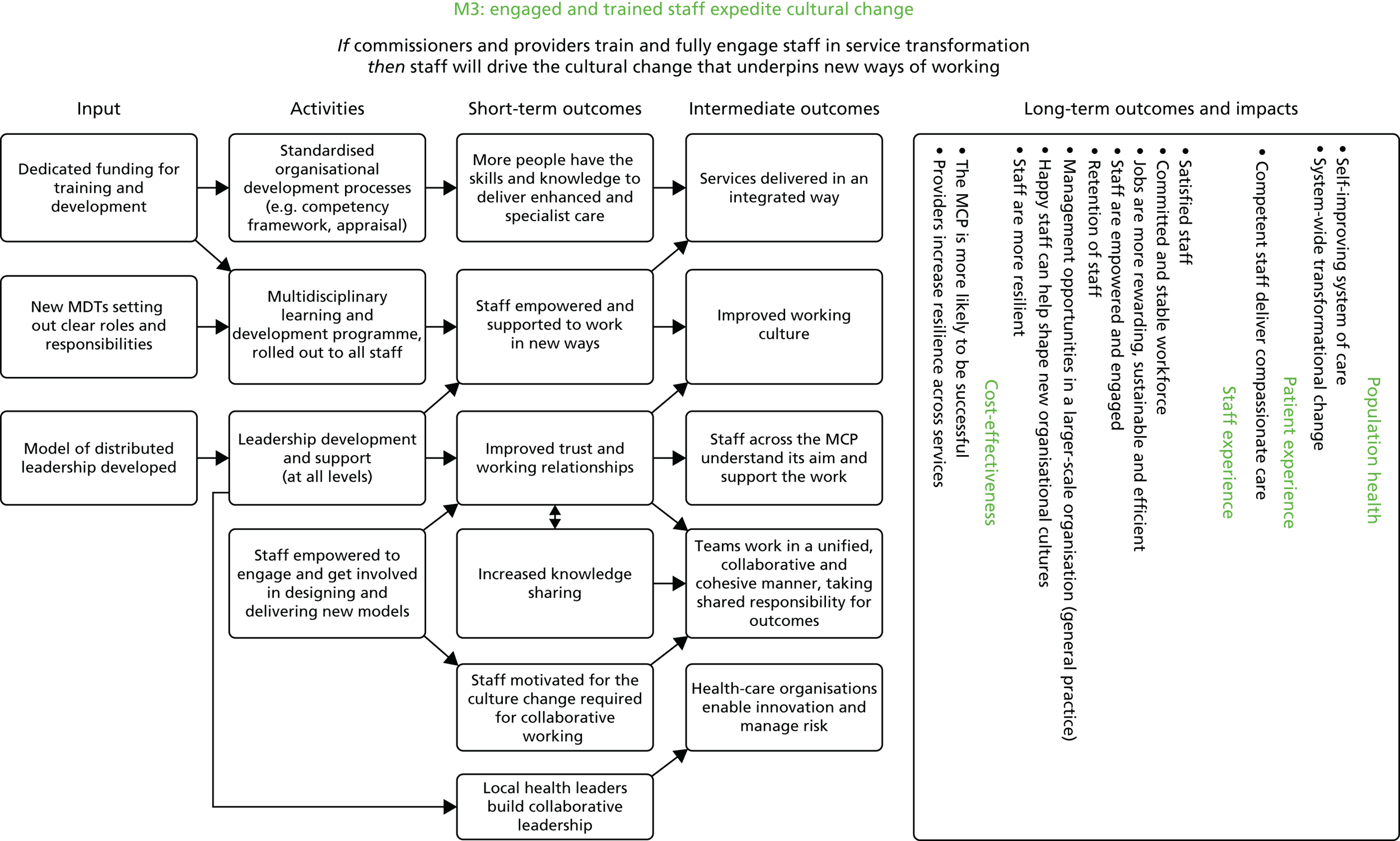

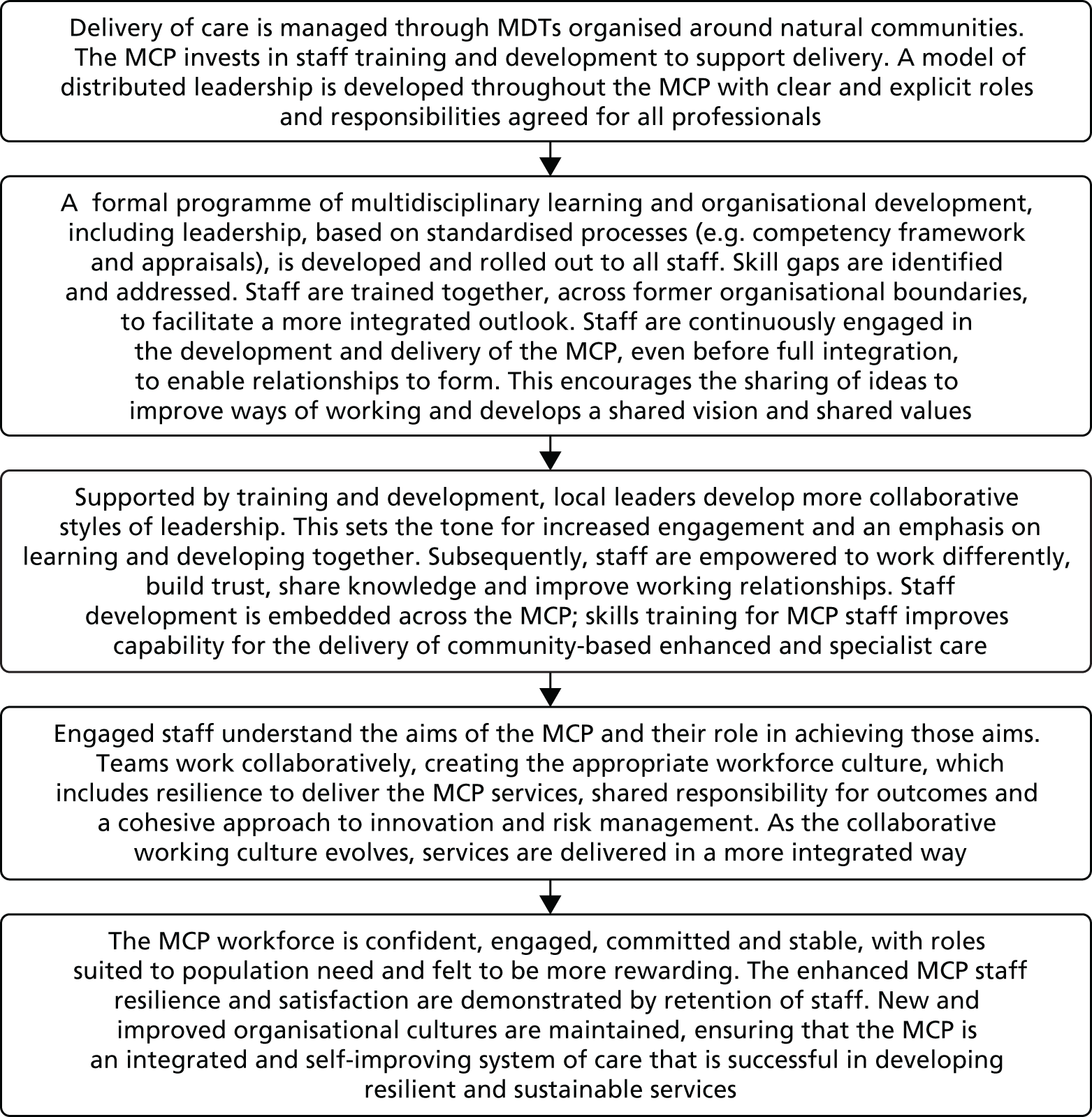

M3: engaged and trained staff expedite cultural changeIf commissioners and providers train and fully engage staff in service transformation, then staff will drive the cultural change that underpins new ways of working.

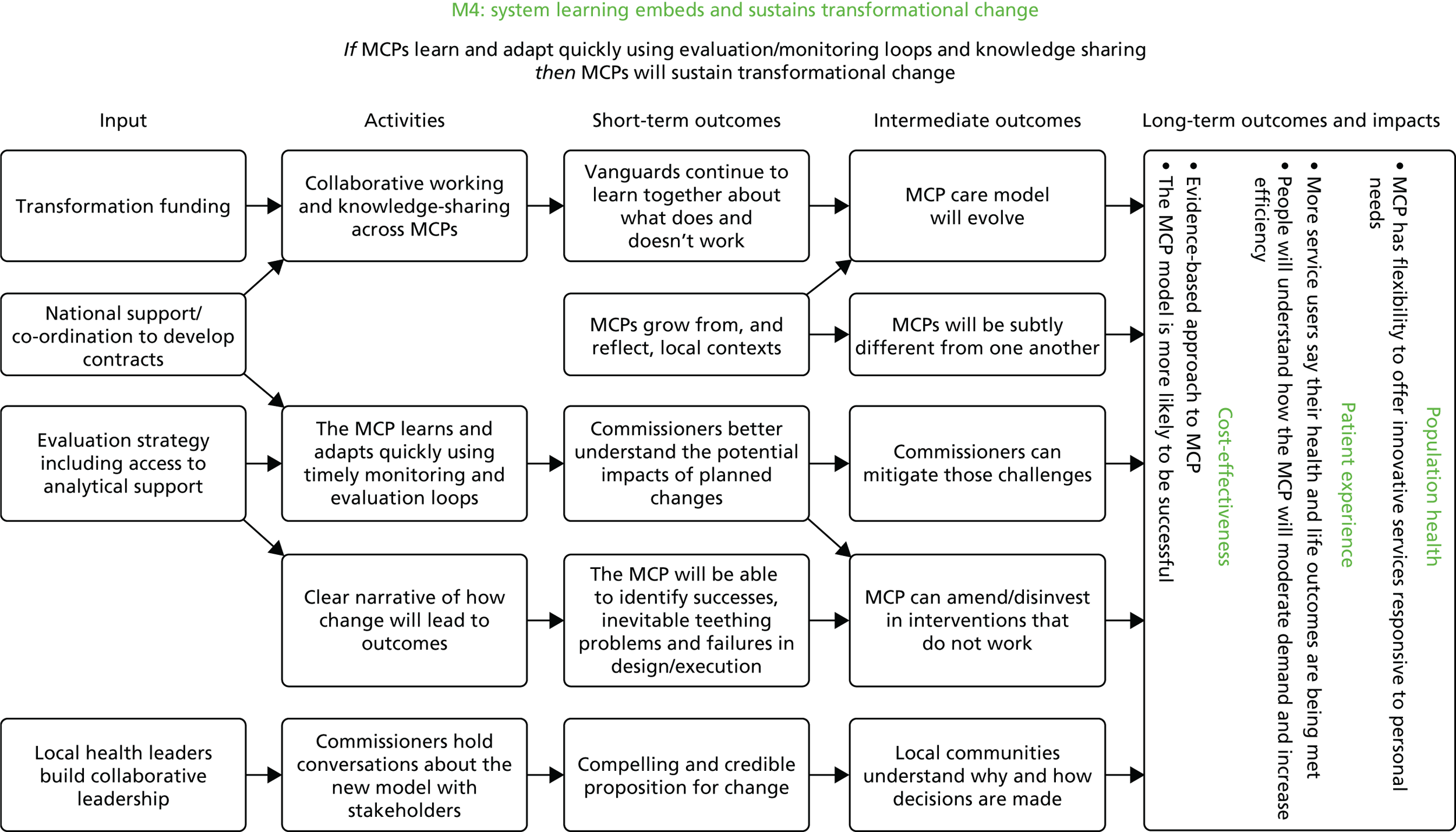

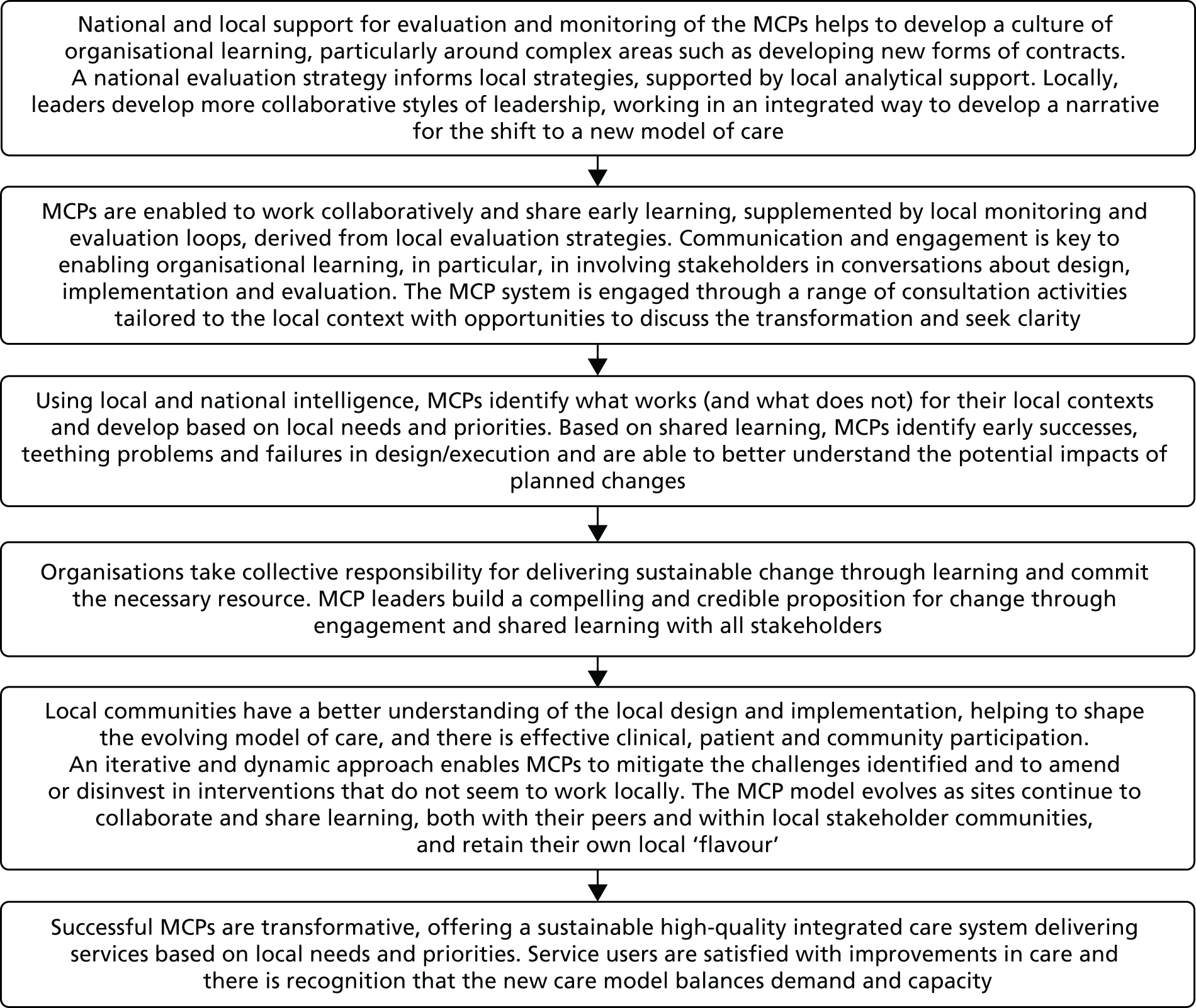

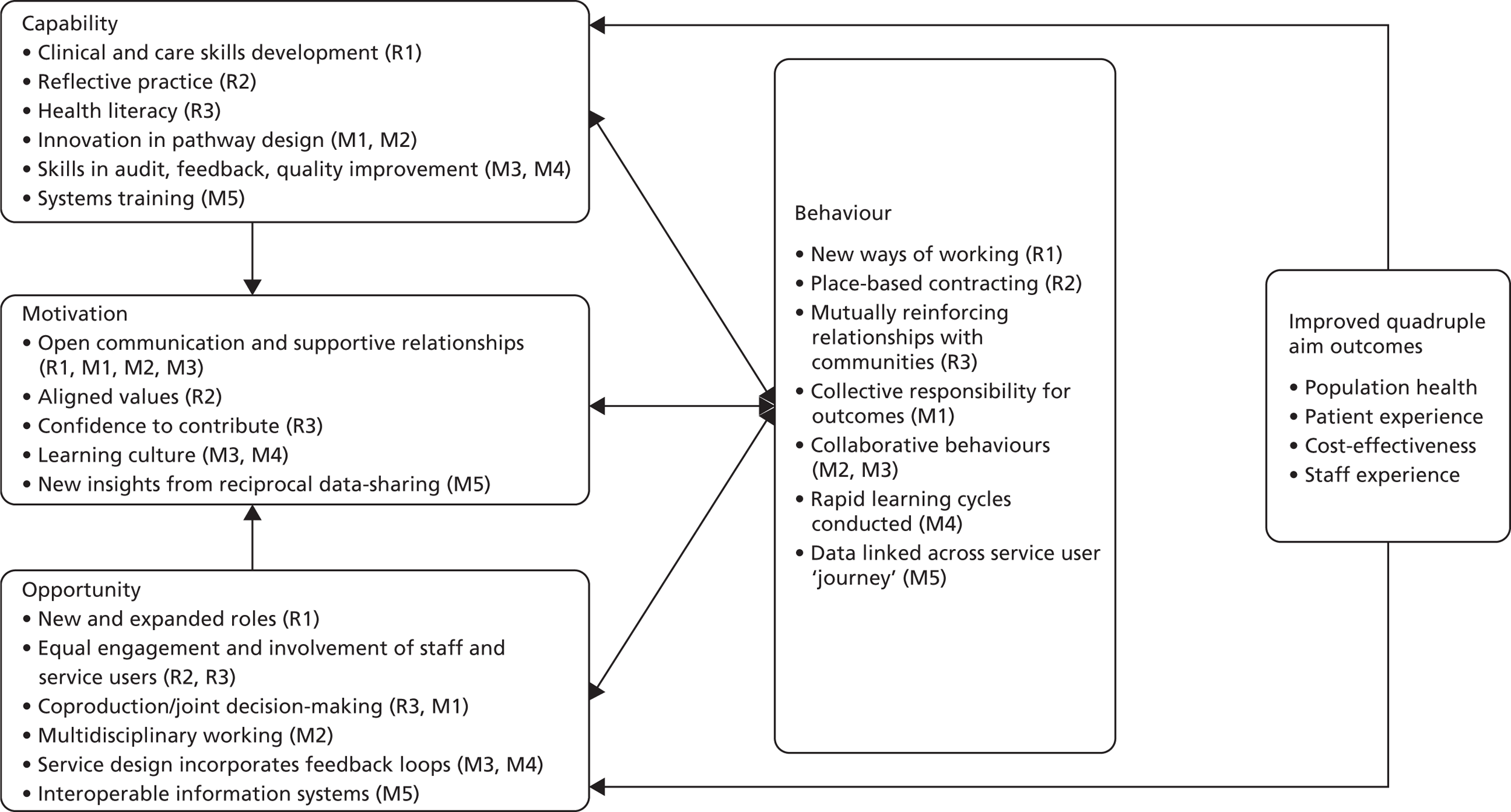

M4: system learning embeds and sustains transformational changeIf MCPs learn and adapt quickly using evaluation/monitoring loops and knowledge-sharing, then MCPs will sustain transformational change.

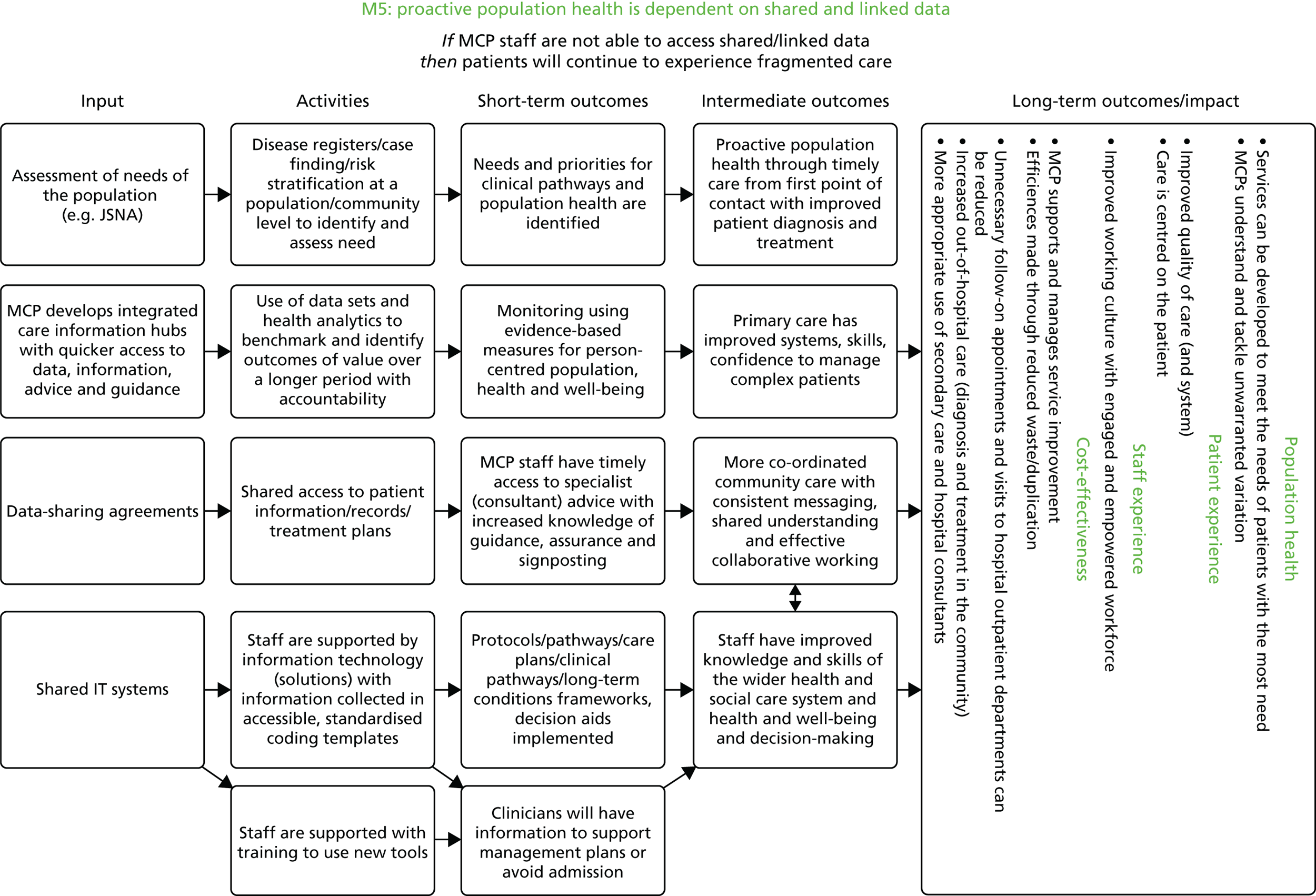

M5: proactive population health is dependent on shared and linked dataIf MCP staff are not able to access shared/linked data, then patients will continue to experience fragmented care.

The draft conceptual model was verified with key stakeholders from within the MCP vanguards and NHSE via individual follow-up telephone interviews (February to March 2017). Advisory group members and wider contacts were thus used to ensure that the model was fit for purpose and meaningful to decision-makers and practitioners.

The methodology we employed offered a systematic vehicle for harnessing the exploratory potential of the realist lens within an accelerated time scale for practitioner benefit. Thematic coding against the best-fit framework allowed us to synthesise the underlying programme theories behind the MCP model by building up causal chains. This was followed by the identification of theoretical, empirical and practice evidence with which to test the programme theories, and appraisal, extraction and analysis of evidence, to include reconciling confirmatory and contradictory evidence.

Identifying and searching for abstract theories

Once the candidate programme theories were finalised, the next step was to seek to make connections between these lower-level service-based theories and higher-level, more abstract theories. This allowed us to develop a series of hypotheses that would be testable against empirical studies identified from systematic searching. More importantly, the level at which such theories operate would make it possible to produce transferable lessons about how, and in what circumstances, new care models produce their intended outcomes.

To identify the abstract theories, we pursued references from within the relevant literature, in particular analyses, commentaries and opinion pieces. This required looking beyond the actual programme theory to identify more specific mechanisms that might be activated by a MCP component (e.g. governance and control, local identity and place, collective ownership). In doing this, we sought to answer such questions as ‘how might we typify this intervention?’, ‘what core underlying idea is at work here?’ and ‘what other interventions are underpinned by similar ideas?’. Several key ideas underpinned more than one of the prioritised programme theories:

-

demand management

-

shared accountability

-

community ownership and resilience.

Abstract theories also emerged from the search for empirical evidence, as described below (see Table 3). Programme theory-related searches do not distinguish between empirical and theoretical literature, so it is efficient to look for examples of each when reviewing identified items. Our systematic approach, utilising Publish and Perish 5.23.9 software [(Harzing.com, Hendon, UK) see Data extraction, quality assessment and synthesis for the realist reviews] represents an improved and more auditable strategy than that used in comparable projects, such as screening the first five pages of Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) results. 63

Searching for empirical evidence and selection of studies

The next stage of our realist synthesis involved searching for empirical evidence in order to test and refine our programme theories. Following initial validation and prioritisation of the programme theories, we translated key concepts into a search strategy for four core bibliographic databases: MEDLINE, Health Management Information Consortium (HMIC), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) and EMBASE (for a sample MEDLINE search strategy, see Appendix 2). A systematic search was conducted to identify research- and practice-derived evidence produced between January 2000 and December 2016. Given that we were unable to identify a specific date from which the forerunners of the MCP model became apparent, any date cut-off point should be considered arbitrary. We therefore sought to achieve a balance that captures the historical legacy of a variety of MCP models, but which focuses on contemporary evidence. We considered that the team would be able to implement a cut-off date of 2000 in a more consistent manner than by calculating a 15-year cut-off date. The bibliographic databases searched included MEDLINE, PreMEDLINE, CINAHL, EMBASE, HMIC and The Cochrane Library, together with grey literature sources, such as The King’s Fund and the Nuffield Trust.

A search strategy was developed by qualified information specialists within the review team to identify published studies against which to test our theories (see Appendix 2). Candidate search terms were identified by analysing documentation, including logic models, from the MCP demonstrator sites. Terms were reviewed by the review team, with particular support from The Strategy Unit colleagues involved in supporting new care models. Further input came from the advisory group set up to support the synthesis.

The strategy covered all four prioritised theories, to avoid potential duplication from running separate searches. Results were screened and supplemented with searches of grey literature sources (see Appendix 3).

Test screening of a single set was initially performed independently by both screeners for 25% of the included records (Table 3). Regular debriefing sessions were held after each batch of records (e.g. after the first 100) to ensure ongoing consistency and identify any systemic reasons for disagreement. As the review team became more sensitised to the types of evidence available, this figure was downgraded to 20% for the remaining batches. Once acceptable agreement was reached, screening proceeded on an individual basis. Test screening was undertaken in batches to check consistency first. Disagreements were referred to one of the principal investigators.

| Broad themes | Number of records screened | Test screening percentage | Screeners |

|---|---|---|---|

| Access | 7965 | 25% (n = 1992) | Three pairs/six screeners |

| MCP | 2230 (2160 from searches, plus 70 additional records) | 25% (n = 558) | One pair/two screeners |

| Community | 8772 | 20% (n = 1755) | Two pairs/three screeners |

| Contracting | 2695 [original total of 2741, but identified 46 duplicates in Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA)] | 20% (n = 540) | Three pairs/three screeners |

| Ways of working | 8843 | 20% (n = 1770) | Three pairs/three screeners |

Data extraction, quality assessment and synthesis for the realist reviews

To address the study questions, we sought a recognisably vast and diffuse evidence base with literature comprising four main types:

-

before-and-after studies or interrupted time series from previous or current initiatives [i.e. MCPs or forerunners, such as ACOs (in the USA)]

-

descriptive reports/case studies of current MCP initiatives, offering contextual detail and programme theory

-

commentaries, editorial and opinion pieces on the characteristics and rationale of MCPs and their forerunners

-

policy documents (e.g. from NHSE). 61

For all types of evidence, we focused on their theoretical or contextual contribution, recognising that formal quality assessment of such heterogeneous items would be of little value. For conceptual and contextual types of evidence, we employed a reflexive approach to locate the contribution of each item within the overall body of evidence and to assess its specific contribution.

Our quality procedures were strengthened by an iterative, purposive search for additional confirmatory or disconfirming evidence. Our overall method for quality assessment therefore acknowledged the trade-off between relevance and rigour. 71 In doing this, we sought to clearly identify whether materials had been selected for rigour, for context or for conceptual contribution. In addition, the quality and relevance of the evidence was assessed during the synthesis process, as each lead author weighed up how each individual item contributed to the development of the overall narrative account and to the review question and aims. This approach, which contrasts with the processes of formal quantitative study appraisal, is common within more interpretive synthesis methodologies. 92

Literature of interest could pertain more widely to large-scale transformation as effected by, for example, ACOs (see Chapter 1), or broadly to the different new care model initiatives launched under the FYFV,1 or it could relate specifically to the MCPs. We anticipated generic difficulties with searching for complex social phenomena,93 together with specific difficulties in searching for terms associated with integrated care,94 and thus placed particular emphasis on following up reference lists and conducting forward citation-searching to identify additional evidence. We also anticipated a limited literature examining UK-based MCPs and, therefore, sought to broaden the usefulness of the review by exploring the ‘intellectual heritage’ of the MCP model61 as identified in Chapter 1. In interpreting ‘evidence’, we adopted Williams and Glasby’s95 definition from the management domain, comprising empirical evidence from research; practice-based and experiential evidence from service delivery; and theoretical evidence. Consequently, our search strategy sought to include research studies (trials and reviews), service evaluations and case studies, in addition to thought-leading papers.

For the full realist reviews, we grouped studies together by programme theory. Each item of evidence was used to test the individual programme theory component and the degree to which studies supported, nuanced or challenged that theory. Each review was written up as a narrative account, following the example offered in previous commissioned realist syntheses. 63 As described in Strategy for prioritisation and finalisation of the candidate programme theories, this provides a transparent and auditable account of how each study contributed to theory testing, while allowing the reader to engage with the study findings and our interpretations of them. This process also allowed us to assess the quality of studies supporting, or contradicting, each programme theory component. We offer a summary of the theories in the next chapter before proceeding through each of the realist reviews and realist mapping reviews in turn, in the subsequent sections of the report.

We were aware that relatively few papers within our wider systematic search of related literature looked specifically at the characteristics of MCPs.

The development of the search strategy was iterative; as further keywords were identified within the accompanying narrative, each programme theory component lead ran supplementary search strategies to identify further relevant material. Materials were sifted by each reviewer, and references were privileged, first by relevance (e.g. UK based and contemporary), and then by their reach and significance (i.e. systematic reviews, multiple case studies to increase generalisability). As this was an interpretative and theory-testing review, the emphasis was on indicative evidence that could offer insights, rather than a comprehensive and exhaustive identification of the literature.

Our preferred pragmatic approach to data extraction was to use Google Forms (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA), rather than NVivo (QSR International, Warrington, UK), which has been used by comparable teams. 63 This enabled us to collate, categorise and code information more rapidly, using drop-down categories in recognition of the specific mapping role of these reviews. This approach allows for a formative assessment of review categories and the contributions of literature extracted to date, and identifies gaps for further purposive searching. This approach also enabled us to itemise mechanisms and outcomes, and to map the papers that address these mechanisms and outcomes. A prototype form was developed and tested, incorporating the data extraction logic of ‘confirming/negating/modifying evidence’ from a previous comparable review. 70 One form was completed for each paper.

Data extraction, quality assessment and synthesis for the mapping reviews

For each of the four mapping reviews, we started with a core set of documents (step 1). We then used accepted ‘pearl-growing’ and ‘citation-chasing’ strategies96 to follow up citations and references (step 2). As the intention was to describe and engage with relevant bodies of literature, illustrated by substantive contributions, rather than analysing and interpreting the findings, we did not seek to be comprehensive. We accept that other relevant items could be identified, but we believe that our focus on reviews, overviews and key empirical studies offers a structured foray into these contiguous fields. This interpretive process was selected to correspond to the underlying intent of the overall review methodology and, therefore, contrasts with the more familiar aggregative search procedures utilised by a systematic review. Nevertheless, the search procedures were designed to be auditable, reproducible and ‘systematic’, utilising structured search software (the use of Publish and Perish is described later in this section).

Finally, as particular themes or intervention components were identified, we sought to purposively identify reviews from the broader literature (step 3). Given that the separation of the overarching programme theory into component programme theories and the relative emphasis of review and mapping approaches was decided on primarily pragmatic and logistic grounds, we sought to be as parsimonious and efficient as possible (e.g. when a paper contributed to multiple component theories, one person read it and extracted data for the benefit of the other analytical subteams).

We used a formalised process for searching Google Scholar using the freely available Publish or Perish software to identify, capture and document citation patterns. This process augmented the necessarily limited searches of title and abstract that characterise systematic reviews. We had already identified in our protocol the need for broad full-text searching to identify concepts otherwise buried within journal articles, books or reports. An exemplar for M7 is shown in Table 4.

| M7 system learning embeds and sustains transformational change | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| If MCPs learn and adapt quickly using evaluation/monitoring loops and knowledge-sharing, then MCPs will sustain transformational change | |||

| Concepts | Concept 1 | Concept 2 | Number of references |

| MCPs | Training | 31 | |

| MCP | Training | 59 | |

| MCPs | Transformational change | 59 | |

| MCP | Transformational change | 33 | |

| MCPs | Organisational learning | 22 | |

| MCP | Organisational learning | 61 | |

| Total before removal of duplicates | 264 | ||

| Final total | 99 | ||

Papers identified from the new care models systematic searches (see Table 3), together with the results of individual forays into the literature (pursuing references, citation searches and full-text Google Scholar searching), were initially mapped to any of the component theories identified by the review team. For data extraction, in contrast with the extraction approach used for the reviews, our realist mapping methodology looked for the presence of key contributions to the programme theory, either in supporting or contributing additional insights or nuances (e.g. around the influence of context), or by negating or challenging the theory. A sample data extraction form can be found in Appendix 4.

Follow-up to realist reviews and realist maps

Once a preliminary analysis had been undertaken for a substantive proportion of the realist reviews and maps, the team convened a stakeholder event in Birmingham in May 2017. This small group event targeted MCP vanguard sites, together with the project advisory group members.

In accordance with the NHS Health Research Authority’s statement on public involvement, members of the public/NHS staff were involved in the research process as part of the planning and design of this review. They helped to co-produce the findings, rather than the event being to/for/about them. Our focus group was conducted with members as ‘part of an advisory group, providing valuable knowledge and expertise based on their experience’97 and thus, their involvement did not require ethics approval. This was confirmed by the Health Research Authority’s decision tool assessment. 98

We invited advisory group members, MCP vanguard teams and other stakeholders who had been in contact with the project via related communication activities. On the day, 11 attendees participated, in addition to seven members of the core project team. Of these, two individuals were patient and public involvement (PPI) representatives; three represented commissioners; three came from MCP sites; two were communications specialists; and one was a NHSE lead. We chose a central Birmingham venue because of its accessibility and convenience for many of the 14 MCP vanguards.

The purpose of this event, using focus group methodology, was to explore three key questions:

-

Can community-based, co-ordinated care manage demand?

-

Can place-based contracting and payment systems incentivise shared accountability?

-

Can partnerships with community groups, local small and medium-sized enterprises and other public services build community resilience?

Designed in the format of a focus group and influenced by the realist interviewing technique,99 this stakeholder event offered an opportunity to test and validate the finalised programme theory components and emerging findings with key stakeholder groups. On the day, the project lead and other core team members delivered an introduction to the project (aims/objectives/progress to date) and then walked attendees through the emerging findings for each of the three theory components (R1–R3). Participants were then invited to join a discussion on a relevant theory component. Permission was obtained to record the three discussions, subject to good data management procedures and the lead for each theory component then summarised the group’s responses to the articulated theory and emerging findings (i.e. whether or not these were complete and accurate and whether or not findings resonated with their experience in their various contexts).

As a result, the team was able to collect and analyse a broad range of insights from participants, including decision-makers and operational staff from current and planned MCPs; research and support services staff; and PPI representatives.

Chapter summary

In this chapter, we have described the iterative process through which we integrated data from the preliminary logic models with insights from stakeholders and broader findings from the literature. In following the RAMESES guidelines,62 we have sought to make the process as transparent as possible. We have explained our reasons for selecting a realist review methodology, and described how we searched for programme theories, how we selected our programme theories, how we identified and selected papers and how we synthesised the papers.

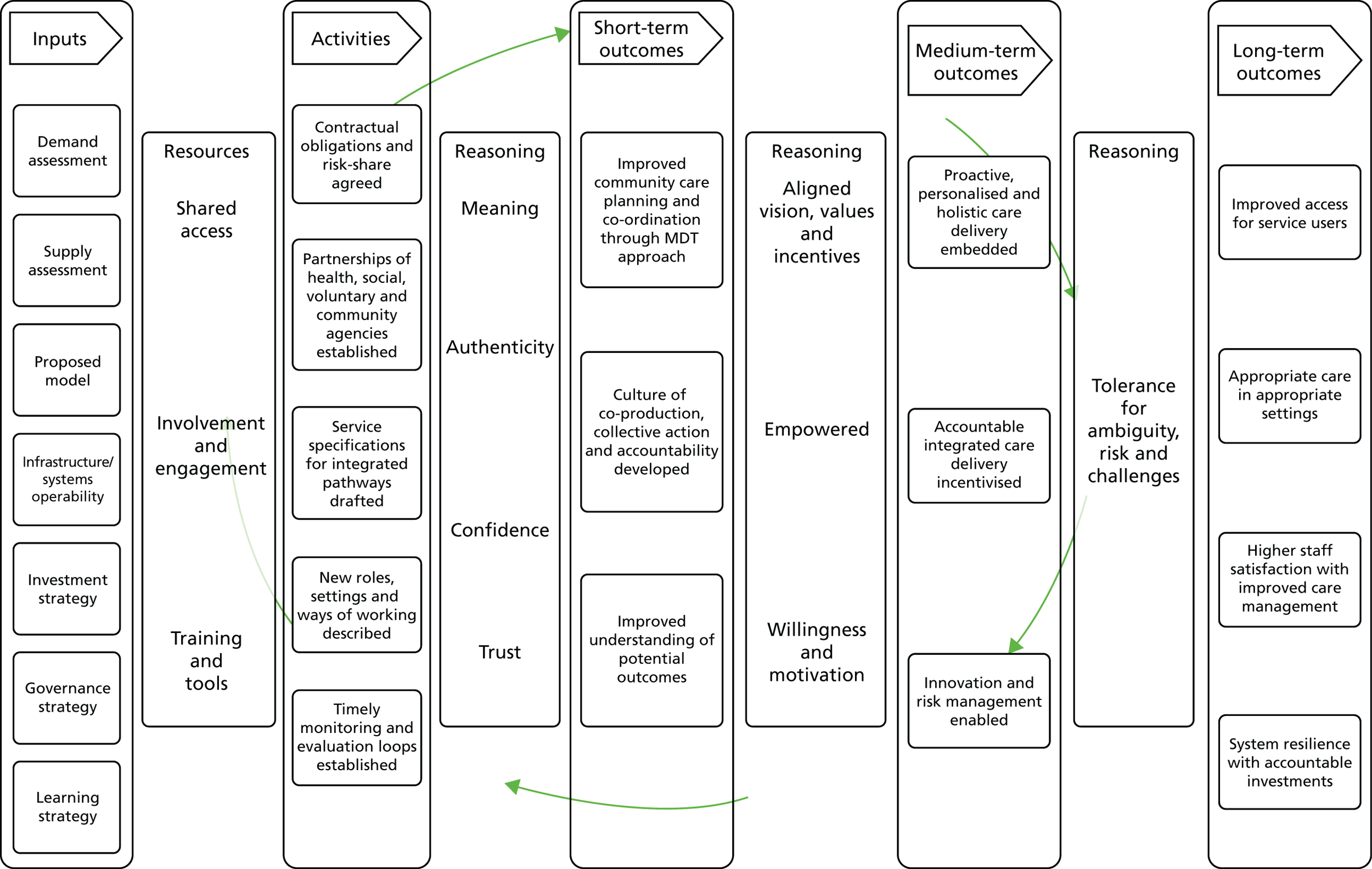

Chapter 3 Programme theory

In Chapter 2, we set out the methodology for deriving the eight programme theory components (Box 2). In this chapter, we describe our understanding of these final refined programme theory components (see Box 2), illustrated by selected quotations from MCP vanguard logic models. These components have been gleaned from the analysis of individual logic models to capture causal links, through if–then statement extraction, followed by reconstruction of causal pathways, according to common themes. The logic models prepared by the MCP vanguards varied greatly in terms of the granularity and depth of detail, perhaps reflective of the maturity of the transformation programmes; those which were building on a legacy of earlier initiatives, such as GP Access Funds31 (previously known as the Prime Minister’s Challenge Fund), typically comprised multiple models to represent key activities.

R1: community-based, co-ordinated care is more accessible.

R2: place-based contracting and payment systems incentivise shared accountability.

R3: fostering relational behaviours builds resilience within communities.

M1: collective responsibility improves quality and safety outcomes.

M2: MDTs provide continuity for patients with long-term conditions/complex needs.

M3: engaged and trained staff expedite cultural change.

M4: system learning embeds and sustains transformational change.

M5: proactive population health is dependent on shared and linked data.

The MCP programme theory components encompass an intricate set of overlapping activities and assumptions, highlighting the inherent interdependencies within such a complex service transformation. It is important to note that this complexity is evident in the design of the MCP vanguards and is described in the logic model narratives. For example, the Principia MCP describes the engagement of patients in self-care as a strategy for reducing demand on community-based services, with the aim of releasing capacity within community services, to accommodate a shift from hospital-based to community-based care, and within hospitals to build excellence within core services. 100

Dudley CCG’s approach reflects the different needs of different groups, but with a common focus on access, co-ordination and continuity of care, advocating a central role for primary care in driving integration of care across services. 101

The programme theory components are notable in their coverage of both interventions (what MCPs will do) and ways of working (how MCPs will design and deliver services). The components relate to interventions, such as new contracts, as well as behaviours, such as community involvement. The permutation of activities is shaped by contextual factors, which differ across the 14 MCP vanguards. The documentation associated with MCP logic models recognises enablers of, and barriers to, change but makes little explicit reference, with limited exceptions, to what might be referred to, in realist methodology, as mechanisms.

As described in Chapter 1, the new care models formed an integral part of the FYFV vision,1 signalling a more explicit shift towards system-wide and place-based transformation. As implementation progresses, commentators have advocated a focus beyond integration to a more cohesive approach to population health. 102,103

In this chapter, the underlying logic of each theory component is described further and depicted in a logic model representation, with an accompanying narrative. These were originally developed for stakeholder engagement activities during the study. From MCP vanguard documentation, it is clear that thinking has been influenced, to an extent, by legacy models within the NHS and international models of care; we have indicated models we believe to be pertinent to the various programme theory components.

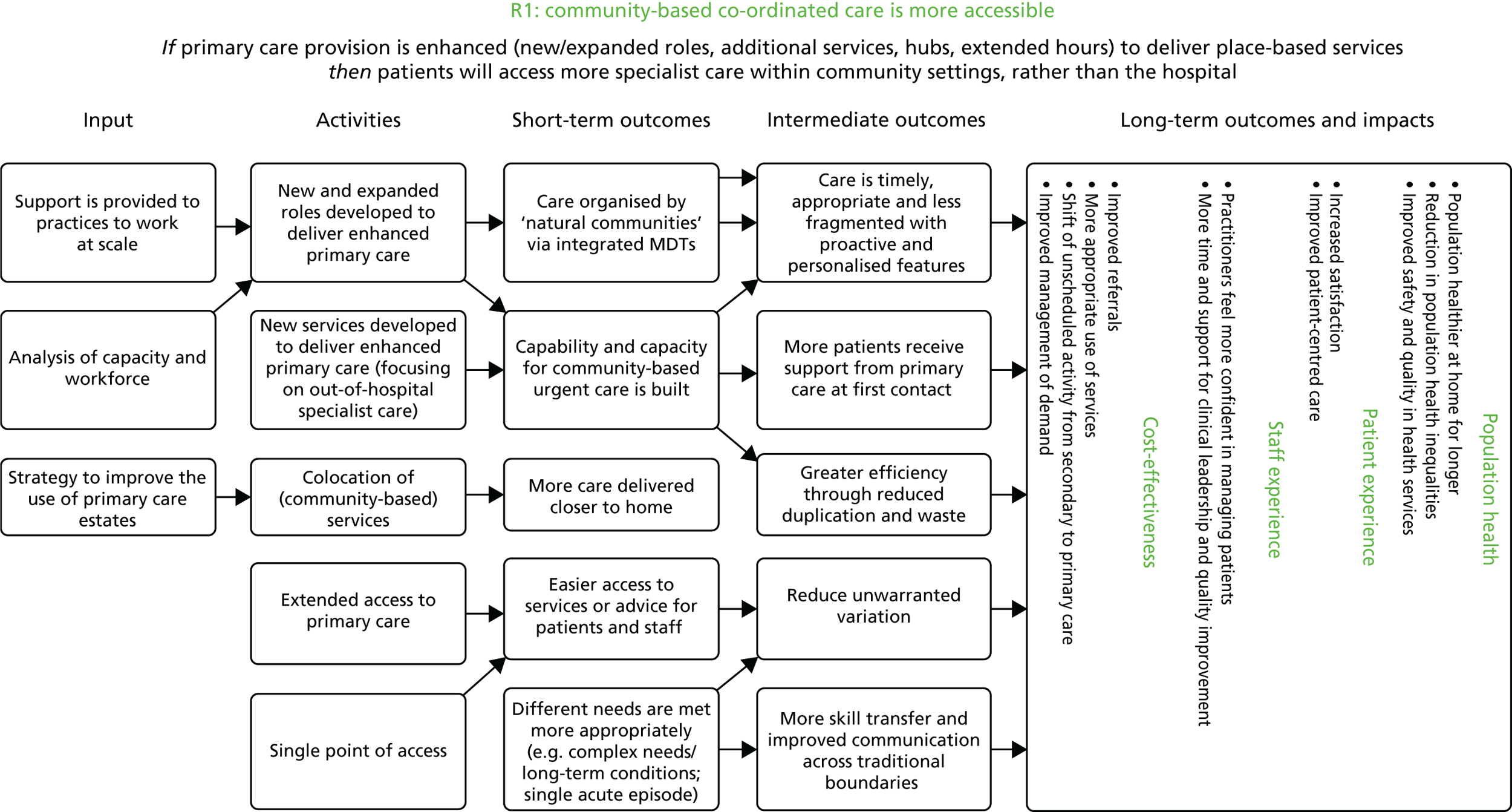

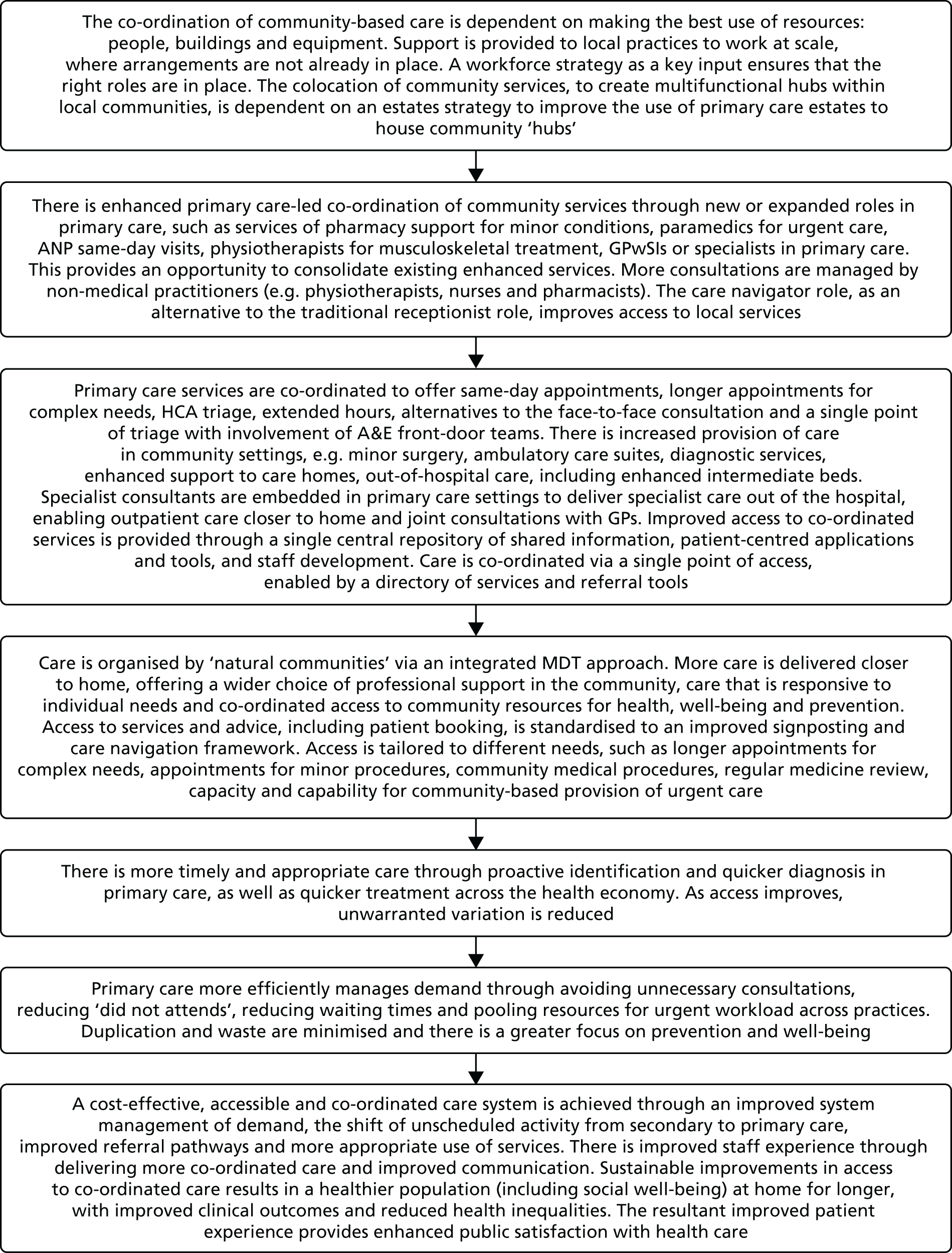

R1: community-based, co-ordinated care is more accessible

If primary care provision is enhanced (new/expanded roles, additional services, hubs, extended hours) to deliver place-based services then patients will access more specialist care within community settings, rather than the hospital.