Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 15/77/10. The contractual start date was in August 2016. The final report began editorial review in August 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Andrew Booth is a member of the National Institute for Health Research Complex Review Research Support Unit funding board.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Baxter et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Rationale

It has been argued that the growing financial and service pressures in the NHS cannot be tackled without transforming how health and social care are delivered. The NHS Five Year Forward View1 sets out a view on how services need to change and what models of care will be required in the future, with a common thread being the need to break down barriers between services through greater integration of care. 2 It is proposed that there should be new networks of provider organisations (organised horizontally as multispecialty community providers or vertically as primary and acute care systems), which form the bedrock of provision. 3 Thirty-seven ‘vanguard sites’ have been identified to develop and test new models of care, including enhanced health in care homes and new approaches to urgent and emergency care as well as multispecialty community providers and primary and acute care systems. The rationale underpinning the development of the vanguard sites programme is to evaluate a small number of different models while allowing flexibility in the way that models are implemented to meet local needs.

A study by The King’s Fund4 highlighted that change was needed at a whole-system and governance level, with the development and rapid implementation of integrated models of care requiring resources and expertise from across the local health system. This primarily qualitative work analysed five case study sites that have developed more integrated models of care. The significant barriers to implementing changed systems included a lack of clarification of roles and responsibilities, competition for funding and challenges in engaging primary care providers. The authors of this work also highlighted that ‘one size does not fit all’, with different models developed at each of the case study sites. Common themes regarding the requisite types of changes included delivering more care beyond the hospital walls, changing the future size and shape of acute hospitals, an increased role in prevention and population health and new organisational models with local partners.

Other studies5 have similarly reported that cultural and structural barriers have proved difficult to overcome in the drive to provide integrated care. A key challenge is to create an environment of collaboration between all providers, including primary and secondary care providers. 3 Authors have highlighted the need for greater understanding regarding how integrated care can be best delivered, and a requirement for further clarity regarding how new models of integration may have an impact on patient outcomes. 6

It has been suggested that models from the USA, such as Accountable Care Organizations, may be useful frameworks from which the NHS can learn. However, it is important to consider the difference in contexts before implementing the same models in different areas. 5 The NHS vanguard sites have been encouraged to develop new models of care by adapting systems to local needs and configurations. 7 However, commentors note that although individual models should be rooted in local communities and have a ‘local resonance’, it is important to identify simple standard approaches and products that can be replicated across the country. 7

The proposed study intended to add to the existing body of knowledge by providing a critical summary of the international literature on new models of care. The review of the literature aimed to provide knowledge regarding key ingredients of care models and identify best practice and areas of learning that may be important in contributing to the success of a programme. It also intended to detail potential outcomes and impacts reported in the literature, which would inform the planned multifaceted approach to the measurement and evaluation of new care models in the NHS.

The proposed methods to synthesise the review findings and add to the body of knowledge were selected to illuminate complex pathways between models of care and long-term health impacts. The work aimed to provide an accessible summary of the literature and inform the logic models being developed within vanguard sites. The proposed study particularly sought to analyse factors related to generalisability and applicability in order to provide key information to commissioners, service managers and practitioners regarding the implementation of care models in their local context. The focus of this element of the work was to support understanding of how care models might be replicated in other local care systems.

Objectives

The proposed study aimed to carry out a rigorous and inclusive systematic review of evidence underpinning new models of health care. It had the following specific objectives:

-

To carry out a systematic review of the international literature on new models of health care.

-

To use a logic model method to outline mechanisms of change underpinning the introduction and outcomes from new models of health-care delivery, including potential barriers and facilitators.

-

To explore how the developed model resonates with the views and experiences of key stakeholders.

-

To develop a framework that details factors that may have an impact on the generalisability or applicability of the research literature, and to use this framework to evaluate the models of care reported.

Research questions

The research questions for the study were:

-

What can be learned from the international literature regarding the key elements of implementation and the potential impacts of new models of care?

-

What are the reported mechanisms of change and outcomes and impacts associated with new models of care?

-

How applicable are the findings from the international literature to different local populations and contexts, and how might mechanisms of change operate differently in differing local services?

Changes from the protocol

The study was carried out in line with the protocol.

Chapter 2 Methods

The proposed study combined established systematic reviewing methods for the identification of literature, with innovative methods of analysis and synthesis to examine mechanisms of change, generalisability and the applicability of international evidence to local contexts.

Identification of literature

Search strategy

A systematic search of key health, medical and social care databases was undertaken to identify relevant studies published from 2006 onwards. We searched from this year as a previous review8 is available that included relevant studies published up to 2006. We were aware (and our scoping review had confirmed) that there was potentially an extensive amount of literature available in the area; we intended that, by including previous systematic reviews, we would capture the main findings from primary studies pre 2006.

Search terms included a combination of medical subject heading (MeSH) (health-care reform, organizational innovation, quality improvement, health priorities, Accountable Care Organizations, delivery of health care and integrated) and free-text [care model(s) and ‘new’ service delivery model(s), health-care model(s), transformation of service or care, integrated care, integrated health system(s), vanguard(s), accountable care, future-proofing, service redesign and ‘five year forward plan’] terms, with the search strategy led by the information specialist on the team. An outline of the search strategy is provided in Appendix 1. The search was limited to studies of humans and those that were published in the English language.

Sources searched

Searches were conducted in the following sources between September and October 2016:

-

MEDLINE via OvidSP (1946 to September 2016)

-

MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations, MEDLINE Epub Ahead of Print and MEDLINE without Revisions via OvidSP (2013 to September 2016)

-

EMBASE via OvidSP (1974 to September 2016)

-

Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature via EBSCOhost (1981 to September 2016)

-

PsycINFO via OvidSP (1967 to September 2016)

-

Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews via The Cochrane Library (2005 to September 2016)

-

Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects via The Cochrane Library (1994 to April 2015; no longer updated, archive only)

-

Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials via The Cochrane Library (1898 to September 2016)

-

Health Technology Assessment database via The Cochrane Library (1989 to September 2016)

-

Science Citation Index via Web of Science (1900 to September 2016)

-

Social Sciences Citation Index via Web of Science (1956 to September 2016).

The search process was recorded in detail, with lists of databases searched, date of search, limits applied, number of hits and duplication as per Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines.

In addition to standard electronic database searching, other iterative searching techniques were employed, including citation searches of a key review8 and hand-searching of the reference lists of primary studies and other reviews. We searched for grey literature using reference lists and UK websites including those of The King’s Fund [www.kingsfund.org.uk (accessed 3 October 2017)] and NHS England [www.england.nhs.uk (accessed 3 October 2017)]. In May 2017, we conducted a citation search to identify any further literature that might have appeared subsequent to the formal bibliographic searches.

Study selection

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following criteria were used to set the parameters of the review:

-

Target population – patients receiving a health-care service and staff delivering services.

-

Target interventions – numerous definitions of integrated care are in common use. In 2011, Shaw et al. 9 reported that around 175 definitions and concepts exist. For the purposes of this study, we drew on the work by Shaw et al. ,9 which highlighted the importance of delineating integrated care from integration processes, and we defined new models of care as ‘changes to service delivery which aim to increase integration and co-ordination’. Examples of potential interventions identified in our scoping search that we aimed to include were:

-

interventions with a focus on service redesign/reconfiguration, such as those with a single point of access, joint clinics or sessions, integrated care pathways (ICPs) or relocation of services

-

interventions with a focus on workforce changes, including changed roles, and provision of further education/training to assist workforce change

-

interventions with a focus on the integration of different services or working across service boundaries

-

initiatives to encourage greater co-operation between services (e.g. using common assessments)

-

interventions with a focus on integration of financial strategies

-

information systems or other technology to promote new ways of integrated working.

-

-

Controls/comparators – the review examined interventions with comparator groups (such as care networks) and those with no comparator.

-

Outcome measures – as one of the objectives of the work was to identify and report measures of outcome and impact that have been used in the literature, we made the decision to not specify a priori the outcome measures that would be included. We therefore included studies with any outcome related to the delivery of services (effectiveness or efficiency measures) or that reported an impact on the delivery of patient care or on staff delivering services. These outcomes included quantitative measures, together with views and perceptions of patients/service users, staff and other key stakeholders.

-

Study design – we included systematic reviews, randomised and non-randomised controlled trials, prospective and retrospective cohort studies with and without comparators, and other before-and-after/longitudinal studies. As a result of the increasing recognition that a broad range of evidence is needed to inform the depth and applicability of review findings, the review encompassed both experimental and observational studies, together with qualitative work reporting views of service users or staff delivering services. Descriptive or discursive papers were excluded.

-

Other criteria – we included studies from any of the 35 countries that are members of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, as studies in these developed countries are of most relevance to UK health systems. We examined studies published in English; however, we considered translation if any key international papers that had abstracts in English were identified.

The screening process

Retrieved citations were uploaded to EndNote [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA], and titles and abstracts (when available) of papers were screened by three reviewers against the inclusion and exclusion criteria, with any queries regarding inclusion being discussed by the full team at regular (fortnightly) team meetings. We initially independently blind-screened citations that had been identified in the scoping search (n = 7256) to establish the degree of consensus between reviewers. The level of agreement between the reviewers regarding citations that should be included or excluded following independent sifting was > 95%, with differing decisions related to overinclusion (when one reviewer had inappropriately suggested inclusion) rather than excluding potentially relevant studies. Further screening was therefore carried out by a lead reviewer, and other team members checked a sample of the citations.

During the screening process, we developed a coding list for marking and provisionally categorising citations of relevance, distinguishing studies that appeared to report initiatives or interventions from the UK, reported UK-based qualitative data, appeared to be systematic reviews, and intervention and qualitative studies from other countries.

Following screening of the database, full-paper copies of citations that were identified as potentially relevant were retrieved for systematic screening. Papers that were excluded at this full-paper screening stage, and details regarding the reason for exclusion were recorded (see Report Supplementary Material 1).

The data collection process

Studies that met the inclusion criteria were read in full and a data extraction was completed for each. A data extraction form was developed using the previous expertise of the review team and trialled on a sample of papers of different study designs by each reviewer. The form was designed to be suitable for all types of primary study design, with a slightly modified version being developed for the extraction of systematic reviews. In privileging higher-quality international studies alongside the UK evidence, we carried out a ‘light touch’ extraction for non-UK studies that did not have comparator group designs or were qualitative studies. We identified and noted where these studies provided data that supported our findings, or where additional or contradictory data were present.

We particularly aimed to extract data relating to factors that might influence the applicability of study findings and, therefore, included an item specifically on the context of the study, and also another category for data in which an author had identified factors that may influence applicability or generalisability. We also included an element highlighting reported associations, which was intended to inform the development of the logic model. The extraction tables were completed by one reviewer and checked by a second. The completed extraction forms for each study are available in Report Supplementary Material 2.

Data items

The extraction form collected data on first author/year, study design, sample size, population characteristics (type of group, condition/department, sex, age and other details reported), context, data collection method, outcome measures, type and details of the intervention, summary of results, main author conclusions, reported associations and potential factors related to applicability. The slightly modified systematic review form included the number of studies included in the review and details of countries and other inclusion criteria. We used a ‘light touch’ extraction form for the international non-comparator and qualitative studies (examined later in the process than the UK, international comparator and systematic reviews), which detailed author, study design and participants, with a column for recording data supporting the results from the other included studies and a column for data that were additional or contrasted with the other findings.

Risk of bias in individual studies

The critical appraisal of included evidence is considered a key part of the review process, although it remains the subject of debate in the field, with no single recognised tool. There is also variation in views regarding the use of scoring systems and methods for appraising strength of evidence across studies (particularly in qualitative work). The approach to appraisal of risk of bias and quality of evidence in the proposed study needed to take account of the wide range of study types that we were likely to find. This was particularly important given that the most rigorous evidence base [in the form of randomised controlled trials (RCTs)] was likely to be dominated by studies from outside the UK, whereas the most relevant studies to answer our research question would be those derived from the UK.

Our approach to consideration of individual study quality and risk of bias in individual studies was therefore based on the established hierarchy of study design, together with use of a variety of checklists designed for each study type. For studies reporting evaluations of integrated care initiatives using controlled designs, we considered sources of potential bias as recommended by Higgins and Green10 (selection bias, performance bias, attrition bias, detection bias and reporting bias). For studies using before-and-after (pre–post) designs with no comparator group, and for systematic reviews, we used the two US National Institutes of Health checklists11 (although we concurred with the Cochrane view10 that scoring/totalling of individual elements is not recommended as individual items may have differing relative importance).

For qualitative studies, we used the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist. 12 Any concerns regarding study quality were identified and recorded using these checklists (the National Institute of Health checklists and the Critical Appraisal Skills Programme checklist) and fully considered during the synthesis of findings. Appendix 2 provides the completed study appraisal checklists. International studies of non-comparator group designs were not quality assessed in line with the ‘light touch’ approach to their inclusion.

Risk of bias and strength of evidence across studies

The summarising of quality and strength of evidence within and across studies is a source of debate in the field of systematic reviews, with the calculation of overall scores discouraged. 10 However, indicating where there is greater strength or confidence in the evidence provides an important indicator for the interpretation of the results of a review. 13 Following assessment of the individual quality and risk of bias of each study, we therefore considered the literature in terms of risk of bias and whether there was a greater or lesser strength of evidence underpinning the outcomes reported.

A key limitation when evaluating the strength of evidence is that a higher number of papers in an area does not necessarily indicate greater strength of evidence; it only indicates that there is a greater amount of research activity. Therefore, it is important that any overall assessment considers not only quality and number of studies, but also considers consistency of the evidence. 14 For this study, we drew on work by Hoogendoorn et al. ,14 together with principles from the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation)15 and GRADE-CERQual (Confidence in the Evidence from Reviews of Qualitative research)13 rating schemes, and our work from a previous systematic review with diverse evidence16 to consider risk of bias and overall strength across studies.

It is important to note that we deliberately used comparator labels for the rating (stronger vs. weaker), therefore strength for each element is relative. Owing to the nature of the interventions, we knew that there were few examples of studies that were able to achieve the ‘gold standards’ of blinding and randomisation and, therefore, provide strong evidence. However, by adopting a relative evaluation, we were able to provide information regarding where there were stronger versus weaker signals in the data ‘noise’.

It is also important to note that we recorded study outcomes in terms of either ‘increase’, ‘reduction’ or ‘no significant difference’, as for many outcomes the perception of whether it is positive or negative depends on the point of view. For example, an increase in service usage may be positive for patients or the service, but may also be negative in terms of costs or detrimental effect on other services. An appraisal of strength of evidence was undertaken by the research team at a series of meetings to establish consensus.

We tabulated the data in terms of outcomes reported and source of the data (comparator study, non-comparator study or systematic review), and applied a rating scale to give an indication of where the evidence was stronger or weaker for each outcome. We separately rated evidence from the UK studies, systematic reviews, international comparator studies and international non-comparator studies and then provided an overall rating across the study types. The rating scale was as follows:

-

stronger evidence = generally consistent findings in multiple studies with a comparator group design or three or more systematic reviews

-

weaker evidence = generally consistent findings in one study with a comparator group design and several non-comparator studies, two systematic reviews or multiple non-comparator studies

-

very limited evidence = a single study is available or perceptions of change only

-

inconsistent evidence = inconsistent findings in multiple studies (< 75% of studies report the same outcome).

Summary measures

It had been proposed that a meta-analysis calculating summary statistics would be used if heterogeneity permitted. However, the wide variety of interventions/initiatives included, with the majority of these containing multiple and complex elements, together with the vast range of outcomes measured, counterindicated the calculation of statistical summary measures to compare effectiveness.

Synthesis of results

We used several methods to synthesise the findings from the included studies. These methods included narrative synthesis, tabulation, use of a logic model framework and consideration of the findings within an applicability framework.

The literature on new models of care presents two key challenges for systematic review synthesis methods. The first challenge arises from the increasing recognition that any intervention in health care can be considered to be complex, with individual and organisational factors affecting if and how interventions lead to improved outcomes. 17 Interventions such as new care models, which act at a system or organisational level, or even across organisational boundaries, provide considerable additional complexity because of their multifactorial processes. The new care models programme has been described as being ‘complex in its breadth and depth’. 7 This complexity presents difficulties for systematic review methodologies that seek to quantify or report clear intervention outcome effects.

A second challenge to the review and synthesis of this literature comes from the variety of models that have been introduced. This diversity in the type of models may be the result of the development of the models in response to differing local needs and configurations. New models of care may adopt different approaches and organising principles that respond to the local context. This diversity presents challenges for considering how applicable the evidence from varied national and international research may be to a particular local context. Our methods of synthesis were therefore required to overcome these two key challenges, and were also needed to enable the integration of a wide variety of different forms of evidence.

Narrative synthesis

Quantitative studies

Data were synthesised with use of tabulation and graphs, in addition to narrative summary of interventions, outcomes and influencing factors. We initially scrutinised the included effectiveness studies that originated in the UK, before an examination of systematic reviews from any country, followed by international studies with comparator group designs. We anticipated that UK studies would provide evidence of most relevance to the NHS, so these were examined first. We included UK effectiveness studies of any design in the synthesis as data from these were considered to be of most relevance, whereas we focused on international systematic reviews and international primary studies with a comparator design, as these were considered to have more rigour. We completed a ‘light touch’ analysis of the international non-comparator studies and qualitative studies, whereby we focused on where data echoed the findings from the other studies and aimed to highlight new or dissonant data. In the synthesis, we explored similarities and differences between findings from the UK and those from other countries. Subgrouping and examining characteristics including the age of participants, intervention content and delivery agent were examined where the number of studies permitted. Relationships between studies and outcomes within these typologies were scrutinised. The heterogeneity of the interventions and outcomes precluded summarising the studies via meta-analysis.

Qualitative studies

Qualitative data were synthesised, drawing on thematic synthesis methods18 to identify recurring perceptions within the data. This method comprised extracting themes reported by authors within the finding sections of studies (which constitute the ‘data’ for the synthesis) and then comparing the themes across studies. The qualitative papers were read in detail and themes noted by the authors were extracted. When data from different studies described the same view or perception, they were combined into a single theme (e.g. data from different studies describing the influence of staff having different status were categorised within an overarching ‘power and status’ theme). When data could not be combined into existing categories, additional themes were added. The ‘views and perceptions’ data form an integral part of the overall logic model data synthesis. In particular, the qualitative data make a specific contribution to the elements of the model that document influencing factors, but are also reported alongside quantitative data outlining measured outcomes, supplementing this evidence with data regarding perceived outcomes.

The use of both qualitative and quantitative data in a single review has potential to shed light on negative trial results, identify social factors, examine issues of implementation and assist in the interpretation of significance and applicability for practitioners and service planners. We intended that our mixed-methods approach to synthesising the data would enable the strengths of each form of evidence to be utilised, in order to understand highly complex interventions and outcomes within health-care systems.

Logic model framework

We employed a logic modelling method to provide a systems perspective to data synthesis. This method, developed by the team,19 has been used successfully in previous systematic review studies20,21 and is ideally suited to the analysis of complex, system-based interventions. Logic model methods provide a graphical description of a system and are designed to identify important elements and relationships within that system. 22 They constitute one form of theory-based evaluation as a means of relating hypothesised links between an intervention and its constituent parts to its outcomes and long-term impacts. Logic models examine the processes of implementation, mechanisms of change and participant responses in order to develop hypothesised links or a ‘theory of change’. 23 They serve as a tool to represent the causal system of interest, set out proposed causal pathways in the relationship between the intervention and its health-related and other outcomes, and identify potential moderators of that relationship. 22 Outcomes are conceptualised as the end of a chain of intermediate changes that the evaluation process seeks to track, with each intermediate point predicting potential future outcomes. 24 Theory-based approaches focus on assessing the validity of the theory on which an intervention is built and are concerned with opening up the ‘black box’ of interventions and outcomes to uncover underlying mechanisms. 25 It is argued that without a clear understanding of the assumptions underlying an intervention and how it is supposed to work, evaluators cannot ascertain whether or not it did work and why it did or did not achieve the intended benefits. 26 The key strength of logic models lies in linking complex system processes to system outcomes, and thus guiding the development of strategies and research tools for making system improvements. 27

We anticipated that a logic model approach to synthesis was well suited to analysing and reporting this literature, as well as examining the mechanisms and impacts underpinning new models of service delivery. This approach to synthesis also resonates with the logic models that the NHS vanguard sites have been developing.

In the logic model method, data from included studies are extracted and analysed to produce elements of a framework that typically comprises an intervention typology, detail regarding the range of outcomes reported, factors that may be influential in the pathway from an intervention to health impacts, and reported associations between elements of the model. The extraction table includes the collection of data regarding associations and outcomes, which facilitates the construction of the framework. Both quantitative and qualitative data underpinned the construction of the elements of the model. The completed model aimed to outline evidence in the literature regarding different models of care, relationships between contextual factors, inputs, processes and outcomes. 22,28 Each element in the model demonstrates the logic or theory of the interventions and portrays ‘if–then’ relationships in the chain from new models of care to system-wide impacts.

Initially, the logic model synthesis used UK-published literature to develop an initial or ‘start’ logic model. Following the development of the UK-based logic model, the second phase of the work entailed examination and synthesis of the international (non-UK) literature to add to a further draft of the model and to enable comparisons and contrasts between the identified evidence. Initially, systematic review-level international studies were added to the model alongside the UK evidence, followed by international primary evidence from the more rigorous comparator design studies and then non-comparator studies to explore gaps in the evidence base. The logic model framework was therefore intended to act as a translation tool between findings from the review of the UK evidence and the international literature, and to enable contextually sensitive synthesis of multiple and diverse evidence types.

Applicability framework

In a parallel phase of work, we developed a framework of factors related to applicability and generalisability from examination and synthesis of the included studies. As outlined earlier in The data collection process, we had included specific sections on context and applicability in our data extraction form to facilitate identification and synthesis of these factors. The development of the applicability framework was intended to inform our analysis of the data and reporting of the systematic review. We planned to use the framework to evaluate and present the evidence with regard to factors that may influence generalisability and applicability of the international literature to varied local contexts. A recent review29 of the assessment of applicability during systematic reviews recommended that authors of reviews should consider applicability for at least one target population, setting and context. We aimed to go beyond this recommendation and develop a framework to act as a reporting tool that would be suitable for the complex organisational interventions that we were evaluating.

The terms ‘generalisability’ and ‘applicability’ are often considered to be synonymous; however, ‘generalisability’ (synonymous with external validity) is usually used to describe how relevant the results of a study might be to general sites and populations, whereas ‘applicability’ typically refers to information regarding the study processes and insights into if and how an intervention may be implemented elsewhere. 30,31 Numerous checklists that include items related to external validity are available, although there is little detail regarding how to report generalisability. 32 The understanding of how evidence (particularly international evidence) is, or is not, applicable to varying local situations and contexts is a key challenge for systematic review synthesis.

In order to develop our applicability framework, we carried out an initial literature review of existing studies using terms such as ‘applicability assessment’ in MEDLINE, and using Google/Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA). The review was not intended to be a rigorous systematic review but to identify any existing examples of frameworks that we could learn from. We found little literature on applicability frameworks; however, a review in 201132 identified 11 assessments of applicability or transferability. None of the methods of assessment were found to be comprehensive, with little evidence regarding their value for systematic reviews. The most well-developed method formed part of a Canadian knowledge translation toolkit,33 which was a useful model but not sufficiently detailed for our purpose. In the absence of existing tools that would suit our needs, we developed a new framework by identifying elements related to applicability within the data extracted from the included studies. We tabulated all of the references to applicability that had been noted on the extraction for each study in a Microsoft Word 2013 (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) document, and then, through a process of cutting and pasting, brought similar text together (e.g. text related to population factors and to the type of context). In a process akin to content analysis, we developed categories and subcategories within the framework. Following the development of a succession of drafts, we consulted with users of systematic reviews (see Stakeholder involvement) to gain views regarding the clarity of our items. In response to the feedback that was received, we further refined and developed the framework to produce the final version.

During the synthesis, the framework was used as an analysis and reporting tool, guiding examination of the evidence within each element. Studies were grouped and tabulated according to framework elements, with examination and reporting of evidence using these items.

Protocol and registration

A review protocol was developed prior to the commencement of the study. The protocol outlined the research questions and detailed the methods for carrying out the review. The protocol encompassed methods for identifying research evidence, the method for selecting studies, the method of data extraction, the process of assessing the methodological rigour of included studies, and synthesis methods. The protocol was registered with the PROSPERO database number 37725 and was made available on the PROSPERO website [www.crd.york.ac.uk/prospero/display_record.php?RecordID=37725 (accessed 19 February 2018)].

Patient and public involvement

We formed a project-specific public involvement advisory group for the duration of the work, with 10 members drawn from across England. Group members were recruited via our meetings with patient advisory groups during the development of the study proposal, from members of advisory groups linked to the local NHS trusts and from advertising on the People in Research website [www.peopleinresearch.org (accessed 25 September 2017)]. We intended for the advisory group to have varied participants in terms of characteristics such as age, sex, health conditions, disability, experience of health care and geographical region. We were successful in achieving this, and our group included both retired and employed people, those with health conditions/disabilities and those with no particular health concerns, and people from the south east, west, central and north-west regions of England, in addition to those who were local to Yorkshire.

The group met three times during the project: in the second month, the seventh month and the 11th month. The involvement of public advisors was facilitated by reimbursement for time and travelling expenses, use of teleconferencing for those unable to attend in person and ensuring that any documentation was sent several weeks in advance of meetings. At the first meeting, the group finalised the wording of the Plain English summary for the NIHR website; discussed experiences of the integration of care, terminology and understanding of the study; and considered areas or issues of most interest to the public. At the second meeting, the intermediate findings were discussed, including formats for making the findings understandable (such as types of visual representations) and potential areas to highlight for a public audience. At the third and final meeting, discussion included the content of the Plain English summary, maximising meaningful messages in the report for lay readers and suggestions for disseminating the findings of the study so as to reach the wider public.

Stakeholder involvement

We accessed knowledge and expertise from stakeholders during the study at key points in the process, including consultation regarding items for the applicability framework and regarding the logic model and findings of the review. We held individual and group meetings to discuss the applicability tool with managers, clinicians, researchers and commissioners during its development, which formed the basis of several iterations. In particular, this consultation informed the grouping of items and the terminology to be used.

In the later stages of the study, we convened a workshop that was attended by 15 delegates, including researchers, NHS staff, commissioners and managers, to explore how the findings of the study resonated with experiences; where the analysis should focus, including key questions to explore; and to discuss the draft logic model and applicability framework. Feedback regarding the draft model was positive, with agreement that it was coherent and provided a clear summary of a highly complex area. Suggested areas of focus had already been identified within our draft applicability framework, although delegates suggested that differentiating interventions with more than three elements and interventions with three elements or fewer may be helpful, as it had been reported that organisations could best cope with a maximum of three elements of change at one time. Workshop attendees also suggested distinguishing between studies in which patient satisfaction was patient-reported and those in which it was staff reported, and to explore whether or not complex conditions compared with non-complex conditions were possible to identify in the analysis.

In the last month of the study, we also provided a seminar for 18 primary care staff members, including researchers and general practitioners (GPs), in which we outlined the findings of the study and sought input regarding the clarity of our approaches to synthesis and key questions for the analysis to explore. Feedback regarding the clarity of the logic model was very positive, and attendees found the strength-of-evidence reporting to be helpful and clear. The group were particularly interested in the results for particular patient subgroups, and commented that outcomes for patients seemed to be under-reported in the literature. Other comments related to the data on organisational and financial change, which were perceived to be of interest by stakeholders.

In the last month of the study, we presented the work to 25 commissioners and senior practitioners; the model and findings were discussed, and feedback on the logic model and presentation style was sought. The group appreciated the clarity of the strength-of-evidence indicators and the wide extent of the review. Further clarity regarding the source of the finding in relation to perceived improved quality (staff or patients) was suggested, and feedback regarding the checklist of factors to be considered during the development of initiatives resulted in further refinement. The group identified particular challenges of the evidence for them, including potential conflicts between the vision of new models and required outcomes, which provided helpful input for the study reporting.

Chapter 3 Results

Study selection

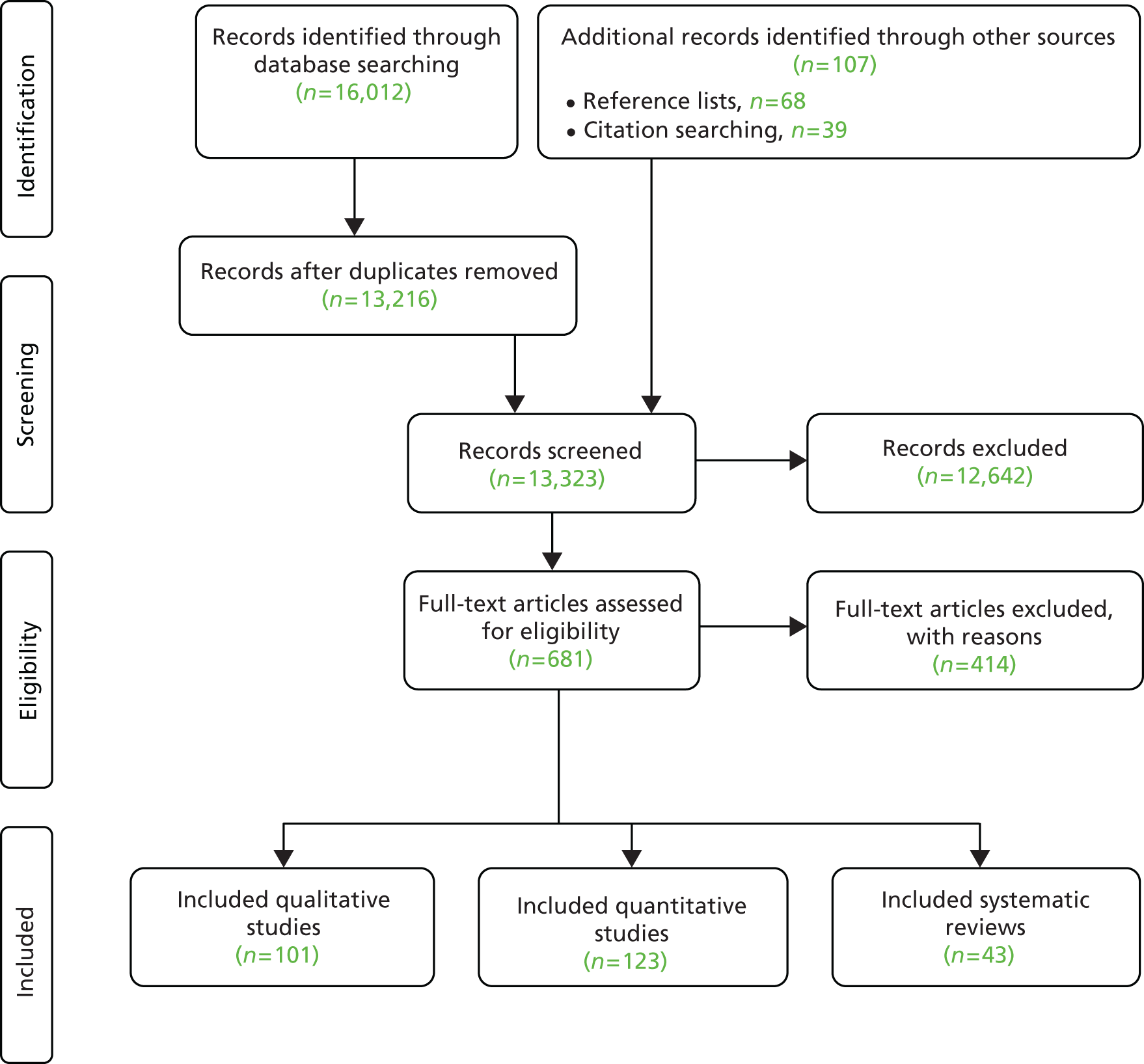

From a database of 13,323 unique citations, we included 267 documents in the review. Figure 1 is a PRISMA flow diagram that illustrates the study selection process.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram illustrating the process of study selection.

Type of studies excluded

The lists of studies that were excluded at the full-paper selection stage and reasons for their exclusion are provided (see Report Supplementary Material 1). During the study selection process, we encountered particular challenges regarding the definition and reporting of intervention type. The term ‘new models of care’ lacks a precise definition and was used variously by authors. In particular, many retrieved citations that were excluded during the initial sifting related to clinical care models rather than service delivery models, such as initiatives aiming to enhance patient self-management delivered by a single practitioner. The term ‘integration’ was often used to refer to different types of clinical treatments or approaches, rather than integration of service delivery. In addition, the term ‘models of care’ often described studies examining particular clinical approaches rather than relating to any aspect of integration. Studies describing ‘case management’ approaches also required careful scrutiny. Such studies often described interventions with a key worker; however, there was no integration between key workers and services, or apparent integration between different services. For other ‘case management’ studies, enhancing integration between services was the key element of the approach.

In addition to the need for close scrutiny of the ‘intervention’ parameters of our inclusion criteria, the ‘outcomes’ inclusion criteria also required careful study selection. The review was focusing on service delivery and care outcomes, rather than clinical outcomes; however, this distinction was not always clear cut and decisions on the inclusion of these documents often required discussion at a team level.

Study characteristics

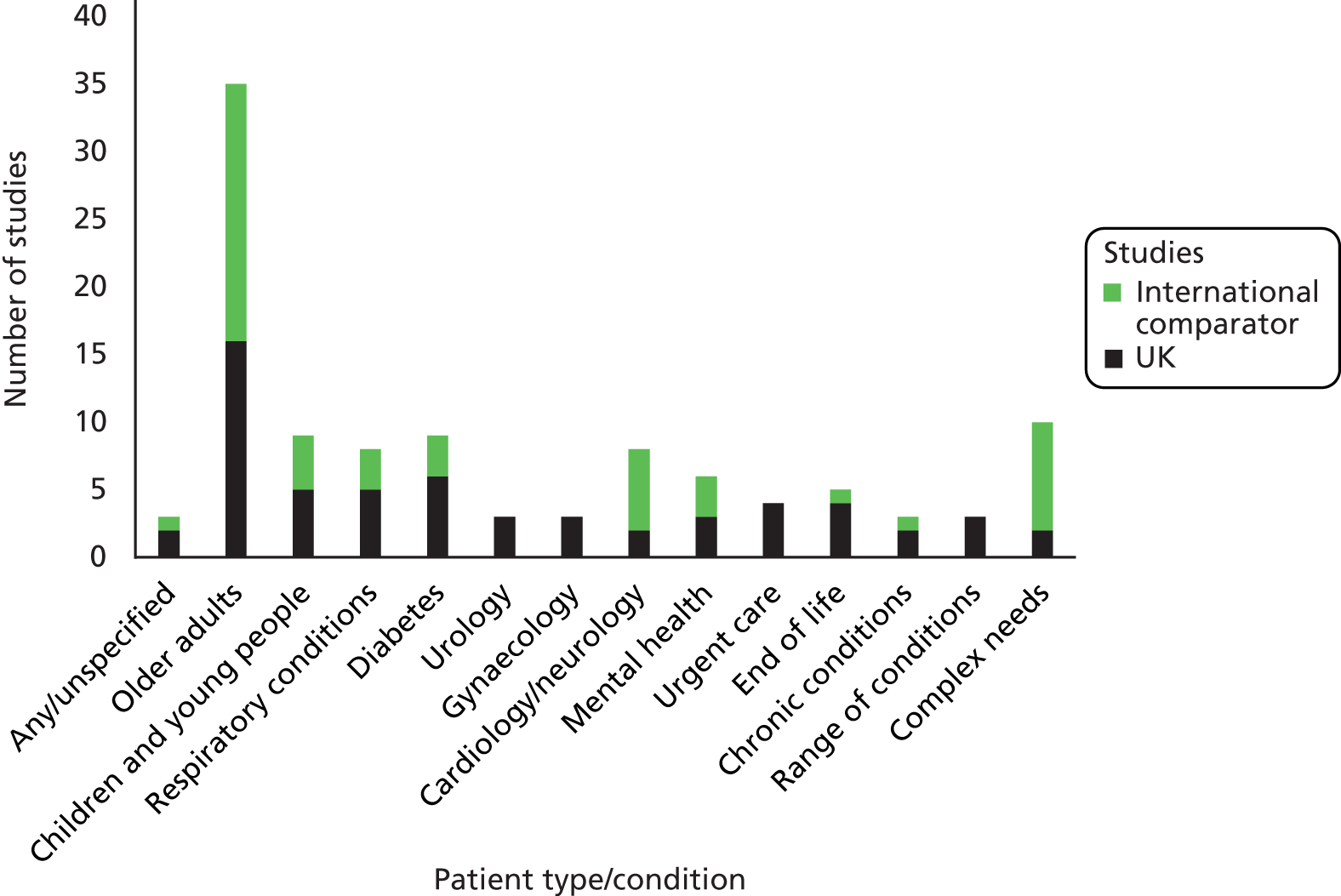

Of the 267 documents included in the review,34–299 54 were UK studies reporting the effectiveness of interventions34–87 and 64 were qualitative studies from the UK. 88–151 The over-representation of UK literature reflects to some extent the greater inclusion of studies of lower-quality designs from the UK, together with grey literature. It may, however, indicate the attention that has been paid to integration in the NHS, with nationally funded programmes including evaluation components.

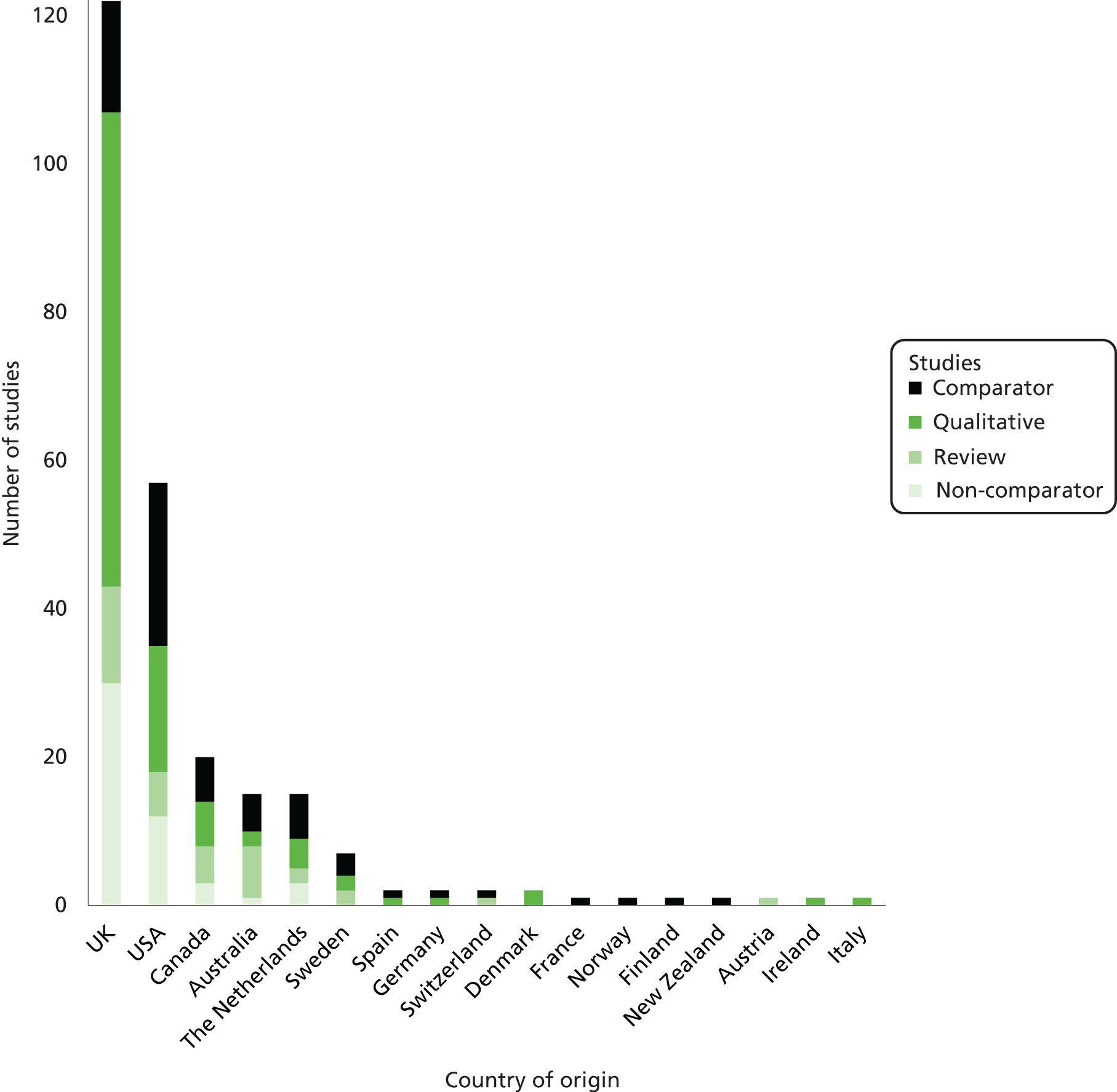

We identified and included 43 systematic reviews8,152–193 and 49 higher-quality studies from outside the UK using comparator group designs. 194–242 In addition, 20 lower-quality non-UK studies (no comparator group)243–262 and 37 qualitative studies from outside the UK263–299 were included within a ‘light touch’ analysis. Figure 2 provides a summary of the country of origin for the different types of study design.

FIGURE 2.

Country of origin of the included studies.

The majority of the systematic reviews included only papers published in English and/or from developed countries. Four reviews153,155,157,180 stated that they placed no restriction on country of origin or language.

Within the group of UK studies, several papers and reports originated from the integrated care pilots. 45,101,126 In particular, nine papers73,74,80,100,115,122,123,134,151 were derived from the work in north-west London. There were four papers81,87,106,144 that reported on the Partnerships for Older People Project. There were two papers48,142 on the Evercare programme.

The international primary studies report an array of programmes and initiatives, although there are several studies that are reported in two or three papers. For example, there are two papers on the System of Integrated Care for Older Persons programme. 196,197 In total, 202 unique studies are represented in the set of 267 included papers.

We examined the studies included in the systematic reviews to ascertain the extent to which we may be ‘double counting’ papers. We observed little overlap between primary studies and reviews because of the publication dates of the reviews, meaning that the majority of their primary studies were published prior to our inclusion period of post 2006. One review,179 however, had four qualitative papers126,142,146,147 that we had included and three reviews182,183,185 each had three papers8,45,49,87,100,109,125,154,196 in common with ours. Two reviews177,189 each had two overlapping papers48,168,196 (the Gravelle et al. 48 paper was included in both). Three reviews181,184,300 each included a single overlapping paper. 108,168,171

The literature in the review comprised predominantly journal papers, although 12 grey literature reports34,45,49,80,81,87,134,139,147,151,178,294 were included.

Risk of bias within studies

We assessed the methodological quality and risk of bias across the UK studies, international reviews and the international comparator studies using assessment tools that were appropriate to each study design. Appendix 2 contains these assessments. For the UK literature, 16 studies39,42,44,45,48,52,54,58,63,74,77,78,81,82,85,86 used higher-quality comparator designs. Of these studies, only two58,63 had utilised some form of random allocation to condition, and the nature of the intervention precluded allocation concealment within studies. Blinding of participants and personnel was also limited or not possible, with only four studies44,45,63,86 achieving this. Blinding of outcome assessment had been achieved in five studies. 45,48,52,58,63 The studies fared better with regard to completion of outcome assessment, and reporting was assessed as being accurate for all but one study,58 which had insufficiently discussed the study limitations. Overall, the studies were all considered to be at risk of potential bias, with none meeting the six criteria for reducing potential sources of bias.

The international comparator studies were rated slightly better in terms of randomisation: 19 studies (reported in 26 papers194–197,201–206,209,210,214,215,217,220,222,225–227,230,233,234,239,241,242) had a random allocation, although only nine studies (reported in 14 papers194,196,197,201–203,205,206,209,210,217,239,241,242) achieved allocation concealment. As with the UK studies, blinding was problematic because patients were unable to be blinded to their study arm. The incomplete reporting of outcomes data meant that in many cases it was not possible to judge the extent of attrition; for three studies (reported in six papers201–203,214,223,224), a large loss to follow-up was reported. Reporting was poor in around one-third of the studies, making it difficult to judge the extent of possible selective reporting. Other limitations included small sample sizes leading to inadequate statistical power, with some concerns regarding the processes of allocation. As with the UK comparator studies, none met all of the criteria for the highest quality.

The quality assessment illustrates the considerable challenges that are inherent in rigorous evaluation of highly complex health-care initiatives such as these, in particular, the difficulties of meeting requirements for randomisation and blinding.

The UK non-comparator before-and-after/longitudinal studies demonstrated similar issues regarding blinding, with only one study80 clearly reporting that outcome assessors were blinded. The studies were generally considered to have recruited participants who were representative of the population of interest, although it was often difficult to ascertain the recruitment process. Just over half of the included studies clearly reported sample sizes that were sufficiently large enough to have confidence in the findings. Only one-third were judged to have clearly described the intervention and its delivery. None of the studies reported taking measurements at multiple time points prior to the intervention and only just over half used statistical measures (such as p-values) to evaluate change over time. The UK qualitative studies were generally of a satisfactory standard, with a minority providing only limited data or containing weak methods sections. Four studies92,93,110,135 met all of the quality criteria. Fifteen89,94,95,97–99,107,108,117,120,130,131,134,136,145 of the qualitative studies met all but one of the criteria.

The systematic reviews exhibited variable quality, with none meeting all 11 quality criteria and only three165,168,189 meeting all except two of the criteria. None of the systematic reviews assessed the likelihood of publication bias, fewer than half considered the quality of studies in their conclusions, around half searched at least two databases and one-third reported that they searched for grey literature.

Synthesis of results

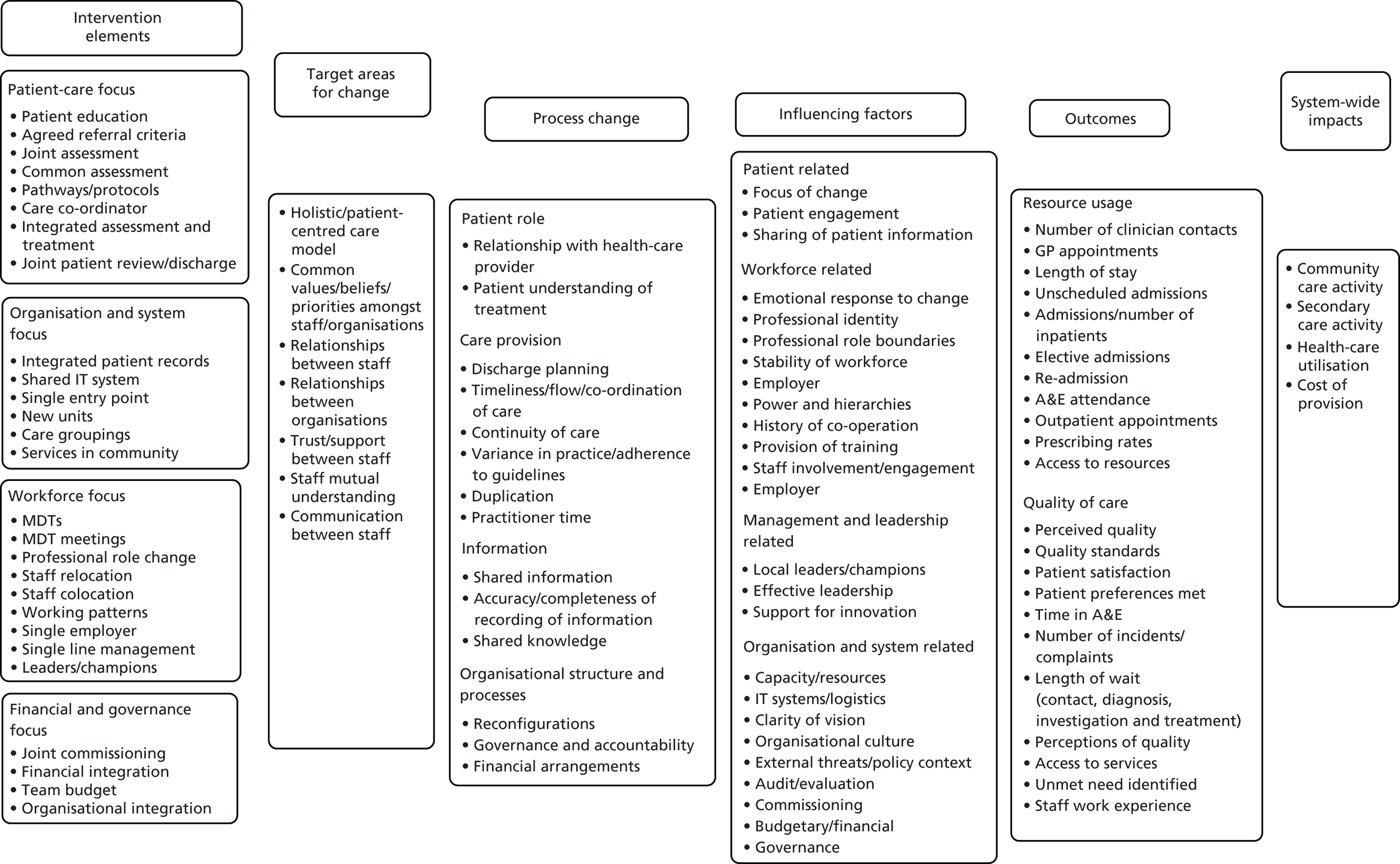

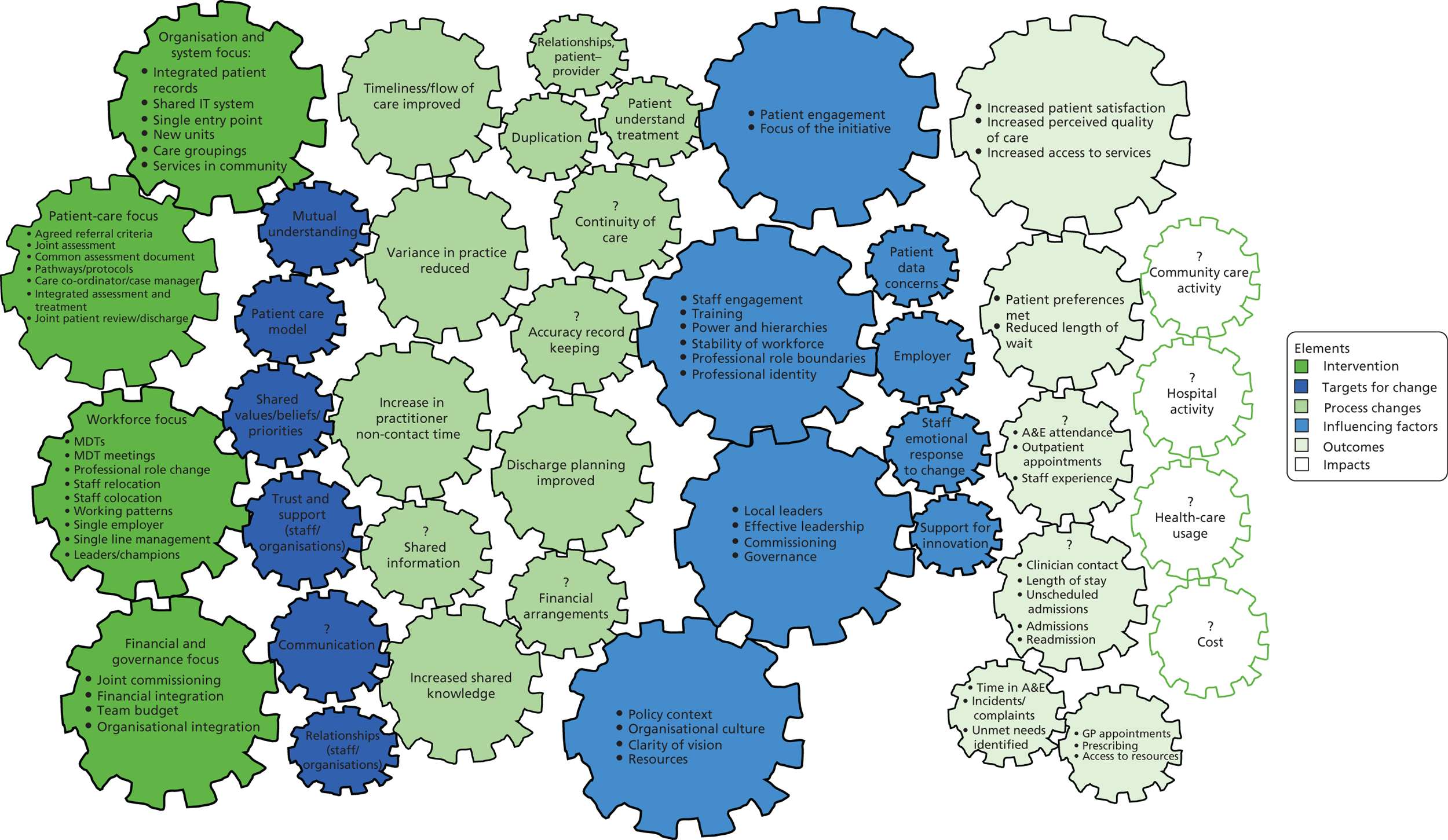

Given the complexity of the interventions, processes and outcomes involved in new models of care, we have summarised the findings of the review using a logic model that sets out the integrated care systems, processes and outcomes identified (Figure 3). Through a mixed-methods approach, rather than separating the quantitative and qualitative data into separate sections, we have integrated and drawn on findings from both the studies that evaluated interventions using quantitative or mixed methods (‘intervention studies’) and studies that examined the views and perceptions of staff or patients (‘qualitative studies’), when they provide findings (‘evidence’) of relevance. Integrating the different types of data in this way may be unfamiliar to those who primarily encounter systematic review findings reported via meta-analyses (statistical summaries), more conventional narrative summaries or qualitative evidence syntheses. However, our focus in the review was the understanding of complex relationships and systems, and using a mixed-methods logic model approach enabled findings from each form of data (quantitative and qualitative) to contribute to an explanation of the pathway. Although we have not separated the data into sections for quantitative and qualitative data within the report, study design and robustness of evidence will be fully outlined as part of the analysis.

FIGURE 3.

Logic model outlining the new models of integrated care.

In Figure 3, progressing from left to right, the model sets out the elements of new models of integrated care as identified by the review, followed by core areas of change within these elements, followed in turn by changes in the process that may result from the intervention elements, and then by factors that may influence implementation and effects, the outcomes that may result from integrated models of care, and finally, data related to system-wide impacts. The model is intended to provide a summary overview of the elements identified in the pathway, from interventions to impacts. In the following sections, we will provide a detailed analysis of the findings in relation to each element of the model. Following a narrative synthesis describing the results of the review in relation to each section of the model, we will examine areas in which the included studies provide stronger or weaker overall evidence.

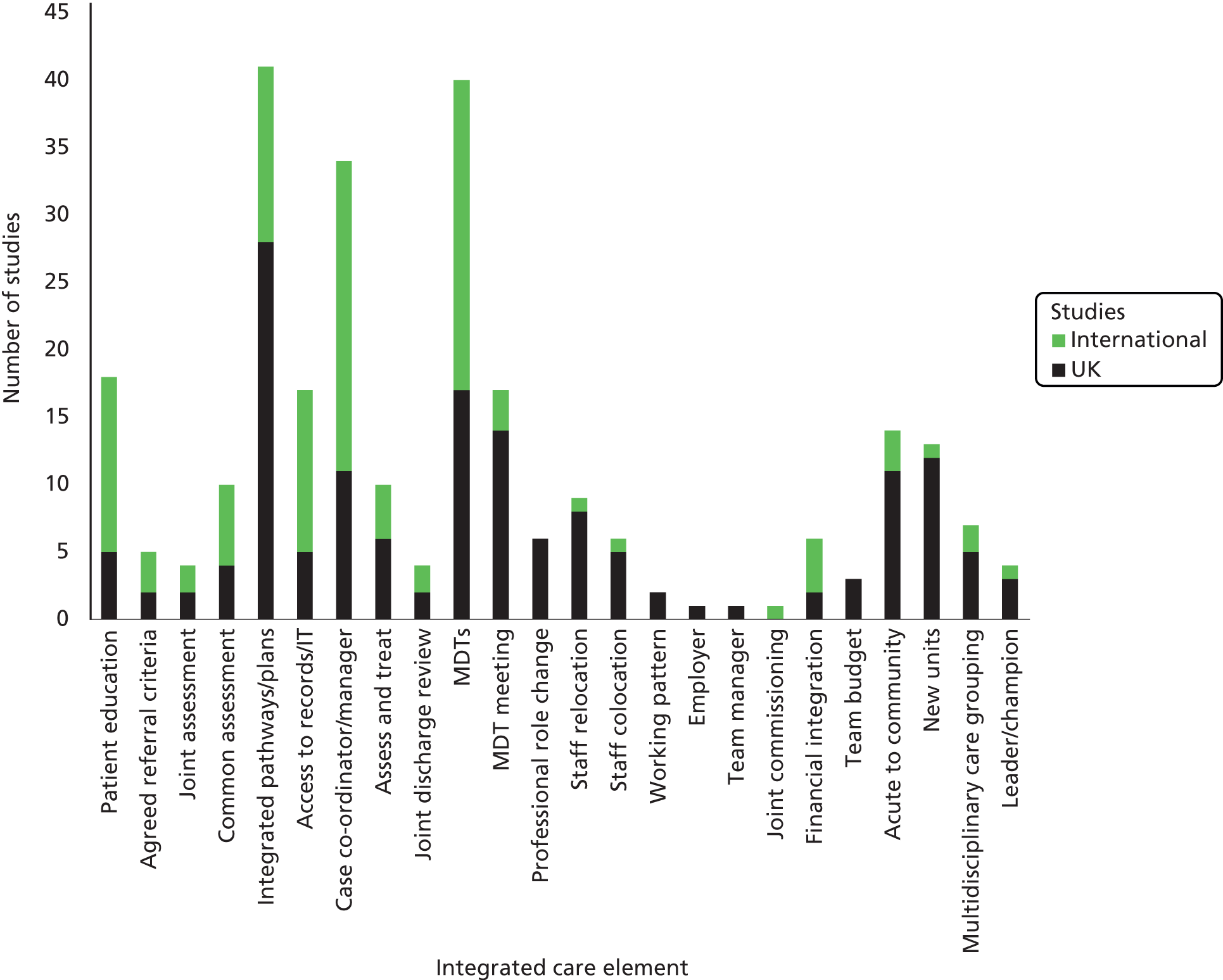

Elements of the interventions

The evidence regarding elements of integrated care initiatives is derived from both the UK and international intervention studies. The majority of the reported new models of integrated care comprised complex and multielement interventions. The elements can be grouped into four main areas: (1) those with a focus on improving patient care directly, (2) those that focused on making changes to organisations and systems, (3) those that focused on changing how staff were employed and worked (workforce) and (4) those that changed financial and governance aspects. Many studies reported new models that included several of these elements, and it was often challenging to elucidate exactly the form and components of new models because of limited reporting. Figure 4 provides a summary of the elements of new models of integrated care that are described in the literature.

FIGURE 4.

Elements of integrated care in the included intervention studies.

We acknowledge that itemisation of each identified element is likely to under-represent elements that were contained within the reported interventions. In identifying these elements, we were reliant on authors’ descriptions, which could be brief overviews rather than detailed outlines. The interventions that were described as case co-ordination/case management in particular were often described as an overall approach, with little detail regarding precisely the processes or systems involved.

The introduction of ICPs was the most commonly occurring element, either as a ‘stand-alone’ intervention or as part of a more complex package. This was closely followed by multidisciplinary teams (MDTs), which was also a frequently described component of UK and international studies. The greatest number of elements in an intervention described by authors was nine, with the least being only one element. Interventions typically included between four and six elements. In general, the non-UK interventions contained fewer elements than those reported from the UK, although one study (two papers)227,301 reported seven components and another211 reported six. The international literature had a greater number of examples of interventions that were described as including a case manager/case co-ordinator, and the UK literature included more studies in which authors described integrated care pathways/plans as an element. There was less description of professional role change and colocation of staff as elements of interventions in the international intervention studies.

The most common identifiable interventions were ICPs, multidisciplinary teams/meetings and the provision of a nominated care co-ordinator or case manager. Many interventions combined two of these elements but only one intervention217 involved all three. Analysis revealed considerable heterogeneity in terms of details of the interventions, patient and staff groups involved, and outcomes. Studies involving the three principal interventions were categorised as simple if the initiative had only one component (e.g. introduction of an ICP) or complex if additional components (including other common interventions, as mentioned previously) were involved. Summary tables are presented for the UK (Table 1) and non-UK (Table 2) studies.

| Study (first author and year) | Simple or complex initiative? | Principal intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICP | MDT | CM | ||

| Ahmad 200735 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Bakerly 200936 | S | ✓ | ||

| Beacon 201537 | S | ✓ | ||

| Clarkson 201142 | S | ✓ | ||

| Cunningham 200844 | S | ✓ | ||

| Department of Health and Social Care 201245 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dodd 201146 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Graffy 200847 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Gravelle 200748 | S | ✓ | ||

| Ham 201049 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Harris 201350 | S | ✓ | ||

| Hockley 201053 | S | ✓ | ||

| Huws 200854 | S | ✓ | ||

| Jha 200755 | S | ✓ | ||

| Johnstone 201156 | S | ✓ | ||

| Johnstone 201257 | S | ✓ | ||

| Julian 200758 | S | ✓ | ||

| Kent 200659 | S | ✓ | ||

| Lamb 201460 | S | ✓ | ||

| Letton 201361 | S | ✓ | ||

| Levelt 200862 | S | ✓ | ||

| MacLean 200864 | S | ✓ | ||

| Mertes 201365 | S | ✓ | ||

| Ng 201466 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Paize 200768 | S | ✓ | ||

| Pettie 201270 | S | ✓ | ||

| Roberts 201273 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Roland 201274 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Rowlandson 200975 | S | ✓ | ||

| Ryan 200776 | S | ✓ | ||

| Smith 201279 | S | ✓ | ||

| Soljak 201380 | S | ✓ | ||

| Steventon 201181 | C | ✓ | ||

| Stokes 201682 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Tucker 200984 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Waller 200785 | S | ✓ | ||

| Wilberforce 201686 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Windle 200987 | C | ✓ | ||

| Study (first author and year) | Simple or complex initiative? | Principal intervention | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICP | MDT | CM | ||

| Aiken 2006194 | S | ✓ | ||

| Battersby 2007195 | C | ✓ | ||

| Béland 2006;196 Béland 2006197 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Bird 2007;199 Bird 2010198 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Boult 2008;202 Boult 2011;203 Boult 2013201 | C | ✓ | ||

| Brännström 2014204 | C | ✓ | ||

| Brown 2012205 | C | ✓ | ||

| Callahan 2006206 | C | ✓ | ||

| Counsell 2007;209 Counsell 2009210 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Dorr 2008211 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Ettner 2006212 | C | ✓ | ||

| Fagan 2010213 | C | ✓ | ||

| Farmer 2011214 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Gray 2010;215 Hogg 2009220 | C | ✓ | ||

| Hajewski 2014216 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Hammar 2009217 | C | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Hébert 2010218 | C | ✓ | ||

| Hullick 2016221 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Janse 2014;223 Janse 2014224 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Martinussen 2012226 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| McGregor 2011;227 Katon 2012225 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Morales-Asencio 2008228 | S | ✓ | ||

| Olsson 2009229 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Parsons 2012230 | C | ✓ | ||

| Paulus 2008;231 Paulus 2008232 | S | ✓ | ||

| Rosenheck 2016233 | C | ✓ | ||

| Sahlen 2016234 | C | ✓ | ||

| Salmon 2012235 | C | ✓ | ||

| de Stampa 2014236 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Stewart 2010237 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| Taylor 2013238 | S | ✓ | ||

| Theodoridou 2015239 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

| van der Marck 2013240 | C | ✓ | ||

| van Gils 2012;302 van Gils 2013241 | C | ✓ | ||

| Wennberg 2010242 | C | ✓ | ✓ | |

Much of the UK literature evaluated simple interventions, typically ICPs. Many of this group of studies evaluated process outcomes rather than service-level outcomes, finding improvements in areas such as staff contact, documentation and decision-making. 56,61,62,85,303,304 Evidence of other effects was limited, with two studies65,68 indicating a reduction in length of stay, but others62,80 suggesting little change in outcomes, with one of these80 suggesting a higher number of admissions in areas with integrated pathways. The findings were also mixed for studies of complex initiatives involving ICPs, although a greater proportion of these studies indicated positive effects than the those concerned with simple interventions. 36,46,47,49,66,74

Multidisciplinary teams were commonly implemented as part of a larger initiative (often in combination with case management and/or patient education). Only three UK studies37,50,60 reported simple MDT initiatives and two of these50,60 looked at process outcomes, reporting mixed results. However, Beacon et al. 37 reported that a multidisciplinary primary care team reduced secondary care activity and the number of emergency admissions. The only non-UK study231 to report on MDT care in isolation found higher total mean costs relative to traditional care in a nursing home setting. In contrast, a number of UK studies reported positive outcomes from more-complex initiatives involving MDTs, including reductions in length of stay and hospital costs;36 reduced length of stay;46 reduced numbers of admissions and readmissions;66 reduced waiting times;75 reductions in the numbers of inappropriate referrals;76 and perceived improvements in care and access to services. 84,86 Some studies81,189 of complex MDT interventions failed to show benefits. Overall, however, there was a tendency for complex MDT interventions to be relatively successful, and this was also observed in the non-UK studies. In two non-UK studies,217,229 initiatives involving both an ICP and a MDT were successful in reducing costs.

Only one UK study48 reported on a ‘simple’ case management initiative, finding no benefit of the intervention using a controlled before-and-after design. One non-UK study238 reported on ‘simple’ case management interventions and found process change improvements in care co-ordination. The sample of studies reporting ‘complex’ case management interventions was considerably larger and the results were correspondingly more challenging to unravel. Most studies reported improvements in one or more outcomes associated with the intervention, but there were also examples in which no effect was detected. 82,195,213,218 In some cases, study authors attributed this to specific factors such as insufficient length of follow-up195 or possible inappropriate use of the emergency department (ED). 218

In summary, ICPs were frequently implemented as ‘stand-alone’ interventions, with some evidence of improved process outcomes but little evidence of change in service delivery outcomes, and only a slightly more positive indicator regarding effectiveness when included within complex interventions. By contrast, MDTs and possibly case management interventions appeared to be generally more effective when combined as part of a number of different elements (although not as stand-alone elements). However, this analysis should be treated with caution as it does not take account of other possible influences on intervention effectiveness such as the setting and the characteristics of the patient group receiving the intervention.

Target areas for change

We scrutinised the included literature to identify the stated aims for the different intervention elements, with the objective of exploring commonalities of purpose across these varying elements. These areas can be considered the espoused mechanisms of change within the model (active ingredients in the interventions), which were presumed to underpin improvements in health service delivery and patient care. The evidence regarding these target areas for change draws heavily from the UK qualitative studies, although the findings were echoed in international systematic reviews and a small number of UK intervention and international primary studies. The intervention studies (both UK and non-UK) tended to describe these areas as targets for change, but instead reported outcomes at a service and system level (e.g. hospital admissions and quality of care).

Seven target areas for change were identified across the different types of initiative, predominantly related to interpersonal aspects of health-care delivery. The areas were (1) the holistic and patient-centred models of care; (2) common values, beliefs and priorities between staff and/or organisations; (3) relationships between staff; (4) relationships between organisations; (5) levels of trust and support among staff; (6) mutual understanding among staff; and (7) communication between staff. Although these target areas referred to individual elements in the studies, it is important to note that there is considerable interconnectedness between them. For example, achieving a patient-centred model is influenced by values, beliefs and priorities; trust and support will be influential in staff and organisational relationships; mutual understanding will influence relationships; and communication may underpin all of these. The evidence we identified in relation to each of these target areas for change is described in more detail in the following sections.

Holistic and patient-centred models of care

The aim of achieving more holistic or patient-centred care in new models was described most frequently in the UK qualitative studies,103,111,125,130,134,135,143,144 but was also reported in the included systematic reviews. 160,183,185,190 The aim of patient-centred care was described particularly in studies that were carried out in populations of older adults and in those focusing on end-of-life care, but was also described in interventions for general patient populations. One UK qualitative study of stroke, kidney and sexual health services111 reported that a patient-centred culture had spread following a modernisation initiative that included integrating services, role changes and new service provision. Other UK qualitative studies129,135 described achieving holistic care as being an important aim in the introduction of MDTs. A more pragmatic reason for including patient-centred care as a key aim of new models was reported in two systematic reviews. 185,190 These reviews described the importance of a patient-centred focus as a way of involving stakeholders involved in new integrated care initiatives.

Common values, beliefs and priorities

The UK qualitative studies with different settings, patient groups and different intervention types described the importance of developing shared beliefs between staff and between organisations, such as views and beliefs regarding the rationale for, and benefits of, change. 126,134 They highlighted that integrated care initiatives need to achieve similar priorities among organisations127 and between different individuals. 99 The development of shared views and goals was described as important in the development of a shared identity. 89

Systematic reviews echoed the importance of goals being aligned within large-scale transformation157,185 and smaller-scale transformation,181 with shared understanding of the purpose and vision underpinning reconfiguration. Reviews also described the need to overcome differing levels of commitment, values, beliefs and ways of thinking in multidisciplinary teamworking171 and when implementing new integrated pathways. 183 A non-comparator international paper255 evaluating the Program of Research to Integrate the Services for the Maintenance of Autonomy concluded that sharing a common philosophy was the key to implementing the initiative. A qualitative study from the USA,286 exploring perceptions of an Accountable Care Organization, described how change was presented as a cultural rather than a structural change, with co-ordination and equal partnership rather than integration. The presentation of this as being the priority was perceived to avoid a perception of reduced autonomy and to overcome mistrust among physicians. Another qualitative study from the USA298 identified alignment of the initiative with organisational priorities as a factor in the success of health-care transformation.

Relationships between staff

The UK studies with various settings and patient groups60,73,108,111,120,141,145 emphasised the importance of developing enhanced working relationships between staff as part of integrated care. Two UK (cross-sectional) intervention studies60,73 reported that relationships improved following integrated care initiatives. One UK qualitative study,145 in contrast, described that on the surface MDT members might appear to have good relationships, but that this could hide an undercurrent of mistrust and criticism. Another UK qualitative study141 found that, 1 year after the introduction of integrated teams, there was a mixed picture regarding relationships. A further UK qualitative study111 found that improved interpersonal relationships had not been sustained in the longer term.

Two systematic reviews echoed the need for initiatives to aim to improve staff relationships, if high-quality team performance was to be achieved. 171,193 One additional review8 of primary care interventions for patients with chronic disease, mental health or aged/palliative care, which focused on relationships between staff or between staff and patients, linked these to a positive effect on health and patient satisfaction outcomes. A non-comparator study from the Netherlands254 found that relational co-ordination (the interaction between communication and relationships) was positively related to integrated care delivery (p > 0.05).

Relationships between organisations

A non-comparator study from Germany219 reported that, although integration had enhanced staff relationships within the same service, relationships with organisations that were external to the initiative were less satisfactory. This was echoed by a non-comparator study from Canada,246 which described reform as having a ‘territorialising effect’. Collaboration with other organisations in the areas that were external to the network areas decreased (from 15% to 4% for collaboration with other primary care organisations and from 21% to 15% for collaboration with hospitals outside the network). A further qualitative study from Germany293 also highlights that, although co-operation between staff based in the same organisational grouping was reported as excellent, relationships with other external organisations were less satisfactory. A qualitative study from the USA287 that explored perceptions of Accountable Care Organizations described them as typically having formed a new relationship or formal partnership between themselves and other health-care providers.

Trust and support among staff

The need for trust and support was described in UK qualitative studies related to MDT interventions, ICP interventions and large-scale integration initiatives in both primary care and hospital settings, and with a range of patient groups including children and older adults. In these studies,90,91,110,113,127 the need to overcome misunderstanding, tension, and organisational and professional barriers in order to achieve trust was described. Systematic reviews92,93 described trust as being vital if co-operation between staff was to be achieved. Other systematic reviews also highlighted the importance of achieving trust and support among staff,162 and the value of processes being put in place to support staff to achieve new ways of working. 184 An Australian qualitative study90 linked staff having trust in other stakeholders to embracing an integrated health service identity.

Mutual understanding among staff

The UK qualitative studies described increasing staff understanding of each other’s roles and skills as a key aim for integrated care interventions. Much of the evidence derives from studies of older adults; however, we also identified studies based in EDs and in primary care mental health and learning disability services. Most of the studies relate to MDT interventions. Papers described limited understanding within a MDT92 and how collaborative approaches could change a ‘blame culture’ to one of mutual understanding. 101 One study90 in particular highlighted a lack of understanding between doctors and other staff, and another147 described a lack of understanding between staff working in primary care and staff working in hospitals. A further UK qualitative study121 suggested a link between improved understanding and more-rapid service delivery.

A systematic review162 similarly reported that there could be a lack of understanding between, and negative perceptions among, different staff groups, including health and social care staff, and another179 reported that a common understanding was important.

Communication between staff

The improvement of communication between staff was frequently described as a target area for change. Staff communication was outlined as a key part of interventions for a wide range of patient populations [including children, older adults, those receiving end-of-life care, those requiring mental health care and those with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)] in both acute and primary care. Regarding whether or not change had been achieved, seven UK intervention studies35,47,60,61,64,74,83 reported that communication had improved, and one50 reported that it was unchanged. Two studies (eight papers)35,47,60,61,64,74,83 that reported an improvement were of a higher-quality comparator design, although they used self-reported data. All of the other intervention studies35,47,60,61,64,74,83 also used self-reported or subjective measures of communication.

Eight systematic reviews,161,171,179,181,183,184,191,193 three of which included only UK studies,161,179,181 echoed the UK effectiveness studies in that communication was a key area for change in integrated care initiatives. Five of these systematic reviews181,183,184,191,193 concluded that integration (general collaboration, team education, MDTs, multidisciplinary case conferences or multidisciplinary meetings) led to improved communication. Three161,171,179 linked improved communication to improved team performance, and, as a result of this, enhanced care. None of the reviews were of the highest quality (meeting nine or more appraisal criteria).

One non-UK comparator intervention study from Canada (of reasonable quality)197 refers to ‘communication challenges’ that were attributable to case managers with poor communication skills. Another non-comparator intervention study (of reasonable quality) from the USA205 describes communication between a case co-ordinator and physicians as being a feature of success. A qualitative study from Canada279 reported that there were perceived views that ICPs enhanced staff communication. A qualitative study from the USA285 supports the importance of in-person contact between staff, and communication in integrated care.

The UK qualitative studies provide mixed evidence regarding whether or not the target of improved communication was met. Five94,98,108,125,147 reported perceptions of improved communication and seven92,113,115,118,141,142,145 reported an ‘uneven’, ‘patchy’ or ‘limited’ effect, communication breakdowns, substantial barriers or medical dominance impeding communication initiatives. A qualitative study from the USA272 concluded that communication and co-ordination between agencies are important influences that moderate the effectiveness of interventions.

Process changes

Within a systems perspective, the intervention elements and target areas for change have the potential to effect changes in the process of care delivery, which may then lead to outcomes and impacts at a service and whole-system level. We analysed the included literature for evidence regarding any effect of new models of integrated care on the process of care delivery. We grouped the evidence that we identified into the four areas of (1) service user change, (2) change in care provision, (3) change in information and (4) organisational change.

Patient role

Relationship with health-care provider

A qualitative study from the UK,100 of the North West London Integrated Care Pilot, indicated mixed results regarding whether or not the intervention changed relationships between patients and providers. Although 54% of participants responded positively to a question regarding an improved relationship in the survey evaluation, the study reports that 54% of participants also responded that they had not experienced any changes. Two international qualitative studies273,279 report more-positive outcomes: that integration of a community worker into a team had improved patient knowledge and engagement,273 and that an ICP had improved patient involvement. 279

Patient understanding of treatment

One UK intervention study59 reported that ICPs were associated with improved patient understanding of treatment and reduced anxiety among patients.

Care provision

Discharge planning