Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/04/33. The contractual start date was in November 2015. The final report began editorial review in November 2016 and was accepted for publication in May 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Mannion et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Whistleblowing: a complex and contested issue

Employee whistleblowing – loosely, the raising of concerns or speaking up about unsafe, unethical or poor-quality care by employees to persons able to effect action – has emerged as a central issue in debates over quality and safety in many health systems. 1 In the English NHS, recent inquiries and reports into poor standards of care have highlighted the vital contribution that whistleblowing can play in the detection and prevention of harm to patients. 2 Yet, for all its importance, the act of whistleblowing is no simple issue3 and is fraught with ambiguity. For example, individual whistleblowers may be perceived as heroes by some (for championing patients’ interests, promoting better care and challenging management) but may be seen as villains by others (for denigrating services and damaging professional and organisational reputations). Indeed, in the popular media whistleblowers are often portrayed either as ‘courageous employees’ who act to maintain standards at great personal cost or as ‘disloyal malcontents’ who ‘snitch’ or ‘grass’ on colleagues and pursue their own interests regardless of the dysfunctional consequences for individuals and organisations. Moreover, it would be naive to assume that all whistleblowers are necessarily motivated entirely by genuine concerns about patient care. Some may be motivated in addition by work grievances or personality clashes; in the extreme, concerns may even be of a malicious nature. In fact, clear delineation between such labels is problematic. Whistleblowing may arise out of complex and contested circumstances, as what is ‘safe’ and what is ‘acceptable’ (in terms of quality) are disputable. Therefore, binary distinctions (such as hero/villain, loyal/disloyal and warranted/unwarranted) are often unhelpful, and disguise the complexity and ambiguity of whistleblowers and whistleblowing.

When concerns are raised, it is also important that organisations respond positively, learn from any mistakes of the past and put in place effective policies to prevent such mistakes from happening again. Unfortunately, in the NHS there have been all too many high-profile examples of front-line staff raising serious concerns that have not been adequately dealt with by the organisation. Patients have suffered as a result, and staff, too, may have been harmed from the direct and indirect consequences of their raising concerns. As Sir Robert Francis’ independent review, Freedom to Speak Up, concluded:

. . . there is a culture within many parts of the NHS which deters staff from raising serious and sensitive concerns and which not infrequently has negative consequences for those brave enough to raise them.

However, whistleblowing always happens in a deeply cultural and highly situated organisational and policy context, and involves managing ambiguity and handling contestation. Whistleblowing policies thus need very careful design, implementation and enacting to protect those raising legitimate concerns, as well as offering support in cases of fallout from more doubtful or even vexatious whistleblowing.

Numerous surveys across different professional groups confirm significant shortcomings (or, at least, perceptions of significant shortcomings) in the protection and support offered to whistleblowers seeking to raise legitimate concerns about poor or unsafe patient care in the NHS. A possible reason for this is the widely held perception among health professionals that they will be victimised, ostracised or bullied if they raise concerns about colleagues or poor standards of care. 4 This is not a new development. More than a decade ago, the report following the Bristol Royal Infirmary Inquiry recognised that many staff, particularly junior staff, remained silent in the face of poor care or wrongdoing as they feared raising concerns and/or challenging superiors because of the possible repercussions:

There is a real fear among staff (particularly among junior doctors and nurses) that to comment on colleagues, particularly consultants, is to endanger their future work prospects. The junior needs a reference and a recommendation; nurses want to keep their jobs. This is a powerful motive for keeping quiet.

These concerns remain current. The 2015 NHS Staff Survey (NSS) found that, when asked whether or not their organisation treated staff involved in near misses, errors and incidents fairly, fewer than half (43%) of staff reported that this was the case. In addition, only half (50%) of staff reported that feedback was given by their organisation about any changes that had been made in response to the reported error or incident. 6 In 2013, the Royal College of Nursing polled its members, with almost one-quarter (24%) saying that they had been warned off or discouraged from whistleblowing and 45% saying that, even after they had spoken out, their employer had taken no action. Similarly, a survey of doctors undertaken in 2012 by the Medical Protection Society reported that only 11% of respondents said that they would be confident in the process if they were to blow the whistle, and 49% of doctors reported that ‘fear of consequences’ is why the whistleblowing process is ineffective. Only one-third (33%) of doctors who had blown the whistle said that colleagues supported their decision and < 40% felt that their concerns had been addressed (with, as a result, 18% feeling isolated, 14% moving location or job and 12% reporting health issues). 4

That there should be so much uncertainty and disquiet about speaking out should not come as a surprise. Local discursive practices (e.g. on the nature of success, failure, risk and performance) and local operational contingencies (such as resource constraints, service rivalries and stakeholder pressure) will have a powerful influence on the willingness of employees to raise concerns and the ability and willingness of employers to respond appropriately. Of course, whatever the local contingencies and discourses, these play out within a larger political, policy and legal context, and it is to these that we now turn.

Policy and legal context

Currently, protection for whistleblowers in England is enshrined entirely within an employment context and is contained in the Employment Rights Act (ERA)7 as amended by the Public Interest Disclosure Act 1998 (PIDA)8 (see Chapter 5, which contains a fuller overview of the legal framework related to whistleblowing in England). PIDA was passed to protect whistleblowers in the wake of the Bristol paediatric cardiac surgery scandal and provides legal protection against detriment for workers who raise concerns in the public interest (also known as making a disclosure) about a danger, risk, malpractice or wrongdoing in the workplace that affects others. For a whistleblower to be protected, the disclosure must be in the public interest, the worker must have a reasonable belief that the information shows the occurrence, or likely occurrence, of one of the categories of wrongdoing listed in the legislation, and the concern must be raised in the correct way. This is now enshrined in the NHS Constitution,9 which mandates that:

-

staff should raise concerns at the earliest opportunity

-

NHS organisations should support staff by ensuring that their concerns are fully investigated and that there is someone independent, outside their team, who can provide support

-

there is a legal right for staff to raise concerns about safety, malpractice or other wrongdoing without suffering any detriment.

Whistleblowing policies have been mandated and promoted for many years outside any strict legal framework – for example by health-care employers, regulators and professional associations – aimed particularly at securing safe and effective services. Professional bodies, including the Royal College of General Practitioners and the UK Nursing and Midwifery Council (NMC), have professional codes that place obligations on registrants to report untoward incidents to their employers, and they have produced guidance for doctors, nurses, midwives and students raising concerns about quality of care. In 2012, NHS Employers launched the Speaking Up Charter,10 which encouraged NHS organisations to pledge publicly a commitment to creating cultures and policies that support staff in raising concerns and a continuous review and evaluation of such policies to ensure that they remain effective. The Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) has also commissioned a whistleblowing helpline that provides free advice and support to staff on whether or not and how to raise concerns at work. Since 2015, a statutory duty of candour has operated that requires NHS bodies and all Care Quality Commission (CQC)-registered providers (rather than individuals) to be open and honest when an unintended or unexpected incident has resulted in, or could result in, death, moderate or severe physical harm, or prolonged psychological harm. In such instances, providers must notify the patient involved, offer an apology and follow up the incident in writing.

The report of the independent Freedom to Speak Up review, chaired by Sir Robert Francis,2 identified 20 principles and associated actions that should underpin whistleblowing polices in the NHS and recommended that the Secretary of State for Health should review, at least annually, the progress made in their implementation. These principles and actions include:

-

a common policy and procedure for raising concerns, including better investigations and promoting a model of good practice in the handling of concerns

-

training for managers and all staff in the raising and handling of concerns

-

cultural change towards creating more open, transparent and learning cultures that value communication and staff engagement

-

Freedom to Speak Up guardians to be appointed to each NHS organisation, supported by an independent national officer (INO)

-

legal changes to antidiscrimination laws to protect whistleblowers from discrimination in recruitment

-

additions to the list of prescribed persons to whom protected disclosures can be made.

In July 2015, the Secretary of State for Health confirmed the steps to be taken to develop a culture of safety, including the appointment of a national guardian alongside a local guardian in every NHS trust, with the goal of promoting the raising of concerns across the NHS. Although all NHS organisations are now required to have policies and procedures in place that urge staff to ‘speak up’ when necessary, there is no requirement for uniformity, and, as noted by Francis,11 different sources of guidance express themselves differently and there is, therefore, a risk that such a plethora of information, advice and guidance may be confusing for staff working in the NHS. For example, staff may not know where to go for the best advice or if, having spoken to a particular organisation, they still need to report their concerns elsewhere.

Aims and objectives of this study

Against this background, it is clear that there are serious uncertainties and challenges in relation to current whistleblowing and speaking up policies in the NHS. Our study addresses these concerns with the aim of developing theoretically grounded and evidence-informed guidance to assist policy-makers, managers and others responsible for designing/implementing effective whistleblowing and speaking up policies.

The specific objectives were to:

-

explore the main strands of the academic and grey literature on whistleblowing and related concepts such as employee silence, and to identify the key theoretical and conceptual frameworks that inform the understanding of employee whistleblowing

-

synthesise empirical evidence from different industries, sectors and countries with regard to the organisational processes, systems, incentives and cultures that serve to facilitate (or impede) employees raising legitimate concerns

-

examine the legal framework for whistleblowing in relation to health care as a mechanism for promoting (or inhibiting patient safety) and review the approaches to whistleblowing in relation to European Union member states and consider what lessons can be learnt at a domestic level from such comparisons

-

distil the lessons for whistleblowing policies and practice from the findings of formal Inquiries into serious failings in NHS care

-

ascertain the views, expectations and experiences of a range of key stakeholders, including service user and carer representatives, about the development of effective whistleblowing policies in the NHS and use these views to help structure and inform the desk research set out above

-

on the basis of findings relating to points 1–5, develop theoretically grounded and evidence-informed practical guidance for policy-makers, managers and others with responsibility for designing and implementing effective whistleblowing policies in the NHS.

Project overview and reporting structure

Full details of the methods used at each stage of the project are reported within the corresponding chapters, which broadly correspond to the six core objectives as set out above. In essence, the study comprised four distinct but overlapping strands:

-

a series of linked narrative literature reviews of the theoretical and empirical literature related to raising concerns, speaking up and whistleblowing across a range of sectors and contexts

-

an overview of the legal issues related to whistleblowing in an international context

-

a review of formal inquiry and government documents related to previous failings of NHS care

-

scoping interviews with key informants.

Throughout the project (completed in 1 year), the whole project team met extensively to discuss the emerging findings from each strand and to ensure that these emerging findings informed and complemented the ongoing work. In that sense, the work reported under separate chapter headings, although having a distinct focus that maps to the core objectives, has been informed by the parallel stands of work reported elsewhere. Supporting this, the scoping interviews with key informants were developed and implemented early in the project and helped to structure and inform the main desk research.

The chapters reporting the key aspects of the research are as follows:

-

Chapter 2 – the conceptual underpinnings of whistleblowing

-

Chapter 3 – empirical evidence on whistleblowing

-

Chapter 4 – the main whistleblowing inquiries and formal responses to inquiry recommendation

-

Chapter 5 – the legal underpinnings of whistleblowing

-

Chapter 6 – key informant interviews.

In compiling this report, we have sought to produce a synthesis that embraces the complexities and ambiguities associated with developing an understanding of whistleblowing and related policies in the context of health-care services, and to identify the different narratives and contours of debate in an inclusive and holistic manner, interweaving and interlinking common themes across the various strands of the study and thereby building a rich picture of whistleblowing across diverse sources of evidence. The final chapter (see Chapter 7) continues this integrative process and draws out the conclusions and research implications.

Chapter 2 The conceptual underpinnings of whistleblowing

Introduction

Any study intending to explore whistleblowing in the NHS requires an understanding of the conceptual underpinnings of whistleblowing and the key theoretical and methodological debates within whistleblowing research. This chapter, therefore, begins the process of unpacking what is meant by whistleblowing and introduces some of the sources of the ideas, conceptual underpinnings and different approaches to understanding whistleblowing and related terms such as ‘speaking up’. The material draws on the systematic literature review detailed in Chapter 3 (see that chapter for an account of the methods by which the literature was uncovered and collated), as well as from the accumulated expertise of the research team and from discussions with leading researchers in the field.

The chapter is structured as follows. We begin by outlining how whistleblowing has developed as a distinctive field of enquiry, and explore how whistleblowing and related concepts such as speaking up have been defined in the literature. We then review the main theoretical perspectives on whistleblowing that have been seen in the literature, and examine emerging perspectives that have the potential to develop our understanding further. We then rehearse the key methodological challenges involved in whistleblowing research, before drawing out some of the implications of these for more thorough NHS-specific research.

The emergence of whistleblowing as a field of study

Whistleblowing was first brought to wide public awareness in the 1970s, and has become progressively more high profile. The release of the Pentagon Papers in 1971 was not the first example of whistleblowing, but it was arguably the first to be widely known. There are three competing explanations for the origins of the term ‘whistleblowing’, and these provide useful insights into the tensions and ambiguities that still surround the practice. The most frequently encountered explanation is that it comes from an analogy with police officers blowing a whistle, to attract the attention of an individual to whom the officer wished to speak, or to bring other officers in the vicinity to the scene (in the days before mobile communications). Another suggested analogy is with the use of a whistle by referees in sport to call a halt to a game after a foul has been committed.

A third, perhaps less likely, but nonetheless intriguing, explanation, is that the term derives from 19th century US legislation that required train drivers to sound a whistle when they approached crossings. Failure to do so could lead to fines, and, moreover, citizens calling attention to these failures could receive payment for doing so. Indeed, in the US legal system it remains the case that those blowing the whistle on financial irregularities can sometimes stand to gain personally from the reporting of such wrongdoing. This articulation of whistleblowing speaks to the still-current concern that whistleblowers might be motivated by personal gain. Taken together, then, these putative etymologies describe whistleblowing variously as an act of calling for help, crying foul or informing the authorities (perhaps) for personal gain.

The academic interest in whistleblowing followed its greater public profile, with a handful of seminal articles published between 1983 and 1985 proving influential (see Chapter 3, Literature review methods). From the outset, whistleblowing research was inherently multidisciplinary, with scholars from law, management, public administration, sociology and psychology all interested in the phenomenon. An unusual feature of the whistleblowing field is the relative lack of definitional debates. Over 30 years ago, Near and Miceli12 defined whistleblowing as ‘the disclosure by organization members (former or current) of illegal, immoral, or illegitimate practices under the control of their employers, to persons or organizations that may be able to effect action’. This definition quickly gained almost universal acceptance and application, and remains the standard definition. The surprising lack of debates on definition among whistleblowing researchers stands in stark contrast to debates within wider society concerning the purpose and value of whistleblowing, the motivation of whistleblowers and the circumstances under which they should receive legal protection for their actions. The last issue is key: prospective whistleblowers are likely to be less concerned about how academics define whistleblowing, and more concerned about how the law defines it and whether or not they can expect protection under the law for their actions. 13

The debate continues as countries around the world consider enacting whistleblowing protection legislation or revising existing laws.

Raising concerns, speaking up or blowing the whistle?

Academics typically define a given social phenomenon more narrowly and precisely than the way in which lay people talk about the phenomenon. Whistleblowing represents an unusual reversal of that pattern, as the most widely used definition12 incorporates behaviour that most employees or citizens would be unlikely to label whistleblowing. Park et al. ,14 who developed a typology of whistleblowing based on a decision tree, illustrate this. They suggest that individuals who have decided to raise concerns face three key choices: to raise issues (1) informally or formally, (2) anonymously or on the record and (3) internally or externally. This typology suggests eight types of whistleblowing, only some of which would fit with how most people would understand the concept. For example, before deciding to blow the whistle employees usually find themselves trying to work out exactly what is happening, often through engaging in dialogue with colleagues. 15 Such behaviour could be consistent with the informal/identified/internal whistleblowing pathway,14 but it seems unlikely that staff would perceive such conversations as a form of whistleblowing. Table 1 details how the Park et al. 14 typology might translate into a health-care context.

| Type of whistleblowing | Examples |

|---|---|

| Informal | |

| Anonymous, internal | Unsigned note sent to a manager in the internal mail; telephone call to HR (or similar) giving no name |

| Anonymous, external | Tip-off to a journalist; anonymous web postings |

| Identified, internal | Discussing one’s concerns with a colleague |

| Identified, external | Posts on social media criticising one’s employer |

| Formal | |

| Anonymous, internal | Leaving a message on a drug error hotline |

| Anonymous, external | Medication error reporting programmes |

| Identified, internal | Raising concerns with a Speaking Up guardian |

| Identified, external | Raising concerns with a regulator; approaching a MP; speaking to a journalist |

Notwithstanding the Park et al. 14 typology detailed above, the academic literature has traditionally focused on a dichotomous choice between whistleblowing and silence; that is, when faced with wrongdoing, an employee makes a conscious choice either to remain silent or to act by raising concerns. 16 Yet, as highlighted by Jones and Kelly,17 this simplistic dichotomy obscures a range of alternative strategies to whistleblowing that may be just as effective in identifying and preventing wrongdoing. Such strategies might include interpersonal approaches such as the use of humour or sarcasm to signal discontent, or informal and off-the-record discussions with managers and employees. Jones and Kelly17 suggest that these ‘informal and circumlocutory’ channels of communication may be valuable organisational mechanisms for addressing poor standards of care. Indeed, they argue that these can prove more effective than formal reporting systems, as they are more likely to circumvent the ‘deaf effect’ (see below). This fits with the current emphasis in NHS policy debates on ‘raising concerns’ and ‘speaking up’, rather than whistleblowing per se, consistent with our observations in Chapter 3 that the relevant literature within health care tends to emphasise voice behaviours rather than formal whistleblowing.

Francis11 notes that many staff appear unhappy with the term whistleblowing, hence the suggestion that terms like ‘raising concerns’ and ‘speaking up’ are to be preferred. However, it is useful to think of raising concerns, speaking up and whistleblowing as a continuum, even though, arguably, all can be subsumed under the academic definition of whistleblowing. We can differentiate between them in various ways, but it may be most useful to think about how employees might distinguish between them. An employee who has concerns about a particular issue that affects quality and safety of patient care might ‘raise concerns’ with their line manager, possibly informally. If they get no response, they may choose to ‘speak up’, potentially talking again to the same manager, but this time more formally and perhaps making clear that they expects their concerns to be a matter of record. If the issue is still not resolved, they may choose to ‘blow the whistle’ to someone more senior, or perhaps go outside the organisation.

From an employee perspective, the act of ‘raising concerns’ may be relatively low risk, something that might be done routinely, perhaps even just in passing (e.g. ‘I think the new health-care assistant is a little brusque with the older patients’). Speaking up is more serious: the very phrasing implies raising one’s voice or breaking a silence. The perceived level of risk may not be very great; in some cases the employee may only risk feeling foolish if they are mistaken, although their concern about this may, in itself, be enough to ensure that they remain silent. 15 Whistleblowing is a more significant act, to which the organisation may respond negatively. Alford18 has argued that whistleblowers are defined post hoc, by the organisation’s response to their action. Using the NHS terminology, someone who thought they were just ‘raising concerns’ or ‘speaking up’ can discover that they are a whistleblower if the organisation responds negatively. The general perception among NHS staff and the wider public is that NHS whistleblowers tend to fare badly,19 so staff thinking about speaking up may, from the outset, be concerned that they will receive a very negative response. This may lead individuals with relatively low-level concerns to refrain from raising them.

In a health-care context, another important distinction between raising concerns/speaking up and whistleblowing may be the focus of the concern. The classic definition of whistleblowing specifies that it is about ‘illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices’. 20 Many issues that could affect care quality and patient safety, and about which we would hope staff would raise any concerns, do not necessarily come under any of those headings. Staffing levels, poor practice or poor performance (e.g. from a colleague dealing with personal problems) are all issues that could have a detrimental effect on patient care, but that staff would probably not view as ‘wrongdoing’ (see below for a more detailed discussion). Nevertheless, such issues may eventually lead to whistleblowing if they are not properly addressed. If a junior doctor raised concerns about a colleague’s confidence in dealing with challenging patients, they are clearly not concerned about ‘illegal, immoral or illegitimate’ behaviour. However, if those concerns are not addressed, and problems continue, a decision to speak to someone more senior about the issue is implicitly speaking up about the failure to address the problem. Such action is more consistent with whistleblowing. This is a subtle but important point that is often missed: whistleblowers are often described as blowing the whistle about a specific issue (e.g. poor practice), but they are often effectively blowing the whistle on management’s failure to act once made aware of the original issue.

Recent discussion of speaking up2,21,22 has tended to frame the problem in terms of creating environments in which staff feel more able to voice their concerns. Yet, as Francis11 and Kelly and Jones19 observe, in many scandals staff had voiced their concerns; the problem was getting someone to listen.

This is consistent with the ‘deaf effect’, a term originally coined by Keil and Robey23 to describe the reluctance of senior managers to hear, accept and act on challenging observations from lower down the organisation. Vandekerckhove et al. 24 suggest that researchers need to pay more attention to the question of how recipients of whistleblowing respond, and in particular to ‘hearer action’, which we might view as the antithesis of the deaf effect. Whereas it is widely recognised that it takes a degree of courage for someone to blow the whistle, it is less immediately obvious that it may also take courage for a manager to take on board the issues and act on them. Just as the whistleblower knows that the line manager may not want to hear bad news, so the line manager knows that more senior management may be similarly reluctant to be informed of breaches or the requirements of remediation. Whistleblowing recipients in management roles know that their actions in raising the whistleblower’s concerns may receive a negative response and may even lead to the sort of retaliation and victimisation that can sometimes be experienced by whistleblowers themselves. For this reason, Vandekerckhove et al. 24 suggest that there is a need for research into ‘hearer courage’ to understand ‘which managers have the courage to hear, under which circumstances, and with regard to which wrongs’ (p. 316). The same issues may pertain to the new Speaking Up guardian roles in the NHS, for whom a whistleblower’s report may feel like the whistleblower taking a burden off their own shoulders and placing it on the guardian’s.

Our analysis of the various public inquiries (see Chapter 4) suggests that senior management may sometimes also suffer from ‘collective myopia’,25 a shared inability to see a problem. This is potentially more problematic than the deaf effect, as it leaves those in management positions genuinely unable to see what the whistleblower is trying to bring to their attention. This could lead an individual to proceed from raising concerns to speaking up to internal whistleblowing, not in search of ‘someone willing to listen’ but in search of ‘someone able to see’. However, the NHS can be viewed as a single large organisation in many ways, and criticisms of regulator responses to cases such as that at the centre of the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust Public Inquiry11 suggest that even when the individual goes outside the immediate organisation, they may still find people unable to see/unwilling to listen. There is a sense in which raising concerns and speaking up in health care adhere to both organisational ‘etiquette’ and the hierarchical chain of command, which inevitably means that management can choose to ignore the issue. There is also a sense that individuals may feel that they have done their duty in raising the issue. 26 Blowing the whistle, especially externally, raises the stakes and is much harder to ignore.

Blowing the whistle on what?

Central to whistleblowing research has been the idea of wrongdoing, a catch-all term that includes everything from persistent acts of minor incivility to multibillion-pound corruption. Within any given organisation, there are various types of wrongdoing on which an individual might feel it necessary to blow the whistle. The focus of the present project is on issues pertaining to the quality and safety of patient care, but it is worth examining the ways in which perceptions of the nature of the wrongdoing might affect whistleblowing. The bulk of whistleblowing research has been concerned with pecuniary wrongdoing such as fraud and corruption, in which there is, in principle, a final legal judgement to be obtained as to whether or not wrongdoing has occurred. In contrast, issues around safety and quality can be much more ambiguous, a point illustrated by two cases that form part of NHS folklore on whistleblowing: the ‘Graham Pink case’27 and Bristol Royal Infirmary. 5

The Graham Pink case is generally remembered as an archetypal whistleblowing narrative. Pink (a nurse) raised concerns with the hospital’s management about dangerously low staffing levels; management would not listen and did not act, so Pink ‘blew the whistle’ and was eventually removed from his post for his trouble. Vinten28 suggests a somewhat different interpretation, arguing that there was ample evidence that management took Pink’s concerns seriously and investigated, but found staffing levels to be appropriate. Pink’s colleagues on the unit agreed with the management’s assessment, but were unable to get this message across to the Royal College of Nursing, who found Pink’s account more compelling against a backdrop of concerns about government policy in the NHS. The Pink case revolved around an issue – staffing levels – about which there was (and is) considerable scope for experienced practitioners to reach very different views. Although there will be a level of staffing that everyone would agree is unsafe, it has proved difficult to develop an evidence-based metric to calculate minimum safe staffing levels and appropriate skill mix. 29

The tragic events surrounding infant heart surgery at Bristol Royal Infirmary might appear to be more amenable to an evidence-based analysis, given that the extensive use of clinical audit data allows comparisons of performance over time and between units. Yet, as Weick and Sutcliffe30 observe, even with such extensive data there is still a need for organisations to make sense of the data, and all sense-making is intentional and social. There was clearly a desire at Bristol Royal Infirmary to believe that the unit was performing acceptably, and management and senior clinicians interpreted the data in terms of a learning curve. They focused on evidence that the unit was improving, and overlooked evidence that it was still underperforming relative to comparable units and that it was improving only slowly.

As the analysis of public inquiries shows (see Chapter 4), issues that appear unambiguous after the event may have seemed open to interpretation of the event at the time. This creates a challenge for policy-makers: we are generally dealing not with malevolent individuals or corrupt systems, but with individuals and systems that are failing in some way, and resistant to hearing the messages about that failure. As the whole premise of whistleblowing is ‘wrongdoing’, and wrongdoing appears a moral appellation, people are reluctant to use the term and recipients are reluctant to hear it. This underlines the importance of developing a greater understanding of hearer courage, particularly in a NHS context.

The inherent ambiguity of many of the situations complained about at the heart of whistleblowing in the NHS draws further attention to the importance of definitional issues. Brown et al. 31 suggest that wrongdoing be defined as ‘when a person or organisation does things that are unlawful, unjust, dangerous or dishonest enough to harm the interests of individuals, the organisation or wider society’. This definition is both more precise and more encompassing than the traditional ‘illegal, immoral or illegitimate practices’,20 and would certainly cover actions/omissions that could have a negative impact on care quality and safety.

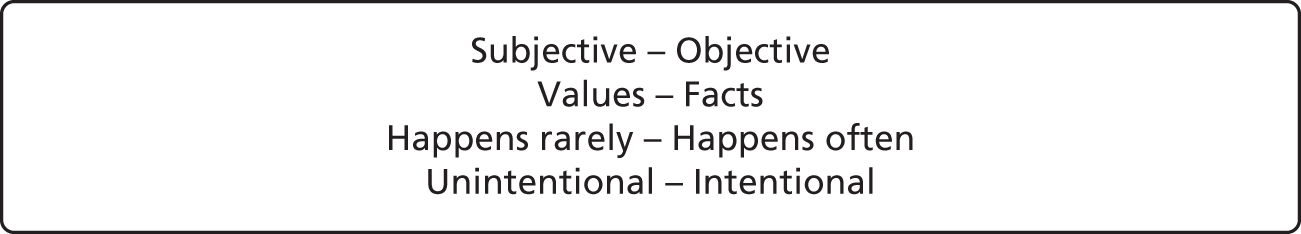

Taking this further, Skivenes and Trygstad32 suggest that there are six ‘intrinsic dimensions’ that affect individuals’ assessment ‘of an alleged act or practice of wrongdoing and the degree of importance (or seriousness) of an act of wrongdoing’ (p. 97). These dimensions are (1) whether the perception of wrongdoing is subject or objective, (2) whether it relates to values (such as dignity) or facts (such as clinical outcomes), (3) the frequency of the wrongdoing (e.g. a rare occurrence or an ongoing problem), (4) whether or not the wrongdoing was intentional, (5) whether or not there is a public interest dimension and (6) the persons/groups affected (e.g. are they vulnerable?). In a NHS context, the final two dimensions are arguably ‘fixed’; the activities of the service always have a public interest dimension, and patients are by definition vulnerable persons even if they would not in the normal course of life be viewed in those terms. It is therefore only the first four dimensions that influence whether or not a situation is assessed as wrongdoing, and, if so, how serious it is (Figure 1; Table 2 provides some simple vignettes that illustrate the opposite ends of these dimensions).

| Example | Assessment against dimensions noted in Figure 1 |

|---|---|

| An Asian man is being admitted to a ward. He is very friendly and chats non-stop to the ward team. The member of staff dealing with his admission asks the nurse in charge which bed to put him in; she points to a bay opposite ward control where three white patients are sitting quietly by their beds, and says ‘Put him in there, he’ll add a bit of colour to the place’. The patient does not say anything, although the nurse thinks he looks rather surprised. She is also surprised, as she feels that the remark was racist, although she has never heard her colleague say anything like that before | Subjective, based on values, a one-off occurrence, (probably) unintentional |

| A long-serving surgeon has a particular way in which he likes to undertake a certain surgical procedure, which differs from that of the other surgeons on the unit and from guidance issued by NICE 3 years ago. This has been raised with him, but he simply states that his approach leads to better outcomes from the patient. The clinical outcomes data do not support his assertion | Objective, based on facts, a repeated occurrence and intentional |

The main purpose of the two examples in Table 2 is to illustrate the assessment dimensions, but vignettes like these are also useful in allowing us to place ourselves in the place of staff observing possible wrongdoing.

Outsider whistleblowing?

The classic definition of whistleblowing is that it is an action taken by current or former members of an organisation. The term ‘member’ is not explicitly defined, but it has generally been taken to mean organisational members or employees. 33 This excludes many individuals who may have links with an organisation and be in a position to observe, and raise concerns about, wrongdoing within the organisation. Miceli et al. 34 note that many significant ‘whistleblowing’ cases reported in the press are technically not examples of whistleblowing, as the person who raised the concerns was not a current or former member of the organisation in question. Acknowledging that these cases are, nevertheless, important, and deserving of further study, the authors propose the term ‘bell-ringing’ to describe the raising of concerns by outsiders. Although we acknowledge the logic of this attempt to bring definitional clarity to this new offshoot of the whistleblowing field, it is difficult for academics to impose such definitional precision retrospectively, once a term is out in the public domain and being used ‘wrongly’. Culiberg and Mihelic33 suggest that rather than framing the issue in terms of whistleblowing versus bell-ringing, it might be more useful to refer to insider versus outsider whistleblowing.

Outsider whistleblowing is potentially a more significant issue for health care than for any other sector. Examples of potential outsider whistleblowers would include patients, relatives and visitors, suppliers, professionals working in other organisations [e.g. social workers and general practitioners (GPs)], clinical tutors and contractors. Outsider whistleblowers might be assumed to be freer to speak up than staff, yet all of these individuals may have reasons to be reluctant to blow the whistle. Patients, relatives and visitors are obvious examples: all are likely to have concerns about the potential for the patient to suffer reprisals for raising concerns. In addition, outsider whistleblowers themselves can be targeted; a recent radio programme discussed the apparent rise in care homes ‘banning’ visitors and relatives who had raised concerns about care. As the model of delivery for NHS services becomes more complex, involving a greater range of non-NHS organisations, there is a need to think carefully about the role of outsider whistleblowers, and how they might be encouraged and supported. This may be particularly important for employees of other organisations, as they are presently unlikely to enjoy any legal protection under PIDA.

Theoretical perspectives on whistleblowing

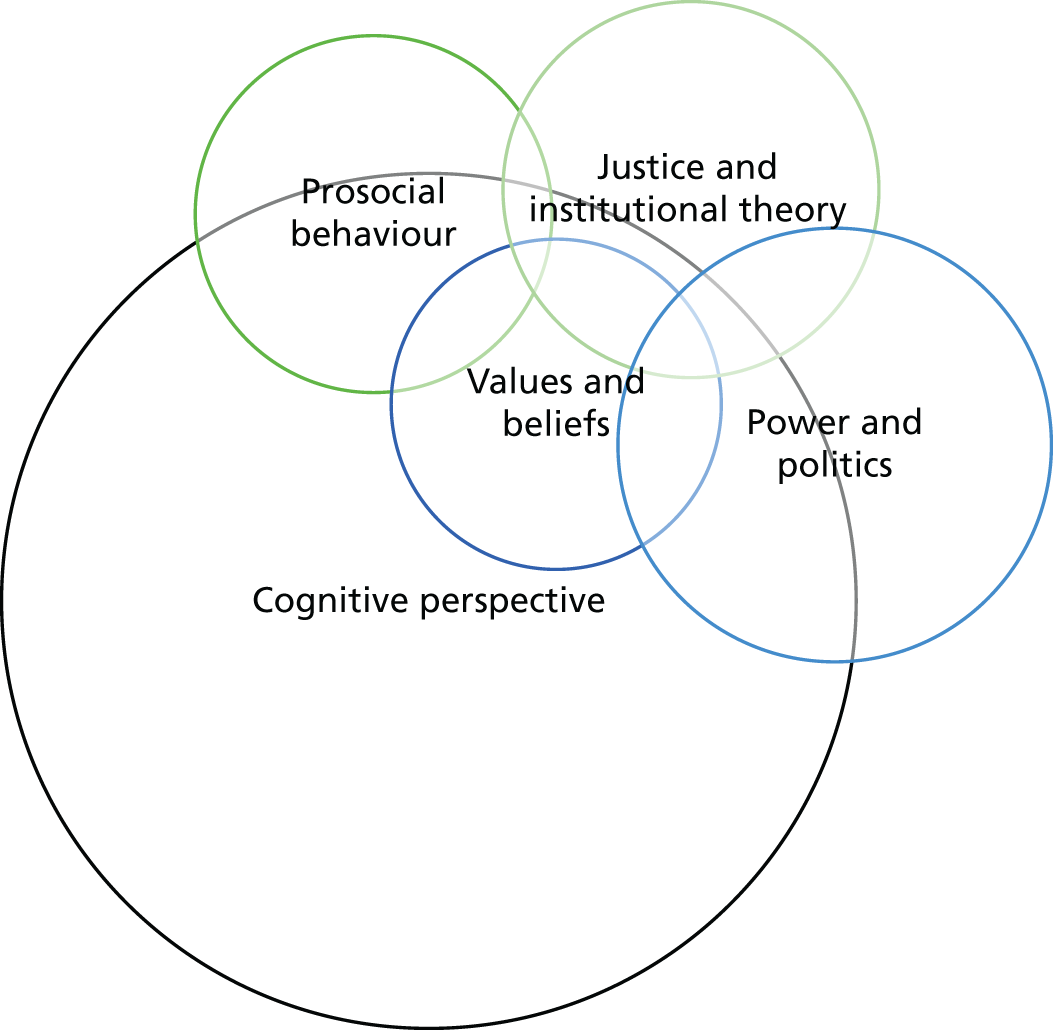

Given the interdisciplinary nature of whistleblowing research, it is perhaps unsurprising that our review of the literature, as with previous reviews (e.g. Kelly and Jones19), did not identify a universal or shared underpinning theoretical framework for whistleblowing research. We can, however, identify a number of different theoretical perspectives that provide useful lenses through which to view the phenomenon (Figure 2). Note that these are not distinct ‘schools of thought’, and researchers often borrow ideas from several perspectives in developing their research. The figure should be viewed as a useful heuristic, rather than a strict mapping of the position of each perspective on some notional x- and y-axes.

FIGURE 2.

Theoretical perspectives on whistleblowing.

In their seminal paper, from which much other work has derived its definition of whistleblowing, Near and Miceli20 identified the steps involved in the whistleblowing process (Table 3). This framework has been widely used in whistleblowing research. At one level, it is simply a description of a sequence of events, but, by emphasising decisions, the framework reinforces a focus on decision-making, which in part explains the dominance of the cognitive perspective in the whistleblowing literature.

| Step 1 | Step 2 | Step 3 | Step 4 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Observer’s decision 1: is the observed activity illegal, immoral or illegitimate? | Observer’s decision 2: should the activity be reported? | Organisation’s decision 1: should the action be halted? | Organisation’s decision 2: should the whistleblower be punished? |

Taking each of the perspectives shown in Figure 2 in turn, we can see that each has distinctive foci of interest, and that each brings to the fore specific insights about the whistleblowing process.

Cognitive perspective

The cognitive view within psychology has been a major influence on whistleblowing research. Considering its relevance to the understanding of how stakeholders respond to misconduct, Barnett35 highlights two key assumptions, namely that ‘people cannot attend to all the stimuli competing for their limited attention’ and ‘factors particular to the person and the situation influence how one allocates his or her attention and responds to stimuli’. Many whistleblowing researchers emphasise the importance of the decision-making process that takes place after an event of potential wrongdoing is witnessed, typically at stage 2 of Near and Miceli’s12 model of the whistleblowing process. The implication is that observers consciously weigh the factors for and against blowing the whistle, such as wanton violation of rules and laws, negligence in a duty of care or abuse of power. However, a cognitive perspective recognises that the decision to blow the whistle is also influenced by factors of which the individual may be largely unaware. Research from this perspective explores whistleblowing as a deed that results from the confluence of an individual’s values and beliefs, and the context in which a problematic act occurs, that is, what behaviours ‘fit’ within the potential whistleblower’s personal paradigm. Whistleblowing research adopting a cognitive perspective recognises that, although the observer may not be fully aware of all of the various influences on their decision, such influences must be accounted for if our understanding of the topic is to be improved. 15,36

Values and beliefs

Research adopting this perspective is concerned with how externally derived values and beliefs influence whistleblowing. These values and beliefs may come from macro-level societal-level influences (e.g. religious teachings or national culture) or by more meso- or micro-level influences, such as the local organisational culture, rules and regulations, or the influence of dominant team leaders. A key assumption is that guidance relating to what is right and wrong is a principal driver of whistleblowing behaviour. This guidance is potentially captured by organisational policies, but also by the teachings and traditions from other occupations. There is a connection here with the cognitive view through cultural influence. However, with the values and beliefs perspective, the distinction is that other parties create the influence on whistleblowing for the individual, whereas the cognitive view presents the influences on the whistleblowing decision as being internally constructed, albeit influenced by a myriad of other overlapping factors. In Figure 2, we located the values and beliefs perspective wholly inside the cognitive perspective, reflecting the fact that values and beliefs can be viewed as an influence on the decision-making process. Thus, religious beliefs may have a strong influence on what individuals perceive as wrongdoing, and their perceptions of their own responsibilities as observers of this wrongdoing, but ultimately the individual still has a decision to make.

For example, Rothwell and Baldwin,37 examining whistleblowing in police agencies in Georgia, USA, noted that uniformed staff, in spite of close personal relationships with colleagues, were more likely than civilian employees to blow the whistle on wrongdoing, suggesting that the external values and formal regulation associated with uniformed service were important. Indeed, Alford38 discusses the threat posed to organisations by the ‘ethical autonomy’ (cf. Kant) of their members. Organisations, therefore, would find work from this perspective useful, as it could provide clues as to how to inculcate values and beliefs that the organisation and wider society deem appropriate to encourage whistleblowing behaviour when necessary. The review by Trevino et al. 39 contributes to this perspective by exploring individual behaviours that were judged as ethical or otherwise when measured against the norms in which those behaviours occur. Sekerka et al. 40 note that organisations typically encourage individuals to behave ethically by imposition of external ‘rules and legal standards’, rather than by encouraging professional moral courage. One of the key insights of this perspective is the importance of setting out clear rules, standards and norms regarding what employees are expected to do if they encounter wrongdoing.

Justice and institutional theories

This perspective considers the impact that the legal system and organisational rules and regulations have on the whistleblowing process. Embedded within the concept of ‘justice’ is that of ‘fairness’, and although recognising the importance of the topic, a number of authors emphasise the range of perceptions of fairness as a factor in whistleblowing. For example, Alleyne et al. ,41 following Rawls,42 suggest that ‘justice is seen as fairness when the allocation of resources in society is considered rationally as advantageous or disadvantageous’. They suggest that perception of injustice is a key driver of the act of whistleblowing, a view supported by Near et al. 43 Gundlach et al. 44 note that ‘looking fair may be more important than being fair’, and, for this reason, there is clear overlap with other theoretical perspectives, given that the cognitive perspective relies on individual perceptions, and what is perceived as prosocial behaviour will vary from one context to another. This raises the difficult question of perception of fairness, a perception that inevitably interacts with national differences. In this review, we have focused on Western cultures, as this is where the bulk of whistleblowing research has been undertaken. However, given the marked cultural and national diversity of the NHS workforce, there is potential for considerable cultural differences in attitudes towards whistleblowing, which may be highly significant.

Within the more institutionalist strand of this perspective, recent research has specifically examined how institutional mechanisms in public sector organisations influence whistleblowing. 45,46 This work has been outside health care and the outside the UK, but could be very relevant to the NHS, particularly in terms of understanding the institutional processes by which policy-makers influence the process (cf. Blenkinsopp and Snowden47).

Power and politics

This perspective explores the impact that power and political actions in all organisations have on whistleblowing. In their seminal work, Near and Miceli20 emphasise the importance of power in the construction of their model of the whistleblowing process, and retaliation from organisations towards whistleblowers can be viewed as a response to the threat they pose to organisational power. 48 Avakian and Roberts49 suggest that ‘Our analysis indicates that the imbalance of power results from the way the whistleblower exercises the hidden knowledge in unexpected ways’. This links to recent work from a Foucauldian perspective, which introduces the concept of parrhesia to whistleblowing research. 50,51 Foucault used this term to describe ‘a specific modality of truth-telling (veridiction) that emerges in the context of asymmetrical power relations’. 51 This line of work offers valuable insights into the various difficulties faced by individuals seeking to raise concerns about matters that are (usually) factual and provide management with information that would appear useful (see Weinstein52 and Alford38 for non-Foucauldian approaches to this issue).

Near et al. 43 also explore the interface between theories of power and justice theory, and comment that when organisations deliberately provide their own legal protection (and hence power) to a ‘role-prescribed whistleblower’ (e.g. internal auditors), positive outcomes for both the whistleblowers and their organisations are experienced. Pittroff53 supports the view of the centrality of power to successful implementation of a whistleblowing system within an organisation, stating that ‘implementation of internal [whistleblowing] systems is ostensibly driven by power theories’.

It is clear, therefore, that the papers exploring whistleblowing through focusing on the influence of power and politics have a major role to play in developing our understanding of the topic. This perspective may be especially relevant to the NHS, which is very hierarchical in nature, with considerable variations in power between different occupational groups and different levels, and the added complication of a further powerful hierarchy above the chief executive, who is ultimately accountable to the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care.

Prosocial theory

The final theme to emerge from our review relates to works that explore the desire to ‘do good for others’ by blowing the whistle. Typically, such papers explore the concept of whistleblowing as an act that benefits the welfare of others both inside and outside the organisation, even though there may be an element of self-interest driving their decision to expose wrongdoing. As Dozier and Miceli54 state, ‘[whistleblowing] is more appropriately viewed as ‘prosocial’ behaviour, involving both selfish (egotistic) and unselfish (altruistic) motives on the part of the actor’. This creates a managerial dilemma; Dungan et al. 55 state that ‘people are moral hypocrites – espousing moral values when judging others, while actively ignoring when self-interest is at stake’. The same authors point to scientific evidence that suggests that prosocial behaviour is intrinsically rewarding, and, for this reason, imply that a natural positive predisposition towards whistleblowing exists. This is important to any attempt to support the reporting of wrongdoing, and perhaps has the potential to challenge a common organisational perception of whistleblowers as ‘trouble causers’.

Alternative perspectives

The work considered in each of the subsections above demonstrates where authors have adopted a particular stance on the topic, and we believe that different and productive interpretations of whistleblowing can be generated by adopting different stances and using different lenses. As whistleblowing becomes more high profile, and researchers from other academic fields become interested in exploring the concept, we are witnessing the publication of articles that examine whistleblowing from new and illuminating perspectives.

Through an examination of language

The definitional complexities alluded to above draw attention to the importance of clarity in the language used, but also the influence of language on how whistleblowing situations are framed. We might describe the same behaviour as ‘raising concerns about an issue affecting patient safety’ or ‘blowing the whistle on poor practice’, but the former phrasing may be more acceptable to staff and management, and more likely to lead to change. It is, therefore, important to consider the language used in and around the act of whistleblowing, with sensitivity to style and content. Contu56 argues that looking at how the language used to explore a whistleblowing event evolves over time ‘opens up an appreciation of the ethical and political valence of the process of whistleblowing’.

Through an examination of sense-making

The sense-making perspective57 offers potentially valuable insights. Its relevance to health care has been acknowledged, as Weick and colleagues have examined ‘high reliability organisations’; for analyses directly relevant to the NHS, see Weick and Sutcliffe30 and Weick et al. 58 Blenkinsopp and Edwards15 drew on the sense-making perspective to develop the concept of ‘cues for inaction’. They suggest that clinical staff are very aware of the risks of whistleblowing (or even of just raising concerns) but are also aware of their responsibility for the patient (under codes of conduct and NHS policies). Caught between a ‘rock and a hard place’, they are motivated to find ways of making sense of the situation that allow them to stay silent. The challenge for organisations is to find ways to create ‘cues for action’, and reduce or even eliminate possible cues for inaction.

Given the diversity of conceptual lenses open to researchers, and the diverse insights thus available to date, future empirical work on whistleblowing in the NHS should carefully exploit the conceptual diversity for fresh insightful gains.

Methodological issues in whistleblowing research

Whistleblowing is an inherently difficult phenomenon to study. Although the act of whistleblowing involves bringing a situation to the attention of others, in most cases that does not bring it to wider attention; cases in which the situation becomes a matter of common knowledge within the organisation will be the exception rather than the rule, and the proportion of cases in which the situation comes to wider public attention is tiny. These high-profile cases of whistleblowing can provide researchers with valuable insights, but the sensitivity of such cases make it difficult to gather data, especially if the situation is the subject of investigations (criminal, disciplinary, fitness to practice) or other legal processes (e.g. negligence claims). A further barrier to data gathering can arise in cases in which the whistleblower’s employment is terminated through the employer and employee reaching a settlement agreement that includes non-disclosure clauses.

Despite these difficulties, researchers have developed various approaches to investigate whistleblowing. Olsen59 identifies the main research methodologies used in whistleblowing research as experimental studies (e.g. Burton and Near60), content analysis of legal cases and press coverage (e.g. Brewer61), analysis of government data (e.g. records of whistleblowers contacting government agencies), qualitative case studies, surveys using hypothetical scenarios and surveys of actual whistleblowing. These last three have been by far the most widely used, and below we consider each in turn (the specific findings emerging from each of these methodological traditions are covered more fully in Chapter 3; here we concentrate on highlighting differences in methodological approach).

Qualitative research

Some of the earliest studies of whistleblowing were qualitative or even journalistic examinations of specific whistleblowing cases,28,62 including biographical and autobiographical accounts of whistleblowers (e.g. Robison, Watkins26). More recent work in this vein includes more theoretically informed analyses of cases. 15,18,30

Surveys using hypothetical situations

This is the most widely used approach in whistleblowing research. The most common research design is cross-sectional, generally using whistleblowing intentions as the dependent variable, as intentions to perform a given behaviour are generally regarded as a good predictor of future behaviour. 63 A typical design would present participants with one or more vignettes describing a situation that might be viewed as wrongdoing and asking how likely they would be to report it. Inviting individuals to imagine what they would do in a given situation is problematic, as it relies on the participant being able to make a realistic appraisal of what they might do in a situation that may be very unfamiliar to them. It does, however, allow researchers to gather data on a range of permutations. A good example for health care is offered by Lawton and Parker,64 who produced nine vignettes which varied across two dimensions: adherence to protocols (compliance, deliberate violation, and improvisation in the absence of a protocol) and outcome for the patient (good, poor or bad).

Surveys of actual whistleblowing

Bjørkelo and Bye65 suggest that approaches to measuring actual whistleblowing can be categorised as having a behavioural versus operational definition. Behavioural approaches (e.g. US Merit Systems Protection Board survey) ask individuals about whether or not they have observed wrongdoing (from a list of examples) and whether or not they reported it, whereas an operational definition approach offers participants an explicit definition of whistleblowing and asks whether or not they have blown the whistle. The behavioural approach has the advantage of providing insights into how frequently wrongdoing is encountered, and what proportion of people blow the whistle on it. However, it assumes that the types of wrongdoing listed are ‘illegal, immoral or illegitimate’ in similar ways across all settings and cultures. The operational approach avoids this difficulty, but leaves us unsure how to categorise those respondents who report that they have not blown the whistle.

Reviews of whistleblowing research59 indicate problems with identifying variables that consistently predict key outcomes (e.g. the decision to blow the whistle, whether or not the action succeeds, whether or not the whistleblower suffers retaliation). We suggest that it is not that the field has been unable to identify key factors, but that contextual differences have a significant impact. Tolstoy once wrote that ‘Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way’,66 and whistleblowing involves very unhappy (organisational) families. Although it would normally be impractical to develop frameworks tailored to specific organisational contexts, there is nonetheless a tradition of looking at this issue for key occupational groups (e.g. auditors) or sectors (e.g. financial services). For an organisation the size of the NHS, it could be feasible to develop a model of what works specifically in that setting. What would be required is research that builds on existing models of whistleblowing to identify how these models apply in the specific context of the NHS, and it is to this that we turn in the next section.

Concluding remarks: further exploration of whistleblowing in the NHS

In this final section, we consider how existing theory and research might be translated into a more thorough and conceptually rooted exploration of whistleblowing in the NHS. We start by considering how much the NHS context matters. We noted above that there are some translational issues in applying insights from mainstream whistleblowing research to health care, because so much of the literature focuses on wrongdoing such as fraud and corruption. However, having acknowledged that health care is different from many other industries, we also need to consider whether or not there are factors associated specifically with the NHS that make it different again.

The first point to note is that the NHS has a uniquely dominant position in health care, different from health-care arrangements in other developed countries. The NHS is monolithic and comprises a large number of organisations (and different types of organisation), each legally a separate employer. However, the reality of ‘working for the NHS’ means that blowing the whistle on wrongdoing in one NHS organisation risks not only retaliation from that organisation, but also an effective ‘blacklisting’ from employment elsewhere in the NHS. Despite some expansion in private health care, the NHS remains the major employer for most health-care professionals, so being excluded from the NHS almost amounts to being excluded from health-care employment. A related point is that in the NHS, linked by formal and informal networks, staff may have concerns about their ability to find an ‘honest broker’, with some former whistleblowers recalling being shocked at how little support they received from professional bodies, regulators, and even unions.

Within the wider literature on organisational citizenship behaviour, there is a small body of research exploring the influence of organisational politics, and in particular employees’ ‘perception of organisational politics’. 67 When organisations are perceived to be highly political, there may be a perception that things are done not for maximum effectiveness and efficiency, but for self-serving reasons. This creates a perception of organisational politics (POP), which is defined as ‘an individual’s subjective evaluation about the extent to which the work environment is characterised by co-workers and supervisors who demonstrate . . . self-serving behaviour’. 68 POP affects our confidence in the organisation following its own policies and procedures, which would clearly make prospective whistleblowers less confident in speaking up.

All organisations are, to some extent, political (with a small ‘p’), but public sector organisations are also political with a big ‘P’, with the NHS arguably the most political of all. Therefore, for the NHS we can envisage a wider notion of POP, in which it may include a perception that the wider health-care system is affected by politicking (even if a specific individual’s work is perceived not to be). This can create situations in which staff perceive that management’s response will be driven by political concerns [e.g. about how a particular issue might play out with politicians (local and national)], rather than by what is in the best interest of patients.

The specific NHS context, then, highlights specific concerns that are not always fully addressed in the existing whistleblowing literature. The variety of conceptual lenses through which whistleblowing has been viewed does, however, provide fresh opportunities to bring these specific contextual issues to the fore through a range of methodologically diverse projects. What follows next, in Chapter 3, is an exploration of what is already known empirically about whistleblowing from diverse contexts including, but not restricted to, those involving patient care.

Chapter 3 Empirical evidence on whistleblowing

Introduction

In the previous chapter, we explored the wide variety of ways in which whistleblowing has been conceived and defined within the theoretical and conceptual literature. In this chapter, we draw on the theoretical insights gleaned to critically review empirical research on whistleblowing undertaken in both health-care and non-health-care contexts. The chapter begins with a description of the innovative methodology used to establish a broad bibliography that formed the basis of the review. We then present a thematic narrative analysis of the literature uncovered. The remaining sections then describe the empirical research findings with regard to the external, internal and personal factors that have influenced whistleblowing, and the evidence on the range of organisational responses to whistleblowing.

Literature review methods

The literature that underpinned both this chapter and Chapter 2 aimed to identify the key theoretical and conceptual frameworks that might inform an understanding of employee whistleblowing in health-care contexts, and also sought to explore the empirical evidence as to how and why whistleblowing plays out as it does. In doing so, we aimed to produce a synthesis that embraced the complexities and ambiguities associated with whistleblowing first introduced in Chapter 1. We detail the review process below; for a schematic overview, see Figures 5 and 6.

Systematic reviews are an established means of summarising available research. A number of approaches are available, and selection depends on the review’s aims and the nature of the evidence to be explored. 69 In developing a protocol for the review, we were guided by the principles advocated by Denyer and Tranfield70 and Macpherson and Jones,71 although some important adaptations were required. Although we undertook a systematic approach to literature sampling and reviewing, we did not evaluate evidence from studies in the manner of a Cochrane review. There are two reasons for this. First, the whistleblowing literature is very diffuse: indeed, some of the relevant literature may not even be labelled as whistleblowing (e.g. research on incident reporting, employee voice and silence). Although there may be valuable insights to be gained from these diverse sources, it would be difficult to achieve a clear synthesis of such widely dispersed and divergently framed research. Second, there are very few studies that gather direct evidence on whistleblowing. The topic is very sensitive, and whistleblowers who agree to participate in research could put themselves at risk of retaliation, professional sanctions or even prosecution. To avoid these problems, empirical researchers have typically explored participants’ responses indirectly, through, for example, hypothetical scenarios. Such studies can clearly be evaluated in terms of the rigour of their research design, and the findings do offer important insights to practitioners and policy-makers, but it would be difficult to utilise the kind of formal weighting of the evidence required for a Cochrane-style review.

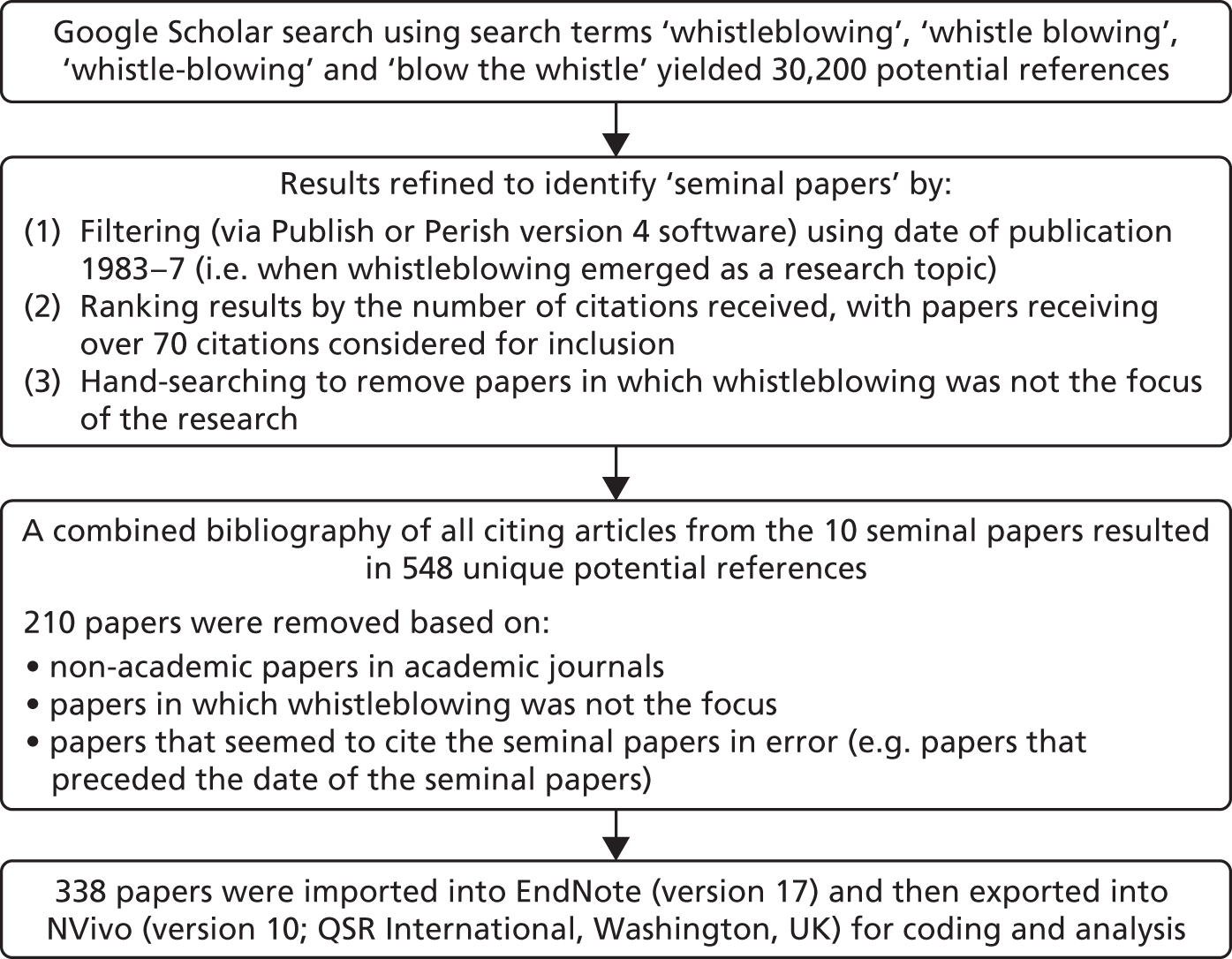

We began by searching Google Scholar (Google, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) using the search terms ‘whistleblowing’, ‘whistle blowing’, ‘whistle-blowing’ and ‘blow the whistle’, but this yielded an unmanageable 30,200 references. We reviewed a sample of these references to try to refine the search, and also to develop inclusion and exclusion criteria to produce a more practicable bibliography. This proved difficult for two reasons. First, whistleblowing research is undertaken by scholars coming from a range of disciplines. It is, therefore, difficult to use disciplinary markers (e.g. journal title or subject-specific databases) to narrow the search. Second, Google Scholar does not allow one to narrow searches to terms found in an article’s abstract and/or keywords. Unable to identify a bibliographic database that could address both of these issues, we sought to create our own de facto database. Academic fields often develop from an initial burst of research activity, and we observed that whistleblowing research had emerged in the early 1980s and developed rapidly. Later research invariably draws on at least one of these early articles, if only to cite the now widely agreed definition of whistleblowing established by these seminal papers. A comprehensive list of papers citing these key early articles would, therefore, provide us with a manageable database of potentially relevant papers that could then be readily searched, browsed and reviewed.

To identify the seminal articles, we searched Google Scholar for work on whistleblowing published before 1985. A 1983 article by Near and Jensen72 appears to represent the earliest example of published whistleblowing research; there are prior scholarly works, both books and articles, some of which have been widely cited (e.g. Westin et al. 73) but they do not represent the headwaters of the subsequent stream of whistleblowing research. Taking 1983 as our starting point, and observing how rapidly the field developed, we undertook a second search of Google Scholar for papers published between 1983 and 1987. We allowed this window because the time delay in academic publishing could mean that articles published in 1987 were written much earlier, and therefore without the authors being aware of key articles written around the same time. Using the ‘Publish or Perish’ software (Harzing AW, 2007; https://harzing.com/resources/publish-or-perish; accessed 3 December 2015) to generate a hierarchy of papers, we ranked the various papers by citation, and observed a natural break after 11 articles: the 11th article on the list had 73 citations, compared with the 12th, which had only 34. As a check on the rigour of this selection of key articles, we repeated the exercise using two other bibliographic databases, Scopus and EBSCOhost, which between them also cover a range of other databases (Academic Search Premier, Business Source Premier, CINAHL complete, ERIC, MEDLINE, PsycARTICLES and PsycINFO). All 11 seminal papers appeared in EBSCOhost, with five of them also found in Scopus. The ranking within the 11 papers was slightly different from that in Google Scholar, but they were still clearly the most highly cited early papers. When reviewing the citations for each article, we identified that one of these, Dworkin and Near,74 represented something of an outlier, so we excluded it from our list (it was cited predominantly in relation to legal proceedings, rather than research on whistleblowing, and the few non-legal citations of the paper were to be found in the citation lists for one or more of the other articles). The 10 remaining ‘seminal papers for whistleblowing research’ are listed in Table 4.

| Citations | Authors | Title | Year | Publication |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 546 | Near and Miceli12 | Organizational dissidence: the case of whistle-blowing | 1985 | Journal of Business Ethics |

| 395 | Dozier and Miceli54 | Potential predictors of whistle-blowing: a prosocial behaviour perspective | 1985 | Academy of Management Review |

| 321 | Miceli and Near75 | The relationship among beliefs, organisation position, and whistle-blowing status: a discriminant analysis | 1984 | Academy of Management Journal |

| 271 | Miceli and Near76 | Characteristics of organizational climate and perceived wrongdoing associated with whistle-blowing decisions | 1985 | Personnel Psychology |

| 175 | Near and Miceli20 | Retaliation against whistleblowers: predictors and effects | 1986 | Journal of Applied Psychology |

| 160 | Greenberger et al.77 | Oppositionists and group norms: the reciprocal influence of whistle-blowers and co-workers | 1987 | Journal of Business Ethics |

| 154 | Brabeck78 | Ethical characteristics of whistle blowers | 1984 | Journal of Research in Personality |

| 146 | Near and Miceli79 | Whistle-blowers in organizations: dissidents or reformers? | 1987 | Research in Organizational Behavior |

| 96 | Near and Jensen72 | The whistleblowing process: retaliation and perceived effectiveness | 1983 | Work and Occupations |

| 73 | Jensen80 | Ethical tension points in whistleblowing | 1987 | Journal of Business Ethics |

This process, then, led to a set of 10 papers that could be seen as seminal to the field. Our next step involved combining the citations from these 10 papers into a single bibliography of works relating to the development of whistleblowing as a research field, starting with the most cited paper (Near and Miceli12) and working down the 10 papers in order of number of citations. The articles citing each seminal paper were downloaded into EndNote [Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thompson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA], using the links provided in Scopus and EBSCOhost. The process by which the bibliography was created is outlined in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Selection process for general literature on whistleblowing.

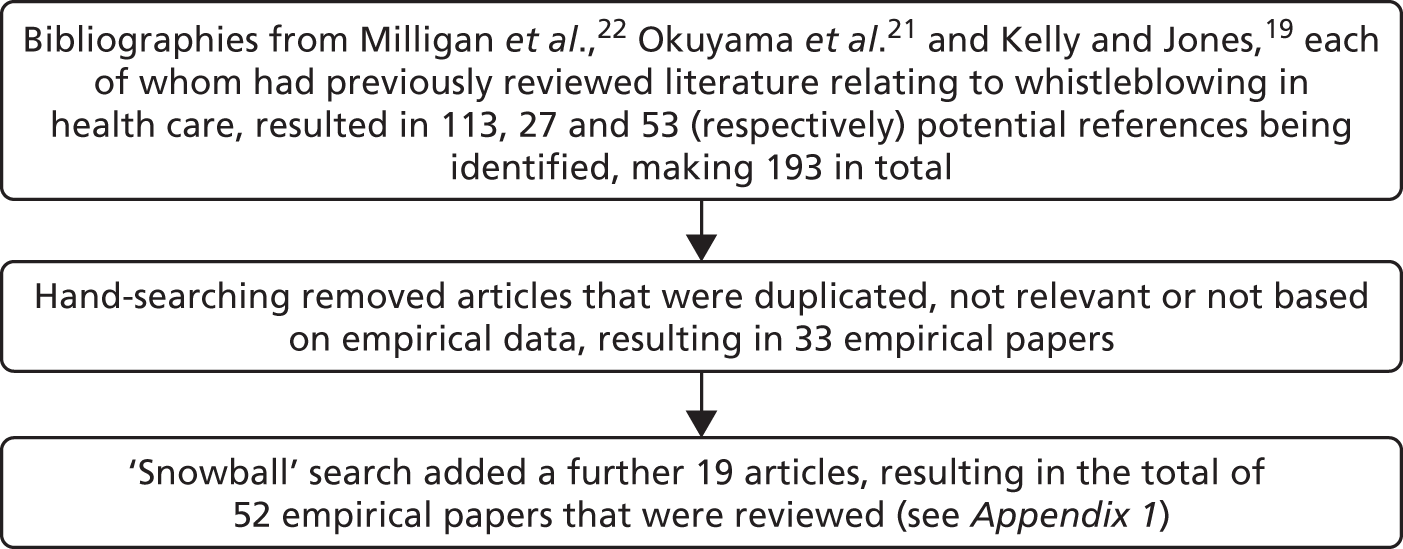

The review process produced a working bibliography of a manageable size, allowing us to review each article in terms of its relevance to the objectives of the project. Although this methodology generated a strong general academic literature, it was recognised that some more recent empirical health-care research papers may not be found using this route. In recognition of this, the papers from the bibliographies of three recent literature reviews in related fields (Milligan et al. ,22 Okuyama et al. 21 and Kelly and Jones19) were converted into an ‘empirical health care’ bibliography (Figure 4). Papers were selected based on an academic judgement of their relevance to this report. Further health-care papers were added via ‘snowballing’ from the initial sources. The most significant papers from the bibliography are summarised in Appendix 1, Tables 8 and 9.

FIGURE 4.

Selection process for empirical papers in health care.

The whistleblowing literature uncovered

Wide dispersal of the whistleblowing literature

The academic whistleblowing literature appears to be very widely dispersed across diverse journals. Within the general literature reviewed, 188 different journals published one or more of the 338 whistleblowing papers uncovered that had been published since 1983. The Journal of Business Ethics was by far the largest contributor of articles, with some 62 papers published here. In contrast, no other single journal accounted for whistleblowing papers numbering into double figures. The empirical health-care literature uncovered (52 papers) was also very widely spread across diverse journals (42 outlets in total). The most common source for these papers was Nurse Education Today, but even this accounted for only eight papers.

Growth in academic publications on whistleblowing

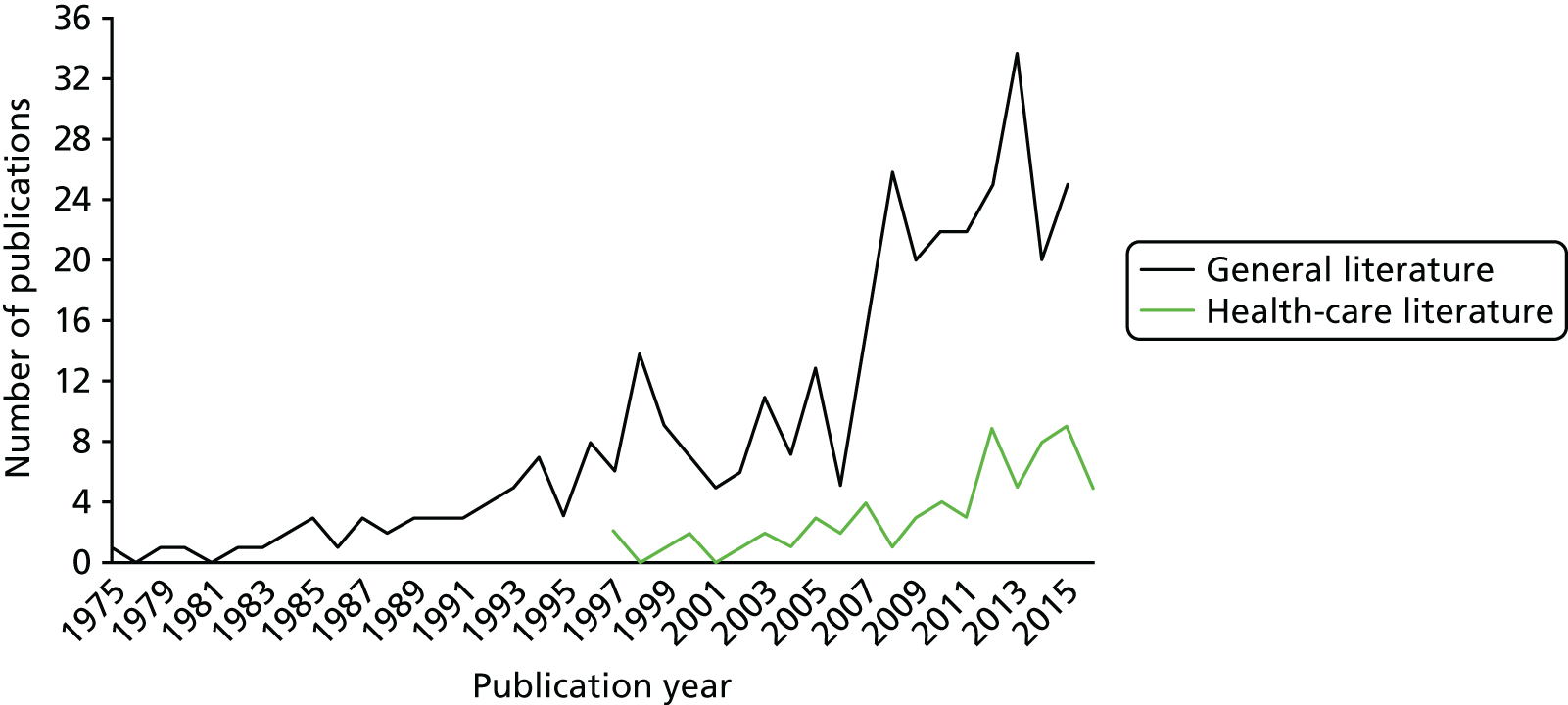

Both the general literature and the specific empirical health-care studies show a marked increase in publication volume since the mid-2000s (Figure 5). The general literature in particular has seen increases to 20–25 new publications per year for each of the past 7–8 years, with the health-care-specific literature contributing 6–8 new papers per year in the same period. (NB owing to the timing of this report, the figures for publications in 2016 account for only the first 6 months of that year.)

FIGURE 5.

Publications on whistleblowing by year since 1975.

Limitations by place of study and participants included

In terms of research specifically on whistleblowing in health care, it is striking the extent to which the UK (29% of papers published) and Australia (27% of papers) dominate the literature, with a relative lack of research emanating from the USA (9.5% of papers). Similarly, about 1 in 10 health-care papers came from Canada (9.5%), with the rest of the world making up only one-quarter of the publications uncovered (25%). Although this pattern undoubtedly reflects a bias in our bibliography towards English-language publications, nonetheless, given the scale and contested nature of US health care, the relatively small research contribution from here is, perhaps, surprising. The domination in this data set of just two countries (the UK and Australia) is a potentially limiting factor in terms of gaining insights into ways in which different health-care systems approach the issue.

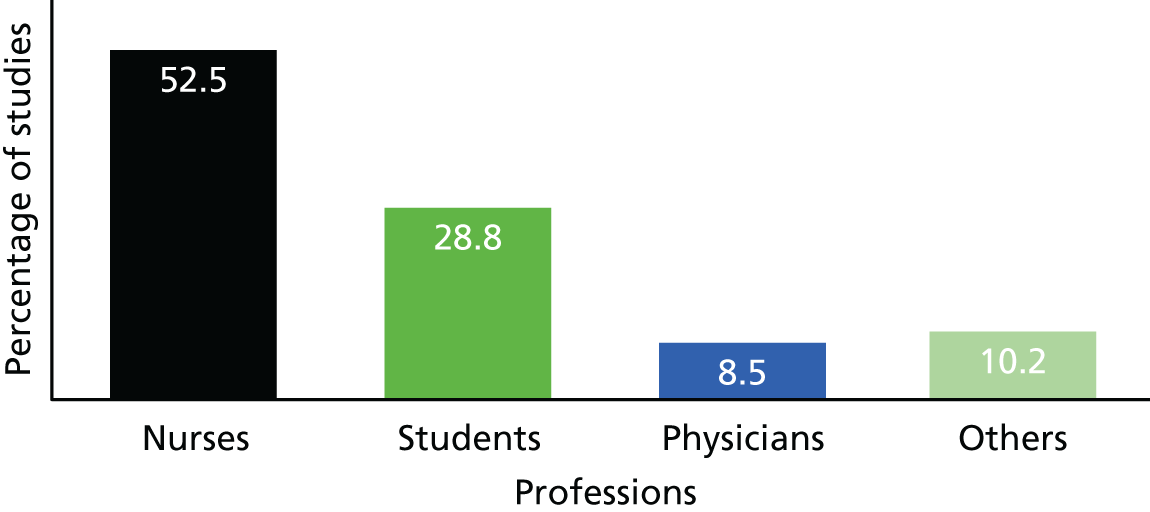

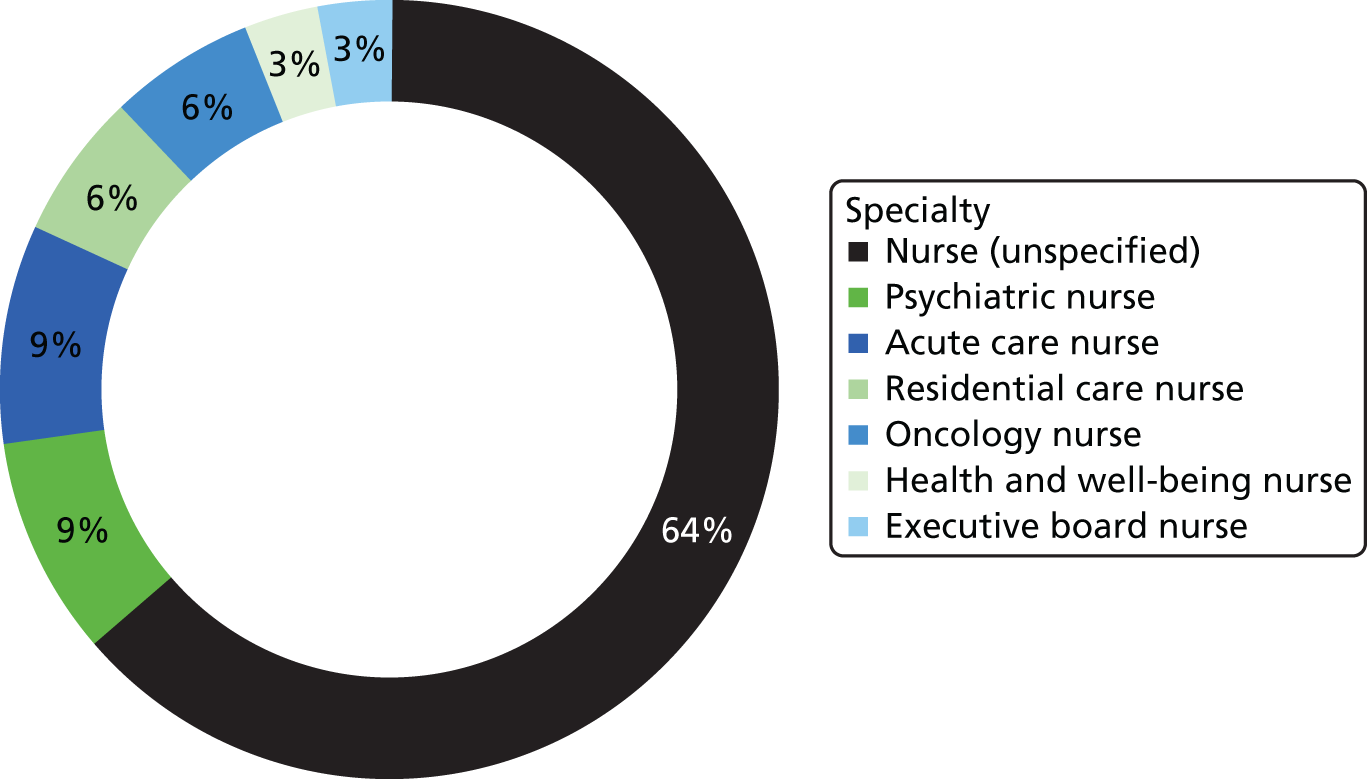

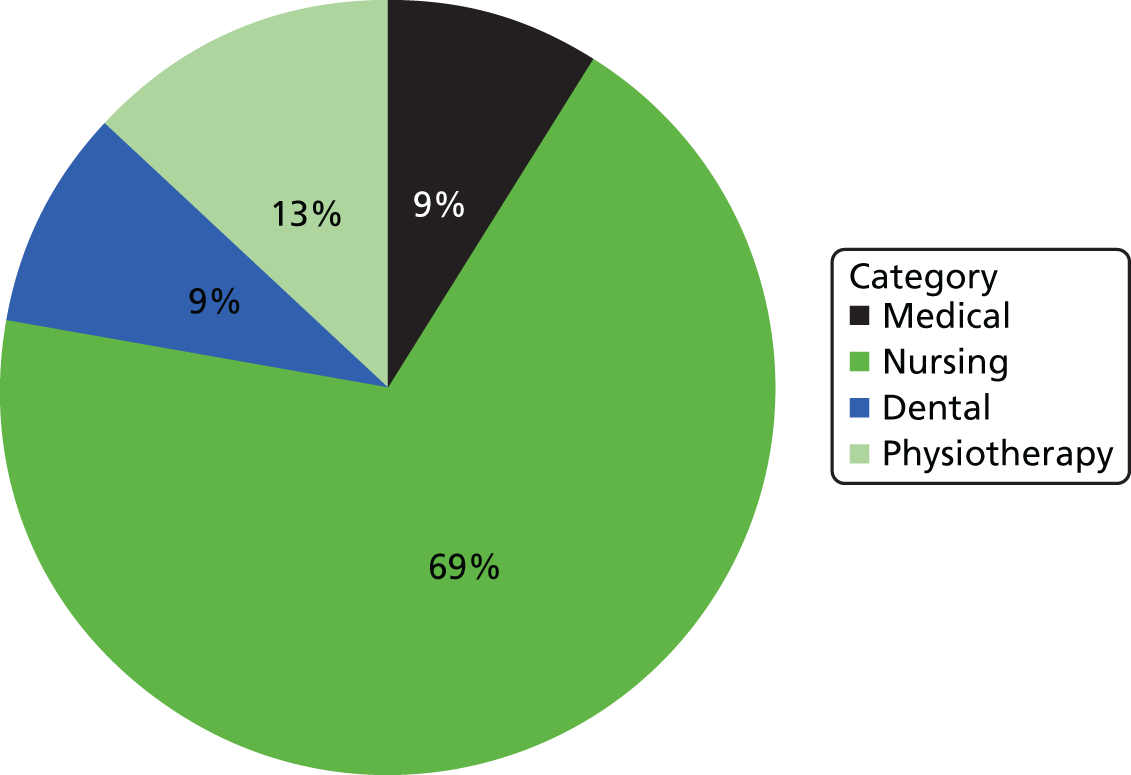

A further potential limitation is that the health-care literature uncovered relates primarily to whistleblowing by nurses: nurses and student nurses account of > 80% of participants in the studies reviewed (Figure 6). Moreover, most of the reported studies leave unspecified the specialty of the nurses under study (64%; Figure 7). Over one-quarter of the health-care studies (29%) used students as study participants (Figure 8), and these were mainly student nurses (69%) with relatively few student doctors included (9%). Furthermore, it is interesting to note that only two authors (Beckstead81 and Monrouxe et al. 82) made an attempt to distinguish between male and female participants, with only Monrouxe et al. 82 commenting on any significant differences between the sexes (specifically, in relation to noting the apparently raised emotions in women after witnessing poor patient care).

FIGURE 6.

Percentage of health-care studies involving different professions.

FIGURE 7.

Percentage of health-care studies involving different nursing specialties.

FIGURE 8.

Percentage of health-care studies involving different student categories.

Limited interconnectivity between the general whistleblowing literature and the health-care-specific literature