Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/130/33. The contractual start date was in April 2014. The final report began editorial review in February 2017 and was accepted for publication in September 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Matt Sutton serves on the Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Commissioning Board (commissioned and researcher led). Mark Hann has a role with the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Research Design Service. Rachel Meacock serves as an associate member of the HSDR Commissioning Board (commissioned and researcher led). Mark Sidaway and John Ainsworth report grants from the NIHR and the Medical Research Council (MRC) during the conduct of the study. Ruth Boaden is Director of the NIHR Collaborations for Leadership in Applied Health Research and Care (CLAHRC) Greater Manchester, which is hosted by Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, one of the organisations that comprise the Salford Integrated Care Programme (SICP), the subject of the research in this report. In addition, Ruth Boaden holds an honorary (unpaid) contract at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust as an Associate Director; however, her CLAHRC role does not involve any relationship with the SICP/integrated care organisation. Ruth Boaden is also a member of the NIHR HSDR Commissioning Board (commissioned and researcher led). Both Iain Buchan and Siobhan Reilly have received grants from MRC. Katherine Checkland reports grant income from the NIHR Policy Research Programme.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Bower et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Long-term conditions and integrated care

The burden of disease worldwide is shifting to long-term conditions. 1,2 Although advances have been made in effective service delivery, major challenges remain, namely projected increases in populations aged ≥ 65 years, the increases in demand associated with an ageing population and government pressure for major efficiency savings.

Current services are organised around single conditions, but many people have more than one (multimorbidity), which means that care is often fragmented and unresponsive to needs. Patient and policy consultation around care for long-term conditions has repeatedly emphasised the need for ‘integration’. 3–5

What is integrated care?

There is a significant body of literature on integration, but a lack of consensus around definition; one review found 175 definitions. 6 A number of different perspectives are possible on the meaning of integration, including managerial, health systems, social science and patient perspectives. 7 The British Medical Association8 has highlighted that integration is a nebulous term, associated with wide-ranging definitions and processes. Analysts have distinguished between different dimensions of integration:9

-

Types of integration – functional (key support and functions, i.e. human resources and financial management), organisational (contracting or strategic alliances between different organisations), professional (joint working, alliance and strategic contracting between professionals) and clinical (co-ordination of patient care services).

-

Breadth of integration – this includes both vertical (bringing together organisations at different hierarchical levels) and horizontal (bringing together organisations that are on the same working level) integration.

-

Degree of integration – full integration or more limited collaboration of services, working practices or organisations.

-

Process of integration – this includes structural (alignments of tasks, functions and activities), cultural (values, norms and working practices) and social (the strengthening of social relationships between individuals) integration.

Models of implementing integration are also diverse. Health and social care systems are complex, with multiple providers and different levels of demand on the system, and so integration is likely to be equally variable. 9 A review referred to three different models of integration:6

-

System level – the focus here is on organisational change, whereby leadership plays a pivotal role in performance.

-

Programme or service level – the emphasis here is to try to improve the patient outcomes by providing more co-ordinated care.

-

Progressive/sequential models – integration is not a specific goal but is a means to try to improve health-care performance in general.

Some partners have adopted a person-centred definition of integrated care, focusing on the ways in which care is experienced by patients. 5 This definition is supported by a number of ‘I statements’, which set out what integrated care should feel like to those in receipt of it. It is suggested that delivering care in this way will fulfil a number of goals (e.g. people feeling more confident to manage their conditions, improved sharing of decisions and relationships, and better sharing of information with the patient and among different services), which will in turn lead to improved outcomes (such as fewer admissions and, crucially, lower costs). However, it has been suggested that a person-centred model of integration might be better achieved through policy innovations such as personal health budgets and direct payments (allowing individuals to join up services in ways that make sense to them), rather than organisational and professional integration. 10 Such a conception has been supported by recent qualitative work within integrated care pilots (ICPs). 11

What is the review evidence for the benefits for ‘integrated care’?

There have been a variety of reviews and syntheses around the effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of integrated care. A ‘stocktake’ of the integrated care literature in 2009 found discussions to be dominated by potential benefits, with a lack of clarity over definitions and standardised outcomes. 6 Although the scope of the literature has improved since that time, there is still a lack of clarity over the main findings in this area.

A metareview12 (or ‘review of reviews’) that included 27 separate reviews explored integrated care for adults across a range of long-term conditions. The authors coded 10 key principles of integration and reported a range of positive outcomes across the reviews, including in relation to hospital admissions (in heart failure and diabetes mellitus), adherence to guidelines [diabetes mellitus, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD) and asthma] and quality of life (diabetes mellitus). Reductions in costs were far less frequently reported. Another review13 of integrated delivery systems found 25 reports, with the majority showing an increase in quality of care associated with integration. Again, there was more limited evidence showing reductions in utilisation associated with integration. A recent ‘review of reviews’14 on integrated care for chronic diseases synthesised data from 50 reviews, which included a wide range of interventions (e.g. case management, variants of the chronic care model,15 multidisciplinary teams and self-management). As with other reviews, there was evidence of positive impacts in many outcomes, but results were not consistent, and the authors again highlighted the gap between the importance of the concept of integration in health policy and the strength of the evidence concerning its benefits.

Although comprehensive, these very broad reviews necessarily include a very wide range of patients and interventions and, therefore, can lack precision. Other reviews in the literature have had a more restricted scope in terms of interventions, populations and outcomes, providing greater specificity over outcomes. A review of integration at the primary–secondary care interface found 10 studies that demonstrated some benefits in terms of process of care (care delivery, disease control), but these generally did not extend to clinical outcomes and were achieved at some increase in costs. 16 A review of co-ordinated and integrated care for the frail elderly found nine studies, with a slim majority reporting improved outcomes and reduced health-care utilisation, but with few data on the effects on caregivers. 17

Case management is a popular method of integration, and a review18 of case management for older people found that the majority of trials showed no reduction in admission rates compared with usual care. A review19 of case management for at-risk patients in primary care reported 36 studies, but the only consistent benefits were in terms of patient satisfaction, with no demonstrable benefit in utilisation, costs or mortality. In contrast, a review20 of hospital-initiated case management for heart failure reported reductions in readmissions and length of stay, although those benefits did not translate to reduced costs. Interventions initiated from the community were less prevalent and showed less evidence of benefit.

A number of previous reviews have suggested that the economic benefits of integrated care are less consistently demonstrated than impacts on the process or quality of care. A review21 restricted to the economic impacts of integrated care identified 19 studies of relevance. As well as identifying a lack of clarity about definitions, the evidence was mixed, with some positive findings; generally, however, the evidence was characterised as ‘weak’. A review22 focused on integrating funding for health and social care found 38 studies. Health outcomes were frequently assessed, but evidence of benefits were limited and only a minority of studies found reduced secondary care costs.

The evidence is clearly mixed. 23 There is a significant amount of evidence, such that a number of studies have used a metareview method, which is an efficient instrument for summarising large numbers of data, but not a very precise method of quantifying gain or assessing patterns in the data, or identifying fruitful approaches to integration. Interpreting the reviews is a challenge because of the complexity of the concept of integrated care and the different scope of the reviews, which is clearly demonstrated in the different numbers of studies included in each review. However, the overall impression is that benefits are inconsistent and most regularly associated with process measures (e.g. quality of care). When impacts on admissions are reported, they are most likely to be related to certain conditions (such as heart failure), rather than demonstrated across broader groups of long-term conditions. Reductions in utilisation may not translate to reduced costs, which may reflect the fact that integrated care is associated with its own costs; benefits of reduced utilisation in one part of the system may be lost when other costs are taken into account. 24 Cost savings may require radical changes such as closing hospital beds,25 which may be unpopular and difficult to implement. 23

Recent empirical evaluations in the UK

The previous section has outlined reviews of the effects of integrated care and highlighted the inconsistency in the evidence. The reviews have been international in scope. Although that brings major benefits in terms of the size and scope of the evidence, it does lead to additional complications in interpretation. Integrated care may have different meanings in different health systems, and the comparator conditions may also vary widely. It is generally accepted that context is an important moderator of the effects of complex interventions,26–28 and the context in which integrated care is introduced may also be very different. 25 This section has a focus on empirical evaluations conducted in the UK.

The Evercare evaluation29 explored the case management of older people at high risk of emergency hospital admission. Although not a formal integrated care intervention, it shares a number of features in terms of the eligible population and the nature of the intervention. Evaluation showed no effects on admissions or other outcomes, although the service was popular with patients and carers. 30

The Partnerships for Older People Projects involved a wide range of community- and hospital-facing services, with a significant focus on prevention. Evaluation using data from the British Household Panel Survey suggested some improvements in quality of life, although the comparator was not particularly strong in methodological terms. Although overall analyses31 suggested that the investment led to savings, more detailed analyses32 of a subgroup of services found no evidence of reductions in hospital admissions, and even suggested some increases.

An early pilot scheme in England33 involved the establishment of 16 ICPs. It should be noted that although these were all introduced into a single health-care system, the pilots did vary, being based on local circumstances in which the care included in the ‘integration’ project was dependent on the local context. Overall, the evaluation found that there was an increase in emergency admissions in the pilot areas and there was mixed evidence about whether or not the ICPs were able to reduce costs. Among the 16 ICPs, case management was perceived to be the best option for reducing secondary care costs (a net reduction in combined inpatient and outpatient costs were reported). Such comparisons lack the rigour of randomisation. The findings were also difficult to interpret as the key outcomes that the services were trying to change (emergency admissions) showed increases in activity, whereas reductions occurred in untargeted elective services. Assessments of patients were also conducted as part of the evaluation of the ICPs. Patients reported that they were more likely to be told that they had a care plan, to feel clear about follow-up arrangements and to know whom to contact, and were less likely to report problems with medication. All of these are relevant outcomes of an integrated care initiative. However, somewhat surprisingly, they also reported being less likely to see the health professional of their choice, being less involved in decisions about their care and being less likely to report that their preferences had been taken into account. Again, all these are relevant outcomes for a person-centred integrated care service. The fact that patients reported reductions in some patient experience measures and improvements in others highlights the difficulties of improving outcomes in this area. 33

The North West London Integrated Care Pilot was a large-scale programme that had an initial focus on people with diabetes mellitus and patients aged > 75 years. The intervention involved information technology to support case finding and multidisciplinary groups (MDGs) to deliver care planning. Although implementation was generally successful (albeit somewhat delayed) and there were some impacts on process of care (including rates of care planning), a matched controls analysis of effects showed no impact on emergency admissions, although the analysis was judged to be preliminary. 34,35

There was also a call for ‘ambitious and visionary’ local areas to become integrated care pioneers, with 14 sites starting in one wave in 2013 and another 11 sites starting in a second wave in 2015. 36 Pioneers were tasked with the conventional outcomes of integration initiatives (improved patient experience, outcomes and financial efficiency), with expert support and some very limited additional funding. Early results from the pioneers (largely on the basis of interviews and self-reports from stakeholders) found a common focus on a particular cohort (older, multimorbid or frail patients) and a wide range of potential interventions (including interventions focused on those in need, as well as longer-term prevention work).

Early evaluation has identified a number of barriers to and facilitators of progress, leading to slow progress and a reining in of ambitions concerning any rapid demonstration of improved outcomes. Patient experience was judged to be the area in which initial gains were most likely to be made. The authors of the report into the pioneers highlighted the ‘integration paradox’, whereby financial and other service pressures both increase the pressure for integration (to manage those pressures) and act as a barrier to its effective implementation. 37

In some ways, the evidence from the UK studies is less positive than the international literature. Although some positive impacts have been observed, these have been matched by some negative findings (including increases in admissions and reductions in some aspects of patient experience). It is not clear why this should be. The UK has a fairly strong primary care system with which patients are generally highly satisfied. 38 It is possible that changes that lead to disruption in existing arrangements can cause difficulties for patients, even if the intention is to improve integration.

Summary

Integration remains a cornerstone of current health policy, but evidence concerning the benefits of integration, optimal methods of achieving it and the factors that influence success is still limited. The identification of models of integration in the UK that are feasible, sustainable and cost-effective remains a priority.

In that context, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme advertised a call for ‘ambitious research studies assessing the cost-effectiveness of new and innovative models of care or clinical pathways for people with long term conditions. The aim is to generate high-impact research which will provide commissioners and providers with useful evidence when re-designing services’. 39

The Salford Integrated Care Programme (SICP) was judged to be ‘a new and innovative model of care . . . for people with long term conditions’. 39 The aims of the SICP were to improve integration of care to provide better health and social care outcomes, improved experience for services users and carers, and reduced health and social care costs.

The broad aims of Comprehensive Longitudinal Assessment of Salford Integrated Care (CLASSIC) were to assess the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of the SICP, with the following research questions.

Implementation

-

How do key stakeholders (commissioners, strategic partners) view the SICP, what do they expect from it and how is it aligned with their objectives and incentives?

-

What is the process of implementation of two key aspects of the SICP [the MDGs and the integrated contact centre (ICC)]?

Outcomes

-

What is the impact of the MDGs on the outcomes and costs of people with long-term conditions?

-

What is the impact of health coaching in the ICC on the outcomes and costs of people with long-term conditions?

Chapter 2 Salford Integrated Care Programme: an overview

Context

The setting was Salford in the north-west of England. At the time of CLASSIC, the population of Salford was 234,916 (of whom 34,000 were aged ≥ 65 years). There are comparatively high levels of deprivation (Salford is one of the 20 local authorities with the highest proportion of areas in the most deprived decile) and illness (22.8% living with a long-term illness, compared with a national rate of 17.9%) (SICP unpublished internal briefing document).

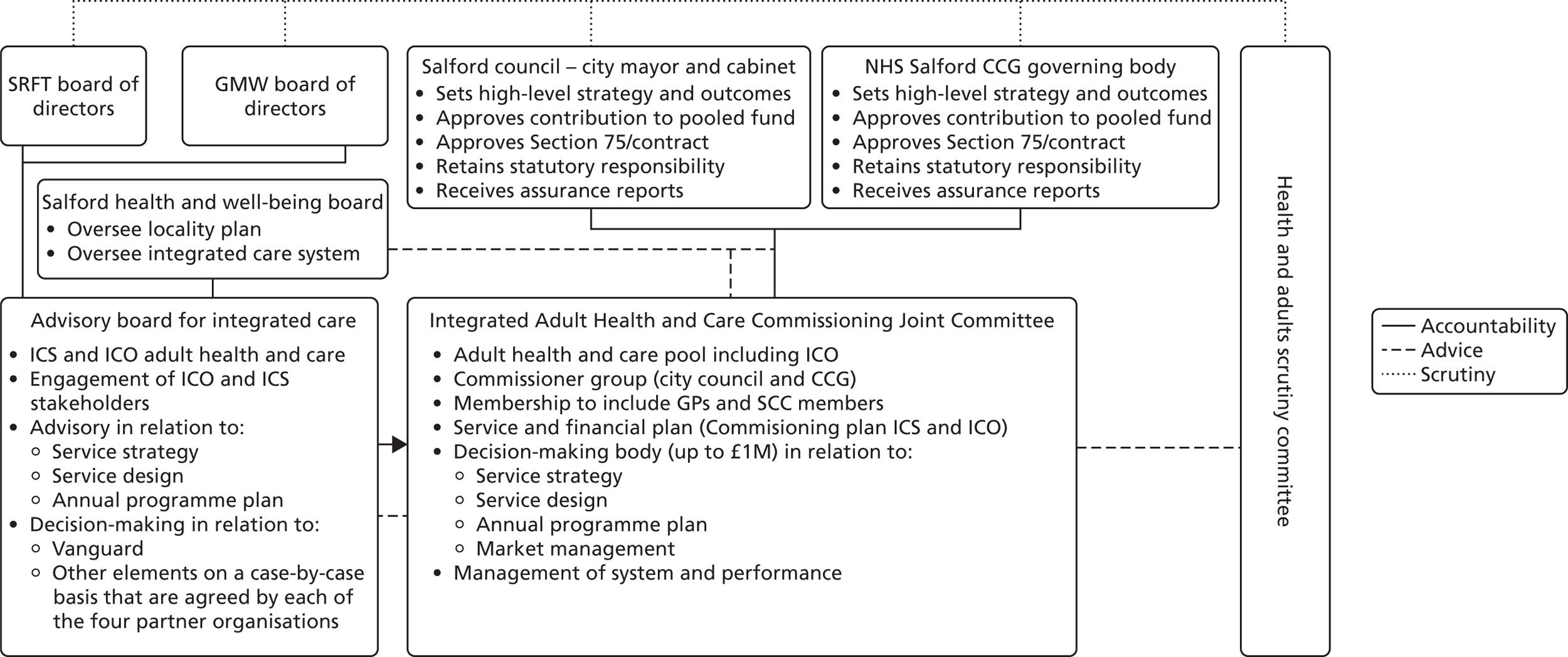

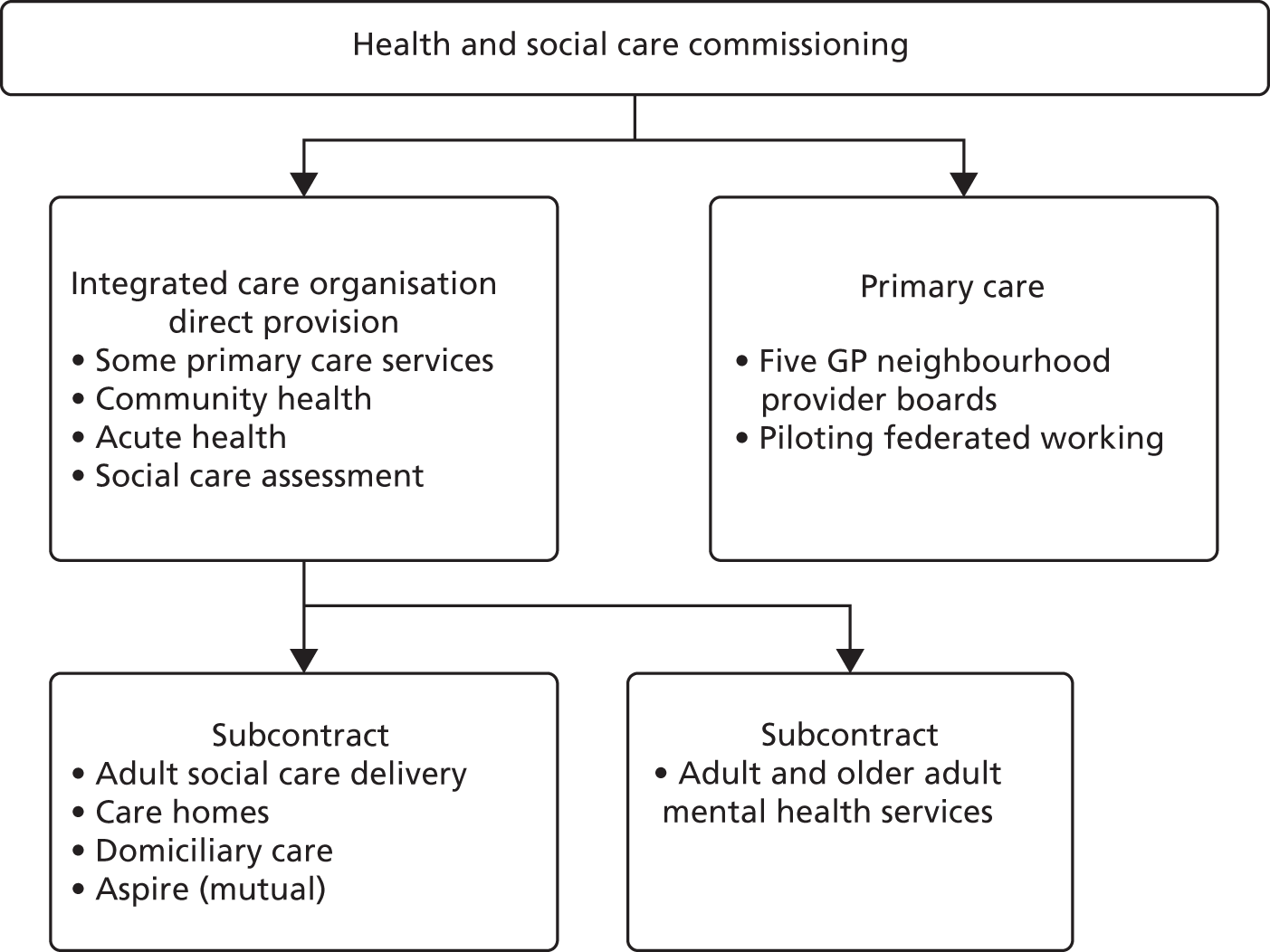

The health and social care system in Salford is largely coterminous, with one local government partner (Salford City Council), a single health commissioner [Salford Clinical Commissioning Group (CCG)], a mental health provider (Greater Manchester West) and a provider of acute and community services (Salford Royal Foundation Trust). Salford contains 52 general practices in eight neighbourhoods.

Salford Integrated Care Programme

The SICP is a large transformational project designed to achieve integration between health and social care to achieve the ‘triple aim’: delivering better health and social care outcomes, improving the experience of service users and carers, and reducing costs.

There is strong history of local integrated working. In 2007, Salford introduced Salford’s Health Investment For Tomorrow programme, a ‘whole economy’ approach to care pathway redesign and the transfer of care from secondary care into community and primary care.

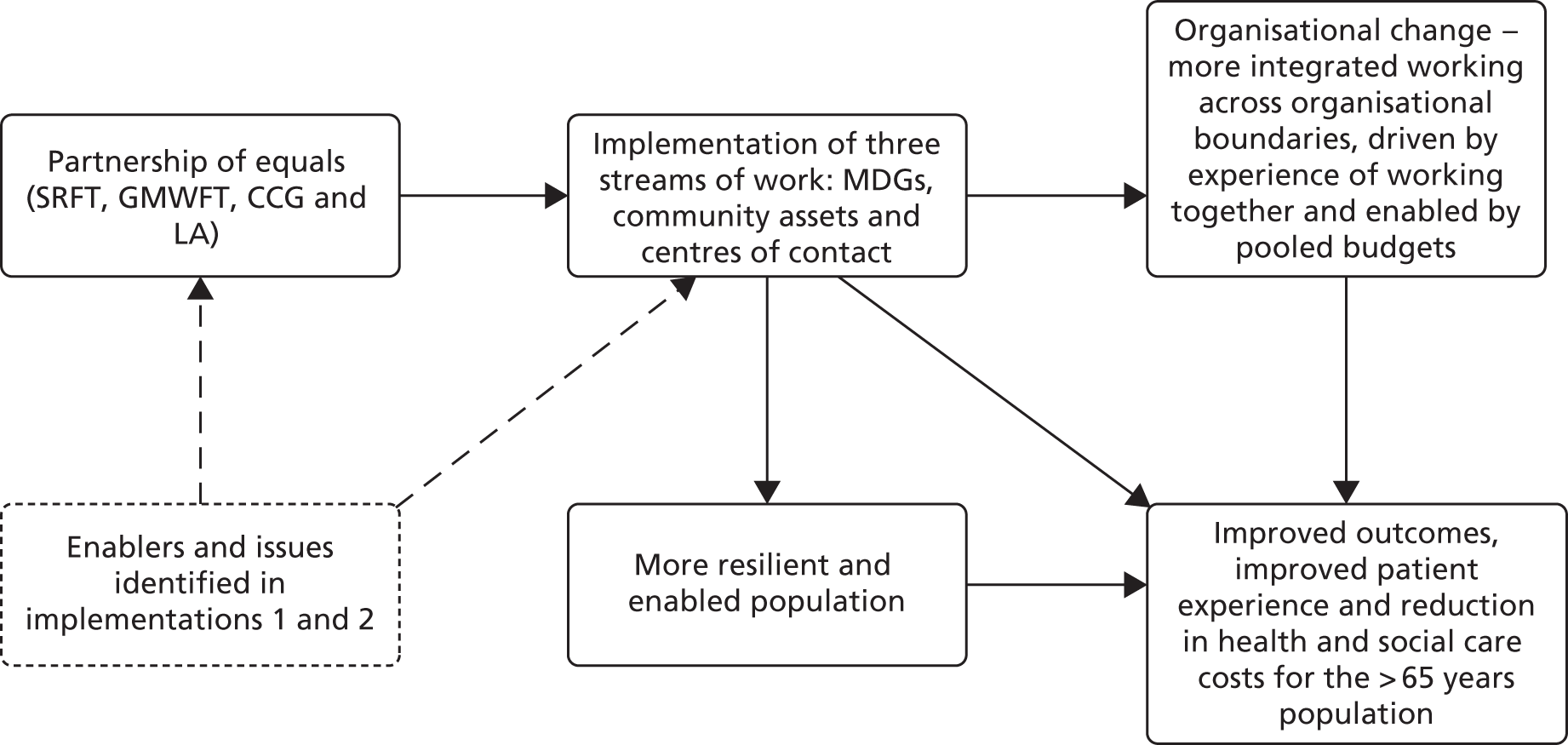

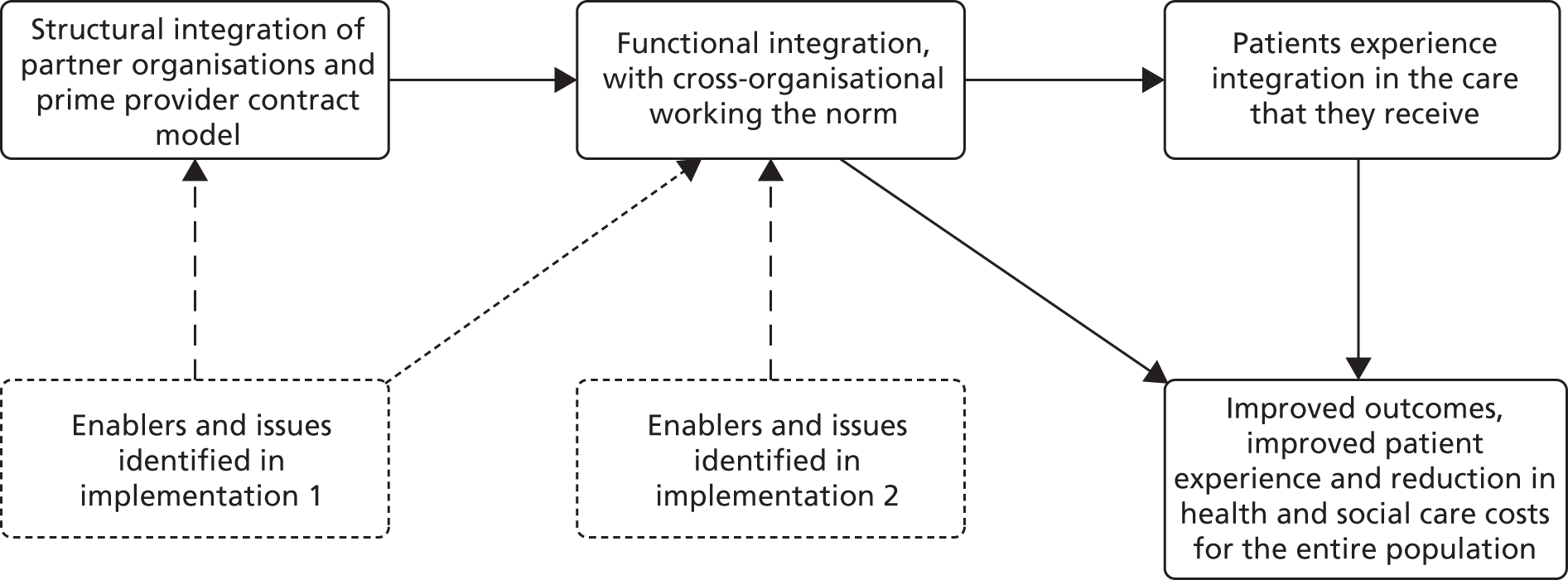

In 2011, Salford Royal Foundation Trust was approached by the Advancing Quality Alliance (AQuA, a quality improvement organisation) and asked to participate in an integrated care programme along with the Salford CCG and Salford City Council (SICP unpublished internal briefing document). With time, a working group developed a case for change and from May 2012 formal governance was established for the SICP. The initial plan was for three programmes:

-

the promotion of local community assets to support increased independence

-

the establishment of an ICC to provide navigation and support

-

the formation of MDGs supporting older people at most risk.

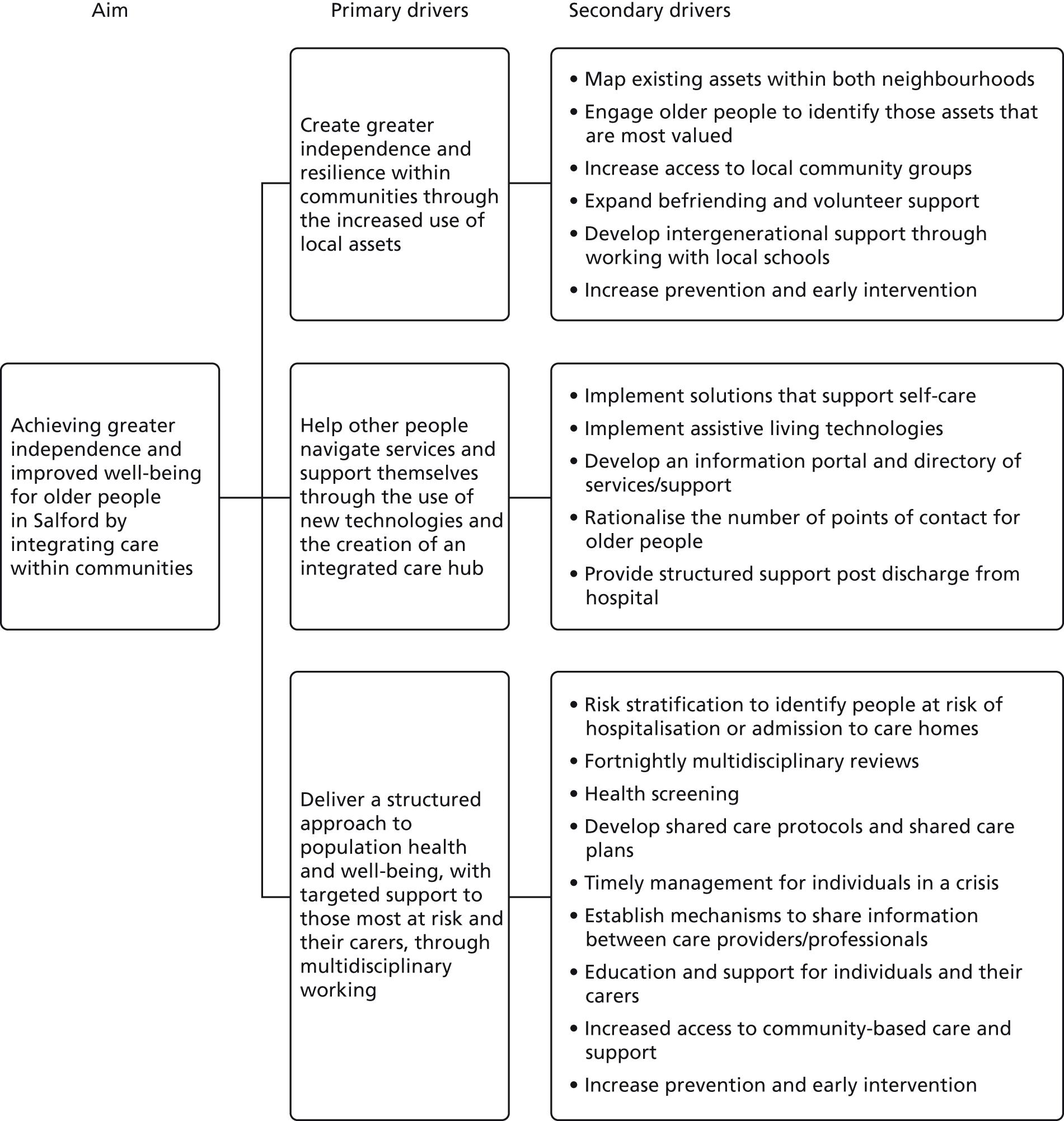

The SICP model and operational plan (Figure 1) outlines aims and ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ drivers. There are seven improvement measures for the SICP for 2020: (1) reduced emergency admissions and readmissions, (2) reduced permanent admissions to residential and nursing care, (3) improved quality of life for users and carers, (4) an increased proportion of people supported to manage their own condition, (5) increased satisfaction with care and support provided, (6) increased flu vaccine uptake and (7) an increased proportion of people who die at home (or in their preferred place).

FIGURE 1.

Salford Integrated Care Programme and programme ‘drivers’. Reproduced with permission from Salford Together from SICP background briefing materials.

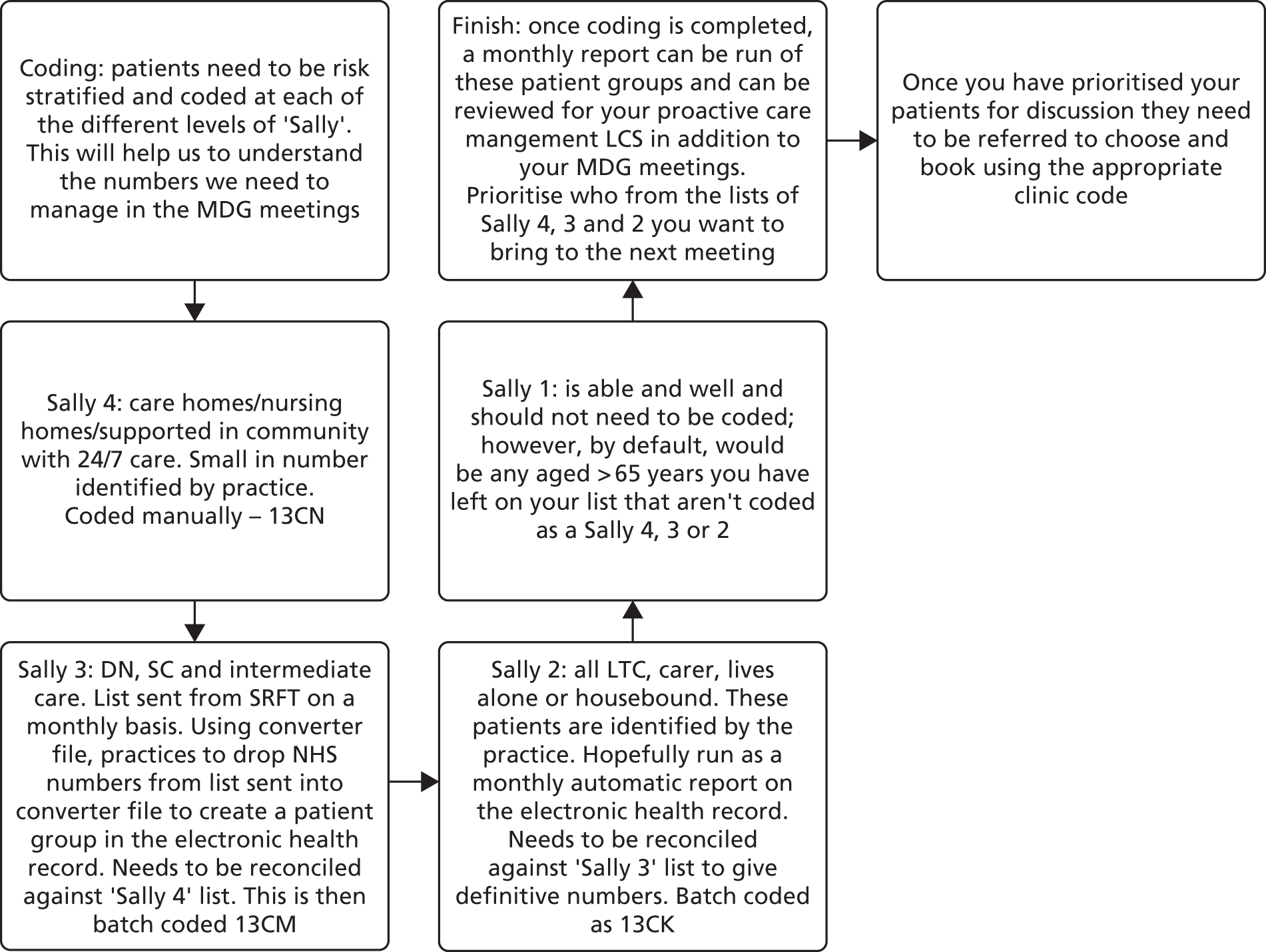

As discussed in Chapter 1, one of the drivers of integrated care was the patient perception that care was not ‘joined up’, which led to the production of a number of ‘principles’ of integrated care designed to enhance the patient experience of care. 3–5 To enhance that ‘patient-centred’ perspective, SICP implementation was based on a fictional character (Sally Ford) and her family. Sally Ford is a 78-year-old woman, who is divorced with no children and experiencing average health. She has family consisting of siblings and their partners, who all experience varying levels of health. The aged > 65 years population was categorised into four different levels of health need (Table 1).

| Level of ‘Sally’ | Level descriptor |

|---|---|

| ‘Able Sally’ | Able to support and sustain own health and well-being needs |

| ‘Needs some help Sally’ | Likely to have contact with at least one service agency. A need for education/intervention to enable self-management. Lower level of social care needs. Provides informal care to another individual. Early diagnosis of dementia |

| ‘Needs some more help Sally’ | Regular visits from health (including mental health) and/or social care services. Intermediate care/reablement. Meets social care eligibility criteria,5 receives formal or informal care |

| ‘Needs a lot of help Sally’ | Needs 24/7 care either in a residential, nursing or EMI home, or at home with high level of need (e.g. often over a 24-hour period) |

The SICP was to be delivered in five phases:

-

phase 1 – refine scope and prepare for implementation (completed)

-

phase 2 – neighbourhood ‘tests of change’ (completed)

-

phase 3 – interim review of impact (scheduled January to March 2014)

-

phase 4 – extend to other neighbourhoods/city wide (April 2014 onwards)

-

phase 5 – formal evaluation (April 2014 to March 2019).

Three core mechanisms of integration were included in the specification of the SICP (Box 1).

This was designed to take advantage of the knowledge and experience of older residents, involving them in local service improvement and strengthening communities. Despite the high levels of deprivation in Salford, there were a number of local assets, which included volunteers, green spaces, leisure centres and local clubs. Better access to these assets could help people engage in healthy behaviour and improve quality of life.

Integrated contact centreThe aim of the centre of contact was to support older people and carers managing long-term conditions by better integrating health and social care functions. This would be achieved by co-locating staff from both adult social care, district nursing and intermediate care.

The centre was expected to provide a number of functions, including support for self-management and links with the ‘community assets’ workstream.

The centre would also provide a range of specific services, including follow-up and support to particular groups of patients (such as those requiring intermediate care following hospital discharge); advice and support for those with long-term conditions, including support for patients with depression via health coaching; and the promotion of self-management via telehealth.

Multidisciplinary groupsMultidisciplinary groups were to be organised around a ‘neighbourhood’ model of federated practices, based on GP clusters that already existed in Salford.

Each group would hold a register of people aged ≥ 65 years, and would use risk stratification tools to assess risk of hospitalisation and care home admission. Support will be based on those identified needs. Patients judged to be at high risk would receive further support from multidisciplinary groups, who would use shared care protocols and care plans to co-ordinate care delivery.

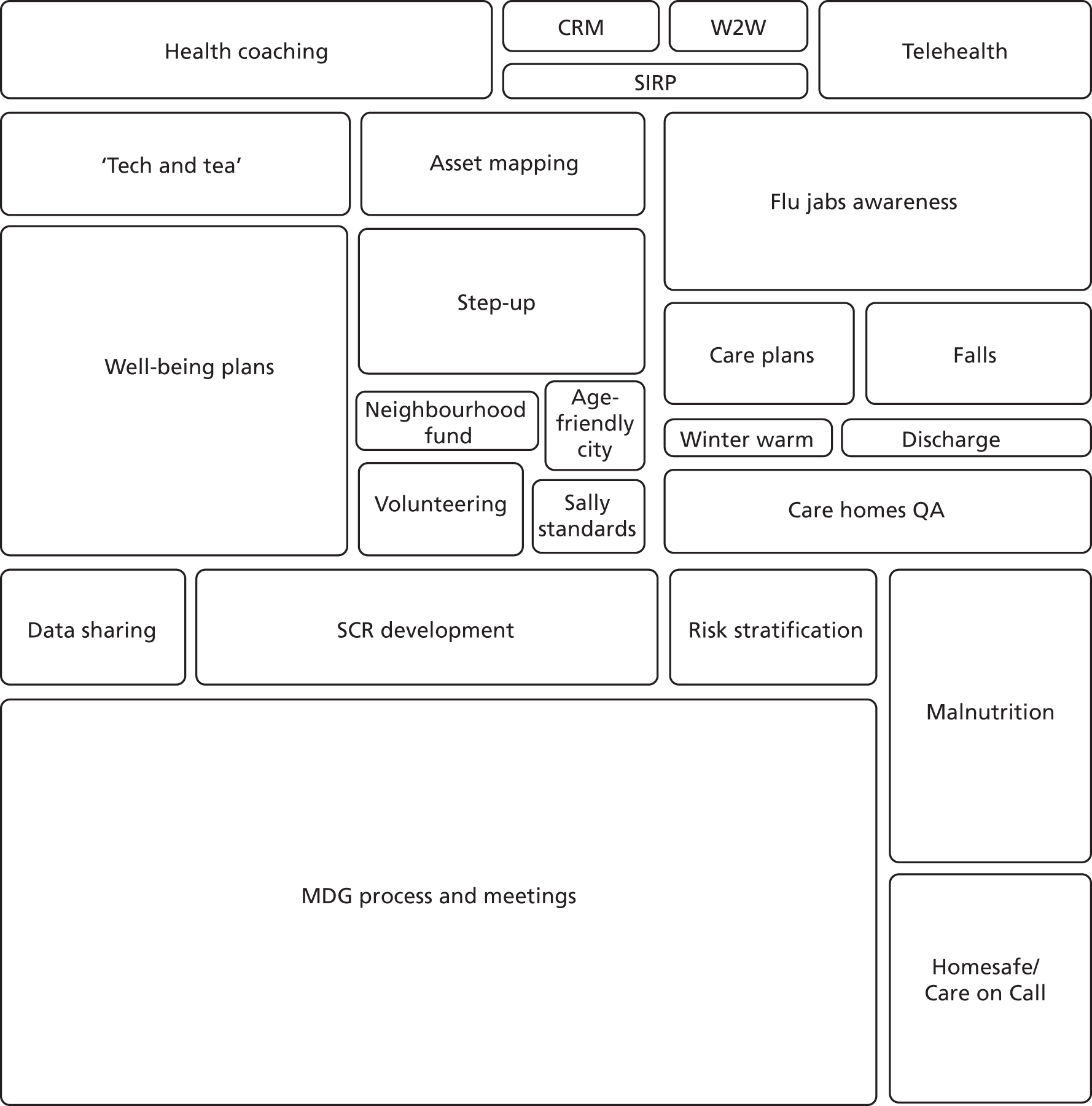

The SICP also involves a wider range of mechanisms. The local health improvement agency [Haelo; see www.haelo.org.uk/ (accessed 3 April 2018)] conducted interim evaluation work alongside CLASSIC, and their report included a schematic, which detailed the full range of mechanisms within the SICP as well as some indication of the relative scope of investment in each (Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Schematic showing range of SICP activities. Reproduced with permission from Haelo (Haelo, Salford Integrated Care Programme: Summary and Lessons Learned, 2016, internal report). CRM, customer relationship management; QA, quality assurance; SCR, shared care record; SIRP, single integrated referral point; W2W, Ways to Well-being.

Two mechanisms were a core focus for the CLASSIC study: MDGs and ‘health coaching’ via the ICC. The MDGs were developed by the SICP team, and we describe their broad nature shortly, with data on their implementation and effects discussed in Chapters 11 and 13. Health coaching via the ICC was developed based on existing local services, but the precise model used was led by the academic team and evaluated through a formal trial. For this reason, the detailed description of the health coaching is provided as part of the trial description in Chapter 8.

Multidisciplinary groups

To describe MDGs, we have drawn on a published descriptive framework40 (Table 2) and mapped the groups in the SICP. There are features of the SICP model that may facilitate effectiveness. At a system and organisational level, the impact of the groups is potentially enhanced by the partnership underlying the SICP model (the CCG, city council, acute trust and mental health trust sharing risk and benefits), the alignment of goals and frameworks that this may achieve, and the potential for effective and co-ordinated leadership. Engagement of general practices should be facilitated by the proposed structure of the groups and the involvement of the CCG as a core partner organisation. The importance of self-management is reflected in the interface between the groups and other core aspects of the SICP (community assets and health coaching). A focus on ‘continuous quality measurement and improvement’ has been identified as an important success factor, and the local development of the model is supported by quality improvement teams to assess the model through small-scale ‘tests of change’.

| General description | Objectives | Development stage | Target population | Population coverage |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MDGs provide targeted support to older people who are most at risk and have a population focus on screening, primary prevention and signposting to community support | The aim is to achieve greater independence and improved well-being for those aged ≥ 65 years by integrating care within communities. The focus is on reviewing and problem-solving complex cases, providing anticipatory care plans and assisting with navigation through the health and social care system | Piloted in two sites, with support from a quality improvement team and regular use of PDSA cycles to develop model | Older people with long-term conditions and social care needs | All older people in local area, although focus is on certain levels of need |

| Caseload | Funders | Breadth and degree of integration | Shared medical records | Risk stratification |

| Each group holds a register of all people who are aged ≥ 65 years. The register is based on the ‘list’ of the practices that are members of the group | Funding comes from the SICP. The four statutory partners (CCG, council, acute trust and mental health trust) have all formally signed up to the SICP and delegated authority to a board | Horizontal integration with some vertical integration based on improvements in co-ordination between primary and acute providers, and between health and social care professionals | Local integrated records provide unique linked primary care and secondary care data. Current linkage with social care less well developed | Uses a four-strata model of risk, with the role of the MDGs focused on those identified at levels 3 and 4 and at risk of escalation |

| Providers | Single point of referral | Patient eligibility criteria | Single assessment | Care planning |

| GP/nurse (with link to community geriatrician when required), social care worker (link into housing and health trainers when required), district nurse (link to hospital and discharge support), mental health, OT and administrator | Patients identified by risk stratification tool complemented by professional judgement, as well as direct referral from members of the MDG | As identified by risk stratification tool or professional judgement, based on risk of hospital emergency admission (and readmission) and admission to care homes | Yes | An integrated care plan is agreed with each individual. Content varies depending on risk and need, but includes a focus on primary and secondary prevention. All individuals are reassessed with frequency determined by level of risk |

| Care co-ordinator/case manager | Multidisciplinary team | Financial and non-financial incentives | Self-management support | Carer assessment and support |

| A small number of individuals with the most complex needs will be discussed at a MDG meeting to help plan and co-ordinate their care. Individuals are assigned a key worker to support their needs. The key worker will be identified based on who is likely to have most input into care for that individual patient | Yes | Partners have signed up to a high-level risk and benefits sharing agreement. As part of the SICP, the partners are exploring pooled budgets for health and social care, a joint venture/alliance contract and a capitation funding model | Provide links to ICC (including care navigation and health coaching) and community assets strands of the SICP (including self-help groups in the community) | Although carer needs may be part of the person-centred assessment and care planning, formal involvement of carers is not prioritised at present |

| Voluntary sector and peer support | Co-production | |||

| Although not a formal part of the MDG remit, the voluntary sector and peer support were identified as important issues in the early piloting and may be involved through MDG links to the community assets theme | Patient involvement has not been a high priority in the design of the MDGs, although there has been input from patients in some of the higher-level learning sessions in the development of the SICP |

Chapter 3 CLASSIC evaluation methods: an overview

Methodological frameworks

Integrated care raises major challenges for evaluation, reflecting the general pressure within health services research whereby increasingly complex service redesign requires rapid and rigorous evaluation. 41,42

The evaluation of health technologies has been heavily influenced by the Medical Research Council (MRC) Complex Interventions Framework,43 and each of the mechanisms of integration in the SICP (MDGs, health coaching, community assets) would probably meet the conventional definition of a ‘complex intervention’ (i.e. ‘interventions with several interacting components’).

The SICP itself may be best characterised as a ‘large-scale transformation’, defined as ‘interventions aimed at co-ordinated, system-wide change affecting multiple organizations and care providers, with the goal of significant improvements in . . . outcomes’. 44 ‘Complex interventions’ are nested within the SICP, but the large-scale transformation is not simply the sum of those interventions, but instead involves wider structural, organisational and cultural changes, which may serve to help or hinder the translation of individual mechanisms of integration into improved outcomes.

To answer our research questions, we adopted a mixed-methods approach using conventional health services research methods:

-

We used qualitative methods (interviews and observations) to explore the implementation of the SICP, both at the level of leadership and management of the major organisations involved (implementation 1), and at the level of managers and clinicians involved in the everyday delivery of the intervention (implementation 2).

-

We used analysis of routine data sets [Hospital Episode Statistics (HES)] and appropriate comparators and non-randomised methodologies45 to explore effects of the SICP on outcomes (‘outcome 1’).

-

We conducted a formal randomised controlled trial (RCT) within the cohort (‘outcome 2’).

In addition, to provide flexibility to assess a variety of aspects of the SICP, we also adopted a patient cohort. This cohort provided an assessment of patient-reported outcomes (health, quality of life and experience of services), which are missing from many integrated care evaluations that use routine data.

The planned cohort also provided an opportunity to explore the innovative cohort multiple randomised controlled trial (cmRCT) design, which at that point had not received significant practical application. 46 In this design, a large population cohort is recruited and followed over time. As well as providing an assessment of the impact of the SICP over time, natural variation in the exposure of patients within the cohort to different mechanisms of integration allowed more sophisticated modelling of effects.

In addition, the cmRCT provided a good conceptual ‘fit’ for the evaluation of health coaching within the CLASSIC study. One of the criticisms of RCTs is that they test innovations in a very selected group of patients, which then fail to ‘scale’ because of low rates of acceptability among the wider population. Pragmatic trials are in part a response to this, but they are still selective, as patients are selectively recruited on the basis of their willingness to engage with the intervention. A pragmatic trial may show effects, but can still be unacceptable to many patients who refuse to engage.

This is less of a problem in the evaluation of interventions where patients are seeking help. However, it has less relevance when an intervention involves services proactively identifying patients on the basis of risk. In the cmRCT, engagement in the wider population is, in principle, built into the design, alongside the usual impact of variable adherence (which is already built in to pragmatic trials).

The cmRCT was felt to be a relevant test of health coaching as applied in integrated care as a population health strategy, aimed in a preventative capacity for those at risk of poor outcomes (rather than a population identified on the basis of previous high utilisation).

Conceptual frameworks

A number of conceptual frameworks are of relevance. First, we drew on realist evaluations,28,47 which move beyond simple questions concerning whether or not an intervention ‘works’ to a more detailed assessment of ‘context’, ‘mechanism’ and ‘outcome’:

The complete realist question is: ‘What works, for whom, in what respects, to what extent, in what contexts, and how?’ In order to answer that question, realist evaluators aim to identify the underlying generative mechanisms that explain ‘how’ the outcomes were caused and the influence of context.

The process of a realist evaluation involves developing initial programme theories, conducting empirical work to test those theories and then analysing the relationships between context, mechanism and outcome to provide insights for those commissioning programmes.

An understanding of context is thus critical, as context can function to make particular mechanisms more or less potent. However, context is a complex concept. 26,27 An analysis49 of the process of managing ‘strategic change’ highlighted the importance of what was being implemented (content – equivalent to realist ‘mechanisms’), how this implementation was being undertaken (process) and the context surrounding change, with a distinction between ‘inner context’ (including concepts such as strategy and culture) and ‘outer context’ (the wider economic, political and social situation). This work also identified a number of features relating to a ‘receptive context’ for change:

-

quality and coherence and policy

-

availability of key people leading change

-

intensity and scale of long-term environmental pressure

-

supportive organisational culture

-

effective managerial–clinical relations

-

co-operative interorganisational networks

-

simplicity and clarity of goals and priorities

-

fit between the change agenda and the locale.

There is already a significant body of literature on large-scale change. As noted previously, a model of ‘large-scale change’ has been developed, which summarises five ‘rules’ underlying such transformations. 44

-

‘engage individuals in leading the change efforts’, highlighting the importance of both ‘designated’ and ‘distributed’ leadership

-

‘establish feedback loops’ concerning the collection and use of measures of progress (which can both help and hinder transformation)

-

‘attend to history’, in the sense of understanding previous efforts at change and their implications for current programmes

-

‘engage physicians’, as they are likely to be crucial to transformation efforts owing to their relative power and autonomy

-

‘involve patients and families’ to enhance outcomes.

In the area of integrated care, previous analyses have outlined important issues that need to be considered. A systematic review50 of factors that supported successful integration of health and social care for people with long-term conditions found seven studies and limited evidence overall, but highlighted a number of themes:

-

colocation of staff and teamwork

-

integrated organisations

-

management support and leadership

-

resources and capacity

-

information technology.

The evaluation of the SICPs also included a detailed analysis of > 200 interviews conducted to drive a ‘bottom-up’ model of barriers to and facilitators of integration,51 many of which were felt to be common to any large-scale change:

-

structure and characteristics of organisations and interventions:

-

size and complexity of the intervention

-

information technology

-

relationships and communication

-

professional engagement and leadership, credibility and shared values

-

-

contextual factors:

-

public service bureaucracy

-

resources allocated to the programme

-

external policy reform

-

organisational culture.

-

As noted earlier, the ‘large-scale transformation’ of the SICP has complex interventions nested within it, which can be viewed as distinct health technologies using a more granular approach. The development and analysis of health technologies can draw on a number of conceptual frameworks, which often relate to the particular logic model underlying an intervention.

For example, normalisation process theory (NPT)52,53 offers a framework to investigate how complex interventions become embedded and become sustainable over time, based on four generative mechanisms: (1) coherence (what is the work to be done?), (2) cognitive participation (participants have to ‘buy in’ to the work, individually and collectively), (3) collective action (what work has to be done to enact and enable new practices?) and (4) reflexive monitoring (what work can be done to help appraise new practices?).

The analysis of complex interventions within the SICP can also draw on frameworks more specifically related to the particular interventions under test. In the current context, this would include psychological models of behaviour change underlying self-management, which use related concepts such as self-efficacy and patient activation54 to understand the mechanisms by which patients undertake self-management. It can also include clinically focused models, such as ‘patient centredness’,55 to explore how mechanisms of integration impact on patient experience of care, as discussed in Chapter 1.

Timeline

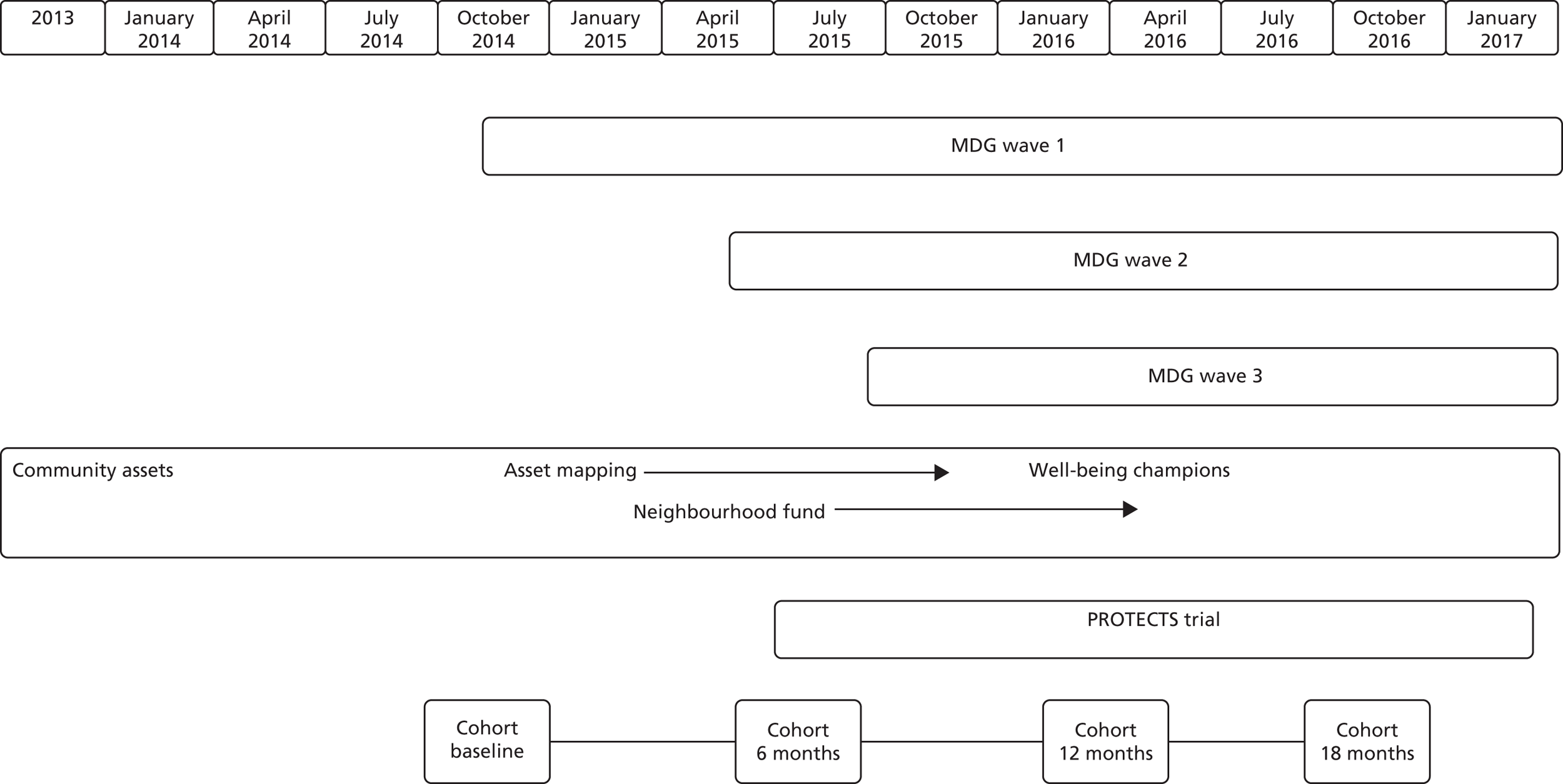

An illustrative timeline of SICP and CLASSIC activities is provided in Figure 3.

FIGURE 3.

Illustrative timeline of the SICP. PROTECTS, Proactive Telephone Coaching and Tailored Support.

Patient and public involvement in SICP and CLASSIC

Funding bodies require patient and public involvement (PPI) to ensure that research is relevant for its intended beneficiaries and that it prioritises issues of importance.

Where applied health research involves the development of interventions, and PPI is often focused on ensuring that those interventions are sensitised to the needs of patients. In the case of CLASSIC and the SICP, the interventions within the SICP involved patient input to the service development outside the formal research context of CLASSIC.

We now describe patient involvement in the initial development of the SICP and the more conventional PPI within the design and delivery of CLASSIC.

Public involvement in the SICP

The SICP aimed to improve person-centred care. Public engagement was undertaken throughout its formation (2011–12), via engagement activities undertaken by public governors and links with existing organisations (Salford Link Project and HealthWatch). As the SICP aimed to integrate health and social care, the programme was able to draw on existing reference groups.

Engagement with the wider community was required and in July 2012 an event was held with older people, which identified their priorities:

-

reducing emergency and permanent admissions to nursing and residential homes

-

enabling people to have more control over daily life

-

improving satisfaction with care

-

supporting people to die in their place of choosing.

Having developed these priorities, a ‘driver diagram’ was used to promote the SICP.

Public involvement was also used to modify the concepts behind ‘Sally Ford’, a character developed to help provide patient focus. By being able to comment on various iterations, group members aimed to make ‘Sally Ford’ more representative.

Additional input meant that ‘Sally Standards’ developed, which outlined how older people could help health and social care providers achieve their outcomes by taking a more active role in their own health and well-being. These underpinned the ‘My Well-being Plan’ developed in collaboration with the community assets team. Public involvement was central to the community assets workstream, with a mapping exercise identifying the unmet need for social groups for older people within neighbourhoods. Older people were encouraged and supported to apply for funding to set up and run local groups themselves. The community assets workstream was steered by its own patient group (the Community Assets Work Stream Group), who began their work by asking three simple questions: (1) ‘What motivates you?’, (2) ‘What makes you feel good?’ and (3) ‘How do you find out about things?’. This identified potential barriers (which included limited physical activity, lack of access to information, not eating well and being socially isolated), thereby forming the focus for ongoing work.

Patient and public involvement in CLASSIC

Ahead of our original NIHR application submission, we consulted with members of a Citizen Scientist Project (www.citizenscientist.org.uk; accessed 16 August 2018) based at Salford Royal NHS Foundation Trust, and other interest groups. In April 2013 we held an engagement event to discuss strategies to ensure older people’s active involvement in CLASSIC. This event highlighted the need for telephone support, engagement through social events (not just written materials) and the importance of peer networks in dissemination of information. The event also helped inform the development of the CLASSIC health coaching intervention.

The CLASSIC Study Advisory Group was formed following assistance from the engagement in research manager from the trust who attended our initial Study Steering Committee. The CLASSIC study was promoted on the Citizen Scientist website, which included an advert for advisory group members. For further meetings, two members of Primary Care Research in Manchester Engagement Resource (PRIMER) [http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/PRIMER (accessed 3 April 2018)] (a local PPI group of long standing) were recruited specifically to work with the CLASSIC team. Its remit included overseeing management of the research, providing a patient voice and commenting on the emerging results and dissemination strategy.

Specific patient and public involvement activity within workstreams

CLASSIC cohort

Our researchers presented the cohort to a local group. In response to their feedback, we made changes to the survey, including increasing font size and type; improving questionnaire layout; providing an indication of time to complete; providing an explanation of why we are asking the questions; adding a statement regarding confidentiality, especially around data sharing; including examples of question completion; providing name and telephone details of a contact to assist with completion; and adding free-text boxes to enable people to add their own comments. The group also provided a ‘critical friend’ approach to letters and participant information sheets being developed to send to potential participants.

In March 2015, we presented to the PRIMER group, and its members provided advice on encouraging people to stay in the cohort and around how we fed back the results from CLASSIC. It was agreed that providing ongoing incentives would help retain participants.

Health coaching

At the meeting in March 2015, PRIMER members discussed the health coaching model, providing guidance on participant recruitment and retention with the telephone-based intervention.

Members of local groups were consulted in 2015 about recruitment methods and gave feedback that many older people were unlikely to answer their telephone to an ‘unknown’ caller. It was therefore agreed that a letter would be sent to potential participants, which included the telephone number that they would be called from, helping increase uptake.

Dissemination of CLASSIC evaluation results

Our two PPI representatives (PB and MM) have commented on the summary findings from the CLASSIC study and assisted with the Plain English summary. Dissemination is ongoing, and we anticipate writing a summary piece in collaboration with our PPI representatives for inclusion on the website (via the SICP communications team) and for inclusion in a local newsletter.

Our website [www.classicsicp.org.uk (accessed 3 April 2018)] will be a repository for publications arising from the CLASSIC study.

Chapter 4 Methods of the CLASSIC cohort

Practice recruitment

Ethics approval was obtained from the National Research Ethics Service (NRES) North West Lancaster (Research Ethics Committee reference 14/NW/0206).

Not all practices were invited to participate as they either had low numbers of patients aged ≥ 65 years or were affiliated with care homes with high numbers of dementia patients. Forty-seven practices were invited and 33 (70%) agreed to participate.

We used FARSITE [a tool for recruitment to research; see http://nweh.co.uk/products/farsite (accessed 18 May 2018)] to generate a list of eligible patients. Each practice was then asked to identify patients meeting exclusion criteria (i.e. in palliative care, those with conditions that reduce capacity to consent).

Practices did not receive incentives but did receive support costs to reimburse their time.

Patient recruitment and retention

Eligible participants were those aged ≥ 65 years and registered as having at least one long-term condition at a general practice.

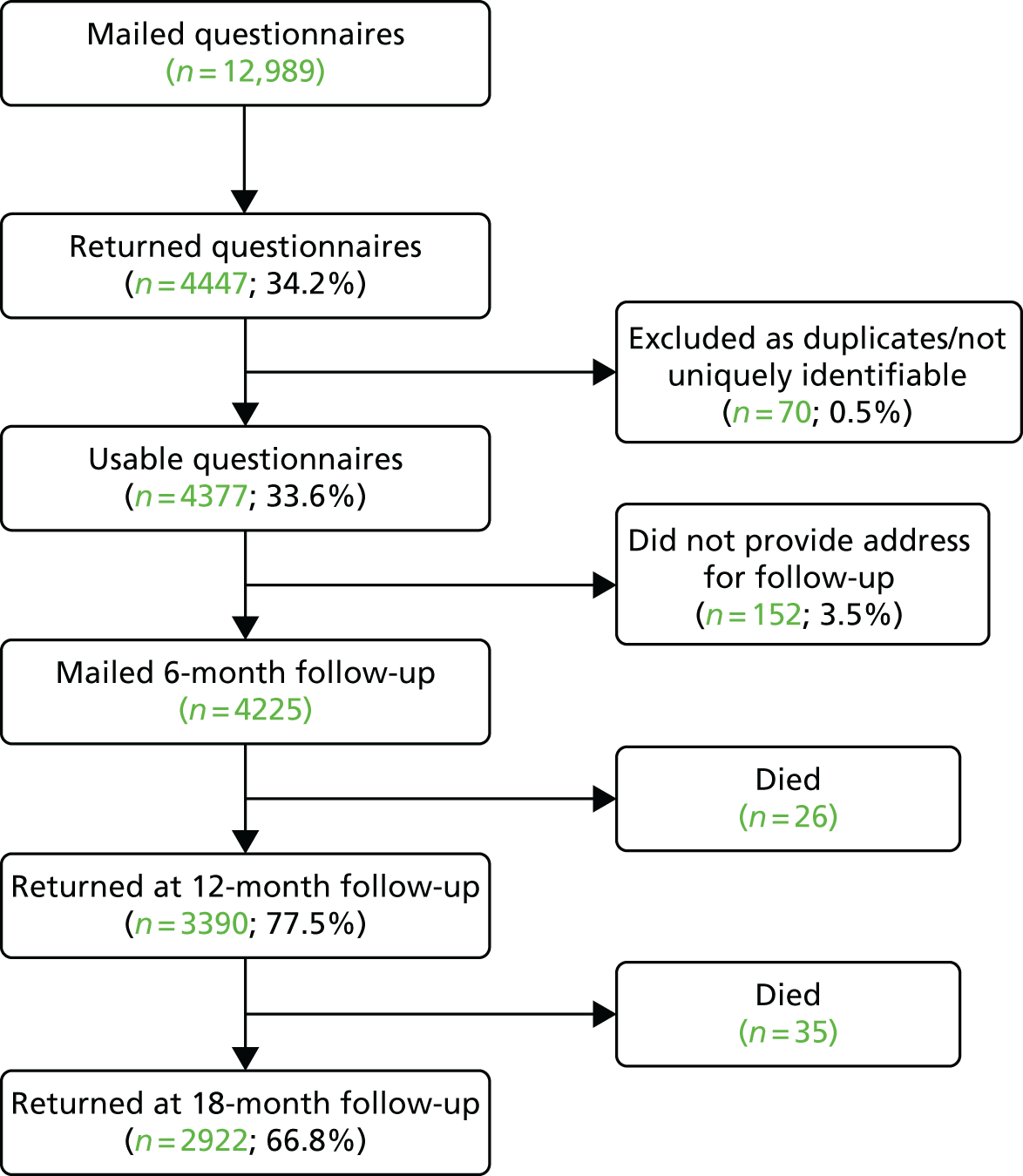

A total of 12,989 patients were eligible and surveyed through general practice between November 2014 and February 2015. If they did not respond, they were sent a reminder and a second copy of the questionnaire 3 weeks later. Participants were offered an incentive of a £10 voucher.

Response was taken to indicate consent to further surveys at 6, 12 and 18 months.

To increase retention, patients were called by a researcher to offer completion of the questionnaire over the telephone. Patients were offered a £5 gift voucher for the completion of the 12- and 18-month follow-ups.

Cohort measures

The following list of measures was used in one or more of the surveys (Table 3).

-

Baseline assessment included sociodemographic questions from the General Practice Patient Survey,56 including sex, age, work situation and qualifications; ethnicity using 17 2011 Census categories;57 a single-item health literacy measure;58 a measure of the number and impact of long-term conditions;59 and use of local community assets. 60

-

The Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care (PACIC),61 which includes items in five subscales (patient activation, delivery system design and decision support, goal-setting, problem-solving, and co-ordination); we used the short 11-item version. 62

-

The Patient Activation Measure (PAM) of patient knowledge, skills and confidence in self-management for long-term conditions;54,63 we used the short 13-item version. 64

-

The Summary of Diabetes Self-Care Activities (SDSCA) measure assesses the number of days per week on which respondents engage in healthy and unhealthy behaviours. 65

-

The Multimorbidity Illness Perceptions Scale (MULTIPleS) assesses patient experience of managing multimorbidity;66 we used 16 items from the MULTIPleS.

-

The Quality, Innovation, Productivity and Prevention (QIPP) measure of personalised long-term condition care. 67

-

The ENRICHD Social Support Instrument (ESSI). 68

-

The EuroQol-5 Dimensions (EQ-5D) measure of health-related quality of life;69 we used the new EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L). 70

-

The Mental Health Inventory – 5 (MHI-5) is a five-item scale that measures general mental health. 71

-

The ICEpop CAPability measure for Older people (ICECAP-O) index of capability measures quality of life for people aged ≥ 65 years in terms of attachment, security, role, enjoyment and control. 72

-

The World Health Organization Quality of Life-BREF (WHOQOL-BREF) 26-item measure of global quality of life across four domains (physical health, psychological health, social relationships and environmental), as well as a single-item scale. 73

-

Health-care utilisation, based on our previous studies;74 continuity of care and care planning from the General Practice Patient Survey;56 and patient experience of safety from the ICPs evaluation.

-

We also used single-item measures assessing other issues, including items assessing issues of interest to stakeholders (e.g. internet use and accommodation).

| Baseline | Follow-up time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 6 months | 12 months | 18 months | |

|

|

|

|

We used a short assessment for carers, including EQ-5D, Patient Health Questionnaire-9 items, ICECAP-O and the Modified Caregiver Strain Index. 75 Carer data are presented in Appendix 1.

Chapter 5 Methods of implementation 1

Implementation 1 was designed to address the following research question:

How do key stakeholders (commissioners, strategic partners) view the SICP, what do they expect from it and how is it aligned with their objectives and incentives?

The specific objectives were to explore and understand:

-

how commissioners view the programme, what they expect from it and how it is seen in terms of their performance objectives

-

how the programme is viewed by strategic partners such as the local authority and how it is sustained under financial pressure

-

how the programme affects the work of the two foundation trusts, in particular how the integrated community and acute provider adapts to reductions in inpatient activity

-

how the programme affects primary care, in particular general practice

-

the extent to which the financial incentives (explicit and implicit) in the local health and social care system are aligned with the ambitions of the programme.

A qualitative approach was adopted to understand how the SICP was developed and how organisations were working together to transform care. Fieldwork took place from November 2014 to September 2016. Data collection included approximately 56 hours of non-participant observations of SICP programme meetings. A researcher attended meetings, including the Alliance Board, Study Steering Group and MDG meetings.

In addition, 28 interviews were carried out with professionals working across the four key stakeholder organisations associated with the SICP. Initially, 22 interviews were carried out in late 2014/early 2015 and six follow-up interviews were carried out with key stakeholders in 2016 to see how the SICP had developed, the factors that influenced the SICP and the relationships across the four key stakeholder organisations (Table 4). Documents, including operational plans and business cases, were collected from the SICP and relevant meetings to provide context.

| Data collection method | Number of interviews | Further information |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews | 28 in total (22 plus six follow-up interviews) |

|

| Observations | 19 (around 56 hours) | Observations included:

|

The data from interviews and observations were coded in the same way and analysis of the data was facilitated by the computerised data analysis package NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK). Initial coding was carried out using a priori codes derived from our existing understanding of the issues associated with commissioning complex programmes. These were supplemented by inductive coding arising from the data. Analytical memos were written and discussed to develop a collective understanding of the issues represented in the data.

Findings relating to the commissioning of the programme were shared with the wider research team and further explored in interviews with those responsible for the implementation of the project.

Chapter 6 Methods of implementation 2

Implementation 2 was designed to address the following research questions.

Multidisciplinary groups:

-

What are the characteristics and composition of the groups?

-

How do the groups function as teams and in collaboration with other providers?

-

How well do the groups achieve fidelity to the original SICP model?

-

What are the key barriers to and facilitators of effective functioning and outcomes?

-

How is the work of the groups experienced by patients and carers?

Integrated contact centre:

-

What services are provided by the centre and which staff provide those services?

-

What is uptake and usage of the ICC services?

-

What are the key barriers to, and facilitators of, effective functioning and outcomes?

-

How are ICC services experienced by patients and carers?

Methods and analysis

As discussed in Chapter 3, we drew on the realist model and the ‘five simple rules of large-scale transformation’ (designated and distributed leadership, presence and use of feedback, attention to historical factors, provider engagement, and PPI)7 as a framework to understand the process of implementation of these two aspects of the SICP. We also drew on NPT and psychological models of self-management and patient centredness to guide analysis.

Study methods: multidisciplinary groups

Multidisciplinary group fieldwork took place from March to December 2015, with fieldwork largely based on non-participatory attendance at neighbourhood MDG meetings. Data collection included 72 hours observing MDG meetings, with sequential fortnightly observations in one neighbourhood MDG for each of the three waves of roll-out (Table 5). Additional observations were undertaken at other meetings supporting the MDG process (including the working group meetings, joint chairpersons’ meetings and administrator meetings) as well as engagement events. Further observations were conducted with MDG nurse and social care co-chairpersons to outline how the work of referring and prioritising patients for discussion and pre-MDG meetings was enacted.

| Data collection method | Number | Further information |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews | 37 |

|

| Observations | 36 (approximately 72 hours) | Observations included:

|

By agreement, field notes made during the MDG meetings did not contain any identifiable patient data. Initials, sex and the general practice were recorded, permitting further questioning around individual cases with the relevant general practitioners (GPs) and to identify potential patients to be invited to participate in qualitative interviews.

Thirty-two face-to-face interviews were carried out with professionals participating in the MDG meetings or those whose work was associated with them. Maximum variation sampling was used to ensure that representatives from all staff groups participating in MDGs were interviewed.

We used routine data (workload and throughput, patient characteristics, links with other services) to contextualise our data. Operational documents were collected from the MDG processes and meetings around them and used to provide information about the implementation.

Study methods: integrated contact centre

Fieldwork took place between October 2015 and July 2016, during which time the single integrated referral point (SIRP) was based within a Salford City Council facility. Colocation with the council corporate team unfortunately meant that permission to carry out observational work within the SIRP was declined. Data collection was therefore based mainly on interviews with 11 ICC staff during which in-depth descriptions of their work were provided in lieu of observations (Table 6).

| Data collection method | Number | Further information |

|---|---|---|

| Interviews | 17 |

|

| Observations | 5 (approximately 11 hours) | Observations included:

|

We explored the various services provided by the centre through individual interviews with participating staff and managers to assess the development of the service over time, how fidelity to the model was achieved and the potential for unintended consequences. We used routine data reported by respondents (workload, patient characteristics, referrals) to contextualise the data.

We described the characteristics of the centre, its staffing and technology, and how the existence and function of the centre is communicated to patients. At the level of the patient, we described the interaction between the staff and patients, through individual interviews with six patients/carers who had direct experience. Observations included 11 hours of non-participant observations of meetings directly related to the centre, including a short visit to the SIRP, observing the locality base, a care homes meeting and initial engagement events promoting the wider SICP. In addition, documents providing evidence of the implementation process and allowing a comparison with the initial plans for the ICC at the start of the SICP were collated. Health coaching data are presented in Appendix 2.

Qualitative analysis methods

Qualitative data from both the ICC and MDG observations and interview transcripts were organised using NVivo 10. Techniques from grounded theory were used for the thematic analysis. 76 Analytical memos were written and discussed to develop a collective understanding of the issues represented in the data. Members of the qualitative team met monthly to discuss emerging themes and to agree subthemes.

Normalisation process theory was used as a starting point to inform the original topic guide used in the qualitative interviews. We considered how data mapped onto the framework, and although there were some connections between concepts, these were limited. We therefore adopted a more responsive approach, using iterative sampling and analysis of data until no new information emerged. This prevented the background framework from constraining the interviews and allowed us to learn from, and develop, the topic guide as the interviews were conducted.

Qualitative data from both the ICC and MDGs observations and interview transcripts were organised using NVivo 10. We conducted a thematic analysis drawing on some techniques from a grounded theory approach, including open coding and the creation of analytical memos as a basis for iterative analysis and sampling as outlined previously. Members of the qualitative team met monthly to discuss emerging themes and subthemes, any unusual cases and to agree the final stage of ‘selective’ coding. These processes of coding and iterative analysis enabled core themes to emerge inductively from the data consistent with a grounded theory approach. 76

Chapter 7 Methods of outcomes 1

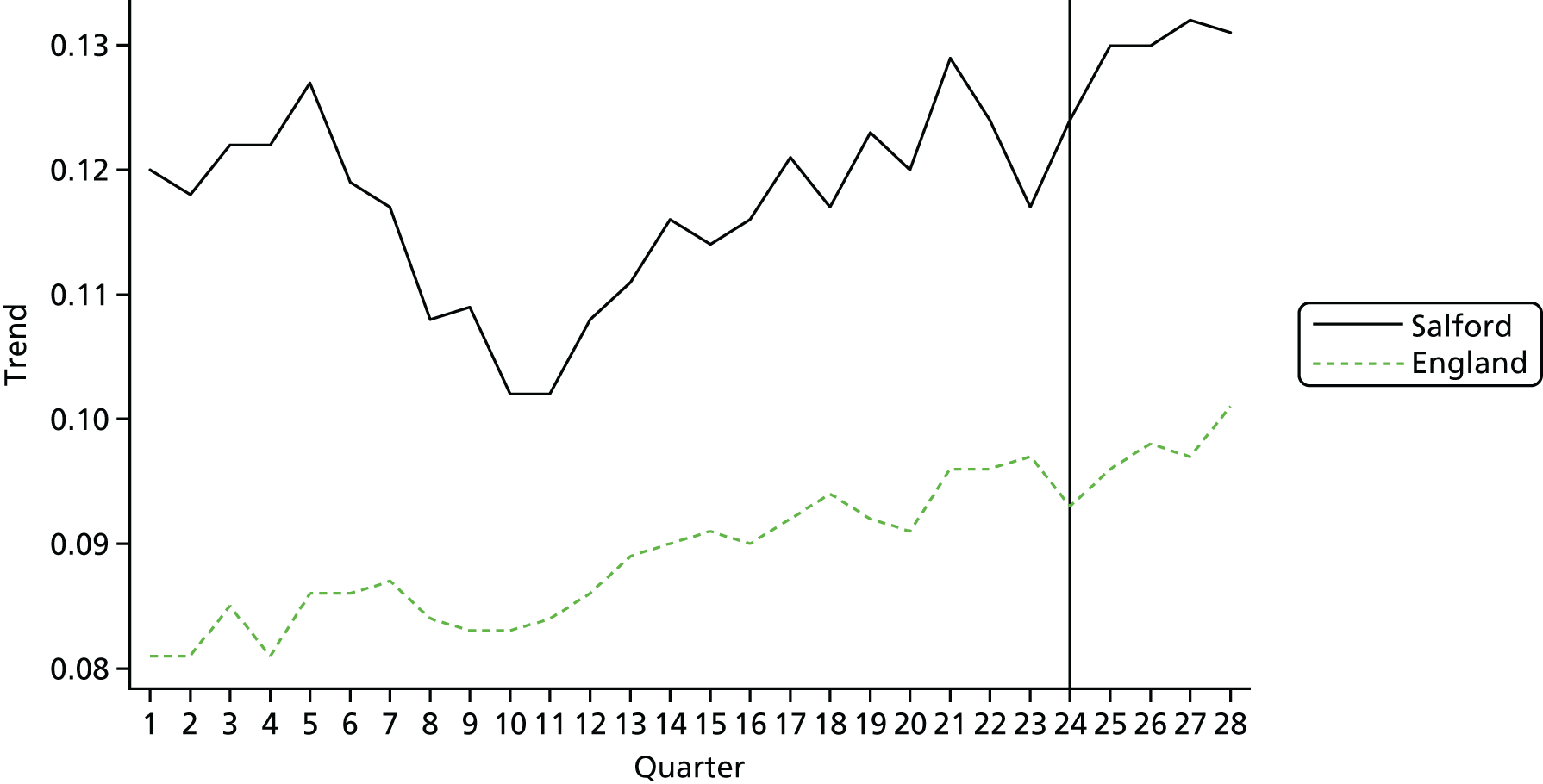

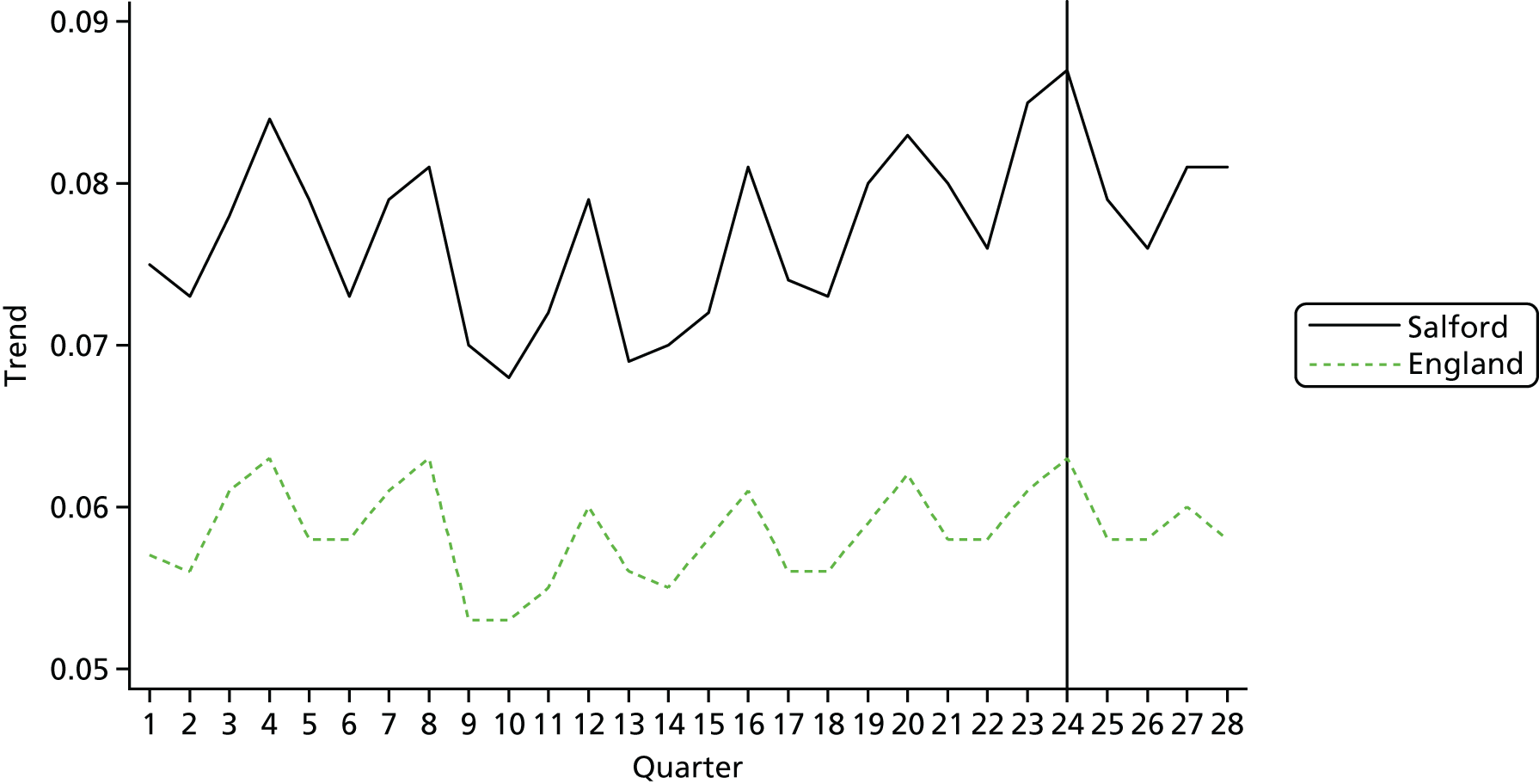

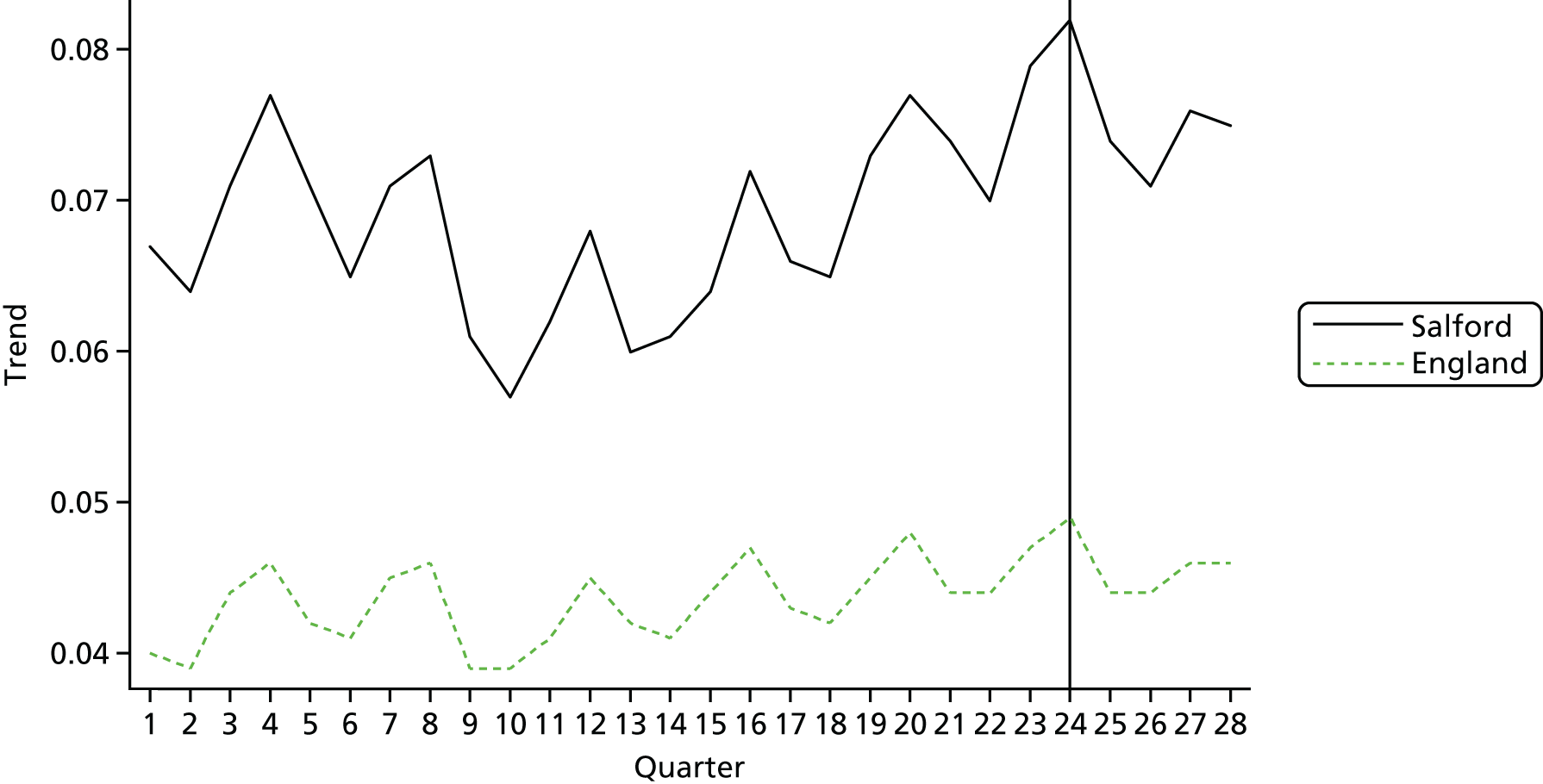

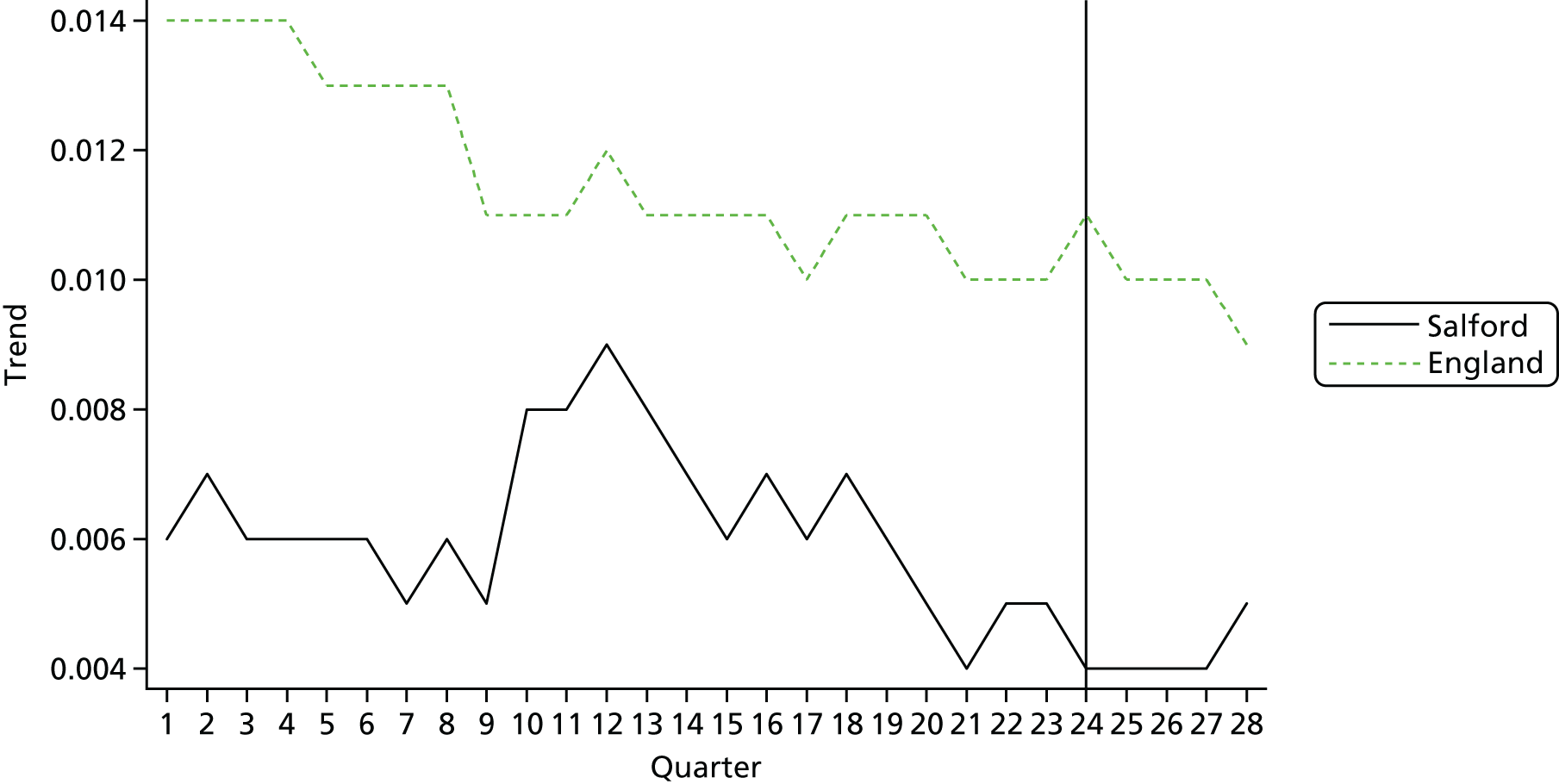

A core SICP aim was to reduce emergency admissions. Although all mechanisms of integration in the SICP have a potential role in reducing admissions, the MDGs are most clearly focused on providing a rapid reduction in the use of hospital services through intervention with patients at high risk of admission.

Multidisciplinary groups and linked case management interventions have an important place in the NHS as a core mechanism of integration. Since the Evercare pilots,29,30 studies have cast some doubt on the evidence that this model can achieve reductions in hospital admissions. 18,19,33,77,78 However, an unpublished survey of CCGs reported that 80% included some variant in their integration plans. 79 There are a number of different models of MDGs and some of the ways in which they vary are outlined in Table 2. In line with the realist model (see Chapter 3), there is also an argument that the general case management ‘mechanism’ is effective only in certain contexts, such as a history of previous joint working among staff in an integrated care service.

Methods

The SICP was targeted at all general practices. Therefore, the primary analysis for the effects of the MDGs compared data from practices in Salford with suitable comparators in other parts of England. However, the introduction of MDGs was staged, and we used this to assess any differential impact relating to the staged introduction.

We adopted lagged dependent variable approaches to estimate the effect of the MDGs. 80 This approach does not require assumptions of parallel trends between intervention and comparator groups imposed by a difference-in-differences specification. The lagged dependent variable approach uses a fixed vector of lagged values of the outcomes prior to the intervention as explanatory variables. The analysis is conducted only on the time points following the intervention. 80

If the parallel trends assumption does not hold, the lagged dependent variable approach is less prone to bias and is more efficient than alternatives such as the creation of synthetic controls. 80 The superiority of the lagged dependent variable approach is increased when data are available on more pre-intervention periods, as is the case in this setting.

Data

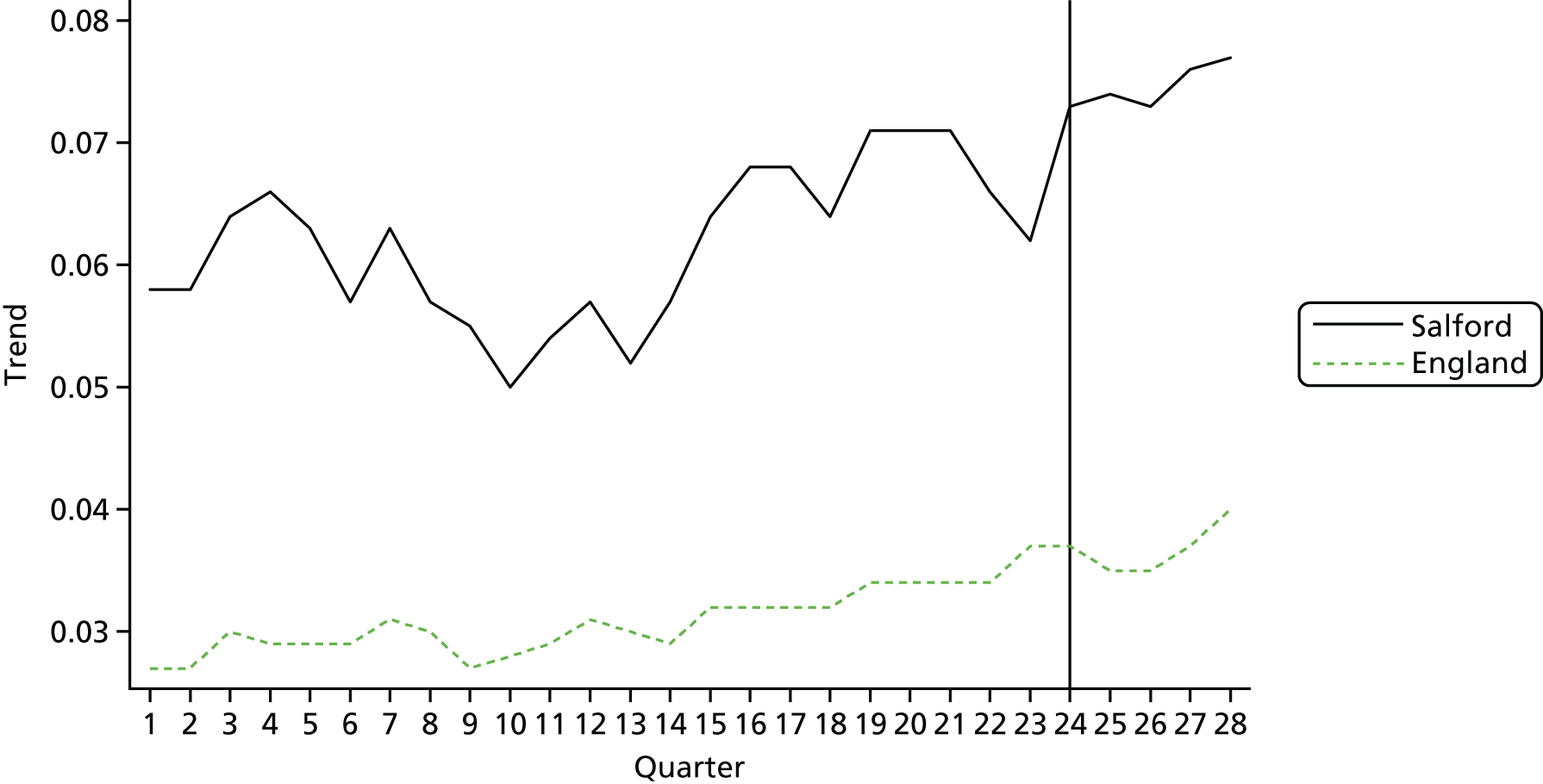

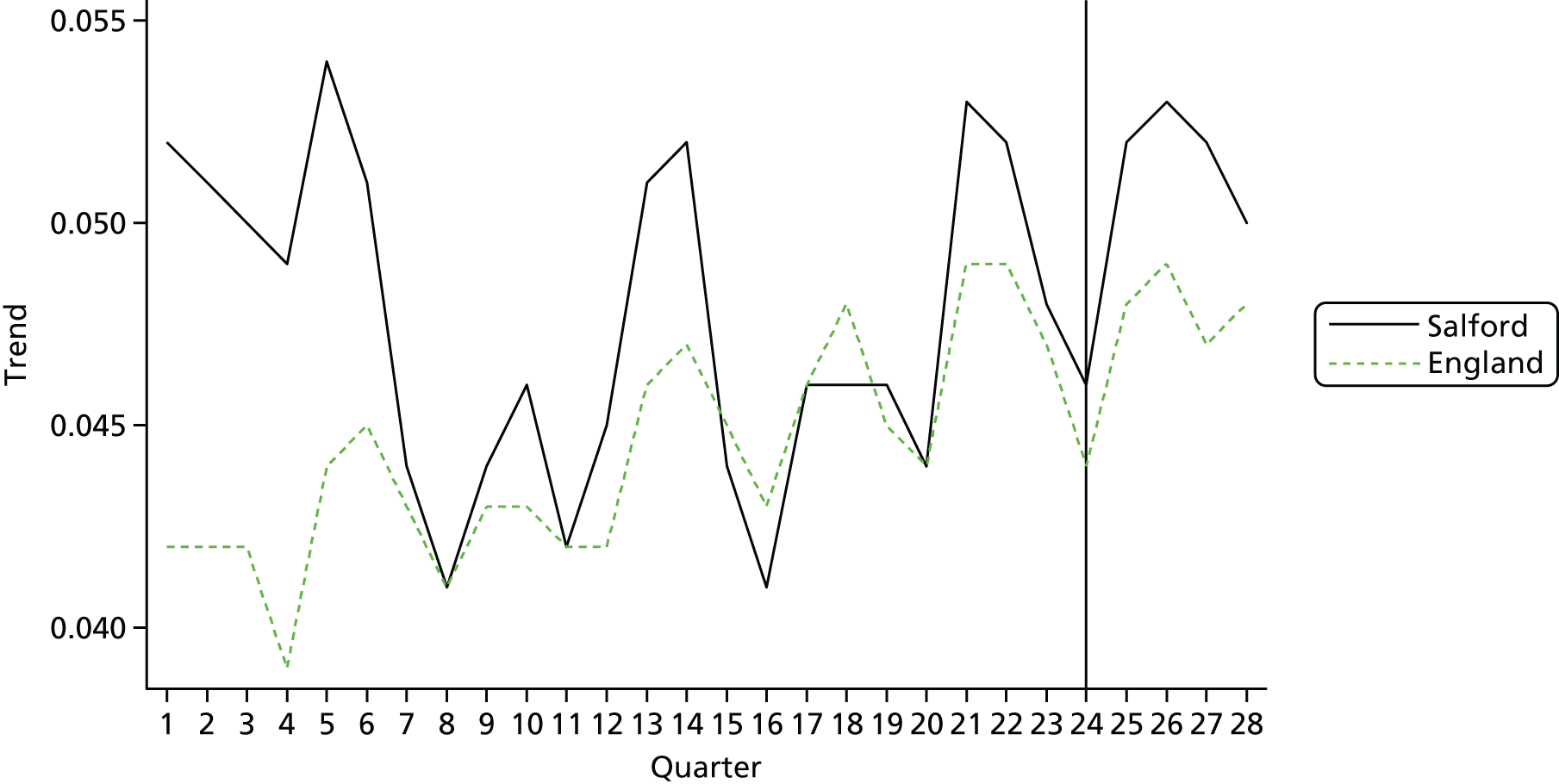

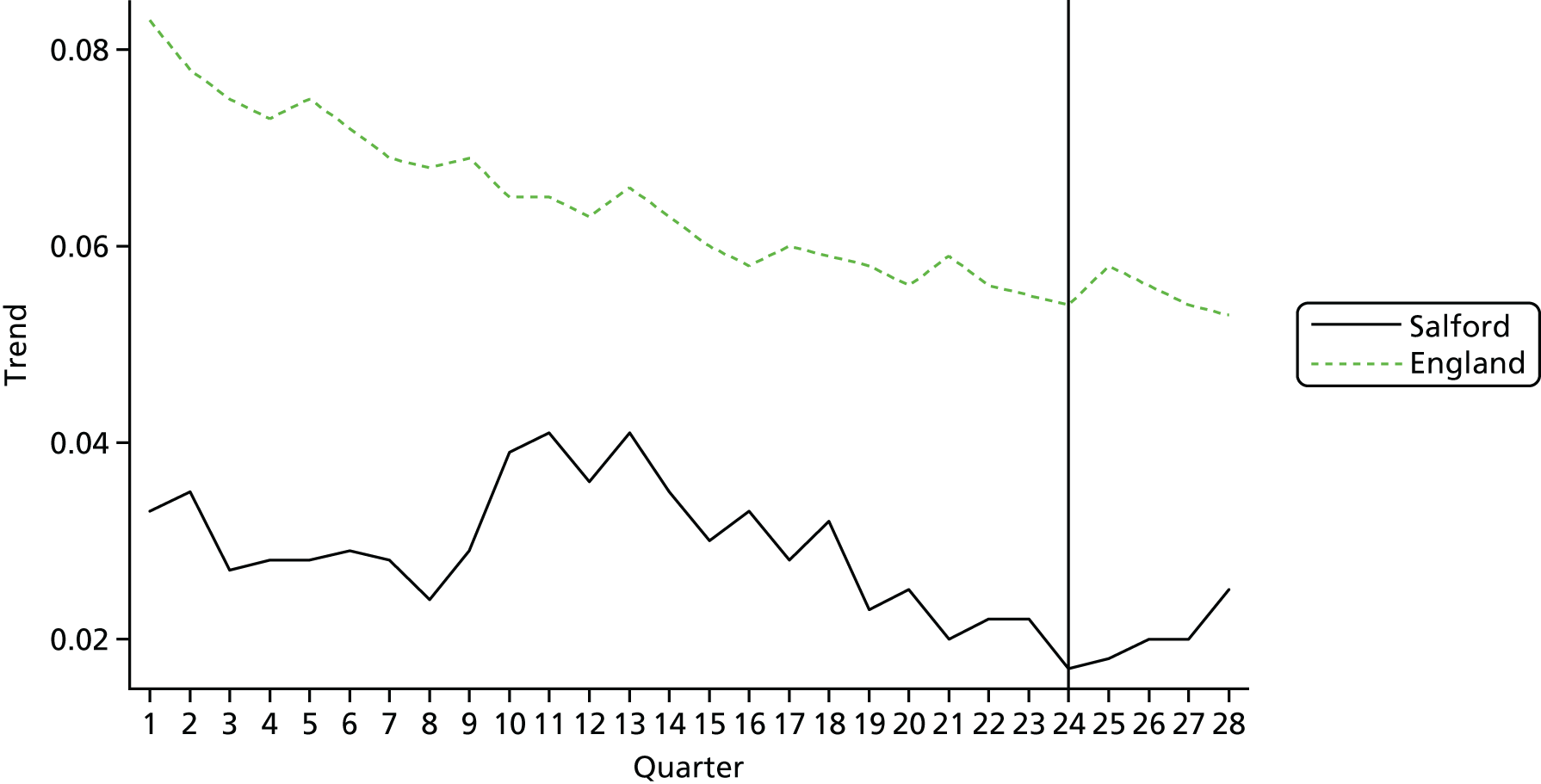

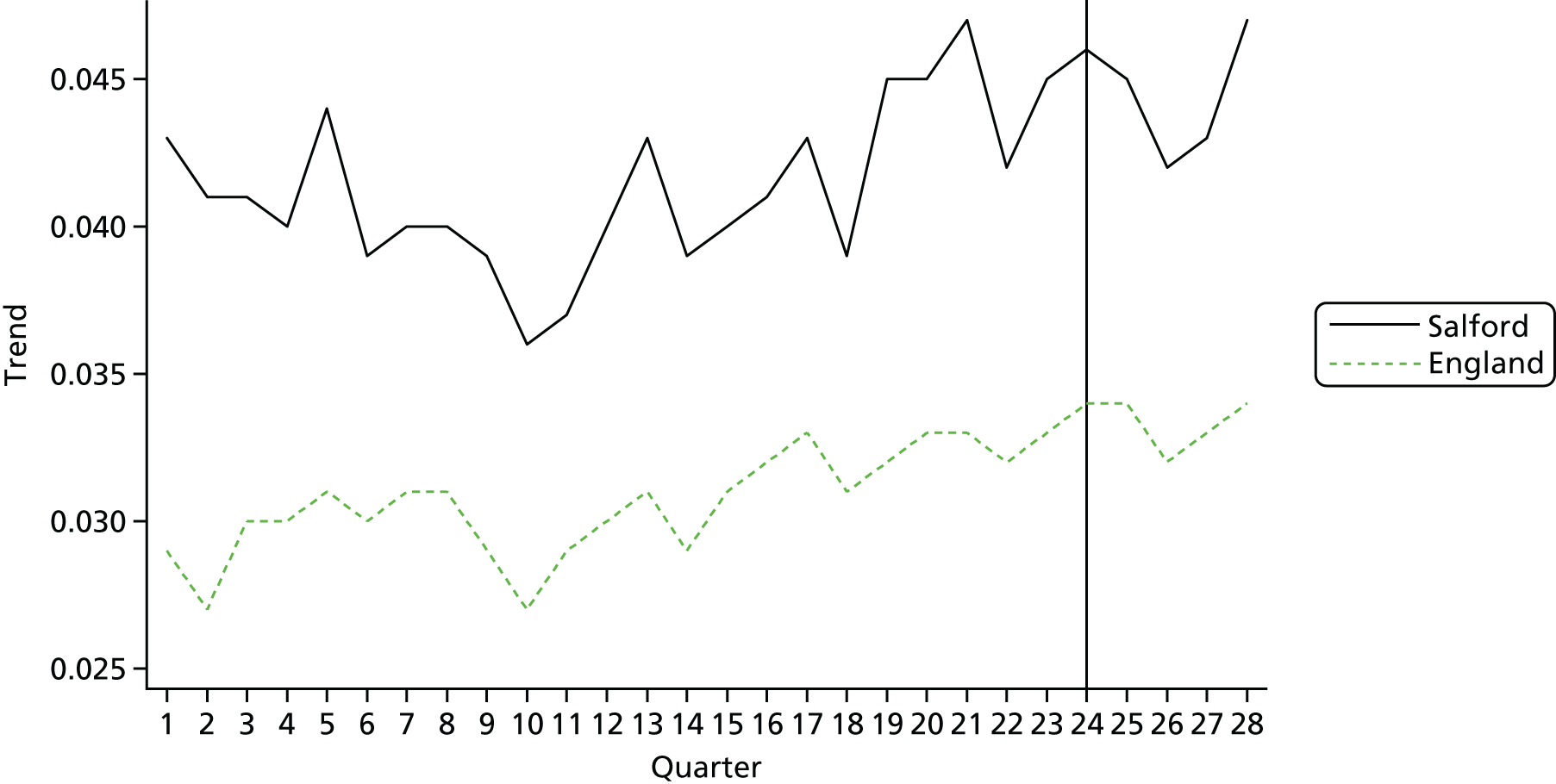

Data were HES from NHS Digital, stratified by financial quarter and general practice (financial years 2009/10–2015/16), for populations aged ≥ 65 years:

-

the number of accident and emergency (A&E) attendances per person

-

the number of A&E attendances referred by health and social care providers per person

-

the number of self-referred A&E attendances per person

-

the number of emergency admissions per person

-

the number of emergency admissions via A&E per person

-

the number of direct emergency admissions per person

-

the number of ambulatory care-sensitive emergency admissions per person

-

the proportion of patients discharged to usual place of residence.

We also obtained general practice patient registration lists for persons aged ≥ 65 years from two sources: (1) the Personal Demographic Service for the financial years 2009/10 and 2010/11 and (2) NHS Digital for the financial years 2013/14 to 2015/16. For the financial years 2008/9, 2011/12 and 2012/13, we used the closest year of data available.

Intervention sites

Practices in Salford CCG were all considered to be the intervention site, but we also identified distinct subgroups (non-adopters, early adopters and late adopters). Non-adopters (n = 5) were excluded from the analysis, leaving three intervention sites:

-

9 early adopters, classified as starting the intervention in April 2014

-

32 later adopters, classified as starting the intervention in April 2015

-

41 adopters, classified as starting the intervention in April 2015.

Comparator sites

Four comparator sites were used outside Salford CCG (Table 7):

-

all practices in Greater Manchester excluding Salford (‘Greater Manchester’)

-

practices in two CCGs to the west of Greater Manchester (‘West’)

-

practices in nine CCGs to the west of Greater Manchester [‘West (extended)’]

-

all practices in England excluding Salford (‘England’).

| Control group | List of CCGs | Number of practices |

|---|---|---|

| Greater Manchester | Bury, Central Manchester, North Manchester, South Manchester, Stockport, Tameside and Glossop, Bolton, Wigan, Heywood Middleton and Rochdale, Trafford, and Oldham | 418 |

| West | Warrington, and Knowsley and St Helens | 89 |

| West (extended) | Warrington, Knowsley and St Helens, West Lancashire, Vale Royal, Halton, Southport and Formby, South Sefton, Wirral, and Liverpool | 339 |

| England | All CCGs in England except Salford | 7434 |

Regressions

In total, we estimated 96 models (Table 8). We weighted all analyses by population size and used robust standard errors to allow for heteroscedasticity. We included proportions of the total practice population aged 65–74, 75–84 and ≥ 85 years as additional controls.

| Intervention site | Comparator site | Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| Early adopters | Greater Manchester | A&E attendances per person |

| Late adopters | West | A&E attendances referred by health/social care per person |

| All adopters | West (extended) | Self-referred A&E attendances per person |

| England | Emergency admissions per person | |

| Emergency admissions via A&E per person | ||

| Direct emergency admissions per person | ||

| Ambulatory care-sensitive emergency admissions per person | ||

| Proportion discharged to usual place of residence |

Robustness

An additional three models were estimated for the primary outcome (emergency admissions per person). For the first test of robustness, we omitted the data for the first financial year (2009/10). We omitted the first four quarters of data owing to small denominators in the general practice list sizes for the comparators ‘West’, ‘West (extended)’ and ‘England’.

For the second test of robustness, we limited the analysis to the period following the 2011 Census. The 2011 Census resulted in a recalibration of practice populations and may have affected the intervention sites in a different way from the comparators.

For the final robustness analysis, we used a difference-in-differences specification. Our models for difference-in-differences analysis control for Index of Multiple Deprivation,81 quarterly time dummies and proportion of practice list size of certain ages (65–74, 75–84 and ≥ 85 years). Difference-in-differences is not used for the primary analysis as this method relies on the parallel trends assumption. Parallel trends assumption requires that both intervention and comparator sites must have parallel trends pre intervention; violations will result in biased estimated treatment effects.

Chapter 8 Methods of outcomes 2

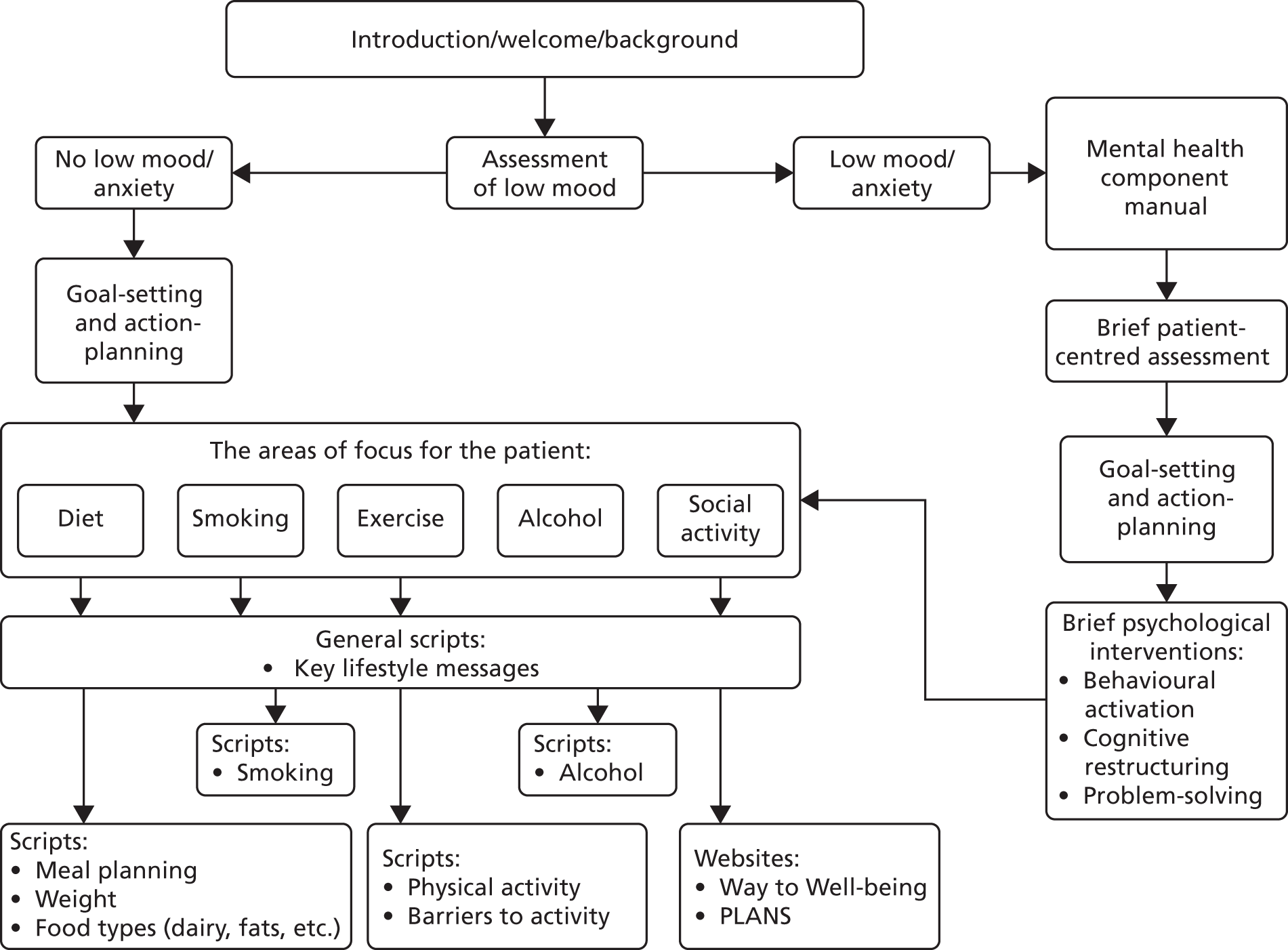

The ICC involves a number of services, but a key one is health coaching in long-term conditions:

Health coaching involves ‘a regular series of phone calls between patient and health professional . . . to provide support and encouragement to the patient, and promote healthy behaviours such as treatment control, healthy diet, physical activity and mobility, rehabilitation, and good mental health’.

McLean et al. 82

Table 9 shows key dimensions of health coaching interventions. 83–86

| Populations | Identification of patients | Technology | Responsiveness | Model |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Coaching can be preventative or target those with existing conditions. If the latter, this can involve those with a specific disorder, a range of conditions or multimorbidity. Other methods of targeting include a focus on high health-care users or those at a high risk of admission | Patients can come to health coaching through self-referral, identification through routine consultations (or post discharge) or the use of formal risk stratification models | Technology can involve conventional telephone and mobiles, or enhancements such as telemonitoring, videophone, automated telephone support, SMS or combinations of technologies | Coaching can recruit patients through referral from services, or proactively identify patients ‘at need’ or ‘at risk’. The delivery of the coaching itself can be more or less scripted | A variety of models of coaching can be used, based on counselling, CBT, self-management and self-efficacy, or motivational interviewing |

| Target | Practitioner | Intensity | Care context | |

| The targeted outcomes for coaching can include education and information, decision-making, motivation and self-efficacy, self-care behaviours, health-care utilisation, mental health and substance abuse | Coaching can be delivered by peers, trained non-clinical staff, clinicians, or may be automated to various degrees | The intensity of coaching may vary in terms of the length and number of calls per week, the overall duration of contacts and the use of ‘booster’ sessions | Coaching can be used as part of a ‘stand-alone’ intervention, or delivered as part of wider programme of care. Linkage to other services (such as primary care) may also vary |

What is the evidence for health coaching?

A number of reviews have tried to assess the overall evidence. A review87 of the effects of health coaching on adults with chronic disease found 13 studies in a broad range of populations and conditions. Only a minority used telephone health coaching. Benefits were reported for a variety of outcomes, with the most consistent results for weight, physical activity and health status. However, the studies included adults of a range of ages rather than older people. A second review85 found 30 studies of health coaching for long-term conditions and, again, reported evidence of positive effects on a range of outcomes (including self-efficacy, satisfaction and health status). An integrative review88 of qualitative and quantitative research found 15 studies and rated 40% as showing improvement in one or more health behaviours. A review84 specific to telephone coaching services for people with long-term conditions found 34 eligible studies, focused on diabetes mellitus or cardiovascular conditions. Most reported some outcomes in favour of health coaching, although reporting of cost outcomes was rare. The variation in the numbers of included studies in reviews highlights variable definitions in this area, but the overall evidence suggests an intervention that is promising but far from proven.

Other recent studies in the last 5 years also give a mixed picture. A quasi-experiment89 exploring the impact of telephone health coaching on care utilisation reported no impact on emergency admissions, but found savings of US$412 in total costs per person, largely through reduced outpatient and inpatient expenditures. Again, the sample was adults and only a small proportion were aged ≥ 65 years. A second quasi-experiment88 in an adult Medicaid population found the opposite: health coaching was not associated with changes in a range of utilisation measures and expenditures, but did reduce emergency department use. A recent evaluation90 of the Birmingham OwnHealth health coaching service in 2698 patients and matched controls explored impacts of a service targeted at people with heart failure, coronary heart disease, diabetes mellitus or COPD. The analysis found no reductions in utilisation with a nurse-led health coaching service, although other outcomes (such as empowerment and quality of life) were not measured. A large (n = 1535) study of health coaching in patients aged ≥ 45 years with one of three long-term conditions and unmet treatment goals found that blood pressure control improved in the intervention group, but found no other benefits on primary end points. 91 A small (n = 43) study92 of health coaching for older patients with multimorbidity in nursing homes in Korea reported benefits in self-management, self-efficacy and health status. A trial93 of 232 patients with long-term conditions and depression found that coaching added only short-term benefits over access to a self-care intervention in an older population (mean age 55 years). A cluster trial94 of 473 patients receiving a practice nurse-based health coaching intervention found no benefits over usual care on glycated haemoglobin (HbA1c) outcomes. A trial of patients95 with coronary heart disease in university teaching hospitals receiving telephone coaching found a significant impact on total cholesterol outcomes at 6 months compared with controls. The PACCTS (Pro-active call centre treatment support) study96 randomised 591 patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus to telephone support from paraprofessionals and found significant changes in only a subgroup of those with poor glucose control at baseline. A trial97 in 436 older patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) found that coaching by paraprofessionals and supported by a bespoke website led to improvements in health-related quality of life and blood pressure control, and was highly likely to be cost-effective.

The overall picture on the effectiveness of health coaching is complex. There are a number of positive evaluations, but the studies have included a very mixed group of patients and interventions. Clearly, further research is required to assess the impact of this promising intervention and its place in integrated care for long-term conditions, especially given the limited evidence base in multimorbidity,98 which is highly prevalent in patients aged ≥ 65 years. 1

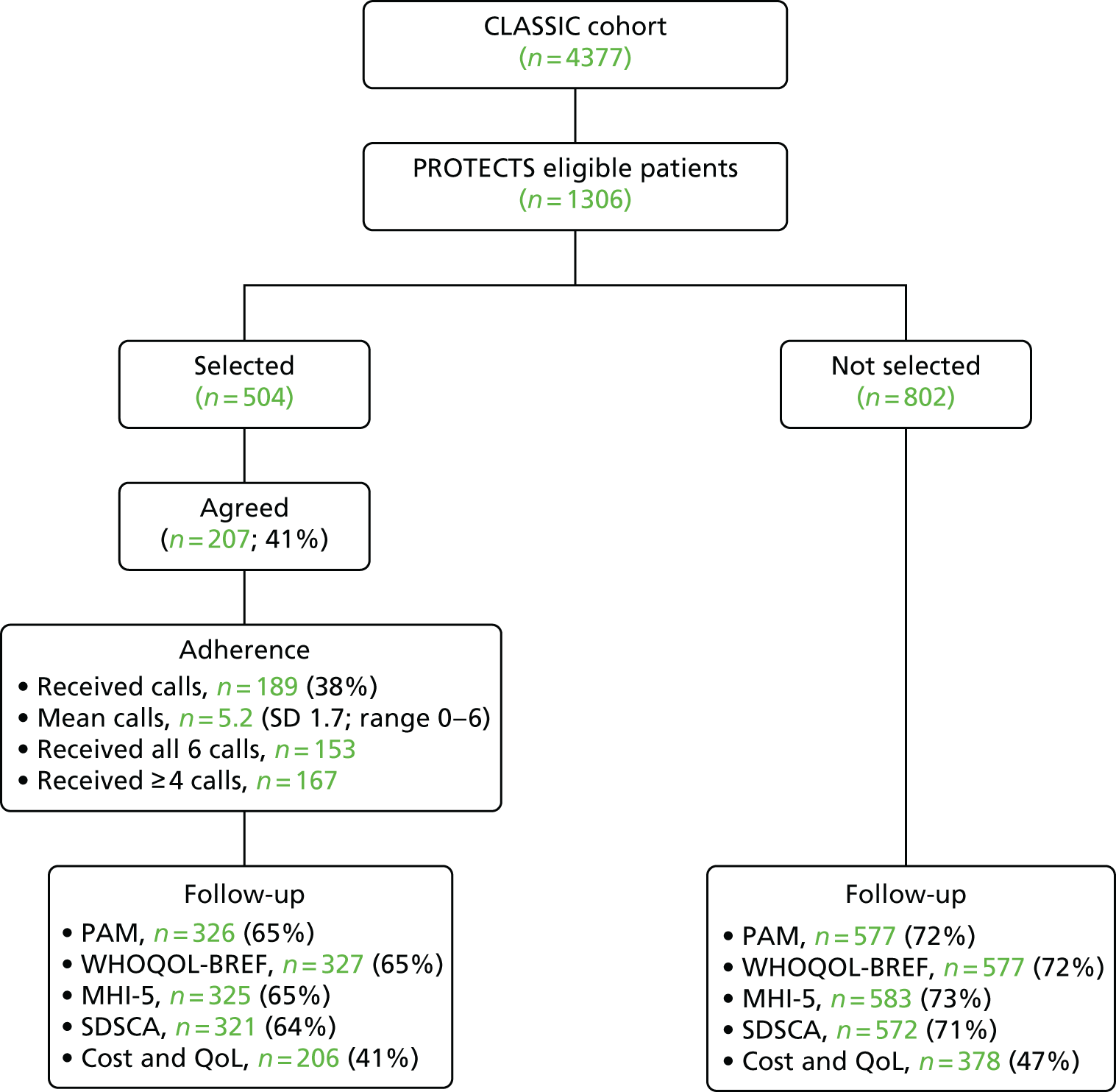

The CLASSIC Proactive Telephone Coaching and Tailored Support (PROTECTS) trial was a pragmatic, individual-level randomised trial to evaluate the clinical effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of telephone coaching.

Eligibility criteria

All patients were aged ≥ 65 years, had two or more existing long-term conditions and were assessed as needing some assistance with self-management. We included the following self-reported conditions: asthma, back pain, cancer, CKD, COPD, diabetes mellitus, heart disease, heart failure, irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), osteoarthritis, osteoporosis, rheumatic disease, rheumatoid arthritis, stroke and thyroid problems.

We assessed self-management with the PAM, and included those with PAM levels of 2 or 3 (Table 10).

| Level | Description |

|---|---|

| 1 | Patients do not feel in charge of their own health and care, with low confidence in their ability to manage health and few problem-solving skills or coping skills |