Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/5001/62. The contractual start date was in May 2013. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in August 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

none

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Edge et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

Schizophrenia and psychoses

Schizophrenia is a syndrome of psychotic disorders. Psychoses/psychotic disorders are severe mental illnesses (SMIs) characterised by delusions, hallucinations, changes in behaviour and related problems of cognition, thoughts and emotions. In their 2012 systematic review, Kirkbride et al. 1 reported the pooled annual incidence of psychotic disorders as 32 cases per 100,000 and of schizophrenia as 15 per 100,000.

Although the incidence of psychotic disorders was once believed to be similar across all populations, Kirkbride et al. ’s1 findings confirm those of studies in the last decade,2–7 indicating that rates of psychoses among Black and minority ethnic (BME) populations are significantly higher than in comparison populations among whom they reside. Overall, evidence suggests that rates of schizophrenia are 5.6 times greater in Black Caribbean people than in White British people [95% confidence interval (CI) 3.4 to 9.2]. Elevated rates were also reported in Black African [relative risk (RR) 4.7, 95% CI 3.3 to 6.8; I2 = 0.47] and Asian groups (RR 2.4, 95% CI 1.3 to 4.5; I2 = 0.42). The Aetiology and Epidemiology of Schizophrenia and Other Psychoses study8 of populations in London, Bristol and Nottingham reported even higher incidence rates among African-Caribbean people (71/100,000 per year). This equates to a risk of diagnosis that is ninefold higher than in the White British population (incidence rate ratio 9.1, 95% CI 6.6 to 12.6).

Schizophrenia and related psychoses are associated with considerable personal, economic and societal burdens. It is estimated that the total annual cost of a broadly defined schizophrenia (non-affective psychoses) is £8.8B. 1 Forty per cent (£3.5B) of this cost is attributable to service use, 47% (£4.1B) to lost employment and 13% to informal care (£1.2B). Although it is not entirely clear why some BME groups are at greater risk of psychosis, it is suggested that ‘urbanicity’, discrimination and socioeconomic disadvantage are important contributory factors. 9,10

African-Caribbean people, schizophrenia and UK mental health services

African-Caribbean people’s elevated risk in the UK is accompanied by poorer utilisation of services and worse clinical and non-clinical outcomes, especially among young men. 2,3,11,12 African-Caribbean people’s experience of specialist mental health services is also poor. 6,13–15 Characterised by delayed access, despite multiple attempts at help-seeking, their care pathways are more adverse than those of their White British counterparts. 15 For example, they are less likely to access specialist services via general practitioners and more likely to do so via the police and criminal justice system,15–17 with high rates of detention under the Mental Health Act 2007. 18 African-Caribbean family members disproportionately report involving the police because they are unable to gain timely access to support from specialist services. 19 This is important because delayed access to diagnosis and treatment increases the duration of untreated symptoms and the illness acuity on contact with services. 20,21

Once in specialist services, African-Caribbean people experience more coercive care than White British people, including higher rates of seclusion and restraint, plus higher mean doses of psychotropic medication and related side effects. 13,15 They are also less likely to be offered psychological therapy, and they experience worse clinical outcomes, such as longer inpatient stay and higher rates of relapse and readmission. 8,13 The Centre for Mental Health22 described African-Caribbean people’s experience of mental health services as a vicious ‘circle of fear’ involving delayed engagement/non-engagement, adverse care pathways, coercive treatment and inferior outcomes. These experiences, combined with perceptions of services as institutionally racist, reinforce African-Caribbean service users’ and families’ fear, mistrust and avoidance of statutory mental health services. 14,22–24 Delayed access to care also creates considerable family tension, conflict and increased burden on carers, which can result in family breakdown. Lack of access to family support and social contact is, in turn, associated with service users’ social isolation and increased risk of relapse. 25

Family intervention and schizophrenia

Family intervention (FI) is a psychosocial treatment with a strong evidence base of clinical effectiveness. 26,27 Since the findings from the first UK trial of FI for schizophrenia were published in 1982, research has consistently shown that undertaking FI with service users diagnosed with schizophrenia and their families improves outcomes. 9,27–30 For example, in their Cochrane review, Pharaoh et al. 26 reported that FI improved medication compliance, self-management and problem-solving, which were associated with reduced risk of psychotic relapse. In a meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials (RCTs),27 FI plus medication yielded better outcomes than medication alone. In addition to decreasing or preventing relapse, improving service users’ social functioning and enhancing their quality of life, a key aim of FI is to reduce carer burden and ill-health. 31

Although there are a number of approaches to FI, they share common core components such as psychoeducation, problem-solving, stress and crisis management, enabling carers to practise good self-care. 26,27 The core principles of FI models include a holistic approach to care and treatment, establishing therapeutic alliance, addressing family tension and setting reasonable and achievable goals and expectations. The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)30 recommends at least 10 sessions of FI for people with schizophrenia diagnoses who are in contact with their families. Few services provide FI for the general population. 32 At a time of significant financial pressures on the NHS and related reduction in staff numbers, perceptions of FI as time and labour intensive and, therefore, costly, mean that FI practitioners are rarely given time to practise. 33

Family intervention and African-Caribbean people

Commenting on care providers’ inconsistent and ineffective response to inequalities in the care and the treatment of African-Caribbean people diagnosed with schizophrenia, NICE11 specifically recommends FI for African-Caribbean people with schizophrenia. The unavailability of FI might disproportionately affect BME service users in general, as they are known to have inferior access to psychological therapies. 15 African-Caribbean service users are likely to have even poorer access to FI owing to high levels of family disruption.

In community consultation to develop this study, African-Caribbean people expressed dissatisfaction with the lack of access to psychological therapy and expressed a strong desire for culturally appropriate ‘talking treatments’. They also wanted to develop better understanding of schizophrenia and improve relationships within families, between African-Caribbean communities and with mental health services.

However, lack of research into the feasibility of delivering psychological therapies in general, and FI in particular, to African-Caribbean people means that it is unclear if the benefits of FI are generalisable to members of this ethnic group. 26 Furthermore, it is unclear if a standard approach to the content and delivery of FI would be acceptable to service users and families whose relationship with mental health services and health-care professionals is characterised by a lack of trust.

In response to concerns and dissatisfaction within African-Caribbean communities, and in response to NICE guidelines,11 we undertook to culturally adapt an evidence-based, cognitive–behavioural model of FI, which was developed by co-applicants Barrowclough and Tarrier. 34 This model was selected because previous work by the principal investigator (PI)35,36 and others37,38 has suggested that African-Caribbean people’s models of mental illness and related attributions require cognitive–behavioural interventions such as FI to be culturally adapted for this group. Additionally, the evidence-based model was developed and is the model of choice in Manchester Mental Health and Social Care NHS Trust (MHSCT), where the study was conducted.

Overview of study

This mixed-methods study was designed to culturally adapt an existing model of FI to make it more specific to the needs of African-Caribbean service users diagnosed with schizophrenia and their families. Our study aimed to address four research questions.

Research questions

-

How can existing evidence-based FI be culturally adapted for African-Caribbean people with schizophrenia and related disorders?

-

Is it feasible for culturally adapted FI to be delivered in hospital and community settings?

-

Can ‘proxy families’ serve as acceptable alternatives where families are unavailable?

-

Will culturally adapted FI be acceptable to service users, families and health professionals?

Aims and objectives

Study aims

-

Assess the feasibility of culturally adapting, implementing and evaluating an innovative approach to FI among African-Caribbean service users with schizophrenia and their families across a range of clinical settings.

-

Test the feasibility and acceptability of delivering Culturally adapted Family Intervention (CaFI) via ‘proxy families’ where families are not available.

Study objectives

-

Involve key stakeholders (service users, families and clinicians) in culturally adapting an existing FI for African-Caribbean people diagnosed with schizophrenia.

-

Produce a manual to support the delivery of the intervention.

-

Identify client- and family-centred outcomes and quality-of-life outcomes.

-

Identify and address the training needs of therapists and ‘proxy families’.

-

Test the feasibility of delivering culturally adapted FI among African-Caribbean people in hospital and community settings.

-

Test the feasibility of recruiting and ‘proxy families’ and delivering the intervention via both.

-

Test the feasibility of recruiting participants in hospital and community settings.

-

Compare recruitment and retention in different clinical settings.

-

Identify outcome measures for future randomised studies and assess the feasibility of collecting them.

-

Assess the acceptability of the intervention to key stakeholders: service users, their families and mental health professionals.

Overview of design and methods

Following the Medical Research Council’s framework for developing complex interventions,39 we used a mixed-methods approach to design and test the feasibility of delivering CaFI for African-Caribbean service users and their families. The study was conducted in three distinct but related phases.

Phase 1: culturally adapting the intervention

The purpose of this phase of the study was to identify the elements of the existing FI model to be culturally adapted, determine how such modifications would be achieved, identify and agree on suitable outcome measures and identify training needs associated with delivery of the intervention. This aspect of the study was conducted in the following three subphases.

Phase 1A: literature review

An initial literature search, undertaken while developing the study, revealed that there was an insufficient number of studies to allow us to conduct a systematic review on culturally adapted psychosocial interventions specifically for African-Caribbean people diagnosed with schizophrenia. We undertook a scoping review40,41 of theoretical and intervention papers, using broad search terms and searching reference lists of key papers, to determine issues of importance in relation to culturally adapting psychosocial interventions. As we found only one trial relating to cultural adaptation and African-Caribbean people, we widened our scope to include other ethnic and cultural groups. Consequently, we undertook a systematic literature review of culturally adapted psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia to provide a cultural adaptation framework to inform our theoretical model of adaptation (see Chapter 2). Our framework was then used to inform the process of culturally adapting the intervention in collaboration with key stakeholders (phases 1B and 1C).

Phase 1B: focus groups

Guided by phase 1A findings, we designed topic guides/interview schedules to enable us to collect qualitative data from key stakeholder groups. First, we conducted three focus groups comprising (i) current and/or former service users, (ii) families, carers and advocates and (iii) health professionals. A fourth, ‘mixed’, focus group, drawn from these three groups, enabled us to resolve any differences between groups and to validate findings from the first three stakeholder focus groups.

Service users were all of African-Caribbean descent, including those who self-identified as ‘Black British’ or of ‘mixed’ heritage but had at least one parent or grandparent of African ancestry who originated from the Caribbean. Other participants came from a range of ethnic backgrounds, including South Asian and White British. The sample was also diverse in terms of age, gender and professional background, thereby providing a range of perspectives on how best to culturally adapt Barrowclough and Tarrier’s model of FI34 and the training that might be needed to enable family therapists to deliver the intervention. Focus groups also explored the feasibility of using ‘proxy families’, individuals who would work with service users who did not have access to families to enable them to participate in CaFI. The training needs of therapists and Family Support Members (FSMs) (‘proxy families’ was used in our original proposal to describe people who would support service users to receive the intervention in the absence of families; this was changed to FSMs during phase 1B of the study) were also discussed. The data were analysed using framework analysis,42 enabling the exploration of both a priori topics and emergent themes in relation to our research questions: specifically, content, outcomes and delivery of the intervention.

Phase 1C: consensus conference

Subsequent to the focus groups, we held a consensus conference43 of ‘experts’ by experience (service users and carers) and by profession (health-care professionals, academics, advocates) and other key stakeholders such as the police. The purpose of the consensus conference was to synthesise findings from the literature review (phase 1A) and focus groups (phase 1B) to agree the content of the culturally adapted FI and the manual to support its delivery. Participants in the consensus conference (experts by experience/profession and other key stakeholders) also agreed on outcome measures and the training needs of the therapists and FSMs.

Phase 2: training

The purpose of the training phase was to recruit and train therapists and FSMs to undertake their role in CaFI, ensuring that we addressed the training needs identified during phase 1 of the study. Underpinned by outcomes from phase 1, we worked with our service users and carers and Just Psychology,44 a Manchester-based social enterprise that specialises in cultural diversity, to develop bespoke cultural competency training for CaFI therapists, co-therapists and FSMs. We also employed Meriden Family Programme45 to deliver bespoke training on culturally specific family work for the therapists. In line with NICE recommendations, to deliver cultural competence training at both organisational and individual levels, we planned to deliver competency sessions in a range of clinical settings, reflecting areas of recruitment into our study. However, organisational issues meant that this was not possible. Instead, we delivered a trust-wide clinical seminar for all staff and delivered presentations to promote the study and cultural awareness among clinical leads, health-care professionals, and service user and carer groups in the NHS and in third-sector organisations.

Phase 3: feasibility study

Phase 3A: delivering and evaluating the intervention

The third and final phase involved testing the feasibility and acceptability of delivering CaFI in hospital and community settings across the then largest mental health trust in Manchester: Manchester Mental Health and Social Care NHS Trust (MHSCT) [this trust has since merged with Greater Manchester and is now called Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust (GMMH)]. We elected to test CaFI in a range of settings to determine whether or not the intervention could be delivered in different clinical contexts and at varying levels of illness acuity and chronicity. Data on uptake, attrition and engagement (including number of completed sessions and reasons for non-completion) were the primary means of assessing feasibility. The key objectives of this phase of the study were to:

-

test the feasibility of delivering CaFI to African-Caribbean service users and their families

-

test the feasibility of recruiting families and FSMs and of delivering the intervention via both

-

test the feasibility of recruiting participants in hospital and community settings

-

compare recruitment and retention in different clinical settings

-

identify suitable primary and secondary outcome measures and the feasibility of collecting them –

-

estimate the parameters for designing future RCTs, including:

-

recruitment, retention, attrition and follow-up response rates

-

characteristics of outcome measures and estimating the standard deviation (SD) and intracluster correlation to enable future sample size calculation

-

-

-

assess the acceptability of the intervention with key stakeholders – service users, their families, FSMs and mental health professionals using in-depth qualitative interviews (see Chapter 7).

Phase 3B: fidelity study

Adherence to the therapy manual and delivery of the intervention was tested by an independent review of 10% of randomly selected CaFI sessions. The first subscale of the fidelity measure comprised a modified version of the Cognitive Therapy Scale for Psychosis. 46 We included a second subscale to provide a descriptive account of the manual components covered in the selected sessions, which included two items from the Family Interventions in Psychosis-Adherence Scale (FIPAS). 47 The third and final subscale was developed to rate the degree of cultural awareness or competencies of the therapists. This subscale was based on the manual and existing cultural competency questionnaires and literature. To help to ensure treatment fidelity and maintain the quality of therapy, digital recordings of sessions were discussed in clinical supervision. The clinical supervisor also rated a therapy session for each therapy pair every 6 months using the fidelity scale and gave detailed feedback.

Service user, carer and community involvement

We have chosen to entitle this section ‘service user, carer and community involvement’ rather than use the most commonly used term, ‘service user and public involvement’, based on the preferences of carers/relatives, community members and service users who constitute our Research Advisory Group (RAG).

What does involvement in CaFI mean?

Having the active involvement of service users, carers/relatives and members of the public was to improve the quality, governance, feasibility and practicality of our research by:

-

including the perspective of African-Caribbean people in the development, management and oversight of the project

-

ensuring that cultural competency training included service user, carer and community member perspectives

-

ensuring that recruitment and consent processes were appropriate for service users and families (family members and ‘FSMs’)

-

ensuring that our communication with the families and ‘FSMs’ was accessible and acceptable

-

discussing and agreeing suitable forms of dissemination with service users and families, drawing on their knowledge and expertise to identify and access suitable outlets.

CaFI Research Advisory Group

The purpose of CaFI’s RAG was to maximise the involvement of service users, carers, families and members of the community in our research. Our RAG panel consists of eight people of African-Caribbean background (six women and two men) who are passionate about making a difference to the lives of African-Caribbean people living with mental health problems in their local community and across the UK.

Research Advisory Group meetings were held (two or three times per year; eight meetings in total) during the 3 years and were chaired by a co-applicant, Paul Grey, who has lived experience and expert knowledge in the area. As a former Delivering Race Equality in Mental Health Care Ambassador, Paul has a wealth of experience delivering seminars and conferences and advising policy-makers and service providers on the mental health of BME communities and their experience of services. He also has > 20 years’ experience of using mental health services.

The RAG advised and supported the team in developing research materials [such as the participant information sheet (PIS) and adverts], as well as advising on appropriate recruitment and dissemination strategies. The RAG also helped to refine the therapy manual, in particular the ‘ethos of delivery’, and co-produced and delivered the training programmes during phase 2. They also participated in the dissemination of our work through conference presentations.

Community launch events

To generate awareness and engage the local community, we hosted two community-level launch events in areas of high population density of African-Caribbean people, both within the MHSCT footprint in South Manchester [Levenshulme Inspire Community Centre (25 October 2013) and Moss Side Leisure Centre (30 October 2013)]. During the events, the PI and research project manager (RPM) delivered presentations to:

-

outline the study’s rationale, aims and objectives

-

highlight opportunities to get involved, including becoming RAG members and FSMs

-

gauge the level of interest and willingness among eligible individuals; we provided food and drink as we know this to be important for socialising and building relationships in African-Caribbean cultures. 48

Altogether, the events were attended by around 100 people, including community members, service representatives, service users, carers, family members, and health and social care professionals. Anecdotal feedback from attendees was extremely positive and many were keen to get involved and support the research, as participants, advisors or collaborators. The majority of attendees left their details so that they could be contacted for further information. Following the event, the RPM was invited to present the CaFI study at third-sector organisations and to host a stall at the African & Caribbean Mental Health Services (ACMHS) Mental Health and Well-being Day (18 October 2013), to further promote the study. The event provided a platform for us to strengthen collaborations with Black-majority churches, community groups and agencies, including the ACMHS, Just Psychology,44 Manchester BME Network,49 Black Health Agency,50 Manchester Carers Forum,51 ReThink: Manchester Carers in Action,52 Self-Help Services,53 Service User Voices54 and Bluesci. 55

Ethics approval

The CaFI study was approved by North West Greater Manchester East National Research Ethics Service Ethics Committee (13/NW/0571).

Report outline

The remaining chapters detail the cultural adaptation process and feasibility testing of an evidence-based FI to ensure its cultural specificity for African-Caribbean service users and their families.

Chapter 2 reports on our systematic review of the current literature on cultural adaptation of psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia and psychosis, identifying key components of our culturally adapted framework.

Chapters 3 and 4 detail the process of co-production by which the extant model of FI was culturally adapted in collaboration with African-Caribbean service users, families and community members, alongside health-care professionals, using focus group and consensus methodologies.

Chapter 5 describes the development and delivery of training for family therapists, co-therapists and FSMs (‘proxy families’) based on the recommendations of key stakeholders in the first phase of the study (see Chapters 3 and 4) and the available literature (see Chapter 2).

Chapter 6 reports the feasibility trial to test our CaFI across a range of clinical and community settings, involving service users with different severity of illness and levels of acuity/chronicity. A novel aspect of the trial involved testing the feasibility of delivering the intervention via FSMs in the anticipated absence of families owing to high levels of family disruption. In this chapter, we also report findings from our embedded fidelity study.

Chapter 7 reports on the acceptability of the intervention from the perspectives of service users, their families, FSMs, therapists and key workers of service users who participated in CaFI.

Chapter 8 presents a discussion of our findings in relation to the available evidence and the original study aims and objectives. While highlighting strengths and limitations of our study, we also suggest implications for policy, practice and future research. We conclude by making recommendations on the basis of our findings.

Chapter 2 Review of the literature

Introduction

Phase 1A consisted of a structured background review of current literature on culturally adapted psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia and psychosis. We initially conducted a broad scoping review40 of existing literature to establish key issues and gaps in knowledge relating to the cultural adaptation of psychological interventions. This provided a useful ‘map’ of the breath of research in relation to the size and scope of existing primary and secondary studies where evidence is limited. 56

Our initial search, using broad search terms (i.e. terms relating to African-Caribbean and culturally adapted intervention and schizophrenia), yielded one trial adapting cognitive–behavioural therapy (CBT) for African-Caribbean culture, but adaptations were reported across multiple minority ethnic groups and were not specific to this group. 57,58 We found no studies of adapted FI for African-Caribbean people in the UK.

Despite the limited work in the African-Caribbean population, there are an increasing number of studies reporting on psychosocial interventions adapted for other ethnic and cultural groups. A systematic review of the existing research in this area was therefore carried out to inform our theoretical model of adaptation and provide a framework of the nature of adaptations to guide research and practice. A thematic analysis59 was undertaken to provide a narrative summary of the key issues that informed the qualitative components of this phase of the study.

Aims and objectives

Phase 1 research question

How can existing evidence-based FI be culturally adapted for African-Caribbean people with schizophrenia and related disorders?

Background

There have been a number of systematic reviews on cultural adaptations of mental health interventions. 60–65 Across these studies, meta-analytic effect sizes have been mostly moderate (range 0.41–0.72) in favour of culturally adapted interventions, which is comparable with those reported in reviews of non-adapted interventions in ‘Western populations’. 66 For example, Griner and Smith62 conducted a meta-analysis of 76 studies and found a moderate effect size (d = 0.45) for culturally adapted treatments targeting various mental health problems. However, the majority of systematic reviews have been heterogeneous, including mixed diagnostic and ethnic samples. Moreover, the reviews tend to focus on outcomes and few make efforts to systematically analyse the nature of cultural adaptations to provide a framework or model of adaptation that is grounded in empirical evidence.

Chowdhary et al. 61 examined both the nature and the effectiveness of adapted psychological treatments for depression. They reported a large effect size (standard mean difference –0.72) for depressive symptoms based on findings from 16 out of 20 reviewed RCTs. Chowdhary et al. 61 systematically identified the nature of treatment adaptations for depression through the application of Bernal and Sáez-Santiago’s67 framework, which has eight components:

-

language

-

therapist matching

-

cultural symbols or metaphors

-

cultural knowledge or content

-

treatment conceptualisation

-

treatment goals

-

treatment methods

-

treatment context.

Using this framework, common adaptations across the reviewed studies were mostly within the language, therapist and context dimensions. However, Chowdhary et al. 61 highlighted the small number of included studies, incompleteness of data and significant heterogeneity relating to diverse contexts and designs, which prevented comparisons of different types of interventions or adaptations. Additionally, they did not comment on the usefulness of Bernal and Sáez-Santiago’s67 framework in terms of its applicability to either their study sample or to other mental health conditions.

Bhui et al. 68 reviewed a wide range of interventions designed to improve therapeutic communications between BME service users and clinicians in psychiatric services. This included 21 articles of multiple intervention types, of which culturally adapted psychotherapies, ethnographic and motivational assessment were found to be effective and preferred by patients and carers. Meta-analytic effect sizes showed benefits for a range of different outcomes, including symptoms and medication adherence (high-quality trials; d = 0.18–0.75). Thematic analyses identified common components of the interventions across the reviewed studies, which were classified using Tseng’s framework69 and categorised into three broad subthemes:

-

patient, including understanding causal explanations and belief systems, pre-therapy preparation, and improving accessibility and training

-

patient and professional, including ethnic matching

-

adaptation of therapy, including changes to structure and content, technical delivery/structure of therapy, working with social systems, and facilitating empowerment and engagement.

Their inclusion criteria were broad in scope and included various study designs, service users diagnoses and interventions that targeted several ethnic groups. Bhui et al. ’s68 review found no differences in symptomatic or service user-reported outcomes for adapted interventions generalised across mixed ethnic samples58 when compared with homogenous ethnic samples,70 but as this was based on findings from two studies no firm conclusions can be inferred about the need for ethnic specificity in adapting interventions. Bhui et al. 68 called for more clinical trials in the UK and the USA, economic evaluations and tests of the effectiveness of specific intervention components.

Evidence-based psychosocial interventions for schizophrenia spectrum diagnoses originally developed in Europe or the USA are important elements of therapy that require adaptation for both minority ethnic groups in Western countries and majority ethnic groups in non-Western countries. Despite the increasing number of trials on culturally adapted interventions in schizophrenia,71 there have been no attempts to summarise this work, and the developing literature in schizophrenia71 has not yet been reviewed systematically. Doing so may enable us to identify common processes within adaptation that could guide future research on adapted psychosocial interventions. A number of frameworks have been developed to provide guidance on cultural adaptations to treatments,67,69,72,73 but none of these approaches focuses on psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia and their application across different ethnic and cultural groups in this area is questionable.

This study aims to:

-

analyse the nature of cultural adaptations of psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia

-

develop a framework to guide the adaptation of evidence-based interventions for different ethnic and cultural contexts.

Method

The systematic review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. 74

Search strategy

On 3 March 2016, the RPM conducted an electronic database search of Ovid MEDLINE, EMBASE, PsycINFO and Web of Science. Databases were searched from inception and no date or language restrictions were specified (see Appendix 1 for the full search strategy and search terms). The titles and abstracts were downloaded into EndNote X8 Management software (version 8; Clarivate Analytics, Philadelphia, PA, USA) and duplicates were removed. The RPM (AD) and research assistant (RA) (SB) independently screened the articles for eligibility using the following inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

-

Studies of any controlled trial design evaluating an adapted evidence-based psychosocial intervention for a specific subculture or ethnic group.

-

Studies reporting on interventions adapted for a minority ethnic population in a Western country or any non-Western population.

-

Studies in which 100% of participants were adults (aged ≥ 18 years) and had a diagnosis of schizophrenia or a related diagnosis [Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, Fourth Edition (DSM-IV) schizophrenia or International Classification of Diseases, Tenth Edition (ICD-10) F20–29: schizophreniform disorder, schizoaffective disorder, delusional disorder or psychosis not otherwise specified].

-

Peer-reviewed articles available in English.

Exclusion criteria

-

Studies in which adaptations were not made for a specific subculture or ethnic group but were generalised across multiple groups (and no findings were available by group, despite contacting the authors).

-

Studies evaluating interventions without specific adaptations for culture, including no change (i.e. assessing the same intervention in a different subculture or ethnic group), direct translation to the language of the population of interest, or adapting for some other characteristic such as age or location (e.g. rural vs. urban needs).

-

Studies testing a novel intervention developed specifically for a particular subculture or ethnic group without an adaptation of an existing evidence-based intervention.

-

Interventions that were neither evidence-based nor psychosocial (e.g. service provision such as assertive community treatment).

-

Non-evaluative unpublished studies (e.g. literature reviews, conference papers, qualitative studies and case studies).

Selection of studies

Full-text papers of potentially relevant articles were accessed and screened by the RPM (AD) and RA (SB). Authors were contacted with requests for English versions of non-English citations and citations that could not be accessed. Interlibrary loans were also sought for inaccessible papers. Reference lists of full-text articles and systematic literature reviews were screened to identify any additional papers not picked up in the search. Key experts were contacted and received the full reference lists to identify any missing studies. All uncertainties or disagreements relating to the eligibility of articles were resolved via discussion with a co-applicant and senior researcher (RD).

Data extraction

Descriptive characteristics of eligible studies were recorded in a data extraction spreadsheet. To address the research question regarding the nature of cultural adaptations, all adaptations to interventions described in the papers were summarised in a second spreadsheet. When there was limited information, corresponding authors were contacted and adaptations were extracted from any additional literature or notes provided by the authors.

Data synthesis

A thematic analysis59 was used to evaluate the nature of cultural adaptations across the reviewed studies. A number of frameworks have been developed to provide guidance on cultural adaptations to treatments67,69,72,73,75 and two of these have been applied to data in recent reviews. 61,68 The thematic analysis was applied inductively to the extracted data to generate themes and subthemes of adaptations emerging from their current application in the field, rather than to deductively apply an existing model to the data.

Results

Included studies

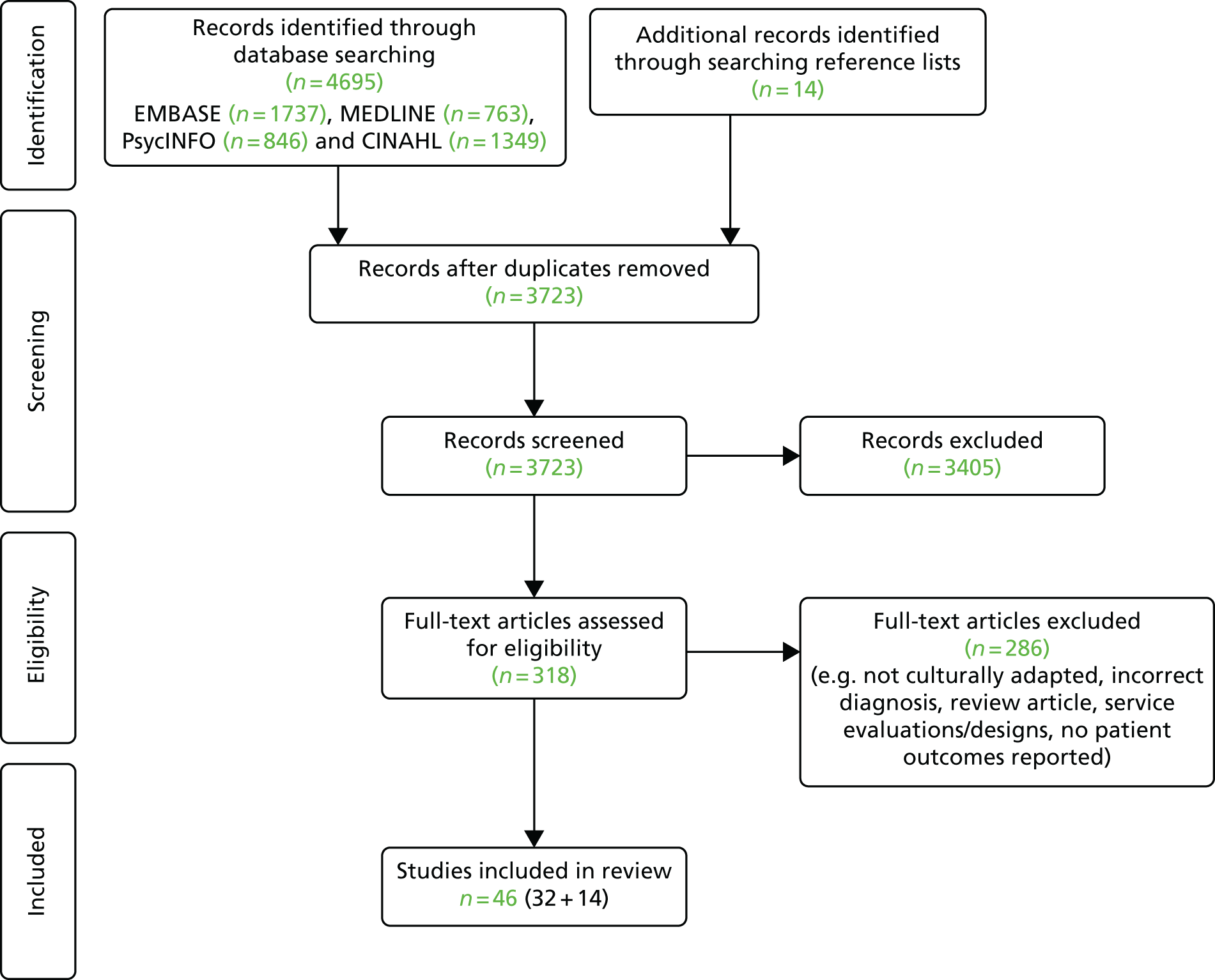

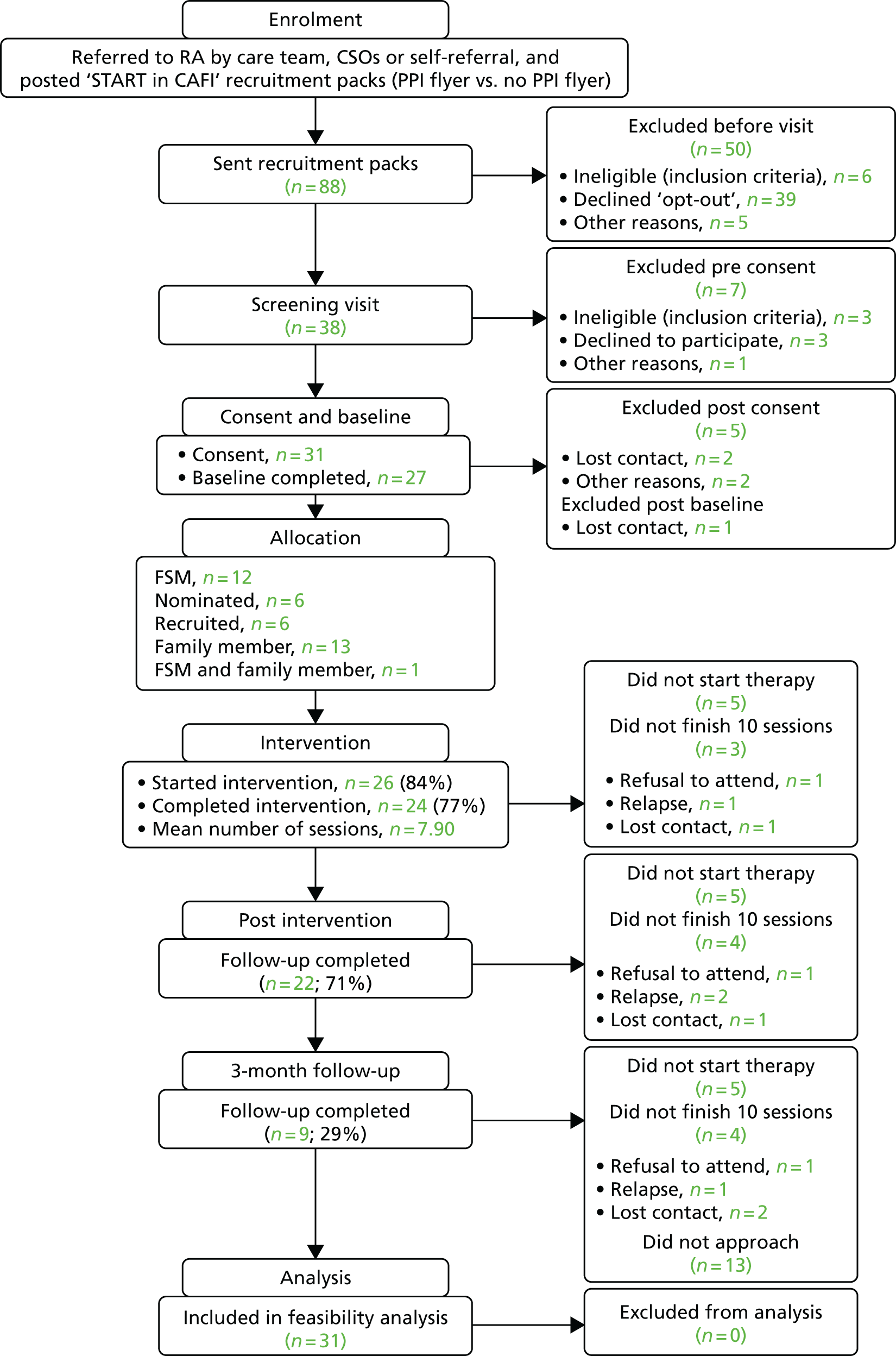

The database search returned 4695 results, providing 3723 unique citations after duplicates were removed. Titles and abstracts were screened and a further 3405 articles were excluded. Full texts of the remaining 318 articles identified as potentially relevant were accessed and examined against the eligibility criteria. Of these, 32 were included in the review. An additional 14 articles were identified for inclusion through e-mailing authors and searching reference lists of the full-text papers. The study selection process is presented in the PRISMA flow diagram shown in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

The PRISMA flow diagram. CINAHL, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature.

Study characteristics

In total, 46 papers reporting 43 individual trials with 7828 participants were included. The characteristics of the reviewed studies are detailed in Appendix 2. Studies comprised 31 RCTs, 12 cluster RCTs, two non-randomised pilot studies and one block RCT. The mean age of service users ranged between 24 and 57 years and, among the studies that reported gender (n = 38), 42% were female. Sample sizes varied across the studies, ranging from six76 to 3082,77 with a mean of 182. All studies included samples of service users who had a diagnosis of schizophrenia spectrum disorder, usually defined using DSM-IV and ICD-10 screening criteria.

Three RCT papers included participants who had been reported in an earlier paper: one paper78 reported 24-month follow-up data of a subsample of an earlier RCT;77 one study79 used the same sample as an earlier paper;80 and one three-armed RCT81 included a subsample of participants reported in an earlier two-armed RCT. 82 Of the 39 studies reporting attrition, the range was from zero83–85 to 43.4%. 86 Attrition was < 15% in 25 studies83–85,87–108 and > 40% in three studies. 86,109,110 Attrition was not reported in seven studies. 71,76,87,111–114

Intervention characteristics

The characteristics of the culturally adapted psychosocial interventions assessed in the reviewed studies are described in Appendix 3. Interventions were delivered in 13 countries. The majority (74%, n = 34) were conducted in Asia (25 in China,77–80,83,84,87,89,94,96–98,100–102,104–110,113–115 two in each of Pakistan,71,92 Taiwan, Province of China,88,116 and India86,112 and one in each of Iran,91 Saudi Arabia76 and Malaysia93). Nine studies (20%) were conducted in the Americas (six in the USA,81,82,85,99,117,118 two in Mexico119,120 and one in Brazil95), and one study (2%) was conducted in each of Italy,90 Australia1 and Egypt. 111 Most interventions (85%, n = 39) were adapted for a majority non-Western population and seven studies (15%) were adapted for a minority population.

Around half of the studies (54%, n = 25) were FIs consisting of a psychoeducational or mutual support component. FIs varied across the studies in terms of their components and the evidence-based models from which they were adapted (see Appendix 3). The majority (88%, n = 2277–80,83–87,89–91,94,98,100,101,104,105,114,115,117,118) involved group family therapy sessions; only three FIs93,96,97 consisted of just individual sessions. In 12 of the FIs studies (48%),80,83,84,87,89,94,98,101,104,105,115,117 all of the sessions were designed for the family members and service users to attend together. In five studies, service users attended at least part of the intervention (25–86% of the sessions) and in the remaining eight studies77–79,85,86,90,91,114 only family members were invited. Ten (22%) studies evaluated some form of cognitive therapy, consisting of three social cognitive skills training,81,82,102 one social cognitive remediation therapy,111 three CBTs,71,92,107 two metacognitive training110,112 and one integrated psychological therapy (IPT). 95 Family members attended two71,121 of the CBT interventions; the remaining eight81,82,95,102,110–112,122 cognitive interventions were for service users only. Three studies73,109,113 were combined interventions comprising components adapted from multiple Western therapy manuals and theoretical frameworks; two of these were symptom-coping programmes and one included family therapy sessions. Five studies99,106,108,119,120 assessed social skills training (SST). Family members attended four of the SST interventions. Of the remaining interventions, two were illness management and recovery (IMR) programmes88,116 and one was a mindfulness-based psychoeducation programme,103 both of which were for service users only.

The majority of interventions (59%, n = 2771,79,80,82–86,88,91,92,94,96–98,101,103–105,107–109,111–113,116,119) were delivered in clinical settings. Six interventions81,90,99,106,114,117 were delivered in community settings and four87,89,93,115 delivered sessions in both clinical and community settings. Nine studies did not report intervention setting. 76–78,95,102,106,110,118,120 The duration of interventions ranged from 3 weeks88 to 2 years,77,78,89,90 with a mean of 8 months. The majority of the interventions were led by mental health professionals (80%, n = 37); five of these (all assessing group FIs) were co-facilitated by a family member participating in the study. Five studies did not specify therapist training (see Appendix 3).

Cultural adaptations of interventions

Culturally adapted themes

Details of extracted themes of cultural adaptation with examples from the reviewed studies are described in Appendix 4. To summarise, nine overarching themes were generated inductively from the reviewed interventions: language; concepts; family; communication; content; cultural norms and practices; context and delivery; therapeutic alliance; and treatment goals. Appendix 5 presents the frequency of each theme against each of the reviewed studies.

Language

Adaptations for language were reported in all studies (n = 46). These took the form of translating the original intervention into the national or local language91,112,114,115 and included local colloquialisms and idioms to improve cultural relevance and acceptability. 71,92,111 For example, So et al. 110 replaced the word ‘Stalinism’ with ‘Communism’ and incorporated colloquial Cantonese words to make the metacognitive training programme better suited to Chinese culture. Additionally, specific terminology was exchanged for more culturally appropriate words (e.g. replacing ‘module’ with ‘treatment areas’),119 and efforts were made to remove jargon and formal terms. 92

Concepts

The majority of interventions (78%, n = 36) were adapted to incorporate culturally appropriate presentations of concepts, with consideration of culture-specific belief systems, enhanced mental health stigma and low levels of education. This included working with alternative explanatory models to the ‘biopsychosocial’ model commonly held in Western countries, including the attribution of mental illness to spiritual or supernatural agents,93,117 predestination and fate91 and an imbalance of yin and yang forces during adolescence. 83 Some studies reported the inclusion of spiritual factors in formulations and discussion of locally held beliefs in psychoeducation sessions. 71,92 Mental health stigma was addressed by sharing personal stories and recovery narratives for normalisation and by holding group forums for participants to discuss their concerns. 80,88,94,109 Owing to a lack of mental health knowledge and low education levels in certain cultural contexts, adaptations were made to alter the complexity and amount of psychoeducation or therapy material provided to make it more manageable for service users and families. 82,85,95

Family

Most interventions (76%, n = 35) were adapted to acknowledge the pivotal role of the family in service users’ care and recovery, as well as culturally distinct family structures and processes. Adaptations included efforts to engage the family and encourage their active and continued involvement throughout the intervention71,90 (e.g. by offering additional sessions or informal home visits for family members and maintaining contact after treatment). 85,89,115,118 Modifications were made to accommodate more interdependent family structures and those that valued familial responsibility and collectivism over individualism. 94,96 These took the form of involving family members in decision-making and assessing the needs of the family as a whole (e.g. placing focus on medication adherence as an action that would benefit the family unit rather than the individual). 81,82,117 Further considerations included being sensitive to culture-specific family roles and expectations, such as in hierarchical families where younger generations are expected not to question their elders. 80,91,119

Communication

Twenty-two (48%) studies71,79–82,84,85,92–94,96–99,101,103,104,107,117–120 reported adaptations to integrate culturally specific ways of communicating and learning in the sessions. This included the use of culturally appropriate methods for dealing with conflict and problem-solving. For example, acknowledging that Chinese people do not tend to openly talk about their concerns and prefer to manage problems through reparative action and touch,80,84,94,97,98 and balancing the concepts of assertiveness and expression of one’s needs in the West with mutual respect and avoidance of confrontation in more family dominant cultures. 71,82,85 Further cultural considerations were made in relation to the disclosure of private information, such as the irrelevance of confidentiality due to the close nature of families,119,120 and reluctance to openly discuss family matters. 98 Additionally, culturally appropriate teaching methods were used in the sessions, for example encouraging collaboration and active participation in more passive cultures,82,99 or facilitating practical rehearsals or using visual aids rather than talking. 97,118

Content

Around half of the interventions (43%, n = 20) were modified by the adding or removing of content. Specific content was removed from original intervention manuals93,95,110,111,119 because it was culturally irrelevant. For example, So et al. 110 removed the Western conspiracy theory about Paul McCartney’s death from their module ‘jumping to conclusions’ in their Chinese metacognitive therapy for delusions (MCTd). Content was also removed due to limited access to appropriate technology or materials; for example, Valencia et al. 119 omitted video-assisted modelling used in the original American SST123 owing to limitations with the Mexican version, and Gohar et al. 111 omitted Arabic video materials from the ‘mentalizing component’ of cognitive remediation. Additional components were also added to intervention manuals to make them more culturally relevant. 93

Cultural norms

Adaptations were made to incorporate culture-specific norms and practices in 31 (67%) studies. 71,76,79–82,84–86,90–94,97–99,101,103–105,107–109,111,113–115,117,119,120 Interventions were modified to accommodate spiritual or religious practices and means of coping, such as the use of traditional healers, religious texts and prayer. 71,76,115 Culturally relevant activities (e.g. karaoke, t’ai chi and mah-jong,113 and Baduanjin relaxation exercises)85 and scenarios were also integrated into interventions (e.g. the use of traditional folk stories and religious characters in role plays, recordings and videos). 71,76,106 Recognising the social structures of certain cultures, additional efforts were made to build social networks and mutual support through group meetings, workshops/seminars and social gatherings outside therapy. 85,100,114 Studies also reported the use of peer leaders to deliver sessions alongside mental health professionals to facilitate community support and shared experiences. 97

Context

Almost half of the studies (48%, n = 2271,77,78,83,85,86,88–92,96,97,100,108,109,111,114–116,119,120) reported adaptations to facilitate feasibility in a particular cultural context by addressing specific cultural norms or organisational barriers due to lack of commitment, funding or resources. 85,88,96 Adaptations included delivering interventions at accessible locations where there were sufficient resources,90,96 offering flexibility in scheduling sessions71,109 and changing the duration of treatment. 85,88 Furthermore, the format of delivery was selected based on cultural appropriateness, including whether to see service users and family together or separately85,86,90 and the use of group versus individual interventions. 80,101

Therapeutic alliance

Adaptations to improve therapeutic alliance were present in 28% (n = 1381,82,85,86,91,93,99,102,115,117,119,120,124) of the studies. These included matching therapists and clients for ethnicity and other characteristics such as age, gender or language to enhance acceptability and shared cultural experiences. 91,115 A few studies reported on the training or supervision of therapists to improve their cultural competency. 99,117 Other studies reported on modifications to build rapport, trust and engagement, for example therapists adopting an informal approach by engaging in small talk and warm-up activities before the intervention99,102,119 and presenting appropriate forms of self-disclosure from their own lives to facilitate a more personalised therapeutic relationship. 119

Treatment goals

Treatment goals were modified in 13 studies79–82,84,86,94,98,101,104,117,119,120 (28%) to develop formulations that were realistic and congruent with cultural values. In some studies, this involved developing shared goals to meet the needs of the family unit and managing expectations of different family members, for example the tendency to expect immediate and practical help from close relatives in Chinese cultures. 79,80

Culturally adapted framework

To develop our evidence-based cultural adaptation framework (Box 1), these nine components were further refined by discussion within the team to increase their cultural specificity for African-Caribbean people. Our six-item framework is modelled on the Department of Health and Social Care’s ‘Six Cs for Caring’125 to increase accessibility to health-care professionals.

-

Concepts.

-

Cultural norms and practices.

-

Culturally relevant content.

-

Communication and language.

-

Context.

-

Cultural competence of practitioners.

Discussion

We conducted the first review of current evidence on the nature of culturally adapted psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia. We were interested in interventions originally developed in the West (Europe or the USA) and adapted for minority ethnic groups in Western countries and majority ethnic groups in non-Western countries. Our systematic search identified 46 articles comprising 43 individual controlled trials with 7828 participants.

Our framework highlights agreement regarding what constitutes adaptation for culture. All studies reported adaptations to language, which included direct translation and/or modifications to incorporate local colloquialisms and acceptable terminology. The majority of studies made adaptations in the domains of concepts, family, and cultural norms and practices. This included the consideration of culturally distinct belief systems, causal models of illness and methods of coping (e.g. spiritual/religious), incorporation of culturally specific activities and stories, involving the family in treatment and decision-making, and acknowledging culturally distinct familial structures such as those that are interdependent and hierarchical. Other common adaptations were to recognise different forms of communication and tackling problems, such as the use of practical aids rather than open discussion, removal of culturally irrelevant content (e.g. local celebrities, technology), and changing the delivery (e.g. location) to recognise contextual barriers. Common adaptations were also made to improve engagement and therapeutic alliance, including ethnic matching of therapists to clients, training therapists in cultural competency, integrating ‘warm-up’ (social) activities and small talk, and developing shared treatment goals. As previously reported in relation to adapted treatments for depression,61 authors did not report changes to the core components of the interventions but rather to their delivery to improve acceptability and feasibility in a specific cultural context, thus adhering to their underlying theoretical models.

Although these studies provide evidence of what to culturally adapt, there remains limited guidance on how to do so. Thematic analyses of cultural adaptations reported in each of the reviewed studies produced a framework comprising six essential components of cultural adaptation that may serve as a benchmark for future adaptations (see Box 1). In Chapters 3 and 4, we provide details of how we applied our framework to produce CaFI.

Conclusion

We have updated the field by empirically deriving a framework from existing trials of adapted treatments in schizophrenia. We used this framework as a guide to culturally adapt FI for African-Caribbean people. Our framework requires further refinement and testing. However, it provides the basis for a useful evidence-based tool to guide clinicians and researchers in the development and reporting of adapted psychosocial interventions in schizophrenia.

Chapter 3 What does cultural adaptation look like and how is it applied?

Introduction

Using findings from the current literature (phase 1A), we developed a cultural adaptation framework and applied it systematically to an extant FI model in collaboration with key stakeholder groups.

Historically adversarial relationships between NHS mental health services, African-Caribbean service users and their families,10,14,23,122 meant that co-producing CaFI with key stakeholders was essential for its credibility both among the African-Caribbean community and health-care professionals.

Co-producing CaFI involved three separate but inter-related phases:

Aims and objectives

How can existing evidence-based FI be culturally adapted for African-Caribbean people with schizophrenia and related disorders?

Phase 1 study objectives

-

Involve key stakeholders (service users, families and clinicians) in culturally adapting an existing FI for African-Caribbean people with schizophrenia (phases 1B and 1C).

-

Produce a manual to support delivery of the intervention (phase 1C).

-

Identify client and family centred outcomes and quality-of-life outcomes (phases 1B and 1C).

-

Identify therapist and FSM training needs (phases 1B and 1C).

Phase 1A: literature review findings

The Chapter 2 literature review generated components of culturally adapted psychosocial interventions. These became the framework for culturally adapting FI (see Box 1).

Working with members of our RAG of eight African-Caribbean service users and carers, we utilised these criteria to pinpoint and develop supporting materials for the cultural adaptation focus groups. For example, the importance of communication and language – going beyond mere translation, involves actively excluding culturally offensive language and incorporating concepts and phrases familiar to members of the ‘in group’. In CaFI, this includes words like ‘obeah’ (a term used in the Caribbean, particularly in Jamaica, denoting folk magic sorcery and witchcraft, and akin to ‘evil eye’; it embodies practices by which supernatural powers are invoked to achieve personal protection and/or the destruction of enemies) and reference to ‘the system’ [shorthand for powerful institutions (such as mental health care and the police) that many African-Caribbean people associate with oppression and institutional racism]. We also sought to address stereotypes and misconceptions such as highlighting the heterogeneity of the Caribbean islands.

Phase 1B: focus groups

The purpose of the focus groups was to ascertain participants’ perspectives on:

-

the perceived need for FI in this ethnic group

-

how FI might be culturally adapted

-

the potential benefits of CaFI

-

an appropriate means of evaluating potential benefits and outcomes

-

how to engage and recruit service users and families into therapy

-

maximising family retention in the study.

Methods

Study design

This was a cross-sectional qualitative cohort study using focus group methodology with key stakeholders. We conducted three separate stakeholder focus groups for service users, carers and advocates, and health professionals. We convened a purposefully selected ‘mixed’ group (comprising stakeholders from the initial focus groups) to verify emergent themes and agree the items to be taken to the consensus conference (phase 1C), where final decisions about CaFI’s content, delivery and associated training were made.

Participants and recruitment procedures

We used novel recruitment strategies building on the PI’s community engagement work at community mental health conferences and with service users (at the request of our service users, this term is used in preference to ‘patient’ throughout the report) and Patient and Public Involvement (PPI) events supported by National Institute for Health Research’s (NIHR’s) Research Design Service’s bursary award. Potential participants were recruited via events in accessible venues, such as churches and community centres. Information was also posted in community newspapers and the Manchester Evening News and the study was presented during live phone-in discussions about mental health and illness on local radio stations instigated by the PI. The PI and RPM made presentations to service user and carer forums, Community Mental Health Teams (CMHTs) and voluntary sector organisations, including our collaborating partner ACMHS. Advertisement posters/flyers (see Appendix 6 for service user example) were also placed strategically at various community locations and sites within the host NHS trust (MHSCT). Recruitment information was also made available via the ‘Get Involved’ page of the Researching African Caribbean Health website [URL: http://research.bmh.manchester.ac.uk/ReACH/getinvolved (accessed 2 December 2017)], which we created for this study.

Inclusion criteria

Service users

-

Current female and male service users, including those receiving treatment from CMHTs or on community treatment orders (CTOs) who clinical teams considered well enough to participate.

-

Former female and male service users who, although not on active treatment, might be subject to periodic reviews by mental health teams and/or in receipt of support from voluntary sector agencies such as ACMHS.

-

Aged ≥ 18 years, who self-identified as being of ‘African-Caribbean origin’, including ‘Black British’ and ‘mixed’ African-Caribbean.

Carers and advocates

Carers (including paid support workers, family and friends) and advocates (such as ACMHS) with experience of working with African-Caribbean people. Unlike service users, carers and advocates could be from any ethnic/cultural background.

Clinical staff

We sought to include as wide a range of professions with differing levels of experience/expertise as possible, including nurses, occupational therapists (OTs), psychologists, psychiatrists and social workers.

Study participants

Participants were service users (n = 10), health professionals (n = 7) and carers and advocates (n = 14). The ‘mixed’ focus group comprised purposefully selected individuals from the previous three stakeholder groups (n = 11). Service users all had ICD-10 F20–F29126 or DSM-IV127 schizophrenia diagnoses. Health professionals included social workers, OTs and registered mental health nurses (RMNs). Carers and advocates were predominantly family members [spouses or partners, siblings, and parents (mostly mothers)] and voluntary sector provider representatives such as ACMHS.

Procedures and materials

Interested individuals who contacted the research team were provided with PISs (see Appendix 7 for service user example), tailored for each stakeholder group and given at least 48 hours to decide whether or not to opt into the study. Potential participants met with the RPM to address any queries and complete consent forms (see Appendix 8 for service user example).

Reflecting the differing perspectives of the stakeholder groups, separate topic guides (see Appendix 9 for service user example) were developed for each focus group based on the literature review (phase 1A) and information generated in discussions with former service users and carers when developing the study. Topic guides and supporting materials were refined via consultation with our RAG.

Each focus group commenced with context setting and establishing ground rules to help create a ‘safe space’ for individuals to talk about potentially sensitive and/or distressing experiences in relation to schizophrenia and mental health care, and to ensure that all participants were afforded the opportunity for their voices to be heard.

Demographic information (age, gender, ethnicity, marital and employment status, postcode and religion) were collected and consent regarding recording and data usage confirmed. Strategies for dealing with distress were also outlined and sources of available support provided (see Appendix 10). All focus groups were facilitated by the PI, supported by the RPM.

Data collection

Initial focus groups

Microsoft PowerPoint® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA) presentations were used to outline the background to the study, the purpose of the focus group, session content and process (see Appendix 11 for service user example).

To collect data, we worked systematically through the topic guide (see Appendix 9), as follows:

-

We explored participants’ experiences of services and perceptions of the need for ‘talking treatments’ in general and CaFI in particular.

-

We gave participants the opportunity to discuss the impact of schizophrenia on the family, cultural models of mental illness and past experiences and perceptions of services and psychological therapies.

-

We presented individual components (Box 2) of the extant evidence-based FI model34 and invited participants to comment on (a) the face validity of the different components and (b) what, if anything, needed to be done to improve their cultural appropriateness – that is, to make the existing components more ‘African-Caribbean specific’ for service users and their families.

-

We sought participants’ views on additional African-Caribbean-specific topics to be included in CaFI.

-

We explored participants’ views about the delivery of CaFI. Specifically:

-

factors related to delivery (number, duration and location of sessions)

-

ethnic matching of therapists and families

-

communication and language use in a therapeutic context

-

suggestions for culturally relevant materials to support delivery

-

factors that might encourage or hinder engagement.

-

-

We identified relevant and important outcome measures from participants’ perspectives.

-

We ascertained participants’ views about maximising recruitment and retention and minimising attrition during the trial phase of the study (phase 3).

-

We sought participants’ views about the involvement of FSMs/’proxy families’ (trusted individuals who would support service users’ participation in the absence of families).

-

We asked participants to comment on the perceived training needs both of FSMs and CaFI therapists.

-

We invited participants to contribute additional information they considered important, but which had been omitted from the topic guide or not covered during discussion.

-

Service user assessment:

-

current and past episodes of illness

-

functioning

-

strengths and resources

-

relationships.

-

-

Family assessment.

-

Psychoeducation.

-

Stress management and coping.

-

Problem-solving and goal-planning.

‘Mixed’ focus groups

To validate findings from the first three stakeholder focus groups and resolve any differences between groups, we conducted a fourth ‘mixed’ focus group comprising purposely selected representatives (n = 11) from the initial focus groups. Participants were tasked with agreeing the essential components of a culturally specific FI to be taken forward to the consensus conference. A topic guide (see Appendix 12 for ‘mixed focus group’ topic guide), based on findings from the three previous focus groups, was used to facilitate data collection.

In common with previous sessions, the ‘mixed’ focus group commenced with the moderator (PI) outlining its purpose and addressing ethical issues. Findings from the earlier focus groups were presented in a structured format using a PowerPoint presentation (see Appendix 13 for ‘mixed focus group’ presentation slides). Additional information was presented on flip-charts or as printed materials. This approach enabled participants to address anomalies/inconsistencies and to resolve differences between groups through discussion using a range of techniques, including ranking, voting and visual models, without losing focus. For example, in relation to therapeutic alliance, we shared findings from previous research about ‘ethnic matching’ and ‘cultural competence’ to facilitate discussion about the utility in delivering CaFI. We also shared materials, including our draft ‘Lay guide to schizophrenia and psychosis’, as well as inviting participants to suggest other resources that could improve the cultural specificity of CaFI’s content and delivery.

All focus groups were digitally recorded and data managed in accordance with The University of Manchester’s data protection policy and management plan and the host trust’s research and development (R&D) policy.

Data analysis

The data were transcribed, checked for accuracy, and identifying material was removed and analysed using framework analysis42 by the RPM and PI, with input from the wider team and qualitative methods experts independent of the team. Framework analysis is a systematic process of data analysis that allows for inclusion of both a priori and emergent themes and concepts. 128,129 A framework approach was particularly suited to our study as there were specific topics we wanted to explore, such as the content and delivery of the intervention, as well as ascertaining participants’ views about key issues, such as the utility of the intervention and recommendations for maximising uptake.

The interconnected stages of framework analysis include familiarisation (through the reading and re-reading of the transcripts), coding, framework development, charting and indexing. This was used to guide data analysis from initial management through to the development of explanatory accounts. Data verification strategies included peer and participant review to examine and verify themes, findings and conclusions. For example, two other experienced qualitative researchers (Baker and a qualitative methods specialist independent of the research team), rigorously reviewed the research process and emergent findings identified by the PI and RPM. In addition, findings were shared with the wider research team and Research Management Group (RMG). The ‘mixed’ focus group served as a means of ‘member checking’ or ‘respondent validation’, were participants were given the opportunity to comment on the validity of findings. These are recognised methods of ensuring ‘trustworthiness’ of the data and subsequent findings. 130,131 NVivo version 10 (QSR International, Warrington, UK) was used to support data management and analysis.

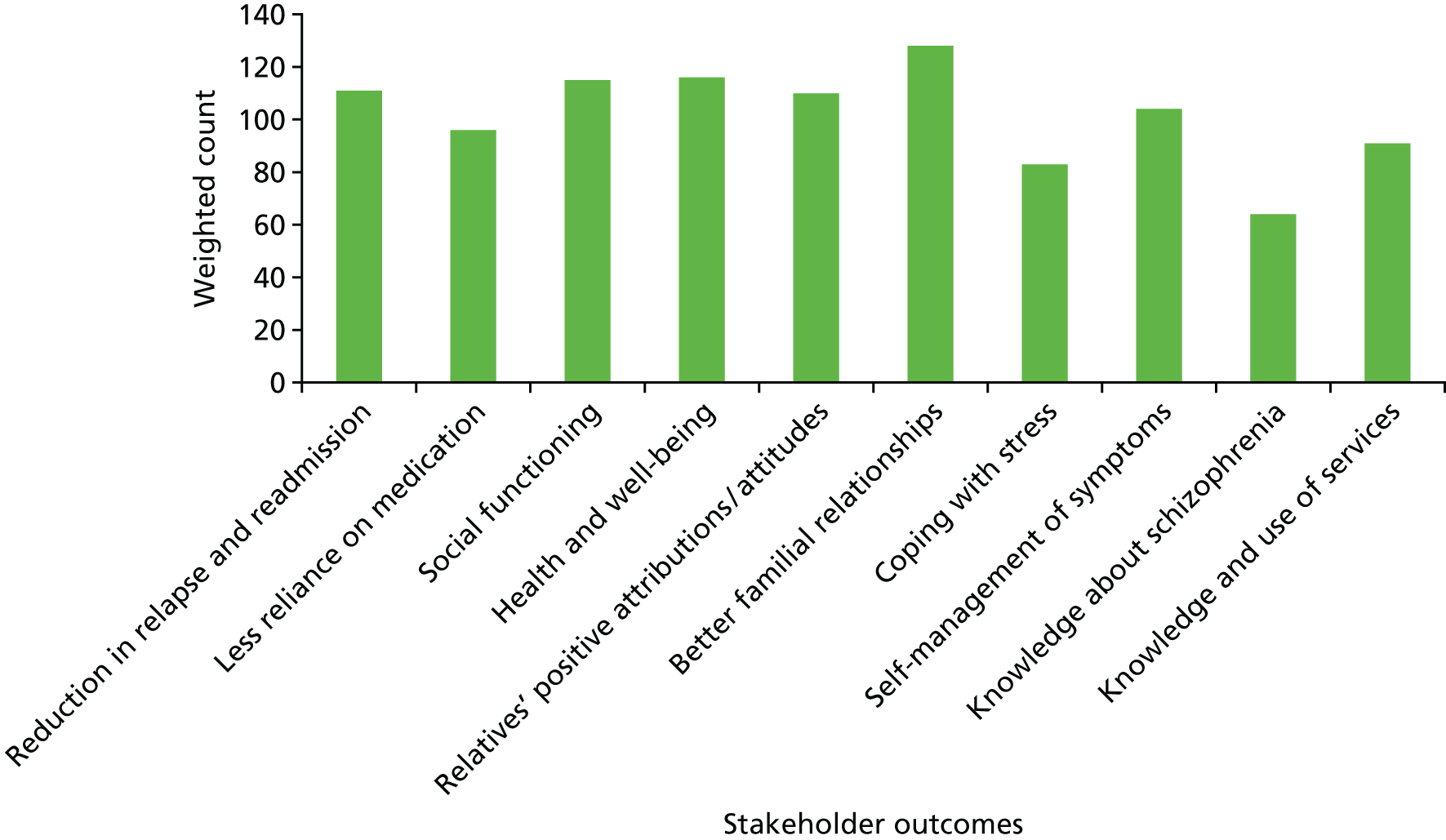

Findings

Presented here are the findings from the fourth ‘mixed’ focus group. They represent the synthesis of data generated from all four phase 1 focus groups, underpinned by the literature. Illustrated by participants’ verbatim quotations, the findings are presented in three overarching themes that reflect the research objectives for this phase of the study, that is, participants’ views on how to make the (1) content, (2) outcomes and (3) delivery of the intervention culturally appropriate for African-Caribbean people.

Theme 1: content of the intervention

Participants did not suggest that any of the current FI content (outlined in Box 2) was irrelevant. Instead, they suggested additional African-Caribbean-specific elements (summarised below) in relation to the different components of FI.

Service user assessment

Participants stated that racism and discrimination should be explicitly explored (Box 3), highlighting the effect of ‘current and previous episodes of illness’ experiences on mental health and help-seeking:

There’s massive talk of institutionalised racism in so many different areas, whether that’s education, crime and other areas. We know it can’t be separate from the health area as well so there has to be an acknowledgement that it’s there.

Male advocate

-

Racism and discrimination.

-

Models of mental health and illness.

-

Prescribed and illicit drugs.

-

Culturally relevant markers of social functioning.

-

Recovery and the future.

-

Family structures and dynamics.

Service users’ ‘models of mental illness’, including spirituality and religious affiliation, the significance of wellness and well-being and perceptions of mental illness as deviance, were regarded as areas of particular relevance for African-Caribbean people and of difference from other ethnic groups:

I remember working in a mental health system and every time I came across somebody from a BME culture, particularly Caribbean, when they had a mental health issue, the family wasn’t saying that they’re not well; they would say ‘they got in with the wrong crowd’ . . . the family would say ‘my brother is strong, he is very intelligent, he got in with the wrong crowd’. So the mental illness is associated with being deviant instead of being associated as being an illness.

Male advocate

There was near-unanimous agreement that service user assessment should include open discussion on beliefs about and experiences of psychotropic ‘medication’, including side effects as well as the relationship between psychotic symptoms and illicit drugs use:

I’ve been on medication for some time and I remember at one stage I was using cannabis and alcohol at the same time and I had a word with someone in authority about it and they said, ‘what you’re doing, you’re self-medicating, because the medication that you’re supposed [to take] . . . is not having its desired effect. So you’re self-medicating’.

Female service user

Social functioning, including developing/regaining social skills and the ability to ‘mix with people’ and establish new relationships, was regarded as especially important for a group with high levels of social isolation linked to stigma. Participants spoke about therapists’ need to be particularly aware of the cultural symbolism of food. For many African-Caribbean people, an individual’s ability to care for and nurture themselves and others is an important indicator of effective social function:

I cook right; chicken, fish, healthy food, food in the oven. My mum comes and I give her food, my sister, I give them food and make sure they’re all okay. They’re very, very grateful. Mum’s very happy with me.

Female service user

African-Caribbean-specific additions to the ‘strengths and resources’ component included a ‘future-focused’, recovery-based approach. Work, studies and entrepreneurship were regarded as significant markers of recovery and enhanced self-esteem:

There’s too much emphasis on ‘illness’ and ‘episodes’. I’d like to have more well-being and self-esteem . . . it’s about also drawing on what is it like for them when they have got their full well-being.

Male carer

Although regarded as a potentially important resource, spirituality was a source of ambivalence. Participants warned against reifying or essentialising the relationship between African-Caribbean people and religious institutions, as interactions with such organisations were not always positive:

They talk about certain things happening in church, and ‘when you get unwell you turn to the church’, but I’ve been taken out of free [three] churches . . .

Male service user

Therapists’ awareness of family structures and dynamics (including age and gender hierarchies) within African-Caribbean families, and how these ‘relationships’ might play out in therapy, was highlighted. Although this could be said of any ethnic group, participants felt that family tension and conflict were especially pertinent for African-Caribbean people owing to delayed access to care and lack of understanding of symptoms:

When you are not ill, [there] maybe a lot of things that you do within the family that’s no problem . . . when you get ill you can’t do those things and not being able to do those things brings accusations that maybe ‘before you do this but now you don’t want to do this’ and that beings lots of tension and argument and can bring lots of problems, because they don’t understand . . .

Female service user

Therapists should also explore perceptions/experiences of services’ seemingly arbitrary and inflexible approaches to engaging with service users’ networks, which contribute to difficulties in maintaining relationships:

Last time I was in [hospital], a lady came to see me, who wasn’t my wife, and they said that she had to have 5 years’ relationship before the doctor would give her permission to find out if I was OK or not.

Male service user

Family assessment

Although participants felt the content of the current FI model was entirely relevant, they also emphasised the significance of African-Caribbean beliefs about mental illness and the impact of service users’ experiences and difficulties on carers and family members (Box 4):

. . . you also have to aware of the belief system within a family, because you might meet up from the spiritual aspect of it where this is caused ‘because someone did this to me’ . . . back home [Caribbean] we call it Obeah . . . and if you come up against that you’re going to have to be prepared for that and how to deal with it.

Female carer

. . . involve other siblings and family members and also recognise their needs so they will understand better why a particular member of the family needs more support instead of creating resentment between the family members.

Male carer and former service user

-

Beliefs about mental illness.

-

Impact of service users’ experiences and difficulties on carers and family members.

-

Concerns about confidentiality and risks associated with disclosure.

Participants highlighted the importance of being able to explore the history of predominantly negative experiences of services during therapy, without these being pathologised, minimised or dismissed. Past experiences of feeling excluded from decision-making and restricted access to information should be addressed in CaFI:

. . . when they are having a meeting for the care plans I’m not there, even though I’m down as the main carer, because apparently he says he doesn’t want me to be there. But how can you care for someone if you don’t know what you’re caring for?

Female carer

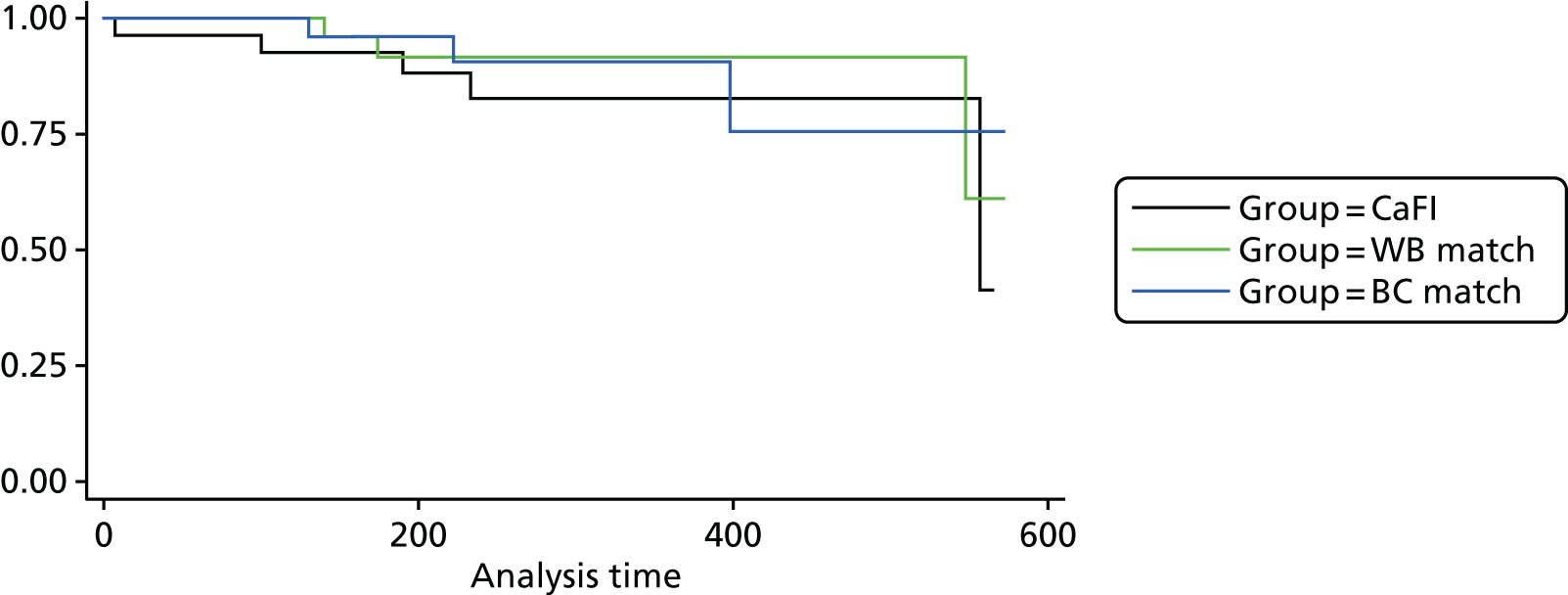

Concerns about confidentiality and cultural sanctions accompanying the risk of disclosure and negative perceptions of help-seeking from statutory services (as indicative of ‘not coping’) had potentially adverse consequences for their families, which made them reluctant to share information with health-care professionals: