Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/07/48. The contractual start date was in December 2014. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in November 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

James Raftery is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Journals Library Editorial Group. He was previously Director of the Wessex Institute and Head of the NIHR, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre (NETSCC).

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Bridges et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Context

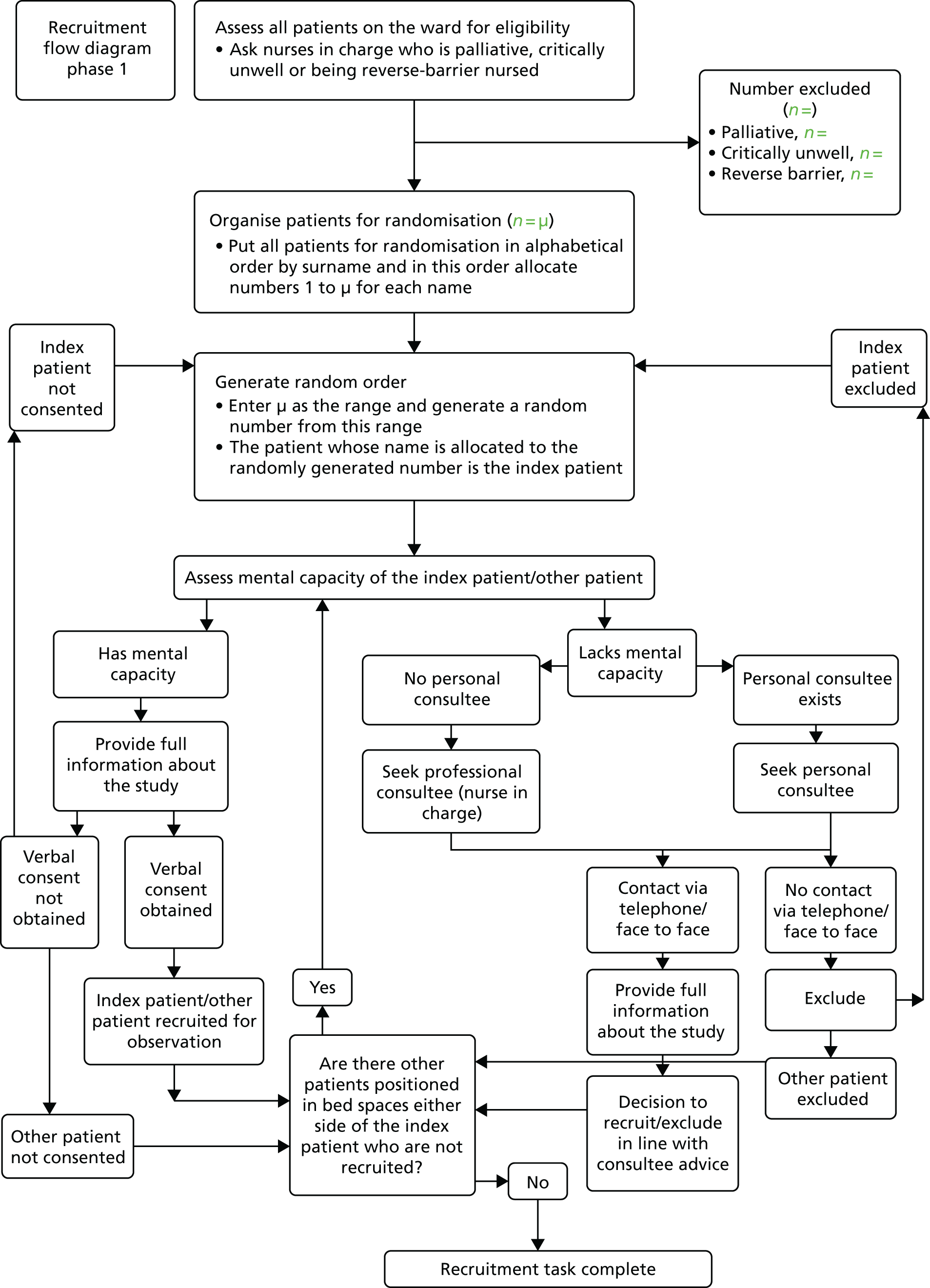

The study reported here aimed to assess the feasibility of implementing the Creating Learning Environments for Compassionate Care (CLECC) programme, a practice development programme aiming to promote compassionate care for older people in acute hospital settings, and to assess the feasibility of conducting a cluster randomised trial (CRT) with associated process and economic evaluations to measure and explain the effectiveness of CLECC.

In this chapter, we describe the background to the study, focusing in particular on the policy and practice context of the UK NHS. We also introduce the CLECC intervention, drawing on the international research literature to illustrate the rationale for designing and deploying this particular intervention.

In April 2013, the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme invited applications for funding research to support NHS organisations in responding to the Francis Inquiry analysis of care failures at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. 1,2 Acknowledging that all NHS organisations could learn from ‘key system weaknesses’ identified in the Francis Inquiry, the call specifically invited applications for ‘robust evaluations of interventions to improve the leadership, organisational culture and quality of frontline care’ (p. 1). 3 This report details a study funded through that call.

The NHS context

The need to strengthen the delivery of compassionate care in UK health and social care services, in particular to older patients, has been consistently identified as a high priority by policy-makers in recent years. 4 In addition to a series of investigations into high-profile failures, substantial and significant variations in the quality of hospital care for older people have been highlighted. 1,5 Variation exists between hospitals, but also between wards within hospitals and between staff within wards. Training, staffing levels, leadership, motivation and organisational culture are all implicated in failures of care. Although these issues are widely reported in the UK, there is evidence to suggest that they are relevant internationally. 6,7

Care failures at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust in the late 2000s, and the inquiries that followed, were a watershed moment for the NHS. Over a period of some years, patient care in many wards and departments at the trust had been of very low quality, with, for instance, patients left in soiled bed clothes for lengthy periods, assistance not provided for patients who could not eat without help, and indifferent and unkind treatment by staff of patients, often older patients, and their families. Two inquiries led by Sir Robert Francis QC examined the causes of the lack of care and high mortality rates. The first inquiry focused on patient care at the trust and offered recommendations for improving practice at the trust. 2 The second inquiry focused on the systems of governance underpinning the care failures and offered recommendations for the NHS as a whole. 1 In the recommendations from the second inquiry, Francis called for a fundamental change in culture across the NHS towards a culture that puts patients first. Several of these recommendations focused on promoting compassionate nursing care. These recommendations focused on how to identify and promote desirable attributes (knowledge, skills, attitudes) in individual nurses. Many other recommendations focus on the systems needed to promote high-quality care and the responsibilities that should be held by key groups and organisations such as trust boards, NHS regulators, professional bodies and educational institutions. Although there is little detail about desirable systems and processes at a ward-team level, recommendations from both inquiries provide an outline of such measures to counteract the potential for the care failures encountered at the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. These include providing mechanisms through which health-care professionals can raise concerns about patient care with colleagues and with senior managers; the ongoing provision of training, support and supervision to nursing staff; and investing in ward leader roles that work alongside team members, providing role modelling and mentorship.

There have been significant changes to UK health-care provision since the establishment of the NHS in 1948. The improvement in medical treatments during this time has contributed to people living longer with more complex health conditions. Acute hospital inpatient beds are now predominantly populated by older people with multiple health conditions. However, recent years in particular have seen the adult social care system and pressures on primary care services affecting secondary care. Acute hospitals have struggled to meet their performance and financial targets. During the time that this study was taking place, health and social care in England was in the midst of unprecedented demand and financial challenges, with NHS providers having overspent by £2.45B by the end of 2015/16. 8

It has been acknowledged that an increase in staffing numbers is required and a safe staffing guideline for nurses working on wards in acute hospitals has been published. 9 Although this was supported by the creation of 24,000 new nursing posts between 2012 and 2015, an increase of 8.1%, demand has outstripped supply with a deficit of 8.5% of the funded establishment recorded in April 2015. 10 This deficit is worse in adult acute nursing, with reported vacancies amounting to 9.7% of the establishment. It is common practice for wards to run with staff vacancies and for the staff complement to be made up of staff from nursing agencies. Recruitment drives targeted at overseas nurses have regained popularity, but this too is a temporary fix, with European Union nurses choosing to exercise their free movement rights. 11

Through the development and tightening of systems for financial control and performance management, the NHS has seen an intensification of health-care work through higher patient numbers and time-based targets. 12–14 Use of staff without professional qualifications is increasing and nursing staff job satisfaction is low. As we developed this study, anecdotal evidence from a number of NHS acute hospitals indicated that the leadership and team practices, such as role modelling, mutual support, reflective learning and dialogue, required to support nursing staff in their caring role15 were unlikely to be in place in most care settings.

Approach and definition of key terms

The literature is both confused and confusing in the way that compassion is used as a term. There are four key components of the narrative of compassion in nursing, and we have found these helpful to guide our thinking in this study about what compassion is. 16 The first is a set of ideas about the moral attributes of a ‘compassionate’ nurse, including wisdom, humanity, love and empathy. 17–19 These moral attributes are expressed through a kind of situational awareness in which vulnerability and suffering are perceived and acknowledged. 19,20 These perceptions underpin participation of the nurse in responsive action that is aimed at relieving suffering and ensuring dignity, and which involves the nurse in a participatory relationship in which the nurse exercises relational capacity 19,21–23 through which empathy is experienced and a caring pastoral relationship is constructed. 15,24,25

Our systematic review of research reporting older patients’ experiences of hospital care highlights the importance of this caring relationship to shaping experiences. 6 Older people want nurses, and others, to use social interactions to see the person behind the patient (‘see who I am’), to establish a warm and human connection (‘connect with me’) and to establish understanding and involvement (‘involve me’). 6 A later review focusing on nurses’ experiences indicates that registered nurses strive to achieve the caring relationship that is valued by patients, indicating that a perceived lack of compassion in nursing may not be attributable to a lack of the necessary moral attributes or situational awareness on the part of individual nurses. The findings reflected that nurses’ relational capacity and capacity for responsive action can depend on ward-level conditions, and that there is a greater tendency for nurses with low relational capacity to avoid relationships with patients and to burnout, in spite of aspirations to a higher standard of care. 15 This study builds on these findings through the development and evaluation of an intervention targeted at improving the capacity of nurses to respond to patient vulnerability and suffering, specifically their relational capacity and capacity for responsive action.

The links between positive patient experiences, leadership, work team climate and the well-being of individual staff are becoming evident through research and so interventions that focus on developing these elements (leadership, work team climate, staff well-being) would appear to be worthwhile to support the development and exercise of relational capacity. A NIHR study on culture change and quality of acute hospital care for older people found that more positive patient and carer assessments of care were correlated with higher staff ratings of a supportive team climate and a shared philosophy of care. 26 In addition, ward leadership was a strong indicator of team members sharing a philosophy of care and feeling highly supported, a finding that, together with the qualitative data, highlighted the vital role of the ward manager in shaping a positive team climate for care. 26 These findings were mirrored in a second NIHR study that highlighted the key role of the ward leader in shaping the local ward climate of care, the importance of staff well-being, and, in particular, staff experiences of good local work-group climate, co-worker support, job satisfaction, positive organisational climate and support, and supervisor support as antecedents of positive patient experiences. 27

Creating Learning Environments for Compassionate Care

Parts of this section are reproduced from Bridges J, Fuller A. Creating learning environments for compassionate care: a programme to promote compassionate care by health and social care teams. Int J Older People Nurs 2015;10:48–58,28 with permission from John Wiley & Sons. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd. CLECC is a team-based implementation programme focused on developing leadership and team practices that enhance team capacity to provide compassionate care. Its objectives are to:

-

create an expansive workplace learning environment that supports work-based opportunities for the development of relational practices across the work team

-

develop and embed sustainable manager and team relational practices, such as dialogue, reflective learning and mutual support

-

optimise and sustain leader and team capacity to develop and support the relational capacity of individual team members

-

embed compassionate approaches in staff–service user interaction and practice, and continue to improve compassionate care following the end of programmed activities.

The CLECC intervention was designed for use by ward nursing teams in inpatient settings for older people, but is potentially transferable for use in other settings. The implementation programme takes place over a 4-month period but it is designed to lead to a longer-term period of service improvement. By envisaging the workplace as a learning environment and the work team as a community of practice, CLECC brings a distinctive approach to promoting compassionate care. It uses insights from workplace learning research to develop practices that enhance the capacity of the manager and work team to provide compassionate care within a complex and dynamic organisational context.

Fuller and Unwin’s research on workplace learning and workforce development in a range of public and private sector industries demonstrates the importance of identifying and analysing both the organisational and pedagogical features that characterise diverse workplaces as learning environments. 29 They argue that this approach allows workplaces (e.g. hospital wards) to be located on the ‘expansive–restrictive’ continuum. Those at the expansive end are characterised by a range of features including the following: the knowledge and skills of the whole workforce (not just the most highly qualified or senior staff) are valued; managers facilitate workforce and individual development; teamwork is valued; innovation is important; the team has shared goals focusing on the continual improvement of services (or products); there is recognition of and support for learning from ‘each other’; learning new knowledge and skills is highly valued; and the importance of planned time for off-the-job reflective learning is recognised. It follows that an expansive approach to workforce development is more likely to facilitate the integration of personal and organisational development. This has important implications for the design of learning interventions as it requires workplace learning to be perceived as something that both shapes and is shaped by the work organisation itself rather than as a separately existing activity. Such an understanding highlights the importance of interventions that situate and integrate individual and team learning in the everyday life of the workplace (in this case the clinical unit/ward/team setting) as well as providing opportunities for off-the-job provision to foster reflection, consolidate learning and deepen understanding, thereby enhancing ownership and sustainability of new practices.

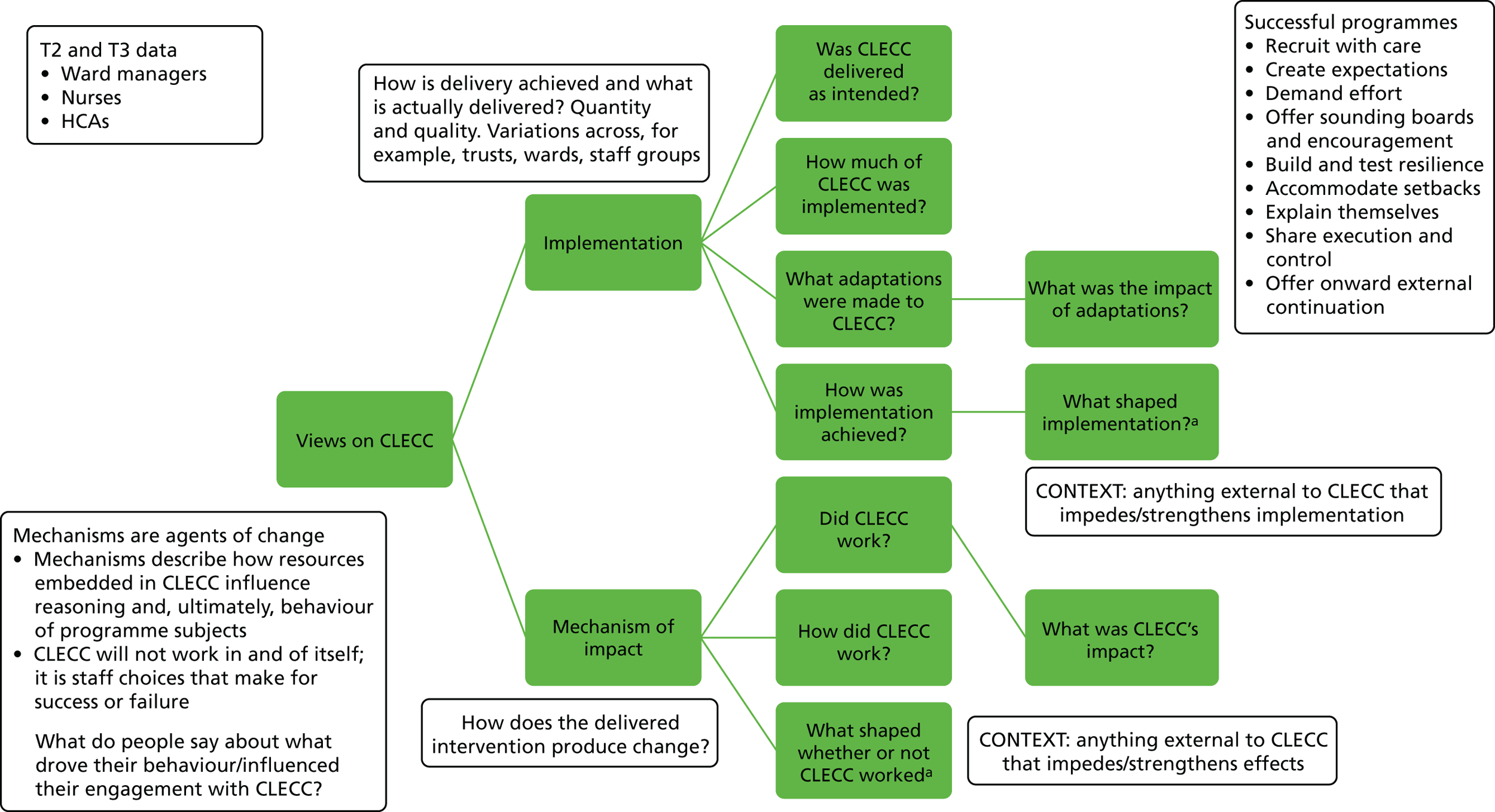

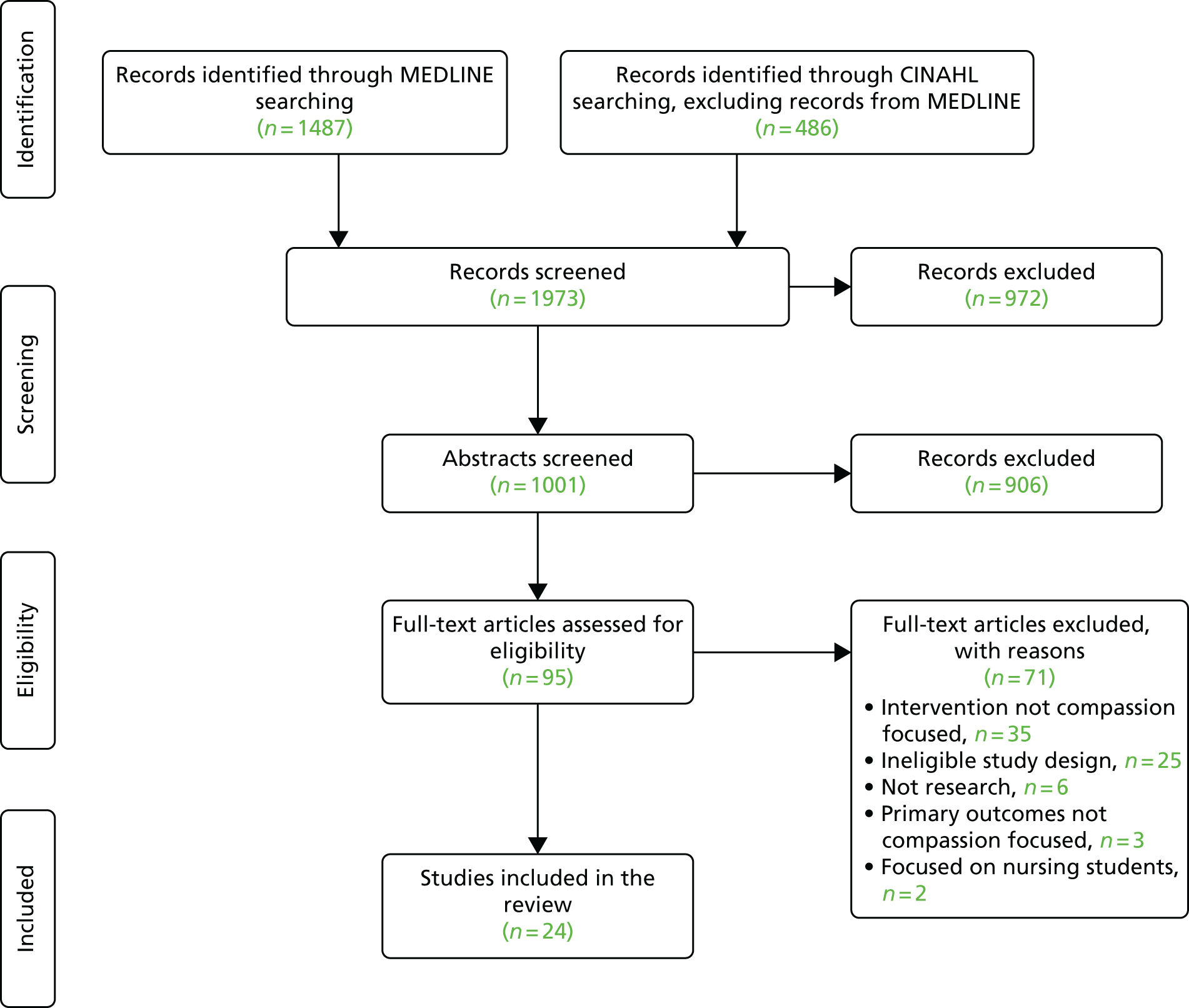

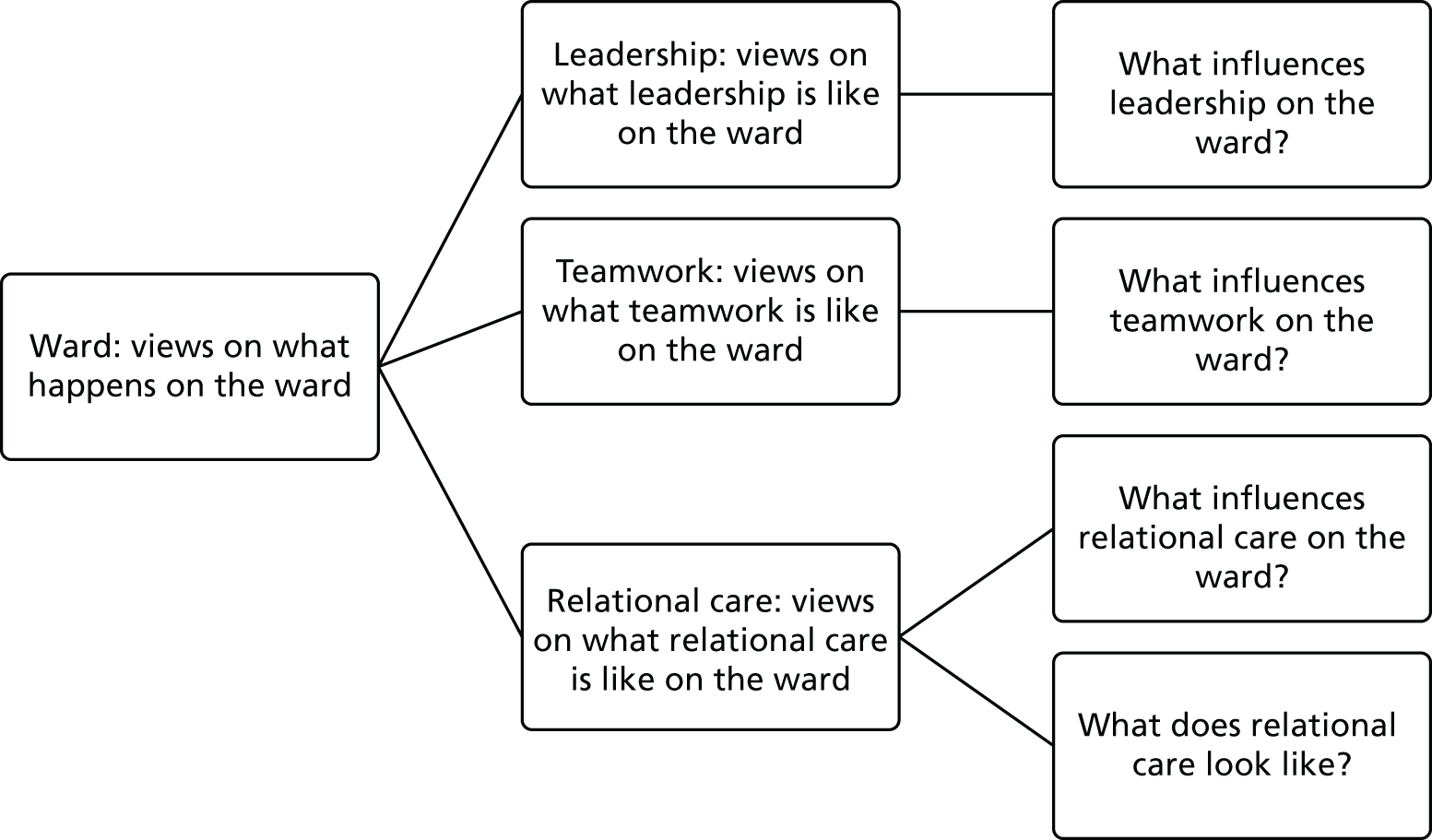

Our synthesis of qualitative research highlights the importance of the relational aspects of care to shaping older people’s hospital experiences. 6 Being compassionate requires ‘relational capacity’ in practitioners, that is, capacity to experience empathy and to engage in a caring relationship. 24 Our research also shows that nurses’ relational capacity can depend on ward-level conditions, and that there is a greater tendency for nurses with low relational capacity to avoid relationships with patients and to burnout, in spite of aspirations to a higher standard of care. 15 CLECC uses workplace learning principles to develop practices that enhance the capacity of the manager and work team to support the ongoing relational capacity of its individual members. This leadership and team capacity are key characteristics of the ward-level conditions needed to support nurses’ relational work15 and thus improve patient experiences, and are an important foundation for team activities, such as using service user feedback constructively. 30 By envisaging the workplace as a learning environment and the work team as a community of practice, CLECC brings a distinctive approach to promoting compassionate care, which enhances the capacity of the manager and work team to provide compassionate care within a complex and dynamic organisational context. 29,31 An overview of this programme theory for CLECC is shown in Figure 1 .

FIGURE 1.

Overview of CLECC programme theory. Reproduced from Bridges J, Fuller A. Creating learning environments for compassionate care: a programme to promote compassionate care by health and social care teams. Int J Older People Nurs 2015;10:48–58,28 with permission from John Wiley & Sons. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

During the 4-month implementation programme, CLECC learning activities are led by a senior (UK band 7) practice development nurse (PDN) or practitioner with strong influencing and interpersonal skills. 28 The PDN delivers the study days, facilitates cluster and reflective discussions, facilitates the action-learning sets and co-ordinates the peer observations of practice (see the following subsections for more detail on each of these activities). This individual is not part of the hierarchy of the ward team and this enables a distinction between CLECC activities and performance management. The activities themselves are characteristic of a practice development approach. 32 CLECC operates at two key levels: team and team manager. A focus on the team aims to develop team capacity to support team members to provide compassionate care. An equivalent focus on the leadership capacity of the team manager (in ward settings this is the ward manager) aims to develop their role in leading the team, role modelling good practice and enhancing and embedding the desired team practices.

Although the programme draws on elements that have been piloted in other programmes, it is novel in combining these elements with an explicit focus on establishing reforms to routine practice and organisational resources that establish the basis for sustained changes in compassionate care. Although the implementation process is a key element, the essence of the programme is the ongoing processes of peer observation, daily cluster discussions, weekly reflective discussion and the use of evidence-based guidelines. Table 1 sets out a typical schedule for the implementation programme.

| Activity | Month | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | |

| Ward leader action-learning sets | Session 1/setting up set, setting ground rules | Session 2/workplace climate/team values/valuing staff | Session 3/enhancing team capacity for compassionate care | Session 4/influencing senior managers |

| Team learning and service user feedback plan | Introduce and discuss | Discussion and draft by ward leader | Finalise, identify resources needed to support, present | Senior manager feeds back response to team plan |

| Peer observations of practice | Identify care-makers | Train care-makers | Observations of practice | Feedback on observations of practice |

| Study days | Team analysis of workplace climate/values clarification | – | – | – |

| Cluster discussions | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing | Ongoing |

| Reflective discussions | ‘I feel valued at work when . . .’ exercise | Team values clarification exercise; BPOP activities | BPOP framework activities; team learning and service user feedback plan discussions | Reflections on feedback from observations of practice |

Action-learning sets

The crucial role of the ward leader in influencing the caring culture and the work culture is well documented, with strong and visible leadership identified as an essential requirement for the delivery of dignified care. 26,33 In CLECC, ward leaders attend four 4-hour action-learning sets during the implementation programme. Action-learning sets have been used in other projects, including other development projects focused on dignity in care and/or care for older people, to provide an extended reflective space for individuals in a key position of influence to explore and develop their leadership role. 34–36

The CLECC action-learning sets follow the McGill and Beaty model37 for action-learning, that is, sets are made up of between four and eight members and are facilitated by an experienced facilitator. Set members may or may not work in the same organisation but often have similar work roles. Participants bring work problems of their own choosing to the session and other set members aid them in reflecting on the issue and drawing up an action plan to address it. In addition, each of the action-learning sessions is themed to encourage a focus on issues related to the manager’s role in supporting the delivery of compassionate care. The first session focuses on establishing relationships among set members and agreeing ground rules. The themes for subsequent sessions are: (session 2) workplace climate/team values/valuing staff, (session 3) enhancing team capacity for compassionate care, and (session 4) influencing senior managers. Reflecting on the results of other programme activities supports discussion in these themes. For instance, during the team study days, all staff will have been invited to complete a questionnaire on perceptions of ward climate. Reflecting on the results of these questionnaires in addition to the results of the ‘I feel valued when . . .’ exercise (see Reflective discussions ) is encouraged in the second action-learning set. 36 In addition to this reflective learning set, participants facilitate each other in developing practical ways of dealing with some of the issues that arise during the programme, these issues being informed by the findings relating to ward leader strategies in an earlier dignity in care project. 38 Participants are encouraged to use the sets to devise a personal plan associated with their current and future role in promoting compassionate care, including planning clinical supervision sessions for themselves with a selected mentor and/or negotiating ongoing action-learning set access.

In addition to action-learning sets, ward leaders are also facilitated to further develop their relationship with their line manager as a way of accessing additional support. This includes a 1-hour meeting every 2 weeks during the 4-month implementation programme. These meetings provide an opportunity for the line manager to learn about the project and to explore opportunities to participate.

Team learning

Interventions to improve care quality at a ward or unit level may succeed, even if the wider organisation has features that inhibit service improvement on a wider scale. 26 Ward-level conditions can strongly influence nurses’ capacity to build and sustain therapeutic relationships with patients. 15 Other work suggests that the work team can function as a buffer to stressors from the wider organisation, but that the team’s capacity to do so depends on the extent to which the group perceives its role as supportive of the relational work of individual members. 39 Social structures and relationships within the team and the capacity of team members to support each other are a primary influence on how individuals learn emotional abilities and how tacit emotional knowledge is transferred. 40 Dialogue and reflection within the team, particularly with a focus on sharing experiences and narratives, appear to be linked with the development of individual emotional abilities, but these activities depend on the extent to which the workplace provides an environment in which staff feel safe to participate. 40 Other work indicates that expecting staff to, for example, use patient feedback constructively in the absence of team preparation to hear the patient feedback is unlikely to lead to service improvements. 30 A strong focus of the intervention is on the development of shared team goals and expectations, team dialogue, reflection and role modelling. Early activities in the intervention reflect a focus on developing a sense of security within the team,41 with dialogue and reflective learning activities providing the forum for the development of individual and team relational capacity, and the creation by the team of sustainable practices and plans to support ongoing capacity through:

-

commitment and role modelling by senior staff in the team – providing information, opportunities for discussion and involvement in goal-setting and decision-making

-

creating facilitated collective and reflective ‘spaces’ through

-

mid-shift scheduled 5-minute cluster discussions, using trigger questions or observations as behavioural nudges in team members’ planned work with patients

-

twice-weekly longer reflective group meetings, which should draw on a variety of toolkit materials to prompt dialogue and reflective learning, and give staff a regular opportunity to stand back from the demands of their operational practice

-

-

building relationships in the team, using activities including team analysis of workplace climate

-

critical reflections by the team on caring for and supporting each other, on team relational capacity and on delivery of compassionate care

-

team values – the clarification and development of a shared vision

-

developing shared ownership of compassionate care and understanding about how learning in the workplace can contribute to improved individual and team practice and ‘expansive outcomes’

-

development of a team learning plan, including a plan for hearing and responding to patient feedback.

Teams can be unidisciplinary or interdisciplinary, but an inclusive approach is essential, so for instance, use of CLECC with a nursing team includes the participation of all nursing staff, namely the ward manager, registered nurses, care assistants/health-care support workers and nursing students.

Peer observations of practice

Two staff volunteers from the team were selected to become ‘care-makers’, with their primary role being to undertake peer observations of practice for feedback to their colleagues. Care-makers receive 4 hours of training in peer observations of practice and undertake 8 hours of observation each during the programme. Peer observations are conducted using the Quality of Interactions Schedule (QuIS)42 and findings are fed back at reflective discussion meetings (see Reflective discussions ) with the help of the PDN. The results from the care-makers’ observations of practice on the ward are shared to trigger discussions about how to build on existing good practice and improve practice when this is needed.

Study days

On each ward, three or four full study days are delivered by the PDN during the first month of the programme to enable all ward members to attend one study day. The purpose of the day is to prepare staff for the workplace elements (including cluster and reflective discussions) of the programme by providing opportunities to experience some of the techniques; to develop an understanding of underlying concepts; and to recognise an active role in their personal and team learning journey. Elements of the programme for classroom training are shown in Box 1 .

Introduction to the BPOP framework. 43

Life shield activity and group discussion: ‘See who I am’.

Questionnaires and discussion on ward climate, dialogue and reflective learning on the ward.

Values clarification exercise about compassionate care. 44

Videos, stories and discussion with service users: ‘Involve me’.

Introduction to workplace learning activities and discussion on how to implement/support/sustain.

BPOP, Best Practice for Older People.

Reproduced from Bridges J, Fuller A. Creating learning environments for compassionate care: a programme to promote compassionate care by health and social care teams. Int J Older People Nurs 2015;10:48–58, 28 with permission from John Wiley & Sons. © 2014 John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Cluster discussions

Mid-shift cluster discussions commence during the first month (following the delivery of study days) and run daily throughout the implementation period. These 5-minute cluster discussions are facilitated initially by the PDN and all nursing staff on the ward at the time of the cluster discussion are encouraged to join the group discussion. The discussion focuses on establishing how the individual staff are at that moment in that context and provides opportunities for the group to offer help and support to members when difficulties are identified. Similar strategies have been used in other projects focused on developing dignity in care/compassionate care. 36,45

Reflective discussions

Twice a week, members of the team on duty at the time scheduled for a reflective discussion (usually the afternoon) arrange their work to enable their attendance at a group meeting facilitated by the PDN. To enable all staff on a shift to participate, two sessions may need to be held on the same day, both attended by the ward leader. This interaction is held in a comfortable meeting room on or near to the place of care, but away from the immediate distractions of care delivery. The meeting is for all team members, including senior members of the team and temporary team members, such as student nurses. The meetings involve a variety of group work tasks, some of which are repeated to enable the maximum number of team members to take part, whereas others will be unique. Tasks are aimed at opening up dialogue and reflective learning among those present, and so are selected to prompt personal reflections and narratives about experiences on the ward. They include:

-

‘I feel valued at work when . . .’ – those present are invited to complete this sentence to trigger discussions about valuing and supporting each other36

-

team values clarification about compassionate care – drawing on collated results of the values clarification exercise in classroom sessions to develop shared vision36,44

-

drawing on collated results of ward climate analyses to identify factors that need to be supported or changed36

-

peer observations of practice – the results from the care-makers’ observations of practice on the ward are shared to trigger discussions about how to build on existing good practice and improve practice when this is needed36

-

the Best Practice for Older People (BPOP) framework – using resources and questions/prompts from the BPOP framework is an essential guide to generating discussion46

-

a team learning plan – working with managers to draw up a team learning plan focusing on compassionate care and using patient feedback.

Best Practice for Older People framework

The BPOP framework is a set of evidence-based UK guidelines for nurses working with older people in acute settings. 43,46 Its successful use in development projects aimed at service improvement indicates that it is useful in guiding the practice of health and social care professionals working with other client groups (i.e. not just nurses working with older people). One example of this wider use is the City University Dignity in Care project at two London hospitals. 36,47 A resource has been published for use alongside the BPOP framework, providing teams with trigger questions and guidance aimed at generating dialogue and reflective learning in the team, and opening up conversations in which team members give and receive support and help with difficult matters, such as talking to patients about dying. 46 In CLECC, this resource is used to identify areas for support, action and learning in the team, and to inform the development of strategies to address these areas. Examples of trigger questions in this resource are:

-

What kind of patients are most difficult to communicate with, and why?

-

What kind of patients are most difficult to involve, and why?

-

What subjects are hardest to talk to patients about, and why?

-

What kind of relatives are most difficult to involve, and why?

The implementation stage of the programme takes 4 months, and during this time ward leaders and their teams develop a team learning plan that includes inviting and responding to patient feedback, and puts in place measures for continuing to develop and support manager and team practices that underpin the delivery of compassionate care. The team learning plan is presented to a senior trust manager, together with a case for support, and the relevant manager is invited to visit the ward team to discuss the plan and respond in person to the proposals.

In summary, the focus of the intervention is on creating an ‘expansive’ environment that supports work-based opportunities for the development of shared goals, dialogue, reflective learning, mutual support and role modelling for all members of the team at an individual and a group level. 29 The programme theory states that such an environment should facilitate staff to engage with and learn from service user experiences and their own emotional responses, share positive strategies and support, and optimise and sustain personal and team relational capacity to embed compassionate approaches in staff–service user interaction and practice. Expansive outcomes are theorised to include high-quality interactions between service users and staff, and between care team members, positive care experiences reported by service users and staff reports of high empathy with patients and carers.

Introduction to the study

Findings from our systematic review, reported in Chapter 2 , highlight the lack of definitive evaluation research on compassionate nursing care. Responding to a general absence of strong evidence for the effectiveness of service improvements related to compassion, and building on compelling evidence indicating that a strategy targeted at improving leadership and local ward team climate could improve patient experiences, the study reported here is a foundational step in addressing the need for well-designed and rigorous evaluation to understand what works best in improving care and patient experiences.

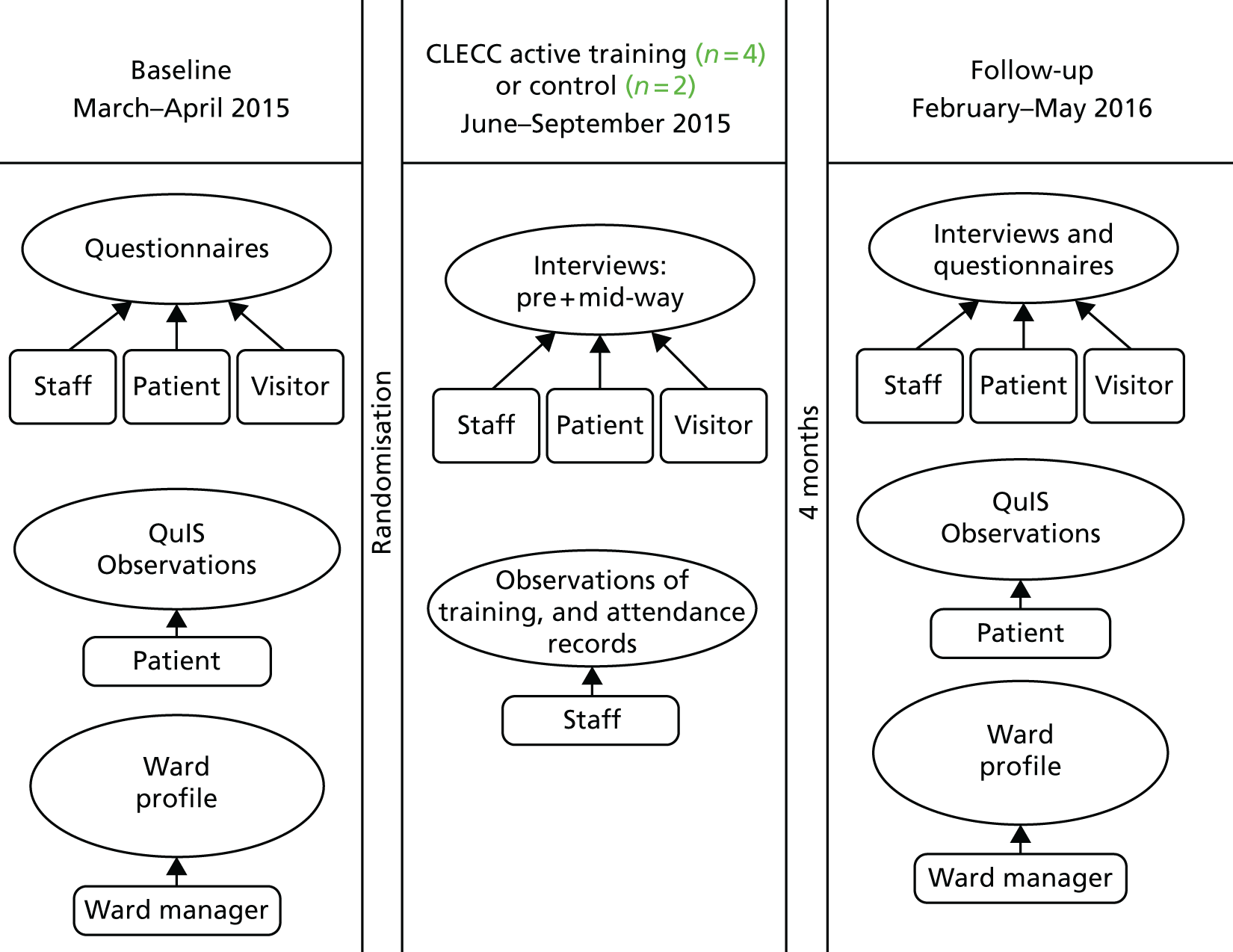

This study, conducted in two English hospitals during 2015–16 and reported in the chapters that follow, aimed to assess the feasibility of implementing CLECC and of conducting a CRT with associated process and economic evaluations to measure and explain its effectiveness. Conducting the study provided an important opportunity to assess the feasibility of a programme with unique characteristics designed to address the issues identified in other studies, and to design an evaluation that includes an assessment of its effectiveness. The process and economic evaluations aimed to provide important information about CLECC’s workability, its integration into practice and to lay the foundations for establishing its value for money. The findings reported below (see Chapters 7–10 ) provide the basis for planning a larger, multicentre evaluation aimed at producing evidence that can be generalised more widely to other NHS acute care providers and, together with a refined intervention package, will be a valuable resource for change and improvement for NHS managers, practitioners and educators.

Chapter 2 Literature review

Although current definitions of compassion in nursing practice are imprecise and sometimes confused (see Chapter 1 ), there is intense interest in this problem both within and outside the profession of nursing. However, little is known about what strategies are effective in promoting compassionate care among nurses. To date there has been no rigorous critical overview of research into interventions designed to promote compassionate care among nurses in practice. This chapter aims to provide an overview of the evidence base on the evaluation of interventions for compassionate nursing care. It begins with an overview of qualitative research on compassionate care interventions. It then reports a systematic review of studies that evaluate the effectiveness of interventions to promote compassionate nursing care.

Qualitative research

Recent years have seen the use of qualitative research methods to underpin the development and evaluation of a number of interventions focused on improving compassionate care, or dignity in care, at the hospital ward level. 30,34,36,47–49 Interventions developed and evaluated in this way have typically been faciliated by a senior nurse, using reflective learning, action research and/or appreciative inquiry to work with ward-based nursing staff (often using patient stories and/or observations of practice) to strengthen support for existing good practice and to make changes when needed. These interventions are often shaped by a ‘relationship-centred’ philosophy in which achieving the well-being of all groups (patients, staff, family carers) is seen as fundamental to high-quality care. 41 They have used democratic and participatory processes involving patients, staff and sometimes family carers to articulate the patient’s needs and to shape the practice changes made.

The accompanying qualitative evaluations have provided important information about the processes of change and the factors enabling and inhibiting sustainable change. Some of these evaluations have reported concrete practice changes resulting from the intervention,36,47–50 while others report more variable success. 30,34 For instance, Dewar and Nolan49 and Dewar50 used appreciative inquiry and action research to involve older people, staff and relatives in developing compassionate relationship-centred care on an acute hospital ward. Methods used included participant observation, interviews, storytelling and group discussions. The findings indicated the value of appreciative caring conversations between staff, patients and relatives enabling all parties to discover ‘who people are and what matters to them’49,50 and ‘how people feel about their experience’49,50, with this knowledge enabling them to ‘work together to shape the way things are done’. 49 In the resulting model, Dewar and Nolan49 detail how older people, staff and relatives can work together to implement compassionate relationship-centred care. 49 In specifying ‘how people can work together to shape the way that things are done here’, Dewar50 identified a number of important conditions for staff to feel able to express emotions, share experiences and ideas with each other, consider others’ perspectives, take risks, use ‘curious questioning’ to examine situations and challenge existing practice, all identified as important actions to support the delivery of compassionate care. These conditions included transformational leadership, the level of support received from colleagues and senior staff, a shared set of principles for caring, open dialogue within the team and opportunities in which people had permission and space to reflect. These conditions echo the findings from other research as conditions at the team level that can support high-quality care. 26,27,51 Dewar50 reports how these conditions developed and how compassionate caring practices became embedded in the work of the team over the course of the year-long project, providing valuable evidence that change of this kind is possible.

However, Dewar’s project took place over the course of 1 year on an already high-performing ward with a strong leader. 50 The findings informed development work across a wider Leadership in Compassionate Care project implemented in a number of settings, but evaluation of the impact of these strategies elsewhere does not report the influence of the ward climate or programme length on outcomes, so evidence is lacking that such strategies can be universally effective regardless of work team context. 52 In a contrasting study to Dewar’s that explored the use of discovery interviews with older hospital patients as a way of improving dignity in care, Bridges and Tziggili30 found that ward teams required strong and consistent leadership and intense preparation before they were able to hear and respond to patient stories about care. Both organisations involved in this dignity project experienced significant delays in the progress of the project and limitations in its impact because of a lack of leadership at the ward level and a lack of preparedness of the ward teams to engage in responding positively to patient feedback. One ward team with a strong leader was able to successfully engage with the patient stories, but only after some months of team preparation. These findings indicate that, while some wards may be ready to engage in programmes, such as Dewar’s, others could benefit from a period of groundwork in which leadership and mutually supportive team practices are established.

The evaluative focus of these studies is the mechanisms for change used, particularly the democratic and participatory processes that involve patients, staff and sometimes family carers in articulating the patients’ needs and shaping the practice changes made. These qualitative accounts often provide a fuller picture of the interventions deployed than the studies reviewed below, and often include an analysis of the enablers and barriers to change. However, they do not examine in depth the process of implementation itself and so fail to systematically identify the contexts in which successful implementation is more likely or, where contexts are not receptive, how resources, relationships and norms in the wider system may need purposeful restructuring to support implementation and sustain longer-term change. 53,54 In addition, as would be expected with a qualitative approach, there is only weak objective evidence of effectiveness of the interventions deployed in these studies in relation to impact on patient outcomes.

Review methods

The remainder of this chapter reports a systematic review of studies that evaluate the effectiveness of interventions for compassionate nursing care, using the four key components of the compassion narrative identified in Chapter 1 to provide an operational definition. The objectives of the review were:

-

to systematically identify, analyse and describe studies that evaluate interventions for compassionate nursing care

-

to assess the descriptions of the interventions for compassionate care used, including design and delivery of the intervention and theoretical framework

-

to evaluate the nature and strength of evidence for the impact of interventions.

The review was conducted, guided by the Cochrane Collaboration methods55 to assure comprehensive search methods and systematic approaches to analysis of the review materials. Sections of this review report are reproduced or adapted with permission from Blomberg et al. 16 and with permission from Elsevier. © 2016 The Authors. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND 4.0 license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Search strategy

A systematic search for primary research evaluating compassionate care interventions was undertaken on CINAHL, MEDLINE and The Cochrane Library databases (including the Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effectiveness, CENTRAL register of controlled trials, Health Technology Assessment Database and Economic Evaluations Database) in June 2015. No date limits were applied to the searches conducted.

Terminology in relation to compassionate care is problematic and as noted above, there is no one agreed definition of compassionate care. Instead, a number of terms are used interchangeably and inconsistently across the health-care literature. A broad and inclusive approach was therefore used in preliminary searches to scope and map the field. As many terms relating to compassionate care were identified and used as possible, but with a focus on identifying studies that reflected one or more of the key components of compassionate care outlined above. Through this mapping, relevant keywords were identified (e.g. professional–patients relations, dignity, person-centred care, relationship centred care, empathy, compassion, caring, and emotional intelligence). These keywords were used in final searches. Terms related to compassion were combined (AND) with terms related to relevant methods and occupational groups. Relevant index terms were included, which varied across databases (see Appendix 1 for MEDLINE and CINAHL search strategies). Although no additional searches for unpublished (so called ‘grey’) literature were conducted, the sources used do index PhD theses (CINAHL) and some conference abstracts (CIHAHL, The Cochrane Library). Searches were limited to the English language.

Selection

An adapted PICO (population, intervention, comparison and outcome) framework was used to guide study selection. 56 We included primary research studies comparing the outcomes of an intervention designed to enhance compassionate nursing care (in any setting to any client group) with those of a control condition. Eligible designs were randomised controlled trials (including CRTs) or other quasi-random studies, interrupted time series and before-and-after studies (controlled or uncontrolled). Studies were excluded if they were focused exclusively on students, or if interventions were not directed at changing nursing staff behaviour.

The lack of conceptual clarity about compassion in the literature necessitated an inclusive approach to studies that were not necessarily labelled as addressing ‘compassion’. We developed selection criteria based on the four elements of the compassion narrative described above (moral attributes of a ‘compassionate’ nurse including empathy, nurses’ situational awareness of vulnerability and suffering, nurses’ responsive action aimed at relieving suffering and ensuring dignity, and nurses’ relational capacity) so that studies were included if they met one or both of the following criteria:

-

explicit goal of the intervention was stated as improving compassionate nursing care (or a closely related construct, i.e. dignity, relational care, emotional care) (through addressing nurses’ moral attributes, situational awareness, responsive action and/or relational capacity) and/or

-

primary outcomes that assessed or evaluated either nurses’ self-reports of compassion and/or ability to deliver compassionate care (moral attributes, relational capacity), and/or observed quality of interactions or other measure of compassion (situational awareness, responsive action), including patient reports of experienced compassion or a closely related construct.

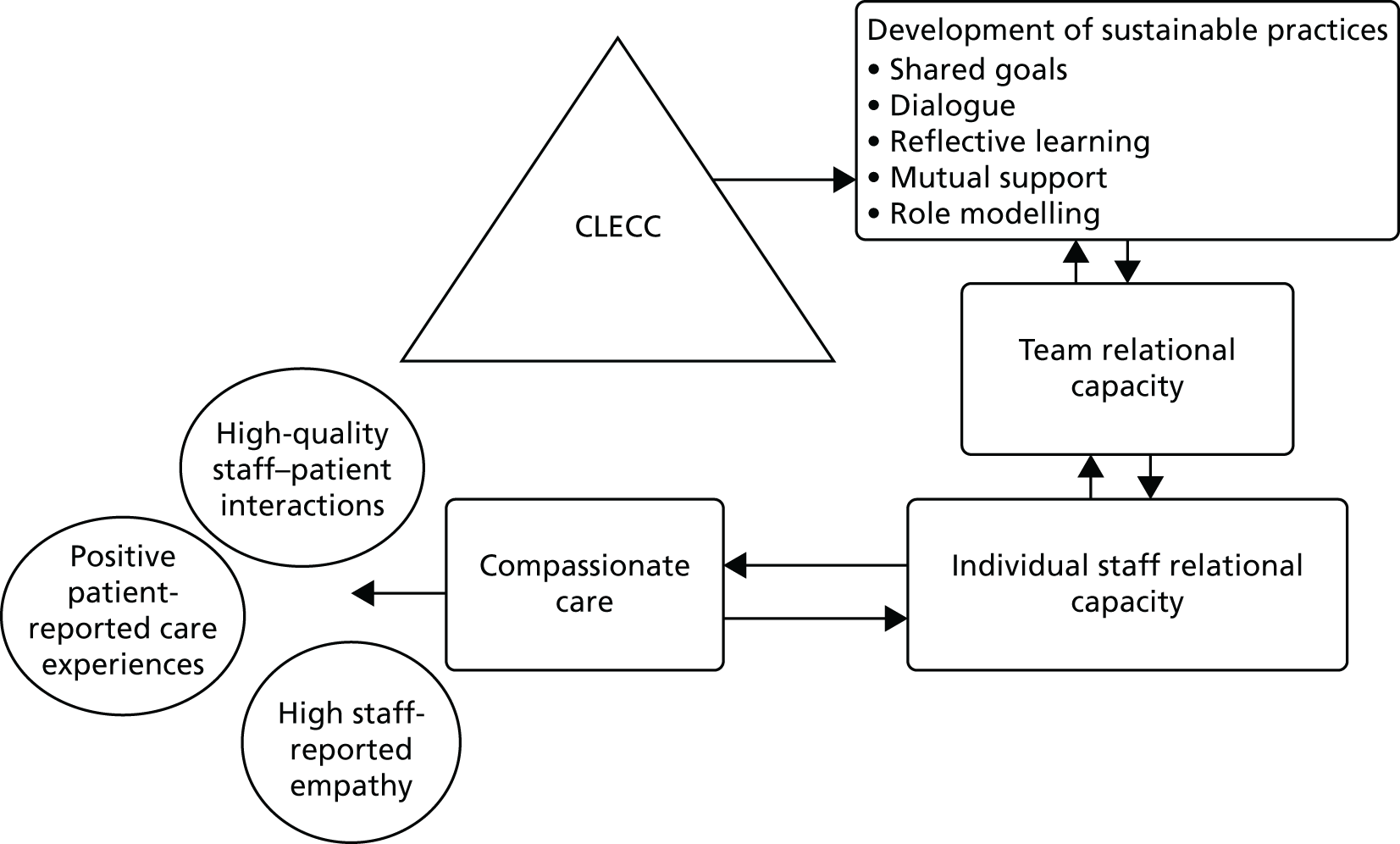

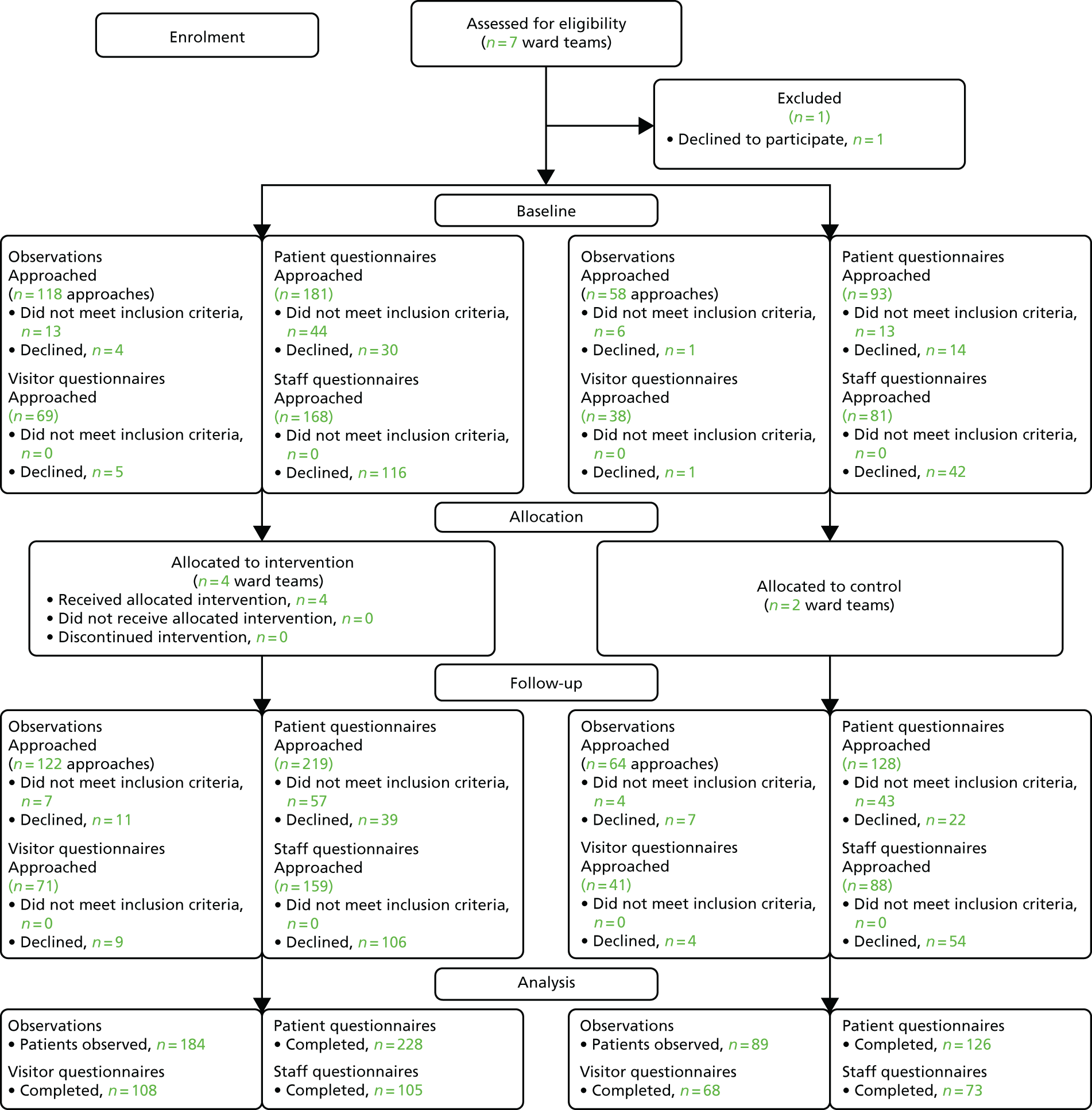

The titles and abstracts from the search were screened against the inclusion criteria independently by individual review team members (JB, KB, PG and YW; see systematic review team members listed in Acknowledgements ). During the screening process, frequent meetings were held by the research team in order to compare independent selections, resolve disagreements and make decisions. On independent rating (i.e. before discussion) reviewer pairs achieved between 80% and 90% agreement. In most cases of disagreement papers were excluded after discussion. Full-text papers were retrieved for all papers that screened positively in the first stage or about which a clear decision could not be taken (due to lack of information). Each full-text paper was reviewed independently by two team members followed by a decision to include or exclude in the final review. These reviews were followed by further team discussion to finalise inclusion into the data set. The reference lists of full-text papers included were scanned for further items. The search and selection process is summarised in the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) flow chart ( Figure 2 ). The number of duplicates removed was not recorded.

FIGURE 2.

Flow diagram for systematic review searches. Adapted from Blomberg et al. 16 with permission from Elsevier. © 2016 The Authors. This is an open access article under the CC BY-NC-ND license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/).

Quality assessment

In order to effectively represent the variation in study quality evident in findings from the preliminary mapping phase, and to properly reflect the strength of evidence, we undertook a simple grading in order to categorise the strength of the underlying design of studies we retrieved. 57 Because of heterogeneity of study design identified in early scoping work, a rating of strong, medium or weak quality was allocated to each study depending on where the study design sat on the hierarchy of evidence for effectiveness in tandem with an assessment of its design and execution. The method selected was in line with the GRADE (Grading of Recommendations Assessment, Development and Evaluation) system as used by Cochrane for rating evidence to guide a broad assessment of individual study quality. 57,58 Studies were rated as high quality where outcomes were compared between treatment (intervention) and control groups, where allocation to groups was random, and where equivalence between groups was explicitly demonstrated. Study designs included here were randomised controlled trials (RCTs) and CRTs which met these conditions. Studies were rated as medium quality where outcomes were compared between intervention and control groups, and where equivalence between groups was demonstrated, but where other methodological issues weakened the design, for instance non-random allocation to groups or small sample size. Study designs included here were CRTs with small numbers of clusters (for instance, n = 2) and controlled before-and-after studies with non-random allocation to groups. Uncontrolled before-and-after studies were rated as low quality as were other studies where other significant methodological shortfalls weakened claims of demonstrating effectiveness (e.g. controlled before-and-after studies where equivalence between groups is not demonstrated). These quality assessments were made by individual members of the review team, and checked with one other team member’s ratings until consistent ratings were achieved.

An evaluation of quality of description of the intervention was also performed for each included study. The material used as the basis for this evaluation was the information provided in the paper about the intervention in addition to further information about the intervention accessed from sources referenced within the original paper. We did not otherwise seek out information about the intervention, wishing to test the extent to which the original paper and its referenced sources provided sufficient information to enable the intervention to be replicated. Each study was analysed against the criteria for description of group-based behaviour change interventions devised by Borek et al. 59 This framework provides a checklist for assessing the reporting of behaviour change interventions against 26 criteria covering intervention design, intervention content, participants and facilitators. Intervention design features assessed included intervention development methods; setting; venue characteristics; number, length and frequency of group sessions; and period of time over which group meetings were held. Intervention content assessed included change mechanisms or theories of change, change techniques, session content, sequencing of sessions, and participants’ materials activities during sessions and methods for checking fidelity of delivery. Participant features assessed included group composition and size, methods for group allocation, and continuity of group membership. Facilitation features assessed included number of facilitators; facilitator characteristics and preparation including professional background, personal characteristics, training in intervention delivery and training in group facilitation; continuity of facilitator’s group assignment, facilitator’s materials and intended facilitation style. These assessments were conducted by one team member, and supplemented and refined in discussion with other team members.

Data analysis

A qualitative analysis was conducted across the different interventions reported to describe intervention types and contexts, and mechanisms for change. This analysis was conducted in smaller groups in the review team but further enriched through discussion of process and emerging findings among all group members.

Data were extracted for each study by Jackie Bridges and Karin Blomberg, including study design, sample and settings, summary details of intervention, outcomes and measurements, results and process issues. Results were tabulated and used to generate summary descriptions across key characteristics. Heterogeneity of studies in terms of interventions, methods and outcomes meant that a meta-analysis was not warranted, and so a more descriptive approach was merited. We considered the potential to pool studies using standard mean differences for measures, but this method requires that the instruments are measuring the same underlying construct and that the interventions have common mechanisms, but this was not clearly the case. The main intervention types were agreed through team discussion, as were key outcome types. Findings on effectiveness of individual interventions were plotted against key outcome types, and this was used as the basis for an analysis of evaluation strategies by intervention type and strength of evidence of effectiveness across intervention type and across the field as a whole. We recorded and tabulated both the direction of differences between groups (where reported) and statistical significance of differences. For controlled before and after studies, where there was no test of between group differences or groupby time interaction, this was categorised as a non-significant difference irrespective of a significant within-group difference. To inform the design of a future evaluation, we undertook a descriptive analysis of feasibility findings and other limitations identified in the medium- and high-quality studies we included.

Review findings

The review findings are presented here to address each of the review objectives in turn. First, we describe study characteristics to give an overview of studies that evaluate interventions for compassionate care. Second, we present an assessment of the quality of reporting of the interventions in the included studies, including their theoretical foundations. Third, we present evidence of effectiveness of the interventions in the included studies and analysis of the quality of that evidence.

Study characteristics

The final data set comprised 24 studies reporting 25 interventions. Twenty-two studies were published in journals60–81 and a further two were doctoral theses. 82,83 Three types of intervention were identified. Staff training interventions (n = 10) focused on the development of new skills and knowledge in nursing staff, such as a training course in empathic skills communication. Care model interventions (n = 9) focused on the introduction of a new care model to a service, such as person-centred care. Nurse support interventions (n = 6) focused on improving nursing staff support and well-being through, for instance, the provision of clinical supervision.

Reports reflect a range of study settings including hospital (n = 14),60,61,63,64,67,68,73,74,76,77,79,81–83 care/nursing homes (n = 6),65,66,69–72 other community settings (n = 3)62,75,78 and one study that used a range of health and social care settings (n = 1). 80 All but one of the staff training studies was conducted in a hospital setting, and six out of eight care model interventions were conducted in care home settings. Nurse support intervention studies were conducted in hospital settings (n = 3), district nursing services (n = 1), hospice at home (n = 1) and outpatient oncology service (n = 1). Eleven studies were conducted in the USA, with the other studies conducted in a range of other countries mostly in Europe but also including Australia, Canada, China and Turkey.

Study participants included nurses, nurse managers, patients and relatives. To evaluate the effect of the interventions a range of measurements was used, mainly self-reported instruments, but the effect was also proxy rated by researchers and using instruments based on researcher assessments of verbal communication and interaction. The outcomes measured in the studies varied widely, but could be classified into three types: nurse-based, quality-of-care and patient-based outcomes.

A table for each intervention type providing summary individual study characteristics and findings can be found in Appendix 2 .

Quality of intervention reporting

Three types of intervention were identified: staff training, care model and nurse support. Interventions varied considerably in the extent to which they drew on an explicit theoretical foundation. Staff training interventions comprised training on verbal interactions, communication, communicating about spirituality and spiritual care, and empathy. Only four staff training interventions in the included studies had an explicit theoretical base. These were solution-focused brief therapy,60 relationship-based care model/caring theories,61 reminiscence theory and adult learning theory,83 and the Tibetan Buddhist tradition. 62 Some interventions drew on definitions of particular concepts, such as empathy63,64,82 and caring behaviours. 81 Other studies lacked an explicit theoretical foundation, referring only to results from previous research studies.

By contrast, all interventions introducing and testing a new care model were underpinned by an explicit framework. Most used theories or models developed in caring and nursing, except for one study using the International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health 84 as the basis for an intervention to promote patient-centred communication with those living with aphasia/communication impairments. 65 Frameworks emphasised the person-centred care/environment/nursing,66–68 the relationship between nurses and patients69–71 or dignity in care. 72

Nurse support interventions were based on reducing compassion fatigue, burnout and/or secondary traumatic stress;73,74 and/or bolstering personal resources, such as compassion satisfaction, resiliency, empathy or sense of coherence. 73–75 Three were based on mindfulness theory. 76–78

Reviewer ratings of the quality of intervention reporting in each study against each item in the Borek et al. 59 frameworkfor description of group-based behaviour change interventions are displayed in Tables 2 and 3 . As is evident, the reporting of the interventions varied across all intervention types but was generally weak, with no intervention reports meeting all of the criteria deemed necessary for full intervention reporting. The design and the content of the interventions tended to be better described than details of the participants and the facilitators of the interventions. Overall compliance for intervention design reporting was 52% of criteria (shown in Table 3 row labelled ‘average % compliance by aspect of reporting’). The intervention design item with highest compliance (inclusion of details of the length of training sessions) was included in 73% (n = 16) of the 22 studies applicable here. The lowest was a specification of venue characteristics (n = 4, 17%).

| Intervention type | Study (first author and year) | Intervention | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Design | Content | ||||||||||||||

| Intervention source or development methods | General setting | Venue characteristics | Total number of group sessions | Length of group sessions | Frequency of group sessions | Duration of the intervention | Change mechanism or theories of change | Change techniques | Session content | Sequencing of sessions | Participants’ materials | Activities during the sessions | Methods for checking fidelity of delivery | ||

| Training | Ançel 200663 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N |

| Boscart 200960 | N | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | |

| Glembocki 201061 | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | |

| La Monica 198764 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | |

| Langewitz 201079 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | |

| Puentes 199583 | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | |

| Searcy 199082 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | |

| Taylor 200980 | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | NA | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | |

| Wasner 200562 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | |

| Yeakel 200381 | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | |

| Care model | Brown Wilson 201369 | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N |

| Chenoweth 201466 | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | |

| Finnema 200170 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | |

| Ho 201672 | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | |

| McCance 200967 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| McGilton 200371 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | |

| McGilton 201165 | N | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | |

| Pipe 201068 | N | Y | Y | NA | NA | NA | N | Y | N | NA | NA | Y | NA | N | |

| Nurse support | Flarity 201373 | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N |

| Gauthier 201576 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | |

| Horner 201477 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | Y | N | |

| Palmer 201078 | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | |

| Pålsson 199675 | N | Y | N | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | Y | N | Y | N | |

| Potter 201374 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | |

| Compliance (%) | 42 | 67 | 17 | 59 | 73 | 55 | 54 | 71 | 46 | 87 | 39 | 33 | 70 | 4 | |

| Average compliance by aspect of reporting (%) | 52 | 50 | |||||||||||||

| Intervention type | Study (first author and year) | Intervention | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Participants | Facilitators | Compliance (%) | Average compliance by intervention type (%) | ||||||||||||

| Group composition | Methods for group allocation | Continuity of participants’ group membership | Group size | Number of facilitators | Continuity of facilitators’ group assignment | Facilitators’ professional background | Facilitators’ personal characteristics | Facilitators’ training in intervention delivery | Facilitators’ training in group facilitation | Facilitators’ materials | Intended facilitation style | ||||

| Training | Ançel 200663 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | Y | 58 | 45 |

| Boscart 200960 | Y | NA | NA | NA | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | 57 | ||

| Glembocki 201061 | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 42 | ||

| La Monica 198764 | Y | N | Y | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | 42 | ||

| Langewitz 201079 | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | 50 | ||

| Puentes 199583 | Y | N | NA | NA | N | NA | N | N | N | N | Y | Y | 57 | ||

| Searcy 199082 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | 50 | ||

| Taylor 200980 | Y | NA | NA | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 50 | ||

| Wasner 200562 | Y | NA | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 40 | ||

| Yeakel 200381 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 12 | ||

| Care model | Brown Wilson 201369 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | Y | 38 | 33 |

| Chenoweth 201466 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 27 | ||

| Finnema 200170 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 35 | ||

| Ho 201672 | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | 27 | ||

| McCance 200967 | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 8 | ||

| McGilton 200371 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | 62 | ||

| McGilton 201165 | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | 35 | ||

| Pipe 201068 | N | NA | N | N | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | NA | 36 | ||

| Nurse support | Flarity 201373 | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 42 | 46 |

| Gauthier 201576 | Y | Y | N | N | Y | Y | Y | N | N | N | N | N | 65 | ||

| Horner 201477 | Y | N | N | N | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | 35 | ||

| Palmer 201078 | Y | N | N | Y | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | N | 12 | ||

| Pålsson 199675 | Y | Y | Y | Y | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 62 | ||

| Potter 201374 | Y | N | N | N | Y | N | Y | N | Y | N | N | N | 58 | ||

| Compliance (%) | 88 | 30 | 14 | 18 | 45 | 14 | 55 | 5 | 32 | 5 | 18 | 23 | |||

| Average compliance by aspect of reporting (%) | 37 | 29 | |||||||||||||

For intervention content, highest compliance was reported for session content (n = 20 of the 21 applicable studies, 87%) and lowest for participants’ materials (n = 8, 33%). Overall compliance for this aspect of intervention reporting was 50% of criteria. For reporting of participants, highest compliance was for description of group composition (n = 21, 88%) and lowest for continuity of participants’ group membership (n = 3, 14% of 21 applicable studies). Overall compliance for this aspect of intervention reporting was 37% of criteria. For reporting of facilitators, highest compliance was for reporting facilitators’ professional background (n = 12, 55% of 22 applicable studies) and lowest was for facilitators’ personal characteristics and training in-group facilitation (both n = 1, 5% of 22 applicable studies). Overall compliance for this aspect of intervention reporting was 25% of criteria. On average, individual study compliance with the criteria was 42%, ranging from 8% to 65%. Of intervention types, care model interventions tended to be less well described than other types (average of 33% compliance).

Evidence of effectiveness

This section presents findings on the quality of evidence of effectiveness of the interventions in the included studies. Overall, methodological quality was low. Most studies either did not randomise to the groups and/or did not demonstrate equivalence between groups, weakening confidence in the findings. Only two studies were assessed as high quality and four as medium. The remaining 18 studies were assessed as low quality. Most studies (n = 16) were uncontrolled before-and-after studies. Four studies were before-and-after studies with separate intervention and control groups. 71,75,77,82 Four studies used a randomised controlled design. Three used a cluster randomised trial design, with clustering at unit or institutional level. 64,66,70 A further study was controlled but only included a post-test measure. 83

Of the 24 studies, only eight studies included more than 100 participants. The largest sample included 115 nurses and 656 patients in an evaluation of an empathy-training programme. 64 The smallest sample included nine nurses in an evaluation of mindfulness based cognitive therapy for district nurses working with women with newly diagnosed breast cancer. 78 The number of clusters in controlled studies ranged from two to 38. Of the studies with experimental or quasi-experimental design,64,66,70,71,75,82 just one66 reported powering of sample size, but was not explicit about which outcome measure was the primary one used for these calculations.

Table 4 provides an overview of results from the individual studies against the range of outcomes used. Eighteen different types of outcomes were reported. For simplicity and brevity results for multiple measures using the same instrument or different instruments measuring same phenomena have been grouped together and treated as one. Across all studies and all outcome types results for 67 outcomes are reported. Further information on effect sizes is displayed in Appendix 2 (see Tables 41–43 ).

| Study (first author and year) | Study quality | Outcome type | |||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nurse | Quality of care | Patient | |||||||||||||||||

| Empathy | Compassion | Burnout | Stress | Mindfulness | Job satisfaction | Caring | Attitude | Other well-being | Quality of interactions | Quality of relationship | Patient centredness | Continuity | Quality of care | Satisfaction/experience | Behavioural (agitation) | Quality of life | Mood/well-being | ||

| Training intervention | |||||||||||||||||||

| La Monica 198764 | Medium | – | – | ▲ | |||||||||||||||

| Searcy 199082 | Medium | – | – | – | |||||||||||||||

| Ançel 200663 | Low | ▲ | |||||||||||||||||

| Boscart 200960 | Low | ▲ | |||||||||||||||||

| Glembocki 201061 | Low | ▲ | |||||||||||||||||

| Langewitz 201079 | Low | ▲ | |||||||||||||||||

| Puentes 199583 | Low | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||||||||||||

| Taylor 200980 | Low | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||||||||||||

| Wasner 200562 | Low | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | |||||||||||||

| Yeakel 200381 | Low | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||||||||||||

| Care model intervention | |||||||||||||||||||

| aChenoweth 2014 (single)66 | High | – | ▲ | △ | △ | ||||||||||||||

| aChenoweth 2014 (combined)66 | High | ▲ | ▽ | △ | △ | ||||||||||||||

| Finnema 200170 | High | ▲ | |||||||||||||||||

| McGilton 200371 | Medium | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||||||||||||

| Brown Wilson 201369 | Low | △ | △ | △ | △ | ||||||||||||||

| Ho 201672 | Low | ▲ | |||||||||||||||||

| McCance 200967 | Low | ▲ | ▲ | ||||||||||||||||

| McGilton 201165 | Low | ▲ | ▲ | △ | ▽ | ||||||||||||||

| Pipe 201068 | Low | ▲ | |||||||||||||||||

| Nurse support intervention | |||||||||||||||||||

| bPålsson 199675 | Medium | – | – | – | |||||||||||||||

| Flarity 201373 | Low | ▲ | ▲ | ▲ | |||||||||||||||

| Gauthier 201576 | Low | △ | – | ▲ | △ | △ | |||||||||||||

| Horner 201477 | Low | – | – | – | – | △ | |||||||||||||

| Palmer 201078 | Low | △ | △ | △ | |||||||||||||||

| Potter 201374 | Low | △ | △ | ▲ | – | ||||||||||||||

Studies of similar intervention types tended to use similar outcome types. Nurse support intervention studies primarily measured nurse-based outcomes. No nurse support studies used quality-of-care outcomes, and just one study used patient-based outcomes. In contrast, care model intervention studies primarily used outcomes related to quality-of-care and patient-based outcomes, but use of nurse outcomes was less common. Training intervention studies used the widest range of outcome types. Although the majority used nurse-based outcomes a small number drew on quality-of-care and patient outcomes.

Nineteen studies (79%) reported a significant positive difference in one or more outcomes (i.e. a beneficial effect of the compassionate care intervention). Only five (21%) of the 24 studies reported no significant difference in any of the outcome types measured. Of the 67 outcome types assessed across all studies, 32 (48%) showed significant positive effects for the intervention, with a further 18 (27%) showing positive but non-significant results. There were no significant negative differences and only three non-significant negative results. Patient outcomes were less likely to show significant differences, with only 5 out of 17 (29%) showing statistically significant differences.

Studies of low methodological quality were more likely to report outcomes in favour of the intervention, with low methodological quality studies reporting a mean of 92% of outcomes in favour of the intervention (significant + non-significant positives), whereas higher-quality (medium, high) studies report 55% of outcomes in favour of the intervention. Although an average of 76% of outcomes reported in studies of training interventions showed a statistically significant benefit, only 21% of outcomes for nurse support interventions were significant. Crucially, no intervention has been evaluated more than once.

Effects on patient-based outcomes

Six care model intervention studies reported patient-based outcomes. Of these, three showed statistically significant effects on a patient-based outcome. Of these, one was rated as high quality. In their CRT with 38 nursing homes, Chenoweth et al. 66 reported that the person-centred care intervention had a significant positive effect on reducing patient agitation, but the combined intervention (person-centred care plus person-centred environment) reported in the same study showed a non-significant effect of increasing patient agitation. This study fared poorly in terms of reporting of intervention description, meeting only 27% of criteria.

Three training intervention studies reported patient-based outcomes and, of these, two showed a significant positive effect. One medium-quality study reported significant positive effects on patient anxiety64 and one low-quality study reported a non-significant positive difference in patient satisfaction. 81 A low-quality nurse support intervention study reported a non-significant improvement in patient satisfaction. 77

Effects on quality-of-care outcomes

Four60,79,81,82 training intervention and five65–67,70,71 care model intervention studies (one of which66 reported two interventions) examined effects on quality-of-care outcomes. Of these, eight60,65–67,70,71,79,81 reported a statistically significant improvement in one or more outcomes. The combined person-centred care model intervention reported by Chenoweth et al. 66 was associated with a significant improvement in quality of interactions, but, although this finding is from a high-quality study, conclusions are tempered by the lack of intervention description noted above. In a CRT rated as high quality,70 the authors reported a significant change in one dimension of quality of care following implementation of emotion-oriented care in nursing home settings, but the intervention description met only 35% of the criteria. A medium-quality evaluation of a relationship-enhancing programme of care in nursing homes71 reported significant improvements in relational care, care providers’ relational behaviour and continuity of care. A medium-quality evaluation of empathy training for hospital nurses82 found no difference in interpersonal support. Other improvements in quality-of-care outcomes were reported in a range of low-quality studies. 60,65,67,79,81

Effects on nurse-based outcomes

Seven61–64,80,83 training, six73–78 nurse support and three65,67,69 care model intervention studies examined effects on nurse-based outcomes and, of these, 1061–63,65,73,74,76,80,83,98 reported a significant improvement associated with the intervention. All of these 10 studies were rated as low quality. Three medium-quality studies64,75,82 investigated nurse-based outcomes but none showed significant differences. No high-quality studies reported on nurse-based outcomes.

Feasibility findings

Findings from our analysis of feasibility issues and limitations documented in the reports of high and medium-quality studies (n = 6) are summarised here. The included studies were either experimental in the form of a cluster RCT or quasi-experimental with before-and-after measurements of intervention and control groups, but no randomisation to groups. Papers varied in the feasibility findings they reported and in the limitations identified but all were able to identify where improvements could be made in future research of this kind.

Two studies64,82 in this subset were conducted in a hospital setting, both single-site hospital US settings. La Monica et al. 64 conducted a cluster RCT in four cancer units (two medical and two surgical) to determine the impact of a nurse empathy training programme on patient outcomes (anxiety, depression, hostility, satisfaction with care) and nurse outcomes (nurse empathy). The study was not focused on older people, and patients too ill or confused to complete the questionnaires were excluded. Baseline data were gathered over a 4-week period, followed by a 4-week empathy training delivery period, followed by a 4-week follow-up assessment period. La Monica et al. 64 reported that patients were not admitted for long enough to take part in both assessment periods of the study. Patient participation rate was reported to be 73% with reasons for non-participation including not feeling well enough, having a conflict with a treatment or personal schedule, being reluctant to rate the nurse, and generally not being interested. The research team also identified a number of issues with the outcome measures involving rating nurse empathy and satisfaction with care. The team noted that patients consistently rated nurses’ empathy higher than nurses rated their own empathy, and speculated that it may be psychologically threatening for patients to rate nurses and nursing care, particularly while still in need of care. 64 In addition, at baseline and follow-up in both experimental groups, nurse- and patient-rated empathy scores were close to maximum, implying a ceiling effect.

Searcy82 conducted a before-and-after study with an intervention group (one ward) and a control group (one ward) to determine the impact of an empathy education programme for hospital nursing staff on patient satisfaction with care, including perceptions of interpersonal support. Baseline data were gathered over a 6-month period, followed by a 2-week training period (consisting of two 1-hour sessions), followed by a 6-month follow-up assessment period. The patient survey was mailed 1 week after discharge to all patients discharged from the two participating units. All patients were adults and no exclusion criteria, such as dementia, were reported. 82 Survey response rate was reported as approximately 25%. Searcy82 reported that baseline ratings were high, implying a ceiling effect to the chosen measure, and also found that older patients rated higher satisfaction than younger patients.