Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 14/194/20. The contractual start date was in April 2016. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in March 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

At the time of receiving funding for this project, Jo Rycroft-Malone was the Director of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme and a member of the NIHR Journals Library Board. Christopher Burton was a member of the HSDR Commissioning Board during the project funding stage.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Burton et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Ensuring patient safety and the delivery of good-quality care within the NHS in the UK is a political and societal imperative. Effective staffing levels are associated with improved patient outcomes. 1 The Francis report highlighted the detrimental impacts of low staffing within the Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust. 2 Further reviews into quality and safety within NHS England set out the requirements for appropriate levels of staffing and the need for transparency of reporting and clear pathways for action where deficits occur. 3,4 Ensuring the right staff, with the right skills, in the right place was an action area in the nursing, midwifery and care staff vision for health Compassion in Practice,5 with expectations for getting staffing right set out by the National Quality Board (NQB) framework in 2013. 6 This was updated in 2016,7 following the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE)’s staffing guidelines in adult inpatient and maternity settings8,9 and the Carter report,10 which called for standardisation in the approaches to managing staffing deployment and the recommendation of care hours per patient day (CHPPD) for consistency of recording and evaluating data.

Workforce planning and deployment tools and technologies (WPTs) are available to support NHS managers in their decision-making and oversight of staffing. These technologies generally employ top-down (e.g. benchmarking), bottom-up (e.g. modelling) or consensus approaches, which are reliant on judgement. 11 Compassion in Practice5 and the NQB guidance7 both refer to the importance of using evidence-based workforce tools for sensitive workforce measures and indicators of quality, safety and productivity, such as the Safer Nursing Care tool,12 the integrated Patient Acuity Monitoring Systems, HealthRoster, SafeCare (Allocate) and the Establishment Genie tool,13 which are all endorsed by NICE. The importance of developing local good-quality dashboards, which provide real-time staffing-related data, is also emphasised. 7,10 Lord Carter noted that digital systems, such as electronic rostering systems (e-rosters) and electronic staff records, are underinvested in. 10 He recommended that cultural change and communication plans are utilised to resolve underlying process or policy issues related to integrating WPTs within organisations. 10 In addition, WPTs need to be used in conjunction with the application of professional judgement, to interpret data, take account of context and patient needs and make informed decisions on day-to-day skill mix requirements. 7 The implementation of WPTs is therefore shaped through the capabilities, capacities and local knowledge of NHS managers. WPTs can provide good-quality data on the nursing workforce, which is vital for planning and deployment;14 however, there are many challenges.

Nurse staffing is an area of high cost in the NHS, reported as being £18.8B in 2014–15,15 particularly with the high demand for nursing and the accompanying increasing agency care costs since the Francis report. 10 Nurse staffing shortages are usually cyclical; 11 however, the current situation appears to be more entrenched, hampered by economic crisis, austerity and barriers to migration. 16 Potentially, recruitment may be further inhibited with the approaching exit of the UK from the European Union. The Health Foundation highlights how one in three new nurse registrations in 2013–14 were of nurses from European Union countries. 17 In addition, the workforce is ageing, bringing the prospect of further losses as a result of retirement rates. 18 The loss of the bursary in England for student education may further affect the already high attrition rates, with a 23% drop in university applications for 2017. 19 This crisis in staffing is set against the backdrop of increasing demands being placed on the NHS and changing patient and rising public expectations. 20

Matching staffing resources and patient needs

Workforce planning and deployment tools and technologies can support NHS managers to match nursing staff to patient requirement, in order to facilitate safe care. Safety is one dimension of good professional practice that is inextricably linked to good-quality care. 21

Having sufficient staff has an intuitive appeal for a positive impact on quality, and evidence does suggest that appropriate staffing is linked to good-quality patient care. 22 This is underpinned by the findings of Ball et al. 23 that 74% of registered nurses (RNs) reported care being left undone on their last shift, which was halved when the RN cared for six or fewer patients, compared with those who cared for 10 or more patients. Some of the evidence indicates that patient outcomes are compromised when there is a reduction in nurse-to-patient ratios, with adverse outcomes in nurse-sensitive indicators. 24,25 Having lower levels of RNs does adversely affect various quality outcomes, for example medication errors and wound infections. 24 Trinier26 noted a statistically significant association between nursing workload hours and patient care errors in paediatric critical care; evidence also suggests that lower staffing levels in the emergency department are associated with patients leaving without being seen and reduced care time. 27 The literature review of 35 studies by Griffiths et al. 28 found mixed evidence on RN staffing numbers for hospital-acquired infections and pressure ulcers, but clear evidence on the positive impact of staffing numbers for reducing falls and length of stay. However the authors commented that, as the analysis in these studies was mainly cross-sectional, no causal inference can be drawn. 28 An evidence review on nurse staffing levels, quality and outcomes of care in NHS hospitals concluded that lower nurse staffing levels are associated with worse patient outcomes in general acute wards and some patient groups; however, the identification of a threshold for safe staffing was difficult, with significant differences noted only when comparisons were made between the best-staffed wards and the worst-staffed wards. 29

Clinical areas with higher nurse staffing levels demonstrate lower patient mortality rates. 25,28,30,31 A systematic review by Kane et al. 25 found that the death rate decreased by 1.98% for every additional total nurse hour per patient day [95% confidence interval (CI) 0.96% to 3%], although this did not significantly change the mortality rate. The effect size for every additional full-time equivalent of a RN per patient day was far greater in surgical patients; the relative risk reduction in mortality was 16% for surgical patients compared with 9% for patients in the intensive care unit (ICU). A further study also found that an increase in nursing workload increased the likelihood of patient mortality within 30 days of admission by 7% [odds ratio (OR) = 1.068%, 95% CI 1.031% to 1.106%]. 32 In their systematic review of 50 studies, Kitson et al. 22 affirmed a clinical and statistical association between increased registered nurse staffing resources and better patient outcomes.

A diluted skill mix may compromise quality outcomes. Kitson et al. 22 suggest that increased RN numbers compared with increased numbers of less-qualified staff decrease the number of adverse events. A further study concluded that a richer RN skill mix may reduce the number of several types of adverse event, including failure to rescue. 33 Griffiths et al. 34 found that lower numbers of health-care support worker (HCSW) staffing were associated with lower mortality rates (risk ratio 0.95, 95% CI 0.91 to 1.00; p = 0.0). Within the Australian context, investigations on nursing care hours per day have not addressed skill mix issues;35 although McGillis Hall et al. 24 found that fewer RNs in the skill mix used more nursing hours. Furthermore, Ball et al. 36 found no impact of HCSW staffing on care left undone in England, and this trend was also noted in Sweden, with little effect being found from HCSW staffing on missed nursing care compared with increasing RN numbers. 23 Although this study did note the contextual difference, with 31% of direct care being provided by English nurses compared with 19% being provided by Swedish nurses, Ball et al. 23 concluded that:

If missed care is regarded as an inverse measure of productivity, it is unlikely that substitution would be an efficient approach to reducing it because the marginal gains from increased RN staffing are so much higher than for assistants.

Ball et al. 23

The Australian Nursing Federation goes further, highlighting that catastrophic and expensive problems can accrue from reducing the proportions of the most highly educated nurses in health-care settings. 37

Griffiths et al. 1 highlighted that, although there are plans in England to increase the number of unregistered support workers, research does not support HCSW staffing as a substitute for RNs. In England, the new associate nurse role may have an impact on skill mix, although its effect has yet to be evaluated. NHS England advises ‘temperature checks’ to assess any changes in RN contact time and their impact on patients, with changes in skill mix being one indicator of this. 38 Certainly, WPTs are a means of determining staffing and skill mix levels and the impact of these on patient outcomes.

Although there appears to be convincing evidence for the positive effects of RN levels and skill mix on patient care quality and safety outcomes, Griffiths et al. 1 highlight that there is a lack of high-quality studies on outcomes in relation to staffing. Furthermore, evidence suggests that nursing sensitivity indicators that are used to measure quality outcomes lack consistency, and variability in the measurement of unfinished care can have an adverse impact on the transferability of findings. 39–41 Kitson et al. 22 recommended the development of standardised metrics. Studies often focus on negative outcomes or adverse events (e.g. falls) rather than positive issues or process measures, such as adherence to care pathways or communication. 39 In addition, there may be discrepancies between staffing data and real-time staffing. 1 However, it is important to note that WPTs can play an important role in the standardisation of staffing data for effective evaluation and benchmarking.

Although patient outcomes appear to be linked to levels of nurse staffing, the evidence may fail to account for confounding variables, such as medical care, geography, the use of temporary staff and other factors. The presence of medical staff appears to be an important factor. Griffiths et al. 34 found that RN levels were significantly associated with reduced mortality rates for medical patients; there was also a significant positive relationship between patient outcomes and the numbers of doctors, although the levels of HCSW staffing had no benefits for patient mortality. 34 The availability of medical and nursing staff increased survival rates in critical care. 30 Furthermore, skill mix may be related not only to RN levels, but also to the qualities and capabilities of a nurse and their educational levels and work patterns. This information can be available for the NHS manager through WPTs. In addition, WPTs can convey data on temporary staffing. This may be the organisation’s own employees (bank) or external staff (agency), or those doing overtime. Float nurses move between clinical areas to cover staffing shortfalls. Temporary nurses may not have the skills and knowledge required for the assigned clinical area, but poor perceptions of agency nurses in relation to good-quality care may be unfounded. 42,43 Dall’Ora and Griffiths44 found mixed evidence for temporary staff, overtime and floating, with little evidence being specific to UK settings; some evidence suggests possible risks with temporary staffing, whereas other studies suggest that temporary staffing may compensate for nurse deficiencies, although effectiveness may be compromised and this would come at a higher cost. 44 Float pools may decrease overtime costs and reduce agency costs, but the economic evidence is limited. 44

Nurses’ education levels and hours worked also appear to influence the quality of care. Higher proportions of nurses with a bachelor’s degree appear to reduce the effect of low nurse staffing levels on clinical care left undone;45 similarly, graduate nurses improve patient outcomes (this was found in surgical patients aged > 50 years, in 300 settings in nine European countries). 32 However, an increased use of overtime is associated with adverse patient outcomes. 44 An evidence review on 12-hour shifts found an established link between adverse patient and staff well-being and increased daily and weekly working hours. 46 A recent study also found that nurses associated shifts of > 12 hours with poor ratings of the quality care and higher ratings of care left undone. 47 WPTs can establish ‘rules’ for working hours and highlight infringements to help the NHS manager deploy effectively.

The care environment and safe staffing

Organisational characteristics, the clinical environment, patient requirements and models of staffing appear to influence safe staffing and patient outcomes. Nurse staffing can have different effects in different hospital settings, so the effect of an additional nursing hour may have dissimilar effects. 48 Patient and hospital characteristics, including the hospital’s commitment to the quality of medical care, are likely to be contributing factors to patient outcomes, with surgical patients being the most sensitive to nurse staffing and the most likely to have improved outcomes as staffing levels and skill mix improve. 48 Ball et al. 23 note the differences in the RN role, which varies with context, commenting that:

A complex set of inter-related factors are associated with care left undone.

Ball et al. 23

Organisational factors also seem to influence the impact of staffing levels. A review of management approaches to staffing found that the presence of supervisory roles and training improved both patient and staff outcomes, as did organisational factors associated with Magnet programmes. 49 Magnet status is associated with transformational leadership, empowerment, professional practice, innovations and improvements. 49 Certainly, strong and clear clinical leadership is an expectation for high-quality care in relation to staffing. 7 A systematic review on models for staffing hospital units found that the introduction of specialist nurses and support may improve patient outcomes and certain models of nursing care, such as primary care and self-scheduling, may improve staff-related outcomes. 50 The impact of WPTs may also be contingent on organisational factors, which may have an impact on their implementation.

Contextual factors, such as hospital location, have an impact on staffing; after controlling for patient care unit type, hospital complexity and unit bed size, Kane et al. 25 found that hospitals located in areas with a lower RN supply employ fewer RNs and more second-level RNs. 25 RN staffing levels decrease as the supply of RNs in the surrounding geographic area decreases. 51 Hurst52 compared patient outcomes with ward layout, finding that the level of direct patient care was higher in Nightingale wards (for which there were higher quality scores), but that it was ‘racetrack’ wards, with a central nursing station, that were the most effective for nurse and patient outcomes. Bay wards could generate heavier workloads, with peaks and troughs of staff presence. 52

The evidence on the impact of nurse staffing has a focus on acute adult care, with evidence for safe staffing in other areas still emerging. The evidence on staffing levels and outcomes for mental health nursing is contradictory and complicated by the day-to-day allocation of staff resources to wards with more seriously ill patients. 53 A review on safe staffing and mental health further highlighted that there were no robust empirical studies to underpin policy for the complex issue of safe staffing in this area. 54 Likewise, recent reviews have also concluded that there is no substantive evidence to guide staffing in learning disabilities or caseload management in the community;55,56 safe staffing in care homes also lacks robust evidence. 57

Safe staffing and cost-effectiveness

Reports and guidance highlight the importance of making the best use of resources for financial sustainability, through efficient staff deployment and minimising agency use. 7,10 WPTs have an important role in budget management, through the potential articulation of staffing costs and spending requirements. Despite the potential for decreased costs resulting from improved patient outcomes, there appears to be cost implications for a richer RN mix. Wage growth for RNs in California, after mandated staffing levels, increased more than in other states, although the impact of the nurse shortage was proposed as one alternative explanation for the increase. 58 One review analysed four cost–benefit studies and five cost-effectiveness studies and found mixed results, and so was unable to draw conclusions around whether or not changing staffing levels and/or skill mix was a cost-effective intervention. 59 Griffiths et al. 28 reviewed five non-UK studies, finding inconsistencies in outcome and nurse staffing measures, with some of the secondary data analysis hampering the conclusions. One American study that was reviewed modelled scenarios to demonstrate that raising the number of RN nursing hours without increasing the total number of nursing hours may lead to net savings as a result of improved patient outcomes. 60 However, Griffiths et al. 28 noted that increasing nursing staffing costs may not be offset by better patient or system outcomes and concluded that the studies reviewed were of limited value for decision-making in the NHS.

Staff satisfaction

NHS Providers indicate that growing demand in NHS England and staff shortages mean that NHS roles are becoming more pressured, with staff being increasingly overworked and stressed. After surveying chief executives, it found that 55% indicated that they were worried that their trusts did not have the right numbers, quality and mix of staff to deliver high-quality care, and that most expect the situation to deteriorate. 61 Given that nurses constitute the majority of the workforce, this has implications for nurse well-being and, importantly, organisational recruitment and retention. When nurses are more satisfied with their working environment, they appear to be less likely to leave, which has a positive impact on staffing levels. Nurse satisfaction appears to be linked to perceptions of safe staffing levels; acute care hospital nurses link higher staffing levels to better patient safety. 62 Nurses also report being able to act as safe practitioners on the days when there are lower patient-to-nurse ratios (p = 0.011). 63

Conversely, when nursing staff are dissatisfied, they are more likely to leave organisations or have more absences from work, which further contributes to existing staffing deficits. The RN4CAST study surveyed nurses from 10 countries and found that nurse dissatisfaction and an intention to leave their job were linked to perceptions of inadequate nurse staffing, high patient-to-nurse ratios and quality and safety issues. 64 Staff dissatisfaction was also apparent when nurses felt that staffing levels were insufficient to produce good-quality care and that there was a lack of opportunity for their development. 65 A low level of occupational satisfaction has been linked to the rationing of care (because of limited resources, such as time, staffing or skill mix); this affects the perceptions of the quality of care that nurses could offer patients. 66 Poor perceptions of the workplace culture were also found to create dissatisfaction, particularly when associated with negative attitudes towards nursing management. 67

Workforce flexibility is important; WPTs can facilitate the identification of staffing resources across the organisation, enabling NHS managers to use their professional judgement to move staff when there are staffing shortages. When nurses are required to float to other areas, this may cause them dissatisfaction. Nurses can perceive that they lack the appropriate knowledge and skills for effective patient care. 68 Dziuba-Ellis68 argued that nurses should be competent to float to similar clinical areas and should be supported to do so. Shift patterns and allocation may also be another source of nurse dissatisfaction. Dall’Ora and Griffiths46 found evidence of risks to staff well-being with working long hours, both daily and weekly, with potentially reduced efficiency on longer shifts. They conclude that, although some staff members prefer 12-hour shifts, the net effect on nurse retention is unclear and there is no economic evidence of the consequences of 12-hour shifts. They recommended that staff should be encouraged to take planned breaks and suggested that fixed shift patterns may reduce risks and improve patient safety.

Increased work pressure from staff shortages, sickness and absences has been described as a downwards spiral, as the remaining nurses come under more pressure and are more likely to leave. 11 The intention of nurses to leave is particularly linked to burnout. 64 Retention and recruitment strategies to ensure nurse satisfaction, linked to career development, are vital components to improve nurse staffing. 7 Increasing staffing levels can have a positive effect; when nurses’ workloads adhered to the California-mandated ratios, the level of nurses’ job dissatisfaction was lower and they reported consistently better quality of care. 69 The creation of supportive environments and the engagement of nursing staff are recommended. 67 Nursing staff had more positive perceptions when they worked in areas that enabled participation in hospital affairs, with good leadership and nurse–physician relationships; positive perceptions of the work environment were linked to a 30% reduction in the intention to leave (OR = 0.57, 95% CI 0.53 to 0.63). 64 It is important that RNs work in an environment in which they feel safe and confident when providing care. 62 Acute organisations with Magnet characteristics were associated with supportive environments and had increased levels of nurse satisfaction and retention compared with other organisations. 49,70 However, financial constraints have the potential for worsening nurses’ level of dissatisfaction, linked to pay. Between 2010–11 and 2020–21, the pay of NHS staff will have declined in real terms by at least 12%. 17 In addition, the Health Foundation points to a lack of a coherent workforce strategy with regard to the integration of funding plans and service delivery models, instead citing piecemeal policy-making on pay and the use of the nursing workforce. 17

Patient and public experience

NHS Providers are required to actively seek the views of patients, carers and staff to determine the impact of their staffing policies, in order to understand the links between staffing and patient experiences and outcomes. 7 Nurse staffing levels and skill mix do appear to have an impact on patient experience, particularly in the hospital setting. Patient care experience is reported to be better in hospitals with a higher level of nurse staffing and a more favourable work environment, in which less clinical care is left undone. 45 Higher levels of rationing care decreased the odds of patient satisfaction (OR = 0.276, 95% CI 0.113 to 0.675). 71 Recent high-profile failures linked to staffing may have implications for patients’ perceptions of their safety associated with safe staffing. The inability to summon staff, owing to a lack of staff presence, made patients feel unsafe in the clinical environment; this was linked to perceptions that the area was short-staffed. 72 Evidence also suggests that the public is concerned about the dilution of skills; for example, the Patients Association in response to the Safe Nurse Staffing Levels (Wales) Bill highlighted concerns about an imbalance between the substitution of health-care assistants for registered nurses in care delivery. 73

Openness has been a major theme of recent policy reform in England, following a lack of transparency and secrecy in recent high-profile failures. This requirement for openness links to staffing levels. 74 Trusts have a legal duty of candour under the Health and Social Care Act regulations75 and are required by NHS England and the Care Quality Commission to display actual staff levels against planned levels outside wards. 76 Staffing levels can therefore be compared between organisations and publicly scrutinised, and WPTs can provide the staffing data required for comparison. However, there is concern that the methods of comparison, such as league tables, may focus on appearance rather than improvement. 74 It is unclear how staffing data will have an impact on public confidence and patient experience.

Legislation, policy and guidance

Safe staffing is a legislative requirement under the Health and Social Care Act regulations75 and one of the fundamental standards of quality and safety monitored and reported on by the Care Quality Commission. However, there is a lack of consensus about whether legislation, mandates within policy or guidance are the best means of ensuring safe staffing levels. Even within the devolved UK nations, there are different approaches; to date, only in Wales has legislation been adopted, with the Nurse Staffing Levels (Wales) Act 2016. 77 Scotland aims to enact similar legislation. 78

A key point of contention is in mandating nurse-to-patient ratios. The Royal College of Nursing has called for mandated staffing levels. 79 However, although Griffiths et al. 1 acknowledge that many sources of evidence suggest that policies are effective in increasing staffing levels, they also state that:

It is difficult to make direct conclusions about the impact of mandatory staffing policies because of the complex inter relationship between changes in staffing levels and system wide changes including patient case mix and other safety initiatives.

Griffiths et al. 1

Compliance with mandated nurse-to-patient ratios in California did appear to have some impact on preventing adverse patient events. 80 However, the Californian nurse-to-patient ratios did not account for nurse competency, and mandated levels also brought unanticipated effects, such as the increased length of emergency department waits, as nursing staff were called in when patient numbers increased. 80 It was suggested that the richer skill mix with mandated ratios reduced the level of appropriate task delegation to support workers. 80 However, there was no evidence that reductions in the number of support workers increased nurses’ workloads in California. 69 The increased use of agencies to fulfil legislative requirements has been found to affect care continuity, which may present an increased patient risk. 81 Furthermore, mandated nurse levels may increase agency costs. In England, since 2016, Monitor for the NHS Improvement programme has placed mandatory caps on agency pay, but evidence suggests that trusts are exceeding this cap. 82

Given the lack of clarity on mandated nurse-to-patient ratios, countries within the UK have explored other means of achieving evidence-based safe staffing through policy and guidance. NICE produced guidance on adult inpatient wards and midwifery. 8,9 The NQB and NHS Improvement 2016 guidance also focused on adult inpatient care. 83 Guidance on learning disabilities, mental health and adult community nursing services is in consultation. 84–86 Although NICE guidance on adult safe staffing8 identified that a threshold of more than eight patients per nurse was linked to increased patient risk, there was a recognition that no one nursing staff-to-patient ratio can be applied across the whole range of wards to assure patient safety.

Following Lord Carter’s recommendations,10 England has adopted nursing CHPPD to identify the number of staff required and staff availability in relation to the number of patients. It is calculated by adding RN hours to HCSW hours and dividing the total by every 24 hours of inpatient admissions; this is a more flexible approach to respond to patient demand in different settings, because, although an average of 9.1 hours of care is provided by RNs and HCSWs per patient day, this figure varies from 6.33 to 15.48 hours. 10 Similar approaches to nursing hours per day have been used in Western Australia, New Zealand and South Africa, with some success. 7 Kane et al. 25 found that this approach did reflect the average level of staffing across a 24-hour period, but did not reflect fluctuations in patient census and scheduling patterns in different shifts; in addition, it did not account for other nursing activities, such as meetings and administration. 25 Northern Ireland also adopted a non-prescriptive approach, with a focus on staffing ranges associated with specific environments, while allowing for a flexible approach to a range of factors, such as absence or sick leave. 87 Scotland uses the Nursing and Midwifery Workload and Workforce Planning Toolkit, which has evolved from a whole-systems approach to developing and testing nurse staffing tools, based on triangulation using professional judgement and local indicators of quality. 88 Wales is following a similar route to develop tools to support the implementation of the Nurse Staffing Levels (Wales) Act 2016. 77

The Health Foundation commented that the guidance in England is a relatively ‘light touch’ in comparison with developments in other countries. 89 In England, the NQB7 supports a triangulated approach to staffing decisions to ensure that the right staff with the right skills are at the right place and point in time. This approach is based on patients’ needs, acuity and risks, which should be monitored to provide appropriate judgements about delivering safe, sustainable and productive staffing. A core component of the expectation of having the right staff is evidence-based WPTs integrated with professional judgement and real-time information on skill mix, staff competencies and staff availability. NHS providers are required to display actual staffing levels against planned staffing levels outside wards, in addition to publishing data comparing actual staffing levels with planned staffing levels, with 6-monthly staffing establishment reviews. 76 Therefore, the accurate measurement of real-time and prospective staffing is essential; data will also be benchmarked against that of other organisations. WPTs are therefore central to the process of measurement, data transparency and decision-making for the achievement of safe staffing in the UK.

Workforce planning and deployment tools and technologies

Workforce planning and deployment tools and technologies can capture data for comparison and enable the transparency of resources and requirements, in addition to modelling solutions to enhance decisions on safe staffing. The Health Foundation indicated that multiple approaches have been used for determining staff levels in NHS trusts, some locally developed and others developed using proprietary systems or professional judgement; however, there has been no recent evaluation of the effectiveness of these approaches or practitioners’ perceptions of them. 90 Tools also need to be aligned with rostering and matched to staff availability in order to be effective. 90

The National Institute for Health and Care Excellence has endorsed staffing tools and recommends resources to support senior nurses to review, plan and budget staffing on adult inpatient wards. The NQB emphasised the need to have an agreed local quality dashboard to triangulate comparative data on staffing, skill mix and other quality metrics; this dashboard should have CHPPD. 7 WPTs can therefore provide data to contribute to benchmarking and the evaluation of organisational outcomes. However, Griffiths et al. 1 suggested that the evidence is unclear on the use of tools to match nurse staffing levels to individually assessed patient needs. Furthermore, the use of modelling technology to aid with the decision process and prediction of staffing need may also require further clarity; modelling studies on the floating of temporary staff to develop solutions have produced mixed results. 44

Most WPTs in NHS England are designed for use in acute care settings. Tools for community caseloads have been developed that are context specific, but their effectiveness is yet to be substantiated. 56 There is also a lack of evidence for the effectiveness of WPTs in learning disabilities and in care-home settings. 55,57 The Health Foundation suggests that more evidence is required on both the effectiveness and the use of tools. 90 They indicate that the fragmented evidence from the English NHS is able neither to provide a solid platform on which to base any universal approach to determining nurse staffing, nor even to indicate best practice in the use of available tools in many care settings. 90

Buchan et al. ,17 also for the Health Foundation, advocated the use of technology to support local decision-making, but emphasised that tools can be effective only if staff fully understand their use and are able to respond to live data; they linked this to empowering people to make staffing decisions, but highlighted the need for training and development. 17

Summary

In the wake of high-profile reviews of breakdowns in health-care quality and evidence that links nurse staffing with patient safety outcomes, delivering safe staffing is a political and professional imperative. A wide range of WPTs are available to support NHS managers to link staffing resources to patient and service demands. The application of these WPTs, in combination with professional judgement, appears to promote effective staffing, principally by providing predictions and rules about staffing requirements in relation to patient need. However, these are one part of a complex system of organisational and other work associated with delivering safe staffing. There are many influences on the system for good-quality care delivery and NHS managers have to make difficult decisions amid multiple demands within limited time frames. Understanding how managers can use WPTs successfully in this system, including the influences on implementation and the impacts on patients and staffing, is therefore an important area for research. This synthesis aims to summarise what is known about how WPTs can support NHS managers’ staffing work. Through ongoing stakeholder engagement, it will be ensured that what is known is contextualised within the systems and policy context shaping this issue within the NHS.

Review question and aims

This evidence synthesis has engaged stakeholders to produce an evidence-based realist programme theory that explains the successful implementation and impact of nursing WPTs by NHS managers. This programme theory will complement the evidence base about the validity and reliability of WPTs and guide the development of management training programmes and implementation.

The research question asked the following: ‘NHS managers’ use of workforce planning and deployment technologies and their impacts on nursing staffing and patient care: what works, for whom, how and in what circumstances?’

The main objectives of the study were to:

-

identify the different WPTs used to deploy the nursing workforce, paying attention to the ways in which these are assumed and observed to work

-

explore the range of observed impacts of these technologies in different health-care settings and other public services, paying attention to contingent factors

-

investigate ways that can help NHS managers to identify, deploy and evaluate the nursing workforce resource in order to have the greatest impact on patient care

-

generate actionable recommendations for management practice and organisational strategy

-

contribute to a wider understanding of the nature of the nursing workforce, nursing work and the quality of patient care.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

The methods used for the evidence synthesis drew on the team’s previous experience of realist synthesis89,91 and adhered to established realist principles and publication standards. 92,93 The synthesis followed four phases, but, unlike the linear process of the traditional systematic review, a realist synthesis adopts a more iterative process because it is theory driven. In this synthesis, as the programme theory emerged from the review of the literature and stakeholder involvement, the search process went back and forth to further develop and refine the programme theory. This meant that there were some intersecting elements within the four phases of the study. This chapter captures the iterative processes that guided the realist synthesis by offering detailed descriptions of the areas of evidence from stakeholders and literature and interview data. The Realist And Meta-narrative Evidence Syntheses: Evolving Standards (RAMESES) publication standards for realist review have been used to structure the report. 93

Stakeholder engagement, including patient and public involvement

Stakeholder engagement is integral in realist work. The realist synthesis approach is based on negotiation between stakeholders and reviewers to develop the programme theory of the area for review; as such, stakeholder engagement is a key component. 94 For this review, stakeholder engagement was designed to help the research team to elaborate on review context, inform the programme theory development and interpretation and advise on the dissemination of findings. The review team followed a recognised systematic approach to stakeholder identification to ensure that the most appropriate people were contributing to the synthesis. 95 Stakeholders comprised NHS managers, RNs and patient and public involvement (PPI); in addition, the review team referred to an advisory group.

The NHS managers contributed multiple perspectives on nurse staffing, as their roles included nurses at the strategic level, directors of nursing, lead nurses, matrons, ward managers and team leaders. Engagement with this group helped to illuminate key concepts within the system of nurse workforce planning and deployment and refine the development of programme theories. The group members also offered information on the use of WPTs. The study engaged with members of the public, patients and carers. One PPI representative had previous experience in realist synthesis. The impacts of this engagement included the development of the review’s theoretical territory, assessment of the relevance of the context–mechanism–outcome (CMO) threads from a patient perspective and the conceptualisation of impacts that are important to patients, family and carers.

The project advisory group included key senior strategic stakeholders. Many of these stakeholders held a remit for strategy and policy development and had high levels of experience in workforce planning design and delivery within nursing and other health-care spheres. Group membership represented key influential organisations; this included nurse representatives in government from some UK countries, representatives from unions and professional bodies, chief nurses from large health-care organisations and representatives from nurse educational bodies. Group membership also included non-nurse health-care professionals who had expertise in workforce planning, policy and strategy (see Appendix 1). The project advisory group met every 6 months to advise on current strategy, policy, evidence and developments in WPTs. This group received detailed information on the development and progress of the study and offered advice on the dissemination of findings.

Stakeholder engagement was embedded throughout the synthesis as follows:

-

Phase 1 –

-

Two co-production workshops with NHS managers.

-

Two PPI co-production workshops.

-

These workshops (1) sought to establish a detailed understanding of the essential elements surrounding the planning and deployment of nursing staff and (2) aimed to facilitate an understanding of the complex issues that NHS managers have to consider in order to make effective staffing decisions.

-

-

The advisory group meeting sought to expand on understanding of the planning and deployment of nursing staff from a broader, strategic perspective. This meeting guided the team’s understanding of the evidence base for WPTs.

-

Ten semistructured interviews with a purposive sample of NHS managers to expand on themes from co-production workshops and capture variations in workforce planning systems across organisational settings.

-

-

Phase 2 –

-

The Advisory group meeting facilitated prioritisation of programme theory areas and informed and guided the development of CMO configurations.

-

-

Phase 3 –

-

Wechat#WeNurses Twitter (Twitter, Inc., San Francisco, CA, USA; www.twitter.com) chat to gather nurse stakeholders’ perspectives.

-

Eleven think-aloud interviews to refine emerging programme theories.

-

A final advisory group meeting to refine the emerging programme theory and advise on the dissemination of findings in October 2017.

-

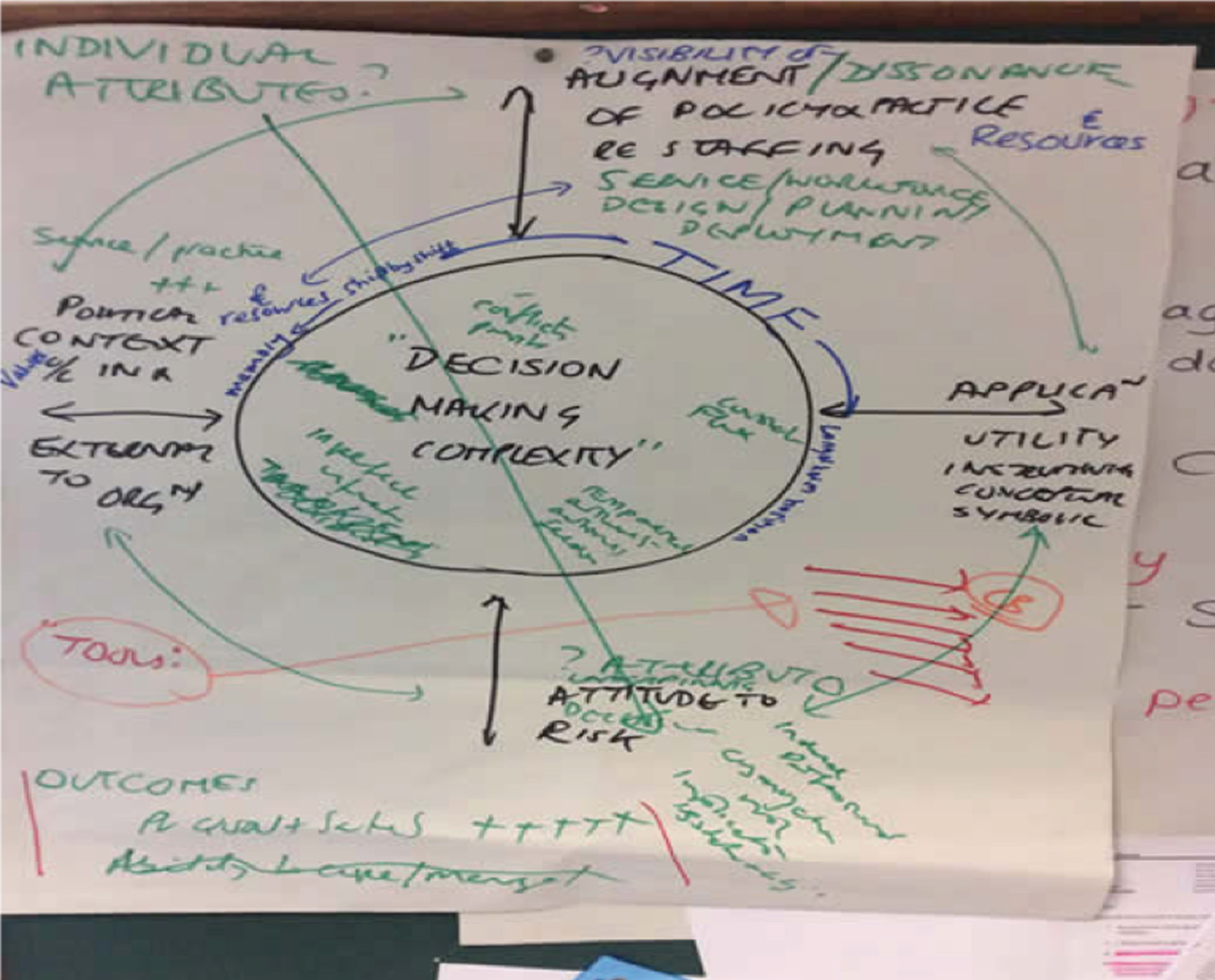

In addition, monthly project team meetings were held. Two PPI representatives accepted an invitation to join the project team, attended the monthly meetings and are co-authors of this report. Supplementary project team meetings were also held. In phase 1, the project team held a theory-building workshop to discuss the initial programme theories, based on the data gathered during the co-production workshops and the exploratory scope of the literature. Figure 1 illustrates the developmental process and formulation of ideas from this workshop. Additional workshops were held for data extraction, analysis and synthesis and to develop the CMO configurations.

FIGURE 1.

An output from the project team’s theory-building workshop.

Rationale for using realist synthesis

Realist synthesis methodology is a theory-driven approach that draws on a heterogeneous evidence base to establish whether or not interventions work, how, in what contexts and for whom. 94,96 It offers the potential to provide practical solutions to, and/or explanations about, challenging problems and issues.

The system of nurse workforce planning and deployment is dynamic and multifaceted, involving many components and influential stakeholders who often have differing, often conflicting, needs. Workforce planning and deployment occurs in health settings characterised by fluctuating demands and requirements; the implementation, use and impacts of nursing WPTs appear to be complex and contingent on organisational context and managers’ expertise. Adopting a realist synthesis approach enabled the consideration of additional contextual influences on the implementation and impact of WPTs at different levels within the health-care system.

Within this realist synthesis, the analytical task was to construct, test and refine a programme theory of causal explanations about what works about WPTs and how NHS managers can be supported to use them. These causal explanations are expressed as plausible hypotheses or relationships between CMOs to show how certain contexts have triggered mechanisms to generate an observed outcome pattern or not. Therefore, a realist synthesis produces recommendations; for example, in situations (context) a complex intervention modified in this way (mechanism), may be appropriate in achieving x, y, z (outcomes). 97 In this review, theory development work was undertaken in phases 1 and 2 to articulate theories about what aspects of WPTs work, for whom and the conditions that may make these successful.

The study was interested in identifying the full range of the potential impacts of WPTs, which may extend beyond health care. These impacts relate to evidence about workforce (e.g. staff satisfaction) and organisation theories (e.g. organisational learning). Impact was conceptualised as a continuum, ranging from conceptual to instrumental or direct impacts, and therefore from awareness, knowledge and understanding, attitudes and perceptions to changes in behaviour. 98

An initial overview of the theoretical territory was developed, drawing largely on seminal theories and key evidence in relation to workforce planning systems and implementation. This guided the scoping review of the evidence and consultation with stakeholders (Table 1). This theoretical territory provided a provisional (hypothetical) explanation of what works and the impact of WPTs by investigating the literature and evidence from separate but interlinked disciplines, around two theory areas: the elements of workforce planning systems and their implementation. This guided the iterative searches.

|

Workforce planning systems (Theoretical domains that may explain how systems work) |

Implementation (Theoretical domains that may explain how the implementation of systems may be related to impacts) |

|---|---|

|

The identification of patient needs and acuity99,100 The nature of nursing work101 Workforce planning strategies (supply- vs. needs-based)102,103 Contracting and rostering practices33,104–106 Deployment, skill mix and nursing workload tools11 |

Technology adoption109 Professional decision-making and judgement110 Organisational and other contextual influences – structural factors affecting the implementation of learning and practices111–113 Organisational learning and knowledge management114 |

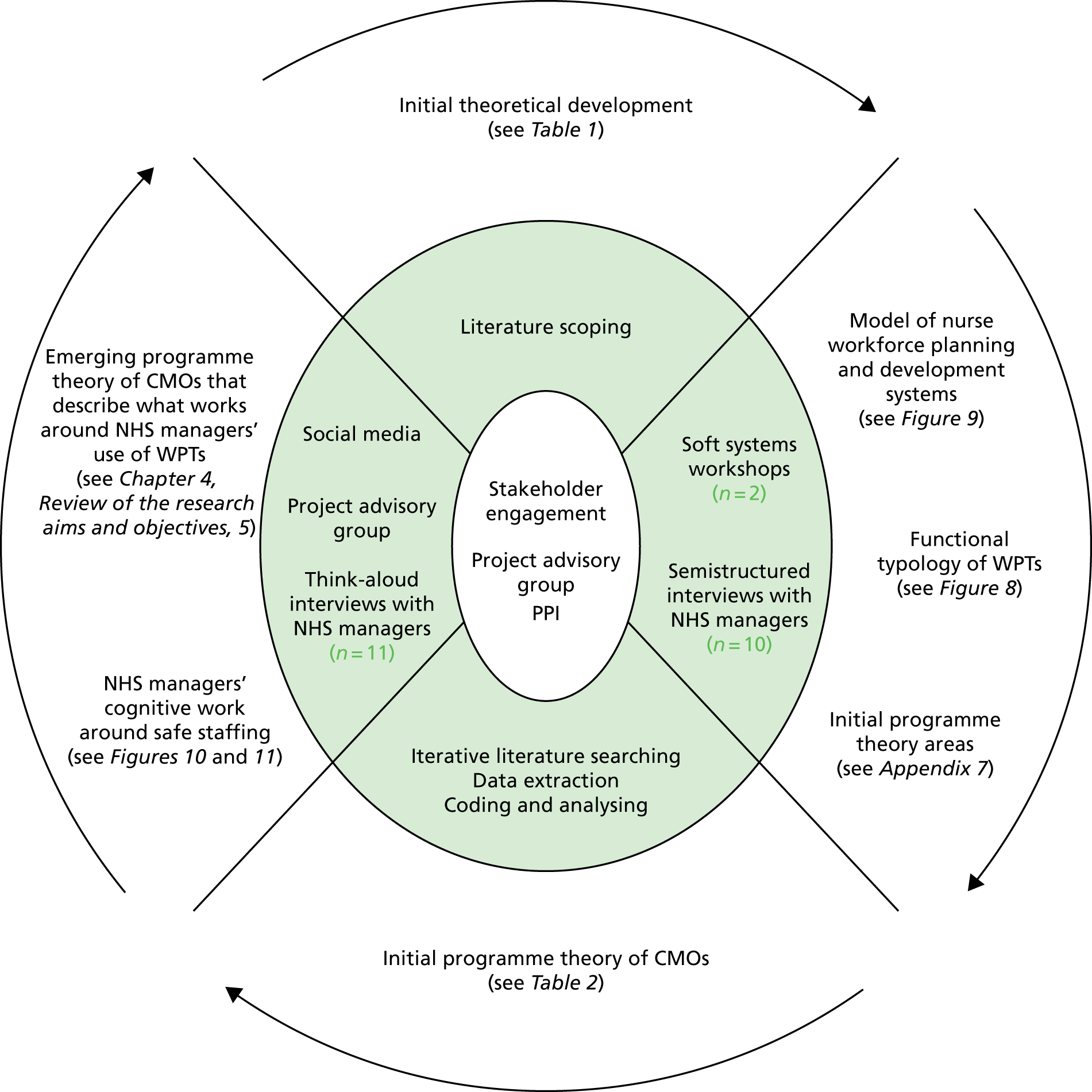

Programme theory development and refinement involved a number of interconnected processes (Figure 2). Figure 2 represents the centrality of stakeholder engagement throughout realist work, whereby stakeholders provided a sense check on the wider political, organisational and professional context of the synthesis, support for the interpretation of findings and advice on the dissemination and knowledge mobilisation activities. In this case, stakeholders included patient and public representatives who provided advice throughout the synthesis, concentrating particularly on the issues of disclosure of staffing to patients and families. Distributed around the core of stakeholder engagement are the methods that were adopted within the synthesis and their associated products. The methods are presented in more traditional sequential phases within this report, but in practice, there was considerable overlap between them.

FIGURE 2.

Synthesis map.

Phase 1: initial programme theory development

This was conducted from April 2016 to December 2016. Programme theory development (i.e. the hypotheses of what works for whom, how and in what context) is fundamental to realist synthesis. Using the theoretical territory as a basis, eight initial theory areas about ‘what works’ were developed with stakeholders through the co-production workshops, semistructured interviews, the advisory group engagement and the scope of the literature.

Initial scope of the literature

To guide the development of the initial programme theory, an exploration of the literature was conducted to help delineate how WPTs are supposed to work in particular contexts and to identify potential barriers to, and enablers of, their successful implementation. The study engaged with an information scientist (BH) with previous experience of realist synthesis, to help clarify the breadth of the resources available to support this synthesis. Scoping searches were conducted between May and September 2016. This scoping involved targeted searches of PubMed, MEDLINE and the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), a search for major reviews by The Cochrane Library and NICE and a search of the grey and allied literature included in key areas relevant to the expertise and networks of the research team (e.g. from UK mental health services). In addition, several health human resources and human resource management journals were searched. Further texts were gained from citation tracking. References were drawn on that were cited in the Royal College of Nursing guidance on safe nurse staffing levels in the UK and the Shelford Group Safer Nursing Care tool implementation guidance11,12 and a search was conducted for citations in identified articles via the Web of Science citation indices. Similarly, references were searched from an evidence review completed for NICE, Effectiveness of Management Approaches and Organisational Factors on Nurse Staffing Sensitive Outcomes;49 this resulted in the identification of six key articles that facilitated an understanding of the system complexity for this evidence synthesis. 118–123 Further scoping searches identified a further 11 sources of evidence from the literature. 124–134 Some of this literature was also identified in later targeted searches.

Conceptualising a model of nursing workforce planning and deployment

To illuminate the complexity of the contexts of the systems in which WPTs are used, soft systems methodology was used within the stakeholder co-production workshops. The format of the workshops, guided by soft systems methodology, was designed to understand the systems in which workforce deployment and planning operate through the co-production of a root definition. Soft systems methodology offers an epistemological approach for analysing complex, real-world issues, which may integrate multiple cognitive, social and cultural perspectives. 135 The methodology is appropriate for the examination of implementation challenges. 136 In addition, it is compatible with a realist approach for mapping complex programmes. 137 This approach accepts that issues that surround complex interventions and their implementation may be contested because of multiple stakeholder perspectives, which makes sense-making difficult. The relationship and synergy between people, systems, WPTs and resources around nurse workforce planning and deployment, can therefore be described as a soft, human adaptive system, which is open to differing perspectives and values about its purpose and impact. Data were explored using the six dimensions of a soft system (worldview, transformation, customers, owners, environment and actors), culminating in a narrative of the system of nurse workforce planning and deployment.

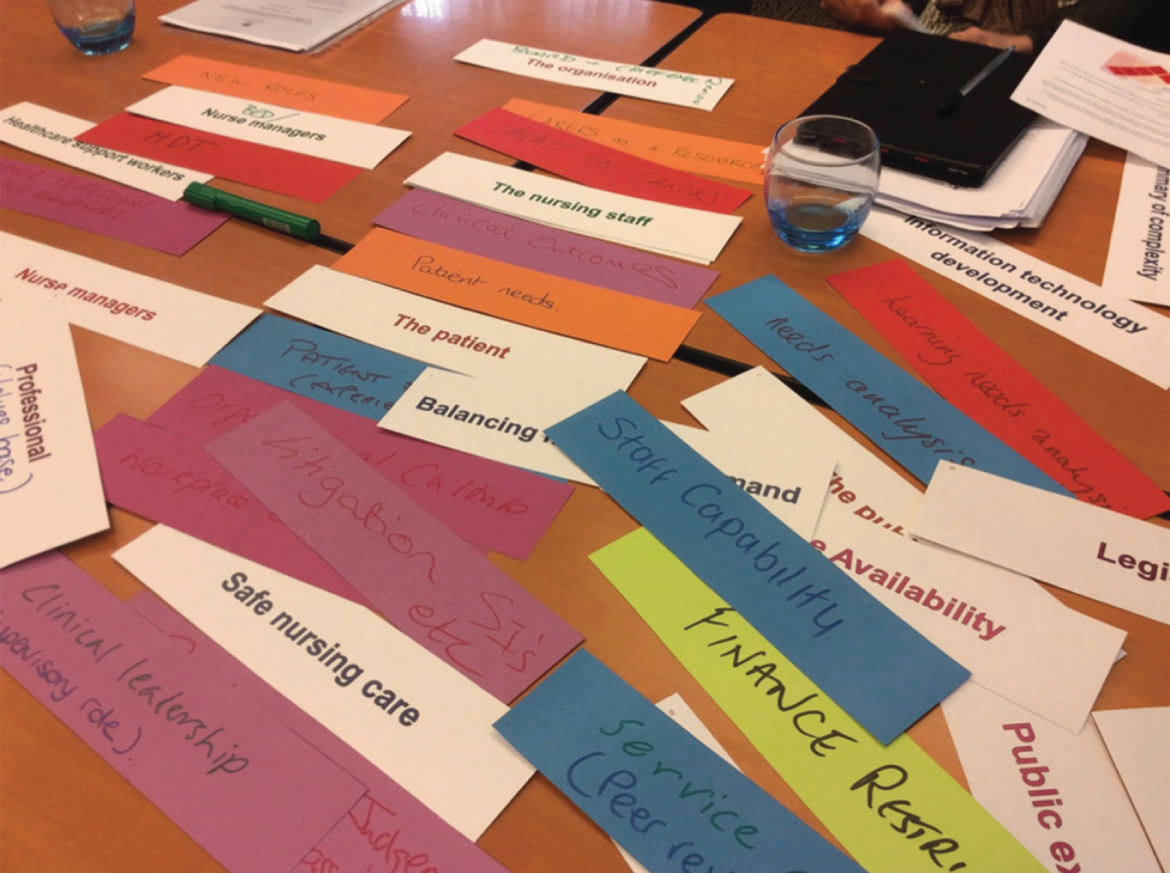

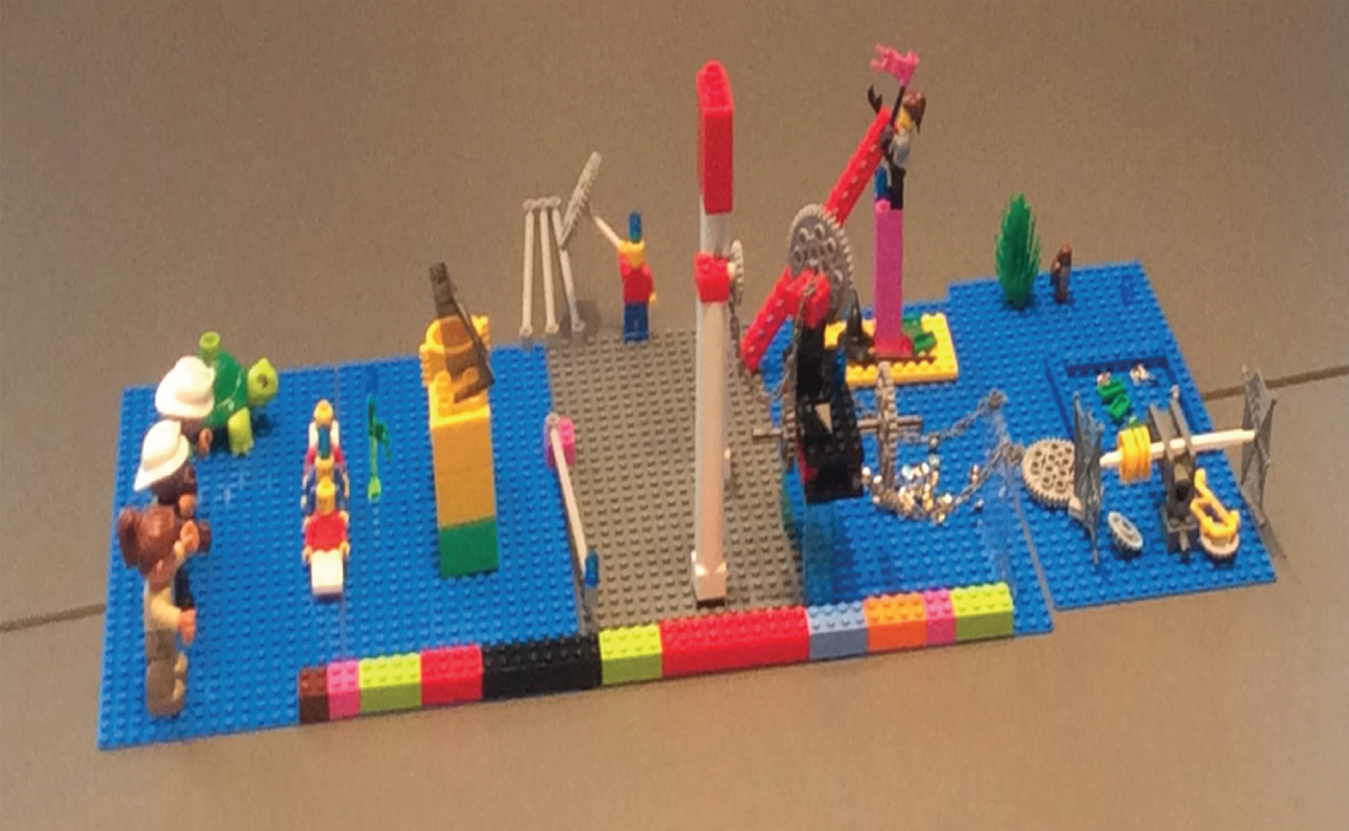

The two co-production workshops with NHS managers comprised a purposive sample of, in one case, 14 participants and, in the other, 17 participants from across NHS organisations and professional bodies within the UK, and combined a range of discussion and practical activities. Using techniques from LEGO® SERIOUS PLAY® (The LEGO Group, Billund, Denmark), individual models of the system of workforce planning and deployment of nurse staffing were constructed and important aspects from each individual model were then combined to create one overall collaborative nurse workforce planning and deployment model. Participants were required to offer explanatory accounts of the components they brought to the collaborative model; in this way, a root definition of the system was created that articulated multiple perspectives (see Appendix 2). Using the same technique, the initial PPI stakeholder groups (of seven participants) were asked to convey their ideas of what makes a good nurse manager (Figure 3). This knowledge contributed to the development of a root definition of a nurse workforce planning and deployment system. A second workshop explored the perceptions of staffing within the NHS. Seven PPI stakeholders participated and discussions centred on how staffing levels made visible by the organisation influence patients’ and their relatives’ perception of care, particularly when there are deficits (see Appendix 3).

FIGURE 3.

Patient and public involvement collaborative LEGO model of a ‘good’ nurse manager. This represents that nurse managers need to have good communication skills (represented by the bridge and chain) and take a high-level view of staffing needs. They should have compassion, courage and the leadership skills required for safe staffing. They need to value people, develop good ideas and remember the past (this is represented by being caught in the web).

Semistructured telephone interviews

Ten interviews were audio-recorded and built on the co-production workshops to explore variations in workforce planning systems across organisational settings and health services. The interview schedule consisted of 11 key themes, structured around the theory areas from the co-production workshops and the initial scoping review of the literature (see the interview material document at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1419420/#/). Several themes intended to build an understanding of how WPTs are assumed to work, the impact of WPTs in different health-care settings and their predictive reliability. Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes. Participants were recruited from NHS organisations from three sites, two of which were in large cities and one of which was in a smaller city within a rural area. Table 2 provides details on participants’ roles. An e-mail invitation to take part in the study was sent out to potential participants with a participant information sheet (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1419420/#/). Written consent was sought prior to participation (see www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1419420/#/). The data from the interviews further contributed to the emerging specifications of the systems of nurse workforce planning and deployment and a functional typology of WPTs.

| Participant | Role | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Ward Manager | Hospital |

| 2 | Assistant Director of Nursing | Hospital |

| 3 | Matron Surgical Wards | Hospital |

| 4 | Improvement Advisor (staffing) | Hospital and community |

| 5 | Corporate Matron (staffing) | Hospital |

| 6 | Ward Manager | Hospital |

| 7 | Lead Nurse | Community hospital |

| 8 | Lead Nurse | Hospital |

| 9 | Lead Nurse | Hospital |

| 10 | Matron | Hospital |

Identification of theory areas

Based on the information from the stakeholder work gathered in phase 1, a complex, multifaceted system of nurse workforce planning and deployment emerged with explanations of the role and functions of WPTs. From this, the project team identified eight theory areas for the main searches of this evidence synthesis; these were operationally defined (see Appendix 4). These theory areas comprised the elements described by stakeholders as having an important influence on NHS managers’ use of WPTs within the system of nurse workforce planning and deployment.

Phase 2: the searching processes

In phase 2, from September 2016 to August 2017, the searching process involved identifying evidence relevant to the programme theory. The aim of this process was to gather the most relevant evidence to support or contradict initial ideas within the programme theory. Adhering to the realist approach, the search strategy was broad and extensive and a number of iterative searches were designed as the understanding of the programme theory developed.

In the first instance, the searches targeted evidence specific to the nursing workforce across hospital, community and third-sector care in the context of UK-based and comparable health systems. It was theorised that there would be transferable lessons from other public services for which the challenges of workforce planning and workforce developments are similar. Later searches were conducted to test the impacts of WPTs in related service fields, for example, in social care and policing, in which there are comparable workforce planning requirements. We drew on the direct experience of the project team in the identification of programmes to implement WPTs within UK mental health services. These included the All Wales Mental Health Acuity Group Project Report138 of the piloting of an acuity tool in six health boards. In addition, snowballing techniques and citation searching (pearling) were used; expertise was also solicited from the project steering group and other key researchers and organisations, to ensure that evidence that might be relevant but not visible through traditional searching methods was not missed.

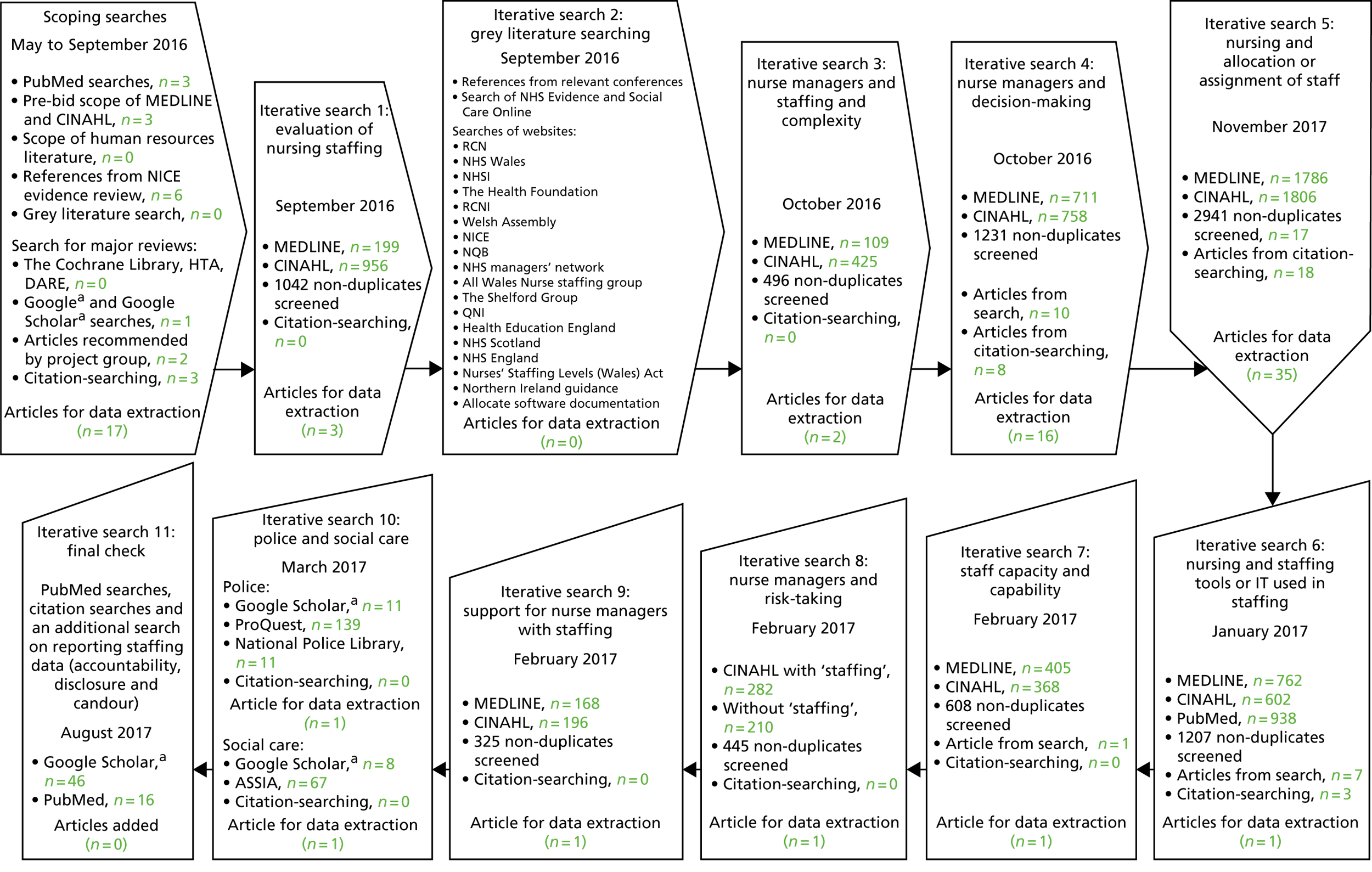

Purposive searches

In total, 11 iterative searches were conducted. These evolved as the programme theory emerged from the review of the literature (Figure 4). For each search, bibliographic databases that were relevant to the topic were selected, and searches were translated for each database to use relevant keywords and make use of available thesauri. Search terms were identified from early scoping work, theory development and stakeholder engagement, and were built on and developed iteratively as common terms were identified from the selected literature (see Appendix 5).

FIGURE 4.

The iterative search process selection and appraisal of documents. ASSIA, Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts; DARE, Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects; HTA, Health Technology Assessment; NHSI, National Health Service Improvement; QNI, Queen's Nursing Institute; RCNI, Royal College of Nursing, (RCNi) is a wholly owned subsidiary of the Royal College of Nursing. a, Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA.

During the early scoping searches, a broad range of databases were used including The Cochrane Library, NHS Centre for Reviews and Dissemination, the Database of Abstracts of Reviews of Effects, the Health Technology Assessment database, PubMed, MEDLINE via EBSCOhost (1950 to March 2017) and CINAHL. Later, the purposive searches on nursing managers’ use of workforce tools and staffing management concentrated on the use of the MEDLINE via EBSCOhost (1950 to March 2017), CINAHL and PubMed databases. Additional specific databases were added for the searches of social care staffing management and for the police sector.

Only one search limit was applied: a date limit of 1983 to the March 2017. In 1983, the NHS Management Inquiry was commissioned to evaluate methods of estimating staffing levels and the classification of workload analysis approaches. 139 Backward reference searching was used to identify any works of relevance to this study that were cited in the selected articles. Forward reference searching was used to identify any newer works of relevance to this study that cited the selected articles.

Initially, the study sought to identify any studies that evaluated the effectiveness of nursing staffing models in the UK (iterative search 1). As the programme theory developed, the literature searches were designed around the complexity of nurse staffing (iterative search 3), a number of searches focused on the nurse managers themselves and how they make decisions (iterative search 4) and take risks (iterative search 8) and the support available to them (iterative search 9). Iterative search 5 was designed to focus on the practicalities of allocating staff to staffing structures, and iterative search 6 was designed to gather evidence on the different tools and information technology (IT) used for staffing management. Iterative search 7 was designed to capture any evidence on how information about the capacity and capability of staff is considered when allocating shifts and planning a rota (see Appendix 6 for an example of a search strategy).

Iterative search 2 focused on the grey literature, such as workforce planning project reports relating to national and local initiatives and evaluative information about these initiatives that is held in the public domain. The project team searched examples of development programmes across multiple services (adult, mental health, learning disability and community) on the evaluation of the use of WPTs. The grey literature search also explored policy, evidence to government, NHS organisational strategies and the reports of workforce technology projects and programmes. None of the pieces of evidence identified in this search was included in the final synthesis; however, the review of the grey literature informed the team’s understanding of the system’s complexity and highlighted contextual influences on the implementation and impact of WPTs.

In order to investigate WPTs in use in the social care sector, a search was designed for the Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts database on the ProQuest platform. For evidence from the police sector, the National Police Library at the College of Policing was contacted and the librarian provided the team with some references from a search of their library catalogue. This was also supplemented with a search of Google Scholar (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and the databases available via the Bangor University ProQuest subscription.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

A systematic process developed by the team in a recently completed realist synthesis was followed to determining relevance. 89 Consistent with Pawson’s suggestion,94 the test for inclusion involved:

-

linkage with the programme theory and explanatory potential

-

discernible ‘nuggets’ of evidence within the source material

-

evidence of trustworthiness.

Reports of WPTs, such as workforce planning, workforce measurement, workforce management, patient acuity and dependency, staffing ratios, professional judgement and skill mix, were included. Evidence on settings was also searched, recognising the shifting patterns of health care and the importance of enabling patient flow and quality across systems of care. As the programme theory developed, a functional typology of WPTs used in safe staffing was developed to encompass tools that (1) help to summarise and aggregate information, (2) aid communication and (3) support standard setting and quality assessment (see Table 4).

In a realist synthesis, evidence is excluded only if it does not relate to, or inform the development of, the programme theory; however, in this review, evidence was not included that had limited transferability to the NHS, such as nursing workforce issues within low-income countries. Evidence was included only if it was generated from different international contexts in comparable health systems in high-income countries. Discrepancies in opinions on the relevance of evidence were resolved through discussion among the project team. Title sifting was cross-checked across four team members (SD, AJ, LW and AM). Levels of agreement among reviewers were scored for 10% of the total titles.

Data extraction, analysis and synthesis process

This aspect of the review process is resource intensive and is reliant on discussion and deliberation, including consultation with a wider group of stakeholders. In a realist evidence synthesis, bespoke data extraction forms are developed to guide the decision-making process for extraction. 94 Based on the initial programme theory of WPTs, a bespoke extraction form was developed, based on the eight theory areas, to interrogate the literature and data were extracted only if the evidence met the test of relevance for the programme theory (see Appendix 7). The theory areas and their sub-elements, specified within the data extraction form, were transposed into ATLAS.ti code manager version 7.5.10 (ATLAS.ti Scientific Software Development GmbH, Berlin, Germany). A total of 90 sources from the literature were entered into ATLAS.ti for coding. Additional codes were also identified (see Appendix 8). The coding of a selection of included data was validated by three members of the project team (SD, CRB and AJ). Three sources of evidence were not able to be coded; therefore, the final selection was 87 sources of literature. This incorporated many types of published evidence, including qualitative interviews, quasi-experimental studies, surveys, evaluations and audits, case studies, frameworks and guidance, theoretical conceptualisations, literature and evidence reviews (see Appendix 9). Commentary evidence was included because it was felt that it was credible and critical to theory development, as it was provided by those directly engaging with WPTs in the field. Following data extraction, the eight theory areas guided the data analysis process. Within each of the eight theory areas and their coded sub-elements, the data were organised into themes (see Appendix 10). Appendix 11 offers an example of the thematic development within theory area 6.

The relationships between CMOs were analysed from the extracted information. This involved organising extracted data into evidence tables to represent the different bodies of literature. Using abduction and retroduction across the evidence themes,140 WPTs were reconceptualised from different angles to identify the underlying structures and emerging demiregularities (patterns) around plausible CMOs, seeking confirming and disconfirming evidence. Linking these demiregularities to develop the initial programme theory provided an explanation of the implementation, utilisation and impacts of nurse WPTs. The resultant seven hypotheses act as synthesised statements of findings around which a narrative can be developed that summarises the nature of the CMO links and the specific characteristics of the evidence underpinning them.

Phase 3: testing and refining the initial programme theory

Advisory group

The initial CMOs were developed by two members of the project team (CRB and LW) and were reviewed extensively in an advisory group meeting in May 2017. This process sought to clarify, develop and refine the CMOs.

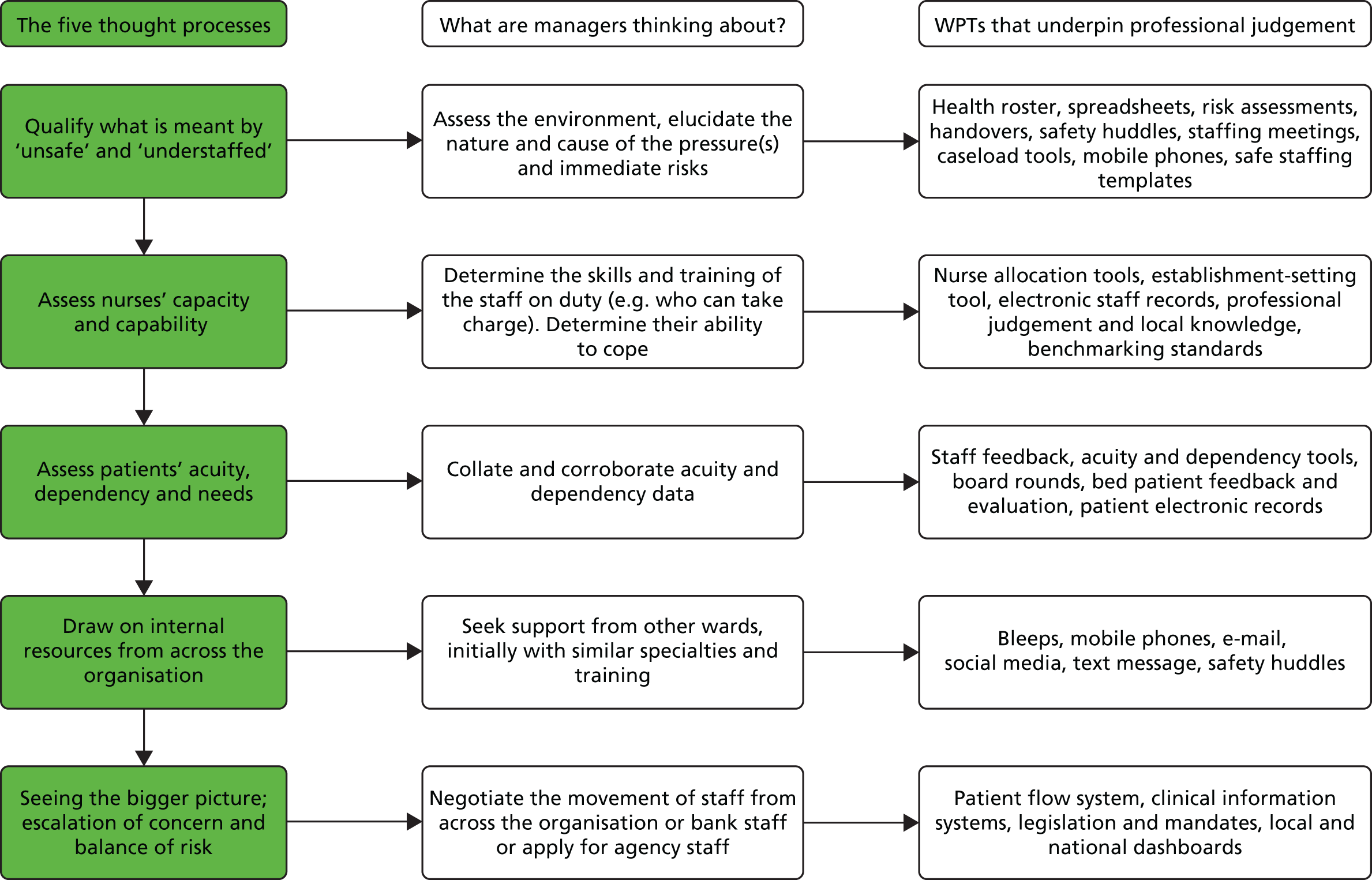

Think-aloud interviews

To further enhance the trustworthiness of the resultant hypotheses and to facilitate the development of a final review narrative, 11 audio-recorded telephone interviews were conducted with NHS managers between July and August 2017. Participants were purposively sampled to obtain different perspectives that were relevant to the review question, including different national contexts and service settings (Table 3). Participants were recruited from four sites (three large cities and one smaller city surrounding a rural area). Interviews lasted approximately 30 minutes. In addition to exploring the synthesis findings, the interviews included a think-aloud technique, whereby NHS managers were given information and asked to describe their ‘thinking work’ around a nurse staffing scenario, validated by the project advisory group (see the interview material document at www.journalslibrary.nihr.ac.uk/programmes/hsdr/1419420/#/). This is a recognised technique for determining the information behind decision-making and judgements,141 which was considered to be a key focus for the operationalisation of the emerging programme theory. The technique illuminates the cues, priorities and strategies that are being considered at a particular point in time. It can identify the rationale and inference being drawn in that moment and can be used to test hypotheses;142 specifically, it was used to test and refine the seven CMOs.

| Participant | Role | Setting |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Matron | Hospital |

| 2 | Specialist Practitioner | Community |

| 3 | Matron | Community |

| 4 | Ward Manager | Hospital |

| 5 | Unit Manager | Hospital |

| 6 | Team Leader | Community |

| 7 | Team Leader | Community |

| 8 | Corporate Matron | Hospital |

| 9 | Matron | Hospital |

| 10 | Matron | Hospital |

| 11 | Unit Manager | Hospital |

WeNurses Twitter chat

A Wechat#WeNurses Twitter chat was held in July 2017 to capture the stakeholder perspective on the use of tools and technology for nurse staffing deployment. This opportunity facilitated the refinement of the understanding of the complexity of NHS managers’ roles in managing the staffing resources day by day and tested the CMOs (see Appendix 12).

Changes to the protocol

Amendments to the protocol were granted in phase 3 of the review. These amendments related to the process of audio-recording verbal consent for telephone interviews with NHS managers in place of written consent and changes to the interview process for the second stage of the telephone interviews, in which the submitted interview schedule was replaced by a think-aloud scenario.

Ethics approval

Ethics approval was granted by the Bangor University Healthcare and Medical Sciences Academic Ethics Committee to conduct up to 10 semistructured telephone interviews in phase 1. Following amendments to the protocol, the team also gained ethics approval for the think-aloud interview technique, to seek audio-recorded verbal consent in phase 3 and to increase the number of interview participants.

Chapter 3 Findings

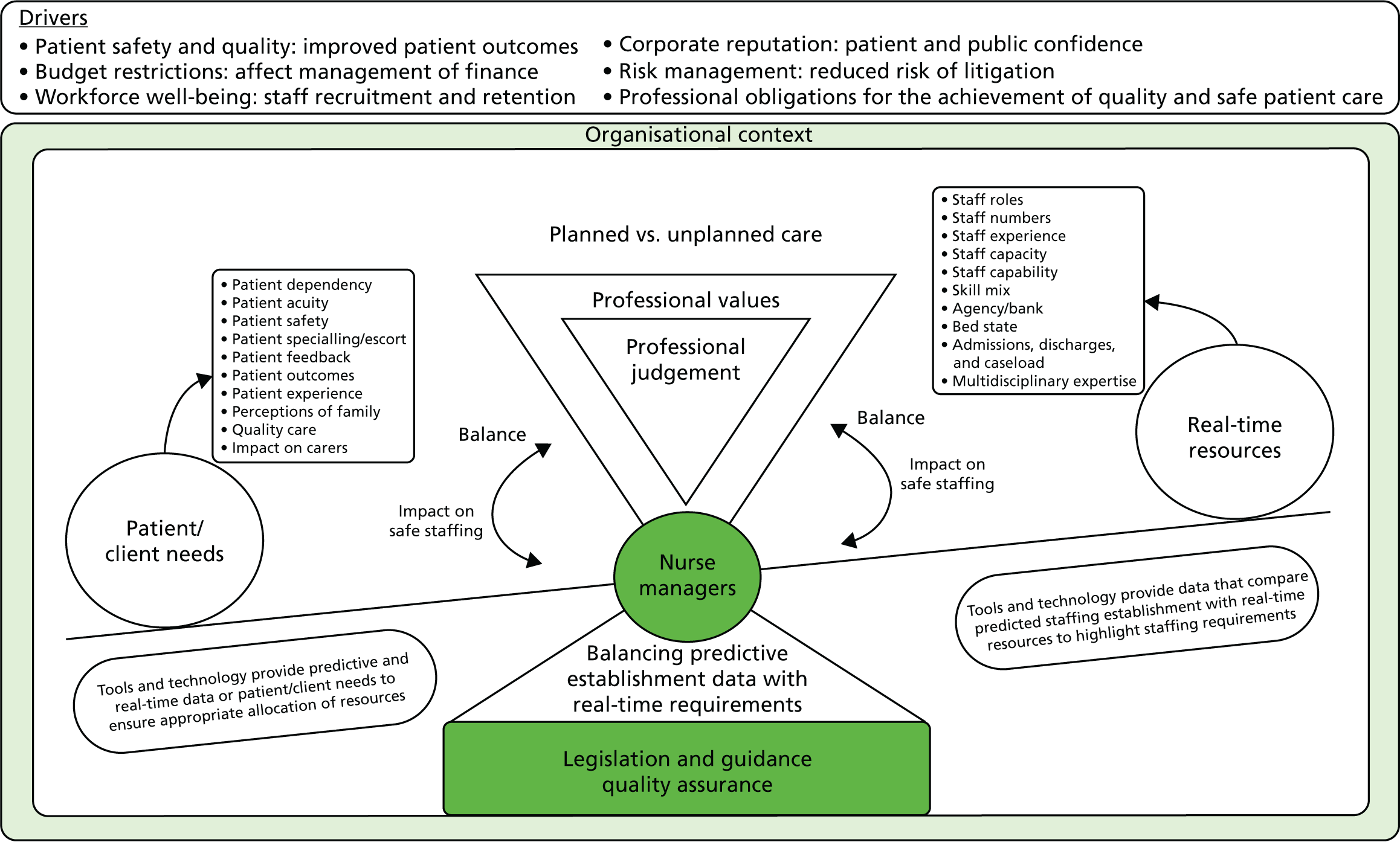

The system of nurse workforce planning and deployment

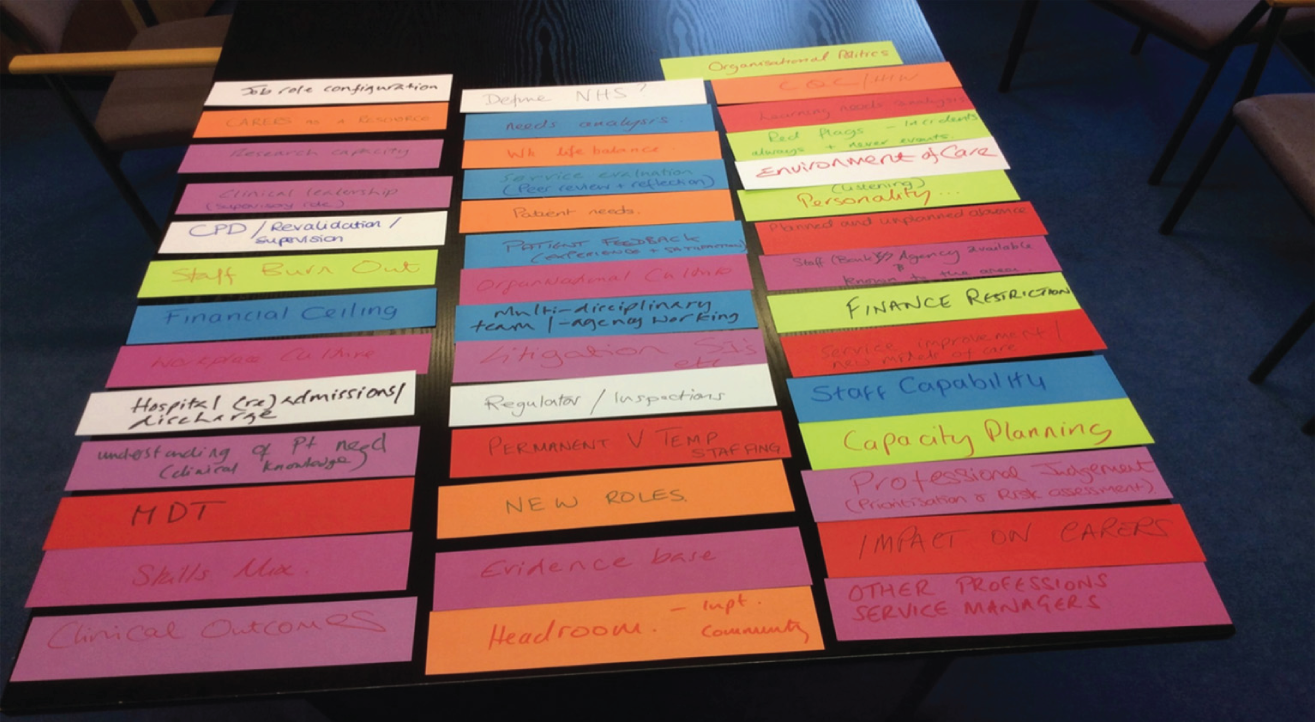

A root definition of the nurse workforce deployment and planning system in which NHS managers were working with WPTs was developed in the co-production workshops using soft systems methodology. 135 This offered a representation of the activities embodied in the system through exploring six dimensions (worldview, transformation, customers, owners, environment and actors) that, when combined, offered explanations of the purposeful activity of the system of nurse workforce planning and deployment. As the advisory group activity demonstrated (Figures 5 and 6), the system is complex, with multiple players and components, and interlinks with layers of different systems, such as social care.

FIGURE 5.

Members from the advisory group were asked to consider the influences on the system of nurse workforce planning and deployment.

FIGURE 6.

The final list compiled by the advisory group of influences on the system of nurse workforce planning and deployment.

In soft systems methodology, the first dimension is the worldview. All stakeholder group members emphasised that the worldview, or core purpose, of the system of nurse workforce planning and deployment is that health-care organisations should provide good-quality care, so that patients are safe. Patient-centred care was described as:

. . . the pinnacle of organisational prioritisation.

NHS manager, group 2

Legislation, evidence-based guidance and corporate requirements for quality assurance exerted powerful influences on the worldview of nurse staffing. The NHS manager groups offered insight into how differing approaches within the UK had affected guidance and NHS managers’ work around staffing planning and deployment. WPTs may facilitate the transparency of data for aggregation and benchmarking between and within organisations, which are key improvement drivers for good-quality care delivery. Nurse regulation was also recognised as an important influence for the worldview. NHS manager groups noted that nurses have a duty of care. Professional care was also linked to individual appraisal of risk, through aligning staffing levels with patient need. The feedback from the advisory and NHS manager groups suggested the potential for dissonance between nurses’ professional values and organisational attitudes to costs and risk.

Transformation, or the system’s purposeful activity, is to achieve good-quality, safe, patient-centred care, mediated through effective planning and deployment of nurse staffing that is appropriate to patient need. A clear vision and a common frame of reference are required to achieve effective nurse staffing. This has to be achieved efficiently; all stakeholder groups inevitably linked staffing to finance, budgets and effective use of resources. The ability to see the ‘financial flows’ is important for budgeting, so data are required. In addition, when balancing need and demand, data can act as a currency to be used in pursuit of transformation:

What can we do differently? Via monitoring through some kind of system so we can see what has worked and what hasn’t and identify where there’s an issue and where we can get help from.

NHS manager, group 1

Workforce planning and deployment tools and technologies are useful for the provision of transparent and aggregated data, so they need to be developed to produce a system ‘that works for us’ (NHS manager, group 2). However, different drivers can produce competing priorities. Adherence to legislation, mandates and evidence-based guidance was considered to be non-negotiable by the advisory and NHS manager groups; however, discussions reflected the fact that adherence was complicated by staff shortages, financial pressures and increased demands. Although all participants agreed that strategic and legal requirements for safe staffing were vital, there was a gap noted between expectation and delivery in the current financial climate. The nursing stakeholder groups discussed the balance between organisational safety and risk management and emphasised the need for systems to have a safety net, ‘to catch people if they miss’ (NHS manager, group 1). A key long-term transformational goal is that nurses are satisfied with the system. NHS manager groups emphasised how this can positively influence the organisational reputation, leading to good levels of recruitment and retention of nursing staff.

There were multiple customers of the system identified by stakeholders. These included nursing staff, patients and members of the public, other health and social care organisations, such as care homes, and IT businesses. NHS manager groups indicated the importance of valuing and developing existing staff, working innovatively and creatively, often in redefining or developing new roles to ensure effective recruitment and retention. All stakeholder groups referred to the impact of the Francis Inquiry and its contribution to articulating the link between inadequate staffing and poor patient outcomes. 2 The powerful influence of patient and public expectations was emphasised by the NHS manager group’s feedback. This was strongly linked to organisational reputation and patient and public confidence in the quality and safety of the care delivered.

Owners were identified as NHS trusts and also legislators, policy-makers, budget holders, regulators and commissioners. NHS trusts have to ‘make do with what they have got’ (NHS manager, group 1). However, all stakeholder groups noted that this has to be balanced with the organisation’s attitude to risk management and the requirements for safe staffing. There were strong associations emphasised between finance, corporate reputation and workforce well-being, recruitment and retention. The advisory group noted that when finance had an adverse impact on nurse staffing, this had a contributory effect to negative nursing outcomes, with poor staff satisfaction, retention and recruitment, leading to poor organisational reputation. If health-care organisations are known for having safe staffing levels, this has a positive impact on patient and public confidence.

There were multiple environment factors that NHS manager stakeholders and the advisory group highlighted as being influential; for example, clinical settings and local geography could exert influences on demand and resource availability. Some clinical areas suffer from shortages of staff; this may be attributable to a lack of nurses with specific qualifications for particular roles. Geography can influence the nature of demand; this may be related to socioeconomic influences, urban or rural settings; geography could also impact on the availability of nurses. Public expectations exert a strong influence, fuelled by the local and national media, which in turn could have an impact on organisational reputation. Organisational context was also highlighted as an important influence on safe staffing. All stakeholders expected NHS organisations to support nurses for professional development. NHS manager stakeholders and the advisory group felt that organisations should facilitate training and education so that nurses can provide evidence-based care and utilise WPTs; therefore, access to IT support was felt to be important. PPI stakeholders expressed concern over bursary changes in England and the lack of professional development:

The problem lies in retaining nurses in the UK once they have qualified. The structure and opportunities for nursing overseas are much greater.

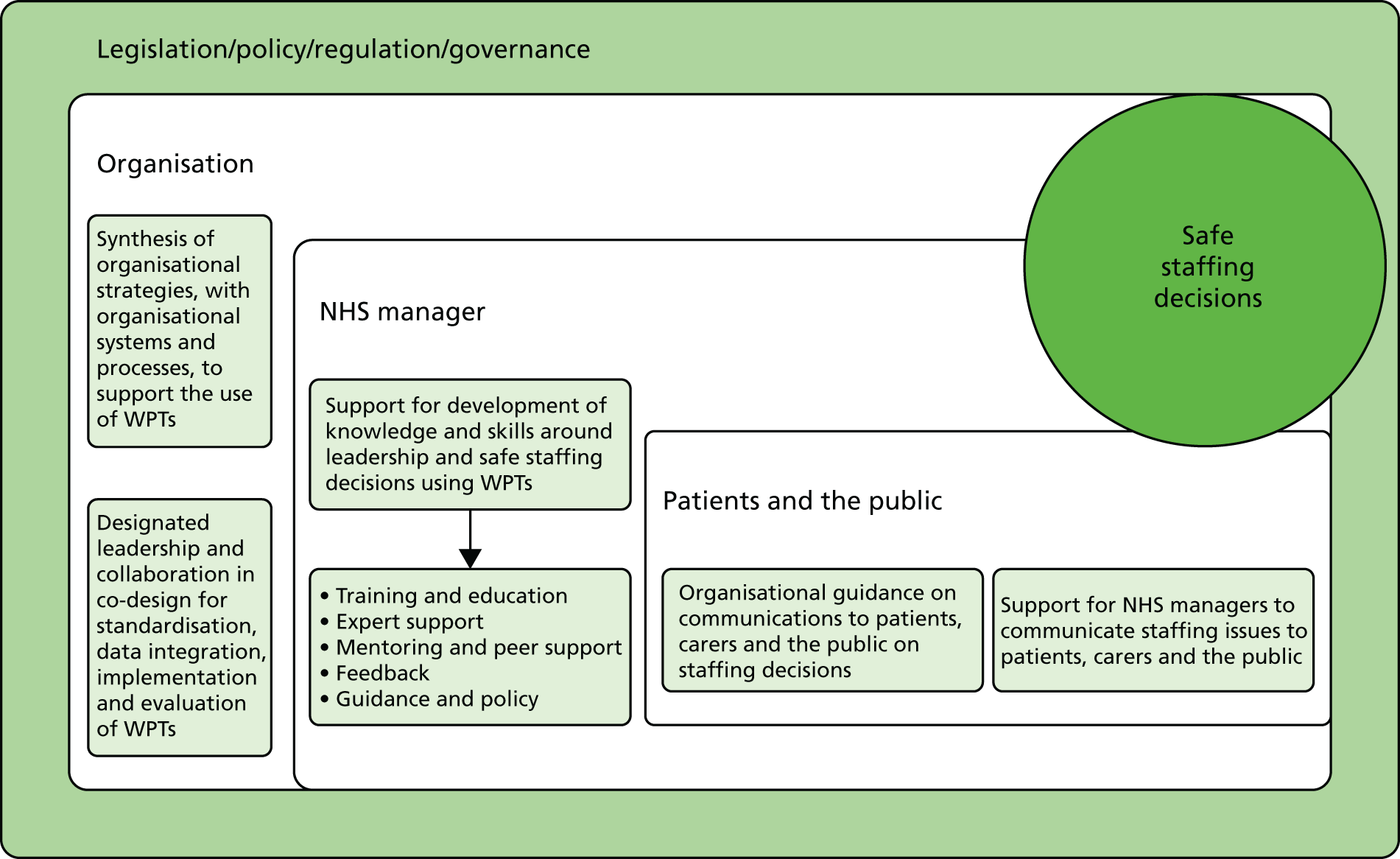

PPI stakeholder, group 2