Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/07/49. The contractual start date was in September 2014. The final report began editorial review in March 2017 and was accepted for publication in July 2017. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Jill Maben reports that she was a member of an advisory group from 2006 to 2009, advising on the development of the Point of Care project at The King’s Fund, and a member of the Point of Care Foundation (PoCF) Board 2013–14; she stepped down as board member at the start of the evaluation. Jeremy Dawson reports that he is a board member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research programme. Shilpa Ross and Laura Bennett report that they are currently employed by The King’s Fund, and Catherine Foot reports that she was previously employed by The King’s Fund. The PoCF, which supports the implementation of Schwartz Center Rounds® in the UK, was set up in 2013 by colleagues who were previously also employed by The King’s Fund between 2007 and 2013.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Maben et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction and background

Introduction

Our mixed methods, realist-informed, two-phase study aimed to evaluate Schwartz Center Rounds® (Rounds), an intervention to support health-care staff to deliver compassionate care. This chapter describes the background to Rounds in the UK and the structure of the report.

Schwartz Center Rounds®

Rounds were developed over 20 years ago and implemented in North America via the Schwartz Center for Compassionate Healthcare (SCCH), which is based in Boston, MA, USA, and is an autonomous, non-profit organisation (www.theschwartzcenter.org). Rounds were implemented in the UK via the Point of Care Foundation (PoCF), which was established in 2013 as an independent charity and has held the licence with SCCH to run Rounds in the UK since 2009. 1 Originally, the Point of Care programme was hosted at The King’s Fund, where the work commenced in 2007. Rounds were inspired by the experiences of a health-care lawyer, Kenneth Schwartz, who became terminally ill with lung cancer and wrote about his experiences of health care in the Boston Globe in 1995. 2 Kenneth noticed that ‘small acts of kindness made the unbearable bearable’2 and reminded caregivers to stay in the moment with their patients. He noted how some health-care staff were able to be compassionate while others were not, and how the same staff member could be compassionate one day and not the next. Before his death, he set up SCCH as a non-profit organisation designed to nurture compassion in health-care workers.

Rounds provide a regular (usually monthly) structured time and a safe, confidential setting for all staff employed in all organisational roles to get together to share the emotional, psychological and social impacts of working in health care. The purpose of Rounds is to support staff and enhance their ability to provide compassionate care. Unlike other types of reflective practice interventions, Rounds are a place not for solving problems or focusing on the clinical aspects of patient care, but for sharing the emotional, social and ethical challenges of providing care. Each Round lasts for 1 hour and begins with a multidisciplinary panel presentation of a patient case by the team who cared for the patient, or a set of different patient stories based around a common theme. The panellists each describe the emotional impact that the experience of looking after the patient has had on them. A trained facilitator then guides a discussion of emerging themes and issues, allowing time and space for the audience to reflect with the panel on similar experiences that they have had. Attendance is voluntary and staff attend as many or as few Rounds as they are able. When we began this work in 2013 (initial proposal), Rounds were running in 300 health-care organisations in the USA and 31 in the UK. At the time of writing, 425 health-care organisations are running Rounds in the USA and over 150 are running them in the UK.

The changing context of Schwartz Rounds development in the UK

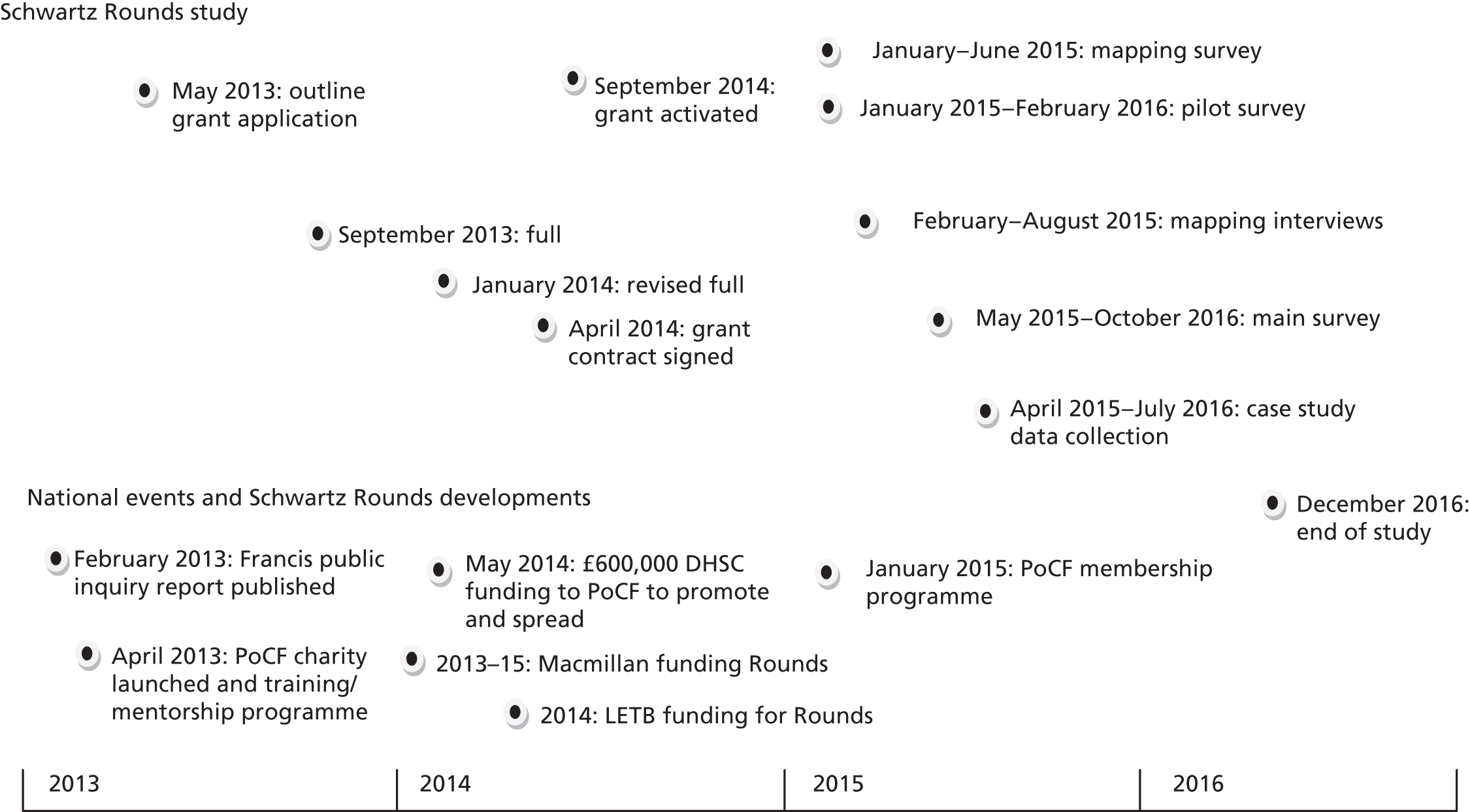

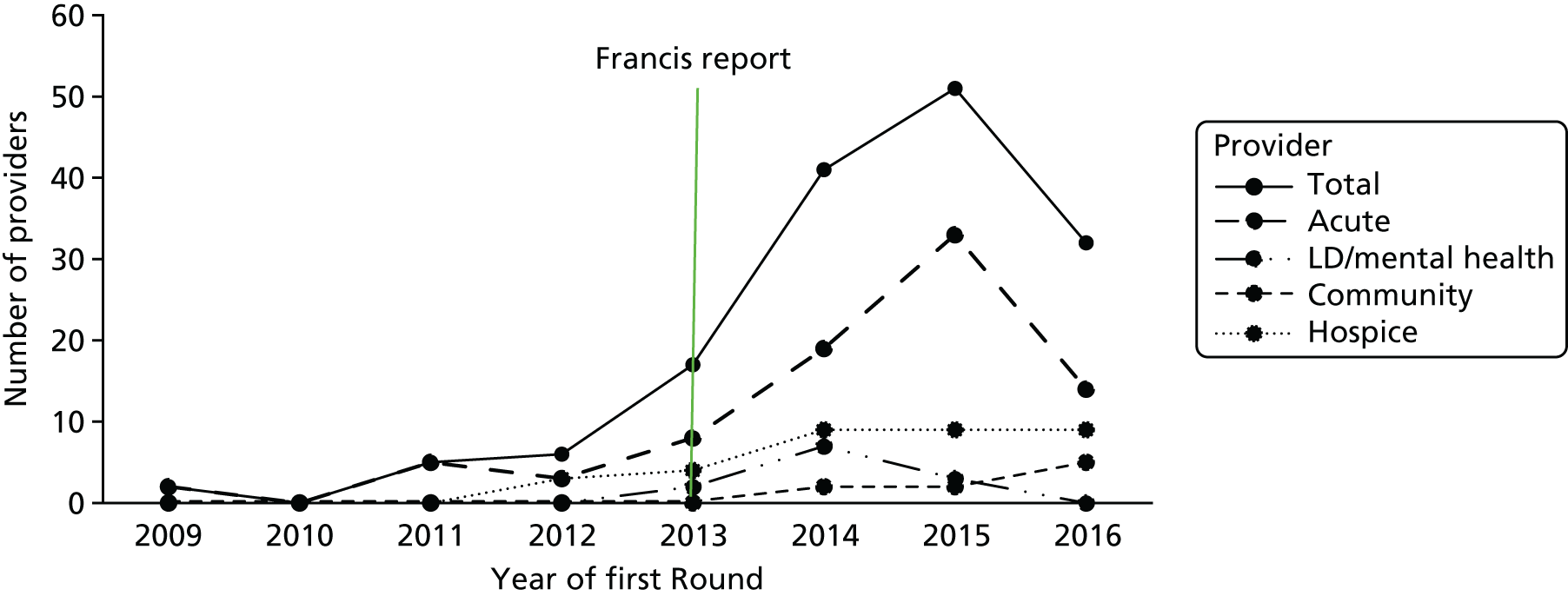

Between the submission of the grant application for this study in May 2013 and the end of the study period in December 2016, the uptake of Rounds in the UK developed substantially. In May 2013, there were 30 organisations running Rounds, and on past uptake we anticipated that, if funded, there would be approximately 40 organisations running Rounds. By the time we started the project in September 2014, there were 77 organisations running Rounds in England, and we absorbed this additional sample into our mapping study without further resource. By the time we completed data collection in June 2016, there were over 150 organisations running Rounds. Our study needs to be understood in the light of certain events, and the reactions to those events, that occurred during this period (Figure 1).

FIGURE 1.

The context of implementation of Schwartz Rounds in the UK in relation to this study. DHSC, Department of Health and Social Care; LETB, Local Education and Training Board.

In February 2013, the Francis report3 into the failings in care at Mid Staffordshire NHS Foundation Trust was published. Francis recommended that:

A sense of there being one team for the patient should be fostered where possible. One way to help in this might be to involve staff of all backgrounds in case reviews, clinical audit, and in overall team meetings [. . .] One method whereby this has been achieved has been by Schwartz rounds [sic].

Volume 3, p. 1394. 3

As part of the UK government’s response to Francis in May 2013, funding of £600,000 was granted to the PoCF over 2 years to promote and spread Rounds across the NHS through training and mentorship. Local Education and Training Boards (LETBs) and Macmillan Cancer Support (Macmillan) invited organisations to apply for funding to support the costs of running Rounds, which may have increased uptake. 1

In April 2013, the Point of Care moved from The King’s Fund, where it had been since 2007, and became the PoCF. It subsequently developed its own training and support for Rounds organisations in the UK, as well as a membership programme (see Figure 1). (See Chapter 7 for further exploration of this.)

Report structure

In Chapter 2, we detail our aims and objectives and present the methods we have used to answer these, and describe how the wider context of our study has changed over the evaluation period in relation to the publication of the Francis report3 and the adoption of Rounds in the UK. Chapter 3 presents our scoping reviews of the literature and provides a composite definition of Rounds to enable us to compare Rounds with other similar interventions. The results of the survey, interviews and secondary data collation we undertook to map Rounds provider profiles in England are presented in Chapter 4. To determine if Rounds have an impact on staff well-being, we report survey findings comparing new Rounds attenders with staff who had never attended Rounds, from 10 Rounds providers, in Chapter 5. Staff experiences of attending, facilitating, presenting and supporting Rounds as steering group members, together with the experiences of non-attenders and board members, are in Chapter 6. Chapters 7 and 8 support our realist evaluation of Rounds reporting data analysis to support our question: what works, for whom, in what respects, to what extent, in what contexts, and how? Finally, we summarise and discuss our findings and present our conclusions in Chapter 9.

Chapter 2 Methods

Introduction

This report is based on data collected in a two-phase mixed-methods evaluation of Rounds. This chapter provides an overview of the research approach and questions. Further specific details are presented in Chapters 4–7.

Our approach has been broadly informed by ‘realist’ principles, and our aim is to understand how, in which contexts and for whom does participation in Rounds affect staff well-being at work, social support for staff, changes in relationships between staff and patients, ‘ripple’ effects in the wider teams and organisation in terms of compassionate care and patient care improvements; and to make recommendations regarding the role of Rounds in health-care provider staff support in order to inform future practice. 4–6

Overview of study

A mixed-methods evaluation of Rounds was conducted in two sequential phases.

-

Phase 1 (scoping reviews, review of relevant theories, interviews with Rounds architects, and national mapping study):

-

scoping reviews of Schwartz Rounds literature and alternative interventions to define Rounds, compare Rounds with alternatives and summarise the evidence base

-

exploring relevant theories and conducting interviews with original Rounds architects to identify programme theory and understand how Rounds might work.

-

-

Phase 2 (survey and nine organisational case studies):

-

a survey of health-care staff who attend Rounds and those who do not (within case controls) in 10 sites to determine if Rounds have an impact on staff engagement and well-being

-

realist informed in-depth organisational case studies to understand how Rounds ‘work’ (context and outcomes), the mechanisms by which well-being and social support might be influenced, and staff experiences of attending, presenting and facilitating Rounds. 4

-

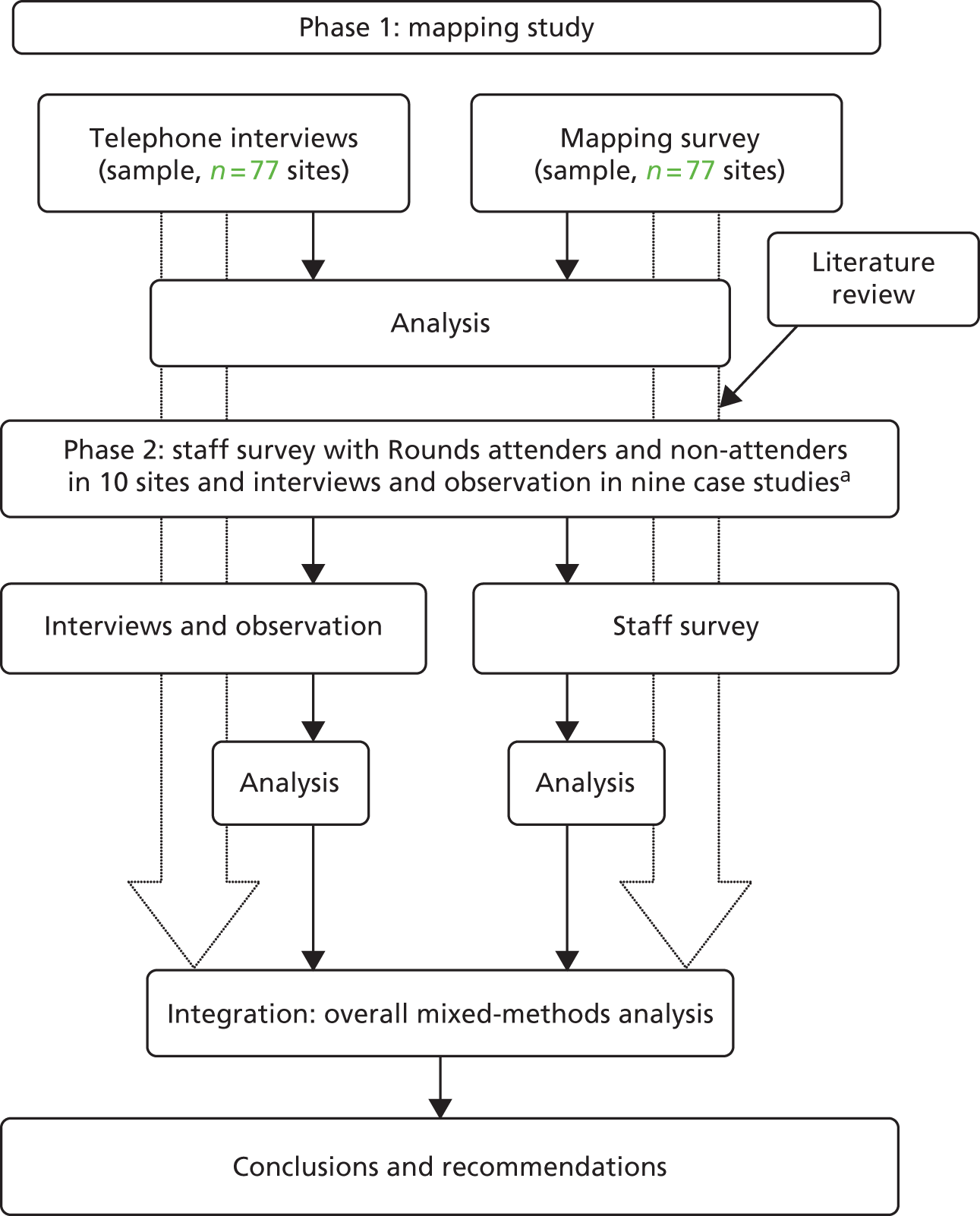

Our mixed-methods approach enabled us to address our varied aims and objectives (Table 1), and to seek elaboration, enhancement and clarification of results from one method with results from another, providing more than the sum of their parts. Some methods were sequential (e.g. mapping interviews were used to further understand data provided in mapping survey) and others were concurrent (phase 2 surveys and case studies). Data were mixed at numerous points (e.g. the mapping survey informed our sampling for phase 2). The quantitative and qualitative phases were equally weighted, and the findings were integrated and discussed after first being analysed and discussed separately. The overall study design is illustrated in Figure 2 and the relationship to the study objectives and data collected is detailed in Table 1.

| Study phase | Key aims and objectives | Research methods |

|---|---|---|

| Phase 1: literature review |

1. Identify literature providing a definition of Rounds to identify key features of Rounds and create a composite definition 2. Identify and critically appraise all empirical evaluations of Rounds 3. Identify alternative interventions, describe their key features and scope their evidence base 4. Compare each intervention in relation to the core features of Rounds 5. Identify how Rounds might work by: |

Scoping reviews of the following literature:

|

| Phase 1: mapping study |

6. Map the profiles of current UK Rounds provider organisations to inform sampling of case study sites for maximum variation: |

Primary data:

|

| Phase 2a: staff survey |

7. Evaluate whether or not regular Rounds attendance has an impact on health-care staff engagement and well-being, social support for staff, behavioural change towards patient and colleagues compared with non-attenders 8. Investigate whether or not frequency of Rounds attendance was associated with greater improvements in health-care staff work engagement, well-being, social support for staff and behavioural change towards patients and colleagues 9. Determine factors associated with Rounds being perceived as useful, or barriers, to attending Rounds |

Two-wave survey in 10 Rounds providers:

|

| Phase 2b: organisational case studies |

10. Examine staff experiences of attending, presenting, facilitating and leading Rounds and reported outcomes 11. Examine how Rounds are operationalised and the mechanisms by which well-being and social support might be influenced (or not), including: 12. Understand how Rounds ‘work’ in the UK, for whom and in what contexts; to suggest ways to improve their effectiveness; to inform decisions about their implementation in other contexts, and to understand what is causing variations in implementation or outcomes |

Case study in nine Rounds providers (realist evaluation):

|

| Overall analysis and cross-case analysis |

13. Establish contexts and mechanisms whereby Rounds influence staff well-being at work and social support 14. Identify and evaluate any changes (outcomes) that take place in relationships between staff who attend Rounds and their patients and colleagues 15. Identify and consider any wider changes that may be felt in teams or across the wider organisation regarding the quality of patient care and staff experience and, if so, how these may be linked 16. Make recommendations regarding the role of Rounds in health-care provider staff support |

Integration of all data:

|

FIGURE 2.

Overview of Schwartz evaluation components and processes. a, Six out of nine case studies (interviews and observation) and six out of 10 sites (survey) were the same.

Phase 1

We undertook two scoping reviews of the literature on Rounds to define Rounds and determine the evidence base, and of other interventions similar to Rounds in order to compare them. 7 We also explored the theoretical literature on reflection, group work and disclosure/discussion of emotional/challenging events to try to identify the mechanisms by which Rounds may work, which helped develop our survey for phase 2 (see Chapter 3), and, together with our interviews with the original architects of Rounds, informed our initial programme theory (see Chapter 8). The methods and findings from the scoping review are reported in detail in Chapter 3 and Taylor et al. 7

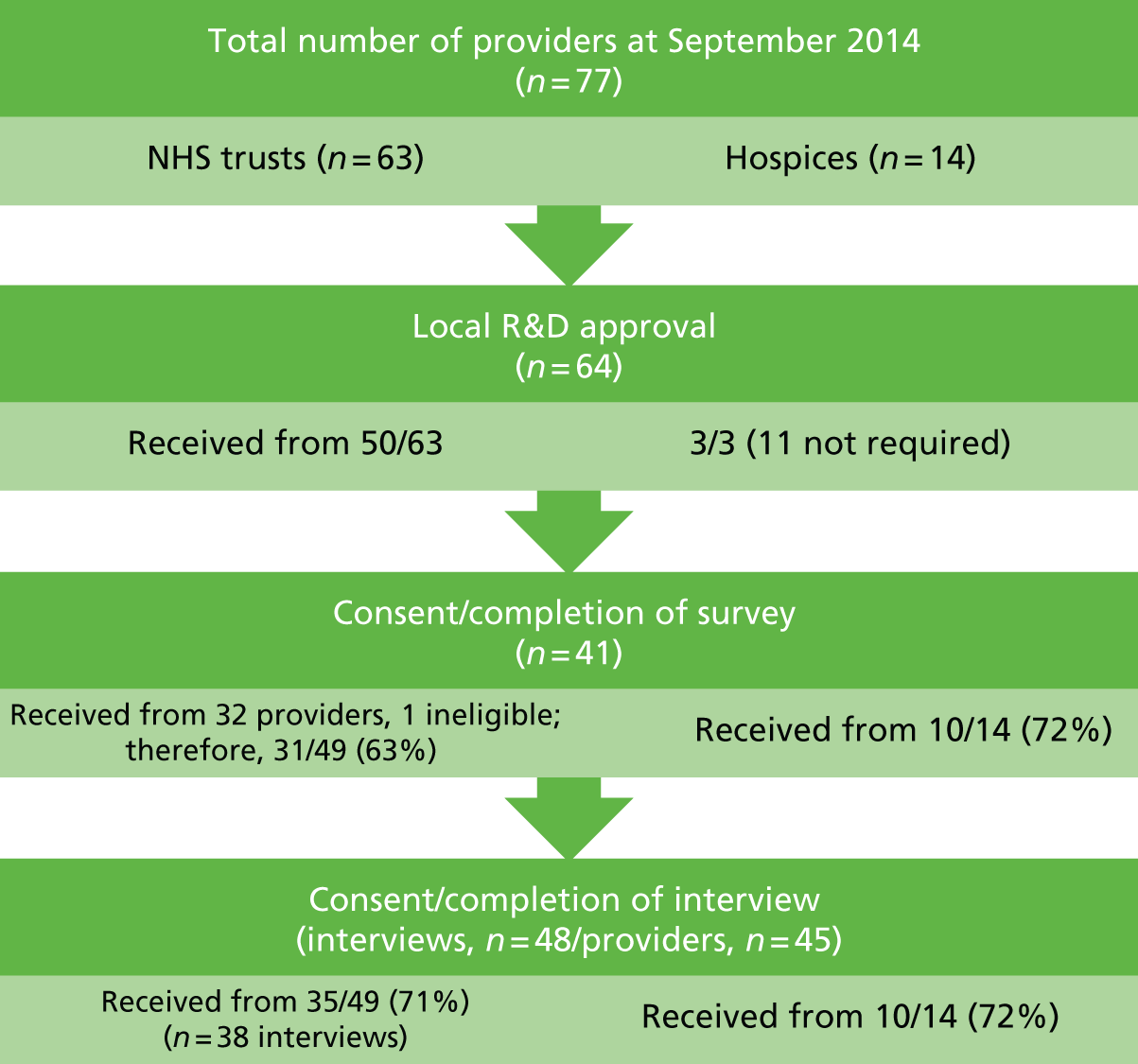

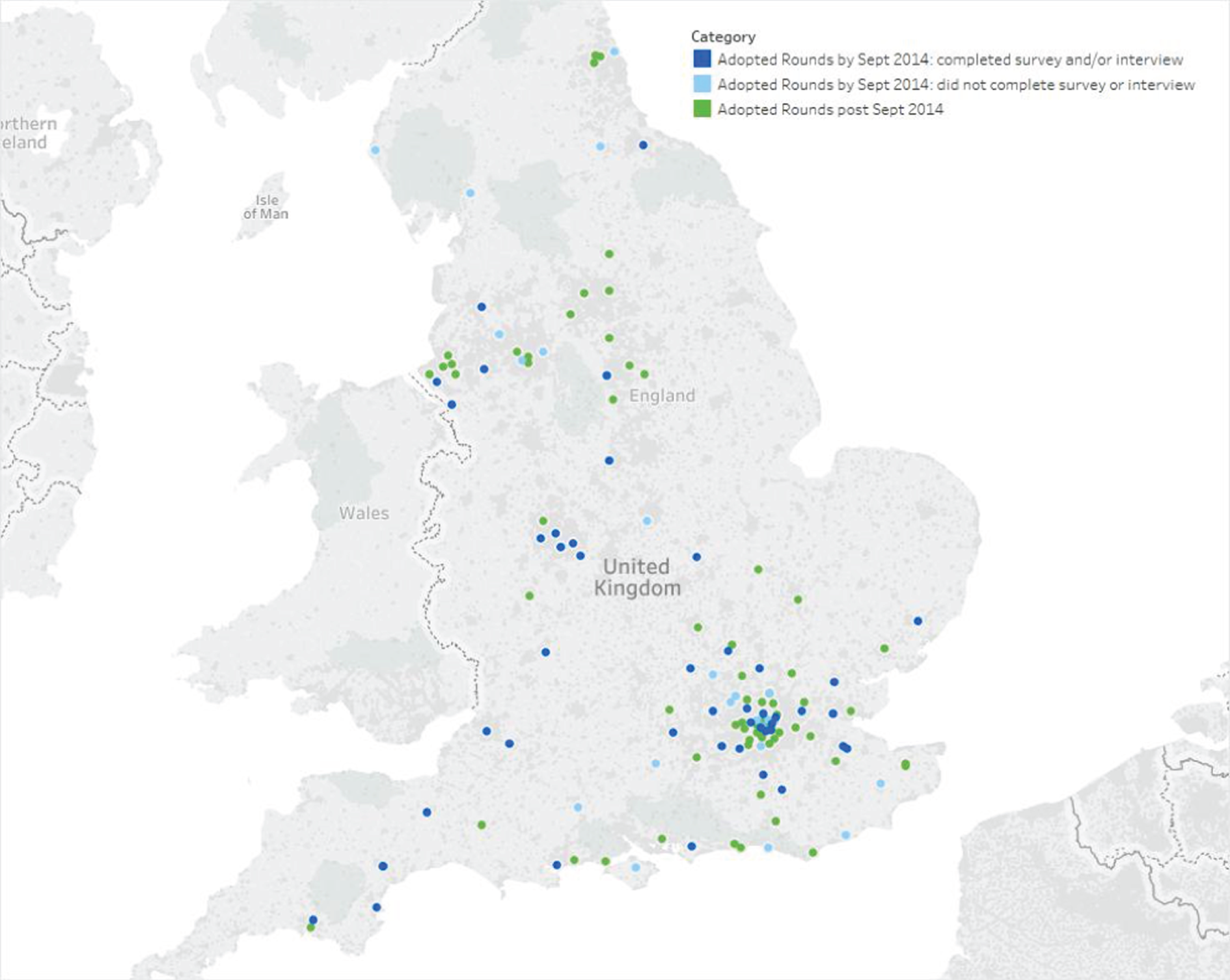

We conducted an online cross-sectional survey of all Rounds providers in England that had signed a contract with the PoCF by the start of the project in September 2014 when the mapping phase began (n = 77). We then undertook telephone interviews with Rounds champions (usually facilitators or clinical leads) in the same sample to explore their reasons for adoption and experiences of implementation further. For the collation and analysis of secondary data to map and profile providers running Rounds, the sample comprised all organisations implementing Rounds in the UK by July 2015 (n = 115). We wanted to map the profiles of current UK Rounds provider organisations to determine the reasons for implementation of and, when adopted, attendance at Rounds, and estimate the resource implications of establishing and sustaining Rounds. These data also informed sampling of the case study sites in phase 2. The methods and findings of the survey and telephone interviews are reported in detail in Chapter 4.

Phase 2

Thirteen providers were purposively sampled from phase 1 [to maximise the variation of organisations in terms of size, location and type of provider (acute trusts, hospice, community/mental health care providers)] and length of time running Rounds to provide 10 sites for the longitudinal survey, and nine organisations for the organisational case studies. Six sites participated in both survey and organisational case study components (Table 2). A long list of potential case study sites was drawn up against the sample quota in our protocol while phase 1 mapping data (survey and interviews) were being gathered. Approximately 20 providers were on this list, and in-depth discussions (including presenting to steering groups) in 16 providers ensued; one declined to take part, one was not suitable as Rounds rotated in four sites, and we decided that one was not suitable for a variety of reasons. Rounds were not sampled as a result of phase 2 survey responses, as survey and in-depth field work were often concurrent.

| Sitea | Survey, case study or both | Sizeb | Type | Location | Date startedc |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mulberry | Both | Large | Acute | Southern England | During study (after 1 September 2014) |

| Juniper | Both | Medium | Acute | Southern England | During study (after 1 September 2014) |

| Cedar | Both | Large | Acute | Southern England | Before 31 December 2012 |

| Cherry | Both | Medium | Mental health | Southern England | During study (after 1 September 2014) |

| Sycamore | Both | Medium | Acute | Southern England | 1 January 2013–1 September 2014 |

| Willow | Both | Large | Acute and mental health | Southern England | 1 January 2013–1 September 2014 |

| Oak | Survey only | Medium | Acute | Southern England | During study (after 1 September 2014) |

| Beech | Survey only | Medium | Acute | Northern England | During study (after 1 September 2014) |

| Elm | Survey only | Small | Hospice | Northern England | During study (after 1 September 2014) |

| Larch | Survey only | Medium | Acute | Northern England | During study (after 1 September 2014) |

| Ash | Case study only | Large | Acute | Southern England | Before 31 December 2012 |

| Elderberry | Case study only | Small | Hospice | Southern England | Before 31 December 2012 |

| Horse-chestnut | Case study only | Medium | Mental health | Northern England | Before 31 December 2012 |

Following a pilot survey, we conducted a two-wave survey with 833 Rounds attenders at baseline (follow-up, n = 484) and 2680 Rounds non-attenders at baseline (follow-up, n = 578), to provide within-case controls. To maximise new attenders, seven sites were selected in which Rounds began during the study (see Chapter 5). Surveys comprised eight validated measures and additional demographic and Rounds-specific information, with a total of 47 items (see Report Supplementary Material 1 for details of the survey items). These items were selected to measure hypothesised mechanisms by which Rounds might be expected to work (see Appendix 1). Surveys were longitudinal and were administered before Rounds attendance (for attenders) and after 8 months (see Appendix 2 for the baseline and follow-up surveys). They were designed to evaluate whether or not regular attendance at Rounds has an impact on health-care staff well-being, social support for staff and behavioural change towards patients and colleagues, compared with staff who do not attend Rounds. The detailed methods and findings of the survey are reported in Chapter 5.

Realist evaluation methods were used in nine case study sites. 4–6,8 These sites were identified, using purposive sampling, to allow more in-depth work to be undertaken through interviews with Rounds attenders, panellists, facilitators, clinical leads, steering group members, board members and non-attenders, and non-participant observation of Rounds, steering group meetings and panel preparation. The case study sites were sampled to provide maximum variation of information-rich cases9,10 that included aspects of Rounds implementation theorised to have an important effect on implementation and Rounds impact (size of institution and percentage of total staff who attend; established and new Rounds providers11,12 and early and late adopters),13 and also a range of providers (see Table 2). Data from case study sites were collected to examine staff experiences of attending, presenting and facilitating Rounds and how Rounds are conceptualised and implemented, and the mechanisms by which well-being and social support might be influenced (or not). This included, for example, reasons for variance in attendance and attendees’ experiences, any influence on team hierarchy/teamwork and on coping with stress, and any reported behaviour change towards patients and colleagues, including wider ‘ripple’ effects felt in day-to-day practice. It had been our intention (as per protocol) to shadow staff in practice to observe ‘ripple’ effects, and we developed observation protocols to observe staff with patients with support from our patient and public involvement (PPI) group members. However, practically, it was very difficult to identify specific ‘ripple’ effects and follow staff in practice at the right times to observe these effects. We therefore omitted this aspect of data collection and informed the National Institute for Health Research of this change to the protocol. ‘Ripple’ effects were gathered through reporting in interviews.

Case study interviewees were identified through purposive and snowball sampling and then invited to take part. Informed written consent was taken and participants were given a unique identification (ID) number to ensure anonymity and confidentiality. The selection of panel preparation, steering groups and Rounds for observation was negotiated with the facilitator/lead site contact with the steering group and with individuals involved (panellists in panel preparation). In practice, researchers tried to observe every Round during their fieldwork period in each case study (5–6 months) and as many steering groups and panel preparation meetings as possible. Consent and confidentiality procedures were more challenging in Rounds. However, every effort was made to inform potential attenders about the presence of the researchers before the Round took place (e.g. on posters and in e-mails), thus giving attenders sufficient time to make a decision about attendance based on their knowledge of our presence. On arrival, attenders were asked to tick a box on a modified sign-in sheet, saying that they were happy for the King’s College London research team to observe the Round. As there was a possibility that attenders would not be aware of our presence prior to the Round, at the start of each Round either the researchers or the facilitators announced that researchers were present and were taking field notes, and explained that any participant could approach the researcher (who was identified to attenders) and ask for any information they may have provided during the Round to be withdrawn and not used in the research. We also undertook two focus group interviews in November 2016 with Rounds experts (mentors from within and outside our case study sites) to test our realist findings. Further details of the methods and findings from the in-depth qualitative case studies are reported in Chapters 6–8.

Mixed-methods analysis

Following the completion of all data analyses, we carefully examined the data from our separate phases/methods;14 for example, three members of the team (JM, CT and JD) interrogated our phase 2 survey data for the six case studies for which we also had qualitative data, and vice versa, and cross-referenced these in our findings where applicable. We reviewed the survey data by case study site and examined the descriptive statistics. Although the small numbers of regular attenders in each case study site prevented us from analysing these data any further, we have explored our divergent and similar results (see Table 28) and present the limitations of each method in Chapter 9. Our phase 1 mapping interviews were also analysed to inform our realist questions in phase 2.

Methodological frameworks

This mixed-methods study is significantly informed by realist evaluation as follows:4,6

-

phase 1: literature review – although we did not undertake a realist synthesis, we did use the literature to identify our initial programme theory and identify proposed mechanisms by which Rounds might work

-

phase 1: mapping survey – not realist informed

-

phase 1: mapping interviews – realist informed regarding identifying mechanisms of action

-

phase 1: visit to SCCH in Boston – informed initial realist programme theory

-

phase 2: survey – measures informed by mechanisms identified in literature

-

phase 2: case study data collection and analysis – realist evaluation.

The realist evaluation approach acknowledges that intervention programmes do not necessarily work for everyone, as people are different and are embedded in different contexts,4 and so it helps researchers to go beyond the simple question ‘do Schwartz Rounds work?’ It seeks to understand better what works, and for whom: which staff, which organisations, in what circumstances. Realist evaluation is concerned with understanding causal mechanisms and the conditions under which they are activated to produce specific outcomes, which is highly relevant for this study. It recognises the interwoven variables that operate at different levels in organisations and thus suits complex social interventions. The realist approach to data collection and analysis is driven by retroduction, which starts with the empirical and explains outcomes and events through identifying the underlying mechanisms that are capable of producing them. 15 (See Chapters 7 and 8 for more details of realist evaluation methodology and analysis, and see Chapters 4–6 for the mixed methods and analysis used in the mapping survey and experience interviews.)

Research ethics

Three different ethics approvals were necessary for this study. The pilot survey and mapping study were not subject to NHS ethics or other NHS research governance processes as they involved only NHS staff, not patients.

-

Ethics approval for the mapping study in phase 1 was granted by the ethics committee at King’s College London (King’s College Psychiatry, Nursing and Midwifery Research Ethics Review Sub-Committee reference PNM/13/14–159). Research and development (R&D) approval and letters of access [CSP (Coordinated System for gaining NHS Permissions) number 148528] were also required for all sites before invitations to participate could be sent. These were issued by individual trusts/hospices (see Data collection access and Figure 3).

-

Ethics approval for the phase 2a pilot survey was obtained from University of Sheffield Research Ethics Committee (REC) (application number 001869).

-

Ethics approval for phase 2 survey and case study interviews and observation was granted by the National Research Ethics Service Committee London-South East (REC reference 15/LO/0053).

Following receipt of the favourable opinion from the REC, we obtained R&D permissions from our study sponsors and then local R&D permissions from each trust with a view to starting data collection. Research passports were obtained for the study researchers who conducted on-site data collection. Once each study site checked and approved the application, letters of access were issued.

Patient and public involvement in the study

Our approach to PPI was based on the principles that such involvement should be meaningful, respectful, relevant and collaborative. Patient representatives were involved from the project’s inception. Patients understood the challenges staff faced and believed, post Francis, that interventions to support staff, which had the potential to have an impact on patients, were very important and required studying. We took the view at the grant application stage, and thereafter, that those whom this study would benefit were both staff (the proximal outcome target group for our intervention) and patients (the distal outcome target group). We therefore involved both throughout the study. We actively involved patients through membership of the Project Steering Group (PSG) in order to improve the quality of the research and relevance of the study to NHS users and to support our dissemination activities. Members of the PSG included two PPI representatives who had previously provided input at the proposal stage, as well as a Schwartz Rounds staff representative. The PSG provided oversight of all aspects of the study, and, alongside other group members, our PPI representatives and Rounds staff members advised on data collection, commented on the findings emerging from the research and supported dissemination through links with their local networks. In phase 2, the PPI representatives were closely involved in drafting the staff and patient information leaflets explaining how we intended to observe and shadow staff in their everyday practice to observe the ‘ripple’ effects of attending Rounds (see above regarding the non-completion of this aspect of data collection). Collectively, their contribution has been highly valued in relation to highlighting the benefits to patients of Rounds. Details of the advisory and steering groups are provided in Acknowledgements.

Study management

The project was led and managed by the principal investigator (PI) at King’s College London. At the University of Sheffield and The King’s Fund there was a lead investigator. To co-ordinate work across the centres, weekly or fortnightly teleconferences were held involving the PI, all of the co-applicants and the staff employed on the grant. During the study period, three project advisory group meetings and five steering group meetings were held (see Acknowledgements for details of the steering group and advisory group membership).

Summary

This chapter reports the methods used in our mixed-methods study, which were significantly informed by realist methods. The study was undertaken in two phases: (1) scoping the literature and mapping of Rounds in the UK and (2) a survey for Rounds attenders and non-attenders in 10 sites and interviews and observation of Rounds in nine case studies. PPI was included throughout the study. Governance arrangements included advisory and steering group meetings. The backdrop to the study was a rapidly changing landscape in terms of uptake of Rounds in the UK following the publication of the Francis report3 and financial support from the Department of Health and Social Care, LETBs and Macmillan.

Chapter 3 Literature reviews

Introduction

This chapter addresses objective 1 to meet the following aims:

-

Part A: (1) to identify literature providing a definition of Rounds to identify the key features of Rounds and create a composite definition; (2) to identify and critically appraise all empirical evaluations of Rounds; (3) to identify alternative interventions, describe their key features and scope their evidence base; and (4) to compare each intervention in relation to the core features of Rounds. 7

-

Part B: (5) to identify how Rounds might work by (a) exploring the theoretical literature on reflection, group work, disclosure and safe environment; and (b) speaking to the original architects of Rounds to determine the underlying ‘programme theory’.

The reviews of literature pertaining to Schwartz Rounds and alternative interventions (part A) are scoping reviews, aimed at summarising the literature in relation to the volume, nature and characteristics of primary research. 16 The exploration of the theoretical literature and the interviews with Rounds architects (part B) were informed by realist evaluation principles in that they aimed to search for explanations regarding the mechanisms by which Rounds work, the processes that might trigger these mechanisms (contexts) and the possible outcomes associated with Rounds.

Part A: defining Rounds, reviewing their evidence base (scoping review 1) and reviewing the evidence base for alternative interventions (scoping review 2) and comparing them with Rounds

Defining Rounds and reviewing their evidence base: methods

Searches for relevant material were made using (1) the databases PsycINFO, Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL), MEDLINE and EMBASE, giving comprehensive coverage of medical, psychological, nursing and social sciences literature (see Appendix 3); (2) contact with experts/Rounds leaders; and (3) internet searches. Searches were from inception to 2015; all searches were conducted between 14 October 2014 and 5 February 2015, except empirical studies evaluating Rounds, which we continued to search for over the duration of the project, resulting in two further papers included for this component.

For the composite definition of Rounds, we included all literature (including non-empirical literature, e.g. letters and editorials), providing that it included a definition of Rounds. Literature contributing to the evidence base for Rounds had to apply explicit research methodology.

Creating a composite definition of Rounds

Literature was screened to remove duplicate definitions (e.g. the same definition in multiple publications) to avoid ‘double counting’. Text describing Rounds (what they were and their aims, e.g. structure and purpose, as well as any text describing what they were ‘not’) was extracted. The text was analysed thematically by four team members independently (Michelle Hope, CT, JM and ML), core concepts were discussed and agreed, and a single definition was produced. The face validity of the definition was confirmed after review by members of the study advisory and steering groups (with expertise in Rounds/well-being interventions in health care).

Evidence base for Rounds

For empirical papers, data were extracted on standard features (authors, setting, aims, design/methodology, measures and findings). Quality assessment of qualitative and quantitative primary studies was undertaken using the tools developed by Jones et al. ,17 which include an assessment of the key criteria and then an overall rating (high, no or few flaws; moderate, some flaws; low, significant flaws). Mixed-methods studies were, in addition, assessed against the six criteria for good reporting of mixed-methods studies developed by O’Cathain et al. 14 Their quality was rated as low (< 3 criteria were met), moderate (3 or 4 criteria were met) or high (≥ 5 criteria were met).

Results

A total of 41 documents/sources were included in the review of definitions for Rounds (see Appendix 4 for the included references). The majority (n = 28) were non-empirical publications (e.g. commentaries, descriptive reports of a single Round, service evaluations of implementation). Thirteen research evaluations were identified (11 via the electronic/internet/expert searches, and two subsequent to this as published in 2016);18,19 however, for three of these20–22 only conference abstracts were available, and thus 10 publications were included in the review of evidence base for Rounds.

Composite definition of Rounds

The definition arising from thematic synthesis is:

Schwartz Rounds are the signature programme of the Schwartz Center for Compassionate Care. They provide a regular (usually monthly) open forum (drop-in rather than by invitation) for multidisciplinary clinical and non-clinical staff at all positions within the health-care organisation to come together in an environment that is safe and confidential. They provide staff with a level playing field to reflect on, explore and tell stories about the difficult, challenging and rewarding experiences they face when delivering patient care, and receive the support of their colleagues. Rounds are typically organised and managed by a steering group, championed by a senior doctor/clinician. They last for 1 hour and are often held during lunch periods (with food provided). They are a group intervention within which multiple perspectives on a theme, scenario or patient case (i.e. their stories) are briefly presented by a pre-arranged and pre-prepared panel and then opened to the audience for group reflection and discussion, usually facilitated by a senior doctor and psychosocial practitioner. The focus is on the non-clinical aspects (e.g. psychosocial, ethical and emotional issues) surrounding the patient–caregiver relationship – thereby addressing a wide range of important topics rarely discussed elsewhere – and the attendees are encouraged to be open and honest, and reflect, discuss and explore their experiences thoughts and feelings. The interaction between the panellists and audience is felt to foster insight and support from colleagues, create a sense of working in a supportive environment and lead to improved relationships and communication within the hospital hierarchy, improved communication and teamwork between staff and patients and among staff, improved well-being of staff including enhanced resilience, improved compassionate care and ultimately impact on organisational culture.

Some sources explicitly articulated what Rounds were not. This included that aims were distinct from traditional clinical/grand rounds; that stories and discussions should not focus on the patient, their diagnosis or plan of care; that Rounds should not be used for problem-solving or to determine what could be learned clinically; and that they were not intended to produce actionable outputs.

The evidence base for Rounds

We included 10 publications18,19,23–30 that reported findings from eight separate studies (four in the USA,24–28 comprising five publications; and four in the UK,18,19,23,29,30 also comprising five publications) (see Report Supplementary Material 2). The majority were mixed-methods evaluations (n = 5 studies,18,19,23,27–30 seven publications), with two quantitative studies25,26 and one qualitative study. 24 Mixed-methods studies typically comprised attenders completing evaluation forms post Round attendance, together with either interviews or focus groups. Only one study23 included non-attenders. No studies reported the characteristics of the audience samples they recruited from (e.g. in relation to professional groups), although one study reported a higher proportion of doctors in one site that they hypothesised was related to Rounds being held in a medical education building and championed by the medical director. 29 Participants in three of the studies18,25,26 were students, and for the qualitative studies were typically purposively selected to represent a range of professional groups and/or roles within Rounds, but findings were not presented according to these characteristics. In two studies19,27 that did report the characteristics of their quantitative sample, most were female and of white ethnicity, and nurses predominated (but neither study reported the seniority of the nurses). In one paper,24 the authors mentioned, when justifying their planned focus group with nurses, that many nurses could not attend Rounds, but did not provide any data to support this. The overall quality of the evidence base is low to moderate: the majority of studies have weak study designs (cross-sectional), use non-validated questionnaires (typically self-report views/satisfaction with Rounds and impact of attendance, most using the same questions as, or similar questions to, the US evaluation),27 and none of the quantitative evaluations had control group (non-attender) comparisons.

The findings show that Rounds are highly valued by attenders. In relation to impact, most studies reported positive impacts on ‘self’ (e.g. improved well-being, improved ability to cope with emotional difficulties at work, self-reflection/validation of experiences),18,19,23,24,26–30 on patients (increased compassion, empathy),23,26–30 and on colleagues (improved teamwork, compassion/empathy). 18,19,23,24,27–30 Four studies (five publications) provide evidence of wider institutional impacts from interviews with attenders, such as improving patient-centredness of care, and access to specific services (e.g. palliative care), and culture change through having dialogue that did not happen elsewhere, helping to build shared values and support a strategic vision. 23,24,27,29,30 Three of the included studies18,25,26 are evaluations of Rounds adapted for educational purposes, all reporting that Rounds were felt to be useful and that students gained knowledge/understanding about the emotional side of providing patient care.

Critical review of the alternatives to Rounds and their evidence base

Methods

Identification of alternative interventions to include in the review

Our prime aim was to identify interventions that aim to help support health professionals with the emotional challenges of delivering patient care. At the outset we identified some aspects of Rounds that we felt were fundamental to the intervention (i.e. hypothesised programme resources offered by the intervention) and that our informed choices regarding ‘alternative’ interventions. This included providing an opportunity for reflection and disclosure, and offering psychological safety. Other inclusion criteria included that interventions needed to focus on the psychological (as opposed to the physical) well-being of staff; be person directed (vs. work directed); and provide primarily emotional rather than cognitive/clinical support (thus, for example, excluding mortality/morbidity meetings that aim to provide lessons in terms of cognitive errors or systems issues). Although Schwartz Rounds are a ‘group’ (rather than an individual) intervention, we chose not to limit alternative interventions by this characteristic because of the importance of reflection and/or disclosure as a key potential mechanism in Rounds that is shared by other, non-group-based interventions. Existing reviews of psychological/emotional support interventions for clinical staff were used to identify alternative interventions. 31–34 Consultation with the PSG and advisory group led to the inclusion of other interventions (including action learning sets, restorative supervision, reflective practice groups, Balint groups and critical incident stress debriefing). A total of 11 alternative interventions were included (see Table 3).

Search strategy

Following the scoping literature review methodology outlined by Arksey and O’Malley,16 the search strategy involved three components: (1) a database search, (2) internet searches and (3) consultation with experts. To be included, evaluations of interventions had to (1) have a health professional sample (either qualified or trainee) and (2) evaluate the intervention using qualitative and/or quantitative methods. The review excluded non-English-language sources, unpublished dissertations or theses and any records not accessible via the methods stated below. Searches were from inception to 2015; all searches were conducted between 14 October 2014 and 5 February 2015, using the same databases as for the Schwartz review (see Appendix 3).

All records were pooled in a bibliographic database. First, records were screened to exclude duplicate entries. Second, the title and abstract of remaining records were reviewed for eligibility. Three attempts were made to access the full texts of papers: (1) university online library, (2) Google Scholar™ (Google, Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and (3) journal website. If the full texts were unavailable through these sources, then the papers were excluded.

Charting the data

The data from the included papers were extracted into a spreadsheet that included standard items to describe the paper (e.g. citation, country, setting, population/sample and overall design) and the evaluation [e.g. length of evaluation, data collection method(s), outcome measures and key findings]. In addition, items were developed that were specific to each intervention, for example whether the intervention was group or individual focused, the size of group, the length/number of sessions, the content of sessions, whether or not the intervention was facilitated and whether or not training was provided for facilitation/supervision. The key findings were examined across all of the included literature and analysed thematically to enable synthesis within, and comparison across, each intervention. This resulted in the identification of three categories regarding outcomes relating to (1) self, (2) others (e.g. patients and colleagues) or (3) organisational level (see Report Supplementary Material 3).

Quality appraisal

A quality assessment of each paper was conducted as described in Evidence base for Rounds.

Synthesis

A detailed descriptive summary of each intervention was produced, which included a narrative description of the intervention [including the number of participants, the original setting and health-care setting(s), and the intended aims/outcomes], the number and type of included papers, the variability in intervention (fidelity to original format), a synthesis of the main findings across papers, and the overall quality of the evidence base. See Table 3 for a summary description of each intervention and see Report Supplementary Material 3 for other information.

Comparing alternative interventions with Rounds

To compare each intervention with Rounds, it was necessary first to define the key features of Rounds. The composite definition of Rounds, and features that were explicitly ‘not’ part of Rounds, underpinned this. Each descriptive feature in the definition was extracted into a table, together with the features that were ‘not’ part of Rounds. Further clarification was added for some descriptive features to ensure clarity of meaning (e.g. ‘reflection’ became ‘provides an explicit opportunity for reflection’), which became the basis for comparison with other interventions (see Tables 4 and 5). The intended outcomes within the composite definition were not included in the comparisons owing to their broad nature and, therefore, lack of discriminatory power. The completed table was shared with the study advisory and steering groups to test the face validity of the ratings.

Results

A total of 11 alternative interventions were identified (Table 3). Electronic searches yielded a total of 1725 papers, of which 146 were included (ranging between 1 and 64 across interventions) (see Appendix 5 for a list of the included references). Of these, 74 were quantitative (randomised controlled trial, observational, quasi-experimental), 41 were qualitative (mixed designs, interviews, focus groups), 22 were mixed methods and nine were secondary studies (literature reviews). The literature was international, with the majority of studies from the USA and the UK; other countries represented included Canada, Australia, Finland, Norway, Sweden, Croatia, Spain, Italy, Israel and South Africa. There was a distinct lack of studies from Asia, although that may have been a result of the requirement that studies had to be in the English language.

| Intervention | Description of intervention | Database search result | Total excluded (duplicates; not eligible; full paper not available) | Papers from experts/internet search | Total number included for review |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ALS | Based on the concept of learning by reflection on (or reviewing) an experience, an ALS usually contains 4–6 members (peers), with (or without) a ‘set advisor’ to facilitate the process. ALSs tend to be held intermittently, over a fixed programme cycle, and most participants contract with the facilitator for an agreed length of time. They are often closed groups. The set is not a team, as the focus is on actions of individuals, rather than shared work objectives | 83 | 70 (8; 36; 26) | 1 | 14 |

| AAR | AARs are facilitated meetings, led by a senior member of staff, that aim to encourage active reflection on performance following a specific event. An AAR is a one-off meeting post event and includes those who were involved with the event. The focus is on gaps in performance, and what could be done differently to enhance the outcome. AARs generally last about 30 minutes | 76 | 74 (9; 64; 1) | 0 | 2 |

| Balint groups | Balint groups meet every 1–4 weeks for 1–3 years. In the group, typically a doctor presents a troubling patient incident while the group listens. The goal of the presentation is to understand the issue from both the patient’s and doctor’s perspectives. The presentation can last about 10 minutes, after which group members can ask clarifying questions. When all questions are exhausted, the group is invited to imagine themselves in the roles of the doctor and the patient | 384 | 358 (170; 151; 37) | 0 | 26 |

| CSP | Originally developed for mental health/learning disability care homes, CSP is described as a theory-based social support intervention aimed at increasing exchanges of social support and decreasing negative social interaction. It consists of six 4- to 5-hour group training sessions (10 managers, 10 direct-care staff and two facilitators) conducted over a 9-week period. Strategies for improvement are drawn from the participants, based on their own experiences | 84 | 83 (10, 71, 2) | 2 | 3 |

| Clinical and restorative supervision | Clinical supervision originally arose out of psychotherapy but has been adopted by other disciplines, such as psychology and nursing. The process has been described as identifying a key issue, describing and defining it, undertaking a critical analysis, examining solutions, formulating an action plan, implementation and evaluation. It can take five different forms: one-to-one with expert from same discipline; one-to-one with supervisor from different discipline; one-to-one with colleague of similar expertise; supervision between groups of colleagues working together, and network supervision between people who do not usually work together | 307 | 252 (42, 160, 50) | 9 | 64 |

| Resilience training | Resilience training is in part based on CBT theories and in its original form is a manualised intervention comprising 18 hours of workshops. The key characteristics are that it is delivered to groups of practitioners who support one another, and is facilitated by an expert in personal and professional transition supervision. One of the better known Resilience training programmes was developed at the University of Pennsylvania and consists of: learning ways to challenge unrealistic negative beliefs, strengthening problem-solving, adopting assertiveness and negotiation skills, improving ability to deal with strong feelings, and learning how to tackle procrastination through use of decision-making and action-planning tools | 144 | 138 (36, 72, 30) | 0 | 6 |

| CISD | In its original form, CISD is a single-issue debriefing session in a group context, led by an external team, following a traumatic event. CISD has seven phases: introduction, fact, thought, reaction, symptom, teaching and re-entry. The debriefing session lasts for approximately 1.5–3 hours and takes place 24–72 hours after the traumatic event. The debriefing team is made up of a leader, a co-leader and a support, who work in conjunction to support the participants and to allow them to feel safe | 388 | 386 (62; 248; 76) | 0 | 2 |

| Peer-supported storytelling | Narrative storytelling is the act of an individual recounting verbally to one or more people a plausible account of an event, or series of events, possessing narrative truth for the teller. The story is arranged in a time sequence with plot, characters, context, intentionality and perspective taking, possibly including the teller’s actions, thoughts and feelings | 4 | 3 (3; 0; 0) | 0 | 1 |

| RPG | RPGs are facilitated groups of about 10 health-care professionals or students in which participants share and explore professional, clinical, ethical, and personal insights arising from their clinical work or training. RPGs are ongoing and convene regularly, with each group lasting for about 1 hour. Discussion topics can be raised by either the facilitator or the participants. The discussion is meant to be supportive as well as challenging, encouraging consideration of alternative viewpoints | 91 | 83 (8; 73; 2) | 0 | 8 |

| Psychosocial intervention training | Psychosocial intervention training involves cognitive behavioural approaches for managing symptoms, understanding symptom-related behaviour, relationship formation and helping service users to cope with symptoms. Teaching sessions are supplemented by small group supervision. Students are required to provide brief case study presentations about service users they are working with and receive feedback. Early courses were developed for nurses but quickly became multidisciplinary | 37 | 35 (6; 25; 4) | 1 | 3 |

| MBSR | The central principle of MBSR is mindfulness: being focused on and aware of the present moment with a non-judging attitude of acceptance. The original training module is 8 weeks long with weekly sessions of 2.5 hours each. There is a 7-hour session, which takes place between weeks 6 and 7, and participants are asked to complete 45 minutes of daily formal mindful practice. They are taught a variety of mindful meditative practices, and there are group discussions about the application of these practices | 127 | 110 (13; 72; 25) | 0 | 17 |

| Total | 1725 | 1592 (367; 972; 253) | 13 | 146 |

A summary of the evidence base for each intervention is provided in Report Supplementary Material 3. For most interventions the evidence was sparse. Populations for many of the interventions lacked diversity across health professions and settings, with many mostly nursing-focused. The aims of studies varied widely, with a few aimed at assessing efficacy/effectiveness, but most were small-scale exploratory descriptive studies. The content/format of interventions (fidelity) was, in most cases, widely heterogeneous (and/or lacked detail), and, consequently, a synthesis of findings is problematic. Most of the quantitative evaluations across all interventions relied on weak study designs (e.g. they were cross-sectional studies or post-intervention evaluations, or were lacking control comparisons), used non-probability sampling and had small samples likely to be underpowered, and used non-validated outcome measures. Many qualitative studies also lacked rigour (e.g. limited reporting of member checking, deviant cases, reflexivity or evidence of data saturation).

Most interventions had been evaluated in relation to impact on all three layers of outcomes (self, others and organisation). Evidence for resilience training, mindfulness-based stress reduction and reflective practice groups lacked inclusion of organisational outcomes.

The findings suggest that all of the interventions had evidence of positive benefits to self (e.g. raised self-awareness, resilience, job satisfaction, empowerment, or overall well-being), and most provided some evidence of positive benefits to ‘others’ (albeit that interpretation is constrained by the methodological limitations highlighted above). For patients, this included a fostering of better relationships, communication with and/or attitudes towards patients; and improved patient-centredness, knowledge of patients’ suffering and empathy. For colleagues, this included associations with better teamwork, peer support and knowledge/understanding of colleagues.

At organisational level, there was evidence from some interventions of association with improved practice, for example reductions in unnecessary prescriptions, an increased uptake of psychosocial support (Balint groups), a reduction in task and co-ordination errors, and an increased uptake of post-fall huddles (after-action reviews). Two interventions provided evidence of a positive impact on the workforce, including providing opportunities for mentoring and advice (action learning sets) and improved staff retention (clinical supervision).

Rounds versus alternative interventions: comparative features

In comparison with the alternative interventions, Rounds offer a unique organisation-wide ‘all-staff’ open forum to share stories about the emotional impact of providing patient care (Tables 4 and 5). Although many of the other interventions expect ‘open, honest communication’ as a key feature, and provide an explicit opportunity for reflection, none is open to all staff (e.g. clinical and non-clinical, voluntary attendance), and many are not ongoing programmes but are instead one-off training courses or events. Some of the training interventions (e.g. mindfulness-based stress reduction or resilience training) are multidisciplinary, but the intended outcome is practice of the skills learned, and so is individual based rather than group based.

| Number | Feature of Rounds | Intervention | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Balint groups | Clinical and restorative supervision | AARs | ALS | RPGs | CISD | ||

| 1 | Share challenging/rewarding experiences about delivering patient care | Yes | Yes | No | Not necessarily | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Focus on psychosocial and emotional issues of patient–caregiver relationships | Yes | Not necessarily | No | Not necessarily | Not necessarily | Not necessarily |

| 3 | Provides an explicit opportunity for reflection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 4 | Open, honest communication | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 5 | Provides an opportunity to give and/or receive peer support | Yes | Yes, if group supervision | Not necessarily | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Telling and hearing stories related by theme, scenario or patient case | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 7 | Ongoing programme (vs. one-off) | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | No |

| 8 | Time-fixed session (vs. flexible length/unspecified) | Yes | Yes | No | No | No | No |

| 9 | Planned provision of food/refreshments | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | Open to all/any clinical and non-clinical staff | No | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 11 | All levels of staff/no hierarchy | No | No | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 12 | Open group membership (vs. closed/invited members only) | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13 | Multidisciplinary | Not necessarily | No | Yes | Yes (can be uni or multi) | No | Yes (can be uni or multi) |

| 14 | Pre-prepared/rehearsed stories or focus | No | No | No | Yes | No | No |

| 15 | Facilitated discussions | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not necessarily | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | Panel presenters tell stories giving their perspectives on a theme, scenario or patient case | No | No | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | Group intervention | Yes | Yes (can be) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Organisational support: senior doctor/clinician champions | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not necessarily | No | Not necessarily |

| 19 | Safe and confidential environment | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Features that define what Rounds are ‘not’ | |||||||

| 1 | Problem-solving | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Not necessarily |

| 2 | Production of actionable outputs | No | Not necessarily | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| 3 | Flexibility in format (vs. licensed/contracta) | Yes (though facilitators should be accredited) | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes, lack a standardised consistent approach | Yes |

| 4 | Focus on clinical aspects of patient care, their diagnosis or plan of care | No | Not necessarily | Not necessarily | Not necessarily | Not necessarily | Not necessarily |

| Number | Feature of Rounds | Intervention | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MBSR programmes | Peer-supported storytelling | Psychosocial intervention training | CSP | Resilience training | ||

| Features that are part of Rounds | ||||||

| 1 | Share challenging/rewarding experiences about delivering patient care | No | Not necessarily | Yes | Not necessarily | Not necessarily |

| 2 | Focus on psychosocial and emotional issues of patient–caregiver relationships | No | Not necessarily | Not necessarily | Not necessarily | Not necessarily |

| 3 | Provides an explicit opportunity for reflection | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not necessarily | Not necessarily |

| 4 | Open, honest communication | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Not necessarily |

| 5 | Provides an opportunity to give and/or receive peer support | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

| 6 | Telling and hearing stories related by theme, scenario or patient case | No | Yes | No | Not necessarily | No |

| 7 | Ongoing programme (vs. one-off) | No | No | No | No | No |

| 8 | Time-fixed session (vs. flexible length/unspecified) | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 9 | Planned provision of food/refreshments | No | No | No | No | No |

| 10 | Open to all/any clinical and non-clinical staff | No | No | No | No (only direct care and managers) | Not necessarily |

| 11 | All levels of staff/no hierarchy | Yes | Yes (probably) | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 12 | Open group membership (vs. closed/invited members only) | No | No | No | No | No |

| 13 | Multidisciplinary | Yes | Not necessarily | Yes | Yes | Not necessarily |

| 14 | Pre-prepared stories/focus; steering group | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| 15 | Facilitated discussions | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 16 | Panel presenters tell stories giving their perspectives on a theme, scenario of patient case | No | No | No | No | No |

| 17 | Group intervention | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 18 | Organisational support: senior doctor/clinical champions | No | No | No | Yes | No |

| 19 | Safe and confidential environment | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Features that define what Rounds are ‘not’ | ||||||

| 1 | Problem-solving | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| 2 | Production of actionable outputs | No | No | No | No | No |

| 3 | Flexibility in format (vs. licensed/contracta) | Yes | Yes | No | Manualised but adapted to experiences of group | Manualised but adapted to experiences of group |

| 4 | Focus on clinical aspects of patient care, their diagnosis or plan of care | No | Not necessarily | Yes | Not necessarily | Not necessarily |

Other key aspects in which Rounds are distinct from the alternative interventions relate to what Rounds are intentionally ‘not’ meant to be. In particular, discussions within Rounds should not ‘problem solve’, whereas problem-solving/action-planning are key features of many of the other interventions (e.g. action learning sets, after-action reviews, critical incident stress debriefing). Most of the alternative interventions also offered flexibility in format, compared with the contractual licence (with stipulated conditions) required for running Rounds.

Arguably the closest types of interventions to Rounds are Balint groups (albeit rooted in unidisciplinary primary care with closed membership) and reflective practice groups (again generally closed membership and can be unidisciplinary). In particular, both are ongoing group programmes in which challenging/rewarding experiences about delivering patient care are shared and discussions are facilitated, and both provide the opportunity to give and/or receive peer support in safe and confidential environments. However, neither offers an organisation-wide opportunity for staff to attend, and both would have an expectation that members/attenders would contribute, whereas in Rounds, attenders can choose to be silent listeners.

Part B: developing an understanding about how Schwartz Rounds may work

To develop an initial understanding about how Rounds may work (to inform the initial programme theory, see Chapter 8, and to inform phase 2 work) we undertook two activities: (1) we explored theories about how rounds may work and (2) we interviewed the original architects of Rounds in Boston, MA, USA.

Exploration of theories about how Rounds may work (e.g. the context, mechanisms and outcomes related to Rounds)

This section aims to answer aim 5 above: to explore the theoretical literature on reflection, group work, disclosure and safe environment. In theorising about how Rounds might work, we needed to try to unpack the ‘black box’ of what happens in the monthly 1 hour of Rounds. To do this we drew on realist terminology, which uses the term ‘mechanisms’ to describe how interventions work, ‘context’ to describe the factors that trigger (or not) the mechanisms and ‘outcomes’ to describe the resulting effects. This initial theorising informed the development of our survey (see Chapter 5) and initial programme theory and interpretation of our study findings (see Chapter 8) (see Appendix 6 for a fuller review).

Methods

Theoretical literature was obtained using multiple strategies, including conducting searches on the internet and using databases such as Google Scholar; using key textbooks;35–38 consulting with our advisory and steering group members; and hand-searching references of key literature. Our approach to inclusion was broad at the outset – we did not restrict to theories that had a health-professional focus – but was focused by our understanding at that time about how Rounds worked and the key components of Rounds (e.g. from our composite definition reported earlier). For example, we initially explored all theories that had ‘reflection’ as a key component, but found that many early theories separated learning and emotion, and as emotion is central to Rounds we instead searched for theories of reflection that included emotion as a key element. We searched for theories describing reflection, group work, disclosure and/or safe environments either as outcomes (enabling us to examine mechanisms/antecedents to them) or as processes/mechanisms in themselves, leading to other outcomes. Theories were examined and included based on (1) their relevance to Rounds (e.g. group setting and emotion central to reflection) and (2) their relationship to context, mechanisms and outcomes based on our developing programme theory.

Disclosure

Disclosure is the action of making new information known. In psychological terms, it is the ‘social sharing of emotion’. 39 Two main theorists on the psychological aspects of disclosure are Rimé and Pennebaker. Rimé and colleagues39–41 have focused on how individuals socially share emotions with others following an emotional event, and the effects of this on emotional recovery. Pennebaker and colleagues35,42–44 have focused on the effects of disclosure of emotional events on physical and psychological health.

Emotion is an essential aspect of describing trauma. People experience greater health benefits if they share emotions and thoughts surrounding trauma than if they share facts;42,45 using language to label an emotion/experience creates a structure, which facilitates understanding of the event. 43 Similarly, Lepore et al. ’s46 ‘completion hypothesis’ states that putting one’s experiences into language allows individuals to impose a narrative around it, making it comprehensible to themselves and others. Conversely, actively inhibiting thoughts and feelings ‘gradually undermines the body’s defences’ (p. 2),35 which leads to reduced physical well-being. Confronting significant events helps us understand and assimilate the event, which improves physical and emotional well-being. 35

Of all emotions, people are least likely to share feelings of guilt or shame. 39 Non-disclosure is associated with the anticipation of negative interpersonal responses to disclosure (e.g. labelling or judging). 47 The benefits of disclosure vary according to the listener’s response to it. 45,48 Nils and Rimé48 identified two responses: the empathic mode buffers emotional distress temporarily (the individual feels better) and the reframing mode leads to emotional recovery (the individual’s basic assumptions are positively modified). However, when disclosure of events is invalidated, any benefits may be diluted. 46

Application of disclosure theories to Rounds

Drawing on the disclosure theories above, Rounds focus on non-clinical aspects of the patient–caregiver relationship, not problem-solving, and allow individuals to share difficult, challenging and rewarding experiences. Rounds allow individuals to disclose emotional experiences; greater health benefits ensue following the sharing of emotions and thoughts rather than the sharing of facts. Round attendees and panellists are encouraged to be open and honest and to discuss their experiences, thoughts and feelings: using language to help understand their emotional response to an event/experience. Effective facilitation by the facilitator/clinical lead can help individuals reframe and label their emotions, and thus begin to process and understand them. The benefits of disclosure vary according to the listener’s response. Group interventions mean that it is difficult to control others’ reactions to what has been disclosed. However, Rounds are designed to be a safe, confidential space where staff can share their experiences without fear of blame or judgement.

Safe environment

A safe emotional environment is important for group work, reflection and disclosure. Emotional safety is achieved in attached relationships where there is openness, vulnerability and trust. Emotional safety at work derives primarily from the experience of feeling valued, accepted, recognised and respected. 49

Emotional safety is one element that generates a sense of community,50 where it is safe to tell the ‘truth’, requiring community empathy, understanding and caring. Boundaries – or containment – ensure that the group is ‘purposeful, bounded and safe’. 51 Effective leaders (in Rounds this means clinical leads and facilitators) are necessary to construct these conditions. Another element necessary to develop a community is a sense of belonging.

Psychological safety ‘is a shared belief that the team is safe for interpersonal risk taking’. 52 In psychologically safe teams, members feel accepted and respected and think less about the potential negative consequences of expressing themselves. Leaders increase psychological safety by empowering members of the group to participate, and in collaboratively addressing concerns. With psychological safety there is a ‘sense of confidence that the team will not embarrass, reject or punish someone for speaking up’. 52

Application of the ‘safe environment’ theories to Rounds

Drawing on the safe environment theories above, the panellists and audience need to feel emotionally safe in Rounds to share their story or experience without fear of reprisal or blame. Facilitators foster a sense of psychological safety in the Round through their skills in facilitation, group work and psychological insights. Ground rules and the use of an established protocol for Rounds helps create a confidential and safe environment that, together with a sense of community, is necessary for Rounds to work (see Chapter 7, Fidelity to the Schwartz Rounds model). The experiences shared are contained as a result of the clear boundaries established, which creates a safe, confidential space for reflection.

Reflection

Reflection is a ‘generic term for those intellectual and affective activities in which individuals engage to explore their experiences in order to lead to new understandings and appreciation’ (p. 3). 53 Theories of reflection suggest that it is a structured learning activity in which questions are answered and knowledge is created36,54,55 and argue that reflection is a rational act, and although emotion is a trigger or catalyst for reflection, its role is limited.

More recently, psychologists and sociologists including Lazarus,56 Mezirow57 and Goleman58 have argued that emotion plays a central role throughout the reflective process and that emotion cannot be separated from learning. Emotional intelligence is said to be highly complementary to reflective practice;58 individuals need to understand not only themselves, but also others, and their feelings and empathy are key to emotional intelligence and important to reflective practice. 59 For a person to ‘grow’, an environment is required that provides genuineness (openness and self-disclosure), acceptance (being seen with unconditional positive regard) and empathy (being listened to and understood). 60

Barriers to reflection can be practical (e.g. finding the time,55 location) and/or psychological (e.g. fear of judgement, criticism). The timing of reflective practice is crucial, especially in relation to stressful/tense experiences. A review soon after an incident is deemed ‘hot’ (emotive): it is subjective and influenced by emotions. Reviews held later are ‘cold’: emotions have cooled and the reflective practice is clearer, more balanced and objective, which leads to improved reflections. 61 Ixer62 suggests that individuals need non-judgemental support; they need to feel ‘safe’; they need a role model (e.g. a mentor who reflects on their own practice); they need opportunities for reflection; and they need time and energy. 63

Application of reflection theories to Rounds

Drawing on the reflection theories above, Rounds are not designed for problem-solving or to determine what can be learned clinically, although learning may occur. Nor are they intended to produce actionable outputs. Theories of experiential learning – where emotion plays a central role in reflection – therefore appear more relevant.

Consideration of the timing of a Round is important and it is, therefore, important that those preparing Rounds carefully consider who they ask to present and when: not too soon, or when the subject matter is too ‘hot’.

Reflective rational enquiry64 seems particularly relevant to the workings of a Round. Rounds are a combination of self-reflection and collective reflective work, which create shared knowledge at the individual and institutional levels. This may include personal outcomes such as improved well-being, dyadic and team-based outcomes such as better communication and teamwork, and institutional outcomes such as changes to hospital culture. 27,29,30 Finally, empathy is key to reflective practice. Increased compassion and empathy is the main intended outcome of Rounds: for the individuals attending but also in their interactions with patients and their families.

Social support and group work

Social support is the perception and actuality that you are cared for, that you have assistance available from other people and that you are part of a supportive social network; ‘group work provides a context in which individuals help each other and can enable individuals and groups to influence and change personal, group, organisation and community problems’ (p. 8). 38

Social support is associated with psychological well-being in the workplace and is hypothesised to work by having either a buffering effect (where it moderates an outcome) or a direct effect (leading directly to something). 65,66 Karasek’s65 job–demands–control model is a ‘buffering model’, as work social support (such as support from colleagues and supervisors) is said to buffer against job demands/lack of control, thereby protecting mental and physical health. 67,68

Social exchange theory details the negotiated exchanges between people (tangible and intangible) as more or less rewarding or costly. 69 Cost could be the effort put into a relationship (e.g. time). Rewards include elements of the relationship that have positive value (e.g. acceptance, support and companionship). Social exchange involves a connection and trust with another and brings satisfaction when people receive fair returns for their expenditures. The effort–reward imbalance is associated with poor health functioning.

Group work is the opportunity to reflect on, and learn from, the nature of the group interaction itself. The group context and group process is explicitly utilised as a mechanism of change by developing, exploring and examining interactions within the group. A number of therapeutic factors that facilitate group work include universality, altruism, instillation of hope, cohesiveness, catharsis, interpersonal learning and self-understanding. 37

Application of social support and group work theories to Rounds

Drawing on the social support and group work theories above, Rounds are a group intervention, with social support provided through group reflection. Social identification as a member of a Round may serve to boost self-esteem as individuals have a sense of belonging to an organisation-wide forum. The cost–benefit analysis of social exchange theory appears pertinent to how a Round works. Costs might include the courage, emotional effort and time put into sharing one’s story publicly (panel preparation, sharing the story during the Round). Rewards may include increased compassion and empathy for others, improved well-being (e.g. reduced stress) and camaraderie (better work engagement and teamwork).

When members tell their story to a supportive audience, they can obtain relief from feelings of shame and guilt. Yalom and Leszcz’s37 therapeutic factors appear relevant to how Rounds work, and these are explored further in Chapter 8.

In addition to work reviewing theories in the literature, which informed our initial programme theory (see Chapter 8) and the selection of items for our survey (see Appendices 1 and 6), we thought it important to understand more about the development and origins of Rounds in Boston, MA, USA, and any programme logic behind their development.

The initial development of Rounds in Boston, MA, USA, and underlying principles

Two members of the research team (ER and ML) visited the SCCH in Boston, MA, USA (8–12 June 2015). The purpose of the trip was to help develop our initial realist evaluation programme theory and identify the underpinning programme logic behind how Rounds are intended to work (see Box 3). This was based on information from those involved in developing and running Rounds, including the ‘programme architects’, Kenneth Schwartz’s family members, facilitators and members of the SCCH, and others currently running Rounds in the USA. We conducted two group interviews and three individual interviews, and observed two Rounds and one debriefing meeting between facilitators and a regional advisor from the SCCH.

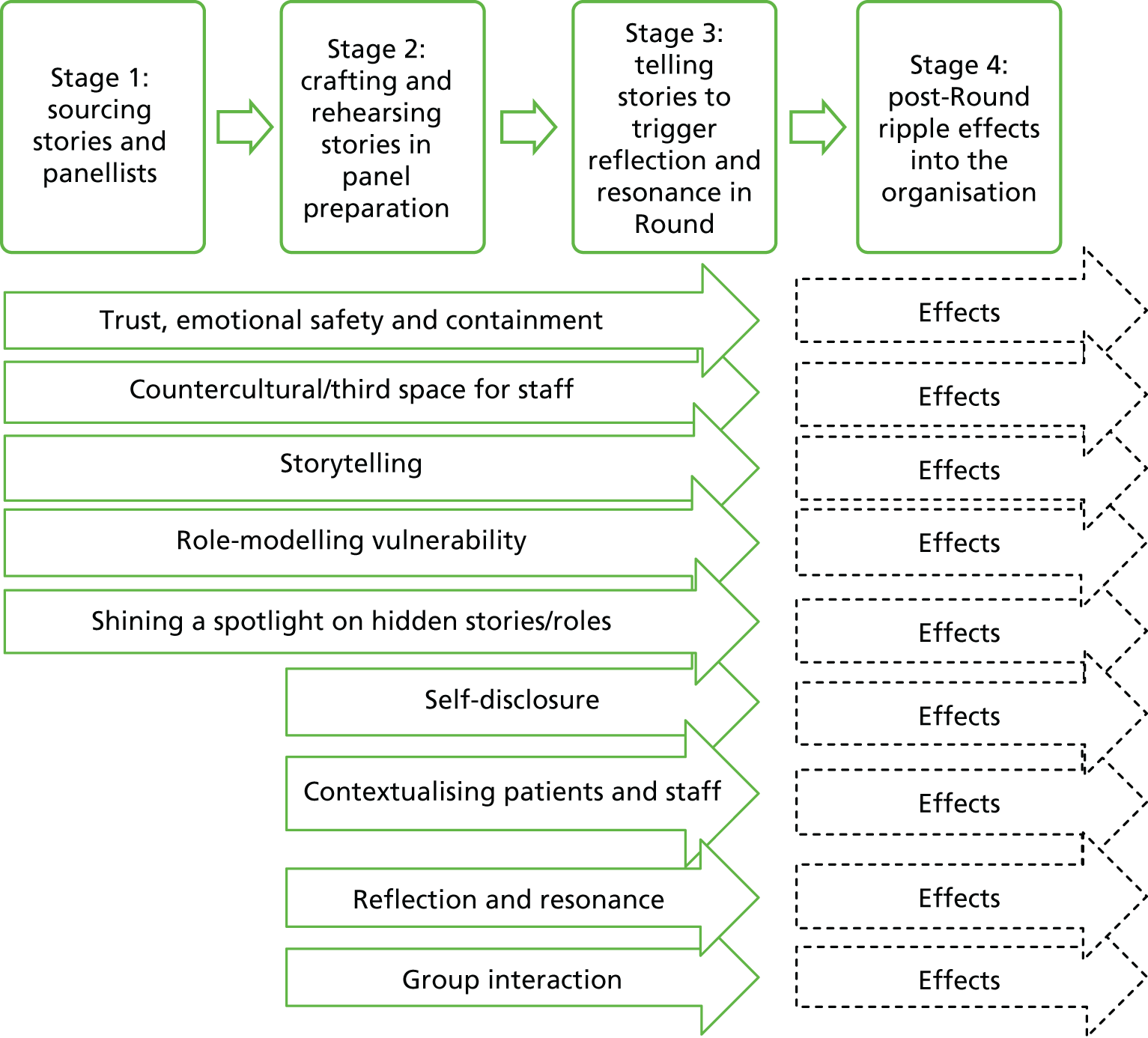

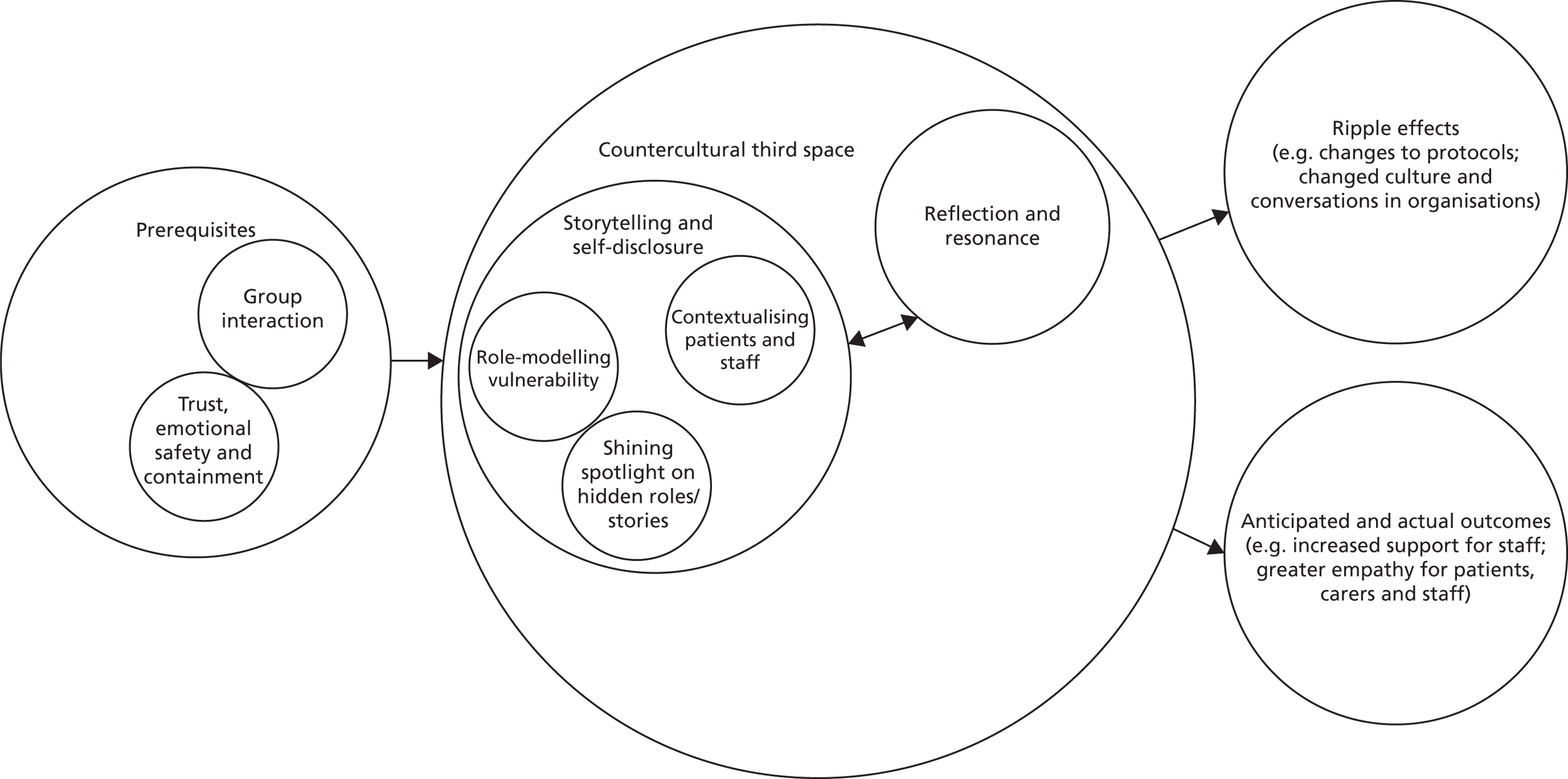

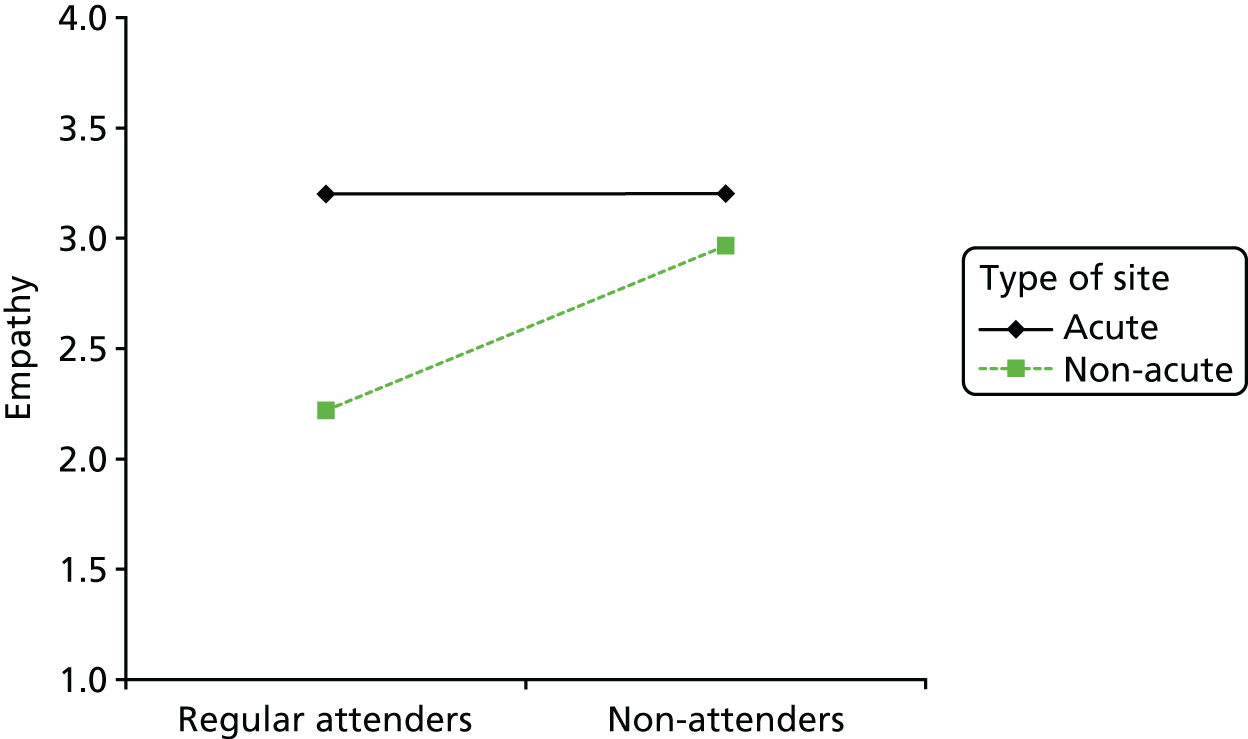

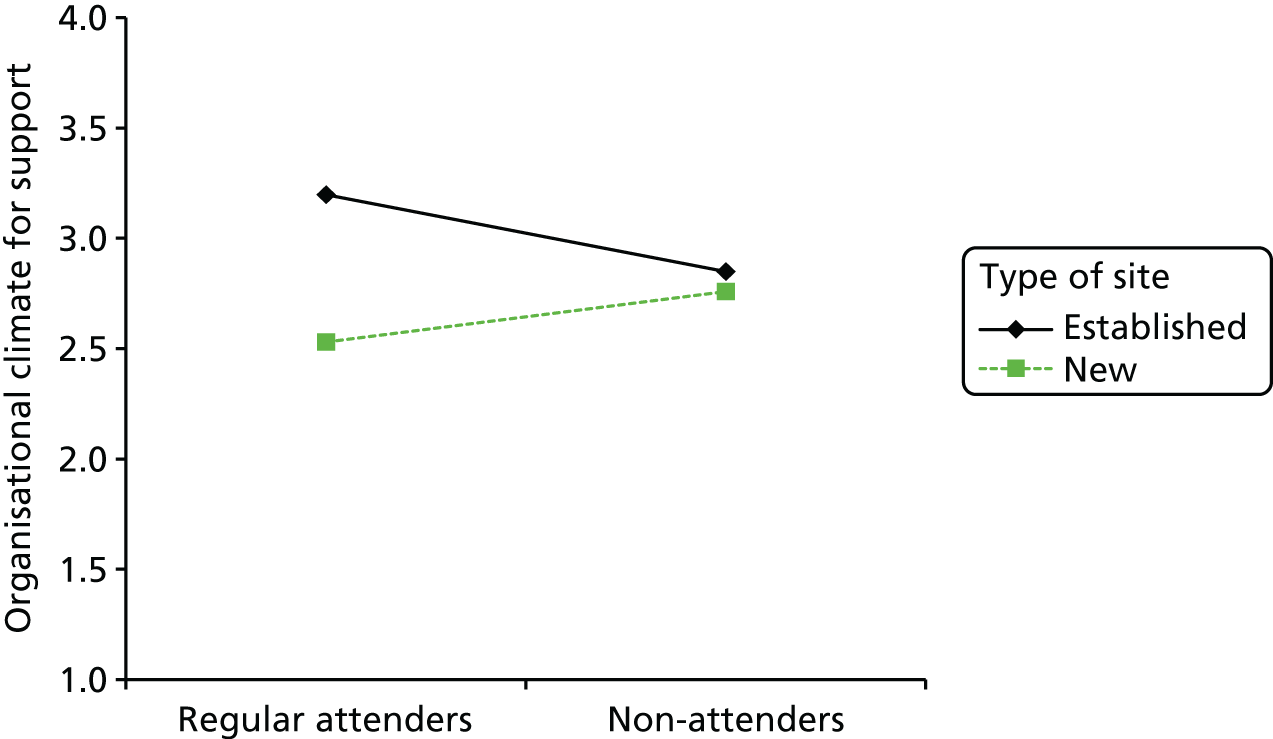

Analysis