Notes

Article history

The research reported here is the product of an HS&DR Evidence Synthesis Centre, contracted to provide rapid evidence syntheses on issues of relevance to the health service, and to inform future HS&DR calls for new research around identified gaps in evidence. Other reviews by the Evidence Synthesis Centres are also available in the HS&DR journal. The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 13/182/13. The contractual start date was in February 2018. The final report began editorial review in April 2018 and was accepted for publication in July 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Rob Anderson is a current member of the National Institute for Health Research Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) (researcher-led) Prioritisation Panel. However, this panel has no role in the allocation of review and research topics to the Exeter HSDR Evidence Synthesis Centre.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2018. This work was produced by Shaw et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2018 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Background

This report is concerned with the ‘Nearest Relative’ (NR) provisions of the Mental Health Act 1983 (MHA 1983). 1 The work was commissioned by the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) programme. The following sections provide a brief overview of the key features of the MHA 19831 and the NR provisions contained within it, or as amended since 1983. Perceived problems regarding the use of the NR provisions are briefly discussed, and the relevant legislative changes that apply to Scotland and Northern Ireland are also described. Finally, justification for the methodological approach and the aims and objectives of the review are set out.

The Nearest Relative provisions of the Mental Health Act 1983

The Mental Health Act 1983

The MHA 19831 is a piece of UK legislation that governs the assessment, care, treatment and related matters pertaining to individuals with a ‘diagnosed mental health disorder’ who are detained in hospital via civil or criminal pathways. The MHA 19831 outlines the process by which individuals may be detained and treated, their rights to appeal and the rights of those receiving aftercare. The MHA 19831 also outlines the rights of the family and carers of the person being detained. The MHA 19831 fully applies to England and Wales, and partly applies in Scotland and Northern Ireland.

‘Sectioning’ under the Mental Health Act 1983: civil pathway

Section 2 of the MHA 19831 states that a person may be involuntarily admitted to hospital for a period of assessment of no longer than 28 days if they are suffering from a mental disorder ‘of a nature or degree which warrants the detention of the service user in a hospital’ (contains public sector information licensed under the Open Government Licence v3.0.) and it is in the interests of the health or safety of the service user or for the protection of the public. 1

A person can be involuntarily admitted to hospital under section 3 of the MHA 19831 for treatment for a period of up to 6 months initially if they are deemed to be suffering from a ‘mental disorder’ requiring treatment in hospital, and it is necessary for the safety of the service user or anyone else that treatment is given under detention. 1

The MHA 19831 has a series of safeguards to ensure that the powers to detain individuals in hospital involuntarily for a period of assessment and/or treatment are used appropriately. Before an individual can be detained under section 2 or 3 of the MHA 1983,1 two medical practitioners should independently assess the service user. The two practitioners should discuss the results of their assessments together, before reporting to an approved mental health professional (AMHP), who then decides whether or not to apply to a hospital to detain the service user. 1 An emergency detention can be sought under section 4 or 5 of the MHA 19831 when seeking an assessment by a second medical professional may ‘involve undesirable delay’. A section 4 detention can be converted to a section 2 or 3 detention if a second assessment, by a different medical professional, is conducted within 72 hours.

A service user sectioned under section 2 or 3 of the MHA 19831 has the right to appeal against the decision via a mental health tribunal. The decision to detain a service user also has to be reviewed regularly, although the time frame for this varies in accordance with which section has been used to detain the service user in hospital. 1

The Nearest Relative provision

The NR provision of the MHA 19831 was intended as another safeguard to protect the rights of a service user who is being involuntary detained. The NR is an individual assigned to the service user who has several rights and responsibilities relating to the care the service user receives. The NR:

-

can make a direct application to a hospital for the detention of the service user

-

can object to the detention of the service user under section 3 and, if this occurs, the service user cannot be compulsorily admitted

-

receives confidential information about the detained person

-

can request that the service user be discharged from sections 2 and 3 and a section 7 guardianship order.

Although a NR can also request the discharge of a service user from a community treatment order (CTO), they are unable to object to the initial imposition of the CTO or the recall of a service user to hospital should they not meet the criteria set by a CTO. 1 For ‘unrestricted’ service users admitted via the criminal pathway on section 37, their NR can apply to the tribunal to request a discharge from their section. 1

Identification of the Nearest Relative

Section 26 of the MHA 19831 defines and differentiates ‘Relatives’ and ‘Nearest Relatives’. ‘Relative’ means anyone in the following hierarchical list:

-

husband, wife or civil partner

-

son or daughter

-

father or mother

-

brother or sister

-

grandparent

-

grandchild

-

uncle or aunt

-

niece or nephew.

Under the MHA 1983,1 the AMHP will proceed through this list from top to bottom until an eligible NR, who meets the criteria required to take up the position, has been identified. To be considered eligible for the NR role a person must be > 18 years of age, living in the UK if this is the service user’s country of residence and, in the case of partnerships, in a relationship with the service user for > 6 months. 1 Ex-partners who have permanently separated from the service user cannot be considered for the role. In circumstances in which two individuals are eligible to fulfil the role (e.g. two siblings), the eldest and/or whole-blood relatives are selected.

Displacement and delegation of the Nearest Relative role

The NR may be ‘displaced’ (i.e. a different person appointed to the role) through application by an AMHP to the County Court. Possible reasons for displacement include when the NR cannot take up their duties because of illness, objects to an admission for treatment (or guardianship application) without good reason, has not considered the service user’s welfare or protection of the public in their application to discharge the service user or is considered unsuitable to act for any other reason. 1 Displacement of the NR is the only way to detain a service user under section 3 of the MHA 19831 if their NR has objected to the detention.

The NR can choose to nominate someone else if they do not wish to take up the responsibilities associated with the role, and may delegate responsibilities to the next eligible NR. 2

Legislative amendments influencing the Nearest Relative provisions

The NR role emerged in the Mental Health Act 19593 and was largely unchanged in the 1983 Act. 4 However, since 1983 elements of the MHA 19831 have been amended or influenced by the development of other legislation and codes of practice, which has influenced how the NR provisions are implemented. The key legislative changes are summarised below.

The Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order, 1986

This legislation is broadly similar to the MHA 1983. 1 It specifies that compulsory admission will normally be on the basis of a recommendation by a general practitioner and application by an approved social worker (ASW). 5 The role of the NR is similar to that detailed by the MHA 1983. 1

The Human Rights Act 1998

The Human Rights Act 19986 outlines the rights and freedoms that everyone in the UK is entitled to. 6 These rights are set out in a series of 12 articles, each of which details a different right. Such rights include the right to life, the right to privacy, freedom from torture and inhumane or degrading treatment, and the right to a fair trial. 6 The Act means that people in the UK can seek justice in court if they feel that their rights have been violated and that public bodies, such as hospitals, courts and the police, must respect people’s rights. 7 The Human Rights Act was implemented in the UK in October 2000.

The implementation of the Human Rights Act provides a context for issues relating to information-sharing, and confidentiality in particular, given that the assigned NR is entitled to receive confidential information about the service user. 6 Because all health legislation post 1998 must be compliant with the Human Rights Act,6 we believe that it is of central importance for interpreting and implementing the MHA 1983. 1

The National Service Framework for Mental Health 1999

The National Service Framework for Mental Health8 section 6 outlines the support that carers of individuals with mental ill health should expect. This includes a yearly assessment of their needs and an implementation of a care plan based on this. The framework also advises that carers are provided with information regarding the mental health needs of the person they care for, including an explanation of the person’s care plan.

The Mental Capacity Act 2005

The Mental Capacity Act (MCA)9 is intended to protect individuals aged ≥ 16 years who do not have the capacity to make certain decisions for themselves. The MCA is intended to support professionals to assess the capacity of an individual regarding a specific choice and, if capacity is lacking, make a decision that is in the best interests of that person. 10

The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003

The Mental Health (Care and Treatment) (Scotland) Act 2003 (MHCT)11 introduced key changes to the processes involved in the detention of people with ‘mental disorders’ in Scotland. The change of greatest relevance to the present review was the introduction of the ‘Named Person’ (NP) role, in place of NR provision. The Millan Committee was established to review the Mental Health (Scotland) Act 1984, which included NR provision as set out in the MHA 1983. 1,12 The NP was recommended in response to a number of concerns over the suitability of the NR, namely that the appointed NR may not be appropriate for reasons of practicality, lack of genuine interest in the service user or the potential for abuse of powers. 13

Under the MHCT, the powers of the NP are reduced, and the service user has choice over who is appointed and can revoke the NP in writing. 11 If the service user does not nominate a NP, an individual can be appointed by default, turning first to the primary carer, and then to the NR hierarchy set out in the MHA 1983 [with the addition of civil partners as set out in the Mental Health Act 2007 (MHA 2007)]. 1,14 Key differences between the NR and NP are shown in Table 1.

| Application of act | NR (MHA 2007)1,14 | NP (MHCT)11 |

|---|---|---|

| Region | England and Wales | Scotland |

| Appointment | By default, in accordance with hierarchy of ‘nearness’ of relatives set out in MHA 19831 | Nominated by service user. In absence of nomination, defaults to primary carer, then in accordance with the hierarchy of ‘nearness’ of relatives set out in MHA 19831 |

| Displacement | Via application to a County Court | Can be revoked in writing by the service user. Can be challenged by a mental health professional if deemed inappropriate |

| Option to decline | Powers can be delegated by the NR to another eligible relative | Can be declined by the NP |

| Rights to information |

|

To:

|

| Discretionary powers | To:

|

To:

|

The Mental Health Act 2007

The MHA 19831 was revised in 2007,14 leading to a number of significant changes to the Act. These include changes to professional roles, such as introducing the AMHP to replace the ASW, introducing CTOs to replace supervised discharge, certain definitions, interaction with the Mental Capacity Act 2005 and the structure of mental health tribunals. 14 Of direct relevance to the NR provisions were the following amendments:

-

When identifying the NR, those in civil partnerships were considered as being of equal status to people who were married.

-

Service users were given the power to displace the NR on grounds of unsuitability. Applications were to be made to a County Court.

Information Sharing and Mental Health: Guidance to Support Information Sharing by Mental Health Services 2009

This Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC) publication15 discusses the rights of service users to know about the information that is held about them by public bodies, and the right of carers and other members of the public to receive enough information to enable them to support the service user and protect themselves. 15 The document also acknowledges the role that carers may play in providing information to services. It recommends criteria that should be fulfilled when sharing information regarding a service user between different parties.

The Mental Health (Wales) Measure 2010 and associated Code of Practice to Parts 2 and 3

The Mental Health (Wales) Measure (MHWM) 201016 details the support people living with a mental health problem should receive in both primary and secondary care. With regard to the NR role, the MHWM 2010 aims to ensure that people receiving secondary mental health services in Wales all have a care and treatment plan. The associated Code of Conduct for parts 2 and 3 of the MHWM 2010 stipulates that the service user should be involved as much as possible with the assessment to inform their care and treatment plan, and their carers and ‘significant others’ should be involved when appropriate. 17

The NHS Five Year Forward View 2014

This policy document18 outlines government proposals regarding new models of care within the NHS. Of particular relevance to the NR role, this document outlines a commitment to improve the support that carers of individuals with long-term conditions receive. The document outlines the goal to improve access to information regarding the service user’s condition, history and care, not only for the service user themselves, but also for any other individuals whom the patient wishes to share this information with.

The Mental Health Act Code of Practice 2015

The Code of Practice provides guidelines for professionals on their roles and responsibilities under the MHA 1983. 1,2 Revisions to the Code were made in 2015, in the light of changes in law and policy since it was first published, and aims to improve protection of the rights of service users, families and carers. It also outlines how to determine when the MHA 19831 should be used instead of the MCA and vice versa. 2

Issues regarding the Nearest Relative provisions

Despite amendments to the MHA 19831 (in 2007)14 and the introduction of a revised Code of Practice (2015)2 to give guidance in applying the MHA 1983,1 there are still concerns about the use of NR provisions. The Care Quality Commission has raised concerns that detained service users are not given enough say in their care. 19 Others have highlighted how the system for involving partners, carers and family members in the care service users receive under the NR provision of the MHA 19831 is inflexible, and does not always represent either the wishes of the service user or the person identified as their NR. 20 This is despite the amendments to the MHA 19831 in 2007, which recognised same-sex relationships within the NR hierarchy and enabled detained service users to displace people who they felt were inappropriate to act for them within the NR role. 14

In 2017, the government commissioned an independent review of the MHA 1983,1 to focus on how the legislation is being used in practice and examine its impact on service users, families and carers. 21

Overall aims and objectives of the systematic review

The aim of this systematic review is to summarise and synthesise experiences of the NR provisions of the MHA 19831 from the perspectives of service users, family members, carers and relevant professionals. More specifically, it aims to gather research evidence to answer the following question: what are the experiences of services users, family members, carers and relevant professionals of the use of the NR provisions in the compulsory detention and ongoing care of people under the MHA 1983?1

This included objectives, from the perspective of service users, family members, carers and relevant professionals. These were to explore:

-

experiences relating to the identification of the NR in the care of an individual who has been compulsorily detained under the MHA 19831

-

experiences of requesting displacement of the assigned NR, including the process of going through a tribunal and issues associated with this, such as influences on ongoing care

-

issues relating to service user confidentiality and information-sharing, relating to all aspects of compulsory detention

-

issues relating to decisions about care during detention and after discharge, including discharge to a CTO

-

issues relating to service users having access to support from individuals who they want to be involved with or informed about their care.

Chapter 2 Methods

This systematic review was conducted in 6 weeks. The methods used to identify and select evidence followed the best practice approach recommended by the University of York’s Centre for Reviews and Dissemination. 22 Reporting of the methods and results was consistent with Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) reporting guidelines23 and Enhancing Transparency in Reporting the synthesis of Qualitative Research (ENTREQ) checklist guidelines. 24 A protocol was registered on the PROSPERO database (PROSPERO CRD42018088237).

Search strategy

Background scoping searches were carried out to help develop a bibliographic database search strategy for the identification of evidence. This predominantly consisted of basic keyword searching in Google (Google Inc., Mountain View, CA, USA) and Google Scholar. Whenever possible, we ensured that relevant papers identified in the background scoping process would be retrieved by our bibliographic database searches by deriving search terms from the titles and abstracts.

An information specialist (SB) developed the bibliographic database search in consultation with the review team. The search strategy made use of both controlled indexing (e.g. medical subject headings in MEDLINE) and free-text (i.e. title and abstract) searching. A qualitative study search filter was used with adaptations to limit the results to qualitative studies. 25 We also included search terms for ‘questionnaires’ and ‘surveys’ in order to complement the limited qualitative evidence that our background scoping indicated would be available to us. The search results were limited to English-language publications in view of the UK focus of our review, and to publications from 1998 onwards in view of the central importance of the Human Rights Act 19986 for interpreting and implementing the MHA 1983. 1 The final search strategy was translated for use in seven bibliographic databases, which were selected based on their relevance to the topic area: MEDLINE (via Ovid), MEDLINE In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations (via Ovid), PsycINFO (via Ovid), Social Policy and Practice (via Ovid), HMIC (via Ovid), Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) (via EBSCOhost) and Applied Social Sciences Index and Abstracts (ASSIA) (via ProQuest). The bibliographic database search strategies are reproduced in Appendix 1, Bibliographic databases.

Forward citation-chasing (identifying papers that cite our included studies) was conducted using Web of Science, Scopus and Google Scholar. Backward citation-chasing (inspecting the reference lists of included studies) was carried out manually by reviewers. The reference lists of previously conducted systematic reviews on topics related to the NR provision of the MHA 19831 were also inspected.

The websites of several relevant organisations that were identified through our background scoping were searched using basic keyword searching, as permitted by the search interfaces of the websites. The website search strategies and list of websites searched are reproduced in Appendix 1, Website searches. Finally, authors of relevant studies were contacted with regard to unpublished or unobtainable studies.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria and exclusion criteria, in accordance with the Population, phenomenon of Interest and Context (PICo)26 categories were applied to the studies identified through the search strategy.

Population

This was defined as people detained under section 2 or 3 of the MHA 1983,1 their family and carers and the individuals involved with their care who work within the remit of the MHA 1983. 1

More specifically, the population may include:

-

current service users

-

former service users

-

service users’ family members and carers

-

health and social care professionals

-

approved mental health professionals (community nurses, psychologists, occupational therapists, social workers)

-

advocates

-

police officers.

Studies were included if the individuals were:

-

a service user who has experience of being compulsorily detained under section 2 or 3 of the MHA 19831

-

carers, relatives related professionals (listed above).

Studies were excluded if the individuals were:

-

people who have agreed to a voluntary admission and carers, relatives and relevant professionals involved in their care

-

people with mental health difficulties not leading to compulsory detention under the MHA 1983. 1

Phenomenon of interest

This was defined as experiences of, or attitudes towards, the application of the NR provisions of the MHA 1983. 1 This includes any experiences in relation to the involvement of relatives, carers or professionals in the care of or decisions about a compulsorily detained person.

Studies were included if data about experiences were obtained through:

-

qualitative means (e.g. interview, focus group)

-

a survey or questionnaire.

Context

This was defined as the use of the NR provisions of the MHA 19831 within the UK only.

Studies were included if:

-

detention took place under the jurisdiction of England, Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland

-

data were from any time since the publication of the Human Rights Act 1998.

Studies were excluded if:

-

detention was not under the jurisdiction of England, Wales, Scotland or Northern Ireland

-

detention of an individual was undertaken by forensic services.

Study design

Studies were included if data came from:

-

studies using stand-alone qualitative studies and from mixed-methods studies using several

-

different methods.

Studies were excluded if data came from:

-

blogs or social media posts

-

commentaries, opinion pieces and editorials

-

case studies

-

conference abstracts

-

case law.

Study selection

Searches were undertaken and all results were downloaded into EndNote [EndNote X8; Clarivate Analytics (formerly Thomson Reuters), Philadelphia, PA, USA] for removal of duplicate records. A pilot screening exercise was carried out on a sample (n = 100) of bibliographic database search results in order to calibrate inclusion/exclusion judgments for all reviewers (MN, LS and SB) and refine the clarity of inclusion criteria. Decisions were discussed in a face-to-face meeting to ensure consistent application of criteria. When necessary, inclusion and exclusion criteria were revised to reflect reviewer interpretation and judgment.

The revised inclusion and exclusion criteria were then applied to the title and abstract of each identified citation independently by two reviewers (MN and LS). Disagreements were resolved through discussion, with unresolved disagreements resulting in inclusion for full-text screening. Sources excluded on the basis of relating to forensic detention were labelled on exclusion.

The full text of each source taken forward from title and abstract screening was assessed independently for inclusion by two reviewers (LS, MN or SB). Disagreements were settled by discussion with a third reviewer when necessary.

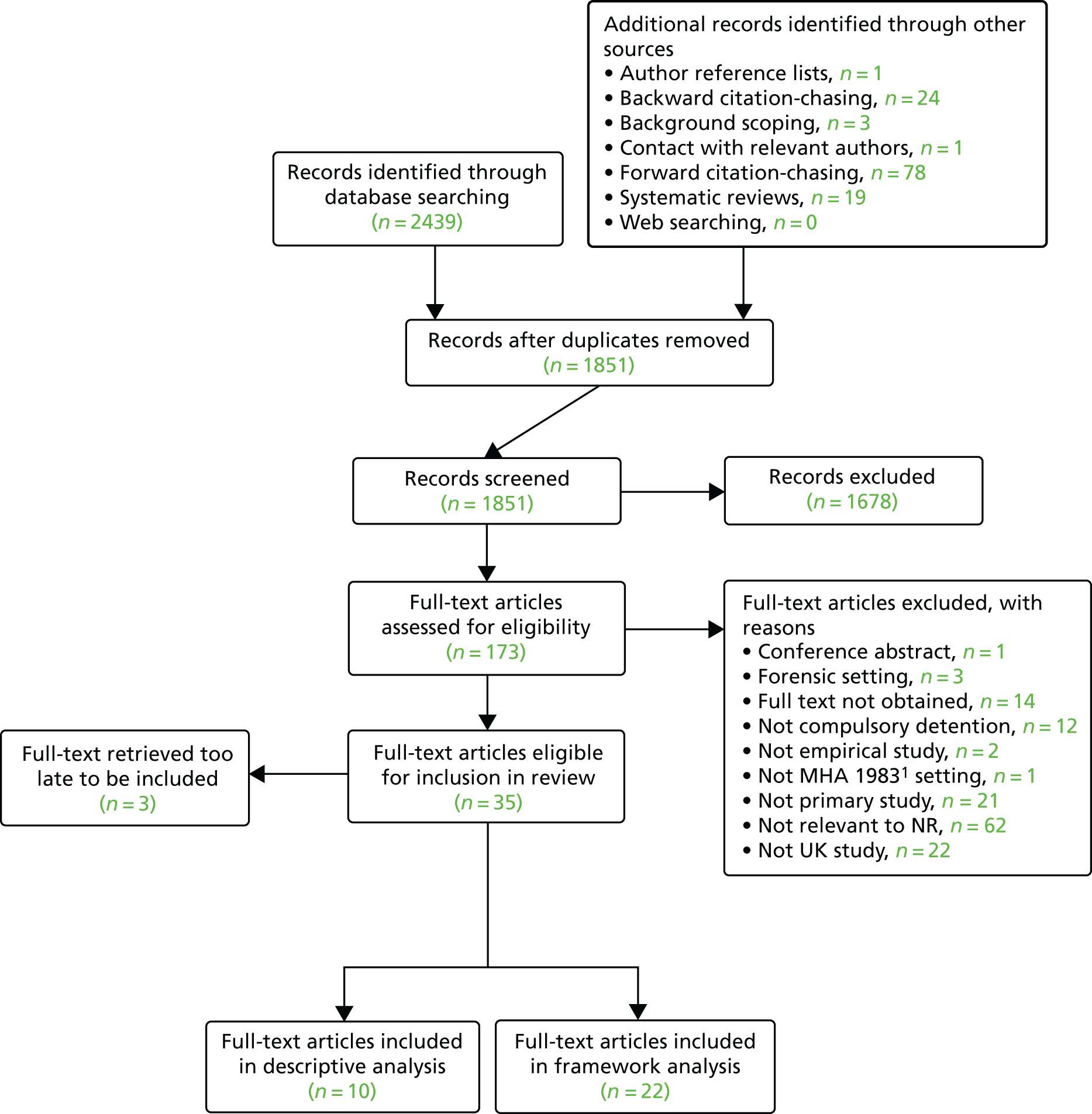

References were managed in EndNote software. Reasons for exclusion were recorded at full-text screening and documented in a PRISMA flow chart (see Figure 2). 23

Data extraction

A data extraction form was developed using Microsoft Excel® (Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA), piloted by Michael Nunns, Liz Shaw and Simon Briscoe and refined accordingly. Summary data were extracted for each study included after full-text screening (both ‘tiers’ of studies) by one reviewer (MN, LS or SB) and checked by a second reviewer (SB, LS or MN). Extracted data included first author, date of source, title of source, focus/aim of source, sample size, sample demographics, stakeholder groups represented, data collection technique (e.g. survey, interviews, focus group), type of analysis done and themes or ideas presented relevant to the research question.

Critical appraisal strategy

Critical appraisal was carried out on studies prioritised for synthesis only (‘top tier’). Critical appraisal was done by one reviewer (LS or MN) during data extraction using the Wallace checklist27 and checked by a second reviewer (MN or LS). Disagreements were resolved through discussion. Critical appraisal did not influence eligibility for inclusion or synthesis, but was intended to provide context to findings.

Methods of data synthesis

Owing to the time restrictions imposed on the review process, after full-text screening decisions had been completed, a purposive sampling approach was applied to prioritise the best available evidence for inclusion. This was a pragmatic step that considered both the quality and the quantity of relevant evidence available in each record. All included studies were rated by two reviewers (MN and LS) based on the number of relevant primary data collected. Studies that contained at least half a page of qualitative data directly relating to the research objectives were prioritised into the ‘top tier’ of included studies, ready for inclusion in the framework synthesis. Data from surveys and questionnaires were not prioritised as there were no free-text responses to open questions presented. Disagreements on the classification of studies were resolved with discussion. Studies that did not meet this rating were retained in the ‘second tier’ of studies. Key details (country, aim of paper, data collection methods and sample characteristics) of studies sorted into the second tier were described and tabulated.

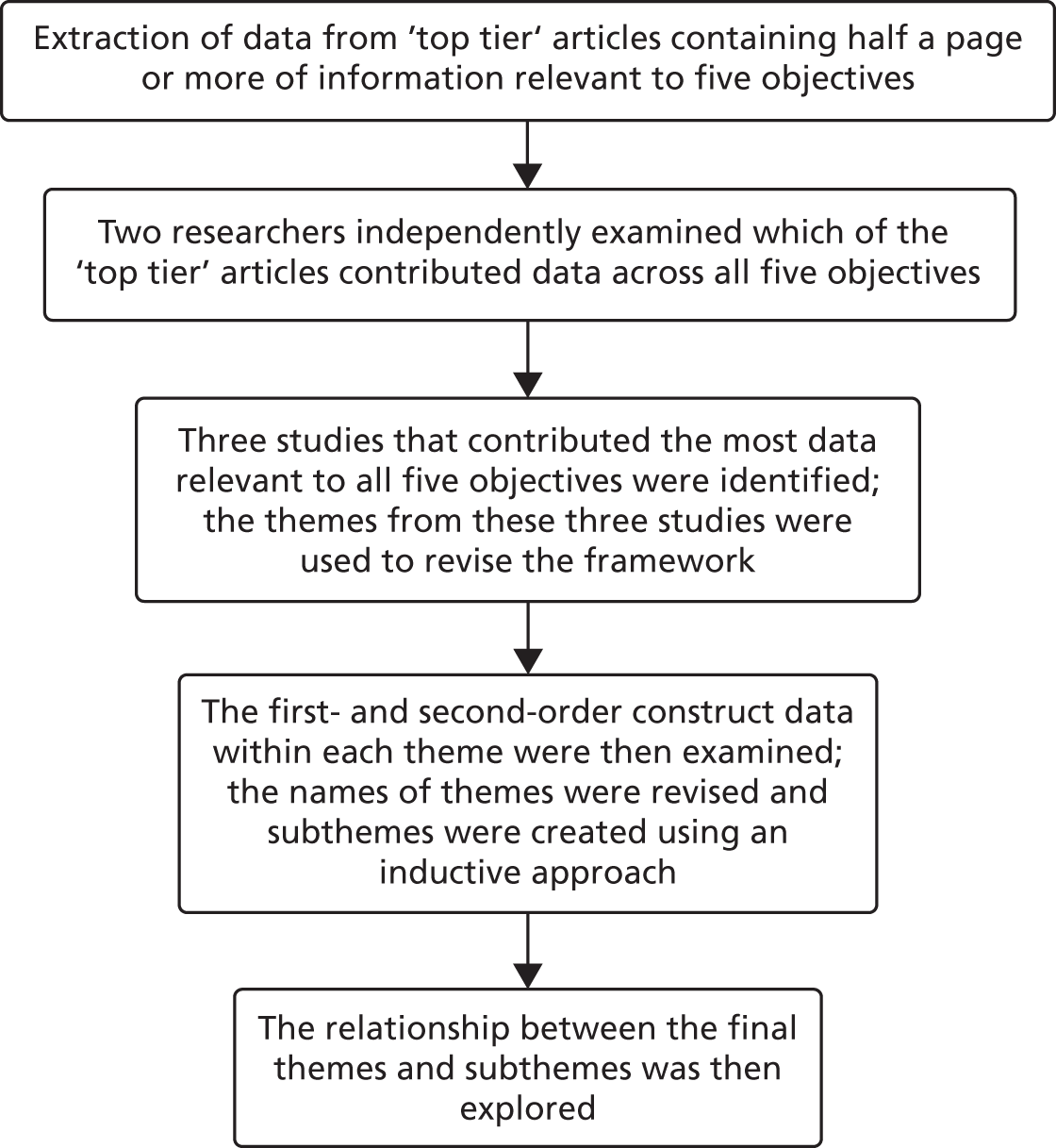

We made a pragmatic decision to use a framework synthesis approach, because a thematic analysis utilising an inductive interpretative approach would not have been possible within the limited period of time available to complete this review. Framework syntheses have been recognised for their utility in making sense of qualitative evidence within the short time frame associated with rapid reviews of health research. 28

Typically, the initial framework used within a framework synthesis would be selected from an existing theory or model relevant to the field or constructed by drawing on a thorough understanding of relevant background literature and related theory (e.g. see Dixon-Woods29). However, our background scoping and preliminary searches did not identify any accessible theory or framework that was relevant to all of our research objectives. Hence, the process used for the framework synthesis differed from that stated in our protocol. The synthesis process used in this review was as follows.

Extraction of data relevant to the research question(s)

Participant quotations illustrating the views of service users, carers and NRs and the author interpretation of these views (known as first- and second-order construct data, respectively30) were extracted from the results section of each ‘top tier’ article. The information was placed within a framework based on our five research objectives by one reviewer (LS or MN), and checked by a second reviewer (MN or LS) using Microsoft Excel®. This information was used to identify which papers contributed towards a range of different research objectives and represented a variety of participant perspectives.

Identification of initial themes

This process was carried out independently by two reviewers (LS and MN) identifying eight ‘top tier’ papers from three studies with the most data relevant to multiple research objectives, accounting for a range of participant perspectives. One of these studies was conducted in England31 and two were conducted in Scotland. 32,33 One reviewer (LS) selected the themes presented in each article that were most relevant to the research objectives. A second reviewer (MN) checked the selection of themes (see Appendix 2), which were then used to revise the stage 1 framework. Studies in the ‘second tier’ of included studies did not influence the identification or development of themes.

Final framework revisions using thematic analysis

The content of each of the themes generated through stage 2 of the synthesis was then re-examined. Within each broad theme, first- and second-order data that appeared to be discussing similar or related concepts were grouped together. This formed the beginnings of descriptive subthemes. The data contained under these subthemes were moved both within and across existing subthemes to reflect changes in their content. Preliminary subthemes were divided and merged and content changed in an inductive, iterative process, in order to capture current or relevant ideas within the included studies that were not represented by the initial framework. As this process evolved and additional interpretation occurred, the names of subheadings and their placement under certain themes were changed in order to reflect the data within them. Towards the end of the process, some theme names were also changed in order to better represent the content of the framework and the reviewer’s understanding of the data.

The synthesis was conducted by one reviewer (LS) within Microsoft Excel®. The names of emerging subthemes and themes were checked with other members of the review team (MN, SB, JTC and RA), whose feedback was incorporated into the developing themes and subthemes to ensure that their names accurately reflected their content.

Relationship between the themes

A figure representing the relationship between the themes identified through the framework synthesis of the ‘top tier’ papers was then developed through discussion (LS, SB, MN, RA and JTC). The data synthesis process is summarised in Figure 1.

FIGURE 1.

Framework synthesis process for prioritised studies.

End-user involvement

One carer with experience of the NR provisions provided feedback on the themes and subthemes identified by the synthesis and commented on the write-up of the results within this report.

Reflexive statement

The methods utilised within this review were reflective of the expertise and experience within the review team. The team consisted of three systematic reviewers (JTC, MN and LS), an information specialist (SB) and a health economist (RA) with prior experience of conducting systematic reviews for the National Institute for Health Research. This prior experience meant that the team aimed to maintain a rigorous methodology throughout the review, despite the limited time frame available. This is reflected in the decision to retain searching across multiple databases, double screening of references at both title/abstract and full-text level, searches within the grey literature and citation-chasing. The team’s prior experience of managing large numbers of retrieved studies within a set time frame meant that we were able to quickly identify a method to prioritise the studies for inclusion in the main synthesis.

The focus of the review was novel for most members of the team. This meant that the background reading and identification of search terms was informed by objective appraisal of existing literature, albeit restrained by the time available. The team knew of some relevant policy because of previous projects and the experience of one reviewer (LS) of working alongside individuals detained under the MHA 19831 and working in accordance with the MCA. This reviewer utilised her prior experience and knowledge gained through her training as a clinical psychologist and of conducting qualitative synthesis within this review. Her experience provided a lens through which the information included in this review was selected, placed within themes and interpreted. This was balanced by the checking of extracted data by a second reviewer (MN) and incorporation of views from other members of the team and a carer with experience of the MHA 1983. 1 The limited time frame necessitated the use of a framework methodology and a more descriptive analysis, which also limited the potential bias during the synthesis process.

Chapter 3 Results

Study selection

The PRISMA flow diagram in Figure 2 summarises the study selection process. Bibliographic database searches identified 2439 records and supplementary search methods identified 126 records. Following the removal of duplicates there were a total of 1851 unique records that were screened against our inclusion and exclusion criteria. The full texts of 173 papers were sought for further consideration. Of these, 159 full texts were successfully retrieved (92%). Following full-text screening, 124 papers were excluded for the reasons specified in Figure 2. Half of the excluded papers (n = 62) were excluded because they did not report relevant data. Other common reasons for exclusion included being a non-UK study (n = 22) and having no primary study data (n = 21). A smaller number of papers were not about compulsory detention (n = 12), were not about the MHA 19831 or a relevant section of the MHA 19831 (n = 1 and 3, respectively) and there was one conference abstract for which no follow-up journal article could be identified. Thirty-eight papers identified at the title and abstract screening stage focused on involuntary hospital admissions through the criminal pathway of the MHA 1983. 1 The citations of these records are listed in Appendix 3. These were not full-text screened and are not included in any further analysis.

FIGURE 2.

The PRISMA flow chart.

In total, 35 papers4,20,31–63 were identified that met our inclusion criteria: 22 papers via searching bibliographic databases and 13 papers via supplementary search methods.

As described in Chapter 2, Inclusion and exclusion criteria, papers that met our inclusion criteria were categorised in accordance with the number of relevant primary data presented. Papers with several paragraphs or more of data were prioritised into the ‘top tier’ of included studies for synthesis, and studies that did not meet this rating were retained in the ‘second tier’ of studies for narrative description.

Description of included studies

Included sources: prioritised studies

Of the 20 studies that met criteria for inclusion in the review, there were 12 studies, reported across 22 papers,4,31–33,36–38,40,45,46,48,49,51–60 that contained enough relevant and usable data for inclusion in the framework synthesis. Table 2 contains a summary of the foci, sample characteristics and qualitative data collection and analytic methods employed in these studies.

| First author, year of publication | Country | Publication type | Study focus | Qualitative data collection method (date of data collection) | Participants providing qualitative data | Study context and sampling | Type of qualitative data analysis |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berzins, 2009;32 2009;37 and 201036 | Scotland | D; JP; JP | Perceptions of NP provisions | Semistructured telephone (carers) and face-to-face (service users) interviews (data collected 2005–7) | Total, N = 46: service users, n = 20; carers, n = 10 (as potential NPs, n = 3; already NPs, n = 4; considering, n = 3; not considering, n = 0); MHOs, n = 7 (social workers); professionals with influence on government policy, n = 9 | MHOs from local authorities, service users and carers recruited from voluntary organisations, policy influencers recruited at national level. Direct contact/newsletter | Thematic analysis |

| Campbell, 200838 | Northern Ireland | JP | Nature of legal advocacy services available after compulsory admission | Focus group interviews and questionnaires (date of collection NR) | Total, N = 44 respondents from five mental health service user groups: carer group, lawyers, mental health review tribunal member, professional advocacy service managers, hospital administrators | Questionnaires posted to solicitors and hospital administrators in Northern Ireland. Focus group recruitment NR | Thematic analysis |

| Dawson, 200933 | Scotland | R | Perceptions of NP provisions | Face-to-face interviews, telephone interviews and focus groups (data collected 2007–8) | Total, N = 44: service users, n = 2; NPs, n = 4; tribunal members, n = 13; MHOs, n = 14; nurse, n = 1; legal reps, n = 3; independent advocates, n = 5; tribunal clerks, n = 2 | Four local authority areas and their associated health board across Scotland. Contact with voluntary sectors, written invitations, bespoke events with stakeholder groups | Framework analysis |

| Henderson, 200245 | England | JP | Service users’ experiences of mental health care after compulsory admission | Semistructured interviews and observation of group discussions (data collected 2001) | Total, N = 21: carers, n = 11; service users, n = 10 | Participants had to be or have been in a relationship in which one partner has a diagnosis of bipolar disorder | Phenomenological framework analysis |

| Jankovic, 201146 | England | JP | Experiences of family caregivers of relatives involuntarily admitted to psychiatric hospital | In-depth, semistructured interviews (date of collection NR) | Total, N = 31 family caregivers | Contact by letter or telephone. Service users recruited in larger national multicentre study on Outcomes of Involuntary Hospital Admission in England provided informed written consent to approach their family caregivers | Thematic analysis |

| Marriott, 200148 | England | JP | Opinions about the MHA 19831 from those subjected to or affected by it | Focus group, telephone interviews, consensus meeting or written responses (date of collection NR) | Total N = 85a in three groups. Group 1, n = 40: mental health nurses, n = 9; ASWs, n = 10; general psychiatrists, n = 4; MHA 19831 administrators, n = 5; service users, n = 5; carers, n = 7. Group 2, n = 19: hospital managers, n = 2; solicitors, n = 2; general practitioners, n = 3; policy-makers, n = 4; police surgeons, n = 2; police liaison officers, n = 3; specialist psychiatrists (one from each of learning disability, forensic, and child and adolescent services), n = 3. Group 3, n = 26, consisting of people leading organisations representing groups 1 and 2: including a number of national organisations representing users and carers and professional groups affected by or using the Act | Initial nominations made by national experts or representative organisations. Contacted by telephone or in writing | Thematic analysis |

| Pinfold, 200449 | England | R | Identify examples of good practice, or issues with information-sharing between mental health practitioners and carers | Telephone interviews, face-to-face group discussions, multidisciplinary workshop events, open-ended survey questions (date of collection NR) | Survey, N = 998: service users, n = 168; professionals, n = 212; carers, n = 496; carer support workers, n = 93; young carers; n = 29. Interviewed, n = 34: service users, n = 5; professionals working in mental health and ageing, n = 5; professionals working in adult mental health services, n = 9; carers for people with severe mental illness, n = 7; carers supporting people with dementia, n = 5; carer support workers n = 3 | National advertising. Convenience, purposive and snowball sampling techniques. Purposive sample recruited via services in mental health charities Rethink Mental Illness and Mind | Thematic analysis of interview data and content analysis of open responses |

| Rapaport, 1999;51 2002;31 2003;52 2004;4 and 201253 | England | JANP; D; JP; JP; JP | Investigate conceptual and ethical issues and carers’ and service users’ perspectives of NR provisions | Focus group interviews, role information, vignettes and group exercises, questionnaires (data collected 1997–9) | Total, N = 79: carers, n = 34; service users, n = 19; ASWs, n = 26 | Recruited through local groups. Invited by letter, followed up by telephone and visit. All had to have experience of NR provisions | Comparative content analysis of historical data. Grounded theory and multiple case design analysis of contemporary data |

| Ridley 2009;56 2010;55 and 201354 | Scotland | R; JP; JP | Experiences and views of the early implementation of MHCT | Focus group and telephone interviews (data collected 2007–9) | Total, N = 120: service users, n = 49; carers, n = 33; professionals, n = 38, of which n = 15 representatives of organisations and n = 23 individual practitioners (general practitioners, psychiatrists, community psychiatric nurses, nurses, psychologists, MHOs, lawyers and advocacy workers) | Purposive sampling from four health board areas in Scotland, chosen to reflect rural, urban and mixed geographical areas (Dumfries and Galloway, Fife, Greater Glasgow and Clyde) and the state hospital | Grounded theory |

| Rugkåsa, 2017;57 and Canvin, 201440 | England | JP; JP | Experiences of carers and involvement of family in CTOs | Interviews (data collected 2012) | Total, n = 24 family carers | Family carers of service users with experience of CTOs | Thematic analysis |

| Smith, 201558 | England | JP | NR’s experiences of mental health crises, identifying improvements that could be made to AMHP practice | Telephone interviews (data collected 2014) | Total, n = 32 NRs | NRs in contact with ASWs in the south of England | Inductive thematic analysis |

| Stroud, 2013;60 and 201559 | England | R; JP | Service user and practitioner experiences of the use of CTOs | In-depth semistructured interviews (data collected 2011–12) | Total, N = 72: service users, n = 21; NRs, n = 7; care co-ordinators, n = 16; responsible clinicians, n = 10; AMHPs, n = 9; service providers, n = 9 | Consulted CTO records from Sussex Partnership NHS Trust, approached by letter of invitation | Thematic analysis |

Among the ‘top tier’ studies, there were two PhD theses31,32 and four reports. 33,49,56,60 The three studies from Scotland32,33,56 consisted solely of government reports and subsequent publications in peer-reviewed journals, all focusing on the implementation of the MHCT, with specific regard to the NPs provisions. One study38 was conducted in Northern Ireland and focused on the views of various stakeholders on advocacy services available after compulsory detention. The remaining eight studies, conducted in England, could broadly be grouped as focusing on experiences of CTOs,57,60 interactions with various mental health professionals49,58 or perceptions of the MHA 19831 and the NR provisions and their implications for care. 31,45,46,48

All of the ‘top tier’ studies collected data using interviews. Other data collection methods used included administering questionnaires with space for open responses,31,38,49 observation of group discussions,45,49 and workshop events or group exercises. 31,48,49 There was a mixture of national and local sampling approaches, resulting in sample sizes ranging from 21 carers45 to 998 survey respondents. 49 Interviews were conducted with samples ranging from 2145 to 11556 individuals, from a range of perspectives. Analysis was described as ‘thematic analysis’ (eight studies),32,36–38,46,48,49,57–60 ‘grounded theory’ (two studies)33,45 or ‘framework analysis’ (two studies). 4,31,51–56

Included sources: ‘second tier’ studies

Ten papers, reporting eight studies, met the inclusion criteria for the review but did not contain enough relevant data for synthesis. 20,34,39,41–44,47,50,61 Table 3 contains a summary of the aims, sample characteristics and methods for these 10 papers.

| First author, year of publications | Country | Aim or focus of paper (from paper) | Sample | Data collection and analytic approach |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Banks, 201634 | England | Understand experiences of CTO practice within the context of the personalisation agenda, in particular, aspects of person-centred support | Total, N = 72: service users, n = 21; practitioners (n = 35, of whom, care coordinators, n = 16; responsible clinicians, n = 10; AMHPs, n = 9); NRs, n = 7; service (supported housing) providers, n = 9 | Thematic analysis of semistructured interviews |

| Campbell, 2001;39 and Manktelow, 200247 | Northern Ireland | Reports on the first extensive survey of ASW activity in Northern Ireland. The research aimed to explore the training, practice and management of ASWs | Total, N = 282: service users/carers, n = 28; ASW managers, n = 11; ASWs, n = 243 survey respondents | Thematic analysis of semistructured interviews conducted via telephone, face to face or in focus groups. Additional postal survey of ASWs |

| De Maynard, 200741 | England | Seeks to examine the experiences of black men detained under the MHA 19831 | Total, n = 8: BME men (specifically of African or African Caribbean descent) living with severe mental illness | Grounded theory approach to analysis of qualitative interviews |

| Department of Health and Social Care, 201542 | England | The Department of Health and Social Care consulted people and organisations about strengthening the rights and choices of people to live in the community, especially people with learning disabilities, autism or mental health conditions. This document summarises the main trends in responses to the consultation | Total, N = 468. Responses from individuals, n = 219: service users (48%); carers, family or friends of service users (25%);a health and social care professionals, support workers and advocates and others (27%). Responses from various organisations, n = 221; other groups, n = 28 | 50-item ‘agree/disagree’ questionnaire, with space for open comments. Content analysis of open responses |

| Gault, 2009;43 and Gault, 201344 | England | Describes people’s experience of being compliant or non-compliant with treatment, their experience of compulsory treatment and how they feel that they should be encouraged to comply | Total, N = 19: service users, n = 11; carers, n = 8 | Two largely unstructured focus groups 10 or 12 months apart, coded with a grounded theory approach |

| Mental Health Alliance, 201720 | England | The survey focuses on the underlying principles of the MHA 19831 and how people’s rights are currently protected, where it is working well and what could be changed and improved | Total, n = 8631: survey responses from service users, carers and mental health professionals | Questionnaire with opportunity for free-text responses |

| Rabiee, 201350 | England | This paper examines the views and experiences of using and providing mental health services from the perspectives of black African and black African Caribbean mental health service users, their carers, voluntary services and a range of statutory mental health professionals and commissioners in Birmingham, UK | Total, N = 65: BME service users, n = 25; carers, n = 24; a range of statutory mental health professionals, n = 16 | Grounded theory approach to analysis of telephone interviews, face-to-face interviews and focus groups |

| Taylor, 201361 | England | Sets out the views of AMHPs on the impact of SCT on their work and their service users’ lives in the community | Total, n = 14 AMHPs | 50-item questionnaire, with opportunity for open comments |

There were eight peer-reviewed journal articles reporting six primary studies34,39,41,43,44,47,50,61 and two survey-based reports. 20,42 Eight papers reported research conducted in England and/or Wales,20,34,41–44,50,61 and two reported research conducted in Northern Ireland. 39,47 The papers by Campbell et al. 39 and Manktelow et al. 47 were based on survey data collected in 1998–9, in the context of the Mental Health (Northern Ireland) Order (1986). 5 Of the studies conducted in England and Wales, only the study by De Maynard41 may have been conducted prior to the 2007 amendments to the MHA 1983,1,14 although the date of data collection was not reported.

Telephone and face-to-face interview and focus groups were used in five studies to capture experiences. 34,39,41,43,50 Survey methods with opportunities for free-text or open responses were used on their own in three studies20,42,61 and used in conjunction with interviews by Campbell et al. 39

The views of service users were captured in seven studies,20,34,39,41–44,47,50 including two focusing on the experiences of black and minority ethnic service users. 41,50 Appointed NR or NPs were specifically sampled only in the study by Banks et al. 34 Other family members or carers (i.e. not necessarily in any formal statutory role) contributed views in five studies. 20,39,42,43,50 Mental health professionals, including AMHPs and ASWs, were sampled in six studies. 20,34,39,42,50,61

Eligible sources retrieved late

Three additional records were identified at title and abstract screening as being eligible for inclusion in the review, but could not be retrieved in time to be considered for data extraction or synthesis because of the rapid review timeline. These consisted of (1) a PhD thesis,62 acquired via expert recommendation, about approved mental health practice in England and Wales; (2) a journal article,35 identified through database searches and retrieved via The British Library, about service users’ experiences of compulsion under the MHA 1983;1 and (3) a report by the Social Services Inspectorate,63 part of the Social Care Group in the Department of Health and Social Care (DHSC), that provided relevant data about the involvement of social workers in the care and treatment of involuntarily detained service users. Of the three additional records, only the PhD thesis62 would have been eligible for inclusion in the framework synthesis, based on the quantity of relevant data presented.

Critical appraisal

The quality of the 12 studies included in the framework synthesis is shown in Table 4. Overall, studies scored well in several domains. All studies provided a clear question and subsequently used appropriate study designs to answer them. Findings were always substantiated by data and largely generalised to an appropriate degree. Reflexivity was explicitly considered only in two studies,31,32 and for this reason they were the only studies in which it was possible to determine the effect of the authors’ ideological or theoretical perspectives on their findings. In terms of the reporting of methods, the context or setting was described well in only 5 out of 12 studies. 31,32,46,49,56 Samples were usually appropriate, or their limitations acknowledged. For the description of data collection, three studies did not provide enough information to be able to reproduce the data collection setting,33,45,60 and there was insufficient evidence of rigorous data collection in two studies that described only the use of an interview schedule. 38,46 Other studies described the use of additional markers of rigorous methods, such as the use of audio-recordings, checking transcripts and supplementary note-taking. Four studies were judged to have lacked evidence of rigorously conducted data analysis. 38,45,58,60 In order to score positively for this outcome, studies needed to have included an explicit description of the process of qualitative data analysis, for example the pathway from initial coding of transcripts to the development of final themes. Finally, there was no explicit reference to ethical issues, ethics approval or confidentiality issues in three studies. 45,48,58

| First author, year of publication | Is the research question clear? | Is the theoretical or ideological perspective of the author (or funder) explicit? | Has this perspective influenced the study design, methods or research findings? | Is the study design appropriate to answer the question? | Is the context or setting adequately described? | Is the sample adequate to explore the range of subjects and settings, and has it been drawn from an appropriate population? | Was the data collection adequately described? | Was data collection rigorously conducted to ensure confidence in the findings? | Was there evidence that the data analysis was rigorously conducted to ensure confidence in the findings? | Are the findings substantiated by the data? | Has consideration been given to any limitations of the methods or data that may have affected the results? | Do any claims to generalisability follow logically and theoretically from the data? | Have ethical issues been addressed and confidentiality respected? |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Berzins, 200932 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Campbell, 200838 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Dawson, 200933 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Henderson, 200245 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | No | No | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Jankovic, 201146 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | Yes | CT | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Marriott, 200148 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Pinfold, 200449 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rapaport, 200231 | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Ridley, 200956 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Rugkåsa, 201757 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes | Yes |

| Smith, 201558 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | No | Yes | Yes | Yes | No | Yes | No | No | No |

| Stroud, 201360 | Yes | No | CT | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | No | Yes | Yes |

Framework synthesis

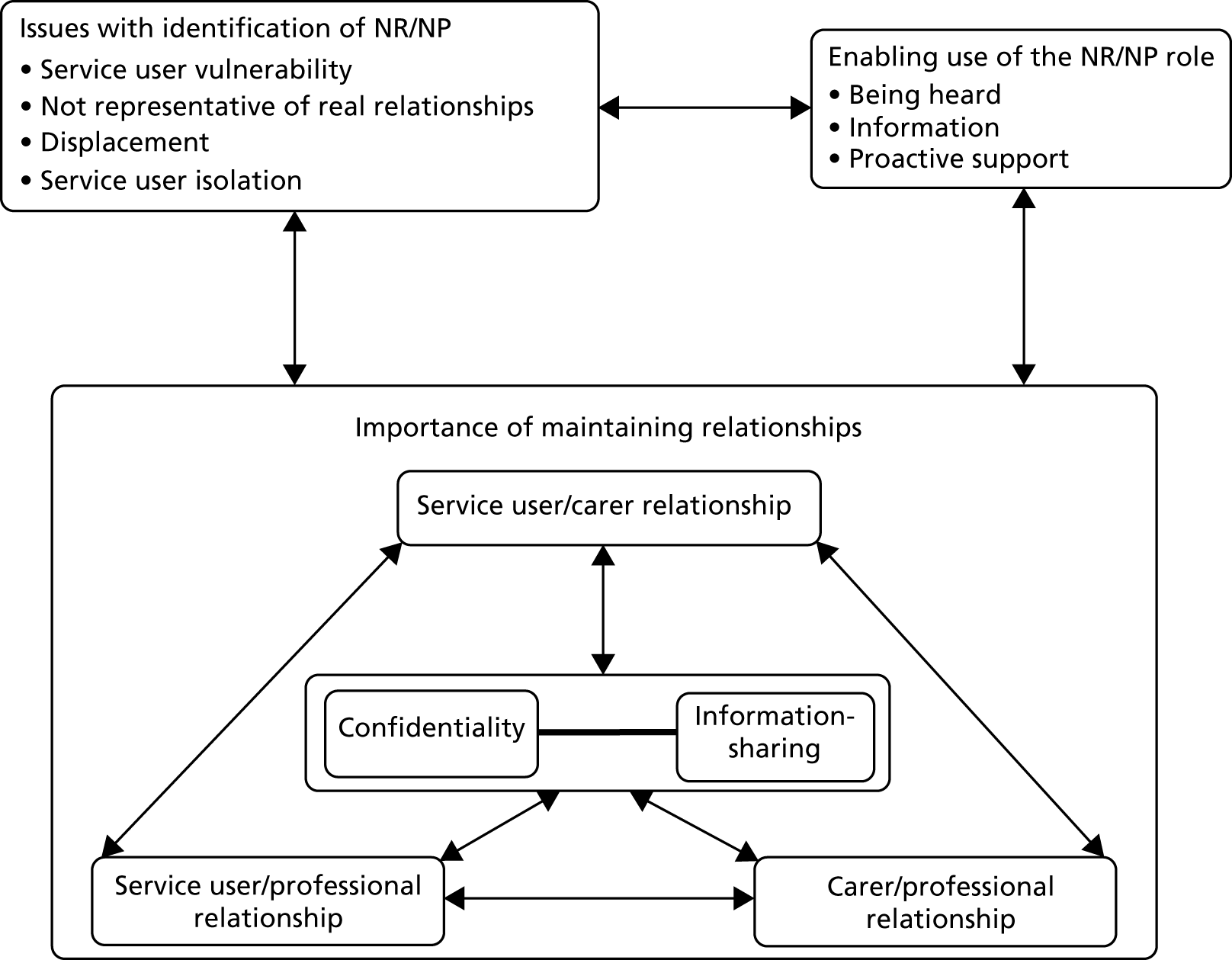

Four themes were identified. These were (1) issues regarding the identification of the NR/NP, (2) confidentiality and information-sharing, (3) enabling the use of the NR/NP role and (4) the importance of maintaining relationships.

The first two of these themes are descriptive in nature and closely reflect our research objectives. Themes 3 and 4 are more interpretative and arose from the thematic analysis. This is because it was felt that themes directly based on our remaining research objectives (‘Exploring issues related to care during detention and after discharge’ and ‘Exploring issues related to service users having access to support from carers’) would not be very meaningful and thus further interpretation by the reviewers was required. Within this synthesis, ‘importance of maintaining relationships’ is considered to be a theme underpinning the other three themes. When there is overlap in the concepts between themes, this has been acknowledged.

The relationship between the four themes identified and our research objectives is detailed in Table 5, which also provides an overview of the studies that contributed towards the development of each theme. Table 5 also highlights which population groups provided data for each theme.

| Participant group | Themes (research objectives)a | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identification of NR/NP (1 and 2) | Confidentiality and information-sharing (3) | Enabling use of the NR/NP role (4 and 5) | Importance of maintaining relationships (4 and 5) | |

| Service users | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [20] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [20] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [20] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [20] |

| Henderson (2002)45 [2001] [11] | Henderson (2002)45 [2001] [11] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [2] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [NS] | |

| Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [19] | Pinfold (2004)49 [NS] [5] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [19] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [2] | |

| Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [49] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [19] | Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [49] | Henderson (2002)45 [2001] [11] | |

| Stroud (2013)60 [2011–12] [21] | Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [49] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [19] | ||

| Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [49] | ||||

| Stroud (2013)60 [2011–12] [21] | ||||

| NRs | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [NS] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [NS] | Henderson (2002)45 [2001] [NS] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [NS] |

| Smith (2015)58 [2014] [32] | Smith (2015)58 [2014] [32] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [NS] | Smith (2015)58 [2014] [32] | |

| Stroud (2013)60 [2011–12] [7] | Smith (2015)58 [2014] [32] | Stroud (2013)60 [2011–12] [7] | ||

| Stroud (2013)60 [2011–12] [7] | ||||

| NPs | Berzins (2005–7; 2009)32 [3] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [7] | Berzins (2005–7; 2009)32 [3] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [3] |

| Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [NS] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [4] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [4] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [NS] | |

| Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [4] | Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [NS] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [NS] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [4] | |

| Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [NS] | Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [NS] | |||

| Carers other than statutory NPs or NRs | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [7] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [7] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [7] | Berzins (2009)32 [2005–7] [7] |

| Henderson (2002)45 [2001] [11] | Jankovic (2011)46 [NS] [31] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [NS] | Henderson (2002)45 [2001] [11] | |

| Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [34] | Pinfold (2004)49 [12] | Pinfold (2004)49 [NS] [12] | Jankovic (2011)46 [NS] [31] | |

| Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [34] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [34] | Pinfold (2004)49 [NS] [12] | ||

| Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [33] | Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [33] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [34] | ||

| Rugkåsa (2017)57 [2012] [24] | Rugkåsa (2017)57 [2012] [24] | Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [33] | ||

| Rugkåsa (2017)57 [2012] [24] | ||||

| AMHPs, ASWs and MHOs | Berzins (2009)32 [7] | Berzins (2009)32 [7] | Berzins (2009)32 [7] | Berzins (2009)32 [7] |

| Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [14] | Pinfold (2004)49 [NS] [NS] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [26] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [14] | |

| Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [26] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [26] | Rapaport (2002)31 [1997–9] [26] | ||

| Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [NS] | ||||

| Legal professionals | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [solicitor, 3] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [solicitor, 3] | Campbell (2008)38 [lawyers, NS] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [solicitor, 3] |

| Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [solicitor, 3] | ||||

| Tribunal members | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [tribunal member, 15] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [tribunal member, 15] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [1] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [1] |

| Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [tribunal member, 15] | ||||

| Health professionals (e.g. general practitioners, nurses) | Stroud (2013)60 [2011–12] [responsible clinician, 10] | Pinfold (2004)49 [NS] [psychiatrist, NS, GP, NS] | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [5] | Ridley (2009)56 [2007–8] [psychiatrist] |

| Mental health advocates | Dawson (2009)33 [2007–8] [5] | |||

| Other | Berzins (2009)32 [policy influencer, 9] | Berzins (2009)32 [policy influencer, 9] | Berzins (2009)37 [policy influencer, 9] | Berzins (2009)37 [policy influencer, 9] |

| Marriott (2001)48 [NS] [mix, NS] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [author views] | Campbell (2008)38 [NS] [NS] | Marriott (2001)48 [NS] [mix, NS] | |

| Marriott (2001)48 [NS] [mix, NS] | ||||

The second-order construct data that contributed towards each theme, along with reviewer interpretation of these data, are discussed within each section and are supported by quotations from the study participants. Each quotation is accompanied by a label to acknowledge the type of participant providing the quotation and, when possible, their relationship to the service user (e.g. carer and mother). When it is clear that the participant is a NR, this has been indicated. When the status of a carer or relative as a NR is unclear, the participant is referred to as a carer. For a breakdown of the quotations and author ideas that contributed to each theme, please contact the corresponding author of this report.

Theme 1: issues with the identification of the Nearest Relative/Named Person

Four subthemes were identified. Subtheme 1.1, ‘service user vulnerability’, explores how the hierarchical nature of the NR provision in England can leave service users vulnerable to abuse and biased care. Subtheme 1.2, ‘not representative of real relationships’, reflects on how the NR provision in England is not always representative of the family circumstances of service users and those involved with supporting them. Subtheme 1.3, ‘displacement’ details service users’, experiences of changing their NR/NP. Subtheme 1.4, ‘service user isolation’, discusses how both the NR provision in England and the NP provision in Scotland do not fully support the needs of individuals who do not have and/or do not wish to have an identified NR/NP. Author and participant views from eight studies support this theme (see Table 5).

Subtheme 1.1: service user vulnerability

This subtheme discusses how the hierarchical nature of the selection process of the NR may leave service users vulnerable to abuse and violation of their privacy. The impact of unconscious carer bias on the process of involuntary detention is also explored, with comparisons made with the NP provision in Scotland.

Vulnerability to abuse

Authors of five studies31–33,45,49 acknowledged the potential of the NR/NP provisions to allow for the disclosure of information to a person who has abused, or is at risk of abusing, the service user. Three of these studies31,45,49 were conducted before the 2007 amendment of the Act that allowed service users to displace people they did not want to act as their NR. Rapaport31 provided several examples that illustrate how the disclosure of sensitive personal information to the NR can be harmful to service users, as illustrated by one ASW:

It’s something so antitherapeutic to be giving the power to the historical abuser, power of information, power to determine whether the patient receives treatment . . . Particularly if one’s feeling that there is a link between that experience in childhood and the illness that they throw out really.

ASW. 31

Pinfold et al. 49 advise caution with respect to sharing information with carers and relatives, suggesting that the quality of the service user’s relationship with the person with whom the intervention was being shared needs to be considered prior to disclosure. They suggest an approach to appropriate and timely information-sharing based upon a series of decisions balancing the needs of carers and service users. However, the acquisition of knowledge regarding the service user’s current and historical social context takes time and may not be available to social workers, or other professionals, when required. 31 Other issues that may influence information-sharing between service users, carers and professionals are discussed within Theme 2: confidentiality and information-sharing.

Berzins32 acknowledges that the NP provision in Scotland permits the service user to choose a person they feel is best suited to the role, whether that is a friend who they feel is familiar with their wishes or a close relative whom they perceive could withstand the pressure/stress associated with the role. One service user talking about the prospect of nominating a NP stated that they would not worry about their prospective NP receiving personal information about them, as they felt that their NP would know it all anyway:

Any friend that I would have nominated I’ve probably told them everything anyway. It’s probably something that I’ve talked about.

Service user32 (p. 162).

Here the service user highlights how they would choose someone to support them who was already familiar with their personal information, whom they knew they could trust. However, the NP provision does not prevent the service user from appointing a person whom other people may view as unsuitable to the role, and this may leave them vulnerable to abuse or manipulation. This was illustrated by Dawson et al.,33 who provided an example of a service user appointing their drug dealer as their NP.

When a NP has not been appointed, the system defaults to a primary carer, and then to the hierarchical system currently still used in England. In first instances of acute mental illness, it is unlikely that a service user will have nominated a NP as they may not be well enough33 or have the time available32 to choose one immediately following an emergency admission. There are a number of additional issues influencing whether or not people identify their NP in advance of them being needed, as well as the potential implications of their choice for the relationship between service users and their carers. These are discussed further in Theme 4: importance of maintaining relationships.

Caregiver bias

The potential for abuse is not the only risk associated with the prescriptive nature of the NR selection process and the use of this hierarchy when identifying a NP when none has been nominated in advance. The pressures associated with caring for someone prior to an involuntary admission (as discussed within Theme 4: importance of maintaining relationships) may affect the ability of the carer to act in accordance with the best interests of the service user within their role as the NR/NP. Author views from three studies31,49,60 highlight how the carer’s own needs may affect their decision-making in relation to the NR role. Pinfold et al. 49 indicate how carers may be deterred from seeking help for themselves, and by extension the patient, because they rely on the patient to meet their own needs. In another study, one clinician describes how a patient’s daughter did not enlighten her mother around the rules associated with a CTO:

The daughter of the [patient] did get it but she knew that what the system was effectively doing was tricking her mother into thinking that we could compel her to have medication.

Responsible clinician60 (p. 48).

Amendments to the MHA 19831 in 2007 mean that family members and carers in England and Wales who have been assigned to the role of NR can now delegate the position to someone else if they do not want the responsibility of the role. 14 In Scotland, revisions to the MHCT11 in 2015 mean that carers can choose to apply through the tribunal process to represent adults who lack the capacity to make decisions about their care. 64 We suggest that these changes may go some way towards alleviating the influence of carer stress on their decision-making. The 2007 amendments to the MHA 19831,14 represent a partial response to this issue, by allowing service users and/or the professionals involved in their care to apply to the County Court to displace their allocated NR on grounds of unsuitability. The issues surrounding the process of the displacement of the NR are discussed in Subtheme 1.3: displacement.

Subtheme 1.2: not representative of real relationships

This subtheme discusses how selection of the person to fulfil the NR role in England may not be representative of a service user’s family circumstances and may inhibit information-sharing with individuals closest to them or with those who support them.

Author views from three studies conducted in England suggest that service users,31 their carers48,58 and the professionals31 involved with supporting them during involuntary admissions did not find the predetermined hierarchy a convenient or useful method of identifying the most appropriate NR. One service user gave her views on how the NR provision distinguishes between the rights of full and half siblings:

I mean what is a half-sister, half-brother? Because sometimes in our family, my mum’s got six kids. All of them are my mother’s kids and as far as I am concerned they’re all my brothers and sisters.

Service user. 31

The above quotation provides an example of how the hierarchy used to identify the NR in England may not always represent the service user’s family circumstances. This is further illustrated by a quotation from an ASW interviewed in the same study:

. . . her father only lived 200 yards away and he was the Nearest Relative as defined by the Act. But the social worker used the mother as the nearest relative on the basis that she was actually offering the care and because it was her mother and so on . . .

ASW. 31

The above quotation illustrates how the concept of NR may not always equate to the person who is usually involved with the service user’s care. 58 As well as causing difficulty in the identification of the NR, the use of the strict NR hierarchy can also create difficulties with the sharing of information. 49,58 One woman expresses her frustration with the way information-sharing was restricted to her alone:

After the assessment another social worker contacted us for an update but would not speak with my husband because I am legally the Nearest Relative, it was upsetting at such a difficult time.

NR58

Restricting information-sharing to only one carer/NR has important implications for the level of expectation and responsibility placed on carers by professionals. This may have an impact on the support they feel able to offer the service user and undermine their relationship with professionals, as discussed further in Theme 2: confidentiality and information-sharing and Theme 4: importance of maintaining relationships.

In summary, family structures in the UK in the 21st century are highly diverse and often quite removed from either the simple or the reliably harmonious and caring relationships between close blood relatives that the NR provisions presume. Furthermore, as well as the presumption of the importance of blood relatives in the service user’s life, the NR provisions imply that there is one person who is at the same time (1) their primary or sole carer/usual support, (2) the person the service user would trust to act in their best interests and (3) the person whom they would trust with personal or sensitive information about them.

Subtheme 1.3: displacement

The 2007 amendments to the MHA 19831,14 mean that the service user, a relative, anyone living with the service user or an AMHP can apply to the County Court to displace a person who is unsuitable for the role and nominate someone whom they feel would be more appropriate. Issues discussed within this subtheme include how the displacement process can be exploited by both NRs and professionals and how the displacement process in Scotland can provide service users with an opportunity for choice and autonomy over the care that they receive. Four studies contributed towards the development of this subtheme. 31,32,56,57

Of the studies relevant to the NR provision in England, only Rapaport31 contributed significantly to this subtheme. This paper was published prior to the 2007 amendments of the MHA 1983,1,14 which means that at this time service users could not apply to the County Court for the displacement of their NR. This study highlights how some professionals viewed the process of displacing an unsuitable person from the role of the NR as time-consuming, expensive and having the potential to jeopardise their working relationships with carers. The author also indicates how the tribunal system could be misused by individuals who did not want to be displaced. One ASW illustrated this by discussing how her team had struggled to displace one woman who had inherited the NR role from another person:

She [NR] got the original Nearest Relative to sign them over to her brother, so she was out of the legal loop . . . He continued to object although he was really doing it by proxy for her. She was still pulling all the strings.

ASW. 31

In this example, the NR managed to use the tribunal system and use their influence within the wider family to retain influence over the service user’s care. Overall, the lack of available evidence regarding experiences of displacing the NR in England, particularly after the 2007 amendments of the MHA 1983,1,14 limits the conclusions that can be drawn.

In Scotland, service users can make a written application to displace (i.e. change) their NP under the MHCT. 11 This seems to be viewed positively by service users:

You might nominate a friend who you’re very friendly with but they might turn out to be totally unsuitable . . . At least you’re not stuck with someone who’s against you and they can always be revoked.

Service user32 (p. 130).

This quotation illustrates how the process for displacing a NP in Scotland can avoid the involvement both of someone the service user does not have a good relationship with, or who they feel would not support them in a way that is consistent with their wishes. The displacement process was also viewed positively by the individuals involved with creating government policy interviewed in the same study:

. . . revisiting of it is important and we stress that . . . just because someone ends up with someone who’s down as the default Named Person that should be reviewed and discussed with the person as soon as they’re in a position to do that and not just set in stone.

Policy influencer32 (p. 120).

This quotation acknowledges that under some circumstances (e.g. an emergency admission), a service user may need to be allocated a NP using the default process. The ability to revisit the decision when they are able provides an important opportunity for the service user to exercise choice and autonomy.

Ridley et al. 56 reflect that by the time participants in their study were interviewed for a second time 1 year later almost one-quarter of the service users had changed their NP. Among the reasons given was that the NP had disagreed with the service user’s wishes. The authors report that carers found the process of being displaced unsettling and that it made them uncertain of their rights and responsibilities. 56 We suggest that this may have important implications for the provision of consistent care and/or maintaining working relationships with professionals in the longer term.

Subtheme 1.4: service user isolation

This subtheme aims to highlight the issues encountered by service users who may not be able, or may not wish to, have someone appointed as a NR in relation to their care/detention.

Author31–33,56,60 and participant31–33,56 views from five studies indicated that the NR provision of the MHA 19831 did not account for the fact that some service users may not have a person to act as their NR. Issues with this situation may arise because of family estrangement60 and relatives living outside the country. 31 A quotation from one service user illustrates how the process of identifying the NR does not account for poor family relationships:

. . . this seems to be geared for, you know, nice families as it were [laughing] you know . . . families where the mother comes round and comes into hospital and says ‘how are you son?’.

Service user. 31

Here, the advantages of the NP provision used in Scotland are easily identifiable, in that service users without a partner or family member to act as their NR can choose to nominate a friend instead. Following the introduction of the MHCT, some service users32,56 and professionals6,32,33 disliked the necessity of a service user having to identify a NP. This is illustrated by two quotations, one from a service user and one from the perspective of a person involved in influencing government, or ‘policy influencer’,32 in this area:

If it’s the patient’s right to name a Named Person than that’s their right. If they say: ‘I don’t want anything to do with that,’ then that’s it. End of story.