Notes

Article history

The research reported in this issue of the journal was funded by the HS&DR programme or one of its preceding programmes as project number 12/130/15. The contractual start date was in March 2014. The final report began editorial review in October 2017 and was accepted for publication in April 2018. The authors have been wholly responsible for all data collection, analysis and interpretation, and for writing up their work. The HS&DR editors and production house have tried to ensure the accuracy of the authors’ report and would like to thank the reviewers for their constructive comments on the final report document. However, they do not accept liability for damages or losses arising from material published in this report.

Declared competing interests of authors

Chris Salisbury is a member of the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research (HSDR) Board. Bruce Guthrie chaired the Guideline Development Group of the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence Multimorbidity Clinical Guideline NG56 and was a member of a HSDR researcher-led panel. Polly Duncan declares a Scientific Foundation Board grant received from the Royal College of General Practitioners for the Pharmacist study, a substudy of the 3D study and a NIHR In-Practice Fellowship.

Permissions

Copyright statement

© Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO 2019. This work was produced by Salisbury et al. under the terms of a commissioning contract issued by the Secretary of State for Health and Social Care. This issue may be freely reproduced for the purposes of private research and study and extracts (or indeed, the full report) may be included in professional journals provided that suitable acknowledgement is made and the reproduction is not associated with any form of advertising. Applications for commercial reproduction should be addressed to: NIHR Journals Library, National Institute for Health Research, Evaluation, Trials and Studies Coordinating Centre, Alpha House, University of Southampton Science Park, Southampton SO16 7NS, UK.

2019 Queen’s Printer and Controller of HMSO

Chapter 1 Introduction

Background

In an attempt to improve the quality of care of long-term conditions in general practice, care has become increasingly driven by standardised protocols, which are delivered using computerised templates by practice nurses. These nurses often have extra training in specific diseases and provide care within disease-specific clinics (e.g. diabetic clinics), which focus on one disease at a time. Primary care clinicians in the UK are incentivised through the NHS Quality and Outcomes Framework (QOF) to achieve targets relating to a limited number of specific long-term conditions. Disease pathways for a range of long-term conditions have been developed to improve vertical integration across primary and secondary care.

These developments fail to take account of the fact that many people have multiple long-term conditions (multimorbidity). 1,2 Sometimes these comorbid conditions have a bigger impact on the patient’s quality of life than any single condition being addressed at a nurse-led chronic disease management clinic. The priorities and incentives for the health professionals dealing with a specific disease may or may not align with the priorities of the patient. 3 Treating patients along care pathways for each disease can mean that one patient is under the care of multiple clinical teams, with little co-ordination between them, and is issued with several different care plans, which can cause confusion, especially if they contain conflicting advice.

Prevalence

The prevalence of multimorbidity depends on how the concept is defined and measured. 4 Multimorbidity is usually defined as the presence of two or more long-term conditions in the same individual, but prevalence will depend on the conditions that are included. Recent UK studies have found that 16% of adults in England had two or more diagnoses from a list of 17 major conditions,2 whereas 23% of people in Scotland had two or more from a list of 40 conditions. 1 A consistent (and unsurprising) finding in all studies is that multimorbidity is much more common in older people,1,2 so this issue is increasingly important owing to the ageing population. The number of people with at least one long-term condition is expected to increase from 15 million in 2009 to 18 million by 2025,5 and the number with multimorbidity is expected to increase from 1.9 million in 2008 to 2.9 million in 2018 at an additional cost to the NHS in England and Wales of £5B. 6

Illness burden

Multimorbidity is important because people affected carry a substantial burden of illness. Patients with multimorbidity are more likely to have poor quality of life7,8 and this is sometimes associated with chronic pain, functional impairment and frailty. They also have a reduced life-expectancy. 9

As well as having an impact on physical health, multimorbidity is also associated with an increased prevalence of depression. 10 The King’s Fund has estimated that at least 30% of people with a long-term physical condition also have a mental health problem, and 46% of people with a mental health problem also have a physical health problem. 11 The relationship between physical and mental health in both directions is reciprocal: people with chronic illnesses are more likely to be depressed and those who are depressed are less likely to manage their long-term conditions well, leading to worse disease control and poorer health outcomes. 12 The association between poor physical health and poor mental health is particularly strong in people with multimorbidity. Gunn et al. 10 have shown that the number of long-term conditions is more predictive of the prevalence of depression than any particular individual condition. People with multimorbidity and depression are also more likely to have unplanned hospital admissions. 13

Treatment burden

Having multimorbidity generates work for the patient to manage their multiple conditions, a phenomenon described as ‘treatment burden’. 14 For patients with multimorbidity, the single-disease approach is inconvenient and inefficient, because they are repeatedly invited to different disease-focused appointments in general practice, where they are asked the same questions and given the same advice (or sometimes conflicting advice, which can be confusing). 3,15–17 Patients may receive inferior quality of care if the specialist nurse is not aware of the impact of the treatment of one disease on other diseases, which can be a particular problem with drug interactions. Alternatively, the disease-focused nurse or doctor may slavishly follow guidelines without recognising that the evidence underlying those guidelines is not necessarily applicable to the individual patient in front of them with multimorbidity (because most guidelines are based on research that excluded patients with multimorbidity). 18,19 If all the recommendations for each long-term condition are considered in isolation and followed, patients with multimorbidity are likely to have numerous investigations and to be prescribed large numbers of drugs. 20,21 This polypharmacy can be burdensome for patients, increases the likelihood of interactions and adverse effects (including those causing hospital admissions) and may reduce medication adherence. 19,22–24

Lack of patient-centred care

As well as an increased illness burden and treatment burden, patients with multimorbidity experience a lack of holistic patient-centred care. Patients with multimorbidity can feel that no one treats them as a ‘whole person’ but rather as ‘a patient with a disease’. 3 Many patients say that they want to have a relationship with one health professional that they can trust and who listens to them, helping them make appropriate decisions in the context of their life circumstances and values. 3 Given the large number of health problems that these patients face and the number of potentially relevant investigations and treatments, they may want to set priorities and make trade-offs so that they are not overinvestigated and medication regimes are not excessively burdensome. For patients, improving quality of life (which might include not spending too much time in contact with the health service or suffering side-effects of medication) might be a higher priority than achieving improved indicators of disease control with a view to greater longevity.

Inequalities in health

Failing to address the problems of patients with multimorbidity will also lead to increased inequalities in health. Multimorbidity is more common in deprived areas,1 and patients with fewer material and personal resources are particularly disadvantaged by having to attend multiple appointments for each of their long-term conditions, and being expected to follow a series of different care plans. 17,25 Their care is also more likely to be complicated by other medical and social factors, such as poor mental health, poor housing and smoking. 26 The prevalence of comorbid depression and physical health problems is much higher in deprived areas than affluent areas. 1 Therefore, improving mental health as well as physical health in people with multimorbidity is a priority.

Importance of multimorbidity for the health service

Patients with multimorbidity are a priority for the health service because they account for a high proportion of resource use in both primary and secondary care (including having high rates of hospital admissions). 13,27,28 The consequences of a single-disease approach for the health service potentially include both duplication and gaps in services (e.g. conditions included in the QOF are prioritised but others are neglected),29 inefficiency (because the same topics are addressed repeatedly by different specialist practice nurses) and waste (because of non-adherence to medication and non-attended appointments). 30 If taken to its logical conclusion, the disease pathways approach would mean that one patient with multimorbidity would have their care managed by several specialist services (each crossing primary and secondary care), but there would be little co-ordination between these specialist services and no one professional who has an overview and takes responsibility for the patient as a whole.

Summary of the problem

In summary, patients with multimorbidity experience problems of illness burden (poor quality of life, depression), treatment burden (multiple unco-ordinated appointments, polypharmacy) and lack of person-centred care (low continuity, little attention paid to patients’ priorities). This research is designed to test the hypothesis that an intervention in general practice designed to address the needs of patients with multimorbidity will improve their health-related quality of life (primary outcome), reduce their burden of illness and treatment and improve their experience of care, while being more cost-effective than conventional service models. This was tested using a cluster randomised controlled trial (RCT), with economic evaluation and mixed-methods process evaluation.

Rationale

The design of the intervention builds on several sources of evidence. First, it takes account of the existing research on the scale and adverse consequences of multimorbidity, as described previously. 1,2,19,21,26,30–33 A regularly updated bibliography of research on multimorbidity is maintained by Professor Martin Fortin (Université de Sherbrooke, QC, Canada) for the virtual International Research Community on Multimorbidity. 34 We reviewed this bibliography to ensure that we had a comprehensive understanding of the relevant literature when developing the intervention and have re-reviewed it since to ensure that we take account of recent research in reporting the findings.

Second, the intervention design takes account of a Cochrane review of interventions to improve outcomes in people with multimorbidity in primary care. 35,36 This review, originally published in 2012, identified 10 studies examining a range of complex interventions. 35 A further eight trials were identified in an update published in 2016, but the conclusions were not substantially altered. 36 The review highlights the paucity of research, with the focus to date being on specific comorbid combinations or multimorbidity in older patients. The limited evidence available suggests that interventions to date have had little effect on clinical health outcomes, apart from a modest effect on improving depressive symptoms. There are very limited data about the costs of different approaches to care and none of the studies included an economic analysis of cost-effectiveness. The authors concluded that there is a need for further pragmatic studies in primary care settings, with clear definitions of participants and consideration of appropriate outcomes. 35

Third, the intervention builds on clinical experience and professional consensus. We discussed the problems of patients with multimorbidity and how to improve care in general practice in three workshops with general practitioners (GPs), nurses and other practice staff, including > 250 participants at the Royal College of General Practitioners (RCGP) Annual Conference in October 2012. These helped to generate ideas for improvement that informed the 3D (Dimensions of health, Depression and Drugs) intervention, which is the subject of this report, and helped to ensure that the intervention was based on a good understanding of current practice in relation to the organisation of care for these patients.

Fourth, in the process of developing the intervention we consulted patients in two public meetings. The participants identified a number of problems with the current organisation of long-term condition review appointments in general practice. These included a lack of continuity of care, having to attend multiple appointments and having difficulty in getting priorities addressed.

Fifth, the intervention builds on the research team’s experience in related trials, particularly the Whole systems Informing Self-management Engagement (WISE) trial37 and the CARE (Consultation and Relational Empathy) Plus feasibility study. 38 The former was a trial of a patient self-management intervention, and the latter was a study of the feasibility of an intervention in middle-aged patients in deprived areas of Scotland, which focused on longer consultations to allow a holistic assessment of biopsychosocial needs and to provide a self-management support pack. The CARE Plus study demonstrated feasibility and showed promising results but it is not powered to definitively assess effectiveness (eight practices, 152 patients). The CARE Plus approach was also very specifically focused on the needs of patients in deprived areas.

Finally, in preparation for this trial we searched the metaregister of controlled trials in order to identify relevant unpublished trials research or ongoing studies, but no such relevant studies were found. There is, therefore, a pressing need for rigorous research to test interventions to improve the management of patients with multimorbidity in general practice.

During the period of this research trial, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) conducted a review of the evidence on multimorbidity and issued final guidelines in September 2016. 39 Although this guidance was being developed around the same time that we developed the 3D intervention, the strategies incorporated in the 3D intervention are entirely consistent with the recommendations of the NICE guidance. The key recommendations in the guidance include:

-

consider how conditions and treatments interact to affect an individual’s quality of life

-

tailor care to take account of each individual’s preferences, priorities and goals

-

consider carefully the risks and benefits of following guidance relating to single conditions

-

seek to improve quality of life by reducing treatment burden and unplanned care, and try to improve co-ordination of care

-

review medicines and other treatments, considering individual risks, benefits and harms, and outcomes important to the individual

-

agree an individualised management plan.

All of these elements are included within the 3D intervention, which is the focus of this study. The NICE guidelines summarised previous trials of interventions to improve care for people with multimorbidity and concluded that most of the evidence was of low to moderate quality and it was not possible to recommend any particular approach. One of the four key recommendations in the NICE report for future research was: ‘What is the clinical and cost-effectiveness of alternative approaches to organising primary care compared with usual care for people with multimorbidity?’. 39 This study contributes to answering this question.

Since this study was planned, the Health Select Committee has also published its findings on the management of patients with long-term conditions, including a section on the management of people with multimorbidity. 5 The conclusions again resonate with the aims of this research. The select committee criticised the current single-disease approach to management, and emphasised that in its view:

The objective of the health and care system in treating people with long-term conditions should be to improve the quality of life of the person. At a time when increasing numbers of people requiring support and treatment from the system have multiple conditions combining physical health, mental health, social care and other support requirements, it seems anachronistic that the Department [of Health]’s definition of long-term conditions appears to emphasise a single-disease approach to treatment. We recommend that the Department revise its working definition of long-term conditions to emphasise the policy objective of treating the person, not the condition, and of treating the person with multiple conditions as a whole.

The select committee strongly endorsed a person-centred approach to care, reinforced by individualised care plans. 5

The need for evidence

Evaluating models of care for long-term conditions was identified as the top research priority by stakeholders advising the National Institute for Health Research (NIHR) Health Services and Delivery Research programme. NIHR highlighted the improvement of the management of multimorbidity in general practice as a priority in a 2013 themed call for research on primary care interventions, and then followed this with a specific call for research on multimorbidity in 2015. Commissioners, professional bodies, academics and other stakeholders have all recognised the growing tension between the single-disease focus of medicine and the needs of patients with multiple long-term conditions. 30,40–43 This is evidenced by reports from the RCGP,44 the Royal College of Physicians45 and NICE,39 as well as from international organisations. 40,46 There is a long-term challenge to redesign the NHS to reflect the needs of patients with multiple long-term conditions47 in light of the ageing population. There has been considerable research on the scale of the problem and the needs of patients with multimorbidity. 3,25,32,48–51 Research is now needed to test interventions to address these problems. 43 As described previously (see Rationale), the recent Cochrane Review and the NICE multimorbidity guidelines both highlighted the urgent need for further pragmatic studies of potential interventions for multimorbidity in primary care settings. 35,39

Some general practices have recognised the problems of providing care for their patients with multimorbidity and, in the absence of research, have themselves innovated in the way they provide care. In particular, some practices have begun to co-ordinate long-term condition reviews into one appointment each year, rather than expecting the patient to attend a different appointment for each condition. However, these changes typically focus on rationalising appointments rather than any fundamental change in the content of the reviews. Because practices are beginning to explore ways of improving care for multimorbidity, the time is right to test the benefits and costs of a new approach.

The intervention described in this proposal includes a number of elements that have become frequently advocated in the management of specific diseases, including an emphasis on patient-centred care, explicit agenda setting, self-management support, shared decision-making and care planning. These are well captured by the House of Care model described by The King’s Fund,52 which is the basis for NHS policy on long-term care. This is an intuitively attractive conceptual model, but it is important to recognise that evidence of benefit from implementation of many of these ideas is limited or indirect. For example, there are parallels between the 3D intervention described in this report and aspects of the Year of Care initiative for diabetes mellitus, itself built on the House of Care model. 53 Although the experience of pilot sites involved in the Year of Care appears to have been positive, evaluation of the approach was mainly qualitative, describing the process of implementation and perceived benefits from the perspective of patients and clinicians. Only limited objective quantitative data were available, and the evaluation did not include any control group or robust economic evaluation. 53

The main focus of the 3D intervention is on improving the management of multimorbidity in general practice. There are several reasons for this focus on general practice rather than on hospitals. General practice provides the foundation for the organised care of most major long-term conditions, with most patients having the vast majority of their NHS contacts and all of their prescriptions provided in general practice. Although patients with multimorbidity have an increased rate of outpatient attendances and inpatient admissions, one of our hypotheses is that these contacts might be reduced by improved management in general practice. Improving the management of patients with multimorbidity in hospital is also a challenge45 but this requires different solutions beyond the scope of this intervention. The aim of the 3D study was to design and evaluate an intervention that is ambitious, but also achievable and likely to lead to patient benefits in the short term.

Study aims and objectives

Aims and hypothesis

The aim is to optimise, implement and evaluate an intervention to improve the management of patients with multimorbidity in general practice.

The hypothesis is that an intervention in general practice designed to improve the management of multimorbidity will improve patients’ health-related quality of life, reduce their burden of illness and treatment and improve their experience of care, while being more cost-effective than conventional service models.

Objectives

-

To optimise an intervention to improve the management of multimorbidity in general practice through piloting in four practices.

-

To implement this intervention in a representative range of general practices.

-

Through a cluster RCT and economic evaluation, to assess the impact of the intervention on health-related quality of life, illness burden, treatment burden, patient experience, carers’ burden and quality of life and cost-effectiveness.

-

Through a mixed-methods process evaluation, to explore how and to what extent the intervention was implemented, the advantages and disadvantages of different models of care for patients with multimorbidity, and how and why the intervention was or was not beneficial.

-

To design educational materials and commissioning guides to ensure that the intervention is delivered consistently in practices in the trial, and that, if beneficial, it can be speedily rolled out nationally following publication of the final report.

Most of the outcomes relate to the effect on individual patients (with allowance made in the analysis for the cluster randomised design), although some of the implementation objectives related to practices.

Chapter 2 Study design and governance

Design

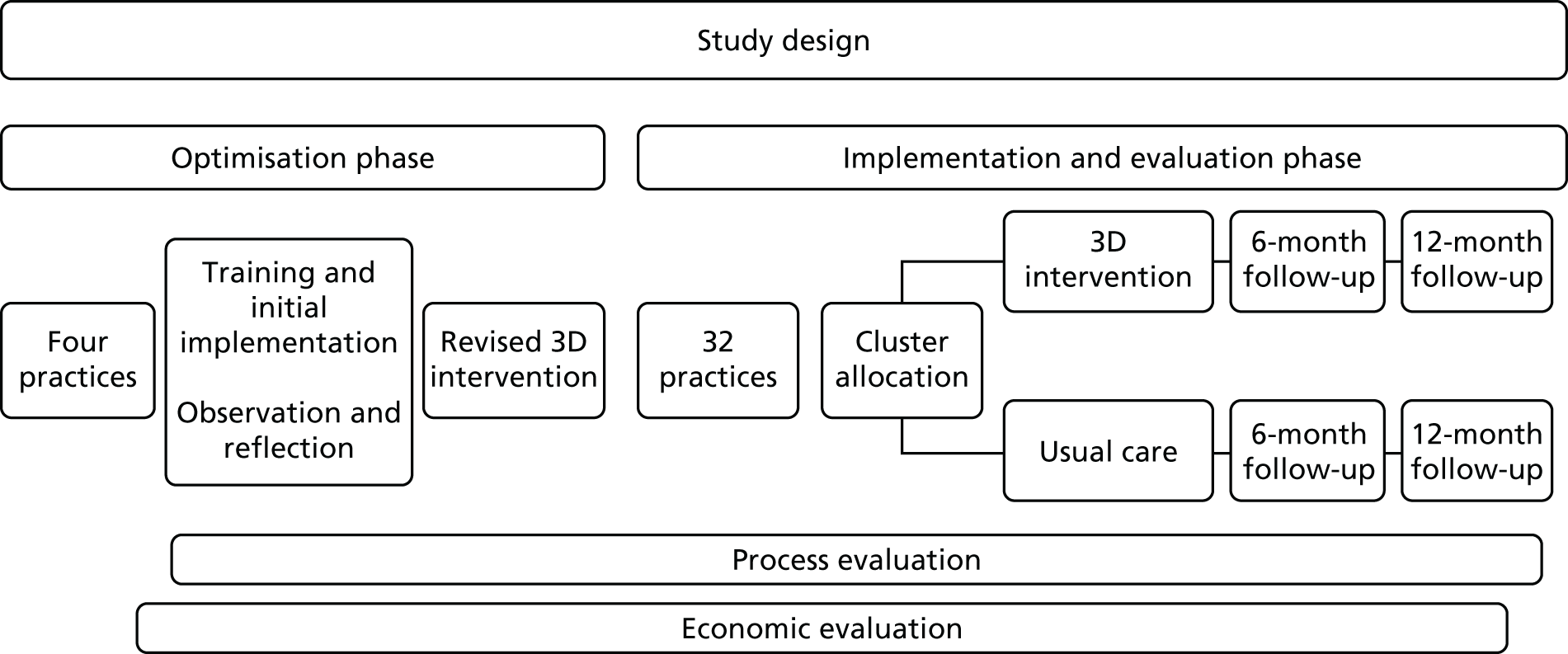

The research design was a pragmatic, cluster RCT comparing the 3D approach (a new approach to the management of multimorbidity) with usual care in general practice. Figure 1 shows the original planned study design, slightly modified later as described in Chapter 4. A cluster design was chosen, with each general practice forming a cluster, because the intervention required organisational change in service delivery at a practice level and because of the likelihood of contamination effects if patients were randomised individually. The trial was designed to be as pragmatic as possible in order to assess the effects of the 3D intervention when implemented in routine practice.

FIGURE 1.

Original plan for study design.

In line with the Medical Research Council (MRC) framework for the evaluation of complex interventions,54 an optimisation phase in a small number of pilot practices allowed for testing the feasibility of the intervention, particularly the training and implementation of the intervention, as well as piloting of study procedures prior to starting the main evaluation phase. Alongside the main trial we conducted a parallel mixed-methods process evaluation to examine how the intervention was implemented by practices and how and why the intervention worked (or did not work).

An economic evaluation was undertaken from the perspectives of (1) NHS and Personal Social Services (PSS) and (2) patients. In a cost–consequences analysis we related the cost of the intervention or usual care to changes in a range of outcomes, and in a cost-effectiveness analysis we estimated the incremental cost per quality-adjusted life-year (QALY) gain.

Study setting

The study was conducted in general practices in three geographical areas: (1) in and around Bristol, (2) Manchester and (3) Ayrshire and Arran. This includes a wide range of deprived and affluent areas, as well as urban, suburban and rural areas. The patient populations from these practices will, therefore, have a wide range of characteristics. Working in different types of area, with different commissioning groups, and in the different health-care systems in England and Scotland, will all help to ensure the generalisability of the research.

Ethics approval and research governance

This study was conducted in accordance with principles of Good Clinical Practice.

Research ethics approval was obtained from the South West (Frenchay) NHS Research Ethics Committee (REC) (reference number 14/SW/0011). Appropriate NHS Research and Development (R&D) governance approvals were also obtained from local Clinical Commissioning Groups (CCGs) and health boards prior to study commencement at sites. Amendments of study protocols and documentations were reviewed and approved by NHS REC, and NHS R&D departments.

Participants were not denied any form of care and had full access to NHS services throughout the duration of their study participation. Any changes in medication prescribing were made by a GP in the context of normal clinical care.

Although randomisation and delivery of the intervention were at the practice level, individual patient-level consent was obtained to collect questionnaire follow-up data.

Trial registration

This trial is registered as Current Controlled Trials ISRCTN06180958.

Trial oversight

The study was hosted by Bristol CCG and the sponsor was the University of Bristol. The 3D study was managed by the Trial Management Group (TMG) consisting of the chief investigator, principal investigators and researchers from each of the recruiting centres (Bristol, Manchester and Glasgow) and co-applicants. Regular meetings (every 6–8 weeks) ensured that study progress, targets or any problems were monitored and reviewed.

Additional governance oversight was provided by an independent Trial Steering Committee (TSC) and Data Monitoring Committee (DMC). A further advisory group made up of key local and national stakeholder organisations was also convened to provide advice about the wider context and facilitate communication and knowledge mobilisation. Member details of these committees are provided in Appendix 1.

Chapter 3 Intervention development and pilot study

The intervention took account of several sources of evidence, as described in Chapter 1. It was further developed through workshops and stakeholder events with patients, carers, health professionals and health service managers. The description below addresses all aspects of the Template for Intervention Description and Replication (TIDieR) framework. 55

Theoretical/conceptual framework

The underlying theoretical basis for the intervention was the patient-centred care model, described by Stewart et al. 56 This is strongly valued by patients57 and there is some evidence that it is associated with improved health outcomes. 58–61 A recent report from the American Geriatric Society has also recommended the patient-centred care model to improve care for multimorbidity. 40

The concept of patient-centred care has been reviewed and developed by other authors following the seminal work of Stewart et al. ,56 but it broadly includes four key components:62,63

-

a focus on the patient’s individual disease and illness experience – exploring the main reasons for their visit, their concerns and need for information

-

a biopsychosocial perspective – seeking an integrated understanding of the whole person, including their emotional needs and life issues

-

finding common ground on what the problem is and mutually agreeing management plans

-

enhancing the continuing relationship between the patient and doctor (the therapeutic alliance).

The conceptual framework for our intervention draws on the existing research evidence about the main types of problems experienced by patients with multimorbidity and their preferences for care, and uses strategies based on the patient-centred care model to seek to address these problems. For example, there is evidence that patients with long-term conditions particularly value relational continuity of care;64 therefore, the intervention includes strategies to improve this.

Our conceptual framework also draws on the Chronic Care model65 and experience in related initiatives, such as the House of Care,66 which include, for example, the importance of promoting patient engagement in self-care through care plans and improving communication between primary and secondary care.

In Chapter 1 we described the problems experienced by patients with multimorbidity in terms of illness burden, treatment burden and a lack of holistic patient-centred care. The intervention was designed to address the problems within this framework.

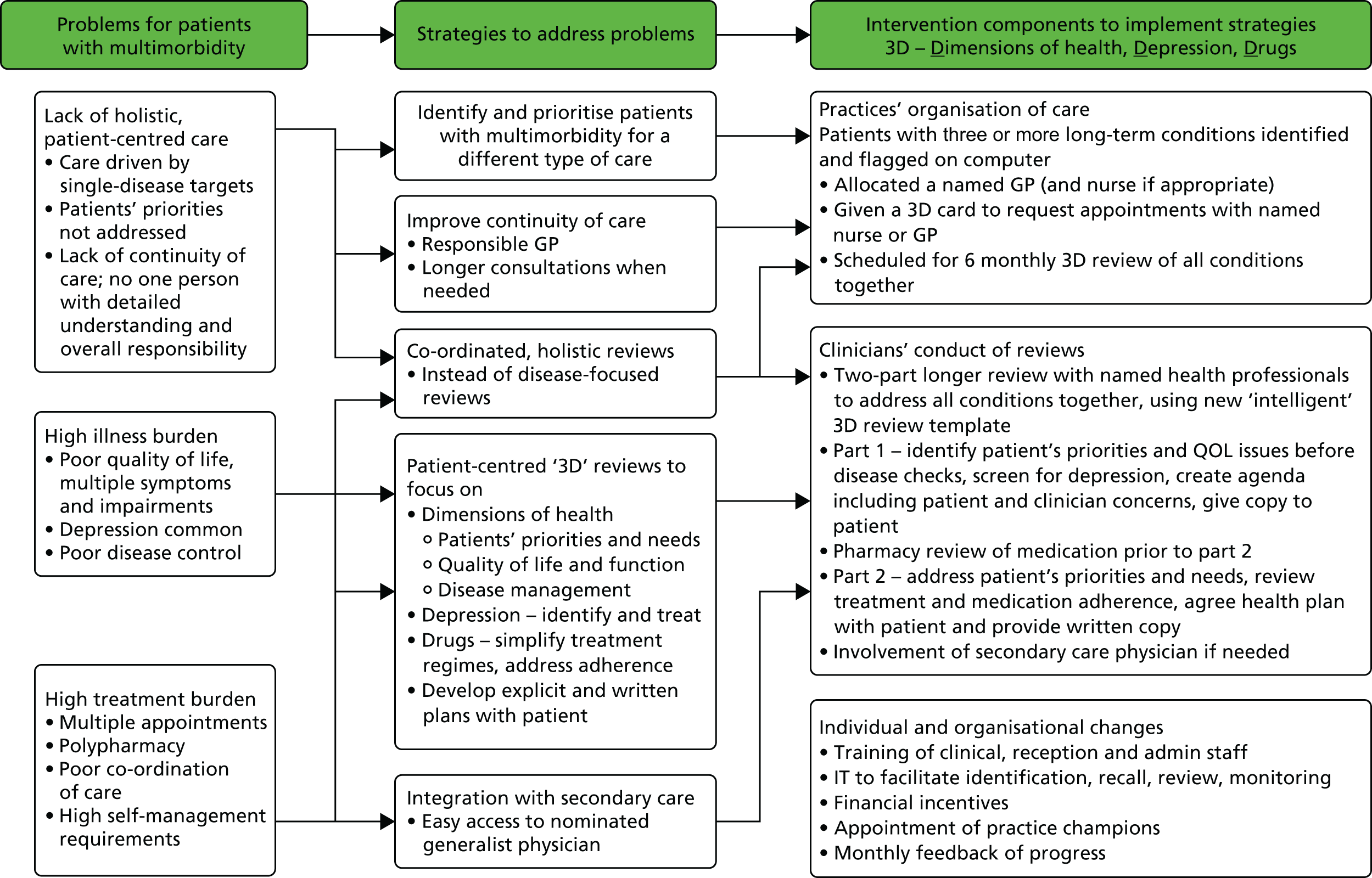

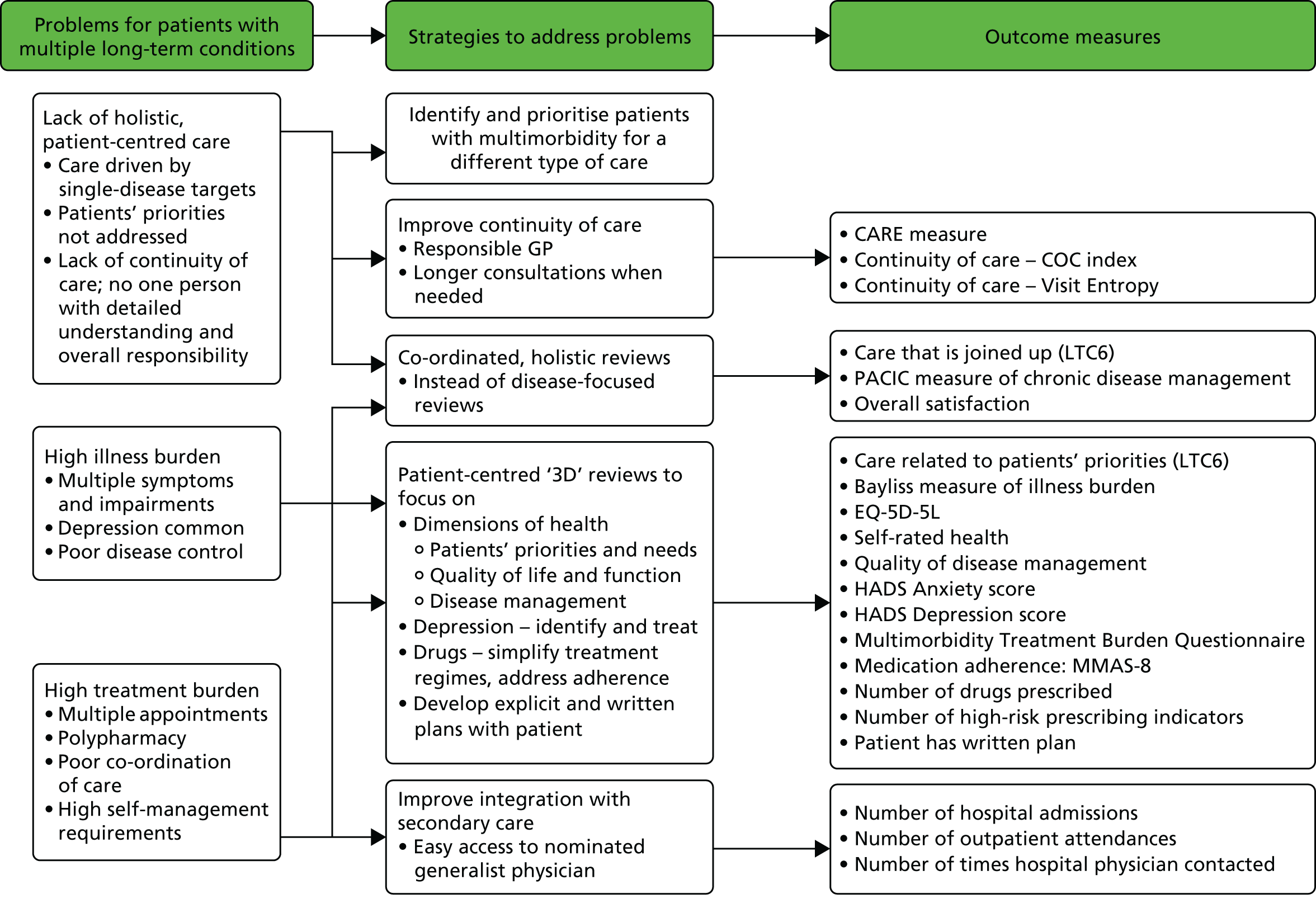

The 3D intervention was a complex intervention with multiple interacting components at different levels. When designing complex interventions it is important to design a clear logic model to show how specific strategies are intended to lead to particular benefits. 67 This also aids the process of selecting intermediate and final outcomes. In the 3D trial we used this process to develop the 3D intervention and the selection of outcomes. Figure 2 shows a logic map of how the different intervention components map on to strategies that address specific problems. These components are described in detail in this chapter. We later show how the logic map also informed the selection of outcome measures (see Figure 5).

FIGURE 2.

Logic model showing how problems are linked to strategies and to components of the intervention. IT, information technology.

In summary, the intervention was designed to:

-

reduce illness burden by placing greater emphasis on quality of life (including pain and activities of daily living) and seeking to identify and address poor mental health

-

reduce treatment burden by addressing polypharmacy, improving medication adherence and providing better co-ordinated care

-

improve patient-centred care through enhanced continuity of care, offering longer appointments, identifying patients’ priorities and needs and addressing these through an individualised written health plan.

Our approach also recognises that the successful and sustained implementation of any intervention in health care requires a range of organisational changes to support and sustain the innovation, and this may also require attitudinal change among clinicians. Implementation of the 3D approach therefore involved a range of enabling and reinforcing strategies, including training of practice staff, regular feedback, financial incentives and the appointment of local GP champions with collaborative working between practices to share experience.

In this way, we recognise that the intervention operates at several levels and cannot be considered simply as the new 3D review offered to patients. First, it begins at the practice level, with a range of strategies and tools provided to practices to support organisational change. Second, it involves the training offered to clinicians and receptionists, with the aim of influencing their attitudes to patients with multimorbidity, training them to use the computerised 3D template and enhancing their skills in identifying patients’ priorities and negotiating care plans. Third, the intervention operates at the level of the patient, as care is provided to them in a new way and they do or do not respond (whether through behaviour change or improved medical treatment).

The name ‘3D’ was chosen for the intervention because it alluded to the concept of a holistic three-dimensional perspective of care and served as a mnemonic for:

-

dimensions of health – patients’ concerns and priorities for improving their quality of life were elicited, before the collection of data about disease metrics, such as weight or blood pressure

-

depression – the Patient Health Questionnaire-9 (PHQ-9) was used to screen for depression, and management was discussed if depression was identified

-

drugs – to address polypharmacy, a pharmacist reviewed patients’ medical records prior to the 3D review and made recommendations to simplify drug regimes or discontinue low-priority medications. As part of the 3D review, GPs reviewed the pharmacist’s comments and recommendations, explored any problems with medication adherence and could modify a patient’s drug regime if required.

The components of the intervention operating at each level are described in more detail below.

Practice-level components relating to the organisation of care

Identification and flagging of participants

Consented participants in intervention practices were ‘flagged’ on practice computer systems to identify that they should receive a different process of care.

Promoting continuity of care

Participants were allocated a named GP who was responsible for their care (and a named nurse when possible, particularly in larger practices where several nurses are involved in long-term disease management). When possible, the named GP was the patient’s usual GP. At the beginning of the study, each participant was sent a letter informing them of their named GP and nurse and explaining why it was important to try to see their named GP and nurse when possible.

Named GP on a ‘3D card’

Patients were given a ‘3D card’, a credit card-sized card that stated their named responsible GP (and nurse if appropriate). This card could be used to identify themselves with the practice and encouraged them to book longer appointments with their named GP if needed (see Appendix 5).

‘Flagging’ for receptionists

A facility was added to Egton Medical Information Systems (EMIS) so that each time a 3D participant made an appointment a ‘flag’ appeared on the receptionist’s computer screen. This identified the patient as a 3D participant and asked the receptionist to encourage the patient to see their named GP.

3D reviews

A key component of the 3D approach was the reorganisation of the participants’ multiple, separate disease-focused review appointments into paired 3D reviews during which all conditions were reviewed at one time. These 3D reviews replaced the need for participants to attend multiple clinics for each disease, at which they were likely to see different health professionals, who were following different computerised disease-specific management templates, which were likely to include a high degree of duplication of questions about topics such as blood pressure, weight and smoking. The 3D reviews were scheduled every 6 months.

Secondary care physician

Each practice was allocated a designated ‘general physician’ (usually a geriatrician) in secondary care whose role was to act as a contact to discuss patients with complex problems and (if possible) help to co-ordinate multiple hospital appointments and investigations.

Components relating to clinicians conduct of reviews

3D template

The 3D reviews were supported by a dynamic template, which populated automatically depending on the relevant conditions of each individual patient. This eliminated the problem of duplication of questions and the need to switch between single-disease templates and also provided a structure to encourage clinicians to follow the 3D approach. Several screenshots from the 3D template are shown in Appendix 6.

The 3D review appointments

Each 3D review consisted of two appointments (every 6 months) with a nurse and then a GP, as well as a pharmacist review (once a year).

In the UK, GPs have a minimum of 5 years’ post-graduate education after their medical degree and provide urgent care, management of long-term conditions, health promotion, prevention and screening activities. They have generalist training and experience across all common health conditions. Practice nurses are fully qualified nurses and come from a range of backgrounds, including hospital or community nursing. In many general practices they undertake most of the review and management of some long-term condition, such as asthma and diabetes mellitus, although they are less often involved in other conditions, particularly mental health problems. The extent and range of experience of nurses in general practice is variable. Many nurses have further training in specific long-term conditions, with different nurses in the same practice sometimes specialising in different conditions. Pharmacists working in general practice have usually worked as community pharmacists and are increasingly working within general practices to support medication review and repeat prescribing.

3D nurse appointment

The first appointment with a practice nurse included collecting information about the patient’s priorities, aspects of quality of life, such as pain and function, screening for depression using the PHQ-9 and organising all relevant blood tests and investigations. These were entered into the nurse consultation section of the 3D template which summarised their assessment to produce a 3D agenda which was given to the patient. Practices were advised to allow 30–40 minutes for the nurse appointment.

Pharmacist review

Once a year a pharmacist reviewed the participant’s medication and made recommendations to the GP. This review was based on the medical records without the pharmacist seeing the patient and was usually conducted remotely. Funding for the pharmacist’s time was based on an estimate of 10 minutes per review. The pharmacist was either seconded from the local CCG/health board or was already working as the practice pharmacist.

3D general practitioner appointment

Practices were advised to invite the patient to attend the second 3D review appointment with their named GP approximately 1 week after the nurse appointment. The GP reviewed the test results, the pharmacist’s recommendations and the 3D agenda following the nurse appointment to address the priorities and identified problems. Goals were negotiated with mutually agreed actions for patients and clinicians. Practices were advised to allow a double appointment (approximately 20 minutes) for the GP 3D review.

Care planning

At the end of the 3D nurse consultation, information about the patient’s priorities was combined with information about test results and any problems identified by the nurse and merged into a ‘patient agenda’ document, which was printed and given to the patient (see Appendix 7). The patient was asked to bring this to their subsequent GP appointment. The idea was that sharing information with the patient would help to promote self-management.

At the end of the 3D GP consultation, goals were agreed between the patient and doctor, accompanied by actions that the patient could take and that the health professionals could take to address each goal. These goals and actions were merged into a 3D health plan, which was printed and given to the patient, again to promote self-management (see Appendix 8). The term ‘health plan’ was chosen to avoid confusion with care plan. At the time of this study, ‘care plans’ were being created for the unplanned admissions directed enhanced service and sent to patients. However, unlike the 3D health plan, these unplanned admission ‘care plans’ mainly consisted of a synopsis of medical information to be shared between health professionals rather than being a document including patient goals to promote self-management.

Components relating to supporting practices to provide the intervention

We used a number of evidence-based strategies to try to ensure that the intervention was implemented in the way intended. 68

Training/researcher intervention

Practice training was delivered within practices over two sessions by at least one researcher and one GP trainer. All clinical staff (GPs, practice nurses and research nurses) who would be delivering the 3D review consultations were expected to attend training. The external pharmacist and hospital consultant/geriatrician were also invited. Although the original intention was to train practices together, the pilot study indicated a need to deliver training in each practice and be flexible over timing, for example by running both sessions in one day or running the sessions multiple times over several practice lunch breaks.

In the first training session (session A), practice staff discussed the problems facing patients with multimorbidity and how their practice currently managed these patients. The principles and strategies of the 3D approach were introduced and, using a case study patient and other examples, discussion took place around how these strategies could be applied. This session primarily focused on identifying patient priorities, promoting patient-centred care and promoting the importance of mental health alongside physical health. Practice staff were encouraged to feed back concerns about implementing the study and what they considered the positive or important aspects of the 3D model.

The second training session (session B) concentrated on more practical elements of the 3D review consultations, including negotiating goal-setting, creating a health plan and using the 3D template. This usually involved using one of the practice’s consented patients as a worked example.

The training materials, including slides and tasks, are included in Report Supplementary Material 1 and 2.

Administrative staff also underwent training, including discussion of the 3D cards, 3D named GP pop-ups and the requirement to offer longer appointments with the named GP or nurse. Suggestions were made for how to implement the last of these (e.g. by reserving an extended appointment slot for participating 3D GPs each day).

Flexibility in delivering the 3D intervention

Owing to the pragmatic nature of the study, local adaptation of the intervention was permitted to reflect local contexts, although key elements of the conceptual framework were maintained. For example, practices were allowed flexibility in how they integrated 3D with their existing systems for organising long-term condition review appointments. A suggested template letter was provided, although some practices used their own letters asking participants to call for an appointment or telephoned participants with a set appointment time. The time allocated for nurse and GP reviews were also flexible and often based on how existing consultation slots were timetabled.

Practices were required to provide two pairs of 3D reviews over 12 months. However, the decision to recall participants for review was made at their discretion. For example, if the practice used a system of recalling patients in the birthday month, or time from last review, they could choose to fit the 3D reviews into their existing systems.

Financial incentives

Practices were reimbursed to cover the cost of staff attending 3D training sessions and setting up the necessary patient recall systems. Practices were also given financial incentives (£30 per patient for each 3D review consisting of both a nurse and a GP consultation). This incentive was not intended to cover the full cost of providing care, because practices are already paid by capitation and completing the 3D review would fulfil their requirements for chronic disease reviews under the QOF, for which they are also paid. Rather, the modest incentive was to encourage them to implement the new form of care, particularly given their concerns that it may generate extra work.

General practitioner practice champions

Each intervention practice nominated a practice champion to monitor and promote the 3D approach. They acted as a direct point of contact for the research team, provided feedback from the practice and disseminated monthly monitoring feedback and newsletters from the research group.

Nominated 3D GP champions were invited to meet other champions in their region every 4 months. This was an opportunity to share ideas and experiences of 3D implementation and delivery within local collaboratives. Local researchers facilitated these meetings following a semistructured format, which included enquiries about what was going well and not so well with the 3D approach and sharing ideas about how to overcome any difficulties. Any important issues raised at the meetings were fed back to the TMG.

Monthly monitoring feedback

All intervention practices were requested to run a monthly purpose-designed search that extracted data on the number of 3D reviews completed and other aspects of the intervention, such as continuity of care and the number of health plans printed. This enabled the research team to monitor the progress of 3D review delivery and the completeness of the reviews but also acted to encourage practices to continue to deliver the intervention. A performance graph comparing all intervention practices was circulated to the GP champions to encourage a sense of competition. (See Appendix 2 for a table of monitoring/feedback items and Appendix 3 for an example of a practice feedback report.)

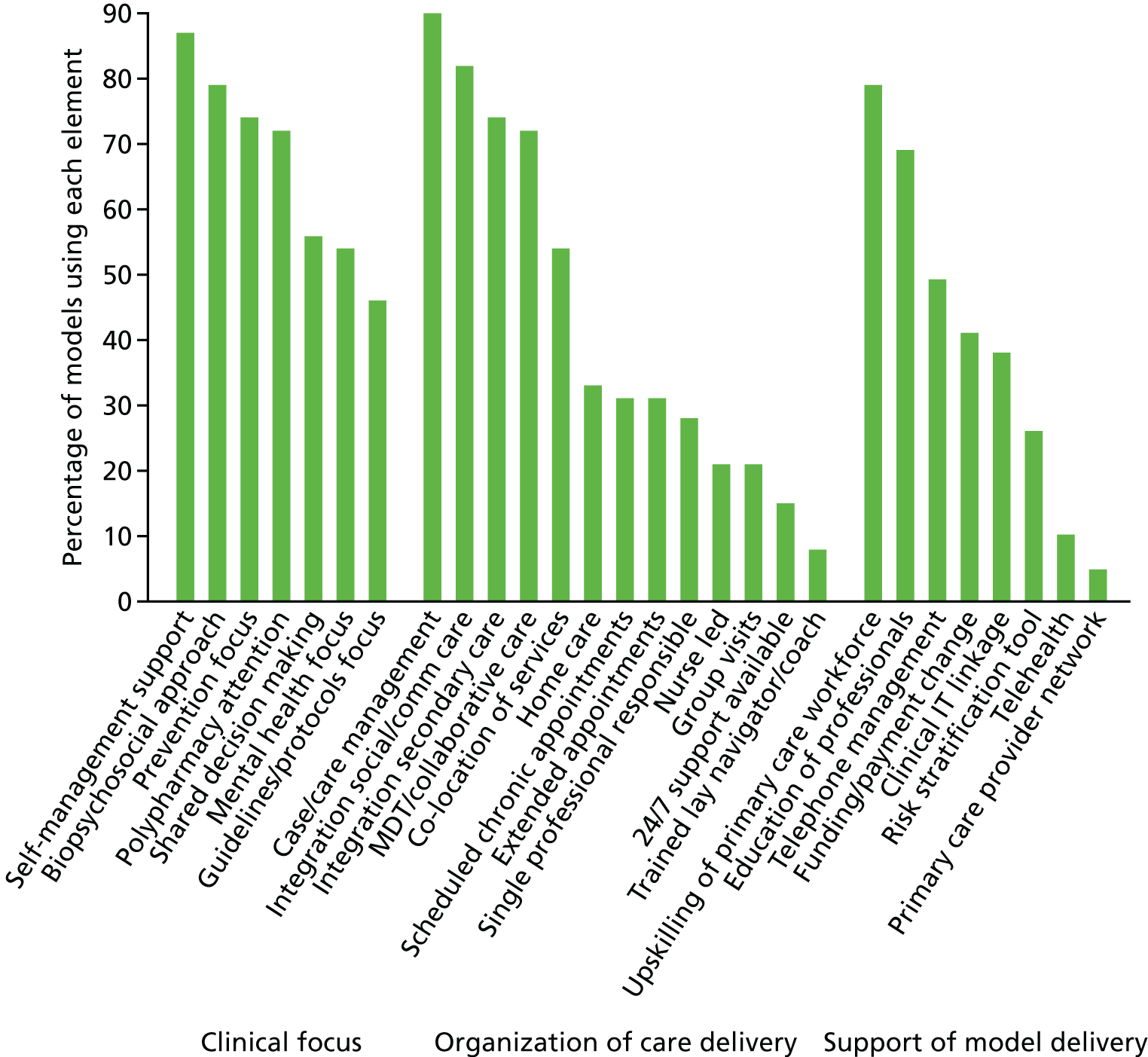

How the 3D intervention compares with other interventions for multimorbidity

During the course of the 3D study we undertook a review of previous models of care for multimorbidity in order to provide a framework by which different interventions could be compared. 69 We identified 39 different models of care described in 68 research papers. Not all of these models have been subject to the rigorous evaluation being conducted for the 3D approach. We created a framework that identifies two foundations for these models (the theoretical basis, and defined target population) and three categories of care elements to implement the model in practice: (1) clinical focus, (2) organisation of care delivery and (3) support for model delivery. Figure 3 shows the percentage of models in the current literature that use each element of the framework. All of the elements shown are included in the 3D approach, except ‘integration of social/community care’, ‘group visits’, ‘trained lay navigator’ and ‘telehealth’. This shows that the 3D approach is relatively comprehensive and covers most of care elements included in other interventions.

FIGURE 3.

Current models of care for multimorbidity: elements included. Reproduced with permission from The Foundations Framework for Developing and Reporting New Models of Care for Multimorbidity, November/December, 2017, Vol. 15, No. 6, issue of Annals of Family Medicine. Copyright © 2017 American Academy of Family Physicians. All Rights Reserved. 69

Optimisation of the intervention and pilot study

Prior to commencing the main trial, three GP practices (two in Bristol and one in Manchester) were recruited to pilot the trial procedures and optimise the intervention. All procedures were delivered as intended for the trial, with additional evaluation from local researchers, the process evaluation team and practice staff feedback. This allowed us to check that our recruitment rate estimates were feasible, training was acceptable and information technology (IT) (computerised search routines, intervention template and data monitoring searches) worked smoothly across a range of practices. Many useful suggestions led to amendments and refinement of the study documentation and procedures. Because the practices were aware of the pilot nature of the intervention, and received additional access, support and feedback from the research team, their patient participant data were not included in the main analyses.

Unfortunately, because of delays in developing the IT, there was insufficient time to complete a full pilot study with complete follow-up before the main study began. The pilot phase began 6 months prior to the main trial, which allowed changes to be made to recruitment, data collection and implementation of the intervention before the main study. The amendments made to the main study as a result of suggestions from the pilot are summarised in Appendix 4 (see Table 37).

There were two significant changes. In the light of experience in the pilot study and the first practices recruited to the main trial, we found that it often took several months to arrange training sessions for intervention practice staff, to install the required IT and for practices to rearrange their appointment systems to invite participating patients. To allow for a lag of approximately 3 months, the time point for collecting outcome data was changed after the pilot study from 6 months and 12 months following recruitment at the baseline time point (T0) to 9 months [9-month post-randomisation time point (T1)] and 15 months [15-month post-randomisation time point (T2)].

Second, we originally designed the trial as a whole-system change in which all patients with multimorbidity in practices allocated to the intervention would receive the 3D approach. This would have replicated as far as possible the organisational changes needed to implement the intervention in real life. However, this design was rejected after the pilot study because of difficulties in recruiting practices, partly because of their concerns that the 3D approach would create additional work, and partly because a whole-system reorganisation required all GPs in the practice to agree to participate in the trial (in many practices, some but not all GPs were willing to participate). Furthermore, this whole-system approach would mean that services had to be reorganised for the large number of patients with multimorbidity, but only a minority of them would contribute data to the research (because we required individual patient consent). This would be a financially inefficient use of research funds. Furthermore, it would be disruptive for both patients and practices to change care for a large number of patients just for 1 year and then to change back again once the research was over. We, therefore, offered the 3D intervention only to patients who gave consent to participate in the trial.

Chapter 4 Methods

The material in this chapter is adapted from Man et al. 70 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

The material in the section on Process Evaluation methods is adapted from Mann et al. 71 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

Study setting

General practices serving three areas: around Bristol and Greater Manchester in England and Ayrshire and Arran in Scotland.

Recruitment of general practices

The study was restricted to practices using the EMIS system (web or PCS versions). EMIS is the most common clinical records system in UK general practice and the intervention template was designed for this system only.

Practice inclusion criteria required a minimum of two GP partners and a minimum list size of 4500. We excluded small practices to ensure an adequate patient population pool and because the intervention may be less relevant and harder to implement in very small practices with few staff and existing high levels of continuity of care.

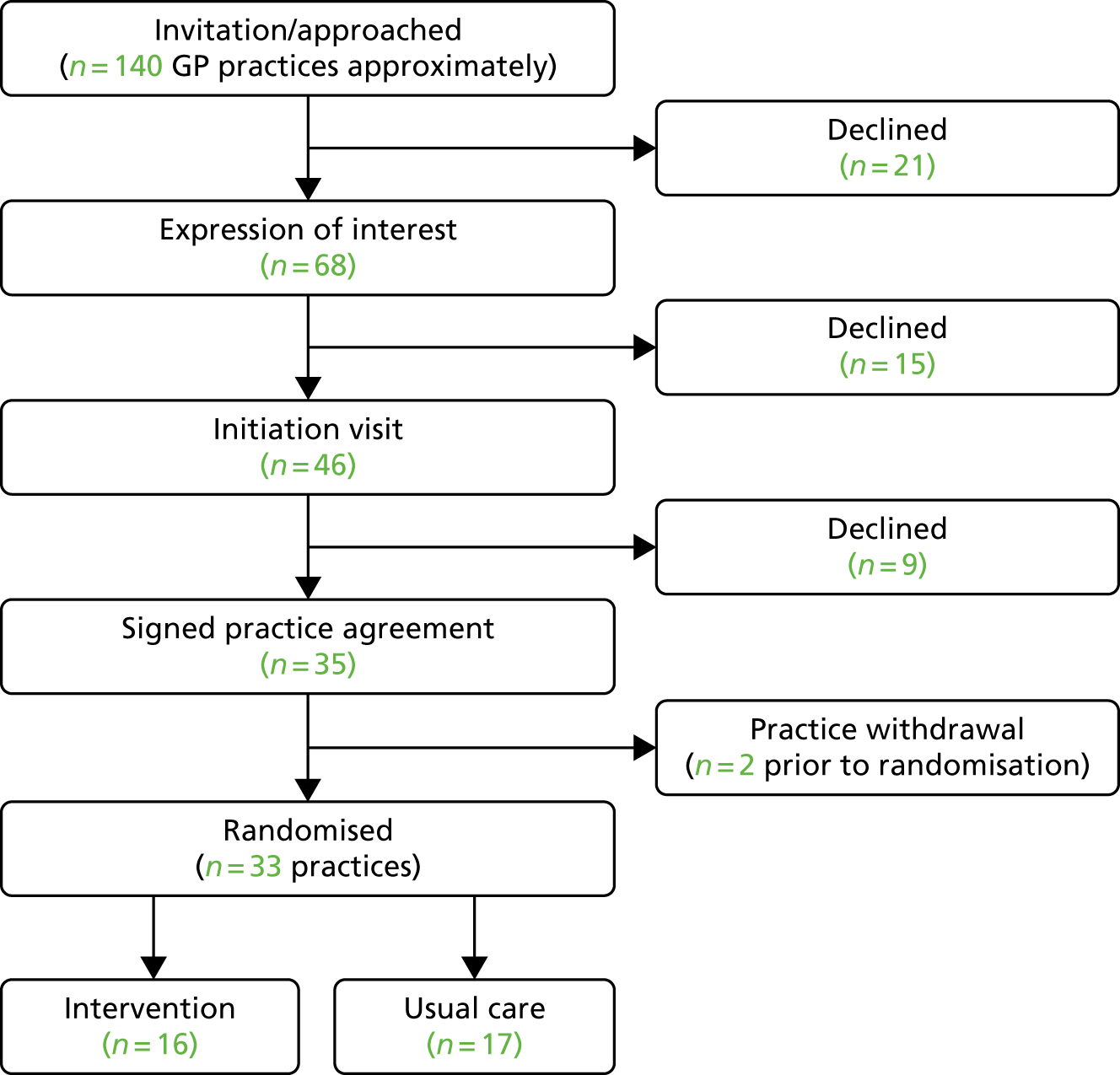

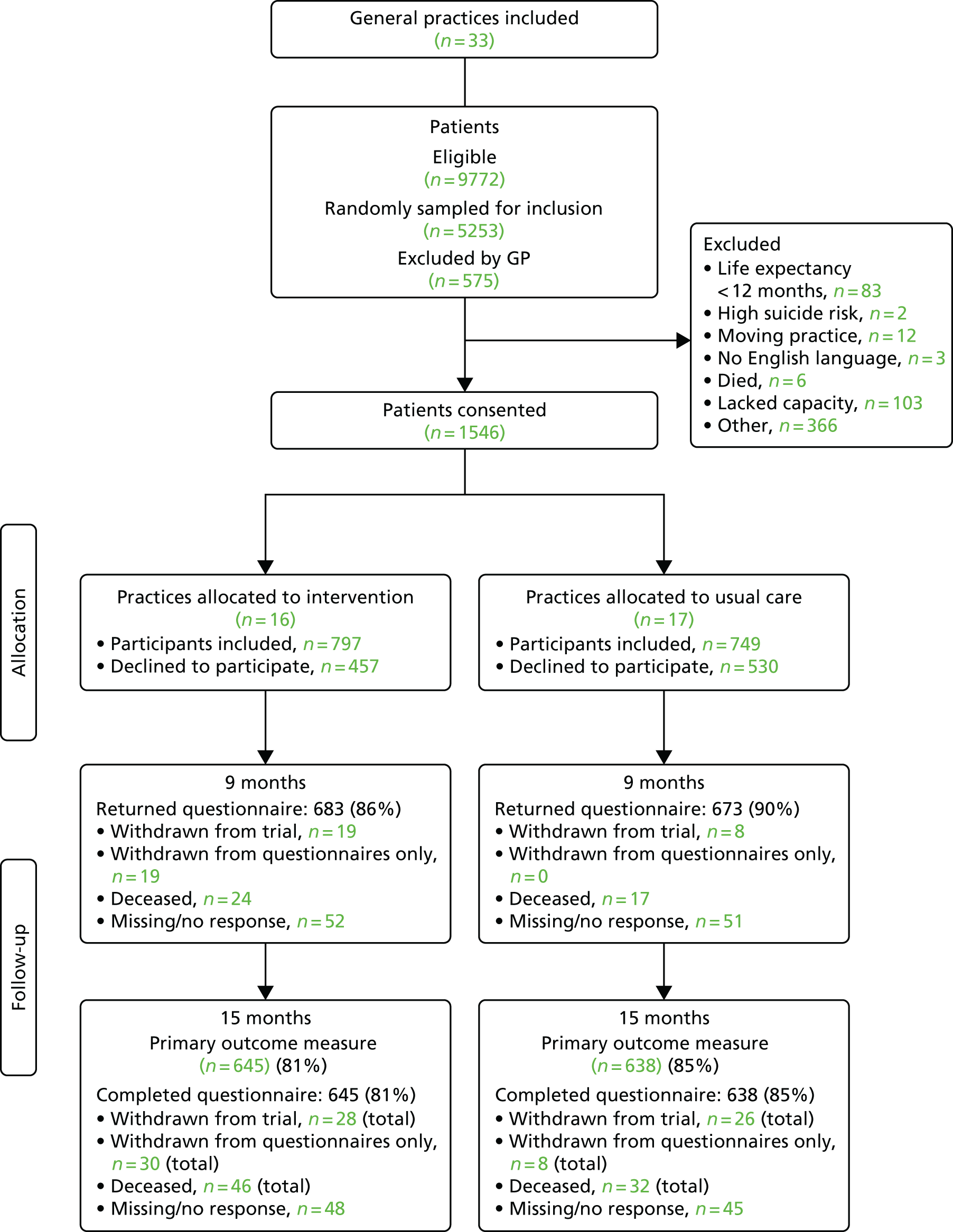

Practices were approached via the Comprehensive Local Research Networks, the Scottish Primary Care Research Network and NHS Clinical Research Network (CRN) events, and cascaded via research active practices. Local researchers met with key practice stakeholders (practice manager, GPs and practice nurses) to explain the study and the organisational changes required. If the practice agreed to take part, a practice-level consent agreement form (see Report Supplementary Material 3) was signed before practices were randomised. Practice recruitment is represented in Figure 4. Because of the variety of ways in which practices heard about the trial, with some just receiving information as part of a newsletter informing research-active practices about studies open to recruitment, it is difficult to define a clear denominator for the number of practices invited to participate.

FIGURE 4.

General practice recruitment flow chart.

Recruitment of participants

Eligibility criteria

Participant inclusion criteria were adults, aged ≥ 18 years and having three or more long-term conditions from a list of those included in the NHS QOF, version 31.0 (Box 1).

-

Cardiovascular disease or chronic kidney disease (including coronary heart disease, hypertension, heart failure, peripheral arterial disease, chronic kidney disease stage 3 to 5). a

-

Stroke.

-

Diabetes mellitus.

-

Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease or asthma. a

-

Epilepsy.

-

Atrial fibrillation.

-

Severe mental health problems (schizophrenia or psychotic illness). a

-

Depression.

-

Dementia.

-

Learning disability.

-

Rheumatoid arthritis.

If a patient had multiple conditions within a group, this was counted only once. For example, having both hypertension and heart failure would just count for one condition.

Reproduced from Man et al. 70 This is an Open Access article distributed in accordance with the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt and build upon this work, for commercial use, provided the original work is properly cited. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/.

Patients were excluded if they had a life expectancy of < 12 months, were deemed by the GP to be at serious suicidal risk, were known to be leaving the practice within 12 months, were unable to complete questionnaires even with the help of carers, were actively taking part in other research involving extra visits to primary care or other health services, lacked capacity to consent (this exclusion applied in Scotland only) or were considered otherwise unsuitable as determined by their GP (e.g. recently bereaved or currently hospitalised). GPs were asked not to exclude people on the basis of being elderly or frail, having a diagnosis of dementia or being housebound. Although these patient groups are frequently excluded from other research studies, this study may be particularly relevant to such patients.

For sites in England, REC approval allowed the inclusion of patients who lacked capacity by obtaining a signed declaration from the patient’s carer, legal guardian or consultee on behalf of the patient (see Report Supplementary Material 4). In Scotland, it is not lawful to recruit patients without capacity if the research could be conducted without them, and patients without capacity to consent were excluded there.

Identification and consent of patients

Participating practices ran a custom-built search, based on pre-defined read-codes, which identified patients with health conditions within the inclusion criteria. The presence of three or more conditions made the patient eligible.

If > 150 patients per practice were eligible, a simple random sample of 150 was selected. GPs screened the resultant list for any patients meeting the exclusion criteria. The remaining patients were sent a patient study invitation pack, containing a study invitation letter, patient information sheet, consent form, baseline questionnaire and a freepost return addressed envelope (see Report Supplementary Material 5–7 and Appendix 9). We estimated that selecting 150 patients would enable us to recruit at least 43 patients per practice (the target from the sample size calculation) after allowing for GP exclusions and patients who were subsequently found to be ineligible, declined participation or failed to respond.

In some practices, not all GPs took part. In practices with > 150 eligible patients, we selected patients with a participating GP and then a sample of other patients where necessary to meet the recruitment target. This was to minimise the number of patients who would be asked to see a different doctor from their usual GP for the purpose of the study.

Patients agreeing to participate signed the consent form, completed the questionnaire and returned both using the return envelope.

During development of the study procedures and the pilot phase, the patient and public involvement (PPI) group reviewed the patient invitation documentation and suggested the need for an active decline procedure (should patients wish to not take part, they were asked to return the empty questionnaire) to ensure that reminders were not sent to people who declined.

Non-respondents were sent one postal reminder and the practice had the option of telephone reminders if the recruitment target was not met.

Recruitment of carers

Formal or informal carers of consented patients were invited to contribute to a substudy investigating their views and experiences. Carer information sheets, carer consent forms and carer baseline surveys were used (see Report Supplementary Material 8–10 and Appendix 10).

Randomisation, concealment and blinding

Practices were the unit of allocation and were allocated in a 1 : 1 ratio to receive either the intervention or continue care as usual (control group). Randomisation was stratified by area (Bristol, Greater Manchester or Ayrshire) and minimised by practice deprivation and list size. The minimisation algorithm retained a probabilistic element, which varied depending on the degree of imbalance between arms (see Appendix 11).

To ensure concealment of allocation, the randomisation procedure was performed by the trial statistician blind to the practice details, using a randomisation system run from the Bristol Randomised Trials Collaboration (BRTC). Allocations were performed in blocks of two in each area. We waited until a pair of practices had been recruited at any one site and then randomly allocated both practices simultaneously and released details of the allocation at the same time to local researchers so that those recruiting practices were unaware of the next allocation. Practice randomisation occurred only after eligible patients had been invited to participate.

After randomisation, the statistician informed the research team, which communicated the allocation to the practice and arranged practice set-up in the intervention practices. The research team also informed participants of their practice’s allocation by post. Participants were notified several weeks after practices were allocated, once practices had been trained and were ready to start delivering the intervention.

Owing to the nature of the intervention, it was not possible to blind participants to their treatment arm after allocation, nor was it possible to blind the research team to allocation when they collected data from GP records. The primary outcome and most secondary outcomes were collected by patient self-report but entered on to the database and analysed blind to allocation. The trial statistician became unblinded when she presented the main results to the TSC and DMC. It was not possible for her to remain blind when analysing the process measures.

Intervention arm

The intervention was the 3D approach to the management of multimorbidity in general practice, which is described in the preceding chapter.

Usual-care arm

Practices allocated to the usual-care arm continued to provide their patients with care as usual. In many practices this meant that patients would be called to different long-term condition clinics, possibly seeing different nurses and doctors, which may focus on collecting data related to QOF targets rather than a patient’s priorities or quality of life.

Usual care was likely to vary between practices depending on the practice size and staffing, the demographics of the practice population, area deprivation levels and local/regional circumstances. In addition, practice circumstances could change with staff being ill or leaving the practice, changes to infrastructure such as practices merging or the introduction of other policies or higher-level initiatives.

The nature of usual care in both intervention and control practices was examined at the beginning and end of the study as part of the process evaluation.

A checklist describing the content of the intervention and usual-care arms using the TIDieR framework55 is provided as Report Supplementary Material 11.

Outcome measures

The outcome measures were chosen to reflect the problems and strategies that the intervention was designed to address (Figure 5). Although this trial included a large number of secondary outcomes, this reflects the complex nature of the intervention, which included a number of strategies operating at the different levels of practice, clinician and consultation.

FIGURE 5.

Relationship between strategies in 3D intervention and outcomes. COC, continuity of care; EQ-5D-5L, EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version; HADS, Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale; LTC6, Six-item Long-Term Conditions questionaire; MMAS-8, Morisky Medication Adherence Scale-8 item; PACIC, Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care Scale.

Outcomes were measured following recruitment (T0), at 9 months (T1) and 15 months (T2). The original plan was to collect data after 6 months and 12 months but this was changed after the pilot study in the light of experience that it took about 3 months for practices to be trained and set up to deliver the intervention.

The first follow-up at 9 months was conducted because it was plausible that the 3D intervention would be effective only in the short-term, with any effects disappearing by 15 months. However, such shorter-term effects may still warrant implementation of 3D into primary care practice. The 15-month follow-up period was chosen as the longest duration of follow-up deemed feasible in this trial, although the effects of the intervention may accumulate over a longer period if the intervention was continued, with regular 3D reviews every 6 months.

Primary outcome measure

The primary outcome was health-related quality of life as measured by the EuroQol-5 Dimensions, five-level version (EQ-5D-5L) at 15 months. This generic health status measure has five dimensions (mobility, self-care, usual activities, pain/discomfort and anxiety/depression), each of which is scored on a five-point scale from ‘no problems’ to ‘extreme problems’.

Secondary outcome measures

A series of secondary outcome measures were collected to examine health domains targeted by the intervention and believed to be important in multimorbidity.

The patient secondary outcomes are listed in Table 1 and described below.

| Secondary outcome | Source | Scale | Time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | |||

| Experience of holistic patient-centred care | |||||

| CARE measure of relational empathy (GP) | Questionnaire – 10 items | 10–50 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| CARE measure of relational empathy (nurse) | Questionnaire – 10 items | 10–50 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Care related to patients’ priorities (LTC6) | Questionnaire – 1 item | 1–4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Care that is joined up (LTC6) | Questionnaire – 1 item | 1–4 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| PACIC measure of chronic disease management | Questionnaire – 20 items | 1–5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Overall satisfaction | Questionnaire – 1 item | 1–5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Burden of illness measures | |||||

| EQ-5D-5L | Questionnaire – 5 items | ✓ | ✓ | ✗a | |

| Self-rated health | Questionnaire – 1 item | 1–5 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Bayliss measure of illness burden | Questionnaire – 27+ items | 0–145 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| HADS Anxiety score | Questionnaire – 7 items | 0–21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| HADS Depression score | Questionnaire – 7 items | 0–21 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Burden of treatment | |||||

| Multimorbidity Treatment Burden Questionnaire | Questionnaire – 10 items | 0–100 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Medication adherence: MMAS-8 | Questionnaire – 8 items | 0–8 | ✓ | ✓ | ✓ |

| Number of drugs prescribed | Practice records | ≥ 0 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Number of high risk prescribing indicators | Practice records | ≥ 0 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Process outcomes | |||||

| Continuity of care – COC index | Practice records | 0–1 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Continuity of care – Visit Entropy | Practice records | 0–log2(1/k) | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Quality of disease management | Practice records | 0–100 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Number of hospital admissions | Practice records | ≥ 0 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Number of outpatient attendances | Practice records | ≥ 0 | ✓ | ✗ | ✓ |

Consultation and Relational Empathy measure (CARE): this is a measure of relational empathy. It consists of a 10-item questionnaire and a total score based on a summation of individual scores. 72

Six-item Long-Term Conditions questionnaire (LTC6): this is a brief 6-item questionnaire designed to measure patient perceptions of aspects of their long-term condition management. Two questions from the LTC6 were included: ‘Did you discuss what was most important to you in managing your own health?’ and ‘Do you think the support you receive is joined up and working for you?’.

Patient Assessment of Chronic Illness Care Scale (PACIC): this is a 20-item questionnaire designed to measure specific actions or qualities of care that reflect patient-centred care within the Chronic Care Model, including patient activation, delivery system design, decision support, goal-setting, problem-solving and follow-up/co-ordination of care. 73

Overall satisfaction: a single question item on a five-point scale about how satisfied the participant was with the care they received at their GP surgery or health centre.

EQ-5D-5L (at 9 months): this was the primary outcome at 15 months but treated as a secondary outcome at 9 months.

Self-rated health: a single question item on a five-point scale about self-rated health, from ‘poor’ to ‘excellent’.

Bayliss measure of illness burden: for each of 27 long-term conditions, respondents selected those that they experience and rated each selected condition on a five-point scale from 1 (interferes with daily activities ‘not at all’) to 5 (interferes with daily activities ‘a lot’). Respondents were additionally allowed to add medical conditions not already on the list. The overall score representing level of morbidity is then the sum of conditions selected weighted by the level of interference assigned to each (i.e. the sum of the interference scores). 74

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Score (HADS): this consists of seven questions on anxiety and depression. Responses are summated to produce separate scores for anxiety and depression. 75

Multimorbidity Treatment Burden Questionnaire (MTBQ): this was based on a new questionnaire developed and validated by the research team. Details of the scale development and validation are published elsewhere. 76 The measure consists of 10 items each scored from 0 to 4. The total score was calculated by calculating the average score for each patient and then multiplying by 2.5 to get a value from 0 to 100.

Morisky Medication Adherence Scale – 8 item (MMAS-8): this is a validated measure of adherence to medication. 77–79 Use of the © MMAS is protected by US Copyright laws. Permission for use is required. A licence agreement is available from Donald E Morisky, MMAS Research LLC, 14725 NE 20th, St Bellevue, WA 98007, USA or from dmorisky@gmail.com.

Number of drugs prescribed: this was based on the number of different drugs prescribed to each participant in the previous 3 months, extracted from medical records. Each different drug name was counted as one, irrespective of dosage or quantity, and multiple prescriptions of the same drug were counted just once.

Number of high-risk prescribing indicators: this was based on a number of > 100 indicators of potentially inappropriate prescribing developed for the Prescribing Outcomes from implementing Enhanced Medication Summaries (POEMS) and Data-Driven Quality Improvement in Primary Care (DQIP) studies80 by one of the research team (BG). The indicators were mainly drawn from existing recognised indicators (Beers, START/STOPP, RCGP criteria)81–83 adapted for implementation in electronic medical records. The score represents the number of adverse warnings of potentially inappropriate prescribing triggered for each patient.

Continuity of care: this was assessed in relation to face-to-face (home or surgery or nursing home) or telephone consultations between participants (not family members/carers) and GPs [not nurses, health-care assistants (HCAs) or medical students] over the 12 months before recruitment and the 15 months after recruitment during which the participant was in the trial. Longitudinal continuity of care was measured in two ways: first, using the well-established Continuity of Care (COC) Index84 and, second, using the Visit Entropy measure. 85 Visit Entropy is a relatively new measure, in which higher entropy indicates greater randomness (i.e. less continuity). Visit Entropy H(X) of a discrete random variable X can be calculated as:

and the probability of visiting the ith provider is estimated as:

where ni is the number of observed visits to the ith provider, k is the total number of possible providers, and N is the total number of observed visits. H(X) approaches its minimum value of zero when a patient has perfect continuity of care, visiting only their primary physician, and approaches its maximum when there is no continuity of care.

Quality of disease control: this is based on the QOF indicators and uses the ‘patient average’ method of Reeves et al. 86 It was measured as a percentage for each individual patient, whereby it represents the percentage of QOF chronic disease management indicators that apply to that patient which were successfully met.

Number of admissions and number of outpatient attendances: these have important consequences for policy and will, therefore, be reported as separate outcomes. They are based on data extracted from medical records.

Carer outcomes

The impact of the 3D intervention on carers was assessed by a self-reported carer survey as part of the carer substudy. The carer outcome measures were collected at the same three time points as the patient questionnaires:

-

Carer experience scale87,88 – this is a 6-item questionnaire. Preference-based index values are available to transform the six responses to a profile measure value between 0 and 100.

-

Carer health-related quality of life (EQ-5D-5L).

-

Multimorbidity Treatment Burden Questionnaire for Carers (adapted from the MTBQ).

Sociodemographic measures

The following sociodemographic measures were collected from the self-reported questionnaires at baseline:

-

age

-

sex

-

ethnicity

-

education

-

work status

-

number of long-term conditions, based on responses to Bayliss measure74

-

deprivation status [Index of Multiple Deprivation (IMD), based on domiciliary postcode].

These baseline demographic characteristics were checked for skewness and balance between the two allocation groups. These could form potential effect modifiers or be adjusted for accordingly in the statistical analyses.

Process measures

Patient-level process of care measures were extracted from practice records using a custom search. Data from 12 months prior to practice randomisation and patient recruitment (T0) and through the 15-month study period were compared between trial arms. The measures collected were:

-

number of GP and nurse consultations

-

mean duration of face-to-face consultations with GP and nurse

-

number of different review consultations [e.g. diabetes mellitus, asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), dementia, mental health and rheumatoid arthritis, also including 3D reviews]

-

patients receiving at least one chronic disease review

-

patients reporting having a written care or treatment plan.

The number of chronic disease reviews for some long-term conditions was summarised for each treatment group [diabetes mellitus (based on diabetic foot risk assessment), asthma, COPD, dementia, mental health and rheumatoid arthritis], in each case using the number of participants in the practice with the relevant condition as the denominator. This list of important long-term conditions did not include all the conditions used as inclusion criteria for the trial. However, these were the only conditions in which all practices are incentivised to record reviews, so data were routinely available.

Additional data were collected to describe implementation of the intervention, as shown in Table 2. These data were not relevant to the usual-care arm of the trial.

| Process measure | Source | Scale | Time point | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T0 | T1 | T2 | |||

| Number of nurse 3D reviews | Practice records | 0, 1, 2 | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Number of GP reviews | Practice records | 0, 1, 2 | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Compliancea | Practice records | None, partial, full reviews | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Most important problem noted | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| EQ-5D-5L pain question noted | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| PHQ-9 entered | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Medication reviewed by pharmacist (at least one comment entered) | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Medication adherence noted | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| First patient goal noted | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| First plan noted (‘what patient can do’) | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| First plan noted (‘what GP can do’) | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Patient agenda printedb | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| 3D plan printedb | Practice records | 0 (No), 1 (Yes) | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

| Number of times hospital physician was contacted | Physician records | ≥ 0 | ✗ | ✗ | ✓ |

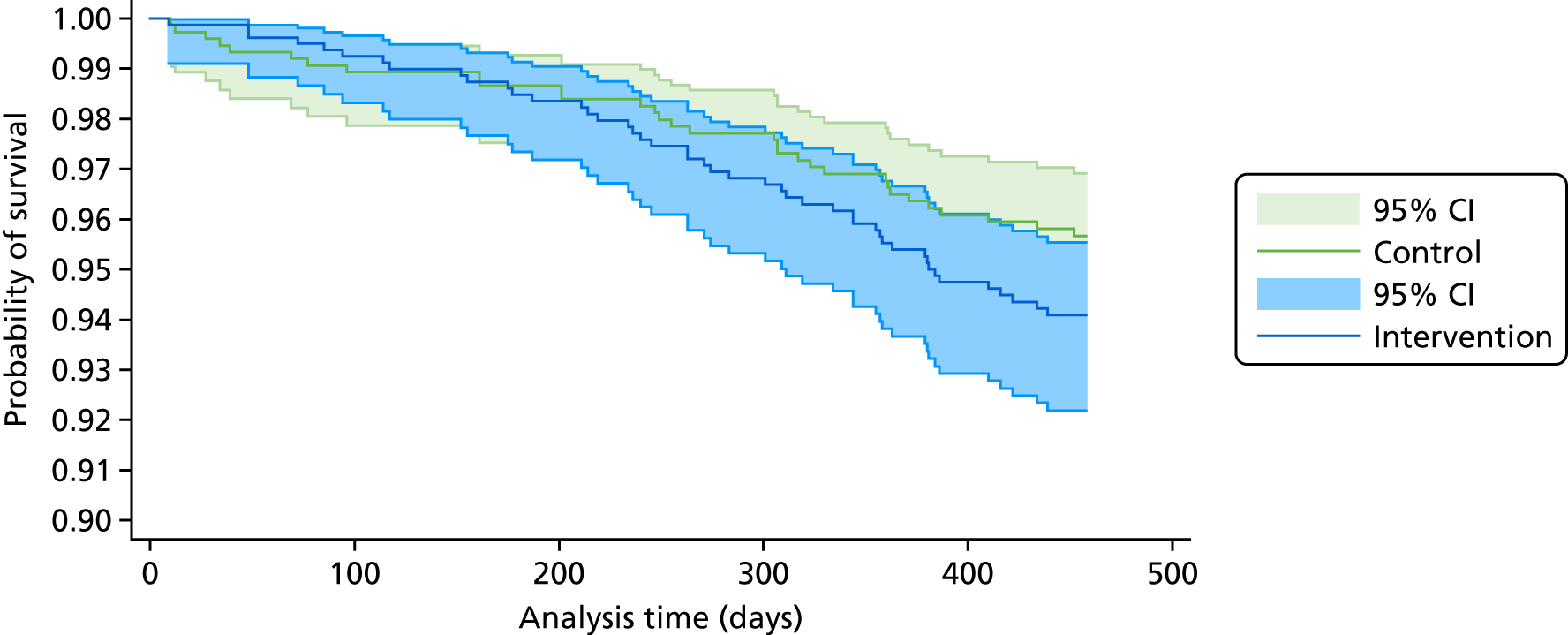

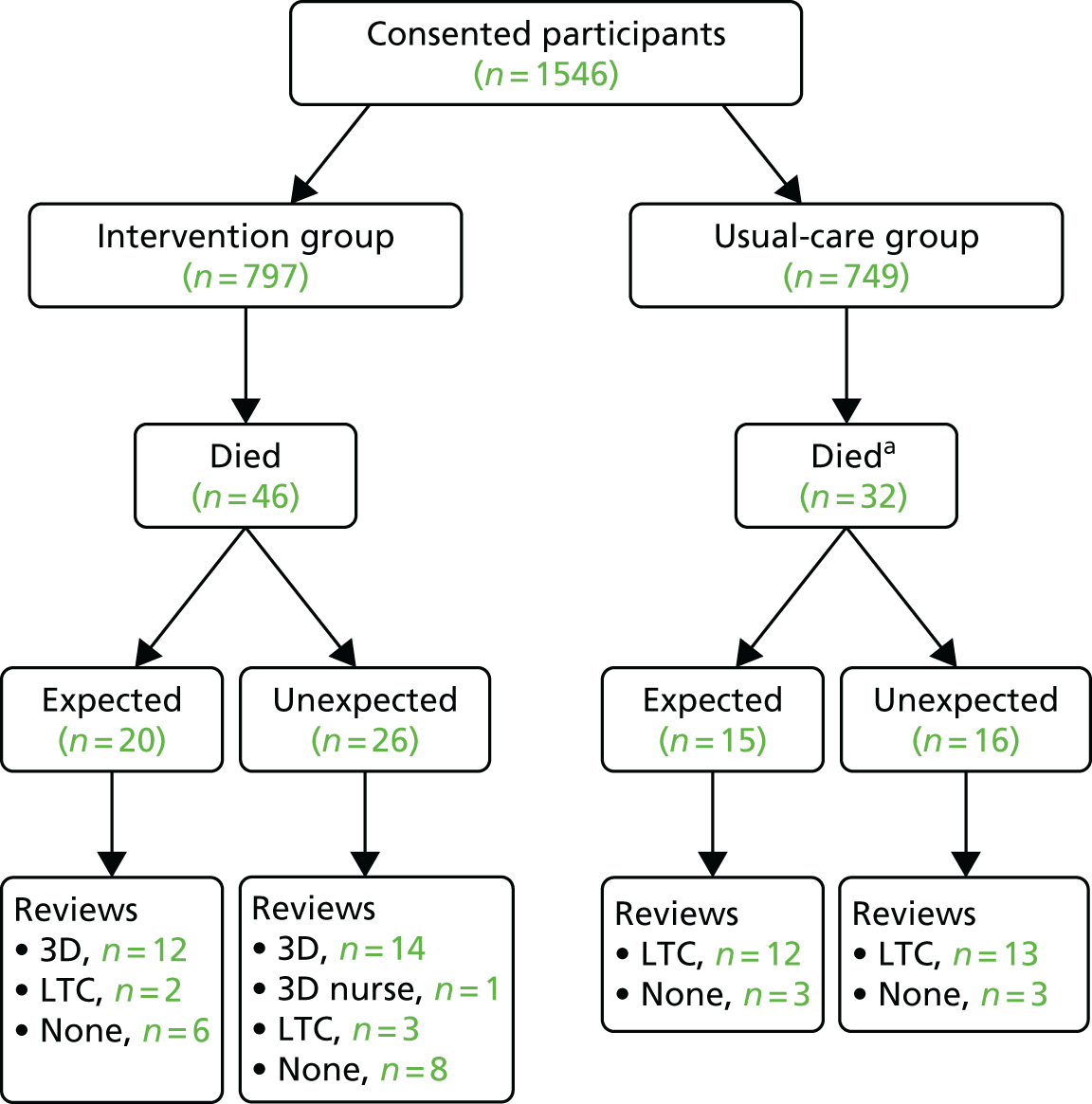

Serious adverse events/reactions and safety

Given the study population, a high frequency of new medical diagnoses, hospital admissions and deaths was expected. It was agreed by all study oversight committees that these would not be considered potential serious adverse events (SAEs) unless participants, practice staff or researchers notified that they considered the event to be related to the intervention or research processes, [i.e. only serious adverse reactions (SARs) would be investigated and reported]. However, all deaths were investigated by requesting than the participant’s GP provide details of the cause of death, expectedness and relatedness to the study (see Report Supplementary Material 12 for deceased reporting form).

All SARs and death reports were reviewed by the trial clinician. Any SARs thought to be related to treatment or research and of unexpected nature were reported immediately to the TSC and funder, and to the REC within 7 days of notification (to allow for further investigation).

Serious adverse events and deaths were monitored and reported regularly to all trial oversight committees.

Data collection, follow-up and data management

Participant study data primarily comprised self-reported questionnaires and the extraction of primary and secondary care usage from patient records.

Questionnaire follow-up procedures

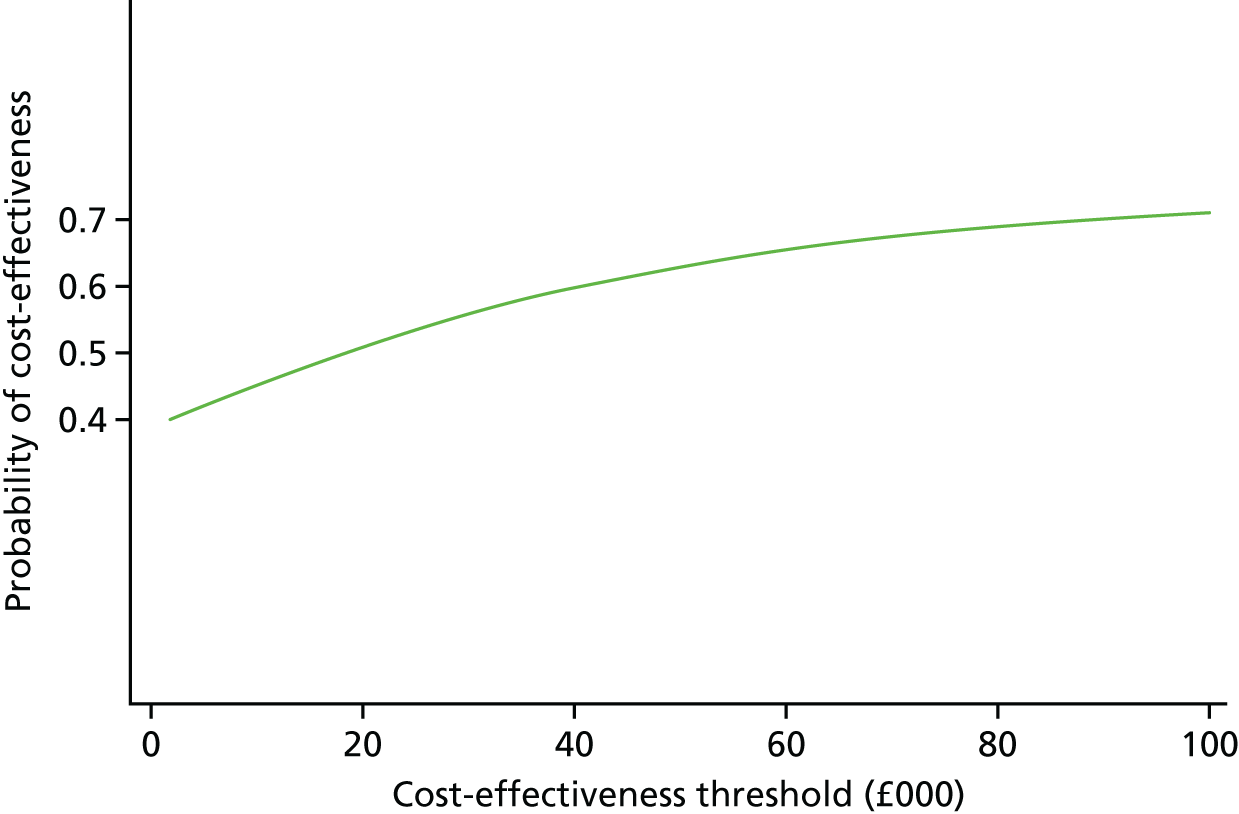

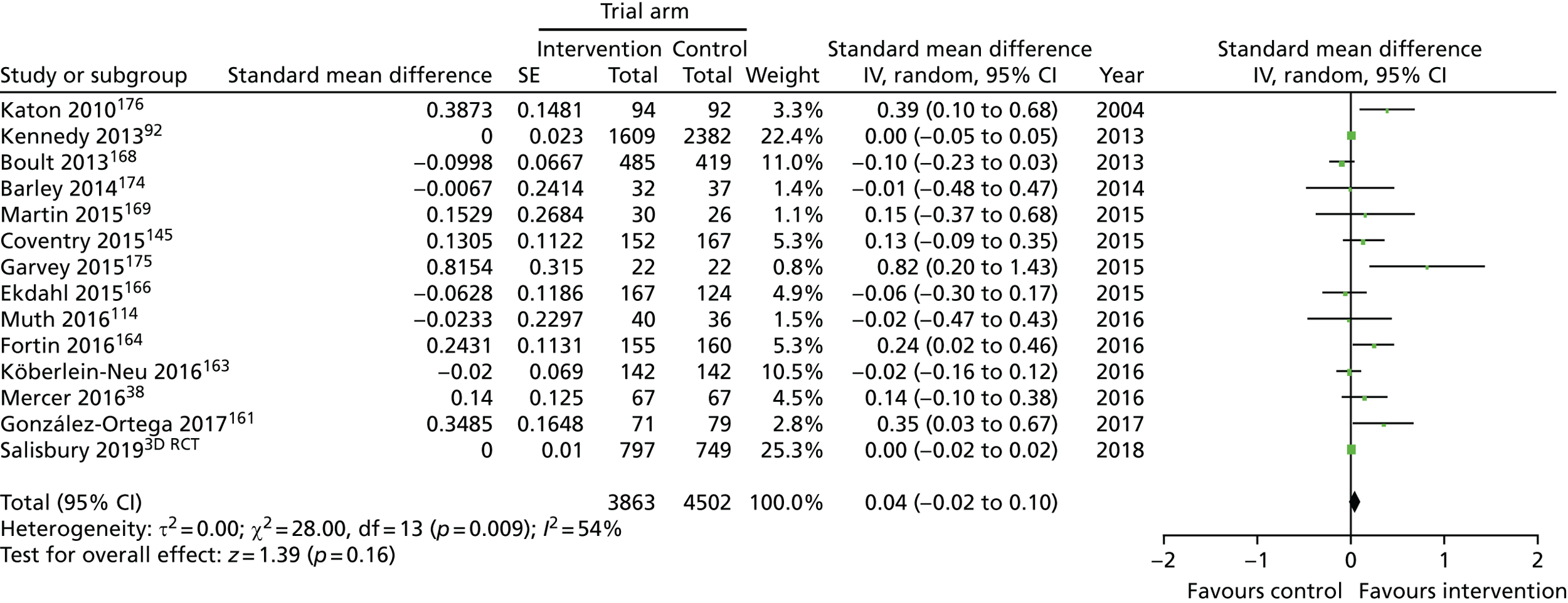

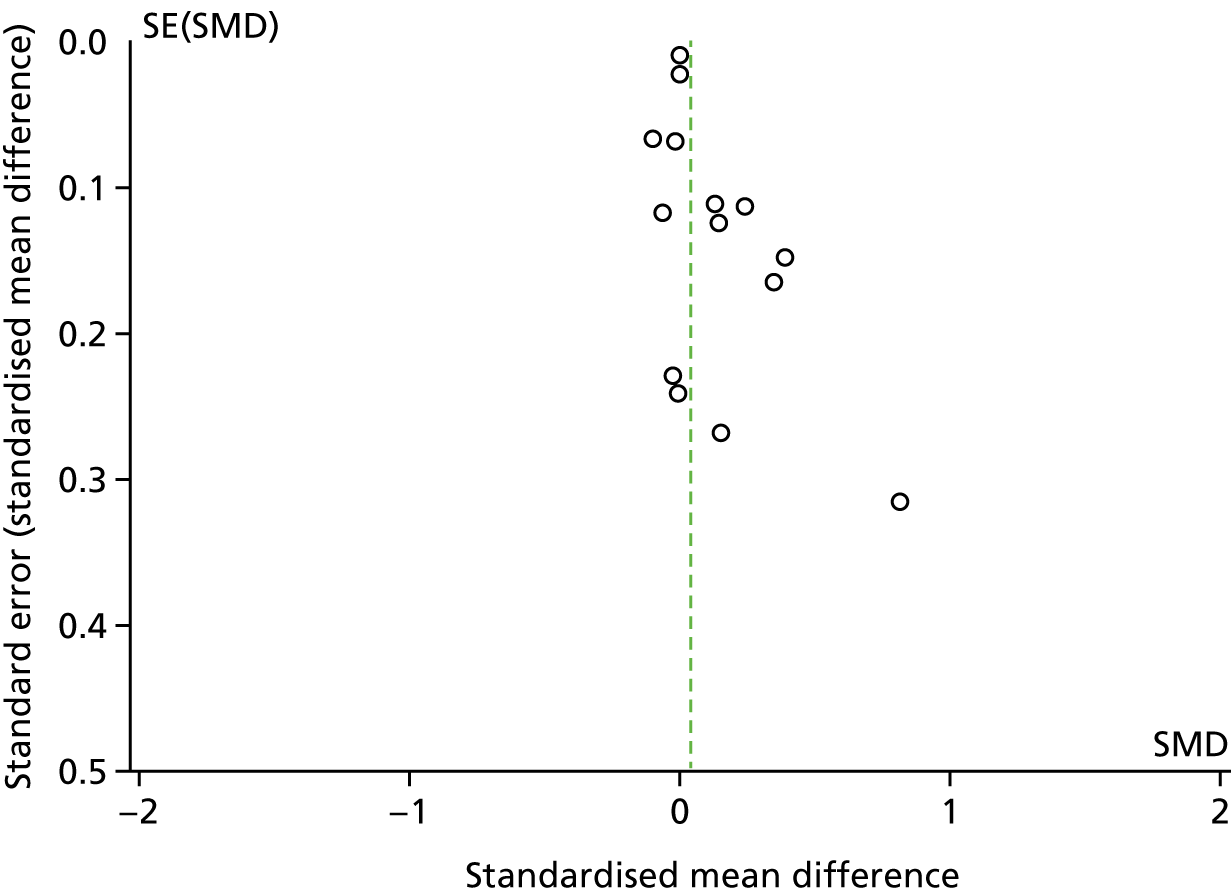

Postal questionnaires were the primary method of data collection. (See Appendices 12 and 13 for copies of the final patient and carer follow-up questionnaires.)